Title: The Religion of Babylonia and Assyria

Author: Morris Jastrow

Release date: March 7, 2007 [eBook #20758]

Most recently updated: January 1, 2021

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/20758

Credits: Produced by Paul Murray and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net. (This file was

produced from images generously made available by the

Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF/Gallica) at

http://gallica.bnf.fr)

[Transcriber's Note: This file was produced from images generously made available by the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF/Gallica) at http://gallica.bnf.fr.]

H. B. J.

MY FAITHFUL COLLABORATOR

It requires no profound knowledge to reach the conclusion that the time has not yet come for an exhaustive treatise on the religion of Babylonia and Assyria. But even if our knowledge of this religion were more advanced than it is, the utility of an exhaustive treatment might still be questioned. Exhaustive treatises are apt to be exhausting to both reader and author; and however exhaustive (or exhausting) such a treatise may be, it cannot be final except in the fond imagination of the writer. For as long as activity prevails in any branch of science, all results are provisional. Increasing knowledge leads necessarily to a change of perspective and to a readjustment of views. The chief reason for writing a book is to prepare the way for the next one on the same subject.

In accordance with the general plan of this Series[1] of Handbooks, it has been my chief aim to gather together in convenient arrangement and readable form what is at present known about the religion of the Babylonians and Assyrians. The investigations of scholars are scattered through a large variety of periodicals and monographs. The time has come for focusing the results reached, for sifting the certain from the uncertain, and the uncertain from the false. This work of gathering the disjecta membra of Assyriological science is essential to future progress. If I have succeeded in my chief aim, I shall feel amply repaid for the labor involved.

In order that the book may serve as a guide to students, the names of those to whose researches our present knowledge of the subject is due have frequently been introduced, and it will be found, I trust, that I have been fair to all.[2] At the same time, I have naturally not hesitated to indicate my dissent from views advanced by this or that scholar, and it will also be found, I trust, that in the course of my studies I have advanced the interpretation of the general theme or of specific facts at various points. While, therefore, the book is only in a secondary degree sent forth as an original contribution, the discussion of mooted points will enhance its value, I hope, for the specialist, as well as for the general reader and student for whom, in the first place, the volumes of this series are intended.

The disposition of the subject requires a word of explanation. After the two introductory chapters (common to all the volumes of the series) I have taken up the pantheon as the natural means to a survey of the field. The pantheon is treated, on the basis of the historical texts, in four sections: (1) the old Babylonian period, (2) the middle period, or the pantheon in the days of Hammurabi, (3) the Assyrian pantheon, and (4) the latest or neo-Babylonian period. The most difficult phase has naturally been the old Babylonian pantheon. Much is uncertain here. Not to speak of the chronology which is still to a large extent guesswork, the identification of many of the gods occurring in the oldest inscriptions, with their later equivalents, must be postponed till future discoveries shall have cleared away the many obstacles which beset the path of the scholar. The discoveries at Telloh and Nippur have occasioned a recasting of our views, but new problems have arisen as rapidly as old ones have been solved. I have been especially careful in this section not to pass beyond the range of[Pg ix] what is definitely known, or, at the most, what may be regarded as tolerably certain. Throughout the chapters on the pantheon, I have endeavored to preserve the attitude of being 'open to conviction'—an attitude on which at present too much stress can hardly be laid.

The second division of the subject is represented by the religious literature. With this literature as a guide, the views held by the Babylonians and Assyrians regarding magic and oracles, regarding the relationship to the gods, the creation of the world, and the views of life after death have been illustrated by copious translations, together with discussions of the specimens chosen. The translations, I may add, have been made direct from the original texts, and aim to be as literal as is consonant with presentation in idiomatic English.

The religious architecture, the history of the temples, and the cult form the subject of the third division. Here again there is much which is still uncertain, and this uncertainty accounts for the unequal subdivisions of the theme which will not escape the reader.

Following the general plan of the series, the last chapter of the book is devoted to a general estimate and to a consideration of the influence exerted by the religion of Babylonia and Assyria.

In the transliteration of proper names, I have followed conventional methods for well-known names (like Nebuchadnezzar), and the general usage of scholars in the case of others. In some cases I have furnished a transliteration of my own; and for the famous Assyrian king, to whom we owe so much of the material for the study of the Babylonian and Assyrian religion, Ashurbanabal, I have retained the older usage of writing it with a b, following in this respect Lehman, whose arguments[3] in favor of this pronunciation for the last element in the name I regard as on the whole acceptable.

I have reasons to regret the proportions to which the work has grown. These proportions were entirely unforeseen when I began the book, and have been occasioned mainly by the large amount of material that has been made available by numerous important publications that appeared after the actual writing of the book had begun. This constant increase of material necessitated constant revision of chapters; and such revision was inseparable from enlargement. I may conscientiously say that I have studied these recent publications thoroughly as they appeared, and have embodied at the proper place the results reached by others and which appeared to me acceptable. The work, therefore, as now given to the public may fairly be said to represent the state of present knowledge.

In a science that grows so rapidly as Assyriology, to which more than to many others the adage of dies diem docet is applicable, there is great danger of producing a piece of work that is antiquated before it leaves the press. At times a publication appeared too late to be utilized. So Delitzsch's important contribution to the origin of cuneiform writing[4] was published long after the introductory chapters had been printed. In this book he practically abandons his position on the Sumerian question (as set forth on p. 22 of this volume) and once more joins the opposite camp. As far as my own position is concerned, I do not feel called upon to make any changes from the statements found in chapter i., even after reading Weissbach's Die Sumerische Frage (Leipzig, 1898),—the latest contribution to the subject, which is valuable as a history of the controversy, but offers little that is new. Delitzsch's name must now be removed from the list of those who accept Halévy's thesis; but, on the other hand, Halévy has gained a strong ally in F. Thureau-Dangin, whose special studies in the old Babylonian inscriptions lend great weight to his utterances on the origin of the cuneiform script. Dr. Alfred Jeremias, of[Pg xi] Leipzig, is likewise to be added to the adherents of Halévy. The Sumero-Akkadian controversy is not yet settled, and meanwhile it is well to bear in mind that not every Assyriologist is qualified to pronounce an opinion on the subject. A special study is required, and but few Assyriologists have made such a study. Accepting a view or a tradition from one's teacher does not constitute a person an authority, and one may be a very good Assyriologist without having views on the controversy that are of any particular value.

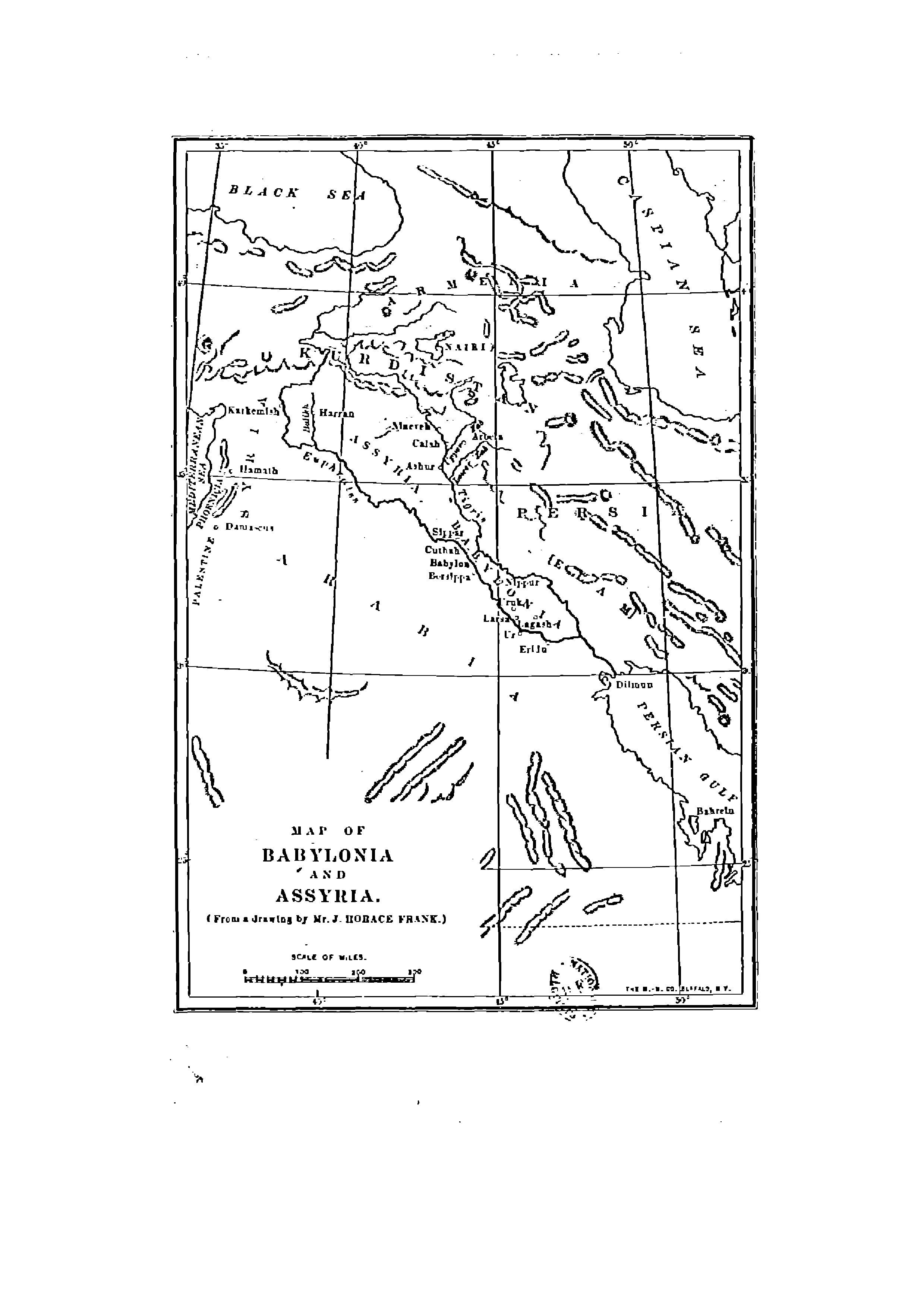

Lastly, I desire to call attention to the Bibliography, on which much time has been spent, and which will, I trust, be found satisfactory. In a list of addenda at the end of the book, I have noted some errors that slipped into the book, and I have also embodied a few additions. The copious index is the work of my student, Dr. S. Koppe, and it gives me pleasure to express my deep obligations to him for the able and painstaking manner in which he has carried out the work so kindly undertaken by him. The drawing for the map was made by Mr. J. Horace Frank of Philadelphia.

To my wife more thanks are due than I can convey in words for her share in the work. She copied almost all of the manuscript, and in doing so made many valuable suggestions. Without her constant aid and encouragement I would have shrunk from a task which at times seemed too formidable to be carried to a successful issue. As I lay down my pen after several years of devotion to this book, my last thought is one of gratitude to the beloved partner of my joys and sorrows.

MORRIS JASTROW, Jr.

University of Pennsylvania,

June, 1898.

[Pg xii]

[1] Set forth in the announcement of the series at the back of the book and in the Editor's Prefatory Note to Volume I.

[2] In the Index, however, names of scholars have only been introduced where absolutely necessary to the subject.

[3] In his work, Shamassum-ukin König von Babylonien, pp. 16-21. Hence, I also write Ashurnasirbal.

[4] Die Entstehung des ältesten Schriftsystems (Leipzig, 1897).

[Transcriber's Note: These changes and additions are printed only here; the main text is as it was in the original.]

Page, Line.

22. See Preface.

35, 10. Isin or Nisin, see Lehmann's Shamash-shumukin, I. 77; Meissner's Beiträge zum altbabylonischen Privatrecht, p. 122.

61. Bau also appears as Nin-din-dug, i.e., 'the lady who restores life.' See Hilprecht, Old Babylonian Inscriptions, I. 2, Nos. 95, 106, 111.

74. On Ã, see Hommel, Journal of Transactions of Victoria Institute, XXVIII. 35-36.

99, 24. Ur-shul-pa-uddu is a ruler of Kish.

102, 13. For Ku-anna, see IIIR. 67, 32 c-d.

102, 24. For another U-mu as a title of Adad, see Delitzsch, Das Babylonische Weltschöpfungsepos, p. 125, note.

111, 2. Nisaba is mentioned in company with the great gods by Nebopolassar (Hilprecht, Old Babylonian Inscriptions, I. 1. Pl. 32, col. II. 15).

165. Note 2. On these proper names, see Delitzsch's "Assyriologische Miscellen" (Berichte der phil.-hist. Classe der kgl. sächs. Gesell. d. Wiss., 1893, pp. 183 seq.).

488. Note 1. See now Scheil's article "Recueil de Travaux," etc., XX. 55-59.

529. The form Di-ib-ba-ra has now been found. See Scheil's "Recueil de Travaux," etc., XX. 57.

589. Note 3. See now Hommel, Expository Times, VIII. 472, and Baudissin, ib. IX. 40-45.[Pg xiii]

I. Introduction

II. The Land and the People

III. General Traits of the Old Babylonian Pantheon

IV. Babylonian Gods Prior to the Days of Hammurabi

V. The Consorts of the Gods

VI. Gudea's Pantheon

VII. Summary

VIII. The Pantheon in the Days of Hammurabi

IX. The Gods in the Temple Lists and in the Legal and Commercial Documents

X. The Minor Gods in the Period of Hammurabi

XI. Survivals of Animism in the Babylonian Religion

XII. The Assyrian Pantheon

XIII. The Triad and the Combined Invocation of Deities

XIV. The Neo-babylonian Period

XV. The Religious Literature of Babylonia

XVI. The Magical Texts

XVII. The Prayers and Hymns

XVIII. Penitential Psalms

XIX. Oracles and Omens

XX. Various Classes of Omens

XXI. The Cosmology of the Babylonians

XXII. The Zodiacal System of the Babylonians

XXIII. The Gilgamesh Epic

XXIV. Myths and Legends

XXV. The Views of Life After Death

XXVI. The Temples and the Cult

XXVII. Conclusion

[Pg xiv]

(From a drawing by Mr. J. HORACE FRANK.)][Pg 1]

Until about the middle of the 19th century, our knowledge of the religion of the Babylonians and Assyrians was exceedingly scant. No records existed that were contemporaneous with the period covered by Babylonian-Assyrian history; no monuments of the past were preserved that might, in default of records, throw light upon the religious ideas and customs that once prevailed in Mesopotamia. The only sources at command were the incidental notices—insufficient and fragmentary in character—that occurred in the Old Testament, in Herodotus, in Eusebius, Syncellus, and Diodorus. Of these, again, only the two first-named, the Old Testament and Herodotus, can be termed direct sources; the rest simply reproduce extracts from other works, notably from Ctesias, the contemporary of Xenophon, from Berosus, a priest of the temple of Bel in Babylonia, who lived about the time of Alexander the Great, or shortly after, and from Apollodorus, Abydenus, Alexander Polyhistor, and Nicolas of Damascus, all of whom being subsequent to Berosus, either quote the latter or are dependent upon him.

Of all these sources it may be said, that what information they furnish of Babylonia and Assyria bears largely upon the political history, and only to a very small degree upon the[Pg 2] religion. In the Old Testament, the two empires appear only as they enter into relations with the Hebrews, and since Hebrew history is not traced back beyond the appearance of the clans of Terah in Palestine, there is found previous to this period, barring the account of the migrations of the Terahites in Mesopotamia, only the mention of the Tigris and Euphrates among the streams watering the legendary Garden of Eden, the incidental reference to Nimrod and his empire, which is made to include the capitol cities of the Northern and Southern Mesopotamian districts, and the story of the founding of the city of Babylon, followed by the dispersion of mankind from their central habitation in the Euphrates Valley. The followers of Abram, becoming involved in the attempts of Palestinian chieftains to throw off the yoke of Babylonian supremacy, an occasion is found for introducing Mesopotamia again, and so the family history of the Hebrew tribes superinduces at odd times a reference to the old settlements on the Euphrates, but it is not until the political struggles of the two Hebrew kingdoms against the inevitable subjection to the superior force of Assyrian arms, and upon the fall of Assyria, to the Babylonian power, that Assyria and Babylonia engage the frequent attention of the chronicler's pen and of the prophet's word. Here, too, the political situation is always the chief factor, and it is only incidentally that the religion comes into play,—as when it is said that Sennacherib, the king of Assyria, was murdered while worshipping in the temple dedicated to a deity, Nisroch; or when a prophet, to intensify the picture of the degradation to which the proud king of Babylon is to be reduced, introduces Babylonian conceptions of the nether world into his discourse.[5] Little, too, is furnished by the Book of Daniel, despite the fact that Babylon is the center of action, and what little there is[Pg 3] bearing on the religious status, such as the significance attached to dreams, and the implied contrast between the religion of Daniel and his companions, and that of Nebuchadnezzar and the Babylonians, loses some of its force by the late origin of the book. The same applies, only in a still stronger degree, to the Book of Judith, in which Nineveh is the center of the incidents described.

The rabbinical literature produced in Palestine and Babylonia is far richer in notices bearing on the religious practices of Mesopotamia, than is the Old Testament. The large settlements of Jews in Babylonia, which, beginning in the sixth century B.C., were constantly being increased by fresh accessions from Palestine, brought the professors of Judaism face to face with religious conditions abhorrent to their souls. In the regulations of the Rabbis to guard their followers from the influences surrounding them, there is frequent reference, open or implied, to Babylonish practices, to the festivals of the Babylonians, to the images of their gods, to their forms of incantations, and other things besides; but these notices are rendered obscure by their indirect character, and require a commentary that can only be furnished by that knowledge of the times which they take for granted. To this difficulty, there must be added the comparatively late date of the notices, which demands an exercise of care before applying them to the very early period to which the religion of the Babylonians may be traced.

Coming to Herodotus, it is a matter of great regret that the history of Assyria, which he declares it was his intention to write,[6] was either never produced, or if produced, lost. In accordance with the general usage of his times, Herodotus included under Assyria the whole of Mesopotamia, both Assyria proper in the north and Southern Mesopotamia. His history would therefore have been of extraordinary value, and since nothing escaped his observant eye and well-trained mind,[Pg 4] the religious customs of the country would have come in for their full share of attention. As it is, we have only a few notices about Babylonia and Assyria, incidental to his history of Persia.[7] Of these, the majority are purely historical, chief among which is an epitome of the country's past—a curious medley of fact and legend—and the famous account of the capture of Babylon by Cyrus. Fortunately, however, there are four notices that treat of the religion of the inhabitants: the first, a description of an eight-storied tower, surmounted by a temple sacred to the god Bel; a second furnishing a rather detailed account of another temple, also sacred to Bel, and situated in the same precinct of the city of Babylon; a third notice speaks, though with provoking brevity, of the funeral customs of the Babylonians; while in a fourth he describes the rites connected with the worship of the chief goddess of the Babylonians, which impress Herodotus, who failed to appreciate their mystic significance, as shameful. We have no reason to believe that Ctesias' account of the Assyrian monarchy, under which he, like Herodotus, included Babylonia, contained any reference to the religion at all. What he says about Babylonia and Assyria served merely as an introduction to Persian history—the real purpose of his work—and the few fragments known chiefly through Diodorus and Eusebius, deal altogether with the succession of dynasties. As is well known, the lists of Ctesias have fallen into utter discredit by the side of the ever-growing confidence in the native traditions as reported by Berosus.

The loss of the latter's history of Babylon is deplorable indeed; its value would have been greater than the history of Herodotus, because it was based, as we know, on the records and documents preserved in Babylonian temples. How much of the history dealt with the religion of the people, it is difficult to determine, but the extracts of it found in various writers show[Pg 5] that starting, like the Old Testament, with the beginning of things, Berosus gave a full account of the cosmogony of the Babylonians. Moreover, the early history of Babylonia being largely legendary, as that of every other nation, tales of the relations existing between the gods and mankind—relations that are always close in the earlier stages of a nation's history—must have abounded in the pages of Berosus, even if he did not include in his work a special section devoted to an account of the religion that still was practiced in his days. The quotations from Berosus in the works of Josephus are all of a historical character; those in Eusebius and Syncellus, on the contrary, deal with the religion and embrace the cosmogony of the Babylonians, the account of a deluge brought on by the gods, and the building of a tower. It is to be noted, moreover, that the quotations we have from Berosus are not direct, for while it is possible, though not at all certain, that Josephus was still able to consult the works of Berosus, Eusebius and Syncellus refer to Apollodorus, Abydenus, and Alexander Polyhistor as their authorities for the statements of Berosus. Passing in this way through several hands, the authoritative value of the comparatively paltry extracts preserved, is diminished, and a certain amount of inaccuracy, especially in details and in the reading of proper names,[8] becomes almost inevitable. Lastly, it is to be noted that the list of Babylonian kings found in the famous astronomical work of Claudius Ptolemaeus, valuable as it is for historical purposes, has no connection with the religion of the Babylonians.

The sum total of the information thus to be gleaned from ancient sources for an elucidation of the Babylonian-Assyrian religion is exceedingly meagre, sufficing scarcely for determining its most general traits. Moreover, what there is, requires for the most part a control through confirmatory evidence which we seek for in vain, in biblical or classical literature.

This control has now been furnished by the remarkable discoveries made beneath the soil of Mesopotamia since the year 1842. In that year the French consul at Mosul, P. E. Botta, aided by a government grant, began a series of excavations in the mounds that line the banks of the Tigris opposite Mosul. The artificial character of these mounds had for some time been recognized. Botta's first finds of a pronounced character were made at a village known as Khorsabad, which stood on one of the mounds in question. Here, at a short distance below the surface, he came across the remains of what proved to be a palace of enormous extent. The sculptures that were found in this palace—enormous bulls and lions resting on backgrounds of limestone, and guarding the approaches to the palace chambers, or long rows of carvings in high relief lining the palace walls, and depicting war scenes, building operations, and religious processions—left no doubt as to their belonging to an ancient period of history. The written characters found on these monuments substantiated the view that Botta had come across an edifice of the Assyrian empire, while subsequent researches furnished the important detail that the excavated edifice lay in a suburb of the ancient capitol of Assyria, Nineveh, the exact site of which was directly opposite Mosul. Botta's labors extended over a period of two years; by the end of which time, having laid bare the greater part of the palace, he had gathered a large mass of material including[Pg 7] many smaller objects—pottery, furniture, jewelry, and ornaments—that might serve for the study of Assyrian art and of Assyrian antiquities, while the written records accompanying the monuments placed for the first time an equally considerable quantity of original material at the disposal of scholars for the history of Assyria. All that could be transported was sent to the Louvre, and this material was subsequently published. Botta was followed by Austen Henry Layard, who, acting as the agent of the British Museum, conducted excavations during the years 1845-52, first at a mound Nimrud, some fifteen miles to the south of Khorsabad, and afterwards on the site of Nineveh proper, the mound Koyunjik, opposite Mosul, besides visiting and examining other mounds still further to the south within the district of Babylonia proper.

The scope of Layard's excavations exceeded, therefore, those of Botta; and to the one palace at Khorsabad, he added three at Nimrud and two at Koyunjik, besides finding traces of a temple and other buildings. The construction of these edifices was of the same order as the one unearthed by Botta; and as at the latter, there was a large yield of sculptures, inscriptions, and miscellaneous objects. A new feature, however, of Layard's excavations was the finding of several rooms filled with fragments of small and large clay tablets closely inscribed on both sides in the cuneiform characters. These tablets, about 30,000 of which found their way to the British Museum, proved to be the remains of a royal library. Their contents ranged over all departments of thought,—hymns, incantations, prayers, epics, history, legends, mythology, mathematics, astronomy constituting some of the chief divisions. In the corners of the palaces, the foundation records were also found, containing in each case more or less extended annals of the events that occurred during the reign of the monarch whose official residence was thus brought to light. Through Layard, the foundations were laid for the Assyrian and Babylonian collections of the British[Pg 8] Museum, the parts of which exhibited to the public now fill six large halls. Fresh sources of a direct character were thus added for the study, not only of the historical unfolding of the Assyrian empire, but through the tablets of the royal library, for the religion of ancient Mesopotamia as well.

The stimulus given by Botta and Layard to the recovery of the records and monuments of antiquity that had been hidden from view for more than two thousand years, led to a refreshing rivalry between England and France in continuing a work that gave promise of still richer returns by further efforts. Victor Place, a French architect of note, who succeeded Botta as the French consul at Mosul, devoted his term of service, from 1851 to 1855, towards completing the excavations at Khorsabad. A large aftermath rewarded his efforts. Thanks, too, to his technical knowledge and that of his assistant, Felix Thomas, M. Place was enabled more accurately to determine the architectural construction of the temples and palaces of ancient Assyria. Within this same period (1852-1854) another exploring expedition was sent out to Mesopotamia by the French government, under the leadership of Fulgence Fresnel, in whose party were the above-mentioned Thomas and the distinguished scholar Jules Oppert. The objective point this time was Southern Mesopotamia, the mounds of which had hitherto not been touched, many not even identified as covering the remains of ancient cities. Much valuable work was done by this expedition in its careful study of the site of the ancient Babylon,—in the neighborhood of the modern village Hillah, some forty miles south of Baghdad. Unfortunately, the antiquities recovered at this place, and elsewhere, were lost through the sinking of the rafts as they carried their precious burden down the Tigris. In the south again, the English followed close upon the heels of the French. J. E. Taylor, in 1854, visited many of the huge mounds that were scattered throughout Southern Mesopotamia in much larger[Pg 9] numbers than in the north, while his compatriot, William K. Loftus, a few years previous had begun excavations, though on a small scale, at Warka, the site of the ancient city of Erech. He also conducted some investigations at a mound Mugheir, which acquired special interest as the supposed site of the famous Ur,—the home of some of the Terahites before the migration to Palestine. Of still greater significance were the examinations made by Sir Henry Rawlinson, in 1854, of the only considerable ruins of ancient Babylonia that remained above the surface,—the tower of Birs Nimrud, which proved to be the famous seven-staged temple as described by Herodotus. This temple was completed, as the foundation records showed, by Nebuchadnezzar II., in the sixth century before this era; but the beginnings of the structure belong to a much earlier period. Another sanctuary erected by this same king was found near the tower. Subsequent researches by Hormuzd Rassam made it certain that Borsippa, the ancient name of the place where the tower and sanctuaries stood, was a suburb of the great city of Babylon itself, which lay directly opposite on the east side of the Euphrates. The scope of the excavations continued to grow almost from year to year, and while new mounds were being attacked in the south, those in the north, especially Koujunjik, continued to be the subject of attention.

Rassam, who has just been mentioned, was in a favorable position, through his long residence as English consul at Mosul, for extracting new finds from the mounds in this vicinity. Besides adding more than a thousand tablets from the royal library discovered by Layard, his most noteworthy discoveries were the unearthing of a magnificent temple at Nimrud, and the finding of a large bronze gate at Balawat, a few miles to the northeast of Nimrud. Rassam and Rawlinson were afterwards joined by George Smith of the British Museum, who, instituting a further search through the ruins of Koujunjik, Nimrud,[Pg 10] Kalah-Shergat, and elsewhere, made many valuable additions to the English collections, until his unfortunate death in 1876, during his third visit to the mounds, cut him off in the prime of a brilliant and most useful career. The English explorers extended their labors to the mounds in the south. Here it was, principally at Abu-Habba, that they set their forces to work. The finding of another temple dedicated to the sun-god rewarded their efforts. The foundation records showed that the edifice was one of great antiquity, which was permitted to fall into decay and was then restored by a ruler whose date can be fixed at the middle of the ninth century B.C. The ancient name of the place was shown to be Sippar, and the fame of the temple was such, that subsequent monarchs vied with one another in adding to its grandeur. It is estimated that the temple contained no less than three hundred chambers and halls for the archives and for the accommodation of the large body of priests attached to this temple. In the archives many thousands of little clay tablets were again found, not, however, of a literary, but of a legal character, containing records of commercial transactions conducted in ancient Sippar, such as sales of houses, of fields, of produce, of stuffs, money loans, receipts, contracts for work, marriage settlements, and the like. The execution of the laws being in the hands of priests in ancient Mesopotamia, the temples were the natural depositories for the official documents of the law courts. Similar collections to those of Sippar have been found in almost every mound of Southern Mesopotamia that has been opened since the days of Rassam. So at Djumdjuma, situated near the site of the ancient city of Babylon, some three thousand were unearthed that were added to the fast growing collections of the British Museum. At Borsippa, likewise, Rawlinson and Rassam recovered a large number of clay tablets, most of them legal but some of them of a literary character, which proved to be in part duplicates of those in the royal library of Ashurbanabal.[Pg 11] In this way, the latter's statement, that he sent his scribes to the large cities of the south for the purpose of collecting and copying the literature that had its rise there, met with a striking confirmation. Still further to the south, at a mound known as Telloh, a representative of the French government, Ernest de Sarzec, began a series of excavations in 1877, which, continued to the present day, have brought to light remains of temples and palaces exceeding in antiquity those hitherto discovered. Colossal statues of diorite, covered with inscriptions, the pottery, tablets and ornaments, showed that at a period as early as 3500 B.C. civilization in this region had already reached a very advanced stage. The systematic and thorough manner in which De Sarzec, with inexhaustible patience, explored the ancient city, has resulted in largely extending our knowledge of the most ancient period of Babylonian history as yet known to us. The Telloh finds were forwarded to the Louvre, which in this way secured a collection from the south that formed a worthy complement to the Khorsabad antiquities.

Lastly, it is gratifying to note the share that our own country has recently taken in the great work that has furnished the material needed for following the history of the Mesopotamian states. In 1887, an expedition was sent out under the auspices of the University of Pennsylvania, to conduct excavations at Niffer,—a mound to the southeast of Babylon, situated on a branch of the Euphrates, and which was known to be the site of one of the most famous cities in this region. The Rev. John P. Peters (now in New York), who was largely instrumental in raising the funds for the purpose, was appointed director of the expedition. Excavations were continued for two years under Dr. Peters' personal supervision, and since then by Mr. John H. Haynes, with most satisfactory success. A great temple dedicated to the god Bel was discovered, and work has hitherto been confined chiefly to laying bare the various parts of the edifice. The foundation of the building[Pg 12] goes back to an earlier period than the ruins of Telloh. It survived the varying fortunes of the city in which it stood, and each period of Babylonian history left its traces at Niffer through the records of the many rulers who sought the favor of the god by enlarging or beautifying his place of worship. The temple became a favorite spot to which pilgrims came from all sides on the great festivals, to offer homage at the sacred shrines. Votive offerings, in the shape of inscribed clay cones, and little clay images of Bel and of his female consort, were left in the temple as witnesses to the piety of the visitors. The archives were found to be well stocked with the official legal documents dating chiefly from the period of 1700 to 1200 B.C., when the city appears to have reached the climax of its glory. Other parts of the mound were opened at different depths, and various layers which followed the chronological development of the place were determined.[9] After its destruction, the sanctity of the city was in a measure continued by its becoming a burial-place. The fortunes of the place can thus be followed down to the ninth or the tenth century of our era, a period of more than four thousand years. Already more than 20,000 tablets have been received at the University of Pennsylvania, besides many specimens of pottery, bowls, jars, cones, and images, as well as gold, copper, and alabaster work.

From this survey of the work done in the last decades in exploring the long lost and almost forgotten cities of the Tigris and of the Euphrates Valley, it will be apparent that a large amount of material has been made accessible for tracing the course of civilization in this region. Restricting ourselves to that portion of it that bears on the religion of ancient Mesopotamia, it may be grouped under two heads, (1) literary, and (2) archaeological. The religious texts of Ashurbanabal's[Pg 13] library occupy the first place in the literary group. The incantations, the prayers and hymns, lists of temples, of gods and their attributes, traditions of the creation of the world, legends of the deities and of their relations to men, are sources of the most direct character; and it is fortunate that among the recovered portions of the library, such texts are largely represented. Equally direct are the dedicatory inscriptions set up by the kings in the temples erected to the honor of some god, and of great importance are the references to the various gods, their attributes, their powers, and their deeds, which are found at every turn in the historical records which the kings left behind them. Many of these records open or close with a long prayer to some deity; in others, prayers are found interspersed, according to the occasion on which they were offered up. Attributing the success of their undertakings—whether it be a military campaign, or the construction of some edifice, or a successful hunt—to the protection offered by the gods, the kings do not tire of singing the praises of the deity or deities as whose favorites they regarded themselves. The gods are constantly at the monarch's side. Now we are told of a dream sent to encourage the army on the approach of a battle, and again of some portent which bade the king be of good cheer. To the gods, the appeal is constantly made, and to them all good things are ascribed. From the legal documents, likewise, much may be gathered bearing on the religion. The protection of the gods is invoked or their curses called down; the oath is taken in their name; while the manner in which the temples are involved in the commercial life of ancient Babylonia renders these tablets, which are chiefly valuable as affording us a remarkable insight into the people's daily life, of importance also in illustrating certain phases of the religious organization of the country. Most significant for the position occupied by the priests, is the fact that the latter are invariably the scribes who draw up the documents.

The archaeological material furnished by the excavations consists of the temples of the gods, their interior arrangement, and provisions for the various religious functions; secondly, the statues of the gods, demigods, and the demons, the altars and the vessels; and thirdly, the religious scenes,—the worship of some deity, the carrying of the gods in procession, the pouring of libations, the performance of rites, or the representation of some religious symbols sculptured on the palace wall or on the foundation stone of a sacred building, or cut out on the seal cylinders, used as signatures[10] and talismans.

Large as the material is, it is far from being exhausted, and, indeed, far from sufficient for illustrating all the details of the religious life. This will not appear surprising, if it be remembered that of the more than one hundred mounds that have been identified in the region of the Tigris and Euphrates as containing remains of buried cities, only a small proportion have been explored, and of these scarcely more than a half dozen with an approach to completeness. The soil of Mesopotamia unquestionably holds still greater treasures than those which it has already yielded. The links uniting the most ancient period—at present, c. 4000 B.C.—to the final destruction of the Babylonian empire by Cyrus, in the middle of the sixth century B.C., are far from being complete. For entire centuries we are wholly in the dark, and for others only a few skeleton facts are known; and until these gaps shall have been filled, our knowledge of the religion of the Babylonians and Assyrians must necessarily remain incomplete. Not as incomplete, indeed, as their history, for religious rites are not subject to many changes, and the progress of religious ideas does not keep pace with the constant changes in the political kaleidoscope of a country; but, it is evident that no exhaustive treatment[Pg 15] of the religion can be given until the material shall have become adequate to the subject.

Before proceeding to the division of the subject in hand, some explanation is called for of the method by which the literary material found beneath the soil has been made intelligible.

The characters on the clay tablets and cylinders, on the limestone slabs, on statues, on altars, on stone monuments, are generally known as cuneiform, because of their wedge-shaped appearance, though it may be noted at once that in their oldest form the characters are linear rather than wedge-shaped, presenting the more or less clearly defined outlines of objects from which they appear to be derived. At the time when these cuneiform inscriptions began to be found in Mesopotamia, the language which these characters expressed was still totally unknown. Long previous to the beginning of Botta's labors, inscriptions also showing the cuneiform characters had been found at Persepolis on various monuments of the ruins and tombs still existing at that place. The first notice of these inscriptions was brought to Europe by a famous Italian traveler, Pietro della Valle, in the beginning of the seventeenth century. For a long time it was doubted whether the characters represented anything more than mere ornamentation, and it was not until the close of the 18th century, after more accurate copies of the Persepolitan characters had been furnished through Carsten Niebuhr, that scholars began to apply themselves to their decipherment. Through the efforts chiefly of Gerhard Tychsen, professor at Rostock, Frederick Münter, a Danish scholar, and the distinguished Silvestre de Sacy of Paris, the beginnings were made which finally led to the discovery of the key to the mysterious writings,[Pg 16] in 1802, by Georg Friedrich Grotefend, a teacher at a public school in Göttingen. The observation was made previous to the days of Grotefend that the inscriptions at Persepolis invariably showed three styles of writing. While in all three the characters were composed of wedges, yet the combination of wedges, as well as their shape, differed sufficiently to make it evident, even to the superficial observer, that there was as much difference between them as, say, between the English and the German script. The conclusion was drawn that the three styles represented three languages, and this conclusion was strikingly confirmed when, upon the arrival of Botta's finds in Europe, it was seen that one of the styles corresponded to the inscriptions found at Khorsabad; and so in all subsequent discoveries in Mesopotamia, this was found to be the case. One of the languages, therefore, on the monuments of Persepolis was presumably identical with the speech of ancient Mesopotamia. Grotefend's key to the reading of that style of cuneiform writing which invariably occupied the first place when the three styles were ranged one under the other, or occupied the most prominent place when a different arrangement was adopted, met with universal acceptance. He determined that the language of the style which, for the sake of convenience, we may designate as No. 1, was Old Persian,—the language spoken by the rulers, who, it was known through tradition and notices in classical writers, had erected the series of edifices at Persepolis, one of the capitols of the Old Persian or, as it is also called, the Achaemenian empire. By the year 1840 the decipherment of these Achaemenian inscriptions was practically complete, the inscriptions had been read, the alphabet was definitely settled, and the grammar, in all but minor points, known. It was possible, therefore, in approaching the Mesopotamian style of cuneiform, which, as occupying the third place, may be designated as No. 3, to use No. 1 as a guide, since it was only legitimate to conclude that Nos. 2 and 3 represented translations[Pg 17] of No. 1 into two languages, which, by the side of Old Persian, were spoken by the subjects of the Achaemenian kings. That one of these languages should have been the current speech of Mesopotamia was exactly what was to be expected, since Babylonia and Assyria formed an essential part of the Persian empire.

The beginning was made with proper names, the sound of which would necessarily be the same or very similar in both, or, for that matter, in all the three languages of the Persepolitan inscriptions.[11] In this way, by careful comparisons between the two styles, Nos. 1 and 3, it was possible to pick out the signs in No. 3 that corresponded to those in No. 1, and inasmuch as the same sign occurred in various names, it was, furthermore, possible to assign, at least tentatively, certain values to the signs in question. With the help of the signs thus determined, the attempt was made to read other words in style No. 3, in which these signs occurred, but it was some time before satisfactory results were obtained. An important advance was made when it was once determined, that the writing was a mixture of signs used both as words and as syllables, and that the language on the Assyrian monuments belonged to the group known as Semitic. The cognate languages—chiefly Hebrew and Arabic—formed a help towards determining the meaning of the words read and an explanation of the morphological features they presented. For all that, the task was one of stupendous proportions, and many were the obstacles that had to be overcome, before the principles underlying the cuneiform writing were determined, and the decipherment placed on a firm and scientific basis. This is not the place to enter upon a detailed illustration of the method adopted by ingenious scholars,—notably[Pg 18] Edward Hincks, Isidor Löwenstern, Henry Rawlinson, Jules Oppert,—to whose united efforts the solution of the great problems involved is due;[12] and it would also take too much space, since in order to make this method clear, it would be necessary to set forth the key discovered by Grotefend for reading the Old Persian inscriptions. Suffice it to say that the guarantee for the soundness of the conclusions reached by scholars is furnished by the consideration, that it was from small and most modest beginnings that the decipherment began. Step by step, the problem was advanced by dint of a painstaking labor, the degree of which cannot easily be exaggerated, until to-day the grammar of the Babylonian-Assyrian language has been clearly set forth in all its essential particulars: the substantive and verb formation is as definitely known as that of any other Semitic language, the general principles of the syntax, as well as many detailed points, have been carefully investigated, and as for the reading of the cuneiform texts, thanks to the various helps at our disposal, and the further elucidation of the various principles that the Babylonians themselves adopted as a guide, the instance is a rare one when scholars need to confess their ignorance in this particular. At most there may be a halting between two possibilities. The difficulties that still hinder the complete understanding of passages in texts, arise in part from the mutilated condition in which, unfortunately, so many of the tablets and cylinders are found, and in part from a still imperfect knowledge of the lexicography of the language. For many a word occurring[Pg 19] only once or twice, and for which neither text nor comparison with cognate languages offers a satisfactory clue, ignorance must be confessed, or at best, a conjecture hazarded, until its more frequent occurrence enables us to settle the question at issue. Such settlements of disputed questions are taking place all the time; and with the activity with which the study of the language and antiquities of Mesopotamia is being pushed by scholars in this country, in England, France, Austria, Germany, Italy, Norway, and Holland, and with the constant accession of new material through excavations and publications, there is no reason to despair of clearing up the obscurities, still remaining in the precious texts that a fortunate chance has preserved for us.

A question that still remains to be considered as to the origin of the cuneiform writing of Mesopotamia, may properly be introduced in connection with this account of the excavations and decipherment, though it is needless to enter into it in detail.

The "Persian" style of wedge-writing is a direct derivative of the Babylonian, introduced in the times of the Achaemenians, and it is nothing but a simplification in form and principle of the more cumbersome and complicated Babylonian. Instead of a combination of as many as ten and fifteen wedges to make one sign, we have in the Persian never more than five, and frequently only three; and instead of writing words by syllables, sounds alone were employed, and the syllabary of several hundred signs reduced to forty-two, while the ideographic style was practically abolished.

The second style of cuneiform, generally known as Median or Susian,[13] is again only a slight modification of the "Persian."[Pg 20] Besides these three, there is a fourth language (spoken in the northwestern district of Mesopotamia between the Euphrates and the Orontes), known as "Mitanni," the exact status of which has not been clearly ascertained, but which has been adapted to cuneiform characters. A fifth variety, found on tablets from Cappadocia, represents again a modification of the ordinary writing met with in Babylonia. In the inscriptions of Mitanni, the writing is a mixture of ideographs and syllables, just as in Mesopotamia, while the so-called "Cappadocian" tablets are written in a corrupt Babylonian, corresponding in degree to the "corrupt" forms that the signs take on. In Mesopotamia itself, quite a number of styles exist, some due to local influences, others the result of changes that took place in the course of time. In the oldest period known, that is from 4000 to 3000 B.C., the writing is linear rather than wedge-shaped. The linear writing is the modification that the original pictures underwent in being adapted for engraving on stone; the wedges are the modification natural to the use of clay, though when once the wedges became the standard method, the greater frequency with which clay as against stone came to be used, led to an imitation of the wedges by those who cut out the characters on stone. In consequence, there developed two varieties of wedge-writing: the one that may be termed lapidary, used for the stone inscriptions, the official historical records, and such legal documents as were prepared with especial care; the other cursive, occurring only on legal and commercial clay tablets, and becoming more frequent as we approach the latest period of Babylonian writing, which extends to within a few decades of our era. In Assyria, finally, a special variety of cuneiform developed that is easily distinguished from the Babylonian by its greater neatness and the more vertical position of the wedges.

The origin of all the styles and varieties of cuneiform writing is, therefore, to be sought in Mesopotamia; and within Mesopotamia,[Pg 21] in that part of it where culture begins—the extreme south; but beyond saying that the writing is a direct development from picture writing, there is little of any definite character that can be maintained. We do not know when the writing originated, we only know that in the oldest inscriptions it is already fully developed.

We do not know who originated it; nor can the question be as yet definitely answered, whether those who originated it spoke the Babylonian language, or whether they were Semites at all. Until about fifteen years ago, it was generally supposed that the cuneiform writing was without doubt the invention of a non-Semitic race inhabiting Babylonia at an early age, from whom the Semitic Babylonians adopted it, together with the culture that this non-Semitic race had produced. These inventors, called Sumerians by some and Akkadians by others, and Sumero-Akkadians by a third group of scholars, it was supposed, used the "cuneiform" as a picture or 'ideographic' script exclusively; and the language they spoke being agglutinative and largely monosyllabic in character, it was possible for them to stop short at this point of development. The Babylonians however, in order to adapt the writing to their language, did not content themselves with the 'picture' method, but using the non-Semitic equivalent for their own words, employed the former as syllables, while retaining, at the same time, the sign as an ideograph. To make this clearer by an example, the numeral '1' would represent the word 'one' in their own language, while the non-Semitic word for 'one,' which let us suppose was "ash," they used as the phonetic value of the sign, in writing a word in which this sound occurred, as e.g., ash-es. Since each sign, in Sumero-Akkadian as well as in Babylonian, represented some general idea, it could stand for an entire series of words, grouped about this idea and associated with it, 'day,' for example, being used for 'light,' 'brilliancy,' 'pure,' and so forth. The variety of syllabic and[Pg 22] ideographic values which the cuneiform characters show could thus be accounted for.

This theory, however, tempting as it is by its simplicity, cannot be accepted in this unqualified form. Advancing knowledge has made it certain that the ancient civilization, including the religion, is Semitic in character. The assumption therefore of a purely non-Semitic culture for southern Babylonia is untenable. Secondly, even in the oldest inscriptions found, there occur Semitic words and Semitic constructions which prove that the inscriptions were composed by Semites. As long, therefore, as no traces of purely non-Semitic inscription are found, we cannot go beyond the Semites in seeking for the origin of the culture in this region. In view of this, the theory first advanced by Prof. Joseph Halévy of Paris, and now supported by the most eminent of German Assyriologists, Prof. Friedrich Delitzsch, which claims that the cuneiform writing is Semitic in origin, needs to be most carefully considered. There is much that speaks in favor of this theory, much that may more easily be accounted for by it, than by the opposite one, which was originally proposed by the distinguished Nestor of cuneiform studies, Jules Oppert, and which is with some modifications still held by the majority of scholars.[14] The question is one which cannot be answered by an appeal to philology alone. This is the fundamental error of the advocates of the Sumero-Akkadian theory, who appear to overlook the fact that the testimony of archaeological and anthropological research must be confirmatory of a philological hypothesis before it can be accepted as an indisputable fact.[15] The time however has not yet come for these two sciences to pronounce their verdict definitely, though it may be added that the supposition of a variety of races once[Pg 23] inhabiting Southern Mesopotamia finds support in what we know from the pre-historic researches of anthropologists.

Again, it is not to be denied that the theory of the Semitic origin of the cuneiform writing encounters obstacles that cannot easily be set aside. While it seeks to explain the syllabic values of the signs on the general principle that they represent elements of Babylonian words, truncated in this fashion in order to answer to the growing need for phonetic writing of words for which no ideographs existed, it is difficult to imagine, as Halévy's theory demands, that the "ideographic" style, as found chiefly in religious texts, is the deliberate invention of priests in their desire to produce a method of conveying their ideas that would be regarded as a mystery by the laity, and be successfully concealed from the latter. Here again the theory borders on the domain of archaeology, and philology alone will not help us out of the difficulty. An impartial verdict of the present state of the problem might be summed up as follows:

1. It is generally admitted that all the literature of Babylonia, including the oldest and even that written in the "ideographic" style, whether we term it "Sumero-Akkadian" or "hieratic," is the work of the Semitic settlers of Mesopotamia.

2. The culture, including the religion of Babylonia, is likewise a Semitic production, and since Assyria received its culture from Babylonia, the same remark holds good for entire Mesopotamia.

3. The cuneiform syllabary is largely Semitic in character. The ideas expressed by the ideographic values of the signs give no evidence of having been produced in non-Semitic surroundings; and, whatever the origin of the system may be, it has been so shaped by the Babylonians, so thoroughly adapted to their purposes, that it is to all practical purposes Semitic.[Pg 24]

4. Approached from the theoretical side, there remains, after making full allowance for the Semitic elements in the system, a residuum that has not yet found a satisfactory explanation, either by those who favor the non-Semitic theory or by those who hold the opposite view.

5. Pending further light to be thrown upon this question, through the expected additions to our knowledge of the archaeology and of the anthropological conditions of ancient prehistoric Mesopotamia, philological research must content itself with an acknowledgment of its inability to reach a conclusion that will appeal so forcibly to all minds, as to place the solution of the problem beyond dispute.

6. There is a presumption in favor of assuming a mixture of races in Southern Mesopotamia at an early day, and a possibility, therefore, that the earliest form of picture writing in this region, from which the Babylonian cuneiform is derived, may have been used by a non-Semitic population, and that traces of this are still apparent in the developed system after the important step had been taken, marked by the advance from picture to phonetic writing.

The important consideration for our purpose is, that the religious conceptions and practices as they are reflected in the literary sources now at our command, are distinctly Babylonian. With this we may rest content, and, leaving theories aside, there will be no necessity in an exposition of the religion of the Babylonians and Assyrians to differentiate or to attempt to differentiate between Semitic and so-called non-Semitic elements. Local conditions and the long period covered by the development and history of the religion in question, are the factors that suffice to account for the mixed and in many respects complicated phenomena which this religion presents.

Having set forth the sources at our command for the study of the Babylonian-Assyrian religion, and having indicated the[Pg 25] manner in which these sources have been made available for our purposes, we are prepared to take the next step that will fit us for an understanding of the religious practices that prevailed in Mesopotamia,—a consideration of the land and of its people, together with a general account of the history of the latter.[Pg 26]

[5] Isaiah, xlv. For the Babylonian views contained in this chapter, see Alfred Jeremias, Die Babylonisch-Assyrischen Vorstellungen vom Leben nach dem Tode, pp. 112-116.

[6] Book i. sec. 184.

[7] Book I. ("Clio"), secs. 95, 102, 178-200.

[8] An instructive instance is furnished by the mention of a mystic personage, "Homoroka," which now turns out to be—as Professor J. H. Wright has shown—a corruption of Marduk. (See Zeitschrift für Assyriologie, x. 71-74.)

[9] The excavations are still being continued, thanks to the generosity of some public-spirited citizens of Philadelphia.

[10] The parties concerned rolled their cylinders over the clay tablet recording a legal or commercial transaction.

[11] Besides those at Persepolis, a large tri-lingual inscription was found at Behistun, near the city of Kirmenshah, in Persia, which, containing some ninety proper names, enabled Sir Henry Rawlinson definitely to establish a basis for the decipherment of the Mesopotamian inscriptions.

[12] The best account is to be found in Hommel's Geschichte Babyloniens und Assyriens, pp. 58-134. A briefer statement was furnished by Professor Fr. Delitzsch in his supplements to the German translation of George Smith's Chaldaean Genesis (Chaldäische Genesis, pp. 257-262). A tolerably satisfactory account in English is furnished by B. T. A. Evetts in his work, New Light on the Bible and the Holy Land, pp. 79-129. For a full account of the excavations and the decipherment, together with a summary of results and specimens of the various branches of the Babylonian-Assyrian literature, the reader may be referred to Kaulen's Assyrien und Babylonien nach den neuesten Entdeckungen (5th edition).

[13] The most recent investigations show it to have been a 'Turanian' language. See Weissbach, Achämeniden Inschriften sweiter Art, Leipzig, 1893.

[14] Besides Delitzsch, however, there are others, as Pognon, Jäger, Guyard, McCurdy and Brinton, who side with Halévy.

[15] See now Dr. Brinton's paper, "The Protohistoric Ethnography of Western Asia" (Proceed. Amer. Philos. Soc., 1895), especially pp. 18-22.

The Babylonians and Assyrians with whom we are concerned in this volume dwelt in the region embraced by the Euphrates and the Tigris,—the Babylonians in the south, or the Euphrates Valley, the Assyrians to the northeast, in the region extending from the Tigris into the Kurdish Mountain districts; while the northwestern part of Mesopotamia—the northern half of the Euphrates district—was the seat of various empires that were alternately the rivals and the subjects of either Babylonia or Assyria.

The entire length of Babylonia was about 300 miles; the greatest breadth about 125 miles. The entire surface area was some 23,000 square miles, or about the size of West Virginia. The area of Assyria, with a length of 350 miles and a breadth varying from 170 to 300 miles, covered 75,000 square miles, which would make it somewhat smaller than the state of Nebraska. In the strict sense, the term Mesopotamia should be limited to the territory lying between the Euphrates and the Tigris above their junction, in the neighborhood of Baghdad, and extending northwards to the confines of the Taurus range; while the district to the south of Baghdad, and reaching to the Persian Gulf, may more properly be spoken of as the Euphrates Valley; and a third division is represented by the territory to the east of the Tigris, from Baghdad, and up to the Kurdish Mountains; but while this distinction is one that may be justly maintained, in view of the different character that the southern valley presents from the northern plain,[Pg 27] it has become so customary, in popular parlance, to think of the entire territory along and between the Euphrates and Tigris as one country, that the term Mesopotamia in this broad sense may be retained, with the division suggested by George Rawlinson, into Upper and Lower Mesopotamia. The two streams, as they form the salient traits of the region, are the factors that condition the character of the inhabitants and the culture that once flourished there. The Euphrates, or, to give the more correct pronunciation, Purat, signifies the 'river' par excellence. It is a quiet stream, flowing along in majestic dignity almost from its two sources, in the Armenian mountains, not far from the town of Erzerum, until it is joined by the Tigris in the extreme south. As the Shatt-el Arab, i.e., Arabic River, the two reach the Persian Gulf. Receiving many tributaries as long as it remains in the mountains, it flows first in a westerly direction, as though making direct for the Mediterranean Sea, then, veering suddenly to the southeast, it receives but few tributaries after it once passes through the Taurus range into the plain,—on the right side, only the Sadschur, on the left the Balichus and the Khabur. From this point on for the remaining distance of 800 miles, so far from receiving fresh accessions, it loses in quantity through the marsh beds that form on both sides. When it reaches the alluvial soil of Babylonia proper, its current and also its depth are considerably diminished through the numerous canals that form an outlet for its waters. Of its entire length, 1780 miles, it is navigable only for a small distance, cataracts forming a hindrance in its northern course and sandbanks in the south. In consequence, it never became at any time an important avenue for commerce, and besides rafts, which could be floated down to a certain distance, the only means of communication ever used were wicker baskets coated within and without with bitumen, or some form of a primitive ferry for passing from one shore to another.[Pg 28]

An entirely different stream is the Tigris—a corrupted form of 'Idiklat.' It is only 1146 miles in length, and is marked, as the native name indicates, by the 'swiftness' of its flow. Starting, like the Euphrates, in the rugged regions of Armenia, it continues its course through mountain clefts for a longer period, and joined at frequent intervals by tributaries, both before it merges into the plain and after doing so, the volume of its waters is steadily increased. Even when it approaches the alluvial soil of the south, it does not lose its character until well advanced in its course to the gulf. Advancing towards the Euphrates and again receding from it, it at last joins the latter at Korna, and together they pour their waters through the Persian Gulf into the great ocean. It is navigable from Diabekr in the north, for its entire length. Large rafts may be floated down from Mosul to Baghdad and Basra, and even small steamers have ascended as far north as Nimrud. The Tigris, then, in contrast to the Euphrates, is the avenue of commerce for Mesopotamia, forming the connecting bond between it and the rest of the ancient world,—Egypt, India, and the lands of the Mediterranean. Owing, however, to the imperfect character of the means of transportation in ancient and, for that matter, in modern times, the voyage up the stream was impracticable. The rafts, resting on inflated bags of goat or sheep skin, can make no headway against the rapid stream, and so, upon reaching Baghdad or Basra, they are broken up, and the bags sent back by the shore route to the north.

The contrast presented by the two rivers is paralleled by the traits distinguishing Upper from Lower Mesopotamia. Shut off to the north and northeast by the Armenian range, to the northwest by the Taurus, Upper Mesopotamia retains, for a considerable extent, and especially on the eastern side, a rugged aspect. The Kurdish mountains run close to the Tigris' bed for some distance below Mosul, while between the Tigris and the Euphrates proper, small ranges and promontories[Pg 29] stretch as far as the end of the Taurus chain, well on towards Mosul.

Below Mosul, the region begins to change its character. The mountains cease, the plain begins, the soil becomes alluvial and through the regular overflow of the two rivers in the rainy season, develops an astounding fertility. This overflow begins, in the case of the Tigris, early in March, reaches its height in May, and ceases about the middle of June. The overflow of the Euphrates extends from the middle of March till the beginning of June, but September is reached before the river resumes its natural state. Not only does the overflow of the Euphrates thus extend over a longer period, but it oversteps its banks with greater violence than does the Tigris, so that as far north as the juncture with the Khabur, and still more so in the south, the country to both sides is flooded, until it assumes the appearance of a great sea. Through the violence of these overflows, changes constantly occur in the course that the river takes, so that places which in ancient times stood on its banks are to-day removed from the main river-bed. Another important change in Southern Babylonia is the constant accretion of soil, due to the deposits from the Persian Gulf.

This increase proceeding on an average of about one mile in fifty years has brought it about that the two rivers to-day, instead of passing separately into the Gulf, unite at Korna—some distance still from the entrance. The contrast of seasons is greater, as may be imagined, in Upper Mesopotamia than in the south. The winters are cold, with snowfalls that may last for several months, but with the beginning of the dry season, in May, a tropical heat sets in which lasts until the beginning of November, when the rain begins. Assyria proper, that is, the eastern side of Mesopotamia, is more affected by the mountain ranges than the west. In the Euphrates Valley, the heat during the dry season, from about May till November, when for weeks, and even months, no cloud is to be seen,[Pg 30] beggars description; but strange enough, the Arabs who dwell there at present, while enduring the heat without much discomfort, are severely affected by a winter temperature that for Europeans and Americans is exhilarating in its influence.

From what has been said, it will be clear that the Euphrates is, par excellence, the river of Southern Mesopotamia or Babylonia, while the Tigris may be regarded as the river of Assyria. It was the Euphrates that made possible the high degree of culture, that was reached in the south. Through the very intense heat of the dry season, the soil developed a fertility that reduced human labor to a minimum. The return for sowing of all kinds of grain, notably wheat, corn, barley, is calculated, on an average, to be fifty to a hundred-fold, while the date palm flourishes with scarcely any cultivation at all. Sustenance being thus provided for with little effort, it needed only a certain care in protecting oneself from damage through the too abundant overflow, to enable the population to find that ease of existence, which is an indispensable condition of culture. This was accomplished by the erection of dikes, and by directing the waters through channels into the fields.

Assyria, more rugged in character, did not enjoy the same advantages. Its culture, therefore, not only arose at a later period than that of Babylonia, but was a direct importation from the south. It was due to the natural extension of the civilization that continued for the greater part of the existence of the two empires to be central in the south. But when once Assyria was included in the circle of Babylonian culture, the greater effort required in forcing the natural resources of the soil, produced a greater variety in the return. Besides corn, wheat and rice, the olive, banana and fig tree, mulberry and vine were cultivated, while the vicinity of the mountain ranges furnished an abundance of building material—wood and limestone—that was lacking in the south. The fertility of Assyria proper, again, not being dependent on the overflow of the Tigris,[Pg 31] proved to be of greater endurance. With the neglect of the irrigation system, Babylonia became a mere waste, and the same river that was the cause of its prosperity became the foe that, more effectually than any human power, contributed to the ruin and the general desolation that marks the greater part of the Euphrates Valley at the present time. Assyria continued to play a part in history long after its ancient glory had departed, and to this day enjoys a far greater activity, and is of considerable more significance than the south.

In so far as natural surroundings affect the character of two peoples belonging to the same race, the Assyrians present that contrast to the Babylonians which one may expect from the differences, just set forth, between the two districts. The former were rugged, more warlike, and when they acquired power, used it in the perfection of their military strength; the latter, while not lacking in the ambition to extend their dominion, yet, on the whole, presented a more peaceful aspect that led to the cultivation of commerce and industrial arts. Both, however, have very many more traits in common than they have marks of distinction. They both belong not only to the Semitic race, but to the same branch of the race. Presenting the same physical features, the languages spoken by them are identical, barring differences that do not always rise to the degree of dialectical variations, and affect chiefly the pronunciation of certain consonants. At what time the Babylonians and Assyrians settled in the district in which we find them, whence they came, and whether the Euphrates Valley or the northern Tigris district was the first to be settled, are questions that cannot, in the present state of knowledge, be answered. As to the time of their settlement, the high degree of culture that the Euphrates Valley shows at the earliest[Pg 32] period known to us,—about 4000 B.C.,—and the indigenous character of this culture, points to very old settlement, and makes it easier to err on the side of not going back far enough, than on the side of going too far. Again, while, as has been several times intimated, the culture in the south is older than that of the north, it does not necessarily follow that the settlement of Babylonia antedates that of Assyria. The answer to this question would depend upon the answer to the question as to the original home of the Semites.[16] The probabilities, however, are in favor of assuming a movement of population, as of culture, from the south to the north. At all events, the history of Babylonia and Assyria begins with the former, and as a consequence we are justified also in beginning with that phase of the religion for which we have the earliest records—the Babylonian.

At the very outset of a brief survey of the history of the Babylonians, a problem confronts us of primary importance. Are there any traces of other settlers besides the Semitic Babylonians in the earliest period of the history of the Euphrates Valley? Those who cling to the theory of a non-Semitic origin of the cuneiform syllabary will, of course, be ready to answer in the affirmative. Sumerians and Akkadians are the names given to these non-Semitic settlers who preceded the Babylonians in the control of the Euphrates Valley. The names are derived from the terms Sumer and Akkad, which are frequently found in Babylonian and Assyrian inscriptions, in connection with the titles of the kings. Unfortunately, scholars are not a unit in the exact location of the districts comprised by these names, some declaring Sumer to be in the north and[Pg 33] Akkad in the south; others favoring the reverse position. The balance of proof rests in favor of the former supposition; but however that may be, Sumer and Akkad represent, from a certain period on, a general designation to include the whole of Babylonia. Professor Hommel goes so far as to declare that in the types found on statues and monuments of the oldest period of Babylonian history—the monuments coming from the mound Telloh—we have actual representations of these Sumerians, who are thus made out to be a smooth-faced race with rather prominent cheek-bones, round faces, and shaven heads.[17] He pronounces in favor of the highlands lying to the east of Babylonia, as the home of the Sumerians, whence they made their way into the Euphrates Valley. Unfortunately, the noses on these old statues are mutilated, and with such an important feature missing, anthropologists, at least, are unwilling to pronounce definitely as to the type represented. Again, together with these supposed non-Semitic types, other figures have been found which, as Professor Hommel also admits, show the ordinary Semitic features. It would seem, therefore, that even accepting the hypothesis of a non-Semitic type existing in Babylonia at this time, the Semitic settlers are just as old as the supposed Sumerians; and since it is admitted that the language found on these statues and figures contains Semitic constructions and Semitic words, it is, to say the least, hazardous to give the Sumerians the preference over the Semites so far as the period of settlement and origin of the Euphratean culture is concerned. As a matter of fact, we are not warranted in going beyond the statement that all evidence points in favor of a population of mixed races in the Euphrates Valley from the earliest period known to us. No positive proof is forthcoming that Sumer and Akkad were ever employed or understood in any other sense than as geographical terms.

[Pg 34] This one safe conclusion, however, that the Semitic settlers of Babylonia were not the sole occupants, but by their side dwelt another race, or possibly a variety of races, possessing entirely different traits, is one of considerable importance. At various times the non-Semitic hordes of Elam and the mountain districts to the east of Babylonia swept over the valley, and succeeded, for a longer or shorter period, in securing a firm foothold. The ease with which these conquerors accommodated themselves to their surroundings, continuing the form of government which they found there, making but slight changes in the religious practices, can best be accounted for on the supposition that the mixture of different races in the valley had brought about an interchange and interlacing of traits which resulted in the approach of one type to the other. Again, it has recently been made probable that as early at least as 2000, or even 2500 B.C., Semitic invaders entering Babylonia from the side of Arabia drove the native Babylonian rulers from the throne;[18] and at a still earlier period intercourse between Babylonia and distant nations to the northeast and northwest was established, which left its traces on the political and social conditions. At every point we come across evidence of this composite character of Babylonian culture, and the question as to the origin of the latter may, after all, resolve itself into the proposition that the contact of different races gave the intellectual impetus which is the first condition of a forward movement in civilization; and while it is possible that, at one stage, the greater share in the movement falls to the non-Semitic contingent, the Semites soon obtained the intellectual ascendency, and so absorbed the non-Semitic elements as to give to the culture resulting from the combination, the homogeneous character it presents on the surface.

Our present knowledge of Babylonian history reaches back to the period of about 4000 B.C. At that time we find the Euphrates Valley divided into a series of states or principalities, parcelling North and South Babylonia between them. These states group themselves around certain cities. In fact, the Babylonian principalities arise from the extension of the city's jurisdiction, just as the later Babylonian empire is naught but the enlargement, on a greater scale, of the city of Babylon.

Of these old Babylonian cities the most noteworthy, in the south, are Eridu, Lagash,[19] Ur, Larsa, Uruk, Isin; and in the north, Agade, Sippar, Nippur, Kutha, and Babylon. The rulers of these cities call themselves either 'king' (literally 'great man') or 'governor,' according as the position is a purely independent one, or one of subjection to a more powerful chieftain. Thus the earliest rulers of the district of Lagash, of whom we have inscriptions (c. 3200 B.C.) have the title of 'king,' but a few centuries later Lagash lost its independent position and its rulers became 'patesis,' i.e., governors. They are in a position of vassalage, as it would appear, to the contemporaneous kings of Ur, though this does not hinder them from engaging in military expeditions against Elam, and in extensive building operations. The kings of Ur, in addition to their title as kings of Ur, are styled kings of Sumer and Akkad. Whether at this time, Sumer and Akkad included the whole of Babylonia, or, as seems more likely, only the southern part, in either case, Lagash would fall under the jurisdiction of these kings, if their title is to be regarded as more than an empty boast. Again, the rulers of Uruk are known simply as kings of that place, while those of Isin incorporate in their titles, kingship over Ur as well as Sumer and Akkad.