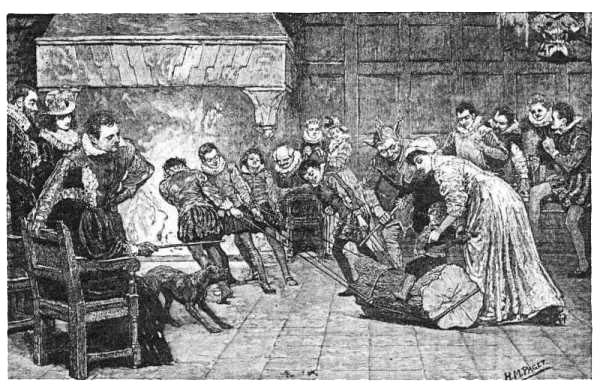

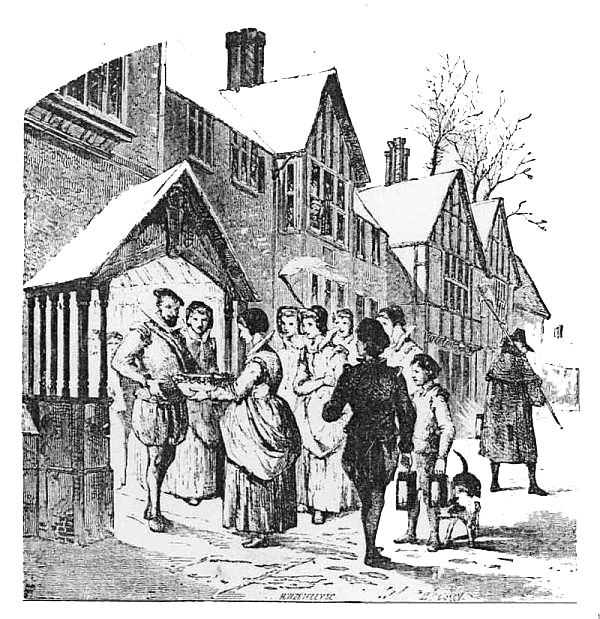

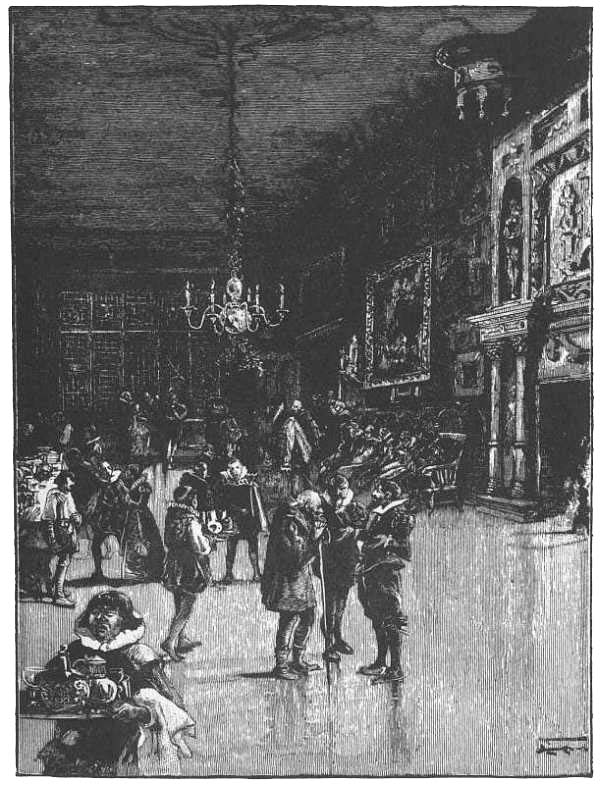

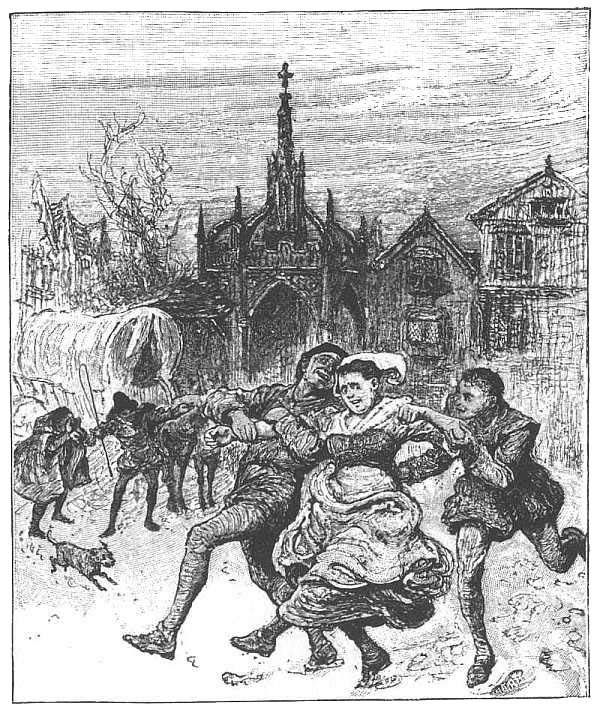

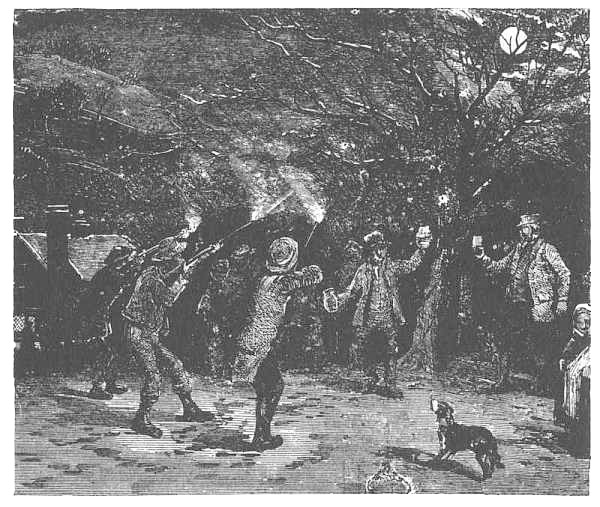

bringing in the yule log. Frontispiece.

bringing in the yule log. Frontispiece.

Title: Christmas: Its Origin and Associations

Author: W. F. Dawson

Release date: July 10, 2007 [eBook #22042]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Robert Cicconetti, Turgut Dincer, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

E-text prepared by Robert Cicconetti, Turgut Dincer,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

At home, at sea, in many distant lands, |

This Kingly Feast without a rival stands! |

In the third quarter of the nineteenth century, it fell to my lot to write an article on Christmas, its customs and festivities. And, although I sought in vain for a chronological account of the festival, I discovered many interesting details of its observances dispersed in the works of various authors; and, while I found that some of its greater celebrations marked important epochs in our national history, I saw, also, that the successive celebrations of Christmas during nineteen centuries were important links in the chain of historical Christian evidences. I became enamoured of the subject, for, in addition to historical interest, there is the charm of its legendary lore, its picturesque customs, and popular games. It seemed to me that the origin and hallowed associations of Christmas, its ancient customs and festivities, and the important part it has played in history combine to make it a most fascinating subject. I resolved, therefore, to collect materials for a larger work on Christmas.

Henceforth, I became a snapper-up of everything relating to Christmastide, utilised every opportunity of searching libraries, bookstalls, and catalogues of books in different parts of the country, and, subsequently, as a Reader of the British Museum Library, had access to that vast storehouse of literary and historical treasures.

Soon after commencing the work, I realised that I had entered a very spacious field of research, and that, having to deal with the accumulated materials of nineteen centuries, a large amount of labour would be involved, and some years must elapse before, even if circumstances proved favourable, I could hope to see the end of my task. Still, I went on with the work, for I felt that a complete account of Christmas, ancient and modern, at home and abroad, would prove generally acceptable, for while the historical events and legendary lore would interest students and antiquaries, the holiday sports and popular celebrations would be no less attractive to general readers.

The love of story-telling seems to be ingrained in human nature. Travellers tell of vari-coloured races sitting round their watch fires reciting deeds of the past; and letters from colonists show how, even amidst forest-clearing, they have beguiled their evening hours by telling or reading stories as they sat in the glow of their camp fires. And in old England there is the same love of tales and stories. One of the chief delights of Christmastide is to sit in the united family circle and hear, tell, or read about the quaint habits and picturesque customs of Christmas in the olden time; and one of the purposes of CHRISTMAS is to furnish the retailer of Christmas wares with suitable things for re-filling his pack.

From the vast store of materials collected it is not possible to do more than make a selection. How far I have succeeded in setting forth the subject in a way suited to the diversity of tastes among readers I must leave to their judgment and indulgence; but I have this satisfaction, that the gems of literature it contains are very rich indeed; and I acknowledge my great indebtedness to numerous writers of different periods whose references to Christmas and its time-honoured customs are quoted.

I have to acknowledge the courtesy of Mr. Henry Jewitt, Mr. E. Wiseman, Messrs. Harper, and Messrs. Cassell & Co., in allowing their illustrations to appear in this work.

My aim is neither critical nor apologetic, but historical and pictorial: it is not to say what might or ought to have been, but to set forth from extant records what has actually taken place: to give an account of the origin and hallowed associations of Christmas, and to depict, by pen and pencil, the important historical events and interesting festivities of Christmastide during nineteen centuries. With materials collected from different parts of the world, and from writings both ancient and modern, I have endeavoured to give in the present work a chronological account of the celebrations and observances of Christmas from the birth of Christ to the end of the nineteenth century; but, in a few instances, the subject-matter has been allowed to take precedence of the chronological arrangement. Here will be found accounts of primitive celebrations of the Nativity, ecclesiastical decisions fixing the date of Christmas, the connection of Christmas with the festivals of the ancients, Christmas in times of persecution, early celebrations in Britain, stately Christmas meetings of the Saxon, Danish, and Norman kings of England; Christmas during the wars of the Roses, Royal Christmases under the Tudors, the Stuarts and the Kings and Queens of Modern England; Christmas at the Colleges and the Inns of Court; Entertainments of the nobility and gentry, and popular festivities; accounts of Christmas celebrations in different parts of Europe, in America and Canada, in the sultry lands of Africa and the ice-bound Arctic coasts, in India and China, at the Antipodes, in Australia and New Zealand, and in the Islands of the Pacific; in short, throughout the civilised world.

In looking at the celebrations of Christmas, at different periods and in different places, I have observed that, whatever views men hold respecting Christ, they all agree that His Advent is to be hailed with joy, and the nearer the forms of festivity have approximated to the teaching of Him who is celebrated the more real has been the joy of those who have taken part in the celebrations.

The descriptions of the festivities and customs of different periods are given, as far as possible, on the authority of contemporary authors, or writers who have special knowledge of those periods, and the most reliable authorities have been consulted for facts and dates, great care being taken to make the work as accurate and trustworthy as possible. I sincerely wish that all who read it may find as much pleasure in its perusal as I have had in its compilation.

william francis dawson.

| CHAPTER I. | page |

The Origin and Associations of Christmas |

5 |

|

|

| CHAPTER II. | |

The Earlier Celebrations of the Festival |

10 |

|

|

| CHAPTER III. | |

Early Christmas Celebrations in Britain |

23 |

|

|

| CHAPTER IV. | |

Christmas, From the Norman Conquest To Magna Charta |

40 |

|

|

| CHAPTER V. | |

Christmas, From Magna Charta To the End of the Wars of the Roses |

62 |

| (a.d. 1215-1485.) | |

|

|

| CHAPTER VI. | |

Christmas Under Henry VII. and Henry VIII. |

94 |

| (a.d. 1485-1547.) | |

|

|

| CHAPTER VII. | |

Christmas Under Edward VI., Mary, and Elizabeth |

115 |

| (a.d. 1547-1603.) | |

|

|

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

Christmas Under James I. |

151 |

| (a.d. 1603-1625.) | |

|

|

| CHAPTER IX. | |

Christmas Under Charles the First and the Commonwealth |

197 |

| (a.d. 1625-1660.) | |

|

|

| CHAPTER X. | |

Christmas, From the Restoration To the Death Of George II. |

215 |

| (a.d. 1660-1760.) | |

|

|

| CHAPTER XI. | |

Modern Christmases at Home |

240 |

|

|

| CHAPTER XII. | |

Modern Christmases Abroad |

294 |

|

|

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

Concluding Carol Service of the Nineteenth Century |

349 |

|

|

INDEX |

351 |

| page | |

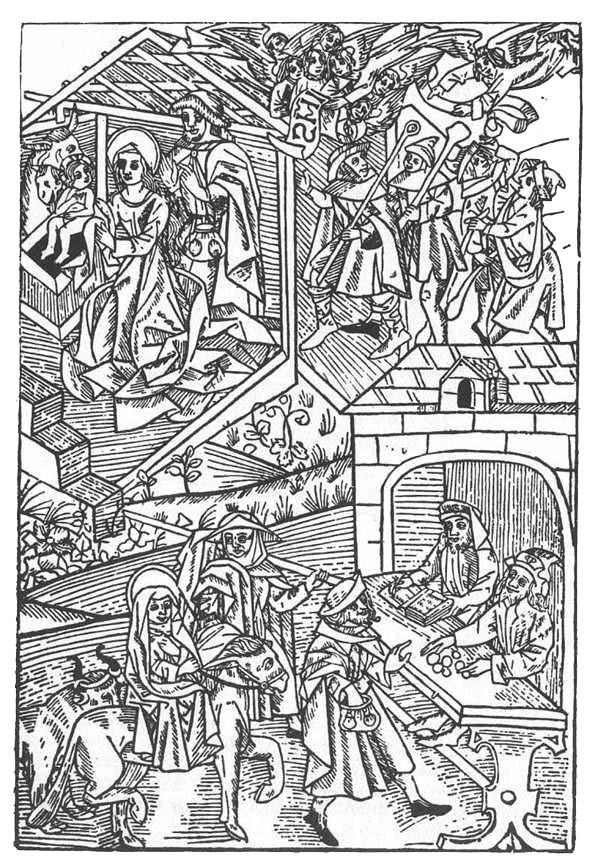

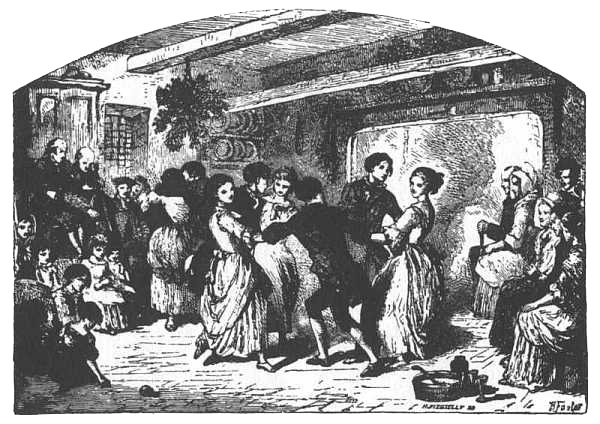

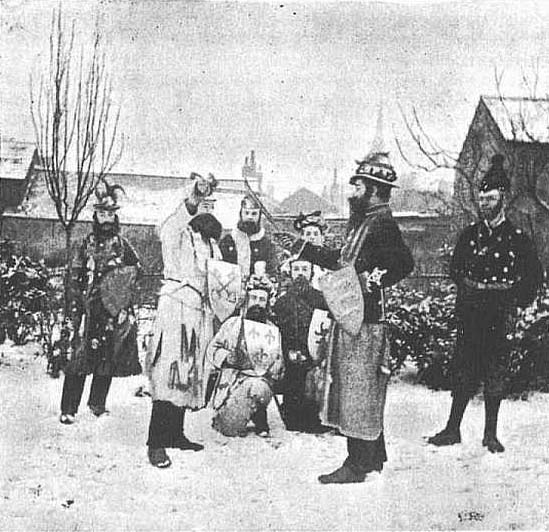

Bringing in the Yule Log |

Frontispiece |

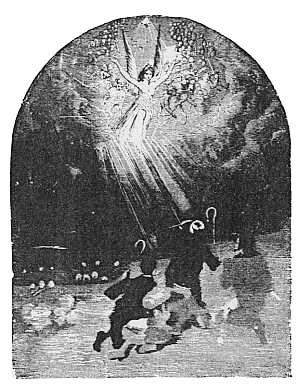

The Herald Angels |

2 |

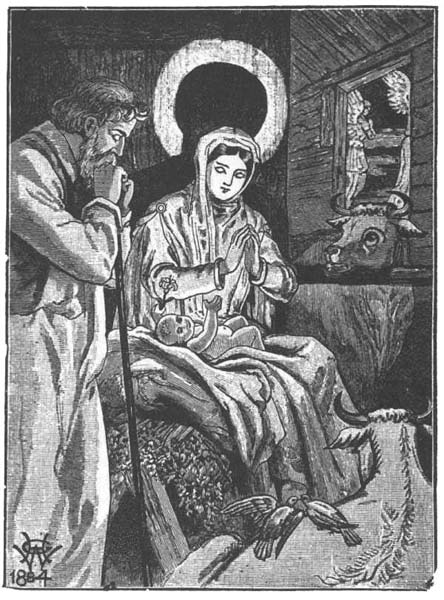

Virgin and Child |

5 |

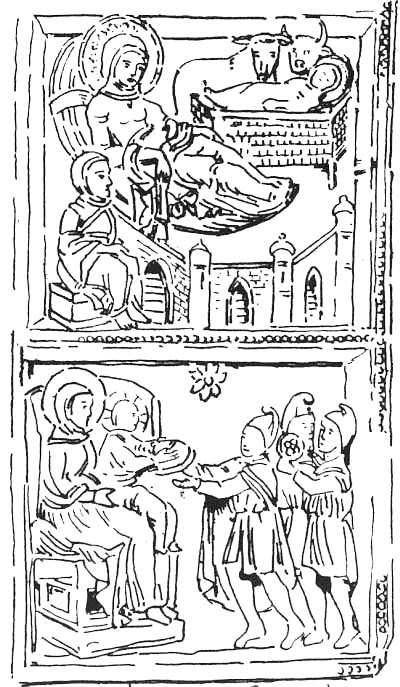

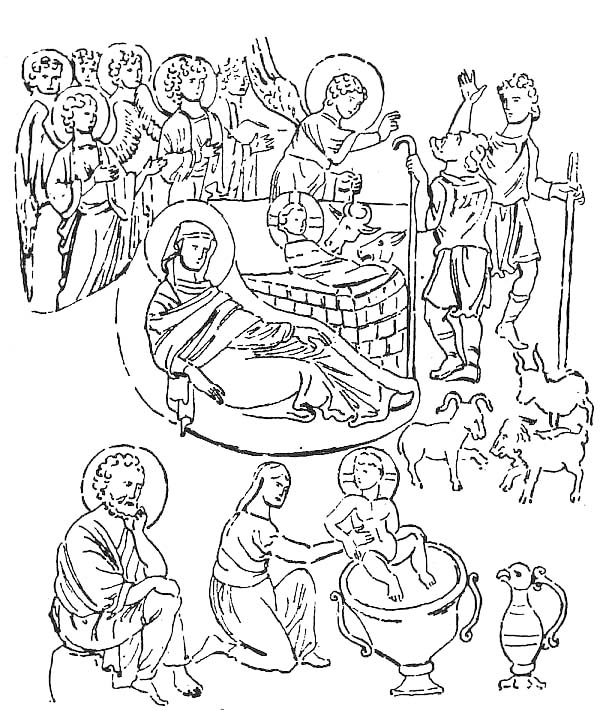

Joseph Taking Mary to be Taxed, and the Nativity Events |

6 |

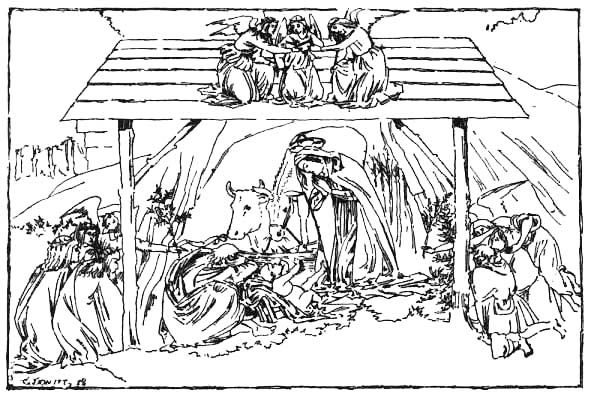

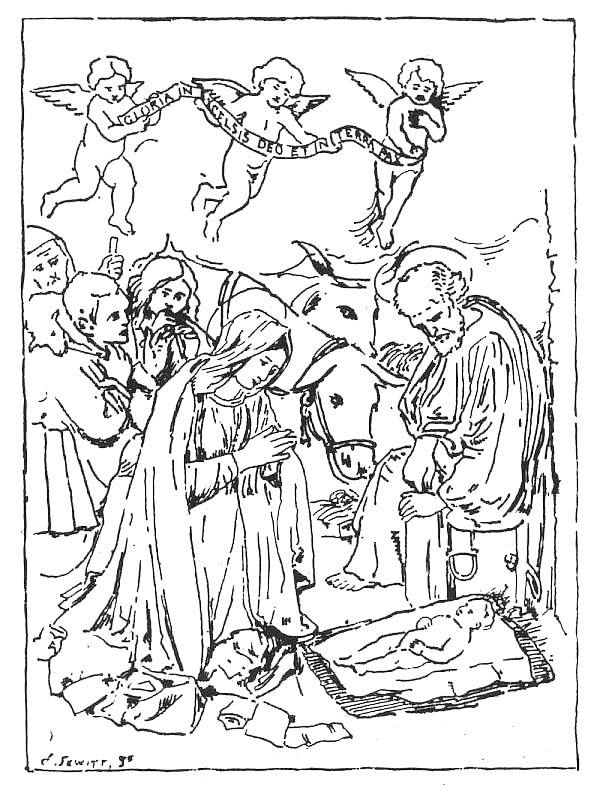

The Nativity (Central portion of Picture in National Gallery) |

8 |

Virgin and Child (Relievo) |

9 |

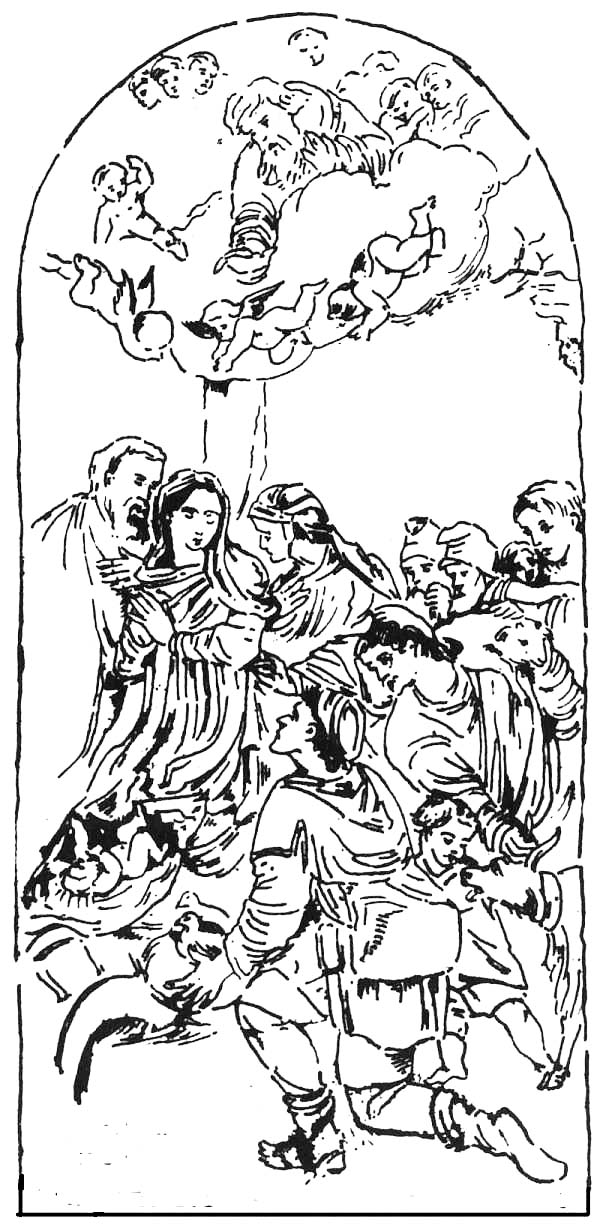

Group from the Angels' Serenade |

10 |

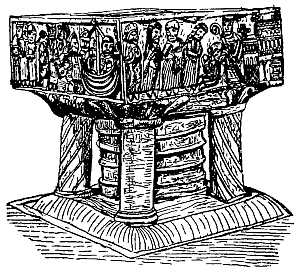

Adoration of the Magi (From Pulpit of Pisa) |

11 |

"The Inns are Full" |

14 |

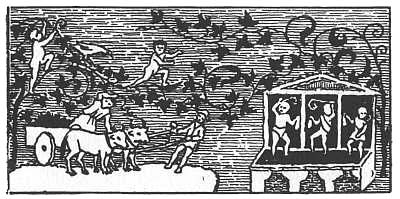

Grape Gathering and the Vintage (Mosaic in the Church of St. Constantine, Rome, A.D. 320) |

16 |

German Ninth Century Picture of the Nativity |

16 |

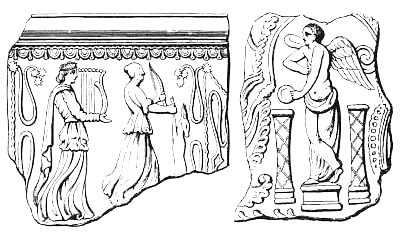

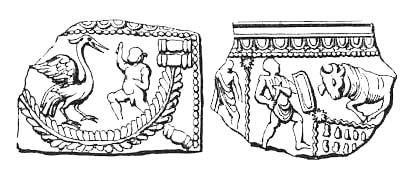

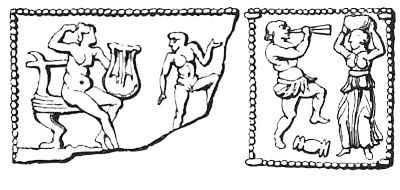

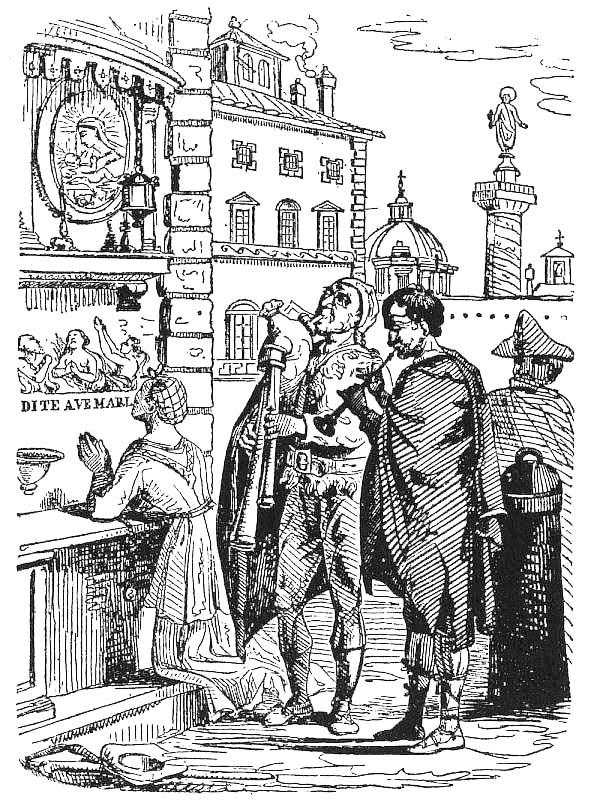

Ancient Roman Illustrations |

17 |

Ancient Roman Illustrations |

18 |

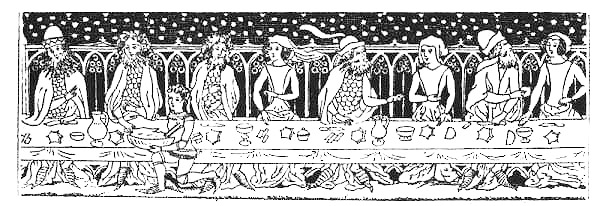

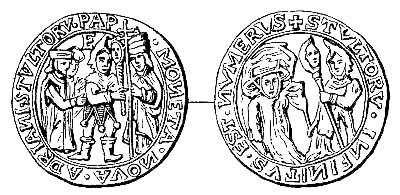

Ancient Agape |

19 |

Ancient Roman Illustrations |

21 |

Early Celebrations in Britain |

23 |

Queen Bertha |

27 |

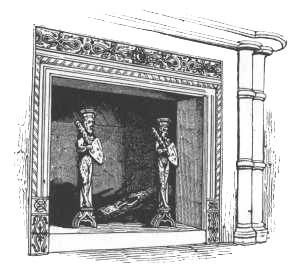

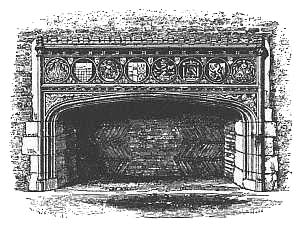

An Ancient Fireplace |

30 |

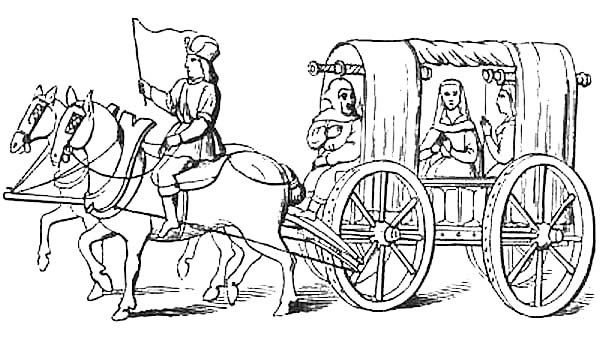

Traveling in the Olden Time, with a "Christmas Fool: on the Front Seat |

31 |

The Wild Boar Hunt: Killing the Boar |

32 |

Adoration of the Magi (Picture of Stained Glass, Winchester Cathedral) |

34 |

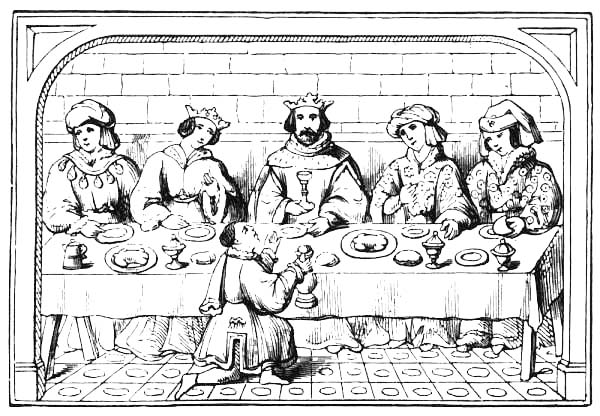

A King at Dinner |

40 |

Blind Minstrel at a Feast |

42 |

Minstrels' Christmas Serenade at an Old Baronial Hall |

44 |

Westminster Hall |

46 |

Strange Old Stories Illustrated (From Harl. MS.) |

50 |

A Cook of the Period (Early Norman) |

55 |

Monk Undergoing Discipline |

56 |

Wassailing at Christmastide |

57 |

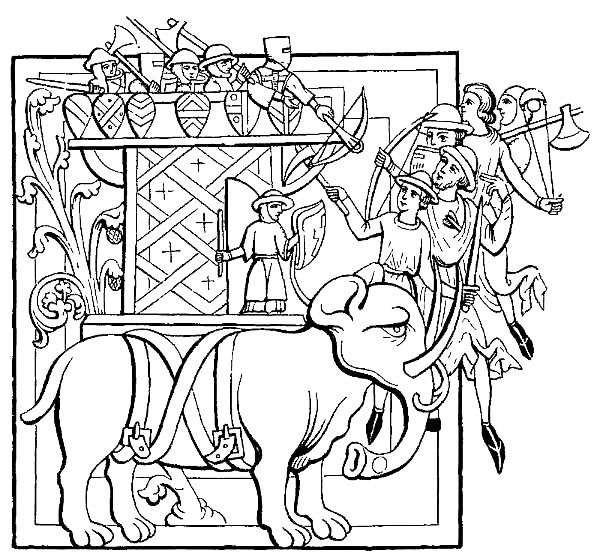

Panoply of a Crusader |

58 |

Royal Party Dining in State |

63 |

Ladies Looking from the Hustings upon the Tournament |

73 |

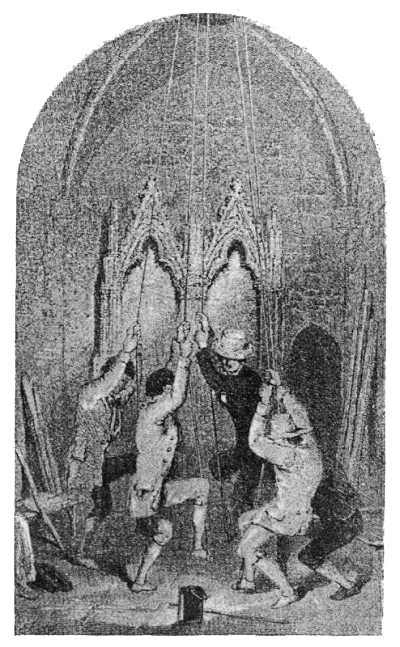

The Lord of Misrule |

74 |

Curious Cuts of Priestly Players in the Olden Time |

76 |

A Court Fool |

77 |

Virgin and Child (Florentine, 1480. South Kensington Museum) |

83 |

Henry VI.'s Cradle |

84 |

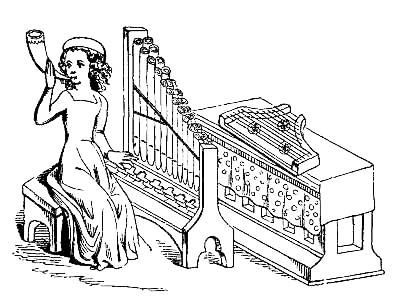

Lady Musician of the Fifteenth Century |

91 |

Rustic Christmas Minstrel with Pipe and Tabor |

92 |

Martin Luther and the Christmas Tree |

106 |

The Little Orleans Madonna of Raphael |

107 |

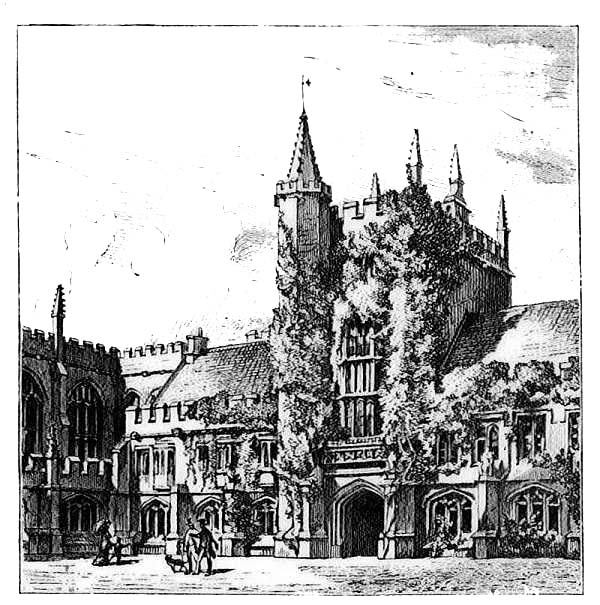

Magdalen College, Oxford |

110 |

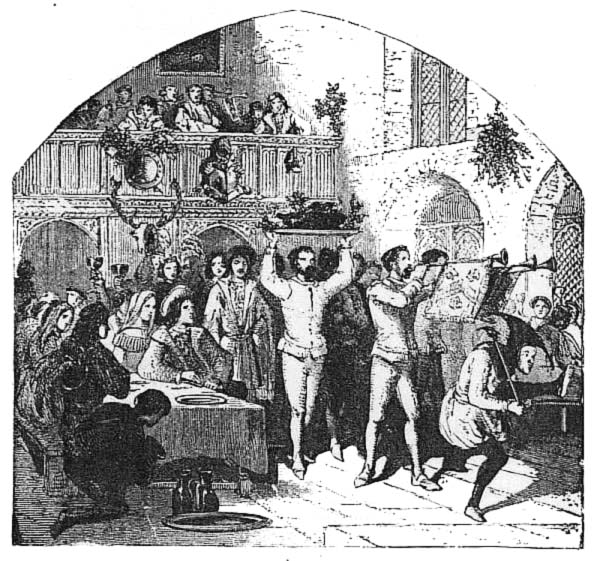

Bringing in the Boar's Head with Minstrelsy |

111 |

Virgin and Child, Chirbury, Shropshire |

118 |

Riding a-Mumming at Christmastide |

121 |

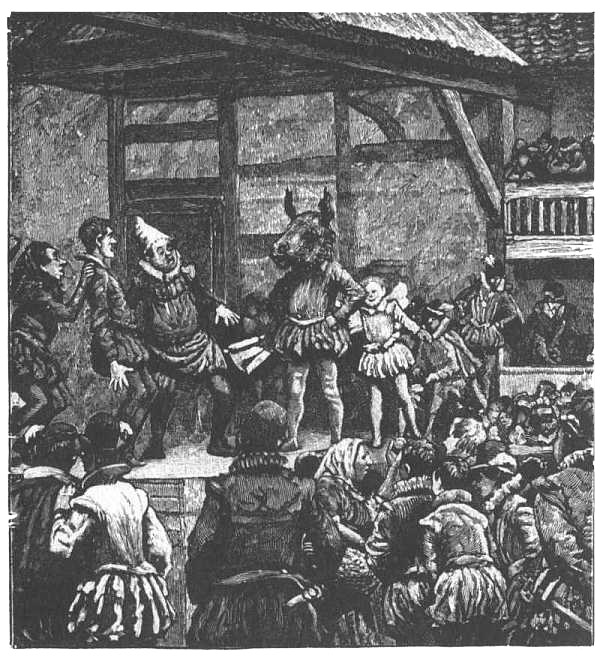

A Dumb Show in the Time of Elizabeth |

123 |

The Fool of the Old Play (From a Print by Breughel) |

137 |

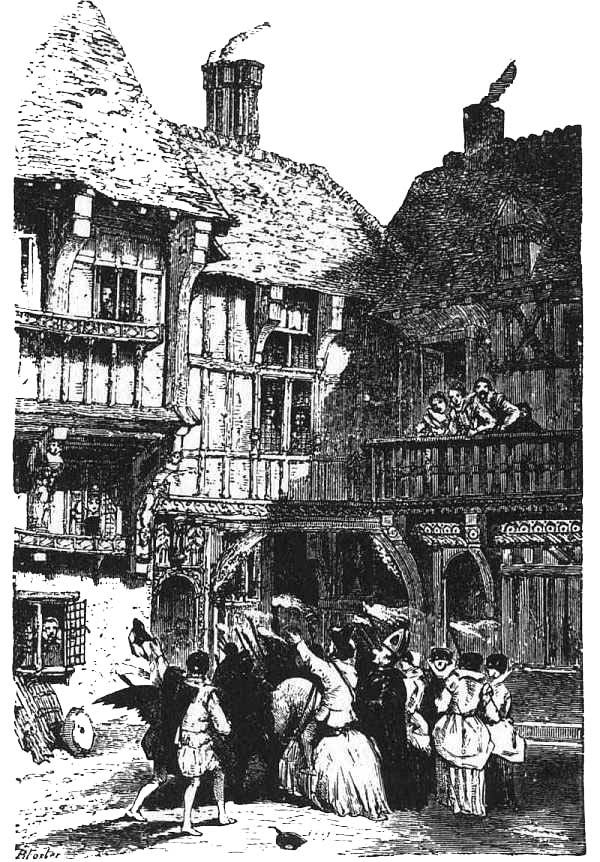

The Acting of one of Shakespeare's Plays in the Time of Queen Elizabeth |

141 |

Neighbours with Pipe and Tabor |

147 |

Christmas in the Hall |

149 |

The Hobby-Horse |

197 |

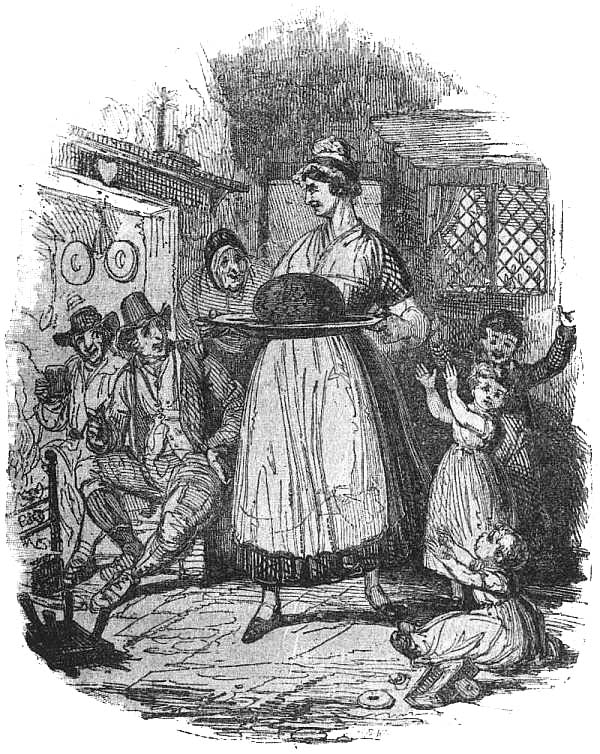

Servants' Christmas Feast |

202 |

"The Hackin" |

216 |

Seafaring Pilgrims |

219 |

An Ancient Fireplace |

225 |

A Druid Priestess Bearing Mistletoe |

228 |

A Nest of Fools |

229 |

"The Mask Dance" |

231 |

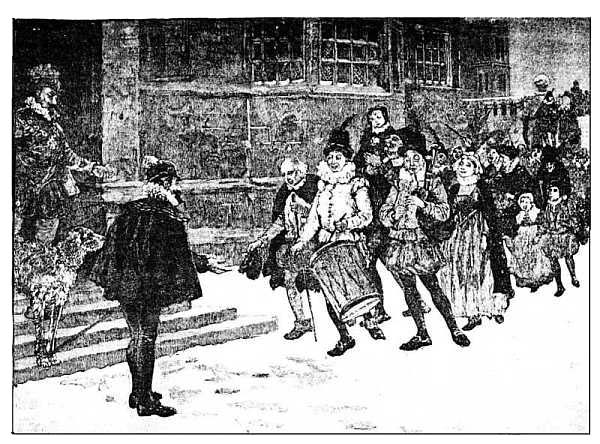

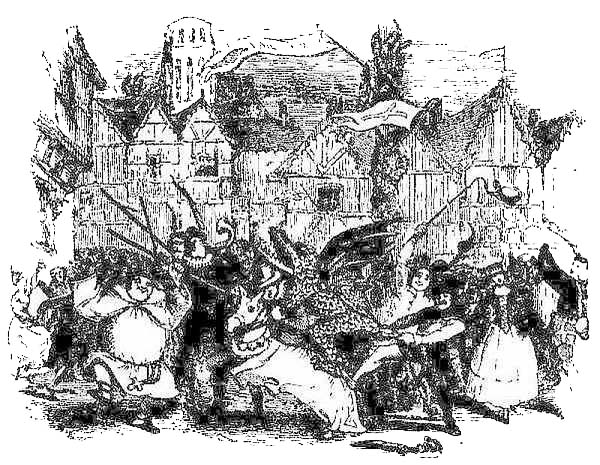

The Christmas Mummers |

234 |

The Waits |

240 |

The Christmas Plum-Pudding |

245 |

Italian Minstrels in London, at Christmas, 1825 |

246 |

Snap Dragon |

247 |

Blindman's Buff |

249 |

The Christmas Dance |

250 |

The Giving Away of Christmas Doles |

257 |

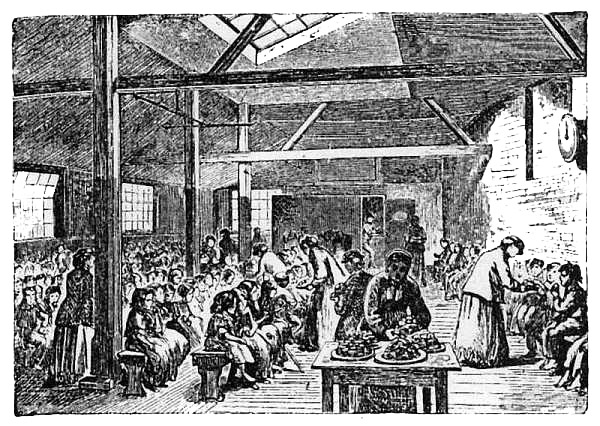

Poor Children's Treat in Modern Times |

265 |

The Christmas Bells |

271 |

Wassailing the Apple-Trees in Devonshire |

279 |

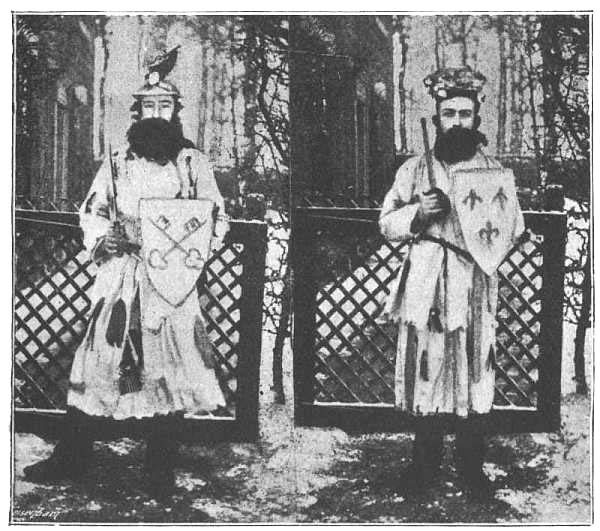

Modern Christmas Performers: Yorkshire Sword-Actors |

282 |

Modern Christmas Characters: "St Peter," "St. Denys" |

283 |

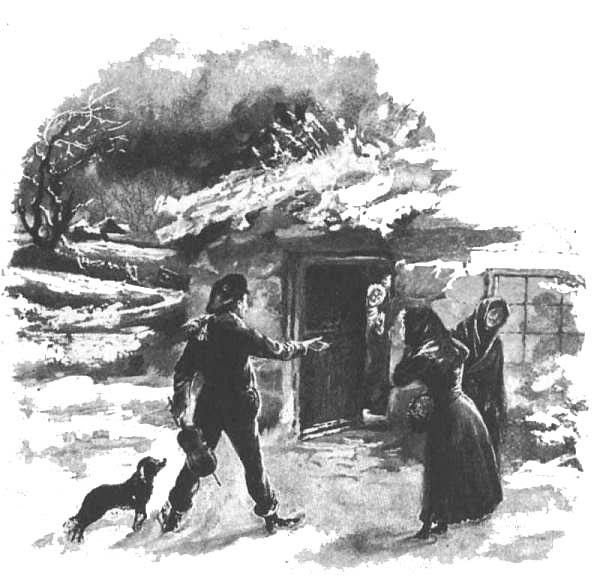

A Scotch First Footing |

285 |

Provençal Plays at Christmastide |

320 |

Nativity Picture (From Byzantine Ivory in the British Museum) |

324 |

Calabrian Shepherds Playing in Rome at Christmas |

329 |

Worshipping the Child Jesus (From a Picture in the Museum at Naples) |

337 |

Angels and Men Worshipping the Child Jesus (From a Picture in Seville Cathedral) |

338 |

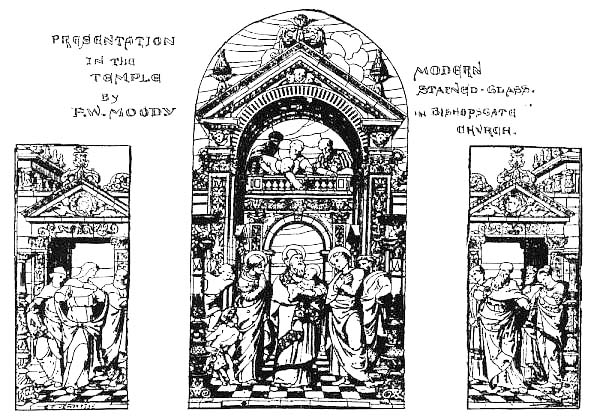

Simeon Received the Child Jesus into his Arms (From Modern Stained Glass in Bishopsgate Church, London) |

348 |

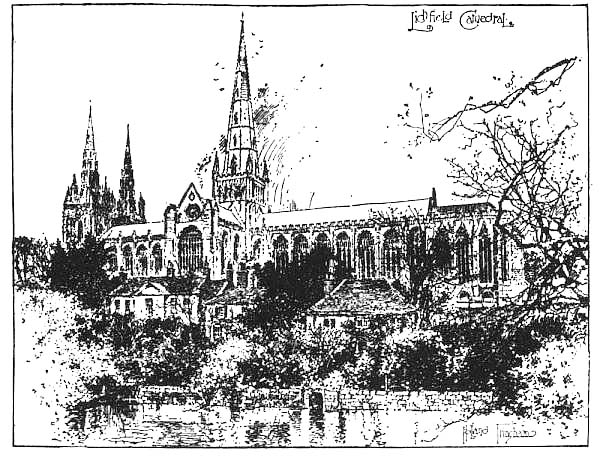

Lichfield Cathedral |

349 |

W. F. D

Now the birth of Jesus Christ was on this wise: When His mother Mary had been betrothed to Joseph, before they came together she was found with child of the Holy Ghost. And Joseph her husband, being a righteous man, and not willing to make her a public example, was minded to put her away privily. But when he thought on these things, behold, an angel of the Lord appeared unto him in a dream, saying, Joseph, thou son of David, fear not to take unto thee Mary thy wife: for that which is conceived in her is of the Holy Ghost. And she shall bring forth a Son; and thou shalt call His name Jesus; for it is He that shall save His people from their sins. Now all this is come to pass, that it might be fulfilled which was spoken by the Lord through the prophet, saying,

Behold, the virgin shall be with child and shall bring forth a Son,

And they shall call His name Immanuel;

006which is, being interpreted, God with us. And Joseph arose from his sleep, and did as the angel of the Lord commanded him, and took unto him his wife; and knew her not till she had brought forth a Son; and he called His name Jesus.

(Matthew i. 18-25.)

"There went out a decree from Cæsar Augustus that all the world should be taxed. And Joseph went to be taxed with Mary his espoused wife, being great with child."

(Luke ii. 1-5.)

And there were shepherds in the same country abiding in the007 field, and keeping watch by night over their flock. And an angel of the Lord stood by them, and the glory of the Lord shone round about them: and they were sore afraid. And the angel said unto them, Be not afraid; for behold, I bring you good tidings of great joy which shall be to all the people: for there is born to you this day in the city of David a Saviour, which is Christ the Lord. And this is the sign unto you; Ye shall find a babe wrapped in swaddling clothes, and lying in a manger. And suddenly there was with the angel a multitude of the heavenly host praising God, and saying,

Glory to God in the highest,

And on earth peace among men in whom He is well pleased.

And it came to pass, when the angels went away from them into heaven, the shepherds said one to another, Let us now go even unto Bethlehem, and see this thing that is come to pass, which the Lord hath made known unto us. And they came with haste, and found both Mary and Joseph, and the Babe lying in the manger. And when they saw it, they made known concerning the saying which was spoken to them about this child. And all that heard it wondered at the things which were spoken unto them by the shepherds. But Mary kept all these sayings, pondering them in her heart. And the shepherds returned, glorifying and praising God for all the things that they had heard and seen, even as it was spoken unto them.

(Luke ii. 8-20.)

The evangelist Matthew tells us that "Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judæa in the days of Herod the king;" and Justin Martyr, who was born at Shechem and lived less than a century after the time of Christ, places the scene of the Nativity in a cave. Over this cave has risen the Church and Convent of the Nativity, and there is a stone slab with a star cut in it to mark the spot where the Saviour was born. Dean Farrar, who has been at the place, says: "It is impossible to stand in the little Chapel of the Nativity, and to look without emotion on the silver star let into the white marble, encircled by its sixteen ever-burning lamps, and surrounded by the inscription, 'Hic de Virgine Maria Jesus Christus natus est.'"

To visit such a scene is to have the thoughts carried back to the greatest event in the world's history, for it has been truly said that the birth of Christ was the world's second birthday.

W. F. D.

"Christmas" (pronounced Kris'mas) signifies "Christ's Mass," meaning the festival of the Nativity of Christ, and the word has been variously spelt at different periods. The following are obsolete forms of it found in old English writings: Crystmasse, Cristmes, Cristmas, Crestenmes, Crestenmas, Cristemes, Cristynmes, Crismas, Kyrsomas, Xtemas, Cristesmesse, Cristemasse, Crystenmas, Crystynmas, Chrystmas, Chrystemes, Chrystemasse, Chrystymesse, Cristenmas, Christenmas, Christmass, Christmes. Christmas has also been called Noël or Nowel. As to the derivation of the word Noël, some say it is a contraction of the French nouvelles (tidings), les bonnes nouvelles, that is "The good news of the Gospel"; others take it as an abbreviation of the Gascon or Provençal nadaü, nadal, which means the same as the Latin natalis, that is, dies natalis, "the birthday." In "The Franklin's Tale," Chaucer alludes to "Nowel" as a festive cry at Christmastide: "And 'Nowel' crieth every lusty man." Some say Noël is a corruption of Yule, Jule, or Ule, meaning "The festival of the sun." The name Yule is still applied to the festival in Scotland, and some other places. Christmas is represented in Welsh by Nadolig, which signifies "the natal, or birth"; in French by Noël; and in Italian by Il Natale, which, together with its cognate term in Spanish, is simply a contraction of dies natalis, "the birthday."

The Angels' Song has been called the first Christmas Carol, and the shepherds who heard this heavenly song of peace and goodwill, and went "with haste" to the birthplace at Bethlehem, where they "found Mary, and Joseph, and the Babe lying in a011 manger," certainly took part in the first celebration of the Nativity. And the Wise Men, who came afterwards with presents from the East, being led to Bethlehem by the appearance of the miraculous star, may also be regarded as taking part in the first celebration of the Nativity, for the name Epiphany (now used to commemorate the manifestation of the Saviour) did not come into use till long afterwards, and when it was first adopted among the Oriental Churches it was designed to commemorate both the birth and baptism of Jesus, which two events the Eastern Churches believed to have occurred on January 6th. Whether the shepherds commemorated the Feast of the Nativity annually does not appear from the records of the Evangelists; but it is by no means improbable that to the end of their lives they would annually celebrate the most wonderful event which they had witnessed.

Within thirty years after the death of our Lord, there were churches in Jerusalem, Cæsarea, Rome, and the Syrian Antioch. In reference to the latter, Bishop Ken beautifully says:—

Clement, one of the Apostolic Fathers and third Bishop of Rome, who flourished in the first century, says: "Brethren, keep diligently feast-days, and truly in the first place the day of012 Christ's birth." And according to another of the early Bishops of Rome, it was ordained early in the second century, "that in the holy night of the Nativity of our Lord and Saviour, they do celebrate public church services and in them solemnly sing the Angels' Hymn, because also the same night He was declared unto the shepherds by an angel, as the truth itself doth witness."

But, before proceeding further with the historical narrative, it will be well now to make more particular reference to the fixing of the date of the festival.

Whether the 25th of December, which is now observed as Christmas Day, correctly fixes the period of the year when Christ was born is still doubtful, although it is a question upon which there has been much controversy. From Clement of Alexandria it appears, that when the first efforts were made to fix the season of the Advent, there were advocates for the 20th of May, and for the 20th or 21st of April. It is also found that some communities of Christians celebrated the festival on the 1st or 6th of January; others on the 29th of March, the time of the Jewish Passover: while others observed it on the 29th of September, or Feast of Tabernacles. The Oriental Christians generally were of opinion that both the birth and baptism of Christ took place on the 6th of January. Julius I., Bishop of Rome (A.D. 337-352), contended that the 25th of December was the date of Christ's birth, a view to which the majority of the Eastern Church ultimately came round, while the Church of the West adopted from their brethren in the East the view that the baptism was on the 6th of January. It is, at any rate, certain that after St. Chrysostom Christmas was observed on the 25th of December in East and West alike, except in the Armenian Church, which still remains faithful to January 6th. St. Chrysostom, who died in the beginning of the fifth century, informs us, in one of his Epistles, that Julius, on the solicitation of St. Cyril of Jerusalem, caused strict inquiries to be made on the subject, and thereafter, following what seemed to be the best authenticated tradition, settled authoritatively the 25th of December as the anniversary of Christ's birth, the Festorum omnium metropolis, as it is styled by Chrysostom. It may be observed, however, that some have represented this fixing of the day to have been accomplished by St. Telesphorus, who was Bishop of Rome A.D. 127-139, but the authority for the assertion is very doubtful. There is good ground for maintaining that Easter and its accessory celebrations mark with tolerable accuracy the anniversaries of the Passion and Resurrection of our Lord, because we know that the events themselves took place at the period of the Jewish Passover; but no such precision of date can be adduced as regards Christmas. Dr. Geikie[1] says: "The 013season at which Christ was born is inferred from the fact that He was six months younger than John, respecting the date of whose birth we have the help of knowing the time of the annunciation during his father's ministrations in Jerusalem. Still, the whole subject is very uncertain. Ewald appears to fix the date of the birth as five years earlier than our era. Petavius and Usher fix it as on the 25th of December, five years before our era; Bengel, on the 25th of December, four years before our era; Anger and Winer, four years before our era, in the spring; Scaliger, three years before our era, in October; St. Jerome, three years before our era, on December 25th; Eusebius, two years before our era, on January 6th; and Ideler, seven years before our era, in December." Milton, following the immemorial tradition of the Church, says that—

But there are still many who think that the 25th of December does not correspond with the actual date of the birth of Christ, and regard the incident of the flocks and shepherds in the open field, recorded by St. Luke, as indicative of spring rather than winter. This incident, it is thought, could not have taken place in the inclement month of December, and it has been conjectured, with some probability, that the 25th of December was chosen in order to substitute the purified joy of a Christian festival for the license of the Bacchanalia and Saturnalia which were kept at that season. It is most probable that the Advent took place between December, 749, of Rome, and February, 750.

Dionysius Exiguus, surnamed the Little, a Romish monk of the sixth century, a Scythian by birth, and who died a.d. 556, fixed the birth of Christ in the year of Rome 753, but the best authorities are now agreed that 753 was not the year in which the Saviour of mankind was born. The Nativity is now placed, not as might have been expected, in a.d. 1, but in b.c. 5 or 4. The mode of reckoning by the "year of our Lord" was first introduced by Dionysius, in his "Cyclus Paschalis," a treatise on the computation of Easter, in the first half of the sixth century. Up to that time the received computation of events through the western portion of Christendom had been from the supposed foundation of Rome (b.c. 754), and events were marked accordingly as happening in this or that year, Anno Urbis Conditæ, or by the initial letters A.U.C. In the East some historians continued to reckon from the era of Seleucidæ, which dated from the accession of Seleucus Nicator to the monarchy of Syria, in b.c. 312. The new computation was received by Christendom in the sixth century, and adopted without adequate inquiry, till the sixteenth century. A more careful examination of the data presented by the Gospel history, and, in particular, by the fact that "Jesus was born014 in Bethlehem of Judæa" before the death of Herod, showed that Dionysius had made a mistake of four years, or perhaps more, in his calculations. The death of Herod took place in the year of Rome a.u.c. 750, just before the Passover. This year coincided with what in our common chronology would be b.c. 4—so that we have to recognise the fact that our own reckoning is erroneous, and to fix b.c. 5 or 4 as the date of the Nativity.

Now, out of the consideration of the time at which the Christmas festival is fixed, naturally arises another question, viz.:—

Sir Isaac Newton[2] says the Feast of the Nativity, and most of the other ecclesiastical anniversaries, were originally fixed at 015cardinal points of the year, without any reference to the dates of the incidents which they commemorated, dates which, by lapse of time, it was impossible to ascertain. Thus the Annunciation of the Virgin Mary was placed on the 25th of March, or about the time of the vernal equinox; the Feast of St. Michael on the 29th of September, or near the autumnal equinox; and the Birth of Christ at the time of the winter solstice. Christmas was thus fixed at the time of the year when the most celebrated festivals of the ancients were held in honour of the return of the sun which at the winter solstice begins gradually to regain power and to ascend apparently in the horizon. Previously to this (says William Sandys, F.S.A.),[3] the year was drawing to a close, and the world was typically considered to be in the same state. The promised restoration of light and commencement of a new era were therefore hailed with rejoicings and thanksgivings. The Saxon and other northern nations kept a festival at this time of the year in honour of Thor, in which they mingled feasting, drinking, and dancing with sacrifices and religious rites. It was called Yule, or Jule, a term of which the derivation has caused dispute amongst antiquaries; some considering it to mean a festival, and others stating that Iol, or Iul (spelt in various ways), is a primitive word, conveying the idea of Revolution or Wheel, and applicable therefore to the return of the sun. The Bacchanalia and Saturnalia of the Romans had apparently the same object as the Yuletide, or feast of the Northern nations, and were probably adopted from some more ancient nations, as the Greeks, Mexicans, Persians, Chinese, &c., had all something similar. In the course of them, as is well known, masters and slaves were supposed to be on an equality; indeed, the former waited on the latter.[4] Presents were mutually given and received, as Christmas presents in these days. Towards the end of the feast, when the sun was on its return, and the world was considered to be renovated, a king or ruler was chosen, with considerable power granted to him during his ephemeral reign, whence may have sprung some of the Twelfth-Night revels, mingled with those in honour of the Manifestation and Adoration of the Magi. And, in all probability, some other Christmas customs are adopted from the festivals of the ancients, as decking with evergreens and mistletoe (relics of Druidism) and the wassail bowl. It is not surprising, therefore, that Bacchanalian illustrations have been found among the decorations in the early Christian Churches. The illustration on the following page is from a mosaic in the Church of St. Constantine, Rome, A.D. 320.

Dr. Cassel, of Germany, an erudite Jewish convert who is little known in this country has endeavoured to show that

017the festival of Christmas has a Judæan origin. He considers that its customs are significantly in accordance with those of the Jewish festival of the Dedication of the Temple. This feast was held in the winter time, on the 25th of Cisleu (December 20th), having been founded by Judas Maccabæus in honour of the cleansing of the Temple in b.c. 164, six years and a half after its profanation by Antiochus Epiphanes. In connection with Dr. Cassel's theory it may be remarked that the German word Weihnachten (from weihen, "to consecrate, inaugurate," and nacht, "night") leads directly to the meaning, "Night of the Dedication."

In proceeding with our historical survey, then, we must recollect that in the festivities of Christmastide there is a mingling of the Divine with the human elements of society—the establishment and development of a Christian festival on pagan soil and in the midst of superstitious surroundings. Unless this be borne in mind it is impossible to understand some customs connected with the celebration of Christmas. For while the festival commemorates the Nativity of Christ, it also illustrates the ancient practices of the various peoples who have taken part in the commemoration, and not inappropriately so, as the event commemorated is also linked to the past. "Christmas" (says Dean Stanley) "brings before us the relations of the Christian religion to the religions which went before; for the birth at Bethlehem was itself a link with the past. The coming of Jesus Christ was not unheralded or unforeseen. Even in the heathen world there had been anticipations of an event of a character not unlike this. In Plato's Dialogue bright ideals had been drawn of the just man; in Virgil's Eclogues there had been a vision of a new and peaceful order of things. But it was in the Jewish nation that these anticipations were most distinct. That wonderful018 people in all its history had looked, not backward, but forward. The appearance of Jesus Christ was not merely the accomplishment of certain predictions; it was the fulfilment of this wide and deep expectation of a whole people, and that people the most remarkable in the ancient world." Thus Dean Stanley links Christianity with the older religions of the world, as other writers have connected the festival of Christmas with the festivals of paganism and Judaism. The first Christians were exposed to the dissolute habits and idolatrous practices of heathenism, as well as the superstitious ceremonials of Judaism, and it is in these influences that we must seek the true origin of many of the usages and institutions of Christianity. The old hall of Roman justice and exchange—an edifice expressive of the popular life of Greece and Rome—was not deemed too secular to be used as the first Christian place of worship: pagan statues were preserved as objects of adoration, being changed but in name; names describing the functions of Church officers were copied from the civil vocabulary of the time; the ceremonies of Christian worship were accommodated as far as possible to those of the heathen, that new converts might not be much startled at the change, and at the Christmas festival Christians indulged in revels closely resembling those of the Saturnalia.

It is known that the Feast of the Nativity was observed as early as the first century, and that it was kept by the primitive Christians even in dark days of persecution. "They wandered in deserts, and in mountains, and in dens and caves of the earth" (Heb. xi. 38). Yet they were faithful to Christ, and the Catacombs of Rome contain evidence that they celebrated the Nativity.

The opening up of these Catacombs has brought to light many most interesting relics of primitive Christianity. In these Christian cemeteries and places of worship there are signs not only of the deep emotion and hope with which they buried their dead, but also of their simple forms of worship and the festive joy with which they commemorated the Nativity of Christ. On the rock-hewn tombs these primitive Christians019 wrote the thoughts that were most consoling to themselves, or painted on the walls the figures which gave them the most pleasure. The subjects of these paintings are for the most part taken from the Bible, and the one which illustrates the earliest and most universal of these pictures, and exhibits their Christmas joy, is "The Adoration of the Magi." Another of these emblems of joyous festivity which is frequently seen, is a vine, with its branches and purple clusters spreading in every direction, reminding us that in Eastern countries the vintage is the great holiday of the year. In the Jewish Church there was no festival so joyous as the Feast of Tabernacles, when they gathered the fruit of the vineyard, and in some of the earlier celebrations of the Nativity these festivities were closely copied. And as all down the ages pagan elements have mingled in the festivities of Christmas, so in the Catacombs they are not absent. There is Orpheus playing on his harp to the beasts; Bacchus as the god of the vintage; Psyche, the butterfly of the soul; the Jordan as the god of the rivers. The classical and the Christian, the Hebrew and the Hellenic elements had not yet parted; and the unearthing of these pictures after the lapse of centuries affords another interesting clue to the origin of some of the customs of Christmastide. It is astonishing how many of the Catacomb decorations are taken from heathen sources and copied from heathen paintings; yet we need not wonder when we reflect that the vine was used by the early Christians as an emblem of gladness, and it was scarcely possible for them to celebrate the Feast of the Nativity—a festival of glad tidings—without some sort of Bacchanalia. Thus it appears that even

(From Withrow's "Catacombs of Rome,' which states that the inscriptions, according to Dr. Maitland, should be expanded thus IRENE DA CALDA[M AQVAM]—"Peace, give hot water,' and AGAPE MISCE MI [VINVM CVM AQVA]—"Love, mix me wine with water," the allusion being to the ancient custom of tempering wine with water, hot or cold)

020 beneath the palaces and temples of pagan Rome the birth of Christ was celebrated, this early undermining of paganism by Christianity being, as it were, the germ of the final victory, and the secret praise, which came like muffled music from the Catacombs in honour of the Nativity, the prelude to the triumph-song in which they shall unite who receive from Christ the unwithering crown.

But they who would wear the crown must first bear the cross, and these early Christians had to pass through dreadful days of persecution. Some of them were made food for the torches of the atrocious Nero, others were thrown into the Imperial fish-ponds to fatten lampreys for the Bacchanalian banquets, and many were mangled to death by savage beasts, or still more savage men, to make sport for thousands of pitiless sightseers, while not a single thumb was turned to make the sign of mercy. But perhaps the most gigantic and horrible of all Christmas atrocities were those perpetrated by the tyrant Diocletian, who became Emperor a.d. 284. The early years of his reign were characterised by some sort of religious toleration, but when his persecutions began many endured martyrdom, and the storm of his fury burst on the Christians in the year 303. A multitude of Christians of all ages had assembled to commemorate the Nativity in the temple at Nicomedia, in Bithynia, when the tyrant Emperor had the town surrounded by soldiers and set on fire, and about twenty thousand persons perished. The persecutions were carried on throughout the Roman Empire, and the death-roll included some British martyrs, Britain being at that time a Roman province. St. Alban, who was put to death at Verulam in Diocletian's reign, is said to have been the first Christian martyr in Britain. On the retirement of Diocletian, satiated with slaughter and wearied with wickedness, Galerius continued the persecutions for a while. But the time of deliverance was at hand, for the martyrs had made more converts in their deaths than in their lives. It was vainly021 hoped that Christianity would be destroyed, but in the succeeding reign of Constantine it became the religion of the empire. Not one of the martyrs had died in vain or passed through death unrecorded.

With the accession of Constantine (born at York, February 27, 274, son of the sub-Emperor Constantius by a British mother, the "fair Helena of York," and who, on the death of his father at York in 306, was in Britain proclaimed Emperor of the Roman Empire) brighter days came to the Christians, for his first act was one of favour to them. He had been present at the promulgation of Diocletian's edict of the last and fiercest of the persecutions against the Christians, in 303, at Nicomedia, soon after which the imperial palace was struck by lightning, and the conjunction of the events seems to have deeply impressed him. No sooner had he ascended the throne than his good feeling towards the Christians took the active form of an edict of toleration, and subsequently he accepted Christianity, and his example was followed by the greater part of his family. And now the Christians, who had formerly hidden away in the darkness of the Catacombs and encouraged one another with "Alleluias," which served as a sort of invitatory or mutual call to each other to praise the Lord, might come forth into the Imperial sunshine and hold their services in basilicas or public halls, the roofs of which (Jerome tells us) "re-echoed with their cries of Alleluia," while Ambrose says the sound of their psalms as they sang in celebration of the Nativity "was like the surging of the sea in great waves of sound." And the Catacombs contain confirmatory evidence of the joy with which relatives of the Emperor participated in Christian festivities. In the tomb of022 Constantia, the sister of the Emperor Constantine, the only decorations are children gathering the vintage, plucking the grapes, carrying baskets of grapes on their heads, dancing on the grapes to press out the wine. This primitive conception of the Founder of Christianity shows the faith of these early Christians to have been of a joyous and festive character, and the Graduals for Christmas Eve and Christmas morning, the beautiful Kyrie Eleisons (which in later times passed into carols), and the other festival music which has come down to us through that wonderful compilation of Christian song, Gregory's Antiphonary, show that Christmas stood out prominently in the celebrations of the now established Church, for the Emperor Constantine had transferred the seat of government to Constantinople, and Christianity was formally recognised as the established religion.

Cyprian, the intrepid Bishop of Carthage, whose stormy episcopate closed with the crown of martyrdom in the latter half of the third century, began his treatise on the Nativity thus: "The much wished-for and long expected Nativity of Christ is come, the famous solemnity is come"—expressions which indicate the desire with which the Church looked forward to the festival, and the fame which its celebrations had acquired in the popular mind. And in later times, after the fulness of festivity at Christmas had resulted in some excesses, Bishop Gregory Nazianzen (who died in 389), fearing the spiritual thanksgiving was in danger of being subordinated to the temporal rejoicing, cautioned all Christians "against feasting to excess, dancing, and crowning the doors (practices derived from the heathens); urging the celebration of the festival after an heavenly and not an earthly manner."

In the Council, generally called Concilium Africanum, held A.D. 408, "stage-playes and spectacles are forbidden on the Lord's-day, Christmas-day, and other solemn Christian festivalls." Theodosius the younger, in his laws de Spectaculis, in 425, forbade shows or games on the Nativity, and some other feasts. And in the Council of Auxerre, in Burgundy, in 578, disguisings are again forbidden, and at another Council, in 614, it was found necessary to repeat the prohibitory canons in stronger terms, declaring it to be unlawful to make any indecent plays upon the Kalends of January, according to the profane practices of the pagans. But it is also recorded that the more devout Christians in these early times celebrated the festival without indulging in the forbidden excesses.

[1] Notes to "Life of Christ."

[2] "Commentary on the Prophecies of Daniel."

[3] Introduction to "Christmas Carols," 1833.

[4] The Emperor Nero himself is known to have presided at the Saturnalia, having been made by lot the Rex bibendi, or Master of the Revels. Indeed it was at one of these festivals that he instigated the murder of the young Prince Britannicus, the last male descendant of the family of the Claudii, who had been expelled from his rights by violence and crime; and the atrocious act was committed amid the revels over which Nero was presiding as master.

It is recorded that there were "saints in Cæsar's household," and we have also the best authority for saying there were converts among Roman soldiers. Cornelius, a Roman centurion, "was a just man and one that feared God," and other Roman converts are referred to in Scripture as having been found among the officers of the Roman Empire. And although it is not known who first preached the Gospel in Britain, it seems almost certain that Christianity entered with the Roman invasion in A.D. 43. As in Palestine some of the earlier converts served Christ secretly "for fear of the Jews," so, in all probability, did they in Britain for fear of the Romans. We know that some confessed Christ and closed their earthly career with the crown of martyrdom. It is also certain that very early in the Christian era Christmas was celebrated in Britain, mingling in its festivities some of the winter-festival customs of the ancient Britons and the Roman invaders, for traces of those celebrations are still seen in some of the Christmas customs of modern times. Moreover, it is known that Christians were tolerated in Britain by some of the Roman governors before the days of Constantine. It was in the time of the fourth Roman Emperor, Claudius, that part of Britain was first really conquered. Claudius himself came over in the year 43, and his generals afterwards went on with the war, conquering one after024 another of the British chiefs, Caradoc, whom the Romans called Caractacus, holding out the longest and the most bravely. This intrepid King of the Silurians, who lived in South Wales and the neighbouring parts, withstood the Romans for several years, but was at last defeated at a great battle, supposed to have taken place in Shropshire, where there is a hill still called Caer Caradoc. Caradoc and his family were taken prisoners and led before the Emperor at Rome, when he made a remarkable speech which has been preserved for us by Tacitus. When he saw the splendid city of Rome, he wondered that an Emperor who lived in such splendour should have meddled with his humble home in Britain; and in his address before the Emperor Claudius, who received him seated on his throne with the Empress Agrippina by his side, Caradoc said: "My fate this day appears as sad for me as it is glorious for thee. I had horses, soldiers, arms, and treasures; is it surprising that I should regret the loss of them? If it is thy will to command the universe, is it a reason we should voluntarily accept slavery? Had I yielded sooner, thy fortune and my glory would have been less, and oblivion would soon have followed my execution. If thou sparest my life, I shall be an eternal monument of thy clemency." Although the Romans had very often killed their captives, to the honour of Claudius be it said that he treated Caradoc kindly, gave him his liberty, and, according to some historians, allowed him to reign in part of Britain as a prince subject to Rome. It is surprising that an emperor who had shown such clemency could afterwards become one of Rome's sanguinary tyrants; but Claudius was a man of weak intellect.

There were several of the Roman Emperors and Governors who befriended the Christians, took part in their Christmas festivities, and professed faith in Christ. The Venerable Bede says: "In the reign of Marcus Aurelius Antonius, and his partner in the Empire, Lucius Verus, when Eleutherius was Bishop of Rome, Lucius, a British king, sent a letter to his prelate, desiring his directions to make him a Christian. The holy bishop immediately complied with this pious request; and thus the Britons, being brought over to Christianity, continued without warping or disturbance till the reign of the Emperor Diocletian." And Selden says: "Howsoever, by injury of time, the memory of this great and illustrious Prince King Lucy hath been embezzled and smuggled; this, upon the credit of the ancient writers, appears plainly, that the pitiful fopperies of the Pagans, and the worship of their idol devils, did begin to flag, and within a short time would have given place to the worship of the true God." As this "illustrious Prince King Lucy"—Lucius Verus—flourished in the latter part of the second century, and is credited with the erection of our first Christian Church on the site of St. Martin's, at Canterbury, it seems clear that even in those025 early days Christianity was making progress in Britain. From the time of Julius Agricola, who was Roman Commander from 78 to 84, Britain had been a Roman province, and although the Romans never conquered the whole of the island, yet during their occupation of what they called their province (the whole of Britain, excepting that portion north of the Firths of Forth and Clyde), they encouraged the Christmas festivities and did much to civilise the people whom they had conquered and whom they governed for more than three hundred years. They built towns in different parts of the country and constructed good roads from one town to another, for they were excellent builders and road-makers. Some of the Roman emperors visited Britain and others were chosen by the soldiers of Britain; and in the reigns of Constantine the Great and other tolerant emperors the Britains lived like Romans, adopted Roman manners and customs, and some of them learned to speak the Latin language. Christian churches were built and bishoprics founded; a hierarchy was established, and at the Council of Arles, in 314, three British bishops took part—those of York, London, and Camulodunum (which is now Colchester or Malden, authorities are divided, but Freeman says Colchester). The canons framed at Arles on this occasion became the law of the British Church, and in this more favourable period for Christians the Christmas festival was kept with great rejoicing. But this settled state of affairs was subsequently disturbed by the departure of the Romans and the several invasions of the Anglo-Saxons and the Danes which preceded the Norman Conquest.

The outgoing of the Romans and the incoming of the Angles, the Saxons, and the Jutes disastrously affected the festival of Christmas, for the invaders were heathens, and Christianity was swept westward before them. They had lived in a part of the Continent which had not been reached by Christianity nor classic culture, and they worshipped the false gods of Woden026 and Thunder, and were addicted to various heathenish practices, some of which now mingled with the festivities of Christmastide. Still, as these Angles came to stay and have given their name to our country, it may be well to note that they came over to Britain from the one country which is known to have borne the name of Angeln or the Engle-land, and which is now called Sleswick, a district in the middle of that peninsula which parts the Baltic from the North Sea or German Ocean. The Romans having become weakened through their conflicts with Germany and other nations, at the beginning of the fifth century, the Emperor Honorius recalled the Roman legions from Britain, and this made it much easier for the Angles and Saxons (who had previously tried to get in) to come and remain in this country. Thus our Teuton forefathers came and conquered much the greater part of Britain, the Picts and Scots remaining in the north and the Welsh in the west of the island. It was their custom to kill or make slaves of all the people they could, and so completely did they conquer that part of Britain in which they settled that they kept their own language and manners and their own heathenish religion, and destroyed or desecrated Christian churches which had been set up. Hence Christian missionaries were required to convert our ancestral worshippers of Woden and Thunder, and a difficult business it was to Christianise such pagans, for they stuck to their false gods with the same tenacity that the northern nations did.

In his poem of "King Olaf's Christmas" Longfellow refers to the worship of Thor and Odin alongside with the worship of Christ in the northern nations:—

In England, too, Christ and Thor were worshipped side by side for at least 150 years after the introduction of Christianity, for while some of the English accepted Christ as their true friend and Saviour, He was not accepted by all the people. Indeed, the struggle against Him is still going on, but we anticipate the time when He shall be victorious all along the line.

The Christmas festival was duly observed by the missionaries who came to the South of England from Rome, headed by Augustine, and in the northern parts of the country the Christian027 festivities were revived by the Celtic missionaries from Iona, under Aidan, the famous Columbian monk. At least half of England was covered by the Columbian monks, whose great foundation upon the rocky island of Iona, in the Hebrides, was the source of Christianity to Scotland. The ritual of the Celtic differed from that of the Romish missionaries, and caused confusion, till at the Synod of Whitby (664) the Northumbrian Kingdom adopted the Roman usages, and England obtained ecclesiastical unity as a branch of the Church of Rome. Thus unity in the Church preceded by several centuries unity in the State.

In connection with Augustine's mission to England, a memorable story (recorded in Green's "History of the English People") tells how, when but a young Roman deacon, Gregory had noted the white bodies, the fair faces, the golden hair of some youths who stood bound in the market-place of Rome. "From what country do these slaves come?" he asked the traders who brought them. "They are English, Angles!" the slave-dealers answered. The deacon's pity veiled itself in poetic humour. "Not Angles, but Angels," he said, "with faces so angel-like! From what country come they?" "They028 come," said the merchants, "from Deira." "De ira!" was the untranslatable reply; "aye, plucked from God's ire, and called to Christ's mercy! And what is the name of their king?" "Ælla," they told him, and Gregory seized on the words as of good omen. "Alleluia shall be sung in Ælla's land!" he cried, and passed on, musing how the angel-faces should be brought to sing it. Only three or four years had gone by when the deacon had become Bishop of Rome, and the marriage of Bertha, daughter of the Frankish king, Charibert of Paris, with Æthelberht, King of Kent, gave him the opening he sought; for Bertha, like her Frankish kinsfolk, was a Christian.

And so, after negotiations with the rulers of Gaul, Gregory sent Augustine, at the head of a band of monks, to preach the gospel to the English people. The missionaries landed in 597, on the very spot where Hengest had landed more than a century before, in the Isle of Thanet; and the king received them sitting in the open air on the chalk-down above Minster, where the eye nowadays catches, miles away over the marshes, the dim tower of Canterbury. Rowbotham, in his "History of Music," says that wherever Gregory sent missionaries he also sent copies of the Gregorian song as he had arranged it in his "Antiphonary." And he bade them go singing among the people. And Augustine entered Kent bearing a silver cross and a banner with the image of Christ painted on it, while a long train of choristers walked behind him chanting the Kyrie Eleison. In this way they came to the court of Æthelberht, who assigned them Canterbury as an abode; and they entered Canterbury with similar pomp, and as they passed through the gates they sang this petition: "Lord, we beseech Thee to keep Thy wrath away from this city and from Thy holy Church, Alleluia!"

As papal Rome preserved many relics of heathen Rome, so, in like manner, Pope Gregory, in sending Augustine over to convert the Anglo-Saxons, directed him to accommodate the ceremonies of the Christian worship as much as possible to those of the heathen, that the people might not be much startled at the change; and, in particular, he advised him to allow converts to kill and eat at the Christmas festival a great number of oxen to the glory of God, as they had formerly done to the honour of the devil. The clergy, therefore, endeavoured to connect the remnants of Pagan idolatry with Christianity, and also allowed some of the practices of our British ancestors to mingle in the festivities of Christmastide. The religion of the Druids, the priests of the ancient Britons, is supposed to have been somewhat similar to that of the Brahmins of India, the Magi of Persia, and the Chaldeans of Syria. They worshipped in groves, regarded the oak and mistletoe as objects of veneration, and offered sacrifices. Before Christianity came to Britain December was called "Aerra Geola," because the sun then "turns his glorious course." And under different names,029 such as Woden (another form of Odin), Thor, Thunder, Saturn, &c., the pagans held their festivals of rejoicing at the winter solstice; and so many of the ancient customs connected with these festivals were modified and made subservient to Christianity.

Some of the English even tried to serve Christ and the older gods together, like the Roman Emperor, Alexander Severus, whose chapel contained Orpheus side by side with Abraham and Christ. "Rœdwald of East Anglia resolved to serve Christ and the older gods together, and a pagan and a Christian altar fronted one another in the same royal temple."[5] Kent, however, seems to have been evangelised rapidly, for it is recorded that on Christmas Day, 597, no less than ten thousand persons were baptized.

Before his death Augustine was able to see almost the whole of Kent and Essex nominally Christian.

Christmas was now celebrated as the principal festival of the year, for our Anglo-Saxon forefathers delighted in the festivities of the Halig-Monath (holy month), as they called the month of December, in allusion to Christmas Day. At the great festival of Christmas the meetings of the Witenagemot were held, as well as at Easter and Whitsuntide, wherever the Court happened to be. And at these times the Anglo-Saxon, and afterwards the Danish, Kings of England lived in state, wore their crowns, and were surrounded by all the great men of their kingdoms (together with strangers of rank) who were sumptuously entertained, and the most important affairs of state were brought under consideration. There was also an outflow of generous hospitality towards the poor, who had a hard time of it during the rest of the year, and who required the Christmas gifts to 030provide them with such creature comforts as would help them through the inclement season of the year.

Readers of Saxon history will remember that chieftains in the festive hall are alluded to in the comparison made by one of King Edwin's chiefs, in discussing the welcome to be given to the Christian missionary Paulinus: "The present life of man, O King, seems to me, in comparison of that time which is unknown to us, like to the swift flight of a sparrow through the hall where you sit at your meal in winter, with your chiefs and attendants, warmed by a fire made in the middle of the hall, while storms of rain or snow prevail without."

The "hall" was the principal part of a gentleman's house in Saxon times—the place of entertainment and hospitality—and at Christmastide the doors were never shut against any who appeared to be worthy of welcome. And with such modes of travelling as were in vogue in those days one can readily understand that, not only at Christmas, but also at other seasons, the rule of hospitality to strangers was a necessity.

To this period belong the princely pageants and the magnificent

and the Knights of his Round Table. We know that some people are inclined to discredit the accounts which have come down to us of this famous British King and Christian hero, but for our own part we are inclined to trust the old chroniclers, at all events so far as to believe that they give us true pictures031 of the manners and customs of the times of which they write; and in this prosaic age it may surely be permitted to us at Christmastide to linger over the doings of those romantic days,

Sir John Froissart tells us of the princely pageants which King Arthur held at Windsor in the sixth century, and of the sumptuous Christmas banquetings at his Round Table—the very Round Table (so we are to believe, on the authority of Dr. Milner)[7] which has been preserved in the old chapel, now termed the county hall, at Winchester. It consists of stout oak plank, perforated with many bullets, supposed to have been shot by Cromwell's soldiers. It is painted with a figure to represent King Arthur, and with the names of his twenty-four knights as they are stated in the romances of the old chroniclers. This famous Prince, who instituted the military order of the Knights of the Round Table, is also credited with the reintroduction of Christianity at York after the Saxon invaders had destroyed the first churches built there. He was unwearying in his warfare against enemies of the religion of Christ. His first great enterprise was the siege of a Saxon army at York, and, having afterwards won brilliant victories in Somersetshire and other parts of southern England, he again marched northward and penetrated Scotland to attack the Picts and Scots, who had long harassed the border. On returning from Scotland, Arthur rested his wearied army at York and kept Christmas with great bountifulness. Geoffrey of Monmouth says he was a prince of "unparalleled courage and generosity," and his Christmas at York was kept with the greatest joy and festivity. Then was the round table filled with jocund guests, and the minstrels, gleemen, harpers, pipe-players, jugglers, and dancers were as happy round about their log-fires as if they had shone in the blaze of a thousand gas-lights.

King Arthur and his Knights also indulged in out-door amusements, as hunting, hawking, running, leaping, wrestling, jousts, and tourneys. "So," says Sir Thomas Malory,[8] "passed forth all the winter with all manner of hunting and hawking, and jousts and tourneys were many between many great lords. And ever, in all manner of places, Sir Lavaine got great worship, that he was nobly renowned among many of the knights of the Round Table. Thus it passed on until Christmas, and every day there were jousts made for a diamond, that whosoever joust best should have a diamond. But Sir Launcelot would not joust, but if it were a great joust cried; but Sir Lavaine jousted there all the Christmas passing well, and most was praised; for there were few that did so well as he; wherefore all manner of knights deemed that Sir Lavaine should be made a Knight of the Round Table, at the next high feast of Pentecost."

are referred to by some of the old chroniclers, intemperance being a very prevalent vice at the Christmas festival. Ale and mead were their favourite drinks; wines were used as occasional luxuries. "When all were satisfied with dinner," says an old chronicler, "and their tables were removed, they continued drinking till the evening." And another tells how drinking and gaming went on through the greater part of the night. Chaucer's one solitary reference to Christmastide is an allegorical representation of the jovial feasting which was the characteristic feature of this great festival held in "the colde frosty season of December."

The Saxons were strongly attached to field sports, and as the "brawn of the tuskéd swine" was the first Christmas dish, it was provided by the pleasant preliminary pastime of hunting the wild boar; and the incidents of the chase afforded interesting table talk when the boar's head was brought in ceremoniously to the Christmas festival.

Prominent among the Anglo-Saxon amusements of Christmastide, Strutt mentions their propensity for gaming with dice, as derived from their ancestors, for Tacitus assures us that the ancient Germans would not only hazard all their wealth, but even stake their liberty, upon the turn of the dice: "and he who loses submits to servitude, though younger and stronger than his antagonist, and patiently permits himself to be bound and sold in the market; and this madness they dignify by the name of honour." Chess and backgammon were also favourite games with the Anglo-Saxons, and a large portion of the night was appropriated to the pursuit of these sedentary amusements, especially at the Christmas season of the year, when the early darkness stopped out-door games.

Our Saxon forefathers were very superstitious. They had many pretenders to witchcraft. They believed in the powers of philtres and spells, and invocated spirits; and they relished a blood-curdling ghost story at Christmas quite as much as their twentieth-century descendants. They confided in prognostics, and believed in the influence of particular times and seasons; 034and at Christmastide they derived peculiar pleasure from their belief in the immunity of the season from malign influences—a belief which descended to Elizabethan days, and is referred to by Shakespeare, in "Hamlet":—

We cannot pass over this period without mentioning a great Christmas in the history of our Teutonic kinsmen on the Continent, for the Saxons of England and those of Germany have the same Teutonic origin. We refer to

The coronation took place at Rome, on Christmas Day, in the year 800. Freeman[11] says that when Charles was King of the Franks and Lombards and Patrician of the Romans, he was on very friendly terms with the mighty Offa, King of the Angles that dwelt in Mercia. Charles and Offa not only exchanged letters and gifts, but each gave the subjects of the other various 035rights in his dominions, and they made a league together, "for that they two were the mightiest of all the kings that dwelt in the Western lands." As conqueror of the old Saxons in Germany, Charles may be regarded as the first King of all Germany, and he was the first man of any Teutonic nation who was called Roman Emperor. He was crowned with the diadem of the Cæsars, by Pope Leo, in the name of Charles Augustus, Emperor of the Romans. And it was held for a thousand years after, down to the year 1806, that the King of the Franks, or, as he was afterwards called, the King of Germany, had a right to be crowned by the Pope of Rome, and to be called Emperor of the Romans. In the year 1806, however, the Emperor Francis the Second, who was also King of Hungary and Archduke of Austria, resigned the Roman Empire and the Kingdom of Germany. Since that time no Emperor of the Romans has been chosen; but a new German Emperor has been created, and the event may be regarded as one of Christmastide, for the victorious soldiers who brought it about spent their Christmas in the French capital, and during the festival arranged for the re-establishment of the German Empire. So it happens, that while referring to the crowning of the first German Emperor of the Roman Empire, on Christmas Day, 800, we are able to record that more than a thousand years afterwards the unification of the German Empire and the creation of its first Emperor also occurred at Christmastide, under the influence of the German triumphs over the French in the war of 1870. The imposing event was resolved upon by the German Princes on December 18, 1870, the preliminaries were completed during the Christmas festival, and on January 18, 1871, in the Galerie des Glaces of the château of Versailles, William, King of Prussia, was crowned and proclaimed first Emperor of the new German Empire.

Now, going back again over a millennium, we come to

During the reign of Alfred the Great a law was passed with relation to holidays, by virtue of which the twelve days after the Nativity of our Saviour were set apart for the celebration of the Christmas festival. Some writers are of opinion that, but for Alfred's strict observance of the "full twelve holy days," he would not have been defeated by the Danes in the year 878. It was just after Twelfth-night that the Danish host came suddenly—"bestole," as the old Chronicle says—to Chippenham. Then "they rode through the West Saxons' land, and there sat down, and mickle of the folk over sea they drove, and of others the most deal they rode over; all but the King Alfred; he with a little band hardly fared after the woods and on the moor-fastnesses." But whether or not Alfred's preparations for the battle just referred to were hindered by his enjoyment of the festivities036 of Christmastide with his subjects, it is quite certain that the King won the hearts of his people by the great interest he took in their welfare. This good king—whose intimacy with his people we delight to associate with the homely incident of the burning of a cottager's cakes—kept the Christmas festival quite as heartily as any of the early English kings, but not so boisterously as some of them. Of the many beautiful stories told about him, one might very well belong to Christmastide. It is said that, wishing to know what the Danes were about, and how strong they were, King Alfred one day set out from Athelney in the disguise of a Christmas minstrel, and went into the Danish camp, and stayed there several days, amusing the Danes with his playing, till he had seen all he wanted, and then went back without any one finding him out.

Now, passing on to

we find that in 961 King Edgar celebrated the Christmas festival with great splendour at York; and in 1013 Ethelred kept his Christmas with the brave citizens of London who had defended the capital during a siege and stoutly resisted Swegen, the tyrant king of the Danes. Sir Walter Scott, in his beautiful poem of "Marmion," thus pictures the "savage Dane" keeping the great winter festival:—

When the citizens of London saw that Swegen had succeeded all over England except their own city, they thought it was no use holding out any longer, and they too, submitted and gave hostages. And so Swegen was the first Dane who was king, or (as Florence calls him) "Tyrant over all England;" and Ethelred, sometimes called the "Unready," King of the West Saxons, who had struggled unsuccessfully against the Danes, fled with his wife and children to his brother-in-law's court in Normandy. On the death of Swegen, the Danes of his fleet chose his son037 Cnut to be King, but the English invited Ethelred to return from Normandy and renew the struggle with the Danes. He did so, and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says: "He held his kingdom with great toil and great difficulty the while that his life lasted." After his death and that of his son Edmund, Cnut was finally elected and crowned. Freeman,[12] in recording the event, says that: "At the Christmas of 1016-1017, Cnut was a third time chosen king over all England, and one of the first things that he did was to send to Normandy for the widowed Lady Emma, though she was many years older than he was. She came over; she married the new king; and was again Lady of the English. She bore Cnut two children, Harthacnut and Gunhild. Her three children by Ethelred were left in Normandy. She seems not to have cared at all for them or for the memory of Ethelred; her whole love passed to her new husband and her new children. Thus it came about that the children of Ethelred were brought up in Normandy, and had the feelings of Normans rather than Englishmen, a thing which again greatly helped the Norman Conquest."

Cnut's first acts of government in England were a series of murders; but he afterwards became a wise and temperate king. He even identified himself with the patriotism which had withstood the stranger. He joined heartily in the festivities of Christmastide, and atoned for his father's ravages by costly gifts to the religious houses. And his love for monks broke out in the song which he composed as he listened to their chant at Ely: "Merrily sang the monks in Ely when Cnut King rowed by" across the vast fen-waters that surrounded their Abbey. "Row, boatmen, near the land, and hear we these monks sing."[13]

It is said that Cnut, who is also called Canute, "marked one of his royal Christmases by a piece of sudden retributive justice: bored beyond all endurance by the Saxon Edric's iteration of the traitorous services he had rendered him, the King exclaimed to Edric, Earl of Northumberland: 'Then let him receive his deserts, that he may not betray us as he betrayed Ethelred and Edmund!' upon which the ready Norwegian disposed of all fear on that score by cutting down the boaster with his axe, and throwing his body into the Thames."[15]

In the year 1035, King Cnut died at Shaftesbury, and was buried in Winchester Cathedral. His sons, Harold and Harthacnut, did not possess the capacity for good government, otherwise the reign of the Danes might have continued. As it was, their 038reigns, though short, were troublesome. Harold died at Oxford in 1040, and was buried at Westminster (being the first king who was buried there); Harthacnut died at Lambeth at a wedding-feast in 1042, and was buried beside his father in Winchester Cathedral. And thus ended the reigns of the Danish kings of England.

Now we come to

who, we are told, was heartily chosen by all the people, for the two very good reasons, that he was an Englishman by birth, and the only man of either the English or the Danish royal families who was at hand. He was the son of Ethelred and Emma, and at the Christmas festival of his coronation there was great rejoicing. As his early training had been at the court of his uncle, Richard the Good, in Normandy, he had learnt to prefer Norman-French customs and life to those of the English. During his reign, therefore, he brought over many strangers and appointed them to high ecclesiastical and other offices, and Norman influence and refinement of manners gradually increased at the English court, and this, of course, led to the more stately celebration of the Christmas festival. The King himself, being of a pious and meditative disposition, naturally took more interest in the religious than the temporal rejoicings, and the administration of state affairs was left almost entirely to members of the house of Godwin during the principal part of his reign. Many disturbances occurred during Edward's reign in different parts of the country, especially on the Welsh border. At the Christmas meeting of the King and his Wise Men, at Gloucester, in 1053, it was ordered that Rhys, the brother of Gruffydd, the South Welsh king, be put to death for his great plunder and mischief. The same year, the great Earl Godwine, while dining with the king at Winchester at the Easter feast, suddenly fell in a fit, died four days after, and was buried in the old cathedral. A few years later (1065), the Northumbrians complained that Earl Tostig, Harold's brother, had caused Gospatric, one of the chief Thanes, to be treacherously murdered when he came to the King's court the Christmas before. King Edward kept his last Christmas (1065), and had the meeting of his Wise Men in London instead of Gloucester as usual. His great object was to finish his new church at Westminster, and to have it hallowed before he died. He lived just long enough to have this done. On Innocent's Day the new Minster was consecrated, but the King was too ill to be there, so the Lady Edith stood in his stead. And on January 5, 1066, King Edward, the son of Ethelred, died. On the morning of the day following his death, the body of the Confessor was laid in the tomb, in his new church; and on the same day039—

in his stead. Thus three very important events—the consecration of Westminster Abbey, the death of Edward the Confessor, and the crowning of Harold—all occurred during the same Christmas festival.

In the terrible year 1066 England had three kings. The reign of Harold, the son of Godwine, who succeeded Edward the Confessor, terminated at the battle of Senlac, or Hastings, and on the following

by Archbishop Ealdred. He had not at that time conquered all the land, and it was a long while before he really possessed the whole of it. Still, he was the king, chosen, crowned, and anointed, and no one ever was able to drive him out of the land, and the crown of England has ever since been held by his descendants.

[5] Green's "History of the English People."

[6] Tennyson.

[7] "History of Winchester."

[8] "History of King Arthur and His Noble Knights."

[9] "The Franklin's Tale."

[10] "Romance of Ipomydon."

[11] "Old English History."

[12] "Short History of the Norman Conquest."

[13] "History of the English People."

[14] J. G. Whittier.

[15] "Chambers's Journal," Dec. 28, 1867.

Now we come to the

Lord Macaulay says "the polite luxury of the Normans presented a striking contrast to the coarse voracity and drunkenness of their Saxon and Danish neighbours." And certainly the above example of a royal dinner scene (from a manuscript of the fourteenth century) gives an idea of stately ceremony which is not found in any manuscripts previous to the coming over of the Normans. They "loved to display their magnificence, not in huge piles of food and hogsheads of strong drink, but in large and stately edifices, rich armour, gallant horses, choice falcons,041 well-ordered tournaments, banquets delicate rather than abundant, and wines remarkable rather for their exquisite flavour than for their intoxicating power." Quite so. But even the Normans were not all temperate. And, while it is quite true that the refined manners and chivalrous spirit of the Normans exercised a powerful influence on the Anglo-Saxons, it is equally true that the conquerors on mingling with the English people adopted many of the ancient customs to which they tenaciously clung, and these included the customs of Christmastide.

The Norman kings and nobles displayed their taste for magnificence in the most remarkable manner at their coronations, tournaments, and their celebrations of Christmas, Easter, and Whitsuntide. The great councils of the Norman reigns which assembled at Christmas and the other great festivals, were in appearance a continuation of the Witenagemots, but the power of the barons became very formal in the presence of such despotic monarchs as William the Conqueror and his sons. At the Christmas festival all the prelates and nobles of the kingdom were, by their tenures, obliged to attend their sovereign to assist in the administration of justice and in deliberation on the great affairs of the kingdom. On these occasions the King wore his crown, and feasted his nobles in the great hall of his palace, and made them presents as marks of his royal favour, after which they proceeded to the consideration of State affairs. Wherever the Court happened to be, there was usually a large assemblage of gleemen, who were jugglers and pantomimists as well as minstrels, and were accustomed to associate themselves in companies, and amuse the spectators with feats of strength and agility, dancing, tumbling, and sleight-of-hand tricks, as well as musical performances. Among the minstrels who came into England with William the Conqueror was one named Taillefer, who was present at the battle of Hastings, and rode in front of the Norman army, inspiriting the soldiers by his songs. He sang of Roland, the heroic captain of Charlemagne, tossing his sword in the air and catching it again as he approached the English line. He was the first to strike a blow at the English, but after mortally wounding one or two of King Harold's warriors, he was himself struck down.

At the Christmas feast minstrels played on various musical instruments during dinner, and sang or told tales afterwards, both in the hall and in the chamber to which the king and his nobles retired for amusement. Thus it is written of a court minstrel:—

After the Conquest the first entertainments given by William the Conqueror were those to his victorious warriors:—

In 1067 the Conqueror kept a grand Christmas in London. He had spent eight months of that year rewarding his warriors and gratifying his subjects in Normandy, where he had held a round of feasts and made a grand display of the valuable booty which he had won by his sword. A part of his plunder he sent to the Pope along with the banner of Harold. Another portion, consisting of gold, golden vases, and richly embroidered stuffs, was distributed among the abbeys, monasteries, and churches of his native duchy, "neither monks nor priests remaining without a guerdon." After spending the greater part of the year in splendid entertainments in Normandy, apparently undisturbed by the reports which had reached him of discontent and insurrection among his new subjects in England, William at043 length embarked at Dieppe on the 6th of December, 1067, and returned to London to celebrate the approaching festival of Christmas. With the object of quieting the discontent which prevailed, he invited a considerable number of the Saxon chiefs to take part in the Christmas festival, which was kept with unusual splendour; and he also caused a proclamation to be read in all the churches of the capital declaring it to be his will that "all the citizens of London should enjoy their national laws as in the days of King Edward." But his policy of friendship and conciliation was soon changed into one of cruelty and oppression.