Title: The Story of a Cannoneer Under Stonewall Jackson

Author: Edward Alexander Moore

Release date: July 13, 2007 [eBook #22067]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Suzanne Shell,Graeme Mackreth and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

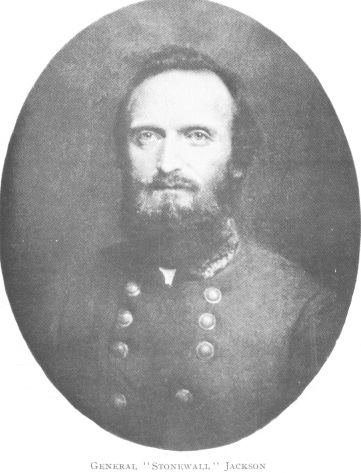

General "Stonewall" Jackson

Fully Illustrated by Portraits

NEW YORK AND WASHINGTON

THE NEALE PUBLISHING COMPANY

1907

Copyright, 1907, by

Introduction by Capt. Robert E. Lee, Jr

Introduction by Henry St. George Tucker

General "Stonewall" Jackson

Captain William T. Poague, April, 1862—April, 1863

Gun from which was fired the first hostile cannon-shot

in the Valley of Virginia

Robert A. Gibson

Edward A. Moore, March, 1862

John M. Brown (war-time portrait)

William M. Willson (Corporal)

W. S. McClintic

D. Gardiner Tyler

R. T. Barton

B. C. M. Friend

Edward A. Moore, February, 1907

Edward H. Hyde (Color-bearer)

Randolph Fairfax

Robert Frazer

John M. Brown

Fac-simile of parole signed by General Pendleton

More than thirty years ago, at the solicitation of my kinsman, H. C. McDowell, of Kentucky, I undertook to write a sketch of my war experience. McDowell was a major in the Federal Army during the civil war, and with eleven first cousins, including Gen. Irvin McDowell, fought against the same number of first cousins in the Confederate Army. Various interruptions prevented the completion of my work at that time. More recently, after despairing of the hope that some more capable member of my old command, the Rockbridge Artillery, would not allow its history to pass into oblivion, I resumed the task, and now present this volume as the only published record of that company, celebrated as it was even in that matchless body of men, the Army of Northern Virginia.

E. A. M.

The title of this book at once rivets attention and invites perusal, and that perusal does not disappoint expectation. The author was a cannoneer in the historic Rockbridge (Va.) Artillery, which made for itself, from Manassas to Appomattox, a reputation second to none in the Confederate service. No more vivid picture has been presented of the private soldier in camp, on the march, or in action. It was written evidently not with any commercial view, but was an undertaking from a conviction that its performance was a question of duty to his comrades. Its unlabored and spontaneous character adds to its value. Its detail is evidence of a living presence, intent only upon truth. It is not only carefully planned, but minutely finished. The duty has been performed faithfully and entertainingly.

We are glad these delightful pages have not been marred by discussion of the causes or conduct of the great struggle between the States. There is no theorizing or special pleading to distract our attention from the unvarnished story of the Confederate soldier.

The writer is simple, impressive, and sincere. And his memory is not less faithful. It is a striking and truthful portrayal of the times under the standard of one of the greatest generals of ancient or modern times. It is from such books that data will be gathered by the future historian for a true story of the great conflict between the States.

For nearly a year (from March to November, 1862) I served in the battery with this cannoneer, and for a time we were in the same mess. Since the war I have known him intimately, and it gives me great pleasure to be able to say that there is no one who could give a more honest and truthful account of the events of our struggle from the standpoint of a private soldier. He had exceptional opportunities for observing men and events, and has taken full advantage of them.

Robert E. Lee.

Between 1740 and 1750 nine brothers by the name of Moore emigrated from the north of Ireland to America. Several of them settled in South Carolina, and of these quite a number participated in the Revolutionary War, several being killed in battle. One of the nine brothers, David by name, came to Virginia and settled in the "Borden Grant," now the northern part of Rockbridge County. There, in 1752, his son, afterward known as Gen. Andrew Moore, was born. His mother was a Miss Evans, of Welsh ancestry. Andrew Moore was educated at an academy afterward known as Liberty Hall. In early life with some of his companions he made a voyage to the West Indies; was shipwrecked, but rescued, after many hardships, by a passing vessel and returned to the Colonies. Upon his return home he studied law in the office of Chancellor Wythe, at Williamsburg, and was licensed to practice law in 1774. In 1776 he entered the army as lieutenant, in Morgan's Riflemen, and was engaged in those battles which resulted in the capture of Burgoyne's army, and at the surrender of the British forces at Saratoga. For courage and gallantry in battle he was promoted to a captaincy. Having served three years with Morgan, he returned home and took his seat as a member of the Virginia legislature, taking such an active and distinguished part in the deliberations of that body that he was elected to Congress, and as a member of the first House of Representatives was distinguished for his services to such a degree that he was re-elected at each succeeding election until 1797, when he declined further service in that body, but accepted a seat in the Virginia House of Delegates. He was again elected to Congress in 1804, but in the first year of his service he was elected to the United States Senate, in which body he served with distinguished ability until 1809, when he retired. He was then appointed United States Marshal for the District of Virginia, which office he held until his death, April 14, 1821. His brother William served as a soldier in the Indian wars, and the Revolutionary War. He was a lieutenant of riflemen at Pt. Pleasant, and carried his captain, who had been severely wounded, from the field of battle, after killing the Indian who was about to scalp him—a feat of courage and strength rarely equaled. Gen. Andrew Moore's wife was Miss Sarah Reid, a descendant of Capt. John McDowell, who was killed by the Indians, December 18, 1842, on James River, in Rockbridge County. She was the daughter of Capt. Andrew Reid, a soldier of the French and Indian War.

Our author's father was Capt. David E. Moore, for twenty-three years the Attorney for the Commonwealth for Rockbridge County, and a member of the Constitutional Convention, 1850-51. His mother was Miss Elizabeth Harvey, a descendant of Benjamin Borden, and daughter of Matthew Harvey, who at sixteen years of age ran away from home and became a member of "Lee's Legion," participating in the numerous battles in which that distinguished corps took part.

Thus it will be seen that our author is of martial stock and a worthy descendant of those who never failed to respond to the call to arms; the youngest of four brothers, one of whom surrendered under General Johnston, the other three at Appomattox, after serving throughout the war. It is safe to say that Virginia furnished to the Confederate service no finer examples of true valor than our author and his three brothers.

Henry St. George Tucker.

Lexington, Va.,

December 20, 1906.

Captain William T. Poague

(April, 1862—April, 1863)

At the age of eighteen I was a member of the Junior Class at Washington College at Lexington, Virginia, during the session of 1860-61, and with the rest of the students was more interested in the foreshadowings of that ominous period than in the teachings of the professors. Among our number there were a few from the States farther south who seemed to have been born secessionists, while a large majority of the students were decidedly in favor of the Union.

Our president, the Rev. Dr. George Junkin, who hailed from the North, was heart and soul a Union man, notwithstanding the fact that one of his daughters was the first wife of Major Thomas J. Jackson, who developed into the world-renowned "Stonewall" Jackson. Another daughter was the great Southern poetess, Mrs. Margaret J. Preston, and Dr. Junkin's son, Rev. W. F. Junkin, a most lovable man, became an ardent Southern soldier and a chaplain in the Confederate Army throughout the war.

At the anniversary of the Washington Literary Society, on February 22, 1861, the right of secession was attacked and defended by the participants in the discussion, with no less zeal than they afterward displayed on many bloody battlefields.

We had as a near neighbor the Virginia Military Institute, "The West Point of the South," where scores of her young chivalry were assembled, who were eager to put into practice the subjects taught in their school. Previous to these exciting times not the most kindly feelings, and but little intercourse had existed between the two bodies of young men. The secession element in the College, however, finding more congenial company among the cadets, opened up the way for quite intimate and friendly relations between the two institutions. In January, 1861, the corps of cadets had been ordered by Governor Wise to be present, as a military guard, at the execution of John Brown at Harper's Ferry. After their return more than the usual time was given to the drill; and target-shooting with cannon and small arms was daily practised in our hearing.

Only a small proportion of the citizens of the community favored secession, but they were very aggressive. One afternoon, while a huge Union flag-pole was being raised on the street, which when half-way up snapped and fell to the ground in pieces, I witnessed a personal encounter between a cadet and a mechanic (the latter afterward deserted from our battery during the Gettysburg campaign in Pennsylvania, his native State), which was promptly taken up by their respective friends. The cadets who were present hastened to their barracks and, joined by their comrades, armed themselves, and with fixed bayonets came streaming at double-quick toward the town. They were met at the end of Main street by their professors, conspicuous among whom was Colonel Colston on horseback. He was a native of France and professor of French at the Institute; he became a major-general in the Confederate Army and later a general in the Egyptian Army. After considerable persuasion the cadets were induced to return to their barracks.

Instead of the usual Saturday night debates of the College literary societies, the students either joined the cadets in their barracks at the Institute or received them at the College halls to harangue on the one absorbing topic.

On the top of the main building at the College was a statue of Washington, and over this statue some of the students hoisted a palmetto flag. This greatly incensed our president. He tried, for some time, but in vain, to have the flag torn down. When my class went at the usual hour to his room to recite, and before we had taken our seats, he inquired if the flag was still flying. On being told that it was, he said, "The class is dismissed; I will never hear a recitation under a traitor's flag!" And away we went.

Lincoln's proclamation calling for 75,000 men from Virginia, to whip in the seceded States, was immediately followed by the ordinance of secession, and the idea of union was abandoned by all. Recitation-bells no longer sounded; our books were left to gather dust, and forgotten, save only to recall those scenes that filled our minds with the mighty deeds and prowess of such characters as the "Ruling Agamemnon" and his warlike cohorts, and we could almost hear "the terrible clang of striking spears against shields, as it resounded throughout the army."

There was much that seems ludicrous as we recall it now. The youths of the community, imbued with the idea that "cold steel" would play an important part in the conflict, provided themselves with huge bowie-knives, fashioned by our home blacksmith, and with these fierce weapons swinging from their belts were much in evidence. There were already several organized military companies in the county. The Rockbridge Rifles, and a company of cavalry left Lexington April 17, under orders from Governor John Letcher, our townsman, who had just been inaugurated Governor of Virginia, to report at Harper's Ferry. The cavalry company endeavored to make the journey without a halt, and did march the first sixty-four miles in twenty-four hours.

The students formed a company with J. J. White, professor of Greek, as their captain. Drilling was the occupation of the day; the students having excellent instructors in the cadets and their professors. Our outraged president had set out alone in his private carriage for his former home in the North.

Many of the cadets were called away as drillmasters at camps established in different parts of the South, and later became distinguished officers in the Confederate Army, as did also a large number of the older alumni of the Institute.

The Rockbridge Artillery Company was organized about this time, and, after a fortnight's drilling with the cadets' battery, was ordered to the front, under command of Rev. W. N. Pendleton, rector of the Episcopal Church, and a graduate of West Point, as captain.

The cadets received marching orders, and on that morning, for the first time since his residence in Lexington, Major Jackson was seen in his element. As a professor at the Virginia Military Institute he was remarkable only for strict punctuality and discipline. I, with one of my brothers, had been assigned to his class in Sunday-school, where his regular attendance and earnest manner were equally striking.

It was on a beautiful Sunday morning in May that the cadets received orders to move, and I remember how we were all astonished to see the Christian major, galloping to and fro on a spirited horse, preparing for their departure.

In the arsenal at the Institute were large stores of firearms of old patterns, which were hauled away from time to time to supply the troops. I, with five others of the College company, was detailed as a guard to a convoy of Wagons, loaded with these arms, as far as Staunton. We were all about the same size, and with one exception members of the same class. In the first battle of Manassas four of the five—Charles Bell, William Wilson, William Paxton and Benjamin Bradley—were killed, and William Anderson, now Attorney-General of Virginia, was maimed for life.

There was great opposition on the part of the friends of the students to their going into the service, at any rate in one body, but they grew more and more impatient to be ordered out, and felt decidedly offended at the delay.

Finally, in June, the long-hoped-for orders came. The town was filled with people from far and near, and every one present, old and young, white and black, not only shed tears, but actually sobbed. My father had positively forbidden my going, as his other three sons, older than myself, were already in the field. After this my time was chiefly occupied in drilling militia in different parts of the country. And I am reminded to this day by my friends the daughters of General Pendleton of my apprehensions "lest the war should be over before I should get a trip."

Gun from which was fired the first hostile cannon-shot in the Valley of Virginia

Jackson's first engagement took place at Hainesville, near Martinsburg, on July 2, one of the Rockbridge Artillery guns firing the first hostile cannon-shot fired in the Valley of Virginia. This gun is now in the possession of the Virginia Military Institute, and my brother David fired the shot. Before we knew that Jackson was out of the Valley, news came of the battle of First Manassas, in which General Bee conferred upon him and his brigade the soubriquet of "Stonewall," and by so doing likened himself to "Homer, who immortalized the victory won by Achilles."

In this battle the Rockbridge Artillery did splendid execution without losing a man, while the infantry in their rear, and for their support, suffered dreadfully. The College company alone (now Company I of the Fourth Virginia Regiment) lost seven killed and many wounded.

In August it was reported that a force of Federal cavalry was near the White Sulphur Springs, on their way to Lexington. Numbers of men from the hills and mountains around gathered at Collierstown, a straggling village in the western portion of the county, and I spent the greater part of the night drilling them in the town-hall, getting news from time to time from the pickets in the mountain-pass. The prospect of meeting so formidable a band had doubtless kept the Federals from even contemplating such an expedition.

The winter passed drearily along, the armies in all directions having only mud to contend with.

Since my failure to leave with the College company it had been my intention to join it the first opportunity; but, hearing it would be disbanded in the spring, I enlisted in the Rockbridge Artillery attached to the Stonewall Brigade, and with about fifty other recruits left Lexington March 10, 1862, to join Jackson, then about thirty miles south of Winchester. Some of us traveled on horseback, and some in farm-wagons secured for the purpose. We did not create the sensation we had anticipated, either on leaving Lexington or along the road; still we had plenty of fun. I remember one of the party—a fellow with a very large chin, as well as cheek—riding up close to a house by the roadside in the door of which stood a woman with a number of children around her, and, taking off his hat, said, "God bless you, madam! May you raise many for the Southern Confederacy."

We spent Saturday afternoon and night in Staunton, and were quartered in a hotel kept by a sour-looking old Frenchman. We were given an abominable supper, the hash especially being a most mysterious-looking dish. After retiring to our blankets on the floor, I heard two of the party, who had substituted something to drink for something to eat, discussing the situation generally, and, among other things, surmising as to the ingredients of the supper's hash, when Winn said, "Bob, I analyzed that hash. It was made of buttermilk, dried apples, damsons and wool!"

The following day, Sunday, was clear and beautiful. We had about seventy miles to travel along the Valley turnpike. In passing a stately residence, on the porch of which the family had assembled, one of our party raised his hat in salutation. Not a member of the family took the least notice of the civility; but a negro girl, who was sweeping off the pavement in front, flourished her broom around her head most enthusiastically, which raised a general shout.

We arrived at Camp Buchanan, a few miles below Mount Jackson, on Monday afternoon. I then, for the first time since April, 1861, saw my brother John. How tough and brown he looked! He had been transferred to the Rockbridge Artillery shortly before the first battle of Manassas, and with my brother David belonged to a mess of as interesting young men as I ever knew. Some of them I have not seen for more than forty years. Mentioning their names may serve to recall incidents connected with them: My two brothers, both graduates of Washington College; Berkeley Minor, a student at the University of Virginia, a perfect bookworm; Alex. Boteler, student of the University of Virginia, son of Hon. Alex. Boteler, of West Virginia, and his two cousins, Henry and Charles Boteler, of Shepherdstown, West Virginia; Thompson and Magruder Maury, both clergymen after the war; Joe Shaner, of Lexington, Virginia, as kind a friend as I ever had, and who carried my blanket for me on his off-horse at least one thousand miles; John M. Gregory, of Charles City County, an A.M. of the University of Virginia. How distinctly I recall his large, well-developed head, fair skin and clear blue eyes; and his voice is as familiar to me as if I had heard it yesterday. Then the brothers, Walter and Joe Packard, of the neighborhood of Alexandria, Virginia, sons of the Rev. Dr. Packard, of the Theological Seminary, and both graduates of colleges; Frank Preston, of Lexington, graduate of Washington College, who died soon after the war while professor of Greek at William and Mary College, a whole-souled and most companionable fellow; William Bolling, of Fauquier County, student of University of Virginia; Frank Singleton, of Kentucky, student of University of Virginia, whom William Williamson, another member of the mess and a graduate of Washington College, pronounced "always a gentleman." Williamson was quite deaf, and Singleton always, in the gentlest and most patient way, would repeat for his benefit anything he failed to hear. Last, and most interesting of all, was George Bedinger, of Shepherdstown, a student of the University of Virginia.

There were men in the company from almost every State in the South, and several from Northern States. Among the latter were two sons of Commodore Porter, of the United States Navy, one of whom went by the name of "Porter-he," from his having gone with Sergeant Paxton to visit some young ladies, and, on their return, being asked how they had enjoyed their visit, the sergeant said, "Oh, splendidly! and Porter, he were very much elated."

Soon after my arrival supper was ready, and I joined the mess in my first meal in camp, and was astonished to see how they relished fat bacon, "flap-jacks" and strong black coffee in big tin cups. The company was abundantly supplied with first-rate tents, many of them captured from the enemy, and everybody seemed to be perfectly at home and happy.

I bunked with my brother John, but there was no sleep for me that first night. There were just enough cornstalks under me for each to be distinctly felt, and the ground between was exceedingly cold. We remained in this camp until the following Friday, when orders came to move.

We first marched about three miles south, or up the Valley, then countermarched, going about twenty miles, and on Saturday twelve miles farther, which brought us, I thought, and it seemed to be the general impression, in rather close proximity to the enemy. There having been only a few skirmishes since Manassas in July, 1861, none of us dreamed of a battle; but very soon a cannon boomed two or three miles ahead, then another and another. The boys said, "That's Chew's battery, under Ashby."

Pretty soon Chew's battery was answered, and for the first time I saw and heard a shell burst, high in the air, leaving a little cloud of white smoke. On we moved, halting frequently, as the troops were being deployed in line of battle. Our battery turned out of the pike and we had not heard a shot for half an hour. In front of us lay a stretch of half a mile of level, open ground and beyond this a wooded hill, for which we seemed to be making. When half-way across the low ground, as I was walking by my gun, talking to a comrade at my side, a shell burst with a terrible crash—it seemed to me almost on my head. The concussion knocked me to my knees, and my comrade sprawling on the ground. We then began to feel that we were "going in," and a most weakening effect it had on the stomach.

I recall distinctly the sad, solemn feeling produced by seeing the ambulances brought up to the front; it was entirely too suggestive. Soon we reached the woods and were ascending the hill along a little ravine, for a position, when a solid shot broke the trunnions of one of the guns, thus disabling it; then another, nearly spent, struck a tree about half-way up and fell nearby. Just after we got to the top of the hill, and within fifty or one hundred yards of the position we were to take, a shell struck the off-wheel horse of my gun and burst. The horse was torn to pieces, and the pieces thrown in every direction. The saddle-horse was also horribly mangled, the driver's leg was cut off, as was also the foot of a man who was walking alongside. Both men died that night. A white horse working in the lead looked more like a bay after the catastrophe. To one who had been in the army but five days, and but five minutes under fire, this seemed an awful introduction.

The other guns of the battery had gotten into position before we had cleared up the wreck of our team and put in two new horses. As soon as this was done we pulled up to where the other guns were firing, and passed by a member of the company, John Wallace, horribly torn by a shell, but still alive. On reaching the crest of the hill, which was clear, open ground, we got a full view of the enemy's batteries on the hills opposite.

In the woods on our left, and a few hundred yards distant, the infantry were hotly engaged, the small arms keeping up an incessant roar. Neither side seemed to move an inch. From about the Federal batteries in front of us came regiment after regiment of their infantry, marching in line of battle, with the Stars and Stripes flying, to join in the attack on our infantry, who were not being reinforced at all, as everything but the Fifth Virginia had been engaged from the first. We did some fine shooting at their advancing infantry, their batteries having almost quit firing. The battle had now continued for two or three hours. Now, for the first time, I heard the keen whistle of the Minie-ball. Our infantry was being driven back and the Federals were in close pursuit.

Seeing the day was lost, we were ordered to limber up and leave. Just then a large force of the enemy came in sight in the woods on our left. The gunner of the piece nearest them had his piece loaded with canister, and fired the charge into their ranks as they crowded through a narrow opening in a stone fence. One of the guns of the battery, having several of its horses killed, fell into the hands of the enemy. About this time the Fifth Virginia Regiment, which, through some misunderstanding of orders, had not been engaged, arrived on the crest of the hill, and I heard General Jackson, as he rode to their front, direct the men to form in line and check the enemy. But everything else was now in full retreat, with Minie-balls to remind us that it would not do to stop. Running back through the woods, I passed close by John Wallace as he lay dying. Night came on opportunely and put an end to the pursuit, and to the taking of prisoners, though we lost several hundred men. I afterward heard Capt. George Junkin, nephew of the Northern college president, General Jackson's adjutant, say that he had the exact number of men engaged on our side, and that there were 2,700 in the battle. The enemy's official report gave their number as 8,000. Jackson had General Garnett, of the Stonewall Brigade, suspended from office for not bringing up the Fifth Regiment in time.

It was dusk when I again found myself on the turnpike, and I followed the few indistinct moving figures in the direction of safety. I stopped for a few minutes near a camp-fire, in a piece of woods, where our infantry halted, and I remember hearing the colored cook of one of their messes asking in piteous tones, over and over again, "Marse George, where's Marse Charles?" No answer was made, but the sorrowful face of the one interrogated was response enough. I got back to the village of Newtown, about three miles from the battlefield, where I joined several members of the battery at a hospitable house. Here we were kindly supplied with food, and, as the house was full, were allowed to sleep soundly on the floor. This battle was known as Kernstown.

The next dawn brought a raw, gloomy Sunday. We found the battery a mile or two from the battlefield, where we lay all day, thinking, of course, the enemy would follow up their victory; but this they showed no inclination to do. On Monday we moved a mile or more toward our old camp—Buchanan. On Tuesday, about noon, we reached Cedar Creek, the scene of one of General Early's battles more than two years afterward, 1864. The creek ran through a narrow defile, and, the bridge having been burned, we crossed in single file, on the charred timbers, still clinging together and resting on the surface of the water. Just here, for the first time since Kernstown, the Federal cavalry attacked the rear of our column, and the news and commotion reached my part of the line when I was half-across the stream. The man immediately in front of me, being in too much of a hurry to follow the file on the bridge-planks, jumped frantically into the stream. He was fished out of the cold waters, shoulder deep, on the bayonets of the infantry on the timbers.

We found our wagons awaiting us on top of a high hill beyond, and went into camp about noon, to get up a whole meal, to which we thought we could do full justice. But, alas! alas! About the time the beans were done, and each had his share in a tin plate or cup, "bang!" went a cannon on the opposite hill, and the shell screamed over our heads. My gun being a rifled piece, was ordered to hitch up and go into position, and my appetite was gone. Turning to my brother, I said, "John, I don't want these beans!" My friend Bedinger gave me a home-made biscuit, which I ate as I followed the gun. We moved out and across the road with two guns, and took position one hundred yards nearer the enemy. The guns were unlimbered and loaded just in time to fire at a column of the enemy's cavalry which had started down the opposite hill at a gallop. The guns were discharged simultaneously, and the two shells burst in the head of their column, and by the time the smoke and dust had cleared up that squadron of cavalry was invisible. This check gave the wagons and troops time to get in marching order, and after firing a few more rounds we followed.

As we drove into the road again, I saw several infantrymen lying horribly torn by shells, and the clothes of one of them on fire. I afterward heard amusing accounts of the exit of the rest of the company from this camp. Quartermaster "John D." had his teams at a full trot, with the steam flying from the still hot camp-kettles as they rocked to and fro on the tops of the wagons. In a day or two we were again in Camp Buchanan, and pitched our tents on their old sites and kindled our fires with the old embers. Here more additions were made to the company, among them R. E. Lee, Jr., son of the General; Arthur A. Robinson, of Baltimore, and Edward Hyde, of Alexandria. After a few nights' rest and one or two square meals everything was as gay as ever.

An hour or two each day was spent in going through the artillery manual. Every morning we heard the strong, clear voice of an infantry officer drilling his men, which I learned was the voice of our cousin, James Allen, colonel of the Second Virginia Regiment. He was at least half a mile distant. About the fourth or fifth day after our return to camp we were ordered out to meet the enemy, and moved a few miles in their direction, but were relieved on learning that it was a false alarm, and countermarched to the same camp. When we went to the wagons for our cooking utensils, etc., my heavy double blanket, brought from home, had been lost, which made the ground seem colder and the stalks rougher. With me the nights, until bedtime, were pleasant enough. There were some good voices in the company, two or three in our mess; Bedinger and his cousin, Alec Boteler, both sang well, but Boteler stammered badly when talking, and Bedinger kept him in a rage half the time mocking him, frequently advising him to go back home and learn to talk. Still they were bedfellows and devoted friends. I feel as if I could hear Bedinger now, as he shifted around the fire, to keep out of the smoke, singing:

"Though the world may call me gay, yet my feelings I smother,

For thou art the cause of this anguish—my mother."

A thing that I was very slow to learn was to sit on the ground with any comfort; and a log or a fence, for a few minutes' rest, was a thing of joy. Then the smoke from the camp-fires almost suffocated me, and always seemed to blow toward me, though each of the others thought himself the favored one. But the worst part of the twenty-four hours was from bedtime till daylight, half-awake and half-asleep and half-frozen. I was, since Kernstown, having that battle all over and over again.

I noticed a thing in this camp (it being the first winter of the war), in which experience and necessity afterward made a great change. The soldiers, not being accustomed to fires out-of-doors, frequently had either the tails of their overcoats burned off, or big holes or scorched places in their pantaloons.

Since Jackson's late reverse, more troops being needed, the militia had been ordered out, and the contingent from Rockbridge County was encamped a few miles in rear of us. I got permission from our captain to go to see them and hear the news from home. Among them were several merchants of Lexington, and steady old farmers from the county. They were much impressed with the accounts of the battle and spoke very solemnly of war. I had ridden Sergeant Baxter McCorkle's horse, and, on my return, soon after passing through Mt. Jackson, overtook Bedinger and Charley Boteler, with a canteen of French brandy which a surgeon-friend in town had given them. As a return for a drink, I asked Bedinger to ride a piece on my horse, which, for some time, he declined to do, but finally said, "All right; get down." He had scarcely gotten into the saddle before he plied the horse with hat and heels, and away he went down the road at full speed and disappeared in the distance.

This was more kindness than I had intended, but it afforded a good laugh. Boteler and the brandy followed the horseman, and I turned in and spent the night with the College company, quartered close by as a guard to General Jackson's headquarters. I got back to camp the next afternoon, Sunday. McCorkle had just found his horse, still saddled and bridled, grazing in a wheat-field.

From Camp Buchanan we fell back to Rude's Hill, four miles above Mt. Jackson and overlooking the Shenandoah River. About once in three days our two Parrott guns, to one of which I belonged, were sent down to General Ashby, some ten miles, for picket service to supply the place of Chew's battery, which exhausted its ammunition in daily skirmishes with the enemy. Ashby himself was always there; and an agreeable, unpretending gentleman he was. His complexion was very dark and his hair and beard as black as a raven. He was always in motion, mounted on one of his three superb stallions, one of which was coal-black, another a chestnut sorrel, and the third white. On our first trip we had a lively cannonade, and the white horse in our team, still bearing the stains of blood from the Kernstown carnage, reared and plunged furiously during the firing. The Federal skirmish line was about a mile off, near the edge of some woods, and at that distance looked very harmless; but when I looked at them through General Ashby's field-glass it made them look so large, and brought them so close, that it startled me. There was a fence between, and, on giving the glass a slight jar, I imagined they jumped the fence; I preferred looking at them with the naked eye. Bob Lee volunteered to go with us another day (he belonged to another detachment). He seemed to enjoy the sport much. He had not been at Kernstown, and I thought if he had, possibly he would have felt more as did I and the white horse.

On our way down on another expedition, hearing the enemy were driving in our pickets, and that we would probably have some lively work and running, I left my blanket—a blue one I had recently borrowed—at the house of a mulatto woman by the roadside, and told her I would call for it as we came back. We returned soon, but the woman, learning that a battle was impending, had locked up and gone. This blanket was my only wrap during the chilly nights, so I must have it. The guns had gone on. As I stood deliberating as to what I should do, General Ashby came riding by. I told him my predicament and asked, "Shall I get in and get it?" He said, "Yes, certainly." With the help of an axe I soon had a window-sash out and my blanket in my possession. From these frequent picket excursions I got the name of "Veteran." My friend Bolling generously offered to go as my substitute on one expedition, but the Captain, seeing our two detachments were being overworked, had all relieved and sent other detachments with our guns.

From Rude's Hill about fifty of us recruits were detailed to go to Harrisonburg—Lieutenant Graham in command—to guard prisoners. The prisoners were quartered in the courthouse. Among them were a number of Dunkards from the surrounding country, whose creed was "No fight." I was appointed corporal, the only promotion I was honored with during the war, and that only for the detailed service. Here we spent a week or ten days, pleasantly, with good fare and quarters. Things continued quiet at the front during this time.

The enemy again advanced, and quite a lively cavalry skirmish was had from Mt. Jackson to the bridge across the Shenandoah. The enemy tried hard to keep our men from burning this bridge, and in the fray Ashby's white horse was mortally wounded under him and his own life saved by the daring interposition of one of his men. His horse lived to carry him out, but fell dead as soon as he had accomplished it; and, after his death, every hair was pulled from his tail by Ashby's men as mementoes of the occasion.

Robert A. Gibson

Jackson fell back slowly, and, on reaching Harrisonburg, to our dismay, the head of the column filed to the left, on the road leading toward the Blue Ridge, thus disclosing the fact that the Valley was to be given up a prey to the enemy. Gloom was seen on every face at feeling that our homes were forsaken. We carried our prisoners along, and a miserable-looking set the poor Dunkards were, with their long beards and solemn eyes. A little fun, though, we would have. Every mile or so, and at every cross-road, a sign-post was stuck up, "Keezletown Road, 2 miles," and of every countryman or darky along the way some wag would inquire the distance to Keezletown, and if he thought we could get there before night.

By dawn next morning we were again on the march. I have recalled this early dawn oftener, I am sure, than any other of my whole life. Our road lay along the edge of a forest, occasionally winding in and out of it. At the more open places we could see the Blue Ridge in the near distance. During the night a slight shower had moistened the earth and leaves, so that our steps, and even the wheels of the artillery, were scarcely heard. Here and there on the roadside was the home of a soldier, in which he had just passed probably his last night. I distinctly recall now the sobs of a wife or mother as she moved about, preparing a meal for her husband or son, and the thoughts it gave rise to. Very possibly it helped also to remind us that we had left camp that morning without any breakfast ourselves. At any rate, I told my friend, Joe McAlpin, who was quite too modest a man to forage, and face a strange family in quest of a meal, that if he would put himself in my charge I would promise him a good breakfast.

In a few miles we reached McGaheysville, a quiet, comfortable little village away off in the hills. The sun was now up, and now was the time and this the place. A short distance up a cross-street I saw a motherly-looking old lady standing at her gate, watching the passing troops. Said I, "Mac, there's the place." We approached, and I announced the object of our visit. She said, "Breakfast is just ready. Walk in, sit down at the table, and make yourselves at home." A breakfast it was—fresh eggs, white light biscuit and other toothsome articles. A man of about forty-five years—a boarder—remarked, at the table, "The war has not cost me the loss of an hour's sleep." The good mother said, with a quavering tone of voice, "I have sons in the army."

We reached the south branch of the Shenandoah about noon, crossed on a bridge, and that night camped in Swift Run Gap. Our detail was separated from the battery and I, therefore, not with my own mess. We occupied a low, flat piece of ground with a creek alongside and about forty yards from the tent in which I stayed. The prisoners were in a barn a quarter of a mile distant. Here we had most wretched weather, real winter again, rain or snow almost all the time. One night about midnight I was awakened by hearing a horse splashing through water just outside of the tent and a voice calling to the inmates to get out of the flood. The horse was backed half into the tent-door, and, one by one, my companions left me. My bunk was on a little rise. I put my hand out—into the water. I determined, however, to stay as long as I could, and was soon asleep, which showed that I was becoming a soldier—in one important respect at least. By daylight, the flood having subsided, I was able to reach a fence and "coon it" to a hill above.

While in this camp, as the time had expired for which most of the soldiers enlisted, the army was reorganized. The battery having more men than was a quota for one company, the last recruits were required to enlist in other companies or to exchange with older members who wished to change. Thus some of our most interesting members left us, to join other commands, and the number of our guns was reduced from eight to six. The prisoners were now disposed of, and I returned to my old mess. After spending about ten days in this wretched camp we marched again, following the Shenandoah River along the base of the mountains toward Port Republic. After such weather, the dirt-roads were, of course, almost bottomless. The wagons monopolized them during the day, so we had to wait until they were out of the way. When they halted for the night, we took the mud. The depth of it was nearly up to my knees and frequently over them. The bushes on the sides of the road, and the darkness, compelled us to wade right in. Here was swearing and growling, "Flanders and Flounders." An infantryman was cursing Stonewall most eloquently, when the old Christian rode by, and, hearing him, said, in his short way, "It's for your own good, sir!" The wagons could make only six miles during the day, and, by traveling this distance after night, we reached them about nine o'clock. We would then build fires, get our cooking utensils, and cook our suppers, and, by the light of the fires, see our muddy condition and try to dry off before retiring to the ground. We engaged in this sort of warfare for three days, when we reached Port Republic, eighteen miles from our starting-point and about the same distance from Staunton. Our movements, or rather Jackson's, had entirely bewildered us as to his intentions.

While we were at Swift Run, Ewell's division, having been brought from the army around Richmond, was encamped just across the mountain opposite us. We remained at Port Republic several days. Our company was convenient to a comfortable farmhouse, where hot apple turnovers were constantly on sale. Our hopes for remaining in the Valley were again blasted when the wagons moved out on the Brown's Gap road and we followed across the Blue Ridge, making our exit from the pass a few miles north of Mechum's River, which we reached about noon of the following day.

There had been a good deal of cutting at each other among the members of the company who hailed from different sides of the Blue Ridge—"Tuckahoes" and "Cohees," as they are provincially called. "Lit" Macon, formerly sheriff of Albemarle County, an incessant talker, had given us glowing accounts of the treatment we would receive "on t'other side." "Jam puffs, jam puffs!" Joe Shaner and I, having something of a turn for investigating the resources of a new country, took the first opportunity of testing Macon's promised land. We selected a fine-looking house, and, approaching it, made known our wants to a young lady. She left us standing outside of the yard, we supposed to cool off while she made ready for our entertainment in the house. In this we were mistaken; for, after a long time, she returned and handed us, through the fence, some cold corn-bread and bacon. This and similar experiences by others gave us ample means to tease Macon about the grand things we were to see and enjoy "on t'other side."

We were now much puzzled as to the meaning of this "wiring in and wiring out," as we had turned to the right on crossing the mountain and taken the road toward Staunton. To our astonishment we recrossed the mountain, from the top of which we again gazed on that grand old Valley, and felt that our homes might still be ours. A mile or two from the mountain lay the quiet little village of Waynesboro, where we arrived about noon. As I was passing along the main street, somewhat in advance of the battery, Frank Preston came running out of one of the houses—the Waddells'—and, with his usual take-no-excuse style, dragged me in to face a family of the prettiest girls in Virginia. I was immediately taken to the dining-room, where were "jam puffs" sure enough, and the beautiful Miss Nettie to divide my attention.

The next day we camped near Staunton and remained a day. Conjecturing now as to Jackson's program was wild, so we concluded to let him have his own way. The cadets of the Virginia Military Institute, most of whom were boys under seventeen, had, in this emergency, been ordered to the field, and joined the line of march as we passed through Staunton, and the young ladies of that place made them the heroes of the army, to the disgust of the "Veterans" of the old Stonewall Brigade. Our course was now westward, and Milroy, who was too strong for General Ed. Johnson in the Alleghanies, was the object. About twenty miles west of Staunton was the home of a young lady friend, and, on learning that our road lay within four miles of it, I determined at least to try to see her. Sergeant Clem. Fishburne, who was related to the family, expected to go with me, but at the last moment gave it up, so I went alone. To my very great disappointment she was not at home, but her sisters entertained me nicely with music, etc., and filled my haversack before I left. Just before starting off in the afternoon I learned that cannonading had been heard toward the front. When a mile or two on my way a passing cavalryman, a stranger to me, kindly offered to carry my overcoat, which he did, and left it with the battery.

The battery had marched about fifteen miles after I had left it, so I had to retrace my four miles, then travel the fifteen, crossing two mountains. I must have walked at least five miles an hour, as I reached the company before sundown. They had gone into camp. My brother John, and Frank Preston, seeing me approach, came out to meet me, and told me how excessively uneasy they had been about me all day. A battle had been fought and they had expected to be called on every moment, and, "Suppose we had gone in, and you off foraging!" How penitent I felt, and at the same time how grateful for having two such anxious guardians! While expressing this deep interest they each kept an eye on my full haversack. "Well," said I, "I have some pabulum here; let's go to the mess and give them a snack." They said, "That little bit wouldn't be a drop in the bucket with all that mess; let's just go down yonder to the branch and have one real good old-fashioned repast." So off we went to the branch, and by the time they were through congratulating me on getting back before the battery had "gotten into it," my haversack was empty. The battle had been fought by Johnson's division, the enemy whipped and put to flight. The next day we started in pursuit, passing through McDowell, a village in Highland County, and near this village the fight had occurred. The ground was too rough and broken for the effective use of artillery, so the work was done by the infantry on both sides. This was the first opportunity that many of us had had of seeing a battlefield the day after the battle. The ghastly faces of the dead made a sickening and lasting impression; but I hoped I did not look as pale as did some of the young cadets, who proved gallant enough afterward. We continued the pursuit a day or two through that wild mountainous country, but Milroy stopped only once after his defeat, for a skirmish. In a meadow and near the roadside stood a deserted cabin, which had been struck several times during the skirmish by shells. I went inside of it, to see what a shell could do. Three had penetrated the outer wall and burst in the house, and I counted twenty-seven holes made through the frame partition by the fragments. Being an artilleryman, and therefore to be exposed to missiles of that kind, I concluded that my chances for surviving the war were extremely slim.

While on this expedition an amusing incident occurred in our mess. There belonged to it quite a character. He was not considered a pretty boy, and tried to get even with the world by taking good care of himself. We had halted one morning to cook several days' rations, and a large pile of bread was placed near the fire, of which we were to eat our breakfast and the rest was to be divided among us. He came, we thought, too often to the pile, and helped himself bountifully; he would return to his seat on his blanket, and one or two of us saw, or thought we saw, him conceal pieces of bread under it. Nothing was said at the time, but after he had gone away Bolling, Packard and I concluded to examine his haversack, which looked very fat. In it we found about half a gallon of rye for coffee, a hock of bacon, a number of home-made buttered biscuit, a hen-egg and a goose-egg, besides more than his share of camp rations. Here was our chance to teach a Christian man in an agreeable way that he should not appropriate more than his share of the rations without the consent of the mess, so we set to and ate heartily of his good stores, and in their place put, for ballast, a river-jack that weighed about two pounds. He carried the stone for two days before he ate down to it, and, when he did, was mad enough to eat it. We then told him what we had done and why, but thought he had hidden enough under his blanket to carry him through the campaign.

Before leaving the Valley we had observed decided evidences of spring; but here it was like midwinter—not a bud nor blade of grass to be seen. Milroy was now out of reach, so we retraced our steps. On getting out of the mountains we bore to the left of Staunton in the direction of Harrisonburg, twenty-five miles northeast of the former. After the bleak mountains, with their leafless trees, the old Valley looked like Paradise. The cherry and peach-trees were loaded with bloom, the fields covered with rank clover, and how our weary horses did revel in it! We camped the first night in a beautiful meadow, and soon after settling down I borrowed Sergeant Gregory's one-eyed horse to go foraging on. I was very successful; I got supper at a comfortable Dutch house, and at it and one or two others I bought myself and the mess rich. As I was returning to camp after night with a ham of bacon between me and the pommel of the saddle, a bucket of butter on one arm, a kerchief of pies on the other, and chickens swung across behind, my one-eyed horse stumbled and fell forward about ten feet with his nose to the ground. I let him take care of himself while I took care of my provisions. When he recovered his feet and started, I do not think a single one of my possessions had slipped an inch.

The next day we who were on foot crossed the Shenandoah on a bridge made of wagons standing side by side, with tongues up-stream, and boards extending from one wagon to another. We reached Bridgewater about four P.M. It was a place of which I had never heard, and a beautiful village it proved to be, buried in trees and flowers. From Bridgewater we went to Harrisonburg, and then on our old familiar and beaten path—the Valley pike to New Market. Thence obliquely to the right, crossing the Massanutten Mountain into Luray Valley. During the Milroy campaign Ewell had crossed into the Valley, and we now followed his division, which was several miles in advance. Banks was in command of the Union force in the Valley, with his base at Winchester and detachments of his army at Strasburg, eighteen miles southwest, and at Front Royal, about the same distance in the Luray Valley. So the latter place was to be attacked first. About three P.M. the following day cannonading was heard on ahead, and, after a sharp fight, Ewell carried the day. We arrived about sundown, after it was all over. In this battle the First Maryland Regiment (Confederate) had met the First Maryland (Federal) and captured the whole regiment. Several members of our battery had brothers or other relatives in the Maryland (Confederate) regiment, whom they now met for the first time since going into service. Next day we moved toward Middletown on the Valley pike, and midway between Winchester and Strasburg.

Jackson's rapid movements seemed to have taken the enemy entirely by surprise, and we struck their divided forces piecemeal, and even after the Front Royal affair their troops at Strasburg, consisting chiefly of cavalry, had not moved. Two of our guns were sent on with the Louisiana Tigers, to intercept them at Middletown. The guns were posted about one hundred and fifty yards from the road, and the Tigers strung along behind a stone fence on the roadside. Everything was in readiness when the enemy came in sight. They wavered for a time, some trying to pass around, but, being pushed from behind, there was no alternative. Most of them tried to run the gauntlet; few, however, got through. As the rest of us came up we met a number of prisoners on horseback. They had been riding at a run for nine miles on the pike in a cloud of white dust. Many of them were hatless, some had saber-cuts on their heads and streams of blood were coursing down through the dust on their faces. Among them was a woman wearing a short red skirt and mounted on a tall horse.

Confined in a churchyard in the village were two or three hundred prisoners. As we were passing by them an old negro cook, belonging to the Alleghany Rough Battery of our brigade, ran over to the fence and gave them a hearty greeting, said he was delighted to see them "thar," and that we would catch all the rest of them before they got back home. Banks's main force was at Winchester, and thither we directed our course.

Newtown was the next village, and there we had another skirmish, our artillery being at one end of the town and the enemy's at the opposite. In this encounter two members of our battery were wounded. There was great rejoicing among the people to see us back again and to be once more free from Northern soldiers. As the troops were passing through Newtown a very portly old lady came running out on her porch, and, spreading her arms wide, called out, "All of you run here and kiss me!"

Night soon set in, and a long, weary night it was; the most trying I ever passed, in war or out of it. From dark till daylight we did not advance more than four miles. Step by step we moved along, halting for five minutes; then on a few steps and halt again. About ten o'clock we passed by a house rather below the roadside, on the porch of which lay several dead Yankees, a light shining on their ghastly faces. Occasionally we were startled by the sharp report of a rifle, followed in quick succession by others; then all as quiet as the grave. Sometimes, when a longer halt was made, we would endeavor to steal a few moments' sleep, for want of which it was hard to stand up. By the time a blanket was unrolled, the column was astir again, and so it continued throughout the long, dreary hours of the night.

At last morning broke clear and beautiful, finding us about two miles from Winchester. After moving on for perhaps half a mile, we filed to the left. All indications were that a battle was imminent, Banks evidently intending to make one more effort. The sun was up, and never shone on a prettier country nor a lovelier May morning. Along our route was a brigade of Louisiana troops under the command of Gen. Dick Taylor, of Ewell's division. They were in line of battle in a ravine, and as we were passing by them several shells came screaming close over our heads and burst just beyond. I heard a colonel chiding his men for dodging, one of whom called out, in reply, "Colonel, lead us up to where we can get at them and then we won't dodge!" We passed on, bearing to the right and in the direction from which the shells came. General Jackson ordered us to take position on the hill just in front. The ground was covered with clover, and as we reached the crest we were met by a volley of musketry from a line of infantry behind a stone fence about two hundred yards distant.

My gun was one of the last to get into position, coming up on the left. I was assigned the position of No. 2, Jim Ford No. 1. The Minie-balls were now flying fast by our heads, through the clover and everywhere. A charge of powder was handed me, which I put into the muzzle of the gun. In a rifled gun this should have been rammed home first, but No. 1 said, "Put in your shell and let one ram do. Hear those Minies?" I heard them and adopted the suggestion; the consequence was, the charge stopped half-way down and there it stuck, and the gun was thereby rendered unavailable. This was not very disagreeable, even from a patriotic point of view, as we could do but little good shooting at infantry behind a stone fence. On going about fifty yards to the rear, I came up with my friend and messmate, Gregory, who was being carried by several comrades. A Minie-ball had gone through his left arm into his breast and almost through his body, lodging in the right side of his back. Still he recovered, and was a captain of ordnance at the surrender, and two years ago I visited him at his own home in California. As my train stopped at his depot, and I saw a portly old gentleman with a long white beard coming to meet it, I thought of the youth I remembered, and said, "Can that be Gregory?"

Then came Frank Preston with his arm shattered, which had to be amputated at the shoulder. I helped to carry Gregory to a barn one hundred and fifty yards in the rear, and there lay Bob McKim, of Baltimore, another member of the company, shot through the head and dying. Also my messmate, Wash. Stuart, who had recently joined the battery. A ball had struck him just below the cheek-bone, and, passing through the mouth, came out on the opposite side of his face, breaking out most of his jaw-teeth. Then came my brother John with a stream of blood running from the top of his head, and, dividing at the forehead, trickled in all directions down his face. My brother David was also slightly wounded on the arm by a piece of shell. By this time the Louisianians had been "led up to where they could get at them," and gotten them on the run. I forgot to mention that, as one of our guns was being put into position, a gate-post interfered. Captain Poague ordered John Agnor to cut the post down with an axe. Agnor said, "Captain, I will be killed!" Poague replied, "Do your duty, John." He had scarcely struck three blows before he fell dead, pierced by a Minie-ball.

In this battle, known as First Winchester, two of the battery were killed and twelve or fourteen wounded. The fighting was soon over and became a chase. My gun being hors de combat, I remained awhile with the wounded, so did not witness the first wild enthusiasm of the Winchester people as our men drove the enemy through the streets, but heard that the ladies could not be kept indoors. Our battery did itself credit on this occasion. I will quote from Gen. Dick Taylor's book, entitled "Destruction and Reconstruction": "Jackson was on the pike and near him were several regiments lying down for shelter, as the fire from the ridge was heavy and searching. A Virginian battery, the Rockbridge Artillery, was fighting at great disadvantage, and already much cut up. Poetic authority asserts that 'Old Virginny never tires,' and the conduct of this battery justified the assertion of the muses. With scarce a leg or wheel for man and horse, gun or caisson, to stand on, it continued to hammer away at the crushing fire above." And further on in the same narrative he says, "Meanwhile, the Rockbridge Battery held on manfully and engaged the enemy's attention." Dr. Dabney's "Life of Stonewall Jackson," page 377, says: "Just at this moment General Jackson rode forward, followed by two field-officers, to the very crest of the hill, and, amidst a perfect shower of balls, reconnoitred the whole position.... He saw them posting another battery, with which they hoped to enfilade the ground occupied by the guns of Poague; and nearer to his left front a body of riflemen were just seizing a position behind a stone fence when they poured a galling fire upon the gunners and struck down many men and horses. Here this gallant battery stood its ground, sometimes almost silenced, yet never yielding an inch. After a time they changed their front to the left, and while a part of their guns replied to the opposing battery the remainder shattered the stone fence, which sheltered the Federal infantry, with solid shot and raked it with canister."

In one of the hospitals I saw Jim ("Red") Jordan, an old schoolmate and member of the Alleghany Roughs, with his arm and shoulder horribly mangled by a shell. He had beautiful brown eyes, and, as I came into the room where he lay tossing on his bed, he opened them for a moment and called my name, but again fell back delirious, and soon afterward died.

The chase was now over, and the town full of soldiers and officers, especially the latter. I was invited by John Williams, better known as "Johnny," to spend the night at his home, a home renowned even in hospitable Winchester for its hospitality. He had many more intimate friends than I, and the house was full. Still I thought I received more attention and kindness than even the officers. I was given a choice room all to myself, and never shall I forget the impression made by the sight of that clean, snow-white bed, the first I had seen since taking up arms for my country, which already seemed to me a lifetime. I thought I must lie awake awhile, in order to take in the situation, then go gradually to sleep, realizing that to no rude alarm was I to hearken, and once or twice during the night to wake up and realize it again. But, alas! my plans were all to no purpose; for, after the continual marching and the vigils of the previous night, I was asleep the moment my head touched the pillow, nor moved a muscle till breakfast was announced next morning.

After camping for a day or two about three miles below Winchester we marched again toward Harper's Ferry, thirty miles below. Four of the six guns of the battery were sent in advance with the infantry of the brigade; the other two guns, to one of which I belonged, coming on leisurely in the rear. As we approached Charlestown, seated on the limbers and caissons, we saw three or four of our cavalrymen coming at full speed along a road on our left, which joined the road we were on, making an acute angle at the end of the main street. They announced "Yankee cavalry" as they passed and disappeared into the town. In a moment the Federals were within one hundred yards of us. We had no officer, except Sergeant Jordan, but we needed none. Instantly every man was on his feet, the guns unlimbered, and, by the time the muzzles were in the right direction, No. 5 handed me a charge of canister, No. 1 standing ready to ram. Before I put the charge into the gun the enemy had come to a halt within eighty yards of us, and their commanding officer drew and waved a white handkerchief. We, afraid to leave our guns lest they should escape or turn the tables on us, after some time prevailed on our straggling cavalry, who had halted around the turn, to ride forward and take them. There were seventeen Federals, well-mounted and equipped. Our cavalry claimed all the spoils, and I heard afterward most of the credit, too. We got four of the horses, one of which, under various sergeants and corporals, and by the name of "Fizzle," became quite a celebrity.

Edward A. Moore

(March, 1862)

Delighted with our success and gallantry, we again mounted our caissons and entered the town at a trot. The people had been under Northern rule for a long time, and were rejoiced to greet their friends. I heard a very old lady say to a little girl, as we drove by, "Oh, dear! if your father was just here, to see this!" The young ladies were standing on the sides of the streets, and, as our guns rattled by, would reach out to hand us some of the dainties from their baskets; but we had had plenty, so they could not reach far enough. The excitement over, we went into camp in a pretty piece of woods two miles below the town and six from Harper's Ferry. Here we spent several days pleasantly.

Mayor Middleton, of our town, Lexington, had followed us with a wagon-load of boxes of edibles from home. So many of the company had been wounded or left behind that the rest of us had a double share. Gregory's box, which Middleton brought from the railroad, contained a jar of delicious pickle. I had never relished it before, but camp-life had created a craving for it that seemed insatiable. The cows of the neighborhood seemed to have a curiosity to see us, and would stroll around the camp and stand kindly till a canteen could be filled with rich milk, which could soon be cooled in a convenient spring. Just outside of Charlestown lived the Ransons, who had formerly lived near Lexington and were great friends of my father's family. I called to see them. Buck, the second son, was then about fifteen and chafing to go into the army. I took a clean shave with his razor, which he used daily to encourage his beard and shorten his stay in Jericho. He treated me to a flowing goblet of champagne and gave me a lead-colored knit jacket, with a blue border, in which I felt quite fine, and wore through the rest of the campaign. It was known in the mess as my "Josey." Buck eventually succeeded in getting in, and now bears the scars of three saber-cuts on his head.

It was raining the day we broke camp and started toward Winchester, but our march was enlivened by the addition of a new recruit in the person of Steve Dandridge. He was about sixteen and had just come from the Virginia Military Institute, where he had been sent to be kept out of the army. He wore a cadet-cap which came well over the eyes and nose, and left a mass of brown, curly hair unprotected on the back of his head. His joy at being "mustered in" was irrepressible. He had no ear for music, was really "too good-natured to strike a tune," but the songs he tried to sing would have made a "dog laugh." Within an hour after his arrival he was on intimate terms with everybody and knew and called us all by our first names.

The march of this day was one of the noted ones of the war. Our battery traveled about thirty-five miles, and the infantry of the brigade, being camped within a mile of Harper's Ferry, made more than forty miles through rain and mud. The cause of this haste was soon revealed. General Fremont, with a large army, was moving rapidly from the north to cut us off, and was already nearer our base than we were, while General Shields, with another large force, was pushing from the southeast, having also the advantage of us in distance, and trying to unite with Fremont, and General McDowell with 20,000 men was at Fredericksburg. The roads on which the three armies were marching concentrated at Strasburg, and Jackson was the first to get there. Two of our guns were put in position on a fortified hill near the town, from which I could see the pickets of both the opposing armies on their respective roads and numbers of our stragglers still following on behind us, between the two. Many of our officers had collected around our guns with their field-glasses, and, at the suggestion of one of them, we fired a few rounds at the enemy's videttes "to hurry up our stragglers."

The next day, when near the village of Edinburg, a squadron of our cavalry, under command of General Munford, was badly stampeded by a charge of Federal cavalry. Suddenly some of these men and horses without riders came dashing through our battery, apparently blind to objects in their front. One of our company was knocked down by the knees of a flying horse, and, as the horse was making his next leap toward him, his bridle was seized by a driver and the horse almost doubled up and brought to a standstill. This was the only time I ever heard a field-officer upbraided by privates; but one of the officers got ample abuse from us on that occasion.

I had now again, since Winchester, been assigned to a Parrott gun, and it, with another, was ordered into position on the left of the road. The Federals soon opened on us with two guns occupying an unfavorable position considerably below us. The gunner of my piece was J. P. Smith, who afterward became an aide on General Jackson's staff, and was with him when he received his death-wound at Chancellorsville. One of the guns firing at us could not, for some time, be accurately located, owing to some small trees, etc., which intervened, so the other gun received most of our attention. Finally, I marked the hidden one exactly, beyond a small tree, from the puff of smoke when it fired. I then asked J. P., as we called him, to let me try a shot at it, to which he kindly assented. I got a first-rate aim and ordered "Fire!" The enemy's gun did not fire again, though its companion continued for some time. I have often wished to know what damage I did them.

The confusion of the stampede being over, the line of march was quietly resumed for several miles, until we reached "The Narrows," where we again went into position. I had taken a seat by the roadside and was chatting with a companion while the guns drove out into a field to prepare for action, and, as I could see the ground toward the enemy, I knew that I had ample time to get to my post before being needed. When getting out the accouterments the priming-wire could not be found. I being No. 3 was, of course, responsible for it. I heard Captain Poague, on being informed who No. 3 was, shout, "Ned Moore, where is that priming-wire?" I replied, "It is in the limber-chest where it belongs." There were a good many people around, and I did not wish it to appear that I had misplaced my little priming-wire in the excitement of covering Stonewall's retreat. The captain yelled, as I thought unnecessarily, "It isn't there!" I, in the same tone, replied, "It is there, and I will get it!" So off I hurried, and, to my delight, there it was in its proper place, and I brought it forth with no small flourish and triumph.

After waiting here for a reasonable time, and no foe appearing, we followed on in rear of the column without further molestation or incident that I can now recall. We reached Harrisonburg after a few days' marching.

The College company had as cook a very black negro boy named Pete, who through all this marching had carried, on a baggage-wagon, a small game rooster which he told me had whipped every chicken from Harrisonburg to Winchester and back again. At last he met defeat, and Pete consigned him to the pot, saying, "No chicken dat kin be whipped shall go 'long wid Jackson's headquarters." At Harrisonburg we turned to the left again, but this time obliquely, in the direction of Port Republic, twenty miles distant. We went into camp on Saturday evening, June 7, about one mile from Port Republic and on the north side of the Shenandoah. Shields had kept his army on the south side of this stream and had been moving parallel with us during our retreat. Jackson's division was in advance. Instead of going into camp, I, with two messmates, Bolling and Walter Packard, diverged to a log-house for supper. The man of the house was quiet; his wife did the talking, and a great deal of it. She flatly refused us a bite to eat, but, on stating the case to her, she consented to let us have some bread and milk. Seated around an unset dining-table we began divesting ourselves of our knapsacks. She said, "Just keep your baggage on; you can eat a bite and go." We told her we could eat faster unharnessed. She sliced a loaf of bread as sad as beeswax, one she had had on hand for perhaps a week, and gave us each a bowl of sour milk, all the while reminding us to make our stay short. For the sake of "argument" we proposed to call around for breakfast. She scorned the idea, had "promised breakfast to fifty already." "Staying all night? Not any." We said we could sleep in the yard and take our chances for breakfast. After yielding, inch by inch, she said we could sleep on the porch. "Well, I reckon you just as well come into the house," and showed us into a snug room containing two nice, clean beds, in one of which lay a little "nigger" about five years old, with her nappy head on a snow-white pillow. We took the floor and slept all night, and were roused next morning to partake of a first-rate breakfast.

About eight or nine o'clock this Sunday morning we were taking our ease in and about camp, some having gone to the river to bathe, and the horses turned loose in the fields to graze. I was stretched at full length on the ground, when "bang!" went a Yankee cannon about a mile in our rear, toward Port Republic. We were up and astir instantly, fully realizing the situation. By lending my assistance to the drivers in catching and hitching up the horses, my gun was the first ready, and started immediately in the direction of the firing, with Captain Poague in the lead, the other guns following on as they got ready.

Three or four hundred yards brought us in full view of Port Republic, situated just across the river. Beyond, and to the left of the village, was a small body of woods; below this, and lying between the river and mountain, an open plain. We fired on several regiments of infantry in the road parallel to and across the river, who soon began moving off to the left. The other guns of the battery, arriving on the scene one at a time, took position on our left and opened vigorously on the retreating infantry. My gun then moved forward and unlimbered close to a bridge about two hundred yards below the town, where we took position on a bluff in the bend of the river. We commenced firing at the enemy's cavalry as they emerged from the woods and crossed the open plain. One of our solid shots struck a horse and rider going at full gallop. The horse reared straight up, then down both fell in a common heap to rise no more.

While in this position General Jackson, who had narrowly escaped being captured in his quarters in the town, came riding up to us. Soon after his arrival we saw a single piece of artillery pass by the lower end of the village, and, turning to the right, drive quietly along the road toward the bridge. The men were dressed in blue, most of them having on blue overcoats; still we were confident they were our own men, as three-fourths of us wore captured overcoats. General Jackson ordered, "Fire on that gun!" We said, "General, those are our men." The General repeated, "Fire on that gun!" Captain Poague said, "General, I know those are our men." (Poague has since told me that he had, that morning, crossed the river and seen one of our batteries in camp near this place.) Then the General called, "Bring that gun over here," and repeated the order several times. We had seen, a short distance behind us, a regiment of our infantry, the Thirty-seventh Virginia. It was now marching in column very slowly toward us. In response to Jackson's order to "bring that gun over here," the Federals, for Federals they were, unlimbered their gun and pointed it through the bridge. We tried to fire, but could not depress our gun sufficiently for a good aim.

The front of the infantry regiment had now reached a point within twenty steps of us on our right, when the Federals turned their gun toward us and fired, killing the five men of the regiment at the front. The Federals then mounted their horses and limber, leaving their gun behind, and started off. The infantry, shocked by their warm reception, had not yet recovered. We called on them, over and over, to kill a horse as the enemy drove off. They soon began shooting, and, I thought, fired shots enough to kill a dozen horses; but on the Federals went, right in front of us, and not more than one hundred yards distant, accompanied by two officers on horseback. When near the town the horse of one officer received a shot and fell dead. The Thirty-seventh Virginia followed on in column through the bridge, its front having passed the deserted gun while its rear was passing us. The men in the rear, mistaking the front of their own regiment for the enemy, opened fire on them, heedless of the shouts of their officers and of the artillerymen as to what they were doing. I saw a little fellow stoop, and, resting his rifle on his knee, take a long aim and fire. Fortunately, they shot no better at their own men than they did at the enemy, as not a man was touched. Up to this time we had been absorbed in events immediately at hand, but, quiet being now restored, we heard cannonading back toward Harrisonburg. Fremont had attacked Ewell at Cross Keys, about four miles from us. Soon the musketry was heard and the battle waxed warm.

Remaining in this position the greater portion of the day, we listened anxiously to learn from the increasing or lessening sound how the battle was going with Ewell, and turned our eyes constantly in the opposite direction, expecting a renewal of the attack from Shields. Toward the middle of the afternoon the sound became more and more remote—Ewell had evidently won the day, which fact was later confirmed by couriers. We learned, too, of the death of General Ashby, which had occurred the preceding day.

About sundown we crossed on the bridge, and our wagons joining us we went into bivouac. In times of this kind, when every one is tired, each has to depend on himself to prepare his meal. While I was considering how best and soonest I could get my supper cooked, Bob Lee happened to stop at our fire, and said he would show me a first-rate plan. It was to mix flour and water together into a thin batter, then fry the grease out of bacon, take the meat out of the frying pan and pour the batter in, and then "just let her rip awhile over the fire." I found the receipt a good one and expeditious.

About two miles below us, near the river, we could plainly see the enemy's camp-fires. Early next morning we were astir, and crossed the other fork of the river on an improvised bridge made of boards laid on the running-gear of wagons.