Title: The Way of the Wild

Author: F. St. Mars

Illustrator: Harry Rountree

Release date: January 21, 2006 [eBook #17567]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

| I | GULO THE INDOMITABLE |

| II | BLACKIE AND CO. |

| III | UNDER THE YELLOW FLAG |

| IV | NINE POINTS OF THE LAW |

| V | PHARAOH |

| VI | THE CRIPPLE |

| VII | "SET A THIEF"—— |

| VIII | THE WHERE IS IT? |

| IX | LAWLESS LITTLE LOVE |

| X | THE KING'S SON |

| XI | THE HIGHWAYMAN OF THE MARSH |

| XII | THE FURTIVE FEUD |

| XIII | THE STORM PIRATE |

| XIV | WHEN NIGHTS WERE COLD |

| XV | FATE AND THE FEARFUL |

| XVI | THE EAGLES OF LOCH ROYAL |

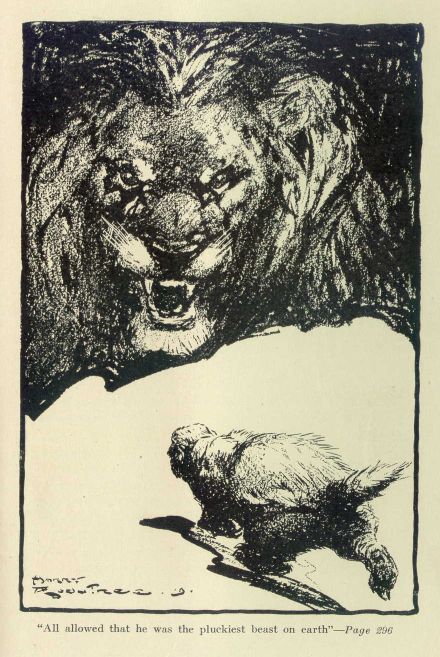

| XVII | RATEL, V.C. |

| XVIII | THE DAY |

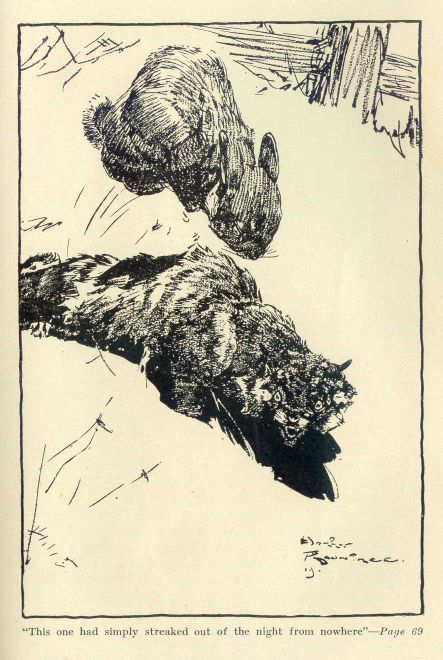

If his father had been a brown bear and his mother a badger, the result in outward appearance would have been Gulo, or something very much like him. But not all the crossing in the world could have accounted for his character; that came straight from the Devil, his master. Gulo, however, was not a cross. He was himself, Gulo, the wolverine, alias glutton, alias carcajou, alias quick-hatch, alias fjeldfras in the vernacular, or, officially, Gulo luscus. But, by whatever name you called him, he did not smell sweet; and his character, too, was of a bad odor. A great man once said that he was like a bear cub with a superadded tail; but that great man cannot have seen his face. If he had, he would have looked for his double among the fiends on the top of Notre Dame. There was, in fact, nothing like him on this earth, only in a very hot place not on the earth.

He was, in short, a beast with brains that only man, and no beast, ought to be trusted with; and he had no soul. God alone knows if love, which softens most creatures, had ever come to Gulo; his behavior seemed to show that it had not. Perhaps love was afraid of him. And, upon my soul, I don't wonder.

It was not, however, a hot, but a very cold, place in the pine-forest where Gulo stood, and the unpitying moon cast a dainty tracery through the tasseled roof upon the new and glistening snow around him—the snow that comes early to those parts—and the north-east wind cut like several razors. But Gulo did not seem to care. Wrapped up in his ragged, long, untidy, uncleanly-looking, brown-black cloak—just his gray-sided, black fiend's face poking out—he seemed warm enough. When he lifted one paw to scratch, one saw that the murderous, scraping, long claws of him were nearly white; and as he set his lips in a devilish grin, his fangs glistened white in the moonlight, too.

Verily, this was no beast—he would have taped four feet and a quarter from tip to tip, if you had worn chain-mail and dared to measure him—no beast, I say, to handle with white-kid ball gloves. Things were possible from him, one felt, that were not possible of any other living creature—awful things.

Suddenly he looked up. The branches above him had stirred uneasily, as if an army were asleep there. And an army was—of wood-pigeons. Thousands upon thousands of wood-pigeons were asleep above his head, come from Heaven knows where, going to—who could tell in the end?

All at once one fell. Without apparent reason or cause, it fell. And the wolverine, with his quick, intelligent eyes, watched it fall, from branch to branch, turning over and over—oh! so softly—to the ground. When he had poked his way to it—walking flat-footed, like a bear or a railway porter—it was dead. Slain in a breath! Without a flutter, killed! By what? By disease—diphtheria. But not here would the terrible drama be worked out. This was but an isolated victim, first of the thousands that would presently succumb to the fell disease far, far over there, to the westward, hundreds of miles away, in England and Wales, perhaps, whither they were probably bound.

But the poor starved corpse, choked to death in the end maybe, was of no use to the wolverine. As he sniffed it he found that out. The thing was wasted to the bones even. And turning away from it—he suddenly "froze" in his tracks where he stood.

One of those little wandering eddies which seem to meander about a forest in an aimless sort of way, coming from and going now hither, as if the breeze itself were lost among the still aisles, had touched his wet muzzle; and its touch spelt—"Man!"

If it had been the taint of ten thousand deaths it could not have affected him more. He became a beast cast in old, old bronze, and as hard as bronze; and when he moved, it was stiffly, and all bristly, and on end.

Animals have no counting of time. In the wild, things happen as swiftly as a flash of light; or, perhaps, nothing happens at all for a night, or a day, or half a week. Therefore I do not know exactly how long that wolverine was encircling that scent, and pinning it down to a certain spot—himself unseen. All animals, almost, can do that, but none, not even the lynx or the wild cat, so well as the wolverine. He is the one mammal that, in the wild, is a name only—a name to conjure with.

He found, in the end, that there was no man; but there had been. He found—showing himself again now—that a man—a hunter, a trapper, one after fur—had made himself here a cache, a store under the earth; and—well, the wolverine's great, bear-like claws seemed made for digging.

He dug—and, be sure, if there had been any danger there he would have known it. He dug like a North-Country miner, with swiftness and precision, stopping every now and again to sit back on his haunches, and, with humped shoulders, stare—scowl, I mean—round in his lowering, low-browed fashion.

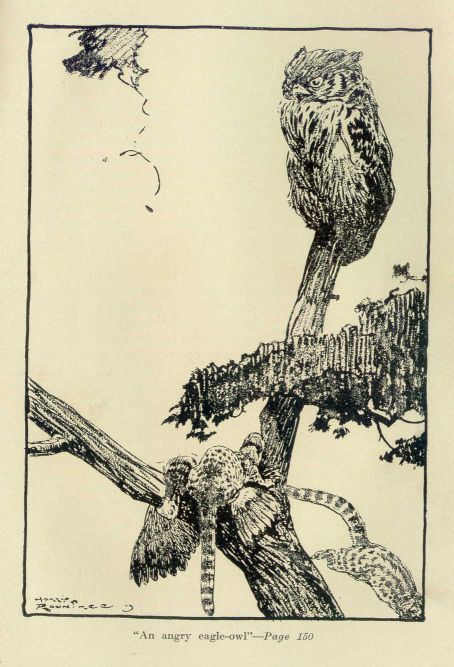

Once a bull-elk, nearly a six-footer, but he loomed large as an elephant, came clacking past between the ranked tree-boles, stopping a moment to straddle a sapling and browse; while the wolverine, sitting motionless and wide-legged, watched him. Once a lynx, with its eternal, set grin, floated by, half-seen, half-guessed, as if a wisp of wood mist had broken loose and was floating about. Once a fox, somewhere in the utter silence of the forest depths, barked a hoarse, sharp, malicious sound; and once, hoarser still and very hollowly, a great horned owl hooted with disconcerting suddenness. (The scream of a rabbit followed these two, but whether fox or owl had been in at that killing the wolverine never knew.) Twice a wood-hare turning now to match the whiteness of its surroundings, finicked up one of the still, silent forest lanes towards him, stopped, faced half-round, sat "frozen" for a fraction, and vanished as if it were a puff of wind-caught snow. (And, really, one had no idea till now that the always apparently lifeless forest could have been so full of life in the dark hours.)

But all these things made no difference to the wolverine, to Gulo, though he "froze" with habitual care to watch them—for your wild creature rarely takes chances. Details must never be overlooked in the wild. He dug on, and in digging came right to the cache, roofed and anchored all down, safe beyond any invasion, with tree-trunks. And—and, mark you, not being able to pull tree-trunks out of the ground, and being too large to squeeze between them, he gnawed through one! Gnawed through it, he did, and came down to the bazaar below.

So far, he had been only beast. Now we see why I said he had more brains than were good for any animal except man.

He bit through the canvas, or whatever it was that protected the cached articles. He got his head inside. He felt about purposefully, and backed out, dragging a trap with him. With it he removed into the inky shadows, and it was never found again.

He returned. He thrust his head in a second time, got hold of something, and backed out. It was another trap, and with it he vanished also; and it, too, was never found. He returned, and went, and a third trap went with him.

The fourth investigation revealed an ax. It he partly buried. The fifth yielded a bag of flour, which he tore up and scattered all over the place. The sixth inroad produced a haunch of venison, off which he dined. The seventh showed another haunch, and this he buried somewhere unseen in the shades. The eighth overhaul gave up some rope, in which he nearly got himself entangled, and which he finally carried away, bitten and frayed past use. The ninth search rewarded him with tea, which he scattered, and bacon, which he buried.

What he could not drag out, he scattered. What he failed to remove, he defiled. And, at last, when he had made of the place, not an orderly cache, but a third-rate débâcle, he sauntered, always slouching, always grossly untidy, hump-backed, stooping, low-headed, and droop-tailed, shabbily unrespectable, out into the night, and the darkness of the night, under the trees.

By the time day dawned he was as if he never had been—a memory, no more. Heaven knows where he was!

Gulo appeared quite suddenly and very early, for him, next afternoon, beside some tangled brush on the edge of a clearing. He was sitting up, almost bolt-upright, and he was shading his eyes with his forepaws. A man could not have done more. And, in fact, he did not look like an animal at all, but like some diabolically uncouth dwarf of the woods.

A squirrel was telling him, from a branch near by, just what everybody thought of his disgraceful appearance; and two willow-grouse were clucking at him from some hazel-tops; whilst a raven, black as coal against the white of the woods, jabbed in gruff and very rude remarks from time to time.

But Gulo was taking no notice of them. He was used to attentions of that kind; it was a little compliment—of hate—they all paid him. He was looking persistently down the ranked, narrowing perspective of the buttressed forest glade to where it faded in the blue-gray mist, southward, as if he expected something to come from there. Something was coming from there now; and there had been a faint, uneasy sort of whisper in that direction for some time. Now it was unmistakable.

A cow-elk, first of the wary ones to move on alarm, came trotting by, her Roman nose held well out; a red-deer hind, galloping lightly like some gigantic hare, her big ears turned astern; a wolf, head up, hackles alift, alternately loping and pivoting, to listen and look back, a wild reindeer, trotting heavily, but far more quickly than he seemed to be—all these passed, now on one side, now on the other, often only glimpses between the tree-boles, while the wolverine sat up and shaded his eyes with his paws. Something was moving those beasts, those haunters of the forest, and no little thing either. Something? What?

Very softly down the glade runs a waiting, watching shade,

And the whisper spreads and widens far and near;

And the sweat is on thy brow, for he passes even now—

He is Fear, O Little Hunter, he is Fear.

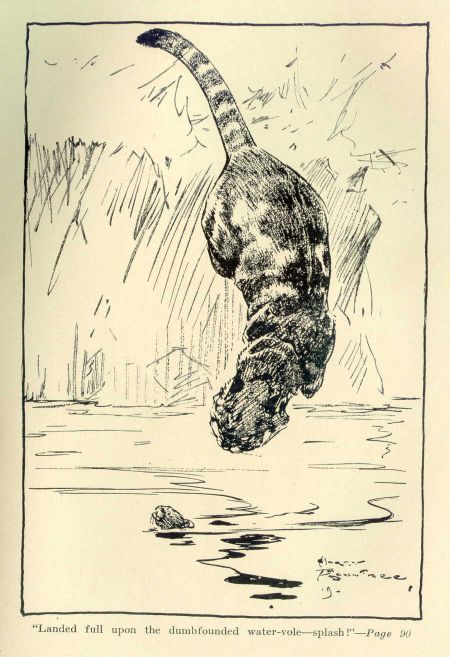

Down came Gulo in that grim silence which was, except for his domestic arguments, characteristic of the beast, and trotted to a pool hard by. The pool was spring-fed, and covered, as to every dead leaf and stone, with fine green moss of incomparable softness. He drank swiftly and long, then flung about with a half-insolent, half-aggressive wave of his tail, and set off at a rolling, clumsy, shuffling shamble.

At ordinary times that deceiving gait would have left nearly everything behind, but this afternoon it was different. Gulo had barely shed the shelter of the dotted thickets before he realized, and one saw, the fact. He broke his trot. He began to plunge. Nevertheless, he got along. There was pace, of a sort. Certainly there was much effort. He would have outdistanced you or me easily in no time, but it was not you or I that came, and who could tell how fast that something might travel?

The trouble was the snow—that was the rub, and a very big and serious rub, too, for him. Now, if the snow had been a little less it would not have mattered—a little more, and he could have run easily along the hard crust of it; but it was as it was, only about two feet, just enough to retard him, and no more. And it is then, when the snow is like that, just above a couple of feet deep, that man can overtake friend wolverine—if he knows the way. Most men don't. On that he trusted. At any other time—but this was not any other time.

Sound carries a long way in those still parts, and as he hurried Gulo heard, far, far behind in the forest, the faint, distant whir of a cock-capercailzie—the feathered giant of the woods—rising. It was only a whisper, almost indistinguishable to our ears, but enough, quite enough, for him. Taken in conjunction with the mysterious shifting of the elk and the red deer and the reindeer and the wolf, it was more than enough. He increased his pace, and for the first time fear shone in his eyes—it was for the first time, too, in his life, I think.

A lynx passed him, bounding along on enormous, furry legs. It looked all legs, and as it turned its grinning countenance to look at him he cursed it fluently, with a sudden savage growl, envious, perhaps, of its long, springing hindlegs. Something, too—the same something—must have moved the lynx, and Gulo shifted the faster for the knowledge.

Half-an-hour passed, an hour slid by, and all the time Gulo kicked the miles behind him, with that dogged persistency that was part of his character. Nothing had passed him for quite a while, and he was all alone in the utterly still, silent forest and the snow, pad-pad-padding along like a moving, squat machine rather than a beast.

At last he stopped, and, spinning round, sat up. A gray-blue haze, like the color on a wood-pigeon, was creeping over everything, except in the west, where the sky held a faint, luminous, pinky tinge that foretold frost. It was very cold, and the snow, which had never quite left off, was falling now only in single, big, wandering flakes. The silence was almost terrifying.

Then, as Gulo sat up, from far away, but not quite so far away, his rounded ears, almost buried in fur, caught faintly—very, very faintly—a sound that brought him down on all fours, and sent him away again at a gallop with a strange new light burning in his little, wide-set eyes. It was the unmistakable sound of a horse sneezing—once. Gulo did not wait to hear if it sneezed twice. He was gone in an instant. Man, it seemed, had not been long in answering that challenge of the cache escapade.

After that there was no such thing as time at all, only an everlasting succession of iron-hard tree-trunks sliding by, and shadows—they ran when they saw him, some of them, or gathered to stare with eyes that glinted—dancing past. The moon came and hung itself up in the heavens, mocking him with a pitiless, stark glare. (He would have given his right forepaw for a black night and a blinding snowstorm.) It almost seemed as if they were all laughing at him, Gulo the dreaded, the hated hater, because it was his turn at last, who had so freely dealt in it, to know fear.

Hours passed certainly, hours upon hours, and still, his breath coming quickly and less easily now with every mile, Gulo stuck to the job of putting the landscape behind him with that grim pertinacity of his that was almost fine.

At last the trees stopped abruptly, and he was heading, straighter than crows fly, across a plain. The plain undulated a little, like a sea, a dead sea, of spotless white, with nothing alive upon it—only his hunched, slouching, untidy, squat form and his shadow, "pacing" him. At the top of the highest undulation he stopped, and glowered back along the trail.

Ahead, the forest, starting again, showed as a black band a quarter of an inch high. Behind, the forest he had already left lay dwarfed in a ruled, serried line. But that was not all. Something was moving out upon the spotless plain of snow, something which appeared to be no more than crawling, ant-like, but was really traveling very fast. It looked like a smudged dot, nothing more; but it was a horse, really, galloping hard, with a light sleigh, and a man in it, behind. The horse had no bells, and it was not a reindeer as usual. Pace was wanted here, and the snow was not deep enough to impede the horse, who possessed the required speed under such conditions.

The horse had been trotting along the trail, till it came to the place where Gulo had looked back and heard the sneeze, and knew he was being followed. Then it had started to gallop, and, with ears back and teeth showing, had never ceased to gallop. This, apparently, was not the first wolverine that horse had trailed. It seemed to have a personal grudge against the whole fell clan of wolverine, and to be bent upon trampling Gulo to death.

Gulo watched it for about one quarter of a second. Then he quitted, and the speed he had put up previously was nothing to that which he showed now—uselessly. And, far behind him, the man in the sleigh drew out his rifle from under the fur rugs. He judged that the time had about come. The end was very near.

But he judged wrong. Gulo made the wood at length. With eyes of dull red, and breath coming in short, rending sobs, he got in among the trees. He did it, though the feat seemed impossible, for the trees had been so very far away. Got in among the trees—yes, but dead-beat, and—to what end? To be "treed" ignominiously and calmly shot down, picked off like a squirrel on a larch-pole. That was all. And that was the orthodox end, the end the man took for granted.

In a few minutes the horse was in the forest too, was close behind Gulo. In spite of the muffling effect of snow, his expectant ears could hear the quadruple thud of the galloping hoofs, and—

Hup! Whuff! Biff-biff! Grrrrrr! Grr-ur-ururrh! Grrrr-urr!

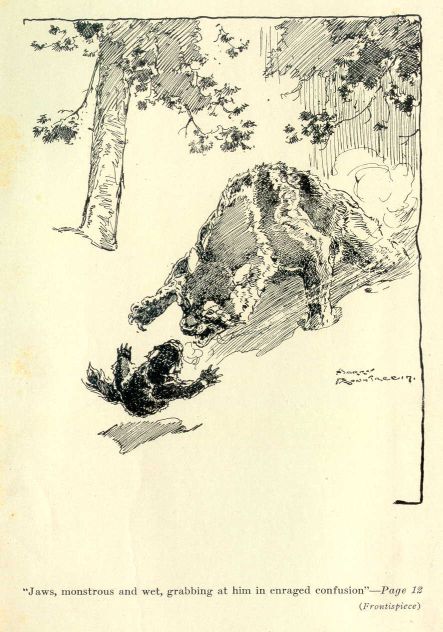

It had all happened quick as a flash of light. A huge, furry, reeking mass rising right in the wolverine's path from behind a tree, towering over him, almost mountainous to his eyes, like the very shape of doom! Himself hurling sideways, and rolling over and over, snarling, to prevent the crowning disaster of collision with this terrible portent! A blow, two blows, with enormous paws whose claws gleamed like skewers, whistling half-an-inch above his ducked head! Jaws, monstrous and wet, grabbing at him in enraged confusion, and rumblings deep down in the inside of the thing that ran cold lightning-sparks all up his spine. That was what Gulo saw and heard.

The wolverine rolled, clawing and biting, three times, and without a pause sprang to his feet again, and leapt madly clear, stumbled on a hidden tree-root, rolled over again twice, and up, and hurled, literally with his last gasp and effort, headlong through the air behind a tree-bole, where he remained all asprawl and motionless, except for his heaving sides, too utterly done at last for any terror to move him.

There followed instantly a horse's wild snort; another; a shout; the crack of a rifle cutting the silence as a knife cuts a taut string; another crack; an awful, hoarse growl; the furious thudding of horse's hoofs stampeding and growing fainter and fainter; and an appalling series of receding, short, coughing, terrifying, grunting roars. Then silence and utter stillness only, and the cold, calm moon staring down over all.

Gulo picked himself up after a bit, and slouched round the tree to investigate. He found tracks there, and blood; and the tracks were the biggest footprints of a bear—a brown bear—that he had ever come across, and I suppose that he must have sniffed at a few in his time.

Presumably the man had fired at the bear when the startled horse shied. Presumably, too, the bear was hit. He had gone straight away in the track of horse and man, anyway, and—he had saved the wolverine's life, after, with paw and teeth, doing his best to end it. Possibly he had been disturbed in the process of making his winter home.

Gulo lay low, or hunted very furtively, after that for some time, until it was little less dark in the east than it had been, and the gaunt tree-trunks were standing out a fraction from the general gloom. The moon had apparently nearly burnt itself out. Still, it yet appeared to be night.

Gulo was a long way out of his own hunting-district, and guessed that it was about time for him to get himself out of sight. He had a passionate hatred of the day, by the way, even beyond most night hunters.

On the way he smelt out and dug up a grouse beneath the snow.

Dawn found him, or, rather, failed to find him, hidden under a tangled mass that was part windfall, part brush-wood, and part snow. The place had belonged to a fox the night before, and that red worthy returned soon after dawn. He thrust an inquiring sharp muzzle inside, took one sniff, and, with every hair alift, retired in haste, without waiting to hear the villainous growl that followed him. The smell was enough for him—a most calamitous stink.

It snowed all that day, and things grew quieter and quieter, except in the tree-tops, where the wind spoke viciously between its teeth. When Gulo came out that evening, he had to dig part of the way, and he viewed a still and silent, white world, under a sky like the lid of a lead box, very low down. He stood higher against the tree-trunks than he had done the night before, and, though he did not know it, was safe from any horse, for the snow was quite deep. The cold was awful, but it did not seem to trouble him, as he slouched slowly southward.

There appeared to be nothing alive at all throughout this white land, but you must never trust to that in the wild. Things there are very rarely what they seem. For instance, Gulo came into a clearing, dim under the night sky, though it would never be dark that night. To the ear and the eye that clearing was as empty as a swept room. To Gulo's nose it was not, and he was just about to crouch and execute a stalk, when half the snow seemed to get up and run away. The runners were wood-hares. They had "frozen" stiff on the alarm from their sentries. But it was not Gulo who had caused them to depart. Him, behind a tree, they had not spotted. Something remained—something that moved. And Gulo saw it when it moved—not before. It was an ermine, a stoat in winter dress, white as driven snow. Then it caught sight of Gulo, or, more likely, the gleam of his eyes, and departed also.

Gulo slouched on, head down, back humped, tail low, a most dejected-looking, out-at-heels tramp of the wilderness.

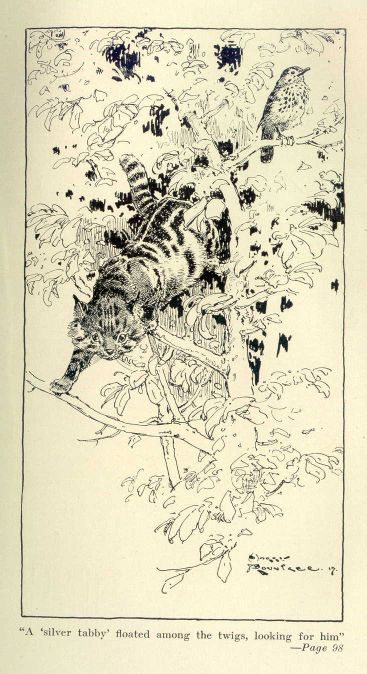

Once he came upon a wild cat laying scientific siege to a party of grouse. The grouse were nowhere to be seen; nor was the wild cat, after Gulo announced his intention to break his neutrality. Gulo knew where the grouse were. He dug down into the snow, and came upon a tunnel. He dug farther, and came upon other tunnels, round and clean, in the snow. All the tunnels smelt of grouse, but devil a grouse could he find. He had come a bit early. It was as yet barely night, and he should have waited till later, when they would be more asleep. However, he dug on along the tunnels, driving the grouse before him. And then a strange thing happened. About three yards ahead of him the snow burst—burst, I say, like a six-inch shell, upwards. There was a terrific commotion, a wild, whirring, whirling smother, a cloud of white, and away went five birds, upon heavily beating wings, into the gathering gloom. Gulo went away, too, growling deep down inside of, and to, himself.

He was hungry, was Gulo. Indeed, there did not seem to be many times when he was not hungry. Also, being angry—not even a wild animal likes failure—he was seeking a sacrifice; but he had crossed the plain, which the night before had been as a nightmare desert to him, and the moon was up before his chance came.

He crossed the trail of the reindeer. He did not know anything about those reindeer, mark you, whether they were wild or semi-tame; and I do not know, though he may have done, how old the trail was. It was sufficient for him that they were reindeer, and that they had traveled in the general direction that he wanted to go. For the rest—he had the patience, perhaps more than the patience, of a cat, the determination of a bulldog, and the nose of a bloodhound. He trailed those reindeer the better part of that night, and most of the time it snowed, and part of the time it snowed hard.

By the time a pale, frozen dawn crept weakly over the forest tree-tops Gulo must have been well up on the trail of that herd, and he had certainly traveled an astonishing way. He had dug up one lemming—a sort of square-ended relation of the rat, with an abbreviated tail—and pounced upon one pigmy owl, scarce as large as a thrush, which he did not seem to relish much—perhaps owl is an acquired taste—before he turned a wild cat out of its lair—to the accompaniment of a whole young riot of spitting and swearing—and curled up for the day.

He was hungry when he went to sleep. Also, it was snowing then. When he woke up it was almost dark, and snowing worse than ever. If it could have been colder, it was.

While he cleaned himself Gulo took stock of the outside prospect, so far as the white curtain allowed to sight, and by scent a good deal that it did not. This without appearing outside the den, you understand. And if there had been any enemy in hiding, waiting for him outside, he would have discovered the fact then. He had many enemies, and no friends, had Gulo. All that he received from all whom he met was hate, but he gave back more than he got. In the lucid terms of the vernacular, he "was a hard un, if you like."

Nothing and nobody saw the wolverine leave that lair that was not his. He must have chosen one blinding squall of snow for the purpose, and was half a mile away, still on the track of the reindeer, before he showed himself—shuffling along as usual, a ragged, hard-bitten ruffian. And three hours later he came up with his prey.

Gulo knew it, but nobody else could have done. There were just the straight trees ahead, and all around the eternal white, frozen silence, and the snow falling softly over everything; but Gulo was as certain that there was the herd close ahead as he was that he was ravenous. And thereafter Gulo got to work, the peculiar work, a special devilish genius for which appears to be given to the wolverine.

He ceased to exist. At least, nothing of him was seen, not a tail, not an eye-gleam. Yet during the next two hours he learnt everything, private and public, there was to be learnt. Also, he had been over the surroundings almost to a yard. Nothing could have escaped him. No detail of risk and danger, of the chance of being seen even, had been overlooked; for he was a master at his craft, the greatest master in the wild, perhaps. The wolf? My dear sirs, the wolf was an innocent suckling cub beside Gulo, look you, and his brain and his cunning were not the brain and the cunning of a beast at all, but of a devil.

When, after a very long time, he reappeared upon his original track, it was as a dark blotch, indistinguishable from a dozen other dark blots of moon-shadow, creeping forward belly-flat in the snow. This belly-creep, hugging always every available inch of cover, he kept up till he came to a big clearing, and—there were the reindeer. At least, there was one reindeer, a doe, standing with her back towards him—a quite young doe. The rest were half-hidden in the snow, which they had trampled into a maze of paths in and out about the clearing, which was, in fact, what is called their "yard."

A minute of tense silence followed after Gulo had got as close as he could without being seen. Then he rushed.

The reindeer swung half-round, gave one snort, and a great bound. But Gulo had covered half the intervening space before she knew, and when she bounded it was with him hanging on to her.

Followed instantly a wild upspringing of snorting beasts, and a mad, senseless stampede of floundering deer all round and about the clearing—a fearful mix-up, somewhere in the midst of which, half-hidden by flying, finely powdered snow, Gulo did his prey horribly to death.

There was something ghastly about this murder, for the deer was so big, and Gulo comparatively small. The fearful work of his jaws and his immense strength seemed wrong somehow, and out of all proportion to his size. This remarkable power of his jaws had that sinister disproportion only paralleled by the power of the jaws of a hyena; indeed, his teeth very much resembled a hyena's teeth.

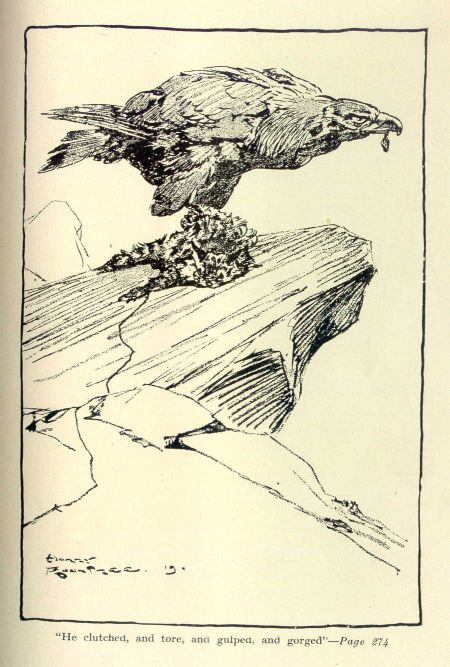

With the deer rushing all around him, Gulo fed, ravenously and horribly, but not for long. A new light smoldered in his eyes now as he lifted his carmine snout, and one saw that, for the moment, the beast was mad, crazed with the lust of killing, seeing red, and blinded by blood.

Then the massacre began. It was not a hunt, because each deer, thinking only of itself, feared to break from the trodden mazy path of the "yard," and risk the slow, helpless, plunging progress necessary in the deep snow. Wherefore panic took them all over again, and they dashed, often colliding, generally hindering each other, hither and thither, up and down the paths of the "yard" with the hopeless, helpless, senseless, blind abandon of sheep. The result was a shambles.

This part we skip. Probably—nay, certainly—Nature knows best, and is quite well aware what she is up to, and it is perhaps not meant that we should put her in the limelight in her grisly moods. Suffice it to say that Gulo seemed to stop at length, simply because even he could not "see red" forever, and with exhaustion returned sense, and with sense—in his case—in-born caution. He removed, leaving a certain number of reindeer bleeding upon the ground. Some of them were dead.

In an hour dawn would be conspiring to show him up before the world, and he was not a beast sweet to look upon at that moment—indeed, at any moment, but less so now.

Now, it is surprising how far a wolverine can shift his clumsy-looking body over snow in an hour, especially if he has reasons. This one had good reasons, and he was no fool. He knew quite well the kind of little hell he had made for himself behind there, and he did not stay to let the snow cover him. He traveled as if he were a machine and knew no fatigue; and the end of that journey was a hole in a hollow among rocks.

Dawn was throwing a wan light upon all things when he thrust his short, sharp muzzle inside that hole, to be met by a positively hair-raising volley of rasping, vicious growls.

He promptly ripped out a string of ferocious, dry, harsh growls in return, and for half-a-minute the air became full of growls, horrible and blood-curdling, each answering each.

Then he lurched in over the threshold, and coolly dodged a thick paw, with tearing white claws, that whipped at him with a round-arm stroke out of the pitch-darkness. The stroke was repeated, scraping, but in nowise hurting his matted coat, as he rose on his hindlegs and threw himself upon the striker.

Followed a hectic thirty seconds of simply diabolical noises, while the two rolled upon the ground, grappling fiendishly in the darkness. Then they parted, got up, growled one final roll of fury at each other, fang to fang, and, curling up, went to sleep. But it was nothing, only the quite usual greeting between Gulo and his wife. They were a sweet couple.

There appeared to be no movement, or any least sign of awakening, on the part of either of the couple between that moment and sometime in the afternoon, when, so far as one could see, Gulo suddenly rolled straight from deep sleep out on to the snow, and away without a sound, at his indescribable shamble and at top speed.

Mrs. Gulo executed precisely the same amazing maneuver, and at exactly the same moment, as far as could be seen, on the other side, and shuffled off into the forest. They gave no explanation for so doing. They said never a word—nothing. One moment they were curled up, asleep; the next they had gone, scampered, apparently into the land of the spirits, and were no more. Nor did there seem to be any reason for this extraordinary conduct except—except—— Well, it is true that a willow-grouse, white as the snowy branch he sat upon, did start clucking somewhere in the dim tree regiments, a snipe did come whistling sadly over the tree-tops, and a raven, jet against the white, did flap up, barking sharply, above the pointed pine-tops; but that was nothing—to us. To the wolverines it was everything, a whole wireless message in the universal code of the wild, and they had read it in their sleep. Through their slumbers it had spelt into their brains, and instantly snapped into action that wonderful, faultless machinery that moved them to speed as if automatically.

Then the chase began, grim, steady, relentless, dogged—the chase of death, the battle of endurance.

A pause followed after the vanishing of the hated wolverines. A crow lifted on rounded vans, marking their departure, and it was seen. A blackcock launched from a high tree with a whir and a bluster like an aeroplane, showing their course, and it was noted. An eagle climbed heavily and ponderously over the low curtain of the snow mist, pointing their way, and it was followed. All the wild, all the world, seemed to be against the wolverines. The brigands were afoot by day. The scouts were marking their trail.

Then a lynx, moving with great bounds on his huge swathed paws, shot past between the iron-hard tree-boles; a fox followed, scudding like the wind on the frozen crest; a hare, white as a waste wraith, flashed by, swift as a racing white cloud-shadow; a goshawk screamed, and drew a straight streaking line across a glade. And then came the men, side by side, deadly dumb, with set faces, the pale sun glinting coldly cruel upon the snaky, lean barrels of their slung rifles, moving with steady, fleet, giant strides on their immense spidery ski that were eleven feet long, which whispered ghostily among the silent aisles of Nature's cathedral of a thousand columns. The Brothers were on the death-trail of Gulo at last; the terrible, dreaded Brothers, who could overtake a full-grown wolf in under thirty minutes on ski, and whose single bullet spelt certain death. Now for it; now for the fight. Now for the great test of the "star" wild outlaw against the "star" human hunters—at last. The reindeer were to be avenged.

Then Time took the bit of silence between his teeth and seconds became hours, and minutes generations.

No sound made the wolverines as they rolled along in Indian file, except for the soft whisper of the snow underfoot.

No noise encompassed the Brothers as they sped swiftly side by side over the glittering white carpet, save for the slither of the snow under their weight.

All the wild seemed to be standing still, holding its breath, looking on, spell-bound; and save for the occasional crash of a collapsing snow-laden branch, sounding magnified as in a cave, all the forest about there was as still as death.

Half-an-hour passed, and Gulo flung his head around, glancing over his shoulder a little uneasily, but with never a trace of fear in his bloodshot eyes. Then he grunted, and the two fell apart silently and instantly, gradually getting farther and farther from each other on a diverging course, till his wife faded out among the trees. But never for an instant did either of them check that tireless, deceptive, clumsy, rolling slouch, that slid the trees behind, as telegraph-poles slide behind the express carriage window.

Half-an-hour passed, and one of the Brothers, peering up and along the trail a little anxiously, saw the forking of the line ahead. Then he grunted, and the two promptly separated without a word, gradually increasing the distance between them on the widening fork till they were lost to each other among the marshaled trunks. But never for an instant did they relax that swift, ghostly glide on the wonderful ski, that slid the snow underfoot as a racing motor spins over the ruts.

An hour passed. Sweat was breaking out in beads upon the faces of the Brothers, now miles apart, but both going in the same general direction over the endless wastes of snow, and upon their faces was beginning to creep the look of that pain that strong men unbeaten feel who see a beating in sight; but never for a moment did they slacken their swift, mysterious glide.

An hour passed. Foam began to fleck the evilly up-lifted lips glistening back to the glistening fangs of the wolverines, now miles apart, but still heading in the same general line, and upon their faces began to set a look of fiends under torture; but never for a moment did they check their indescribable shuffling slouch.

After that all was a nightmare, blurred and horrible, in which endless processions of trees passed dimly, interspersed with aching blanks of dazzling white that blinded the starting eyes, and man and beast stumbled more than once as they sobbed along, forcing each leg forward by sheer will alone.

At last, on the summit of a hog-backed, bristling ridge, Gulo stopped and looked back, scowling and peering under his low brows. Beneath him, far away, the valley lay like a white tablecloth, all dotted with green pawns, and the pawns were trees. But he was not looking for them. His keen eyes were searching for movement, and he saw it after a bit, a dot that crept, and crept, and crept, and—stopped!

Gulo sat up, shading his eyes against the watery sun with his forepaws, watching as perhaps he had never watched in his life before.

For a long, long while, it seemed to him, that dot remained there motionless, far, far away down in the valley, and then at length, slowly, so slowly that at first the movement was not perceptible, it turned about and began to creep away—creep, creep, creep away by the trail it had come.

Gulo watched it till it was out of sight, fading round a bend of the hills into a dark, dotted blur that was woods. Then he dropped on all fours, and breathed one great, big, long, deep breath. That dot was the one of the Brothers that had been hunting him.

And almost at the same moment, five miles away, his wife had just succeeded in swimming a swift and ice-choked river. She was standing on the bank, watching another dot emerge into the lone landscape, and that dot was the other one of the Brothers.

They had failed to avenge the reindeer, and the wolverines were safe. Safe? Bah! Wild creatures are never safe. Nature knows better than that, since by safety comes degeneration.

There was a warning—an instant's rustling hissing in the air above—less than an instant's. But that was all, and for the first time in his life—perhaps because he was tired, fagged—Gulo failed to take it. And you must never fail to take a warning if you are a wild creature, you know! There are no excuses in Nature.

Retribution was swift. Gulo yelled aloud—and he was a dumb beast, too, as a rule, but I guess the pain was excruciating—as a hooked stiletto, it appeared, stabbed through fur, through skin, deep down through flesh, right into his back, clutching, gripping vise-like. Another stiletto, hooked, too, worse than the first one, beat at his skull, tore at his scalp, madly tried to rip out his eyes. Vast overshadowing pinions—as if they were the wings of Azrael—hammered in his face, smothering him, beating him down.

Ah, but I have seen some fights, yet never such a fight as that; and never again do I want to see such a fight as the one between Gulo and the golden eagle that made a mistake in his pride of power.

All the awful, cruel, diabolical, clever, devilish, and yet almost human fury that was in that old brute of a Gulo flamed out in him at that moment, and he fought as they fight who go down to hell. It was frightful. It was terrifying. Heaven alone knows what the eagle thought he had got his claws into. It was like taking hold of a flash of forked lightning by the point. It was—great!

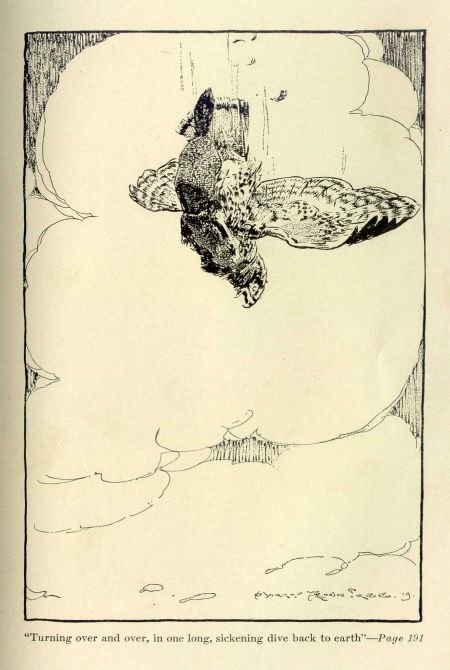

Still, flight is flight, and lifting-power is lifting-power. Gulo, even Gulo, could not get over that. He could not stop those vast vans from flapping; and as they flapped they rose, the eagle rose, he—though it was like the skinning of his back alive—rose too, wriggling ignominiously, raging, foaming, snapping, kicking, but—he rose.

Slowly, very slowly, the great bird lifted his terrible prey up and up—ten, twenty, thirty, forty feet, but no higher. That was the limit of his lift, the utmost of his strength; and at that height parallel with the ridge, he began to carry the wolverine along, the wolverine that was going mad with rage in his grasp.

It was a mistake, of course—a mistake for the wolverine to be out on the open ridge in stark daylight; another mistake for the eagle, presuming on his fine, lustful pride of strength, to attack him.

And then suddenly Gulo got his chance. It hit him bang in the face, nearly blinding him as it passed—the tree-top. Like lightning Gulo's jaws clashed shut upon it, his claws gripped, and—he thought his back was going to come off whole. But he stuck it. He was not called Gulo the Indomitable for nothing. And the eagle stopped too. He had to, for he would not let go; nor would Gulo.

An awful struggle followed, in the middle of which the pine-top broke, gave way, and, before either seemed to know quite what was happening, down they both came, crashing from branch to branch, to earth.

The fall broke the king of the birds' hold, but not the fighting fury of the most hated of all the beasts. He rose up, half-blind, almost senseless, but mad with rage beyond any conception of fury, did old Gulo, and he hurled himself upon that eagle.

What happened then no man can say. There was just one furious mix-up of whirling, powdered snow, that hung in the air like a mist, out of which a great pinion, a clawing paw, a snapping beak, a flash of fangs, a skinny leg and clutching, talons, a circling bushy tail appeared and vanished in flashes, to the accompaniment of stupendous flappings and abominably wicked growls.

That night the lone wolf, scouting along the ridge-top, stopped to sniff intelligently at the scattered, torn eagle's feathers lying about in the trampled snow, at the blood, at the one skinny, mailed, mightily taloned claw still clutching brown-black, rusty fur and red skin; at the unmistakable flat-footed trail of Gulo, the wolverine, leading away to the frowning, threatening blackness of the woods. He could understand it all, that wolf. Indeed, it was written there quite plainly for such as could read. He read, and he passed on. He did not follow Gulo's bloody trail. No—oh, dear, no! Probably, quite probably, he had met Gulo the Indomitable before, and—was not that enough?

Blackie flung himself into the fight like a fiery fiend cut from coal. He did not know what the riot was about—and cared less. He only knew that the neutrality of his kingdom was broken. Some one was fighting over his borders; and when fighting once begins, you never know where it may end! (This is an axiom.) Therefore he set himself to stop it at once, lest worse should befall.

He found two thrushes apparently in the worst stage of d.t.'s. One was on his back; the other was on the other's chest. Both were in a laurel-bush, half-way up, and apparently they kept there, and did not fall, through a special dispensation of Providence. Both fought like ten devils, and both sang. That was the stupefying part, the song. It was choked, one owns; it was inarticulate, half-strangled with rage, but still it was song.

A cock-chaffinch and a hen-chaffinch were perched on two twigs higher up, and were peering down at the grappling maniacs. Also two blue titmice had just arrived to see what was up, and a sparrow and one great tit were hurrying to the spot—all on Blackie's "beat," on Blackie's very own hunting-ground. Apparently a trouble of that kind concerned everybody, or everybody thought it did.

Blackie arrived upon the back of the upper and, presumably, winning thrush with a bang that removed that worthy to the ground quite quickly, and in a heap. The second thrush fetched up on a lower branch, and by the time the first had ceased to see stars he had apparently regained his sanity. He beheld Blackie above him, and fled. Perhaps he had met Blackie, professionally, before, I don't know. He fled, anyway, and Blackie helped him to flee faster than he bargained for.

By the time Blackie had got back, the first thrush was sitting on a branch in a dazed and silly condition, like a fowl that has been waked up in the night. Blackie presented him with a dig gratis from his orange dagger, and he nearly fell in fluttering to another branch. And Blackie flew away, chuckling. He knew that, so far as that thrush was concerned, there would be no desire to see any more fighting for some time.

But, all the same, Blackie was not pleased. He was worked off his feet providing rations for three ugly youngsters in a magnificently designed and exquisitely worked and interwoven edifice, interlined with rigid cement of mud, which we, in an off-hand manner, simply dismiss as "A nest." The young were his children; they might have been white-feathered angels with golden wings, by the value he put on them. The thrush episode was only a portent, and not the first. He had no trouble with the other feathered people he tolerated on his beat.

Blackie went straight to the lawn. (Jet and orange against deep green was the picture.)

Now, if you and I had searched that dry lawn with magnifying-glasses, in the heat of the sun, there and then, we should not have found a single worm, not the hint or the ghost of one; yet that bird took three long, low hops, made some quick motion with his beak—I swear it never seemed to touch the ground, even, let alone dig—-executed a kind of jump in the air—some say he used his legs in the air—and there he was with a great, big, writhing horror of a worm as big as a snake (some snakes).

Thrushes bang their worms about to make them see sense and give in; they do it many times. Blackie banged his giant only a little once or twice, and then not savagely, like a thrush. Also, again, he may or may not have used his feet. Moreover, he gave up two intervals to surveying the world against any likely or unlikely stalking death. Yet that worm shut up meekly in most unworm-like fashion, and Blackie cut it up into pieces. The whole operation took nicely under sixty seconds.

Blackie gave no immediate explanation why he had reduced his worm to sections. It did not seem usual. Instead, he eyed the hedge, eyed the sky, eyed the surroundings. Nothing seemed immediately threatening, and he hopped straight away about three yards, where instantly, he conjured another and a smaller worm out of nowhere. With this unfortunate horror he hopped back to the unnice scene of the first worm's decease, and carved that second worm up in like manner. Then he peeked up all the sections of both worms, packing them into his beak somehow, and flew off. And the robin who was watching him didn't even trouble to fly down to the spot and see if he had left a joint behind. He knew his blackbird, it seemed.

Blackie flew away to his nest, but not to a nest in a hedge. To dwell in a hedge was a rule of his clan, but the devil a rule did he obey. Nests in hedges for other blackbirds, perhaps. He, or his wife, had different notions. Wherefore flew he away out into the grass field behind the garden. Men had been making excavations there, for what mad man-purpose troubled him not—digging a drain or something. No matter.

Into the excavation he slipped—-very, very secretly, so that nobody could have seen him go there—and down to the far end, where, twelve feet below the surface, on a ledge of wood, where the sides were shored with timber, his mate had her nest. Here he delivered over his carved joints to the three ugly creatures which he knew as his children and thought the world of, and appeared next flying low and quickly back to the garden. That is to say, he had contrived to slip from the nest so secretly that that was the first time he showed.

A sparrow-hawk, worried with a family of her own, took occasion to chase him as he flew, and he arrived in among the young lime-trees that backed the garden, switchbacking—that was one of his tricks of escape, made possible by a long tail—and yelling fit to raise the world. The sparrow-hawk's skinny yellow claw, thrust forward, was clutching thin air an inch behind his central tail-feathers, but that was all she got of him—just thin air. There was no crash as he hurled into the green maze; but she, failing to swerve exactly in time, made a mighty crash, and retired somewhat dazed, thankful that she retained two whole wings to fly with. There is no room for big-winged sparrow-hawks in close cover, anyway, and Blackie, who was born to the leafy green ways, knew that.

Blackie's yells had called up, as if by magic, a motley crowd of chaffinches, hedge-sparrows, wrens, robins, &c., from nowhere at all, and they could be seen whirling in skirmishing order—not too close—about the retreating foe. Blackie himself needed no more sparrow-hawk for a bit, and preferred to sit and look on. If the little fools chose to risk their lives in the excitement of mobbing, let them. His business was too urgent.

Twenty lightning glances around seemed to show that no death was on the lurk near by. Also, a quick inspection of other birds' actions—he trusted to them a good deal—appeared to confirm this.

Then he flew down to the lawn, and almost immediately had a worm by the tail. Worms object to being so treated, and this one protested vigorously. Also, when pulled, they may come in halves. So Blackie did not pull too much. He jumped up, and, while he was in the air, scraped the worm up with his left foot, or it may have been both feet. The whole thing was done in the snap of a finger, however, almost too quickly to be seen.

The worm, once up, was a dead one. Blackie seemed to kill it so quickly as almost to hide the method used. In a few seconds more it was a carved worm in three or four pieces—an unnice sight, but far more amenable to reason that way.

Blackie was in rather long grass, and nerve-rackingly helpless, by the same token. He could not see anything that was coming. Wherefore every few seconds he had to stand erect and peer over the grass-tops. It made no difference to the worm, however; it was carved just the same.

Blackie now hopped farther on in search of more worms, but found a big piece of bread instead. It was really the hen-chaffinch who found the bread, and he who commandeered it from her. Now he disclosed one fact, and that was that bread would do for his children as well as worms. Anyhow, he stuffed his beak about half up with bread, returned for the pieces of worm, collected these, and retired up into the black cover of a fir-tree.

No doubt he was expected to go right home with that load, then and there. Even a cock-blackbird with young, however, must feed, and, if one judged by the excess amount of energy—if that were possible—used up, must feed more than usual. That seemed to be why he hid his whole load in the crook of a big bough, and, returning to the lawn, ate bread—he could wait to catch no worms for his own use, it appeared—as fast as he could. Three false alarms sent him precipitantly into his tree upon this occasion, and one real alarm—a passing boy—caused a fourth retreat.

These operations were not performed in a moment, and by the time he got back to his nest—mind, he had to contrive to approach it so that he was seen by nobody, and his was a conspicuous livery, too—his children appeared to be in the last stages of exhaustion. That, however, is young birds all over; they expect their parents to be mere feeding-machines, guaranteed to produce so many meals to the hour, and hang the difficulties and the risks.

There was no sign of Blackie's wife. Presumably she was working just as hard on her own "beat" as he had been on his—their hunting-grounds were separate, though they joined—and would soon be back.

Blackie did not wait. He managed again the miracle of getting away from his nest without appearing to do so, and next turned up on the summer-house roof. Fatherlike, he thought he had done enough for a bit, and would enjoy a "sunning reaction" on the summerhouse roof. It was rather a good place, a look-out tower from which he could slip over the side into the hedges, which met at the corner where it was, if trouble turned up.

Trouble did turn up, but not quite what he had expected. He had been sitting there, wing-stretching, leg-stretching, and "preening" his feathers, and had finally left off just to sit and do nothing, when—lo! his wife popped up over the side without warning, and right upon him.

She was very dark brown, not black, and had a paler throat than the palish throat of most hen blackbirds—nearly white, in fact. She said nothing. Nor did Blackie, but he looked very uncomfortable. She did more than say nothing. She went for him, beak first, and very angrily indeed; and he, not waiting to receive her, fled down to the lawn, and began worm-hunting for dear life. A whole lecture could not have said more.

Mrs. Blackie remained on the roof for about a minute, looking round, and then flew off to her own hunting-ground. She was wilder and less trusting of the world than Blackie, and did not care for his lawn in full view of the house windows. And Blackie did not even stop his work to watch her go. Apparently they had, previously in their married life, arrived at a perfect understanding.

This time, too, Blackie got a big and a small worm. The small he coiled like a rope, and held up towards the base of his beak; the big he carved up into sections, which he held more towards the tip. The large ones, it seemed, were too awkward and lively simply to carry off rolled up whole.

The journey that followed was a fearful one in Blackie's life, for he met half-way the very last foe in the world he was expecting—namely, an owl. Truly, it was a very small owl, scarce bigger than himself; but it was an owl, and, like all its tribe, armed to the teeth. Men called it a little owl. That was its name—little owl. Blackie didn't care what men called it; he knew it only as one of the hundred or so shapes that death assumed for his benefit.

Just at that time it happened to be cloudy, and little owls often hunt by day. But how was Blackie to know that, little owls being a comparatively new introduction into those parts?

Blackie screamed and fled. The owl did not scream, but fled, too—after Blackie. Blackie had no means of judging how close that foe was behind by the whir of its wings. Owls' wings don't talk, as a rule; they have a patent silencer, so to speak, in the fluffy-edged feathers. Therefore Blackie was forced to do his best in breaking the speed record, and trust to luck.

It was a breathless and an awful few seconds, and it seemed to him like a few hours. The owl came up behind, going like a cloud-shadow, and about as fast, and Blackie, glancing over his shoulder, I suppose, yelled afresh. The terror was so very close.

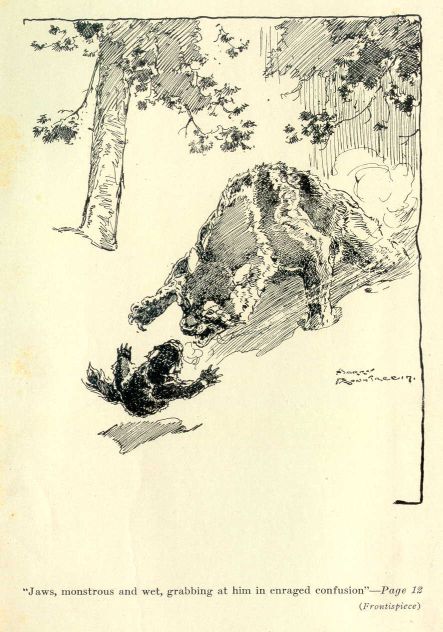

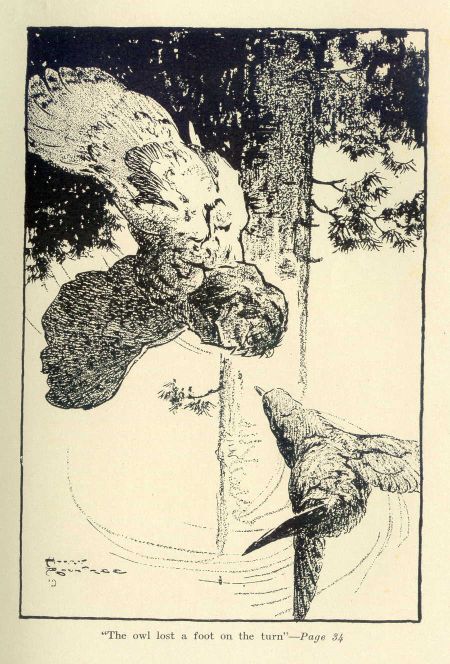

Then Blackie remembered another excavation, just like the one his nest was in, a little off his course to the left, and he tacked towards it, twisting his course wonderfully, thanks to the long tail. And the owl lost a foot on the turn. I think it was expecting Blackie to make for the hedge at all costs. But, be that as it may, that foot was never made up again, for Blackie vanished into the trench next instant, like a blown-out light, and, though the hunter searched for him carefully, he never put in an appearance again while that owl was within sight of the place.

All signs of uproar on the passing of the little owl had died down some time before Blackie turned up again, and then it was in the garden, so he must have got from the tunnel unseen.

He still hung gamely to the food for his young, and now made another attempt to deliver that food where it belonged. He was half-way there, indeed, before he saw the boys—three boys—with two rows of birds' eggs threaded on strings. They were passing so close to the trench that one nearly fell into it, and, of course, any one could see that they were bird-nesting.

Blackie swerved off sharply to the far hedge, his heart nearly bursting with anxiety, little knowing that the boys had never even thought of looking in the trench for nests. It seemed the last place in the world to find one. It may have been, moreover, that he feared that his wife was home, in which case she might have lost her head, and, dashing out with a scream, "blown the whole gaff," as they say in the vernacular.

Apparently madam was not at home, by good luck, for the boys passed, and Blackie once more executed the magic of getting into his nest without seeming to do so. And here he stayed. Dusk was setting in, and his young were fourteen days old. They showed it in their disobedience, and were not in the least inclined to keep as quiet as they should, considering their father had but just warned them, in his own way, to "lie doggo," because of the gray shape he had seen sliding out into the field, a gray shape which was a cat.

They were more like thrushes than blackbirds, those youngsters, with their speckly fawn breasts; and they were not like the adults of either in their frog-like attitudes and heavy ways. Frankly, they were not beautiful, even at that stage; and a fortnight before, when they had been larger than the eggs they had come out of, they were positively reptilian and repulsive.

Blackie said the blackbird equivalent to "Be quiet, you little fools!" as quietly and as sternly as he could three or four times, and perched on the top of a wheelbarrow to watch the gray shadow which was a cat. That sudden death, however, was more afraid of the open than Blackie, even, and, moreover, wasn't expecting blackbirds' nests in the middle of fields. It turned back; and at length Mrs. Blackie, who had been on a general survey round about to see what foes of the night were on the move—and a fine hubbub she had made in the process—came home, reporting all well.

Then they slept; at least, they ceased to be any further seen or heard. Think, however, how you would sleep if every few minutes you could hear sounds in your house one-third of which were probably the noises of a burglar. Think, also, how you would feel if you knew that that burglar was a murderer, and that that murderer was, in all likelihood, looking for you, or some one just like you. Yet those birds were happy enough, I fancy.

It was barely pale gray. It was cold and wan and washed, and wonderfully clean and sweet, and wet with dews, when a lark climbed invisibly into the sky and suddenly burst into song, next morning. There was something strange and out of place, in a way, in this song, breaking out of the night; and as it and another continued to break the utter silence for ten minutes, it seemed rather as if it were still night, and not really dawn at all. Dawn appeared to be waiting for something else to give it authority, so to speak, and at the end of ten minutes that something else came—the slim form of Blackie, streaking, phantom-like, through the mist from the trench out in the field to the summer-house in the garden. Here, mounted upon the very top, he stood for a moment, as one clearing his throat before blowing a bugle, and then, full, rich, deep, and flute-like, he lazily gave out the first bars of his song. Instantly, almost as if it had been a signal, a great tit-mouse sang out, "Tzur ping-ping! tzur ping-ping!" in metallic, ringing notes; a thrush struck in with his brassy, clarion challenge, thrush after thrush taking it up, till, with the clear warble of robin and higher, squeaking notes of hedge-sparrow and wren joining in, the wonderful first bars of the Dawn Hymn of the birds rolled away over the fields to the faraway woods, and beyond.

Blackie sang on for a bit, in spite of the fact that people said that it was not considered "the thing" for a blackbird with such domestic responsibilities to sing. And two other blackbirds helped him to break the man-made rule.

As a matter of fact, I fancy he was not taking chances upon the ground while the mist hung to cover late night prowlers, for as soon as the gay and gaudy chaffinches had stuck themselves up in the limes and the sycamores, and started their own smashing idea of song, he was down upon the lawn giving the early worm a bad time.

Then it was that he heard a rumpus that shot him erect, and sent his extraordinarily conspicuous orange dagger of a beak darting from side to side in that jerky way of listening that many birds affect.

"Twet-twet-et-et-et! twet! twet-twet-twet-et-et-twet!" came the unmistakable voice of one in a temper, scolding loudly. And he knew that scold—had heard it before, by Jove! And who should know it if not he, since it was the voice of his wife?

Perhaps he heaved a sigh as he rose from the deliciously cool, wet lawn—where it was necessary to take long, high hops if you wanted to avoid getting drenched—and winged his way towards the riot. His wife was calling him, and it came from the other side of the garden, her side, behind the house. Perhaps it was a cat, or a rat, or something. Anything, almost, would set her on like that if experience, plus the experience of blackbirds for hundreds of generations working blindly in her brain—and not the experience of books—had taught her that the precise creature whom she saw was a danger and a menace to young blackbirds.

All the same, when Blackie arrived he was surprised, for all that he saw was a grayish bird with "two lovely black eyes," not by any means as large as a blackbird. When it flew it kept low, with a weak and peculiar flight that was deceiving; and when Mrs. Blackie, following it, and yelling like several shrews, got too close, it turned its head, and said, "Wark! wark!" in a harsh and warning way.

Blackie joined in with his deeper "Twoit-twoit-twoit!" just by way of lending official dignity to the proceedings. Whereupon his wife, feeling that he had backed her up, redoubled her excitement and shrill abuse.

And they spent two solid hours at this fool's game, helped by a robin, a blue tit, and a chaffinch or two—the chaffinch must have his finger in every pie—following that gray bird from nowhere, while it moved about the garden in its shuffling flight, or alternately sat and scowled at them. But it must be admitted that Blackie himself looked rather bored, and might have gone off for breakfast any time, if he had dared.

As a matter of fact, however, the bird did not stand upon the Register of Bad Deeds as being a terror of even the mildest kind of blackbirds. Red-backed shrike was her name, female was her sex, and from Africa had she come. Goodness knows where she was going, but not far, probably; and the largest thing in the bird line she appeared able to tackle was something of the chaffinch size. But, all the same, Mrs. Blackie seemed jolly well certain that she knew better.

Then arrived the bombshell.

One of the Blackie youngsters, stump-tailed, frog-mouthed, blundering, foolish, gawky, and squawking, landed, all of a heap, right into the very middle of the picnic-party.

Mrs. Blackie very nearly had a fit on the spot, and the shrike judged that the time had about arrived for her to quit that vicinity.

Blackie himself, to do him justice, kept cool enough to do nothing. Wives will say that he was just husband all over, but there were reasons abroad. One of them shot past Blackie, who was low down, a second later and a yard away, and had he not been absolutely still, and therefore as invisible as one of the most conspicuous of birds in the wild can be, he would have known in that instant, or the next, what lies upon the other side of death.

Another reason shot through the lower hedge, and, both together, they fell upon the young bird.

They were the cat of the house and her half-grown kitten, and they were upon the unhappy youngster before you could shout, "Murder!"

What followed was painful. Mrs. Blackie went clean demented. Blackie went—not so demented. (It always appeared to me that his was a more practical mind than his wife's, perhaps because he wore a more conspicuous livery.) Mrs. Blackie kept passing and repassing the cats' backs, flying from bough to bough, and sometimes touching and sometimes not touching them. It was useless, of course, this pathetic charging; and it was foolish.

Blackie charged, too, but not within feet.

Suddenly the old cat, who had had one eye upon Mrs. Blackie the whole time, sprang up and struck quickly twice. There was a chain of shrieks from Mrs. Blackie, and down she went in the grip of the clawed death. She never got up again.

What had happened was simple enough. One of the laborers working on the trench, knowing of the nest, had, out of curiosity, approached a little too close, when the bevy of youngsters, being ready to fly, but not knowing it before this great fright, burst apart at his approach like a silent cannon cracker. The fear showed them they could use their wings.

All three had made, flying low and weakly, for the nearest hedge, which was the garden hedge—two to the side which comprised their father's hunting-ground, and one to the side dominated by their ma. And the old cat and her kitten had seen them coming, and had given chase.

Blackie discovered his remaining progeny sitting about in bushes, squawking, a few minutes later, when he returned, somewhat agitated to his precious lawn, and there he promptly proceeded to feed them. The task was such a large one, and took so long, and so many worms had to be cut up, and so much bread, and, I may say, when all else failed, so many daisies had to be picked, before he finally silenced their ceaseless, craving remarks, that, by the time he had finished feeding himself and had a clean up, something of the pain of the tragedy had gone from him.

And fine fat blackbirds he made of those youngsters, too, in the end, I want to tell you, for he stuck to 'em like a brick.

A little past noon each day the sun covered a crack between two boards on the summer-house floor, and up through that aperture, for three days, had come a leggy, racy-looking, wolfish black spider. Each day, as it grew hotter, she extended her sphere of jerky investigation, vanishing down the crack again when the sun passed from it.

To-day she prolonged her roamings right up the wall of the summer-house and along a joist bare of all save dust, and—well, the spider walked straight on, moving with little jerks as if by intermittent clockwork, and she seemed to stroll right on top of the wasp lying curled up on her side. Only when one of the latter's delicate feelers shifted round towards her, as though in some uncanny way conscious of her approach, did she leap back as if she had touched an electric wire. Then she froze—flat. The wasp was lying curled up, as we have said, upon her side, her head tucked in, her wings drawn down, her jaws tight shut upon a splinter of wood. She had been there half-a-year, asleep, hibernating, and in that state, without any other protection than the summer-house roof and walls, had survived the frosts of winter.

The wasp did not move further.

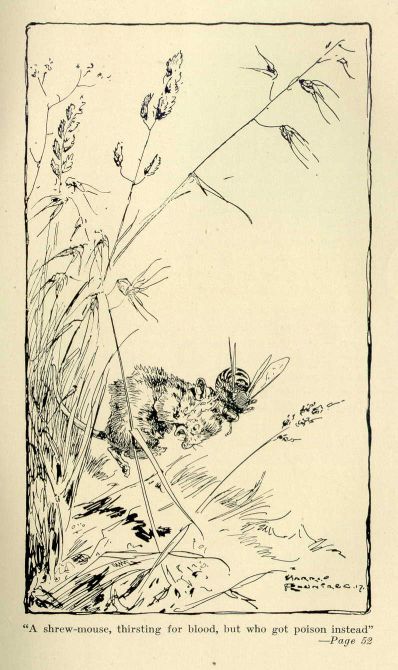

The spider appeared to be taking things in, measuring her chances, weighing the risk against her famished hunger—possibly her late husband had been her last meal, months ago—marking the vital spot upon her prey, aiming for the shot, which must be true, for one does not miss in attacking a wasp—and live. Only, she would not have risked it at all, perhaps, if the wasp had seemed alive, or more alive, at any rate.

Then came the shot—one cannot in justice call it a spring; it was too instant to be termed that. The spider simply was upon the wasp without seeming to go there; but the wasp was not there, or, rather, her vital spot wasn't. She had kicked herself round on her side, like a cart-wheel, lying flat, with her feet, and the spider's jaws struck only hard cuirass. Before the spider, leaping back, wolf-like, could lunge in her lightning second stroke, the wasp was on her feet, a live thing, after all.

The warmth had been already soaking the message of spring into her cold-drugged brain, and now this sudden attack had finished what the warmth had begun. She was awake, on her feet, a live and dangerous proposition; groggy, it is true; dazed, half-working, so to speak; but a force to be reckoned with—after half-a-year. And one saw, too, at a glance that she was different from ordinary wasps—would make two, in fact, of any ordinary wasp; and her great jaws looked as if they could eat one and comfortably deal with more; whilst her dagger-sting, now unsheathed and ready—probably for the first time—could deliver a wound twice as deep and deadly as the ordinary wasp. She was, in short, a queen-wasp; a queen of the future, if Fate willed; a queen as yet without a kingdom, a sovereign uncrowned, but of regal proportions and queenly aspect, for all that; for in the insect world royalties are fashioned upon a super-standard that marks them off from the common herd.

The spider hesitated. She knew the danger of the stripes of yellow—the yellow flag, so to speak. The fear of it is upon every insect that lives. At the same time, the queen was undoubtedly yet numb.

Antagonists decide in the insect world like a flash of light, and quick as thought they act. The spider attacked now so quickly that she seemed to have vanished, and she met—jaws. Back she shot, circled, shot in again, and she met—sting!

It was never clear whether that sting went home. The spider did. She fell—fell plump to the floor, only not breaking what spiders have in place of a neck because of the fact that, being a spider, she never moved anywhere, not even upon a spring, without anchoring a line of web down first. Therefore, an inch from the ground, she fetched up with a jerk upon the line that she had anchored up on the joist, spun round, let herself drop the rest of the way, and ran into the crack between the boards of the floor. Goodness knows if she lived.

The wasp, with that extremely droll, lugubrious look on her long, mask-like face which makes the faces of insects so funny and uncanny, like pantomime masks, sat down as if nothing had happened, apparently to scheme out the best way to possess herself of a kingdom and become a queen in fact as well as in name. Really, she was cleaning herself—combing her antennae with her forelegs, provided with bristle hairs for the purpose, scraping and polishing her wings, as if they did not already shine like mother-o'-pearl, and washing her quaint face.

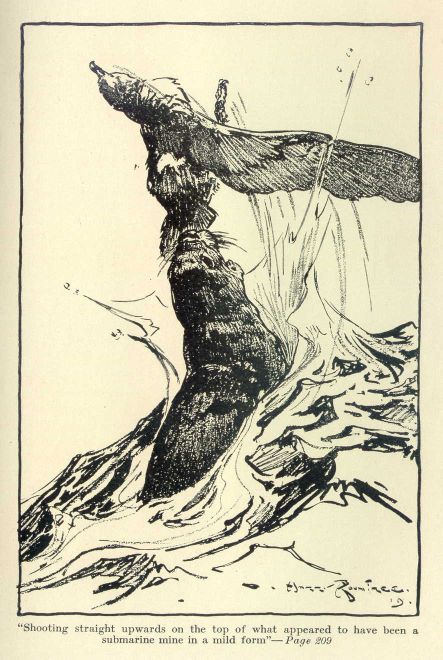

She was still rather groggy from the effects of her long sleep and the cold endured—it is a wonder how she had stood the latter at all—and when, with a subdued inward sort of hum, she finally launched herself in flight, she nearly fell to the ground before righting herself and flying in a zigzag heavily across the lawn.

A cock-chaffinch up in the limes saw her, and condescending at last to break his song, described a flashing streak of wine-red breast and white wing-bars in the sun. He appeared to recognize her sinister yellow shield in time, however, and returned to his perch with a flourish, leaving the wasp to go on and begin dancing up the wall of the house till she came to the open window. Here she vanished within.

The sunlight sat on the floor of the room inside, and the baby sat in the sunlight; and the wasp, apparently still half-awake, went, or, rather, nearly tumbled, and sat beside the baby.

They made an odd picture there—the golden sun, the sunny, golden-headed baby, and that silent, yellow she-devil, crawling, crawling, crawling, with her narrow wings gleaming like gems.

Then the child put out her chubby hand to seize that bright-yellow object—how was she to know that it was the yellow signal of danger in the insect world that she saw? And, of course, being a baby, she was going to stuff it into her mouth. But Fate had use for that wasp—perhaps for that baby. Wherefore there was a little scream, a pair of woman's arms swept down and whisked that baby into the air, and a high-heeled shoe whisked the astonished wasp into a corner. Here she swore savagely, vibrating her head with tremendous speed in the process, rose heavily and menacingly, made to fly out, hit the upper window, which was shut, and which she could not see, but felt, and fell to the floor again, where she apparently had brain-fever, buzzing round and round on her back like a top the while.

And then, rising suddenly, the queen flew away, hitting nothing in the process, but getting through the lower and open part of the window. She seemed anxious to make sure of not getting into the house again. She flew right away, rising high to top the garden hedge, and dropping low on the far side, to buzz and poke about in and out, up along the hedge-bank that bordered the hayfield.

She flew as one looking for something, and every insect in her way took jolly good care—in the shape of scintillating streaks and dashes—to get out of it. The mere sight of that yellow-banded cuirass shining in the sun was apparently quite enough for them—most of them, anyway. As a matter of fact, she was looking for a site for a city. She had ambition, and would found her a city, a city of her very own, with generous streets at right angles, on the American plan; and she would be queen of it. It was a big idea, and we should have said an impossible one, seeing that at that moment she was the city and its population and its queen all rolled into one, so to speak. Queen-wasps, however, also on the American plan, ruled the word "impossible" out of their dictionary long ago. They "attempt the end, and never stand to doubt."

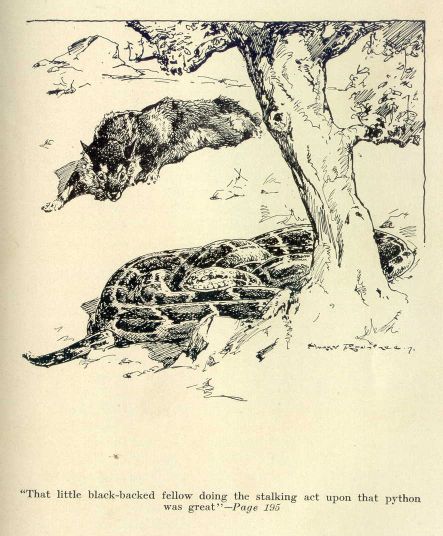

The queen came to rest on a bare patch of ground an front of a hole, and a black and hairy spider, with two hindlegs missing on the offside, spun round in the entrance of that hole to face her. He had not been noticeable until he moved.

She left him in a hurry, and thereafter resumed her endless searching along the hedge-bank. A dozen times she vanished into a hole, and, after a minute or so, came out again with the air of one dissatisfied. Half-a-dozen times she came out tail first, buzzing warnings and very angry, at the invitation of a bumble-bee queen, a big, hook-jawed, carnivorous beetle in shining mail, and so forth, but she never lost her head.

Finally, she came to a mole-hole that suited her. The other burrows had all turned out to be field-mouse holes, leading ultimately into a main tunnel that ran the whole length of the hedge apparently, and was a public way for all the little whiskered ones. But this tunnel, bored by the miner mole, ran nowhither, having caved in not far from the entrance, and was very sound of construction, with a nice dry slope. She selected a wide spot where the tunnel branched, each branch forming a cul-de-sac. Here she slew swiftly several suspicious-looking little tawny beetles and one field-cricket, who put up a rare good fight for it, found loafing about the place.

It pleased the queen that here, in this spot, she would found her a city. But first she must, as it were, take the latitude and the longitude of this her stronghold to be. She must know where her city was, must make absolutely dead sure, certain, of finding it again when she went out. Otherwise, if she lost it—well, there would be an end to it before it had begun, so to speak. For this purpose, therefore, she rose slowly, humming to herself some royal incantation—rose, upon a gradually widening corkscrew spiral, into the air.

She was, in point of fact, surveying the district round her capital to be, marking each point—bush, stone, grass-tuft, tree-trunk, flower-cluster, clod, branch, anything and everything, great and small—and jotting down in indelible memory fluid, upon whatever she kept for a brain, just precisely the position of every landmark. And as she rose her circles ever widened, so that at last her big compound eyes took in quite a big stretch of sunlit picture, to be photographed upon her memory, and there remain forevermore.

It took her some time, for it was some job; but once done, it was done for good.

Next, alighting with great hustle—now that the work was once begun—the queen ran into her tunnel, and made sure that nobody had "jumped her claim" in the interval. She found an ant, red and ravenous, taking too professional an interest in the place, and she abolished that ant with one nip; though, as you may be sure, the tiny insect fought like a bulldog.

Then she executed a shallow excavation upon the site of the future city itself, carrying each pellet of earth outside beyond the entrance. This also took time, though she worked at fever-pitch, almost with fury; but she managed to finish it, and fly away into the landscape in a remarkably short while, considering.

Here once again she appeared to be searching for something through the yellow sunshine and the falling blossom-petals—confetti from Spring's wedding. And presently she found it, or seemed to—an old gate, off its hinges. But the wood was rotting, and she was no fool. She knew her job—the job she had never done before, by the way—and after humming around it in a fretful, undecided sort of fashion for some while, she flew on. Apparently she was looking for wood, but not any wood. Cut wood appeared to be her desire, and that oak; at least, she put behind her a deal board lying half-overgrown, after one careful professional inspection.

Her way was through a perilous world, beset by a thousand foes, mostly in the nature of traps and lines and barbed-wire entanglements set by spiders. As a rule you didn't see these last at all—nor did she; but her yellow-and-black badge usually won her a way of respect—and hate—and she cut or struggled herself clear of such web-lines as her feelers failed to spot in time.

At last she found some real oak rails, and set to work upon them at once, planing with her sharp shear-jaws. A tiger-beetle, gaudy and hungry-eyed, sought to pounce upon her in this task. He was long-legged, and keen, and lean, and very swift; but she shot aloft just in time; and when she came down again, with a z-zzzzp, as quickly as she went up, sting first, he had wisely dodged into a cranny, where he defied her with open and jagged jaws.

Again getting to work, she planed off a pellet of good sound wood—it looked like a nail-scrape, the mark she made—and masticating it and moistening it with saliva, whirred back like a homing aeroplane to her city in the making.

There was a whir and a buzz as she passed through the portals of her main gate from the light of day, and she reappeared again, backing out, "looking daggers," as we say, and brandishing her poisoned dart—her sting, if you insist, on the end of her tail—in the air. But she still hung on to her pellet.