Title: Rimrock Jones

Author: Dane Coolidge

Illustrator: George W. Gage

Release date: December 10, 2006 [eBook #20076]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

| CHAPTER | |

| I. | THE MAN WITH A GUN |

| II. | WHEN RICHES FLY |

| III. | MISS FORTUNE |

| IV. | AS A LOAN |

| V. | THE PRODIGAL'S RETURN |

| VI. | RIMROCK PASSES |

| VII. | BUT COMES BACK FOR MORE |

| VIII. | A FLIER IN STOCKS |

| IX. | YOU DON'T UNDERSTAND |

| X. | THE FIGHT FOR THE OLD JUAN |

| XI. | A LITTLE TROUBLE |

| XII. | RIMROCK'S BIG DAY |

| XIII. | THE MORNING AFTER |

| XIV. | RIMROCK EXPLAINS |

| XV. | A GAME FOR BIG STAKES |

| XVI. | THE TIGER LADY |

| XVII. | AN AFTERTHOUGHT |

| XVIII. | NEW YORK |

| XIX. | WHERE ALL MEN MEET |

| XX. | A LETTER FROM THE SECRETARY |

| XXI. | THE SECOND ANNUAL MEETING |

| XXII. | A FOOL |

| XXIII. | SOLD OUT |

| XXIV. | THE NEW YEAR |

| XXV. | AN ACCOUNTING |

| XXVI. | A CHAPTER OF HATE |

| XXVII. | THE SHOW-DOWN |

| XXVIII. | A GIFT |

| XXIX. | RIMROCK DOES IT HIMSELF |

The peace of midday lay upon Gunsight, broken only by the distant chang, chang of bells as a ten-mule ore-team came toiling in from the mines. In the cool depths of the umbrella tree in front of the Company's office a Mexican ground-dove crooned endlessly his ancient song of love, but Gunsight took no notice. Its thoughts were not of love but of money.

The dusty team of mules passed down the street, dragging their double-trees reluctantly, and took their cursing meekly as they made the turn at the tracks. A switch engine bumped along the sidings, snaking ore-cars down to the bins and bunting them up to the chutes, but except for its bangings and clamor the town was still. An aged Mexican, armed with a long bunch of willow brush, swept idly at the sprinkled street and Old Hassayamp Hicks, the proprietor of the Alamo Saloon, leaned back in his rawhide chair and watched him with good-natured contempt.

The town was dead, after a manner of speaking, and yet it was not dead. In the Gunsight Hotel where the officials of the Company left their women-folks to idle and fret and gossip, there was a restless flash of white from the upper veranda; and in the office below Andrew McBain, the aggressive President of the Gunsight Mining and Developing Company, paced nervously to and fro as he dictated letters to a typist. He paused, and as the clacking stopped a woman who had been reading a novel on the veranda rose up noiselessly and listened over the railing. The new typist was really quite deaf—one could hear every word that was said. She was pretty, too,—and—well, she dressed too well, for one thing.

But McBain was not making love to his typist. He had stopped with a word on his lips and stood gazing out the window. The new typist had learned to read faces and she followed his glance with a start. Who was this man that Andrew McBain was afraid of? He came riding in from the desert, a young man, burly and masterful, mounted on a buckskin horse and with a pistol slung low on his leg. McBain turned white, his stern lips drew tighter and he stood where he had stopped in his stride like a wolf that has seen a fierce dog; then suddenly he swung forward again and his voice rang out harsh and defiant. The new typist took the words down at haphazard, for her thoughts were not on her work. She was thinking of the man with a gun. He had gone by without a glance, and yet McBain was afraid of him.

A couple of card players came out of the Alamo and stopped to talk with Hassayamp.

"Well, bless my soul," exclaimed the watchful Hassayamp as he suddenly brought his chair down with a bump, "if hyer don't come that locoed scoundrel, Rimrock! Say, that boy's crazy, don't you know he is—jest look at that big sack of rocks!"

He rose up heavily and stepped out into the street, shading his eyes from the glare of the sun.

"Hello thar, Rimmy!" he rumbled bluffly as the horseman waved his hand, "whar you been so long, and nothin' heard of you? There's been a woman hyer, enquirin' for you, most every day for a month now!"

"'S that so?" responded Rimrock guardedly. "Well, say, boys, I've struck it rich!"

He leaned back to untie a sack of ore, but Old Hassayamp was not to be deterred.

"Yes sir," he went on opening up his eyes triumphantly, "a widdy woman—says you owe her two-bits for some bread!"

He laughed uproariously at this pointed jest and clambered back to the plank sidewalk where he sat down convulsed in his chair.

"Aw, you make me tired!" said Rimrock shortly. "You know I don't owe no woman."

"You owe every one else, though," came back Hassayamp with a Texas yupe; "I got you there, boy. You shore cain't git around that!"

"Huh!" grunted Rimrock as he swung lightly to the ground. "Two bits, maybe! Four bits! A couple of dollars! What's that to talk about when a man is out after millions? Is my credit good for the drinks? Well, come on in then, boys; and I'll show you something good!"

He led the way through the swinging doors and Hassayamp followed ponderously. The card players followed also and several cowboys, appearing as if by miracle, lined up along with the rest. Old Hassayamp looked them over grimly, breathed hard and spread out the glasses.

"Well, all right, Rim," he observed, "between friends—but don't bid in the whole town."

"When I drink, my friends drink," answered Rimrock and tossed off his first drink in a month. "Now!" he went on, fetching out his sack, "I'll show you something good!"

He poured out a pile of blue-gray sand and stood away from it admiringly.

Old Hassayamp drew out his glasses and balanced them on his nose, then he gazed at the pile of sand.

"Well," he said, "what is it, anyway?"

"It's copper, by grab, mighty nigh ten per cent copper, and you can scoop it up with a shovel. There's worlds of it, Hassayamp, a whole doggoned mountain! That's the trouble, there's almost too much! I can't handle it, man, it'll take millions to do it; but believe me, the millions are there. All I need is a stake now, just a couple of thousand dollars——"

"Huh!" grunted Hassayamp looking up over his glasses, "you don't reckon I've got that much, do you, to sink in a pile of sand?"

"If not you, then somebody else," replied Rimrock confidently. "Some feller that's out looking for sand. I heard about a sport over in London that tried on a bet to sell five-pound notes for a shilling. That's like me offering to sell you twenty-five dollars for the English equivalent of two bits. And d'ye think he could get anyone to take 'em? He stood up on a soap box and waved those notes in the air, but d'ye think he could get anybody to buy?"

He paused with a cynical smile and looked Hassayamp in the eye.

"Well—no," conceded Hassayamp weakly.

"You bet your life he could!" snapped back Rimrock. "A guy came along that knowed. He took one look at those five-pound notes and handed up fifty cents."

"'I'll take two of 'em,' he says; and walks off with fifty dollars!"

Rimrock scooped up his despised sand and poured it back into the bag, after which he turned on his heel. As the doors swung to behind him Old Hassayamp looked at his customers and shook his head impressively. From the street outside Rimrock could be heard telling a Mexican in Spanish to take his horse to the corrals. He was master of Gunsight yet, though all his money had vanished and his credit would buy nothing but the drinks.

"Well, what d'ye know about that?" observed Hassayamp meditatively. "By George, sometimes I almost think that boy is right!"

He cleared his throat and hobbled towards the door and the crowd took the hint to disperse.

On the edge of the shady sidewalk Rimrock Jones, the follower after big dreams, sat silent, balancing the sack of ore in a bronzed and rock-scarred hand. He was a powerful man, with the broad, square-set shoulders that come from much swinging of a double jack or cranking at a windlass. The curling beard of youth had covered his hard-bitten face and his head was unconsciously thrust forward, as if he still glimpsed his vision and was eager to follow it further. The crowd settled down and gazed at him curiously, for they knew he had a story to tell, and at last the great Rimrock sighed and looked at his work-worn hands.

"Hard going," he said, glancing up at Hassayamp. "I've got a ten-foot hole to sink on twenty different claims, no powder, and nothing but Mexicans for help. But I sure turned up some good ore—she gets richer the deeper you go."

"Any gold?" enquired Hassayamp hopefully.

"Yes, but pocketty. I leave all that chloriding to the Mexicans while I do my discovery work. They've got some picked rock on the dump."

"Why don't you quit that dead work and do a little chloriding yourself? Pound out a little gold—that's the way to get a stake!"

Old Hassayamp spat the words out impatiently, but Rimrock seemed hardly to hear.

"Nope," he said, "no pocket-mining for me. There's copper there, millions of tons of it. I'll make my winning yet."

"Huh!" grunted Hassayamp, and Rimrock came out of his trance.

"You don't think so, hey?" he challenged and then his face softened to a slow, reminiscent smile.

"Say, Hassayamp," he said, "did you ever hear about that prospector that found a thousand pounds of gold in one chunk? He was lost on the desert, plumb out of water and forty miles from nowhere. He couldn't take the chunk along with him and if he left it there the sand would cover it up. Now what was that poor feller to do?"

"Well, what did he do?" enquired Hassayamp cautiously.

"He couldn't make up his mind," answered Rimrock, "so he stayed there till he starved to death."

"You're plumb full of these sayings and parables, ain't you?" remarked Hassayamp sarcastically. "What's that got to do with the case?"

"Well," began Rimrock, sitting down on the edge of the sidewalk and looking absently up the street, "take me, for instance. I go out across the desert to the Tecolotes and find a whole mountain of copper. You don't have to chop it out with chisels, like that native copper around the Great Lakes; and you don't have to go underground and do timbering like they do around Bisbee and Cananea. All you have to do is to shoot it down and scoop it up with a steam shovel. Now I've located the whole danged mountain and done most of my discovery work, but if some feller don't give me a boost, like taking that prospector a canteen of water, I've either got to lose my mine or sit down and starve to death. If I'd never done anything, it'd be different, but you know that I made the Gunsight."

He leaned forward and fixed the saloon keeper with his earnest eyes and Old Hassayamp held up both hands.

"Yes, yes, boy, I know!" he broke out hurriedly. "Don't talk to me—I'm convinced. But by George, Rim, you can spend more money and have less to show for it than any man I know. What's the use? That's what we all say. What's the use of staking you when you'll turn right around in front of us and throw the money away? Ain't I staked you? Ain't L. W. staked you?"

"Yes! And he broke me, too!" answered Rimrock, raising his voice to a defiant boom. "Here he comes now, the blue-faced old dastard!"

He thrust out his jaw and glared up the street where L. W. Lockhart, the local banker, came stumping down the sidewalk. L. W. was tall and rangy, with a bulldog jaw clamped down on a black cigar, and an air of absolute detachment from his surroundings.

"Yes, I mean you!" shouted Rimrock insultingly as L. W. went grimly past. "You claim to be a white man, and then stand in with that lawyer to beat me out of my mine. I made you, you old nickel-pincher, and now you go by me and don't even say: 'Have a drink!'"

"You're drunk!" retorted Lockhart, looking back over his shoulder, and Rimrock jumped to his feet.

"I'll show you!" he cried, starting angrily after him, and L. W. turned swiftly to meet him.

"You'll show me what?" he demanded coldly as Rimrock put his hand to his gun.

"Never mind!" answered Rimrock. "You know you jobbed me. I let you in on a good thing and you sold me out to McBain. I want some money and if you don't give it to me I'll—I'll go over and collect from him."

"Oh, you want some money, hey?" repeated Lockhart. "I thought you was going to show me something!"

The banker scowled as he rolled his cigar, but there was a twinkle far back in his eyes. "You're bad now, ain't you?" he continued tauntingly. "You're just feeling awful! You're going to jump on Lon Lockhart and stomp him into the ground! Huh!"

"Aw, shut your mouth!" answered Rimrock defiantly, "I never said a word about fight."

"Uhhr!" grunted L. W. and put his hand in his pocket at which Rimrock became suddenly expectant.

"Henry Jones," began the banker, "I knowed your father and he was an honorable, hardworking man. You're nothing but a bum and you're getting worse—why don't you go and put up that gun?"

"I don't have to!" retorted Rimrock but he moved up closer and there was a wheedling turn to his voice. "Just two thousand dollars, Lon—that's all I ask of you—and I'll give you a share in my mine. Didn't I come to you first, when I discovered the Gunsight, and give you the very best claim? And you ditched me, L. W., dad-burn you, you know it; you sold me out to McBain. But I've got something now that runs up into millions! All it needs is a little more work!"

"Yes, and forty miles of railroad," put in L. W. intolerantly. "I wouldn't take the whole works for a gift!"

"No, but Lon, I'm lucky—you know that yourself—I can go East and sell the old mine."

"Oh, you're lucky, are you?" interrupted L. W. "Well, how come then that you're standing here, broke? But here, I've got business, I'll give you ten dollars—and remember, it's the last that you get!"

He drew out a bill, but Rimrock stood looking at him with a slow and contemptuous smile.

"Yes, you doggoned old screw," he answered ungraciously, "what good will ten dollars do?"

"You can get just as drunk on that," replied L. W. pointedly, "as you could on a hundred thousand!"

A change came over Rimrock's face, the swift mirroring of some great idea, and he reached out and grabbed the money.

"Where you going?" demanded L. W. as he started across the street.

"None of your business," answered Rimrock curtly, but he headed straight for the Mint.

The Mint was Gunsight's only gambling house. It had a bar, of course, and a Mexican string band that played from eight o'clock on; besides a roulette wheel, a crap table, two faro layouts, and monte for the Mexicans. But the afternoon was dull and the faro dealer was idly shuffling a double stack of chips when Rimrock brushed in through the door. Half an hour afterwards the place was crowded and all the games were running big. Such is the force of example—especially when you win.

Rimrock threw his bill on the table, bought a stack of white chips, placed it on the queen and told the dealer to turn 'em. The queen won and Rimrock took his chips and played as the spirit moved. He won more, for the house was unlucky from the start, and soon others began to ride his bets. If he bet on the seven, eager hands reached over his shoulder and placed more chips on the seven. Petty winners drifted off to try their luck at monte, the sports took a flier at roulette; and as the gambling spirit, so subtly fed, began to rise to a fever, Rimrock Jones, the cause of all this heat, bet more and more—and still won.

It was at the height of the excitement when, with half of the checks in the rack in front of him, Rimrock was losing and winning by turns, that the bull-like rumble of L. W. Lockhart came drifting in to him above the clamor of the crowd.

"Why don't you quit, you fool?" the deep voice demanded. "Cash in and quit—you've got your stake!"

Rimrock made a gesture of absent-minded impatience and watched the slow turn of the cards. Not even the dealer or the hawk-eyed lookout was more intently absorbed in the game. He knew every card that had been played and he bet where the odds were best. Every so often a long, yellow hand reached past him and laid a bet by his stake. It was the hand of a Chinaman, those most passionate of faro players, and at such times, seeing it follow his luck, the face of Rimrock lightened up with the semblance of a smile. He called the last turn and they paused for the drinks, while the dealer mopped his brow.

"Where's Ike?" he demanded. "Well, somebody call him—he's hiding out, asleep, upstairs."

"Yes, wake him up!" shouted Rimrock boastfully. "Tell him Rimrock Jones is here."

"Aw, pull out, you sucker!" blared L. W. in his ear, but Rimrock only shoved out his bets.

"Ten on the ace," droned the anxious dealer, "the jack is coppered. All down?"

He held up his hand and as the betting ceased he slowly pushed out the two cards.

"Tray loses, ace wins!" he announced and Rimrock won again.

Then he straightened up purposefully and looked about as he sorted his winnings into piles.

"The whole works on the queen," he said to the dealer and a hush fell upon the crowd.

"Where's Ike?" shrilled the dealer, but the boss was not to be found and he dealt, unwillingly, for a queen. But the fear was on him and his thin hands trembled; for Ike Bray was not the type of your frozen-faced gambler—he expected his dealers to win. The dealer shoved them out, and an oath slipped past his lips.

"Queen wins," he quavered, "the bank is broke." And he turned the box on its side.

A shout went up—the glad yell of the multitude—and Rimrock rose up grinning.

"Who said to pull out?" he demanded arrogantly, looking about for the glowering L. W. "Huh, huh!" he chuckled, "quit your luck when you're winning? Quit your luck and your luck will quit you—the drinks for the house, barkeep!"

He was standing at the bar, stuffing money into his pockets, when Ike Bray, the proprietor, appeared. Rimrock turned, all smiles, as he heard his voice on the stairs and lolled back against the bar. More than once in the past Bray had taken his roll but now it was his turn to laugh.

"Lemme see," he remarked as he felt Bray's eyes upon him, "I wonder how much I win."

He drew out the bills from his faded overalls and began laboriously to count them out into his hat.

Ike Bray stopped and looked at him, a little, twisted man with his hair still rumpled from the bed.

"Where's that dealer?" he shrilled in his high, complaining voice. "I'll kill the danged piker—that bank ain't broke yet—I got a big roll, right here!"

He waved it in the air and came limping forward until he stood facing Rimrock Jones.

"You think you broke me, do you?" he demanded insolently as Rimrock looked up from his count.

"You can see for yourself," answered Rimrock contentedly, and held out his well-filled hat.

"You're a piker!" yelled Bray. "You don't dare to come back at me. I'll play you one turn win or lose—for your pile!"

A hundred voices rang out at once, giving Rimrock all kinds of advice, but L. W.'s rose above them all.

"Don't you do it!" he roared. "He'll clean you, for a certainty!" But Rimrock's blue eyes were aflame.

"All right, Mr. Man," he answered on the instant, and went over and sat down in his chair. "But bring me a new pack and shuffle 'em clean, and I'll do the cutting myself."

"Ahhr!" snarled Bray, who was in villainous humor, as he hurled himself into his place. "Y'needn't make no cracks—I'm on the square—and I'll take no lip from anybody!"

"Well, shuffle 'em up then," answered Rimrock quietly, "and when I feel like it I'll make my bet."

It was the middle of the night, as Bray's days were divided, and even yet he was hardly awake; but he shuffled the cards until Rimrock was satisfied and then locked them into the box. The case-keeper sat opposite, to keep track of the cards, and a look-out on the stand at one end, and while a mob of surging onlookers fought at their backs they watched the slow turning of the cards.

"Why don't you bet?" snapped Bray; but Rimrock jerked his head and beckoned him to go on.

"Yes, and lose half on splits," he answered grimly, "I'll bet when it comes the last turn."

The deal went on till only three cards remained in the bottom of the box. By the record of the case-keeper they were the deuce and the jack—the top card, already shown, did not count.

"The jack," said Rimrock and piled up his money on the enameled card on the board.

"You lose," rasped out Bray without waiting for the turn and then drew off the upper card. The jack lay, a loser, in the box below and as he shoved it slowly out the deuce appeared underneath.

"How'd you know?" flashed back Rimrock as Bray reached for his money, but the gambler laughed in his face.

"I outlucked you, you yap," he answered harshly. "That dealer—he wasn't worth hell room!"

"Gimme a fiver to eat on!" demanded Rimrock as Bray banked the money, but he flipped him fifty cents. It was the customary stake, the sop thrown by the gambler to the man who has lost his last cent, and Bray sloughed it without losing his count.

"Go on, now," he said, still keeping to the formula, "go back and polish a drill!"

It was the form of dismissal for the hardrock miners whose earnings he was wont to take, but Rimrock was not particular.

"All right, Ike," he said and as he drifted out the door his prosperity friends disappeared. Only L. W. remained, a scornful twist to his lips, and the sight of him left Rimrock sick. "Yes, rub it in!" he said defiantly and L. W., too, walked away.

In his sober moments—when he was out on the desert or slugging away underground—Rimrock Jones was neither childish nor a fool. He was a serious man, with great hopes before him; and a past, not ignoble, behind. But after months of solitude, of hard, yegging work and hopes deferred, the town set his nerves all a-tingle—even Gunsight, a mere dot on the map—and he was drunk before he took his first drink. Drunk with mischief and spontaneous laughter, drunk with good stories untold, new ideas, great thoughts, high ambitions. But now he had had his fling.

With fifty cents to eat on, and one more faro game behind him, Rimrock stood thoughtfully on the corner and asked the old question: What next? He had won, and he had lost. He had made the stake that would have taken him far towards his destiny; and then he had dropped it, foolishly, by playing another man's game. He could see it now; but then, we all can—the question was, what next?

"Well, I'll eat," he said at last and went across the street to Woo Chong's. "The American Restaurant" was the way the sign read, but Americans don't run restaurants in Arizona. They don't know how. Woo Chong had fed forty miners when he ran the cookhouse for Rimrock, for half what a white man could; and when Rimrock had lost his mine, at the end of a long lawsuit, Woo Chong had followed him to town. There was a long tally on the wall, the longest of all, which told how many meals Rimrock owed him for; but Rimrock knew he was welcome. Adversity had its uses and he had learned, among other things, that his best friends were now Chinamen and Mexicans. To them, at least, he was still El Patron—the Boss!

"Hello there, Woo!" he shouted at the doorway and a rapid-fire of Chinese ceased. The dining-room was deserted, but from the kitchen in the rear he could hear the shuffling slippers of Woo.

"Howdy-do, Misse' Jones!" exclaimed Woo in great excitement as he came hurrying out to meet him. "I see you—few minutes ago—ove' Ike Blay's place! You blakum falo bank, no?"

"No, I lose," answered Rimrock honestly. "Ike Bray, he gave me this to eat on."

He showed the fifty-cent piece and sat down at a table whereat Woo Chong began to giggle hysterically.

"Aw! Allee time foolee me," he grinned facetiously. "You no see me the'? Me playum, too. Win ten dolla', you bet!"

"Well, all right, Woo," said Rimrock. "Just give me something to eat—we won't quarrel about who won."

He leaned back in his chair and Woo Chong said no more till he appeared again with a T-bone steak.

"You ketchum mine, pletty soon?" he questioned anxiously. "All lite, me come back and cook."

Rimrock sighed and went to eating and Woo remembered the coffee, but somehow even that failed to cheer.

A shadow of doubt came across Woo's watchful face and he hurried away for more bread.

"You no bleakum bank?" he enquired at last and Rimrock shook his head.

"No, Woo," he said, "Ike Bray, he came down and win all my money back."

"Aw, too bad!" breathed Woo Chong and slipped quietly away; but after a while he came back.

"Too bad!" he repeated. "You my fliend, Misse' Jones." And he laid five dollars by his hand.

"Ah, no, no!" protested Rimrock, rising up from his place as if he had suffered a blow. "No money, Woo. You give me my grub and that's enough—I haven't got down to that!"

Woo Chong went away—he knew how to make gifts easy—and Rimrock stood looking at the gold. Then he picked it up, slowly, and as slowly walked out, and stood leaning against a post.

There is one street in Gunsight, running grandly down to the station; but the rest is mostly vacant lots and scattered adobe houses, creeping out into the infinitude of the desert. At noon, when he had come to town, the street was deserted, but now it was coming to life. Wild-eyed Mexican boys, mounted on bare-backed ponies, came galloping up from the corrals; freight wagons drifted past, hauling supplies to distant mining camps; and at last, as he stood there thinking, the women began to come out of the hotel.

All day they stayed there, idle, useless, on the shaded veranda above the street; and then, when the sun was low, they came forth like indolent butterflies to float up and down the street. They sauntered by in pairs, half-hidden beneath silk parasols, and their skirts swished softly as they passed. Rimrock eyed them sullenly, for a black mood was on him—he was thinking of his lost mine. Their faces were powdered to an unnatural whiteness and their hair was elaborately coiffed; their dresses, too, were white and filmy and their high heels clacked as they walked. But who was keeping these women, these wives of officials, and superintendents and mining engineers? Did they glance at the man who had discovered their mine and built up the town where they lived? Well, probably they did, but not so as he could notice it and take off his battered old hat.

Rimrock looked up the road and, far out across the desert, he could see his own pack-train, coming in. There was money to be got, to buy powder and grub, but who would trust Rimrock Jones now? Not the Gunsight crowd, not McBain and his hirelings—they needed the money for their women! He gazed at them scowling as they went pacing by him, with their eyes fixed demurely on space; and all too well he knew that, beneath their lashes, they watched him and knew him well. Yes, and spoke to each other, when they were off up the street, of what a bum he had become. That was women—he knew it—the idle kind; they judged a man by his roll.

The pack-train strung by, each burro with its saw-horse saddle, and old Juan and his boy behind.

"Al corral!" directed Rimrock as they looked at him expectantly, and then he remembered something.

"Oyez, Juan," he beckoned, calling his man servant up to him, "here's five dollars—go buy some beans and flour. It is nothing, Juanito, I'll have more pretty soon—and here's four bits, you can buy you a drink."

He smiled benevolently and Juan touched his hat and went sidling off like a crab and then once more the black devil came back to plague him, hissing Money, Money, MONEY! He looked up the street and a plan, long formless, took sudden shape in his brain. There was yet McBain, the horse-leech of a lawyer who had beaten him out of his claim. More than once, in black moments, he had threatened to kill him; but now he was glad he had not. Men even raised skunks, when the bounty on them was high enough, and took the pay out of their hides. It was the same with McBain. If he didn't come through—Rimrock shook up his six-shooter and stalked resolutely off up the street.

The office of the Company was on the ground floor of the hotel—the corner room, with a rented office beyond—and as Rimrock came towards it he saw a small sign, jutting out from the farther door:

He glanced at it absently, for strange emotions came over him as he peered in through that plateglass window. It had been his office, this same expensive room; and he had been robbed of it, under cover of the law. He shaded his eyes from the glare of the street and looked in at the mahogany desk. It was vacant—the whole place was vacant—and silently he tried the door. That was locked. McBain had seen him and slipped away till he should get out of town.

"The sneaking cur!" muttered Rimrock in a fury and a passing woman drew away and half-screamed. He ignored her, pondering darkly, and then to his ears there came a familiar voice. He listened, intently, and raised his head; then tiptoed along the wall. That voice, and he knew it, belonged to Andrew McBain, the man that stole mines for a living. He paused at the door where Mary Fortune had her sign, then suddenly forced his way in.

Without thinking, impulsively, he had moved towards that voice as a man follows some irresistible call. He opened the door and stood blinking in the doorway, his hand on the pistol at his side. Then he blinked again, for in the gloom of the back office there was nothing but a desk and a girl. She wore a harness over her head, like a telephone operator, and rose up to meet him tremulously.

"Is there anything you wish?" she asked him quietly and Rimrock fumbled and took off his hat.

"Yes—I was looking for a man," he said at last. "I thought I heard him—just now."

He came down towards her, still looking about him, and there was a stir from behind the desk.

"No, I think you're mistaken," she answered bravely, but he could see the telltale fear in her eyes.

"You know who I mean!" he broke out roughly, "and I guess you know why I've come!"

"No, I don't," she answered, "but—but this is my office and I hope you won't make any trouble."

The words came with a rush, once she found her courage, but the appeal was lost upon Rimrock.

"He's here, then!" he said. "Well, you tell him to come out. I'd like to talk with him on business—alone!"

He took a step forward and then suddenly from behind the desk a shadow rose up and fled. It was Andrew McBain, and as he dashed for the rear door the girl valiantly covered his retreat. There was a quick slap of the latch, a scuffle behind her, and the door came shut with a bang.

"Oho!" said Rimrock as she faced him panting, "he must be a friend of yourn."

"No, he isn't," she answered instantly, and then a smile crept into her eyes. "But he's—well, he's my principal customer."

"Oh," said Rimrock grimly, "well, I'll let him live then. Good-bye."

He turned away, still intent on his purpose, but at the door she called him back.

"What's that?" he asked as if awakened from a dream. "Why, yes, if you don't mind, I will."

It was very informal, to say the least, for Mary Fortune to invite him to stay. To be sure, she knew him—he was the man with the gun, the man of whom McBain was afraid—but that was all the more reason, to a reasoning woman, why she should keep silent and let him depart. But there was a business-like brevity about him, a single-minded directness, that struck her as really unique. Quite apart from the fact that it might save McBain, she wanted him to stay there and talk. At least so she explained it, the evening afterwards, to her censorious other-self. What she did was spontaneous, on the impulse of the moment, and without any reason whatever.

"Oh, won't you sit down a moment?" she had murmured politely; and the savage, fascinating Westerner, after one long look, had with equal politeness accepted.

"Yes, indeed," he answered when he had got his wits together, "you're very kind to ask me, I'm sure."

He came back then, a huge, brown, ragged animal and sat down, very carefully, in her spare chair. Why he did so when his business, not to mention a just revenge, was urgently calling him thence, was a question never raised by Rimrock Jones. Perhaps he was surprised beyond the point of resistance; but it is still more likely that, without his knowing it, he was hungry to hear a woman's voice. His black mood left him, he forgot what he had come there for, and sat down to wonder and admire.

He looked at her curiously, and his eyes for one brief moment took in the details of the headband over her ear; then he smiled to himself in his masterful way as if the sight of her pleased him well. There was nothing about her to remind him of those women who stalked up and down the street; she was tall and slim with swift, capable hands, and every line of her spoke subtly of style. Nor was she lacking in those qualities of beauty which we have come to associate with her craft. She had quiet brown eyes that lit up when she smiled, a high nose and masses of hair. But across that brown hair that a duchess might have envied lay the metal clip of her ear-'phone, and in her dark eyes, bright and steady as they were, was that anxious look of the deaf.

"I hope I wasn't rude," she stammered nervously as she sat down and met his glance.

"Oh, no," he said with the same carefree directness, "it was me, I reckon, that was rude. I certainly didn't count on meeting a lady when I came in here looking for—well, McBain. He won't be back, I reckon. Kind of interferes with business, don't it?"

He paused and glanced at the rear door and the typist smiled, discreetly.

"Oh, no," she said. And then, lowering her voice: "Have you had trouble with Mr. McBain?"

"Yes, I have," he answered. "You may have heard of me—my name is Henry Jones."

"Oh—Rimrock Jones?"

Her eyes brightened instantly as he slowly nodded his head.

"That's me," he said. "I used to run this whole town—I'm the man that discovered the mines."

"What, the Gunsight mines? Why, I thought Mr. McBain——"

"McBain what?"

"Why, I thought he discovered the mines."

Rimrock straightened up angrily, then he sat back in his chair and shook his head at her cynically.

"He didn't need to," he answered. "All he had to do was to discover an error in the way I laid out my claim. Then he went before a judge that was as crooked as he was and the rest you can see for yourself."

He thrust his thumb scornfully through a hole in his shirt and waved a hand in the direction of the office.

"No, he cleaned me out, using a friend of mine; and now I'm down to nothing. What do you think of a law that will take away a man's mine because it apexes on another man's claim? I discovered this mine and I formed the company, keeping fifty-one per cent. of the stock. I opened her up and she was paying big, when Andy McBain comes along. A shyster lawyer—that's the best you can say for him—but he cleaned me, down to a cent."

"I don't understand," she said at last as he seemed to expect some reply. "About these apexes—what are they, anyway? I've only been West a few months."

"Well, I've been West all my life, and I've hired some smart lawyers, and I don't know what an apex is yet. But in a general way it's the high point of an ore-body—the highest place where it shows above ground. But the law works out like this: every time a man finds a mine and opens it up till it pays these apex sharps locate the high ground above him and contest the title to his claim. You can't do that in Mexico, nor in Canada, nor in China—this is the only country in the world where a mining claim don't go straight down. But under the law, when you locate a lode, you can follow that vein, within an extension of your end-lines, under anybody's ground. Anybody's!"

He shifted his chair a little closer and fixed her with his fighting blue eyes.

"Now, just to show you how it works," he went on, "take me, for instance. I was just an ordinary ranch kid, brought up so far back in the mountains that the boys all called me Rimrock, and I found a rich ledge of rock. I staked out a claim for myself, and the rest for my folks and my friends, and then we organized the Gunsight Mining Company. That's the way we all do, out here—one man don't hog it all, he does something for his friends. Well, the mine paid big, and if I didn't manage it just right I certainly never meant any harm. Of course I spent lots of money—some objected to that—but I made the old Gunsight pay.

"Then—" he raised his finger and held it up impressively as he marked the moment of his downfall—"then this McBain came along and edged into the Company and right from that day, I lose. He took on as attorney, but it wasn't but a minute till he was trying to be the whole show. You can't stop that man, short of killing him dead, and I haven't got around to that yet. But he bucked me from the start and set everybody against me and finally he cut out Lon Lockhart. There was a man, by Joe, that I'd stake my life on it he'd never go back on a friend; but he threw in with this lawyer and brought a suit against me, and just naturally took—away—my—mine!"

Rimrock's breast was heaving with an excitement so powerful that the girl instinctively drew away; but he went on, scarcely noticing, and with a fixed glare in his eyes that was akin to the stare of a madman.

"Yes, took it away; and here's how they did it," he went on, suddenly striving to be calm. "The first man I staked for, after my father and kin folks, was L. W. Lockhart over here. He was a cowman then and he had some money and I figured on bidding him in. So I staked him a good claim, above mine on the mountain, and sure enough, he came into the Company. He financed me, from the start; but he kept this claim for himself without putting it in with the rest. Well, as luck would have it, when we sunk on the ledge, it turned at right angles up the hill. Up and down, she went—it was the main lode of quartz and we'd been following in on a stringer—and rich? Oh, my, it was rotten!"

He paused and smiled wanly, then his eyes became fixed again, and he hurried on with his tale.

"I was standing out in front of my office one day when Tuck Edwards, the boy I had in charge of the mine, came riding up and says:

"'Rim, they've jumped you!'

"'Who jumped me?' I says.

"'Andrew McBain and L. W.!' he says and I thought at first he was crazy.

"'Jumped our mine?' I says. 'How can they jump it when it's part their own already?'

"'They've jumped it all,' he says. 'They had a mining expert out there for a week and he's made a report that the lode apexes on L. W.'s claim.'

"I couldn't believe it. L. W.? I'd made him. He used to be nothing but a cowman; and here he was in town, a banker. No, I couldn't believe it; and when I did it was too late. They'd taken possession of the property and had a court order restraining me from going onto the grounds. Not only did they claim the mine, but every dollar it had produced, the mill, the hotel, everything! And the judge backed them up in it—what kind of a law is that?"

He leaned forward and looked her in the eyes and Mary Fortune realized that she was being addressed not as a woman, impersonally, but as a human being.

"What kind of a law is that?" he demanded sternly and took the answer for granted.

"That cured me," he said. "After this, here's the only law I know."

He tapped his pistol and leaned back in his chair, smiling grimly as she gazed at him, aghast.

"Yes, I know," he went on, "it don't sound very good, but it's that or lay down to McBain. The judges are no better—they're just promoted lawyers——"

He checked himself for she had risen from her chair and her eyes were no longer scared.

"Excuse me," she said, "my father was a judge." And Rimrock reached for his hat.

"Whereabouts?" he asked, groping for a chance to square himself.

"Oh—back East," she said evasively, and Rimrock heaved a sigh of relief.

"Aw, that's different," he answered. "I was just talking about the Territory. Well, say, I'll be moving along."

He rose quickly, but as he started for the door a rifle-cartridge fell from his torn pocket. It rolled in a circle and as he stooped swiftly to catch it the bullet came out like a cork and let spill a thin yellow line.

"What's that?" she asked as he dropped to his knees; and he answered briefly:

"Gold!"

"What—real gold?" she cried rapturously, "gold from a mine? Oh, I'd like——"

She stopped short and Rimrock chuckled as he scooped up the elusive dust.

"All right," he said as he rose to his feet, "I'll make you a present of it, then," and held out the cartridge of gold.

"Oh, I couldn't!" she thrilled, but he only smiled encouragingly and poured out the gold in her hand.

"It's nothing," he said, "just the clean-up from a pocket. I run across a little once in a while."

A panic came over her as she felt the telltale weight of it, and she hastily poured it back.

"I can't take it, of course," she said with dignity, "but it was awful good of you to offer it, I'm sure."

"Aw, what do we care?" he protested lightly, but she handed the corked cartridge back. Then she stood off and looked at him and the huge man in overalls became suddenly a Croesus in her eyes.

"Is that from your mine?" she asked at last and of a sudden his bronzed face lighted up.

"You bet it is—but look at this!" and he fetched a polished rock from his pocket. "That's azurite," he said, "nearly forty per cent. copper! I'm not telling everybody, but I find big chunks of that, and I've got a whole mountain of low-grade. What's a gold mine compared to that?"

He gave her the rich rock with its peacock-blue coloring and plunged forthwith into a description of his find. Now at last he was himself and to his natural enthusiasm was added the stimulus of her spellbound, wondering eyes. He talked on and on, giving all the details, and she listened like one entranced. He told of his long trips across the desert, his discovery of the neglected mountain of low-grade copper ore; and then of his enthusiasm when in making a cut he encountered a pocket of the precious peacock-blue azurite. And then of his scheming and hiring American-born Mexicans to locate the whole body of ore, after which he engaged them to do the discovery work and later transfer the claims to him. And now, half-finished, with no money to pay them, and not even food to keep them content, the Mexicans had quit work and unless he brought back provisions all his claims would go by default.

"I've got a chance," he went on fiercely, "to make millions, if I can only get title to those claims! And now, by grab, after all I've done for 'em, these pikers won't advance me a cent!"

"How much would it cost?" she asked him quickly, "to finish the work and pay off the men?"

"Two thousand dollars," he answered wearily. "But it might as well be a million."

"Would—would four hundred dollars help you?"

She asked it eagerly, impulsively, almost in his ear, and he turned as if he had been struck.

"Don't speak so loud," she implored him nervously. "These women in the hotel—they're listening to everything you say. I can hear all right if you only whisper—would four hundred dollars help you out?"

"Not of your money!" answered Rimrock hoarsely. "No, by God, I'll never come to that!"

He started away, but she caught him by the arm and held him back till he stopped.

"But I want to do it!" she persisted. "It's a good thing—I believe in it—and I've got the money!"

He stopped and looked at her, almost tempted by her offer; then he shook his great head like a bull.

"No!" he said, talking half to himself. "I won't do it—I've sunk low enough. But a woman? Nope, I won't do it."

"Oh, quit your foolishness!" she burst out impatiently, "I guess I know my own mind. I came out to this country to try and recoup myself and I want to get in on this mine. No sentiment, understand me, I'm talking straight business; and I've got the money—right here!"

"Well, what do you want for it?" he demanded roughly. "If that's the deal, what's your cut? I never saw you before, nor you me. How much do you want—if we win?"

"I want a share in the mine," she answered instantly. "I don't care—whatever you say!"

"Well, I'll go you," he said. "Now give me the money and I'll try to make both of us rich!"

His voice was trembling and he followed every movement as she stepped back behind her desk.

"Just look out the window," she said as he waited; and Rimrock turned his head. There was a rustle of skirts and a moment later she laid a roll of bills in his hand.

"Just give me a share," she said again and suddenly he met her eyes.

"How about fifty-fifty—an undivided half?" he asked with a dizzy smile.

"Too much," she said. "I'm talking business."

"All right," he said. "But so am I."

Rimrock Jones left town with four burro-loads of powder, some provisions and a cargo of tools. He paid cash for his purchases and answered no question beyond saying that he knew his own business. No one knew or could guess where he had got his money—except Miss Fortune, and she would not tell. From the very first she had told herself that the loan was nothing to hide, and yet she was too much of a woman not to have read aright the beacon in Rimrock's eyes. He had spoken impulsively, and so had she; and they had parted, as it turned out, for months.

The dove that had crooned so long in the umbrella tree built a nest there and cooed on to his mate. The clear, rainless winter gave place to spring and the giant cactus burst into flower. It rained, short and hard, and the desert floor took on suddenly a fine mat of green; and still he did not come. He was like the rain, this wild man of the desert; swift and fierce, then gone and forgotten. Once she saw his Mexican, the old, bearded Juan, with his string of shaggy burros at the store; but he brought her no word and went off the next day with more powder and provisions in his packs.

It was all new to Mary Fortune, this stern and barren country; and its people were new to her, too. The women, for some reason, had regarded her with suspicion and her answer was a patrician aloofness and reserve. When the day's work was done she took off her headband and sat reading in the lobby, alone. As for the men of the hotel, the susceptible young mining men who passed to and fro from Gunsight, they found her pleasant, but not quite what they had expected—not quite what Dame Rumor had painted her. They watched her from the distance, for she was undeniably goodlooking—and so did the women upstairs. They watched, and they listened, which was not the least of the reasons why Mary Fortune laid her ear-'phone aside. No person can enjoy the intimacies of life when they are shouted, ill-advisedly, to the world.

But if when she first came to town, worn and tired from her journey, she had seemed more deaf than she was, Mary Fortune had learned, as her hearing improved, to artfully conceal the fact. There was a certain advantage, in that unfriendly atmosphere, in being able to overhear chance remarks. But no permanent happiness can come from small talk, and listening to petty asides; and, for better or worse, Mary took off her harness and retired to the world of good books. She read and she dreamed and, quite unsuspected, she looked out the window for him.

The man! There is always a man, some man, for every woman who dreams. Rimrock Jones had come once and gone as quickly, but his absence was rainbowed with romance. He was out on the desert, far away to the south, sinking shafts on his claims—their claims. He had discovered a fortune, but, strong as he was, he had had to accept help from her. He would succeed, this fierce, ungovernable desert-man; he would win the world's confidence as he had won her faith by his strength and the bold look in his eyes. He would finish his discovery work and record all his claims and then—well, then he would come back.

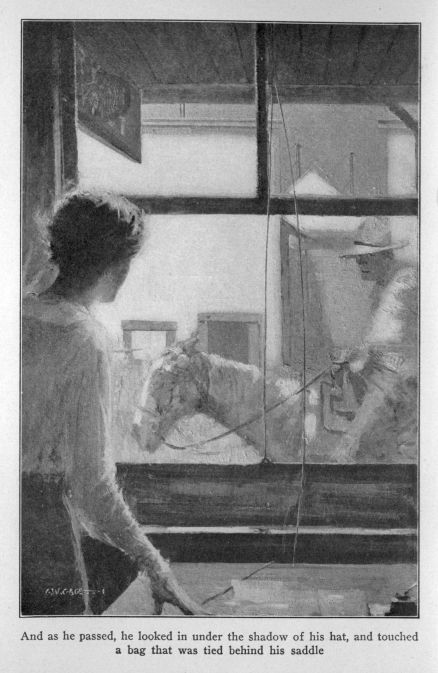

So she watched for him, furtively, glancing quickly out the window whenever a horseman passed by; and one day, behold, as she looked up from her typing, he was there, riding by on his horse! And as he passed he looked in, under the shadow of his hat, and touched a bag that was tied behind his saddle. He was more ragged than ever, and one hand had a bandage around it; but he was back, and he would come. She abandoned her typewriting—one of those interminable legal papers that McBain was always leaving on her desk—and stepped out to look down the street.

The air, warm and soft, was spiced with green odors and the resinous tang of the greasewood; the ground dove in his tree seemed swooning with passion as he crooned his throaty, Kwoo, kwoo-o. It was the breath of spring, but tropical, sense-stealing; it lulled the brain and bade the heart leap and thrill. This vagabond, this rough horseman with his pistol and torn clothing and the round sack of ore lashed behind; who would ever dream that an adventurer like him could make her forget who she was? But he came from the mine she had helped him to save and the sack might be heavy with gold. So she watched, half-concealed, until he stopped at the bank and went striding in with the bag.

As for Rimrock Jones, he rode by the saloon and went direct to L. W., the banker. It was life or death, as far as the Tecolote was concerned, for his four hundred dollars was gone. That had given him the powder to shoot out his holes to the ten feet required by law, and enough actual cash to pay his Mexican locators and make a legal transfer of the claims; but four hundred dollars will not last a lifetime and Rimrock Jones was broke. He needed more money and he went perforce to the only man who could give it. It would be a fight, for L. W. was stubborn; but Rimrock was stubborn himself.

"L. W.," he said, when he found the banker in his private office in the rear, "you used to be white and I want you to listen before you spit out what you've got in your craw. You may have a grievance, and I don't deny it; but remember, I've got one, too. No, it isn't about my mine—I wouldn't sell you one share in it for your whole little jim-crow bank. I've done my first work and I've recorded my claims, and I'll offer them—somewhere's else. All you know is gold and before we go any further, just run your eyes over that."

He dumped the contents of his bag on the polished desk and L. W. blinked as he looked. It was picked gold quartz of the richest kind, with jewelry specimens on top, and as L. W. ran his hand through it his tight mouth relaxed from its bulldog grip on the cigar.

"Where'd you get it?" he grunted and Rimrock's eyes flashed as he answered shortly:

"My mine."

"How much more you got?"

L. W. asked it suspiciously, but the gold-gleam had gone to his heart.

"About two tons of the best, scattered around on the different dumps, and a whole scad more that will ship. I knew you wouldn't lend on anything but gold-ore and I need money to pay off my Mexicans. I've got to save some ore bags to sack that picked rock in, and hire freighters to haul it in. Then there's the freight and the milling and with one thing and another I need about two thousand dollars."

"Oh! Two thousand dollars. Seems to me," observed L. W., "I've heard that sum mentioned before."

"You have, dad-burn ye, and this time I want it. What's the matter, ain't that ore good for it all?"

"It is, if you've got it, but I've come to the point where I don't place absolute confidence in your word."

"Oh, the hell you have!" said Rimrock sarcastically, "that sounds like some lawyer talk. You might've learned it from Apex McBain when you was associated with him in a deal. I won't say what deal, but, refreshing your memory now, ain't my word as good as yours?"

He gazed intently at the hard-visaged L. W. whose face slowly turned brick red.

"Now to get down to business," went on Rimrock quietly, "I tell you that ore is there. If you'll loan me the money to haul in that rock I'll pay you back from my check. And I'll give you my note at one per cent. a month, compounded monthly and all that. I guess a man that can show title to twenty claims that turn out picked ore like that—well, he's entitled, perhaps, to a little more consideration than you boys have been showing me of late."

L. W. sat silent, his burning eyes on the gold, the cigar clutched fiercely in his teeth—then without a word he wrote a check and threw it across the desk.

"Much obliged," said Rimrock and without further words he stepped out and cashed the check. And then Rimrock Jones disappeared.

The last person in Gunsight to hear what had happened was Mary Fortune. She worked at her desk that day in a fever of expectation, now stopping to wonder at the strange madness that possessed her, now pounding harder to still her tumultuous thoughts. She did not know what it was that she expected, only something great and new and wonderful, something to lift her at last from the drudgery of her work and make her feel young and gay. Something to rouse her up to the wild joy of living and make her forget her misfortunes. To be poor, and deaf, and alone—all these were new things to Mary Fortune; but she was none of them when he was near. What need had she to hear when she could read in his eyes that instant admiration that a woman values most? And poor? The money she had given had helped him, perhaps, to gain millions!

She worked late, that afternoon; and again, in the evening, she made an excuse to keep her office lit up. Still he did not come and she paced up the street, even listened as she passed by the saloons—then, overwhelmed with shame that she had seemed to seek him, she fled to her room and wept. The next day, and the next, she watched and listened and at last she overheard the truth. It was Andrew McBain, the hard, fighting Scotchman, who told the dreadful news—and she hated him for it, always.

"Well, I'm glad he's gone," he had replied to L. W., who had beckoned him out to the door. "He's a dangerous man—I've been afraid of him—you're lucky to get off at that."

"Lucky!" yelled L. W., suddenly forgetting his caution, "he touched me for two thousand dollars! Do you call that lucky? And here's the latest—he hasn't got a pound of picked ore! Even took away what he had; and that old, whiskered Mexican says he up and borrowed that from him!"

"That's a criminal act," explained McBain exultantly, as he signaled L. W. to be calm. "Shh, not so loud, the girl might hear you. Let him go, and hold it over his head."

"No, I'll kill the dastard!" howled L. W. rebelliously and slammed the door in a rage.

A swooning sickness came over Mary Fortune as she sat, waiting stonily, at her desk; but when McBain came back and sat down beside her she typed on, automatically, as he spoke. Then she woke at last, as if from a dream, to hear his harsh, discordant voice; and a sudden resentment, a fierce, passionate hatred, swept over her as he shouted in her ear. A hundred times she had informed him politely that she was not deaf when she wore her ear-'phone, and a hundred times he had listened impatiently and gone on in his sharp, rasping snarl. She drew away shuddering as he looked over some papers and cleared his throat for a fresh start; and then, without reason that he could ever divine, she burst into tears and fled.

She came back later, but the moment he began dictating she pushed back her chair and rose up.

"Mr. McBain," she said tremulously, "you don't need to shout at me. I give you notice—I shall leave on the first."

It was plainly a tantrum, such as he had observed in women, a case, pure and simple, of nerves; but Andrew McBain let it pass. She could spell—a rare quality in typists—and was familiar with legal forms.

"Ah, my dear Miss Fortune," he began propitiatingly, "I hope you will reconsider, I'm sure. It's a habit I have, when dictating a brief, to speak as though addressing the court. Perhaps, under the circumstances, you could take off your instrument and my voice would be—ahem—just about right."

"No! It drives me crazy!" she cried in a passion. "It makes everybody think I'm so deaf!"

She broke down at that and McBain discreetly withdrew and was gone for the rest of the day. It was best, he had learned, when young women became emotional, to absent himself for a time. And the next day, sure enough, she came back, smiling cheerfully, and said no more of leaving her job. She was, in fact, more obliging than before and he judged that the tantrum had passed.

With L. W., however, the case was different. He claimed to be an Indian in his hates; and a mining engineer, dropping in from New York, told a story that staggered belief. Rimrock Jones was there, the talk of the town, reputed to be enormously rich. He smoked fifty-cent cigars, wore an enormous black hat and put up at the Waldorf Hotel. Not only that but he was in all the papers as associating with the kings of finance. So great was his prestige that the engineer, in fact, had been requested to report on his mine.

"A report?" shouted L. W., "what, a report on the Tecolotes? Well, I can save you a long, dusty trip. In the first place Rimrock Jones is a thorough-paced scoundrel, not only a liar but a crook; and in the second place these claims are forty miles across the desert with just two sunk wells on the road. I wouldn't own his mines if you would make me a present of them and a million dollars to boot. I wouldn't take them for a gift if that mountain was pure gold—how's he going to haul the ore to the railroad? Now listen, my friend, I've known that boy since he stood knee-high to a toad and of all the liars in Arizona he stands out, preëminently, as the worst."

"You question his veracity, then?" enquired the engineer as he fumbled for some papers in his coat.

"Question nothing!" raved L. W. "I'm making a statement! He's not only a liar—he's a thief! He robbed me, the dastard; he got two thousand dollars of my money without giving me the scratch of a pen. Oh, I tell you——"

"Well, that's curious," broke in the engineer as he stared at a paper, "he's got your name down here as a reference."

It is an engineer's duty, when he is sent out to examine a mine, to make a report on the property, regardless. The fact that the owner is a liar and a thief does not necessarily invalidate his claims; and an all-wise Providence has, on several occasions, allowed such creatures to discover bonanzas. So the engineer hired a team and disappeared on the horizon and L. W. went off buying cattle.

A month passed by in which the derelictions of Rimrock were capped by the machinations of a rival cattle buyer, who beat L. W. out of a buy that would have netted him up into the thousands. Disgusted with everything, L. W. boarded the west-bound at Bowie Junction and flung himself into a seat in the half-empty smoker without looking to the right or left. He was mad—mad clear through—and the last of his cigars was mashed to a pulp in his vest. He had just made this discovery when another cigar was thrust under his nose and a familiar voice said:

"Try one of mine!"

L. W. looked at the cigar, which was undoubtedly expensive, and then glanced hastily across the aisle. There, smiling sociably, was Rimrock Jones.

L. W. squinted his eyes. Yes, Rimrock Jones, in a large, black hat; a checked suit, rather loud, and high boots. His legs were crossed and with an air of elegant enjoyment he was smoking a similar cigar.

"Don't want it!" snarled L. W. and, rising up in a fury, he moved off towards the far end of the car.

"Oh, all right," observed Rimrock, "I'll smoke it myself, then." And L. W. grunted contemptuously.

They rode for some hours across a flat, joyless country without either man making a move, but as the train neared Gunsight Rimrock rose up and went forward to where L. W. sat.

"Well, what're you all bowed up about?" he enquired bluffly. "Has your girl gone back on you, or what?"

"Go on away!" answered L. W. dangerously, "I don't want to talk to you, you thief!"

"Oh, that's what's the matter with you—you're thinking about the money, eh? Well, you always did hate to lose."

An insulting epithet burst from L. W.'s set lips, but Rimrock let it pass.

"Oh, that's all right," he said. "Never mind my feelings. Say, how much do you figure I owe you?"

"You don't owe me nothing!" cried L. W. half-rising. "You stole from me, you scoundrel—I can put you in the Pen for this!"

"Aw, you wouldn't do that," answered Rimrock easily. "I know you too well for that."

"Say, you go away," panted L. W. in a frenzy, "or I'll throw you out of this car."

"No you won't either," said Rimrock truculently. "You'll have to eat some more beans before you can put me on my back."

Rimrock squared his great shoulders and his eyes sparkled dangerously as he faced L. W. in the aisle.

"Now listen!" he went on after a tense moment of silence, "what's the use of making a row? I know I lied to you—I had to do it in order to get the money. I just framed that on purpose so I could get back to New York where a proposition like mine would be appreciated. I was a bum, in Gunsight; but back in New York, where they think in millions, they treated me like a king."

"I don't want to talk to you," rumbled L. W. moving off, "you lied once too often, and I've quit ye!"

"All right!" answered Rimrock, "that suits me, too. All I ask is—what's the damage?"

"Thirty-seven hundred and fifty-five dollars," snapped back L. W. venomously, "and I'd sell out for thirty-seven cents."

"You won't have to," said Rimrock with business directness and flashed a great roll of bills.

"There's four thousand," he said, peeling off four bills, "you can keep the change for pilon."

There was one thing about L. W., he was a poker player of renown and accustomed to thinking quick. He took one look at that roll of bills and waved the money away.

"Nope! Keep it!" he said. "I don't want your money—just let me in on this deal."

"Huh!" grunted Rimrock, "for four thousand dollars? You must think I've been played for a sucker. No, four hundred thousand dollars wouldn't give you a look-in on the pot that I've opened this trip."

"W'y, you lucky fool!" exclaimed L. W. incredulously, his eyes still glued to the roll. "What's the proposition, Rimmy? Say, you know me, Rim!"

"Yeh! Sure I do!" answered Rimrock dryly, and L. W. turned from bronze to a dull red. "I know the whole bunch of you, from the dog robber up, and this time I play my own hand. I was a sucker once, but the only friends I've got now are the ones that stayed with me when I was down."

"But I helped you, Rim!" cried L. W. appealingly. "Didn't I lend you money, time and again?"

"Yes, and here it is," replied Rimrock indifferently as he held out the four yellow bills. "You loaned me money, but you treated me like dirt—now take it or I'll ram it down your throat."

L. W. took the money and stood gnawing his cigar as the train slowed down for Gunsight.

"Say, come over to the bank—I want to speak to you," he said as they dropped off the train.

"Nope, can't stop," answered Rimrock curtly, "got to go and see my friends."

He strode off down the street and L. W. followed after him, beckoning feverishly to every one he met.

"Say, Rimrock's struck it rich!" he announced behind his hand and the procession fell in behind.

Straight down the street Rimrock went to the Alamo where old Hassayamp stood shading his eyes, and while the crowd gathered around them he took Hassayamp's hand and shook it again and again.

"Here's the best man in town," he began with great feeling. "An old-time Arizona sport. There never was a time, when I was down and out, that my word wasn't good for the drinks."

And Hassayamp Hicks, divining some great piece of good fortune, invited him in for one more.

"Here's to Rimrock Jones," he said to the crowd, "the livest boy in this town."

They drank and then Rimrock drew out his roll and peeled off an impressive yellow bill.

"Just take out what I owe you," he said to old Hassayamp, "and let the boys drink up the rest."

With that he was gone and the crowd, scarce believing, stayed behind and drank to his health. Not a word was said by Rimrock or his friends as to the source of this sudden wealth. For once in his life Rimrock Jones was reticent, but the roll of bills spoke for itself. He came out of Woo Chong's restaurant with a broad grin on his face and looked about for the next man he owed.

"You can talk all you want to," he observed to the onlookers, "but a Chink is as white as they make 'em. And any man in this crowd," he added impressively, "that ever loaned me a cent, all he has to do is to step out and say so and he gets his money back—and then some."

The crowd surged about, but no one stepped forward. Strange stories were in the air, resurrected from the past, of Rimrock and the way he paid. When the Gunsight mine, after many difficulties, began to pay back what it had cost, Rimrock had appeared on the street with a roll. And then, as now, he had announced his willingness to pay any bill, good or bad, that he owed. He stood there waiting, with the bills in his hand, and he paid every man who applied. He even paid men who slipped in meanly with stories of loans when he was drunk; but he noted them well and from that day forward they received no favors from him.

"Ah, there's the very man I'm looking for," exclaimed Rimrock in Spanish as he spied old Juan in the crowd and, striding forward, he held out his hand and greeted him ceremoniously. Old Juan it was of whom he had borrowed the gold ore that had coaxed the two thousand dollars from L. W.—and he had never sent the picked rock back.

"How are you, Juan?" he enquired politely in the formula that all Mexicans love. "And your wife, Rosita? Is she well also? Yes, thank God, I am well, myself. Where is Rico now? He is a good boy, truly—will you do one more thing for me, Juan?"

"Sí, Sí, Señor!" answered Juan deferentially; and Rimrock smiled as he patted his shoulder.

"You are a good man, Juan," he said. "A good friend of mine—I will remember it. Now get me an ore-sack—a strong one—like the one that contained the picked gold."

"Un momento!" smiled Juan hurrying off towards the store and the Mexicans began to swarm to and fro. Some reward, they knew, was to be given to Juan to compensate him for the loss of his gold. His gold and his labor and all the unpaid debt that was owing to him and his son and the rest. The streets began to clatter with flying hoofs as they rode off to summon el pueblo, and by the time Old Juan returned with his sack all Mexican town was there.

"Muy bien," pronounced Rimrock as he inspected the ore-sack, "now come with me, Amigo!"

Amigo Juan went, and all his friends after him, to see what El Patron would do. Something generous and magnificent, they knew very well, for El Patron was gentleman, muy caballero. He led the way to the bank, still enquiring most solicitously about Juan's relations, his children, his burros and so on; and Juan, sweating like a packed jack under the stress of the excitement, answered courteously, as one should to El Patron, and clung eagerly to his sack. The crowd entered the bank and as L. W. came out Rimrock placed Juan's sack on the table.

"Bring out new silver dollars, fresh from the mint," he said, "and fill up this sack for Juan!"

"Santa Maria!" exclaimed Juan fervently as the cashier came staggering forth with a sack, and Rimrock took the bag, containing a thousand bulging dollars, and set it down before him. He broke the seal and as the shining silver burst forth he spilled it in a huge windrow on the table.

"Now fill up your ore-sack," he said to Juan, "and all you can stuff into it is yours."

"For a gift?" faltered Juan, and as Rimrock nodded he buried his hands in the coin. The dollars clanged and rattled as they spilled on the table and a great silence came over the crowd. They gazed at Old Juan as if he were an Aladdin, or All Baba in his treasure-cave. Old, gray-bearded Juan who hauled wood for a living, or packed cargas on his burros for El Patron! Yes, here he was with his fists full of dollars, piling them faster and faster into his bag.

"Now shake the bag down," suggested El Patron, "and perhaps you can get in some more."

"Some more?" panted Juan and quite mad with great riches he stuffed the sack to the top.

"Very well," said Rimrock, "now take them home, and give part of the money to Rosita. Then take what is left in this other bag and give a fiesta to the boys who worked for me."

"Make way!" cried Juan and as the crowd parted before him he went staggering down the street. A few shiny dollars heaped high on the top, fell off and were picked up by his friends. They went off together, Old Juan and his amigos, and L. W. came over to Rimrock.

"Now listen to me, Henry Jones," he began; but Rimrock waved him away.

"I don't need to," he said, "I know what you'll say—but Juan there has been my friend."

"Well, you don't need to spoil him—to break his back with money—when ten dollars will do just as well."

"Yes, I do!" said Rimrock, "didn't I borrow his picked rock? Well, keep out then; I know my friends. He'll be drunk for a month and at the end of his fiesta he won't have a dollar to his name, but as long as he lives he can tell the other hombres about that big sack of money he had."

Rimrock laid down one big bill, which paid for all the dollars, and walked out of the bank on air. He was feeling rich—that wealthy feeling that penny-pinchers never know—and all the world, except L. W. Lockhart, seemed responsive to his smile. Men who had shunned him for years now shook his hand and refused to take back what they had lent. They even claimed they had forgotten all about it or had intended their loans as stakes. With his pockets full of money it was suddenly impossible for Rimrock to spend a dollar. In the Alamo Saloon, where his friends were all gathered in a determined assault on the bar, his popularity was so intense that the drinks fairly jumped at him and he slipped out the back way to escape. There was one duty more—both a duty and a pleasure—and he headed for the Gunsight Hotel.

The news of his success, whatever it was, had preceded him hours before. Andrew McBain had hid out, the idle women were all a-twitter; but Mary Roget Fortune was calm. She had heard the news from the very first moment, when L. W. had dropped in on McBain; but the more she heard of his riotous prodigality the more it left her cold. His return to town reminded her painfully of that other time when he had come. She had watched for him then, her knight from the desert, worn and ragged but with his sack full of gold; but he had passed her by without a word, and now she did not care.

She looked up sharply as he came at last, a huge form, half-blocking the door; and Rimrock noticed the change. Perhaps his sudden popularity had made him unduly sensitive—he felt instinctively that she did not approve.

"Do you mind my cigar?" he asked, stopping awkwardly half way to her desk; and he suddenly came to life as she answered:

"Why, yes. Since you ask me, I do."

That was straight enough and Rimrock cast his fifty-cent cigar like a stogie out of the door. Then he came back towards her with his big head thrust out and a searching look in his eyes. She had greeted him politely, but it was not the manner of the girl he had expected to see. Somehow, without knowing why, he had expected her to meet him with a different look in her eyes. It had been there before, but now it was absent—a look that he liked very much. In fact, he had remembered it and thought, apropos of nothing, that it was a pity she was so deaf. He looked again and smiled very slightly. But no, the look had fled.

In the big moments of life when we have triumphed over difficulties and quaffed the heady wine of success there is always something—or the lack of something—to bring us back to earth. Rimrock Jones had returned in a Christmas spirit and had taken Gunsight by storm. He had rewarded his friends and rebuked his enemies and all those who grind down the poor. He had humbled L. W. and driven McBain into hiding; and now this girl, this deaf, friendless typist, had snatched the cup from his lips. The neatly turned speech—the few well-chosen words in which he had intended to express his appreciation for her help—were effaced from his memory and in their place there came a doubt, a dim questioning of his own worth. What had he done, or neglected to do, that had taken that look from her eyes? He sank down in a chair and regarded her intently as she sat there, composed and still.

"Well, it's been quite a while," he said at last, "since I've been round to see you."

"Yes, it has," she replied and the way she said it raised a more poignant question in his mind. Was she miffed, perhaps, because he had failed to call on her, that time when he came back to town? He had borrowed her money—she might have been worried, that time when he went to New York.

"I just got in, a little while ago—been back to New York about my mine. Well, it's doing all right now and I've come around to see you and pay back that money I owe."

"Oh, that four hundred dollars? Why, I don't want it back. You were to give me a share in your mine."

Rimrock stopped with his roll half out of his pocket and gazed at her like a man struck dumb. A share in his mine! He put the money back and mopped the sudden sweat from his brow.

"Well, now say," he began, "I've made other arrangements. I've sold a big share already. But I'll give you the money, it'll come to the same thing!" He whipped out his roll and smiled at her hopefully but she drew back and shook her head.

"No," she said, "I don't want your money. I want a share in that mine."

She faced him, determined, and Rimrock went weak for he remembered that she had his word. He had given his word and unless she excused him he would have to make it good. And if he did—well, right there he would lose control of his mine.

"Say, now listen a minute," he began mysteriously, "I'm not telling this on the street——"

"Well, don't tell it here, then," she interrupted hastily, "they're listening, most of the time."

She pointed towards the door that led to the hotel lobby and Rimrock tiptoed towards it. He was just in time, as he snatched it open, to see McBain bounding up the back stairs; and a woman in a rocker, after a guilty stare, rose up and moved hastily away.

"Well, well," observed Rimrock as he banged the door. "I don't know which is worse, these women or peeping Andrew McBain. Are you still working for that fellow?" he enquired confidentially as he sat down and spoke low in her 'phone; and for the first time that day the smile came back and dwelt for a moment in her eyes.

"Yes," she answered, "I still do his work for him. What's the matter—don't you fully approve?"

Her gaze was a challenge and he let it pass with a grin and a jerk of the head.

"Just sorry for you," he said. "You'd better take this money and get a job with a man that's half white."

He drew out his roll and counted out four thousand dollars and laid them before her on the desk.

"Now listen," he began. "That four hundred then was worth four thousand to me now. I had to have it, and I sure appreciate it—now just accept that as a payment in part."

He pushed over the money, but she shook her head and met his gaze with resolute eyes.

"Not much," she said, "I don't want your money and, what's more, I won't accept it. I gave you four hundred dollars—all the money I had—to get me a share in that mine, and now I want it. I don't care how much, but I want a share in that mine."

Rimrock shoved back his chair and once more the sweat appeared on his troubled brow. He rose up softly and peeped out the door, then came back and sat very close.

"What's the idea?" he asked. "Has some one been telling you who I've got in with me on this deal? Well, what's the matter then? Why won't you take the money? I'll give you more than you could get for the stock."

"No, all my life it's been my ambition to own a share in a mine. That's why I gave you the last of my money—I had confidence in your mine from the start."

"Well, what did you think, then?" enquired Rimrock sardonically, "when I jumped out of town without seeing you? You'd have sold out cheap, if I'd've come to you then, but now everybody knows I've won."

"Never mind what I thought," she answered darkly, "I took a chance, and I won."

"Say, you're strictly business, now ain't you?" observed Rimrock and muttered under his breath. "How much of a share do you expect me to give you?" he asked after a long anxious pause and her eyes lit up and were veiled.

"Whatever you say," she answered quietly and then: "I believe you mentioned fifty-fifty—an undivided half."

"My—God!" exclaimed Rimrock starting wildly to his feet. "You don't—say, you didn't think I meant that?"

"Why, no," she said with a faint flicker of venom, "I didn't, to tell you the truth. That's why I told you I was talking business; but you said: 'Well, so am I.'"

"Well, holy Jehosophrats!" cursed Rimrock to himself and turned to look her straight in the eyes.

"Now let's get down to business," he went on sternly, "what do you want, and where am I at?"

"I want a share in that mine," she answered evenly, "whatever you think is right."

"Oh, that's the deal! You don't want fifty-fifty? You leave what it is to me?"

"That's what I said from the very first. And as for fifty-fifty—no, certainly I do not."

There were tears, half of anger, gathering back in her eyes, but Rimrock took no thought of that.

"Oh, you don't like my style, eh?" he came back resentfully. "All you want out of me is my money."

"No, I don't!" she retorted. "I don't want your money! I want a share in that mine!"

"Say, who are you, anyway?" burst out Rimrock explosively. "Are you some wise one that's on the inside?"

"That's none of your business," she answered sharply, "you were satisfied when you took all my money."