Title: Little Abe, or, the Bishop of Berry Brow

Author: F. Jewell

Release date: December 2, 2006 [eBook #19990]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

I desire to express my thanks to all those friends who have kindly assisted me in collecting materials for these pages; and I am especially indebted to my friends the Rev. T. D. Crothers and the Rev. W. J. Townsend for the cheerful services they have rendered me in preparing the little work for printing.

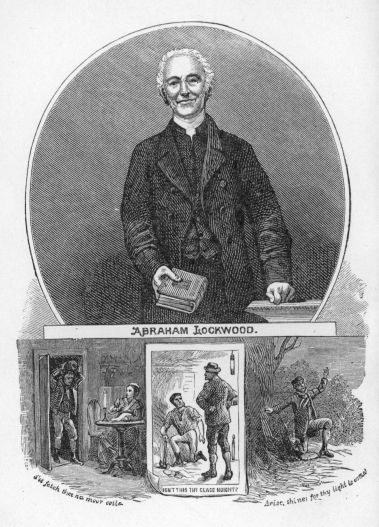

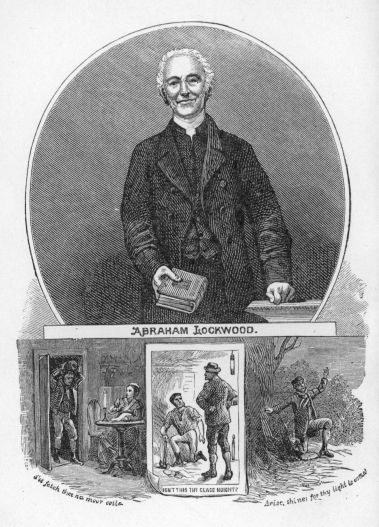

Whilst trying to give a faithful account of the life and character of

Abraham Lockwood, I have done my best to make the narrative both

readable and profitable; but I am sensible that there are many faults

in the volume. Such as it is, however, I humbly offer it to the

public, with the earnest prayer that it may prove a blessing to many.

F. JEWELL.

BETHEL VILLA,

HULL, 1880.

Abraham Lockwood was born on the 3rd November, 1792. His birthplace, also called Lockwood, is situated about a mile and half out of Huddersfield.

It makes no pretensions to importance in any way. The only public building which it boasts, is the Mechanics' Institute, a structure of moderate size, yet substantially built. Its one main street is lined with some very excellent shops, some of whose owners, report says, have made a nice little competency there. It still boasts a toll-bar of its own, which is guarded on either side by two white wooden posts, that take the liberty of preventing all cattle, horses, and asses from evading the gate, and of unceremoniously squeezing into the narrowest limits every person who prefers pavement to the highroad. Lockwood is also important enough to receive the attention of two or three 'buses which ply to and fro between there and Huddersfield, as well as to have the honour of a railway station on the L. and Y. line. Of course years ago, when Abraham Lockwood was brought into the world, this locality was not so attractive as it now is; only a few cottages straggled along the level or up the hill towards Berry Brow, mostly inhabited by weavers and others employed in the cloth manufacture of the neighbourhood. Among these humble cottages there stood, on what is known as the Scarr, one even more unpretentious than the rest: it boasted only one story and two or three rooms in all; it was what Abe used to call a "one-decker."

In this little hut dwelt the parents of Abe Lockwood; the fact of their residing in such a humble home, shows sufficiently that they were poor, perhaps poorer than their neighbours. However, in that same single-storied cot in Lockwood, Abe Lockwood was born, a Lockwoodite by double right, and though age has seriously told upon its appearance, it stands to this day. We sometimes see little old men living on, and year by year growing less and less, until we begin to speculate about the probable time it will require at their rate of diminution for nothing to remain of them; and the same may be said of the little old house in which Abe Lockwood was born; it was always little, but as years have slowly added to its age, it has gradually begun to look less, and now, as other houses of larger size and more improved style have sprung up all around the neighbourhood, it has shrunk into the most diminutive little hut that can well be imagined as a dwelling house, and it only requires time enough for it to be gone altogether.[1]

Abe's parents were a poor but honest pair, and laboured hard to make ends meet. William Lockwood, his father, was a cloth-dresser, and worked on Almondbury common, about a mile from his home, earning but a scanty living for the family. In those days, when machinery was almost unknown in the manufacture and finish of cloth, the men had to work harder and longer and earned much less than now. Those were the times when hard-working men thought that the introduction of machinery into cloth mills would take all the work out of their hands, and all the bread out of their mouths; and this was the very locality where the greatest hostility was shown by the people to such innovations. Many a threatened outbreak was heard of about that time, and in two or three instances the smouldering fire in the men's minds actually burst forth into riot and rising, when they found that the great masters were determined to have their own way and introduce machinery into their mills. Abe himself was led, some years after, to take part in one of these risings, and narrowly escaped the hands of the law, while several others were lodged for some time in York jail in recognition of the part they had taken in the riots.

Abe's father was a quiet, moral-living man, whose chief aim for many years seemed to be to provide for his own household; but in after times his thoughts were drawn to things higher as well, and he became a God-fearing man; yet during Abe's early life, the most that can be said for his father is that he was an honest, hard-working, and well-disposed man.

His mother was a good Christian woman, and was for a long time a member with the Methodists in Huddersfield, and attended the old chapel which formerly stood on Chapel Hill. There is no doubt that the early teaching of his kind and pious mother had a great deal to do with the formation of Abe's Christian character in after years. Certainly a long time elapsed before there was any sign of spiritual life in her son; indeed, she was called away to her eternal rest before there was any indication of good in his heart; what matters that? the good seed was there; it would bide its time and then grow all the stronger. Sometimes people conclude that because there is not immediate growth there is no life; this does not follow; the grain may slumber for years, then wake up and grow rapidly. I on one occasion saved some orange pippins, dried and planted them with the hope that they might grow; as time went on, I watered and watched them, but there was no indication of growth; months went by: I lost heart, gave over watering, threw the plant-pot in which they were sown out of doors; a year was gone by and more, when one day my eye fell on this same pot all covered with green growth. "Hey! what's this?" why, positively, they are young orange plants, standing up hardy and healthy, protesting against my want of faith and patience. It is often the same with the growth of other seed in the human breast; when parents have waited long in vain, their faith grows gradually less and less, until it dies out in despair; but the good seed may not die, it is sleeping, it lives its winter life, and then under the tender and genial touch of some spring-like influences it begins to grow. "Be not afraid, only believe," said the Master of the vineyard.

Why the young baby that had come to reside in that little cot should have the honourable name of Abraham may be a subject of question by some. It evidently was not to perpetuate his father's name, though from the beginning of generations this has been a sufficient argument for calling son after father; on that ground John Baptist had a narrow escape from being called Zacharias. That however could not influence the decision in Abraham Lockwood's case, because his father's name was William. Perhaps it was that the child indicated a patriarchal spirit, and conducted himself like a stranger in a strange land, in which case there might be a suggestion of that name. Perhaps it was a piece of parental forethought, for knowing well that they could never confer riches upon him, or place him in a position to make them himself, they determined to do that for him, which everyone must say is far better, they would see to it that he had a good name among men, and so they called him Abraham. This ancient and venerable name, however, soon underwent a transformation, and appeared in the undignified form of "Abe." The alteration at least exhibited a mark of economy, even if it involved the sacrifice of good taste; there certainly was a saving of time in saying "Abe" instead of "Abraham," which is very important when things have to be done in a hurry; and then it may be that to some ears it would sound more musical and familiar than the full-length designation. Howbeit, there always seemed a strange contrariness between Abe and his name. When he was a baby they called him by the antiquated name of "Abraham." As he grew older and bigger, they shortened his name to "Abe," and when he was a full-grown man, and father of a family, he was commonly known as "Little Abe." The name and the bearer seemed to have started to run a circle in contrary directions, till they met exactly at the opposite point in old age, when for the first time there was seen the fitness between the man and his name, and he was respectfully called "Abraham Lockwood."

[1] Since the above was written, this little cottage has been removed to afford room for a larger building.

Nothing particular is reported of his early life in that little home; there are no accounts of any hair-breadth escapes from being run over by cart-wheels, or of his being nearly burnt to death while playing with the kitchen fire, or of his straying away from home and taking to the adjacent woods, and the whole neighbourhood being out in quest of him, or that he even, during this interesting period of his history, either fell headlong into a coal-pit, or wandered out of his depth in the canal near by; there is, however, every probability, considering his lively disposition, that his mother had her time pretty well occupied in keeping him within bounds.

On reaching the notable age of six years, a very important change came over the even course of his young life. His parents sent him to work in a coal-pit; people in these days will scarcely credit such a thing, but it is nevertheless true; nor was this an extraordinary case, for children of poor parents were commonly sent to work in the pits at that early age, when Abe was a child. The work which they did was not difficult; perhaps it might be the opening or shutting of a door in one of the drifts; but whatever it was our hearts revolt at the idea of sending a child of such tender years into a coal mine, and thanks to the advance of civilization, and an improved legislation on these things, such an enormity would not now be permitted.

In some dark corner of that deep mine poor little Abe was found day by day doing the work assigned to him, and earning a trifle of wages which helped to keep bread in the little home at Lockwood Scarr. He went out early in the morning, and came home late at night, with the men who wrought in the same pit, his little hands and feet often benumbed with cold and wet, and he so tired with his toils that many a time his poor mother has had to lift him out of bed of a morning, and put his little grimy suit of clothes on him, and send him off with the rest almost before the child was awake. Many a time he was so weary on coming out of the pit that he has not been able to drag himself along home, and some kind collier seeing his tears has lifted him on his shoulder and carried him, while he has slept there as soundly as if on a bed of down.

Some few years passed on, during which time Abe continued to work in the coal pit with but little change, except that as he grew older and stronger he was put to other work, and earned a better wage. His parents, however, were not satisfied that their son should live and die a collier, they thought him capable of something else; besides that, there were always the dangers associated with that calling in which so many were maimed or killed. They therefore determined that their son should be a mechanic, and learn to earn his bread above ground. After a while they found a master who was willing to take him into his employ and teach him his handicraft. It was customary in those days for a master to take the apprentice to live with him in his house, and find him in food and clothes. So Abe was given over to his new master, with the hope that he would do well for him, and the boy would turn out a good servant.

Now it is quite possible all this was done by the kind parents without consulting Abe's mind on the subject, which certainly had a good deal to do with the realization of their hopes, more perhaps than they thought; however they soon discovered it, for in a day or two Abe returned home with the information that he didn't like it, and should not be bound to any man. It was a sad disappointment to the honest pair, who had begun to indulge in expectations that some time "aar Abe may be mester hissen;" they however saw that it was of no use pressing him to go back, and so they compromised the matter by setting about to find him another master. Abe was again despatched from home with many a kind word of advice, and the hope that he would mind his work, learn the trade, and turn out to be a good man. But what was their surprise and pain at the end of about a week to see Abe walk into the house again with a bundle in his hand. "Oh, Abe, my lad, what's brought thee here so sooin? what's ta gotton in th' bundle?" exclaimed his mother. "Why, gotton my things to be sure; I couldn't leave them behind when I'm going back no maar;" and sure enough he had come home with the information as before, he didn't like being bound to any man.

The probability is that there was something in the kind of treatment Abe met with in both those cases that helped to set his mind so much against the life of an apprentice away from home. All masters in those days were not particularly kind in their manners towards apprentices: some honourable exceptions could easily be found no doubt, but as a rule, boys in such positions were not very kindly used; hard work from early morning to late at night, hard fare at meal times, hard cuffs between meals, and a hard bed with scanty covering at nights,—it was no very enviable position for a youth to occupy, and certainly not one to which a spirited lad would quietly submit. It may be that Abe, during the short probations he had served at these two places, had learnt too much of the ways of the establishments for so young a hireling, and found they would not suit his peculiar tastes, and therefore he decided twice over to return home, bringing his bundle of clothes without giving any explanations or notice to any one.

Be that as it may, here he was at home again a second time, much to the annoyance of his father, who was bent upon the lad learning some handicraft. Abe remained at home a short time, when one day his father told him he had got another place for him, with an excellent man, who would take him a little while on trial, and if they liked each other he might then be indentured. His father had been at some trouble to find a master farther away from home, in the hope that when once Abe was a good way off he might be induced to stay; in this he was acting on the principle that the power of attraction is weakened by a wider radius, which may be correct when applied to some things, but not to all. This new master lived in Lancashire, and thither young Abraham was sent in due course. A month or so passed away, and all seemed to promise a satisfactory arrangement, until one morning Abe heard a conversation in the family, from which he gathered that his master was going to Marsden, where he expected to meet Mr. Lockwood at a certain inn, and make final arrangements for Abe's apprenticeship. This opened the old sore; Abe couldn't rest: "he wouldn't stay, that he wouldn't, he would be off home;" but how was he to get there? he didn't know the way, and thirty miles or more was a long journey in those days. He determined therefore to keep his eye on his master until he saw him off for Marsden, which was more than half the distance to his home, and then he set away after him on the same road, never losing sight of him for one minute. On they went mile after mile along the roads until they reached Marsden, where he saw his master enter the inn. Now Abe had to pass in front of this very house, but he didn't want to be discovered, so he adroitly turned up his coat collar over the side of his face, and pulled down his cap, and set off running as fast as he could, and just as he was passing the inn he took one hurried look from under his mask, and there, in the open window, he saw two men side by side, his master and his father. Of course he concluded they must have seen him, and would be out immediately to fetch him back; this idea only lent speed to his weary feet, so that he ran faster than ever on through the solitary street of the old village, away out on the road, never turning to look behind, lest he might see all Marsden coming in pursuit of him. Exhausted nature however at length compelled him to slacken his pace, and on turning to look back he found he had only been pursued by his own fears. The two men sat still in the inn, talking over and settling the terms of the apprenticeship, fixing the time when the indenture should be signed and the boy bound to his new master. Each of them took his journey homeward; neither of them was prepared for what awaited him. One of them found on arriving home that Abe had gone, and the other discovered the very opposite, that he had come, and both were alike vexed.

It is likely that poor Abe would have had to trot back again the next day if his mother had not taken his part. Dear woman, she had been a whole month without seeing her boy, and many an anxious thought had she about him during that period; many a time when her fond heart yearned for him, she had well nigh said she wished they had never sent him away; many a time when some foot had been heard at the door her heart stopped at the thought, that it might be him; and now that he had come, really come, had run so far to be near her, had come so weary, footsore, and hungry, had laid his weary head on the end of the table and wept tears of trouble and pleasure, had fallen asleep there as he sat, she put her kind arms around him, kissed his hot forehead and said, "Dear lad, they shall not take him away from his mother any more for all the masters and trades in the land." So it was of no use that Mr. Lockwood should argue for his going back; he had to yield inevitably, for what man can think to contend long against his better half? From that time all attempt to bring Abraham up as an artificer ended, and he found employment with his father as a cloth-finisher, at which he worked most of his lifetime afterwards.

Soon after these stirring little events had gone by, another happened in that household which brought far more pain and anxiety than anything that had preceded it. The youth who would not be parted from his mother, could not prevent his mother from leaving him, and the separation took place; death stept in, and without regard to the fond feelings which bound that little household together, bore away the wife and mother to the spirit land, while her body was laid among the dust of others in the yard of the old brick chapel in Chapel Hill, Huddersfield.

What a gap it made in that house! in the hearts of its inmates it left an open wound which only long months of patient endurance could heal. When a mother's dust is carried out and laid in the grave, it is the light of the domestic hearth gone out; it is the sweetest string gone from the family harp; that bereavement is like the breath of winter among tender flowers; the live tree around which entwined tender creepers is torn up, and they lie entangled on the ground, disconsolate and helpless, until the Great Father of us all shall give them strength to stand alone.

Abraham Lockwood's mother was dead, and a kind restraining hand, which many a time kept his wild and wayward spirit in subjection, was thereby withdrawn, and the ill effects in time began to show themselves in his conduct. As he grew older, and the trouble consequent on the loss of his mother wore off, Abe gradually associated with evil companions, fell into their habits, until he became a wild and wicked young man. He never sank into those low habits of which some are guilty, who neglect the appearance and cleanliness of their own person, and go about on Sundays and weekdays unwashed and in their working attire. Abe had more respect for himself, and was always looked upon among his friends as a dandy. I have heard old people say he was a proud young man, and withal of a very sprightly appearance.

Abe took great pride in his personal appearance, and when not in his working clothes he usually wore a blue coat in the old dress style, such as "Father Taylor" would call "a gaf-topsail jacket." There were the usual and attractive brass buttons to the coat, drab knee-breeches, blue stockings, low tied shoes with buckles; and really everyone who knew Abe thought he was a proud young man. Perhaps he was, but it is not always an indication of pride when young people bestow more care upon their appearance than do their fellows; it may arise from a desire to appear respectable and be respected. No one will think I am trying to extenuate the foolish and extravagant love of dress which some people show, who adorn themselves in silks or broadcloth, for which they have to go into debt without the means of paying. Some are most unsparing in the way they lavish money on their own persons, but only ask them to bestow something on a charitable institution, or on the cause of God, and how poor they are; how careful not to be guilty of the sin of extravagance; how anxious not to be generous before being just.

There is a propriety which ought to be observed with regard to dress as well as other things, and it will commend itself to the judgment as well as to the eye. Some young people are the very opposite to Abe; they bestow scanty attentions on their appearance,—how can they think that any one else will pay them any regard? Their appearance is like the index to a book; you see in a minute what the work contains, and so you may generally form a correct idea of the character of an individual by his habitual personal appearance. "Character shows through," is a good saying, and would make a profitable study for most of us; it shows through the skin, the dress, the manners, the speech, through everything; people ought to remember this, and it would have a good influence on their conduct.

A few years after his mother's death his father married again, and removed about a mile further up the hill, to a place called Berry Brow. This village is situated about two miles out of Huddersfield, and is the notable place where "little Abe" spent the greater part of his days. It stands on the brow of a hill which bounds one side of the wealthy and picturesque valley that winds along from Huddersfield to Penistone. It boasts one main street, which sidles along down the hill-side with here and there a clever curve, just enough to prevent you from taking a full-length view of the street; on and down it goes, the houses on the one side looking down on those opposite, and evidently having the advantages of being higher up in the world than their neighbours, until it terminates in the highroad leading out of the village towards Honley and Penistone.

Run your eye down over the breast of the hill, and you have a delightful landscape picture, comprising almost everything which an artist would deem desirable for an effective painting, and a little to spare. There, nearly at the bottom of the gradient, stands the handsome old village church, with its tower and pinnacles, reaching up among the tall trees; and around it, a consecrated enclosure, guarding the monuments of the dead, which are mingled with melancholy shrubs, planted there by hands of mourners whose memories of the departed are fitly symbolized by those perpetual evergreens. On this side and beyond the sleeping graveyard, on either arm, are scattered, in pretty confusion, the houses of those who have retired from the main street for the sake of a little garden plot or other convenience. Now there is some pretence at a terrace, numbering two or three dwellings; then an abrupt break, and houses stand independent and alone as if quietly contemplating the lovely scenery of valley, hill, and forest, which are visible from that spot. Down there in the bottom of the valley, stand those mighty many-windowed cloth mills, whose great flat, unspeakable faces, seem to be covered all over with spectacles, out of which they can look for ever without winking; there the men, women, and children, born and bred in the hills, find honest toil with which to win bread and comforts; while with a twisting course there runs along the wealthy dale a little river, from which these giant mills suck up their daily drink. Across the narrow valley and you are into a dense woody growth, which climbs the hills to their very crown, and sweeps away, mingling with the sky.

To this village the Lockwood family removed; and coming more directly under religious influences, the father very soon became converted, and united with the Methodist Church, along with his wife. This had a great influence on Abe for good; he began to attend the Sunday-school, which was conducted in a room, in what was called the Steps Mill, on the road between Berry Brow and Honley. This was Abe's college; here he began, and here he finished his education; no other school did he ever attend; and for what little knowledge he had, he was indebted to the kindness of those who taught in that school; yet all he learnt here was to read. Writing was a branch of study which Abe thought altogether beyond his power; many times he endeavoured to learn the mysterious art, but after struggling on as far as the stage of pothooks and crooks, he gave up in disgust, and never tried again. He used to say he firmly believed the Lord never meant him to be a writer, or he would have given him a talent for it. Now in this Abe was certainly labouring under a false impression, and underrating his own ability; he was as well able to learn the art of writing as many others in similar circumstances. How many persons have we known who have grown up to manhood and womanhood, before they knew one letter from another, and yet they have commenced to learn, and persevered in the work, until they have attained at least a moderate proficiency, and some even more than that. What Abe lacked more than talent, was a determination to learn; for if he had been resolved, he could have become a good penman as well as others; in this he was to blame, whether he thought so or not. Education can only be had by those who will work for it, and considering its immense value to every person, all who neglect it are blameworthy, and must pay the penalties, as Abe did all through his life.

People talk of great changes in life, and point to periods and events which seem to have turned their whole course into a different channel; but there is nothing that can happen to any individual which will make such an alteration in his life as conversion. Thousands of persons who had been almost useless in the world, after that event have become valuable members of society; others who have neglected and abused their talents and opportunities, have become thoughtful and diligent; others who have lived in riot and sin, wasting the energies of body and mind, have learnt to live at peace with all men, and walk in the fear of God and hope of heaven. Having become new creatures, they have shown it in every line of their conduct. "Old things have passed away, and behold, all things have become new."

It was never more strikingly illustrated than in the case of Abraham Lockwood. For a length of time after he had begun to attend Sunday-school, there was a manifest difference in Abe's manner. Not that he was really living a better life, for he was just as sinful as before, only he was not now thoughtless; he might go to the ale-house with his associates, but he went home to think about it after; he might swear and laugh like the rest of them when they were together, but he was no sooner alone than he felt the stings of a remorseful conscience; he was gradually getting into that state when a man dreads to be alone with himself; there was always something speaking to him from within, and the voice was getting stronger and stronger every week, till sometimes it fairly startled him, and made him afraid; often he would try to run away from it, but it was of no use; the moment he stopped, panting from the exertion, it was there again; many a time he tried to deaden the voice in the deafening noise of the mill, but the more he endeavoured to destroy it, by some mysterious contradiction, the more intently he found himself listening for it; it spoilt all the pleasures of sin by its presence; it was with him night and day; it followed him in his sleep, and was waiting for him when he awoke; it made him miserable. Poor Abe was under conviction of sin; he was tasting the wormwood of a guilty conscience, than which nothing is more dreadful, and nothing is more hopeful, because it is the bitter that oft worketh itself sweet; it was so with Abe. While he was in this state of mind, the Rev. David Stoner came to preach in the Wesleyan Chapel at Almondbury. His fame drew many to hear him, and among the rest Abraham Lockwood. He went partly out of curiosity, and partly in the hope of getting relief to his mind; however, he only came away worse than before; he was miserable, and it now began to show itself to his companions. "Pain will out," like murder. "What's the matter, Abe?" they would say to him. "Oh, nothing particular," he would reply. And then among themselves they said, "Abe looks very queer, he's ill;" then they tried to enliven him. "Come, cheer up, old boy, we'll have a yarn." One would tell some droll tale, and another would say something comical in order to make him laugh; and laugh he did, he must laugh; it would never do to let those fellows know what was passing in his mind; so he laughed loud as any of them, but what a laugh!—how empty and hollow, how joyless and unreal, how unlike his former bursts of feeling!—a got-up laugh, which shewed plainer than ever something was wrong. Abe knew it, and he felt it was of no use trying any longer to keep up a sham happiness, and all the time be in torments from a guilty conscience; he therefore resolved to give up sin and lead a new life. He probably was hastened to that decision by a remark which fell from his father's lips; the old man had noticed for some time that Abe was not in his usual spirits. He would come home of an evening and sit looking into the fire for an hour without speaking or moving; he had given over singing in the house, and he seemed as if he hadn't spirit enough left to whistle to the little bird in the cage; his meals lay almost untasted, and his tea would go cold before he had taken any.

"Come, my lad, thaa mun get thee tea thaa knows," said the old father one evening.

"Yes," said Abe, as he pretended to push something into his mouth.

"What's matter with th'?" the father inquired; "thaa's not like theesen, nor hasn't been for mony a week."

Abe's eyes grew moist, and his chin trembled, but he called himself to order, no babyism now.

The old man, still looking at him, and keen enough to notice the struggle he had to master his feelings, went on to say, "Thaa's poorly, my lad, thaa mun goa to th' doctor, and see if he canna gie thee some'at."

"No earthly doctor can do onything for me," answered Abe; "it's th' Physician of souls that I want. Oh, father, I am unhappy; my sins are troubling me noight and day; I don't know what will become of me: I feel like lost."

"My poor lad, the Lord have mercy on thee," replied the old man, as Abe put on his cap and walked hurriedly out of the house. He went out scarcely knowing why; perhaps to hide his trouble from his dear old father; perhaps to smother his emotions, which were rapidly gaining the mastery over him, or maybe he knew not why,—an impulse was upon him, and it carried him forth into the cool evening air; away he went at a brisk walk from the village in the direction of Almondbury common. Faster and faster he went, faster and faster as if to keep up with the rapid current of his thoughts; the distance was uncounted, the direction unheeded, the time forgotten; one thought only occupied his tempest-torn mind, what must he do to be saved! There are some who would think him very foolish to give himself so much concern on a matter of that sort; but the fact is, Abe was just beginning to act the part of a wise man in renouncing his old habits and declaring for Christ. No human eye followed him on that lonely walk to the common, and no human friend accompanied him; he was alone, the thought pleased him; he looked around all over the face of the common, but no person was visible. Abe was alone with God, and he determined to speak to Him, and tell Him all his burden of sorrow. Near to where he stood, there was a large tree growing, whose lofty branches were uplifted to heaven; it stood just at the bottom of a little grassy slope of four or five yards deep, and close to the side of a small clear stream of water, which ran gurgling and rippling along, moistening the great roots of this tree; it was here, under its spreading boughs and gnarled trunk, Abe found a place for prayer. Down on his knees he cast himself, and his first utterance consecrated that spot as a closet, "God be merciful to me a sinner!" He only needed to utter the first cry, others followed in rapid and earnest succession, till all the restraints upon his soul were broken asunder, and in an agony he wrestled for salvation. Hour after hour fled by; twilight gave place to darkness; lights shone from the cottage windows away on the hill-sides; distant watch-dogs answered each other's unwearying bark; neighbours in the village yonder, stood chatting by their open doors in the quiet night, and in many a cottage home hard by, children and grown-up men sat quietly eating their last meal before retiring to bed: but none of them knew that out on Almondbury common, at the foot of a great rude tree, a man, one of their neighbours, a sinner like themselves, was praying. No, no, they didn't know: there is many a thing goes on of vital interest to us, which even our nearest friends know nothing about; but there are other eyes, invisible, which look down upon us from their starry heights seeing all our ways. So they looked, while Abe wrestled for liberty. His chief snare at this time was, that he was too bad for Christ to save; it was a terrible thought to him, and had so much of seeming truth in it, that he at times almost despaired; then again he remembered that he could not be too bad for Christ to save; no, HE could save to the very uttermost all that came unto Him; Abe tried to believe that with all his heart, and as he struggled against his doubts and fears, faith grew stronger and bolder, then in a moment the snare broke, the dark cloud over his soul burst, and out from the cleft there came a voice, which thrilled his whole being. "Arise, shine; for thy light is come, and the glory of the Lord is risen upon thee." "Glory! Glory!! Glory!!!" burst from his enraptured lips; his "light was come,"—what a light! a soul full, full of the light of Divine smiles. No wonder Abe forgot everything else, in the joys of that ecstatic moment. He leaped, laughed, wept shouted the praises of God till his voice might have been heard far away over the waste, as he turned his steps towards home that night. "Why, he's made a bron new man o' me. I hardly know mysen. Hallelujah!"

He was not long in reaching home, nor long in letting them know, when he got there, what a change had come over him. In he went, with a face shining in all the brightness of his new-found joy. "He's made a bron new man o' me! He's made a bron new man o' me. Hallelujah! Hallelujah!"

The change in his whole manner and appearance was so great, that his poor old father was at first alarmed lest he had gone wrong in his mind; but Abe assured him he had just got right, and by God's help he meant to keep so.

Oh, if Abe had just got right by the wonderful change which God had wrought in him, (and who can doubt it?) how many there are in the world who are all wrong, living the wrong life, striving for the wrong things, going the wrong way, and running towards the wrong goal! Oh, how many are spending this short life in the pursuit of things which are worthless and worse; sacrificing their souls' best interests for the brief indulgence of sinful tastes, or spending the rapidly accumulating years of their life in dark indifference to eternal things!

The escape of one such sinner as Abe from the captivity in which the ungodly are all held, may for a brief hour excite remark, perhaps a desire for liberty, too, in the minds of some others; but these good desires are often only of short duration, they die where they were born, and almost as soon, and the soul returns to its former state; the sleeper slumbers on; the drunkard drinks harder; the swearer blasphemes more fiercely; the libertine indulges in greater excesses; and all these hordes of ungodly men push on again down the broad and easy incline to the pit of Hell. Do people know that the end of a sinful life is Hell? Do people believe? Why, then, do they press their way down to such a place?

"Hast ta yeard th' news?" said one neighbour to another, on the morning following the happy event narrated in the preceding chapter.

"What news dost ta mean?"

"Aye well, thaa has'n't yeard what happened last noight; doan't look so scared, mon; th' mill worn't burnt daan; nor th' river droid up; nor Amebury (Almondbury) common transported; but some'at stranger nor that."

"Why, whatever dost ta mean?"

"I mean that Abe Lockwood's been and gotton converted last noight, and he's up and off to his wark this morning, shaating and singing like a madman."

"Abe Lockwood converted!" replied the other in astonishment, and pausing between each word, as if to realize his own sayings. "Nay,—I'll niver believe that."

"It's as true as thaa and me is here; his father telled me he wor aat hoalf at noight on Amebury common, crying and praying by a big tree roit, and he gat converted there all alone; and when he came into th' haase, his face was shining like th' moonloight."

Here was news for the people of Berry Brow, and how it flew from mouth to mouth, and from house to house, till, before many hours, almost every person in the village knew of the wonderful change which had come over Abe. Some doubted the report,—"It canna be soa," said one; another "would sooiner think of ony one than him; he's making game on't, I'll lay onything." Others thought, "If he's turned religious, it's no matter; he'll be as wild as iver by th' week-end." It was out of all character for Abe Lockwood to be anything else than he had been, a rollicksome, laughing, drinking, ungodly young man.

How often people talk in this way, when they hear of some giving their hearts to God; "They won't stand long; give them a month, and it will be all over," and such like injudicious things are said even by some who ought to have more discretion. People talk without thinking, or make such statements to cover their own shortcomings and faults. Why shall they not stand? are they in the keeping of a feeble or fickle Saviour? isn't His grace as strong as sin? is not Jesus always mightier than the devil? and have not millions of the greatest sinners who have found the Lord, stood firm against the snares of the world, and all the devices of the wicked one? "He won't stand," is an old lie, which every young believer must set at defiance. "Stand fast, therefore, in the liberty wherewith Christ hath made us free, and be not entangled again with the yoke of bondage."

"Weant I stand," said Abe, "then I'll fall, but it shall be at the feet of Jesus." Ah, that is the best way to stand; fall at the feet of Jesus. It may seem a paradox in terms, but it is not in truth; it is on the Apostolic principle, "When I'm weak, then am I strong." So poor Abe laid himself down in order that he might not fall, and this is a plan which others might try in times of spiritual peril, and so escape the danger of backsliding.

Among others who canvassed the subject of his conversion were his old companions. One had gone out from among them that they were sorry to lose; he was such a merry fellow; his face was always sunny; his comical sayings had filled the public-house with roars of laughter many a time; he could sing a song better than any of them, and he was always ready; he was open-handed with his money whenever he had any; and indeed, he possessed most of the qualities which make a man a favourite among boon companions. His going out left a blank which was more felt than seen; a vacant seat in a public-house is soon filled; so if Abe was not there to occupy his own place someone else was; but no matter who of his old associates were present, everyone felt Abe was absent, and couldn't help showing it in some way.

They had all observed that he had not been exactly himself lately; "a little down in the mouth," and very quiet at times; but never divining the reason, they had put it down to the wrong cause, or thought very little about it; and then Abe had so often roused himself out of these moods of mental abstraction by taking "another glass," and having another song, that he had kept his companions completely ignorant of the work which was going on in his mind. So now it burst upon them like a gun-shot; they were amazed; but the devil seldom deserts his victims at a time like that; it would not be safe, he might lose some more of them; he comes to their help and counsels them as to their conduct. "Well," says one of them as they gathered in their usual place of resort one night, "I s'pose Abe Lockwood will be gone to prayer-meeting to sing Psalms with the old women," at which the whole company burst into a loud laugh at Abe's expense, and yet it cost him nothing, which was more than any of them could say of the drink they consumed that night.

Abe Lockwood had left them,—he was a changed man; he had been converted on Amebury common; he had turned off into an entirely different course from theirs; he was a better man than any of them: many such thoughts as these would obtrude themselves on the minds of his former friends, and linger there in spite of all their efforts to keep clear of them.

Some time elapsed before any of these old associates were brought into immediate contact with Abe; whether they purposely kept out of his way, or he out of theirs, is not easy to say; perhaps both would be correct. He no doubt felt safest and happiest away from his old companions and everything which reminded him of them; they, too, had a misgiving that whenever they did meet Abe, he would say something that might make them uncomfortable; for they knew he would not beat about the bush, he would tell them his mind about their ways: so on the whole it was best to keep out of his way as long as they could.

Meanwhile, Abe was gathering strength day by day, for he was living in the constant spirit of prayer, which is the way to be strong. Night after night, a lone man might be seen kneeling at the root of a great tree on Almondbury common, pouring out his soul in prayer to God, until that spot became to the new convert the very gate of heaven; and for long years after, when Abe was established in the faith, he still frequently found his way there to pray; during the whole of his subsequent life, he never passed that spot without turning aside to hear what the Lord would say to him. Many of the most delightful times he ever had were experienced at the foot of that tree; and a visit there, where he breathed the native air of his spiritual life, invariably brought the glow of religious health to his soul.

As weeks and months went by, the people of Berry Brow became used to the fact of Abe Lockwood's conversion, and it ceased to excite any particular remark, except such as might pass between neighbours on seeing him go by.

"Aye, mun, what a change is in yon lad," one would say.

"You are roight naa," would be the response.

"He wor as big a rake as ony i' th' parish a few months sin'; I'd never ha' thowt o' Abe Lockwood turning religious."

"No, nor me noather, but we niver know what 'll come to us."

"No,—gooid-noight."

One day Abe and a former companion of his met full in front; there was no sliding away on either side,—they must speak. Both of them experienced a slight nervousness at first, but Abe plucked up courage and came boldly on.

"Naa, lad, haa art ta?"

"Oh, why, middling like, haa's yersen?"

"Aye, mun," said Abe, "it gets better and better, religion is th' best thing i' th' world; it's made me th' happiest chap i' Berry Braa."

"Why, thaa looks merry," said his companion.

"I is merry, and only wish thaa wor like me," and then Abe went on in his own simple, earnest, and homely manner to preach Jesus to his friend; and before they parted, the man had proof enough that Abe had found a better way of living than his former one.

Many a time, as weeks and months rolled by, he was thrown for a short time into company with one or another of his old yoke-fellows in sin; and often did they endeavour to lead him back again into the ways and haunts he had forsaken; but no, no, he was not to be moved out of the new path which he had taken for time and for eternity.

Abe was a very plain-spoken man, and sometimes used phrases which were anything but refined, but this was compensated for by their good sense. Sometimes, when Satan was tempting him to give up his religion, and return again into the ways of sin, he would exclaim, "What! give up my blessed religion and return to thy swill-tub agean; I should be a great fooil to do that,—does th' want to mak' me like an owd saa (sow), that's been weshed, and then runs back into t' muck agean; nay, thaa's rolled me i' sin lang enough; I'm thankful to be aat o' thy mud-hoil, and by the help of God, thaa'll get me there no maar." Then perhaps, when in conversation with some unconverted neighbour on the all-absorbing theme of religion, he would break out, "Aye, mun, yoa doan't know haa grand it feels being weshed, weshed i' th' blood of th' Lamb. I wor that mucky, all th' waiter i' Holmfirth dam couldn't mak' me daacent, but a drop of His blood did it in a moment. Glory to God!"

Ah! the precious blood of Jesus can make the foulest clean; no matter how long or how deep sin has reigned in his heart, Jesus is able to remove it entirely, and bring in His grace and peace. He is a wonderful Physician, there is none like Him; He has never been baffled yet, though for nearly two thousand years He has been called to exercise His power on the outcasts and incurables of our race. He knows the disease with which every poor sinner is afflicted, and He also understands the cure; sinners who have long been given up by themselves, and others as well—poor, abandoned things, who have been kicked out of all orderly society, and left to rot in the moral filth of the streets, or die in the sewers of iniquity, have been found by Him, lifted out of the mire, washed in the streams of His grace, clothed in His righteousness, and made fit to sit among princes.

"Jesus, Thy blood and righteousness

My beauty are, my glorious dress;

'Midst flaming worlds, in these arrayed,

With joy shall I lift up my head."

As soon as Abe Lockwood found the Lord, he felt it was his duty and privilege to unite himself with the people of God, and he therefore lost no time in seeking membership.

THE METHODIST NEW CONNEXION at that time had no chapel in Berry Brow, but conducted prayer-meetings, and held a weekly class in a cottage somewhere in the village. Abe knew these humble, earnest people, and felt drawn towards them by strong sympathy; he was sure he could feel at home among them, and they would be of very great assistance to him in building up his Christian character. What made him all the more willing to throw in his lot among them, was the fact that some of them had frequently shown an interest in his spiritual welfare before he became converted, and had endeavoured to induce him to attend their meetings; and now when they all knew the change that had taken place in him, they were the first to go after him and offer him the right hand of fellowship,—so he at once united himself heart and hand to their little band.

It would be well if that zeal and watching for souls, which characterized the early Methodists, were more frequently displayed among their successors; how many who are now merely hovering outside the Christian Church, afraid to run after the pleasures of sin, ashamed to avow themselves in quest of salvation, would be brought to decision, and enabled to lead a happy and useful life.

There are many thus hanging on the skirts of almost every Church, waiting to be gathered up, and shame on the members who quietly and indifferently permit this! It must not be; men's souls are too precious to be trifled with; they have cost too much for us to allow them to starve and die on our doorstep; open the door, put forth your hand, draw them kindly, but firmly, into the family of the Lord; few of them will have heart to resist such efforts to save them; but if they do, then go out to them, stay with them, persuade and entreat them, pray for them, pray on and on, and in the end you will prevail. We want more of this watching and waiting for souls in Churches; may God lay these souls on our hearts!

Abe became a member of the Methodist New Connexion in Berry Brow when it could scarcely be considered a Church, inasmuch as neither Christian sacrament nor preaching services were established there: it was merely a class belonging to the society in Huddersfield. That class, however, was the living germ out of which was in due time developed a strong and flourishing Church, having now a commodious chapel, and also an excellent Sunday School, in which are growing up hundreds of interesting children, who will some day be a blessing to the neighbourhood, and an honour to the Church of Christ.

To this little band of disciples our friend Abe was a most valuable addition; not that either then or afterwards he brought them wealth, for he was always poor, but because he contributed a zealous, praying spirit, and encouraged the little flock to fresh exertions.

He was no sooner admitted among them, than he began to exercise his talents in prayer-meetings, and although he sometimes got confused in his utterances, he didn't care much, for he used to say, "Th' Lord knows what I mean, and He can soort th' words, and put 'em in their roight places; bless Him, He can read upsoide daan, or insoide aat." But time and constant exercise made a wonderful improvement in this respect, and as Abe felt less difficulty in uttering what he meant, he also experienced less restraint of spirits, and began to show himself in his own peculiar style.

He had a way of responding to almost everything that was prayed for, and interlacing remarks, and sometimes explanations, when he thought them necessary. Possibly these comments were more to himself than for any one else, and were often made quite unconsciously—a kind of thinking aloud. A rather amusing instance is given where Abe's notes of explanation were called forth. It appears that one night the weekly prayer-meeting was conducted as usual in the cottage of one of the members. Abe was there among a number of others, and they were having a very lively time together. As one after another engaged in earnest intercession at the throne of grace, the feelings of all present became very elevated, and they shouted for joy. At length, while one brother was praying, another got so happy that he could remain on his knees no longer. Springing to his feet, therefore, he began to jump, and in one of his upward movements he brought his head into sudden and violent contact with a basket of apples, which hung by a nail to the ceiling; the basket oscillated a time or two, then slipped over the head of the nail, and spilt its contents on the head of the man that was praying. This singular event was deemed by him a sufficient reason for suspending his exercises, and opening his eyes to ascertain the cause. As soon as Abe observed the suspension of prayer, he exclaimed, "Pray on, lad! it's nobbut th' owd woman's apple-cart upset," on receiving which timely exposition of the state of things, the good man resumed his intercessions, and the meeting returned to its former happy flow of feeling. The time came when Abe was looked upon as the life and soul of these little meetings: his quaint sayings, his earnest prayers, his happy experience, always animated and strengthened those who were present, and made the meetings real means of grace. Then Abe was always there; he could be relied upon whoever might fail, so that they all began to depend upon him, look to him, and follow him, till, almost without knowing it, he had become greatly responsible for the spiritual life of the little flock in Berry Brow, and mainly instrumental in laying the foundations of the cause there, which has now grown to very interesting and influential proportions.

Marriage is a most important step in the life of any person; happiness or misery in this world depend on it far more than many young people think. Nothing demands more careful thought, discrimination, and prayer, than the choice of a life partner. Especially professors of religion should consider this, lest they be tempted to break the apostolic injunction, and become "unequally yoked together with unbelievers."

It is painful to see how little regard is paid to this subject by some who profess to be disciples of Jesus, and yet allow their affections to be centred upon someone of the world. Pleased by an attractive appearance, winning manners, or something else of this kind, they are beguiled away beyond the line of demarcation which divides the church from the world, until, by-and-bye, they consummate a union of the flesh, where there cannot be a union of spirit, and light and darkness make a poor attempt to dwell together.

Self-deception is a very easy thing in matters of this sort; it is seldom difficult to find arguments in favour of that which the heart is set upon. The one that knows the Lord, will pray until the other is brought to him; neither will be guilty of casting the slightest hindrance in the way of the other, etc., etc., but how often have these pretty delusive devices been cast to the winds, or broken to atoms like glass toys in after life, and their framers made to pay the bitter penalties of disappointment, regret, and even backsliding for their early transgressions? The selection of a husband or wife is not a question of mere sentiment or feeling, but one which involves an important principle. In making it, we should take God into our counsel, and abide by His decisions. A young man who was a member in one of our churches once opened his mind to me on this subject; he very much admired a young person whom he mentioned; he said he had been praying about marriage with her for some time, and had left it entirely with the Lord, but said he, "I must have her, come what may." Prayer with submission like that is only a solemn mockery, and is sure to meet with its deserved reward. If we ask God to guide us, we must permit Him to lead; and whether the outcome suit our feelings or not, we may rest assured it will be for our ultimate welfare.

In the choice of his wife Abe Lockwood was wisely led, as a long and happy life together afterwards proved. It appears that soon after his conversion, Abe, who was always fond of singing, joined the choir of the Huddersfield Chapel. That was the age before organs were thought of in Methodist places of worship; other musical instruments obtained in those good old times: fiddles and bass viols, clarionets, flutes, hautboys, cornets, trombones, bassoons and serpents, delighted the ears and stirred the souls of our forefathers with their sacred harmony. Grand old times those were too; there was some scope for the musical genius and taste of men in those days, when if a man could not manipulate the keys and evoke the religious tones of a clarionet, he might vent his zeal in the trombone, or make melody on a triangle; then, the orchestra was a kind of safety valve, where zealous men might exert their powers until they were bathed in perspiration and exhausted. In those days the musicians were men of considerable influence in the public services; they could any time keep the congregation waiting while they tuned up to harmony, or while the first fiddle mended his string, or rosined his stick. True, a little accident would occasionally happen in the midst of the service, such as the falling of a bridge, but nobody was hurt, it was only a fiddle-bridge; a nervous preacher might be just a little startled by the thwack behind him, and a few of the light sleepers might be suddenly aroused from their deep meditations to venture an inappropriate response; and other little matters might occasionally happen, as when some conspicuous instrument became excited, and played somewhat sharper than the others in the band, thereby giving a twinge of neuralgia to a few sensitive persons in the congregation; but then they shouldn't be so sensitive,—others were not, not even the musicians, and why should they? Besides, all these things, and a great many more, too numerous to mention, helped to throw some variety and feeling into the proceedings, and frequently afforded matter for lively conversation when the people came out of chapel. Can any one wonder, therefore, that the musical taste of the past should steadfastly resist every effort to bring about a change in the composition and conduct of our chapel orchestras?

Abe lived and flourished as a singer in those good old days, and it was one of his greatest enjoyments to take his place among the singers in the old High Street Chapel, and raise his alto voice in honour of Him "whose praise can ne'er be told."

But there was another little pleasure which Abe very much enjoyed after the services, and that was to walk home in company with a young woman, one of the singers, too, named Sarah Bradley. She lived at Berry Brow, and was a member in the same class as himself; she was about his own age, and while she made no pretensions to beauty, she was what the neighbours called "a real bonny lass." Abe thought her the nicest and handsomest young woman he ever gazed upon. She was the very light of his eyes, and her conversation was real music to him; he was so charmed with her, that he would run a mile any time to look at her bonny face; his affections were entirely won by her,—which was, by the way, no little pleasure to herself, inasmuch as she regarded him with very similar feelings.

There seemed quite a propriety in the mutual affection of these two young people; it was, to say the least of it, quite patriarchal that Abraham should love Sarah; but whether Abe ever thought of Scripture precedent for indulging such sentiment or not, one thing is certain, he followed the example set by one of old, and took Sarah to be his wife.

The wedding took place on the 10th May, 1818. There was no extravagant or improvident display on the occasion. Abe did, however, put on his best clothes, and stay from work for that day; and Sally, as he now began to call her, appeared in a stuff dress, that served as her Sunday frock for a long time afterwards. A few friends attended the ceremony by invitation, and a few more of the gentler sex just dropped in as they were, to see that the affair was properly done, as well as to indulge a pardonable liking for that kind of religious service. Some of them probably never attended a place of worship except on such interesting occasions, or in connection with a christening. Here, then, was an opportunity for these people to indulge their select tastes, and they failed not to embrace it.

The ceremony over, the happy pair came forth to be pelted, according to custom, with rice and old shoes, symbolizing the wishes of the bystanders, that all through life they might enjoy plenty, prosperity, and good luck. Then came the walk home through the village arm-in-arm; Abe nervous, and Sally blushing under the kind yet familiar congratulations of their friends.

The day was spent in a quiet, happy manner among the members of the wedding party, and nothing particular occurred until a little before seven o'clock in the evening, when all at once Abe got up, reached down his hat, and prepared for going out.

"Where's ta going?" someone asked. Sally was looking at him rather curiously, as if she could not understand his movements.

"Why," said he, "doant yoa know it's my class noight?"

"Well, what by that? they'll niver expect thee t'-noight."

"Oh, but I mun goa."

All present laughed right heartily at his remark, and one of them said, "Nay, lad, thaa mu'nt goa t'-noight and leave th' wife and all th' friends; foak 'll laugh at thee."

"Let 'em laugh; th' devil 'll laugh if I doant goa, and foak 'll laugh if I do. I'm sure to be laughed at, ony way; I'll goa." He looked at Sally for a moment, and saw, at any rate, that she understood him, although she did smile; so opening the door he shot out, saying, "I shalln't be long, lass." He went to his meeting just the same as usual, and no matter to Abe if his leader and class-mates were all surprised to see him, he was quite as comfortable as if a wedding were an every-day event with him. Abe's maxim was to allow no hindrance to stand in the way of his duty to God. Christ came first with him, his wife stood next; and as he began, so he continued through all his marriage life.

This worthy couple began housekeeping in a very humble way,—it was really "love in a cot,"—and with very limited means; but they were happy in each other and happy in God. Sally made a good wife, and contributed greatly not only to her husband's happiness, but also to his usefulness in the Church. Too much can hardly be said in honour of that humble and devoted woman, whose great study, during all their life together, was to make home most attractive to her husband, and his path, as a Christian, easy. When the charge of a large family came upon them, she cheerfully and studiously undertook the multitudinous little offices and cares that always come, under the circumstances, and threw as little as possible upon her partner in the house; for she used to say, "Dear man, he has enough to do to find us in bread, without troubling to put it into our mouths." Ah, and when there was scarcely even bread for them, which often happened in those hard times, she would scorn to murmur at her husband, or utter a word that seemed like a reflection upon him; no, she was united to him "for better, for worse," and she bore whatever came with a noble and patient fortitude. Many a time, however, had she, poor thing, to go to her heavenly Father with her cares, and vent her anguish in a shower of tears, which Abe never saw, and perhaps never heard about; and when he came home from his day's toil, she always tried to have a cheerful face and a smile for the dear man.

Besides attending to the duties of her household like an exemplary wife, she was often engaged in her own house burling cloth for the manufacturers, by which means she earned a scanty addition to their income. Frequently when Abe retired to rest, she would pretend she was scarcely ready, and then, after he had fallen soundly asleep, she might be seen by the dim light of a candle, hour after hour, till far away into the morning, picking at the cloth in order to get it finished; then, tired in body and spirit, she would throw herself down to sleep, and recruit for the struggles of another day. Whenever the children had any new clothes, which was too seldom, they were made by her hands. Necessity had taught that thrifty little woman many a thing, until in time she learnt not only to earn and make their clothes, but even to mend their shoes herself. Many a homely patch did she put upon their clogs, and many a sole, too. She had fingers for anything, and never stood fast whatever came in her way. While many others in her position would have sat wondering and despairing, she arose, stuck to her task, got it done, and if she had any time, she did the wondering afterwards.

Go when you would to Sally Lockwood's house, it was always tidy, and there was a clean chair for you to sit upon. Although their clothes were coarse, and patched with more pieces, if not more colours than Joseph's coat, the children were always clean, though many a time they hadn't a change of garment to put on. What that means in a large family, the thrifty wives of hard-working men will understand. The frequent late washings on Saturday nights, when the little ones were gone to bed, were something wonderful, and what was even more remarkable still was, that Sunday morning found their things all clean and dried, ready for them to go to school like other children.

Ah, Sunday morning, beginning of the day of rest,—how welcome to poor Sally after her hard week's toils and anxieties! When the family were gone to school, and her honest man was somewhere at work in the Master's vineyard, she could slip on her bonnet and shawl and just run into the preaching service close by, and gather strength and encouragement from the earnest prayers and humble exhortations of those men whom God had found in the quarry, at the loom, in the mine, or at the lapstone, and sent forth Sunday by Sunday into the villages to preach a homely gospel to the poor, and comfort to His flock.

And thus she struggled on from week to week and year to year, bearing with uncomplaining fortitude her own burdens, and lightening, when she could, those of her husband; setting an example of patience, industry, and piety before her family, thus by example, as well as precept, training them up in the fear of the Lord.

No wonder that one of Abe's greatest boasts was his wife. Next to his Lord and Master, whose praise was ever on his lips, Sally came in for honours. "Aar Sally," which was the usual homely and affectionate way in which he spoke of her, was, humanly speaking, his sheet anchor; her word was more to him than counsel's opinion, and considerably cheaper; what "aar Sally" said was Act of Parliament in that little house. She had gained a power there which was due to her, and which she exercised for the benefit of the whole.

"Aar Sally" often figured in Abe's sermons, and always in a favourable light, which shows the estimation he cherished for the worthy partner of his joys and sorrows. Although, as years went on, time, labour, and anxiety made their unmistakable impressions upon her, she was always bonny to Abe; and up to the last, when he was a feeble old man, and she was stricken in years, he used to say, "Aar Sally is th' handsomest woman i' th' world." It is possible that this assertion may have been the occasion of some tender disputes in some quarters, but nothing was ever heard to that effect, and no one ever openly ventured to enter into competition with Sally for the honour which was ascribed to her, so that she was, without dispute, the handsomest woman in the world.

"Handsome is he, that handsome doth,

And handsome, indeed, that's handsome enough."

Beauty is only skin deep, but goodness goes right through. Sally was a good wife, a good mother, a good Christian, and now her soul rests in the presence of Him "who is fairest among ten thousand, and altogether lovely."

When Sally gave her hand to Abe, we have said it was "for better, for worse," but she soon found there was a good deal of "worse" in it. What a sad thing it seems that nearly all the pretty castles which young people build for themselves in the air, should so soon fall to pieces! What a wonderful contribution it would be to the science of architecture if the ideas of these erections could only be realized in substance! Ah, but such is the nature of things, that castles without foundations can only be built in the air, and commonplace men are unable to do that. It has been a great disappointment to the constructors of these buildings, that they have never been permitted to spend a single hour in them; so very attractive as they looked, too, covered all over with gilt and flowers, and furnished in a style that out-rivalled the pictures of the "Arabian Nights."

A real prince might be happy if he could only get in. Some of them have taken years to bring to such a state of perfection; now, a little addition is made here, and then a slight alteration there, until it is finished, and the happy pair set off to take possession of the fairy palace. But they never enter it: the more eager they are to get in, the more confused they become as to the position of the doorway; one thinks it is at the front, the other fancies it must be at the side, and every time they go around the house seeking the entrance, by some mysterious means the house seems further from them, and another effort is necessary to reach it. How tiresome! but they must be in, for storms begin to gather, and they are not prepared for them; the wind blows and whistles as if calling up other evil forces for mischief; night, like a dismal monster in a black cloak, and barefooted, is coming on; the pretty castle is fading out of view among the darkening objects around,—quick! quick! we must be in, for the hour is wild. On they hurry, and in their haste, they find an open door and enter; there is shelter and rest for them, but when daylight comes they open their eyes, and lo, the lovely castle is gone, and the home is a weaver's cottage!

There is no doubt that Abe and his young wife played their part at castle-building, like most others in their position, and like others they found it a great deal easier to erect than inhabit. However, there is this to be said for them, which cannot be said for all, they had fortitude to endure their lot without complaint; and though their castle was but a very little cot, it was commodious enough to hold them, and left room for a variety of joys and sorrows as well.

At the time when they were married, Abe was working as a cloth-finisher in a mill near Almondbury common, but not long afterwards, the work at this place failed, and he, with a number of others, was thrown out of employment. This was a sore reverse, for which they were ill-prepared. If trade had been good in the neighbourhood, he could easily have obtained work under some other master, but alas! the reasons which induced his employer to discharge his men, operated with others in the same way, and consequently left no opening for Abe.

What was to be done? Ah! that was the inquiry which often passed between Abe and Sally in their little home. The bread-winner was stopped, then the bread must soon stop, and then would come a dark period, that is, a full stop.

In their day of trouble they carried their case to the Lord, and asked His fatherly aid; many a time did they go together to vent their burden of trouble in His ear, and obtain strength to endure their trial. One day, after Abe had been in this way asking help and counsel of the Lord, he came and sat in a chair at one end of the table, while his wife sat near him, quietly stitching away at an old garment she was mending. For a few minutes neither of them spoke; by-and-by Sally looked up from her work to thread her needle, and their eyes met. She had a very sad look upon her face, for her heart was full of trouble, and she was just ready for what she called "a good cry;" but the moment she saw his face, which was covered all over with a comical smile, she caught the infection, and burst into a laugh,—a kind of hysterical laugh that had more sorrow than mirth in it. She laughed and he laughed, one at the other, till tears came from the eyes of both, and their poor sorrow-sick hearts seemed as if they would rise into their throats and choke them.

"Naa, lass, what's matter with the'?" at length exclaimed Abe.

"Why, it's thee made me laugh soa."

"Me, what did I do?"

"Ay, thaa may weel ask," said Sally, wiping her eyes with her apron. "Why, thaa looked a'most queer enough to mak' a besom-shank laugh; thaa's made my soides ache."

"Well, it 'll do thee gooid; thaa wants a bit of a change, for thaa's had heartache lang enough," responded her husband.

Sally resumed her work, but said nothing; her only response was a deep-drawn sigh. A few moments of silence again ensued, which Abe broke by saying, "Sally, haa would the' loike to see me wi' a black face?"

"What's 'ta say?"

"Haa w'd th' loike to see me wi' a black face?" repeated Abe.

"What art ta going to blacken thee face forr doesn't th' like thee own colour? what does ta mean?" inquired Sally looking at him.

"I mean," replied Abe with great earnestness, "that I'm gooin to turn collier."

"Nay, niver, lad!" cried his wife in dismay.

"Why, it's only for a bit till things brighten up in aar loine, and then thaa knows I can get wark at th' mill agean."

Poor Sally wept in earnest now; it was a shock to her feelings that she was not prepared for. At length she said, "I niver thought of thee goin daan a coil-pit, thaa isn't used to it, and thaa 'll happen break thee neck."

"Nay, not soa; I've warked mony a day in a coil-pit," said Abe. "Bless thee, my lass, when I were nowt but a bairn I used to wark i' th' pits; niver fear, I'm an owd hand, I can do a bit o' hewing wi' ony on um." And then when Abe saw the first burst of feeling on his wife's part was giving way, he went on to make good his position: "Thaa knows I mun do some'at, and there is nowt else I can see to turn to, and it 'll keep us going till I can get back to my own wark; we mu'nt be praad in these times, thaa knows. I'll promise to wesh th' black dust off my face every day," said he, laughing, and trying to get her to do the same. "Cheer up, my lass, we mun look th' rock i' th' face."

"Ah, th' Lord help us," responded Sally.

"Naa I like to year thee say that," said Abe, "because I believe it was the Lord that put it into my yead, for I niver thowt abaat such a thing till I were telling Him my troubles just naa, and then it came to me all in a moment, like as if someone spake to me, and I says, I'll goa."

And he did go, and he got employment in one of the coal-pits in the neighbourhood, where he received so much per week as wages, and a lump of coal every day as large as he could carry home, as a perquisite. Of course he took as big a lump as he could manage, and sometimes he was tempted to overtax his strength. Many a time poor Abe had to stop on the way home, lift the coal down from his head, where he usually carried it, and rub the sore place; and many an expedient, in the way of padding, had he to resort to, in order to compensate for the soft place which nature, so prodigal in her gifts to some, had denied him. However, day after day he struggled along under his dark and heavy load, each day finding himself oppressed by another weight—of coals.

The new work was hard and trying to him, but he kept toiling on, and patiently waiting for the time when his heavenly Father would open up another sphere for him; meanwhile there was this consolation, that his toils kept fire in the hearth, and bread in the cupboard at home, and knowing this he was happy. He didn't envy any man his wealth, or his ease; he many a time on his way home, with the lump of coal on his head, was happier than the rich employer who passed him in his carriage; he had no ambitious schemes with which to harass his mind, his highest object was to glorify God in a consistent Christian life, and try to lead others to do the same. When his day's work was ended, he could lift his burden on his head, and journey homeward with a light heart; the only weight he felt was upon his head; many a day he came over the ground singing, certainly under a difficulty, but no matter, he did sing. Abe was an alto singer in the chapel choir, but in these homeward songs one would almost fancy he would have to take another part, as the lump on his head would render it rather inconvenient for him to reach the higher notes; ground-bass would be more in keeping with his circumstances, and probably he himself was more inclined to sink than soar; be that as it may, he sang and trudged along home, and any one that met him, might know he was happy as a king, aye, and happier than many.

Abe had not long laboured in the coal-pit before all about him began to feel he was a good man. He did not hide his light from anyone, masters or men, and though they may not have followed his godly example and Christian counsel, they all respected him for his pious and consistent life among them.

It so turned out that one day the foreman ordered all the men to stay and work overtime at night, in order to complete some important matter which they had in hand. This was a terrible blow to Abe, for it was his class-night, and he had never yet missed that means of grace, nor would he, if he could by any possibility get there; but now, what was he to do? He felt it was his duty to obey his master, and take his share of the extra work if required; on the other hand, his heart yearned for the fellowship of saints: how dear that little classroom seemed to him then. All the day his mind dwelt upon the subject; he fancied his own accustomed seat empty, and his leader and classmates wondering why he was not there; he prayed earnestly for deliverance from this snare, and yet saw no way of escape. Evening came, and the usual hour for leaving work, but no bell rang the men out; on they all went at their task, and Abe along with the rest, yet all the time he was groaning in spirit; half an hour passed away, when the foreman came in. He was a hard, resolute man, that seemed to have neither fear of God nor devil before his eyes. "Abe Lockwood," said he, "isn't this thy class noight?" Abe looked up in an instant, and replied, "It is." "Drop thee wark this minute and go then; if I'm going to hell, I won't hinder another man from trying to get to a better place," and before Abe could find time to thank him, he was gone again. In a twinkling Abe was out of the place, and away over Almondbury common, like a fleet hound just slipt from the leash. He went to his class-meeting and was very happy there, but he did not forget in his own happiness to pray for the man who in this instance had bowed to the better spirit within him, and shown him such a mark of favour.

There is a heart in every man, however hard he may be, and when once the Spirit of God assails that heart, He may break it, or at least reason it into submission. We don't know all the power that God has, nor the many ways in which He can exert that power on the minds of men; we often hinder its operation by our want of faith. O Lord, increase our faith! Then "all things are possible to him that believeth."