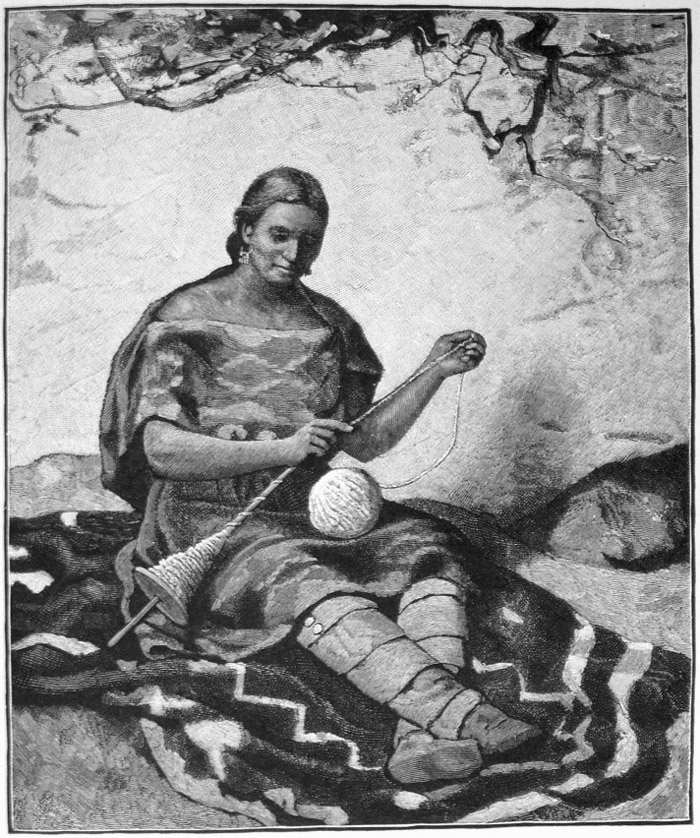

PL. XXXIV.—NAVAJO WOMAN SPINNING.ToList

Title: Navajo weavers

Author: Washington Matthews

Release date: February 10, 2006 [eBook #17742]

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/17742

Credits: Produced by PM for Bureau of American Ethnology, Jeannie

Howse and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by the Bibliothèque nationale

de France (BnF/Gallica) at http://gallica.bnf.fr)

| Page. | ||

| Plate XXXIV.— | Navajo woman spinning | 376 |

| XXXV.— | Weaving of diamond-shaped diagonals | 380 |

| XXXVI.— | Navajo woman weaving a belt | 384 |

| XXXVII.— | Zuñi women weaving a belt | 388 |

| XXXVIII.— | Bringing down the batten | 390 |

| Fig. 42.— | Ordinary Navajo blanket loom | 378 |

| 43.— | Diagram showing formation of warp | 379 |

| 44.— | Weaving of saddle-girth | 382 |

| 45.— | Diagram showing arrangement of threads of the warp in the healds and on the rod | 383 |

| 46.— | Weaving of saddle-girth | 383 |

| 47.— | Diagram showing arrangement of healds in diagonal weaving | 384 |

| 48.— | Diagonal cloth | 384 |

| 49.— | Navajo blanket of the finest quality | 385 |

| 50.— | Navajo blankets | 386 |

| 51.— | Navajo blanket | 386 |

| 52.— | Navajo blanket | 387 |

| 53.— | Navajo blanket | 387 |

| 54.— | Part of Navajo blanket | 388 |

| 55.— | Part of Navajo blanket | 388 |

| 56.— | Diagram showing formation of warp of sash | 388 |

| 57.— | Section of Navajo belt | 389 |

| 58.— | Wooden heald of the Zuñis | 389 |

| 59.— | Girl weaving (from an Aztec picture) | 391 |

§ I. The art of weaving, as it exists among the Navajo Indians of New Mexico and Arizona, possesses points of great interest to the student of ethnography. It is of aboriginal origin; and while European art has undoubtedly modified it, the extent and nature of the foreign influence is easily traced. It is by no means certain, still there are many reasons for supposing, that the Navajos learned their craft from the Pueblo Indians, and that, too, since the advent of the Spaniards; yet the pupils, if such they be, far excel their masters to-day in the beauty and quality of their work. It may be safely stated that with no native tribe in America, north of the Mexican boundary, has the art of weaving been carried to greater perfection than among the Navajos, while with none in the entire continent is it less Europeanized. As in language, habits, and opinions, so in arts, the Navajos have been less influenced than their sedentary neighbors of the pueblos by the civilization of the Old World.

The superiority of the Navajo to the Pueblo work results not only from a constant advance of the weaver's art among the former, but from a constant deterioration of it among the latter. The chief cause of this deterioration is that the Pueblos find it more remunerative to buy, at least the finer serapes, from the Navajos, and give their time to other pursuits, than to manufacture for themselves; they are nearer the white settlements and can get better prices for their produce; they give more attention to agriculture; they have within their country, mines of turquoise which the Navajos prize, and they have no trouble in procuring whisky, which some of the Navajos prize even more than gems. Consequently, while the wilder Indian has incentives to improve his art, the more advanced has many temptations to abandon it altogether. In some pueblos the skill of the loom has been almost forgotten. A growing fondness for European clothing has also had its influence, no doubt.

§ II. Cotton, which grows well in New Mexico and Arizona, the tough fibers of yucca leaves and the fibers of other plants, the hair of different quadrupeds, and the down of birds furnished in prehistoric days the materials of textile fabrics in this country. While some of the Pueblos still weave their native cotton to a slight extent, the Navajos grow no cotton and spin nothing but the wool of the domestic sheep, which animal is, of course, of Spanish introduction, and of which the Navajos have vast herds.

The wool is not washed until it is sheared. At the present time it is combed with hand cards purchased from the Americans. In spinning, the simplest form of the spindle—a slender stick thrust through the center of a round wooden disk—is used. The Mexicans on the Rio Grande use spinning-wheels, and although the Navajos have often seen these wheels, have had abundant opportunities for buying and stealing them, and possess, I think, sufficient ingenuity to make them, they have never abandoned the rude implement of their ancestors. Plate XXXIV illustrates the Navajo method of handling the spindle, a method different from that of the people of Zuñi.

They still employ to a great extent their native dyes: of yellow, reddish, and black. There is good evidence that they formerly had a blue dye; but indigo, originally introduced, I think, by the Mexicans, has superseded this. If they, in former days, had a native blue and a native yellow, they must also, of course, have had a green, and they now make green of their native yellow and indigo, the latter being the only imported dye-stuff I have ever seen in use among them. Besides the hues above indicated, this people have had, ever since the introduction of sheep, wool of three different natural colors—white, rusty black, and gray—so they had always a fair range of tints with which to execute their artistic designs. The brilliant red figures in their finer blankets were, a few years ago, made entirely of bayeta, and this material is still largely used. Bayeta is a bright scarlet cloth with a long nap, much finer in appearance than the scarlet strouding which forms such an important article in the Indian trade of the North. It was originally brought to the Navajo country from Mexico, but is now supplied to the trade from our eastern cities. The Indians ravel it and use the weft. While many handsome blankets are still made only of the colors and material above described, American yarn has lately become very popular among the Navajos, and many fine blankets are now made wholly, or in part, of Germantown wool.

The black dye mentioned above is made of the twigs and leaves of the aromatic sumac (Rhus aromatica), a native yellow ocher, and the gum of the piñon (Pinus edulis). The process of preparing it is as follows: They put into a pot of water some of the leaves of the sumac, and as many of the branchlets as can be crowded in without much breaking or crushing, and the water is allowed to boil for five or six hours until a strong decoction is made. While the water is boiling they attend to other parts of the process. The ocher is reduced to a fine powder between two stones and then slowly roasted over the fire in an earthen or metal vessel until it assumes a light-brown color; it is then taken from the fire and combined with about an equal quantity in size of piñon gum; again the mixture is put on the fire and constantly stirred. At first the gum melts and the whole mass assumes a mushy consistency; but as the roasting progresses it gradually becomes drier and darker until it is at last reduced to a fine black powder. This is removed from the [Pg 377]fire, and when it has cooled somewhat it is thrown into the decoction of sumac, with which it instantly forms a rich, blue-black fluid. This dye is essentially an ink, the tannic acid of the sumac combining with the sesquioxide of iron in the roasted ocher, the whole enriched by the carbon of the calcined gum.

There are, the Indians tell me, three different processes for dyeing yellow; two of these I have witnessed. The first process is thus conducted: The flowering tops of Bigelovia graveolens are boiled for about six hours until a decoction of deep yellow color is produced. When the dyer thinks the decoction strong enough, she heats over the fire in a pan or earthen vessel some native almogen (an impure native alum), until it is reduced to a somewhat pasty consistency; this she adds gradually to the decoction and then puts the wool in the dye to boil. From time to time a portion of the wool is taken out and inspected until (in about half an hour from the time it is first immersed) it is seen to have assumed the proper color. The work is then done. The tint produced is nearly that of lemon yellow. In the second process they use the large, fleshy root of a plant which, as I have never yet seen it in fruit or flower, I am unable to determine. The fresh root is crushed to a soft paste on the metate, and, for a mordant, the almogen is added while the grinding is going on. The cold paste is then rubbed between the hands into the wool. If the wool does not seem to take the color readily a little water is dashed on the mixture of wool and paste, and the whole is very slightly warmed. The entire process does not occupy over an hour and the result is a color much like that now known as "old gold."

The reddish dye is made of the bark of Alnus incana var. virescens (Watson) and the bark of the root of Cercocarpus parvifolius; the mordant being fine juniper ashes. On buckskin this makes a brilliant tan-color; but applied to wool it produces a much paler tint.

§ III. Plate XXXVIII and Fig. 42 illustrate ordinary blanket-looms. Two posts, a a, are set firmly in the ground; to these are lashed two cross-pieces or braces, b c, the whole forming the frame of the loom. Sometimes two slender trees, growing at a convenient distance from one another, are made to answer for the posts, d is a horizontal pole, which I call the supplementary yarn-beam, attached to the upper brace, b, by means of a rope, e e, spirally applied. f is the upper beam of the loom. As it is analogous to the yarn-beam of our looms, I will call it by this name, although once only have I seen the warp wound around it. It lies parallel to the pole d, about 2 or 3 inches below it, and is attached to the latter by a number of loops, g g. A spiral cord wound around the yarn-beam holds the upper border cord h h, which, in turn, secures the upper end of the warp i i. The lower beam of the loom is shown at k. I will call this the cloth-beam, although the finished web is never wound around it; it is tied firmly to the lower brace, c, of the frame, and to it is secured the lower border cord of the blanket. The original distance between the two beams is the length of the blanket. Lying[Pg 378] between the threads of the warp is depicted a broad, thin, oaken stick, l, which I will call the batten. A set of healds attached to a heald-rod, m, are shown above the batten. These healds are made of cord or yarn; they include alternate threads of the warp, and serve when drawn forward to open the lower shed. The upper shed is kept patent by a stout rod, n (having no healds attached), which I name the shed-rod. Their substitute for the reed of our looms is a wooden fork, which will be designated as the reed-fork (Fig. 44, a).

For convenience of description, I am obliged to use the word "shuttle," although, strictly speaking, the Navajo has no shuttle. If the figure to be woven is a long stripe, or one where the weft must be passed through 6 inches or more of the shed at one time, the yarn is wound on a slender twig or splinter, or shoved through on the end of such a piece of wood; but where the pattern is intricate, and the weft passes at each turn through only a few inches of the shed, the yarn is wound into small skeins or balls and shoved through with the finger.

§ IV. The warp is thus constructed: A frame of four sticks is made, not unlike the frame of the loom, but lying on or near the ground, instead of standing erect. The two sticks forming the sides of the frame are rough saplings or rails; the two forming the top and bottom are smooth rounded poles—often the poles which afterwards serve as the beams of the loom; these are placed parallel to one another, their distance apart depending on the length of the projected blanket.

On these poles the warp is laid in a continuous string. It is first firmly tied to one of the poles, which I will call No. 1 (Fig. 43); then it is passed over the other pole, No. 2, brought back under No. 2 and over No. 1, forward again under No. 1 and over No. 2, and so on to the end. Thus the first, third, fifth, &c., turns of the cord cross in the middle the second, fourth, sixth, &c., forming a series of elongated figures 8, as shown in the following diagram—

and making, in the very beginning of the process, the two sheds, which are kept distinct throughout the whole work. When sufficient string has been laid the end is tied to pole No. 2, and a rod is placed in each shed to keep it open, the rods being afterwards tied together at the ends to prevent them from falling out.

This done, the weaver takes three strings (which are afterwards twilled into one, as will appear) and ties them together at one end. She now sits outside one of the poles, looking towards the centre of the frame, and proceeds thus: (1) She secures the triple cord to the pole immediately to the left of the warp; (2) then she takes one of the threads (or strands as they now become) and passes it under the first turn of the warp; (3) next she takes a second strand, and twilling it once or oftener with the other strands, includes with it the second bend of the warp; (4) this done, she takes the third strand and, twilling it as before, passes it under the third bend of the warp, and thus she goes on until the entire warp in one place is secured between the strands of the cord; (5) then she pulls the string to its fullest extent, and in doing so separates the threads of the warp from one another; (6) a similar three stranded cord is applied to the other end of the warp, along the outside of the other pole.

At this stage of the work these stout cords lie along the outer surfaces of the poles, parallel with the axes of the latter, but when the warp is taken off the poles and applied to the beams of the loom by the spiral thread, as above described, and as depicted in Plate XXXVIII and Fig. 42, and all is ready for weaving, the cords appear on the inner sides of the beams, i.e., one (Pl. XXXVIII and Fig. 42, h h) at the lower side of the yarn-beam, the other at the upper side of the cloth-beam, and when the blanket is finished they form the stout end margins of the web. In the coarser grade of blankets the cords are removed and the ends of the warp tied in pairs and made to form a fringe. (See Figs. 54 and 55.)

When the warp is transferred to the loom the rod which was placed in the upper shed remains there, or another rod, straighter and smoother, [Pg 380]is substituted for it; but with the lower shed, healds are applied to the anterior threads and the rod is withdrawn.

§ V. The mode of applying the healds is simple: (1) the weaver sits facing the loom in the position for weaving; (2) she lays at the right (her right) side of the loom a ball of string which she knows contains more than sufficient material to make the healds; (3) she takes the end of this string and passes it to the left through the shed, leaving the ball in its original position; (4) she ties a loop at the end of the string large enough to admit the heald-rod; (5) she holds horizontally in her left hand a straightish slender rod, which is to become the heald-rod—its right extremity touching the left edge of the warp—and passes the rod through the loop until the point of the stick is even with the third (second anterior from the left) thread of the warp; (6) she puts her finger through the space between the first and third threads and draws out a fold of the heald-string; (7) she twists this once around, so as to form a loop, and pushes the point of the heald-rod on to the right through this loop; (8) she puts her finger into the next space and forms another loop; (9) and so on she continues to advance her rod and form her loops from left to right until each of the anterior (alternate) warp-threads of the lower shed is included in a loop of the heald; (10) when the last loop is made she ties the string firmly to the rod near its right end.

When the weaving is nearly done and it becomes necessary to remove the healds, the rod is drawn out of the loops, a slight pull is made at the thread, the loops fall in an instant, and the straightened string is drawn out of the shed. Illustrations of the healds may be seen in Plates XXXV and XXXVIII and Figs. 42, 44, and 46, that in Fig. 46 being the most distinct.

§ VI. In making a blanket the operator sits on the ground with her legs folded under her. The warp hangs vertically before her, and (excepting in a case to be mentioned) she weaves from below upwards. As she never rises from this squatting posture when at work, it is evident that when she has woven the web to a certain height further work must become inconvenient or impossible unless by some arrangement the finished web is drawn downwards. Her cloth-beam does not revolve as in our looms, so she brings her work within easy reach by the following method: The spiral rope (Plate XXXVIII and Fig. 42) is loosened, the yarn-beam is lowered to the desired distance, a fold is made in the loosened web, and the upper edge of the fold is sewed down tightly to the cloth-beam. In all new blankets over two feet long the marks of this sewing are to be seen, and they often remain until the blanket is worn out. Plate XXXV, representing a blanket nearly finished, illustrates this procedure.

Except in belts, girths, and perhaps occasionally in very narrow blankets, the shuttle is never passed through the whole width of the warp at once, but only through a space which does not exceed the length of the batten; for it is by means of the batten, which is rarely more than 3 feet long, that the shed is opened.

[Pg 381] Suppose the woman begins by weaving in the lower shed. She draws apportion of the healds towards her, and with them the anterior threads of the shed; by this motion she opens the shed about 1 inch, which is not sufficient for the easy passage of the woof. She inserts her batten edgewise into this opening and then turns it half around on its long axis, so that its broad surfaces lie horizontally; in this way the shed is opened to the extent of the width of the batten—about 3 inches; next the weft is passed through. In fig. 42 the batten is shown lying edgewise (its broad surfaces vertical), as it appears when just inserted into the shed, and the weft, which has been passed through only a portion of the shed, is seen hanging out with its end on the ground. In Plate XXXV the batten is shown in the second position described, with the shed open to the fullest extent necessary, and the weaver is represented in the act of passing the shuttle through. When the weft is in, it is shoved down into its proper position by means of the reed-fork, and then the batten, restored to its first position (edgewise), is brought down with firm blows on the weft. It is by the vigorous use of the batten that the Navajo serapes are rendered water-proof. In Plate XXXVIII the weaver is seen bringing down this instrument "in the manner and for the purpose described," as the letters patent say.

When the lower shed has received its thread of weft the weaver opens the upper shed. This is done by releasing the healds and shoving the shed-rod down until it comes in contact with the healds; this opens the upper shed down to the web. Then the weft is inserted and the batten and reed-fork used as before. Thus she goes on with each shed alternately until the web is finished.

It is, of course, desirable, at least in handsome blankets of intricate pattern, to have both ends uniform even if the figure be a little faulty in the center. To accomplish this some of the best weavers depend on a careful estimate of the length of each figure before they begin, and weave continuously in one direction; but the majority weave a little portion of the upper end before they finish the middle. Sometimes this is done by weaving from above downwards; at other times it is done by turning the loom upside down and working from below upwards in the ordinary manner. In Fig. 49, which represents one of the very finest results of Navajo work, by the best weaver in the tribe, it will be seen that exact uniformity in the ends has not been attained. The figure was of such a nature that the blanket had to be woven in one direction only.

I have described how the ends of the blanket are bordered with a stout three-ply string applied to the folds of the warp. The lateral edges of the blanket are similarly protected by stout cords applied to the weft. The way in which these are woven in, next demands our attention. Two stout worsted cords, tied together, are firmly attached at each end of the cloth-beam just outside of the warp; they are then carried upwards and loosely tied to the yarn-beam or the supplementary[Pg 382] yarn-beam. Every time the weft is turned at the edge these two strings are twisted together and the weft is passed through the twist; thus one thread or strand of this border is always on the outside. As it is constantly twisted in one direction, it is evident that, after a while, a counter-twist must form which would render the passage of the weft between the cords difficult, if the cords could not be untwisted again. Here the object of tying these cords loosely to one of the upper beams, as before described, is displayed. From time to time the cords are untied and the unwoven portion straightened as the work progresses. Fig. 44 and Plate XXXVIII show these cords. The coarse blankets do not have them. (Fig 42.)

Navajo blankets are single-ply, with designs the same on both sides, no matter how elaborate these designs may be. To produce their varigated patterns they have a separate skein, shuttle, or thread for each component of the pattern. Take, for instance, the blanket depicted in Fig. 49. Across this blanket, between the points a—b, we have two serrated borders, two white spaces, a small diamond in the center, and twenty-four serrated stripes, making in all twenty-nine component parts of the pattern. Now, when the weaver was working in this place, twenty-nine different threads of weft might have been seen hanging from the face of the web at one time. In the girth pictured in Fig. 44 five different threads of woof are shown depending from the loom.

When the web is so nearly finished that the batten can no longer be inserted in the warp, slender rods are placed in the shed, while the weft is passed with increased difficulty on the end of a delicate splinter and the reed-fork alone presses the warp home. Later it becomes necessary to remove even the rod and the shed; then the alternate threads are separated by a slender stick worked in tediously between them, and two threads of woof are [Pg 383] inserted—one above and the other below the stick. The very last thread is sometimes put in with a darning needle. The weaving of the last three inches requires more labor than any foot of the previous work.

In Figs. 49, 50, 51, 52, and 53 it will be seen that there are small fringes or tassels at the corners of the blankets; these are made of the redundant ends of the four border-cords (i.e., the portions of the cord by which they were tied to the beams), either simply tied together or secured in the web with a few stitches.

The above is a description of the simplest mechanism by which the Navajos make their blankets; but in manufacturing diagonals, sashes, garters, and hair-bands the mechanism is much more complicated.

§ VII. For making diagonals the warp is divided into four sheds; the uppermost one of these is provided with a shed-rod, the others are supplied with healds. I will number the healds and sheds from below upwards. The following diagram shows how the threads of the warp are arranged in the healds and on the rod.

When the weaver wishes the diagonal ridges to run upwards from right to left, she opens the sheds in regular order from below upwards thus: First, second, third, fourth, first, second, third, fourth, &c. When she wishes the ridges to trend in the contrary direction she opens the sheds in the inverse order. I found it convenient to take my illustrations of this mode of weaving from a girth. In Figs. 44 and 46 the mechanism is plainly shown. The lowest (first) shed is opened and the first set of healds drawn forward. The rings of the girth take the place of the beams of the loom.

There is a variety of diagonal weaving practiced by the Navajos which produces diamond figures; for this the mechanism is the same [Pg 384]as that just described, except that the healds are arranged differently on the warp. The following diagram will explain this arrangement.

To make the most approved series of diamonds the sheds are opened twice in the direct order (i.e., from below upwards) and twice in the inverse order, thus: First, second, third, fourth, first, second, third, fourth, third, second, first, fourth, third, second, first, fourth, and so on. If this order is departed from the figures become irregular. If the weaver continues more than twice consecutively in either order, a row of V-shaped figures is formed, thus: VVVV. Plate XXXV represents a woman weaving a blanket of this pattern, and Fig. 48 shows a portion of a blanket which is part plain diagonal and part diamond.

§ VIII. I have heretofore spoken of the Navajo weavers always as of the feminine gender because the large majority of them are women.[Pg 385] There are, however, a few men who practice the textile art, and among them are to found the best artisans in the tribe.

§ IX. Navajo blankets represent a wide range in quality and finish and an endless variety in design, notwithstanding that all their figures consist of straight lines and angles, no curves being used. As illustrating the great fertility of this people in design I have to relate that in the finer blankets of intricate pattern out of thousands which I have examined, I do not remember to have ever seen two exactly alike. Among the coarse striped blankets there is great uniformity.

The accompanying pictures of blankets represent some in my private collection. Fig. 49 depicts a blanket measuring 6 feet 9 inches by 5 feet 6 inches, and weighing nearly 6 pounds. It is made entirely of Germantown yarn in seven strongly contrasting colors, and is the work of a man who is generally conceded to be the best weaver in the tribe. A month was spent in its manufacture. Its figures are mostly in serrated stripes, which are the most difficult to execute with regularity. I have heard that the man who wove this often draws his designs on sand before he begins to work them on the loom. Fig. 50 a shows a[Pg 386] blanket of more antique design and material. It is 6 feet 6 inches by 5 feet 3 inches, and is made of native yarn and bayeta. Its colors are black, white, dark-blue, red (bayeta) and—in a portion of the stair-like figures—a pale blue. Fig. 50 b depicts a tufted blanket or rug, of a kind not common, having much the appearance of an Oriental rug; it is made of shredded red flannel, with a few simple figures in yellow, dark blue, and green. Fig. 51 represents a gaudy blanket of smaller size (5 feet 4 inches by 3 feet 7 inches) worn by a woman. Its colors are[Pg 387] yellow, green, dark blue, gray, and red, all but the latter color being in native yarn. Figs. 52 and 53 illustrate small or half-size blankets made for children's wear. Such articles are often used for saddle blankets (although the saddle-cloth is usually of coarser material) and are in great demand among the Americans for rugs. Fig. 53 has a regular border of uniform device all the way around—a very rare thing in Navajo blankets. Figs. 54 and 55 show portions of coarse blankets made more for use use than ornament. Fig. 55 is made of loosely-twilled yarn, and is very warm but not water-proof. Such blankets [Pg 388]make excellent bedding for troops in the field. Fig. 54 is a water-proof serape of well-twilled native wool.

The aboriginal woman's dress is made of two small blankets, equal in size and similar in design, sewed together at the sides, with apertures left for the arms and no sleeves. It is invariably woven in black or dark-blue native wool with a broad variegated stripe in red imported yarn or red bayeta at each end, the designs being of countless variety. Plates XXXIV and XXXV represent women wearing such dresses.

[Pg 389]§ X. Their way of weaving long ribbon-like articles, such as sashes or belts, garters, and hair-bands, which we will next consider, presents many interesting variations from, the method pursued in making blankets. To form, a sash the weaver proceeds as follows: She drives into the ground four sticks and on them she winds her warp as a continuous string (however, as the warp usually consists of threads of three different colors it is not always one continuous string) from, below upwards in such a way as to secure two sheds, as shown in the diagram, Fig. 56.

Every turn of the warp passes over the sticks a, and b; but it is alternate turns that pass over c and d. When the warp is laid she ties a string around the intersection of the sheds at e, so as to keep the sheds separate while she is mounting the warp on the beams. She then places the upper beam of the loom in the place of the stick b and the lower beam in the place of the stick a. Sometimes the upper and lower beams are secured to the two side rails forming a frame such as the warp of a [Pg 390]blanket is wound on (§ IV), but more commonly the loom is arranged in the manner shown in Plate XXXVI; that is, the upper beam is secured to a rafter, post, or tree, while to the lower beam is attached a loop of rope that passes under the thighs of the weaver, and the warp is rendered tense by her weight. Next, the upper shed is supplied with a shed-rod, and the lower shed with a set of healds. Then the stick at f (upper stick in Plate XXXVI) is put in; this is simply a round stick, about which one loop of each thread of the warp is thrown. (Although the warp may consist of only one thread I must now speak of each turn as a separate thread.) Its use is to keep the different threads in place and prevent them from crossing and straggling; for it must be remembered that the warp in this case is not secured at two points between three stranded cords as is the blanket warp.

When this is all ready the insertion of the weft begins. The reed-fork is rarely needed and the batten used is much shorter than that employed in making blankets. Fig. 57 represents a section of a belt. It will be seen that the center is ornamented with peculiar raised figures; these are made by inserting a slender stick into the warp, so as to hold up certain of the threads while the weft is passed twice or oftener underneath them. It is practically a variety of damask or two-ply weaving; the figures on the opposite side of the belt being different. There is a limited variety of these figures. I think I have seen about a dozen different kinds. The experienced weaver is so well acquainted with the "count" or arrangements of the raised threads appropriate to each pattern that she goes on inserting and withdrawing the slender stick referred to without a moment's hesitation, making the web at the rate of 10 or 12 inches an hour. When the web has grown to the point at which she cannot weave it further without bringing the unfilled warp nearer to her, she is not obliged to resort to the clumsy method used with blankets. She merely seizes the anterior layer of the warp and pulls it down towards her; for the warp is not attached to the beams, but is movable on them; in other words, while still on the loom the belt is endless. When all the warp has been filled except about one foot, the weaving is completed; for then the unfilled warp is cut in the center and becomes the terminal fringes of the now finished belt.

The only marked difference that I have observed between the mechanical appliances of the Navajo weaver and those of her Pueblo neighbor is to be seen in the belt loom. The Zuñi woman lays out her warp, not as a continuous thread around two beams, but as several disunited threads. She attaches one end of these to a fixed object, usually a rafter in her dwelling, and the other to the belt she wears around her body. She has a set of wooden healds by which she actuates the alternate threads of the warp. Instead of using the slender stick of the Navajos to elevate the threads of the warp in forming her figures, she lifts these threads with her fingers. This is an easy matter with her [Pg 391]style of loom; but it would be a very difficult task with that of the Navajos. Plate XXXVII represents a Zuñi woman weaving a belt. The wooden healds are shown, and again, enlarged, in Fig. 58. The Zuñi women weave all their long, narrow webs according to the same system; but Mr. Bandelier has informed me that the Indians of the Pueblo of Cochiti make the narrow garters and hair-bands after the manner of the Zuñis, and the broad belts after the manner of the Navajos.

§ XI. I will close by inviting the reader to compare Plate XXXVI and Fig. 59. The former shows a Navajo woman weaving a belt; the latter a girl of ancient Mexico weaving a web of some other description. The one is from a photograph, taken from life; the other I have copied from Tylor's "Anthropology" (p. 248); but it appears earlier in the copy of Codex Vaticana in Lord Kingsborough's "Antiquities of Mexico." The way in which the warp is held down and made tense, by a rope or band secured to the lower beam and sat upon by the weaver, is the same in both cases. And it seems that the artist who drew the original rude sketch, sought to represent the girl, not as working "the cross-thread of the woof in and out on a stick," but as manipulating the reed-fork with one hand and grasping the heald-rod and shed-rod in the other.

Note.—The engravings were prepared while the author was in New Mexico and could not be submitted for his inspection until the paper was ready for the press. Some alterations were made from the original pictures. The following are the most important to be noted: In Plate XXXVIII the batten should appear held horizontally, not obliquely. Fig. 5 is reduced and cannot fairly delineate the gradations in color and regular sharp outlines of the finely-serrated figures. Fig. 53 does not convey the fact that the stripes are of uniform width and all the right-angles accurately made.