Title: The Modern Scottish Minstrel, Volume 3.

Editor: Charles Rogers

Release date: September 26, 2006 [eBook #19385]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Susan Skinner, Ted Garvin and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

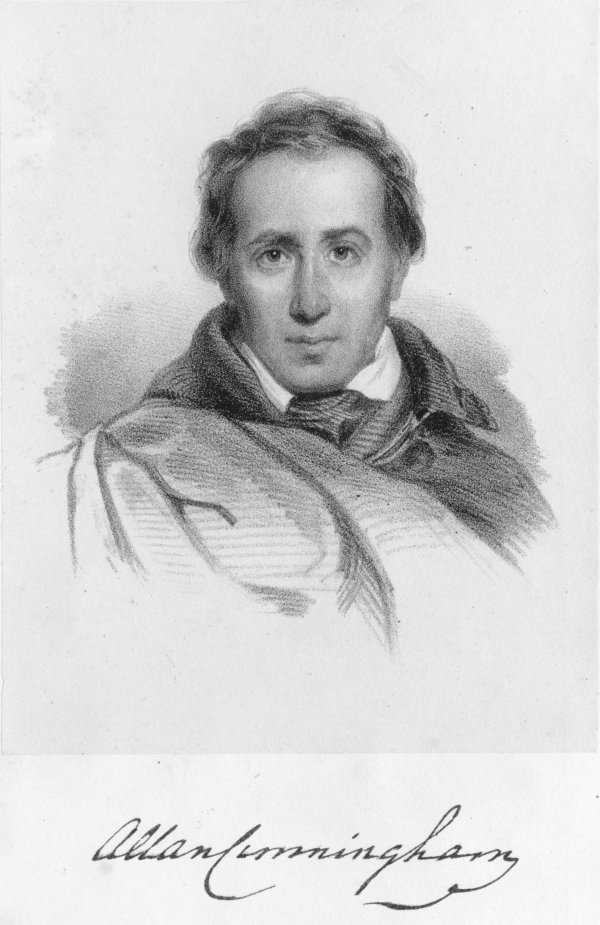

Allan Cunningham.

Allan Cunningham.IN SIX VOLUMES;

VOL. III.

EDINBURGH: ADAM & CHARLES BLACK, NORTH BRIDGE, BOOKSELLERS AND PUBLISHERS TO HER MAJESTY.

M.DCCC.LVI.

EDINBURGH:

PRINTED BY BALLANTYNE AND COMPANY,

PAUL'S WORK.

TO

LIEUTENANT-COLONEL

SIR JAMES EDWARD ALEXANDER,

K.L.S., AND K.ST.J.,

A DISTINGUISHED TRAVELLER, A GALLANT OFFICER, AND

A PATRIOTIC SCOTSMAN,

THIS THIRD VOLUME

OF

The Modern Scottish Minstrel

IS DEDICATED,

WITH SENTIMENTS OF RESPECT AND GRATITUDE,

BY

HIS VERY OBEDIENT, FAITHFUL SERVANT,

CHARLES ROGERS.

Men who compare themselves with their nearest neighbours are almost invariably conceited, speak boastingly of themselves, and disrespectfully of others. But if a man extend his survey, if he mingle largely with people whose feelings and opinions have been modified by quite different circumstances, the result is generally beneficial. The very act of accommodating his mind to foreign modes of thought expands his nature; and he becomes more liberal in his sentiments, more charitable in his construction of deeds, and more capable of perceiving real goodness under whatever shape it may present itself. So when a Scotsman criticises Scotch poetry viewed by itself alone, he is apt to be carried away by his patriotism,—he sees only the delightful side of the subject, and he ventures on assertions which flatter himself and his country at the expense of all other nations. If, however, we place the productions of our own country side by side with those of another, the excellences and the deficiencies of both are seen in stronger relief; the contrasts strike the mind,[Pg vi] and the heart is widened by sympathising with goodness and beauty diversely conceived and diversely portrayed. For this reason, we shall attempt a brief comparison of Hellenic and Scottish songs.

Before we enter on our characterisation of these, we must glance at the materials which we have to survey. Greek lyric poetry arose about the beginning of the eighth century before the Christian era, and continued in full bloom down to the time when it passed into drama on the Athenian stage. The names of the poets are universally known, and have become, indeed, almost part of our poetic language. Every one speaks of an Anacreon, a Sappho, and a Pindar; and the names of Archilochus, Alcman, Alcæus, Stesichorus, Simonides, Ibycus, and Bacchylides, if not so often used, are yet familiar to most. Few of these lyrists belonged to Greece proper. They belonged to Greece only in the sense in which the Greeks themselves used the word, as including all the colonies which had gone forth from the motherland. Most of the early Greek song-writers dwelt in Asia Minor—some were born in the islands of the Cyclades, and some in Southern Italy; but all of them were proud of their Greek origin, all of them were thorough Greeks in their hearts. It is only the later bards who were born and brought up on the Greek mainland, and most of these lived to see the day when almost all the lyric poets took their grandest flights in the choral odes of their dramas. These odes, however, do not fall within the province of our comparison. The lyrical efforts both of Æschylus and Sophocles were inwoven with the structure of their plays, the chorus in Æschylus being generally one of the actors; and they have their modern representatives, not in the songs of the people, but in the arias of operas.[Pg vii] Setting these aside, we have few genuine efforts of the Greek lyric muse belonging to the dramatic period—the most important being several songs sung by the Greeks at their banquets, which have fortunately been preserved. After this era, we have no lyric poems of the Greeks worth mentioning. The verse-writers took henceforth to epigrams—epigrams on everything on the face of the earth. These have been collected into the "Greek Anthology;" but the greater part of them are contemptible in a poetic point of view. They are interesting as throwing light on the times; but they are weak and vapid as expressions of the beatings of the human heart, and they are full of conceits. Besides these, there are the Anacreontic odes, known to all Greek scholars and to a great number of English, since they have been frequently translated. With one or two exceptions, they were all written between the third and twelfth centuries of the Christian era, though some scholars have boldly asserted that they were forgeries even of a later date. Most of them seem to be expansions of lines of Anacreon. They are in general neat, pretty, and gaysome, but tame and insincere. There is nothing like earnestness in them, nothing like genuine deep feeling; but thus they are all the more suited for a certain class of lovers and drinkers, who do not wish to be greatly moved by anything under the sun.

Scotch lyric poetry may be said to commence with the lyrics attributed to James I., or with those of Henryson. There is clear proof, indeed, that long before this time the Scotch were much given to song-making and song-singing; but of these early popular lilts, almost nothing remains. Henryson's lyrics, however, belonged more to the class that were intended to be read than to be sung, and this is true of a considerable number of his suc[Pg viii]cessors, such as Dunbar, and Maitland of Lethington, who were learned men, and wrote with a learned air, even when writing for the people. The Reformation, as surely as it threw down every carved stone, shut up the mouth of every profane songster. Wedderburne's "Haly Ballats" may have been spared for a time by the iconoclasts, because they had helped to build up their own temple; but they could not survive long,—they were cast in a profane mould, they were sung to profane tunes, and away they must go into oblivion. Our song-writers, for a long time after, are unknown minstrels, who had no character to lose by making or singing profane songs,—they were of the people, and sang for them. So matters continued, until, at the commencement of the eighteenth century, Scottish songs began to be the rage both in England and Scotland, and an eager desire arose to gather up old snatches and preserve them. Henceforth Scotch poetry held up its head, and a few remarkable poets won their way into the hearts of large masses of the people. At last appeared the emancipator of Scottish song in the form of a ploughman, stirring the deepest feelings of all classes with songs that may be justly styled the best of all national popular songs, and for ever settling the claims of a song-writer to one of the highest niches in the temple of Fame.

The first thing that strikes us, on dipping into a book of Greek songs, and then a book of Scotch, is the different position of the poets. The Greek poet was regarded as a kind of superior being—an interpreter between gods and men; and, supposed to be under the special protection of Divinity, he was highly honoured and reverenced wherever he went. The Scotch bard, on the other hand, is a poor wanderer, whose name is unknown, who received little respect, and whose knowledge of God and[Pg ix] the higher purposes of life cannot be reckoned in any way great. There may be a few exceptions. We find nobles sometimes writing popular songs, and occasionally a learned man may have contributed strains; but these are generally not superior either in wit, pathos, or morality, to the verses of the unknown and hard-toiling. This striking contrast arises from a change that had taken place in the history of song. In Greece, all the teeming ideas of the fertile-minded people found expression in harmonious measures, and their songs touched every chord of their varied existence. This was partly owing to their innate love of melody, and partly to the public life which they led. From the earliest ages, they were fond of sweet sounds; and their continual public gatherings gave innumerable opportunities for using their vocal powers unitedly, and turning music to all its best and noblest purposes. They sang sacred songs as they marched in procession to their temples; and on entering, they hymned the praises of the gods. When they rushed on to battle, they shouted their inspiring war-songs; and if victory crowned the fight, the battle-field rang with their joyous pæans, and their poets tuned their lyres in honour of the brave that had fallen. A victor in the Olympic games would have lost one of his greatest rewards, if no poet had sung his fame. Then, in their banquets, the Greeks amused themselves in stringing together pretty verses, and joined in merry and jovial drinking-songs. If there happened to be a marriage, the young people assembled round the house, and late in the evening and early in the morning sang the praises of bride and bridegroom, prayed for blessings on the couple, and sometimes discussed the comparative blessedness of single and married life. Or if a notable person happened to die, his dirge was sung, and the poet[Pg x] composed an encomium on him, full of wise reflections on destiny, and the fate that awaits all. There was, in fact, no public occasion which the Greeks did not beautify with song.

It is entirely different with us. Our minister now performs the function of the Greek poet at marriages and funerals. Our funeral sermons and newspaper paragraphs have taken the place of the Greek encomiums. Our fiddles or piano do duty instead of the Greek dithyrambs, hyporchems, and other dancing songs. Our warriors are either left unsung, or celebrated in verse that reads much better than it sings. The members of the "Benevolent Pugilistic Association" do not stand so high in the British opinion as the wrestlers of old stood in the Greek; and our jockeys have fallen frightfully from the grand position which the Greek racers occupied in the plains of Olympia. Very few in these days would think the champion of England, or the winner of the Derby, worth a noble ode full of old traditions and exalted religious aspirations. Through various causes, song has thus come to be very circumscribed in its limits, and to perform duty within a comparatively small sphere in modern life.

Indeed, song in these days does exactly what the Greeks rarely attempted: it concerns itself with private life, and especially with that most characteristic feature of modern private life—love. Love is, consequently, the main topic of Scottish song. It is a theme of which neither the song-writer nor the song-singer ever wearies. It is the one great passion with which the universal modern mind sympathises, and from the expressions of which it quaffs inexhaustible delight. This holds true even of the cynical people who profess a distaste for love and lovers. For love has for them its comic side,—it[Pg xi] appears to them exquisitely humorous in the human weakness it causes and brings to light; and if they do not enjoy the song in its praise, they seldom fail to laugh heartily at the description of the plights into which it leads its devotees.

Perhaps no country contains a richer collection of love-songs than Scotland. We have a song for every phase of the motley-faced passion,—from its ludicrous aspect to its highest and most rapturous form. Every pulsation of the heart, as moved by love, has had its poetic expression; and we have lovers pouring out the depths of their souls to all kinds of maids, and in all kinds of situations. And maids are represented as bodying forth their feelings, also, under the sway of love. Many of these feminine lyrics are written by women themselves. Some of them exult in the full return which their love meets; but for the most part, it is a keen sorrow that forces women to poetic composition. They thus contribute our most pathetic songs—wails sometimes over blasted hopes and blighted love, as in "Waly, Waly;" or over the death of a deeply-loved one, as in Miss Blamire's "Waefu' Heart;" or over the loss of the brave who have fallen in battle, as in Miss Jane Elliot's "Flowers of the Forest."

Peculiarly characteristic of Scotland are the songs that describe the development of love, after the lovers have been married. Here the comical phase is most predominant. For the most part, the Scottish songster delights in describing the quarrels between the goodman and the goodwife—the goodwife in the early poems invariably succeeding in making John yield to her. Sometimes, however, there is a deeper and purer current of feeling, to which Burns especially has given expression. How intensely beautiful is the affection in "John Anderson, my Jo!" And we have in "Are ye sure the news is[Pg xii] true?" the whole character of a very loving wife brought out by a simple incident in her life,—the expected return of her husband. Some of these songs also have been written by poetesses, such as Lady Nairn's exquisite "Land of the Leal;" and really there is such delicacy, such minute accuracy in the portrayal of a woman's feelings in "Are ye sure the news is true?" that one cannot help thinking it must have been written by Jean Adams, or some woman, rather than by Mickle:—

What man has an ear so delicate as to hear such music?

The contrast between Greek poetry and Scotch is very marked in this point. There is not one Greek lyric devoted to what we should designate love, with perhaps something like an exception in Alcman. In fact, while moderns rarely make a tragedy or comedy, a poem or novel, without some love-concern which is the pivot of the whole, all the great poems and dramas of the ancients revolve on entirely different passions. Love, such as we speak of, was of rather rare occurrence. Women were in such a low position, that it was a condescension to notice them,—there was no chivalrous feeling in regard to them; they were made to feel the dominion of their absolute lords and masters. Besides this, the greater number of them were confined to their private chambers, and seldom saw any man who was not nearly related. Those who were on free terms of intercourse with men, were for the most part strangers, whose morals were low, and who could not be expected to win the respectful esteem of true lovers. The men enjoyed the society of these—their tumbling, dancing, singing, and lively chat; but the distance was too great to permit that deep devo[Pg xiii]tion which characterises modern love. Moreover, when a Greek speaks of love, we have to remember that he fell in love as often with a male companion as with a woman—he admired the beauty of a fair youth, and he felt in his presence very much as a modern lover feels in the presence of his sweetheart. We have, therefore, to examine expressions of love cautiously. Anacreon says, for instance, that love clave him with an axe, like a smith; but it seems far more likely that the reference is to the affection excited by some charming youth.[1] We have a specimen remaining of the nonchalant style in which he addressed a woman, in the ode commencing "O Thracian mare!"—Schneidewin, Poet. Lyr. Anac. fr. 47.

The great poet of Love was not Anacreon, but Sappho, whose heart and mind were both of the finest. Her life is involved in obscurity, but it is probable that she was a strong advocate of woman's rights in her own land; and as she found men falling in love with other men, so she took special pains to win the affections of the young Æolian ladies, to train them in all the accomplishments suited to woman's nature, and to initiate them into the art of poetry,—that art without which, she says, a woman's memory would be for ever forgotten, and she would go to the house of Hades, to dwell with the shadowy dead, uncared for and unknown. We have two poems of hers which have come down to us tolerably complete, both, we think, addressed to some of her female friends, and both remarkably sweet, touching, and beautiful. [Pg xiv]

The Scottish songs devoted to other subjects than love are few, and almost exclusively descriptive. Our sense of the humorous gives us a delight in queer and odd characters, in which the Greeks probably would not have participated. Though they had an abundance of wit, and a keen perception of the ridiculous, no songs have reached us which are intended to please by their pure absurdity and good-natured foolishness. Archilochus and Hipponax wrote many a jocular song; but the fun of the thing would have been lost, had the sting which they contained been extracted.

Nor do the Greeks seem to have cared much for descriptive songs. They frequently introduced their heroes into their odes, but these were ever living, ever present to their minds; and several of the songs written on particular occasions were probably sung when the singer had no connexion with the events. But they lived, like boys, too much in the present, to throw themselves back into the past. They wished to give utterance to the feelings of the moment in their own persons, and directly; while we are content to be mere listeners, and are often as much pleased by the occurrences of another's life as by the sentiments of our own hearts.

We are remarkably deficient in what are called class-songs. The Greeks had none of these, for there scarcely existed any classes but free and slave. The people were all one—had the same interests and the same emotions. There was far less of individuality with them than with us, and there was still less of that feeling which divides society into exclusive circles. A Greek turned his hand to anything that came in his way, while division of labour has reached its utmost limit among us. We can find, therefore, no contrast here between Greek and Scotch songs; but we find a very marked one between[Pg xv] Scotch and German. We have no student-songs, very few expressive of the feelings of soldiers (Lockhart's are almost the only), sailors, or of any other class.

Indeed, we are deficient not only in class-songs, but in social-songs. The Scotch propensity to indulge in drink is, unfortunately, notorious; and yet our drinking-songs of a really social nature would be comprised in a few pages. One sings of his coggie, as if he were in the custom of gulping his whisky all alone; many describe the boisterous carousals in which they made fools of themselves; not a few extol the power and properties of whisky, and incite to Bacchanalian pleasures; and we have several good songs suitable for singing at the close of an evening pleasantly spent, but almost none which express the feelings that naturally well-up when one sees his friends around him, becomes exhilarated through pleasant social intercourse, and finds the path of life smoothed and sweetened by the aid of his brothers.

The reason of this peculiar circumstance is not far to seek. It lies in the distinctive character of the two great classes into which the Scotch have been divided since the Reformation, called, at the early period of Scottish song, the Covenanters and the Cavaliers. The one party bowed before religion, most scrupulously abstained from all worldly pleasures, and regarded and denounced as sin, or something akin to it, every approach to levity or frivolity. The other party was a wild rebound from this. Sanctimoniousness was hateful in their eye; and not being able to find a medium, they abjured religion, and rushed into the pleasures of this life with headlong zest. The poets, in accordance with their joy-loving natures, allied themselves to the latter class. There was thus in Scotland a deep, dark gulf between the religious and the poetical or beautiful, which has not yet been[Pg xvi] completely bridged over. The consequence is, that the elder Scottish songs, of all songs, contain the fewest references to the Divine Being. The name of God is never mentioned unless in the caricatures of the Covenanters; and a foreigner, taking up a book of Scottish songs written since the Reformation, and judging of the religion of the Scotch from them alone, would be prone to suppose that, if Scotland had any religion at all, it consisted in using the name of the devil occasionally with respect or with dread. The Cavaliers, in their most energetic moods, swore by him and by no other; while the Covenanters had no songs at all, scarcely any poetry of any kind, and doubtless would have regarded as impious the tracing of any but the most spiritual pleasures to God. The words, for instance, which Allan Cunningham puts into the mouth of a Covenanter, "I hae sworn by my God, my Jeanie" (p. 17 of this volume), would still be regarded by many people as profane.

The case was the very opposite with the Greeks. Every joy, every sorrow, was traced to the gods. They almost never opened their lips without an allusion to their divinities. They sang their praises in their processions and in all their public ceremonials. Wine was a gift from a kind and beneficent god, to cheer their hearts and soothe the sorrows of life. And they delighted in invoking his presence, in celebrating his adventures, and in using moderately and piously the blessings which he bestowed on them. Then, again, when love seized them, it was a god that had taken possession of their minds. They at once recognised a superior power, and they worshipped him in song with heart and soul. In fact, whatever be the subject of song, the gods are recognised as the rulers of the destinies of men, and the causes of all their joys and sorrows. We cannot expect[Pg xvii] such a strong infusion of the supernatural in modern lays, but still we have enough of it in German songs to form a remarkable contrast to Scotch. Take any German song-book, and you will immediately come upon a recognition of a higher power as the spring of our joys, and upon an expressed desire to use them, so as to bring us nearer one another, and to make us more honest, upright, happy, and contented men. Let this one verse, taken from a song of Schiller's, in singing which a German's heart is sure to glow, suffice:—

Chorus.

We meet with the contrast in the Reformers of the respective nations—Knox and Luther. Knox, ever stern, frowning on all the amusements of the palace and the people, and indifferent to every species of poetry; Luther, often drinking his mug of ale in a tavern, making and singing his tunes and songs, and though frequently[Pg xviii] enough tormented by devils, yet still ready to throw aside the cares of life for a while, and enjoy himself in hearty intercourse with the various classes of the people. Who would have expected the German Reformer to be the author of the couplet—

And yet he was. And his songs, sacred though most of them be, have a place in German song-books to this day.

Though Scottish songs seldom refer to a Divine Being, yet they are very far from being without their noble sentiments and inspirations. On the contrary, they have frequently sustained the moral life of a man. "Who dare measure in doubt," says William Thom in his "Recollections," "the restraining influences of these very songs? To us, they were all instead of sermons.... Poets were indeed our priests. But for those, the last relict of our moral existence would have surely passed away!"

Yet there is a marked contrast between the very aims of Scottish and Greek song-writers. The Scottish wish merely to please, and consequently never concern themselves with any of the deeper subjects of this life or the life to come. There is seldom an allusion to death, or to any of the great realities that sternly meet the gaze of a contemplative man. There may be a few exceptions in the case of pious song-writers, like Lady Nairn; but even such poets are shy of making songs the vehicle of what is serious or profound. The Greeks, on the other hand, regarding their poets as inspired, expected from them the deepest wisdom, and in fact delighted in any verse which threw light on the great mysteries of life and death. Thus it happens that the remains of the Greek[Pg xix] lyric poets, especially the later, such as Simonides and Bacchylides, are principally of a deeply moral cast. The Greeks do not seem to have had the extravagant rage which now prevails for merely figurative language. They sought for truth itself, and the man became a poet who clothed living truths in the most appropriate and expressive words.

There is a remarkable contrast between the Scotch and Greeks in their historical songs. The lyric muse sings at great epochs, because then the deepest emotions of the human heart are roused. But since, in Greece, the states were small, and every emotion thrilled through all the free citizens, there was more of determined and unanimous feeling than with us, and consequently a greater desire to see the heroic deeds of themselves or their fellows wedded to verse. And then, too, the poet did not live apart; he was one of the people, a soldier and a citizen as well as others, and animated by exactly the same feelings, though with greater rapture. This is the reason why the Greeks abounded in songs in honour of their brave. At the time of the resistance to the Persian invasion, there was no end to the encomiums and pæans. Almost every individual hero was celebrated, and these songs were made by the acknowledged masters of the lyre, such as Æschylus and Simonides. With us, great deeds have to wait their poets. Distance of time must first throw around them a poetic hue; and after the hero has sunk unnoticed into a nameless grave, the bard showers his praises on him, and his worth is universally recognised. Or if his merits are discerned before his death, song is not one of the appointed organs through which our people demand that he should be praised. If a heroic action gets its poet, the people will listen; but if it pass unsung, none will regret it. Besides, we do[Pg xx] not discern the poetry of the present so strongly as the Greeks did. Everything with them seems to have been capable of finding its way into verse. Alcman delights in speaking of his porridge, and Alcæus of the various implements of war which adorned his hall. The real world in which the Greeks moved had the most powerful attraction for them. This is also, in a great measure, true of the unknown poets, who have contributed so much to Scottish minstrelsy in the days of the later Stuarts. There is no squeamishness about the introduction of realities, whatever they be; and the people took delight in a mere series of names skilfully strung together, or even in an enumeration of household articles or dishes.[3]

This pleasure in the contemplation of the actual things around us, is not nearly so great in modern cultivated minds. We are continually trying to get out of ourselves, to transport ourselves to other times, and to throw ourselves into bygone scenes and characters. Hence it is that almost all our best historical songs, written in these days, have their basis in the past; and the one which moves us most powerfully, "Scots wha hae wi' Wallace bled," actually carries us back to the times of Robert the Bruce.

It is rather singular that most of the Scottish songs which refer to our history, are essentially aristocratic, and favourable to the divine right of kings. The Covenanters—our true freemen—disdained the use of the poet's pen. They uttered none of their aspirations for freedom in song, and thus the Royalists had the whole field of song-writing to themselves. Such was the state of matters until Burns rose from amidst the people, and sang in his own grand way of the inherent dignity of man as[Pg xxi] man, and of the rights of labour. It is one of the frequent contradictions which we see in human nature, that the very same people who sing "A Man's a Man for a' that," and "Scots wha hae," mourn over the unfortunate fate of Bonnie Prince Charlie, and lament his disasters, as if his succession to the throne of Scotland would have been a blessing. Notwithstanding, however, what Burns has done, Scotland is still deficient in songs embodying her ardent love of freedom. Liberty and her blessings are still unsung. It was not so in Greece, especially in Athens. The whole city echoed with hymns in its praise, and the people wiled away their leisure in making little chants on the men who they fancied had given the death-blow to tyranny. The scolia of Callistratus, beginning, "I'll wreathe my sword in myrtle bow," are well known.

Few of the patriotic songs of the Greeks are extant, and it is probable that they were not so numerous as ours. Institutions had a more powerful hold on them than localities. They were proud of themselves as Greeks, and of their traditions; but wherever they wandered, they carried Greece with them, for they were part of Greece themselves. Thus we may account for the absence of Greek songs expressive of longing for their native land, and of attachment to their native soil. We, on the other hand, have very many patriotic songs, full of that warm enthusiasm which every Scotsman justly feels for his country, and containing frequently a much higher estimate of ourselves and our position than other nations would reckon true or fair. In these songs, we are exceedingly confined in our sympathies. The nationality is stronger than the humanity. We have no such songs as the German, "Was ist des Deutschen Vaterland?"[Pg xxii]

Perhaps there is no point in which the Greeks contrast with the Scotch and all moderns more strikingly than in their mode of describing nature. This contrast holds good only between the cultivated Greek and the cultivated modern; for the cultivated Greek and the uncultivated Scotsman are one in this respect. Perhaps we should state it most correctly, if we say that the Greek never pictures natural scenery with words—the modern often makes the attempt. There is no song like Burns's "Birks o' Aberfeldy," or even like the "Welcome to May"[4] of early Scottish poetry, in the Greek lyric poets. The Greek poet seizes one or two characteristic traits in which he himself finds pleasure; but his descriptions are not nicely shaded, minute, or calculated to bring the landscape before the mind's eye. No doubt, the Greek was led to this course by an instinct. For, first, his interest in inanimate nature was nothing as compared to his strong sympathies with man. He had not discovered that "God made the country, and man made the town." The gods, according to his notion, ruled the destinies of man, and every thought and device of man were inspirations from above. He saw infinitely more of deity in his fellow-men—in his and their pleasures, pursuits, and hopes—than in all the insentient things on the face of the earth; and consequently he clung to men. He delighted in representations of them; and in embodying his conceptions of the gods, he gave them the human form as the noblest and most beautiful of all forms. Nature was merely a background exquisitely beautiful, but not to be enjoyed without the presence of man. And, secondly, though the Greeks may not have enunciated the principle, that poetry is not the art suited for picturing nature, still[Pg xxiii] they probably had an instinctive feeling of its truth. Poetry, as Lessing pointed out in his Laocoon, has the element of time in it, and is therefore inapplicable in the description of those things which, while composed of various parts, must be comprehended at one glance before the right impression is produced. Look how our modern poet goes to work! He has a fair scene before his fancy. He paints every part of it, with no reason why one part should be placed before another,—and as you read it, you have to piece each part together, as in a child's dissected map; and after you have constructed the whole out of the fragments, you have to imagine the effect. The Greek told you the effect at once,—he gave up the attempt to picture the scene in words. But when he had to deal with any part of nature that had life or motion in it—in fact, any element of time—then he was as minute as the most thorough Wordsworthian could wish. How admirably, for instance, does Homer describe the advance of a foam-crested wave, or the rush of a lion, the swoop of an eagle, or the trail of a serpent!

The Greeks were as much gladdened by the sight of flowers as moderns. Did they not use them continually on all festive occasions, public and private? But minuteness of detail was out of the question in poetry. The poet was not to play the painter or the naturalist. And it had not yet become the fashion to profess a mysterious inexpressible joy in the observation of natural scenery. Nor had men as yet retired from human society in disgust, or in search of freedom from sin, and betaken themselves to the love of pure inanimate objects instead of the love of sin-stained man. It had not yet become unlawful, as it did with the Arabs afterwards, to represent the human form in sculpture. Human nature was not looked on as so contemptible, that it[Pg xxiv] would be appropriate to represent human bodies writhing under gargoyles, as in Gothic churches, or beneath pillars, as in Stirling Palace. The human form was then considered diviner than the forms of lions or flowers.

In bold personification of natural objects, the Greeks could not be easily surpassed. In reality, it was not personification with them,—it was simply the result of the ideas they had formed regarding causation. If a river flowed down, fringed with flowery banks, they imagined there must be some cause for this, and so they summoned up before their fancy a beautiful river-god crowned with a garland. Even in the more common process of making nature pour back on us the sentiments we unconsciously lend her, the Greeks were very far from deficient. The passage in which Alcman describes the hills, and all the tribes of living things as asleep,[5] and the celebrated fragment of Simonides on Danae, where she says, "Let the deep sleep, let immeasurable evil sleep," are only two out of very many instances that might be quoted.

Perhaps the most marked instance of the poetic instinct of the Greeks, is their avoiding descriptions of personal beauty. Though they were permeated by the idea, and thrillingly sensitive to it, it is easier to tell what a Scotch poet regards as elements of beauty than what a Greek did. A beautiful person with the Greek is a beautiful person; and that is all he says about the matter. This is not true of the Anacreontics, or of the Latin poets. Now, in Scotland, again, there is little feeling of beauty of any kind. A Scottish boy wantonly mars a beautiful object for mere fun. There is not a[Pg xxv] monument set up, not a fine building or ornament, but will soon have a chip struck off it, if a Scotch boy can get near it. And the Scotsman, as a general matter, sees beauty nowhere except in a "bonnie lassie." Even then, when he comes to define what he thinks beautiful features, he is at fault, and there are songs in praise of the narrow waist, and other enormities—

It is needless to say that we are very far from having exhausted our subject. Few contrasts could be greater than that which exists between Greek and Scotch songs, and perhaps mainly for this reason, that Scotland has felt so very little of the influence of Greek literature. German poetry had its origin in a revived study of the great Greek classics; and such a study is the very thing required to give breadth to our character, and to supplement its most striking deficiencies.[Pg xxvii][Pg xxvi]

Allan Cunningham was born at Blackwood, in Nithside, Dumfriesshire, on the 7th December 1784. Of his ancestry, some account has been given in the memoir of his elder brother Thomas.[6] He was the fourth son of his parents, and from both of them inherited shrewdness and strong talent.[7] Receiving an ordinary elementary education at a school, taught by an enthusiastic Cameronian, he was apprenticed in his eleventh year to his eldest brother James as a stone-mason. His hours of[Pg 2] leisure were applied to mental improvement; he read diligently the considerable collection of books possessed by his father, and listened to the numerous legendary tales which his mother took delight in narrating at the family hearth. A native love for verse-making, which he possessed in common with his brother Thomas, was fostered and strengthened by his being early brought into personal contact with the poet Burns. In 1790, his father removed to Dalswinton, in the capacity of land-steward to Mr Miller, the proprietor, and Burns' farm of Ellisland lay on the opposite side of the Nith. The two families in consequence met very frequently; and Allan, though a mere boy, was sufficiently sagacious to appreciate the merits of the great bard. Though, at the period of Burns' death, in 1796, he was only twelve years old, the appearance and habits of the poet had left an indelible impression on his mind.

In his fifteenth year, Allan had the misfortune to lose his father, who had sunk to the grave under the pressure of poverty and misfortune; he thus became necessitated to assist in the general support of the family. At the age of eighteen he obtained the acquaintance of the Ettrick Shepherd; Hogg was then tending the flocks of Mr Harkness of Mitchelslack, in Nithsdale, and Cunningham, who had read some of his stray ballads, formed a high estimate of his genius. Along with his elder brother James, he paid a visit to the Shepherd one autumn afternoon on the great hill of Queensberry; and the circumstances of the meeting, Hogg has been at pains minutely to record. James Cunningham came forward and frankly addressed the Shepherd, asking if his name was Hogg, and at the same time supplying his own; he then introduced his brother Allan, who diffidently lagged behind, and proceeded to[Pg 3] assure the Shepherd that he had brought to see him "the greatest admirer he had on earth, and himself a young aspiring poet of some promise." Hogg warmly saluted his brother bard, and, taking both the strangers to his booth on the hill-side, the three spent the afternoon happily together, rejoicing over the viands of a small bag of provisions, and a bottle of milk, and another of whisky. Hogg often afterwards visited the Cunninghams at Dalswinton, and was forcibly struck with Allan's luxuriant though unpruned fancy. He had already written some ingenious imitations of Ossian, and of the elder Scottish bards.

On the publication of the "Lay of the Last Minstrel," in 1805, Cunningham contrived to save twenty-four shillings of his wages to purchase it, and forthwith committed the poem to memory. On perusing the poem of "Marmion," his enthusiasm was boundless; he undertook a journey to Edinburgh that he might look upon the person of the illustrious author. In a manner sufficiently singular, his wish was realised. Passing and repassing in front of Scott's house in North Castle Street, he was noticed by a lady from the window of the adjoining house, who addressed him by name, and caused her servant to admit him. The lady was a person of some consideration from his native district, who had fixed her residence in the capital. He had just explained to her the object of his Edinburgh visit, when Scott made his appearance in the street. Passing his own door, he knocked at that of the house from the window of which his young admirer was anxiously gazing on his stalwart figure. As the lady of the house had not made Scott's acquaintance, she gently laid hold on Allan's arm, inducing him to be silent, to notice the result of the proceeding. Scott, in a reverie of thought,[Pg 4] had passed his own door; observing a number of children's bonnets in the lobby, he suddenly perceived his mistake, and, apologising to the servant, hastily withdrew.

Cunningham's elder brother Thomas, and his friend Hogg, were already contributors to the Scots' Magazine. Allan made offer of some poetical pieces to that periodical which were accepted. He first appears in the magazine in 1807, under the signature of Hidallan. In 1809, Mr Cromek, the London engraver, visited Dumfries, in the course of collecting materials for his "Reliques of Robert Burns;" he was directed to Allan Cunningham, as one who, having known Burns personally, and being himself a poet, was likely to be useful in his researches. On forming his acquaintance, Cromek at once perceived his important acquisition with respect to his immediate object, but expressed a desire first to examine some of his own compositions. Allan acceded to the request, but received only a moderate share of praise from the pedantic antiquary. Cromek urged him to collect the elder minstrelsy of Nithsdale and Galloway as an exercise more profitable than the composition of verses. On returning to London, Cromek received from his young friend packets of "old songs," which called forth his warmest encomiums. He entreated him to come to London to push his fortune,—an invitation which was readily accepted. For some time Cunningham was an inmate of Cromek's house, when he was entrusted with passing through the press the materials which he had transmitted, with others collected from different sources; and which, formed into a volume, under the title of "Remains of Nithsdale and Galloway Song," were published in 1810 by Messrs Cadell and Davies. The work excited no inconsiderable attention, though most of the readers perceived, what Cromek had not even sus[Pg 5]pected, that the greater part of the ballads were of modern origin. Cromek did not survive to be made cognizant of the amusing imposition which had been practised on his credulity.

Fortune did not smile on Cunningham's first entrance into business in London. He was compelled to resume his former occupation as a mason, and is said to have laid pavement in Newgate Street. From this humble position he rose to a situation in the studio of Bubb, the sculptor; and through the counsel of Eugenius Roche, the former editor of the "Literary Recreations," and then the conductor of The Day newspaper, he was induced to lay aside the trowel and undertake the duties of reporter to that journal. The Day soon falling into the hands of other proprietors, Cunningham felt his situation uncomfortable, and returned to his original vocation, attaching himself to Francis Chantrey, then a young sculptor just commencing business. Chantrey soon rose, and ultimately attained the summit of professional reputation; Cunningham continued by him as the superintendent of his establishment till the period of his death, long afterwards.

Devoted to business, and not unfrequently occupied in the studio from eight o'clock morning till six o'clock evening, Cunningham perseveringly followed the career of a poet and man of letters. In 1813, he published a volume of lyrics, entitled "Songs, chiefly in the Rural Language of Scotland." After an interval of nine years, sedulously improved by an ample course of reading, he produced in 1822 "Sir Marmaduke Maxwell, a Dramatic Poem." In this work, which is much commended by Sir Walter Scott in the preface to the "Fortunes of Nigel," he depicts the manners and traditions he had seen and heard on the banks of the Nith. In 1819, he[Pg 6] began to contribute to Blackwood's Magazine, and from 1822 to 1824 wrote largely for the London Magazine. Two collected volumes of his contributions to these periodicals were afterwards published, under the title of "Traditional Tales." In 1825, he gave to the world "The Songs of Scotland, Ancient and Modern, with an Introduction and Notes," in four volumes 8vo. This work abounds in much valuable and curious criticism. "Paul Jones," a romance in three volumes, was the product of 1826; it was eminently successful. A second romance from his pen, "Sir Michael Scott," published in 1828, in three volumes, did not succeed. "The Anniversary," a miscellany which appeared in the winter of that year, under his editorial superintendence, obtained an excellent reception. From 1829 to 1833, he produced for "Murray's Family Library" his most esteemed prose work, "The Lives of the Most Eminent British Painters, Sculptors, and Architects," in six volumes. "The Maid of Elvar," an epic poem in the Spenserian stanza, connected with the chivalrous enterprise displayed in the warfare between Scotland and England, during the reign of Henry VIII., was published in 1832. His admirable edition of the works of Robert Burns appeared in 1834, and 5000 copies were speedily sold.[8] In 1836, he published "Lord Roldan," a romance. From 1830 to 1834, he was a constant writer in The Athenæum, to which, among many interesting articles, he contributed his sentiments regarding the literary characters of the times, in a series of papers entitled "Literature of the Last Fifty Years."[Pg 7] He wrote a series of prose descriptions for "Major's Cabinet Gallery," a "History of the Rise and Progress of the Fine Arts," for the "Popular Encyclopædia;" an introduction, and a few additional lives, for "Pilkington's Painters," and a life of Thomson for Tilt's illustrated edition of "The Seasons." He contemplated a great work, to be entitled "Lives of the British Poets," and this design, which he did not live to accomplish, is likely to be realised by his son, Mr Peter Cunningham. His last publication was the "Life of Sir David Wilkie," which he completed just two days before his death. He was suddenly seized with an apoplectic attack, and died after a brief illness on the 29th October 1842. His remains were interred in Kensal-green Cemetery. He had married, in July 1811, Miss Jane Walker of Preston Mill, near Dumfries, who still survives. Of a family of four sons and one daughter, three of the sons held military appointments in India, and the fourth, who fills a post in Somerset House, is well known for his contributions to literature.

Allan Cunningham ranks next to Hogg as a writer of Scottish song. He sung of the influences of beauty, and of the hills and vales of his own dear Scotland. His songs abound in warmth of expression, simplicity of sentiment, and luxuriousness of fancy. Of his skill as a Scottish poet, Hogg has thus testified his appreciation in the "Queen's Wake":—

As a prose writer, Cunningham was believed by Southey to have the best style ever attained by any one born north of the Tweed, Hume only excepted. His moral qualities were well appreciated by Sir Walter Scott, who commonly spoke of him as "Honest Allan." His person was broad and powerful, and his countenance wore a fine intelligence.[Pg 9]

Ebenezer Picken was the only son of a silk-weaver in Paisley, who bore the same Christian name. He was born at the Well-meadow of that town, about the year 1769. Intending to follow the profession of a clergyman, he proceeded to the University of Glasgow, which he attended during five or six sessions. With talents of a high order, he permitted an enthusiastic attachment to verse-making to interfere with his severer studies and retard his progress in learning. Contrary to the counsel of his father and other friends, he published, in 1788, while only in his nineteenth year, a thin octavo volume of poems; and afterwards gave to the gay intercourse of lovers of the muse, many precious hours which ought to have been applied to mental improvement. Early in 1791 he became teacher of a school at Falkirk; and on the 14th of April of the same year appeared at the Pantheon, Edinburgh, where he delivered an oration in blank verse on the comparative merits of Ramsay and Fergusson, assigning the pre-eminence to the former poet. In this debate his fellow-townsman and friend, Alexander Wilson, the future ornithologist, advocated in verse the merits of Fergusson; and the productions of both the youthful adventurers were printed in a pamphlet entitled the "Laurel Disputed." In occupying the position of schoolmaster at Falkirk, Picken proposed to raise funds to aid him in the prosecution of his theological studies; but the circumstance of his having formed a matrimonial union with a young lady,[Pg 23] a daughter of Mr Beveridge of the Burgher congregation in Falkirk, by involving him in the expenses of a family, proved fatal to his clerical aspirations. He accepted the situation of teacher of an endowed school at Carron, where he remained till 1796, when he removed to Edinburgh. In the capital he found employment as manager of a mercantile establishment, and afterwards on his own account commenced business as a draper. Unsuccessful in this branch of business, he subsequently sought a livelihood as a music-seller and a teacher of languages. In 1813, with the view of bettering his circumstances, he published, by subscription, two duodecimo volumes of "Poems and Songs," in which are included the pieces contained in his first published volume. His death took place in 1816.

Picken is remembered as a person of gentlemanly appearance, endeavouring to confront the pressure of unmitigated poverty. His dispositions were eminently social, and his love of poetry amounted to a passion. He is commemorated in the poetical works of his early friend, Wilson, who has addressed to him a lengthened poetical epistle. In 1818, a dictionary of Scottish words, which he had occupied some years in preparing, was published at Edinburgh by "James Sawers, Calton Street," and this publication was found of essential service by Dr Jamieson in the preparation of his "Supplement" to his "Dictionary of the Scottish Language." Among Picken's poetical compositions are a few pieces bearing the impress of genius.[11] [Pg 24]

Tune—"On a Primrosy Bank."

Stuart Lewis, the mendicant bard, was the eldest son of an innkeeper at Ecclefechan in Annandale, where he was born about the year 1756. A zealous Jacobite, his father gave him the name of Stuart, in honour of Prince Charles Edward. At the parish school, taught by one Irving, an ingenious and learned person of eccentric habits, he received a respectable ground-work of education; but the early deprivation of his father, who died bankrupt, compelled him to relinquish the pursuit of learning. At the age of fifteen, with the view of aiding in the support of his widowed mother, with her destitute family of other five children, he accepted manual employment from a relation in the vicinity of Chester. Subsequently, along with a partner, he established himself as a merchant-tailor in the town of Chester, where he remained some years, when his partner absconded to America with a considerable amount, leaving him to meet the demands of the firm. Surrendering his effects to his creditors, he returned to his native place, almost penniless, and suffering mental depression from his misfortunes, which he recklessly sought to remove by the delusive remedy of the bottle. The habit of intemperance thus produced, became his scourge through life. At Ecclefechan he commenced business as a tailor, and married a young country girl, for whom he had formed a devoted attachment. He established a village library, and debating[Pg 28] club, became a diligent reader, a leader in every literary movement in the district, and a writer of poetry of some merit. A poem on the melancholy story of "Fair Helen of Kirkconnel," which he composed at this period, obtained a somewhat extensive popularity. To aid his finances, he became an itinerant seller of cloth,—a mode of life which gave him an opportunity of studying character, and visiting interesting scenery. The pressure of poverty afterwards induced him to enlist, as a recruit, in the Hopetoun Fencibles; and, in this humble position, he contrived to augment his scanty pay by composing acrostics and madrigals for the officers, who rewarded him with small gratuities. On the regiment being disbanded in 1799, he was entrusted by a merchant with the sale of goods, as a pedlar, in the west of England; but this employment ceased on his being robbed, while in a state of inebriety. Still descending in the social scale, he became an umbrella-maker in Manchester, while his wife was employed in some of the manufactories. Some other odd and irregular occupations were severally attempted without success, till at length, about his fiftieth year, he finally settled into the humble condition of a wandering poet. He composed verses on every variety of theme, and readily parted with his compositions for food or whisky. His field of wandering included the entire Lowlands, and he occasionally penetrated into Highland districts. In his wanderings he was accompanied by his wife, who, though a severe sufferer on his account, along with her family of five or six children, continued most devoted in her attachment to him. On her death, which took place in the Cowgate, Edinburgh, early in 1817, he became almost distracted, and never recovered his former composure. He now roamed wildly through the country,[Pg 29] seldom remaining more than one night in the same place. He finally returned to Dumfriesshire, his native county; and accidentally falling into the Nith, caught an inflammatory fever, of which he died, in the village of Ruthwell, on the 22d September 1818. Lewis was slender, and of low stature. His countenance was sharp, and his eye intelligent, though frenzied with excitement. He always expressed himself in the language of enthusiasm, despised prudence and common sense, and commended the impulsive and fanciful. He published, in 1816, a small volume, entitled "The African Slave; with other Poems and Songs." Some of his lyrics are not unworthy of a place in the national minstrelsy.[Pg 30]

Air—"Miss Forbes' Farewell to Banff."

David Drummond, author of "The Bonnie Lass o' Levenside," a song formerly of no inconsiderable popularity, was a native of Crieff, Perthshire. Along with his four brothers, he settled in Fifeshire, about the beginning of the century, having obtained the situation of clerk in the Kirkland works, near Leven. In 1812, he proceeded to India, and afterwards attained considerable wealth as the conductor of an academy and boarding establishment at Calcutta. A man of vigorous mind and respectable scholarship, he had early cultivated a taste for literature and poetry, and latterly became an extensive contributor to the public journals and periodical publications of Calcutta. The song with which his name has been chiefly associated, was composed during the period of his employment at the Kirkland works,—the heroine being Miss Wilson, daughter of the proprietor of Pirnie, near Leven, a young lady of great personal attractions, to whom he was devotedly attached. The sequel of his history, in connexion with this lady, forms the subject of a romance, in which he has been made to figure much to the injury of his fame. The correct version of this story, in which Drummond has been represented as faithless to the object of his former affections, we have received from a gentleman to whom the circumstances were intimately known. In con[Pg 35]sequence of a proposal to become his wife, Miss Wilson sailed for Calcutta in 1816. On her arrival, she was kindly received by her affianced lover, who conducted her to the house of a respectable female friend, till arrangements might be completed for the nuptial ceremony. In the interval, she became desirous of withdrawing from her engagement; and Drummond, observing her coldness, offered to pay the expense of her passage back to Scotland. Meanwhile, she was seized with fever, of which she died. Report erroneously alleged that she had died of a broken heart on account of her lover being unfaithful, and hence the memory of poor Drummond has been most unjustly aspersed. Drummond died, at Calcutta, in 1845, about the age of seventy. He was much respected among a wide circle of friends and admirers. His personal appearance was unprepossessing, almost approaching to deformity,—a circumstance which may explain the ultimate hesitation of Miss Wilson to accept his hand. "The Bonnie Lass o' Levenside" was first printed, with the author's consent, though without acknowledgment, in a small volume of poems, by William Rankin, Leven, published in 1812. The authorship of the song was afterwards claimed by William Glass,[13] an obscure rhymster of the capital. [Pg 36]

Air—"Up amang the Cliffy Rocks."

The "Posthumous Poetical Works" of James Affleck, tailor in Biggar, with a memoir of his life by his son, were published at Edinburgh in 1836. Affleck was born in the village of Drummelzier, in Peeblesshire, on the 8th September 1776. His education was scanty; and after some years' occupation as a cowherd, he was apprenticed to a tailor in his native village. He afterwards prosecuted his trade in the parish of Crawfordjohn, and in the town of Ayr. In 1793, he established himself as master tailor in Biggar. Fond of society, he joined the district lodge of freemasons, and became a leading member of that fraternity. He composed verses for the entertainment of his friends, which he was induced to give to the world in two separate publications. He possessed considerable poetical talent, but his compositions are generally marked by the absence of refinement. The song selected for the present work is the most happy effort in his posthumous volume. His death took place at Biggar, on the 8th September 1835.[Pg 39]

James Stirrat was born in the village of Dalry, Ayrshire, on the 28th March 1781. His father was owner of several houses in the place, and was employed in business as a haberdasher. Young Stirrat was educated at the village school; in his 17th year, he composed verses which afforded some indication of power. Of a delicate constitution, he accepted the easy appointment of village postmaster. He died in March 1843, in his sixty-second year. Stirrat wrote much poetry, but never ventured on a publication. Several of his songs appeared at intervals in the public journals, the "Book of Scottish Song," and the "Contemporaries of Burns." The latter work contains a brief sketch of his life. He left a considerable number of MSS., which are now in the possession of a relative in Ayr. Possessed of a knowledge of music, he excelled in playing many of the national airs on the guitar. His dispositions were social, yet in society he seldom talked; among his associates, he frequently expressed his hope of posthumous fame. He was enthusiastic in his admiration of female beauty, but died unmarried.[Pg 41]

Air—"Roy's Wife of Aldivalloch."

John Grieve, whose name is especially worthy of commemoration as the generous friend of men of genius, was born at Dunfermline on the 12th September 1781. He was the eldest son of the Rev. Walter Grieve, minister of the Cameronian or Reformed Presbyterian church in that place; his mother, Jane Ballantyne, was the daughter of Mr George Ballantyne, tenant at Craig, in the vale of Yarrow. While he was very young, his father retired from the ministerial office, and fixed his residence at the villa of Cacrabank, in Ettrick. After an ordinary education at school, young Grieve became clerk to Mr Virtue, shipowner and wood-merchant in Alloa: and, early in 1801, obtained a situation in a bank at Greenock. He soon returned to Alloa, as the partner of his friend Mr Francis Bald, who had succeeded Mr Virtue in his business as a wood-merchant. On the death of Mr Bald, in 1804, he proceeded to Edinburgh to enter into copartnership with Mr Chalmers Izzet, hat-manufacturer on the North Bridge. The firm subsequently assumed, as a third partner, Mr Henry Scott, a native of Ettrick.

Eminently successful in business, Mr Grieve found considerable leisure for the cultivation of strong literary tastes. Though without pretension as a man of letters, he became reputed as a contributor to some of the more[Pg 44] respectable periodicals.[16] In his youth he had been a votary of the Muse, and some of his early lyrics he was prevailed on to publish anonymously in Hogg's "Forest Minstrel." The songs marked C., in the contents of that work, are from his pen. In the encouragement of men of genius he evinced a deep interest, affording them entertainment at his table, and privately contributing to the support of those whose circumstances were less fortunate. Towards the Ettrick Shepherd his beneficence was munificent. Along with his partner, Mr Scott, a man of kindred tastes and of ample generosity, he enabled Hogg to surmount the numerous difficulties which impeded his entrance into the world of letters. In different portions of his works, the Shepherd has gracefully recorded his gratitude to his benefactors. In his "Autobiography," after expressing the steadfast friendship he had experienced from Mr Grieve, he adds, "During the first six months that I resided in Edinburgh, I lived with him and his partner Mr Scott, who, on a longer acquaintance, became as firmly attached to me as Mr Grieve; and I believe as much so as to any other man alive.... In short, they would not suffer me to be obliged to any one but themselves for the value of a farthing; and without this sure support, I could never have fought my way in Edinburgh. I was fairly starved into it, and if it had not been for Messrs Grieve and Scott, would, in a very short time, have been starved out of it again." To Mr Grieve, Hogg afterwards dedicated his poem "Mador of the Moor;" and in the character of one of the com[Pg 45]peting bards in the "Queen's Wake," he has thus depicted him:—

Affected with a disorder in the spine, Mr Grieve became incapacitated for business in his thirty-seventh year. In this condition he found an appropriate solace in literature; he made himself familiar with the modern languages, that he might form an acquaintance with the more esteemed continental authors. Retaining his usual cheerfulness, he still experienced satisfaction in intercourse with his friends; and to the close of his life, his pleasant cottage at Newington was the daily resort of the savans of the capital. Mr Grieve died unmarried on the 4th April 1836, in the fifty-fifth year of his age. His remains were interred in the sequestered cemetery of St Mary's, in Yarrow. The few songs which he has written are composed in a vigorous style, and entitle him to rank among those whom he delighted to honour.[17] [Pg 46]

Air—"Fingal's Lament."

Air—"Gowd in gowpens."

Air—"Banks of the Devon."

Charles Gray was born at Anstruther-wester, on the 10th March 1782. He was the schoolfellow and early associate of Dr Thomas Chalmers, and Dr William Tennant, the author of "Anster Fair," who were both natives of Anstruther. He engaged for some years in a handicraft occupation; but in 1805, through the influence of Major-General Burn,[19] his maternal uncle, was fortunate in procuring a commission in the Woolwich division of the Royal Marines. In 1811 he published an octavo volume of "Poems and Songs," of which a second edition was called for at the end of three years. In 1813 he joined Tennant and some other local poets in establishing the "Musomanik Society of Anstruther,"—an association which existed about four years, and gave to the world a collection of respectable verses.[20] After thirty-six years' active service in the Royal Marines, he was enabled to retire in 1841, on a Captain's full pay. He now established his head-quarters in Edinburgh, where he cultivated the society of lovers of Scottish song. In 1841, in compliance with the wishes[Pg 51] of numerous friends, expressed in the form of a Round Robin, he published a second volume of verses, with the title of "Lays and Lyrics." This work appeared in elegant duodecimo, illustrated with engravings of the author's portrait and of his birthplace. In the Glasgow Citizen newspaper, he subsequently published "Cursory Remarks on Scottish Song," which have been copiously quoted by Mr Farquhar Graham, in his edition of the "Songs of Scotland."

Of cheerful and amiable dispositions, Captain Gray was much cherished by his friends. Intimately acquainted with the productions of the modern Scottish poets, he took delight in discussing their merits; and he enlivened the social circle by singing his favourite songs. Of his lyrical compositions, those selected for this work have deservedly attained popularity. An ardent admirer of Burns, he was led to imitate the style of the great national bard. In person he was of low stature; his gray weather-beaten countenance wore a constant smile. He died, after a period of declining health, on the 13th April 1851. He married early in life, and his only son is now a Captain of Marines.[Pg 52]

Air—"My only Jo and Dearie O!"

Air—"Bonnie Dundee."

John Finlay, a short-lived poet of much promise, was born at Glasgow in 1782. His parents were in humble circumstances, but they contrived to afford him the advantages of a good education. From the academy of Mr Hall, an efficient teacher in the city, he was sent, in his fourteenth year, to the University. There he distinguished himself both in the literary and philosophical classes; he became intimately acquainted with the Latin and Greek classics, and wrote elegant essays on the subjects prescribed. His poetical talents first appeared in the composition of odes on classical subjects, which were distinguished alike by power of thought and smoothness of versification. In 1802, while still pursuing his studies at college, he published a volume entitled "Wallace, or the Vale of Ellerslie, with other Poems," of which a second edition[24] appeared, with considerable additions. Soon after, he published an edition of Blair's "Grave," with many excellent notes; produced a learned life of Cervantes; and superintended the publication of a new edition of Smith's "Wealth of Nations." In the hope of procuring a situation in one of the public offices, he proceeded to London in 1807, where he contributed many learned articles, particularly on antiquarian subjects, to different periodicals. Disappointed in obtaining a suit[Pg 58]able post in the metropolis, he returned to Glasgow in 1808; and the same year published, in two duodecimo volumes, a collection of "Scottish Historical and Romantic Ballads." This work is chiefly valuable from some interesting notes, and an ingenious preliminary dissertation on early romantic composition in Scotland. About this period, Professor Richardson, of Glasgow, himself an elegant poet, offered him the advance of sufficient capital to enable him to obtain a share in a printing establishment, and undertook to secure for the firm the appointment of printers to the University; he declined, however, to undergo the risk implied in this adventure. Again entertaining the hope of procuring a situation in London, he left Glasgow towards the close of 1810, with the intention of visiting his college friend, Mr Wilson, at Elleray, in Cumberland, to consult with him on the subject of his views. He only reached the distance of Moffat; he was there struck with an apoplectic seizure, which, after a brief illness, terminated his hopeful career, in the 28th year of his age. His remains were interred in the churchyard of Moffat. Possessed of a fine genius, extensive scholarship, and an amiable heart, John Finlay, had he been spared, would have adorned the literature of his country. He entertained worthy aspirations, and was amply qualified for success; for his energies were co-extensive with his intellectual gifts. At the period of his death, he was meditating a continuation of Warton's History of Poetry. His best production is the poem of "Wallace," written in his nineteenth year; though not free from defects, it contains many admirable descriptions of external nature, and displays much vigour of versification. His lyrics are few, but these merit a place in the minstrelsy of his country. [Pg 59]

Tune—"Roslin Castle."

Air—"Gramachree."

Air—"Here 's a health to ane I love dear."

William Nicholson, known as the Galloway poet, was born at Tannymaus, in the parish of Borgue, on the 15th August 1782. His father followed the occupation of a carrier; he subsequently took a farm, and finally kept a tavern. Of a family of eight children, William was the youngest; he inherited a love of poetry from his mother, a woman of much intelligence. Early sent to school, impaired eyesight interfered with his progress in learning. Disqualified by his imperfect vision from engaging in manual labour, he chose the business of pedlar or travelling merchant. In the course of his wanderings he composed verses, which, sung at the various homesteads he visited with his wares, became popular. Having submitted some of his poetical compositions to Dr Duncan of Ruthwell, and Dr Alexander Murray, the famous philologist, these gentlemen commended his attempting a publication. In the course of a personal canvass, he procured 1500 subscribers; and in 1814 appeared as the author of "Tales in Verse, and Miscellaneous Poems descriptive of Rural Life and Manners," Edinburgh, 12mo. By the publication he realised £100, but this sum was diminished by certain imprudent excesses. With the balance, he republished some tracts on the subject of Universal Redemption, which exhausted the remainder of his profits. In 1826[Pg 64] he proceeded to London, where he was kindly entertained by Allan Cunningham and other distinguished countrymen. On his return to Galloway, he was engaged for a short time as assistant to a cattle-driver. In 1828, he published a second edition of his poems, which was dedicated to Henry, now Lord Brougham, and to which was prefixed a humorous narrative of his life by Mr Macdiarmid. Latterly, Nicholson assumed the character of a gaberlunzie; he played at merrymakings on his bagpipes, for snuff and whisky. For sometime his head-quarters were at Howford, in the parish of Tongland; he ultimately was kept by the Poors' Board at Kirk-Andrews, in his native parish. He died at Brigend of Borgue, on the 16th May 1849. He was rather above the middle size, and well formed. His countenance was peculiarly marked, and his eyes were concealed by his bushy eye-brows and long brown hair. As a poet and song-writer he claims a place in the national minstrelsy, which the irregular habits of his life will not forfeit. The longest poem in his published volume, entitled "The Country Lass," in the same measure as the "Queen's Wake," contains much simple and graphic delineation of life; while the ballad of "The Brownie of Blednoch," has passages of singular power. His songs are true to nature.[Pg 65]

Tune—"White Cockade."

Tune—"Ewe Bughts, Marion."

Tune—"Sin' my Uncle 's dead."

Tune—"Will ye walk the woods with me?"

Alexander Rodger was born on the 16th July 1784, at East Calder, Midlothian. His father, originally a farmer, was lessee of the village inn; he subsequently removed to Edinburgh, and latterly emigrated to Hamburgh. Alexander was apprenticed in his twelfth year to a silversmith in Edinburgh. On his father leaving the country, in 1797, he joined his maternal relatives in Glasgow, who persuaded him to adopt the trade of a weaver. He married in his twenty-second year; and contrived to add to the family finances by cultivating a taste for music, and giving lessons in the art. Extreme in his political opinions, he was led in 1819 to afford his literary support to a journal originated with the design of promoting disaffection and revolt. The connexion was attended with serious consequences; he was convicted of revolutionary practices, and sent to prison. On his release from confinement he was received into the Barrowfield Works, as an inspector of cloths used for printing and dyeing. He held this office during eleven years; he subsequently acted as a pawnbroker, and a reporter of local intelligence to two different newspapers. In 1836 he became assistant in the publishing office of the Reformers' Gazette, a situation which he held till his death. This event took place on the 26th September 1846.[Pg 72]

Rodger published two small collections of verses, and a volume of "Poems and Songs." Many of his poems, though abounding in humour, are disfigured by coarse political allusions. Several of his songs are of a high order, and have deservedly become popular. He was less the poet of external nature than of the domestic affections; and, himself possessed of a lively sympathy with the humbler classes, he took delight in celebrating the simple joys of the peasant's hearth. A master of the pathetic, his muse sometimes assumed a sportive gaiety, when the laugh is irresistible. Among a wide circle he was held in estimation; he was fond of society, and took pleasure in humorous conversation. In 1836, about two hundred of his fellow-citizens entertained him at a public festival and handed him a small box of sovereigns; and some admiring friends, to mark their respect for his memory, have erected a handsome monument over his remains in the Necropolis of Glasgow.[Pg 73]

Air—"Good-morrow to your night-cap."

Air—"For lack o' gowd."

John Wilson, one of the most heart-stirring of Scottish prose writers, and a narrative and dramatic poet, is also entitled to rank among the minstrels of his country. The son of a prosperous manufacturer, he was born in Paisley, on the 18th of May 1785. The house of his birth, an old building, bore the name of Prior's Croft; it was taken down in 1787, when the family removed to a residence at the Town-head of Paisley, which, like the former, stood on ground belonging to the poet's father. His elementary education was conducted at the schools of his native town, and afterwards at the manse of Mearns, a rural parish in Renfrewshire, under the superintendence of Dr Maclatchie, the parochial clergyman. To his juvenile sports and exercises in the moor of Mearns, and his trouting excursions by the stream of the Humbie, and the four parish lochs, he has frequently referred in the pages of Blackwood's Magazine. In his fifteenth year he became a student in the University of Glasgow. Under the instructions of Professor Young, of the Greek Chair, he made distinguished progress in classical learning; but it was to the clear and masculine intellect of Jardine, the distinguished Professor of Logic, that he was, in common with Jeffrey, chiefly indebted for a decided impulse in the path of mental cultivation. In 1804 he proceeded to Oxford, where he entered in Magdalen College as a gentleman-commoner. A leader in every species of recreation, foremost in every sport and merry-making, and famous for his feats of agility and strength, he assiduously con[Pg 82]tinued the prosecution of his classical studies. Of poetical genius he afforded the first public indication by producing the best English poem of fifty lines, which was rewarded by the Newdigate prize of forty guineas. On attaining his majority he became master of a fortune of about £30,000, which accrued to him from his father's estate; and, having concluded a course of four years at Oxford, he purchased, in 1808, the small but beautiful property of Elleray, on the banks of the lake Windermere, in Westmoreland. During the intervals of college terms, he had become noted for his eccentric adventures and humorous escapades; and his native enthusiasm remained unsubdued on his early settlement at Elleray. He was the hero of singular and stirring adventures: at one time he joined a party of strolling-players, and on another occasion followed a band of gipsies; he practised cock-fighting and bull-hunting, and loved to startle his companions by his reckless daring. His juvenile excesses received a wholesome check by his espousing, in 1811, Miss Jane Penny, the daughter of a wealthy Liverpool merchant, and a lady of great personal beauty and amiable dispositions, to whom he continued most devotedly attached. He had already enjoyed the intimate society of Wordsworth, and now sought more assiduously the intercourse of the other lake-poets. In the autumn of 1811, on the death of his friend James Grahame, author of "The Sabbath," he composed an elegy to his memory, which attracted the notice of Sir Walter Scott; in the year following he produced "The Isle of Palms," a poem in four cantos.

Hitherto Wilson had followed the career of a man of fortune; and his original patrimony had been handsomely augmented by his wife's dowry. But his guardian (a maternal uncle) had proved culpably remiss[Pg 83] in the management of his property, he himself had been careless in pecuniary matters, and these circumstances, along with others, convinced him of the propriety of adopting a profession. His inclinations were originally towards the Scottish Bar; and he now engaged in legal studies in the capital. In 1815 he passed advocate, and, during the terms of the law courts, established his residence in Edinburgh. He was early employed as a counsel at the circuit courts; but his devotion to literature prevented him from giving his heart to his profession, and he did not succeed as a lawyer. In 1816 appeared his "City of the Plague," a dramatic poem, which was followed by his prose tales and sketches, entitled "Lights and Shadows of Scottish Life," "The Foresters," and "The Trials of Margaret Lindsay."

On the establishment of Blackwood's Magazine, in 1817, Wilson was one of the staff of contributors, along with Hogg, Lockhart, and others; and on a difference occurring between the publisher and Messrs Pringle and Cleghorn, the original editors, a few months after the undertaking was commenced, he exercised such a marked influence on the fortunes of that periodical, that he was usually regarded as its editor, although the editorial labour and responsibility really rested on Mr Blackwood himself. In 1820 he was elected by the Town-Council of Edinburgh to the Chair of Moral Philosophy in the University, which had become vacant by the death of Dr Thomas Brown. In the twofold capacity of Professor of Ethics and principal contributor to a popular periodical, he occupied a position to which his genius and tastes admirably adapted him. He possessed in a singular degree the power of stimulating the minds and drawing forth the energies of youth; and wielding in periodical literature the vigour of a master intellect, he[Pg 84] riveted public attention by the force of his declamation, the catholicity of his criticism, and the splendour of his descriptions. Blackwood's Magazine attained a celebrity never before reached by any monthly periodical; the essays and sketches of "Christopher North," his literary nom-de-guerre, became a monthly treasure of interest and entertainment. His celebrated "Noctes Ambrosianæ," a series of dialogues on the literature and manners of the times, appeared in Blackwood from 1822 till 1835. In 1825 his entire poetical works were published in two octavo volumes; and, on his ceasing his regular connexion with Blackwood's Magazine, his prose contributions were, in 1842, collected in three volumes, under the title of "Recreations of Christopher North."