|

"BLUE BONNET . . . WATCHED THE SUN RISE OUT OF THE PRAIRIE." (See page 303.) |

Title: Blue Bonnet's Ranch Party

Author: Caroline Elliott Hoogs Jacobs

Edyth Ellerbeck Read

Illustrator: John Goss

Release date: June 28, 2007 [eBook #21960]

Most recently updated: January 2, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Suzanne Lybarger, Brian Janes and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

|

"BLUE BONNET . . . WATCHED THE SUN RISE OUT OF THE PRAIRIE." (See page 303.) |

|

THE COSY CORNER SERIES By Caroline E. Jacobs Each, one vol., small 12mo, illustrated $0.75

53 Beacon Street, Boston, Mass. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| First Impression, July, 1912 |

| Second Impression, October, 1912 |

| Third Impression, May, 1913 |

| Fourth Impression, January, 1914 |

| Fifth Impression, April, 1914 |

| Sixth Impression, February, 1915 |

| Seventh Impression, June, 1915 |

| Eighth Impression, July, 1916 |

| Ninth Impression, April, 1917 |

| Tenth Impression, March, 1918 |

| Eleventh Impression, July, 1919 |

| Twelfth Impression, May, 1920 |

| Thirteenth Impression, December, 1921 |

| chapter | page | |

| I. | The Wanderer | 1 |

| II. | In the Blue Bonnet Country | 16 |

| III. | The Glorious Fourth | 32 |

| IV. | The Round Robin | 45 |

| V. | The Swimming Hole | 60 |

| VI. | An Adventure | 71 |

| VII. | A Falling Out | 86 |

| VIII. | Consequences | 101 |

| IX. | Texas and Massachusetts | 112 |

| X. | Enter Carita | 124 |

| XI. | Camping by the Big Spring | 142 |

| XII. | Poco Tiempo | 155 |

| XIII. | Around the Camp-fire | 169 |

| XIV. | A Falling In | 183 |

| XV. | Sunday | 200 |

| XVI. | The Lost Sheep | 215 |

| XVII. | Secrets | 230 |

| XVIII. | Some Arrivals | 242 |

| XIX. | Blue Bonnet's Birthday | 259 |

| XX. | Conferences | 275 |

| XXI. | Blue Bonnet Decides | 290 |

| XXII. | Hasta la Vista | 300 |

| page | |

| "Blue Bonnet . . . watched the sun rise out of the prairie" (See page 303) | Frontispiece |

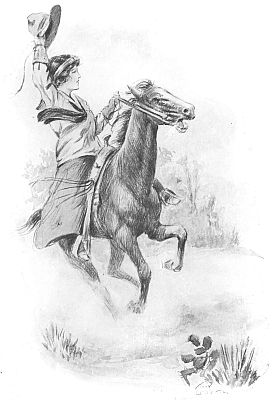

| "Comanche . . . leaped forward like a cat" | 41 |

| "'I believe the only way to learn to swim is to dive in head-first'" | 96 |

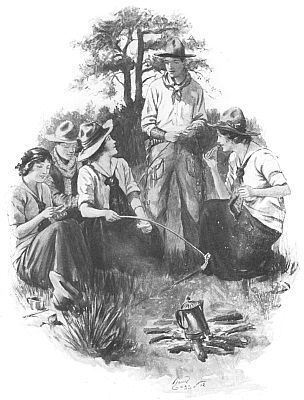

| "They all gathered gypsy-fashion about the fire" | 187 |

| "It was an exquisite miniature, painted on ivory" | 261 |

| "Alec surveyed her proud little profile" | 290 |

[1]

Blue Bonnet put her head out of the car window for the hundredth time that hour, and drew it back with a sigh of utter exasperation.

"Uncle Cliff," she declared impatiently, "if The Wanderer doesn't move a little faster I'll simply have to get out and push!"

"Better blame the engine, Honey," said Uncle Cliff in his slow, soothing way. "The Wanderer is doing her best. Might as well blame the wagon for not making the horses gallop!"

"I know," she confessed. "But it seems as if we'd never get to Woodford. This is the longest-seeming journey I ever took—even if it is in a private car." Then, fearing to appear inappreciative, she added quickly: "But I do think it is mighty good of Mr. Maldon to let us take his very own car. I can just see the We are Sevens' eyes pop right out when they see this style of travelling." Blue Bonnet's own eyes roamed over the luxurious interior of The Wanderer, dwelling with approval[2] on the big, swinging easy chairs, the book-case cunningly set in just over a writing-desk, the buffet shining with cut glass and silver, and the thousand and one details that made the car a veritable palace on wheels.

Blue Bonnet had been spending a few days in New York with her uncle, who had insisted that she should have a little "lark" after her long months in school. Now, in a private car belonging to one of Uncle Cliff's friends, they were on their way back to Woodford, there to gather up Grandmother Clyde, Alec Trent, and the other six of Blue Bonnet's "We are Seven" Club, and bear them off to Texas for the summer.

"I reckon Sarah Blake and Kitty Clark aren't very used to travelling?" suggested Uncle Cliff, more to draw out Blue Bonnet than with any consuming desire for information.

"Used to travelling! Why, Uncle Cliff—" Blue Bonnet shook her head emphatically—"not one of the other We are Sevens has ever so much as seen the inside of a Pullman in all her life!"

Mr. Ashe hid a smile under his moustache. The fact that Blue Bonnet's own introduction to a Pullman car had occurred just nine months before, seemed to have escaped the young lady's mind.

"Well, well," ejaculated Blue Bonnet's uncle, "they've some experiences ahead of them, to be sure!"[3]

"Oh, Uncle,"—Blue Bonnet was struck with a sudden fear,—"do you suppose they will all be ready to go? We're two whole days earlier than we said we'd be—"

"They'll be ready, don't you worry. Your grandmother is not one of the unprepared sort, and the girls don't need much of a wardrobe for the ranch. Besides, I wired them explicit directions—to meet The Wanderer and be ready to come aboard immediately. We shall have only a few minutes in Woodford."

Blue Bonnet settled back in her red velvet reclining chair and shut her eyes. Slowly a smile wreathed her lips.

"What's the joke, Honey?"

Blue Bonnet looked up with dancing eyes. "Benita!" she laughed. "Won't she be just—petrified, when she sees seven girls instead of one? And can't you imagine the boys—"

"Benita had better not get petrified this summer," interrupted Uncle Cliff. "She has to do some tall hustling. I've wired Uncle Joe to get extra help while the ranch party is in session. If they can get old Gertrudis from the Lone Star Ranch—she's the finest cook in the state of Texas. And her granddaughter might wait on table."

"Oh, I do think a ranch party is the grandest thing in the world," cried Blue Bonnet. "I've read of house parties, but they must be downright tame[4] compared with this kind of a party. And it's not to last just over a week-end either, but two whole months! Why, Uncle Cliff, any ordinary man would be scared to pieces at the prospect."

"But I'm not an ordinary man, eh?" Mr. Ashe looked pleased as a boy as he put the question.

"Well, I reckon not! You're a fairy godfather. You grant my wishes before they're fairly out of my mouth. And I seem to have plenty of wishes. Just think, Uncle, how many things I've wished for since my last birthday!"

"First," said Uncle Cliff, "you wished to go away from the ranch."

Blue Bonnet nodded assent. "Because I was—afraid—to ride. Doesn't it seem ridiculous, now I'm over that silliness? But oh, how I did wish I could get over being afraid! That was about the only wish you couldn't grant, Uncle Cliff."

"That wish was never expressed, Honey—don't forget that. Maybe I could have helped even there," Mr. Ashe suggested gently.

"I know, it was my own fault. But I was—ashamed, Uncle Cliff. You don't suppose—" Blue Bonnet's face clouded, "you don't think, do you, that the fear will come again when I get back where I saw José—dragged?" She shut her eyes and shuddered.

"Nonsense, Honey. That fear died and was buried the day you rode Alec's horse, Victor. A[5] good canter on Firefly over the Blue Bonnet country will make you wonder that such a feeling was ever born."

"Dear old Firefly! Won't I make it up to him though! Isn't it queer how many of my wishes have come true? It makes me feel almost—breathless. I no sooner got through wishing I could leave the ranch and go East and be with Grandmother—than I woke up in Woodford. And I wanted—thought I wanted—to be called Elizabeth. Blue Bonnet became Elizabeth!"

"A real lightning change artist," murmured Uncle Cliff.

"And I wanted to go to school. Granted. I wanted to know a lot of girls, and behold the We are Sevens!"

"And when was it you changed names again?" Uncle Cliff asked slyly.

"When I got tired of being Elizabethed. Everybody thinks Blue Bonnet suits me better, except Aunt Lucinda—on occasions."

"And the next wish? They're stacking up."

"I reckon it was about the Sargent prize in school. I wanted Alec Trent to win it—and he did. And next I wished to pass my school examinations—"

"And even that miracle was achieved!" said Uncle Cliff, pinching her cheek.

"And, finally, I wanted to go back to Texas, and,[6] at the same time, I wished I didn't have to leave Grandmother and Alec and the girls. That might seem a contrary pair of wishes, but it doesn't daunt Godfather Ashe. He straightway makes a private car arise from—from what, Uncle Cliff?"

"Tobacco smoke," promptly supplied Mr. Ashe, with a reminiscent smile on his lips.

"Why tobacco smoke?" asked Blue Bonnet wonderingly.

"I taught Maldon to smoke when he was a young chap visiting out our way, and we've been friends ever since. The private car seems to have grown out of that," replied her uncle.

"I see," Blue Bonnet nodded. "But don't tell Aunt Lucinda,—I fancy she doesn't approve of smoking."

"So I've noticed," rather grimly rejoined Mr. Ashe. Blue Bonnet's prim New England aunt had not suffered him to remain long in ignorance of her disapproval of tobacco in any form.

"There's one thing I don't understand at all," Blue Bonnet knitted her pretty brows. "And that is what was in Uncle Joe Terry's telegram the other day. Won't you tell me, Uncle?"

"Nothing much,—only that I must be back at the ranch Monday evening without fail," answered Uncle Cliff with an air of evasion.

"There's some deep reason, I can just feel it. You mean well, Uncle, but I just hate secrets."[7] Blue Bonnet laid a coaxing hand on her uncle's arm.

"Secret indeed!" scoffed Uncle Cliff, avoiding his niece's eye.

"You can't pretend a bit well," Blue Bonnet assured him gravely. "You look just the way my dog Solomon does when he's pretending to be asleep—and can't keep his tail from wagging!"

"Thank you!" said Uncle Cliff with well-assumed indignation.

"You're quite welcome. He's a mighty wise dog, Uncle Cliff—that's why I named him Solomon. You know I think—" Blue Bonnet went on sagely, "I think there is some trouble at the ranch,—because I saw the big box you sent with our trunks and it was labelled 'dangerous.' Now, be nice, and tell me what was in it."

"I understood that Miss Kitty was the inquisitive member of your Club," Uncle Cliff parried provokingly.

Blue Bonnet sighed. "Well, I can thank Uncle Joe for cutting us out of two whole days in New York. I'm sure Aunt Lucinda will be disappointed."

"Aunt Lucinda—?" echoed Mr. Ashe.

"Yes, you see it was this way: Aunt Lucinda gave me a list of things I ought to see in New York. Every day when you asked me 'what next?'—as you did, you nice fairy godfather—I[8] chose the things I'd rather see and left the—the educational things for the last. You see the shops, the Hippodrome, Coney Island, Peter Pan and the Goddess of Liberty were so fascinating, and I'd wanted so long to see them, that— Well, to face the bitter truth, Uncle Cliff, we left New York without one weenty peek in at the Metropolitan Museum!"

"Horrors!" Uncle Cliff looked properly stunned. Then he said craftily, "Keep it dark, Honey. Maybe we can bluff."

Blue Bonnet shook her head. "Nobody can bluff Aunt Lucinda—I ought to know! Why—Uncle Cliff—I believe we're there!"

And "there" they certainly were. While Blue Bonnet had been busily chattering, The Wanderer had drawn in to the Woodford station.

Half the population of the village was assembled on the platform, it seemed to Blue Bonnet as she sprang from the car steps. Grandmother and Aunt Lucinda she saw first, and back of them Denham, the coachman, bearing suitcases, umbrellas, magazines and wraps, besides holding on by main force to a leash at which Solomon was straining frantically. Beside him were Katie and Delia, on hand for a final farewell to Blue Bonnet and Mrs. Clyde. Then came Kitty and Doctor Clark; Amanda and the Parkers; Sarah and the whole crowd of Blakes, big and little; Alec and the General; Debby, and[9] a collection of sisters, cousins, uncles and aunts that overflowed the platform and straggled clear out to the line of hitching-posts, where all of Woodford's family conveyances seemed drawn up at once.

The report of Blue Bonnet's ranch party had spread like wildfire through the town, and the going away of so many of its most prominent citizens to far-off Texas, had aroused quiet Woodford to a pitch of excitement equalled only by that of a prohibition election, or a visit from the President.

Blue Bonnet was swallowed up by the crowd the moment she alighted, and it was a full five minutes before she emerged, flushed and minus her hat, to ask breathlessly, "Oh, is everybody here?—I can't see anybody for the crowd!"

"No time to lose," warned Mr. Ashe. "We must pull out in ten minutes in order to reach Boston in time for the 5.17 to-night."

Even as he spoke, The Wanderer began to move.

"Uncle Cliff," cried Blue Bonnet in a panic, "they're going without us!"

"Just switching," soothed her uncle. "The Wanderer has to be on the other track so as to hook on to the train for Boston. That's due in five minutes. Get your good-byes said so that everybody can go aboard when she comes alongside."

During that five minutes while each girl was[10] occupied with her own family, Blue Bonnet had a moment alone with her aunt. "It's a good thing we said our real good-bye before I went to New York, isn't it, Aunt Lucinda?" she asked, slipping her hand shyly into that of her tall, prim aunt. Somehow Aunt Lucinda had never seemed so dear as in this moment of parting. Perhaps it was the look as of unshed tears in her eyes, or the flush on her usually pale face that made her seem more approachable. Blue Bonnet could not tell exactly what it was, but there was a vague something about Aunt Lucinda that made her appear almost—yes, almost, pathetic. Suddenly Blue Bonnet remembered—they were leaving Aunt Lucinda all alone. Her heart reproached her. "Aunt Lucinda," she whispered hurriedly, "won't you come, too?"

One of her rare sweet smiles lit Miss Clyde's face. "Thank you, dear—it is sweet of you to want me. But not this time, for I have promised friends to go abroad with them. I shall miss you, Blue Bonnet,—you won't forget to write often?"

"No, indeed!" Blue Bonnet assured her, at the same moment registering a solemn vow that she would write every week without fail. "And you'll write too, Aunt Lucinda? It'll be so exciting getting letters from funny, foreign places. And now it's good-bye. You—you are sure you've no—a—advice to give me?"

Miss Clyde restrained an odd smile at the significant[11] question. "No, dear. Only this: be considerate of your grandmother, and bring her back safely to me."

"I will! I will!" cried Blue Bonnet, and with another kiss was gone.

There was only a moment for a handshake with Katie and Delia, who openly mopped their eyes at parting; a word with General Trent, a chorus of good-byes to a score of We are Seven relations, and then everybody crowded about the steps of The Wanderer.

"Grandmother first," said Blue Bonnet. "Denham, you'd better go aboard and get her settled. Here, Bennie Blake—you hold Solomon till I'm ready to take him. Now then, We are Sevens—forward!"

Suddenly Blue Bonnet gave a queer little exclamation and clapped her hand on a leather case which hung from her shoulder. "Stop, everybody, till I get a picture—I nearly forgot! And I want pictures of every stage of the ranch party. Grandmother, please stay on the top step and I'll group the girls below."

"That's right," cried Kitty. "Take one now and another when we get back, and we can label them 'Before and After Taking!'"

Sarah, Kitty, Amanda and Debby, amid the teasing remarks of sundry small boys, obediently took their places as designated by the young artist. Then[12] Blue Bonnet's eyes turned in search of the other two girls.

"Susy! Ruth!" she called. "Why—where are they?"

An embarrassed hush fell on the group about the car. Blue Bonnet looked inquiringly at the telltale faces. It did not take her long to scent a mystery.

"What's the matter?" she cried impatiently.

Doctor Clark stepped forward, clearing his throat queerly. "Fact is, Miss Blue Bonnet," he began, "they—they can't go."

"Can't go?" Blue Bonnet started incredulously at the stammering doctor.

"No, you see,—well, in fact, they're ill," he completed lamely. Why didn't some one help him out, the doctor fumed inwardly, instead of letting him be the one to cloud that beaming face?

Suddenly Kitty leaned down from the car step and whispered: "Scarlet fever!"

"Both?" exclaimed the startled Blue Bonnet.

"No, only Ruth. But Susy was exposed and Father didn't think it safe for her to come."

"Oh, Kitty!" The tears sprang to Blue Bonnet's eyes—she fought them but they would come.

"We're all broken up over it," said Kitty with her own lips trembling; "but it might have been worse. It's only because we've been too busy to go out there, that we weren't all exposed. Then it would have been good-bye to the ranch party."[13]

"Oh, Kitty, suppose you had!" The thought of the narrow escape dried Blue Bonnet's tears. "I'm mighty glad you four could come. But it won't be complete. And you know how I love to have things complete!"

"Never mind, Blue Bonnet, you still have me!" cried Alec, coming in with a cheerful note.

"'The poor ye have always with you!'" chimed in Kitty, and while everybody was laughing over this sally, Blue Bonnet took a snap-shot of the group, and then all the travellers trooped aboard.

Mr. Ashe looked over the heads of the chattering crowd in the car and met Mrs. Clyde's amused eye. "How do you like mothering a family of this size?" he asked jocosely.

"I fancy I feel much like the hen that hatched duck's eggs," Mrs. Clyde returned.

There was a laugh at this, in the midst of which Sarah Blake was heard to remark solemnly: "Yes, children are a great responsibility."

Whereat there was more laughter, and hardly had it subsided when from outside came the conductor's sonorous "All aboo—ard!"

"Girls, we're really going!" gasped Kitty.

There was a last vigorous waving of handkerchiefs out of the window. Suddenly a wail burst from Blue Bonnet: "Solomon! Solomon!"

All looked at one another aghast. In the excitement[14] of the last moments no one had thought of the dog.

"Find Bennie Blake—he had Solomon last," cried Blue Bonnet, rushing to the platform.

"I'll find him, don't you worry," exclaimed Alec, swinging down the steps just as the first creaks of the car gave notice of starting.

"Alec—you'll get left!" cried Blue Bonnet. "There's Bennie,—oh, quick!"

Sure enough, there on the edge of the crowd was Bennie, but alack!—no Solomon.

"Stop the train, can't you, Uncle Cliff?" wailed Blue Bonnet. "Alec will be left—and Solomon too—"

Uncle Cliff leaped to the bottom step,—the train was still only crawling,—and with one hand on the rail leaned out and peered after Alec. Blue Bonnet gave a nervous clutch at his sleeve. What he saw evidently reassured Mr. Ashe, for suddenly he straightened up and held out both arms. A second later a brown furry object came hurtling through the air and was caught ignominiously by the tail. Quick as a flash Uncle Cliff tossed the indignant Solomon to Blue Bonnet, and bent down to lend a helping hand to Alec. That young gentleman scrambled up with more haste than elegance, just as the train ceased to crawl and settled down to the real business of travelling.

"I'll never forget this, Alec Trent, as long as I[15] live,—I think you deserve a Carnegie medal!" Blue Bonnet cried fervently. "I'd never get over it if Solomon should be lost."

"He wouldn't have been—lost, exactly," returned Alec in an odd tone.

"Why, what do you mean? Where did you find him?" Blue Bonnet demanded.

And Alec, bursting into a laugh in spite of his awful news, returned: "I found him just where that Blake boy left him—tied on to the end of the car!"[16]

"If one of you speaks aloud in the next five minutes," declared Blue Bonnet earnestly, "I'll never forgive you."

No one being inclined to risk Blue Bonnet's undying enmity, there was complete silence for the space of time imposed. They were rolling along the smooth white road between the railway station and the ranch, Grandmother Clyde and the girls in a buckboard drawn by sturdy little mustangs, while Alec, Uncle Joe and Uncle Cliff, who had stayed behind to look after the luggage, were following on horseback.

Blue Bonnet sat tense and still, her hands clasped in her lap, the color coming and going in her face in rapid waves of pink and white; her eyes very shiny, her lips quivering. This home-coming was having an effect she had not dreamed of. Every familiar object, every turn of the road that brought her nearer the beloved ranch, gave her a new and delicious thrill.

As they neared the modern wire fence two dusky little greaser piccaninnies rose out of the chaparral, hurled themselves on the big gate and held it open,[17] standing like sentinels, bursting with importance, as the buckboard rolled through.

"They're Pancho's twins!" cried Blue Bonnet. "Stop, Miguel, while I give them something." Hurriedly seizing a half-eaten box of candy from Amanda's surprised hands, Blue Bonnet leaned down and tossed it to the grinning youngsters.

"Muchas gracias, Señorita!" they cried in a duet, their black eyes wide with joy.

"Bless the babies!" exclaimed Kitty, "—did you hear what they called you?"

Blue Bonnet laughed. "I'm never called anything else here. They meant 'Many thanks, Ma'am.' You will be 'Señorita' too,—better get used to it."

"Oh, I shall love it," cried Kitty. "It sounds like a title—'my lady' or 'your grace' or something grand."

"Grandmother will be 'Señora'—doesn't it just suit her, girls?" asked Blue Bonnet.

"Mrs. Clyde, may we call you 'Señora,' too?" asked Debby, "—just while we're on the ranch?"

"Debby believes in the eternal fitness of things," put in Kitty.

"Certainly, you may call me Señora," said Mrs. Clyde. "When you're in Texas do as the Texans do," she paraphrased.

"I intend to learn all the Spanish I can while I'm[18] here," remarked Sarah. "I brought a grammar and a dictionary—"

A chorus of indignation went up from the other girls.

"This isn't a 'General Culture Club,' Sarah Blake," scolded Kitty. "We didn't come to the Blue Bonnet ranch for mutual improvement—but for fun!"

"We'll make a bonfire of those books," warned Blue Bonnet.

"All the Spanish that I can absorb through my—pores, is welcome to stick," said Debby, "but I'm not going to dig for it."

Sarah tactfully changed the subject. "Your house is a good way from the gate, Blue Bonnet," she remarked.

"Nearly two miles," Blue Bonnet smiled.

"There's nothing like owning all outdoors!" commented Kitty.

"Grandfather used to own nearly all outdoors," returned Blue Bonnet. "When father was a little boy nobody had fences and the cattle ranged through two or three counties. But now we keep a lot of fence-riders, who don't do a thing but mend fences, day after day. There's the bridge,—now as soon as we cross the river you can see the ranch-house."

"Is this what you call the 'river?'" Sarah asked, as they rattled over the pretty little stream.[19]

"We call it a 'rio' in Texas, and you'd better not insult us by calling it a creek, Señorita Blake," Blue Bonnet warned her.

"I won't—'rio' is such a pretty name," said Sarah, making a mental note of it for future use.

"There!" cried Blue Bonnet, "behold the 'casa' of the Blue Bonnet ranch!"

What they saw was a long, low, rambling house, with wide, hospitable verandas embowered in half-tropical vines. It had evidently started out as a one-roomed, Spanish 'adobe,' and, as the needs of the family demanded it, an ell had been added here, a room there, like cells in a bee-hive, until now it covered a good deal of territory, still keeping its one-storied, Mission-like character.

"Oh, Blue Bonnet—it's just what I wanted it to be," exclaimed Kitty. "It looks as if a fat, Spanish monk might come out of that door this very minute."

"Instead of which there is my dear old Benita, and Pancho and his wife and the children and—oh, everybody!" Blue Bonnet was bouncing up and down now with excitement.

Alec and the other two riders came up in a cloud of dust just as Miguel raced the mustangs up to the veranda steps, where all the ranch hands were gathered to greet the young Señorita.

"Señorita mia!" cried Benita, and Blue Bonnet[20] leaped from the wheel straight into her old nurse's arms.

"And this is Grandmother, Benita," said Blue Bonnet, helping Mrs. Clyde from her place.

"The little Señora's mother—God bless you!" cried Benita in Spanish. Then, in spite of her stiff joints, she made a deep, old-fashioned curtsy.

Tears sprang to the eyes of the Eastern woman. "Thank you, Benita," she said. "My daughter always wrote lovingly of you."

"Blessed Señora!" breathed Benita fervently.

"This is my grandmother, everybody," said Blue Bonnet, presenting Mrs. Clyde to the entire circle, "and these are my friends—'amigos' from Massachusetts."

"Pleased to know ye!" said Pinto Pete and Shady, the only American cowboys on the ranch; while the Mexicans, as one voice, gave a hearty chorus of greeting.

The six "amigos" from Massachusetts were thrilled to the core, although at the same time a trifle embarrassed as to the correct way of responding to this vociferous welcome. Blue Bonnet set them all an example: she had a smile and a word for every man, woman and child, and finally sent them all off with a—"Come back when my trunks arrive!" And the hint brought a fresh gleam to already beaming faces.

Later, after a bountiful supper, they all gathered[21] once more on the broad veranda while Blue Bonnet distributed her gifts. That those days in New York had been profitably spent was fully attested now when the contents of the many trunks were displayed. There were ribbons, scarfs and gay beads for the women, toys and sweets for the children, and wonderful pocket-knives, pipes and tobacco pouches for the men.

The Blue Bonnet ranch had been part of an original Spanish land-grant in the days when Texas was still part of Mexico, and had descended from father to son until it came into the hands of Blue Bonnet's grandfather. Many of the Mexican ranch-hands had been born on the place and looked on the Ashe family as their natural guardians and protectors. As yet they had not acquired a Yankee sense of independence, nor had they lost the soft Southern courtesy inherent in their race. They came up one at a time to Blue Bonnet as she stood at the top of the steps, her gifts in a great heap beside her; and each one, as he received his gift from her hand, called down a blessing on the head of the young Señorita. Then, laughing, chatting, and comparing gifts like a crowd of children, they trooped away, the single men to the "bunk-house" by the big corral, the married couples and their children to little cabins scattered over the place.

"It's just like some old Spanish tale," declared Alec. "Blue Bonnet is a princess just returned to[22] her castle, and all the serfs are come to pay her homage."

"I suppose Don Quixote will be off soon, hunting wind-mills?" suggested Kitty, with a mocking glance at Alec, whose new gun was the pride of his heart.

Alec deigned no reply.

"Look!" said Mrs. Clyde, softly, "—there goes the sun."

They followed her glance across the prairie that stretched away, green and softly undulating, in front of the veranda, and watched the red disk as it sank in a blaze of glory at the edge of the plain.

"Now you know," said Blue Bonnet, "why I felt like pushing back the houses in Woodford—at first they just suffocated me."

Mrs. Clyde smiled with new understanding. "You probably agree with our Massachusetts writer who complained that people in cities live too close together and not near enough," she said, patting Blue Bonnet's head as the girl, sitting on the step below her, leaned against her knee.

"Didn't you ever get lonesome here?" asked Debby, snuggling up to Amanda. She had been brought up among houses.

"Lonesome?" echoed Blue Bonnet. "I never knew what lonesome meant—till my first day in school!"

All too soon came bedtime.[23]

"Where are we all to sleep?" Blue Bonnet asked Benita. It was like Blue Bonnet not to give the matter a thought until beds were actually in demand.

Benita led the way proudly. "The Señora will have the little Señora's room," she said, throwing open the door of that long unused chamber.

Mrs. Clyde entered it with softened eyes.

"Señorita's own room is ready for her, and here is place for the others." Benita proceeded to the very end of a long ell to a huge airy room, seemingly all windows. It was Blue Bonnet's old nursery, and, next to the living-room, the largest room in the house. Four single beds, one in each corner, showed how Benita had solved the sleeping problem.

The girls gave a shout of delight; visions of bedtime frolics and long talks after lights were out, sent them dancing about the place.

"I tell you what," announced Blue Bonnet, "—if you imagine I am going off by myself when there's a sleeping-party like this going on, you're mistaken. I say—" here she turned on Sarah, "—you've always wanted a bed-room all to yourself; you told me so, one day. Well, here's your chance—you're welcome to every inch of mine!"

Sarah, quite willing to confine her "parties" to daylight hours, accepted the proposition eagerly.[24] Maybe then she could get a peek at those Spanish books.

"Are you sure you're willing to give it up?" she asked quite honestly.

And Blue Bonnet with an incredulous stare returned: "Are you quite willing to give this up?"

"Perfectly!" exclaimed Sarah with such promptness that Blue Bonnet dismissed her lurking suspicion that Sarah was just "being polite" and accepted the exchange.

It was a happy Sarah who tucked herself away in a little bed all to herself, in a dainty room destined to be her very own for two long months. Four times happy was the quartet who shared the nursery. It was a long time before they subsided. There were so many things to be observed and discussed in that delightful place. Uncle Joe Terry had had a hand in its arrangement, and now that worthy man would have felt well repaid if he could have heard the gales of merriment over his masterpieces of interior decoration.

In her childhood Blue Bonnet had been blessed—or afflicted—with more dolls than ever fell to the lot of child before. Now the long-discarded nursery-folk formed a frieze around the entire room, the poor darlings being, like Blue-beard's wives, suspended by their hair. Every nationality and every degree of mutilation was there represented,[25] and the effect was funny beyond description. On the broad mantel-shelf over the stone fireplace reposed drums, merry-go-rounds, trumpets and toy horses; while on the hearth was a tiny kitchen range bearing a complete assortment of pots and pans of a most diminutive size. In every available nook of the room stood doll-carriages, rocking-horses, go-carts and fire-engines, each showing the scars of Blue Bonnet's stormy childhood.

"I wish," cried Kitty, "that we weren't any of us a day over seven!"

While the girls were still making merry over her childhood treasures Blue Bonnet slipped away. She had not had a word alone with Uncle Cliff for days, and had exchanged only a hurried greeting with Uncle Joe at the station. And there were such heaps of things to talk over!

She found them both on the veranda, enjoying the evening breeze that came laden with sweet scents from off the prairie. Blue Bonnet clapped her hands over Uncle Joe's eyes in her old madcap fashion.

"It's Blue Bon—er—Elizabeth, I mean," he guessed promptly.

"Wrong!" cried Blue Bonnet sternly. "Elizabeth Ashe was left behind in Massachusetts, and only Blue Bonnet has come back to the ranch."

"Thank goodness for that!" breathed Uncle Joe devoutly. "Elizabeth came mighty hard. It didn't[26] fit, somehow. I reckon you're glad to get home, Blue Bonnet?"

"Glad? Why, there isn't a word in the whole English dictionary that means just what I feel, Uncle Joe," replied Blue Bonnet, perching on the arm of his chair. "I love every inch of the state of Texas."

The two men exchanged a significant glance that was not lost on Blue Bonnet.

"Oh, I know what you are thinking of, Uncle Cliff. You remember the day when I said I hated the West and all it stood for. I meant that too—then. But I feel different now. It isn't that I'm sorry I went away; I just had to go, feeling as I did. I reckon I'll always be that way—I have to find things out for myself."

Uncle Joe smiled humorously. "Reckon we're most of us built that way, eh, Cliff?"

Mr. Ashe gave a rueful nod. "Yes, what the other fellow has been through doesn't count for much. We all have to blister our fingers before we'll believe that fire really burns."

They were all silent for a moment.

"Has any one seen Solomon?" asked Blue Bonnet suddenly.

"I think Don is showing him over the ranch," replied Uncle Joe. "I saw them both headed for the stables a while ago."

"I'm glad they're going to get on well," said[27] Blue Bonnet in a relieved tone. "I was afraid Don would be jealous." She gave a clear loud whistle, and a moment later the two animals came racing across the yard, tumbling over each other in their eagerness to be first up the steps. Blue Bonnet stooped and picked up the smaller dog, fondling him and saying foolish things. Don, the big collie, gave a low whine and looked up at her piteously.

"Not jealous, did you say?" laughed Uncle Joe.

Blue Bonnet patted the collie's head. "Good dog," she said soothingly. "You're too big to be carried, Don." Then she put down Solomon and bending put a hand under Don's muzzle; his soft eyes met hers affectionately. "I'm going to put Solomon in your charge—understand? You must warn him about snakes, Don,—and don't let the coyotes get him." A sharp bark from Don Blue Bonnet was satisfied to take for an affirmative answer, and with another pat sent him off for the night.

"Has Alec some place to sleep?" inquired Blue Bonnet, her hospitable instincts suddenly and rather tardily aroused.

"Benita has put him in the ell by me. He's there now, unpacking to-night so that he won't have to waste any time to-morrow. I never saw a boy so keen about ranch-life as he is. He seems to look on himself as a sort of pioneer in a new country," Uncle Joe chuckled.[28]

"It's all new to him," rejoined Blue Bonnet. "This is his first glimpse of the West. I hope he gets strong and well out here—General Trent worries so about him."

"It will be the making of him," Uncle Cliff assured her. "He'll go back to Massachusetts as husky as Pinto Pete, if he'll just learn to live outdoors, and leave books alone for a while."

"I'm going to hide every book he has brought with him," declared Blue Bonnet. "And Sarah Blake will need looking after—she has the book habit, too."

Uncle Joe shook his head. "It seems to be a germ disease they have back there in Massachusetts. Glad you didn't catch it, Blue Bonnet."

"Oh, I'm immune!" laughed she, as she said good-night and went to seek Benita.

She found her old nurse in the kitchen, resting after an arduous day. Gertrudis, the famous cook "loaned" for the summer by a neighboring ranch, was mixing something mysterious in a wooden bowl, while her granddaughter Juanita, a nut-brown beauty, pirouetted about the room, showing off her new rosettes in a Spanish dance.

Blue Bonnet clapped her hands. "That's a pretty step, Juanita,—will you teach it to me some day?"

"Si, Señorita," she assented eagerly, showing all her white teeth in a delighted smile. "It is the cachucha."[29]

"The girls will all want to learn it," Blue Bonnet assured her. She draw Benita into the dining-room and then gave her a hearty squeeze. "Everything's just lovely, you old dear," she cried. "The girls are crazy about the nursery, and they think you are the dearest ever!"

Benita's wrinkled face beamed. "If the Señorita is pleased, old Benita is happy," she said deprecatingly.

"Benita, I missed you dreadfully, off there in Woodford. I had to make my own bed and do my own mending!"

Benita gave an odd little sound of distress. "But Benita will do it now," she urged anxiously.

"You'll have to get around Grandmother then, Benita,—I can't."

"The Señora is kind—" Benita began.

"—but firm," added Blue Bonnet. "I leave her to you!"

It was so late before the girls finally settled down into their respective corners, that it seemed only about five minutes before they were awakened at daybreak by the most terrific tumult that ever smote the ears of slumbering innocence.

Bang, bang! Boom, crash, bang! Shouts, yells, wild Comanche-like cries rent the ear, and punctuated the incessant booming that shook even the thick adobe walls of the nursery.

Four terrified faces were raised simultaneously[30] from four white beds, and four voices in chorus whispered: "What is it?" No one dared stir.

Suddenly the door was burst open and in sprang a white-robed figure, hair flying, eyes wide with terror. Straight to Blue Bonnet's bed the spectre flew and leaped into the middle of it with a plump that made its occupant gasp.

"Oh, girls, it's Indians!" wailed the newcomer; and then they saw that it was Sarah.

"Indians?" exclaimed Blue Bonnet. "There aren't any Indians around here. Get off my chest and I'll go see."

Casting off the bed-clothes and the startled Sarah at the same time, with one spring Blue Bonnet was at the window. What she saw there was hardly reassuring; the whole space between the house and the stables seemed to be filled with a howling, whirling mass of men. In the gray half-light of early dawn she could recognize no one. Suddenly a fresh explosion set the windows rattling; there was a hiss and a glare of red. In the glow she caught a glimpse of Alec; he held a revolver and was shooting it with sickening rapidity, not stopping to take aim.

Blue Bonnet staggered back faint with horror, and the girls gathered fearfully about her. Uncle Cliff's voice giving an order came to them from outside. Blue Bonnet leaned out and shrieked—"Uncle,[31] Uncle—what's the matter—oh, what is it?"

Never had voice seemed so welcome as those calm, soothing tones, when Uncle Cliff replied: "Reckon you've forgotten what day it is, Honey."

Blue Bonnet turned on the girls. "What—what day is it?"

And the light from within was suddenly greater than that from without as they answered in a sheepish chorus:

"The Fourth of July!"[32]

"To think that a crowd of New England girls, of all people, should forget the Fourth of July!" exclaimed Alec, when they met around the big breakfast table, later that morning.

Sarah looked positively pained. "I never forgot it before in my whole life," she said plaintively. "But there have been so many new things to think of, and travelling, you know—" she ended lamely.

"Are New England people supposed to be more patriotic than those of other states?" inquired Blue Bonnet, bristling a little in defence of Texas.

"Certainly!" cried Alec. "New England folks are fed on Plymouth Rock and the Declaration of Independence from the cradle to the grave. That's the diet of patriots."

"H'm!" murmured Blue Bonnet scornfully. "I'll wager that Patriot Alec Trent would have forgotten Independence Day, too, if Uncle Cliff hadn't let him into the secret. Now I know, Uncle Cliff, what was in that box labelled 'dangerous.' Wasn't I a goose not to think of it? And Uncle Joe telegraphed so as to get us here in time. Grandmother," here she turned a rueful countenance on[33] Mrs. Clyde, "going to school hasn't helped my head a bit, I'm just downright dull."

Uncle Cliff gave an amused laugh. "I'm glad to have caught you napping for once, young lady. Now, as soon as Gertrudis stops sending in corncake, I propose that we adjourn to the stables and look over the mounts. Pinto Pete says he has a nice little bunch of ponies."

"Why do they call him 'Pinto?'" asked Debby. "I thought that meant a spotted horse."

"Haven't you noticed Pete's freckles?" asked Uncle Joe. "He has more and bigger ones than any other human in Texas, and the boys called him 'Pinto Pete' the first minute they clapped eyes on him. He don't mind—it's the way of the West."

"And is 'Shady' a nickname, too?" Debby asked.

"No—just short for good old-fashioned Shadrach. Shadrach Stringer's his name, and he's the best twister in the county."

Debby had a third question on her lips but checked it as she met Kitty's saucy eye. Kitty, known as "Little Miss Why," was always on the alert to bequeath the name to a successor. But Sarah saw none of the by-play and asked at once:

"What's a 'twister?'"

"A bronco buster," replied Uncle Joe.

Sarah's look of mystification at this definition sent Alec off into a fit of laughter. Blue Bonnet came to[34] the rescue. "A twister breaks in the wild horses, Sarah. Some day we'll get him to give an exhibition. You'd never believe how he can stick on,—it'll frighten you the first time you see it. The way the horse rears and bucks and runs, why—" Blue Bonnet suddenly choked and turned pale. Mrs. Clyde and Uncle Cliff read her thoughts at the same moment and both rose hurriedly.

"Come on, everybody," exclaimed Mr. Ashe in a resolutely cheerful tone, "we must make the most of the morning."

"Why?" asked Kitty before she thought, and then bit her lip. That word "why" was such a pitfall.

"Everybody has to take a siesta in the afternoon," explained Blue Bonnet. "It's too hot to move."

"Every afternoon?" demanded Debby.

"Every afternoon," repeated Uncle Cliff. "Anybody caught awake between one and four p. m. will be severely dealt with. It's a law of the human constitution and the penalty is imprisonment in the hospital, headache, and loss of appetite."

"What a waste of time," Sarah commented, privately resolving that she would not spend two or three precious hours every afternoon in sleep. One didn't come to Texas every summer.

"I see mutiny in Sarah's eye," said Blue Bonnet. "Wait till you've had a sunstroke, Sarah, then[35] you'll wish you hadn't possessed such oceans of energy." She had put all unpleasant memories from her by now and was leading the way to the stables. Straight to Firefly's stall she went and threw her arms around her old playfellow's neck. In the few seconds before the others came in she had whispered into his velvet ear something that was both a confession and an apology, while Firefly nosed her softly and looked as pleased as a mere horse-countenance is capable of looking.

"Isn't he a beauty?" she challenged as the rest entered.

"A stunner," Alec agreed warmly, coming up to admire. "Wouldn't Chula's nose be out of joint if she could see you petting Firefly?"

"Victor has a rival too. Where's Alec's horse, Uncle Joe?"

Pinto Pete came up just then, his freckles seeming to the girls to loom up larger and browner than ever now that they knew the origin of his nickname. "Shady says the roan's too skittish for any of the young ladies—" he suggested.

"Strawberry?—oh, she's splendid! Alec, you'll think you're in a cradle."

The pretty creature, just the color of her namesake, was brought out and put through her paces, and the exhibition proved to the satisfaction of all the young ladies that Shady's verdict was quite just. Strawberry pranced, bared her teeth at any[36] approach, and in general did her best to live up to her reputation for skittishness. The fighting blood in Alec made him resolve to change that adjective to "kittenish" before he had ridden her many times.

The four ponies provided for the girls were next brought out for inspection, and met with unqualified approval from all but Sarah. These slender, restless little steeds seemed not at all related to the fat placid beasts to which she had heretofore trusted herself. Her face betokened her unspoken dismay.

"Sallikins, I know the best mount for you," exclaimed Kitty innocently.

"Oh, do you?" cried Sarah hopefully.

"Um-hum,—Blue Bonnet's old rocking-horse in the nursery!" laughed Kitty; whereupon Pinto Pete let out a loud guffaw, changing it at once into an ostentatious fit of coughing when he saw that Sarah was inclined to resent Kitty's insult.

Her mild blue eyes almost flashed as she returned: "You can pick out any one of those four horses you choose for me, Kitty Clark, and I'll show you if I'm afraid to ride!"

This outburst from Sarah the placid rather startled the We are Sevens. But Kitty, after a surprised stare at the ruffled one, picked up the gauntlet. She appraised the horses with a calculating glance, then picked out a chestnut who[37] showed the whites of his eyes in a most terrifying manner.

"How does that one suit you, Señorita Blake?" she asked tauntingly.

"Very well," returned Sarah with a toss of her flaxen braids. This was sheer bravado, but it passed muster. No one dreamed of the shivers of abject fear that were chasing up and down the girl's spine at sight of the fiery little chestnut with the awful eyes.

"Why, that's Comanche!" exclaimed Blue Bonnet. "He has a heavenly gait."

"Comanche!" Alec echoed, and then withdrew hastily to a convenient stall. The thought of the plump, blond Sarah mounted on a steed bearing such a wild Indian name was too much for him. He emerged a moment later very red in the face and unable to meet Blue Bonnet's eye. Their sense of humor was curiously akin, and Blue Bonnet knew, without being told, what mental picture filled Alec's mind.

"Why not have a ride this morning,—there's plenty of time before noon," suggested Uncle Joe. "Here, Lupe, bring out the saddles," he called.

Guadalupe, the "wrangler," appeared from an inner room, looking like a chief of the Navajo tribe, so burdened was he with the bright-hued Indian saddle-blankets. The girls watched him with[38] eager eyes, but when he was followed by several boys bearing huge cowboy saddles, there was a little murmur of dismay from the group.

"Men's saddles for us!" exclaimed Debby in a shocked undertone.

Blue Bonnet laughed outright. "Didn't you hear Grandmother say: 'When you're in Texas do as the Texans do?' Well, turn and turn about is fair play. Didn't I ride a side-saddle as proper as pie in Woodford? Now it's your turn."

Sarah gave an approving look at the high pommels of the saddles, and at the strong hair-bridle that was being fitted over Comanche's wicked little head.

Blue Bonnet gave the same bridle a look that was far from approving. "Lupe, isn't that a Spanish bit you're using?"

"Si, Señorita," said Guadalupe guiltily.

"Then take it right off!" commanded Blue Bonnet in her old imperious way. "They're cruel wicked things that cut a horse's mouth to pieces, and I won't have them used," she explained to the girls. "Lupe knows I hate them." She turned accusingly on the boy.

Lupe looked at her appealingly. "It is the safer for the Señoritas," he urged.

Blue Bonnet was inexorable. "We're not going to do any lassoing or branding, Lupe, and can manage very well without them. We'll have to organize[39] a humane society, girls, and reform these cruel cowmen," she suggested.

Lupe discarded the offending bits and substituted others more to the Señorita's liking, and then the girls went in to dress for the ride.

"How can we ride across the saddle in these skirts?" demanded Debby.

Blue Bonnet and Uncle Cliff exchanged a significant glance, the reason for which was explained a moment later when the girls entered the nursery. There on the beds lay five complete riding suits: divided skirts of khaki, "middy" blouses of a cooler material, and soft Panama hats, each wound with a blue scarf and finished with a smart bow.

"How darling of you!" cried the girls, falling on Blue Bonnet rapturously.

"It's all Uncle Cliff," exclaimed Blue Bonnet. "He saw some suits like these in a shop window while we were in New York and went in and ordered seven! But Susy and Ruth won't have a chance to wear theirs," she ended regretfully.

The girls, too excited to spend time mourning the absent ones, were already getting into the fascinating suits. These were all of a size, close lines not being demanded of a middy blouse, and all were pronounced perfect except Sarah's, which, as Kitty remarked, "fitted too soon." Gauntlet gloves and natty riding whips completed the equipment of the riders, and when they went out ready to mount[40] they were as neat a crowd of equestriennes as ever graced Central Park.

Notwithstanding that they were all dressed alike, each girl's particular type stood out quite clearly. Kitty had more "style" than the other Woodford girls, and a carriage that had more of conscious vanity in it; her "middy" set more trimly and the little hat was set on her ruddy locks at a little more daring angle than that of the others. Amanda and Debby appeared the same unremarkable sort of schoolgirls that they always were. The costume was not designed for maidens of Sarah's build, and it looked quite as uncomfortable on her as she felt in it. Blue Bonnet appeared as she always did in this sort of attire: as though it had grown on her.

"Whew!" exclaimed Alec, "such elegance!"

"Strikes me you're not so slow yourself," returned Kitty. "Isn't he 'got up regardless,' girls?"

Alec was dressed for his part with elaborate attention to details. Mr. Ashe had been anxiously consulted, for the Eastern boy had no desire to be dubbed a tenderfoot; and now, except for its spotless newness, his costume was quite "Western and ranchified"—according to Blue Bonnet.

"COMANCHE . . . LEAPED FORWARD LIKE A CAT."

"COMANCHE . . . LEAPED FORWARD LIKE A CAT."

He was in khaki, too, with trousers that tucked into high "puttees"—thick pigskin leggings which gave his long limbs quite a substantial appearance[41] and himself no end of comfort. A soft shirt and a carelessly knotted bandana gave the finishing touches to his attire. He had even turned in the neck of his shirt so as to be quite one of the cowmen, secretly hoping that the girls would not notice how white his throat was.

It was a gay cavalcade that cantered out of the big corral, the five girls leading; Alec, Pinto Pete, and Uncle Joe forming a rear guard, with Don and Solomon capering at their heels; while a crowd of little "greasers" clung on to the bars, their eyes big with the wonder of it all.

"Lucky we're not on the streets of Woodford," remarked Alec, looking with amused eyes over the well mounted company.

"Why?" asked Blue Bonnet a trifle resentfully. "Aren't we grand enough for the East?"

"Sure! But I'm afraid we'd be arrested for running a circus without a license!"

This piece of wit so tickled Pinto Pete that he nearly stampeded the bunch by bursting again into his ear-splitting laugh. Sarah grabbed the handy pommel with a nervous clutch that was eloquent of her state of mind. And that action was all that saved her. For Comanche, taking Pete's guffaw for a command, leaped forward like a cat, and a moment later the whole crowd was galloping madly across the level meadow.

It is probable that if Sarah's hair had not already[42] been as light as hair can well be, that wild ride would have turned it several shades lighter. The terrors that were compressed into those two hours are beyond description, while the bobbing, bumping and shaking of her poor plump body left reminders that only time and witch hazel were able to eradicate.

When they returned at noon Gertrudis had a wonderful dinner awaiting them, and the riders, with their appetites freshened by the air and exercise, fell upon it like a pack of famished wolves. All except Sarah. Protesting that she was not in the least hungry, she went at once to her room. On the little stand by her bed lay the Spanish grammar and dictionary, mute evidences of the way she had intended to spend the siesta hour. She gave them not so much as a glance, but stepping out of her clothes left them in a heap where they fell,—an action indicating a state of demoralization hardly to be believed of the parson's daughter,—and flung herself into bed with a groan.

Two hours later she was awakened by the other four girls who had turned inquisitors, and while two were stripping off the bedclothes the other two applied a feather to the soles of her feet.

"Oh—is it morning?" gasped Sarah, sitting up and rubbing her eyes. "It doesn't seem as if I had been asleep a minute."

"Such a waste of time!" quoted Kitty mockingly.[43] "There's such a thing, Sarah, as overdoing the siesta," she taunted.

Sarah drew up her feet and sat on them, smothering the groan that arose to her lips at the action. Every bone and joint had a new and awful kind of ache, and in that minute Sarah wished she had never heard of the Blue Bonnet ranch. Just then came the welcome clatter of dishes and at the doorway appeared Benita bearing a tray of good things, while back of her was Grandmother Clyde.

"Now off with you,—you tormentors," the Señora commanded gaily. "This poor child must be nearly famished."

"Grandmother's pet!" sang Blue Bonnet over her shoulder, as obeying orders, the four girls left the suffering Sarah in peace.

Existence assumed a brighter hue to Sarah when she had eaten the generous repast Benita set before her; and when she had bathed and rubbed herself with the Pond's Extract Mrs. Clyde had secretly provided her with, life seemed once more worth living. But she was very quiet and moved with great circumspection for the rest of the day, quite content to leave to the others the handling of the fireworks in the evening.

Uncle Cliff's "dangerous" box yielded still more wonders. The noisy bombs and giant crackers of the morning were followed by pyrotechnics that aroused unbounded admiration from the grown-ups[44] and caused an excitement among the small greasers that threatened to end in a human conflagration. A small fortune went up in gigantic pin-wheels; flower-pots that sent up amazing blossoms in all the hues of the rainbow; rockets that burst in mid-air and let fall a shower of coiling snakes, which, in their turn, exploded into a myriad stars; Roman candles that sometimes went off at the wrong end and caused a wild scattering of the audience in their immediate vicinity; and "set-pieces" that were the epitome of this school of art.

It would have been hard to say which was most tired, the hostess or her guests, when the last spark faded from the big "Lone Star" of Texas which ended the show. No bedtime frolic to-night; the four in the nursery undressed in a dead quiet and fell asleep before their heads fairly touched the pillows. In her own little room Sarah held another seance with the witch hazel bottle, and went to sleep only to dream of a wild ride across the meadows on Blue Bonnet's rocking-horse, with a fierce band of Comanche Indians pursuing her, yelling fiendishly all the while, and keeping up a mad fusillade of Roman candles.[45]

"What's the program for this morning?" asked Uncle Cliff, as the ranch party assembled on the veranda after a very late breakfast.

"I don't know what the others are going to do," said Sarah, "but I'm going to write letters."

The other girls exchanged amused glances: it was evident that Sarah wished to forestall suggestions of another ride. Kitty was beginning to show symptoms of sauciness when Mrs. Clyde interrupted kindly with—"I think Sarah's suggestion quite in order. Every one at home will be looking for letters."

"Uncle Cliff telegraphed," said Blue Bonnet, loath to settle down to so prosaic a pursuit.

"But a telegram isn't very satisfying to mothers and fathers, dear," replied her grandmother. "And think of poor Susy and Ruth."

"I intend to write them, too," remarked Sarah.

"Let's all write them!" exclaimed Blue Bonnet.

"That's the right spirit," said Señora with an approving nod. "A 'round-robin' letter will cheer the poor girls wonderfully."[46]

"You hear the motion, are all in favor?" asked Alec.

"Will you write a 'robin,' too?" bargained Kitty, who loved to torment the youth.

"Sure!" he agreed at once, thus taking the wind out of her sails.

"Aye, aye, then!" they all exclaimed, and the motion was declared carried.

There was a scattering for paper and ink, after which every one settled down for an hour's scribbling, some using the broad rail of the veranda as a table, others repairing to desks in the house. Blue Bonnet doubled up jack-knife fashion on one of the front steps, using her knees for a pad; while Sarah, complaining that she could not think with so many people about her, took herself off to the window-seat in the nursery.

"The idea of wanting to think!" exclaimed Kitty. "I never stop to think when I write letters."

"You don't need to tell that to any one who has ever heard from you," remarked Blue Bonnet. "The one letter I had from you in New York took me an hour to puzzle out,—it began in the middle and ended at the top of the first page, and there were six 'ands' and four 'ifs' in one sentence."

"That's quite an accomplishment—I'll wager you couldn't get in half so many," retorted Kitty. And then for a while there was silence, broken only by the scratching of pens and the query from Blue[47] Bonnet as to whether there were two s's or two p's in "disappoint."

"You Poor Dears: You'll never know if you live to be a thousand years old what a fearful disappointment it was when Doctor Clark told me the awful news. Where did you get it? Is it very bad? And do you have to gargle peroxide of hydrogen? Amanda says she just lived on it when her throat was bad. Are you honestly as red as lobsters? It's a perfect shame you should have to be sick—and in vacation, too. There might be some advantages if it should happen—say at examination time. Grandmother says it is very unusual to have scarlet fever in warm weather,—it just seems as if you must have gone out of your way to get it—or it went out of its way to get you.

"The ranch party isn't a bit complete without you. I'm going to take pictures of everything and everybody so as to show you when we get back. That sounds as if I meant to go back again next fall, when really it isn't decided yet. I'm more in love with the ranch than ever and feel as if I never wanted to leave it again. It's so fine and big out here. There's so much air to breathe and such a[48] long way to look, and you can throw a stone as far as you like without 'breaking a window or a tradition'—as Alec says. We have our traditions, too, but they can stand any amount of stone-throwing—in fact that's part of them.

"It's worth crossing the continent to see Sarah on horseback, riding across the saddle in a wild Western way that would shock her reverend father out of a whole paragraph. Kitty dared her and I must say she showed pluck—Comanche can go some when he gets started, and Sarah stayed with him to the finish. But you can imagine why she wanted to write letters to-day instead of riding again. You can thank her for the round robin. There, I've reached the bottom of the page before I've begun to tell you anything. But the others will make up for it, I reckon. No more now—I must save strength for a letter to Aunt Lucinda. Do hurry and get well and out of quarantine so that you can write to

"Dear Susy and Ruth: We arrived on Monday evening after a very pleasant journey. The name of the station where you get off is Jonah—isn't that odd? We had to drive twenty miles in a very queer kind of vehicle in order to reach Blue Bonnet's home, and this letter will have to go back[49] over the same road in order to be posted. I think I had better go back to the beginning and tell you all about our trip from the time we left Woodford.

"The private car we came in is called The Wanderer and it is really a pity you could not have shared it with us. It is much grander than Mrs. Clyde's drawing-room at home,—the mahogany shone till you could see your face in it, and wherever there was not mahogany there was a mirror, and Slivers, the porter, dusted everything about twenty times a day. If you could see Slivers I should not have to explain why he is called by that name. I am sure he is the tallest and slimmest man I have ever seen. And that is odd, too, for you always think of them as plump and fat. He is a negro, you know, and doesn't seem to mind it a bit, but is as jolly as if he were white and as fat as you think he ought to be, and sang and played his banjo in the evenings quite like a civilized person. He waited on table, too, while the chief—the cook, you know—prepared our meals in the most cunning little kitchen you can imagine.

"It was a very interesting trip. Sometimes we would begin our breakfast in one state and before we had finished we would be in another, and yet there would seem to be no difference. I think travelling is a very interesting way to learn Geography, for you forget to think of Kansas as yellow[50] and Oklahoma as purple, and think of them as real places with trees and farms and other things like Massachusetts. I knew already that Texas is as big as all the New England states put together, but I never really grasped it before. I am learning new things every day, some Spanish, though not as much as I could wish. Yesterday I learned to ride astride. That is, nearly learned. I don't feel entirely at home that way yet and it has tired me considerably, but I dare say it will come easier after a while. My horse is named Comanche, and he looks just that way. There is more white to his eyes than anything else.

"Benita is Blue Bonnet's old nurse. She does the most exquisite drawn-work and is going to teach me (it would be as well for you not to mention this when you write) the spider-web stitch and the Maltese cross, so that I can do a waist for Blue Bonnet. She is doing so much for us all that I want to make some return for her hospitality. Blue Bonnet, I mean, not Benita.

"I do hope you will soon be better. I felt so mean at leaving without even saying good-bye. But I had to think of all my brothers and sisters and the girls—I couldn't expose them to the fever, you know. I hope you liked the postals we sent. Amanda and I came very near being left once when we couldn't find the post-box at Kansas City,—we had to run a block, while Alec and Kitty stood[51] on the back platform and laid bets on the winner. (Amanda won.)

"We are all well and hope you are the same,—I mean I hope you are better and will soon be well.

"Oh, girls, I am simply speechless and can't find a word to say when I try to describe our grand trip and this perfect peach of a place, and the glorious time we have had and are having ever since we left pokey old Woodford and arrived at the Blue Bonnet ranch. I keep pinching myself to see if I'm really me, but it isn't at all convincing, and I suppose I'll simply go on treading air and not believe in the reality of a thing till I come to earth in time to hear the Jolly Good say—'Miss Kitty, you may take problem number ninety-four'—and wake up to the monotonous old grind again—oh, if you could only see this darling old house and the picturesque Mexicans—rather dirty some of them (I suppose that's why they are called greasers) and the perfectly dear way they adore Blue Bonnet and their deference to her 'amigos'—I tell you I feel like a princess when they call me 'Señorita' with a musical accent that makes you downright sick with envy. Why anybody on earth ever left the West to go and settle up the East I don't see,—you may think I mean that the other way about but I don't, for anybody[52] can see at half a glance that this country is as old as Methusalem—the live-oaks look as if they'd been here forever and ever and would stay as much longer—they're all 'hoary with moss' and all that sort of thing like that poem of Tennyson's—or maybe it is Longfellow's—it doesn't matter which in vacation, thank goodness. I don't like to seem to be rubbing it in about our good times, for it's just too hateful that you can't be here, too, and ride like mad for miles without coming to a fence and wear the adorable riding-suits Mr. Ashe got for us in New York—all seven alike and as becoming as anything—and have the best things to eat, wear, do, and see every minute of the day.

"This won't go into the envelope with the rest if I run on any longer so I'll close,—with a fat hard hug and lots of love to you both,

"Dear Girls: Don't you ever go and get conditioned at school; take my solemn warning. That awful thing hanging over me is going to do its best to spoil my grand summer in Texas. I intended to do a lot of studying as soon as we arrived here, so that I might have a few weeks perfectly free from worry; but goodness me, how can anybody open a book when there's something going on every blessed minute of the day? It's a pity it wasn't[53] Sarah who was conditioned. She actually likes to study and if it came to a choice between a horseback ride and doing ten pages of grammar, she'd jump at the grammar. Sometimes I think Sarah isn't made like other girls. Not quite normal, you know.

"Now that I've seen Blue Bonnet at home, I realize what a hard time she must have had in Woodford, at first especially. She's treated like a perfect queen here, and doesn't have to mind a soul except Señora—that's what we call Mrs. Clyde. Fancy having run the ranch all your life and then at fifteen having to start in and obey Miss Clyde, and Mr. Hunt, and the rest of those mighty ones! I think she's a brick to have done it at all, and I take back every criticism I ever made of her. She must be terribly rich, but doesn't put on any airs at all.

"How is little old Woodford getting along without us? I'm almost ashamed to write Mother and Father, for I can't say I'm homesick and parents always expect you to be. Debby wants to finish my page, so no more now from

"Dear Susy and Ruth: There's only room for me to say hello, and how are you? I wish I were a grand descriptive genius like Robert Louis Stevenson so that I could describe this wonderful Texas. But description isn't my strong point—you know[54] how I just scraped through Eng. Comp. so I'll not try any flights.

"It isn't half as wild as we used to imagine it. The cowboys don't go shooting up towns and hanging horse-thieves to all the trees the way they do in most of the Western stories. Even the cattle are tame, but Blue Bonnet says that is because they are fenced nowadays, and most of them de-horned. All the cowboys except two are Mexicans, and they are so picturesque and—different. Mr. Ashe says Texas is filling up with negroes but he won't have any on the ranch,—he sticks to the Mexicans, and I'm mighty glad, for they seem just to suit the atmosphere. Juanita, who waits on the table, is a beauty, with the most coquettish airs. Miguel is in love with her, and we all hope she won't keep him waiting too long, for if they are really going to be married, we want a grand wedding while we are here. Wouldn't that be thrilling?

"I've just room to sign my name,

"To the absent two-sevenths of the 'We-are-Its'—Greeting! Please don't imagine that I forced my way into this Round Robin affair. My masculine chirography probably looks out of place in this epistolary triumph—ahem!—but you can thank Kitty Clark for it. I don't know whether or[55] not this is intended as a letter of condolence, but it surely ought to be,—anybody who has to miss this summer-session on the Blue Bonnet ranch deserves flowers and slow music.

"This letter will be postmarked 'Jonah'—but don't be alarmed; they say it's a harmless one. I'm going to ride over with the mail. Just a little matter of twenty miles, a trifle out here! Kitty says she doesn't see how we can expect any letters to reach a place with such a name, but I've faith in the collection of relatives left behind in Woodford.

"Now I advise you both, the next time you go into the vicinity of anything catching, cross your fingers and say 'King's Ex.' for you're missing the time of your young lives. As a place of residence, Texas certainly has my vote. A fellow can breathe his lungs full here without robbing the next fellow of oxygen.

Blue Bonnet collected the literary installments from each of the different authors and put them in a big envelope.

"This 'round-robin' is as plump as a partridge," she remarked. "I hope Susy and Ruth won't strain their eyes devouring it."

"The Woodford postman in our part of town[56] will have an unusually warm greeting, I fancy," said Mrs. Clyde, gathering up all the other letters and placing them with the round-robin in the roomy mail-bag.

"I think Father had better have a social at the church for the We-are-Seven relatives and ask them to bring our letters. Reading and passing them around would make a very interesting evening's entertainment," said Sarah.

Blue Bonnet paused long enough to shake her. "Don't you dare suggest such a horrible thing to your father, Sarah! My letter wasn't intended for—public consumption."

"Nor mine!" exclaimed Kitty. "Father and mother know what a scatter-brain I am, but it's a family skeleton which they don't care to have aired."

"Is the mail all in?" asked Alec in an official tone.

"All in, postmaster," replied Mrs. Clyde, fastening the bag and handing it to him with a smile. "You're not going alone, are you?"

"No, Shady is going along this trip, Señora," he replied.

"Why don't we all go?" asked Blue Bonnet; "it isn't much of a ride."

Sarah looked up in alarm, but met Mrs. Clyde's reassuring glance. "Not this time, dear," she returned to Blue Bonnet. "So far you have had all[57] play and no work. The piano hasn't been touched since we arrived."

Blue Bonnet said nothing, but into her eyes there sprang a sudden rebellion. Out there by the stables Don and Solomon were frolicking, ready at a moment's notice to dash away at Firefly's heels. Away in front of the house stretched the road and the prairie, calling irresistibly to her restless, roving spirit. And vacation had been so long in coming! If grandmother were going to be like Aunt Lucinda—Again there flashed into her mind the wish so often voiced in Woodford: that there might be two of her, so that one might stay at home and be taught things while the other went wandering about as she liked. All at once she remembered Alec's suggestion—that she adopt Sarah as her "alter ego." A smile drove the cloud from her eyes. "Can't Sarah do my practising while I do her riding?" she asked coaxingly.

Her grandmother hid a smile as she said: "I was under the impression that my coming to the ranch was to see that Blue Bonnet Ashe did her practising, mending, and had coffee only on Sundays."

Blue Bonnet colored. She had uttered those very words, and nobody should say that an Ashe was not sincere. Straightening up she met the questioning looks of the other girls with a resolute glance. "Grandmother is right, as she always is, girls. I'll go and practise, and you—what will you do?"[58]

"I'm sure all the girls will be glad of a little time to themselves," said the Señora. "Let us all do as we like until dinner-time. I've been longing to sit in the shade of the big magnolia ever since I came. I shall take a book and spend my two hours out there, and any one who wishes may share my bower."

"Then I'll be off," said Alec. "Any commissions for me in Jonah?" He stood like an orderly at attention, with the mail-bag slung over one shoulder and his whole bearing expressive of the importance of his mission. The sun and the wind of the prairie had already tanned his smooth skin to the ruddy hue of health, but Mrs. Clyde, observing him closely, could not fail to note how very slim and frail the erect young figure was.

"Isn't twenty miles a rather long ride on a hot day?" she asked tactfully, fearing to wound the sensitive lad.

"We shall reach Kooch's ranch by noon, and we are to rest there until it is cool again," he replied, flushing a little under her solicitous glance.

"Well, keep an eye on Shady!" said Blue Bonnet, waving him good-bye as she went to do her practising.

Fifteen minutes later each member of the ranch party was busily engaged in doing "just as she liked." Mrs. Clyde, deep in a book, sat under the fragrant magnolia; Kitty reclined on a Navajo[59] blanket near her, lazily watching the gay-plumaged birds that made the tree a rendezvous. From the open windows of the living-room came a conscientious rendering of a "Czerny" exercise, enlivened now and then by a bar or two of a rollicking dance, with which Blue Bonnet sugar-coated her pill. In the kitchen Debby and Amanda were deep in the mysteries of "pinoche" under the tutelage of Lisa and Gertrudis; while Sarah, safe inside her own little sanctum, sat and drew threads rapturously, and later, coached by the delighted Benita, wove them into endless spider-webs.[60]

They sat up late that evening waiting for Alec to come with the mail. Mrs. Clyde and Blue Bonnet were somewhat uneasy, for they knew he had intended to be back in time for their late supper; and when ten o'clock came and no Alec or Shady appeared, they grew openly anxious.

Uncle Cliff refused to share their worry. "Shady's no tenderfoot," he scoffed, "and holding up the mail has gone out of fashion in these parts."

Blue Bonnet had no fear of hold-ups and did not care to express her suspicion that the ride had proved too much for Alec. She found reason to reproach herself: a forty-mile ride for a delicate boy like him was a foolish undertaking and she should have realized it. She had ridden that distance herself innumerable times; but she had practically been reared in the saddle and had lived all her life in this land of great distances. It was very different with Alec. The day of their picnic in Woodford came back to her, and again she saw the boy, worn out by a much shorter ride, lying white and unconscious before the fire in the hunter's cabin. She[61] grew almost provoked with her grandmother for having insisted upon her practising instead of riding to Jonah as she had wished. If she had gone along, she at least would have known what to do for Alec in an emergency.

At eleven the moon came up, and rising out of the prairie simultaneously with the golden disk, came Shady, riding alone. A rapid fire of questions greeted him as he came up with the mail.

"Left the young fella at Kooch's," he explained briefly.

"What was the matter?" asked Blue Bonnet anxiously.

"Well, ye see—it was this way,—" Shady paused and then stood awkwardly shifting his sombrero from hand to hand. Blue Bonnet guessed instantly that Alec had sworn the cowboy to secrecy concerning the real reason for his non-appearance, and she refrained from further questioning. But her grandmother took alarm.

"Is he hurt—or ill?" Mrs. Clyde asked quickly.

For a moment Shady avoided her eyes, then resolutely squaring his shoulders he lied boldly: "No, Señora,—the mare went lame on him. He'll be over in the morning."

Mrs. Clyde drew a quick breath of relief; but Blue Bonnet was not so easily reassured. That Kooch had a dozen horses which Alec might have ridden if Strawberry was really disabled, was something[62] her grandmother did not know; but the little Texan, used all her life to the easy give and take of ranch life, understood at once that Alec's real reason for staying at the Dutchman's was quite different from the one Shady had so glibly given. She knew better, however, than to press the cowboy, and let him go off to the cook-house without attempting to get at the truth.

"Grammy Kooch will take good care of him," said Uncle Joe; and with her fears thus set at rest, Mrs. Clyde proposed an adjournment to the house to read their letters.

The next morning Blue Bonnet was up before any one else in the house was stirring, and, dressing without arousing any of the other occupants of the nursery, she stole out of the house and made her way to the stable. Some of the Mexicans were already up, feeding the stock and doing the "chores," and one of them saddled Firefly. None of them wondered at Blue Bonnet's early appearance, for since her infancy she had ridden whenever the fancy took her, and now as she dashed out of the corral with Don and Solomon racing madly after her, the men grinned with satisfaction that the Señorita had returned to the ranch unchanged.

As she neared the Kooch ranch she saw a solitary horseman emerging from the gate. He was not looking towards her, and after a moment's scrutiny she began to whistle "All the Blue Bonnets."[63] With a start of surprise Alec glanced up the road and at once galloped towards her.

"Is it really you?" he asked, hardly believing his eyes.

"Nae ither!" she laughed, turning Firefly and falling in with the strawberry mare—whose four legs, she noted, were as sound as ever.

"Well, you are an early bird."

"Lucky you're not a worm,—I'm hungry enough to eat one!" she said gaily. Under cover of the jest she stole a quick look at him. Yes, in spite of the sunburn he looked worn out and ill; he needed to rest and be taken care of. She refrained from asking how he felt and instead kept up a steady fire of nonsense, describing their dull day at the ranch without him. If Alec had felt any resentment at her coming for him, it melted under her light treatment of the situation; and by the time they reached the little "rio" he was more like his usual, interested self.

"I think I'd like to follow up this cree—er—river, I mean," he remarked, looking up the winding, willow-grown course.

"Not before breakfast, thank you!"

"Well, I didn't mean right this minute, but sometime," he corrected.

"We will, surely. I want to introduce you to the lovely spots of the ranch, just as you showed me the charming places about Woodford. It will be[64] different from following the brook as we used to do there, but I think you'll like it. There are picnic places along San Franciscito that can't be beat."

"San Francescheeto?" he echoed; "where's that?"

"That's the name of this river," she replied loftily.