George Manville Fenn

"Brownsmith's Boy"

Chapter One.

The Boy in the Garden.

I always felt as if I should like to punch that boy’s head, and then directly after I used to feel as if I shouldn’t care to touch him, because he looked so dirty and ragged.

It was not dirty dirt, if you know what I mean by that, but dirt that he gathered up in his work—bits of hay and straw, and dust off a shed floor; mud over his boots and on his toes, for you could see that the big boots he wore seemed to be like a kind of coarse rough shell with a great open mouth in front, and his toes used to seem as if they lived in there as hermit-crabs do in whelk shells. They used to play about in there and waggle this side and that side when he was standing still looking at you; and I used to think that some day they would come a little way out and wait for prey like the different molluscs I had read about in my books.

But you should have seen his hands! I’ve seen them so coated with dirt that it hung on them in knobs, and at such times he used to hold them up to me with the thumbs and fingers spread out wide, and then down he would go again and continue his work, which, when he was in this state, would be pulling up the weeds from among the onions in the long beds.

I didn’t want him to do it, but he used to see me at the window looking out; and I being one lonely boy in the big pond of life, and he being another lonely boy in the same big pond, and both floating about like bits of stick, he seemed as if he wanted to gravitate towards me as bits of stick do to each other, and in his uncouth way he would do all sorts of things to attract my attention.

Sometimes it seemed as if it was to frighten me, at others to show how clever he was; but of course I know now that it was all out of the superabundant energy he had in him, and the natural longing of a boy for a companion.

I’ll just tell you what he’d do. After showing me his muddy fingers, and crawling along and digging them as hard as he could into the soil to tear out the weeds, all at once he would kick his heels up in the air like a donkey. Then he would go on weeding again, look to see if I was watching him, and leave his basket and run down between two onion beds on all-fours like a dog, run back, and go on with his work.

Every now and then he would pull up a young onion with the weeds and pick it out, give it a rub on his sleeve, put one end in his mouth, and eat it gradually, taking it in as I’ve seen a cow with a long strand of rye or grass.

Another time he would fall to punching the ground with his doubled fist, make a basin-like depression, put his head in, support himself by setting his hands on each side of the depression, and then, as easily as could be, throw up his heels and stand upon his head.

It seemed to be no trouble to him to keep his balance, and when up like that he would twist his legs about, open them wide, put them forwards and backwards, and end by insulting me with his feet, so it seemed to me, for he would spar at me with them and make believe to hit out.

All at once he would see one of the labourers in the distance, and then down he would go and continue his weeding.

Perhaps, when no one was looking, he would start up, look round, go down again on all-fours, and canter up to a pear-tree, raise himself up, and begin scratching the bark like one of the cats sharpening its claws; or perhaps trot to an apple-tree, climb up with wonderful activity, creep out along a horizontal branch, and pretend to fall, but save himself by catching with and hanging by one hand.

That done he would make a snatch with his other hand, swing about for a few moments, and then up would go his legs to be crossed over the branch, when he would swing to and fro head downwards, making derisive gestures at me with his hands.

So it was that I used to hate that boy, and think he was little better than a monkey; but somehow I felt envious of him too when the sun shone—I didn’t so much mind when it was wet—for he seemed so free and independent, and he was so active and clever, while whenever I tried to stand on my head on the carpet I always tipped right over and hurt my back.

That was a wonderful place, that garden, and I used to gaze over the high wall with its bristle of young shoots of plum-trees growing over the coping, and see the chaffinches building in the spring-time among the green leaves and milky-white blossoms of the pear-trees; or, perhaps, it would be in a handy fork of an apple-tree, with the crimson and pink blossoms all around.

Those trees were planted in straight rows, so that, look which way I would, I could see straight down an avenue; and under them there were rows of gooseberry trees or red currants that the men used to cut so closely in the winter that they seemed to be complete skeletons.

Where there were no gooseberries or currants, the rows of rhubarb plants used to send up their red stems and great green leaves; and in other places there would be great patches of wallflowers, from which wafts of delicious scent would come in at the open window. In the spring there would be great rows of red and yellow tulips, and later on sweet-william and rockets, and purple and yellow pansies in great beds.

I used to wonder that such a boy was allowed to go loose in such a garden as that, among those flowers and strawberry beds, and, above all, apples, and pears, and plums, for in the autumn time the trees trained up against the high red-brick wall were covered with purple and yellow plums, and the rosy apples peeped from among the green leaves, and the pears would hang down till it seemed as if the branches must break.

But that boy went about just as he liked, and it often seemed very hard that such a shaggy-looking wild fellow in rags should have the run of such a beautiful garden, while I had none.

There was a little single opera-glass on the chimney-piece which I used to take down and focus, so that I could see the fruit that was ripe, and the fruit that was green, and the beauty of the flowers. I used to watch the birds building through that glass, and could almost see the eggs in one little mossy cup of a chaffinch’s nest; but I could not quite. I did see the tips of the young birds’ beaks, though, when they were hatched and the old ones came to feed them.

It was by means of that glass that I could see how the boy fastened up his trousers with one strap and a piece of string, for he had no braces, and there were no brace buttons. Those corduroy trousers had been made for somebody else, I should say for a man, and pieces of the legs had been cut off, and the upper part came well over his back and chest. He had no waistcoat, but he wore a jacket that must have belonged to a man. It was a jacket that was fustian behind, and had fustian sleeves, but the front was of purple plush with red and yellow flowers, softened down with dirt; and the sleeves of this jacket were tucked up very high, while the bottom came down to his knees.

He did not wear a hat, but the crown of an old straw bonnet, the top of which had come unsewed, and rose and fell like the lid of a round box with one hinge, and when the lid blew open you could see his shaggy hair, which seemed as if it had never been brushed since it first came up out of his skin.

The opera-glass was very useful to me, especially as the boy fascinated me so, for I used to watch him with it till I knew that he had two brass shank-buttons and three four-holes of bone on his jacket, that there were no buttons at all on his shirt, and that he had blue eyes, a snub-nose, and had lost one of his top front teeth.

I must have been quite as great an attraction to him as he was to me, but he showed it in a very different way. There would be threatening movements made with his fists. After an hour’s hard work at weeding, without paying the slightest heed to my presence, he would suddenly jump up as if resenting my watching, catch up the basket, and make believe to hurl it at me. Perhaps he would pick up a great clod and pretend to throw that, but let it fall beside him; while one day, when I went to the window and looked out, I found him with a good-sized switch which had been the young shoot of a pear tree, and a lump of something of a yellowish brown tucked in the fork of a tree close by where he worked.

He had a basket by his side and was busily engaged as usual weeding, for there was a great battle for ever going on in that garden, where the weeds were always trying to master the flowers and vegetables, and that boy’s duty seemed to be to tear up weeds by the roots, and nothing else.

But there by his side stuck in the ground was the switch, and as soon as he saw me at the window he gave a look round to see if he was watched, and then picked up the stick.

“I wonder what he is going to do!” I thought, as I twisted the glass a little and had a good look.

He was so near that the glass was not necessary, but I saw through it that he pinched off a bit of the yellowish-brown stuff, which was evidently clay, and, after rolling it between his hands, he stuck what seemed to be a bit as big as a large taw marble on the end of the switch, gave it a flourish, and the bit of clay flew off.

I could not see where it went, but I saw him watching it, as he quickly took another piece, kneaded it, and with another flourish away that flew.

That bit evidently went over our house; and the next time he tried—flap! the piece struck the wall somewhere under the window.

Five times more did he throw, the clay flying swiftly, till all at once thud! came a pellet and stuck on the window pane just above my head.

I looked up at the flattened clay, which was sticking fast, and then at that boy, who was down on his knees again weeding away as hard as he could weed, but taking no more notice of me, and I saw the reason: his master was coming down the garden.

Chapter Two.

Old Brownsmith.

I used to take a good deal of notice of that boy’s master as I sat at the window, and it always seemed to me that he went up and down his garden because he was so fond of it.

Later on I knew that it was because he was a market-gardener, and was making his plans as to what was to be cut or picked, or what wanted doing in the place.

He was a pleasant-looking man, with white hair and whiskers, and a red face that always used to make me think of apples, and he was always dressed the same—in black, with a clean white shirt front, and a white cravat without any starch. Perhaps it was so that they might not get in the mud, but at any rate his black trousers were very tight, and his tail-coat was cut very broad and loose, with cross pockets like a shooting-jacket, and these pockets used to bulge.

Sometimes they bulged because he had bast matting for tying up plants, and a knife in one, and a lot of shreds and nails and a hammer in the other; sometimes it was because he had been picking up fruit, or vegetable marrows, or new potatoes, whatever was in season. They always made me think of the clown’s breeches, because he used to put everything in, and very often a good deal would be sticking out.

I remember once seeing him go down the garden with a good-sized kitten in each pocket, for there were their heads looking over the sides, and they seemed to be quite contented, blinking away at the other cats which were running and skipping about.

For that boy’s master, who was called Brownsmith, was a great man for cats; and whenever he went down his garden there were always six or eight blacks, and black and whites, and tabbies, and tortoise-shells running on before or behind him. When he stopped, first one and then another would have a rub against his leg, beginning with the point of its nose, and running itself along right to the end of its tail, crossing over and having a rub on the other side against the other leg.

So sure as one cat had a rub all the others that could get a chance had a rub as well. Then perhaps their master would stoop down with his knife in his teeth, and take a piece of bast from his pocket, to tie up a flower or a lettuce, when one of the cats was sure to jump on his back, and stop there till he rose, when sometimes it would go on and sit upon his shoulder, more often jump off.

It used to interest me a good deal to watch old Brownsmith and his cats, for I had never known that a cat would run after any one out of doors like a dog. Then, too, they were so full of fun, chasing each other through the bushes, crouching down with their tails writhing from side to side, ready to spring out at their master, or dash off again up the side of a big tree, and look down at him from high upon some branch.

I say all this used to interest me, for I had no companions, and went to no school, but spent my time with my poor mother, who was very ill; and I know now how greatly she must have suffered often and often, when, broken down in health and spirit, suffering from a great sorrow, she used to devote all her time to teaching me.

Our apartments, as you see, overlooked old Brownsmith’s market-garden, and very often, as I sat there watching it, I used to wish that I could be as other boys were, running about free in the fields, playing cricket and football, and learning to swim, instead of being shut up there with my mother.

Perhaps I was a selfish boy, perhaps I was no worse than others of my age. I know I was very fond of my mother, for she was always so sweet, and gentle, and tender with me, making the most tedious lessons pleasant by the way she explained them, and helping me when I was worried over some arithmetical question about how many men would do so much work in such and such a number of days if so many men would do the same work in another number of days.

These sums always puzzled me, and do now; perhaps it is because I have an awkwardly shaped brain.

Sometimes, as we sat over the lessons, I used to see a curious pained look spread over my mother’s face, and the tears would come in her eyes, but when I kissed her she would smile directly and call my attention to the beauty of the rime frost on the fruit-trees in Brownsmith’s garden; or, if it was summer, to the sweet scent of the flowers; or to the ripening fruit in autumn.

Ah, if I had known then, I say to myself, how different I might have been; how much more patient and helpful to her! But I did not know, for I was a very thoughtless boy.

Now it came to pass one day that an idea entered my head as I saw my mother seated with her pale cheek resting upon her hand, looking out over old Brownsmith’s garden, which was just then at its best. It was summer time, and wherever you looked there were flowers—not neat flower-beds, but great clumps and patches of roses, and sweet-williams and pinks, and carnations, that made the air thick with their sweet odours. Her eyes were half closed, and every now and then I saw her draw in a long breath, as if she were enjoying the sweet scent.

As I said, I had an idea, and the idea was that I would slip out quietly and go and spend that sixpence.

Which sixpence?

Why, that sixpence—that red-hot one that tried so hard to burn a hole through my pocket.

I had had it for two days, and it was still at the bottom along with my knife, a ball of string, and that piece of india-rubber I had chewed for hours to make a pop patch. I had nearly spent it twice—the first time on one of these large white neatly-sewn balls, with “Best Tennis” printed upon them in blue; the second time in a pewter squirt.

I had wanted a squirt for a long time, for those things had a great fascination for me, and I had actually entered the shop door to make my purchase when something seemed to stop me, and I ran home.

And now I thought I would go and spend that coin.

I slipped quietly to the other window, and had a good look round, but I could not see that boy, for if I had seen him I don’t think I should have had the heart to go, feeling sure, as I did, that he had a spite against me. As I said, though, he was nowhere visible, so I slipped downstairs, ran along the lane to the big gate, and walked boldly in.

There were several people about, but they took no notice of me—stout hard-looking women, with coarse aprons tied tightly about their waists and legs; there were men too, but all were busy in the great sheds, where they seemed to be packing baskets, quite a mountain of which stood close at hand.

There were high oblong baskets big enough to hold me, but besides these there were piles upon piles of round flat baskets of two sizes, and hanging to the side of one  of the sheds great bunches of white wood strawberry pottles, looking at a distance like some kind of giant flower, all in elongated buds.

of the sheds great bunches of white wood strawberry pottles, looking at a distance like some kind of giant flower, all in elongated buds.

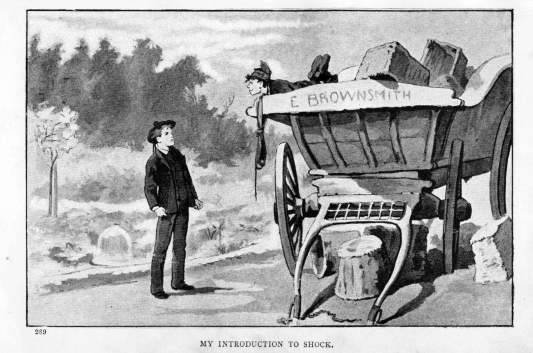

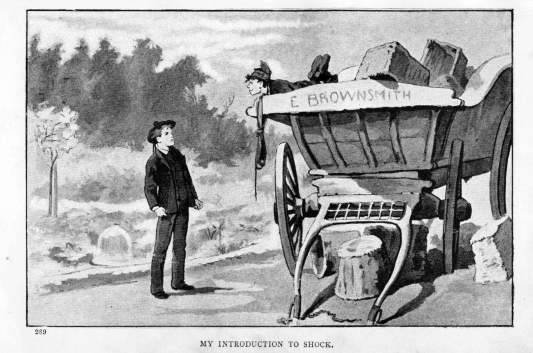

Close by was a cart with its shafts sticking up in the air. Farther on a wagon with “Brownsmith” in yellow letters on a great red band; and this I passed to go up to the house. But the door was closed, and it was evident that every one was busy in the garden preparing the night’s load for market.

I stood still for a minute, thinking that I could not be very wrong if I went down the garden, to see if I could find Mr Brownsmith, and my heart began to beat fast at the idea of penetrating what was to me a land of mystery, of which, just then, I held the silver pass-key in the shape of that sixpence.

“I’ll go,” I said. “He can’t be very cross;” and, plucking up courage, but with the feeling upon me that I was trespassing, I went past the cart, and had gone half-way by the wagon, when there was a creaking, rattling noise of baskets, and something made a bound.

I started back, feeling sure that some huge dog was coming at me; but there in the wagon, and kneeling on the edge to gaze down at me with a fierce grin, was that boy.

I was dreadfully alarmed, and felt as if the next minute he and I would be having a big fight; but I wouldn’t show my fear, and I stared up at him defiantly with my fists clenching, ready for his first attack.

He did not speak—I did not speak; but we stared at each other for some moments, before he took a small round turnip out of his pocket and began to munch it.

“Shock!” cried somebody just then; and the boy turned himself over the edge of the wagon, dropped on to the ground, and ran towards one of the sheds, while, greatly relieved, I looked about me, and could see Mr Brownsmith some distance off, down between two rows of trees that formed quite an avenue.

It seemed so beautiful after being shut up so much in our sitting-room, to walk down between clusters of white roses and moss roses, with Anne Boleyne pinks scenting the air, and far back in the shade bright orange double wallflowers blowing a little after their time.

I had not gone far when a blackbird flew out of a pear-tree, and I knew that there must be a nest somewhere close by. Sure enough I could see it in a fork, with a curious chirping noise coming from it, as another blackbird flew out, saw me, and darted back.

I would have given that sixpence for the right to climb that pear-tree, and I gave vent to a sigh as I saw the figure of old Brownsmith coming towards me, looking much more stern and sharp than he did at a distance, and with his side pockets bulging enormously.

“Hallo, young shaver! what’s your business?” he said, in a quick authoritative way, as we drew near to each other.

I turned a little red, for it sounded insulting for a market gardener to speak to me like that, for I never forgot that my father had been a captain in an Indian regiment, and was killed fighting in the Sikh war.

I did not answer, but drew myself up a little, before saying rather consequentially:

“Sixpenn’orth of flowers and strawberries—good ones.”

“Oh, get out!” he said gruffly, and he half turned away. “We’ve no time for picking sixpenn’orths, boy. Run up into the road to the greengrocer’s shop.”

My face grew scarlet, and the beautiful garden seemed as if it was under a cloud instead of the full blaze of sunshine, while I turned upon my heel and was walking straight back.

“Here!”

I walked on.

“Hi, boy!” shouted old Brownsmith.

I turned round, and he was signalling to me with the whole of his crooked arm.

“Come on,” he shouted, and he thrust a hand and the greater part of his arm into one of his big pockets, and pulled out one of those curved buckhorn-handled knives, which he opened with his white teeth.

He did not look quite so grim now, as he said:

“Come o’ purpose, eh?”

“Yes,” I said.

“Ah! well, I won’t send you back without ’em, only I don’t keep a shop.”

I looked rather haughty and consequential, I believe, but the looks of such a boy as I made no impression, and he began to cut here and there moss, and maiden’s blush, and cabbage roses—simple old-fashioned flowers, for the great French growers had not filled England with their beautiful children, and a gardener in these days would not have believed in the possibility of a creamy Gloire de Dijon or that great hook-thorned golden beauty Maréchal Niel.

He cut and cut, long-stalked flowers with leaf and bud, and thrust them into his left hand, his knife cutting and his hand grasping the flower in one movement, while his eye selected the best blossom at a glance.

At last there were so many that I grew fidgety.

“I said sixpenn’orth, sir, flowers and strawberries,” I ventured to remark.

“Not deaf, my lad,” he replied with a grim smile. “Here, let’s get some of these.”

These were pinks and carnations, of which he cut a number, pushing one of the cats aside with his foot so that it should not be in his way.

“Here you are!” he cried. “Mind the thorns. My roses have got plenty to keep off pickers and stealers. Now, what next?”

“I did want some strawberries,” I said, “but—”

“Where’s your basket, my hearty?”

I replied that I had not brought one.

“You’re a pretty fellow,” he said. “I can’t tie strawberries up in a bunch. Why didn’t you bring a basket? Oh, I see; you want to carry ’em inside?”

“No,” I said shortly, for he seemed now unpleasantly familiar, and the garden was not half so agreeable as I had expected.

However he seemed to be quite good-tempered now, and giving me a nod and a jerk of his head, which meant—“This way,” he went down a path, cut a great rhubarb leaf, and turned to me.

“Here, catch hold,” he cried; “here’s one of nature’s own baskets. Now let’s see if there’s any strawberries ripe.”

I saw that he was noticing me a good deal as we went along another path towards where the garden was more open, but I kept on in an independent way, smelling the pinks from time to time, till we came to a great square bed, all straw, with the great tufts of the dark green strawberry plants standing out of it in rows. The leaves looked large, and glistened in the sunshine, and every here and there I could see the great scarlet berries shining as if they had been varnished, and waiting to be picked.

“Ah, thief!” shouted my guide, as a blackbird flew out of the bed, uttering its loud call. “Why, boys, boys, you ought to have caught him.”

This was to the cats, one of which answered by giving itself a rub down his leg, while he clapped his hand upon my shoulder.

“There you are, my hearty. It isn’t so far for you to stoop as it would be for me. Go and pick ’em.”

“Pick them?” I said, looking at him wonderingly.

“To be sure. Go ahead. I’ll hold your flowers. Only take the ripe ones, and see here—do you know how to pick strawberries?”

I felt so amused at such a silly question that I looked up at him and laughed.

“Oh, you do?” he said.

“Why, anybody could pick strawberries,” I replied.

“Really, now! Well, let’s see. There’s a big flat fellow, pick him.”

I handed him the flowers, and stepping between two rows of plants, stooped down, and picked the great strawberry he pointed out.

“Oh, you call that picking, do you?” he said.

“Yes, sir. Don’t you?”

“No: I call it tearing my plants to pieces. Why, look here, if my pickers were to go to work like that, I should only get half a crop and my plants would be spoiled.”

I looked at him helplessly, and wished he would pick the strawberries himself.

“Look here,” he said, stooping over a plant, and letting a great scarlet berry specked with golden seeds fall over into his hand. “Now see: finger nail and thumb nail; turn ’em into scissors; draw one against the other, and the stalk’s through. That’s the way to do it, and the rest of the bunch not hurt. Now then, your back’s younger than mine. Go ahead.”

I felt hot and uncomfortable, but I took the rhubarb leaf, stepped in amongst the clean straw, and, using my nails as he had bid me, found that the strawberries came off wonderfully well.

“Only the ripe ones, boy; leave the others. Pick away. Poor old Tommy then!”

I looked up to see if he was speaking to me, but he had let one of the cats run up to his shoulder, and he was stroking the soft lithe creature as it rubbed itself against his head.

“That’s the way, boy,” he cried, as I scissored off two or three berries in the way he had taught me. “I like to see a chap with brains. Come, pick away.”

I did pick away, till I had about twenty in the soft green leaf, and then I stopped, knowing that in flowers and fruit I had twice as much as I should have obtained at the shop.

“Oh, come, get on,” he cried contemptuously. “You’re not half a fellow. Don’t stop. Does your back ache?”

“No, sir,” I said; “but—”

“Oh, you wouldn’t earn your salt as a picker,” he cried. As he said this he came on to the bed, and, bending down, seemed to sweep a hand round the strawberry plant, gathering its leaves aside, and leaving the berries free to be snipped off by the right finger and thumb. He kept on bidding me pick away, but he sheared off three to my one, and at the end of a few minutes I was holding the rhubarb leaf against my breast to keep the fruit from falling over the side.

“There you are,” he cried at last. “That do?”

“Oh, yes, sir,” I said; “but—”

“That’s enough,” he cried sharply. “Here, hand over that sixpence. Money’s money, and you can’t get on without it, youngster.”

I gave him the coin, and he took it, span it up in the air, caught it, and after dragging out a small wash-leather bag he dropped it in, gave me a comical look as he twisted a string about the neck, tucked it in, and replaced the bag in his pocket.

“There you are,” he cried. “Small profits and quick returns. No credit given. Toddle; and don’t you come and bother me again. I’m a market grower, my young shaver, and can’t trade your fashion.”

“I did not know, sir,” I said, trying to look and speak with dignity, for it was very unpleasant to be addressed so off-handedly by this man, just as if I had been asking him a favour.

“I’m very much obliged to you,” I added, for I had glanced at the bunch of roses; and as I looked at the fresh sweet-scented beauties I thought of how delighted my poor mother would be, and I could not help feeling that old Brownsmith had been very generous.

Then making him rather an awkward bow, I stalked off, feeling very small, and was some distance back towards the gate, wondering whether I should meet “Shock,” when from behind there came a loud “Hi!”

I paid no heed and went on, for it was not pleasant to be shouted at like that by a market grower, and my dignity was a good deal touched by the treatment I had received; but all at once there came from behind me such a roar that I was compelled to stop, and on turning round there was old Brownsmith trotting after me, with his cats skipping about in all directions to avoid being trodden on and to keep up.

He was very much more red in the face now, for the colour went all down below his cheeks and about his temples, and he was shining very much.

“Why, I didn’t know you with your cap on,” he cried. “Take it off. No, you can’t. I will.”

To my great annoyance he snatched off my cap.

“To be sure! I’m right,” he said, and then he put my cap on again, uncomfortably wrong, and all back: for no one can put your cap on for you as you do it yourself. “You live over yonder at the white house with the lady who is ill?”

I nodded.

“The widow lady?”

“I live with mamma,” I said shortly.

“Been very ill, hasn’t she?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Ah! bad thing illness, I suppose. Never was ill, only when the wagon went over my leg.”

“Yes, sir, she has been very bad.”

I was fidgeting to go, but he took hold of one of the ends of my little check silk tie, and kept fiddling it about between his finger and thumb.

“What’s the matter?”

“Dr Morrison told Mrs Beeton, our landlady, that it was decline, sir.”

“And then Mrs Beeton told you?”

“No, sir, I heard the doctor tell her.”

“And then you went and frightened the poor thing and made her worse by telling her?”

“No, I did not, sir,” I said warmly.

“Why not?”

“Because I thought it might make her worse.”

“Humph! Hah! Poor dear lady!” he said more softly. “Looked too ill to come to church last Sunday, boy. Flowers and fruit for her?”

I nodded.

“She send you to buy ’em?”

I shook my head, for I was so hurt by his abrupt way, his sharp cross-examination, and the thoughts of my mother’s illness, that I could not speak.

“Who sent you then—Mrs Beeton?”

“No, sir.”

“Who did?”

“Nobody, sir. I thought she would like some, and I came.”

“For a surprise, eh?”

Yes, sir.

“Own money?”

I stared at him hard.

“I said, Own money? the sixpence? Where did you get it?”

“I have sixpence a week allowed me to spend.”

“Hah! to be sure,” he said, still holding on by my tie, and staring at me as he fumbled with one hand in his trousers pocket. “Get out, Dick, or I’ll tread on you!” this to one of the cats, who seemed to think because he was black and covered with black fur that he was a blacking-brush, and he was using himself accordingly all over his master’s boots.

“If you please, I want to go now,” I said hurriedly.

“To be sure you do,” he said, still holding on to the end of my tie—“to be sure you do. Hah! that’s got him at last.”

I stared in return, for there had been a great deal of screwing about going on in that pocket, as if he could not get out his big fist, but it came out at last with a snatch.

“Here, where are you?” he said. “Weskit? why, what a bit of a slit it is to call a pocket. Hold the sixpence though, won’t it?”

“If you please I’d rather pay for the flowers,” I cried, flushing as he held on by the tie with one hand, and thrust the sixpence back in my pocket with the other.

“Dessay you would,” he replied; “but I told you before I’m market grower and dursen’t take small sums. Not according to Cocker. Didn’t know Cocker, I suppose, did you?”

“No, sir.”

“Taught ’rithmetic. Didn’t learn his ’rithmetic then?”

“No, sir,” I replied, “Walkinghame’s.”

“Did you though? There, now, you play a walking game, and get home and count your strawberries.”

“Yes, sir, but—”

“I say, what a fellow you are to but! Why, you’re like Teddy, my goat, I once had. No, no! No money. Welcome to the fruit, ditto flowers, boy. This way.”

He was leading me towards the gate now like a dog by a string, and it annoyed me that he would hold me by the end of my tie, the more so that I could see Shock with a basket turned over his head watching me from down amongst the trees.

“Come on again, my lad, often as you like. Lots growing—lots spoils.”

“Thank you, sir,” I said diffidently, “but—”

“Woa, Teddy,” he cried, laughing. “There; that’ll do. Look here, why don’t you bring her for a walk round the garden—do her good? Glad to see her any time. Here, what a fellow you are, dropping your strawberries. Let it alone, Dick. Do for Shock.”

I had let a great double strawberry roll off the top of my heap, and a cat darted at it to give it a sniff; but old Brownsmith picked it up and laid it on the top of a post formed of a cut-down tree.

“Now, then, let’s get a basket. Look better for an invalid. One minute: some leaves.”

He stooped and picked some strawberry leaves, and one or two very large ripe berries, which he told me were Myatt’s.

Then taking me to a low cool shed that smelt strongly of cut flowers, he took down a large open strawberry basket from a nail, and deftly arranged the leaves and fruit therein, with the finest ripened fruit pointing upwards.

“That’s the way to manage it, my lad,” he said, giving me a queer look; “put all the bad ones at the bottom and the good ones at the top. That’s what you’d better do with your qualities, only never let the bad ones get out.”

“Now, your pinks and roses,” he said; and, taking them, he shook them out loosely on the bench beneath a window, arranged them all very cleverly in a bunch, and tied it up with a piece of matting.

“I’m sure I’m very much obliged to you, sir,” I said, warmly now, for it seemed to me that I had been making a mistake about Mr Brownsmith, and that he was a very good old fellow after all.

“That’s right,” he said, laughing. “So you ought to be. Good-bye. Come again soon. My dooty to your mamma, and I hope she’ll be better. Shake hands.”

I held out my hand and grasped his warmly as we reached the gate, seeing Shock watching me all the time. Then as I stood outside old Brownsmith laughed and nodded.

“Mind how you pack your strawberries,” he said with a laugh; “bad ’uns at bottom, good ’uns at top. Good-bye, youngster, good-bye.”

Chapter Three.

Old Brownsmith’s Visitor.

The time glided on, but I did not go to the garden again, for my mother felt that we must not put ourselves under so great an obligation to a stranger. Neither did I take her over for a walk, but we sat at the window a great deal after lesson time; and whenever I was alone and Shock was within sight, he used to indulge in some monkey-like gesture, all of which seemed meant to show me what a very little he thought of me.

At the end of a fortnight, as I was sitting at the window talking to a boy who went to a neighbouring school, and telling him why I did not go, a great clod of earth came over the wall and hit the boy in the back.

“Who’s that!” he cried sharply. “Did you shy that lump?”

“No,” I said; and before I could say more, he cried:

“I know. It was Brownsmith’s baboon shied that. Only let us get him out in the fields, we’ll give it him. You know him, don’t you?”

“Do you mean Shock?” I said.

“Yes, that ragged old dirty chap,” he cried. “You can see him out of your window, can’t you?”

“I can sometimes,” I said; “but I can’t now.”

“That’s because he’s sneaking along under the wall. Never mind; we’ll pay him some day if he only comes out.”

“Doesn’t he come out then?”

“No. He’s nobody’s boy, and sleeps in the sheds over there. One of Brownsmith’s men picked him up in the road, and brought him home in one of the market carts. Brownsmith sent him to the workhouse, but he always runs away and comes back. He’s just like a monkey, ain’t he? Here, I must go; but I say, why don’t you ask your ma to let you come and play with us; we have rare games down the meadows, bathing, and wading, and catching dace?”

“I should like to come,” I said dolefully.

“Ah, there’s no end of things to see down there—water-rats and frogs; and there’s a swan’s nest, with the old bird sitting; and don’t the old cock come after you savage if you go near! Oh, we do have rare games there on half-holidays! I wish you’d come.”

“I should like to,” I said.

“Ain’t too proud; are you?”

“Oh no!” I said, shaking my head.

“Because I was afraid you were. Well, I shall catch it if I stop any longer. I say, is your ma better?”

I shook my head.

“Ain’t going to die, is she?”

“Oh no!” I said sharply.

“That’s all right. Well, you get her to let you come. What’s your name?”

“Grant,” I said.

“Grant! Grant what?”

“Dennison.”

“Oh, all right, Grant! I shall call for you next half-holiday; and mind you come.”

“Stop a moment,” I said. “What’s your name?”

“George Day,” he replied; and then my new friend trotted off, swinging half-a-dozen books at the end of a strap, and I sat at the window wishing that I too could go to school and have a strap to put round my books and swing them, for my life seemed very dull.

All at once I saw something amongst the bristly young shoots of the plum-trees along the wall, and on looking more attentively I made out that it was the top of Shock’s straw head-piece with the lid gone, and the hair sticking out in the most comical way.

I watched him intently, fully expecting to see another great clod of earth come over, and wishing I had something to throw back at him; but I had nothing but a flower-pot with a geranium in it, and the shells upon the chimney-piece, and they were Mrs Beeton’s, and I didn’t like to take them.

The head came a little higher till the whole of the straw bonnet crown was visible, and I could just make out the boy’s eyes.

Of course he was watching me, and I sat and watched him, feeling that he must have turned one of the trained plum-trees into a ladder, and climbed up; and I found myself wondering whether he had knocked off any of the young fruit.

Then, as he remained perfectly still, watching me, I began to wonder why he should be so fond of taking every opportunity he could find to stare at me; and then I wondered what old Brownsmith would say to him, or do, if he came slowly up behind him and caught him climbing up his beautifully trained trees.

Just then I heard a loud cough that I knew was old Brownsmith’s, for I had heard it dozens of times, and Shock’s head disappeared as if by magic.

I jumped up to see, for I felt sure that Shock was going to catch it, and then I saw that old Brownsmith was not in his garden, but in the lane on our side, and that he was close beneath the window looking up at me.

He nodded, and I had just made up my mind that I would not complain about Shock, when there was a loud thump of the knocker, and directly after I heard the door open, a heavy step in the passage, the door closed, and then the sound of old Brownsmith wiping his shoes on the big mat.

His shoes could not have wanted wiping, for it was a very dry day, but he kept on rub—rub—rub, till Mrs Beeton, who waited upon us as well as let us her apartments, came upstairs, knocked at my mother’s door, and went down again.

Then there was old Brownsmith’s heavy foot on the stair, and he was shown in to where I was waiting.

“Mrs Dennison will be here directly,” said our landlady, and the old man smiled pleasantly at me.

I say old man, for he was in my eyes a very old man, though I don’t suppose he was far beyond fifty; but he was very grey, and grey hairs in those days meant to me age.

“How do?” he said as soon as he saw me. “Being such a nigh neighbour I thought I’d come and pay my respects.”

He had a basket in his hand, and just then my mother entered, and he turned and began backing before her on to me.

“Like taking a liberty,” he said in his rough way, “but your son and me’s old friends, ma’am, and I’ve brought you a few strawberries before they’re over.”

Before my mother could thank him he went on:

“Been no rain, you see, and the sun’s ripening of ’em off so fast. A few flowers, too, not so good as they should be, ma’am, but he said you liked flowers.”

I saw the tears stand in my mother’s eyes as she thanked him warmly for his consideration, and begged him to sit down.

But no. He was too busy. Lot of people getting ready for market and he was wanted at home, he said, but he thought he would bring those few strawberries and flowers.

“I told him, you know, how welcome you’d be,” he continued. “Garden’s always open to you, ma’am. Come often. Him too.”

He was at the door as he said this, and nodding and bowing he backed out, while I followed him downstairs to open the door.

“Look here,” he said, offending me directly by catching hold of one end of my neckerchief, “you bring her over, and look here,” he went on in a severe whisper, “you be a good boy to her, and try all you can to make her happy. Do you hear?”

“Yes, sir,” I said. “I do try.”

“That’s right. Don’t you worry her, because—because it’s my opinion that she couldn’t bear it, and boys are such fellows. Now you mind.”

“Yes, sir,” I said, “I’ll mind;” and he went away, while, when I returned to the room where my mother was holding the flowers to her face, and seeming as if their beauty and sweetness were almost more than she could bear, I glanced towards the window, and there once more, with his head just above the wall, and peering through the thick bristling twigs, was that boy Shock, watching our window till old Brownsmith reached his gate.

Hardly a week had passed before the old man got hold of me as I was going by his gate, taking me as usual by the end of my tie and leading me down the garden to cut some more flowers.

“You haven’t brought her yet,” he said. “Look here, if you don’t bring her I shall think you are too proud.”

“He shall not think that,” my mother said; and for the next week or two she went across for a short time every day, while I walked beside her, for her to lean upon my shoulder, and to carry the folding seat so that she might sit down from time to time.

Upon these occasions I never saw Shock, and old Brownsmith never came near us. It was as if he wanted us to have the garden to ourselves for these walks, and to a great extent we did.

Of course I used to notice how often I had to spread out that chair for her to sit down under the shady trees; but I thought very little more of it. She was weak. Well, I knew that; but some people were weak, I said, and some were strong, and she would be better when it was not so hot.

Chapter Four.

A Lesson in Swimming.

It was hot! One of those dry summers when the air seems to quiver with the heat, and one afternoon, as I was in my old place at the window watching Shock go to and fro, carrying baskets of what seemed to be beans, George Day came along.

“I say,” he cried, “ask leave to come with us. We’ve got a half-holiday.”

Just then I saw the bristling shoots on the wall shake, but I paid no heed, for I was too much interested in my new friend’s words.

“Where are you going?” I asked.

“Oh, down the meadows! that’s the best place, and there’s no end of fun to be had. I’ll take a fishing-rod.” I went to where my mother was lying down and asked her consent, receiving a feeble yes, and her hand went up to my neck, to draw me down that she might kiss me.

“Be back in good time,” she whispered. “George Day, you said?”

“Yes; his father is something in London, and he goes to the grammar-school.”

“Be back in good time,” she whispered again; and getting my cap, I just caught sight of Shock at the top of the wall as I ran by the window.

“Poor fellow!” I thought, “how he, too, would like a holiday!”

“Here I am,” I cried; and feeling as if I had been just released from some long confinement, I set off with my companion at a sharp run.

We had to call at his house, a large red brick place just at the end of the village, close to Isleworth church, where the rod was obtained, with a basket to hold bait, lines, and the fish that we were going to catch; and soon after we were down where the sleek cows were contentedly lying about munching, and giving their heads an angry toss now and then to keep off the flies.

Rich grass, golden butter-cups, bushes and trees whose boughs swept down towards the ground, swallows and swifts darting here and there, and beneath the vividly blue sky there was the river like so much damascened silver, for in those days one never thought about the mud.

I cannot describe the joy I felt in running here and there with my companion, and a couple of his school-fellows who had preceded us, and who saluted us as we approached with a shout.

We ran about till we were tired, and then the fishing commenced from the bank, for the tide was well up, and according to my companion’s account the fish were in plenty.

Perhaps they were, but though bait after bait was placed upon the hook, and the line thrown out to float along with the current, not a fish was caught, no vestige of that nerve-titillating tremble of the float—a bite—was seen.

Every now and then some one struck sharply, trying to make himself believe that roach or dace had taken the bait, but the movement of the float was always due to the line dragging the gravelly ground, or the bait touching one of the many weeds.

The sun was intensely hot, and scorched our backs, and burned our faces by flashing back from the water, which looked cool and tempting, as it ran past our feet.

We fished on, sometimes one handling the rod and sometimes the other—beginning by throwing in the line with whispered words, so as not to frighten the fish that were evidently not there, and ending by sending in bait and float with a splash, and with noise and joking.

“There’s a big one,” some one would cry, and a clod torn out from the bank, or a stone, would be thrown in amidst bursts of laughter.

“Oh it’s not a jolly bit of good,” cried one of the boys; “they won’t bite to-day. I’m so thirsty, let’s have a drink.”

“No, no, don’t drink the water,” I said; “it isn’t good enough.”

“What shall we do then—run after the cows for a pen’orth of milk?”

“I say, look there,” cried George Day; “the tide’s turned. It’s running down. We shall get plenty of fish now.”

“Why, there’s somebody bathing down below there,” cried another of the boys.

“Yes, and can’t he swim!”

“Let’s all have a bathe,” cried young Day.

“Ah, come on: it will be jolly here. Who’s first in?”

I looked on half in amazement, for directly after catching sight of the head of some lad in the water about a couple of hundred yards below us, who seemed to be swimming about in the cool water with the greatest ease, my companions began to throw off caps and jackets, and to untie and kick off their boots.

“But we haven’t got any towels,” cried George Day.

“Towels!” cried one of the others; “why, the sun will dry us in five minutes; come on. What a day for a swim!”

It did look tempting there at the bottom of that green meadow, deep in grass and with the waving trees to hide us from observation, though there was not a house within a mile, nor, saving an occasional barge with a sleepy man hanging over the tiller, a boat to be seen, and as I watched the actions of my companions, I, for the first time in my life, felt the desire to imitate them come on me strongly.

They were not long undressing, one kicking off his things anyhow, another carefully folding them as he took them off, and tucking his socks inside his boots. But careful and careless alike, five minutes had not elapsed before to my delight George Day, who was a boy of about fourteen, ran back a dozen yards from the river’s brink and threw up his arms.

“One, two, three, cock warning!” he shouted, ran by me swiftly, and plunged into the river with a tremendous splash.

I felt horrified, but the next moment his head reappeared bobbing about, and he swam along easily and well.

“Oh it’s so lovely,” he cried. “Come along.”

“All right!” cried one of his friends, sitting down on the edge of the bank, and lowering himself in gently, to stand for a few moments up to his arm-pits, and then duck his head down twice, rubbing his eyes to get the water out, and then stooping down and beginning to swim slowly and laboriously, and with a great deal of puffing.

“Oh, what a cowardly way of getting in!” said the third, who stood on the bank, hesitating.

“Well, let’s see you, then,” cried George Day, who was swimming close at hand. “Jump in.”

“Oh, I can’t jump in like you do,” said the other; “it gives me the headache.”

“Why, you’re afraid.”

“No, I’m not.”

“Yes, you are. Come in, or I’ll pull you down.”

“There!”

The boy jumped in feet first, and as soon as he came up he struggled to the bank, and puffed and panted and squeezed the water out of his hair.

“Oh my, isn’t it jolly cold!” he cried. “It takes all my breath away.”

“Cold!” cried the others; “it’s lovely. Here you, Dennison, come in.”

“I can’t swim,” I said, feeling a curious shrinking on the one side, quite a temptation on the other.

“And you never will,” cried George Day, “if you don’t try. It’s so easy: look here!”

He swam a few yards with the greatest ease, turned round, and began swimming slowly back.

“Go on—faster,” I cried, for I was interested.

“Can’t,” he cried, “tide runs so sharp. If I didn’t mind I should be swept right away. Come in. I’ll soon teach you.”

I shook my head.

“Oh, you are a fellow. Come on.”

“No, I sha’n’t bathe,” I said in a doubtful tone.

“Oh, here’s a chap! I say isn’t he a one! Always tied to his mother’s apron-string: can’t play cricket, or rounders, or football, and can’t swim. I say, isn’t he a molly.”

The others laughed, and being now out of their misery, as they termed it, they were splashing about and enjoying the water, but neither of them went far from the bank.

“I say, why don’t you come in?” cried the boy who jumped in feet first. “You will like it so.”

“Yes: come along, and try to swim. I can take five strokes. Look here.”

I watched while the boy went along puffing and panting, and making a great deal of splashing.

“Get out!” said the other; “he has got one leg on the ground. This is the way to learn to swim. Look here, Dennison, my father showed me.”

I looked, and he waded out three or four yards, till the water was nearly over his shoulders.

“Oh, I say, isn’t the tide strong!” he cried. “Now, then, look.”

He threw up his arms, joined his hands as he stood facing me, made a sort of jump and turned right over, plunging down before me, his legs and feet coming right out, and then for some seconds there was a great deal of turmoil and splashing in the muddy water, and he came up close to the bank.

“That’s the way,” he cried, panting. “You have to try to get to the bottom, and that gives you confidence.”

“I didn’t learn that way,” shouted George Day. “See me float!”

We all looked, and he turned over on his back, but splashed a good deal to keep himself up. Then all at once he went under, and my heart seemed to stand still, but he came up again directly, shaking his head and spitting.

“Tread water!” he cried; and he seemed to be wading about with difficulty.

“Is it deep there?” I shouted.

“Look,” he cried; and raising his hands above his head he sank out of sight, his hands disappearing too, and then he was up again directly and swam to the bank.

“I wish I could swim like you do,” I said, looking at him with admiration.

“Well, it’s easy enough,” he said. “Come along.”

“Shall I?”

“Yes. Why, what are you afraid of? Nobody ever comes down here except us boys who want a bathe. Slip off your clothes and have a good dip. You’re sure to like it.”

“But I’ve never been used to it,” I protested.

“Then get used to it,” he cried. “I say, boys, he ought to learn, oughtn’t he?”

“Yes,” cried the others. “Let’s get out and make him.”

“Oh, I don’t want any making,” I said proudly. “But I say—is it dangerous?”

“Dangerous! Hark at him! Ha—ha—ha!” laughed Day. “Why, what are you afraid of? There, jump out of your jacket. I sha’n’t stop in much longer, and I want to give you a lesson.”

“He’s afraid,” shouted the other two boys.

“Am I! You’ll see,” I said sturdily; and, feeling as if I were going to do something very desperate, and with a curious sensation of dread coming all over me, even to the roots of my hair, I rapidly undressed and went to the edge.

“Hooray!” shouted Day. “Now, look here: you can jump in head first, which is the proper way, or sneak in toes first, like they do. Show ’em you aren’t afraid. They daren’t jump in head first. Come on; I’ll take care you don’t come up too far out, as you can’t swim.”

“Would it matter if I did?” I said excitedly.

“Get along with you! no,” cried Day.

I hesitated, for the water looked very dreadful, and in spite of the burning sunshine it seemed cold. I felt so helpless too, and would gladly have run back to my clothes and dressed, instead of standing on the brink of the river.

“In with you,” shouted Day, backing away from the bank, and the other two boys stood a little way off, with the water up to their chests, grinning and jeering.

“He daren’t.”

“He’s afraid.”

“I say, don’t you jump in: you’ll get wet.”

“I say, young ’un, don’t. You learn to swim in the washing-tub in warm water.”

“Don’t you take any notice of them,” cried Day. “You jump in. Join your hands above your head and go in with a regular good leap. They can’t.”

I felt desperate. The water seemed to drive me back, but all the time the jeers of the boys pricked and stirred me on, and at last, obeying Day to the letter, I placed my hands above my head, diver fashion, and took the plunge down into the darkness of the chilly water, which seemed to roar and thunder in my ears, and then, before I knew where I was, I found myself standing up, spitting, half blind, with a curious burning sensation in my nostrils, and a horrible catching of the breath.

“Hooray!” shouted Day. “You’ve beat them hollow. Now you’re out of your misery and can show them. I bet a penny you learn to swim before they can.”

This was encouraging, and I began to feel a warm glow of satisfaction in my veins.

“Catch hold of my hand,” cried Day.

“No, no,” I cried excitedly. “You’ll take me where it’s deep.”

“Get out!” he said. “I shouldn’t be such a fool. There, go on then by yourself. Don’t go where it’s more than up to your chin.”

“Oh, no!” I said, stooping and rising, and letting the water, as it ran swiftly, send a curious cold thrill all over me. And then, as I began cautiously to wade about, panting, and with my breath coming in an irregular manner, there was a very pleasurable sensation in it all. First I began to notice how firm and close and heavy the water felt, and how it pressed against me. Then I began to think of how hard it was to walk, the water keeping me back; and directly after, as I stepped suddenly in a soft place all mud, which seemed to ooze up between my toes, the water came to my shoulders, and I felt as if I were being lifted from my feet.

“I say how do you like it?” cried Day, who was swimming a few yards away.

“I don’t know,” I panted. “I think I like it.”

“Oh, you’ll soon think it glorious,” he replied. “You’ll love it as soon as you can swim.”

The other two had waded on for some distance against the current, taking no further interest in me now I had made my plunge.

“I should like to swim,” I said.

“Oh it’s easy enough once you get used to it. That chap down below there swims twice as well as I can, but I don’t know who he is.”

“What shall I do first?” I asked.

“Oh, throw yourself flat on the water, and kick out your arms and legs like I do—like a frog. You’ll soon learn. Now I’m going to swim up as far as they are, and then let myself float back. You’ll see me come down. It’s so easy. You watch.”

“All right!” I said.

“You keep close in to the bank,” he shouted; “the tide don’t run there. Keep on trying to throw yourself down and kick out like a frog. You’ll soon swim.”

I nodded, and stood holding on by a tuft of coarse sedge, watching him as he threw himself on his side, and went off pretty close to the bank, where the water was eddying; and the next minute he was beyond a clump of sedge that projected into the river, and I was alone.

I felt no dread now, for the water seemed pleasantly cool, and I began to grow more confident. The buoyancy was delicious, and I found that by holding on with both hands to the long rushes I could float on the water, throwing myself down and keeping close to the surface, but with my legs gradually sinking, till I gave them a kick and rose again.

I amused myself this way for a minute or two, and then, leaving the tuft of rushes, I began to wade slowly along with the water up to my chest, and every now and then I stooped down, so that it came above my shoulders, and struck out with my hands; but I dare not throw myself flat with my legs off the bottom. That was too much to expect, and I had not recovered yet from the desperate plunge in, the recollection of which made me wonder at my temerity.

It was very nice, that first lesson in the water’s buoyancy, and as I jumped up, or lowered myself down, or held on by the tufts by the brink, and let myself float, I could not help comparing myself to the soap in the bathtub at home, for that almost floated, but gradually settled down to the bottom, just as my body seemed to do.

“I shall soon swim,” I thought to myself; but I felt no inclination to risk the first plunge and begin the struggle. It was far more pleasant to keep on wading there with the water up to my chest, and the delicious sensation of novelty, half fear, half pleasure, making me now venture out a few inches into deeper water, now shrink back towards the bank.

How beautiful it all seemed, with the mellow afternoon sunlight dancing on the water as a puff of warm wind came now and then along the river. The trees were so green and the sky so blue, and the barges, and horses that drew them by the towing-path on the other side, all seemed to add to my pleasure, for the barges seemed to glide along so easily, and they floated, and that was what I wanted to do.

I forgot all about my companions, who must have been a couple of hundred yards higher up the river, while I was wading down.

By degrees I found the water a little deeper, and I shrank from it at first, but I was close to the bank and had only to stretch out my hand to catch hold of a tuft of grass or sedge, and, after the shrinking sensation, it seemed pleasant to have the water higher up about my shoulders. It was so much harder to walk, and I could feel myself almost panting. Beside this there was a nice soft muddy bottom, pleasanter to the feet than the gravel where I had plunged in.

Yes: I thought it a much nicer place there, and I was slowly and cautiously wading on, while all at once I found the water seeming to come in the opposite direction, curving round towards me in a place where the bank was scooped out.

It looked so smooth that I pressed on, taking one step forward, so that the water might rush up against me, and—then I was floating, for my feet found no bottom, and with an excited thrill of delight I felt that I could swim.

Yes; there was no doubt about it. I could swim as easily as George Day, only I was not moving my hands, while the water was bearing me up and carrying me round as in a whirlpool just once, and then I was swept into the tide-way with the water thundering in my ears, a horrible strangling sensation in my nostrils, and a dimness coming over my aching eyes.

I could never remember much about it, only that it was all a confusion of thundering in my ears and rushing sounds. I kept on beating the water with my hands as I had seen a dog beat the surface when he could not swim, and I seemed to throw my head right back as I gasped for breath. But I do not remember that it was very horrible, or that I was drowning, as I surely was. Confusion is the best expression for explaining my sensations as I was swept rapidly down by the tide.

What do I remember next? I hardly know. Only a sensation of some one catching me by the wrist, from somewhere in the darkness that was closing me in. But the next thing after that is, I remember shutting my eyes, because the sun shone in them so fiercely as I lay on my back in the grass, with my head aching furiously, and a strange pain at the back of my neck, as if some one had been trying to break my head off, as a mischievous child would serve a doll.

Just then I heard some one sobbing and crying, and I felt as if I must be asleep and dreaming all this.

“Don’t make that row. He’s all right, I tell you. He isn’t drowned. What’s the good of making a row like that!”

It was George Day’s voice, and opening my eyes I said hoarsely:

“What’s the matter? Is he hurt?”

“No: it’s only Harry Leggatt thought you were—you were hurt, you know. Can you get up, and run? All our clothes are two fields off. Come on. The sun will dry you.”

I got up, feeling giddy and strange, and the aching at the back of my head was almost unbearable; but I began to walk with Day holding my hand, and after a time—he guiding me, for I felt very stupid—I began to trot; and at last, with my head throbbing and whirring, I found myself standing by my clothes, and my companions helped me to dress.

“You went out too far,” Day said. “I told you not, you know.”

I was shivering with cold and terribly uncomfortable with putting on my things over my wet chilled body. It had been a hard task too, especially with my socks, but I hardly spoke till we were walking home, and when I did it was during the time I was smoothing my wet hair with a pocket comb lent me by one of the boys.

“How was it I went too far?” I said at last, dolefully.

“I don’t know,” said Day. “I shouldn’t have known anything if that chap Shock hadn’t come shouting to us; and when we came, thinking he was going to steal our clothes, he brought us and showed us where he had dragged you out on to the bank. It was him we saw swimming when we first went in.”

“Where is he now?” I said wearily. “Let’s ask him all about it.”

“I don’t know,” replied Day. “He ran off to dress himself, I suppose, and he didn’t come back. But I say, you’re better now.”

“Oh yes!” I said, “I’m better now;” and by degrees the walk in the warm afternoon sunshine seemed to make me feel more myself; beside which I was dry when I got back home, but very low-spirited and dull.

I did not say anything, for my mother was lying down, and Mrs Beeton never invited my confidence; beside which I felt rather conscience-stricken, and after having my solitary tea I went to the window, feeling warmer, and less disposed to shiver.

And as I sat there about seven o’clock on that warm summer evening it almost seemed as if my afternoon’s experience had been a dream, and that Shock had not swum out and saved me from drowning, for there he was under one of the pear-trees, with a switch and a piece of clay, throwing pellets at our house, one of which came right in at the open window close by my cheek, and struck against Mrs Beeton’s cheffonier door.

Chapter Five.

Beginning a New Life.

I don’t want to say much about a sad, sad time in my life, but old Brownsmith played so large a part in it then that I feel bound to set it all down.

I saw very little more of George Day, for just about that time he was sent off to another school; and I am glad to recollect that I went little away from the invalid who used to watch me with such wistful eyes.

I had no more lessons in swimming, but I saved up a shilling for a particular purpose, and that was to give to Shock; but though I tried to get near him time after time when I was in the big garden with my mother, no sooner did I seem to be going after him than the boy went off like some wild thing—diving in amongst the bushes, and, knowing the garden so well, he soon got out of sight.

I did not want to send the present by anybody, for that seemed to me like entering into explanations why I sent the money; and I knew that if the news reached my mother’s ears that I had been half-drowned, it would come upon her like a terrible shock; and she was, I knew now, too ill to bear anything more.

So though I was most friendly in my disposition towards Shock, and wanted to pay him in my mild way for saving my life, he persisted in looking upon me as an enemy, and threw clay, clods, and, so to speak, derisive gestures, whenever we met at a distance.

“I won’t run after him any more,” I said to myself one day. “He’s half a wild beast, and if he wants us to be enemies, we will.”

I suppose I knew a good deal for my age, as far as education went. If I had been set to answer the questions in an examination paper I believe I should have failed; but all the same I had learned a great deal of French, German, and Latin, and I could write a fair hand and express myself decently on paper. But when I sat at our window watching Shock’s wonderful activity, and recalled how splendidly he must be able to swim, I used to feel as if I were a very inferior being, and that he was a long way ahead of me.

As the time went on our visits to the garden used to grow less frequent; but whenever the weather was fine and my mother felt equal to the task, we used to go over; and towards the end old Brownsmith’s big armed Windsor chair, with its cushions, used to be set under a big quince tree in the centre walk, just where there were most flowers, and as soon as we had reached it the old fellow used to come down with a piece of carpet to double up and put beneath my mother’s feet.

“Used to be a bit of a spring here,” he said with a nod to me; “might be a little damp.”

Then he would leave a couple of cats, “just for company like,” he would say, and then go softly away.

I did not realise it was so near when that terrible time came and I followed my poor mother to her grave, seeing everything about me in a strange, unnatural manner. One minute it seemed to be real; then again as if it were all a dream. There were people about me in black, and I was in black, but I was half stunned, listening to the words that were said; and at last I was left almost alone, for those who were with me stepped back a yard or two.

I was gazing down with my eyes dimmed and a strange aching feeling at my heart, when I felt someone touch my elbow, and turning round to follow whoever it was, I found old Brownsmith there, in his black clothes and white neckerchief, holding an enormous bunch of white roses in his arms.

“Thought you’d like it, my lad,” he said in a low husky voice. “She used to be very fond o’ my white roses, poor soul!”

As he spoke he nodded and took his great pruning-knife from his coat pocket, opened it with his teeth, and cut the strip of sweet-scented Russia mat. Then holding them ready in his arms he stood there while I slowly scattered the beautiful flowers down more and more, more and more, till the coffin was nearly covered, and instead of the black cloth I saw beneath me the fragrant heap of flowers, and the dear, loving face that had gazed so tenderly in mine seemed once more to be looking in my eyes.

I held the last two roses in my hand for a moment or two, hesitating, but I let them fall at last; and then the tears I had kept back so long came with a rush, and I sank down on my knees sobbing as if my heart would break.

It was one of my uncles who laid his hand upon my shoulder and made me start as he bent over me, and said in a low, chilling voice:

“Get up, my boy; we are going back. Come!—be a man!”

I did get up in a weary, wretched way, and as I did so I looked round after old Brownsmith, and there he was a little distance off, watching me, it seemed. Then we went back, my relatives who were there taking very little notice of me; and I was made the more wretched by hearing one cousin, whom I had never seen before, say angrily that he did not approve of that last scene being made—“such an exhibition with those flowers.”

It was about a month after that sad scene that I went over to see old Brownsmith. I was very young, but my life with my invalid mother had, I suppose, made me thoughtful; and though I used to sit a great deal at the window I felt as if I had not the heart to go into the great garden, where every path and bed would seem to bring up one of the days when somebody used to be sitting there, watching the flowers and listening to the birds.

I used to fancy that if I went down any of her favourite walks I should burst out crying; and I had a horror of doing that, for the knowledge was beginning to dawn upon me that a great change was coming over my life, and that I must begin to think of acting like a man.

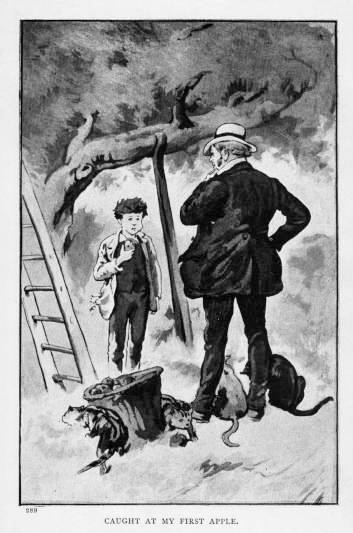

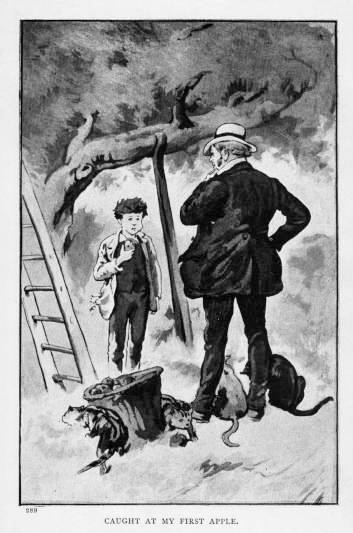

As I turned in at the gate I saw Shock at the door of one of the lofts over the big packing-sheds. He had evidently gone up there after some baskets, and as soon as I saw him I walked quickly in his direction; but he darted out of sight in the loft; and if I had any idea of scaling the ladder and going up to him to take him by storm, it was checked at once, for a half-sieve basket—one of those flat, round affairs in which fruit is packed—came flying out of the door, and then another and another, one after the other, at a tremendous rate, quite sufficient to have knocked me backwards before I was half-way up.

“A brute!” I said angrily to myself. “I’ll treat him with contempt;” and striding away I went down the garden, with the creaking, banging of the falling baskets going on. And when I turned to look, some fifty yards away, there was a big heap of the round wicker-work flats at the foot of the ladder, and others kept on flying out of the door.

I had not gone far before I saw old Brownsmith busy as usual amongst his cats; and as he rose from stooping to tie up a plant he caught sight of me, and immediately turned down the path where I was.

He held out his great rough hand, took mine, and shook it up and down gently for quite a minute, just as if it had been the handle of a pump.

“Seen my new pansies?” he said.

I shook my head.

“No, of course you haven’t,” he said. “Well, how are you?”

I said I was pretty well, and hoped he was. “Middling,” he replied. “Want more sun. Can’t get my pears to market without more sun.”

“It has been dull,” I said.

“Splendid for planting out, my lad, but bad for ripening off. Well, how are you?”

I said again that I was very well; and he looked at me thoughtfully, put one end of a bit of matting between his teeth, and drew it out tightly with his left hand. Then he began to twang it thoughtfully, and made it give out a dull musical note.

“Seen my new pansies?” he said—“no, of course not,” he added quickly; “and I asked you before. Come and look at them.”

He led me to a bed which was full of beautifully rounded, velvety-petalled flowers.

“What do you think of them?” he said—“eh? There’s a fine one, Mulberry Superb; rich colour—eh?”

“They are lovely,” I said warmly.

“Hah! yes!” he said, looking at me thoughtfully; “she liked white roses, though—yes, white roses—and they are all over.”

My lip began to quiver, but I mastered the emotion and he went on:

“Thought I should have seen you before, my lad. Didn’t think I should see you for some time. Thought perhaps I should never see you again. Thought you’d be sure to come and say ‘Good-bye!’ before you went. Contradictions—eh?”

“I always meant to come over and see you, Mr Brownsmith,” I said.

“Of course you did, my lad. Been damp and cold. Want more sun badly.”

I said I hoped the weather would soon change, and I began to feel uncomfortable and was just thinking I would go, when he thrust the piece of matting in his pocket, and took up and began stroking one of the cats.

“Ah! it’s a bad job, my lad!” he said softly—“a terrible job!”

I nodded.

“A sad job, my lad!—a very sad job!”

I nodded again, and waited till a choking sensation had gone off.

“Boys don’t think enough about their mothers—some boys don’t,” he went on. “I didn’t, till she was took away. You did—stopped with her a deal.”

“I’m afraid,”—I began.

“I’m not,” he said, interrupting me hastily. “I notice a deal—weather, and people, and children, and boys, and things growing. Want sun badly—don’t we?”

“Yes, sir,” I said; and I looked up in his florid face, with its bushy white whiskers; and then I looked at his great bulging pockets, and next down lower at his black legs, which the cats were turning into rubbing-posts; and as they served me the same in the most friendly manner I began wondering whether he ever brushed his black trousers, and thought of what a job I should have to get all the cats’ hairs off mine.

For there they all were, quite a little troop, arching their backs and purring, sticking their tails straight up, and every now and then giving their ends a flick.

They were so friendly in their rubbings against me that I did not like to refuse to accept their salutes; but it seemed to me as if only the light-coloured hairs came off, and in a short time I was furry from the knees of my black trousers down to my boots.

There was something, too, of welcome in their ways that was pleasant to me in my desolate position, for just then I seemed as if I had not one friend in the world; and even Mr Brownsmith seemed strange and cold, and as if he would be very glad when I was gone and he could get along with his work.

“There, there,” he cried suddenly, “we mustn’t fret about it, you know. It’s what we must all come to, and I don’t hold with people making it out dreadful. It’s very sad, boy, so it is. Dull weather too. When all my trees and plants die off for the winter, we don’t call that dreadful, because we know they’ll all bud and leaf and blossom again after their long sleep; and so it is with them as has gone away. There, there, there, you must try to be a man.”

“Yes, sir,” I said; “I am trying very hard.”

“That’s the way,” he cried; “that’s the way;” and he clapped me on the shoulder. “To be sure it is hard work, though, when you are on’y twelve or thirteen years old.”

“Yes, sir.”

“But look here, boy, there’s a tremendous deal done by a lad who makes up his mind to try; do you see?”

“Yes sir, I see,” I said, looking at him wonderingly, for he did not seem to want to get rid of me now, as he was holding me tightly by the arm.

“’Member coming for the strawberries?” he said drily.

“Yes, sir.”

“Thought me a disagreeable old fellow, didn’t you then?”

I hesitated, but he looked at me sharply.

“Yes, sir, I did then,” I said. “I did not know how kind you could be.”

“That’s just what I am,” he said gruffly; “very disagreeable.”

I shook my head.

“I am,” he said. “Ask any of my men and women. Here—what’s going to become of you, my lad—what are you going to be—soldier like your father?”

“Oh no!” I said.

“What then?”

“I don’t know, sir. I believe I am to wait till my uncles and my father’s cousin have settled.”

“How many of them are to settle it, boy?”

“Four, sir.”

“Four, eh, my boy! Ah, then I suppose it will take a lot of settling! You’ll have to wait.”

“Yes, sir, I’ve got to wait,” I said.

“But have you no prospects?”

“Oh yes, sir!” I said. “I believe I have.”

“Well, what?”

“My uncle Frederick said that I must make up my mind to go somewhere and earn my own living.”

“That’s a nice prospect.”

“Yes, sir.”

He was silent for a moment or two, and then smiled.

“Well, you’re right,” he said. “It is a nice prospect, though you and I were thinking different things. I like a boy to make up his mind to earn his living when he is called upon to do it. Makes him busy and self-reliant—makes a man of him. Did he say how?”

“Who, sir—my uncle Frederick?”

“Yes.”

“No, sir, he only said that I must wait.”

“Like I have to wait for the sun to ripen my fruit, eh? Ah, but I don’t like that. If the sun don’t come I pick it, and store it under cover to ripen as well as it will.”

I looked at him wonderingly.

“That waiting,” he went on, “puts me in mind of the farmer and his corn in the fable—get out, cats!—he waited till he found that the proper thing to do was to get his sons to work and cut the corn themselves.”

“Yes, sir,” I said smiling; “and then the lark thought it was time to take her young ones away.”

“Good, lad; right!” he cried. “That fable contains the finest lesson a boy can learn. Don’t you wait for others to help you: help yourself.”

“I’ll try, sir.”

“That’s right. Ah! I wish I had always been as wise as that lark.”

“Then you would not wait if you were me, sir?” I said, looking up at him wonderingly.

“Not a week, my lad, if you can get anything to do. Fact is, I’ve been looking into it, and your relations are all waiting for each other to take you in hand. There isn’t one of them wants the job.”

I sighed, and said:

“I’m afraid I shall be a great deal of trouble to them, sir, and an enormous expense.”

“Oh, you think so, do you!” he said, stooping down and lifting up first one cat and then another, stroking them gently the while. Then one of them, as usual, leaped upon his back. “Well, look here, my boy,” he said thoughtfully, “that’s all nonsense about expense! I—”

He stopped short and went on stroking one cat’s back, as it rubbed against his leg, and he seemed to be thinking very deeply.

“Yes, all nonsense. See here; wait for a week or two, perhaps one of your uncles may find you something to do, or send you to a good school, eh?”

“No, sir,” I said; “my uncle Frederick said I must not expect to be sent to a school.”

“Oh he did, did he?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Well, then, if nothing better turns up—if they don’t find you a good place, you might come and help me.”

“Help you, sir!” I said wonderingly; “what, learn to be a market-gardener?”

“Yes, there’s nothing so very dreadful in that, is there?”

“Oh no, sir! but what could I do?”

“Heaps of things. Tally the bunches and check the sieves, learn to bud and graft, and how to cut young trees, and—oh, I could find you enough to do.”

I looked at him aghast, and began to see in my mind’s eye rough, dirty Shock, crawling about on his hands and knees, and digging out the weeds from among the onions with his fingers.

“Oh, there’s lots of things you could do!” he continued. “Why, of a night you might use your pen and help me do the booking, and read and improve yourself while I sat and smoked my pipe. Cats don’t come into the house.”

“Do you mean that I should come and live with you, sir?” I said.

“That’s it, my boy, always supposing you couldn’t do any better. Could you?”