Title: A Fantasy of Mediterranean Travel

Author: Samuel G. Bayne

Release date: July 22, 2007 [eBook #22115]

Most recently updated: January 2, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

Produced by Al Haines

MADEIRA

SPAIN

CADIZ

SEVILLE

ALHAMBRA

ALGIERS

MALTA

GREECE

TURKEY

CONSTANTINOPLE

ASIA MINOR

SMYRNA

HOLY LAND

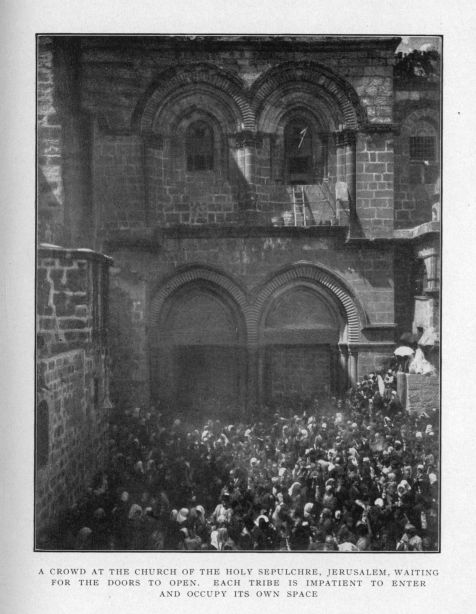

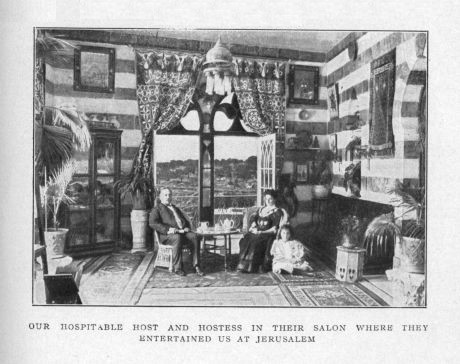

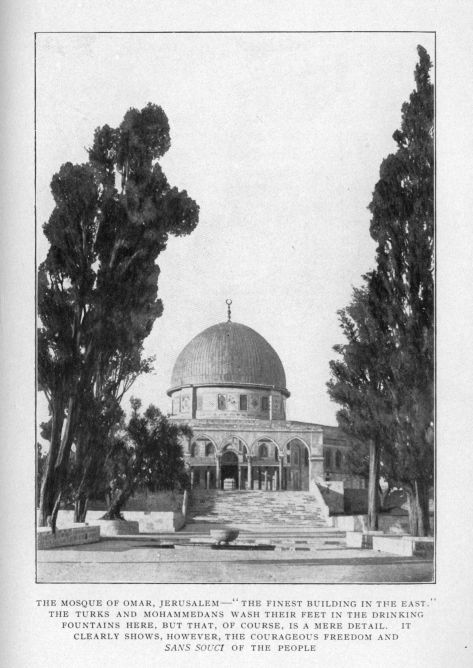

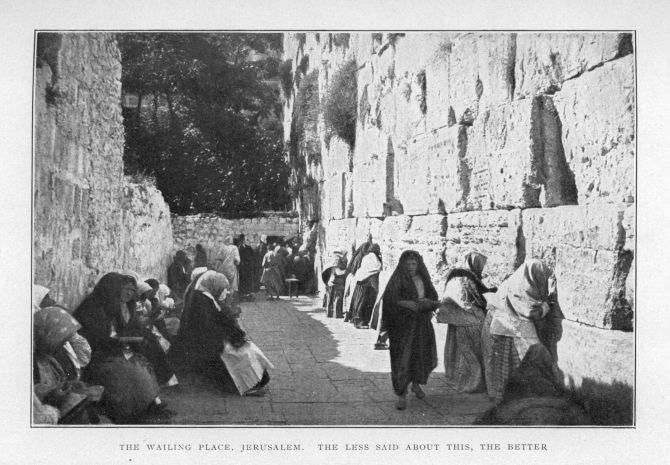

JERUSALEM

RIVER JORDAN

JERICHO

DEAD SEA

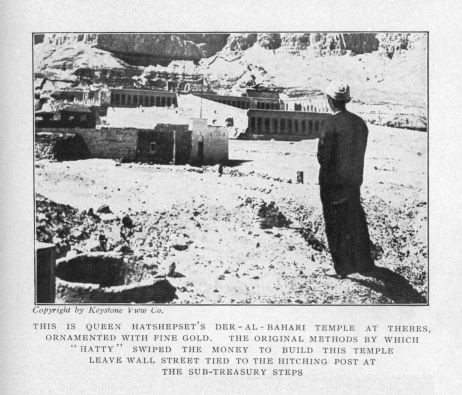

EGYPT

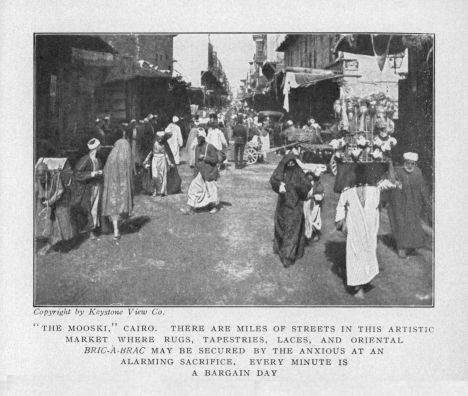

CAIRO

THE NILE

MESSINA

NAPLES

POMPEII

ROME

VILLEFRANCHE

NICE

MONTE CARLO

ENGLAND

The King of Cork was a funny ship

As ever ploughed the maine:

She kep' no log, she went whar she liked;

So her Cap'n warn't to blaime.

The Management was funnier still.

We always thought it dandy—

Till it wrecked us on the Golden Horn,

When we meant to land at Kandy.

The Cap'n ran the boat ashore

In aerated waters;

The Purser died by swallowin' gas,

Thus windin' up these matters.

L'Envoi

Fate's relentless finger,

Points to the Purser's doom:

He gulped the seltzer quickly—

Then bust with an air-tight boom!

Taking my cue from this short, spasmodic dream I had one evening in a steamer chair, of what I imagined was to happen on our coming voyage, I started to scribble; and following the fantastic idea in the vision, I shall adopt the abbreviated name of The Cork, for our good ship—although some of the passengers preferred to call her The Corker, as she was big and fine, and justly celebrated among those who go down to the sea in fear and trembling. The fame of this ship and her captain spread so far and wide that a worthy band of male and female pilgrims besought him to take them to foreign parts, for a consideration.

There was great ado at starting, and when we finally steamed out of New York harbor past the "Goddess of Liberty" one fine morning, the air was rent with the screeching of steam sirens and the tooting of whistles. The "Goddess" stood calm and silent on her pedestal; she looked virtuous (which was natural to her, being made of metal), but her stoic indifference was somewhat upset by an icy stalactite that hung from her classic nose. One of the passengers remarked that Bartholdi ought to have supplied her with a handkerchief, but this suggestion was considered flippant by his Philistine audience, and it made no impression whatever.

The list of passengers stood at seven hundred, and an extensive programme of entertainments was promoted for their amusement, consisting of balls, lectures, glees, games of bridge whist and progressive euchre, concerts, readings, and a bewildering schedule of functions, too numerous to mention; in fact, it was a case of three rings under one tent and a dozen side shows.

The passenger list comprised many examples of eccentric characters, rarely found outside of the pages of Dickens; the majority, however, were very interesting and refined people, and the exceptional types only served to accentuate the desirability and variety of their companionship on a voyage of this character. Here is a description of some of them, exaggerated perhaps in places, but not far from the facts when the peculiar conditions surrounding them are fully considered. Many of them were doing their best to attract attention in a harmless way, and in most cases they succeeded, as there is really nothing so immaterial that it escapes all notice from our fellows.

For instance, there was a human skyscraper, a giant, who had an immense pyramid of tousled hair—a Matterhorn of curls and pomatum—who gloried in its possession and scorned to wear hat, bonnet or cap. When it rained he went out to enjoy a good wetting, and came back a dripping bear. The sight made those of us who had but little hair atop our pates green with envy, as all we could now hope for was not hair but that the shellac finish on our polls might be dull and not shiny. This man also sat or stood in the sun by the hour to acquire that brick-red tan that is "quite English, you know;" and he got it, but it did not altogether match with the other coloring which nature had bestowed upon him. Then we had a "fidgetarian," who was one of the unlaundered ironies of life; he could not keep still for a moment. This specimen was from Throgg's Neck, and danced the carmagnole in concentric circles all by himself, twisting in and out between the waltzers evidently with the feeling that he was the "whole show," and that the other dancers were merely accessories to the draught he made, and followed in his wake. He was a half portion in the gold-filled class, and a charter member of the Forty-second Street Country Club.

We were also honored by the presence of Mrs. Handy Jay Andy, of Alexandry, who had "stunted considerable" in Europe, and was anxious to repeat the performance in the Levant. She didn't carry a pug dog, but she thought a "lady" ought to tote round with her something in captivity, so she compromised on a canary, which she bought in Smyrna, where all the good figs come from. She was a colored supplement to high-toned marine society.

No collection of this kind would be complete without a military officer, and we had him all right; we called him "the General," a man who jested at scars and who had a beard out of which a Pullman pillow might be easily constructed. On gala nights he decorated himself with medals, and on the whole was a very ornamental piece of human bric-à-brac. Of course we had the man with the green—but not too French green—hat. He had a curly duck's tail, dyed green, sticking up in its rear, so that the view from the back would resemble Emperor William. He attracted attention, but somehow seemed like an empty green bottle thrown in the surf.

Some of the ladies had their little peculiarities also. There was Mrs. Galley-West from North Fifth Avenue, New York, a "widow-lady," whose name went up on the social electric-light sign when she began to ride home in a limousine. She stated that everybody who was anybody in that great city knew who she was and all about her. Nobody disputed her statements. As time elapsed she became very confidential, and one day stated that she was matrimonially inclined and intimated that she would welcome an introduction to an aged millionaire in delicate health, as it might result in her being able to carry out some ambitious plans she had made in "philomathy." By the time we reached Cairo she had lowered her figures to a very modest amount—but she is still a widow.

The human mushroom was also in evidence—the girl narrow and straight up-and-down, like a tube ending in a fishtail, with a Paquin wrap and a Virot hat, reinforced with a steel net wire neck-band—the very latest fads from Paris. Her gowns were grand, her hats were great, I tell you! When some one was warbling at the piano, she would put her elbow on the lid of the "baby grand," face the audience, and strike a stained-glass attitude that would make Raphael's cartoons look like subway posters.

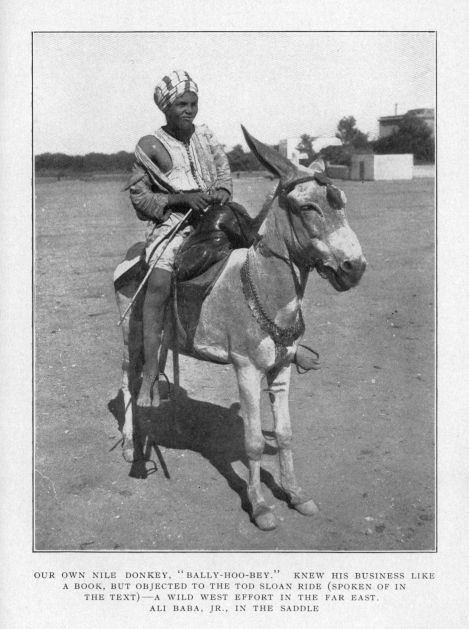

Among those present who came all the way from Medicine Hat was the cowboy girl, who could ride a mustang, toss a steer with a lariat, shoot a bear or climb a tree. She wore a sombrero, rolled up her sleeves, and was just dying to show what she could do if she had only half a chance. She got it when we came to the donkey rides in Egypt. She was a "Dreadnaught girl," sure enough.

The claims of the pocket "Venus" from the "Soo," must not be forgotten. She was small and of the reversible, air-cooled, selective type, but as perfect as anything ever seen in a glass case. She wore a spray of soft-shell crab-apple blossoms in her hair, which stamped her with the bloom of Arcady. She spilled her chatter lavishly, and had the small change of conversation right at her finger-tips. She had an early-English look, and was deservedly popular with the boys.

The beet-sugar man from Colorado also had his place. This specialist put his table to sleep before we lost sight of land. He stifled his listeners with sugar statistics, informing them how many tons of beets the State produced and what they were worth in money; how much to expect from an acre, and the risks and profits of the industry: a collection of facts that were the mythology of alleged truth. If you were good the gods would make you a sugar-king in the world to come, and Colorado was to be financially sugar-cured in the sweet by-and-by. His whole song was a powerful anaesthetic, and many at the table did not know the meal was over till the steward woke them up.

One among our crowd who really mattered was a tall, gloomy, dyspeptic man, hard to approach, but once known he never failed to harp on his favorite string,—the old masters and the Barbizon school of painting. This man had all the ready veneer of the art connoisseur. He used to talk by the hour about the great pictures he had seen, and gave each artist a descriptive niche for what he thought him famous: such as, the expression of Rubens; the grace of Raphael; the purity of Domenichino; the correggiosity of Correggio; the learning of Poussin; the air of Guido; the taste of Coraceis, and the drawing of Michelangelo. This, of course, was all Greek to most of us, but it raised the tone of the smoking-room and enveloped the entire ship in a highly artistic atmosphere which no odors from the galley could overcome. Incidentally I may say, however, he didn't know all about them, for one day a wag set a trap for him by saying he had had a fine bit of Botticelli at dinner.

"My dear sir," exclaimed our "authority," "Botticelli isn't a cheese; he was a famous fiddler!"

"I have always had an impression he was an old master," said another passenger, who was an amused listener.

It is impossible for any large body of travelers to escape the man who by every device tries to impress his fellows with the idea that he is a Mungo Park on his travels, and so our harmless impostor had his "trunkage" plastered with labels from all parts of the world, sold to him by hotel porters, who deal in them. He wore the fez, of course, and sported a Montenegrin order on his lapel; he had Turkish slippers; he carried a Malacca cane; he wrapped himself in a Mohave blanket and he wore a Caracas carved gold ring on his four-in-hand scarf. But his crowning effort was in wearing the great traveling badge, the English fore-and-aft checked cap, with its ear flaps tied up over the crown, leaving the front and rear scoops exposed. Not all of the passengers carried this array of proofs, but many dabbled in them just a little bit. It doesn't do, however, when assuming this role to have had your hair cut in Rome, New York, or to have bought your "pants" in Paris, Texas, for if you are guilty in those matters you will give the impression of being a mammoth comique on his annual holiday.

The dear lady who delights in "piffle," and to whom "pifflage" is the very breath of life, had also her niche in our affairs. She hailed from Egg Harbor and was an antique guinea hen of uncertain age. When you are thinking of the "white porch of your home," she will tell you she "didn't sleep a wink last night!" that "the eggs on this steamer are not what they ought to be," that the cook doesn't know how to boil them, and that as her husband is troubled with insomnia her son is quite likely to run down from the harbor to meet her at the landing two months hence. Then she will turn to the query by asking if you think the captain is a fit man to run this steamer; if the purser would be likely to change a sovereign for her; what tip she should give her steward; whether you think Mrs. Galley-West's pearls are real, and whether the Customs are as strict with passengers as they used to be; whether any real cure for seasickness has yet been found, and why are they always painting the ship? Not being able to think of anything else she leaves her victim, to his infinite relief. Oh you! iridescent humming-bird!

The men who yacht and those who motor are of course anxious to attract attention. The freshwater yachtsman (usually river or pond), plants his insignia of office on his cap. It is generally a combination of a spread-eagle and a "hydriad," surrounded by the stars and stripes. These things lift him above the level of those who would naturally be his peers, and effect his purpose. The motorer sports his car duster on all possible occasions, and thinks his goggles are necessary to protect his eyes from the glare of the sun on the deck of the steamer. He has large studs of motors, and always proposes to keep in front of the main squeeze. The chatter relating to cars and yachts when these men were in evidence was insistent and incessant. You were never allowed to forget for a moment that they owned cars, power boats and runabouts, and that their tours averaged thousands of miles. The man from the stogie sections does not, of course, fear to fire his fusee in this company and he always does it—it keeps up the steam.

A row of three extinct volcanoes was frequently to be seen seated side by side in the smoking-room, where they recounted the scenes of their youth with evident gusto. One would recall the days of '49, spring of '50, and tell his companions all about the excitement of mining in those early times,—"Glorious climate, California!" was the way he usually wound up his reminiscences. Another would draw his picture of the firing on Fort Sumter, and would assert that the battle of Antietam in which he took part was the hottest of the war. The favorite topic of the third raconteur was the flush times on Oil Creek in the early '60's, when he had drilled a dry hole near "Colonel Drake's" pioneer venture. And so it would go till it was time to "douse the glim." One thing they all agreed on—that the whiskey was good but the drinks were small on the Cork.

There was a young southern Colonel on board who was a charming companion and a good-natured, all-round fellow, always willing to do anything for anybody, young or old. The ladies soon found out his weakness, and they "pulled his leg" "right hard," as he would have put it. When ashore he bought them strawberries, ice-cream, wine, confectionery, lemonade, and anything else he could think of. He was a veritable packhorse, and many times when he was already loaded with impedimenta they would, as a matter of course, toss him wraps, umbrellas and fans, followed by photo's, bric-à-brac and other purchases, till the man was fairly loaded to the gunwales. This they would do with an airy grace all their own, remarking perhaps:

"Here, Colonel, I see you haven't much to carry; take this on board for me like a good boy, won't you?"

He stood the strain like a Spartan to the bitter end, and when the trip was over he, like Lord Ullen, was left lamenting in the shuffle of the forgotten, and didn't even get a kiss in the final good-byes, when they fell as thick as the leaves in Vallombrosa.

The most picturesque and amusing man on board was a Mexican rubber planter from Guadalajara, known on the ship's list as Señor Cyrano de Bergerac. He hadn't a Roman nose—but that's a mere detail; he had a Numidian mane of blue-black hair which swung over his collar so that he looked like the leader of a Wild West show. He was a contradiction in terms: his voice proclaimed him a man of war, while all the fighting he ever did, so far as we knew, was with the flies on the Nile. To look at him was to stand in the presence of a composite picture of Agamemnon, Charles XII. and John L. Sullivan; but to hear him shout—ah! that voice was the megaphone of Boanerges! It held tones that put a revolving spur on every syllable and gave a dentist-drill feeling as they ploughed their way through space. It was alleged that when he struck his plantation and shouted at the depot as he leaped from the train that he had arrived, all the ranch hands fell down and crossed themselves, thinking it was the sound of the last trump and their time had come. We have no actual proof of it, but undoubtedly these announcements were heard on Mars, and might better be utilized as signals to that planet than anything that has yet been suggested. He had a fatal faculty of stringing together big words from Webster's "Unabridged," and connecting them with conjunctions quite irrespective of the sense, so that the product was like waves of hot air from a vast, reverberating furnace. It was the practice of this orator to jump from his seat at all gatherings without warning, and make detonating announcements on all kinds of subjects to the utterly helpless passengers, the captain, the officers and the stewards. These hardy sons of the sea, who had often faced imminent danger, would visibly flinch, set their faces and cover their ears till the ordeal was over. But they were never safe, as he made two or three announcements daily, and they had to listen to his thunder in all parts of the ship till it returned to New York. His incessant shouting was a flock of dinosauria in the amber of repose; it upset our nerves, but as it added to our opportunities for killing time, many forgave him and thought him well worth the price of admission. In many respects his disposition was kindly and generous; but oh, my! how he could and did talk!

There were two men with us who represented a type known to the Cork's other passengers as "the Impressionists." When they came on board orders were given in a loud voice as to the disposal of their luggage, the chauffeurs were asked whether everything had been taken from the cars, and the travelers then made their way to the chief steward. After receiving a tip, that personage became satisfied that they were deep enough in dry goods to entitle them to seats at an officer's table, which were given them. Their opportunity came next day when they had donned their "glad rags," and stood in the centre of the smoking-room. A few minutes before the dinner gong sounded they drank a Martini, and looked over the heads of the crowd with an air of conscious superiority. Dinner started, they surrounded themselves with table waters and Rhine wines, ostentatiously popping corks and making a great show of "bottlage" for very little money. When they left their seats they were the men of the ship—in their own estimation; but they had shot their bolt and could go no further, so they settled down in a condition of social decay that became very distressing. This recalls an incident of Thackeray's: he once saw an unimportant looking man strutting along the deck of a steamer. Stepping up to him he said:

"Excuse me, sir, but are you any person in particular?"

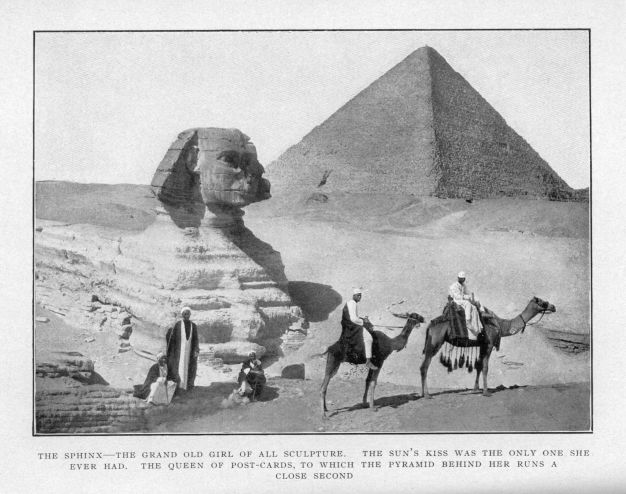

Now we reach the post-card mania. This is the most pernicious disease that has ever seized humanity since the days of the Garden of Eden, and in no better place can it be seen at its worst than on a steamer calling at foreign ports: once it gets a foothold it supplants almost all other vices and becomes a veritable Frankenstein. It is harder to break away from this habit than from poker, gossiping, strong drink, tobacco, or even eating peas with your knife if you have been brought up that way. The majority of the "Corks" when landing at a port would not have stopped to say "Good morning" to Adam, to take a peep at Bwana Tumbo's hides and horns, or to pick up the Declaration of Independence if it lay at their feet—in their eager rush to load up with the cards necessary to let all their friends know that they had arrived at any given place on the map. This is but the first act in the drama, for stamps must be found, writing places must be secured, pencils, pens and ink must be had, together with a mailing list as long as to-day and to-morrow. The smoking-room is invaded, the lounge occupied, and every table, desk and chair in the writing-room is preempted, to the exclusion of all who are not addressing post-cards. Although we toiled like electrified beavers we got behind on the schedule, so that those who did not finish at Malta had to work hard to get their cards off at Constantinople, and so on through the trip. The chariot of Aurora would hardly hold their output at a single port. At the start it was a mild, pleasurable fad, but later it absorbed the victim's mind to such an extent that he thought of nothing but the licking of stamps and mailing of cards to friends—who get so many of them that they are for the most part considered a nuisance and after a hasty glance are quietly dropped in the waste-basket. Many had such an extensive collection of mailing lists that it became necessary to segregate them into divisions; in some cases these last were labeled for classification, "Atlantic Coast Line," "Middle West," "Canadian Provinces," "New England," "Europe," etc. Again they were subdivided into trades and professions, such as lawyers, ministers, politicians, stock brokers, real estate agents, bankers (in jail and out of it), dermatologists and "hoss-doctors." This habit obtained such a hold on people who were otherwise respectable that they would enter into any "fake," to gratify their obsession. Some of the "Corks" did not tour Spain but remained on the ship; many of these would get up packages of cards, dating them as if at Cadiz, Seville or Granada, and request those who were landing to mail them at the proper places, so as to impose on their friends at home. I felt no hesitancy, after silently receiving my share of this fraud, in quietly dropping them overboard as a just punishment for this impertinence. Incidents like this will account in part for the non-delivery of post-cards and the disappointment of those who did not receive them.

Our Purser had what is known in tonsorial circles as a "walrus" or drooping moustache; he was plied with so many foolish questions in regard to this mailing business that he became very nervous and tugged vigorously at this ornament whenever something new was sprung on him. It is said that water will wear a hole in stone, and so it came to pass that he pulled his moustache out, hair by hair, till there were left only nine on a side. The style of his adornment was then necessarily changed to the "baseball," by which it was known to the "fans" on board.

The handling of this enormous output has already become an international postal problem of grave importance in many countries; the mails have been congested and demoralized, and thousands of important letters have been delayed because Mrs. Galley-West would have her friends on Riverside Drive thoroughly realize that she has got as far as Queenstown on her triumphal tour, and that she and all the little Galley-Wests are "feeling quite well, I thank you."

The ultimate fate of the post-card mania is as yet undecided. It may, like the measles or the South Sea Bubble, run its course and that will end it; on the other hand, it may grow to such proportions that it will shut out all human endeavor and bring commercial pursuits to a complete standstill. In any case its foundations are laid in vanity and

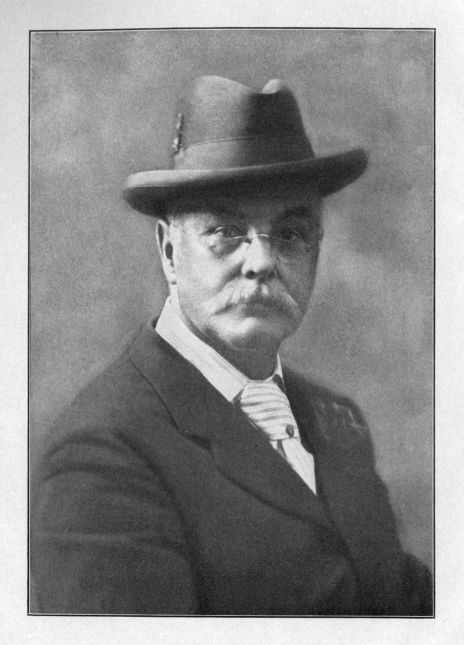

We lit right out for Madeira, and after a pleasant but uneventful voyage cast anchor in the harbor of Funchal, the capital, in less than nine days.

The Madeira Islands are owned by Portugal, but the natives all wish they were not and are most anxious to get under Uncle Sam's wing, à la Porto Rico. The islands are of volcanic origin and some of the mountain peaks are over six thousand feet high. The climate is delightful and the variation in temperature is not much over thirty degrees. Semi-tropical vegetation and flowers abound everywhere, and the place is beautifully clad with verdure. The natives have "that tired feeling," and do just as little work as will earn them a scanty living. They, however, blame this condition on the Government.

The group was at one time celebrated for its wines, but a blight came on the vines and the business of wine-making is greatly reduced; besides, Madeira wine has gone out of fashion of late years.

FUNCHAL

The Madeirans dress like comic opera bandits and are very picturesque in appearance, and while they look like Lord Byron's corsairs, they never cut a throat nor scuttle a ship under any circumstances; they are the mildest of men. While strolling in the public market I noticed a bit of local color: one of the fierce looking pirates had for sale half a dozen little red pigs with big, black, polka dots on them. I stopped to look at them and the corsair insisted that I should buy one at least and take it with me for a souvenir.

The principal feature of the place is that wheels are at a discount and most of the locomotion is done by sliding. The streets and sidewalks are paved with large, oblong pebbles which become highly polished by friction. Over these the sleds, with oxen attached to them, glide with ease, at the rate of three miles an hour. On this account it's the most tiresome place to walk in that I know of. Even most of the natives have stone-bruised feet and "hirple" along as if finishing a six-day walk in "the Garden."

While we were there a Portuguese man-of-war entered the harbor and there was a great waste of powder both from the forts and the battle-ship. The harbor was filled with little boats containing boys and men who dive for the coins thrown into the water for them by the passengers. They never fail to reach the money.

I asked a gentlemanly native where the flower market was and he very politely walked with me for three blocks and landed me in front of a flour mill. I explained his mistake and he then insisted on taking me to where they sold flowers, at which point we had an elaborate fare-welling—hat-lifting, laughing and handshaking. I asked him to visit me in New York, but he said with marked sadness in his voice that he hadn't the price and therefore must forego the pleasure.

The passenger list of the Cork being a large and notable one, the City Club gave us a ball at the Casino. It was alleged that the bluest blood on the island took part in this, the largest function of the season.

Madeira has been described by a distinguished traveler as "a neglected paradise." Part of this appearance is given it by the luxuriant growth of the Bougainvillea vine which has rich purple flowers, masses of which can be seen decorating the villas when one approaches Funchal from the sea. Madeira is some three hundred miles from Africa, and yet when sand storms arise on that continent the sand is blown across the sea and great mounds of it are piled up on this island; arrangements have to be made to prevent it from entering the houses.

The main island, Madeira, is thirty-three miles long and thirteen broad, with a population of 151,000. Funchal has 50,000 inhabitants, and is a quaint and interesting city. The island was known to the Romans, but was settled by Zargo in the interests of Portugal. Columbus married his wife at this port. Captain Cook bombarded Funchal in 1768 and brought that city to his terms. Napoleon was sent here on his way to St. Helena in 1815. So, on the whole, Madeira has had a fair amount of checkered history.

The Casino was started as an imitation of Monte Carlo, but caused such disaster that it was suppressed. The Lisbon officials now visit it once a year to see that there is no gambling going on; the owners know when they sail and remove the tables, and after the "inspection" is over and the officials have returned home, business is resumed in safety and with the usual profit to the proprietors.

The Cork is one of the marine giants, and when all the first-cabin rooms were sold the company painted up the second-cabin quarters and sold them at full first-class rates. I joined the party only a few days before it started and was glad to get an outside, single room, about the size and shape of a Pullman section. Its distinction was that it had a port-hole of its own through which I could freely admit the local climate. When I first surveyed the contracted proportions of this stateroom, the paucity of its fittings and entire lack of the usual accommodations, I was filled as full of acute melancholia as an egg is of meat and had I not paid the passage money I would have bolted from the Cork out into utter darkness; but I was "in for it," and determined to make the best of the situation; so I got some clothes lines and screw hooks, and with them constructed a labyrinth of handy landing nets for all my belongings, which resembled the telegraph wires on Tenth Avenue before Mayor Grant cut them down. I also hung my top coat and mackintosh in convenient places, and used their pockets for storage vaults. One pocket served as a complete medicine chest, another accommodated slippers, collars, cuffs and shaving tackle, while I utilized the sleeve openings (closed at the cuffs with safety pins), to hold a full line of clothes, hair and tooth brushes, and tied small things to the buttons, which shook with the vibration of the ship as sleigh-bells are shaken by the vaudeville artist when he plays Comin' Through the Rye on them for an encore. The whole arrangement was a marvelous and instantaneous success, and so proud was I of the achievement that I invited my neighbors to peep into the stateroom to see its glories and utilities. Some of them proceeded at once to copy my best ideas—but that is the fate of all inventors. However, they were grateful, for they named the passageway on which eight rooms opened, "Harp Alley," in honor of my nationality, and placed a card with this legend on it at the entrance:

HARP ALLEY

NIGHT & DAY HOUSE

On the South Corner

With a Port-Hole on the Side

Hot Meals

and

Other Entertainments

at all hours

"WE NEVER SLEEP"

The rush of arrivals was so great that I was soon obliged to remove the sign and "close the house."

But a great catastrophe was shortly to happen which cast a gloom over the Alley and plunged us into a miniature Republic disaster. A big salt water pipe was hung from the ceiling of the Alley passage; and what do you think! under strong pressure it burst with a loud noise one morning when we were dressing for breakfast and flooded the rooms of the entire colony before we could say "Jack Robinson!" Such a scurrying into bath robes and jumping out of staterooms were never seen! I felt that owing to my high standing and responsible position in the "Alley," and having in mind the fame of Binns (of the Republic, the "wireless" hero of Nantucket shoals), it was incumbent on me to ignore my personal effects and comfort in an attempt to save the ladies and their lingerie at any price. So I slipped on my trusty rain coat, and handed them out under a spread umbrella, one by one, to a place of safety, I being the very last man to leave the Alley and even then with reluctance. But mind you, I never took my eyes off the floor! they were glued to it all the while this transfer was being made. (Although when I afterward mentioned this circumstance, some lady slung the javelin into me from ambush by saying sarcastically—"Oh, yes indeed! 'glued to the floor' the way the average man's eyes are riveted to the sidewalk when he passes the Flatiron Building on a windy day!") But I was determined to make it a wholesale sacrifice, and I did it! This Spartan performance was generously rewarded, for I was added instanter to the Cork's "Hall of Fame" as the "Hero of the Deluge."

All our things were taken down to the furnace room and dried in a short time, and the Alley quickly regained its dignity and composure. I had to repair the damages to my room, but soon got it in perfect running order again; with added improvements it became a veritable Bohemian dream and I would not have left it for worlds. I could lie on my bed and get a drink of water without rising, reach for a cigar, sew on a missing button, open my treasury vaults to see how the funds were holding out, and when dressing could sit down on my only seat, a ten-cent camp stool, and take a short smoke while Steward Griffiths was filling my bath tub. But I was far from civilization, as the first-cabin baths were up two deck flights, then down one and back through a passage underneath where you started from; the round trip was a ten minutes' walk. I consoled myself with the reflection that it was needed exercise and in the best interests of hygiene.

The delights of Funchal exhausted, we were off again for a visit to

CADIZ

There is not much to see in Cadiz but its Cathedral and the busy life of its people, who number 70,000. It is thoroughly calcimined in chromatic tints and looks fine as you approach it from the sea, but your enthusiasm wanes somewhat when you get into the picture and see that there are many places where the gilt has been knocked off the gingerbread and has not been put back again. But we must all take off our hats to the "old town," for it was there, indisputably, that Columbus rigged up and started for America. If he had only known what he was about and the people had understood all that was to happen, they would have had a brass band on the pier and have set off plenty of skyrockets in the evening. 'Twas ever thus! The "knockers" boo-ed him from their shores and said he was crazy, but history plants his feet on the topmost rung of fame long after the bitter end, when short commons were with him uncommon short.

SEVILLE

The "Corkonians" took the train for Seville, and it was a corker in length for it took three engines and all the first-class carriages in Andalusia to carry us to our destination.

The management had about a carload of plaited straw lunch baskets and filled them with good things, so we had a continuous picnic en route. When we arrived we found almost every carriage in this city of 150,000 people lined up in a big square for the distribution of the party, as the principle of procedure was, first come first served. There was a motion picture for you that lasted twenty minutes, but there was a place for every man and every man had his place, so we were all comparatively happy and started in to "do" the town.

Seville has one of the largest, finest and richest Gothic Cathedrals in existence; it has absolutely everything that can in reason be demanded of a cathedral, with or without price, including in part a full line of old masters, headed by Murillo and Velasquez (who were born here); bones of the good dead ones—and some bad ones—silver gilt organs, a court of orange trees in full bloom, the Columbian library (established by Fernando, Columbus' son), containing nothing but books, books, books! Then again there are acres—I was going to say—of stained glass windows, but perhaps I had better stick to the simple truth and say innumerable windows, showing every variation of the rainbow in their brilliant, deftly interwoven tints. Once more we find jewels of great price, solid silver trophies (which before the slump in silver would have placed any honest man above the corrosion of carking care); and wood-carving by masters of the trade whose artistic feeling was graphically described by our learned guide—known to the "Corks" as "Red Lead," on account of the lurid color of his hair. He wore an Oscar Hammerstein opera hat and seemed condemned to live on earth but for a certain time—and all whom he met wished for its speedy expiration. In a single, simple, instructive sentence he requested us to "Joost look at dat figger and see how the master have carve them feets; they are both two much alike."

Most of these things, and many more, were the gifts of King Charles V., King Ferdinand, Queen Isabella and others, with a Sultan or two thrown in for good measure. All this grandeur is spread over 124,000 square feet, exceeded only a little by St. Peter's in Rome.

In the plethora of good things I had almost forgotten to mention the Tomb of Columbus, a finely carved sarcophagus in solid bronze. Heroic, allegorical figures support it and it is an imposing coffin in every respect.

The size of this great Cathedral is three hundred and eighty by two hundred and fifty feet, and a week might be spent in seeking out the vast treasures which run the gamut of art and money from its top round to the bottom. There are many other churches here, but to try to write of them after attempting to describe the Cathedral would be like an introduction to Tom Thumb after having spent the day with Chang, the Chinese giant. However, we can hardly overlook the Alcazar, which "cuts" considerable "ice," even in this hot climate. It is the palace of the late Moorish kings, containing the famous Court of the Maidens and the Hall of the Ambassadors. It cost a good many millions of pesetas to erect its front elevations, not to speak of its elaborate interior decorations, although the workmen only received two pence per day, and they had a local "blue card" union at that.

The "Order of the Corks," both men and women, all went to see a grand series of Spanish dances at the theatre, got up for their delectation and amusement. No band of enthusiastic pilgrims ever started in such high feather to see a dramatic and terpsichorean feast as did we. There was an expression of mystery and expectancy on every face. Mary Garden and all she does would be a mere flea bite to what we should see of pure and simple naughtiness. But alack and alas for our blasted hopes and the human weakness that had been worked on by the adroit press agent! The show was a "fake:" there was nothing naughty about it—and very little that was nice. No refrigerating plant ever contained a freezing room so dank, cold and gloomy as that theatre! After the first act, the ladies—Heaven help them!—put on their furs; in the second, an odd man or two began to sneak out, and by the time the curtain rose on the last act there was hardly a soul in the house! The weary "Corkonians" wended their way to the hotels in disconsolate groups, and the simple but convincing words, "Stung again!" hung on every lip as we toddled up the dark stairs to our beds, wiser but sadder men. There may be allurements in Andalusian dancing—but if there are, we certainly did not see them.

In the cold, gray dawn of the next morning we gathered up our belongings, and after an early breakfast, reinforced by another "management" basket lunch, we made for the train. An all-day's ride to Granada was before us. You see, you couldn't get anything to eat at a Spanish station but garlic, onions and chocolate, so we had to prepare for the worst. "The worst" came all right, in the sanitary arrangements at the stations (for there were none on the trains), but we justly blamed all our troubles on Spain and not on the management of the trip. It all passed, however, like a summer cloud when we landed in time for a late dinner at Granada. Dinner over we went out and saw some of the gay life of this famous city. The local color was there—in fact, it was highly colored; and as for "atmosphere," why, the air was full of it! The ladies squirmed a little, but the men stood nobly by their guns till the last candle had been snuffed out; and so we went to bed, after arranging to give a full day to the Alhambra next morning, and slept the sleep of the just.

GRANADA

Morning came as usual with the rising sun, and we set out, twenty-five to a guide. I transmitted Mark Twain's name of "Billfinger" to our man, and he was very much pleased by this notable mark of distinction; in fact, he felt that he had to speak and act up to his title; but his voice gave out in the second round, and he had to whisper his historical jokes and quips about the harems to a "Cork" from Chicago, who repeated them in a louder tone to the audience. This man was a human calliope, and had the voice of an African lion when out of meat. His trained organ was so ear-piercing that much to "Billfinger's" annoyance several ladies deserted our party and fled to one of the other guides who had a soft, sweet voice.

The party was large and each guide was obliged to keep twenty minutes behind the band before him. This was done like clockwork, and yet, such is the uncertainty of such arrangements and the intensity of the human desire to get ahead of one's neighbors that, do as he would, Billfinger was constantly butting his leaders into the rear of the enemy—for such they were regarded, once the procession got into full swing and the excitement had reached its zenith. This led to endless confusion, and the members of party No. 9 (our set) had to be fished out and sorted from the ranks of Nos. 10 and 8, thus producing many violent squabbles among the guides. Adjustments were slow and by the time they were made a general congestion had set in at the rear and the "Corks" were all bobbing round in hopeless confusion, extending even to the outer gates at which we had entered the citadel. But the man with the voice from Chicago now came into his own and showed how easily he could quell a friendly riot. He mounted a parapet and with a green umbrella as a baton shouted back his orders, and they were obeyed with such telling effect that in a short time the procession moved like a well oiled machine and we had no further trouble. By most of the pilgrims it was considered that this was hardly a fitting or dignified entrance into one of the noblest ruins of any time or country; but this is a practical age, and we got right down to the business of inspecting what is left of the Alhambra. When such a man as Washington Irving was so inspired by the marvelous beauty of this place and lived ninety days in one of these buildings (which was pointed out to us by Billfinger), in order to get the spirit of the times and place in which these halls were erected and peopled, and there wrote his celebrated historical and romantic book, Tales of the Alhambra, published in 1829 (obtainable in any library), it would seem best that I leave the reader to peruse that famous work for ideas and details which, should they be supplied by the ordinary scribbler, could but belittle such a noble subject. I therefore suggest that those interested procure that book and read it for themselves.

We went to bed early, for we had to rise long before daylight and take the train for Gibraltar, where the King of Cork lay waiting for us, for she had steamed from Cadiz to "The Rock" after we left her; and although we had enjoyed every minute of the trip, we were glad to get back to the only home we had, on the water.

We had made quite a circuit through Spain, and it had been a most interesting journey. We had thought of Spain as a land of dust, sand and rocky mountains, but instead of that we found broad, fertile plains, well cultivated and with every sign of prosperity. Above all other things the feature of the country is the thousands of well kept olive orchards; then there are sugar-cane, and grapes and other fruit, in abundance. Some of the buildings on the ranches are very fine and imposing, reminding the visitor of English estates. We were fortunate in passing through the cork producing district, and saw the whole process of barking the trees, cutting the bark in oblong squares and stacking it up like lumber in a large yard. The trees grow their bark again after it is stripped off and from time to time it is again cut as before. At the first sight the "Corks" got of this industry, they showed their interested appreciation by taking a thousand and one snap-shots before the train left the station.

Most intelligent Spaniards will tell you that they were angry when we took Cuba and the Philippines from them, but now they regard it as a blessing in disguise, as they had no business with expensive colonies, are better off at the present time than they have been for decades, and hope for a new era of prosperity. The largest blot on the country is the cruel bull fighting, but their English Queen has set her face against it and it is distinctly on the wane.

ALGERIA

When we had finished up the stereotyped sights of Gibraltar and had thrown overboard a New Jersey insurance agent for criminally mentioning "Dryden's Hole," that bewhiskered "chestnut," in connection with the time-honored "Rock," we steamed across the Mediterranean to Algiers, some four hundred and ten miles away. Algeria has a water front of six hundred miles, and extends back two hundred and fifty from the shore. It was conquered by the Romans in 46 B.C.; subsequently the coast of Barbary became the dread of every ship that sailed the sea. With varying success, many nations, including Spain, France, England and the United States (fleet commanded by Commodore Decatur), took a hand in trying to tame the horde of cut-throat pirates who for centuries committed unspeakable atrocities and cruelties. It is hard to realize that only seventy-five years ago these sanguinary pirates held complete sway on the Mediterranean, and that England alone had six thousand of her subjects captured and enslaved by them in 1674. It is estimated that six hundred thousand from all the nations were captured and worked to death in chains. This spot is the "chamber of horrors" in all human history. To the French belongs the honor of finally taming these wretches and drawing their claws. Algeria is now a French colony, is well ordered and quite safe for the visitor.

This people is made up of many breeds: we saw thin, bandy-legged Arabs, fat, burly Turks, ramrod-like Bedouins; Kalougis, with a complexion suggesting old sole leather; Greeks, with frilled petticoats; Romans, of course with the toga; Kabeles, with black hair and wearing a robe like a big gas-bag; Moors, with the Duke's nose and spindle shanks; Mohammedans, carrying bannocks with holes in them; and dragomans, with "bakshish" stamped on every department of their anatomy. But beneath the furtive glance and in the wicked eyes you see the cut-throat still lurking, awaiting the first opportunity to embark again in the trade that is close to their hearts, although the only active pirates here now are the cab drivers.

Every breed has its own outlandish costume with a large range of startling colors in robes, turbans and slippers, but their shanks are bare, thin and brick red, an easy mark for flies. A considerable percentage of their time is devoted to stamping their feet to shake off these pests, which somehow do not seem to know they are not wanted and keep the lazy rascals busy, thus preventing them from devoting the entire day to sleep and the worship of Allah.

To round out the picture we must not forget the French Zouave regiment—fine-looking men, with their elaborately frogged jackets, and trousers like big red bags, large enough to make balloons if filled with gas, and the whole topped off with a scarlet, "swagger" fez with a tassel hanging down to the waist.

Algeria has a population of about 5,000,000, while the town of Algiers contains 140,000 people. The climate is tropical with plenty of rain. Oranges, lemons, pineapples, dates, figs, cocoanuts and spices are seen everywhere. There is a fine, tropical, public garden-park, and the Governor's Palace with its grounds makes a handsome showing in flowers and fruits. French officialdom strikes a gay and festive note everywhere, and the very latest Parisian novelties are seen on the streets. They have motor cars, but it must be confessed that these do not as yet class with a Studebaker "Limousine."

The passengers slept on the Cork at the wharf. They tried one meal at the hotel, with the ship's stewards assisting, but did not essay a second. Seven hundred in two relays would have tested the ability of Mr. Boldt, but still when the battle was over we had all had enough; in fact, the management came out with flying colors in this severe test.

Perhaps at this point it might be interesting to report on the progress that the Alley had made since it was last mentioned. The development of ship characters takes time, and the big men and women do not pop at once into the lime-light. There were other alleys and some of them contained hidden stars. It was our business to lasso these (just as base-ball players are "signed"), and annex them to the Alley, so with this in mind and hat in hand we approached the haughty but accomplished Purser (with a big P), the man who is covered with gold lace and clothed with vast responsibility; who, in fact, holds the destinies of the ship in the hollow of his hand. We laid our case before him and said we wanted "Gassigaloopi" from Alley No. 9, the two "Condensed Milkmaids" with their chaperon from the midship flats, and "Fumigalli," who bunked near the condenser. The great man of course frowned and pulled his "walrus"—the kind that has hanging, hairy selvages on it, such as serve as warnings for "low bridge" on the railroads—smote his desk firmly, and said it would never do! However, we could clearly see that beneath the mask of his importance he was jubilant over the knowledge of his power, and that if we could only pull some other string we would gain our object; so we inveigled the queen of the poop-deck into joining hands with us, and the day was won without further effort. Then with joy and gladness we informed the new people whom we had delighted to honor of their social elevation, and with willing hands we carried their belongings down in triumph to Harp Alley. Two of the staterooms had been vacated at Gibraltar, and so all difficulties connected with the transfer were easily overcome. "Gassigaloopi" was a tower of strength in himself; he was a retired Italian politician and spoke so many languages that when he got excited he mixed them thoroughly, utterly routing all contestants in any arguments that might come up. He was a human geyser, and when his linguistic power got under full headway he fairly tore up all the tongues by their roots and trampled them under foot in the rush of his stinging invective. Although of Italian origin, "Gassy" was born near the site of the Tower of Babel, and its propinquity and influence gave him that varied volubility in expressing fine shades of meaning in many languages that made him the pride of the profession of which he was a distinguished light. His ebullitions were frequently hurled at the "boots" for neglecting his oxfords, placed outside his stateroom door, but soon afterward he became himself again, much to the general joy of the Alley.

"Fumigalli" smoked so much that he gave all his time to thought, and we used him to plan future triumphs for us. Though he thought much he produced but little. We all knew that he was evolving great projects mentally, but somehow he could not get them out in front of the spot-light. His one great achievement was calling a meeting of protest against the Señor's boredom in the smoking-room. The meeting was held and two resolutions were drafted to be read at dinner in the saloon; but somehow no one liked to hurt the Señor's feelings, and they were never read.

The "Condensed Milkmaids" were a pair of small, temperamental, clever girls, so trim and smart that one would think they had just left the Trianon Dairy Farm in Versailles Park, after having milked a pint of cream for the Queen, or for the royal favorite, Comtesse Du Barry. They wore Louis the XIV. (Street) high-heeled slippers, and were purely decorative. Having no part in the executive management they knew their place and kept it.

A young lady and her mother from New England (both members), gave the Alley a boost at the last concert. The daughter played a violin solo, accompanied by her mother, with such attack, feeling and technique that if Paganini had been on earth he would have taken off his hat to her.

It is perhaps true that the Alley had no tremendous personages in its membership, but its innate strength lay in this weakness for it represented the very embodiment of what is known as the concrete social spirit, "one for all, all for one," and with this motto it might have—and really did—stand against the entire ship. Neither the Purser, the Captain nor the crew dared oppose its opinions or wishes; in fact, the Alley thought of running down to Zanzibar and taking a whack at the lions before "Bwana Tumbo" even saw them. We don't like to brag, but one of our members could, with one eye shut, hit any button on the metal man's coat in the shooting gallery, and with both shut could bring down a wildebeeste. The mission of the Alley and its fate now lie in the "womb of time," and we must not hustle its destiny

We left for Malta, which was reached in two days, and cast anchor in the harbor of Valetta, the capital. The island is celebrated as the home of the Knights of Malta, the original birth-place of the Maltese cat, and the spot where the Maltese cross was invented—but not patented. This island was conquered by the Romans 259 B.C.; afterward by Napoleon, from whom it was taken by England in 1800, and now indeed it's "quite English, you know." Oh my! how English it is, to be sure! It's nothing but Tommy Atkins here, and Files-on-parade there; battle-ships "beyant," and cruisers in the "offin'," mixed up with gunboats and bumboats and "gundulas," till you would think you were standing on the pier at "Suthampton."

The marine bands mostly play Rule Britannia, but some of them essay Annie Laurie, and when these airs get mixed, it would try the soul of Richard Wagner to stand the discord without resorting to profanity. Anyway, Mr. Bull has this island all to himself. Its fortifications and harbor are the finest to be found on the globe, but how sad to think they have been rendered useless by the modern battle-ship with the long guns. (I was going to say the "long greens," as they and battle-ships always go together, no matter who pays the taxes.) But still it charms the visitor with its fine climate and gay people. It was Carnival Day when we arrived, and the motley crowds in the street, in variegated raiment, pelted the "Corks" with all kinds of flowers with the utmost good humor.

There is a church on the water-front that is lined with the skulls and bones of the various armies of defenders: its name is "Old Bones," which certainly bears out its character.

A whole lot might be written about how the Knights of Malta became very great, then very small and degenerate, and finally were pushed into the discard by the relentless hands of time and public opinion. Valetta has quite a number of people living there besides the soldiers and sailors, some 80,000 I believe, but most of them are tired of climbing the steep streets, many of which contain stairs. Lord Byron, having a game foot, got angry at them when he wrote:

"Adieu, ye cursèd streets of stairs,

How surely he who mounts you swears!"

We were shown the spot where St. Paul was ship-wrecked. The Maltese erected a colossal statue to Paul on Selmoon Island about fifty years ago. They hold an annual feast there on February 10th, the alleged date of his shipwreck, and as they have two hundred additional feast days they have just one hundred and sixty-four days left for their regular business—loafing. They have novel names for their hotels and saloons,—the "Sea and Land Hotel," "The Pirates' Roost" saloon, the "Quick Fire" lunch-room, "The Englishers' Chop-House," and "The Camel's Drink," are some examples. Not from greed, but purely out of curiosity, mind you, we tested the latter, and it would have taken three of what they gave us to make a regular "Waldorf highball." Thus does the retributive principle of temperance put the rod in pickle for

We left Malta and had Greece before us, which we reached in two days. Lord Byron aptly describes it in his famous poem which opens with:

"The isles of Greece, the isles of Greece!

Where burning Sappho loved and sung,

Where grew the arts of war and peace,—

Where Delos rose, and Phoebus sprung!

Eternal summer gilds them yet,

But all, except their sun, is set."

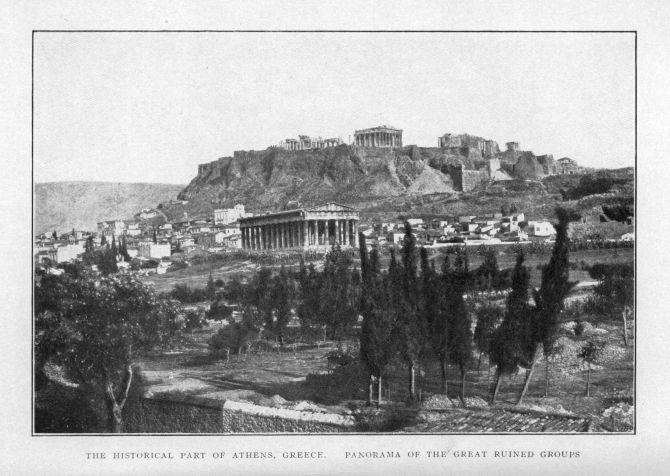

ATHENS

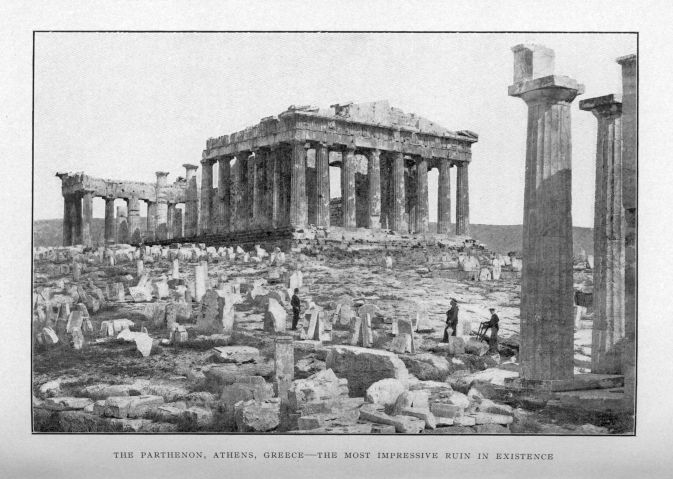

The Acropolis, or rocky mountain on which the celebrated group of buildings is found, was fortified more than a thousand years before Christ. It is the central spot of all that is greatest in art, letters, history, statecraft and philosophy since time began. This has been the undisputed opinion of critics and historians for about three thousand years and stands uncontradicted to-day as it did in the very beginning of things learned and artistic.

You are met toward the top of the ascent by the Propylaea that "brilliant jewel set on the rocky coronet of the Acropolis" as a kind of introductory vestibule to further greatness. It is the most important secular work in Athens, consisting of a central gateway and two wings. It was begun in 439 B.C. It contains a wealth of Doric marble columns, beautiful, carved friezes and metopes, with five gateways spanned by great marble beams twenty feet long. All these wonders compel the stranger to stand spellbound at the magnificence of their combined effect.

Near by stands the Temple of Athena Nike, and close at hand is the site of Phidias' colossal statue of Athena Promachos, the "fighter of the van," made of the spoils taken from the Persians at the battle of Marathon; sixty-six feet high, in full armor, her poised lance was always a landmark for those approaching Athens.

We now reach the temple, attached to which is the Portico of the Maidens, the Caryatides, and containing the shrine of Athena Polias.

Next comes the great Parthenon, "the most impressive monument of ancient art," built by Pericles in 438 B.C. It was adorned by statues and monuments by Praxiteles, Phidias and Myron. It had fifty statues, one hundred Doric columns, ninety-two metopes, and five hundred and twenty-four feet of bas-relief frieze, thus realizing the highest dream of plastic art and the immortality of constructive genius. Within the inner sanctuary Phidias placed his chryselephantine figure of Athena Parthenos, the virgin, thirty-nine feet high, the flesh parts being in ivory and the garments of fine gold. It is estimated that this gold was worth almost 200,000 pounds. For more than six centuries the virgin goddess received here the worship of her devoted votaries. In the fifth century the Parthenon became a Christian church; when the Turks came they made it a mosque. The edifice remained in good preservation till the seventeenth century. In 1687 the Venetian, Morosini, besieged Athens and a shell from one of his guns ignited the powder which the Turks had stored in the Parthenon. A destructive explosion followed and thus the most magnificent structure of the ages, which twenty-one centuries had spared, was reduced to ruins. What remains of it is still most majestic and when seen by moonlight inspires the greatest reverence. There is no speculative guess-work in these statements, for in 1674 Jacques Carrey made a series of one hundred careful drawings of the Parthenon, which were confirmed by two English travellers, Messrs. Spon and Wheler, in 1675. These were the last visitors who saw it before its destruction.

The Acropolis Museum is also built on the hill. It contains many interesting things that could not be allowed to remain exposed to the weather.

The vast Theatre of Dionysius, which held 30,000 people, is also here.

There are many other fine buildings, statues and temples on the Acropolis, but space will not permit of their description.

We descend to a lower plateau and there find the remains of the vast Temple of Zeus Olympus, called by Aristotle, "a work of despotic grandeur," "in accordance," as Livy adds, "with the greatness of the god." It contained an immense statue of Zeus. Originally it had more than one hundred imposing marble Corinthian columns, arranged in double rows of twenty each on the north and south sides, and triple rows of eight each at the ends. Its size was three hundred and fifty-three by one hundred and thirty-four feet, which was exceeded only by the Temple of Diana. To its left is the Arch of Hadrian. Looking east is seen the Stadium or racecourse. Here the Pan-Athenian games were held in olden times. It was laid out in 330 B.C., and has been restored in solid white marble by a rich Greek. It cost a large sum of money and will accommodate a multitude of spectators. The first year in which the revival of the games took place the Greek youths won twelve out of twenty-seven prizes, the others going to various nationalities.

Beyond in the suburbs lies the public park owned by Academus in the fifth century before Christ. Plato and many other philosophers taught their pupils here, and from the name of the owner is derived the word academy.

These are but a few of the commanding sights of Athens. No attempt will be made to speak of the men and the wars that made her the multum in parvo of human history. The modern Greeks are a serious and decent people; they seem to be impressed with the fact that their ancestors were the salt of the earth, and at least try to be worthy of them. There is no begging in the streets (the Greeks being too proud to beg), and the people are quite respectable for their opportunities. Their city is well laid out and built in modern style; it is prospering, having had only 45,000 inhabitants in 1870, while the population is now 150,000. One cannot afford to treat either the Greeks or Athens

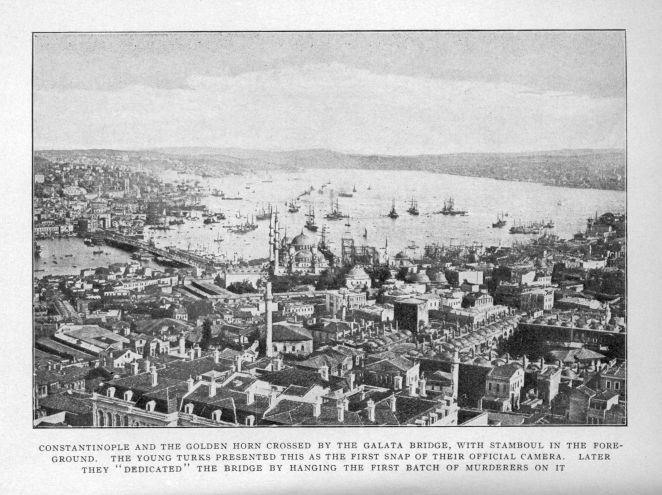

CONSTANTINOPLE

After leaving Greece we threaded our way through the islands of the Aegean Sea, the Dardanelles, the Sea of Marmora and the Bosphorus, to Constantinople, where we anchored at the mouth of the Golden Horn. I must leave to the historian the dramatic and sensational history of the capital of Turkey in its various shifts of ownership; perhaps no other city has surpassed it as a factor in European affairs for a period of two thousand years. It was named after Constantine, the Roman Emperor, who was its chief builder. He tried to call it New Rome, but this title would not stick. On the Galata Bridge that leads to Stamboul, a racial panorama may be seen that embraces all the peoples of the Orient, and everywhere signs appeal in half a dozen languages. The private histories of its rulers have also been of the most absorbing and exciting character, and were they described by a pen of authority and with the necessary inside knowledge and information they would still further shock and astonish the uninformed.

The city was founded by the Dorian Greeks some seven hundred years before the beginning of the Christian era; later the Persians captured it, then the Romans came and took charge. The Goths were the next men in possession, followed by Basil of Macedonia, who became Dictator. Then Mohammed was the man of destiny: the city fell into his hands and from that day to this the "unspeakable Turk" has ruled it. All these changes were brought about by battles at sea and on land, by sieges and through treachery, and with great loss of life, treasure and time.

We employed a guide to take us to the Mosque of Sancta Sophia and the other principal show places. This man had formerly called himself "Teddy Roosevelt," but he changed his name to "George Washington Taft," in honor of our worthy President, thus making his cognomen thoroughly American and bringing it up to date at a stroke of the pen; but we told him this was no kind of a name for a guide in Turkey, and then and there changed it to "Muley-Molech;" he was much pleased with his new historical title. "Muley-Molech" had a nose of vast proportions—while not so large as the Lusitania's helm, yet it was exactly the same shape; and he wore a moustache that ended in large, hirsutical corkscrews; his teeth were like small bits of marble stained with tobacco juice, and they had the effect of an arc made from the spear of a sword fish, grim and terrible. Altogether he was a remarkable man—one to be feared at night when near the Bosphorus; although, if the bitter truth must be told, he avoided impartially both salt water and fresh, whenever possible. My word! "Muley" was no ordinary, amateur Munchhausen! he was full of exact statements which he encrusted with legends that were utterly bare-faced. After hearing one of his flights of fancy, a fat brewer from the West remarked:

"It's better not to believe so much or to know so many facts that aren't so; but this is the devil of a place, anyhow; that's right!"

Muley looked at him with fine scorn and went on at his usual gait. Later I told him (Muley), the story of the Irish judge who once said to a prisoner whom he was about to sentence:

"We don't want anything from you but silence—and very little of that!"

This hint had a depressing effect, and Muley lost his nerve and the character he had enjoyed with us of being a picturesque and fearless liar.

Sancta Sophia was built in Stamboul across the Golden Horn by the Emperor Justinian in 537 A.D. (fire having destroyed the edifice originally erected by Constantine and replaced by the church built by Theodosia, which was also burned). The dome is one hundred and eighty feet from the floor. To adorn it, the Temple of Diana at Ephesus was ravaged of eight serpentine columns, and eight more of porphyry were taken from the Temple of the Sun at Baalbek to add to its beauty. It is alleged that its cost approached $64,000,000, including the "graft." Its artistic value is greatly depreciated by the squalor of its environment. Looking at this great pile, a speculative wag remarked, with a twinkle in his eye:

"It's all a question of money. Give me the financial assistance of J. D. R., and with one of the big American construction companies to take the contract I can produce a building fully equal to this in less time and for very much less money."

He was right. It would be only a question of deciding to do it. The Landis' comic-opera fine would be sufficient.

The Sultan's Palace and the ancient Hippodrome are also places of great interest. In the latter were deposited the four gilded bronze horses, supposed to have been brought from Scio, once mounted on Trajan's Arch at Rome, brought here by Constantine. They were taken to Venice by Dandolo, then Napoleon gave them to Paris, and finally after Waterloo they were restored again to St. Mark's at Venice.

In Constantinople we also saw three or four other Mosques of great size, and the Seraglio grounds and Palace. In the latter we saw the gates through which the odalisks who had lost the sultan's favor passed beyond to be executed. The passage of this gate made our flesh creep when we thought of all it meant to the unfortunates; but near by, in agreeable contrast, is the "Gate of Felicity," which is the entrance to the sultan's harem. Through this the new favorites entered and remained till they had grown old and lost their charm.

The Imperial Ottoman Museum is full of good things purloined from other art centres. It contains many fine examples of Greco-Roman sculptures, statues and reliefs, in marbles, terra-cotta and bronze. The figures of dancing women have a swing and their draperies a palpable swish—as if a breeze were stirring them—seen only in this school of art. It also contains Alexander the Great's sarcophagus, which is regarded as one of the finest examples of Greek art in existence.

The Grand Bazaar is both a sight and a town in itself, full of streets, entries, lanes and alleys, covered here and there as an arcade, into which the sun never penetrates. The dim light, the great crowds of strangely costumed people,—veiled women with their children in hand, attended by eunuchs, some chattering, some silent and aloof—but all intent on bargaining and eager for the fray. This novel and engrossing picture is made possible and is enhanced by the bewildering variety and display of Oriental goods and wares—rugs, perfumes, cosmetics, weapons, shawls, embroideries, inlaid tables, porcelains, brassware, silks, fans, jewels, laces, gold and silver ornaments of infinite variety—all piled up and strewn about as if they had been pitchforked by some magician into an enchanted market-place, with the god of greed and chance presiding.

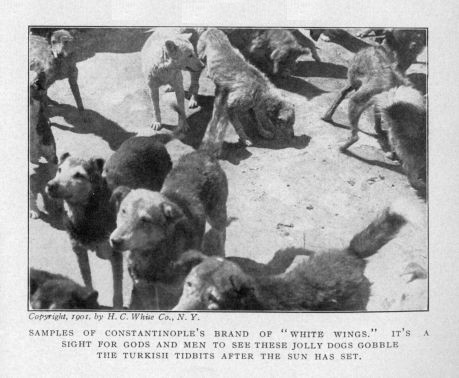

Limited space forbids the further description of things that are wonderful and interesting, but a few words must be said in regard to facts we would rather not think about. The population is about 1,125,000, and most visitors think there is a mangy, flea-bitten dog for each inhabitant; but the official dog census has placed the canine population at about 125,000. The dogs of Stamboul and Constantinople are a necessity and a book might be written about them alone, as they have ruled these cities from a sanitary point of view for over a thousand years. If they did not set out at night and partially clean up the town, Heaven only knows what it would be like! Their sway is undisputed, and woe betide him who either hurts or kills them—he is a marked man, not only by the Moslems but by the followers of other religions. They have no distinctive owners and just live by their wits, which are keen to an advanced degree; they have rules of the road of their own making, and the luckless cur that breaks them is put out of business in the twinkling of an eye. No one likes them, but they are a thoroughly protected nuisance, for that protection means life to the people. Without their services as devourers the population would die like flies, from epidemics and pestilence. All attempts at doing away with the dogs have resulted in riots and bloodshed: when Mehemet II. rounded them up and exiled them to an island, a great epidemic immediately set in and the rioters compelled the Sultan at the point of the sword to bring them back again. A later attempt was made by an Ottoman chief-of-police to deport these canine "white wings" to Asia Minor: he threw them overboard when out of sight of land, and when this was made public the mob literally tore him limb from limb. So it does not pay to monkey with the Sultan's pets in the home of their nativity. Although no one would suspect it, they have a high order of intelligence and an acute instinct for local government. By some unwritten law they divide the town into districts with sharply defined boundaries invisible to the human eye, yet plainly apparent to the animal. If an intruder crosses this line he is sorry for it before he reaches his first bone. The neighboring dogs pounce on him from all directions, biting his legs, tail and ears, but stopping short when they in turn reach the line, for fear they may also get into trouble for trespassing. When one of the members of a district becomes sick and helpless his comrades do not wait for him to die; they just eat him up and have done with it. So no one ever sees a dead dog in Stamboul: professional pride and esprit de corps step in, and the victim is wafted to the happy hunting grounds in less time than it takes to tell of it.

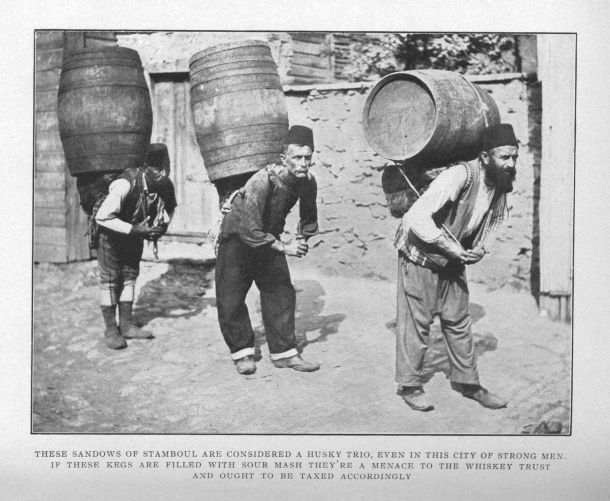

The porters are celebrated for their great strength and the big loads they can carry. To see them do their work is a most interesting sight: four of them will carry a great cask filled with fluid and suspended from two poles placed on their shoulders—a fair load for a team of horses. They carry these loads with the aid of ingenious appliances and harness, and the amount of lumber, coal, dressed beef and live animals they transport for short distances is simply incredible.

Soldiers are drilling everywhere and a raw lot they are. The treasury is empty, and many of them have only one shoe, and some none at all, only a coarse stocking bound round with rags. They may be experts at killing women and children, but they would make a sorry showing against trained soldiers. And then there are the "battleships:" fierce, devilish-looking bulldogs that could demolish any tin-lined fort in existence if they could only hit it, or even if the sailors could manage to fire the guns—or in fact, if only the guns could be fired by any one—which is exceedingly doubtful.

In smells, the vilest of the vile, including the acrid variety that cuts the nostrils like a razor, Constantinople stands forever and alone on a plinth of infamy, and no language that can be dragged into the arena of expression can be utilized to describe them. They paralyze the intellect and dull the sense of punishment and acute agony. No gladiator could enter the lists with them in deadly combat and live to tell the tale. They arise in part from the debris and remnants of cheese whose position in the flight of time was contemporaneous with that of Alexander the Great; from fish that must have darted beneath the keels of the ships at the battle of Salamis; from tallow, used to grease the chariot wheels at the battle of Marathon (now sold as butter); and from the embalmed beef that was left over from the Crimean War. These with many powerful additions supply the main force and foundation of all this pervading "sweetness;" but the distinguishing "high lights" come from minor causes, such as the onions of last year rotting in nets hanging in the sun, strings of garlic returned to circulation by the Argonauts when they came back from hunting the golden fleece, but now hung as a badge of trade on the door-jambs; and the frying of eggs, that have long lost their market value, with Bombay ghee and young garlic, the whole mellowed and perhaps refined by the continual vapors from open sewers. One fragrance that perhaps tickles the olfactory nerve with more delicacy than all others and might be called a perfumed "dream," comes from baking a garlic pie piping hot in the open, with Turkish Limburger as a substantial ingredient. This zephyr when in full action sets at naught the vain attempt of asafoetida to hold its place in the history of smells that used to rank with Araby the Blest. If Alexander had inhaled one whiff of this combination in its full purity it would have floored him in Constantinople and he could not have lived to conquer the world. One of the "Corks" fainted when he hit the embalmed beef zone and was taken to the rear in a red cross ambulance.

The sights in these places are too dreadful for publication, and as for the taste—well, I tried a speck of fried sausage and thought I had touched a live wire! it left a scar on my tongue. We made a special excursion to see these sights and experience the smells. The driver of our carriage took advantage of a stop to take a drink at a Turkish café; the procession of vehicles began to move, and as we were in the middle of it our horses had to move too. This left us without a driver and I had to mount his seat and drive half a mile at a walk before our man caught up with us. In the crowded, narrow streets this experience was not a pleasant one, but I did the best I could and nothing happened of note excepting that in turning a sharp corner the team ran up on the sidewalk, from which I was chased with wild gestures and eastern profanity by a Turkish son of a wooden gun, much to the amusement of the natives and the rest of the procession. Still, the Turks, who are steeped in these conditions, seem to enjoy them: they laugh and joke at the unsuccessful attempts of the outlander to acquire their tastes. If they are happy, why should we object?

The costumes of the Turk are without number: there is no cut nor pattern of garment that is not embraced in their fashion plates and the colors run riot through all the gamut of the rainbow. But, seriously, they beat all other nations in the arrangement of their head-dress; no Turk is too poor or too low in caste to devote his time and attention to what he wears on his head. Of course, the rich ones have immense turbans, woven with stranded ropes of cloth in bright parti-colors, placed on the head as a finish to the toilet with as much care as a wedding cake is posed on a table; but the poor Turk takes a red fez as a basis to build on, and will, with cheese-cloth, or a strip of old toweling, or a wisp of worn-out silk and some feathers, turn out an effect that it is almost impossible to imitate even where ample facilities are at hand. Some of them wear their turbans well back on the head, some pitched forward, many with a rake to the side; but all with the artistic instinct that compels instant admiration. They are the "old masters" of headgear and their masterpieces may be seen by the thousand in any crowded street.

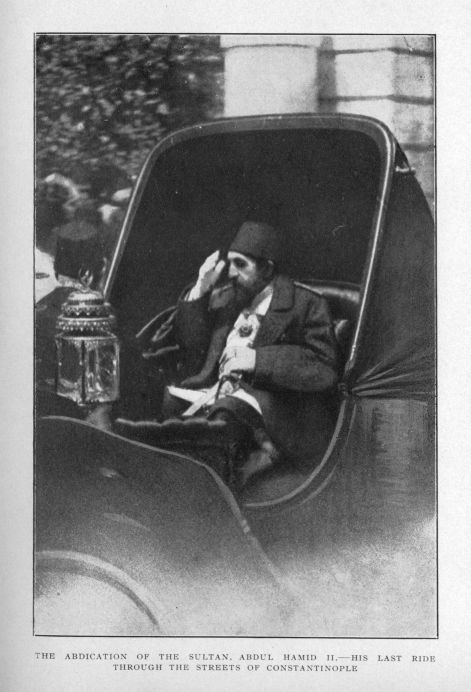

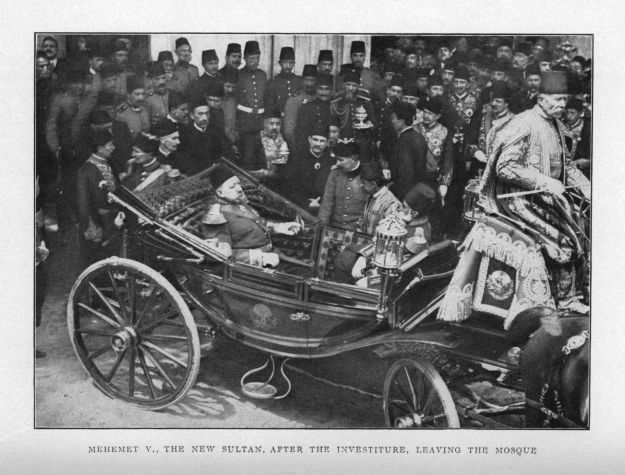

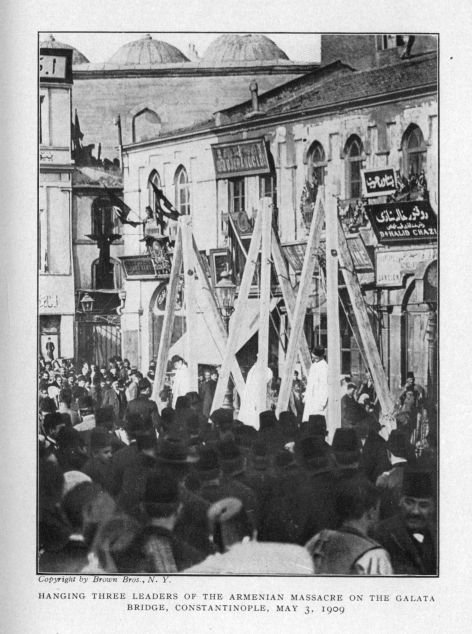

About the time we were in Constantinople, the new Turkish political force known the world over as the "Young Turks' movement," was just springing into life. The members of this body were eager to meet and mix with visitors and obtain their views and opinions of the probabilities of success, and a general endorsement of their work; so it was no trouble to have them visit us on the Cork, as she lay at anchor at the mouth of the Golden Horn. We conversed with them freely and listened to the recital of their wrongs and how they proposed to right and correct them. Political corruption and "graft," they said, were rampant everywhere, destroying the country and blighting every enterprise and industry. A Young Turk told me that many manufactories would be started were it not that the rapacity of the horde of petty officials was such that all must get a share of the spoils before a license could be granted, and that paying this toll would amount to much more than the cost of the factory. From the sultan down to the smallest custom house official, all must get a squeeze out of the victim whom they meet in any kind of business. The appellation, "The Sick Man of the East," presents in brief the picture of an unwholesome looking man, who is allowed to sit tight on his throne and plunder his people because the Powers can't agree on the division of his empire. When one looks at Abdul in his carriage one sees at a glance a coffee-colored knave who, when he gazes at the crowd from behind the mask of his face, is simply engaged in scheming a new twist in "graft," and wondering whether or not they can stand it and live. The Sultan is an expert pistol-shot and has killed many native visitors without the slightest proof that they were about to do him harm; if they made a suspicious movement of any kind he shot them down in cold blood and had them thrown into the Bosphorus. Abdul had an eye on the main chance and did not consider it wise to have all his eggs in one basket, so he deposited the hundred million dollars he wrung from his people—what is called his "private fortune"—in banks all over the world. The Young Turks are after this "pile," and he is not likely to retain it all and save his neck from the rope. Perhaps his most horrible crime was instigating the annihilation of 360,000 Armenians: this act alone places him on the pedestal of infamy for all time. But the pedestal is rocking, and his hour is near at hand. His territory in Europe has shrunk from 230,000 to 60,000 square miles. In a little while there won't be much left to divide, but there are other forces at work, and these serious natives tell you that nothing can now stop the progress of the task they are engaged in and that the days of the sultan are numbered. We believed in their sincerity and determination, and wished them every success. As a wind-up it will perhaps amuse the reader to note the high-sounding list of titles that the sultan—this "cutpurse and king of shreds and patches"—has given to himself. Here they are, all fresh roasted, with a few added words to fill in the interstices of his portrait:

THE SULTAN'S TITLES

"Abdul Hamid, Beloved Sultan of Sultans, Emperor of Emperors;"

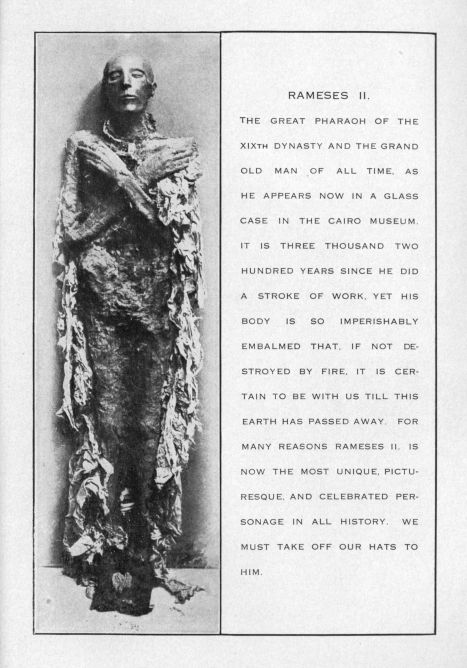

"The Shadow of God upon the Earth;"