Title: The Hero of the Humber; Or, The History of the Late Mr. John Ellerthorpe

Author: Henry Woodcock

Release date: February 6, 2007 [eBook #20520]

Most recently updated: January 1, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stacy Brown, David Clarke and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

BEING A RECORD OF REMARKABLE INCIDENTS IN HIS CAREER AS A SAILOR; HIS CONVERSION AND CHRISTIAN USEFULNESS; HIS UNEQUALLED SKILL AS A SWIMMER, AND HIS EXPLOITS ON THE WATER, WITH A MINUTE ACCOUNT OF HIS DEEDS OF DARING IN SAVING, WITH HIS OWN HANDS, ON SEPARATE AND DISTINCT OCCASIONS, UPWARDS OF FORTY PERSONS FROM DEATH BY DROWNING: TOGETHER WITH AN ACCOUNT OF HIS LAST AFFLICTION, DEATH, ETC.

|

'My tale is simple and of humble birth, A tribute of respect to real worth.' |

S. W. Partridge, 9, Paternoster Row; Wesleyan Book Room,

66, Paternoster Row; Primitive Methodist Book Room, 6, Sutton

Street, Commercial Road, E.; and of all Booksellers.

TO

THE SEAMEN OF GREAT BRITAIN,

TO WHOSE

SKILL, COURAGE, AND ENDURANCE,

ENGLAND OWES MUCH OF HER GREATNESS,

THIS VOLUME—

CONTAINING A RECORD OF THE CHARACTER AND DEEDS OF ONE,

WHO, FOR UPWARDS OF THIRTY YEARS,

BRAVED THE HARDSHIPS AND PERILS OF A SAILOR'S LIFE,

AND

WHOSE GALLANTRY AND HUMANITY

WON FOR HIM THE TITLE

OF

'THE HERO OF THE HUMBER,'

IS MOST RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED,

WITH THE EARNEST PRAYER

THAT THEY MAY EMBRACE THAT BENIGN RELIGION

WHICH NOT ONLY RESCUED THE 'HERO' FROM THE EVILS IN WHICH

HE HAD SO LONG INDULGED,

AND ENRICHED HIM WITH THE GRACES OF THE

CHRISTIAN CHARACTER,

BUT ALSO GAVE

A BRIGHTER GLOW AND GREATER ENERGY

TO THAT

COURAGE, GALLANTRY, AND HUMANITY

BY WHICH HE HAD BEEN LONG DISTINGUISHED.

THE AUTHOR.

TO THE SECOND EDITION.

Mr. Gladstone, in a recent lecture thus defines a hero: quoting Latham's definition of a hero,—'a man eminent for bravery,' he said he was not satisfied with that, because bravery might be mere animal bravery. Carlyle had described Napoleon I. as a great hero. 'Now he (Mr. Gladstone) was not prepared to admit that Napoleon was a hero. He was certainly one of the most extraordinary men ever born. There was more power concentrated in that brain than in any brain probably born for centuries. That he was a great man in the sense of being a man of transcendent power, there was no doubt; but his life was tainted with selfishness from beginning to end, and he was not ready to admit that a man whose life was fundamentally tainted with selfishness was a hero. A greater hero than Napoleon was the captain of a ship which was run down in the Channel three or four years ago, who, when the ship was quivering, and the water was gurgling round her, and the boats had been lowered to save such persons as could be saved, stood by the bulwark with a pistol in his hand and threatened to shoot dead the first man who endeavoured to get into the boat until every woman and child was provided for. His true idea of a hero was this:—A hero was a man who must have ends beyond himself, in casting himself as it were out of himself, and must pursue these ends by means which were honourable, the lawful means, otherwise he might degenerate into a wild enthusiast. He must do this without distortion or disturbance of his nature as a man, because there were cases of men who were heroes in great part, but who were so excessively given to certain ideas and objects of their own, that they lost all the proportion of their nature. There were other heroes, who, by giving undue prominence to one idea, lost the just proportion of things, and became simply men of one idea. A man to be a hero must pursue ends beyond himself by legitimate means. He must pursue them as a man, not as a dreamer. Not to give to some one idea disproportionate weight which it did not deserve, and forget everything else which belonged to the perfection and excellence of human nature. If he did all this he was a hero, even if he had not very great powers; and if he had great powers, then he was a consummate hero.'

Now, if we cannot claim for the late Mr. Ellerthorpe 'great powers' of intellect, we are quite sure that all who read the following pages will agree that the title bestowed upon him by his grateful and admiring townsman,—'The Hero of the Humber,' was well and richly deserved. He was a 'Hero,' though he lived in a humble cottage. He was a man of heroic sacrifices; his services were of the noblest kind; he sought the highest welfare of his fellow-creatures with an energy never surpassed; his generous and impulsive nature found its highest happiness in promoting the welfare of others. He is held as a benefactor in the fond recollection of thousands of his fellow countrymen, and he received rewards far more valuable and satisfying than those which his Queen and Government bestowed upon him: more lasting than the gorgeous pageantries and emblazoned escutcheon that reward the hero of a hundred battles.

The scene of most of his gallant exploits in rescuing human lives was 'The river Humber;' hence the title given him by a large gathering of his fellow townsmen.

The noble river Humber, upon which the town of Kingston-upon-Hull is seated, may be considered the Thames of the Midland and Northern Counties of England. It divides the East Riding of Yorkshire from Lincolnshire, during the whole of its course, and is formed by the junction of the Ouse and the Trent. At Bromfleet, it receives the little river Foulness, and rolling its vast collection of waters eastward, in a stream enlarged to between two and three miles in breadth, washes the town of Hull, where it receives the river of the same name. Opposite to Hedon and Paul, which are a few miles below Hull, the Humber widens into a vast estuary, six or seven miles in breadth, and then directs it's course past Great Grimsby to the German Ocean, which it enters at Spurn Head. No other river system collects waters from so many important towns as this famous stream. 'The Humber,' says a recent writer, 'resembling the trunk of a vast tree spreading its branches in every direction, commands, by the numerous rivers which it receives, the navigation and trade of a very extensive and commercial part of England.'

The Humber, between its banks, occupies an area of about one hundred and twenty-five square miles. The rivers Ouse and Trent which, united, form the Humber, receive the waters of the Aire, Calder, Don, Old Don, Derwent, Idle, Sheaf, Soar, Nidd, Yore, Wharfe, &c., &c.

From the waters of this far-famed river—the Humber—Mr. Ellerthorpe rescued thirty-one human beings from drowning.

For the rapid sale of 3,500 copies of the 'Life of the Hero,' the Author thanks a generous public. A series of articles extracted from the first edition appeared in 'Home Words.' An illustrated article also appears in Cassell's 'Heroes of Britain in Peace and War,' in which the writer speaks of the present biography as 'That very interesting book in which the history of Ellerthorpe's life is told. (p. 1. 2. part xi.) The Author trusts that the present edition, containing an account of 'The Hero's' last affliction, death, funeral, etc., will render the work additionally interesting.

THE WRITER.

53, Leonard Street, Hull, Aug. 4th, 1880.

| I. | His wicked and reckless career | 1 |

| II. | His conversion and inner experience | 6 |

| III. | His Christian labours | 14 |

| IV. | His staunch teetotalism | 22 |

| V. | His bold adventures on the water | 31 |

| VI. | His method of rescuing the drowning | 44 |

| VII. | His gallant and humane conduct in rescuing the drowning | 51 |

| VIII. | The honoured hero | 95 |

| IX. | His general character, death, etc. | 116 |

| X. | The hero's funeral | 122 |

HIS WICKED AND RECKLESS CAREER AS A SAILOR.

The fine old town of Hull has many institutions of which it is deservedly proud. There is the Charter house, a monument of practical piety of the days of old. There is the Literary and Philosophical Institute, with its large and valuable library, and its fine museum, each of which is most handsomely housed. There is the new Town Hall, the work of one of the town's most gifted sons. There is the tall column erected in honour of Wilberforce, in the days when the representatives of the law were expected to obey the laws, and when the cultivation of a philanthropic feeling towards the negro had not gone out of fashion. There is the Trinity House, with its magnificent endowments, which have for more than five centuries blessed the mariners of the port, and which is now represented by alms-houses, so numerous, so large, so externally beautiful, and so trimly kept as to be both morally and architecturally among the noblest ornaments of the town. There is the Port of Hull Society, with its chapel, its reading-rooms, its orphanage, its seaman's mission, all most generously supported. There is that leaven of ancient pride which also may be classed among the[Pg 2] institutions of the place, and which operates in giving to a population by no means wealthy a habit of respectability, and a look for the most part well-to-do. But among none of these will be found the institution to which we are about to refer. The institution that we are to-day concerned to honour is compact, is self-supporting, is eminently philanthropic, has done more good with very limited means than any other, and is so much an object of legitimate pride, that we have pleasure in making this unique institution more generally known. A life-saving institution that has in the course of a few brief years rescued about fifty people from drowning, and that has done so without expectation of reward, deserves to be named, and the name of this institution is simply that of a comparatively poor man—John Ellerthorpe, dock gatekeeper, at the entrance of the Humber Dock.'

Such was the strain in which the Sheffield Daily Telegraph, in a Leader (March 17th, 1868), spoke of the character and doings of him whom a grateful and admiring town entitled 'The Hero of the Humber.'

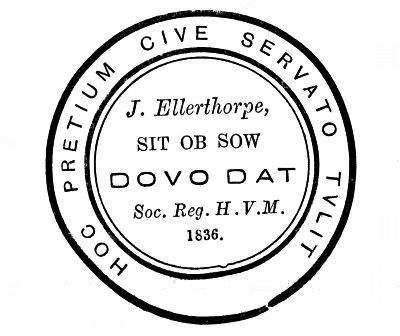

He was born at Rawcliffe, a small village near Snaith, Yorkshire, in the year 1806. His ancestors, as far as we can trace them, were all connected with the sea-faring life. His father, John Ellerthorpe, owned a 'Keel' which sailed between Rawcliffe and the large towns in the West Riding of Yorkshire, and John often accompanied him during his voyages. His mother was a woman of great practical sagacity and unquestionable honesty and piety, and from her young John extended many of the high and noble qualities which distinguished his career. Much of his childhood, however, was passed at the 'Anchor' public house, Rawcliffe, kept by his paternal grandmother, where he early became an adept swearer and a lover of the pot, and for upwards of forty years—to use his own language—he was 'a drunken blackard.'[Pg 3]

When John was ten years of age his father removed to Hessle. About this time John heard that flaming evangelist, the Rev. William Clowes, preach near the 'old pump' at Hessle, and he retired from the service with good resolutions in his breast, and sought a place of prayer. Soon after he heard the famous John Oxtoby preach, and he says, 'I was truly converted under his sermon, and for sometime I enjoyed a clear sense of forgiveness.' His mother's heart rejoiced at the change; but from his father, who was an habitual drunkard, he met with much opposition and persecution, and being but a boy, and possessing a very impressionable nature, John soon joined his former corrupt associates and cast off, for upwards of thirty years, even the form of prayer.

Ellerthorpe was born with a passion for salt water. He was reared on the banks of a well navigated river, the Humber, and, in his boyhood, he liked not only to be on the water, but in it. He also accompanied his father on his voyages, and when left at home he spent most of his time in the company of seamen, and these awakened within him the tastes and ambition of a sailor. He went to sea when fourteen years of age, and for three years sailed in the brig 'Jubilee,' then trading between Hull and London. The next four years were spent under Captain Knill, on board of the 'Westmoreland,' trading between Hull and Quebec, America. Afterwards he spent several years in the Baltic trade. When the steam packet, 'Magna Charter,' began to run between Hull and New Holland, John became a sailor on board and afterwards Captain of the vessel. He next became Captain of a steamer that ran between Barton and Hessle. He then sailed in a vessel between Hull and America. In 1845, he entered the service of the Hull Dock Company, in which situation he remained up to the time of his death.

Fifty years ago our sailors, generally speaking, were a grossly wicked class of men. A kind of[Pg 4] special license to indulge in all kinds of sin was given to the rough and hardy men whose occupation was on the mighty deep. Landsmen, while comfortably seated round a winter's fire, listening to the storm and tempest raging without, were not only struck with amazement at the courage and endurance of sailors in exposing themselves to the elements, but, influenced by their imagination, magnified the energy and bravery that overcame them. Peasants gazed with wild astonishment on the village lad returned, after a few years absence, a veritable 'Jack tar.' The credulity of these delighted listeners tempted Jack to 'spin his yarns,' and tell his tales of nautical adventures, real or imaginary. Hence, he was everywhere greeted with a genial and profuse hospitality. The best seat in the house, the choicest drinks in the cellar, were for Jack. Our ships of commerce, like so many shuttles, were rapidly weaving together the nations of the earth in friendly amity. Besides, a romantic sentiment and feeling, generated to a great extent by the victories which our invincible navy had won during the battles of the Nile, and perpetuated by Nelson's sublime battle cry, 'England expects every man to do his duty,' helped to swell the tide of sympathy in favour of the sailor. Under these circumstances Jack became Society's indulged and favoured guest; and yet he remained outside of it. 'Peculiarities incident to his profession, and which ought to have been corrected by education and religion, became essential features of character in the public mind. A sailor became an idea—a valuable menial in the service of the commonwealth, but as strange and as eccentric in his habits as the walk of some amphibious animal, or web-footed aquatic on land. To purchase a score of watches, and to fry them in a pan with beer, to charter half a dozen coaches, and invite foot passengers inside, while he 'kept on deck,' or in any way to scatter his hard[Pg 5] earnings of a twelvemonth in as many hours, was considered frolicsome thoughtlessness, which was more than compensated by the throwing away of a purse of gold to some poor woman in distress.' Land-sharks and crimps beset the young sailor in every sea port; low music halls and dingy taverns and beer shops presented their attractions; and there the 'jolly tars' used to swallow their poisonous compounds, and roar out ribald songs, and dance their clumsy fandangoes with the vilest outcasts of society. 'It is a necessary evil,' said some; 'it is the very nature of sailors, poor fellows.' While the thoughtless multitude were immensely tickled with Jack's mad antics and drolleries. Generous to a fault to all who were in need, Jack's motto was:—

Amid such scenes as these our friend spent a great portion of his youth and early manhood. The loud ribald laugh, the vile jest and song, the midnight uproar, the drunken row, the flaunting dress and impudent gestures of the wretched women who frequent our places of ungodly resort—amid such scenes as these, did he waste his precious time and squander away much of his hard earned money. But though a wild and reckless sailor, his warm and generous heart was ever impelling him to noble and generous deeds. If he sometimes became the dupe of the designing, and indulged in the wild revelry of passion, at other times he gave way to an outburst of generosity bordering on prodigality, relieving the necessities of the poor, or true to the instincts of a British tar standing up to redress the wrongs of the oppressed.

HIS CONVERSION AND INNER EXPERIENCE.

When far away on the sea, and while mingling in all the dissipated scenes of a sailor's life, John would sometimes think of those youthful days—the only sunny spot in his life's journey—when he 'walked in the fear of the Lord and in the comfort of the Holy Ghost.' Serious thoughts would rise in his mind, and those seeds of truth, sown in his heart while listening to Clowes and Oxtoby, and which for years seemed dead, would be quickened into life. He had often wished to hear Mr. Clowes once more, and on seeing a placard announcing that he would preach at the opening of the Nile Street Chapel, Hull (1846), he hastened home, and, sailor-like, quaintly observed to his wife, 'Why that old Clowes is living and is going to preach. Let's go and hear him.' On the following Sunday he went to the chapel, but it was so many years since he had been to God's house that he now felt ashamed to enter, and for some minutes he wandered to and fro in front of the chapel. At length he ventured to go in, and sat down in a small pew just within the door. His mind was deeply affected, and ere the next Sabbath he had taken two sittings in the chapel.

About this time, the Rev. Charles Jones, of blessed memory, began his career as a missionary in Hull. He laboured during six years, with great success, in the streets, and yards, and alleys of the town; and scores now in heaven and hundreds on their way thither, will, through all eternity, have to bless God that Primitive Methodism ever sent him to labour in Hull. The Rev. G. Lamb prepared the people to receive him by styling him 'a bundle of love.' John went to hear him, and charmed by his preaching and allured by the grace of God, his religious feelings were deepened. Soon after this, and through the[Pg 7] labours of Mr. Lamb, he obtained peace with God, and I have heard him say at our lovefeasts, 'Jones knocked me down, but it was Mr. Lamb that picked me up.'

Being invited by two Christian friends to attend a class meeting on the following Sabbath morning, he went. As he sat in that old room in West Street Chapel, a thousand gloomy thoughts and fearful apprehensions crossed his mind, and casting many a glance towards the door, he 'felt as though he must dart out.' But when Mr. John Sissons, the leader of the class, said, with his usual kind smile and sympathizing look:—'I'm glad to see you,' and then proceeded to give him suitable council and encouragement, John's heart melted and his eyes filled with tears; and, on being invited to repeat his visit on the following Sabbath, he at once consented. One of the friends who had accompanied him to the class, said, 'Now God has sown the seed of grace in your heart and the enemy will try to sow tares, but if you resist the devil he will flee from you,' and scarcely had John left the room ere the battle began. 'Oh, what a fool' he thought, 'I was to promise to go again,' and when he got home he said to his wife, 'I've been to class, and what is worse, I have promised to go again, and I dar'nt run off.' Mrs. Ellerthorpe, who had begun to watch with some interest her husband's struggles, wisely replied, 'Go, for you cannot go to a better place, I intend to go to Mr. Jones' class.' All the next week John was in great perplexity, thinking, 'What can I say if I go? If I tell them the same tale I told them last week they will say I've got it off by memory.' On the following Sabbath morning he was in the street half resolved not to go to class, when he thought, 'Did'nt my friend say the devil would tempt me and that I was to resist him? Perhaps it is the devil that is filling me with these distressing feelings, but I'll[Pg 8] resist him,' and, suiting his action to his words, in a moment, John was seen darting along the street at his utmost speed; nor did he pause till, panting and almost breathless, he found himself seated in the vestry of the Primitive Methodist Chapel, West Street. HIS CONVERSION.He regarded that meeting as the turning point in his spiritual history, and in the review it possessed to him an undying charm. There a full, free, and present salvation was pressed on the people. The short way to the cross was pointed out. The blessedness of the man whose transgression is forgiven was realized. The direct and comforting witness of the Holy Spirit to the believer's adoption was proclaimed. And there believers were exhorted to grow richer in holiness and riper in knowledge every day. And while John sat and listened to God's people, he felt a divine power coming down from on high, which he could not comprehend, but which, however, he joyously experienced. He joined the class that morning and continued a member five years, when he became connected with our new chapel in Thornton Street. Around these services in the old vestry at West Street, cluster the grateful recollections of many now living and of numbers who have crossed the flood. How often has that room resounded with the cries of penitent sinners and the songs of rejoicing believers?

Soon after our friend had united himself with the people of God he paid a visit to his mother, who was in a dying state. It was on a beautiful Sabbath morning, in the month of June, and while walking along the road, between Hull and Hessle, and reflecting on the change he had experienced, he was filled 'unutterably full of glory and of God.' That morning, with its glorious visitation of grace, he never forgot. His soul had new feelings; his heart throbbed with a new, a strange, a divine joy. Peace reigned within and all around was lovely. The sun seemed to shine more brightly, and the birds sang a[Pg 9] sweeter song. The flowers wore a more beautiful aspect, and the very grass seemed clothed in a more vivid green. It was like a little heaven below. 'As I walked along,' he says, 'I shouted, glory, glory, glory, and I am sure if a number of sinners had heard me they would have thought me mad.'

But was he mad? Did not the pentecostal converts 'eat their meat with gladness and singleness of heart, praising God?' Did not the converts in Samaria 'make great joy in the city?' Did not the Ethiopian Eunuch, having obtained salvation, 'go on his way rejoicing?' And Charles Wesley, four days after his conversion, thus expressed the joy he felt—

And surely God's people have as much right to give utterance to their joy as the dupes of the devil have to give expression to theirs; and though the religion of the Saviour requires us to surrender many pleasures and endure peculiar sorrows, yet it is, supremely, the religion of peace, joy, and overflowing gladness.

Mr. Ellerthorpe was never guilty of proclaiming with the trumpet tongue of a Pharisee, either what he felt or did, and though he kept a carefully written diary, extending over several volumes, and the reading of which has been a great spiritual treat to the writer of this book,—revealing, as it does, the secret of that intense earnestness, unbending integrity, active benevolence, and readiness for every good word and work by which our friend's religious career was distinguished,—yet of that diary our space will permit us to make but the briefest use. Take the following extracts:—

'January 1, 1852.—I, John Ellerthorpe, here in the presence of my God, before whom I bow, covenant to live nearer to Him than I have done in the year that has rolled into eternity.'[Pg 10]

Resolutions.

'1st. I will bow three times a day in secret.

2nd. I will attend all the means of grace I can.

3rd. I will visit what sick I can.

4th. I will speak ill of no man.

5th. I will hear nothing against any man, especially those who belong to the same society.

6th. I will respect all men, especially Christians.

7th. I will pray for a revival.

8th. I will guard against all bad language and ill feeling.

9th. I will never speak rash to any man.

10th. I will be honest in all my dealings.

11th. I will always speak the truth.

12th. I will never contract a debt without a proper prospect of payment.

13th. I will read three chapters of the Bible daily.

14th. I will get all to class I possibly can.

15th. I will set a good example before all men, and especially my own family.

16th. I will not be bound for any man.

17th. I will not argue on scripture with any man.

18th. I will endeavour to improve my time.

19th. I will endeavour to be ready every moment.

20th. I will leave all my concerns in the hands of my God, for Christ's sake. All these I intend, by the help of my God, diligently to perform.'

That he always carried out these resolutions is more than his diary will warrant us to say. He sometimes missed the mark, and came short of his aim. He suffered from a certain hastiness of temper, and ruggedness of disposition, which, to use his own words, 'cost him a vast deal of watching and praying. But the Lord,' he adds, 'has helped me in a wonderful manner, and I believe I shall reap if I faint not.' The following extracts from his diary will give some idea of his inner experience:[Pg 11]—

'January 1850. 5th.—I feel the hardness of my heart and the littleness of my love, yet I am in a great degree able to deny myself to take up my cross to follow Christ through good and evil report. 7th.—I feel that I am growing in grace and that I have more power over temptation, and over myself than I had some time since, but I want the witness of full sanctification. 8th.—What is now the state of my mind? Do I now enjoy an interest in Christ? Am I a child of God? It is suggested by Satan that I am guilty of many imperfections. I know it, but I know also if any man sin, etc. Feb. 18th.—I feel my heart is very hard and stubborn, that I am proud and haughty and very bad tempered, but God can, and I believe he will, break my rocky heart in pieces. March 3rd.—This has been a good Sabbath; we had a good prayer meeting at 7 o'clock, a profitable class at 9, in the school the Lord was with us, and the preaching services were good. 4th.—Last night I had a severe attack of my old complaint and suffered greatly for many hours, but I called upon God and he delivered me. 16th.—I am in good health, for which, and the use of my reason, and all the blessings that God bestows upon me, I am thankful. I am unworthy of the least of them. O that I could love God ten thousand times more than I do; for I feel ashamed of myself that I love him so little. 19th.—I am ill in body but well in soul. The flesh may give way, and the devil may tempt me, and all hell may rage, yet I believe the Lord will bring me through. April 6th.—To-day, in the haste of my temper, I called a man a liar. I now feel that I did wrong in the sight of God and man. I am deeply sorry. May God forgive me, and may I sin no more. May 6th.—O God make me faithful and give to thy servant the spirit of prayer. Like David, I want to resolve, "Speak, Lord; for thy servant heareth"; like Mary I want to "ponder these things in my heart"; like[Pg 12] the Bereans I want to "search the scriptures" daily and in the spirit of Samuel to say "Speak, Lord; for thy servant heareth." May 20th.—I am at Hessle feast, and thank God it has been a feast to my soul. I have attended one prayer meeting, two class meetings, three preaching services. Bless God for these means of grace. My little book is full and I do trust I am a better man than when I began to write my diary. 29th.—My dear wife is very ill, but the Lord does all things well. I know that He can, and believe that He will, raise her up again and that the affliction of her body will turn to the salvation of her soul. 30th.—I am now laid under fresh obligations to God. He has given me another son. May he be a goodly child, like Moses, and grow up to be a man after God's own heart. July 3rd.—This day the Victoria docks have been opened. It has been a day of trial and conflict, for I ran the Packet into a Schooner and did £10 damage. It was a trial of my faith, and through the assistance of God I overcame. HIS INNER EXPERIENCE.August 20th.—Sunday.—How thankful I am that God has set one day in seven when we can get away from the wear and tear of life and worship Him under our own vine and fig tree none daring to make us afraid. It is all of God's wisdom, and mercy, and goodness. September 11th.—To-night I put my wife's name in the class book; may she be a very good member, such a one as Thou wilt own when Thou numbers up Thy jewels. October 11th.—I did wrong last night, being quite in a passion at my wife, which grieved her. Lord help me and make me never differ with her again. 12th.—I feel much better in my soul this morning and will, from this day promise in the strength of grace, never to allow myself to be thrown into a passion again: it grieves my soul, it hurts my mind. 1851. January 7th.—Five years this day I entered my present situation under the Hull Dock Company. Then I was a drunken man, and a great[Pg 13] swearer; but I thank God he has changed my heart. 18th.—This has been a very troublesome day to my soul. I have been busy with the sunken packet all day and hav'nt had time to get to prayer. My soul feels hungry. 29th.—This has been a day of prayerful anxiety about my son; he has passed his third examination, God having heard my prayer on his behalf. Feb. 24th.—I have been to the teetotal meeting and have taken the pledge, and I intend, through the grace of God, to keep as long as I live. March 1st.—The Rev. W. Clowes is still alive. May the Lord grant that he may not have much pain. While brother Newton and I were in the room with him we felt it good; O the beauty of seeing a good man in a dying state. May I live the life of the righteous and may my last end be like Mr. Clowes's. 2nd.—The first thing I did this morning was to go and inquire after Mr. Clowes. I found that life was gone and that his happy spirit had taken its flight to heaven. 4th.—I am more than ever convinced of the great advantage we derive from entire sanctification; it preserves the soul in rest amid the toils of life; it gives satisfaction with every situation in which God pleases to place us.'

Sailor like Mr. Ellerthorpe was earnest, impulsive, enthusiastic, carrying a warm ardour and a brisk life into all his duties. He did not love a continual calm, rather he preferred the storm. He did not believe that because he was on board a good ship, had shaped his course aright, and had a compass never losing its polarity, that he would reach port whether he made sail or not, whether he minded his helm or not. He knew he couldn't drift into port. With waterlogged and becalmed Christians or those who heaved to crafts expecting to drift to the celestial heaven, he had but little fellowship. Such he would cause to shake out reefs and have yards well trimmed to catch every breeze from the millenial trade winds.

HIS CHRISTIAN LABOURS.

Having become a subject of saving grace, Mr. Ellerthorpe felt an earnest desire that others should participate in the same benefit. Nor was there any object so dear to his heart, and upon which he was at all times so ready to speak, as the conversion of sinners. He knew he did not possess the requisite ability for preaching the gospel, and therefore he sought out a humbler sphere in which his new-born zeal might spend its fires, and in that sphere he laboured, with remarkable success, during a quarter of a century. I now refer to the sick chamber.

During all that time he took a deep interest in the sick and the dying; and for several years after his conversion, having much time at his disposal, he would often visit as many as twenty families per day, for weeks together. When Cholera, that mysterious disease, with its sudden attacks, its racking cramps, its icy cold touch, and its almost resistless progress, swept through the town of Hull, in the year 1849, leaving one thousand eight hundred and sixty,—or one in forty of the entire population,—dead, our friend was at any one's call, and never refused a single application; indeed, he was known as a great visitor of the sick and dying, and was often called in extreme cases to visit those from whom others shrank lest they should catch the contagion of the disorder. The scenes of suffering and distress which he witnessed baffled description. On one occasion he entered a room where a whole family were smitten with cholera. The wife lay cold and dead in one corner of the room, a child had just expired in another corner, and the husband and father was dying, amidst excruciating pain, in the middle of the room. John knelt down and spoke words of Christian comfort to the man, who died in a few moments.[Pg 15]

For years, he was in the habit of accompanying Mr. Jones, when visiting the miserable garrets, obscure yards, and wretched alleys in Hull, and was considered his 'right hand man,' in helping to hold open-air services. They often went in company to such wretched localities as 'Leadenhall Square,' then the greatest cesspool of vice in the Port, and, well supplied with tracts, visited every house. During the intervals of public worship, on the Sabbath day, when he might have been enjoying himself in the circle of his family, on a clean hearth, before a bright fire, he was pointing perishing sinners to the Lamb of God. When our new and beautiful chapel in Great Thornton Street was discovered to be on fire, at noon,—March, 1856, he was at the bedside of an afflicted woman, Mrs. Wright, speaking to her of her past sins and of a precious Saviour. He had spent some time with her daily for months, but just at this time he became Foreman of the Victoria Dock and could no longer pay his daily visits to the sick, which greatly distressed Mrs. Wright and others; but duty called him elsewhere and he obeyed its voice. He says, 'I durst not make any fresh engagements to visit the sick, and up to the present time (1867) I have rarely been able to visit, except on the Sabbath day, all my time being required at the dock gates. But on the Sabbath I love to get to the bedside of the sick; nothing does me more good; there my soul is often refreshed and my zeal invigorated.'

Those who are most averse to religion in life, generally desire to share its benefits in death. Their religion is very much like the great coats which persons of delicate health wear in this changeable climate, and which they use in foul weather, but lay aside when it is fair. 'Lord,' says David, 'in trouble they visited thee, they poured out a prayer when thy chastening was upon them.'

Nor would we intimate that none truly repent of their sins and obtain forgiveness, under such circumstances.[Pg 16] Though late repentance is seldom genuine, yet, as Mr. Jay remarks, genuine repentance is never too late. God can pardon the sins of a century as easily as those of a day. Our friend was the means, in the hand of God, of leading many, when worn by sickness and at the eleventh hour of life, to the Lamb of God. His carefully kept diary records many such instances. We give one. He says, 'I remember one Sunday coming from Hessle with the Rev. C. Jones. Our "hearts burned within us as we talked by the way," and when we got to Coultam Street, a number of well-dressed young men overheard our conversation, and began to shout after us and call us approbrious names. Mr. J. talked with them, but to no purpose. Four months after, Mr. Jones and myself went, as usual, to visit the inmates of the infirmary; Mr. J. took one side and I the other, and when I came to a person who needed special counsel and advice, I used to call my friend to my aid. Well, we met with a young man who burst into a flood of tears, and casting an imploring look towards Mr. Jones, he said, "O sir, do forgive me." "Forgive you what?" said Mr. J. "what have you done that you should ask me to forgive you?" "Sir," said he, "I am one of those young men who were so impertinent to you one Sunday when you were returning from Hessle; do forgive me, sir." "I freely forgive you," replied my friend, "you must ask God to forgive you, for it is against him you have sinned." We then prayed with him, and asked God to forgive him. He was suffering from a broken leg, and I often used to visit him after our first interview. He obtained pardon, and rejoiced in Christ as his Saviour. He was a brand plucked from the burning.'

But Mr. Ellerthorpe also tells us that though he visited, during twenty-five years, hundreds of persons who cried aloud for mercy and professed to obtain forgiveness, on what was feared would be their dying[Pg 17] beds, yet, he did not remember more than five or six who, on being restored to health, lived so as to prove their conversion genuine. The rest returned 'like the dog to its vomit, and the sow that was washed to her wallowing in the mire.' The Sabbath-breaker forgot his vows and promises, and returned to his Sunday pleasures. The swearer allowed his tongue to move as unchecked in insulting his Maker as before. The drunkard thirsted for his intoxicating cups and returned to the scenes of his former dissipations; and the profligate, who avowed himself a 'changed man,' when health was fully restored, laughed at religion as a fancy, and hastened to wallow in the mire of pollution. He had scarcely a particle of faith in sick-bed repentances, but believed that in most instances they are solemn farces.

Deeply affecting and admonitory are some of the instances he records. He says, 'One night an engineer called me out of bed to visit his wife, who was attacked with cholera. While I was praying with her, he was seized with the complaint. I visited them again the next day, when the woman died, but the husband, after a long affliction, recovered. He seemed sincerely penitent and made great promises of amendment. But, alas! like hundreds more whom I visited, he no sooner recovered, than he sought to shun me. At length he left the part of the town where he resided when I first visited him, as he said, "to get out of my way." But at that time, I visited in all parts of the town, and I often met him, and it used to pain me to see the dodges he had recourse to in order to avoid meeting me in the street.'

He also records the case of a carter who resided in Collier Street. He was attacked with small pox, and was horrible to look at and infectious to come near, but being urged to visit him, 'I went to see him daily for a long time,' says John. 'One day when I called I found him, his wife, and child bathed[Pg 18] in tears, for the doctor had just told them that the husband and father would be dead in a few hours. We all prayed that God would spare him, and spared he was. I continued to visit him thrice a day, and he promised that he would accompany me to class when he got better. At that time he seemed as though he would have had me ever with him. One day, as I entered his room, he said, "O Mr. Ellerthorpe, how I love to hear your foot coming into my house." I replied, 'Do you think it possible that there will come a time when you will rather see any one's face and hear any one's voice than mine?' "Never, no never," was his reply. I answered, 'Well, I wish and hope it may never happen as I have supposed.' Now, what followed? He went once to class, but I could not attend that night, having to watch the tide, and he never went again. I have seen him in the streets when he would go anywhere, or turn down any passage, rather than meet me; and when compelled to meet me he would look up at the sky or survey the chimney tops rather than see me.'

'On one occasion, when visiting at the Infirmary, going from ward to ward, and from bed to bed, I met with a young man, S. B——. He was very bad, and was afraid he was going to die. I talked with him often and long, pointing him to the Saviour, and prayed with him. With penitential tears and earnest cries he sought mercy, and at length professed to obtain salvation. He recovered. One Sunday, when at Hessle, visiting my dying mother, I met this young man, and I shall never forget his agitated frame, and terrified appearance, when he saw me. He looked this way and that way; I said, 'Well, B——, are you all right? Have you kept the promises you made to the Lord?' A blush of shame covered his face. I said 'Why do you look so sad? Have I injured you?' 'No, Sir.' 'Have you injured me?' 'I hope not,' was his reply. 'Then look me in the face; are you[Pg 19] beyond God's reach, or do you think that because he has restored your health once, he will not afflict you again? Ah! my boy, the next time may be much worse than the last. And do you think God will believe you if you again promise to serve him? He looked round him and seemed as though he would have leaped over a drain that was close by.'

Conscience is a busy power within the breast of the most desperate, and when roused by the prospect of death and judgment, it speaks in terrible tones. The notorious Muller denied the murder of Mr. Briggs, until, with cap on his face and the rope round his neck, he submitted to the final appeal and acknowledged, as he launched into eternity, 'Yes, I have done it.' But the cries of these persons seem to have arisen, not from an abhorrence of sin, but from a dread of punishment; they feared hell, and hence they wished for heaven; they desired to be saved from the consequences of sin, but were not delivered from the love of it. Need we wonder that our friend had but little faith in a sick-bed repentance? Scripture and reason alike warn us against trusting to such repentance, 'Be not deceived; God is not mocked: for whatsoever a man soweth, that shall he also reap. For he that soweth to the flesh shall of the flesh reap corruption; but he that soweth to the Spirit shall of the Spirit reap life everlasting.'

While our friend felt that he would have been unworthy the name of a Christian had he not felt more for the spiritual than for the temporal woes of his fellow creatures, yet the latter were not forgotten by him; and it sometimes grieved him that he could not more largely minister to the temporal wants of the poor, the fatherless, the orphans, and the widows, whom he visited.

And perhaps one of the most painful trials a visitor of the sick endures is, to go moneyless to a chamber that has been crossed by want, and whose inmate is[Pg 20] utterly unable to supply his own necessities; but when the visitor can relieve the physical as well as the spiritual necessities of the sufferer, with what a buoyant step and cheerful heart he enters the abode of poverty and suffering! And his words, instead of falling like icicles on the sufferer's soul, fall on it as refreshing as a summer rain, warm as the tempered ray, and welcome as a mother's love. Such a visitor has often chased despair from the abode of wretchedness, and filled it with the atmosphere of hope.

Hence, that he might participate in this joy, and have wherewith to relieve the needy, Mr. Ellerthorpe abstained from the use of tobacco, of which, at one period of his life, he was an immoderate consumer. One Sabbath morning, while he and Mr. Harrison were visiting the sick, they met two wretched-looking boys, fearfully marked with small pox (from an attack of which complaint they were beginning to recover), and crying for a drink of milk. Their father, who was far advanced in life, could not supply their wants. John's heart was touched, and he thought, 'Here am I, possessed of health, food, and raiment, while these poor children are festering with disease, but scantily clothed, and not half fed. A sixpence, a basin of milk, or a loaf of bread, would be a boon to them. Can I help them?' He gave the old man sixpence, while he and Mr. Harrison told the milkman to leave a quantity of milk at the man's house daily, for which they would pay. It was with a radiant face, and a tremble of glad emotion in his voice, that our friend, in relating this circumstance to us one day, said:—'I felt a throb of pleasure when I did that little act of kindness, such as I had never felt before,' when, quick as lightning, the thought crossed his mind, 'Why I smoke six pennyworth of tobacco every week!' and there and then he resolved to give up the practice. On the next Friday, when Mrs. Ellerthorpe was setting down on[Pg 21] paper a list of the groceries wanted, she proceeded, as usual, to say, 'Tea—Coffee—Sugar—Tobacco—,' 'Stop,' said her husband, 'I've done with that. I'll have no more.' Now, Mrs. E. had always enjoyed seeing her husband smoke; it had often proved a powerful sedative to him when wearied with the cares of life, and the numberless irritations of his trying vocation, and therefore she replied, 'Nonsense, you will soon repent of that whim. I shall get two ounces as usual, and I know you'll smoke it.' 'I shall never touch it again,' was his firm reply, and ever after kept his word.

A world full of misery, both temporal and spiritual, surrounds us, and which might be effectually relieved, were all Christians, many of whom are laggard in effort and niggard in bounty, to manifest a tithe of the self-denial which Mr. Ellerthorpe practiced. 'What maintains one vice, would support two children.' Robert Hall says:—It is the practice of self-denial in a thousand little instances which forms the truest test of character.' Mr. Fletcher, Vicar of Madeley, was on one occasion driven close for means to discharge the claims of the poor, when he said to his wife, 'O Polly, can we not do without beer? Let us drink water, and eat less meat. Let our necessities give way to the extremities of the poor.' And at a meeting held the other night, a donation was announced thus:—'A poor man's savings from tobacco, £5.' And are there not tens of thousands of professors who could present similar offerings if they, in the name and spirit of their great Master, tried? Do we not often come in contact with men who complain that they cannot contribute to the cause of God and humanity, who, at the same time, indulge in the use of snuff, tobacco, or intoxicating drinks; all of which might be laid aside to the gain of God's cause, and without at all lessening either the health, reputation, or happiness of the consumer? And are there not[Pg 22] others, of good social position, who do not give as much to relieve the temporal sufferings of their fellow creatures, during twelve months, as it costs them to provide a single feast for a few well-to-do friends? The merchant who sold his chips and shavings, and presented the proceeds to the cause of God, while he kept the solid timber for himself, is the type of too many professors of religion!

HIS STAUNCH TEETOTALISM.

Perhaps no class of men have suffered more from the evils of intemperance than our brave sailors, fishermen, and rivermen. Foreigners tell our missionaries to convert our drunken sailors abroad, and when they wish to personify an Englishman, they mockingly reel about like a drunken man. And what lives have been lost through the intemperance of captains and crews! The 'St. George,' with 550 men: 'The Kent,' 'East Indiaman,' with most of her passengers and crew: 'The Ajax,' with 350 people: 'The Rothsway Castle,' with 100 men on board, with many others we might name, were all lost through the drunkenness of those in charge of the vessels. Of the forty persons whom our friend rescued from drowning, a very large percentage got overboard through intemperance. We read that on the morning following the Passover night in Egypt, there was not a house in which there was not one dead, and it would be difficult to find a house in our land, occupied by sailors, in which this monster evil has not slain its victim, either physically or morally.

Our friend, speaking of his own family, says:—'I owe my Christian name to the favour with which drunkenness was regarded by my relatives. Soon after I was born, one of my uncles asked, "What is the lad's name to be?" "Thomas," replied my[Pg 23] mother. "Never," said my uncle, in surprise, "we had two Thomas's, and they both did badly; call him John. I have known four John's in the family, and they were all great drunkards, but that was the worst that could be said of them." 'So it appears,' said our friend, 'that at that time it was thought no very bad thing for a man to get drunk, if he was not in the habit of being brought before the magistrate for theft, &c.' John's father was one of the four drunkards. In early life he became a hard drinker, and he continued the practice until a damaged constitution, emptied purse, a careworn wife, and a neglected family, were the bitter fruits of his inebriation. 'He drank hard,' says John, 'spending almost all his money in drink, and was at last forced to sell his vessel and take to the menial work of helping to load and unload vessels. At length he went to sea, and for a long time we heard nothing of him; nor did my mother receive any money from him. In old age he was quite destitute, and while it gave me great pleasure to minister to his necessities, it often grieved me to think of the cause of his altered circumstances.'

Nightly, when ashore, John, the elder, went to the public house, and it was his invariable rule never to return home until his wife fetched him. Often, when Mrs. Ellerthorpe was in a feeble state of health, and amid the howling winds and drenching rains of a winter's night, would she go in search of her drunken husband, and by her winning ways and kind entreaties induce him to return home. She was known to be a God-fearing woman, and often on the occasion of these visits, her husband's companions—some of whom were 'tippling professors' of religion—would try to entangle her in religious conversation, but to every entreaty she had one reply, 'If you want to talk with me about religion come to my house. I will not speak of it here; for I am determined never to fight the devil on his own ground.'[Pg 24]

And was this Christian woman wrong in calling the public house the devil's ground? We have 140,000 of these houses in our land, and are they not so many reservoirs from whence the devil floods our country with crime, wretchedness, and woe? Is it not there that his deluded victims, in thousands of instances, destroy their fortune, ruin their health, and form those habits which wither the beauty, scatter the comforts, blast the reputation, and bury once happy families in the tomb of disgrace? And is it not at the public house that the sounds of blasphemy, cursing, and swearing, sedition, uncleanness, laciviousness, hatred, quarrels, murders, gambling, revelling, and such like, are begun? And you might as reasonably expect to preserve your health in a pest-house, your modesty in a brothel, and high-souled principles amongst gamesters, as to expect to preserve your religious character undamaged amid the impure atmosphere of a public house. Can a man go upon hot coals and his feet not be burnt? One hour spent around the drunkard's table has often done an amount of harm to the cause of God and the souls of men which the devotion of years could not undo.

A youth, on being urged to take the pledge, said, 'My father drinks, and I don't want to be better than my father.' And, alas! for our friend, he early imbibed the tastes and followed the example of his father, for drink got the mastery of him. Speaking of his boyhood, he says, 'I remember a man saying to my father, "Your son is a sharp lad, and he will make a clever man, if only you set him a good example, and keep him from drink." To which my father replied, "O drink will not hurt him; if he does nothing worse than take a sup of drink he'll be all right; drink never hurt anyone." But, alas! my father lived to see that a "little sup" did not serve me, for I have heard him say with sorrow, "The lad drinks hard." But he was the first to set me the example, and if[Pg 25] parents wish their children to abstain from intoxicating drinks, they should set the example by being abstainers themselves. The best and most lasting way of doing good to a family is for parents first to do right themselves.' But with such a training as John had, what wonder that he became a 'hard drinker.' For years previous to his marriage his experience was something like that of an old 'hard-a-weather' on board a homeward-bound Indiaman, who was asked by a lady passenger, 'Whether he would not be glad to get home and see his wife and children, and spend the summer with them in the country?' Poor Jack possessed neither home, nor wife, nor chick nor child; and his recollections of green fields and domestic enjoyments were dreamily associated with early childhood. And hence a big tear rolled down his weather-beaten but manly cheek as he said to his fair questioner, 'Well, I don't know, I suppose it will be another roll in the gutter, and away again.' Our friend was for years a 'reeling drunkard,' and often, during this sad period of his existence, he literally 'rolled in the gutter.'

But when he experienced a saving change he at once became a sober man, and began to treat public houses after the fashion of the fox in the fable—who declined the invitation to the lion's den, because he had observed that the only footsteps in its vicinity were towards it and none from it. He further saw that to indulge in the use of intoxicating drinks, and then pray, 'Lead me not into temptation,' savoured less of piety than of presumption. He attended a temperance meeting at which the Rev. G. Lamb spoke of the importance of Christian professors abstaining for the good of others, as well as for their own safety. John felt that his sphere of action was limited in its range and insignificant in its character; yet he knew he possessed influence; as a husband and father, and as a member of civil and religious society,[Pg 26] he knew that his conduct would produce an effect on those to whom he was related, and with whom he had to do. 'No man liveth to himself.' He knew how to do good, and not to have done it would have been sin. And that thought decided him. At the close of the meeting, persons were invited to take the pledge of total abstinence, but not one responded to the invitation. John saw, sitting at his right hand, a man who had been a great drunkard, and whose shattered nerves, unsteady hand, and bloodshot eyes, told of the sad effects of his conduct. Placing his hand on this man's shoulder, he said, 'Will you take the pledge?' 'I will if you will,' was the man's reply. 'Done,' said John, and scarcely had they reached the platform, when about twenty others followed and took the pledge.

His Diary contains this record, 'February 24th, 1851. I have been to the Teetotal Meeting, and I have taken the pledge, and I intend, through the grace of God, to keep it as long as I live.'

From that night John became a practical and pledged abstainer from all intoxicating drinks, and induced many a poor drunkard to follow his example. No man stood higher than he in Temperance circles. He adorned that profession. In his extensive intercourse with his fellow men, he proved himself the fast friend and unflinching advocate of total abstinence, having delivered hundreds of addresses and circulated thousands of tracts, in vindication of its principles.

A few years before his death, he was travelling from Hull to Howden, by rail; the compartment was full of passengers, and he began, as usual, to circulate his tracts and to speak in favour of temperance.

An aged clergyman present said, 'I always give you Hull folks great credit for being teetotalers.' 'And why the people of Hull more than the people of any other place?' asked John. 'Because your water is filthy and dirty, and I never could drink it[Pg 27] without a mixture of brandy.' 'That our water is dirty I admit,' said John, 'but I have drank it both with brandy and without, and if you felt as I feel, I am sure, sir, you would discontinue the practice of brandy drinking.' 'Oh, I suppose you are one of those men who get all the drink you can and when you can get no more you turn teetotaller,' was the rejoinder. 'You are mistaken, sir; for I can call most of the persons present to witness, that I laid aside the intoxicating glass when I possessed the most ample means and every opportunity of getting plenty of drink, and at little or no cost to myself. But I saw that I should be a safer and happier man myself, and a greater blessing to others if I abstained, and therefore I signed the pledge; and you must pardon me, sir, when I say, that if you felt as I feel, you would, as a minister of the gospel, pursue the same course.' 'O!' said he, with indignation lowering in his countenance and thundering in his voice, 'I have taken my brandy daily for years, and it never did me any hurt.' 'Granted,' replied our friend, 'but if you can drink with safety, can others? Have you never seen the evil effects of tampering with the glass? Have none of your acquaintances or friends fallen victims to drunkenness? Let me give you a case, sir. One of my former employers had a son who, up to the twentieth year of his age, had never tasted intoxicating drinks. But he had a weak constitution and a slender frame, and the doctor ordered him to take a little brandy and water twice a day. He did so, and began to like it. He soon wanted it oftener, and told the man to make it stronger, and the man did as he was told. One day he had put but a few drops of water into a large glass of brandy, but the young gentleman said, 'Did'nt I tell you to make it stronger? Let the next glass be stronger.' He soon called for the next glass, and having swallowed it, said, in a rage, 'What a fool you are. I told you to let[Pg 28] me have it stronger.' 'Sir,' said the man, 'you can't have it stronger, for the glass you have just drank was "neat" as it came from the bottle.' 'And is that a fact,' exclaimed the young gentleman. 'Has it come to this? Am I to be a slave to that liquid? Never! Take it away, and from this day I'll never drink another glass.' This statement was listened to with marked attention by all the passengers, and when the train arrived at Howden station, they gave forth a spontaneous burst of applause. The clergyman sat ashamed and speechless, and, on leaving the train, refused to shake hands with our friend who had administered to him this well-timed and well-merited rebuke.

I have stated that our friend spoke at hundreds of temperance meetings, and his bluntness of manner, curt style of address, and nautical phrases, won for him a ready hearing. Whenever he rose on the platform eyes beamed and hearts throbbed with delight. Not that his hearers expected to listen to an eloquent speech, or to be amused by laughter-exciting and fun-making eccentricities, but he rose with the influence of established character, combined with an ardent temperament, a ready wit, and a face beaming with the sunshine of piety towards God and good-will to men. Besides, there was a just appreciation of his many deeds of gallantry, some of which he occasionally related, and which rarely failed to fill his hearers with admiration for the brave heart that could prompt and the ready skill that could perform them. Hence, he was listened to in the town and neighbourhood of Hull with an amount of sympathy, attention, and respect which no other advocate of total abstinence, possessed of the same mental abilities, could command.

The Band of Hope had a warm friend and powerful advocate in the person of Mr. Ellerthorpe, and it was in connexion with its services that he found his most[Pg 29] congenial employment. 3,000,000 of the inhabitants of our country are now pledged abstainers from intoxicating drinks, and this number includes upwards of 2,000 ministers of the Gospel. But thirty years ago this cause was regarded with disfavour even by the religious public. Hence, when Mr. Ellerthorpe and others sought to form a Band of Hope in connexion with the Primitive Methodist Sabbath School, Great Thornton Street, Hull, they met with much opposition from several members of the Society, and also from some of the teachers in the school, who were 'tipplers,' and could not endure the idea of a Band of Hope. But the Band was formed, with Mr. Ellerthorpe as president, and it soon numbered three hundred members. Before his death he saw upwards of thirty of these Juvenile Bands formed in Hull. He attended most of their anniversaries, throwing a flood of genial merriment, just like dancing sunlight, over his young auditors. Hundreds of these 'cold water drinkers' sometimes listened to him on these occasions, and as he related some of the scenes of his eventful life, their young hearts throbbed and their eyes filled with tears.

We cannot close this chapter of our little book without asking, Were the motives which led our friend to sign the pledge, right or wrong? The celebrated Paley lays down this axiom, 'That where one side is doubtful and one is safe, we are as morally bound to take the safe side as if a voice from heaven said, "This is the way, walk ye in it."' And is not total abstinence the only safe side for the abstainer himself? Some men have a strong predisposition for intoxicating drinks, and they must abstain or be ruined. Naturalists tell us that in order to tame a tiger he must never be allowed to taste blood. Let him have but one taste and his whole nature is changed. And the men to whom I refer are humane, upright, chaste, kind to their children and affectionate to their wives,[Pg 30] while they can be kept from intoxicating drinks, but let them taste, only taste, and their passions become so strong and their appetites so rampant, that they are inspired with the most ferocious dispositions, and perpetrate deeds, the mere mention of which would appal them in their sober moments. And where is the moderate drinker who can point to the glass and say, 'I am safe?' As that dexterous murderer, Palmer, administered his doses in small quantities, and thus gradually and daily undermined the constitution of his victims, and, as it were, muffled the footfalls of death, so strong drink does not all at once over master its victims; but how often have we known it gradually, and after years of tippling, lead them captive into the vortex of drunkenness.

But admitting, for the sake of argument, that you can drink with safety to yourself, can you drink with safety to others? 'No man liveth to himself.' We are all a kind of chameleon, and naturally derive a tinge from that which is near us. Our friend attributes his early drunkenness to the influence and example of his father. You should view your drinking habits in the light of these passages of Scripture, 'Look not every man on his own things, but every man also on the things of others.' 'It is good neither to eat flesh, nor to drink wine, nor anything whereat thy brother stumbleth or is made weak.' So that you may look at Paley's saying, in its application to the use of strong drinks, again and again; you may examine it as closely as you like, and criticise it as often as you please, still it remains true, that to drink is doubtful, while to abstain is safe, and that we are as morally bound to choose the latter as if a voice from heaven said, 'This is the way, walk ye in it.' 'Let us not, therefore, judge one another any more, but judge this rather that no man put a stumblingblock or an occasion, to fall in his brother's way.'—Rom. xiv. 13.

HIS BOLD ADVENTURES ON THE WATER.

That swimming is a noble and useful art, deserving the best attention of all classes of the community, is a fact few will dispute. 'Swimming,' says Locke, 'ought to form part of every boy's education!' It is an art that is easily acquired; it is healthy and pleasurable as an exercise, being highly favourable to muscular development, agility of motion, and symmetry of form; and it is of inconceivable benefit as the means of preserving or saving life in seasons of peril, when death would otherwise prove inevitable. Mr. Ellerthorpe early became an accomplished swimmer; he often fell overboard, and but for his skill in the art under consideration he would have been drowned. He also enjoyed the happiness of having saved upwards of forty persons, who, but for his efforts must, to all human appearance, have perished.

To a maratime nation like ours, with a rugged and dangerous coast-line of two thousand miles, indented by harbours, few and far from each other, and with a sea-faring population of half a million, it seems as necessary that the rising generation should learn to swim as that they should be taught the most common exercises of youth. And yet 'this natatory art' is but little cultivated amongst us. On the Continent, and among foreigners generally, swimming is practised and encouraged far more than it is in England. In the Normal Swimming school of Denmark, some thirty years ago, there were educated 105 masters destined to teach the art throughout the kingdom. In France, Vienna, Copenhagen, Stockholm, Berne, Amsterdam, &c., similar means were adopted, and very few persons in those countries are entirely destitute of a knowledge of the art. But so generally is this department of juvenile training neglected by us as a people, that only one in every ten who gain their livelihood on the water are able to swim.[Pg 32]

Mr. Ellerthorpe, in a characteristic letter, says: 'I think no schoolmaster should regard the education of his scholars complete unless he has taught them to swim. That art is of service when everything else is useless. I once heard of a professor who was being ferried across a river by a boatman, who was no scholar. So the professor said, "Can you write, my man?" "No, Sir," said the boatman. "Then you have lost one third of your life," said the professor. "Can you read?" again asked he of the boatman. "No," replied the latter, "I can't read." "Then you have lost the half of your life," said the professor. Now came the boatman's turn. "Can you swim?" said the boatman to the professor. "No," was his reply. "Then," said the boatman, "you have lost the whole of your life, for the boat is sinking and you'll be drowned." Now, Sir, I think that if those fathers who spend so much money on the intellectual education of their children, would devote but a small portion of it to securing for them a knowledge of the art of swimming, they would confer a great blessing on those children, and also on society at large. I would have every one learn to swim females as well as males; for many of both sexes come under my notice every year who are drowned, but who, with a little skill in swimming, might have been saved. Not fewer than forty men and boys were lost from the Hull Smacks alone during the year 1866, of whom twenty per cent, might have been saved had they been able to swim.'

Mr. Ellerthorpe was, for many years, Master of the 'Hull Swimming Club,' and also of 'The College Youth's Swimming Club,' and his whole life was a practical lesson on the value of the art of swimming. He contended that the youths of Hull ought to be taught this art, and pleaded that a sheet of water which had been waste and unproductive for twenty years should be transformed into a swimming bath.[Pg 33] The local papers favoured the scheme, and Alderman Dennison, moved in the Town Council, that £350 should be devoted to this object, which was carried by a majority. The late Titus Salt, Esq., who had given £5,000 to the 'Sailor's Orphan Home,' said at the time, 'I think your corporation ought to make the swimming bath alluded to in the enclosed paper; do ask them.' 'The private individual who gives his fifty hundreds to a particular Institution,' to use the words of the Hull and Eastern Counties' Herald, Oct. 10th, 1857, 'has surely a right to express an opinion that the municipal corporation ought to grant three hundreds, if by so doing the public weal would be provided. If the voice of such a man is to be disregarded, then it may truly be said that our good old town has fallen far below the exalted position it occupied when it produced its Wilberforce and its Marvel.'

For upwards of forty years Mr. Ellerthorpe was known as a fearless swimmer and diver, and during that period he saved no fewer than forty lives by his daring intrepidity. In his boyhood, he, to use his own expression, 'felt quite at home in the water,' and betook himself to it as natively and instinctively as the swan to the water or the lark to the sky. 'This art,' to use the words of an admirable article in the Shipwrecked Mariners' Magazine for October, 1862, 'he has cultivated so successfully that in scores of instances he has been able to employ it for the salvation of life and property. Perhaps the history of no other living person more fully displays the value of this art than John Ellerthorpe. Joined with courage, promptitude, and steady self-possession, it has enabled him repeatedly to preserve his own life, and what is far more worthy of record, to save not fewer than thirty-nine of his fellow creatures, who, humanly speaking, must otherwise have met with a watery grave.'[Pg 34]

It is but right to state that, in the early period of his history, a thoughtless disregard of his own life, and an overweening confidence in his ability to swim almost any length, and amid circumstances of great peril, often led him to deeds of 'reckless daring,' which in riper years he would have trembled to attempt. Respecting most of the following circumstances he says, 'I look upon those perilous adventures as so many foolish and wicked temptings of Providence. I have often wondered I was not drowned, and attribute my preservation to the wonder-working providence of God, who has so often 'redeemed my life from destruction, and crowned me with loving kindness and tender mercies.'

And certainly we should remember that heroism is one thing, reckless daring another. Two or three instances will illustrate this. A few years ago Blondin, for the sake of money, jeopardized his life at the Crystal Palace, by walking blindfolded on a tight-rope, and holding in his hand a balancing pole. In so doing he was foolhardy, but not heroic. But a certain Frenchman, at Alencon, walked on one occasion on a rope over some burning beams into a burning house, otherwise inaccessible, and succeeded in saving six persons. This was the act of a true hero. When Mr. Worthington, the 'professional diver,' plunged into the water and saved six persons from drowning, who, but for his skill and dexterity as a swimmer, would certainly have met with a watery grave, he acted the part of a 'hero;' but when, the other day, he made a series of nine 'terrific plunges' from the Chain Pier at Brighton—a height of about one hundred and twenty feet—merely to gratify sensational sightseers, or to put a few shillings into his own pocket, he acted the part of a foolhardy man. Can we wonder that he was within an ace of losing his life in this mad exploit? And when John Ellerthorpe dived to the bottom of 'Clarke's Bit,' to[Pg 35] gratify a number of young men who had 'more money than wit,' and struggled in the water with a bag of coals on his back, he put himself on a par with those men who place their lives in imminent danger by dancing on ropes, swinging on cords, tying themselves into knots like a beast, or crawling on ceilings like some creeping thing! But when he used his skill to save his fellow creatures, he was a true hero, and was justified in perilling his own life, considering that by so doing the safety of others might be secured.

We shall close this chapter by recording a few of his deeds of reckless daring.

'My first attempt at swimming took place at Hessle, when I was about twelve years of age. There was a large drain used for the purpose of receiving the water from both the sea and land. My father managed the sluice, which was used for excluding, retaining, and regulating the flow of water into this drain. It was a first rate place for lads to bathe in, and I have sometimes bathed in it ten times a day; indeed, I regret to say, I spent many days there when I ought to have been at school. I soon got to swim in this drain, but durst not venture into the harbour. But one day I accidentally set my dirty feet upon the shirt of a boy who was much older and bigger than myself, and in a rage he took me up in his arms and threw me into the harbour. I soon felt safe there, nor did I leave the harbour till I had crossed and recrossed it thirty-two times. The next day I swam the whole length of the harbour twice, and from that day I began to match myself with expert swimmers, nor did I fear swimming with the best of them. Some other lads were as venturesome as myself, and we used to go up the Humber with the tides, for several miles at once. I remember on one occasion it blew a strong gale of wind from S.W., several[Pg 36] vessels sank in the Humber, and a number of boats broke adrift, while a heavy sea was running: I stripped and swam to one of the boats, got into her, and brought her to land, for which act the master of the boat gave me five shillings. During the same gale a keel came ashore at Hessle; I stripped and swam to her and brought a rope on shore, by the assistance of which, two men, a woman, and two children escaped from the vessel. The tide was receding at the time, so that they were enabled, with the assistance of the rope, to walk ashore. There are several old men living now who well remember this circumstance.

'Soon after this occurrence, I remember one Saturday afternoon, going with some other boys of my own age, and swimming across the Humber, a distance of two miles. We started from Swanland Fields (which was then enclosed), Yorkshire, and landed at the Old Warp, Lincolnshire. Here we had a long run and a good play, and then we recrossed the Humber. But in doing so we were carried up as far as Ferriby Sluice, and had to run back to where we had left our clothes in charge of some lads, but when we got there the lads had gone, and we didn't know what to do. We sought for our clothes a full hour, when a man, in the employ of Mr. Pease told us that the lads had put them under some bushes, where we at last found them. We were in the water four hours. This was an act of great imprudence.

'On another occasion myself and some other lads played truant from school, and went towards the Humber to bathe, but the schoolmaster, Mr. Peacock, followed us closely. He ran and I ran, and I had just time to throw off my clothes and leap into the water, when he got to the bank. He was afraid I should be drowned, and called out 'If you will come back I won't tell your father and mother.' But I refused to return, for at that time I felt no fear in doing what I durst not have attempted when I got older.[Pg 37]

'On several occasions some young gentlemen, who were scholars at Hessle boarding school, got me to go and bathe with them. They had plenty of money, and I had none; and as they offered to pay me, I was glad to go with them. One day while we were bathing, the eldest son of Mr. Earnshaw, of Hessle, had a narrow escape from drowning. I was a long way from him at the time, but I did all I could to reach and rescue him. He was very ill for some days, and the doctor forbade him bathing for a long time to come. This deterred us from bathing for awhile, but we soon forgot it. We agreed to have a swimming match, and the boy that swam the farthest was to have sixpence. We started at three o'clock in the afternoon from the third jetty below Hessle harbour, and went up with the tide. One of the boys got the lead of me and I could not overtake him until we got opposite Cliffe Mill, about a mile and a half from where we started. He then began to fag, while I felt as brisk as a lark and fresher than when I began. I soon took the lead, and when I got to Ferriby Lane-end, I lost my mate altogether. However, I knew he was a capital swimmer, and I felt afraid lest he should turn up again, so I swam as far as Melton brickyard, and fairly won the prize. I had swam about seven miles, and believe I could have swam back without landing.

'When I was about fifteen years of age a steam packet came to Hessle, bringing a number of swimmers from Hull. Soon alter their arrival a lad came running to me and said, "Jack, there's some of those Hull chaps bathing, and they say they can beat thee." I didn't like that; and when I got to them, a young gentleman said, pointing to me, "Here is a lad that shall swim you for what you like." One of them said, "Is he that Ellerthorpe of Hessle?" "No matter who he is," replied the young man, "I'll back him for a sovereign," when one of the young gentlemen[Pg 38] called out, "It is Jack Ellerthorpe, I won't have aught to do with him, for he can go as fast feet foremost as I can with my hands foremost, he's a first-rate swimmer." By this time I was stripped, and at once plunged into the river. I crept on my hands and knees on the water, and then swam backwards and forwards with my feet foremost, and not one among them could swim with me. I showed them the "porpoise race," which consisted in disappearing under the water, and then coming "bobbing" up suddenly, at very unlikely spots. I then took a knife and cut my toe-nails in the water. The young gents were greatly delighted, and afterwards they would have matched me to swim anybody, to any distance. And I believe that at that time I could have swam almost any length; for after I had swam two or three miles my spirits seemed to rise, and my strength increased. When other lads seemed thoroughly beaten out, I was coming to my best, and the longer I remained in the water the easier and faster I could swim.