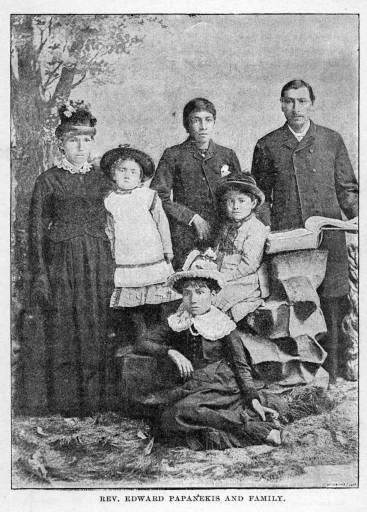

Egerton Ryerson Young

"By Canoe and Dog-Train"

Chapter One.

The summons to the Indian work—The decision—The valedictory services—Dr Punshon—The departure—Leaving Hamilton—St. Catherine’s—Milwaukee custom-house delays—Mississippi—St. Paul’s—On the prairies—Frontier settlers—Narrow escape from shooting one of our school teachers—Sioux Indians and their wars—Saved by our flag—Varied experiences.

Several letters were handed into my study, where I sat at work among my books.

I was then pastor of a Church in the city of Hamilton. Showers of blessing had been descending upon us, and over a hundred and forty new members had but recently been received into the Church. I had availed myself of the Christmas holidays by getting married, and now was back again with my beloved, when these letters were handed in. With only one of them have we at present anything to do. As near as I can remember, it read as follows:—

“Mission Rooms, Toronto, 1868.

“Reverend Egerton R. Young.

“Dear Brother,—At a large and influential meeting of the Missionary Committee, held yesterday, it was unanimously decided to ask you to go as a missionary to the Indian tribes at Norway House, and in the North-West Territories north of Lake Winnipeg. An early answer signifying your acceptance of this will much oblige,

“Yours affectionately,

“E. Wood,

“L. Taylor.”

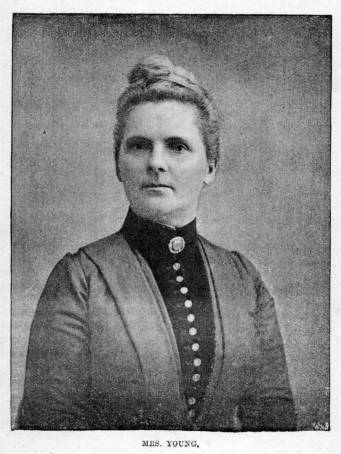

I read the letter, and then handed it, without comment, across the table to Mrs Young—the bride of but a few days—for her perusal. She read it over carefully, and then, after a quiet moment, as was quite natural, asked, “What does this mean?”

“I can hardly tell,” I replied; “but it is evident that it means a good deal.”

“Have you volunteered to go as a missionary to that far-off land?” she asked.

“Why, no. Much as I love, and deeply interested as I have ever been in the missionary work of our Church, I have not made the first move in this direction. Years ago I used to think I would love to go to a foreign field, but lately, as the Lord has been so blessing us here in the home work, and has given us such a glorious revival, I should have thought it like running away from duty to have volunteered for any other field.”

“Well, here is this letter; what are you going to do about it?”

“That is just what I would like to know,” was my answer.

“There is one thing we can do,” she said quietly; and we bowed ourselves in prayer, and “spread the letter before the Lord,” and asked for wisdom to guide us aright in this important matter which had so suddenly come upon us, and which, if carried out, would completely change all the plans and purposes which we, the young married couple, in all the joyousness of our honeymoon, had just been marking out. We earnestly prayed for Divine light and guidance to be so clearly revealed that we could not be mistaken as to our duty.

As we arose from our knees, I quietly said to Mrs Young, “Have you any impression on your mind as to our duty in this matter?”

Her eyes were suffused in tears, but the voice, though low, was firm, as she replied, “The call has come very unexpectedly, but I think it is from God, and we will go.”

My Church and its kind officials strongly opposed my leaving them, especially at such a time as this, when, they said, so many new converts, through my instrumentality, had been brought into the Church.

I consulted my beloved ministerial brethren in the city, and  with but one exception the reply was, “Remain at your present station, where God has so abundantly blessed your labours.” The answer of the one brother who did not join in with the others has never been forgotten. As it may do good, I will put it on record. When I showed him the letter, and asked what I should do in reference to it, he, much to my surprise, became deeply agitated, and wept like a child. When he could control his emotions, he said, “For my answer let me give you a little of my history.

with but one exception the reply was, “Remain at your present station, where God has so abundantly blessed your labours.” The answer of the one brother who did not join in with the others has never been forgotten. As it may do good, I will put it on record. When I showed him the letter, and asked what I should do in reference to it, he, much to my surprise, became deeply agitated, and wept like a child. When he could control his emotions, he said, “For my answer let me give you a little of my history.

“Years ago, I was very happily situated in the ministry in the Old Land. I loved my work, my home, and my wife passionately. I had the confidence and esteem of my people, and thought I was as happy as I could be this side (of) heaven. One day there came a letter from the Wesleyan Mission Rooms in London, asking if I would go out as a missionary to the West Indies. Without consideration, and without making it a matter of prayer, I at once sent back a positive refusal.

“From that day,” he continued, “everything went wrong with me. Heaven’s smile seemed to have left me. I lost my grip upon my people. My influence for good over them left me, I could not tell how. My once happy home was blasted, and in all my trouble I got no sympathy from my Church or in the community. I had to resign my position, and leave the place. I fell into darkness, and lost my hold upon God. A few years ago I came out to this country. God has restored me to the light of His countenance. The Church has been very sympathetic and indulgent. For years I have been permitted to labour in her fold, and for this I rejoice. But,” he added, with emphasis, “I long ago came to the resolve that if ever the Church asked me to go to the West Indies, or to any other Mission field, I would be careful about sending back an abrupt refusal.”

I pondered over his words and his experience, and talked about them with my good wife, and we decided to go. Our loving friends were startled at our resolve, but soon gave us their benedictions, united to tangible evidences of their regard. A blessed peace filled our souls, and we longed to be away and at work in the new field which had so suddenly opened before us.

“Yes, we will go. We may no longer doubt

To give up friends, and home, and every tie,

That binds our heart to thee, our country.

Henceforth, then,

It matters not if storms or sunshine be

Our earthly lot, bitter or sweet our cup.

We only pray, God fit us for the work,

God make us holy, and our spirits nerve

For the stern hour of strife. Let us but know

There is an Arm unseen that holds us up,

An Eye that kindly watches all our path,

Till we our weary pilgrimage have done.

Let us but know we have a Friend that waits

To welcome us to glory, and we joy

To tread that drear and northern wilderness.”

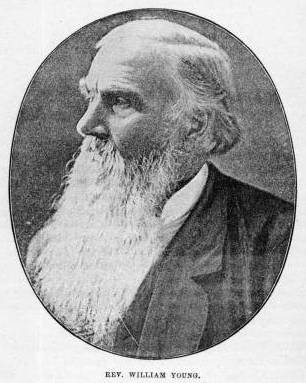

The grand valedictory services were held in the old Richmond Street Church, Toronto, Thursday, May 7th, 1868. The church was crowded, and the enthusiasm was very great. The honoured President of the Conference for that year, the Reverend James Elliott, who presided, was the one who had ordained me a few months before. Many were the speakers. Among them was the Reverend George McDougall, who already had had a varied experience of missionary life. He had something to talk about, to which it was worth listening. The Reverend George Young, also, had much that was interesting to say, as he was there bidding farewell to his own Church and to the people, of whom he had long been the beloved pastor. Dr Punshon, who had just arrived from England, was present, and gave one of his inimitable magnetic addresses. The memory of his loving, cheering words abode with us for many a day.

It was also a great joy to us that my honoured father, the Reverend William Young, was with us on the platform at this impressive farewell service. For many years he had been one of that heroic band of pioneer ministers in Canada who had laid so grandly and well the foundations of the Church which, with others, had contributed so much to the spiritual development of the country. His benedictions and blessings were among the prized favours in these eventful hours in our new career.

My father had been intimately acquainted with William Case  and James Evans, and at times had been partially associated with them in Indian evangelisation. He had faith in the power of the Gospel to save even Indians, and now rejoiced that he had a son and daughter who had consecrated themselves to this work.

and James Evans, and at times had been partially associated with them in Indian evangelisation. He had faith in the power of the Gospel to save even Indians, and now rejoiced that he had a son and daughter who had consecrated themselves to this work.

As a long journey of many hundreds of miles would have to be made by us after getting beyond cars or steamboats in the Western States, it was decided that we should take our own horses and canvas-covered waggons from Ontario with us. We arranged to make Hamilton our starting-point; and on Monday, the 11th of May, 1868, our little company filed out of that city towards St. Catherine’s, where we were to take passage in a “propeller” for Milwaukee. Thus our adventurous journey was begun.

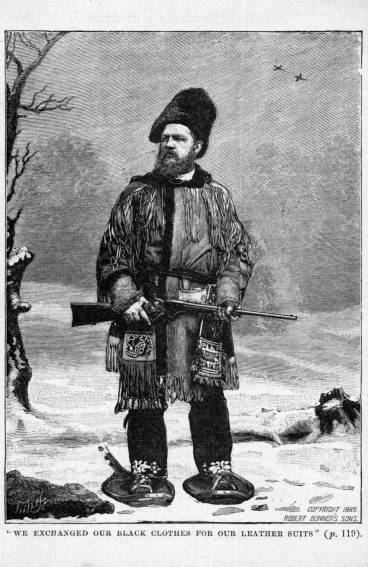

The following was our party. First, the Reverend George McDougall, who for years had been successfully doing the work of a faithful missionary among the Indians in the distant Saskatchewan country, a thousand miles north-west of the Red River country. He had come down to Canada for reinforcements for the work, and had not failed in his efforts to secure them. As he was an old, experienced Western traveller, he was the guide of the party.

Next was the Reverend George Young, with his wife and son. Dr Young had consented to go and begin the work in the Red River Settlement, a place where Methodism had never before had a footing. Grandly and well did he succeed in his efforts.

Next came the genial Reverend Peter Campbell, who, with his brave wife and two little girls, relinquished a pleasant Circuit to go to the distant Mission field among the Indians of the North-West prairies. We had also with us two Messrs Snyders, brothers of Mrs Campbell, who had consecrated themselves to the work as teachers among the distant Indian tribes. Several other young men were in our party, and in Dacota we were joined by “Joe” and “Job,” a couple of young Indians.

These, with the writer and his wife, constituted our party of fifteen or twenty. At St. Catherine’s on the Welland Canal we shipped our outfit, and took passage on board the steamer Empire for Milwaukee.

The vessel was very much crowded, and there was a good deal of discomfort. In passing through Lake Michigan we encountered rough weather, and, as a natural result, sea-sickness assailed the great majority of our party.

We reached Milwaukee on Sabbath, the 17th of May. We found it then a lively, wide-awake Americo-German city. There did not seem to be, on the part of the multitudes whom we met, much respect for the Sabbath. Business was in full blast in many of the streets, and there were but few evidences that it was  the day of rest. Doubtless there were many who had not defiled their garments and had not profaned the day, but we weary travellers had not then time to find them out.

the day of rest. Doubtless there were many who had not defiled their garments and had not profaned the day, but we weary travellers had not then time to find them out.

Although we had taken the precaution to bond everything through to the North-West, and had the American Consular certificate to the effect that every regulation had been complied with, we were subjected to many vexatious delays and expenses by the Custom House officials. So delayed were we that we had to telegraph to head-quarters at Washington about the matter and soon there came the orders to the over-officious officials to at once allow us to proceed. Two valuable days, however, had been lost by their obstructiveness. Why cannot Canada and the United States, lying side by side, from the Atlantic to the Pacific, devise some mutually advantageous scheme of reciprocity, by which the vexatious delays and annoyances and expense of these Custom Houses can be done away with?

We left Milwaukee for La Crosse on the Mississippi on Tuesday evening at eight o’clock. At La Crosse we embarked on the steamer Milwaukee for St. Paul’s. These large flat-bottomed steamers are quite an institution on these western rivers. Drawing but a few inches of water, they glide over sandbars where the water is very shallow, and, swinging in against the shore, land and receive passengers and freight where wharves are unknown, or where, if they existed, they would be liable to be swept away in the great spring freshets.

The scenery in many places along the upper Mississippi is very fine. High bold bluffs rise up in wondrous variety and picturesque beauty. In some places they are composed of naked rock. Others are covered to their very summit with the richest green. Here, a few years ago, the war-whoop of the Indians sounded, and the buffalo swarmed around these Buttes, and quenched their thirst in these waters. Now the shrill whistle of the steamer disturbs the solitudes, and echoes and re-echoes with wondrous distinctness among the high bluffs and fertile vales.

“Westward the Star of Empire takes its way.”

We arrived at St. Paul’s on Thursday forenoon and found it to be a stirring city, beautifully situated on the eastern side of the Mississippi. We had several hours of good hard work in getting our caravan in order, purchasing supplies, and making all final arrangements for the long journey that was before us. For beyond this the iron horse had not yet penetrated, and the great surging waves of immigration, which soon after rolled over into those fertile territories, had as yet been only little ripples.

Our splendid horses, which had been cooped up in the holds of vessels, or cramped up in uncomfortable freight cars, were now to have an opportunity for exercising their limbs, and showing of what mettle they were made. At 4 PM we filed out of the city. The recollection of that first ride on the prairie will live on as long as memory holds her throne. The day was one of those gloriously perfect ones that are but rarely given us, as if to show what earth must have been before the Fall. The sky, the air, the landscape—everything seemed in such harmony and so perfect, that involuntarily I exclaimed, “If God’s footstool is so glorious, what will the throne be?”

We journeyed a few miles, then encamped for the night. We were all in the best of spirits, and seemed to rejoice that we were getting away from civilisation, and more and more out into the wilderness, although for days we were in the vicinity of frontier villages and settlements, which, however, as we journeyed on, were rapidly diminishing in number.

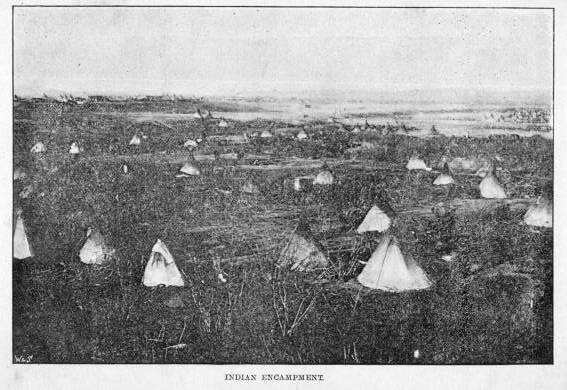

After several days’ travelling we encamped on the western side of the Mississippi, near where the thriving town of Clear Water now stands. As some of our carts and travelling equipage had begun to show signs of weakness, it was thought prudent to give everything a thorough overhauling ere we pushed out from this point, as beyond this there was no place where assistance could be obtained. We had in our encampment eight tents, fourteen horses, and from fifteen to twenty persons, counting big and little, whites and Indians. Whenever we camped our horses were turned loose in the luxuriant prairie grass, the only precaution taken being to “hobble” them, as the work of tying their forefeet together is called. It seemed a little cruel at first, and some of our spirited horses resented it, and struggled a good deal  against it as an infringement on their liberties. But they soon became used to it, and it served the good purpose we had in view—namely, that of keeping them from straying far away from the camp during the night.

against it as an infringement on their liberties. But they soon became used to it, and it served the good purpose we had in view—namely, that of keeping them from straying far away from the camp during the night.

At one place, where we were obliged to stop for a few days to repair broken axle-trees, I passed through an adventure that will not soon be forgotten. Some friendly settlers came to our camp, and gave us the unpleasant information, that a number of notorious horse-thieves were prowling around, and it would be advisable for us to keep a sharp look-out on our splendid Canadian horses. As there was an isolated barn about half a mile or so from the camp, that had been put up by a settler who would not require it until harvest, we obtained permission to use it as a place in which to keep our horses during the nights while we were detained in the settlement. Two of our party were detailed each night to act as a guard. One evening, as Dr Young’s son George and I, who had been selected for this duty, were about starting from the camp for our post, I overheard our old veteran guide, the Reverend George McDougall, say, in a bantering sort of way, “Pretty guards they are! Why, some of my Indian boys could go and steal every horse from them without the slightest trouble.”

Stung to the quick by the remark, I replied, “Mr McDougall, I think I have the best horse in the company; but if you or any of your Indians can steal him out of that barn between sundown and sunrise, you may keep him!”

We tethered the horses in a line, and fastened securely all the doors but the large front one. We arranged our seats where we were partially concealed, but where we could see our horses, and could command every door with our rifles. In quiet tones we chatted about various things, until about one o’clock, when all became hushed and still. The novelty of the situation impressed me, and, sitting there in the darkness, I could not help contrasting my present position with the one I had occupied a few weeks before. Then the pastor of a city Church, in the midst of a blessed revival, surrounded by all the comforts of civilisation; now out here in Minnesota, in this barn, sitting on a bundle of prairie grass through the long hours of night with a breech-loading rifle in hand, guarding a number of horses from a band of horse-thieves.

“Hush! what is that?”

A hand is surely on the door feeling for the wooden latch. We mentally say, “You have made too much noise, Mr Thief, for your purpose, and you are discovered.” Soon the door opened a little. As it was a beautiful starlight night, the form of a tall man was plainly visible in the opening. Covering him with my rifle, and about to fire, quick as a flash came the thought, “Better be sure that that man is a horse-thief, or is intent on evil, ere you fire; for it is at any time a serious thing to send a soul so suddenly into eternity.” So keeping my rifle to my shoulder, I shouted out, “Who’s there?”

“Why, it’s only your friend Matthew,” said our tall friend, as he came stumbling along in the darkness; “queer if you don’t know me by this time.”

As the thought came to me of how near I had been to sending him into the other world, a strange feeling of faintness came over me, and, flinging my rifle from me, I sank back trembling like a leaf.

Meanwhile the good-natured fellow, little knowing the risk he had run, and not seeing the effect his thoughtless action had produced on me, talked on, saying that as it was so hot and close over at the tents that he could not sleep there, he thought he would come over and stop with us in the barn.

There was considerable excitement, and some strong words were uttered at the camp next morning at his breach of orders and narrow escape, since instructions had been given to all that none should, under any consideration, go near the barn while it was being guarded.

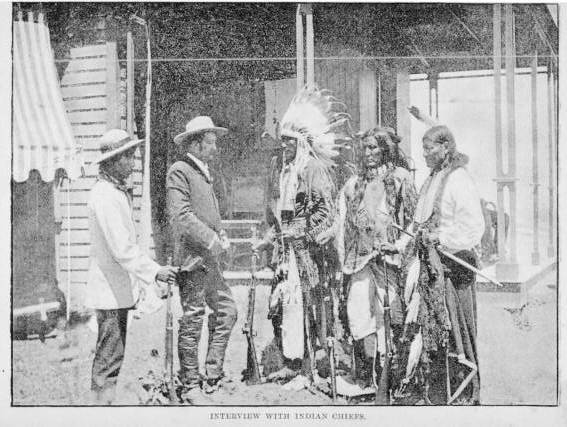

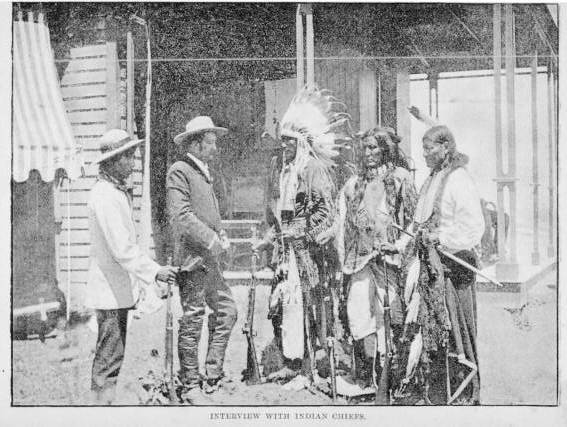

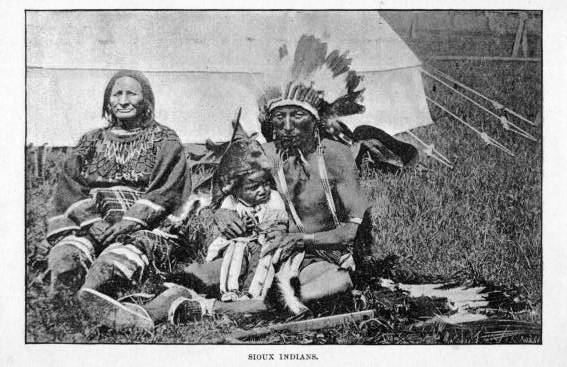

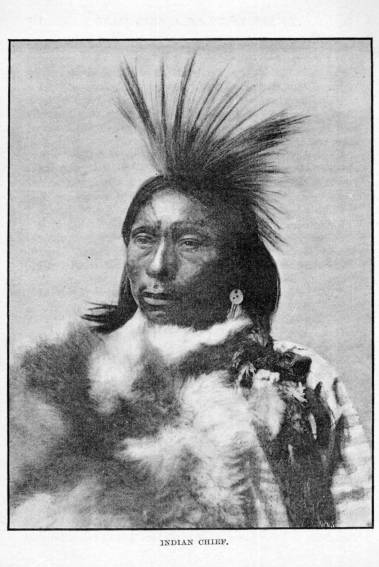

At another place in Minnesota we came across a party who were restoring their homes, and “building up their waste places” desolated by the terrible Sioux wars of but a short time before. As they had nearly all of them suffered by that fearful struggle, they were very bitter in their feelings towards the Indians, completely ignoring the fact that the whites were to blame for that last sanguinary outbreak, in which nine hundred lives were lost, and a section of country larger than some of the New England States was laid desolate. It is now an undisputed fact that the greed and dishonesty of the Indian agents of the United States caused that terrible war of 1863. The principal agent received 600,000 dollars in gold from the Government, which belonged to the Indians, and was to be paid to Little Crow and the other chiefs and members of the tribe. The agent took advantage of the premium on gold, which in those days was very high, and exchanged the gold for greenbacks, and with these paid the Indians, putting the enormous difference in his own pocket. When the payments began, Little Crow, who knew what he had a right to according to the Treaty, said, “Gold dollars worth more than paper dollars. You pay us gold.” The agent refused, and the war followed. This is only one instance out of scores, in which the greed and selfishness of a few have plunged the country into war, causing the loss of hundreds of lives and millions of treasure.

In addition to this, these same unprincipled agents, with their hired accomplices and subsidised press, in order to hide the enormity of their crimes, and to divert attention from themselves and their crookedness, systematically and incessantly misrepresent and vilify the Indian character.

“Stay and be our minister,” said some of these settlers to me in one place. “We’ll secure for you a good location, and will help you get in some crops, and will do the best we can to make you comfortable.”

When they saw we were all proof against their appeals, they changed their tactics, and one exclaimed, “You’ll never get through the Indian country north with those fine horses and all that fine truck you have.”

“O yes, we will,” said Mr McDougall; “we have a little flag that will carry us in safety through any Indian tribe in America.”

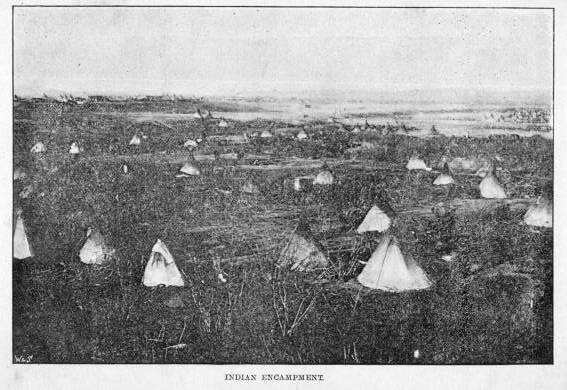

They doubted the assertion very much, but we found it to be literally true, at all events as regarded the Sioux; for when, a few days later, we met them, our Union Jack fluttering from the whip-stalk caused them to fling their guns in the grass, and come crowding round us with extended hands, saying, through those who understood their language, that they were glad to see and shake hands with the subjects of the “Great Mother” across the waters.

When we, in our journey north, reached their country, and saw them coming down upon us, at Mr McDougall’s orders we stowed away our rifles and revolvers inside of our waggons, and met them as friends, unarmed and fearless. They smoked the pipe of peace with those of our party who could use the weed, and others drank tea with the rest of us. As we were in profound ignorance of their language, and they of ours, some of us had not much conversation with them beyond what could be carried on by a few signs. But, through Mr  McDougall and our own Indians, they assured us of their friendship.

McDougall and our own Indians, they assured us of their friendship.

We pitched our tents, hobbled our horses and turned them loose, as usual. We cooked our evening meals, said our prayers, unrolled our camp-beds, and lay down to rest without earthly sentinels or guards around us, although the camp-fires of these so-called “treacherous and bloodthirsty” Sioux could be seen in the distance, and we knew their sharp eyes were upon us. Yet we lay down and slept in peace, and arose in safety. Nothing was disturbed or stolen.

So much for a clean record of honourable dealing with a people who, while quick to resent when provoked, are mindful of kindnesses received, and are as faithful to their promises and treaty obligations, as are any other of the races of the world.

We were thirty days in making the trip from St. Paul’s to the Red River settlement. We had to ford a large number of bridgeless streams. Some of them took us three or four days to get our whole party across. We not unfrequently had some of our waggons stuck in the quicksands, or so sunk in the quagmires that the combined strength of all the men of our party was required to get them out. Often the ladies of our company, with shoes and stockings off, would be seen bravely wading across wide streams, where now in luxurious comfort, in parlour cars, travellers are whirled along at the rate of forty miles an hour. They were a cheerful, brave band of pioneers.

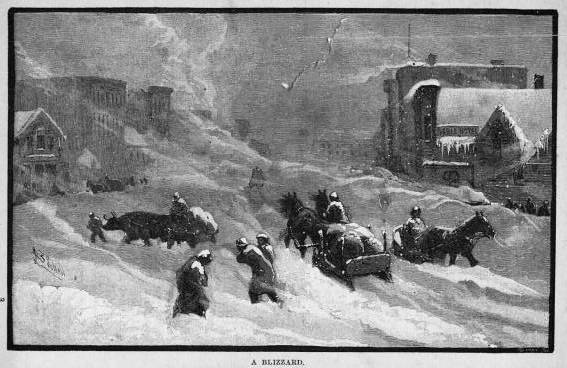

The weather, on the whole, was pleasant, but we had some drenching rain-storms; and then the spirits of some of the party went down, and they wondered whatever possessed them to leave their happy homes for such exile and wretchedness as this. There was one fearful, tornado-like storm that assailed us when we were encamped for the night on the western bank of Red River. Tents were instantly blown down. Heavy waggons were driven before it, and for a time confusion reigned supreme. Fortunately nobody was hurt, and most of the things blown away were recovered the next day.

Our Sabbaths were days of quiet rest and delightful communion with God. Together we worshipped Him Who dwelleth not in  temples made with hands. Many were the precious communions we had with Him Who had been our Comforter and our Refuge under other circumstances, and Who, having now called us to this new work and novel life, was sweetly fulfilling in us the blessed promise: “Lo, I am with you alway, even unto the end of the world.”

temples made with hands. Many were the precious communions we had with Him Who had been our Comforter and our Refuge under other circumstances, and Who, having now called us to this new work and novel life, was sweetly fulfilling in us the blessed promise: “Lo, I am with you alway, even unto the end of the world.”

Chapter Two.

Still on the route—Fort Garry—Breaking up of our party of missionaries—Lower Fort—Hospitable Hudson’s Bay officials—Peculiarities—Fourteen days in a little open boat on stormy Lake Winnipeg—Strange experiences—Happy Christian Indian boatmen—“In perils by waters.”

At Fort Garry in the Red River settlement, now the flourishing city of Winnipeg, our party, which had so long travelled together, broke up with mutual regrets. The Reverend George Young and his family remained to commence the first Methodist Mission in that place. Many were his discouragements and difficulties, but glorious have been his successes. More to him than to any other man is due the prominent position which the Methodist Church now occupies in the North-West. His station was one calling for rare tact and ability. The Riel Rebellion, and the disaffection of the Half-breed population, made his position at times one of danger and insecurity; but he proved himself to be equal to every emergency. In addition to the many duties devolving upon him in the establishment of the Church amidst so many discordant elements, a great many extra cares were imposed upon him by the isolated missionaries in the interior, who looked to him for the purchasing and sending out to them, as best he could, of their much-needed supplies. His kindly laborious efforts for their comfort can never be forgotten.

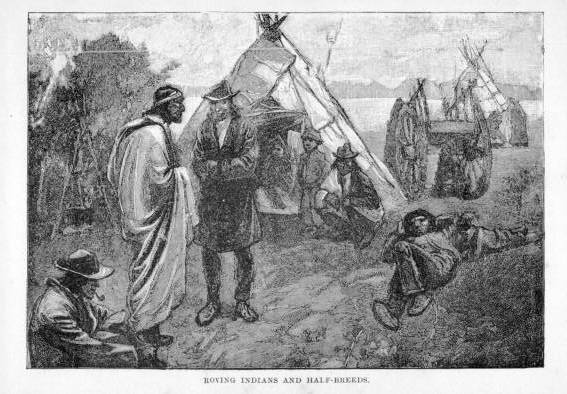

The Revs. George McDougall and Peter Campbell, with the teachers and other members of the party, pushed on, with their horses, waggons, and carts, for the still farther North-West, the great North Saskatchewan River, twelve hundred miles farther into the interior.

During the first part of their journey over the fertile but then unbroken prairies, the only inhabitants they met were the roving Indians and Half-breeds, whose rude wigwams and uncouth noisy carts have long since disappeared, and have been replaced by the comfortable habitations of energetic settlers, and the swiftly moving trains of the railroads.

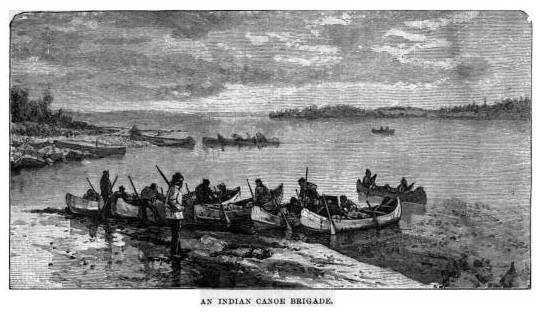

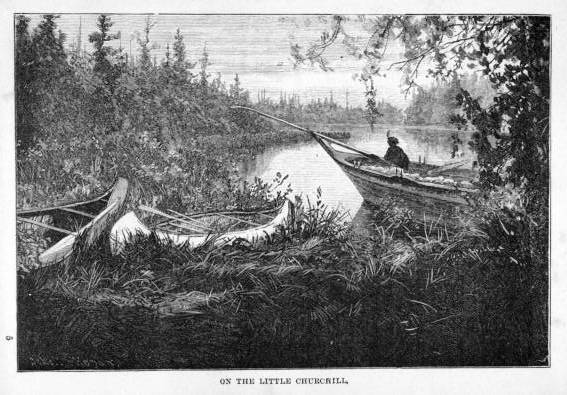

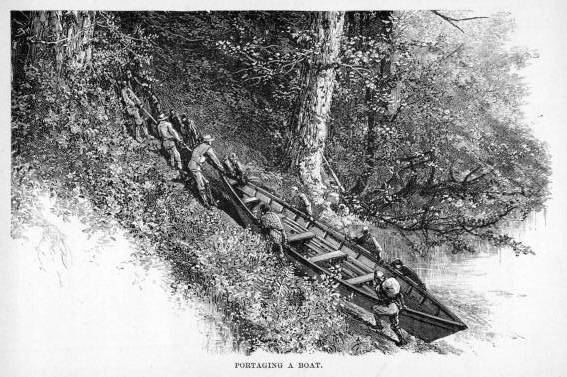

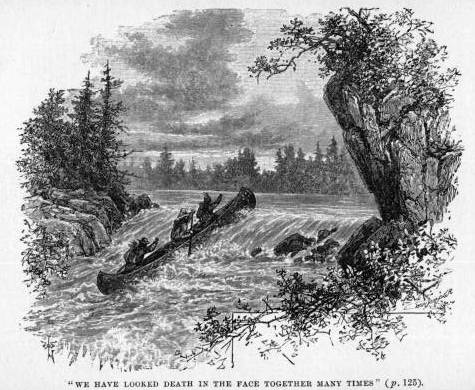

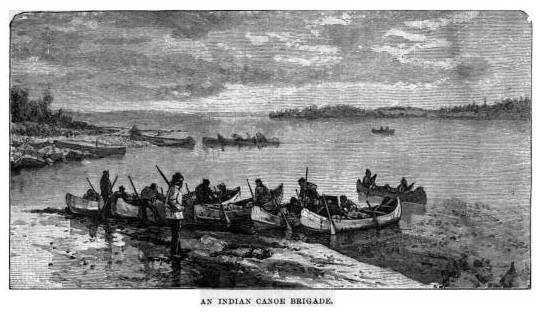

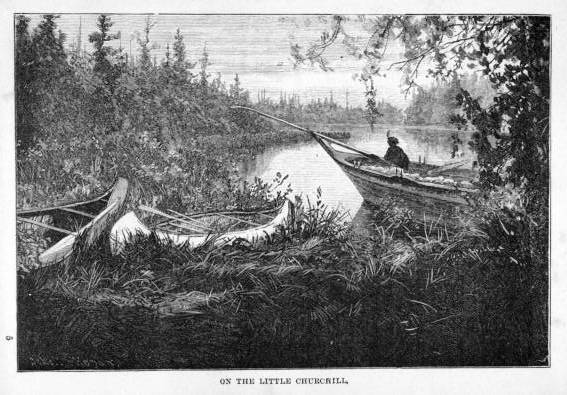

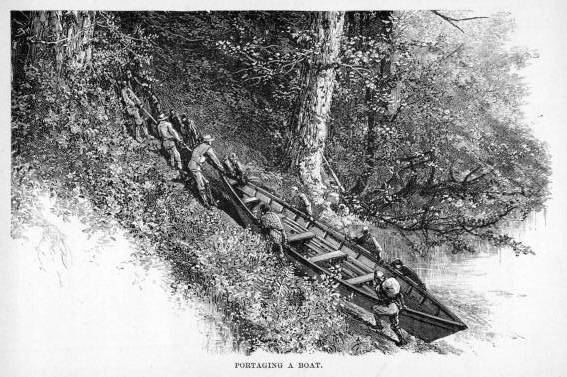

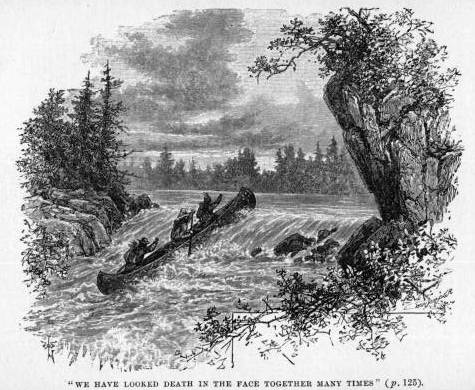

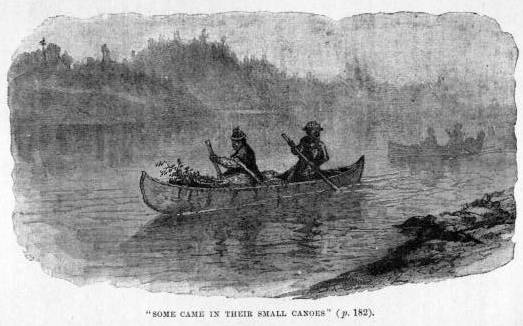

From Fort Garry Mrs Young and myself performed the rest of our journey by water, going down the Red River to its mouth, and then along the whole length of the stormy Lake Winnipeg, and beyond, to our own far-off northern home. The trip was made in what is called “the Hudson’s Bay inland boat.” These boats are constructed like large skiffs, only each end is sharp. They have neither deck nor cabin. They are furnished with a mast and a large square sail, both of which are stowed away when the wind is not favourable for sailing. They are manned by six or eight oarsmen, and are supposed to carry about four tons of merchandise. They can stand a rough sea, and weather very severe gales, as we found out during our years of adventurous trips in them. When there is no favourable wind for sailing, the stalwart boatmen push out their heavy oars, and, bending their sturdy backs to the work, and keeping the most perfect time, are often able to make their sixty miles a day. But this toiling at the oar is slavish work, and the favouring gale, even if it develops into a fierce storm, is always preferable to a dead calm. These northern Indians make capital sailors, and in the sudden squalls and fierce gales to which these great lakes are subject, they display much courage and judgment.

Our place in the boat was in the hinder part near the steersman, a pure Indian, whose name was Thomas Mamanowatum, familiarly known as “Big Tom,” on account of his almost gigantic size. He was one of Nature’s noblemen, a grand, true man, and of him we shall have more to say hereafter. Honoured indeed was the missionary who led such a man from Paganism to Christianity.

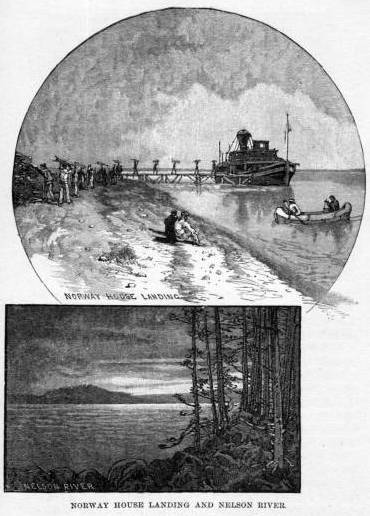

We journeyed on pleasantly for twenty miles down the Red  River to Lower Fort Garry, where we found that we should have to wait for several days ere the outfit for the boats would be ready. We were, however, very courteously entertained by the Hudson’s Bay officials, who showed us no little kindness.

River to Lower Fort Garry, where we found that we should have to wait for several days ere the outfit for the boats would be ready. We were, however, very courteously entertained by the Hudson’s Bay officials, who showed us no little kindness.

This Lower Fort Garry, or “the Stone Fort,” as it is called in the country, is an extensive affair, having a massive stone wall all around it, with the Company’s buildings in the centre. It was built in stormy times, when rival trading parties existed, and hostile bands were ever on the war path. It is capable of resisting almost any force that could be brought against it, unaided by artillery. We were a little amused and very much pleased with the old-time and almost courtly etiquette which abounded at this and the other establishments of this flourishing Company. In those days the law of precedents was in full force. When the bell rang, no clerk of fourteen years’ standing would think of entering before one who had been fifteen years in the service, or of sitting above him at the table. Such a thing would have brought down upon him the severe reproof of the senior officer in charge. Irksome and even frivolous as some of these laws seemed, doubtless they served a good purpose, and prevented many misunderstandings which might have occurred.

Another singular custom, which we did not like, was the fact that there were two dining-rooms in these establishments, one for the ladies, and the other for the gentlemen of the service. It appeared to us very odd to see the gentlemen with the greatest politeness escort the ladies into the hall which ran between the two dining-rooms, and then gravely turn to the left, while the ladies all filed off into the room on the right. As the arrangement was so contrary to all our ideas and education on the subject, we presumed to question it; but the only satisfaction we could get in reference to it was, that it was one of their old customs, and had worked well. One old crusty bachelor official said, “We do not want the women around us when we are discussing our business matters, which we wish to keep to ourselves. If they were present, all our schemes and plans would soon be known to all, and our trade might be much injured.”

Throughout this vast country, until very lately, the adventurous  traveller, whose courage or curiosity was sufficient to enable him to brave the hardships or run the risks of exploring these enormous territories, was entirely dependent upon the goodwill and hospitality of the officials of the Hudson’s Bay Company. They were uniformly treated with courtesy and hospitably entertained.

traveller, whose courage or curiosity was sufficient to enable him to brave the hardships or run the risks of exploring these enormous territories, was entirely dependent upon the goodwill and hospitality of the officials of the Hudson’s Bay Company. They were uniformly treated with courtesy and hospitably entertained.

Very isolated are some of these inland posts, and quite expatriated are the inmates for years at a time. These lonely establishments are to be found scattered all over the upper half of this great American Continent. They have each a population of from five to sixty human beings. These are, if possible, placed in favourable localities for fish or game, but often from one to five hundred miles apart. The only object of their erection and occupancy is to exchange the products of civilisation for the rich and valuable furs which are to be obtained here as nowhere else in the world. In many instances the inmates hear from the outside world but twice, and at times but once, in twelve months. Then the arrival of the packet is the great event of the year.

We spent a very pleasant Sabbath at Lower Fort Garry, and I preached in the largest dining-room to a very attentive congregation, composed of the officials and servants of the Company, with several visitors, and also some Half-breeds and Indians who happened to be at the fort at that time.

The next day two boats were ready, and we embarked on our adventurous journey for our far-off, isolated home beyond the northern end of Lake Winnipeg. The trip down Red River was very pleasant. We passed through the flourishing Indian Settlement, where the Church of England has a successful Mission among the Indians. We admired their substantial church and comfortable homes, and saw in them, and in the farms, tangible evidence of the power of Christian Missions to elevate and bless those who come under their ennobling influences. The cosy residence of the Venerable Archdeacon Cowley was pointed out to us, beautifully embowered among the trees. He was a man beloved of all; a life-long friend of the Indians, and one who was as an angel of mercy to us in after years when our Nellie died, while Mrs Young was making an adventurous journey in an open boat on the stormy, treacherous Lake Winnipeg.

This sad event occurred when, after five years’ residence among the Crees at Norway House, we had instructions from our missionary authorities to go and open up a new Indian Mission among the then pagan Salteaux. I had orders to remain at Norway House until my successor arrived; and as but one opportunity was offered for Mrs Young and the children to travel in those days of limited opportunities, they started on several weeks ahead in an open skiff manned by a few Indians, leaving me to follow in a birch canoe. So terrible was the heat that hot July, in that open boat with no deck or awning, that the beautiful child sickened and died of brain-fever. Mrs Young found herself with her dying child on the banks of Red River, all alone among her sorrowing Indian boatmen, “a stranger in a strange land;” no home to which to go; no friends to sympathise with her. Fortunately for her, the Hudson’s Bay officials at Lower Fort Garry were made aware of her sorrows, and received her into one of their homes ere the child died. The Reverend Mr Cowley also came and prayed for her, and sympathised with her on the loss of her beautiful child.

As I was far away when Nellie died, Mrs Young knew not what to do with our precious dead. A temporary grave was made, and in it the body was laid until I could be communicated with, and arrangements could be made for its permanent interment. I wrote at once by an Indian to the Venerable Archdeacon Cowley, asking permission to bury our dead in his graveyard; and there came promptly back, by the canoe, a very brotherly, sympathetic letter, ending up with, “Our graveyards are open before you; ‘in the choicest of our sepulchres bury thy dead.’” A few weeks after, when I had handed over my Mission to Brother Ruttan, I hurried on to the settlement, and with a few sympathising friends, mostly Indians, we took up the little body from its temporary resting-place, and buried it in the St. Peter’s Church graveyard, the dear archdeacon himself being present, and reading the beautiful Burial Service of his Church. That land to us has been doubly precious since it has become the repository of our darling child.

As we floated down the current, or were propelled along by the  oars of our Indian boatmen, on that first journey, little did we imagine that this sad episode in our lives would happen in that very spot a few years after. When we were near the end of the Indian Settlement, as it is called, we saw several Indians on the bank, holding on to a couple of oxen. Our boats were immediately turned in to the shore near them, and, to our great astonishment, we found out that each boat was to have an addition to its passenger list in the shape of one of these big fellows. The getting of these animals shipped was no easy matter, as there was no wharf or gangway; but after a good deal of pulling and pushing, and lifting up of one leg, and then another, the patient brutes were embarked on the frail crafts, to be our companions during the voyage to Norway House. The position assigned to the one in our boat was just in front of us, “broadside on,” as the sailors would say; his head often hanging over one side of the boat, and his tail over the other side. The only partition there was between him and us was a single board a few inches wide. Such close proximity to this animal for fourteen days was not very agreeable; but as it could not be helped it had to be endured.

oars of our Indian boatmen, on that first journey, little did we imagine that this sad episode in our lives would happen in that very spot a few years after. When we were near the end of the Indian Settlement, as it is called, we saw several Indians on the bank, holding on to a couple of oxen. Our boats were immediately turned in to the shore near them, and, to our great astonishment, we found out that each boat was to have an addition to its passenger list in the shape of one of these big fellows. The getting of these animals shipped was no easy matter, as there was no wharf or gangway; but after a good deal of pulling and pushing, and lifting up of one leg, and then another, the patient brutes were embarked on the frail crafts, to be our companions during the voyage to Norway House. The position assigned to the one in our boat was just in front of us, “broadside on,” as the sailors would say; his head often hanging over one side of the boat, and his tail over the other side. The only partition there was between him and us was a single board a few inches wide. Such close proximity to this animal for fourteen days was not very agreeable; but as it could not be helped it had to be endured.

At times, during the first few days, the ox made some desperate efforts to break loose; and it seemed as though he would either smash our boat to pieces or upset it; but, finding his efforts unsuccessful, he gracefully accepted the situation, and behaved himself admirably. When storms arose he quietly lay down, and served as so much ballast to steady the boat. “Tom,” the guide, kept him well supplied with food from the rich nutritious grasses which grew abundantly along the shore at our different camping-places.

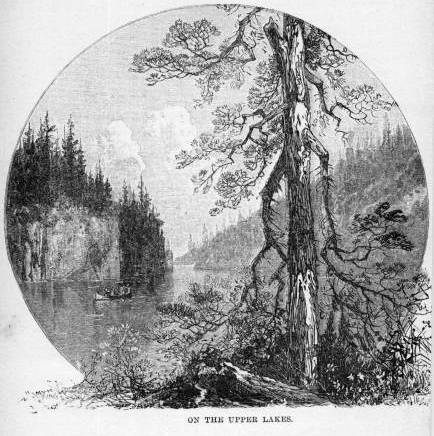

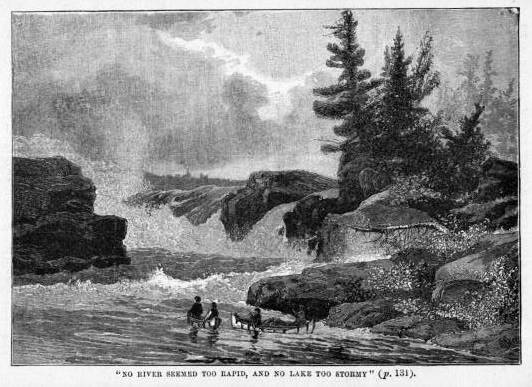

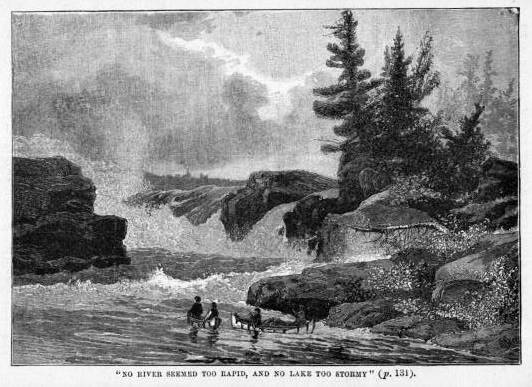

Winnipeg is considered one of the stormiest lakes on the American Continent. It is about three hundred miles long, and varies from eighty to but a few miles in width. It is indented with innumerable bays, and is dangerous to navigators, on account of its many shoals and hidden rocks. Winnipeg, or Wenipák, as some Indians pronounce it, means “the sea,” and Keche Wenipák means “the ocean.”

The trip across Lake Winnipeg was one that at the present day would be considered a great hardship, taking into consideration the style of the boat and the way we travelled.

Our method of procedure was about as follows. We were aroused very early in the morning by the guide’s cry of Koos koos kwa! “Wake up!” Everybody was expected to obey promptly, as there was always a good deal of rivalry between the boats as to which could get away first. A hasty breakfast was prepared on the rocks; after which a morning hymn was sung, and an earnest prayer was offered up to Him Who holds the winds and waves under His control.

Then “All aboard” was the cry, and soon tents, kettles, axes, and all the other things were hurriedly gathered up and placed on board. If the wind was favourable, the mast was put up, the sail hoisted, and we were soon rapidly speeding on our way. If the oars had to be used, there was not half the alacrity displayed by the poor fellows, who well knew how wearisome their task would be. When we had a favourable wind, we generally dined as well as we could in the boat, to save time, as the rowers well knew how much more pleasant it was to glide along with the favouring breeze than to be obliged to work at the heavy oars. Often during whole nights we sailed on, although at considerable risks in that treacherous lake, rather than lose the fair wind. For, if there ever was, in this world of uncertainties, one route of more uncertainty than another, the palm must be conceded to the voyages on Lake Winnipeg in those Hudson’s Bay Company’s inland boats. You might make the trip in four days, or even a few hours less; and you might be thirty days, and a few hours over.

Once, in after years, I was detained for six days on a little rocky islet by a fierce northern gale, which at times blew with such force that we could not keep up a tent or even stand upright against its fury; and as there was not sufficient soil in which to drive a tent pin, we, with all our bedding and supplies, were drenched by the pitiless sleet and rain. Often in these later years, when I have heard people, sitting in the comfortable waiting-room of a railway station, bitterly complaining because a train was an hour or two late, memory has carried me back to some of those long detentions amidst the most disagreeable surroundings, and I have wondered at the trifles which can upset the equanimity of some or cause them to show such fretfulness.

When the weather was fine, the camping on the shore was very enjoyable. Our tent was quickly erected by willing hands; the camp fire was kindled, and glowed with increasing brightness as the shadows of night fell around us. The evening meal was soon prepared, and an hour or two would sometimes be spent in pleasant converse with our dusky friends, who were most delightful travelling companions. Our days always began and closed with a religious service. All of our Indian companions in the two boats on this first trip were Christians, in the best and truest sense of the word. They were the converts of the earlier missionaries of our Church. At first they were a little reserved, and acted as though they imagined we expected them to be very sedate and dignified. For, like some white folks, they imagined the “black-coat” and his wife did not believe in laughter or pleasantry. However, we soon disabused their minds of those erroneous ideas, and before we reached Norway House we were on the best of terms with each other. We knew but little of their language, but some of them had a good idea of English, and, using these as our interpreters, we got along finely.

They were well furnished with Testaments and hymn-books, printed in the beautiful syllabic characters; and they used them well. This worshipping with a people who used to us an unknown tongue was at first rather novel; but it attracted and charmed us at once. We were forcibly struck with the reverential manner in which they conducted their devotions. No levity or indifference marred the solemnity of their religious services. They listened very attentively while one of their number read to them from the sacred Word, and gave the closest attention to what I had to say, through an interpreter.

Very sweetly and soothingly sounded the hymns of praise and adoration that welled up from their musical voices; and though we understood them not, yet in their earnest prayers there seemed to be so much that was real and genuine, as in pathetic tones they offered up their petitions, that we felt it to be a great privilege and a source of much blessing, when with them we bowed at the mercy-seat of our great loving Father, to Whom all languages of earth are known, and before Whom all hearts are open.

Very helpful at times to devout worship were our surroundings. As in the ancient days, when the vast multitudes gathered around Him on the seaside and were comforted and cheered by His presence, so we felt on these quiet shores of the lake that we were worshipping Him Who is always the same. At times delightful and suggestive were our environments. With Winnipeg’s sunlit waves before us, the blue sky above us, the dark, deep, primeval forest as our background, and the massive granite rocks beneath us, we often felt a nearness of access to Him, the Sovereign of the universe, Who “dwelleth not in temples made with hands,”—but “Who covereth Himself with light as with a garment; Who stretcheth out the heavens like a curtain; Who layeth the beams of His chambers in the waters; Who maketh the clouds his chariot; Who walketh upon the wings of the wind; Who laid the foundations of the earth, that it should not be removed for ever.”

Our Sabbaths were days of rest. The Christian Indians had been taught by their faithful missionaries the fourth commandment, and they kept it well. Although far from their homes and their beloved sanctuary, they respected the day. When they camped on Saturday night, all the necessary preparations were made for a quiet, restful Sabbath. All the wood that would be needed to cook the day’s supplies was secured, and the food that required cooking was prepared. Guns were stowed away, and although sometimes ducks or other game would come near, they were not disturbed. Generally two religious services were held and enjoyed. The Testaments and hymn-books were well used throughout the day, and an atmosphere of “Paradise Regained” seemed to pervade the place.

At first, long years ago, the Hudson’s Bay Company’s officials bitterly opposed the observance of the Sabbath by their boatmen and tripmen; but the missionaries were true and firm, and although persecution for a time abounded, eventually right and truth prevailed,  and our Christian Indians were left to keep the day without molestation. And, as has always been found to be the case in such instances, there was no loss, but rather gain. Our Christian Indians, who rested the Sabbath day, were never behindhand. On the long trips into the interior or down to York Factory or Hudson Bay, these Indian canoe brigades used to make better time, have better health, and bring up their boats and cargoes in better shape, than the Catholic Half-breeds or pagan Indians, who pushed on without any day of rest. Years of studying this question, judging from the standpoint of the work accomplished and its effects on men’s physical constitution, apart altogether from its moral and religious aspect, most conclusively taught me that the institution of the one day in seven as a day of rest is for man’s highest good.

and our Christian Indians were left to keep the day without molestation. And, as has always been found to be the case in such instances, there was no loss, but rather gain. Our Christian Indians, who rested the Sabbath day, were never behindhand. On the long trips into the interior or down to York Factory or Hudson Bay, these Indian canoe brigades used to make better time, have better health, and bring up their boats and cargoes in better shape, than the Catholic Half-breeds or pagan Indians, who pushed on without any day of rest. Years of studying this question, judging from the standpoint of the work accomplished and its effects on men’s physical constitution, apart altogether from its moral and religious aspect, most conclusively taught me that the institution of the one day in seven as a day of rest is for man’s highest good.

Thus we journeyed on, meeting with various adventures by the way. One evening, rather than lose the advantage of a good wind, our party resolved to sail on throughout the night. We had no compass or chart, no moon or fickle Auroras lit up the watery waste. Clouds, dark and heavy, flitted by, obscuring the dim starlight, and adding to the risk and danger of our proceeding. On account of the gloom part of the crew were kept on the watch continually. The bowsman, with a long pole in his hands, sat in the prow of the boat, alert and watchful. For a long time I sat with the steersman in the stern of our little craft, enjoying this weird way of travelling. Out of the darkness behind us into the vague blackness before us we plunged. Sometimes through the darkness came the sullen roar and dash of waves against the rocky isles or dangerous shore near at hand, reminding us of the risks we were running, and what need there was of the greatest care.

Our camp bed had been spread on some boards in the hinder part of our little boat; and here Mrs Young, who for a time had enjoyed the exciting voyage, was now fast asleep. I remained up with “Big Tom” until after midnight; and then, having exhausted my stock of Indian words in conversation with him, and becoming weary, I wrapped a blanket around myself and lay down to rest. Hardly had I reached the land of dreams,  when I was suddenly awakened by being most unceremoniously thrown, with wife, bedding, bales, boxes, and some drowsy Indians, on one side of the boat. We scrambled up as well as we could, and endeavoured to take in our situation. The darkness was intense, but we could easily make out the fact that our boat was stuck fast. The wind whistled around us, and bore with such power upon our big sail that the wonder was that it did not snap the mast or ropes. The sail was quickly lowered, a lantern was lit, but its flickering light showed no land in view.

when I was suddenly awakened by being most unceremoniously thrown, with wife, bedding, bales, boxes, and some drowsy Indians, on one side of the boat. We scrambled up as well as we could, and endeavoured to take in our situation. The darkness was intense, but we could easily make out the fact that our boat was stuck fast. The wind whistled around us, and bore with such power upon our big sail that the wonder was that it did not snap the mast or ropes. The sail was quickly lowered, a lantern was lit, but its flickering light showed no land in view.

We had run upon a submerged rock, and there we were held fast. In vain the Indians, using their big oars as poles, endeavoured to push the boat back into deep water. Finding this impossible, some of them sprang out into the water which threatened to engulf them; but, with the precarious footing the submerged rock gave them, they pushed and shouted, when, being aided by a giant wave, the boat at last was pushed over into the deep water beyond. At considerable risk and thoroughly drenched, the brave fellows scrambled on board; the sail was again hoisted, and away we sped through the gloom and darkness.

Chapter Three.

Arrival at Norway House—Our new home—Reverend Charles Stringfellow—Thunderstorm—Reverend James Evans—Syllabic Characters invented—Difficulties overcome—Help from English Wesleyan Missionary Society—Extensive use of the Syllabic Characters—Our people, Christian and pagan—Learning lessons by dear experience—The hungry woman—The man with the two ducks—The first Sabbath in our new field—Sunday School and Sabbath services—Family altars.

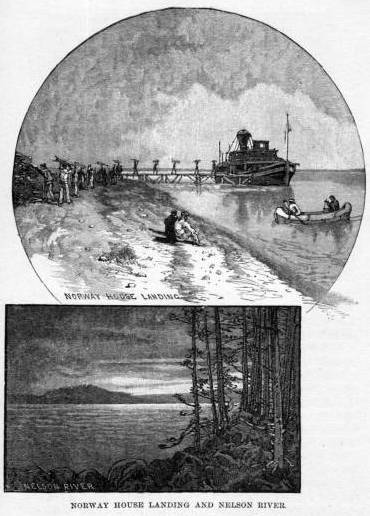

We reached Norway House on the afternoon of the 29th of July, 1868, and received a very cordial welcome from James Stewart, Esquire, the gentleman in charge of this Hudson’s Bay post. This is one of the most important establishments of this wealthy fur-trading Company. For many years it was the capital, at which the different officers and other officials from the different districts of this vast country were in the habit of meeting annually for the purpose of arranging the various matters in connection with their prosecution of the fur trade. Here Sir George Simpson, for many years the energetic and despotic Governor, used to come to meet these officials, travelling by birch canoe, manned by his matchless crew of Iroquois Indians, all the way from Montreal, a distance of several thousand miles. Here immense quantities of furs were collected from the different trading posts, and then shipped to England by way of Hudson’s Bay.

The sight of this well-kept establishment, and the courtesy and cordial welcome extended to us, were very pleasing after our long toilsome voyage up Lake Winnipeg. But still we were two  miles and a half from our Indian Mission, and so we were full of anxiety to reach the end of our journey. Mr Stewart, however, insisted on our remaining to tea with him, and then took us over to the Indian village in his own row-boat, manned by four sturdy Highlanders. Ere we reached the shore, sweet sounds of melody fell upon our ears. The Wednesday evening service was being held, and songs of praise were being sung by the Indian congregation, the notes of which reached us as we neared the margin and landed upon the rocky beach. We welcomed this as a pleasing omen, and rejoiced at it as one of the grand evidences of the Gospel’s power to change. Not many years ago the horrid yells of the conjurer, and the whoops of the savage Indians, were here the only familiar sounds. Now the sweet songs of Zion are heard, and God’s praises are sung by a people whose lives attest the genuineness of the work accomplished.

miles and a half from our Indian Mission, and so we were full of anxiety to reach the end of our journey. Mr Stewart, however, insisted on our remaining to tea with him, and then took us over to the Indian village in his own row-boat, manned by four sturdy Highlanders. Ere we reached the shore, sweet sounds of melody fell upon our ears. The Wednesday evening service was being held, and songs of praise were being sung by the Indian congregation, the notes of which reached us as we neared the margin and landed upon the rocky beach. We welcomed this as a pleasing omen, and rejoiced at it as one of the grand evidences of the Gospel’s power to change. Not many years ago the horrid yells of the conjurer, and the whoops of the savage Indians, were here the only familiar sounds. Now the sweet songs of Zion are heard, and God’s praises are sung by a people whose lives attest the genuineness of the work accomplished.

We were cordially welcomed by Mrs Stringfellow in the Mission house, and were soon afterwards joined by her husband, who had been conducting the religious services in the church. Very thankful were we that after our long and adventurous journeyings for two months and eighteen days, by land and water, through the good providence of God we had reached our field of toil among the Cree Indians, where for years we were to be permitted to labour.

Mr and Mrs Stringfellow remained with us for a few days ere they set out on their return trip to the province of Ontario. We took sweet counsel together, and I received a great deal of valuable information in reference to the prosecution of our work among these Red men. For eleven years the missionary and his wife had toiled and suffered in this northern land. A goodly degree of success had attended their efforts, and we were much pleased with the state in which we found everything connected with the Mission.

While we were at family prayers the first evening after our arrival, there came up one of the most terrific thunderstorms we ever experienced. The heavy Mission house, although built of logs, and well mudded and clap-boarded, shook so much while we were on our knees that several large pictures fell from the walls; one of which, tumbling on Brother Stringfellow’s head, put a very sudden termination to his evening devotions.

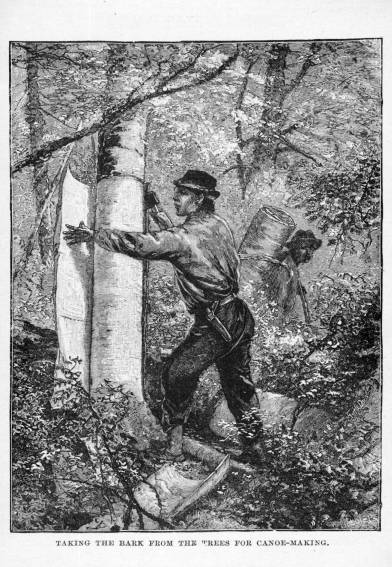

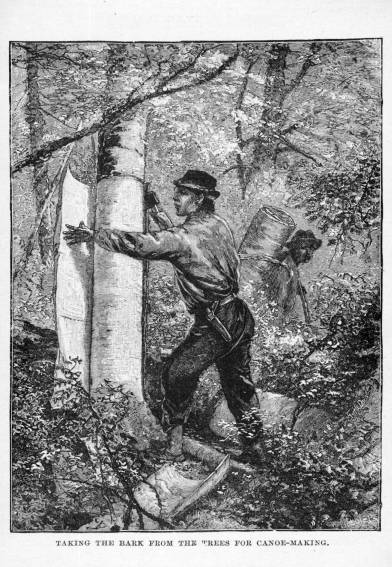

Rossville Mission, Norway House, was commenced by the Reverend James Evans in the year 1840. It has been, and still is, one of the most successful Indian Missions in America. Here Mr Evans invented the syllabic characters, by which an intelligent Indian can learn to read the Word of God in ten days or two weeks. Earnestly desirous to devise some method by which the wandering Indians could acquire the art of reading in a more expeditious manner than by the use of the English alphabet, he invented these characters, each of which stands for a syllable. He carved his first type with his pocket-knife, and procured the lead for the purpose from the tea-chests of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s post. His first ink he made out of the soot from the chimney, and his first paper was birch bark. Great was the excitement among the Indians when he had perfected his invention, and had begun printing in their own language. The conjurers, and other pagan Indians, were very much alarmed, when, as they expressed it, they found the “bark of the tree was beginning to talk.”

The English Wesleyan Missionary Society was early impressed with the advantage of this wonderful invention, and the great help it would be in carrying on the blessed work. At great expense they sent out a printing press, with a large quantity of type, which they had had specially cast. Abundance of paper, and everything else essential, were furnished. For years portions of the Word of God, and a goodly number of hymns translated into the Cree language, were printed, and incalculable good resulted.

Other missionary organisations at work in the country quickly saw the advantage of using these syllabic characters, and were not slow to avail themselves of them. While all lovers of Missions rejoice at this, it is to be regretted that some, from whom better things might have been expected, were anxious to take the credit of the invention, instead of giving it to its rightful claimant, the Reverend James Evans. It is a remarkable fact, that so perfectly did Mr Evans do his work, that no improvement has been made as regards the use of these characters among the Cree Indians.

Other missionaries have introduced them among other tribes, with additions to meet the sounds used in those tribes which are not found among the Crees. They have even been successfully utilised by the Moravians among the Esquimaux.

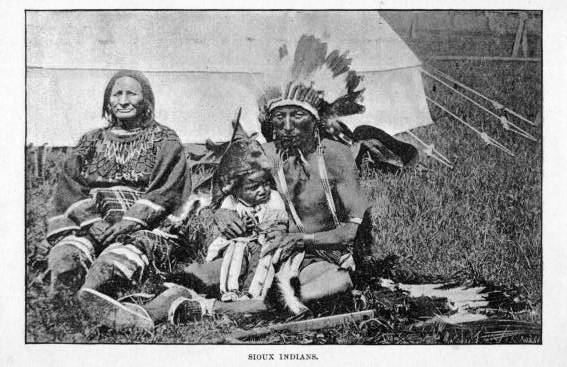

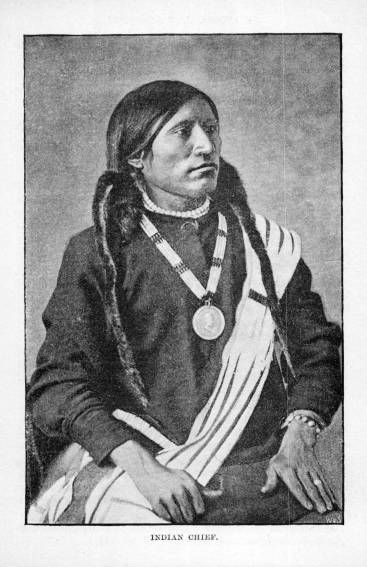

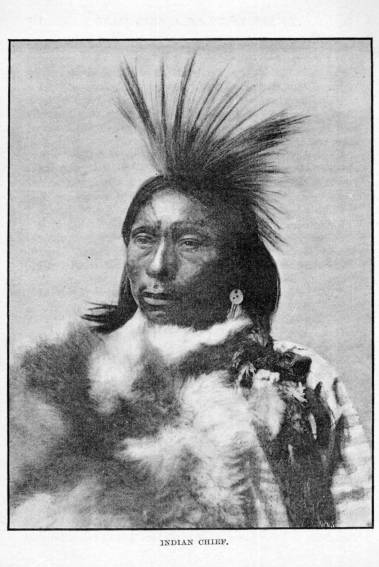

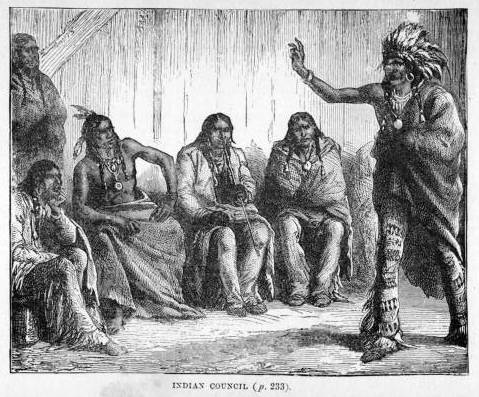

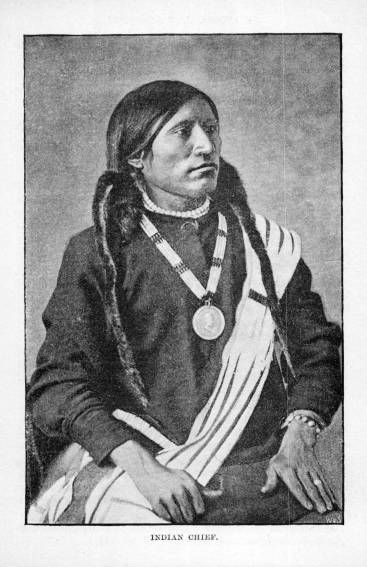

On our arrival at Rossville the Indians crowded in to see the new missionary and his wife, and were very cordial in their greetings. Even some pagan Indians, dressed up in their wild picturesque costumes, came to see us, and were very friendly.

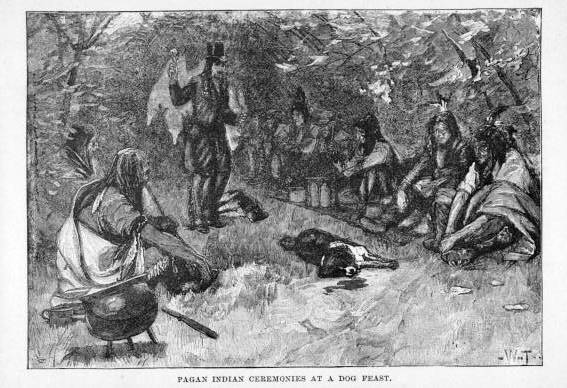

As quickly as possible we settled down to our work, and tried to grasp its possibilities. We saw many pleasing evidences of what had been accomplished by faithful predecessors, and were soon convinced of the greatness of the work yet to be done. For, while from our church, and the houses of our Christian people, the songs of Zion were heard, our eyes were saluted by the shouts and yells of old Indian conjurers and medicine-men, added to the monotonous sounds of their drums, which came to us nightly from almost every point in the compass, from islands and headlands not far away.

Our first Sabbath was naturally a very interesting day. Our own curiosity to see our people was doubtless equalled by that of the people to see their new missionary. Pagans flocked in with Christians, until the church was crowded. We were very much pleased with their respectful demeanour in the house of God. There was no laughing or frivolity in the sanctuary. With their moccasined feet and cat-like tread, several hundred Indians did not make one quarter the noise often heard in Christian lands, made by audiences one-tenth the size. We were much delighted with their singing. There is a peculiar plaintive sweetness about Indian singing that has for me a special attractiveness. Scores of them brought their Bibles to the church. When I announced the lessons for the day, the quickness with which they found the places showed their familiarity with the sacred volume. During prayers they were old-fashioned Methodists enough to kneel down while the Sovereign of the universe was being addressed. They sincerely and literally entered into the spirit of the Psalmist when he said: “O come, let us worship and bow down: let us kneel before the Lord our Maker.”

I was fortunate in securing for my interpreter a thoroughly good Indian by the name of Timothy Bear. He was of an emotional nature, and rendered good service to the cause of Christ. Sometimes, when interpreting for me the blessed truths of the Gospel, his heart would get fired up, and he would become so absorbed in his theme that he would in a most eloquent way beseech and plead with the people to accept this wonderful salvation.

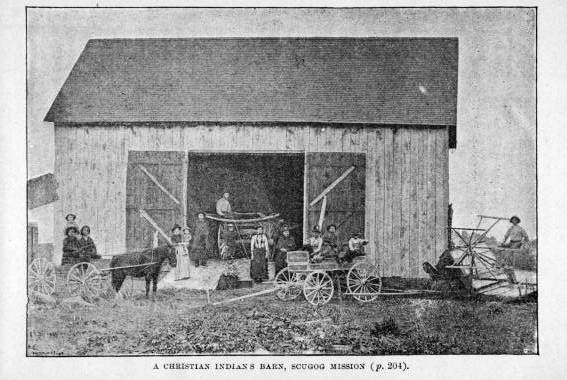

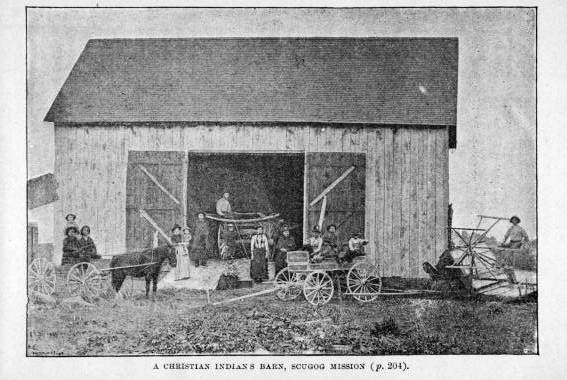

As the days rolled by, and we went in and out among them, and contrasted the pagan with the Christian Indian, we saw many evidences that the Gospel is still the power of God unto salvation, and that, whenever accepted in its fulness, it brings not only peace and joy to the heart, but is attended by the secondary blessings of civilisation. The Christian Indians could easily be picked out by the improved appearance of their homes, as well as by the marvellous change in their lives and actions.

We found out, before we had been there many days, that we had much to learn about Indian customs and habits and modes of thought. For example: the day after Mr and Mrs Stringfellow had left us, a poor woman came in, and by the sign language let Mrs Young know that she was very hungry. On the table were a large loaf of bread, a large piece of corned beef, and a dish of vegetables, left over from our boat supplies. My good wife’s sympathies were aroused at the poor woman’s story, and, cutting off a generous supply of meat and bread, and adding thereto a large quantity of the vegetables and a quart of tea, she seated the woman at the table before the hearty meal. Without any trouble the guest disposed of the whole, and then, to our amazement, began pulling up the skirt of her dress at the side till she had formed a capacious pocket. Reaching over, she seized the meat, and put it in this large receptacle, the loaf of bread quickly followed, and lastly, the dish of vegetables. Then, getting up from her chair, she turned towards us, saying, “Na-nas-koo-moo-wi-nah,” which is the Cree for thanksgiving. She gracefully  backed out of the dining-room, holding carefully onto her supplies. Mrs Young and I looked in astonishment, but said nothing till she had gone out. We could not help laughing at the queer sight, although the food which had disappeared in this unexpected way was what was to have been our principal support for two or three days, until our supplies should have arrived. Afterwards, when expressing our astonishment at what looked like the greediness of this woman, we learned that she had only complied with the strict etiquette of her tribe. It seems it is their habit, when they make a feast for anybody, or give them a dinner, if fortunate enough to have abundance of food, to put a large quantity before them. The invited guest is expected to eat all he can, and then to carry the rest away. This was exactly what the poor woman did. From this lesson of experience we learnt just to place before them what we felt our limited abilities enabled us to give at the time.

backed out of the dining-room, holding carefully onto her supplies. Mrs Young and I looked in astonishment, but said nothing till she had gone out. We could not help laughing at the queer sight, although the food which had disappeared in this unexpected way was what was to have been our principal support for two or three days, until our supplies should have arrived. Afterwards, when expressing our astonishment at what looked like the greediness of this woman, we learned that she had only complied with the strict etiquette of her tribe. It seems it is their habit, when they make a feast for anybody, or give them a dinner, if fortunate enough to have abundance of food, to put a large quantity before them. The invited guest is expected to eat all he can, and then to carry the rest away. This was exactly what the poor woman did. From this lesson of experience we learnt just to place before them what we felt our limited abilities enabled us to give at the time.

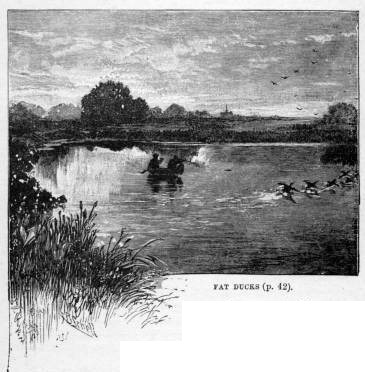

One day a fine-looking Indian came in with a couple of fat ducks. As our supplies were low, we were glad to see them; and in taking them I asked him what I should give him for them. His answer was, “O, nothing; they are a present for the missionary and his wife.” Of course I was delighted at this exhibition of generosity on the part of this entire stranger to us so soon after our arrival in this wild land. The Indian at once made himself at home with us, and kept us busy answering questions and explaining to him everything that excited his curiosity. Mrs Young had to leave her work to play for his edification on the little melodeon. He remained to dinner, and ate one of the ducks, while Mrs Young and I had the other. He hung around all the afternoon, and did ample justice to a supper out of our supplies. He tarried with us until near the hour for retiring, when I gently hinted to him that I thought it was about time he went to see if his wigwam was where he left it.

“O,” he exclaimed, “I am only waiting.”

“Waiting?” I said; “for what are you waiting?”

“I am waiting for the present you are going to give me for the present I gave you.”

I at once took in the situation, and went off and got him something worth half-a-dozen times as much as his ducks, and he went off very happy.

When he was gone, my good wife and I sat down, and we said, “Here is lesson number two. Perhaps, after we have been here a while, we shall know something about the Indians.”

After that we accepted of no presents from them, but insisted on paying a reasonable price for everything we needed which they had to sell.

Our Sunday’s work began with the Sunday School at nine o’clock. All the boys and girls attended, and often there were present many of the adults. The children were attentive and respectful, and many of them were able to repeat large portions of Scripture from memory. A goodly number studied the Catechism translated into their own Language. They sang the hymns sweetly, and joined with us in repeating the Lord’s Prayer.

The public service followed at half-past ten o’clock. This morning service was always in English, although the hymns, lessons, and text would be announced in the two languages. The Hudson’s Bay officials who might be at the Fort two miles away, and all their employés, regularly attended this morning service. Then, as many of the Indians understood English, and our object was ever to get them all to know more and more about it, this service usually was largely attended by the people. The great Indian service was held in the afternoon. It was all their own, and was very much prized by them. At the morning service they were very dignified and reserved; at the afternoon they sang with an enthusiasm that was delightful, and were not afraid, if their hearts prompted them to it, to come out with a glad “Amen!”

They bring with them to the sanctuary their Bibles, and very sweet to my ears was the rustle of many leaves as they rapidly turned to the Lessons of the day in the Old or New Testament. Sermons were never considered too long. Very quietly and reverently did the people come into the house of God, and with equal respect for the place, and for Him Whom there they had worshipped, did they depart. Dr Taylor, one of our missionary secretaries, when visiting us, said at the close of one of these hallowed afternoon services, “Mr Young, if the good people who help us to support Missions and missionaries could see what my eyes have beheld to-day, they would most cheerfully and gladly give us ten thousand dollars a year more for our Indian Missions.”

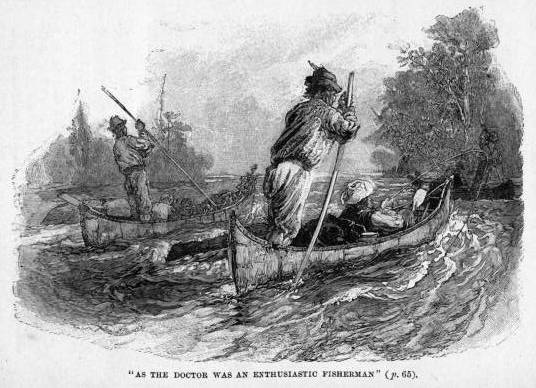

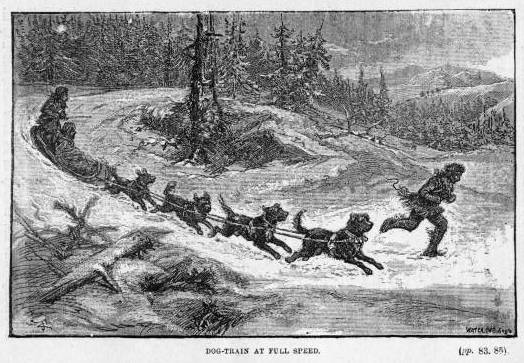

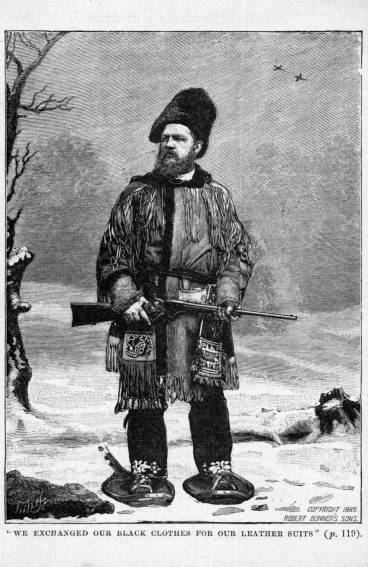

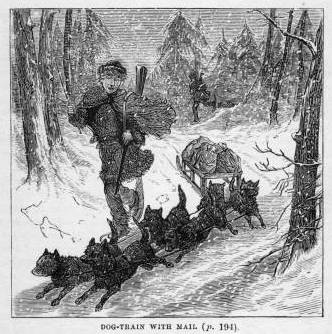

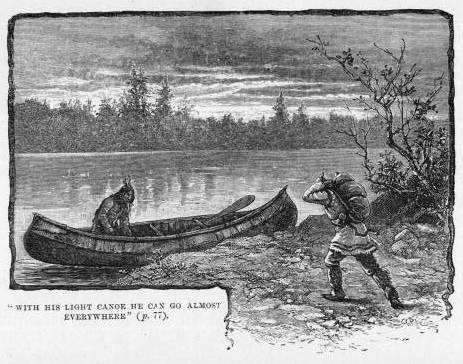

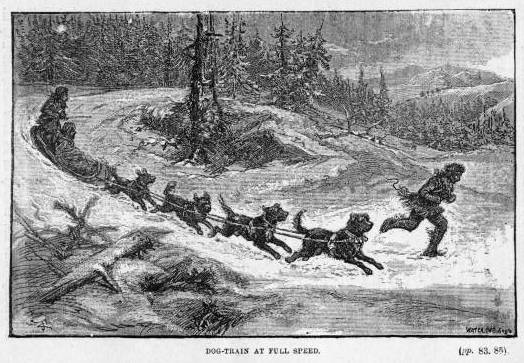

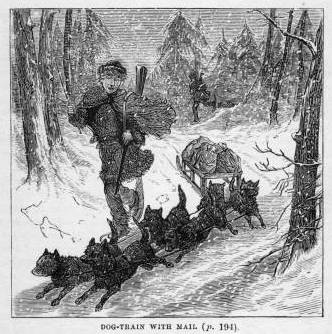

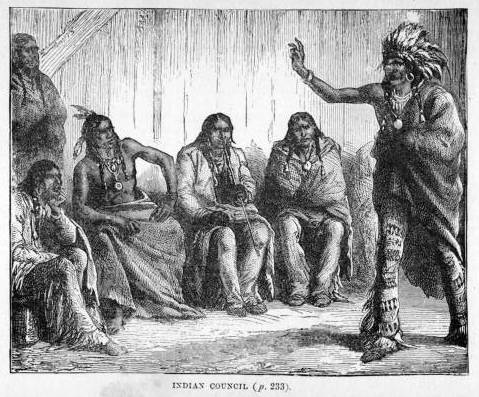

Every Sunday evening I went over to the Fort, by canoe in summer, and dog-train in winter, and held service there. A little chapel had been specially fitted up for these evening services. Another service was also held in the church at the Mission by the Indians themselves. There were among them several who could preach very acceptable sermons, and others who, with a burning eloquence, could tell, like Paul, the story of their own conversion, and beseech others to be likewise reconciled to God.

We were surprised at times by seeing companies of pagan Indians stalk into the church during the services, not always acting in a way becoming to the house or day. At first it was a matter of surprise to me that our Christian Indians put up with some of these irregularities. I was very much astounded one day by the entrance of an old Indian called Tapastonum, who, rattling his ornaments, and crying, “Ho! Ho!” came into the church in a sort of trot, and gravely kissed several of the men and women. As my Christian Indians seemed to stand the interruption, I felt that I could. Soon he sat down, at the invitation of Big Tom, and listened to me. He was grotesquely dressed, and had a good-sized looking-glass hanging on his breast, kept in its place by a string hung around his neck. To aid himself in listening, he lit his big pipe and smoked through the rest of the service. When I spoke to the people afterwards about the conduct of this man, so opposite to their quiet, respectful demeanour in the house of God, their expressive, charitable answer was: “Such were we once, as ignorant as Tapastonum is now. Let us have patience with him, and perhaps he, too, will soon decide to give his heart to God. Let him come; he will get quiet when he gets the light.”

The week evenings were nearly all filled up with services of one kind or another, and were well attended, or otherwise, according as the Indians might be present at the village, or away hunting, or fishing, or “tripping” for the Hudson’s Bay Company. What pleased us very much was the fact that in the homes of the people there were so many family altars. It was very delightful to take a quiet walk in the gloaming through the village, and hear from so many little homes the voice of the head of the family reading the precious volume, or the sounds of prayer and praise. Those were times when in every professed Christian home in the village there was a family altar.

Chapter Four.

Constant progress—Woman’s sad condition in paganism—Illustrations—Wondrous changes produced by Christianity—Illustrations—New Year’s Day Christian Festival—The aged and feeble ones first remembered—Closing Thanksgiving services.

We found ourselves in a Christian village surrounded by paganism. The contrast between the two classes was very evident.

Our Christians, as fast as they were able to build, were living in comfortable houses, and earnestly endeavouring to lift themselves up in the social circle. Their personal appearance was better, and cleanliness was accepted as next to godliness. On the Sabbaths they were well dressed, and presented such a respectable and devout appearance in the sanctuary as to win the admiration of all who visited us. The great majority of those who made a profession of faith lived honest, sober, and consistent lives, and thus showed the genuineness of the change wrought in them by the glorious Gospel of the Son of God.

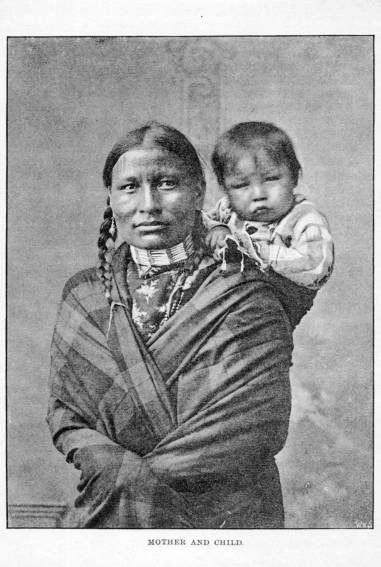

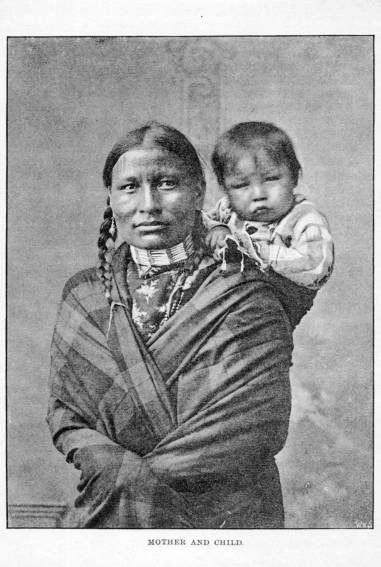

One of the most delightful and tangible evidences of the thoroughness and genuineness of the change was seen in the improvement in the family life. Such a thing as genuine home life, with mutual love and sympathy existing among the different members of the family, was unknown in their pagan state. The men, and even boys, considered it a sign of courage and manliness to despise and shamefully treat their mothers, wives, or sisters. Christianity changed all this; and we were constant witnesses of the genuineness of the change wrought in the hearts and lives of this people by the preaching of the Gospel, by seeing how woman was uplifted from her degraded position to her true place in the household.

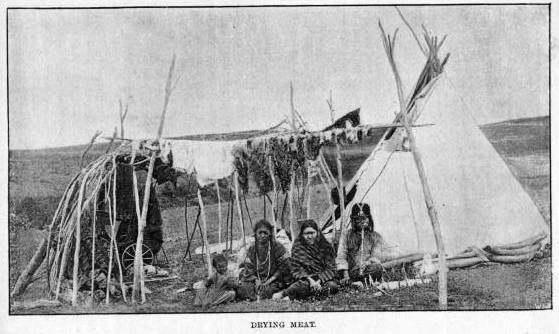

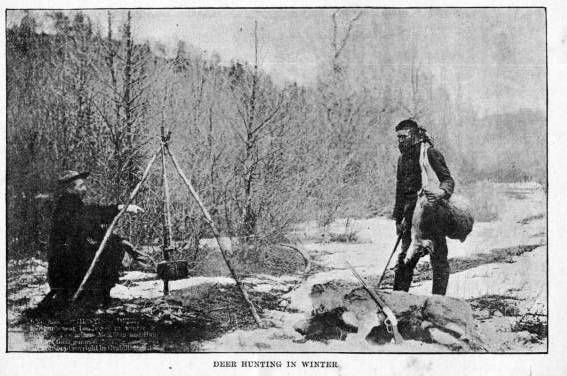

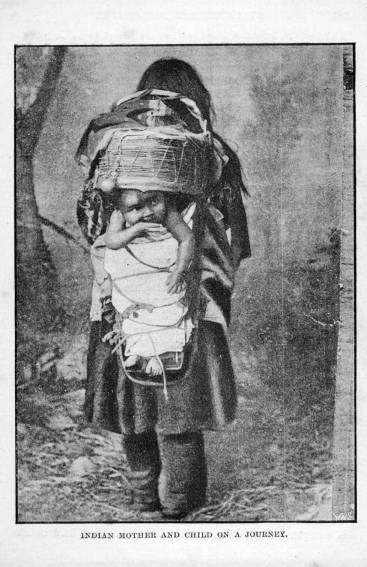

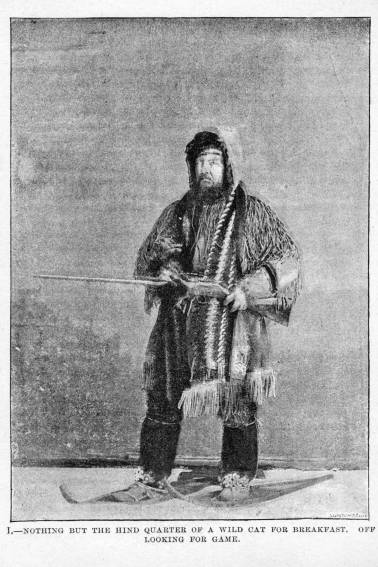

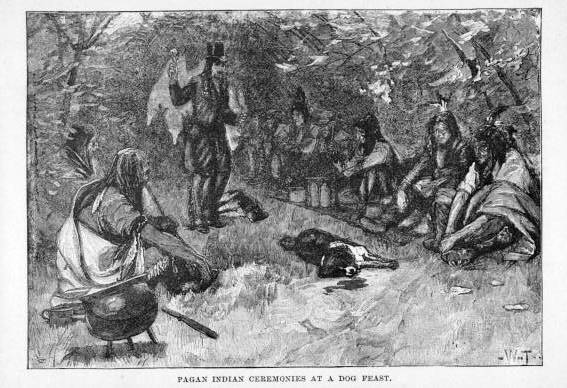

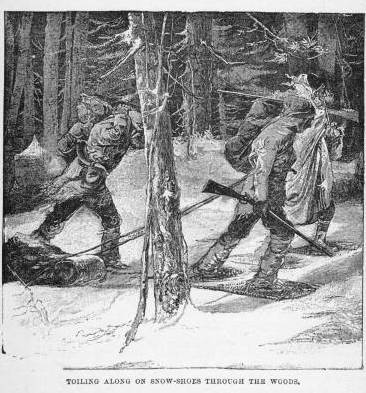

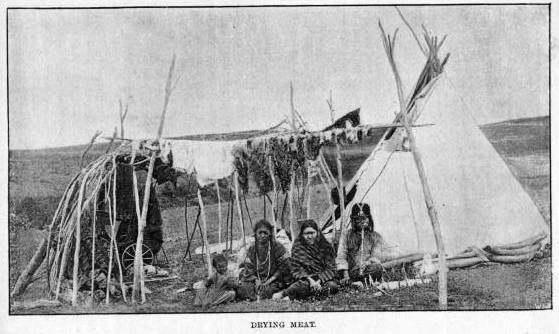

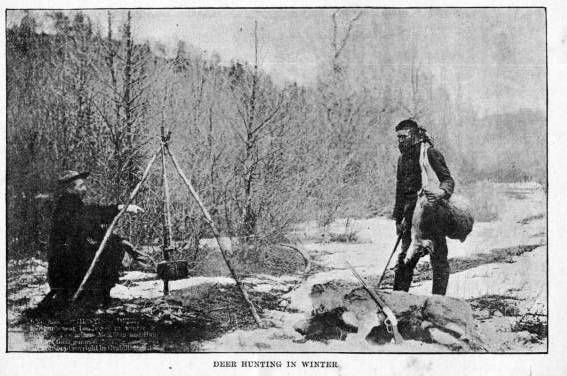

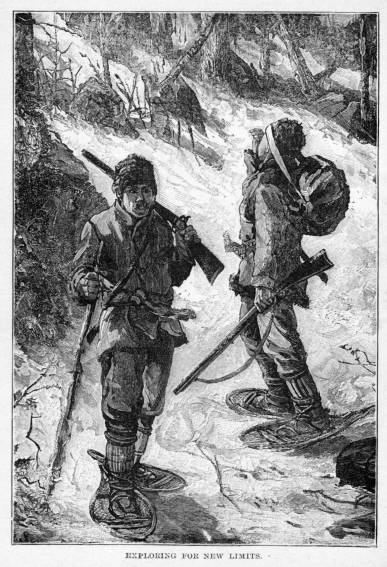

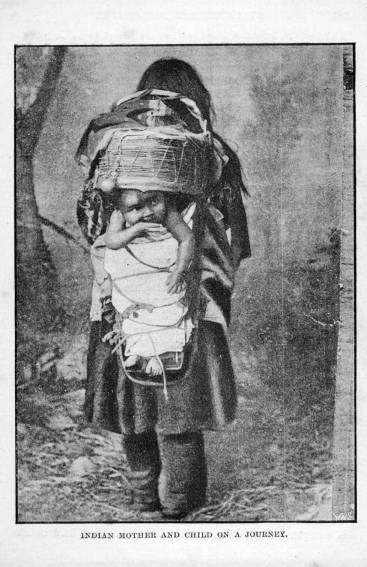

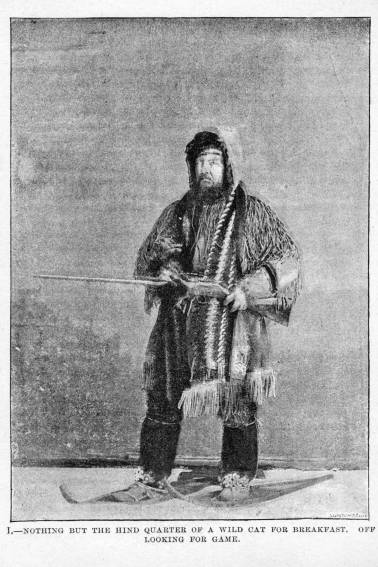

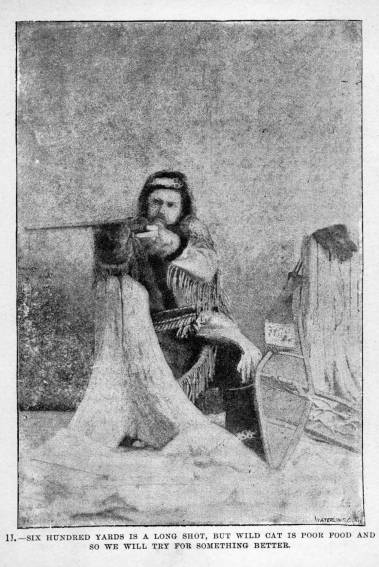

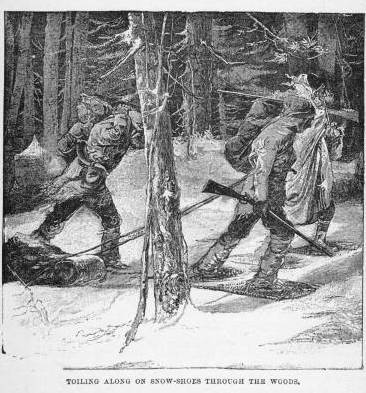

My heart was often pained at what I saw among some of the wild savage bands around us. When, by canoe in summer, or dog-train in winter, I have visited these wild men, I have seen the proud, lazy hunter come stalking into the camp with his gun on his shoulder, and in loud, imperative tones shout out to his poor wife, who was busily engaged in cutting wood, “Get up there, you dog, my squaw, and go back on my tracks in the woods, and bring in the deer I have shot; and hurry, for I want my food!” To quicken her steps, although she was hurrying as rapidly as possible, a stick was thrown at her, which fortunately she was able to dodge.

Seizing the long carrying strap, which is a piece of leather several feet in length, and wide at the middle, where it rests against the forehead when in use, she rapidly glides away on the trail made by her husband’s snow-shoes, it may be for miles, to the spot where lies the deer he has shot. Fastening one end of the strap to the haunches of the deer, and the other around its neck, after a good deal of effort and ingenuity, she succeeds at length in getting the animal, which may weigh from a hundred and fifty to two hundred pounds, upon her back, supported by the strap across her forehead. Panting with fatigue, she comes in with her heavy burden, and as she throws it down she is met with a sharp stern command from the lips of the despot called her husband, who has thought it beneath his dignity to carry in the deer himself, but who imagines it to be a sign of his being a great brave thus to treat his wife. The gun was enough for him to carry. Without giving the poor tired creature a moment’s rest, he shouts out again for her to hurry up and be quick; he is hungry, and wants his dinner.

The poor woman, although almost exhausted, knows full well, by the bitter experiences of the past, that to delay an instant would bring upon herself severe punishment, and so she quickly seizes the scalping knife and deftly skins the animal, and fills a pot with the savoury venison, which is soon boiled and placed before his highness. While he, and the men and boys whom he may choose to invite to eat with him, are rapidly devouring the venison, the poor woman has her first moments of rest. She goes and seats herself down where women and girls and dogs are congregated, and there women and dogs struggle for the half-picked bones which the men, with derisive laughter, throw among them!

This was one of the sad aspects of paganism which I often had to witness as I travelled among those bands that had not, up to that time, accepted the Gospel. When these poor women get old and feeble, very sad and deplorable is their condition. When able to toil and slave, they are tolerated as necessary evils. When aged and weak, they are shamefully neglected, and, often, put out of existence.

One of the missionaries, on visiting a pagan band, preached from those blessed words of the Saviour: “Come unto Me, all ye that labour and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest.” In his sermon he spoke about life’s toils and burdens, and how all men had to work and labour. The men of the congregation were very angry at him; and at an indignation meeting which they held, they said, “Let him go to the squaws with that kind of talk. They have to carry all the heavy burdens, and do the hard work. Such stuff as that is not for us men, but for the women.” So they were offended at him.

At a small Indian settlement on the north-eastern shores of Lake Winnipeg lived a chief by the name of Moo-koo-woo-soo, who deliberately strangled his mother, and then burnt her body to ashes. When questioned about the horrid deed, he coolly and heartlessly said that as she had become too old to snare rabbits or catch fish, he was not going to be bothered with keeping her, and so he deliberately put her to death. Such instances could be multiplied many times. Truly “the tender mercies of the wicked are cruel.”

In delightful contrast to these sad sights among the degraded savages around us, were the kindly ways and happy homes of our converted Indians. Among them a woman occupied her true position, and was well and lovingly treated. The aged and infirm, who but for the Gospel would have been dealt with as Moo-koo-woo-soo dealt with his mother, had the warmest place in the little home and the daintiest morsel on the table. I have seen the sexton of the church throw wide open the door of the sanctuary, that two stalwart young men might easily enter, carrying in their arms their invalid mother, who had expressed a desire to come to the house of God. Tenderly they supported her until the service ended, and then they lovingly carried her home again. But for the Gospel’s blessed influences on their haughty natures they would have died ere doing such a thing for a woman, even though she were their own mother.

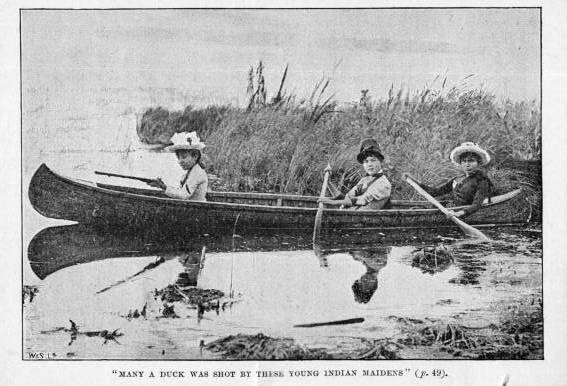

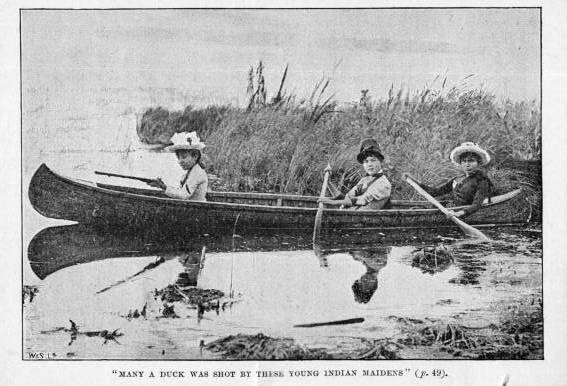

Life for the women was not now all slavery. They had their happy hours, and knew well how to enjoy them. Nothing, however, seemed so to delight them as to be gliding about in the glorious summer time in their light canoes. And sometimes, combining pleasure with profit, many a duck was shot by these young Indian maidens.

This changed feeling towards the aged and afflicted ones we have seen manifested in a very expressive and blessed way at the great annual New Year’s Feast. It was customary for the Indians, long before they became Christians, to have a great feast at the beginning of the New Year. In the old times, the principal article of food at these horrid feasts was dogs, the eating of which was accompanied by many revolting ceremonies. The missionaries, instead of abolishing the feast, turned it into a religious festival. I carried out the methods of my worthy predecessors at Norway House, and so we had a feast every New Year’s Day.