George Manville Fenn

"Nic Revel"

Chapter One.

Captain Revel is Cross.

“Late again, Nic,” said Captain Revel.

“Very sorry, father.”

“Yes, you always are ‘very sorry,’ sir. I never saw such a fellow to sleep. Why, when I was a lad of your age—let’s see, you’re just eighteen.”

“Yes, father, and very hungry,” said the young man, with a laugh and a glance at the breakfast-table.

“Always are very hungry. Why, when I was a lad of your age I didn’t lead such an easy-going life as you do. You’re spoiled, Nic, by an indulgent father.—Here, help me to some of that ham.—Had to keep my watch and turn up on deck at all hours; glad to eat weavilly biscuit.—Give me that brown bit.—Ah, I ought to have sent you to sea. Made a man of you. Heard the thunder, of course?”

“No, father. Was there a storm?”

“Storm—yes. Lightning as we used to have it in the East Indies, and the rain came down like a waterspout.”

“I didn’t hear anything of it, father.”

“No; you’d sleep through an earthquake, or a shipwreck, or— Why, I say, Nic, you’ll soon have a beard.”

“Oh, nonsense, father! Shall I cut you some bread?”

“But you will,” said the Captain, chuckling. “My word, how time goes! Only the other day you were an ugly little pup of a fellow, and I used to wipe your nose; and now you’re as big as I am—I mean as tall.”

“Yes; I’m not so stout, father,” said Nic, laughing.

“None of your impudence, sir,” said the heavy old sea-captain, frowning. “If you had been as much knocked about as I have, you might have been as stout.”

Nic Revel could not see the common-sense of the remark, but he said nothing, and went on with his breakfast, glancing from time to time through the window at the glittering sea beyond the flagstaff, planted on the cliff which ran down perpendicularly to the little river that washed its base while flowing on towards the sea a mile lower down.

“Couldn’t sleep a bit,” said Captain Revel. “But I felt it coming all yesterday afternoon. Was I—er—a bit irritable?”

“Um—er—well, just a little, father,” said Nic dryly.

“Humph! and that means I was like a bear—eh, sir?”

“I did not say so, father.”

“No, sir; but you meant it. Well, enough to make me,” cried the Captain, flushing. “I will not have it. I’ll have half-a-dozen more watchers, and put a stop to their tricks. The land’s mine, and the river’s mine, and the salmon are mine; and if any more of those idle rascals come over from the town on to my grounds, after my fish, I’ll shoot ’em, or run ’em through, or catch ’em and have ’em tied up and flogged.”

“It is hard, father.”

“‘Hard’ isn’t hard enough, Nic, my boy,” cried the Captain angrily. “The river’s open to them below, and it’s free to them up on the moors, and they may go and catch them in the sea if they want more room.”

“If they can, father,” said Nic, laughing.

“Well, yes—if they can, boy. Of course it’s if they can with any one who goes fishing. But I will not have them come disturbing me. The impudent scoundrels!”

“Did you see somebody yesterday, then, father?”

“Didn’t you hear me telling you, sir? Pay attention, and give me some more ham. Yes; I’d been up to the flagstaff and was walking along by the side of the combe, so as to come back home through the wood path, when there was that great lazy scoundrel, Burge, over from the town with a long staff and a hook, and I was just in time to see him land a good twelve-pound salmon out of the pool—one of that half-dozen that have been lying there this fortnight past waiting for enough water to run up higher.”

“Did you speak to him, father?”

“Speak to him, sir!” cried the Captain. “I let him have a broadside.”

“What did he say, father?”

“Laughed at me—the scoundrel! Safe on the other side; and I had to stand still and see him carry off the beautiful fish.”

“The insolent dog!” cried Nic.

“Yes; I wish I was as young and strong and active as you, boy. I’d have gone down somehow, waded the river, and pushed the scoundrel in.”

He looked at his father and smiled.

“But I would, my boy: I was in such a fit of temper. Why can’t the rascals leave me and mine alone?”

“Like salmon, I suppose, father,” said the young man.

“So do we—but they might go up the river and catch them.”

“We get so many in the pool, and they tempt the idle people.”

“Then they have no business to fall into temptation. I’ll do something to stop them.”

“Better not, father,” said Nic quietly. “It would only mean fighting and trouble.”

“Bah!” cried Captain Revel, with his face growing redder than usual. “What a fellow to be my son! Why, sir, when I was your age I gloried in a fight.”

“Did you, father?”

“Yes, sir, I did.”

“Ah! but you were in training for a fighting-man.”

“And I was weak enough, to please your poor mother, to let you be schooled for a bookworm, and a man of law and quips and quiddities, always ready to enter into an argument with me, and prove that black’s white and white’s no colour, as they say. Hark ye, sir, if it was not too late I’d get Jack Lawrence to take you to sea with him now. He’ll be looking us up one of these days soon. It’s nearly time he put in at Plymouth again.”

“No, you would not, father,” said the young man quietly.

“Ah! arguing again? Why not, pray?”

“Because you told me you were quite satisfied with what you had done.”

“Humph! Hah! Yes! so I did. What are you going to do this morning—read?”

“Yes, father; read hard.”

“Well, don’t read too hard, my lad. Get out in the fresh air a bit. Why not try for a salmon? They’ll be running up after this rain, and you may get one if there is not too much water.”

“Yes, I might try,” said the young man quietly; and soon after he strolled into the quaint old library, to begin poring over a heavy law-book full of wise statutes, forgetting everything but the task he had in hand; while Captain Revel went out to walk to the edge of the high cliff and sat down on the stone seat at the foot of the properly-rigged flagstaff Here he scanned the glittering waters, criticising the manoeuvres of the craft passing up and down the Channel on their way to Portsmouth or the port of London, or westward for Plymouth, dreaming the while of his old ship and the adventures he had had till his wounds, received in a desperate engagement with a couple of piratical vessels in the American waters, incapacitated him for active service, and forced him to lead the life of an old-fashioned country gentleman at his home near the sea.

Chapter Two.

A Wet Fight.

The Captain was having his after-dinner nap when Nic took down one of the rods which always hung ready in the hall, glanced at the fly to see if it was all right, and then crossed the garden to the fields. He turned off towards the river, from which, deep down in the lovely combe, came a low, murmurous, rushing sound, quite distinct from a deep, sullen roar from the thick woodland a few hundred yards to his right.

“No fishing to-day,” he said, and he rested his rod against one of the sturdy dwarf oaks which sheltered the house from the western gales, and then walked on, drawing in deep draughts of the soft salt air and enjoying the beauty of the scene around.

For the old estate had been well chosen by the Revels of two hundred years earlier; and, look which way he might, up or down the miniature valley, there were the never-tiring beauties of one of the most delightful English districts.

The murmur increased as the young man strode on down the rugged slope, or leaped from mossy stone to stone, amongst heather, furze, and fern, to where the steep sides of the combe grew more thickly clothed with trees, in and amongst which the sheep had made tracks like a map of the little valley, till all at once he stood at the edge of a huge mass of rock, gazing through the leaves at the foaming brown water which washed the base of the natural wall, and eddied and leaped and tore on along its zigzag bed, onward towards the sea.

From where he stood he gazed straight across at the other side of the combe, one mass of greens of every tint, here lit up by the sun, there deep in shadow; while, watered by the soft moist air and mists which rose from below, everything he gazed upon was rich and luxuriant in the extreme.

“The rain must have been tremendous up in the moor,” thought the young man, as he gazed down into the lovely gully at the rushing water, which on the previous day had been a mere string of stony pools connected by a trickling stream, some of them deep and dark, the haunts of the salmon which came up in their season from the sea. “What a change! Yesterday, all as clear as crystal; now, quite a golden brown.”

Then, thinking of how the salmon must be taking advantage of the little flood to run up higher to their spawning-grounds among the hills, Nic turned off to his right to follow a rugged track along the cliff-like side, sometimes low down, sometimes high up; now in deep shadow, now in openings where the sun shot through to make the hurrying waters sparkle and flash.

The young man went on and on for quite a quarter of a mile, with the sullen roar increasing till it became one deep musical boom; and, turning a corner where a portion of the cliff overhung the narrow path, and long strands of ivy hung down away from the stones, he stepped out of a green twilight into broad sunshine, to stand upon a shelf of rock, gazing into a circular pool some hundred feet across.

Here was the explanation of the deep, melodious roar. For, to his right, over what resembled a great eight-foot-high step in the valley, the whole of the little river plunged down from the continuation of the gorge, falling in one broad cascade in a glorious curve right into the pool, sending up a fine spray which formed a cloud, across which, like a bridge over the fall, the lovely tints of a rainbow played from time to time.

It was nothing new to Nic, that amphitheatre, into which he had gazed times enough ever since he was a child; but it had never seemed more lovely, nor the growth which fringed it from the edge of the water to fifty or sixty feet above his head more beautiful and green.

But he had an object in coming, and, following the shelf onward, he was soon standing level with the side of the fall, gazing intently at the watery curve and right into the pool where the water foamed and plunged down, rose a few yards away, and then set in a regular stream round and round the amphitheatre, a portion flowing out between two huge buttresses of granite, and then hurrying downstream.

Nic was about fifteen feet above the surface of the chaos of water, and a little above the head of the pool; while below him were blocks of stone, dripping bushes, and grasses, and then an easy descent to where he might have stood dry-shod and gazed beneath the curve of the falling water, as he had stood scores of times before.

But his attention was fixed upon the curve, and as he watched he saw something silvery flash out of the brown water and fall back into the pool where the foam was thickest.

Again he saw it, and this time it disappeared without falling back. For the salmon, fresh from the sea, were leaping at the fall to gain the upper waters of the river.

It was a romantic scene, and Nic stood watching for some minutes, breathing the moist air, while the spray began to gather upon his garments, and the deep musical boom reverberated from the rocky sides of the chasm.

It was a grand day for the fish, and he was thinking that there would be plenty of them right up the river for miles, for again and again he saw salmon flash into sight as, by one tremendous spring and beat of their tails, they made their great effort to pass the obstacle in their way.

“Plenty for every one,” he said to himself; “and plenty left for us,” he added, as he saw other fish fail and drop back into the foam-covered amber and black water, to sail round with the stream, and in all probability—for their actions could not be seen—rest from their tremendous effort, and try again.

All at once, after Nic had been watching for some minutes without seeing sign of a fish, there was a flash close in to where he stood, and a large salmon shot up, reached the top of the fall, and would have passed on, but fortune was against it. For a moment it rested on the edge, and its broad tail and part of its body glistened as a powerful stroke was made with the broad caudal fin.

But it was in the air, not in the water; and the next moment the great fish was falling, when, quick as its own spring up, there was a sudden movement from behind one of the great stones at the foot of the fall just below where Nic stood, and the salmon was caught upon a sharp hook at the end of a stout ash pole and dragged shoreward, flapping and struggling with all its might.

The efforts were in vain, for its captor drew it in quickly, raising the pole more and more till it was nearly perpendicular, as he came out from behind the great block of dripping stone which had hidden him from Nic, and, as it happened, stepped backward, till his fish was clear of the water.

It was all the matter of less than a minute. The man, intent upon his fish—a magnificent freshly-run salmon, glittering in its silver scales—passed hand over hand along his pole, released his right, and was in the act of reaching down to thrust a hooked finger in the opening and closing gills to make sure of his prize in the cramped-up space he occupied, when the end of the stout ash staff struck Nic sharply on his leg.

But the man did not turn, attributing the hindrance to his pole having encountered a stone or tree branch above his head, and any movement made by Nic was drowned by the roar of the fall.

The blow upon the leg was sharp, and gave intense pain to its recipient, whose temper was already rising at the cool impudence of the stout, bullet-headed fellow, trespassing and poaching in open daylight upon the Captain’s grounds.

Consequently, Nic did take notice of the blow.

Stooping down as the end of the pole wavered in the air, he made a snatch at and seized it, gave it a wrench round as the man’s finger was entering the gill of the salmon, and the hook being reversed, the fish dropped off, there was a slight addition to the splashing in the pool, and then it disappeared.

The next moment the man twisted himself round, holding on by the pole, and stared up; while Nic, still holding on by the other end, leaned over and stared down.

It was a curious picture, and for some moments neither stirred, the poacher’s not ill-looking face expressing profound astonishment at this strange attack.

Then a fierce look of anger crossed it, and, quick as thought, he made a sharp snatch, which destroyed Nic’s balance, making him loosen his hold of the pole and snatch at the nearest branch to check his fall.

He succeeded, but only for a moment, just sufficient to save himself and receive another heavy blow from the pole, which made him lose his hold and slip, more than fall, down to where he was on the same level with his adversary, who drew back to strike again.

But Nic felt as if his heart was on fire. The pain of the blows thrilled him, and, darting forward with clenched fists, he struck the poacher full in the mouth before the pole could swing round.

There was the faint whisper of a hoarse yell as the man fell back; Nic saw his hands clutching in the air, then he went backward into the boiling water, while the end of the pole was seen to rise above the surface for a moment or two, and then glide towards the bottom of the fall and disappear.

For the current, as it swung round the pool, set towards the falling water on the surface, and rushed outward far below.

Nic’s rage died out more quickly than it had risen, and he craned forward, white as ashes now, watching for the rising of his adversary out somewhere towards the other side; while, as if in triumphant mockery or delight at the danger having been removed, another huge salmon leaped up the fall.

Chapter Three.

A Game of Tit for Tat.

“I’d have pushed him in.”

Captain Revel’s threat flashed through his son’s brain as the young man stood staring wildly over the agitated waters of the pool, every moment fancying that he saw some portion of the man’s body rise to the surface; but only for it to prove a patch of the creamy froth churned up by the flood.

It was plain enough: the man had been sucked in under the falls, and the force of the falling water was keeping him down. He must have been beneath the surface for a full minute now—so it seemed to Nic; and, as he grew more hopeless moment by moment of seeing him rise, the young man’s blood seemed to chill with horror at the thought that he had in his rage destroyed another’s life.

Only a short time back the shut-in pool had been a scene of beauty; now it was like a black hollow of misery and despair, as the water dashed down and then swirled and eddied in the hideous whirlpool.

Then it was light again, and a wild feeling of exultation shot through Nic’s breast, for he suddenly caught sight of the man’s inert body approaching him, after gliding right round the basin. It was quite fifty feet away, and seemed for a few moments as if about to be swept out of the hollow and down the gully; but the swirl was too strong, and it continued gliding round the pool, each moment coming nearer.

There was no time for hesitation. Nic knew the danger and the impossibility of keeping afloat in foaming water like that before him, churned up as it was with air; but he felt that at all cost he must plunge in and try to save his adversary before the poor fellow was swept by him and borne once more beneath the fall.

Stripping off his coat, he waited a few seconds, and then leaped outward so as to come down feet first, in the hope that he might find bottom and be able to wade, for he knew that swimming was out of the question.

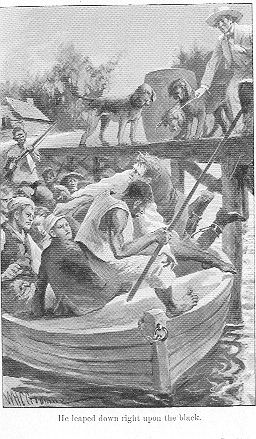

It was one rush, splash, and hurry, for the water was not breast-deep, and by a desperate effort he kept up as his feet reached the rugged, heavily-scoured stones at the bottom. Then the pressure of the water nearly bore him away, but he managed to keep up, bearing sidewise, and the next minute had grasped the man’s arm and was struggling shorewards, dragging his adversary towards the rugged bank.

Twice-over he felt that it was impossible; but, as the peril increased, despair seemed to endow him with superhuman strength, and he kept up the struggle bravely, ending by drawing the man out on to the ledge of stones nearly on a level with the water, where he had been at first standing at the foot of the fall.

“He’s dead; he’s dead!” panted Nic, as he sank upon his knees, too much exhausted by his struggle to do more than gaze down at the dripping, sun-tanned face, though the idea was growing that he must somehow carry the body up into the sunshine and try to restore consciousness.

Comic things occur sometimes in tragedies, and Nic’s heart gave a tremendous leap, for a peculiar twitching suddenly contracted the face beside which he knelt, and the man sneezed violently, again and again. A strangling fit of coughing succeeded, during which he choked and crowed and grew scarlet, and in his efforts to get his breath he rose into a sitting position, opened his eyes to stare, and ended by struggling to his feet and standing panting and gazing fiercely at Nic.

“Are you better?” cried the latter excitedly, and he seized the man by the arms, as he too rose, and held him fast, in the fear lest he should fall back into the whirlpool once more.

That was enough! Pete Burge was too hardy a fisher to be easily drowned. He had recovered his senses, and the rage against the young fellow who had caused his trouble surged up again, as it seemed to him that he was being seized and made prisoner, not a word of Nic’s speech being heard above the roar of the water.

“Vish as much mine as his,” said the man to himself; and, in nowise weakened by his immersion, he closed with Nic. There was a short struggle on the ledge, which was about the worst place that could have been chosen for such an encounter; and Nic, as he put forth all his strength against the man’s iron muscles, was borne to his left over the water and to his right with a heavy bang against the rocky side of the chasm. Then, before he could recover himself, there was a rapid disengagement and two powerful arms clasped his waist; he was heaved up in old West-country wrestling fashion, struggling wildly, and, in spite of his efforts to cling to his adversary, by a mighty effort jerked off. He fell clear away in the foaming pool, which closed over his head as he was borne in turn right beneath the tons upon tons of water which thundered in his ears, while he experienced the sudden change from sunshine into the dense blackness of night.

“How do you like that?” shouted the man; but it was only a faint whisper, of which he alone was conscious.

There was a broad grin upon his face, and his big white teeth glistened in the triumphant smile which lit up his countenance.

“I’ll let you zee.”

He stood dripping and watching the swirling and foaming water for the reappearance of Nic.

“Biggest vish I got this year,” he said to himself. “Lost my pole, too; and here! where’s my cap, and—?”

There was a sudden change in his aspect, his face becoming full of blank horror now as he leaned forward, staring over the pool, eyes and mouth open widely; and then, with a groan, he gasped out:

“Well, I’ve done it now!”

Chapter Four.

Nic will not shake Hands.

History repeats itself, though the repetitions are not always recorded.

A horrible feeling of remorse and despair came over the man. His anger had evaporated, and putting his hands to the sides of his mouth, he yelled out:

“Ahoy, there! Help—help!”

Again it was a mere whisper in the booming roar.

“Oh, poor dear lad!” he muttered to himself. “Bother the zammon! Wish there waren’t none. Hoi, Master Nic! Strike out! Zwim, lad, zwim! Oh, wheer be ye? I’ve drowned un. Oh, a mercy me! What have I done?—Hah! there a be.”

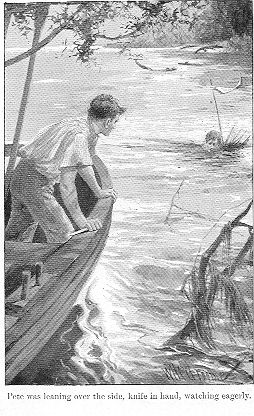

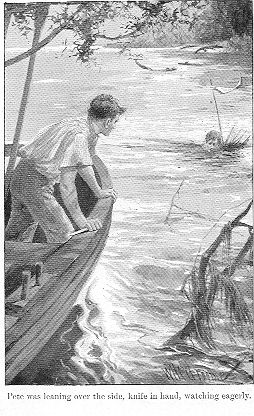

There was a plunge, a splash, and a rush against the eddying water, with the man showing a better knowledge of the pool, from many a day’s wading, than Nic had possessed. Pete Burge knew where the shallow shelves of polished stones lay out of sight, and he waded and struggled on to where the water was bearing Nic round in turn. Then, after wading, the man plunged into deep water, swam strongly, and seized his victim as a huge dog would, with his teeth, swung himself round, and let the fierce current bear him along as he fought his way into the shallow, regained his footing, and the next minute was back by the ledge. Here he rose to his feet, and rolled and thrust Nic ashore, climbed out after him, and knelt in turn by his side.

“Bean’t dead, be he?” said the man to himself. “Not in the water long enough. Worst o’ these here noblemen and gentlemen—got no stuff in ’em.”

Pete Burge talked to himself, but he was busy the while. He acted like a man who had gained experience in connection with flooded rivers, torrents, and occasional trips in fishing-boats at sea; and according to old notions, supposing his victim not to be already dead, he did the best he could to smother out the tiny spark of life that might still be glowing.

His fine old-fashioned notion of a man being drowned was that it was because he was full of water. The proper thing, then, according to his lights, must be to empty it out, and the sooner the better. The sea-going custom was to lay a man face downward across a barrel, and to roll the barrel gently to and fro.

“And I aren’t got no barrel,” muttered Pete.

To make up for it he rolled Nic from side to side, and then, as his treatment produced no effect, he seized him by the ankles, stood up, and raised the poor fellow till he was upside down, and shook him violently again and again.

Wonderful to relate, that did no good, his patient looking obstinately lifeless; so he laid him in the position he should have tried at first—extended upon his back; and, apostrophising him all the time as a poor, weakly, helpless creature, punched and rubbed and worked him about, muttering the while.

“Oh, poor lad! poor dear lad!” he went on. “I had no spite again’ him. I didn’t want to drownd him. It weer only tit for tat; he chucked me in, and I chucked him in, and it’s all on account o’ they zammon.—There goes another. Always a-temptin’ a man to come and catch ’em—lyin’ in the pools as if askin’ of ye.—Oh, I say, do open your eyes, lad, and speak! They’ll zay I murdered ye, and if I don’t get aboard ship and zail away to foreign abroad, they’ll hang me, and the crows’ll come and pick out my eyes.—I zay.—I zay lad, don’t ye be a vool. It was on’y a drop o’ watter ye zwallowed. Do ye come to, and I’ll never meddle with the zammon again.—I zay, ye aren’t dead now. Don’t ye be a vool. It aren’t worth dying for, lad. Coom, coom, coom, open your eyes and zit up like a man. You’re a gentleman, and ought to know better. I aren’t no scholard, and I didn’t do zo.—Oh, look at him! I shall be hanged for it, and put on the gibbet, and all for a bit o’ vish.—Zay, look here, if you don’t come to I’ll pitch you back again, and they’ll think you tumbled in, and never know no better. It’s voolish of ye, lad. Don’t give up till ye’re ninety-nine or a hundred. It’s time enough to die then. Don’t die now, with the sun shining and the fish running up the valls, and ye might be so happy and well.”

And all the while Pete kept on thumping and rubbing and banging his patient about in the most vigorous way.

“It’s spite, that’s what it is,” growled the man. “You hit me i’ th’ mouth and tried to drownd me, and because you couldn’t you’re trying to get me hanged; and you shan’t, for if you don’t come-to soon, sure as you’re alive I’ll pitch you back to be carried out to zea.—Nay, nay, I wouldn’t, lad. Ye’d coom back and harnt me. I never meant to do more than duck you, and Hooray!”

For Nic’s nature had at last risen against the treatment he was receiving. It was more than any one could stand; so, in the midst of a furious bout of rubbing, the poor fellow suddenly yawned and opened his eyes, to stare blankly up at the bright sun-rays streaming down through the overhanging boughs of the gnarled oaks. He dropped his lids again, but another vigorous rubbing made him open them once more; and as he stared now at his rough doctor his lips moved to utter the word “Don’t!” but it was not heard, and after one or two more appeals he caught the man’s wrists and tried to struggle up into a sitting position, Pete helping him, and then, as he knelt there, grinning in his face.

Nic sat staring at him and beginning to think more clearly, so that in a few minutes he had fully grasped the position and recalled all that had taken place.

It was evident that there was to be a truce between them, for Pete Burge’s rough countenance was quite smiling and triumphant, while on Nic’s own part the back of his neck ached severely, and he felt as if he could not have injured a fly.

At last Nic rose, shook himself after the fashion of a dog to get rid of some of the water which soaked his clothes, and looked round about him for his cap, feeling that he would be more dignified and look rather less like a drowned rat if he put it on.

Pete came close to him, placed his lips nearly to his ear, and shouted, “Cap?”

Nic nodded.

“Gone down the river to try and catch mine for me,” said the man, with a good-humoured grin, which made Nic frown at the insolent familiarity with which it was said.

“You’ll have to buy me another one, Master Nic,” continued the man, “and get the smith to make me a noo steel hook. I’ll let you off paying for the pole; I can cut a fresh one somewheres up yonder.”

“On our grounds?” cried Nic indignantly, speaking as loudly as he could.

“Well, there’s plenty, aren’t there, master? And you’ve lost mine,” shouted back the man, grinning again.

“You scoundrel!” cried Nic, who was warming up again. “I shall have you up before the Justices for this.”

“For what?” said the man insolently.

“For throwing me into the pool.”

“Zo shall I, then,” shouted the man. “It was only tit for tat. You zent me in first.”

“Yes; and I caught you first hooking our salmon, sir.”

“Tchah! much my zammon as your own, master. Vish comes out of the zea for everybody as likes to catch them.”

“Not on my father’s estate,” cried Nic. “You’ve been warned times enough.”

“Ay, I’ve heerd a lot o’ talk, master; but me and my mates mean to have a vish or two whenever we wants ’em. You’ll never miss ’em.”

“Look here, Pete Burge,” cried Nic; “I don’t want to be too hard upon you, because I suppose you fished me out of the pool after throwing me in.”

“Well, you’ve no call to grumble, master,” said the man, grinning good-humouredly. “You did just the zame.”

“And,” continued Nic, shouting himself hoarse, so as to be heard, and paying no heed to the man’s words, “if you faithfully promise me that you’ll never come and poach on my father’s part of the river again, I’ll look over all this, and not have you before the Justices.”

“How are you going to get me avore the Justice, Master Nic?” said the man, with a merry laugh.

“Send the constable, sir.”

“Tchah! he’d never vind me; and, if he did, he dursen’t tackle me. There’s a dozen o’ my mates would break his head if he tried.”

“Never mind about that,” cried Nic. “You promise me. My father warned you only yesterday.”

“So he did,” said the man, showing his teeth. “In a regular wax he was.”

“And I will not have him annoyed,” cried Nic. “So now then, you promise?”

“Nay, I shan’t promise.”

“Then I go straight to the constable, and if I do you’ll be summoned and punished, and perhaps sent out of the country.”

“What vor?—pulling you out when you was drownding?”

“For stealing our salmon and beating our two keepers.”

“Then I’d better have left you in yonder,” said the man, laughing.

“You mean I had better have left you in yonder, and rid the country of an idle, poaching scoundrel,” cried Nic indignantly. “But there, you saved my life, and I want to give you a chance. Look here, Pete Burge, you had better go to sea.”

“Yes, when I like to try for some vish. Don’t ketch me going for a zailor.”

“Will you give me your word that you will leave the fish alone?”

“Nay; but I’ll shake hands with you, master. You zaved my life, and I zaved yourn, so we’re square over that business.”

“You insolent dog!” cried Nic. “Then I’ll go straight to the Justice.”

“Nay; you go and put on zome dry clothes. It don’t hurt me, but you’ll ketch cold, my lad. Look here, you want me to zay I won’t take no more zammon.”

“Yes.”

“Then I won’t zay it. There’s about twenty of us means to have as many fish out o’ the river as we like, and if anybody, keepers or what not, comes and interveres with us we’ll pitch ’em in the river; and they may get out themzelves, for I’m not going in after they. Understand that, master?”

“Yes, sir, I do.”

“Then don’t you set any one to meddle with us, or there may be mischief done, for my mates aren’t such vools as me. Going to give me a noo steel hook?”

“No, you scoundrel!”

“Going to zhake hands?”

“No, sir.”

“Just as you like, young master. I wanted to be vriends and you won’t, so we’ll be t’other. On’y mind, if there’s mischief comes of it, you made it. Now then, I’m going to walk about in the sun to get dry, and then zee about getting myself a noo cap and a hook.”

“To try for our salmon again?”

The fellow gave him a queer look, nodded, and climbed up the side of the ravine, followed by Nic.

At the top the man turned and stared at him for a few moments, with a peculiar look in his eyes; and the trees between them and the falls shut off much of the deep, booming noise.

“Well,” said Nic sharply, “have you repented?”

“Nothing to repent on,” said the man stolidly. “On’y wanted to zay this here: If you zees lights some night among the trees and down by the watter, it means vishing.”

“I know that,” said Nic sternly.

“And there’ll be a lot there—rough uns; so don’t you come and meddle, my lad, for I shouldn’t like to zee you hurt.”

The next minute the man had disappeared among the trees, leaving Nic to stand staring after him, thinking of what would be the result if the salmon-poachers met their match.

Chapter Five.

The Captain cannot let it rest.

“Hullo, Nic, my boy; been overboard?”

The young man started, for he had been thinking a good deal on his way back to the house. His anger had cooled down as much as his body from the evaporation going on. For, after all, he thought he could not find much fault with Pete Burge. It would seem only natural to such a rough fellow to serve his assailant as he had himself been served.

“And he did save my life afterwards, instead of letting me drown,” thought Nic, who decided not to try to get Pete punished.

“I’ll give him one more chance,” he said; and he had just arrived at this point as he was walking sharply through the trees by the combe, with the intention of slipping in unseen, when he came suddenly upon his father seated upon a stone, and was saluted with the above question as to having been overboard.

“Yes, father,” he said, glancing down at his drenched garments, “I’ve been in.”

“Bah! you go blundering about looking inside instead of where you’re steering,” cried the Captain. “Aren’t drowned, I suppose?”

Nic laughed.

“Well, slip in and get on some dry things. Look alive.”

Nic did not want to enter into the business through which he had passed, so he hurried indoors, glad to change his clothes.

Then, as the time went on he felt less and less disposed to speak about his adventure, for it seemed hard work to make an effort to punish the man who had, after all, saved his life.

About a fortnight had passed, when one morning, upon going down, he encountered his father’s old sailor-servant, who answered his salute with a grin.

“What are you laughing at, Bill?” asked Nic.

“They’ve been at it again, sir.”

“What! those scoundrels after the salmon?”

“Yes, sir; in the night. Didn’t you hear ’em?”

“Of course not. Did you?”

“Oh yes, I heerd ’em and seed ’em too; leastwise, I seed their lights. So did Tom Gardener.”

“Then why didn’t you call me up?” cried Nic angrily.

“’Cause you’d ha’ woke the Captain, and he’d have had us all out for a fight.”

“Of course he would.”

“And he was a deal better in his bed. You know what he is, Master Nic. I put it to you, now. He’s got all the sperrit he always did have, and is ripe as ever for a row; but is he fit, big and heavy as he’s growed, to go down fighting salmon-poachers?”

“No; but we could have knocked up Tom Gardener and the other men, and gone ourselves.”

“Oh!” ejaculated the old sailor, laughing. “He’d have heared, perhaps. Think you could ha’ made him keep back when there was a fight, Master Nic?”

“No, I suppose not; but he will be horribly angry, and go on at you fiercely when he knows.”

“Oh, of course,” said the man coolly. “That’s his way; but I’m used to that. It does him good, he likes it, and it don’t do me no harm. Never did in the old days at sea.”

“Has any one been down to the river?”

“Oh yes; me and Tom Gardener went down as soon as it was daylight; and they’ve been having a fine game.”

“Game?”

“Ay, that they have, Master Nic,” said the man, laughing. “There’s no water coming over the fall, and the pool was full of fish.”

“Well, I know that, Bill,” cried Nic impatiently; “but you don’t mean to say that—”

“Yes, I do,” said the man, grinning. “They’ve cleared it.”

“And you laugh, sir!”

“Well, ’taren’t nowt to cry about, Master Nic. On’y a few fish.”

“And you know how particular my father is about the salmon.”

“Oh, ay. Of course I know; but he eats more of ’em than’s good for him now. ’Sides, they left three on the side. Slipped out o’ their baskets, I suppose.”

Nic was right: the Captain was furious, and the servants, from William Solly to the youngest gardener, were what they called “tongue-thrashed,” Captain Revel storming as if he were once more rating his crew aboard ship.

“They all heard, Nic, my boy,” he said to his son. “I believe they knew the scoundrels were coming, and they were too cowardly to give the alarm.”

This was after a walk down to the pool, where the water was clear and still save where a little stream ran sparkling over the shelf of rock instead of a thunderous fall, the gathering from the high grounds of the moors.

“I’m afraid they heard them, father,” said Nic.

“Afraid? I’m sure of it, boy.”

“And that they did not like the idea of your getting mixed up in the fight.”

“Ah!” cried the Captain, catching his son by the shoulder; “then you knew of it too, sir? You wanted me to be kept out of it.”

“I do want you to be kept out of any struggle, father,” said Nic.

“Why, sir, why?” panted the old officer.

“Because you are not so active as you used to be.”

“What, sir? Nonsense, sir! A little heavy and—er—short-winded perhaps, but never better or more full of fight in my life, sir. The scoundrels! Oh, if I had been there! But I feel hurt, Nic—cruelly hurt. You and that salt-soaked old villain, Bill Sally, hatch up these things between you. Want to make out I’m infirm. I’ll discharge that vagabond.”

“No, you will not, father. He’s too good and faithful a servant. He thinks of nothing but his old Captain’s health.”

“A scoundrel! and so he ought to. Wasn’t he at sea with me for five-and-twenty years—wrecked with me three times?—But you, Nic, to mutiny against your father!”

“No, no, father; I assure you I knew nothing whatever about it till I came down this morning.”

“And you’d have woke me if you had known?”

“Of course I would, father.”

“Thank you, Nic—thank you. To be sure: you gave me your word of honour you would. But as for that ruffian Bill Solly, I’ll blow him out of the water.”

“Better let it rest, father,” said Nic. “We escaped a bad fight perhaps. I believe there was a gang of fifteen or twenty of the scoundrels, and I’d rather they had all the fish in the sea than that you should be hurt.”

“Thank you, Nic; thank you, my boy. That’s very good of you; but I can’t, and I will not, lie by and have my fish cleared away like this.”

“There’ll be more as soon as the rain comes again in the moors, and these are gone now.”

“Yes, and sold—perhaps eaten by this time, eh?”

“Yes, father; and there’s as good fish in the sea.”

“As ever came out of it—eh, Nic?”

“Yes, father; so let the matter drop.”

“Can’t help myself, Nic; but I must have a turn at the enemy one of these times. I cannot sit down and let them attack me like this. Oh, I’d dearly like to blow some of ’em out of the water!”

“Better put a bag of powder under the rock, father, and blow away the falls so that the salmon can always get up, and take the temptation away from these idle scoundrels.”

“I’d sooner put the powder under my own bed, sir, and blow myself up. No, Nic, I will not strike my colours to the miserable gang like that. Oh! I’d dearly like to know when they are going to make their next raid, and then have my old crew to lie in wait for them.”

“And as that’s impossible, father—”

“We must grin and bear it, Nic—eh?”

“Yes, father.”

“But only wait!”

Chapter Six.

Plots and Plans.

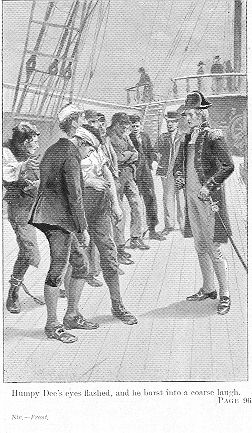

The rain came, as Nic had said it would, and as it does come up in the high hills of stony Dartmoor. Then the tiny rills swelled and became rivulets, the rivulets rivers, and the rivers floods. The trickling fall at the Captain’s swelled up till the water, which looked like porter, thundered down and filled the pool, and the salmon came rushing up from the sea till there were as many as ever. Then, as the rainy time passed away, Captain Revel made his plans, for he felt sure that there would be another raid by the gang who had attacked his place before, headed by Pete Burge and a deformed man of herculean strength, who came with a party of ne’er-do-weels from the nearest town.

“That rascal Pete will be here with his gang,” said the Captain, “and we’ll be ready for them.”

But the speaker was doing Pete Burge an injustice; for, though several raids had been made in the neighbourhood, and pools cleared out, Pete had hung back from going to the Captain’s for some reason or another, and suffered a good deal of abuse in consequence, one result being a desperate fight with Humpy Dee, the deformed man, who after a time showed the white feather, and left Pete victorious but a good deal knocked about.

So, feeling sure that he was right, Captain Revel made his plans; and, unwillingly enough, but with the full intention of keeping his father out of danger, Nic set to work as his father’s lieutenant and carried out his orders.

The result was that every servant was armed with a stout cudgel, and half-a-dozen sturdy peasants of the neighbourhood were enlisted to come, willingly enough, to help to watch and checkmate the rough party from the town, against whom a bitter feeling of enmity existed for depriving the cottagers from getting quietly a salmon for themselves.

The arrangements were made for the next night, a stranger having been seen inspecting the river and spying about among the fir-trees at the back of the pool.

But no one came, and at daybreak the Captain’s crew, as he called it, went back to bed.

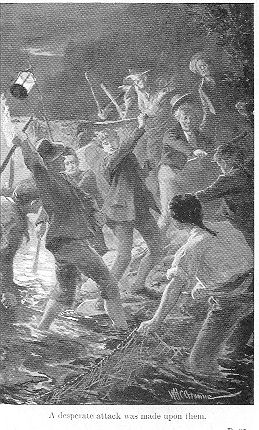

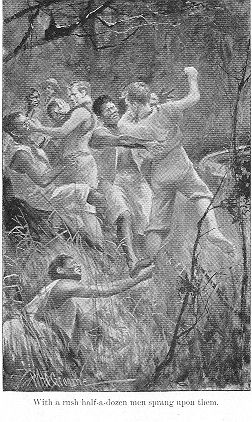

The following night did not pass off so peacefully, for soon after twelve, while the watchers, headed by the Captain and Nic, were well hidden about the pool, the enemy came, and, after lighting their lanthorns, began to net the salmon.

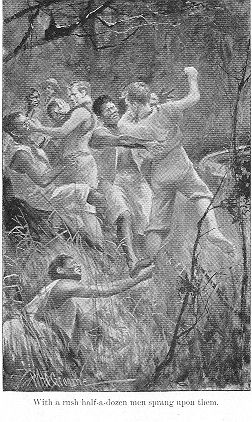

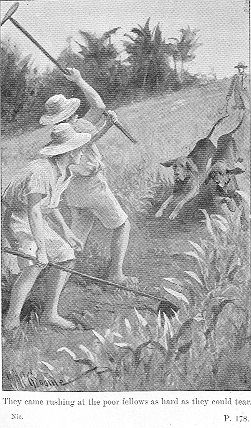

Then a whistle rang out, a desperate attack was made upon them, and the Captain nearly had a fit. For his party was greatly outnumbered. The raiders fought desperately, and they went off at last fishless; but not until the Captain’s little force had been thoroughly beaten and put to flight, with plenty of cuts and bruises amongst them, Nic’s left arm hanging down nearly helpless.

“But never mind, Nic,” said the Captain, rubbing his bruised hand as he spoke. “I knocked one of the rascals down, and they got no fish; and I don’t believe they’ll come again.”

But they did, the very next night, and cleared the pool once more, for the watchers were all abed; and in the morning the Captain was frantic in his declarations of what he would do.

To Nic’s great delight, just when his father was at his worst, and, as his old body-servant said, “working himself into a fantigue about a bit o’ fish,” there was a diversion.

Nic was sitting at breakfast, getting tired of having salmon at every meal—by the ears, not by the mouth—when suddenly there was the dull thud of a big gun out at sea, and Captain Revel brought his fist down upon the table with a bang like an echo of the report.

“Lawrence!” he cried excitedly. “Here, Nic, ring the bell, and tell Solly to go and hoist the flag.”

The bell was rung, and a maid appeared.

“Where’s Solly?” cried the Captain angrily.

“Plee, sir, he’s gone running up to the cliff to hoist the flag,” said the girl nervously.

“Humph! that will do,” said the Captain, and the maid gladly beat a retreat.—“Not a bad bit of discipline that, Nic. Wonder what brings Lawrence here! Ring that bell again, boy, and order them to reset the breakfast-table. He’ll be here in half-an-hour, hungry. He always was a hungry chap.”

The maid appeared, received her orders, and was about to go, when she was arrested.

“Here, Mary, what is there that can be cooked for Captain Lawrence’s breakfast?”

“The gardener has just brought in a salmon he found speared and left by the river, sir.”

The Captain turned purple with rage.

“Don’t you ever dare to say salmon to me again, woman!” he roared.

“No, sir; cert’n’y not, sir,” faltered the frightened girl, turning wonderingly to Nic, her eyes seeming to say, “Please, sir, is master going mad?”

“Yes; tell the cook to fry some salmon cutlets,” continued the Captain; and then apologetically to his son: “Lawrence likes fish.”

As the maid backed out of the room the Captain rose from the table.

“Come along, my boy,” he said; “we’ll finish our breakfast with him.”

Nic followed his father into the hall, and then through the garden and up to the edge of the cliff, passing William Solly on his way back after hoisting the flag, which was waving in the sea-breeze.

“Quite right, William,” said the Captain as the old sailor saluted and passed on. “Nothing like discipline, Nic, my boy. Ha! You ought to have been a sailor.”

The next minute they had reached the flagstaff, from whence they could look down at the mouth of the river, off which one of the king’s ships was lying close in, and between her and the shore there was a boat approaching fast.

As father and son watched, it was evident that they were seen, for some one stood up in the stern-sheets and waved a little flag, to which Nic replied by holding his handkerchief to be blown out straight by the breeze.

“Ha! Very glad he has come, Nic,” said the Captain. “Fine fellow, Jack Lawrence! Never forgets old friends. Now I’ll be bound to say he can give us good advice about what to do with those scoundrels.”

“Not much in his way, father, is it?” said Nic.

“What, sir?” cried the Captain fiercely. “Look here, boy; I never knew anything which was not in Jack Lawrence’s way. Why, when we were young lieutenants together on board the Sovereign, whether it was fight or storm he was always ready with a good idea. He will give us—me—well, us—good advice, I’m sure. There he is, being carried ashore. Go and meet him, my boy. I like him to see that he is welcome. Tell him I’d have come down myself, but the climb back is a bit too much for me.”

Nic went off at a trot along the steep track which led down to the shore, and in due time met the hale, vigorous, grey-haired officer striding uphill in a way which made Nic feel envious on his father’s behalf.

“Well, Nic, my boy,” cried the visitor, “how’s the dad? Well? That’s right. So are you,” he continued, gazing searchingly at the lad with his keen, steely-grey eyes. “Grown ever so much since I saw you last. Ah, boy, it’s a pity you didn’t come to sea!”

Then he went on chatting about being just come upon the Plymouth station training men for the king’s ships, and how he hoped to see a good deal now of his old friend and his son.

The meeting between the brother-officers was boisterous, but there was something almost pathetic in the warmth with which they grasped hands, for they had first met in the same ship as middies, and many a time during Captain Lawrence’s visits Nic had sat and listened to their recollections of the dangers they had gone through and their boyish pranks.

William Solly was in the porch ready to salute the visitor, and to look with pride at the fine, manly old officer’s greeting. He made a point, too, of stopping in the room to wait table, carefully supplying all wants, and smiling with pleasure as he saw how the pleasant meal was enjoyed by the guest.

“We were lying off the river late last night, but I wouldn’t disturb you,” he said. “I made up my mind, though, to come to breakfast. Hah! What delicious fried salmon!”

“Hur–r–ur!” growled Captain Revel, and Solly cocked his eye knowingly at Nic.

“Hallo! What’s the matter?” cried the visitor.

“The salmon—the salmon,” growled Captain Revel, frowning and tapping the table.

“De-licious, man! Have some?—Here, Solly, hand the dish to your master.”

“Bur–r–ur!” roared the Captain. “Take it away—take it away, or I shall be in another of my rages, and they’re not good for me, Jack—not good for me.”

“Why, what is it, old lad?”

“Tell him, Nic—tell him,” cried Captain Revel; and his son explained the cause of his father’s irritation.

“Why, that was worrying you last time I was here—let me see, a year ago.”

“Yes, Jack; and it has been worrying me ever since,” cried Captain Revel. “You see, I mustn’t cut any of the scoundrels down, and I mustn’t shoot them. The law would be down on me.”

“Yes, of course; but you might make the law come down on them.”

“Can’t, my lad. Summonses are no use.”

“Catch them in the act, make them prisoners, and then see what the law will do.”

“But we can’t catch them, Jack; they’re too many for us,” cried the Captain earnestly. “They come twenty or thirty strong, and we’ve had fight after fight with them, but they knock us to pieces. Look at Solly’s forehead; they gave him that cut only a few nights ago.”

The old sailor blushed like a girl.

“That’s bad,” said the visitor, after giving the man a sharp look. “What sort of fellows are they?”

“Big, strong, idle vagabonds. Scum of the town and the country round.”

“Indeed!” said the visitor, raising his eyes. “They thrash you, then, because you are not strong enough?”

“Yes; that’s it, Jack. Now, what am I to do?”

“Let me see,” said the visitor, tightening his lips. “They only come when the pool’s full of salmon, you say, after a bit of rain in the moors?”

“Yes; that’s it, Jack.”

“Then you pretty well know when to expect them?”

“Yes; that’s right.”

“How would it be, then, if you sent me word in good time in the morning? Or, no—look here, old fellow—I shall know when there is rain on the moor, and I’ll come round in this direction from the port. I’m cruising about the Channel training a lot of men. You hoist a couple of flags on the staff some morning, and that evening at dusk I’ll land a couple of boats’ crews, and have them marched up here to lay up with you and turn the tables upon the rascals. How will that do?”

Solly forgot discipline, and bent down to give one of his legs a tremendous slap, while his master made the breakfast things dance from his vigorous bang on the table.

“There, Nic,” he cried triumphantly; “what did I say? Jack Lawrence was always ready to show the way when we were on our beam-ends. Jack, my dear old messmate,” he cried heartily, as he stretched out his hand—“your fist.”

Chapter Seven.

The Captain will “wherrit.”

Captain Lawrence spent the day at the Point, thoroughly enjoying a long gossip, and, after an early dinner, proposed a walk around the grounds and a look at the river and the pool.

“What a lovely spot it is!” he said, as he wandered about the side of the combe. “I must have such a place as this when I give up the sea.”

“There isn’t such a place, Jack,” said Captain Revel proudly. “But I want you to look round the pool.—I don’t think I’ll climb down, Nic. It’s rather hot; and I’ll sit down on the stone for a few minutes while you two plan where you could ambush the men.”

“Right,” said Captain Lawrence; and he actively followed Nic, pausing here and there, till they had descended to where the fall just splashed gently down into the clear pool, whose bigger stones about the bottom were now half-bare.

“Lovely place this, Nic, my boy. I could sit down here and doze away the rest of my days. But what a pity it is that your father worries himself so about these poaching scoundrels! Can’t you wean him from it? Tell him, or I will, that it isn’t worth the trouble. Plenty more fish will come, and there must be a little grit in every one’s wheel.”

“Oh, I’ve tried everything, sir,” replied Nic. “The fact is that he is not so well as I should like to see him; and when he has an irritable fit, the idea of any one trespassing and taking the fish half-maddens him.”

“Well, we must see what we can do, my boy. It ought to be stopped. A set of idlers like this requires a severe lesson. A good dose of capstan bar and some broken heads will sicken them, and then perhaps they will let you alone.”

“I hope so, sir.”

“I think I can contrive that it shall,” said the visitor dryly. “I shall bring or send some trusty men. There, I have seen all I want to see. Let’s get back.”

He turned to climb up the side of the gorge; and as Nic followed, the place made him recall his encounter with Pete Burge, and how different the pool looked then; and, somehow, he could not help hoping that the big, bluff fellow might not be present during the sharp encounter with Captain Lawrence’s trusty men.

“Hah! Began to think you long, Jack,” said Captain Revel; and they returned to the house and entered, after a glance seaward, where the ship lay at anchor.

Towards evening Solly was sent to hoist a signal upon the flagstaff, and soon after a boat was seen pulling towards the shore. Then the visitor took his leave, renewing his promise to reply to a signal by sending a strong party of men.

Nic walked down to the boat with his father’s friend, and answered several questions about the type of men who came after the salmon.

“I see, I see,” said Captain Lawrence; “but do you think they’ll fight well?”

“Oh yes; there are some daring rascals among them.”

“So much the better, my dear boy. There, good-bye. Mind—two small flags on your signal-halyards after the first heavy rain upon the moor, and you may expect us at dusk. If the rascals don’t come we’ll have another try; but you’ll know whether they’ll be there by the fish in the pool. They’ll know too—trust ’em. Look, there’s your father watching us—” and he waved his hand. “Good-bye, Nic, my dear boy. Good-bye!”

He shook hands very warmly. Two of his men who were ashore joined hands to make what children call a “dandy-chair,” the Captain placed his hands upon their shoulders, and they waded through the shallow water to the boat, pausing to give her a shove off before climbing in; and then, as the oars made the water flash in the evening light, Nic climbed the long hill again, to stand with his father, watching the boat till she reached the side of the ship.

“Now then, my boy,” said the old man, “we’re going to give those fellows such a lesson as they have never had before.”

He little knew how truly he was speaking.

“I hope so, father,” said Nic; and he was delighted to find how pleased the old officer seemed.

The next morning, when Nic opened his bedroom window, the king’s ship was not in sight; and for a week Captain Revel was fidgeting and watching the sky, for no rain came, and there was not water enough in the river for fresh salmon to come as far as the pool.

“Did you ever see anything like it, Nic, my boy?” the Captain said again and again; “that’s always the way: if I didn’t want it to rain, there’d be a big storm up in the hills, and the fall would be roaring like a sou’-wester off the Land’s End; but now I want just enough water to fill the river, not a drop will come. How long did Jack Lawrence say that he was going to stop about Plymouth?”

“He didn’t say, father, that I remember,” replied Nic. “Then he’ll soon be off; and just in the miserable, cantankerous way in which things happen, the very day he sets sail there’ll be a storm on Dartmoor, and the next morning the pool will be full of salmon, and those scoundrels will come to set me at defiance, and clear off every fish.”

“I say, father,” said Nic merrily, “isn’t that making troubles, and fancying storms before they come?”

“What, sir? How dare you speak to me like that?” cried the Captain.—“And you, Solly, you mutinous scoundrel, how dare you laugh?” he roared, turning to his body-servant, who happened to be in the hail.

“Beg your honour’s pardon; I didn’t laugh.”

“You did laugh, sir,” roared the Captain—“that is, I saw you look at Master Nic here and smile. It’s outrageous. Every one is turning against me, and I’m beginning to think it’s time I was out of this miserable world.”

He snatched up his stick from the stand, banged on the old straw hat he wore, and stamped out of the porch to turn away to the left, leaving Nic hesitating as to what he should do, deeply grieved as he was at his father’s annoyance and display of temper. One moment he was for following and trying to say something which would tend to calm the irritation. The next he was thinking it would be best to leave the old man to himself, trusting to the walk in the pleasant grounds having the desired result.

But this idea was knocked over directly by Solly, who had followed his master to the porch, and stood watching him for a few moments.

“Oh dear, dear! Master Nic,” he cried, turning back, “he’s gone down the combe path to see whether there’s any more water running down; and there aren’t, and he’ll be a-wherriting his werry inside out, and that wherrits mine too. For I can’t abear to see the poor old skipper like this here.”

“No, Solly, neither can I,” said Nic gloomily.

“It’s his old hurts does it, sir. It aren’t nat’ral. Here he is laid up, as you may say, in clover, in as nice a place as an old sailor could end his days in.”

“Yes, Solly,” said Nic sadly; “it is a beautiful old place.”

“Ay, it is, sir; and when I cons it over I feel it. Why, Master Nic, when I think of all the real trouble as there is in life, and what some folks has to go through, I asks myself what I’ve ever done to have such good luck as to be safely moored here in such a harbour. It’s a lovely home, and the troubles is nothing—on’y a bit of a gale blowed by the skipper now and then along of the wrong boots as hurts his corns, or him being a-carrying on too much sail, and bustin’ off a button in a hurry. And who minds that?”

“Ah! who minds a trifle like that, Solly?” sighed Nic. “Well, sir, you see he does. Wind gets up directly, and he talks to me as if I’d mutinied. But I don’t mind. I know all the time that he’s the best and bravest skipper as ever lived, and I’d do anything for him to save him from trouble.”

“I know you would, Solly,” said Nic, laying a hand upon the rugged old sailor’s shoulder.

“Thank ye, Master Nic; that does a man good. But look here, sir; I can’t help saying it. The fact is, after his rough, stormy life, everything here’s made too easy for the skipper. He’s a bit worried by his old wounds, and that’s all; and consekens is ’cause he aren’t got no real troubles he wherrits himself and makes quakers.”

“Makes quakers?” said Nic wonderingly.

“Sham troubles, Master Nic—wooden guns, as we call quakers out at sea or in a fort. Strikes me, sir, as a real, downright, good, gen-u-wine trouble, such as losing all his money, would be the making of the Captain; and after that he’d be ready to laugh at losing a few salmon as he don’t want. I say, Master Nic, you aren’t offended at me for making so bold?”

“No, Solly, no,” said the young man sadly. “You mean well, I know. There, say no more about it. I hope all this will settle itself, as so many troubles do.”

Nic strolled out into the grounds and unconsciously followed his father, who had gone to the edge of the combe; but he had not walked far before a cheery hail saluted his ears, and, to his great delight, he found the Captain looking radiant.

“Nic, my boy, it’s all right,” he cried; “my left arm aches terribly and my corns are shooting like mad. Well, what are you staring at? Don’t you see it means rain? Look yonder, too. Bah! It’s of no use to tell you, boy. You’ve never been to sea. You’ve never had to keep your weather-eye open. See that bit of silvery cloud yonder over Rigdon Tor? And do you notice what a peculiar gleam there is in the air, and how the flies bite?”

“Yes—yes, I see all that, father.”

“Well, it’s rain coming, my boy. There’s going to be a thunderstorm up in the hills before many hours are past. I’m not a clever man, but I can tell what the weather’s going to be as well as most folk.”

“I’m glad of it, father, if it will please you.”

“Please me, boy? I shall be delighted. To-morrow morning the salmon will be running up the river again, and we may hoist the signal for help. I say, you don’t think Jack Lawrence has gone yet?”

“No, father,” said Nic; “I do not.”

“Why, Nic?—why?” cried the old sailor.

“Because he said to me he should certainly come up and see us again before he went.”

“To be sure; so he did to me, Nic. I say, my boy, I—that is—er—wasn’t I a little bit crusty this morning to you and poor old William Solly?”

“Well, yes; just a little, father,” said Nic, taking his arm.

“Sorry for it. Change of the weather, Nic, affects me. It was coming on. I must apologise to Solly. Grand old fellow, William Solly. Saved my life over and over again. Man who would die for his master, Nic; and a man who would do that is more than a servant, Nic—he is a friend.”

Chapter Eight.

The Captain’s Prophecy.

Before many hours had passed the Captain’s words proved correct. The clouds gathered over the tors, and there was a tremendous storm a thousand feet above the Point. The lightning flashed and struck and splintered the rugged old masses of granite; the thunder roared, and there was a perfect deluge of rain; while down near the sea, though it was intensely hot, not a drop fell, and the evening came on soft and cool.

“Solly, my lad,” cried the Captain, rubbing his hands, “we shall have the fall roaring before midnight; but don’t sit up to listen to it.”

“Cert’n’y not, sir,” said the old sailor.

“Your watch will begin at daybreak, when you will hoist the signal for Captain Lawrence.”

“Ay, ay, sir!”

“And keep eye to west’ard on and off all day, to try if you can sight the frigate.”

“Ay, ay, sir!”

“And in the course of the morning you will go quietly round and tell the men to rendezvous here about eight, when you will serve out the arms.”

“Ay, ay, sir.”

“The good stout oak cudgels I had cut; and if we’re lucky, my lad, we shall have as nice and pleasant a fight as ever we two had in our lives.”

“Quite a treat, sir,” said the old sailor; “and I hope we shall be able to pay our debts.”

The Captain was in the highest of glee all the evening, and he shook his son’s hand very warmly when they parted for bed.

About one o’clock Nic was aroused from a deep sleep by a sharp knocking at his door.

“Awake, Nic?” came in the familiar accents.

“No, father. Yes, father. Is anything wrong?”

“Wrong? No, my boy; right! Hear the fall?”

“No, father; I was sound asleep.”

“Open your window and put out your head, boy. The water’s coming down and roaring like thunder. Good-night.”

Nic slipped out of bed, did as he was told, and, as he listened, there was the deep, musical, booming sound of the fall seeming to fill the air, while from one part of the ravine a low, rushing noise told that the river must be pretty full.

Nic stood listening for some time before closing his window and returning to bed, to lie wakeful and depressed, feeling a strange kind of foreboding, as if some serious trouble was at hand. It was not that he was afraid or shrank from the contest which might in all probability take place the next night, though he knew that it would be desperate—for, on the contrary, he felt excited and quite ready to join in the fray; but he was worried about his father, and the difficulty he knew he would have in keeping him out of danger. He was in this awkward position, too: what he would like to do would be to get Solly and a couple of their stoutest men to act as bodyguard to protect his father; but, if he attempted such a thing, the chances were that the Captain would look upon it as cowardice, and order them off to the thick of the cudgel-play.

Just as he reached this point he fell asleep.

Nic found the Captain down first next morning, looking as pleased as a boy about to start for his holidays.

“You’re a pretty fellow,” he cried. “Why, I’ve been up hours, and went right to the falls. Pool’s full, Nic, my boy, the salmon are up, and it’s splendid, lad.”

“What is, father?”

“Something else is coming up.”

“What?”

“Those scoundrels are on the qui vive. I was resting on one of the rough stone seats, when, as I sat hidden among the trees, I caught sight of something on the far side of the pool—a man creeping cautiously down to spy out the state of the water.”

“Pete Burge, father?” cried Nic eagerly.

“Humph! No; I hardly caught a glimpse of his face, but it was too short for that scoundrel. I think it was that thick-set, humpbacked rascal they call Dee.”

“And did he see you, father?”

“No: I sat still, my boy, and watched till he slunk away again. Nic, lad, we shall have them here to-night, and we must be ready.”

“Yes, father, if Captain Lawrence sends his men.”

“Whether he does or no, sir. I can’t sit still and know that my salmon are being stolen. Come—breakfast! Oh, here’s Solly.—Here, you, sir, what about those two signal flags? Hoist them directly.”

“Run ’em up, sir, as soon as it was light.”

“Good. Then, now, keep a lookout for the frigate.” The day wore away with no news of the ship being in the offing, and the Captain began to fume and fret, so that Nic made an excuse to get away and look out, relieving Solly, stationing himself by the flagstaff and scanning the horizon till his eyes grew weary and his head ached.

It was about six o’clock when he was summoned to dinner by Solly, who took his place, and Nic went and joined his father.

“Needn’t speak,” said the old man bitterly; “I know; Lawrence hasn’t come. We’ll have to do it ourselves.”

Nic was silent, and during the meal his father hardly spoke a word.

Just as they were about to rise, Solly entered the room, and the Captain turned to him eagerly.

“I was going to send for you, my lad,” he said. “Captain Lawrence must be away, and we shall have to trap the scoundrels ourselves. How many men can we muster?”

“Ten, sir.”

“Not half enough,” said the Captain; “but they are strong, staunch fellows, and we have right on our side. Ten against twenty or thirty. Long odds; but we’ve gone against heavier odds than that in our time, Solly.”

“Ay, sir, that we have.”

“We must lie in wait and take them by surprise when they’re scattered, my lads. But what luck! what luck! Now if Lawrence had only kept faith with me we could have trapped the whole gang.”

“Well, your honour, why not?” said Solly sharply.

“Why not?”

“He’ll be here before we want him.”

“What?” cried Nic. “Is the frigate in sight?”

“In sight, sir—and was when you left the signal station.”

“No,” said Nic sharply; “the only vessel in sight then was a big merchantman with her yards all awry.”

“That’s so, sir, and she gammoned me. The skipper’s had her streak painted out, and a lot of her tackle cast loose, to make her look like a lubberly trader; but it’s the frigate, as I made out at last, coming down with a spanking breeze, and in an hour’s time she’ll be close enough to send her men ashore.”

The Captain sprang up and caught his son’s hand, to ring it hard.

“Huzza, Nic!” he cried excitedly. “This is going to be a night of nights.”

It was.

Chapter Nine.

Ready for Action.

“That’s about their size, Master Nic,” said Solly, as he stood in the coach-house balancing a heavy cudgel in his hand—one of a couple of dozen lying on the top of the corn-bin just through the stable door.

“Oh, the size doesn’t matter, Bill,” said Nic impatiently.

“Begging your pardon, sir, it do,” said the old sailor severely. “You don’t want to kill nobody in a fight such as we’re going to have, do ye?”

“No, no; of course not.”

“There you are, then. Man’s sure to hit as hard as he can when his monkey’s up; and that stick’s just as heavy as you can have ’em without breaking bones. That’s the sort o’ stick as’ll knock a man silly and give him the headache for a week, and sarve him right. If it was half-a-hounce heavier it’d kill him.”

“How do you know?” said Nic sharply.

“How do I know, sir?” said the man wonderingly. “Why, I weighed it.”

Nic would have asked for further explanations; but just then there were steps heard in the yard, and the gardener and a couple of labourers came up in the dusk.

“Oh, there you are,” growled Solly. “Here’s your weepuns;” and he raised three of the cudgels. “You may hit as hard as you like with them. Seen any of the others?”

“Yes,” said the gardener; “there’s two from the village coming along the road, and three of us taking the short cut over the home field. That’s all I see.”

“Humph!” said Solly. “There ought to be five more by this time.”

“Sick on it, p’r’aps,” grumbled the gardener; “and no wonder. We are.”

“What! Are you afraid?” cried Nic.

“No, sir, I aren’t afraid; on’y sick on it. I like a good fight, and so do these here when it’s ’bout fair and ekal, but every time we has a go in t’other side seems to be the flails and we only the corn and straw. They’re too many for us. I’m sick o’ being thrashed, and so’s these here; and that aren’t being afraid.”

“Why, you aren’t going to sneak out of it, are you?” growled Solly.

“No, I aren’t,” said the gardener; “not till I’ve had a good go at that Pete Burge and Master Humpy Dee. But I’m going to sarcumwent ’em this time.”

“Here are the others coming, Bill,” cried Nic.—“What are you going to do this time?” he said to the gardener.

“Sarcumwent ’em, Master Nic,” said the man, with a grin. “It’s no use to hit at their heads and arms or to poke ’em in the carcass—they don’t mind that; so we’ve been thinking of it out, and we three’s going to hit ’em low down.”

“That’s good,” said Solly; “same as we used to sarve the black men out in Jay-may-kee. They’ve all got heads as hard as skittle-balls, but their shins are as tender as a dog’s foot.”

Just then five more men came up and received their cudgels; and directly after three more came slouching up; and soon after another couple, and received their arms.

“Is this all on us?” said one of the fresh-comers, as the sturdy fellows stood together.

“Ay, is this all, Master Nic?” cried another.

“Why?” he said sharply.

“Because there aren’t enough, sir,” said the first man. “I got to hear on it down the village.”

“Ah! you heard news?” cried Nic.

“Ay, sir, if you call such ugly stuff as that news. There’s been a bit of a row among ’em, all along o’ Pete Burge.”

“Quarrelling among themselves?”

“That’s right, sir; ’cause Pete Burge said he wouldn’t have no more to do with it; and they’ve been at him—some on ’em from over yonder at the town. I hear say as there was a fight, and then Pete kep’ on saying he would jyne ’em; and then there was another fight, and Pete Burge licked the second man, and then he says he wouldn’t go. And then there was another fight, and Pete Burge licked Humpy Dee, and Humpy says Pete was a coward, and Pete knocked him flat on the back. ‘I’ll show you whether I’m a coward,’ he says. ‘I didn’t mean to have no more to do wi’ Squire Revel’s zammon,’ he says; ‘but I will go to-night, for the last time, just to show you as I aren’t a cowards,’ he says, ‘and then I’m done.’”

“Ay; and he zays,” cried another man from the village, “‘If any one thinks I’m a coward, then let him come and tell me.’”

“Then they are coming to-night?” cried Nic, who somehow felt a kind of satisfaction in his adversary’s prowess.

“Oh, ay,” said the other man who had grumbled; “they’re a-coming to-night. There’s a big gang coming from the town, and I hear they’re going to bring a cart for the zammon. There’ll be a good thirty on ’em, Master Nic, zir; and I zay we aren’t enough.”

“No,” said Nic quietly; “we are not enough, but we are going to have our revenge to-night for all the knocking about we’ve had.”

“But we’re not enough, Master Nic. We’re ready to fight, all on us—eh, mates?”

“Ay!” came in a deep growl.

“But there aren’t enough on us.”

“There will be,” said Nic in an eager whisper, “for a strong party of Jack-tars from the king’s ship that was lying off this evening are by this time marching up to help us, and we’re going to give these scoundrels such a thrashing as will sicken them from ever meddling again with my father’s fish.”

“Yah!” growled a voice out of the gloom.

“Who said that?” cried Nic.

“I did, Master Nic,” said the gardener sharply; “and you can tell the Captain if you like. I say it aren’t fair to try and humbug a lot o’ men as is ready to fight for you. It’s like saying ‘rats’ to a dog when there aren’t none.”

“Is it?” cried Nic, laughing. “How can that be? You heard just now that there will be about thirty rats for our bulldogs to worry.”

“I meant t’other way on, sir,” growled the man sulkily. “No sailor bulldogs to come and help us.”

“How dare you say that?” cried Nic angrily.

“’Cause I’ve lived off and on about Plymouth all my life and close to the sea, and if I don’t know a king’s ship by this time I ought to. That’s only a lubberly old merchantman. Why, her yards were all anyhow, with not half men enough to keep ’em square.”

“Bah!” cried Solly angrily. “Hold your mouth, you one-eyed old tater-grubber. What do you mean by giving the young master the lie?”

“That will do, Solly,” cried Nic. “He means right. Look here, my lads; that is a king’s ship, the one commanded by my father’s friend; and he has made her look all rough like that so as to cheat the salmon-gang, and it will have cheated them if it has cheated you.”

A cheer was bursting forth, but Nic checked it, and the gardener said huskily:

“Master Nic, I beg your pardon. I oughtn’t to ha’ said such a word. It was the king’s ship as humbugged me, and not you. Say, lads, we’re going to have a night of it, eh?”

A low buzz of satisfaction arose; and Nic hurried out, to walk in the direction of the signal-staff, where the Captain had gone to look out for their allies.

“Who goes there?” came in the old officer’s deep voice.

“Only I, father.”

“Bah!” cried the Captain in a low, angry voice. “Give the word, sir—‘Tails.’”

“The word?—‘Tails!’” said Nic, wonderingly.

“Of course. I told you we must have a password, to tell friends from foes.”

“Not a word, father.”

“What, sir? Humph, no! I remember—I meant to give it to all at once. The word is ‘Tails’ and the countersign is ‘Heads,’ and any one who cannot give it is to have heads. Do you see?”

“Oh yes, father, I see; but are the sailors coming?”

“Can’t hear anything of them, my boy, and it’s too dark to see; but they must be here soon.”

“I hope they will be, father,” said Nic.

“Don’t say you hope they will be, as if you felt that they weren’t coming. They’re sure to come, my boy. Jack Lawrence never broke faith. Now, look here; those scoundrels will be here by ten o’clock, some of them, for certain, and we must have our men in ambush first—our men, Nic. Jack Lawrence’s lads I shall place so as to cut off the enemy’s retreat, ready to close in upon them and take them in the rear. Do you see?”

“Yes, father; excellent.”

“Then I propose that as soon as we hear our reinforcement coming you go off and plant your men in the wood behind the fall. I shall lead the sailors right round you to the other side of the pool; place them; and then there must be perfect silence till the enemy has lit up his torches and got well to work. Then I shall give a shrill whistle on the French bo’sun’s pipe I have in my pocket, you will advance your men and fall to, and we shall come upon them from the other side.”

“I see, father.”

“But look here, Nic—did you change your things?”

“Yes, father; got on the old fishing and wading suit.”

“That’s right, boy, for you’ve got your work cut out, and it may mean water as well as land.”

“Yes, I expect to be in a pretty pickle,” said Nic, laughing, and beginning to feel excited now. “But do you think the sailors will find their way here in the dark?”

“Of course,” cried the Captain sharply. “Jack Lawrence will head them.”

“Hist!” whispered Nic, placing his hand to his ear and gazing seaward.

“Hear ’em?”

Nic was silent for a few moments.

“Yes,” he said. “I can hear their soft, easy tramp over the short grass. Listen.”

“Right,” said the Captain, as from below them there came out of the darkness the regular thrup, thrup of a body of men marching together. Then, loudly, “king’s men?”

“Captain Revel?” came back in reply.

“Right. Captain Lawrence there?”

“No, sir; he had a sudden summons from the port admiral, and is at Plymouth. He gave me my instructions, sir—Lieutenant Kershaw. I have thirty men here.”

“Bravo, my lad!” cried the Captain. “Forward, and follow me to the house. Your men will take a bit of refreshment before we get to work.”

“Forward,” said the lieutenant in a low voice, and the thrup, thrup of the footsteps began again, not a man being visible in the gloom.

“Off with you, Nic,” whispered the Captain. “Get your men in hiding at once. This is going to be a grand night, my boy. Good luck to you; and I say, Nic, my boy—”

“Yes, father.”

“No prisoners, but tell the men to hit hard.” Nic went off at a run, and the lieutenant directly after joined the Captain, his men close at hand following behind.

Chapter Ten.

A Night of Nights.

Nic’s heart beat fast as he ran lightly along the path, reached the house, and ran round to the stable-yard, where Solly and the men were waiting.

“Ready, my lads?” he said in a low, husky voice, full of the excitement he felt.

“We’ll go on round to the back of the pool at once. The sailors are here, thirty strong, with their officer; so we ought to give the enemy a severe lesson.—Ah! Don’t cheer. Ready?—Forward. Come, Solly; we’ll lead.”

“Precious dark, Master Nic,” growled the old sailor in a hoarse whisper. “We shan’t hardly be able to tell t’other from which.”

“Ah! I forgot,” cried Nic excitedly. “Halt! Look here, my men. Our password is ‘Tails,’ and our friends have to answer ‘Heads.’ So, if you are in doubt, cry ‘Tails,’ and if your adversary does not answer ‘Heads’ he’s an enemy.”

“Why, a-mussy me, Master Nic?” growled Solly, “we shan’t make heads or tails o’ that in a scrimble-scramble scrimmage such as we’re going to be in. What’s the skipper thinking about? Let me tell ’em what to do.”

“You heard your master’s order, Solly,” replied Nic.