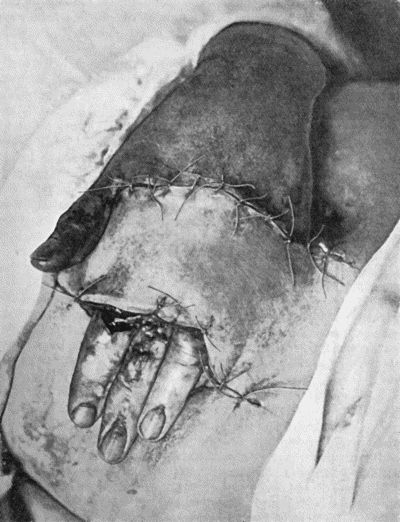

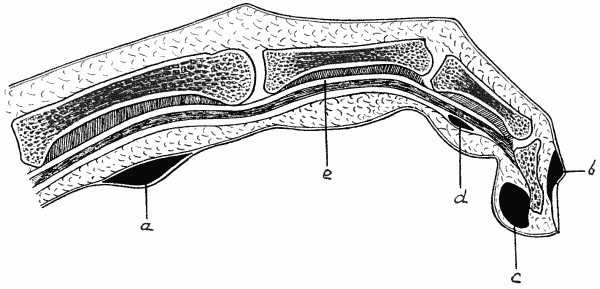

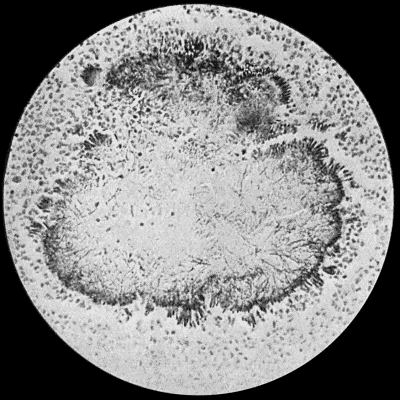

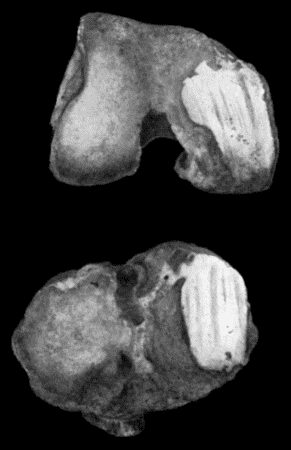

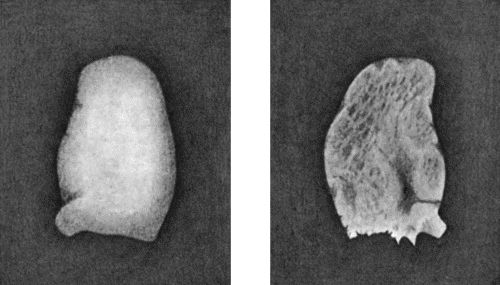

Fig. 1.—Ulcer of back of Hand covered by flap of skin raised from anterior abdominal wall. The lateral edges of the flap are divided after the graft has adhered.

Title: Manual of Surgery Volume First: General Surgery. Sixth Edition.

Author: Alexis Thomson

Alexander Miles

Release date: March 4, 2006 [eBook #17921]

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/17921

Credits: Produced by Jonathan Ingram, Laura Wisewell and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

VOLUME FIRST

GENERAL SURGERY

SIXTH EDITION REVISED

WITH 169 ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON

HENRY FROWDE and HODDER & STOUGHTON

THE LANCET BUILDING

1 & 2 BEDFORD STREET, STRAND, W.C.2

| First Edition | 1904 |

| Second Edition | 1907 |

| Third Edition | 1909 |

| Fourth Edition | 1911 |

| ""Second Impression | 1913 |

| Fifth Edition | 1915 |

| ""Second Impression | 1919 |

| Sixth Edition | 1921 |

Printed in Great Britain by

Morrison and Gibb Ltd., Edinburgh

Much has happened since this Manual was last revised, and many surgical lessons have been learned in the hard school of war. Some may yet have to be unlearned, and others have but little bearing on the problems presented to the civilian surgeon. Save in its broadest principles, the surgery of warfare is a thing apart from the general surgery of civil life, and the exhaustive literature now available on every aspect of it makes it unnecessary that it should receive detailed consideration in a manual for students. In preparing this new edition, therefore, we have endeavoured to incorporate only such additions to our knowledge and resources as our experience leads us to believe will prove of permanent value in civil practice.

For the rest, the text has been revised, condensed, and in places rearranged; a number of old illustrations have been discarded, and a greater number of new ones added. Descriptions of operative procedures have been omitted from the Manual, as they are to be found in the companion volume on Operative Surgery, the third edition of which appeared some months ago.

We have retained the Basle anatomical nomenclature, as extended experience has confirmed our preference for it. For the convenience of readers who still employ the old terms, these are given in brackets after the new.

This edition of the Manual appears in three volumes; the first being devoted to General Surgery, the other two to Regional Surgery. This arrangement has enabled us to deal in a more consecutive manner than hitherto with the surgery of the Extremities, including Fractures and Dislocations.

We have once more to express our thanks to colleagues in the Edinburgh School and to other friends for aiding us in providing new illustrations, and for other valuable help, as well as to our publishers for their generosity in the matter of illustrations.

Edinburgh,

March 1921.

| page | |

|---|---|

| CHAPTER I | |

| Repair | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Conditions which interfere with Repair | 17 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Inflammation | 31 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Suppuration | 45 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| Ulceration and Ulcers | 68 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Gangrene | 86 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Bacterial and other Wound Infections | 107 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Tuberculosis | 133 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| Syphilis | 146 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| Tumours | 181 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| Injuries | 218 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| Methods of Wound Treatment | 241 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| Constitutional Effects of Injuries | 249 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| The Blood Vessels | 258 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| The Lymph Vessels and Glands | 321 |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| The Nerves | 342 |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| Skin and Subcutaneous Tissues | 376 |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

| The Muscles, Tendons, and Tendon Sheaths | 405 |

| CHAPTER XIX | |

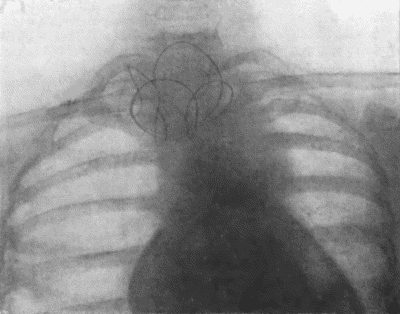

| The Bursæ | 426 |

| CHAPTER XX | |

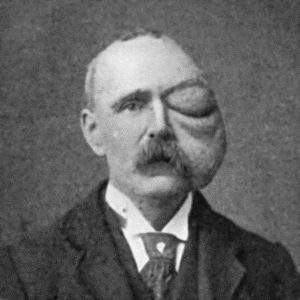

| Diseases of Bone | 434 |

| CHAPTER XXI | |

| Diseases of Joints | 501 |

| INDEX | 547 |

| fig. | page | |

|---|---|---|

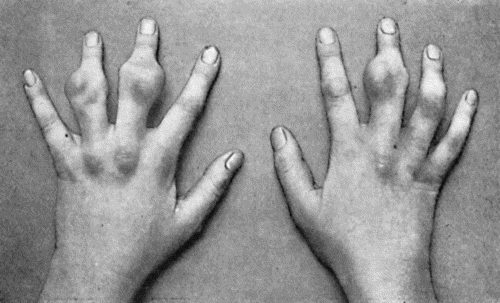

| 1. | Ulcer of Back of Hand grafted from Abdominal Wall | 15 |

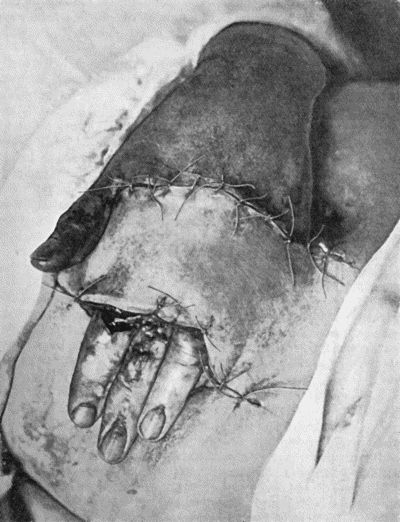

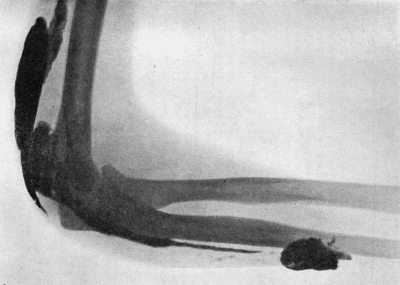

| 2. | Staphylococcus aureus in Pus from case of Osteomyelitis | 25 |

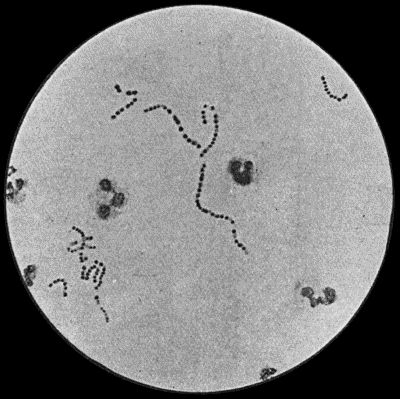

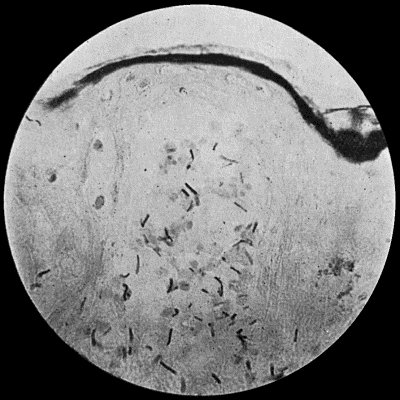

| 3. | Streptococci in Pus from case of Diffuse Cellulitis | 26 |

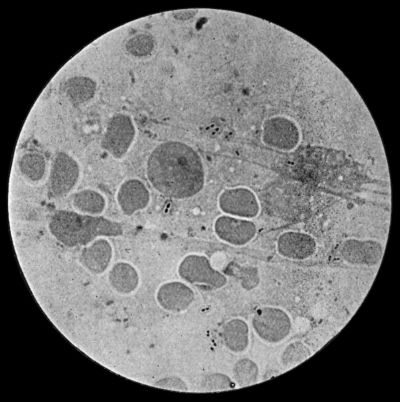

| 4. | Bacillus coli communis in Pus from Abdominal Abscess | 27 |

| 5. | Fraenkel's Pneumococci in Pus from Empyema following Pneumonia | 28 |

| 6. | Passive Hyperæmia of Hand and Forearm induced by Bier's Bandage | 37 |

| 7. | Passive Hyperæmia of Finger induced by Klapp's Suction Bell | 38 |

| 8. | Passive Hyperæmia induced by Klapp's Suction Bell for Inflammation of Inguinal Gland | 39 |

| 9. | Diagram of various forms of Whitlow | 56 |

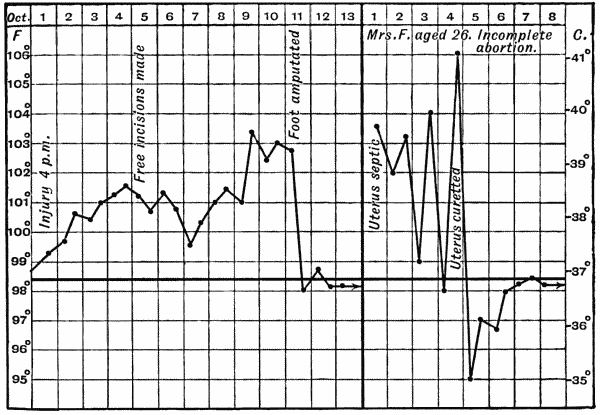

| 10. | Charts of Acute Sapræmia | 61 |

| 11. | Chart of Hectic Fever | 62 |

| 12. | Chart of Septicæmia followed by Pyæmia | 63 |

| 13. | Chart of Pyæmia following on Acute Osteomyelitis | 65 |

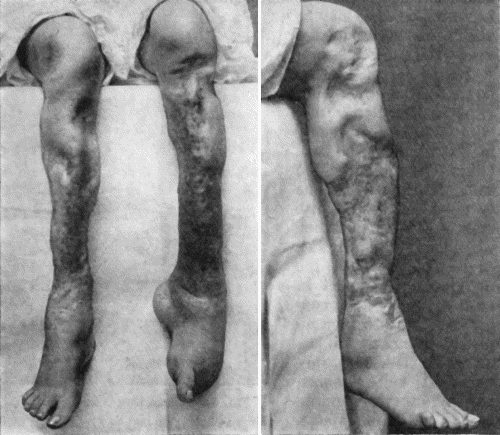

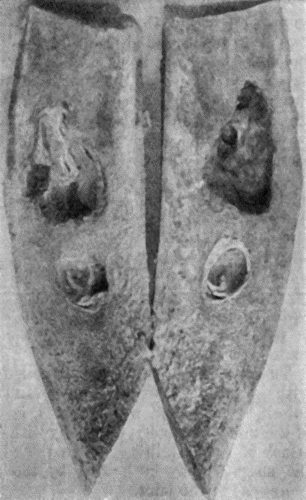

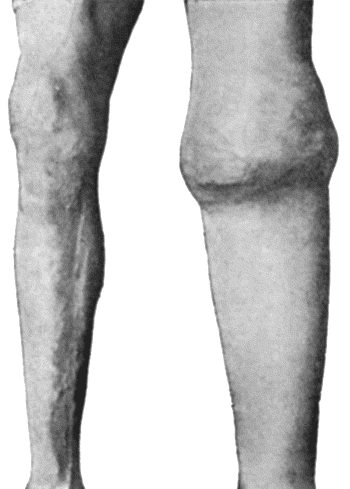

| 14. | Leg Ulcers associated with Varicose Veins | 71 |

| 15. | Perforating Ulcers of Sole of Foot | 74 |

| 16. | Bazin's Disease in a girl æt. 16 | 75 |

| 17. | Syphilitic Ulcers in region of Knee | 76 |

| 18. | Callous Ulcer showing thickened edges | 78 |

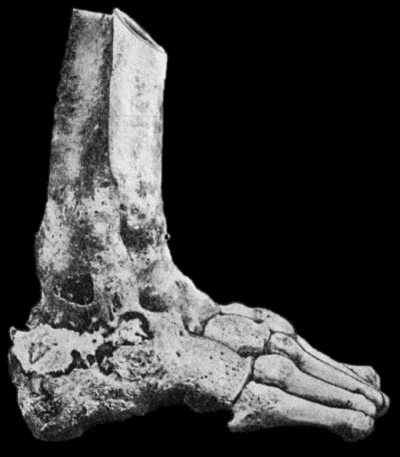

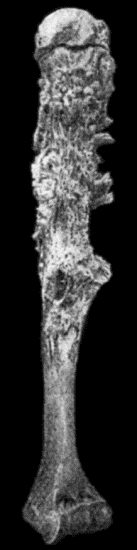

| 19. | Tibia and Fibula, showing changes due to Chronic Ulcer of Leg | 80 |

| 20. | Senile Gangrene of the Foot | 89 |

| 21. | Embolic Gangrene of Hand and Arm | 92 |

| 22. | Gangrene of Terminal Phalanx of Index-Finger | 100 |

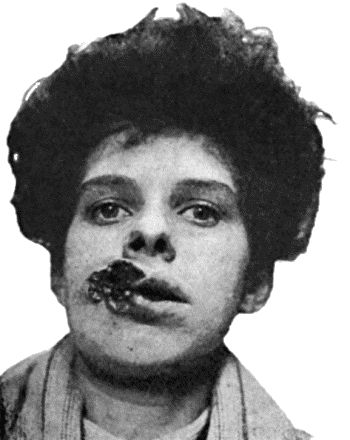

| 23. | Cancrum Oris | 103 |

| 24. | Acute Bed Sores over right Buttock | 104 |

| 25. | Chart of Erysipelas occurring in a wound | 108 |

| 26. | Bacillus of Tetanus | 113 |

| 27. | Bacillus of Anthrax | 120 |

| 28. | Malignant Pustule third day after infection | 122 |

| 29. | Malignant Pustule fourteen days after infection | 122 |

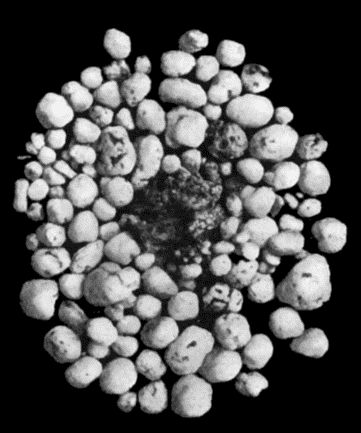

| 30. | Colony of Actinomyces | 126 |

| 31. | Actinomycosis of Maxilla | 128 |

| 32. | Mycetoma, or Madura Foot | 130 |

| 33. | Tubercle bacilli | 134 |

| 34. | Tuberculous Abscess in Lumbar Region | 141 |

| 35. | Tuberculous Sinus injected through its opening in the Forearm with Bismuth Paste | 144 |

| 36. | Spirochæte pallida | 147 |

| 37. | Spirochæta refrigerans from scraping of Vagina | 148 |

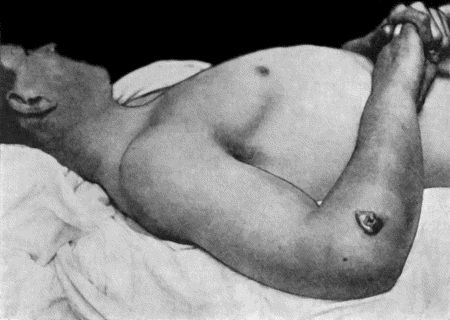

| 38. | Primary Lesion on Thumb, with Secondary Eruption on Forearm | 154 |

| 39. | Syphilitic Rupia | 159 |

| 40. | Ulcerating Gumma of Lips | 169 |

| 41. | Ulceration in inherited Syphilis | 170 |

| 42. | Tertiary Syphilitic Ulceration in region of Knee and on both Thumbs | 171 |

| 43. | Facies of Inherited Syphilis | 174 |

| 44. | Facies of Inherited Syphilis | 175 |

| 45. | Subcutaneous Lipoma | 185 |

| 46. | Pedunculated Lipoma of Buttock | 186 |

| 47. | Diffuse Lipomatosis of Neck | 187 |

| 48. | Zanthoma of Hands | 188 |

| 49. | Zanthoma of Buttock | 189 |

| 50. | Chondroma growing from Infra-Spinous Fossa of Scapula | 190 |

| 51. | Chondroma of Metacarpal Bone of Thumb | 190 |

| 52. | Cancellous Osteoma of Lower End of Femur | 192 |

| 53. | Myeloma of Shaft of Humerus | 195 |

| 54. | Fibro-myoma of Uterus | 196 |

| 55. | Recurrent Sarcoma of Sciatic Nerve | 198 |

| 56. | Sarcoma of Arm fungating | 199 |

| 57. | Carcinoma of Breast | 206 |

| 58. | Epithelioma of Lip | 209 |

| 59. | Dermoid Cyst of Ovary | 213 |

| 60. | Carpal Ganglion in a woman æt. 25 | 215 |

| 61. | Ganglion on lateral aspect of Knee | 216 |

| 62. | Radiogram showing pellets embedded in Arm | 228 |

| 63. | Cicatricial Contraction following Severe Burn | 236 |

| 64. | Genealogical Tree of Hæmophilic Family | 278 |

| 65. | Radiogram showing calcareous degeneration of Arteries | 284 |

| 66. | Varicose Vein with Thrombosis | 289 |

| 67. | Extensive Varix of Internal Saphena System on Left Leg | 291 |

| 68. | Mixed Nævus of Nose | 296 |

| 69. | Cirsoid Aneurysm of Forehead | 299 |

| 70. | Cirsoid Aneurysm of Orbit and Face | 300 |

| 71. | Radiogram of Aneurysm of Aorta | 303 |

| 72. | Sacculated Aneurysm of Abdominal Aorta | 304 |

| 73. | Radiogram of Innominate Aneurysm after Treatment by Moore-Corradi method | 309 |

| 74. | Thoracic Aneurysm threatening to rupture | 313 |

| 75. | Innominate Aneurysm in a woman | 315 |

| 76. | Congenital Cystic Tumour or Hygroma of Axilla | 328 |

| 77. | Tuberculous Cervical Gland with Abscess formation | 331 |

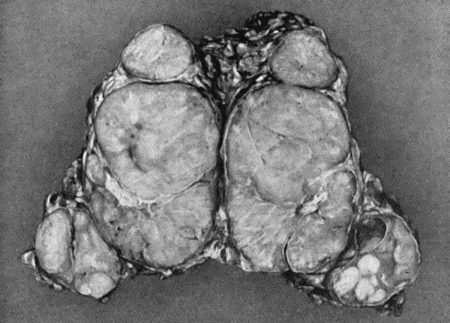

| 78. | Mass of Tuberculous Glands removed from Axilla | 333 |

| 79. | Tuberculous Axillary Glands | 335 |

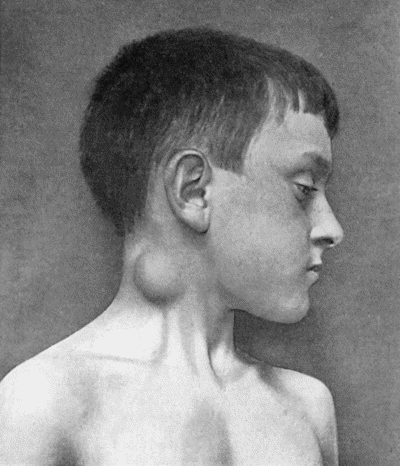

| 80. | Chronic Hodgkin's Disease in boy æt. 11 | 337 |

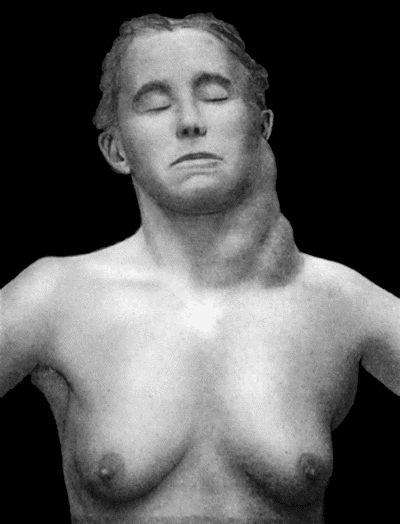

| 81. | Lymphadenoma in a woman æt. 44 | 338 |

| 82. | Lympho Sarcoma removed from Groin | 339 |

| 83. | Cancerous Glands in Neck, secondary to Epithelioma of Lip | 341 |

| 84. | Stump Neuromas of Sciatic Nerve | 345 |

| 85. | Stump Neuromas, showing changes at ends of divided Nerves | 354 |

| 86. | Diffuse Enlargement of Nerves in generalised Neuro-Fibromatosis | 356 |

| 87. | Plexiform Neuroma of small Sciatic Nerve | 357 |

| 88. | Multiple Neuro-Fibromas of Skin (Molluscum fibrosum) | 358 |

| 89. | Elephantiasis Neuromatosa in a woman æt. 28 | 359 |

| 90. | Drop-Wrist following Fracture of Shaft of Humerus | 365 |

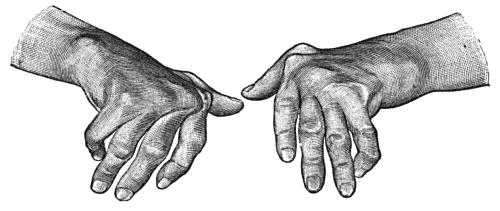

| 91. | To illustrate the Loss of Sensation produced by Division of the Median Nerve | 367 |

| 92. | To illustrate Loss of Sensation produced by Complete Division of Ulnar Nerve | 368 |

| 93. | Callosities and Corns on Sole of Foot | 377 |

| 94. | Ulcerated Chilblains on Fingers | 378 |

| 95. | Carbuncle on Back of Neck | 381 |

| 96. | Tuberculous Elephantiasis | 383 |

| 97. | Elephantiasis in a woman æt. 45 | 387 |

| 98. | Elephantiasis of Penis and Scrotum | 388 |

| 99. | Multiple Sebaceous Cysts or Wens | 390 |

| 100. | Sebaceous Horn growing from Auricle | 392 |

| 101. | Paraffin Epithelioma | 394 |

| 102. | Rodent Cancer of Inner Canthus | 395 |

| 103. | Rodent Cancer with destruction of contents of Orbit | 396 |

| 104. | Diffuse Melanotic Cancer of Lymphatics of Skin | 398 |

| 105. | Melanotic Cancer of Forehead with Metastasis in Lymph Glands | 399 |

| 106. | Recurrent Keloid | 401 |

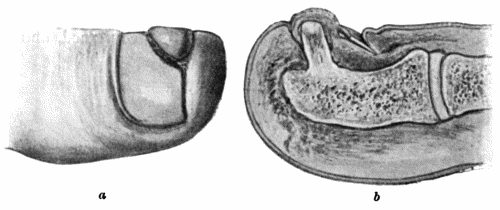

| 107. | Subungual Exostosis | 403 |

| 108. | Avulsion of Tendon | 410 |

| 109. | Volkmann's Ischæmic Contracture | 414 |

| 110. | Ossification in Tendon of Ilio-psoas Muscle | 417 |

| 111. | Radiogram of Calcification and Ossification in Biceps and Triceps | 418 |

| 112. | Ossification in Muscles of Trunk in generalised Ossifying Myositis | 419 |

| 113. | Hydrops of Prepatellar Bursa | 427 |

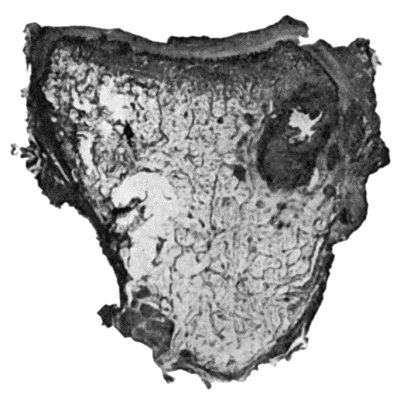

| 114. | Section through Gouty Bursa | 428 |

| 115. | Tuberculous Disease of Sub-Deltoid Bursa | 429 |

| 116. | Great Enlargement of the Ischial Bursa | 431 |

| 117. | Gouty Disease of Bursæ | 432 |

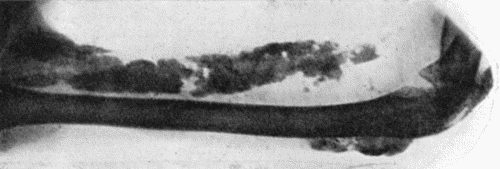

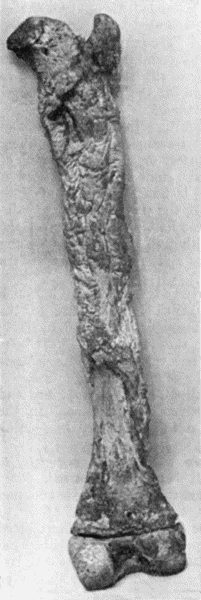

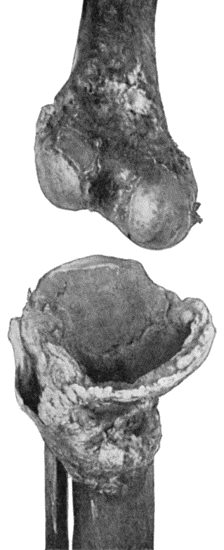

| 118. | Shaft of the Femur after Acute Osteomyelitis | 444 |

| 119. | Femur and Tibia showing results of Acute Osteomyelitis | 445 |

| 120. | Segment of Tibia resected for Brodie's Abscess | 449 |

| 121. | Radiogram of Brodie's Abscess in Lower End of Tibia | 451 |

| 122. | Sequestrum of Femur after Amputation | 453 |

| 123. | New Periosteal Bone on Surface of Femur from Amputation Stump | 454 |

| 124. | Tuberculous Osteomyelitis of Os Magnum | 456 |

| 125. | Tuberculous Disease of Tibia | 457 |

| 126. | Diffuse Tuberculous Osteomyelitis of Right Tibia | 458 |

| 127. | Advanced Tuberculous Disease in Region of Ankle | 459 |

| 128. | Tuberculous Dactylitis | 460 |

| 129. | Shortening of Middle Finger of Adult, the result of Tuberculous Dactylitis in Childhood | 461 |

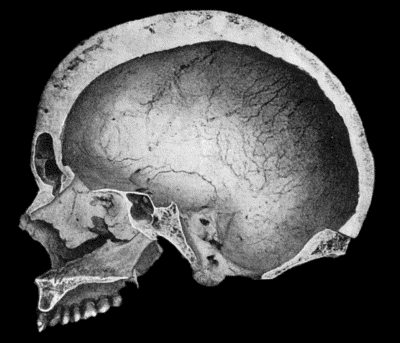

| 130. | Syphilitic Disease of Skull | 463 |

| 131. | Syphilitic Hyperostosis and Sclerosis of Tibia | 464 |

| 132. | Sabre-blade Deformity of Tibia | 467 |

| 133. | Skeleton of Rickety Dwarf | 470 |

| 134. | Changes in the Skull resulting from Ostitis Deformans | 474 |

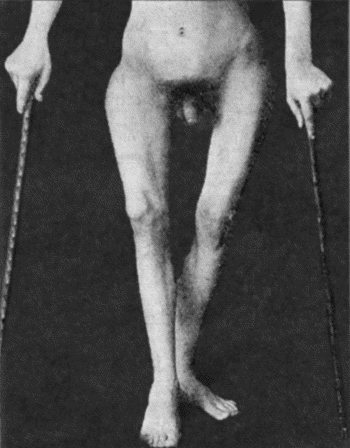

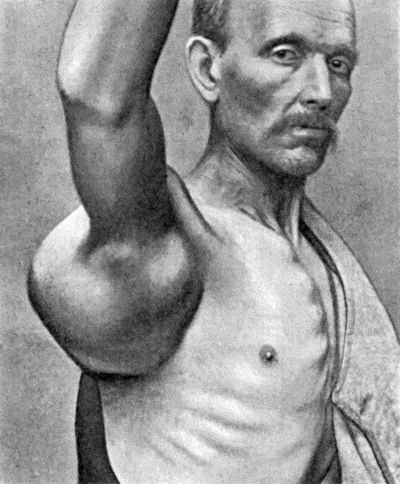

| 135. | Cadaver, illustrating the alterations in the Lower Limbs resulting from Ostitis Deformans | 475 |

| 136. | Osteomyelitis Fibrosa affecting Femora | 476 |

| 137. | Radiogram of Upper End of Femur in Osteomyelitis Fibrosa | 478 |

| 138. | Radiogram of Right Knee showing Multiple Exostoses | 482 |

| 139. | Multiple Exostoses of Limbs | 483 |

| 140. | Multiple Cartilaginous Exostoses | 484 |

| 141. | Multiple Cartilaginous Exostoses | 486 |

| 142. | Multiple Chondromas of Phalanges and Metacarpals | 488 |

| 143. | Skiagram of Multiple Chondromas | 489 |

| 144. | Multiple Chondromas in Hand | 490 |

| 145. | Radiogram of Myeloma of Humerus | 492 |

| 146. | Periosteal Sarcoma of Femur | 493 |

| 147. | Periosteal Sarcoma of Humerus | 493 |

| 148. | Chondro-Sarcoma of Scapula | 494 |

| 149. | Central Sarcoma of Femur invading Knee Joint | 495 |

| 150. | Osseous Shell of Osteo-Sarcoma of Femur | 495 |

| 151. | Radiogram of Osteo-Sarcoma of Femur | 496 |

| 152. | Radiogram of Chondro-Sarcoma of Humerus | 497 |

| 153. | Epitheliomatus Ulcer of Leg invading Tibia | 499 |

| 154. | Osseous Ankylosis of Femur and Tibia | 503 |

| 155. | Osseous Ankylosis of Knee | 504 |

| 156. | Caseating focus in Upper End of Fibula | 513 |

| 157. | Arthritis Deformans of Elbow | 525 |

| 158. | Arthritis Deformans of Knee | 526 |

| 159. | Hypertrophied Fringes of Synovial Membrane of Knee | 527 |

| 160. | Arthritis Deformans of Hands | 529 |

| 161. | Arthritis Deformans of several Joints | 530 |

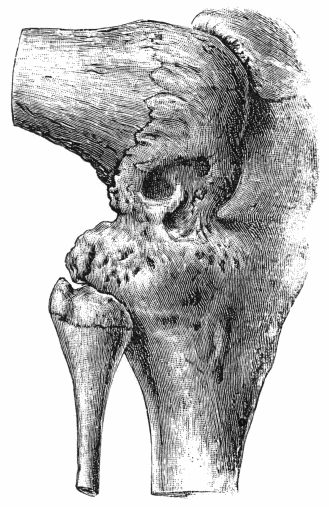

| 162. | Bones of Knee in Charcot's Disease | 533 |

| 163. | Charcot's Disease of Left Knee | 534 |

| 164. | Charcot's Disease of both Ankles: front view | 535 |

| 165. | Charcot's Disease of both Ankles: back view | 536 |

| 166. | Radiogram of Multiple Loose Bodies in Knee-joint | 540 |

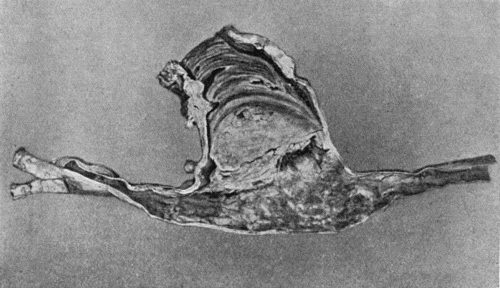

| 167. | Loose Body from Knee-joint | 541 |

| 168. | Multiple partially ossified Chondromas of Synovial Membrane from Shoulder-joint | 542 |

| 169. | Multiple Cartilaginous Loose Bodies from Knee-joint | 543 |

To prolong human life and to alleviate suffering are the ultimate objects of scientific medicine. The two great branches of the healing art—Medicine and Surgery—are so intimately related that it is impossible to draw a hard-and-fast line between them, but for convenience Surgery may be defined as “the art of treating lesions and malformations of the human body by manual operations, mediate and immediate.” To apply his art intelligently and successfully, it is essential that the surgeon should be conversant not only with the normal anatomy and physiology of the body and with the various pathological conditions to which it is liable, but also with the nature of the process by which repair of injured or diseased tissues is effected. Without this knowledge he is unable to recognise such deviations from the normal as result from mal-development, injury, or disease, or rationally to direct his efforts towards the correction or removal of these.

The process of repair in living tissue depends upon an inherent power possessed by vital cells of reacting to the irritation caused by injury or disease. The cells of the damaged tissues, under the influence of this irritation, undergo certain proliferative changes, which are designed to restore the normal structure and configuration of the part. The process by which this restoration is effected is essentially the same in all tissues, but the extent to which different tissues can carry the recuperative process varies. Simple structures, such as skin, cartilage, bone, periosteum, and tendon, for example, have a high power of regeneration, and in them the reparative process may result in almost perfect restitution to the normal. More complex structures, on the other hand, such as secreting glands, muscle, and the tissues of the central nervous system, are but imperfectly restored, simple cicatricial connective tissue taking the place of what has been lost or destroyed. Any given tissue can be replaced only by tissue of a similar kind, and in a damaged part each element takes its share in the reparative process by producing new material which approximates more or less closely to the normal according to the recuperative capacity of the particular tissue. The normal process of repair may be interfered with by various extraneous agencies, the most important of which are infection by disease-producing micro-organisms, the presence of foreign substances, undue movement of the affected part, and improper applications and dressings. The effect of these agencies is to delay repair or to prevent the individual tissues carrying the process to the furthest degree of which they are capable.

In the management of wounds and other diseased conditions the main object of the surgeon is to promote the natural reparative process by preventing or eliminating any factor by which it may be disturbed.

Healing by Primary Union.—The most favourable conditions for the progress of the reparative process are to be found in a clean-cut wound of the integument, which is uncomplicated by loss of tissue, by the presence of foreign substances, or by infection with disease-producing micro-organisms, and its edges are in contact. Such a wound in virtue of the absence of infection is said to be aseptic, and under these conditions healing takes place by what is called “primary union”—the “healing by first intention” of the older writers.

Granulation Tissue.—The essential and invariable medium of repair in all structures is an elementary form of new tissue known as granulation tissue, which is produced in the damaged area in response to the irritation caused by injury or disease. The vital reaction induced by such irritation results in dilatation of the vessels of the part, emigration of leucocytes, transudation of lymph, and certain proliferative changes in the fixed tissue cells. These changes are common to the processes of inflammation and repair; no hard-and-fast line can be drawn between these processes, and the two may go on together. It is, however, only when the proliferative changes have come to predominate that the reparative process is effectively established by the production of healthy granulation tissue.

Formation of Granulation Tissue.—When a wound is made in the integument under aseptic conditions, the passage of the knife through the tissues is immediately followed by an oozing of blood, which soon coagulates on the cut surfaces. In each of the divided vessels a clot forms, and extends as far as the nearest collateral branch; and on the surface of the wound there is a microscopic layer of bruised and devitalised tissue. If the wound is closed, the narrow space between its edges is occupied by blood-clot, which consists of red and white corpuscles mixed with a quantity of fibrin, and this forms a temporary uniting medium between the divided surfaces. During the first twelve hours, the minute vessels in the vicinity of the wound dilate, and from them lymph exudes and leucocytes migrate into the tissues. In from twenty-four to thirty-six hours, the capillaries of the part adjacent to the wound begin to throw out minute buds and fine processes, which bridge the gap and form a firmer, but still temporary, connection between the two sides. Each bud begins in the wall of the capillary as a small accumulation of granular protoplasm, which gradually elongates into a filament containing a nucleus. This filament either joins with a neighbouring capillary or with a similar filament, and in time these become hollow and are filled with blood from the vessels that gave them origin. In this way a series of young capillary loops is formed.

The spaces between these loops are filled by cells of various kinds, the most important being the fibroblasts, which are destined to form cicatricial fibrous tissue. These fibroblasts are large irregular nucleated cells derived mainly from the proliferation of the fixed connective-tissue cells of the part, and to a less extent from the lymphocytes and other mononuclear cells which have migrated from the vessels. Among the fibroblasts, larger multi-nucleated cells—giant cells—are sometimes found, particularly when resistant substances, such as silk ligatures or fragments of bone, are embedded in the tissues, and their function seems to be to soften such substances preliminary to their being removed by the phagocytes. Numerous polymorpho-nuclear leucocytes, which have wandered from the vessels, are also present in the spaces. These act as phagocytes, their function being to remove the red corpuscles and fibrin of the original clot, and this performed, they either pass back into the circulation in virtue of their amœboid movement, or are themselves eaten up by the growing fibroblasts. Beyond this phagocytic action, they do not appear to play any direct part in the reparative process. These young capillary loops, with their supporting cells and fluids, constitute granulation tissue, which is usually fully formed in from three to five days, after which it begins to be replaced by cicatricial or scar tissue.

Formation of Cicatricial Tissue.—The transformation of this temporary granulation tissue into scar tissue is effected by the fibroblasts, which become elongated and spindle-shaped, and produce in and around them a fine fibrillated material which gradually increases in quantity till it replaces the cell protoplasm. In this way white fibrous tissue is formed, the cells of which are arranged in parallel lines and eventually become grouped in bundles, constituting fully formed white fibrous tissue. In its growth it gradually obliterates the capillaries, until at the end of two, three, or four weeks both vessels and cells have almost entirely disappeared, and the original wound is occupied by cicatricial tissue. In course of time this tissue becomes consolidated, and the cicatrix undergoes a certain amount of contraction—cicatricial contraction.

Healing of Epidermis.—While these changes are taking place in the deeper parts of the wound, the surface is being covered over by epidermis growing in from the margins. Within twelve hours the cells of the rete Malpighii close to the cut edge begin to sprout on to the surface of the wound, and by their proliferation gradually cover the granulations with a thin pink pellicle. As the epithelium increases in thickness it assumes a bluish hue and eventually the cells become cornified and the epithelium assumes a greyish-white colour.

Clinical Aspects.—So long as the process of repair is not complicated by infection with micro-organisms, there is no interference with the general health of the patient. The temperature remains normal; the circulatory, gastro-intestinal, nervous, and other functions are undisturbed; locally, the part is cool, of natural colour and free from pain.

Modifications of the Process of Repair.—The process of repair by primary union, above described, is to be looked upon as the type of all reparative processes, such modifications as are met with depending merely upon incidental differences in the conditions present, such as loss of tissue, infection by micro-organisms, etc.

Repair after Loss or Destruction of Tissue.—When the edges of a wound cannot be approximated either because tissue has been lost, for example in excising a tumour or because a drainage tube or gauze packing has been necessary, a greater amount of granulation tissue is required to fill the gap, but the process is essentially the same as in the ideal method of repair.

The raw surface is first covered by a layer of coagulated blood and fibrin. An extensive new formation of capillary loops and fibroblasts takes place towards the free surface, and goes on until the gap is filled by a fine velvet-like mass of granulation tissue. This granulation tissue is gradually replaced by young cicatricial tissue, and the surface is covered by the ingrowth of epithelium from the edges.

This modification of the reparative process can be best studied clinically in a recent wound which has been packed with gauze. When the plug is introduced, the walls of the cavity consist of raw tissue with numerous oozing blood vessels. On removing the packing on the fifth or sixth day, the surface is found to be covered with minute, red, papillary granulations, which are beginning to fill up the cavity. At the edges the epithelium has proliferated and is covering over the newly formed granulation tissue. As lymph and leucocytes escape from the exposed surface there is a certain amount of serous or sero-purulent discharge. On examining the wound at intervals of a few days, it is found that the granulation tissue gradually increases in amount till the gap is completely filled up, and that coincidently the epithelium spreads in and covers over its surface. In course of time the epithelium thickens, and as the granulation tissue is slowly replaced by young cicatricial tissue, which has a peculiar tendency to contract and so to obliterate the blood vessels in it, the scar that is left becomes smooth, pale, and depressed. This method of healing is sometimes spoken of as “healing by granulation”—although, as we have seen, it is by granulation that all repair takes place.

Healing by Union of two Granulating Surfaces.—In gaping wounds union is sometimes obtained by bringing the two surfaces into apposition after each has become covered with healthy granulations. The exudate on the surfaces causes them to adhere, capillary loops pass from one to the other, and their final fusion takes place by the further development of granulation and cicatricial tissue.

Reunion of Parts entirely Separated from the Body.—Small portions of tissue, such as the end of a finger, the tip of the nose or a portion of the external ear, accidentally separated from the body, if accurately replaced and fixed in position, occasionally adhere by primary union.

In the course of operations also, portions of skin, fascia, or bone, or even a complete joint may be transplanted, and unite by primary union.

Healing under a Scab.—When a small superficial wound is exposed to the air, the blood and serum exuded on its surface may dry and form a hard crust or scab, which serves to protect the surface from external irritation in the same way as would a dry pad of sterilised gauze. Under this scab the formation of granulation tissue, its transformation into cicatricial tissue, and the growth of epithelium on the surface, go on until in the course of time the crust separates, leaving a scar.

Healing by Blood-clot.—In subcutaneous wounds, for example tenotomy, in amputation wounds, and in wounds made in excising tumours or in operating upon bones, the space left between the divided tissues becomes filled with blood-clot, which acts as a temporary scaffolding in which granulation tissue is built up. Capillary loops grow into the coagulum, and migrated leucocytes from the adjacent blood vessels destroy the red corpuscles, and are in turn disposed of by the developing fibroblasts, which by their growth and proliferation fill up the gap with young connective tissue. It will be evident that this process only differs from healing by primary union in the amount of blood-clot that is present.

Presence of a Foreign Body.—When an aseptic foreign body is present in the tissues, e.g. a piece of unabsorbable chromicised catgut, the healing process may be modified. After primary union has taken place the scar may broaden, become raised above the surface, and assume a bluish-brown colour; the epidermis gradually thins and gives way, revealing the softened portion of catgut, which can be pulled out in pieces, after which the wound rapidly heals and resumes a normal appearance.

Skin and Connective Tissue.—The mode of regeneration of these tissues under aseptic conditions has already been described as the type of ideal repair. In highly vascular parts, such as the face, the reparative process goes on with great rapidity, and even extensive wounds may be firmly united in from three to five days. Where the anastomosis is less free the process is more prolonged. The more highly organised elements of the skin, such as the hair follicles, the sweat and sebaceous glands, are imperfectly reproduced; hence the scar remains smooth, dry, and hairless.

Epithelium.—Epithelium is only reproduced from pre-existing epithelium, and, as a rule, from one of a similar type, although metaplastic transformation of cells of one kind of epithelium into another kind can take place. Thus a granulating surface may be covered entirely by the ingrowing of the cutaneous epithelium from the margins; or islets, originating in surviving cells of sebaceous glands or sweat glands, or of hair follicles, may spring up in the centre of the raw area. Such islets may also be due to the accidental transference of loose epithelial cells from the edges. Even the fluid from a blister, in virtue of the isolated cells of the rete Malpighii which it contains, is capable of starting epithelial growth on a granulating surface. Hairs and nails may be completely regenerated if a sufficient amount of the hair follicles or of the nail matrix has escaped destruction. The epithelium of a mucous membrane is regenerated in the same way as that on a cutaneous surface.

Epithelial cells have the power of living for some time after being separated from their normal surroundings, and of growing again when once more placed in favourable circumstances. On this fact the practice of skin grafting is based (p. 11).

Cartilage.—When an articular cartilage is divided by incision or by being implicated in a fracture involving the articular end of a bone, it is repaired by ordinary cicatricial fibrous tissue derived from the proliferating cells of the perichondrium. Cartilage being a non-vascular tissue, the reparative process goes on slowly, and it may be many weeks before it is complete.

It is possible for a metaplastic transformation of connective-tissue cells into cartilage cells to take place, the characteristic hyaline matrix being secreted by the new cells. This is sometimes observed as an intermediary stage in the healing of fractures, especially in young bones. It may also take place in the regeneration of lost portions of cartilage, provided the new tissue is so situated as to constitute part of a joint and to be subjected to pressure by an opposing cartilaginous surface. This is illustrated by what takes place after excision of joints where it is desired to restore the function of the articulation. By carrying out movements between the constituent parts, the fibrous tissue covering the ends of the bones becomes moulded into shape, its cells take on the characters of cartilage cells, and, forming a matrix, so develop a new cartilage.

Conversely, it is observed that when articular cartilage is no longer subjected to pressure by an opposing cartilage, it tends to be transformed into fibrous tissue, as may be seen in deformities attended with displacement of articular surfaces, such as hallux valgus and club-foot.

After fractures of costal cartilage or of the cartilages of the larynx the cicatricial tissue may be ultimately replaced by bone.

Tendons.—When a tendon is divided, for example by subcutaneous tenotomy, the end nearer the muscle fibres is drawn away from the other, leaving a gap which is speedily filled by blood-clot. In the course of a few days this clot becomes permeated by granulation tissue, the fibroblasts of which are derived from the sheath of the tendon, the surrounding connective tissue, and probably also from the divided ends of the tendon itself. These fibroblasts ultimately develop into typical tendon cells, and the fibres which they form constitute the new tendon fibres. Under aseptic conditions repair is complete in from two to three weeks. In the course of the reparative process the tendon and its sheath may become adherent, which leads to impaired movement and stiffness. If the ends of an accidentally divided tendon are at once brought into accurate apposition and secured by sutures, they unite directly with a minimum amount of scar tissue, and function is perfectly restored.

Muscle.—Unstriped muscle does not seem to be capable of being regenerated to any but a moderate degree. If the ends of a divided striped muscle are at once brought into apposition by stitches, primary union takes place with a minimum of intervening fibrous tissue. The nuclei of the muscle fibres in close proximity to this young cicatricial tissue proliferate, and a few new muscle fibres may be developed, but any gross loss of muscular tissue is replaced by a fibrous cicatrix. It would appear that portions of muscle transplanted from animals to fill up gaps in human muscle are similarly replaced by fibrous tissue. When a muscle is paralysed from loss of its nerve supply and undergoes complete degeneration, it is not capable of being regenerated, even should the integrity of the nerve be restored, and so its function is permanently lost.

Secretory Glands.—The regeneration of secretory glands is usually incomplete, cicatricial tissue taking the place of the glandular substance which has been destroyed. In wounds of the liver, for example, the gap is filled by fibrous tissue, but towards the periphery of the wound the liver cells proliferate and a certain amount of regeneration takes place. In the kidney also, repair mainly takes place by cicatricial tissue, and although a few collecting tubules may be reformed, no regeneration of secreting tissue takes place. After the operation of decapsulation of the kidney a new capsule is formed, and during the process young blood vessels permeate the superficial parts of the kidney and temporarily increase its blood supply, but in the consolidation of the new fibrous tissue these vessels are ultimately obliterated. This does not prove that the operation is useless, as the temporary improvement of the circulation in the kidney may serve to tide the patient over a critical period of renal insufficiency.

Stomach and Intestine.—Provided the peritoneal surfaces are accurately apposed, wounds of the stomach and intestine heal with great rapidity. Within a few hours the peritoneal surfaces are glued together by a thin layer of fibrin and leucocytes, which is speedily organised and replaced by fibrous tissue. Fibrous tissue takes the place of the muscular elements, which are not regenerated. The mucous lining is restored by ingrowth from the margins, and there is evidence that some of the secreting glands may be reproduced.

Hollow viscera, like the œsophagus and urinary bladder, in so far as they are not covered by peritoneum, heal less rapidly.

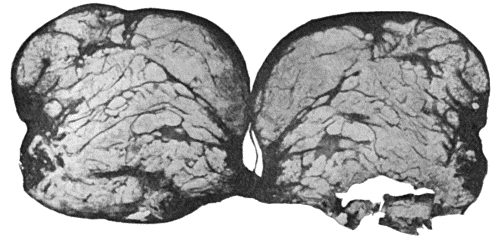

Nerve Tissues.—There is no trustworthy evidence that regeneration of the tissues of the brain or spinal cord in man ever takes place. Any loss of substance is replaced by cicatricial tissue.

The repair of Bone, Blood Vessels, and Peripheral Nerves is more conveniently considered in the chapters dealing with these structures.

Rate of Healing.—While the rate at which wounds heal is remarkably constant there are certain factors that influence it in one direction or the other. Healing is more rapid when the edges are in contact, when there is a minimum amount of blood-clot between them, when the patient is in normal health and the vitality of the tissues has not been impaired. Wounds heal slightly more quickly in the young than in the old, although the difference is so small that it can only be demonstrated by the most careful observations.

Certain tissues take longer to heal than others: for example, a fracture of one of the larger long bones takes about six weeks to unite, and divided nerve trunks take much longer—about a year.

Wounds of certain parts of the body heal more quickly than others: those of the scalp, face, and neck, for example, heal more quickly than those over the buttock or sacrum, probably because of their greater vascularity.

The extent of the wound influences the rate of healing; it is only natural that a long and deep wound should take longer to heal than a short and superficial one, because there is so much more work to be done in the conversion of blood-clot into granulation tissue, and this again into scar tissue that will be strong enough to stand the strain on the edges of the wound.

Conditions are not infrequently met with in which healing is promoted and restoration of function made possible by the transference of a portion of tissue from one part of the body to another; the tissue transferred is known as the graft or the transplant. The simplest example of grafting is the transplantation of skin.

In order that the graft may survive and have a favourable chance of “taking,” as it is called, the transplanted tissue must retain its vitality until it has formed an organic connection with the tissue in which it is placed, so that it may derive the necessary nourishment from its new bed. When these conditions are fulfilled the tissues of the graft continue to proliferate, producing new tissue elements to replace those that are lost and making it possible for the graft to become incorporated with the tissue with which it is in contact.

Dead tissue, on the other hand, can do neither of these things; it is only capable of acting as a model, or, at the most, as a scaffolding for such mobile tissue elements as may be derived from, the parent tissue with which the graft is in contact: a portion of sterilised marine sponge, for example, may be observed to become permeated with granulation tissue when it is embedded in the tissues.

A successful graft of living tissue is not only capable of regeneration, but it acquires a system of lymph and blood vessels, so that in time it bleeds when cut into, and is permeated by new nerve fibres spreading in from the periphery towards the centre.

It is instructive to associate the period of survival of the different tissues of the body after death, with their capacity of being used for grafting purposes; the higher tissues such as those of the central nervous system and highly specialised glandular tissues like those of the kidney lose their vitality quickly after death and are therefore useless for grafting; connective tissues, on the other hand, such as fat, cartilage, and bone retain their vitality for several hours after death, so that when they are transplanted, they readily “take” and do all that is required of them: the same is true of the skin and its appendages.

Sources of Grafts.—It is convenient to differentiate between autoplastic grafts, that is those derived from the same individual; homoplastic grafts, derived from another animal of the same species; and heteroplastic grafts, derived from an animal of another species. Other conditions being equal, the prospects of success are greatest with autoplastic grafts, and these are therefore preferred whenever possible.

There are certain details making for success that merit attention: the graft must not be roughly handled or allowed to dry, or be subjected to chemical irritation; it must be brought into accurate contact with the new soil, no blood-clot intervening between the two, no movement of the one upon the other should be possible and all infection must be excluded; it will be observed that these are exactly the same conditions that permit of the primary healing of wounds, with which of course the healing of grafts is exactly comparable.

Preservation of Tissues for Grafting.—It was at one time believed that tissues might be taken from the operating theatre and kept in cold storage until they were required. It is now agreed that tissues which have been separated from the body for some time inevitably lose their vitality, become incapable of regeneration, and are therefore unsuited for grafting purposes. If it is intended to preserve a portion of tissue for future grafting, it should be embedded in the subcutaneous tissue of the abdominal wall until it is wanted; this has been carried out with portions of costal cartilage and of bone.

The Blood lends itself in an ideal manner to transplantation, or, as it has long been called, transfusion. Being always a homoplastic transfer, the new blood is not always tolerated by the old, in which case biochemical changes occur, resulting in hæmolysis, which corresponds to the disintegration of other unsuccessful homoplastic grafts. (See article on Transfusion, Op. Surg., p. 37.)

The Skin.—The skin was the first tissue to be used for grafting purposes, and it is still employed with greater frequency than any other, as lesions causing defects of skin are extremely common and without the aid of grafts are tedious in healing.

Skin grafts may be applied to a raw surface or to one that is covered with granulations.

Skin grafting of raw surfaces is commonly indicated after operations for malignant disease in which considerable areas of skin must be sacrificed, and after accidents, such as avulsion of the scalp by machinery.

Skin grafting of granulating surfaces is chiefly employed to promote healing in the large defects of skin caused by severe burns; the grafting is carried out when the surface is covered by a uniform layer of healthy granulations and before the inevitable contraction of scar tissue makes itself manifest. Before applying the grafts it is usual to scrape away the granulations until the young fibrous tissue underneath is exposed, but, if the granulations are healthy and can be rendered aseptic, the grafts may be placed on them directly.

If it is decided to scrape away the granulations, the oozing must be arrested by pressure with a pad of gauze, a sheet of dental rubber or green protective is placed next the raw surface to prevent the gauze adhering and starting the bleeding afresh when it is removed.

Methods of Skin-Grafting.—Two methods are employed: one in which the epidermis is mainly or exclusively employed—epidermis or epithelial grafting; the other, in which the graft consists of the whole thickness of the true skin—cutis-grafting.

Epidermis or Epithelial Grafting.—The method introduced by the late Professor Thiersch of Leipsic is that almost universally practised. It consists in transplanting strips of epidermis shaved from the surface of the skin, the razor passing through the tips of the papillæ, which appear as tiny red points yielding a moderate ooze of blood.

The strips are obtained from the front and lateral aspects of the thigh or upper arm, the skin in those regions being pliable and comparatively free from hairs.

They are cut with a sharp hollow-ground razor or with Thiersch's grafting knife, the blade of which is rinsed in alcohol and kept moistened with warm saline solution. The cutting is made easier if the skin is well stretched and kept flat and perfectly steady, the operator's left hand exerting traction on the skin behind, the hands of the assistant on the skin in front, one above and the other below the seat of operation. To ensure uniform strips being cut, the razor is kept parallel with the surface and used with a short, rapid, sawing movement, so that, with a little practice, grafts six or eight inches long by one or two inches broad can readily be cut. The patient is given a general anæsthetic, or regional anæsthesia is obtained by injections of a solution of one per cent. novocain into the line of the lateral and middle cutaneous nerves; the disinfection of the skin is carried out on the usual lines, any chemical agent being finally got rid of, however, by means of alcohol followed by saline solution.

The strips of epidermis wrinkle up on the knife and are directly transferred to the surface, for which they should be made to form a complete carpet, slightly overlapping the edges of the area and of one another; some blunt instrument is used to straighten out the strips, which are then subjected to firm pressure with a pad of gauze to express blood and air-bells and to ensure accurate contact, for this must be as close as that between a postage stamp and the paper to which it is affixed.

As a dressing for the grafted area and of that also from which the grafts have been taken, gauze soaked in liquid paraffin—the patent variety known as ambrine is excellent—appears to be the best; the gauze should be moistened every other day or so with fresh paraffin, so that, at the end of a week, when the grafts should have united, the gauze can be removed without risk of detaching them. Dental wax is another useful type of dressing; as is also picric acid solution. Over the gauze, there is applied a thick layer of cotton wool, and the whole dressing is kept in place by a firmly applied bandage, and in the case of the limbs some form of splint should be added to prevent movement.

A dressing may be dispensed with altogether, the grafts being protected by a wire cage such as is used after vaccination, but they tend to dry up and come to resemble a scab.

When the grafts have healed, it is well to protect them from injury and to prevent them drying up and cracking by the liberal application of lanoline or vaseline.

The new skin is at first insensitive and is fixed to the underlying connective tissue or bone, but in course of time (from six weeks onwards) sensation returns and the formation of elastic tissue beneath renders the skin pliant and movable so that it can be pinched up between the finger and thumb.

Reverdin's method consists in planting out pieces of skin not bigger than a pin-head over a granulating surface. It is seldom employed.

Grafts of the Cutis Vera.—Grafts consisting of the entire thickness of the true skin were specially advocated by Wolff and are often associated with his name. They should be cut oval or spindle-shaped, to facilitate the approximation of the edges of the resulting wound. The graft should be cut to the exact size of the surface it is to cover; Gillies believes that tension of the graft favours its taking. These grafts may be placed either on a fresh raw surface or on healthy granulations. It is sometimes an advantage to stitch them in position, especially on the face. The dressing and the after-treatment are the same as in epidermis grafting.

There is a degree of uncertainty about the graft retaining its vitality long enough to permit of its deriving the necessary nourishment from its new surroundings; in a certain number of cases the flap dies and is thrown off as a slough—moist or dry according to the presence or absence of septic infection.

The technique for cutis-grafting must be without a flaw, and the asepsis absolute; there must not only be a complete absence of movement, but there must be no traction on the flap that will endanger its blood supply.

Owing to the uncertainty in the results of cutis-grafting the two-stage or indirect method has been introduced, and its almost uniform success has led to its sphere of application being widely extended. The flap is raised as in the direct method but is left attached at one of its margins for a period ranging from 14 to 21 days until its blood supply from its new bed is assured; the detachment is then made complete. The blood supply of the proposed flap may influence its selection and the way in which it is fashioned; for example, a flap cut from the side of the head to fill a defect in the cheek, having in its margin of attachment or pedicle the superficial temporal artery, is more likely to take than a flap cut with its base above.

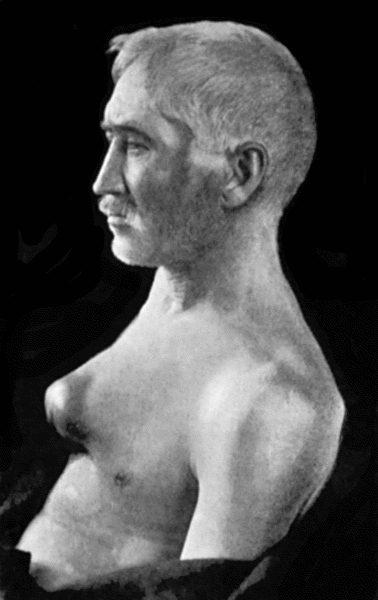

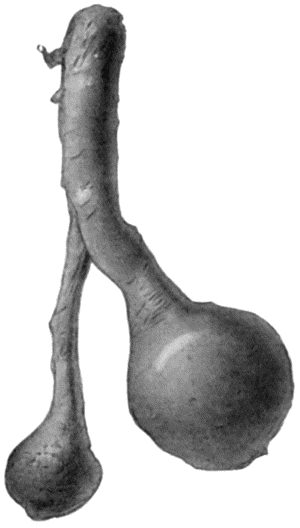

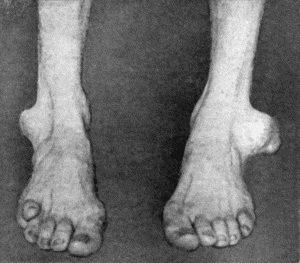

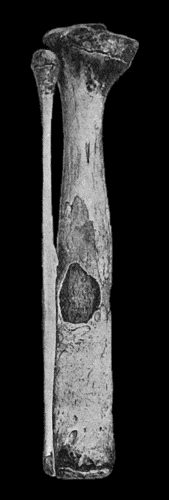

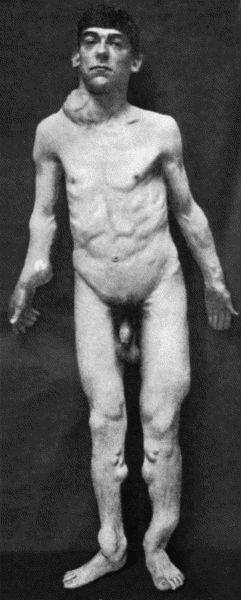

Another modification is to raise the flap but leave it connected at both ends like the piers of a bridge; this method is well suited to defects of skin on the dorsum of the fingers, hand and forearm, the bridge of skin is raised from the abdominal wall and the hand is passed beneath it and securely fixed in position; after an interval of 14 to 21 days, when the flap is assured of its blood supply, the piers of the bridge are divided (Fig. 1). With undermining it is usually easy to bring the edges of the gap in the abdominal wall together, even in children; the skin flap on the dorsum of the hand appears rather thick and prominent—almost like the pad of a boxing-glove—for some time, but the restoration of function in the capacity to flex the fingers is gratifying in the extreme.

Fig. 1.—Ulcer of back of Hand covered by flap of skin raised from anterior abdominal wall. The lateral edges of the flap are divided after the graft has adhered.

The indirect element of this method of skin-grafting may be carried still further by transferring the flap of skin first to one part of the body and then, after it has taken, transferring it to a third part. Gillies has especially developed this method in the remedying of deformities of the face caused by gunshot wounds and by petrol burns in air-men. A rectangular flap of skin is marked out in the neck and chest, the lateral margins of the flap are raised sufficiently to enable them to be brought together so as to form a tube of skin: after the circulation has been restored, the lower end of the tube is detached and is brought up to the lip or cheek, or eyelid, where it is wanted; when this end has derived its new blood supply, the other end is detached from the neck and brought up to where it is wanted. In this way, skin from the chest may be brought up to form a new forehead and eyelids.

Grafts of mucous membrane are used to cover defects in the lip, cheek, and conjunctiva. The technique is similar to that employed in skin-grafting; the sources of mucous membrane are limited and the element of septic infection cannot always be excluded.

Fat.—Adipose tissue has a low vitality, but it is easily retained and it readily lends itself to transplantation. Portions of fat are often obtainable at operations—from the omentum, for example, otherwise the subcutaneous fat of the buttock is the most accessible; it may be employed to fill up cavities of all kinds in order to obtain more rapid and sounder healing and also to remedy deformity, as in filling up a depression in the cheek or forehead. It is ultimately converted into ordinary connective tissue pari passu with the absorption of the fat.

The fascia lata of the thigh is widely and successfully used as a graft to fill defects in the dura mater, and interposed between the bones of a joint—if the articular cartilage has been destroyed—to prevent the occurrence of ankylosis.

The peritoneum of hydrocele and hernial sacs and of the omentum readily lends itself to transplantation.

Cartilage and bone, next to skin, are the tissues most frequently employed for grafting purposes; their sphere of action is so extensive and includes so much of technical detail in their employment, that they will be considered later with the surgery of the bones and joints and with the methods of re-forming the nose.

Tendons and blood vessels readily lend themselves to transplantation and will also be referred to later.

Muscle and nerve, on the other hand, do not retain their vitality when severed from their surroundings and do not functionate as grafts except for their connective-tissue elements, which it goes without saying are more readily obtainable from other sources.

Portions of the ovary and of the thyreoid have been successfully transplanted into the subcutaneous cellular tissue of the abdominal wall by Tuffier and others. In these new surroundings, the ovary or thyreoid is vascularised and has been shown to functionate, but there is not sufficient regeneration of the essential tissue elements to “carry on”; the secreting tissue is gradually replaced by connective tissue and the special function comes to an end. Even such temporary function may, however, tide a patient over a difficult period.

In the management of wounds and other surgical conditions it is necessary to eliminate various extraneous influences which tend to delay or arrest the natural process of repair.

Of these, one of the most important is undue movement of the affected part. “The first and great requisite for the restoration of injured parts is rest,” said John Hunter; and physiological and mechanical rest as the chief of natural therapeutic agents was the theme of John Hilton's classical work—Rest and Pain. In this connection it must be understood that “rest” implies more than the mere state of physical repose: all physiological as well as mechanical function must be prevented as far as is possible. For instance, the constituent bones of a joint affected with tuberculosis must be controlled by splints or other appliances so that no movement can take place between them, and the limb may not be used for any purpose; physiological rest may be secured to an inflamed colon by making an artificial anus in the cæcum; the activity of a diseased kidney may be diminished by regulating the quantity and quality of the fluids taken by the patient.

Another source of interference with repair in wounds is irritation, either by mechanical agents such as rough, unsuitable dressings, bandages, or ill-fitting splints; or by chemical agents in the form of strong lotions or other applications.

An unhealthy or devitalised condition of the patient's tissues also hinders the reparative process. Bruised or lacerated skin heals less kindly than skin cut with a smooth, sharp instrument; and persistent venous congestion of a part, such as occurs, for example, in the leg when the veins are varicose, by preventing the access of healthy blood, tends to delay the healing of open wounds. The existence of grave constitutional disease, such as Bright's disease, diabetes, syphilis, scurvy, or alcoholism, also impedes healing.

Infection by disease-producing micro-organisms or pathogenic bacteria is, however, the most potent factor in disturbing the natural process of repair in wounds.

The influence of micro-organisms in the causation of disease, and the rôle played by them in interfering with the natural process of repair, are so important that the science of applied bacteriology has now come to dominate every department of surgery, and it is from the standpoint of bacteriology that nearly all surgical questions have to be considered.

The term sepsis as now used in clinical surgery no longer retains its original meaning as synonymous with “putrefaction,” but is employed to denote all conditions in which bacterial infection has taken place, and more particularly those in which pyogenic bacteria are present. In the same way the term aseptic conveys the idea of freedom from all forms of bacteria, putrefactive or otherwise; and the term antiseptic is used to denote a power of counteracting bacteria and their products.

General Characters of Bacteria.—A bacterium consists of a finely granular mass of protoplasm, enclosed in a thin gelatinous envelope. Many forms are motile—some in virtue of fine thread-like flagella, and others through contractility of the protoplasm. The great majority multiply by simple fission, each parent cell giving rise to two daughter cells, and this process goes on with extraordinary rapidity. Other varieties, particularly bacilli, are propagated by the formation of spores. A spore is a minute mass of protoplasm surrounded by a dense, tough membrane, developed in the interior of the parent cell. Spores are remarkable for their tenacity of life, and for the resistance they offer to the action of heat and chemical germicides.

Bacteria are most conveniently classified according to their shape. Thus we recognise (1) those that are globular—cocci; (2) those that resemble a rod—bacilli; (3) the spiral or wavy forms—spirilla.

Cocci or micrococci are minute round bodies, averaging about 1 µ in diameter. The great majority are non-motile. They multiply by fission; and when they divide in such a way that the resulting cells remain in pairs, are called diplococci, of which the bacteria of gonorrhœa and pneumonia are examples (Fig. 5). When they divide irregularly, and form grape-like bunches, they are known as staphylococci, and to this variety the commonest pyogenic or pus-forming organisms belong (Fig. 2). When division takes place only in one axis, so that long chains are formed, the term streptococcus is applied (Fig. 3). Streptococci are met with in erysipelas and various other inflammatory and suppurative processes of a spreading character.

Bacilli are rod-shaped bacteria, usually at least twice as long as they are broad (Fig. 4). Some multiply by fission, others by sporulation. Some forms are motile, others are non-motile. Tuberculosis, tetanus, anthrax, and many other surgical diseases are due to different forms of bacilli.

Spirilla are long, slender, thread-like cells, more or less spiral or wavy. Some move by a screw-like contraction of the protoplasm, some by flagellæ. The spirochæte associated with syphilis (Fig. 36) is the most important member of this group.

Conditions of Bacterial Life.—Bacteria require for their growth and development a suitable food-supply in the form of proteins, carbohydrates, and salts of calcium and potassium which they break up into simpler elements. An alkaline medium favours bacterial growth; and moisture is a necessary condition; spores, however, can survive the want of water for much longer periods than fully developed bacteria. The necessity for oxygen varies in different species. Those that require oxygen are known as aërobic bacilli or aërobes; those that cannot live in the presence of oxygen are spoken of as anaërobes. The great majority of bacteria, however, while they prefer to have oxygen, are able to live without it, and are called facultative anaërobes.

The most suitable temperature for bacterial life is from 95° to 102° F., roughly that of the human body. Extreme or prolonged cold paralyses but does not kill micro-organisms. Few, however, survive being raised to a temperature of 134½° F. Boiling for ten to twenty minutes will kill all bacteria, and the great majority of spores. Steam applied in an autoclave under a pressure of two atmospheres destroys even the most resistant spores in a few minutes. Direct sunlight, electric light, or even diffuse daylight, is inimical to the growth of bacteria, as are also Röntgen rays and radium emanations.

Pathogenic Properties of Bacteria.—We are now only concerned with pathogenic bacteria—that is, bacteria capable of producing disease in the human subject. This capacity depends upon two sets of factors—(1) certain features peculiar to the invading bacteria, and (2) others peculiar to the host. Many bacteria have only the power of living upon dead matter, and are known as saphrophytes. Such as do nourish in living tissue are, by distinction, known as parasites. The power a given parasitic micro-organism has of multiplying in the body and giving rise to disease is spoken of as its virulence, and this varies not only with different species, but in the same species at different times and under varying circumstances. The actual number of organisms introduced is also an important factor in determining their pathogenic power. Healthy tissues can resist the invasion of a certain number of bacteria of a given species, but when that number is exceeded, the organisms get the upper hand and disease results. When the organisms gain access directly to the blood-stream, as a rule they produce their effects more certainly and with greater intensity than when they are introduced into the tissues.

Further, the virulence of an organism is modified by the condition of the patient into whose tissues it is introduced. So long as a person is in good health, the tissues are able to resist the attacks of moderate numbers of most bacteria. Any lowering of the vitality of the individual, however, either locally or generally, at once renders him more susceptible to infection. Thus bruised or torn tissue is much more liable to infection with pus-producing organisms than tissues clean-cut with a knife; also, after certain diseases, the liability to infection by the organisms of diphtheria, pneumonia, or erysipelas is much increased. Even such slight depression of vitality as results from bodily fatigue, or exposure to cold and damp, may be sufficient to turn the scale in the battle between the tissues and the bacteria. Age is an important factor in regard to the action of certain bacteria. Young subjects are attacked by diphtheria, tuberculosis, acute osteomyelitis, and some other diseases with greater frequency and severity than those of more advanced years.

In different races, localities, environment, and seasons, the pathogenic powers of certain organisms, such as those of erysipelas, diphtheria, and acute osteomyelitis, vary considerably.

There is evidence that a mixed infection—that is, the introduction of more than one species of organism, for example, the tubercle bacillus and a pyogenic staphylococcus—increases the severity of the resulting disease. If one of the varieties gain the ascendancy, the poisons produced by the others so devitalise the tissue cells, and diminish their power of resistance, that the virulence of the most active organisms is increased. On the other hand, there is reason to believe that the products of certain organisms antagonise one another—for example, an attack of erysipelas may effect the cure of a patch of tuberculous lupus.

Lastly, in patients suffering from chronic wasting diseases, bacteria may invade the internal organs by the blood-stream in enormous numbers and with great rapidity, during the period of extreme debility which shortly precedes death. The discovery of such collections of organisms on post-mortem examination may lead to erroneous conclusions being drawn as to the cause of death.

Results of Bacterial Growth.—Some organisms, such as those of tetanus and erysipelas, and certain of the pyogenic bacteria, show little tendency to pass far beyond the point at which they gain an entrance to the body. Others, on the contrary—for example, the tubercle bacillus and the organism of acute osteomyelitis—although frequently remaining localised at the seat of inoculation, tend to pass to distant parts, lodging in the capillaries of joints, bones, kidney, or lungs, and there producing their deleterious effects.

In the human subject, multiplication in the blood-stream does not occur to any great extent. In some general acute pyogenic infections, such as osteomyelitis, cellulitis, etc., pure cultures of staphylococci or of streptococci may be obtained from the blood. In pneumococcal and typhoid infections, also, the organisms may be found in the blood.

It is by the vital changes they bring about in the parts where they settle that micro-organisms disturb the health of the patient. In deriving nourishment from the complex organic compounds in which they nourish, the organisms evolve, probably by means of a ferment, certain chemical products of unknown composition, but probably colloidal in nature, and known as toxins. When these poisons are absorbed into the general circulation they give rise to certain groups of symptoms—such as rise of temperature, associated circulatory and respiratory derangements, interference with the gastro-intestinal functions and also with those of the nervous system—which go to make up the condition known as blood-poisoning, toxæmia, or bacterial intoxication. In addition to this, certain bacteria produce toxins that give rise to definite and distinct groups of symptoms—such as the convulsions of tetanus, or the paralyses that follow diphtheria.

Death of Bacteria.—Under certain circumstances, it would appear that the accumulation of the toxic products of bacterial action tends to interfere with the continued life and growth of the organisms themselves, and in this way the natural cure of certain diseases is brought about. Outside the body, bacteria may be killed by starvation, by want of moisture, by being subjected to high temperature, or by the action of certain chemical agents of which carbolic acid, the perchloride and biniodide of mercury, and various chlorine preparations are the most powerful.

Immunity.—Some persons are insusceptible to infection by certain diseases, from which they are said to enjoy a natural immunity. In many acute diseases one attack protects the patient, for a time at least, from a second attack—acquired immunity.

Phagocytosis.—In the production of immunity the leucocytes and certain other cells play an important part in virtue of the power they possess of ingesting bacteria and of destroying them by a process of intra-cellular digestion. To this process Metchnikoff gave the name of phagocytosis, and he recognised two forms of phagocytes: (1) the microphages, which are the polymorpho-nuclear leucocytes of the blood; and (2) the macrophages, which include the larger hyaline leucocytes, endothelial cells, and connective-tissue corpuscles.

During the process of phagocytosis, the polymorpho-nuclear leucocytes in the circulating blood increase greatly in numbers (leucocytosis), as well as in their phagocytic action, and in the course of destroying the bacteria they produce certain ferments which enter the blood serum. These are known as opsonins or alexins, and they act on the bacteria by a process comparable to narcotisation, and render them an easy prey for the phagocytes.

Artificial or Passive Immunity.—A form of immunity can be induced by the introduction of protective substances obtained from an animal which has been actively immunised. The process by which passive immunity is acquired depends upon the fact that as a result of the reaction between the specific virus of a particular disease (the antigen) and the tissues of the animal attacked, certain substances—antibodies—are produced, which when transferred to the body of a susceptible animal protect it against that disease. The most important of these antibodies are the antitoxins. From the study of the processes by which immunity is secured against the effects of bacterial action the serum and vaccine methods of treating certain infective diseases have been evolved. The serum treatment is designed to furnish the patient with a sufficiency of antibodies to neutralise the infection. The anti-diphtheritic and the anti-tetanic act by neutralising the specific toxins of the disease—antitoxic serums; the anti-streptcoccic and the serum for anthrax act upon the bacteria—anti-bacterial serums.

A polyvalent serum, that is, one derived from an animal which has been immunised by numerous strains of the organism derived from various sources, is much more efficacious than when a single strain has been used.

Clinical Use of Serums.—Every precaution must be taken to prevent organismal contamination of the serum or of the apparatus by means of which it is injected. Syringes are so made that they can be sterilised by boiling. The best situations for injection are under the skin of the abdomen, the thorax, or the buttock, and the skin should be purified at the seat of puncture. If the bulk of the full dose is large, it should be divided and injected into different parts of the body, not more than 20 c.c. being injected at one place. The serum may be introduced directly into a vein, or into the spinal canal, e.g. anti-tetanic serum. The immunity produced by injections of antitoxic sera lasts only for a comparatively short time, seldom longer than a few weeks.

“Serum Disease” and Anaphylaxis.—It is to be borne in mind that some patients exhibit a supersensitiveness with regard to protective sera, an injection being followed in a few days by the appearance of an urticarial or erythematous rash, pain and swelling of the joints, and a variable degree of fever. These symptoms, to which the name serum disease is applied, usually disappear in the course of a few days.

The term anaphylaxis is applied to an allied condition of supersensitiveness which appears to be induced by the injection of certain substances, including toxins and sera, that are capable of acting as antigens. When a second injection is given after an interval of some days, if anaphylaxis has been established by the first dose, the patient suddenly manifests toxic symptoms of the nature of profound shock which may even prove fatal. The conditions which render a person liable to develop anaphylaxis and the mechanism by which it is established are as yet imperfectly understood.

Vaccine Treatment.—The vaccine treatment elaborated by A. E. Wright consists in injecting, while the disease is still active, specially prepared dead cultures of the causative organisms, and is based on the fact that these “vaccines” render the bacteria in the tissues less able to resist the attacks of the phagocytes. The method is most successful when the vaccine is prepared from organisms isolated from the patient himself, autogenous vaccine, but when this is impracticable, or takes a considerable time, laboratory-prepared polyvalent stock vaccines may be used.

Clinical Use of Vaccines.—Vaccines should not be given while a patient is in a negative phase, as a certain amount of the opsonin in the blood is used up in neutralising the substances injected, and this may reduce the opsonic index to such an extent that the vaccines themselves become dangerous. As a rule, the propriety of using a vaccine can be determined from the general condition of the patient. The initial dose should always be a small one, particularly if the disease is acute, and the subsequent dosage will be regulated by the effect produced. If marked constitutional disturbance with rise of temperature follows the use of a vaccine, it indicates a negative phase, and calls for a diminution in the next dose. If, on the other hand, the local as well as the general condition of the patient improves after the injection, it indicates a positive phase, and the original dose may be repeated or even increased. Vaccines are best introduced subcutaneously, a part being selected which is not liable to pressure, as there is sometimes considerable local reaction. Repeated doses may be necessary at intervals of a few days.

The vaccine treatment has been successfully employed in various tuberculous lesions, in pyogenic infections such as acne, boils, sycosis, streptococcal, pneumococcal, and gonococcal conditions, in infections of the accessory air sinuses, and in other diseases caused by bacteria.

From the point of view of the surgeon the most important varieties of micro-organisms are those that cause inflammation and suppuration—the pyogenic bacteria. This group includes a great many species, and these are so widely distributed that they are to be met with under all conditions of everyday life.

The nature of the inflammatory and suppurative processes will be considered in detail later; suffice it here to say that they are brought about by the action of one or other of the organisms that we have now to consider.

It is found that the staphylococci, which cluster into groups, tend to produce localised lesions; while the chain-forms—streptococci—give rise to diffuse, spreading conditions. Many varieties of pyogenic bacteria have now been differentiated, the best known being the staphylococcus aureus, the streptococcus, and the bacillus coli communis.

Staphylococcus Aureus.—This is the commonest organism found in localised inflammatory and suppurative conditions. It varies greatly in its virulence, and is found in such widely different conditions as skin pustules, boils, carbuncles, and some acute inflammations of bone. As seen by the microscope it occurs in grape-like clusters, fission of the individual cells taking place irregularly (Fig. 2). When grown in artificial media, the colonies assume an orange-yellow colour—hence the name aureus. It is of high vitality and resists more prolonged exposure to high temperatures than most non-sporing bacteria. It is capable of lying latent in the tissues for long periods, for example, in the marrow of long bones, and of again becoming active and causing a fresh outbreak of suppuration. This organism is widely distributed: it is found on the skin, in the mouth, and in other situations in the body, and as it is present in the dust of the air and on all objects upon which dust has settled, it is a continual source of infection unless means are taken to exclude it from wounds.

The staphylococcus albus is much less common than the aureus, but has the same properties and characters, save that its growth on artificial media assumes a white colour. It is the common cause of stitch abscesses, the skin being its normal habitat.

Fig. 3.—Streptococci in Pus from an acute abscess in subcutaneous tissue. × 1000 diam. Gram's stain.

Streptococcus Pyogenes.—This organism also varies greatly in its virulence; in some instances—for example in erysipelas—it causes a sharp attack of acute spreading inflammation, which soon subsides without showing any tendency to end in suppuration; under other conditions it gives rise to a generalised infection which rapidly proves fatal. The streptococcus has less capacity of liquefying the tissues than the staphylococcus, so that pus formation takes place more slowly. At the same time its products are very potent in destroying the tissues in their vicinity, and so interfering with the exudation of leucocytes which would otherwise exercise their protective influence. Streptococci invade the lymph spaces, and are associated with acute spreading conditions such as phlegmonous or erysipelatous inflammations and suppurations, lymphangitis and suppuration in lymph glands, and inflammation of serous and synovial membranes, also with a form of pneumonia which is prone to follow on severe operations in the mouth and throat. Streptococci are also concerned in the production of spreading gangrene and pyæmia.

Division takes place in one axis, so that chains of varying length are formed (Fig. 3). It is less easily cultivated by artificial media than the staphylococcus; it forms a whitish growth.

Bacillus Coli Communis.—This organism, which is a normal inhabitant of the intestinal tract, shows a great tendency to invade any organ or tissue whose vitality is lowered. It is causatively associated with such conditions as peritonitis and peritoneal suppuration resulting from strangulated hernia, appendicitis, or perforation in any part of the alimentary canal. In cystitis, pyelitis, abscess of the kidney, suppuration in the bile-ducts or liver, and in many other abdominal conditions, it plays a most important part. The discharge from wounds infected by this organism has usually a fœtid, or even a fæcal odour, and often contains gases resulting from putrefaction.

It is a small rod-shaped organism with short flagellæ, which render it motile (Fig. 4). It closely resembles the typhoid bacillus, but is distinguished from it by its behaviour in artificial culture media.

Fig. 5.—Fraenkel's Pneumococci in Pus from Empyema following Pneumonia. × 100 diam. Stained with Muir's capsule stain.

Pneumo-bacteria.—Two forms of organism associated with pneumonia—Fraenkel's pneumococcus (one of the diplococci) (Fig. 5) and Friedländer's pneumo-bacillus (a short rod-shaped form)—are frequently met with in inflammations of the serous and synovial membranes, in suppuration in the liver, and in various other inflammatory and suppurative conditions.

Bacillus Typhosus.—This organism has been found in pure culture in suppurative conditions of bone, of cellular tissue, and of internal organs, especially during convalescence from typhoid fever. Like the staphylococcus, it is capable of lying latent in the tissues for long periods.

Other Pyogenic Bacteria.—It is not necessary to do more than name some of the other organisms that are known to be pyogenic, such as the bacillus pyocyaneus, which is found in green and blue pus, the micrococcus tetragenus, the gonococcus, actinomyces, the glanders bacillus, and the tubercle bacillus. Most of these will receive further mention in connection with the diseases to which they give rise.

Leucocytosis.—Most bacterial diseases, as well as certain other pathological conditions, are associated with an increase in the number of leucocytes in the blood throughout the circulatory system. This condition of the blood, which is known as leucocytosis, is believed to be due to an excessive output and rapid formation of leucocytes by the bone marrow, and it probably has as its object the arrest and destruction of the invading organisms or toxins. To increase the resisting power of the system to pathogenic organisms, an artificial leucocytosis may be induced by subcutaneous injection of a solution of nucleinate of soda (16 minims of a 5 per cent. solution).

The normal number of leucocytes per cubic millimetre varies in different individuals, and in the same individual under different conditions, from 5000 to 10,000: 7500 is a normal average, and anything above 12,000 is considered abnormal. When leucocytosis is present, the number may range from 12,000 to 30,000 or even higher; 40,000 is looked upon as a high degree of leucocytosis. According to Ehrlich, the following may be taken as the standard proportion of the various forms of leucocytes in normal blood: polynuclear neutrophile leucocytes, 70 to 72 per cent.; lymphocytes, 22 to 25 per cent.; eosinophile cells, 2 to 4 per cent.; large mononuclear and transitional leucocytes, 2 to 4 per cent.; mast-cells, 0.5 to 2 per cent.

In estimating the clinical importance of a leucocytosis, it is not sufficient merely to count the aggregate number of leucocytes present. A differential count must be made to determine which variety of cells is in excess. In the majority of surgical affections it is chiefly the granular polymorpho-nuclear neutrophile leucocytes that are in excess (ordinary leucocytosis). In some cases, and particularly in parasitic diseases such as trichiniasis and hydatid disease, the eosinophile leucocytes also show a proportionate increase (eosinophilia). The term lymphocytosis is applied when there is an increase in the number of circulating lymphocytes, as occurs, for example, in lymphatic leucæmia, and in certain cases of syphilis.