Title: Recollections of Old Liverpool

Author: James Stonehouse

Release date: May 5, 2007 [eBook #21324]

Most recently updated: September 6, 2015

Language: English

Credits: This ebook was transcribed by Les Bowler

This ebook was transcribed by Les Bowler.

entered at sta. hall

price 3/6

liverpool.

j. f. hughes,

1863

2nd. 1,000.

PREFACE.

CHAPTER I.

Birth of Author; Strong Memory; A Long-lived Family; Tree in St. Peter’s Church-yard; Cruelty of Town Boys; The Ducking-stool; The Flashes in Marybone; Mode of Ducking; George the Third’s Birthday; Frigates; Launch of the Mary Ellen; The Interior of a Slaver; Liverpool Privateers; Unruly Crews; Kindness of Sailors; Sailors’ Gifts; Northwich Flatmen; The Salt Trade; The Salt Tax; The Salt Houses; Salt-house Dock; The White House and Ranelagh Gardens; Inscription over the Door; Copperas-hill; Hunting a Hare; Lord Molyneux; Miss Brent; Stephens’ Lecture on Heads; Mathews “At Home”; Brownlow Hill; Mr. Roscoe; Country Walks; Moss Lake Fields; Footpads; Fairclough (Love) Lane; Everton Road; Loggerheads Lane; Richmond Row; The Hunt Club Kennels.

CHAPTER II.

The Gibson’s; Alderman Shaw; Mr. Christian; Folly Tavern; Gardens in Folly Lane; Norton Street; Stafford Street; Pond by Gallows Mill; Skating in Finch Street; Folly Tower; Folly Fair; Fairs in Olden Times; John Howard the Philanthropist; The Tower Prison; Prison Discipline; Gross Abuses; Howard presented with Freedom; Prisons of 1803; Description of Borough Gaol; Felons; Debtors; Accommodations; Escape of Prisoners; Cells; Courtyards; Prison Poultry; Laxity of Regulations; Garnish; Fees; Fever; Abuses; Ball Nights; Tricks played upon “Poor Debtors”; Execution of Burns and Donlevy for Burglary; Damage done by French Prisoners; their Ingenuity; The Bridewell on the Fort; Old Powder Magazine; Wretched State of the Place; Family Log; Durand—His Skill; Escape of Prisoners—Their Recapture; Durand’s Narrative—His Recapture; House of Correction; Mrs. Widdows.

The Volunteers; Liverpool in ‘97; French Invasion; Panic; Warrington Coach; The Fat Councillor; Excitement in Liverpool; Its Defences; French Fisherman; Spies; Pressgangs—Cruelty Practised; Pressgang Rows; Woman with Three Husbands; Mother Redcap—Her Hiding-places; The Passage of the River; Ferrymen; Woodside Ahoy!; Cheshire an Unknown Country to Many; Length of passage there; The Rock Perch; Wrecking; Smuggling; Storms; Formby Trotters; Woodside—No Dwellings there; Marsh Level; Holt Hill—Oxton; Wallasey Pool; Birkenhead Priory; Tunnel under the Mersey; Tunnel at the Red Noses—Exploration of it; The Old Baths; Bath Street; The Bath Woman; The Wishing Gate; Bootle Organs; Sandhills; Indecency of Bathers; The Ladies Walk; Mrs. Hemans; the Loggerheads; Duke Street; Campbell the Poet; Gilbert Wakefield; Dr. Henderson; Incivility of the Liverpool Clergy; Bellingham—His Career and History, Crime, Death; Peter Tyrer; The Comfortable Coach.

CHAPTER IV.

Colonel Bolton; Mr. Kent; George Canning; Liverpool Borough Elections; Divisions caused by them; Henry Brougham; Egerton Smith; Mr. Mulock; French Revolution; Brougham and the Elector on Reform; Ewart and Denison’s Election; Conduct of all engaged in it; Sir Robert Peel; Honorable Charles Grant; Sir George Drinkwater; Anecdote of Mr. Huskisson; The Deputation from Hyde; Mr. Huskisson’s opinion upon Railway Extension; Election Processions; The Polling; How much paid for Votes; Cost of the Election; Who paid it; Election for Mayor; Porter and Robinson; Pipes the Tobacconist; Duelling; Sparling and Grayson’s Duel; Dr. McCartney; Death of Mr. Grayson; The Trial; Result; Court Martial on Captain Carmichael; His Defence; Verdict; The Duel between Colonel Bolton and Major Brooks; Fatal Result.

Story of Mr. Wainwright and Mr. Theophilus Smith; Burning of the Town Hall; Origin and Progress of the Fire; Trial of Mr. Angus.

CHAPTER VI.

State of the Streets; Dale Street; The obstinate Cobbler; The Barber; Narrowness of Dale-street; The Carriers; Highwaymen; Volunteer Officers Robbed; Mr. Campbell’s Regiment; The Alarm; The Capture; Improvement in Lord Street; Objections to Improvement; Castle Ditch; Dining Rooms; Castle-street; Roscoe’s Bank; Brunswick-street; Theatre Royal Drury Lane; Cable Street; Gas Lights; Oil Lamps; Link Boys; Gas Company’s Advertisement; Lord-street; Church-street; Ranelagh-street; Cable-street; Redcross-street; Pond in Church-street; Hanover-street; Angled Houses; View of the River; Whitechapel; Forum in Marble-street; Old Haymarket; Limekiln-lane; Skelhorn-street; Limekilns; London-road; Men Hung in ‘45; Gallows Field; White Mill; The Supposed Murder; The Grave found; Islington Market; Mr. Sadler; Pottery in Liverpool; Leece-street; Pothouse lane; Potteries in Toxteth Park; Watchmaking; Lapstone Hall; View of Everton; Old Houses; Clayton-square; Mrs. Clayton; Cases-street; Parker-street; Banastre street; Tarleton-street; Leigh-street; Mr. Rose and the Poets; Mr. Meadows and his Wives; Names of old streets; Dr. Solomon; Fawcett and Preston’s Foundry; Button street; Manchester-street; Iron Works; Names of Streets, etc.

Everton; Scarcity of Lodgings there; Farm Houses swept away; Everton under Different Aspects; the Beacon; Fine View from it; View described; Description of the Beacon; Beacons in Olden Time; Occupants of the Beacon; Thurot’s Expedition; Humphrey Brook and the Spanish Armada; Telegraph at Everton; St. Domingo; The Mere Stones; Population of Everton.

CHAPTER VIII.

Everton Cross; Its situation; Its mysterious Disappearance; How it was Removed; Its Destination; Consternation of the Everton Gossips; Reports about the Cross; The Round House; Old Houses; Everton; Low-hill; Everton Nobles; History of St. Domingo, Bronte, and Pilgrim Estates; Soldiers at Everton; Opposition of the Inhabitants to their being quartered there; Breck-road; Boundary-lane; Whitefield House; An Adventure; Mr. T. Lewis and his Carriage; West Derby-road; Zoological Gardens; Mr. Atkins; His good Taste and Enterprise; Lord Derby’s Patronage; Plumpton’s Hollow; Abduction of Miss Turner; Edward Gibbon Wakefield.

CHAPTER IX.

The Powder House; Moss Lake Fields; Turbary; Bridge over Moss Lake Gutter; Edge-hill; Mason-street; Mr. Joseph Williamson; His Eccentricities; His Originality; Marriage; Appearance; Kindness to the Poor; Mr. Stephenson’s opinion of Mr. Williamson’s Excavations; The House in Bolton-street; Mr. C. H. the Artist; Houses in High-street; Mr. Williamson, the lady, and the House to Let; How to make a Nursery; Strange Noises in the Vaults; Williamson and Dr. Raffles; A strange Banquet; The surprise, etc.

Joseph Williamson’s Excavations; The future of Liverpool; Williamson’s Property; Changes in his Excavations of late years; Description of the Vaults and Passages; Tunnels; Arches; Houses in Mason-street; Houses without Windows; Terraced Gardens; etc.

CHAPTER XI.

The Mount Quarry; Berry-street; Rodney-street; Turning the Tables; Checkers at Inn Doors; The De Warrennes Arms; Cock-fighting; Pownall Square; Aintree Cock Pit; Dr. Hume’s Sermon; Rose Hill; Cazneau-street; St. Anne-street; Faulkner’s Folly; The Haymarket; Richmond Fair.

CHAPTER XII.

Great Charlotte-street; The Sans Pareil; the Audience there; Actors and Performances; Mr. and Mrs. Holloway; Maria Monk, or the Murder at the Red Barn; The two Sweeps; A strange Interruption; Stephen Price and John Templeton; Malibran; W. J. Hammond; the Trick played by him at the Adelphi Hotel; the Water Drinkers—Harrington or Bootle; Mr. S--- and the Pew in St Anne’s Church.

CHAPTER XIII.

The year 1816; Distress of all Classes; Battle of Waterloo; High rate of taxation; Failure of Harvest; Public Notice about Bread; Distress in London; Riots there; The Liverpool Petition; Good Behaviour of the Working class in Liverpool; Great effort made to give relief; Amateur Performances; Handsome Sum realized; Enthusiasm exhibited on the occasion; Lord Cochrane; His Fine; Exertion of his Friends in Liverpool; The Penny Subscription; How the Amount was paid.

Fall of St. Nicholas’ Church Spire; Dreadful calamity; Riots at the Theatre Royal; Half-price or Full Price; Incendiary Placards; Disgraceful Proceedings; Trials of the rioters; Mr. Statham, Town Clerk; Attempts at Compromise; Result of Trial.

CHAPTER XV.

Old Favourites; Ennobled Actresses; John Kemble; his Farewell of Liverpool Audiences; Coriolanus; Benefits in the last Century; Paganini; His Wonderful Style; the Walpurgis Nacht; De Begnis; Paganini’s Caution; Mr. Lewis’ Liberality; Success of Paganini’s Engagement; Paganini at the Amphitheatre; The Whistlers; Mr. Clarke and the Duchess of St. Alban’s; Her kindness and generosity; Mr. Banks and his cook; Mrs. Banks’ estimate of Actors; Edmund Kean; Miss O’Neil; London favourites not always successful; Vandenhoff; Vandenhoff and Salter-off.

CHAPTER XVI.

High Price of Provisions in 1816; Highway Robberies; Dangerous state of Toxteth Park; Precautions Adopted; Sword Cases in Coaches; Robbery at Mr. Yates’ house; Proceedings of the Ruffians; Their Alarm; Flight of the Footman; Escape of Thieves; Their Capture, Trial and Execution; Further Outrages; Waterloo Hotel; Laird’s Roperies; The Fall Well; Alderman Bennett’s Warehouse; The Dye House Well; Wells on Shaw’s Brow.

CHAPTER XVII.

Progress of Liverpool; Privateers; Origin of the Success of the Port; Children owning Privateers; Influence, Social and Moral; Wonderful increase of Trade; etc.

The “Recollections of Old Liverpool,” contained in the following pages, appeared originally the Liverpool Compass, their publication extending over a period of several months.

When they were commenced it was intended to limit them to three, or at the most four, chapters, but such was the interest they created, that they were extended to their present length.

Those who have recorded the green memories of an old man, as told while seated by his humble “ingle nook” have endeavoured to adhere to his own words and mode of narration—hence the somewhat rambling and discursive style of these “Recollections”—a style which does not, in the opinion of many, by any means detract from their general interest.

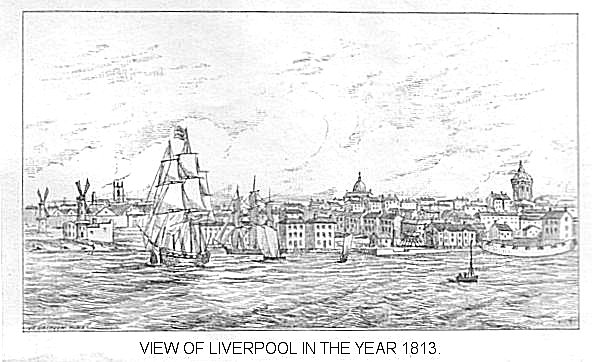

The frontispiece is copied (by special permission) from part of a very finely-painted view of Liverpool, by Jenkinson, dated 1813, in the possession of Thomas Dawson, Esq., Rodney-street. The vignette of the Mill which stood at the North end of the St. James’ Quarry in the title page, is from an original water colour drawing by an amateur (name unknown), dated 1821.

November, 1863.

I was born in Liverpool, on the 4th of June in 1769 or ’70. I am consequently about ninety-three years old. My friends say I am a wonderful old man. I believe I am. I have always enjoyed such excellent health, that I do not know what the sensation is of a medical man putting his finger on my wrist. I have eaten and drunk in moderation, slept little, risen early, and kept a clear conscience before God and man. My memory is surprising. I am often astonished at myself in recalling to mind events, persons, and circumstances, that occurred so long ago as to be almost forgotten by everybody else.

I can recollect every occurrence that has fallen under my cognizance, since I was six years old. I do not remember so well events that have taken place during the last twenty or thirty years, as they seem confused to me; but whatever happened of p. 6which I had some knowledge during my boyish days and early manhood, is most vividly impressed upon my memory. My family have been long-livers. My father was ninety odd, when he died, my mother near that age at her death. My brother and sister are still living, are healthy, and, like myself, in comfortable circumstances.

I may be seen any fine day on the Pier-head or Landing-stage, accompanied by one of my dear great grandchildren; but you would not take me to be more than sixty by my air and appearance.

We lived in a street out of Church-street, nearly opposite St. Peter’s. I was born there. At that time the churchyard was enclosed by trees, and the gravestones were erect. One by one the trees died or were destroyed by mischievous boys, and unfortunately they were not replaced. The church presented then a very pretty appearance. Within the last thirty years there was one tree standing nearly opposite to the Blue Coat School. When that tree died, I regretted its loss as of an old friend. The stocks were placed just within the rails, nearly opposite the present extensive premises occupied by the Elkingtons. Many and many a man have I seen seated in them for various light offences, though in many cases the punishment was heavy, especially if the culprit was obnoxious in any way, or had made himself so by his own conduct. The town boys were very p. 7cruel in my young days. It was a cruel time, and the effects of the slave-trade and privateering were visible in the conduct of the lower classes and of society generally. Goodness knows the town boys are cruel now, but they are angels to what their predecessors were. I think education has done some good. All sorts of mischievous tricks used to be played upon the culprits in the stocks; and I have seen stout and sturdy fellows faint under the sufferings they endured. By the way, at the top of Marybone, there was once a large pond, called the Flashes, where there was a ducking-post and this was a favourite place of punishment when the Lynch Law of that time was carried out. I once saw a woman ducked there. She might have said with Queen Catherine:—

“Do with me what you will,

For any change must better my condition.”

There was a terrible row caused once by the rescue of a woman from the Cuckstool. At one time it threatened to be serious. The mayor was dining at my father’s, and I recollect he was sent for in a great hurry, and my father and his guests all went with him to the pond. The woman was nearly killed, and her life for long despaired of. She was taken to the Infirmary, on the top of Shaw’s Brow, where St. George’s Hall now stands. The way they ducked was this. A long pole, which acted as a lever, was placed on a post; at p. 8the end of the pole was a chair, in which the culprit was seated; and by ropes at the other end of the lever or pole, the culprit was elevated or dipped in the water at the mercy of the wretches who had taken upon themselves the task of executing punishment. The screams of the poor women who were ducked were frightful. There was a ducking tub in the House of Correction, which was in use in Mr. Howard’s time. I once went with him through the prison (as I shall describe presently) and saw it there. It was not till 1804 or 1805 that it was done away with.

My father was owner and commander of the Mary Ellen. She was launched on the 4th of June, my birthday, and also the anniversary of our revered sovereign, George III. We used to keep his majesty’s birthday in great style. The bells were set ringing, cannon fired, colours waved in the wind, and all the schools had holiday. We don’t love the gracious Lady who presides over our destinies less than we did her august grandfather, but I am sure we do not keep her birthday as we did his. The Mary Ellen was launched on the 4th of June, 1775. She was named after and by my mother. The launch of this ship is about the first thing I can remember. The day’s proceedings are indelibly fixed upon my memory. We went down to the place where the ship was built, accompanied by our friends. We made quite p. 9a little procession, headed by a drum and fife. My father and mother walked first, leading me by the hand. I had new clothes on, and I firmly believed that the joy bells were ringing solely because our ship was to be launched. The Mary Ellen was launched from a piece of open ground just beyond the present Salt-house Dock, then called, “the South Dock.” I suppose the exact place would be somewhere about the middle of the present King’s Dock. The bank on which the ship was built sloped down to the river. There was a slight boarding round her. There were several other ships and smaller vessels building near her; amongst others, a frigate which afterwards did great damage to the enemy during the French war. The government frequently gave orders for ships to be built at Liverpool. The view up the river was very fine. There were few houses to be seen southward. The mills on the Aigburth-road were the principal objects.

It was a pretty sight to see the Mary Ellen launched. There were crowds of people present, for my father was well-known and very popular. When the ship moved off there was a great cheer raised. I was so excited at the great “splash” which was made, that I cried, and was for a time inconsolable, because they would not launch the ship again, so that I might witness another great “splash.” I can, in my mind’s eye, see “the p. 10splash” of the Mary Ellen even now. I really believe the displacement of the water on that occasion opened the doors of observation in my mind. After the launch there was great festivity and hilarity. I believe I made myself very ill with the quantity of fruit and good things I became possessed of. While the Mary Ellen was fitting-up for sea, I was often taken on board. In her hold were long shelves with ring-bolts in rows in several places. I used to run along these shelves, little thinking what dreadful scenes would be enacted upon them. The fact is that the Mary Ellen was destined for the African trade, in which she made many very successful voyages. In 1779, however, she was converted into a privateer. My father, at the present time, would not, perhaps, be thought very respectable; but I assure you he was so considered in those days. So many people in Liverpool were, to use an old and trite sea-phrase, “tarred with the same brush” that these occupations were scarcely, indeed, were not at all, regarded as anything derogatory from a man’s character. In fact, during the privateering time, there was scarcely a man, woman, or child in Liverpool, of any standing, that did not hold a share in one of these ships. Although a slave captain, and afterwards a privateer, my father was a kind and just man—a good father, husband, and friend. His purse and advice were always ready p. 11to help and save, and he was, consequently, much respected by the merchants with whom he had intercourse. I have been told that he was quite a different man at sea, that there he was harsh, unbending and stern, but still just. How he used to rule the turbulent spirits of his crews I don’t know, but certain it is that he never wanted men when other Liverpool ship-owners were short of hands. Many of his seamen sailed voyage after voyage with him. It was these old hands that were attached to him who I suspect kept the others in subjection. The men used to make much of me. They made me little sea toys, and always brought my mother and myself presents from Africa, such as parrots, monkeys, shells, and articles of the natives’ workmanship. I recollect very well, after the Mary Ellen had been converted into a privateer, that, on her return from a successful West Indian cruise, the mate of the ship, a great big fellow, named Blake, and who was one of the roughest and most ungainly men ever seen, would insist upon my mother accepting a beautiful chain, of Indian workmanship, to which was attached the miniature of a very lovely woman. I doubt the rascal did not come by it very honestly, neither was a costly bracelet that one of my father’s best hands (once a Northwich salt-flatman) brought home for my baby sister. This man would insist upon putting it on the baby somewhere, in spite of p. 12all my mother and the nurse could say; so, as its thigh was the nearest approach to the bracelet in size of any of its little limbs, there the bracelet was clasped. It fitted tightly and baby evidently did not approve of the ornament. My mother took it off when the man left. I have it now. This man used to tell queer stories about the salt trade, and the fortunes made therein, and how they used to land salt on stormy and dark nights on the Cheshire or Lancashire borders, or into boats alongside, substituting the same weight of water as the salt taken out, so that the cargo should pass muster at the Liverpool Custom House. The duty was payable at the works, and the cargo was re-weighed in Liverpool. If found over weight, the merchant had to pay extra duty; and if short weight, he had to make up the deficiency in salt. The trade required a large capital, and was, therefore, in few hands. One house is known to have paid as much as £30,000 for duty in six weeks. My grandfather told me that in 1732 (time of William and Mary), when he was a boy, the duty on salt was levied for a term of years at first, but made perpetual in the third year of George II. Sir R. Walpole proposed to set apart the proceeds of the impost for his majesty’s use.

The Salt houses occupied the site of Orford-street (called after Mr. Blackburne’s seat in Cheshire). I have often heard my grandfather p. 13speak of them as an intolerable nuisance, causing, at times, the town to be enveloped in steam and smoke. These Salt houses raised such an outcry at last that in 1703 they were removed to Garston, Mr. Blackburne having obtained an act of Parliament relative to them for that purpose.

The fine and coarse salts manufactured in Liverpool were in the proportion of fifteen tons of Northwich or Cheshire rock-salt to forty-five tons of seawater, to produce thirteen tons of salt. To show how imperishable salt must be, if such testimony be needed, it is a fact that, in the yard of a warehouse occupied by a friend of mine in Orford-street, the soil was always damp previous to a change of weather, and a well therein was of no use whatever, except for cleansing purposes, so brackish was the water.

To return to the launch. After the feasting was over my father treated our friends to the White House and Ranelagh Tea Gardens, which stood at the top of Ranelagh-street. The site is now occupied by the Adelphi Hotel. The gardens extended a long way back. Warren-street is formed out of them. These gardens were very tastefully arranged in beds and borders, radiating from a centre in which was a Chinese temple, which served as an orchestra for a band to play in. Round the sides of the garden, in a thicket of lilacs and laburnums, the beauty of which, in p. 14early summer, was quite remarkable, were little alcoves or bowers wherein parties took tea or stronger drinks. About half-way up the garden, the place where the Warren-street steps are now, there used to be a large pond or tank wherein were fish of various sorts. These fish were so tame that they would come to the surface to be fed. This fish feeding was a very favourite amusement with those who frequented the garden. In the tank were some carp of immense size, and so fat they could hardly swim. Our servant-man used to take me to the Ranelagh Gardens every fine afternoon, as it was a favourite lounge. Over the garden door was written—

“You are welcome to walk here I say,

But if flower or fruit you pluck

One shilling you must pay.”

The garden paling was carried up Copperas-hill (called after the Copperas Works, removed in 1770, after long litigation) across to Brownlow-hill, a white ropery extending behind the palings. To show how remarkably neighbourhoods alter by time and circumstance, I recollect it was said that Lord Molyneux, while hunting, once ran a hare down Copperas-hill. A young lady, Miss Harvey, who resided near the corner, went out to see what was the cause of the disturbance she heard, when observing the hare, she turned it back. Miss Harvey used to say “the gentlemen swore terribly” p. 15at her for spoiling their sport. This was not seventy years ago!

To return to the Ranelagh Gardens. There was, at the close of the gala nights, as they were called, a display of fireworks. They were let off on the terrace. I went to see the last exhibition which took place in 1780. There was, on that occasion, a concert in which Miss Brent, (who was, by the way, a great favourite) appeared. Jugglers used to exhibit in the concert-room, which was very capacious, as it would hold at least 800 to 1000 persons. This concert-room was also used as a dinner-room on great occasions, and also as a town ball-room. Stephens gave his lecture on “Heads” in it very frequently.

G. A. Stephens was an actor, who, after playing about in the provincial highways and bye-ways of the dramatic world, went to London, where he was engaged at Covent Garden in second and third rate parts. He was a man of dissipated habits, but a jovial and merry companion. He wrote a great many very clever songs, which he sang with great humour. He got the idea of the lectures on “Heads” from a working man about one of the theatres, whom he saw imitating some of the members of the corporation of the town in which he met with him. Stephens, who was quick and ready with his pen, in a short time got up his lecture, which he delivered all through England, p. 16Scotland, Ireland, and America. He realised upwards of £10,000, which he took care of, as he left that sum behind him at his death, in 1784. He was at the time, a completely worn-out, imbecile old man. Many of the leading actors of his day followed up the lecture on “Heads,” in which they signally failed to convey the meaning of the author. I saw him, and was very much amused; but I do not think he would be tolerated in the present day. The elder Mathews evidently caught the idea of his “At Homes” from Stephens’s lecture.

Brownlow-hill was so called after Mr. Lawrence Brownlow, a gentleman who held much property thereabout. Brownlow-hill was a very pleasant walk. There were gardens on it, as, also, on Mount Pleasant, then called Martindale’s-hill, of which our friend Mr. Roscoe has sung so sweetly. Martindale’s-hill was quite a country walk when I was a little boy. There was also a pleasant walk over the Moss Lake Fields to Edge Hill. Where the Eye and Ear Infirmary stands there was a stile and a foot-path to the Moss Lake Brook, across it was a wooden foot bridge. The path afterwards diverged to Smithdown-lane. The path-road also went on to Pembroke-place, along the present course of Crown-street. I have heard my father speak of an attempt being made to rob him on passing over the stile which stood where now you find p. 17the King William Tavern. He drew his sword (a weapon commonly worn by gentlemen of the time) which so frightened the thieves that they ran away, and, in their flight, went into a pit of water, into which my father also ran in the darkness which prevailed. The thieves roared loudly for help, which my father did not stop to accord them. He, being a good swimmer, soon got out, leaving the thieves to extricate themselves as they could. There were several very pleasant country walks which went up to Low-hill through Brownlow-street, and by Love-lane (now Fairclough-lane). I recollect going along Love-lane many a time with my dear wife, when we were sweethearting. We used to go to Low-hill and thence along Everton-road (then called Everton-lane), on each side of which was a row of large trees, and we returned by Loggerhead’s-lane (now Everton Crescent), and so home by Richmond-row, (called after Dr. Sylvester Richmond, a physician greatly esteemed and respected.) I recollect very well the brook that ran along the present Byrom-street, whence the tannery on the right-hand side was supplied with water. At the bottom of Richmond-row used to be the kennels of the Liverpool Hunt Club. They were at one time kept on the North-shore.

I was very sorry when the Ranelagh Gardens were broken up. The owner, Mr. Gibson, was the brother of the Mr. Gibson who kept the Folly Gardens at the bottom of Folly-lane (now Islington) and top of Shaw’s Brow (called after Mr. Alderman Shaw, the great potter, who lived in Dale-street, at the corner of Fontenoy-street—whose house is still standing). Many a time have I played in the Folly Tea Gardens. It was a pretty place, and great was the regret of the inhabitants of Liverpool when it was resolved to build upon it. The Folly was closed in 1785. Mr. Philip Christian built his house, now standing at the corner of Christian-street, of the bricks of which the Tavern was constructed. The Folly was a long two-storied house, with a tower or gazebo at one end. Gibson, it was said, was refused permission to extend the size of his house, so “he built it upright,” as he said “he could not build it along.” The entrance p. 19to the Gardens was from Folly-lane, up a rather narrow passage. I rather think the little passage at the back of the first house in Christian-street was a part of it. You entered through a wooden door and went along a shrubberied path which led to the Tavern. Folly-lane (now Islington) was a narrow country lane, with fields and gardens on both sides. I recollect there was a small gardener’s cottage where the Friends’ Institute now stands; and there was a lane alongside. That lane is now called “King-street-lane, Soho.” I remember my mother, one Sunday, buying me a lot of apples for a penny, which were set out on a table at the gate. There were a great many apple, pear, and damson trees in the garden. When the Friends’ Institute was building I heard of the discovery of an old cottage, which had been hidden from view as it were for many years. I went to see it—the sight of it brought tears in my old eyes, for I recognised the place at once, and thought of my good and kind mother, and her friendly and loving ways. Where the timber-yard was once in Norton-street, there used to be a farm-house. The Moss-lake Stream ran by it on its way to Byrom-street. I can very well remember Norton-street and the streets thereabout being formed. At the top of Stafford-street, laid out at the same time, there was a smithy and forge; the machinery of the bellows was turned by the water from the Moss-lake Brook, p. 20which ran just behind the present Mill Tavern. There the water was collected in an extensive dam, in shape like a “Ruperts’ Drop,” the overflow turned some of the mill machinery. Many and many a fish have I caught out of that mill-dam. The fields at the back, near Folly-lane, were flooded one winter, and frozen over, when I and many other boys went to slide on them.

The Folly Gardens were very tastefully laid out. Mr. Gibson was a spirited person, and spared no expense to keep the place in order. There were two bowling-greens in it, and a skittle-alley. There was a cockpit once, outside the gardens; but that was many years before my time. It was laid bare when they were excavating for Islington Market. When I was a boy its whereabouts was not known; it was supposed to have been of great antiquity. How time brings things to light! The gardens were full of beautiful flowers and noble shrubs. There was a large fish-pond in the middle of a fine lawn, and around it were benches for the guests, who, on fine summer evenings, used to sit and smoke, and drink a sort of compound called “braggart,” which was made of ale, sugar, spices, and eggs, I believe. I used to sail a little ship in that pond, made for me by the mate of the Mary Ellen. I one day fell in, and was pulled out by Mr. Gibson himself, who fortunately happened to be passing near at hand. He took p. 21me in his arms dripping as I was, into the tavern and I was put to bed, while a man was sent down to Church-street, to acquaint my parents with my disaster, and for dry clothes. My mother came up in a terrible fright, but my father only laughed heartily at the accident, saying he had been overboard three times before he was my age. He must have had a charmed life, if he spoke true, for I don’t think I could have been above eight years old then. My father was well acquainted with Mr. Gibson, and after I had got on my dry clothes, he took us up to the top of the Gazebo, or look-out tower. It was a beautiful evening, and the air was quite calm and clear. The view was magnificent. We could see Beeston Castle quite plainly, and Halton Castle also, as well as the Cheshire shore and the Welsh mountains. The view out seaward was truly fine. Young as I was, I was greatly struck with the whole scene. It was just at the time when the Folly Fair was held, and the many objects at our feet made the whole view one of intense interest. The rooms in the tower were then filled with company. Folly Fair was held on the open space of ground afterwards used as Islington Market. Booths were erected opposite the Infirmary and in Folly Lane. It was like all such assemblages—a great deal of noise, drunkenness, debauchery, and foolishness. But fairs were certainly different then from what they p. 22have been of late years. They are now conducted in a far more orderly manner than they were formerly. I went to a large one some years ago, in Manchester, and, on comparing it with those of my young days, I could hardly believe it was a fair. It seemed to be only the ghost of one, so grim and ghastly were the proceedings.

I recollect the celebrated Mr. John Howard, “the philanthropist,” coming to Liverpool in 1787. He had a letter of introduction to my father, and was frequently at our house. He was a thin, spare man, with an expressive eye and a determined look. He used to go every day to the Tower Prison at the bottom of Water-street; and he exerted himself greatly to obtain a reform in the atrocious abuses which then existed in prison discipline. In the present half-century there has been great progress made in the improvement of prison discipline, health, and economy. Where formerly existed notorious and disgraceful abuses, the most abject misery, and the very depth of dirt, we find good management, cleanliness, reformatory measures, and firm steps taken to reclaim both the bodies and souls of the erring. It is a most strange circumstance that the once gross and frightful abuses of the prison system did not force themselves upon the notice of government—did not attract the attention of local rulers, and cry out themselves for change. Still more strange is it that, although p. 23Mr Howard in 1787, and again in 1795, and Mr. James Nield (whose acquaintance I also made in 1803), pointed out so distinctly the abuses that existed in our prisons, the progress of reform therein was strangely slow, and moved with most apathetic steps. Howard lifted up the veil and exposed to light the iniquities prevalent within our prison walls; but no rapid change was noticeable in consequence of his appalling revelations. To show how careless the authorities were about these matters, we can see what Mr. Nield said eight years after Mr. Howard’s second visit, in 1795, in his celebrated letters to Dr. Lettsom, who, by the way, resided in Camberwell Grove, Surrey, in the house said to have belonged to the uncle of George Barnwell. Now, it should be borne in mind that Mr. Howard actually received the freedom of the borough, with many compliments upon his exertions in the cause of the poor inmates of the gaol, and yet few or no important steps were taken to remedy the glaring evils which he pointed out. Some feeble reforms certainly did take place immediately after his first and second visits to Liverpool, but a retrograde movement succeeded, and things relapsed into their usual jog-trot way of dirt and disorder. When Mr. Howard received the freedom of the borough an immense fuss was made about him; people used to follow him in the street, and he was feted and invited to dinners and p. 24parties; and there was no end of speechifying. But what did it all come to? Why, nothing, except a little cleaning out of passages and whitewashing of walls. I went with Mr. Howard several times, over the Tower Prison, and also with Mr. Nield, in 1803. As it then appeared I will try to describe it.

The keeper of the Tower or Borough Gaol, which stood at the bottom of Water-street in 1803, was Mr. Edward Frodsham, who was also sergeant-at-mace. His salary was £130 per annum. His fees were 4s. for criminal prisoners, and 4s. 6d. for debtors. The Rev. Edward Monk was the chaplain. His salary was £31 10s. per annum; but his ministrations did not appear to be very efficacious, as, on one occasion, when Mr. Nield went to the prison chapel in company with two of the borough magistrates, he found, out of one hundred and nine prisoners, only six present at service. The sick were attended by a surgeon from the Dispensary, in consideration of 12 guineas per annum, contributed by the corporation to that most praiseworthy institution. There was a sort of sick ward in the Tower, but it was a wretched place, being badly ventilated and extremely dirty. When Mr. Nield and I visited the prison in 1803, we did not find the slightest order or regulation. The prisoners were not classed, nor indeed, separated; men and women, boys and p. 25girls, debtor and felon, young and old, were all herded together, meeting daily in the courtyards of the prison. The debtors certainly had a yard to themselves, but they had free access to the felon’s yard, and mixed unrestrainedly with them. The prison allowance was a three-penny loaf of 1lb. 3oz. to each prisoner daily. Convicts were allowed 6d. per day. The mayor gave a dinner at Christmas to all the inmates. Firing was found by the corporation throughout the building. There were seventy-one debtors and thirty-nine felons confined on the occasion of our visit. In one of the Towers there were seven rooms allotted to debtors, and three in another tower, in what was called “the masters side.” The poorer debtors were allowed loose straw to lie upon. Those who could afford to do so, paid ls. per week for the use of a bed provided by the gaoler. The detaining creditor of debtors had to pay “groating money,” that is to say, 4d. per day for their maintenance. In the chapel there was a gallery, close to which were five sleeping-rooms for male debtors. The size of these cells was six feet by seven. Over the Pilot Office in Water-street were two rooms appropriated to the use of female debtors. One of these rooms contained three beds, the other only one. This latter room had glazed windows, and a fire-place, and was, comparatively speaking, comfortable. The same charge was made for the beds in these p. 26rooms as in other parts of the prison. The debtors were also accommodated with rooms in a house adjoining the gaol, from which, by the way, an escape of many of the prisoners, felon and debtor, took place in 1807—a circumstance which created immense public interest. When the prisoners were discovered, they stood at bay, and it was not until they were fired upon, that they surrendered. The criminals were lodged in seven close dungeons 6½ feet by 5 feet 9 inches. These cells were ranged in a passage 11 feet wide, under ground, and were approached by ten steps. Over each cell door was an aperture which admitted such light and air as could be found in such a place. Some improvement took place in this respect after Mr. Howard’s visit. There was also a large dungeon or cell which looked upon the street, in which twelve prisoners were confined. This dungeon was not considered safe, so that only deserters were put into it. As many as forty persons have been incarcerated in it at one time. In five of the cells there were four prisoners; in the other two, there were only three.

The court-yards (one of which was 20 yards by 30, the other 20 yards by 10) were kept in a most filthy state, although a fine pump of good water was readily accessible. The yards were brick-paved. In one yard I noticed a large dung-heap, which, I was informed, was only removed once a p. 27month. There were numbers of fowls about the yard, belonging to the prison officials and to the prisoners. In these yards, as may readily be supposed, scenes of great disorder took place. The utmost licentiousness was prevalent in the prison throughout. Spirits and malt liquors were freely introduced without let, hindrance, or concealment, though against the prison rules—not one of which, by the way, (except the feeing portion) was kept. The felons’ “garnish,” as it was called, was abolished previous to 1809, but the debtors’ fee remained. The prison was dirty in the extreme; the mud almost ankle deep in some parts in the passages, and the walls black and grimy. There seemed to be no system whatever tending towards cleanliness, and as to health that was utterly disregarded. Low typhoid fever was frequently prevalent, and numbers were swept off by it. The strong prisoners used to tyrannise over the weak, and the most frightful cases of extortion and cruelty were practised amongst them, while the conduct of the officials was culpable in the highest degree. At one time the chapel was let as an assembly room. The prisoners used to get up, on public ball nights, dances of their own, as the band could be plainly heard throughout the prison. The debtors used to let down a glove or bag by means of a stick, from their tower into the street, dangling it up and down to attract the p. 28notice of passengers, who dropped in pieces of money for the use of the “poor debtors,” which money was invariably spent in feasting and debauchery. The town boys used to put stones into the bags, and highly relished the disappointment of the “poor debtors,” on discovery of their “treasure.”

I recollect an execution taking place in front of the Tower, which created an immense sensation throughout the country. In March 1789, two men named Burns and Dowling, suffered the extreme penalty of the law for robbing the house of Mrs. Graham, which stood on Rose Hill. They broke into the lady’s dwelling, and acted with great ferocity. It was on the 23rd December previous; they entered the house, with two others, about seven o’clock in the morning. One stayed below, while the others went into the different rooms armed with pistols and knives, threatening the various members of the family with death if they made any alarm. They robbed some guests in the house of nineteen guineas, and some silver; and from Mrs. Graham they took bills to a large amount. On the 7th January, following, Burns and Dowling were arrested at Bristol, in consequence of an anonymous letter sent to the mayor of that city, giving information of their being in the neighbourhood. They were on the point of embarking for Dublin, having several packages p. 29containing Mrs. Graham’s property on board the vessel, besides £1000 in Bills of Exchange. Dowling made a fierce resistance, and would have escaped, but was held by the leg by a dog belonging to one of the constables. Rose Hill at that time was quite in the suburbs, and was a very fashionable locality. The town was crowded with strangers from all parts to witness the execution of these villains. Men of the present day would be horror-struck at the number of executions that took place at that time in England. I recollect once when in London (I was only three days going there) seeing three men hanging at Newgate, while the coal waggoners were letting off their waggons as stages for spectators at twopence per head.

The various prisoners in the Tower were all removed to the new gaol, or French prison, as it was called, on the French being released from custody, at the peace of 1812. This prison, which stood in Great Howard-street—I little thought I should live to see it swept away—was designed by Mr. Howard. Great Howard-street was called after him. The Frenchmen did so much damage to the gaol, that it cost £2000 to put it in order after their departure. These people maintained themselves by making fancy articles, and carved bone and ivory work. I once saw a ship made by one of them—an exquisite specimen of ingenuity and craftsmanship. The ropes, which were all spun p. 30to the proper sizes, were made of the prisoner’s wife’s hair. I had in my possession for many years, two cabinets, with drawers, &c., made of straw, and most beautifully inlaid.

I went with Mr. Nield, in one of his visits to Liverpool, to inspect the Bridewell which stood on the Fort. The building was intended for a powder magazine; but being found damp, it was not long used for that purpose. The keeper was Robert Walton, who was paid one guinea per week wages. There were no perquisites attached to this place, neither in “fees” nor “garnish.” In fact, the prisoners confined within its dreary, damp walls had nothing to pay for, nor expect. There were no accommodations of any sort. The corporation certainly found “firing,” but nothing else, either in beds or food, not even water. There was no yard to it, nor convenience of any kind. Under ground were two dreary, damp, dark vaults, approached by eight steps. One of them was 18 feet by 12, the other 12 feet by 7½. They received little light through iron-barred windows. Above were two rooms. One was 18 feet by 10, the other 10 feet by 9. Adjoining these two rooms, devoid of fire-grate or windows, were two cells, each 5 feet by 6 feet high. The prisoners in this dreadful place, were herded together, unemployed in any way, and dependent entirely upon their friends for food. It was a disgrace to humanity. p. 31It was damp, dirty, and in a most miserable condition.

An interesting circumstance connected with the Tower I find detailed in a book of my father’s, which he called “The Family Log.” It relates to the escape of some prisoners-of-war confined in the Tower. My father in this “Log,” used to enter up at the week’s end any little circumstance of interest that might have come under his notice. At the date of Sunday, May 6th, 1759, I find “That fifteen French prisoners escaped from the Tower, Durand amongst the number”; and then follows a narrative which I shall presently transcribe. I may say, incidentally, that the prisoners-of-war in the Tower were principally Frenchmen, who had been captured during some of our naval engagements with them. They employed their time in making many curious and tasteful articles, and displayed great ingenuity in many ways. Discipline in the Tower was not very stringent, so that escapes of prisoners frequently occurred. From the want of energy displayed by the authorities in recapturing those that did escape, it was thought that government was not sorry to get rid of some of these persons at so easy a rate, for they were a great burden on the nation. The reason why Durand’s name was mentioned as one of those who had fled, was this:—my mother had a very curiously-constructed foreign box, which had been p. 32broken, and which the tradesmen in the town had one and all declined even to attempt to repair. As “the Frenchmen” in the Tower were noted for their ingenuity, my father made some inquiry as to whether any of them would undertake the restoration of this box. Amongst others to whom it was shown was one Felix Durand, who at once said he would try to put it in order if my father was in no hurry for it, as it would be a tedious task in consequence of having so many separate pieces to join together, and it would be necessary to wait the fast binding of each cemented piece to its corresponding fragment.

My father often went to see Durand, and was much pleased with his conversation, amusing stories, and natural abilities. My father spoke French well, so that they got on capitally together, and the consequence was that my father obtained several little favours for him, and even interceded with some friends in the government to obtain his release. Durand knew of this, and, therefore, when my father found he had escaped with the others, he was much annoyed as it completely frustrated his good intentions towards him. My father used to tell us that according to agreement he went for his box on a certain day when it was to be finished. On reaching the gaol he was told of the escape of the party, and that some of them had already been recaptured. It seems that as soon as they got p. 33into the street the party dispersed, either singly or in twos and threes; but having neither food nor money, and being quite ignorant of the English language or the localities round Liverpool, they were quite helpless and everywhere betrayed who they were, what they were, and where they came from. Some fell in with the town watchmen; others struck out into the country, and after wandering about in a starved, hungry, and miserable state, were very glad to get back to their old shelter, bad as they thought it, and hardly as they considered they had been treated. They admitted that their party was too large, that they had no friends to co-operate with them outside, and no plan of action which was possibly or likely to be carried out successfully. The lot of these, however, was not shared by all, for Durand, as will be seen by his recital, had not done amiss, thanks to his wit, ingenuity, and cleverness.

The following is Durand’s narrative:—

“As you know, Monsieur Le Capitaine (he always called my father so), I am a Frenchman, fond of liberty and change, and this detestable prison became so very irksome to me, with its scanty food and straw beds on the floor, that I had for some time determined to make my escape and go to Ireland, where I believe sympathies are strong towards the French nation. I am, as you know, acquainted with Monsieur P---, who resides in Dale-street; I have done some work for him. He has a niece who is toute a faite charmante. She has been a p. 34constant ambassador between us, and has brought me work frequently, and taken charge of my money when I have received any, to deposit with her uncle on my account. I hold that young lady in the highest consideration. This place is bad for anyone to have property in, although we are in misery alike. Some of us do not know the difference between my own and thy own. We have strange communist ideas in this building. Now “Monsieur Le Capitaine” you want to know how I got away, where I went, and how I came back. I will tell you. I could not help it. I have had a pleasing three months’ holiday, and must be content to wait for peace or death, to release me from this sacre place. The niece of Monsieur P--- is very engaging, and when I have had conversation with her in the hall where we are permitted to see our friends, I obtained from her the information that on the east side of our prison there were two houses which opened into a short narrow street. One of these houses had been lately only partly tenanted, while the lower portion of it had been under repair. Mademoiselle is very complacent and kind. She took the trouble to go for me to the house and examine it, and reported that there was an open yard under the eastern prison-wall, and if anybody could get through that wall he might easily continue his route through the house and into the street. My mind was soon made up. I imparted my intention to my companions. There were fifteen of us, altogether, penned up at night in a vile cell or vault, and, of course, the intended escape could not be kept a secret; what was known by one, must be known by all. We all resolved to escape. Our cell was dirty and miserable. We obtained light and air from the street as well as from a grating over the door. Choosing a somewhat stormy night, we commenced by loosening the p. 35stonework in the east wall. Now we knew that after we were locked up for the night we should not be disturbed, and if we could not effect the removal of the stones in one night, there would be no fear of discovery during the next day, as we were seldom molested by any of the gaolers. We could walk about the prison just as we liked and mix with the other prisoners, whether felons or debtors. In fact your Liverpool Tower contains a large family party. We worked all night at the wall, and just before daybreak contrived to remove a large stone and soon succeeded in displacing another, but light having at length broken, we gathered up all the mortar and rubbish we had made, stuffing some of it into our beds, and covering the rest with them in the best way we could. To aid us in preventing the gaoler discovering what we had been about, one of our party remained in bed when the doors were unlocked, and we curtained the window grating with a blanket, stating that our compatriote was very ill and that he could not bear the light. We had no dread of a doctor coming to visit him, for unless special application was made for medical attendance on the sick nobody seemed to care whether we lived or died. The day passed over without any suspicions arising from our preparations. The afternoon set in stormy, as the preceding evening had done, and in the course of the night of our escape we had a complete hurricane of rain and wind, which eventually greatly favoured us by clearing the streets of any stragglers who might be prowling about. No sooner were we locked in at night than we recommenced our work at the wall, and were not long in making a hole sufficient to allow a man to creep through, which one of us did. He reported himself to be in an open yard, that it was raining very heavily, and that the night was affreuse; we all then crept through. We found p. 36ourselves in a dark yard, with a house before us. We obtained a light in a shed on one side of the yard, and then looked about. We found a sort of cellar door by the side of a window. We tried to open it: to our surprise it yielded. Screening our light we proceeded into a passage, taking off our shoes and stockings first (some of us had none to take off, poor fellows!) so that we should make no noise. The house was quite still; we scarcely dared to breathe. We went forward and entered a kitchen in which were the remains of a supper. We took possession of all that was eatable on the table. It was wonderful that nobody heard us, for one of us let fall a knife after cutting up a piece of beef into pieces, so that each man might have a share. Although there were people in the house no one heard us; truly you Englishmen sleep well! Before us was a door—we opened it. It was only a closet. We next thought of the window, for we dared not climb up stairs to the principal entrance. We tried the shutters which we easily took down and, fortunately without noise, opened the window, through which one of us crept to reconnoitre. He was only absent about a minute or two, returning to tell us that not a soul was to be seen anywhere; that the wind was rushing up the main street from the sea, and that the rain was coming down in absolute torrents. Just as the neighbouring church clock struck two we were assembled under an archway together. We determined to disperse, and let every man take care of himself. Bidding my friends good bye I struck out into the street. At first I thought of going to the river, but suddenly decided to go inland. I therefore went straight on, passed the Exchange, and down a narrow street facing it (Dale-street) in which I knew mademoiselle dwelt. I thought of her, but had no hope of seeing her as I did not know the house wherein she resided. I p. 37pushed on, therefore, until I came to the foot of a hill; I thought I would turn to the left, but shutting my eyes with superstitious feelings I left myself to fate, and determined to go forward with my eyes closed until I had by chance selected one of the four cross roads [Old Haymarket, Townsend-lane (now Byrom-street), Dale-street, and Shaw’s-brow] which presented themselves for my choice.

“I soon found I was ascending a hill, and on opening my eyes I discovered that I was pursuing my route in an easterly direction. I passed up a narrow street with low dirty-looking houses on each side, and from the broken mugs and earthenware my feet encountered in the darkness, I felt sure I was passing through the outskirts of Liverpool—famous for its earthenware manufactures. During all this time I had not seen a living thing; in fact it was scarcely possible for anything to withstand the storm that raged so vehemently. In this, however, rested my safety. I sped on, and soon mounting the hill paused by the side of a large windmill (Townsend mill) which stood at the top of London-road. Having gained breath, I pushed forward, taking the road to the right hand which ran before me (then called the road to Prescot). I began now to breathe freely and feel some hope in my endeavour to escape. My limbs, which, from long confinement in prison, were stiff at first, now felt elastic and nimble and I pushed on at a quick pace, the wind blowing at my back the whole time; still onward I went until I got into a country lane and had another steep hill to mount. The roads were very heavy. The sidewalk was badly kept, and the rain made it ankle-deep with mud. On surmounting the hill, which I afterwards learned was called Edge-hill, I still kept on to the right hand road, which was lined on both sides p. 38with high trees. I at length arrived at a little village (Wavertree) as a clock was striking three; still not a soul was visible. I might have been passing through a world of the dead. After traversing this village I saw, on my left hand, a large pond, at which I drew some water in my cap. I was completely parched with my unusual exertions. Resting under a large tree which proved some shelter, I ate up the bread and meat I had procured from the kitchen of the house through which we had escaped. Having rested about half-an-hour I again started forward. I now began to turn over in my mind what I should do. I felt that if I could get to Ireland I could find friends who would assist me. I knew a French priest in Dublin on whom I could rely for some aid. I at length hit upon a course of action which I determined to pursue. Through narrow lanes I went, still keeping to the right, and after walking for more than an hour I found myself in a quaint little village (Hale) in which there was a church then building. The houses were constructed principally of timber, lath, and plaster and were apparently of great antiquity. Onward still I went, the rain beating down heavily and the wind blowing. In about a quarter of an hour I gained a sight of the river or the sea, I know not which, but I still continued my road until I came up to a little cottage, the door of which opened just as I was passing it. An old woman came out and began to take down the shutters. Now, as I came along the road I had made up my mind to personate a deaf and dumb person, which would preclude the necessity of my speaking. I felt I could do this well and successfully. I determined to try the experiment upon this old lady. I walked quietly up to her, took the shutters out of her hands and laid them in their proper places. I then took a broom and began sweeping away the water p. 39which had accumulated in front of her cottage, and seeing a kettle inside the door, I walked gravely into the house, took it, and filled it at a pump close by. The old woman was dumb-struck. Not a word did she say, but stood looking on with mute amazement, which was still more intensely exhibited when I went to the fire-place, raked out the cinders, took up some sticks and commenced making a fire. Not a word passed between us. It was with great difficulty I could keep my countenance. We must have looked a curious couple. The woman standing staring at me, I sitting on a three-legged stool, with my elbows on my knees looking steadfastly at her. At length she broke this unnatural silence. Speaking in her broad Lancashire dialect I could scarcely make her out. My own deficiency in not understanding much English increased my difficulty, but I understood her to ask “Who I was, and whither I was going.” This she repeated until, having sufficiently excited her curiosity, I opened my mouth very wide, kept my tongue quite close so that it might seem as if I had none, and with my fingers to my ears made a gesture that I was deaf and dumb. She then said, “Poor man, poor man,” with great feeling and gave me a welcome. So I sat before the fire, and commenced drying my clothes, which were saturated during my walk. I suppose I must have fallen asleep, for the next thing I noticed was a substantial meal laid on the table, consisting of bread, cold bacon, and beer. Pointing to the food the old woman motioned to me to partake, and this I was not loath to do. I made a hearty meal. I should tell you, before we sat down to the table I had pulled out my pockets to show her I had no money. The woman made a sign that she did not want payment for her kindness. When we had finished our meal I looked about me, and seeing that several things wanted p. 40putting to rights, such as emptying a bucket, getting in some coals, and cleaning down the front pavement of the house, I commenced working hard as some repayment for the hospitality I had received. We Frenchmen can turn our hands to almost anything, and my dexterity quite pleased the old lady. While I was busily sweeping the hearth, I heard the sound of a horse’s feet coming swiftly onward. Terror-struck, I did a foolish thing. Fancying it must be some one in pursuit of me, I dropped the little broom I was using, seized my cap from one of the chairs, opened the back door of the cottage, and fled along the garden walk, over-leaped a hedge, crossed a brook, and was off like a hunted hare across the open fields. This was a silly proceeding, because if the horseman had been any one in pursuit, the chances were that, should he have entered the cottage, I might not have been recognized; and if I had simply hid myself in some of the outbuildings that were near I might have escaped notice altogether, while by running across the fields I exposed myself to observation, and to be taken. When half over a field I found there a small clump of trees, and a little pond. Down the side of this pond I slipped and hid myself amongst the rushes; but I need not have given myself any anxiety or trouble, for I saw the horseman, whatever might have been his errand, flying along the winding road in the distance.

“Having satisfied myself of my security, I started off and soon found myself on the highroad again, and after a time I came near a fine old mansion which presented a most venerable appearance. I could not stop, however, to look at it, for I found I had taken a wrong turn and was going back to Liverpool. I therefore retraced my steps and passed on, going I know not whither. After walking for about an hour in a southerly direction, feeling p. 41tired and seeing a barn open I went to it and found two men therein threshing wheat. I made signs to them that I was deaf and dumb, and asked leave to lie in the straw. They stared at me very much, whispered amongst themselves, and at length, made a sign of assent. I fell asleep. When I awoke the sun was up and bright, while all trace of the night-storm had disappeared. I wondered at first where I was. Seeing the fresh straw lying about, an idea struck me that I could earn a few pence by a little handiwork. I thereupon commenced making some straw baskets, the like of which you have often seen myself and fellow-prisoners manufacture. By the time I had completed two or three the men came again into the barn and began to work with their flails. I stepped forward with my baskets, which seemed to surprise them. The like they had evidently never seen before—they examined them with the greatest attention. One of the men, pulling some copper money out of his pocket, offered it for one of them. Grateful for the shelter I had received, I pushed back the man’s hand which contained the money and offered him the basket as a present, pointing to my bed of straw. The honest fellow would not accept it, saying I must have his money. I therefore sold him one of the baskets, and another was also purchased by one of the other men. They seemed astonishingly pleased with their bargains. Just as they had concluded their dealings with me a big man came into the barn, who I found out was the master. The men showed him the baskets and pointed to me, telling the farmer that I was a “dumby and deafy.” The big farmer hereupon bawled in my ear the question, “who was I, and where had I come from?” I put on a perfectly stolid look although the drum of my ears was almost split by his roaring. The farmer had a soft heart, however, in his big and burly frame. Leaving p. 42the barn, he beckoned me to follow him. This I did. He went into the farm-house, and, calling his wife, bade her get dinner ready. A capital piece of beef, bread, and boiled greens or cabbages were soon on the table, to which I sat down with the farmer and his wife. Their daughter, soon after we had commenced eating, came in. Her attention was immediately attracted by my remaining basket, which I had placed by them. I got up from the table and presented it to her. Her father then told her of my supposed infirmities. I could scarcely help laughing while I heard them canvass my personal appearance, my merits and demerits. Pity, however, seemed to be the predominant feeling. When the dinner was over, I happened to look up at an old clock and saw that it had stopped. I went up to it, and took it from the nail. I saw it wanted but very little to make it go again. I therefore quietly, but without taking notice of my companions, set to work to take off the face and do the needful repairs. A pair of pincers on the window-ledge and some iron wire, in fact, an old skewer, were all the tools necessary; and very soon, to the satisfaction of my host, his wife, and his fair daughter, the clock was set going as well as it ever had done. The farmer slapped me on the back and gave me great encouragement. I then cast my eyes about to see what I could do next. I mended a chair, repaired a china image, cleaned an old picture, and taking a lock from a door repaired it, altering the key so that it became useful. In fact, I so busied myself, and with such earnestness that by night-time I had done the farmer a good pound’s worth of repairing. I then had my supper, and was made to understand I might sleep in the barn, if I liked. On the next morning the farmer’s daughter found me very busy in the yard with the pigs, which I was feeding; in fact, the whole of that day I p. 43worked hard, because I thought if I could remain where I was until the wonder of our escapade was over, I might eventually get away altogether from England by some unforeseen piece of good fortune. For some time I worked at this farm, for, as if by mutual consent of the farmer and myself, I remained, getting only my food for my work; however, at the end of each week the farmer’s wife gave me quietly some money. I made several little fancy articles for Mademoiselle which she seemed highly to prize; but it was through her that I left my snug quarters. The principal labourer on the farm was courting, on the sly, this young woman, and I noticed he became sulky with me, as Miss Mary on several occasions selected me to perform some little service for her. From an expression I heard him make use of to one of the other men I felt sure he was about to do me some act of treachery and unkindness, and, as I was no match for the great Hercules he seemed to be, I thought it best to leave the place, as any disturbance might draw down attention upon me too closely. I therefore put up my spare clothes, some of which had been given to me by the farmer’s wife—a kindly, Christian woman she was—and hiding my little store of money securely in my breeches’ waistband, very early one fine morning I set off with a heart by no means light, from the place where I had been so well-treated, not knowing where on earth to go or what next to do. Before I went, however, to show I was grateful for their kindness, I made up a little parcel which I addressed to the farmer’s wife, in which I put a tobacco-box for Mr. John Bull, a bodkin-case for herself, and a little ring for Miss Mary, all of which I had made in my leisure time. I dare say they were sorry to part with me. I am sure Miss Mary was, for I fancied she suspected I was not what I seemed, and had begun to take an evident p. 44liking to me. I had taught her some French modes of cooking, which excited surprise, as well as gratification to their palates, and I taught her also two or three little ways of making fancy articles that pleased her exceedingly. It was through her manifesting a preference for me that, as I have told you, Monsieur le Capitaine, I felt obliged to absent myself from her father’s employment. It was most difficult at first to restrain myself from talking. But I soon got over that, for when I was about to speak I made an uncertain sort of noise, which turned off suspicion. That the head labourer had some doubt about me, I verily believe. I thought at first I would try to get to London, but the roads thereto, I learnt, were so bad and travelling so insecure, even for the poorest, that I considered it best to remain in this neighbourhood, as I wanted to see Mademoiselle P--- once more, and settle with her uncle for the money of mine in his hands. I thought if I could only communicate with him he would befriend me, so I went on my way.

“I travelled all that day until I got into a place called Warrington, by the side of a river. It is a town full of old quaint houses built of timber and plaster. I was very tired when I arrived there at nightfall, but obtained shelter in an old house near the bridge, and as I had the money my mistress gave me I bought some food at a little shop; a Frenchman does not want very heavy meals, so that I did pretty well. The next day I went to a baker’s and got some more bread. I interested the baker’s wife, and when she found I was deaf and dumb, she not only would not take money for her bread, but also gave me some meat and potatoes. It seemed she had a relation affected as I was supposed to be. I then went out to a farm-yard, and having begged some straw I turned to my never-failing fountain of help—basket p. 45making. I made a number of baskets and other little things, all of which on taking into the town I sold readily. I begged some more straw of a man at a stable, and set to work again. I sold off my baskets and fancy articles much quicker than I could make them. I soon got so well known that I excited some attention; but one day being at a public tavern, where I had gone to deliver a basket ordered, the word ‘Liverpool’ fell upon my ears and caused me to tremble. Near me sat two men who looked like drovers. They were talking about Liverpool affairs: one of them told the other that there had been lately a great fire near the dock, where a quantity of provisions had been burnt, and much property destroyed besides. They then spoke of the escape of my companions and myself, and for the first time I heard of their fate, and how, one by one, they had been recaptured or willingly returned. I then heard of their trials and the miseries they had encountered. The drovers also spoke of one prisoner who had disappeared and got away completely, but that there was a hot search after him, as he, it was supposed, was the ringleader in the late outbreak, and that it was planned and carried out by him. I felt that they alluded to myself, and that this place would grow too warm for me, as I knew that I was already an object of public remark, owing to my supposed infirmities and the extraordinary dexterity of my fingers. It will be recollected that I bought some bread at a little shop near the market-place. Passing there the day after I arrived, I saw a bill in the window bearing the words “lodgings to let.” I, therefore, by signs made the woman of the shop comprehend that I wanted such accommodation. I took the bill out of the window, pointed to the words, and the to myself; then I laid my hand on my head as if in the attitude of sleep. The good woman quite comprehended p. 46me, and nodding her head to my dumb proposition led the way up a small flight of stairs, and at once installed me in the vacant room. It was small and poorly furnished, but very clean. I soon made myself at home; and never wanted anything doing for me, so that the widow’s intercourse with me was very limited. I knew I could not write without betraying my foreign origin, so the way I did first was to get a book and pick out words signifying what I wanted, and from these words the good woman made out a sentence. I wanted so little that we had no difficulty in making out a dialogue. After hearing the talk of the drovers I determined to leave the town without delay, for my fears of recapture quite unmanned me, making me needlessly dread any intercourse with strangers. Having thus resolved to leave Warrington I bade goodbye to my kind landlady, giving her a trifle over her demand, and then shaped my way to the northward. I went to several towns, large and small, and stayed in Manchester a week, where I sold what I made very readily. My supposed infirmities excited general commiseration everywhere, and numerous little acts of kindness did I receive. I wandered about the neighbouring towns in the vicinity for a long time, being loth to leave it for several reasons; in fact I quite established a connection amongst the farmers and gentry, who employed me in fabricating little articles of fancy work and repairing all sorts of things most diverse in their natures and uses. At one farm-house I mended a tea-pot and a ploughshare, and at a gentleman’s house, near St. Helen’s, repaired a cart, and almost re-built a boat, which was used on his fish-pond. I turned my hand to any and everything. I do not say I did everything well, but I did it satisfactorily to those who employed me. I now began to be troubled about my money which was accumulating, being p. 47obliged to carry it about with me, as I feared being pillaged of it. I therefore resolved on coming back to Liverpool and finding out Monsieur P--- at all hazards, trusting to chance that I should not be recognised. Who could do so? Who would know me in the town save the Tower gaolers who would scarcely be out at night; even they would not recollect me in the dark streets of the town? When this resolve came upon me I was at a place called Upholland where I had been living three or four days, repairing some weaver’s looms—for there are a good many weavers in that little town. I had nearly finished the work I had undertaken, and was intending to come to Liverpool direct at the end of the following week, when my design was frustrated by a curious and most unexpected circumstance. About three miles from Upholland there is a very high hill called Ashurst. On the top of this is a beacon tower which looks at a distance like a church steeple rising over the top of the hill, just as if the body of the church were on the other side of the crest. This beacon is intended to communicate alarm to the neighbouring country in war time, it being one of a line of beacons to and from different places. I had once or twice walked to this high place to enjoy the fine prospect. On Sunday last I had gone there and extended my walk down the hill to a place where the road, after passing a pretty old entrance-gateway, moat, and old hall, dips very prettily down to bridge over a small stream. This bridge (Cobb’s Brow Bridge) is covered with ivy, and is very picturesque. Just before the road rather abruptly descends there are, on the right hand side of it, a number of remarkably old and noble oak trees, quite giants. Some are hollowed out, and one is so large that it will accommodate several persons. This tree has been used by what you call gipsies—and shows that fire has been made in it.