Title: Ruth Arnold

or, The country cousin

Author: Lucy Byerley

Release date: July 7, 2006 [eBook #18777]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by David Clarke, Mary Meehan, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

E-text prepared by David Clarke, Mary Meehan,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net/)

CHAPTER I. A Letter

CHAPTER II. Talking it Over.

CHAPTER III. Ruth's Decision

CHAPTER IV. The Journey

CHAPTER V. Cousins

CHAPTER VI. Stonegate

CHAPTER VII. A Poor Relation

CHAPTER VIII. Sea-side Pleasures

CHAPTER IX. The Picnic

CHAPTER X. Busyborough

CHAPTER XI. School-girl Gossip

CHAPTER XII. Julia's Humiliation

CHAPTER XIII. Hard at Work

CHAPTER XIV. An Adventure

CHAPTER XV. Examination

CHAPTER XVI. A Downward Step

CHAPTER XVII. The Prize

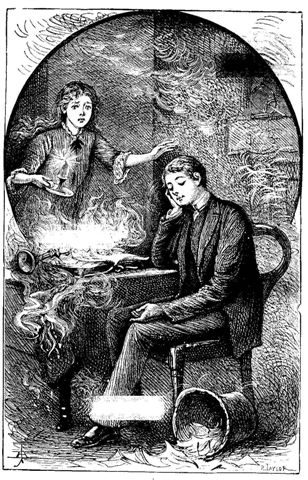

CHAPTER XVIII. So as by Fire

CHAPTER XIX. Living it Down

CHAPTER XX. Home Again

School was over, and the holidays were beginning once more, summer holidays, with all their promise of pleasure for dwellers in the country. The scent of sweet new hay was borne on the afternoon breeze, and the broad sunlight lay on fields of waving corn which would soon be ready for the sickle, and on green meadows from which the hay was being carried.

Ruth Arnold slowly wended her way home-wards along the hot dusty road, turned down a shady green lane, opened a little gate and walked up the garden path; and then, instead of running indoors as usual, she sat down in the little rose-covered porch and looked rather thoughtfully at the book in her hand.

It was a new book, a prize which had been awarded her that afternoon; but she felt very little pride in it, for she had known all through the half-year that the prize would be hers unless she was very idle or lazy. Nor did she anticipate much pleasure in reading it, for it was only a new English grammar, and grammar was not a study in which she felt particularly interested at that moment.

It was not often that Ruth sat down to think, for she was a merry lively girl; but this afternoon she felt rather discontented with her lot. The truth was that she had been at Miss Green's school, the only one in the village, ever since she was six years old; and now she had turned fourteen, and began to feel some contempt for the elementary catechisms which had been her only lesson-books, and which were certainly not calculated to make learning attractive or interesting. The mode of instruction at Miss Green's was the old-fashioned one of saying lessons by rote from the said catechisms, and when the pupils had reached the end of the book they had to begin again at the first chapter.

"I'm sure I don't know what I've learnt this half-year," said Ruth to herself. "I can't remember learning a single thing which I didn't know six months ago; and yet mother says that I must not leave school until I am fifteen. I wonder what books they use in large boarding-schools, and if they ever get beyond Mangnall's Questions in the first class. I suppose I shouldn't trouble about it if it were not for father's teaching us in the winter evenings; but he knows so much, that we see how ignorant we are."

"I didn't know that you were at home, Ruth. How long have you been here?" asked her mother's voice.

"Only a few minutes."

"Where is your prize? And why did you not show it to me?"

"Here it is, mother; but I don't much care for it. There is so little credit in getting a prize at Miss Green's, where one makes so little progress, and has to do the same thing over and over again."

"Yes," said Mrs. Arnold with a little sigh, "and so you will find it in life, dear, the same thing over and over again, every day and every year. But now," she added smiling, "as everyone is busy in the hay-field, and baby has to be nursed and the cows to be milked every day, will you help me to do one thing or the other?"

"Yes," said Ruth as she went to put on a large blue pinafore; "I'll go and help Mary with the milking."

Five minutes later she was seated on a low stool beside her favourite cow, Beauty, which had been reared on the farm, and named by Ruth herself, who petted and talked to her like an old friend. The afternoon was very warm, but still and sweet and quiet, with the summer hush upon everything, even the lowing of the cows in the farm-yard, the murmur of the brook, and the voices of the workers in the distant hay-field.

"Ah me, old Beauty!" sighed Ruth, as she pressed the milk into the pail, "mother says that it is the same thing over and over again all our lives, and I suppose it is true, but I wish I could have something different."

Beauty only lowed; but if she could have spoken English she might have said, "If you find life monotonous, what must it be for me? In the morning I rise and crop the grass, then I come in to be milked. I go back to the meadow and bathe in the stream or eat as much grass as I want; in the afternoon I lie under the shade of the trees and chew the cud; and in the evening I come again to be milked, and once more return to the meadows. If I have a calf of my own, it is taken from me and sent—I know not where. Yes, it is the same thing over and over again. Yet I am quite content."

Whatever Beauty meant as she lowed and looked at Ruth with her great patient eyes, the young girl did not understand, but went on thinking aloud: "Yes, it is breakfast, dinner, tea and supper every day, and mother has to see to it all; and the children to be washed and dressed and nursed, and the cows to be milked, and the cream to be skimmed; and then every year father has the ploughing, and sowing, and haying, and the har——"

"Ah, Ruth, I see you are making yourself useful," cried her father, as he entered the farm-yard followed by two merry looking boys aged respectively seventeen and twelve. It was evident from a single glance that they were Ruth's brothers, although their hands and faces were brown and sunburnt, and Will, the elder, was fully a head taller than his sister.

"Guess what Will has got for you, Ruth!" cried roguish little Ned.

"Oh, Will!" she exclaimed, looking up brightly, all her grave thoughts gone in a moment, "have you brought a new plant for my garden? No! Has Annie Price sent the pattern she promised for my wool-work? Well then, is it the new tune-book you were talking of yesterday, with both the music and words?"

"No, you are quite wrong; and as I can't tell whether it is anything good or bad, I may as well give it to you at once. It's from a girl, I think," continued Will, as he took a letter from his pocket.

"A letter for me! Who can it be from? Yes, I see it comes from a girl by the writing. What a pretty hand! ever so much better than mine; and here is the post-mark—Busyborough; it must be from Cousin Julia," she said as she turned the letter over.

Then she opened it and began to read, while her brothers stood by full of interest, and saw a look of mingled wonder, surprise, and delight spread over her face. They waited as long as their curiosity would permit, and then both cried eagerly, "What does she say? What is it all about?"

"She wants me—that is, aunt has invited me—to spend my holidays with them at the sea-side," said Ruth, speaking very slowly, and looking as if she could hardly understand the idea of such a piece of good fortune coming in her way. "But there," she added with a sigh, as she refolded the letter and put it into her pocket and tried to banish the visions of brightness it had called forth, "of course it is quite out of the question. I couldn't go away now when every one is so busy."

She walked slowly back to the house, and tried not to think of the bright dream of pleasure the letter had suggested; but this was not an easy matter, as her father and mother were already sitting at the tea-table talking over the same subject, for Mrs. Arnold had also received a letter from Busyborough that afternoon.

"Have you read your cousin's letter, Ruth?" asked her mother as she took her seat. "Why, what makes you look so unhappy?" she exclaimed, observing the girl's grave face.

"It's very silly, I know, mother; and I didn't mean to be vexed about it," she began, "but Julia said something about my going to the sea-side with them to spend the holidays. Of course I know very well that you couldn't spare me,—but I can't help crying—just a minute, mother, that is all," said Ruth, while her tears dropped slowly.

"Don't cry, child; we'll talk it over to-night, and see what can be done," said her father cheerfully.

"But, father!" cried Ruth, starting up in surprise, her tears quite forgotten, "you don't think really that there is any chance of my going, do you? Just see how busy you are with the haying, and then there are the boys and the little ones——"

"Well, well, your mother and I will talk it over," he repeated, as he took up his hat and set out again for the hay-field.

The summer evening soon slipped away, and Ruth knew better than to worry her mother by asking foolish questions; but when supper was over, and her head lay at rest upon the pillow, her brain was busy, and it was a long time before sleep overtook her. Delightful visions of sea-side places such as she had read of in her favourite books, of picnics and boating, of rambles in search of shells, rare stones and long sea-weeds, filled her mind; and as she heard the monotonous sounds of her parents' voices talking in low tones in the room beneath her, and knew that they were discussing the important question Was she to go or stay? her impatience almost got the better of her, and she longed to run downstairs and take part in the conversation.

Presently the voices ceased, there were footsteps on the stairs, the light of a candle showed through the chink of her door, the footsteps receded and a door was shut, and Ruth knew that the decision was made and her mother had gone to bed. And as she could not know the result of the conversation that night, she very wisely closed her eyes and went to sleep.

Early the next morning she was awakened by the sun shining in at her window. She rose at once, dressed quickly, and was soon downstairs, but not before her mother, who was busily preparing the breakfast. There was so much to be done before the meal was ready, so much chatter over it, and so many last words to the boys and their father before they set out for the hay-field, that Ruth could not find an opportunity to ask her mother the question that was burning upon her lips, until all trace of the meal was removed and the children had gone to play in the orchard.

Then she went upstairs to help her make the beds, and there was time for a quiet chat.

Mrs. Arnold began by inquiring, "What did your cousin say in her letter yesterday?"

"She asked if I could spend my holidays with them at the sea-side," replied Ruth, blushing with joy at the very thought.

"And you would like to go?"

"Oh yes, indeed I should, very, very much; that is—of course—if you could spare me," she added hesitatingly.

"I suppose then that you do not know what your aunt has suggested. She writes to know if we will spare you, not only for the holidays, but for a whole twelvemonth, to be a companion to your cousin and go to school with her (What are you doing with the pillows, Ruth?), to share her studies and amusements."

"Should I see none of you for a whole year?"

"I am not sure; that would depend upon your aunt."

"But—mother—you don't think of letting me go, do you?" asked Ruth, almost over-whelmed with pleasure and surprise.

"I don't know. Your father thinks it would be good for you, but I am not sure, Ruth. I am afraid whether, after living in a handsome well-appointed house, waited upon by servants, and surrounded with comforts and luxuries, you would grow discontented with our quiet country life. I know you love your home now, but I fear lest a life in town should spoil you, and make you no longer our little Ruth, but a grown-up young lady, who would feel herself above our simple joys and pleasures, and only bring herself to tolerate them from a sense of duty."

"Mother, mother!" cried Ruth, bursting into tears, "don't talk so. I'll never go away. How can you think so of me?"

"Perhaps I have done wrong to say so much to you, darling," replied her mother; "but I must tell you that your father does not fear anything of the sort for you. He says that you need to go to a good school, and that he is thankful for the opportunity which is now offered. He feels sure that you would be happy with his sister, and does not fear your growing discontented with home. Besides, as he says, when you come back you will be able to teach the younger children, and that will be a good object to have in view while you are studying. So we have determined to leave it for you to decide. We will give you to-day to think it over, and to-morrow you must tell us what you wish to do. Pray over it, Ruth, and don't let anything I have said prejudice you against the idea of going. Indeed, dear," she added in a lower tone, "I don't think I should have any fear for you if I were sure that you were not going alone, if I knew that you had an almighty Friend to be with you and guide you in the right way."

It was very rarely that Mrs. Arnold said so much to any of her children, and Ruth was quite overcome. She ran off to her own little room to give vent to her feelings, and to think over all that she had heard.

For the first few moments Ruth felt quite determined not to leave home; but as she thought over the advantages and disadvantages of the plan her resolution wavered. How often she had wished, though vainly, to go to a good boarding-school! and now there was an opportunity for her to have a twelvemonth's education, without the great drawback of living at school among strangers and losing the comforts and freedom of home. It was true that she had only seen her aunt for a short time several years before, and her cousins were quite unknown, except for the short notes she usually received at Christmas, with a present from Julia. Still they were relatives, and would not regard her as a stranger.

There were so many arguments for accepting her aunt's invitation: the pleasure of the sea-side trip, the change, the novelty of living in a town, of having Julia for a companion and many school-fellows of her own age; of exchanging Miss Green's school, with its catechisms and needlework, for a young ladies' college, with its modern plans of study, its classes and professors. And all these inducements had the charm of being new and untried, so that only their agreeable side appeared to view, the other being unknown.

Yet if there were fewer reasons against the plan, they were very weighty, for how would mother contrive to do without her? And how could she bear to live a year without a glimpse of the dear home faces?

"But I only help in the mornings and evenings," she mused, "for I am at school all day, and perhaps I could come home for a few days at Christmas. I'm sure I don't know what to do. I wish father and mother had settled it. It is so difficult to know how to decide."

She did not forget the advice which had been given her—to pray over the matter. Indeed, I doubt if she would in any case have come to a decision without taking counsel of her Heavenly Father, for Ruth had for years been in the habit of carrying her childish troubles and perplexities to the one unfailing Guide.

And yet she was hardly sure that she was a Christian; and although she longed to set her mother's mind at rest upon that point, she could not venture to do so just yet. Like many another child of pious parents, she had been trained to love good and hate evil; she had been taught to pray and to desire to live a Christian life; she had long since begun the never-ending conflict against evil and tried to rule her life and actions by God's Word; and yet she could not tell whether the promptings and impulses towards the Saviour which often came to her heart, were merely the result of the loving sanctified home-influence which had surrounded her from her birth, or if she had indeed become a disciple, though but a feeble one, of the meek and lowly Jesus.

In the quiet calm of a summer day, when the wind scarcely ruffles the waters of the bay, it is difficult to say whether the fair ship riding at anchor will prove herself seaworthy. It is when the storm rises in its fury and the billows dash over her that the testing time comes, and she proves the strength of her bows and the soundness of her timbers, or she sinks a hopeless wreck.

And it remained for Ruth's visit to Busyborough, to test her and prove how strong was her desire to follow Christ. If it were but a weak earth-born feeling, it would soon be upset by the winds of temptation; but if it were indeed of God, although it might be roughly handled and somewhat shaken for a time, it would come forth triumphant at last.

"Well, Ruth, what do you intend to do?" asked her father, as they sat at breakfast the next morning. "Do you intend to go to Busyborough, and find out how ignorant you are, and then set to work to study with all your might, or do you mean to be the pattern eldest scholar at Miss Green's? Do you mean to rub shoulders with others, or are you going to stay at home and fancy yourself a prodigy of wisdom and learning?"

"I think, that if you and mother can spare me, I will go to Busyborough, and rub shoulders with the others," said Ruth, steadily.

"That's right; I am glad to hear it; for although we shall miss you very much, I am sure the change will benefit you. Go and learn all the good you can, and tell us all about it when you come back. Ah! your mother looks grave: I know she rather fears your picking up some fantastical notions and growing to look down on your own people. But I don't fear it. I look forward to seeing my little Ruth again next summer, grown somewhat taller, perhaps, and wiser too, but still always my own Ruth."

"Yes, father," she answered, with something like a sob.

But Will, the eldest brother, who found that his father's speech and Ruth's face were getting too much for his feelings, jumped up and seized his hat, saying in his queer way that he must be off to the hay-field if there was a prospect of showers, and he hoped Ruth would not run away before he came back.

The other members of the family soon dispersed; and although Ruth's departure was for days the all-absorbing topic of conversation, it was generally referred to in a cheery way, and not in what Will called "the sentimental strain."

Several letters passed between Mrs. Arnold and her sister-in-law; and as it was arranged that Ruth was to go the following week, there was not much time for preparation, and every spare minute was fully occupied. Her entire wardrobe had to be inspected and replenished, as far as slender means would permit; old garments were made to look as much like new as possible, and little bits of ribbon and lace which had not seen the light for years, because there were so few suitable occasions for wearing them in a quiet country place, now reappeared in the form of bows and tuckers for the neck.

As Mrs. Woburn, Ruth's aunt, lived a great many miles from Cressleigh, it was decided that her niece should go direct to Stonegate, the watering-place where they were to spend the holidays. She was therefore to take a long railway journey, quite an event in itself, as she had rarely been farther by rail than the county town, twelve miles distant, and even there she had always been accompanied by her father or mother. But just now there was so much to be done on the farm, that her father could spare neither the time nor money for a long journey, and the young girl was obliged to travel alone, a formidable undertaking, which seemed almost to spoil the anticipated pleasure of the sea-side visit.

One bright morning in the early part of July, Ruth woke with the thought, "I am really going away to-day, and perhaps I may not sleep in this dear little room for a whole year, or for six months at least."

She had rarely called her chamber a "dear little room" before; in fact, she had often grumbled because it was so small; but now that she was about to go away it had suddenly become dear, for was it not part of her home, and what place in the world could ever be so dear as home?

How strange it all seemed that morning! The coming downstairs and finding the little trunk packed and corded in the hall; the hurried breakfast, at which every one but mother talked very fast, because they had so much to say and such a short time in which to say it; the leave-takings, the good-byes, and parting injunctions.

Ruth drove off at last beside her father, feeling like one in a dream, so dimly did she see everything through the mist of tears which hung about her eyes.

There was another farewell to be said at the railway junction, for Mr. Arnold could only wait a few minutes to see her into a comfortable carriage, and then returned home to Cressleigh. When he waved his hand and the train was fairly in motion, Ruth began to realize that she was being separated for a long, long time from all whom she loved best in the world; she heaved one great sob, and crouching into a corner of the carriage gave way to a flood of tears. She wept for several minutes undisturbed, then a kind motherly-looking lady, who was sitting opposite to her, asked, "What is the matter, my dear? Are you going away to school?"

"Yes, ma'am; at least, I mean no, not yet. I am going to the sea-side to stay with my cousins for a few weeks."

"I don't think that most girls would be so distressed at the thought of a visit to the sea-side," said the old lady, smiling.

"But I'm not coming back for ever so long," replied Ruth, drying her tears, however. Then she informed her new friend how long she was going to be away, and what she hoped to see and do during her absence from home, and the old lady seemed so much interested that Ruth soon grew bright and merry, and began to notice the pretty country through which they were passing; and when the train stopped at a rustic station, where a little pony trap was waiting to convey the old lady to her own home, they felt as if they had known each other for years instead of hours, and were really very sorry to part.

The rest of the journey seemed rather dull and tedious, and it was late in the afternoon when the train drew up at the Stonegate station. There were a good many people on the platform, and Ruth was wondering if any one had come to meet her, when a lady looked in at the carriage door and inquired in a pleasant manner, "Your name is Ruth Arnold, is it not?"

"Yes, it is," she replied rather shyly, as she bent forward to look at her aunt. But that look told her a great deal.

She saw a fair placid face which she felt sure she should love, for the dark blue eyes reminded her of her father's, though the fair hair and small mouth were strangely unlike his. But there was something familiar in the tone of her voice, and when she called a cab, gave instructions about the luggage, and took her seat beside her niece, Ruth was quite at ease and felt that she was going to be happy.

"You will see Julia very soon," said Mrs. Woburn, "but this is our first day at the sea-side, and she was out when I started. I am afraid that she will be angry with me, for I know that she intended to come herself to meet you, and I think she will be disappointed."

"It was very kind of you to come," said Ruth; "I was getting quite frightened, and thought that perhaps you might not know me, and that I should be all alone in a strange place."

"There is not much fear that any one who has seen your mother would not recognise her daughter," was Mrs. Woburn's smiling reply.

"Do you think me so much like her?" asked Ruth eagerly, looking greatly pleased.

"Indeed I do. But this is our lodging. I see Julia looking out of the window."

In another minute Ruth had followed her aunt into a large cheerful sitting-room, with two bay-windows overlooking the beach and sea.

"Oh! mamma, what a shame of you to go without me!" cried a voice from the window where a young girl was standing.

"You were so late, dear," said Mrs. Woburn gently. "Here is your cousin; take her to her room; I am sure she must be tired after her long journey."

Julia, a pretty fair-haired fashionably-dressed girl, came forward and shook hands, saying, "How d'ye do, Ruth? I am glad mamma met you. Will you come upstairs?"

She led the way to a pretty bedroom, much larger than the one in which Ruth had slept at Cressleigh. There was a splendid view of the sea from the windows, and the furniture of the room was all of light polished wood; a pretty dressing-table stood between the windows, which were hung with white muslin curtains, and the hangings and cover-lids of the two little beds were snowy white.

"What a pretty room!" said Ruth, as she entered.

"Do you think so? I think it is awfully small and poky. And we are both to sleep here, which I am sure will be very inconvenient; but we couldn't get anything better, so I suppose we must put up with it. Lodgings are always the great drawback to the sea-side, you know."

Ruth did not know what reply to make, she was so taken aback by the grandeur of Julia's air and manner.

"Tea is ready, miss," said a trim maid-servant at the door of the bedroom where the two girls were talking, and Ruth followed her cousin downstairs to the large cheerful room she had entered upon her arrival.

Mrs. Woburn had already taken her seat behind the urn, and the two boys who were sitting beside her rose to meet their cousin. Ernest, the elder of the two, was a tall, thin lad of fifteen, with a pair of large brown eyes, the only striking feature in his plain but sensible face.

Rupert was a merry little schoolboy of seven, bright-eyed and curly-haired, a mischievous little sprite, no doubt, but a very affectionate lovable little fellow. He chattered continually during the meal, and did a great deal to take off the sense of shyness that Ruth felt in the company of Julia and Ernest, and her aunt asked questions about the farm-life at Cressleigh, and talked of their plans for the next few weeks.

"Oh! you will have a great deal to see," said Julia, "as this is your first visit to the sea-side. I think we had better put on our hats and go for a long walk at once, it is a shame to be indoors this lovely evening."

"That will hardly do for your cousin, dear; she looks rather tired, and we must remember that she has had a long journey to-day."

Ruth was very tired, and, much as she longed to go for a walk along the shore, she felt that that pleasure must be deferred until the next morning. But she was rather dismayed by Julia's saying, "Well, I don't see any reason for our remaining indoors. Of course Ernest won't come, he is too much taken up with that book about—shellology. So he can stay with Ruth while you come out with us."

"Why can't you call things by their right names, and say 'conchology'?" asked Ernest quietly.

"Really, Julia, I don't think we must leave your cousin this evening," said Mrs. Woburn, doubtfully.

"Don't stay at home on my account, auntie," replied Ruth, putting aside her own feelings, though she did not much like the idea of spending the evening with Ernest, such a grave, quiet boy, so very different from her brothers.

Julia carried her point, and started in a few minutes for a walk with her mother and Rupert, leaving the cousins to their own resources. Ruth took a seat near the window, and watched the waves breaking gently upon the beach, while the boy appeared to be entirely occupied with his book. It was rather dull, this first evening away from home; it seemed scarcely possible that she had really only left Cressleigh that morning, and she began to wonder if they had missed her very much, and what they were doing now, and when she should see them all again, and as she thought of the months that must elapse first she heaved a weary sigh.

The sigh roused Ernest, who had quite forgotten his companion in the charms of his book, and he at once endeavoured to make amends for his neglect in his kind but awkward way.

"Oh! I beg your pardon," he began, "I almost forgot—do you like conchology?" he asked, by way of starting a conversation.

"I don't know anything about it," was Ruth's meek reply, "but I believe it is the science of shells, is it not?"

"Yes. I thought you wouldn't care for it. Girls never do."

"Perhaps I might learn," she said humbly; "but I haven't had a chance to study any 'ologies,' they did not teach them at Miss Green's. Are you studying it as a holiday task?"

"No, for amusement. They won't let me study in the holidays, but I enjoy this. Just look at these shells, aren't they beauties?" and he showed her one of the illustrations in his book.

"Oh! how beautiful!" she exclaimed; and the boy, seeing she was interested, told her what he had been reading, and promised to get her some specimens the next day, and the time slipped rapidly by, until Mrs. Woburn and Julia returned.

"What have you been doing all the evening?" asked Julia, when they were in their room that night. "Was Ernest civil?"

"He was very kind, and showed me his book on conchology, and explained about the shells, and he is going to get me some specimens to-morrow."

"Indeed!" said Julia, rather surprised, "I should not have thought that you cared for that sort of thing."

Ruth was too tired to answer, and had soon forgotten the events of the day in sound refreshing sleep. When she awoke, the sun was shining brightly, and she was astonished to find that she had slept until half-past seven. She was accustomed to rise very early at home, and was afraid that her cousins would be shocked at her laziness, until she found that Julia was still sleeping quietly in the bed beside her.

"Julia! Julia!" she cried, "it's very late. We must get up at once."

"What is the time?" was asked drowsily.

"Half-past seven."

"Why can't you let me rest?" said Julia crossly. "We always breakfast at eight at home, but I don't intend to get up so early at the sea-side."

She closed her eyes and went to sleep again; but Ruth, who was wide awake, rose at once, dressed quickly, brushed her brown curls, and went downstairs. There was no one about, and the morning air was so fresh, and the sunshine so inviting, that she took her hat and ran down to the beach, feeling so full of joy and gladness that she could hardly restrain herself from singing, as she often did in the fields at Cressleigh. The sunlight sparkled upon the crested waves as they broke gently upon the shore, and the tide came in, slowly creeping up the shingle, now bearing away a dry piece of sea-weed and making it look alive and fresh, advancing and retreating, yet ever creeping slowly upward, until one wave almost broke over her feet and reminded her of the old and oft-repeated adage, "Time and tide wait for no man."

She hurried back, to find her aunt and cousins waiting breakfast for her; and as she told them about her morning ramble, she did not notice the unpleasant glances which Julia bestowed upon her dress, a blue cotton one, made very simply, but somewhat old-fashioned, and washed until the colour was rather faded.

"We must certainly go out this lovely morning," said Mrs. Woburn after breakfast. "Where do you think your cousin would like to go, dear?"

"Oh! we'll go to the Esplanade of course," replied Julia, as she ran off to get ready. She came down a few minutes later looking very nice in her pretty holland dress trimmed with red, and shady straw hat with muslin and lace bows, and dainty gloves.

"You don't mean to say that you are going out like that, Ruth!" she exclaimed, as she caught sight of her cousin sitting by the window still wearing her print dress and shabby straw hat.

"Yes," she replied, and was going to ask "Why not?" but the sight of her cousin's simple but pretty costume stopped her, and she blushed rosy red.

"Then of course we cannot go to the Esplanade," said Julia in a pointed manner.

"The Esplanade did you say, girls?" asked Mrs. Woburn, entering at that moment.

"No, mamma, we don't care about it; any other place will do," replied Julia sulkily.

"We will walk along the beach to Brill Head then," said Mrs. Woburn, "and I dare say Ernest would like to accompany us; he will find plenty of specimens there."

"Shall I stay at home, Aunt Annie?" asked Ruth timidly.

"Certainly not, unless you wish it; Julia has been longing to have you for a companion, and this will be such a delightful walk."

But the pleasure of the walk was gone for Ruth. Julia was quiet, and scarcely spoke to any one, and her mother could not understand what was the matter, and although she tried her best to bring back the look of delight to her niece's face, she was not successful. It was not until they reached Brill Head, and Ernest began his search for specimens, that Ruth recovered her wonted liveliness, and the sunshine returned to her face and the gladness to her heart, and she felt so full of life and energy that she challenged Rupert to a race.

"Just look at her, mamma!" exclaimed Julia, who was sitting beside her mother on a rustic seat. "Did you ever see any one so wild and vulgar? And that frightful dress, as old-fashioned as possible! To think of our going on the Esplanade with her!"

"Is that the reason you did not wish to go there?"

"Of course it was. Every one would have stared at her antiquated dress. Indeed, she is altogether old-fashioned; she actually asked me last night if I had any dolls, and if I went to Sunday-school. I didn't think that having a poor relation to live with us would be quite so annoying and humiliating."

Mrs. Woburn was very seldom angry with her spoilt child, but now she was thoroughly roused, and said in low distinct tones, "Remember, Julia, that you speak of my brother's daughter. While Ruth is here she will be treated as your sister. You little know what you owe to your uncle, and if I ever hear you speak in that contemptuous way of any of his family I will send you to your room at once."

Such a threat was quite strange to Julia, who at fourteen began to consider herself almost grown-up, and quite above reproof or punishment; but it was sufficiently determined to prevent her making any more remarks of the sort in her mother's hearing, though it did not increase her affection for her cousin.

During the walk home Ruth was merry as ever, romping with Rupert, chatting with that usually shy lad, Ernest, and planning an afternoon on the shore to collect sea-weeds. But Julia walked slowly beside her mother, so evidently determined to be silent that the rest of the party tacitly agreed to leave her to herself.

Mr. Woburn and his eldest son, Gerald, arrived at Stonegate that afternoon, and Ruth saw them for the first time. She soon felt at home with her uncle, a plain-featured, middle-aged man of business, but with his son she felt wonderfully shy. It seemed hardly possible that the handsome young man with the dark moustache and manly bearing could be her cousin. She had expected to see a boy two or three years older than Will, but still a boy, not a polite and self-possessed young man, who by his way of speaking to her made her feel a very little girl indeed.

"How have you been improving the shining hours, my lad?" was his greeting to Ernest.

"He has been down on the shore collecting shells for Ruth," said Julia mischievously.

"Ernest becoming a lady's man! Dear me! the country cousin is working wonders," he cried in feigned surprise.

Ruth felt the hot blood rushing to her cheeks, though she tried to look as if she had not heard the remark; but it spoilt her pleasure in seeking for shells, and she decided mentally that she should never like Cousin Gerald. The arrival of her brother seemed to have restored Julia's good-humour, and when in the evening he proposed a stroll on the pier she gladly assented, and the whole party set out to hear the band which played there two or three evenings in the week.

Ruth thought that she had never known anything so charming as that evening. It was so pleasant to sit in a sheltered corner listening to the finest music she had ever heard, played by a military band and accompanied by the gentle splash of the waves against the pier; to feel the cool fresh sea-breeze blowing around her, and to see the gay dresses of the ladies as they walked up and down talking to their friends, until by-and-by the quiet stars came out and the silver moon shone upon the scene.

Julia was not contented to sit still and look on; she begged Gerald to let her promenade with him, and for a few minutes he gratified her whim; but Ruth, although she had changed the dress which had proved so obnoxious that morning, did not consider herself to be attired richly enough to mingle with the gay throng that passed and re-passed her in her quiet corner.

"What do you think of Gerald?" asked Julia, when the two girls had retired to their bedroom that evening. "Is he not very handsome?"

"Yes," said Ruth, glad that her cousin had asked a question to which she could give her assent so easily. "But I didn't know that he was so old; I expected he would be a boy."

"He is only nineteen," said Julia; "but I am sure he looks older."

"Only nineteen! Why, Will is seventeen, and he is quite a boy compared with Cousin Gerald."

"That is very likely, for he has been brought up in the country, and that makes a great difference. Now I am sure that Gerald knows quite as much as most men do, and I think it is too bad for father to treat him like a boy."

"Does he?" asked Ruth innocently.

"Yes; he won't even allow him to have a latch-key, and then he complains if Gerald is rather late home in the evening, and he has to sit up for him. And even mamma annoys him dreadfully sometimes by calling him 'her dear boy.'"

"I thought mothers did that even when their sons were quite grown up," said Ruth.

"I don't think they should," was Julia's reply. "But it is quite too bad of papa to expect poor Gerald to slave away in that office all day. He is quite a tyrant, and grudges the poor fellow any pleasure."

"Julia! Julia! I am sure it is very wrong of you to talk in that way of your parents," cried Ruth reproachfully. "Don't you know the Bible says, 'Honour thy father and mother'?"

"What an old-fashioned, tiresome creature you are!" muttered Julia in a sleepy voice.

"When are we to have the picnic, mamma?" asked Julia at breakfast the next morning.

"Any day will suit me; but as your father and Gerald will only be here for a short time, I think we must arrange to have it as early as possible the week after next."

"Let us have it on Monday. Yes, Monday," cried Rupert and Julia together.

"I am going out boating on Monday," said Gerald lazily.

"Tuesday or Wednesday," suggested Mrs. Woburn.

"I am engaged for Tuesday also, but Wednesday is clear, I believe," replied the young man in a careless manner, as if it did not signify much to him whether he formed one of the party or not.

"How horrid of you to put it off so long," exclaimed his sister angrily. "I daresay Wednesday will be wet."

"Nous verrons," he replied, as he sauntered from the room with his hands in his pockets. He looked in again at the door to say, "I shall not be back until the evening, mother;" and in another moment the banging of the front-door told them that he had left the house.

"It is too bad of Gerald to go off like that the very first day he is here," said Julia. "I suppose he has taken his bicycle and gone out with his friends, the Goodes. Horrid people! Yes, there he is," she cried as Gerald and two other young men on bicycles passed the house bowing and smiling towards the window where the two girls were standing.

"Gerald out with the Goodes? I wish he would choose some other companions," said Mr. Woburn, who had scarcely noticed their previous conversation.

"You see how papa finds fault with him," whispered Julia to her cousin.

"Ruth, I want you to come to my room for a few minutes," said Mrs. Woburn; and her niece followed her upstairs.

"I should like you to try on these things and see how they fit you," she said, as she pointed to some pretty dresses spread out on the bed. There was a pale pink, trimmed with dainty white lace; a figured sateen covered with tiny rosebuds, and finished off here and there with knots and bows of rose-coloured ribbon; a simple holland dress trimmed with white braid, and a shady straw hat with bows of lace and a tiny bunch of rosebuds. Ruth gazed at the garments with admiration and astonishment, then she glanced at her own shabby print frock, blushed rosy red, and the tears began to gather in her eyes.

"What is the matter, Ruth? Do you not like them?" asked her aunt kindly.

"They are very pretty, and you are very kind, auntie; but I would rather not wear them," said the girl, trying hard to repress the tears of mortification that stood in her eyes.

"But, my dear, they have been bought on purpose for you to wear at the sea-side. Do at least try them."

"Thank you, auntie, I would much rather not do so;" and Ruth turned aside to the window, from which she could see nothing for the mist before her eyes caused by the storm of passion and pride surging within her breast.

There was no reply, and when she looked round again she found that she was alone. The sunshine was streaming into the room, shining upon the white hat and the pretty dresses, just such garments as Ruth would have chosen if she had had an opportunity of buying such a stock of clothes for herself. But she remembered Julia's words and manner the previous morning, and felt so proud and angry that she deliberately shut her eyes as she walked out of the room, and gave not a thought to her aunt's kindness.

"It is too bad! I'll not stand it!" she murmured. "I did not come here to be treated like a poor relation. If they don't like me as I am, I will go home again. Yes, I'll go and tell auntie so at once," she continued, her pride rising higher and higher until she reached the bay-windowed drawing-room where her aunt was sitting with Ernest. She did not observe his presence, but went straight to her aunt, her cheeks crimson and her eyes flashing.

"Aunt Annie," she said as calmly as her emotion would permit, "Aunt Annie, I think that I had better go home."

"My dear child, what is the matter?" cried Mrs. Woburn, dropping her work in her amazement.

"I think that if you don't like me as I am, I had better go home," she repeated.

"What do you mean?" asked her aunt, still more perplexed; while Ernest looked up from his book and inquired, "Has Julia been annoying her?"

"No," said Ruth; "but, oh, auntie! I can't bear to be—a poor relation, and—and have clothes given me."

The pent-up sobs would have their way at last, and the girl sank down beside her aunt, who tried to soothe and comfort her.

"Have those dresses troubled you so much, dear?" she asked gently. "I had no idea that that was the cause of your annoyance, but fancied you did not like the style in which they were made. If I had thought that you would have any objection I would have acted differently; but as your mother——"

"Did mother know that you were getting them for me?" inquired Ruth.

"Yes, and she wrote to say that she should be glad for you to be treated in every way like your cousin. And you must never think, dear, that we regard you as 'a poor relation.' Remember that your father is my brother, and whatever I give you has been paid for, and far more than paid for, years ago."

"Thank you, auntie; I am glad to know that," she said quietly.

"I did not think you were so proud, Ruth," whispered Ernest as she left the room, and went up to her own chamber to have a good cry over her foolish behaviour. But, to her dismay, Julia was there dressing for a walk, an occupation which she knew would take her a considerable time.

Oh, how she longed for her little room at home, where she had so often taken her childish troubles, or for a quiet nook upon the shore, such as she had often read of, but which is rarely to be found in a fashionable watering-place. There was no solitude for her just then, and she was obliged to fight the battle within silently, while her companion rallied her upon her mournful looks and red eyes; and to send up her prayer for help from the heart, without using the lips. But help came, and she conquered at last the pride and temper of which she was now thoroughly ashamed. She was anxious to obtain her aunt's forgiveness for the rude reception of her kindness, and tried to make amends by arraying herself in the pink dress and pretty hat, which she showed to Julia, saying how kind it was of auntie to get such lovely things for her. By-and-by when she had an opportunity she said in a low voice, "I am very sorry that I was so proud and rude just now, auntie. I'll try to behave better in future."

And Mrs. Woburn, looking at her niece's dress, saw that her repentance was not only expressed in words.

A week spent at Stonegate had taught Ruth more of her own frailties and weaknesses, and had shown her more of the various sorts of people of which the world is composed, than she would have learnt in a whole year spent in the quiet sheltered seclusion of her home at Cressleigh.

The novelty, the continued round of pleasure, the excitement and gaiety, were bewildering and delightful to the simple country girl. It seemed to her that she had been suddenly transported from the commonplace ordinary work-a-day world in which she had hitherto dwelt, to a fairyland of sunshine, music, and pleasure. It was almost impossible at times to realize that the sun which brightened the Esplanade, and gilded the edge of the rippling waves, was the same sun which was shining upon her father's harvest-field at home, upon the labourers toiling at the sickle, the women binding the sheaves, and the servants briskly moving hither and thither, all as busy as bees throughout the whole of the long summer day.

Everything at the sea-side was new to Ruth, and she exulted in the freshness and novelty of all around her, for she was still at that happy age

Alas, that that time is being gradually shortened, and that children say good-bye at such an early age to the simple pleasures of youth!

How few years there are in which one can be young, and how many in which one must be old!

But Ruth was still young, far younger in her capacity to enjoy than Julia, who was her junior by some months. She was in good health, with fine animal spirits, and had not tasted half the pleasures which had already grown stale to her cousin. The boating, the chatter, the strolls, the music on the pier, the glorious sunsets, the very stones and shells upon the beach, the fresh breezes and the ever-changing sea, all contributed to afford her such pleasure as it would have been impossible for Julia to feel, because she, poor child, was already disenchanted at fourteen, was already wearied with frequent repetition of the amusements which were new to her cousin, and also because she had imbibed the idea that it was ill-bred, and a mark of ignorance, to show or even to feel extreme pleasure in anything, yet was ever selfishly seeking some new gratification.

"You appear to be enjoying yourself very much, Ruth," observed her aunt, as she sat beside her on the pier the evening before the day arranged for the picnic.

"How can I help it, auntie? You are so kind, and everything is so enchanting," was the enthusiastic reply.

"I think that many of the richest people here would give all they possess to have that child's keen sense of delight," remarked Mrs. Woburn to her husband, as Ruth tripped away to join her cousins.

"Oh, Julia," she exclaimed, "what a charming piece the band has been playing!"

"That old thing!" replied the other contemptuously. "It is the overture to 'La Sonnambula,' and I perfectly hate it, for I learnt it at school ages ago, and Signor Touchi used to get awfully angry about it."

Julia often acted as a sort of wet blanket upon her cousin's enthusiastic outbursts; though it was a long time before the country girl learnt to express her delight in the usual formula of a fashionable young lady, "Very charming," or "Awfully nice," pronounced in a manner which seems to imply, "Just tolerable."

Wednesday morning rose clear and bright, and soon after sunrise Ruth peeped out of the window to see if the weather were favourable, and when she saw the sunshine she could remain in bed no longer, but dressed quickly and ran down to the beach, her favourite retreat in the early morning, and the only place where she ever found an opportunity for quiet thought amidst all the excitement of pleasure-seeking.

What a long time it seemed since she had left home! And yet it was only a few days. What would her mother think, she wondered, of the life she was leading now? She had only received one short letter from her, written after all the rest of the household were in bed, and Ruth could guess how very busy every one was, although there was but a casual reference to the fact in the letter.

"I hope that mother is not doing too much," she mused, "it was very kind of her to let me have so much pleasure; but how hard it would be to go back now after all this gaiety. I trust that I am not getting spoilt, yet——"

"Have you been looking for anemones, Ruth?" asked a boyish voice beside her. "This is not the place to find them."

"I had no idea that you were near, Ernest," was her reply, "but I have not been looking for anything, only thinking."

"Well, it is almost breakfast time now. You know that we are to be early this morning on account of the picnic to which you are all going."

"But surely you are going with us?" said Ruth in surprise.

"No," he answered quietly, "I should only be in the way. Gerald and his fellows don't want me, and Julia and her friends only snub me and think me a nuisance, and of course I am too old to romp and be petted like little Ru. So I shall have a quiet day on the shore collecting fresh specimens, and you shall see them to-morrow. Now we must go in to breakfast."

Ernest had grown very fond of his country cousin, who was so different from his sister and her friends that she could actually take an interest in his pursuits, and who, under her father's guidance, had learnt many interesting facts of natural history which the town-bred boy had never had opportunities of observing.

Breakfast was a hurried meal, and directly it was over there followed the bustle of preparation for the day's excursion. Hampers were sent off, duly packed with all kinds of delicacies; Rupert was running up and down stairs continually, and getting in the way as much as Ernest, who remained stationary near the door; while Julia rushed from her room to her mother's, declaring that she was quite certain they would all be late, and then ran back to ask Ruth to help her to dress.

Everything was ready at last, and the whole family started for the pier, where they were to meet their friends. Such a crowd of people surrounded them upon their arrival, that Ruth, who merely knew a few of them slightly, felt quite over-whelmed, and wished that her usual companion, Ernest, had been beside her.

The steamer which had been chartered for the occasion now came alongside the pier, and every one was occupied with the business of embarking. When all the party were safely on board, Ruth found herself amongst a number of strangers, far away from Julia, who had evidently quite forgotten her, and was laughing and chatting with a little group of girls at the other end of the vessel. Her aunt was entertaining the ladies, and her uncle walking up and down the deck in earnest conversation with two gentlemen; Rupert was trying to get on the paddle-box, and there was no one near her but Gerald, the facetious leader of a knot of young men. Ruth felt very lonely and rather sorrowful; she had been eagerly anticipating this picnic, and now she seemed to be quite neglected, while every one else was gay and happy. She had not the courage to make her way through the visitors to reach Julia at the other end of the boat, for she had an undefined feeling that if she went she would not be welcomed there. Her thoughts flew back to the one spot of earth where she was always wanted and ever welcomed, and she heaved a little sigh.

"What is the matter, my fair coz?" asked Gerald, who was standing near and heard the sigh. "Are the Fates very unpropitious?"

"No, Cousin Gerald," she answered shyly.

She could not understand the young man who patronized her, and talked to her as if she were a little child, and she fancied that he was making fun of her.

"Then why do you sigh?" he inquired.

"I have nothing else to do," she said, smiling.

"Has Julia left you without any introduction? Well, we will soon remedy that," he said as he led her towards a very fair young girl, dressed in blue and white, and having introduced the two girls he left them talking, and strolled off with a friend.

Ruth's companion was by no means shy, she had a great deal to say, and began by making remarks upon the people on board, and telling little scraps of their personal histories.

"You see that old gentleman walking with Mr. Woburn. That is Mr. Amass, the banker. They say that he is awfully rich, but I am sure that he is a terrible screw. Only look at his wife, and see how shabbily she dresses. Don't you see her over there with the daisies in her bonnet? And that is her niece, Miss Game, flirting with Mr. Trim. Ah! he is walking away now; he prefers a chat with Edith Thorpe. How amused they look! I suppose he is telling her what Miss Game has been saying. Yes, I am sure they are laughing at her!"

"But surely," said Ruth, looking rather shocked, "he would not be so rude as to talk to a young lady, and then go away and laugh at her!"

"My dear child," replied the other, laughing, "every one does it, more or less."

"But are none of them friends? Do none of them care for each other sufficiently to refrain from laughing?" asked Ruth earnestly.

"Very few persons care enough for their friends to be quiet about their follies and weaknesses," replied this worldly-wise young lady, and then she continued her running commentary upon the visitors until the steamer arrived at its destination, a beautiful little bay where the water was so clear that one could see the sea-weeds growing underneath. Tall trees grew not far from the shore, and upon a slight eminence was situated an old castle, not possessing many historical associations, but in a fairly good state of preservation, and much frequented by pleasure parties from Stonegate.

The older ladies at once made their way to a shady nook under the trees, and the rest of the party strolled about the grounds in twos and threes until a tempting repast had been spread, not upon the grass, but upon long wooden tables in the castle yard.

Ruth was utterly astonished. Her ideas of a picnic were gathered from the simple and joyous little parties held in the woods near her home, when the hamper, filled with cold meat, tartlets, and milk or lemonade, was sent on in the milk cart or one of the farm wagons, a white cloth was spread under the shade of a tree, and the whole party sat on the grass round it, and were merry and lively, regarding the little accidents which would occasionally happen as so much cause for mirth.

But this sumptuous collation, with its garnished dishes of poultry and joints, salads, tarts, jellies, blancmange, ices and champagne, with various fruits, all tastefully arranged, and the accessories of glass and flowers, silver forks and spoons, and long seats, with waiters hurrying about, made a picnic quite a different affair, and—Ruth was unfashionable enough to think—took away all the fun of it. She could see that her aunt was somewhat anxious, and was quite as vexed at any slight accident which occurred as if she had been giving a party in her own house.

Of course there were several toasts and a good deal of speech-making, and a considerable quantity of champagne was drunk before the guests left the tables and dispersed, some to the tennis court, others to explore the castle, and a few to take a country walk in the green lanes.

The afternoon was very warm, but the hush of the summer's stillness was broken by the merry voices of the girls as they made their way through the old castle and peeped out of the windows at their friends in the tennis court below. There was a continual flutter of light dresses through the low doorways and up the dingy stairs, and merry sounds of laughter echoed through the empty chambers. It was the first castle that romantic little Ruth had ever seen; and although she could not gather much of its history from the little books sold at the gate, she tried to imagine the scenes that had been enacted there, to people it with knights in armour, and to fancy that the girlish faces which peeped through the windows were those of "fayre ladyes" of bygone days.

She was aroused from her day-dream by a scream from one of the girls, and saw Gerald, looking white and scared, hurrying towards a small door leading to the keep. The tennis players ceased their game, all eyes were turned in one direction, and a frightened whisper ran through the crowd as Mr. Woburn hastened across the ground. On the very edge of a broken tottering wall projecting from the side of the keep sat Rupert—ever an adventurous little fellow—his face white and his legs dangling. He had crept up into the keep alone, and climbed as high as he could, just to give them all a fright. And he had succeeded, but not without risk to himself, for the shriek of terror which some one gave upon seeing him had awakened him to a sense of his danger, and looking down upon the terrified faces below he grew frightened and almost lost the power to keep his seat. It was a terrible moment, and every one paused in horror-stricken silence.

"That's right, Ruey, sit still!" cried a clear, ringing voice. "Shall I come up to keep you company? But you must get to the other end of the wall. Don't try to crawl; push yourself along like this," cried Ruth, sitting on a low fence and propelling herself sideways, clutching it with her hands on either side, quite regardless of the notice she was attracting. It was the best thing she could have done, for the boy, hearing her cheery tones and seeing that the faces below were no longer upturned in terror, began to regain his courage, and imitated his cousin's movements, thus getting farther and farther from the dangerous corner and nearer to the firmer masonry of the keep, through which the young men were hurrying to his rescue. Slowly and awkwardly he shuffled along, and reached the end of the wall just as Ruth reached the end of her fence, for she had kept on all the time for the sake of example.

"Thank God he is safe!" cried Mr. Woburn, as Gerald caught the little fellow in his arms and disappeared within the walls of the building.

"And this young lady has saved him," said a gentleman who had just appeared upon the scene. He had been taking a country ramble, had seen the boy's danger from a considerable distance, and arrived, almost breathless, in the castle yard just as Rupert was lifted from his perilous position.

"If he had fainted or turned giddy he must have fallen, and that wall would not have borne another person. Indeed, if the boy had not been a very light weight, I am afraid it would have given way;" and as if to verify his words a small piece of stone, which had probably been loosened by the boy's movements, came crashing down from the wall.

Ruth was now the universal object of attention, and she felt dreadfully bashful and awkward as one after another gathered round her and praised "her wonderful presence of mind," and "her remarkable courage." "So fearless, too," said one young dandy, who would not on any account have risked his dainty limbs. "I really thought she was going to climb up and fetch him down."

"I should not have been surprised if she had done so," said a young lady near him.

The poor girl blushed, and began to wonder if she had done rightly in calling out so loudly and drawing every one's attention to herself, for her mother had always told her that a young girl should seek to avoid notice.

"And yet," she thought, "it cannot be wrong. I only wanted to cheer little Ru, and I could not stop to think of any other way."

The appearance of little Rupert in the castle yard diverted attention from his blushing cousin, while friends and relatives crowded round him to scold, applaud, or pet, as they deemed fit. His mother, overcome by the anxiety and suspense of those terrible moments, fainted directly he was brought down to her, but was soon restored, and grew very anxious that the affair should not interfere with the happiness of her guests. Some, indeed, proposed returning at once to Stonegate, but they were overruled by the younger members of the party, who were anxious to remain until the moon had risen, and also by Mrs. Woburn's desire not to curtail their enjoyment; and it was finally settled that the steamer should not return until ten o'clock.

Tea, coffee, and other refreshments were handed round, and the interrupted games were resumed and carried on until the summer evening grew chilly. The dew began to fall, and gave warning that it was too late for out-of-door sports, and drove them into the shelter of the old castle, where the young people proposed a dance. There was a spacious room in the lower part of the building which had been often used for such a purpose, and after hunting up a village musician and pressing him into their service, hats and wraps were thrown aside and the dancing commenced. Ruth did not understand the steps, but sat down near the married ladies and looked on at what, to her unaccustomed eyes, was a gay and lively scene. Yet she could not enter into it as she had entered into the pleasures of the preceding days. She could not forget the alarm of the afternoon; she was sure that her aunt was feeling ill and weary, and she felt that the gaiety around was rather ill-timed and out of harmony with the feelings of the hostess. The hours passed slowly to those who were merely looking on, but at ten the dancing ceased, the old fiddler was dismissed, and amidst a great deal of laughter and chatter the gay party left the castle and made their way to the steamer.

The moon was shining brilliantly, and the walls of the old castle gleamed in its light or were hidden in dense shadow by the surrounding trees. The steamer lay in the little bay just below, every inch of her visible in the moonlight, and all agreed that it was a perfect night for a water trip.

Ruth longed for a little quiet, and strove to escape from her lively companions, whose mirth did not accord with her feelings. She sat in a sheltered corner, and looked at the vast expanse of water and at the quiet stars keeping watch overhead. Nothing so much reminded her of home as the stars, which shone upon her just as they had shone at home, and with the thought of home came a remembrance of the Heavenly Father of whom she had thought so little lately, but who had watched over her unceasingly and had helped her that day to save her little cousin from a horrible fate.

Mr. Woburn and Gerald returned to Busyborough a few days after the picnic, and the remaining weeks of the sea-side holiday passed all too quickly for Ruth, who was never tired of the delights of sea and shore and all the varied amusements that Stonegate afforded.

Still, she was anxious to commence her studies at the young ladies' college her cousin attended, and spent many an hour thinking of it and trying to imagine what the school, the governesses, and the pupils would be like. It was of little use to question Julia, who always declared that she "didn't want to be bothered about school in the holidays," and that Ruth would soon find out "how horrid it was."

It was in September that they bade farewell to Stonegate and left for Busyborough. The days were growing shorter and colder, and as the railway journey occupied two or three hours it was late in the day when they reached their destination, and the street lamps and shop windows were all aglow with gas-light.

What a large noisy place it seemed to country-bred Ruth, as their cab rattled through street after street brilliantly lighted, down long roads, past handsome houses and gardens, until it stopped before a large many-windowed house, with a long flight of stone steps and a small garden, enclosed by massive iron railings.

Rupert and Julia ran up the steps and disappeared, and Ruth followed her aunt into the tile-paved hall, where two servants were waiting to receive them. It was a home-coming to all the others, but to the country cousin it was quite strange and new.

"It is good to be at home again," said Mrs. Woburn. "Come, Ruth, I will show you your room."

She led the way upstairs and opened the door of a pleasant little room, furnished tastefully with every requisite for a young girl's apartment. Everything was so pretty, and the bright fire burning in the grate gave the room such a cosy look, that Ruth was delighted, and tried to express her grateful thanks, but was simply bidden to make herself at home and to be very happy.

Left alone in the room which was to be her own, she began to look around her and to admire the pretty French bedstead, the light modern furniture, and the pictures, bookshelves, and brackets upon the walls. How much larger and more elegant it was than the tiny room which had been hers at Cressleigh! She felt that she was indeed growing farther away from the old life every day. "If it were not for Julia, and the fact that I am so far from home, I could be perfectly happy here," was her mental comment.

They were two large "if's," and Julia was the one which occupied the principal share of her thoughts. She did not "take to" her cousin, neither did she try to make the best of the very apparent fact that their tastes were dissimilar. Instead of seeking for points on which they could agree, she allowed her mind to dwell continually upon their diversity, and was beginning to return her cousin's ill-concealed contempt for her rustic and unfashionable notions by a growing scorn and proud dislike, which though at first secretly cherished could not fail to show themselves in time.

Studies will be resumed on Tuesday, 25th inst. Such was the intimation sent out by Miss Elgin, the principal of the ladies' college which the girls were to attend.

Accordingly on Tuesday morning Ruth accompanied her cousin to Addison College, where she was kindly received by Miss Elgin, and introduced to several of the girls, who seemed friendly and agreeable.

The lofty spacious schoolroom, with its comfortable seats and desks, its splendid maps and numerous modern appliances and convenient arrangements, the school library, with its rows of standard authors in uniform binding, the music-room, the pianos—in fact, the whole establishment exceeded Ruth's brightest dreams of school; and her desire for knowledge, which had somewhat lessened during her sojourn at the sea-side, seemed at once to be kindled afresh.

She answered readily the questions given to test her previously acquired knowledge, and it soon became evident that what she professed to know had been thoroughly learnt. In English studies she was pronounced fairly proficient for her age; but in French, music, and other accomplishments she was very backward, and she found that she would have to work very hard in order to obtain a good place in her class.

The work of the morning was so novel and interesting to Ruth, that she was quite astonished when the bell rang for recess, and the girls trooped off to an anteroom, where their tongues were unloosed and the pleasures and events of the holidays were discussed, with many other topics.

"Have you heard the news about Mr. Stanley?" asked a bright lively girl, Ethel Thompson by name, the gossip and news-monger of the school.

"No; what is it?" cried several voices.

"Well, you must keep it to yourselves, you know," she said in a confidential tone, "but he has failed, he is a bankrupt."

"Are you sure it is true?" asked one and another.

"How do you know?"

"I am sure it is quite true, for my father was talking about it last night, and of course I understood how it was that Mabel's place was vacant this morning," continued Ethel.

"Vacant! I should think it was! You don't suppose she would show her face here, do you?" exclaimed Julia Woburn. "Of course no one would take any notice of her. Only fancy the idea of being seen with a bankrupt's daughter!" she added scornfully.

"Well, it is not her fault." "I suppose she could not help it," said one or two of the girls.

"If it is not her fault it is her father's, and of course it is a great disgrace to the family. I shouldn't think they would ever hold up their heads again," remarked Julia proudly.

"It is very sad." "I always thought them rich." "Mabel was never proud," began a chorus of voices, but the luncheon bell ringing at that moment put an end to the conversation.

The subject was not forgotten, however, and was referred to again in the afternoon, when the girls were preparing to return home.

"What do you think the Stanleys will do?" asked a girl of Ethel Thompson, who having brought the news was expected to know everything relating to her unfortunate school-fellow's family affairs.

"I don't know," replied Ethel. "Perhaps Mr. Stanley will begin business again, men do sometimes, you know; or he may go away from the town and start elsewhere."

"The best thing he can do, I consider," cried Julia. "I can't conceive how people can show themselves in a place where every one knows they have failed. I am sure I could not do it. But some persons have coarse natures and do not feel things as much as others."

"I am quite sure that the Stanleys have feelings as keen as any of us," remarked a shy quiet-looking girl. "You know how sensitive poor Mabel is, and I do hope that if she comes back we shall all be kind to her and not let her know that we have ever heard about her father's misfortunes."

"That may be your opinion, Nora Ellis," said Julia, "but for my part I do not choose to associate with a bankrupt's daughter. If she should return here, of course no one would speak to her; but I do not suppose that there is any fear of it. Miss Elgin would be making a great mistake if she were to receive Mabel Stanley, and would be ruining her school and acting against her own interests."

"I daresay Miss Elgin will do as she thinks best," retorted Ethel Thompson, sorry to have raised a storm which it was not easy to subdue.

Julia and Ruth did not reach school the following morning until nearly ten o'clock, the hour at which Miss Elgin's pupils assembled for their morning classes.

They had scarcely entered the cloak-room before they became aware that something unusual had occurred, something which was evidently connected with the young girl standing apart from the rest, at the end of the room, and looking tearful and timid. In a moment Ruth guessed, from the scornful expression of her cousin's face, that the new-comer was Mabel Stanley who had been so freely discussed the previous day, and that the poor child had met with a very cool reception on her return to school.

Pity for the unfortunate girl, indignation at the freezing glances bestowed upon her, mingled perhaps with a vague idea of vexing Julia, caused Ruth to make a sudden resolution to befriend her; and when upon entering the schoolroom she found that their desks were side by side, she did not delay to take advantage of the fact and endeavour to set Mabel at ease by referring to her occasionally for help in little matters of school routine with which she (Ruth) was unacquainted. The questions were politely answered, but her sensitive neighbour seemed either too proud or too shy to respond to her friendly advances.

"Ruth Arnold," exclaimed Julia in the cloak-room at the close of the day, when Mabel Stanley had dressed quickly in silence and taken her departure with only a half-whispered "Good-afternoon" to Ruth, "did you know that the girl you have been sitting next all day is the very one we were talking about yesterday?"

"Yes, I imagined so," was the quiet reply.

"But I thought you knew that we had all determined to cut her if she came back, and not to say one word more to her than we were really obliged," continued Julia.

"Why?" asked Ruth sharply.

"Because she has no business here, because she degrades the school. A bankrupt's daughter ought not to come here," said Julia haughtily, "and I hope you will not associate with her."

Ruth's eyes were flashing and her cheeks crimson as she retorted angrily, "That is no reason why I should not be friendly with her; and indeed, Julia, I do not intend to ask you whom I am to choose for my friends."

"Do as you like, and go your own way," said Julia with a scornful laugh. "Mabel must be destitute of all fine feeling, but perhaps you have a fancy for people of that sort. If any one belonging to me had ever been a bankrupt, I should never show my face in the town again."

She left the house a moment later with one or two of her chosen friends, and Ruth was slowly walking home alone, trying to swallow her indignation, and letting the cool breeze fan her hot cheeks, when Ethel Thompson overtook her.

"I really think," she began, "that Julia has been terribly down on Mabel, and I am glad that you took her part and would not give in. Our coolness to her to-day was all Julia's doing, and I know that she is wild with you, for she cannot bear to be crossed. But Mabel has not done anything; and after all, I don't see why we should cut her to please Julia, who wants to dictate to every one."

Ruth made an indifferent reply, and hastened to change the subject, for she did not care to discuss her cousin's shortcomings with one whom she knew but slightly.

Very few words passed between the cousins upon their return home that evening; but on their way to school the next morning Julia asked scornfully, "Do you still intend to cultivate your aristocratic acquaintance, Ruth?"

"I shall do as I please," said the other shortly.

The girls at Miss Elgin's were mostly the children of wealthy parents, but unhappily many of them, though rich and fashionable, were sadly lacking in refinement of heart and mind. Money was the god revered and worshipped in most of their homes, the one thing talked of and held in honour, and it was not surprising that the girls, from constantly hearing their neighbours' worth reckoned solely by the amount of money they possessed, had come to regard it as the chief good, and to consider the want of it as something like a crime. Julia had been reared in a somewhat different atmosphere, but she had adopted the tone of her school-fellows, and even surpassed them in scorn and disdain for those who were poor or unfortunate.

But she was about to meet with a terrible humiliation.

A tender conscience is easily aroused, and Ruth's had been troubling her since the previous afternoon. She knew that although she had done right in befriending Mabel she had not done it in a Christian spirit. She almost decided that she ought to beg her cousin's pardon, and was even thinking what it would be advisable to say, when Julia's question stirred her worst feelings to activity, and she answered curtly that she should do as she pleased.

A lively conversation was being carried on in the cloak-room, but suddenly ceased as they entered. The exciting cause of it was Ethel Thompson, whose busy tongue often brought both herself and others into trouble. She had carried home a full account of the quarrel between the cousins the day before, and had concluded by imitating Julia's haughty manner when she said, "If any one belonging to me had ever been a bankrupt, I should never show my face in the town again."

"Humph! Did she say that?" asked Mr. Thompson. "Well 'people who live in glass houses shouldn't throw stones.'"

"Why do you say that?" inquired Ethel curiously.

"Because her own father failed some years ago."

"Are you quite sure?"

"Oh yes, I remember it very well, though I suppose it must have been quite nine or ten years ago, time flies so fast. But he is a very prosperous man now."

Ethel did not wait to hear more, but went to school next day full of the idea of humbling Julia by means of this wonderful piece of news. She had already whispered it to two or three girls when the cousins appeared at the door and the bell rang for class.

Julia was rather late, and in her hurry she placed her hat upon the nearest vacant peg, which happened to be Mabel Stanley's. Mabel entered at that moment, and seeing that her peg was occupied, quietly asked Julia to remove her hat. She did so with a very bad grace, and without saying a word hastened to join her companions in the schoolroom.

"How shamefully Julia Woburn treats that poor child!" said one of the elder girls who lingered in the cloak-room, "and I hear that it is simply because Mr. Stanley has failed in business."

"Yes," replied the other, "and what makes it more disgraceful is—that her own father was a bankrupt not very long ago!"

"Her father? Mr. Woburn? Surely you are mistaken!"

"No, indeed. Ethel Thompson brought the information this morning, and is quite full of it."

It so happened that Julia was returning to the cloak-room for a book which she had forgotten, when she heard her own name mentioned, and pausing for an instant on the threshold overheard all that was said.

She ran in and confronted the two girls, her eyes flashing and her heart beating fast, and exclaimed, "Did Ethel really say that? How dare she tell such an untruth!"

"Perhaps it was only a joke," said the girl who had spoken first.

"It is a slander, an insult, and I'll not stand it!" said Julia indignantly.