i

I.

Life of Quintilian.

It would be possible to state in a

very few lines all that is certainly known about Quintilian’s personal

history; but much would remain to be said in order to convey an adequate

idea of the large place he must have filled in the era of which he is so

typical a representative. The period of his activity at Rome is nearly

co-extensive with the reign of the Flavian emperors,—Vespasian,

Titus, and Domitian. For twenty years he was the recognised head of the

teaching profession in the capital, and a large proportion of those who

came to maturity in the days of Trajan and Hadrian must have received

their intellectual training in his school. It is in itself a sign of the

tendencies of the age that Quintilian should have enjoyed the immediate

patronage of the reigning emperor in the conduct of work which would

formerly have attracted little notice. In earlier days the profession of

teaching had been held in low repute at Rome1. The first attempt to open a

school of rhetoric, in B.C. 94, was

looked on with the greatest suspicion and disfavour. Even Cicero adopts

a tone of apology in the rhetorical text-books which he wrote for the

instruction of others. But now all was changed, and education had come

to be, as it was in a still greater degree under Nerva, Trajan, and the

Antonines, a department of the government itself. Vespasian was the

founder of a new dynasty; and, though he had little culture to boast of

himself, he was shrewd enough to appreciate the advantages to be derived

from systematising the education of the Roman youth, and maintaining

friendly relations

ii

with those to whom it was entrusted. Quintilian, for his part, seems to

have diligently seconded, in the scholastic sphere, his patron’s efforts

to efface the memory of the time of trouble and unrest which had

followed the extinction of the Julian line in the person of Nero. After

his retirement from the active duties of his profession, he received the

consular insignia from Domitian,—the promotion of a teacher of

rhetoric to the highest dignity in the State being regarded as a most

unexampled phenomenon by the conservative opinion of the day, which had

failed to recognise the significance of the alliance between prince and

pedagogue. The interest with which the publication of the Institutio

Oratorio was looked forward to, at the close of his laborious

professional career, is sufficient evidence of the authoritative

position Quintilian had gained for himself at Rome. It was a tribute not

only to the successful teacher, but also to the man of letters who,

conscious that his was an age of literary decadence, sought to probe the

causes of the national decline and to counteract its evil

influences.

Like so many of the distinguished men of his time, Quintilian was a

Spaniard by birth. There must have been something in the Spanish

national character that rendered the inhabitants of that country

peculiarly susceptible to the influences of Roman culture: certainly no

province assimilated more rapidly than Spain the civilisation of its

conquerors. The expansion of Rome may be clearly traced in the history

of her literature. Just as Italy, rather than the imperial city itself,

had supplied the court of Augustus with its chiefest literary ornaments,

so now Spain sends up to the centre of attraction for all things Roman a

band of authors united, if by nothing else, at least by the ties of a

common origin. Pomponius Mela is said to have come from a place called

Cingentera, on the bay of Algesiras; Columella was a native of Gades,

Martial of Bilbilis; the two Senecas and Lucan were born in Corduba. The

emperor Trajan came from Italica, near Seville; while Hadrian belonged

to a family which had long been settled there. Quintilian’s birthplace

was the town of Calagurris (Calahorra) on the Ebro, memorable in

previous history only for the resistance which it enabled Sertorius to

offer to Metellus and Pompeius: it was the last place that submitted

after the murder of the insurgent general in B.C. 72.

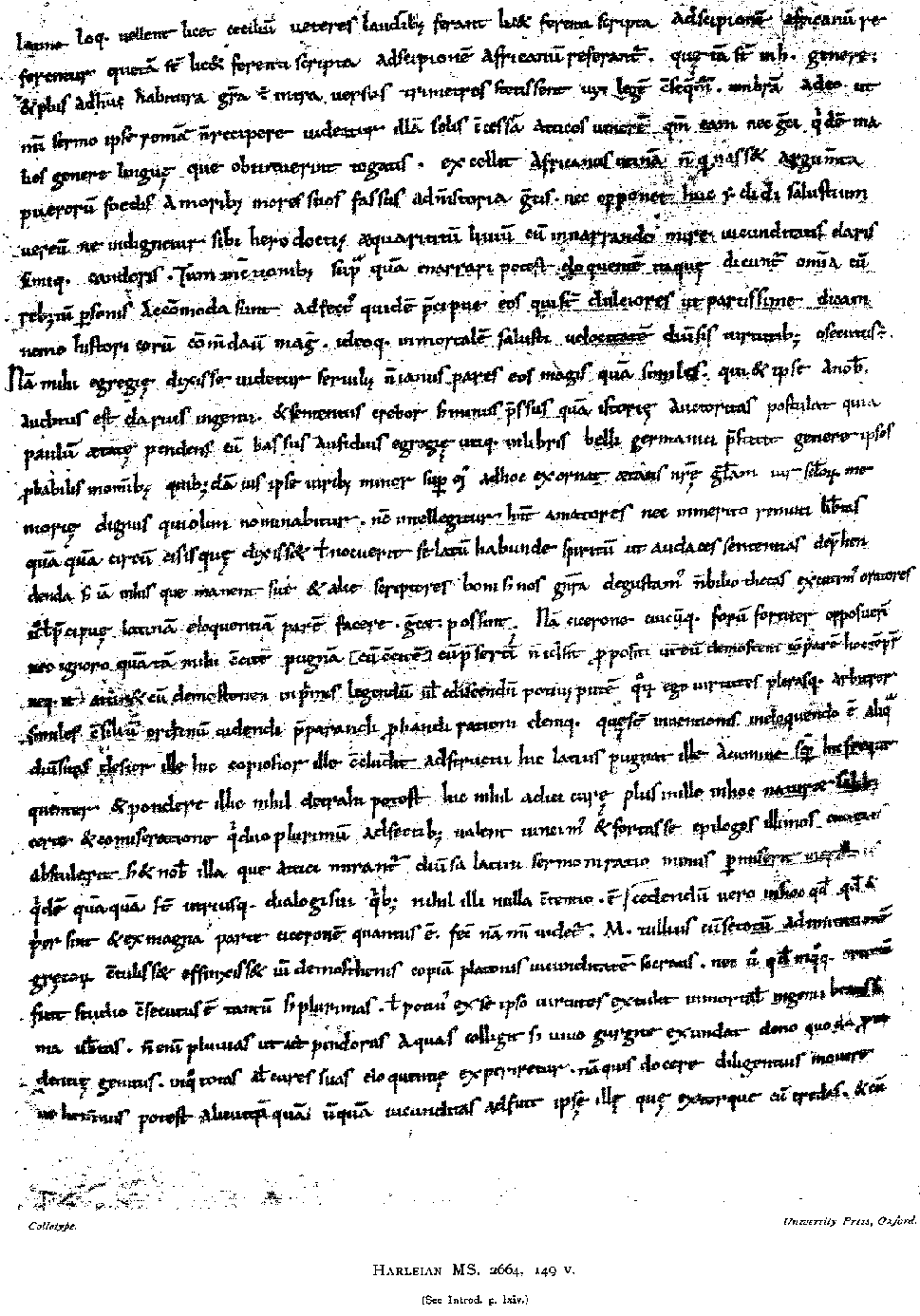

In most of the older editions of Quintilian an anonymous Life

appears, the author of which (probably either Omnibonus Leonicenus or

Laurentius Valla) prefers a conjecture of his own to the ‘books of the

time,’ and makes out that Quintilian was born in Rome. His main argument

is that Martial does not include his name among those of the

distinguished authors to whom he refers as being of Spanish origin (e.g.

Epigr. i.

iii

61 and 49), though he addresses him separately in complimentary terms

(Epigr. ii. 90). Against this we may set, however, the line in which

Ausonius embodies what was evidently a well-known and accepted tradition

(Prof. i. 7):—

Adserat usque licet Fabium Calagurris

alumnum;

and the statement of Hieronymus in the Eusebian

Chronicle:—Quintilianus, ex Hispania

Calagurritanus, primus Romae publicam scholam [aperuit]. The

latter extract carries additional weight if we accept the conjecture of

Reifferscheid2 that Jerome here follows the authority of Suetonius

(Roth, p. 272) in his work on the grammarians and rhetoricians.

The fact of Quintilian’s Spanish origin may therefore be regarded as

fully established, though we cannot cite the authority of Quintilian

himself on the subject. His removal to Rome, at a very early period of

his life, would naturally make him more of a Roman than a Spaniard; and

this is probably the reason why he nowhere refers to the accident of his

birth-place. Indeed his work does not lend itself to autobiographical

revelations. Most of his reminiscences, some of which occur in the Tenth

Book (1 §§23 and

86,

3 §12: cp. v. 7, 7: vi. 1,

14: xii. 11, 3) are suggested by some detail connected with his

subject. Apart from the famous introduction to Book VI, where his grief

for the loss of his wife and two sons is allowed to interrupt the

continuity of his argument, he speaks of his father only once (ix.

3, 73), and then simply to quote, not without some diffidence,

a bon mot of his in illustration of a figure of speech. The

father was himself a rhetorician, and seems to have taught the subject

both at Calagurris and also after the family removed to Rome: whether he

is identical with the Quintilianus mentioned as a declaimer of moderate

reputation by the elder Seneca (Controv. x. praef. 2: cp. ib.

33, 19) cannot now be ascertained.

The date of Quintilian’s birth has been variously given as A.D. 42, A.D. 38, and A.D.

35, the last being now most commonly adopted. It cannot be determined

with certainty, though a few considerations may here be adduced to show

why it seems necessary to discard any theory that would put it after

A.D. 38. Dodwell, in his ‘Annales

Quintilianei’ (see Burmann’s edition, vol. ii. p. 1117), arrived at

the year A.D. 42, after a careful

examination of all the passages on which he thought it allowable to base

an inference. But Quintilian tells us himself that he was a young man

(nobis adulescentibus vi. 1, 14) at the trial of Cossutianus

Capito,

iv

which we know from Tacitus (Ann. xiii. 33) took place in A.D. 57: a fact which is in itself enough to show

that Dodwell is at least two years too late. Another indication is

derived from the references which Quintilian makes to his teacher

Domitius Afer, who is known to have died at a ripe old age in A.D. 59: cp. xii. 11, 3 vidi ego ...

Domitium Afrum valde senem: v. 7, 7 quem adulescentulus senem

colui: x.

1, 86 quae ex Afro

Domitio iuvenis excepi. Unfortunately we do not know the date of the

trial of Volusenus Catulus referred to in x.

1, 23: Quintilian was a

boy at the time (nobis pueris). In the preface to Book VI he

writes like an old man: this appears especially in the reference he

makes to the wife whom he had lost and who was only

nineteen,—aetate tam puellari praesertim meae comparata

§5. If we may infer that

Quintilian was nearer sixty than fifty when he wrote these words, in

A.D. 93 or 94, we may be certain that

he was born not later than A.D. 38,

and probably two or three years earlier.

Quintilian received his early education at Rome, and his father’s

position as a teacher of rhetoric, as well as the whole tendency of the

education of the day, no doubt gave it a rhetorical turn from the very

first. Even boys at school practised declamation, as may be seen from

the following passage of the Institutio:—

‘Non inutilem scio servatum esse a praeceptoribus meis morem, qui

cum pueros in classes distribuerant, ordinem dicendi secundum vires

ingenii dabant; et ita superiore loco quisque declamabat ut praecedere

profectu videbatur. Huius rei iudicia praebebantur: ea nobis ingens

palma, ducere vero classem multo pulcherrimum. Nec de hoc semel decretum

erat: tricesimus dies reddebat victo certaminis potestatem. Ita nec

superior successu curam remittebat, et dolor victum ad depellendam

ignominiam concitabat. Id nobis acriores ad studia dicendi faces

subdidisse quam exhortationem docentium, paedagogorum custodiam, vota

parentium, quantum animi mei coniectura colligere possum,

contenderim.’—i. 2, 23-25.

The same style of exercise was kept up at a later stage, when the boy

passed into the hands of a professed teacher of rhetoric, such as the

notorious Remmius Palaemon, who is said by the scholiast on Juvenal (vi.

451) to have been Quintilian’s master:—

‘Solebant praeceptores mei neque inutili et nobis etiam iucundo

genere exercitationis praeparare nos coniecturalibus causis, cum

quaerere atque exsequi iuberent “cur armata apud Lacedaemonios Venus” et

“quid ita crederetur Cupido puer atque volucer et sagittis ac face

armatus” et similia, in quibus scrutabamur voluntatem.’—ii.

4, 26.

He now came into contact with, and listened to the eloquence of, the

most celebrated orators of the day. In his relations with the greatest

of

v

these, Domitius Afer, Quintilian seems to have acted on the maxim which

he himself lays down for the budding advocate: oratorem sibi aliquem,

quod apud maiores fieri solebat, deligat, quem sequatur, quem

imitetur x.

5, 19. To Afer he

attached himself (adsectabar Domitium Afrum Plin. Ep. ii.

14, 10), and was in all probability by him initiated in the

business of the law-courts and public life generally: cp. v. 7, 7

adulescentulus senem colui (Domitium). In this passage

Afer is said to have written two books on the examination of witnesses;

and from vi. 3, 42 it would appear that his ‘dicta’ or witticisms were

sufficiently distinguished to merit the honour of publication. He had

held high office under Tiberius, Caligula, and Nero, and his

pre-eminence at the bar was undisputed: xii. 11, 3 principem fuisse

quondam fori non erat dubium. In his review of Latin oratory,

Quintilian gives him high praise: arte et toto genere dicendi

praeferendus, et quem in numero veterum habere non timeas x.

1, 118. The pupil was

fortunate therefore in his master, and he drew upon his reminiscences of

Afer’s teaching when he himself came to instruct others (Plin. l.c.).

Among other notable orators of the day were Servilius Nonianus (x.

1, 102), Iulius

Africanus (x.

1, 118: xii.

10, 11), Iulius Secundus (x.

1, 120:

3, 12: xii. 10, 11),

Galerius Trachalus (x.

1, 119: xii.

10, 11), and Vibius Crispus (ibid.).

When he was about twenty-five years of age some motive induced

Quintilian to return to Calagurris, his native town; and there he spent

several years in the practice of his profession as teacher and

barrister. We know that he came back to Rome with Galba in A.D. 68: the evidence for this is again the

statement made by Hieronymus in the Eusebian Chronicle,

M. Fabius Quintilianus Romam a Galba perducitur. Galba had

been governor of Hispania Tarraconensis under Nero (A.D. 61-68), and it is not improbable that

Quintilian, when he returned to his native country, was in some way

attached to his official retinue; the numerous bons mots which he

records in the third chapter of the Sixth Book (§§62, 64, 66,

80, 90) seem to point to a certain amount of personal intercourse

between himself and the future emperor3.

At Rome Quintilian must soon have proved himself thoroughly qualified

for the work of teaching and training the young. The imperial

countenance afterwards shown him by Vespasian was in all probability

only an official expression of the esteem felt in the Roman community

for one who was serving with such distinction in a sphere of which the

importance was coming now to be more adequately recognised. Quintilian

was not only a learned man and a great teacher: he was a great

vi

moral power in the midst of a people which had long been demoralised by

the vices of its rulers. The fundamental principle of his teaching,

non posse oratorem esse nisi virum bonum (i. pr. §9 and

xii. 1), shows the high ideal he cherished and the wide view he

took of the opportunities of his position. He felt himself strong enough

to make a protest against the literary influence of Seneca, then the

popular favourite, and to endeavour to recall a vitiated taste to more

rigorous standards: corruptum et omnibus vitiis fractum dicendi genus

revocare ad severiora iudicia contendo (x.

1, 125). And when, in

the evening of his days, he wrote his great treatise on the ‘technical

training’ of the orator, it was from himself and his own successful

practice that he drew many of his most cogent illustrations, e.g. vi. 2,

36, and (in regard to his powers of memory) xi. 2, 39 and iv.

2, 86.

In the earlier years of his career at Rome, before he became absorbed

in the work of teaching, Quintilian must have had a considerable amount

of practice at the bar. He tells us himself of a speech which he

published, ductus iuvenali cupiditate gloriae viii. 2, 24. It was

of a common type. A certain Naevius Arpinianus was accused of

having killed his wife, who had fallen from a window; and we may infer

with certainty from the tone of Quintilian’s reference to the

circumstances of the case that he succeeded in securing the acquittal of

Naevius—more fortunate than the wife-killer of whom we read in

Tacitus (Ann. iv. 22). A more distinguished cause was that of

Berenice, the Jewish Queen before whom St. Paul appeared (Acts xxv.

13), and whose subsequent visit to Rome was connected with the

ascendency she had established over the heart of the youthful Titus

(Tac. Hist. ii. 2: Suet. Tit. 7). We can only speculate on the

nature of the issue involved, as Quintilian confines himself to a bare

statement of fact—ego pro regina Berenice apud ipsam causam

dixi iv. 1, 19. It was in all probability a civil suit brought or

defended by Berenice against some Jewish countryman; and the phenomenon

of the queen herself presiding over a trial in which she was an

interested party is accounted for by the hypothesis that, at least in

civil suits, Roman tolerance allowed the Jews to settle their own

disputes according to their national law. On such occasions the person

of highest rank in the community to which the disputants belonged might

naturally be designated to preside over the tribunal4.

vii

In another case, Quintilian seems to have shown some of the dexterity

attributed to him in the oft-quoted line of Juvenal (vi. 280) Dic

aliquem, sodes, dic, Quintiliane, colorem. He was counsel for a

woman who had been party to an arrangement by which the provisions of

the Voconian law (passed B.C. 169 to

prevent the accumulation of property in the hands of females) had been

evaded by the not uncommon method of a fraudulent disposition to a third

person5.

Quintilian’s client was accused of having produced a forged will. This

charge it was easy to rebut, though it rendered necessary the

explanation that the heirs named in the will had really undertaken to

hand the property over to the woman; and if this explanation were openly

given it would involve the loss of the estate. There is an evident tone

of satisfaction in Quintiiian’s description of what happened: ita

ergo fuit nobis agendum ut iudices illud intellegerent factum, delatores

non possent adprehendere ut dictum, et contigit utrumque (ix.

2, 74).

Unlike his great model Cicero, who was considered most effective in

the peroratio of a great case, where the work was divided among

several pleaders, Quintilian was generally relied on to state a case

(ponere causam) in its main lines for subsequent elaboration:

me certe, quantacunque nostris experimentis habenda est fides,

fecisse hoc in foro, quotiens ita desiderabat utilitas, probantibus et

eruditis et iis qui iudicabant, scio: et (quod non adroganter dixerim,

quia sunt plurimi quibuscum egi qui me refellere possint si mentiar)

fere a me ponendae causae officium exigebatur iv. 2, 86. His

methodical habit of mind would render him specially effective for this

department of work. Other orators may have been more brilliant, more

full of fire, and more able to work upon the feelings of an audience: if

Quintilian had not the ‘grand style’—if he represents the type of

an orator that is ‘made’ rather than ‘born’—we may at least

believe that he was unsurpassed for judicious, moderate, and effective

statement. His model in this as in other matters was probably Domitius

Afer, of whom Pliny says (Ep. ii. 14, 10) apud decemviros

dicebat graviter et lente, hoc enim illi actionis genus erat. His

character and training would secure him a place apart from the common

herd. ‘Among the orators of the day, some ignorant and coarse, having

left mean occupations, without any preliminary study, for the bar, where

they made up in audacity for lack of talent, and in noisy conceit for a

defective knowledge

viii

of law—others trained in the practice of delation to every form of

trickery and violence—Quintilian, honest, able, and moderate stood

by himself6.’

It was after Quintilian had attained some distinction in the practice

of his profession, probably in the year 72, that his activity became

invested with an official and public character. We learn the facts from

Suetonius’s Life of Vespasian (ch. 18): primus e fisco latinis

graecisque rhetoribus annua centena constituit: and the Eusebian

chronicle (see Roth’s Suetonius, p. 272), Quintilianus, ex

Hispania Calagurritanus, qui primus Romae publicam

(‘state-supported’) scholam [aperuit] et salarium e

fisco accepit, claruit—the zenith of his fame being placed

between the years 85 and 89 A.D.

Vespasian, in fact, created and endowed a professorial Chair of

Rhetoric, and Quintilian was its first occupant. He thus became the

official head of the foremost school of oratory at Rome, and the

‘supreme controller of its restless youth’:

Quintiliane, vagae moderator summe iuventae,

Gloria Romanae, Quintiliane, togae.

—Mart. ii. 90, 1-2.

In this capacity he must have exercised the greatest possible

influence on the rising youth of Rome. The younger Pliny was his pupil,

and evidently retained a grateful memory of the instruction which he

received from him: Ep. ii. 14, 9 and vi. 6, 3. The same is true, in

all probability, of Pliny’s friend Tacitus, who has much in common with

Quintilian: possibly also of Suetonius. If Juvenal was not actually his

pupil,—he is believed to have practised declamation till well on

in life,—we may infer from the complimentary references which

occur in his Satires that he at least appreciated Quintilian’s work and

recognised its healthy influence7.

After a public career at Rome, extending over a period of twenty

years8,

Quintilian definitely retired from both teaching and pleading at

ix

the bar. He seems to have profited by the example of his model, Domitius

Afer, who would have done better if he had retired earlier (xii.

11, 3): Quintilian thought it was well to go while he would still

be missed,—et praecipiendi munus iam pridem deprecati sumus et

in foro quoque dicendi, quid honestissimum finem putabamus desinere dum

desideraremur, ii. 12, 12. The wealth which he had acquired by the

practice of his profession (Juv. vii. 186-189) enabled him to go into

retirement with a light heart. The first-fruits of his leisure was a

treatise in which he sought to account for that decline in eloquence for

which the Institutio Oratoria was afterwards to provide a remedy.

It was entitled De causis corruptae eloquentiae, and was long

confounded with the Dialogue on Oratory, now ascribed to Tacitus: he

refers to this work in vi. pr. §3: viii. 6, 76: possibly also in ii. 4,

42: v. 12, 23: vi. pr. §3: viii. 3, 58, and 6, 769. This treatise is no longer

extant, and we have lost also the two books Artis Rhetoricae,

which were published under Quintilian’s name (1 pr. §7), neque

editi a me neque in hoc comparati: namque alterum sermonem per biduum

habitum pueri quibus id praestabatur exceperant, alterum pluribus sane

diebus, quantum notando consequi potuerant, interceptum boni iuvenes sed

nimium amantes mei temerario editionis honore vulgaverant10. In a recent

edition of the ‘Minor Declamations’ (M. Fabii Quintiliani

declamationes quae supersunt cxlv Lipsiae, 1884), Const. Ritter

endeavours to show that this is the work referred to in the passage

quoted above, from the preface to the Institutio: cp. Die

Quintilianischen Declamationen, Freiburg i.B., und

x

Tübingen, 1881, p. 246 sqq.11 Meister’s view, however, is that, like the

‘Greater Declamations,’ which are generally admitted to have been

composed at a later date, the ‘Minor Declamations’ also were written

subsequently either by Quintilian himself or (more probably) by

imitators who had caught his style and were glad to commend their

compositions by the aid of his great name. Even in his busy professional

days Quintilian had suffered from the zeal of pirate publishers: he

tells us (vii. 2, 24) that several pleadings were in circulation

under his name which he could by no means claim as entirely his own:

nam ceterae, quae sub nomine meo feruntur, neglegentia excipientium

in quaestum notariorum corruptae minimam partem mei habent.

While living in retirement, and engaged on the composition of his

work, Quintilian received a fresh mark of Imperial favour, this time

from Domitian. This prince had adopted two grand-nephews, whom he

destined to succeed him on the throne,—the children of his niece

Flavia Domitilla, and of Flavius Clemens, a cousin whom he associated

with himself about this time in the duties of the consulship. They were

rechristened Vespasian and Domitian (Suet. Dom. 15), and the care of

their education was entrusted to Quintilian (A.D. 93). He accepted it with fulsome expressions of

gratitude and appreciation12; but did not exercise it for long13, as the

children, with their parents, became the victims of the tyrant’s

capriciousness shortly before his murder, and were ruined as rapidly as

they had risen. Flavius Clemens was put to death, and his wife

Domitilla, probably accompanied by her two sons, was sent into exile.

They seem to have embraced the Jewish faith; and it is interesting to

speculate on the possibility that through intercourse with them, and

with their children, Quintilian may have come into contact with a

religion which was the forerunner of that which was destined soon

afterwards to achieve so universal a triumph.

It was while he was acting as tutor to the two princes that

Quintilian received, through the influence of their father Flavius

Clemens, the compliment of the consular insignia. This we learn from

Ausonius, himself the recipient of a similar favour from his pupil

Gratian: Quintilianus per Clementem ornamenta consularia sortitus,

honestamenta nominis potius videtur quam insignia potestatis

habuisse. It was probably in allusion to

xi

this promotion, unexampled at that time in the case of a teacher of

rhetoric, that Juvenal wrote (vii. 197-8)—

Si Fortuna volet, fies de rhetore consul;

Si volet haec eadem, fies de consule rhetor:

while another parallel is chronicled by Pliny, Ep. iv. 11, 1

praetorius hic modo ... nunc eo decidit ut exsul de senatore, rhetor

de oratore fieret. Itaque ipse in praefatione dixit dolenter el

graviter: ‘quos tibi Fortuna, ludos facis?’ facis enim ex professoribus

senatores, ex senatoribus professores.

The flattery with which Quintilian loads the emperor for these and

similar favours is the only stain on a character otherwise invariably

manly, honourable, and straightforward. It is startling for us to hear

that monster of iniquity, the last of the Flavian line, invoked as an

‘upright guardian of morals’ (sanctissimus censor iv. pr. §3),

even when he was ‘tearing in pieces the almost lifeless world.’ There

may have been a grain of sincerity in the compliments which Quintilian,

like Pliny, pays to his literary ability. Domitian’s poetical

productions are said not to have been altogether wanting in merit; and

his attachment to literary pursuits is shown by the festivals he

instituted in honour of Minerva and Jupiter Capitolinus, in which

rhetorical, musical, and artistic contests were a prominent feature (see

on x.

1, 91). But this is no

justification for the fulsome language employed by Quintilian in the

introduction to the Fourth Book, where the emperor is spoken of as the

protecting deity of literary men: ut in omnibus ita in eloquentia

eminentissimum ... quo neque praesentius aliud nec studiis magis

propitium numen est; nor for his profession of belief that nothing

but the cares of government prevented Domitian from becoming the

greatest poet of Rome: Germanicum Augustum ab institutis studiis

deflexit cura terrarum, parumque dis visum est esse eum maximum

poetarum x.

1, 91 sq. Few would

recognise Domitian in the following reference: laudandum in quibusdam

quod geniti immortales, quibusdam quod immortalitatem virtute sint

consecuti: quod pietas principis nostri praesentium quoque temporum

decus fecit iii. 7, 9. Such servility can only be partially

explained by Quintilian’s official relations to the Court and by the

circumstances of the time at which he wrote. It was a vice of the age:

Quintilian shares it with Martial, Statius, Silius Italicus, and

Valerius Flaccus. The indignant silence which Tacitus and Juvenal

maintained during the horrors of this reign is a better expression of

the virtue of old Rome, which seems to have burned with steadier flame

in the hearts of her genuine sons than in those of the ‘new men’

xii

from the provinces, with neither pride of family nor pride of

nationality to save them from the corrupting influences of their

surroundings14.

That Quintilian acquired considerable wealth, partly as a teacher and

partly by work at the bar, is evident from the pointed references made

by Juvenal in the seventh Satire. After showing how insignificant are

the fees paid by Roman parents for their children’s education, when

compared with their other expenses, the satirist suddenly breaks

off,—unde igitur tot Quintilianus habet saltus? How does it

come about (if his profession is so unremunerative) that Quintilian owns

so many estates? The only answer which Juvenal can give to this

conundrum is that the great teacher was one of the fortunate: ‘he is a

lucky man, and your lucky man, like Horace’s Stoic, unites every good

quality in himself, and can expect everything15.’ We must remember however,

that, while Quintilian acquired wealth in the practice of his

profession, no charge is made against him as having placed his abilities

at the disposal of an unscrupulous ruler for his own advancement. Under

Nero, Marcellus Eprius assisted in procuring the condemnation of

Thrasea, and received over £42,000 for the service (Tac. Ann. xvi. 33):

if Quintilian’s name had ever been associated with such a trial, Juvenal

would have been more direct in his reference. But with Quintilian, as

with so many others, the advantages of position and fortune were

counterbalanced by grave domestic losses. In a less rhetorical age the

memorable introduction to the Sixth Book of the Institutio would

perhaps have taken a rather more simple form; but it is none the less a

testimony to the warm human heart of the writer, now a childless

widower. He had married, when already well on in life, a young girl

whose death at the early age of nineteen made him feel as if in her he

had lost a daughter rather than a wife: cum omni virtute quae in

feminas cadit functa insanabilem attulit marito dolorem, tum aetate tam

puellari, praesertim meae comparata, potest et ipsa numerari inter

vulnera orbitatis vi. pr. 5. She left him two sons, the younger

of whom did not long survive her; he had just completed his fifth year

when he died. The father now concentrated all his affection

xiii

on the elder, and it was with his education in view that he made all

haste to complete his great work, which he considered would be the best

inheritance he could leave to him,—hanc optimum partem

relicturus hereditatis videbar, ut si me, quod aequum et optabile fuit,

fata intercepissent, praeceptore tamen patre uteretur ib. §1. But

the blow again descended, and his house was desolate: at me fortuna

id agentem diebus ac noctibus festinantemque metu meae mortalitatis ita

subito prostravit ut laboris mei fructus ad neminem minus quam ad me

pertineret. Illum enim, de quo summa conceperam et in quo spem unicam

senectutis reponebam, repetito vulnere orbitatis amisi ib. §2.

This would be about the year 94 A.D., and the Institutio Oratoria is said to

have seen the light in 95. After that we hear no more of Quintilian.

Domitian was assassinated in 96, and under the new régime it is

possible that the favourite of the Flavian emperors may have been under

a cloud. But his work was done; even if he lived on for a few years

longer in retirement, his career had virtually closed with the

publication of his great treatise. It used to be believed that he lived

into the reign of Hadrian, and died about 118 A.D., but this idea is founded on a misconception16.

Probably he did not even see the accession of Nerva in 96: if he did, he

must have died soon afterwards, for there are two letters of Pliny’s

(one written between 97 and 100, and the other about 105) in which Pliny

does not speak of his old teacher as of one still alive.

II.

The Institutio Oratoria.

Though Quintilian spent little more than two years on the composition

of the Institutio Oratorio, his work really embodies the

experience of a

xiv

lifetime. No doubt much of it lay ready to his hand, even before he

began to write, and he would willingly have kept it longer; but the

solicitations of Trypho, the publisher, were too much for him. His

letter to Trypho shows that he fully appreciated the magnitude of his

task; and there is even the suggestion that (like many a busy teacher

since his time) he only realised when called upon to publish that he had

not covered the whole ground of his subject17. The opening words of the

introduction (post impetratam studiis meis quietem, quae per viginti

annos erudiendis iuvenibus impenderam, &c.) show that the

Institutio was the work of his retirement: and various

indications lead us to fix the date of its composition as falling

between A.D. 93 and 95. The

introduction to the Fourth Book was evidently written when (probably in

93) Domitian had appointed Quintilian tutor to his grand-nephews; the

Sixth Book, where he refers to his family losses, must have followed

shortly afterwards; while the harshness of his references to the

philosophers in the concluding portions of the work (cp. xi. 1, 30, xii.

3, 11, with 1, pr. 15, which may have been written, or at least revised,

after the rest was finished) seems to suggest that their expulsion by

Domitian (in 94) was already an accomplished fact18. The book is dedicated to

Victorius Marcellus, to whom Statius also addresses the Fourth Book of

his Silvae, evidently as to a person of some consideration and an

orator of repute (cp. Stat. Silv. iv. 4, 8, and 41 sq.). Marcellus had a

son called Geta (Inst. Or. i. pr. 6: Stat. Silv. iv. 4, 71), and it

was originally with a view to the education of this youth (erudiendo

Getae tuo) that Quintilian associated the father’s name with his

work. Geta is again referred to, along with Quintilian’s elder son, and

also the grand-nephews of Domitian, in the introduction to the Fourth

Book; but the opening words of the Sixth Book show that they are all

gone, and the epilogue, at the conclusion of Book xii, is addressed to

Marcellus on behoof of ‘studiosi iuvenes’ in general.

The plan of the Institutio Oratorio cannot be better given

than in its author’s own words (i. pr. 21 sq.): Liber primus ea quae

sunt ante officium rhetoris continebit. Secundo prima apud rhetorem

elementa et quae de ipsa rhetorices substantia quaeruntur tractabimus,

quinque deinceps inventioni (nam huic et dispositio subiungitur)

quattuor elocutioni, in cuius partem memoria ac pronuntiatio veniunt,

dabuntur. Unus accedet in quo nobis orator ipse informandus est, et qui

mores eius, quae in

xv

suscipiendis, discendis, agendis causis ratio, quod eloquentiae genus,

quis agendi debeat esse finis, quae post finem studia, quantum nostra

valebit infirmitas, disseremus. The first book deals with what the

pupil must learn before he goes to the rhetorician; it gives an account

of home-training and school discipline, and contains also a statement of

Quintilian’s views of grammar. The second book treats of rhetoric in

general: the choice of a proper instructor, as well as his character and

function, and the nature, principles, aims, and use of oratory. It is in

these early books especially that Quintilian reveals the high tone which

has made him an authority on educational morals, as well as rhetorical

training: see especially i. 2, 8, where he enlarges on Juvenal’s dictum,

maxima debetur puero reverentia; ii. 4, 10, where he advocates

gentle and conciliatory methods in teaching; and ii. 2, 5,—a

picture of the ideal teacher in language which might be applied to

Quintilian himself19. The remaining books, except the twelfth, are devoted

to the five ‘parts of rhetoric,’—invention, arrangement, style,

memory, and delivery (Cic. de Inv. i. 7, 9). In the third book we

have a classification of the different kinds of oratory. Next he treats

of the ‘different divisions of a speech, the purpose of the exordium,

the proper form of a statement of facts, what constitutes the force of

proofs, either in confirming our own assertions or refuting those of our

adversary, and of the different powers of the peroration, whether it be

regarded as a summary of the arguments previously used, or as a means of

exciting the feelings of the judge rather than of refreshing his

memory.’ This brings us to the end of the sixth book,

which closes with remarks on the uses of humour and of altercation20. The

discussion of arrangement finishes with the seventh book, which is

extremely technical: style (elocutio) is the main subject of the

four books which follow. Of these the eighth and ninth treat of the

elements of a good style,—such as perspicuity, ornament, &c.;

the tenth of the practical studies and exercises (including a course of

reading) by which the actual command of these elements may be obtained;

while the eleventh deals with appropriateness (i.e. the different kinds

of oratory which suit different audiences), memory, and delivery. The

twelfth book—which Quintilian calls the most grave and important

part of the whole work—treats of the high moral qualifications

requisite in the perfect orator:

xvi

just as the first book, introductory to the whole, describes the early

training which should precede the technical studies of the orator, so

the last book sets forth that ‘discipline of the whole man’ which is

their crown and conclusion21. “Lastly, the experienced teacher gives advice

when the public life of an orator should begin, and when it should end.

Even then his activity will not come to an end. He will write the

history of his times, will explain the law to those who consult him,

will write, like Quintilian himself, a treatise on eloquence, or set

forth the highest principles of morality. The young men will throng

round and consult him as an oracle, and he will guide them as a pilot.

What can be more honourable to a man than to teach that of which he has

a thorough knowledge? ‘I know not,’ he concludes, ‘whether an orator

ought not to be thought happiest at that period of his life when,

sequestered from the world, devoted to retired study, unmolested by

envy, and remote from strife, he has placed his reputation in a harbour

of safety, experiencing while yet alive that respect which is more

commonly offered after death, and observing how his character will be

regarded by posterity22.’”

The Institutio Oratoria differs from all other previous

rhetorical treatises in the comprehensiveness of its aim and method. It

is a complete manual for the training of the orator, from his cradle to

the public platform. Founding on old Cato’s maxim, that the orator is

the vir bonus dicendi peritus, Quintilian considers it necessary

to take him at birth in order to secure the best results, as regards

both goodness of character and skill in speaking. His work has therefore

for us a double value and a twofold interest: it is a treatise on

education in general, and on rhetorical education in particular.

Throughout the whole, oratory is the end for the sake of which

everything is undertaken,—the goal to which the entire moral and

intellectual training of the student is to be directed. Quintilian’s

high conception of his subject is reflected in the language of the

‘Dialogue on Oratory’: Studium quo non aliud in civitate nostra vel

ad utilitatem fructuosius vel ad voluptatem dulcius vel ad dignitatem

amplius vel ad urbis famam pulchrius vel ad totius imperii atque omnium

gentium notitiam inlustrius excogitari potest (ch. 5). Though

the field for the practical display of eloquence had been greatly

limited by

xvii

the extinction of the old freedom of political life, rhetoric

represented, in Quintilian’s day, the whole of education. It was to the

Romans what μουσική was

to the Greeks, and was valued all the more by them because of its

eminently practical purpose. The student of rhetoric must therefore be

fully equipped. “Quintilian postulates the widest culture: there is no

form of knowledge from which something may not be extracted for his

purpose; and he is fully alive to the importance of method in education.

He ridicules the fashion of the day, which hurried over preliminary

cultivation, and allowed men to grow grey while declaiming in the

schools, where nature and reality were forgotten. Yet he develops all

the technicalities of rhetoric with a fulness to which we find no

parallel in ancient literature. Even in this portion of the work the

illustrations are so apposite and the style so dignified and yet sweet,

that the modern reader, whose initial interest in rhetoric is of

necessity faint, is carried along with much less fatigue than is

necessary to master most parts of the rhetorical writings of Aristotle

and Cicero. At all times the student feels that he is in the company of

a high-toned Roman gentleman who, so far as he could do without ceasing

to be a Roman, has taken up into his nature the best results of ancient

culture in all its forms23.”

It is in connection with the general rather than with the technical

training of his pupils that Quintilian establishes a claim to rank with

the highest educational authorities,—as for example in his

insistence on the necessity of good example both at home24 and in school, and

on the respect due to the young25, as well as his catalogue of the

qualifications required in the trainer of youth (ii. 2, 5: 4, 10),

his protest against corporal punishment (i. 3, 14), and his

consistent advocacy of the moral as well as the intellectual aspects of

education. His system was conceived as a remedy for the existing state

of things at Rome, where eloquence and the arts in general had, as

Messalla puts it in the ‘Dialogue on Oratory,’ “declined from their

ancient glory, not from the dearth of men, but from the indolence of the

young, the carelessness of parents, the ignorance of teachers, and

neglect of the old discipline26.” Under it parents and teachers were to

be united in the effort to develop the moral and intellectual qualities

of the Roman youth: and through education the state was to recover

something of her old vigour and virtue.

The work was expected with the greatest interest before its

publication, and we may infer, from the high authority assigned to

Quintilian in the

xviii

literature of the period, that it long held an honoured place in Roman

schools. But it is curious that the earliest known references are not to

the Institutio but to the Declamationes. In an interesting

chapter of the Introduction to a recent volume27, M. Fierville has

gathered together all the references that occur in the literature of the

early centuries of our era. Trebellius Pollio and Lactantius (both of

the 3rd century) speak of the Declamations, and Ausonius (4th century)

refers to Quintilian without naming his writings: the first definite

mention of the Institutio is made by Hilary of Poitiers (died

367) and afterwards by St. Jerome (died 420). Later Cassiodorus

(468-562) pronounced a eulogy which may stand as proof of his high

appreciation: Quintilianus tamen doctor egregius, qui post fluvios

Tullianos singulariter valuit implere quae docuit, virum bonum dicendi

peritum a prima aetate suscipiens, per cunctas artes ac disciplinas

nobilium litterarum erudiendum esse monstravit, quem merito ad

defendendum totius civitatis vota requirerent (de Arte

Rhetor.—Rhet. Lat. Min., ed. Halm, p. 498). The Ars Rhetorica

of Julius Victor (6th century) is largely borrowed from Quintilian: see

Halm, praef. p. ix. Isidore, Bishop of Seville (570-630), studied

Quintilian in conjunction with Aristotle and Cicero. After the Dark Age,

Poggio’s discovery, at St. Gall in 1416, of a complete manuscript

of Quintilian was ranked as one of the most important literary events in

what we know now as the era of the Renaissance28. The great scholars of the

fifteenth century worked hard at the emendation of the text. The

editio princeps was given to the world by G. A. Campani in

1470; and in the concluding words of his preface the editor reflects

something of the enthusiasm for his author which had already been

expressed by Petrarch, Poggio, and others,—proinde de

Quintiliano sic habe, post unam beatissimam et unicam felicitatem

M. Tullii, quae fastigii loco suspicienda est omnibus et tamquam

adoranda, hunc unum esse quem praecipuum habere possis in eloquentia

ducem: quem si assequeris, quidquid tibi deerit ad cumulum

consummationis id a natura desiderabis non ab arte deposces. This

edition was followed in rapid succession by various others, so that by

the end of the 16th century Quintilian had been edited a hundred times

over29. The 17th century is not so rich in editions, but

Quintilian still reigned in the schools as the great master of rhetoric:

students of English literature

xix

will remember how Milton (Sonnet xi) uses the authority of his name when

referring to the roughness of northern nomenclature:—

Those rugged names to our like mouths grow sleek

That would have made Quintilian stare and gasp.

In his ‘Tractate on Education’ too Milton strongly recommends the

first two or three books of the Institutio. The 18th century

provided the notable editions of Burmann (1720), Capperonier (1725),

Gesner (1738), and witnessed also the commencement of Spalding’s

(1798-1816), whose text, as revised by Zumpt and Bonnell, practically

held the field till the publication of Halm’s critical edition (1868).

Towards the close of last century it would appear that Quintilian was as

much studied as he had ever been,—probably by many who believed

in, as well as by some who would have rejected the application of the

maxim ‘orator nascitur non fit.’ William Pitt, for example,

shortly after his arrival at Cambridge (1773), and while ‘still bent on

his main object of oratorical excellence,’ attended a course of lectures

on Quintilian, which caused him on one occasion to interrupt his

correspondence with his father30. His lasting popularity must have been

due, not only to his own intrinsic merits, but to the fact that his

writings harmonised well with the studies of those days: it was promoted

also by the serviceable abridgments of the Institutio, either in

whole or in part, that were from time to time published,—notably

that of Ch. Rollin in 1715. In our own day men whose education was

moulded on the old lines—such as J. S. Mill—considered

Quintilian an indispensable part of a scholar’s equipment. Macaulay read

him in India, along with the rest of classical literature. Lord

Beaconsfield professed that he was ‘very fond of Quintilian31.’ But by our

classical scholars he has been almost entirely neglected, no complete

edition having appeared in this country since a revised text was issued

in London in 1822. German criticism, on the other hand, has of late paid

Quintilian special attention, with conspicuous results for the

emendation and illustration of his text: to the great names of Spalding,

Zumpt, and Bonnell, must be added those of Halm, Meister, Becher,

Wölfflin, and Kiderlin.

Besides the literary criticism for which it has always attracted

attention, and which will form the subject of the next section, the

Tenth Book of the Institutio contains valuable precepts in regard

to various practical matters which are still of as great importance as

they were in Quintilian’s day. Among these are the practice of writing,

the use of an amanuensis,

xx

the art of revision, the limits of imitation, the best exercises in

style, the advantages of preparation, and the faculty of

improvisation.

The following list of Loci

Memoriales (mainly taken from Krüger’s third edition, pp.

108-110) will give some idea of the various points on which, especially

in the later chapters of the Tenth Book, Quintilian states his opinion

weightily and often with epigrammatic terseness:

1 §112

(p. 110) Ille se profecisse sciat cui Cicero valde placebit.

2 §4

(p. 124) Pigri est ingenii contentum esse iis quae sint ab aliis

inventa.

2 §7

(p. 125) Turpe etiam illud est, contentum esse id consequi quod

imiteris.

2 §8

(p. 126) Nulla mansit ars qualis inventa est, nec intra initium

stetit.

2 §10

(pp. 126-7) Eum vero nemo potest aequare cuius vestigiis sibi utique

insistendum putat; necesse est enim semper sit posterior qui

sequitur.

2 §10

(p. 127) Plerumque facilius est plus facere quam idem.

2 §12

(ibid.) Ea quae in oratore maxima sunt imitabilia non sunt, ingenium,

inventio, vis, facilitas, et quidquid arte non traditur.

2 §18

(p. 131) Noveram quosdam qui se pulchre expressisse genus illud

caelestis huius in dicendo viri sibi viderentur, si in clausula

posuissent ‘esse videatur.’

2 §20

(p. 132) (Praeceptor) rector est alienorum ingeniorum atque formator.

Difficilius est naturam suam fingere.

2 §22

(ibid.) Sua cuique proposito lex, suus decor est.

2 §24

(p. 134) Non qui maxime imitandus, et solus imitandus est.

3 §2

(p. 136) Scribendum ergo quam diligentissime et quam plurimum. Nam ut

terra alte refossa generandis alendisque seminibus fecundior fit, sic

profectus non a summo petitus studiorum fructus effundit uberius et

fidelius continet.

3 §2

(p. 137) Verba in labris nascentia.

3 §3

(ibid.) Vires faciamus ante omnia, quae sufficiant labori certaminum et

usu non exhauriantur. Nihil enim rerum ipsa natura voluit magnum effici

cito, praeposuitque pulcherrimo cuique operi difficultatem.

3 §7

(p. 139) Omnia nostra dum nascuntur placent, alioqui nec

scriberentur.

3 §9

(ibid.) Primum hoc constituendum, hoc obtinendum est, ut quam optime

scribamus: celeritatem dabit consuetudo.

3 §10

(ibid.) Summa haec est rei: cito scribendo non fit ut bene scribatur,

bene scribendo fit ut cito.

3 §15

(p. 142) Curandum est ut quam optime dicamus, dicendum tamen pro

facultate.

3 §22

(p. 146) Secretum in dictando perit.

xxi

3 §26

(p. 148) Cui (acerrimo labori) non plus inrogandum est quam quod somno

supererit, haud deerit.

3 §27

(ibid.) Abunde, si vacet, lucis spatia sufficiunt: occupatos in noctem

necessitas agit. Est tamen lucubratio, quotiens ad eam integri ac

refecti venimus, optimum secreti genus.

3 §29

(ibid.) Non est indulgendum causis desidiae. Nam si non nisi refecti,

non nisi hilares, non nisi omnibus aliis curis vacantes studendum

existimarimus, semper erit propter quod nobis ignoscamus.

3 §31

(p. 149) Nihil in studiis parvum est.

4 §1

(p. 151) Emendatio, pars studiorum longe utilissima; neque enim sine

causa creditum est stilum non minus agere, cum delet. Huius autem operis

est adicere, detrahere, mutare.

4 §4

(p. 152) Sit ergo aliquando quod placeat aut certe quod sufficiat, ut

opus poliat lima, non exterat.

5 §23

(p. 166) Diligenter effecta (sc. materia) plus proderit quam plures

inchoatae et quasi degustatae.

6 §1

(p. 167) Haec (sc. cogitatio) inter medios rerum actus aliquid invenit

vacui nec otium patitur.

6 §2

(p. 168) Memoriae quoque plerumque inhaeret fidelius quod nulla

scribendi securitate laxatur.

6 §5

(ibid.) Sed si forte aliqui inter dicendum effulserit extemporalis

color, non superstitiose cogitatis demum est inhaerendum.

6 §6

(p. 169) Refutare temporis munera longe stultissimum est.

6 §6

(ibid.) Extemporalem temeritatem malo quam male cohaerentem

cogitationem.

7 §1

(p. 170) Maximus vero studiorum fructus est et velut praemium quoddam

amplissimum longi laboris ex tempore dicendi facultas.

7 §4

(p. 171) Perisse profecto confitendum est praeteritum laborem, cui

semper idem laborandum est. Neque ego hoc ago ut ex tempore dicere

malit, sed ut possit.

7 §12

(p. 175) Mihi ne dicere quidem videtur nisi qui disposite, ornate,

copiose dicit, sed tumultuari.

7 §15

(p. 176) Pectus est enim, quod disertos facit, et vis mentis.

7 §§16-17

(p. 177) Extemporalis actio auditorum frequentia, ut miles congestu

signorum, excitatur. Namque et difficiliorem cogitationem exprimit et

expellit dicendi necessitas, et secundos impetus auget placendi

cupido.

7 §18

(ibid.) Facilitatem quoque extemporalem a parvis initiis paulatim

perducemus ad summam, quae neque perfici neque contineri nisi usu

potest.

7 §20

(p. 178) Neque vero tanta esse umquam fiducia facilitatis

xxii

debet ut non breve saltem tempus, quod nusquam fere deerit, ad ea quae

dicturi sumus dispicienda sumamus.

7 §21

(p. 178) Qui stultis videri eruditi volunt, stulti eruditis

videntur.

7 §24

(p. 179) Rarum est ut satis se quisque vereatur.

7 §26

(p. 180) Studendum vero semper et ubique.

7 §27

(p. 180-1) Neque enim fere tan est ullus dies occupatus ut nihil

lucrativae ... operae ad scribendum aut legendum aut dicendum rapi

aliquo momento temporis possit.

7 §28

(p. 181) Quidquid loquemur ubicumque sit pro sua scilicet portione

perfectum.

7 §28

(ibid.) Scribendum certe numquam est magis, quam cum multa dicemus ex

tempore.

7 §29

(p. 181-2) Ac nescio an si utrumque cum cura et studio fecerimus,

invicem prosit, ut scribendo dicamus diligentius, dicendo scribamus

facilius. Scribendum ergo quotiens licebit, si id non dabitur,

cogitandum; ab utroque exclusi debent tamen sic dicere ut neque

deprehensus orator neque litigator destitutus esse videatur.

III.

Quintilians’s Litary Criticism.

It was the conviction that a cultured orator is better than an orator

with no culture that induced Quintilian to devote so considerable a part

of the Tenth Book to a review of Greek and Roman literature. He was

aware that in order to speak with effect it is necessary for a man to

know a good deal that lies outside the scope of the particular case

which he may undertake to plead; and while the ‘firm facility’ ἕξις at which he taught the

orator to aim could only be attained by a variety of exercises and

qualifications, a course of wide and careful reading must always, he

considered, form one of the factors in the combination.

In judging of the merits of Quintilian’s literary criticism we must

not forget the point of view from which he wrote. He is not dealing with

literature in and for itself. His was not the cast of mind in which the

faculty of literary appreciation finds artistic expression in the form

in which criticism becomes a part of literature itself. We cannot think

of the author of the Tenth Book of the Institutio as one whom a

divinely implanted instinct for literature impelled, towards the evening

of his days, to leave a record of the personal impressions he had

derived from contact with those whom we now recognise as the

master-minds of classical antiquity. Quintilian writes, not as the

literary man for a sympathetic brotherhood, but as the professor of

rhetoric for students in his school. If, in the

xxiii

course of his just and sober, but often trite and obvious criticisms, he

characterises a writer in language which has stood the test of time, it

is always when that writer touches his main interest most nearly, as one

from whom the student of style may learn much. In short, his work in the

department of literary criticism is done much in the same spirit as that

which, in these later days, has moved many sober and sensible, but on

the whole average persons, conversant with the general current of

contemporary thought, and not without the faculty of appreciative

discrimination, to draw up a list of the ‘Best Hundred Books.’ Their

aim, however, has been to guide and direct the work of that peculiar

product of modern times, the ‘general reader’: Quintilian’s victim was

the professed student of rhetoric.

But this limitation, arising partly out of the special aim which he

had imposed upon himself, partly, also, in all probability, from the

constitution of his own mind, ought not to blind us to the value of the

comprehensive review of ancient literature which Quintilian has left us

in this Tenth Book. “His literary sympathies are extraordinarily wide.

When obliged to condemn, as in the case of Seneca, he bestows generous

and even extravagant praise on such merit as he can find. He can

cordially admire even Sallust, the true fountain-head of the style which

he combats, while he will not suffer Lucilius to lie under the

aspersions of Horace.... The judgments which he passes may be in many

instances traditional, but, looking to all the circumstances of the

time, it seems remarkable that there should then have lived at Rome a

single man who could make them his own and give them expression. The

form in which these judgments are rendered is admirable. The gentle

justness of the sentiments is accompanied by a curious felicity of

phrase. Who can forget the ‘immortal swiftness of Sallust,’ or the

‘milky richness of Livy,’ or how ‘Horace soars now and then, and is full

of sweetness and grace, and in his varied forms and phrases is most

fortunately bold’? Ancient literary criticism perhaps touched its

highest points in the hands of Quintilian.”32

The course of reading which Quintilian recommends is selected with

express reference to the aim which he had in view, and which is put

prominently forward in connection with nearly every individual

criticism. The young man who aspires to success in speaking must have

his taste formed: when he reads Homer, let him note that, great poet as

Homer is, and admirable in every respect, he is also oratoria virtute

eminentissimus (1 §46). Alcaeus is plerumque

oratori similis (1 §63): Euripides is, on that

ground, to be preferred to Sophocles (1 §67): Lucan is magis

oratoribus quam poetis imitandus (1 §70): and the old Greek comedy

is

xxiv

specially recommended as a form of poetry ‘than which probably none is

better suited to form the orator’ (1 §65). With the prose writers

Quintilian is thoroughly at home, and he nowhere lets in so much light

on his own sympathies as in the estimates he gives us of Cicero (1 §§105-112) and Seneca (1 §§125-131). His

criticism of Cicero is precisely what might have been expected from the

general tone of the references throughout the Institutio. Cicero

is Quintilian’s model, to whom he looks up with reverential admiration:

he will not hear of his faults. In his own day the great orator had been

attacked by Atticists of the severer type for the richness of his style

and the excessive attention which they alleged that he paid to rhythm.

The ‘plainness’ of Lysias was their ideal, and they failed to recognise

the fact that, with the more limited resources of the Latin language,

such simplicity and condensation would be perilously near to baldness

(cp. note on

1 §105). Cicero they

regarded as an Asianist in disguise; in the words of his devoted

follower, they “dared to censure him as unduly turgid and Asiatic and

redundant; as too much given to repetition, and sometimes insipid in his

witticisms; and as spiritless, diffuse, and (save the mark!) even

effeminate in his arrangement” (Inst. Or. xii. 10, 12, quoted on

1 §105). That this

criticism had not been forgotten in Quintilian’s own day is obvious not

only from the Institutio but also from the discussion in the

Dialogus de Oratoribus, where Aper is represented as saying “We

know that even Cicero was not without his disparagers, who thought him

inflated, turgid, not sufficiently concise, but unduly diffuse and

luxuriant, and far from Attic” (ch. 18). To such detractors of his great

model Quintilian will have nothing to say, and in his criticism of

Cicero he gives full expression to his enthusiastic admiration for the

genius of one who had brought eloquence to the highest pinnacle of

perfection (vi. 31 Latinae eloquentiae princeps: cp. x.

1 §§105-112: xii. 1,

20 stetisse ipsum in fastigio eloquentiae fateor: 10, 12 sqq.

in omnibus quae in quoque laudantur eminentissimum).

With such an absorbing enthusiasm for Cicero, it was hardly to be

expected that Quintilian would show an adequate appreciation of Seneca.

Seneca’s influence was the great obstacle in the way of a general return

to the classical tradition of the Golden Age, and this was the literary

reform which Quintilian had at heart—corruptum et omnibus

vitiis fractum dicendi genus revocare ad severiora iudicia contendo

x.

1, 125. It is probable

that, in spite of the appearance of candour which he assumes in dealing

with him, Quintilian approached Seneca with a certain degree of

prejudice33. Quintilian represents the literature of erudition, and

his

xxv

standard is the best of what had been done in the past: Seneca was, like

Lucan, the child of a new era, to whom it seemed perfectly natural that

new thoughts should find utterance in new forms of expression. Seneca’s

motto was ‘nullius nomen fero,’—he gave free rein to the play of

his fancy, and rejected all method34: Quintilian looked with horror (in the

interest of his pupils) on a liberty that was so near to licence, and

set himself to check it by recalling men’s minds to the ‘good old ways,’

and extolling Cicero as the synonym for eloquence itself. In such a

conflict of tastes as regards things literary, and apart from the

ambiguous character of Seneca’s personal career, it is not surprising

that Quintilian should have been unfavourably disposed towards him. He

had a grudge, moreover, against philosophers in general, especially the

Stoics. They had encroached on what his comprehensive scheme of

education impelled him to believe was the province of the teacher of

rhetoric,—the moral training of the future orator35.

He was morbidly anxious to show that rhetoric stood in need of no

extraneous assistance: even the ‘grammatici’ he teaches to know their

proper place (see esp. i. 9, 6). But it was mainly, no doubt, as

representing certain literary tendencies of which he disapproved that

Seneca must have incurred Quintilian’s censure. It is probable that in

many passages of the Institutio, where he is not specially named,

it is Seneca that is in the writer’s mind: the tone of the references

corresponds in several points with the famous passage of the Tenth

Book36. In this passage

xxvi

Quintilian is evidently putting forward the whole force of his authority

in order to counteract Seneca’s influence. He has kept him waiting in a

marked manner, to the very end of his literary review: and when he comes

to deal with him he does not confine his criticism to a few words or

phrases, but devotes nearly as much space to him as he did to Cicero

himself. In his estimate of Seneca nothing is more remarkable than the

careful manner in which Quintilian mingles praise and blame. But the

praise is reluctant and half-hearted: it is Seneca’s faults that his

critic wishes to make prominent. He admits his ability (ingenium

facile et copiosum

§128), and even goes the

length of saying that it would be well if his imitators could rise to

his level (foret enim optandum pares ac saltem proximos illi viro

fieri

§127). But praise is no

sooner given than it is immediately recalled. It was his faults that

secured imitators for Seneca (placebat propter sola vitia ib.);

if he was distinguished for wide knowledge (plurimum studii, multa

rerum cognitio

§128), he was often misled

by those who assisted him in his researches; if there is much that is

good in him, ‘much even to admire’ (multa ... probanda in eo, multa

etiam admiranda sunt

§131), still it requires

picking out. In short, so dangerous a model is he, that he should be

read only by those who have come to maturity, and then not so much,

evidently, for improvement, as for the reason that it is good to ‘see

both sides,’—quod exercere potest utrimque iudicium,

ib.

It has already been suggested that the secret of a great part of

Quintilian’s antipathy to Seneca may have been his dislike of the

philosophers, whom his imperial patrons found it necessary from time to

time to suppress. He was anxious to exalt rhetoric at the expense of

philosophy. But he was no doubt also honestly of opinion—and his

position as an instructor of youth would make him feel bound to express

his view distinctly—that Seneca was a dangerous model for the

budding orator to imitate. His merits were many and great: but his

peculiarities lent themselves readily to degradation. Quintilian wished

to put forward a counterblast to the fashionable tendency of the day,

and to recall—in their own interests—to severer models

Seneca’s youthful imitators,—those of whom he writes ad ea

(i.e. eius vitia) se quisque dirigebat effingenda, quae

poterat; deinde quum se iactaret eodem modo dicere, Senecam

infamabat

§127. Seneca was of course

not responsible for the exaggerations of his imitators, and Quintilian

would never have encouraged in his pupils exclusive devotion to any

particular model, especially if that model were characterised by such

peculiar features of style as distinguished Sallust or Tacitus. But he

could not forgive

xxvii

Seneca for his share in the reaction against Cicero37. Admirers of Seneca think

that he failed to make allowance for the influences at work on the

philosopher’s style, and that he judged him too much from the standpoint

of a rhetorician. They admit Seneca’s faults—his tendency to

declamation, the want of balance in his style, his excessive subtlety,

his affectation, his want of method: but they contend that these faults

are compensated by still greater virtues38.

M. Rocheblave, who possesses the appreciation of Seneca traditional among

Frenchmen, follows Diderot in inclining to believe that the philosopher was the

victim of envy and dislike39. For himself he protests in the following terms against what

he considers the inadequacy of Quintilian’s estimate: ‘Da mihi quemvis Annaei

librorum ignarum, et dicito num ex istis Quintiliani laudibus non modo

perspicere, sed suspicari etiam possit quanto sapientiae doctrinaeque gradu

steterit scriptor qui in tota latina facundia optima senserit, humanissima

docuerit, maxima et multo plurima excogitaverit, ita ut, multis ex antiqua

morali philosophia seu graeca seu latina depromptis, adiectis pluribus,

potuerit in unum propriumque saporem omnia illa quasi sapientiae humanae

libamenta confundere? Credisne a tali lectore scriptorem vivo gurgite

exundantem, sensibus scatentem, legentes in perpetuas rapientem cogitationes,

eum denique quem ob vim animi ingeniique acumen iure anteponat Tullio Montanius

noster40, protinus

agnitum iri? ...facile credo pusillas Fabii laudes multum infra viri meritum

stetisse (quod detrectationis sit tutissimum genus) omnes mecum confessuros’

(pp. 44-5).

Whether they were altogether deserved or not, there can be no doubt

xxviii

that the strictures made by so great a literary leader as Quintilian was

in his own day must have greatly contributed to the overthrow of

Seneca’s influence. There is more than one indication, in the literature

of the next generation, that he is no longer regarded as a safe model

for imitation. Tacitus, in reporting the panegyric which Nero delivered

on Claudius after his death, and which was the work of Seneca, says that

it displayed much grace of style (multum cultus), as was to be

expected from one who possessed ingenium amoenum et temporis eius

auribus accommodatum (Ann. xiii. 3). Suetonius tell us how

Caligula disparaged the lenius comtiusque scribendi genus which

Seneca represented; and here (Calig. 53) occurs a similar reference to a

fame that had passed away,—Senecam tum maxime

placentem, just as the elder Pliny, writing about the time of

Seneca’s death, speaks of him as princeps tum eruditorum

(Nat. Hist. xiv. 51). Later writers, such as Fronto and Aulus Gellius41 were

much more unreserved and even immoderate in their censure. And it is a

remarkable fact (noted by M. Rocheblave) that the name of the great

Stoic nowhere occurs in the writings of his successors, Epictetus and

Marcus Aurelius. He who had been the greatest literary ornament of

Nero’s reign disappears almost from notice in the second century.

In regard to the general body of Quintilian’s literary criticism, the

question of greatest interest for modern readers is the degree of its

originality. How far is Quintilian giving us his own independent

judgments on the writings of authors whom he had read at first hand? How

far is he merely registering current criticism, which must already have

found more or less definite expression in the writings and teaching of

previous rhetoricians and grammarians? The circumstances of the case

make it impossible for us to approach the special questions which it

involves with any great prejudice in favour of Quintilian’s originality

in general. The extent of his indebtedness to previous writers, as

regards the main body of his work, may be inferred from a glance at the

‘Index scriptorum et artificum’ in Halm’s edition. In many places he is

merely simplifying the rules of the Greek rhetoricians whom he followed.

Probably he was not equally well up in all the departments of the

subject of which he treats, and he naturally relied, to some extent, on

the works of those who had preceded him. But did he take his literary

criticism from others? Was Quintilian one of those reprehensible persons

who do not scruple to borrow, and to give forth as their own, the

estimate formed and expressed

xxix

by some one else of authors whose works they may never themselves have

read?

In endeavouring to find an answer to this question, it will be

convenient to consider Quintilian’s criticism of the Greek writers apart

from that which he applies to his own countrymen, with whose works he

might a priori be expected to be more familiar. The notes to

that part of the Tenth Book in which he deals with Greek literature (1 §§46-84) will show too

many instances of parallelism for us to believe that, in addressing

himself to this portion of his subject, Quintilian scrupulously avoided

incurring any obligations to others42. No doubt in his long career as a

teacher he had come into contact with traditional opinion as to the

merits and characteristics not only of the Greek but also of the Latin

writers; and in the two years which he tells us he devoted to the

composition of the Institutio43 he may still further have increased his

debt to extraneous sources. It was in fact impossible that Quintilian

should have been unaware of the nature of the criticism current in his

own day, and of what had previously been said and written by others. But

he is not to be thought of as one who, before indicating his opinion of

a particular writer, carefully refers, not to that writer’s works, but

to the opinion of others concerning them. The cases in which he

reproduces, in very similar language, the verdict of others are not

always to be explained on the hypothesis of conscious borrowing44. The

coincidences which can be traced certainly do detract from the

originality of his work.

xxx

But we do not need to believe that, in writing his individual

criticisms, Quintilian always had recourse to the works of others: he no

doubt had them at hand, and his career as a teacher had probably

impressed on his memory many dicta which he could hardly fail to

reproduce, in one form or another, when he came to gather together the

results of his teaching.

Literary criticism at Rome before Quintilian’s time is associated

mainly with the names of Varro, Cicero, and Horace45. Varro was the author of

numerous works bearing on the history and criticism of literature: such

were his de Poetis, de Poematis, περὶ χαρακτήρων, de Actionibus

Scaenicis, Quaestiones Plautinae. Our knowledge of their

scope and character is however derived only by inference from a few

scattered fragments, and in regard to these it is impossible to say

definitely to which of his treatises they severally belong. Quintilian’s

references to his literary activity as well as his great learning

(vir Romanorum eruditissimus x.

1, 95), and the

quotation of his estimate of Plautus (ib. §99), are sufficient evidence

that he was not unacquainted with Varro’s writings. Cicero he knew

probably better than he knew any other author: the extent of his

indebtedness to such works as the Brutus may be inferred from the

parallelisms which occur in his treatment of the Attic orators (x.

1, 76-80). He dissents

expressly from Horace’s estimate of Lucilius (ib. §94): and the

frequency of his references to other literary judgments of Horace (cp.

§§24, 56, 61, 63) shows that he must have been in the habit of

illustrating his teaching by quotations from the works of that cultured

critic of literature and life.

But the author with whom Quintilian’s literary criticism has most in

common is undoubtedly Dionysius of Halicarnassus. It is true that in the

Tenth Book he nowhere expressly mentions him; but references to him by

name as an authority on rhetorical matters are common enough in other

parts of the Institutio46. Quintilian no doubt knew his works

well, especially that which originally consisted of three books περὶ μιμήσεως47. The second

book of this treatise has long been known to scholars

xxxi

in the shape of a fragmentary epitome, which presents so many striking

resemblances to the literary judgments contained in the first chapter of

Quintilian’s Tenth Book, that early commentators, such as, for instance,

H. Stephanus, concluded that Quintilian had borrowed freely from

the earlier writer: multa hinc etiam mutuatum constat; quibus modo

nomine suppresso pro suis utitur, modo addito verbo putant sua

non esse declarat. The parallelisms in question were fully drawn out

by Claussen in the work mentioned above, though Usener justly remarks

that he wrongly includes a good deal that was the common property not

only of Dionysius and Quintilian, but of the whole learned world of the

day: they will all be found duly recorded in the notes to this edition,

1 §§46-84.

The general resemblances between Quintilian and Dionysius are

apparent in their order of treatment. In his introduction to the

Iudicium de Thucydide, the latter sets forth the plan of his

second book in terms which present many points of analogy with the

scheme of the Tenth Book of the Institutio: ἐν τοῖς προεκδοθεῖσι Περὶ τῆς μιμήσεως ὑπομνηατισμοῖς

ἐπεληλυθὼς οὓς ὑπελάμβανον ἐπιφανεστάτους εἶναι ποιητάς τε καὶ

συγγραφεῖς ... καὶ δεδηληκὼς ἐν ὀλίγοις τίνας ἕκαστος αὐτῶν εἰσφέρεται

πραγματικάς τε καὶ λεκτικὰς ἀρετὰς καὶ πῇ μάλιστα χείρων ἑαυτοῦ γίνεται

... ἵνα τοῖς προαιρουμένοις γράφειν τε καὶ λέγειν εὖ καλοὶ καὶ

δεδοκιμασμένοι κανόνες ὦσιν ἐφ᾽ ὧν ποιήσονται τὰς κατὰ μέρος γυμνασίας,

μὴ πάντα μιμούμενοι τὰ παρ᾽ ἐκείνοις κείμενα τοῖς ἀνδράσιν, ἀλλὰ τὰς μὲν

ἀρετὰς αὐτῶν λαμβάνοντες, τὰς δ᾽ ἀποτυχίας φυλαττόμενοι‧ ἁψάμενός τε τῶν

συγγραφέων ἐδήλωσα καὶ περὶ Θουκουδίδου τὰ δοκοῦντά μοι συντόμῳ τε καὶ

κεφαλαιώδει γραφῇ περιλαβών, ... ὡς καὶ περὶ τῶν ἄλλων ἐποίησα‧ οὐ γὰρ

ἦν ἀκριβῆ καὶ διεξοδικὴν δήλωσιν ὑπὲρ ἑκάστου τῶν ἀνδρῶν ποιεῖσθαι

προελόμενον εἰς ἐλάχιστον ὄγκον συναγαγεῖν τὴν πραγματείαν. In