Title: Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves, Volume IV, Georgia Narratives, Part 2

Author: United States. Work Projects Administration

Release date: July 28, 2007 [eBook #22166]

Most recently updated: January 2, 2021

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/22166

Credits: Produced by Janet Blenkinship and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by the

Library of Congress, Manuscript Division)

Transcribers note:

[TR:] = Transcriber Note

[HW:] = Handwritten Note

Every effort was made to faithfully reflect the distinctive character of this document. Some obvious typographic errors have been corrected. The above notes are placed inline, to cover all other unusual comments.

Hover over HW: with a mouse to see the changes made.

| Garey, Elisha Doc | 1 |

| Garrett, Leah | 11 |

| Gladdy, Mary | 17 |

| Gray, Sarah | 28 |

| Green, Alice | 31, 38 |

| Green, Isaiah (Isaac) | 48, 57 |

| Green, Margaret | 60 |

| Green, Minnie | 64 |

| Gresham, Wheeler | 66 |

| Griffin, Heard | 72 |

| Gullins, David Goodman | 78 |

| Hammond, Milton | 91 |

| Harmon, Jane Smith Hill | 97 |

| Harris, Dosia | 103 |

| Harris, Henderson | 115 |

| Harris, Shang | 117 |

| Hawkins, Tom | 126 |

| Heard, Bill | 136 |

| Heard, Emmaline | 147, 154, 160 |

| Heard, Mildred | 165 |

| Heard, Robert | 170 |

| Henderson, Benjamin | 173 |

| Henry, Jefferson Franklin | 178 |

| Henry, Robert | 194 |

| Hill, John | 200 |

| Hood, Laura | 208 |

| Hudson, Carrie | 211 |

| Hudson, Charlie | 220 |

| Huff, Annie | 233 |

| Huff, Bryant | 238 |

| Huff, Easter | 244 |

| Hunter, Lina | 252 |

| Hurley, Emma | 273 |

| Hutcheson, Alice | 281 |

| Jackson, Amanda | 289 |

| Jackson, Camilla | 294 |

| Jackson, Easter | 299 |

| Jackson, Snovey | 303 |

| Jake, Uncle | 310 |

| Jewel, Mahala | 315 |

| Johnson, Benjamin | 322 |

| Johnson, Georgia | 327 |

| Johnson, Manuel | 337 |

| Johnson, Susie | 343 |

| Jones, Estella | 345 |

| Jones, Fannie | 351 |

| Jones, Rastus | 356 |

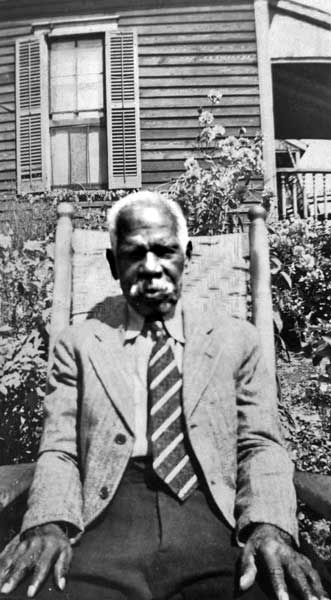

Asked for the story of his early life and his recollections of slavery, Elisha replied: "Yes Ma'am, 'deed I'll tell you all I knows 'bout dem days." His next words startled the interviewer. "I knowed you was comin' to write dis jedgment," he said. "I seed your hand writin' and long 'fore you got here I seed you jus' as plain as you is now. I told dese folks what I lives wid, a white 'oman was comin' to do a heap of writin'.

"I was born on de upper edge of Hart County, near Shoal Crick. Sarah Anne Garey was my Ma and I was one of dem shady babies. Dere was plenty of dat kind in dem times. My own sister was Rachel, and I had a half sister named Sallie what was white as anybody. John, Lindsay, David, and Joseph was my four brothers.

"What did us chillun do? Us wukked lak hosses. Didn't nobody eat dar 'less dey wukked. I'se been wukkin' ever since I come in dis world.

"Us lived in log huts. Evvy hut had a entry in de middle, and a mud chimbly at each end. Us slep' in beds what was 'tached to de side of de hut, and dey was boxed up lak wagon bodies to hold de corn shucks and de babies in. Home-made rugs was put on top of de shucks for sheets, and de kivver was de same thing.

"I still 'members my grandma Rachel. De traders fotched her here f'um Virginny, and she never did learn to talk plain. Grandma Sallie Gaines was too old for field wuk, so she looked atter de slave babies whilst deir Ma's was wukkin' in de field. Grandpa Jack Gaines was de shoemaker.[Pg 3]

"Most of de time I was up at de big house waitin' on our white folks, huntin' eggs, pickin' up chips, makin' fires, and little jobs lak dat. De onliest way I could find to make any money in dem days was to sell part'idges what I cotched in traps to dem Yankees what was allus passin' 'round. Dey paid me ten cents apiece for part'idges and I might have saved more of my money if I hadn't loved dat store boughten pep'mint candy so good.

"What I et? Anything I could git. Peas, green corn, 'tatoes, cornbread, meat and lye hominy was what dey give us more dan anything else. Bakin' was done in big old ovens what helt three pones of bread and in skillets what helt two. Big pots for bilin' was swung over de coals in de fireplace. Dey was hung on hooks fastened to de chimbly or on cranes what could be swung off de fire when dey wanted to dish up de victuals. Hit warn't nothin' for us to ketch five or six 'possums in one night's huntin'. De best way to tote 'possums is to split a stick and run deir tails thoo' de crack—den fling de stick crost your shoulders and tote de 'possums 'long safe and sound. Dat way dey can't bite you. Dey's bad 'bout gnawin' out of sacks. When us went giggin' at night, us most allus fotched back a heap of fishes and frogs. Dere was allus plenty of fishes and rabbits. Our good old hound dog was jus' 'bout as good at trailin' rabbits in de daytime as he was at treein' 'possums at night. I was young and spry, and it didn't seem to make no diff'unce what I et dem days. Big gyardens was scattered over de place whar-some-ever Marster happened to pick out a good gyarden spot. Dem gyardens all b'longed to our Marster, but he fed us all us wanted out of 'em.[Pg 4]

"All dat us chillun wore in summer was jus' one little shirt. It was a long time 'fore us knowed dere was folks anywhar dat put more dan one piece of clothes on chillun in summer. Grandpa Jack made de red shoes us wore widout no socks in winter. Our other winter clothes was cotton shirts and pants, and coats what had a little wool in 'em. Summer times us went bar headed, but Unker Ned made bullrush hats for us to wear in winter. Dere warn't no diff'unt clothes for Sunday. Us toted our shoes 'long in our hands goin' to church. Us put 'em on jus' 'fore us got dar and tuk 'em off again soon as us got out of sight of de meetin' house on de way back home.

"Marse Joe Glover was a good man and he never whupped his Niggers much. His wife, our Miss Julia, was all right too—dat she was. Deir three chilluns was Miss Sue, Miss Puss, and Marster Will. Marse Joe done all his own overseein'. He used to tuck his long white beard inside his shirt and button it up.

"Dat was a fine lookin' turn-out of Marse Joe's—dat rock-a-way car'iage wid bead fringe all 'round de canopy, a pair of spankin' black hosses hitched to it, and my brother, David, settin' so proud lak up on de high seat dey put on de top for de driver.

"Dere warn't no slave, man or 'oman, livin' on dat plantation what knowed how many acres was in it. I 'spects dere was many as 500 slaves in all. Marster 'pinted a cullud boy to git de slaves up 'fore day, and dey wukked f'um sunup to sundown.

"Jails? Yes Ma'am, dere was sev'ral little houses dat helt 'bout two or three folks what dey called jails. White folks used to git locked up in 'em but I never did see no Niggers in one of dem little jailhouses. I never seed no Niggers sold, but I did see 'em[Pg 5] in wagons gwine to Mississippi to be sold. I never seed no slave in chains.

"Some few slaves could read and write, and dem what could read was most allus called on by de others for preachin'. Charlie McCollie was de fust cullud preacher I ever seed. White folks 'lowed slaves to make brush arbors for churches on de plantations, and Nigger boys and gals done some tall courtin' at dem brush arbors. Dat was de onliest place whar you could git to see de gals you lakked de best. Dey used to start off services singin', 'Come Ye Dat Loves De Lawd.' Warn't no pools in de churches to baptize folks in den, so dey tuk 'em down to de crick. Fust a deacon went in and measured de water wid a stick to find a safe and suitable place—den dey was ready for de preacher and de canidates. Evvybody else stood on de banks of de crick and jined in de singin'. Some of dem songs was: 'Lead Me to de Water for to be Baptized,' 'Oh, How I love Jesus,' and 'Oh, Happy Day dat Fixed my Choice.'

"I hates to even think 'bout funerals now, old as I is. 'Course I'se ready to go, but I'se a thinkin' 'bout dem what ain't. Funerals dem days was pretty much lak dey is now. Evvybody in de country would be dar. All de coffins for slaves was home-made. Dey was painted black wid smut off of de wash pot mixed wid grease and water. De onliest funeral song I 'members f'um dem days is:

'Oh, livin' man

Come view de ground

Whar you must shortly lay.'

"How in de name of de Lawd could slaves run away to de North wid dem Nigger dogs on deir heels? I never knowed nary one to[Pg 6] run away. Patterollers never runned me none, but dey did git atter some of de other slaves a whole lot. Marse Joe Allus had one pet slave what he sont news by.

"When slaves come in f'um de fields at night, dey was glad to jus' go to bed and rest deir bones. Dey stopped off f'um field wuk at dinner time Saddays. Sadday nights us had stomp down good times pickin' de banjo, blowin' on quills, drinkin' liquor, and dancin'. I was sho' one fast Nigger den. Sunday was meetin' day for grown folks and gals. Boys th'owed rocks and hunted birds' nests dat day.

"Chris'mas mornin's us chillun was up 'fore squirrels, lookin' up de chimbly for Santa Claus. Dere was plenty to eat den—syrup, cake, and evvything.

"New Year's Day de slaves all went back to wuk wid most of 'em clearin' new ground dat day. Dere was allus plenty to do. De only other holidays us had was when us was rained out or if sleet and snow drove us out of de fields. Evvybody had a good time den a frolickin'. When us was trackin' rabbits in de snow, it was heaps of fun.

"Marse Joe had piles and piles of corn lined up in a ring for de corn shuckin's. De gen'ral pitched de songs and de Niggers would follow, keepin' time a-singin' and shuckin' corn. Atter all de corn was shucked, dey was give a big feast wid lots of whiskey to drink and de slaves was 'lowed to dance and frolic 'til mornin'.

"If a neighbor got behind in geth'rin' his cotton, Marse Joe sont his slaves to help pick it out by moonlight. Times lak dem days, us ain't never gwine see no more.[Pg 7]

"I ain't never seed no sich time in my life as dey had when Marse Will Glover married Miss Moorehead. She had on a white satin dress wid a veil over her face, and I 'clare to goodness I never seed sich a pretty white lady. Next day atter de weddin' day, Marse Will had de infare at his house and I knows I ain't never been whar so much good to eat was sot out in one place as dey had dat day. Dey even had dried cow, lak what dey calls chipped beef now. Dat was somepin' brand new in de way of eatin's den. I et so much I was skeered I warn't gwine to be able to go 'long back to Marse Joe's plantation wid de rest of 'em.

"Old Marster put evvy foot forward to take care of his slaves when dey tuk sick, 'cause dey was his own property. Dey poured asafiddy (asafetida) and pinetop tea down us, and made us take tea of some sort or another for 'most all of de ailments dere was dem days. Slaves wore a nickel or a copper on strings 'round deir necks to keep off sickness. Some few of 'em wore a dime; but dimes was hard to git.

"One game us chillun played was 'doodle.' Us would find us a doodle hole and start callin' de doodle bug to come out. You might talk and talk but if you didn't promise him a jug of 'lasses he wouldn't come up to save your life. One of de songs us sung playin' chilluns games was sorter lak dis:

"Whose been here

Since I been gone?

A pretty little gal

Wid a blue dress on."

"Joy was on de way when us heared 'bout freedom, if us did[Pg 8] have to whisper. Marse Joe had done been kilt in de war by a bomb. Mist'ess, she jus' cried and cried. She didn't want us to leave her, so us stayed on wid her a long time, den us went off to Mississippi to wuk on de railroad.

"Dem Yankees stole evvything in sight when dey come along atter de surrender. Dey was bad 'bout takin' our good hosses and corn, what was $16 a bushel den. Dey even stole our beehives and tuk 'em off wropt up in quilts.

"My freedom was brought 'bout by a fight dat was fit 'twixt two men, and I didn't fight nary a lick myself. Mr. Jefferson Davis thought he was gwine beat, but Mr. Lincoln he done de winnin'. When Mr. Abraham Lincoln come to dis passage in de Bible: 'My son, therefore shall ye be free indeed,' he went to wuk to sot us free. He was a great man—Mr. Lincoln was. Booker Washin'ton come 'long later. He was a great man too.

"De fust school I went to was de Miller O. Field place. Cam King, de teacher, was a Injun and evvywhar he went he tuk his flute 'long wid him.

"Me and my fust wife, Essie Lou Sutton, had a grand weddin', but de white folks tuk her off wid 'em, and I got me a second wife. She was Julia Goulder of Putman County. Us didn't have no big doin's at my second marriage. Our onliest two chillun died whilst dey was still babies."

Asked about charms, ghosts and other superstitions, he patted himself on the chest, and boasted: "De charm is in here. I just dare any witches and ghosties to git atter me. I can see ghosties any time I want to.

"Want me to tell you what happened to me in Gainesville,[Pg 9] Georgia? I was out in de woods choppin' cordwood and I felt somepin' flap at me 'bout my foots. Atter while I looked down, and dere was one of dem deadly snakes, a highland moccasin. I was so weak I prayed to de Lawd to gimme power to kill dat snake, but he didn't. De snake jus' disappeared. I thought it was de Lawd's doin', but I warn't sho'. Den I tuk up my axe and moved over to a sandy place whar I jus' knowed dere warn't no snakes. I started to raise my axe to cut de wood and somepin' told me to look down. I did, and dere was de same snake right twixt my foots again. Den and dere I kilt him, and de Sperrit passed th'oo me sayin': 'You is meaner dan dat snake; you kilt him and he hadn't even bit you.' I knowed for sho' den dat de Lawd was speakin'.

"I was preachin' in Gainesville, whar I lived den, on de Sunday 'fore de tornado in April 1936. Whilst I was in dat pulpit de Sperrit spoke to me and said: 'Dis town is gwine to be 'stroyed tomorrow; 'pare your folks.' I told my congregation what de Sperrit done told me, and dem Niggers thought I was crazy. Bright and early next mornin' I went down to de depot to see de most of my folks go off on de train to Atlanta on a picnic. Dey begged me to go along wid 'em, but I said: 'No, I'se gwine to stay right here. And 'fore I got back home dat tornado broke loose. I was knocked down flat and broke to pieces. Dat storm was de cause of me bein' hitched up in dis here harness what makes me look lak de devil's hoss.

"Tuther night I was a-singin' dis tune: 'Mother how Long 'fore I'se Gwine?' A 'oman riz up and said: 'You done raised de daid.' Den I laughed and 'lowed: 'I knows you is a Sperrit. I'se one too.' At dat she faded out of sight.[Pg 10]

"I think folks had ought to be 'ligious 'cause dat is God's plan, and so I jined de church atter Christ done presented Hisself to me. I'se fixin' now to demand my Sperrit in de Lawd.

"Yes Ma'am, Miss, I knowed you was a-comin'. I had done seed you, writin' wid dat pencil on dat paper, in de Sperrit."

Leah Garrett, an old Negress with snow-white hair leaned back in her rocker and recalled customs and manners of slavery days. Mistreatment at the hands of her master is outstanding in her memory.

"I know so many things 'bout slavery time 'til I never will be able to tell 'em all," she declared. "In dem days, preachers wuz just as bad and mean as anybody else. Dere wuz a man who folks called a good preacher, but he wuz one of de meanest mens I ever seed. When I wuz in slavery under him he done so many bad things 'til God soon kilt him. His wife or chillun could git mad wid you, and if dey told him anything he always beat you. Most times he beat his slaves when dey hadn't done nothin' a t'all. One Sunday mornin' his wife told him deir cook wouldn't never fix nothin' she told her to fix. Time she said it he jumped up from de table, went in de kitchen, and made de cook go under de porch whar he always whupped his slaves. She begged and prayed but he didn't pay no 'tention to dat. He put her up in what us called de swing, and beat her 'til she couldn't holler. De pore thing already had heart trouble; dat's why he put her in de kitchen, but he left her swingin' dar and went to church, preached, and called hisself servin' God. When he got back home she wuz dead. Whenever your marster had you swingin' up, nobody[Pg 13] wouldn't take you down. Sometimes a man would help his wife, but most times he wuz beat afterwards.

"Another marster I had kept a hogshead to whup you on. Dis hogshead had two or three hoops 'round it. He buckled you face down on de hogshead and whupped you 'til you bled. Everybody always stripped you in dem days to whup you, 'cause dey didn't keer who seed you naked. Some folks' chillun took sticks and jobbed (jabbed) you all while you wuz bein' beat. Sometimes dese chillun would beat you all 'cross your head, and dey Mas and Pas didn't know what stop wuz.

"Another way marster had to whup us wuz in a stock dat he had in de stables. Dis wuz whar he whupped you when he wuz real mad. He had logs fixed together wid holes for your feet, hands, and head. He had a way to open dese logs and fasten you in. Den he had his coachman give you so many lashes, and he would let you stay in de stock for so many days and nights. Dat's why he had it in de stable so it wouldn't rain on you. Everyday you got dat same number of lashes. You never come out able to sit down.

"I had a cousin wid two chillun. De oldest one had to nuss one of marster's grandchildren. De front steps wuz real high, and one day dis pore chile fell down dese steps wid de baby. His wife and daughter hollered and went on turrible, and when our marster come home dey wuz still hollerin' just lak de baby wuz dead or dyin'. When dey told him 'bout it, he picked up a board[Pg 14] and hit dis pore little chile 'cross de head and kilt her right dar. Den he told his slaves to take her and throw her in de river. Her ma begged and prayed, but he didn't pay her no 'tention; he made 'em throw de chile in.

"One of de slaves married a young gal, and dey put her in de "Big House" to wuk. One day Mistess jumped on her 'bout something and de gal hit her back. Mistess said she wuz goin' to have Marster put her in de stock and beat her when he come home. When de gal went to de field and told her husband 'bout it, he told her whar to go and stay 'til he got dar. Dat night he took his supper to her. He carried her to a cave and hauled pine straw and put in dar for her to sleep on. He fixed dat cave up just lak a house for her, put a stove in dar and run de pipe out through de ground into a swamp. Everybody always wondered how he fixed dat pipe, course dey didn't cook on it 'til night when nobody could see de smoke. He ceiled de house wid pine logs, made beds and tables out of pine poles, and dey lived in dis cave seven years. Durin' dis time, dey had three chillun. Nobody wuz wid her when dese chillun wuz born but her husband. He waited on her wid each chile. De chillun didn't wear no clothes 'cept a piece tied 'round deir waists. Dey wuz just as hairy as wild people, and dey wuz wild. When dey come out of dat cave dey would run everytime dey seed a pusson.

"De seven years she lived in de cave, diffunt folks helped keep 'em in food. Her husband would take it to a certain[Pg 15] place and she would go and git it. People had passed over dis cave ever so many times, but nobody knowed dese folks wuz livin' dar. Our Marster didn't know whar she wuz, and it wuz freedom 'fore she come out of dat cave for good.

"Us lived in a long house dat had a flat top and little rooms made like mule stalls, just big enough for you to git in and sleep. Dey warn't no floors in dese rooms and neither no beds. Us made beds out of dry grass, but us had cover 'cause de real old people, who couldn't do nothin' else, made plenty of it. Nobody warn't 'lowed to have fires, and if dey wuz caught wid any dat meant a beatin'. Some would burn charcoal and take de coals to deir rooms to help warm 'em. Every pusson had a tin pan, tin cup, and a spoon. Everybody couldn't eat at one time, us had 'bout four different sets. Nobody had a stove to cook on, everybody cooked on fire places and used skillets and pots. To boil us hung pots on racks over de fire and baked bread and meats in de skillets.

"Marster had a big room right side his house whar his vittals wuz cooked. Den de cook had to carry 'em upstairs in a tray to be served. When de somethin' t'eat wuz carried to de dinin' room it wuz put on a table and served from dis table. De food warn't put on de eatin' table.

"De slaves went to church wid dey marsters. De preachers always preached to de white folks first, den dey would preach to de slaves. Dey never said nothin' but you must be good, don't steal, don't talk back at your marsters, don't run away, don't[Pg 16] do dis, and don't do dat. Dey let de colored preachers preach but dey give 'em almanacs to preach out of. Dey didn't 'low us to sing such songs as 'We Shall Be Free' and 'O For a Thousand Tongues to Sing'. Dey always had somebody to follow de slaves to church when de colored preacher was preachin' to hear what wuz said and done. Dey wuz 'fraid us would try to say something 'gainst 'em."

Her story: "I was a small girl when the Civil War broke out, but I remember it distinctly. I also remember the whisperings among the slaves—their talking of the possibility of freedom.

"My father was a very large, powerful man. During his master's absence, in '63 or '64, a colored foreman on the Hines Holt place once undertook to whip him; but my father wouldn't allow him to do it. This foreman then went off and got five big buck Negroes to help him whip father, but all six of them couldn't 'out-man' my daddy! Then this foreman shot my daddy with a shot-gun, inflicting wounds from which he never fully recovered.

"In '65, another Negro foreman whipped one of my little brothers. This foreman was named Warren. His whipping my brother made me mad and when, a few days later, I saw some men on horseback whom I took to be Yankees, I ran to them and told them about Warren—a common Negro slave—whipping my brother. And they said, 'well, we will see Warren about that.' But Warren heard[Pg 18] them and took to his heels! Yes, sir, he flew from home, and he didn't come back for a week! Yes, sir, I sholy scared that Negro nearly to death!

"My father's father was a very black, little, full-blooded, African Negro who could speak only broken English. He had a son named Adam, a brother of my father, living at Lochapoka, Ala. In 1867, after freedom, this granpa of mine, who was then living in Macon, Georgia, got mad with his wife, picked up his feather bed and toted it all the way from Macon to Lochapoka! Said he was done with grandma and was going to live with Adam. A few weeks later, however, he came back through Columbus, still toting his feather bed, returning to grandma in Macon. I reckon he changed his mind. I don't believe he was over five feet high and we could hardly understand his talk.

"Since freedom, I have lived in Mississippi and other places, but most of my life has been spent right in and around Columbus. I have had one husband and no children. I became a widow about 35 years ago, and I have since remained one because I find that I can serve God better when I am not bothered with a Negro man."

Mary Gladdy claims to have never attended school or been privately taught in her life. And she can't write or even form the letters of the alphabet, but she gave her interviewer a very convincing demonstration of her ability to read. When asked how she mastered the art of reading, she replied: "The Lord revealed it to me."

For more than thirty years, the Lord has been revealing his work, and many other things, to Mary Gladdy. For more than twenty[Pg 19] years, she has been experiencing "visitations of the spirit". These do not occur with any degree of regularity, but they do always occur in "the dead hours of the night" after she has retired, and impel her to rise and write in an unknown hand. These strange writings of her's now cover eight pages of letter paper and bear a marked resemblance to crude shorthand notes. Off-hand, she can "cipher" (interpret or translate) about half of these strange writings; the other half, however, she can make neither heads nor tails of except when the spirit is upon her. When the spirit eases off, she again becomes totally ignorant of the significance of that mysterious half of her spirit-directed writings.

"Aunt" Mary appears to be very well posted on a number of subjects. She is unusually familiar with the Bible, and quotes scripture freely and correctly. She also uses beautiful language, totally void of slang and Negro jargon, "big" words and labored expressions.

She is a seventh Day Adventist; is not a psychic, but is a rather mysterious personage. She lives alone, and ekes out a living by taking in washing. She is of the opinion that "we are now living in the last days"; that, as she interprets the "signs", the "end of time" is drawing close. Her conversion to Christianity was the result of a hair-raising experience with a ghost—about forty years ago, and she has never—from that day to this—fallen from grace for as "long as a minute".

To know "Aunt" Mary is to be impressed with her utter sincerity and, to like her. She is very proud of one of her grandmothers, Edie Dennis, who lived to be 110 years old, and concerning whom a reprint from the Atlanta Constitution of November 10, 1900, is appended. Her story of Chuck, and the words of two spirituals and one slave canticle which "Aunt" Mary sang for her interviewer, are also appended.

Quite a remarkable case of longevity is had in the person of Edie Dennis, a colored woman of Columbus, who has reached the unusual age of 109 years of age and is still in a state of fair health.

Aunt Edie lives with two of her daughters at No. 1612 Third Avenue, in this city. She has lived in three centuries, is a great-great grandmother and has children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren and great-great-grandchildren, aggregating in all over a hundred persons. She lives with one of her "young" daughters, sixty-six.

Edie Dennis is no doubt one of the oldest persons living in the United States. Cases are occasionally reported where 105 years is reached, but 109 years is an age very seldom attained. A wonderful feature of this case is that this old woman is the younger sister of another person now living. Aunt Edie has a brother living at Americus, Georgia, who is 111 years old.

Notwithstanding her great age, Aunt Edie is in fairly good health. She is naturally feeble and her movements are limited. Even in her little home, from which she never stirs. Although she is feeble, her faculties seem clear and undimmed and she talked interestingly and intelligently to[Pg 21] a Constitution reporter who called upon her recently.

Aunt Edie was born in 1791, just eight years before the death of George Washington occurred. She was a mother when the war of 1812 took place. The establishment of Columbus as a city was an event of her mature womanhood. The Indian War of the thirties she recalls very distinctly. She was getting old when the Mexican War took place. She was an old woman when the great conflict between the states raged. She was seventy-five years of age when she became free.

It is quite needless to say that Aunt Edie was a slave all her life up to the year 1866. She was born in Hancock County, Georgia, between Milledgeville and Sparta. She was the property of Thomas Schlatter. She came to Columbus just after the town had been laid off, when she was a comparatively young woman. She became the property of the family of Judge Hines Holt, the distinguished Columbus lawyer. She says that when she first came here there was only a small collection of houses. Where her present home was located was then nothing but swamp land. The present location of the court house was covered with a dense woods. No event in those early years impressed itself more vividly upon Aunt Edie's mind than the Indian War, in the thirties. She was at the home of one of the Indians when she first heard of the uprising against the whites, and she frankly says that she was frightened almost to death when she listened to the cold-blooded plots to exterminate the white people. Not much attention was paid to her on account of her being a Negro. Those were very thrilling times and Aunt Edie confesses that she was exceedingly glad when the troubles with the red men were over. Another happening of the thirties which Aunt Edie recalls quite distinctly is the falling of the stars. She says quaintly that there was more religion that year in Georgia than there ever was before or has been since. The wonderful manner in which the stars shot across the heavens by the thousands, when every sign seemed to point to the destruction of the earth, left a lasting impression upon her brain.

Aunt Edie says that she was kindly treated by her masters. She says that they took interest in the spiritual welfare of their slaves and that they were called in for prayer meeting regularly. Aunt Edie was such an old woman when she was freed that the new condition meant very little change in life for her, as she had about stopped[Pg 22] work, with the exception of light tasks about the house.

There seems to be no doubt that Aunt Edie is 109 years old. She talks intelligently about things that occurred 100 years ago. All her children, grandchildren, etc., asserts that her age is exactly as stated. Indeed, they have been the custodians of her age, so to speak, for nearly half a century. It was a matter of great interest to her family when she passed the 100 mark.

Aunt Edie is religious and she delights in discussing scriptural matters. She has practical notions, however, and while she is morally sure she will go to a better world when she dies, she remarks, "That we know something about this world, but nothing about the next."

Perhaps this is one reason why Aunt Edie has stayed here 109 years.

NOTE: Mary Gladdy (806½ - Sixth Avenue, Columbus, Georgia). A grand-daughter of Edie Dennis, states that her grandmother died in 1901, aged 110.

Chuck was a very intelligent and industrious slave, but so religious that he annoyed his master by doing so much praying, chanting, and singing.

So, while in a spiteful mood one day, this master sold the Negro to an infidel. And this infidel, having no respect for religion whatsoever, beat Chuck unmercifully in an effort to stop him from indulging in his devotions. But, the more and the harder the infidel owner whipped Chuck, the more devout and demonstrative the slave became.[Pg 23]

Finally, one day, the infidel was stricken ill unto death; the wicked man felt that his end was near and he was afraid to die. Moreover, his conscience rebuked him for his cruel treatment of this slave. The family doctor had given the infidel up: the man apparently had but a few hours to live. Then, about 8 o'clock at night, the dying man asked his wife to go down in the slave quarter and ask Chuck if he would come to his bedside and pray for him.

The white lady went, as requested, and found Chuck on his knees, engaged in prayer.

"Chuck", she called, "your master is dying and has sent me to beg you to come and pray for him."

"Why, Maddom", replied Chuck, "I has been praying fer Marster tonight—already, and I'll gladly go with you."

Chuck then went to his Master's bed side and prayed for him all night, and the Lord heard Chuck's prayers, and the white man recovered, was converted, joined the church, and became an evangelist. He also freed Chuck and made an evangelist of him. Then the two got in a buggy and, for years, traveled together all over the country, preaching the gospel and saving souls.

NOTE: Mary Gladdy believes this to be a true story, though she knew neither the principals involved, nor where nor when they lived and labored. She says that the story has been "handed down", and she once saw it printed in, and thus confirmed by, a Negro publication—long after she had originally heard it.[Pg 24]

Fire, fire, O, keep the fire burning while your soul's fired up.

O, keep the fire burning while your soul's fired up;

Never mind what satan says while your soul's fired up.

You ain't going to learn how to watch and pray,

Less you keep the fire burning while your soul's fired up.

Old Satan is a liar and a cunjorer, too;

If you don't mind, he'll cunjor you;

Keep the fire burning while your soul's fired up.

Never mind what satan says while, your soul's fired up.

Sung for interviewer by:

Mary Gladdy, Ex-slave,

806½ - Sixth Avenue,

Columbus, Georgia.

December 17, 1936.

[Pg 25]

Never seen the like since I've been born,

The people keep a-coming, and the train's done gone;

Too late, too late, the train's done gone,

Too late, sinner, too late, the train's done gone;

Never seen the like since I've been born,

The people keep a-coming, and the train's done gone;

Too late, too late, the train's done gone.

Went down into the valley to watch and pray,

My soul got happy and I stayed all day;

Too late, too late, the train's done gone;

Too late, sinner, too late, the train's done gone;

Never seen the like since I've been born,

The people keep a-coming and the train's done gone.

Too late, too late, the train's done gone.

[Pg 26]

Sung for interviewer by:

Mary Gladdy, ex-slave,

806½ - 6th Avenue,

Columbus, Georgia,

December 17, 1936

My sister, I feels 'im, my sister I feels 'im;

All night long I've been feelin 'im;

Jest befoe day, I feels 'im, jest befoe day I feels 'im;

The sperit, I feels 'im, the sperit I feels 'im!

My brother, I feels 'im, my brother, I feels 'im;

All night long I've been feelin 'im,

Jest befoe day, I feels 'im, jest befoe day, I feel 'im;

The sperit, I feels 'im!

According to Mary Gladdy, ex-slave, 806½ - 6th Avenue, Columbus, Georgia, it was customary among slaves during the Civil War period to secretly gather in their cabins two or three nights each week and hold prayer and experience meetings. A large, iron pot was always placed[Pg 27] against the cabin door—sideways, to keep the sound of their voices from "escaping" or being heard from the outside. Then, the slaves would sing, pray, and relate experiences all night long. Their great, soul-hungering desire was freedom—not that they loved the Yankees or hated their masters, but merely longed to be free and hated the institution of slavery.

Practically always, every Negro attendant of these meetings felt the spirit of the Lord "touch him (or her) just before day". Then, all would arise, shake hands around, and begin to chant the canticle above quoted. This was also a signal for adjournment, and, after chanting 15 or 20 minutes, all would shake hands again and go home—confident in their hearts that freedom was in the offing for them.

Sarah Gray is an aged ex-slave, whose years have not only bent her body but seem to have clouded her memory. Only a few facts relating to slavery could, therefore, be learned from her. The events she related, however, seemed to give her as much pleasure as a child playing with a favorite toy.

The only recollection Sarah has of her mother is seeing her as she lay in her coffin, as she was very young when her mother died. She remembers asking her sisters why they didn't give her mother any breakfast.

Sarah's master was Mr. Jim Nesbit, who was the owner of a small plantation in Gwinnett County. The exact number of slaves on the plantation were not known, but there were enough to carry on the work of plowing, hoeing and chopping the cotton and other crops. Women as well as men were expected to turn out the required amount of work, whether it was picking cotton, cutting logs, splitting rails for fences or working in the house.

Sarah was a house slave, performing the duties of a maid. She was often taken on trips with the mistress, and treated more as one of the Nesbit family than as a slave. She remarked, "I even ate the same kind of food as the master's family."

The Nesbits, according to Sarah, followed the customary practice of the other slave owners in the matter of the punishment of slaves. She says, however, that while there were stories of some very cruel masters, in her opinion the slave owners of those days were not as cruel as some people today. She said occasionally slave owners appointed some of the slaves as overseers, and very often these slave-overseers were very cruel.[Pg 30]

When the war began, the Nesbits and other plantation owners grouped together, packed their wagons full of supplies, took all of their slaves, and started on a journey as refugees. They had not gone very far when a band of Yankee soldiers overtook them, destroyed the wagons, took seventy of the men prisoners and marched off taking all of the horses, saying they were on their way to Richmond and when they returned there would be no more masters and slaves, as the slaves would be freed. Some of the slaves followed the Yankees, but most of them remained with their masters' families.

They were not told of their freedom immediately on the termination of the war, but learned it a little later. As compensation, Mr. Nesbit promised them money for education. She declares, however, that this promise was never fulfilled.

Sarah Gray's recollections of slavery, for the most part, seem to be pleasant. She sums it up in the statement, "In spite of the hardships we had to go through at times, we had a lot to be thankful for. There were frolics, and we were given plenty of good food to eat, especially after a wedding."

The aged ex-slave now lives with a few distant relatives. She is well cared for by a family for whom she worked as a nurse for 35 years, and she declares that she is happy in her old age, feeling that her life has been usefully spent.

Alice Green's supposed address led the interviewer to a cabin with a padlocked front door. A small Negro girl who was playing in the adjoining yard admitted, after some coaxing, that she knew where Alice could be found. Pointing down the street, she said: "See dat house wid de sheet hangin' out in front. Dat's whar Aunt Alice lives now." A few moments later a rap on the door of the house designated was answered by a small, slender Negress.

"Yes Mam, I'm Alice Green," was her solemn response to the inquiry. She pondered the question of an interview for a moment and then, with unsmiling dignity, bade the visitor come in and be seated. Only one room of the dilapidated two-room shack was usable for shelter and this room was so dark that lamplight was necessary at 10:00 o'clock in the morning. Her smoking oil lamp was minus its chimney.

A Negro child about two or three years old was Alice's sole companion. "I takes keer of little Sallie Mae whilst her Mammy wuks at a boardin' house," she explained. "She's lots of company for me.

"Charles and Milly Green was my daddy and mammy. Daddy's overseer was a man named Green, and dey said he was a powerful mean sort of man. I never did know whar it was dey lived when Daddy was borned. Mammy's marster was a lawyer dat[Pg 33] dey called Slickhead Mitchell, and he had a plantation at Helicon Springs. Mammy was a house gal and she said dey treated her right good. Now Daddy, he done field work. You know what field work is, hoein', plowin', and things lak dat. When you was a slave you had to do anything and evvything your marster told you to. You was jus' 'bliged to obey your marster no matter what he said for you to do. If you didn't, it was mighty bad for you. My two oldest sisters was Fannie and Rena. Den come my brothers, Isaac and Bob, and my two youngest sisters, Luna and Violet. Dere was seven of us in all.

"Slaves lived in rough little log huts daubed wid mud and de chimblys was made out of sticks and red mud. Mammy said dat atter de slaves had done got through wid deir day's work and finished eatin' supper, dey all had to git busy workin' wid cotton. Some carded bats, some spinned and some weaved cloth. I knows you is done seen dis here checkidy cotton homespun—dat's what dey weaved for our dresses. Dem dresses was made tight and long, and dey made 'em right on de body so as not to waste none of de cloth. All slaves had was homespun clothes and old heavy brogan shoes.

"You'll be s'prised at what Mammy told me 'bout how she got her larnin'. She said she kept a school book hid in her bosom all de time and when de white chillun got home from school[Pg 34] she would ax 'em lots of questions all 'bout what dey had done larned dat day and, 'cause she was so proud of evvy little scrap of book larnin' she could pick up, de white chillun larned her how to read and write too. All de larnin' she ever had she got from de white chillun at de big house, and she was so smart at gittin' 'em to larn her dat atter de war was over she got to be a school teacher. Long 'fore dat time, one of dem white chillun got married and tuk Mammy wid her to her new home at Butler, Georgia.

"Now my daddy, he was a plum sight sho' 'nough. He said dat when evvythin' got still and quiet at night he would slip off and hunt him up some 'omans. Patterollers used to git atter him wid nigger hounds and once when dey cotch him he said dey beat him so bad you couldn't lay your hand on him nowhar dat it warn't sore. Dey beat so many holes in him he couldn't even wear his shirt. Most of de time he was lucky enough to outrun 'em and if he could jus' git to his marster's place fust dey couldn't lay hands on him. Yes Mam, he was plenty bad 'bout runnin' away and gittin' into devilment.

"Daddy used to talk lots 'bout dem big cornshuckin's. He said dat when dey got started he would jump up on a big old pile of corn and holler loud as he could whilst he was a snatchin' dem shucks off as fast as greased lightin'.[Pg 35]

"When Mammy was converted she jined the white folks church and was baptized by a white preacher 'cause in dem days slaves all went to de same churches wid deir marster's famblies. Dere warn't no separate churches for Negroes and white people den.

"I warn't no bigger dan dis here little Sallie Mae what stays wid me when de War ended and dey freed de slaves. A long time atter it was all over, Mammy told me 'bout dat day. She said she was in de kitchen up at de big house a-cookin' and me and my sisters was out in de yard in de sandbed a-playin' wid de little white chillun when dem yankee sojers come. Old Miss, she said to Mammy: 'Milly, look yonder what's a-comin'. I ain't gwine to have nothin' left, not even a nickels worth, 'cause dere comes dem yankees.' Dey rid on in de yard, dem sojers what wore dem blue jackets, and dey jus' swarmed all over our place. Dey even went in our smokehouse and evvywhar and took whatever dey wanted. Dey said slaves was all freed from bondage and told us to jus' take anything and evvything us wanted from de big house and all 'round de plantation whar us lived. Dem thievin' sojers even picked up one of de babies and started off wid it, and den Old Miss did scream and cry for sho'. Atter dey had done left, Old Miss called all of us together and said she didn't want none of us to leave her and so us stayed wid her a whole year atter freedom had done come.[Pg 36]

"Not many slaves had a chance to git property of deir own for a long time 'cause dey didn't have no money to buy it wid. Dem few what had land of deir own wouldn't have had it if deir white folks hadn't give it to 'em or holp 'em to git it. My uncle, Carter Brown, had a plenty 'cause his white folks holped him to git a home and 'bout evvything else he wanted. Dem Morton Negroes got ahead faster dan most any of de others 'round here but dey couldn't have done it if deir white folks hadn't holped 'em so much.

"Soon as I got big enough, I started cookin' for well-off white folks. Fact is, I ain't never cooked for no white folks dat didn't have jus' plenty of money. Some of de white folks what has done et my cookin' is de Mitchells, Upsons, Ruckers, Bridges, and Chief Seagraves' fambly. I was cookin' for Chief Buesse's mammy when he was jus' a little old shirttail boy. Honey, I allus did lak to be workin' and I have done my share of it, but since I got so old I ain't able to do much no more. My white folks is mighty good to me though.

"Now Honey, you may think it's kind of funny but I ain't never been much of a hand to run 'round wid colored folks. My mammy and my white folks dey raised me right and larned me good manners and I'm powerful proud of my raisin'. I feels lak now dat white folks understands me better and 'preciates me more.[Pg 37]"

Why, jus' listen to dis! When Mr. Weaver Bridges told me his mother had done died, he axed me did I want to go to the funeral and he said he was goin' to take me to de church and graveyard too, and sho' 'nough dey did come and git me and carry me 'long. I was glad dey had so many pretty flowers at Mrs. Bridges' funeral 'cause I loved her so much. She was a mighty sweet, good, kind 'oman.

"All my folks is dead now 'cept me and my chillun, Archie, Lila, and Lizzie. All three of 'em is done married now. Archie, he's got a house full of chillun. He works up yonder at de Georgian Hotel. I loves to stay in a little hut off to myself 'cause I can tell good as anybody when my chillun and in-laws begins to look cross-eyed at me so I jus' stays out of deir way.

"I'm still able to go to church and back by myself pretty reg'lar. 'Bout four years ago I jined Hill's Baptist Church. Lak to a got lost didn't I? If I had stayed out a little longer it would have been too late, and I sho' don't want to be lost."

Alice Green's address led to a tumble down shack set in a small yard which was enclosed by a sagging poultry wire fence. The gate, off its hinges, was propped across the entrance.

The call, "Alice!" brought the prompt response, "Here I is. Jus' push de gate down and come on in." When a little rat terrier ran barking out of the house to challenge the visitor, Alice hobbled to the door. "Come back here and be-have yourself" she addressed the dog, and turning to the interviewer, she said: "Lady, dat dog won't bite nothin' but somepin' t'eat—when he kin git it." Don't pay him no 'tention. Won't you come in and have a seat?"

Alice has a light brown complexion and bright blue eyes. She wore a soiled print dress, and a dingy stocking cap partly concealed her white hair. Boards were laid across the seat of what had been a cane-bottomed chair, in which she sat and rocked.

Asked if she would talk of her early life the old Negress replied: "Good Lord! Honey, I done forgot all I ever knowed 'bout dem days. I was born in Clarke County. Milly and Charley Green was my mammy and pappy and dey b'longed to Marse Daniel Miller. Mammy, she was born and raised in Clarke County but my pappy, he come from southwest Georgia. I done forgot de town whar he was brung up. Dere[Pg 40] was seven of us chillun: me and Viola, Lula, Fannie, Rene, Bob, and Isaac. Chillun what warn't big 'nough to wuk in de fields or in de house stayed 'round de yard and played in de sand piles wid de white chillun.

"Slaves lived in mud-daubed log huts what had chimblies made out of sticks and mud. Lordy Honey! Dem beds was made wid big high posties and strung wid cords for springs. Folks never had no wire bedsprings dem days. Our mattresses was wheat straw put in ticks made out of coarse cloth what was wove on de loom right dar on de plantation.

"I don't know nothin' 'bout what my grandmammies done in slav'ry time. I never seed but one of 'em, and don't 'member much 'bout her. I was jus' so knotty headed I never tuk in what went on 'cause I never 'spected to be axed to tell 'bout dem days.

"Money! Oh-h-h, no Ma'am! I never seed no money 'til I was a great big gal. My white folks was rich and fed us good. Dey raised lots of hogs and give us plenty of bread and meat wid milk and butter and all sorts of vegetables. Marster had one big garden and dere warn't nobody had more good vegetables den he fed to his slaves. De cookin' was done in open fireplaces and most all de victuals was biled or fried. Us had all de 'possums, squirrels, rabbits, and fish us wanted cause our marster let de mens go huntin' and fishin' lots.[Pg 41]

"Us jus' wore common clothes. Winter time dey give us dresses made out of thick homespun cloth. De skirts was gathered on to tight fittin' waisties. Us wore brass toed brogan shoes in winter, but in summer Niggers went bar'foots. Us jus' wore what us could ketch in summer. By dat time our winter dresses had done wore thin and us used 'em right on through de hot weather.

"Marse Daniel Miller, he was some kinder good to Mammy, and Miss Susan was good to us too. Now Honey, somehow I jus' cain't 'member deir chilluns names no more. And I played in de sand piles all day long wid 'em too.

"Oh-h-h! Dat was a great big old plantation, and when all dem Niggers got out in de fields wid horses and wagons, it looked lak a picnic ground; only dem Niggers was in dat field to wuk and dey sho' did have to wuk.

"Marster had a carriage driver to drive him and Ole Miss 'round and to take de chillun to school. De overseer, he got de Niggers up 'fore day and dey had done et deir breakfast, 'tended to de stock, and was in de field by sunup and he wuked 'em 'til sundown. De mens didn't do no wuk atter dey got through tendin' to de stock at night, but Mammy and lots of de other 'omans sot up and spun and wove 'til 'leven or twelve o'clock lots of nights.

"My pappy was a man what b'lieved in havin' his fun and he would run off to see de gals widout no pass. Once when he slipped off[Pg 42] dat way de patterollers sicked dem nigger hounds on him and when dey cotched him dey most beat him to death; he couldn't lay on his back for a long time.

"If dey had jails, I didn't know nothin' 'bout 'em. De patterollers wid deir nigger hounds made slaves b'have deirselfs widout puttin' 'em in no jails. I never seed no Niggers sold, but Mammy said her and her whole fambly was sold on de block to de highes' bidder and dat was when Ole Marster got us.

"Mammy, she was de cook up at de big house, and when de white chillun come back from school in de atternoon she would ax 'em to show her how to read a little book what she carried 'round in her bosom all de time, and to tell her de other things dey had larn't in school dat day. Dey larned her how to read and write, and atter de War was over Mammy teached school and was a granny 'oman (midwife) too.

"Dey made us go to church on Sundays at de white folks church 'cause dere warn't no church for slaves on de plantation. Us went to Sunday School too. Mammy jined de white folks church and was baptized by de white preacher. He larnt us to read de Bible, but on some of de plantations slaves warn't 'lowed to larn how to read and write. I didn't have no favorite preacher nor song neither, but Mammy had one song what she sung lots. It was 'bout 'Hark from de Tombs a Doleful Sound.' I never seed nobody die and I never went to no buryin' durin' slav'ry time, so I cain't tell nothin' 'bout things lak dat.[Pg 43]

"Lordy Honey! How could dem Niggers run off to de North when dem patterollers and deir hounds was waitin' to run 'em down and beat 'em up? Now some of de slaves on other places might have found some way to pass news 'round but not on Ole Marster's place. You sho' had to have a pass 'fore you could leave dat plantation and he warn't goin' to give you no pass jus' for foolishment. I never heared tell of no uprisin's twixt white folks and Niggers but dey fussed a-plenty. Now days when folks gits mad, dey jus' hauls off and kills one another.

"Atter slaves got through deir wuk at night, dey was so tired dey jus' went right off to bed and to sleep. Dey didn't have to wuk on Sadday atter dinner, and dat night dey would pull candy, dance, and frolic 'til late in de night. Dey had big times at cornshuckin's and log rollin's. My pappy, he was a go-gitter; he used to stand up on de corn and whoop and holler, and when he got a drink of whiskey in him he went hog wild. Dere was allus big eatin's when de corn was all shucked.

"Christmas warn't much diffunt from other times. Us chillun had a heap of fun a-lookin' for Santa Claus. De old folks danced, quilted, and pulled candy durin' de Christmastime. Come New Year's Day, dey all had to go back to wuk.

"What for you wants to know what I played when I was a little gal? Dat was a powerful long time ago. Us played in de sand piles, jumped rope, played hide and seek and Old Mother Hubbard."[Pg 44]

At this time a little girl, who lives with Alice, asked for a piece of bread. She got up and fed the child, then said: "Come in dis here room. I wants to show you whar I burned my bed last night tryin' to kill de chinches: dey most eats me up evvy night." In the bedroom an oil lamp was burning. The bed and mattress showed signs of fire. The mattress tick was split from head to foot and cotton spilling out on the floor. "Dat's whar I sleep," declared Alice. The atmosphere of the bedroom was heavy with nauseous odors and the interviewer hastened to return to the front of the house desiring to get out of range of the chinch-ridden bed. Before there was time to resume conversation the terrier grabbed the bread from the child's hand and in retaliation the child bit the dog on the jaw and attempted to retrieve the bread. Alice snatched off her stocking cap and beat at the dog with it. "Git out of here, Biddy. I done told you and told you 'bout eatin' dat chile's somepin t'eat. I don't know why Miz. Woods gimme dis here dog no how, 'cause she knows I can't feed it and it's jus' plum starvin'. Go on out, I say.

"Lordy! Lady, dar's one of dem chinches from my bed a-crawlin' over your pretty white dress. Ketch him quick, 'fore he bites you." Soon the excitement was over and Alice resumed her story.

"Dey tuk mighty good care of slaves when dey got sick. Dey had to, 'cause slaves was propity and to let a slave die was to lose money. Ole Miss, she looked atter de 'omans and Ole Marster, he had de doctor[Pg 45] for de mens. I done forgot most of what dey made us take. I know dey made us wear assfiddy (asafetida) sacks 'round our necks, and eat gumgoo wax. Dey rubbed our heads wid camphor what was mixed wid whiskey. Old folks used to conjure folks when dey got mad at 'em. Dey went in de woods and got certain kinds of roots and biled 'em wid spider webs, and give 'em de tea to drink.

"One day us chillun was playin' in de sand pile and us looked up and seed a passel of yankees comin'. Dere was so many of 'em it was lak a flock of bluebirds. 'Fore dey left some folks thought dey was more lak blue devils. My mammy was in de kitchen and Ole Miss said: 'Look out of dat window, Milly; de yankees is comin' for sho' and dey's goin' to free you and take you and your chillun 'way from me. Don't leave me! Please don't leave me, Milly!' Dem yankees swarmed into de yard. Dey opened de smokehouse, chicken yard, corncrib, and evvything on de place. Dey tuk what dey wanted and told us de rest was ours to do what us pleased wid. Dey said us was free and dat what was on de plantation b'longed to us, den dey went on off and us never seed 'em no more.

"When de War was over Ole Miss cried and cried and begged us not to leave her, but us did. Us went to wuk for a man on halves. I had to wuk in de field 'til I was a big gal, den I went to wuk for rich white folks. I ain't never wuked for no pore white folks in my whole life.

"It was a long time 'fore Niggers could buy land for deirselfs 'cause dey had to make de money to buy it wid. I couldn't rightly say when[Pg 46] schools was set up for de Niggers. It was all such a long time ago, and I never tuk it in nohow.

"I don't recollect when I married George Huff or what I wore dat day. Didn't live wid him long nohow. I warn't goin' to live wid no man what sot 'round and watched me wuk. Mammy had done larnt me how to wuk, and I didn't know nothin' else but to go ahead and wuk for a livin'. I don't know whar George is. He might be dead for all I know; if he ain't, he ought to be. I got three chillun. Two of 'em is gals, Lizzie and Lila, and one is a boy. My oldest gal, she lives in Atlanta." She ignored the question as to where her other daughter lives. "My son wuks at de Georgian Hotel. But understand now, dem ain't George Huff's chillun. Deir pappy was my sweetheart what got into trouble and runned away. I ain't gwine to tell his name.

"Honey, I jus' tell you de truth; de reason why I jined de church was 'cause I was a wild gal, and dere warn't nothin' too mean for me to do for a long time. Mammy and my sisters kept on beggin' me to change my way of livin', but I didn't 'til four years ago. I got sick and thought I was goin' to die, and den I begged de good Lord to forgive me and promised Him if He would let me git well 'nough to git out of dat bed, I would change and do good de rest of my life. When I was able to git up, I jined de church. I didn't mean to burn in hell lak de preachers said I would. I thinks evvybody ought to jine de church and live right.

"Oh-h-h! Lady, I sho' do thank you for dis here dime. I'm gwine to buy me some meat wid it. I ain't had none dis week. My white folks is mighty good to me, but Niggers don't pay me no mind.[Pg 47]

"Has you axed me all you wants to? I sho' is glad 'cause I ain't had nothin' t'eat yit." She pulled down her stocking to tie the coin in its top and revealed an expanse of sores from ankle to knee. A string was tied above each knee. "A white lady told me dem strings soaked in kerosene would drive out de misery from my laigs," Alice explained. "Goodbye Honey, and God bless you."

Isaiah Green, an ex-slave, still has a clear, agile mind and an intelligent manner. With his reddish brown complexion, straight hair, and high cheek bones, he reminds you of an old Indian Chief, and he verifies the impression by telling you that his grandfather was a full blooded Indian.

Isaiah Green was born in 1856 at Greensboro, Ga. Cleary Mallory Willis and Bob Henderson were his parents, but he did not grow up knowing the love and care of a father, for his father was sold from his mother when he was only two years. Years later, his mother lost track of his father and married again. There were eleven children and Isaiah was next to the youngest.

His master was Colonel Dick Willis, who with his wife "Miss Sally" managed a plantation of 3,000 acres of land and 150 slaves. Col. Willis had seven children, all by a previous marriage. Throughout the State he was known for his wealth and culture. His plantation extended up and down the Oconee River.

His slave quarters were made up of rows of 2-room log cabins with a different family occupying each room. The fireplaces were built three and four feet in length purposely for cooking. The furniture, consisting of a bed, table, and chair, was made from pine wood and kept clean by scouring with sand. New mattresses and pillows were made each spring from wheat straw.

Old Uncle Peter, one of the Willis slaves, was a skilled carpenter and would go about building homes for other plantation owners. Sometimes he was gone as long as four or five months.[Pg 50]

Every two weeks, rations of meal, molasses and bacon were given each slave family in sufficient quantity. The slaves prepared their own meals, but were not allowed to leave the fields until noon. A nursing mother, however, could leave between times.

Large families were the aim and pride of a slave owner, and he quickly learned which of the slave women were breeders and which were not. A slave trader could always sell a breeding woman for twice the usual amount. A greedy owner got rid of those who didn't breed. First, however, he would wait until he had accumulated a number of undesirables, including the aged and unruly.

There was an old slave trader in Louisiana by the name of Riley who always bought this type of slave, and re-sold them. When ready to sell, a slave owner notified him by telegram. When Riley arrived, the slaves were lined up, undressed and closely inspected. Too many scars on the body meant a "bad slave" and no one would be anxious to purchase him.

Green related the story of his grand mother Betsy Willis. "My grandmother was half white, since the master of the plantation on which she lived was her father." He wished to sell her, and when she was placed on the block he made the following statement: "I wish to sell a slave who is also my daughter. Before anyone can purchase her, he must agree not to treat her as a slave but as a free person. She is a good midwife and can be of great service to you." Col. Dick Willis was there, and in front of everyone signed the papers.

The Willis plantation was very large and required many workers. There were 75 plow hands alone, excluding those who were required to do the hoeing. Women as well as men worked in the fields. Isaiah Green declares that his mother could plow[Pg 51] as well as any man. He also says that his work was very easy in the spring. He dropped peas into the soft earth between the cornstalks, and planted them with his heel. Cotton, wheat, corn, and all kinds of vegetables made up the crops. A special group of women did the carding and spinning, and made the cloth on two looms. All garments were made from this homespun cloth. Dyes from roots and berries were used to produce the various colors. Red elm berries and a certain tree bark made one kind of dye.

Besides acting as midwife, Green's grandmother Betsy Willis, was also a skilled seamstress and able to show the other women different points in the art of sewing. Shoes were given to the slaves as often as they were needed. Green's step-father was afflicted and could not help with the work in the field. Since he was a skilled shoe maker his job was to make shoes in the winter. In summer, however, he was required to sit in the large garden ringing a bell to scare away the birds.

Col. Willis was a very kind man, who would not tolerate cruel treatment to any of his slaves by overseers. If a slave reported that he had been whipped for no reason and showed scars on his body as proof, the overseer was discharged. On the Willis Plantation were 2 colored men known as "Nigger Drivers." One particularly, known as "Uncle Jarrett," was very mean and enjoyed exceeding the authority given by the master. Green remarked, "I was the master's pet. He never allowed anyone to whip me and he didn't whip me himself. He was 7-ft. 9 in. tall and often as I walked with him, he would ask, "Isaiah, do you love your old master?' Of course I would answer, yes, for I did love him."

Col. Willis did not allow the "patterrollers" to interfere with any of his slaves. He never gave them passes, and if any were caught out without one the "patterrollers" were afraid[Pg 52] to whip them.

Mr. John Branch was considered one of the meanest slave owners in Green County, and the Negroes on his plantation were always running away. Another slave owner known for his cruelty was Colonel Calloway, who had a slave named Jesse who ran away and stayed 7 years. He dug a cave in the ground and made fairly comfortable living quarters. Other slaves who no longer could stand Col. Calloway's cruelty, would join him. Jesse visited his wife, Lettie, two and three times a week at night. Col. Calloway could never verify this, but became suspicious when Jesse's wife gave birth to two children who were the exact duplicate of Jesse. When he openly accused her of knowing Jesse's whereabouts, she denied the charges, pretending she had not seen him since the day he left.

When the war ended, Jesse came to his old master and told him he had been living right on the plantation for the past 7 years. Col. Calloway was astonished; he showed no anger toward Jesse, however, but loaned him a horse and wagon to move his goods from the cave to his home.

There were some owners who made their slaves steal goods from other plantations and hide it on theirs. They were punished by their master, however, if they were caught.

Frolics were held on the Willis plantation as often as desired. It was customary to invite slaves from adjoining plantations, but if they attended without securing a pass from their master, the "patterrollers" could not bother them so long as they were on the Willis plantation. On the way home, however, they were often caught and beaten.[Pg 53]

In those days there were many Negro musicians who were always ready to furnish music from their banjo and fiddle for the frolics. If a white family was entertaining, and needed a musician but didn't own one, they would hire a slave from another plantation to play for them.

Col. Willis always allowed his slaves to keep whatever money they earned. There were two stills on the Willis plantation, but the slaves were never allowed to drink whiskey at their frolics. Sometimes they managed to "take a little" without the master knowing it.

On Sunday afternoons, slaves were required to attend white churches for religious services, and over and over again the one sermon drummed into their heads was, "Servants obey your mistress and master; you live for them. Now go home and obey, and your master will treat you right." If a slave wished to join the church, he was baptized by a white minister.

The consent of both slave owners was necessary to unite a couple in matrimony. No other ceremony was required. If either master wished to sell the slave who married, he would name the price and if it was agreeable to the other, the deal was settled so that one owner became master of both. The larger and stronger the man, the more valuable he was considered.

Slaves did not lack medical treatment and were given the best of attention by the owner's family doctor. Sometimes slaves would pretend illness to escape work in the field. A quick examination, however, revealed the truth. Home remedies such as turpentine, castor oil, etc., were always kept on hand for minor ailments.

Green remembers hearing talk of the war before he actually saw signs of it. It was not long before the Yankees visited[Pg 54] Greensboro, Ga., and the Willis plantation. On one occasion, they took all the best horses and mules and left theirs which were broken down and worn from travel. They also searched for money and other valuables. During this period a mail wagon broke down in the creek and water soon covered it. When the water fell, Negroes from the Willis plantation found sacks of money and hid it. One unscrupulous Negro betrayed the others; rather than give back the money, many ran away from the vicinity. Isaiah's Uncle managed to keep his money but the Ku Klux Klan learned that he was one of the group. One night they kidnaped and carried him to the woods where they pinned him to the ground, set the dry leaves on fire, and left him. In the group he recognized his master's son Jimmie. As fate would have it the leaves burned in places and went out. By twisting a little he managed to get loose, but found that his feet were badly burned. Later, when he confronted the master with the facts, Col. Willis offered to pay him if he would not mention the fact that his son Jimmie was mixed up in it, and he sent the man to a hospital to have his burns treated. In the end, all of his toes had to be amputated.

Another time, the Yankees visited the Willis plantation and offered Green a stick of candy if he would tell them where the master hid his whiskey. Isaiah ignorantly gave the information. The leader of the troops then blew his trumpet and his men came from every direction. He gave orders that they search for an underground cellar. Very soon they found the well-stocked hiding place. The troops drank as much as they wanted and invited the slaves to help themselves. Later, when Col. Willis arrived and the mistress, who was furious, told him,[Pg 55] she said, "If it hadn't been for that little villain, the Yankees would never have found your whiskey." The master understood, however, that Isaiah hadn't known what he was doing, and refused to punish him.

The Yankees came to the Willis plantation to notify the Negroes of their freedom. One thing they said stands out in Green's memory. "If your mistress calls you 'John,' call her 'Sally.' You are as free as she is and she can't whip you any more. If you remain, sign a paper so that you will receive pay for your work." Mrs. Willis looked on with tears in her eyes and shook her head sadly. The next day the master notified each slave family that they could remain on his plantation if they desired and he would give each $75.00 at Christmas. Looking at Isaiah's step-father, he told him that since he was afflicted he would pay him only $50.00, but this amount was refused. Wishing to keep the man, Col. Willis finally offered him as much as he promised the ablebodied men.

Some slave owners did not let their slaves know of their freedom, and kept them in ignorance as long as six months; some even longer.

Green's family remained on the Willis plantation until they were forced to move, due to their ex-master's extravagance. As Isaiah remarked, "He ran through with 3,000 acres of land and died on rented land in Morgan County."

Directly after the war, Col. Willis was nominated for the office of legislator of Georgia. Realizing that the vote of the ex-slaves would probably mean election for him, he rode through his plantation trying to get them to vote for him. He was not successful, however, and some families were asked to move off[Pg 56] his plantation, especially those whom he didn't particularly like.

Years later, Green's family moved to Atlanta. Isaiah is now living in the shelter provided by the Dept. of Public Welfare. He appears to be fairly contented.

Following is the account of slavery as told by Mr. Isaac Green, who spent a part of his childhood as a slave.

"I wus born in Greene County, Georgia, eighty-one years ago. My marster wus named Colonel Willis. He wus a rich man an' he had a whole lots o' slaves—'bout seventy-five or more. Besides my mother an' me I had nine sisters. I wus de younges' chile. I didn't know 'bout my father 'till after surrender, 'cause ol' marster sold him 'way fum my mother when I wus two years old.

"When I wus big enuff I had to go to de fiel' wid de res' o' de chillun an' drap corn an' peas. We'd take our heels an' dent a place in de groun' an' in every dent we had to drap two peas. Sometimes we'd make a mistake an' drap three seeds instead o' two an' if we did dis too often it meant de strap fum de overseer. On our plantation we had a colored an' a white overseer.

"My ol' marster never did whup me an' he didn't 'low none o' de overseers to whup me either. He always say: 'Dat's my nigger—I sol' his father when I coulda saved him—he wus de bes' man I had on de plantation.' De rest o' de slaves uster git whuppins sometimes fer not workin' like dey should. When dey didn't work or some other little thing like dat dey would git twenty-five or fifty lashes but de marster would tell de overseer: 'Don't you cut my nigger's hide or scar him.' You see if a slave wus scarred he wouldn't bring as much as one with a smooth hide in case de marster wanted to sell 'im, 'cause de buyers would see de scars an' say dat he wus a bad nigger.

"Sometimes de women uster git whuppins fer fightin'. Ol' marster uster tell my mother all de time dat he wus goin' to give her one-hundred lashes if she didn't stop fightin', but he never did do it though. My grandmother never did git[Pg 58] whupped. Colonel Black, her first marster, wus her father an' when he went broke he had to sell her. When he went broke he put her on de block—in dem days dey put slaves on de block to sell 'em jes' like dey do horses an' mules now—he say to de gentlemen gathered 'roun: 'Dis is my nigger an' my chile; she is a midwife an' a extraordinary weaver an' whoever buys her has got to promise to treat her like a white chile.' My marster bought her an' he treated her like she wus white, too. He never did try to hit her an' he wouldn't let nobody else hit her.

"We always had a plenty to eat an' if we didn't we'd go out in somebody's pasture an' kill a hog or sheep an' clean him by a branch an' den hide de meat in de woods or in de loft of de house. Some of de white folks would learn you how to steal fum other folks. Sometimes ol' marster would say to one o' us: 'Blast you—you better go out an' hunt me a hog tonight an' put it in my smokehouse—-dey can search you niggers' houses but dey can't search mine.'

"Once a week de marster give us three pounds of pork, a half gallon o' syrup, an' a peck o' meal. You had to have a garden connected wid yo' house fer yo' vegetables. De marster would let you go out in de woods an' cut you as large a space as you wanted. If you failed to plant, it wus jes' yo' bad luck. If you wanted to you could sell de corn or de tobacco or anything else dat you raised to de marster an' he would pay you. 'Course he wusn't goin' to pay you too much fer it.

"All de slaves had to work—-my mother wus a plow han'. All de aged men an' women had to tend to de hogs an' de cows an' do de weavin' an' de sewin'. Sometimes ol' marster would let us have a frolic an' we could dance all night if we wanted to as long as we wus ready to go to de fiel' when de overseer blowed de bugle 'fo day nex' mornin'. De fiel' han's had to git up early enuff to fix dey breakfas' befo' dey went to de fiel'. We chillun took dinner to 'em at twelve o'clock. We used baskets to take de dinner in, an' large pails to take de milk in. Dey had to fix supper fer dey selves when dey lef' de fiel' at dark.[Pg 59]

"All de clothes we wore wuz made on de plantation. De women had to card, spin an' weave de thread an' den when de cloth wuz made it wuz dyed wid berries. My step-father wuz de shoemaker on de plantation an' we always had good shoes. He beat ol' marster out o' 'bout fifteen years work. When he didn't feel like workin' he would play like he wuz sick an' ol' marster would git de doctor for him. When anybody got sick dey always had de doctor to tend to him."

Regarding houses, Mr. Green says: "We lived in log houses dat had wood floors. Dere wuz one window an' a large fireplace where de cookin' wuz done in de ashes. De chinks in de walls wuz daubed wid mud to keep de weather out. De beds wuz made by hand an' de mattresses wuz big tickin's stuffed wid straw."

Continuing he says: "Yo' actual treatment depended on de kind o' marster you had. A heap o' folks done a heap better in slavery dan dey do now. Everybody on our plantation wuz glad when de Yankee soldiers tol' us we wuz free."

Margaret Green, 1430 Jones Street was born in 1855 on the plantation of Mr. Cooke McKie in Edgefield County, South Carolina.

Margaret's house was spotlessly clean, her furniture of the golden oak type was polished, and the table cover and sideboard scarfs were beautifully laundered. Margaret is a small, trim little figure dressed in a grey print dress with a full gathered skirt and a clean, starched apron with strings tied in a big bow. She has twinkling eyes, a kindly smile and a pleasant manner.

"Yes, mam, I remembers slavery times very well. I wuz a little girl but I could go back home and show you right where I wuz when the sojers come through our place with their grey clothes and bright brass buttons. They looked mighty fine on their hosses ridin' round. I could show you right where those sojers had the camp".

Margaret described "the quarters" and told of the life. "Each fam'ly had a garden patch, and could raise cotton. Only Marse Cooke raised cotton; what we raised we et".

"Margaret were the slaves on your master's plantation mistreated?"

"What you say? Mistreat? Oh! you mean whipped! Yes, man, sometime Marse Cooke whip us when we need it, but he never hurt nobody. He just give 'em a lick or two make 'em mind they business. Marse[Pg 62] Cooke was a good man, and he never let a overseer lay a finger on one of his niggers!"

"Margaret were you ever whipped?"

Margaret laughed; with her eyes twinkling merrily she replied, "Marse Cooke say he wuz gonna whip me 'cause I was so mischievious. He was on his horse. I broke and run, and Marse ain't give me that whippin' till yet!"

"Yes, mam, I hearn stories o' ghos'es and hants, but I never did b'lieve in none of 'em. I uster love to play and to get out of all the work I could. The old folk on the plantashun uster tell us younguns if we didn't hurry back from the spring with the water buckets, the hants and buggoos would catch us. I ain't never hurry till yet, and I never see a hant. I wished I could, 'caus' I don't b'lieve I would be scart."

"Margaret, did you learn to read?"

"Oh! no mam, that wus sumpin' we wuzn't 'lowed to do; nobody could have lessons. But we went to Church to the Publican Baptist Church. Yes, mam, I'se sho' dat wuz the name—the Publican Baptist Church—ain't I been there all my life 'till I been grown and married? We uster go mornin' and evenin', and the white people sat on one side and the slaves on the other."

Margaret said her mother was a seamstress and also a cook. Three other seamstresses worked on the plantation. There was a spinning wheel and a loom, and all the cotton cloth for clothing was woven and then made into clothes for all the slaves. There were three shoe makers on the place who made shoes for the slaves, and did all the saddle and harness repair.[Pg 63]

Margaret was asked who attended the slaves when they were sick.

"Marse Cooke's son was a doctor", she replied, and he 'tended anybody who was bad sick. Granny Phoebe was the midwife at our plantashun and she birthed all the babies. She was old when I was a little gal, and she lived to be 105. Marse Cooke never let any of his slaves do heavy work 'till dey wuz 18 years old." Margaret's father went to the war with "Marse Cooke" as his body servant, and her mother went also, to cook for him!

"To tell you the truth, man," said the old woman, "I 'member more 'bout that war back yonder than I member 'bout the war we had a few years ago."