Title: Five years in New Zealand (1859 to 1864)

Author: Robert B. Booth

Release date: March 28, 2006 [eBook #18068]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Jonathan Ingram, Martin Pettit and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

The islands of New Zealand, discovered by the Dutch navigator, Tasman, in 1642, and surveyed and explored by Captain Cooke in 1769, remained unnoticed until 1814, when the first Christian Missionaries landed, and commenced the work of converting the inhabitants, who, up to that time had been cannibals.

The Missionaries had been unusually successful, and prepared the way for the first emigrants, who landed at Wellington in the North Island in 1839. A year later the Maori Chiefs signed a treaty acknowledging the Sovereignty of Queen Victoria, and the colonisation of the country quickly followed.

The seat of Government was first placed at Auckland, where resided the Governor, and there were formed ten provinces under the jurisdiction of superintendents. The head of the Government was subsequently transferred to Wellington, the provincial system abolished, and their powers exercised by local boards directly under the Governor.

The total area of the three islands is about 105,000 square miles, and the population, which has been steadily increasing, was in 1865 upwards of 700,000.

The Maori race is almost entirely confined to the North Island, and, although it was then gradually dying out, numbered about 30,000. They are of fine physique, tall and robust, and are said to belong to the Polynesian type, probably having come over from the Fiji Islands, or some of the Pacific group, in their canoes.

When first discovered they lived in villages or "Pahs," comprising a number of small circular huts, with a larger one for the Chief, mud-walled and thatched with grass or flax. The pahs usually occupied a commanding position, and were fenced round with one or more palisades of rough timber.

The Maori dress consisted of a simple robe made of woven flax, an indigenous plant growing in profusion over most of the country. They practised to a large extent the custom of tattooing their faces and bodies, and further decorated themselves with ear-rings of greenstone, bone, etc.

Owing to subsequent education and intercourse with Europeans, their savage habits have now mostly given way to modern customs.

In 1860 commenced the disastrous Taranaki war, which lasted some years, and was caused in the first instance by the encroachment of European settlers on the lands originally granted exclusively to the Aborigines. Since the settlement of this trouble, peace and prosperity have reigned, and the Maoris have become an important item in the community, many of them holding positions of trust and office under the Colonial Government.

The Province of Canterbury, forming the central portion of the middle island, was founded about 1845 by the Irishmen Godley, Harman, and others; and the English Church, under Bishop Harpur, was established at Christchurch, the capital of the Province.

Otago, in the south, was founded by the Scotch, and the free church established at Dunedin. The Province of Nelson formed the upper or northern portion of the Island.

It is to these three Provinces that the scenes of the following pages refer.

It has been said that the true and unvarnished history of any person's life, no matter how commonplace, would be interesting. It was not because I thought that a history of any part of my life would prove interesting to others, that I first decided to write the following story of the experiences of a young emigrant to New Zealand between the ages of 16 and 21. I wrote it many years ago, when all was fresh in my memory; then I laid it by. Now when I have retired, after a life's service passed in foreign lands, it has been a pleasure to me to recall and live over again in memory the scenes of my earliest life.

It may, however, be possible that the account of the adventures, successes, and failures of a lad, thrown on his own resources at so early an age, may prove of some value to others starting under similar circumstances in life's race; and if it in any way shows that the Colonies are a good field for a young man who wishes to adopt the life that may be open to him there, and who is determined to work steadily, keeping always his good name and honour as guiding lights to hold fast to and steer by, the story may not be quite useless.

The Colonies are as good to-day as forty years ago, better I should say, for they offer more varied openings now than they did then.

The great colonial dependencies of Great Britain were founded and worked into power by the emigrants who overflowed thence from the Motherland. These, for the most part, took with them little or nothing beyond their pluck, energy, strong hearts, and trust in God, and still they go and will go. It is a duty they owe to the mother-country as well as to themselves, and the great Colonies of Canada, Australia, and New Zealand are calling for more and more of the right sort of workers to join in and take their share in building up great nations, and extending the glory and civilising influence of Great Britain over all the world.

I would say to all young men in this country who have no sufficient call or opening at home, especially to those who have not succeeded in obtaining professional positions, and who wait on, hoping for something to turn up, go out while there is yet time, to the great countries waiting to welcome you to a man's work and a man's place in the world, and don't rest content with an idle, useless, and dependent position where you have no place or occupation. Do your plain duty honestly and fearlessly. Treat the world well and it will treat you well.

I do not, of course, give this advice to all. There are men who will not succeed in the Colonies any better than here. Some will fail anywhere. I mean the idle and lazy, the untrustworthy, the drunkard, and the incapable; these classes go to the bad quickest in the Colonies. There is no place or shelter for them there, where only honest workers are wanted or tolerated.

For the man who is prepared to put his hand to anything he finds to do, and can be trusted, there is always employment and promotion waiting; but for him who is too proud or too lazy to work, or who prefers to fritter his time in dissipation and amusement, there is nothing but failure and ruin ahead.

My advice does not apply either to those who have good prospects, professional or otherwise, in this country, and whose duties call them to remain, but to the thousands of the middle and lower classes who are not so circumstanced, and it must be remembered that the men who are specially and constantly needed in the Colonies are those of the labouring and farming classes, or who may intend to adopt that life and are fitted for it by health and will. For the artisan and the professional who can only work at their own trade or profession, the openings naturally are not so plentiful, but there is abundance of employment for them until openings occur, if they choose to occupy their time otherwise in the meanwhile.

For the young man who can afford the time, and many can, a few years' fling in the Colonies would be the best of educations, but he should determine to see all that was to be seen on the spot, and take part in all that was doing, and not rest content only with a few days' sojourn in an hotel here and there, or joining in the gaieties and dissipations of the towns.

How I Came to Emigrate.

I was one of a family of nine, of which four were sons. My eldest brother was destined for the Church; the second had entered a mercantile house in Liverpool; and I, who was third on the list, it was my father's intention, should be educated for the Royal Engineers, and at the time my story opens I was prosecuting my studies for admission to the Academy at Woolwich, and had attained the age of sixteen, when my health failed, and I was sent home for rest and change. I did not again resume my studies, because it was soon after decided that I should emigrate to New Zealand.

The decision was principally, if not entirely, due to my own wishes. I had long entertained a strong bent to seeing the world for myself, and the idea was congenial to my boyish and quixotic notions of being the arbiter of my own fortunes. I recollect I was much given to reading tales of wild life in America and elsewhere; they contained a peculiar attraction for me, and influenced my mind in no small degree detrimental to continuing my studies for the Army or any specified profession at home.

When I first proposed what was in my mind it created somewhat of a sensation in the old home, and my father would not hear of any such madness as to throw up my studies after having advanced so far, and go away to the antipodes on a mere wild-goose chase, etc. On consulting his friends, however, many advised him to let me have my will; others (more wisely perhaps) expressed their opinions that I should be forced to resume my work, and that the ill-health was imagination, or foxing! (I have often since been inclined to agree with the latter supposition.)

The final decision, however, was that I should emigrate to Canterbury, New Zealand, in the following April. This colony was at that time about fourteen years' old, and was highly thought of as a field for youthful enterprise, and it was then the fashion to consider such tendencies as I expressed to be an omen of future success which should not be baulked.[Pg 2]

A young friend, C——, son of a neighbouring squire, offered to accompany me as my chum and partner. He was six years my senior, and had had considerable experience in farming, so was considered very suitable for a colonial life; whereas I knew literally nothing of farming or anything else beyond my school work.

Our preparations were put in hand, and our passages booked by the good ship "Mary Anne," to sail from St. Katherine's Docks, London, on April 29th, 1859.

When all was finally settled my elation was supreme. The feeling that school grind was past and gone, that the world was open to me, and that I was free to do and act as I would was exhilarating. I felt that I had already attained to manhood, and that the world was at my feet, and a glorious life before me; well, I suppose most boys prematurely let loose would think the same, and I don't know that it is any harm to start under the circumstances with a hopeful and happy heart.

The day of parting at length arrived. It was a bright and lovely morning, about the middle of April, when I said goodbye to all my playmates at the old home, took a last look at the guns and fishing-rods, visited the various animals in the stables, gave a loving embrace to the great Newfoundland Juno, whom I could not hope to see again, submitted to be blessed and kissed by the servants and labourers, who had assembled to see me off, and took my seat on the car with my father, mother, and eldest brother, for the railway station, where C—— was to meet us.

C—— and I went direct to Liverpool from Drogheda, to which place my eldest brother accompanied us. My father and mother, having business en route, were to meet us there on the following day.

We had a rough passage to Liverpool, and the steamer was laden with cattle and pigs, the stench from which, combined with sea-sickness, was, I recollect, a terrible experience, and it was in no enviable condition of mind or body we arrived at the Liverpool Docks on a foggy, wet and dismal morning. My mercantile brother, Tom, came on board, and had all our belongings speedily conveyed to the lodgings we were to occupy during our stay. On the following day my father and mother arrived, and we spent a few days pleasantly seeing the lions of the great city and visiting friends. On arrival at London we found that we had a week or more before the ship sailed. Neither my father nor mother had been[Pg 3] in London before; all was as new to them as to us, and we made the best of the time at our disposal.

On the evening of the day before the ship sailed, after seeing our luggage on board, and cabins made ready for occupation, we accompanied my father, mother, and brother to Euston Station, where they were to bid us God-speed. I was in good spirits till then, but when on the railway platform, a few minutes before the train started, my dear mother fairly broke down, and the tears were stealing down my father's cheeks. The less said about such partings the better; it was soon over, and the train started. I never saw my dear old father again.

C—— and I, after watching the train disappear, started for the docks, and before bed-time had made acquaintance with some of our future compagnons de voyage.

The scene on deck was confusing and affecting. Upwards of four hundred emigrants were on board, and the partings from their friends and relatives, the kissings and blessings and cryings, mingled with the shouting of sailors, hauling in of cargo and luggage, and general noise and confusion incident to starting upon a long voyage, continued without intermission until we were fairly under weigh about 11 o'clock at night.

After the unusual exertion and excitement of the day, we both slept soundly, and when we awoke next morning, off Gravesend, we were disappointed at having missed the "Great Eastern," lately launched and then lying in the river.

By 12 noon we were fairly out at sea, with a favourable breeze, and the pilot left us in view (it might be the last) of the old country we were leaving behind.

Before my eyes again rested on the cliffs of old England I had seen many lands and people, had mixed and worked with all sorts and conditions of men, had many experiences and adventures; and although I did not find the fortune at once which I thought was waiting for me to pick up, I found that there is always a fortune, be it great or small, according to their deserts, waiting for those who determine to work honestly and heartily for it, and that every man's future success or failure depends mainly on himself.

The Voyage and Incidents Thereon—Rats on Board, the White Squall, Harpooning a Shark, Burial of the Twins, a Tropical Escapade—Icebergs—Exchange of Courtesies at Sea, etc.

The "Mary Anne" was, as I stated, an emigrant ship, and carried on the voyage about four hundred men, women, and children, sent out chiefly through the Government Emigration Agents. Persons going out in this way were assisted by having a portion of their passage paid for them as an advance, to be refunded after a certain time passed in the colony. The only first-class passengers in addition to C——and myself were two old maiden ladies, the Misses Hunt, who, with the doctor and his wife, the captain and first-mate, comprised our cabin party. In the second-class were three passengers—T. Smith, whose name will frequently appear in these pages, and two brothers called Leach, going out to join a rich cousin, a sheep farmer in Canterbury. Smith was the son of a wealthy squire, with whom, it appeared, he had fallen out respecting some family matters, and in a fit of pique left his home and took passage to New Zealand. His funds were sufficient to procure him a second-class berth, but on representing matters to the captain, who knew something of his family, it was arranged that he should join us in the saloon, hence he became one of our comrades, and eventually a particular friend.

The captain's name was Ashby, and he soon proved to be a most jolly and agreeable companion. The first-mate, Lapworth, also became a favourite with us all.

The doctor was usually drunk, or partly so, and led his wife, a kind and amiable little lady, a very unpleasant life. The Misses Hunt were elderly, amiable, and generally just what they should be.

Our cabins we had (in accordance with the usages of emigrant ships) furnished ourselves, and they were roomy and comfortable, but I will not readily forget the horror with which I woke up during the first night at sea, with an indescribable feeling that I was being crawled over[Pg 5] by some loathsome things. In a half-wakeful fit, I put out my hand, to find it rest upon a huge rat, which was seated on my chest. I started up in my bunk, when, as I did so, it appeared that a large family of rats had been holding high carnival upon me and my possessions; fully a dozen must have been in bed with me. I had no light, nor could I procure one, so I dressed and went on deck until morning. As a boy I was fond of carpentering, and was considerably expert in that way. My father thinking some tools would be useful to me, provided me with a small chest of serviceable ones (not the ordinary amateur's gimcracks), and this chest I had with me in my cabin. On examination I discovered several holes beneath the berth, where no doubt the previous night's visitors had entered. I set to work, and with the aid of some deal boxes given me by the steward, I had all securely closed up by breakfast, where the others enjoyed a hearty laugh at my experience of the night. The captain said there were doubtless hundreds of rats on board, and seemed to regard the fact with complacency rather than otherwise. Sailors consider that the presence of rats is a guarantee of the seaworthiness of the ship, and they will never voluntarily take passage in a vessel that is not sound.

The captain's supposition proved true enough, and it was not unusual of an evening to see these friendly rodents taking an airing on the ropes and rigging, and upon the hand-rails around the poop deck, and while so diverting themselves, I have endeavoured to shake them overboard, but always in vain; they were thoroughbred sailors, knew exactly when and where to jump, and flopping on the deck at my feet would disappear, with a twist of their tails amidships.

I do not think that the sailors approved of the rats being destroyed, and rather preferred their society than otherwise.

We soon settled down to our sea life, and the groans of sickness and the screaming of children from between decks ceased in time. Our own party of nine had the poop to ourselves, and were very comfortable; we soon got to like the life, and generally arranged some way of spending each day agreeably. We had a fair library, chess, backgammon, whist, etc., and when we got into the Tropics and had occasional calms, we went out in the captain's gig; then further south we had shooting matches at Cape pigeons and[Pg 6] albatrosses, and in all our amusements the captain and Lapworth took part.

There were not many incidents on the voyage worthy of note, but I will mention the most interesting of them which I can recollect. The first was when we encountered a white squall about a week out from England. It was a lovely evening, a slight breeze sending us along some four knots under full sail. We were lounging on deck watching the sunset, and occupied with our thoughts, when suddenly there was a cry from the "look out" in the main fore-top which created an instantaneous and marvellous scene of activity on board. It was then that we witnessed the first example of thorough seamanship and discipline; the shrill boatswain's whistle, the captain shouting a few orders, passed on by the mates, a crowd of sailors appearing like magic in the rigging, and in another instant the ship riding under bare masts; a deathlike stillness for a few seconds, and then a snow white wall of foam, stretching as far as the eye could reach, came down upon us with a sweeping wind, striking the ship broadsides, and over she went on her beam ends. Half a minute's hesitation or bungling would in all probability have sent us over altogether. There was a shout to us novices to look out—away went deck chairs and tables. The Misses Hunt—poor old ladies—who had been quietly knitting unconscious of any coming danger, were unceremoniously precipitated into the lee scuppers. I seized the mizen-mast, while C—— falling foul of a roving hen-coop, grasped it in a loving embrace, and accompanied it to some haven of safety, where he stretched himself upon it until permitted to walk upright again. The officers and crew appeared like so many cats in the facility with which they moved about; so much so that deciding to have a try myself, I was instantly sent rolling over to the two old ladies, creating a shout of laughter from all hands. The squall lasted about half an hour, and was succeeded by a fine night and a spanking breeze.

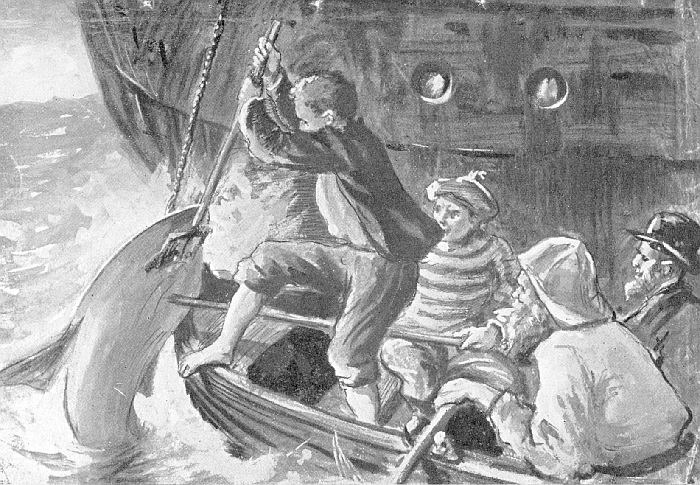

Harpooning a Shark.

Another bit of excitement was the harpooning and capture of a shark which had been following the ship for days. This is always an omen of ill-luck with sailors, who are very superstitious, believing that a shark under such circumstances is waiting for a body dead or alive, and will follow the ship until its desire is appeased. They are always, therefore, keen to kill a shark when opportunity offers. Fortunately, for our purpose, a calm came on while the shark was visiting [Pg 7]us, and he kept moving about under the stern in a most friendly manner. The plan of operations was as follows:—A large junk of pork was made fast to a rope and suspended from the stern, letting it sink about a foot under the surface. C——, Smith, and I were in the captain's boat, with three sailors, under the orders of Lapworth, who had taken his stand immediately above with a harpoon. The shark came up, nibbling and smelling at the pork, so close to us in the boat that he almost rubbed along the side without apparent alarm or taking any notice of our presence. He was a monster, nearly nine feet in length, and as he came alongside, his back fin rose some inches above the surface. He did not seem inclined to seize the pork until Lapworth had it quickly jerked up, when the brute made a dash at it, half turning as he did so, and at the same instant received the harpoon through his neck. I recollect the monster turning over on his back, Lapworth swinging himself over into the boat, a little organised commotion among the men, and in a few moments running nooses were passed over head and tail, and he was hoisted on deck and speedily despatched. The body was cut up and divided amongst the crew, some of whom were partial to shark steak. A piece of the backbone I secured for myself as a memento of the occasion.

As if to bear out the superstition I have mentioned, a few days subsequently a death, or rather two deaths, did actually take place; they were the twins and only children of a Scottish shepherd and his wife, both on board. Pretty little girls of eight, as I remember them, playing about the deck, and favourites with all, they died within a day of each other. The father was a gigantic fellow, and I have pleasant recollections of him in after years, when time and other children had helped to assuage his and his wife's grief for the loss of their two darlings at sea by one stroke of illness.

There is something more affecting in a burial at sea than one on land. In this instance the little body was wrapped in a white cloth, to which a small bag of coals was fastened, and laid upon a slide projecting from the stern of the vessel ready for immersion. The captain read the Burial Service, all on board standing uncovered. At the words "Dust to dust," etc., the body was allowed to slide into the sea—where it immediately disappeared. The mother was too ill to be present, and the father's grief was severe, as it might well be, to witness his child laid in so lonely a resting place in mid-ocean without sign or mark. The following evening a[Pg 8] similar scene was enacted when the body of the other little sister was committed to the deep, and the father had to be taken away before the service was completed.

No ceremonies I ever beheld impressed and affected me so much as the burial of the little twins at sea.

While in the Tropics we had occasional calms, sometimes lasting for two or three days; the sea was like molten glass, and the sun burnt like a furnace. On such occasions we were permitted to row about within a reasonable distance of the ship, so that if a breeze suddenly sprang up we might not be left behind. Once this very nearly occurred, when we had rowed a long way off, after what was supposed to be a whale spouting. We suddenly felt a gentle breath of air, and noticed the glassy surface giving place to a slight disturbance. We were a mile off the ship, but could distinctly hear the summons from aboard, and noticed the sails filling. We rowed with all our strength, stripped to the waist, and succeeded in getting up when the ship was well under weigh. It was a stiff piece of work, and the captain was so concerned and annoyed at our disobedience of his orders that he refused to allow us to boat again during the voyage. We suffered sorely for our escapade, for not knowing the strength of a tropical sun, we exposed ourselves so that the skin was burned and peeled off, and we were in misery for several days, while our arms and necks were swathed in cotton wool and oil.

After leaving the tropics we had a pleasant voyage and fair winds until we rounded the Cape, where we encountered some rough weather, and at 56° S.L., it being then almost winter in those latitudes, we passed many icebergs of more or less extent. Few of them appeared to be more than ten or fifteen feet above water, but the greater portion of such blocks are submerged, and considerable caution had to be observed night and day to steer clear of them. They were usually observable at first from the large number of birds resting on them, causing them to appear like a dark speck on the horizon. One of these icebergs (according to an entry made in the ship's log) was stated to be five miles long and of great height, and we were supposed to have passed it at the latter end of the night so near that "a biscuit might be thrown upon it." I am afraid the entry was open to criticism, and that the existence, or at any rate, the extent of this particular iceberg might have been due to an extra glass of grog on the mate's imagination.[Pg 9]

We sighted no land during the voyage, except the Peak of Teneriffe, as it emerged above a cloud; and but few vessels, and of those only two closely. One was a Swedish barque, homeward bound, the other a large American clipper ship. We spoke the latter when the vessels were some miles apart, but as the courses were parallel, she being bound for London, while we were from thence, we gradually neared, when an amusing conversation by signals took place. Our captain, by mistake of the signaller, invited the Yankee captain to dinner, and the reply from the American, who good-naturedly took it as a joke, was "Bad roadstead here." Our captain thought they were chaffing him, and had not the mistake been discovered in time, the rencontre might not have ended as pleasantly as it did. Our captain and second mate went on board the Yankee, and their captain returned the visit. While this was proceeding the two ships appeared to be sailing round each other, and the sight was very imposing. When the ceremonies were over, and a few exchanges of newspapers, wines, etc., were made and bearings compared, the vessels swung round to their respective courses, up flew the sails, and a prolonged cheer from both ships told us this little interchange of courtesies in the midst of the South Pacific was at an end.

I think it was the same night that we experienced a very heavy gale; the lightning, thunder, rain, and wind were terrific, and the sea ran mountains high. I stayed on deck nearly all the night, half perished with wet and cold; but such a storm carries with it a peculiar attraction, and one which I could not resist. I do not know anything more weird and impressive than the chant of the sailors hauling on the ropes, mingled with the fierce fury of the storm, and every now and again the dense darkness lit up by a vivid flash of lightning; the deck appears for the moment peopled by phantoms combined with the fury of the elements to bring destruction on the noble little vessel with its precious freight struggling and trembling in their grasp.

The following morning the storm had quite abated, but the sea was such as can be seen only in mid-ocean. Our little ship (she was only 700 tons) appeared such an atom in comparison with the enormous mountains of water. At one moment we would be perched on the summit of a wave, seemingly hundreds of feet high, and immediately below a terrible abyss into which we were on the point of sinking;[Pg 10] the next we would be placed between two mountains of water which seemed going to engulf us.

I always took a place with the sailors on emergencies, to give a hand at hauling the ropes, and got to be fairly expert at climbing into the rigging. The rope-hauling was done to some chant started by the boatswain or one of the sailors—this is necessary to ensure that the united strength of the pullers is exerted at the same moment. One of the chants I well remember. It was:—

The chant is sung out in stentorian notes by the leader, and on the word in italics every man joins in a tremendous and united pull.

Crowds of Cape pigeons and albatrosses accompanied us all across the South Pacific. These birds never seem to tire and but rarely rest on the water, except when they swoop down and settle a moment to pick up something that has been thrown overboard; this is quickly devoured, and they are again in pursuit. The albatrosses, some white, some grey, and some almost black, are huge birds; some that we shot, and for which the boat was sent, measured nine feet from tip to tip of wings.

On August 1st we rounded Stewart's Island, the southern-most of the New Zealand group. It is little more than a barren rock, and was not then inhabited, whatever it may be now. Although it was the winter season, and the latitude corresponded to that of the North of England, we remarked how mild and dry was the atmosphere in comparison. Indeed the weather was glorious and seemed to welcome us to the land we were coming to.

On the 3rd of August we sighted the coast of Canterbury, and at daylight on the 4th we found ourselves lying becalmed about 12 miles off Port Lyttelton Heads, from whence the captain signalled for a pilot steamer to take the ship to harbour. In the clear rare atmosphere, and the pure invigorating feeling of that glorious morning, we were all impatient of delay. A couple of fishing boats were lying not far off, and we begged the captain to let us row out to[Pg 11] them and he permitted us, conditionally that we returned and kept near the ship, because immediately the tug arrived we would start. We rowed to the boats and obtained some information from the fishermen, with whom were two of the natives, Maori lads; indeed, I think the boat partly belonged to the Maoris, for these people do not take service with the white settlers. They pointed out to us where the entrance lay, and told us that Port Lyttelton was some five miles further down a bay.

Before we returned to breakfast we had decided to anticipate matters by going ahead of the ship. We quietly laid in a small supply of food and appeared at the cabin table like good and obedient boys. Incidentally, one of us asked the captain if it would be easy to row into port, and he replied that it would be very risky to attempt it; it was a long way, and the wind or a squall might get up at any moment, or the tide might be contrary, and he positively forbade us to entertain any such idea. All this, however, only increased our desire for the "lark," as we called it, and about 9 o'clock, having rowed about quietly for a while, we suddenly bade good-bye to the "Mary Anne" and steered straight for the Heads, where we had been told Port Lyttelton lay. Our crew consisted of Smith, the two Leaches, C——, and myself, with a man named Kelson, who was a good oarsman, and we thought he would be useful as an extra hand, but he had no notion of our freak when we started, and was considerably chagrined when he discovered our real intention; he had a young wife on board, whom he feared would be in distress about him.

For some time we pulled away manfully, but at length began with some dismay to notice two facts, one, that we were losing sight of the ship, and the other that the hills did not appear to be any nearer!

Some one suggested returning, but as that would have looked like funk, it was overruled, and we went to the oars with renewed vigour. After some hours pulling we had the satisfaction to find that although the masts of the ship were scarcely visible we were certainly drawing nearer to the land, and could occasionally distinguish waves breaking on the rocks. The coast apparently was quite uninhabited, with no sign of life on land or sea. We had evidently been working against the tide or some current, for we had been[Pg 12] rowing steadily from 9 to 4, which would have amounted to less than two miles an hour, whereas we could pull five. Our course must have been true, as also the directions we received, for on entering between the heads we found ourselves in a lovely bay stretching away to where we were able to discern the masts of vessels in the distance, and soon after a large white object lying upon the shore. To satisfy our curiosity and obtain news of our whereabouts we rowed over and found that the white object was the carcase of a whale which had been washed on shore, and on which several men were engaged cutting it up. These speedily discovered our "new chum" appearance, but with true Colonial hospitality at once offered us a nip of rum, at the same moment somewhat disturbing our equanimity by telling us that if we went on to the Port we would be put in choky for leaving the ship before the Medical Officer examined her.

It was strange and very pleasant to feel the solid ground under our feet after 94 days at sea, and we sat awhile with the whale men before resuming our boat. Then we proceeded quietly down the Bay, which was very beautiful, the dense and variegated primeval forests clothing the lower portions of the hills and fringing the ravines and gullies to the shore, the pretty caves and bays lying in sheltered nooks, with a mountain stream or cascade to complete the picture, and all undefiled by the hand of man. The bold outline of the bare rocky summits, the deep blue of the silent calm bay, and the distant view of the little Port of Lyttelton picturesquely sloping up the hillside.

Seeing no sign of the ship, and fearing to approach the town, we rowed into a little sandy cove, where we fastened the boat and proceeded to ascend the hill to endeavour to discover the ship's whereabouts. About half-way we came upon a neat shepherd's cottage in one of the most picturesque localities imaginable, and commanding a magnificent view of the bay and harbour. On calling we found the cottage occupied by the shepherd's wife, a pleasant buxom Scots-woman, who immediately proffered us food, an offer too tempting to be declined, and we presently sat down to our first Colonial meal of excellent home-made bread, mutton, and tea, and how delighted we were to taste the fine fresh mutton after many weeks of salt junk and leathery fowls on board the "Mary Anne"![Pg 13]

We had finished our hearty dinner, and were giving our loquacious hostess all the news we could of the old country, when the ship hove in sight, towed by a little tug steamer. We ran for our boat and gave chase, but only reached her side as the anchor was being dropped in Lyttelton Harbour. We received from the Captain and Lapworth a sound but good-humoured rating, but there would be no opportunity of further "larks" from the "Mary Anne"! The voyage was over, and a most pleasant one it had been, especially for our small party, and I am sure that no voyagers to the New World ever had the luck to travel with kinder or more sympathetic captain and officers, or with abler seamen, than those in command of the good ship "Mary Anne."

Poor Mrs. Kelson was in sore distress about her husband, whom she persisted in giving up for lost, and doubtless she looked pretty sharply after his movements for a while.

Lyttelton and Christchurch.—Call on Our Friends. —Visit Malvern Hill.

Port Lyttelton at the time was but an insignificant town in comparison with what it has since become, although from its confined situation it is unlikely ever to attain to any great size. It is the port of the capital of the province, Christchurch, from which it is separated by a chain of hills. A rough and somewhat dangerous cart road led from it to the capital, along and around the hill side, which was twelve miles in length, but there was also a bridle track direct across the hills, by which the distance was reduced by one-half. This path, however, could be used only by pedestrians, or on horseback with difficulty. In 1862 it was decided to connect the port with Christchurch by a railway, cutting a tunnel through the hill, and the project was completed in 1866. In 1859 Port Lyttelton was built entirely of wood, the houses being for the most part single-storeyed. There was a main street running parallel to the beach, with two or three branch streets, running up the hill therefrom; there were a few shops, several stores, stables, and small inns. The harbour was an open roadstead, and possessed but a primitive sort of quay or landing place for boats and vessels of small tonnage.

We were invited on shore by the Leach's sheep-farming cousin, who had come to meet them, but we returned on board to sleep. The following morning, getting our luggage together, we all four started for Christchurch on hired horses, sending our kit round the hill by cart. The climb up the bridle path (we had to lead the horses) was a stiff pull for fellows just out of a three months' voyage, but we were repaid on reaching the top by the magnificent panorama opened out before us. To our right was the open ocean, blue and calm, dotted with a few white sails; to the left the long low range of hills encircling the bay, and on a pinnacle of which we stood. At our feet lay Christchurch, with its few well-laid-out streets and white houses, young farms, fences, trees, gardens, and all the numerous signs of a prosperous and thriving young colony, the little river Avon winding its peaceful way to the sea and encircling[Pg 15] the infant town like a silver cord, and the muddy Heathcote with its few white sails and heavily-laden barges. While beyond stretched away for sixty miles the splendid Canterbury Plains bounded in their turn by the southern Alps with their towering snow-capped peaks and glaciers sparkling in the sun; the patches of black pine forest lying sombre and dark against the mountain sides, in contrast with the purple, blue, and gray of the receding gorges, changing, smiling, or frowning as clouds or sunshine passed over them. All this heightened by the extremely rare atmosphere of New Zealand, in which every detail stood out at even that distance clear and distinct, made up a picture which for beauty and grandeur can rarely be equalled in the world.

Upon arrival at Christchurch we put up at a neat little inn on the outskirts of the town, called Rule's accommodation house. It was a picture of neatness, cleanliness, and comfort. We found it occupied by several squatters of what might be called the better class, who, on their occasional business visits to Christchurch, preferred a quiet establishment to the larger and more noisy hotels, of which the town possessed two.

These gentlemen were clothed in cord breeches and high boots, with guernsey smock frocks, in which costume they appeared to live. English coats and collars and light boots were luxuries unknown or contemned by these hardy sons of the bush, whom we found very pleasant company, but who, it was apparent to us before we were many minutes in their society, regarded us as very raw material indeed. According to bush custom it was usual to dub all fresh arrivals "new chums" until they had satisfactorily passed certain ordeals in bush life. They should be able to ride a buckjumper, or, at any rate, hold on till the saddle went, use a stockwhip, cut up and light a pipe of tobacco with a single wax vesta while riding full speed in the teeth of a sou'-wester, and be ready and competent to take a hand at any manual labour going.

After dinner some of our new acquaintances entertained us with some miraculous tales of bush life, while others looked carelessly on to see how far we could be gulled with impunity. An amusing incident, however, occurred presently which rapidly increased their respect for the raw material. C—— was a young giant, six feet three in his stockings, and the last man to put up with an indignity.[Pg 16] One of the party—a rough, vulgar sort of fellow, who had been romancing considerably, and who evidently was not on the most cordial terms with the rest of the company—carried his rudeness so far as to drop into C——'s seat when the latter had vacated it for a moment. On his return C—— asked him to leave it, which the fellow refused to do. C—— put his hand on his collar. "Now," said he, "get out! Once, twice, three times"—and at the last word he lifted the chap bodily and threw him over the table, whence he fell heavily on the floor. He was thoroughly cowed, and with a few oaths left the room. It needed only such an incident as this to put us on the friendliest terms with them all, and we enjoyed a pleasant afternoon and gathered much information.

The Arrival of Lapworth.

The following morning, whilst waiting for breakfast, sitting out on the grass in front of the house, we heard a stampede coming along the road from the direction of the Fort, and presently there hove in sight Lapworth astride a hired nag, coming ahead at a gallop, one hand grasping the mane and the other the crupper, while stirrups and reins were flying in the wind. In his rear were Bob Stavelly, third mate, and the boatswain, astride another animal, Bob steering, and the boatswain holding on, seemingly by the tail. Lapworth, a quarter of a mile off, was shouting "Stop her! Stop her!" but the mare needed no assistance; she evidently understood where she was required to go, and decided to do it in her own time and way. Galloping to the grass plot on which we were standing she suddenly stopped short and deposited Lapworth ignominiously at our feet. The other animal followed suit, but did not succeed in clearing itself, and after some tacking Bob and the boatswain got under weigh again and steered for the "White Hart," where they were bent on a spree.

Christchurch at this time was about fourteen years in existence. It consisted of only a few hundred houses, chiefly single-storeyed and entirely constructed of timber. The streets were well laid out, broad, and on the principle of the best modern towns, but few of them were as yet made or metalled. There were not many buildings of architectural pretensions, but all were characterised by an air of comfort, neatness, and suitability, and it was apparent the rapid strides the young colony was making would ere long place it high in the rank of its order. There were two churches, a town hall, used on occasion as court house, [Pg 17]ball-room, or theatre; three hotels, some very presentable shops and stores, and a few particularly neat and handsome residences standing in luxuriant grounds, such as those occupied by the Superintendent, Bishop, Judge, etc. The suburbs were extending on all sides with the fencing in of farms, erection of homesteads, and conversion of the native soil into land suitable for growing English corn and grass.

Through the rising city wound the little river Avon, only twenty to thirty yards in width, spanned by two wooden bridges, and a couple of mills had also been erected upon it. The river was only about fifteen miles from its source to the sea, and at the time to which I refer was almost covered with watercress. This plant was not indigenous; it was introduced a few years before by a colonist, who was so partial to the vegetable that he brought some roots from home with him, and planted them near the source of the river, where he squatted. The watercress took so kindly to the soil that it had now covered the river to its mouth, and the Colonial Government were put to very considerable annual expense to remove it.

As I have already stated, we had been provided with introductions to some of the most influential families in Christchurch—namely, the Bishop, the Chief Justice Gresson, and some others. The following day we made our calls and were most hospitably received, especially by Mr. and Mrs. Gresson, who from that time during my stay in New Zealand were my constant and valued friends. We were introduced to many of the best up-country people, and a month was passed pleasantly visiting about to enable us to decide on what line we would take up as a commencement. We possessed very little money, so a life of service in some form was an absolute necessity at the beginning.

While awaiting events, C—— and I were invited by young Mr. H——, son of the Bishop, to visit his sheep station at Malvern Hills, some forty-five miles distant across the plains, where we could see what station life was like and have some sport after wild pigs, ducks, etc. Procuring the loan of a couple of horses we all started early one morning, what change of clothes we needed being strapped with our blankets before and behind on our saddles, and I carried a gun.

It was an exhilarating ride in the cool, fragrant atmosphere, although a description would lead one to think it would be monotonous to ride forty-five miles over an almost perfectly flat plain, with no more than an occasional shepherd's[Pg 18] hut, a mob of sheep, or an isolated homestead to break the surrounding view. The plain was almost bare of vegetation, beyond short yellow grass here and there burnt in patches, and now and then a solitary cabbage tree (a kind of palm) dotted the wide expanse. Beyond a few paradise ducks feeding on the burnt patches, or an occasional family of wild pigs, we met with no animal life. Quail used to be abundant, but the run fires were fast destroying them. We had before us the nearing view of the Malvern Hills, the sloping pine forests and scrub, with the long, undulating spurs running back to the foot of great snow-clad peaks.

The station, or homestead, stood on a plateau some fifty feet above the plain; it consisted of two huts, mud-walled and thatched with snow grass. One of these contained the general kitchen and sleeping room for the station hands, the other was the residence of the squatter and his overseer. Behind these there were a wool shed for clipping and pressing the wool, with sheep yards attached, a stockyard for cattle, and a fenced in paddock in which a few station hacks were kept for daily use.

On arrival our first duty was to remove saddles, bridles, and swags and lead the horses to some good pasture, where they were each tethered to a tussock by thirty yards of fine hemp rope, which they carried tied about their necks. Then, after a rough wash in the open, we were soon gathered round a hospitable table in the kitchen, where all sat in common to a substantial meal of mutton, bread, and tea, the standard food with little variation of a squatter's homestead.

Night had closed in by now, and we were soon glad to retire to our blankets, and the sweet fresh beds of Manuka twigs laid on the floor of Harper's hut, for the temporary accommodation of us visitors. We slept like tops till roused at daybreak to breakfast, after which the forenoon was spent in being shown over the station and in a climb to the forests, where we saw the pine trees being felled, and split up into posts and rails. After the midday meal a pig hunt was organised, and a few animals were accounted for, falling chiefly to Harper's rifle. (Pig hunting I will specially refer to later on.) We passed a pleasant and instructive week at Malvern Station, taking a hand in all the routine work, riding after the stock, working in the bush, and occasionally taking a cross-country ride of fifteen or twenty miles to visit a neighbouring station.

A Period of Uncertainty as to Occupation.—Eventually Leave for Nelson as Cadets on a Sheep Run.

On our return to Christchurch we were beset with a diversity of advice not calculated to bring us to a speedy decision. Some advised us to go on a sheep run for a year or two as cadets to learn the routine, with a view to obtaining thereafter an overseership, and in time a possible partnership. Others advised our setting up as carters between the Port and Christchurch, while, again, others recommended us to invest what money we possessed in land and take employment up country until we had saved enough to farm it. All advice was excellent, and had we decided on one line it would have been well, or if we had had fewer advisers perhaps it would have been better. We were waiting and talking about work instead of going at it, living at some expense, and keeping up appearances without means to support them. But it was not easy under the circumstances to decide. To go upon a sheep station and work as a labourer or overseer was very obnoxious to C——. With his home experience of farming he expected too much all at once, and naturally I was guided by him. Farming on a small scale, even if we had sufficient money to buy and work a farm, would not pay. There was not then a large enough home market for the crops produced. Land-holders held on, hoping that as the wealth of the Colony increased and the town extended and peopled, land would proportionately increase in value, and market for their produce would be found at home or abroad. But the Colony was then very young, and the staple produce of the country upon which everything depended was wool, which was only partially developed. The country was not then a tenth stocked. Sheep-farming was decidedly the thing to go in for whenever we could contrive to do so, but in the meantime what were we to take up for a living. The answer should have been simple enough. But, however, there is no need to dwell on our petty disappointments; they were only[Pg 20] what hundreds feel and have felt who have gone to the Colonies with too sanguine expectations that it was an easy and pleasant road to fortune. That it is a road to fortune is very true, if a young man is content and determined to begin at the beginning and go steadily on; but it is not always an easy road at first for the youngster who has very little or nothing to commence upon, especially if he be a gentleman born, and has only his hands to help him. He must put his pride in his pocket and learn to be content to be taken at his present value. If he does that he will find, that his birth and education will stand to him, and that no matter what occupation he may be forced to take up, if his life and conduct be manly and reliable he will command as much or more respect from his (for the time being) fellow workers as he would do under different circumstances. It is a huge mistake to suppose that the gentleman lowers himself anywhere—and especially in the Colonies—by undertaking any kind of manual labour. I have known the sons of gentlemen of good family working as bullock-drivers, shepherds, stockdrivers, bushmen, for a yearly wage, and nobody considered the employment derogatory. On the contrary, these are the men who get on and in time become wealthy.

A sad event occurred about this time, which, as it was in a way connected with our ship, I will relate here. It was the custom of Government at that time to send out to the Australian Colonies for employment as domestic servants, possibly wives for young colonists (women being much in the minority), a number of girls from the Reformatory Schools in London; and in the "Mary Anne" some twenty or thirty of them had arrived. While on board they were under the charge of matrons, and on arrival were received in a house maintained at Government expense, until they obtained service or were otherwise disposed of. This house was under the superintendence of a medical man, Dr. T——, whose acquaintance we had made on our first arrival. He was a middle-aged man, a thorough gentleman, a bachelor, and a great favourite in Christchurch society. Amongst the shipment of young women was a very handsome, ladylike, and well-educated girl, and an accomplished musician. The doctor was smitten, proposed to her, and married her quietly. On the day on which we first heard of the event we happened to be sitting with some acquaintances in the public room of the White Hart Hotel, when Dr. T—— entered, and walking over to the[Pg 21] fire, called for a glass of water, nodding to us all round in his usual friendly way. On receiving the water, he threw into it and stirred up a powder which he took from his pocket, and immediately drank off the mixture. "I've done it now," he said; "I have taken strychnine!" and remained standing with his back to the fire in an unconcerned manner. We scarcely heeded his remark, taking it as a joke, till he suddenly crossed to a sofa, and called to us for God's sake to send for a doctor. One was sent for, but he arrived too late, if indeed his presence could have been of use at any time. A doctor knows how much to take to ensure death. After a few fits of convulsions, very terrible to witness, Dr. T—— was a corpse. The cause of his committing suicide was due to his discovery, very soon after his marriage, of the true character of the woman he had taken to his home.

I do not know whether the custom of sending out to the Colonies persons of this class still exists, but it certainly cannot be a good one, and I fear that but a very small percentage of them really turn over a new leaf. There must be now, at any rate, better means of disposing of the surplus members of reformatory establishments in the Old Country than sending them to run wild amidst the freedom and temptations of the new world—a custom as hurtful to them as to the Colony which receives them.

C—— and I at length decided to commence work as carriers; we rented a four-acre paddock, and built a small wooden hut, and were in treaty for the purchase of the necessary drays and teams, but it was all being done in a half-hearted way, as well as in opposition to the best of our advisers. C——'s aversion to undertake anything where he was not entirely his own master was unconquerable. Doubtless the carrying business would have answered very well, for a time at any rate, and there was no actual hurry, so long as we were employed and earning a living, but it was not to be.

We were invited to meet at dinner at the Chief Justice's a Mr. and Mrs. Lee from Nelson Province. Mr. Lee was a large sheep-farmer, and before we left that evening we had accepted a most kind invitation from him to go to his run for a month or two at any rate, before deciding finally to take up the rough and uncertain business we had proposed for ourselves. The Judge so strongly advised this course for us both, that C—— could not refuse, although he was by[Pg 22] no means keen about it. The judge explained that the opportunity was an excellent one, and would in all probability lead to his (C——'s) being offered the overseership, if he decided to take up the life after a fair trial. I did not know then, as I did soon after, that C—— had serious intentions of abandoning the country before giving it a fair trial; everything he saw was obnoxious to him, and he evidently yearned for his home in Ireland and his little farm again.

I purchased for my own use a small but powerful bay mare, C—— obtained a mount from Mr. Lee, and in the course of a few days we started in company with Mr. and Mrs. Lee, all on horseback, for their station of Highfield.

Highfield was, as well as I recollect, nearly three hundred miles from Christchurch, and we accomplished the distance in a little over a week, Mrs. Lee riding with us all the way. Indeed, there was no other means of travelling over that wild track, and she was, like most squatters' wives in those days, an experienced horsewoman.

Our luggage was carried on three pack horses, which we drove before us, and in this manner we accomplished from thirty to forty miles each day.

At night we rested, either at a rough accommodation house (a kind of private hotel) or a squatter's station, and during the day's ride we sometimes halted for lunch at any convenient locality where we could find water to make tea and firewood to boil it with. Then the packs and saddles were removed from the horses, which were allowed to roll and feed on the native grass while we refreshed the inner man with the usual bush fare, of which a sufficient supply was carried with us.

After crossing the Hurunui river, the boundary between Canterbury and Nelson, we soon left the plains behind and entered a fine undulating country watered by abundant streams and some large rivers, which latter could be forded only with considerable care and judgment, being sometimes full of quicksands, and always rapid.

On approaching our destination, which, as its name implies, stood on an elevated situation, the gorges and river-bed flats, along which our track ran, narrowed and became more wooded and picturesque, till we at length passed through the narrow precipitous gorge that led us to the open plateau upon which the station buildings stood. These comprised the dwelling house, a long, low, commodious[Pg 23] building, furnished most comfortably in English fashion; the men's huts, comprising three sleeping rooms, the kitchen and dining-room for the hands, the store, dairy, etc., with an enclosed yard, formed one group, while at some distance away stood the woolshed and sheep yards, paddocks, stock yards for cattle and sheds for cows and working bullocks. In front of the dwelling was a pretty and rather extensive garden plot, through the centre of which wound a small stream of pure spring water. The entire group of buildings, with the garden, paddocks, etc., occupied the centre of a piece of undulating land, open towards the south, where a fine view of the country over which we had journeyed was visible, and on all other sides was bounded by hills, which to the north and west stretched away to the Alps. It was a grand site to make a home upon, although I could not help the feeling that it was a somewhat lonely one; the nearest neighbours were fifteen to twenty miles distant.

Mr. Lee's run comprised about 30,000 acres, principally hills, with occasional stretches of flat land upon which the cattle and horses grazed, while the sheep fed on the mountain sides.

We speedily fell into the life, and found it exhilarating. Mr. Lee was a fine specimen of the English country squire, a good horseman and sportsman, and he could put his hand to any kind of work. He had a large store and workshop near the yards, where every conceivable thing needed for use on a station so far from supplies was kept, and he was an excellent carpenter and smith. Indeed, a great portion of the rather extensive buildings and yards he had erected himself, with such assistance as he could derive from raw station hands, while only such articles as doors and windows, furniture, and suchlike were brought from Christchurch. The house walls, roofs, and floors were all of green timber cut in the neighbouring pine forest. The walls of the living houses were composed of a framing of round pine averaging 4 or 5 inches thick, covered on the outside with weather boarding, and on the inside with laths, the space between of four inches being filled with clay and chopped grass, and the whole surface afterwards plastered with clay and mud-washed. The roofs were made of pine framing covered with boards and pine shingles. The outbuildings were usually built with roughly squared framing to which heavy split slabs would be vertically fastened, the inside being left rough or plastered with mud as desired; and[Pg 24] the roofs were of round pine framing covered with rickers (young pine plants) and thatched with snow grass. Squatters soon learnt to be their own architects, and very good ones many of them turned out.

The country immediately surrounding the station was almost treeless, and Mr. Lee was doing a good deal of planting, and had a very fine garden under formation. Some two miles to the rear of the station, in a deep cleft of the hills, lay a considerable black and white pine forest. It is a peculiarity of New Zealand that the pine forests indigenous to that country (and which bear no similarity to European pines) are invariably found in more or less accurately defined patches, growing thickly and never scattered to any appreciable extent. One may ride twenty miles through spurs and hills with no vegetation on them, and then suddenly stumble on a densely wooded ravine or mountain side so accurately contained within itself as to lead one to imagine it had been originally planted.

Within twenty miles of Highfield was another station, called Parnassus, belonging to Mr. Edward Lee, our Mr. Lee's brother. We soon rode over to see him, and made excursions to other neighbours, none living nearer than ten miles.

There were upwards of one hundred horses at Highfield, including all ages and sexes, of which the main body of course ran wild, while a few were kept in paddocks for use. The horse Mrs. Lee rode from Christchurch was a new purchase and a very fine animal, named Maseppa, and, strange to say, although he carried her perfectly all the journey to Highfield, he had now, after a few weeks on the run, developed into a vicious buckjumper. One day, when Mr. Lee wanted to ride him, he was driven in with the mob and saddled. Immediately he was mounted the brute bucked and sent Mr. Lee flying. Fortunately the ground was soft, and he escaped with a few bruises. C—— then had a try, with more success, but the horse was never safe for a lady to ride, and he was soon after disposed of to a stock-rider on the Waiou.

It may be interesting here to give a general sketch of a sheep-farmer's life and work on his station, obtained from my experience at Highfield, and occasionally on other runs, during my five years' residence in the country, and this I will endeavour to do in the next chapter.

Working of a Sheep-Run--Scab—C——'s Departure for Home, etc.

The intending squatter might either purchase a sheep run outright, if opportunity offered, or if he was fortunate enough to discover a tract of unclaimed country, he could occupy it at once by paying the Provincial Government a nominal rental, something like half a farthing an acre. This would only be the goodwill of the land, which was liable to be purchased outright by anybody else direct from Government, at the upset price fixed, which in Nelson was one pound per acre for hilly land, and two pounds for flat land suitable for cultivation. Nobody could purchase outright a run or portion of it while another occupier held the goodwill of it without first challenging the latter, who retained the presumptive right to purchase.

To protect themselves as much as possible from land being purchased away from them, or from being obliged to purchase themselves, goodwill holders were in the habit of buying up the best flat land, as well as making the land around their homesteads private property. A run so divided and cut up would not be so tempting to a rich man, and would effectually debar the man of small means, as the present occupier would not sell his private property unless at a price which would reimburse him for the loss of his interest in the goodwill of the run, and the new-comer, if he did not possess the scraps of private property as well as the remainder of the run, would be continually harassed by the previous owner occupying the best portions, and would be liable to fine for trespass, etc.

When a tract of country is occupied for the first time, it will usually be found covered with tussocks of grass scattered far apart and lying matted and rank on the ground. The first thing to do is to apply the match and burn all clean to the roots, and after a few showers of rain the grass will begin to sprout from the burnt stumps. Then the sheep are turned on to it, and the cropping, tramping, and manuring it receives, with occasional further burnings, renders it in a couple of years fair grazing country. An even sod takes the place of the isolated tussock, and the grass from being wild and unsavoury becomes sweet and tender.[Pg 26]

It takes, however, three to five years to transform a wild mountain side (if the land be moderately good) into an ordinarily fair sheep-run calculated to carry one sheep to every five acres—that is, of course, for the native or indigenous grass; the same ground cleared and laid down in English grass would carry three to five sheep to the acre.

A settler having obtained his run is bound by Government to stock it within a year with a stipulated number of sheep per 1,000 acres, failing which he forfeits his claim to possession. A man holding a fairly good run of 30,000 acres may feed from 3,000 to 4,000 sheep upon it, making due allowance for increase and disability to dispose of surplus stock.

The farming is conducted as follows: The flock is divided into two or more parts, in all cases the wethers being kept separate from the ewes and lambs, and occupying different portions of the run, the object being that the ewes and lambs may have rest, the wethers being liable to be driven in for sale or slaughter.

A shepherd is put in charge of each flock, and he resides at some convenient place on the boundary, whence it is his duty to walk or ride round his boundary at least once a day, and see that no sheep have crossed it. If he discovers tracks made during his absence he must follow them until he recovers his wanderers.

It is not necessary that a shepherd should see his sheep daily; he may not see a third of his flocks for months, unless he wishes to discover their actual whereabouts; he has only to assure himself that they have not left the run, and it is practically impossible for them to do so without leaving their footprints to be discovered on the boundary.

The breeding season is spring and the shearing season summer, which corresponds to our winter in England. The usual increase of lambs, if the ewes be healthy and strong, is 75 to 95 per cent. in about equal proportions of male and female.

When the lambs are about six weeks old the entire flock is driven in for cutting, tailing, and earmarking. The tails are cut off and the ear nicked or punched with the registered earmark of the station, and a certain number of the most approved male lambs are reserved. A good hand can cut and mark two thousand lambs per day, and not over one per cent. will die from the consequences. When the operation is over, the flock is counted out and handed over to the shepherd to take them back to their run until the shearing season.[Pg 27]

At this time a complete muster is made; all hands turn out on the hills, and every sheep is brought in that can be found. Not infrequently in the hilly country an exciting chase is had after a wild mob that have defied the exertions of the shepherds and their dogs for a considerable time. These animals will run up the most inaccessible places, skirt the edges of precipices at a height at which they can be discovered only by the aid of a telescope, and have been known to maintain their freedom in spite of man or dog for years. When at length caught they present a ludicrous appearance; their fleeces have become tangled and matted, hanging to the ground in ragged tails, and can with difficulty be removed, their feet have grown crooked and deformed, and they rarely again become domesticated with the flock.

The shearing is carried on in a large shed, divided into pens or small compartments, each connected separately with the attached yards. It is usually done by contract, the price being £1 to £1 5s. per hundred sheep. Each man has his pen, which is cleared out and refilled as often as necessary, and at each clearance the number therein are counted to his name. The shorn sheep are passed direct to the branding yard, and from thence to a common yard, from which all are counted out at nightfall for return to the run.

A good shearer will clip one hundred sheep in a day, the average for a gang of men being 75.

Upon the fleece being removed it is gathered up by an attendant placed for the purpose, and handed over to the sorter, who spreads it upon a table and removes dirty and jagged parts, and sometimes it is classed. It is then rolled up and thrown into the wool press to be packed for export.

The wool bales so pressed measure 9 ft. by 4 ft. by 4 ft., and contain on an average one hundred fleeces, and each fleece runs from three to four pounds in weight. The lambs' wool is pressed separately, and commands a higher price than that of the adult sheep.

The hand press is a wooden box, made the size of the canvas bale, which is suspended therein by hooks from the open top; the box has a movable side, which is loosened out to give exit to the bale when pressed. The pressing is done by the feet, assisted by a blunt spade, and the bales are generally very creditably turned out, the sheep-farmer priding himself on a neatly pressed bale. When pressed the end is sewn up and the bale rolled over to a convenient place for branding, when it is ready for loading on the dray.[Pg 28]

Previous to shearing, the sheep are sometimes driven through a deep running stream and roughly washed, to remove sand and grease. Wool certified to have been so cleaned will command a higher price than unwashed wool.

At the time to which I refer, most of the runs in Nelson Province were "unclean"—that is, infected with scab; and it became so general that it was considered almost impossible to eradicate. The disease was most infectious. A mob of clean, healthy sheep merely driven over a run upon which infected sheep had recently fed would almost surely catch the disease.

A sheep severely infected with scab becomes a pitiful object. The body gets covered with a yellow scaly substance, the wool falls off or is rubbed off in patches, the disease causing intense itchiness, the animal loses flesh and appetite, and unless relieved sickens and dies.

The Nelson settlers, although they could not hope to speedily eradicate the pest, were nevertheless bound by the Provincial Government to adopt certain precautions against its spreading. Every station was provided with a scab yard and a tank in which the flocks were periodically bathed in hot tobacco water, and such animals as were unusually afflicted received special attention and hand-dressing. These arrangements strictly enforced proved successful to a great extent in keeping the disease in check.

Mr. Lee's run was scabby, although not so bad as some of his neighbour's, and the strictest precautions were observed to keep it as clean as possible.

Upon arrival at Highfield we had immediate opportunity to see for ourselves the most interesting part of the working of the run. The cutting season had just commenced, and the mustering and shearing would ere long follow.

My chum C—— was a particularly smart fellow at everything appertaining to this kind of life. He speedily picked up the routine, and made himself so generally valuable that Mr. Lee offered him the post of overseer, with £60 a year as a beginning, and all found. But C——, on the plea that the pay was too small, refused it. This was his great mistake, to refuse what ninety-nine men in a hundred would have jumped at in his circumstances! It would have been the first step on the ladder, and with his abilities and experience he had only to wait a certain time to become a partner. But his heart was not in the country, and nothing would reconcile him to remaining in it. Within two months of our coming to Highfield he determined to return home.[Pg 29]

This resolution being taken, nothing would shake it, and the day was fixed for his departure. He and I were badly suited I fear to work together, and had he had some other chum perhaps he might have agreed with the new life better, and turned out a successful colonist; for most certainly, although we were not able to see it at the time, he had eminent opportunities open to him for becoming one.

I rode twenty miles with him on his way to Christchurch. He was to stay the first night at a station twenty-five miles from Highfield. On the bank of the Waiou river we parted—we two chums who had come all the way from the Old Country to work and stick together. I thought it then hard of C——, although I had no right to expect him to stay in New Zealand in opposition to his own wishes and judgment to please me. As I watched him cross the river and presently disappear between the hills further on, a feeling of strange loneliness came over me. Well, I was not much more than a child!

I must have sat there ruminating for a considerable time, for when I came to myself it was dark, and I remembered that I was in an almost trackless region which I had passed through only once before in daylight, and in company, when we had a view of the hills to guide us, and that I was at least seven miles from the nearest station (Rutherford's), but of the exact direction of which I was not certain. However, I had been long enough in the country to have passed more than one night in the open air, and at the worst this could only happen again, and I was provided with a blanket strapped to my saddle. I was not, however, to be without bed or supper. I mounted my mare, which had been browsing beside me, and gave her her head—the wisest course I could have taken. After an hour's sharp walk I discovered lights in the distance, which soon after proved to be those of Rutherford's station, where I was most hospitably received.

Considerable astonishment was expressed at C——'s—to them—unaccountably foolish action in throwing over, after two months' trial, an opportunity which most men situated as he was would have worked for years to obtain.

C—— reached the Old Country in due time, resumed his small farm, married, had a large family, and died a poor man.

The following morning I returned to Highfield feeling myself a better man and more independent now that I had myself only to depend on.

Shepherd's Life—Driving Sheep to Christchurch—Killing a Wild Sow—Arrival in Christchurch.

I passed nearly a year at Highfield, during which time I made myself acquainted with all the routine of a sheep-farmer's life. I learned to ride stock, shoe horses, shear sheep, plough, fence, fell and split timber, and everything else that an experienced squatter ought to be able to do, not omitting the accomplishment of smoking. Mr. Lee then offered me what he had offered C——, and I agreed to accept it pending a visit I meditated making to Christchurch to consult my friend Mr. Gresson about a desire I entertained of entering the Government Land Office and to become a surveyor.

I had done my best to like the life of a sheep-farmer, but I was becoming weary of it, and something was always prompting me to seek for more congenial employment. So far as stockriding, pig-hunting, and shooting were concerned, the life was delightful, but such recreations could be enjoyed anywhere. To sheep and sheep-farming I conceived a growing aversion as a life's work, and although I was prepared to hold to it if nothing better to my mind presented itself, I was equally determined to find something else if it were possible.

Mr. Lee had three shepherds at this time in charge of flocks, who resided in different places at least four miles from each other and from the home station. Two of these were the sons of gentlemen in the Old Country, and one of them a distant relation. The life of the boundary shepherd is a peculiarly lonely one, especially if he be young and single. His residence is a little one-roomed hut, sometimes two rooms, built of mud and thatched with grass, an earthen floor, with a large chimney and fireplace occupying one end. His furniture consists of a table, bunk, and a couple of chairs, and if he be an educated man and fond of reading he will have a table for his books and writing materials. He is supplied monthly with a sack of flour and a bag of tea and sugar, salt, etc. His cooking utensils are a kettle, camp oven, and frying pan, to which are added a few plates,[Pg 31] knives and forks, and two or three tin porringers. He always possesses at least one dog and a horse, and possibly a cat. The only light is that procured from what is called a slush lamp, made by keeping an old bowl or pannikin replenished by refuse fat or dripping in which is inserted a thick cotton wick. He cooks for himself, washes his own clothes, cuts up his firewood, and fetches water for daily use. Such luxuries as eggs, butter, or milk are unknown. Perhaps once a month he may have occasion to visit the home station, or somebody passing may call at his hut, or he may occasionally meet a neighbouring shepherd on his round. With these exceptions he has no intercourse with his fellow-beings, and all his affection is bestowed on his dog and horse; he would be badly off, indeed, without them.

One of these young men, by name Wren, became a great friend of mine, and many a time I visited him or spent a night in his lonely little hut, which was located in a small clearing surrounded by dense bush and immediately over a small and turbulent stream, which he used to say was always good company and prevented his feeling so lonely during the long dark nights as he otherwise would. It is strange how in the course of time a person will get accustomed to such a lonely life, and many like it, but it cannot be good for a young man to have too much of it, and fortunately for Wren a few years would see him located at headquarters. To take charge of a boundary was part of his education as a cadet.

It was different with the other. He was an unfortunate of that class so frequently met with in the Colonies, a "ne'er-do-well" who had while at home contracted habits of dissipation, and he was sent out to New Zealand under the then very mistaken supposition that he would thereby be cured. But there is no permanent cure for such a man; his life may be prolonged a little by enforced abstinence, but he will never, or rarely ever, recover his power of will so far as to avoid temptation if it comes in his way. If it be possible to do such a man any real good, there may be some chance for him at home, where he would have the care and influence of his friends to support him, but there is no chance for him in the Colonies. Such a man will under pressure abstain for months, but the moment that pressure is removed he will make for the nearest place where his propensity can be indulged, and give himself up to the devil body and soul, so long as he has the means to do so, or can obtain what he[Pg 32] desires by fair means or foul. He knows no shame; all honourable and manly feeling has become callous within him; and it is a happy release indeed for all connected with him when his pitiable life is ended.