Title: The Gap in the Fence

Author: Frederica J. Turle

Illustrator: Watson Charlton

Release date: May 21, 2007 [eBook #21547]

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/21547

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

| CHAPTER | |

| I.— | HAVER GRANGE |

| II.— | A QUEER VISITOR |

| III.— | THE LITTLE FOREIGN GIRL |

| IV.— | FAIRIES |

| V.— | HAPPY DAYS |

| VI.— | UNA ASKS A QUESTION |

| VII.— | SECRETS |

| VIII.— | THE GYPSIES ON THE COMMON |

| IX.— | UNA'S PET |

| X.— | WHAT THE YOUNG MAN SAID |

| XI.— | SAD DAYS |

| XII.— | HER FATHER'S SECRET |

Think of the prettiest garden you have ever seen: a dear, old-fashioned, sunny garden, with masses of snapdragon and white lilies and carnations, and big yellow sunflowers; and damask roses, and white cluster roses, and sweet-smelling pink cabbage roses, and tiny yellow Scotch roses—in fact, every kind of rose you can think of, except modern ones. Then you can imagine the Vicarage garden at Haversham.

Not that all these flowers were out in August; indeed, the best of the roses and all the carnations were over by then, but the garden was still gay with lots of other kinds of flowers; and dear little twisting paths led the way under shady nut-trees to the kitchen garden and orchard, where apricots and plums turned golden and red in the sunshine, and the apple-trees were so laden that it seemed quite wonderful to think the branches did not break with the weight of the fruit.

The summer holidays were half over now, and already Mother had begun to look over the boys' socks and shirts for the next term at school, and the girls had begun to talk seriously of the holiday tasks, which had been lightheartedly put on one side when they first came home from school with eight long weeks of idleness before them.

They were all having tea under the big ash-tree on the lawn one very hot afternoon, when Philip announced a rather important piece of news.

"Haver Grange is let," he said.

"Is it? Oh, Philip, how do you know? Who told you? Who has taken it, and when are they coming?" asked the others.

For over twelve years now the old Grange had been empty—except for a very deaf old man and his wife who lived there as caretakers. The present owner liked better to travel about the world than to live quietly in England, and his sons generally spent their holidays with him abroad.

But although the same old board had stood beside the big iron gates with "This House to be Let Furnished" written upon it in large white letters, no one had come to live in it, and the children had grown to look upon the Grange garden, with its moss-grown walks and weedy flower beds, as their especial property.

"Mrs. Mills told me when I went to buy mother's stamps just now," said the boy. "She said an Italian gentleman had taken it, or an Austrian or a Frenchman—she didn't know which," and Philip laughed as he helped himself to a piece of cake.

Just then the vicar turned in at the gate and crossed the lawn towards them.

"Don't bother father with questions until he has had a cup of tea," said Mrs. Carew, and six eager faces were turned towards the vicar as, with a sigh of relief, he seated himself under the shade of the tree.

"I think to-day is the hottest day we have had this year," he said, as he took the cup Ruth handed him and began to stir his tea, while he chatted to his wife about the poor woman he had been to see.

Ruth sighed.

"Isn't your tea nice, father?" she asked. "You have hardly drunk any of it yet."

"Very nice, thank you, dear," said her father.

Norah got down from her seat and carried the big milk jug round to his side.

"Won't you have some more milk, father?" she said. "Perhaps your tea is too hot, and you can't drink it quickly."

"But I don't want to drink it quickly," said her father.

He looked in a puzzled way at his wife, and Mrs. Carew laughed.

"I told the children to let you drink one cup of tea in peace before they bothered you with questions," said she.

"I think I know what the questions will be about," said the vicar.

He drank the rest of his tea and handed the cup to Philip.

"Father! Have you heard Haver Grange is let?" said the boy.

"And whom it's let to?" asked Ruth.

"And whether there are any children?" asked Norah.

"One question at a time!" said their father, laughing. "Yes, I heard from Mr. Denny that the Grange had been let to a foreign gentleman, who is coming to live there very soon, I believe, as the caretakers have orders to have the house in readiness before the end of this week; but where he comes from and whether he has any children I do not know."

Dan had been opening and shutting his mouth for the last two minutes.

"Father!" he burst out at last, "Do you think he will have the gap in the fence boarded up?"

"The gap in the fence? My dear Dan, what do you mean?" asked his father.

"He means the gap where we used to get through and have picnics in the Grange grounds," said Ruth, "but we haven't been there for a long time now. Have you and Dan been lately, Norah?"

"Yes," said Norah, "Dan and I often go and sit there. Shan't we ever be able to go any more?" And the little girl looked quite sad.

"No," said Mr. Carew; "certainly you must not go again. Little trespassers! I had no idea you were in the habit of going there for picnics or anything else."

"What's trespassers?" asked Dan.

"People who break through other people's fences and get taken up and put in prison," said Philip, as Mr. and Mrs. Carew left the tea-table and went towards the house. "Just fancy! You and Norah might have been quietly having a picnic in the glen one day when some fat old policeman would come along and take you both off to prison."

"Levick wouldn't," said Norah stoutly. "Levick's a very nice man. Dan and I often go to see him and his wife and baby."

"Well, Levick isn't the only policeman in the world," said Philip teasingly. "I saw a very fat, red-faced old policeman in Borsham the other day, and he had a little twinkle in his eye, which seemed to say: 'Where are the little boy and girl who have been breaking through the Grange fence?'"

"Oh, Philip, don't be silly," said Mary, seeing that her little brother was looking rather grave. "You know policemen wouldn't take up people and put them in prison unless they were doing anything really wrong."

"But perhaps some policemen would, Mary," said Dan. "Perhaps all policemen are not nice, kind policemen like Levick, who live in dear little white cottages like Levick's cottage, and have dear little babies like Levick's baby, and lots of little pigs like Levick's pigs."

The other children burst out laughing.

"No, of course they are not all exactly like Levick," said Philip, who was a little ashamed of himself for having frightened his little brother; "but I was only joking when I said that about the policeman in Borsham, Dan. What a little duffer you are!"

"Tell us about Jack the Giant-killer, then," said Dan coaxingly; and Philip sat down good-naturedly and told his little brother and sister story after story, until it was bedtime.

The next morning, when Philip went to the schoolroom to finish the Latin translation which he meant to have done the evening before, he found Ruth seated at the table with pen, ink and paper before her, and a very blank look on her face.

"What are you doing?" he asked in surprise; for Ruth was a very lazy little girl as a rule, and was seldom seen either reading, writing or working.

"It's my holiday task," she said dismally. "I can't think of anything to say."

"What have you got to write about?" asked Philip.

"Alfred the Great," said Ruth. "I know about him burning the cakes; but I can't think of anything else, and Mary has half done hers. Miss Long has offered a prize for the one who does it best."

"I wish old Jones would offer a prize for my holiday task," said Philip. "I can't get this stuff into my head!" and the boy turned to his Latin with a sigh.

"It's because we've had holidays, I think," said Ruth. "My mind feels quite empty, you know; and I think of all sorts of silly things instead of my essay."

"Perhaps that is why we have holiday tasks," said Philip.

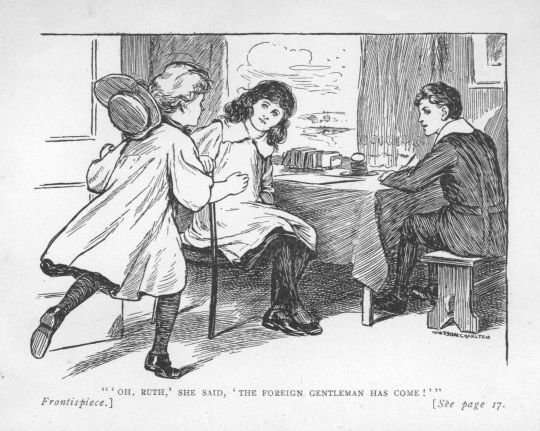

Just then hasty footsteps sounded along the passage, and Norah burst into the room like a whirlwind.

"Oh, Ruth," she said, quite out of breath with running so fast, "the foreign gentleman has come; and what do you think? He has got children; at least, he has a little girl, and she's about my age, Mrs. Mills says; because Mrs. Brown's son has been doing some painting at the Grange, and he saw a little girl one day, and Mrs. Brown told Mrs. Mills that he said she looked a 'regular caution.' I wonder what that means—not like little English girls, I expect. Oh, Ruth! don't you wish we could see her?"

"Norah, you really do talk too much," said Ruth, as her little sister paused for breath. "You bring out all your words in a rush together, and no one can hear half you say; and I'm sure mother wouldn't like you to chatter like that with Mrs. Mills. What have you been to the shop at all for, this morning?"

"To buy some string for Tom," said Norah. She was generally rather hurt when Ruth put on her elder-sisterly air, because she tried so hard to be "old" and sensible during the holidays, so that Ruth might talk to her sometimes and tell her secrets as she did to Mary, instead of always treating her as one of the little ones. But to-day she was too excited to pay much attention to Ruth's reproof, and turned to Philip for sympathy.

"Philip, isn't it lovely?" she said. "Perhaps we shall be great friends, the little girl and I, and go to tea with each other, and do things like that. Oh, I should love to have a little girl to be friends with!"

For some days nothing more was heard of the new tenants at Haver Grange, and when Sunday came the children were quite excited at the idea of seeing the foreign gentleman and his little girl in church.

When Stephen said that perhaps they would not come to church this first Sunday, the others scouted the idea with scorn, and the eyes of all the Carews were turned towards the Grange pew as they went in.

It was a big, old-fashioned, high-walled pew, and no one had ever sat in it as long as the children could remember; though Mrs. Jinks; the verger's wife, dusted it well and beat up the cushions with great energy every Thursday when she cleaned the church.

The pew was empty this morning; but it was early yet, and the children sat in eager expectation until the last clang of the bell sounded and the vicar entered.

"Such a pity to be late the first morning," thought Norah, as she rose to her feet with the others; but as the minutes passed, and still neither the foreign gentleman nor his little girl appeared, she began to think that perhaps Stephen was right after all.

"Oh, mother, when do you think we shall see her?" said Norah, on their way home from church that morning. "They've been here ever since Tuesday, and we haven't seen anything of them yet. Don't you think they will ever come to church here, mother—the little foreign girl and her father?"

"I don't know, dear," said her mother. "Perhaps they will later on; but father is going to call on Monsieur Gen (I think that is the foreign gentleman's name) in a few days, and perhaps, afterwards, he will be able to tell you something about the little girl."

But when the vicar called at the Grange a few days later, the strange, foreign-looking servant who opened the door told him that his master did not receive visitors; and as Mr. Carew walked down the drive he wondered what reason the foreign gentleman could have for coming to live at Haversham.

The last few days of the holidays went by very quickly; and it was just two days before the elder children went back to school that they saw their new little neighbour for the first time.

"If you want to see the little Spanish girl, come quick!" cried Tom, throwing open the schoolroom door; and in a moment the others had flung down their books and work and had followed him downstairs and out into the garden.

"Hurry!" cried Tom, panting as he rushed across the lawn; and they reached the gate just as a stout, elderly woman and a pale-faced little girl, dressed in a quaintly-frilled black frock, paused for one moment before it.

The child gazed solemnly at the group of rosy-faced, happy-looking children on the other side of the gate; then she said something in a strange language to the nurse, and they moved on slowly.

"What a queer little girl!" said Ruth, as soon as the woman and the child were out of hearing. "Hadn't she a comical little skirt?—all tiny frills; and her hair looked so funny in those tight little pig-tails."

"I think she must be French," said Mary. "Little French girls always do their hair like that, in pictures—in two plaits tied with big bows. And the nurse was dressed like a French bonne, with those long streamers in her cap."

"She looks so sad," said Norah. "Poor little girl! Did you see how sad her eyes were when she looked at us, Mary? I don't expect she has anyone to play with her all day long."

"And the nurse looked a grim old thing," said Stephen. "You'd better offer to go and play with her, Norah; you are always wanting a friend of your own age to play with, and here's one all ready and waiting."

"She doesn't look as if she could play," said Philip. "Come on, Tom, I want to let the rabbits out for a run after I've given these mulberry leaves to the silk-worms."

The children had planned to have tea in Weedon Woods that afternoon, but before dinner-time the sky became so cloudy and angry-looking that their mother feared a storm, and said that it would be wiser to put off their picnic until another day.

And at one o'clock the rain began—down it came in torrents, then hail, then rain again; and the children stood at the windows and watched it, feeling glad that they had not started for the picnic.

"We shouldn't have liked the wood today," said Dan, pressing up rather closely to Mary as a loud rumble of thunder sounded very near to them.

"No," said Mary, "I'm glad mother wouldn't let us go; we should have been soaked through by this time."

Just then Ellen, the housemaid, put her head in at the door.

"If you please, Miss Mary," she said, looking very much inclined to laugh, "there's a strange gentleman in the drawing-room asking to see you."

"To see me, Ellen? Are you sure?" asked Mary in surprise. "Didn't he ask to see father or mother?"

"The master and mistress are both out, Miss," said Ellen; "and he asked if you were in"; and then she hurried away in answer to a ring at the back-door bell.

"Oh, Ruth, supposing it's the foreign gentleman!" said Norah.

"Nonsense, Norah," said Ruth; "you never think of anything else."

When Mary opened the drawing-room door, however, she began to think that perhaps Norah was right after all, and the queer-looking old gentleman on the sofa was really the foreign gentleman who had come to live at the Grange.

He wore a pair of very large, blue spectacles, and had a long, white beard and bushy, white eyebrows which almost met over his nose; and he had a tight, little black silk cap on his head, and was dressed in a long, loose black coat, which showed glimpses of a crimson silk waistcoat underneath.

He was quite a short, old gentleman, Mary saw, as he rose to his feet and made her a very low bow; and he was very fat, the little girl thought to herself—almost as broad as he was long.

She held out her hand very politely, however, and said "How do you do?" and the little, old gentleman bowed three times, and then sat down again on the sofa.

"I cannot speak your language very well," he said, in a high, squeaky voice. "But I want to make your acquaintance, and the acquaintance of your brothers and your sisters. Where are they, if you please?"

"I'll go and fetch them," said Mary; and she went out into the hall, and called the other children, who were all sitting in a row at the foot of the staircase.

They jumped up when they saw Mary, and followed her across the hall in great glee when they heard that the foreign gentleman wanted to see them also.

"He is a very queer old gentleman," she whispered: "but you mustn't laugh, any of you, or look at each other—promise!"

"We promise," cried the children; and they pressed eagerly into the room, with Snap, the fox-terrier, bringing up the rear.

Before the children had time to shake hands with the old gentleman, Snap darted forward and sprang upon him eagerly—not barking or sniffing round his feet and ankles, as he usually did to strangers, making them feel as if he were looking out for a nice place for a bite, but jumping up and throwing himself upon him with little yelps of delight, behaving, indeed, just as he always did if he thought anyone was going to take him for a walk.

And what do you think the old gentleman said? He said: "Down Snap, down Snap!" rather crossly and in a voice that the children knew quite well; and almost before they had time to think how funny it was that he should know their dog's name, or, indeed, to wonder about anything at all, Snap made another frantic leap, and seizing hold of the old gentleman's white beard, dragged it off his chin, and darted off round the table with it in his mouth, shaking it as if it were a rabbit or a rat!

"Philip! Oh, Philip!" cried the children.

And Philip it was; naughty Philip, who had dressed himself up that wet afternoon to pretend that he was the foreign gentleman from the Grange; and, indeed, he had taken them all in finely.

"Oh, Philip! Philip! Why didn't I guess who you were?" cried Mary, as her brother leant back laughing against the sofa-cushions. "And fancy my not knowing my own sash!" pointing to the crimson waistcoat, which—now that her brother had thrown off his coat—she saw was her own best silk sash wound round and round him.

"And father's great coat!" said Ruth.

"And the white horsehair stuff out of the fireplace," said Philip, pointing to the empty grate. "It made a good beard, didn't it?"

"And the cap, Philip? Where did you get the cap from?" asked Mary.

"It's the lining out of my old straw hat," said Philip laughing. "Oh, didn't I take you all in!"

The next day the three elder children went back to school, and would very likely have forgotten all about the new people at the Grange if Tom and Norah had not written long letters from home telling them some of the strange tales which were being told in the village about the Grange tenants.

The foreign gentleman—Monsieur Gen as he was called—only left the grounds once a week, when he drove to the station in a closed carriage, and no information could be got out of the two old men-servants, who were the only other people in the house besides the little girl and her elderly nurse.

"Queer kind of folk too, them servants be," Giles, the baker, said one day to Rose, the little maid who usually took the children for walks when their mother was too busy to go with them. "There's one of them jabbers double-Dutch, and the other talks Dutch-double—except the few English words he's picked up since he's been here; and the names of all the foods—he knows them right enough!" And Giles laughed aloud at his own joke.

The children listened eagerly. They were always interested in hearing anything about the people at the Grange, and Norah often lay awake at night weaving strange fancies about the little girl who looked so sad and who must lead such a lonely life.

October was nearly at an end, however, before they saw the little foreign girl once more.

It was a bright, sunny afternoon; and Norah and Dan had gone to look for chestnuts in the wood.

They often went out alone, these two, when Tom was doing lessons with his father and Rose busy about the house; for, although rather a harum-scarum little damsel as a rule, Norah was always careful of Dan; and Mrs. Carew knew that so long as they kept away from the main road, with its never-ending whir of motorcars, Norah could be trusted with Dan anywhere; and the little girl felt very proud and happy as she pushed Dan's invalid chair down the drive, and knew that her little brother was in her charge for the afternoon.

Dan had fallen out of his perambulator when quite a tiny baby, and had twisted his back in some way, so that he would never be tall and strong like Stephen and Philip, or sturdy and straight like Tom; but he was a very happy little boy all the same, after a strange, quiet fashion of his own, and he liked best of all to be alone with Norah in the woods or by the river, when they would make up all sorts of fancies about queer little elves and fairies who, they said, lived in the trees or bushes, and in the sticklebacks' nests in the river.

It was so warm in the wood, this afternoon, that it felt almost like summer as the children hunted for chestnuts among the leaves, Dan leaning out of his chair and poking about with a walking stick, and Norah bringing the burrs to him as she found them, so that he might break them open and thread the nuts on to a piece of string he had brought with him.

"Dan," said Norah suddenly, when they had found quite a lot of chestnuts and were beginning to be rather tired of looking for them, "shall we go and see if the gap in the fence is still there? It's quite early still, and it's not so very far away."

"Oh, yes," said Dan. "It's such a long time since we've been there. Do you think, if it's not filled up, we might go in just for a minute?"

Norah shook here head.

"No, I don't think we can," she said. "You know father said we had been trespassing when we went there before, and nobody lived there then, so I suppose it would be more trespassing still if we went now; that's why we've never been to look at it all this time, because I knew if we did we should want to go in."

Dan sighed.

"And however much we want, this afternoon, we mustn't go in," he said. "I almost wish the people hadn't come to the Grange, Norah; it used to be so nice when we used to go and sit on our own little bank there, and nobody else ever came."

"But we couldn't go now, even if it was empty," said Norah, "because father said—— Oh, Dan!" she exclaimed, breaking off suddenly, "the gap is still there! Do you think I might peep through?"

"Yes," said Dan. "That's not trespassing. People often stop and look in at our gate, and we don't mind a bit. Do go and look in, Norah; you can leave me here in the chair, and if it looks very nice you must come and help me down the bank just to peep through once more."

Norah crept through the bushes cautiously, and popped her head in at the gap. Then she gave a little gasp of surprise.

There on Norah's own particular seat—a mossy stone shaped very like a stumpy armchair—sat the foreign little girl reading a book.

She raised her head and looked at Norah gravely.

They were a strange contrast—the pale, delicate-looking, little dark-eyed foreigner, and fair-haired, blue-eyed, rosy-cheeked Norah. For a few moments they looked at each other in silence, then the foreign child spoke.

"You are the little girl I saw on the other side of the gate," she said, speaking slowly and distinctly, as if she wanted to be quite sure of saying the English words in the right way. "And all the other boys and girls—are they also with you?"

"No," said Norah, "only Dan."

For the first time in her short life she felt shy and awkward. The little girl spoke so precisely and had such dignified manners, "almost like a grown-up princess," as Norah said afterwards when telling her mother all about it; but if she had only known, the little girl was really a great deal shyer than she was, and had never before spoken to another little girl.

"And Dan—is he there?" she asked. "I don't think I do very much like boys."

"Oh, you would like Dan," said Norah quickly. "Everyone likes Dan. He will be surprised when I tell him that you were sitting in our own glen. We always call it 'our glen,' because nobody else knows about it, and it looks quite the kind of place for fairies to come and play in, doesn't it?"

"I don't think I know what you mean," said the little girl in a puzzled kind of way. "What are fairies?"

"Don't know what fairies are? Oh, how funny!" said Norah. "You must get Dan to tell you about them; he knows ever so much more about them than I do. That is my seat you're sitting on now, and that is Dan's seat over there," pointing to a mossy corner, and quite forgetting that the glen belonged to the little foreign girl now, and that she and Dan had no longer any right to it.

The little foreign girl rose to her feet quickly.

"Won't you come and sit here now?" she said. "Please do! And won't Dan come and sit on his seat too?" glancing towards the corner Norah had pointed out.

Norah felt that she had been rather rude, and hastened to make amends.

"No, I don't think we can come to-day," she said, "though thank you very much for asking us; and it was very rude of me to have said the seats belonged to us," added the little girl, getting rather red. "Of course, the glen is yours now, and the seats too."

"Oh, but do come and sit in it sometimes," said the other child eagerly. "I am always, always alone all day, except for old Marie; and it would be so nice to have someone, not quite big, to talk to."

"We will come to-morrow," said Norah,—she felt very sorry for the little girl when she spoke so sadly of being alone all day—"but I must go now. I can hear Dan calling, and it is getting late."

"Good-bye," said the little girl. "Won't you tell me your name, please?"

"Norah—Norah Carew."

"And mine is Una. Good-bye, Norah. Please do come to-morrow."

"Yes, I promise we will come, unless it rains; and then, of course, you wouldn't be out either," said Norah. "Good-bye."

"Norah!" said Dan severely, as his sister pushed her way up through the bushes to the top of the bank, "you have been a very long time down in the glen, and I have called you lots and lots of times and you wouldn't answer. I think you must have heard!"

"Dan, dear, really I didn't hear," said Norah. "I was talking to the little foreign girl. Didn't you hear us? She was sitting in our glen, and her name is Una, and she is a very nice little girl; and she wants us to come and see her to-morrow, and I said we would if it was fine. Aren't you pleased, Dan?"

"Yes," said Dan, "very! I heard you talking to someone, and that is why I wanted to come down too. That's what made me cross, Norah; but I think the crossness has all gone away now, and I do want to hear about the little foreign girl, please," and Dan leant back comfortably in his chair as his sister began to wheel him over the mossy ground.

"Poor Dan!" said Norah; "it was horrid of me not to have heard you calling."

"I thought perhaps you were talking to a fairy," said Dan.

Norah laughed.

"I wish it had been a fairy," she said. "I would have wished for ever so many things. Oh dear, Dan, look at the sun! it's quite low, and mother will be wondering where we are."

"Here's Tom," said Dan. "Mother must have sent him to look for us."

Long before Tom reached them, however, he had begun to cry aloud his news.

"Mother's gone away! Aunt Edna's ill, and they sent a telegram for mother. Father's gone too, but he is coming back to-morrow."

"Oh, Tom!" said Norah.

And, "Oh, Tom!" echoed Dan blankly. It seemed so terrible to think of going home and finding no mother or father there.

"Who's going to look after us, and everything?" asked Dan.

"Kate is going to look after the house, and I'm to look after you—mother said so," said Tom importantly.

But the next morning Master Tom forgot his charge, and went off on some expedition of his own; and Norah and Dan were left on their own devices once more.

"I am glad father is coming back this evening," said Norah, as she pushed Dan's wheelchair through the wood on their way to see Una.

"So am I," said Dan; "but I do wish mother was coming too."

A low laugh sounded from somewhere close at hand, and Norah stopped wheeling the chair and looked about her.

"Norah, do you think it's fairies?" whispered Dan.

He had hardly said the words when a little girl sprang suddenly into the path in front of them. She was dressed in some soft, thick, white material, and had a long gauzy white shawl thrown over her head and shoulders.

"It's Una!" said Norah, and her little brother gave a sigh of disappointment. He had really almost thought that the little girl might be a fairy as she danced lightly on the path before them.

"I thought I would come and meet you to-day," said Una, "so I came through the—what do you call it?—the gap; and then when I heard you coming, I hid. I thought it might be someone I did not know, and Marie does not like me to be out alone."

"Is Marie your nurse?" asked Norah.

"Yes," said the little girl; "my very good nurse from the country of France."

"Are you a little French girl, then?" asked Dan.

Una looked at him gravely.

"No," she said. "I am cos—cos—it is such a very long word that I always forget it—cos-mo-pol-i-tan," she said slowly.

"Oh," said Norah, "that is a long word. And is that the name of the country where you come from?"

"I don't know," said Una. "Papa told me to tell anyone who asked me that I was cosmo—, you know, the long word again; and I think it means belonging to lots of different countries. Papa said it meant something like that when I asked him once; and we have lived in so many countries that I can't remember all the names."

"How nice to have lived in lots of different countries," said Dan. "When I'm a man I mean to be an explorer and go to every country in the world."

Norah looked a little unhappy. She always felt sad when Dan talked about all he meant to do when he was grown up, for she knew that he would never be strong enough to travel about the world as he wished.

"Why don't you be an author, Dan, and write books?" she said, "or a great painter, or a clergyman, like father?"

"I might be a clergyman," said Dan, "but if I was I should be a missionary, and go and preach to black people. Oh, Una!" he said, breaking off suddenly, "do you know, twice now I have thought you were a fairy—once when you were talking to Norah yesterday, and again to-day. And do you know what I was going to ask you if you had been a fairy? To give me and Norah a carpet so that we could go wherever we liked. Mother read us a tale about a fairy carpet last winter."

Again the puzzled look which Norah had noticed the day before came into Una's face.

"I don't know what you do mean," she said. "What are fairies? Are they people, or just little children?"

"Why," said Dan, "fairies are dear little people who live in a lovely country called Fairyland, and nobody knows where that country is—only there are lots and lots of doors to fairyland if only we knew where to find them.

"Norah and I have looked for a fairy door everywhere," he went on, "but we have never found one yet. And we have never found a fairy either, though we know exactly what we should ask her for if we did see one; and fairies do come out of fairyland sometimes; it says so in nearly all the fairy-tale books. Let's all wish now!" he cried suddenly. "Out loud, you know, so that if there should be a fairy hiding somewhere around she'll hear what we are asking for, and perhaps give it us!"

"Oh, but Dan——," Norah was beginning, when Una sprang to her feet and made a queer sort of little dance in front of them.

"Fairies! fairies!" she cried, clapping her hands as though she were a little fairy queen herself, calling all her little people together. "I want father to be quite happy, please, and not to have to work so hard in that nasty dark study, and I want some little boys and girls to play with and do lessons with, just as if they were my very own brothers and sisters; and I want a puppy-dog for my very own, please, fairies, and——"

"Oh, Una, Una! stop!" cried Norah. "You are spoiling all your wishes saying them out loud like that. Fairies never grant people's wishes if they call them out loud for everyone to hear."

But whether there were any fairies hiding in the wood that afternoon or not, at any rate one of little Una's wishes came true, as we shall see.

Nearly every day, after that first meeting, the children played with Una in the wood and joined her in the glen.

"The glen's nicer now it's Una's than when it was ours," said Dan one day, as he sat munching one of the nice little sugar cakes which Marie had made for them that morning.

"It wasn't ever ours really," said Norah.

"Well, anyway, it's Una's now, and it's much nicer," said Dan, looking gravely into the basket Una held out to him, and choosing a round, pink cake with a cherry in the middle.

Then one day something still nicer came to pass. The foreign gentleman came to call on Mr. Carew, to ask if he would allow his children to come every day and have lessons with his little girl.

The children were delighted when they heard of this. They had met the foreign gentleman in the lane as they were coming home from a walk with Rose, and they had wondered whether he had been to see their father.

"I hope he has not been to say we mustn't go and play with Una in the glen any more," Dan had said; but they had no idea what the foreign gentleman's visit had really been about until their father told them the next morning, after breakfast.

Mr. and Mrs. Carew had needed a little time in which to think about and talk over Monsieur Gen's proposal, and they did not want the children to know anything about it until all was settled.

For the last year—ever since Mary and Ruth had gone to school, and since Miss Rice, the governess who had been with them for over six years, had got married—the younger children had only had lessons when their mother or father could find time to teach them.

The school fees of the four elder children came to so large a sum of money that the vicar could not afford to have a governess at home for Norah and Tom and Dan; and as both Mr. and Mrs. Carew led very busy lives, lessons had sometimes to be put on one side altogether, and the children were beginning to forget a great deal which they had learned a year ago with Miss Rice.

The foreign gentleman's offer, therefore, had been a great relief to Mr. and Mrs. Carew, and the children were delighted at the idea of going to the Grange every day to do their lessons with Una.

"And we shall be able to tell Una more about the Bible now, shan't we, father?" said Norah. "She wants to know such a lot more. Nobody has ever told her about Christmas before—that it is Jesus Christ's birthday, I mean; and that that is why everyone is so happy then and tries to make everyone else happy, just like He used to do. And she didn't know God made the world, or that He takes care of us, or anything."

"Poor little girl!" said Mrs. Carew.

"Poor child, indeed!" said the vicar. "I wonder why Monsieur Gen——," and then he stopped suddenly, thinking, no doubt, that the children were quite curious enough already about their foreign neighbours. "After all, it is not for us to pry into other people's affairs," he said, with a smile. "Teach little Una all you can about the Bible and God's love, Norah; but do not worry her with questions about her father and his doings."

A week later the children went to the Grange for their first morning's lessons with Una.

"I feel just as if we were going into a magic palace," whispered Norah, as they waited for the door to be opened.

"And as if we should be turned into snakes and wolves and all sorts of horrid animals, before we came out again," said Tom.

"Or into one of those marble statues," whispered Dan, as they followed the servant across the hall to the foot of the staircase, where another servant met them and led the way upstairs. At the end of a long passage he paused and flung open a door, standing aside for the children to pass.

"Here lives the wizard!" murmured Tom under his breath; but it was only little Una who advanced to meet them across the big, bare room, bowing primly to each of the three in turn, then turning to introduce the English governess who was seated at a table near the window.

"Miss Berrill, my good English gouvernante," she said; and Miss Berrill smiled at the child's introduction, and told her to go with her little friends to take off their hats and coats, and that then she would try to find out how much they all knew.

The children thoroughly enjoyed those morning lessons and the hour of play afterwards. Week after week glided by until the Christmas holidays drew near, and pale, silent, little Una seemed turned into a different child.

In vain had the children begged for her to spend Christmas Day with them at the vicarage.

"My daughter does not visit," Monsieur Gen had replied; and the children felt that there was nothing more to be said.

They still stood very much in awe of Una's tall grave father, who looked in upon them now and again while they were at lessons or play, but never stopped to chat or romp with his little girl; and merely bent his head in acknowledgment of the stiff little curtsey with which Una always greeted him in obedience to Marie's directions.

On the afternoon of Christmas Day the children carried a small parcel of home-made gifts and almond toffee to Una; then stayed with her to sing some Christmas hymns and carols, and to tell her over again that wonderful old story of the first Christmas morning so many years ago.

With eager face and hungry eyes Una drank in Norah's words, turning to Tom every now and then for the explanation of some difficult word, or to Dan for a description of that Eastern stable; and long after the children had gone back to the merry home circle where "Peace" and "Goodwill," welcome angels, hovered around, the little foreigner sat gazing at the simple print, in its plain oak frame, of the Magi worshipping the Infant Christ,—a gift from the vicar to his children's friend.

January, February, March, April passed by, and one sunny morning in May Una awoke with the feeling that something very wonderful had happened the day before.

For a few moments she could not think what it was, as she lay listening dreamily to the songs of the birds outside; then all at once she remembered.

The day before she had been for a long walk with old Marie through the wood. Neither of them had ever been so far before; but Una had coaxed her old Nurse first up one winding path, then down another—begging her to walk just as far as the bluebells they could see in the distance, or to the tall fir-trees where they could listen to the wood-pigeons cooing overhead, or "just a little further," on the chance of catching a glimpse of the cuckoo they had heard calling all the afternoon—until old Marie had sat down on the stump of a tree, fanning herself with a handkerchief, and declaring that she could walk no more.

"Just a little further—only a little way more, Marie, please," Una begged. "I only want to see if the white flowers over there are the dog-daisies Tom told me about. Such a funny name, isn't it? Daisies which belong to the dogs!" And the little girl laughed merrily.

"No more, no more, Miss Una," the old Frenchwoman said. "You may run on by yourself for a little way, like a good child, if you keep within call." And Marie closed her eyes drowsily—quite overcome with the long walk and the warm afternoon—while Una hunted for birds' nests among the bushes, and added more blossoms to the already large bunch of flowers she had picked as she came along.

She had wandered further away from old Marie than she knew, when she came suddenly to a high, ivy-covered wall, and was able to go no further.

On either side it stretched away from her. The little girl was not able to see where the wall began or where it ended, and she thought that this must be the end of the wood at last, for the wall was so high that she could not see if trees grew on the other side of it.

Presently she began to hunt for birds' nests among the ivy—Tom had told her once that wrens and robins often built in ivy-covered walls—and then it was that she had made the wonderful discovery.

There, in the old brick wall, half hidden by the ivy, was a tiny oak door.

"The door to fairyland!" Una said to herself.

Then old Marie had called to her through the trees, and Una dropped the curtain of ivy and turned to meet her nurse with flushed cheeks and shining eyes, for had not Norah and Dan told her that only those who found the door to fairyland could enter in? They must not show it to others.

"I'll come by myself to-morrow," the little girl had thought to herself; and she sat up in bed the next morning with a little happy laugh of remembrance.

"I'll be in fairyland to-day," she whispered softly.

That afternoon, as soon as dinner was over and Marie had settled herself for her afternoon nap, Una slipped through the gap in the fence—how well she knew it now!—and started off by herself to try and find again the door into Fairyland.

On she ran, until she came to a place where three paths met, and was uncertain which to take.

A yellow butterfly, dancing gaily along one of the paths, decided her, and Una followed it gleefully.

"Perhaps it's a fairy sent to meet me," she thought.

At last she came to the stump of a tree where Marie had rested, and from there she soon found her way to the old wall in which was the secret door.

It took her longer to find the door than the little girl had expected. The ivy grew so thickly over the wall that she had to walk quite a long way—pushing aside the branches and peering between the leaves—before she found the little door once more.

Then she pulled away the twisted branches of the ivy which had grown across the door, and turned the handle timidly.

For a moment she thought the door was locked; then she heard a queer sort of grating sound and something fell on the other side of the wall. Una pulled once more, and the door opened slowly towards her.

What the little girl saw on the other side of the wall was so lovely that she gave a gasp of delight, and then stood, quite still, looking through the small doorway.

As far as she could see was a long bower of lovely pink and white flowers. Hundreds of bees hummed amongst the blossoms; but to Una the buzzing sounded like hundreds of tiny voices, and she thought she heard the fairies talking.

"Fairies! Fairies!" she called softly. But no one answered, and very soon the little girl stepped through the doorway and walked down the apple-blossom path, looking from side to side to see if there were any fairies hiding near.

On she went, until the pink and white bower turned into a wide walk with masses of gay May flowers on either side, and this in turn ended in a big square garden with stone walks and bright flower-beds, and a fountain sparkling in the midst.

In the stone basin of the fountain were pretty gold and silver fish.

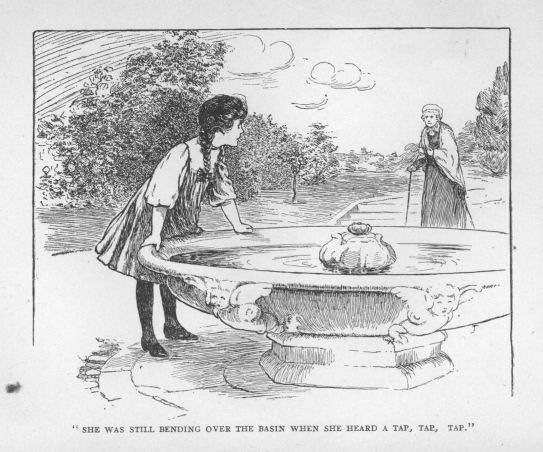

"Fairy fishes!" Una thought, for she had never seen goldfish before, and she was still bending over the basin when she heard a tap, tap, tap on the stone pathway, and, turning quickly, saw a very small, very old lady coming towards her.

"A fairy godmother," thought Una. "I didn't know they lived in Fairyland."

Then she went to meet the old lady, giving a quaint little curtsey and waiting for her to speak.

"Well, little girl," said the old lady kindly, "and who are you?"

"I'm Una," said the child gravely.

Then she gave a sudden jump in the air.

"Oh, fairy-godmother, how kind of you—there's my puppy dog!" she cried, as a fat retriever puppy gambolled down the path and flung itself playfully upon her.

The old lady looked amused.

"A fairy godmother, am I?" she said, smiling. "What can I do for you, then?"

"Oh, such a lot of things!" said Una. Then a surprised look came into her face: "Why, here's an old gentleman!" she said. "I didn't know there were fairy godfathers too. Do you live in Fairyland together?"

The old lady laughed outright.

"Dear child, do you think this is Fairyland?" she asked.

"Isn't it Fairyland?" said Una. "Oh, dear, I thought it must be when I came through the little door."

"The little door?" said the old lady. "Where is that?"

"The door in the wall," said Una. "I found it yesterday when I was in the wood, and I thought it was one of the doors to Fairyland."

"Ah! the little door at the end of the apple walk," said the old lady "I had almost forgotten it, it is so long since it has been used—and I thought it was locked, too," she added, half to herself. "Edward," she said, raising her voice a little as she spoke to the old gentleman, "here is a little girl who has found her way into our garden thinking it was Fairyland."

"And a very nice kind of Fairyland too," said the old gentleman, "especially when this kind of little fairy comes to visit us," and he held out his hand to Una kindly.

"You are the little girl from the Grange, are you not?" asked the old lady; then, remembering some rather queer tales she had heard of the new people at the Grange, she asked no more questions, but said that tea would soon be ready, and invited Una to stay and have it with them.

After all it was almost as nice as being in Fairyland, Una thought, as they sat under a large cherry tree covered with snowy blossoms, and drank tea out of the thinnest of china cups, each one shaped like a different flower, with a beetle or a bird or a butterfly for the handle. The clearest of honeycomb was on the table, which the old gentleman had sent for especially for Una; and the black puppy sat at her side all tea-time, opening his wet, black mouth for tastes of bread and butter, and rubbing his head against her knee if she forgot to give him any.

When tea was over Una looked at the sun.

"Oh, dear," she said, "the sun is getting quite low, and Marie will think I am lost."

"Dear, dear! We ought to have thought of that," said the old lady. "Will not your father be anxious also?"

"Papa is away from home for a few days," said Una.

Then she made a little curtsey.

"May I go now, please?" she asked; and the old lady walked with her as far as the little door.

"Come another afternoon to Fairyland," she said, as she stooped to kiss the little girl.

Una promised readily, and only remembered when she was half way through the wood that her father did not like her to visit at strange houses.

"I'll tell him where I've been directly he comes home to-morrow," she thought.

But when she pushed her way through the bushes in the Grange garden she saw her father coming quickly across the lawn towards her, with a short, stout gentleman beside him.

"My little girl, where have you been?" he said. "Marie came to me in great distress just now and told me that Mademoiselle Una was lost, and we have been looking for you everywhere."

"Father, dear father, don't be angry, please," said Una coaxingly; "but I've been to tea this afternoon with a dear old lady and gentleman, and they live in the loveliest garden in the world—at least I think it must be. And they want me to come again; and I do want to go very much, please, father. So don't say 'no,' as you do when I want to go to tea with Norah and Dan. Please, please, father, say 'yes.'"

Monsieur Gen hesitated and glanced towards his friend. But the little stout gentleman was frowning, and Una thought what a disagreeable man he was, and wished that he had not come home with her father, when they might have had such a nice evening together, just he and she alone.

"It is not wise to let the child go anywhere she likes among strangers. You know what children's tongues are like, and how easily stories get afloat," the stranger said in French.

But Una understood French as well as she understood English, and she felt very angry with the stranger for trying to persuade her father not to let her go and see the dear old lady and gentleman again.

"No, dear. You must learn to stay quietly here in the garden," said her father; and Una said no more then, but walked slowly across the lawn into the house and upstairs to the nursery, where she was scolded by old Marie for having run away by herself that afternoon.

And it was not until some hours later—after she had watched the strange gentleman driving away to the station—that she ran downstairs to the library and asked the question which had been puzzling her little brain for the last few weeks.

"Father," she said, "I want to know why I mayn't go and see other little boys and girls, and go to church, and go to see the people in the cottages, as Norah and Tom and Ruth do."

"What makes you ask that question, Una?" said her father. "When we have lived in other countries you have never asked to have little boys and girls to play with, or worried about why you may not go and see people and go to church; and here you have Norah and Tom and Dan to play with. Surely that is enough?"

"But I didn't know before that little boys and girls did play with each other," said Una—"at least, when I saw other little boys and girls playing with each other I thought they were brothers and sisters, or cousins, and, of course, I haven't got any brothers or sisters or cousins of my very own; but now that I know what little boys and girls do, I do want to go to church and go to tea with them in their houses, and do things like them. Please, father, let me!" And Una clasped her hands coaxingly as she thought of the dear old lady and gentleman she had been to tea with, that afternoon.

The flower-filled garden, the yellow honeycomb, the gold-fish and the black puppy—and the cockatoo the old gentleman had promised to show her the next time she came—all floated through her brain as she waited for her father's answer. But Monsieur Gen shook his head.

"No, dear," he said.

To himself he was thinking that perhaps he had been foolish to allow Una to be friends with the vicar's children at all; he might have known that it would make her restless, and dissatisfied with the quiet life she had been quite content to live before.

Then he roused himself and looked down kindly at his little girl.

"Are you very disappointed? Poor little Una!" he said, putting his arm round her and drawing her to his side. "Don't look so sad, and I will try and explain to you why it is that you have never had little friends and companions of your own age."

Una looked at him, still gravely, but with the light of a growing interest in her eyes. Then she fetched a little stool and sat down at her father's feet.

"You must know, Una dear," said her father, smiling rather sadly, as he looked down at her, "that each one of us has some kind of work to do in the world. We may do it badly or we may do it well, or we may not even try to do it at all, but each one of us ought to try to do something to help our fellow-men. Do you understand, little one?"

Una nodded.

"Yes, father; I quite understand," she said.

It was not often that her father talked in this way—it was rather like listening to the vicar's sermon the only Sunday she had ever been to church, she thought, as she leant her head against her father's knee; and Monsieur Gen went on speaking:

"Well, dear, sometimes people can help each other to do their bits of work in the world, and sometimes, too, they can spoil other people's work; and there are some people who are trying very hard to spoil the work which I am doing."

Una sprang to her feet.

"Father! How dare they?" she said indignantly. "Horrid people, … I hate them!"

Her father reached out his hand and drew her to him.

"But as long as they cannot find out exactly what I am doing," he said, "or how I am doing it, they cannot really spoil my work; and that is why I have never made friends with people in any of the different places where we have stayed, in case the people who want to spoil my work should try and find out through these new friends who I am, and what I am doing. And that is why I want you, my little Una, to help me to keep my work as secret as possible."

"Oh, father, I will, I will!" cried Una. "Only—only I don't quite see how I can let out a secret if I don't exactly know what it is."

"I cannot tell you all the secret, little Una," said her father—"at least not until you are older and can understand more about it. But if I were to let you make friends and go about wherever you like people would begin to wonder where you came from, and who you were, and to ask you questions about me and what I did; and although not really knowing my secret, you might let out little bits of it, until people began to wonder and talk about you and me. One can never be too careful," he added, half to himself.

"Yes, I understand, father," said Una gravely; and she sat at her father's feet, looking into the fire and not talking much, until the little clock on the mantelpiece struck seven, and Marie came to tell her that it was bedtime.

"I wonder whether I was wise in telling her so much," Monsieur Gen thought to himself, when his little daughter had gone. "But it seemed the only thing to be done, and she is prudent beyond her years, poor little, lonely girl. I do not think she will chatter about anything I have told her."

For some time after this Una was rather quiet and sad, more like what she had been when Norah and Dan first got to know her, and not nearly so ready to laugh and play as she had been of late.

The secret her father had told her weighed heavily on the little girl's mind—she was so afraid that she might have let out to her little friends, though unknowingly, something about her father's work, and she was careful now not to say anything which might lead them to ask questions about him.

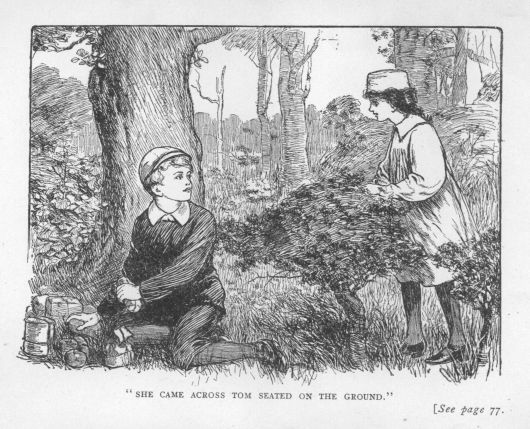

One afternoon she was walking by herself in the wood, when she came across Tom seated on the ground with a number of paper bags and packages strewn around him.

"Hullo, Una, what are you doing?" he said, glancing rather guiltily at the parcels, as if he hoped Una would not ask what was in them.

"I came to see if I could find any flowers," answered the little girl. "Marie has a headache this afternoon, and she said I might go in the wood just a little way by myself, because I am so tired of being in the garden."

"I'll show you where you can get some honeysuckle in a minute," said Tom; "it's just out now, and I know where there are some wild forget-me-nots growing all round a pool, a little way from here."

He got up and began to collect some of the paper packages into his arms; then he looked at Una.

"I say, I wonder if you'd help me to carry some of these?" he said. "I kept dropping them coming along, and the marmalade jar has got cracked—it's all dripping through the paper; and the apples keep rolling all over the place," making a sudden dive after a large red apple as he spoke, and dropping half the other parcels in his efforts to catch it.

"I will, if it's not farther than the wood," said Una. "I mayn't go in the road by myself, you know."

"You wouldn't be by yourself, you'd have me," said Tom. "But, anyway, I'm not going outside the wood—at least, only just on to the common, and you needn't come so far as that. I say, Una, shall I tell you a secret?"

Una threw out her hands in the funny little foreign way which was natural to her, and which always made the little Carews laugh.

"Oh, no, no!" she cried. "Not a secret! Please, Tom, don't tell me one."

Tom stared at Una in surprise.

"Well, you are a funny girl," he said, rather gruffly. "I thought you'd be pleased; it's not often you catch me telling a girl a secret."

Una bent down and began to pick up some of the fallen parcels. She was sorry that she had offended Tom, for it was not often that he condescended to play with or talk to her, and she had felt rather proud when he had asked her to help him that afternoon.

"I thought all girls liked secrets," went on the boy. "You're not a bit like Norah. Why, she'd give anything to know my secret this afternoon."

"Would she? How funny!" said Una, genuinely surprised. "I think secrets are horrid."

"Secrets horrid? Why, they're lovely!" said Tom. "When Barnes—he's our gardener, you know—says he has got a secret to tell me, I know that Bruno has puppies, or that the peaches are ripe and he's going to give me a basketful to take to mother; or he's found a wild bees' nest in the wood and he wants me to help him to dig the honeycomb out; or—or—oh, I can't think of any more now, but secrets are always jolly."

"No, they are not—not quite always," said Una gravely. "But is yours a jolly one, Tom?"

"Yes," said Tom, "awfully!"

"Oh, then, I do want to hear it," said Una eagerly. "Please, Tom, tell me."

"Well," said Tom, "it's just like this: there are some gipsies camping on the common now, and they've got four tiny children, and one's only a baby; and the father broke his leg, some weeks ago, and he's in a hospital at Lawton—the woman told mother all about it when she came to sell chairs and things this morning. She makes dear little chairs, Una, out of oak-apples and chestnuts and things like that; and little picture-frames with grey lichen and acorns and bits of twigs stuck all round; and mother bought a chair for Norah's doll, because, she says, it's much better for them to try and make things like that and try to sell them than just to come round begging, as so many of them do."

Una nodded, as Tom paused for breath.

"Yes, Tom," she said; "go on."

"Well," said the boy, "mother sent Barnes round this morning to see if it was all true; and it is true, quite true, Barnes says. And so mother said I might take them some bread and a pot of marmalade, and butter, and a packet of tea, and sixpence to buy milk with, and then just as I was starting father gave me the six-pence he said he would for weeding the big bed beside the lawn; and so I spent it on biscuits and sugar for the children, because tea is horrid without sugar, isn't it? And that's the secret, Una," said Tom, getting rather red in the face, "and I haven't told anyone but you, because, because, oh—I don't know! But I don't want anybody to know, so you won't tell, will you?"

"No, I promise I won't tell," said Una. "And I think it is an awfully nice secret, Tom dear, and thank you very much for telling me."

"You see," went on Tom, feeling that Una was rather a nice little girl to tell things to, "you know what father said in his sermon last Sunday about not letting your right hand know what your left hand does? Oh, no; I forgot you weren't there. Well, it means if you go and do anything for anyone, or give anything away, or anything like that, don't go and tell everyone what you're doing, just for them to say what a jolly good sort you are."

"Oh, yes, I see!" said Una; "that would be a horrid way of giving things, wouldn't it, Tom? Yours is an ever so much nicer kind of way."

Tom grunted, feeling all of a sudden rather bashful; for it was not often that he talked about himself or his own doings. He was rather the odd one of the family—Norah and Dan being such very great friends, and having so many little plays and fancies together in which he had no share; and Philip and the elder girls being rather inclined to class him with Norah and Dan—as one of the "little ones"—when they came home for the holidays.

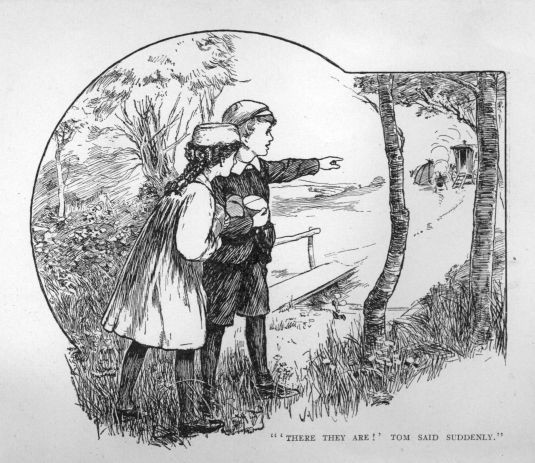

"There they are!" he said suddenly. "Look, Una, you can see their wigwam through the trees—that funny sort of hut-place with a rounded roof."

"The gipsies?" said Una. "Oh, Tom, do they live in that funny little house?"

"Yes," said Tom, "and when they want to go somewhere else they just pack up their hut—it all comes to piece somehow—and then go off in that cart. It must be awfully jolly to live like that."

"Yes, in the summer," Una agreed, "but not in the winter, Tom. Oh, no!—not in the cold, cold winter, when the snow is on the ground," and Una gave a little shiver at the thought.

"No," said Tom, "not in the winter, perhaps, and not when they haven't enough to eat, like these now. The woman said she'd only had half a loaf of bread to give her children all yesterday, and that is why mother sent them a great can of soup by Barnes this morning, and I'm taking them these things now, because they're going on to-morrow towards the hospital where the children's father is. Now, what are you going to do, Una? Are you coming too, or going to stay here?"

"I'll stay here," said Una, "if you can carry all the parcels."

"Yes, I can," said Tom. "I carried them all the way from the shop to where I met you in the wood."

Una piled the parcels carefully one on the top of the other in Tom's arms, then sat down on the mossy root of a tree, and watched him as he crossed the common towards the little brown hut among the gorse bushes.

A thin wreath of smoke curled upwards from a small fire in front of the hut; and as Tom drew nearer two children began to throw twigs and branches on the fire, making it crackle and blaze while they danced wildly round the flames, giving little squeals of delight and hitting at each other with the sticks they held in their hands.

It was all fun, however. Una could tell that by the peals of laughter which reached her ears, and she laughed, too, when a little thin black dog sprang out of the hut, joining madly in the dance, and barking furiously when he caught sight of Tom coming towards them.

The children stopped dancing and looked at Tom gravely; then they disappeared inside the hut, calling to someone within, and the next moment a woman came out with a baby in her arms, and another little one clinging to her skirts.

She bobbed a curtsey to Tom, and presently began to take the parcels one by one out of his arms, bobbing lots of little curtseys as she did so; but Una was too far off to hear what Tom and the woman were saying to each other, and she was disappointed when they all went behind the hut and she could not see them any more.

She could still see the parcels where the woman had laid them in a little white heap beside the fire; and by-and-by one of the children came round from the back of the hut and began to open each of the packages in turn, giving little hops and skips of joy as he saw the nice things inside.

Then the other children appeared again, followed by Tom and the gipsy-woman; and they all bobbed curtseys to Tom once more before he left them and came across the heather towards Una, carrying something very carefully in a red pocket-handkerchief.

Una went to meet him through the trees.

"What have you got there, Tom?" she asked.

"Another secret!" he cried, waving the handkerchief to and fro before her eyes.

"Another secret? Oh, Tom!" said Una.

"It's a nice one, too," said Tom. "Guess what I've got here, Una."

Una looked hard at the handkerchief for some moments; then she slowly shook her head.

"I can't, Tom," she said, wondering if Norah would have been able to guess, and fearing that Tom must think her a very stupid little girl indeed.

But Tom only laughed gleefully.

"I knew you couldn't," he said; "and I don't expect you'll know what to call it, even when you've seen it."

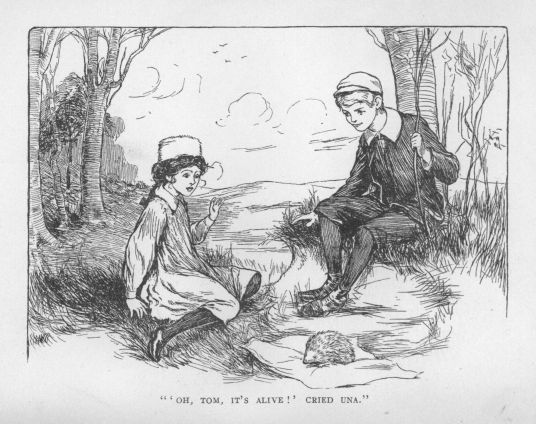

He knelt down on the moss and opened the handkerchief, exhibiting a funny-looking, spiky ball.

"Oh, Tom, what is it?" asked Una. "A ball made of pine-needles?"'

"Pine-needles!" laughed Tom. "You touch the point of one, and see!"

Una pressed one of the spikes gently with her finger, and gave a little cry as the ball moved slightly and became half unrolled; then curled itself up as before.

"Oh, Tom, it's alive!" she cried.

"Yes, it's alive," said Tom. "It's a hedge-hog, Una. The little gipsy-boy found it this morning under a gorse-bush, among some leaves. Hedgehogs go to sleep all the winter, rolled up like this in a ball; and they store up a lot of food somewhere near in case they wake up and get hungry during the winter; and when the spring comes they wake quite up, and begin to move about. That is why this one is really awake now, only he has rolled himself up, and pretends to be asleep, because he's frightened."

"Oh, the funny little thing!" said Una, bending down to see if she could catch a glimpse of the hedgehog's bright little eyes.

"What do you think I'm going to do with it?" asked Tom.

"Keep it?" suggested Una.

"No," said the boy, "I'm going to give it to you."

"Oh, Tom—what for?" asked the little girl, trying to look very pleased and grateful, but wondering whatever she was to do with such a prickly present.

"What for? Why, for you to have as a pet," said Tom. "You're not half such a silly girl as I thought you were; and, of course, you can't help not being English," he added magnanimously. "And, you know, I do think it is awfully dull for you, shut up in that big garden, when we're not there to play with you: and now you'll have the hedgehog to play with."

"So I shall," said Una. "What—what shall I do with it, Tom?"

"Why, feed it," said the boy, "and teach it to know you and to come when you call. You'll have to name it, Una, and teach it tricks and all sorts of things," and poor Tom gave one big sigh as he thought how he would have liked to keep that hedgehog for himself instead of giving it to Una.

Una was too polite, however, to say she did not want the little animal. She knew that it was very kind of Tom to have given it to her, though she had no idea how much he wanted it himself; and she asked him to come home with her that afternoon and make a house for it in the garden, so that it should not run away and get lost in the woods.

After all, Tom's present turned out a great success. It was the first time Una had ever had a pet in her life, and she became so fond of the little creature that she would spend hours playing with it in the garden, tickling its little head with the tip of her finger, and feeding it with dandelion flowers, which it loved.

It was through the hedgehog that rather a queer thing happened one day in the garden.

I think I told you that Una's father went away somewhere by train once a week, and usually came back either the next day or two or three days later, but I don't think I told you that sometimes he brought back gentlemen to stay with him; and occasionally these gentlemen stayed until Monsieur Gen went away again the next week, though more frequently they remained only one night at the Grange and went away again the next day. Now and then, however, they stayed much longer than that—for weeks together indeed; and Una noticed that the ones who stayed longest always looked very pale and thin, and very, very sad, as if they had had much trouble.

But she did not see very much of any of her father's visitors—only coming across one or another of them sometimes on the stairs or in the garden; and the little Carews had never seen any of them, for when they were playing there with Una the strange gentlemen did not come into the garden.

Una used to wonder sometimes what made all the gentlemen who came to her father's house look so sad. All men did not look sad, she knew, for the baker's man who came to the house looked quite jolly, and had a round, red face which seemed always laughing; and Mr. Carew, her little friends' father, looked quite cheerful, too, quite different from her own grave father.

Poor little girl! It was sad for her, this mystery which hung about her life; and I think she would have grown into a very quiet, grave little maiden in those days if she had not had the little Carews to play and be merry with.

One day the children had been having a game on the terrace in the front of the house. It was a new game which Tom had made up, and which they all liked very much. One of them stood, blindfolded, in front of a heap of little sticks at one end of the terrace, and the others all had to hop on one leg and try to get the sticks, one by one, without the blindfolded one catching them; the fun of the game being that it was very difficult not to make a noise hopping on the gravel, and the "blind man" usually pretended not to hear, and then made a dash at the hopping thief just as he or she was carrying off a stick.

They had been playing so long at this game that they had made themselves quite tired and hot, and had sat down on the lawn to rest; and then it was that Una remembered that she had forgotten to shut up "Snoozy," as she had named the hedgehog, after she had given him his breakfast that morning, and now she could not think what had become of him.

The hedgehog had got so tame now that he would follow his little mistress about the garden, and come when she called or whistled; and Una generally let him have a run in the garden every morning, and then shut him up again when she went in to lessons.

To-day, however, although she called and whistled, and looked in all the little animal's usual haunts, she could not find him, and they had almost begun to think that he must have run away into the wood, when Tom thought of the drooping ash-tree at the end of the lawn, and wondered whether "Snoozy" might have hidden himself in there.

"How silly of us," cried Norah. "Why, of course, he must be there. Fancy not thinking of looking there before!"

"I don't know," said Una, "he has never hidden there before; but we can go and look," and they all raced across the lawn, and pushed their way through the drooping branches of the tree.

Yes, there was the hedgehog, curled up into a little ball against the trunk of the tree—thinking, no doubt, that evening had come round again; for the branches and leaves were so thick that it was quite dark under the ash-tree—and beside the hedgehog, leaning carelessly against the trunk of the tree, with folded arms and a scowl upon his face, was a tall, pale-faced, black-haired young man.

For some moments the children stared at the young man without saying a word—they were so surprised at finding him there; and he scowled back at them fiercely, as though he thought they had no right to have come under the ash-tree at all.

"We came to look for my hedgehog," said Una at last, making just the suspicion of a curtsey as she spoke, for this young man was so much younger than most of her father's visitors that she was not quite sure whether her old nurse would have told her to curtsey to him or not.

The young man looked at her, then muttered something to himself in a strange language, and shook his head.

Then Una spoke in French.

"We came to look for the little animal there," she said, pointing to the hedgehog; and the young man smiled as he pushed it gently with his foot and rolled it towards her.

He looked so much nicer when he smiled that the children began to feel more at ease with him, and to think that he was not such an ugly young man after all; but very soon the gloomy look came back to his face, and he pushed his way out through the branches, as if anxious to get away from the shade of tree and his own thoughts at the same time.

The children followed him out into the sunshine, and the young man looked down at them with a queer sort of expression in his black eyes; then he said something quickly in the strange language in which he had spoken before, and looked at Una as if he thought she would understand; but the little girl stared blankly back at him, and he saw that she did not know what he had said.

It was not the first time Una had heard that language, however. Her father had sometimes talked to her like that in soft caressing tones as she sat on his knee before the fire, or when they walked together in the garden; but he had always laughed when Una had asked him what he was saying, and had told her that she would understand some day. The only other people whom she had heard speak in that tongue were the strange gentlemen who sometimes came to stay in the house.

Then the young man began to speak in French—a little slowly at first, as if he were not at all sure that his listeners would understand; but when he saw that Una understood quite well, he brightened up and began to speak quickly, pouring out such a torrent of words that Tom and Norah and Dan had not the least idea what he was talking about, and wondered how it was possible for Una to understand what he said.

That Una did understand was quite certain, for her little face paled and flushed at the young man's words; her dark eyes grew big with fear, then filled with tears, and by-and-by a little sob broke from her throat, and the children saw that she was crying bitterly—not loudly, but very, very sadly, as if she could not help it and really hardly knew that she was crying at all.

When the young man saw Una's tears he suddenly stopped talking, and looked uncomfortable; then he softly stroked the little girl's fair hair, and whispered something to her so gently and kindly that Una smiled at him through her tears, and the children felt that they liked him a little bit after all; though just before, Tom had been wishing very much that he were quite big, so that he could knock the strange man down for making Una cry.

Then the young man turned to go, but came back to ask Una a question; and the little girl answered him eagerly in French, repeating something several times over, and nodding her head firmly as if she were making a promise. The young man smiled at her once more, and then went away into the house.

"Well!" Tom burst out as soon as the stranger was out of hearing, "I should like to know what all that gibberish was about, Una."

"And me, too," said Norah. "Please tell us, Una. I couldn't understand one word he said."

"Nor anyone else," said Tom; "at least—I forgot—Una did. I suppose that's because you gabble such a lot of French to Marie, isn't it, Una? Marie talks as fast as seven cats all rolled into one."

"Cats don't talk!" said Una, smiling; then she grew very grave. "Oh Tom," she said, "I don't feel a bit like laughing, really. He told me such sad, sad things, that man. He said there is a country, a long way off, where the little children are quite miserable—not happy and laughing like us. He said that it was seeing us all playing and laughing just now made him feel quite cross and angry with us, because it made him think of his little brothers and sisters—at least, I am not quite sure if he did say his little brothers and sisters, or some other little children he knows.

"They have been turned out of their home and have to live in a nasty, cold, snowy country with no friends, except their mother; yes, she is there; but their father has to work in a horrid sort of prison, and he hasn't done anything wrong—that isn't why he's being punished. And he says—the man I mean—that there are lots of little children like that in that country, and they are all sad and cold and hungry and miserable.

"He told me the name of that country, too," the little girl went on; "but I mustn't tell you, because it is a secret and I promised not to. Oh, dear! I hope it is not naughty of me to have told you all this," cried Una, suddenly bursting into tears. "I do hope I'm not letting out any of father's secret; but it made me feel so sad all that the man told me, and I wanted to talk to someone about it, and—and I never thought of it being anything to do with—Oh, dear! oh, dear! now I'm letting out more and making it worse!"

"Never mind, Una! Don't cry. We won't tell, anyone, we promise faithfully we won't," cried the children, much distressed at Una's tears; and soon the little girl dried her eyes and was at last satisfied by their promise not to tell anyone about the poor little unhappy children she had told them of. She bade her little friends good-bye then, and carried "Snoozy" away rather sadly to his home in the kitchen garden—a disused cucumber frame, where he was generally put for safety when his little mistress was not with him in the garden.

Una met the black-haired young man several times after that in the house and garden, but he did not talk to her again about the little boys and girls who lived in that other country, which was so different from kind, peaceful old England. After a time he went away, and no more strange gentlemen came to the house. And then, one day, Una's father went away also.

This was not one of Monsieur Gen's usual visits to London, when he stayed sometimes one night, sometimes two, or even came back the very same day to Haversham. This time he would be away for some weeks, perhaps a month, perhaps longer, he said, as he kissed his little girl one sunny June morning; and now August had come, and Una's father had not come back again, and the little girl felt very lonely as she wandered among the weedy flower-beds in the rose-garden.

There were not many roses out that morning, and the few that still bloomed on the bushes were poor specimens compared with the beauties that used to scent the air in that old garden. For years the Grange roses had been noted for miles around; but it was long since pruning shears had touched those branches, or since care of any sort had been shown to the Grange grounds, and it was only the children who thought the flower-beds beautiful and the garden itself a play-ground of bliss.

It was indeed a pleasant place to them, that overgrown old garden; for no gardener looked askance when they dug holes in the gravel paths, or turned the rockery into a grotto large enough to get into themselves and play at elves and witches and mermaids and other delightful games; and no one said them nay when they built a hut upon the lawn—with willow branches and rushes from beside the pond—where they "camped out" many a long summer afternoon, pretending to be gipsies, or soldiers, or Ancient Britons, whichever their fancy pleased.

The days did not pass quite so happily, just now, for Una. Philip and Stephen Carew had brought home a boy friend with them from school, and Tom liked to play cricket with the elder boys in the vicarage meadow, while Mary and Ruth and Norah were generally asked to field, and Dan looked on and clapped encouragement from the bank where he usually sat to watch the players.