Title: The Kensington District

Author: G. E. Mitton

Editor: Walter Besant

Release date: May 30, 2007 [eBook #21643]

Most recently updated: January 2, 2021

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/21643

Credits: Produced by Susan Skinner and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Cloth, price 1s. 6d. net; leather, price 2s. net each.

THE STRAND DISTRICT.

By Sir Walter Besant and G. E. Mitton.

WESTMINSTER.

By Sir Walter Besant and G. E. Mitton.

HAMPSTEAD AND MARYLEBONE.

By G. E. Mitton. Edited by Sir Walter Besant.

CHELSEA.

By G. E. Mitton. Edited by Sir Walter Besant.

KENSINGTON.

By G. E. Mitton. Edited by Sir Walter Besant.

HOLBORN AND BLOOMSBURY.

By Sir Walter Besant and G. E. Mitton.

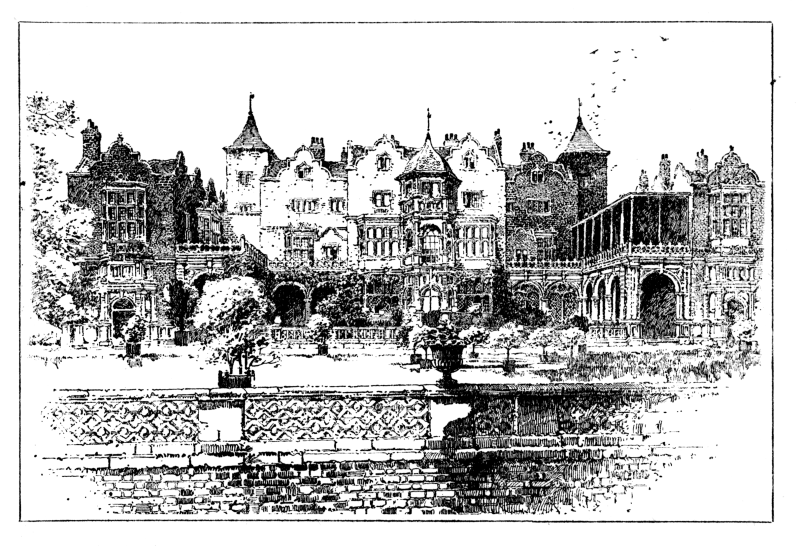

Herbert Railton

Herbert Railton

BY

G. E. MITTON

EDITED BY

SIR WALTER BESANT

LONDON

ADAM & CHARLES BLACK

1903

A survey of London, a record of the greatest of all cities, that should preserve her history, her historical and literary associations, her mighty buildings, past and present, a book that should comprise all that Londoners love, all that they ought to know of their heritage from the past—this was the work on which Sir Walter Besant was engaged when he died.

As he himself said of it: "This work fascinates me more than anything else I've ever done. Nothing at all like it has ever been attempted before. I've been walking about London for the last thirty years, and I find something fresh in it every day."

Sir Walter's idea was that two of the volumes of his survey should contain a regular and systematic perambulation of London by different persons, so that the history of each parish should be complete in itself. This was a very original feature in the great scheme, and one in which he took the keenest interest. Enough has been[Pg viii] done of this section to warrant its issue in the form originally intended, but in the meantime it is proposed to select some of the most interesting of the districts and publish them as a series of booklets, attractive alike to the local inhabitant and the student of London, because much of the interest and the history of London lie in these street associations.

The difficulty of finding a general title for the series was very great, for the title desired was one that would express concisely the undying charm of London—that is to say, the continuity of her past history with the present times. In streets and stones, in names and palaces, her history is written for those who can read it, and the object of the series is to bring forward these associations, and to make them plain. The solution of the difficulty was found in the words of the man who loved London and planned the great scheme. The work "fascinated" him, and it was because of these associations that it did so. These links between past and present in themselves largely constitute The Fascination of London.

G. E. M.

When people speak of Kensington they generally mean a very small area lying north and south of the High Street; to this some might add South Kensington, the district bordering on the Cromwell and Brompton Roads, and possibly a few would remember to mention West Kensington as a far-away place, where there is an entrance to the Earl's Court Exhibition. But Kensington as a borough is both more and less than the above. It does not include all West Kensington, nor even the whole of Kensington Gardens, but it stretches up to Kensal Green on the north, taking in the cemetery, which is its extreme northerly limit.

If we draw a somewhat wavering line from the west side of the cemetery, leaving outside the Roman Catholic cemetery, and continue from here to Uxbridge Road Station, thence to Addison Road Station, and thence again through West Brompton to Chelsea Station, we shall have traced roughly the western boundary of the borough. It covers an immense area, and it begins and ends in a[Pg 2] cemetery, for at the south-western corner is the West London, locally known as the Brompton, Cemetery. In shape the borough is strikingly like a man's leg and foot in a top-boot. The western line already traced is the back of the leg, the Brompton Cemetery is the heel, the sole extends from here up Fulham Road and Walton Street, and ends at Hooper's Court, west of Sloane Street. This, it is true, makes a very much more pointed toe than is usual in a man's boot, for the line turns back immediately down the Brompton Road. It cuts across the back of Brompton Square and the Oratory, runs along Imperial Institute Road, and up Queen's Gate to Kensington Gore. Thence it goes westward to the Broad Walk, and follows it northward to the Bayswater Road. Thus we leave outside Kensington those essentially Kensington buildings the Imperial Institute and Albert Hall, and nearly all of Kensington Gardens. But we shall not omit an account of these places in our perambulation, which is guided by sense-limits rather than by arbitrary lines.

The part left outside the borough, which is of Kensington, but not in it, has belonged from time immemorial to Westminster (see same series, Westminster, p. 2).

If we continue the boundary-line we find it after the Bayswater Road very irregular, travers[Pg 3]ing Ossington Street, Chepstow Place, a bit of Westbourne Grove, Ledbury Road, St. Luke's Road, and then curving round on the south side of the canal for some distance before crossing it at Ladbroke Grove, and continuing in the Harrow Road to the western end of the cemetery from whence we started.

The borough is surrounded on the west, south, and east respectively by Hammersmith, Chelsea, and Paddington, and the above boundaries, roughly given as they are, will probably be detailed enough for the purpose.

The heart and core of Kensington is the district gathered around Kensington Square; this is the most redolent of interesting memories, from the days when the maids of honour lived in it to the present time, and in itself has furnished material for many a book. Close by in Young Street lived Thackeray, and the Square figures many times in his works. Further northward the Palace and Gardens are closely associated with the lives of our kings, from William III. onward. Northward above Notting Hill is a very poor district, poor enough to rival many an East-End parish. Associations cluster around Campden and Little Campden Houses, and the still existing Holland House, where gathered many who were notable for ability as well as high birth. To Campden House Queen Anne, then Princess, brought her[Pg 4] sickly little son as to a country house at the "Gravel Pits," but the child never lived to inherit the throne. Not far off lived Sir Isaac Newton, the greatest philosopher the world has ever known, who also came to seek health in the fresh air of Kensington.

The southern part of the borough is comparatively new. Within the last sixty years long lines of houses have sprung up, concealing beneath unpromising exteriors, such as only London houses can show, comfort enough and to spare. This is a favourite residential quarter, though we now consider it in, not "conveniently near," town. Snipe were shot in the marshes of Brompton, and nursery gardens spread themselves over the area now devoted to the museums and institute. It is rather interesting to read the summary of John Timbs, F.S.A., writing so late as 1867: "Kensington, a mile and a half west of Hyde Park Corner, contains the hamlets of Brompton, Earl's Court, the Gravel Pits, and part of Little Chelsea, now West Brompton, but the Royal Palace and about twenty other houses north of the road are in the parish of St. Margaret's, Westminster." He adds that Brompton has long been frequented by invalids on account of its genial air. Faulkner, the local historian of all South-West London, speaks of the "delightful fruit-gardens of Brompton and Earl's Court."[Pg 5]

The origin of the name Kensington is obscure. In Domesday Book it is called Chenesitum, and in other ancient records Kenesitune and Kensintune, on which Lysons comments: "Cheneesi was a proper name. A person of that name held the Manor of Huish in Somersetshire in the reign of Edward the Confessor." This is apparently entirely without foundation. Other writers have attempted to connect the name with Kings-town, with equal ill-success. The true derivation seems to be from the Saxon tribe of the Kensings or Kemsings, whose name also remains in the little village of Kemsing in Kent.

From Domesday Book we learn that the Manor of Kensington had belonged to a certain Edward or Edwin, a thane, during the reign of Edward the Confessor. It was granted by William I. to Geoffrey, Bishop of Coutances, under whom it was held by Alberic or Aubrey de Ver or Vere. The Bishop died in 1093, and Aubrey then held it directly from the Crown.

Aubrey's son Godefrid or Geoffrey, being under obligations to the Abbot of Abingdon, persuaded his father to grant a strip of Kensington to the Abbot. This was done with the consent of the next heir. The strip thus granted became a subordinate manor; it is described as containing[Pg 6] "2 hides and a virgate" of land, or about 270 acres. This estate was cut right out of the original manor, and formed a detached piece or island lying within it.

The second Aubrey de Vere was made Great Chamberlain of England by King Henry I. This office was made hereditary. The third Aubrey was created Earl of Oxford by Queen Matilda, a purely honorary title, as he held no possessions in Oxfordshire. The third Earl, Robert, was one of the guardians of the Magna Charta. The fifth of the same name granted lands, in 1284, to one Simon Downham, chaplain, and his heirs, at a rent of one penny. This formed another manor in Kensington. This Robert and the three succeeding Earls held high commands. The ninth Earl was one of the favourites of Richard II., under whom he held many offices. He was made Knight of the Garter, Marquis of Dublin (the first Marquis created in England), and later on Duke of Ireland. His honours were forfeited at Richard's fall. However, as he died without issue, this can have been no great punishment. Eventually his uncle Aubrey was restored by Act of Parliament to the earldom, and became the tenth Earl. Kensington had, however, been settled on the widowed Duchess of Ireland, and at her death in 1411 it went to the King. By a special gift in 1420 it was restored to the twelfth Earl. In 1462[Pg 7] he was beheaded by King Edward IV., and his eldest son with him. The thirteenth Earl was restored to the family honours and estates under King Henry VII., but he was forced to part with "Knotting Barnes or Knotting barnes, sometimes written Notting or Nutting barns." This is said to have been more valuable than the original manor itself. It formed the third subordinate manor in Kensington. The thirteenth Earl was succeeded by his nephew, who died young. The titles went to a collateral branch, and the Manor of Kensington was settled on the two widowed Countesses, and later upon three sisters, co-heiresses of the fourteenth Earl.

We have now to trace the histories of the secondary manors after their severance from the main estate. The Abbot's manor still survives in the name of St. Mary Abbots Church. About 1260 it was discovered that Aubrey de Vere had not obtained the consent of the Archbishop of Canterbury or the Bishop of London before granting the manor to the Abbot. Thereupon a great dispute arose as to the Abbot's rights over the land in question, and it was finally decided that the Abbot was to retain half the great tithes, but that the vicarage was to be in the gift of the Bishop of London. The Abbot's manor was leased to William Walwyn in the beginning of the sixteenth century. It afterwards was held by the[Pg 8] Grenvilles, who had obtained the reversion. In 1564 the tithes and demesne lands were separated from the manor and rectory, which were still held by the Grenvilles. The tithes passed through the hands of many people in succession, as did also the manor. In 1595 one Robert Horseman was the lessee under the Crown. The Queen sold the estate to Walter (afterwards Sir Walter) Cope, and a special agreement was made by which Robert Horseman still retained his right to live in the manor house. This is important, as it led to the foundation of Holland House by Cope, who had no suitable residence as lord of the manor.

West Town, created out of lands known as the Groves, was granted by the fifth Earl, as we have seen, to his chaplain Simon Downham. This grant is described by Mr. Loftie thus: "It appears to have been that piece of land which was intercepted between the Abbot's manor and the western border of the parish, and would answer to Addison Road and the land on either side of it." Robins, in his "History of Paddington," mentions an inquisition taken in 1481, in which "The Groves, formerly only three fields, had extended themselves out of Kensington into Brompton, Chelsea, Tybourn, and Westbourne."

The manor passed later to William Essex. It was bought from him in 1570 by the Marquis of Winchester, Lord High Treasurer of England.[Pg 9] He sold it to William Dodington, who resold it to Christopher Barker, printer to Queen Elizabeth, who was responsible for the "Breeches" Bible. It was bought from him by Walter Cope for £1,300.

Knotting Barnes was sold by the thirteenth Earl, whose fortunes had been impoverished by adhesion to the House of Lancaster. It was bought by Sir Reginald Bray, who sold it to the Lady Margaret, Countess of Richmond, mother of King Henry VII. This manor seems to have included lands lying without the precincts of Kensington, for in an indenture entered into by the Lady and the Abbot of Westminster in regard to the disposal of her property we find mentioned "lands and tenements in Willesden, Padyngton, Westburn, and Kensington, in the countie of Midd., which maners, lands, and tenements the said Princes late purchased of Sir Reynolds Bray knight." The Countess left the greater part of her property to the Abbey at Westminster, and part to the two Universities at Oxford and Cambridge. On the spoliation of the monasteries, King Henry VIII. became possessed of the Westminster property; he took up the lease, granting the lessee, Robert White, other lands in exchange, and added it to the hunting-ground he purposed forming on the north and west of London. At his death King Edward VI. inherited it, and[Pg 10] leased it to Sir William Paulet. In 1587 it was held by Lord Burghley. In 1599 it was sold to Walter Cope.

Earl's Court or Kensington Manor we traced to the three sisters of the last Earl. One of these died childless, the other two married respectively John Nevill, Lord Latimer; and Sir Anthony Wingfield. Family arrangements were made to prevent the division of the estate, which passed to Lucy Nevill, Lord Latimer's third daughter. She married Sir W. Cornwallis, and left one daughter, Anne, who married Archibald, Earl of Argyll, who joined with her in selling the manor to Sir Walter Cope in 1609. Sir Walter Cope had thus held at one time or another the whole of Kensington. He now possessed Earl's Court, West Town, and Abbot's Manor, having sold Notting Barns some time before. His daughter and heiress married Sir Henry Rich, younger son of the first Earl of Warwick. Further details are given in the account of Holland House (p. 76).

Perambulation.—We will begin at the extreme easterly point of the borough, the toe of the boot which the general outline resembles. We are here in Knightsbridge. The derivation of this word has been much disputed. Many old writers, including Faulkner, have identified it with Kingsbridge—that is to say, the bridge over the Westbourne in the King's high-road. The Westbourne[Pg 11] formed the boundary of Chelsea, and flowed across the road opposite Albert Gate. The real King's bridge, however, was not here, but further eastward over the Tyburn, and as far back as Henry I.'s reign it is referred to as Cnightebriga. Another derivation for Knightsbridge is therefore necessary. The old topographer Norden writes: "Kingsbridge, commonly called Stone bridge, near Hyde Park Corner, where I wish no true man to walk too late without good guard, as did Sir H. Knyvett, Kt., who valiantly defended himself, being assaulted, and slew the master-thief with his own hands." This, of course, has reference to the more westerly bridge mentioned above, but it seems to have served as a suggestion to later topographers, who have founded upon it the tradition that two knights on their way to Fulham to be blessed by the Bishop of London quarrelled and fought at the Westbourne Bridge, and killed each other, and hence gave rise to the name. This story may be dismissed as entirely baseless; the real explanation is much less romantic. The word is probably connected with the Manor of Neyt, which was adjacent to Westminster, and as pronunciation rather than orthography was relied upon in early days, this seems much the most likely explanation. Lysons says: "Adjoining to Knightsbridge were two other ancient manors called Neyt and Hyde." We still have[Pg 12] the Hyde in Hyde Park, and Neyt is thus identified with Knightsbridge.

Until the middle of the nineteenth century Knightsbridge was an outlying hamlet. People started from Hyde Park Corner in bands for mutual protection at regular intervals, and a bell was rung to warn pedestrians when the party was about to start. In 1778, when Lady Elliot, after the death of her husband, Sir Gilbert, came to Knightsbridge for fresh air, she found it as "quiet as Teviotdale." About forty years before this the Bristol mail was robbed by a man on foot near Knightsbridge. The place has also been the scene of many riots. In 1556, at the time of Wyatt's insurrection, the rebel and his followers arrived at the hamlet at nightfall, and stayed there all night before advancing on London. As already explained, the Borough of Kensington does not include Knightsbridge, but only touches it, and the part we are now in belongs to Westminster.

The Albert Gate leading into the park was erected in 1844-46, and was, of course, called after Prince Albert. The stags on the piers were modelled after prints by Bartolozzi, and were first set up at the Ranger's Lodge in the Green Park. Part of the foundations of the old bridge outside were unearthed at the building of the gate, and, besides this bridge, there was another within the park. The French Embassy, recently enlarged,[Pg 13] stands on the east side of the gate—the house formerly belonged to Mr. Hudson, the "railway king"—and to the west are several large buildings, a bank, Hyde Park Court, etc., succeeded by a row of houses. Here originally stood a famous old tavern, the Fox and Bull, said to have been founded in the time of Queen Elizabeth; if so, it must have retained its popularity uncommonly long, for it was noted for its gay company in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. It is referred to in the Tatler (No. 259), and was visited by Sir Joshua Reynolds and George Morland, the former of whom painted the sign, which hung until 1807. It is said that the Elizabethan house had wonderfully carved ceilings and immense fire-dogs, still in use in 1799. The inn was later the receiving office of the Royal Humane Society, and to it was brought the body of Shelley's wife after she had drowned herself in the Serpentine.

In the open space opposite is an equestrian statue of Hugh Rose—Lord Strathnairn—by Onslow Ford, R.A. Close by is a little triangular strip of green, which goes by the dignified name of Knightsbridge Green. It has a dismal reminiscence, having been a burial-pit for those who died of the plague. The last maypole was on the green in 1800, and the pound-house remained until 1835.[Pg 14]

The entrance to Tattersall's overlooks the green. This famous horse-mart was founded by Richard Tattersall, who had been stud-groom to the last Duke of Kingston. He started a horse market in 1766 at Hyde Park Corner, and his son carried it on after him. Rooms were fitted up at the market for the use of the Jockey Club, which held its meetings there for many years. Charles James Fox was one of the most regular patrons of Tattersall's sales. The establishment was moved to its present position in 1864.

The cavalry barracks on the north side of Knightsbridge boast of having the largest amount of cubic feet of air per horse of any stables in London.

An old inn called Half-way House stood some distance beyond the barracks in the middle of the roadway until well on into the nineteenth century, and proved a great impediment to traffic. On the south side of the road, eastward of Rutland Gate, is Kent House, which recalls by its name the fact that the Duke of Kent, father of Queen Victoria, once lived here. Not far off is Princes Skating Club, one of the most popular and expensive of its kind in London. Rutland Gate takes its name from a mansion of the Dukes of Rutland, which stood on the same site. The neighbourhood is a good residential one, and the houses bordering the roads have the advantage[Pg 15] of looking out over the Gardens. There is nothing else requiring comment until we reach the Albert Hall, so, leaving this part for a time, we return to the Brompton Road. This road was known up to 1856 as the Fulham Road, though a long row of houses on the north side had been called Brompton Row much earlier.

Brompton signifies Broom Town, carrying suggestions of a wide and heathy common. Brompton Square, a very quiet little place, a cul-de-sac, which has also the great recommendation that no "street music" is allowed within it, can boast of having had some distinguished residents. At No. 22, George Colman, junior, the dramatist, a witty and genial talker, whose society was much sought after, lived for the ten years previous to his death in 1836. The same house was in 1860 taken by Shirley Brooks, editor of Punch. The list of former residents also includes the names of John Liston, comedian, No. 40, and Frederick Yates, the actor, No. 57.

The associations of all of this district have been preserved by Crofton Croker in his "Walk from London to Fulham," but his work suffers from being too minute; names which are now as dead as their owners are recorded, and the most trivial points noted. Opposite Brompton Square there was once a street called Michael's Grove, after its builder, Michael Novosielski, architect of[Pg 16] the Royal Italian Opera House. In 1835 Douglas Jerrold, critic and dramatist, lived here, and whilst here was visited by Dickens. Ovington Square covers the ground where once stood Brompton Grove, where several well-known people had houses; among them was the editor (William Jerdan) of the Literary Gazette, who was visited by many literary men, and who held those informal conversation parties, so popular in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, which must have been very delightful. Tom Hood was among the guests on many occasions. Before being Brompton Grove, this part of the district had been known as Flounder's Field, but why, tradition does not say.

The next opening on the north side is an avenue of young lime-trees leading to Holy Trinity Church, the parish church of Brompton. It was opened in 1829, and the exterior is as devoid of beauty as the date would lead one to suppose. There are about 1,800 seats, and 700 are free. The burial-ground behind the church is about 4½ acres in extent, and was consecrated at the same time as the church. Croker mentions that it was once a flower-garden. Northward are Ennismore Gardens, named after the secondary title of the Earl of Listowel, who lives in Kingston House. The house recalls the notorious Duchess of Kingston, who occupied it[Pg 17] for some time. The Duchess, who began life as Elizabeth Chudleigh, must have had strong personal attractions. She was appointed maid of honour to Augusta, Princess of Wales, and after several love-affairs was married secretly to the Hon. Augustus John Hervey, brother of the Earl of Bristol. She continued to be a maid of honour after this event, which remained a profound secret. Her husband was a lieutenant in the navy, and on his return from his long absences the couple quarrelled violently. It was not, however, until sixteen years later that Mrs. Hervey began a connection with the Duke of Kingston, which ended in a form of marriage. It was then that she assumed the title, and caused Kingston House to be built for her residence; fifteen years later her real husband succeeded to the title of Earl of Bristol, and she was brought up to answer to the charge of bigamy, on which she was proved guilty, but with extenuating circumstances, and she seems to have got off scot-free. She afterwards went abroad, and died in Paris in 1788, aged sixty-eight, after a life of gaiety and dissipation. From the very beginning her behaviour seems to have been scandalous, and she richly merited the epithet always prefixed to her name. Sir George Warren and Lord Stair subsequently occupied the house, and later the Marquis Wellesley, elder brother of the famous Duke[Pg 18] of Wellington. Intermediately it was occupied by the Listowel family, to whom the freehold belongs.

All Saints' Church in Ennismore Gardens was built by Vulliamy, and is in rather a striking Lombardian style, refreshing after the meaningless "Gothic" of so many parish churches.

The Oratory of St. Philip Neri, near Brompton Church, is surmounted by a great dome, on the summit of which is a golden cross. It is the successor of a temporary oratory opened in 1854, and the present church was opened thirty years later by Cardinal Manning. The oratory is built of white stone, and the entrance is under a great portico. The style followed throughout is that of the Renaissance, and all the fittings and furniture are costly and beautifully finished, so that the whole interior has an appearance of richness and elegance. A nave of immense height and 51 feet in width is supported by pillars of Devonshire marble, and there are many well-furnished chapels in the side aisles. The floor of the sanctuary is of inlaid wood, and the stalls are after a Renaissance Viennese model, and are inlaid with ivory; both of these fittings were the gift of Anne, Duchess of Argyll. The central picture is by Father Philpin de Rivière, of the London Oratory, and it is surmounted by onyx panels in gilt frames. The two angels on each side of a cartouche are of Italian workmanship,[Pg 19] and were given by the late Sir Edgar Boehm. The oratory is famous for its music, and the crowds that gather here are by no means entirely of the Roman Catholic persuasion. Near the church-house is a statue of Cardinal Newman.

Not far westward the new buildings of the South Kensington Museum are rapidly rising. The laying of their foundation-stone was one of the last public acts of Queen Victoria. Until these buildings were begun there was a picturesque old house standing within the enclosure marked out for their site, and some people imagined this was Cromwell House, which gave its name to so many streets in the neighbourhood; this was, however, a mistake. Cromwell House was further westward, near where the present Queen's Gate is, and the site is now covered by the gardens of the Natural History Museum.

All that great space lying between Queen's Gate and Exhibition Road, and bounded north and south by Kensington Gore and the Cromwell Road, has seen many changes. At first it was Brompton Park, a splendid estate, which for some time belonged to the Percevals, ancestors of the Earls of Egmont. A large part of it was cut off in 1675 to form a nursery garden, the first of its kind in England, which naturally attracted much attention, and formed a good strolling-ground for the idlers who came out from town. Evelyn[Pg 20] mentions this garden in his diary at some length, and evidently admired it very much. It was succeeded by the gardens of the Horticultural Society, and the Imperial Institute now stands on the site. The Great Exhibition of 1851 (see p. 66) was followed by another in 1862, which was not nearly so successful, and this was held on the ground now occupied by the Natural History Museum; it in turn was followed by smaller exhibitions held in the Horticultural Society's grounds.

In an old map we see Hale or Cromwell House standing, as above indicated, about the western end of the Museum gardens. Lysons gives little credence to the story of its having been the residence of the great Protector. He says that during Cromwell's time, and for many years afterwards, it was the residence of the Methwold family, and adds: "If there were any grounds for the tradition, it may be that Henry Cromwell occupied it before he went out to Ireland the second time." This seems a likely solution, for it is improbable that a name should have impressed itself so persistently upon a district without some connection, and as Henry Cromwell was married in Kensington parish church, there is nothing improbable in the fact of his having lived in the parish. Faulkner follows Lysons, and adds a detailed description of the house. He says:[Pg 21]

"Over the mantelpiece there is a recess formed by the curve of the chimney, in which it is said that the Protector used to conceal himself when he visited the house, but why his Highness chose this place for concealment the tradition has not condescended to inform us."

In Faulkner's time the Earl of Harrington, who had come into possession of the park estate by his marriage with its heiress, owned Cromwell House; his name is preserved in Harrington Road close by. When the Manor of Earl's Court was sold to Sir Walter Cope in 1609, Hale House, as it was then called, and the 30 acres belonging to it, had been especially excepted. In the eighteenth century the place was turned into a tea-garden, and was well patronized, but never attained the celebrity of Vauxhall or Ranelagh, and later was eclipsed altogether by Florida Gardens further westward (see p. 32). The house was taken down in 1853.

The Natural History Museum is a branch of the British Museum, and, though commonly called the South Kensington Museum, has no claim at all to that title. The architect was A. Waterhouse, and the building rather suggests a child's erection from a box of many coloured bricks. The material is yellow terra-cotta with gray bands, and the ground-plan is simple enough, consisting of a central hall and long straight galleries running from it east and west. The[Pg 22] mineralogical, botanical, zoological, and geological collections are to be found here in conformity with a resolution passed by the trustees of the British Museum in 1860, though the building was not finished until twenty years later. The collections are most popular, especially that of birds and their nests in their natural surroundings; and as the Museum is open free, it is well patronized, especially on wet Sunday afternoons. The South Kensington Museum, that part of it already standing on the east side of Exhibition Road, is the outcome of the Great Exhibition, and began with a collection at Marlborough House. The first erection was a hideous temporary structure of iron, which speedily became known as the "Brompton Boilers," and this was handed over to the Science and Art Department. In 1868 this building was taken down, and some of the materials were used for the branch museum at Bethnal Green.

The buildings have now spread and are spreading over so much ground that it is a matter of difficulty to enumerate them all. The elaborate terra-cotta building facing Exhibition Road is the Royal College of Science, under the control of the Board of Education, for the Museum is quite as much for purposes of technical education as for mere sightseeing. Behind this lie the older parts of the Museum, galleries, etc., which are so[Pg 23] much hidden away that it is difficult to get a glimpse of them at all. Across the road, behind the Natural History Museum, are the Southern Galleries, containing various models of machinery actually working; northward of this, more red brick and scaffolding proclaim an extension, which will face the Imperial Institute Road, and parts have even run across the roads in both directions north and westward. The whole is known officially as the Victoria and Albert Museum, but generally goes by the name of the South Kensington Museum. The galleries and library are well worth a visit, and official catalogues can be had at the entrance.

From an architectural point of view, the Imperial Institute is much more satisfactory than either of the above. It is of gray stone, with a high tower called the Queen's Tower, rising to a height of 280 feet; in this is a peal of bells, ten in number, called after members of the royal family, and presented by an Australian lady. The Institute was the national memorial for Queen Victoria's Jubilee, and was designed to embody the colonial or Imperial idea by the collection of the native products of the various colonies, but it has not been nearly so successful as its fine idea entitled it to be. It was also formed into a club for Fellows on a payment of a small subscription, but was never very warmly supported.[Pg 24] It is now partly converted to other uses. The London University occupies the main entrance, great hall, central block, and east wings (except the basement). There are located here the Senate and Council rooms, Vice-Chancellor's rooms, Board-rooms, convocation halls and offices, besides the rooms of the Principal, Registrars, and other University officers. At the Institute are also the physiological theatre and laboratories for special advanced lectures and research. The rest of the building is now the property of the Board of Trade, under whom the real Imperial Institute occupies the west wing and certain other parts of the building.

The Horticultural Gardens, which the Imperial Institute superseded, were taken by the Society in 1861, in addition to its then existing gardens at Chiswick. They were laid out in a very artificial and formal style, and were mocked in a contemporary article in the Quarterly Review: "So the brave old trees which skirted the paddock of Gore House were felled, little ramps were raised, and little slopes sliced off with a fiddling nicety of touch which would have delighted the imperial grandeur of the summer palace, and the tiny declivities thus manufactured were tortured into curvilinear patterns, where sea-sand, chopped coal, and powdered bricks atoned for the absence of flower or shrub." Every vestige of this has, of course, now vanished,[Pg 25] and a new road has been driven past the front of the Institute.

The Albert Hall was opened by Queen Victoria in 1871, and, like the other buildings already mentioned, is closely associated with the earlier half of her reign. The idea was due to Prince Albert, who wished to have a large hall for musical and oratorical performances. It is in the form of a gigantic ellipse covered by a dome, and the external walls are decorated by a frieze. The effect is hardly commendable, and the whole has been compared to a huge bandbox. However, it answers the purpose for which it was designed, having good acoustic properties, and its concerts, especially the cheap ones on Sunday afternoons, are always well attended. The organ is worked by steam, and is one of the largest in the world, having close on 9,000 pipes. The hall stands on the site of Gore House, in its time a rendezvous for all the men and women of intellect and brilliancy in England. It was occupied by Wilberforce from 1808 to 1821. He came to it after his illness at Clapham, which had made him feel the necessity of moving nearer to London, that he might discharge his Parliamentary duties more easily. His Bill for the Abolition of Slavery had become law shortly before, and he was at the time a popular idol. His house was thronged with visitors, among whom were his associates,[Pg 26] Clarkson, Zachary Macaulay, and Romilly. What charmed him most in his new residence was the garden "full of lilacs, laburnum, nightingales, and swallows." He writes:

"We are just one mile from the turnpike at Hyde Park Corner, having about 3 acres of pleasure-ground around our house, or rather behind it, and several old trees, walnut and mulberry, of thick foliage. I can sit and read under their shade with as much admiration of the beauties of nature as if I were 200 miles from the great city."

In 1836 the clever and popular Lady Blessington came to Gore House, and remained there just so long as Wilberforce had done—namely, thirteen years. The house is thus described in "The Gorgeous Lady Blessington" (Mr. Molloy):

"Lying back from the road, from which it was separated by high walls and great gates, it was approached by a courtyard that led to a spacious vestibule. The rooms were large and lofty, the hall wide and stately, but the chiefest attraction of all were the beautiful gardens stretching out at the back, with their wide terraces, flower-beds, extensive lawns, and fine old trees."

Kensington Gore was then considered to be in the country, and spoken of as a mile from London. Count D'Orsay, who had married Lady Blessington's stepdaughter, rather in compliance with her father's wishes than his own inclination, spent much of his time with his mother-in-law, and at her receptions all the literary talent of the age was gathered together—Bulwer Lytton, Disraeli,[Pg 27] and Landor were frequent visitors, and Prince Louis Napoleon made his way to Gore House when he escaped from prison. Lady Blessington died in 1849. The house was used as a restaurant during the 1851 Exhibition, and afterwards bought with the estate by the Commissioners.

The name "gore" generally means a wedge-shaped insertion, and, if we take it as being between the Kensington Gardens and Brompton and Cromwell Roads, might be applicable here, but the explanation is far-fetched. Leigh Hunt reminds us that the same word "gore" was previously used for mud or dirt, and as the Kensington Road at this part was formerly notorious for its mud, this may be the meaning of the name, but there can be no certainty. Lowther Lodge, a picturesque red-brick house, stands back behind a high wall; it was designed by Norman Shaw, R.A. In the row of houses eastward of it facing the road, No. 2 was once the residence of Wilkes, who at that time had also a house in Grosvenor Square and another in the Isle of Wight. Croker says that the actor Charles Mathews was once, with his wife, Madame Vestris, in Gore Lodge, Brompton. He was certainly a friend of the Blessingtons, and stayed abroad with them in Naples for a year, and may have been attracted to their neighbourhood at the Gore.[Pg 28]

Behind the Albert Hall are various buildings, such as Alexandra House for ladies studying art and music, also large mansions and maisonnettes recently built. The Royal College of Music, successor of the old College, which stood west of the Albert Hall, is in Prince Consort Road. It was designed by Sir Arthur Blomfield, and opened in 1894. The cost was defrayed by Mr. Samson Fox, and in the building is a curious collection of old musical instruments known as the Donaldson Museum and open free daily. In the same road a prettily designed church, to be called Holy Trinity, Kensington Gore, is rapidly rising. In the northern part of Exhibition Road is the Technical Institute of the City and Guilds in a large red and white building, and just south of it the Royal School of Art Needlework for Ladies, founded by Princess Christian.

Queen's Gate is very wide; in the southern part stands St. Augustine's Church, opened for service in 1871, though the chancel was not completed until five years later. The architect was Mr. Butterfield, and the church is of brick of different colours, with a bell gable at the west end. In Cromwell Place, near the underground station, Sir John Everett Millais lived in No. 7; the fact is recorded on a tablet. Harrington Road was formerly Cromwell Lane, and there is extant a letter of Leigh Hunt's dated from this[Pg 29] address in 1830. Pelham Crescent, behind the station, formerly looked out upon tea-gardens. Guizot, the notable French Minister, came to live here after the fall of Louis Philippe. He was in No. 21, and Charles Mathews, the actor, lived for a time in No. 25. The curves of the old Brompton Road suggest that it was a lane at one time, curving to avoid the fields or different properties on either side.

Onslow Square stands upon the site of a large lunatic asylum. In it is St. Paul's Church, built in 1860, and well known for its evangelical services. There is nothing remarkable in its architecture save that the chancel is at the west end. The pulpit is of carved stone with inlaid slabs of American onyx. Marochetti, an Italian sculptor, who is responsible for many of the statues in London, including that of Prince Albert on the Memorial, lived at No. 34 in the square in 1860. But its proudest association is that Thackeray came to the house then No. 36, from Young Street, in 1853. "The Newcomes" was at that time appearing in parts, and continued to run until 1855, so that some of it was probably written here. He published also while here "The Rose and the Ring," the outcome of a visit to Rome with his daughters, and after "The Newcomes" was completed he visited America for a second time on a tour of lectures, subse[Pg 30]quently embodied in a book, "The Four Georges." By his move from Young Street he was nearer to his friends the Carlyles in Chelsea, a fact doubtless much appreciated on both sides. He contested Oxford in 1857, and in the following year began the publication of "The Virginians," which was doubtless inspired by his American experiences. In 1860 he was made editor of the Cornhill, from which his income came to something like £4,000 a year, and on the strength of this accession of fortune he began to build a house in Palace Green, to which he moved when it was complete (p. 53).

It has been remarked that this is rather a dismal neighbourhood, with the large hospitals for Cancer and Consumption facing each other across the Fulham Road, and the Women's Hospital quite close at hand. It is with the Consumption Hospital alone we have to do here, as the others are in Chelsea. This hospital stands on part of the ground which belonged to a famous botanical garden owned by William Curtis at the end of the eighteenth century. The building is of red brick, faced with white stone, and it is on a piece of ground about 3 acres in extent, lined by small trees, under which are seats for the wan-faced patients. The ground-plan of the building resembles the letter H, and the system adopted inside is that of galleries used as day-rooms and filled with chairs and couches. From[Pg 31] these the bedrooms open off. The galleries make a superior sort of ward, and are bright, with large windows, and polished floors. There is a chapel attached to the hospital, which was chiefly presented by the late Sir Henry Foulis, after whom one of the galleries is named, and who is also recalled in the name of a neighbouring terrace. The west wing of the hospital was added in 1852, and towards it Jenny Lind, who was resident in Brompton, presented £1,600, the proceeds of a concert for the cause. There is also an extension building across the road. Here there is a compressed air-bath, in which an enormous pressure of air can be put upon the patient, to the relief of his lungs. This item, rendered expensive by its massive structure and iron bolts and bars, cost £1,000, and is one of the only two of the kind in existence, the other being in Paris. A Miss Read bequeathed to the hospital the sum of £100,000, and in memory of her a slab beneath a central window is inscribed: "In Memoriam Cordelia Read, 1879." It was due to her beneficence that the extension building was added.

In Cranley Gardens, which takes its name from the secondary title of the Earl of Onslow, is St. Peter's Church, founded in 1866. Cranley Gardens run into Gloucester Road, which formerly bore the much less aristocratic title of Hogmore Lane.[Pg 32]

Just above the place where the Cromwell Road cuts Gloucester Road, about the site of the National Provincial Branch Bank, once stood a rather important house. It had been the Florida Tea-gardens, and having gained a bad reputation was closed, and the place sold to Sophia, Duchess of Gloucester, who built there a house on her own account, and called it Orford Lodge, in honour of her own family, the Walpoles. She had married privately William Henry, Duke of Gloucester, brother of George III. The marriage, which took place in 1766, was not revealed to King George II. until six years had passed, and when it was the Duke and Duchess fell under the displeasure of His Majesty. They travelled abroad for some time, but in 1780 were reinstated in royal favour. The Duke died in 1805, and the Duchess two years later. After her death her daughter, Princess Sophia, sold the house to the great statesman George Canning, who renamed it Gloucester Lodge, and lived in it until his death eighteen years later. It was to this house he was brought after his duel with Lord Castlereagh, when he was badly wounded in the thigh. Crabbe, the poet, visited him at Gloucester Lodge, and records the fact in his journal, commenting on the gardens, and remarking that the place was much secluded. Canning also received here the unhappy Queen Caroline, whose cause he had[Pg 33] warmly espoused. The house was pulled down about the middle of last century, but its memory is kept alive in Gloucester Road.

Thistle Grove Lane is one of those quaint survivals which enable us to reconstruct the past topographically, in the same way as the silent letters in a word, apparently meaningless, enable us to reconstruct the philological past. It is no longer a lane, but a narrow passage, and about midway down is crossed by a little street called Priory Grove. Faulkner makes mention of Friars' Grove in this position, and the two names are probably identical. Brompton Heath lay east of this lane, and westward was Little Chelsea, a small hamlet in fields, situated by itself, quite detached from London, separated from it by the dreary heath, that no man might cross with impunity after dark.

The Boltons is an oval piece of ground with St. Mary's Church in the middle. The church was opened in 1851, and the interior is surprisingly small in comparison with the exterior. It was fully restored about twenty years after it had been built. The land had been for many years the property of the Bolton family, whose name impressed itself on the place.

Returning to the Fulham Road, and continuing westward, we pass the site of an old manor-house, afterwards used as an orphanage; near it was an[Pg 34] additional building of the St. George's Union, which is opposite. There is a tradition that Boyle, the philosopher, once occupied this additional house, and was here visited by Locke. The present Union stands on the site of Shaftesbury House, built about 1635, and bought by the third Earl of Shaftesbury in 1699. Addison, who was a great friend of the Earl's, often stayed with him in Shaftesbury House.

Redcliffe Gardens was formerly called Walnut-Tree Walk, another rural reminiscence. At the eastern corner was Burleigh House, and an entry in the Kensington registers, May 15, 1674, tells of the birth of "John Cecill, son and heir of John, Lord Burleigh," in the parish. There is no direct evidence to show that Lord Burleigh was then living in this house, but the probability is that he was. To the east of this house again was a row of others, with large gardens at the back; one was Lochee's well-known military academy, and another, Heckfield Lodge, was taken by the brothers of the Priory attached to the Roman Catholic church, Our Lady of Seven Dolours, which faces the street. The greater part of this church was built in 1876, but a very fine rectangular porch with figures of saints in the niches, and a narthex in the same style, were added later. The square tower with corner pinnacles is a conspicuous object in the Fulham Road.[Pg 35]

Among other important persons who lived at Little Chelsea in or about Fulham Road were Sir Bartholomew Shower, a well-known lawyer, in 1693; the Bishop of Gloucester (Edward Fowler), 1709; the Bishop of Chester (Sir William Dawes), who afterwards became Archbishop of York; and Sir Edward Ward, Chief Baron of the Exchequer, in 1697. It is odd to read of a highway murder occurring near Little Chelsea in 1765. The barbarity of the time demanded that the murderers should be executed on the spot where their crime was committed, so that the two men implicated were hanged, the one at the end of Redcliffe Gardens, and the other near Stamford Bridge, Chelsea Station. These men were Chelsea pensioners, and must have been active for their years to make such an attempt. The gibbet stood at the end of the present Redcliffe Gardens for very many years.

Ifield Road was once Honey Lane. To the west are the entrance gates of the cemetery, which is about 800 yards in extreme length by 300 in the broadest part. The graves are thickly clustered together at the southern end, with hardly two inches between the stones, which are of every variety. The cemetery was opened for burial in June, 1840. Sir Roderick Murchison, the geologist, is among those who lie here. In the centre of the southern part of the cemetery is a[Pg 36] chapel; two colonnades and a central building stand over the catacombs, which are not now used. At the northern end is a Dissenters' chapel. Having thus come to the extreme limits of the district, we turn to the neighbourhood of Earl's Court.

Earl's Court can show good cause why it should hold both its names, for here the lords of the manor, the Earls of Oxford, held their courts. The earlier maps of Kensington are all of the nineteenth century. Before that time the old topographers doubtless thought there was nothing out of which to make a map, for except by the sides of the high-road, and in the detached villages of Brompton, Earl's Court, and Little Chelsea, there were only fields. Faulkner's 1820 map is very slight and sketchy. He says: "In speaking of this part, proceeding down Earl's Court Lane [Road], we arrive at the village of Earl's Court." The 1837 Survey shows a considerable increase in the number of houses, though Earl's Court is still a village, connected with Kensington by a lane. Daw's map of 1846 for some reason shows fewer houses, but his 1858 map gives a decided increase.

Near where the underground station now is stood the old court-house of Earl's Court. From 1789 to 1875 another building superseded it, but the older house was standing until 1878. There was[Pg 37] a medicinal spring at Earl's Court in the beginning of the nineteenth century. Beside these two facts, there is very little that is interesting to note. John Hunter, the celebrated anatomist, founder of the Hunterian Museum, lived here in a house he had built for himself. He had a passion for animals, particularly strange beasts, and gathered an odd collection round him, somewhat to the dismay of his neighbours.

The popular Earl's Court Exhibition is partly in Kensington and partly in Fulham; it is the largest exhibition open in London, and is patronized as much because it is one of the few places to which the Londoner can go to sit out of doors and hear a band after dinner, as for its more varied entertainments.

One of the comparatively old houses of the neighbourhood of Earl's Court, that has only recently been demolished, was Coleherne Court, at the corner of Redcliffe Gardens and the Brompton Road. It is now replaced by residential flats. This was possibly the same house as that mentioned by Bowack (1705): "The Hon. Col. Grey has a fine seat at Earl's Court; it is but lately built, after the modern manner, and standing upon a plain, where nothing can intercept the sight, looks very stately at a distance. The gardens are very good." The house was later occupied by the widow of General Ponsonby,[Pg 38] who fell in the Battle of Waterloo. Its companion, Hereford House, further eastward, was used as the headquarters of a cycling club before its demolition.

The rest of the district eastward to Gloucester Road has no old association. St. Jude's Church, in Courtfield Gardens, was built in 1870. The reredos is of red-stained alabaster, coloured marble, and mosaics by Salviati. St. Stephen's, in Gloucester Road, is a smaller church, founded in 1866. Beyond it Gloucester Road runs into Victoria Road, once Love Lane. General Gordon was at No. 8, Victoria Grove, in 1881. Returning again to Earl's Court Road, we see St. Stephen's, another of the numerous modern churches in which the district abounds; it was built partly at the expense of the Rev. D. Claxton, and was opened in 1858. In Warwick Gardens, westward, is St. Mathias, which rivals St. Cuthbert's, in Philbeach Gardens, in the ritualism of its services. Both churches are very highly decorated. In St. Cuthbert's the interior is of great height, and the walls ornamentally worked in stone; there is a handsome oak screen, and a very fine statue of the Virgin and Child by Sir Edgar Boehm in the Lady Chapel; in both churches the seats are all free.

Edwardes Square, with its houses on the north side bordering Kensington Road, is peculiarly[Pg 39] attractive, with a large garden in the centre, and an old-world air about its houses, which are mostly small. Leigh Hunt says that it was (traditionally) built by a Frenchman at the time of the threatened French invasion, and that so confident was this good patriot of the issue of the war that he built the square, with its large garden and small houses, to suit the promenading tastes and poorly-furnished pockets of Napoleon's officers. The name was taken from the family name of Lord Kensington.

Mrs. Inchbald stayed as a boarder at No. 4 in the square when she was sixty-five. She seems to have chosen the life for the sake of company rather than by reason of lack of means, for she was not badly off, having been always extraordinarily well paid for her work. She is described as having been above the middle height, of a freckled complexion, and with sandy hair, but nevertheless good-looking. Leigh Hunt himself was at No. 32 for some years before 1853, when he removed to Hammersmith. He mentions, on hearsay, that Coleridge once stayed in the square, but this was probably only on the occasion of a visit to friends. In recent times Walter Pater was a resident here.

Leaving aside for a time Holland House, standing in beautiful grounds, which line the northern side of the road, and turning eastward, we find[Pg 40] the Roman Catholic Pro-Cathedral, almost hidden behind houses. It is of dark-red brick, and was designed by Mr. Goldie, but the effect of the north porch is lost, owing to the buildings which hem it in; this defect will doubtless be remedied in time as leases expire. The interior of the cathedral is of great height, and the light stone arches are supported by pillars of polished Aberdeen granite.

After Abingdon Road comes Allen Street, in which there is the Kensington Independent Chapel, a great square building with an imposing portico, built in 1854, "for the worshippers in the Hornton Street Chapel." The houses at the northern end of Allen Street are called Phillimore Terrace, and here Sir David Wilkie came in the autumn of 1824, having for the previous thirteen years lived in Lower Phillimore Place. His life in Kensington was quiet and regular. He says: "I dine at two o'clock, paint two hours in the forenoon and two hours in the afternoon, and take a short walk in the Park or through the fields twice a day." His mother and sister lived with him, and though he was a bachelor, his domestic affections were very strong. The time in Phillimore Terrace was far from bright; it was while he lived here that his mother died, also two of his brothers and his sister's fiancé; and many other troubles, including money worries, came upon him. He eventually moved, though[Pg 41] not far, only to Vicarage Gardens (then Place), near Church Street.

In Kensington Road, beyond Allen Street, was an ancient inn, the Adam and Eve, in which it is said that Sheridan used to stop for a drink on the way to and from Holland House, and where he ran up a bill which he coolly left to be settled by his friend Lord Holland. The inn is now replaced by a modern public-house of the same name. Between this and Wright's Lane the aspect of the place has been entirely changed in the last few years by the erection of huge red-brick flats. On the other side of Wright's Lane the enlarged premises of Messrs. Ponting have covered up the site of Scarsdale House, which only disappeared to make way for them. Scarsdale House is supposed to have been built by one of the Earls of Scarsdale (first creation), the second of whom married Lady Frances Rich, eldest daughter of the Earl of Warwick and Holland, but there is not much evidence to support this conjecture. At the same time, the house was evidently much older than the date of the second Scarsdale creation—namely, 1761. The difficulty is surmounted by Mr. Loftie, who says: "John Curzon, who founded it, and called it after the home of his ancestors in Derbyshire, had bought the land for the purpose of building on it."

At the end of this lane is the Home for Crippled[Pg 42] Boys, established in Woolsthorpe House. The house was evidently named after the home of Sir Isaac Newton at Woolsthorpe, near Grantham. But apparently he never lived in it. His only connection with this part is that here stood "a batch of good old family houses, one of which belonged to Sir Isaac Newton." It is possible that the name was given by an enthusiastic admirer, moved thereto by the fact that Newton had lived in Bullingham House, Church Street, not so far distant.

In the 1837 map of the district Woolsthorpe is marked "Carmaerthen House." The front and the entrance are old, and in one of the rooms there is decorative moulding on the ceiling and a carved mantelpiece, but the schoolrooms and workshops built out at the back are all modern. The home had a very small beginning, being founded in 1866 by Dr. Bibby, who rented one room, and took in three crippled boys.

In Marloes Road, further south, are the workhouse and infirmary.

Returning to the High Street, the Free Library and the Town Hall attract attention. The latter is nearly on the site of the old free schools, which were built by Sir John Vanbrugh with all the solidity characteristic of his style; and Leigh Hunt opined, if suffered to remain, they would probably outlast the whole of Kensington. However, no such misfortune occurred, and the only relics of[Pg 43] them remaining are the figures of the charity children of Queen Anne's period, which now stand above the doorway of the new schools at the back of the Town Hall.

William Cobbett, "essayist, politician, agriculturist," lived in a house on the site of some of the great shops on the south side of the High Street, opposite the Town Hall. His grounds bordered on those of Scarsdale House, and he established in them a seed garden in which to carry out his practical experiments in agriculture. His pugnacity and sharp tongue led him into many a quarrel, and he was never a favourite with those who were his neighbours. He advocated Queen Caroline's cause with warmth, and was the real author of her famous letter to the King. But he will always be remembered best by his Weekly Register, a potent political weapon.

The parish church of St. Mary Abbots, with its high spire, forms a very striking object on the north side of the road. There is a stone porch over the entrance to the churchyard, and a picturesque cloistered passage leading round the south side. Within the cloister is a tablet commemorating the fact that it was partly built by Rev. E. C. Glyn and his wife in memory of his mother, who died in 1892. A little further on, immediately facing the south door, is another tablet, stating that the porch at the entrance to[Pg 44] the cloister was erected by the widow of James Liddle Fairless in memory of her husband, who died in 1891. Within the church the walls are thickly covered with memorial tablets, and on the north and south walls are rows of them set in coloured marble. The reredos is a representation of the four evangelists in mosaic work in four panels, enclosed in a Gothic canopy of marble. On the north side of the chancel is a fresco painting enclosed in marble, presented by the Archbishop of York on leaving the parish. On the south side there is also a small fresco painting, but the greater part of the wall is occupied by the sedilia. The transept on the south side of the nave contains numerous memorial tablets and two brasses: nearly all of these belong to the eighteenth century. The monument of the Rich family is against the west wall in this transept, and is a conspicuous object. A large marble slab against the wall bears the name of Edward Rich, last Earl of Warwick and Holland (died 1759), his wife Mary, who survived him ten years, and their only child Charlotte, who died unmarried. Above are the names of the Rich family, and below is the statue of the young Earl of Warwick and Holland, the stepson of Addison, who died in 1721, aged twenty-four. He is in Roman dress, life-size, and is represented seated with his right elbow resting on an urn.[Pg 45]

On the further side of the south door we have a curious old white marble monument to the memory of Mr. Colin Campbell (died 1708). This was in the old church, and was placed in its present position by a descendant of the Campbell family. The font, a handsome marble basin, stands in the north aisle. Near it is a marble bust of Dr. Rennell, a former vicar of Kensington, by Chantrey. In the north chapel there is a large marble tablet to the memory of William Murray, third son of the Earl of Dunmore. The pulpit is of dark carved oak, and stood in the old church. The west porch is very handsomely ornamented with stonework. In the churchyard are buried several persons of note, including Mrs. Inchbald, the authoress; and a son of George Canning, whose monument is by Chantrey.

Among other entries in the registers may be noticed the marriage of Henry Cromwell, already mentioned. There are many records of the Hicks (Campden) family, also of the Winchilsea and Nottingham, Lawrence, Cecil, Boyle, Howard of Effingham, Brydges, Dukes of Chandos, Molesworth, and Godolphin families. The plate belonging to the church is very valuable. The oldest piece is a cup dating from 1599, and a silver tankard is of the year 1619. A full description of the plate was given by Mr. Cripps in the parish magazine in 1879.[Pg 46]

The church owes its additional name of Abbots to the fact of its having belonged to the Abbot and convent of Abingdon, as set forth in the history of the parish. Bowack says: "It does not appear that this church was ever dedicated to any saint, nor can we find, after a very strict search, by whom it was founded, though we have traced its vicars up to the year 1260."

It has already been explained that Aubrey de Vere made a present to the Abbot of the slice of land on which the church stands, and that this formed a secondary manor in Kensington. This transfer had been made with the consent of Pope Alexander, but without the consent of the Bishop of London or the Archbishop. In consequence of this omission the title of the Abbey to the land was disputed, and it was at length settled that the patronage of the vicarage should be vested in the Bishop. This was in 1260. At the time of the dissolution of the monasteries the Abbot's portion became vested in the Crown, from which it passed to various persons; and when Sir Walter Cope bought the manor a special arrangement had to be made with Robert Horseman, who was then in possession.

So much for the history. The actual fabric has been subject to much change, and has been rebuilt many times. It is known that a church was standing on this site in 1102, but how old[Pg 47] it was then is only matter for conjecture; in 1370 it was wholly or partly rebuilt. And this church was pulled down about 1694, with the exception of the tower, and again rebuilt; but in seven years the new building began to crack, and in 1704 the roof was taken off, and the north and south walls once more rebuilt. After this Bowack describes it as "of brick and handsomely finished; but what it was formerly may be guessed by the old tower now standing, which has some appearance of antiquity, and looks like the architecture of the twelfth or thirteenth centuries." In his encomium he probably spoke more in accordance with convention than with real approbation, for this church has been described by many other independent persons as an unsightly building, with no architectural beauty whatever; and as far as may be gathered from the prints still extant this is the true judgment. In 1811 it showed signs of decay, and underwent thorough restoration; and in 1869 it was entirely demolished, and the present church built from the designs of Sir Gilbert Scott. The spire, added a few years later, is only exceeded by two in England—namely, those of Salisbury and Norwich Cathedrals.

There are many parish charities, which it would be out of place to enumerate here, and among them are several bequests for the cleansing and repair of tombs.[Pg 48]

The fine shops on the south side of the street inherit a more ancient title than might be supposed. Bowack, writing in 1705, speaks of the "abundance of shopkeepers and all sorts of artificers" along the high-road, "which makes it appear rather like a part of London than a country village."

Leaving aside for the time Church Street and all the interesting district on the north, we turn to Kensington Square, which was begun about the end of James II.'s reign, and from the very first was a notably fashionable place, and more especially so after the Court was established at Kensington Palace. In Queen Anne's reign, "for beauty of buildings and worthy inhabitants," it "exceeds several noted squares in London." The eminent inhabitants have indeed been so numerous that it is difficult to prevent any account of them from degenerating into a mere catalogue. "In the time of George II. the demand for lodgings was so great that an Ambassador, a Bishop, and a physician were known to occupy apartments in the same house" (Faulkner).

The two houses, Nos. 10 and 11, in the eastern corner on the south side are the two oldest that look on to the square. They were reserved for the maids of honour when the Court was at Kensington, and the wainscoted rooms and little powdering closets speak volumes as to their by[Pg 49]gone days; these two were originally one house, as the exterior shows. Next door is the women's department of King's College. J. R. Green, the historian, lived at No. 14 until his death, and in No. 18 John S. Mill was living in 1839. Three Bishops at least are known to have been domiciled in the square: Bishop Mawson of Ely, who died here in 1770; Bishop Herring of Bangor, a very notable prelate, who was afterwards Archbishop of Canterbury; and in the south-western corner Bishop Hough of Oxford, Lichfield, and Worcester had a fine old house until 1732. The Convent of the Assumption now covers the same ground in Nos. 20 to 24. The original object of the convent was prayer for the conversion of England to the Roman Catholic faith, but the sisters now devote themselves to the work of teaching; they have a pleasant garden, more than an acre in extent, stretching out at the back of the house. In the chapel there is a fresco painting by Westlake.

No. 26 is the Kensington Foundation Grammar School. Talleyrand lived in Nos. 36 and 37, formerly one house. He succeeded Bishop Herring in the occupancy, after a lapse of fifty years, and the man who had abandoned the vocation of the Church to follow diplomacy was thus sheltered by the same roof that had sheltered a Churchman by vocation, if ever there were one. Many foreign ambassadors patronized the square[Pg 50] at various times. The Duchess of Mazarin, already mentioned in the volume on Chelsea, was here in 1692, and six years later moved to her Chelsea home, where she died; but her day was over many years before she came here. Joseph Addison lodged in the square for a time, four or five years before his marriage with the Countess of Warwick. At No. 41 Sir Edward Burne-Jones lived for three years, subsequently removing to West Kensington, but the association which has most glorified the square is its proximity to Young Street, so long the home of Thackeray. He came to No. 16, then 13, in 1846, aged only thirty-five, but with the romance of his life behind him. A tablet marks the window in which he used to work. Six years previously his wife, whom he had tenderly loved, had developed melancholia, and, soon becoming a confirmed invalid, had had to be placed permanently under medical care. Their married life had been very short, only four or five years, but Thackeray had three little daughters to remind him of it. He had passed through many vicissitudes, from the comparatively opulent days of youth and the University to the time when he had lost all his patrimony and been forced to support himself precariously by pen and pencil. Yearly he had become better known, and by the time he came to Young Street he was sufficiently removed from[Pg 51] money troubles to be without that worst form of worry, anxiety for the future. He had contributed to the Times, Frazer's Magazine, and Punch. It is rather odd to read that at the time when Punch was started one of Thackeray's friends was rather sorry that he should become a contributor, fearing that it would lower his status in the literary world! It was in Punch, nevertheless, that his first real triumph was won. The "Snob Papers" attracted universal attention, and were still running when he moved to Young Street. Here he began more serious work, and scarcely a year later "Vanity Fair" was brought out in numbers, according to the fashion made popular by Dickens. It did not prove an instantaneous success, but by the time it had run its course its author's position was assured. In spite of the sorrow that overshadowed his domestic life—and he had by this time for many years given up any hope of communicating with his wife—the time he spent in this house cannot have been unhappy. He had congenial work, many friends, among whom were numbered his fellow contributor Leech, also G. F. Watts, Herman Merivale, the Theodore Martins, Monckton Milnes, Kinglake, and others. He had also his daughters, and he was a loving and sympathetic father, realizing that children need brightness in their lives as well as mere care, and taking his little family about when[Pg 52]ever he could to parties and shows; and he had a growing reputation in the literary world. "Pendennis" was published in 1848, and before it had finished running Thackeray suffered from a severe illness, that left its mark on all his succeeding life.

It was after this that Miss Brontë came to dine with him in Young Street. She had admired "Vanity Fair" immensely, and was ready to offer hero-worship; but the sensitive, dull little governess did not reveal in society the fire that had made her books live, and we are told that Thackeray, although her host, found the dinner so dull that he slipped away to his club before she left. He had now a good income from his books, and added to it by lecturing. "Esmond" appeared in 1852, and the references to my Lady Castlewood's house in Kensington Square and the Greyhound tavern (the name of the inn opposite to Thackeray's own house) will be remembered by everyone. The novelist visited America shortly after, and then went with his children to Switzerland, and it was in Switzerland that the idea for "The Newcomes" came to him. Young Street can only claim a part of that book, for in 1853 he moved to Onslow Square, and the last number of "The Newcomes" did not appear until 1855. However, this was not his last connection with this part of Kensington, for in 1861 he built[Pg 53] himself a house in Palace Green, but he only occupied it for two years, when his death occurred at the early age of fifty-two.

The houses in Kensington Court, near by, are elaborately decorated with ornamental terra-cotta mouldings. They stand just about the place where once was Kensington House, which had something of a history. It was for a while the residence of the Duchess of Portsmouth (Louise de Querouaille), and later was the school of Dr. Elphinstone, referred to in Boswell's "Life of Johnson," and supposed, on the very slightest grounds, to have been the original of one of Smollett's brutal schoolmasters in "Roderick Random"; though the driest of pedagogues, Elphinstone was the reverse of brutal. The house was subsequently a Roman Catholic seminary, and then a boarding-house, where Mrs. Inchbald lodged, and in which she died in 1821.

Close by was another old house, made notorious by its owner's miserliness; this man, Sir Thomas Colby, died intestate, and his fortune of £200,000 was divided among six or seven day labourers, who were his next of kin. A new Kensington House was built on the site of these two, and is said to have cost £250,000, but its owner got into difficulties, and eventually the costly house was pulled down, and its fittings sold for a twentieth part of their value. Near at hand[Pg 54] are De Vere Gardens, to which Robert Browning came in June, 1887, from Warwick Crescent.

Further eastward we come to Palace Gate. Some of this property belongs to the local charities. It is known as Butts Field Estate, and was so called from the fact that the butts for archery practice were once set up here.

The Gardens are so intimately connected with the Palace that it is impossible to touch upon the one without the other, and though Leigh Hunt caustically remarked that a criticism might be made on Kensington that it has "a Palace which is no palace, Gardens which are no gardens, and a river called the Serpentine which is neither serpentine nor a river," yet in spite of this the Palace, the Gardens, and the river annually give pleasure to thousands, and possess attractions of their own by no means despicable. The flower-beds in the gardens nearest to Kensington Road are beautiful enough in themselves to justify the title of gardens. This is the quarter most patronized by nursemaids and their charges. There are shady narrow paths, also the Broad Walk, with its leafy overarching boughs resembling one of Nature's aisles, and the Round Pond, pleasant in spite of its primness. The Gardens were not always open to the public, but partly belonged[Pg 55] to the palace of time-soiled bricks to which the public is now also admitted.

The first house on this site of which we have any reliable detail is that built by Sir Heneage Finch, the second of the name, who was Lord Chancellor under Charles I. and was created Earl of Nottingham in 1681, though it is probable that there had been some building on or near the same place before, possibly the manor-house of the Abbot. The first Earl of Nottingham had bought the estate from his younger brother, Sir John, and it was from his successor, the second earl, that William III. bought Nottingham House, as it was then called.

William suffered much from asthma, and the gravel pits of Kensington were then considered very healthy, and combined the advantages of not being very far from town with the pure air of the country. Of course, the house had to be enlarged in order to be suitable for a royal residence, but it was not altogether demolished, and there are parts of the original Nottingham House still standing, probably the south side of the courtyard, where the brick is of a deeper shade than the rest. King William's taste in the matter of architecture knew no deviation; his model was Versailles, and as he had commissioned Wren to transform the Tudor building of Hampton into a palace resembling Versailles, so he directed him to repeat the experi[Pg 56]ment here. The long, low red walls, with their neat exactitude, speak still of William's orders; a building of heterogeneous growth, with a tower here and an angle there, would have disgusted him: his ideal would have found its fulfilment in a modern barrack. Wren's taste, later aided by the lapse of time, softened down the hard angularity of the building, but it can in no sense be considered admirable. Thus Kensington Palace was built, and its walls and its park like gardens were to be as closely associated with the Hanoverian Sovereigns as the building and park of St. James's had been associated with the Stuarts whom William had supplanted.