WILD NATURE WON BY KINDNESS.

|

BY THE SAME AUTHOR.

More about Wild Nature. With Portrait

Inmates of my House and Garden.

Glimpses into Plant Life. Fully Illustrated. |

|

WILD NATURE WON BY KINDNESS BY MRS. BRIGHTWEN Vice-President of the Selborne Society AUTHOR OF "INMATES OF MY HOUSE AND GARDEN," ETC. ILLUSTRATED EIGHTH EDITION T. FISHER UNWIN PATERNOSTER SQUARE 1898 |

All rights reserved.

Sir JAMES PAGET, Bart., F.R.S., D.C.L., Etc., Etc.

My dear Sir James,—

The little papers which are here reprinted would scarcely

have been written but for the encouragement of your sympathy and the

stimulus of what you have contributed to the loving study of nature.

Shall you, then, think me presumptuous if I venture to dedicate to the

friend what I could never dream of presenting to the professor, and if

I ask you to pardon the poorness of the gift in consideration of the

sincerity with which it is given.

Pray believe me to be

Yours very sincerely,

ELIZA BRIGHTWEN

The Grove, Great Stanmore.

June, 1898.

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

| INTRODUCTION. | 11 |

| 1. REARING BIRDS FROM THE NEST. | 18 |

| 2. DICK THE STARLING. | 21 |

| 3. RICHARD THE SECOND. | 25 |

| 4. VERDANT. | 44 |

| 5. THE WILD DUCKS. | 51 |

| 6. THE JAY. | 59 |

| 7. A YOUNG CUCKOO. | 67 |

| 8. THE TAMING OF OUR PETS. | 70 |

| 9. BIRDIE. | 80 p. 6 |

| 10. ZÖE, THE NUTHATCH. | 87 |

| 11. TITMICE. | 99 |

| 12. BLANCHE, THE PIGEON. | 108 |

| 13. GERBILLES. | 112 |

| 14. WATER SHREWS. | 121 |

| 15. SQUIRRELS. | 126 |

| 16. A MOLE. | 131 |

| 17. HARVEST MICE. | 136 |

| 18. THE CALIFORNIAN MOUSE. | 140 |

| 19. SANCHO THE TOAD. | 143 |

| 20. ROMAN SNAILS. | 146 |

| 21. AN EARWIG MOTHER. | 152 |

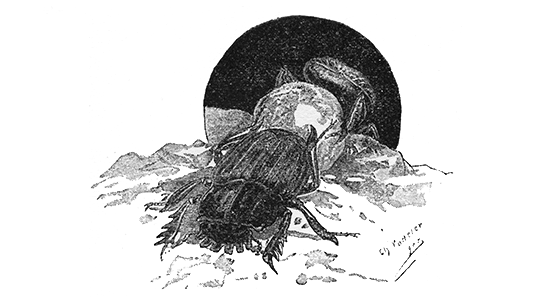

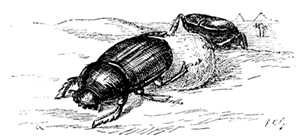

| 22. THE SACRED BEETLE. | 157 |

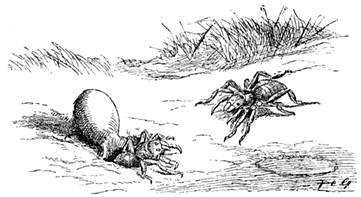

| 23. SPIDERS. | 163 |

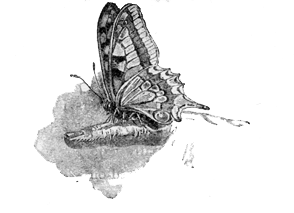

| 24. TAME BUTTERFLIES. | 173 |

| 25. ANT-LIONS. | 178 |

| 26. ROBINS I HAVE KNOWN. | 183 |

| 27. ROBERT THE SECOND. | 188 |

| 28. FEEDING BIRDS IN SUMMER | 195 |

| 29. RAB, MINOR. | 202 |

| 30. A VISIT TO JAMRACH. | 207 |

| 31. HOW TO OBSERVE NATURE | 214 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

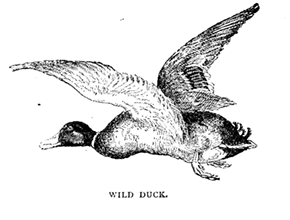

| FLYING WILD DUCK | 5 |

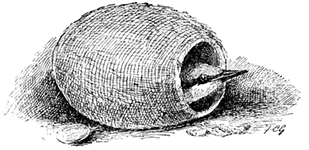

| SACRED BEETLE | 7 |

| SWALLOW | 11 |

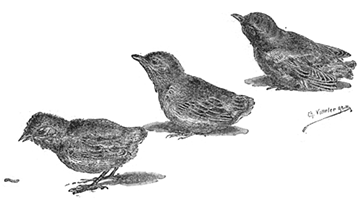

| REARING BIRDS FROM THE NEST | 18 |

| STARLINGS | 21 |

| FLYING STARLINGS | 25 |

| STARLING IN SEARCH OF FOOD | 43 |

| WILD DUCK | 51 |

| TINY, SIR FRANCIS DRAKE AND LUTHER | 58 |

| JAY | 59 |

| ANOTHER JAY | 61 |

| A YOUNG CUCKOO. | 66p. 8 |

| BUTTERFLY AND CATERPILLAR | 67 |

| YOUNG CUCKOO ATTACKED BY BIRDS | 69 |

| ARABESQUE | 79 |

| ZÖE, THE NUTHATCH | 87 |

| NUTHATCH IN A COCOANUT | 98 |

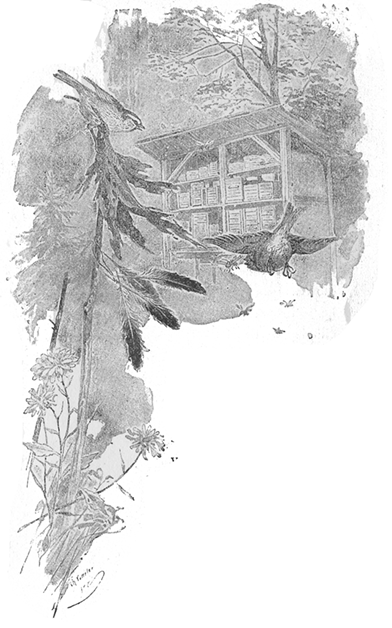

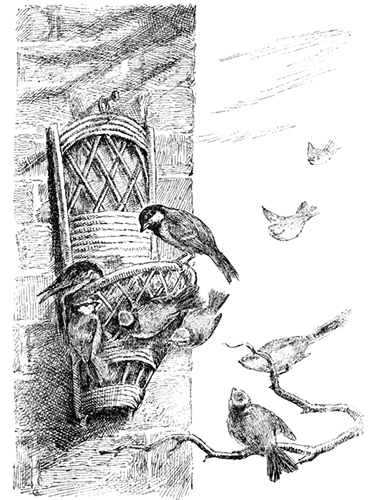

| TITMICE IN PURSUIT OF BEES | 99 |

| TITMICE | 101 |

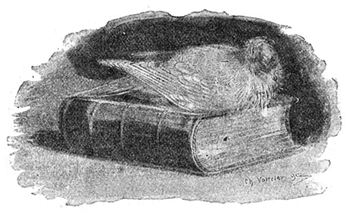

| BLANCHE THE PIGEON | 108 |

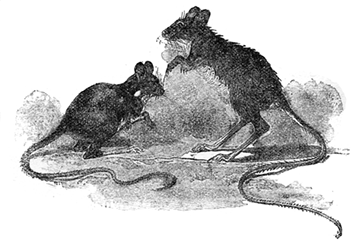

| GERBILLES | 112 |

| WATER SHREW | 125 |

| SQUIRREL | 126 |

| MOLE | 131 |

| MICE | 140 |

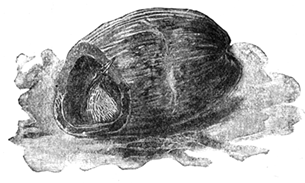

| ROMAN SNAILS | 146 |

| EARWIG | 156 |

| EGYPTIAN BEETLES | 157 |

| FLYING BEETLE | 162 |

| TRAP-DOOR SPIDERS | 163 |

| BUTTERFLY | 173 |

| ANT-LION | 178 |

| THE ROBIN | 183 |

| YOUNG BIRDS | 195 |

| CHILD AND PET BIRD | 201 |

| RAB MINOR | 202 |

| RAB MINOR RUNNING | 206 |

| NESTLINGS | 207 |

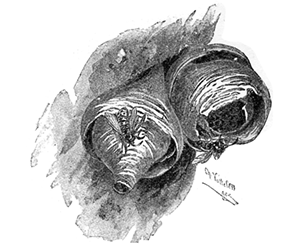

| NEST OF WASPS | 214 |

| SNAKE IN A CIRCLE | 230 |

PREFACE TO THE FIFTH

EDITION.

WO short chapters, one describing the life of an Ant-lion, and the other the habits of a tame Toad, were added to the second edition, which was in other respects a reproduction of the first.

The present edition has been improved by the adoption of a number of illustrations which were designed for the German translation of this book.

HAVE often wished I could convey to others a little of the happiness I have enjoyed all through my life in the study of Natural History. During twenty years of variable health, the companionship of the animal world has been my constant solace and delight. To keep my own memory fresh, in the first instance, and afterwards with a distinct intention of repeating my single experiences to others, I have kept notes of whatever has seemed to me worthy of record in the life of my pets. Some of these papers have already appeared in The Animal World; the majority are now printed for the first time.

In the following chapters I shall try to have quiet talks with my readers and tell them in a simple way about the many pleasant friendships I have had with animals, birds, and insects. I use the word friendships advisedly, because truly to know and enjoy the society of a pet creature you must make it feel that you are, or wish to be, its friend, one to whom it can always look for food, shelter, and solace; it must be at ease and at home with you before its instincts and curious ways will be shown. Sometimes when friends have wished me to see their so-called "pet," some scared animal or poor fluttering bird has been brought, for whom my deepest sympathy has been excited; and yet there may have been perhaps the kindest desire to make the creature happy, food provided in abundance, and a pleasant home; but these alone will not avail. For lack of the quiet gentle treatment which is so requisite, the poor little captive will possibly be miserable, pining for liberty, hating its prison, dreading the visits of its jailor, and so harassed in its terror that in some cases the poor little heart is broken, and in a few hours death is the result. In the following simple sketches of animal, bird,p. 13 and insect life, I have tried to show how confidence must be gained, and the little wild heart won by quiet and unvarying kindness, and also by the endeavour to imitate as much as possible the natural surroundings of its own life before its capture. I must confess it requires a large fund of patience to tame any wild creature, and it is rarely possible to succeed unless one's efforts begin in its very early days, before it has known the sweets of liberty.

In many cases I have kept a wild animal or bird for a few days to learn something of its ways, possibly to make a drawing of its attitudes or plumage, and then let it go, else nearly all my pets, except imported creatures, have been reared from infancy, an invalid's life and wakefulness making early-morning feeding of young fledglings less difficult than it would have been in many cases, and often have painful hours been made bearable and pleasant by the interest arising from careful observation of the habits and ways of some new pet animal or bird.

I have always strongly maintained that the love of animated nature should be fostered far morep. 14 than it usually is, and especially in the minds of the young; and that, in fact, we lose an immense amount of enjoyment by passing through life as so many do without a spark of interest in the marvellous world of nature, that book whose pages are ever lying open before us.

The beauties of the country might as well have been left uncreated for all the interest that thousands take in them. Not only town dwellers, who might be excused for their ignorance, but those who live in the midst of fields and woods, often know so little about the curious creatures in fur and feathers that exist around them that they are surprised when told the simplest facts about these, their near neighbours.

One reason may be, that it is now so much the fashion to spend the year in various places, and those always moving about have neither the time nor opportunity to cultivate the little undergrowths of quiet pleasures which spring out of a settled home in the country, with its well-tended garden and farmyard, greenhouses, stable, and fields—the horses and cattle, petted and kindly cared for from their birth, dogs and poultry, and all kinds of special favourites.

There is a healthy, happy tone about such a life, and where it exists and is rightly maintained, good influence is, or ought to be, felt in and around the home. Almost all children have a natural love of living creatures, and if they are told interesting facts about them they soon become ardent naturalists. I well remember that in my childhood I had a great dread of toads and frogs, and a relative, to whom I owe much for having directed my mind into the love of animated nature, took up a frog in her hand and made me look at the beautiful gold circle round its eyes, its curious webbed feet, its leaping power arising from the long hind legs; she told me also of its wonderful tongue, so long and flexible that it folded back in its mouth, and that the frog would sit at the edge of an ant-hill and throwing out the tongue with its sticky point, would pick off the ants one by one as they came out. When I learnt all this, I began to watch such a curious reptile; my fears vanished, and like Kingsley's little daughter, who had been wisely led to care for all living things and came running to show her father a "dear delightful worm" she had found! so I, too, have been led all through myp. 16 life to regard every created thing, great or small, attractive or otherwise, as an object well worth the most reverent study.

Perhaps I ought to explain that I have described methods of taming, feeding, and housing one's pets with extreme minuteness in order to help those of my readers who may be very fond of live creatures, and yet from lack of opportunity may have gained no knowledge of their mode of life, and what is required to keep them happily in health and vigour. I have had to learn by experience that attention to very small details is the road to success in keeping pets as well as in other things, and the desire to pass on that experience must be my excuse to more scientific readers for seeming triviality.

Many admirable books have been written by those well qualified to impart their knowledge in every branch of Natural History, and the more such books are read the better, but the following pages simply contain the life histories of my pets and what I personally have observed about them. I shall be glad indeed if they supply any useful information, or lead others to the more careful study of the common every-day things around them with a view top. 17 more kindness being shown to all living creatures, and tender consideration for them. I trust I may feel that this little book will then have attained its purpose. May it especially tend to lead the young to see how this beautiful world is full of wonders of every kind, full of evidences of the Great Creator's wisdom and skill in adapting each created thing to its special purpose, and from the whole realm of nature may they be taught lessons in parables, and their hearts be led upward to God Himself, who made all things to reflect His own perfection and glory.

|

"Gem, flower, and fish, the bird, the brute, Of every kind occult or known (Each exquisitely form'd to suit Its humble lot, and that alone), Through ocean, earth, and air fulfil Unconsciously their Maker's will." ELIZA BRIGHTWEN. |

HE most delightful of all pets are the birds one has taken the pains to rear from the nest; they never miss the freedom of outdoor life, they hardly know what fear is, they become devotedly attached to the one who feeds and educates them, and all their winsome ways seem developed by the love and care which is given to them.

I strongly deprecate a whole nest being taken; one would not willingly give the happy little parentp. 19 birds the distress of finding an empty home. After all their trouble in building, laying, sitting, and hatching, surely they deserve the reward of bringing up their little babes.

Too often when boys thus take a nest they simply let the young birds starve to death from ignorance as to their proper food and not rising early enough to feed them.

It is a different matter if, out of a family of six, one takes two to bring up by hand—the labour of the old birds is lightened, and four fledglings will sufficiently reward their toil.

The birds should be taken before they are really feathered, just when the young quills begin to show, as at that stage they will not notice the change in their diet and manner of feeding. They need to be carefully protected from cold, kept at first in a covered basket in flannel, and if the weather is cold they should be near a fire, as they miss the warmth of the mother bird, especially at night.

I confess it involves a good deal of trouble to undertake the care of these helpless little creatures. They should be fed every half-hour, from four in the morning until late in the evening, and that forp. 20 many weeks until they are able to feed themselves.

The kind of food varies according to the bird we desire to bring up, and it requires care to make sure that it is not too dry or too moist, and that it has not become sour, or it will soon prove fatal, for young birds have not the sense of older ones—they take blindly whatever is given them.

EW people would think a cat could possibly be a tender nurse to young birds! but such was really the case with a very interesting bird I possessed some years ago.

A young starling was brought up from the nest by the kind care of our cook and the cat! Both were equally sympathetic, and pitied the little unfledged creature, who was by some accident left motherless in his early youth. Cook used to get up at some unheard-of hour in the morning to feedp. 22 her clamorous pet, and then would bring him down with her at breakfast-time and consign him to pussy's care; she, receiving him with a gentle purr of delight, would let him nestle into her soft fur for warmth.

As Dick became feathered, he was allowed the run of the house and garden, and used to spend an hour or so on the lawn, digging his beak into the turf, seeking for worms and grubs, and when tired he would fly in at the open window and career about until he could perch on my shoulder, or go in search of his two foster-mothers in the kitchen.

His education was carried on with such success that he could soon speak a few words very clearly. Strangers used to be rather startled by a weird-looking bird flying in from the garden, and saying, "Beauty dear, puss, puss, miaow!" But it was still more strange to see Dick sitting on the cat's back and addressing his endearments to her in the above words. Pussy would allow him to investigate her fur with exemplary patience, only objecting to his inquisitive beak being applied to her eyelids to prize them open when she was enjoying her afternoonp. 23 nap. Dick's love of water led him to bathe in most inconvenient places. One morning, when I returned to the dining-room after a few minutes' absence, I found him taking headers into a glass filter and scattering the contents on the sideboard. After dinner, too, he would dive into the finger-glasses with the same intention, and when hindered in that design would visit the dessert dishes in succession, stopping with an emphatic "Beauty dear!" at the sight of some coveted dainty, to which he would forthwith help himself liberally.

In summer Dick had to resist considerable temptation from wild birds of his own kind, who evidently made matrimonial overtures to him, but though he "camped out" for a few nights now and then, he never seemed to find a mate to his mind, and elected to remain a bachelor and enjoy our society instead of that of his own kith and kin.

Dick was certainly a pattern of industrious activity, never still for two minutes. He seemed haunted by the idea that caterpillars and grubs existed all over the house, and his search for them was carried on under all possible circumstances—every plait of one's dress, every button-hole, wouldp. 24 be inquired into by his prying little beak in case some choice morsel might chance to be lurking there. Dick lived for a few happy years, and then his bathing propensities most unhappily led to his untimely death. One severely cold day in winter he was missed and searched for everywhere, and after some hours his poor little body was found stiff and cold in a water-tank in the stable-yard, where the ice had been broken. He had as usual plunged in for a bath, and we can only suppose the intense cold had caused an attack of cramp, so that he could not get out again, and thus was drowned. Many tears were shed for the loss of the cheery little bird, who seemed like a bright ubiquitous sunbeam about the house, and our only consolation was the thought that, as far as we knew, he had never had a sorrow in his life, and we can only hope that if there are "happy hunting-grounds" for birds our Dick may be there, bright and happy still.

N a wet stormy day in May a young unfledged bird was blown out of its nest and was picked up in a paved yard where, somehow, it had fallen unhurt.

There he was found by my kind-hearted butler, who appeared with the little shivering thing in his hand to see if I would adopt it. The butler pleaded for it, and it squawked its own petition piteously enough, but I was far from strong, and I knew at what very early hours these young feathered people required to be fed. I therefore felt I ought hardlyp. 26 to give up the time which sometimes brought me the precious boon of sleep after a wakeful night. Very reluctantly I refused the gift, and felt wretchedly hard-hearted in doing so. I will confide to my readers that in my secret heart I thought the poor orphan was a blackbird or thrush, and they are birds I feel ought never to be caged; they pine and look so sadly longing for liberty; even their song has a minor key of plaintiveness when it comes through prison bars, and this feeling helped my decision.

A few days after I heard that the birdie was adopted in the pantry, and was being fed "in the intervals of business." When a few days later I was definitely informed that the birdie waif was a starling, then I confess I did begin to long for another little friend such as my former "Dick" had been, and it ended in my receiving Richard the Second, as we called him for distinction, into my own care and keeping, and month after month I was his much-enduring mother. Most fledglings are much the same at first; whenever I came in sight the gaping beak was ever ready for food, and the capacity for receiving it was wonderful.p. 27 Richard grew very fast; little quills appeared and opened out into feathers; his walking powers increased till he could make a tottering run upon the carpet; and then he began to object to his basket and would have a perch like a grown-up bird, practised going to sleep on one leg, which for a long time was a downright failure and ended in constant tumbles.

He was always out of his cage whilst I was dressing, and was full of fun and play, scheming to get his bath before I did, and running off with anything he could carry. When he was about two months old I had to go to Buxton for a month's visit and decided that I could not leave Richard behind, as he needed constant feeding with little pieces of raw meat and was just old enough to miss my training and care. He was therefore to make his first start as a traveller, in a small cage, papered round the sides, the top being left open for light and air. He was wonderfully brave and good, very observant of everything, and if scared a word from me would reassure him, until at last even an express train dashing past did not make him start. It was very amusing to see the attention bestowed upon him atp. 28 the various stations where we had to get out. A little crowd would gather round and stare at such a self-possessed small bird. I was asked "if it was a very rare bird?" It seemed almost absurd to have to reply, "No, only a common starling;" but people are so accustomed to see a caged pet flutter in terror at its unusual surroundings, that my kingly Richard rather puzzled his admirers.

When we began life in our apartments, one important consideration in the day's proceedings was the starling's food. There was no home larder to fall back upon, so a daily portion of tender rump-steak had to be obtained, to the great amusement of the butcher with whom we dealt for our own joints.

About this time the plain grey plumage began to be varied by two patches of brilliant little purple feathers, tipped with greyish-white, which appeared on each side of his breast. Some began to peep out of his back and head. He moulted his tail, and had rich, dark feathers all over, in time, till he arrived at being what he was often called, "a perfect beauty"—glossy and brilliant, bronze gold and purple, with reflets of rich green, and little specksp. 29 of greyish-white all over his breast; this richness of colour, combined with his beautiful sleek shape, made Richard a very attractive bird.

When we returned from Buxton, I was so confident of the bird's tameness I used to carry him in my hand out to the tulip tree, and there I often sat and read, while Richard would pry into the moss and the bark of the tree, searching for insects, and though he could fly well by this time, he did not try to do so, but seemed content to keep near me.

One morning I heard his first articulate word, "Beauty," spoken so clearly it quite startled me. I had been diligently teaching him, by constant repetition, for many weeks, and by degrees he gained the power of speaking one word after another, till at last he was able to say, "Little beauty," "'Ow de doo?" "Pretty, pretty," "Beauty, dear," "Puss, puss," "Miaow," and imitated kissing exactly. All this was intermingled with his native whistle and sundry inarticulate sounds, intended, I suppose, to result in words and sentences some day. Whilst talking and singing, his head was held very upright, and his wings flappedp. 30 incessantly against his sides, after the manner of the wild birds.

Nothing stirred my indignation more keenly than the question so often asked, "Have you had your starling's tongue slit to make him talk so well?" I beg emphatically to entreat all my readers to do their utmost to put an end to this cruel and perfectly useless custom. My bird's talking powers were remarkable, but they were the result of his intelligence being drawn out and cultivated by constant, loving care, attention to his little wants, and being talked to and played with, and made into a little feathered friend of the family.

Now must be told an episode which cost me no little heartache. Richard was out in my room one morning as usual, when the room door happening to be open, away he flew into the next room, and out at an open window into the garden. I saw him alight on a tree, but by the time I could reach the garden he had gone. I saw a group of starlings in a beech tree near by, and another set were chattering on the house roof, but there was no telling if my Richard was one of them. I called till I wasp. 31 tired, and continued to do so at intervals all day, but no wanderer appeared. His cage had been put on the lawn, but to no purpose. I feared I should never see my pet again, because I supposed he might be lured by the wild birds till he got out of hearing of any familiar voice. I confess it was hard to think of my bright young birdie starving under some hedge, for I felt sure he was too much of a gentleman from his artificial bringing-up to be able to earn his own living. All I could do was to resolve to be up very early next day, and call again and again, on the chance of his being within hearing. Before six o'clock next morning I was seeking the truant. Plenty of wild birds were about, the bright sun glancing on their sleek coats—all looking so like my pet it was impossible to distinguish him. I little knew that he was then starving and miserable under a bush in the upper part of the garden. I continued calling and seeking him until breakfast-time, and fast losing all hope of ever seeing him again. About eleven o'clock I was returning from the kitchen garden, with my hands full of fruit and flowers, when, to my intense delight, poor little Richard came slowly out from under ap. 32 laurel, and stood in the path before me, as veritable a type of a birdish prodigal son as could well be imagined.

His feathers were ruffled, his wings drooping, his whole aspect irresistibly reminded one of the Jackdaw of Rheims; and the way he sidled up to me, with half-closed eyes and drooping head, was one of the most pathetic things I ever experienced. He so plainly said, "I'm very sorry—hope you'll forgive me; won't do it again"; and certainly his mute appeal was not in vain, for down went my fruit and flowers, and with loving words I took up my lost darling, and cooed over him all sorts of affectionate rubbish until we reached home and he was restored to his cage. There his one desire was water. Poor fellow! he was nearly famished. I think another hour would have seen his end. There is no water in the garden, except in the stone vase in front of the dining-room window, and he would not have known how to find that, so he must have been twenty-eight hours without drinking anything beyond a possible drop of dew now and then. I had to feed him with great care—a little food, and very often, until he recovered ap. 33 measure of strength. He was very drooping all day, and I quite feared he might not live after all, he was so nearly starved to death. After some days, however, "Richard was himself again," and as bright and amusing as ever. I have not related the amusing characteristics of his "daily tub." His love of water was a perfect passion, and water he would have. At first he was treated to a large glass dish on the matting in the dining-room, but he sent up such a perfect fountain of spray over curtains, couch, and chairs, that the housemaid voted "that bird" a nuisance, and a better plan was devised. In the conservatory is a pool of water, with rock-work and ferns at the back, and there is a central tube where a fountain can be turned on. I made a small island of green moss a little above the water, and, placing Richard upon it, I turned the fountain on to play a delicate shower of spray over him. He was perfectly enchanted, and fluttered, turned about, and frisked, like a bird possessed. As he became accustomed to it, I began to throw handfuls of water over him, and that he did enjoy. He would cower down, and lie with his wings expanded and beak open, receiving charge afterp. 34 charge of water till quite out of breath; then he would run a few paces away on his island till he recovered himself, and then would go back and place himself ready for a renewed douche. I never saw such a plucky bird. If I had been trying to drown him I could not have done more, for sometimes he was knocked backwards into the pool; but no matter, he was up again, and all ready in a minute. He generally tired me out, and when I turned off the fountain, he would either fly or run after me into the drawing-room and go into his cage, which always stood there; and there followed a very careful toilette—a general oiling and pluming and fluttering, until his bonnie little feathers were all in good order; and then would follow endless chatter, and he would inform the world that he was a "little beauty," "pretty little dear," &c.

Starlings seem to have an abundant supply of natural oil in the gland where it is stored, for his feathers were never really much wetted by his tremendous baths, and he was a slippery fellow to hold, his plumage was so glossy and sleek.

A word must be said about his temper; it wasp. 35 decidedly not meek by any means, and his will was strong, so the least thing would bring a shower of pecks in token of disapproval, and if scolded his attitude was most absurd; he would draw himself up to a wonderful height, set up his crest feathers, and stand ready to meet all comers, like a little fighting cock; and when a finger was pointed at him he would scold and peck, and flap with his wings with the utmost fury; and yet if a kind word was said all his wrath vanished, and he would come on your hand and prize your fingers apart, looking for grubs as usual. It seemed strange that his habit of thus searching for insects everywhere should continue, though he was never by any chance rewarded by finding one. A starling's range of ideas may be summed up in the word "Grubs." It was always immensely amusing to strangers to see Richard, when out in the room, searching with his inquisitive beak in the most hopeless places with a cheerful happy activity, as if he always felt sure that long-looked-for grub, for which he had searched all the years of his life, must be close by, round the corners somewhere, under the penwiper, behind that book, amongstp. 36 these coloured silks; and if interfered with he would give a peck and a chirp, as much as to say, "Do let me alone, I'm busy; I've got my living to get, and grubs seem scarce." Richard was the only bird I have ever had who learnt the nature of windows, he never flew against them; he had one or two severe concussions, and being a very sensible bird he "concluded" he wouldn't do it again; he would fly backwards and forwards in the drawing-room in swift flight, but I never feared either the windows or the fire, as he avoided both.

Several times Master Richard was found flying about in the drawing-room, and yet no one had let him out; we could only suppose that by some mischance the door must have been left open; yet we all felt morally certain it had been fastened properly, and there was much puzzlement about the matter.

However, the mystery was soon solved by my watching Richard's proceedings. I heard a prolonged hammering and found he was at work upon the hasp of his cage door. He managed to raise it up higher and higher, till by a well-directed peck he sent it clear out of the loop of wire which heldp. 37 it in its place. Still the door was shut, and it required a good many more pecks to force it open, but he succeeded in time, and out he flew—delighted to find himself entirely master of the situation. Then I watched with much amusement his deliberate survey of the room.

I was ill at the time, and he first flew to greet me and talk a little; he hopped upon my hand, and holding firmly on my forefinger he went through his usual morning toilette, first an application to his oil gland, then he touched up all his plumage, drew out his wing and tail feathers, fluttered himself into shape, and when quite in order he began to examine the contents of my breakfast tray; took a little sugar, looked to see if there were any grubs under the tray cloth, peered into the cream jug, decided that he didn't like the salt, gave me two or three hard pecks to express his profound affection, and then went off on a voyage of discovery, autour de ma chambre. He squeezed himself between every ornament on the mantlepiece, flew to the drawers, and found there some grapes which were very much to his taste; so he was busy for some time helping himself. Hep. 38 visited every piece of furniture, threw down all the little items that he could lift, and, as I was reading, I did not particularly notice what he was about, until he came on a small table near my bed, and then I heard a suspicious noise, and turned to find the indefatigable bird with his beak in my ink bottle, and the sheet already plentifully bespattered with black splashes and little streams of ink trickling over the table cover; such misplaced zeal was not to be borne, so Richard had to be caged. When he was seven months old, his beak began to turn from black to yellow. The colour began to show first at the base of the beak, and it went on gradually, until in a month's time it was nearly all yellow, though it was black at the tip for some time longer. As time went on, Richard's talking powers increased; he quite upset any grave conversation that might be going on; his voice dropped at times to a sort of stage whisper, as if he wished to convey some profound secrets. "Oh, you little beauty, pretty little dear, 'ow de doo?" used to mingle most absurdly with the conversation of his elders and betters. When he could not have his bath in the conservatory, I used still p. 39 to give him his glass dish, which we used together, for he would never enjoy his ablutions without me, and I became considerably sprinkled in the process. His delight was to have a water fight, pecking at my fingers, scolding, as if in a great rage, using his claws, and all the while calling me "Dear little Dicky; beauty; pretty little dear," &c., for he had no harder words to scold with; certainly the effect was most comical. When he supposed he had gained the victory, he would settle down to a regular bathe, fluttering and taking headers until he was dripping wet and delightfully happy, and the next thing would be to perch on one's chair, and shake a regular shower of drops over one's books or work.

Richard was not, as a rule, at all frightened by noises, or by being carried about in his cage in strange places, but early one morning, when he was out in my room, he flew away from the window with a piercing scream of terror, and hid himself quite in the dark, behind my pillow, shivering with fright, as if he felt his last hour had come. We found out, when this had occurred several times, that his bête noire was a great heron, whichp. 40 used occasionally to leave the lake, and circle round the house, high up in the air. It could only have been by pure instinct that Richard was inspired with such terror whenever he saw the great winged bird, and it showed that artificial training, though it develops additional powers and habits, in no way interferes with natural instinct.

The starling has a remarkably active brain; its quickness of movement, swift flight, and never-tiring activity, all show the working of its inner mind; but more than that, it seems to be capable of something akin to reasoning. Richard sometimes dropped a piece of meat on his sanded floor, and I have often seen him take it up and well rinse it in his water, till the sand was cleansed away, and then he would swallow it; and a dry piece of meat he would moisten in the same way. Now this involved a good deal of mental intuition, and I often wondered whether he found out that water would remove the sand by accident, or by a process of thought; in either case, it showed cleverness and adaptability. So also with the processes of opening the door of his cage. He had first to prize up the latch with his beak to a certain height,p. 41 and then by sudden sharp pecks send it clear of the hasp; then descend to the floor, and by straight pecks send the door open. If he could not get the door to open thus, he understood at once that the latch was not clear of the hasp, so he went back to his perch and pecked at it until he saw it fall down, and then he knew all was right.

When the second summer of Richard's life came round, some young starlings were obtained, as we much wished to rear a hen as a mate for Richard in the following year. These birds were placed in a cage in the same room with him, as we hoped he would prove their tutor, and save us the trouble of teaching them. But no; Richard evidently felt profoundly jealous of these intruders, and day after day remained perfectly dumb and out of temper. This went on for a week, and then fearing he might lose his talking powers, I was obliged to remove them and pay special attention to him, to soothe his ruffled feelings. He did not begin to talk until more than a week had passed by, evidently resolving to mark in this way his extreme displeasure at others being admitted top. 42 share our friendship—a curious instance of innate jealousy in a bird's mind.

For more than five years Richard was a source of constant pleasure and amusement, and was so much a part of my home-life that when anything unusual happened, in the way of a garden-party or a change in daily events from any cause, one's first thought was to provide for his comfort being undisturbed. I confess I dreaded the thought of his growing old, and could not bear to look on to the time when I must learn to do without his sweet, cheering little voice and pleasant companionship. Alas! that time has come, and I must now tell how the little life was quenched.

In a room to which he had access, there was a small aquarium half-full of water thickly covered with pond-weed. I had left Richard to have his usual bath whilst I went down to breakfast, and when I returned I could nowhere find my pet. His usual bath was unused; I called and searched, and at last in the adjoining room I saw the little motionless body floating in the aquarium. The temptation had been too strong; Richard thought to have a lovely bathe, had flown down into thep. 43 water, no doubt his claws were hopelessly entangled in the weed and thus, as was the case with my former starling Dick, the intense love of bathing led to a fatal end.

The sorrow one feels for the loss of a pet so interwoven with one's life is very real; many may smile at it and call it weakness, but true lovers of animals and birds will know what a blank is felt and how intensely I shall ever regret the untimely fate of my much-loved little Richard.

NE day in early summer I found on a gravel walk a poor little unfledged birdie, sitting calmly looking up into the air, as if he hoped that some help would come to him, some pitying hand and heart have compassion upon his desolate condition.

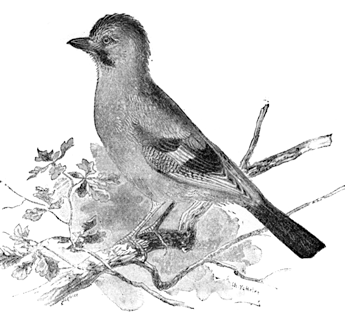

I carried him indoors, and "mothered" the little helpless thing as well as I could, by feeding him with hard-boiled yolk of egg mixed with brown bread and water. Being a hard-billed bird, I supposed that would be suitable food, and certainlyp. 45 he throve upon it. The little blue quills began to tell of coming feathers, his vigorous chirpings betokened plenty of vocal power, and in due time he grew into a young greenfinch of the most irrepressible and enterprising character. His lovely hues of green and yellow led to the name of Verdant being bestowed upon him, and his early experiences made it a somewhat suitable name.

Poor little man! he had no parents to instruct him, and he consequently got into all manner of scrapes. He only learnt the nature of windows and looking-glasses by bitter experience; flying against them with great force, he was often taken up for dead; but his solid little skull resisted all these concussions, and by pouring cold water upon his head and some down his throat, he always managed to recover. He once overbalanced into a bath, and was nearly drowned; he fell behind a wardrobe, and was nearly suffocated; later on he almost squeezed himself to death between the bars of his cage—in fact, he had endless escapes of various kinds. He was very amusing in his early youth. Whilst I was dressing he wouldp. 46 delight in picking up my scissors, pins, buttonhook, and anything else he could lift, and would carry them to the edge of the dressing-table and throw them down, turning his sly little head to see where they had fallen. He delighted in mischief, and was ever on the watch to carry off or misplace things; and yet he was a winning little pet, fearless in his confidence, perching on one's head or shoulder, and hindering all dressing operations by calmly placing his little body in the way, regardless of consequences.

He lived in his cage during the day, and next to him, on the same table, lived a bullfinch—a very handsome bird, but heavy and lethargic to a degree; he sang exquisitely, and for that gift I suppose Verdant admired him, for his delight was to be as near him as possible. Perched on the top of his cage, he gazed down at his friend, and in great measure imitated his singing. Bully, on the contrary, hated Verdant, and would have nothing to do with him. The two characters were a great source of amusement to us.

Verdant was always let out at meal-times to fly about and enjoy his liberty, and I am sorry to sayp. 47 he was always on the look-out for any mischief that might be possible. Bully's water-jar was fastened outside by a small pin; this Verdant discovered was movable, and before long we were startled by the fall of the said water-jar, the greenfinch having pulled out the pin; he then began upon the seed-box, and that also fell, to his great delight; he was then talked to and scolded, and up went his pretty yellow wings with angry flappings, and his open beak scolded back again in the most hardened manner. He was greatly interested in watching the numerous birds frequenting a basket filled with fat which hung outside the window, and he would swing backwards and forwards on the tassel of the blind, chirping to the outsiders, and watching all their little squabbles. Sunflower seeds were his greatest dainty; he would perch upon the hand to receive one, or if it were held between the lips he would flutter and poise upon the wing to take it. A sort of swing with a chain and movable wheel was provided, upon which Verdant soon learned to perch and swing, whilst he amused himself by pecking at the chain till he disengaged the sunflower seeds I hadp. 48 fixed in the links. When he was more than a year old, and I thought he might be depended upon, I tried the rather anxious experiment of letting him out of doors. He soon became quietly happy, investigating the wonders of tree branches, inquiring into the taste of leaves and all kind of novelties, when two or three sparrows flew at him and scared him considerably. Away he went, followed by the sparrows, and I began to repent my experiment, and feared he might go beyond my ken and lose himself. He was out nearly an hour, but at last he returned and went quietly into his cage. It seemed strange that the wild birds should so soon discover that he was not one of their clique, but I suppose Verdant revealed the secret by looking frightened, and the others could not resist the fun of chasing him. For more than a year and a half my birdie was a constant pleasure. Whenever he entered the dining-room my first act was to open Verdant's cage, when he would always fly to the bullfinch's cage and greet him with a chirp, then look to see if his friend had any provender that he could get at—a piece of lettuce between the bars, or a spray of millet to which he could helpp. 49 himself; no matter that Bully remonstrated with open beak, Verdant calmly feasted on stolen goods con gusto, and then scouted around for any dainties on the carpet, where he sometimes found a stray sunflower seed, always his greatest delight. After his summer moulting he became wonderfully vigorous, and would fly round the room with such velocity that I often felt afraid he might some day fly against the plate-glass windows and injure himself.

That mournful day came at last! He had been out as usual at breakfast-time, came on my finger for a seed, had his bath, and went on the little swing for more seeds, and flew about with all his joyous life and vigour. We had only left the room for a few moments, when, on returning, the dear little bird lay dead beneath the window, against which he had flown with such force as to break his neck and cause instant death.

The sorrow of that moment will never be forgotten; indeed, I cannot even now think of my little pet with undimmed eyes—he was a moment before so full of life and beauty, so fearless, such a "sonsie" little fellow; and then to hold the littlep. 50 golden green body in my hand and watch the fast-glazing eye, and think that I should never again have my cheery little friend to greet me and be glad at my coming, was one of those sharp pangs that true lovers of nature alone can understand. From all such I know I shall have sympathy in the tragic death of my much-loved little Verdant.

HEN our grass was being cut the

mowers came upon a wild duck's

nest containing eight eggs; they

were carried whilst still warm and

placed under a sitting hen; in a

week's time she brought out eight

fluffy little ducklings, which were

placed with her under a coop in the farmyard. I

paid them a visit the next day, but, alas! I saw

four little corpses lying about in the grass, the

remaining four were chirping piteously, and the henp. 52

was in despair at being unable to comfort her

uncanny children. Evidently their diet was in

fault; I thought I would take them in hand, and

therefore had the coop brought round to the

garden, and placed under the drooping boughs of a

deodar near the drawing-room window, where I

could watch over them.

I gave the wee birdies a pan of water, and placed in it some finely-shred lettuce, with grits and brown bread crumbs, not forgetting suitable food for the poor distracted hen. It was charming to hear the little happy twitterings of the downy babes, how they gobbled and sputtered and talked to each other over their repast, swimming to and fro as if they had been ducks of mature age and experience, instead of mere yellow fluffs of a day old; and, finally, they seemed to remember they had a warm, comfortable mother somewhere, and sought refuge under her kindly wings, where I left them exchanging confidences in little drowsy chirps.

I found it needful to guard my little brood with fine wire-work, for some carrion crows kept hovering near, and a weasel was constantly on the watch to carry them off; but these enemies werep. 53 successfully baffled, and three of the ducks survived all dangers and grew to beautiful maturity, the fourth having died in infancy from an accidental peck from the hen. In rearing all wild creatures the great thing is to study and imitate, as nearly as possible, their natural surroundings, and especially their diet. Chopped lettuce and worms made a fair substitute for their natural food, but the jubilation that went on when a mass of water-weed, full of insects, water snails, &c., was brought them, showed that they knew by instinct what suited them best. With constant care and attention they grew very tame, and would eat out of one's hand, and when let out of the coop would follow me to a certain heap of dead leaves where worms abounded, and there, with the most amusing eagerness, they pounced upon their wriggling prey, snatching the worms out of each other's beak, and tumbling over one another in their excitement, all the while making a special chirp of exceeding happiness.

They were named Tiny, Sir Francis Drake, and Luther—I fear the last name had a covert allusion to the "Diet of Worms."

When the purple feathers began to show in their wings, and they considered themselves quite too old to pay any allegiance to their hen-mother, they began to absent themselves for some hours each afternoon, and this, too, in a most secret fashion, for I could never tell how they disappeared, but they returned in due time, walking quietly in Indian file, and lay down in their coop. At last I traced them to a pond a long distance off—it really seemed as if they had scented the water, for they had to traverse a lawn and wood, go across a drive, and through a hedge and field, and then the pond was in a hollow where they could not possibly have seen it; but there I found my little friends in high glee, darting over the surface of the water, splashing, diving, sending up showers of spray from their wings, and going on as if they were possessed. I called to them, and in a moment they quieted down, and behaved exactly as children would have done when caught tripping—they came out of the water and followed me, in the meekest and most penitent manner, back to their home under the deodar.

These birds would stay the whole morning with me in perfect content if they were allowed top. 55 nestle into a wool mat placed at the doorstep of the French window leading out upon the lawn; there they would plume themselves and sometimes preen each other, and I could watch the way in which the feathers were drawn through the apparently awkward bill, yet I suppose so suited for its various uses; anyway the feathers came out from its manipulations as smooth and sleek as velvet, and when the toilet was over the head found its rest behind the wing, and profound sleep followed. Sometimes my friends would make a spring upon the sofa by my side, I fear with a view to forthcoming worms, of which they well knew I was the purveyor; and nothing could exceed the slyness of their eyes as they looked up at me and mutely suggested an expedition to that heap of leaves!

I must say I derived an immense amount of amusement from those ducks; they had such innate character of their own, quite unlike any other bird I ever came across.

I had often looked forward to the time when they would take to their wings and come down upon the lawn from aerial heights with a grand fuss andp. 56 fluttering of wings, but that desire they never gratified. The day came at last when I saw them circling high up in the air, so high that they were mere specks in the sky, but where they alighted I never could find out. They always re-appeared, walking solemnly (the little hypocrites!) one after the other, as if they had been doing nothing in particular, and were now coming in exemplary fashion to be fed. I believe it is very rarely the case that wild ducks, however they may appear domesticated, will remain all the year through with those who have reared them, and really take their place in the poultry-yard with the other inmates. Still it has been known, and I will subjoin an account given me by a friend, which goes to prove that such a state of things is possible. My friend gave me in substance the following account of her wild ducks:—

"There are different kinds of wild ducks; these are mallards. The first we had were hatched by hens. They feed with the other ducks, but show a decided preference for Indian corn. They are very troublesome about laying, often leaving their eggs exposed, where the crows find them and carry themp. 57 off. We gather most of them we find, to take care of them (though the ducks lay in different places each time their nest is robbed) until there are preparations for sitting, when, if we have been fortunate enough to discover the fact, we add a number of the previously gathered eggs.

"The sitting duck comes for food every two or three days, and that is all we see of her for some time, until at length she may be seen coming through the meadow, the half-grown mowing grass behind her trembling and waving in an unusual manner: by-and-by, the road or shorter grass is reached, when it is found the proud mother is bringing home her little fluffy family of perhaps eight to eleven darkie ducklings—quick, active, tiny things that refuse at first all friendly advances, but becoming accustomed to their surroundings soon behave much in the manner of their elders. There are dreadful fights on the pond when two or more little families arrive about the same time, the mother of one flock tyrannizing over the members of another, and thus causing many deaths. They often fly away, but they always come back again. All through the winter they go under cover withp. 58 the other ducks, but when spring comes they are not to be found at night; nevertheless they are sure to be ready for breakfast next morning."

I confess I always had a faint hope that my ducks might stay with me, or at any rate return from time to time, but their wild nature prevailed, and they finally left; only Luther reappeared alone one day and took his last "diet" from my hand; but there was a look in his pretty blue eye which said plainly, "You will never see me again," and he had his final caress and departed "to fresh woods and pastures new."

Y Jay was taken from the parent nest, built on the stem of an ivy-covered tree which had been blown down in the winter. A young jay is a curious-looking creature: the exquisite blue wing feathers begin to show before the others are more than quills; the eyes are large and bright blue, and when the great beak opens it shows a large throat of deepest carmine, so that it possesses the beauty of colourp. 60 from its earliest days, and when full grown and in fine plumage it is one of the handsomest of our birds. In its babyhood my jay was much like other young things of his kind, always clamouring for food, and seeming to care for little else, but as he grew up he attached himself to me with a wonderful strength of affection which entirely reversed this order of things, for whenever I came into the room he was restless and unhappy until I came near enough for him to feed me, he would look carefully into his food-trough, and at last select what he thought the most tempting morsel, and then put it through the bars of his cage into my mouth. He would sometimes feed other people, but as a rule he disliked strangers, and I have known him even take water in his beak and squirt it at those who displeased him. On the whole, a jay is not a very desirable pet; he is restless in a cage, and too large to be quite convenient when loose in a room; again, his great timidity is a drawback—the least noise, the sight of a cat or dog, puts him in a nervous fright, and he flutters about with anxious notes of alarm. He is p. 61 seen to best advantage hopping about on a lawn,

where he may be attracted by acorns being strewn in winter and spring. It is a pity that his marauding habits in game preserves lead to his being so ruthlessly shot by gamekeepers till it is almost a rare sight to see the handsome bird and hear his note of alarm in the woods. One morning I saw a jay on the lawn near the house, and rather wondering as to what he was seeking, in a minute or two I saw him pounce upon a young half-fledged bird and carry it off in his beak, a helpless little baby wing fluttering in the air as he flew away. Their sight is wonderfully keen, and their cunning is amusing to watch as they steal by careful steps nearer and nearer to their prey, and at last by a sudden dart secure it and make off in rapid flight.

After a year or two my poor jay met with a very sad fate. A garden-party was to take place, and knowing the jay's terror of any unusual noise or upstir, I carried his cage to a quiet room where I hoped he would be quite happy and hear nothing.

I, however, did not happen to notice that, later on, the band had established their quarters near this room, and I suppose the unwonted soundsp. 64 drove the poor bird into a wild state of terror, and that in his flutterings he had caught his leg in the bars of the cage; anyway, I went up about the middle of the party to see how my pet was faring, when I found him in utter misery clinging to the bars, his thigh dislocated and his leg hopelessly broken. It was a mournful duty to carry him away to merciful hands that would end his torture by an instant death. For many a day I missed that bright, handsome birdie who had always a welcome for me and the offer of such hospitality as his cage afforded.

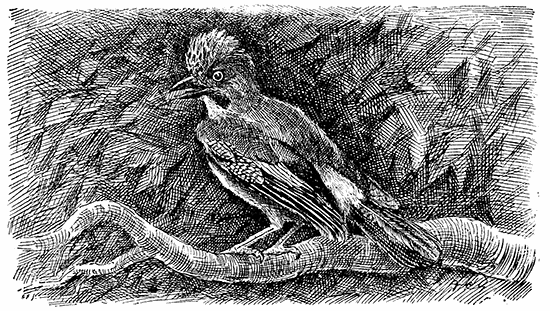

OOKING out of my window before six o'clock one bright morning in early summer, I chanced to see a large bird sitting quietly on the gravel walk. Its feathers were ruffled as if it felt cold and miserable, and its drooping head told a tale of unhappiness from some cause or other. Whilst I was watching it, a little bird darted with all its force against the larger one, and made it roll over on the path; it slowly rose up again, but in another minute a bird from the other side flew against it and again rolled it over. Such conduct could notp. 68 be tolerated, so, dressing quickly, I went out, and picking up the strange bird I found it was a young cuckoo nearly starved to death, having, as I supposed, lost its foster-parents. The bird was in beautiful plumage, except down the front of its throat, where the repeated attacks of the small birds in showing their usual enmity towards the cuckoo, had stripped off the feathers. The poor bird was only skin and bone, nearly dying from lack of food and persecution, and made no resistance when I brought him in to see if I could act the part of foster-mother. Finely-mixed raw meat and brown bread seemed to me the best substitute for his insect diet—but he was an awkward baby to feed—though sinking for want of nourishment he would not open his great beak, and every half-hour he had to be fed sorely against his will with many flapping of his wings and other protests of his bird nature. He would not stay quiet in any sort of cage, but when allowed to perch on the rim of a large basket quite free, he remained happily enough by the hour together. After a few days he grew into a vigorous, active bird, flying round the room, and too wild to be retained with safetyp. 69 He was therefore let loose, and soon flew quite out of sight. I should hope he was quite able to support himself by his own exertions. I must say he showed no gratitude for my benevolent succour in his time of need.

INCE the love of animal and bird pets seems so universal, both amongst rich and poor, it is well that the desire to keep creatures in captivity should be wisely directed, and that young people especially should be led to think of the things that are requisite to make their pets live and prosper in some degree of happiness.

I have often been consulted by some sweet, impulsive child about its "pet robin" or "dear little swallow," as to why it did not seem to eat or feel happy? and have found the poor victims quietly starving to death on a diet of oats, canarysp. 71 seed, or even green leaves, the infant mind not feeling quite sure what the "pretty birdies" lived upon.

It is needless to say we might as well try to keep a bird on pebbles as give hard grain to a soft-billed insect-eating bird; but this kind of cruelty is constantly practised simply from ignorance. I would therefore endeavour to give a few general rules for the guidance of those who have a new pet of some kind, which they wish to domesticate and tame.

To begin with animals; suitable food, a comfortable home, means of cleanliness, and exercise are essential to their health and comfort. These four requisites are seldom fully attended to. Often a large dog is kept in a back yard in London chained up week after week—kept alive, it is true, by food and water, but without exercise, and with no means of ridding himself of dirt and insects by a plunge now and then into a pond or river. No wonder his piteous howls disturb the neighbours, and he is spoken of as "that horrid dog!" as if it was his fault poor fellow! that he feels miserable and uses his only language of complaint.

One would suggest, it is better not to keep suchp. 72 a dog in a confined space in town, but if he is to be retained he should have one or two daily scampers for exercise, the opportunity of bathing, if he is a water-dog, plenty of fresh water, dog-biscuits, and a few bones twice a day, and a clean house and straw for bedding.

I would call attention to the piece of solid brimstone so persistently put into dogs' water pans. It is placed there with the best intention, but is utterly useless, seeing it is a perfectly insoluble substance, but a small teaspoonful of powdered brimstone mixed now and then with the water would be lapped up when the animal drinks, and would tend to keep his skin and coat in good condition.

Different animals need treating according to their nature and requirements, and surely it is well to try and find out from some of the many charming books on natural history all the information which is needed to make the new pet happy in its captivity. It is both useless and cruel to try to keep and tame newly caught, full-grown English birds. After being used to their joyous life amongst tree branches, in happy fellowship withp. 73 others of their own kind, living on food of their own selection, it is hardly likely they can be reconciled to the narrow limits of a cage and the dreariness of a solitary life; it is far better not to attempt keeping them, for what pleasure can there be in seeing the incessant flutterings of a miserable little creature that we know is breaking its heart in longings for liberty, and though it may linger a while is sure to die at last of starvation and sorrow. No, the only way to enjoy friendships with full-grown birds is to tame them by food and kindness, till such a tie of love is formed that they will come into our houses and give us their sweet company willingly.

No cruelty of any kind whatever should be tolerated for a moment in our treatment of the tender dumb creatures our Heavenly Father has given us to be a solace and joy during our life on earth.

The taming of pets requires a good many different qualities—much patience, a very quiet manner, and a cheery way of talking to the little creatures we desire to win into friendship with us; it is wonderful how that prevents needless terrors.

There are no secrets that I am aware of in taming anything, but love and gentleness. Directly a bird flutters, one must stop and speak kindly; the human voice has wonderful power over all animated nature, and then try to see what is the cause of alarm, and remove it if possible. In entering a room where your pet is, always speak to it, and by the time you have led it to give an answering chirp, the taming will go on rapidly, because there is an understanding between you, and the little lonely bird feels it has a friend, and takes you instead of its feathered companions, and begins to delight in your company.

A person going silently to a cage and dragging out the bottom tray will frighten any bird into flutterings of alarm, which effectually hinders any taming going on; but approach gently, talking to the bird by name, pull the tray quietly a little way, and then stop and speak, and so draw it out by degrees and the thing is done, and no fright experienced. A better way still is to have a second cage, and let birdie hop into that while you clean the other, and then it is amusing to see the pleasure and curiosity shown on his return whenp. 75 he finds fresh seed, pure water, and some dainty green food supplied; the loud chirpings tell of great delight and satisfaction, and the dreaded process is at last looked forward to as a time of recreation. It is much best that one person only should attend to the needs of a pet; indeed, I doubt if taming can ever go on satisfactorily unless this rule is observed; a bird is perplexed and scared if plans are changed, and, not knowing what is required of him, he grows flurried, and the training of weeks past may be undone in a single day.

Only those who have tried to educate birds can have any idea of the way in which their little minds will respond to affectionate treatment shown in a sensible way. They have a language of their own which we must set ourselves to learn if we would be en rapport with them. Their different chirpings each mean something, and a little observation will soon show what it is; for instance, my canary fairly shrieks when she sees lettuce on the breakfast-table, and her grateful note of thanks when it is bestowed upon her is of quite a different character. So also is her tender little sound ofp. 76 rejoicing when I give her some broken egg-shell; she seems to value it immensely, and chirps to me with a great piece of it in her bill, quite regardless of good manners. I often think with pain how much birds must suffer when hour after hour they call and chirp and entreat for something they want, which they can see and long for, and yet the dull-minded human beings they live with pay no heed to them, food and water are given, but, in many cases, nothing more all day long, not even a little chickweed or groundsel, or the much-needed egg-shell to supply strength to their little bones. A bright word or two for birdie now and then, and a few friendly chirps as we enter the room, would do much to cheer the little prisoner's life, and would soon bring a charming response in fluttering wings and evident pleasure at our return.

This state of things cannot be attained in a day or a month; it is only by persistent kindness, exercised patiently, until the little heart is won to a perfect trust in you as a true friend.

Birds can easily be trained to come out for their daily bath, and then go back to their cage of their own accord, but it needs patience at first.p. 77 The bird must never be caught by the hand or driven about, but if the cage is put on the floor with some nice food in it, and the bird is called and gently guided to it, though it may take an hour to do it the first time, it will at last hop in, and then the door may be very quietly shut. Next time he will know what you wish and will be much more amenable, until at last it will be the regular thing to go home when the bath is over.

I would condemn the practice of making birds draw up their own water; they are never free to satisfy their thirst without toilsome effort, and are much more liable to accident when chained to an open board than when kept in a cage. It is also sad to know that dozens of birds are starved to death or die of thirst whilst being taught this trick—frequently but one out of many is found to have the aptitude to learn it.

It is a great help if some specially favourite food can be discovered by which the pet creature can be rewarded for good conduct. I never take away food or water to induce obedience by privation—a practice which I fear is often resorted to in trainingp. 78 creatures for public exhibition—but an additional dainty I much enjoy to bestow, as a means of winning what is at first, it is true, merely cupboard love, but it soon grows into something far deeper, a lifelong friendship, quite apart from the food question.

Cleanliness is a very important item in a bird's happiness. Whilst kept in a cage with but little sand and an outside water-glass which affords no means of washing its feathers, a bird is apt to become infested with insects; it is tormented by them day and night, and having no means of ridding itself of them, it grows thin and mopy, and at last dies a miserable death.

There should be a bath supplied daily, suited to the size of the bird, and so planned that the cage itself may not get wet, else it may give the bird cramp to have to sit on a damp perch or floor. When its feathers are dry, some insect powder may be carefully dusted under the bird's wings, at the back of his head, where parasites are especially apt to congregate, and all over the body, only taking care that the powder may not get into the bird's eyes. The cage itself should be well washed with p. 79 carbolic soap and water, all the corners scrubbed with a small brush; and, when dry, it might be sponged with carbolic lotion over the wire-work to kill any insects which may yet remain.

MONGST all the different birds which are kept in cages, either for their beauty or song, there is one which to my mind far excels all others, not only in its vocal powers, which are remarkable, but for its very unusual intelligence. I refer to the Virginian nightingale. It is a handsome, crimson plumaged bird, rather smaller than a starling, not unfrequently seen in bird-sellers' collections, but seen there to the worst possible advantage, for, being extremely shy and sensitive, and taking keen notice of everythingp. 81 around, the slightest voice or movement in the shop will make it flutter against the bars of its cage in an agony of fright, and it therefore looks a most unlikely bird to become an interesting pet; but I will try to show what may be done by gentle kindness to overcome this natural timidity. This will be seen in the history of Birdie, my first Virginian nightingale, my daily companion for fourteen years.

He had belonged to a relative, and there was no way of tracing the age of the bird when first obtained; I can therefore only speak of those years in which he was in my possession. Birdie had been accustomed to live in a cage on a high shelf in the kitchen, well cared for, no doubt, but, untamed and unnoticed, he led a lonely life, and was one of the wildest birds I ever met with. For many months his flutterings, when any one came near his cage, could not be calmed, but by always speaking to him when entering the room, and if possible giving him a few hemp-seeds or any little dainty, he grew to endure one's presence; then, later on, he would begin to greet one with a little clicking note, though still retreating to the furthestp. 82 corner of the cage, and a year or two passed by before he would take anything out of my hand, but this was attained by offering him his one irresistible temptation, i.e., a lively spider; this he would seize and hold in his beak while he hopped about the cage, clicking loudly with delight. After a time I began to let him out for an hour or two, first releasing him when he was moulting and could not fly very easily. He learned to go back to his cage of his own accord, and was rewarded by always finding some favourite morsel there. Thus, by slow degrees, he lost all fear, and attached himself to me with a strength of affection that expressed itself in many endearing little ways. When called by name he would always answer with a special chirp and look up expectantly, either to receive something or to be let out. His song was very similar to the English nightingale, extremely liquid and melodious, with the same "jug-jug," but more powerful and sustained. On my return to the room after a short absence he would greet me with delight, fluttering his outspread wings and singing his sweetest song, looking intently at me, swaying his head from side top. 83 side, and whilst this ecstasy of song lasted he would even refuse to notice his most favourite food, as if he must express his joy before appetite could be gratified. After a few years he seemed to adopt me as a kind of mate! for as spring came round he endeavoured to construct a nest by stealing little twigs out of the grate and flying with them to a chosen retreat behind an ornamental scroll at the top of the looking-glass. He spent a great deal of time fussing about this nest, which never came to anything, but he very obligingly attended to my supposed wants by picking up an occasional fly, or piece of sugar, and, hovering before me on the wing, would endeavour to put it into my mouth; or, if he was in his cage, would mince up a spider or caterpillar with water, and then, with his beak full of the delicious compound, would call and chirp unceasingly until I came near and "made believe" to taste it, and not till then would he be content to enjoy it himself.

During an absence from home, Birdie once escaped out of doors, and was seen on the roof of the house singing in high glee; the servants called him, the cage was put out, but all to nop. 84 purpose, he evidently meant to have "a real good time," and kept flying from one tree to another until he was a quarter of a mile from home. A faithful servant kept him in sight for three hours, by which time hunger made him return to our garden, where he feasted on some raspberries, took a leisurely bath in a tub of water, and at length flew in at a bedroom window, where he was safely caged. I never knew a bird with so much intelligence, one might almost say reasoning power. He was once very thirsty after being out of his cage for many hours, and at luncheon he went to an empty silver spoon and time after time pretended to drink, looking fixedly at me as if he felt sure I should know what he meant, and waited quietly until I put water into the spoon. Another curious trait was his sense of humour. Whilst I was writing one day he went up to a rose, which was at the far end of the table, and began pecking at the leaves. I told him not to do it, when, to my surprise, he immediately ran the whole length of the table and made a scolding noise up in my face, and then, just like a naughty child, went back and did it again. He would sometimes try to teasep. 85 me away from my writing by taking hold of my pen and tugging at a corner of the paper, and whenever the terrible operation of cutting his claws had to be gone through, he quietly curled up his toes and held the scissors with his beak, so that it needed two people to circumvent his clever resistance. He had wonderfully acute vision, and would let me know directly a hawk was in sight, though it might be but the merest speck in the sky. He once had a narrow escape, for a sparrow-hawk made a swoop at him in his cage just outside the drawing-room window, and had no one been at hand would probably have dragged him through the bars. Whenever he saw a jay or magpie, a jackdaw or cat, his clicking note always told me of some enemy in sight. For many years Birdie was my cherished pet, never was there a closer friendship. As I passed his cage each night I put my hand in to stroke his feathers, and was always greeted with a low, murmuring note of affection never heard in the daytime.

It was with deep concern that I watched Birdie's declining strength; there was no disease, only weakness, and at last appetite failed, but even thenp. 86 he would take whatever I offered him and hold it in his beak as if to show that even to the last he would try to please me as far as he could, but he wanted nothing but the quiet rest which came at length, and dear little Birdie is now only a cherished memory of true friendship.

VISIT to a bird-dealer's shop always awakens a deep feeling of pity in my mind as I look at the unhappy, flutter-little captives, and think of the breezy hill-sides and pleasant lanes from which they came, to be shut up in cages a few inches square, with but little light, a stifling atmosphere, strange diet, and no means of washing their ruffled feathers or stretching their wings in flight. Truly, they are in evil case, and no wonder so many die off within a few days of their capture! In some places they are better cared for than in p. 88 others, but in most bird-shops dirt and misery seem to prevail amongst the tenants of the cages.

One such place I have often visited for the sake of meeting with live curios. The owner was a kind-hearted woman, and did not intentionally ill-treat her live-stock; but the shop was very dark and dirty, and one could but wonder how anything contrived to live in such close, stivy air. On going in one day, I nearly walked over a large, pensive-looking duckling which stood in the middle of the shop. His brother had been considered suitable for the adornment of a table-lamp with a looking-glass stand, on which a bright yellow duckling was placed, as if swimming on water; this bird, having some darker markings, was of no use for that purpose and had been allowed to live. He had a strange, old-fashioned look, and gave one the impression that he was already tired of life and felt bored. A lark on its little piece of turf, fluttering and looking up for a glimpse of blue sky; a dejected robin, with no tail to speak of, and sundry other sad-looking specimens met my pitying gaze, and I suppose I had caught their sorrowful expression, for I was startled by a sharp voice near me,p. 89 saying, "What's the matter?" I turned to reply, and found the inquiry was made by a grey parrot, who introduced himself as "Pretty Poll," and was ready to make friends to any extent. But my attention had been caught by seeing what looked like a nuthatch: only it was moping and ill, with eyes shut and feathers ruffled. I asked about it, and was told it had some injury to its foot, and was unsaleable, as the woman feared it would not live. I made a bid for it, and it was accepted. I confess I was not sorry to leave the stilling air of the shop and bring my new pet home. I fitted up a large cage with pieces of wood and tree-bark, a pan for bathing, sand, and fine gravel; a bone with a little meat upon it hung from the roof of the cage, and other suitable food was placed in a tin. The poor birdie was a pitiable object for some days; she ate now and then, but remained for the most part quite still, with closed eyes, from morning till night. Then she began to creep up and down the small tree-stem I had placed in the cage. She took a bath and plumed herself, and in less than a fortnight she became quite well and vigorous, and very amusingp. 90 in a variety of ways. Never was there a more active, busy little creature.

Her characteristic was life, so she was named "Zöe," and before long she seemed to recognize her name, and would give an answering chirp. The pieces of bark appeared to afford a never-failing interest. They were examined and investigated in every crevice. Like a little woodpecker hanging head downwards, Zöe would hammer at a nut fixed in the cracks of the bark, and would hide away unfortunate mealworms not required for immediate use.

Zöe regularly honeycombed the little tree-stem with her incessant hammering, and in the numerous holes thus made she kept her supply of food. No sooner was her tin filled with small pieces of raw meat than she began stowing them all away for future use. She seemed to exercise a good deal of thought about the matter; a morsel would be put in and out of a hole half a dozen times before it was considered settled and suitable, and then it had to be well rammed in and fixed, and off went the busy little creature to fetch another piece, and so on, till all was disposed of, andp. 91 the tin left empty. Zöe was greatly exercised by a half-opened Brazil nut: it was too large to fix into the bark, it would not keep steady while she pecked at it, and yet there were good things inside which must be obtained. I watched her various devices with great amusement. She hung head downwards from the tree-stem and hammered at it on the ground, but it shifted about, and she made no way; then she carried it in her beak and tried fitting it into various places. I hope she did not swear at it, but she seemed to think the thing was possessed, for it was not like the ordinary nuts: she could manage them; they would go into holes in the bark; this wouldn't fit anywhere, and yet she could not give it up. At last, by a bright inspiration, she got it fixed into a space between the tree-stem and the side of the cage. Now she was in high glee, and all the household might have heard the rapping that went on while she scooped out the inside and chipped off pieces to be hidden carefully away in some secret place.

Zöe had a cosy nook under a sloping piece of bark, to which she would retire at times, and sitting down on the bottom of her cage in thep. 92 shadow, looked like a little grey mouse. When appetite brought her out again, she would go to her tree-larder and pick out the choice hidden morsels, as if they were the insects which would have been her food if her lot had been cast amongst tree-branches instead of in a cage.