Title: Lucia Rudini: Somewhere in Italy

Author: Martha Trent

Illustrator: Charles L. Wrenn

Release date: February 2, 2006 [eBook #17666]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Al Haines

E-text prepared by Al Haines

| CHAPTER | |

| I | CELLINO |

| II | MARIA |

| III | BEFORE DAYBREAK |

| IV | LOST |

| V | IN THE TOOL SHED |

| VI | GARIBALDI PERFORMS |

| VII | THE BEGGAR |

| VIII | THE SURPRISE ATTACK |

| IX | THE BRIDGE |

| X | GARIBALDI, STRETCHER-BEARER |

| XI | THE AMERICAN |

| XII | A REUNION |

| XIII | AN INTERRUPTED DREAM |

| XIV | THE FAIRY GODFATHER |

| XV | EXCITING NEWS |

| XVI | THE KING |

| XVII | GOOD-BY TO CELLINO |

| XVIII | IN THE GARDEN |

| XIX | BACK TO FIGHT |

| XX | AN INTERRUPTED SAIL |

| XXI | THE END OF THE STORY |

Lucia Rudini folded her arms across her gaily-colored bodice, tilted her dark head to one side and laughed.

"I see you, little lazy bones," she said. "Wake up!"

A small body curled into a ball in the grass at her feet moved slightly, and a sleepy voice whimpered, "Oh, Lucia, go away. I was having such a nice dream about our soldiers up there, and I was just killing a whole regiment of Austrians, and now you come and spoil it."

A curly black head appeared above the tops of the flowers, and two reproachful brown eyes stared up at her.

Lucia laughed again. "Poor Beppino, some one is always disturbing your fine dreams, aren't they? But come now, I have something far better than dreams for you," she coaxed.

"What?" Beppi was on his feet in an instant, and the sleepy look completely disappeared.

"Ha, ha, now you are curious," Lucia teased, "aren't you? Well, you shan't see what I have, until you promise to do what I ask."

Beppi's round eyes narrowed, and a cunning expression appeared in their velvety depth.

"I suppose I am not to tell Nana that you left the house before sunrise this morning," he said.

Lucia looked at him for a brief moment in startled surprise, then she replied quickly, "No, that is not it at all. What harm would it do if you told Nana? I am often up before sunrise."

"Yes, but you don't go to the mountains," Beppi interrupted. "Oh, I saw you walking smack into the guns. What were you doing?" He dropped his threatening tone, so incongruous with his tiny body, and coaxed softly, "please tell me, sister mine."

"Silly head!" Lucia was breathing freely again, "there is nothing to tell. I heard the guns all night, and they made me restless, so I went for a walk. Go and tell Nana if you like, I don't care."

Beppi's small mind returned to the subject at hand.

"Then if it isn't that, what is it you want me to do?" he inquired, and continued without giving his sister time to reply. "It's to take care of them, I suppose," he grumbled, pointing a browned berry-stained little finger at a herd of goats that were grazing contentedly a little farther down the slope.

"Yes, that's it, and good care of them too," Lucia replied. "You are not to go to sleep again, remember, and be sure and watch Garibaldi, or she will stray away and get lost."

"And a good riddance too," Beppi commented under his breath.

He did not share in the general admiration for the "Illustrious and Gentile Señora Garibaldi," the favorite goat of his sister's herd. Perhaps the vivid recollection of Garibaldi's hard head may have accounted for his aversion. Lucia heard his remark and was quick to defend her pet.

"Aren't you ashamed to speak so?" she exclaimed, "I've a good mind not to give you the candy after all."

"Oh, Lucia, please, please!" Beppi begged. "I will take such good care of them, I promise, and if you like, I will pick the tenderest grass for old crosspatch," he added grudgingly.

Lucia smiled in triumph, and from the pocket of her dress she pulled out a small pink paper bag.

"Here you are then," she said; "and I won't be away very long. I am just going to see Maria for a few minutes."

Beppi caught the bag as she tossed it, and lingered over the opening of it. He wanted to prolong his pleasure as long as possible. Candy in war times was a treat and one that the Rudinis seldom indulged in.

As if to echo his thoughts, Lucia called back over her shoulder as she walked away, "Don't eat them fast, for they are the last you will get for a long time."

Beppi did not bother to reply, but he acted on the advice, and selected a big lemon drop that looked hard and everlasting, and set about sucking it contentedly.

Lucia walked quickly over the grass to a small white-washed cottage a little distance away. She approached it from the side and peeked through one of the tiny windows. Old Nana Rudini, her grandmother, was sitting in a low chair beside the table in the low-ceilinged room. Her head nodded drowsily, and the white lace that she was making lay neglected in her lap. Lucia smiled to herself in satisfaction and stole gently away from the window.

The Rudinis lived about a mile beyond the north gate of Cellino, an old Italian town built on the summit of a hill. Cellino was not sufficiently important to appear in the guide books, but it boasted of two possessions above its neighbors,—a beautiful old church opposite the market place, and a broad stone wall that dated back to the days of Roman supremacy. It was still in perfect preservation, and completely surrounded the town giving it the appearance of a mediaeval fortress, rather than a twentieth century village. Two roads led to it, one from the south through the Porto Romano, and one from the north, up-hill and from the valley below. It was up the latter that Lucia walked. She was in a hurry and she swung along with a firm, graceful step, her head, crowned by its heavy dark hair, held high and her shoulders straight.

The soldier on guard at the gate watched her as she drew nearer. She was a pleasing picture in her bright-colored gown against the glaring sun on the dusty white road. Roderigo Vicello had only arrived that morning in Cellino, and Lucia was not the familiar little figure to him that she was to the other soldiers. But she was none the less welcome for that, after the monotony of the day, and Roderigo as she came nearer straightened up self-consciously and tilted his black patent leather hat with its rakish cluster of cock feathers a little more to one side.

"Good day, Señorina," he said smiling, as Lucia paused in the grateful shadow of the wall to catch her breath.

"Good day to you," she replied good-naturedly.

"You're new, aren't you? I never saw you before. Where is Paolo?"

"Paolo and his regiment go up to the front this afternoon," Roderigo replied. "We have just come to relieve them for a short time, then we too will follow."

Lucia nodded. "You come from the south, don't you?" she inquired, looking at him with frank admiration; "from near Napoli I should guess by your speech."

Roderigo laughed. "You guess right, I do, and now it is my turn to ask questions. Where do you come from?"

"Down there about a mile," Lucia pointed, "in the white cottage by the road."

Roderigo looked at the dark hair and eyes and the gaudily colored dress before him, and shook his head.

"Now perhaps," he admitted, "but you were born in the south where the sun really shines and the sky is blue and not a dull gray, or else where did you come by those eyes and those straight shoulders?"

Lucia looked up at the dazzling sky above her and laughed.

"And I suppose that spot is Napoli," she teased. "Well, you don't guess as well as I do, for I was born here and I have lived here all my life."

"'All my life,'" Roderigo mimicked. "How very long you make that sound, Señorina, and yet you look no older than my little sister."

Lucia drew herself up to her full height and did not deign a direct reply.

"Fourteen years is a long time, Señor," she said gravely, "when you have many worries."

"But you are too young to have many worries," Roderigo protested; "or I beg your pardon, perhaps you have some one up there?" he pointed to the north, where the high peaks of the Alps were visible at no great distance.

"No, not now," Lucia replied; "for my father was killed a year ago."

Roderigo was silent for a little, then he raised one shoulder in a characteristic shrug.

"War," he said slowly. "We all have our turn."

Lucia nodded and returned almost at once to her gay mood.

"But you are still wondering how I got my black hair and eyes up here," she laughed.

"Well, I will tell you. My mother came from your beautiful Napoli, and Nana, that is my grandmother, says I inherited my foolish love of gay clothes from her. Nana does not like gay clothes, but my father always liked me to wear them."

"Then your mother is dead too?" Roderigo asked respectfully.

"When I was a little girl, and when Beppino was a tiny baby. Beppi is my little brother," Lucia explained.

Roderigo's eyes were shining with delight. There was something in Lucia's soft tones that filled his homesick heart with joy. She was so different from most of the girls from the north, with their strange high voices and unfriendly manners. If she wasn't exactly from the south she was near it. He wanted to sit down beside her and tell her all about his home and his family, for he was very young and very homesick, but Lucia decreed otherwise.

"Now do see what you have done," she scolded suddenly. "You have kept me talking here until the sun is well down, and I will have to hurry if I want to see Maria and return home before Nana misses me. So much for gabbing on the high road with some one who should be watching for suspicious spies instead of asking questions," she finished with a provoking toss of her head.

Which sentence, considering that she had asked the first questions herself, was unjust. Roderigo, however, did not seem to resent the blame laid upon him. He did not even offer to contradict, but watched Lucia until she disappeared around a corner a few streets beyond the gate, and then he turned resolutely about and scanned the road with searching determination, as if he really believed that the open, smiling country about him might be concealing a spy.

When Lucia disappeared around the comer of the narrow street that led to the market place, she stopped long enough to laugh softly to herself.

"The great silly! He took all the blame himself instead of boxing my ears for being impertinent. A fine soldier he'll make! If I can scare him, what will the guns do?" she said aloud, and then with a roguish gleam of mischief in her eyes she hurried on.

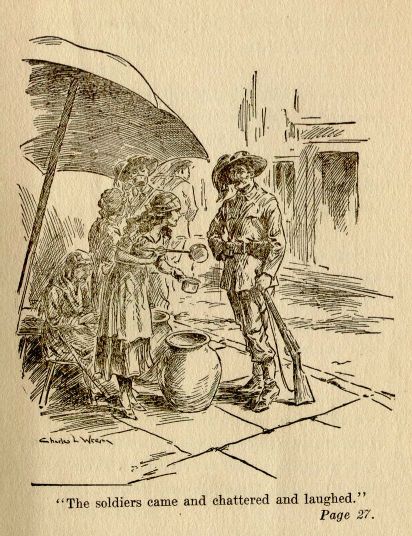

The narrow side streets through which she passed were almost deserted, but when she reached the market place it was thronged with people. Every one was out to look at the new troops, and in the little square the great white umbrellas over the market stalls were surrounded by soldiers. Their picturesque uniforms added a gala note to the commonplace little scene.

Lucia elbowed her way through the jostling, laughing men to a certain umbrella, a little to one side of the open space left clear before the church.

A neatly-dressed, dumpy little woman in a black dress and shawl sat beneath it, and behind a row of stone crocks beside her was a young girl several years older than Lucia, who ladled out cupfuls of the milk that the crocks contained, and gave them, always accompanied by a shy little smile, to the soldiers in return for their pennies. She was Maria Rudini, Lucia's cousin, a pretty, gentle-featured girl with shy, bewildered eyes.

People often spoke of her quiet loveliness until they saw her younger cousin. Then their attention was apt to be diverted, for Maria's delicate charms seemed pale beside Lucia's southern beauty, and in the same manner her courage grew less. Although she was three years older, Maria never questioned Lucia's authority to lead.

When Lucia's father had died, the kindly heart of Maria's mother had prompted her to offer her home to his children, but Lucia had declined the offer. She said she would undertake the support of old Nana and Beppi and herself. There was considerable disapproval over her decision, but as was generally the case, Lucia had her own way. Her method of wage-earning was a simple one. Her father had owned a herd of goats and a garden, and the two had provided ample support for the needs of the family. At his death Lucia, with characteristic selection, had given up the garden and kept the goats.

Every morning she milked them and carried the bright pails to town, where her aunt sold them at her little stall along with cheese and sausage. The profits wore not great, but they wore enough.

"Is that the milk I brought in this morning?" Lucia asked incredulously as she approached the stall.

"No, no, my dear," her aunt replied, shaking her head. "You brought scarcely two full pails, and they were gone before you had reached the gate. We have had a great day, so many soldiers, it is a shame that you cannot bring in more, for we could sell it. Just see, we had to send to old Paolo's for this, and it is not as rich as yours of course, for his poor beasts have only the weeds between the cobblestones to eat."

"That is because he is a lazy old man and won't take the trouble to lead his herd out on the slopes to graze," Lucia replied. She put her hands on her hips and swayed back and forth as she talked. It was a little trait she had inherited from her mother, and one of her most characteristic poses.

"How well you look to-day!" Maria said, smiling. "I have been wishing you would come, we are so busy—see, here come a group of soldiers all together. Will you help me?" She held out a dipper with a long handle, which Lucia accepted critically.

"I don't like charging full price for this milk which is more like water," she said.

"Nonsense, child, it is business, the soldiers know no difference; it is only your silly pride," her aunt scolded. She was a little in awe of her determined niece, and very often she was provoked at her.

"If you can't bring us more milk, we must do the best we can," she said meaningly. "You used to bring us twice this much."

Lucia shrugged her shoulders and tossed her head. "I can bring no more than I bring," she said, and turned her attention to the soldiers before her.

But the explanation did not satisfy her thrifty aunt. She was no authority on goats, but she had enough sense to know that the supply of milk does not dwindle to one-half the usual quantity over night. Still she did not voice her suspicions.

Lucia and Maria were busy for the rest of the afternoon. Lucia's flowered dress and brilliantly-colored bandana that she wore tied over her head, were added attractions to Señora Rudini's stall, and the soldiers from the south came and chattered and laughed.

"What a pity we have no more," Maria said as the last crock was emptied, and they set about preparing to return home. "We could go on selling all night now that Lucia is here."

"Well, it is high time to go home, I am tired," her mother replied crossly. "Hurry with what you are doing."

Lucia was busy closing the big umbrella.

"It is late, I will have to hurry, or Beppi will have let all my goats run away—he and his dreams. He is a lazy little one, but I can't bear to scold him," she said. "He is too little to understand."

Her aunt nodded. "Let him dream, but if you are not careful, he will be badly spoiled."

"No fear of that," Lucia replied, "while Nana has a word to say. She is always for bringing him up properly, but little good it does. Now we are ready, I will help you carry home your things, if you will let Maria walk with me to the gate," Lucia bargained.

"Oh, she may I suppose, though she should be at home helping me prepare the dinner. I suppose you have some secrets between you that an old grayhead can't hear," she grumbled good-naturedly.

"Oh, yes a fine secret!" Lucia replied laughing, as she picked up the greatest share of the burden and led the way.

Maria and her mother lived in an old stone house that had once been a palace. It was hardly palatial now, but it was very picturesque. It housed five families besides the Rudinis, and in spite of the many lines of wash that floated from its windows, it still retained enough of its old grandeur to be an interesting spot to the occasional tourist who visited Cellino. Maria and her mother were very proud of this distinction. It made up somewhat for the loss of their house, which they had been forced to leave, when six months before Maria's two brothers had gone off to fight.

The new quarters were not far from the market place and they soon reached them. Their rooms were on the ground floor, and Lucia and Maria made haste to drop what they were carrying and start off again at a much slower pace for the gate. The sun was low in the west. It was setting in a bank of golden clouds over the little river that ran parallel with the west wall of the town. Lucia stopped to look at it.

"Rain to-morrow, I suppose, by the look of those clouds," she said, a real pucker of concern between her eyes.

"And no wonder," Maria agreed, "with all this banging of guns one would think it would rain all the time out of pity for so much suffering."

"Now, Maria, don't begin to cry," Lucia protested not unkindly. "It will do you no good, and it will only make things look worse than they really are."

"How can they?" Maria demanded, with more show of resentment than was usual with her quiet acceptance of things. "Only this morning I sold milk to such a sweet boy from the south. He had great sad, brown eyes like yours, and he was very young and unhappy. His father and brother were both killed, and now he is going."

"But perhaps he won't be killed," Lucia said practically. "Anyway, he will get a chance to do a little killing first, and surely that is enough to satisfy any one, or ought to be."

"Oh, Lucia you are cruel sometimes," Maria protested. "Who wants to kill? Surely not these happy boys, and they don't want to be killed either. It is all too terrible to think about, and you are an unnatural girl to talk as you do. Why, I don't believe you have cried once since the war began, even when the poor wounded were brought here, and we saw their faces all shot away."

Maria's anger rose as she talked, and Lucia listened curiously. It was something new for Maria to take her to task. Her mind flew back over the past year, and she saw herself with her face buried in the grass and her hands clenched, and remembered her furious anger and her vows of vengeance, but she had to admit that her cousin was right; she had shed no tears.

"We are not made the same way, I guess," she replied ruefully to Maria's charges. "I cannot cry, I can only hate."

"But hate won't do any good," Maria protested feebly.

"It will do more than tears," Lucia replied shortly.

They continued their walk in silence, now and then nodding to an acquaintance or bowing respectfully to the Sisters of Charity who lived at the big Convent just outside the Porto Romano, and who came to town to take care of the sick and cheer the broken-hearted. When they reached the north gate Lucia stopped. Roderigo was still on duty, but this time he did not pause in his brisk walk up and down to chat. He never even glanced in the girls' direction.

Maria nodded towards him and whispered excitedly, "That is the boy I was just now speaking of. Doesn't he look sad?"

"No, he looks quite cross," Lucia replied in a voice loud enough to be overheard, and her eyes sparkled with mischief as she added, "I wonder if he will let me through the gate to get home."

"May I pass, sir, please? I live a little beyond the wall, but I am not a spy," she said with mock humility.

Roderigo blushed. A soldier does not like to be made fun of, particularly when some one else is present.

"Pass," he said gruffly.

Lucia laughed provokingly.

"Good night, Maria," she said as she kissed her cousin. "Sweet dreams. I may not be in very early in the morning, there is so much to do, you know, but I will bring as much milk as possible," she finished. Then without even a glance at Roderigo she walked through the gate and down the wall.

When she had walked for a little distance she looked back. Maria and the soldier were in earnest conversation. Maria in her timid way was apologizing for her cousin's rudeness, and Roderigo was beginning to have doubts of the superiority of Southern beauty over the Northern, particularly when a gentle spirit was added to the charm of the latter. Lucia did not know she was the subject of their talk. She shrugged her shoulders and turned her thoughts to a more important question that was puzzling her. It was, how to slip out of the house the next morning without disturbing the already suspicious Beppi.

Lucia found Beppi asleep in the grass, curled up in the same position that he had been in earlier in the day. One of his little hands had tight hold of the precious pink bag, and a sticky smile of blissful content turned up the corners of his full red lips.

Lucia looked at him and shook her head. There might have been twenty-seven instead of seven years between them, for there was something protective in her expression.

"Little lazy bones, asleep again!" she said, shaking him gently.

Beppi stirred, one eye opened, and then with a sudden rush of memory he sat up and began excitedly: "I just this minute fell asleep, just this very second, truly, Lucia! I have watched the goats, oh, so carefully, and they have not stirred,—see there they are only a little farther away than when you left. I only closed my eyes because I thought I might go on with that nice dream, but I didn't," he finished sorrowfully.

Lucia laughed.

"Look at the sun," she pointed. "It is late, you should have driven the goats home long ago. But I knew you would go to asleep after you ate up all the candy, such a naughty little brother that you are. What kind of a soldier would you make, I'd like to know, dreaming every few minutes? Come along, get up,—we must hurry back to Nana, or she will be worried."

She took his hand and together they drove the goats before them to the cottage.

Nana Rudini was waiting for them at the door. She was a little, wrinkled-up, old woman with bright blue eyes and thin gray hair. She spoke very seldom and always in a high querulous voice.

"So you're back at last, are you?" she greeted, when the children were within hearing. "Supper's been on the stove for too long. What kept you?"

"Very busy day, Nana," Lucia spoke in much the same tone she had used towards Beppi. "I had to help Aunt and Maria at market. More troops have arrived and the streets are crowded."

"Oh, sister, you never told me that!" Beppi said accusingly. "Where are they from?"

"The south mostly," Lucia replied, "fine soldiers they are too, if you can judge by their looks."

"Which you can't," old Nana interrupted shortly. "Stop your talking and come in to supper."

"Right away," Lucia promised, and hurried off to shut up her goats in the small, half-tumbled-down shack at the back of the cottage.

Supper at the Rudinis consisted of boiled spaghetti, black bread and cheese, with a cup full of milk apiece. It was not a very tempting meal, but Lucia was hungry and ate with a hearty appetite.

After the three bowls had been washed and put away in the cupboard, she helped her grandmother undress, and settled her comfortably in the green enameled bed with its brass trimmings, that occupied a good part of the small room. Lucia's mother had brought it with her from Naples, and it was the most cherished and admired article of furniture that the Rudinis owned.

"Are you comfortable, Nana?" Lucia inquired gently, as she smoothed the fat, hard pillows in an attempt to make a rest for the old gray head.

"Yes, go to bed, child," Nana replied, and without more ado she closed her eyes and went to sleep.

Lucia climbed up the ladder to the loft, and was soon cuddled down beside Beppi in a bed of fresh straw. Though she persisted in her determination that her grandmother sleep in state in the best bed, she herself preferred a simple and softer resting place.

"Tell me a story," Beppi demanded; "not about fairies and silly make believes, but about soldiers."

"But there are no pretty stories about soldiers, Beppino mio," Lucia protested.

"Who wants pretty stories!" Beppi replied scornfully. "I don't—tell me an exciting one about guns and war."

"Very well I'll try, but be still," Lucia gave in, well knowing that she would not have to go very far.

"Once upon a time," she began, "there was a soldier. He had very big eyes, and he came from the south where the sun is very warm and the sky and the water are very, very blue."

"Was he brave?" Beppi interrupted sleepily.

"Oh, yes, he was very brave," Lucia replied hurriedly, "very brave, and he loved his country more than anything else in the world."

She waited but Beppi's voice commanded.

"Go on, don't stop."

"Well, one day he was sent to guard a gate of a city, and he walked up and down before it with his gun on his shoulders, and no one could pass him unless it was a friend."

She paused again. Beppi was breathing regularly.

"Old sleepy head!" Lucia whispered, and kissed him tenderly.

The story was not continued and before many minutes she was fast asleep herself.

It was an hour before sunrise when she awoke. The air that found its way into the little attic was damp and chill. Lucia crept out of bed, being very careful not to disturb Beppi, and slipped hurriedly into her clothes. With her shoes in her hand, she climbed gingerly down the ladder past her sleeping grandmother and out to the shed.

"Good morning, Garibaldi, how are you this morning?" she said as she patted the stocky little neck of her pet.

Garibaldi submitted to her caress with a condescension worthy of the position her name gave her, and the other goats crowded to the open door, eager to leave their cramped quarters.

"Not yet, my dears," Lucia said softly, "it isn't time. Here, Esther, I will milk you first. You must all be good to-day, and Garibaldi, I don't want you to go running away if I have to leave you with Beppi," she continued. "You're nothing but goats, of course, but you know perfectly well that we are at war, and that you are very important, and must do your part. Stop it, Miss, none of your pranks, I'm in a hurry," she chided the refractory Esther for an attempt at playfulness.

"There now, that's enough, I can't carry any more or I would. Two pails only half full aren't much, but they help, I guess. Now if it won't rain until I get there it will be all right, but I'll cover the pails to be on the safer side." She found two covers and fitted them securely over the pails. "Now children, good-by. Be good till I come back, and don't go making any noise."

She paused long enough to give Garibaldi a farewell pat and then left the shed closing the door behind her. She looked up uneasily at the cottage, but everything seemed to be very still, so she picked up her pails and started off at as brisk a pace as possible.

She followed the main road that looked unnaturally white and ghostly in the pale dawn of the early morning. It was down hill for about a mile, and traveling was comparatively easy at first, but when the road reached the bottom of the valley it stopped and seemed to straggle off into numerous little foot-paths. The broadest and most traveled looking path Lucia followed, picking her way carefully for fear of stumbling and thus losing some of the precious milk.

The path led up the other side of the valley. It was a steep climb, and Lucia was tired when she reached the top. She sat down for a while to rest before going on the remainder of the way. The next path that she took turned abruptly to the right, and led up an even steeper hill to a tiny plateau above. From it one could look down on Cellino across the valley. When Lucia reached it she put down her pails in the shade of a big rock and looked about cautiously.

Nothing seemed to stir. The guns were quiet and nothing in the peaceful, secluded little spot suggested the close proximity of battle. The only human touch in sight was a small scrap of paper, held down by a stone on the flat rock above the pails.

Lucia was not surprised, for she had done the same thing every morning for a week now. She unfolded it. As she expected, she found four brightly polished copper pennies and the words, "Thanks to the little milk maid," written in heavy pencil.

Lucia picked up the money and put it into her pocket, then with a pencil that she had brought especially for the purpose she wrote, "You are welcome, my friends; good luck!" below the message, and tucked the paper back under the stone. Then with another curious look around, which discovered nothing, she started back, this time running as fleet and fast as any of her sure-footed little goats.

She reached home before either Nana or Beppino were awake, and hurried to finish her milking. When the scant breakfast was over, she was ready to start for town with her pails.

When she entered the market-place, it was to find a very different scene from the one of the day before. The place was thronged with soldiers, but they were not laughing and jesting; instead, little groups congregated around the stalls and talked excitedly. Some of the old women had covered their faces with their black aprons, and were rocking back and forth on their chairs in an extremity of woe.

There was an unnatural hush, and men and women alike lowered heir voices instinctively as they talked.

Lucia had seen the same thing many times before. She guessed, and rightly too, that a battle was going on, and that news of some disaster had reached the little town. She did not go at once to her aunt's stall, but left her pails inside the big bronze door of the church, and slipped quietly inside. The place was deserted, and the lofty dome was in dark shadow. Long rays of pale yellow light from the morning sun came through the narrow windows and made queer patches on the marble floor. In the dim recesses of the little chapels tiny candles flickered like stars in the dark.

Lucia looked about her to make sure that she was alone, and then walked quickly to one of the chapels and dropped four shining copper pennies into the mite box that stood on a little shelf beside the altar. She stayed only long enough to say a hasty little prayer, and then hurried out again into the sunshine. The clouds of the night before and the mist of the early morning had disappeared, and the market-place was bathed in warm golden sunshine.

Lucia picked up her pails and hurried to her aunt's stall.

"Well, you are late," Maria said. "We thought you had stubbed your toe and spilled all the milk."

"And only two half-full pails again," Señora Rudini grumbled. "But no matter, we can get more from old Paolo. Have you heard the news?" she asked abruptly.

"No," Lucia replied indifferently. "What is it?"

"A big gain by the enemy. They have taken thousands of our men, and they say we may be ordered to leave Cellino at any minute."

"Think of it! They are as near as that!" Maria said excitedly. "Oh if we must move, where can we go to? I am so frightened."

"Nonsense," Lucia spoke shortly. There was an angry gleam in her big eyes and her cheeks flushed a dark red.

"Leave Cellino, indeed! The very idea! Since when must Italians make way for Austrians, I'd like to know?"

"But if the enemy are advancing as they say," Maria protested nervously, "we will either have to leave, or be shelled to death by those dreadful guns."

"Or be taken prisoners, and a nice thing that would be," her mother added. "No, if the order to evacuate comes we must go at once. There will be no time to spare. Other towns have been captured, and there is only that between us."

She pointed to the zigzag mountain peaks so short a distance beyond the north gate. As if to give her words weight, a heavy thunder of guns rumbled ominously.

Maria shuddered. "There, that is ever so much nearer. Oh, I am frightened,—something dreadful is happening over there just out of sight."

"Silly! those are our own guns. Ask any of our soldiers," Lucia said.

"Here comes your guard, the handsome Roderigo Vicello, maybe he can tell us. Good morning to you!" she called gayly and beckoned the soldier to come to them.

"I hope you are well this morning," Roderigo said respectfully, bowing to Señora Rudini.

"Oh, we are well, but very frightened," Maria replied, trying hard to imitate her cousin's gaiety.

"Maria thinks that the guns we heard just now are Austrian, and I have been trying to tell her that they are Italian. Which of us is right? You are a soldier and ought to know."

"Our guns, of course. They have a different sound," Roderigo explained impressively.

He had never been any nearer to the front than he was at this moment, but he spoke with the assurance of an old soldier, partly to quiet Maria's fears, but mostly to still his own nervous forebodings. It would never do to let the little black-eyed Lucia see that he was even a little afraid.

"There, what did I tell you!" Lucia was triumphant. "I knew, but of course you would not believe me. Now perhaps you will tell her that we will not have to run away at a minute's notice, too?"

She turned to Roderigo, but eager as he was to display his importance he could not give the assurance she asked. The little knowledge that he had, made him think that the evacuation was very likely to occur at any day.

He covered his fears, however, by replying vaguely: "One can never be sure. War is war, and perhaps it may be necessary, as well as safer, for you to leave for the time being."

Lucia looked at him narrowly.

"What makes you say that?" she demanded. "Have you heard any of the officers talking?"

"No, but this morning's news is very bad. We have our orders to be ready to start at any moment."

"Oh!" Maria caught her breath sharply, and her eyes filled with tears as she looked at Roderigo shyly.

He saw the tears in surprise, and a contented warmth settled around his heart. He looked half expectantly at Lucia. Surely, if this calm, shy girl of the north would shed a tear for him, she with the warm blood of the south in her veins would weep. But Lucia's eyes were dry, and the only expression he could find in them was envy. He turned away in disgust. He did not admire too much courage in girls, for he was very young and very sentimental, and he enjoyed being cried over.

A bugle sounded from the other end of the street, and in an instant everything was in confusion. The soldiers hurried to answer, and the people crowded about to see what was going to happen.

Lucia, eager and excited, snatched Maria's hand and pulled her into the very center of the crowd. An officer, with the bugler beside him, read an order from the steps of the town hall, an old gray stone building that had stood in silent dignity at the end of the square for many centuries.

The girls were not near enough to hear the order, but they soon found Roderigo in the excited mass of soldiers, and he explained it to them.

"We are to leave for the front at once," he cried excitedly. "We have not a moment to spare. Tavola has been captured by the enemy, and our troops are retreating through the Pass."

"The Saints preserve us!" Señora Rudini covered her face with her apron and cried. "My sons! My sons! Where are they, dead or prisoners?"

"No, no, they are safe," Lucia protested. "They are with the Army. Don't worry, when the reënforcements reach them they will go forward again."

But her aunt refused to be comforted. Everywhere in the street women were calling excitedly, and a number of them besieged the officers for information.

The soldiers hurried to their billets and got together their kits. The square buzzed and hummed with excitement and the guns kept up a steady bass accompaniment.

The bugle sounded a different order every little while. Some of the more prudent women went home and began packing their household treasures, but for the most part every one stayed in the market-place and argued shrilly.

"Come!" Lucia exclaimed, catching Maria's hand. "We can watch them march off from the top of the wall by the gate."

They ran quickly through the side streets, and by taking many turns they at last reached the broad top of the wall, which they ran along until they were just above the north gate.

"Here they come!" Maria exclaimed. "I can hear them."

The paved streets of the town rang with the heavy tramp, tramp of men marching, and before long they appeared before the gate. The order to walk four abreast was given. The men took their places, and then at a brisk pace they marched through the old gate, a sea of bobbing black hats and cock feathers.

The townspeople followed to cheer them excitedly. Lucia and Maria leaned dangerously over the edge of the wall in their attempt to recognize the familiar faces under the hats.

The soldiers looked up and called out gayly at sight of Lucia. She had taken off her flowered kerchief and was waving it excitedly. The wind caught her dark hair and blew it across her face, and her bright skirts in the sunshine made a vivid spot of color against the stone wall. The men turned often to look back at her as they marched along the wide road.

Maria did not lift her eyes from the sea of hats beneath her. She was waiting for one face to look up. At last she had her wish. Roderigo's place was towards the end of the column; when he walked under the gate he looked up and smiled. It was a sad smile, full of regret.

Without exactly meaning to, Maria dropped the flower she was wearing in her bodice. Roderigo caught it and tucked it, Neapolitan fashion, behind his ear, then he blew a kiss to Maria and marched on.

Lucia watched the little scene. She was half amused and half contemptuous. Her little heart under its gay bodice was filled with a fine hate that left no room for pretty romance.

When the soldiers had climbed out of sight into the mountains, Maria walked slowly back to find her mother, and Lucia after a hurried good-by ran home to tell Nana and Beppino the news.

She was far more worried over the possible order to evacuate than she would admit. As their cottage was the farthest north on the road, it would be the nearest to the Austrian guns. Personally Lucia scorned the very idea of the Austrian guns, but she could not help realizing the danger to Nana and Beppino and Garibaldi. She was still undecided what to do when she reached the cottage.

Nana Rudini was standing in the doorway, shading her eyes with her withered old hand, and staring intently in the direction that the soldiers had taken.

"Did you see the troops, Nana?" Lucia asked cheerfully. "They were a fine lot, eh? I guess they will be able to stop the enemy from coming any nearer."

"Nearer?" queried Nana, "what are you saying?"

"We have had bad luck," Lucia explained. "Tavola has been captured, and our soldiers are retreating. In town they say we may have to evacuate before to-morrow."

The old woman received the news without comment, but a look of despair came into her usually bright eyes, and for the moment made them tragic. Long years before, when Austria had crossed the mountains and entered Cellino, she had been a young girl. Now in her old age they were to come again, and there was no reason to hope that this time they would be less brutal in their triumph than they had been formerly. The memory of their brutality was still a vivid one.

"We will leave at once," she said at last, and her decision was so unexpected, that Lucia gasped in surprise.

"Leave? But, Nana, where will we go? What will become of our things?" she exclaimed. "Surely we had better wait at least until we are ordered out."

"No, we will leave at once," Nana replied firmly. "The order may come too late, as it did before. What do those boys who swagger about in men's places know about the enemy? There is not one that can remember them. But I, old Nana, have known them and their ways, and I say we must go at once."

Lucia looked at the new light of determination in her grandmother's eyes, and realized with a shock of surprise that to protest would be useless.

"Where is Beppi?" she asked. "I will go and find him."

"With the goats," Nana replied. "Call him, I will go in and start packing."

Lucia ran around the house and off to the sunny slope where she had left Beppi a few hours before. She saw the flock of goats grazing, and called, "Beppino mio, where are you?"

No one answered her. She hurried on, believing him to have fallen asleep.

"Beppi!" she shouted, "I have something exciting to tell you. Stop hiding from me."

She waited, but still no answer came.

In a sudden frenzy of fear she began running aimlessly up and down the hillside, and looking down into the tall grasses, but there was no sign of Beppi. There were no trees or houses in sight, no place that he could hide behind, nearer than the mountain path at the foot of the valley.

Lucia looked about her despairingly, then she went over to the goats. Garibaldi was not there.

"She has strayed away, and Beppi has gone after her," she said aloud in relief, and returned to the cottage.

Nana nodded when she explained. She was busy tying up the household treasures in sheets, and Lucia helped her.

Every few minutes she would go to the door and call, but Beppi did not reply. The afternoon wore on slowly and a bank of rain clouds hid the sun. Lucia's confidence gave way to her first feeling of terror, and Nana was growing impatient.

"Where can he be?" Lucia exclaimed. "I am frightened, he has been gone so long."

Nana shook her head. "He was off after the soldiers, I suppose," she replied. "He is always disobeying—no good will come to him and his naughty ways."

Lucia's eyes flashed.

"He is not naughty," she protested angrily, "and he may be lost this very minute. Anyway I am going to find him and I am not coming home until I do. If you are afraid to stay here go to Maria, she and aunt will look after you, and when I find Beppi I will meet you there."

Nana Rudini protested excitedly, but Lucia did not wait to hear what she said. She ran out of the house and down the road towards the footpath. She had no idea of where she was going, but fear lead her on. Beppi, her adored little brother, and Garibaldi were lost, and she was going to find them.

At the end of the road she paused and looked ahead of her. The sky was dark with rain-clouds and thunder rumbled in the west, an echo of the guns. Lucia took the path that she had taken early that morning, and as she climbed up the steep ascent she called and shouted. Her own voice came back to her from the flat rocks ahead, but there was no sound of Beppi.

Instead of going on to the little plateau where she left her pails, she branched off to the left. It was hard climbing, and after repeated shouts of "Beppi," she sat down and tried to think.

Big drops of rain were beginning to fall, and with the sun out of sight the fall air was damp and cold. She pulled her thin shawl around her shoulders and shivered.

"If Garibaldi ran away she came up here; she always does," she argued to herself. "She loves to climb, and she must have come this way in the hope of finding grass. Up above, and a little over to the left, there is a sort of sheltered spot. Perhaps—" she did not finish the thought, but jumped up and started to climb.

She hunted until she discovered a way to find the spot. It was not difficult, for she knew every foot of the mountains from long association. But Beppi was not to be seen, nor was Garibaldi. Lucia stopped, discouraged. Fear and helplessness were getting the better of her, and she would most likely have given way to the tears she so despised had her eye not caught sight of a tuft of fur on the ground. She seized upon it eagerly. It was without doubt part of Garibaldi's shaggy coat.

With a cry of joy she started off up the tiny trail that led higher up into the rocks.

"Beppi, Beppi!" she called, and stopped. Still no answer, but she was not discouraged for the guns were making so much noise that she realized her voice could not carry any great distance.

The rain was coming down in earnest now, and it was hard to keep from losing her footing on the slippery rocks. She stumbled on regardless of the danger, hoping against hope that she had chosen the right path, and that each step was bringing her nearer to Beppi. Between calling and climbing, she was tired, and she stopped for a moment to catch her breath.

A sound, faint but unmistakable, reached her.

"Naa, Naa!"

Garibaldi was complaining about the weather, at no very great distance away from her.

In her relief Lucia laughed excitedly.

"Beppi, Beppi, where are you?" she shouted, and waited eagerly for a reply, but none came. She looked puzzled and then Garibaldi answered her:

"Naa! Naa!"

The sound came from directly over her head, and she climbed up the steep rock as fast as she could. Garibaldi was standing at the opening of a cave. Lucia ran to her.

"Oh, my pet, I have found you at last. Where is Beppi?" she cried. Garibaldi did not exactly reply, but she stepped a little to one side, and Lucia saw Beppino curled up on a bed of dry leaves sheltered and snug from the storm, and sleeping quite as contentedly as he did on the mattress in the attic at home.

Lucia ran to him and shook him. He opened his eyes, and a dazed look came into them, then he said:

"Oh, yes, I remember, it began to rain and we were lost, your old crosspatch Garibaldi and I, so I found this nice little place, and I was going to pretend that I was a gypsy brigand, but I fell asleep."

Lucia was far too happy to attempt the scolding that she knew Beppi deserved. She picked him up in her arms, and hugged and kissed him, then she encircled Garibaldi's neck and kissed her too.

"My darlings, I thought you were both lost. What a terrible fright you have given me! But we are safe now, and we will wait until sunrise to-morrow, and then we will go home," she said happily.

"I saw the soldiers go away," Beppi said, pushing her face from him as she tried to kiss him again, "and they looked so fine with their shiny hats. It was while I looked at them that old crosspatch ran away. I did have a chase, I can tell you, she had such a big start."

"Are you very hungry, little one?" Lucia asked gently. "I should have brought bread with me, but I did not think."

Beppi giggled, and from the pocket of his little tunic he produced the pink paper bag.

"Two left," he announced as he opened it, "and both long ones. Here's yours and here's mine. Garibaldi's been eating grass all day, so she's not hungry."

Lucia accepted the candy, and they both had a drink of milk. Then Beppi snuggled down in his sister's arms and his eyelids grew heavy.

"Go on with that story," he said, "the one about the soldier at the gate."

Lucia smiled in the dark and hugged him tight. The guns were silent, and only occasional peals of thunder broke the stillness.

"Well, one day," she began, "a very cross girl came to the gate, and the soldier who was always on the lookout for the stolen princess stopped her and spoke to her. But the cross girl was feeling very mean indeed, and she teased the soldier and made him very unhappy. But later on in the afternoon she was ashamed, and so she found the nice girl who was really the stolen princess, and took her with her to the gate, and the soldier—"

Lucia broke off and sat up suddenly to listen. A queer "rat, tat, tat," detached itself from the other night noises. Beppi was sound asleep, and she rolled him gently into the nest of leaves, then she listened again. The sound came again.

"Rat, tat, tat." It was a sharp staccato hammering, muffled by the wall of rock behind her.

She stood up and crept softly to the mouth of the cave.

The wind and the rain made such a noise that she could hear nothing, and it was already too dark to distinguish anything but the vaguest outlines. She crept back into the shelter, believing that she had just imagined what she had heard, but she had not taken her place beside Beppi before she heard it again—a persistent "rat, tat, tat," too metallic and too regular to be accounted for by a natural cause.

Lucia's mind was alert at once. She put her ear up against the rock and listened again. Muffled sounds too indistinct to recognize came to her. Whatever they were, they were not far off, and right in a line with the back of the cave.

Lucia thought of several explanations, but could accept none of them. She tried to argue against her fears by saying over and over again that if it was a sound made by men, those men were surely Italian soldiers, but her arguments could not still the frightened beating of her heart, as the voice became more distinct. She was filled with terror.

Rumors of underground tunnels and mines blowing off whole mountain tops, that she had heard from the soldiers, came back to her and left her cold with fear.

Beppi had rolled over beside the goat for warmth, and was sleeping soundly. Lucia looked at him and then went once more to the mouth of the cave.

The cold rain in her face gave her back her courage, and she felt her way around the cliff and up between the crevices of the two rocks, until she was on the roof of the cave. It was flat and the ground seemed to stretch out level for quite a distance before her. She listened for a moment, but the rain beating down made it impossible for her to distinguish any other sound.

She lay down flat on the wet ground, and crawled forward for a few feet, then listened again. At first she heard only the rain and the wind, but after a little wait there was a muffled bang as if a bomb had exploded deep down in the earth, and the ground beneath her trembled.

Lucia sprang to her feet and ran terrified back to the cave. It was fortunate that she was as sure-footed as her goats, for the way was steep and slippery, and she did not pause to take care.

Over in the cave, with her hand on Beppi's curly head, she sat down to think. Her mind was not capable of arriving at any logical explanation. Two thoughts stood out clearly and beyond doubt. First, the enemy was doing something of which the Italians were unaware, and second, the Italians must be warned before it was too late. That she must warn them she realized at once, but the way was not easy to determine.

The mountains were tricky. From one side they might look deserted, and yet a whole army could be in hiding just over the other side. The giant peaks formed formidable and wellnigh impassable barriers between one range and the next. Lucia had seen the troops disappear that morning, as if the great rocks had opened and devoured them, and she knew that at this moment they might be within a half a mile of her, but where to begin to find them she did not know.

The close proximity of the Austrians frightened her, and she was afraid to go off at random, or even to call. Throughout the night she tried to think and plan as she sat up with her back against the rock listening for the rat, tat, tat, which began again after she returned to the cave, and continued at regular intervals.

Before dawn the rain stopped and the wind blew the clouds away. At the first streak of light Lucia stole softly away from the sleeping Beppi and Garibaldi, and crept down the tiny path to the plateau below. Once there she was on familiar ground and even in the pale light she could tell her way.

During the night she had decided to go to the rock where she took her milk in the morning, surely the mysterious hand that left the pennies for her would be there, and she was determined, to wait for him.

She reached the spot without encountering any difficulties, and sat down to wait. The sun rose east of Cellino, and she watched it as it climbed over the hill and lighted the windows of the church with its yellow low rays.

All the world looked as if it had just been bathed and freshly clothed to step out glistening and very clean to greet the day. The air was chilly, but so fresh and sweet that Lucia took long grateful breaths of it. She was just wondering how long she would have to wait, when a stone rolled down beside her and hit her foot. She jumped and turned around. A soldier with a broad smile that showed all his fine white teeth was climbing down towards her.

Lucia put her fingers to her lip to caution silence, and his smile changed to a look of sudden anxiety.

"What is it?" he demanded.

"Don't make any noise," Lucia warned. "Listen to me."

She told him all that she had discovered during the night.

"Are you sure of what you say?" the soldier questioned her seriously.

"Oh, yes, sir, I tell you I crawled out and listened. The sound was very near."

"Can you show me the place?"

"Yes, yes, I have just come from there, but it is a slippery climb." Lucia looked at him interrogatively.

The man nodded. "Never mind that, lead the way."

Lucia did not hesitate, but hurried back along the rocks, choosing the safest footholds and sometimes leaving her companion far behind.

When she reached the little grassy plateau, she stopped and pointed. "It is above here, sir."

She started to ascend, and the soldier followed in silence. When they reached the cave she pointed to the back wall and said: "Listen there."

The soldier was so tall that he had to stoop down before he could enter, but he was very careful to be quiet and not disturb the still sleeping Beppi.

He put his ear to the wall and Lucia watched him excitedly. By the expression of his face she knew he was hearing the "rat, tat, tat."

"Can you show me the place where you thought you heard the explosion?" he whispered.

Lucia nodded and beckoned to him to follow. In her eagerness she forgot that he could not climb as nimbly as she could, and she was on the roof of the cave before he had started to ascend.

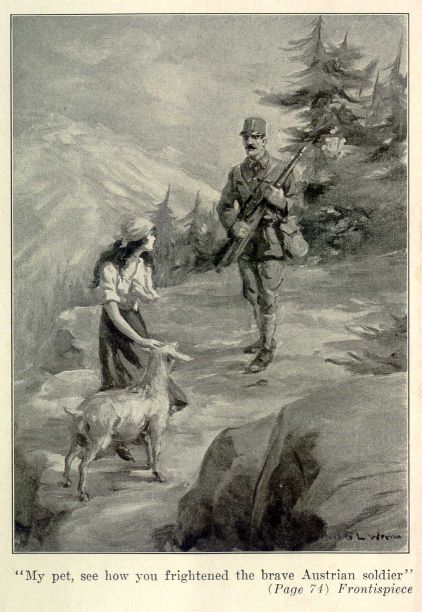

It was fortunate that she was, for not ten feet ahead of her, crawling along the ground, his helmet shining in the sun, was a soldier in the Austrian uniform.

At sight of her he jumped to his feet.

"Halt!" he commanded, unnecessarily, for Lucia was far too frightened to move.

She was thinking of the soldier whose head would appear at any moment over the ledge of rock behind, and her one wish was to stop him.

"I won't move, sir!" she cried loudly, "I see you have a big gun and I am all alone." She spoke in Italian, but the Austrian seemed to understand.

"What are you doing prowling around here at this time of day?" he demanded angrily, speaking to her in her own language.

"Oh, sir, I am lost," Lucia replied, not daring to look below her. "My goat wandered away in the storm and I came out to find her, and now I am very, very far away from home."

She walked towards the man as she spoke. She was terrified for fear he would discover the cave below her.

"Where did you sleep?" he demanded.

"Oh, I have not slept, sir. See my dress it is wet from the rain, there is no shelter anywhere, and the wind and the rain frightened me so I did not know where I was, and I was afraid to stay still."

The Austrian eyed her suspiciously.

"Why didn't you go to the soldiers and ask for shelter?" he inquired harshly.

"The soldiers?" Lucia's brown eyes opened wide in surprise. "But there are no soldiers near here. They are miles away with the guns. How could I reach them? My home is over there," she pointed in the opposite direction from the cave, "and I think I will go back to it, now that it is day."

"Oh, no, you won't," the Austrian replied. "You'll come with me."

"But why, what have I done?" Lucia inquired.

"That's not the point," the soldier replied. "You're an Italian, and if I let you go you'll run home and tell all the troops in the town that I was here. Oh, no, my little lady, we can't allow that—you're coming along with me."

His lordly tone and the sneer on his lips infuriated Lucia. She thought all danger of his discovering the cave was over, so she replied angrily. "And suppose I won't come? Don't think you can frighten me, for you can't. I tell you, I won't go a step with you."

The Austrian was about to reply, when a sound that had been so welcome only a few hours ago struck terror to Lucia's ears.

"Naa, Naa!"

"What's that?" the soldier jumped nervously. He was startled and frightened. Lucia saw it and her own courage returned.

"My goat," she said as Garibaldi appeared above the rock.

Lucia ran to him.

"My pet, here you are, I have found you at last. Where have you been? you are a bad girl. See how you frightened the brave Austrian soldier."

The sarcasm and scorn in her voice were unmistakable. The soldier was indignant.

"Here, that is enough from you. Come along, I will take you where they will teach you better manners."

He caught her roughly by the shoulder, and Lucia went with him only too gladly. If she could get him well away from the cave, it would be time enough to think of herself. She, had no doubt that she would be able to run away from him later on.

As they walked along the noise underground grew louder. Every now and then the man would turn and look at her suspiciously. He did not speak to her, however, and they walked for quite a distance in silence. When Lucia considered that they had gone far enough she stopped.

"Where are you taking me?" she demanded with spirit.

"Never mind, you come along," the man replied impatiently. "Time enough for you to know when we get there."

"But I won't go any further." Lucia was determined. "Do you think that I will be taken prisoner by an Austrian? Never!"

Her eyes blazed indignantly. She planned so many times just what she would do, if she was ever brought face to face with her hated enemy, that the feeling of helplessness that she felt under the big man's hand infuriated her.

"Come along, I will not speak again," the Austrian commanded, and once more Lucia went on, unable to withstand the strength of his arm.

The flat ground ended abruptly, and they had to climb down jagged rocks. Lucia thought that her chance of escape had come, but the Austrian never lessened his hold on her arm.

They had traveled this far without meeting any one. The only signs of life had been the mysterious noise underground, and the click of Garibaldi's sharp hoofs as they hit the stone.

When they reached a certain point the soldier stopped. "If you make any noise," he said roughly, "I will have to shoot you."

Lucia opened her mouth to scream, but before the sound came she changed her mind. A new and splendid idea had just come to her. She stopped holding back and walked obediently beside her guard. They did not go very far, before he told her to lie down and crawl, and before she realized where she was going, she was in a deep trench that ran along the base of the rock and was completely hidden from sight.

Garibaldi followed them, picking her way daintily, and stopping every now and then to let out a mournful "Naa!" The Austrian did not seem to hear her. If he did, he paid no attention, but led Lucia hurriedly along the dark passage.

They had not gone far before a sentry stopped them. Lucia's guard said something to him that she could not understand. The sentry disappeared, to return in a few minutes with another man. From the respectful salutes that he received, Lucia decided he must be a very high officer. More talk followed which she could not understand, and then her guard turned to her.

"Follow me," he directed, and led her out of the passage across a stretch of open ground, and over to a shed. Another soldier opened the door, and before Lucia quite got her breath, she heard the key turn in a lock and the thud, thud of the men's boots as they marched away.

The shed had been hastily put together, and served as a place for picks and shovels. There were so many of them, in fact, that Lucia at first had difficulty in finding a place to stand, but by rearranging them she cleared a portion of the floor and sat down to think.

The shed was by no means airtight, for the boards had been nailed up so far apart that not only did the air and light enter between the cracks, but it was also possible for Lucia to see everything that was going on about her.

At first it looked as if the soldiers were just hurrying about aimlessly, but by watching them closely, especially the guard that had caught her, she saw that they were preparing to leave.

A bugle sounded from a dugout at the end of the passage, and all the soldiers in sight fell into marching order and waited at attention. Then the officer who had ordered Lucia shut up in the tool-house, gave them some orders that she could not understand.

One soldier came over to the shed and unlocked the door. He beckoned Lucia to step outside, and as the men filed past the door he handed each one a pick and shovel. When they had all received them, and Lucia expected to return, the Captain spoke to her. His Italian was so very bad she pretended not to understand.

"What is your name?" was his first question.

Lucia shook her head.

"Your name?" he persisted. "Marie, Louise, Josephine?"

"No, Señor," Lucia replied bewildered.

"Well then, what is it?"

"I don't understand."

"Your name?"

"No, Señor."

"Your name? Have you no sense—stupid!" The Captain's patience was fast giving way.

Now to call an Italian stupid is the worst possible insult, and Lucia's cheeks flushed hotly. She was very angry, and she determined not to reply now at any cost. She shook her head therefore, and a very stubborn and unpromising light came into her brown eyes.

The Captain looked at her in disgust.

"Well, I suppose your name does not matter anyway," he said gruffly. "Where do you live?"

Another shake of the small black head, and an expressive shrug.

"You live in Cellino, so why not say so? Come, no more sulking. If you won't answer me of your own free will, you must be made to answer."

"No, Señor," Lucia smiled provokingly.

"No—what in thunder do you mean?"

"No, Señor," there was not a trace of impertinence in her face.

The officer looked at her in despair.

"Do you, or don't you understand what I am saying?" he demanded.

"No, Señor," Lucia reiterated.

"Where is the soldier who found this girl?" the Captain shouted to an orderly.

Lucia did not understand what he said, but she knew that her captor was well out of sight with his pick and shovel by now, and in all probability would not return and give her away, and she was beginning to enjoy the part of a "stupid."

Just as the Captain turned to continue his questioning, Garibaldi, who had been grazing about unmolested at a little distance from the shed, saw Lucia and came bounding over to her. In her delight at finding her young mistress she very nearly succeeded in butting over the officer.

Lucia had difficulty in repressing a smile, but she put her arms around the goat's neck and patted her.

"Does that animal belong to you?" The Captain demanded, puffing a little in the effort to retain his balance.

Lucia only smiled and nodded. Garibaldi kicked up her heels in an ecstasy of joy and sent the soft mud flying. The Captain's anger broke all bounds.

"Take that animal and shoot her," he demanded, but before the soldier could obey, he withdrew the order. "Tie her to the tree instead, we may be able to milk her," he said.

The soldier nodded and advanced towards Garibaldi with ponderous assurance, but Garibaldi was not going to be tied, she preferred her freedom. She was not, however, unwilling to play a friendly game of tag; it was her favorite sport and she was very proficient in it. When the big soldier would come within reach of her, she would lower her head and duck under his arm, and before the astonished pursuer could collect his wits and look around, she would be browsing innocently close by.

This game kept up for a long time. The men who were in sight dropped what they were doing and made an admiring circle; even the Captain had to smile. Lucia wanted to laugh outright, but she managed to keep her face set in grave lines.

At last the soldier gave up the chase and retired among the jeers of his comrades to the side lines. The Captain saw an opportunity to amuse his men, and perhaps end their grumbling for the time being. He offered a reward to the man that could catch the goat.

First one soldier and then another attempted it, but none of them succeeded. After a while the fun of the chase wore off for Garibaldi, and she became angry. She had a little trick of butting that had won her Beppi's dislike, and she used it to the discomfiture of the Austrian army.

Lucia saw them one after another rub their shins and their knees, for although Garibaldi did not have horns, her head was very, very hard indeed, and she was afraid that some one of them might grow angry and hurt her pet. She looked at the officer and pointed to the goat.

"I can catch her," she said simply.

"Well, do it then," the Captain replied.

Lucia called softly and made a queer clicking noise. Garibaldi stopped butting, and walked soberly over to her. She smiled good-naturedly at the men, and tied the rope that one of them handed to her around the goat's neck. One of the soldiers pointed to a tree behind the shed, and she tied the rope securely around it Garibaldi protested mildly, but she patted her and left her lying contentedly in the mud.

She took time to look hastily about her before returning to the shed. The tree to which the goat was tied was on the edge of a steep hill that fell away abruptly from the little clearing.

Lucia looked down it, and could hardly believe her eyes; for there, far below, was a silver stream glistening in the sunshine, and she realized with a sense of thankfulness that it could be no other than the little river that flowed below the west wall of Cellino, and right under the windows of the Convent. If she could only get away, it would be an easier matter to go back that way, than over the dangerous route by which she had come. But she was not very eager to return at once, for the idea that had come to her earlier in the day still tempted her to wait and listen.

When she returned to the shed the Captain was nowhere in sight, and one of the soldiers pointed to the open door. She nodded and walked in, the key grated in the lock, and she was once more a prisoner.

As the sun rose higher, a quiet settled over the clearing. The men talked and smoked, and the Captain read a newspaper at the door of his dugout.

No one bothered Lucia, and she kept very quiet. She had had nothing to eat since the night before and she was very hungry, but she would not for the world ask her enemies for food. She was not above accepting it, however, when a little before noon one of the soldiers brought her a hard and tasteless biscuit and a cup of water. She ate greedily, and then tired out from so much excitement she fell asleep.

She awoke an hour later to a scene of activity. She could see through the peek-hole that the Captain was consulting his watch every little while, and the men were hurrying about excitedly. They all looked up at a certain mountain above with suspicious eyes, and Lucia could tell by the tone of their voices that they were angry about something.

A few minutes later the arrival of a very muddy and tired soldier from the opposite direction created a diversion. He saluted the Captain and handed him a message. Whatever the message was, it pleased the Captain, for he brought his fist down on his knee and laughed. Then he gave some very long; and to Lucia, unintelligible orders, and the men lost some of their ugly rebellious look.

He chose two soldiers from the group before him, and motioned them into his dugout. Lucia tried to make something out of the strange words that the other men spoke, but she could not. They were eagerly questioning the messenger and giving him food and water. He was answering them, and from the expression of their faces his replies were not cheering. At last he stood up, shrugged his shoulders and for the first time noticed Garibaldi.

The other soldiers explained, and Lucia knew they were discussing her when they pointed to the shed. The messenger evidently suggested milking the goat, for after a little laughing and jesting, one of the men took a pail and approached Garibaldi.

Now, no one had ever milked Garibaldi in all her life but Lucia, and from the disastrous attempts on the part of the soldiers it was evident that no one was ever going to, if that very particular animal could prevent it, and she seemed quite able to, to judge from the results.

Lucia watching through the cracks in the shed laughed softly to herself. She was not surprised when, a few minutes later, one of the men opened the door and told her to come out.

He could not speak Italian and he resorted to the sign language. Lucia nodded in understanding. She might have pretended blank stupidity, but she wanted some milk herself, and this was a good way to get it. Besides, she decided that she would do something to make it impossible for them to lock her up again on her return.

Garibaldi stood quite still as she milked her, and submitted meekly to her affectionate pats.

The messenger drank greedily from the pail, and when he had finished there seemed to be nothing else for Lucia to do but return to the shed. She walked back to the door as slowly as possible, and looked hard at the lock. It was just an ordinary padlock and it hung open on the rusty catch. She looked quickly at the men behind her. They were busy talking, and did not appear to be paying any attention to her.

Very quickly, without seeming to do it, she touched the padlock; it swung on the catch, and then fell into the mud. Lucia put her foot over it and ground it in with her heel.

When the soldier remembered her a few minutes later, and came over to shut the door, he grumbled at the loss of the lock, but he did not apparently connect her with its disappearance, nor did he bother much about looking for it. He shut the door and walked back to join the group that still surrounded the messenger.

Lucia sat down again and watched the door of the Captain's dugout. She had wondered all day what the smiling Italian soldier and Beppi had done after she left. She knew that Beppi could easily find his way back to the cottage, and in case Nana had already gone, and Lucia knew that in spite of her threats she would not go off alone, he would go into the town and some one would take care of him.

As for the soldier, he would hear the rat, tat, tat, and know what it meant, and return to his comrades for help. She listened, but there was no sound of guns near enough to mean a fight close at hand.

The thought puzzled her, but she dismissed it as the Captain and the two soldiers came out of the dugout. The men looked cross and sullen, but the Captain was still smiling. He walked over to the messenger, handed him a folded paper, and the man disappeared as mysteriously as he came.

Lucia did not pay any attention to him, however, for she was interested in the two soldiers. They were very busy buckling on their kit bags in preparation for a departure. When they were ready, they stood at attention before the Captain. After more orders from him, they started off down the hill just back of the shed.

Lucia guessed that they were going to the river, with a cold feeling around her heart, she realized that they could go straight to the wall of Cellino. She did not stop to consider the many sentries who walked up and down the walls day and night, or the fact that two enemy soldiers would hardly walk up and attempt to enter a town in broad daylight. She only knew that the river led to Cellino, and that all she loved most in the world was there.

She was sick with fear. She looked back at the Captain; he was again consulting his watch. The soldiers looked at him and fell to grumbling again. After a moment of indecision he called to them.

They stood up and saluted. He gave a very peremptory order, and in a few minutes almost all of them had their guns on their shoulders, and waited his next word. The Captain himself buckled on his revolver, and the party started off at a brisk pace through the tunnel.

Lucia watched them go. In a hazy way she realized that they were going out in search of the men who had left earlier in the morning. This was correct in part, but they were also going to look for another party of men, the ones who had been responsible for the rat, tat, tat, Lucia had heard.

The diggers, led by her captor, had been sent out that morning to relieve their comrades already at work. When none of them returned the Captain grew anxious, and was himself leading the searching party.

If Lucia had known, she would have realized that her Italian soldier was in some way responsible for their absence, and she would have been delighted. As it was, she dismissed the Captain with a shrug and turned her attention to the few soldiers who remained. They were a little distance from her, and most of them had their backs to her.

Lucia determined to try to slip out unnoticed. She waited until they were all talking at once. By their angry gestures they appeared to be discussing something of great importance; none of them even glanced towards the shed.

Lucia pushed open the door very gently and waited. No one noticed it, then she laid down flat and crawled out into the mud; it was slow work, but in the end it proved the best way, for she reached the tree and Garibaldi without being discovered. The shed hid her from sight. She hurriedly untied the rope and freed the goat. It had never entered her mind to escape and leave her behind.

Garibaldi, free once more, ran down the steep hill her hoofs making no more than a soft, pad, pad noise in the mud. Lucia dropped to the ground again and crawled slowly after her. Below her, almost at the river's edge, she could see the two soldiers slipping and stumbling along.

She wriggled on in the mud until she was well below the crest of the hill, then she got up and began to run. She jumped from one rock to the next, always keeping the two men in sight, but keeping under cover herself. The men kept to the bank of the river and moved forward cautiously. Lucia kept abreast of them, but stayed high up above their heads.

It was a long walk, for the river twisted and turned many times before it reached the walls of Cellino. But it did not tire Lucia, as it did the two men. They walked slower and slower as the afternoon wore on, stopping every few minutes to rest and talk excitedly.

At a little before sunset the guns grew louder and seemed to be much nearer. All day there had been a dull rumble, but now they burst out into a terrific roar. Lucia saw the men below her stop and look up. They stood still for a long time, and then hurried on. Until now the road had been deserted, but ahead at the end of a footbridge, just around a sharp turn, Lucia, from her vantage point, could see another figure. The soldiers could not have seen him, but when they reached the turn of the road they both left the open and took cover in the rocks above.

Lucia watched narrowly. They did not stop as she half expected them to do, but crept on until they were abreast of the man. He was a beggar to judge by his shabby clothes, and he was apparently whiling away his afternoon by staring into the river.

Lucia's first thought was that the Austrians would shoot him. She caught her breath sharply when a queer thing happened. One of the soldiers picked up a stone and threw it down into the stream.

Without turning his head, the beggar picked up a stone and tossed it into the river. He repeated this twice.

Lucia watched, fascinated. The soldiers left their hiding-place and came down to the road. The beggar took something out of the pocket of his coat, handed it to one of the soldiers, and shuffled off in the opposite direction.

Lucia waited to see what the soldiers would do. She expected them to return, but instead they waited until the beggar was out of sight, and then hurried across the foot-bridge and plunged hurriedly into the mountains opposite.

Lucia caught sight of their shining helmets every now and then as they climbed higher and higher, and finally disappeared. She was undecided what to do, but after a little hesitation she determined to follow the beggar. Now that the Austrians were out of sight there was no need for her to avoid the open path, and she hurried to it and ran quickly in the direction that the man had taken. She did not know where she was, or how far she would have to go before she reached Cellino. She had seen nothing of the town from the mountains, and she guessed that it was much farther away than she had at first supposed.

She walked on as fast as she could, keeping a sharp lookout for the beggar, but he had apparently disappeared, for she could not find him or any trace of him.

It was late in the afternoon when she reached a part of the river that was familiar to her, and with a start she realized that she was still a good three miles from Cellino. She was very tired and very hungry, but she sat down to consider the best plan to follow. She knew nothing of what had passed between the men at the bridge, but she had sense enough to realize that whatever it was, it was not for the good of the Italian forces.

Some one must be warned, and soon, for the speed of the Austrian soldiers made her feel that the danger was imminent.

"I will go on to town and warn them," she said aloud to Garibaldi, "that is the best plan, and then I can find something to eat."