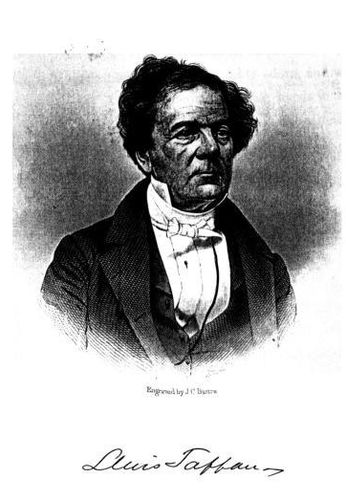

J. B. Giddings (Engraved by J. C. Buttre.)

J. B. Giddings (Engraved by J. C. Buttre.)

Title: Autographs for Freedom, Volume 2 (of 2) (1854)

Editor: Julia Griffiths

Release date: November 28, 2006 [eBook #19949]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Curtis Weyant, Richard J. Shiffer and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This file was produced from images produced by the Wright

American Fiction Project.)

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1854, by

ALDEN, BEARDSLEY & CO.,

In the Clerk's Office of the District Court for the Northern District

of New York.

STEREOTYPED BY

THOMAS B. SMITH,

216 William St. N. Y.

J. B. Giddings (Engraved by J. C. Buttre.)

J. B. Giddings (Engraved by J. C. Buttre.)

In commending this, the second volume of "the Autographs for Freedom," to the attention of the public, "the Rochester Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society" would congratulate themselves and the friends of freedom generally on the progress made, during the past year, by the cause to which the book is devoted.

We greet thankfully those who have contributed of the wealth of their genius; the strength of their convictions; the ripeness of their judgment; their earnestness of purpose; their generous sympathies; to the completeness and excellence of the work; and we shall hope to meet many of them, if not all, in other numbers of "The Autograph," which [Pg vi]may be called forth ere the chains of the Slave shall be broken, and this country redeemed from the sin and the curse of Slavery.

On behalf of the Rochester Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society.

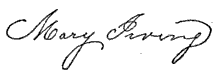

(signature) Julia Griffiths

(signature) Julia Griffiths

Sec'y.

Rochester, N. Y.

| Subject | Author | page |

| Introduction (The Colored People's "Industrial College") | Prof. C. L. Reason | 11 |

| Massacre at Blount's Fort | Hon. J. R. Giddings | 14 |

| The Fugitive Slave Act | Hon. Wm. Jay | 27 |

| The Size of Souls | Antoinette L. Brown | 41 |

| Vincent Ogé | George B. Vashon | 44 |

| The Law of Liberty | Rev. Dr. Wm. Marsh | 61 |

| The Swiftness of Time in God | Theodore Parker | 63 |

| Visit of a Fugitive Slave to the Grave of Wilberforce | Wm. Wells Brown | 70 |

| Narrative of Albert and Mary | Dr. W. H. Brisbane | 77 |

| Toil and Trust | Hon. Chas. F. Adams | 128 |

| Friendship for the Slave is Friendship for the Master | Jacob Abbott | 134 |

| Christine | Anne P. Adams | 139 |

| The Intellectual, Moral, and Spiritual Condition of the Slave | J. M. Langston | 147 |

| The Bible versus Slavery | Rev. Dr. Willis | 151 |

| The Work Goes Bravely on | W. J. Watkins | 156 |

| Slaveholding not a Misfortune but a Crime | Rev Win Brock | 158 |

| The Illegality of Slaveholding | Rev. W. Goodell | 159 |

| "Ore Perennius" | David Paul Brown | 160 |

| The Mission of America | John S. C. Abbott | 161 |

| Disfellowshipping the Slaveholder | Lewis Tappan | 163 |

| A Leaf from my Scrap Book | Wm. J. Wilson | 165 |

| Who is my Neighbor | Rev. Thos. Starr King | 174 |

| Consolation for the Slave | Dr. S. Willard | 175 |

| The Key | Dr. S. Willard | 177 |

| The True Mission of Liberty | Dr. W. Elder | 178 |

| The True Spirit of Reform | Mary Willard | 180 |

| A Welcome to Mrs. H. B. Stowe, on her return from Europe | J. C. Holly | 184 |

| Forward (from the German) | Rev. T. W. Higginson | 186 |

| What has Canada to do with Slavery? | Thos. Henning | 187 |

| A Fragment | Rev. Rufus Ellis | 190 |

| The Encroachment of the Slave Power | John Jay, Esq. | 192 |

| The Dishonor of Labor | Horace Greeley | 194 |

| The Evils of Colonization | Wm. Watkins | 198 |

| The Basis of the American Constitution | Hon. Wm. H. Seward | 201 |

| A Wish | Mrs. C. M. Kirkland | 207 |

| A Dialogue | C. A. Bloss | 210 |

| A time of Justice will come | Hon. Gerit Smith | 225 |

| Hope and Confidence | Prof. G. L. Reason | 226 |

| A Letter that speaks for itself | Jane G. Swisshelm | 230 |

| On Freedom | R. W. Emerson | 235 |

| Mary Smith. An Anti-Slavery Reminiscence | Hon S. E. Sewell | 236 |

| Freedom—Liberty | Dr. J. McCune Smith | 241 |

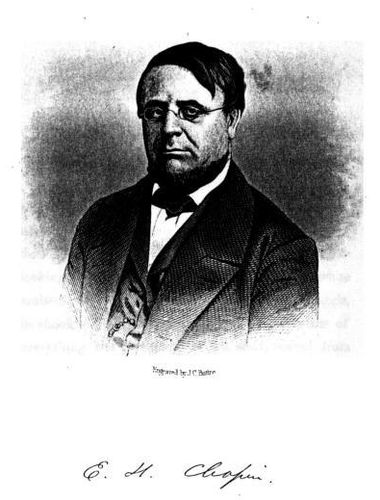

| An Aspiration | Rev. E. H. Chapin | 242 |

| The Dying Soliloquy of the Victim of the Wilkesbarre Tragedy | Mrs. H. H. Greenough | 243 |

| Let all be Free | Hon. C. M. Clay | 248 |

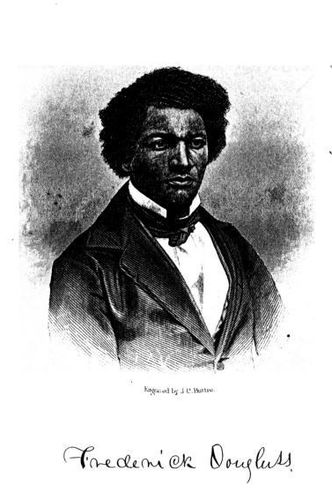

| Extract from a Speech | Frederick Douglass | 251 |

| Extract from an Unpublished Poem on Freedom | William D. Snow | 256 |

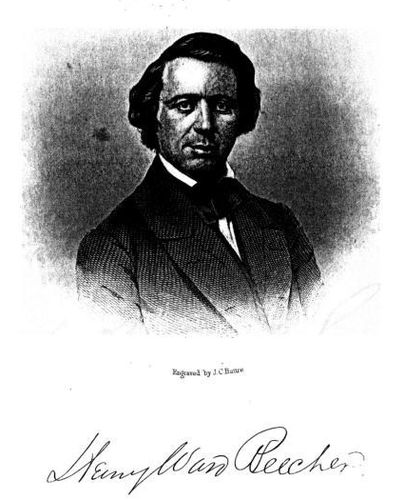

| Letter | Rev. H. Ward Beecher | 273 |

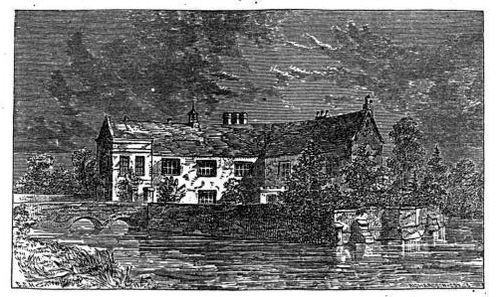

| A Day Spent at Playford Hall | Mrs. Harriet B. Stowe | 277 |

| Teaching the Slave to Read | Mary Irving | 304 |

A word oft-times is expressive of an entire policy. Such is the term Abolition. Though formerly used as a synonym of Anti-Slavery, people now clearly understand that the designs of those who have ranged themselves under the first of these systems of reform are of deeper significance and wider scope than are the objects contemplated by the latter, and concern themselves not only with the great primary question of bodily freedom, but take in also the collateral issues connected with human enfranchisement, independent of race, complexion, or sex.

The Abolitionist of to-day is the Iconoclast of the age, and his mission is to break the idolatrous images[Pg 12] set up by a hypocritical Church, a Sham Democracy, or a corrupt public sentiment, and to substitute in their stead the simple and beautiful doctrine of a common brotherhood. He would elevate every creature by abolishing the hinderances and checks imposed upon him, whether these be legal or social—and in proportion as such grievances are invidious and severe, in such measure does he place himself in the front rank of the battle, to wage his emancipating war.

Therefore it is that the Abolitionist has come to be considered the especial friend of the negro, since he, of all others, has been made to drink deep from the cup of oppression.

The free-colored man at the north, for his bond-brother as for himself, has trusted hopefully in the increasing public sentiment, which, in the multiplication of these friends, has made his future prospects brighter. And, to-day, while he is making a noble struggle to vindicate the claims of his entire class, depending mainly for the accomplishment of that end on his own exertions, he passes in review the devotion and sacrifices made in his behalf: gratitude is in his heart, and thanks fell from his lips. But, in one department[Pg 13] of reformatory exertion he feels that he has been neglected. He has seen his pledged allies throw themselves into the hottest of the battle, to fight for the Abolition of Capital Punishment—for the Prohibition of the Liquor Traffic—for the Rights of Women, and similar reforms,—but he has failed to see a corresponding earnestness, according to the influence of Abolitionists in the business world, in opening the avenues of industrial labor to the proscribed youth of the land. This work, therefore, is evidently left for himself to do. And he has laid his powers to the task. The record of his conclusions was given at Rochester, in July, and has become already a part of history.

Though shut out from the workshops of the country, he is determined to make self-provision, so as to triumph over the spirit of caste that would keep him degraded. The utility of the Industrial Institution he would erect, must, he believes, commend itself to Abolitionists. But not only to them. The verdict of less liberal minds has been given already in its favor. The usefulness, the self-respect and self-dependence,—the combination of intelligence and handicraft,—the accumulation of the materials of wealth, all referable[Pg 14] to such an Institution, present fair claims to the assistance of the entire American people.

Whenever emancipation shall take place, immediate though it be, the subjects of it, like many who now make up the so-called free population, will be in what Geologists call, the "Transition State." The prejudice now felt against them for bearing on their persons the brand of slaves, cannot die out immediately. Severe trials will still be their portion—the curse of a "taunted race" must be expiated by almost miraculous proofs of advancement; and some of these miracles must be antecedent to the great day of Jubilee. To fight the battle on the bare ground of abstract principles, will fail to give us complete victory. The subterfuges of pro-slavery selfishness must now be dragged to light, and the last weak argument,—that the negro can never contribute anything to advance the national character, "nailed to the counter as base coin." To the conquering of the difficulties heaped up in the path of his industry, the free-colored man of the North has pledged himself. Already he sees, springing into growth, from out his foster work-school, intelligent young laborers, competent to enrich the world with necessary products—industrious[Pg 15] citizens, contributing their proportion to aid on the advancing civilization of the country;—self-providing artizans vindicating their people from the never-ceasing charge of a fitness for servile positions.

Abolitionists ought to consider it a legitimate part of their great work, to aid in such an enterprise—to abolish not only chattel servitude, but that other kind of slavery, which, for generation after generation, dooms an oppressed people to a condition of dependence and pauperism. Such an Institution would be a shining mark, in even this enlightened age; and every man and woman, equipped by its discipline to do good battle in the arena of active life, would be, next to the emancipated bondman, the most desirable "Autograph for Freedom."

(signature) Chas. L. Reason

(signature) Chas. L. Reason

On the west side of the Appalachicola River, some forty miles below the line of Georgia, are yet found the ruins of what was once called "Blount's Fort." Its ramparts are now covered with a dense growth of underbrush and small trees. You may yet trace out its bastions, curtains, and magazine. At this time the country adjacent presents the appearance of an unbroken wilderness, and the whole scene is one of gloomy solitude, associated as it is with one of the most cruel massacres which ever disgraced the American arms.

The fort had originally been erected by civilized troops, and, when abandoned by its occupants at the close of the war, in 1815, it was taken possession of by the refugees from Georgia. But little is yet known of that persecuted people; their history can only be[Pg 17] found in the national archives at Washington. They had been held as slaves in the State referred to; but during the Revolution they caught the spirit of liberty, at that time so prevalent throughout our land, and fled from their oppressors and found an asylum among the aborigines living in Florida.

During forty years they had effectually eluded, or resisted, all attempts to re-enslave them. They were true to themselves, to the instinctive love of liberty, which is planted in every human heart. Most of them had been born amidst perils, reared in the forest, and taught from their childhood to hate the oppressors of their race. Most of those who had been personally held in degrading servitude, whose backs had been seared by the lash of the savage overseer, had passed to that spirit-land where the clanking of chains is not heard, where slavery is not known. Some few of that class yet remained. Their gray hairs and feeble limbs, however, indicated that they, too, must soon pass away. Of the three hundred and eleven persons residing in "Blount's Fort" not more than twenty had been actually held in servitude. The others were descended from slave parents, who fled from Georgia, and, according to the laws of slave[Pg 18] States, were liable to suffer the same outrages to which their ancestors had been subjected.

It is a most singular feature in slave-holding morals, that if the parents be robbed of their liberty, deprived of the rights with which their Creator has endowed them, the perpetrator of these wrongs becomes entitled to repeat them upon the children of their former victims. There were also some few parents and grandchildren, as well as middle-aged persons, who sought protection within the walls of the Fort against the vigilant slave-catchers who occasionally were seen prowling around the fortifications, but who dare not venture within the power of those whom they sought to enslave.

These fugitives had planted their gardens, and some of them had flocks roaming in the wilderness; all were enjoying the fruits of their labor, and congratulating themselves upon being safe from the attacks of those who enslave mankind. But the spirit of oppression is inexorable. The slaveholders finding they could not themselves obtain possession of their intended victims, called on the President of the United States for assistance to perpetrate the crime of enslaving their fellow men. That functionary had been[Pg 19] reared amid southern institutions. He entertained no doubt of the right of one man to enslave another. He did not doubt that if a man held in servitude should attempt to escape, he would be worthy of death. In short, he fully sympathised with those who sought his official aid. He immediately directed the Secretary of War to issue orders to the Commander of the "Southern Military District of the United States" to send a detachment of troops to destroy "Blount's Fort," and to "seize those who occupied it and return them to their masters."[1]

General Jackson, at that time Commander of the Southern Military District, directed Lieut.-Colonel Clinch to perform the barbarous task. I was at one time personally acquainted with that officer, and know the impulses of his generous nature, and can readily account for the failure of his expedition. He marched to the vicinity of the Fort, made the necessary recognisance, and returned, making report that "the fortification was not accessible by land."[2][Pg 20]

Orders were then issued to Commodore Patterson, directing him to carry out the directions of the Secretary of War. He at that time commanded the American flotilla lying in "Mobile Bay," and instantly issued an order to Lieut. Loomis to ascend the Appalachicola River with two gun-boats, "to seize the people in Blount's Fort, deliver them to their owners, and destroy the Fort."

On the morning of the 17th Sept., A. D. 1816, a spectator might have seen several individuals standing upon the walls of that fortress watching with intense interest the approach of two small vessels that were slowly ascending the river, under full-spread canvas, by the aid of a light southern breeze. They were in sight at early dawn, but it was ten o'clock when they furled their sails and cast anchor opposite the Fort, and some four or five hundred yards distant from it.

A boat was lowered, and soon a midshipman and twelve men were observed making for the shore. They were met at the water's edge by some half dozen of the principal men in the Fort, and their errand demanded.

The young officer told them he was sent to make[Pg 21] demand of the Fort, and that its inmates were to be given up to the "slaveholders, then on board the gun-boat, who claimed them as fugitive slaves!" The demand was instantly rejected, and the midshipman and his men returned to the gun-boats and informed Lieut. Loomis of the answer he had received.

As the colored men entered the Fort they related to their companions the demand that had been made. Great was the consternation manifested by the females, and even a portion of the sterner sex appeared to be distressed at their situation. This was observed by an old patriarch, who had drunk the bitter cup of servitude, one who bore on his person the visible marks of the thong, as well as the brand of his master, upon his shoulder. He saw his friends faultered, and he spoke cheerfully to them. He assured them that they were safe from the cannon shot of the enemy—that there were not men enough on board the vessels to storm their Fort, and finally closed with the emphatic declaration: "Give me liberty or give me death!" This saying was repeated by many agonized fathers and mothers on that bloody day.

A cannonade was soon commenced upon the Fort, but without much apparent effect. The shots were[Pg 22] harmless; they penetrated the earth of which the walls were composed, and were there buried, without further injury. Some two hours were thus spent without injuring any person in the Fort. They then commenced throwing bombs. The bursting of these shells had more effect. There was no shelter from these fatal messages. Mothers gathered their little ones around them and pressed their babes more closely to their bosoms, as one explosion after another warned them of their imminent danger. By these explosions some were occasionally wounded and a few killed, until, at length, the shrieks of the wounded and groans of the dying were heard in various parts of the fortress.

Do you ask why these mothers and children were thus butchered in cold blood? I answer, they were slain for adhering to the doctrine that "all men are endowed by their Creator with the inalienable right to enjoy life and liberty." Holding to this doctrine of Hancock and of Jefferson, the power of the nation was arrayed against them, and our army employed to deprive them of life.

The bombardment was continued some hours with but little effect, so far as the assailants could discover.[Pg 23] They manifested no disposition to surrender. The day was passing away. Lieut. Loomis called a council of officers and put to them the question, what further shall be done? An under officer suggested the propriety of firing "hot shot at the magazine." The proposition was agreed to. The furnaces were heated, balls were prepared, and the cannonade was resumed. The occupants of the Fort felt relieved by the change. They could hear the deep humming sound of the cannon balls, to which they had become accustomed in the early part of the day, and some made themselves merry at the supposed folly of their assailants. They knew not that the shot was heated, and was therefore unconscious of the danger which threatened them.

The sun was rapidly descending in the west. The tall pines and spruce threw their shadows over the fortification. The roar of the cannon, the sighing of the shot, the groans of the wounded, the dark shades of approaching evening, all conspired to render the scene one of intense gloom. They longed for the approaching night to close around them in order that they might bury the dead, and flee to the wilderness for safety.

Suddenly a startling phenomena presented itself to their astonished view. The heavy embankment and[Pg 24] timbers protecting the magazine appeared to rise from the earth, and the next instant the dreadful explosion overwhelmed them, and the next found two hundred and seventy parents and children in the immediate presence of a holy God, making their appeal for retributive justice upon the government who had murdered them, and the freemen of the north who sustained such unutterable crimes.[3]

Many were crushed by the falling earth and the timbers; many were entirely buried in the ruins. Some were horribly mangled by the fragments of timber and the explosion of charged shells that were in the magazine. Limbs were torn from the bodies to which they had been attached. Mothers and babes lay beside each other, wrapped in that sleep which knows no waking.

The sun had set, and the twilight of evening was closing around them, when some sixty sailors, under the officer second in command, landed, and, without opposition, entered the Fort. The veteran sailors, accustomed to blood and carnage, were horror-stricken as they viewed the scene before them. They were accompanied, however, by some twenty slaveholders,[Pg 25] all anxious for their prey. These paid little attention to the dead and dying, but anxiously seized upon the living, and, fastening the fetters upon their limbs, hurried them from the Fort, and instantly commenced their return towards the frontier of Georgia. Some fifteen persons in the Fort survived the terrible explosion, and they now sleep in servile graves, or moan and weep in bondage.

The officer in command of the party, with his men, returned to the boats as soon as the slaveholders were fairly in possession of their victims. The sailors appeared gloomy and thoughtful as they returned to their vessels. The anchors were weighed, the sails unfurled, and both vessels hurried from the scene of butchery as rapidly as they were able. After the officers had retired to their cabins, the rough-featured sailors gathered before the mast, and loud and bitter were the curses they uttered against slavery and against those officers of government who had then constrained them to murder women and helpless children, merely for their love of liberty.

But the dead remained unburied; and the next day the vultures were feeding upon the carcasses of young men and young women, whose hearts on the previous[Pg 26] morning had beaten high with expectation. Their bones have been bleaching in the sun for thirty-seven years, and may yet be seen scattered among the ruins of that ancient fortification.

Twenty-two years elapsed, and a representative in Congress, from one of the free States, reported a bill giving to the perpetrators of these murders a gratuity of five thousand dollars from the public treasury, as a token of the gratitude which the people of this nation felt for the soldierly and gallant manner in which the crime was committed toward them. The bill passed both houses of Congress, was approved by the President, and now stands upon our statute book among the laws enacted at the 3d Session of the 25th Congress.

The facts are all found scattered among the various public documents which repose in the alcoves of our National Library. But no historian has been willing to collect and publish them, in consequence of the deep disgrace which they reflect upon the American arms, and upon those who then controlled the government.

(signature) J. R. Giddings

(signature) J. R. Giddings

[1] Vide Executive documents of the 2d Session 13th Congress.

[2] It is believed that this report was suggested by the humanity of Col. Clinch. He was reputed one of the bravest and most energetic officers in the service. He possessed an indomitable perseverance, and could probably have captured the Fort in one hour, had he desired to do so.

[3] That is the number officially reported by the officer in command, vide Executive doc. of the 13th Congress.

Few laws have ever been passed better calculated than this to harden the heart and benumb the conscience of every man who assists in its execution. It pours contempt upon the dictates of justice and humanity. It levels in the dust the barriers erected by the common law for the protection of personal liberty. Its victims are native born Americans, uncharged with crime. These men are seized, without notice, and instantly carried before an officer, by whom they are generally hurried off into a cruel bondage, for the remainder of their days, and sometimes without time being allowed for a parting interview with their families. Such treatment would be cruel toward criminals; but these men are adjudged to toil, to stripes, to ignorance, to poverty, to hopeless degradation, on the pretence that they "owe service."[Pg 28] This allegation all know to be utterly false, they having never promised to serve, and being legally incapable of making any contract. Every act of Christian kindness to these unhappy people, tending to secure to them the rights which our declaration of independence asserts belong to all men, is made by this accursed law a penal offence, to be punished with fine and imprisonment. Mock judges, unknown to the constitution, and bribed by the promise of double fees to re-enslave the fugitive, are commanded to decide, summarily, the most momentous personal issue, with the single exception of life and death, that could possibly engage the attention of a legal tribunal of the most august character. Yet this tremendous issue of liberty or bondage, is to be decided, not only in a hurry, but on such prima facie evidence as may satisfy the judge, and this judge, too, selected from a herd of similar creatures, by the claimant himself!! An ex parte affidavit, made by an absent and interested party, with the certificate of an absent judge that he believes it to be true, is to be received as conclusive, in the face of any amount of oral and documentary testimony to the contrary. "Can a man take fire into his bosom and not be burned?" Can a man aid[Pg 29] in executing such a law without defiling his own conscience? Yet does this profligate statute, with impious arrogance, command "all good citizens" to assist in enforcing it, when required so to do by an official slave-catcher!

It is a singular fact, in the history of this enactment, that Mr. Mason, who introduced the bill, and Mr. Webster, who, in advance, pledged to it his support "to the fullest extent," both confessed, on the floor of Congress, that in their individual judgments, it was unconstitutional,—that is, that the constitution, as they expounded it, imposed upon the States severally, the obligation to surrender fugitive slaves, and gave Congress no power to legislate on the subject. The Supreme Court, however, having otherwise determined, these gentlemen acquiesced in its decision, without being convinced by it. It is well known how grossly Mr. Webster, in his subsequent canvass for the Presidency, insulted all who, like himself, denied the constitutionality of the law. Another significant fact in the same history is, that the law was passed by a minority of the House of Representatives. Of 232 members, only 109 recorded their names in its favor. Many, deterred either by scruples of conscience[Pg 30] or doubts of the popularity of the measure, declined voting, while party discipline prevented them from offering to it an open and manly resistance. A third fact in this history, worthy to be remembered, is, that the advocates of the law are conscious that its revolting provisions would not bear discussion, forced its passage under the previous question, thus preventing any remarks on its enormities—any appeals to the consciences of the members—against the perpetration of such detestable wickedness.

Seldom has any public iniquity been committed to which the words of the Psalmist have been so applicable: "Surely the wrath of man shall praise Thee; and the remainder of wrath shalt Thou restrain."

It was happily so ordered, that several of the early seizures and surrenders under this law were conducted with such marked barbarity, such cruel indecent haste, such wanton disregard of justice and of humanity, as to shock the moral sense of the community, and to render the law intensely hateful.

Very soon after the law went into operation, one of the pseudo judges created by it, surrendered an alleged slave, on evidence which no jury would have deemed sufficient to establish a title to a dog. In vain[Pg 31] the wretched man declared his freedom—in vain he named six witnesses whom he swore could prove his freedom—in vain he implored for a delay of one hour. He was sent off as a slave, guarded, at the expense of the United States treasury, to his pretended master in Maryland, who honestly refused to receive him. The judge had made a mistake (!) and had sent a free man instead of a slave.

This vile law, although of course receiving the sanction of the Democrats, it being a bid for the Presidency, was a device of the Whig party, and could not have been carried but by the co-operation of Webster, Clay, and Fillmore. As if to enhance the value of the bid, the Administration affected a desire to baptise it in northern blood, by making resistance to the law, a crime to be punished with death. The hustling of an officer, and the consequent escape of an arrested fugitive, were declared, by the Secretary of State, to be a levying of war against the United States—of course an act of high treason, to be expiated on the gallows; and the rioters at Christiana were prosecuted for high treason, in pursuance of orders forwarded from Washington. This wretched sycophancy won no favor from the slaveholders,[Pg 32] and the result of the abominable and absurd prosecution only brought on the authors and advocates of the law fresh obloquy. When men obtain some rich and splendid prize, by their wrong-doing, many admire their boldness and dexterity, but foolish, profitless wickedness ensures only contempt. The northern Whigs, in doing obeisance to the slave power, sinned against their oft-repeated and solemn professions and pledges. They sinned in the expectation of thereby electing a President, and enjoying the patronage he would dispense. Most bitterly were these men disappointed, first in the candidate selected, and next in the result of the election. The party has been beaten to death, and it died unhonored and unwept. Let the Fugitive Slave Law be its epitaph. Truly the Whig politicians were "snared in the work of their own hands."

Certain fashionable Divines deemed it expedient to second the efforts of the politicians in catching slaves, by talking from their pulpits about Hebrew slavery, and the reverence due to the "powers that be ordained of God." Yet the injunctions of the fugitive law were so obviously at variance with the "higher law" of justice and mercy which these gentlemen[Pg 33] were required by their Divine Master to inculcate, that "cotton divinity" fell into disrepute, nor could the plaudits of politicians and union committees save its clerical professors from forfeiting the esteem and confidence of multitudes of Christian people.

But Whig politicians and cotton Divines are not the only friends of the fugitive law to whom it has made most ungrateful returns. The Democratic leaders, bidding against the Whigs for the Presidency, were most vociferous in expressions of the delight they took in the human chase. Democratic candidates for the Presidency, to the goodly number of nine, gave public attestations under their signs manual, of their approbation of a law outraging the principles of Democracy, as well as of common justice and humanity. Each and all of these men were rejected, and the slaveholders selected an individual whom they were well assured would be their obsequious tool, but who had offered no bribe for their votes.

But did the slaveholders themselves gain more by this law than their northern auxiliaries? They, indeed, hailed its passage as a mighty triumph. The nation had given them a law, drafted by themselves, laying down the rules of the hunt, as best suited their[Pg 34] pleasure and interest. Wealthy and influential gentlemen in our commercial cities, out of compliment to southern electors, became amateur huntsmen, and in New York and Boston the chase was pursued with all the zeal and apparent delight that could have been expected in Guinea or Virginia. Slave-catching was the test, at once, of patriotism and gentility, while sympathy for the wretched fugitive was the mark of vulgar fanaticism. The north was humbled in the dust, by the action of her own recreant sons. Every "good citizen" found himself, for the first time in the history of mankind, a slave-catcher by law. Every official, appointed by a slave-catching judge, was invested with the authority of a High Sheriff, being empowered to call out the posse comitatus, and compel the neighbors to join in a slave chase. Well, indeed, might the slaveholders rejoice and make merry;—well, indeed, in the insolence of triumph, might they command the people of the north to hold their tongues about "the peculiar institution," under pain of their sore displeasure.

But amid this slavery jubilee, a woman's heart was swelling and heaving with indignant sorrow at the outrages offered to God and man by the fugitive[Pg 35] law. Her pent up emotions struggled for utterance, and at last, as if moved by some mighty inspiration, and in all the fervor of Christian love, she put forth a book which arrested the attention of the world. A miracle of authorship, this book attained, within twelve months, a circulation without a parallel in the history of printing. In that brief space, about two millions of volumes proclaimed, in the languages of civilization, the wrongs of the slave and the atrocities of the american fugitive law. The gaze of mankind is now turned upon the slaveholders and their northern auxiliaries, both clerical and lay. The subjects of European despotisms console themselves with the grateful conviction, that however harsh may be their own governments, they make no approach to the baseness or to the cruelty and tyranny of the "peculiar institution" of the Model Republic.[4] [Pg 36]

One slaveholder, together with the cotton men of the north, fretted and vexed by their sudden and unenviable notoriety, foolishly attempted to obviate the impressions made by the book, by denouncing it as a lying fiction. Nay, one of the most affecting illustrations of pure and undefiled Christianity that ever proceeded from an uninspired pen, was gravely declared, by an organ of cotton divinity, to be an Anti-Christian book.[5] Truly, indeed, the wisdom of man is[Pg 37] foolishness with God. "He disappointeth the devices of the crafty."

Branded with falsehood and impiety, the author was happily put on her trial before the civilized world. She collected, arranged, and gave to the press, a mass of unimpeachable documents, consisting of laws, judicial decisions, trials, confessions of slaveholders, advertisements from southern papers, and testimonies of eye-witnesses. The proof was conclusive and overwhelming that the picture she had drawn of American slavery was unfaithful, only because the coloring was faint, and wanted the crimson dye of the original. A verdict of not guilty of exaggeration has been rendered by acclamation.

It has long been the standing refuge of the slaveholders, that northern men and Europeans, in condemning slavery, were passing judgment against an institution of which they were ignorant. The "peculiar institution" was represented as some great mystery which could not be understood beyond the slave region. Thanks to the fugitive law, it has led to the construction of a "key," which has unlocked our Republican bastile, thrown open to the sunlight its hideous dungeons, and exposed the various instruments of[Pg 38] torture for subjecting the soul, as well as the body, to hopeless and unresisting bondage. The iniquity of our cherished institution is no longer a MYSTERY. All Christendom is now made familiar with it, and is sending forth a cry of indignant remonstrance and of taunting scorn. Such is the suppression of anti-slavery agitation given to the slaveholders by their northern friends—such the strength imparted by the fugitive slave law to the system of human bondage. How applicable to the inventors and supporters of that statute are the words of David, in regard to some politician of his own day: "Behold he travaileth with iniquity, and hath conceived mischief, and brought forth falsehood. He made a pit, and digged it, and is fallen into the ditch which he made. His mischief shall return upon his own head, and his violent dealing shall come down upon his own pate;" and then he adds, "I will praise the Lord." So also let the Christian bless and magnify Him, who by his infinite wisdom brings good out of evil, and in the case of the fugitive law, hath caused the wrath of man to praise Him.

But there is still a remainder of wrath. The law is still on the Statute Book, and hungry politicians are[Pg 39] promising that there it shall ever remain; and terrible threats come from the south, of the ruin that shall overwhelm the free States, should the law be repealed or rendered less abominable than at present. Yet, in spite of northern promises, and professions of security, and in spite of the great swelling words of the dealers in human flesh, the practical, like the moral working of the law, has been very far from what its authors anticipated. The law was passed the 18th September, 1850, and, in two years and nine months, not fifty slaves have been recovered under it—not an average of eighteen slaves a year! Poor compensation this to the slaveholders for making themselves a bye-word, a proverb, and a reproach to Christendom—for giving a new and mighty impulse to abolition, and for deepening the detestation felt by the true friends of liberty and humanity, for an institution asking and obtaining for its protection a law so repugnant to the moral sense of mankind. But while this artful and wicked law, with its army of ten-dollar judges, and marshals, and constables, and office-seekers, and politicians, with the President and his cabinet all striving to enforce it, "to the fullest extent," has restored to their masters not eighteen slaves[Pg 40] a year; the escapes from the prison house have probably never been more numerous, nor the aid and sympathy afforded by Christians more abundant. Thus has the remainder of wrath been restrained. In the marvellous conversion of this odious law into an anti-slavery agency, let us find a new motive for unceasing and unwearied agitation against slavery, and a new pledge of ultimate triumph.

(signature) William Jay

(signature) William Jay

Bedford, June 1853.

[4] A late American traveller, in Germany, invited to an evening party at the house of a Professor, attempted to compliment the company by expressing his indignation at the oppression which "the dear old German fatherland" suffered at the hands of its rulers. The American's profferred sympathy was coldly received. "We admit," was the reply, "that there is much wrong here, but we do not admit the right of your country to rebuke it. There is a system now with you, worse than any thing which we know of tyranny—your slavery. It is a disgrace and blot on your free government and on a Christian State. We have nothing in Russia or Hungary which is so degrading, and we have nothing which so crushes the mind. And more than this, we hear you have now a law, just passed by your National Assembly, which would disgrace the cruel code of the Czar. We hear of free men and women, hunted like dogs on your mountains, and sent back, without trial, to bondage worse than our serfs have ever known. We have, in Europe, many excuses in ancient evils and deep-laid prejudices, but you, the young and free people, in this age, to be passing again, afresh, such measures of unmitigated wrong!"—Home life in Germany, by Charles Loving Brace. Mr. Brace honestly adds: "I must say that the blood tingled to my cheek with shame, as he spoke."

[5] "We have read the book, and regard it as Anti-Christian, on the same grounds that the chronicle regards it decidedly anti ministerial."—New York Observer, September 22, 1852.—Editorial. The Bishop of Rome also regards the book as Anti-Christian, and has forbidden his subjects to read it. On the other hand, the clergy of Great Britain differ most widely from the reverend gentlemen of the "Observer" and the Vatican, in their estimate of the character of the book. Said Dr. Wardlaw, who on this subject may be regarded as the representative of the Protestant Divines of Europe: "He who can read it without the breathings of devotion, must, if he call himself a Christian, have a Christianity as unique and questionable as his humanity."

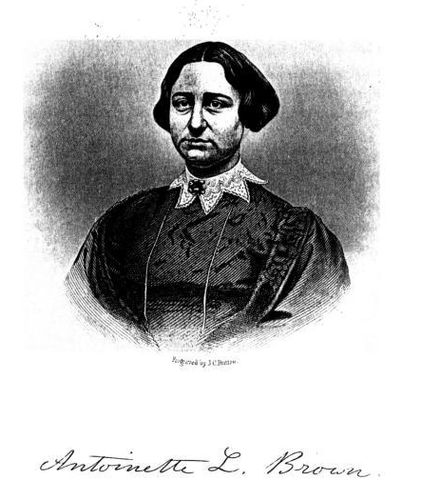

Antoinette L. Brown (Engraved by J. C. Buttre)

Antoinette L. Brown (Engraved by J. C. Buttre)

A quaint old writer describes a class of persons who have souls so very small that "500 of them could dance at once upon the point of a cambric needle." These wee people are often wrapped up in a lump of the very coarsest of human clay, ponderous enough to give them the semblance of full-grown men and women. A grain of mustard seed, buried in the heart of a mammoth pumpkin, would be no comparison to the little soul, sheathed in its full grown body. The contrast in size would be insufficient to convey an adequate impression; and the tiny soul has little of the mustard seed spiciness.

Yet if this mass of flesh is only wrapped up in a white skin, even though it is not nearly thick enough to conceal the grossness and coarseness of the veiled material, the poor "feeble folk" within will fancy[Pg 42] that he really belongs to the natural variety of aristocratic humanity. He has the good taste to refuse condescension sufficient to allow him to eat at table with a Frederick Douglass, a Samuel R. Ward, or a Dr. Pennington. Poor light little soul! It can borrow a pair of flea's legs, and, hopping up to the magnificent lights of public opinion, sit looking down upon the whole colored race in sovereign contempt.

Take off the thin veneering of a white skin, substitute in its stead the real African ebony, and then place him side by side with one of the above-mentioned men. Measure intellect with intellect—eloquence with eloquence! Mental and moral infancy stand abashed in the presence of nature's noblemen!

So, mere complexion is elevated above character. Sensible men and women are not ashamed of the acknowledgment. The fact has a popular endorsement. People sneer at you if you are not ready to comprehend the fitness of the thing. If you cannot weigh mind in a balance with a moiety of coloring matter, and still let the mind be found wanting, expect, in America, to lose cast yourself for want of approved taste.

If sin is capable of being made to look mean,[Pg 43] narrow, contemptible—to exhibit itself in its character of thorough, unmitigated bitterness—it is when exhibited in the light of our "peculiar" prejudices. Mind, Godlike, immortal mind, with its burden of deathless thought, its comprehensive and discriminating reason, its brilliant wit, its genial humor, its store-house of thrilling memories—a voice of mingled power and pathos, words burning with the unconsuming fire of genius, virtues gathering in ripened beauty upon a brave heart, and moral integrity preeminent over all else—all this could not make a black man the social equal of a white coxcomb, even though his brain were as blank as white paper, and his heart as black as darkness concentrated. May heaven alleviate our undiluted stupidity!

[Fragments of a poem hitherto unpublished, upon a revolt of the free persons of color, in the island of St. Domingo (now Hayti), in the years 1790-1.]

Syracuse, N. Y., August 31st, 1853.

Freedom, under the proper restraint of Law and Duty, is a political good, for that which is morally wrong can never be politically right.

Fine moral sense will pour indignation on oppression, as well as applause on worth. It will give sympathy to the afflicted, and treasures to relieve the needy. Such a spirit will exalt a nation, and command the respect of other nations. But general freedom can only flourish beneath the undisturbed dominion of equitable laws.

Governments should aim at the welfare of the people, and that government which secures the person, the property, the liberty, the lives of dutiful subjects, and thus makes the common good the rule and measure of its government, will receive a blessing from God.[Pg 62]

Let America act on her own avowed principles, that every man is born free, and she will be exalted, when tyrannical, persecuting, slaveholding nations will come to nought.

(signature) Wm. Marsh, D. D.

(signature) Wm. Marsh, D. D.

from the knaben wunderhorn. (b.i. p. 73, et seq.)

(signature) Theo. Parker

(signature) Theo. Parker

On a beautiful morning in the month of June, while strolling about Trafalgar Square, I was attracted to the base of the Nelson column, where a crowd was standing gazing at the bas-relief representations of some of the great naval exploits of the man whose statue stands on the top of the pillar. The death-wound which the hero received on board the Victory, and his being carried from the ship's deck by his companions, is executed with great skill. Being no admirer of warlike heroes, I was on the point of turning away, when I perceived among the figures (which were as large as life) a full-blooded African, with as white a set of teeth as ever I had seen, and all the other peculiarities of feature that distinguish that race from the rest of the human family, with[Pg 71] musket in hand and a dejected countenance, which told that he had been in the heat of the battle, and shared with the other soldiers the pain in the loss of their commander. However, as soon as I saw my sable brother, I felt more at home, and remained longer than I had intended. Here was the Negro, as black a man as was ever imported from the coast of Africa, represented in his proper place by the side of Lord Nelson, on one of England's proudest monuments. How different, thought I, was the position assigned to the colored man on similar monuments in the United States. Some years since, while standing under the shade of the monument erected to the memory of the brave Americans who fell at the storming of Fort Griswold, Connecticut, I felt a degree of pride as I beheld the names of two Africans who had fallen in the fight, yet I was grieved but not surprised to find their names colonized off, and a line drawn between them and the whites. This was in keeping with American historical injustice to its colored heroes.

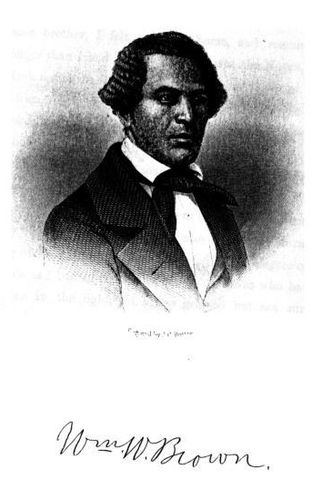

Wm. W. Brown. (Engraved by J. C. Buttre)

Wm. W. Brown. (Engraved by J. C. Buttre)

The conspicuous place assigned to this representative of an injured race, by the side of one of England's greatest heroes, brought vividly before my eye[Pg 72] the wrongs of Africa and the philanthropic man of Great Britain, who had labored so long and so successfully for the abolition of the slave trade, and the emancipation of the slaves of the West Indies; and I at once resolved to pay a visit to the grave of Wilberforce.

A half an hour after, I entered Westminster Abbey, at Poets' Corner, and proceeded in search of the patriot's tomb; I had, however, gone but a few steps, when I found myself in front of the tablet erected to the memory of Granville Sharpe, by the African Institution of London, in 1816; upon the marble was a long inscription, recapitulating many of the deeds of this benevolent man, and from which I copied the following:—"He aimed to rescue his native country from the guilt and inconsistency of employing the arm of freedom to rivet the fetters of bondage, and establish for the negro race, in the person of Somerset, the long-disputed rights of human nature. Having in this glorious cause triumphed over the combined resistance of interest, prejudice, and pride, he took his post among the foremost of the honorable band associated to deliver Africa from the rapacity of Europe, by the abolition of the slave-trade; nor was death[Pg 73] permitted to interrupt his career of usefulness, till he had witnessed that act of the British Parliament by which the abolition was decreed." After viewing minutely the profile of this able defender of the negro's rights, which was finely chiselled on the tablet, I took a hasty glance at Shakspeare, on the one side, and Dryden on the other, and then passed on, and was soon in the north aisle, looking upon the mementoes placed in honor of genius. There stood a grand and expressive monument to Sir Isaac Newton, which was in every way worthy of the great man to whose memory it was erected. A short distance from that was a statue to Addison, representing the great writer clad in his morning gown, looking as if he had just left the study, after finishing some chosen article for the Spectator. The stately monument to the Earl of Chatham is the most attractive in this part of the Abbey. Fox, Pitt, Grattan, and many others, are here represented by monuments. I had to stop at the splendid marble erected to the memory of Sir Fowell Buxton, Bart. A long inscription enumerates his many good qualities, and concludes by saying:—"This monument is erected by his friends and fellow-laborers, at home and abroad, assisted by[Pg 74] the grateful contributions of many thousands of the African race." A few steps further and I was standing over the ashes of Wilberforce. In no other place so small do so many great men lie together. The following is the inscription on the monument erected to the memory of this devoted friend of the oppressed and degraded negro race:—

"To the memory of William Wilberforce, born in Hull, August 24, 1759, died in London, July 29, 1833. For nearly half a century a member of the House of Commons, and for six parliaments during that period, one of the two representatives for Yorkshire. In an age and country fertile in great and good men, he was among the foremost of those who fixed the character of their times; because to high and various talents, to warm benevolence, and to universal candor, he added the abiding eloquence of a Christian life. Eminent as he was in every department of public labor, and a leader in every work of charity, whether to relieve the temporal or the spiritual wants of his fellow men, his name will ever be specially identified with those exertions which, by the blessings of God, removed from England the guilt of the African slave-trade, and prepared the way for the abolition[Pg 75] of slavery in every colony of the empire. In the prosecution of these objects, he relied not in vain on God; but, in the progress, he was called to endure great obloquy and great opposition. He outlived, however, all enmity, and, in the evening of his days, withdrew from public life and public observation, to the bosom of his family. Yet he died not unnoticed or forgotten by his country; the Peers and Commons of England, with the Lord Chancellor and the Speaker at their head, in solemn procession from their respective houses, carried him to his fitting place among the mighty dead around, here to repose, till, through the merits of Jesus Christ his only Redeemer and Saviour, whom in his life and in his writings he had desired to glorify, he shall rise in the resurrection of the just."

The monument is a fine one; his figure is seated on a pedestal, very ingeniously done, and truly expressive of his age, and the pleasure he seemed to derive from his own thoughts. Either the orator or the poet have said or sung the praises of most of the great men who lie buried in Westminster Abbey, in enchanting strains. The statues of heroes, princes, and statesmen are there to proclaim their power, worth, or brilliant[Pg 76] genius, to posterity. But as time shall step between them and the future, none will be sought after with more enthusiasm or greater pleasure than that of Wilberforce. No man's philosophy was ever moulded in a nobler cast than his; it was founded in the school of Christianity, which was, that all men are by nature equal; that they are wisely and justly endowed by their Creator with certain rights which are irrefragable, and no matter how human pride and avarice may depress and debase, still God is the author of good to man; and of evil, man is the artificer to himself and to his species. Unlike Plato and Socrates, his mind was free from the gloom that surrounded theirs. Let the name, the worth, the zeal, and other excellent qualifications of this noble man, ever live in our hearts, let his deeds ever be the theme of our praise, and let us teach our children to honor and love the name of William Wilberforce.

London.

It was a beautiful morning as ever glittered over the broad Atlantic. The sun had the brightness and the sky the soft cerulean with which the month of June adorns the latitude of Carolina. The sea was not heavy nor rolling, but its motion was just enough to make its waves sparkle under the slanting rays of the morning sun.

Mary stood with her betrothed in the bow of the boat, as it gracefully ploughed its way towards New York. She was only eighteen, and Albert was just twenty.

Mary was on her way to Troy, to complete her studies in the excellent institution for young ladies, which has sent out some of the brightest ornaments of their sex, to refine and bless the world. She had been entrusted to Albert's care, who was to spend[Pg 78] his summer in New York, in the pursuit of the legal profession. They were both Carolinians, and had no little of that ardent spirit which distinguishes the youth of the South; while their well-developed forms, their intellectual countenances, and their sensible speech, placed them in association beyond their years.

As Mary leaned upon the arm of her gallant protector, their conversation sparkled as the ocean spray that dashed against steamer's bow. But suddenly, as the jet black eye of Albert Gillon caught the soft blue of Mary's, he started at the discovery of a tear trembling upon her eye-lash.

"Sweet Mary, what saddens you?"

"Ah! Albert, the greatest trial of my feelings is the thought that you have never yet consecrated yourself to Christ."

"I have," replied Albert, "no natural repugnance to religion. On the contrary, I see and acknowledge God in all his works and in all his providence, as the author and supreme ruler of all things. But, Mary, I do not understand the God of the Bible. I do not understand how they who claim to be God's own people, and have the distinguishing title of Christians,[Pg 79] are, many of them, far worse in moral character, than those who make no such profession. I do not mean hypocrites; but those who are actually respected as orthodox Christians. There is Mr. Verse, of Philadelphia, for instance, who has a high place as a religious editor, and discusses the doctrines of Christianity with a zeal which shows he takes deep interest in his work, and yet young as I am, and gay as I am, I can see that in his practical application of Christianity, he teaches sentiments at variance with the plainest principles of moral truth; and he sets himself against those whose moral character is above reproach; and rebukes them as infidels in their very efforts to elevate the moral tone of society. How is it that Mr. Verse is recognized as a Christian, and these excellent men are avoided as infidels? Why is he fit for heaven, and they must be cast down to hell? I don't understand it."

"I know," replied Mary, "that wiser heads than mine find difficulty in answering your question; and it would be presumptuous in me to signify that I can solve it to your satisfaction. But still, Albert, your observations only confirm, in my own mind, your total ignorance of what constitutes a Christian. Albert,[Pg 80] it is not morality; it is not consistency of practice with profession; it is not the doing right that makes a Christian, for if man could have attained to entire correctness in morals, there would have been no such thing as Christianity. But it is because of man's wickedness and his inconsistency, both in theory and in practice, that the Christian religion is presented as the means of attaining to salvation. Christ makes the Christian—the Christian in Christ and Christ in the Christian—a loving, affectionate, endearing union—of ignorance with wisdom, of infirmity with strength, of immorality with virtue. Christ throws his robe of righteousness over the follies and the wickedness of the converted soul, and by covering him with himself, gradually similates him to himself until what is carnal being cast off, the spiritual remains at death a pure child of God."

"Dear me, Mary, you look lovely as you speak this mysterious theology. And I really pant after such feelings as I see beaming from your countenance; but you might just as well speak to me in Arabic for any understanding I can have of this thing called Christianity. It must be something good, or it could not thus fill your own soul, intelligent as you are,[Pg 81] with a joy that makes you indifferent to those gaieties of life which give me pleasure."

"You need," said Mary, "the teachings of God's spirit. You know I took delight in those things a year ago, but God's spirit taught me that I was sinning in partaking of them. I was at Fayolle's, dancing, and, in the midst of a figure in the cotillon, my head became giddy, and I had to be supported to a seat. I soon recovered, but the thought of a sudden death distressed me, for it came very forcibly to my mind—I am a wicked sinner."

"O, Mary, Mary," interrupted Albert, "you did not think yourself a sinner!"

"Yes, Albert, I did. I had never thought so before, but had rather prided myself upon being called a good girl by all my acquaintances. But I now saw things in a different light; and when I went home and began self-examination, I soon found I had a very wicked heart. I tried to do better, but the more I tried to live unto God the more I discovered the proneness of my heart to sin. I tried to think good thoughts, and evil thoughts came directly in my way to mar my peace. Day after day I made effort to purify my thoughts. It was all in vain. A pure[Pg 82] thought immediately suggested its opposite, and I found myself more familiar with the evil than the good. It shocked me. But I penetrated deeper and deeper into my own heart—into the iniquity of my soul, until I despaired of ever sounding its depth. I then cried to God to have mercy on me. He heard my prayer, and Jesus Christ came to my help. I felt that he had suffered in my stead, and had poured out his blood as an atonement for my sins. I found peace to my soul as I cast myself, a poor, helpless sinner, upon his atoning altar, and bathed myself in his all-cleansing blood."

Mary could proceed no farther, for the tears began to flow too rapidly, and her emotion might have been noticed by others than Albert.

The wind, too, began to rise, and it blew so fresh that they retired to the cabin, where Albert occupied himself with a game of chess, and Mary read, with evident pleasure, such parts of her dearly-prized Bible which suited the state of her mind, occasionally calling Albert's attention to some passage particularly striking.

In the afternoon, Mary took her seat in a position to enjoy the best view of the western sky, in which[Pg 83] floated, in all their gorgeousness, the variegated sun-lit clouds.

Albert soon joined her. "Well, Mary, you seem to be meditating; but allow me to participate in the luxury of your reflections upon that splendid horizon."

"Indeed, Albert, I was thinking how much more impressive is such scenery than the traveller on land enjoys. In the rapid succession of scenery and variety of faces, as the coach or the steam car drives rapidly onward, everything one sees increases the mind's confusion. Whatever he casts his eye upon, worthy of admiration, attracts his attention but a moment; and the sublimity of mountain heights, the gaudy decorations of fertile valleys, and the frowning grandeur of rocks, as they cast their dark shadow upon some foaming torrent, flit by him as a dream of twilight, and leave upon his memory only pencil outlines of the beautiful and the sublime. Not so the voyager on the ocean. Here the beautiful imprints itself ineffaceably in all its sparkling and its gorgeous variety upon the enchanted mind, and the grand and the sublime raise such a tempest of wonder in the soul that the ocean ever after rolls its foaming waves over the broad expanse of memory."[Pg 84]

"Mary," said Albert, "these clouds, floating so gracefully on the ocean, and this gorgeous horizon inspiring your poetic fancy, are something more than mere sky drapery, for you'll perceive that the wind is becoming boisterous, and I fear we are going to have a stormy night."

"You do not feel alarmed, do you Albert?"

"I cannot say I feel alarmed; but I would be more comfortable at this time if I had not so precious a charge. There may be no real danger, but there can be no harm in preparing for what might happen. If we should have a storm I wish you would take your seat on that large box, so as to appropriate it and keep it. Your father brought me two life-preservers and a good cord, when we came on board, and charged me to use them in case of accident. You smile, Mary, at my earnestness, and perhaps my love for you induces anxiety which circumstances do not warrant. Still you can keep in mind my directions."

Albert walked towards the bow of the steamer, while Mary again fixed her attention upon the variegated clouds. She did not participate in Albert's apprehensions, and thought his anxiety needless. Yet his earnest request made that sort of impression upon[Pg 85] her mind which rather conduced to religious contemplation.

The broad disk of the sun could be seen through the floating cloud, and as Albert returned, Mary remarked:—"Albert, an hour ago I tried to look at the sun, but his light dazzled my eyes to blindness. I could not mark its shape nor perceive its beauty. But now the cloud floats before it, and through its light vapor I see the sun's circular infinity, and admire its beauty and its glory undazzled by its effulgence. So it is I see God through Christ, as he transmits the glory of his Father. And it is by thus seeing God through Christ, instead of by the eyes of intellect and mere mental observation, that I obtain hope in God and feel prepared to enter upon the realities of that world which is eternally lighted by the invisible presence of Jehovah. Seeing him in Christ Jesus, I feel an assurance of his mercy, and am freed from those apprehensions which your scepticism and distrust occasion yourself."

"My dear Mary," replied Albert, "do not suppose my counsel to you originated in any fear for myself personally. It may be from want of reflection, but really I do not know what the fear of death is. Your[Pg 86] safety, Mary, is the cause of my present anxiety. I do not doubt your preparation for eternity, but I am not willing to resign you yet to the companionship of angels. If you perish beneath these billows, and I survive, my hope for happiness in this life is blasted. What is to be beyond the grave I know not; and my religion concerns the life that now is. I must make the best of time, and leave eternity to be taken account of when I am fairly launched into it. Perhaps enjoying this world with you, I might learn from you to prepare for eternity. At present my care must be to get my dear Mary safely over this treacherous ocean."

The sun now sank beneath the western horizon. The variegated colors of the sky were rapidly commingling into one dense canopy of gloom.

The passengers earnestly inquired of the captain about the prospect. He hoped to run into the port of Wilmington, but he exhorted them to have brave hearts for the danger was imminent. The storm was rapidly increasing. All urged that the pressure of steam be increased to the utmost capacity of the boat.

O, what an anxious crowd were upon the deck of that steamer, as they strained their eyes towards the[Pg 87] land, and anon lost their balance by the dashing of the billows! The lightning played with terrific splendor, alternating with the blackness of the heavens; and the roar of the waves was only hushed by the awful artillery of the skies.

Mary was sitting where Albert had directed, awaiting with great calmness the result of the storm.

Albert carefully fastened her with a cord to the box, having first placed beneath her arms the life-preserver. Placing another life-preserver around himself, he stood by Mary's side with watchful anxiety. Suddenly a heavy sea threw the boat forcibly to one side, and Albert mechanically stretching forth his hand to save himself, accidentally got caught in the rope that he had entwined about the box, and with Mary was tossed into the sea and overwhelmed with the waves.

The steamer was several hundred yards ahead of them before Albert succeeded in adjusting his position to maintain a good hold upon the box. His first thought was to examine how Mary was situated. The lightning gave him sufficient assurance that she was alive and unhurt. At that moment a dreadful explosion directed their eyes towards the steamer,[Pg 88] and the awful sight was exhibited of their late associates blown into the air and then sinking beneath the waves.

The loss of the Pulaski has made many a flowing tear. But few were left to tell the horrors of that night. The public are familiar with their description of the sad disaster. But they knew not the fate of Albert and Mary, and only added them to the catalogue of the lost.

It was with the greatest difficulty that Albert could afford his charge any aid, and they must both soon have perished if the storm had been long protracted. But fortunately, the wind shifting, the clouds were soon dispersed, and the stars shone out brightly.

Before morning they were rescued from their perilous situation, and found themselves, on recovering from their exhaustion, in the comfortable cabin of a fast-sailing brig. The storm, although exceedingly perilous to a steamboat, was not such as to damage a well-trimmed vessel; and the brig, soon after the explosion, bore down towards the wreck, and recovered from a watery grave the interesting subjects of our narrative.[Pg 89]

Mary was taken on board in a state of entire unconsciousness, while Albert was too much interested for her to make any special observation of the persons by whom they were rescued.

After seeing her sufficiently restored to animation to be left to repose, he retired from her state-room and suffered himself to be assisted to a berth.

The sun was high in the heavens when they were awaked from their slumber and invited to breakfast. Every accommodation in the way of dry clothing was supplied them, and they met in the saloon of the brig to embrace, in the transport of grateful hearts.

Having recovered their self-possession, they looked around for their deliverers. None were in the saloon with them but a highly-accomplished looking lady and the steward and stewardess.

The lady saluted them in the blandest and most refined manner, and expressed her sincere gratification that they had been so soon delivered from their perilous situation, and were already so well recovered from their exhaustion.

"To whom, Madam," said Albert, "are we indebted for these expressions of kindness and tender solicitude?"[Pg 90]

"I am, sir, the wife of the captain and master of this brig. My husband will pay you his respects as soon as you have partaken of some of this warm Java and these hot rolls."

"I would not," said Mary, "be doing justice to my own feelings were I to sit down to breakfast without first asking your liberty, Madam, to read a beautiful psalm which occurs to my mind at this moment."

"Certainly," said the lady; "and, steward, invite the chaplain in to offer prayer. Doubtless it will be perfectly agreeable to our young guests."

A reverend and benevolent looking gentleman, in black, soon entered from the deck, and, in the kindest manner and address, saluted the young couple, expressing, with deep emotion, his sympathy with them and his anxiety in their behalf.

Mary pointed out to him the Psalm she had selected. He read it; made a few highly-appropriate comments, and, while all knelt, such a strain of grateful praise and of fervent prayer flowed from the lips of the warm-hearted minister as seldom is surpassed.

Mr. Gracelius, for this was the minister's name, was of the orthodox faith, and had long been engaged in preaching the doctrines of the Calvinistic school. Yet[Pg 91] he was not bigoted or rigid. His heart was full of the milk of human kindness, and he carried conviction to his hearers, not more by the strength of his logic than the benignity of his address. He was just such a minister as the devout and accomplished Mary St. Clair would have full confidence in. She was delighted to think that she had been so fortunate as to meet such a friend and spiritual counsellor at such a time; and she at once gave utterance to the warm feelings of her heart, and begged that Mr. Gracelius would feel at perfect liberty to counsel and advise her.

"My advice then is, my dear young sister, that first of all you sit down to your breakfast, and allow Mrs. Templeton to help you and the young gentleman to your coffee."

Albert and Mary could not but feel that they had fallen among true friends. And, having eaten a cheerful breakfast, they both expressed their sincere gratitude to their kind hostess, which she received with equally deep emotion.

Captain Templeton now entered, and with great courteousness, blended with warmth of address, gave his hand to Albert, and, with a graceful bow to Mary, expressed the pleasure he felt in having rescued them[Pg 92] from a watery grave. "And now, my young friends," said the Captain, "I wish you to make yourselves perfectly at home in my vessel; and as soon as I can with safety restore you to your friends, I shall do so."

"Permit me to inquire," said Albert, "to what port you are destined?"

"We do not go into any harbor in the United States," replied the Captain; "but should we meet with a merchant vessel under favorable circumstances, you will be placed on board."

"Is not this a merchant vessel?" inquired Albert.

"No, sir. This is an armed brig."

"Of what nation?" asked Albert.

The Captain smiled as, with a courteous bow, he replied, "We are pirates;" and immediately went on deck, leaving Albert and Mary in perfect amazement.

Recovering himself in a moment, Albert said to Mrs. Templeton: "Your husband is very jocose!"

"No, sir; he was serious in what he said. We are pirates. But you need be under no apprehension of danger, nor feel the slightest alarm. I know that you have been trained to believe that pirates are necessarily devoid of humane feelings, and are ever thirsting for blood. But I trust we are as hospitable and[Pg 93] kind a people to our guests, as are to be found on land."

Albert and Mary were indeed the guests of a piratical crew; but they were soon relieved of all apprehension of personal danger; for there was that in the deportment of all on board which satisfied them of a sincere desire to serve and accommodate them in every way.

A few days brought them into such intimacy with the crew that they spoke with freedom, even on the subject of piracy. They were indeed astonished to find that even Mr. Gracelius advocated the claims of pirates as a civilized and religious people.

On board the brig they had morning and evening prayers, and a lecture one evening in the week, and two sermons on the Sabbath. What seemed particularly remarkable was the sound evangelical faith of the Captain and his family, and the unexceptionable doctrines that were preached by their minister. There was so much fervor, earnestness, and pathos in the sermons of Mr. Gracelius, that Mary was constrained to admit to Mrs. Templeton that she had never heard better.

They had been on the brig about three weeks,[Pg 94] without any event calculated to disturb the sensibilities of our young friends, beyond the unaccountably strange sentiments of the piratical crew. Everything was conducted with so much order and propriety, good taste and moral deportment, that they could scarcely believe at times otherwise than that a mere sportive hoax was being played upon them.

But the tranquil, social pastimes were now interrupted by a new scene of action.

It was a pleasant morning; a gentle breeze filled the sails. An unusual arrangement of the vessel attracted the attention of Albert. Soon he observed men at the guns, and Captain Templeton standing in a commanding position. The brig was bearing down upon a French merchantman.

Albert hastened to Mary, and disclosed to her the state of things. Mary at first trembled, but soon composed herself with trust in God. Albert, taking her arm into his, led her to where Captain Templeton was standing:

"Captain," said Albert, "I perceive you are bearing down upon that merchant vessel. Is it your object to place us on board, or do you design to capture her?"[Pg 95]

"Mr. Gillon," replied the Captain, "I shall see to it that you and your young charge are safely provided for; and that you may be perfectly easy on that score, I now inform you that when I take possession of that merchantman, I shall make arrangements for you to be taken in her to a suitable port, whence you can find your way to your friends. Be composed now, and pay such attention to Miss St. Clair as the unusual occasion may seem in your judgment to require. In a few moments we shall have something to do, and perhaps a necessity to use our guns. But I hope not. If you will retire to the cabin, Mrs. Templeton will entertain you there better than you are likely to be on deck."

There was so much politeness in the Captain's manner, and yet evident fixedness of purpose, that Albert attempted no answer. There was now no doubt that their hospitable entertainers were pirates. They retired to the cabin, and sat there in profound silence. Soon Mrs. Templeton came in, and in her gentle winning manner began to prepare Mary for the scenes that might transpire.

"You must not be alarmed, my dear. You will be perfectly safe. I only regret we are so soon likely to lose your company."[Pg 96]

"O Mrs. Templeton!" said Mary, "how can you prosecute such a life! It is so wicked! Excuse me, ma'am, but I cannot suppress my feelings of horror."

At this moment the conversation was interrupted by the entrance of Captain Templeton, who, with a calm countenance, said:—

"Wife, I perceive that there are several guns on that vessel, and I judge that the crew and passengers are somewhat numerous. We shall have to proceed with caution, and as we are likely to have somewhat of a warm time, I think I should feel better satisfied to have a season of prayer."

Albert knit his brow in moody silence. Mary heaved a deep sigh. Mr. Gracelius was called in, and having read the 20th Psalm, he offered up the following prayer:—

"Oh! Thou mighty God of Jacob, who didst accompany Thine ancient Israel through all their trials, and didst fight their battles for them, we thank Thee that Thou hast taught us to put our trust in Thee. And we beseech Thee, oh! blessed Father, for the sake of Thine own Son Jesus Christ, to help us at this time in our endeavor to appropriate to the support of this branch of thy Zion, the treasures which, for the mere[Pg 97] purposes of an unhallowed commerce, are being transported to that people who have ever distinguished themselves by their infidelity, and by their scorn of all true religion; who have also by their mighty leaders devastated kingdoms and shed seas of blood to gratify a vain-glorious ambition.

"Oh! Lord, we would not shed blood needlessly, and we therefore pray Thee to enable us in the approaching conflict, to have a single eye to Thy glory, and thus preserve a calm and kind temper, whatsoever may be the resistance offered on this occasion. And wilt Thou, O Lord, assist our beloved captain to do his duty, and to so command his men and order the battle, that when all shall be over, he may have a conscience void of offence towards God and towards man. And whatsoever treasures may come to us, may we gratefully employ in Thy service and to Thy glory, remembering that Jesus Christ, who died for us and rose again for our justification, first became poor, that we through his poverty might be made rich, and therefore that we ought to use our wealth to the advancement of Christianity in our own souls and among our fellow-beings, as the best evidence of our gratitude for our earthly prosperity, and for those[Pg 98] treasures which are laid up for us in heaven; and to Thy gracious name, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, be the praise forever. Amen."

The tone of the chaplain's voice, the fervid manner and the striking pathos of this short prayer, had a strong effect upon Captain Templeton and his wife. They both rose from their knees with tears in their eyes.

The Captain grasped the hand of Mr. Gracelius, and earnestly said: "I feel strengthened, my brother; and I can now say, If the Lord be for us, who can be against us!" He then passed out and resumed his position on the deck.

"Miss St. Clair," said Mrs. Templeton, "do you think that can be wickedness which the Lord sanctifies with his communion?"

Before Mary could reply, the loud report of a cannon gave notice that the action had commenced.

The struggle was a short one, the French vessel was captured, with the loss of her commander, who fell at the first fire. It took but a short time to have all on the merchantman in fetters, and the vessel manned by the pirates.[Pg 99]

It was not until the morning after the capture that matters became composed on the pirates' vessel, and everything in usual order.

At breakfast Mary took the liberty to ask the Captain what he designed to do with his prisoners.

"I always endeavor," he replied, "to remember the obligations of humanity and Christianity. Sometimes, for our own safety, we are compelled to put our captives to death, but I do so always with great reluctance, and never without prayer to God that their souls might be saved. In this case I think we shall not be under this painful necessity."

"Captain," said Albert, "it is perfectly unaccountable to me how a man of your naturally humane and benevolent disposition can engage in this business of robbery and murder."

"Well, Mr. Gillon," replied the Captain, "I make every allowance for one who has been educated as you have been, and taught that pirates were only worthy of the gallows; although I cannot but feel that your language is not such as your refined and polished manners would warrant me to expect and require. Our business is not robbery and murder. The laws under which we live, both social and political,[Pg 100] are as decidedly opposed to such crimes as among any other people."

"I did not," replied Albert, "intend to be ungentlemanly in my language, and was not aware that these terms were offensive to you. But, sir, you only increase my amazement. I cannot comprehend how you can characterize your business by terms more appropriate. Is it not so that piracy is but the practice of robbery and murder, when it takes away a man's possessions, and then destroys his life to make the booty secure?"

"I perceive, Mr. Gillon, that you labor under the delusion that all pirates are bad and cruel men. I confess, sir, there are many of our people who treat their prisoners with unnecessary severity, and frequently inflict death when the occasion does not demand it. But, my dear sir, this is the abuse of piracy, not its legitimate use."

"And do you really mean to say, Captain Templeton," said Mary, "that piracy can be made an honorable business?"

"Of course I do, miss," replied the Captain, "and I regret that Miss St. Clair can suppose I would engage in a business that I did not believe to be honorable."[Pg 101]