Harry Collingwood

"The Cruise of the Thetis"

Chapter One.

A friend—and a mysterious stranger.

“Hillo, Singleton, old chap, how are you?” exclaimed a young fellow of about eighteen years of age, as he laid his hand upon the shoulder of a lad about his own age, who, on a certain fine July day in the year of grace 1894, was standing gazing into the window of a shop in Piccadilly.

The speaker was a somewhat slightly-built youth, rather tall and slim, by no means ill-looking, of sallow complexion and a cast of features that betrayed his foreign origin, although his English was faultless. The young man whom he had addressed was, on the other hand, a typical Englishman, tall, broad, with “athlete” written large all over him; fair of skin, with a thick crop of close-cut, ruddy-golden locks that curled crisply on his well-shaped head, and a pair of clear, grey-blue eyes that had a trick of seeming to look right into the very soul of anyone with whom their owner happened to engage in conversation. Just now, however, there was a somewhat languid look in those same eyes that, coupled with an extreme pallor of complexion and gauntness of frame, seemed to tell a tale of ill health. The singularly handsome face, however, lighted up with an expression of delighted surprise as its owner turned sharply round and answered heartily:

“Why, Carlos, my dear old chap, this is indeed an unexpected pleasure! We were talking about you only last night—Letchmere, Woolaston, Poltimore, and I, all old Alleynians who had foregathered to dine at the Holborn. Where in the world have you sprung from?”

“Plymouth last, where I arrived yesterday, en route to London from Cuba,” was the answer. “And you are the second old Alleynian whom I have already met. Lancaster—you remember him, of course—came up in the same compartment with me all the way. He is an engineer now in the dockyard at Devonport, and was on his way to join his people, who are off to Switzerland, I think he said.”

“Yes, of course I remember him,” was the answer, “but I have not seen him since we all left Dulwich together. And what are you doing over here, now—if it is not an indiscreet question to ask; and how long do you propose to stay?”

The sallow-complexioned, foreign-looking youth glanced keenly about him before replying, looked at his watch, and then remarked:

“Close upon half-past one—lunch-time; and this London air of yours has given me a most voracious appetite. Suppose we go in somewhere and get some lunch, to start with; afterwards we can take a stroll in the Park, and have a yarn together—that is to say, if you are not otherwise engaged.”

“Right you are, my boy; that will suit me admirably, for I have no other engagement, and, truth to tell, was feeling somewhat at a loss as to how to dispose of myself for the next hour or two. Here you are, let us go into Prince’s,” answered Singleton. The two young men entered the restaurant, found a table, called a waiter, and ordered lunch; and while they are taking the meal the opportunity may be seized to make the reader somewhat better acquainted with them.

There is not much that need be said by way of introduction to either of them. Carlos Montijo was the only son of Don Hermoso Montijo, a native of Cuba, and the most extensive and wealthy tobacco planter in the Vuelta de Abajo district of that island. He was also intensely patriotic, and was very strongly suspected by the Spanish rulers of Cuba of regarding with something more than mere passive sympathy the efforts that had been made by the Cubans from time to time, ever since ’68, to throw off the Spanish yoke. He was a great admirer of England, English institutions, and the English form of government, which, despite all its imperfections, he considered to be the most admirable form of government in existence. It was this predilection for things English that had induced him to send his son Carlos over to England, some nine years prior to the date of the opening of this story, to be educated at Dulwich, first of all in the preparatory school and afterwards in the College. And it was during the latter period that Carlos Montijo became the especial chum of Jack Singleton, a lad of the same age as himself, and the only son of Edward Singleton, the senior partner in the eminent Tyneside firm of Singleton, Murdock, and Company, shipbuilders and engineers. The two lads had left Dulwich at the same time, Carlos to return to Cuba to master the mysteries of tobacco-growing, and Singleton to learn all that was to be learnt of shipbuilding and engineering in his father’s establishment. A year ago, however, Singleton senior had died, leaving his only son without a near relation in the world—Jack’s mother having died during his infancy: and since then Jack, as the dominant partner in the firm, had been allowed to do pretty much as he pleased. Not that he took an unwise advantage of this freedom—very far from it: he clearly realised that, his father being dead, there was now a more stringent necessity than ever for him to become master of every detail of the business; and, far from taking things easy, he had been working so hard that of late his health had shown signs of giving way, and at the moment when we make his acquaintance he was in London for the purpose of consulting a specialist.

During the progress of luncheon there had been, as was to be expected, a brisk crossfire of question and answer between the two young men, in the course of which Montijo had learned, among other things, that his friend Jack had been ordered by the specialist to leave business very severely alone for some time to come, and, if possible, to treat himself to at least six months’ complete change of air, scene, and occupation.

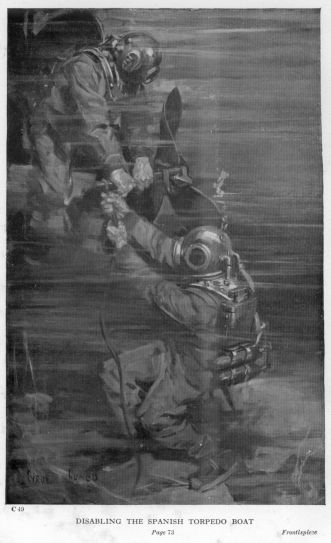

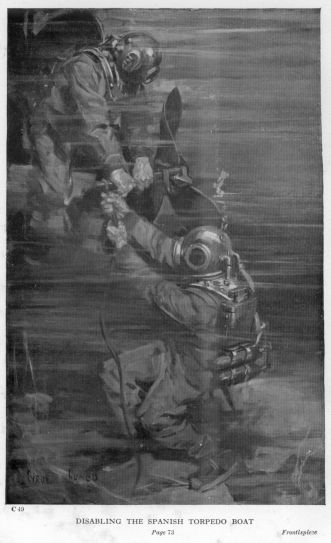

“It fortunately so happens,” said Jack, “that my position in the firm will enable me to do this very well, since Murdock, the other partner, is, and has been since my father’s death, the actual manager of the business; and as he has been with us for nearly thirty years he knows all that there is to know about it, and needs no assistance from me. Also, I have at last completed the submarine which has been my pet project for almost as long as I can remember, and now all that I need is the opportunity to try her: indeed, but for Oxley’s strict injunctions to me to cut business altogether, I should certainly spend my holiday in putting the boat to a complete series of very much more thorough and exhaustive tests than have thus far been possible. As it is, I really am at an almost complete loss how to spend my six months’ holiday.”

“Do you mean to say that you have no plans whatever?” demanded Montijo, as he and his friend rose from the table to leave the restaurant.

“None but those of the most vague and hazy description possible,” answered Singleton. “Oxley’s orders are ‘change of scene, no work, and a life in the open air’; I am therefore endeavouring to weigh the respective merits of a cruise in my old tub the Lalage, and big-game shooting somewhere in Central Africa. But neither of them seems to appeal to me very strongly; the cutter is old and slow, while as for the shooting project, I really don’t seem to have the necessary energy for such an undertaking, in the present state of my health.”

“Look here, Jack,” observed Montijo eagerly, as he slid his hand within his friend’s arm and the pair wheeled westward toward Hyde Park, “I believe I have the very scheme to suit you, and I will expound it to you presently, when we get into the Park and can talk freely without the risk of being overheard. Meanwhile, what was it that you were saying just now about a submarine? I remember, of course, that you were always thinking and talking about submarines while we were at Dulwich, and also that you once made a model which you tested in the pond, and which dived so effectually that, unless you subsequently recovered her, she must be at the bottom of the pond still.”

“Ay,” answered Jack with a laugh; “I remember that ill-fated model. No, I never recovered her, but she nevertheless served her purpose; for her mishap gave me my first really useful idea in connection with the design of a submarine boat. And at last I have completed a working model which thus far has answered exceedingly well. She is only a small affair, you know, five feet in diameter by twenty-five feet long, but she is big enough to accommodate two men—or even three, at a pinch. I have been as deep as ten fathoms in her, and have no doubt she could descend to twice that depth; while she has an underwater speed of twenty knots, which she can maintain for five hours.”

“By Jove, that’s splendid—very much better than anything that anyone else has done, thus far!” exclaimed Montijo admiringly. “You ought to make your fortune with a boat of that sort. And you are pining for an opportunity to subject her to a thoroughly practical test? Well, my scheme, which I will explain in full when we get into the Park, will enable you to do that.”

“Is that so?” commented Jack. “Then that alone would very strongly predispose me in favour of it. But why make such a secret of it, old chap? Is it of such a character that a passer-by, catching a few words of it, would be likely to hand us over to the nearest policeman as a couple of conspirators?”

“Well, no; it is scarcely so bad as that,” answered Montijo, laughing: “but it is of such a nature that I would prefer not to speak of it, if you don’t mind, until we are somewhere in the Park where we can converse freely without the fear of being overheard. You see, the Pater and I are pretty well-known to—and not too well liked by—the Spanish authorities in Cuba, and it is by no means certain that they may not think it quite worth their while to have us watched over here; therefore—”

“Yes, of course, I understand,” returned Jack; “therefore for the present ‘mum’s the word’, eh?”

Montijo nodded, and the two lads strode along, conversing upon various topics, until they reached Hyde Park Corner, and swung in through the Park gates, and so on to the grass.

“Ah, now at last I can speak freely!” remarked Montijo with a sigh of relief. “First of all, Singleton,” he continued, “you must understand that what I am about to say will be spoken in the strictest confidence; and, whether you should agree to my proposal or not, I must ask you to pledge your honour as a gentleman that you will not repeat a single word of what I say to anyone—anyone, mind you—without first obtaining my consent, or that of my Pater.”

“All right, Carlos, my boy,” answered Singleton, cheerily; “I promise and vow all that you ask. There is nobody on the face of this earth of ours who can keep a secret better than I can, as you ought to know by this time.”

“Yes, I do know it, perfectly well,” agreed Montijo. “Well,” he continued, “the fact is that the Pater and I have at last begun to interest ourselves actively in Cuban politics. We Cubans, as you perhaps know, have been trying, ever since ’68, to induce the Spaniards to govern us mildly and justly, but thus far all our efforts have been fruitless: we are still being ground down and tyrannised over until the lives of many of us have become a burden; neither the property, the liberty, nor the life of any Cuban is safe to-day, unless he is well-known to be a supporter of the Spanish Government. After more than a quarter of a century of patient but ineffectual effort, therefore, it has been determined to take up arms, strike a blow for liberty, and never rest until Cuba is free from the hated Spanish yoke.

“It is in connection with this movement that the Pater and I are now in England. It is now nearly a year since Señor Marti—the man who above all others has been conspicuous in his efforts on behalf of Cuba—got hold of the Pater and succeeded in convincing him that it is the duty of every Cuban to do his utmost to free his country from the grasp of the tyrant; and one of the first-fruits of this was the giving of an order by the Pater—through a friend—for the construction of a fast steam-yacht, to be used as may be required in the service of the country, but primarily for the purpose of smuggling arms, ammunition, and necessaries of all kinds into the island. Now, by a singular coincidence, this friend and agent of the Pater chose your firm as that which should build the yacht; and now we, having been advised that she is ready for delivery—”

“What!” exclaimed Singleton, “you surely don’t mean to say that Number 78 is your boat?”

“Yes,” answered Montijo quietly; “that is the number by which she is at present known, I believe.”

“Then, Carlos, my dear boy, accept my most hearty congratulations!” exclaimed Singleton. “Our naval constructor has let himself go, and fairly outdone himself over that craft. It was a difficult task that you gave him to do when you asked for a boat of not less than three hundred tons on eight feet draught of water, and with a sea speed of twenty-two knots; but he has done it, and the result is that you have, in Number 78, the prettiest little boat that ever swam. Why, man, she has already done twenty-four knots over the measured mile, on her full draught of water, and in a fairly heavy sea; and she is the very sweetest sea boat that it is possible to imagine. Of course we could not have done it had we not boldly adopted the new-fashioned turbine principle for her engines; but they work to perfection, and even when she is running at full speed one can scarcely feel a tremor in her.”

“I am delighted to receive so excellent an account of her,” answered Montijo, “and so will the Pater be when I tell him—or, rather, when you tell him; for, Singleton, I want you to promise that you will dine with us to-night, and make the Pater’s acquaintance. He is the very dearest old chap that you ever met—your own father, of course, excepted—and he will be enchanted to make your acquaintance. He already knows you well enough by name to speak of you as ‘Jack’.”

“I will do so with pleasure,” answered Singleton heartily. “I have no other engagement, and after one has been to a theatre or a concert every night for a week—as I have—one begins to wish for a change. And while I don’t wish to flatter you, Carlos, my boy, if your father is anything like you he is a jolly good sort, and I shall be glad to know him. But we have run somewhat off the track, haven’t we? I understood that you have some sort of proposal to make.”

“Yes,” answered Montijo, “I have. Let me see—what were we talking about? Oh, yes, the yacht! Well, now that she is built, we are in something of a difficulty concerning her—a difficulty that did not suggest itself to any of us until quite recently. That difficulty is the difficulty of ownership. She has been built for the service of Cuba, but somebody must be her acknowledged owner; and if she is admitted to be the property of the Pater, of Marti, or, in fact, of any Cuban, she will at once become an object of suspicion to the Spanish Government, and her movements will be so jealously watched that it will become difficult, almost to the verge of impossibility, for her to render any of those services for which she is specially intended. You see that, Jack, don’t you?”

“Certainly,” answered Singleton, “that is obvious to the meanest intellect, as somebody once remarked. But how do you propose to get over the difficulty?”

“There is only one way that the Pater and I can see out of it,” answered Montijo, “and that is to get somebody who is not likely to incur Spanish suspicion to accept the nominal ownership of the yacht, under the pretence of using her simply for his own pleasure.”

“Phew!” whistled Singleton. “That may be all right for the other fellow, but how will it be for you? For that scheme to work satisfactorily you must not only find a man who will throw himself heart and soul into your cause, but also one whose honesty is proof against the temptation to appropriate to himself a yacht which will cost not far short of forty thousand pounds. For you must remember that unless the yacht’s papers are absolutely in order, and her apparent ownership unimpeachable, it will be no good at all; she must be, so far at least as all documentary evidence goes, the indisputable property of the supposititious man of whom we have been speaking: and, that being the case, there will be nothing but his own inherent honesty to prevent him from taking absolute possession of her and doing exactly as he pleases with her, even to selling her, should he be so minded. Now, where are you going to find a man whom you can trust to that extent?”

“I don’t know, I’m sure,” answered Montijo; “at least, I didn’t until I met you, Jack. But if you are willing to be the man—”

“Oh, nonsense, my dear fellow,” interrupted Jack, “that won’t do at all, you know!”

“Why not?” asked Montijo. “Is it because you don’t care to interfere in Cuban affairs? I thought that perhaps, as you are obliged to take a longish holiday, with change of scene and interests, an outdoor life, and so on, you would rather enjoy the excitement—”

“Enjoy it?” echoed Singleton. “My dear fellow, ‘enjoy’ is not the word, I should simply revel in it; all the more because my sympathies are wholly with the Cubans, while I—or rather my firm, have an old grudge against the Spaniards, who once played us a very dirty trick, of which, however, I need say nothing just now. No, it is not that; it is—”

“Well, what is it?” demanded Montijo, seeing that Jack paused hesitatingly.

“So near as I can put it,” answered Jack, “it is this. Your father doesn’t know me from Adam; and you only know as much as you learned of me during the time that we were together at Dulwich. How then can you possibly tell that I should behave on the square with you? How can you tell that, after having been put into legal possession of the yacht, I should not order you and your father ashore and forbid you both to ever set foot upon her decks again?”

Montijo laughed joyously. “Never mind how I know it, Jack,” he answered. “I do know it, and that is enough. And if that is not a sufficiently convincing argument for you, here is another. You will admit that, in order to avoid the difficulty which I have pointed out, we must trust somebody, mustn’t we? Very well. Now I say that there is no man in all the world whom I would so implicitly trust as yourself; therefore I ask you, as a very great favour, to come into this affair with us. It will just nicely fill up your six months’ holiday—for the whole affair will be over in six months, or less—and give you such a jolly, exciting time as you may never again meet with during the rest of your life. Now, what do you say to that?”

“I say that your Pater must be consulted before the matter is allowed to go any further,” answered Jack. “You can mention it to him between now and to-night, if you like, and if the idea is agreeable to him we can discuss it after dinner. And that reminds me that you have not yet mentioned the place or the hour of meeting.”

“We are staying at the Cecil, and we dine at seven sharp,” answered Montijo. “But don’t go yet, old chap, unless I am boring you. Am I?”

“Do you remember my once punching your head at Dulwich for some trifling misdemeanour?” asked Jack laughingly, as he linked his arm in that of Montijo. “Very well, then. If you talk like that you will compel me to do it again. Do you know, Carlos, this scheme of yours is rapidly exercising a subtle and singularly powerful fascination over me? and even if your father should hesitate to entrust his boat to me, I feel very like asking him to let me take a hand in the game, just for the fun of the thing. And what a splendid opportunity it would afford for testing the powers of my submarine! Oh, by Jove, I think I must go, one way or another!”

The two young men wandered about the Park for nearly an hour longer, discussing the matter eagerly, and even going so far as to make certain tentative plans; and then they separated and went their respective ways, with the understanding that they were to meet again at the Cecil.

Jack was putting up at Morley’s Hotel, in Trafalgar Square, and his nearest way back to it was, of course, down Piccadilly; but as he passed out through the Park gate he suddenly bethought himself of certain purchases that he wished to make at the Army and Navy Stores, and he accordingly crossed the road and entered the Green Park, with the intention of passing through it and Saint James’s Park, and so into Victoria Street by way of Queen Anne’s Gate and the side streets leading therefrom. He had got about halfway across Green Park when he became aware of quick footsteps approaching him from behind, and the next moment he was overtaken and accosted by a rather handsome man, irreproachably attired in frock-coat, glossy top-hat, and other garments to match. The stranger was evidently a foreigner—perhaps a Spaniard, Jack thought, although he spoke English with scarcely a trace of accent. Raising his hat, he said:

“Pardon me, sir, but may I venture to enquire whether the gentleman from whom you parted a few minutes ago happens to be named Montijo?”

“Certainly,” answered Jack; “there can be no possible objection to your making such an enquiry, somewhat peculiar though it is. But whether I answer it or not must depend upon the reason which you may assign for asking the question. It is not usual, here in England, for total strangers to ask such personal questions as yours without being prepared to explain why they are asked.”

“Precisely!” assented the stranger suavely. “My reason for asking is that I am particularly anxious to see Señor Montijo on very important business of a strictly private nature, and should your friend happen to be the gentleman in question I was about to ask if you would have the very great goodness to oblige me with his present address.”

“I see,” said Jack. “What caused you to think that my friend might possibly be the individual you are so anxious to meet?”

“Simply a strong general resemblance, nothing more,” answered the stranger.

“Then, my dear sir,” said Jack, “since you saw my friend—for otherwise you could not have observed his strong general resemblance to the person whom you are so anxious to meet—will you permit me to suggest that obviously the proper thing for you to have done was to accost him when the opportunity presented itself to you, instead of following me. Before I answer your question I am afraid I must ask you to favour me with your card, as a guarantee of your bona fides, you know.”

“Certainly,” answered the stranger unhesitatingly, as he felt in the breast pocket of his coat for his card-case. His search, however, proved ineffectual, or at least no card-case was produced; and presently, with an air of great vexation, he exclaimed:

“Alas! sir, I regret to say that I appear to have lost or mislaid my card-case, for I certainly have not it with me. My name, however, is—Mackintosh,” with just the slightest perceptible hesitation.

“Mackintosh!” exclaimed Jack with enthusiasm; “surely not one of the Mackintoshes of Inveraray?”

“Certainly, my dear sir,” answered the stranger effusively. “You have no doubt heard of us, and know us to be eminently respectable?”

“Never heard of you before,” answered Jack, with a chuckle. “Good-morning, Mr Mackintosh!” And with a somewhat ironical bow he left the stranger gaping with astonishment.

“Now, what is the meaning of this, and what does Mr—Mackintosh—of Inveraray—want with Carlos, I wonder?” mused the young man, as he strode off across the Park. He considered the matter carefully for a few minutes, and presently snapped his fingers as he felt that he had solved the puzzle.

“I don’t believe he is in the least anxious to obtain Montijo’s address,” he mused, “otherwise he would have followed Carlos—not me! But I suspect that he has been quietly dogging Carlos, with a view to discovering what friends he and his father make here in England; and, having seen Carlos and me together for some hours to-day, he was desirous of obtaining an opportunity to become acquainted with my features and general appearance. Shouldn’t wonder if he follows me up and tries to discover where I live—yes, there the beggar is, obviously following me! Very well, I have no objection; on the contrary, the task of dodging him will add a new zest to life. And I’ll give him a good run for his money!”

And therewith Jack, who had thus far been sauntering very quietly along, suddenly stepped out at his smartest pace, and was greatly amused to observe the anxiety which the stranger evinced to keep up with him. Out through the gate by the corner of Stafford House grounds strode Jack, across the Mall, through the gate into Saint James’s Park, and along the path leading to the bridge, where he stopped, ostensibly to watch some children feeding the ducks, but really to see what the stranger would do. Then on again the moment that the latter also stopped, on past the drinking fountain and through the gate, across Birdcage Walk, and so into Queen Anne’s Gate, a little way along York Street, then to the left and through into Victoria Street, across the road, and into the main entrance of the Army and Navy Stores. As he ran up the steps he glanced over his shoulder and saw his pursuer frantically striving to dodge between a ’bus and a hansom cab and still to keep his eyes on Jack, who passed in through the heavy swing doors, through the grocery department, sharp round to the right through the accountant’s office into the perfumery department, and so out into Victoria Street again, making sure, as he passed out, that he had baffled his pursuer. Turning to the left, Jack then walked a little way down the street towards Victoria Station until he saw a Camden Town ’bus coming up, when he quietly crossed the road, boarded the ’bus, and ten minutes later stepped off it again as it pulled up at its stopping-place at the corner of Trafalgar Square. Jack now looked carefully round once more, to make quite sure that he had thrown “Mr Mackintosh” off the scent, satisfied himself that the individual in question was nowhere in sight, and entered his hotel.

Chapter Two.

Lieutenant Milsom, R.N.

The evening was fine, and the distance not far from Morley’s to the Cecil; Jack therefore did not trouble to take a cab, but, slipping on a light dust-coat over his evening dress, set out to walk down the Strand on his way to dine with his friend. As he went his thoughts were dwelling upon the incident of his afternoon encounter with the mysterious “Mr Mackintosh, of Inveraray”; and he decided that he would let Carlos and his father know that someone appeared to be taking rather a marked interest in them and their movements. A walk of some ten minutes’ duration sufficed to take him to his destination; and as he turned in at the arcade which gives access to the hotel from the Strand, whom should he see but the mysterious stranger, apparently intently studying the steamship advertisements displayed in one of the windows of the arcade, but in reality keeping a sharp eye upon the hotel entrances.

“Ah!” thought Jack; “watching, are you? All right; I’ll see if I can’t give you a bit of a scare, my friend!” And, so thinking, the young giant walked straight up to the stranger, and, gripping him firmly by the arm, exclaimed:

“Hillo, Mackintosh, waiting for Mr Montijo, eh? Is this where he is stopping? Because, if so, we may as well go in together, and see if he is at home. The sight of you reminds me that I rather want to see him myself. Come along, old chap!” And therewith Jack, still retaining his grip upon the stranger’s arm, swung him round and made as though he would drag him along to the hotel.

“Carrajo! How dare you, sir!” exclaimed the stranger, vainly striving to wrench himself free from Jack’s grasp. “Release me, sir; release me instantly, you young cub, or I will call a policeman!”

“What!” exclaimed Jack, in affected surprise; “don’t you wish to see your friend Montijo? Very well; run along, then. But take notice of what I say, Mr Mackintosh; if I find you hanging about here again I will call a policeman and give you in charge as a suspicious character. Now, be off with you, and do not let me see you again.”

And, swinging him round, Jack thrust him away with such force that it was with difficulty the man avoided falling headlong into the carriage-way. Then, calmly passing into the hotel, Singleton enquired for Señor Montijo, and was ushered to that gentleman’s private suite of rooms by an obsequious waiter.

He found both father and son waiting for him in a very pretty little drawing-room, and, Carlos having duly introduced his friend, the three stood chatting together upon the various current topics of the day until dinner was announced, when they filed into a small dining-room adjoining. Here also the conversation was of a strictly general character, so long, at least, as the waiters were about; but at length the latter withdrew, and the two young men, at Señor Montijo’s request, drew up their chairs closer to his.

Don Hermoso Montijo was a man in the very prime of life, being in his forty-third year; and, fortune having been kind to him from the first, while sickness of every description had carefully avoided him, he looked even younger than his years. He was a tall, powerful, and strikingly handsome man, of very dark complexion, with black hair, beard, and moustache, and dark eyes that sparkled with good humour and vivacity; and his every movement and gesture were characterised by the stately dignity of the true old Spanish hidalgo. He had spoken but little during dinner, his English being far from perfect; moreover, although he had paid the most elaborately courteous attention to what Jack said, his thoughts had seemed to be far away. Now, however, he turned to his guest and said, with an air of apology:

“Señor Singleton, I must pray you to me pardon if I have silent been during—the—meal—of dinner, but I have not much of English, as you have doubtless noticed. Have you the Spanish?”

Jack laughed as he replied in that language: “What I have, Señor, I owe entirely to Carlos here. He may perhaps have told you that we two used to amuse ourselves by teaching each other our respective tongues. But I am afraid I was rather a dull scholar; and if my Spanish is only half as good as Carlos’s English I shall be more than satisfied.”

“I am afraid I am unable to judge the quality of Carlos’s English,” answered Don Hermoso, “but I beg to assure you, Señor, that your Spanish is excellent; far better, indeed, than that spoken by many of my own countrymen. If it be not too tedious to you, Señor, I would beg you to do me the favour of speaking Spanish for the remainder of the evening, as I find it exceedingly difficult to make myself quite clearly understood in English.”

Jack having expressed his perfect readiness to fall in with this suggestion, Don Hermoso continued:

“Carlos has been telling me what passed between you and him to-day, Señor Singleton, and although I was naturally somewhat disinclined to give an unqualified assent to his suggestion before I had seen you, permit me to say that now, having seen, watched, and conversed with you, nothing will give me greater pleasure than to endorse his proposal, unless it be to hear that you agree to it.”

“To be perfectly candid, Don Hermoso, I feel very strongly inclined to do so,” answered Jack. “But before I can possibly give my assent to Carlos’s proposal you must permit me to clearly indicate the risks to you involved in it. You know absolutely nothing of me, Señor, beyond what you have learned from your son; and it is in the highest degree essential that you should clearly understand that what Carlos suggested to me this afternoon involves you in the risk of losing your yacht, for the carrying into effect of that proposal would make the vessel positively my own, to do as I pleased with; and if I should choose to retain possession of her, neither you nor anybody else could prevent me.”

“I very clearly understand all that, my dear young friend,” answered Don Hermoso, “and I am perfectly willing to take the risks, for several reasons. In the first place, if you were the kind of individual to do what you have just suggested, I do not for an instant believe that you would have warned me that the proposal involved me in the risk of losing my yacht. In the next place, although, as you say, I know little or nothing about you, my son Carlos knows you pretty intimately, and I can rely upon his judgment of you. And, finally, I do not believe that any Englishman in your position would or could be guilty of such infamous conduct as you have suggested. The fact is that we shall certainly be obliged to trust somebody—for if it were once known that the yacht belonged to me she would be so strictly watched that we could do little or nothing with her; and I would naturally trust you, rather than a stranger.”

“Of course,” answered Jack, “that is only natural, and I can quite understand it. Nevertheless I will not give you an answer at present; you must have sufficient time to think the matter over at leisure, and perhaps while doing so you may hit upon some alternative scheme that will suit you better. Meanwhile, let me tell you of a little adventure that I had this afternoon, just after I had parted from you, Carlos—and its continuation this evening. It will perhaps interest you, for I am greatly mistaken if it does not concern you both, even more than it does me.”

And therewith Jack proceeded to give a humorous relation of his two encounters with the foreign-looking gentleman claiming to be one of the Mackintoshes of Inveraray. When at length he finished, father and son looked at each other with glances of alarm, and simultaneously exclaimed:

“Now, who can that possibly be?”

“Your description of the man does not in the least degree suggest any particular individual to me,” continued Don Hermoso; “but that, of course, is not surprising, for a man must have a singularly striking personality to allow of his being identified from verbal description only. But let him be who he may, I am quite disposed to agree with you that his object in accosting you this afternoon was to enable him to familiarise himself with your personal appearance; while the fact that you caught him watching the hotel this evening would seem to indicate that our presence in London is known, and that our visit is regarded with a certain amount of suspicion. This only strengthens my conviction that your aid, my dear Señor Singleton, will be of the greatest value to us, if we can succeed in persuading you to give it.”

Don Hermoso’s manner was such as to leave no room for doubt in the mind of Singleton as to the sincerity of the Cuban, while the latter and his son were easily able to see that their proposal strongly appealed to the adventurous spirit of the young Englishman: it is therefore not surprising that ere they parted that evening Singleton had definitely agreed to become, for the time being, the apparent owner of the new steam-yacht, and to take part in the gun-running adventure; also agreeing to take along with him the working model of his submarine, which all three were of opinion might be found exceedingly useful, while the service upon which they were about to engage would afford Jack an opportunity to put the craft to the test of actual work.

These important points having been arranged, it was further agreed that, since the two Montijos were evidently under Spanish surveillance, they should advertise their connection with the yacht as little as possible, leaving the matters of the final trials of the vessel, the payment of the last instalment of her cost, and her transfer to Jack’s ownership entirely in the hands of the agent who had thus far managed the business for them; taking a holiday on the Continent, meanwhile, and joining the vessel only at the last moment prior to her departure for Cuba. And it was further arranged that the ordering and shipment of the arms, ammunition, and supplies destined for the use of the insurgents should also be left absolutely in the hands of the agent and Jack conjointly; by which means the Montijos would effectually avoid embroilment with the Spanish authorities, while it was hoped that, by occupying the attention of those authorities themselves, that attention would be completely diverted from Jack and the yacht. The settlement of these details and of others incidental to them kept the three conspirators busy until nearly midnight, when Jack rose to go, having already arranged to leave the hotel by the side entrance in order to baffle the eminently respectable “Mr Mackintosh”, should that individual happen to be still on the watch. As it happened, he was; for upon leaving the hotel Jack sauntered along the Embankment as far as Waterloo Bridge, then made his way up into Lancaster Place, and there took a cab, in which he drove up the Strand, where he saw his man, evidently on guard, strolling slowly to and fro in front of the main entrance to the Cecil.

Now Jack, although a yacht owner, was not a member of any yacht club, his cutter Lalage being such an out-of-date craft, and so seldom in use, that he had not thus far thought it worth while to very intimately identify himself with what is the Englishman’s pastime par excellence. But as he thought over the events of the evening while smoking a final pipe before turning in that night, it occurred to him that if he was to successfully pose as the owner of a fine new steam-yacht, it was imperative that he should become a member of some smart club; and as he happened to have two or three intimate friends who belonged to the Royal Thames, he decided upon attempting to procure election into that somewhat exclusive club. Accordingly, the next morning he addressed letters to those friends, requesting them to undertake the matter of his election, with the result, it may here be mentioned, that about three weeks later he received a communication from the secretary of the club, intimating his enrolment, and requesting the payment of his entrance fee and first subscription. This matter having been attended to, Jack next addressed a letter to Señor Montijo’s agent, making an appointment with him for the afternoon; and then went out to interview his tailor and outfitter, for the purpose of procuring a suitable outfit.

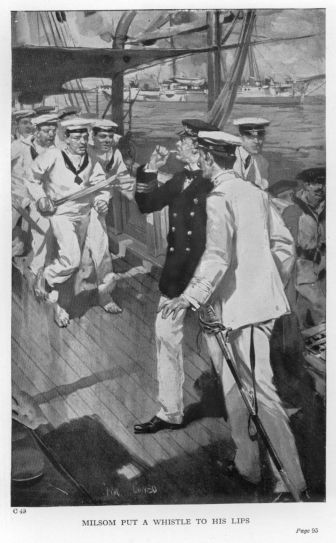

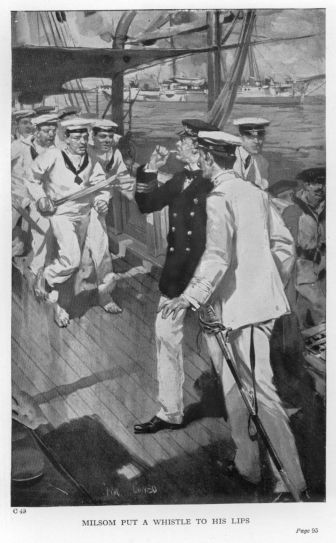

Then it occurred to him that for the especial work which the new yacht was required to do she would need a first-rate crew, every man of whom must be absolutely to be depended upon under all circumstances. The eight or ten hands comprising the crew of the Lalage were all well-known to him, having indeed belonged to the cutter for years, while she was still the property of Jack’s father, and they would doubtless serve as the nucleus of the new ship’s crew: but of course they would go but a little way towards the manning of a steam-yacht of three hundred and forty tons measurement; while Perkins, satisfactory as he had proved himself in his capacity of skipper of the cutter, would never do as commander of the new ship—though he might perhaps make a very good chief officer. Having arrived at this point in his meditations, Jack suddenly bethought himself of Lieutenant Philip Milsom, R.N. (retired), who would make a perfectly ideal skipper for the new craft, and would probably be glad enough to get to sea again for a few months, and supplement his scanty income by drawing the handsome pay which the captain of a first-class modern steam-yacht can command. Whereupon the young man turned into the next telegraph office that he came to, and dispatched a wire to Milsom, briefly informing him that he had heard of a berth which he thought would suit him, and requesting him to call at Morley’s Hotel on the following day. And at lunch-time Jack received a letter from Carlos Montijo, announcing the departure of his father and himself for Paris, en route for Switzerland, and containing an itinerary and list of dates for Singleton’s guidance in the event of his finding it necessary to communicate with them.

Jack had finished his luncheon, and was taking a cup of coffee with his cigarette in the smoke-room, when a waiter entered, bearing a card the owner of which was enquiring for Mr Singleton. The card bore the name of “James M. Nisbett”, and Jack knew that Señor Montijo’s agent had arrived. He accordingly directed the waiter to show Mr Nisbett up into his private sitting-room.

Mr Nisbett was one of those agents whose business is generally brought to them by foreign and colonial clients; and his transactions consisted of obtaining for and forwarding to those clients anything and everything that they might chance to require, whether it happened to be a pocket knife, a bridal trousseau, or several hundred miles of railway; a needle, or an anchor. And, being a keen man of business, it was only necessary to mention to him the kind of article required, and he was at once prepared to say where that article might be best obtained. Also, being a tremendously busy man, he was wont to get straight to business, without any circumlocution; and he did so in the present instance by producing a letter which he had that morning received from Don Hermoso Montijo, detailing the arrangement arrived at on the previous night between himself and Jack, and authorising Nisbett to act upon Jack’s instructions precisely as though these instructions emanated directly from Don Hermoso himself. This letter very effectually cleared the ground, and Jack at once began to detail to Nisbett full particulars of all the arms, ammunition, stores, and articles generally which it was intended to put on board the yacht for conveyance to Cuba; after which arrangements were made for the final trials of the yacht prior to her acceptance by Nisbett on behalf of his clients, and her subsequent transference to Jack’s ownership. It was perfectly clear to Jack that this last arrangement was distinctly unpalatable to Nisbett, who thought he saw in it some deep-laid scheme for the theft of the yacht from her actual owners; but when Jack explained the reasons which had actuated the Montijos in making the proposal, and further cheerfully offered to consent to any alternative scheme which would achieve the same result, the man at once gave in, frankly admitting that the arrangement already come to was the best that could be suggested. He remained with Jack two full hours, carefully discussing with him every point affecting the success of the expedition; and when at length he retired he was fully primed with all the information necessary to enable him to satisfactorily perform his share of the task.

The following morning brought Jack a visitor of a very different but equally thorough type, in the person of Lieutenant Philip Milsom, R.N., who sent in his card while the young man was still dawdling over a rather late breakfast.

“Bring the gentleman in here,” ordered Jack; and a minute later the waiter re-appeared, conducting a dapper-looking, clean-shaven man of medium height, attired in a suit of blue serge, the double-breasted jacket of which he wore buttoned tight to his body. This individual spotted Jack instantly, and, pushing the waiter on one side, bustled up with outstretched hand to the table at which the young man was sitting, exclaiming in a brisk, cheery voice:

“Hillo, Jack, my hearty, what cheer? Gad! what a big lump of a chap you have become since I saw you last—how long ago?—ay, it must be more than two years. But, nevertheless, I should have known you anywhere, from your striking likeness to your poor father. Well, and how are you, my lad, eh? Not very much the matter with you, I should say—and yet I don’t know; you look a trifle chalky about the gills, and your clothes seem to hang rather more loosely than they should. What have you been doing with yourself, eh?”

“Oh, nothing very dreadful!” laughed Jack, “only overworking myself a trifle, so I am told. But sit down, there’s a good fellow, and—have you breakfasted, by the way?”

“Breakfasted very nearly three hours ago, my boy,” was the answer. “But if you want me to join you—I see you are still busy at it—don’t be bashful, but say so straight out, and I’ll not refuse, for the journey up has given me a fresh appetite.”

“That’s right,” said Jack. “Now, which will you have, coffee or tea? And you can take your choice of ham and eggs, steak, chop, and fish.”

“Thanks!” said Milsom, “I’ll take coffee—and a steak, rather underdone. And while the steak is getting ready I’ll amuse myself with one of those rolls and a pat of butter, if you don’t mind. I got your telegram, by the way, or of course I shouldn’t be here. What is the job, my boy, eh? I suppose it is something that a gentleman may undertake, or you wouldn’t have thought of me, eh?”

“Of course,” said Jack; “that is to say, I think so. But you must judge for yourself whether the post is such as you would care to accept. The fact is that, as I told you just now, I have been overworking myself; and a specialist whom I have come down here to consult tells me that I must take a long holiday in the open air. I have therefore decided to go on a yachting cruise—to the West Indies, probably—and I want you to take command of the ship for me. She is a brand-new, three-hundred-and-forty-ton steam-yacht, of eight hundred indicated horse-power, and her guaranteed sea speed is twenty-two knots.”

Milsom pursed up his lips and gave vent to a prolonged whistle as Jack enunciated these particulars; then his features relaxed into a broad smile as he extended his right hand across the table to Jack, exclaiming:

“I’m your man! As I came along in the train this morning I was cogitating what was the smallest amount of pay that I would take for this job—whatever it might be; but, by the piper, Jack, the mere pleasure of commanding such a craft would be payment enough for me, and I’m quite willing to take it on free, gratis, and for nothing, if you say so.”

“The pay,” said Jack, “will be at the rate of thirty pounds sterling per calendar month, with uniform and your keep, of course, thrown in.”

“Good enough!” exclaimed Milsom enthusiastically. “You may take it that upon these terms I accept the command of the—what’s her name?”

“She is so new,” said Jack, “that she has not yet been given a name. At present she is known simply as Number 78. But”—lowering his voice—“I have not yet told you everything; you had better wait until you have heard all that I have to say before you definitely decide. Meanwhile, here comes your steak and some fresh coffee, so you had better get your breakfast; and when you have finished we will both go up to my private room.”

“Right ho!” acquiesced Milsom, who forthwith turned his attention to his second breakfast, saying very little more until he intimated that he had finished, and was now quite ready to resume the discussion of the matter that had brought him up to town. Accordingly, Jack conducted his friend up to his private sitting-room, waved him into a chair, and took one himself.

“Ah!” exclaimed Milsom, in a tone that conveyed his complete satisfaction with things in general; “this is all right. I suppose, by the way, a chap may smoke here, mayn’t he?”

“Of course,” said Jack; “smoke away as hard as you please, old man. Have a cigar?”

“No, thanks,” answered the Navy man; “good, honest, stick tobacco, smoked out of a well-seasoned brier, is good enough for me—unless one can get hold of a real, genuine Havana, you know; but they are scarcely to be had in these days.”

“All the same, I think we may perhaps manage to get hold of one or two where we are going,” said Jack; “that is to say, if you are still willing to take on the job after you have heard what I am bound to tell you.”

“Ah!” exclaimed Milsom; “something in the background, eh? Well, it can’t be very terrible, I fancy, Jack, or you would not be mixed up in it. However, heave ahead, my lad, and let us hear the worst, without further parley.”

“Well,” said Jack, “the fact is that the yachting trip is all a ‘blind’, and is in reality neither more nor less than a gun-running expedition in aid of the Cuban revolutionaries. And the yacht is really not mine, but belongs to a certain very wealthy Cuban gentleman who, being, like most Cubans, utterly sick of the Spanish misgovernment of the island, has thrown in his lot with the patriots, and has had the craft specially built for their service. But, recognising that to declare his ownership of her would at once arouse the suspicion of the Spaniards, and attract a tremendous amount of unwelcome attention to her, he has persuaded me to assume the apparent ownership of the vessel, and to undertake a trip to the West Indies in her, ostensibly for my health, but actually to run into the island a consignment of arms and ammunition, and otherwise to assist the patriots in every possible way.”

“I see,” observed Milsom thoughtfully. “That means, of course, that I should really be in the service of the Cuban gentleman, instead of in yours. That makes a very important difference, Jack, for, you see, I shall have to look to him, instead of to you, for my pay; and smuggling contraband of war is a very different matter from navigating a gentleman’s private yacht, and is work for which I shall expect to be well paid.”

“Then am I to understand that you regard thirty pounds per month as insufficient?” demanded Jack.

“Not at all, my dear boy,” answered Milsom quickly, “do not misunderstand me; I am quite content with the pay, but as the service is one that I can see with half an eye will involve a good deal of risk, I want to be quite certain of getting it. Now, is your friend to be absolutely depended upon in that respect? You see, if this insurrection should fail—as it probably will—your friend may be killed, or imprisoned, and all his property confiscated; and then I may whistle for my money.”

“I think not,” said Jack. “For my friend has left the management of everything in my hands, and I will see that you are all right. But I am very glad that you have raised the point; for it has enabled me to see that the proper thing will be to deposit a sufficient sum in an English bank to cover the pay of all hands for a period of—well, say twelve months. What do you say to that?”

“I say,” answered Milsom, “that it will be quite the proper thing to do, and will smooth away a very serious difficulty. But, Jack, my boy, has it occurred to you that you will be running a good many quite unnecessary risks by mixing yourself up in this affair? For you must remember that we may be compelled to fight, before all is done; while, if we are captured, it may mean years of imprisonment in a Spanish penal settlement, which will be no joke, I can assure you, my lad!”

“Ah!” answered Jack. “To be quite frank, I had not thought of the last contingency you mention. But ‘in for a penny, in for a pound’; I’ll take the risk, and trust to my usual good luck to keep me out of a Spanish prison. The fact is, Phil, that I am fairly aching for a bit of adventure, and I simply must have it.”

“Very well,” said Milsom grimly; “I think you have hit upon a most excellent scheme for getting it! My advice to you, Jack, is to leave the whole thing severely alone; but, whether you do or not, I am in it, so please give me your orders. And, mind you, Jack, I take them from you, and from nobody else.”

“Very well,” said Jack. “It may be necessary for you to modify that resolution later on, but let that pass; at present, at all events, you will receive all instructions from me, and regard me as the owner of the vessel. Now the first thing to be done is to secure a good crew; and, as I have told you precisely the kind of work that will have to be done, I shall look to you to provide the right sort of officers and men. I suppose you will have to give them a hint that they will be required to do something more than mere everyday yachting work—and you must arrange their pay accordingly; but, while doing this, you must be careful not to let out the true secret, or it will not remain such for very long. And you need not trouble to provide the engine-room staff; I think I can manage that part of the business myself.”

“I see,” answered Milsom. “You wish me to engage merely the officers, seamen, and stewards? Very well. How many guns will she carry?”

“Guns?” echoed Jack. “By Jove, I had not thought of that! Will she need any guns?”

“She certainly will, if she is to be as useful as she ought to be,” answered Milsom.

“Um!” said Jack; “that complicates matters a bit, doesn’t it? I am afraid that I must refer that point to Señor Montijo, the actual owner. What sort of armament would you recommend for such a craft, Phil?”

“Oh! not a very heavy one,” answered Milsom; “probably four 12-pounders, of the latest pattern, and a couple of Maxims would be sufficient.”

Jack made a note of these particulars for reference to Señor Montijo, and then said:

“Now, is there anything else that you can think of, Phil?”

“Nothing except an outfit of small arms—rifles, revolvers, and cutlasses, you know, for the crew,” answered Milsom. “If anything else should occur to me I will write and mention it.”

“Very well; pray do so,” said Jack. “Now, I think that is all for the present. Pick a first-class, thoroughly reliable crew, Phil. I give you a week in which to look for them, by which time I expect the boat will be ready to receive them. Then you can bring them all north with you, and we will ship them in the proper orthodox style. Now, good-bye; and good luck to you in your search!”

Chapter Three.

The S.Y. Thetis, R.T.Y.C.

The next day was spent by Jack, at Mr Nisbett’s invitation, in visiting, in the company of that gentleman, the establishments of certain manufacturers of firearms, where he very carefully inspected and tested the several weapons submitted to him for approval; finally selecting a six-shot magazine rifle, which was not only a most excellent weapon in all other respects, but one especially commending itself to him on account of the simplicity of its mechanism, which he believed would prove to be a very strong point in its favour when put into the hands of such comparatively unintelligent persons as he strongly suspected the rank and file of the Cuban insurgents would prove to be. He also decided upon an exceedingly useful pattern of sword-bayonet to go with the rifle, and also a six-shot revolver of an especially efficient character; and there and then gave the order—through Mr Nisbett—for as large a number of these weapons, together with ammunition for the same, as he believed the yacht could conveniently stow away. This done, he returned to his hotel, reaching it just in good time for dinner; and devoted the evening to the concoction of a letter to Señor Montijo, at Lucerne, reporting all that he had thus far done, also referring to Don Hermoso the important question of the yacht’s armament, and somewhat laboriously transcribing the said letter into cipher.

Jack’s business in London was now done; on the following morning, therefore, he took train back to Newcastle. He called upon Mr Murdock, his partner, in the evening, explaining the arrangement which he had made to pay a visit to Cuba, including the rather singular proposal of Señor Montijo to which he had consented, as to the apparent ownership of the new yacht; and listened patiently but unconvinced to all Murdock’s arguments against what the canny Northumbrian unhesitatingly denounced as an utterly hare-brained scheme. The next two days he devoted to the task of putting all his affairs in order, lest anything serious should happen to him during the progress of his adventure; and on the third day Nisbett presented himself, with his consulting naval architect, to witness the final trials of the yacht before accepting her, on behalf of Señor Montijo, from the builders. These trials were of a most searching and exhaustive character, lasting over a full week, at the end of which came the coal-consumption test, consisting of a non-stop run northward at full speed, through the Pentland Firth, round Cape Wrath; then southward outside the Hebrides and past the west coast of Ireland, thence from Mizen Head across to Land’s End; up the English Channel and the North Sea, to her starting-point. The run down past the west coast of Ireland, and part of the way up the Channel, was accomplished in the face of a stiff south-westerly gale and through a very heavy sea, in which the little craft behaved magnificently, the entire trial, from first to last, being of the most thoroughly satisfactory character, and evoking the unmeasured admiration of the naval architect under whose strict supervision it was performed. Jack was on board throughout the trial, as the representative of the builders, and his experience of the behaviour of the boat was such as to fill him with enthusiasm and delight at the prospect of the coming trip. The contract was certified as having been faithfully and satisfactorily completed, the final instalment of the contract price was paid, and Nisbett, on behalf of Señor Montijo, took over the vessel from the builders, at once transferring the ownership of her to Jack. Meanwhile a letter had arrived from Señor Montijo, authorising the arming of the ship in accordance with Milsom’s suggestion, and the Thetis, as she had been named, was once more laid alongside the wharf to receive certain extra fittings which were required to admit of the prompt mounting of her artillery when occasion should seem to so require.

In the meantime Jack had written to Milsom, extending the time allowed the latter in which to pick up a suitable crew, and at the same time suggesting that Perkins and the rest of the crew of the Lalage should be afforded an opportunity to join the Thetis, should they care to do so, subject, of course, to Milsom’s approval of them; and by the time that the extra fittings were in place, and the little ship drydocked and repainted outside, the Navy man had come north with his retinue, and the hands were duly shipped, Jack having, with the assistance of the superintendent of his fitting-shops, meanwhile selected a first-rate engine-room staff and stokehold crew.

The completing of all these arrangements carried the time on to the last week of July; and on the 28th day of that month the Thetis steamed down the Tyne on her way to Cowes, Jack having decided to give as much vraisemblance as possible to his apparent ownership of the vessel, and to the pretence that he was yachting for health’s sake, by putting in the month of August in the Solent, during which the order for arms, ammunition, etcetera, would be in process of execution. Although Jack was not a racing man—the Lalage being of altogether too ancient a type to pose as a racer—he was by no means unknown in the yachting world, and he found a host of acquaintances ready and willing to welcome his appearance in Cowes Roads, especially coming as he did in such a fine, handsome little ship as the Thetis; and for the first fortnight of the racing the new steamer, with her burgee and blue ensign, was a quite conspicuous object as, with large parties of friends, both male and female, on board, she followed the racers up and down the sparkling waters of the Solent. Jack was precisely of that light-hearted, joyous temperament which can find unalloyed pleasure amid such surroundings, and he threw himself heart and soul into the daily gaieties with an abandon that was sufficient, one would have thought, to have utterly destroyed all possible suspicion as to the existence of ulterior motives. Yet, happening to be ashore one afternoon with a party of friends, he was startled, as they walked down the High Street at Cowes, to see coming toward him a man whom he believed he had met somewhere before. The individual did not appear to be taking very particular notice of anything just at the moment, seeming indeed to be sunk deep in thought; but when he was about ten yards from Jack’s party he suddenly looked up and found the young man’s eyes fixed enquiringly upon him. For an instant he stopped dead, and an expression of mingled annoyance and fear flashed into his eyes; then he turned quickly and sprang, as if affrighted, into the door of a shop opposite which he had paused. But in that instant Jack remembered him; he was “Mr Mackintosh, of Inveraray!”

“Now what, in the name of fortune, is that chap doing down here?” wondered Singleton. “Is it accident and coincidence only, or has he discovered something, and come down here to watch my doings and those of the yacht? That is a very difficult question to answer, for one meets all sorts of people at Cowes during August; yet that fellow does not look as though he knew enough about yachts to have been attracted here by the racing. And he was evidently desirous of avoiding recognition by me, or why did he bolt into that shop as he did? I am prepared to swear that he did not want to buy anything; he had not the remotest intention of entering the place until he saw me. Of course that may have been because of the scare I gave him that night at the Cecil—or, on the other hand, it may have been because he did not wish me to know that he was anywhere near me. Anyhow, it does not matter, for my doings down here have been absolutely innocent, and such as to disarm even the suspicion of a suspicious Spanish spy; and in any case he cannot very well follow me wherever I go. Perhaps before the month is out his suspicions—if he has any—will be laid at rest, since I am just now doing absolutely nothing to foster or strengthen them, and he will come to the conclusion that there is no need to watch me. But I am very glad that the idea occurred to me of never running the boat at a higher speed than fourteen knots while we have been down here; there is nothing to be gained by giving away her real speed, and—who knows?—a little harmless deception in that matter may one day stand us in good stead.”

Thenceforward, whenever Jack had occasion to go ashore, he always kept a particularly smart lookout for “Mr Mackintosh”; but he saw him no more during the remainder of his stay in the Solent. Yet a few days later an incident occurred which, although unmarked by any pronounced significance, rather tended to impress upon Jack the conviction that somebody was evincing a certain amount of interest in the speed qualifications of the Thetis, although it was quite possible that he might have been mistaken. This incident took the form of a somewhat sudden proposal to get up a race for steam-yachts round the island, for a cup of the value of fifty guineas. Such a proposal was a little remarkable, from the fact that steam-yacht racing is a form of sport that is very rarely indulged in by Englishmen, at least in English waters; yet everything must necessarily have a beginning, and there was no especial reason why steam-yacht racing should not be one of those things, particularly as the idea appeared to be received with some enthusiasm by certain owners of such craft. When the matter was first mentioned to Singleton, and it was suggested that he should enter the Thetis for the race, he evinced a disposition to regard the proposal with coldness, as he had already arrived at the conclusion that it might be unwise to reveal the boat’s actual capabilities; but his attitude was so strongly denounced as unsportsmanlike, and he found himself subjected to such urgent solicitations—not to say pressure—that he quickly grew suspicious, and mentioned the matter to Milsom. Milsom, in turn, after considering the matter for a little, suggested that the chief engineer of the boat should be consulted, with the result that it was ultimately decided to enter the Thetis for the race, Macintyre undertaking that while the yacht should present to onlookers every appearance of being pushed to the utmost—plenty of steam blowing off, and so on—her speed should not be permitted to exceed fifteen knots, and only be allowed to reach that at brief intervals during the race. With this understanding Jack agreed to enter, and the race duly came off in splendid weather, and was pronounced to be a brilliant success, the Thetis coming in third, but losing the race by only eight seconds on her time allowance. Nobody was perhaps better pleased at the result than Jack, for the new boat made a brave show and apparently struggled gamely throughout the race to win the prize, the “white feather” showing from first to last on the top of her waste pipe, and a thin but continuous film of light-brown smoke issuing from her funnel from start to finish. If anyone happened to have taken the trouble to get up the race with the express object of ascertaining the best speed of the Thetis, they knew it now; it was fourteen knots, rising to nearly fifteen for a few minutes occasionally when the conditions were especially favourable!

With the approach of the end of the month the yachts began to thin out more and more perceptibly every day, the racers going westward and the cruisers following them; the steam-yachts hanging on to accompany the Channel Match to Weymouth. The Thetis was one of these; and Jack allowed it to be pretty generally understood that after the Weymouth regatta was over he intended to run north for a month or so, visiting the Baltic, and perhaps proceeding as far east as Cronstadt. But yachtsmen are among the most capricious of men—some of them never know from one moment to another what they really intend to do; thus it is, after all, not very surprising that when the Thetis arrived off the mouth of the Tyne Jack Singleton should suddenly give orders for her nose to be turned shoreward, and that, an hour or two later, she should glide gently up alongside and make fast to the private wharf of Singleton, Murdock, and Company. What is surprising is that, when she was seen approaching, some fifty of Singleton, Murdock, and Company’s most trusty hands received sudden notice that they were required for an all-night job; and that at dawn the next morning the Thetis drew a full foot more water than she had done when she ran alongside the wharf some twelve hours earlier, although in the interim she had not taken an ounce of coal into her bunkers.

It so happened that Mr Murdock was absent on important business when the Thetis arrived alongside the wharf, and he did not return to Newcastle until nearly midnight, when he, of course, made the best of his way to his own house. But he was at the works betimes next morning, and, knowing that the yacht was expected, he took the wharf on his way to the office, with the object of ascertaining whether she had arrived. The sight of her lying alongside in all her bravery of white enamel paint, gilt mouldings, and polished brasswork caused him to heave a great sigh of relief; and he joyously hurried forward to greet Jack, whom he saw standing on the wharf engaged in earnest conversation with the yard foreman.

“Good-morning, Singleton!—Morning, Price!” he exclaimed as he approached the two. “Well, Jack,” he continued, “so you arrived up to time, eh? And by the look of the boat I should say that you’ve got the stuff on board; is that so? Ah! that’s all right; I am precious glad to hear it, I can tell you, for to have those cases accumulating here day after day has been a source of great anxiety to me.”

“Sorry!” remarked Jack cheerfully. “But why should they worry you, old chap? Everything is securely packed in air-tight, zinc-lined cases, so that there was really no very serious cause for anxiety or fear, even of an explosion. Such a thing could not possibly happen except by the downright deliberate act of some evil—disposed individual; and I don’t think—”

“Precisely,” interrupted Murdock; “that was just what was worrying me—at least, it was one of the things that was worrying me. Not on account of our own people, mind you; I believe them to be loyal and trustworthy to a man. But I cannot help thinking that some hint of your expedition must have leaked out, for we have never had so many strangers about the place since I have been in the business as we have had during the last fortnight, while those cases have been arriving. We have simply been overwhelmed with business enquiries of every description—enquiries as to our facilities for the execution of repairs; enquiries as to the quickest time in which we could build and deliver new ships; enquiries respecting new engines and machinery of every conceivable kind, not one of which will probably come to anything. And the thing that troubled me most was that every one of these people wanted to be shown over the place from end to end, in order that they might judge for themselves, as they explained, whether our works were sufficiently extensive and up-to-date to enable us to execute the particular kind of work that they wanted done: and every mother’s son of them gravitated, sooner or later, to the spot where those precious cases of yours were stacked, and seemed profoundly interested in them; while one chap, who was undoubtedly a foreigner, had the impudence to insinuate that the marks and addresses on the cases, indicating that they were sugar machinery for Mauritius, were bogus! I sent him to the rightabout pretty quickly, I can tell you. Why, what the dickens are you laughing at, man? It is no laughing matter, I give you my word!”

For Jack had burst into a fit of hearty laughter at Murdock’s righteous indignation.

“No, no; of course not, old chap,” answered Jack, manfully struggling to suppress his mirth; “awfully annoying it must have been, I’m sure. Well, is that all?”

“No,” answered Murdock indignantly, “it is not; nor is it the worst. Only the day before yesterday we had a man poking about here who said he was from the Admiralty. He wanted nothing in particular for the moment, he said, but was simply making a tour of the principal shipyards of the country, with the view of ascertaining what were the facilities of each for the execution of Admiralty work. He, too, was vastly interested in those precious cases of yours, so much so, indeed, that I should not have been at all surprised if he had asked to have the whole lot of them opened! Oh, yes! of course I know he could not have gone to such a length as that without assigning some good and sufficient reason; but I tell you, Jack, that we are playing a dangerous game, and I will not be a party to a repetition of it. A pretty mess we should be in if the British Government were to discover that we are aiding and abetting insurgents in arms against the authority of a friendly Power! Why, it would mean nothing short of ruin—absolute ruin—to us!”

“Yes, you are quite right, old chap, it would,” agreed Jack soberly; “and if Señor Montijo wants to ship any more stuff after this, it must not be through this yard. But it is all aboard and out of sight now, and we leave for—um—Mauritius, shall we say?—this afternoon; so there is no need for you to worry any further about it.”

“Well, to be perfectly candid with you, Jack,” said Murdock, “I shall not be at all sorry to see the Thetis safely away from this and on her way down the river, for I shall not be quite comfortable and easy in my mind until I do. And you will have to be very careful what you are about, my boy; ‘there is no smoke without fire’, and all this fuss and prying about of which I have been telling you means something, you may depend. It would not very greatly surprise me if you discover that you are being followed and watched.”

“We must take our chance of that,” laughed Jack. “Not that I am very greatly afraid. The fact is, Murdock, that you are constitutionally a nervous man, and you have worried yourself into a perfect state of scare over this business. But never mind, your anxiety will soon be over now, for here comes our coal, if I am not mistaken; and I promise you that we will be off the moment that we have taken our last sack on board. But I will run into the office and say good-bye before I go.”

The church clocks were just striking two when, Jack having duly fulfilled his promise to say good-bye to his partner, and to exchange a final word or two with him, the Thetis cast off from the wharf, backed out into the stream, and, swinging round, swept away down the river at the modest rate of fourteen knots, that being her most economical speed, and the pace at which, in order to make her coal last out, it had been decided that she should cross the Atlantic. She sat very deep in the water, and her decks, fore and aft, were packed with coal, in sacks so closely stowed that there was only a narrow gangway left between them from the foot of the ladder abaft the deck-house to the companion, and a similar gangway from the fore end of the bridge deck to the forecastle. If it was necessary for the men to pass to any other part of the ship, such as to the ensign staff, for instance, they had to climb over the sacks. She was particularly well equipped with boats, too: there were a steam pinnace and a whaler in chocks on the starboard side of the deck-house, balanced by the lifeboat and cutter on the other; and she carried no less than four fine, wholesome boats at her davits aft, all nicely covered over with canvas, to protect them from the sun—and also, in one case, to screen from too curious eyes Jack’s submarine, which was snugly stowed away in the largest quarter boat, that craft having had her thwarts removed to make room for the submarine. Twenty-six hours later, namely, at four o’clock on the following afternoon, the Thetis anchored off Boulogne; the steam pinnace was lowered, and Jack, accompanied by four seamen, proceeded into the harbour, landing at the steps near the railway station. From thence it was a very short walk to the hotel to which he was bound; and in a few minutes he was at his destination, enquiring for Monsieur Robinson. “Yes,” he was informed, “Monsieur Robeenson was in, and was expecting a Monsieur Singleton. Possibly Monsieur might be the gentleman in question?” Jack confessed that he was; and, being piloted upstairs, was presently shown into a room where he found Don Hermoso Montijo and his son Carlos obviously waiting for him. As he entered they both sprang to their feet and advanced toward him with outstretched hands.

“Ah, Señor Singleton,” exclaimed Don Hermoso, “punctual to the minute, or, rather”—glancing at his watch—“a few minutes before your time! We duly received your wire in Paris this morning, and came on forthwith. I am delighted to learn that everything has gone so smoothly. Do I understand that you are now ready to sail for Cuba?”

“Certainly, Don Hermoso,” answered Jack; “we can be under way in half an hour from this, if you like; or whenever you please. It is for you to say when you would like to start.”

“Then in that case we may as well be off at once,” said Don Hermoso. “For the first fortnight or three weeks of our tour through Switzerland we were undoubtedly the objects of a great deal of interested attention, but latterly we have not been so acutely conscious of being followed and watched; everything that we did was so perfectly open and frank that I think the persons who had us under surveillance must have become convinced that their suspicions of us were groundless, and consequently they relaxed their attentions. And I believe that we managed to get away from Paris this morning without being followed. If that is the case we have of course managed to throw the watchers off the scent, for the moment at least, and it will no doubt be wise to get away from here before it is picked up again. I hope that you, Señor, have not been subjected to any annoyance of that kind?”

“No,” said Jack laughingly, “I have not, beyond meeting at Cowes with that man who called himself Mackintosh—of which I informed you in one of my letters—I have had little or no cause to believe that I have become an object of suspicion to the Spanish Government. It is true that a race for steam-yachts was got up, a little while before I left the Solent, under circumstances which suggested to me that an attempt was being made to ascertain the best speed of the Thetis; but the attempt might have existed only in my imagination, and if it was otherwise, the plan was defeated, so no harm was done. But my partner has been a good deal worried recently by the incursions of a number of inquisitive strangers, who have obtruded themselves upon him and invaded our works with what he considers very inadequate excuses. His fixed impression is that a whisper was somehow allowed to get abroad that arms, ammunition, and stores were to be shipped from our yard for the use of the Cuban insurgents, and that the inquisitive strangers were neither more nor less than emissaries of the Spanish Government, sent down to investigate into the truth of the matter. They one and all appear to have betrayed a quite remarkable amount of interest in the cases, and one individual at least seems to have pretty broadly hinted his doubts as to the genuineness of the markings on them. Also, our own Government appears to have received a hint of what we were doing, and to have sent a man down to investigate; I am afraid, therefore, that despite all our precautions, we have not wholly succeeded in avoiding suspicion. And if such should be the case it will be a pity, for it will certainly mean trouble for us all later on.”

“The stronger the reason why we should start without further delay,” said Don Hermoso. “Carlos, oblige me by ringing the bell.”

The bell was rung, the bill asked for and paid, the various servants generously tipped, and the little party set out. The Montijos’ luggage had been left in the hall of the hotel: there was nothing therefore but for the four seamen to seize it, shoulder it, and carry it down to the pinnace; and this occupied but a few minutes. A quarter of an hour later the party had gained the deck of the yacht, and the pinnace was once more reposing in her chocks on the bridge deck.

“Get your anchor up, Mr Milsom, if you please,” said Jack, allowing his eyes to stray shoreward as Milsom repeated the order to the mate. As he looked, he became aware of something in the nature of a commotion or disturbance at the end of the pier; and, entering the chart-house, he brought forth a pair of splendid binoculars with which to investigate. Upon applying the glasses to his eyes he saw that there was a little crowd of perhaps fifty people gathered on the pier end, all eagerly listening to a man who was talking and gesticulating with great vehemence as he pointed excitedly toward the yacht. The man appeared to be particularly addressing two gendarmes who were among the crowd, but everybody was clustering close round him and listening, apparently in a state of the greatest excitement, to what he had to say, while occasionally one or another in the crowd would face seaward and shake his fist savagely at the yacht.