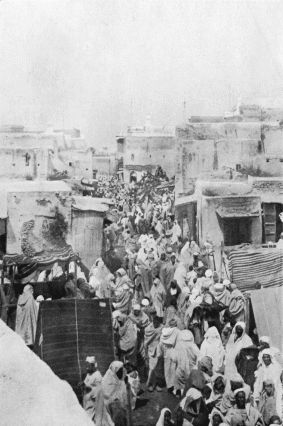

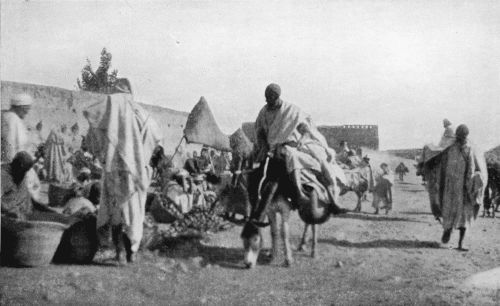

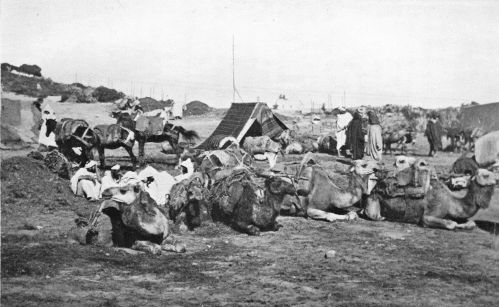

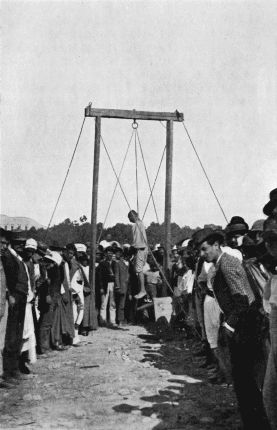

Photograph by Edward Lee, Esq., Saffi.

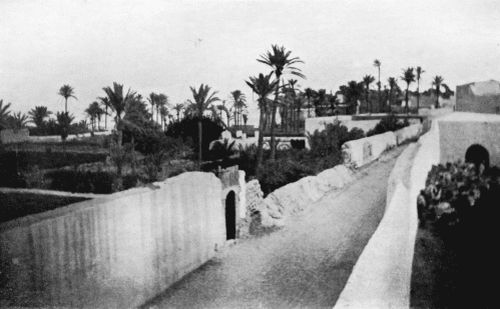

A MOORISH THOROUGHFARE.

Title: Life in Morocco and Glimpses Beyond

Author: Budgett Meakin

Release date: July 6, 2006 [eBook #18764]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Michael Ciesielski, Lesley Halamek and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

In uniform style. Demy 8vo, 15s. each.

THE MOORS: an Account of People and Customs. With 132 Illustrations.

Contents:—"The Madding Crowd"—Within the Gates—Where the Moors Live—How the Moors Dress—Moorish Courtesy and Etiquette—What the Moors Eat and Drink—Everyday Life—Slavery and Servitude—Country Life—Trade—Arts and Manufactures—Matters Medical.

Some Moorish Characteristics—The Mohammedan Year (Feasts and Fasts)—Places of Worship—Alms, Hospitality, and Pilgrimage—Education—Saints and Superstitions—Marriage—Funeral Rites.

The Morocco Berbers—The Jews of Morocco—The Jewish Year.

THE LAND OF THE MOORS: A Comprehensive Description. With a New Map and 83 Illustrations.

Contents:—Physical Features—Natural Resources—Vegetable Products—Animal Life.

Descriptions and Histories of Tangier, Tetuan, Laraiche, Salli-Rabat, Dar el Baida, Mazagan, Saffi and Mogador; Azîla, Fedála, Mehedia, Mansûrîya, Azammûr and Waladîya; Fez, Mequinez and Marrákesh; Zarhôn, Wazzán and Shesháwan; El Kasar, Sifrû, Tadla, Damnát, Táza, Dibdû and Oojda; Ceuta, Velez, Alhucemas, Melilla and the Zaffarines; Sûs, the Draa, Tafilált, Fîgîg, and Tûát.

Reminiscences of Travel—In the Guise of a Moor—To Marrákesh on a Bicycle—In Search of Miltsin.

THE MOORISH EMPIRE: A Historical Epitome. With Maps, 118 Illustrations, and a unique Chronological, Geographical, and Genealogical Chart.

Contents:—Mauretania—The Mohammedan Invasion—Foundation of Empire—Consolidation of Empire—Extension of Empire—Contraction of Empire—Stagnation of Empire—Personification of Empire—The Reigning Shareefs—The Moorish Government—Present Administration.

Europeans in the Moorish Service—The Salli Rovers—Record of the Christian Slaves—Christian Influences in Morocco—Foreign Relations—Moorish Diplomatic Usages—Foreign Rights and Privileges—Commercial Intercourse—The Fate of the Empire.

Works on Morocco reviewed (213 vols. in 11 languages)—The Place of Morocco in Fiction—Journalism in Morocco—Works Recommended—Classical Authorities on Morocco.

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARABIC OF MOROCCO: Vocabulary, Grammar Notes, Etc., in Roman Characters. Specially prepared for Visitors and Beginners on a new and eminently practical system.

Crown 8vo, Cloth, Round Corners for Pocket, 6s.

Also, Uniform with this, in English or Spanish, Price 4s.

Photograph by Edward Lee, Esq., Saffi.

A MOORISH THOROUGHFARE.

Which of us has yet forgotten that first day when we set foot in Barbary? Those first impressions, as the gorgeous East with all its countless sounds and colours, forms and odours, burst upon us; mingled pleasures and disgusts, all new, undreamed-of, or our wildest dreams enhanced! Those yelling, struggling crowds of boatmen, porters, donkey-boys; guides, thieves, and busy-bodies; clad in mingled finery and tatters; European, native, nondescript; a weird, incongruous medley—such as is always produced when East meets West—how they did astonish and amuse us! How we laughed (some trembling inwardly) and then, what letters we wrote home!

One-and-twenty years have passed since that experience entranced the present writer, and although he has repeated it as far as possible in practically every other oriental country, each fresh visit to Morocco brings back somewhat of the glamour of that maiden plunge, and somewhat of that youthful ardour, as the old associations are renewed. Nothing he has seen elsewhere excels Morocco in point of life and colour save Bokhára; and[page vi] only in certain parts of India or in China is it rivalled. Algeria, Tunisia and Tripoli have lost much of that charm under Turkish or western rule; Egypt still more markedly so, while Palestine is of a population altogether mixed and heterogeneous. The bazaars of Damascus, even, and Constantinople, have given way to plate-glass, and nothing remains in the nearer East to rival Morocco.

Notwithstanding the disturbed condition of much of the country, nothing has occurred to interfere with the pleasure certain to be afforded by a visit to Morocco at any time, and all who can do so are strongly recommended to include it in an early holiday. The best months are from September to May, though the heat on the coast is never too great for an enjoyable trip. The simplest way of accomplishing this is by one of Messrs. Forwood's regular steamers from London, calling at most of the Morocco ports and returning by the Canaries, the tour occupying about a month, though it may be broken and resumed at any point. Tangier may be reached direct from Liverpool by the Papayanni Line, or indirectly viâ Gibraltar, subsequent movements being decided by weather and local sailings. British consular officials, missionaries, and merchants will be found at the various ports, who always welcome considerate strangers.

Comparatively few, even of the ever-increasing number of visitors who year after year bring this only remaining independent Barbary State within[page vii] the scope of their pilgrimage, are aware of the interest with which it teems for the scientist, the explorer, the historian, and students of human nature in general. One needs to dive beneath the surface, to live on the spot in touch with the people, to fathom the real Morocco, and in this it is doubtful whether any foreigners not connected by ties of creed or marriage ever completely succeed. What can be done short of this the writer attempted to do, mingling with the people as one of themselves whenever this was possible. Inspired by the example of Lane in his description of the "Modern Egyptians," he essayed to do as much for the Moors, and during eighteen years he laboured to that end.

The present volume gathers together from many quarters sketches drawn under those circumstances, supplemented by a resumé of recent events and the political outlook, together with three chapters—viii., xi., and xiv.—contributed by his wife, whose assistance throughout its preparation he has once more to acknowledge with pleasure. To many correspondents in Morocco he is also indebted for much valuable up-to-date information on current affairs, but as most for various reasons prefer to remain unmentioned, it would be invidious to name any. For most of the illustrations, too, he desires to express his hearty thanks to the gentlemen who have permitted him to reproduce their photographs.

Much of the material used has already appeared[page viii] in more fugitive form in the Times of Morocco, the London Quarterly Review, the Forum, the Westminster Review, Harper's Magazine, the Humanitarian, the Gentleman's Magazine, the Independent (New York), the Modern Church, the Jewish Chronicle, Good Health, the Medical Missionary, the Pall Mall Gazette, the Westminster Gazette, the Outlook, etc., while Chapters ix., xix., and xxv. to xxix. have been extracted from a still unpublished picture of Moorish country life, "Sons of Ishmael."

Hampstead,

November 1905.

| CHAPTER |

PAGE | ||

| I. | RETROSPECTIVE | 1 | |

| II. | THE PRESENT DAY | 14 | |

| III. | BEHIND THE SCENES | 36 | |

| IV. | THE BERBER RACE | 47 | |

| V. | THE WANDERING ARAB | 57 | |

| VI. | CITY LIFE | 63 | |

| VII. | THE WOMEN-FOLK | 71 | |

| VIII. | SOCIAL VISITS | 82 | |

| IX. | A COUNTRY WEDDING | 88 | |

| X. | THE BAIRNS | 94 | |

| XI. | "DINING OUT" | 102 | |

| XII. | DOMESTIC ECONOMY | 107 | |

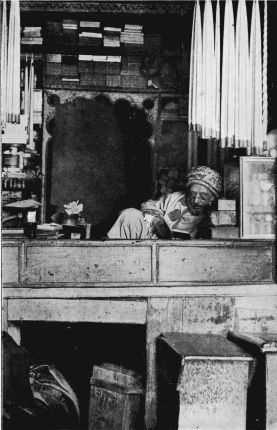

| XIII. | THE NATIVE "MERCHANT" | 113 | |

| XIV. | SHOPPING | 118 | |

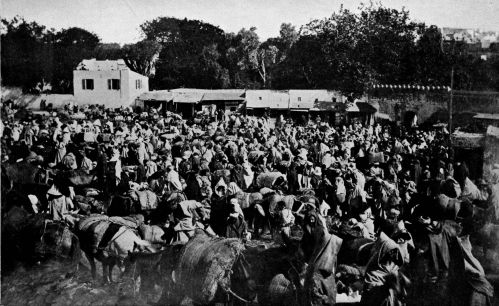

| XV. | A SUNDAY MARKET | 125 | |

| XVI. | PLAY-TIME | 133 | |

| XVII. | THE STORY-TELLER | 138 | |

| XVIII. | SNAKE-CHARMING | 151 | |

| XIX. | IN A MOORISH CAFÉ | 159 | |

| XX. | THE MEDICINE-MAN | 166 | |

| XXI. | THE HUMAN MART | 179 | |

| XXII. | A SLAVE-GIRL'S STORY | 185 | |

| XXIII. | THE PILGRIM CAMP | 191 | |

| XXIV. | RETURNING HOME | 201 | |

| XXV. | DIPLOMACY IN MOROCCO | 205 |

| XXVI. | PRISONERS AND CAPTIVES | 233 |

| XXVII. | THE PROTECTION SYSTEM | 242 |

| XXVIII. | JUSTICE FOR THE JEW | 252 |

| XXIX. | CIVIL WAR IN MOROCCO | 261 |

| XXX. | THE POLITICAL SITUATION | 267 |

| XXXI. | FRANCE IN MOROCCO | 292 |

| XXXII. | ALGERIA VIEWED FROM MOROCCO | 307 |

| XXXIII. | TUNISIA VIEWED FROM MOROCCO | 318 |

| XXXIV. | TRIPOLI VIEWED FROM MOROCCO | 326 |

| XXXV. | FOOT-PRINTS OF THE MOORS IN SPAIN | 332 |

| "MOROCCO NEWS" | 381 | |

| INDEX | 395 |

Note.—The system of transliterating Arabic adopted by the Author in his previous works has here been followed only so far as it is likely to be adopted by others than specialists, all signs being omitted which are not essential to approximate pronunciation.

"The firmament turns, and times are changing."

Moorish Proverb.

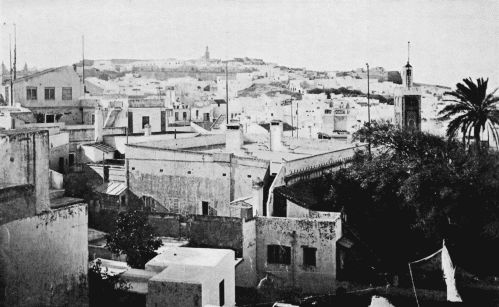

By the western gate of the Mediterranean, where the narrowed sea has so often tempted invaders, the decrepit Moorish Empire has become itself a bait for those who once feared it. Yet so far Morocco remains untouched, save where a fringe of Europeans on the coast purvey the luxuries from other lands that Moorish tastes demand, and in exchange take produce that would otherwise be hardly worth the raising. Even here the foreign influence is purely superficial, failing to affect the lives of the people; while the towns in which Europeans reside are so few in number that whatever influence they do possess is limited in area. Moreover, Morocco has never known foreign dominion, not even that of the Turks, who have left their impress on the neighbouring Algeria and Tunisia. None but the Arabs have succeeded in obtaining a foothold among its Berbers, and they, restricted to the plains, have long become part of [page 2] the nation. Thus Morocco, of all the North African kingdoms, has always maintained its independence, and in spite of changes all round, continues to live its own picturesque life.

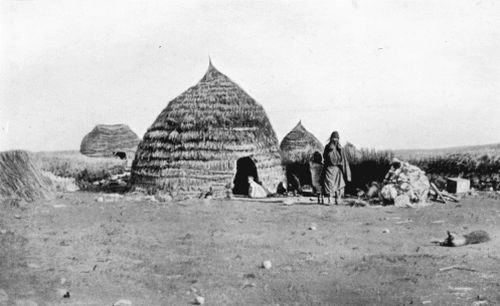

Picturesque it certainly is, with its flowing costumes and primitive homes, both of which vary in style from district to district, but all of which seem as though they must have been unchanged for thousands of years. Without security for life or property, the mountaineers go armed, they dwell in fortresses or walled-in villages, and are at constant war with one another. On the plains, except in the vicinity of towns, the country people group their huts around the fortress of their governor, within which they can shelter themselves and their possessions in time of war. No other permanent erection is to be seen on the plains, unless it be some wayside shrine which has outlived the ruin fallen on the settlement to which it once belonged, and is respected by the conquerors as holy ground. Here and there gaunt ruins rise, vast crumbling walls of concrete which have once been fortresses, lending an air of desolation to the scene, but offering no attraction to historian or antiquary. No one even knows their names, and they contain no monuments. If ever more solid remains are encountered, they are invariably set down as the work of the Romans.

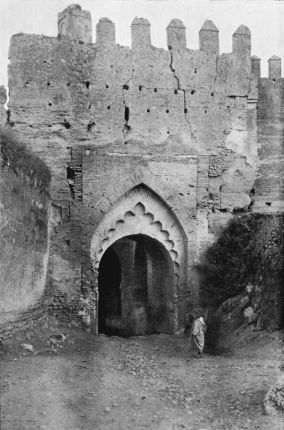

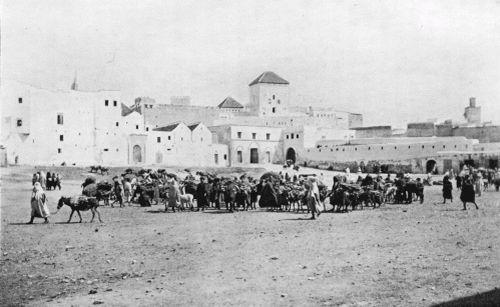

Cavilla, Photo., Tangier.

GATE OF THE SEVEN VIRGINS, SALLI.

Yet Morocco has a history, an interesting history indeed, one linked with ours in many curious ways, as is recorded in scores of little-known volumes. It has a literature amazingly voluminous, but there were days when the relations with other lands were much closer, if less cordial, the days of the crusades and the Barbary pirates, the days of European[page 3] tribute to the Moors, and the days of Christian slavery in Morocco. Constantly appearing brochures in many tongues made Europe of those days acquainted with the horrors of that dreadful land. All these only served to augment the fear in which its people were held, and to deter the victimized nations from taking action which would speedily have put an end to it all, by demonstrating the inherent weakness of the Moorish Empire.

But for those whose study is only the Moors as they exist to-day, the story of Morocco stretches back only a thousand years, as until then its scattered tribes of Berber mountaineers had acknowledged no head, and knew no common interests; they were not a nation. War was their pastime; it is so now to a great extent. Every man for himself, every tribe for itself. Idolatry, of which abundant traces still remain, had in places been tinged with the name and some of the forms of Christianity, but to what extent it is now impossible to discover. In the Roman Church there still exist titular bishops of North Africa, one, in particular, derives his title from the district of Morocco of which Fez is now the capital, Mauretania Tingitana.

It was among these tribes that a pioneer mission of Islám penetrated in the eighth of our centuries. Arabs were then greater strangers in Barbary than we are now, but they were by no means the first strange faces seen there. Phœnicians, Romans and Vandals had preceded them, but none had stayed, none had succeeded in amalgamating with the Berbers, among whom those individuals who did remain were absorbed. These hardy clansmen,[page 4] exhibiting the characteristics of hill-folk the world round, still inhabited the uplands and retained their independence. In this they have indeed succeeded to a great extent until the present day, but between that time and this they have given of their life-blood to build up by their side a less pure nation of the plains, whose language as well as its creed is that of Arabia.

To imagine that Morocco was invaded by a Muslim host who carried all before them is a great mistake, although a common one. Mulai Idrees—"My Lord Enoch" in English—a direct descendant of Mohammed, was among the first of the Arabian missionaries to arrive, with one or two faithful adherents, exiles fleeing from the Khalîfa of Mekka. So soon as he had induced one tribe to accept his doctrines, he assisted them with his advice and prestige in their combats with hereditary enemies, to whom, however, the novel terms were offered of fraternal union with the victors, if they would accept the creed of which they had become the champions. Thus a new element was introduced into the Berber polity, the element of combination, for the lack of which they had always been weak before. Each additional ally meant an augmentation of the strength of the new party out of all proportion to the losses from occasional defeats.

In course of time the Mohammedan coalition became so strong that it was in a position to dictate terms and to impose governors upon the most obstinate of its neighbours. The effect of this was to divide the allies into two important sections, the older of which founded Fez in the days of the son[page 5] of Idrees, accounted the second ameer of that name, who there lies buried in the most important mosque of the Empire, the very approaches of which are closed to the Jew and the Nazarene. The only spot which excels it in sanctity is that at Zarhôn, a day's journey off, in which the first Idrees lies buried. There the whole town is forbidden to the foreigner, and an attempt made by the writer to gain admittance in disguise was frustrated by discovery at the very gate, though later on he visited the shrine in Fez. The dynasty thus formed, the Shurfà Idreeseeïn, is represented to-day by the Shareef of Wazzán.

In southern Morocco, with its capital at Aghmát, on the Atlas slopes, was formed what later grew to be the kingdom of Marrákesh, the city of that name being founded in the middle of the eleventh century. Towards the close of the thirteenth, the kingdoms of Fez and Marrákesh became united under one ruler, whose successor, after numerous dynastic changes, is the Sultan of Morocco now.*

But from the time that the united Berbers had become a nation, to prevent them falling out among themselves again it was necessary to find some one else to fight, to occupy the martial instinct nursed in fighting one another. So long as there were ancient scores to be wiped out at home, so long as under cover of a missionary zeal they could continue intertribal feuds, things went well for the victors; but as soon as excuses for this grew scarce, it was needful to fare afield. The pretty story—told,[page 6] by the way, of other warriors as well—of the Arab leader charging the Atlantic surf, and weeping that the world should end there, and his conquests too, may be but fiction, but it illustrates a fact. Had Europe lain further off, the very causes which had conspired to raise a central power in Morocco would have sufficed to split it up again. This, however, was not to be. In full view of the most northern strip of Morocco, from Ceuta to Cape Spartel, the north-west corner of Africa, stretches the coast of sunny Spain. Between El K'sar es-Sagheer, "The Little Castle," and Tarifa Point is only a distance of nine or ten miles, and in that southern atmosphere the glinting houses may be seen across the straits.

History has it that internal dissensions at the Court of Spain led to the Moors being actually invited over; but that inducement was hardly needed. Here was a country of infidels yet to be conquered; here was indeed a land of promise. Soon the Berbers swarmed across, and in spite of reverses, carried all before them. Spain was then almost as much divided into petty states as their land had been till the Arabs taught them better, and little by little they made their way in a country destined to be theirs for five hundred years. Córdova, Sevílle, Granáda, each in turn became their capital, and rivalled Fez across the sea.

The successes they achieved attracted from the East adventurers and merchants, while by wise administration literature and science were encouraged, till the Berber Empire of Spain and Morocco took a foremost rank among the nations of the day. Judged from the standpoint of their time, they seem to us a[page 7] prodigy; judged from our standpoint, they were but little in advance of their descendants of the twentieth century, who, after all, have by no means retrograded, as they are supposed to have done, though they certainly came to a standstill, and have suffered all the evils of four centuries of torpor and stagnation. Civilization wrought on them the effects that it too often produces, and with refinement came weakness. The sole remaining state of those which the invaders, finding independent, conquered one by one, is the little Pyrenean Republic of Andorra, still enjoying privileges granted to it for its brave defence against the Moors, which made it the high-water mark of their dominion. As peace once more split up the Berbers, the subjected Spaniards became strong by union, till at length the death-knell of Moorish rule in Europe sounded at the nuptials of the famous Ferdinand and Isabella, linking Aragon with proud Castile.

Expelled from Spain, the Moor long cherished plans for the recovery of what had been lost, preparing fleets and armies for the purpose, but in vain. Though nominally still united, his people lacked that zeal in a common cause which had carried them across the straits before, and by degrees the attempts to recover a kingdom dwindled into continued attacks upon shipping and coast towns. Thus arose that piracy which was for several centuries the scourge of Christendom. Further east a distinct race of pirates flourished, including Turks and Greeks and ruffians from every shore, but they were not Moors, of whom the Salli rover was the type. Many thousands of Europeans were carried off by Moorish corsairs into slavery, including not[page 8] a few from England. Those who renounced their own religion and nationality, accepting those of their captors, became all but free, only being prevented from leaving the country, and often rose to important positions. Those who had the courage of their convictions suffered much, being treated like cattle, or worse, but they could be ransomed when their price was forthcoming—a privilege abandoned by the renegades—so that the principal object of every European embassy in those days was the redemption of captives. Now and then escapes would be accomplished, but such strict watch was kept when foreign merchantmen were in port, or when foreign ambassadors came and went, that few attempts succeeded, though many were made.

Sympathies are stirred by pictures of the martyrdom of Englishmen and Irishmen, Franciscan missionaries to the Moors; and side by side with them the foreign mercenaries in the native service, Englishmen among them, who would fight in any cause for pay and plunder, even though their masters held their countrymen in thrall. And thrall it was, as that of Israel in Egypt, when our sailors were chained to galley seats beneath the lash of a Moor, or when they toiled beneath a broiling sun erecting the grim palace walls of concrete which still stand as witnesses of those fell days. Bought and sold in the market like cattle, Europeans were more despised than Negroes, who at least acknowledged Mohammed as their prophet, and accepted their lot without attempt to escape.

Dark days were those for the honour of Europe, when the Moors inspired terror from the Balearics to the Scilly Isles, and when their rovers swept the[page 9] seas with such effect that all the powers of Christendom were fain to pay them tribute. Large sums of money, too, collected at church doors and by the sale of indulgences, were conveyed by the hands of intrepid friars, noble men who risked all to relieve those slaves who had maintained their faith, having scorned to accept a measure of freedom as the reward of apostasy. Thousands of English and other European slaves were liberated through the assistance of friendly letters from Royal hands, as when the proud Queen Bess addressed Ahmad II., surnamed "the Golden," as "Our Brother after the Law of Crown and Sceptre," or when Queen Anne exchanged compliments with the bloodthirsty Ismáïl, who ventured to ask for the hand of a daughter of Louis XIV.

In the midst of it all, when that wonderful man, with a household exceeding Solomon's, and several hundred children, had reigned forty-three of his fifty-five years, the English, in 1684, ceded to him their possession of Tangier. For twenty-two years the "Castle in the streights' mouth," as General Monk had described it, had been the scene of as disastrous an attempt at colonization as we have ever known: misunderstanding of the circumstances and mismanagement throughout; oppression, peculation and terror within as well as without; a constant warfare with incompetent or corrupt officials within as with besieging Moors without; till at last the place had to be abandoned in disgust, and the expensive mole and fortifications were destroyed lest others might seize what we could not hold.

Such events could only lower the prestige of [page 10] Europeans, if, indeed, they possessed any, in the eyes of the Moors, and the slaves up country received worse treatment than before. Even the ambassadors and consuls of friendly powers were treated with indignities beyond belief. Some were imprisoned on the flimsiest pretexts, all had to appear before the monarch in the most abject manner, and many were constrained to bribe the favourite wives of the ameers to secure their requests. It is still the custom for the state reception to take place in an open courtyard, the ambassador standing bareheaded before the mounted Sultan under his Imperial parasol. As late as 1790 the brutal Sultan El Yazeed, who emulated Ismáïl the Bloodthirsty, did not hesitate to declare war on all Christendom except England, agreeing to terms of peace on the basis of tribute. Cooperation between the Powers was not then thought of, and one by one they struck their bargains as they are doing again to-day.

Yet even at the most violent period of Moorish misrule it is a remarkable fact that Europeans were allowed to settle and trade in the Empire, in all probability as little molested there as they would have been had they remained at home, by varying religious tests and changing governments. It is almost impossible to conceive, without a perusal of the literature of the period, the incongruity of the position. Foreign slaves would be employed in gangs outside the dwellings of free fellow-countrymen with whom they were forbidden to communicate, while every returning pirate captain added to the number of the captives, sometimes bringing friends and relatives of those who lived in[page 11] freedom as the Sultan's "guests," though he considered himself "at war" with their Governments. So little did the Moors understand the position of things abroad, that at one time they made war upon Gibraltar, while expressing the warmest friendship for England, who then possessed it. This was done by Mulai Abd Allah V., in 1756, because, he said, the Governor had helped his rebel uncle at Arzîla, so that the English, his so-called friends, did more harm than his enemies—the Portuguese and Spaniards. "My father and I believe," wrote his son, Sidi Mohammed, to Admiral Pawkers, "that the king your master has no knowledge of the behaviour towards us of the Governor of Gibraltar, ... so Gibraltar shall be excluded from the peace to which I am willing to consent between England and us, and with the aid of the Almighty God, I will know how to avenge myself as I may on the English of Gibraltar."

Previously Spain and Portugal had held the principal Moroccan seaports, the twin towns of Rabat and Salli alone remaining always Moorish, but these two in their turn set up a sort of independent republic, nourished from the Berber tribes in the mountains to the south of them. No Europeans live in Salli yet, for here the old fanaticism slumbers still. So long as a port remained in foreign hands it was completely cut off from the surrounding country, and played no part in Moorish history, save as a base for periodical incursions. One by one most of them fell again into the hands of their rightful owners, till they had recovered all their Atlantic sea-board. On the Mediterranean, Ceuta, which had belonged to Portugal, came under[page 12] the rule of Spain when those countries were united, and the Spaniards hold it still, as they do less important positions further east.

The piracy days of the Moors have long passed, but they only ceased at the last moment they could do so with grace, before the introduction of steamships. There was not, at the best of times, much of the noble or heroic in their raids, which generally took the nature of lying in wait with well-armed, many-oared vessels, for unarmed, unwieldy merchantmen which were becalmed, or were outpaced by sail and oar together.

Early in the nineteenth century Algiers was forced to abandon piracy before Lord Exmouth's guns, and soon after the Moors were given to understand that it could no longer be permitted to them either, since the Moorish "fleets"—if worthy the name—had grown so weak, and those of the Nazarenes so strong, that the tables were turned. Yet for many years more the nations of Europe continued the tribute wherewith the rapacity of the Moors was appeased, and to the United States belongs the honour of first refusing this disgraceful payment.

The manner in which the rovers of Salli and other ports were permitted to flourish so long can be explained in no other way than by the supposition that they were regarded as a sort of necessary nuisance, just a hornet's-nest by the wayside, which it would be hopeless to destroy, as they would merely swarm elsewhere. And then we must remember that the Moors were not the only pirates of those days, and that Europeans have to answer for the most terrible deeds of the[page 13] Mediterranean corsairs. News did not travel then as it does now. Though students of Morocco history are amazed at the frequent captures and the thousands of Christian slaves so imported, abroad it was only here and there that one was heard of at a time.

To-day the plunder of an Italian sailing vessel aground on their shore, or the fate of too-confident Spanish smugglers running close in with arms, is heard of the world round. And in the majority of cases there is at least a question: What were the victims doing there? Not that this in any way excuses the so-called "piracy," but it must not be forgotten in considering the question. Almost all these tribes in the troublous districts carry European arms, instead of the more picturesque native flint-lock: and as not a single gun is legally permitted to pass the customs, there must be a considerable inlet somewhere, for prices are not high.

* For a complete outline of Moorish history, see the writer's "Moorish Empire."

"What has passed has gone, and what is to come is distant; Thou hast only the hour in which thou art."

Moorish Proverb.

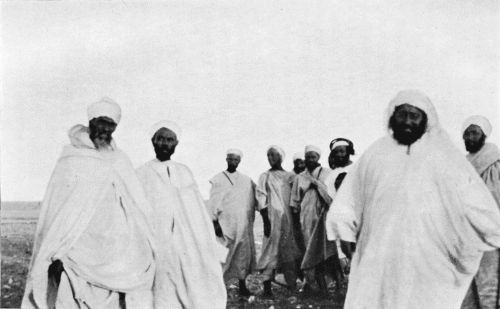

Far from being, as Hood described them, "poor rejected Moors who raised our childish fears," the people of Morocco consist of fine, open races, capable of anything, but literally rotting in one of the finest countries of the world. The Moorish remains in Spain, as well as the pages of history, testify to the manner in which they once flourished, but to-day their appearance is that of a nation asleep. Yet great strides towards reform have been made during the past century, and each decade sees steps taken more important than the last. For the present decade is promised complete transformation.

But how little do we know of this people! The very name "Moor" is a European invention, unknown in Morocco, where no more precise definition of the inhabitants can be given than that of "Westerners"—Maghribîn, while the land itself is known as "The Further West"—El Moghreb el Aksa. The name we give to the country is but a corruption of that of the southern capital, Marrákesh ("Morocco City") through the Spanish version, Marueccos.

The genuine Moroccans are the Berbers among whom the Arabs introduced Islám and its civilization, later bringing Negroes from their raids across the Atlas to the Sudán and Guinea. The remaining important section of the people are Jews of two classes—those settled in the country from prehistoric times, and those driven to it when expelled from Spain. With the exception of the Arabs and the Blacks, none of these pull together, and in that case it is only because the latter are either subservient to the former, or incorporated with them.

First in importance come the earliest known possessors of the land, the Berbers. These are not confined to Morocco, but still hold the rocky fastnesses which stretch from the Atlantic, opposite the Canaries, to the borders of Egypt; from the sands of the Mediterranean to those of the Sáhara, that vast extent of territory to which we have given their name, Barbary. Of these but a small proportion really amalgamated with their Muslim victors, and it is only to this mixed race which occupies the cities of Morocco that the name "Moor" is strictly applicable.

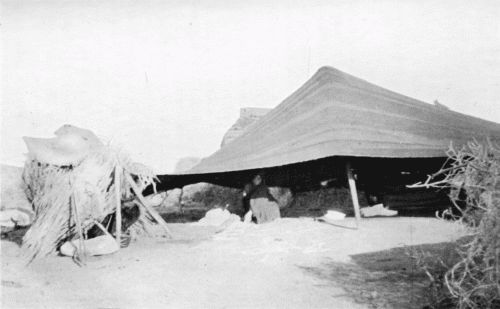

On the plains are to be found the Arabs, their tents scattered in every direction. From the Atlantic to the Atlas, from Tangier to Mogador, and then away through the fertile province of Sûs, one of the chief features of Morocco is the series of wide alluvial treeless plains, often apparently as flat as a table, but here and there cut up by winding rivers and crossed by low ridges. The fertility of these districts is remarkable; but owing to the misgovernment of the country, which renders native[page 16] property so insecure, only a small portion is cultivated. The untilled slopes which border the plains are generally selected by the Arabs for their encampments, circles or ovals of low goat-hair tents, each covering a large area in proportion to the number of its inhabitants.

The third section of the people of Morocco—by no means the least important—has still to be glanced at; these are the ubiquitous, persecuted and persecuting Jews. Everywhere that money changes hands and there is business to be done they are to be found. In the towns and among the thatched huts of the plains, even in the Berber villages on the slopes of the Atlas, they have their colonies. With the exception of a few ports wherein European rule in past centuries has destroyed the boundaries, they are obliged to live in their own restricted quarters, and in most instances are only permitted to cross the town barefooted and on foot, never to ride a horse. In the Atlas they live in separate villages adjoining or close to those belonging to the Berbers, and sometimes even larger than they. Always clad in black or dark-coloured cloaks, with hideous black skull-caps or white-spotted blue kerchiefs on their heads, they are conspicuous everywhere. They address the Moors with a villainous, cringing look which makes the sons of Ishmael savage, for they know it is only feigned. In return they are treated like dogs, and cordial hatred exists on both sides. So they live, together yet divided; the Jew despised but indispensable, bullied but thriving. He only wins at law when richer than his opponent; against a Muslim he can bear no testimony; there is scant pretence at justice. He[page 17] dares not lift his hand to strike a Moor, however ill-treated, but he finds revenge in sucking his life's blood by usury. Receiving no mercy, he shows none, and once in his clutches, his prey is fortunate to escape with his life.

The happy influence of more enlightened European Jews is, however, making itself felt in the chief towns, through excellent schools supported from London and Paris, which are turning out a class of highly respectable citizens. While the Moors fear the tide of advancing westernization, the town Jews court it, and in them centres one of the chief prospects of the country's welfare. Into their hands has already been gathered much of the trade of Morocco, and there can be little doubt that, by the end of the thirty years' grace afforded to other merchants than the French, they will have practically absorbed it all, even the Frenchmen trading through them. They have at least the intimate knowledge of the people and local conditions to which so few foreigners ever attain.

When the Moorish Empire comes to be pacifically penetrated and systematically explored, it will probably be found that little more is known of it than of China, notwithstanding its proximity, and its comparatively insignificant size. A map honestly drawn, from observations only, would astonish most people by its vast blank spaces.* It would be noted that the limit of European exploration—with the exception of the work of two or three hardy travellers in disguise—is less than two hundred miles from the coast, and that this limit[page 18] is reached at two points only—south of Fez and Marrákesh respectively,—which form the apices of two well-known triangular districts, the contiguous bases of which form part of the Atlantic coast line, under four hundred miles in length. Beyond these limits all is practically unknown, the language, customs and beliefs of the people providing abundant ground for speculation, and permitting theorists free play. So much is this the case, that a few years ago an enthusiastic "savant" was able to imagine that he had discovered a hidden race of dwarfs beyond the Atlas, and to obtain credence for his "find" among the best-informed students of Europe.

But there is also another point of view from which Morocco is unknown, that of native thought and feeling, penetrated by extremely few Europeans, even when they mingle freely with the people, and converse with them in Arabic. The real Moor is little known by foreigners, a very small number of whom mix with the better classes. Some, as officials, meet officials, but get little below the official exterior. Those who know most seldom speak, their positions or their occupations preventing the expression of their opinions. Sweeping statements about Morocco may therefore be received with reserve, and dogmatic assertions with caution. This Empire is in no worse condition now than it has been for centuries; indeed, it is much better off than ever since its palmy days, and there is no occasion whatever to fear its collapse.

Few facts are more striking in the study of Morocco than the absolute stagnation of its people, except in so far as they have been to a very limited extent affected by outside influences. Of what[page 19] European—or even oriental—land could descriptions of life and manners written in the sixteenth century apply as fully in the twentieth as do those of Morocco by Leo Africanus? Or even to come later, compare the transitions England has undergone since Höst and Jackson wrote a hundred years ago, with the changes discoverable in Morocco since that time. The people of Morocco remain the same, and their more primitive customs are those of far earlier ages, of the time when their ancestors lived upon the plain of Palestine and North Arabia, and when "in the loins of Abraham" the now unfriendly Jew and Arab were yet one. It is the position of Europeans among them which has changed.

In the time of Höst and Jackson piracy was dying hard, restrained by tribute from all the Powers of Europe. The foreign merchant was not only tolerated, but was at times supplied with capital by the Moorish sultans, to whom he was allowed to go deeply in debt for custom's dues, and half a century later the British Consul at Mogador was not permitted to embark to escape a bombardment of the town, because of his debt to the Sultan. Many of the restrictions complained of to-day are the outcome of the almost enslaved condition of the merchants of those times in consequence of such customs. Indeed, the position of the European in Morocco is still a series of anomalies, and so it is likely to continue until it passes under foreign rule.

The same old spirit of independence reigns in the Berber breast to-day as when he conquered Spain, and though he has forgotten his past and cares naught for his future, he still considers himself a superior being, and feels that no country can rival[page 20] his home. In his eyes the embassies from Europe and America come only to pay the tribute which is the price of peace with his lord, and when he sees a foreign minister in all his black and gold stand in the sun bareheaded to address the mounted Sultan beneath his parasol, he feels more proud than ever of his greatness, and is more decided to be pleasant to the stranger, but to keep him out.

Instead of increased relations between Moors and foreigners tending to friendship, the average foreign settler or tourist is far too bigoted and narrow-minded to see any good in the native, much less to acknowledge his superiority on certain points. Wherever the Sultan's authority is recognized the European is free to travel and live, though past experience has led officials not to welcome him. At the same time, he remains entirely under the jurisdiction of his own authorities, except in cases of murder or grave crime, when he must be at once handed over to the nearest consul of his country. Not only are he and his household thus protected, but also his native employees, and, to a certain extent, his commercial and agricultural agents.

Thus foreigners in Morocco enjoy within the limits of the central power the security of their own lands, and the justice of their own laws. They do not even find in Morocco that immunity from justice which some ignorant writers of fiction have supposed; for unless a foreigner abandons his own nationality and creed, and buries himself in the interior under a native name, he cannot escape the writs of foreign courts. In any case, the Moorish authorities will arrest him on demand, and hand him over to his consul to be dealt with according to law. The[page 21] colony of refugees which has been pictured by imaginative raconteurs is therefore non-existent. Instead there are growing colonies of business men, officials, missionaries, and a few retired residents, quite above the average of such colonies in the Levant, for instance.

For many years past, though the actual business done has shown a fairly steady increase, the commercial outlook in Morocco has gone from bad to worse. Yet more of its products are now exported, and there are more European articles in demand, than were thought of twenty years ago. This anomalous and almost paradoxical condition is due to the increase of competition and the increasing weakness of the Government. Men who had hope a few years ago, now struggle on because they have staked too much to be able to leave for more promising fields. This has been especially the case since the late Sultan's death. The disturbances which followed that event impoverished many tribes, and left behind a sense of uncertainty and dread. No European Bourse is more readily or lastingly affected by local political troubles than the general trade of a land like Morocco, in which men live so much from hand to mouth.

It is a noteworthy feature of Moorish diplomatic history that to the Moors' love of foreign trade we owe almost every step that has led to our present relations with the Empire. Even while their rovers were the terror of our merchantmen, as has been pointed out, foreign traders were permitted to reside in their ports, the facilities granted to them forming the basis of all subsequent negotiations. Now that concession after concession has been wrung from[page 22] their unwilling Government, and in spite of freedom of residence, travel, and trade in the most important parts of the Empire, it is disheartening to see the foreign merchant in a worse condition than ever.

The previous generation, fewer in number, enjoying far less privileges, and subjected to restrictions and indignities that would not be suffered to-day, were able to make their fortunes and retire, while their successors find it hard to hold their own. The "hundred tonners" who, in the palmy days of Mogador, were wont to boast that they shipped no smaller quantities at once, are a dream of the past. The ostrich feathers and elephants' tusks no longer find their way out by that port, and little gold now passes in or out. Merchant princes will never be seen here again; commercial travellers from Germany are found in the interior, and quality, as well as price, has been reduced to its lowest ebb.

A crowd of petty trading agents has arisen with no capital to speak of, yet claiming and abusing credit, of which a most ruinous system prevails, and that in a land in which the collection of debts is proverbially difficult, and oftentimes impossible. The native Jews, who were interpreters and brokers years ago, have now learned the business and entered the lists. These new competitors content themselves with infinitesimal profits, or none at all in cases where the desideratum is cash to lend out at so many hundreds per cent. per annum. Indeed, it is no uncommon practice for goods bought on long credit to be sold below cost price for this purpose. Against such methods who can compete?

Yet this is a rich, undeveloped land—not exactly[page 23] an El Dorado, though certainly as full of promise as any so styled has proved to be when reached—favoured physically and geographically, but politically stagnant, cursed with an effete administration, fettered by a decrepit creed. In view of this situation, it is no wonder that from time to time specious schemes appear and disappear with clockwork regularity. Now it is in England, now in France, that a gambling public is found to hazard the cost of proving the impossibility of opening the country with a rush, and the worthlessness of so-called concessions and monopolies granted by sheïkhs in the south, who, however they may chafe under existing rule which forbids them ports of their own, possess none of the powers required to treat with foreigners.

As normal trade has waned in Morocco, busy minds have not been slow in devising illicit, or at least unusual, methods of making money, even, one regrets to say, of making false money. Among the drawbacks suffered by the commerce which pines under the shade of the shareefian umbrella, one—and that far from the least—is the unsatisfactory coinage, which till a few years ago was almost entirely foreign. To have to depend in so important a matter on any mint abroad is bad enough, but for that mint to be Spanish means much. Centuries ago the Moors coined more, but with the exception of a horrible token of infinitesimal value called "floos," the products of their extinct mints are only to be found in the hands of collectors, in buried hoards, or among the jewellery displayed at home by Mooresses and Jewesses, whose fortunes, so invested, may not be seized for debt. Some[page 24] of the older issues are thin and square, with well-preserved inscriptions, and of these a fine collection—mostly gold—may be seen at the British Museum; but the majority, closely resembling those of India and Persia, are rudely stamped and unmilled, not even round, but thick, and of fairly good metal. The "floos" referred to (sing. "fils") are of three sizes, coarsely struck in zinc rendered hard and yellow by the addition of a little copper. The smallest, now rarely met with, runs about 19,500 to £1 when this is worth 32½ Spanish pesetas; the other two, still the only small change of the country, are respectively double and quadruple its value. The next coin in general circulation is worth 2d., so the inconvenience is great. A few years ago, however, Europeans resident in Tangier resolutely introduced among themselves the Spanish ten and five céntimo pieces, corresponding to our 1d. and ½d., which are now in free local use, but are not accepted up-country.

What passes as Moorish money to-day has been coined in France for many years, more recently also in Germany; the former is especially neat, but the latter lacks style. The denominations coincide with those of Spain, whose fluctuations in value they closely follow at a respectful distance. This autumn the "Hasáni" coin—that of Mulai el Hasan, the late Sultan—has fallen to fifty per cent. discount on Spanish. With the usual perversity also, the common standard "peseta," in which small bargains are struck on the coast, was omitted, the nearest coin, the quarter-dollar, being nominally worth ptas. 1.25. It was only after a decade, too, that the Government put in circulation the dollars struck in France,[page 25] which had hitherto been laid up in the treasury as a reserve. And side by side with the German issue came abundant counterfeit coins, against which Government warnings were published, to the serious disadvantage of the legal issue. Even the Spanish copper has its rival, and a Frenchman was once detected trying to bring in a nominal four hundred dollars' worth of an imitation, which he promptly threw overboard when the port guards raised objections to its quality.

The increasing need of silver currency inland, owing to its free use in the manufacture of trinkets, necessitates a constant importation, and till recently all sorts of coins, discarded elsewhere, were in circulation. This was the case especially with French, Swiss, Belgian, Italian, Greek, Roumanian, and other pieces of the value of twenty céntimos, known here by the Turkish name "gursh," which were accepted freely in Central Morocco, but not in the north. Twenty years ago Spanish Carolus, Isabella and Philippine shillings and kindred coins were in use all over the country, and when they were withdrawn from circulation in Spain they were freely shipped here, till the country was flooded with them. When the merchants and customs at last refused them, their astute importers took them back at a discount, putting them into circulation later at what they could, only to repeat the transaction. In Morocco everything a man can be induced to take is legal tender, and for bribes and religious offerings all things pass, this practice being an easier matter than at first sight appears; so in the course of a few years one saw a whole series of coins in vogue,[page 26] one after the other, the main transactions taking place on the coast with country Moors, than whom, though none more suspicious, none are more easily gulled.

A much more serious obstacle to inland trade is the periodically disturbed state of the country, not so much the local struggles and uprisings which serve to free superfluous energy, as the regular administrative expeditions of the Moorish Court, or of considerable bodies of troops. These used to take place in some direction every year, "the time when kings go forth to war" being early summer, just when agricultural operations are in full swing, and every man is needed on his fields. In one district the ranks of the workers are depleted by a form of conscription or "harka," and in another these unfortunates are employed preventing others doing what they should be doing at home. Thus all suffer, and those who are not themselves engaged in the campaign are forced to contribute cash, if only to find substitutes to take their places in the ranks.

The movement of the Moorish Court means the transportation of a numerous host at tremendous expense, which has eventually to be recouped in the shape of regular contributions, arrears of taxes and fines, collected en route, so the pace is abnormally slow. Not only is there an absolute absence of roads, and, with one or two exceptions, of bridges, but the Sultan himself, with all his army, cannot take the direct route between his most important inland cities without fighting his way. The configuration of the empire explains its previous sub-division into the kingdoms of Fez, Marrákesh,[page 27] Tafilált and Sûs, and the Reef, for between the plains of each run mountain ranges which have never known absolute "foreign" rulers.

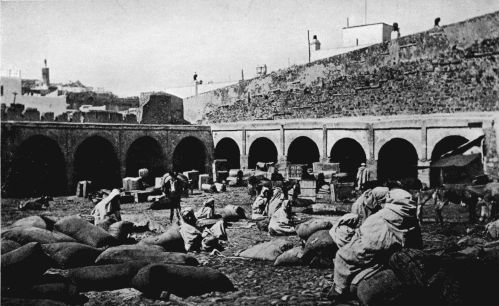

Molinari, Photo., Tangier.

CROSSING A MOROCCO RIVER.

To European engineers the passes through these closed districts would offer no great obstacles in the construction of roads such as thread the Himalayas, but the Moors do not wish for the roads; for, while what the Government fears to promote thereby is combination, the actual occupants of the mountains, the native Berbers, desire not to see the Arab tax-gatherers, only tolerating their presence as long as they cannot help it, and then rising against them.

Often a tribe will be left for several years to enjoy independence, while the slip-shod army of the Sultan is engaged elsewhere. When its turn comes it holds out for terms, since it has no hope of successfully confronting such an overwhelming force as is sooner or later brought against it. The usual custom is to send small detachments of soldiers to the support of the over-grasping functionaries, and when they have been worsted, to send down an army to "eat up" the province, burning villages, deporting cattle, ill-treating the women, and often carrying home children as slaves. The men of the district probably flee and leave their homes to be ransacked. They content themselves with hiding behind crags which seem to the plainsmen inaccessible, whence they can in safety harass the troops on the march. After more or less protracted skirmishing, the country having been devastated by the troops, who care only for the booty, women will be sent into the camp to make terms, or one of the shareefs or religious nobles who accompany the army is sent out to treat with the rebels. The terms are usually[page 28] hard—so much arrears of tribute in cash and kind, so much as a fine for expenses, so many hostages. Then hostages and prisoners are driven to the capital in chains, and pickled heads are exposed on the gateways, imperial letters being read in the chief mosques throughout the country, telling of a glorious victory, and calling for rejoicings. To any other people the short spell of freedom would have been too dearly bought for the experiment to be repeated, but as soon as they begin to chafe again beneath the lawless rule of Moorish officials, the Berbers rebel once more. It has been going on thus for hundreds of years, and will continue till put an end to by France.

In Morocco each official preys upon the one below him, and on all others within his reach, till the poor oppressed and helpless villager lives in terror of them all, not daring to display signs of prosperity for fear of tempting plunder. Merit is no key to positions of trust and authority, and few have such sufficient salary attached to render them attractive to honest men. The holders are expected in most cases to make a living out of the pickings, and are allowed an unquestioned run of office till they are presumed to have amassed enough to make it worth while treating them as they have treated others, when they are called to account and relentlessly "squeezed." The only means of staving off the fatal day is by frequent presents to those above them, wrung from those below. A large proportion of Moorish officials end their days in disgrace, if not in dungeons, and some meet their end by being invited to corrosive sublimate tea, a favourite beverage in Morocco—for others. Yet there is[page 29] always a demand for office, and large prices are paid for posts affording opportunities for plunder.

The Moorish financial system is of a piece with this method. When the budget is made out, each tribe or district is assessed at the utmost it is believed capable of yielding, and the candidate for its governorship who undertakes to get most out of it probably has the task allotted to him. His first duty is to repeat on a small scale the operation of the Government, informing himself minutely as to the resources under his jurisdiction, and assessing the sub-divisions so as to bring in enough for himself, and to provide against contingencies, in addition to the sum for which he is responsible. The local sheïkhs or head-men similarly apportion their demands among the individuals entrusted to their tender mercy. A fool is said to have once presented the Sultan with a bowl of skimmed and watered milk, and on being remonstrated with, to have declared that His Majesty received no more from any one, as his wazeers and governors ate half the revenue cream each, and the sheïkhs drank half the revenue milk. The fool was right.

The richer a man is, the less proportion he will have to pay, for he can make it so agreeable—or disagreeable—for those entrusted with a little brief authority. It is the struggling poor who have to pay or go to prison, even if to pay they have to sell their means of subsistence. Three courses lie before this final victim—to obtain the protection of some influential name, native or foreign, to buy a "friend at court," or to enter Nazarene service. But native friends are uncertain and hard to find, and, above all, they may be alienated by a higher[page 30] bid from a rival or from a rapacious official. Such affairs are of common occurrence, and harrowing tales might be told of homes broken up in this way, of tortures inflicted, and of lives spent in dungeons because display has been indulged in, or because an independent position has been assumed under cover of a protection that has failed. But what can one expect with such a standard of honour?

Foreigners, on the other hand, seldom betray their protégés—although, to their shame be it mentioned, some in high places have done so,—wherefore their protection is in greater demand; besides which it is more effectual, as coming from outside, while no Moor, however well placed, is absolutely secure in his own position. Thus it is that the down-trodden natives desire and are willing to pay for protection in proportion to their means; and it is this power of dispensing protection which, though often abused, does more than anything else to raise the prestige of the foreigner, and in turn to protect him.

The claims most frequently made against Moors by foreign countries are for debt, claims which afford the greatest scope for controversy and the widest loophole for abuse. Although, unfortunately, for the greater part usurious, a fair proportion are for goods delivered, but to evade the laws even loan receipts are made out as for goods to be delivered, a form in which discrimination is extremely difficult. The condition of the country, in which every man is liable to be arrested, thrashed, imprisoned, if not tortured, to extort from him his wealth, is such as furnishes the usurer with crowding clients; and the condition of things among the Indian cultivators,[page 31] bad as it is, since they can at least turn to a fair-handed Government, is not to be compared to that of the down-trodden Moorish farmer.

The assumption by the Government of responsibility for the debts of its subjects, or at all events its undertaking to see that they pay, is part of the patriarchal system in force, by which the family is made responsible for individuals, the tribe for families, and so on. No other system would bring offenders to justice without police; but it transforms each man into his brother's keeper. This, however, does not apply only to debts the collection of which is urged upon the Government, for whom it is sufficient to produce the debtor and let him prove absolute poverty for him to be released, with the claim cancelled. This in theory: but in practice, to appease these claims, however just, innocent men are often thrown into prison, and untold horrors are suffered, in spite of all the efforts of foreign ministers to counteract the injustice.

A mere recital of tales which have come under my own observation would but harrow my readers' feelings to no purpose, and many would appear incredible. With the harpies of the Government at their heels, men borrow wildly for a month or two at cent. per cent., and as the Moorish law prohibits interest, a document is sworn to before notaries by which the borrower declares that he has that day taken in hard cash the full amount to be repaid, the value of certain crops or produce of which he undertakes delivery upon a certain date. Very seldom, indeed, does it happen that by that date the money can be repaid, and generally the[page 32] only terms offered for an extension of time for another three or six months are the addition of another fifty or one hundred per cent. to the debt, always fully secured on property, or by the bonds of property holders. Were not this thing of everyday occurrence in Morocco, and had I not examined scores of such papers, the way in which the ignorant Moors fall into such traps would seem incredible. It is usual to blame the Jews for it all, and though the business lies mostly in their hands, it must not be overlooked that many foreigners engage in it, and, though indirectly, some Moors also.

But besides such claims, there is a large proportion of just business debts which need to be enforced. It does not matter how fair a claim may be, or how legitimate, it is very rarely that trouble is not experienced in pressing it. The Moorish Courts are so venal, so degraded, that it is more often the unscrupulous usurer who wins his case and applies the screw, than the honest trader. Here lies the rub. Another class of claims is for damage done, loss suffered, or compensation for imaginary wrongs. All these together mount up, and a newly appointed minister or consul-general is aghast at the list which awaits him. He probably contents himself at first with asking for the appointment of a commission to examine and report on the legality of all these claims, and for the immediate settlement of those approved. But he asks and is promised in vain, till at last he obtains the moral support of war-ships, in view of which the Moorish Government most likely pays much more than it would have got off with at first, and then proceeds to victimize the debtors.

It is with expressed threats of bombardment that the ships come, but experience has taught the Moorish Government that it is well not to let things go that length, and they now invariably settle amicably. To our western notions it may seem strange that whatever questions have to be attended to should not be put out of hand without requiring such a demonstration; but while there is sleep there is hope for an Oriental, and the rulers of Morocco would hardly be Moors if they resisted the temptation to procrastinate, for who knows what may happen while they delay? And then there is always the chance of driving a bargain, so dear to the Moorish heart, for the wazeer knows full well that although the Nazarene may be prepared to bombard, as he has done from time to time, he is no more desirous than the Sultan that such an extreme measure should be necessary.

So, even when things come to the pinch, and the exasperated representative of Christendom talks hotly of withdrawing, hauling down his flag and giving hostile orders, there is time at least to make an offer, or to promise everything in words. And when all is over, claims paid, ships gone, compliments and presents passed, nothing really serious has happened, just the everyday scene on the market applied to the nation, while the Moorish Government has once more given proof of worldly wisdom, and endorsed the proverb that discretion is the better part of valour.

An illustration of the high-handed way in which things are done in Morocco has but recently been afforded by the action of France regarding an alleged Algerian subject arrested by the Moorish[page 34] authorities for conspiracy. The man, Boo Zîan Miliáni by name, was the son of one of those Algerians who, when their country was conquered by the French, preferred exile to submission, and migrated to Morocco, where they became naturalized. He was charged with supporting the so-called "pretender" in the Reef province, where he was arrested with two others early in August last. His particular offence appears to have been the reading of the "Rogi's" proclamations to the public, and inciting them to rebel against the Sultan. But when brought a prisoner to Tangier, and thence despatched to Fez, he claimed French citizenship, and the Minister of France, then at Court, demanded his release.

This being refused, a peremptory note followed, with a threat to break off diplomatic negotiations if the demand were not forthwith complied with. The usual communiqués were made to the Press, whereby a chorus was produced setting forth the insult to France, the imminence of war, and the general gravity of the situation. Many alarming head-lines were provided for the evening papers, and extra copies were doubtless sold. In Morocco, however, not only the English and Spanish papers, but also the French one, admitted that the action of France was wrong, though the ultimate issue was never in doubt, and the man's release was a foregone conclusion. Elsewhere the rights of the matter would have been sifted, and submitted at least to the law-courts, if not to arbitration.

While the infliction of this indignity was stirring up northern Morocco, the south was greatly exercised by the presence on the coast of a French[page 35] vessel, L'Aigle, officers from which proceeded ostentatiously to survey the fortifications of Mogador and its island, and then effected a landing on the latter by night. Naturally the coastguards fired at them, fortunately without causing damage, but had any been killed, Europe would have rung with the "outrage." From Mogador the vessel proceeded after a stay of a month to Agadir, the first port of Sûs, closed to Europeans.

Here its landing-party was met on the beach by some hundreds of armed men, whose commander resolutely forbade them to land, so they had to retire. Had they not done so, who would answer for the consequences? As it was, the natives, eager to attack the "invaders," were with difficulty kept in hand, and one false step would undoubtedly have led to serious bloodshed. Of course this was a dreadful rebuff for "pacific penetration," but the matter was kept quiet as a little premature, since in Europe the coast is not quite clear enough yet for retributory measures. The effect, however, on the Moors, among whom the affair grew more grave each time it was recited, was out of all proportion to the real importance of the incident, which otherwise might have passed unnoticed.

* An approximation to this is given in the writer's "Land of the Moors."

"He knows of every vice an ounce."

Moorish Proverb.

Though most eastern lands may be described as slip-shod, with reference both to the feet of their inhabitants and to the way in which things are done, there can be no country in the world more aptly described by that epithet than Morocco. One of the first things which strikes the visitor to this country is the universality of the slipper as foot-gear, at least, so far as the Moors are concerned. In the majority of cases the men wear the heels of their slippers folded down under the feet, only putting them up when necessity compels them to run, which they take care shall not be too often, as they much prefer a sort of ambling gait, best compared to that of their mules, or to that of an English tramp.

Nothing delights them better as a means of agreeably spending an hour or two, than squatting on their heels in the streets or on some door-stoop, gazing at the passers-by, exchanging compliments with their acquaintances. Native "swells" consequently promenade with a piece of felt under their arms on which to sit when they wish, in[page 37] addition to its doing duty as a carpet for prayer. The most public places, and usually the cool of the afternoon, are preferred for this pastime.

The ladies of their Jewish neighbours also like to sit at their doors in groups at the same hour, or in the doorways of main thoroughfares on moonlight evenings, while the gentlemen, who prefer to do their gossiping afoot, roam up and down. But this is somewhat apart from the point of the lazy tendencies of the Moors. With them—since they have no trains to catch, and disdain punctuality—all hurry is undignified, and one could as easily imagine an elegantly dressed Moorish scribe literally flying as running, even on the most urgent errand. "Why run," they ask, "when you might just as well walk? Why walk, when standing would do? Why stand, when sitting is so much less fatiguing? Why sit, when lying down gives so much more rest? And why, lying down, keep your eyes open?"

In truth, this is a country in which things are left pretty much to look after themselves. Nothing is done that can be left undone, and everything is postponed until "to-morrow." Slipper-slapper go the people, and slipper-slapper goes their policy. If you can get through a duty by only half doing it, by all means do so, is the generally accepted rule of life. In anything you have done for you by a Moor, you are almost sure to discover that he has "scamped" some part; perhaps the most important. This, of course, means doing a good deal yourself, if you like things done well, a maxim holding good everywhere, indeed, but especially here.

The Moorish Government's way of doing things—or rather, of not doing them if it can find an[page 38] excuse—is eminently slip-shod. The only point in which they show themselves astute is in seeing that their Rubicon has a safe bridge by which they may retreat, if that suits their plans after crossing it. To deceive the enemy they hide this as best they can, for the most part successfully, causing the greatest consternation in the opposite camp, which, at the moment when it thinks it has driven them into a corner, sees their ranks gradually thinning from behind, dribbling away by an outlet hitherto invisible. Thus, in accepting a Moor's promise, one must always consider the conditions or rider annexed.

This can be well illustrated by the reluctant permission to transport grain from one Moorish port to another, granted from time to time, but so hampered by restrictions as to be only available to a few, the Moorish Government itself deriving the greatest advantage from it. Then, too, there is the property clause in the Convention of Madrid, which has been described as the sop by means of which the Powers were induced to accept other less favourable stipulations. Instead of being the step in advance which it appeared to be, it was, in reality, a backward step, the conditions attached making matters worse than before.

In this way only do the Moors shine as politicians, unless prevarication and procrastination be included, Machiavellian arts in which they easily excel. Otherwise they are content to jog along in the same slip-shod manner as their fathers did centuries ago, as soon as prosperity had removed the incentive to exert the energy they once possessed. The same carelessness marks their[page 39] conduct in everything, and the same unsatisfactory results inevitably follow.

But to get at the root of the matter it is necessary to go a step further. The absolute lack of morals among the people is the real cause of the trouble. Morocco is so deeply sunk in the degradation of vice, and so given up to lust, that it is impossible to lay bare its deplorable condition. In most countries, with a fair proportion of the pure and virtuous, some attempt is made to gloss over and conceal one's failings; but in this country the only vice which public opinion seriously condemns is drunkenness, and it is only before foreigners that any sense of shame or desire for secrecy about others is observable. The Moors have not yet attained to that state of hypocritical sanctimoniousness in which modern society in civilized lands delights to parade itself.

The taste for strong drink, though still indulged comparatively in secret, is steadily increasing, the practice spreading from force of example among the Moors themselves, as a result of the strenuous efforts of foreigners to inculcate this vice. European consular reports not infrequently note with congratulation the growing imports of wines and liqueurs into Morocco, nominally for the sole use of foreigners, although manifestly far in excess of their requirements. As yet, it is chiefly among the higher and lower classes that the victims are found, the former indulging in the privacy of their own homes, and the latter at the low drinking-dens kept by the scum of foreign settlers in the open ports. Among the country people of the plains and lower hills there are hardly any who would touch[page 40] intoxicating liquor, though among the mountaineers the use of alcohol has ever been more common.

Tobacco smoking is very general on the coast, owing to contact with Europeans, but still comparatively rare in the interior, although the native preparations of hemp (keef), and also to some extent opium, have a large army of devotees, more or less victims. The latter, however, being an expensive import, is less known in the interior. Snuff-taking is fairly general among men and women, chiefly the elderly. What they take is very strong, being a composition of tobacco, walnut shells, and charcoal ash. The writer once saw a young Englishman, who thought he could stand a good pinch of snuff, fairly "knocked over" by a quarter as much as the owner of the nut from which it came took with the utmost complacency.

The feeling of the Moorish Government about smoking has long been so strong that in every treaty with Europe is inserted a clause reserving the right of prohibiting the importation of all narcotics, or articles used in their manufacture or consumption. Till a few years ago the right to deal in these was granted yearly as a monopoly; but in 1887 the late Sultan, Mulai el Hasan, and his aoláma, or councillors, decided to abolish the business altogether, so, purchasing the existing stocks at a valuation, they had the whole burned. But first the foreign officials and then private foreigners demanded the right to import whatever they needed "for their own consumption," and the abuse of this courtesy has enabled several tobacco factories to spring up in the country. The position with regard to the liquor traffic is almost the same. If the[page 41] Moors were free to legislate as they wished, they would at once prohibit the importation of intoxicants.

Of late years, however, a great change has come over the Moors of the ports, more especially so in Tangier, where the number of taverns and cafés has increased most rapidly. During many years' residence there the cases of drunkenness met with could be counted on the fingers, and were then confined to guides or servants of foreigners; on the last visit paid to the country more were observed in a month than then in years. In those days to be seen with a cigarette was almost a crime, and those who indulged in a whiff at home took care to deodorize their mouths with powdered coffee; now Moors sit with Europeans, smoking and drinking, unabashed, at tables in the streets, but not those of the better sort. Thus Morocco is becoming civilized!

However ashamed a Moor may be of drunkenness, no one thinks of making a pretence of being chaste or moral. On the contrary, no worse is thought of a man who is wholly given up to the pleasures of the flesh than of one who is addicted to the most innocent amusements. If a Moor is remonstrated with, he declares he is not half so bad as the "Nazarenes" he has come across, who, in addition to practising most of his vices, indulge in drunkenness. It is not surprising, therefore, that the diseases which come as a penalty for these vices are fearfully prevalent in Morocco. Everywhere one comes across the ravages of such plagues, and is sickened at the sight of their victims. Without going further into details, it will suffice to[page 42] mention that one out of every five patients (mostly males) who attend at the dispensary of the North Africa Mission at Tangier are direct, or indirect, sufferers from these complaints.

The Moors believe in "sowing wild oats" when young, till their energy is extinguished, leaving them incapable of accomplishing anything. Then they think the pardon of God worth invoking, if only in the vain hope of having their youth renewed as the eagle's. Yet if this could happen, they would be quite ready to commence a fresh series of follies more outrageous than before. This is a sad picture, but nevertheless true, and, far from being exaggerated, does not even hint at much that exists in Morocco to-day.

The words of the Korán about such matters are never considered, though nominally the sole guide for life. The fact that God is "the Pitying, the Pitiful, King of the Day of Judgement," is considered sufficient warrant for the devotees of Islám to lightly indulge in breaches of laws which they hold to be His, confident that if they only perform enough "vain repetitions," fast at the appointed times, and give alms, visiting Mekka, if possible, or if not, making pilgrimages to shrines of lesser note nearer home, God, in His infinite mercy, will overlook all.

An anonymous writer has aptly remarked—"Every good Mohammedan has a perpetual free pass over that line, which not only secures to him personally a safe transportation to Paradise, but provides for him upon his arrival there so luxuriously that he can leave all the cumbersome baggage of his earthly harem behind him, and begin his celestial house-keeping with an entirely new outfit."

Here lies the whole secret of Morocco's backward state. Her people, having outstepped even the ample limits of licentiousness laid down in the Korán, and having long ceased to be even true Mohammedans, by the time they arrive at manhood have no energy left to promote her welfare, and sink into an indolent, procrastinating race, capable of little in the way of progress till a radical change takes place in their morals.

Nothing betrays their moral condition more clearly than their unrestrained conversation, a reeking vapour arising from a mass of corruption. The foul ejaculations of an angry Moor are unreproducible, only serving to show extreme familiarity with vice of every sort. The tales to which they delight to listen, the monotonous chants rehearsed by hired musicians at public feasts or private entertainments, and the voluptuous dances they delight to have performed before them as they lie sipping forbidden liquors, are all of one class, recounting and suggesting evil deeds to hearers or observers.

The constant use made of the name of God, mostly in stock phrases uttered without a thought as to their real meaning, is counterbalanced in some measure by cursing of a most elaborate kind, and the frequent mention of the "Father of Lies," called by them "The Liar" par excellence. The term "elaborate" is the only one wherewith to describe a curse so carefully worded that, if executed, it would leave no hope of Paradise either for the unfortunate addressee or his ancestors for several generations. On the slightest provocation, or without that excuse, the Moor can roll forth the most intricate genealogical objurgations, or rap out an oath. In ordinary[page 44] cases of displeasure he is satisfied with showering expletives on the parents and grand-parents of the object of his wrath, with derogatory allusions to the morals of those worthies' "better halves." "May God have mercy on thy relatives, O my Lord," is a common way of addressing a stranger respectfully, and the contrary expression is used to produce a reverse effect.

I am often asked, "What would a Moor think of this?" Probably some great invention will be referred to, or some manifest improvement in our eyes over Moorish methods or manufactures. If it was something he could see, unless above the average, he would look at it as a cow looks at a new gate, without intelligence, realizing only the change, not the cause or effect. By this time the Moors are becoming familiar, at least by exaggerated descriptions, with most of the foreigner's freaks, and are beginning to refuse to believe that the Devil assists us, as they used to, taking it for granted that we should be more ingenious, and they more wise! The few who think are apt to pity the rush of our lives, and write us down, from what they have themselves observed in Europe as in Morocco, as grossly immoral beside even their acknowledged failings. The faults of our civilization they quickly detect, the advantages are mostly beyond their comprehension.

Some years ago a friend of mine showed two Moors some of the sights of London. When they saw St. Paul's they told of the glories of the Karûeeïn mosque at Fez; with the towers of Westminster before them they sang the praises of the Kûtûbîya at Marrákesh. Whatever they[page 45] saw had its match in Morocco. But at last, as a huge dray-horse passed along the highway with its heavy load, one grasped the other's arm convulsively, exclaiming, "M'bark Allah! Aoûd hadhá!"—"Blessed be God! That's a horse!" Here at least was something that did appeal to the heart of the Arab. For once he saw a creature he could understand, the like of which was never bred in Barbary, and his wonder knew no bounds.