Title: The Triumph of John Kars: A Story of the Yukon

Author: Ridgwell Cullum

Release date: August 16, 2006 [eBook #19064]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Al Haines

E-text prepared by Al Haines

| I. | AT FORT MOWBRAY |

| II. | THE MISSION OF ST. AGATHA |

| III. | THE LETTER |

| IV. | ON BELL RIVER |

| V. | IN THE NIGHT |

| VI. | JOHN KARS |

| VII. | AT SNAKE RIVER LANDING |

| VIII. | TWO MEN OF THE NORTH |

| IX. | MURRAY TELLS HIS STORY |

| X. | THE MAN WITH THE SCAR |

| XI. | THE SECRET OF THE GORGE |

| XII. | DR. BILL DISPENSES AID AND ARGUMENT |

| XIII. | THE FALL TRADE |

| XIV. | ARRIVALS IN THE NIGHT |

| XV. | FATHER JOSÉ PROBES |

| XVI. | A MAN AND A MAID |

| XVII. | A NIGHT IN LEAPING HORSE |

| XVIII. | ON THE NORTHERN SEAS |

| XIX. | AT THE GRIDIRON |

| XX. | THE "ONLOOKERS" AGAIN |

| XXI. | DR. BILL INVESTIGATES |

| XXII. | IN THE SPRINGTIME |

| XXIII. | THE DARKNESS BEFORE DAWN |

| XXIV. | THE FIRST STREAK OF DAWN |

| XXV. | THE OUT-WORLD |

| XXVI. | THE DEPUTATION |

| XXVII. | THE BATTLE OF BELL RIVER |

| XXVIII. | THE HARVEST OF BATTLE |

| XXIX. | THE LAP OF THE GODS |

| XXX. | THE END OF THE TERROR |

| XXXI. | THE CLOSE OF THE LONG TRAIL |

| XXXII. | THE SUMMER OF LIFE |

Murray McTavish was seated at a small table, green-baized, littered with account-books and a profusion of papers. But he was not regarding these things. Instead, his dark, intelligent eyes were raised to the smallish, dingy window in front of him, set in its deep casing of centuries-old logs. Nor was the warm light shining in his eyes inspired by the sufficiently welcome sunlight beyond. His gaze was entirely absorbed by a fur-clad figure, standing motionless in the open jaws of the gateway of the heavily timbered stockade outside.

It was the figure of a young woman. A long coat of beaver skin, and a cap of the same fur pressed down low over her ruddy brown hair, held her safe from the bitter chill of the late semi-arctic fall. She, too, was absorbed in the scene upon which she was gazing.

Her soft eyes, so gray and gentle, searched the distance. The hills, snow-capped and serrated. The vast incline of ancient glacier, rolling backwards and upwards in discolored waves from the precipitate opposite bank of Snake River. The woods, so darkly overpowering as the year progressed towards its old age. The shaking tundra, treacherous and hideous with rank growths of the summer. The river facets of broken crags awaiting the cloak of winter to conceal their crude nakedness. Then the trail, so slight, so faint. The work of sleds and moccasined feet through centuries of native traffic, with the occasional variation of the hard shod feet of the white adventurer.

She knew it all by heart. She read it all with the eyes of one who has known no other outlook since first she opened them upon the world. Yes, she knew it all. But that which she did not know she was seeking now. Beyond all things, at that moment, she desired to penetrate some of the secrets that lay beyond her grim horizon.

Her brows were drawn in a slight frown. The questions she was asking peeped out of the depths of her searching eyes. And they were the questions of a troubled mind.

A step sounded behind her, but she did not turn. A moment later the voice of Murray McTavish challenged her.

"Why?"

The brief demand was gentle enough, yet it contained a sort of playful irony, which, at the moment, Jessie Mowbray resented. She turned. There was impatience in the eyes which confronted him. She regarded him steadily.

"Why? It's always why—with you, when feelings get the better of me. Maybe you never feel dread, or doubt, or worry. Maybe you never feel anything—human. Say, you're a man and strong. I'm just a woman, and—and he's my father. He's overdue by six weeks. He's not back yet, and we've had no word from him all summer."

Her impatience became swallowed up by her anxiety again. The appeal of her manner, her beauty were not lost upon the man.

"So you stand around looking at the trail he needs to come over, setting up a fever of trouble for yourself figgering on the traps and things nature's laid out for us folk beyond those hills. Guess that's a woman sure."

Hot, impatient words rose to the girl's lips, but she choked them back.

"I can't argue it," she cried, a little desperately. "Father should have been back six weeks ago. You know that. He isn't back. Well?"

"Allan and I have run this old post ten years," Murray said soberly. "In those ten years there's not been a single time that Allan's hit the northern trail on a trade when he's got back to time by many weeks—generally more than six. It don't seem to me I've seen his little girl standing around same as she's doing now—ever before."

The girl drew her collar up about her neck. The gesture was a mere desire for movement.

"I guess I've never felt as I do now," she said miserably.

"How?"

The girl's words came in a sudden passionate rush.

"Oh, it's no use!" she cried. "You wouldn't understand. You're a good partner. You're a big man on the trail. Guess there's no bigger men on the trail than you and father—unless it's John Kars. But you all fight with hard muscle. You figure out the sums as you see them. You don't act as women do when they don't know. I've got it all here," she added, pressing her fur mitted hands over her bosom, her face flushed and her eyes shining with emotion. "I know, I feel there's something amiss. I've never felt this way before. Where is he? Where did he go this time? He never tells us. You never tell us. We don't know. Can't help be sent? Can't I go with an outfit and search for him?"

The man's smile had died out. His big eyes, strange, big dark eyes, avoided the girl's. They turned towards the desolate, sunlit horizon. His reply was delayed as though he were seeking what best to say.

The girl waited with what patience she could summon. She was born and bred to the life of this fierce northern world, where women look to their men for guidance, where they are forced to rely upon man's strength for life itself.

She gazed upon the round profile, awaiting that final word which she felt must be given. Murray McTavish was part of the life she lived on the bitter heights of the Yukon territory. In her mind he was a fixture of the fort which years since had been given her father's name. He was a young man, a shade on the better side of thirty-five, but he possessed none of the features associated with the men of the trail. His roundness was remarkable, and emphasized by his limited stature. His figure was the figure of a middle-aged merchant who has spent his life in the armchair of a city office. His neck was short and fat. His face was round and full. The only feature he possessed which lifted him out of the ruck of the ordinary was his eyes. These were unusual enough. There was their great size, and a subtle glowing fire always to be discovered in the large dark pupils. They gave the man a suggestion of tremendous passionate impulse. One look at them and the insignificant, the commonplace bodily form was forgotten. An impression of flaming energy supervened. The man's capacity for effort, physical or mental, for emotion, remained undoubted.

But Jessie Mowbray was too accustomed to the man to dwell on these things, to notice them. His easy, smiling, good-natured manner was the man known to the inhabitants of Fort Mowbray, and the Mission of St. Agatha on the Snake River.

The man's reply came at last. It came seriously, earnestly.

"I can't guess how this notion's got into you, Jessie," he said, his eyes still dwelling on the broken horizon. "Allan's the hardest man in the north—not even excepting John Kars, who's got you women-folk mesmerized. Allan's been traipsing this land since two years before you were born, and that is more than twenty years ago. There's not a hill, or valley, or river he don't know like a school kid knows its alphabet. Not an inch of this devil's playground for nigh a range of three hundred miles. There isn't a trouble on the trail he's not been up against, and beat every time. And now—why, now he's got a right outfit with him, same as always, you're worrying. Say, there's only one thing I can figger to beat Allan Mowbray on the trail. It would need to be Indians, and a biggish outfit of them. Even then I'd bet my last nickel on him." He shook his head with decision. "No, I guess he'll be right along when his work's through."

"And his work?"

The girl's tone was one of relief. Murray's confidence was infectious in spite of her instinctive fears.

The man shrugged his fleshy shoulders under his fur-lined pea-jacket.

"Trade, I guess. We're not here for health. Allan don't fight the gods of the wilderness or the legion of elemental devils who run this desert for the play of it. No, this country breeds just one race. First and last we're wage slaves. Maybe we're more wage slaves north of 60 degrees than any dull-witted toiler taking his wage by the hour, and spending it at the end of each week. We're slaves of the big money, and every man, and many of the women, who cross 60 degrees are ready to stake their souls as well as bodies, if they haven't already done so, for the yellow dust that's to buy the physic they'll need to keep their bodies alive later when they've turned their backs on a climate that was never built for white men."

Then the seriousness passed for smiling good-nature. It was the look his round face was made for. It was the manner the girl was accustomed to.

"Guess this country's a pretty queer book to read," he went on. "And there aren't any pictures to it, either. Most of us living up here have opened its covers, and some of us have read. But I guess Allan's read deeper than any of us. I'd say he's read deeper even than John Kars. It's for that reason I sold my interests in Seattle an' joined him ten years ago in the enterprise he'd set up here. It's been tough, but it's sure been worth it," he observed reflectively. "Yep. Sure it has." He sighed in a satisfied way. Then his smile deepened, and the light in his eyes glowed with something like enthusiasm. "Think of it. You can trade right here just how you darn please. You can make your own laws, and abide by 'em or break 'em just as you get the notion. Think of it, we're five hundred miles, five hundred miles of fierce weather, and the devil's own country, from the coast. We're three hundred miles from the nearest law of civilization. And, as for newspapers and the lawmakers, they're fifteen hundred miles of tempest and every known elemental barrier away. We're kings in our own country—if we got the nerve. And we don't need to care a whoop so the play goes on. Can you beat it? No. And Allan knows it all—all. He's the only man who does—for all your John Kars. I'm glad. Say, Jessie, it's dead easy to face anything if you feel—just glad."

As he finished speaking the eyes which had held the girl were turned towards the gray shadows eastward. He was gazing out towards that far distant region of the Mackenzie River which flowed northwards to empty itself into the ice-bound Arctic Ocean. But he was not thinking of the river.

Jessie was relieved at her escape from his masterful gaze. But she was glad of his confidence and unquestioned strength. It helped her when she needed help, and some of her shadows had been dispelled.

"I s'pose it's as you say," she returned without enthusiasm. "If my daddy's safe that's all I care. Mother's good. I just love her. And—Alec, he's a good boy. I love my mother and my brother. But neither of them could ever replace my daddy. Yes, I'll be glad for him to get back. Oh, so glad. When—when d'you think that'll be?"

"When his work's through."

"I must be patient. Say, I wish I'd got nerve."

The man laughed pleasantly.

"Guess what a girl needs is for her men-folk to have nerve," he said. "I don't know 'bout your brother Alec, but your father—well, he's got it all."

The girl's eyes lit.

"Yes," she said simply. Then, with a glance westwards at the dying daylight, she went on: "We best get down to the Mission. Supper'll be waiting."

Murray nodded.

"Sure. We'll get right along."

A haunting silence prevails in the land beyond the barrier of the Yukon watershed. It is a world apart, beyond, and the other land, the land where the battle of civilization still fluctuates, still sways under the violent passions of men, remains outside.

Its fascination is beyond all explanation. Yet it is as great as its conditions are merciless. Murray McTavish had sought the explanation, and found it in the fact that it was a land in which man could make his own laws and break them at his pleasure. Was this really its fascination? Hardly. The explanation must surely lie in something deeper. Surely the primitive in man, which no civilization can out-breed, would be the better answer.

In Allan Mowbray's case this was definitely so. Murray McTavish had served his full apprenticeship where the laws of civilization prevail. His judgment could scarcely be accepted in a land where only the strong may survive.

The difference between the two men was as wide as the countries which had bred them, and furthermore Allan had survived on the banks of the Snake River for upwards of twenty-five years. For twenty-five years he had lived the only life that appealed to his primitive instincts and powers. And before that he had never so much as peeped beyond the watershed at the world outside. His whole life was instinct with courage. His years had been years of struggle and happiness, years in which a loyal and devoted wife had shared his every disappointment and success, years in which he had watched his son and daughter grow to the ripeness of full youth.

The whole life of these people was a simple enough story of passionate energy, and a slow, steady-growing prosperity, built out of a wilderness where a moment's weakness would have yielded them complete disaster. But they were merciless upon their own powers. They knew the stake, and played for all. The man played for the tiny lives which had come to cheer his resting moments, and the defenceless woman who had borne them. The woman supported him with a loyal devotion and courage that was invincible.

For years Allan Mowbray had scoured the country in search of his trade. His outfit was known to every remote Indian race, east and west, and north—always north. His was a figure that haunted the virgin woodlands, the broad rivers, the unspeakable wastes of silence at all times and seasons. Even the world outside found an echo of his labors.

These two had fought their battle unaided from the grim shelter of Fort Mowbray. And, in the clearing of St. Agatha's Mission, at the foot of the bald knoll, upon the summit of which the old Fort stood, their infrequent moments of leisure were spent in the staunch log hut which the man had erected for the better comfort of his young children.

Then had come the greater prosperity. It was the time of a prosperity upon which the simple-minded fur-hunter had never counted. The Fort became a store for trade. It was no longer a mere headquarters where furs were made ready for the market. Trade developed. Real trade. And Allan was forced to change his methods. The work was no longer possible single-handed. The claims of the trail suddenly increased, and both husband and wife saw that their prospects had entirely outgrown their calculations.

Forthwith long council was taken between them. Either the trail, with its possibilities, which had suddenly become an enormous factor in their lives, or the store at the Fort, which was almost equally important, must be abandoned, or a partner must be found and taken. Allan Mowbray was not the man to yield a detail of the harvest he had so laboriously striven for. So decision fell upon the latter course.

Murray McTavish was not twenty-five when he arrived at the Fort. He was a man of definite personality and was consumed with an abundance of determination and resource. His inclination to stoutness was even then pronounced. But above all stood out his profound, concentrated understanding of American commercial methods, and the definite, almost fixed smile of his deeply shining eyes.

There was never a doubt of the wisdom of Allan's choice from the moment of his arrival. Murray plunged himself unreservedly into the work of the enterprise, searching its possibilities with a keenly businesslike eye, and he saw that they had been by no means overestimated by his partner. There was no delay. With methods of smiling "hustle" he took charge of the work at the Fort, and promptly released the overburdened Allan for the important work of the trail.

Nor was Ailsa Mowbray the least affected by the new partner's coming. It was early made clear that her years of labor were at last to yield her that leisure she craved for the upbringing of her little family, which was, even now, receiving education under the cultured guidance of the little French-Canadian priest who had set up his Mission in this wide wilderness. For the first time in all her married life she found herself free to indulge in the delights of a domesticity her woman's heart desired.

It was about the end of the summer, after Murray's coming to the Fort, that an element of trouble began to disquiet the peace of the Mission on Snake River. It almost seemed as if the change from the old conditions had broken the spell of the years of calm which had prevailed. Yet the trouble was remote enough. Furthermore it seemed natural enough.

First came rumor. It traveled the vast, silent places in that mysterious fashion which never seems clearly accounted for. Well over a hundred and fifty miles of mountain, and valley, and trackless woodlands separated the Fort from the great Mackenzie River, yet, on the wings of the wind, it seemed, was borne a story of war, of massacre, of savage destruction. The hitherto peaceful fishing Indians of Bell River had suddenly become the hooligans of the north. They were carrying fire and slaughter to all lesser Indian settlements within a radius of a hundred miles of their own sombre valley.

The Fort was disturbed. The whole Mission struck a note of panic. Father José saw grave danger for his small flock of Indian converts. He remembered the white woman and her children, too. He was seriously alarmed. Allan was away, so he sought the advice of those remaining. Murray was untried in the conditions of the life of the country, but Ailsa Mowbray possessed all the little man's confidence.

In the end, however, it was Murray who decided. He took upon himself the position of leader in his partner's absence, and claimed the right to probe the trouble to its depths. The priest and Ailsa yielded reluctantly. They, at least, understood the risk of his inexperience. But Murray forcefully rejected any denial, and, with characteristic energy, and no little skill, he gathered an outfit together and promptly set out for Bell River.

It was the one effort needed to assure him of his permanent place in the life of the Fort on Snake River. It left him no longer an untried recruit, but a soldier in the battle of the wilderness.

A month later he returned from his perilous enterprise with his work well and truly done. The information he brought was comprehensive and not without comfort. The Bell River Indians had certainly taken to the war-path. But it was only in defence of their fishing on the river which meant their whole existence. They were defending it successfully, but, in their success, their savage instincts had run amuck. Not content with slaying the invaders they had annexed their enemy's property and squaws. Then, with characteristic ruthlessness, they had set about carrying war far and near, but only amongst the Indians. Their efforts undoubtedly had a dual purpose, The primary object was the satisfying of a war lust suddenly stirred into being in savage hearts by their first successes. The other was purely politic. They meant to establish a terror, and so safeguard their food supplies for all time.

Murray's story was complete. It was thorough. It had not been easy. His capacity henceforth became beyond all question.

So the cloud passed for the moment. But it did not disappear. The people at the Fort, even Allan Mowbray, himself, when he returned, dismissed the matter without further consideration. He laughed at the panic which had arisen in his absence, while yet he commended Murray's initiative and courage.

After the first lull, however, fresh stories percolated through. They reached the Fort again and again, at varying intervals, until the Bell River Valley became a black, dangerous spot in the minds of all people, and both Indians, and any chance white adventurer, who sought shelter at the Fort, received due warning to avoid this newly infected plague spot.

It was nearly ten years since these things had occurred. And during all that time the primitive life on the banks of Snake River had continued to progress in its normal calm. Each year brought its added prosperity, which found little enough outward display beyond the constant bettering of trade conditions which went on under Murray's busy hands. A certain added comfort reached the mother's home in the Mission clearing. But otherwise the outward and visible signs of the wealth that was being stored up were none.

Father José's Mission grew in extent. The clearing widened and the numbers of savage converts increased definitely. The charity and medical skill of the little priest, and the Mission's adjacency to a big trading post, were responsible for drawing about the place every begging Indian and the whole of his belongings. The old man received them, and his benefits were placed at their service; the only return he demanded was an attendance at his religious services, and that the children should be sent to the classes which he held in the Mission House. It was a pastoral that held every element of beauty, but as an anachronism in the fierce setting north of "sixty" it was even more perfect.

Allan Mowbray looked on at all these things in his brief enough leisure. Nor was he insensible to the changed conditions of comfort in his own home, due to the persistent genius of his partner. The old, rough furnishings had gone to be replaced by modern stuff, which must have demanded a stupendous effort in haulage from the gold city of Leaping Horse, nearly three hundred miles distant. But Ailsa was pleased. That was his great concern. Ailsa was living the life he had always desired for her, and he was free to roam the wilderness at his will. He blessed the day that had brought Murray McTavish into the enterprise.

Just now Allan had been away from the Fort nearly the whole of the open season. His return was awaited by all. These journeys of his brought, as a result, a rush of business to the Fort, and an added life to the Mission. Then there was the mother, and her now grown children, waiting to welcome the man who was their all.

But Allan Mowbray had not yet returned, and Jessie, young, impulsive, devoted, was living in a fever of apprehension such as her experienced mother never displayed.

Supper was ready at the house when Murray and Jessie arrived from the Fort. Ailsa Mowbray was awaiting them. She regarded them smilingly as they came. Her eyes, twins, in their beauty and coloring, with her daughter's, were full of that quiet patience which years of struggle had inspired. For all she was approaching fifty, she was a handsome, erect woman, taller than the average, with a figure of physical strength quite unimpaired by the hard wear of that bitter northern world. Her greeting was the greeting of a mother, whose chief concern is the bodily welfare of her children, and a due regard for her domestic arrangements.

"Jessie's young yet, and maybe that accounts for a heap. But you, Murray, being a man, ought to know when it's food time. I guess it's been waiting a half hour. Come right in, and we'll get on without waiting for Alec. The boy went out with his gun, an' I don't think we'll see him till he's ready."

Jessie's serious eyes had caught her mother's attention. Ailsa Mowbray possessed all a mother's instinct. Her watch over her pretty daughter, though unobtrusive, was never for a moment relaxed. Some day she supposed the child would have to marry. Well, the choice was small enough. It scarcely seemed a thing to concern herself with. But she did. And her feelings and opinions were very decided.

Murray smilingly accepted the blame for their tardiness.

"Guess it's up to me," he said. "You see, Jessie was good enough to let me yarn about the delights of this slice of God's country. Well, when a feller gets handing out his talk that way to a bright girl, who doesn't find she's got a previous engagement elsewhere, he's liable to forget such ordinary things as mere food."

Mrs. Mowbray nodded.

"That's the way of it—sure. Specially when you haven't cooked it," she said, with a smile that robbed her words of all reproach.

She turned to pass within the rambling, log-built house. But at that moment two dogs raced round the angle of the building and fawned up to her, completely ignoring the others.

"Guess Alec's—ready," was Murray's smiling comment.

There was a shadow of irony in the man's words, which made the mother glance up quickly from the dogs she was impartially caressing.

"Yes," she said simply, and without warmth. Her regard though momentary was very direct.

Murray turned away as the sound of voices followed in the wake of the dogs.

"Hello!" he cried, in a startled fashion. "Here's Father José, and—Keewin!"

"Keewin?"

It was Jessie who echoed the name. But her mother had ceased caressing the dogs. She stood very erect, and quite silent.

Three men turned the corner of the house. Alec came first. He was tall, a fair edition of his mother, but without any of the strength of character so plainly written on her handsome features. Only just behind him came Father José and an Indian.

The Padre of the Mission was a white-haired, white-browed man of many years and few enough inches. His weather-stained face, creased like parchment, was lit by a pair of piercing eyes, which were full of fire and mental energy. But, for the moment, no one had eyes for anything but the stoic placidity of the expressionless features of the Indian. The man's forehead was bound with a blood-stained bandage of dirty cloth.

Ailsa Mowbray's gentle eyes widened. Her firm lips perceptibly tightened. Direct as a shot came her inquiry.

"What's amiss?" she demanded.

She was addressing the white man, but her eyes were steadily regarding the Indian.

A moment later a second inquiry came.

"Why is Keewin here? Why is he wounded?"

The Padre replied. It was characteristic of the country in which they lived, the lives they lived, that he resorted to no subterfuge, although he knew his tidings were bad.

"Keewin's got through from Bell River. It's a letter to you from—Allan."

The woman had perfect command of herself. She paled slightly, but her lips were even firmer set. Jessie hurried to her side. It was as though the child had instinctively sought the mother's support in face of a blow which she knew was about to fall.

Ailsa held out one hand.

"Give it to me," she said authoritatively. Then, as the Padre handed the letter across to her, she added: "But first tell me what's amiss with him."

The Padre cleared his throat.

"He's held up," he said firmly. "The Bell River neches have got him surrounded. Keewin got through with great difficulty, and has been wounded. You best read the letter, and—tell us."

Ailsa Mowbray tore off the fastening which secured the outer cover of discolored buckskin. Inside was a small sheet of folded paper. She opened it, and glanced at the handwriting. Then, without a word, she turned back into the house. Jessie followed her mother. It was nature asserting itself. Danger was in the air, and the sex instinct at once became uppermost.

The men were left alone.

Murray turned on the Indian. Father José and Alec Mowbray waited attentively.

"Tell me," Murray commanded. "Tell me quickly—while the missis and the other are gone. They got his words. You tell me yours."

His words came sharply. Keewin was Allan Mowbray's most trusted scout.

The man answered at once, in a rapid flow of broken English. His one thought was succor for his great white boss.

"Him trade," he began, adopting his own method of narrating events, which Murray was far too wise in his understanding of Indians to attempt to change. "Great boss. Him much trade. Big. Plenty. So we come by Bell River. One week, two week, three week, by Bell River." He counted off the weeks on his fingers. "Bimeby Indian—him come plenty. No pow-wow. Him come by night. All around corrals. Him make big play. Him shoot plenty. Dead—dead—dead. Much dead." He pointed at the ground in many directions to indicate the fierceness of the attack. "Boss Allan—him big chief. Plenty big. Him say us fight plenty—too. Him say, him show 'em dis Indian. So him fight big. Him kill heap plenty too. So—one week. More Indian come. Boss Allan then call Keewin. Us make big pow-wow. Him say ten Indian kill. Good Indian. Ten still fight. Not 'nuff. No good ten fight whole tribe. Him get help, or all kill. So. Him call Star-man. Keewin say Star-man plenty good Indian. Him send Star-man to fort. So. No help come. Maybe Star-man him get kill. So him pow-wow. Keewin say, him go fetch help. Keewin go, not all be kill. So Keewin go. Indian find Keewin. They shoot plenty much. Keewin no care that," he flicked his tawny fingers in the air. "Indian no good shoot. Keewin laugh. So. Keewin come fort."

The man ceased speaking, his attitude remaining precisely as it was before he began. He was without a sign of emotion. Neither the Padre nor Alec spoke. Both were waiting for Murray. The priest's eyes were on the trader's stern round face. He was watching and reading with profound insight. Alec continued to regard the Indian. But he chafed under Murray's delay.

Before the silence was broken Ailsa Mowbray reappeared in the doorway. Jessie had remained behind.

The wife's face was a study in strong courage battling with emotion. Her gray eyes, no longer soft, were steady, however. Her brows were markedly drawn. Her lips, too, were firm, heroically firm.

She held out her letter to the Padre. It was noticeable she did not offer it to Murray.

"Read it," she said. Then she added: "You can all read it. Alec, too."

The two men closed in on either side of Father José. The woman looked on while the three pairs of eyes read the firm clear handwriting.

"Well?" she demanded, as the men looked up from their reading, and the priest thoughtfully refolded the paper.

Alec's tongue was the more ready to express his thoughts.

"God!" he cried. "It means—massacre!"

The priest turned on him in reproof. His keen eyes shone like burnished steel.

"Keep silent—you," he cried, in a sharp, staccato way.

The hot blood mounted to the boy's cheek, whether in abashment or in anger would be impossible to say. He was prevented from further word by Murray McTavish who promptly took command.

"Say, there's no time for talk," he said, in his decisive fashion. "It's up to us to get busy right away." He turned to the priest. "Father, I need two crews for the big canoes right off—now. You'll get 'em. Good crews for the paddle. Best let Keewin pick 'em. Eh, Keewin?" The Indian nodded. "Keewin'll take charge of one, and I the other. I can make Bell River under the week. I'll drive the crews to the limit, an' maybe make the place in four days. I'll get right back to the store now for the arms and ammunition, and the grub. We start in an hour's time."

Then he turned on Alec. There was no question in his mind. He had made his decisions clearly and promptly.

"See, boy," he said. "You'll stay right here. I'm aware you don't fancy the store. But fer once you'll need to run it. But more than all you'll be responsible nothing goes amiss for the women-folk. Their care is up to you, in your father's absence. Get me? Father José'll help you all he knows."

Then, without awaiting reply, he turned to Allan Mowbray's wife. His tone changed to one of the deepest gravity.

"Ma'am," he said, "whatever man can do to help your husband now, I'll do. I'll spare no one in the effort. Certainly not myself. That's my word."

The wife's reply came in a voice that was no longer steady.

"Thank you, Murray—for myself and for Allan. God—bless you."

Murray had turned already to return to the Fort when Alec suddenly burst out in protest. His eyes lit—the eyes of his mother. His fresh young face was scarlet to the brow.

"And do you suppose I'm going to sit around while father's being done to death by a lot of rotten Indians? Not on your life. See here, Murray, if there's any one needed to hang around the store it's up to you. Father José can look after mother and Jessie. My place is with the outfit, and—I'm going with it. Besides, who are you to dictate what I'm to do? You look after your business; I'll see to mine. You get me? I'm going up there to Bell River. I——"

"You'll—stop—right—here!"

Murray had turned in a flash, and in his voice was a note none of those looking on had ever heard before. It was a revelation of the man, and even Father José was startled. The clash was sudden. Both the mother and the priest realized for the first time in ten years the antagonism underlying this outward display.

The mother had no understanding of it. The priest perhaps had some. He knew Murray's energy and purpose. He knew that Alec had been indulged to excess by his parents. It would have seemed impossible in the midst of the stern life in which they all lived that the son of such parents could have grown up other than in their image. But it was not so, and no one knew it better than Father José, who had been responsible for his education.

Alec was weak, reckless. Of his physical courage there was no question. He had inherited his father's and his mother's to the full. But he lacked their every other balance. He was idle, he loathed the store and all belonging to it. He detested the life he was forced to live in this desolate world, and craved, as only weak, virile youth can crave, for the life and pleasure of the civilization he had read of, heard of, dreamed of.

Murray followed up his words before the younger man could gather his retort.

"When your father's in danger there's just one service you can do him," he went on, endeavoring to check his inclination to hot words. "If there's a thing happens to you, and we can't help your father, why, I guess your mother and sister are left without a hand to help 'em. Do you get that? I'm thinking for Allan Mowbray the best I know. I can run this outfit to the limit. I can do what any other man can do for his help. Your place is your father's place—right here. Ask your mother."

Murray looked across at Mrs. Mowbray, still standing in her doorway, and her prompt support was forthcoming.

"Yes," she said, and her eyes sought those of her spoiled son. "For my sake, Alec, for your father's, for your sister's."

Ailsa Mowbray was pleading where she had the right to command. And to himself Father José mildly anathematized the necessity.

Alec turned away with a scarcely smothered imprecation. But his mother's appeal had had the effect Murray had desired. Therefore he came to the boy's side in the friendliest fashion, his smile once more restored to the features so made for smiling.

"Say, Alec," he cried, "will you bear a hand with the arms and stuff? I need to get right away quick."

And strangely enough the young man choked back his disappointment, and the memory of the trader's overbearing manner. He acquiesced without further demur. But then this spoilt boy was only spoiled and weak. His temper was hot, volcanic. His reckless disposition was the outcome of a generous, unthinking courage. In his heart the one thing that mattered was his father's peril, and the sadness in his mother's eyes. Then he had read that letter.

"Yes," he said. "Tell me, and I'll do all you need. But for God's sake don't treat me like a silly kid."

"It was you who treated yourself as one," put in Father José, before Murray could reply. "Remember, my son, men don't put women-folk into the care of 'silly kids.'"

It was characteristic of Murray McTavish that the loaded canoes cast off from the Mission landing at the appointed time. For all the haste nothing was forgotten, nothing neglected. The canoes were loaded down with arms and ammunition divided into thirty packs. There were also thirty packs of provisions, enough to last the necessary time. There were two canoes, long, narrow craft, built for speed on the swift flowing river. Keewin commanded the leading vessel. Murray sat in the stern of the other. In each boat there were fourteen paddles, and a man for bow "lookout."

It was an excellent relief force. It was a force trimmed down to the bone. Not one detail of spare equipment was allowed. This was a fighting dash, calculating for its success upon its rapidity of movement.

There had been no farewell or verbal "Godspeed." The old priest had watched them go.

He saw the round figure of Murray in the stern of the rear boat. He watched it out of sight. The figure had made no movement. There had been no looking back. Then the old man, with a shake of the head, betook himself back through the avenue of lank trees to the Mission. He was troubled.

The glowing eyes of Murray gazed out straight ahead of him. He sat silent, immovable, it seemed, in the boat. That curious burning light, so noticeable when his strange eyes became concentrated, was more deeply lurid than ever. It gave him now an intense aspect of fierceness, even ferocity. He looked more than capable, as he had said, of driving his men, the whole expedition, to the "limit."

It was an old log shanty. Its walls were stout and aged. Its roof was flat, and sloped back against the hillside on which it stood. Its setting was an exceedingly limited plateau, thrusting upon the precipitous incline which overlooked the gorge of the Bell River.

The face of the plateau was sheer. The only approaches to it were right and left, and from the hill above, where the dark woods crowded. A stockade of heavy trunks, felled on the spot, and adapted where they fell, had been hastily set up. It was primitive, but in addition to the natural defences, and with men of resolution behind it, it formed an almost adequate fortification.

The little fortress was high above the broad river. It was like an eyrie of creatures of the air rather than the last defences of a party of human beings. Yet such it was. It was the last hope of its defenders, faced by a horde of blood-crazed savages who lusted only for slaughter.

Five grimly silent men lined the stockade at the most advantageous points. Five more lay about, huddled under blankets for warmth, asleep. A single watcher had screened himself upon the roof of the shack, whence his keen eyes could sweep the gorge from end to end. All these were dusky creatures of a superior Indian race. Every one of them was a descendant of the band of Sioux Indians which fled to Canada after the Custer massacre. Inside the hut was the only white man of the party.

A perfect silence reigned just now. There was a lull in the attack. The Indians crowding the woods below had ceased their futile fire. Perhaps they were holding a council. Perhaps they were making new dispositions for a fresh attack. The men at the defences relaxed no vigilance. The man on the roof noted and renoted every detail of importance to the defence which the scene presented. The man inside the hut alone seemed, at the moment, to be taking no part in the enactment of the little drama.

Yet it was he who was the genius of it all. It was he who claimed the devotion of these lean, fighting Indians. It was he who had contrived thus far to hold at bay a force of at least five hundred Indians, largely armed with modern firearms. It was he who had led the faithful remnant of his outfit, in a desperate night sortie, from his indefensible camp on the river, and, by a reckless dash, had succeeded in reaching this temporary haven.

But he had been supported by his half civilized handful of creatures who well enough knew what mercy to expect from the enemy. And, anyway, they had been bred of a stock with a fighting history second to no race in the world. To a man, the defenders were prepared to sell their lives at a heavy price. And they would die rifle in hand and facing the enemy.

The man inside called to the watcher on the roof.

"Anything doing, Keewin?"

"Him quiet. Him see no man. Maybe him make heap pow-wow."

"No sign, eh?"

"Not nothin', boss."

Allan Mowbray turned again to the sheet of paper spread out on the lid of an ammunition box which was laid across his knees. He was sitting on a sack of flour. All about him the stores they had contrived to bring away were lying on the ground. It was small enough supply. But they had not dared to overload in the night rush to their present quarters.

He read over what he had written. Then he turned appraisingly to the stores. His blue eyes were steady and calculating. There was no other expression in them.

There was a suggestion of the Viking of old about this northern trader. His fair hair, quite untouched with the gray due to his years, his fair, curling beard, and whiskers, and moustache, his blue eyes and strong aquiline nose. These things, combined with a massive physique, without an ounce of spare flesh, left an impression in the mind of fearless courage and capacity. He was a fighting man to his fingers' tips—when need demanded.

He turned back to his writing. It was a labored effort, not for want of skill, but for the reason he had no desire to fret the heart of the wife to whom it was addressed.

At last the letter was completed. He signed it, and read it carefully through, considering each sentence as to effect.

"Bell River.

"MY DEAREST WIFE:

"I've had a more than usually successful trip, till I came here. Now things are not so good."

He glanced up out of the doorway, and a shadowy smile lurked in the depths of his eyes. Then he turned again to the letter:

"I've already written Murray for help, but I guess the letter's kind of

miscarried. He hasn't sent the help. Star-man took the letter. So

now I'm writing you, and sending it by Keewin. If anybody can get

through it's Keewin. The Bell River Indians have turned on me. I

can't think why. Anyway, I need help. If it's to do any good it's got

to come along right away. I needn't say more to you. Tell Murray.

Give my love to Jessie and Alec. I'd like to see them again. Guess I

shall, if the help gets through—in time. God bless you, Ailsa, dear.

I shall make the biggest fight for it I know. It's five hundred or so

to ten. It'll be a tough scrap before we're through.

"Your loving

"ALLAN."

He folded the sheet of paper in an abstracted fashion. For some seconds he held it in his fingers as though weighing the advisability of sending it. Then his abstraction passed, and he summoned the man on the roof.

A moment or two later Keewin appeared in the doorway, tall, wiry, his broad, impassive face without a sign.

"Say, Keewin," the white chief began, "we need to get word through to the Fort. Guess Star-man's dead, hey?"

"Star-man plenty good scout. Boss Murray him no come. Maybe Star-man all kill dead. So."

"That's how I figger."

Allan Mowbray paused and glanced back at the trifling stores.

"No much food, hey? No much ammunition. One week—two weeks—maybe."

"Maybe."

The Indian looked squarely into his chief's eyes. The latter held up his letter.

"Who's going? Indians kill him—sure. Who goes?"

"Keewin."

The reply came without a sign. Not a movement of a muscle, or the flicker of an eyelid.

The white man breathed deeply. It was a sign of emotion which he was powerless to deny. His eyes regarded the dusky face for some moments. Then he spoke with profound conviction.

"You haven't a dog's chance—gettin' through," he said.

The information did not seem to require a reply, so far as the Indian was concerned. The white man went on:

"It's mad—crazy—but it's our only chance."

The persistence of his chief forced the Indian to reiterate his determination.

"Keewin—him go."

The tone of the reply was almost one of indifference. It suggested that the white man was making quite an unnecessary fuss.

Allan Mowbray nodded. There was a look in his eyes that said far more than words. He held out his letter. The Indian took it. He turned it over. Then from his shirt pocket he withdrew a piece of buckskin. He carefully wrapped it about the paper, and bestowed it somewhere within his shirt.

The white man watched him in silence. When the operation was complete he abruptly thrust out one powerful hand. Just for an instant a gleam of pleasure lit the Indian's dark eyes. He gingerly responded. Then, as the two men gripped, the "spat" of rifle-fire began again. There was a moment in which the two men stood listening. Then their hands fell apart.

"Great feller—Keewin!" said Mowbray kindly.

Nor was the white man speaking for the benefit of a lesser intelligence, nor in the manner of the patronage of a faithful servant. He meant his words literally. He meant more—much more than he said.

The rifle fire rattled up from below. The bullets whistled in every direction. The firing was wild, as is most Indian firing. A bullet struck the lintel of the door, and embedded itself deeply in the woodwork just above Keewin's head.

Keewin glanced up. He pointed with a long, brown finger.

"Neche damn fool. No shoot. Keewin go. Keewin laugh. Bell River Indian all damn fool. So."

It was the white man who had replaced the Indian at the lookout on the roof. He was squatting behind a roughly constructed shelter. His rifle was beside him and a belt full of ammunition was strapped about his waist.

The wintry sky was steely in the waning daylight. Snow had fallen. Only a slight fall for the region, but it had covered everything to the depth of nearly a foot. The whole aspect of the world had changed. The dark, forbidding gorge of the Bell River no longer frowned up at the defenders of the plateau. It was glistening, gleaming white, and the dreary pine trees bowed their tousled heads under a burden of snow. The murmur of the river no longer came up to them. Already three inches of ice had imprisoned it, stifling its droning voice under its merciless grip.

Attack on attack had been hurled against the white man and his little band of Indians. For days there had been no respite. The attacks had come from below, from the slopes of the hill above, from the approach on either side. Each attack had been beaten off. Each attack had taken its heavy toll of the enemy. But there had been toll taken from the defenders, a toll they could ill afford. There were only eight souls all told in the log fortress now. Eight half-starved creatures whose bones were beginning to thrust at the fleshless skin.

Allan Mowbray's hollow eyes scanned the distant reaches of the gorge where it opened out southward upon low banks. His straining gaze was searching for a sign—one faint glimmer of hope. All his plans were laid. Nothing had been left to the chances of his position. His calculations had been deliberate and careful. He had known from the beginning, from the moment he had realized the full possibilities of his defence, that the one thing which could defeat him was—hunger. Once the enemy realized this, and acted on it, their doom, unless outside help came in time, was sealed. His enemies had realized it.

There were no longer any attacks. Only desultory firing. But a cordon had been drawn around the fortress, and the process of starvation had set in.

He was giving his Fate its last chance now. If the sign of help he was seeking did not appear before the feeble wintry light had passed then the die was cast.

The minutes slipped by. The meagre light waned. The sign had not come. As the last of the day merged into the semi-arctic night he left his lookout and wearily lowered himself to the ground. His men were gathered, huddled in their blankets for warmth, about a small fire burning within the hut.

Allan Mowbray imparted his tidings in the language of the men who served him. With silent stoicism the little band of defenders listened to the end.

Keewin, he told them, had had time to get through. Full time to reach the Fort, and return with the help he had asked for. That help should have been with them three days ago. It had not come. Keewin, he assured them, must have been killed. Nothing could otherwise have prevented the help reaching them. He told them that if they remained there longer they would surely die of hunger and cold. They would die miserably.

He paused for comment. None was forthcoming. His only reply was the splutter of the small fire which they dared not augment.

So he went on.

He told them he had decided, if they would follow him, to die fighting, or reach the open with whatever chances the winter trail might afford them. He told them he was a white man who was not accustomed to bend to the will of the northern Indian. They might break him, but he would not bend. He reminded them they were Sioux, children of the great Sitting Bull. He reminded them that death in battle was the glory of the Indian. That no real Sioux would submit to starvation.

This time his words were received with definite acclamation. So he proceeded to his plans.

Half an hour later the last of the stores was being consumed by men who had not had an adequate meal for many days.

The aurora lit the night sky. The northern night had set in to the fantastic measure of the ghostly dance of the polar spirits. The air was still, and the temperature had fallen headlong. The pitiless cold was searching all the warm life left vulnerable to its attack. The shadowed eyes of night looked down upon the world through a gray twilight of calculated melancholy.

The cold peace of the elements was unshared by the striving human creatures peopling the great white wilderness over which it brooded. War to the death was being fought out under the eyes of the dancing lights, and the twinkling contentment of the pallid world of stars.

A small bluff of lank trees reared its tousled snow-crowned head above the white heart of a wide valley. It was where the gorge of the Bell River opened out upon low banks. It was where the only trail of the region headed westwards. The bowels of the bluff were defended by a meagre undergrowth, which served little better purpose than to partially conceal them. About this bluff a ring of savages had formed. Low-type savages of smallish stature, and of little better intelligence than the predatory creatures who roamed the wild.

With every passing moment the ring drew closer, foot by foot, yard by yard.

Inside the bluff prone forms lay hidden under the scrub. And only the flash of rifle, and the biting echoes of its report, told of the epic defence that was being put up. But for all the effort the movement of the defenders, before the closing ring, was retrograde, always retrograde towards the centre.

Slowly but inevitably the ring grew smaller about the bluff. Numbers of its ranks dropped out, and still forms littered the ground over which it had passed. But each and every gap thus made was automatically closed as the human ring drew in.

The last phase began. The ring was no longer visible outside the bluff. It had passed the outer limits, and entered the scrub. In the centre, in the very heart of it, six Indians and a white man crouched back to back—always facing the advancing enemy. Volley after volley was flung wildly at them from every side, regardless of comrade, regardless of everything but the lust to kill. The tumult of battle rose high. The demoniac yells filled the air to the accompaniment of an incessant rattle of rifle fire. The Bell River horde knew that at last their lust was to be satisfied. So their triumph rose in a vicious chorus upon the still air, and added its terror to the night.

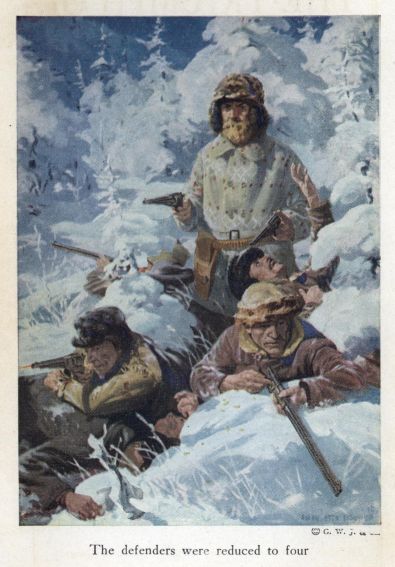

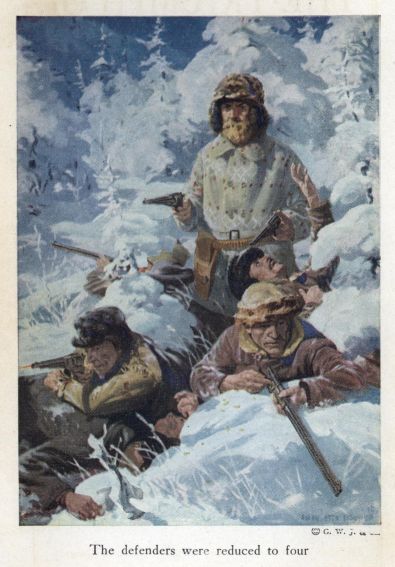

The defenders were further reduced to four. The white man had abandoned his rifle. Now he stood erect, a revolver in each hand, in the midst of the remainder of his faithful band. He was wounded in many places. Nor had the Indians with him fared better. Warm blood streamed from gaping wounds which were left unheeded. For the fight was to the finish, and not one of them but would have it so.

Nor was the end far off. It came swiftly, ruthlessly. It came with a ferocious chorus from throats hoarse with their song of battle. It came with a wild headlong rush, that recked nothing of the storm of fire with which it was met. A dozen lifeless bodies piled themselves before the staunch resistance. It made no difference. The avalanche swept on, and over the human barricade, till it reached striking distance for its crude native weapons.

Allan Mowbray saw each of his last three men go down in a welter of blood. His pistols were empty and useless. There was a moment of wild physical struggle. Then, the next, he was borne down under the rush, and life was literally hacked out of him.

The living-room in Ailsa Mowbray's home was full of that comfort which makes life something more than a mere existence in places where the elements are wholly antagonistic. The big square wood-stove was tinted ruddily by the fierce heat of the blazing logs within. Carefully trimmed oil lamps shed a mellow, but ample, light upon furnishings of unusual quality. The polished red pine walls reflected the warmth of atmosphere prevailing. And thick furs, spread over the well-laid green block flooring, suggested a luxury hardly to be expected.

The furniture was stout, and heavy, and angular, possessing that air of strength, as well as comfort, which the modern mission type always presents. The ample central table, too, was significant of the open hospitality the mistress of it all loved to extend to the whole post, and even to those chance travelers who might be passing through on the bitter northern trail.

Ailsa Mowbray had had her wish since the passing of the days when it had been necessary to share in the labors of her husband. The simple goal of her life had been a home of comfort for her growing children, and a wealth of hospitality for those who cared to taste of it.

The long winter night had already set in, and she was seated before the stove in a heavy rocking-chair. Her busy fingers were plying her needle, a work she loved in spite of the hard training of her early days in the north. At the other side of the glowing stove Jessie was reading one of the books with which Father José kept her supplied. The wind was moaning desolately about the house. The early snowfall was being drifted into great banks in the hollows. Up on the hilltop, where the stockade of the Fort frowned out upon the world, the moaning was probably translated into a tense, steady howl.

The mother glanced at the clock which stood on the bureau near by. It was nearly seven. Alec would be in soon from his work up at the store, that hour of work which he faced so reluctantly after the evening meal had been disposed of. In half an hour, too, Father José would be coming up from the Mission. She was glad. It would help to keep her from thinking.

She sighed and glanced quickly over at her daughter. Jessie was poring over her book. The sight of such absorption raised a certain feeling of irritation in the mother. It seemed to her that Jessie could too easily throw off the trouble besetting them all. She did not know that the girl was fighting her own battle in her own way. She did not know that her interest in her book was partly feigned. Nor was she aware that the girl's effort was not only for herself, but to help the mother she was unconsciously offending.

The anxious waiting for Murray's return had been well-nigh unbearable. These people, all the folk on Snake River, knew the dangers and chances of the expedition. Confidence in Murray was absolute, but still it left a wide margin for disaster. They had calculated to the finest fraction the time that must elapse before his return. Three weeks was the minimum, and the three weeks had already terminated three nights ago. It was this which had set the mother's nerves on edge. It was this knowledge which kept Jessie's eyes glued to the pages of her book. It was this which made the contemplation of the later gathering of the men in that living-room a matter for comparative satisfaction to Ailsa Mowbray.

Her needle passed to and fro under her skilful hands. There was almost feverish haste in its movements. So, too, the pages of Jessie's book seemed to be turned all too frequently.

At last the mother's voice broke the silence.

"It's storming," she said.

"Yes, mother." Jessie had glanced up. But her eyes fell to her book at once.

"But it—won't stop them any." The mother's words lacked conviction. Then, as if she realized that this was so, she went on more firmly. "But Murray drives hard on the trail. And Allan—it would need a bigger storm than this to stop him. If the river had kept open they'd have made better time." She sighed her regret for the ice.

"Yes, mother." Jessie again glanced up. This time her pretty eyes observed her mother more closely. She noted the drawn lines about the soft mouth, the deep indentation between the usually serene brows. She sighed, and the pain at her own heart grew sharper.

Quite suddenly the mother raised her head and dropped her sewing in her lap.

"Oh, child, child, I—I could cry at this—waiting," she cried in desperate distress. "I'm scared! Oh, I'm scared to death. Scared as I've never been before. But things—things can't have happened. I tell you I won't believe that way. No—no! I won't. I won't. Oh, why don't they get around? Why doesn't he come?"

The girl laid her book aside. Her movement was markedly calm. Then she steadily regarded her troubled mother.

"Don't, mother, dear," she cried. "You mustn't. 'Deed you mustn't." Her tone was a gentle but decided reproof. "We've figured it clear out. All of us together. Father José and Alec, too. They're men, and cleverer at that sort of thing than we are. Father José reckons the least time Murray needs to get back in is three weeks. It's only three days over. There's no sort of need to get scared for a week yet."

The reproof was well calculated. It was needed. So Jessie understood. Jessie possessed all her mother's strength of character, and had in addition the advantage of her youth.

Her mother was abashed at her own display of weakness. She was abashed that it should be necessary for her own child to reprove her. She hastily picked up her work again.

But Jessie had abandoned her reading for good. She leaned forward in her chair, gazing meditatively at a glowing, red-hot spot on the side of the stove.

Suddenly she voiced the train of thought which had held her occupied so long.

"Why does our daddy make Bell River, mother?" she demanded. "It's a question I'm always asking myself. He's told me it's not a place for man, devil, or trader. Yet he goes there. Say, he makes Bell River every year. Why? He doesn't get pelts there. He once said he'd hate to send his worst enemy up there. Yet he goes. Why? That's how I'm always asking. Say, mother, you ran this trade with our daddy before Murray came. You know why he goes there. You never say. Nor does daddy. Nor Murray. Is—it a secret?"

Ailsa replied without raising her eyes.

"It's not for you to ask me," she said almost coldly.

But Jessie was in no mood to be easily put off.

"Maybe not, mother," she replied readily. "But you know, I guess. I wonder. Well, I'm not going to ask for daddy's secrets. I just know there is a secret to Bell River. And that secret is between you, and him, and Murray. That's why Alec had to stop right here at the Fort. Maybe it's a dangerous secret, since you keep it so close. But it doesn't matter. All I know our daddy is risking his life every time he hits the Bell River trail, and, secret or no secret, I ask is it right? Is it worth while? If anything happened to our daddy you'd never, never forgive yourself letting him risk his life where he wouldn't send his worst enemy.'"

The mother laid her work aside. Nor did she speak while she folded the material deliberately, carefully.

When at last she turned her eyes in her daughter's direction Jessie was horrified at the change in them. They were haggard, hopeless, with a misery of suspense and conviction of disaster.

"It's no use, child," she said decidedly. "Don't ask me a thing. If you guess there's a secret to Bell River—forget it. Anyway, it's not my secret. Say, you think I can influence our daddy. You think I can persuade him to quit getting around Bell River." She shook her head. "I can't. No, child. I can't, nor could you, nor could anybody. Your father's the best husband in the world. And I needn't tell you his kindness and generosity. He's all you've ever believed him, and more—much more. He's a big man, so big, you and I'll never even guess. But just as he's all we'd have him in our lives, so he's all he needs to be on the bitter northern trail. The secrets of that trail are his. Nothing'll drag them out of him. Whatever I know, child, I've had to pay for the knowing. Bell River's been my nightmare years and years. I've feared it as I've feared nothing else. And now—oh, it's dreadful. Say, child, for your father's sake leave Bell River out of your thoughts, out of your talk. Never mention that you think of any secret. As I said, 'forget it.'"

Her mother's distress, and obvious dread impressed the girl seriously. She nodded her head.

"I'll never speak of it, mother," she assured her. "I'll try to forget it. But why—oh, why should he make you endure these years of nightmare? I——"

Her mother abruptly held up a finger.

"Hush! There's Father José."

There was the sharp rattle of a lifted latch, and the slam-to of the outer storm door. They heard the stamping of feet as the priest freed his overshoes of snow. A moment later the inner door was pushed open.

Father José greeted them out of the depths of his fur coat collar.

"A bad night, ma'am," he said gravely. "The folks on the trail will feel it—cruel."

The little man divested himself of his coat.

"The folk on the trail? Is there any news?" Ailsa Mowbray's tone said far more than her mere words.

Jessie had risen from her chair and crossed to her mother's side. She stood now with a hand resting on the elder woman's shoulder. And the priest, observing them as he advanced to the stove, and held his hands to the comforting warmth, was struck by the twin-like resemblance between them.

Their beauty was remarkable. The girl's oval cheeks were no more perfect in general outline than her mother's. Her sweet gray eyes were no softer, warmer. The youthful lips, so ripe and rich, only possessed the advantage of her years. The priest remembered Allan Mowbray's wife at her daughter's age, and so he saw even less difference between them than time had imposed.

"That's what I've been along up to see Alec at the store for. Alec's gone out with a dog team to bear a hand—if need be."

The white-haired man turned his back on the stove and faced the spacious room. He withdrew a snuffbox from his semi-clerical vest pocket, and thoughtfully tapped it with a forefinger. Then he helped himself to a large pinch of snuff. As far as the folks on Snake River knew this was the little priest's nearest approach to vice.

"Alec gone out? You never told us?" Ailsa Mowbray's eyes searched the sharp profile of the man, whose face was deliberately averted. "Tell me," she demanded. "You've had news. Bad? Is it bad? Tell me! Tell me quickly!"

The man fumbled in an inner pocket and produced a folded paper. He opened it, and gazed at it silently. Then he passed it to the wife, whose hands were held out and trembling.

"I've had this. It came in by runner. The poor wretch was badly frost-bitten. It's surely a cruel country."

But Ailsa Mowbray was not heeding him. Nor was Jessie. Both women were examining the paper, and its contents. The mother read it aloud.

"DEAR FATHER JOSE:

"We'll make the Fort to-morrow night if the weather holds. Can you

send out dogs and a sled? Have things ready for us.

"MURRAY."

During the reading the priest helped himself to another liberal pinch of snuff. Then he produced a great colored handkerchief, and trumpeted violently into it. But he was watching the women closely out of the corners of his hawk-like eyes.

Ailsa read the brief note a second time, but to herself. Then, with hands which had become curiously steady, she refolded it, retaining it in her possession with a strangely detached air. It was almost as if she had forgotten it, and that her thoughts had flown in a direction which had nothing to do with the letter, or the Padre, or——

But Jessie came at the man in a tone sharpened by the intensity of her feelings.

"Say, Father, there's no more than that note? The runner? Did he tell you—anything? You—you questioned him?"

"Yes."

Suddenly the mother took a step forward. One of her hands closed upon the old priest's arm with a grip that made him wince.

"The truth, Father," she demanded, in a tone that would not be denied. Her eyes were wide and full of a desperate conviction. "Quick, the truth! What was there that Murray didn't write in that note? Allan? What of Allan? Did he reach him? Is—is he dead? Why did he want that sled? Tell me. Tell it all, quick!"

She was breathing hard. Her desperate fear was heart-breaking. Jessie remained silent, but her eyes were lit by a sudden terror no less than her mother's.

Suddenly the priest faced the stove again. He gazed down at it for a fraction of time. Then he turned to the woman he had known in her girlhood, and his eyes were lit with infinite kindness, infinite grief and sympathy.

"Yes," he said in a low voice. "There was a verbal message for my ears alone. Murray feared for you. The shock. So he told me. Allan——"

"Is dead!" Ailsa Mowbray whispered the words, as one who knows but cannot believe.

"Is dead." The priest was gazing down at the stove once more.

No word broke the silence of the room. The fire continued to roar up the stovepipe. The moaning of the wind outside deplorably emphasized the desolation of the home. For once it harmonized with the note of despair which flooded the hearts of these people.

It was Jessie who first broke down under the cruel lash of Fate. She uttered a faint cry. Then a desperate sob choked her.

"Oh, daddy, daddy!" she cried, like some grief-stricken child.

In a moment she was clasped to the warm bosom of the woman who had been robbed of a husband.

Not a tear fell from the eyes of the mother. She stood still, silent, exerting her last atom of moral strength in support of her child.

Father José stirred. His eyes rested for a moment upon the two women. A wonderfully tender, misty light shone in their keen depths. No word of his could help them now, he knew. So with soundless movement he resumed his furs and overshoes, and, in silence, passed out into the night.

The wind howled against the ramparts of the Fort. It swept in through the open gates, whistling its fierce glee as it buffeted the staunch buildings thus uncovered to its merciless blast. The black night air was alive with a fog of snow, swept up in a sort of stinging, frozen dust. The lights of Nature had been extinguished, blotted out by the banking storm-clouds above. It seemed as though this devil's playground had been cleared of every intrusion so that the riot of the northern demons might be left complete.

A fur-clad figure stood within the great gateway. The pitiful glimmer of a lantern swung from his mitted hand. His eyes, keen, penetrating, in spite of the blinding snow, searched the direction where the trail flowed down from the Fort. He was waiting, still, silent, in the howl of the storm.

A sound came up the hill. It was a sound which had nothing to do with the storm. It was the voices of men, urgent, strident. A tiny spark suddenly grew out of the blackness. It was moving, swinging rhythmically. A moment later shadowy figures moved in the darkness. They were vague, uncertain. But they came, following closely upon the spark of light, which was borne in the hand of a man on snowshoes.

The fur-clad figure swung his lantern to and fro. He moved himself from post to post of the great gateway. Then he stood in his original position.

The spark of light came on. It was another lantern, borne in the hand of another fur-clad figure. It passed through the gateway. A string of panting dogs followed close behind, clawing at the ground for foothold, bellies low to the ground as they hauled at the rawhide tugs which harnessed them to their burden behind. One by one they passed the waiting figure. One by one they were swallowed up by the blackness within the Fort. Five in all were counted. Then came a long dark shape, which glided over the snow with a soft, hissing sound.

The waiting man made a sign with his mitted hand as the shape passed him. His lips moved in silent prayer. Then he turned to the gates. They swung to. The heavy bars lumbered into their places under his guidance. Then, as though in the bitterness of disappointment, the howling gale flung itself with redoubled fury against them, till the stout timbers creaked and groaned under the wanton attack.

Seven months of dreadful winter had passed. Seven months since the mutilated body of Allan Mowbray had been packed home by dog-train to its last resting place within the storm-swept Fort he had labored so hard to serve. It was the open season again. That joyous season of the annual awakening of the northern world from its nightmare of stress and storm, a nightmare which drives human vitality down to the very limit of its mental and physical endurance.

Father José and Ailsa Mowbray had been absent from the post for the last three months of the winter. Their return from Leaping Horse, the golden heart of the northern wild, had occurred at the moment when the ice-pack had vanished from the rivers, and the mud-sodden trail had begun to harden under the brisk, drying winds of spring. They had made the return journey at the earliest moment, before the summer movements of the glacial fields had converted river and trail into a constant danger for the unwary.

Allan Mowbray had left his affairs in Father José's hands. They were as simple and straight as a simple man could make them. The will had contained no mention of his partner, Murray's name, except in the way of thanks. To the little priest he had confided the care of his bereaved family. And it was obvious, from the wording of his will, that the burden thus imposed upon his lifelong friend had been willingly undertaken.

His wishes were clear, concise. All his property, all his business interests were for his wife. Apart from an expressed desire that Alec should be given a salaried appointment in the work of the post during his mother's lifetime, and that at her death the boy should inherit, unconditionally, her share of the business, and the making of a monetary provision for his daughter, Jessie, the disposal of his worldly goods was quite unconditional.

Father José had known the contents of the will beforehand. In fact, he had helped his old friend in his decisions. Nor had Alec's position been decided upon without his advice. These two men understood the boy too well to chance helping to spoil his life by an ample, unearned provision. They knew the weak streak in his character, and had decided to give him a chance, by the process of time, to obtain that balance which might befit him for the responsibility of a big commercial enterprise.

When Murray learned the position of affairs he offered no comment. Without demur he concurred in every proposition set before him by Father José. He rendered the little man every assistance in his power in the work which had been so suddenly thrust upon his shoulders.

So it was that more than one-half of the winter was passed in delving into the accounts of the enterprise Allan and his partner had built up, while the other, the second half, was spent by Mrs. Mowbray and Father José at Leaping Horse, where the ponderous legal machinery was set in motion for the final settlement of the estate.

For Father José the work was not without its compensations. His grief at Allan's dreadful end had been almost overwhelming, and the work in which he found himself involved had come as a help at the moment it was most needed. Then there was Ailsa, and Jessie, and Alec. His work helped to keep him from becoming a daily witness of their terrible distress. Furthermore, there were surprises for him in the pages of the great ledgers at the Fort. Surprises of such a nature that he began to wonder if he were still living in the days of miracles, or if he were simply the victim of hallucination.

He found that Allan was rich, rich beyond his most exaggerated dreams. He found that this obscure fur post carried on a wealth of trade which might have been the envy of a corporation a hundred times its size. He found that for years a stream of wealth had been pouring into the coffers at the post in an ever-growing tide. He found that seven-tenths of it was Allan's, and that Murray McTavish considered himself an amply prosperous man on the remaining three-tenths.

Where did it all come from? How did it come about? He expressed no wonder to anybody. He gave no outward sign of his astonishment. There was a secret. There must be a secret. But the books yielded up no secret. Only the broad increasing tide of a trade which coincided with the results. But he felt for all their simple, indisputable figures, they concealed in their pages a cleverly hidden secret, a profound secret, which must alone have been shared by the partners, and possibly Ailsa Mowbray. Allan Mowbray's fortune, apart from the business, closely approximated half a million dollars. It was incredible. It was so stupendous as to leave the simple little priest quite overwhelmed.

However, with due regard for his friendship, he spared himself nothing. Nothing was neglected. Nothing was left undone in his stewardship. And so, within seven months of Allan's disastrous end, he found himself once more free to turn to the simple cares of the living in his administration of the Mission on Snake River, which was the sum total of his life's ambition and work.

His duty to the dead was done. And it seemed to his plain thinking mind that the episode should have been closed forever. But it was not. Moreover, he knew it was not. How he knew was by no means clear. Somehow he felt that the end was far off, somewhere in the dim future. Somehow he felt that he was only at the beginning of things. A secret lay concealed under his friend's great wealth, and the thought of it haunted him. It warned him, too, and left him pondering deeply. However, he did not talk, not even to his friend's widow.

The round form of Murray McTavish filled the office chair to overflowing. For a man of his energy and capacity, for a man so perfectly equipped, mentally, and in spirit, for the fierce battle of the northern latitudes, it was a grotesque freak of Nature that his form, so literally corpulent, should be so inadequate. However, there it was. And Nature, seeming to realize the anachronism, had done her best to repair her blunder. If he were laboring under a superfluity of adipose, she had equipped him with muscles of steel and lungs of tremendous expansion, a fierce courage, and nerves of a tempering such as she rarely bestowed.

He was smoking a strong cigar and reading a letter in a decided handwriting. It was a man's letter, and it was of a business nature. Yet though it entailed profit for its recipient it seemed to inspire no satisfaction.

The big eyes were a shade wider than usual. Their glowing depths burned more fiercely. He was stirred, and the secret of his feelings lay in the signature at the end of the letter. It was a signature that Murray McTavish disliked.

"John Kars," he muttered aloud.

There was no friendliness in his tone. There was no friendliness in the eyes which were raised from the letter and turned on the deep-set window overlooking the open gates beyond.

For some silent moments he sat there thinking deeply. He continued to smoke, his gaze abstractedly fixed upon the blue film which floated before it upon the still air. Gradually the dislike seemed to pass out of his eyes. The fire in them to die down. Something almost like a smile replaced it, a smile for which his face was so perfect a setting. But his smile would have been difficult to describe. Perhaps it was one of pleasure. Perhaps it was touched with irony. Perhaps, even, it was the smile, the dangerous smile of a man who is fiercely resentful. It was a curiosity in Murray that his smile could at any time be interpreted into an expression of any one of the emotions.

But suddenly there came an interruption. In a moment his abstraction was banished. He sprang alertly from his chair and moved to the door which he held open. He had seen the handsome figure of Ailsa Mowbray pass his window. Now she entered the office in response to his silent invitation. She took the chair which always stood ready before a second desk. It was the desk which had been Allan Mowbray's, and which now was used by his son.

"I've come to talk about Alec," the mother said, turning her chair about, and facing the man who was once more at his desk.

"Sure." The man nodded. His smile had vanished. His look was all concern. He knew, none better than he, that Alec must be discussed between them.