1911.:: :: THE :: ::Empire AnnualFor GIRLS.Edited by A. R. BUCKLAND, M.A.With Contributions by

Etc., etc.

With Coloured Plates

and Sixteen Black and White Illustrations. |

Title: The Empire Annual for Girls, 1911

Author: Various

Editor: A. R. Buckland

Release date: June 23, 2006 [eBook #18661]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Michael Ciesielski, Emmy, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

E-text prepared by Michael Ciesielski, Emmy,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net/)

1911.:: :: THE :: ::Empire AnnualFor GIRLS.Edited by A. R. BUCKLAND, M.A.With Contributions by

Etc., etc.

With Coloured Plates

and Sixteen Black and White Illustrations. |

|

LONDON: 4 BOUVERIE STREET, E.C. |

RACE FOR LIFE. See page 72

RACE FOR LIFE. See page 72

| page | |

| THE CHRISTMAS CHILD | 9 |

| Mrs. G. de Horne Vaizey | |

| The story of a happy thought, a strange discovery, and a deed of love | |

| ANNA | 22 |

| Mrs. Macquoid | |

| A girl's adventure for a father's sake | |

| TO GIRLS OF THE EMPIRE | 39 |

| Mrs. Creighton | |

| Words of encouragement and stimulus to the daughters of the Nation | |

| MY DANGEROUS MANIAC | 45 |

| Leslie M. Oyler | |

| The singular adventure of two young people | |

| JIM RATTRAY, TROOPER | 52 |

| Kelso B. Johnson | |

| A story of the North-West Mounted Police | |

| MARY'S STEPPING ASIDE | 59 |

| Edith C. Kenyon | |

| Self-sacrifice bringing in the end its own reward | |

| A RACE FOR LIFE | 66 |

| Lucie E. Jackson | |

| A frontier incident from the Far West [4] | |

| WHICH OF THE TWO? | 74 |

| Agnes Giberne | |

| A question of duty or inclination | |

| A CHRISTMAS WITH AUSTRALIAN BLACKS | 89 |

| J. S. Ponder | |

| An unusual but interesting Christmas party described | |

| MY MISTRESS ELIZABETH | 96 |

| Annie Armitt | |

| A story of self-sacrifice and treachery in Sedgemoor days | |

| GIRL LIFE IN CANADA | 114 |

| Janey Canuck | |

| Girl life described by a resident in Alberta | |

| SUCH A TREASURE! | 120 |

| Eileen O'Connor | |

| How a New Zealand girl found her true calling | |

| ROSETTE IN PERIL | 131 |

| M. Lefuse | |

| A girl's strange adventures in the war of La Vendée | |

| GOLF FOR GIRLS | 143 |

| An Old Stager | |

| Some practical advice to beginners and others | |

| SUNNY MISS MARTIN | 148 |

| Somerville Gibney | |

| A story of misunderstanding, patience, and reconciliation | |

| WHILST WAITING FOR THE MOTOR | 160 |

| Madeline Oyler | |

| A warning to juvenile offenders | |

| THE GRUMPY MAN | 165 |

| Mrs. Hartley Perks | |

| A child's intervention and its results [5] | |

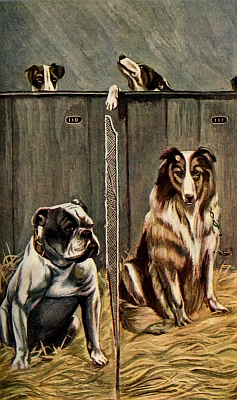

| DOGS WE HAVE KNOWN | 183 |

| Lady Catherine Milnes-Gaskell | |

| True stories of dog life | |

| DAFT BESS | 197 |

| Kate Burnley Bent | |

| A tale of the Cornish Coast | |

| A SPRINGTIME DUET | 203 |

| Mary Leslie | |

| A domestic chant for spring-cleaning days. | |

| OUT OF DEADLY PERIL | 204 |

| K. Balfour Murphy | |

| A skating episode in Canada | |

| THE PEARL-RIMMED LOCKET | 211 |

| M. B. Manwell | |

| The detection of a strange offender | |

| REMBRANDT'S SISTER | 221 |

| Henry Williams | |

| A record of affection and self-sacrifice | |

| HEPSIE'S XMAS VISIT | 230 |

| Maud Maddick | |

| A child's misdeed and its unexpected results | |

| OUR AFRICAN DRIVER | 238 |

| J. H. Spettigue | |

| A glimpse of South African life | |

| CLAUDIA'S PLACE | 247 |

| A. R. Buckland | |

| How Claudia changed her views | |

| FAMOUS WOMEN PIONEERS | 260 |

| Frank Elias | |

| Some of the women who have helped to open up new lands [6] | |

| POOR JANE'S BROTHER | 266 |

| M. Ling | |

| The strange adventures of two little people | |

| THE SUGAR-CREEK HIGHWAYMAN | 285 |

| Adela E. Orpen | |

| An alarm and a discovery | |

| DOROTHY'S DAY | 294 |

| M. E. Longmore | |

| A day beginning in sorrow and ending in joy | |

| A STRANGE MOOSE HUNT | 310 |

| H. William Dawson | |

| A hunt that nearly ended in a tragedy | |

| A GIRL'S PATIENCE | 317 |

| C. J. Blake | |

| A difficult part well played | |

| THE TASMANIAN SISTERS | 342 |

| E. B. Moore | |

| A story of loving service and changed lives | |

| THE QUEEN OF CONNEMARA | 362 |

| Florence Moon | |

| An Irish girl's awakening |

| ROSALIND'S RACE FOR LIFE | Frontispiece Facing Page |

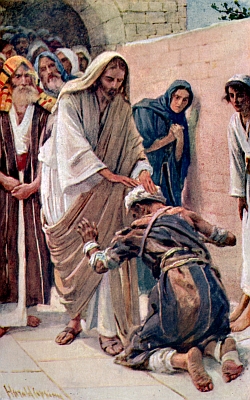

| "THE SON OF MAN CAME NOT TO BE MINISTERED UNTO, BUT TO MINISTER" | 44 |

| "YOUR SISTER IS COMING?" HE SAID | 80 |

| MRS. MEADOWS' BROTHER ARRIVED | 130 |

| AT THE SHOW | 184 |

| "DO FORGIVE ME, MOTHER DARLING!" | 232 |

| HER HOSTESS HAD BEEN FEEDING THE PEACOCKS | 308 |

| "I SHAN'T PLAY IF YOU FELLOWS ARE SO ROUGH!" | 38 |

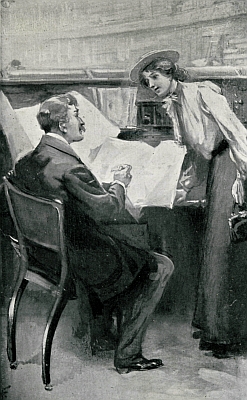

| GERALD LOOKS PUZZLED | 46 |

| IT WAS UNDER A NOBLE TREE THAT MAX ASKED MARY TO MARRY HIM | 64 |

| "GALLANTS LOUNGING IN THE PARK" | 98 |

| LOOKING AT HIM, I SAW THAT HE WAS HAGGARD AND STRANGE | 106 |

| GOLF FOR GIRLS—A BREEZY MORNING | 144 |

| SELINA MARTYN GAVE HER ANSWER | 158 |

| "I SUPPOSE YOU'VE COME ABOUT THE GAS BILL" | 170 |

| THE ROCK SHE CLUNG TO GAVE WAY | 200 |

| SPRING CLEANING | 203 |

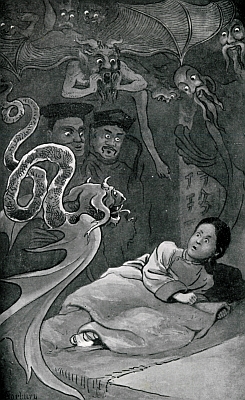

| HORRIBLE DREAMS OF MONSTERS AND DEMONS | 216 |

| HER VERY YOUTH PLEADED FOR HER | 249 |

| BARBARA'S VISIT | 268 |

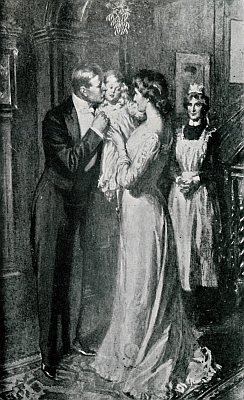

| "AS HE KISSED HIS FIRSTBORN UNDER THE MISTLETOE" | 340 |

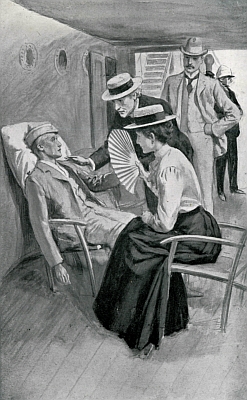

| "NOW I AM GOING TO FAN YOU," SHE SAID | 348 |

| EILY STOOD A FORLORN, DESOLATE FIGURE ON EUSTON PLATFORM | 366 |

| PAGE | |

| ARMITT, ANNIE | 96 |

| BENT, KATE BURNLEY | 197 |

| BLAKE, C. J. | 317 |

| BUCKLAND, A. R. | 247 |

| CANUCK, JANEY | 114 |

| CREIGHTON, MRS. | 39 |

| DAWSON, H. WILLIAM | 310 |

| ELIAS, FRANK | 260 |

| GIBERNE, AGNES | 74 |

| GIBNEY, SOMERVILLE | 148 |

| JACKSON, LUCIE E. | 66 |

| JOHNSON, KELSO B. | 52 |

| KENYON, EDITH C. | 59 |

| LEFUSE, M. | 131 |

| LESLIE, MARY | 203 |

| LING, M. | 266 |

| LONGMORE, M. E. | 294 |

| MACQUOID, MRS. | 22 |

| MADDICK, MAUD | 230 |

| MANWELL, M. B. | 211 |

| MILNES-GASKELL, LADY CATHERINE | 183 |

| MOON, FLORENCE | 362 |

| MOORE, E. B. | 342 |

| MURPHY, K. BALFOUR | 204 |

| O'CONNOR, EILEEN | 120 |

| OLD STAGER, AN | 143 |

| OYLER, LESLIE M. | 45 |

| OYLER, MADELINE | 160 |

| ORPEN, ADELA E. | 285 |

| PERKS, MRS. HARTLEY | 165 |

| PONDER, J. S. | 89 |

| SPETTIGUE, J. H. | 238 |

| VAIZEY, MRS. G. DE HORNE | 9 |

| WILLIAMS, HENRY | 221 |

Jack said: "Nonsense! We are all grown up now. Let Christmas alone. Take no notice of it; treat it as if it were an ordinary day."

Margaret said: "The servants have all begged for leave. Most of their mothers are dying, and if they are not, it's a sister who is going to be married. Really, it's a servants' ball which the Squire is giving in the village hall. Mean, I call it, to decoy one's maids just when one needs them most!"

Tom said: "Beastly jolly dull show anyhow, to spend the day alone with your brothers and sisters. Better chuck it at once!"

Peg said firmly and with emphasis: "Heathen! Miserable, cold-blooded, materially-minded frogs! Where's your Christmas spirit, I should like to know? . . . If you have none for yourselves, think of other people. Think of me! I love my Christmas, and I'm not going to give it up for you or any one else. My very first Christmas at home as a growed-up lady, and you want to diddle me out of it. . . . Go to! Likewise, avaunt! Now by my halidom, good [10]sirs, you know not with whom you have to deal. 'Tis my royal pleasure the revels proceed!"

Jack grimaced eloquently at Margaret, who grimaced back.

"With all the pleasure in the world," he said suavely. "Show me a revel, and I'll revel with the best. I like revels. What I do not like is to stodge at home eating an indigestible meal, and pretending that I'm full of glee, when in reality I'm bored to death. If you could suggest a change. . . ."

Margaret sighed; Tom sniffed; Peg pursed up her lips and thought. Presently her eyes brightened. "Of course," she remarked tentatively, "there are the Revells!"

Jack flushed and bit his lips.

"Quite so! There are. Fifty miles away, and not a spare bed in the house. Lot of good they are to us, to be sure! Were you going to suggest that we dropped in for a quiet call? Silly nonsense, to talk of a thing like that."

Jack was quite testy and huffed, for the suggestion touched a tender point. The Revells were the friends par excellence of the family of which he was the youthful head. It seemed, indeed, as if the two households had been specially manufactured so that each should fit the wants of the other. Jack was very certain that, in any case, Myra Revell supplied all that he lacked, and the very thought of spending Christmas Day in her company sent a pang of longing through his heart. Margaret cherished a romantic admiration for Mrs. Revell, who was still a girl at heart despite the presence of a grown-up family. Dennis was at Marlborough with Tom; while Pat or Patricia was Peg's bosom chum.

What could you wish for more? A Christmas spent with the Revells would be a pure delight; but alas! fifty miles of some of the wildest and bleakest country in England stretched between the two homes, which, being on different lines of railway, were inaccessible by the ordinary route. Moreover, the Revells were, as [11]they themselves cheerfully declared, "reduced paupers," and inhabited a picturesquely dilapidated old farmhouse, and the problem, "Where do they all sleep?" was as engrossing as a jig-saw puzzle to their inquisitive friends. Impossible that even a cat could be invited to swing itself within those crowded portals; equally impossible to attempt to separate such an affectionate family at Christmas-time of all seasons of the year.

And yet here was Peg deliberately raking up the painful topic; and after the other members of the family had duly reproached and abused, ready to level another bolt at their heads.

"S—uppose we went a burst—hired a car, drove over early in the morning, and marched into church before their very eyes!"

Silence! Sparkling eyes; alert, thoughtful gaze. Could they? Should they? Would it be right? A motor for the day meant an expenditure of four or five pounds, and though the exchequer was in a fairly prosperous condition, five-pound notes could not be treated with indifference. Still, in each mind ran the echo of Peg's words. It was Christmas-time. Why should they not, just for once, give themselves a treat—themselves, and their dear friends into the bargain?

The sparkle deepened; a flash passed from eye to eye, a flash of determination! Without a word of dissent or discussion the proposal was seconded, and carried through.

"Fifty miles! We can't go above twenty-five an hour through those bad roads. We shall have to be off by nine, if we want to be in time for church. What will they think when they see us marching in?"

"No, no, we mustn't do that. Mrs. Revell would be in a fever the whole time, asking herself, 'Will the pudding go round?' It really wouldn't be kind," pleaded Margaret earnestly, and her hearers chuckled reminiscently. Mrs. Revell was a darling, but she was also an appallingly bad housekeeper. Living two miles from the nearest shop, she yet appeared constitutionally [12]incapable of "thinking ahead"; and it was a common experience to behold at the afternoon meal different members of the family partaking respectively of tea, coffee, and cocoa, there being insufficient of any one beverage to go round.

Margaret's sympathies went out involuntarily towards her friend, but her listeners, it is to be feared, were concerned entirely for themselves. It might be the custom to abuse the orthodox Christmas dinner, but since it was a national custom which one did not care to break, it behoved one to have as good a specimen as possible, and the prospect of short commons, and indifferent short commons at that, was not attractive. Who could be sure that the turkey might not arrive at the table singed and charred, and the pudding in a condition of soup?

Schoolboy Tom was quick with a suggestion.

"I say—tell you what! Do the surprise-party business, and take a hamper with us. . . . Only decent thing to do, when you march in four strong to another person's feed. Dennis would love a hamper——"

"Ha! Good! Fine idea! So we will! A real old-fashioned hamper, full of all the good things they are least likely to have. Game pie——"

"Tongue—one of those big, shiny fellows, with scriggles of sugar down his back——"

"Ice-pudding in a tin——"

"Fancy creams——"

"French fruits——"

"Crackers! Handsome ones, with things inside that are worth having——"

"Bon-bons——"

Each one had a fresh suggestion to make, and Margaret scribbled them all down on the ivory tablet which hung from her waist, and promptly adjourned into the kitchen to give the necessary orders, and to rejoice the hearts of her handmaidens by granting a day's leave all round.

On further consideration it was decided to attend [13]early service at home, and to start off on the day's expedition at eleven o'clock, arriving at the Revell homestead about one, by which time it was calculated that the family would have returned from church, and would be hanging aimlessly about the garden, in the very mood of all others to welcome an unexpected excitement.

Christmas Day broke clear and bright. Punctual to the minute the motor came puffing along, the youthful-looking chauffeur drawing up before the door with an air of conscious complaisance.

Despite his very professional attire—perhaps, indeed, because of it—so very youthful did he appear, that Jack was visited by a qualm.

"Er—er—are you going to drive us all the way?" he inquired anxiously. "When I engaged the car, I saw . . . I thought I had arranged with——"

"My father, sir. It was my father you saw. Father said, being Christmas Day, he didn't care to turn out, so he sent me——"

"You are a qualified driver—quite capable. . . ?"

The lad smiled, a smile of ineffable calm. His eyelids drooped, the corners of his mouth twitched and were still. He replied with two words only, an unadorned "Yes, sir," but there was a colossal, a Napoleonic confidence in his manner, which proved quite embarrassing to his hearers. Margaret pinched Jack's arm as a protest against further questionings; Jack murmured something extraordinarily like an apology; then they all tumbled into the car, tucked the rugs round their knees, turned up the collars of their coats, and sailed off on the smooth, swift voyage through the wintry air.

For the first hour all went without a hitch. The youthful chauffeur drove smoothly and well; he had not much knowledge of the countryside; but as Jack knew every turn by heart, having frequently bicycled over the route, no delay was caused, and a merrier party of Christmas revellers could not have been found [14]than the four occupants of the tonneau. They sang, they laughed, they told stories, and asked riddles; they ate sandwiches out of a tin, and drank hot coffee out of a thermos flask, and congratulated themselves, not once, but a dozen times, over their own ingenuity in hitting upon such a delightful variation to the usual Christmas programme.

More than half the distance had been accomplished; the worst part of the road had been reached, and the car was beginning to bump and jerk in a somewhat uncomfortable fashion. Jack frowned, and looked at the slight figure of the chauffeur with a returning doubt.

"He's all right on smooth roads, but this part needs a lot of driving. Another time——" He set his lips, and mentally rehearsed the complaints which he would make to "my father" when he paid the bill. Margaret gave a squeal, and looked doubtfully over the side.

"I—I suppose it's all right! What would happen if he lost control, and we slipped back all the way downhill?"

"It isn't a question of control. It's a question of the strength of the car. It's powerful enough for worse hills than this."

"What's that funny noise? It didn't sound like that before. Kind of a clickety-clack. . . . Don't you hear it?"

"No. Of course not. Don't be stupid and imagine things that don't exist. . . . What's the difference between——"

Jack nobly tried to distract attention from the car, but before another mile had been traversed, the clickety-clack noise grew too loud to be ignored, the car drew up with a jerk, and the chauffeur leaped out.

"I must just see——" he murmured vaguely; vaguely also he seemed to grope at the machinery of the car, while the four occupants of the tonneau hung over the doors watching his progress; then once more springing to his seat, he started the car, and they went bumping unevenly along the road. No more [15]singing now; no more laughing and telling of tales; deep in each breast lay the presage of coming ill; four pairs of eyes scanned the dreary waste of surrounding country, while four brains busily counted up the number of miles which still lay between them and their destination. Twenty miles at least, and not a house in sight except one dreary stone edifice standing back from the road, behind a mass of evergreen trees.

"This fellow is no good for rough roads. He would wear out a car in no time, to say nothing of the passengers. Can't think why we haven't had a puncture before now!" said Jack gloomily; whereupon Margaret called him sharply to order.

"Don't say such things . . . don't think them. It's very wrong. You ought always to expect the best——"

"Don't suppose my thinking is going to have any effect on rubber, do you?" Jack's tone was decidedly snappy. He was a lover, and it tortured him to think that an accident to the car might delay his meeting with his love. He had never spent a Christmas Day with Myra before; surely on this day of days she would be kinder, sweeter, relax a little of her proud restraint. Perhaps there would be mistletoe. . . . Suppose he found himself alone with Myra beneath the mistletoe bough? Suppose he kissed her? Suppose she turned upon him with her dignified little air and reproached him, saying he had no right? Suppose he said, "Myra! will you give me the right?" . . .

No wonder that the car seemed slow to the lover's mind; no wonder that every fresh jerk and strain deepened the frown on his brow. The road was strewn with rough, sharp stones; but in another mile or two they would be on a smooth high-road once more. If only they could last out those few miles!

Bang! A sharp, pistol-like noise rent the air, a noise which told its own tale to the listening ears. A tyre had punctured, and a dreary half-hour's delay must be faced while the youthful chauffeur repaired the damage. The passengers leaped to the ground, and [16]exhausted themselves in lamentations. They were already behind time, and this new delay would make them later than ever. . . . Suddenly they became aware that they were cold and tired—shivering with cold. Peg looked down at her boots, and supposed that there were feet inside, but as a matter of sensation it was really impossible to say. Margaret's nose was a cheery plaid—blue patches neatly veined with red. Jack looked from one to the other and forgot his own impatience in anxiety for their welfare.

"Girls, you look frozen! Cut away up to that house, and ask them to let you sit by the fire for half an hour. Much better than hanging about here. I'll come for you when we are ready."

The girls glanced doubtfully at the squat, white house, which in truth looked the reverse of hospitable; but the prospect of a fire being all-powerful at the moment, they turned obediently, and made their way up a worn gravel path, leading to the shabbiest of painted doors.

Margaret knocked; Peg rapped; then Margaret knocked again; but nobody came, and not a sound broke the stillness within. The girls shivered and told each other disconsolately there was no one to come. Who would live in such a dreary house, in such a dreary, solitary waste, if it were possible to live anywhere else? Then they strolled round the corner of the house, and caught the cheerful glow of firelight, which settled the question, once for all.

"Let's try the back door!" said Margaret, and the back door being found, they knocked again, but knocked in vain. Then Peg gave an impatient shake to the handle, and lo and behold! it turned in her hand, and swung slowly open on its hinges, showing a glimpse of a trim little kitchen, and beyond that a narrow passage leading to the front door.

"Is any one there? Is any one there?" chanted Margaret loudly. She took a hesitating step into the passage—took two; repeated the cry in an even higher [17]key; but still no answer came, still the same uncanny silence brooded over all.

The girls stood still, and gazed in each other's eyes; in each face were reflected the same emotions—curiosity, interest, a tinge of fear.

What could it mean? Could there be some one within these silent walls who was ill, helpless, in need of aid?

"I think," declared Margaret firmly, "that it is our duty to look. . . ." In after days she always absolved herself from any charge of curiosity in this decision, and declared that her action was dictated solely by a feeling of duty; but her hearers had their doubts. Be that as it might, the decision fell in well with Peg's wishes, and the two girls walked slowly down the passage, repeating from time to time the cry "Is any one there?" the while their eyes busily scanned all they could see, and drew Sherlock Holmes conclusions therefrom.

The house belonged to a couple who had a great many children and very little money. There was a cupboard beneath the stairs filled with shabby little boots; there was a hat-rack in the hall covered with shabby little caps. They were people of education and culture, for there were books in profusion, and the few pictures on the walls showed an artistic taste; they were tidy people also, for everything was in order, and a peep into the firelit room on the right showed the table set ready for the Christmas meal. It was like wandering through the enchanted empty palaces of the dear old fairy-tales, except that it was not a palace at all, and the banquet spread out on the darned white cloth was of so meagre a description, that at the sight the beholders flushed with a shamed surprise.

That Christmas table—should they ever forget it? If they lived to be a hundred years old should they ever again behold a feast so poor in material goods, so rich in beauty of thought? For it would appear that though money was wanting, there was no lack of love and poetry in this lonely home. The table [18]was decked with great bunches of holly, and before every seat a little card bore the name of a member of the family, printed on a card, which had been further embellished by a flower or spray, painted by an artist whose taste was in advance of his skill—"Father," "Mother," "Amy," "Fred," "Norton," "Mary," "Teddums," "May." Eight names in all, but nine chairs, and the ninth no ordinary, cane-seated chair like the rest, but a beautiful, high-backed, carved-oak erection, ecclesiastical in design, which looked strangely out of place in the bare room.

There was no card before this ninth chair, but on the uncushioned seat lay a square piece of cardboard, bordered with a painted wreath of holly, inscribed on which were four short words.

Margaret and Peg read them with a sudden shortening of the breath and smarting of the eyes:

"For the Christ Child!"

"Ah-h!" Margaret's hand stretched out, seized Peg's, and held it fast. In the rush and bustle of the morning it had been hard to realise the meaning of the day: now, for the first time, the spirit of Christmas flooded her heart, filled it with love, with a longing to help and to serve.

"Peg! Peg!" she cried breathlessly. "How beautiful of them! They have so little themselves, but they have remembered the old custom, the sweet old custom, and made Him welcome. . . ." Her eyes roamed to the window, and lit with sudden inspiration. She lifted her hand and pointed to a distant steeple rising above the trees. "They have all gone off to church—father and mother, and Amy and Fred—all the family together! That's why the house is empty. And dinner is waiting for their return!"

She turned again to the table, her housekeeper's eye taking in at a flash the paucity of its furnishings. "Peg! can this be all? All that they have to eat. . . ? Let us look in the kitchen. . . . I must make quite sure. . . ."[19]

There was no feeling of embarrassment, no consciousness of impertinent curiosity, in the girls' minds as they investigated the contents of kitchen and larder. At that moment the house seemed their own, its people their people; they were just two more members of a big family, whose duty it was to look after the interests of their brothers and sisters while they were away; and when evidences of poverty and emptiness met them on every side, the two pairs of eyes met with a mutual impulse, so strong that it needed not to be put into words.

In another moment they had left the house behind and were running swiftly across the meadow towards the car. The chauffeur was busily engaged on the tyre, Jack and Tom helping, or hindering as the case might be. The hamper lay on the ground where it had been placed for greater security during the repairs. The girls nipped it up by its handles, and ran off again, regardless of protests and inquiries.

It was very heavy, delightfully heavy: the bearers rejoiced in its weight, wished it had been three times as heavy; the aching of their arms was a positive joy to them as they bore their burden into the little dining-room, and laid it down upon the floor.

"Now! What shall we do now? Shall we lay out the things and make a display on the table, or shall we put the pie in the oven beside that tiny ghost of a joint, and the pudding in a pan beside the potatoes? Which do you think would be best?"

But Margaret shook her head.

"Neither! Oh! don't you see, both ways would look too human, too material. They would show too plainly that strangers had been in, and had interfered. I want it to look like a Christmas miracle . . . as if it had come straight. . . . We'll lay the basket just as it is, on the Christ Child's chair. . . ."

Peg nodded. She was an understanding Peg, and she rose at once to the poetry of the idea. Gently, reverently, the girls lifted the basket which was to [20]have furnished their own repast, laid it on the carved-oak chair, and laid on its lid the painted card; then for a moment they stood side by side, gazing round the room, seeing in imagination the scene which would follow the return of the family from church . . . the incredulity, the amaze, the blind mystification, the joy. . . . Peg beamed in anticipation of the delight of the youngsters; Margaret had the strangest, eeriest feeling of looking straight into a sweet, worn face; of feeling the clasp of work-worn hands. It was imagination, she told herself, simple imagination, yet the face was alive. . . . Its features seemed more distinct than many which she knew in the flesh. She shivered slightly, and drew her sister from the room.

"Now, Peg, to cover up our tracks; to leave everything as we found it! This door was shut. . . . Have we moved anything from its place, left any footmarks on the floor? Be careful, dear, be careful! . . . Push that chair into place. . . ."

The tyre was repaired. The chauffeur was straightening his back after the long stoop. Jack and Tom were indignantly demanding what had been done with the hamper. Being hungry and unromantic, it took some little time to convince them that there had been no choice in the matter, and that the large family had a right to their luxuries which was not to be gainsaid. They had not seen the pitiful emptiness of the Christmas table; they had not seen the chair set ready for the Christ Child. The girls realised as much and dealt gently with them, and in the outcome no one felt the poorer; for the welcome bestowed upon the surprise party was untinged by any shadow of embarrassment, and they sat around a festal board, happy to feel that their presence was hailed as the culminating joy of the day.

It was evening when the car again approached the [21]lonely house, and Margaret, speaking down the connecting tube, directed the chauffeur to drive at his slowest speed for the next quarter of a mile.

Jack was lying back in his corner, absorbed in happy dreams. Never so long as he lived could he forget this Christmas Day, which had seen the fulfilment of his hopes in Myra's sweetness, Myra's troth. Tom was fast asleep, dreaming of "dorm." suppers, and other escapades of the last term. The two sisters were as much alone as if the only occupants of the car.

They craned forward, eager for the first glimpse of the house, and caught sight of a beam of light athwart the darkness of the night.

The house was all black save for one window, but that was as a lighthouse in a waste, for the curtains were undrawn, and fire and lamp sent out a rosy glow which seemed the embodiment of cheer.

Against the white background of the wall a group of figures could be seen standing together beneath the lamp; the strains of a harmonium floated sweetly on the night air, a chorus of glad young voices singing the well-known words:

With a common impulse the two girls waved their hands from the window as the car plunged forward.

"Good-night, little sisters!"

"Good-night, little brothers!"

"Sleep well, little people. The Christ Child is with you. You asked Him, and He came——"

"And the wonderful thing," said Peg, "the most wonderful thing is, that He came through us!"

"But that," answered Margaret thoughtfully, "is just how He always does come."[22]

Three thousand feet up the side of a Swiss mountain a lateral valley strikes off in the direction of the heights that border the course of the Rhine on its way from Coire to Sargans. The closely-cropped, velvet-smooth turf, the abundant woods, sometimes of pine-trees and sometimes of beech and chestnut, give a smiling, park-like aspect to the broad green track, and suggest ideas of peace and plenty.

As the path gradually ascends on its way to Fadara the wealth of wild flowers increases, and adds to the beauty of the scene.

A few brown cow-stables are dotted about the flower-sprinkled meadows; a brook runs diagonally across the path, and some freshly-laid planks show that inhabitants are not far off; but there is not a living creature in sight. The grasshoppers keep up their perpetual chirrup, and if one looks among the flowers one can see the gleam of their scarlet wings as they jump; for the rest, the flowers and the birds have it all to themselves, and they sing their hymns and offer their incense in undisturbed solitude.

When one has crossed the brook and climbed an [23]upward slope into the meadow beyond it, one enters a thick fir-wood full of fragrant shadow; at the end is a bank, green and high, crowned by a hedge, and all at once the quiet of the place has fled.

Such a variety of sounds come down the green bank! A cock is crowing loudly, and there is the bleat of a young calf; pigs are squeaking one against another, and in the midst of the din a dog begins to bark. At the farther corner, where the hedge retreats from its encroachments on the meadow, a grey house comes into view, with a signboard across its upper part announcing that here the tired traveller may get dinner and a bed.

Before the cock has done crowing—and really he goes on so long that it is a wonder he is not hoarse—another voice mingles with the rest.

It is a woman's voice, and, although neither hoarse nor shrill, it is no more musical than the crow of the other biped, who struts about on his widely-spread toes in the yard, to which Christina Fasch has come to feed the pigs. There are five of them, pink-nosed and yellow-coated, and they keep up a grunting and snarling chorus within their wooden enclosure, each struggling to oust a neighbour from his place near the trough while they all greedily await their food.

"Come, Anna, come," says the hard voice; "what a slow coach you are! I would do a thing three times over while you are thinking about it!"

The farmyard was bordered by the tall hedge, and lay between it and the inn. The cow-house, on one side, was separated from the pigstyes by a big stack of yellow logs, and the farther corner of the inn was flanked by another stack of split wood, fronted by a pile of brushwood; above was a wooden balcony that ran also along the house-front, and was sheltered by the far-projecting eaves of the shingled roof.

Only the upper part of the inn was built of logs, the rest was brick and plaster. The house looked [24]neatly kept, the yard was less full of the stray wood and litter that is so usual in a Swiss farmyard, but there was a dull, severe air about the place. There was not a flower or a plant, either in the balcony or on the broad wooden shelves below the windows—not so much as a carnation or a marigold in the vegetable plot behind the house.

A shed stood in the corner of this plot, and at the sound of Christina's call a girl came out of the shed; she was young and tall and strong-looking, but she did not beautify the scene.

To begin with, she stooped; her rough, tangled hair covered her forehead and partly hid her eyes; her skin was red and tanned with exposure, and her rather wide lips drooped at the corners with an expression of misery that was almost grotesque. She carried a pail in each hand.

"Do be quick!" Christina spoke impatiently as she saw her niece appear beyond the wood-stack.

Anna started at the harsh voice as if a lash had fallen on her back; the pig's food splashed over her gown and filled her heavy leather shoes.

"I had better have done it myself," cried her aunt. "See, unhappy child, you have wasted food and time also! Now you must go and clean your shoes and stockings; your gown and apron are only fit for the wash-tub! Ah!"

She gave a deep sigh as she took up first one pail and then the other and emptied the wash into the pig-trough without spilling a drop by the way. Anna stood watching her admiringly.

"Well!" Christina turned round on her. "I ask myself, what is the use of you, child? You are fifteen, and so far it seems to me that you are here only to make work for others! When do you mean to do things as other people do them? I ask myself, what would become of you if your father were a poor man, and you had to earn your living?"

Anna had stooped yet more forward; she seemed [25]to crouch as if she wanted to get out of sight. Christina suddenly stopped and looked at her for an answer. Anna fingered her splashed apron; she tried to speak, but a lump rose in her throat, and she could not see for the hot tears that would, against her will, rush to her eyes.

"I shall never do anything well," she said at last, and the misery in her voice touched her aunt. "I used not to believe you, aunt, but now I see that you are right. I can never be needful to any one." Then she went on bitterly: "It would have been better if father had taken me up to the lake on Scesaplana when I was a baby and drowned me there as he drowned the puppies in the wash-tub."

Christina looked shocked; there was a frown on her heavy face, which was usually as expressionless as if it had been carved in wood.

"Fie!" she said. "Think of Gretchen's mother, old Barbara; she does not complain of the goître; though she has to bear it under her chin, she tries to keep it out of sight. I wish you would do the same with your clumsiness. There, go and change your clothes, go, you unlucky child, go!"

You are perhaps wondering how it comes to pass that an inn can exist placed alone in the midst of green pasture-land, and only approached by a simple foot track, which more than once leads the wayfarer across mere plank bridges, and which passes, only at long intervals, small groups of cottages that call themselves villages. You naturally wonder how the guests at this lonely inn fare with regard to provisions. It is true that milk is sent down every day from the cows on the green Alps higher up the mountain, and that the farm boasts of plenty of ducks and fowls, of eggs and honey. There are a few sheep and goats, too; we have seen that there are pigs. Fräulein Christina Fasch makes good bread, and she is famous for her delicate puddings and sauces; the puzzle is, [26]whence come the groceries, and the extras, and the wines that are consumed in the inn?

A mile or so beyond, on a lower spur of the mountain ridge that overlooks the Rhine, a gap comes in the hedge that screens an almost precipitous descent into the broad, flat valley. The descent looks more perilous than it is, for constant use has worn the slender track into a series of rough steps, which lead to the vine-clad knoll on which is situated Malans, and at Malans George Fasch, the landlord of our inn, can purchase all he needs, for it is near a station on the railway line between Zurich and Coire and close to the busy town of Mayenfeld in the valley below.

Just now there are no visitors at the inn, so the landlord only makes his toilsome journey once a fortnight; but when there is a family in the house he visits the valley more frequently, for he cannot bring very large stores with him, although he does not spare himself fatigue, and he mounts the natural ladder with surprising rapidity, considering the load he carries strapped to his shoulders.

The great joy of Anna was to meet her father at the top of the pass, and persuade him to lighten his burden by giving her some of it to carry; and to-day, when she had washed her face and hands, and had changed her clothes, she wished that he had gone to Malans; his coming back would have helped her to forget her disaster. Her aunt's words clung to the girl like burs; and now, as they rang in her ears again, she went into the wood to have her cry out, unobserved.

She stood leaning against a tree; and, as the tears rolled over her face, she turned and hid it against the rough red bark of the pine. She was crying for the loss of the dear, gentle mother who had always helped her. Her mother had so screened her awkwardness from public notice that Anna had scarcely been aware of it. Her Aunt Christina had said, when she was summoned four years ago to manage her brother's [27]household, "Your wife has ruined Anna, brother. I shall have hard work to improve her."

Anna was not crying now about her aunt's constant fault-finding; there was something in her grief more bitter even than the tears she shed for her mother; it seemed to the girl that day by day she was becoming more and more clumsy and stupid; she broke the crockery, and even the furniture; she spoiled her frocks; and, worst of all, she had more than once met her father's kind blue eyes fixed on her with a look of sadness that went to her heart. Did he, too, think that she would never be useful to herself or to any one?

At this thought her tears came more freely, and she pressed her hot face against the tree.

"I wonder why I was made!" she sobbed.

There came a sharp crackling sound, as the twigs and pine-needles snapped under a heavy tread.

Anna caught up her white apron and vigorously rubbed her eyes; then she hurried out to the path from her shelter among the trees.

In another minute her arms were round her father, and she was kissing him on both cheeks.

George Fasch kissed her and patted her shoulder; then a suppressed sob caught his ear. He held Anna away from him, and looked at her face.

It was red and green in streaks, and her eyes were red and inflamed. The father was startled by her appearance.

"What is the matter, dear child?" he said. "You are ill."

Then his eyes fell on her apron. Its crumpled state, and the red and green smears on it, showed the use to which it had been put, and he began to guess what had happened.

Anna hung her head.

"I was crying and I leaned against a tree. Oh, dear, it was a clean apron! Aunt will be vexed."

Her father sighed, but he pitied her confusion.[28]

"Why did you cry, my child?" he said, half-tenderly, half in rebuke. "Aunt Christina means well, though she speaks abruptly."

He only provoked fresh tears, but Anna tried so hard to keep them back that she was soon calm again.

"I am not vexed with Aunt Christina for scolding me," she said; "I deserved it; I am sorry for myself."

"Well, well," he said cheerfully, "we cannot expect old heads on young shoulders." His honest, sunburned face was slightly troubled as he looked at her. "You will have to brush up a bit, you know, when Christina goes to Zurich. You are going to be left in charge of the house for a week or so."

Anna pressed her hands nervously together. She felt that the house would suffer greatly under her guidance; but then, she should have her father all to herself in her aunt's absence, and she should be freed from those scathing rebukes which made her feel all the more clumsy and helpless when they were uttered in her father's presence.

George Fasch, however, had of late become very much aware of his daughter's awkwardness, and secretly he was troubled by the prospect of her aunt's absence. He was a kind man and an affectionate father, but he objected to Gretchen's unaided cookery, and he had therefore resolved to transact some long-deferred business in Zurich during his sister's stay there. This would lessen the number of his badly-cooked dinners at home.

"I shall start with Christina," he said—"some one must go with her to Pardisla; and next day I shall come home by Malans, so you will have to meet me on Wednesday evening at the old place, eh, Anna?"

She nodded and smiled, but she felt a little disappointed. She reflected, however, that she should have her father alone for some days after his return.

Christina was surprised to see how cheerful the girl looked when she came indoors.

Rain fell incessantly for several days, and even [29]when it ceased masses of white vapour rose up from the neighbouring valleys and blotted out everything. The vapour had lifted, however, when Fasch and his sister started on their expedition, and Anna, tired of her week's seclusion, set out on a ramble. A strange new feeling came over the girl as soon as she lost sight of her aunt's straight figure. She was free, there would be no one to scold her or to make her feel awkward; she vaulted with delight, and with an ease that surprised her, over the fence that parted the two meadows; she looked down at her skirt, and she saw with relief that she had not much frayed it, yet she knew there were thorns, for there had been an abundance of wild roses in the hedge.

A lark was singing blithely overhead, and the grasshoppers filled the air with joyful chirpings. Anna's face beamed with content.

"If life could be always like to-day!" she thought, "oh, how nice it would be!"

Presently she reached the meadow with the brook running across it, and she gave a cry of delight; down in the marsh into which the brook ran across the sloping field she saw a mass of bright dark-blue. These were gentian-flowers, opening blue and green blossoms to the sunshine, and in front of them the meadow itself was white with a sprinkling of grass of Parnassus.

Anna had a passionate love of flowers, and, utterly heedless of all but the joy of seeing them, she ran down the slope, and only stopped when she found herself ankle-deep in the marsh below, in which the gentian grew.

This sobered her excitement. She pulled out one foot, and was shocked to find that she had left her shoe behind in the black slime; she was conscious, too, that her other foot was sinking deeper and deeper in the treacherous marsh. There was nothing to hold by, there was not even an osier near at hand; behind the gentian rose a thicket of rosy-blossomed willow-herb, and here and there was a creamy tassel of [30]meadowsweet, but even these were some feet beyond her grasp.

Anna looked round her in despair. From the next field came a clicking sound, and as she listened she guessed that old Andreas was busy mowing.

He was old, but he was not deaf, and she could easily make him hear a cry for help; but she was afraid of Andreas. He kept the hotel garden in order, and if he found footmarks on the vegetable plots, or if anything went wrong with the plants, he always laid the blame on Anna; he was as neat as he was captious, and the girl shrank from letting him see the plight she was in.

She stooped down and felt for her shoe, and as she recovered it she nearly fell full length into the bog; the struggle to keep her balance was fatal; her other foot sank several inches; it seemed to her that she must soon be sucked down by the horrible black water that spurted up from the marsh with her struggles.

Without stopping to think, she cried out as loud as she could, "Help me, Andreas! Help! I am drowning!"

At the cry the top of a straw hat appeared in sight, and its owner came up-hill—a small man, with twisted legs, in pale clay-coloured trousers, a black waistcoat, and brown linen shirtsleeves. His wrinkled face looked hot, and his hat was pushed to the back of his head. He took it off and wiped his face with his handkerchief while he looked round him.

"Pouf!" He gave a grunt of displeasure. "So you are once more in mischief, are you? Ah, ah, ah! What, then, will the aunt, that ever to be respected Fräulein, say, when she hears of this?"

He called this out as he came leisurely across the strip of meadow that separated him from Anna.

She was in an agony of fear lest she should sink still farther in before he reached her; but she knew Andreas far too well to urge him even by a word to greater haste. So she stood shivering and pale with [31]fear while she clasped her bog-stained shoe close to her.

Andreas had brought a stake with him, and he held this out to Anna, but when she tried to draw out her sinking foot she shook her head, it seemed to be stuck too fast in the bog.

Andreas gave a growl of discontent, and then went slowly up to the plank bridge. With some effort he raised the smaller of the two planks and carried it to where Anna stood fixed like a statue among the flowering water-plants. Then he pushed the plank out till it rested on a hillock of rushes, while the other end remained on the meadow.

"Ah!"—he drew a long breath—"see the trouble you give by your carelessness."

He spoke vindictively, as if he would have liked to give her a good shaking; but Anna smiled at him, she was so thankful at the prospect of release.

The mischievous little man kept her waiting some minutes. He pretended to test the safety of the plank by walking up and down it and trying it with his foot. At last, when the girl's heart had become sick with suspense, he suddenly stretched out both hands and pulled her on to the plank, then he pushed her along before him till she was on dry ground once more.

"Oh, thank you, Andreas," she began, but he cut her thanks very short.

"Go home at once and dry yourself," he said. "You are the plague of my life, and if I had been a wise man I should have left you in the marsh. Could not your senses tell you that all that rain meant danger in boggy places? There'll be mischief somewhere besides this; a landslip or two, more than likely. There, run home, child, or you'll get cold."

He turned angrily away and went back to his work.

Anna hurried to the narrowest part of the brook and jumped across it. She could not make herself in a worse plight than she was already; her skirts were dripping with the black and filthy water of the marsh.[32]

Heavy rain fell again during the night, and continued throughout the morning, but in the afternoon there was a glimpse of sunshine overhead. This soon drew the vapour up again from the valley, and white steam-clouds sailed slowly across the landscape.

Gretchen had been very kind and compassionate about Anna's disaster; she made the girl go to bed for an hour or two, and gave her some hot broth, and Anna would have forgotten her trouble but for the certainty she felt that old Andreas would make as bad a story of it as he could to her Aunt Christina. But this morning the girl was looking forward to her father's home-coming, and she was in good spirits; she had tried to make herself extra neat, and to imitate as closely as she could her Aunt Christina's way of tidying the rooms; but one improvement suggested itself to Anna which would certainly not have occurred to her tidy aunt; if she had thought of it, she would have scouted the idea as useless, and a frivolous waste of time.

Directly after the midday meal Anna went out to gather a wild-flower nosegay, to place in the sitting-room in honour of her father's return. It seemed to her the only means she had of showing him how glad she was to see him again.

While she was busy gathering Andreas crossed the meadow; he did not see Anna stooping over the flowers, and she kept herself hidden; but the sight of him brought back a haunting fear. What was it? What had Andreas said that she had forgotten? He had said something which had startled her at the time, and which now came pressing urgently on her for remembrance, although she could not distinctly recall it.

What was it? Anna stood asking herself; the flowers fell out of her hand on to the grass among their unplucked companions; she stood for some minutes absorbed in thought.

Andreas had passed out of sight, and she could not venture to follow him, for she did not know what she wanted him to tell her.[33]

A raindrop fell on her hand, and she looked up. Yes, the rain had begun again. Anna gave a sudden start; she left the flowers and set off running towards the point at which she was accustomed to meet her father.

With the raindrop the clue she had been seeking had come to her. Andreas had said there might very likely be landslips, and who could say that there might not have been one on the hillside above Malans? Anna had often heard her father say that, though he could climb the steep ascent with his burden, he should be sorry to have to go down with it. If the track had been partly carried away, he might begin to climb without any warning of the danger that lay before him. . . .

Anna trembled and shivered as she thought of the danger. It would be growing dusk before her father began to climb, and who could say what might happen?

She hurried on to the place at which she always met her father. When she had crossed the brook that parted the field with the gap from the field preceding it, Anna stood still in dismay. The hedge was gone, and so was a good strip of the field it had bordered.

There had already been a landslip.

Anna had learned wisdom by her mischance yesterday, and she went on slowly and cautiously till she drew near the edge; then she knelt down on the grass, and, creeping along on her hands and knees, she peered over the broken, slippery edge. The landslip seemed to have reached midway down the cliff, but the rain had washed the earth and rubbish to one side.

So far as Anna could make out, the way up, half-way, was as firm as ever; then there came a heap of debris from the fall of earth, and then the bare rock rose to the top, upright and dreadful.

Anna's head turned dizzy as she looked down the precipice, and she forced herself to crawl backward from the crumbling edge only just in time, for it seemed [34]to her that some mysterious power was beckoning her from below.

When she got on her feet she stood and wondered what was to be done. How was she to warn her father of this danger?

She looked at the sun; it was still high up in the sky, so she had some hours before her. There was no other way to Malans but this one, unless by going back half-way to Seewis, to where a path led down to Pardisla, and thence into the Landquart valley, where the high-road went on to Malans, past the corner where the Landquart falls into the Rhine. Anna had learned all this as a child from the big map which hung in the dining-room at the inn. But on the map it looked a long, long way to the Rhine valley, and she had heard her father tell her Aunt Christina that she must take the diligence at Pardisla; it would be too far, he said, to walk to Landquart, and Anna knew that Malans was farther still. She stood wondering what could be done.

In these last four years she had become by degrees penetrated with a sense of her own utter uselessness, and she had gradually sunk into a melancholy condition. She did only what she was told to do, and she always expected to be told how to do it.

Her first thought now was, how could she get help or advice? she knew only two people who could help her—Gretchen and Andreas. The last, she reflected, must be already at some distance. When she saw him, he was carrying a basket, and he had, no doubt, gone to Seewis, for it was market-day in that busy village. As to Gretchen, Anna felt puzzled. Gretchen never went from home; what could she know about time and the distance from the Rhine valley?

Besides, while the girl stood thinking her sense of responsibility unfolded, the sense that comes to every rational creature in a moment that threatens danger to others; and she saw that by going back even to consult with Gretchen she must lose many precious [35]minutes. There was no near road to the valley, but it would save a little to keep well behind the inn on her downward way to Pardisla.

As Anna went along the day cleared again. The phantom-like mists drifted aside and showed on the opposite mountain's side brilliant green Alps in the fir-wood that reached almost to the top. The lark overhead sang louder, and the grasshopper's metallic chirp was incessant under foot.

Anna's heart became lighter as she hurried on; surely, she thought, she must reach Malans before her father had begun to climb the mountain. She knew that he would have left his knapsack at Mayenfeld, and that he must call there for it on his way home. Unless the landslip was quite recent it seemed to her possible that some one might be aware of what had happened, and might give her father warning; but Anna had seen that for a good way above Malans the upward path looked all right, and it was so perpendicular that she fancied the destruction of its upper portion might not have been at once discovered, especially if it had occurred at night. No, she was obliged to see that it was extremely doubtful whether her father would receive any warning unless she reached the foot of the descent before he did.

So she went at her utmost speed down the steep stony track to Pardisla. New powers seemed to have come to her with the intensity of her suspense.

George Fasch had every reason to be content with the way in which he had managed his business at Zurich; and yet, as he travelled back to Mayenfeld, he was in a desponding mood. All the way to Zurich his sister had talked about Anna. She said she had tried her utmost with the girl, and that she grew worse and worse.

"She is reckless and thoroughly unreliable," she said, "and she gets more stupid every day. If you were wise you would put her into a reformatory."[36]

George Fasch shrugged his shoulders.

"She is affectionate," he said bluntly, "and she is very unselfish. I should be sorry to send her from home."

Christina held up her hands.

"I call a girl selfish who gives so much trouble. Gretchen has to wash out three skirts a week for Anna. She is always spoiling her clothes. I, on the contrary, call her very selfish, brother."

George Fasch shrugged his shoulders again; he remembered the red and green apron, and he supposed that Christina must be right; and now, as he travelled back alone, he asked himself what he must do. Certainly he saw no reason why he should place Anna in a reformatory—that would be, he thought, a sure way of making her unhappy, and perhaps even desperate; but Christina's words had shown him her unwillingness to be plagued with his daughter's ways, and he shrank from the idea of losing his useful housekeeper. He had been accustomed to depend on his sister for the management of the inn, and he felt that no paid housekeeper would be able to fill Christina's place. Besides, it would cost more money to pay a stranger.

Yes, he must send Anna away, but he shrank from the idea. There was a timid, pathetic look in the girl's dark eyes that warned him against parting her from those she loved. After all, was she not very like her mother? and his sweet lost wife had often told George Fasch how dreamy and heedless and stupid she had been in childhood. He was sure that Anna would mend in time, if only he could hit on some middle course at present.

The weather had been fine at Zurich; and he was surprised, when he quitted the train, to see the long wreaths of white vapour that floated along the valley and up the sides of the hill. It was clearer when he had crossed the river; but before he reached Malans evening was drawing in, and everything grew misty.[37]

He had made his purchases at Mayenfeld so as to avoid another stoppage; and, with his heavy load strapped on his back, he took a by-path that skirted Malans, and led him straight to the bottom of the descent without going through the village. There was a group of trees just at the foot of the path, which increased the gathering gloom.

"My poor child will be tired of waiting," he thought, and he began to climb the steep ascent more rapidly than usual.

All at once a faint cry reached him; he stopped and listened, but it did not come again.

The way was very slippery, he thought; his feet seemed to be clogged with soft earth, and he stopped at last to breathe. Then he heard another cry, and the sound of footsteps behind him.

Some one was following him up the dangerous ascent. And as his ears took in the sound he heard Anna's voice some way below.

"Father! father! stop! stop!" she cried; "there is a landslip above; you cannot climb to-night."

George Fasch stopped. He shut his eyes and opened them again. It seemed to him that he was dreaming. How came Anna to be at the foot of the pass if it was not possible to climb to the top of it?

"What is it, Anna? Do you mean that I must come down again?" he said wonderingly.

"Yes, yes; the path above is destroyed."

And once more he wondered if all this could be real.

"Father, can you come down with the pack, or will you unfasten it and leave it behind?"

George Fasch thought a moment.

"You must go down first," he said, "and keep on one side; the distance is short, and I think I can do it; but I may slip by the way."

There were minutes of breathless suspense while Anna stood in the gathering darkness, and then the heavy footsteps ceased to descend, and she found herself suddenly hugged close in her father's arms.[38]

"My good girl," he said, "my good Anna, how did you come here?"

Anna could not speak. She trembled like a leaf, and then she began to sob. The poor girl was completely exhausted by the terrible anxiety she had gone through, and by fatigue.

"I thought I was too late," she sobbed; "it looked so dark. I feared you could not see; I cried out, but you did not answer. Oh, father!"—she caught at his arms—"if I had been really too late!"

Her head sank on his shoulder.

George Fasch patted her cheek. He was deeply moved, but he did not speak; he would hear by-and-by how it had all happened. Presently he said cheerfully:

"Well, my girl, we must let Gretchen wonder what has happened to us to-night. You and I will get beds at Malans. My clever Anna has done enough for one day."

Three years have passed since Anna's memorable journey. Her Aunt Christina has married, and she has gone to live in Zurich; Anna is now alone with her father and Gretchen. She has developed in all ways; that hurried journey to the foot of the mountain had been a mental tonic to the girl. She has learned to be self-reliant in a true way, and she has found out the truth of a very old proverb, which says, "No one knows what he can do till he tries."

There are those who speak of patriotism as selfish, and bid us cultivate a wider spirit, and think and work for the good of the whole world rather than for the good of our own country. It is true that there is a narrow and a selfish patriotism which blinds us to the good in other nations, which limits our aspirations and breeds a spirit of jealousy and self-assertion. The true patriotism leads us to love our country, and to work for it because we believe that God has given it a special mission, a special part to play in the development of His great purpose in the world, and that ours is the high privilege of helping it to fulfil that mission.

At this moment there seems to come a special call to women to share in the work that we believe the British Empire is bidden to do for the good of the whole world. If we British people fail to rise to the great opportunity that lies before us, it will be because we love easy ways, and material comfort, and all the pleasant things that come to us so readily, because we have lost the spirit of enterprise, the [40]capacity to do hard things, and are content with trying to get the best out of life for ourselves.

We need to keep always a high ideal before us, and as civilisation increases and brings ever new possibilities of enjoyment, the maintenance of that high ideal becomes always more difficult. Nothing helps so much to keep us from low ideals as the conviction that life is a call from God to service, and that our truest happiness is to be found in using every gift, every capacity that we possess, for the good of others.

Girls naturally look forward into life and wonder what it will bring them. Those will probably be the happiest who early in life are obliged or encouraged to prepare themselves for some definite work. But however this may be, they should all from the first realise the bigness of their position, and see themselves as citizens of a great country, with a great work to do for God in the world.

It may be that they will be called to what seems the most natural work for women—to have homes of their own and to realise their citizenship as wives and mothers, doing surely the most important work that any citizen can fulfil. Or they may have either for a time or for life some definite work of their own to do. Everywhere the work of women is being increasingly called for in all departments of life, yet women do not always show the enterprise to embark on new lines or the energy to develop their capacities in such a way as to fit them to do the work that lies before them.

It is so easy after schooldays are ended to enjoy all the pleasant things that lie around, to slip into what comes easiest, to wait for something to turn up, and so really to lose the fruits of past education because it is not carried into practice or used as a means for further development.

This is the critical period of a girl's life. For a boy every one considers the choice of a definite profession imperative; for a girl, unless necessity compels it, the general idea is that it would be a pity for her [41]to take to any work, let her at any rate wait a bit and enjoy herself, then probably something will turn up. This might be all very well if the waiting time were used for further education, for preparation for the work of life. But in too many cases studies begun at school are carried no further, habits of work are lost, and intellectual development comes to a standstill.

We are seeing increasingly in every department of life how much depends upon the home and upon the training given by the mother, and yet it does not seem as if girls as a rule prepared themselves seriously for that high position. The mother should be the first, the chief religious teacher of her children, but most women are content to be vaguely religious themselves whilst hardly knowing what they themselves believe, and feeling perfectly incapable of teaching others.

Yet how are they to fulfil the call which will surely come to them to teach either their own children or those of others if they have not troubled to gain religious knowledge for themselves? The Bible, which becomes each day a more living book because of all the light thrown upon it by recent research, should be known and studied as the great central source of teaching on all that concerns the relations between God and man. But sometimes we are told that it is less well known now than formerly, when real knowledge of it was much more difficult.

Women are said to be naturally more religious than men, but that natural religion will have all the stronger influence the more it is founded on knowledge, and so is able to stand alone, apart from the stimulus of beautiful services or inspiring preaching. Women who follow their husbands into the distant parts of the earth, and are called to be home-makers in new lands, may find themselves not only compelled to stand alone, but called upon to help to maintain the religious life in others. They will not be able to do this if, when they had the opportunity, they neglected to lay sure foundations for their own religious life.[42]

These thoughts may seem to lead us far away from the occupations and interests of girlhood; but they emphasise what is the important thing—the need to recognise the years of girlhood as years of preparation. This is not to take away from the joy of life. The more we learn to find joy in all the beauty of life, in books, in art, in nature, the more permanent sources of joy we are laying up for the future. We must not starve our natures; we should see that every part of ourselves is alive and vigorous.

It is because so many women really hardly live at all that their lives seem so dull and colourless. They have never taken the trouble to develop great parts of themselves, and in consequence they do not notice all the beautiful and interesting things in the world around them. They have not learnt to use all their faculties, so they are unfit to do the work which they might do for the good of others.

Many girls have dreams of the great things they would like to do. But they do not know how to begin, and so they are restless and discontented. The first thing to do is to train themselves, to do every little thing that comes along as well as they can, so as to fit themselves for the higher work that may come. It is worth while for them to go on with their studies, to train their minds to habits of accurate thought, to gain knowledge of all kinds, for all this may not only prove useful in the future, but will make them themselves better instruments for any work that may come to them to do. It is very worth while to learn to be punctual and orderly in little things, to gain business-like habits, even to keep accounts and to answer notes promptly—all these will be useful in the greater business of life. We must be tried in little things before we can be worthy to do big things.

Meanwhile doors are always opening to us whilst we are young, only very often we do not think it worth while to go in at the open door because it strikes us as dull or unimportant and not the great opportunity [43]that we hoped for. But those who go in at the door that opens, that take up the dull little job that offers, and do it as well as they can, will find, first that it is not so dull as they thought, and then that it leads on to something else, and new doors open, and interests grow wider, and more important work is offered. Those who will not go in, but choose to wait till some more interesting or inviting door opens, will find that opportunities grow fewer, that doors are closed instead of opened, and life grows narrower instead of wider.

"THE SON OF MAN CAME NOT TO BE MINISTERED UNTO, BUT TO MINISTER."

"THE SON OF MAN CAME NOT TO BE MINISTERED UNTO, BUT TO MINISTER."

It is of course the motive that inspires us that makes all the difference. To have once realised life, not as an opportunity for self-pleasing, but as an opportunity for service, makes us willing to do the small tasks gladly, that they may fit us for the higher tasks. It would seem as if to us now came with ever-increasing clearness the call to realise more truly throughout the world the great message that Christ proclaimed of the brotherhood of men. It is this sense of brotherhood that stirs us to make the conditions of life sweet and wholesome for every child in our own land, that rouses us to think of the needs of those who have never heard the Christian message of love. As we feel what it means to know God as our Father, we learn to see all men as our brothers, and hence to hear the call to serve them.

It is not necessary to go far to answer this call; brothers and sisters who need our love and help are round our doors, even under our own roof at home; this sense of brotherhood must be felt with all those with whom we come in contact. To some may come the call to realise what it means to recognise our brotherhood with peoples of other race and other beliefs. Even within our own Empire there are, especially in India, countless multitudes waiting for the truth of the gospel to bring light and hope into their lives. Do we feel as we should the call that comes to us from our sisters the women of India? They are needing teachers, doctors, nurses, help that only other [44]women can bring them. Is it not worth while for those who are looking out into life, wondering what it will mean to them, to consider whether the call may not come to them to give themselves to the service of their sisters in the East?

But however this may be, make yourselves ready to hear whatever call may come. There is some service wanted from you; to give that service will be your greatest blessing, your deepest joy. Whether you are able to give that service worthily will depend upon the use you make of the time of waiting and preparation. It must be done, not for your own gratification, but because you are the followers of One who came, "not to be ministered unto, but to minister."

that makes you feel how good it is to be alive and young—and, incidently, to hope that the tennis-courts won't be too dry.

You see Gerald, my brother, and I were invited to an American tournament for that afternoon, which we were both awfully keen about; then mother and father were coming home in the evening, after having been away a fortnight, and, though on the whole I had got on quite nicely with the housekeeping, it would be a relief to be able to consult mother again. Things have a knack of not going so smoothly when mothers are away, as I daresay you've noticed.

I had been busy making strawberry jam, which had turned out very well, all except the last lot. Gerald called me to see his new ferret just after I had put the sugar in, and, by the time I got back, the jam had, most disagreeably, got burnt.

That's just the way with cooking. You stand and watch a thing for ages, waiting for it to boil; but immediately you go out of the room it becomes [46]hysterical and boils all over the stove; so it is borne in on me that you must "keep your eye on the ball," otherwise the saucepan, when cooking.

However, when things are a success it feels quite worth the trouble. Gerald insisted on "helping" me once, rather against cook's wish, and made some really delicious meringues, only he would eat them before they were properly baked!

The gong rang, and I ran down to breakfast; Gerald was late, as usual, but he came at last.

"Here's a letter from Jack," I remarked, passing it across; "see what he says."

Jack was one of our oldest friends; he went to school with Gerald, and they were then both at Oxford together. He had always spent his holidays with us as he had no mother, and his father, who was a most brilliant scholar, lived in India, engaged in research work; but this vac. Mr. Marriott was in England, and Jack and he were coming to stay with us the following day.

GERALD LOOKED PUZZLED.

GERALD LOOKED PUZZLED.

Gerald read the letter through twice, and then looked puzzled.

"Which day were they invited for, Margaret?" he asked.

"To-morrow, of course, the 13th."

"Well, they're coming this evening by the 7.2."

I looked over his shoulder; it was the 12th undoubtedly. "And mother and father aren't coming till the 9.30," I sighed; "I wish they were going to be here in time for dinner to entertain Mr. Marriott; he's sure to be eccentric—clever people always are."

"Yes," agreed Gerald, "he'll talk miles above our heads; but never mind, there'll be old Jack."

Cook and I next discussed the menu. I rather thought curry should figure in it, as Mr. Marriott came from India; but cook overruled me, saying it was "such nasty hot stuff for this weather, and English curry wouldn't be like Indian curry either."

When everything was in readiness for our guests[47] Gerald and I went to the Prescotts', who were giving the tournament.

We had some splendid games, and Gerald was still playing in an exciting match when I found that the Marriotts' train was nearly due. Of course he couldn't leave off, so I said that I would meet them and take them home; we only lived about a quarter of a mile from the station, and generally walked.

I couldn't find my racquet for some time, and consequently had a race with the train, which luckily ended in a dead heat, for I reached the platform just as it steamed in.

The few passengers quickly dispersed, but there was no sign of Jack; a tall, elderly man, wrapped in a thick overcoat, in spite of the hot evening, stood forlornly alone. I was just wondering if he could be Jack's father when he came up to me and said, "Are you Margaret?"

"Yes," I answered.

"I have often heard my boy speak of you," he said, looking extremely miserable.

"But isn't he coming?" I cried.

He replied "No" in such a hopeless voice and sighed so heavily that I was beginning to feel positively depressed, when he changed the subject by informing me that his bag had been left behind but was coming on by a later train, so, giving instructions for it to be sent up directly it arrived, I piloted him out of the station.

I had expected him to be eccentric, but he certainly was the oddest man I had ever met; he seemed perfectly obsessed by the loss of his bag, and would talk of nothing else, though I was longing to know why Jack hadn't come. The absence of his dress clothes seemed to worry him intensely. In vain I told him that we need not change for dinner; he said he must, and wouldn't be comforted.

"How is Jack?" I asked at last; "why didn't he come with you?"[48]

He looked at me for a moment with an expression of the deepest grief, and then said quietly, "Jack is dead."

"Dead?" I almost shouted. "Jack dead! You can't mean it!"

But he only repeated sadly, "Jack is dead," and walked on.

It seemed incredible; Jack, whom we had seen a few weeks before so full of life and vigour, Jack, who had ridden with us, played tennis, and been the leading spirit at our rat hunts, it was too horrible to think of!

I felt quite stunned, but the sight of the poor old man who had lost his only child roused me.

"I am more sorry than I can say," I ventured; "it must be a terrible blow to you."

"Thank you," he said; "you, who knew him well, can realise it more than any one; but it was all for the best—I felt that when I did it."

"Did what?" I inquired, thinking that he was straying from the point.

"When I shot him through the head," he replied laconically, as if it were the most natural thing in the world.

If he had suddenly pointed a pistol at my head I could not have been more astonished; I was absolutely petrified with horror, for the thought flashed into my brain that Jack's father must be mad!

His peculiar expression had aroused my curiosity at the station, and his next remark confirmed my suspicion.

"You see, he showed unmistakable symptoms of going mad——"

(I had heard that madmen invariably think every one around them is mad, and that they themselves are sane.)

"——so I felt it my duty to shoot him; it was all over in a moment."

"Poor Jack!" I cried involuntarily.

"Yes," he answered, "but I should do just the same again if the occasion arose."[49]

And he looked at me fixedly.

I felt horribly frightened. Did he think I was mad? And I fell to wondering, when he put his hand in his pocket, whether he had the revolver there. We had reached our garden gate by this time, where, to my infinite relief, we were joined by Gerald, flushed and triumphant after winning his match.

After an agonised aside "Don't ask about Jack," I murmured an introduction, and we all walked up to the house together. In the hall I managed to tell Gerald of our dreadful position, and implored him to humour the madman as much as possible until we could form some plan for his capture.

"We'll give him dinner just as if nothing has happened, and after that I'll arrange something," said Gerald hopefully; "don't you worry."

Never shall I forget that dinner! We were on tenterhooks the whole time, and it made me shudder to see how Mr. Marriott caressed the knives. I could scarcely prevent myself screaming when he held one up, and, feeling the blade carefully with his finger, said:

"I rather thought of doing this little trick to-night, if you would like it; it is very convincing and doesn't take long."

I remembered his remark, "it was all over in a moment," and trembled; but Gerald tactfully drew his attention to something else, and dinner proceeded peaceably; but he had a horrible fondness for that knife, and, when dessert was put on the table, kept it in his hand, "to show us the trick afterwards."

I stayed in the dining-room when we had finished; I couldn't bear to leave Gerald, and he and I exchanged apprehensive glances when Mr. Marriott refused to smoke, giving as his reason that he wanted a steady hand for his work later.