Title: Little Masterpieces of American Wit and Humor, Volume I

Editor: Thomas L. Masson

Release date: April 21, 2007 [eBook #21196]

Most recently updated: January 2, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Bryan Ness, Janet Blenkinship and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

| Washington Irving | Oliver Wendell Holmes | |

| Benjamin Franklin | "Josh Billings" | |

| "Mark Twain" | Charles Dudley Warner | |

| James T. Fields | Henry Ward Beecher | |

| and others | ||

Copyright, 1903, by

Doubleday, Page & Company

Published, October, 1903

This anthology of American Humor represents a process of selection that has been going on for more than fifteen years, and in giving it to the public it is perhaps well that the Editor should precede it with a few words of explanation as to its meaning and scope.

Not only all that is fairly representative of the work of our American humorists, from Washington Irving to "Mr. Dooley," has been gathered together, but also much that is merely fugitive and anecdotal. Thus, in many instances literary finish has been ignored in order that certain characteristic and purely American bits should have their place. The Editor is not unmindful of the danger of this plan. For where there is such a countless number of witticisms (so-called) as are constantly coming to the surface, and where so many of them are worthless, it must always take a rare discrimination to detect the genuine from the false. This difficulty is greatly increased by the difference of opinion that exists, even among the elect, with regard to the merit of particular jokes. To paraphrase an old adage, what is one man's laughter may be another man's dirge. The Editor desires to make it plain, however, that the responsibility in this particular instance is entirely his own. He has made his selections without consulting any one, knowing that if a consultation of experts should attempt to decide about the contents of a volume of American humor, no volume would ever be published.

The reader will doubtless recognize, in this anthology, many old friends. He may also be conscious of omissions. These omissions are due either to the restrictions of publishers, or the impossibility of obtaining original copies, or the limited space.

Acknowledgments are made herewith to the following publishers, who have kindly consented to allow the reproduction of the material designated.

F. A. Stokes & Company, New York: "A Rhyme for Priscilla," F. D. Sherman; "The Bohemians of Boston," Gelett Burgess; "A Kiss in the Rain," "Bessie Brown, M. D.," S. M. Peck.

Dodd, Mead & Company, New York: Four Extracts, E. W. Townsend ("Chimmie Fadden").

Bowen-Merrill Company, Indianapolis: "The Elf Child," "A Liz-Town Humorist," James Whitcomb Riley.

Lee & Shepard, Boston: "The Meeting of the Clabberhuses," "A Philosopher," "The Ideal Husband to His Wife," "The Prayer of Cyrus Brown," "A Modern Martyrdom," S. W. Foss; "After the Funeral," "What He Wanted It For," J. M. Bailey.

Bacheller, Johnson & Bacheller, New York: "The Composite Ghost," Marion Couthouy Smith.

D. Appleton & Company, New York: "Illustrated Newspapers," "Tushmaker's Tooth-puller," G. H. Derby ("John Phœnix").

T. B. Peterson & Company, Philadelphia: "Hans Breitmann's Party," "Ballad," C. G. Leland.

Century Company, New York: "Miss Malony on the Chinese Question," Mary Mapes Dodge; "The Origin of the Banjo," Irwin Russell; "The Walloping Window-Blind," Charles E. Carryl; "The Patriotic Tourist," "What's in a Name?" "'Tis Ever Thus," R. K. Munkittrick.

Forbes & Company, Chicago: "If I Should Die To-Night," "The Pessimist," Ben King.

J. S. Ogilvie & Company, New York: Three Short Extracts, C. B. Lewis ("Mr. Bowser").

The Chelsea Company, New York: "The Society Reporter's Christmas," "The Dying Gag," James L. Ford.

Keppler & Schwarzmann, New York: "Love Letters of Smith," H. C. Bunner.

Small, Maynard & Company, Boston: "On Gold-Seeking," "On Expert Testimony," F. P. Dunne ("Mr. Dooley"); "Tale of the Kennebec Mariner," "Grampy Sings a Song," "Cure for Homesickness," Holman F. Day.

Belford, Clarke & Company, Chicago: "A Fatal Thirst," "On Cyclones," Bill Nye.

Duquesne Distributing Company, Harmanville, Pennsylvania: "In Society," William J. Kountz, Jr. (from the bound edition of "Billy Baxter's Letters").

R. H. Russell, New York: Nonsense Verses—"Impetuous Samuel," "Misfortunes Never Come Singly," "Aunt Eliza," "Susan"; "The City as a Summer Resort," "Avarice and Generosity," "Work and Sport," "Home Life of Geniuses," F. P. Dunne ("Mr. Dooley"); "My Angeline," Harry B. Smith.

H. S. Stone & Company, Chicago: "The Preacher Who Flew His Kite." "The Fable of the Caddy," "The Two Mandolin Players," George Ade.

American Publishing Company, Hartford: "A Pleasure Excursion," "An Unmarried Female," Marietta Holley; "Colonel Sellers," "Mark Twain."

G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York: "Living in the Country," "A Glass of Water," "A Family Horse," F. S. Cozzens.

George Dillingham, New York: "Natral and Unnatral Aristocrats," "To Correspondents," "The Bumblebee," "Josh Billings"; "Among the Spirits," "The Shakers," "A. W. to His Wife," "Artemus Ward and the Prince of Wales," "A Visit to Brigham Young," "The Tower of London," "One of Mr. Ward's Business Letters," "On 'Forts,'" Artemus Ward; "At the Musicale," "At the Races," Geo. V. Hobart ("John Henry").

Thompson & Thomas, Chicago: "How to Hunt the Fox," Bill Nye.

Little, Brown & Company, Boston: "Street Scenes in Washington," Louisa May Alcott.

E. H. Bacon & Company, Boston: "A Boston Lullaby," James Jeffrey Roche.

Houghton, Mifflin & Company, Boston: "My Aunt," "The Wonderful One-hoss Shay," "Foreign Correspondence," "Music-Pounding" (extract), "The Ballad of the Oysterman," "Dislikes" (short extract), "The Height of the Ridiculous," "An Aphorism and a Lecture," O. W. Holmes; "The Yankee Recruit," "What Mr. Robinson Thinks," "The Courtin'," "A Letter from Mr. Ezekiel Bigelow," "Without and Within," J. R. Lowell; "Five Lives," "Eve's Daughter," E. R. Sill; "The Owl-Critic," "The Alarmed Skipper," James T. Fields; "My Summer in a Garden," "Plumbers," "How I Killed a Bear," C. D. Warner; "Little Breeches," John Hay; "The Stammering Wife," "Coquette," "My Familiar," "Early Rising," J. G. Saxe; "The Diamond Wedding," E. C. Stedman; "Melons," "Society Upon the Stanislaus," "The Heathen Chinee," "To the Pliocene Skull," Bret Harte; "The Total Depravity of Inanimate Things," K. K. C. Walker; "Palabras Grandiosas," Bayard Taylor; "Mrs. Johnson," William Dean Howells; "A Plea for Humor," Agnes Repplier; "The Minister's Wooing," Harriet Beecher Stowe.

In addition, the Editor desires to make his personal acknowledgments to the following authors: F. P. Dunne, Mary Mapes Dodge, Gelett Burgess, R. K. Munkittrick, E. W. Townsend, F. D. Sherman.

For such small paragraphs, anecdotes and witticisms as have been used in these volumes, acknowledgment is hereby made to the following newspapers and periodicals:

Chicago Record, Boston Globe, Texas Siftings, New Orleans Times Democrat, Providence Journal, New York Evening Sun, Atlanta Constitution, Macon Telegraph, New Haven Register, Chicago Times, Analostan Magazine, Harper's Bazaar, Florida Citizen, Saturday Evening Post, Chicago Times Herald, Washington Post, Cleveland Plain Dealer, New York Tribune, Chicago Tribune, Pittsburg Bulletin, Philadelphia Ledger, Youth's Companion, Harper's Magazine, Duluth Evening Herald, Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, Washington Times, Rochester Budget, Bangor News, Boston Herald, Pittsburg Dispatch, Christian Advocate, Troy Times, Boston Beacon, New Haven News, New York Herald, Philadelphia Call, Philadelphia News, Erie Dispatch, Town Topics, Buffalo Courier, Life, San Francisco Wave, Boston Home Journal, Puck, Washington Hatchet, Detroit Free Press, Babyhood, Philadelphia Press, Judge, New York Sun, Minneapolis Journal, San Francisco Argonaut, St. Louis Sunday Globe, Atlanta Constitution, Buffalo Courier, New York Weekly, Starlight Messenger (St Peter, Minn.).

| WASHINGTON IRVING | |

|---|---|

| Wouter Van Twiller | 1 |

| Wilhelmus Kieft | 8 |

| Peter Stuyvesant | 13 |

| Antony Van Corlear | 15 |

| General Van Poffenburgh | 18 |

| BENJAMIN FRANKLIN | |

| Maxims | 21 |

| Model of a Letter of Recommendation of a | |

| Person You Are Unacquainted with | 21 |

| Epitaph for Himself | 22 |

| WILLIAM ALLEN BUTLER | |

| Nothing to Wear | 24 |

| HENRY WARD BEECHER | |

| Deacon Marble | 39 |

| The Deacon's Trout | 41 |

| The Dog Noble and the Empty Hole | 43 |

| ALBERT GORTON GREENE | |

| Old Grimes | 45 |

| OLIVER WENDELL HOLMES | |

| My Aunt | 49 |

| The Deacon's Masterpiece; or, the Wonderful | |

| "One-hoss Shay" | 63 |

| Foreign Correspondence | 106 |

| Music-Pounding | 109 |

| The Ballad of the Oysterman | 142 |

| NATHANIEL PARKER WILLIS | |

| Miss Albina McLush | 51 |

| Love in a Cottage | 125 |

| WILLIAM PITT PALMER | |

| A Smack in School | 56 |

| B. P. SHILLABER ("Mrs. Partington") | |

| Fancy Diseases | 58 |

| Bailed Out | 59 |

| Seeking a Comet | 59 |

| Going to California | 60 |

| Mrs. Partington in Court | 61 |

| EDWARD ROWLAND SILL | |

| Five Lives | 68 |

| JAMES T. FIELDS | |

| The Owl-Critic | 70 |

| The Alarmed Skipper | 104 |

| JOHN HAY | |

| Little Breeches | 74 |

| HENRY W. SHAW ("Josh Billings") | |

| Natral and Unnatral Aristokrats | 77 |

| JAMES RUSSELL LOWELL | |

| The Yankee Recruit | 81 |

| What Mr. Robinson Thinks | 170 |

| CHARLES DUDLEY WARNER | |

| My Summer in a Garden | 90 |

| FREDERICK S. COZZENS | |

| Living in the Country | 111 |

| CHARLES GODFREY LELAND | |

| Hans Breitmann's Party | 127 |

| FRANCES M. WHICHER | |

| Tim Crane and the Widow | 129 |

| JOHN GODFREY SAXE | |

| The Stammering Wife | 135 |

| ANDREW V. KELLEY ("Parmenas Mix") | |

| He Came to Pay | 139 |

| MARIETTA HOLLEY | |

| A Pleasure Exertion | 144 |

| EDMUND CLARENCE STEDMAN | |

| The Diamond Wedding | 162 |

| MISCELLANEOUS | |

| Why He Left | 23 |

| A Boy's Essay on Girls | 38 |

| Identified | 47 |

| One Better | 48 |

| A Rendition | 57 |

| A Cause for Thanks | 73 |

| Crowded | 103 |

| The Wedding Journey | 105 |

| A Case of Conscience | 126 |

| He Rose to the Occasion | 136 |

| Polite | 137 |

| Lost, Strayed or Stolen | 138 |

| A Gentle Complaint | 141 |

| Music by the Choir | 173 |

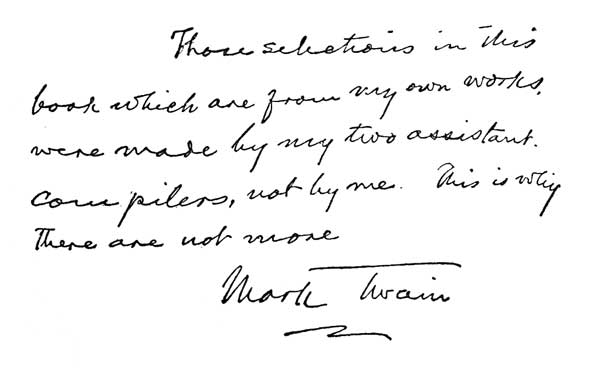

| MARK TWAIN | |

| The Notorious Jumping Frog of Calveras County | 177 |

It was in the year of our Lord 1629 that Mynheer Wouter Van Twiller was appointed Governor of the province of Nieuw Nederlandts, under the commission and control of their High Mightinesses the Lords States General of the United Netherlands, and the privileged West India Company.

This renowned old gentleman arrived at New Amsterdam in the merry month of June, the sweetest month in all the year; when dan Apollo seems to dance up the transparent firmament—when the robin, the thrush, and a thousand other wanton songsters make the woods to resound with amorous ditties, and the luxurious little bob-lincon revels among the clover blossoms of the meadows—all which happy coincidences persuaded the old dames of New Amsterdam, who were skilled in the art of foretelling events, that this was to be a happy and prosperous administration.

The renowned Wouter (or Walter) Van Twiller was descended from a long line of Dutch burgomasters, who had successively dozed away their lives and grown fat upon the bench of magistracy in Rotterdam, and who had comported themselves with such singular wisdom and[Pg 2] propriety that they were never either heard or talked of—which, next to being universally applauded, should be the object of ambition of all magistrates and rulers. There are two opposite ways by which some men make a figure in the world; one, by talking faster than they think, and the other, by holding their tongues and not thinking at all. By the first, many a smatterer acquires the reputation of a man of quick parts; by the other, many a dunderpate, like the owl, the stupidest of birds, comes to be considered the very type of wisdom. This, by the way, is a casual remark, which I would not, for the universe, have it thought I apply to Governor Van Twiller. It is true he was a man shut up within himself, like an oyster, and rarely spoke, except in monosyllables; but then it was allowed he seldom said a foolish thing. So invincible was his gravity that he was never known to laugh or even to smile through the whole course of a long and prosperous life. Nay, if a joke were uttered in his presence that set light-minded hearers in a roar, it was observed to throw him into a state of perplexity. Sometimes he would deign to inquire into the matter, and when, after much explanation, the joke was made as plain as a pike-staff, he would continue to smoke his pipe in silence, and at length, knocking out the ashes, would exclaim, "Well, I see nothing in all that to laugh about."

With all his reflective habits, he never made up his mind on a subject. His adherents ac[Pg 3]counted for this by the astonishing magnitude of his ideas. He conceived every subject on so grand a scale that he had not room in his head to turn it over and examine both sides of it. Certain it is that, if any matter were propounded to him on which ordinary mortals would rashly determine at first glance, he would put on a vague, mysterious look, shake his capacious head, smoke some time in profound silence, and at length observe that "he had his doubts about the matter"; which gained him the reputation of a man slow of belief and not easily imposed upon. What is more, it gained him a lasting name; for to this habit of the mind has been attributed his surname of Twiller; which is said to be a corruption of the original Twijfler, or, in plain English, Doubter.

The person of this illustrious old gentleman was formed and proportioned as though it had been molded by the hands of some cunning Dutch statuary, as a model of majesty and lordly grandeur. He was exactly five feet six inches in height, and six feet five inches in circumference. His head was a perfect sphere, and of such stupendous dimensions that Dame Nature, with all her sex's ingenuity, would have been puzzled to construct a neck capable of supporting it; wherefore she wisely declined the attempt, and settled it firmly on the top of his backbone, just between the shoulders. His body was oblong, and particularly capacious at bottom; which was wisely ordered by Providence[Pg 4] seeing that he was a man of sedentary habits, and very averse to the idle labor of walking. His legs were short, but sturdy in proportion to the weight they had to sustain; so that when erect he had not a little the appearance of a beer barrel on skids. His face, that infallible index of the mind, presented a vast expanse, unfurrowed by those lines and angles which disfigure the human countenance with what is termed expression. Two small gray eyes twinkled feebly in the midst, like two stars of lesser magnitude in a hazy firmament; and his full-fed cheeks, which seemed to have taken toll of everything that went into his mouth, were curiously mottled and streaked with dusky red, like a Spitzenberg apple.

His habits were as regular as his person. He daily took his four stated meals, appropriating exactly an hour to each; he smoked and doubted eight hours, and he slept the remaining twelve of the four-and-twenty. Such was the renowned Wouter Van Twillerï—a true philosopher, for his mind was either elevated above, or tranquilly settled below, the cares and perplexities of this world. He had lived in it for years, without feeling the least curiosity to know whether the sun revolved round it, or it round the sun; and he had watched for at least half a century the smoke curling from his pipe to the ceiling, without once troubling his head with any of those numerous theories by which a philosopher would have perplexed his brain,[Pg 5] in accounting for its rising above the surrounding atmosphere.

In his council he presided with great state and solemnity. He sat in a huge chair of solid oak, hewn in the celebrated forest of the Hague, fabricated by an experienced timmerman of Amsterdam, and curiously carved about the arms and feet into exact imitations of gigantic eagle's claws. Instead of a scepter, he swayed a long Turkish pipe, wrought with jasmine and amber, which had been presented to a stadtholder of Holland at the conclusion of a treaty with one of the petty Barbary powers. In this stately chair would he sit, and this magnificent pipe would he smoke, shaking his right knee with a constant motion, and fixing his eye for hours together upon a little print of Amsterdam which hung in a black frame against the opposite wall of the council chamber. Nay, it has even been said that when any deliberation of extraordinary length and intricacy was on the carpet, the renowned Wouter would shut his eyes for full two hours at a time, that he might not be disturbed by external objects; and at such times the internal commotion of his mind was evinced by certain regular guttural sounds, which his admirers declared were merely the noise of conflict made by his contending doubts and opinions.

It is with infinite difficulty I have been enabled to collect these biographical anecdotes of the great man under consideration. The facts respecting him were so scattered and vague, and[Pg 6] divers of them so questionable in point of authenticity, that I have had to give up the search after many, and decline the admission of still more, which would have tended to heighten the coloring of his portrait.

I have been the more anxious to delineate fully the person and habits of Wouter Van Twiller, from the consideration that he was not only the first but also the best Governor that ever presided over this ancient and respectable province; and so tranquil and benevolent was his reign, that I do not find throughout the whole of it a single instance of any offender being brought to punishment—a most indubitable sign of a merciful Governor, and a case unparalleled, excepting in the reign of the illustrious King Log, from whom, it is hinted, the renowned Van Twiller was a lineal descendant.

The very outset of the career of this excellent magistrate was distinguished by an example of legal acumen that gave flattering presage of a wise and equitable administration. The morning after he had been installed in office, and at the moment that he was making his breakfast from a prodigious earthen dish, filled with milk and Indian pudding, he was interrupted by the appearance of Wandle Schoonhoven, a very important old burgher of New Amsterdam, who complained bitterly of one Barent Bleecker, inasmuch as he refused to come to a settlement of accounts, seeing that there was a heavy balance in favor of the said Wandle. Governor Van[Pg 7] Twiller, as I have already observed, was a man of few words; he was likewise a mortal enemy to multiplying writings—or being disturbed at his breakfast. Having listened attentively to the statement of Wandle Schoonhoven, giving an occasional grunt, as he shoveled a spoonful of Indian pudding into his mouth—either as a sign that he relished the dish, or comprehended the story—he called unto him his constable, and pulling out of his breeches pocket a huge jack-knife, despatched it after the defendant as a summons, accompanied by his tobacco-box as a warrant.

This summary process was as effectual in those simple days as was the seal-ring of the great Haroun Alraschid among the true believers. The two parties being confronted before him, each produced a book of accounts, written in a language and character that would have puzzled any but a High-Dutch commentator or a learned decipherer of Egyptian obelisks. The sage Wouter took them one after the other, and having poised them in his hands and attentively counted over the number of leaves, fell straightway into a very great doubt, and smoked for half an hour without saying a word; at length, laying his finger beside his nose and shutting his eyes for a moment, with the air of a man who has just caught a subtle idea by the tail, he slowly took his pipe from his mouth, puffed forth a column of tobacco smoke, and with marvelous gravity and solemnity pronounced, that, having care[Pg 8]fully counted over the leaves and weighed the books, it was found that one was just as thick and as heavy as the other; therefore, it was the final opinion of the court that the accounts were equally balanced: therefore, Wandle should give Barent a receipt, and Barent should give Wandle a receipt, and the constable should pay the costs.

This decision, being straightway made known, diffused general joy throughout New Amsterdam, for the people immediately perceived that they had a very wise and equitable magistrate to rule over them. But its happiest effect was that not another lawsuit took place throughout the whole of his administration; and the office of constable fell into such decay that there was not one of those losel scouts known in the province for many years. I am the more particular in dwelling on this transaction, not only because I deem it one of the most sage and righteous judgments on record, and well worthy the attention of modern magistrates, but because it was a miraculous event in the history of the renowned Wouter—being the only time he was ever known to come to a decision in the whole course of his life.

As some sleek ox, sunk in the rich repose of a clover field, dozing and chewing the cud, will bear repeated blows before it raises itself, so the province of Nieuw Nederlandts, having waxed fat under the drowsy reign of the Doubter,[Pg 9] needed cuffs and kicks to rouse it into action. The reader will now witness the manner in which a peaceful community advances toward a state of war; which is apt to be like the approach of a horse to a drum, with much prancing and little progress, and too often with the wrong end foremost.

Wilhelmus Kieft, who in 1634 ascended the gubernatorial chair (to borrow a favorite though clumsy appellation of modern phraseologists), was of a lofty descent, his father being inspector of windmills in the ancient town of Saardam; and our hero, we are told, when a boy, made very curious investigations into the nature and operations of these machines, which was one reason why he afterward came to be so ingenious a Governor. His name, according to the most authentic etymologists, was a corruption of Kyver—that is to say, a wrangler or scolder, and expressed the characteristic of his family, which, for nearly two centuries, have kept the windy town of Saardam in hot water and produced more tartars and brimstones than any ten families in the place; and so truly did he inherit this family peculiarity, that he had not been a year in the government of the province before he was universally denominated William the Testy. His appearance answered to his name. He was a brisk, wiry, waspish little old gentleman, such a one as may now and then be seen stumping about our city in a broad-skirted coat with huge buttons, a cocked hat stuck on the back of his[Pg 10] head, and a cane as high as his chin. His face was broad, but his features were sharp; his cheeks were scorched into a dusky red by two fiery little gray eyes, his nose turned up, and the corners of his mouth turned down, pretty much like the muzzle of an irritable pug-dog.

I have heard it observed by a profound adept in human physiology, that if a woman waxes fat with the progress of years, her tenure of life is somewhat precarious, but if haply she withers as she grows old, she lives forever. Such promised to be the case with William the Testy, who grew tough in proportion as he dried. He had withered, in fact, not through the process of years, but through the tropical fervor of his soul, which burnt like a vehement rush-light in his bosom, inciting him to incessant broils and bickerings. Ancient tradition speaks much of his learning, and of the gallant inroads he had made into the dead languages, in which he had made captive a host of Greek nouns and Latin verbs, and brought off rich booty in ancient saws and apothegms, which he was wont to parade in his public harangues, as a triumphant general of yore his spolia opima. Of metaphysics he knew enough to confound all hearers and himself into the bargain. In logic he knew the whole family of syllogisms and dilemmas, and was so proud of his skill that he never suffered even a self-evident fact to pass unargued. It was observed, however, that he seldom got into an argument without getting into a perplexity, and[Pg 11] then into a passion with his adversary for not being convinced gratis.

He had, moreover, skirmished smartly on the frontiers of several of the sciences, was fond of experimental philosophy, and prided himself upon inventions of all kinds. His abode, which he had fixed at a Bowerie or country-seat at a short distance from the city, just at what is now called Dutch Street, soon abounded with proofs of his ingenuity: patent smoke-jacks that required a horse to work them; Dutch ovens that roasted meat without fire; carts that went before the horses; weathercocks that turned against the wind; and other wrong-headed contrivances that astonished and confounded all beholders. The house, too, was beset with paralytic cats and dogs, the subjects of his experimental philosophy; and the yelling and yelping of the latter unhappy victims of science, while aiding in the pursuit of knowledge, soon gained for the place the name of "Dog's Misery," by which it continues to be known even at the present day.

It is in knowledge as in swimming: he who flounders and splashes on the surface makes more noise, and attracts more attention, than the pearl-diver who quietly dives in quest of treasures to the bottom. The vast acquirements of the new Governor were the theme of marvel among the simple burghers of New Amsterdam; he figured about the place as learned a man as a Bonze at Pekin, who had mastered one-half of the Chinese[Pg 12] alphabet, and was unanimously pronounced a "universal genius!" ...

Thus end the authenticated chronicles of the reign of William the Testy; for henceforth, in the troubles, perplexities and confusion of the times, he seems to have been totally overlooked, and to have slipped forever through the fingers of scrupulous history....

It is true that certain of the early provincial poets, of whom there were great numbers in the Nieuw Nederlandts, taking advantage of his mysterious exit, have fabled that, like Romulus, he was translated to the skies, and forms a very fiery little star somewhere on the left claw of the Crab; while others, equally fanciful, declare that he had experienced a fate similar to that of the good King Arthur, who, we are assured by ancient bards, was carried away to the delicious abodes of fairy-land, where he still exists in pristine worth and vigor, and will one day or another return to restore the gallantry, the honor and the immaculate probity which prevailed in the glorious days of the Round Table.

All these, however, are but pleasing fantasies, the cobweb visions of those dreaming varlets, the poets, to which I would not have my judicious readers attach any credibility. Neither am I disposed to credit an ancient and rather apocryphal historian who asserts that the ingenious Wilhelmus was annihilated by the blowing down of one of his windmills; nor a writer of latter times, who affirms that he fell a[Pg 13] victim to an experiment in natural history, having the misfortune to break his neck from a garret window of the stadthouse in attempting to catch swallows by sprinkling salt upon their tails. Still less do I put my faith in the tradition that he perished at sea in conveying home to Holland a treasure of golden ore, discovered somewhere among the haunted regions of the Catskill Mountains.

The most probable account declares that, what with the constant troubles on his frontiers, the incessant schemings and projects going on in his own pericranium, the memorials, petitions, remonstrances and sage pieces of advice of respectable meetings of the sovereign people, and the refractory disposition of his councilors, who were sure to differ from him on every point and uniformly to be in the wrong, his mind was kept in a furnace-heat until he became as completely burnt out as a Dutch family pipe which has passed through three generations of hard smokers. In this manner did he undergo a kind of animal combustion, consuming away like a farthing rush-light; so that when grim death finally snuffed him out there was scarce left enough of him to bury.

Peter Stuyvesant was the last, and, like the renowned Wouter Van Twiller, the best of our ancient Dutch Governors, Wouter having surpassed all who preceded him, and Peter, or Piet,[Pg 14] as he was sociably called by the old Dutch burghers, who were ever prone to familiarize names, having never been equaled by any successor. He was in fact the very man fitted by nature to retrieve the desperate fortunes of her beloved province, had not the Fates, those most potent and unrelenting of all ancient spinsters, destined them to inextricable confusion.

To say merely that he was a hero would be doing him great injustice; he was in truth a combination of heroes; for he was of a sturdy, raw-boned make, like Ajax Telamon, with a pair of round shoulders that Hercules would have given his hide for (meaning his lion's hide) when he undertook to ease old Atlas of his load. He was, moreover, as Plutarch describes Coriolanus, not only terrible for the force of his arm, but likewise of his voice, which sounded as though it came out of a barrel; and, like the self-same warrior, he possessed a sovereign contempt for the sovereign people, and an iron aspect which was enough of itself to make the very bowels of his adversaries quake with terror and dismay. All this martial excellency of appearance was inexpressibly heightened by an accidental advantage, with which I am surprised that neither Homer nor Virgil have graced any of their heroes. This was nothing less than a wooden leg, which was the only prize he had gained in bravely fighting the battles of his country, but of which he was so proud that he was often heard to declare he valued it more than all his other[Pg 15] limbs put together: indeed, so highly did he esteem it that he had it gallantly enchased and relieved with silver devices, which caused it to be related in divers histories and legends that he wore a silver leg.

The very first movements of the great Peter, on taking the reins of government, displayed his magnanimity, though they occasioned not a little marvel and uneasiness among the people of the Manhattoes. Finding himself constantly interrupted by the opposition, and annoyed by the advice of his privy council, the members of which had acquired the unreasonable habit of thinking and speaking for themselves during the preceding reign, he determined at once to put a stop to such grievous abominations. Scarcely, therefore, had he entered upon his authority, than he turned out of office all the meddlesome spirits of the factious cabinet of William the Testy; in place of whom he chose unto himself counselors from those fat, somniferous, respectable burghers who had flourished and slumbered under the easy reign of Walter the Doubter. All these he caused to be furnished with abundance of fair long pipes, and to be regaled with frequent corporation dinners, admonishing them to smoke, and eat, and sleep for the good of the nation, while he took the burden of government upon his own shoulders—an arrangement to which they all gave hearty acquiescence.[Pg 16]

Nor did he stop here, but made a hideous rout among the inventions and expedients of his learned predecessor, rooting up his patent gallows, where caitiff vagabonds were suspended by the waistband; demolishing his flag-staffs and windmills, which, like mighty giants, guarded the ramparts of New Amsterdam; pitching to the duyvel whole batteries of Quaker guns; and, in a word, turning topsy-turvy the whole philosophic, economic and windmill system of the immortal sage of Saardam.

The honest folks of New Amsterdam began to quake now for the fate of their matchless champion, Antony the Trumpeter, who had acquired prodigious favor in the eyes of the women by means of his whiskers and his trumpet. Him did Peter the Headstrong cause to be brought into his presence, and eying him for a moment from head to foot, with a countenance that would have appalled anything else than a sounder of brass—"Pr'ythee, who and what art thou?" said he.

"Sire," replied the other, in no wise dismayed, "for my name, it is Antony Van Corlear; for my parentage, I am the son of my mother; for my profession, I am champion and garrison of this great city of New Amsterdam." "I doubt me much," said Peter Stuyvesant, "that thou art some scurvy costard-monger knave. How didst thou acquire this paramount honor and dignity?" "Marry, sir," replied the other, "like many a great man before me, simply by sounding my own trumpet." "Ay, is it so?"[Pg 17] quoth the Governor; "why, then, let us have a relish of thy art." Whereupon the good Antony put his instrument to his lips, and sounded a charge with such a tremendous outset, such a delectable quaver, and such a triumphant cadence, that it was enough to make one's heart leap out of one's mouth only to be within a mile of it. Like as a war-worn charger, grazing in peaceful plains, starts at a strain of martial music, pricks up his ears, and snorts, and paws, and kindles at the noise, so did the heroic Peter joy to hear the clangor of the trumpet; for of him might truly be said, what was recorded of the renowned St. George of England, "there was nothing in all the world that more rejoiced his heart than to hear the pleasant sound of war, and see the soldiers brandish forth their steeled weapons." Casting his eye more kindly, therefore, upon the sturdy Van Corlear, and finding him to be a jovial varlet, shrewd in his discourse, yet of great discretion and immeasurable wind, he straightway conceived a vast kindness for him, and discharging him from the troublesome duty of garrisoning, defending and alarming the city, ever after retained him about his person as his chief favorite, confidential envoy and trusty squire. Instead of disturbing the city with disastrous notes, he was instructed to play so as to delight the Governor while at his repasts, as did the minstrels of yore in the days of the glorious chivalry—and on all public occasions to rejoice the ears of the people with warlike[Pg 18] melody thereby keeping alive a noble and martial spirit.

It is tropically observed by honest old Socrates, that heaven infuses into some men at their birth a portion of intellectual gold, into others of intellectual silver, while others are intellectually furnished with iron and brass. Of the last class was General Van Poffenburgh; and it would seem as if dame Nature, who will sometimes be partial, had given him brass enough for a dozen ordinary braziers. All this he had contrived to pass off upon William the Testy for genuine gold; and the little Governor would sit for hours and listen to his gunpowder stories of exploits, which left those of Tirante the White, Don Belianis of Greece, or St. George and the Dragon quite in the background. Having been promoted by William Kieft to the command of his whole disposable forces, he gave importance to his station by the grandiloquence of his bulletins, always styling himself Commander-in-Chief of the Armies of the New Netherlands, though in sober truth these armies were nothing more than a handful of hen-stealing, bottle-bruising ragamuffins.

In person he was not very tall, but exceedingly round; neither did his bulk proceed from his being fat, but windy, being blown up by a prodigious conviction of his own importance, until he resembled one of those bags of wind given by Æolus, in an incredible fit of generosity, to that[Pg 19] vagabond warrior Ulysses. His windy endowments had long excited the admiration of Antony Van Corlear, who is said to have hinted more than once to William the Testy that in making Van Poffenburgh a general he had spoiled an admirable trumpeter.

As it is the practice in ancient story to give the reader a description of the arms and equipments of every noted warrior, I will bestow a word upon the dress of this redoubtable commander. It comported with his character, being so crossed and slashed, and embroidered with lace and tinsel, that he seemed to have as much brass without as nature had stored away within. He was swathed, too, in a crimson sash, of the size and texture of a fishing-net—doubtless to keep his swelling heart from bursting through his ribs. His face glowed with furnace-heat from between a huge pair of well-powdered whiskers, and his valorous soul seemed ready to bounce out of a pair of large, glassy, blinking eyes, projecting like those of a lobster.

I swear to thee, worthy reader, if history and tradition belie not this warrior, I would give all the money in my pocket to have seen him accoutred cap-á-pie—booted to the middle, sashed to the chin, collared to the ears, whiskered to the teeth, crowned with an overshadowing cocked hat, and girded with a leathern belt ten inches broad, from which trailed a falchion, of a length that I dare not mention. Thus equipped, he strutted about, as bitter-looking a man of war[Pg 20] as the far-famed More, of Morehall, when he sallied forth to slay the dragon of Wantley. For what says the ballad?

"A friend of mine," said a citizen, "asked me the other evening to go and call on some friends of his who had lost the head of the family the day previous. He had been an honest old man, a laborer with a pick and shovel. While we were with the family an old man entered who had worked by his side for years. Expressing his sorrow at the loss of his friend, and glancing about the room, he observed a large floral anchor. Scrutinizing it closely, he turned to the widow and in a low tone asked, 'Who sent the pick?'"

While Butler was delivering a speech for the Democrats in Boston during an exciting campaign, one of his hearers cried out, "How about the spoons, Ben?" Benjamin's good eye twinkled merrily as he replied: "Now, don't mention that, please. I was a Republican when I stole those spoons."[Pg 21]

Never spare the parson's wine, nor the baker's pudding.

A house without woman or firelight is like a body without soul or sprite.

Kings and bears often worry their keepers.

Light purse, heavy heart.

He's a fool that makes his doctor his heir.

Ne'er take a wife till thou hast a house (and a fire) to put her in.

To lengthen thy life, lessen thy meals.

He that drinks fast pays slow.

He is ill-clothed who is bare of virtue.

Beware of meat twice boil'd, and an old foe reconcil'd.

The heart of a fool is in his mouth, but the mouth of a wise man is in his heart.

He that is rich need not live sparingly, and he that can live sparingly need not be rich.

He that waits upon fortune is never sure of a dinner.

Sir: The bearer of this, who is going to America, presses me to give him a letter of recom[Pg 22]mendation, though I know nothing of him, not even his name. This may seem extraordinary, but I assure you it is not uncommon here. Sometimes, indeed, one unknown person brings another equally unknown, to recommend him; and sometimes they recommend one another! As to this gentleman, I must refer you to himself for his character and merits, with which he is certainly better acquainted than I can possibly be. I recommend him, however, to those civilities which every stranger, of whom one knows no harm, has a right to; and I request you will do him all the favor that, on further acquaintance, you shall find him to deserve. I have the honor to be, etc.

Mr. Dickson, a colored barber in a large New England town, was shaving one of his customers, a respectable citizen, one morning, when a conversation occurred between them respecting Mr. Dickson's former connection with a colored church in that place:

"I believe you are connected with the church in Elm Street, are you not, Mr. Dickson?" said the customer.

"No, sah, not at all."

"What! are you not a member of the African church?"

"Not dis year, sah."

"Why did you leave their communion, Mr. Dickson, if I may be permitted to ask?"

"Well, I'll tell you, sah," said Mr. Dickson, stropping a concave razor on the palm of his hand, "it was just like dis. I jined de church in good fait'; I gave ten dollars toward the stated gospil de first year, and de church people call me 'Brudder Dickson'; de second year my business not so good, and I gib only five dollars. That year the people call me 'Mr. Dickson.' Dis razor hurt you, sah?"

"No, the razor goes tolerably well."

"Well, sah, de third year I feel berry poor; had sickness in my family; I didn't gib noffin' for preachin'. Well, sah, arter dat dey call me 'dat old nigger Dickson'—and I left 'em."[Pg 24]

"Girls are very stuckup and dignefied in their manner and behaveyour. They think more of dress than anything and like to play with dowls and rags. They cry if they see a cow in afar distance and are afraid of guns. They stay at home all the time and go to Church every Sunday. They are al-ways sick. They are al-ways funy and making fun of boys hands and they say how dirty. They cant play marbles. I pity them poor things. They make fun of boys and then turn round and love them. I dont beleave they ever kiled a cat or any thing. They look out every nite and say oh ant the moon lovely. Thir is one thing I have not told and that is they al-ways now their lessons bettern boys."[Pg 39]

How they ever made a deacon out of Jerry Marble I never could imagine! His was the kindest heart that ever bubbled and ran over. He was elastic, tough, incessantly active, and a prodigious worker. He seemed never to tire, but after the longest day's toil, he sprang up the moment he had done with work, as if he were a fine steel spring. A few hours' sleep sufficed him, and he saw the morning stars the year round. His weazened face was leather color, but forever dimpling and changing to keep some sort of congruity between itself and his eyes, that winked and blinked and spilled over with merry good nature. He always seemed afflicted when obliged to be sober. He had been known to laugh in meeting on several occasions, although he ran his face behind his handkerchief, and coughed, as if that was the matter, yet nobody believed it. Once, in a hot summer day, he saw Deacon Trowbridge, a sober and fat man, of great sobriety, gradually ascending from the bodily state into that spiritual condition called sleep. He was blameless of the act. He had struggled against the temptation with the whole virtue of a deacon. He had eaten two or three heads of fennel in vain, and a piece of orange[Pg 40] peel. He had stirred himself up, and fixed his eyes on the minister with intense firmness, only to have them grow gradually narrower and milder. If he held his head up firmly, it would with a sudden lapse fall away over backward. If he leaned it a little forward, it would drop suddenly into his bosom. At each nod, recovering himself, he would nod again, with his eyes wide open, to impress upon the boys that he did it on purpose both times.

In what other painful event of life has a good man so little sympathy as when overcome with sleep in meeting time? Against the insidious seduction he arrays every conceivable resistance. He stands up awhile; he pinches himself, or pricks himself with pins. He looks up helplessly to the pulpit as if some succor might come thence. He crosses his legs uncomfortably, and attempts to recite the catechism or the multiplication table. He seizes a languid fan, which treacherously leaves him in a calm. He tries to reason, to notice the phenomena. Oh, that one could carry his pew to bed with him! What tossing wakefulness there! what fiery chase after somnolency! In his lawful bed a man cannot sleep, and in his pew he cannot keep awake! Happy man who does not sleep in church! Deacon Trowbridge was not that man. Deacon Marble was!

Deacon Marble witnessed the conflict we have sketched above, and when good Mr. Trowbridge gave his next lurch, recovering himself with a[Pg 41] snort, and then drew out a red handkerchief and blew his nose with a loud imitation, as if to let the boys know that he had not been asleep, poor Deacon Marble was brought to a sore strait. But I have reason to think that he would have weathered the stress if it had not been for a sweet-faced little boy in the front of the gallery. The lad had been innocently watching the same scene, and at its climax laughed out loud, with a frank and musical explosion, and then suddenly disappeared backward into his mother's lap. That laugh was just too much, and Deacon Marble could no more help laughing than could Deacon Trowbridge help sleeping. Nor could he conceal it. Though he coughed and put up his handkerchief and hemmed—it was a laugh—Deacon!—and every boy in the house knew it, and liked you better for it—so inexperienced were they.—Norwood.

He was a curious trout. I believe he knew Sunday just as well as Deacon Marble did. At any rate, the Deacon thought the trout meant to aggravate him. The Deacon, you know, is a little waggish. He often tells about that trout. Says he: "One Sunday morning, just as I got along by the willows, I heard an awful splash, and not ten feet from shore I saw the trout, as long as my arm, just curving over like a bow and going down with something for breakfast.[Pg 42] Gracious says I, and I almost jumped out of the wagon. But my wife Polly, says she, 'What on airth are you thinkin' of, Deacon? It's Sabbath day, and you're goin' to meetin'! It's a pretty business for a deacon!' That sort o' cooled me off. But I do say that, for about a minute, I wished I wasn't a deacon. But 'twouldn't make any difference, for I came down next day to mill on purpose, and I came down once or twice more, and nothin' was to be seen, tho' I tried him with the most temptin' things. Wal, next Sunday I came along agin, and, to save my life I couldn't keep off worldly and wanderin' thoughts. I tried to be sayin' my catechism, but I couldn't keep my eyes off the pond as we came up to the willows. I'd got along in the catechism, as smooth as the road, to the Fourth Commandment, and was sayin' it out loud for Polly, and jist as I was sayin': 'What is required in the Fourth Commandment?' I heard a splash, and there was the trout, and, afore I could think, I said: 'Gracious, Polly, I must have that trout.' She almost riz right up, 'I knew you wa'n't sayin' your catechism hearty. Is this the way you answer the question about keepin' the Lord's day? I'm ashamed, Deacon Marble,' says she. 'You'd better change your road, and go to meetin' on the road over the hill. If I was a deacon, I wouldn't let a fish's tail whisk the whole catechism out of my head;' and I had to go to meetin' on the hill road all the rest of the summer."—Norwood.[Pg 43]

The first summer which we spent in Lenox we had along a very intelligent dog, named Noble. He was learned in many things, and by his dog-lore excited the undying admiration of all the children. But there were some things which Noble could never learn. Having on one occasion seen a red squirrel run into a hole in a stone wall, he could not be persuaded that he was not there forevermore.

Several red squirrels lived close to the house, and had become familiar, but not tame. They kept up a regular romp with Noble. They would come down from the maple trees with provoking coolness; they would run along the fence almost within reach; they would cock their tails and sail across the road to the barn; and yet there was such a well-timed calculation under all this apparent rashness, that Noble invariably arrived at the critical spot just as the squirrel left it.

On one occasion Noble was so close upon his red-backed friend that, unable to get up the maple tree, the squirrel dodged into a hole in the wall, ran through the chinks, emerged at a little distance, and sprang into the tree. The intense enthusiasm of the dog at that hole can hardly be described. He filled it full of barking. He pawed and scratched as if undermining a bastion. Standing off at a little distance, he would pierce the hole with a gaze as intense and fixed as if he were trying magnetism on it. Then, with tail[Pg 44] extended, and every hair thereon electrified, he would rush at the empty hole with a prodigious onslaught.

This imaginary squirrel haunted Noble night and day. The very squirrel himself would run up before his face into the tree, and, crouched in a crotch, would sit silently watching the whole process of bombarding the empty hole, with great sobriety and relish. But Noble would allow of no doubts. His conviction that that hole had a squirrel in it continued unshaken for six weeks. When all other occupations failed, this hole remained to him. When there were no more chickens to harry, no pigs to bite, no cattle to chase, no children to romp with, no expeditions to make with the grown folks, and when he had slept all that his dogskin would hold, he would walk out of the yard, yawn and stretch himself, and then look wistfully at the hole, as if thinking to himself, "Well, as there is nothing else to do, I may as well try that hole again!"—Eyes and Ears.

N. P. Willis was usually the life of the company he happened to be in. His repartee at Mrs. Gales's dinner in Washington is famous. Mrs. Gales wrote on a card to her niece, at the other end of the table: "Don't flirt so with Nat Willis." She was herself talking vivaciously to a Mr. Campbell. Willis wrote the niece's reply:

Nathaniel Hawthorne was a kind-hearted man as well as a great novelist. While he was consul at Liverpool a young Yankee walked into his office. The boy had left home to seek his fortune, but evidently hadn't found it yet, although he had crossed the sea in his search. Homesick, friendless, nearly penniless, he wanted a passage home. The clerk said Mr. Hawthorne could not be seen, and intimated that the boy was not American, but was trying to steal a passage. The boy stuck to his point, and the clerk at last went to the little room and said to Mr. Hawthorne: "Here's a boy who insists upon seeing you. He says he is an American, but I know he isn't." Hawthorne came out of the room and looked keenly at the eager, ruddy face of the boy. "You want a passage to America?"

"Yes, sir."

"And you say you're an American?"

"Yes, sir."

"From what part of America?"

"United States, sir."

"What State?"

"New Hampshire, sir."

"Town?"

"Exeter, sir."

Hawthorne looked at him for a minute before asking him the next question. "Who sold the best apples in your town?"[Pg 48]

"Skim-milk Folsom, sir," said the boy, with glistening eye, as the old familiar by-word brought up the dear old scenes of home.

"It's all right," said Hawthorne to the clerk; "give him a passage."

Long after the victories of Washington over the French and English had made his name familiar to all Europe, Doctor Franklin chanced to dine with the English and French Ambassadors, when, as nearly as the precise words can be recollected, the following toasts were drunk:

"England'—The Sun, whose bright beams enlighten and fructify the remotest corners of the earth."

The French Ambassador, filled with national pride, but too polite to dispute the previous toast, drank the following:

"France'—The Moon, whose mild, steady and cheering rays are the delight of all nations, consoling them in darkness and making their dreariness beautiful."

Doctor Franklin then arose, and, with his usual dignified simplicity, said:

"George Washington'—The Joshua who commanded the Sun and Moon to stand still, and they obeyed him."[Pg 49]

I have a passion for fat women. If there is anything I hate in life, it is what dainty people call a spirituelle. Motion—rapid motion—a smart, quick, squirrel-like step, a pert, voluble tone—in short, a lively girl—is my exquisite horror! I would as lief have a diable petit dancing his infernal hornpipe on my cerebellum as to be in the room with one. I have tried before now to school myself into liking these parched peas of humanity. I have followed them with my eyes, and attended to their rattle till I was as crazy as a fly in a drum. I have danced with them, and romped with them in the country, and periled the salvation of my "white tights" by sitting near them at supper. I swear off from this moment. I do. I won't—no—hang me if ever I show another small, lively, spry woman a civility.

Albina McLush is divine. She is like the description of the Persian beauty by Hafiz: "Her heart is full of passion and her eyes are full of sleep." She is the sister of Lurly McLush, my old college chum, who, as early as his sophomore year, was chosen president of the Dolce far niente Society—no member of which was ever known[Pg 52] to be surprised at anything—(the college law of rising before breakfast excepted). Lurly introduced me to his sister one day, as he was lying upon a heap of turnips, leaning on his elbow with his head in his hand, in a green lane in the suburbs. He had driven over a stump, and been tossed out of his gig, and I came up just as he was wondering how in the D——l's name he got there! Albina sat quietly in the gig, and when I was presented, requested me, with a delicious drawl, to say nothing about the adventure—it would be so troublesome to relate it to everybody! I loved her from that moment. Miss McLush was tall, and her shape, of its kind, was perfect. It was not a fleshy one exactly, but she was large and full. Her skin was clear, fine-grained and transparent; her temples and forehead perfectly rounded and polished, and her lips and chin swelling into a ripe and tempting pout, like the cleft of a bursted apricot. And then her eyes—large, liquid and sleepy—they languished beneath their long black fringes as if they had no business with daylight—like two magnificent dreams, surprised in their jet embryos by some bird-nesting cherub. Oh! it was lovely to look into them!

She sat, usually, upon a fauteuil, with her large, full arm embedded in the cushion, sometimes for hours without stirring. I have seen the wind lift the masses of dark hair from her shoulders when it seemed like the coming to life of a marble Hebe—she had been motionless so[Pg 53] long. She was a model for a goddess of sleep as she sat with her eyes half closed, lifting up their superb lids slowly as you spoke to her, and dropping them again with the deliberate motion of a cloud, when she had murmured out her syllable of assent. Her figure, in a sitting posture, presented a gentle declivity from the curve of her neck to the instep of the small round foot lying on its side upon the ottoman. I remember a fellow's bringing her a plate of fruit one evening. He was one of your lively men—a horrid monster, all right angles and activity. Having never been accustomed to hold her own plate, she had not well extricated her whole fingers from her handkerchief before he set it down in her lap. As it began to slide slowly toward her feet, her hand relapsed into the muslin folds, and she fixed her eye upon it with a kind of indolent surprise, drooping her lids gradually till, as the fruit scattered over the ottoman, they closed entirely, and a liquid jet line was alone visible through the heavy lashes. There was an imperial indifference in it worthy of Juno.

Miss McLush rarely walks. When she does, it is with the deliberate majesty of a Dido. Her small, plump feet melt to the ground like snowflakes; and her figure sways to the indolent motion of her limbs with a glorious grace and yieldingness quite indescribable. She was idling slowly up the Mall one evening just at twilight, with a servant at a short distance behind her, who, to while away the time between his steps,[Pg 54] was employing himself in throwing stones at the cows feeding upon the Common. A gentleman, with a natural admiration for her splendid person, addressed her. He might have done a more eccentric thing. Without troubling herself to look at him, she turned to her servant and requested him, with a yawn of desperate ennui, to knock that fellow down! John obeyed his orders; and, as his mistress resumed her lounge, picked up a new handful of pebbles, and tossing one at the nearest cow, loitered lazily after.

Such supreme indolence was irresistible. I gave in—I—who never before could summon energy to sigh—I—to whom a declaration was but a synonym for perspiration—I—who had only thought of love as a nervous complaint, and of women but to pray for a good deliverance—I—yes—I—knocked under. Albina McLush! Thou wert too exquisitely lazy. Human sensibilities cannot hold out forever.

I found her one morning sipping her coffee at twelve, with her eyes wide open. She was just from the bath, and her complexion had a soft, dewy transparency, like the cheek of Venus rising from the sea. It was the hour, Lurly had told me, when she would be at the trouble of thinking. She put away with her dimpled forefinger, as I entered, a cluster of rich curls that had fallen over her face, and nodded to me like a water-lily swaying to the wind when its cup is full of rain.[Pg 55]

"Lady Albina," said I, in my softest tone, "how are you?"

"Bettina," said she, addressing her maid in a voice as clouded and rich as the south wind on an Æolian, "how am I to-day?"

The conversation fell into short sentences. The dialogue became a monologue. I entered upon my declaration. With the assistance of Bettina, who supplied her mistress with cologne, I kept her attention alive through the incipient circumstances. Symptoms were soon told. I came to the avowal. Her hand lay reposing on the arm of the sofa, half buried in a muslin foulard. I took it up and pressed the cool soft fingers to my lips—unforbidden. I rose and looked into her eyes for confirmation. Delicious creature! she was asleep!

I never have had courage to renew the subject. Miss McLush seems to have forgotten it altogether. Upon reflection, too, I'm convinced she would not survive the excitement of the ceremony—unless, indeed, she should sleep between the responses and the prayer. I am still devoted, however, and if there should come a war or an earthquake, or if the millennium should commence, as is expected in 18——, or if anything happens that can keep her waking so long, I shall deliver a declaration, abbreviated for me by a scholar-friend of mine, which, he warrants, may be articulated in fifteen minutes—without fatigue.[Pg 56]

Two old British sailors were talking over their shore experience. One had been to a cathedral and had heard some very fine music, and was descanting particularly upon an anthem which gave him much pleasure. His shipmate listened for awhile, and then said:

"I say, Bill, what's a hanthem?"

"What," replied Bill, "do you mean to say you don't know what a hanthem is?"

"Not me."

"Well, then, I'll tell yer. If I was to tell yer, 'Ere, Bill, give me that 'andspike,' that wouldn't be a hanthem;' but was I to say, 'Bill, Bill, giv, giv, give me, give me that, Bill, give me, give me that hand, handspike, hand, handspike, spike, spike, spike, ah-men, ahmen. Bill, givemethat-handspike, spike, ahmen!' why, that would be a hanthem."[Pg 58]

"Diseases is very various," said Mrs. Partington, as she returned from a street-door conversation with Doctor Bolus. "The Doctor tells me that poor old Mrs. Haze has got two buckles on her lungs! It is dreadful to think of, I declare. The diseases is so various! One way we hear of people's dying of hermitage of the lungs; another way, of the brown creatures; here they tell us of the elementary canal being out of order, and there about tonsors of the throat; here we hear of neurology in the head, there, of an embargo; one side of us we hear of men being killed by getting a pound of tough beef in the sarcofagus, and there another kills himself by discovering his jocular vein. Things change so that I declare I don't know how to subscribe for any diseases nowadays. New names and new nostrils takes the place of the old, and I might as well throw my old herb-bag away."

Fifteen minutes afterward Isaac had that herb-bag for a target, and broke three squares of glass in the cellar window in trying to hit it, before the old lady knew what he was about. She didn't mean exactly what she said.[Pg 59]

"So, our neighbour, Mr. Guzzle, has been arranged at the bar for drunkardice," said Mrs. Partington; and she sighed as she thought of his wife and children at home, with the cold weather close at hand, and the searching winds intruding through the chinks in the windows, and waving the tattered curtain like a banner, where the little ones stood shivering by the faint embers. "God forgive him, and pity them!" said she, in a tone of voice tremulous with emotion.

"But he was bailed out," said Ike, who had devoured the residue of the paragraph, and laid the paper in a pan of liquid custard that the dame was preparing for Thanksgiving, and sat swinging the oven door to and fro as if to fan the fire that crackled and blazed within.

"Bailed out, was he?" said she; "well, I should think it would have been cheaper to have pumped him out, for, when our cellar was filled, arter the city fathers had degraded the street, we had to have it pumped out, though there wasn't half so much in it as he has swilled down."

She paused and reached up on the high shelves of the closet for her pie plates, while Ike busied himself in tasting the various preparations. The dame thought that was the smallest quart of sweet cider she had ever seen.

It was with an anxious feeling that Mrs. Partington, having smoked her specs, directed her[Pg 60] gaze toward the western sky, in quest of the tailless comet of 1850.

"I can't see it," said she; and a shade of vexation was perceptible in the tone of her voice. "I don't think much of this explanatory system," continued she, "that they praise so, where the stars are mixed up so that I can't tell Jew Peter from Satan, nor the consternation of the Great Bear from the man in the moon. 'Tis all dark to me. I don't believe there is any comet at all. Who ever heard of a comet without a tail, I should like to know? It isn't natural; but the printers will make a tale for it fast enough, for they are always getting up comical stories."

With a complaint about the falling dew, and a slight murmur of disappointment, the dame disappeared behind a deal door like the moon behind a cloud.

"Dear me!" exclaimed Mrs. Partington sorrowfully, "how much a man will bear, and how far he will go, to get the soddered dross, as Parson Martin called it when he refused the beggar a sixpence for fear it might lead him into extravagance! Everybody is going to California and Chagrin arter gold. Cousin Jones and the three Smiths have gone; and Mr. Chip, the carpenter, has left his wife and seven children and a blessed old mother-in-law, to seek his fortin, too. This is the strangest yet, and I don't see[Pg 61] how he could have done it; it looks so ongrateful to treat Heaven's blessings so lightly. But there, we are told that the love of money is the root of all evil, and how true it is! for they are now rooting arter it, like pigs arter ground-nuts. Why, it is a perfect money mania among everybody!"

And she shook her head doubtingly, as she pensively watched a small mug of cider, with an apple in it, simmering by the winter fire. She was somewhat fond of a drink made in this way.

"I took my knitting-work and went up into the gallery," said Mrs. Partington, the day after visiting one of the city courts; "I went up into the gallery, and after I had adjusted my specs, I looked down into the room, but I couldn't see any courting going on. An old gentleman seemed to be asking a good many impertinent questions—just like some old folks—and people were sitting around making minutes of the conversation. I don't see how they made out what was said, for they all told different stories. How much easier it would be to get along if they were all made to tell the same story! What a sight of trouble it would save the lawyers! The case, as they call it, was given to the jury, but I couldn't see it, and a gentleman with a long pole was made to swear that he'd keep an eye on 'em, and see that they didn't run away with it. Bimeby in they came again, and they said[Pg 62] somebody was guilty of something, who had just said he was innocent, and didn't know nothing about it no more than the little baby that had never subsistence. I come away soon afterward; but I couldn't help thinking how trying it must be to sit there all day, shut out from the blessed air!"

Apropos of Superintendent Andrews's reported objection to the singing of the "Recessional" in the Chicago public schools on the ground that the atheists might be offended, the Chicago Post says:

For the benefit of our skittish friends, the atheists, and in order not to deprive the public-school children of the literary beauties of certain poems that may be classed by Doctor Andrews as "hymns," we venture to suggest this compromise, taking a few lines in illustration from our National anthem:

A certain learned professor in New York has a wife and family, but, professor-like, his thoughts are always with his books.

One evening his wife, who had been out for some hours, returned to find the house remarkably quiet. She had left the children playing about, but now they were nowhere to be seen.

She demanded to be told what had become of them, and the professor explained that, as they had made a good deal of noise, he had put them to bed without waiting for her or calling a maid.

"I hope they gave you no trouble," she said.

"No," replied the professor, "with the exception of the one in the cot here. He objected a good deal to my undressing him and putting him to bed."

The wife went to inspect the cot.

"Why," she exclaimed, "that's little Johnny Green, from next door."[Pg 68]

A country parson, in encountering a storm the past season in the voyage across the Atlantic, was reminded of the following: A clergyman was so unfortunate as to be caught in a severe gale in the voyage out. The water was exceedingly rough, and the ship persistently buried her nose in the sea. The rolling was constant, and at last the good man got thoroughly frightened. He believed they were destined for a watery grave. He asked the captain if he could not have prayers. The captain took him by the arm and led him down to the forecastle, where the tars were singing and swearing. "There," said he, "when you hear them swearing, you may know there is no danger." He went back feeling better, but the storm increased his alarm. Disconsolate and unassisted, he managed to stagger to the forecastle again. The ancient mariners were swearing as ever. "Mary," he said to his sympathetic wife, as he crawled into his berth after tacking across a wet deck, "Mary, thank God they're swearing yet."[Pg 74]

Artemus Ward, when in London, gave a children's party. One of John Bright's sons was invited, and returned home radiant. "Oh, papa," he explained, on being asked whether he had enjoyed himself, "indeed I did. And Mr. Browne gave me such a nice name for you, papa."

"What was that?"

"Why, he asked me how that gay and festive cuss, the governor, was!" replied the boy.

It was on a train going through Indiana. Among the passengers were a newly married couple, who made themselves known to such an extent that the occupants of the car commenced passing sarcastic remarks about them. The bride and groom stood the remarks for some time, but finally the latter, who was a man of tremendous size, broke out in the following language at his tormenters: "Yes, we're married—just married. We are going 160 miles farther, and I am going to 'spoon' all the way. If you don't like it, you can get out and walk. She's my violet and I'm her sheltering oak."

During the remainder of the journey they were left in peace.[Pg 77]

Natur furnishes all the nobleman we hav.

She holds the pattent.

Pedigree haz no more to do in making a man aktually grater than he iz, than a pekok's feather in his hat haz in making him aktually taller.

This iz a hard phakt for some tew learn.

This mundane earth iz thik with male and femail ones who think they are grate bekause their ansesstor waz luckey in the sope or tobacco trade; and altho the sope haz run out sumtime since, they try tew phool themselves and other folks with the suds.

Sope-suds iz a prekarious bubble.

Thare ain't nothing so thin on the ribs az a sope-suds aristokrat.

When the world stands in need ov an aristokrat, natur pitches one into it, and furnishes him papers without enny flaw in them.

Aristokrasy kant be transmitted—natur sez so—in the papers.

Titles are a plan got up bi humans tew assist natur in promulgating aristokrasy.

Titles ain't ov enny more real use or necessity than dog collars are.[Pg 78]

I hav seen dog collars that kost 3 dollars on dogs that wan't worth, in enny market, over 87½ cents.

This iz a grate waste of collar; and a grate damage tew the dog.

Natur don't put but one ingredient into her kind ov aristokrasy, and that iz virtew.

She wets up the virtew, sumtimes, with a little pepper sass, just tew make it lively.

She sez that all other kinds are false; and i beleave natur.

I wish every man and woman on earth waz a bloated aristokrat—bloated with virtew.

Earthly manufaktured aristokrats are made principally out ov munny.

Forty years ago it took about 85 thousand dollars tew make a good-sized aristokrat, and innokulate his family with the same disseaze, but it takes now about 600 thousand tew throw the partys into fits.

Aristokrasy, like of the other bred stuffs, haz riz.

It don't take enny more virtew tew make an aristokrat now, nor clothes, than it did in the daze ov Abraham.

Virtew don't vary.

Virtew is the standard ov values.

Clothes ain't.

Titles ain't.

A man kan go barefoot and be virtewous, and be an aristokrat.

Diogoneze waz an aristokrat.[Pg 79]

His brown-stun front waz a tub, and it want on end, at that.

Moneyed aristokrasy iz very good to liv on in the present hi kondishun ov kodphis and wearing apparel, provided yu see the munny, but if the munny kind of tires out and don't reach yu, and you don't git ennything but the aristokrasy, you hay got to diet, that's all.

I kno ov thousands who are now dieting on aristokrasy.

They say it tastes good.

I presume they lie without knowing it.

Not enny ov this sort ov aristokrasy for Joshua Billings.

I never should think ov mixing munny and aristokrasy together; i will take mine seperate, if yu pleze.

I don't never expekt tew be an aristokrat, nor an angel; i don't kno az i want tew be one.

I certainly should make a miserable angel.

I certainly never shall hav munny enuff tew make an aristokrat.

Raizing aristokrats iz a dredful poor bizzness; yu don't never git your seed back.

One democrat iz worth more tew the world than 60 thousand manufaktured aristokrats.

An Amerikan aristokrat iz the most ridikilus thing in market. They are generally ashamed ov their ansesstors; and, if they hav enny, and live long enuff, they generally hav cauze tew be ashamed ov their posterity.[Pg 80]

I kno ov sevral familys in Amerika who are trieing tew liv on their aristokrasy. The money and branes giv out sumtime ago.

It iz hard skratching for them.

Yu kan warm up kold potatoze and liv on them, but yu kant warm up aristokratik pride and git even a smell.

Yu might az well undertake tew raze a krop ov korn in a deserted brikyard by manuring the ground heavy with tanbark.

Yung man, set down, and keep still—yu will hay plenty ov chances yet to make a phool ov yureself before yu die.

It is told of an old Baptist parson, famous in Virginia, that he once visited a plantation where the colored servant who met him at the gate asked which barn he would have his horse put in.

"Have you two barns?" asked the minister.

"Yes, sah," replied the servant; "dar's de old barn, and Mas'r Wales has jest built a new one."

"Where do you usually put the horses of clergymen who come to see your master?"

"Well, sah, if dey's Methodist or Baptist we gen'ally puts 'em in de ole barn, but if dey's 'Piscopals we puts 'em in the new one."

"Well, Bob, you can put my horse in the new barn; I'm a Baptist, but my horse is an Episcopalian."[Pg 81]

Mister Buckinum, the follerin Billet was writ hum by a Yung feller of our town that wuz cussed fool enuff to goe a-trottin inter Miss Chiff arter a Drum and fife. It ain't Nater for a feller to let on that he's sick o' any bizness that he went intu off his own free will and a Cord, but I rather cal'late he's middlin tired o' voluntearin By this time. I bleeve yu may put dependunts on his statemence. For I never heered nothin bad on him let Alone his havin what Parson Wilbur cals a pongshong for cocktales, and ses it wuz a soshiashun of idees sot him agoin arter the Crootin Sargient cos he wore a cocktale onto his hat.

His Folks gin the letter to me and I shew it to parson Wilbur and he ses it oughter Bee printed, send It to mister Buckinum, ses he, i don't ollers agree with him, ses he, but by Time, ses he, I du like a feller that ain't a Feared.

I have intusspussed a Few refleckshuns hear and thair. We're kind o' prest with Hayin.

Ewers respecfly,

Two dusky small boys were quarreling; one was pouring forth a volume of vituperous epithets, while the other leaned against a fence and calmly contemplated him. When the flow of language was exhausted he said:

"Are you troo?"

"Yes."

"You ain't got nuffin' more to say?"

"Well, all dem tings what you called me, you is."[Pg 90]

Next to deciding when to start your garden, the most important matter is what to put in it. It is difficult to decide what to order for dinner on a given day: how much more oppressive is it to order in a lump an endless vista of dinners, so to speak! For, unless your garden is a boundless prairie (and mine seems to me to be that when I hoe it on hot days), you must make a selection, from the great variety of vegetables, of those you will raise in it; and you feel rather bound to supply your own table from your own garden, and to eat only as you have sown.

I hold that no man has a right (whatever his sex, of course) to have a garden to his own selfish uses. He ought not to please himself, but every man to please his neighbor. I tried to have a garden that would give general moral satisfaction. It seemed to me that nobody could object to potatoes (a most useful vegetable); and I began to plant them freely. But there was a chorus of protest against them. "You don't want to take up your ground with potatoes,"[Pg 91] the neighbors said; "you can buy potatoes" (the very thing I wanted to avoid doing is buying things). "What you want is the perishable things that you cannot get fresh in the market." "But what kind of perishable things?" A horticulturist of eminence wanted me to sow lines of strawberries and raspberries right over where I had put my potatoes in drills. I had about five hundred strawberry plants in another part of my garden; but this fruit-fanatic wanted me to turn my whole patch into vines and runners. I suppose I could raise strawberries enough for all my neighbors; and perhaps I ought to do it. I had a little space prepared for melons—muskmelons, which I showed to an experienced friend. "You are not going to waste your ground on muskmelons?" he asked. "They rarely ripen in this climate thoroughly before frost." He had tried for years without luck. I resolved not to go into such a foolish experiment. But the next day another neighbor happened in. "Ah! I see you are going to have melons. My family would rather give up anything else in the garden than muskmelons—of the nutmeg variety. They are the most graceful things we have on the table." So there it was. There was no compromise; it was melons or no melons, and somebody offended in any case. I half resolved to plant them a little late, so that they would, and they wouldn't. But I had the same difficulty about string-beans (which I detest), and squash[Pg 92] (which I tolerate), and parsnips, and the whole round of green things.

I have pretty much come to the conclusion that you have got to put your foot down in gardening. If I had actually taken counsel of my friends, I should not have had a thing growing in the garden to-day but weeds. And besides, while you are waiting, Nature does not wait. Her mind is made up. She knows just what she will raise; and she has an infinite variety of early and late. The most humiliating thing to me about a garden is the lesson it teaches of the inferiority of man. Nature is prompt, decided, inexhaustible. She thrusts up her plants with a vigor and freedom that I admire; and the more worthless the plant, the more rapid and splendid its growth. She is at it early and late, and all night; never tiring, nor showing the least sign of exhaustion.