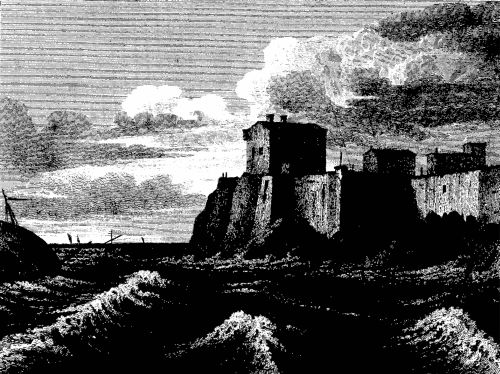

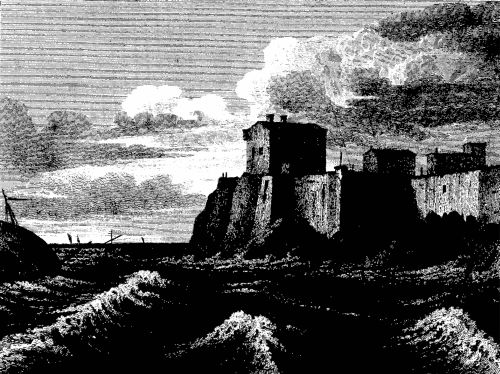

isle of sT marguerite near cannes and prison of masque de fer.

Title: Itinerary of Provence and the Rhone

Author: John Hughes

Release date: March 24, 2007 [eBook #20891]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Carlo Traverso, Chuck Greif and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://dp.rastko.net

(Produced from images of the Bibliothèque nationale de

France (BnF/Gallica) at http://gallica.bnf.fr)

Hughes

South of France

only two hundred and fifty copies printed.

"——I informed my friend that I had just received from England a journal of a tour made in the South of France by a young Oxonian friend of mine, a poet, a draughtsman, and a scholar—in which he gives such an animated and interesting description of the Château Grignan, the dwelling of Madame de Sevigné's beloved daughter, and frequently the place of her own residence, that no one who ever read the book would be within forty miles of the same without going a pilgrimage to the spot. The Marquis smiled, seemed very much pleased, and asked the title at length of the work in question; and writing down to my dictation, 'An Itinerary of Provence and the Rhone made during the year 1819, by John Hughes, A.M. of Oriel College, Oxford,'—observed, that he could now purchase no books for the Château, but would recommend that the Itineraire should be commissioned for the Library to which he was abonné in the neighbouring town,"—Sir Walter Scott's Quentin Durward.

Thomas White, Printer, Johnson's Court.

OF

isle of sT marguerite near cannes and prison of masque de fer.

SECOND EDITION.

LONDON:

JAMES CAWTHORN.

MD.CCCXXIX.

It has been the Author's object to render the following volume a companion to persons visiting the country described. He has therefore not so much studied to compile from known books of historical reference, as to answer those plain and practical questions which suggest themselves during an actual journey, and to enable those whose time is limited, and who wish to employ it actively, to form the necessary calculations as to what is to be seen and done. The best points of view, and the parts which may be passed over rapidly, are therefore specified, as well as the places where good accommodation are to be expected, or imposition to be guarded against.

The subjects of the Illustrations will be mentioned in the course of the Itinerary, for the information of collectors, of whose notice it is trusted they will be rendered worthy by the well-known talents of Mr. Dewint and the Messrs. Cookes.

No one, I imagine, ever yet left an hotel in a central and bustling part of Paris, without feeling the faculty of observation strained to the utmost, and experiencing a whirl and jumble of recollections as little in unison with each other as the well known signs of that whimsical city, the Bœuf à-la-mode, (with his cachemire shawl and his ostrich feathers) and the Mort d'Henri Quartre. The contrasts and varieties of the grave and gay, the affecting and the burlesque, the magnificent and the paltry, which exist and may be sought out in abundance in every great capital, are perhaps more vividly concentrated at Paris than any where else, and brought with less trouble under the eye of those whose spirits or leisure may not allow them to mix in society. In[2] London every thing wears a busy uniform exterior, varied only by the apparition of a Turk, a Lascar, or a Highlander; and home appears to be the place reserved for the development of character: but in Paris, from the fashion of living almost in public, and the freedom which every one enjoys of following his own taste in dress or amusement without notice, the history of most individuals appears to a certain degree written on their exterior; and a morning's walk brings you in contact with all the diversities of character which rapidly succeeding events have created. The old beau, with the identical toupet of 1770; the musty, moth-eaten nondescripts sometimes seen at the mass of Notre Dame, which remind you of a still earlier period; the faded royalist, with a countenance saddened by the recollection of former days; the ex-militaires, whose looks own no friendship with "the world or the world's law;" the old bourgeois riding in the same roundabout with his grandchildren, and enjoying the jeu de bague as cordially,—revolve in succession like the different figures in a magic lantern, while the place of Punch and Pierrot is supplied by a host of laborious drolls and gens à l'incroyable. The various members of this motley assemblage appear also more distinct from each other, as connected in the recollection with places so strongly marked by historical events, or bearing in themselves so peculiar a character:—the place Louis Quinze, the grim old Conciergerie, the deserted Fauxbourg St. Germain, with the grass[3] growing in its streets; the Place de Carousel, the Boulevards, and the Catacombs, the Palais Royal and the Morgue.

To attempt, however, to say any thing new of a place so well known and so fully described as Paris, would be as superfluous as to write the natural history of the dog or cat. The peculiarities of such animals are continually striking one in new and amusing points of view; but verbal delineation has already done its utmost in acquainting us with them. In like manner, every thing relating to Paris, and illustrative of it at a period of interest which probably will not arise again for centuries, has been already made known in Paul's admirable letters, in poor Scott's powerful but unmerciful satire, and finally in a host of books, booklings, and bookatees, teaching us how to spend any period of time at Paris from three to three hundred and sixty-five days; how to enjoy it, how to eat, drink, see, hear, feel, think, and economise in it. Kotzebue has devoted sixty pages to its bon bons and savories; others more modestly give you only a diary of their own fricasseed chicken and champagne, and information of a still lower sort is supplied by the delectable Mr. Hone, for the instruction of our Jerries and Corinthian Toms. I shall commence dates, therefore, from the 26th of April, on which day we quitted the Hôtel de l'Europe, Rue Valois, not sorry to obtain a respite from sounds and sights.[4]

Though in such a country as Tuscany, where every furlong of ground affords a new and rich subject for the pencil, the voiture mode of travelling is preferable to posting; yet no one, I think, would recommend it in traversing the tedious interval which separates Paris from the southern provinces. We had adopted this species of conveyance from the idea that it would afford more leisure for observation to those of the party to whom France was new; but we found in reality that by subjecting us to a dependence on hours, it diverted our attention from those places where we might have spent half a day to advantage, and familiarized us only with one branch of knowledge,—the merit and demerit of most of the inns on the roads, whose characters I shall not fail to give as we found them. Homely as this species of information may be, I have often regretted the want of it beforehand; and concluding that others may be of the same opinion, I shall therefore afford it as far as I am able: premising, that it is as well not to vary, on this or any other road, from the practice of ascertaining beforehand the rate of the aubergiste's charges. The traveller's first impulse certainly is to save himself trouble, by paying whatever is demanded, and not to expend time and attention on a series of petty disputes, which make no great difference in his travelling expenses. There is, however, in all or most of those who are fitted to conduct the business of life, a feeling of shame at being outwitted even in trifles, which naturally rebels[5] against this easy mode of proceeding, and inclines one rather to take the trouble of asking a few questions, than to be laughed at as a grand seigneur by a cunning landlord. This trouble after all may be taken by a servant, and need not subject the master to the necessity of entering every inn like an angry terrier, with his bristles up and ready for battle; and the settlement of preliminaries does not lead to any want of attention on the part of the people of the inn.

We neglected this precaution at Essonne, where we breakfasted on leaving Paris, and where accordingly we paid about double the charge which Tortoni or the Cafe Hardy would have made. It appears, in truth, that at the Croissant d'Or, as at the Emperor Joseph's memorable German inn, "though eggs are not scarce, yet gentry are."

The distance from Paris to this place is about 24 miles: the road of course excellent, as is uniformly the case in the route to Chalons; but the only thing during the stage which remains on my recollection, is an obelisk inscribed, "Dieu, le Roi, et les dames;" a melange perhaps compounded in compliment to Louis XV. who greatly improved a part of this road, which was once nearly impassable. Corbeil, a neat flourishing town within half a mile of Essonne, and possessing large cotton manufactories, derives some interest from the celebrated siege it sustained during[6] the war of the league. Two miles beyond Essonne we remarked, at a short distance to the right, Château Moncey, once the seat of the gay and brilliant Duke de Villeroi and his descendants; and on a hill to the left, Château Coudray, the former residence of the Prince de Chalot. Both the possessors of these estates were guillotined during the reign of terror, and their places are filled by Marechal Jourdan, and some nouveau riche, whose very name the peasants seemed never to have heard, or to have forgotten from want of interest.

We found the Hôtel de la Ville de Lyon at Fontainebleau a good inn, and fair in its charges. The old palace, though not intrinsically worth a visit in point of architecture, yet conveys one of those "sermons in stones," in which the Fauxbourg de St. Germain so much abounds; and presents also more pleasing recollections of Louis Quatorze (a prince possessing many of the good points of the bon Henri) than the bombastic personification of him as Jupiter Tonans, in the palace of Versailles, which is on a par as a painting with Tom Thumb as a tragedy.

April 27.—To Fossard, eighteen miles: the first six through the forest, just sufficiently sylvan to suffer by a comparison with that of Windsor. At the end of two more miles we crossed the valley, in which is situated the town of Moret, to which is attached a history equally curious, as Anquetil observes,[7] with that of the Iron Mask. The following is the extract from the Duke de St. Simon's Memoirs, which he introduces as relative to it.

"Il y avoit à Moret, petite ville auprès de Fontainebleau, un petit couvent, où étoit professé une Mauresse inconnue, et qu'on ne montroit a personne. Bontemps, Gouverneur de Versailles, par qui passoient les choses du secrèt domestique du roi, l'y avoit mise toute jeune, avoit payé une dot assez considerable, et continuoit à lui payer une grosse pension tous les ans. Il avoit attention qu'elle eût son necessaire, que tout ce qu'elle pouvoit desirer en agrémens et douceurs, et qui peut passer pour abondance pour une religieuse, lui fut fourni. La reine y alloit souvent de Fontainebleau, et prenoit grand soin du bien-être du couvent; et Mad. de Maintenon après elle. Ni l'une ni l'autre ne prenoit de cette Mauresse un soin direct, et qui peut se remarquer. Elles ne la voyoient même toutes les fois qu'elles alloient au couvent, mais elles s'informoient curieusement de sa santé, de sa conduite, et de celle de la superieure à son egard. Quoiqu'il n'y eût dans cette maison personne d'un nom connu, Monseigneur (le Dauphin) y a été quelquefois; les princes, ses enfans, aussi; et tous demandoient et voyoient la Mauresse. Elle étoit dans un couvent avec plus de consideration que les autres, et se prevaloit fort des soins qu'on prenoit d'elle, et du mystère qu'on en faisoit. Quoiqu'elle veçut très-religieusement, on s'appercevoit bien que[8] sa vocation avoit été aidée. Il lui echappoit une fois, entendant Monseigneur chasser dans le forêt, de dire negligemment, 'c'est mon frère qui chasse.' On dit qu'elle avoit quelquefois des hauteurs, que sur les plaintes de la superieure, Mad. de Maintenon alla un jour exprès pour tâcher de lui inculquer des sentimens plus conformes a l'humilité religieuse; que lui ayant voulu insinuer qu'elle n'étoit pas ce qu'elle croyoit, elle lui repondit, 'Si cela n'étoit pas, Madame, vous ne prendriez pas la peine de venir me le dire!' Ces indices ont fait conjectures qu'elle étoit fille du roi et de la reine, et que sa couleur l'avoit fait sequestrer, en publiant que la reine avoit fait une fausse couche."

In addition to this extract, Anquetil adds, "En effet, la fantaisie de garder devant ses yeux une naine monstreuse (her favourite negress mentioned previously), peut faire conjecturer que Marie Therèse n'aura pas été assez exacte à detourner ses regards d'objets qu'une femme prudente doit s'interdire; qu'elle les aura fixés sur les negres que le progrès du commerce maritime commençoit de rendre communs en France; et que de là sera venue la couleur de cette infortunée, qu'il aura fallu cacher dans un cloître. Cette Mauresse et l'homme au masque de fer sont les deux mystères du regne de Louis XIV. Le redacteur des Memoires de St. Simon dit qu'elle est morte à Moret en 1732, et que son portrait étoit encore en 1779 dans le cabinet de l'abbesse, d'où,[9] quand cette maison a été réunie ou Prieuré de Champ Benôit à Provins, il a passé dans le cabinet des antiques et curiosités de l'abbaye de St. Genevieve du Mont à Paris, où il est encore. On lit au bas de ce portrait, ces mots, Religieuse de Moret." Such are the words of the extract relative to this singular person.

The Hôtel de Poste, (as it chooses to style itself) at Fossard, is a dismal pot-house; and the people possess none of that good humour and alacrity which cover a multitude of faults. Having swallowed some of their gritty coffee, which might have been very delectable to the palate of a Turk, we walked about a mile and a half to the bridge[1] of Montereau-sur-Yonne, on which John Duke of Burgundy was murdered by Tannegui de Chastel, in the presence, and probably with the connivance of the Dauphin, afterwards[10] Charles VII. Near this spot we remarked a small mass of ruins, the only remains of the once magnificent Château Varennes. Its former owner, the Duke de Châtelet, as we were informed by some market-people, resided for six months in the year at this seat, maintaining or employing most of the poor within his reach, and entertaining his peasantry with a weekly dance at the Château. Like many others, he fell a victim to the guillotine during the reign of terror; his lands, with the exception of a portion recovered by his heirs, were alienated, and the fragment which we observed was the only part of his residence left standing. From the tone and manner in which the French peasantry appear to speak of these very common occurrences, I should judge that the effects of the revolution have not yet eradicated that "subordination of the heart," which is natural among a simple and industrious people, and which nothing but very gross neglect or misconduct on the part of their superiors, or the unchecked licence of political quacks, can destroy. Most of the ravages in question might no doubt be traced to bands of plunderers, organized from the most desperate and notorious characters in many different parishes, and sufficiently countenanced by the revolutionary tribunals to overawe the peaceable and unarmed mass of the population, whom it would be hardly fair to confound with them. Let us fancy for a moment, how quickly, under similar political circumstances, a moveable Spencean brigade might[11] be collected in any district of England from poachers, sheep-stealers, gypsies, incendiaries, and those whose latent love of mischief might be drawn out by proper encouragement, and we may find reason not to condemn the French peasantry in general, as sharers in the outrages which they probably abominated, but could not prevent.

From Fossard to Sens, 21 miles: the country uninteresting as far as Pont-sur-Yonne. Chapelle de Champigny affords a tolerably exact idea of a Spanish village; each farm-house and its premises forming a square, inclosed in blank walls, and opening into the street by folding gates, with hardly a window to be seen. From Pont-sur-Yonne to Sens, the road becomes more cheerful; and its fine old cathedral forms a good central object in the valley, along which the Yonne is seen winding. The principal inn at Sens being full for the night, we found neat and comfortable accommodations, with great civility, at the Bouteille. Whether there be any object worthy of notice in this cheerful little city, besides its cathedral, I do not know; but the latter possesses works of art which deserve an early and attentive visit. Nothing can be more minutely beautiful than the small figures and ornaments on the tomb of the Cardinal du Prat, which is sufficient in itself to give a character to any one church. But the grand object of interest is a large sepulchral group in the centre of the choir, to the memory of[12] the Dauphin and his consort, the parents of Louis XVI. The grace and classical contour of this monument, which is executed by the well-known Nicholas Coustou, would excite admiration even in the studio of Canova, while the deep tone of genuine feeling displayed, particularly in the figure of Hymen quenching his torch, is worthy of the chisel of our own Chantry. Somewhat might perhaps be owing to an evening light, which cast strong mellow shades on the figures, and gave an effect of reality to the fine white marble of which they are composed; but their merits are very striking, and are quite unalloyed by the graphic bombast of which the most able French artists have been with too much truth accused. The character of the Dauphin, whose exemplary life in the midst of a corrupt court, was a tacit reproof which his haughty father could ill brook, is well known.

He was snatched in the flower of his age, in the year 1765, from an evil which was even then brooding, and which might have brought his grey hairs to a bloody end at a more advanced period: and his consort survived him about a year and a half. "They were lovely and pleasant in their lives, and in their deaths they were not divided." The latter monument, as well as others of inferior merit, owed its[13] preservation from revolutionary fury to the conduct and firmness of Mons. Menestrier, an avocat, and mayor of Auxerre during the reign of terror. Ce brave homme (I like the old sacristan's term of brave homme, as it is one of the few untranslateable French words) flew to the cathedral at the moment that a horde of brigands had entered it to commence the work of mutilation; and, seconded by nothing but his known character for resolution, and an athletic person, fairly intimidated and turned them out for the time. Losing not a moment, he removed to a place of safety the Dauphin's monument, the avowed object of their vengeance, before a second visit took place; and desirous also to preserve a fine bas relief which stands in another part of the church, representing St. Nicholas portioning three orphan girls, he engraved on the wall under it an inscription to Benevolence in the republican style, which produced the desired effect. Not very long afterwards he fell a victim to a fever caught by over-exertion in advocating the cause of a poor family; and his wife survived him only a few days, exhibiting an humble copy of the conjugal affection of those whose memorials her husband had so loyally preserved. Whether to give full credit or not to the old sacristan's narration, I do not know; but it appears more probable that even so large a monument was removed piecemeal at short notice, than that the malice of the brigands would have allowed it to stand unhurt; and there is besides an ingenuity and presence of mind shown in the[14] preservation of St. Nicholas, quite consistent with the character of M. Menestrier, as described by the old man. Had the latter felt that inclination to romance, which is not uncommon among his brethren, he would probably have adopted the hacknied legend, that both monuments were miraculously secreted from the eyes of the marauders.

April 28.—To Joigny, where we breakfasted, twenty-one miles. Passed through Villeneuve, a decayed old town, with two singular gateways. Even this place emulates Paris in the possession of a Tivoli, which, in the present instance, consisted of a walled square of court-yard (for garden it could not be called), measuring about thirty yards by twenty, and overshadowed by poplars from three to four feet high: a most pleasant representative, in truth, of the wild olive woods, the sequestered waterfalls, and the classical ruins of the original Tivoli.

On leaving Joigny, a neat pleasant town, extending in one wide street along the Yonne, and crowned by a handsome château, left unfinished by the Due de Villeroi, we reached the heart of the wine district of Burgundy. The country here assumes the appearance of a garden, both from the steep and regular form of the hills, which exactly resemble the[15] Dutch slopes in old-fashioned gardens, and from the high state of culture to which their thin gravelly soil is brought. The hoe and the pruning-knife seem never at rest, and not a weed is to be seen; while the slightest portion of manure dropt on the high road becomes a prize, if not an object of contention, to the nearest vignerons. The air of cheerfulness and beauty, however, which we annex to our notions of high cultivation, is wholly wanting. The appearance of the vines was that of sapless black stumps, about thirty inches high, and pruned so as to leave only four or five eyes; and though the subject of poverty is too serious to joke on, the withered and stunted appearance of the country people exactly corresponded to that of these dry pollards. I trust that we were in some degree deceived by their natural ugliness, and that hard labour and scanty profits are not the only reasons which render their tout ensemble such a contrast to the healthy robust looks of the Normans and Picards, whose very horses show the effects of their abundant corn harvests.

From Joigny to Auxerre, twenty-one miles. We arrived too late to visit the interior of the cathedral, which was not mentioned to us as containing any thing remarkable. Its exterior, however, is fine and venerable, and affords a beautiful evening study, viewed from the opposite bank of the Yonne, about half a mile on the Vermanton road. The rest of the town, seen from this point, is broken into fine masses[16] of conventual and other old buildings; and the river and bridge complete a landscape very well worthy of an accurate sketch.

The excellence of the Hôtel de Beaune, at Auxerre, "tenu par Boillet, gendre Mineau," as his cards inform us, deserves notice. This is one of those palm-islands among a desert of dirty pothouses, most treacherously adapted to lure onward a certain class of fair weather pilgrims, whom one wonders to meet with beyond Paris, and whose dolorous complaints of thin milk and large coffee-spoons, have afforded me no small amusement in casual rencounters. The most fastidious, however, of this class of smelfungi, would find but little to carp at under the roof the civil Mr. Boillet; and would do well to lay in a stock of comfortable recollections in this place, on which to feast as far as Chalons; for the interval between Auxerre and the latter city will prove but a dreary one to a traveller of the gastronomic school.

The general air of Auxerre is ancient and respectable; but conveys no ideas of populousness or commerce. In the opinion, however, of an old sub-matron of the Enfans Trouvées (who looked over my shoulder while sketching, and whom, by way of something to say, I ignorantly complimented on her fine family of grandchildren), there is nothing, or, according to Malthus, much to complain of in[17] the former respect. "Ah, Monsieur, que voulez vous? ce sont les militaires, ils vont par çi, ils vont par là, et puis—voilà des enfans, et où chercher les peres?"

April 29.—To Vermanton, our first stage, eighteen miles: a succession of fine vineyards and square steep hills, such as Uncle Toby might have constructed for his amusement, with Gargantua for an assistant instead of the corporal. About six miles short of Vermanton, at the bottom of a long descent, we remarked Cravant, a little town to the right, fortified in an ancient and picturesque manner, and which, the peasants said, had been the seat of much fighting in days of old. Our informant was ploughing in a fierce cocked hat, with a team composed of a cow and an ass. Query, might not cocked hats, which appear to our ideas an exclusively military costume, have originated in such countries as these, among the vine-dressers? who flap down the sides alternately, in a manner that shows they understood the true use of them as a parasol. Vermanton is a small obscure place, affording an inn slovenly enough, though not glaringly bad.

From hence to Lucy le Bois, where the horses were baited, fifteen miles. A pretty sequestered valley occurs about three miles beyond Vermanton; but the whole of the road, like that of the day before, may be travelled in the dark without any loss:[18] the best part of it consists of a distant view of the vale and town of Avalon, backed by the Nivernois hills. In the old French Fablieux, the valley of Avalon is selected as the spot where a fairy confined Sir Lanval, her mortal lover; but whether the French Avalon, or the beautiful vale of Glastonbury was meant, appears doubtful, as the latter formerly bore the same name. There is a resemblance between the two districts, which amounts to an odd coincidence, particularly with regard to one of the Nivernois hills in the back ground, which presents a strong likeness of Glastonbury Tor. We should have passed through Avalon, but for a trick of the voiturier, who took a cross road to avoid paying the post duty there, and save his money at the expense of our bones. For this manoeuvre he might have been severely punished, had we chosen to interfere.

From Lucy le Bois to Rouvray, where we slept, the level of the country becomes gradually more elevated, and its general features much more English, consisting of corn, woody copses, and pastures full of cowslips. I cannot say, however, that we found any thing to remind us of England at the detestable inn where we were quartered for the night, and have no doubt but that Lucy le Bois or Avalon would have afforded somewhat much better. The only civilized person was a large black baker's dog, who, like Gil Blas's first travelling acquaintance, seemed free of the house, and did the honours of the supper[19] to us with an assiduity as disinterested, "Ah, messieurs," said his civil master, when we stept across the street in the morning, to return the dog's visit in form, "je suis charmé que vous trouvez l'Abri si beau; je suis au desespoir qu'il ne soit pas chez lui a present, mais je vais le chercher partout afin qu'il vous fasse ses hommages." The good man could not have spoken of a favourite son with more unsuspecting complacency.

April 30.—To Saulieu, where we breakfasted at a tolerably good inn, fifteen miles: the morning intensely cold, and one of those white frosts on the ground, which so much endanger the vintage at this season. We observed, however, no vineyards on the elevated ridge of country along which we were travelling, and which was perfectly English. A respectable old château, with a rookery, quick hedges, and extensive woods, thick enough for a fox covert, kept up the illusion agreeably. This style of ground continues beyond Saulieu; and between the latter place and Arnay le Duc, eighteen miles farther, its features are not unromantic. One or two castles of a very baronial air occur; the first of which, reduced to ruins, is visible at about a mile beyond Saulieu, occupying an insulated hill at some distance from the road, and much resembling the remains of an Italian freebooter's stronghold. Another, situated at the head of a glen, about six miles farther on, and overlooking a small village, is more perfect and[20] striking in its appearance. It is the property, as we were informed, of the widow of M. Fenou, a royalist, who, during the revolution, stood a siege within its walls equal to that of Tillietudlem, repulsing a strong body of republicans with considerable loss. Buonaparte subsequently recalled M. Fenou, with the grant of a free pardon; and the estate was, in the course of things, restored to his widow. Such, as far as we could collect from the account of our informant, was the history belonging to Château Torcy la Vachere, which bears some resemblance, in situation and general outline, to Eastnor Castle, the seat of the Earl of Somers, at the foot of the Malvern hills.

Arnay le Duc, a town situated on commanding ground, where we slept, boasts of an earlier celebrity, having been the scene of one of Admiral de Coligni's victories. It possesses several convents, now private property, and one or two fragments of building of a peculiarly antiquated style. Among these I particularly remarked an old iron-shop, supposed, as a bourgeois informed me, to be more than seven hundred years old, and which seems to have communicated with the ancient walls as a guard-house. While busied in sketching this singular relic, we were saluted gracefully by an old chevalier de St. Louis, who was passing, and whose distinguished air would have become the person of Coligni himself. On casually inquiring the name of this[21] gentleman, we learnt that he had been one among the many imprisoned during the reign of terror, and would have fallen by the guillotine, had the fall of Robespierre happened four-and-twenty hours later. This, it must be owned, is a trite and common story; but it is, perhaps, by the very triteness and frequency of such hair-breadth escapes, more than by any other circumstance, that the extent and ferocity of the revolutionary massacres are brought home to the imagination. The appointed victims, whom the delay of a day or an hour preserved from destruction at this crisis, still survive in all parts of France, like widely-scattered land-marks, to remind one of the numbers swept away in the previous deluge of murder.

May 1.—To Rochepot twenty-one miles. We were not sorry to leave the Hôtel de Poste, at Arnay le Duc, which, with higher pretensions than the inn at Rouvray, only differs from it in the ratio of "dear and nasty" to "cheap and nasty;" and to commence a stage which promised more to the eye than any part of our former route. The country still continues to rise in this direction, and soon assumes the air of an extensive forest or chase, enlivened by half-wild herds of cattle, and opening into green glades and vistas of distant ranges of hills. At Ivry, we wound up a steep hill; the summit of which, a wide naked common, might match most parts of Dartmoor in height and bleakness. I had observed heaps[22] of granite and micaceous stone at a much lower elevation in the course of the day before; and conclude that we were now on one of the highest inhabited points which occur in the interior of France. We had not leisure to walk to a telegraph on the right, which, to judge from the occasional glimpses which we had, must command a splendid map of the country near Autun. It had been recommended to us to take the route to Chalons through the latter town, as affording the most objects of interest; but, on the whole, I doubt whether that which we had adopted as the least circuitous, be not also preferable, as possessing the striking panoramic point to which we had climbed. After two or three more miles over an expanse of parched turf, we reached what geologists would call the bluff escarpment of the stratum. The descent before us was so precipitous, as to leave us at first at a loss to make out how the road could be conducted down it: and the prospect which burst upon us in front, had apparently no limit but the power of human vision. Beyond the foreground, which was formed by a series of rocky glens diverging from below the point on which we stood, the immense vale of the Saone extended like a bird's-eye view of the ocean, its relative distances marked by towns and villages glittering like white sails. Above the flat line of haze, which, at the first glance, appears to terminate the prospect at the distance of sixty miles, or more, we distinguished a faint blue outline of[23] lofty mountains, which must have been the barrier separating France from Switzerland; and, as occasional gleams of sunshine broke out, the glittering and jagged lines of a barrier still more distant, and apparently hanging in mid air, became distinctly visible. Among these I recognised, at last, the features of Mont Blanc, in whose peculiar outline I could not be mistaken, and which, according to the map, cannot be less than 110 or 120 miles distant, in a direct line from the Montagne de Rochepot. It is, perhaps, not necessary to be a mountaineer, like Jean Jacques, by birth and education, in order to feel the peculiar expansion of mind, which he describes as caused by breathing mountain-air, and contemplating prospects like this of which I speak.[2] A boundless plain, and enormous mountains, such as the Alps, whether viewed individually, or contrasted with each other, are objects not physically grand alone, but affording also food for deep and enlarged reflection. The mind, while expatiating over the mass of feelings and projects, of hopes and fears, which are passing within the limits of the wide map below, feels the nothingness of the atom which it animates, and the comparative insignificance of its own joys and griefs in the scale of creation, and retires at last into itself, sobered[24] into that calm state which is so favourable to the formation of any momentous decision, or the prosecution of a train of deep thought. A moment's glance changes the scene from culture and population to the silence and solitude of a dead icy desert; from the redundancy of animal and vegetable life to its "solemn syncope and pause." The ideas of obscurity, danger, and infinity, all powerful and acknowledged sources of the sublime, are excited at the view of a range of frozen summits, cold, fixed, and everlasting as the imaginary nature of those destinies, with whom a noble bard has peopled them; alternately glittering in sunshine, and enveloped in clouds, and from the well-known effects of haze and distance, appearing suspended in the air in their full dimensions and relative proportions. The imagination dwells upon the appalling hazards peculiar to their few accessible parts, and on the almost total extinction of life and animal powers, which is the penalty of a few hours sojourn there. And here again, too, the mind is forcibly impressed with the utter helplessness of the speck of dust which it inhabits, and that momentary dependence on Providence, which must be so convincingly felt in traversing such regions. Ascending in the scale of comparison, it may reflect, that these gigantic forms, which fill the eye at a distance at which cities and pyramids would fade into imperceptible specks, are but excrescences on the face of that earth, which itself is but an atom in the map of the universe. But I am wandering[25] from my subject, and from the route, which, in this quarter, is somewhat precipitous. I shall, therefore, only remark what has frequently struck me as not an improbable conjecture, that Milton might have formed his splendid conception of the icy region of Pandæmonium from some of these colossal ranges of Alps with which his eye must have been familiar, seen through the vistas of a stormy sky. In the well-known passage which I shall take the liberty of quoting, one seems to recognise the deep drifts of snow, and the blue crevasses which abound in such a spot as the Mer de Glace, as well as the castellated peaks and glaciers which border on it, and the biting atmosphere which prevails among their summits.

"Mon Dieu, ma fille," says Madame de Sevigné in one of her letters to Mad. de Grignan, "que vous avez raison d'etre fatiguée de cette Montagne de Rochepot! je la hais comme la mort; que de cahots, et quelle cruauté qu'au mois de Janvier les chemins de Bourgogne soient impracticables!" Allowing this to have been the case in her days, I can hardly wonder that even Mad. de Sevigné was insensible to the magnificence of the prospect from this elevated point; and thought only of the safety of her neck. No danger however exists at present, as the road descending to Rochepot is good, and judiciously conducted down the brow of the hill; though the nature of the ground gives no very pleasing idea of what it must have been as a cross-country track. The inn also at Rochepot, situated at the junction of four roads, is clean and comfortable. A household loaf, weighing not less than thirty pounds, stood on the table to welcome us on our arrival, and we saw for the first time straw hats bearing a full proportion to it, the rim of which equalled in size a moderate umbrella.[27]

After breakfast we visited the ruined castle of Rochepot,[3] on which we had at first looked down, but which, seen from the village, bears a strong resemblance to Harlech Castle in North Wales, both in its form, and its position upon a commanding rock. We found upon inquiry that it had been tenanted at a much later period than its appearance would have led us to suppose. M. Blancheton, the proprietor, had made it his chief residence some thirty years ago, and kept it up in a style imitating as nearly as possible its ancient feudal grandeur. At the Revolution however it was forfeited, and has since been sold twice; but though each purchaser has pulled down a part, and sold the materials, enough still remains to give a perfect idea of its former strength and massiveness. M. Blancheton now resides, as we were informed, near Beaune, regretted as a bon seigneur by his poorer neighbours, whom he has not visited since the demolition of his paternal seat. "It would break his heart," said a poor old woman, "to see it as it now is." I could not help thinking of Campbell's "Lines on visiting a spot in Argyleshire," which bear the impress of a real occasion of this sort.

From Rochepot to Chalons-sur-Saone, eighteen miles; commencing with a steep hill, to the left of which winds a rocky valley of a singular description,[28] cultivated to the very top of the abrupt heights which surround it, and so bare of soil, that the eye is surprised by the flourishing state of its corn and fruit-trees. The heat reflected from the rocks upon the thin gravel which supports its vineyards, must boil their juices to a liqueur; at least such was its effect on ourselves, while winding along a series of these natural forcing-houses, through which the road is conducted into the great plain of Chalons. From the ridges which border these valleys, the wide extent of the latter, and its border of Alps, are visible, though not so finely as from the elevation which we had descended. "Mont Blanc, the monarch of mountains," was however more plainly discernible than before, like a thin distinct fabric of vapour, with his "diadem of snow faintly lighted up by the sun;" and I never recollect to have seen this white-headed patriarch of the Alps before in any position which gave so fully the effect of his enormous height, I will not even except the spot near Merges, where from a gap in the intervening mountains, he appears almost to rest his base upon the lake of Geneva.

On emerging from the hilly country near Rochepot, the road to Chalons passes along a dead flat, cheerful from its richness, but rather monotonous. To the right, we looked back upon a semicircular range of well wooded hills, in front of which, on an eminence, stands a stately old château belonging to the Count de Rouilly. It answers very much to the[29] beau ideal of what a French château ought to be, but seldom is. I say "ought to be," premising that most of us have formed our first ideas of French châteaux, from those works of imagination which endow such places so liberally with gothic architecture and haunted woods. The mansion of the Count de Rouilly would not greatly disappoint a reader of Mrs. Ratcliffe's romances; and bears a strong resemblance to Westwood, near Ombersley, in Worcestershire, the seat of Sir John Packington, which is said to have been once a conventual building.

With no small pleasure did we arrive at the handsome town of Chalons, our patience being nearly exhausted by the tiresome running base with which our Noah's ark accompanied the driver's abuse of his clumsy grey mares. Grand chameau, sacre vache, and canaille, where the most genteel and decent terms with which he favoured them, and his perverseness was in proportion. For this precious commodity, selected I should conceive from the most consummate ragamuffins on the road, we were indebted to Mons. Picon, a master voiturier at Paris, who imposed on us both as to the number of horses, and the length of time in which we were to be conveyed to Chalons.

"Hic niger est; hunc tu, Romane, caveto."

Having met with a respectable voiturier, named[30] Veroux, who conveyed us admirably from Calais to Paris, my habitual distrust of this class of gentry had relaxed just at the wrong time, for the benefit of M. Picon.

If cities are to be estimated by their appearance of neatness and opulence, Chalons deserves to be marked on the map in more capital letters than the imposing names of Sens or Auxerre. To no town indeed does it bear a greater resemblance than to Tours, both from the modern air of its houses, and from its noble river, adapted for every purpose of internal commerce. The Hôtel des Trois Faisans is also an excellent inn, and, like that at Auxerre, sufficiently well frequented to find no account in these little beggarly impositions which are practised at inferior places.

May 2.—We walked before breakfast to St. Marcel, a village about a mile from Chalons, to visit the church and monastery where Abelard, after his removal from Cluni, died and was buried. Our excursion however only answered in affording us an hour's healthy exercise; for the monastery has been destroyed, and the church stript of what ornaments it possessed, during the time of the Revolution; and the monument of Abelard is removed to Paris. Nor does the town of Chalons itself, handsome and cheerful as it is, present any food for the pencil, the more particularly as its flat situation offers[31] no favourable point of perspective. The spot from which its stately quay, and its stone bridge ornamented with obelisks, are seen to the most advantage, is about a mile down the river;—in fact from the deck of the coche d'eau, in which we embarked at noon for Lyons. This excellent conveyance is a large covered boat, towed at the rate of six miles an hour by four post-horses, or, when necessary, by six; and performs the journey from Chalons to Lyons, a distance of about ninety miles, in twenty-eight or thirty hours, affording ample time for rest and refreshment at a line of inns of a superior description. The reasonable amount of the fare paid by each person at the bureau des diligences, (nine francs fourteen sous) might induce a fastidious or inexperienced traveller to form an indifferent idea both of the company and accommodations of the coche d'eau. Both however appear unexceptionable in their way, as this is the mode of conveyance adopted for the royal mail, and as generally preferred for the sake of comfort and expedition, as the Margate or Glasgow steam-boats. It affords the range of a tolerably spacious deck, and a couple of cabins, to which the passengers may retire in inclement weather. Had it indeed been less convenient or agreeable, we should have found it a blessed respite after the rumbling tub of penance in which we had been cooped. Indeed, the abuse which our voiturier had vented on the desagremens et disgraces of the coche d'eau, in order to secure himself our company to Lyons, had determined us[32] on trying this conveyance; for the habit of lying is so constant and inveterate in this class of fellows, as to possess all the advantages of truth; inasmuch as you have only to believe the direct contrary of what they say. The only inconvenient and perplexing liars are those who sometimes speak truth by accident; and their fictions moreover are seldom extravagant enough to afford the amusement created by romancers of the former class; among whom I may reckon a beggar, who beset us on the quay of Chalons, maintaining in a strong French accent, that he was the son of a carman of Thames-street, in the parish of St. George Hanovre, and had only been a few months in France.

The élite of our company consisted of a tall well-looking officer, wearing the croix d'honneur; a shrewd old Provençal merchant, to whom we were indebted for much valuable travelling information; two young friends, one of whom sang very agreeably and unaffectedly, and the other, a lively French Falstaff ate and talked enough for both; and last, not least, an old gentleman of the name of C. travelling to his campagne in Languedoc, whose arch quiet manners answered very much to my idea of the imaginary Hermite en Province. At Tournus, we took in a host of additional passengers, not so polished, but unobtrusive and well-behaved. I question however, whether, in the event of a rainy day, we should have found this mode of travelling very desirable; as the[33] common cabin is but small in proportion to the number of persons capable of being accommodated on deck. There is indeed a smaller cabin adjoining, which, though the exclusive right of the diligence passengers from Paris, is usually shared by them with the rest. It is distinguished by the words over the door, "Chambre de Pairs," which some wag had altered into "Chambre des Paris," or the Upper House, inscribing the other cabin with his pencil as the Chambre des Deputés.

Many a person fond of indulging in classical reveries, and not aware of the real breadth of the Clitumnus, may have formed a very spacious idea of that celebrated stream, and longed to contemplate its wide reaches from the foot of its well-known temple. As however the Clitumnus is in this identical spot, not broader than what a Yorkshire farmer would call "a bonny beck," and a Yorkshire fox-hunter would ride at without hesitation, the imaginary picture of it may with real propriety be transferred to the Saone near Tournus, winding as it does through the extensive meadows of a rich champaign country, and reflecting in its broad blue mirror the herds of fine white cattle which we saw paddling in every creek. It bears a strong resemblance to many parts of the Po, excepting in the stillness of its current, which was so great, that it would have been easy while leaning over the bow of the vessel, to fancy the Saone into the blue sky, and the coche[34] d'eau, into Southey's vessel of the Suras, or Wordsworth's ærial skiff.

At seven in the evening we came within view of the stately towers of Mâcon, a town, to all appearance, fully equal to Chalons in size and opulence, and much exceeding it as a subject for the pencil. Its fine navigation, the general richness of the country, and the productive vineyards on the neighbouring hills, all unite to render it a central point of business and bustle. There are several inns on the quay, of a good appearance; but we found the Hôtel de l'Europe, to which we had been directed, in every respect deserving of its high reputation, and inferior, perhaps, to no country inn on the continent. After reconnoitring Mont Blanc again from the windows of the clean and airy bed-rooms to which we had been shown, we dined at the table d'hôte, which was served within a quarter of an hour after the arrival of the coche. Among the more polished company present, I was not a little diverted by some scattered specimens of the French gentleman-farmer, present for the express purpose of wallowing for once in a dinner drest by the Duc d'Angouleme's ci-devant cook; fat and well-clad; their countenances wearing a sort of awkward purse-proud defiance to the cool sarcastic look with which the Parisian travellers eyed them; and their conscious shame struggling with the desire to appropriate all the good things before them. Numps, in the well-known[35] old tale, was but a type of these honest personages, who seemed to be considered as "de trop" by the majority. In spite of the mixtures (I do not mean those made in the stomach) which must necessarily take place on these occasions, and allowing for the English prejudice in favour of privacy, there are advantages in dining at all French table d'hôtes, frequented by tolerable company. To the epicure it ensures better fare and attendance than he can command by any other means, as the landlord and his attendants feel both their credit and interest concerned in displaying the most alacrity, and producing the greatest variety of dishes before a large party; while chance customers, after waiting for a long hungry interval, may have to encounter tired waiters, and partake of the tossed-up leavings of this very table d'hôte;

as Colman pleasantly saith. There is a better and more satisfactory reason for this practice, which is, that it affords the best opportunity of ascertaining those points of local knowledge, which at once give an interest to the district through which you are travelling, and instruct you in the best methods of doing and seeing every thing. A Frenchman's manners and acquirements ought never to be judged of by his travelling suit, which is always avowedly the[36] refuse of his wardrobe; and the importance which he is apt to attach to everything connected with his own town or district, if it leads to ridiculous minuteness, at least insures the accuracy of his details. The marked civility and attention of the French to strangers is too well known to be commented on, particularly to those who pay them the compliment of acquiescing in their national customs. I think I never saw the temper of French travellers thoroughly ruffled but on one occasion, when a shabby-looking Englishman and his gawky son, who had arrived in a cabriolet, made a fruitless attempt to exclude a large diligence party from any share in the table and fire of a country inn. Had they been contented to make their bread-and-butter arrangements in concert with the party, which included a member of the chamber of deputies, and a young officer, their company would have been considered as a pleasure.

May 3.—We embarked at five o'clock in the morning, in the face of a very strong gale, which rendered six horses necessary, and tempted us to wish for warmer clothing. The morning, however, was beautifully clear and bright; and Mont Blanc, which is perceptible even from the low level of the river, was without a cloud. To the right, the Beaujolois hills, at the foot of which Mâcon stands, accompanied us as far as Trevoux, presenting an outline not unlike that of our own Malverns; but more varied and rich, as well as occasionally more[37] lofty, and sprinkled with thousands of white farm-houses and villas: many of the parts are similar, and almost equal, to the hills which front Florence on the Fiesole side.

At noon we stopped to breakfast, or rather dine, at Trevoux. Here the Beaujolois hills (or, at least, a range which runs in an uniform line with them) recede, and conduct the eye to a distant vista of higher mountains, toward the south; while, to the left, the river takes a sudden turn among the steep but cultivated sides of the Limonais. This curve brought us all at once upon such a green sunny nook, as might have served for the hermitage of Alexander Selkirk, in the island of Juan Fernandez; in the centre of which stands Trevoux, crowned by the ruins of an old castle, and overlooking the beautifully fertile valley which skirts the foot of the Limonais hills. From its situation, and the form and disposition of its houses, piled tier above tier to the top of a woody bank, Trevoux affords a perfect idea of a little Tuscan town. The Hôtel du Sauvage, and the Hôtel de l'Europe, are equally well frequented; and, like Oxford pastry-cooks, take care to employ the fair sex as sign-posts to their good cheer. Each inn has its couple of waiting-maids stationed at the waterside, in the costume of shepherdesses at Sadler's Wells, full of petits soins and agrémens, and loud in the praises of their respective hotels. By these pertinacious damsels every passenger is sure to be[38] dragged to and fro in a state of laughing perplexity, like Garrick, contended for by the tragic and comic muse, in Sir Joshua's well-known picture; nor do their persecutions cease, till all are safely housed. We went to the Hôtel de l'Europe, whose table may be supposed not deficient in goodness and variety, from the specimen of one man's dinner eaten there. I shall enumerate its particulars, without attempting to decide on the question so often canvassed, whether our neighbours do not exceed us in versatility and capacity of stomach. Our young Falstaff then (for it was he of whom I speak), ate of soup, bouilli, fricandeau, pigeon, bœuf piquée, salad, mutton cutlets, spinach stewed richly, cold asparagus, with oil and vinegar, a roti, cold pike and cresses, sweetmeat tart, larded sweetbreads, haricots blancs au jus, a pasty of eggs and rich gravy, cheese, baked pears, two custards, two apples, biscuits and sweet cakes. Such was the order and quality of his repast, which I registered during the first leisure moment, and which is faithfully reported; and, be it recollected, that he did not confine himself to a mere taste of any one dish. Perhaps I may be borne out by the experience of those who have had the patience to sit out an old Parisian gourmand, by the help of coffee and newspapers, and observed him employed corporeally and mentally for nearly two hours, digesting and discriminating, with the carte in one hand, and his fork in the other. The solemn concentration of mind displayed by many of these personages is[39] worthy of the pencil of Bunbury; and though French caricaturists have done no more than justice to our guttling Bob Fudges, I question whether they would not find subjects of greater science and physical powers among their own countrymen. On our return to the coche d'eau, our fat companion lighted his cigar, and hastened to lie down in the cabin, observing, "Il faut que je me repose un peu, pour faire ma digestion;" and Monsieur C., instead of leaving him quietly in his state of torpidity, like a boa refreshed with raw buffalo, began to argue with us on the superior nicety of the French in eating. "Nous aimons les mets plus delicats que vous autres," quoth he; at which we laughed, and pointed to the cabin. We found, upon explanation, however, that Mr. C., though well-informed in general upon the subject of English customs, entertained an idea not uncommon in France, viz. that we always despatch the whole of those hospitable haunches and sirloins, which appear at an English table, at one and the same sitting: with this notion, his observation was certainly natural enough.

From Trevoux, the Saone winds between narrow, steep, and picturesque banks as far as Lyons, near which place they close in upon its channel, exhibiting more varieties of rock and wood than before. For the good taste displayed by the rich Lyonnais in their villas and gardens, which began to peep upon us at every step, I cannot in truth say much; but[40] our French companions, who had overlooked the merely natural beauties of the country, found much to commend in these little vagaries of art. A lively bourgeoise, on whom we stumbled the next day behind the counter of a glove-shop, ran up, openmouthed, to explain to us the beauties of one of their show spots, in view of which a sudden turn of the river was just bringing us. A conspicuous inscription on a large vulgar-looking house painted red and yellow, informed us that it was styled the "Hermitage du Mont d'Or." In the space of not quite an acre of ground, on the side of a wooded hill of the highest natural loveliness, the proprietor had contrived to commit a host of the most outrageous and fantastical absurdities, which were hailed with a smile from Mons. C., and a burst of approbation from the rest of the party. At the top of the hill were four scattered pillars of different diminutive forms, with gilt balustrades; all painted with gaudy colours, and none large enough for a moderate tea-garden, or sufficiently solid to have resisted the point-blank stagger of a drunken man. Lower down were two holes in the rock, which, from their size and appearance, I should have taken for a rabbit-burrow and a badger's earth, but for the young lady's joyous exclamation—"Ah! voilà les hermitages. Messieurs, il y a deux hermites là-dedans." "À la bonne heure, Mademoiselle; ils sont vivans, sans doute"—. "Mais pour cela—pas absolument—c'est que—ils sont de cire, voyez vous, mais d'une beauté! ah, c'est une[41] chose à voir!" Then came an inclosure so thickly studded with pillars of different sizes, as to resemble a Mahometan burying ground. "Vous y trouverez des inscriptions de toute espèce, et là vous voyez la colonne de Trajan." This was a wooden obelisk about ten feet high, painted white, at the base of which ROME was written in large black letters, occupying the whole of one side. Immediately above the house stood a small wooden building, with a red and white dome, and pillars and windows painted on the sides. The name COSMORAMA, which took up half the height of the side fronting us, still left us in doubt as to its use or intention; and our fair cicerone could no more explain the nature of her favourite building, than Bardolph could the meaning of the word "accommodate." "Eh, Monsieur, c'est ce qu'on appelle Cosmorama; je ne saurois vous dire precisement; peut-être il y a des bêtes sauvages;—ou—quelque chose de gentil, voyez vous—mais enfin c'est un Cosmorama." "Mais voilà ce qui est vraiment joli," resounded on all sides; and so general and good-humoured was their admiration of this rickety bauble, that we did our best to acquiesce in it. After all, we could admire, without any breach of sincerity, the natural beauties of this spot, which very much resembles the more open parts of the glen where Matlock is situated, and which all these abominations could not entirely deface. How to account for this perversion of eye in a people of sensibility and taste, I am rather at a loss; but this last[42] is by no means a singular instance. "Bientôt vous allez sortir de ces tristes bois," compassionately observed a very gentleman-like officer, with whom we had fallen in during a stage of beautiful forest scenery; and not a soul in a voiture which breakfasted in the salle à manger at Rochepot, could understand why we stopped to admire the distant prospect of the Alps. Not to multiply instances of the indifference to the beauties of simple nature, which will, I think, be allowed to exist in the French, as contrasted with ourselves, I am inclined to extend the line of distinction still farther, and to affirm, that this deficiency in taste appears generally to distinguish the Teutonic from the Southern blood. It is no exaggeration to say, that for one French or Italian traveller in Switzerland, twenty English, or ten Germans, may be reckoned. The French taste in landscape gardening is well known, and that of the Italians[4] is but a shade or two better: witness the detestable baby-house with which they have defaced one of the finest scenes in the world, and which they distinguish, par excellence, as the Isola Bella; to say nothing of a host of similar instances, as[43] contrasted with our own Longleat and Rydal Park.

The fairest account of the matter, perhaps, is, that this inferiority in one branch of taste may result from a difference of temperament in our lively southern neighbours, which, in other respects, has its advantages. Restless, acute, and loquacious, they delight more naturally in those objects which remind them of the "busy hum of men:" and, whatever the force of circumstances may have effected in particular cases, it may be safely asserted, that the diplomatist and man of the world is the indigenous growth of France and Italy, while the powers of abstraction and meditation exist more naturally in English and German minds, inducing the love of solitary nature.

The styles of Claude, who was a German by birth, and of our own Wilson, are strongly contrasted with that of Vernet, as illustrative of the present subject. In the admirable paintings of the latter, bustle and motion are generally the characteristics of the scene represented, and the features of nature seem intended to be subordinate to some human action which is going on. In the pictures of Claude, the combinations of scenery are every thing, and the figures nothing, or rather, merely introduced to illustrate and harmonize with the effect which the landscape itself is to produce: and nothing is allowed[44] to disturb the repose and serenity of the whole. Of Wilson, who delighted more in storms and convulsions of nature, it may be said, that his figures, also are merely subordinate to the effect of a dashing sea, a thunder-cloud, or a forest waving and crashing with the wind; and that they are not strongly enough marked to interrupt the eye in the contemplation of these objects. Gaspar Poussin, I must own, is an instance that a French painter can understand and represent the deep repose of nature; but the style of Poussin is certainly not that of the French school in general, nor that of Salvator to be considered as establishing a rule by which to judge of Italian taste.

Mais revenons à nos moutons. We were surprised to observe how much our fellow-passengers interested themselves about the characters of the royal family of England. Several of its members underwent a free review, though not an ill-natured one; but all who spoke of our late queen Charlotte, did her more justice than has, perhaps, been done in England, and particularly praised the purity of her court, and the excellent domestic example which her private life afforded to Englishwomen in general. On this point we cordially agreed with them; but our sly acquaintance, Mons. C., was not disinclined to lead us to ground more debateable, and lay a trap for our national vanity. The master of the vessel[45] had a wooden leg, which led to the subject of artificial limbs, and the perfection to which the art of making them had arrived in England. We accidentally mentioned the case of Lord Anglesey. "Et qui est ce Lord Anglesey?" said M.C., looking archly. "Un de nos plus grands seigneurs, Monsieur." Still he persisted in inquiring how he lost his leg. "C'était in Flandres." "Ah, vous voulez dire à Vaterloo, n'est ce pas?" said the old gentleman, with a smile, not displeased to observe the motive of our hesitation. He would not allow us to use the word emprunter, as applied to the conduct of his countrymen, with regard to the Louvre collection, "Non, voler, voilà le mot." The little bourgeoise, who had lionized the Hermitage du Mont d'Or so eloquently, grew very communicative on the strength of the display which she had made, and M.C.'s good humour; and volunteered her sentiments on the folly of reflecting too deeply, observing, that all but the old ought to banish the idea of death and such dismal bugbears from their minds. "Mais, songez, Mademoiselle," quoth he, interrupted in some observation rather better worth hearing, "que tout le monde ne possède pas votre force de caractère;" a compliment to which the young lady assented with a grateful curtsy.

By the time F. had finished his sleep and digestion, as he had proposed to do, and learned[46] "Pescator dell' Onda," by repeated trials and lessons, we arrived at the Pierre Incise, at the corner of which the Saone enters Lyons. Tradition says that this spot, which reminded me of St. Vincent's rocks, near Clifton, derives its Latinized name from the great work performed by Agrippa in cutting through the solid rock, and enlarging the channel of the river. The site of the castle of Pierre Incise, formerly a prison, and destroyed at the Revolution, is still visible on a strong height overhanging the river to the right; the bottom of which appears to have been cut away artificially.

On another height, to the left, stands an old fort; on passing which, an abrupt turn of the Saone brought us into the centre of dirt, bustle, and business. Its course becomes in a moment confined between masses of tall, smoky, old houses, and its azure colour stained by party-coloured streams from dyers' shops, and a thousand other abominations, which would defy the pen of a Smollett to describe, and all the breezes from the Alps to purify. There are several bridges in this quarter, mostly appearing from their paltry and irregular character, to have been erected on some sudden emergency; from these, however, the noble Pont de Tilsit, near the cathedral, claims an exception. Long before we approached this last bridge, however, the boat reached the diligence office, and our porter dived[47] with us to the left, through a succession of courts and streets as high and gloomy as the cavern of Posilipo. We emerged into the Place de Terreaux, and took up our quarters opposite to the Hôtel de Ville, a formal, but fine old building.[48]

Every traveller on his first arrival at a large place of any interest, and where his time is limited, must have experienced a difficulty in classing and forming, as it were, into a mental map, the various objects around him, and in familiarizing his eye with the relative position of the most striking features. To meet this difficulty, I should advise any one visiting Lyons, to direct his first walk to the eastern bank of the Rhone, and after crossing a long stone bridge called the Pont la Guillotiere, to follow the course of the river for about a mile along the meadows, towards its junction with the Saone. From this point of view, Lyons really presents a princely appearance.[5] The line of quays facing the Rhone, and which constitute the handsomest and most imposing part of the city, extend along the opposite bank in a lengthened perspective, in which the Hôtel Dieu and its dome form a central and conspicuous feature. In the back ground, the heights which[49] divide the Rhone and Saone from each other rise very beautifully, covered with gardens and country seats. More to the left, and on the other side of the Saone, the hill of Fourvières (anciently Forum Veneris) presents a bold landmark, and forms a very characteristic back-ground to the city. Instead of continuing his walk towards the junction of the Rhone and the Saone, which possesses nothing worthy of notice, I should recommend the traveller to re-cross the Pont la Guillotiere, and make for this eminence. In his way he may pass through the Place Louis le Grand, formerly the Place de Bellecour, of the architecture of which the Lyonnais are very proud, and which is a marked spot in the revolutionary history of Lyons. Though on a costly and extensive plan, its proportions want breadth, and are too much frittered away to convey the idea of grandeur or solidity; and the inscription Vive le Roi, which occupies a place on two of its sides, in enormous letters, assists in giving it the air of a temporary range of building for a loyal fête. Not so the beautiful[6] Pont de Tilsit, by which you cross the Saone soon afterwards. This bridge, built by Buonaparte, to commemorate the treaty of Tilsit, unites elegance, solidity, and chasteness of design in a very great degree. Some of the stones, which I measured, are eighteen feet in length, and proportionably large, and altogether it reminded me of[50] Waterloo bridge upon a smaller scale, and divested of its columns. The cathedral, which stands on the other side of the Saone, nearly at the foot of this bridge, is a venerable black old building of great antiquity, and though far inferior to those of Beauvais, Tours, Abbeville, or Rouen, in its general outline, possesses many detached parts of rich and curious architecture. It bears no marks of the devastation which it suffered in the Revolution, or during the late war, when, as we were told, the Austrians stabled their horses in it. Much of its repair has been owing to Cardinal Fesch, the late archbishop. The windows, rich as they are, have a gloomy effect, from being entirely composed of painted glass; and prevented us from distinguishing much very clearly. A statue of John the Baptist, however, crowned with artificial roses, should not be forgotten. A considerable part of the old town of Lyons lies on this side of the Saone; but as it will not repay the trouble of exploring, the traveller will do well to proceed immediately, or rather climb, to the church of Notre Dame de Fourvières. The fame of peculiar sanctity which this church enjoys, attracts many daily visitors from Lyons, though from its situation, it reminds one of the chapel in Shropshire, which as country legends tell, "the devil removed to the top of a steep hill to spite the church-goers." The continual resort of all ranks hither has attracted also a host of beggars, who have taken their stations in the only footway leading up[51] to the church, some singly, some in parties, every four or five yards, and all besetting you in full chorus. The same cause has drawn to the terrace in front of the church a seller of Catholic legends, who to suit all tastes, mingles the spiritual, the secular, and the loyal, in his profession. The legend of St. Genevieve, Le Testament de Louis XVI., L'Enfant Prodigue, Damon and Henriette, Judith and Holofernes, and Le Portrait du Juif ambulant, might all be bought at his stall, adorned with blue and red wood-cuts. Poor Damon cut but a sorry figure in this goodly company; for though adorned with a crook secundum artem, he looked more rawboned and ugly than Holofernes, and more villainous than the wandering Jew: fully justifying the scorn with which the stiff-skirted Henriette seemed to treat him. It is almost misplaced however to enumerate such follies in a place, which on a fine day presents perhaps one of the most varied and magnificent views in the world: and which a person who had only an hour to spare in Lyons, ought to visit, to the exclusion of every other object of curiosity. By changing one's position from the terrace of the church to some rude and imperfect remains of Roman masonry on the western side of it, a complete panorama of the surrounding country is obtained. The Rhone and Saone are both seen inclining towards each other from the north and north-east, like the two branches of the letter Y; the former issuing like a narrow white thread from the distant gorges of the Alps,[52] and widening into broad reaches through the intermediate plain; and the latter issuing suddenly from among the hills of the Mont d'Or: till after inclosing the peninsula in which the principal part of Lyons is situated, and which lies like a map under your feet, they unite towards the south; and the broad and rapid body of water formed by their junction, loses itself at length among ranges of hills surmounted by Mont Pilate, a lofty mountain near Valence. Towards the east, north-east, and south-east, the view is of the same description as that from Rochepot; a wild chain of Alps seen over a plain of great extent and richness. In a western direction, the broad hilly features of the adjoining country are enlivened by a continual succession of vineyards, woods, gardens, and villas of all sizes, absolutely perplexing to the eye from its undulating richness: with which the sober gray of distant ranges of mountains contrasts well. One cannot form a better idea of this part of the view, than by fancying the most hilly parts of the country near Bath, clothed in a lively French dress; the only deformity of which consists in the high stone walls that enclose every tenement, and whose long white lines cut the eye unpleasantly. Most persons can point out the Château Duchere, which is visible from this spot at the distance of about a mile on the north-west side, and was the scene of a sharp action between the French and Austrians in 1814.

If an hour or two of leisure remain after this walk, they may be filled up by a visit to the public library and the Palais des Arts. The former contains, they say, ninety thousand volumes, rather an embarrass de richesses to a hurrying traveller. I confess I was more amused by the importance with which the little old woman, who acted as concierge, talked of the "esprit mal tournu de Voltaire." The latter building adjoins the Hôtel de Ville, in the Place des Terreaux, the scene of one of the revolutionary fusillades. It contains, besides, several good pictures hung in bad lights, a large collection of Roman altars and sepulchral monuments, arranged in a cloister below, which serves as the exchange; and a cabinet of Roman antiquities found in the environs. The Hôtel de Ville itself is a massy stone building, a good deal in the taste of the Tuileries, and containing two fine statues of the rivers Rhone and Saone, which deserve notice. Whether the interior of Lyons can boast of any thing else worth notice I know not, but from the specimen which we had, too minute a survey of it can hardly be edifying to any one but a scavenger; and no single building can be named of any particular beauty, though its masses of tall well-built houses are imposing at a distance. To complete the short general survey of Lyons, which I mentioned, another not very long walk will suffice; traversing first the fine line of quays which front the Rhone, from the Pont la Guillotiere to the Quai St. Clair. From this point ascend the highest part of[54] the city, called the Croix Rousse, and inquire for a place called Château Montsuy, which stands bordering upon its outskirts, and is best described as the most elevated spot on this line of heights.[7] From hence the view of Mont Blanc and the vale of the Rhone is peculiarly fine on a bright evening; and the whole prospect as rich and extensive as that from Fourvières. Beware of being persuaded by the laquais de place to visit La Tour de la belle Allemande, which is one of their show spots, and so called from some old legend of the imprisonment of a German lady. The view from Château Montsuy must, from the nature of the ground, be just the same, or, perhaps, even superior: and, what is more to the purpose, the Baroness de Vouty, in whose garden this old tower stands, seldom admits either Lyonnese or strangers to see it. On descending from the Croix Rousse, cross the Rhone by the Pont Morand, the wooden bridge next to that of La Guillotiere. Near the foot of this bridge is situated a large open space of ground, called Les Brotteaux, where the most atrocious of the revolutionary massacres took place. The site of the fusillade, by which two hundred and seven royalists perished at one time, is marked by a large chapel, dedicated to the memory of the victims, in the erection of which they are now proceeding. Three only are said to have escaped from this massacre, and to be still[55] living. One of them finding his cords cut asunder by the first shot that reached him, escaped in the confusion, and plunging amid the thick bushes and dwarf willows which bordered upon the Rhone, baffled the pursuit of several soldiers. There is nothing remarkable in the appearance of the Brotteaux at present; but no true lover of his country ought to neglect visiting a spot associated with such warning recollections. One of the stanzas inscribed by Delandine on the cenotaph of his countrymen (which has been removed to make room for the chapel above mentioned), expresses briefly, and much in the spirit of Simonides's well known epitaph on the Spartans, the impressions conveyed by the sight of this Aceldama:

This passage is, indeed, prophetic of the salutary effects of a lesson, which these and a thousand more voices from the tomb will proclaim to future ages; if, indeed, future ages will believe, that a[8] dastardly stroller was allowed to glut his full vengeance on the kindred of those who had hissed him from their stage, and to vow in a fit of wanton frenzy, that an[56] obelisk only should mark the site of the second city in France; that he found himself seconded in this plan of destruction by thousands of hands and voices; that one citizen was executed for supplying the wounded with provisions, another for extinguishing a fire in his own house; and that when these pretexts failed, such ridiculous names as "quadruple" and "quintuple counter-revolutionist" were invented as terms of accusation. Such facts as these, written in the blood of thousands, furnish a strong practical comment on the consequences of anarchy, and the uncompromising firmness which should be displayed in checking its first inroads; the nature of which was never more eloquently or instructively described than in Lord Grenville's words.

"What first occurred? the whole nation was inundated with inflammatory and poisonous publications. Its very soil was deluged with sedition and blasphemy. No effort was omitted of base and disgusting mockery, of sordid and unblushing calumny, which could vilify and degrade whatever the people had been most accustomed to love and venerate. * * * * * * * And when, at last, by the unremitted effect of all this seduction, considerable portions of the multitude had been deeply tainted, their minds prepared for acts of desperation, and familiarized with the thought of crimes, at the bare mention of which they would before have revolted, then it was that they were encouraged to collect[57] together in large and tumultuous bodies; then it was that they were invited to feel their own strength, to estimate and display their numerical force, and to manifest in the face of day their inveterate hostility to all the institutions of their country, and their open defiance of all its authorities."

A vivid description this, and strikingly applicable to the operations of that evil spirit which is still at work, with less excuse and provocation than France could plead for her atrocities. Such are the first and second acts of the drama of modern sedition; the fifth is well delineated in a tract by M. Delandine, the public librarian of Lyons in 1793, as introduced in Miss Plumtre's Tour in France. This interesting narrative, intitled "An Account of the State of the Prisons at Lyons during the Reign of Terror," bears a character of truth and feeling, which bespeaks him an eye-witness of the horrors he describes. Torn from his family without any assignable cause, and imprisoned in the hourly expectation of death, his own apprehensions seem at no time to have absorbed his interest in the fate of his suffering friends; and to their merit and misfortunes he does justice in the verses before alluded to. The following is a free translation of them.