Title: Abe and Mawruss: Being Further Adventures of Potash and Perlmutter

Author: Montague Glass

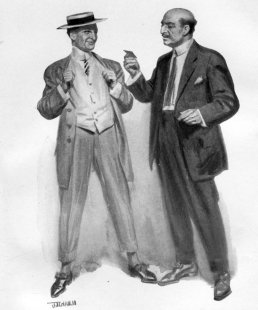

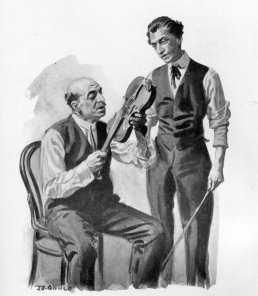

Illustrator: J. J. Gould

Martin Justice

Release date: June 29, 2006 [eBook #18714]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by YaTHauSeR Taltari, Suzanne Shell and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

"I come down on the subway with Max Linkheimer this morning, Mawruss," Abe Potash said to his partner, Morris Perlmutter, as they sat in the showroom one hot July morning. "That feller is a regular philantropist."

"I bet yer," Morris replied. "He would talk a tin ear on to you if you only give him a chance. Leon Sammet too, Abe, I assure you. I seen Leon in the Harlem Winter Garden last night, and the goods he sold while he was talking to me and Barney Gans, Abe, in two seasons we don't do such a business. Yes, Abe; Leon Sammet is just such another one of them fellers like Max Linkheimer."

"What d'ye mean—'such another one of them fellers like Max Linkheimer'?" Abe repeated. "Between Leon Sammet and Max Linkheimer is the difference like day from night. Max Linkheimer is one fine man, Mawruss."

Morris shrugged. "I didn't say he wasn't," he rejoined. "All I says was that Leon Sammet is another one of them philantro fellers too, Abe. Talks you deef, dumb and blind."

Abe rose to his feet and stared indignantly at his partner.

"I don't know what comes over you lately, Mawruss," he cried. "Seemingly you don't understand the English language at all. A philantropist ain't a schmooser, Mawruss."

"I know he ain't, Abe; but just the same Max Linkheimer is a feller which he got a whole lot too much to say for himself. Furthermore, Abe, my Minnie says Mrs. Linkheimer tells her Max ain't home a single night neither, and when a man neglects his family like that, Abe, I ain't got no use for him at all."

"That's because he belongs to eight lodges," Abe replied. "There ain't a single Sunday neither which he ain't busy with funerals too, Mawruss."

"Is that so?" Morris retorted. "Well, if I would be in the button business, Abe, I would be a philantropist too. A feller's got to belong to eight lodges if he's in the button business, Abe, because otherwise he couldn't sell no goods at all."

Abe continued:

"Linkheimer ain't looking to sell goods to lodge brothers, Mawruss. He's too old established a business for that. He's got a heart too, Mawruss. Why the money that feller spends on charity, Mawruss, you wouldn't believe at all. He told me so himself. Always he tries to do good. Only this morning, Mawruss, he was telling me about a young feller by the name Schenkmann which he is trying to find a position for as stock clerk. Nobody would take the young feller on, Mawruss, because he got into trouble with a house in Dallas, Texas, which they claim the young feller stole from them a hundred dollars, Mawruss. But Linkheimer says how if you would give a dawg a bad name, Mawruss, you might just as well give him to the dawgcatcher. So Linkheimer is willing to take a chance on this here feller Schenkmann, and he gives him a job in his own place."

"Dawgs I don't know nothing about at all, Abe," Morris commented. "But I would be willing to give the young feller a show too, Abe, if I would only got plain bone and metal buttons in stock. But when you carry a couple hundred pieces silk goods, Abe, like we do, then that's something else again."

"Well, Mawruss, Gott sei dank we don't got to get a new shipping clerk. Jake has been with us five years now, Mawruss, and so far what I could see he ain't got ambition enough to ask for a raise even, let alone look for a better job."

"You shouldn't congradulate yourself too quick, Abe," Morris replied. "Ambition he's got it plenty, but he ain't got the nerve. We really ought to give the feller a raise, Abe. I mean it. Every time I go near him at all he gives me a look, and the first thing you know, Abe, he would be leaving us."

"Looks we could stand it, Mawruss; but if we would start in giving him a raise there would be no end to it at all. Lass's bleiben. If the feller wants a raise, Mawruss, he should ask for it."

Barely two weeks after the conversation above set forth, however, Jake entered the firm's private office and tendered his resignation.

"Mr. Perlmutter," he said, "I'm going to leave."

"Going to leave?" Morris cried. "What d'ye mean—going to leave?"

"Going to leave?" Abe repeated crescendo. "An idea! You should positively do nothing of the kind."

"It wouldn't be no more than you deserve, Jake, if we would fire you right out of the store," Morris added. "You work for us here five years and then you come to us and say you are going to leave. Did you ever hear of such a thing? If you want it a couple dollars more a week, we would give it to you and fartig. But if you get fresh and come to us and tell us you are going to leave, y'understand, then that's something else again."

"Moost I work for you if I don't want to?" Jake asked.

"'S enough, Jake," Abe said. "We heard enough from you already."

"All right, Mr. Potash," he replied. "But just the same I am telling you, Mr. Potash, you should look for a new shipping clerk, as I bought it a candy, cigar and stationery store on Lenox Avenue, and I am going to quit Saturday sure."

"Well, Abe, what did I told you?" Morris said bitterly, after Jake had left the office. "For the sake of a couple of dollars a week, Abe, we are losing a good shipping clerk."

Abe covered his embarrassment with a mirthless laugh.

"Good shipping clerks you could get any day in the week, Mawruss," he said. "We ain't going to go out of business exactly, y'understand, just because Jake is leaving us. I bet yer if we would advertise in to-morrow morning's paper we would get a dozen good shipping clerks."

"Go ahead, advertise," Morris grunted. "This is your idee Jake leaves us, Abe, and now you should find somebody to take his place. I'm sick and tired making changes in the store."

"Always kicking, Mawruss, always kicking!" Abe retorted. "By Saturday I bet yer we would get a hundred good shipping clerks already."

But Saturday came and went, and although in the meantime old and young shipping clerks of every degree of uncleanliness passed in review before Abe and Morris, none of them proved acceptable.

"All right, Abe," Morris said on the Monday morning after Jake had gone, "you done enough about this here shipping clerk business. Give me a show. I ain't got such liberal idees about shipping clerks as you got, Abe, but all the same, Abe, I think I could go at this business with a little system, y'understand."

"You shouldn't trouble yourself, Mawruss," Abe replied, with an airy wave of his hand. "I hired one already."

"You hired one already, Abe!" Morris repeated. "Well, ain't I got something to say about it too?"

"Again kicking, Mawruss?" Abe exclaimed. "You yourself told me I should find a shipping clerk, and so I done so."

"Well," Morris cried, "ain't I even entitled to know the feller's name at all?"

"Sure you are entitled to know his name," Abe answered. "He's a young feller by the name of Schenkmann."

"Schenkmann," Morris said slowly. "Schenkmann? Where did I—you mean that feller by the name Schenkmann which he works by Max Linkheimer?"

Abe nodded.

"What's the matter with you, Abe?" Morris cried. "Are you crazy or what?"

"What do you mean am I crazy?" Abe said. "We carry burglary insurance, ain't it? And besides he ain't, Mawruss, Max Linkheimer says, missed so much as a button since the feller worked for him."

"A button," Morris shouted; "let me tell you something, Abe. Max Linkheimer could miss a thousand buttons, and what is it? But with us, Abe, one piece of silk goods is more as a hundred dollars."

"'S all right, Mawruss," Abe interrupted. "Max Linkheimer says we shouldn't be afraid. He says he trusts the young feller in the office with hundreds of dollars laying in the safe, and he ain't touched a cent so far. Furthermore, the young feller's got a wife and baby, Mawruss."

"Well I got a wife and baby too, Abe."

"Sure, I know, Mawruss, and so you ought to got a little sympathy for the feller."

Morris laughed raucously.

"Sure, I know, Abe," he replied. "A good way to lose money in business, Abe, is to got sympathy for somebody. You sell a feller goods, Abe, because he's a new beginner and you got sympathy for him, Abe, and the feller busts up on you. You accommodate a concern with five hundred dollars—a check against their check dated two weeks ahead, Abe—because their collections is slow and you got sympathy for them, and when the two weeks goes by, Abe, the check is N. G. You give a feller out in Kansas City two months an extension because he done a bad spring business, and you got sympathy for him, and the first thing you know, Abe, a jobber out in Omaha gets a judgment against him and closes him up. And that's the way it goes. If we would hire this young feller because we got sympathy for him, Abe, the least that happens us is that he gets away with a couple hundred dollars' worth of piece goods."

"Max Linkheimer says positively nothing of the kind," Abe insisted. "Max says the feller has turned around a new leaf, and he would trust him like a brother."

"Like a brother-in-law, you mean, Abe," Morris jeered. "That feller Linkheimer never trusted nobody for nothing, Abe. Always by the first of the month comes a statement, and if he don't get a check by the fifth, Abe, he sends another with 'past due' stamped on to it."

"So much the better, Mawruss. If Max Linkheimer don't trust nobody, Mawruss, and he lets this young feller work in his store, Mawruss, then the feller must be O. K. Ain't it?"

Morris rose wearily to his feet.

"All right, Abe," he said. "If Linkheimer is so anxious to get rid of this feller, let him give us a recommendation in writing, y'understand, and I am satisfied we should give this here young Schenkmann a trial. He could only get into us oncet, Abe, so go right over there and see Linkheimer, and if in writing he would give us a guaranty the feller is honest, go ahead and hire him."

"Right away I couldn't do it, Mawruss," Abe said. "When I left Linkheimer in the subway this morning he said he was going over to Newark and he wouldn't be back till to-night. I'll stop in there the first thing to-morrow morning."

With this ultimatum, Abe proceeded to the back of the loft and personally attended to the shipment of ten garments to a customer in Cincinnati. Under his supervision a stock boy placed the garments in a wooden packing box, and after the first top board was in position Abe took a wire nail and held it 'twixt his thumb and finger point down on the edge of the case. Then he poised the hammer in his right hand and carefully closing one eye he gauged the distance between the upraised hammer and the head of the nail. At length the blow descended, and forthwith Abe commenced to dance around the floor in the newborn agony of a smashed thumb.

It was while he was putting the finishing touches on a bandage that made up in bulk what it lacked in symmetry that Morris entered.

"What's the matter, Abe?" he cried. "Did you hurted yourself?"

Abe transfixed his partner with a malevolent glare.

"No, Mawruss," he said, as he started for the front of the store, "I ain't hurted myself at all. I'm just tying this here handkerchief on my thumb to remind myself what a fool I got it for a partner."

Morris waited till Abe had nearly reached the door.

"I don't got to tie something on my thumb to remind myself of that, Abe," he said.

Ever since the birth of his son it had seemed to Morris that the Lenox Avenue express service had grown increasingly slow. Nor did the evening papers contain half the interesting news of his early married life, and he could barely wait until the train had stopped at One Hundred and Sixteenth Street before he was elbowing his way to the platform.

On the Monday night of his partner's mishap he made his accustomed dash from the subway station to his home on One Hundred and Eighteenth Street, confident that as soon as his latchkey rattled in the door Mrs. Perlmutter and the baby would be in the hall to greet him; but on this occasion he was disappointed. To be sure the appetizing odour of gedampftes kalbfleisch wafted itself down the elevator shaft as he entered the gilt and plaster-porphyry entrance from the street, but when he crossed the threshold of his own apartment the robust wail of his son and heir mingled with the tones of Lina, the Slavic maid. Of Mrs. Perlmutter, however, there was no sign.

"Where's Minnie?" he demanded.

"Mrs. Perlmutter, she go out," Lina announced, "and she ain't coming home yet."

Not since the return from their honeymoon had Minnie failed to be at home to greet her husband on his arrival from business, and Morris was about to telephone a general alarm to police headquarters when the doorbell rang sharply and Mrs. Perlmutter entered. Her hat, whose size and weight ought to have lent it stability, was tilted at a dangerous angle, and beneath its broad brim her eyes glistened with unmistakable tears.

"Minnie leben," Morris cried, as he clasped her in his arms, "what is it?"

Sympathy only opened anew the floodgates of Mrs. Perlmutter's emotions, and before she was sufficiently calm to disclose the cause of her distress, the gedampftes kalbfleisch gave evidence of its impending destruction by a strong odour of scorching. Hastily Mrs. Perlmutter dried her eyes and ran to the kitchen, so that it was not until the rescued dinner smoked on the dining-room table that Morris learned the reason for his wife's tears.

"Such a room, Morris," Mrs. Perlmutter declared; "like a pigsty, and not a crust of bread in the house. I met the poor woman in the meat market and she tried to beg a piece of liver from that loafer Hirschkein. Not another cent of my money will he ever get. I bought a big piece of steak for her and then I went home with her. Her poor baby, Morris, looked like a little skeleton."

Morris shook his head from side to side and made inarticulate expressions of commiseration through his nose, his mouth being temporarily occupied by about half a pound of luscious veal.

"Her husband has a job for eight dollars a week," she continued, "and they have to live on that."

Morris swallowed the veal with an effort.

"In Russland," he began, "six people—"

"I know," Mrs. Perlmutter interrupted, "but this is America, and you've got to go around with me right after dinner and see the poor people."

Morris shrugged his shoulders.

"If I must, I must," he said, helping himself to more of the veal stew, "but I could tell you right now, Minnie, I ain't got twenty-five cents in my clothes, so you got to lend me a couple of dollars till Saturday."

"I'll cash a check for you," Mrs. Perlmutter said firmly, and as soon as dinner was concluded Morris drew a check for ten dollars and Mrs. Perlmutter gave him that amount out of her housekeeping money.

It was nearly nine o'clock when Morris and Minnie groped along the dark hallway of a tenement house in Park Avenue. On the iron viaduct that bestrides that deceptively named thoroughfare heavy trains thundered at intervals, and it was only after Morris had knocked repeatedly at the door of a top-floor apartment that its inmates heard the summons above the roar of the traffic without.

"Well, Mrs. Schenkmann," Minnie cried cheerfully, "how's the baby to-night?"

"Schenkmann?" Morris murmured; "Schenkmann? Is that the name of them people?"

"Why, yes," Minnie replied. "Didn't I tell you that? Mrs. Schenkmann, this is my husband. And I suppose this is Mr. Schenkmann."

A tall, gaunt person rose from the soap box that did duty as a chair and ducked his head shyly.

"Schenkmann?" Morris repeated. "You ain't the Schenkmann which he works by Max Linkheimer?"

Nathan Schenkmann nodded and Mrs. Schenkmann groaned aloud.

"Ai zuris!" she cried, "for his sorrow he works by Max Linkheimer. Eight dollars a week he is supposed to get there, and Linkheimer makes us live here in his house. Twelve dollars a month we pay for the rooms, lady, and Linkheimer takes three dollars each week from Nathan's money. We couldn't even get dispossessed like some people does and save a month's rent oncet in a while maybe. The rooms ain't worth it, lady, believe me."

"Does Max Linkheimer own this house?" Morris asked.

"Sure, he's the landlord," Mrs. Schenkmann went on. "I am just telling you. For eight dollars a week a man should work! Ain't it a disgrace?"

"Well, why doesn't he get another job?" Morris inquired; and then, as Mr. and Mrs. Schenkmann exchanged embarrassed looks and hung their heads, Morris blushed.

"What a fine baby!" he cried hurriedly. He chucked the infant under its chin and made such noises with his tongue as are popularly supposed by parents to be of a nature entertaining to very young children. In point of fact the poor little Schenkmann child, with its blue-white complexion, looked more like a cold-storage chicken than a human baby, but to the maternal eye of Mrs. Schenkmann it represented the sum total of infantile beauty.

"God bless you, mister," she said. "I seen you got a good heart, and if you know Max Linkheimer, he must told you why my husband couldn't get another job. He tells everybody, lady, and makes 'em believe he gives my husband a job out of charity. So sure as I got a baby which I hope he would grow up to be a man, lady, my husband never took no money in Dallas. Them people gives him a hundred dollars he should deposit it in the bank, and he went and lost it. If he would stole it he would of gave it to me, lady, because my Nathan is a good man. He ain't no loafer that he should gamble it away."

There was a ring of truth in Mrs. Schenkmann's tones, and as Morris looked at the twenty-eight-years old Nathan, aged by ill nutrition and abuse, his suspicions all dissolved and gave place only to a great pity.

"Don't say no more, Mrs. Schenkmann," he cried; "I don't want to hear no more about it. To-morrow morning your man leaves that loafer Max Linkheimer and comes to work by us for eighteen dollars a week."

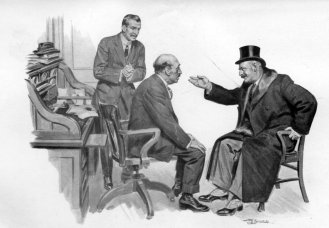

Easily the most salient feature of Mr. Max Linkheimer's attire was the I. O. M. A. jewel that dangled from the tangent point of his generous waist line. It had been presented to him by Harmony Lodge, 122, at the conclusion of his term of office as National Grand Corresponding Secretary, and it weighed about eight ounces avoirdupois. Not that the rest of Mr. Linkheimer's wearing apparel was not in keeping, for he affected to be somewhat old-fashioned in his attire, with just a dash of bonhomie. This implies that he wore a wrinkled frock coat and low-cut waistcoat. But he had discarded the black string tie that goes with it for a white ready-made bow as being more suitable to the rôle of philanthropist. The bonhomie he supplied by not buttoning the two top buttons of his waistcoat.

"Why, hallo, Abe, my boy!" he cried all in one breath, as Abe Potash entered his button warerooms on Tuesday morning; "what can I do for you?"

He seized Abe's right hand in a soft, warm grip, slightly moist, and continued to hold it for the better part of five minutes.

"I come to see you about Schenkmann," Abe replied. "We decide we would have him come to work by us as a shipping clerk."

"I'm glad to hear it," said Linkheimer, "As I told you the other day, I've just been asked by a lodge I belong to if I could help out a young feller just out of an orphan asylum. He's a big, strong, healthy boy, and he's willing to come to work for half what I'm paying Schenkmann. So naturally I've got to get rid of Schenkmann."

"I wonder you got time to bother yourself breaking in a new beginner," Abe commented.

Linkheimer waggled his head solemnly.

"I can't help it, Abe," he said. "I let my business suffer, but nevertheless I'm constantly giving the helping hand to these poor inexperienced fellows. I assure you it costs me thousands of dollars in a year, but that's my nature, Abe. I'm all heart. When would you want Schenkmann to come to work?"

"Right away, Mr. Linkheimer."

"Very good, I'll go and call him."

He rose to his feet and started for the door.

"Oh, by the way, Abe," he said, as he paused at the threshold, "you know Schenkmann is a married man with a wife and child, and I understand Mrs. Schenkmann is inclined to be extravagant. For that reason I let him live in a house I own on Park Avenue, and I take out the rent each week from his pay. It's really a charity to do so. The amount is—er—sixteen dollars a month. I suppose you have no objection to sending me four dollars a week out of his wages?"

"Well, I ain't exactly a collecting agency, y'understand," Abe said; "but I'll see what my partner says, and if he's agreeable, I am. Only one thing though, Mr. Linkheimer, my partner bothers the life out of me I should get from you a recommendation."

"I'll give you one with pleasure, Abe," Linkheimer replied; "but it isn't necessary."

He returned to the front of the office and went to the safe.

"Why just look here, Abe," he said. "I have here in the safe five hundred dollars and some small bills which I put in there last night after I come back from Newark. It was money I received the day before yesterday as chairman of the entertainment committee of a lodge I belong to. The safe was unlocked from five to seven last night and Schenkmann was in and out here all that time."

He opened the middle compartment and pulled out a roll of bills.

"You see, Abe," he said, counting out the money, "here it is: one hundred, two hundred, three hundred, four hundred and—"

Here Mr. Linkheimer paused and examined the last bill carefully, for instead of a hundred-dollar bill it was only a ten-dollar bill.

"Well, what d'ye think of that dirty thief?" he cried at last. "That Schenkmann has taken a hundred-dollar bill out of there."

"What?" Abe exclaimed.

"Just as sure as you are sitting there," Linkheimer went on excitedly. "That feller Schenkmann has pinched a hundred-dollar bill on me."

Here his academic English completely forsook him and he continued in the vernacular of the lower East Side.

"Always up to now I have kept the safe locked on that feller, and the very first time I get careless he goes to work and does me for a hundred dollars yet."

"But," Abe protested, "you might of made a mistake, ain't it? If the feller took it a hundred dollars, why don't he turn around and ganver the other four hundred? Ain't it? The ten dollars also he might of took it. What?"

"A ganef you couldn't tell what he would do at all," Linkheimer rejoined, and Abe rose to his feet.

"I'm sorry for you, Mr. Linkheimer," he said, seizing his hat, "but I guess I must be getting back to the store. So you shouldn't trouble yourself about this here feller Schenkmann. We decided we would get along without him."

But Abe's words fell on deaf ears, for as he turned to leave Mr. Linkheimer threw up the window sash and thrust his head out.

"Po-lee-eece, po-lee-eece!" he yelled.

When Abe arrived at his place of business after his visit to Max Linkheimer he found Morris whistling cheerfully over the morning mail.

"Well, Abe," Morris cried, "did you seen it Max Linkheimer?"

Abe hurriedly took off his hat and coat, and catching the bandaged thumb in the sleeve lining he swore long and loud.

"Yes, I seen Max Linkheimer," he growled, "and I'm sick and tired of the whole business. Go ahead and get a shipping clerk, Mawruss. I'm through."

"Why?" Morris asked. "Wouldn't Linkheimer give a recommendation, because if he wouldn't, Abe, I am satisfied we should take the feller without one. In fact I'm surprised you didn't bring him along."

"You are, hey?" Abe broke in. "Well, you shouldn't be surprised at nothing like that, Mawruss, because I didn't bring him along for the simple reason, Mawruss, I don't want no ganef working round my place. That's all."

"What do you mean—ganef?" Morris cried. "The feller ain't no more a thief as you are, Abe."

Abe's moustache bristled and his eyes bulged so indignantly that they seemed to rest on his cheeks.

"You should be careful what you say, Mawruss," he retorted. "Maybe he ain't no more a ganef as I am, Mawruss, but just the same, he is in jail and I ain't."

"In jail," Morris exclaimed. "What for in jail?"

"Because he stole from Linkheimer a hundred dollars yesterday, Mawruss, and while I was there yet, Linkheimer finds it out. So naturally he makes this here feller arrested."

"Yesterday, he stole a hundred dollars?" Morris interrupted.

"Yesterday afternoon," Abe repeated. "With my own eyes I seen it the other money which he didn't stole."

"Then," Morris said, "if he stole it yesterday afternoon, Abe, he didn't positively do nothing of the kind."

Forthwith he related to Abe his visit to Schenkmann's rooms and the condition of poverty that he found.

"I give you my word, Abe," he said, "the feller didn't got even a chair to sit on."

"What do you know, Mawruss, what he got and what he didn't got?" Abe rejoined impatiently. "The feller naturally ain't going to show you the hundred dollars which he stole it—especially, Mawruss, if he thinks he could work you for a couple dollars more."

"Say, lookyhere, Abe," Morris broke in; "don't say again that feller stole a hundred dollars, because I'm telling you once more, Abe, I know he didn't take nothing, certain sure."

"Geh wek, Mawruss," Abe cried disgustedly; "you talk like a fool!"

"Do I?" Morris shouted. "All right, Abe. Maybe I do and maybe I don't, but just the same so positive I am he didn't done it, I'm going right down to Henry D. Feldman, and I will fix that feller Linkheimer he should work a poor half-starved yokel for five dollars a week and a couple of top-floor tenement rooms which it ain't worth six dollars a month. Wait! I'll show that sucker."

He seized his hat and made for the elevator door, which he had almost reached when Abe grabbed him by the arm.

"Mawruss," he cried, "are you crazy? What for you should put yourself out about this here young feller? He ain't the last shipping clerk in existence. You could get plenty good shipping clerks without bothering yourself like this. Besides, Mawruss, if he did steal it or if he didn't steal it, what difference does it make to us? With the silk piece goods which we got it around our place, Mawruss, we couldn't afford to take no chances."

"I ain't taking no chances, Abe," Morris maintained stoutly. "I know this feller ain't took the money."

"Sure, that's all right," Abe agreed; "but you couldn't afford to be away all morning right in the busy season. Besides, Mawruss, since when did you become to be so charitable all of a suddent?"

"Me charitable?" Morris cried indignantly. "I ain't charitable, Abe. Gott soll hüten! I leave that to suckers like Max Linkheimer. But when I know a decent, respectable feller is being put into jail for something which he didn't do at all, Abe, then that's something else again."

At this juncture the elevator arrived, and as he plunged in he shouted that he would be back before noon. Abe returned to the rear of the loft where a number of rush orders had been arranged for shipment. Under his instruction and supervision the stock boy nailed down the top boards of the packing cases, but in nearly every instance, after the case was strapped and stencilled, they discovered they had left one garment out, and the whole process had to be repeated. Thus it was nearly one o'clock before Abe's task was concluded, and although he had breakfasted late that morning, when he looked at his watch he became suddenly famished. "I could starve yet," he muttered, "for all that feller cares."

He walked up and down the showroom floor in an ecstasy of imaginary hunger, and as he was making the hundredth trip the elevator door opened and Max Linkheimer stepped out. His low-cut waistcoat disclosed that his shirtfront, ordinarily of a glossy white perfection, had fallen victim to a profuse perspiration. Even his collar had not escaped the flood, and as for his I. O. M. A. charm, it seemed positively tarnished.

"Say, lookyhere, Potash," he began, "what d'ye mean by sending your partner to bail out that ganef?"

"Me send my partner to bail out a ganef?" Abe exclaimed. "What are you talking, nonsense?"

"I ain't talking nonsense," Linkheimer retorted. "Look at the kinds of conditions I am in. That feller Feldman made a fine monkey out of me in the police court."

"Was Feldman there too?" Abe asked.

"You don't know, I suppose, Feldman was there," Linkheimer continued; "and your partner went on his bail for two thousand dollars."

Abe shrugged his shoulders.

"In the first place, Mr. Linkheimer," he said, "I didn't tell my partner he should do nothing of the kind. He done it against my advice, Mr. Linkheimer. But at the same time, Mr. Linkheimer, if he wants to go bail for that feller, y'understand, what is it my business?"

"What is it your business?" Linkheimer repeated. "Why, don't you know if that feller runs away the sheriff could come in here and clean out your place? That's all."

"What?" Abe cried. He sat down in the nearest chair and gaped at Linkheimer.

"Yes, sir," Linkheimer repeated, "you could be ruined by a thing like that."

Abe's lower jaw fell still further. He was too dazed for comment.

"W-what could I do about it?" he gasped at length.

"Do about it!" Linkheimer cried. "Why, if I had a partner who played me a dirty trick like that I'd kick him out of my place. There ain't a copartnership agreement in existence that doesn't expressly say one partner shouldn't give a bail bond without the other partner's consent."

Abe rocked to and fro in his chair.

"After all these years a feller should do a thing like that to me!" he moaned.

Linkheimer smiled with satisfaction, and he was about to instance a striking and wholly imaginary case of one partner ruining another by giving a bail bond when the door leading to the cutting room in the rear opened and Morris Perlmutter appeared. As his eyes rested on Linkheimer they blazed with anger, and for once Morris seemed to possess a certain dignity.

"Out," he commanded; "out from mein store, you dawg, you!"

As he rushed on the startled button dealer, Abe grabbed his coat-tails and pulled him back.

"Say, what are we here, Mawruss," he cried, "a theaytre?"

"Let him alone, Abe," Linkheimer counselled in a rather shaky voice. "I'm pretty nearly twenty years older than he is, but I guess I could cope with him."

"You wouldn't cope with nobody around here," Abe replied. "If youse two want to cope you should go out on the sidewalk."

"Never mind," Morris broke in, his valour now quite evaporated; "I'll fix him yet."

"Another thing, Mawruss," Abe interrupted; "why don't you come in the front way like a man."

"I come in which way I please, Abe," Morris rejoined. "And furthermore, Abe, when I got with me a poor skeleton of a feller like Nathan Schenkmann, Abe, I don't take him up the front elevator. I would be ashamed for our competitors that they should think we let our work-people starve. The feller actually fainted on me as we was coming up the freight elevator."

"As you was coming up the freight elevator?" Abe repeated. "Do you mean to tell me you got the nerve to actually bring this feller into mein place yet?"

"Do I got to get your permission, Abe, I should bring who I want to into my own place?" Morris rejoined.

"Then all I got to say is you should take him right out again," Abe said. "I wouldn't have no ganévim in my place. Once and for all, Mawruss, I am telling you I wouldn't stand for your nonsense. You are giving our stock as a bail for this feller, and if he runs away on us, the sheriff comes in and—"

"Who says I give our stock as a bail for this feller?" Morris demanded. "I got a surety company bond, Abe, because Feldman says I shouldn't go on no bail bonds, and I give the surety company my personal check for a thousand dollars which they will return when the case is over. That's what I done it to keep this here Schenkmann out of jail, Abe, and if it would be necessary to get this here Linkheimer into jail, Abe, I would have another check for a thousand dollars for keeps."

Abe grew somewhat abashed at this disclosure. He looked at Linkheimer and then at Morris, but before he could think of something to say the elevator door opened and Jake stepped out. It was perhaps the first time in all their acquaintance with Jake that Abe and Morris had seen him with his face washed. Moreover, a clean collar served further to conceal his identity, and at first Abe did not recognize his former shipping clerk.

"Hallo, Mr. Potash!" Jake said.

"I'll be with you in one moment, Mister—er," Abe began. "Just take a—why, that's Jake, ain't it?"

Here he saw a chance for a conversational diversion and he jumped excitedly to his feet.

"What's the matter, Jake?" he asked. "You want your old job back?"

"It don't go so quick as all that, Mr. Potash," Jake answered. "I got a good business, Mr. Potash. I carry a fine line of cigars, candy, and stationery, and already I got an offer of twenty-five dollars more as I paid for the business. But I wouldn't take it. Why should I? I took in a lot money yesterday, and only this morning, Mr. Potash, a feller comes in my place and—why, there's the feller now!"

"Feller! What d'ye mean—feller?" Abe cried indignantly. "That ain't no feller. That's Mr. Max Linkheimer."

"Sure, I know!" Jake explained. "He's the feller I mean. Half an hour ago I was in his place, and they says there he comes up here. You was in mein store this morning, Mr. Linkheimer, ain't that right, and you bought from me a package of all-tobacco cigarettes?"

"Nu, nu, Jake," Morris broke in. "Make an end. You are interrupting us here."

Jake drew back his coat and clumsily unfastened a large safety pin which sealed the opening of his upper right-hand waistcoat pocket. Then he dug down with his thumb and finger and produced a small yellow wad about the size of a postage stamp. This he proceeded to unfold until it took on the appearance of a hundred-dollar bill.

"He gives me this here," Jake announced, "and I give him the change for a ten-dollar bill. So this here is a hundred-dollar bill, ain't it, and it don't belong to me, which I come downtown I should give it him back again. What isn't mine I don't want at all."

This was perhaps the longest speech that Jake had ever made, and he paused to lick his dry lips for the peroration.

"And so," he concluded, handing the bill to Linkheimer, "here it is, and—and nine dollars and ninety cents, please."

Linkheimer grabbed the bill automatically and gazed at the figures on it with bulging eyes.

"Why," Abe gasped, "why, Linkheimer, you had four one-hundred-dollar bills and a ten-dollar bill in the safe this morning. Ain't it?"

Linkheimer nodded. Once more he broke into a copious perspiration, as he handed a ten-dollar bill to Jake.

"And so," Abe went on, "and so you must of took a hundred-dollar bill out of the safe last night, instead of a ten-dollar bill. Ain't it?"

Linkheimer nodded again.

"And so you made a mistake, ain't it?" Abe cried. "And this here feller Schenkmann didn't took no money out of the safe at all. Ain't it?"

For the third time Linkheimer nodded, and Abe turned to his partner.

"What d'ye think of that feller?" he said, nodding his head in Linkheimer's direction.

Morris shrugged, and Abe plunged his hands into his trousers pockets and glared at Linkheimer.

"So, Linkheimer," he concluded, "you made a sucker out of yourself and out of me too! Ain't it?"

"I'm sorry, Abe," Linkheimer muttered, as he folded away the hundred-dollar bill in his wallet.

"I bet yer he's sorry," Morris interrupted. "I would be sorry too if I would got a lawsuit on my hands like he's got it."

"What d'ye mean?" Linkheimer cried. "I ain't got no lawsuit on my hands."

"Not yet," Morris said significantly, "but when Feldman hears of this, you would quick get a summons for a couple of thousand dollars damages which you done this young feller Schenkmann by making him false arrested."

"It ain't no more than you deserve, Linkheimer," Abe added. "You're lucky I don't sue you for trying to make trouble between me and my partner yet."

For one brief moment Linkheimer regarded Abe sorrowfully. There were few occasions to which Linkheimer could not do justice with a cut-and-dried sentiment or a well-worn aphorism, and he was about to expatiate on ingratitude in business when Abe forestalled him.

"Another thing I wanted to say to you, Linkheimer," Abe said; "you shouldn't wait until the first of the month to send us a statement. Mail it to-night yet, because we give you notice we close your account right here and now."

One week later Abe and Morris watched Nathan Schenkmann driving nails into the top of a packing case with a force and precision of which Jake had been wholly incapable; for seven days of better housing and better feeding had done wonders for Nathan.

"Yes, Abe," Morris said as they turned away; "I think we made a find in that boy, and we also done a charity too. Some people's got an idee, Abe, that business is always business; but with me I think differencely. You could never make no big success in business unless you got a little sympathy for a feller oncet in a while. Ain't it?"

Abe nodded.

"I give you right, Mawruss," he said.

There was an intimate connection between Abe Potash's advent in the lobby of the Prince Clarence Hotel one hot summer day in June and the publication in that morning's Arrival of Buyers column of the following statement and news item:

Griesman, M., Dry Goods Company, Syracuse; M. Griesman, ladies' and misses' cloaks, suits, waists, and furs; Prince Clarence Hotel. |

Nevertheless, when Abe caught sight of Mr. Griesman lolling in one of the hotel's capacious fauteuils he quickly looked the other way and passed on to the clerk's desk. Then he asked in a loud tone for Mr. Elkan Reinberg, of Boonton, New Jersey; and, almost before the clerk told him that no such person was registered, he turned about and recognized Mr. Griesman with an elaborate start.

"Why, how do you do, Mr. Griesman?" he exclaimed. "Ain't it a pleasure to see you! What are you doing here in New York?"

Griesman looked hard at his interlocutor before replying.

Some two years earlier there had been an acrimonious correspondence between them with reference to a shipment of skirts lost in transit—a correspondence ending in threatened litigation; and Mr. Griesman had transferred his account with Potash & Perlmutter to Sammet Brothers. Hence he regarded Abe's proffered hand coldly, and instead of rising to his feet he continued to puff at his cigar for a few moments.

"I know your face," he said at length, "but your name ain't familiar."

"Think again, Mr. Griesman," Abe said, quite unmoved by the rebuff. "Where did you seen me before?"

"I think I seen you in a law office oncet," Griesman said. "To the best of my recollection the occasion was one which you said you didn't give a damn about my business at all, and if I wouldn't pay for the skirts you would make it hot for me. But so far what I hear it, I ain't paid for the skirts, and I didn't sweat none either."

"Why not let bygones be bygones, Mr. Griesman?" Abe rejoined.

"I ain't got no bygones, Abe," Griesman replied. "The bygones is all on your side. I ain't got the skirts; so I didn't pay for 'em."

"Well, what is a few skirts that fellers should be enemies about 'em, Mr. Griesman? The skirts is vorbei schon long since already. Why don't you anyhow come down to our place oncet in a while and see us, Moe?"

"What would I do in your place, Abe?"

"You still use a couple garments, like we make it, in your business, Moe," Abe continued. "You got to buy goods in New York oncet in a while. Ain't it?"

"Well, I do and I don't, Abe," Moe rejoined. "I ain't the back number which I oncet used to was, Abe. I got fresh idees a little too, Abe. Nowadays, Abe, a buyer couldn't rely on his own judgment at all. Before he buys a new season's goods he's got to find out what they're wearing on the other side first. So with me, Abe, I go first to Paris, Abe. Then I see there what I want to buy here, Abe, and when I come back to New York I buy only them goods which has got the idees I seen it in Paris."

"But how do you know we ain't got the idees you would seen it in Paris, Moe?"

"I don't know, Abe," Moe replied, "because I ain't been to Paris yet so far. I am now on my way over to Paris, Abe; and furthermore, Abe, if I would been to Paris, y'understand, what does a feller like Mawruss know about designing?"

"What d'ye mean, what does a feller like Mawruss know about designing?" Abe repeated. "Don't you fool yourself, Moe; Mawruss is a first-class, A number one designer. He gets his idees straight from the best fashion journals. Then too, Moe, when it comes to up-to-date styles, I ain't such a big fool neither, y'understand. I know one or two things about designing myself, Moe, and you could take it from me, Moe, there ain't no house in the trade, Moe, which they got better facilities for giving you the latest up-to-the-minute style like we got it."

"Sure, I know," Moe continued; "but as I told it you before, Abe, I ain't in the market for my fall goods now. I am now only on my way to Paris, and when I would come back it would be time for you to waste your breath."

"I could waste my breath all I want to, Moe," Abe rejoined. "I ain't like some people, Moe; my breath don't cost me nothing."

"What d'ye mean?" Moe cried indignantly. He had allowed himself the unusual indulgence of a cocktail that morning as a corollary to a rather turbulent evening with Leon Sammet, and he had been absently chewing a clove throughout the interview with Abe.

"I mean Hymie Salzman, designer for Sammet Brothers," Abe replied. "There's a feller which he got it such a breath, Moe, he ought to put a revenue stamp on his chin."

"That may be, Abe; but the feller delivers the goods. Sammet Brothers are sending him to Paris this year too, Abe. He is sailing with Leon Sammet on the same ship with me, Abe."

"Well, then all I could say to you is, Moe, you should look out for yourself and don't play no auction pinocle with that feller. Every afternoon he is playing with such sharks like Moe Rabiner and Marks Pasinsky, and if he ever got out of a job as designer he could go on the stage at one of them continual performances as a card juggler yet. A three-fifty hand is the least that feller deals himself."

"One thing is sure, Abe, you couldn't never sell me no goods by knocking Hymie Salzman."

"I ain't trying to sell you no goods, Moe; I am only talking to you like an old friend should talk to another. When are you coming back?"

"About July 1st I should be here," Moe replied, "and if you want to come and see me like an old friend, Abe, you are welcome. Only I got to say this to you, Abe, I forgot them skirts long since ago already, and I wish you the same."

When Abe entered his showroom that morning Morris Perlmutter had just arranged a high-neck evening gown on a wire model.

"Well, Abe, what d'ye think of it?" he exclaimed proudly, as he wiped his glistening brow. Abe fingered the garment's silken folds and puffed critically at a black cigar.

"What could I think, Mawruss?" he replied. "The garment looks all right, Mawruss, and I ain't kicking, y'understand; but I tell you the honest truth, Mawruss, the way things is nowadays, Mawruss, a feller could be Elijah the Prophet already, and he couldn't tell in June what is going to please the garment buyers in September."

Morris flushed angrily.

"I don't know what comes over you lately, Abe; nothing suits you," he cried. "I got here a garment which if we would be paying a designer ten thousand dollars a year yet he couldn't turn us out nothing better, and yet you are kicking."

"What d'ye mean, kicking?" Abe rejoined. "I ain't kicking. I am only passing a remark, Mawruss. I am saying I couldn't tell nothing about it, Mawruss, because so far ahead of time like this, Mawruss, a garment could look ever so rotten, Mawruss, and it could turn out to be a record-seller anyhow."

"So, Abe," Morris broke out furiously, "you think the garment looks rotten! What? Well, all I got to say is this, Abe; if the garment looks so rotten you should quick hire some one which could design a better one, because I am sick and tired of your kicking."

"What's the matter, you got pepper up your nose all of a sudden, Mawruss?" Abe protested. "I ain't saying nothing about the garment is rotten. I am only saying it gets so nowadays that in June a feller turns out a style which if we was making masquerade costumes already it would be freaky anyhow; and yet, Mawruss, it would go big in September. You get the idee what I am talking about, Mawruss?"

"I get the idee all right," Morris retorted with bitter emphasis. "You got the nerve to stand there and tell me this here garment is freaky like a masquerade costume. Schon gut, Abe. From now on I wash myself of the whole thing. I am through, Abe. You should right away advertise for a designer."

Abe rose wearily to his feet.

"With a touchy proposition like you, Mawruss," he said, "a feller couldn't open his mouth at all. I ain't saying nothing about you as a designer, Mawruss. All I am saying, Mawruss, is, a designer could be a feller which he is so high-grade like Paquin or any of them Frenchers, but if he gets his idees from fashion papers oder the Daily Cloak and Suit Gazette, Mawruss, then oncet in a while he turns out a sticker."

Morris was stripping the garment from the display form, but he paused to favour his partner with a glare.

"What would you want me to do, then?" he asked. "Make up styles out from my own head, Abe? If I wouldn't get my idees from the fashion papers, Abe, where would I get 'em?"

"Where would you get 'em?" Abe repeated. "Why, where does Hymie Salzman, designer for Sammet Brothers, and Charles Eisenblum, designer for Klinger & Klein, get their idees, Mawruss?"

This was purely a rhetorical question, but as Abe paused to heighten the effect of the peroration, Morris undertook to supply an answer.

"Them suckers don't get their idees, Abe," he said; "they steal 'em. If a concern gets a run on a certain garment, Abe, them two highway robbers makes a duplicate of it before you could turn around your head. That's the kind of cut-throats them fellers is, Abe."

"Sure, I know," Abe continued; "but they got to turn out some garments of their own, Mawruss, and they get their idees right from headquarters. They get their idees from Paris, Mawruss. Only this morning I hear it that Hymie Salzman sails for Paris on Saturday."

"Well, I couldn't stop him, Abe," Morris commented.

"Sure, I know, Mawruss," Abe went on; "but things is very quiet here in the store, Mawruss, and for a month yet we wouldn't do hardly no business. I could get along here all right until, say, July 15th anyhow."

For two minutes Morris looked hard at his partner.

"What are you driving into, Abe?" he asked at length.

"Why, I am driving into this, Mawruss," Abe continued. "Why don't you go to Paris?"

"Me go to Paris!" Morris exclaimed.

"Why not?" Abe murmured. The suggestion did seem preposterous after all.

"Why not!" Morris repeated. "There's a whole lot of reasons why not, Abe, and the first and foremost is that the Atlantic Ocean would got to run dry and they got to build a railroad there first, Abe. I crossed the water just oncet, Abe, and I wouldn't cross it again if I never sold another dollar's worth more goods so long as I live, Abe; and that's all there is to it."

"What are you talking nonsense, Mawruss? On them big boats like the Morrisania there ain't no more motion than if a feller would be going to Coney Island, Mawruss."

"That's all right, Abe," Morris replied firmly. "Me, if I would go to Coney Island, I am taking always the trolley, Abe, from the New York side of the bridge. Furthermore, Abe, if Sammet Brothers sends a drinker like Hymie Salzman to Paris, Abe, they got a right to spend their money the way they want to; but all I got to say is that we shouldn't be afraid they would cop out any of our trade on that account, Abe. Hymie would come home with new idees of tchampanyer wine and not garments, Abe."

"Sure, I know, Mawruss," Abe retorted; "but if you would go over to Paris, Mawruss, you would come back with some new idees which you would turn out some real snappy stuff, Mawruss. As it is, Mawruss, with a sticker like you got it there, Mawruss, we would ruin our business."

"All right, Abe; I heard enough. You got altogether too much to say for a feller which comes downtown at ten o'clock with no excuse nor nothing."

At this point Abe interrupted his partner long enough to relate his visit to Moe Griesman, but the information entirely failed to placate Morris.

"All right, Abe," he shouted; "why don't you go to Paris? That's all you're fit for. I got a wife and baby, Abe; but with a feller which he has got no more interest in his home, y'understand, than he wants to go to Paris, Abe—all right! Go ahead, Abe; go to Paris. I am satisfied."

Abe regarded his partner for one hesitating moment.

"Schon gut, I will go to Paris," he said; and the next moment the elevator door closed behind him.

For five minutes after Abe's departure Morris gazed earnestly at his newest creation. He had intended the model as a pleasant surprise to his partner, since not only had he conceived the garment to be a triumph of the dressmaker's art, but it had been finished far in advance of the season for originating new styles. He had confidently expected an enthusiastic reception of this chef-d'oeuvre; but in view of Abe's scathing criticism, he commenced to doubt his own estimate of the beauty of the dress. Indeed, the longer he looked at it the uglier it appeared, until at length he grabbed it roughly and literally tore it from the wire form. He had rolled it into a ball and was about to cast it into a corner when the elevator door opened and a young lady stepped out.

"Good morning, Mr. Perlmutter," she said.

Morris turned his face in the direction of the speaker and at once his mouth expanded into a broad grin.

"Why, Miss Smith!" he exclaimed as he rushed forward to greet her. "How do you do? Me and Mrs. Perlmutter was just talking about you to-day. How much you think that boy weighs now?"

"Sixteen pounds," Miss Smith replied.

"Twenty-two," Morris cried—"net."

"You don't say so!" said Miss Smith.

"We got you to thank for that, Miss Smith," Morris continued. "The doctor says without you anything could happen."

Miss Smith deprecated this compliment to her professional skill with a smiling shake of the head.

"We wouldn't forget it in a hurry," Morris declared. "Everything what that boy is to-day, Miss Smith, we owe it to you."

"You're making it hard for me, Mr. Perlmutter," Miss Smith replied, "because I've come to ask you a favour."

"A favour?" Morris replied. "You couldn't ask me to do you a favour because it wouldn't be no favour. It would be a pleasure. What could I do for you?"

"I have to leave town to-morrow on a case," Miss Smith explained, "and I need a dress in a hurry, something light for evening wear."

Morris frowned perplexedly.

"That's too bad," he said, "because just at present we got nothing but last year's goods in stock—all except—all except this."

He unfolded the model and shook it out.

"What a pretty dress!" Miss Smith cried, clasping her hands.

"Pretty!" Morris exclaimed. "How could you say it was pretty?"

"It's perfectly stunning," Miss Smith continued. "What size is it, Mr. Perlmutter?"

"The usual size," Morris replied; "thirty-six."

"Why, that's just my size," Miss Smith declared. "Let me see it." Morris handed her the dress and she examined it carefully. "What a pity," she said, "it has a slight rip in front. Somebody's been handling it carelessly."

"Sure, I know," Morris said. "I tore it myself, Miss Smith; but if you really and truly like it, Miss Smith, which I tell you the truth I don't, and my partner neither, you are welcome to it, and I would give you a little piece from the same goods which you could fix up the rip with."

"I couldn't think of it," Miss Smith replied.

"Not at all, Miss Smith. You would do me a favour if you would take it along with you right now."

Miss Smith fairly beamed as she opened her handbag.

"How much is it?" she asked.

"How much is it?" Morris repeated. "Why, Miss Smith, you could take that dress only on one condition. The condition is that you wouldn't pay me nothing for it, and that next fall, when we really got something in stock, you would come in and pick out as many of our highest-price garments as you would want."

Morris's hand shook so with this unusual access of generosity that he could hardly wrap up the garment.

"Also, Miss Smith, I expect you will come up and have dinner with us as soon as you get back from wherever you are going. Already the baby commences to recognize people which he meets, and we want him he should never forget you, Miss Smith."

The cordiality with which Morris ushered Miss Smith into the elevator was in striking contrast to the brusk manner in which he greeted Abe half an hour later.

"Nu!" he growled. "Where was you now?"

"By the steamship office," Abe replied. "I am going next Saturday."

"Going next Saturday?" Morris repeated. "Where to?"

"To Paris," Abe replied, "on the same ship with Moe Griesman, Leon Sammet and Hymie Salzman."

Morris nodded slowly as the news sank in.

"Well, all I could say is, Abe," he commented at length, "that I don't wish you and the other passengers no harm, y'understand; but, with them three suckers on board the ship, I hope it sinks."

The five days preceding Abe's departure were made exceedingly busy for him by Morris, who soon became reconciled to his partner's fashion-hunting trip, particularly when he learned that Moe Griesman formed part of the quarry.

"You got to remember one thing, Abe," he declared. "Extremes is nix. Let the other feller buy the freaks; what we are after is something in moderation."

"You shouldn't worry about that, Mawruss," Abe replied. "I wouldn't bring you home no such model like you showed it me this week."

"You would be lucky if you wouldn't bring home worser yet," Morris retorted. "But anyhow that ain't the point. I got here the names of a couple commission men which it is their business to look out for greenhorns."

"What d'ye mean, greenhorn?" Abe cried indignantly. "I ain't no greenhorn."

"That's all right," Morris went on; "in France only the Frenchers ain't greenhorns. You ain't told me what kind of a stateroom you got it."

"Well, the outside rooms was one hundred and twenty-five dollars and the inside room, was eight-five dollars," Abe explained; "so I took an inside room because the light wouldn't come in and wake me up so early in the morning, Mawruss, and forty dollars is as good to me as it is to them suckers what runs the steamboat company. Ain't it?"

Nevertheless, when Abe found himself in his upper berth the morning after he had parted with Minnie, Rosie, and Morris at the pier, he had reason to regret his economy. He shared his stateroom with a singer of minor operatic rôles, who, as a souvenir of a farewell luncheon ashore, carried into that narrow precinct an odour of garlic that persisted for the entire voyage. In addition, the returning artist smoked Egyptian cigarettes and anointed his generous head of hair with violet brilliantine. Hence it was not until the boat was passing Brow Head that Abe staggered up the companionway to the promenade deck.

"Why, hallo, Abe!" cried a bronzed and bulky figure. "I ain't seen you for almost a week."

"No?" Abe murmured. "Well, if you would wanted to seen me, Leon, you knew where you could find me: just below the pantry my stateroom was, inside. A dawg shouldn't got to live in such a place."

At this juncture Salzman appeared to summon his employer to a game of auction pinocle in the smoking room, and as Abe started to make a feeble promenade around the deckhouse he encountered Moe Griesman. After Moe had taken Abe's hand in a limp clasp he nodded in the direction of the smoking room.

"What d'ye think of them two suckers?" he croaked. "They ain't missed a meal since they came aboard."

"What could you expect from a couple of tough propositions like that?" Abe replied. "Was you sick, Moe?"

"Sick!" Griesman exclaimed. "I give you my word, Abe, last Thursday night I was so sick that I commenced to figure out already how much I would of saved in premiums if my insurings policies would be straight life instead of endowment. No, Abe; this here business of going to Paris for your styles ain't what it's cracked up to be. Always up to now I got fine weather crossing, but the way the water has been the last six days, Abe, I am beginning to think I could get just so good idees of the season's models right in New York."

"D'ye know, Moe," said Abe, "I'm starting to feel hungry? I wish that feller with the shofar would come."

Hardly had he spoken when the ship's bugler announced luncheon, but it was some minutes before Moe could summon up sufficient courage to go below to the dining saloon, and when they entered they found Leon Sammet and Hymie Salzman had nearly concluded their meal.

"Steward," Leon shouted as Moe sat down next to him, "bring me a nice piece of Camembert cheese."

"One moment, Leon," Griesman interrupted; "if you bring that stuff under my nose here I would never buy from you a dollar's worth more goods so long as I live!"

"The feller goes too far, Abe," he said, after Leon had cancelled the order and departed to drink his coffee in the smoking room. "The feller goes too far. Yesterday afternoon I was sitting on deck, and the way I felt, Abe, my worst enemy wouldn't got to feel it. Do you believe me, Abe, that feller got the nerve to offer me a cigar yet! It pretty near finished me up. He only done it out of spite, Abe, but I fooled him. I took the cigar and I got it in my pocket right now."

"Don't show me," Abe cried hurriedly. "I'll tell you the truth: there ain't nothing in the smoking habit. I'm going to cut it out. Waiter, bring me only a plate of clear soup and some dry toast. There ain't no need for a feller to smoke, Moe; it's only an extra expense."

"I think you're right, Abe," Moe said; "but I know that this here cigar cost Leon a quarter on board ship here, and I thought I would show him he shouldn't get so gay."

Despite Abe's resolution, however, a large black cigar protruded from his moustache when he stood on the wharf at Cherbourg, twenty-four hours later, and a small, ill-shaven stevedore, clad in a dark blouse and shabby corduroy trousers, pointed to the cloud of smoke that issued from Abe's lips and chattered a voluble protest.

"What does he say, Moe?" Abe asked.

"I don't know," Moe replied. "He's talking French."

"French!" Abe exclaimed. "What are you trying to do—kid me? A dirty schlemiel of a greenhorn like him should talk French! What an idee!"

Nevertheless, Abe was made to throw away his cigar, and it was not until the quartette were snugly enclosed in a first-class compartment en route to Paris that Abe felt safe to indulge in another cigar. He explored his pockets, but without result.

"Moe," he said, "do you got maybe another cigar on you?"

"I'm smoking the one which Leon give it me on the ship the other day," Moe replied. "Leon, be a good feller; give him a cigar."

"I give you my word, Moe, this is the last one," Leon replied as he bit the end off a huge invincible.

"You got something there bulging in your vest pocket, Abe. Why don't you smoke it?"

"That ain't a cigar," Abe answered; "that's a fountain pen."

"Smoke it anyhow," Leon advised; "because the only cigars you could get on this train is French Government cigars, and I'd sooner tackle a fountain pen as one of them rolls of spinach."

"That's a country!" Abe commented. "Couldn't even get a decent cigar here!"

"In Paris you could get plenty good cigars," Hymie Salzman said, and Hymie was right for, at the Gare St. Lazare, M. Adolphe Kaufmann-Levi, commissionnaire, awaited them, his pockets literally spilling red-banded perfectos at every gesture of his lively fingers. M. Kaufmann-Levi spoke English, French, and German with every muscle of his body from the waist up.

"Welcome to France, Mr. Potash," he said. "You had a good voyage, doubtless; because you Americans are born sailors."

"Maybe we are born sailors," Abe admitted, "but I must of grew out of it. I tell you the honest truth, if I could go back by trolley, and it took a year, I would do it."

"The weather is always more settled in July than in August," said M. Kaufmann-Levi, "and I wouldn't worry about the return trip just now. I have rooms for you gentlemen all on one floor of a hotel near the Opera, and taximeters are in waiting. After you have settled we will take dinner together."

Thus it happened that, at half past six that evening, M. Kaufmann-Levi conducted his four guests from the Restaurant Marguery to a sidewalk table of the Café de la Paix, and for almost an hour they watched the crowd making its way to the Opera.

"You see, Moe," Abe said, "everything is tunics this year; tunics oder chiffon overskirts, net collars and yokes."

Moe nodded absently. His eyes were glued to a lady sitting at the next table.

"You got to come to Paris to see 'em, Abe," he murmured. "They don't make 'em like that in America."

"We make as good garments in America as anywhere," Abe protested.

"Garments I ain't talking about at all," Moe whispered hoarsely; "I mean peaches. Did y'ever see anything like that lady there sitting next to you? Look at the get-up, Abe. Ain't it chic?"

"It's a pretty good-looking model, Moe," Abe replied, "but a bit too plain for us. See all the fancy-looking garments there are round here."

"Plain nothing!" Moe muttered. "Look at the way it fits her. I tell you, Abe, the French ladies know how to wear their clothes."

A moment later the couple at the next table passed along toward the Opera, and once more Abe and Moe turned their attention to the crowds on the boulevard.

For the remainder of their stay in Paris Abe and Leon spent their time in a ceaseless hunt for new models and their nights in plying Moe Griesman with entertainment. It cannot be said that Moe discouraged them to any marked degree, for while he occasionally hinted to Abe that the New York cloak and suit trade was an open market, and garment buyers had a large field from which to choose, he also told Leon that he saw no reason why he should not continue to buy goods from Sammet Brothers, provided the prices were right.

Nearly every evening found them sitting at the corner table of the Café de la Paix, and upon many of these occasions the next table was occupied by the same couple that sat there on the night of Abe's arrival in Paris.

"You know, Abe, that dress is the most uniquest thing in Paris," Moe exclaimed on the evening of the last day in Paris. "I ain't seen nothing like it anywhere."

"Good reason, Moe," Leon Sammet cried; "it's rotten. That's one of last year's models."

"What are you talking nonsense? One of the last year's models!" Moe Griesman cried indignantly. "Don't you think I know a new style when I see it?"

"Moe is right, Leon," Abe said. "You ain't got no business to talk that way at all. The style is this year's model."

"Of course, Abe," Leon said with ironic precision, "when a judge like you says something, y'understand, then it's so. Take another of them sixty-cent ice-creams, Moe."

Ordinarily Abe would have turned Leon's sarcasm with a retort in kind, but Leon's remark fell on deaf ears, for Abe was listening to a conversation at the next table and the language was English.

"It's time to start back to the hotel," said the young lady to her escort, who was an elderly gentleman.

Abe turned to Moe and Leon.

"Excuse me for a few minutes," he said; "I got to go back to the hotel for something."

He handed Leon a twenty-franc piece.

"If I shouldn't get back, pay the bill!" he cried, and jumping to his feet he followed the couple from the next table.

The old gentleman walked feebly with the aid of a cane, and the young lady held him by the arm as they proceeded to the main entrance of the Grand Hotel. Abe dogged their footsteps until the old gentleman disappeared into the lift and the young lady retired to the winter garden that forms the interior court of the hotel. As she seated herself in a wicker chair Abe approached with his hat in his hand.

"Lady, excuse me," he began; "I ain't no loafer. I'm in the cloak and suit business, and I would like to speak to you a few words—something very particular."

The young lady turned in her chair. She was not alarmed, only surprised.

"I hope you don't think I am asking you anything out of the way," Abe said, without further prelude; "but you got a dress on, lady, which I don't know how much you paid for it, but if three hundred of these here—now—francs would be any inducement I'd like to buy it from you. Of course I wouldn't ask you to take it off right now, but if you would leave it at the clerk's desk here I could call for it in half an hour."

The young lady made no reply, instead she threw back her head and laughed heartily.

"It ain't no joke, lady," Abe continued as he laid three flimsy notes of the Bank of France in her lap. "That's as good as American greenbacks."

The young lady ceased laughing, and for a minute, hesitated between indignation and renewed mirth, but at last her sense of humour conquered.

"Very well," she said; "stay here for a few minutes."

Half an hour later she returned with the dress wrapped up in a paper parcel.

"How did you know I wouldn't go off with the money, dress and all?" she asked as Abe seized the package.

"I took a chance, lady," he said; "like you are doing about the money which I give you being good."

"Have no scruples on that score," the young lady replied. "I had it examined at the clerk's office just now."

When M. Adolphe Kaufmann-Levi bade farewell to Moe, Abe, Leon, and Hymie Salzman, at the Gare St. Lazare, he uttered words of encouragement and cheer which failed to justify themselves after the four travellers' embarkment at Cherbourg.

"You will have splendid weather," he had declared. "It will be fine all the way over."

When the steamer passed out of the breakwater into the English Channel she breasted a northeaster that lasted all the way to the Banks. Even Hymie Salzman went under, and Leon Sammet walked the swaying decks alone. Twice a day he poked his head into the stateroom occupied by Moe Griesman and Abe Potash, for Abe had thrown economy to the winds and had gone halves with Moe in the largest outside room on board.

"Boys," Leon would ask, "ain't you going to get up? The air is fine on deck."

Had he but known it, Moe Griesman developed day by day, with growing intensity, that violent hatred for Leon that the hopelessly seasick feel toward good sailors; while toward Abe, who groaned unceasingly in the upper berth, Moe Griesman evinced the affectionate interest that the poor sailor evinces in any one who suffers more keenly than himself.

At length Nantucket lightship was passed, and as the sea grew calmer two white-faced invalids, that on close scrutiny might have been recognized by their oldest friends to be Moe and Abe, tottered up the companionway and sank exhausted into the nearest deckchairs.

"Well, Moe," Leon cried, as he bustled toward them smoking a large cigar and clad in a suit of immaculate white flannels, "so you're up again?"

The silence with which Moe received this remark ought to have warned Leon, but he plunged headlong to his fate.

"We are now only twenty hours from New York," he said, "and suppose I go downstairs and bring you up some of them styles which I got in Paris."

"You shouldn't trouble yourself," Moe said shortly.

"Why not?" Leon inquired.

"Because, for all I care," Moe replied viciously, "you could fire 'em overboard. I would oser buy from you a button."

"What's the matter?" Leon cried.

"You know what's the matter," Moe continued.

"You come every day into my stateroom and mock me yet because I am sick."

"I mock you!" Leon exclaimed.

"That's what I said," Moe continued; "and if you wouldn't take that cigar away from here I'll break your neck when I get on shore again."

Leon backed away hurriedly and Moe turned to Abe.

"Am I right or wrong?" he said.

Abe nodded. He was incapable of audible speech, but hour by hour he grew stronger until at dinner-time he was able to partake of some soup and roast beef, and even to listen with a wan smile to Moe's caustic appraisement of Leon Sammet's character. Finally, after a good night's rest, Moe and Abe awoke to find the engine stilled at Quarantine. They were saved the necessity of packing their trunks for the cogent reason that they had been physically unable to open them, let alone unpack them. Hence they repaired at once to breakfast.

Leon was already seated at table, and he hastily cancelled an order for Yarmouth bloater and asked instead for a less fragrant dish.

"Good morning, Moe," he said pleasantly.

Moe turned to Abe. "To-morrow morning at nine o'clock, Abe," he said, "I would be down in your store to look over your line."

"Steward," Leon Sammet cried, "never mind that steak. I would take the bloater anyhow."

Abe and Moe breakfasted lightly on egg and toast, and returned to their stateroom as they passed the Battery.

"Say, lookyhere, Moe," Abe said; "I want to show you something which I bought for you as a surprise the night before we left Paris. I got it right in the top of my suitcase here, and it wouldn't take a minute to show it to you."

Abe was unstrapping his suitcase as he spoke, and the next minute he shook out the gown he had purchased from the young lady of the Cafe de la Paix, and exposed it to Moe's admiring gaze.

"How did you get hold of that, Abe?" Moe asked.

Abe narrated his adventure at the Grand Hotel, while Moe gaped his astonishment.

"I always thought you got a pretty good nerve, Abe," he declared, "but this sure is the limit. How much did you pay for it?"

"Three hundred of them—now—francs," Abe replied; "but I've been figuring out the cost of manufacturing and material, and I could duplicate it in New York for forty dollars a garment."

"You mean thirty-five dollars a garment, don't you?" Moe said.

"No, I don't," Abe replied. "I mean forty dollars a garment. Why do you say thirty-five dollars?"

"Because at forty dollars apiece, Abe, I could use for my Sarahcuse, Rochester, and Buffalo stores about fifty of these garments, and you ought to figure on at least five dollars' profit on a garment."

"Well, maybe I am figuring it a little too generous, y'understand; so, if that goes, Moe, I will quote the selling price at, say, forty dollars a garment to you, Moe."

"Sure, it goes," Moe said; "and I'll be at your store to-morrow morning at nine o'clock to decide on sizes and shades."

Abe's passage through the customs examination was accomplished with ease, for nearly all his Paris purchases were packed in the hold to be cleared by a custom-house broker. His stateroom baggage contained no dutiable articles save the gown in question and a few trinkets for Rosie, who was at the pier to greet him. Indeed, she bestowed on him a series of kisses that reechoed down the long pier, and Abe's pallor gave way to the sunburnt hue of his amused fellow-passengers. In one of them Abe recognized with a start the tanned features of the young lady of the Café de la Paix.

"Moe," he said, nudging Griesman, "there's your friend."

Moe turned in the direction indicated by Abe, and his interested manner was not unnoticed by Mrs. Potash.

"How is your dear wife and daughter, Mr. Griesman?" she asked significantly. "I suppose you missed 'em a whole lot."

When Moe assured her that he did she sniffed so violently that it might have been taken for a snort.

"Well, Abe," he said at length, "I'll be going on to the Prince Clarence, and I'll see you in the store to-morrow morning. Good-by, Mrs. Potash."

"Good-by," Mrs. Potash replied, with an emphasis that implied "good riddance," and then, as Moe disappeared toward the street, she sniffed again. "It don't take long for some loafers to forget their wives!" she said.

"Well, Abe," Morris said, after the first greetings had passed between them that afternoon, "I'm glad to see you back in the store."

"You ain't half so glad to see me back, Mawruss, as I am that I should be back," Abe replied. "Not that the trip ain't paid us, Mawruss, because I got a trunkful of samples on the way up here which I assure you is a work of art."

"Sure, I know!" Morris commented with just a tinge of bitterness in his tones; "Paris is the place for styles. Us poor suckers over here don't know a thing about designing."

"Well, Mawruss, I'll tell you," Abe went on: "you are a first-class, A number one designer, I got to admit, and there ain't nobody that I consider is better as you in the whole garment trade; but"—here he paused to unfasten his suitcase—"but, Mawruss," he continued, "I got here just one sample style which I brought it with me, Mawruss, and I think, Mawruss, you would got to agree with me, such models we don't turn out on this side."

Here he opened the suitcase, and carefully taking out the dress of the Café de la Paix he spread it on a sample table.

"What d'ye think of that, Mawruss?" he asked.

Morris made no answer. He was gazing at the garment with bulging eyes, and beads of perspiration ran down his forehead.

"Abe!" he gasped at length, "where did you get that garment from?"

Before Abe could answer, the elevator door opened and a young lady stepped out. It was now Abe's turn to gasp, for the visitor was no other than the tanned and ruddy young person from the Café de la Paix.

"Good afternoon, Mr. Perlmutter," she said. "I've just got back."

"Oh, good afternoon, Miss Smith!" Morris cried.

"I hope I'm not interrupting you," she continued.

"Not at all," Morris said; "not at all."

Then a wave of recollection came over him, and he muttered a half-smothered exclamation.

"Abe, Miss Smith," he almost shouted, and then he sat down. "Say, lookyhere, Abe, what is all this, anyway? Miss Smith comes in here and—"

"Well, upon my word!" Miss Smith interrupted; "if it isn't the gentleman from the Café de la Paix—and, of all things, there is the very dress!"

Abe shrugged his shoulders.

"That's right, Miss Whatever-your-name is," Abe admitted; "that's the dress, and since I paid you sixty dollars for it I don't think you got any kick coming."

"Sixty dollars!" Morris cried. "Why, that dress as a sample garment only cost us twenty-two-fifty to make up."

"Cost us?" Abe repeated. "As a sample garment? What are you talking about?"

"I am talking about this, Abe," Morris replied: "that dress is the self-same garment which I designed it, and which you says was rotten and freaky, and which I give it to Miss Smith here for a present, and which you paid Miss Smith sixty dollars for."

"And here is the sixty dollars now," Miss Smith broke in. "I hurried here as fast as I could to give it to you, Mr. Perlmutter."

"One moment," Abe said. "I don't know who this young lady is or nothing; but do you mean to told me that this here dress which I bought it in Paris was made up right here in our place?"

"Here, Abe," Morris said, "I want to show you something. Here is from the same goods a garment, and them goods as you know we get it from the Hamsuckett Mills. So far what I hear it, the Hamsuckett Mills don't sell their output in Paris. Am I right or wrong?"

Abe nodded slowly.

"Well, Mr. Perlmutter," Miss Smith said, "here's your sixty dollars. I've got to get back to my patient. You know that I went to Paris with a rheumatic case, and I've left the old gentleman in charge of a friend. I came here to settle up."

"Excuse me," said Abe; "I ain't been introduced to this young lady yet."

"Why, I thought you knew her," Morris said. "This is Miss Smith, the trained nurse which was so good to my Minnie when my Abie was born."

"Is that so?" Abe cried. "Well, Miss Smith, you should take that sixty dollars and keep it, because, Mawruss, on the way over I sold Moe Griesman fifty garments of that there style of yours at forty dollars apiece."

"You don't say so!" Morris cried. "You don't say so! Well, all I got to say is, Miss Smith, in the first place, if Abe wouldn't of told you to keep that sixty dollars I sure would of done so, and in the second place, I want you to come in here next week and pick out half a dozen dresses. Ain't that right, Abe?"

"I bet yer that's right, Mawruss; we wouldn't take no for an answer," Abe replied. "And you should also leave us your name and address, Miss Smith, because, Gott soll hüten, if I should be sick, y'understand, I don't want nobody else to nurse me but you."

"Say, lookyhere, Abe," Morris said the following morning, "that trunkful of Paris samples which the custom-house says we would get this morning ain't come yet."

Abe clapped his partner on the shoulder and grinned happily.

"What do I care, Mawruss?" he said. "For my part they should never come. I ain't got no use for Paris fashions at all. Styles which Mawruss Perlmutter originates is good enough for me, because I always said it, Mawruss, you are a cracker-jack, high-grade, A number one designer!"