This e-text contains a few letters with unusual diacritics:

ā ē ī ō ū (vowel with macron or

“long” mark)

ă ĕ ĭ ŏ ŭ (vowel with breve or

“short” mark)

If any of these characters do not display properly—in particular,

if the diacritic does not appear directly above the

letter—or if the quotation marks in this paragraph appear as

garbage, you may have an incompatible browser or unavailable fonts.

First, make sure that the browser’s “character set” or “file encoding”

is set to Unicode (UTF-8). You may also need to change your browser’s

default font. Note that the accent marks, as in “Midē´wiwin,” are

not meant to display on top of any letter.

Some typographical errors have been corrected. They have been

marked in the text with mouse-hover popups. The variation between “Ojibwa” and

“Ojibway” is as in the original.

Technical note on MIDI files.

143

THE MIDĒ´WIWIN OR “GRAND MEDICINE SOCIETY”

OF

THE OJIBWA.

BY

W. J. HOFFMAN.

145

CONTENTS.

147

ILLUSTRATIONS.

Illustrations have been placed as close as practicable to their

discussion in the text. Multi-part Plates have been divided. The printed

page numbers show the original location of the illustrations.

Plates and Figures were numbered continuously within each Bureau of

Ethnology volume, so there is no Plate I in this article.

| |

Page. |

| Plate II. |

Map showing present distribution of Ojibwa |

150 |

| III. |

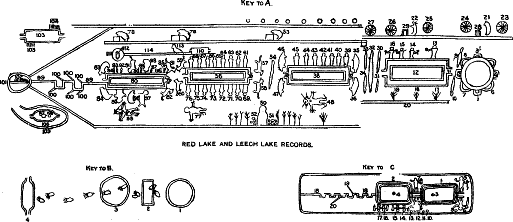

Red Lake and Leech Lake records |

166 |

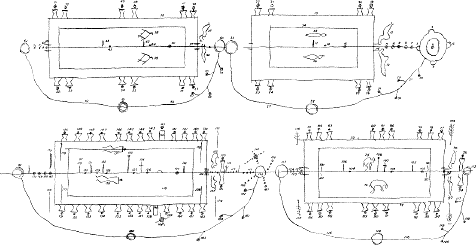

| IV. |

Sikas´sige’s record |

170 |

| V. |

Origin of Âníshinâ´bēg |

172 |

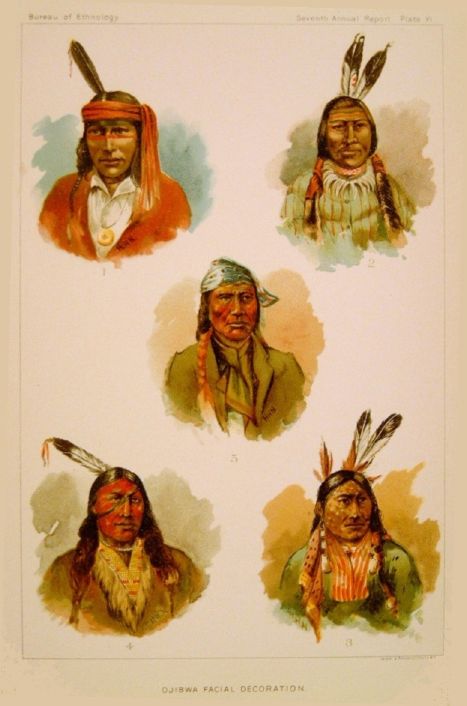

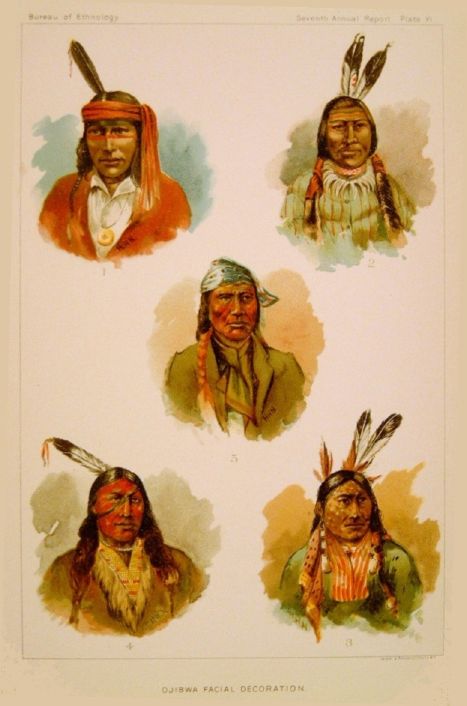

| VI. |

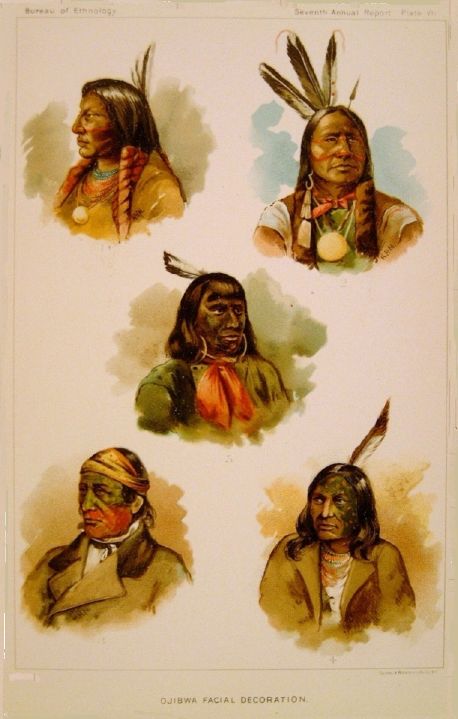

Facial decoration |

174 |

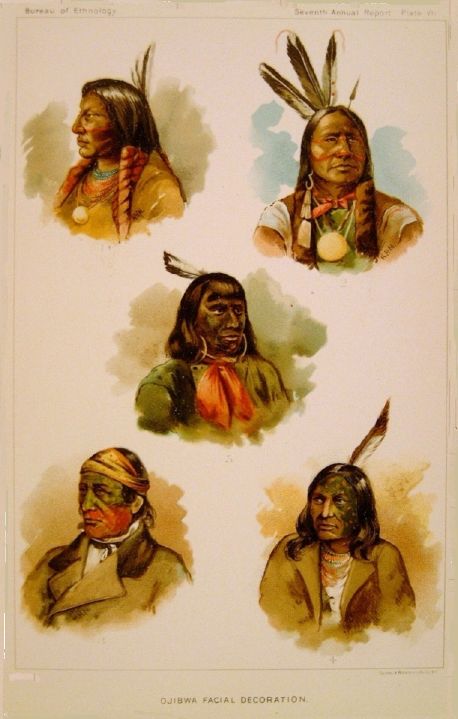

| VII. |

Facial decoration |

178 |

| VIII. |

Ojibwa’s record |

182 |

| IX. |

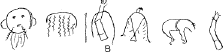

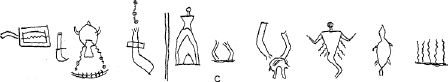

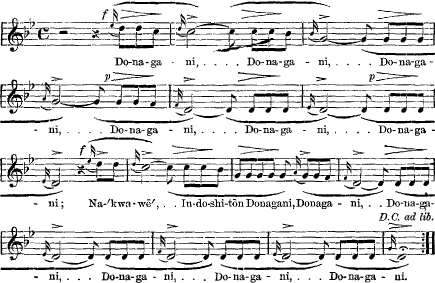

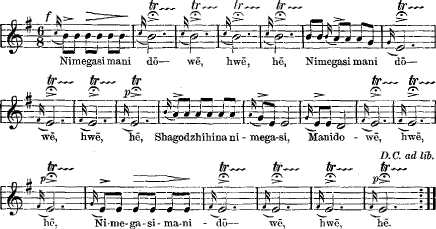

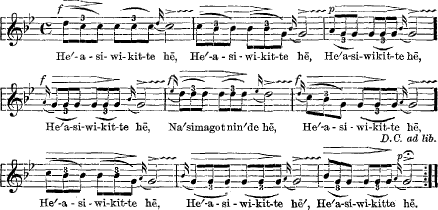

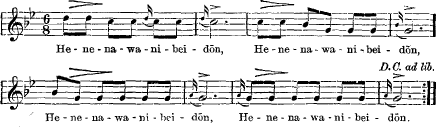

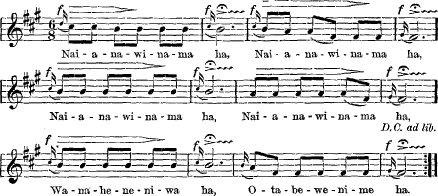

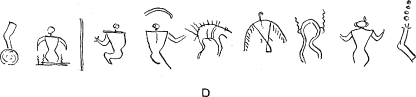

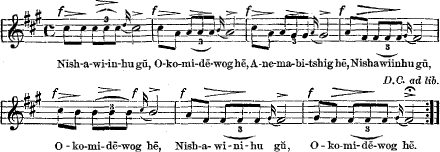

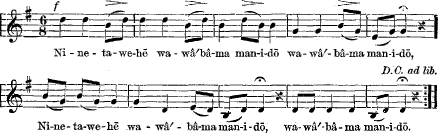

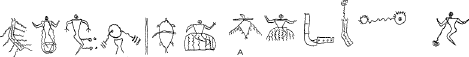

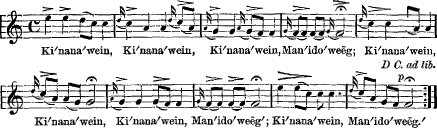

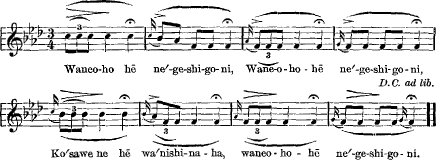

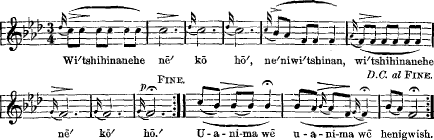

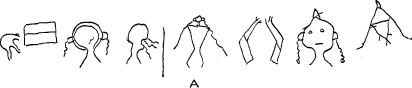

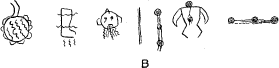

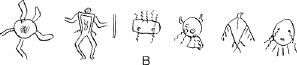

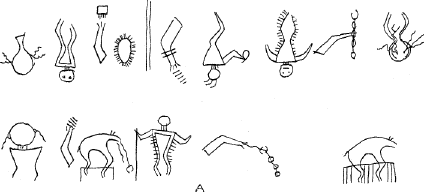

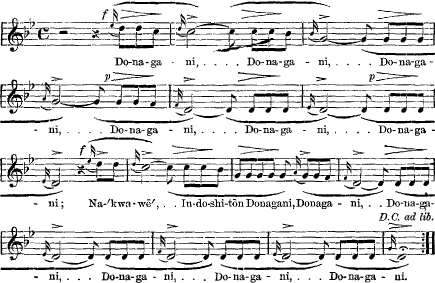

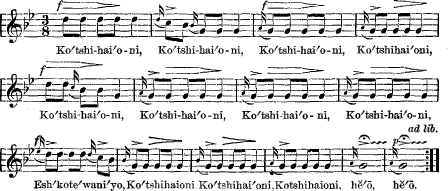

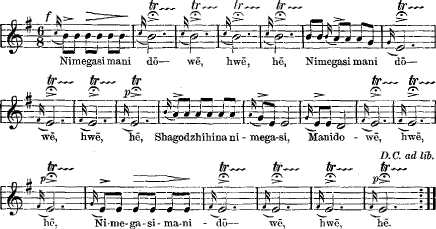

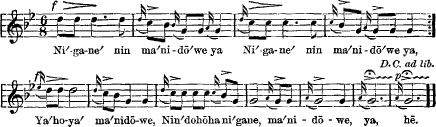

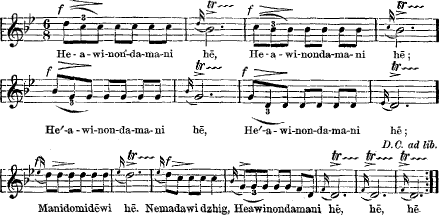

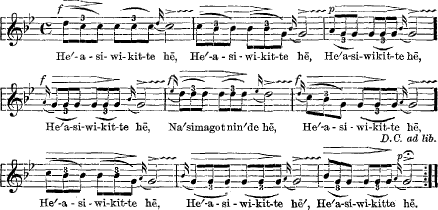

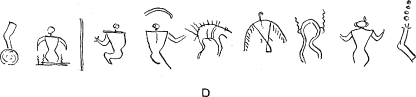

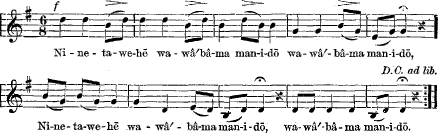

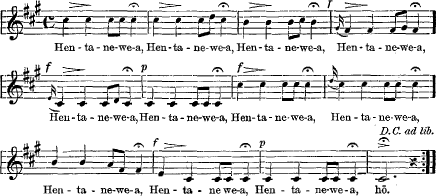

Mnemonic songs:

IX.a —

IX.b —

IX.c |

193 |

| X. |

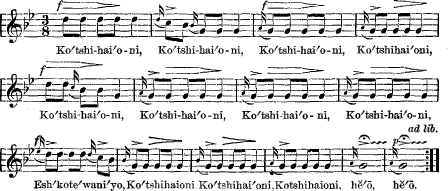

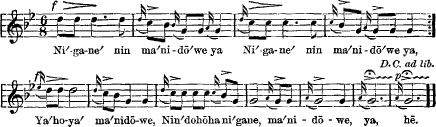

Mnemonic songs:

X.a —

X.b —

X.c —

X.d |

202 |

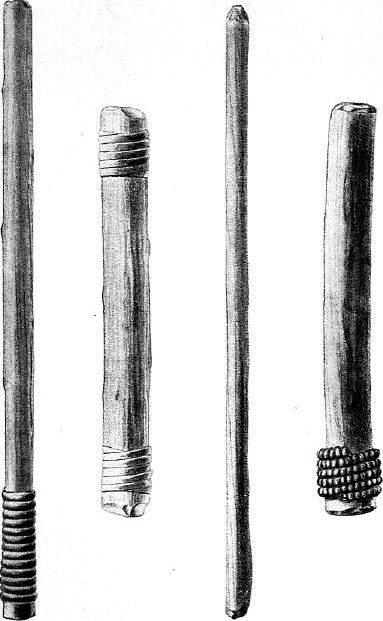

| XI. |

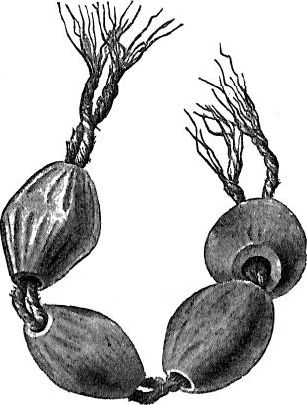

Sacred objects |

220 |

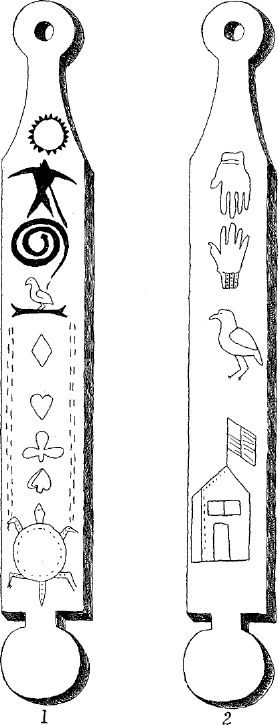

| XII. |

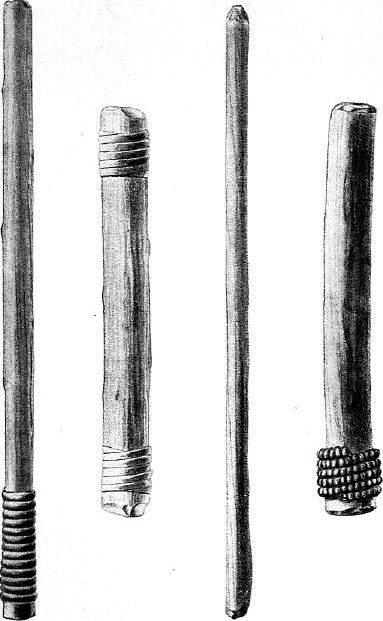

Invitation sticks |

236 |

| XIII. |

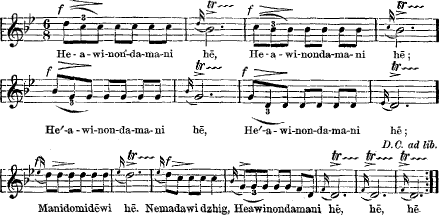

Mnemonic songs:

XIII.a —

XIII.b —

XIII.c —

XIII.d |

238 |

| XIV. |

Mnemonic songs:

XIV.a —

XIV.b —

XIV.c —

XIV.d |

288 |

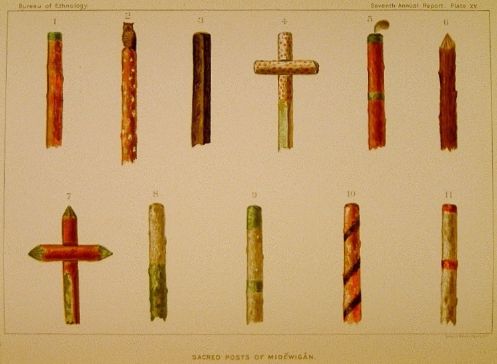

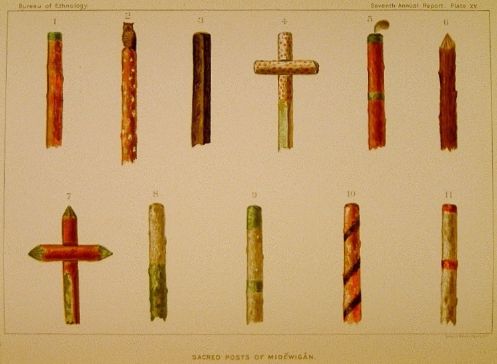

| XV. |

Sacred posts |

240 |

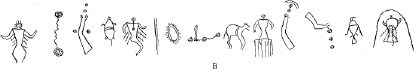

| XVI. |

Mnemonic songs:

XVI.a —

XVI.b —

XVI.c —

XVI.d |

244 |

| XVII. |

Mnemonic songs:

XVII.a —

XVII.b |

266 |

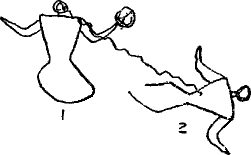

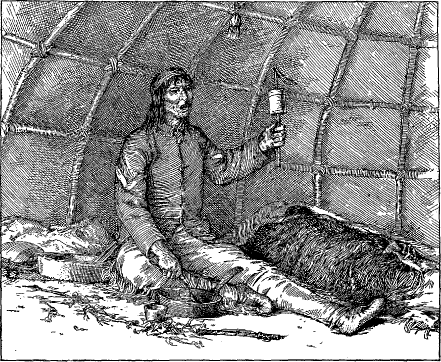

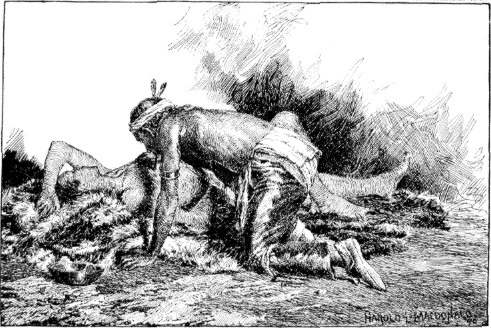

| XVIII. |

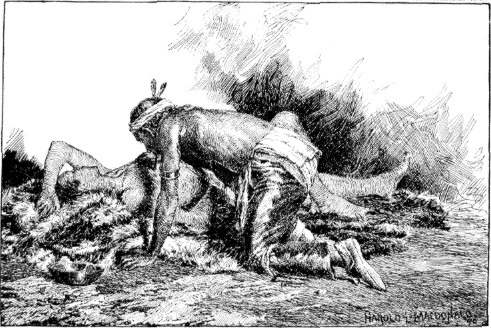

Jĕs´sakkīd´ removing disease |

278 |

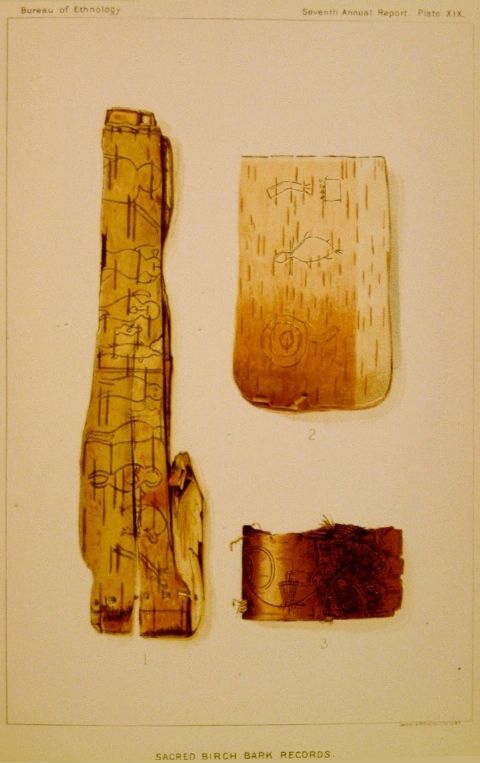

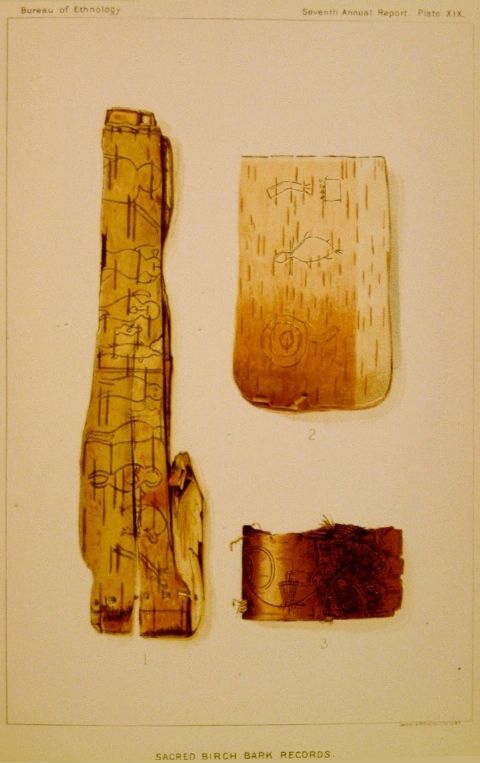

| XIX. |

Birch-bark records |

286 |

| XX. |

Sacred bark scroll and contents |

288 |

| XXI. |

Midē´ relics from Leech Lake |

390 |

| XXII. |

Mnemonic songs:

XXII.a —

XXII.b |

392 |

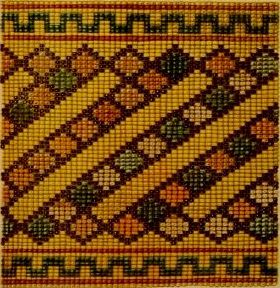

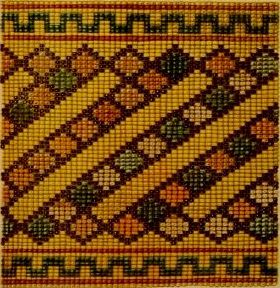

| XXIII. |

Midē´ dancing garters |

298 |

|

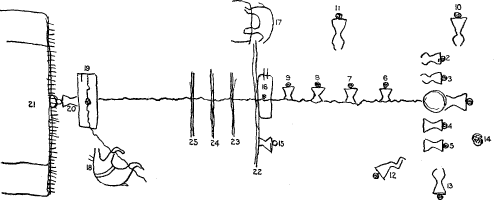

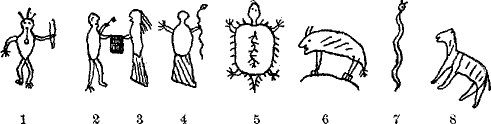

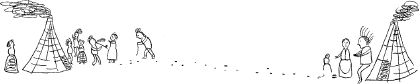

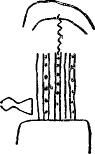

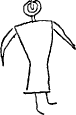

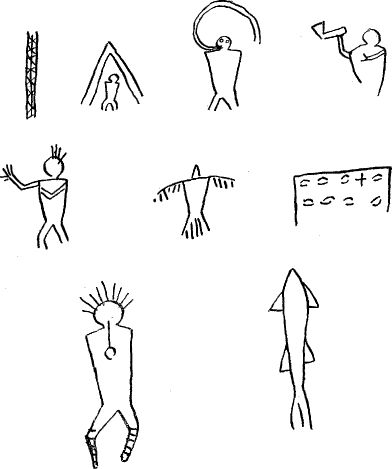

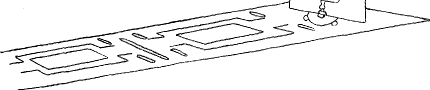

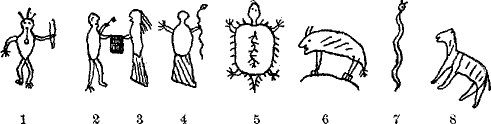

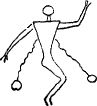

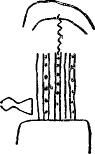

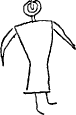

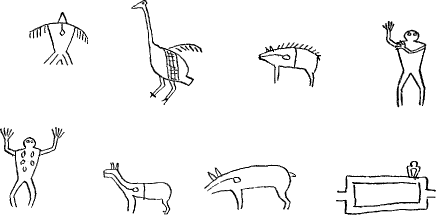

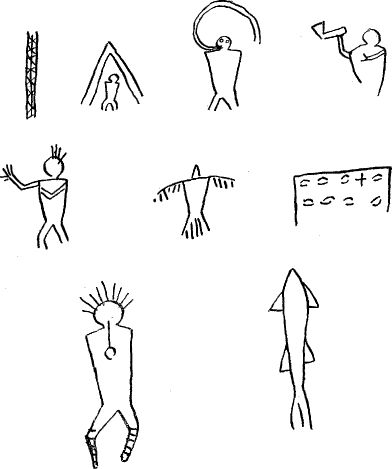

Fig. 1. |

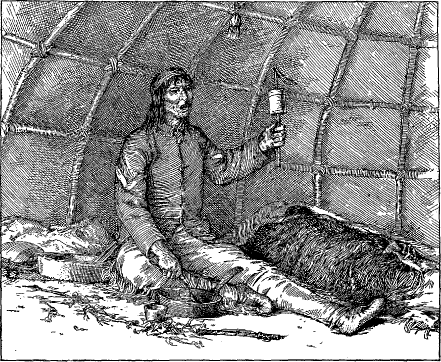

Herbalist preparing medicine and treating patient |

159 |

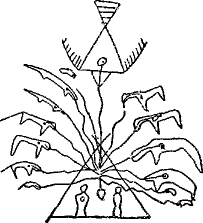

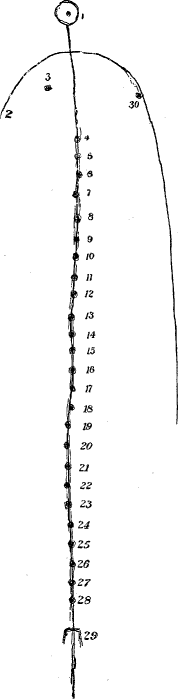

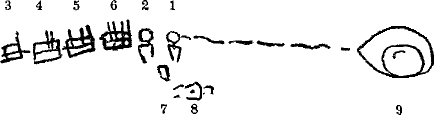

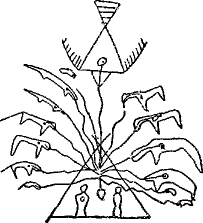

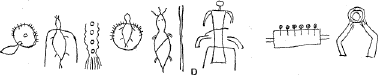

| 2. |

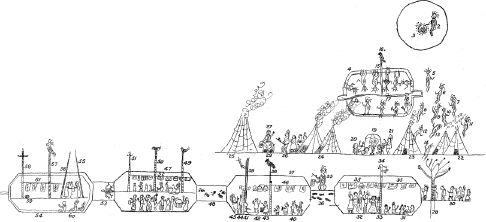

Sikas´sigĕ’s combined charts, showing descent of Mī´nabō´zho |

174 |

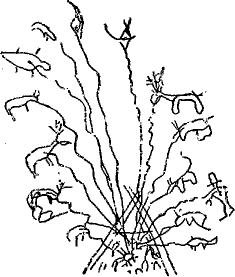

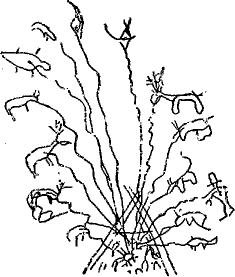

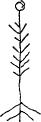

| 3. |

Origin of ginseng |

175 |

| 4. |

Peep-hole post |

178 |

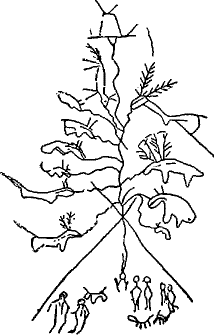

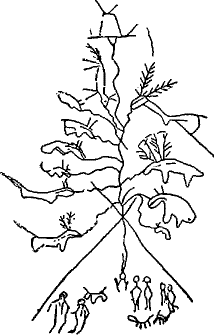

| 5. |

Migration of Âníshinâ´bēg |

179 |

| 6. |

Birch-bark record, from White Earth |

185 |

| 7. |

Birch-bark record, from Bed Lake |

186 |

| 8. |

Birch-bark record, from Red Lake |

186 |

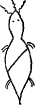

| 9. |

Eshgibō´ga |

187 |

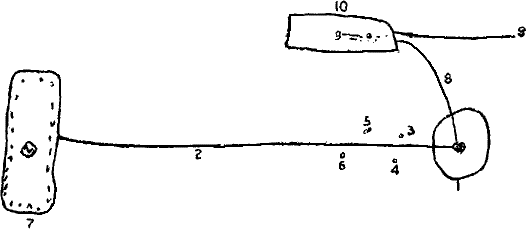

| 10. |

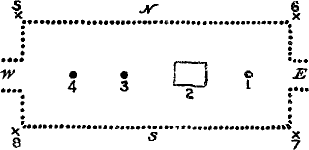

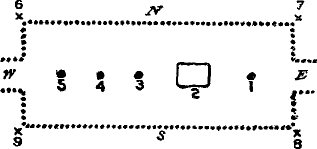

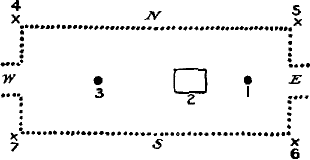

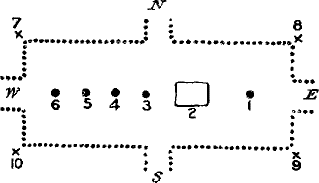

Diagram of Midē´wigân of the first degree |

188 |

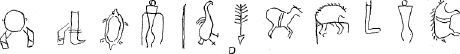

| 11. |

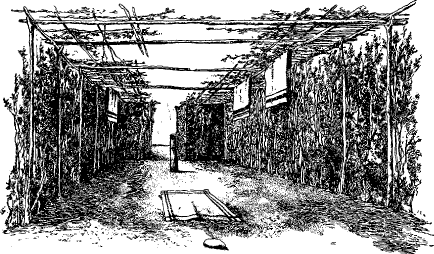

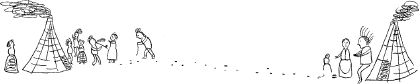

Interior of Midē´wigân |

188 |

| 12. |

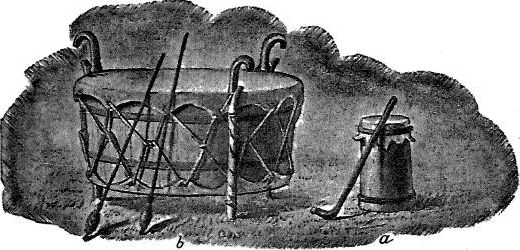

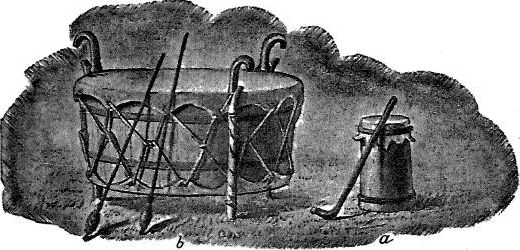

Ojibwa drums |

190 |

| 13. |

Midē´ rattle |

191 |

| 14. |

Midē´ rattle |

191 |

| 15. |

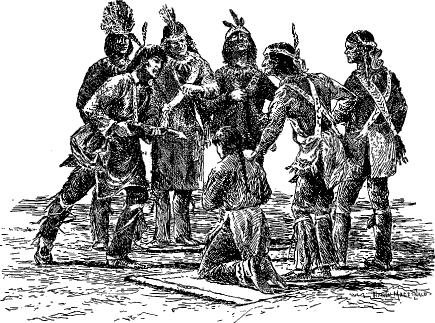

Shooting the Mīgis |

192 |

| 16. |

Wooden beads |

205 |

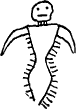

| 17. |

Wooden effigy |

205 |

| 18. |

Wooden effigy |

205 |

| 19. |

Hawk-leg fetish |

220 |

| 20. |

Hunter’s medicine |

222 |

| 21. |

Hunter’s medicine |

222 |

| 22. |

148

Wâbĕnō´ drum |

223 |

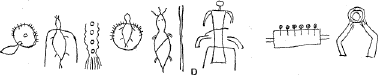

| 23. |

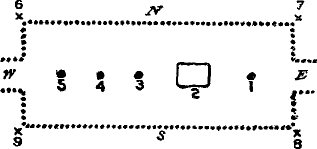

Diagram of Midē´wigân of the second degree |

224 |

| 24. |

Midē´ destroying an enemy |

238 |

| 25. |

Diagram of Midē´wigân of the third degree |

240 |

| 26. |

Jĕs´sakkân´, or juggler’s lodge |

252 |

| 27. |

Jĕs´sakkân´, or juggler’s lodge |

252 |

| 28. |

Jĕs´sakkân´, or juggler’s lodge |

252 |

| 29. |

Jĕs´sakkân´, or juggler’s lodge |

252 |

| 30. |

Jĕs´sakkân´, or juggler’s lodge |

252 |

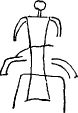

| 31. |

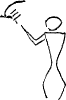

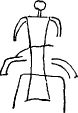

Jĕs´sakkīd´ curing woman |

255 |

| 32. |

Jĕs´sakkīd´ curing man |

255 |

| 33. |

Diagram of Midē´wigân of the fourth degree |

255 |

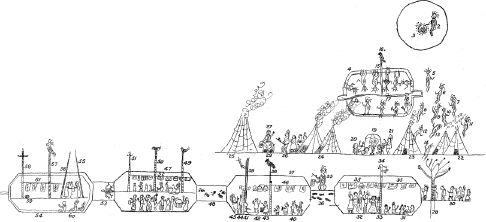

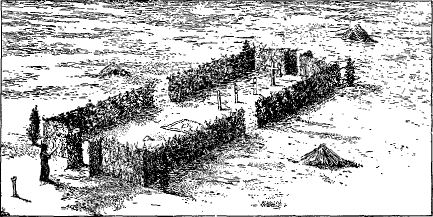

| 34. |

General view of Midē´wigân |

256 |

| 35. |

Indian diagram of ghost lodge |

279 |

| 36. |

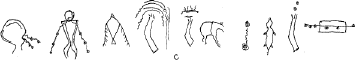

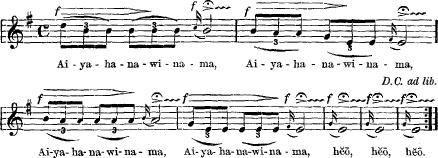

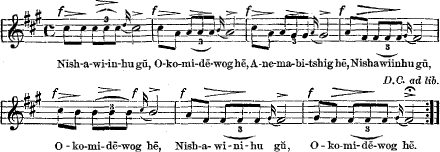

Leech Lake Midē´ song |

295 |

| 37. |

Leech Lake Midē´ song |

296 |

| 38. |

Leech Lake Midē´ song |

297 |

| 39. |

Leech Lake Midē´ song |

297 |

Larger

Map

|

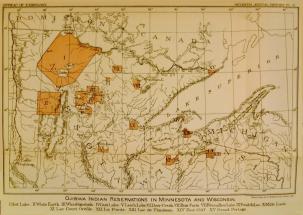

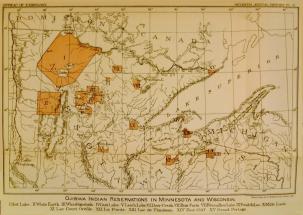

Plate II.

Ojibwa Indian Reservations in Minnesota and Wisconsin.

I Red Lake. II White Earth. III

Winnibigoshish. IV Cass Lake. V Leech Lake. VI Deer Creek. VII Bois

Forte. VIII Vermillion Lake. IX Fond du Lac. X Mille Lacs. XI Lac Court

Oreílle. XII La Pointe. XIII Lac de Flanibeau. XIV Red Cliff. XV Grand

Portage.

|

149

THE MIDĒ´WIWIN OR “GRAND MEDICINE

SOCIETY”

OF THE OJIBWAY.

By W. J. Hoffman.

The Ojibwa is one of the largest tribes of the United States, and it

is scattered over a considerable area, from the Province of Ontario, on

the east, to the Red River of the North, on the west, and from Manitoba

southward through the States of Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan. This

tribe is, strictly speaking, a timber people, and in its westward

migration or dispersion has never passed beyond the limit of the timber

growth which so remarkably divides the State of Minnesota into two parts

possessing distinct physical features. The western portion of this State

is a gently undulating prairie which sweeps away to the Rocky Mountains,

while the eastern portion is heavily timbered. The dividing line, at or

near the meridian of 95° 50' west longitude, extends due north and

south, and at a point about 75 miles south of the northern boundary the

timber line trends toward the northwest, crossing the State line, 49°

north latitude, at about 97° 10' west longitude.

Minnesota contains many thousand lakes of various sizes, some of

which are connected by fine water courses, while others are entirely

isolated. The wooded country is undulating, the elevated portions being

covered chiefly with pine, fir, spruce, and other coniferous trees, and

the lowest depressions being occupied by lakes, ponds, or marshes,

around which occur the tamarack, willow, and other trees which thrive in

moist ground, while the regions between these extremes are covered with

oak, poplar, ash, birch, maple, and many other varieties of trees and

shrubs.

Wild fowl, game, and fish are still abundant, and until recently have

furnished to the Indians the chief source of subsistence.

Tribal organization according to the totemic system is practically

broken up, as the Indians are generally located upon or near the several

reservations set apart for them by the General Government, where they

have been under more or less restraint by the United States Indian

agents and the missionaries. Representatives of various totems or gentes

may therefore be found upon a single reservation,

150

where they continue to adhere to traditional customs and beliefs, thus

presenting an interesting field for ethnologic research.

The present distribution of the Ojibwa in Minnesota and Wisconsin is

indicated upon the accompanying map, Pl. II. In the southern portion many of

these people have adopted civilized pursuits, but throughout the

northern and northwestern part many bands continue to adhere to their

primitive methods and are commonly designated “wild Indians.” The

habitations of many of the latter are rude and primitive. The bands on

the northeast shore of Red Lake, as well as a few others farther east,

have occupied these isolated sites for an uninterrupted period of about

three centuries, as is affirmed by the chief men of the several villages

and corroborated by other traditional evidence.

Father Claude Alloüez, upon his arrival in 1666 at Shagawaumikong, or

La Pointe, found the Ojibwa preparing to attack the Sioux. The

settlement at this point was an extensive one, and in traditions

pertaining to the “Grand Medicine Society” frequent allusion is made to

the fact that at this place the rites were practiced in their greatest

purity.

Mr. Warren, in his History of the Ojibwa Indians,1 bases his belief upon

traditional evidence that the Ojibwa first had knowledge of the whites

in 1612. Early in the seventeenth century the French missionaries met

with various tribes of the Algonkian linguistic stock, as well as with

bands or subtribes of the Ojibwa Indians. One of the latter, inhabiting

the vicinity of Sault Ste. Marie, is frequently mentioned in the Jesuit

Relations as the Saulteurs. This term was applied to all those people

who lived at the Falls, but from other statements it is clear that the

Ojibwa formed the most important body in that vicinity. La Hontan speaks

of the “Outchepoues, alias Sauteurs,” as good warriors. The name

Saulteur survives at this day and is applied to a division of the

tribe.

According to statements made by numerous Ojibwa chiefs of importance

the tribe began its westward dispersion from La Pointe and Fond du Lac

at least two hundred and fifty years ago, some of the bands penetrating

the swampy country of northern Minnesota, while others went westward and

southwestward. According to a statement2 of the location of the tribes of Lake

Superior, made at Mackinaw in 1736, the Sioux then occupied the southern

and northern extremities of that lake. It is possible, however, that the

northern bands of the Ojibwa may have penetrated the region adjacent to

the Pigeon River and passed west to near their present location, thus

avoiding their enemies who occupied the lake shore south of them.

151

From recent investigations among a number of tribes of the Algonkian

linguistic division it is found that the traditions and practices

pertaining to the Midē´wiwin, Society of the Midē´ or Shamans, popularly

designated as the “Grand Medicine Society,” prevailed generally, and the

rites are still practiced at irregular intervals, though in slightly

different forms in various localities.

In the reports of early travelers and missionaries no special mention

is made of the Midē´, the Jes´sakkīd´, or the Wâbĕnō´, but the term

sorcerer or juggler is generally employed to designate that class of

persons who professed the power of prophecy, and who practiced

incantation and administered medicinal preparations. Constant reference

is made to the opposition of these personages to the introduction of

Christianity. In the light of recent investigation the cause of this

antagonism is seen to lie in the fact that the traditions of Indian

genesis and cosmogony and the ritual of initiation into the Society of

the Midē´ constitute what is to them a religion, even more powerful and

impressive than the Christian religion is to the average civilized man.

This opposition still exists among the leading classes of a number of

the Algonkian tribes, and especially among the Ojibwa, many bands of

whom have been more or less isolated and beyond convenient reach of the

Church. The purposes of the society are twofold; first, to preserve the

traditions just mentioned, and second, to give a certain class of

ambitious men and women sufficient influence through their acknowledged

power of exorcism and necromancy to lead a comfortable life at the

expense of the credulous. The persons admitted into the society are

firmly believed to possess the power of communing with various

supernatural beings—manidos—and in order that certain

desires may be realized they are sought after and consulted. The purpose

of the present paper is to give an account of this society and of the

ceremony of initiation as studied and observed at White Earth,

Minnesota, in 1889. Before proceeding to this, however, it may be of

interest to consider a few statements made by early travelers respecting

the “sorcerers or jugglers” and the methods of medication.

In referring to the practices of the Algonkian tribes of the

Northwest, La Hontan3 says:

When they are sick, they only drink Broth, and eat

sparingly; and if they have the good luck to fall asleep, they think

themselves cur’d: They have told me frequently, that sleeping and

sweating would cure the most stubborn Diseases in the World. When they

are so weak that they cannot get out of Bed, their Relations come and

dance and make merry before ’em, in order to divert ’em. To conclude,

when they are ill, they are always visited by a sort of Quacks,

(Jongleurs); of whom ’t will now be proper to subjoin two or

three Words by the bye.

A

Jongleur is a sort of

Physician, or rather a

Quack, who being once cur’d of some dangerous Distemper, has the

Presumption and Folly to fancy that he is immortal, and possessed of the

Power of curing all Diseases, by speaking to the Good and Evil Spirits.

Now though every Body rallies upon these Fellows when

152

they are absent, and looks upon ’em as Fools that have lost their Senses

by some violent Distemper, yet they allow ’em to visit the Sick; whether

it be to divert ’em with their Idle Stories, or to have an Opportunity

of seeing them rave, skip about, cry, houl, and make Grimaces and Wry

Faces, as if they were possess’d. When all the Bustle is over, they

demand a Feast of a Stag and some large Trouts for the Company, who are

thus regal’d at once with Diversion and Good Cheer.

When the Quack comes to visit the Patient, he examines him

very carefully; If the Evil Spirit be here, says he, we shall

quickly dislodge him. This said, he withdraws by himself to a little

Tent made on purpose, where he dances, and sings houling like an Owl;

(which gives the Jesuits Occasion to say, That the Devil converses

with ’em.) After he has made an end of this Quack Jargon, he comes

and rubs the Patient in some part of his Body, and pulling some little

Bones out of his Mouth, acquaints the Patient, That these very Bones

came out of his Body; that he ought to pluck up a good heart, in regard

that his Distemper is but a Trifle; and in fine, that in order to

accelerate the Cure, ’t will be convenient to send his own and his

Relations Slaves to shoot Elks, Deer, &c., to the end they may all

eat of that sort of Meat, upon which his Cure does absolutely

depend.

Commonly these Quacks bring ’em some Juices of Plants, which

are a sort of Purges, and are called Maskikik.

Hennepin, in “A Continuation of the New Discovery,” etc.,4 speaks of the

religion and sorcerers of the tribes of the St. Lawrence and those

living about the Great Lakes as follows:

We have been all too sadly convinced, that almost all the

Salvages in general have no notion of a God, and that they are not able

to comprehend the most ordinary Arguments on that Subject; others will

have a Spirit that commands, say they, in the Air. Some among ’em look

upon the Skie as a kind of Divinity; others as an Otkon or

Manitou, either Good or Evil.

These People admit of some sort of Genius in all things;

they all believe there is a Master of Life, as they call him, but hereof

they make various applications; some of them have a lean Raven, which

they carry always along with them, and which they say is the Master of

their Life; others have an Owl, and some again a Bone, a Sea-Shell, or

some such thing;

There is no Nation among ’em which has not a sort of Juglers

or Conjuerers, which some look upon to be Wizards, but in my Opinion

there is no Great reason to believe ’em such, or to think that their

Practice favours any thing of a Communication with the

Devil.

These Impostors cause themselves to be reverenced as

Prophets which fore-tell Futurity. They will needs be look’d upon to

have an unlimited Power. They boast of being able to make it Wet or Dry;

to cause a Calm or a Storm; to render Land Fruitful or Barren; and, in a

Word to make Hunters Fortunate or Unfortunate. They also pretend to

Physick, and to apply Medicines, but which are such, for the most part

as have little Virtue at all in ’em, especially to Cure that Distemper

which they pretend to.

It is impossible to imagine, the horrible Howlings and

strange Contortions that those Jugglers make of their Bodies, when they

are disposing themselves to Conjure, or raise their

Enchantments.

Marquette, who visited the Miami, Mascontin and Kickapoo Indians in

1673, after referring to the Indian herbalist, mentions also the

ceremony of the “calumet dance,” as follows:

They have Physicians amongst them, towards whom they are

very liberal when they are sick, thinking that the Operation of the

Remedies they take, is proportional to the Presents they make unto those

who have prescrib’d them.

153

In connection with this, reference is made by Marquette to a certain

class of individuals among the Illinois and Dakota, who were compelled

to wear women’s clothes, and who were debarred many privileges, but were

permitted to “assist at all the Superstitions of their Juglers,

and their solemn Dances in honor of the Calumet, in which they

may sing, but it is not lawful for them to dance. They are call’d to

their Councils, and nothing is determin’d without their Advice; for,

because of their extraordinary way of Living, they are look’d upon as

Manitous, or at least for great and incomparable Genius’s.”

That the calumet was brought into requisition upon all occasions of

interest is learned from the following statement, in which the same

writer declares that it is “the most mysterious thing in the World. The

Sceptres of our Kings are not so much respected; for the Savages have

such a Deference for this Pipe, that one may call it The God of Peace

and War, and the Arbiter of Life and Death. Their Calumet of

Peace is different from the Calumet of War; They make use of

the former to seal their Alliances and Treaties, to travel with safety,

and receive Strangers; and the other is to proclaim War.”

This reverence for the calumet is shown by the manner in which it is

used at dances, in the ceremony of smoking, etc., indicating a religious

devoutness approaching that recently observed among various Algonkian

tribes in connection with the ceremonies of the Midē´wiwin. When the

calumet dance was held, the Illinois appear to have resorted to the

houses in the winter and to the groves in the summer. The above-named

authority continues in this connection:

They chuse for that purpose a set Place among Trees, to

shelter themselves against the Heat of the Sun, and lay in the middle a

large Matt, as a Carpet, to lay upon the God of the Chief of the

Company, who gave the Ball; for every one has his peculiar God, whom

they call Manitoa. It is sometime a Stone, a Bird, a Serpent, or

anything else that they dream of in their Sleep; for they think this

Manitoa will prosper their Wants, as Fishing, Hunting, and other

Enterprizes. To the Right of their Manitoa they place the

Calumet, their Great Deity, making round about it a Kind of

Trophy with their Arms, viz. their Clubs, Axes, Bows, Quivers, and

Arrows. ***Every Body sits down afterwards,

round about, as they come, having first of all saluted the

Manitoa, which they do in blowing the Smoak of their Tobacco upon

it, which is as much as offering to it Frankincense. ***This Preludium being over, he who is to begin

the Dance appears in the middle of the Assembly, and having taken the

Calumet, presents it to the Sun, as if he wou’d invite him to

smoke. Then he moves it into an infinite Number of Postures sometimes

laying it near the Ground, then stretching its Wings, as if he wou’d

make it fly, and then presents it to the Spectators, who smoke with it

one after another, dancing all the while. This is the first Scene of

this famous Ball.

The infinite number of postures assumed in offering the pipe appear

as significant as the “smoke ceremonies” mentioned in connection with

the preparatory instruction of the candidate previous to his initiation

into the Midē´wiwin.

154

In his remarks on the religion of the Indians and the practices of the

sorcerers, Hennepin says:

As for their Opinion concerning the Earth, they make use of

a Name of a certain Genius, whom they call Micaboche, who

has cover’d the whole Earth with water (as they imagine) and relate

innumerable fabulous Tales, some of which have a kind of Analogy with

the Universal Deluge. These Barbarians believe that there are certain

Spirits in the Air, between Heaven and Earth, who have a power to

foretell future Events, and others who play the part of Physicians,

curing all sorts of Distempers. Upon which account, it happens, that

these Savages are very Superstitious, and consult their Oracles

with a great deal of exactness. One of these Masters-Jugglers who pass

for Sorcerers among them, one day caus’d a Hut to be erected with ten

thick Stakes, which he fix’d very deep in the Ground, and then made a

horrible noise to Consult the Spirits, to know whether abundance of Snow

wou’d fall ere long, that they might have good game in the Hunting of

Elks and Beavers: Afterward he bawl’d out aloud from the bottom of the

Hut, that he saw many Herds of Elks, which were as yet at a very great

distance, but that they drew near within seven or eight Leagues of their

Huts, which caus’d a great deal of joy among those poor deluded

Wretches.

That this statement refers to one or more tribes of the Algonkian

linguistic stock is evident, not only because of the reference to the

sorcerers and their peculiar methods of procedure, but also that the

name of Micaboche, an Algonkian divinity, appears. This Spirit,

who acted as an intercessor between Ki´tshi Man´idō (Great Spirit) and

the Indians, is known among the Ojibwa as Mi´nabō´zho; but to this full

reference will be made further on in connection with the Myth of the

origin of the Midē´wiwin. The tradition of Nokomis (the earth) and the

birth of Manabush (the Mi´nabō´zho of the Menomoni) and his brother, the

Wolf, that pertaining to the re-creation of the world, and fragments of

other myths, are thrown together and in a mangled form presented by

Hennepin in the following words:

Some Salvages which live at the upper end of the River St.

Lawrence, do relate a pretty diverting Story. They hold almost

the same opinion with the former [the Iroquois], that a Woman came down

from Heaven, and remained for some while fluttering in the Air, not

finding Ground whereupon to put her Foot. But that the Fishes moved with

Compassion for her, immediately held a Consultation to deliberate which

of them should receive her. The Tortoise very officiously offered its

Back on the Surface of the Water. The Woman came to rest upon it, and

fixed herself there. Afterwards the Filthiness and Dirt of the Sea

gathering together about the Tortoise, there was formed by little and

little that vast Tract of Land, which we now call

America.

They add that this Woman grew weary of her Solitude, wanting

some body for to keep her Company, that so she might spend her time more

pleasantly. Melancholy and Sadness having seiz’d upon her Spirits, she

fell asleep, and a Spirit descended from above, and finding her in that

Condition approach’d and knew her unperceptibly. From which Approach she

conceived two Children, which came forth out of one of her Ribs. But

these two Brothers could never afterwards agree together. One of them

was a better Huntsman than the other; they quarreled every day; and

their Disputes grew so high at last, that one could not bear with the

other. One especially being of a very wild Temper, hated mortally his

Brother who was of a milder Constitution, who being no longer able to

endure the Pranks of the other,

155

he resolved at last to part from him. He retired then into Heaven,

whence, for a Mark of his just Resentment, he causeth at several times

his Thunder to rore over the Head of his unfortunate

Brother.

Sometime after the Spirit descended again on that Woman, and

she conceived a Daughter, from whom (as the Salvages say) were

propagated these numerous People, which do occupy now one of the

greatest parts of the Universe.

It is evident that the narrator has sufficiently distorted the

traditions to make them conform, as much as practicable, to the biblical

story of the birth of Christ. No reference whatever is made in the

Ojibwa or Menomoni myths to the conception of the Daughter of Nokomis

(the earth) by a celestial visitant, but the reference is to one of the

wind gods. Mi´nabō´zho became angered with the Ki´tshi Man´idō, and the

latter, to appease his discontent, gave to Mi´nabō´zho the rite of the

Midēwiwin. The brother of Mi´nabō´zho was destroyed by the malevolent

underground spirits and now rules the abode of shadows,—the “Land

of the Midnight Sun.”

Upon his arrival at the “Bay of Puans” (Green Bay, Wisconsin),

Marquette found a village inhabited by three nations, viz: “Miamis,

Maskoutens, and Kikabeux.” He says:

When I arriv’d there, I was very glad to see a great Cross

set up in the middle of the Village, adorn’d with several White Skins,

Red Girdles, Bows and Arrows, which that good People had offer’d to the

Great Manitou, to return him their Thanks for the care he had

taken of them during the Winter, and that he had granted them a

prosperous Hunting. Manitou, is the Name they give in general to

all Spirits whom they think to be above the Nature of Man.

Marquette was without doubt ignorant of the fact that the cross is

the sacred post, and the symbol of the fourth degree of the Midē´wiwin,

as will be fully explained in connection with that grade of the society.

The erroneous conclusion that the cross was erected as an evidence of

the adoption of Christianity, and possibly as a compliment to the

visitor, was a natural one on the part of the priest, but this same

symbol of the Midē´ Society had probably been erected and bedecked with

barbaric emblems and weapons months before anything was known of

him.

The result of personal investigations among the Ojibwa, conducted

during the years 1887, 1888 and 1889, are presented in the accompanying

paper. The information was obtained from a number of the chief Midē´

priests living at Red Lake and White Earth reservations, as well as from

members of the society from other reservations, who visited the last

named locality during the three years. Special mention of the

peculiarity of the music recorded will be made at the proper place; and

it may here be said that in no instance was the use of colors detected,

in any birch-bark or other records or mnemonic songs, simply to heighten

the artistic effect; though the reader would be led by an examination of

the works of Schoolcraft to believe this to be a common practice. Col.

Garrick Mallery; U.S. Army, in a paper read before the Anthropological

Society of

156

Washington, District of Columbia, in 1888, says, regarding this

subject:

The general character of his voluminous publications has not

been such as to assure modern critics of his accuracy, and the wonderful

minuteness, as well as comprehension, attributed by him to the Ojibwa

hieroglyphs has been generally regarded of late with suspicion. It was

considered in the Bureau of Ethnology an important duty to ascertain how

much of truth existed in these remarkable accounts, and for that purpose

its pictographic specialists, myself and Dr. W. J. Hoffman as

assistant, were last summer directed to proceed to the most favorable

points in the present habitat of the tribe, namely, the northern region

of Minnesota and Wisconsin, to ascertain how much was yet to be

discovered. ***The general results of the

comparison of Schoolcraft’s statements with what is now found shows

that, in substance, he told the truth, but with much exaggeration and

coloring. The word “coloring” is particularly appropriate, because, in

his copious illustrations, various colors were used freely with apparent

significance, whereas, in fact, the general rule in regard to the

birch-bark rolls was that they were never colored at all; indeed, the

bark was not adapted to coloration. The metaphorical coloring was also

used by him in a manner which, to any thorough student of the Indian

philosophy and religion, seems absurd. Metaphysical expressions are

attached to some of the devices, or, as he calls them, symbols, which,

could never have been entertained by a people in the stage of culture of

the Ojibwa.

There are extant among the Ojibwa Indians three classes of mystery

men, termed respectively and in order of importance the Midē´, the

Jĕs´sakkīd´, and the Wâbĕnō´, but before proceeding to elaborate in

detail the Society of the Midē´, known as the Midē´wiwin, a brief

description of the last two is necessary.

The term Wâbĕnō´ has been explained by various intelligent Indians as

signifying “Men of the dawn,” “Eastern men,” etc. Their profession is

not thoroughly understood, and their number is so extremely limited that

but little information respecting them can be obtained. Schoolcraft,5 in

referring to the several classes of Shamans, says “there is a third form

or rather modification of the medawin,

***the Wâbĕnō´; a term denoting a kind of midnight orgies, which

is regarded as a corruption of the Meda.” This writer furthermore

remarks6

that “it is stated by judicious persons among themselves to be of modern

origin. They regard it as a degraded form of the mysteries of the

Meda.”

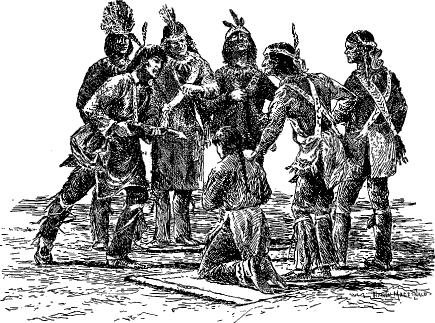

From personal investigation it has been ascertained that a Wâbĕnō´

does not affiliate with others of his class so as to constitute a

society, but indulges his pretensions individually. A Wâbĕnō´ is

primarily prompted by dreams or visions which may occur during his

youth, for which purpose he leaves his village to fast for an indefinite

number of days. It is positively affirmed that evil man´idōs favor his

desires,

157

and apart from his general routine of furnishing “hunting medicine,”

“love powders,” etc., he pretends also to practice medical magic. When a

hunter has been successful through the supposed assistance of the

Wâbĕnō´, he supplies the latter with part of the game, when, in giving a

feast to his tutelary daimon, the Wâbĕnō´ will invite a number of

friends, but all who desire to come are welcome. This feast is given at

night; singing and dancing are boisterously indulged in, and the

Wâbĕnō´, to sustain his reputation, entertains his visitors with a

further exhibition of his skill. By the use of plants he is alleged to

be enabled to take up and handle with impunity red-hot stones and

burning brands, and without evincing the slightest discomfort it is said

that he will bathe his hands in boiling water, or even boiling maple

sirup. On account of such performances the general impression prevails

among the Indians that the Wâbĕnō´ is a “dealer in fire,” or

“fire-handler.” Such exhibitions always terminate at the approach of

day. The number of these pretenders who are not members of the

Midē´wiwin, is very limited; for instance, there are at present but two

or three at White Earth Reservation and none at Leech Lake.

As a general rule, however, the Wâbĕnō´ will seek entrance into the

Midē´wiwin when he becomes more of a specialist in the practice of

medical magic, incantations, and the exorcism of malevolent man´idōs,

especially such as cause disease.

The Jĕs´sakkīd´ is a seer and prophet; though commonly designated a

“juggler,” the Indians define him as a “revealer of hidden truths.”

There is no association whatever between the members of this profession,

and each practices his art singly and alone whenever a demand is made

and the fee presented. As there is no association, so there is no

initiation by means of which one may become a Jĕs´sakkīd´. The gift is

believed to be given by the thunder god, or Animiki´, and then only at

long intervals and to a chosen few. The gift is received during youth,

when the fast is undertaken and when visions appear to the individual.

His renown depends upon his own audacity and the opinion of the tribe.

He is said to possess the power to look into futurity; to become

acquainted with the affairs and intentions of men; to prognosticate the

success or misfortune of hunters and warriors, as well as other affairs

of various individuals, and to call from any living human being the

soul, or, more strictly speaking, the shadow, thus depriving the victim

of reason, and even of life. His power consists in invoking, and causing

evil, while that of the Midē´ is to avert it; he attempts at times to

injure the Midē´ but the latter, by the aid of his superior man´idos,

becomes aware of, and averts such premeditated injury. It sometimes

happens that the demon possessing a patient is discovered, but the Midē´

alone has the power to expel him. The exorcism of demons is one of the

chief pretensions of this personage, and evil spirits are sometimes

removed

158

by sucking them through tubes, and startling tales are told how the

Jĕs´sakkīd´ can, in the twinkling of an eye, disengage himself of the

most complicated tying of cords and ropes, etc. The lodge used by this

class of men consists of four poles planted in the ground, forming a

square of three or four feet and upward in diameter, around which are

wrapped birch bark, robes, or canvas in such a way as to form an upright

cylinder. Communion is held with the turtle, who is the most powerful

man´idō of the Jĕs´sakkīd´, and through him, with numerous other

malevolent man´idōs, especially the Animiki´, or thunder-bird. When the

prophet has seated himself within his lodge the structure begins to sway

violently from side to side, loud thumping noises are heard within,

denoting the arrival of man´idōs, and numerous voices and laughter are

distinctly audible to those without. Questions may then be put to the

prophet and, if everything be favorable, the response is not long in

coming. In his notice of the Jĕs´sakkīd´, Schoolcraft affirms7 that “while he

thus exercises the functions of a prophet, he is also a member of the

highest class of the fraternity of the Midâwin—a society of men

who exercise the medical art on the principles of magic and

incantations.”

The fact is that there is not the slightest connection

between the practice of the Jĕs´sakkīd´ and that of the Midē´wiwin, and

it is seldom, if at all, that a Midē´ becomes a Jĕs´sakkīd´, although

the latter sometimes gains admission into the Midē´wiwin, chiefly with

the intention of strengthening his power with his tribe.

The number of individuals of this class who are not members of the

Midē´wiwin is limited, though greater than that of the Wâbĕnō´. An idea

of the proportion of numbers of the respective classes may be formed by

taking the case of Menomoni Indians, who are in this respect upon the

same plane as the Ojibwa. That tribe numbers about fifteen hundred, the

Midē´ Society consisting, in round numbers, of one hundred members, and

among the entire population there are but two Wâbĕnō´ and five

Jĕs´sakkīd´.

It is evident that neither the Wâbĕnō´ nor the Jĕs´sakkīd´ confine

themselves to the mnemonic songs which are employed during their

ceremonial performances, or even prepare them to any extent. Such bark

records as have been observed or recorded, even after most careful

research and examination extending over the field seasons of three

years, prove to have been the property of Wâbĕnō´ and Jĕs´sakkīd´, who

were also Midē´. It is probable that those who practice either of the

first two forms of ceremonies and nothing else are familiar with and may

employ for their own information certain mnemonic records; but they are

limited to the characteristic formulæ of exorcism, as their practice

varies and is subject to changes according to circumstances and the

requirements and wants of the applicant when words are chanted to accord

therewith.

159

Some examples of songs used by Jĕs´sakkīd´, after they have become

Midē´, will be given in the description of the several degrees of the

Midē ’wiwin.

There is still another class of persons termed Mashkī´kĭkē´winĭnĭ, or

herbalists, who are generally denominated “medicine men,” as the Ojibwa

word implies. Their calling is a simple one, and consists in knowing the

mysterious properties of a variety of plants, herbs, roots, and berries,

which are revealed upon application and for a fee. When there is an

administration of a remedy for a given complaint, based upon true

scientific principles, it is only in consequence of such practice having

been acquired from the whites, as it has usually been the custom of the

Catholic Fathers to utilize all ordinary and available remedies for the

treatment of the common disorders of life. Although these herbalists are

aware that certain plants or roots will produce a specified effect upon

the human system, they attribute the benefit to the fact that such

remedies are distasteful and injurious to the demons who are present in

the system and to whom the disease is attributed. Many of these

herbalists are found among women, also; and these, too, are generally

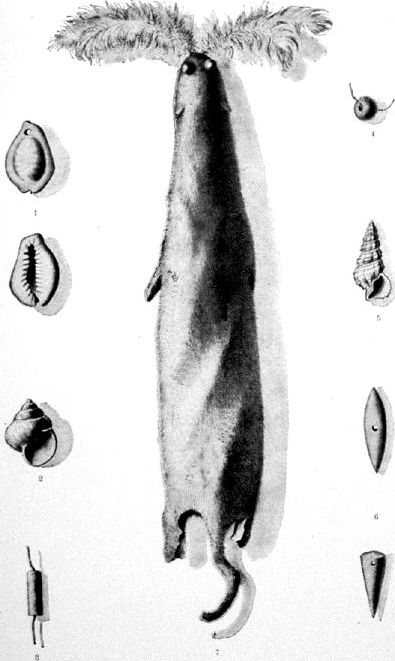

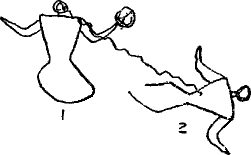

members of the Midē´wiwin. In Fig. 1 is shown

an herbalist preparing a mixture.

Fig. 1.—Herbalist preparing

medicine and treating patient.

160

The origin of the Midē´wiwin or Midē´ Society, commonly, though

erroneously, termed Grand Medicine Society, is buried in obscurity. In

the Jesuit Relations, as early as 1642, frequent reference is made to

sorcerers, jugglers, and persons whose faith, influence, and practices

are dependent upon the assistance of “Manitous,” or mysterious spirits;

though, as there is no discrimination made between these different

professors of magic, it is difficult positively to determine which of

the several classes were met with at that early day. It is probable that

the Jĕs´sakkīd´, or juggler, and the Midē´, or Shaman, were

referred to.

The Midē´, in the true sense of the word, is a Shaman, though he has

by various authors been termed powwow, medicine man, priest, seer,

prophet, etc. Among the Ojibwa the office is not hereditary; but among

the Menomoni a curious custom exists, by which some one is selected to

fill the vacancy one year after the death of a Shaman. Whether a similar

practice prevailed among other tribes of the Algonkian linguistic stock

can be ascertained only by similar research among the tribes

constituting that stock.

Among the Ojibwa, however, a substitute is sometimes taken to fill

the place of one who has been prepared to receive the first degree of

the Midē´wiwin, or Society of the Midē´, but who is removed by death

before the proper initiation has been conferred. This occurs when a

young man dies, in which case his father or mother may be accepted as a

substitute. This will be explained in more detail under the caption of

Dzhibai´ Midē´wigân or “Ghost Lodge,” a collateral branch of the

Midē´wiwin.

As I shall have occasion to refer to the work of the late Mr.

W. W. Warren, a few words respecting him will not be inappropriate.

Mr. Warren was an Ojibwa mixed blood, of good education, and later a

member of the legislature of Minnesota. His work, entiled “History of

the Ojibwa Nation,” was published in Vol. V of the Collections of the Minnesota Historical

Society, St. Paul, 1885, and edited by Dr. E. D. Neill. Mr.

Warren’s work is the result of the labor of a lifetime among his own

people, and, had he lived, he would undoubtedly have added much to the

historical material of which the printed volume chiefly consists. His

manuscript was completed about the year 1852, and he died the following

year. In speaking of the Society of the Midē´,8 he says:

The grand rite of Me-da-we-win (or, as we have learned to

term it, “Grand Medicine

,”)and

the beliefs incorporated therein, are

not yet fully understood by the whites. This important custom is still

shrouded in mystery even to my own eyes, though I have taken much pains

to inquire and made use of every advantage possessed by speaking their

language perfectly, being related to them, possessing their friendship

and intimate confidence has given me, and yet I frankly acknowledge that

I stand as yet, as it were, on the threshold of the Me-da-we lodge. I

believe, however, that I have obtained full as much and more general and

true information

161

on this matter than any other person who has written on the subject, not

excepting a great and standard author, who, to the surprise of many who

know the Ojibways well, has boldly asserted in one of his works that he

has been regularly initiated into the mysteries of this rite, and is a

member of the Me-da-we Society. This is certainly an assertion hard to

believe in the Indian country; and when the old initiators or Indian

priests are told of it they shake their heads in incredulity that a

white man should ever have been allowed

in truth to become a

member of their Me-da-we lodge.

An entrance into the lodge itself, while the ceremonies are

being enacted, has sometimes been granted through courtesy; though this

does not initiate a person into the mysteries of the creed, nor does it

make him a member of the Society.

These remarks pertaining to the pretensions of “a great and standard

authority” have reference to Mr. Schoolcraft, who among numerous other

assertions makes the following, in the first volume of his Information

Respecting the Indian Tribes of the United States, Philadelphia, 1851,

p. 361, viz:

I had observed the exhibitions of the Medawin, and the

exactness and studious ceremony with which its rites were performed in

1820 in the region of Lake Superior; and determined to avail myself of

the advantages of my official position, in 1822, when I returned as a

Government agent for the tribes, to make further inquiries into its

principles and mode of proceeding. And for this purpose I had its

ceremonies repeated in my office, under the secrecy of closed doors,

with every means of both correct interpretation and of recording the

result. Prior to this transaction I had observed in the hands of an

Indian of the Odjibwa tribe one of those symbolic tablets of pictorial

notation which have been sometimes called “music boards,” from the fact

of their devices being sung off by the initiated of the Meda Society.

This constituted the object of the explanations, which, in accordance

with the positive requisitions of the leader of the society and three

other initiates, was thus ceremoniously made.

This statement is followed by another,9 in which Mr. Schoolcraft, in a

foot-note, affirms:

Having in 1823 been myself admitted to the class of a Meda

by the Chippewas, and taken the initiatory step of a Sagima and Jesukaid

in each of the other fraternities, and studied their pictographic system

with great care and good helps, I may speak with the more decision on

the subject.

Mr. Schoolcraft presents a superficial outline of the initiatory

ceremonies as conducted during his time, but as the description is

meager, notwithstanding that there is every evidence that the ceremonies

were conducted with more completeness and elaborate dramatization nearly

three-quarters of a century ago than at the present day, I shall not

burden this paper with useless repetition, but present the subject as

conducted within the last three years.

Mr. Warren truly says:

In the Me-da-we rite is incorporated most that is ancient

amongst them—songs and traditions that have descended not orally,

but in hieroglyphs, for at least a long time of generations. In this

rite is also perpetuated the purest and most ancient idioms of their

language, which differs somewhat from that of the common everyday

use.

162

As the ritual of the Midē´wiwin is based to a considerable extent upon

traditions pertaining to the cosmogony and genesis and to the thoughtful

consideration by the Good Spirit for the Indian, it is looked upon by

them as “their religion,” as they themselves designate it.

In referring to the rapid changes occurring among many of the Western

tribes of Indians, and the gradual discontinuance of aboriginal

ceremonies and customs, Mr. Warren remarks10 in reference to the

Ojibwa:

Even among these a change is so rapidly taking place, caused

by a close contact with the white race, that ten years hence it will be

too late to save the traditions of their forefathers from total

oblivion. And even now it is with great difficulty that genuine

information can be obtained of them. Their aged men are fast falling

into their graves, and they carry with them the records of the past

history of their people; they are the initiators of the grand rite of

religious belief which they believe the Great Spirit has granted to his

red children to secure them long life on earth and life hereafter; and

in the bosoms of these old men are locked up the original secrets of

this their most ancient belief.

***

They fully believe, and it forms part of their religion,

that the world has once been covered by a deluge, and that we are now

living on what they term the “new earth.” This idea is fully accounted

for by their vague traditions; and in their Me-da-we-win or religion,

hieroglyphs are used to denote this second earth.

Furthermore,

They fully believe that the red man mortally angered the

Great Spirit which caused the deluge, and at the commencement of the new

earth it was only through the medium and intercession of a powerful

being, whom they denominate Manab-o-sho, that they were allowed to

exist, and means were given them whereby to subsist and support life;

and a code of religion was more lately bestowed on them, whereby they

could commune with the offended Great Spirit, and ward off the approach

and ravages of death.

It may be appropriate in this connection to present the description

given by Rev. Peter Jones of the Midē´ priests and priestesses. Mr.

Jones was an educated Ojibwa Episcopal clergyman, and a member of the

Missasauga—i.e., the Eagle totemic division of that tribe of

Indians living in Canada. In his work11 he states:

Each tribe has its medicine men and women—an order of

priesthood consulted and employed in all times of sickness. These

powwows are persons who are believed to have performed extraordinary

cures, either by the application of roots and herbs or by incantations.

When an Indian wishes to be initiated into the order of a powwow, in the

first place he pays a large fee to the faculty. He is then taken into

the woods, where he is taught the names and virtues of the various

useful plants; next he is instructed how to chant the medicine song, and

how to pray, which prayer is a vain repetition offered up to the Master

of Life, or to some munedoo whom the afflicted imagine they have

offended.

The powwows are held in high veneration by their deluded

brethren; not so much for their knowledge of medicine as for the magical

power which they are supposed to possess. It is for their interest to

lead these credulous people to believe that they can at pleasure hold

intercourse with the munedoos, who are ever ready to give them whatever

information they require.

163

The Ojibwa believe in a multiplicity of spirits, or man´idōs, which

inhabit all space and every conspicuous object in nature. These

man´idōs, in turn, are subservient to superior ones, either of a

charitable and benevolent character or those which are malignant and

aggressive. The chief or superior man´idō is termed Ki´tshi

Man´idō—Great Spirit—approaching to a great extent the idea

of the God of the Christian religion; the second in their estimation is

Dzhe Man´idō, a benign being upon whom they look as the guardian spirit

of the Midē´wiwin and through whose divine provision the sacred rites of

the Midē´wiwin were granted to man. The Ani´miki or Thunder God is, if

not the supreme, at least one of the greatest of the malignant man´idōs,

and it is from him that the Jĕs´sakkīd´ are believed to obtain their

powers of evil doing. There is one other, to whom special reference will

be made, who abides in and rules the “place of shadows,” the hereafter;

he is known as Dzhibai´ Man´idō—Shadow Spirit, or more commonly

Ghost Spirit. The name of Ki´tshi Man´idō is never mentioned but with

reverence, and thus only in connection with the rite of Midē´wiwin, or a

sacred feast, and always after making an offering of tobacco.

The first important event in the life of an Ojibwa youth is his first

fast. For this purpose he will leave his home for some secluded spot in

the forest where he will continue to fast for an indefinite number of

days; when reduced by abstinence from food he enters a hysterical or

ecstatic state in which he may have visions and hallucinations. The

spirits which the Ojibwa most desire to see in these dreams are those of

mammals and birds, though any object, whether animate or inanimate, is

considered a good omen. The object which first appears is adopted as the

personal mystery, guardian spirit, or tutelary daimon of the entranced,

and is never mentioned by him without first making a sacrifice. A small

effigy of this man´idō is made, or its outline drawn upon a small piece

of birch bark, which is carried suspended by a string around the neck,

or if the wearer be a Midē´ he carries it in his “medicine bag” or

pinji´gosân. The future course of life of the faster is governed by his

dream; and it sometimes occurs that because of giving an imaginary

importance to the occurrence, such as beholding, during the trance some

powerful man´idō or other object held in great reverence by the members

of the Midē´ Society, the faster first becomes impressed with the idea

of becoming a Midē´. Thereupon he makes application to a prominent Midē´

priest, and seeks his advice as to the necessary course to be pursued to

attain his desire. If the Midē´ priest considers with favor the

application, he consults with his confrères and action is taken, and the

questions of the requisite preliminary instructions, fees, and presents,

etc., are formally discussed. If the Midē´ priests are in accord with

the desires of the applicant an instructor or preceptor is designated,

to whom he must present himself

164

and make an agreement as to the amount of preparatory information to be

acquired and the fees and other presents to be given in return. These

fees have nothing whatever to do with the presents which must be

presented to the Midē´ priests previous to his initiation as a member of

the society, the latter being collected during the time that is devoted

to preliminary instruction, which period usually extends over several

years. Thus ample time is found for hunting, as skins and peltries, of

which those not required as presents may be exchanged for blankets,

tobacco, kettles, guns, etc., obtainable from the trader. Sometimes a

number of years are spent in preparation for the first degree of the

Midē´wiwin, and there are many who have impoverished themselves in the

payment of fees and the preparation for the feast to which all visiting

priests are also invited.

Should an Indian who is not prompted by a dream wish to join the

society he expresses to the four chief officiating priests a desire to

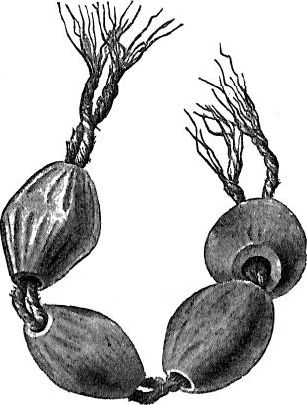

purchase a mī´gis, which is the sacred symbol of the society and

consists of a small white shell, to which reference will be made further

on. His application follows the same course as in the preceding

instance, and the same course is pursued also when a Jĕs´sakkīd´ or a

Wâbĕnō´ wishes to become a Midē´.

The Midē´wiwin—Society of the Midē´ or Shamans—consists

of an indefinite number of Midē´ of both sexes. The society is graded

into four separate and distinct degrees, although there is a general

impression prevailing even among certain members that any degree beyond

the first is practically a mere repetition. The greater power attained

by one in making advancement depends upon the fact of his having

submitted to “being shot at with the medicine sacks” in the hands of the

officiating priests. This may be the case at this late day in certain

localities, but from personal experience it has been learned that there

is considerable variation in the dramatization of the ritual. One

circumstance presents itself forcibly to the careful observer, and that

is that the greater number of repetitions of the phrases chanted by the

Midē´ the greater is felt to be the amount of inspiration and power of

the performance. This is true also of some of the lectures in which

reiteration and prolongation in time of delivery aids very much in

forcibly impressing the candidate and other observers with the

importance and sacredness of the ceremony.

It has always been customary for the Midē´ priests to preserve

birch-bark records, bearing delicate incised lines to represent

pictorially the ground plan of the number of degrees to which the owner

is entitled. Such records or charts are sacred and are never exposed to

the public view, being brought forward for inspection only when

165

an accepted candidate has paid his fee, and then only after necessary

preparation by fasting and offerings of tobacco.

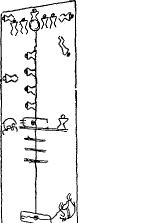

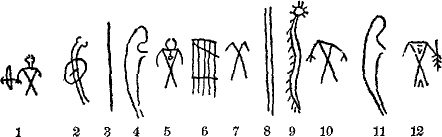

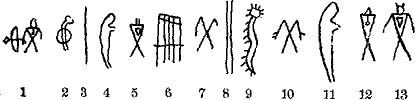

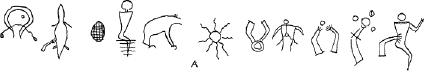

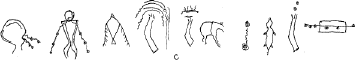

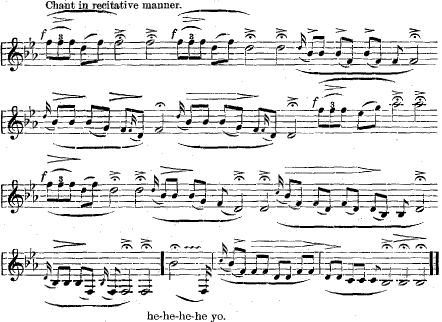

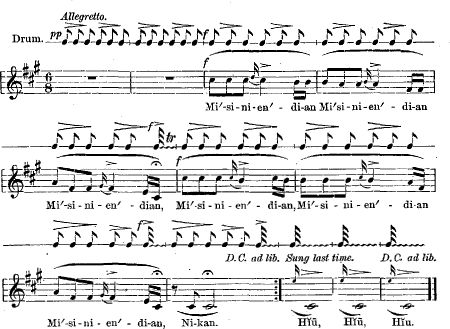

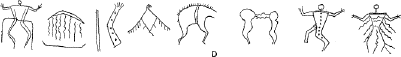

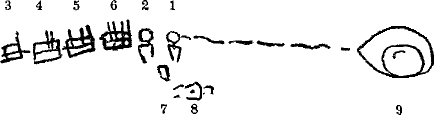

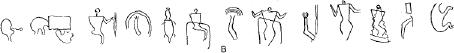

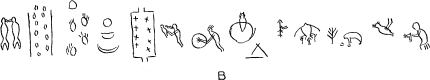

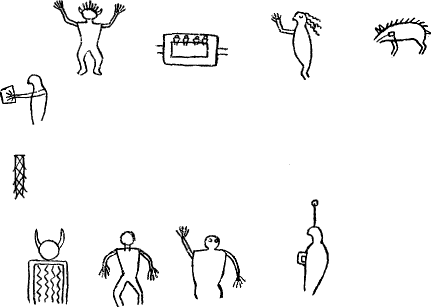

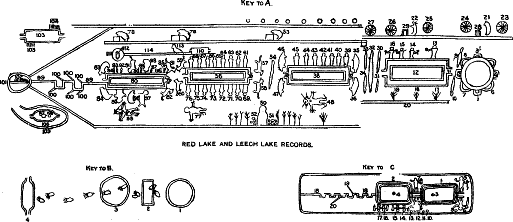

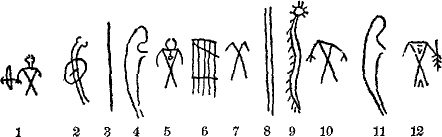

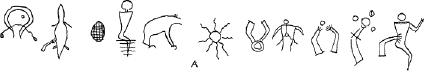

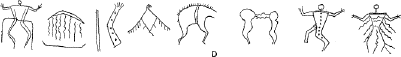

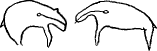

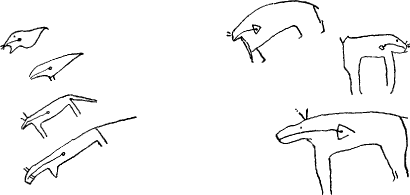

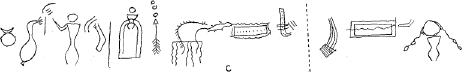

Plate III. Red Lake And Leech Lake Records (key).

Complete

Plate

During the year 1887, while at Red Lake, Minnesota, I had the good

fortune to discover the existence of an old birch-bark chart, which,

according to the assurances of the chief and assistant Midē´ priests,

had never before been exhibited to a white man, nor even to an Indian

unless he had become a regular candidate. This chart measures 7 feet 1½

inches in length and 18 inches in width, and is made of five pieces of

birch bark neatly and securely stitched together by means of thin, flat

strands of bass wood. At each end are two thin strips of wood, secured

transversely by wrapping and stitching with thin strands of bark, so as

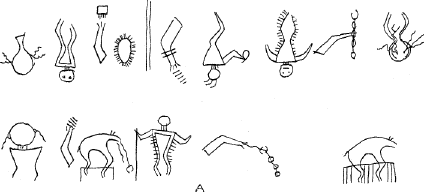

to prevent splitting and fraying of the ends of the record. Pl. III A, is a

reproduction of the design referred to.

It had been in the keeping of Skwēkŏ´mĭk, to whom it was intrusted at

the death of his father-in-law, the latter, in turn, having received it

in 1825 from Badâ´san, the Grand Shaman and chief of the Winnibē´goshish

Ojibwa.

It is affirmed that Badâ´san had received the original from the Grand

Midē´ priest at La Pointe, Wisconsin, where, it is said, the Midē´wiwin was at

that time held annually and the ceremonies conducted in strict

accordance with ancient and traditional usage.

The present owner of this record has for many years used it in the

preliminary instruction of candidates. Its value in this respect is very

great, as it presents to the Indian a pictorial résumé of the

traditional history of the origin of the Midē´wiwin, the positions

occupied by the various guardian man´idos in the several degrees, and

the order of procedure in study and progress of the candidate. On

account of the isolation of the Red Lake Indians and their long

continued, independent ceremonial observances, changes have gradually

occurred so that there is considerable variation, both in the pictorial

representation and the initiation, as compared with the records and

ceremonials preserved at other reservations. The reason of this has

already been given.

A detailed description of the above mentioned record, will be

presented further on in connection with two interesting variants which

were subsequently obtained at White Earth, Minnesota. On account of the

widely separated location of many of the different bands of the Ojibwa,

and the establishment of independent Midē´ societies, portions of the

ritual which have been forgotten by one set may be found to survive at

some other locality, though at the expense of some other fragments of

tradition or ceremonial. No satisfactory account of the tradition of the

origin of the Indians has been obtained, but such information as it was

possible to procure will be submitted.

166

In all of their traditions pertaining to the early history of the tribe

these people are termed A-nish´-in-â´-bēg—original people—a

term surviving also among the Ottawa, Patawatomi, and Menomoni,

indicating that the tradition of their westward migration was extant

prior to the final separation of these tribes, which is supposed to have

occurred at Sault Ste. Marie.

Mi´nabō´zho (Great Rabbit), whose name occurs in connection with most

of the sacred rites, was the servant of Dzhe Man´idō, the Good Spirit,

and acted in the capacity of intercessor and mediator. It is generally

supposed that it was to his good offices that the Indian owes life and

the good things necessary to his health and subsistence.

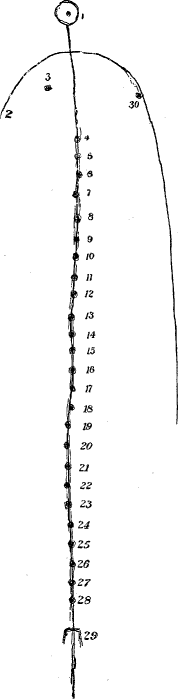

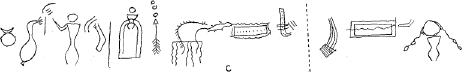

The tradition of Mi´nabō´zho and the origin of the Midē´wiwin, as

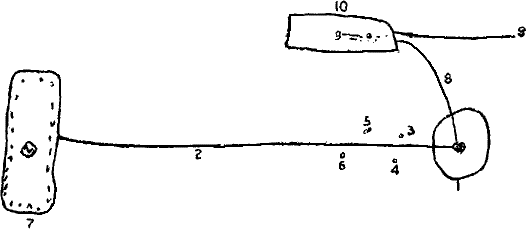

given in connection with the birch-bark record obtained at Red Lake (Pl. III A), is as follows:

When Mi´nabō´zho, the servant of Dzhe Man´idō, looked down upon the

earth he beheld human beings, the Ani´shinâ´bēg, the ancestors of the

Ojibwa. They occupied the four quarters of the earth—the

northeast, the southeast, the southwest, and the northwest. He saw how

helpless they were, and desiring to give them the means of warding off

the diseases with which they were constantly afflicted, and to provide

them with animals and plants to serve as food and with other comforts,

Mi´nabō´zho remained thoughtfully hovering over the center of the earth,

endeavoring to devise some means of communicating with them, when he

heard something laugh, and perceived a dark object appear upon the

surface of the water to the west (No. 2). He could not recognize

its form, and while watching it closely it slowly disappeared from view.

It next appeared in the north (No. 3), and after a short lapse of

time again disappeared. Mi´nabō´zho hoped it would again show itself

upon the surface of the water, which it did in the east (No. 4).

Then Mi´nabō´zho wished that it might approach him, so as to permit him

to communicate with it. When it disappeared from view in the east and

made its reappearance in the south (No. 1), Mi´nabō´zho asked it to

come to the center of the earth that he might behold it. Again it

disappeared from view, and after reappearing in the west Mi´nabō´zho

observed it slowly approaching the center of the earth (i.e., the centre

of the circle), when he descended and saw it was the Otter, now one of

the sacred man´idōs of the Midē´wiwin. Then Mi´nabō´zho instructed the

Otter in the mysteries of the Midē´wiwin, and gave him at the same time

the sacred rattle to be used at the side of the sick; the sacred Midē´

drum to be used during the ceremonial of initiation and at sacred

feasts, and tobacco, to be employed in invocations and in making

peace.

The place where Mi´nabō´zho descended was an island in the middle of

a large body of water, and the Midē´ who is feared by all the others is

called Mini´sino´shkwe (He-who-lives-on-the-island). Then

167

Mi´nabō´zho built a Midē´wigân (sacred Midē´ lodge), and taking his drum

he beat upon it and sang a Midē´ song, telling the Otter that Dzhe

Man´idō had decided to help the Aníshinâ´bōg, that they might always

have life and an abundance of food and other things necessary for their

comfort. Mi´nabō´zho then took the Otter into the Midē´wigân and

conferred upon him the secrets of the Midē´wiwin, and with his Midē´ bag

shot the sacred mī´gis into his body that he might have immortality and

be able to confer these secrets to his kinsmen, the Aníshinâ´bēg.

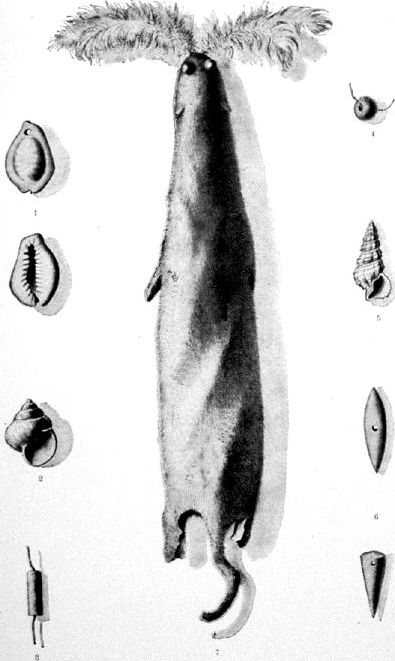

The mī´gis is considered the sacred symbol of the Midē´wigân, and may

consist of any small white shell, though the one believed to be similar

to the one mentioned in the above tradition resembles the cowrie, and

the ceremonies of initiation as carried out in the Midē´wiwin at this

day are believed to be similar to those enacted by Mi´nabō´zho and the

Otter. It is admitted by all the Midē´ priests whom I have consulted

that much of the information has been lost through the death of their

aged predecessors, and they feel convinced that ultimately all of the

sacred character of the work will be forgotten or lost through the

adoption of new religions by the young people and the death of the Midē´

priests, who, by the way, decline to accept Christian teachings, and are

in consequence termed “pagans.”

My instructor and interpreter of the Red Lake chart added other

information in explanation of the various characters represented

thereon, which I present herewith. The large circle at the right side of

the chart denotes the earth as beheld by Mi´nabō´zho, while the Otter

appeared at the square projections at Nos. 1, 2, 3, and 4; the

semicircular appendages between these are the four quarters of the

earth, which are inhabited by the Ani´shinâ´bēg, Nos. 5, 6, 7, and 8.

Nos. 9 and 10 represent two of the numerous malignant man´idōs, who

endeavor to prevent entrance into the sacred structure and mysteries of

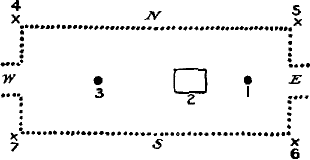

the Midē´wiwin. The oblong squares, Nos. 11 and 12, represent the

outline of the first degree of the society, the inner corresponding

lines being the course traversed during initiation. The entrance to the

lodge is directed toward the east, the western exit indicating the

course toward the next higher degree. The four human forms at Nos. 13,

14, 15, and 16 are the four officiating Midē´ priests whose services are

always demanded at an initiation. Each is represented as having a

rattle. Nos. 17, 18, and 19 indicate the cedar trees, one of each of

this species being planted near the outer angles of a Midē´ lodge. No.

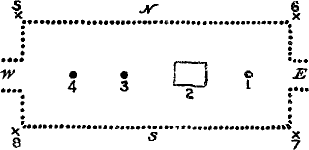

20 represents the ground. The outline of the bear at No. 21 represents

the Makwa´ Man´idō, or Bear Spirit, one of the sacred Midē´ man´idōs, to

which the candidate must pray and make offerings of tobacco, that he may

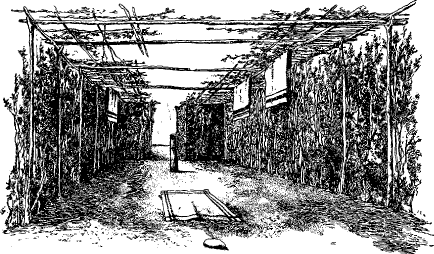

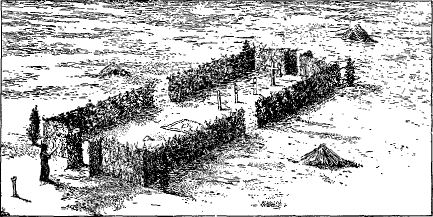

compel the malevolent spirits to draw away from the entrance to the

Midē´wigân, which is shown in No. 28. Nos 23 and 24 represent the sacred

drum which

168

the candidate must use when chanting the prayers, and two offerings must

be made, as indicated by the number two.

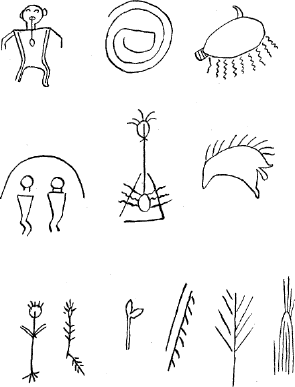

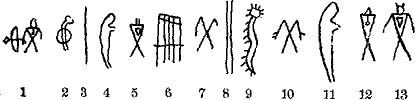

After the candidate has been admitted to one degree, and is prepared

to advance to the second, he offers three feasts, and chants three

prayers to the Makwa´ Man´idō, or Bear Spirit (No. 22), that the

entrance (No. 29) to that degree may be opened to him. The feasts

and chants are indicated by the three drums shown at Nos. 25, 26,

and 27.

Nos. 30, 31, 32, 33, and 34 are five Serpent Spirits, evil man´idōs

who oppose a Midē´’s progress, though after the feasting and prayers

directed to the Makwa´ Man´idō have by him been deemed sufficient the

four smaller Serpent Spirits move to either side of the path between the

two degrees, while the larger serpent (No. 32) raises its body in

the middle so as to form an arch, beneath which passes the candidate on

his way to the second degree.

Nos. 35, 36, 46, and 47 are four malignant Bear Spirits, who guard

the entrance and exit to the second degree, the doors of which are at

Nos. 37 and 49. The form of this lodge (No. 38) is like the

preceding; but while the seven Midē´ priests at Nos. 39, 40, 41, 42, 43,

44, and 45 simply indicate that the number of Midē´ assisting at this

second initiation are of a higher and more sacred class of personages

than in the first degree, the number designated having reference to

quality and intensity rather than to the actual number of assistants, as

specifically shown at the top of the first degree structure.

When the Midē´ is of the second degree, he receives from Dzhe Man´idō

supernatural powers as shown in No. 48. The lines extending upward from

the eyes signify that he can look into futurity; from the ears, that he

can hear what is transpiring at a great distance; from the hands, that

he can touch for good or for evil friends and enemies at a distance,

however remote; while the lines extending from the feet denote his

ability to traverse all space in the accomplishment of his desires or

duties. The small disk upon the breast of the figure denotes that a

Midē´ of this degree has several times had the

mī´gis—life—“shot into his body,” the increased size of the

spot signifying amount or quantity of influence obtained thereby.

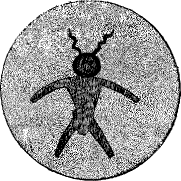

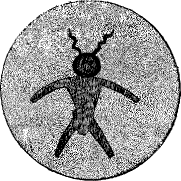

No. 50 represents a Mi´tsha Midē´ or Bad Midē´, one who employs his

powers for evil purposes. He has the power of assuming the form of any

animal, in which guise he may destroy the life of his victim,

immediately after which he resumes his human form and appears innocent

of any crime. His services are sought by people who wish to encompass

the destruction of enemies or rivals, at however remote a locality the

intended victim may be at the time. An illustration representing the

modus operandi of his performance is reproduced and explained in Fig. 24, page 238.

Persons possessed of this power are sometimes termed witches, special

reference to whom is made elsewhere. The illustration, No.

169

50, represents such an individual in his disguise of a bear, the

characters at Nos. 51 and 52 denoting footprints of a bear made by him,

impressions of which are sometimes found in the vicinity of lodges

occupied by his intended victims. The trees shown upon either side of

No. 50 signify a forest, the location usually sought by bad Midē´ and

witches.

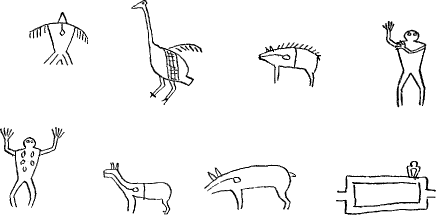

If a second degree Midē´ succeeds in his desire to become a member of

the third degree, he proceeds in a manner similar to that before

described; he gives feasts to the instructing and four officiating

Midē´, and offers prayers to Dzhe Man´idō for favor and success. No. 53

denotes that the candidate now personates the bear—not one of the

malignant man´idōs, but one of the sacred man´idōs who are believed to

be present during the ceremonials of initiation of the second degree. He

is seated before his sacred drum, and when the proper time arrives the

Serpent Man´idō (No. 54)—who has until this opposed his

advancement—now arches its body, and beneath it he crawls and

advances toward the door (No. 55) of the third degree (No. 56)

of the Midē´wiwin, where he encounters two (Nos. 57 and 58) of the

four Panther Spirits, the guardians of this degree.

Nos. 61 to 76 indicate midē´ spirits who inhabit the structure of

this degree, and the number of human forms in excess of those shown in

connection with the second degree indicates a correspondingly higher and

more sacred character. When an Indian has passed this, initiation he

becomes very skillful in his profession of a Midē´. The powers which he

possessed in the second degree may become augmented. He is represented

in No. 77 with arms extended, and with lines crossing his body and arms

denoting darkness and obscurity, which signifies his ability to grasp

from the invisible world the knowledge and means to accomplish

extraordinary deeds. He feels more confident of prompt response and

assistance from the sacred man´idōs and his knowledge of them becomes

more widely extended.

Nos. 59 and 60 are two of the four Panther Spirits who are the

special guardians of the third degree lodge.

To enter the fourth and highest degree of the society requires a

greater number of feasts than before, and the candidate, who continues

to personate the Bear Spirit, again uses his sacred drum, as he is shown

sitting before it in No. 78, and chants more prayers to Dzhe Man´idō for

his favor. This degree is guarded by the greatest number and the most

powerful of malevolent spirits, who make a last effort to prevent a

candidate’s entrance at the door (No. 79) of the fourth degree

structure (No. 80). The chief opponents to be overcome, through the

assistance of Dzhe Man´idō, are two Panther Spirits (Nos. 81

and 82) at the eastern entrance, and two Bear Spirits (Nos. 83

and 84) at the western exit. Other bad spirits are about the

structure, who frequently gain possession and are then enabled to make

strong and prolonged resistance to the candidate’s entrance.

170

The chiefs of this group of malevolent beings are Bears (Nos. 88

and 96), the Panther (No. 91), the Lynx (No. 97), and

many others whose names they have forgotten, their positions being

indicated at Nos. 85, 86, 87, 89, 90, 92, 93, 94, and 95, all but the

last resembling characters ordinarily employed to designate

serpents.

The power with which it is possible to become endowed after passing

through the fourth degree is expressed by the outline of a human figure

(No. 98), upon which are a number of spots indicating that the body

is covered with the mī´gis or sacred shells, symbolical of the

Midē´wiwin. These spots designate the places where the Midē´ priests,

during the initiation, shot into his body the mī´gis and the lines

connecting them in order that all the functions of the several

corresponding parts or organs of the body may be exercised.

The ideal fourth degree Midē´ is presumed to be in a position to

accomplish the greatest feats in necromancy and magic. He is not only

endowed with the power of reading the thoughts and intentions of others,

as is pictorially indicated by the mī´gis spot upon the top of the head,

but to call forth the shadow (soul) and retain it within his grasp at

pleasure. At this stage of his pretensions, he is encroaching upon the

prerogatives of the Jĕs´sakkīd´, and is then recognized as one, as he

usually performs within the Jĕs´sakkân or Jĕs´sakkīd´ lodge, commonly

designated “the Jugglery.”

The ten small circular objects upon the upper part of the record may

have been some personal marks of the original owner; their import was

not known to my informants and they do not refer to any portion of the

history or ceremonies or the Midē´wiwin.

Extending toward the left from the end of the fourth degree inclosure

is an angular pathway (No. 99), which represents the course to be

followed by the Midē´ after he has attained this high distinction. On

account of his position his path is often beset with dangers, as

indicated by the right angles, and temptations which may lead him

astray; the points at which he may possibly deviate from the true course

of propriety are designated by projections branching off obliquely

toward the right and left (No. 100). The ovoid figure (No. 101) at the

end of this path is termed Wai-ĕk´-ma-yŏk´—End of the

road—and is alluded to in the ritual, as will be observed

hereafter, as the end of the world, i.e., the end of the individual’s

existence. The number of vertical strokes (No. 102) within the ovoid

figure signify the original owner to have been a fourth degree Midē´ for

a period of 14 years.

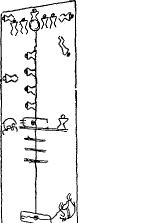

The outline of the Midē´wigân (No. 103) not only denotes that the

same individual was a member of the Midē´wiwin, but the thirteen

vertical strokes shown in Nos. 104 and 105 indicate that he was chief

Midē´ priest of the society for that number of years.

The outline of a Midē´wigân as shown at No. 106, with the place upon

the interior designating the location of the sacred post (No.

171

107) and the stone (No. 108) against which the sick are placed during

the time of treatment, signifies the owner to have practiced his calling

of the exorcism of demons. But that he also visited the sick beyond the

acknowledged jurisdiction of the society in which he resided, is

indicated by the path (No. 109) leading around the sacred inclosure.

Upon that portion of the chart immediately above the fourth degree

lodge is shown the outline of a Midē´wiwin (No. 110), with a path (No.

114), leading toward the west to a circle (No. 111), within which is

another similar structure (No. 112) whose longest diameter is at right

angles to the path, signifying that it is built so that its entrance is

at the north. This is the Dzhibai´ Midē´wigân or Ghost Lodge.

Around the interior of the circle are small V-shaped characters

denoting the places occupied by the spirits of the departed, who are

presided over by the Dzhibai´ Midē´, literally Shadow Midē´.

No. 113 represents the Kŏ´-kó-kŏ-ō´ (Owl) passing from the Midē´wigân

to the Land of the Setting Sun, the place of the dead, upon the road of

the dead, indicated by the pathway at No. 114. This man´idō is

personated by a candidate for the first degree of the Midē´wiwin when

giving a feast to the dead in honor of the shadow of him who had been

dedicated to the Midē´wiwin and whose place is now to be taken by the

giver of the feast.

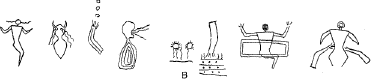

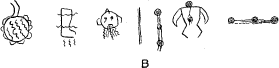

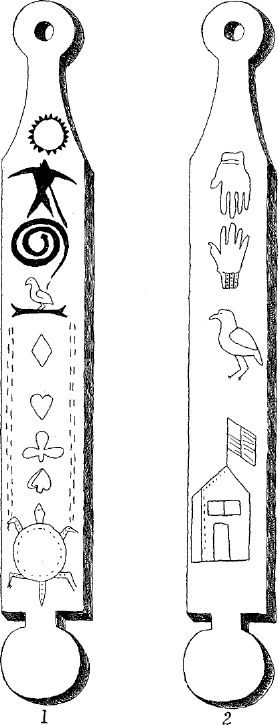

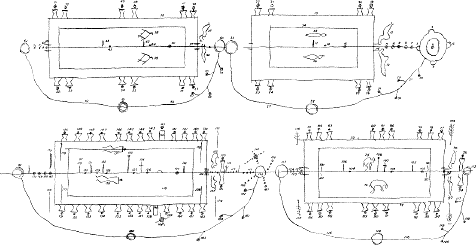

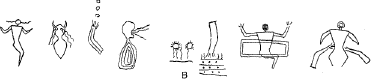

Upon the back of the Midē´ record, above described, is the personal

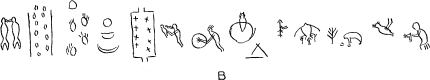

record of the original owner, as shown in Pl.

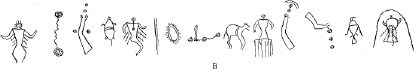

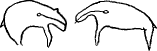

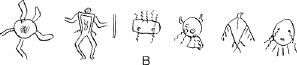

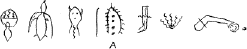

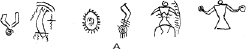

III B. Nos. 1, 2, 3, and 4

represent the four degrees of the society into which he has been

initiated, or, to use the phraseology of an Ojibwa, “through which he

has gone.” This “passing through” is further illustrated by the bear

tracks, he having personated the Makwa´ Man´idō or Bear Spirit,

considered to be the highest and most powerful of the guardian spirits

of the fourth degree wigwam.

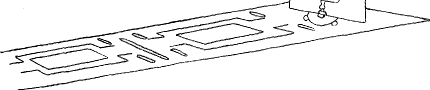

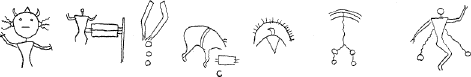

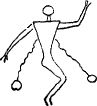

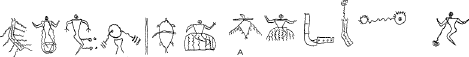

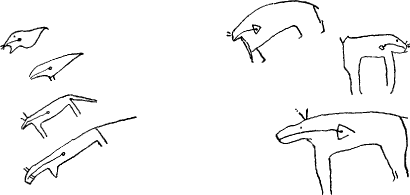

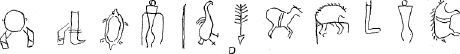

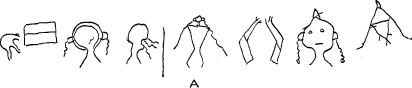

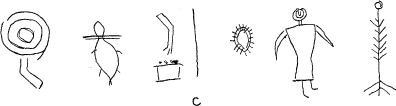

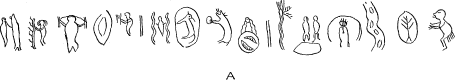

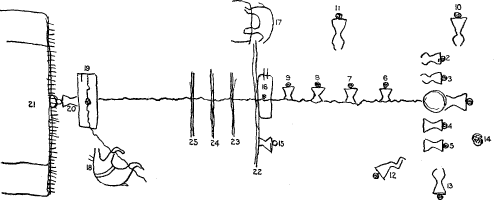

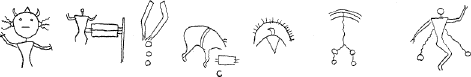

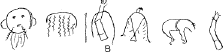

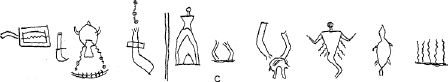

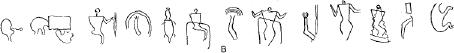

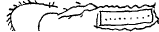

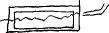

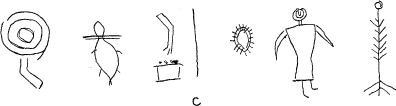

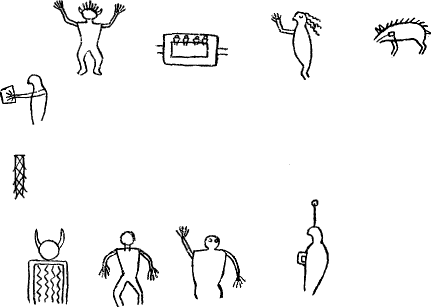

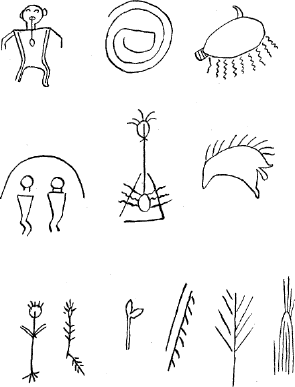

The illustration presented in Pl. III C represents the outlines of a

birch-bark record (reduced to one-third) found among the effects of a

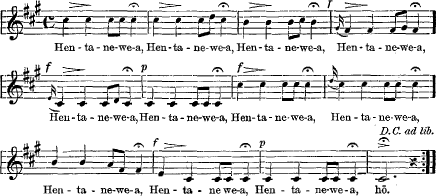

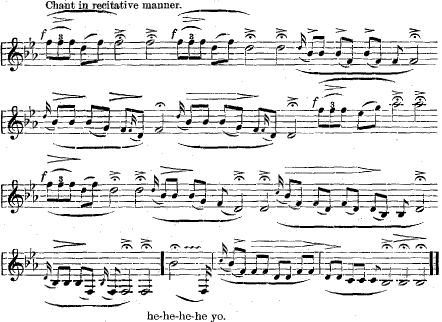

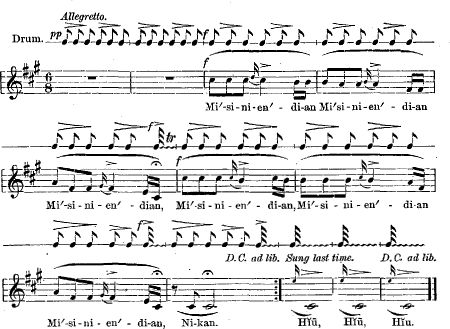

lately deceased Midē´ from Leech Lake, Minnesota. This record, together