FRANCE

AND THE REPUBLIC

A RECORD OF THINGS SEEN AND LEARNED

IN THE FRENCH PROVINCES DURING

THE 'CENTENNIAL' YEAR 1889

By

WILLIAM HENRY HURLBERT

AUTHOR OF 'IRELAND UNDER COERCION'

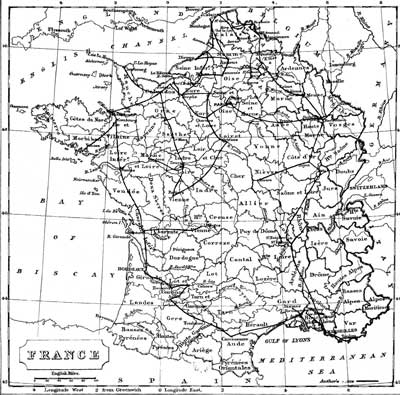

WITH A MAP

LONDON

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.

AND NEW YORK: 15 EAST 16th STREET

1890

All rights reserved

PRINTED BY

SPOTTISWOODE AND CO., NEW-STREET SQUARE

LONDON

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1890

by William Henry Hurlbert

in the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington

[Pg v]

CONTENTS

| INTRODUCTION | PAGE |

|---|

| |

| I. |

Scope of the book—French Republicanism condemned by Swiss and

American experience—Its relations to the French people |

xxiii |

| II. |

M. Gambetta's Parliamentary revolution—What Germany

owes to the French Republicans—Legislative usurpation

in France and the United States |

xxvi |

| III. |

The Executive in France, England, and America—Liberty

and the hereditary principle—General Grant on the

English Monarchy—Washington's place in American

history |

xxxvii |

| IV. |

The legend of the First Republic—A carnival of incapacity

ending in an orgie of crime—The French people never

Republican—Paris and the provinces—The Third Republic

surrendered to the Jacobins, and committed to

persecution and corruption—Estimated excess of expenditure

over income from 1879 to 1889, 7,000,000,000 francs

or 280,000,000l |

li |

| V. |

Danton's maxim, 'To the victors belong the spoils'—Comparative

cost of the French and the British Executive

machinery—The Republican war against religion.—The

present situation as illustrated by past events |

lxviii |

| VI. |

Foreign misconceptions of the French people—An English

statesman's notion that there are 'five millions of

Atheists' in France—Mr. Bright and Mr. Gladstone the last

English public men who will 'cite the Christian Scriptures

as an authority'—Signor Crispi on modern constitutional

government and the French 'principles of 1789'—Napoleon

the only 'Titan of the Revolution'—The debt of

[Pg vi]

France for her modern liberty to America and to England |

lxxvi |

| VII. |

The Exposition of 1889 an electoral device—Panic of the

Government caused by Parisian support of General

Boulanger—Futile attempt of M. Jules Ferry to win back

Conservatives to the Republic—Narrow escape of the

Republic at the elections of 1889—Steady increase of

monarchical party since 1885—-Weakness of the Republic

as compared with the Second Empire |

lxxxix |

| VIII. |

How the Republic maintains itself—A million of people

dependent on public employment—M. Constans 'opens

Paradise' to 13,000 Mayors—Public servants as political

agents—Open pressure on the voters—Growing strength

of the provinces.—The hereditary principle alone can now

restore the independence of the French Executive—Diplomatic

dangers of actual situation—Socialism or a

Constitutional Monarchy the only alternatives |

xcvi |

| |

| CHAPTER I |

| IN THE PAS-DE-CALAIS |

| Calais—Natural and artificial France—The provinces and the

departments—The practical joke of the First Consulate—The

Counts of Charlemagne and the Prefects of Napoleon—President

Carnot at Calais—Politics and Socialism in Calais—Immense

outlay on the port, but works yet unfinished—Indifference

of the people—A president with a grandfather—The 'Great Carnot'

and Napoleon—The party of the 'Sick at heart'—The Louis XVI. of

the Republic—Léon Say and the 'White Mouse'—Gambetta's victory

in 1877—Political log-rolling, French and American—Republican

extravagance and the 'Woollen Stocking'—Boulanger and his

legend—Wanted a 'Great Frenchman'—The Duc d'Aumale

and the Comte de Paris—The Republican law of exile—The

French people not Republican—The Legitimists and the farmers—A

French journalist explains the Presidential progress—Why

decorations are given |

1-22 |

| |

| CHAPTER II |

| IN THE PAS-DE-CALAIS (continued) |

| Boulogne—Arthur Young and the Boulonnais—Boulogne and Quebec—The

English and French types of civilisation—A French ecclesiastic

on the religious question—The oppressive school law of

1886—The Church and the Concordat—Rural communes paying

double for free schools—Vexatious regulations to prevent establishment

of free schools—All ministers of religion excluded from

school councils—Government officers control the whole system—Permanent

magistrates also excluded—Revolt of the religious

sentiment throughout France against the new system—Anxiety

of Jules Ferry to make peace with the Church—Energy shown

by the Catholics in resistance—St.-Omer—The Spanish and

scholastic city of Guy Fawkes and Daniel O'Connell—M. De la

Gorce, the historian of 1848—High character of the

population—Improvement in tone of the French army—Morals of the

soldiers—Devotion of the officers to their profession—Derangement of

the Executive in France by the elective principle—The 'laicisation'

of the schools—Petty persecutions—Children forbidden to

attend the funeral of their priest—The Marist Brethren at Albert—Albert

and the Maréchal d'Ancre—A chapter of history in a

name—Little children stinting their own food, to send another

child to school—President Carnot and the nose of M. Ferry—French

irreligion in the United States—The case of Girard

College—Can Christianity be abolished in France?—The declared

object of the Republic—Morals of Artois—Dense population—Fanatics

of the family—Increase of juvenile crime—American

experience of the schools without religion—A New England report

on 'atrocious and flagrant crimes in Massachusetts'—Relative

increase of native white population and native crime in America—An

American Attorney-General calls the public school system

'a poisonous fountain of misery and moral death'—A local

heroine of St.-Omer—The statue of Jacqueline Robins—The

Duke of Marlborough and the Jesuits College—A curious sidelight

on English politics in 1710—How St.-Omer escaped a

siege |

23-43 |

| |

| CHAPTER III |

| IN THE PAS-DE-CALAIS (continued) |

| Aire-sur-la-Lys—Local objections to a national railway—A visit to a

councillor-general—Pentecost in Artois—The Artesians in 1789—Wealth

and power of the clergy—Recognition of the Third

Estate long before the Revolution—The English and the French

clergy in the last century—Lord Macaulay and Arthur Young—Sympathy

of the curés with the people—Turgot, Condorcet and

the rural clergy—-The Revolution and public education—M. Guizot

the founder of the French primary schools—The liberal school

ordinance of 1698—The Bishop of Arras, in 1740, on the duty of

educating the people—The experience of Louisiana as to public

schools and criminality—The two Robespierres saved and educated

by priests—What came of it—A rural church and congregation

in Artois—The notary in rural France—A village procession—'Beating

the bounds' in France—An altar of verdure and roses—The

villagers singing as they march—Ancient customs in

Northern France |

44-52 |

| |

| CHAPTER IV |

| IN THE PAS-DE-CALAIS (continued) |

| Aire-sur-la-Lys—Local and general elections in France—A public meeting

in rural Artois—A councillor-general and his constituents—Artois

in the 18th and 19th centuries—Well-tilled fields, fine

roads, hedges, and orchards—Effect of long or short leases—A

meeting in a grange—French, English, and American audiences—Favouritism

under the conscription—Extravagant outlay on

scholastic palaces—Almost a scene—A political disturbance

promoted—Canvassing in England and France—Tenure of office in

the French Republic—'To the victors belong the spoils,' the

maxim not of Jackson but of Danton—'Epuration,' what it

means—If Republicans are not put into office 'they will have

civil war'—'No justice of the peace nor public school teacher to

be spared'—'Terror and anarchy carried into all branches of the

public service'—M. de Freycinet declares that 'servants of the

State have no liberty in politics'—The Tweed régime of New

York officially organised in France—-Men of position reluctant

to take office—The expense of French elections—1,300,000l.

sterling the estimated cost of an opposition campaign—A little

dinner in a French country house—The French cuisine national

and imported—An old Flemish city—Devastations of the Revolution—The

beautiful Church of St.-Pierre—A picturesque Corps

de Garde—The tournament of Bayard at Aire—Sixteenth-century

merry-makings at Aire—Gifts to Mary of England on her marriage

to Philip of Spain—The ancient city of Thérouanne—Public

schools in the 17th century—Small landholders in France before

1789. |

53-72 |

| |

| CHAPTER V |

| IN THE SOMME |

| Amiens—Picardy Old and New—Arthur Young and Charles James

Fox in Amiens—'The look of a capital'—The floating gardens

of Amiens—A stronghold of Boulangism—Protest of Amiens

against the Terror of 1792—The French nation and the Commune

of Paris—Vergniaud denounces the Parisians as the 'slaves of the

vilest scoundrels alive'—Gambetta and his balloon—Amiens and

the Revolution of September 1870—The rise of M. Goblet—The

'great blank credit opened to the Republic in 1870'—What has

become of it—The Prussians in Amiens—Warlike spirit of the

Picards—A political portrait of M. Goblet by a fellow citizen—A

Roman son and his father's funeral—A typical Republican senator

and mayor—How M. Petit demolished the crosses in the cemetery—M.

Spuller as Prefect of the Somme—The Christian Brothers and

their schools—M. Jules Ferry withholds the salaries earned by

teachers—The Emperor Julian of Amiens—How the Sisters were

turned out of their schools—The mayor, the locksmith, and the

curate—Mdlle. de Colombel—A senatorial epistle—Ulysses

deserted by Calypso—Why Boulangism flourishes at Amiens—The

First Republic invoked to justify the destruction of crosses

on graves—The Cathedral of Amiens and Mr. Ruskin. |

73-94 |

| |

| CHAPTER VI |

| IN THE SOMME—(continued) |

| Amiens—Party names taken from persons—The effect of Republican

misrule at Amiens—Why the Monarchists acted with the

Boulangists—The Picards incline towards the Empire—How the

Republic of 1848 captured France—Armand Marrast and the

French mail coaches—Mr. Sumner's story—The political value

of paint—Paris and the provinces—M. Mermeix offers with a

few million francs and a few thousand rowdies to change the

French Government—General Boulanger's campaign in Picardy—Capturing

the mammas by kissing the babies—The Monarchical

peasantry—The National Accounts of France not balanced for

years—Conservatives excluded from the Budget Committee—The

Boulanger programme—Expenses of the political machine in

France, England, and America—The Boulangist campaign conducted

by voluntary subscriptions—General Boulanger and the

army—The common sewer of the discontent of France—The

local finances of a French city—Municipal expenses of Amiens—Pressure

of the octroi—A local deficit of millions since the

Republicans got into power—The mayor and the prefect control

the accounts—Immense expenditure on scholastic palaces—Estimated

annual increase in France since 1880 of local indebtedness,

10,000,000l. sterling—M. Goblet on the growth of young men's

monarchical clubs—History of the octroi—General prosperity of

Picardy—Rural ideas of aristocracy—Land ownership in Ireland

and France—'Land-grabbing' in Picardy a hundred years ago—The

corvée abolished before the Revolution, but it still exists

under the Republic, as a prestation en nature—Public education

in Picardy two centuries ago—Small tenants as numerous under

Edward II. in Picardy as small proprietors now are—Home rule

needed in France—'The opinion of a man's legs' |

95-124 |

| |

| CHAPTER VII |

| IN THE AISNE |

| St.-Gobain—Paris and the Ile-de-France—Reclamation of the

commons—Mischievous haste in the Revolutionary transfer of

lands—The evolution of property and order in France and

England—The flower gardens of France—The home counties

around London compared with the departments around Paris—Superiority

of the French fruit and vegetable markets—The

military city of La Fère—A local cabbage-leaf—French farmers

and the Treaties of Commerce—Arthur Young at St.-Gobain—The

largest mirror in the world—The great French glassworks—'An

industrial flower on a seignorial stalk, springing from a feudal

root'—Evolution without Revolution—Two centuries and a half of

industrial progress—Labour in the Middle Ages—The Irish apostle

of North-eastern France—The forests of France—A factory in a

château—A centenarian royal porter—The Duchesse de Berri and

the Empress Eugénie—A co-operative association of consumers—A

great manufacturing company working on lines laid down under

Louis XIV.—Glass-working, Venetian and French—A jointstock

company of the 18th century—The old and new school of factory

discipline—French industry and the Terror—'Two aristocrats'

called in to save a confiscated property—St.-Gobain and the Eiffel

Tower—Royal luxuries in 1673, popular necessaries of life in 1889—How

great mirrors are cast—Beauty of the processes—The

coming age of glass—Glass pavements and roofs—The hereditary

principle among the working classes—Practical co-operation of

capital and labour—Schools, asylums, workmen's houses and

gardens, social clubs, and savings-banks—Co-operative pension

funds—A great economic family—Of 2,650 workpeople more than

50 per cent. employed for more than ten years—A subterranean

lake—The crypts of St.-Gobain and the Cisterns of Constantinople—A

spectral gondolier—A Venetian promenade with coloured

[Pg xi]lanterns underground

|

125-161 |

| |

| CHAPTER VIII |

| IN THE AISNE—(continued) |

| Laon, Chauny, and St.-Gobain—The French Revolution and Spanish

soda—The most extensive chemical works in France—A miniature

Rotterdam—A Cité Ouvrière—The religious war in Chauny—Local

and immigrant labour—M. Allain-Targé on Boulanger, the

High Court of Justice, common sense and common honesty—-French

elections, matters of bargain and sale—'The blackguardocracy'—Sketches

by a Republican minister—French freemasonry

a persecuting sect—Their power in the Government—Utterly unlike

the freemasonry of England, Germany, or America—The war

against Christianity in France and Spanish America—1867 and

the industrial progress of France—Extent of the chemical works

of France—Retiring pensions for workmen—Chauny in the olden

time—How the honest burghers freed their city in 1432—A contrast

with the rioters of the Bastille in 1789—Henri IV. and La

Belle Gabrielle—Chauny and the Revolution—The murder of

d'Estaing—Chauny acclaims the Restoration, and gives a gold

medal to the Prussian commandant—Public charity and public

education in the 12th century—Benevolent foundations pillaged

in 1793—Law and order under the ancien régime—A canal in

the law courts—An enterprising American turns rubbish into

indiarubber at Chauny |

162-185 |

| |

| CHAPTER IX |

| IN THE AISNE—(continued) |

| Laon—A feudal fortress home—Chauny and the green monkeys of

Rabelais—The festival of the jongleurs and the learned dogs—A

damsel of Chauny on English good sense and Queen Victoria—A

region of parks and châteaux—The cradle of the French Monarchy—How

the Revolution robbed France—The rural reign of pillage

and murder—Horrors committed in the provinces during 1789—Arthur

Young and Gouverneur Morris on the general depravation

and lawlessness—The National Assembly a mere noisy 'mob'—The

outbreak of crime which preceded the Terror—The truth

about Madame Roland—Her hatred of Marie Antoinette and her

thirst for blood—The legend of the Gironde—Brissot de Warville

on robbery as a virtuous action—The relations of the French

Revolution to property—France more free before 1789 than after

it—The laws against emigrants—Girls of fourteen condemned to

death—Emigration made a crime, that property might be pillaged—How

Irène de Tencin defended the family estate—The story of

the Saporta family—The Laonnais in the 18th century—Wide-spread

ruin of its churches, convents, and châteaux—Destruction

of accumulated capital—How syndicates of rogues stole bronzes,

brasswork, and monuments—The story of two châteaux—The

bishop's château at Anizy—The burghers and the seigneurs in

the 16th century—The local 'directory' in 1790—Wreck, ruin,

and robbery—The Château of Pinon—Once the property of a

granddaughter of Edward III. of England—A domain of the Duc

d'Orléans—A tragedy of love and murder—Death of the Marquis

d'Albret—How Pinon passed to the family of De Courvals—The

present owner an American lady—The finest château in the

Laonnais—What has the Laonnais gained from the ruin of the

Anizy? | 186-225 |

| |

| CHAPTER X |

| IN THE AISNE—(continued) |

| Laon—The ruins of Coucy-le-Château—A rural inn in France—The

sugar crisis—The birthplace of César de Vendóme—The bell

which tolls and is heard by the dying alone—The hanging of boys

for killing rabbits—Game laws, French and English—The true

story of Enguerrand de Coucy—A little feudal city—The finest

donjon in France—An official guardian—A dinner with four

councillors-general—'What France really wants is a man'—Agricultural

philosophers—How a councillor-general tested chemicals—Peasantry

on the highway—A land of gardens—A city set

on a hill—Simple good-natured people—A raging Boulangist at

Laon—What a barber saw in Tonkin—The diamond belt of King

Norodom—Castelin the friend of Boulanger—A revolutionary

shoemaker on government by committees—Evils of the

Exposition—Foreigners steal the ideas of France—The railways, the

new feudal system—They are the real 'enemy' of the people—Extravagance

of the ministers—Freemasonry at Laon—How it

controls the press—The rise of Deputy Doumer—How he lost

his seat in 1889—The author of 'Chez Paddy' at Château

Thierry—Over-zeal of the curés—The question of working men's unions—M.

Doumer's report on the Law of Associations—He proves that

the Republic has done absolutely nothing with this law—'Five

years' spent in drawing up a report—'The Republic never existed

until 1879'—And nothing done for working men until 1888—M.

de Freycinet and M. Carnot only 'studied measures which might

be taken;' but were not!—The first practical step taken by M.

Doumer by making an enormous report in 1888, recommending

[Pg xiii]things to be done hereafter—The true Republic eluding for ten

years questions which the Emperor grappled with in 1867—The

voters of Laon in September defeat M. Doumer—A curious little

chapter of French politics—M. Doumer's coquetry with General

Boulanger—After his defeat M. Doumer becomes secretary of

the President of the Chamber and lets the working men's question

alone—Politics as a profession in France and the United

States—Intense centralisation of power in France makes it easier

and more profitable than in America |

226-258 |

| |

| CHAPTER XI |

| IN THE NORD |

| Valenciennes—The shabbiest historic town in North-eastern

France—Perfect cultivation of French Flanders—Cock-fighting and

flowers—Prosperity of the cabarets—One to every forty-four inhabitants

around Valenciennes—Growth of the mining and manufacturing

towns—Interesting buildings in Valenciennes—Carelessness of the

citizens about their city—A graceful edifice of the 15th century

falling into ruins—Valenciennes in the days of the Hanse of

London—Mediæval burghers and their sovereigns—A citizen of

Valenciennes, in 1357, the richest man in Europe—Festivals in

the olden times—Religious wars—Vauban at Valenciennes—How

the clothworkers fled from the Spanish persecution—Dumouriez

at Valenciennes—The Hôtel de Ville—Interesting local artists

from Simon Marmion down to Watteau and Pater—The triptych

of Rubens—Some historic portraits—The Musée Carpeaux—The

coal mines of Anzin—14,035 workmen there employed and

200,210,702 tons of coal extracted—Competition with Belgium,

the Pas-de-Calais, England, and Germany—The coal mines of

Anzin organised a century and a half ago—The discovery of coal

in North-eastern France—Energy shown by the local noblesse—Pierre

Mathieu, an engineer, strikes the vein in 1734—The lords

of the soil claim their rights over the coal—A long lawsuit ending

in a compromise—A business arrangement under the ancien

régime—The hereditary principle recognised in the organisation

and undisturbed by the Revolution—An orderly, quiet, and prosperous

town—A region of factories intermingled with farms—Charming

home of the director—The company encourages workmen's

homes, with gardens and allotments—An improvement on the

Cité Ouvrière—2,628 model homes now occupied by workmen—For

three francs a month a workman secures a well-built cottage,

with drainage and cellarage, six good rooms and closets, and a

plot of ground—2,500 families hold garden sites for cultivation—Fuel

allowed, and a general 'participation in profits' of a practical

sort—The right of the workmen to be consulted recognised at

Anzin a century and a half ago—Beneficial and educational

institutions—An industrial republic—How the National Assembly

meddled with the mines—Mining laws in France, ancient and

modern—Influence of politics on the output of the mines—Every

Republican development at Paris diminishes, and every check to

Republicanism at Paris develops, the great coal industry—The

great strike of 1884—During that year the company expended for

the benefit of the workmen a sum equivalent to the profits divided

amongst the shareholders—What caused the collision therefore

between capital and labour?—A syndicate of miners under a

former Anzin workman, Basly, puts a pressure from Paris upon

the workmen at Anzin to develop the strike—The pretext found in

contracts granted to good workmen—The object of the strike

to establish the equality of bad with good workmen—Boycotting

and intimidation—Dynamite and Radical deputies from

Paris—A Republican minister asks the company to accept Basly

and his syndicate as an umpire—Bitter opposition of the Basly

syndicate to the saving fund system—They demand a State

pension fund—And pending this a fund controlled by the syndicate—A

despotism of agitators—Upshot of the strike—The mines in

the Pas-de-Calais—Visits to workmen's houses—Fine appearance

and carriage of the miners—Their politics—Women and children—Good

ventilation and sanitation of the mines—'No man can be

a miner not bred to it as a boy'—Excellent housekeeping of the

women—Miners of Southern and Northern France—Influence of

high altitudes on character—The elective principle in the mines—Morals

and conduct of the mining people—Churches and

schools—A children's school at St. Waast—A digression into the

Artois—What the Tiers-Etat of Northern France wanted in 1789—The

cahiers of the Tiers-Etat—Respect for vested interests—A

visit to St.-Amand—The conspiracy of Dumouriez—Ruin of a

magnificent abbey—A beautiful belfry—Interesting pictures by

Watteau—Co-operation at Anzin—What its advantages are to the

workmen—Eight per cent. dividends to the members in 1866, and

an average during 23 years to 1889 of 11-80/100 per cent.—How the

workmen and their families live—Table of articles purchased—Attendance

upon the schools—Influence of women and families—Increase

of juvenile crime under irreligious education in France

and the United States—Louis Napoleon's National Retiring Fund

for Old Age—Regulations of the Anzin Council affecting this

fund—Average expenditure of the Anzin company for the benefit of

workmen 'fifty centimes for every ton of coal extracted'—The

Decazeville strikes in 1888—They begin with the murder of one

of the best engineers and end with a workman's banquet to the

engineer-in-chief |

259-331 |

| |

| CHAPTER XII |

| IN THE NORD—(continued) |

| Lille—The Flamand flamingant—Pertinacity of the Flemish tongue—A

historic city without monuments—Old customs and traditions—The

Musée Wicar—The unique wax bust—A 'pious foundation'

of art, and M. Carolus Duran—Excellent educational institutions

of Le Nord—A land flowing with beer—Increase of the factory

populations—Decrease of drunkenness in the cities—Increase in

the rural districts—Special cabarets for women—Should women

smoke?—Flemish cock-fighting and the example of England—A

model Republican prefect—Juvenile prostitution—The souls of

the people and their votes—Danton's system of uneducated judges—Dislike

of good people to politics—A pessimist rebuked—The

Monarchist majorities in Lille—Inaccurate representation of the

people in the Chamber—Hazebrouck and its Dutch gardens—The

Republic hated for its extravagance—Relative strength of

Republican and Monarchical majorities—Elections conducted

under secret instructions—Cutting down majorities—The case of

M. Leroy-Beaulieu in the Hérault—Keeping out dangerous

economists—Ballot 'stuffing' in France and the United States—The

methods of Robespierre readopted—Systematic 'invalidation'

of elections—The people must not choose the wrong men—Boulanger

and Joffrin—'Tactical necessities' in politics—The

delusion of universal suffrage—An Austrian view of the elective

and hereditary principles—Energy of the Catholics in North-eastern

France—Father Damien—Public charity—Hereditary mendicants

in French Flanders—Dogs and douaniers—The division of

communes—Foundling hospitals and the struggle for life—Mutual

Aid Societies—Is woman a 'Clubbable' animal?—M. Welche and

the agricultural syndicates—'Les Prévoyants de l'Avenir,' a phenomenal

success—It begins in 1882 with 757 members and 6,237

francs; in 1889 it numbers 59,932 members, with a capital of

1,541,868 francs—The Franco-German war and the religious

sentiment—The great Catholic University—Private contributions

of 11,000,000 francs—The scientific and medical schools—M.

Ferry and the free universities—Catholic education in France

and the United States—The case of Girard College—The dangers

of the French system—The monopoly of the University of France—Liberal

outlay of the Catholics of Paris—A mediæval Catholic

merchant—'The work of God' in a business partnership—Mutual

assistance in the Lille factories—Model houses at Roubaix—A

true Mont-de-Piété—The Masurel fund of 1607—Loans without

interest—A prosperous charity plundered by the Republic—A

benevolent fund of 455,454 francs in 1789 reduced to 10,408

francs in 1803—The fund restored under the Monarchy and

Second Empire—The 'King William's Fund' of the Netherlanders

in London—Count de Bylandt and Sir Polydore de

Keyser |

332-368 |

| |

| CHAPTER XIII |

| IN THE MARNE |

| Reims—The capital of the French kings—Clotilde and Clovis, Jeanne

d'Arc and Urban II.—Vineyards and factories—The wines of

Champagne known and unknown—The red wine of Bouzy—Mr.

Canning and still Champagne—The syndication of famous brands—A

visit to the cardinal archbishop—Employers and employed—The

Catholic workmen's clubs and the Christian corporations—M.

Léon Harmel—The religious education of a factory—How the

workmen Christianised themselves—The conversion of a wife by

a gown—The local authorities discouraging religion—'Planting

Christians like vines'—'The Rights of Man' and capital and

labour—Mediæval and modern methods compared—Capital and

universal suffrage—Money in the first Revolution—Le Pelletier,

the millionaire, and the mobs of the Palais Royal—The dramatic

justice of a murder—Unwritten chapters of revolutionary history—The

duty of employers—'The Masters' Catechism'—The invasion

of 1870 and the Christian corporations—Modern syndications and

the ancient maîtrise—Professional syndicates and professional

strikes—Good out of evil—The working men and the upper classes—Count

Albert de Mun—A popular vote against universal suffrage—The

Holy See and the Catholic labour movement in France—The

parochial clergy and the laymen—The Wesleyans and the

Catholics—Privileged purveyors—The financial aspect of the

Catholic corporations—A revival of the old guilds—The national

system of the corporations—Provincial and general assemblies—The

German Cultur-Kampf and the French Catholic clubs—The

Republican attack on religion—Religious freedom and freedom

from religion—The State church of unbelief—The 'moral unity'

men—Napoleon and Guizot—The Jacobins of 1792 and 1879—Moral

unity under Louis XIV.—Alva and M. Jules Ferry—A

chapter of the Revolution at Reims—Mr. Carlyle's little 'murder

of about eight persons'—The political influence of massacres—The

'days of September' and the elections to the Convention—How

they chose Jacobin deputies at Reims—The documentary

story of the eight murders—Mayors under the Republic—The

defence of Lille—How the Republic voted a monument and Louis

[Pg xvii]Philippe built it—Desecration of a great cathedral—The legend of

Ruhl and the sacred ampulla—The demolition of St.-Nicaise and

the bargain of Santerre—How Napoleon disciplined the Faubourg

St.-Antoine—Is the Cathedral of Reims in danger?—Its restoration

under the cardinal archbishop—The budget of public worship—Expenses

of the administration—The salaries of the clergy, Protestant

and Catholic—Jewish rabbis paid less than servants in the

Ministère—Steady cutting down of the budget—No statistics of religious

opinion in France—A Benedictine archbishop—Great increase of

the religious sentiment in Reims—The Church driven by the

Republic into opposition—Léon Say and the present Government—The

home of Montaigne—A deputy of the Dordogne invalidated

to snub Léon Say—Socrates and David Hume in modern France—Dogmatic

irreligion—Jules Simon on the proscription of Christianity—Abolishing

the history of France—A practical protest of

the Catholic Marne—The great pope of the crusades—Catholic

and Masonic processions—The Triduum of Urban II.—A great

celebration at Châtillon—Hildebrand and his disciple—The

Angelus and the 'Truce of God'—Mgr. Freppel on the anti-religious

war—Jeanne d'Arc at Reims—A magnificent festival—Gounod's

Mass of the Maid of Orléans—Catholic protest against

the persecution of the Jews—The Republic threatens the grand

rabbis with the archbishops—Deriding a death-bed in a

hospital—The amnesty of the Communards—The rehabilitation of

crime—Tyranny in the village schools—Religious freedom in

France and Turkey—The home of Jeanne d'Arc—'Laicising'

Domrémy-la-Pucelle—Piety and hypnotism—The chamber and garden of

Jeanne—Louis XI. and the French yeomen—A shrine converted

into a show—A scurvy job in a place of pilgrimage—The banner

of Patay—Jeanne and her voices—A western worshipper of the

Maid of Orléans—The Château de Bourlémont—The Princesse

d'Hénin and Madame de Staël—The revolutionary traffic in passports—A

generous act of Madame Du Barry—'Laicisation' in the

Vosges—The defeat of Jules Ferry—The Monarchists going up,

the Republicans going down |

369-436 |

| |

| XIV |

| IN THE CALVADOS |

| Val Richer—The home of Guizot—The French Protestants and the

Third Republic—Free education in France the work of Guizot—Education

in France checked by the Revolution—Mediæval provisions

for public education—The effect of the English and the

religious wars upon education in France—Indiscriminate destruction

of educational foundations by the First Republic—Progress

[Pg xviii]of illiteracy after 1793—The guillotine as a financial expedient—The

Directory painted by themselves—The two Merlins—'Republican

Titans' wearing royal livery—Barras on the cruelty of

poltroons—Education under Napoleon—The Concordat and the

Church—Napoleon's University of France—A machine for creating

moral unity—The despotism of 1802 and 1882—The Liberals of

1830—Primary education under M. Guizot—The rights of the

family and the encroachments of the State—Catholic vindication

of Protestant liberty under Louis XIV.—The heirs of M. Guizot

in Normandy and Languedoc—M. de Witt at Val Richer—Three

historic châteaux—The birthplace of Montesquieu at La Brède—The

Abbey of Thomas à-Becket—The Château de Broglie—Lisieux—M.

Guizot as a landscape gardener—A Protestant statesman

among the Catholics of the Calvados—The Sieur de Longiumeau and the

sacred right of insurrection—'Moral unity' and 'moral

harmony'—Catholicism in the Calvados, Brittany, and Poitou—Charlotte

Corday—The historic family of De Witt—An election in the Calvados—The

people and the functionaries—Bonnebosq—The Normans and personal

liberty—The procedure of a French election—Mayors with votes in their

sleeves—Glass urns and wooden boxes—Gerrymandering in France and

America—Catholic constituents congratulating their Protestant

candidate—'Vive le roi!'—M. Bocher on two Republican

presidents—Wilsonism and the Norman farmers—The domestic

distilleries—The war against religion in Normandy—'The Church as the

key of trade'—How the officials revise the elections—Prefects

interfering in the elections—A solid Monarchist department—Politics

and the apple crop—The weak point of the Monarchists—The

traditions of Versailles and 'modern high life'—Louis XV. and

Barras—Madame Du Barry and Madame Tallien—The 'noble'

grooms of ignoble cocottes—The Legitimists under the Empire—The

war of 1870-71, and the fusion of classes—Historic names

in the French army—Officers and the châteaux—An American

minister and the Comte de Paris—The Monarchist and the Republican

representatives—The Duc de Broglie in the Eure—Architectural

evidence as to the social life of the ancien régime—The

war of classes a consequence, not a cause, of the Revolution—The

Vicomte de Noailles and Artemus Ward—Feudal serfs and New

York anti-renters—Jefferson and lettres de cachet—The Bastille

and the Tower of London—Don Quixote and the wine skins—The

Château d'Eu—Private rights in the 14th century—The 'Nonpareil'

of the world—La Grande Mademoiselle and her lieges at

Eu—Her hospitals and charities—A quick-witted mayor—A model

Republican prefect—The Duc de Penthièvre—The Orléans family

at Eu—Local popularity of the Comte and Comtesse de Paris—Norman

grievances, old and new—A Protestant movement in

Normandy—American associations with Broglie, La Brède, and

[Pg xix]Val Richer—Mr. Bancroft on the ministers of Louis Philippe—The

'military council' of Royalist officers in the Revolution—Louis

Philippe and Thiers—The rights of property under the

Second Empire—The seizure of the Orléans property—The

Jacobin levelling of incomes—The reformer Réal as an opulent

count—The Orléans property restored in 1872, as a matter of

'common honesty'—What the princes recovered, and what they

presented to France—The 'wounded conscience' of a nation—The

daughter of Madame de Staël—The present Duc de Broglie and the

anti-religions war—The Conservative republic made impossible—The

Radical Jacobins rule the roast—'The Republic commits

suicide to save itself from slaughter'—Floquet the master of

Carnot—The war against God—Two statesmen of the South—Nîmes

and M. Guizot—The religious wars in Languedoc—The

son of M. Guizot at Uzès—Politics in the Gard—Catholics and

Protestants fighting side by side—The late M. Cornelis de Witt—The

hereditary principle in Holland—What the United States

learned from the Netherlands and from England—How the Duke

of York missed an American throne—A Protestant monarchist

in the Lot-et-Garonne—The plums of Agen and the apricots of

Nicole—Cœur de Lion and Bertrand de Boru—The home of

Nostradamus—Why the Germans beat the French—The barber

bard of Languedoc—Scaliger and the Huguenots—Nérac and the

Reine Margot—The 'Lovers' War'—The Revocation and the

Revolution—The ruin of property in 1793—Decline of the wealth

of France—The monarchists of the Aveyron—A banquet of

monarchist mayors—The need of a man in France—'A bolt out

of the blue'—How the Duc d'Orléans demoralised the government—The

young conscript at Clairvaux—Carnot surrenders to

the Commune—A Russian verdict on the republican blunder—The

'Prince' of the people—How the Government has helped the

Comte de Paris—Irregularities of republican taxation—Corsica

and the Corrèze—France the most heavily taxed country in the

world—Steady and enormous increase of taxation—Cost of collecting

the revenue—Political dishonesty on the stump—The persecution

of candidates—Invasion of private life—Bullying the

magistrates—Public servants ordered to the polls—Curés fined

for preaching religious duty—The Conférences du Sud-Ouest—M.

Princeteau at Bordeaux—The fête of the Bastille at Bordeaux

and Nîmes—A 'Fils de Dieu' at Nîmes—Socialism at

Alais—The suppression of inheritances—'Property a privilege to

be abolished'—'Opulence an infamy'—The Socialists and the

Government—Persecution of the Protestants—'Pray, what is

God?'—Strength of Socialism in South-eastern France—Two

typical departments—Socialism in the Bouches-du-Rhône—Historic

France in the Calvados—Boulanger at Marseilles—A Socialist

coachman at Arles—A great Catholic employer of labour at Marseilles—The

[Pg xx]largest glycerine works in the world—Church candles

and dynamite—Taxing industries to death—Dutch competition

with France—A Christian corporation in Marseilles—'An economical

kitchen'—An uphill fight for law and order—The Christians

of the 4th and of the 19th centuries—The Radicals hold the

bridle—Shall France be Christian or Nihilist?—Ernest Renan on

the situation in 1872—Jules Simon on the situation in 1882—The

'civic duties' of man and the guillotine—What will the situation

be in 1892? |

437-515 |

| |

| MAP OF FRANCE at end of book |

Errata

P. 24, 11 lines from top, for rival read rural.

P. 64, line 1, for de Royes read de Royer.

P. 91, line 6 from top. M. Spuller, Prefect of the Somme in 1880, was

the brother of the present Minister of Foreign Affairs, not the Minister

himself.

P. 96, line 5 from top, for Montauban read Montaudon.

P. 105, line 4 from bottom, for being read long.

P. 395, 3 lines from top, for Abbeys read Abbaye.

Wherever found, for de Fallières read Fallières.[Pg xxi]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

As I have not wished to swell the bulk of this book by references, and

as many statements made in it concerning men and things of the first

Republic may seem to my readers to need verification, I subjoin a brief

list of authorities consulted by me in this connection. It is

incomplete, but will be found to cover every material point concerning

the epoch to which it refers.

Biré, E. La Légende des Girondins.

Campardon, Emile. Le Tribunal Révolutionnaire à Paris d'après les Documents Originaux.

Dauban, C. A. La Démagogie à Paris en 1793.

Dauban, C. A. Les Prisons de Paris sous la Révolution.

Dauban, C. A. Mémoires Inédits de Pétion, de Buzot et de Barbaroux.

Dauban, C. A. Mémoires de Madame Roland. Etude sur Madame Roland.

Lettres en partie inédites de Madame Roland.

De Barante. Histoire de la Convention Nationale.

De Lavergne, L. (de l'Institut). Economie rurale de la France depuis 1789.

De Montrol, F. Mémoires de Brissot, publiés par son fils.

De Pressensé, Edmond. L'Eglise et la Révolution Française.

Doniol, H. Histoire des Classes Rurales en France.

Du Bled. Les Causeurs de la Révolution.

Durand de Maillane. Histoire de la Convention Nationale.

Feuillet de Conches. Louis XVI., Marie Antoinette et Madame Elisabeth.

Forneron, H. Histoire Générale des Emigrés.

Gallois, Léonard. Histoire des Journaux et des Journalistes de la Révolution Française.

Goncourt, Edmund et Jules. Histoire de la Société Française pendant la Révolution.

Granier de Cassagnac. Histoire des Girondins et des Massacres de Septembre.

[Pg xxii]

Guillon, l'Abbé. Les Martyrs de la Foi pendant la Révolution Française.

Hamel, Ernest. Histoire de Robespierre.

Jefferson, Thomas. Memoirs and Correspondence.

Laferrière (de l'Institut). Essai sur l'histoire du Droit Français.

Mallet du Pan. Mémoires et Correspondance.

Masson, Frédéric. Le Département des Affaires Etrangères pendant la Révolution.

Morris, Gouverneur. Diary and Letters.

Mortimer-Ternaux. Histoire de la Terreur, 1792-1794, d'après des documents authentiques et inédits.

Rocquain, F. L'Esprit Révolutionnaire avant la Révolution.

Tissot, P. F. Histoire complète de la Révolution Française.

Vatel, Ch. Charlotte Corday.

Young, Arthur. Voyages en France pendant les années 1787-89.

Traduction de M. Le Sage; Introduction par L. de Lavergne.

[Pg xxiii]

INTRODUCTION

I

This volume is neither a diary nor a narrative. To have given it either

of these forms, each of which has its obvious advantages, would have

extended it beyond all reasonable limits. It is simply a selection from

my very full memoranda of a series of visits paid to different parts of

France during the year 1889.

These visits would never have been made, had not my previous

acquaintance with France and with French affairs, going back now—such

as it is—to the early days of the Second Empire, given me reasonable

ground to hope that I might get some touch of the actual life and

opinions of the people in the places to which I went. My motive for

making these visits was the fact that what it has become the fashion to

call 'parliamentary government,' or, in other words, the unchecked

administration of the affairs of a great people by the directly elected

representatives of the people, is now formally on its trial in France.

We do not live under this form of government in the United States, but

as a thoughtless tendency towards this form of government has shown

itself of late years even in the United States and much more strongly in

Great Britain, I thought it worth[Pg xxiv] while to see it at work and form some

notion of its results in France.

Republican Switzerland has carefully sought to protect herself against

this form of government. The Swiss Constitution of 1874 reposes

ultimately on the ancient autonomy of the Cantons. Each Canton has one

representative in the Federal Executive Council. The members of this

Council are elected for three years by the Federal Assembly, and from

among their own number they choose the President of the Confederation,

who serves for one year only—a provision probably borrowed from the

first American Constitution. The Cantonal autonomy was further

strengthened in 1880 by the establishment of the Federal Tribunal on

lines taken from those of the American Supreme Court. There is a

division of the Executive authority between the Federal Assembly and the

Federal Council, which is yet to be tested by the strain of a great

European war, but which has so far developed no serious domestic

dangers.

The outline map which accompanies this volume will show that my visits,

which began with Marseilles and the Bouches-du-Rhône, upon my return

from Rome to Paris in January 1889, on the eve of the memorable election

of General Boulanger as a deputy for the Seine in that month, were

extended to Nancy in the east of France, to the frontiers of Belgium and

the coasts of the English Channel in the north, to Rennes, Nantes, and

Bordeaux in the west, and to Toulouse, Nîmes, and Arles in the south. I

went nowhere without the certainty of meeting persons who could and

would put me[Pg xxv] in the way of seeing what I wanted to see, and learning

what I wanted to learn. I took with me everywhere the best books I could

find bearing on the true documentary history of the region I was about

to see, and I concerned myself in making my memoranda not only with the

more or less fugitive aspects of public action and emotion at the

present time, but with the past, which has so largely coloured and

determined these fugitive aspects. Naturally, therefore, when I sat down

to put this volume into shape, I very soon found it to be utterly out of

the question for me to try to do justice to all that had interested and

instructed me in every part of France which I had visited.

I have contented myself accordingly with formulating, in this

Introduction, my general convictions as to the present condition and

outlook of affairs in France and as to the relation which actually

exists between the Third Republic, now installed in power at Paris, and

the great historic France of the French people; and with submitting to

my readers, in support of these convictions, a certain number of digests

of my memoranda, setting forth what I saw, heard, and learned in some of

the departments which I visited with most pleasure and profit.

In doing this I have written out what I found in my note-books less

fully than the importance of the questions involved might warrant. But

what I have written, I have written out fairly and as exactly as I

could. I do not hold myself responsible for the often severe and

sometimes scornful judgments pronounced by my friends in the provinces

upon public men at Paris. But I had[Pg xxvi] no right to modify or withhold

them. In the case of conversations held with friends, or with casual

acquaintances, I have used names only where I had reason to believe

that, adding weight to what was recorded, they might be used without

injury or inconvenience of any kind to my interlocutors.

The sum of my conclusions is suggested in the title of this book. I

speak of France as one thing, and of the Republic as another thing. I do

not speak of the French Republic, for the Republic as it now exists does

not seem to me to be French, and France, as I have found it, is

certainly not Republican.

II

The Third French Republic, as it exists to-day, is just ten years old.

It owes its being, not to any direct action of the French people, but to

the success of a Parliamentary revolution, chiefly organised by M.

Gambetta. The ostensible object of this revolution was to prevent the

restoration of the French Monarchy. The real object of it was to take

the life of the executive authority in France. M. Gambetta fell by the

way, but the evil he did lives after him.

He was one of the celebrities of an age in which celebrity has almost

ceased to be a distinction. But the measure of his political capacity is

given in the fact that he was an active promoter of the insurrection of

September 4, 1870, in Paris against the authority of the Empress

Eugénie. A more signal instance is[Pg xxvii] not to be found in history of that

supreme form of public stupidity which President Lincoln stigmatised, in

a memorable phrase, as the operation of 'swapping horses while crossing

a stream.'

It was worse than an error or a crime, it was simply silly. The

inevitable effect of it was to complete the demoralisation of the French

armies, and to throw France prostrate before her conquerors. A very

well-known German said to me a few years ago at Lucerne, where we were

discussing the remarkable trial of Richter, the dynamiter of the

Niederwald: 'Ah! we owe much to Gambetta, and Jules Favre, and Thiers,

and the French Republic. They saved us from a social revolution by

paralysing France. We could never have exacted of the undeposed Emperor

at Wilhelmshöhe, with the Empress at Paris, the terms which those

blubbering jumping-jacks were glad to accept from us on their knees.'

The imbecility of September 4, 1870, was capped by the lunacy of the

Commune of Paris in 1871. This latter was more than France could bear,

and a wholesome breeze of national feeling stirs in the 'murders grim

and great,' by which the victorious Army of Versailles avenged the

cowardly massacre of the hostages, and the destruction of the Tuileries

and the Hôtel de Ville.

With what 'mandate,' and by whom conferred, M. Thiers went to Bordeaux

in 1871, is a thorny question, into which I need not here enter. What he

might have done for his country is, perhaps, uncertain. What he did we

know. He founded a republic of which, in one of his characteristic

phrases, he said that: 'it must be Conservative, or it could not be,'

and this he did with[Pg xxviii] the aid of men without whose concurrence it would

have been impossible, and of whom he knew perfectly well that they were

fully determined the Republic should not be Conservative. He became

Chief of the State, and this for a time, no doubt, he imagined would

suffice to make the State Conservative.

He was supported by an Assembly in which the Monarchists of France

predominated. The triumphant invasion and the imminent peril of the

country had brought monarchical France into the field as one man. M.

Gambetta's absurd Government of the National Defence, even in that

supreme moment of danger when the Uhlans were hunting it from pillar to

post, actually compelled the Princes of the House of France to fight for

their country under assumed names, but it could not prevent the sons of

all the historic families of France from risking their lives against the

public enemy. All over France a general impulse of public confidence put

the French Conservatives forward as the men in whose hands the

reconstitution of the shattered nation would be safest. The popular

instinct was justified by the result.

From 1871 to 1877, France was governed, under the form of a republic, by

a majority of men who neither had, nor professed to have, any more

confidence in the stability of a republican form of government, than

Alexander Hamilton had in the working value of the American Constitution

which he so largely helped to frame, and which he accepted as being the

best it was possible in the circumstances to get. But they did their

duty to France, as he did his duty to America.[Pg xxix] To them—first under M.

Thiers, and then under the Maréchal-Duc de Magenta—France is indebted

for the reconstruction of her beaten and disorganised army, for the

successful liquidation of the tremendous war-indemnity imposed upon her

by victorious Germany, for the re-establishment of her public credit,

and for such an administration of her national finances as enabled her,

in 1876, to raise a revenue of nearly a thousand millions of francs, or

forty millions of pounds sterling, in excess of the revenue raised under

the Empire seven years before, without friction and without undue

pressure. In 1869, the Empire had raised a revenue of 1,621,390,248

francs. In 1876, the Conservative Republic raised a revenue of

2,570,505,513 francs. With this it covered all the cost of the public

service, carried the charges resulting from the war and its

consequences, set apart 204,000,000 francs for public works, and yet

left in the Treasury a balance of 98,000,000 francs.

It is told of one of the finance ministers of the Restoration, Baron

Louis, that when a deputy questioned him once about the finances, he

replied, 'Do you give us good politics and I will give you good

finances.' It seems to me that the budget of 1876 proves the politics of

the Conservative majority in the French Parliament of that time to have

been good. The Maréchal-Duc de Magenta was then president. M. Thiers had

resigned his office in 1873, in consequence of a dispute with the

Assembly, the true history of which may one day be edifying, and the

Assembly had elected the Maréchal-Duc to fill his place.

I have been told by one of the most distinguished[Pg xxx] public men in France

that, in his passionate desire to prevent the election of the Maréchal

Duc, M. Thiers was bent upon promoting a movement to bring against the

soldier of Magenta an accusation like that which led to the condemnation

of the Maréchal Bazaine, and that he was with difficulty restrained from

doing this.

Monstrous as this attempt would have been, it hardly seems more

monstrous than the abortive attempt which was actually made, under the

inspiration of M. Gambetta and his friends, to convict the Maréchal Duc

and his ministers, 'the men of the 16th of May,' of conspiring, while in

possession of the executive power, to bring about the overthrow of the

Republic and the restoration of the Monarchy.

M. Gambetta and his party having formed in 1877 what is known as 'the

alliance of the 363,' determined to drive the Maréchal-Duc from the

Presidency, to take the control of public affairs entirely into their

own hands, and to reduce the Executive to the position created for Louis

XVI. by the revolutionists of the First Republic, before the atrocious

plot of August 10, 1792, made an end of the monarchy and of public order

altogether, and prepared the way for the massacres of September. Whether

the Maréchal-Duc might not have resisted this revolutionary conspiracy

to the end it is not worth while now to inquire. Suffice it that he gave

way finally, and, refusing to submit to the degradation of the high post

he held, accepted M. Gambetta's alternative and relinquished it.

It appears to me that the true aim of the Republicans (who had carried

the elections of 1877 by persuading[Pg xxxi] France that Germany would at once

invade the country if the Conservatives won the day) is sufficiently

attested by the fact that they chose, as the successor of the

Maréchal-Duc, a public man chiefly conspicuous for the efforts he had

made to secure the abolition of the Executive office!

M. Grévy had failed to get the Presidency of the Republic suppressed

when the organic law was passed in 1875. He was more successful when, on

January 30, 1879, he consented to accept the Presidency. When he entered

the Elysée, the executive authority went out of it. The Third French

Republic, such as it now exists, was constituted on that day—the

anniversary, by the way, oddly enough, of the decapitation of Charles I.

of England at Whitehall.

That is the date, not 'centennial,' but 'decennial,' which ought to have

been celebrated in 1889 by the Third French Republic. In his first

Message, February 7, 1879, M. Grévy formally said: 'I will never resist

the national will expressed by its constitutional organs.' From that

moment the parliamentary majority became the Government of France.

Something very like this French parliamentary revolution of 1879 to

which France is indebted for the Third Republic as it exists to-day, was

attempted in the United States about ten years before.

In both instances the intent of the parliamentary revolutionists was to

take the life of a Constitution without modifying its forms. The failure

of the American is not less instructive than the success of the French

parliamentary revolution, and as all my readers,[Pg xxxii] perhaps, are not as

familiar with American political history as with some other topics, I

hope I may be pardoned for briefly pointing this out.

Upon the assassination of President Lincoln in April 1865 the

Vice-President, Andrew Johnson, became President. He was a Southern man,

and as one of the Senators from the Southern State of Tennessee he had

refused to go with his State in her secession from the Union. To this he

owed his association on the Presidential ticket with Mr. Lincoln at the

election in 1864. He was no more and no less opposed to slavery in the

abstract than President Lincoln, of whom it is well known that he

regarded his own now famous proclamation of 1863 freeing the slaves in

the seceded States, as an illegal concession to the Anti-Slavery feeling

of the North and of Europe, and that he spoke of it with undisguised

contempt, as a 'Pope's bull against the comet.' Like Mr. Lincoln, Andrew

Johnson was devoted to the Union, but he was a Constitutional Democrat

in his political opinions, and the Civil War having ended in the defeat

of the Confederacy, he gradually settled down to his constitutional

duty, as President of the United States, towards the States which had

formed the Confederacy. This earned for him the bitter hostility of the

then dominant majority in both Houses of Congress, led by a man of

unbridled passions and of extraordinary energy, Thaddeus Stevens, a

representative from Pennsylvania, a sort of American Couthon, infirm of

body but all compact of will. It was the purpose of this majority to

humiliate and chastise, not to conciliate, the defeated South. Already,

under President Lincoln,[Pg xxxiii] this purpose had brought the leaders of the

majority more than once into collision with the Executive. Under

President Johnson they forced a collision with the Veto power of the

President, by two unconstitutional bills, one attainting the whole

people of the South, and the other aimed at the authority of the

Executive over his officers. In the policy thus developed they had the

co-operation of the Secretary at War, Mr. Stanton, and during the recess

of Congress in August 1867 it became apparent that with his assistance

they meant to subjugate the Executive. President Johnson quickly brought

matters to an issue. He first, during the recess, suspended Mr. Stanton

from the War Office, putting General Grant in charge of it, and upon the

reassembling of Congress in December 1867 'removed' him, and directed

him to hand over his official portfolio to General Thomas, appointed to

fill the place ad interim. Thereupon the majority of the House carried

through that body a resolution of impeachment, prepared, by a committee,

the necessary articles, and brought the President to trial before the

Senate, constituted as a court for 'high crimes and misdemeanours.' Two

of the articles of impeachment were founded upon disrespect alleged to

have been publicly shown by the President to Congress. The President, by

his counsel, among whom were Mr. Evarts, since then Secretary of State,

and now a Senator for New York, and Mr. Stanberry, an Attorney-General

of the United States, appeared before the Senate on March 13, 1868. The

President asked for forty days, in which to prepare an answer. The

Senate, without a division, refused this, and ordered the answer to be

filed[Pg xxxiv] within ten days. The trial finally began on March 30, and, after

keeping the country at fever-heat for two months, ended on May 26, in

the failure of the impeachment. Only three out of the eleven articles

were voted upon. Upon each thirty-five Senators voted the President to

be 'Guilty,' and nineteen Senators voted him to be 'Not guilty.' As the

Constitution of the United States requires a two-thirds vote in such a

trial, the Chief Justice declared the President to be acquitted, and the

attempt of the Legislature to dominate the Executive was defeated. Seven

of the nineteen Senators voting 'Not guilty' were of the Republican

party which had impeached the President, and it will be seen that a

change of one vote in the minority would have carried the day for the

revolutionists. So narrow was our escape from a peril which the founders

of the Constitution had foreseen, and against which they had devised all

the safeguards possible in the circumstances of the United States. What,

in such a case, would become of a French President?

The American President is not elected by Congress except in certain not

very probable contingencies, and when the House votes for a President,

it votes not by members but by delegations, each state of the Union

casting one vote. The French President is elected by a convention of the

Senate and the Chamber of Deputies, in which every member has a vote,

and the result is determined by an actual majority. The Senate of the

United States is entirely independent of the House. A large proportion

of the members of the French Senate are elected by the Assembly, and the

Chamber outnumbers[Pg xxxv] the Senate by nearly two to one. What the procedure

of the French Senate, sitting as a High Court on the impeachment of a

President by the majority of the Chamber, would probably be, may be

gathered from the recent trial by that body of General Boulanger.

With the resignation of the Maréchal-Duc and the election of M. Grévy

the Government of France, ten years ago, became what it now is—a

parliamentary oligarchy, with absolutely no practical check upon its

will except the recurrence every four years of the legislative

elections. And as these elections are carried out under the direct

control, through the prefects and the mayors, of the Minister of the

Interior, himself a member of the parliamentary oligarchy, the weakness

of this check might be easily inferred, had it not been demonstrated by

facts during the elections of September 22 and October 6, 1889.

How secure this parliamentary oligarchy feels itself to be, when once

the elections are over, appears from the absolutely cynical coolness

with which the majority goes about what is called the work of

'invalidating' the election of members of the minority. Something of the

sort went on in my own country during the 'Reconstruction' period which

followed the Civil War, but it never assumed the systematic form now

familiar in France. As practised under the Third Republic it revives the

spirit of the methods by which Robespierre and the sections 'corrected

the mistakes' made by the citizens of Paris in choosing representatives

not amenable to the discipline of the 'sea-green incorruptible'; and as

a matter of principle, leads straight on to that[Pg xxxvi] usurpation of all the

powers of the State by a conspiracy of demagogues which followed the

subsidized Parisian insurrection of August 10, 1792.

Such a régime as this sufficiently explains the phenomenon of

'Boulangism,' by which Englishmen and Americans are so much perplexed.

Put any people into the machinery of a centralized administrative

despotism in which the Executive is merely the instrument of a majority

of the legislature, and what recourse is there left to the people but

'Boulangism'? 'Boulangism' is the instinctive, more or less deliberate

and articulate, outcry of a people living under constitutional forms,

but conscious that, by some hocus-pocus, the vitality has been taken out

of those forms. It is the expression of the general sense of insecurity.

In a country situated as France now is, it is natural that this

inarticulate outcry should merge itself at first into a clamour for the

revision of a Constitution which has been made a delusion and a snare;

and then into a clamour for a dynasty which shall afford the nation

assurance of an enduring Executive raised above the storm of party

passions, and sobering the triumph of party majorities with a wholesome

sense of responsibility to the nation.

There would have been no lack of 'Boulangism' in France forty years ago

had M. Thiers and his legislative cabal got the better of the Prince

President in the 'struggle for life' which then went on between the

Place St.-Georges and the Elysée![Pg xxxvii]

III

There are two periods, one in the history of modern England, the other

in the history of the United States, which directly illuminate the

history of France since the overthrow of the ancient French Monarchy in

1792.

One of these is the period of the Long Parliament in England. The other

is the brief but most important interval which elapsed between the

recognition of the independence of the thirteen seceded British colonies

in America, at Versailles in 1783, and the first inauguration of

Washington as President of the United States at New York on April 30,

1789. No Englishman or American, who is reasonably familiar with the

history of either of these periods, will hastily attribute the phenomena

of modern French politics to something essentially volatile and unstable

in the character of the French people.

My own acquaintance, such as it is, with France—for I should be sorry

to pretend to a thorough knowledge of France, or of any country not my

own—goes back, as I have intimated, to the early days of the Second

Empire. It has been my good fortune, at various times, to see a good

deal of the social and political life of France, and I long ago learned

that to talk of the character of the French people is almost as slipshod

and careless as to talk of the character of the Italian people.

The French people are not the outgrowth of a common stock, like the

Dutch or the Germans.

The people of Provence are as different in all[Pg xxxviii] essential particulars

from the people of Brittany, the people of French Flanders from the

people of Gascony, the people of Savoy from the people of Normandy, as

are the people of Kent from the people of the Scottish Highlands, or the

people of Yorkshire from the people of Wales. The French nation was the

work, not of the French people, but of the kings of France, not less but

even more truly than the Italian nation, such as we see it gradually now

forming, is the work of the royal House of Savoy.

The sudden suppression of the National Executive by a parliamentary

conspiracy at Paris in 1792 violently interrupted the orderly and

natural making of France, just as the sudden suppression of the National

Executive in 1649 after the occupation of Edinburgh by Argyll and the

surrender of Colchester to Fairfax had put England at the mercy of

Cromwell's 'honest' troopers, and of knavish fanatics like Hugh Peters,

violently interrupted the making of Britain. It took England a century

to recover her equilibrium. Between Naseby Field in 1645 and Culloden

Moor in 1746 England had, except during the reign of Charles II., no

better assurance of continuous domestic peace than France enjoyed first

under Louis Philippe and then under the Second Empire. During those

hundred years Englishmen were thought by the rest of Europe to be as

excitable, as volatile, and as unstable as Frenchmen are not uncommonly

thought by the rest of mankind now to be. There is a curious old Dutch

print of these days in which England appears as a son of Adam in the

hereditary costume, standing at gaze amid a great disorder[Pg xxxix] of garments

strewn upon the floor, while a scroll displayed above him bears this

legend:

I am an Englishman, and naked I stand here,

Musing in my mind what garment I shall wear.

Now I will wear this, and now I will wear that,

And now I will wear—I don't know what!

There was as much—and as little—reason thus to depict the England of

the seventeenth, as there is thus to depict the France of the nineteenth

century.

If there had ever been, a hundred years ago, such a thing as a French

Republic, founded, as the American Republic of 1787 was founded, by the

deliberate will of the people, and offering them a reasonable prospect

of maintaining liberty and law, that Republic would exist to-day. That

we are watching the desperate effort of a centralised parliamentary

despotism at Paris in the year 1890 to maintain a 'Third Republic' is

conclusive proof that this was not the case.

France—the French people, that is—- had no more to do with the

overthrow of the monarchy of Louis XVI., with the fall of the monarchy

of Charles X., with the collapse of the monarchy of July, or with the

abolition of the Second Empire, than with the abdication of Napoleon I.

at Fontainebleau.

Not one of these catastrophes was provoked by France or the French

people; not one of them was ever submitted by its authors to the French

people for approval.

Only two French governments during the past century can be accurately

said to have been definitely branded and condemned as failures by the

deliberate[Pg xl] voice of the French people. One of these was the First

Republic, which after going through a series of convulsions equally

grotesque and ghastly, was swept into oblivion by an overwhelming vote

of the French people in response to the appeal of the first Napoleon.

The other was the Second Republic, which was put upon trial by the Third

Napoleon on December 10, 1851, and condemned to immediate extinction by

a vote of 7,439,219 to 640,737. I am at a loss to see how it is possible

to deduce from these simple facts of French history the conclusion that

the French people are, and for a century have been, madly bent upon

getting a Republic established in France, unless, indeed, I am to

suppose that the French Republicans proceed upon the principle said to

be justified by the experience of countries in which the standard of

mercantile morality is not absolutely puritanical—that three successive

bankruptcies will enable a really clever man to retire from business

with a handsome fortune!

If it were possible, as happily it is impossible, that the American

people could be afflicted with a single year of such a Republic as that

which now exists in France, we would rid ourselves of it, if necessary,

by seeking annexation to Canada under the crown of our common ancestors,

or by inviting the exiled Dom Pedro to recross the Atlantic and accept

the throne of a North American Empire, with substantial guarantees that

if we should ever change our minds and put him politely on board a ship

again for Europe, the cheque given to him on his departure would not be

dishonoured on presentation to the national bankers![Pg xli]

It is the penalty, I suppose, of our position in the United States, as

the first and, so far, the only successful great republic of modern

times, that we are expected to accept a sort of moral responsibility for

all the experiments in republicanism, no matter how absurd, odious, or

preposterous they may be, which it may come into the heads of people

anywhere else in the world to try. I do not see why Americans who are

not under some strenuous necessity of making stump speeches in or out of

Congress, with an eye to some impending election, should submit to this

without a protest. Imitation may be the sincerest form of flattery: it

does not follow that it is the most agreeable.

I do not know that Western drawing-rooms take more delight in the

Japanese, who most amiably present themselves everywhere in the

regulation dress-coat and white cravat of modern Christendom, than in

the Chinese, who calmly and haughtily persist in wearing the ample,

stately, and comfortable garments of their own people.

The framers of the French Republican Constitution of 1875 did the United

States the honour to copy incorrectly, and absolutely to misapply,

certain leading features of our organic law. In order to accomplish

purposes absolutely inconsistent with all American ideas of liberty and

of justice, the parliamentary revolutionists who got possession of power

in France in 1879 have so twisted to their own ends this French

Constitution of 1875, that their government of the Third French Republic

in 1890 really resembles the government of the Akhoond of Swat about as

nearly as[Pg xlii] it resembles the government of the American Republic under

Washington.

The parliamentary revolutionists of the Third French Republic are

Republicans first and then Frenchmen. The framers of the American

Republic were Americans first and then Republicans. The Republic which

they framed was an experiment imposed upon the American people, not by

philosophers and fanatics, but by the force of circumstances. The ablest

of the men who framed it were not Republicans by theory. On the

contrary, they had been born and bred under a monarchy. Under that

monarchy they had enjoyed a measure of civil and religious liberty which

the Third Republic certainly refuses to Frenchmen in France to-day. M.

Jules Ferry and M. Constans have no lessons to give in law or in liberty

to which George Washington, or John Adams, or even Thomas Jefferson,

would have listened with toleration while the Crown still adorned the

legislative halls of the British colonies in America. Our difficulties

with the mother country began, not with the prerogative of the

Crown—that gave our fathers so little trouble that one of the original

thirteen States lived and prospered under a royal charter from Charles

II. down to the middle of the nineteenth century—but with the

encroachments of the Parliament. The roots of the affection which binds

Americans to the American Republic strike deep down into the history of

American freedom under the British monarchy. The forms have changed, the

living substance is the same. Americans know at least as well as

Englishmen what the most intelligent of French Republicans apparently

have still[Pg xliii] to learn, that liberty is impossible without loyalty to

something higher than self-interest and self-will.

This sufficiently explains to me a remark often cited as made to Sir

Theodore Martin by General Grant during the ex-President's visit to

England, to the effect that Englishmen 'live under institutions which

Americans would give their ears to possess.'

General Grant neither was, nor did he pretend to be, a great statesman.

But he was an American of the Americans. Four years of Civil War and

eight years of Presidential power had not been thrown away upon him. He

came into the Presidency as the successor of Andrew Johnson, who was

made President by the bullet of an assassin, and who was impeached, as I

have said, before the Senate for doing his plain constitutional duty, by

an unscrupulous parliamentary cabal.

He left the Presidency, to be succeeded in it by a President who derived

the more than doubtful title under which he took his seat from a

Commission unknown to the Constitution, and accepted by the American

people only as the alternative of political chaos and of a fresh civil

war.

Through his position at the head of the American army, General Grant, as

I have already mentioned, had been drawn into the contest between

President Johnson and the parliamentary cabal bent on breaking down the

constitutional authority of the Executive.

Going into the Presidency fresh from this drama, in 1869, General Grant

went out of the Presidency in 1877, after a drama not less impressive