Title: Canada

Author: John George Bourinot

Editor: William H. Ingram

Release date: September 10, 2007 [eBook #22557]

Most recently updated: January 2, 2021

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/22557

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

First Edition . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1897

Second Impression . . . . . . . . . . . 1901

Second Edition (Third Impression) . . . 1908

Third Edition (Fourth Impression) . . . 1922

[Transcriber's note: Page numbers in this book are indicated by numbers enclosed in curly braces, e.g. {99}. They have been located where page breaks occurred in the original book, in accordance with Project Gutenberg's FAQ-V-99. For its Index, a page number has been placed only at the start of that section. In the HTML version of this book, page numbers are placed in the left margin.]

In writing this story of Canada I have not been able to do more, within the limited space at my command, than briefly review those events which have exercised the most influence on the national development of the Dominion of Canada from the memorable days bold French adventurers made their first attempts at settlement on the banks of the beautiful basin of the Annapolis, and on the picturesque heights of Quebec, down to the establishment of a Confederation which extends from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. Whilst the narrative of the French régime, with its many dramatic episodes, necessarily occupies a large part of this story, I have not allowed myself to forget the importance that must be attached to the development of institutions of government and their effect on the social, intellectual, and material conditions of the people since the beginning of the English régime. Though this story, strictly speaking, ends with the successful accomplishment of the federal union of all the provinces in 1873, when Prince Edward Island became one of its members, I have deemed it necessary to refer briefly to those events which have {vi} happened since that time—the second half-breed rebellion of 1885, for instance—and have had much effect on the national spirit of the people. I endeavour to interest my reader in the public acts of those eminent men whose names stand out most prominently on the pages of history, and have made the deepest impress on the fortunes and institutions of the Dominion. In the performance of this task I have always consulted original authorities, but have not attempted to go into any historical details except those which are absolutely necessary to the intelligent understanding of the great events and men of Canadian annals. I have not entered into the intrigues and conflicts which have been so bitter and frequent during the operation of parliamentary government in a country where politicians are so numerous, and statesmanship is so often hampered and government injuriously affected by the selfish interests of party, but have simply given the conspicuous and dominant results of political action since the concession of representative institutions to the provinces of British North America. A chapter is devoted, at the close of the historical narrative, to a very brief review of the intellectual and material development of the country, and of the nature of its institutions of government. A survey is also given of the customs and conditions of the French Canadian people, so that the reader outside of the Dominion may have some conception of their institutions and of their influence on the political, social, and intellectual life of a Dominion, of whose population they form so important and influential an element. {vii} The illustrations are numerous, and have been carefully selected from various sources, not accessible to the majority of students, with the object, not simply of pleasing the general reader, but rather of elucidating the historical narrative. A bibliographical note has also been added of those authorities which the author has consulted in writing this story, and to which the reader, who wishes to pursue the subject further, may most advantageously refer.

HOUSE OF COMMONS, OTTAWA,

Dominion Day, 1896.

Owing to the passing of Sir John Bourinot, the revisions necessary to bring this work up to date had to be entrusted to another hand. Accordingly, Mr. William H. Ingram has kindly undertaken the task, and has contributed the very judiciously selected information now embodied in Chapter XXX. on the recent development of Canada. Chapter XXVIII. by Mr. Edward Porritt, author of Sixty Years of Protection in Canada, has also been included, as being indicative of the history of the time he describes. Mr. Ingram has also made other revisions of considerable value.

1, ADELPHI TERRACE.

March, 1922.

[Transcriber's note: The page numbers below are those in the original book. However, in this e-book, to avoid the splitting of paragraphs, the illustrations may have been moved to preceding or following pages.]

| PAGE | |

|

THE HON. W. L. MACKENZIE KING Courtesy "Canada." |

Frontispiece |

|

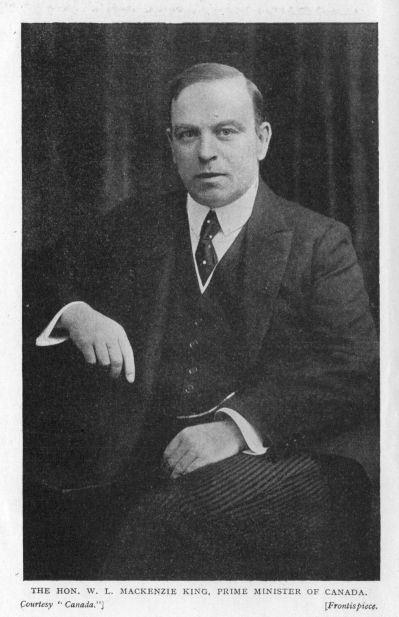

VIEW OF CAPE TRINITY ON THE LAURENTIAN RANGE From a photograph by Topley, Ottawa. |

9 |

|

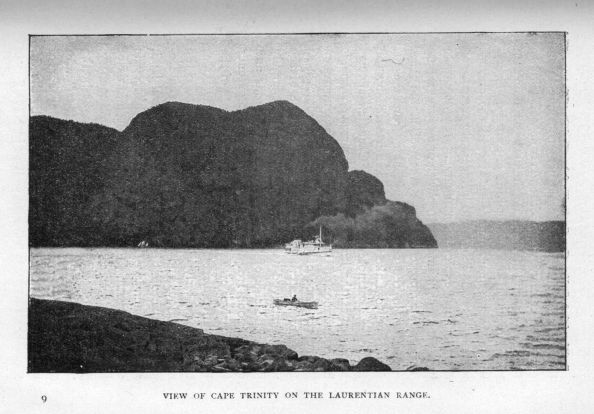

ROCKY MOUNTAINS AT DONALD, BRITISH COLUMBIA From Sir W. Van Horne's Collection of B. C. photographs. |

13 |

|

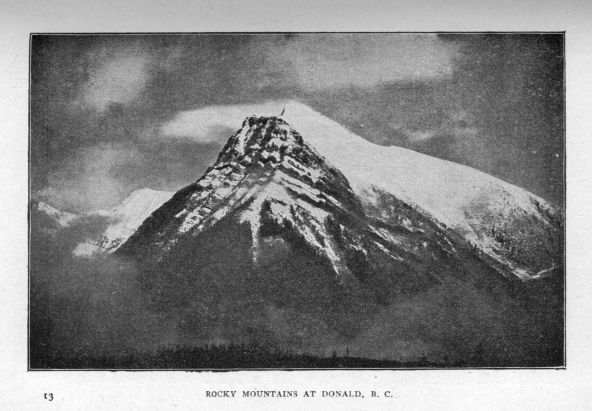

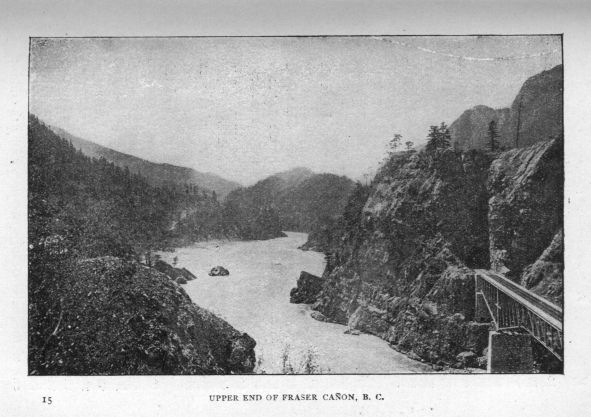

UPPER END OF FRASER CAÑON, BRITISH COLUMBIA Ibid. |

15 |

|

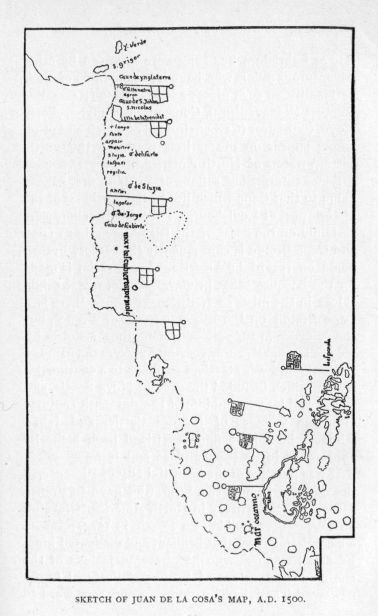

SKETCH OF JUAN DE LA COSA'S MAP, A.D. 1500 From Dr. S. E. Dawson's "Cabot Voyages," in Trans. Roy. Soc. Can., 1894. |

25 |

* To explain these dates it is necessary to note that Champlain lived for years in one of the buildings of the Fort of Saint Louis which he first erected, and the name château is often applied to that structure; but the château, properly so-called, was not commenced until 1647, and it as well as its successors was within the limits of the fort. It was demolished in 1694 by Governor Frontenac, who rebuilt it on the original foundations, and it was this castle which, in a remodelled and enlarged form, under the English régime, lasted until 1834.

|

PORTRAIT OF JACQUES CARTIER From B. Sulte's "Histoire des Canadiens-Français" (Montreal, 1882-'84). |

31 |

|

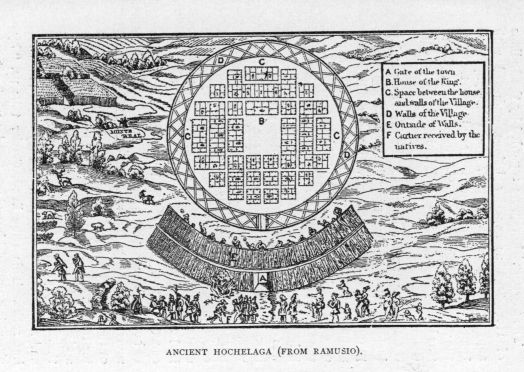

ANCIENT HOCHELAGA From Ramusio's "Navigationi e Viaggi" (Venice, 1565). |

39 |

|

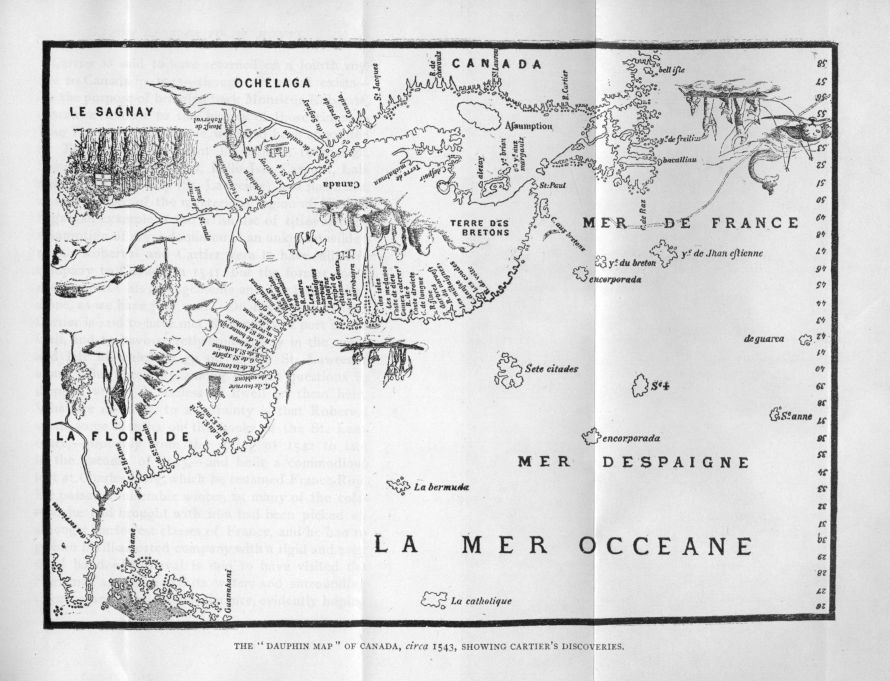

THE "DAUPHIN MAP" OF CANADA, circa 1543, SHOWING CARTIER'S DISCOVERIES From collection of maps in Parliamentary Library at Ottawa. |

44 |

|

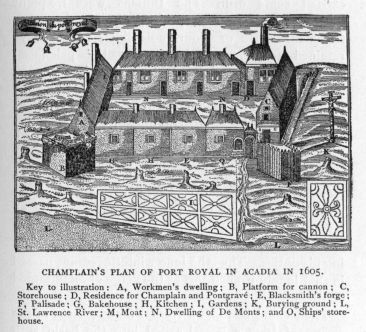

PLAN OF PORT ROYAL IN ACADIA IN 1605 From Champlain's works, rare Paris ed. of 1613. |

57 |

|

CHAMPLAIN'S PORTRAIT From B. Sulte's "Histoire des Canadiens-Français." |

69 |

|

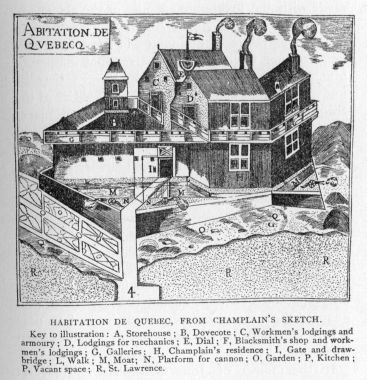

HABITATION DE QUEBEC From Champlain's works, rare Paris ed. of 1613. |

71 |

|

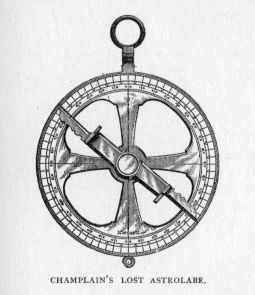

CHAMPLAIN'S LOST ASTROLABE From sketch by A. J. Russell, of Ottawa, 1879. |

79 |

|

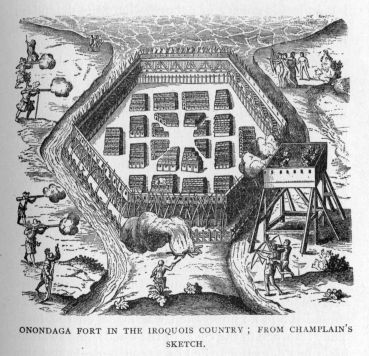

ONONDAGA FORT IN THE IROQUOIS COUNTRY From Champlain's works, rare Paris ed. of 1613. |

83 |

|

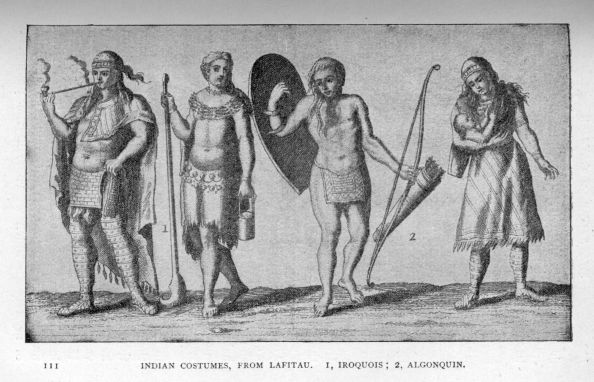

INDIAN COSTUMES From Lafitau's "Moeurs des Sauvages" (Paris, 1724). |

111 |

|

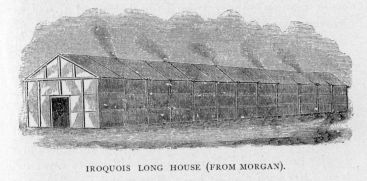

IROQUOIS LONG HOUSE From Morgan's "Houses and Home Life of the Aborigines" (Washington, 1881). |

119 |

|

PORTRAIT OF MARIE GUYARD (MÈRE MARIE DE L'INCARNATION) From S. Sulte's "Histoire des Canadiens-Français." |

131 |

|

PORTRAIT OF MAISONNEUVE Ibid. |

135 |

|

PORTRAIT OF LAVAL, FIRST CANADIAN BISHOP Ibid. |

159 |

|

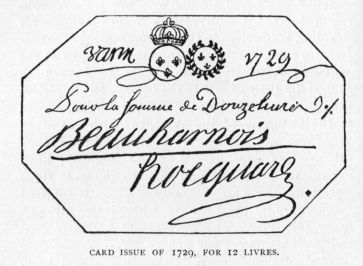

CARD ISSUE (PAPER MONEY) OF 1729, FOR 12 LIVRES From Breton's "Illustrated History of Coins and Tokens Relating to Canada" (Montreal, 1892). |

162 |

|

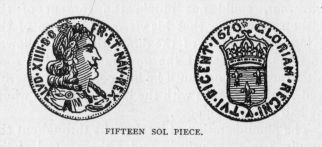

CANADIAN FIFTEEN SOL PIECE Ibid. |

163 |

|

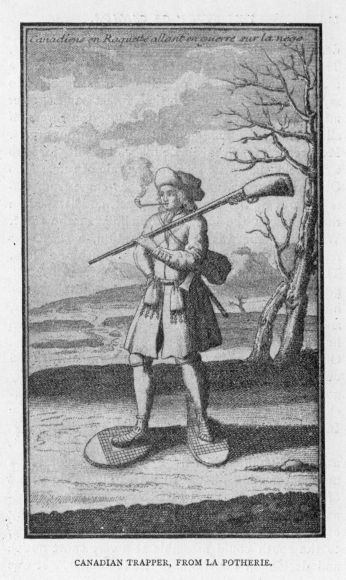

CANADIAN TRAPPER From La Pothérie's "Histoire de l'Amérique Septentrionale" (Paris, 1753). |

173 |

|

PORTRAIT AND AUTOGRAPH OF CAVELIER DE LA SALLE B. Sulte's "Histoire des Canadiens-Francais." |

185 |

|

FRONTENAC, FROM HÉBERT'S STATUE AT QUEBEC From Dr. Stewart's collection of Quebec photographs. |

193 |

|

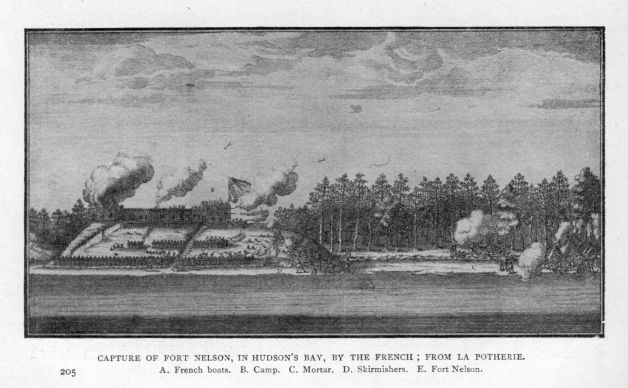

CAPTURE OF FORT NELSON IN HUDSON BAY, BY THE FRENCH From La Pothérie's "Histoire de l'Amérique Septentrionale." |

205 |

|

PORTRAIT OF CHEVALIER D'IBERVILLE From a portrait in Margry's "Découvertes et établissements des François dans le Sud de l'Amérique Septentrionale" (Paris, 1876-'83). |

209 |

|

VIEW OF LOUISBOURG IN 1731 From a sketch in the Paris Archives. |

210 |

|

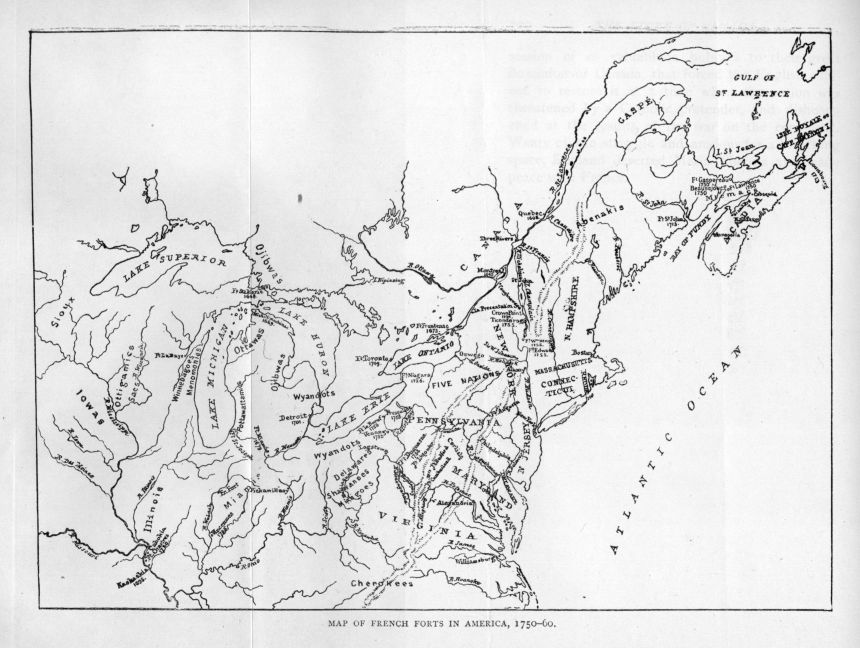

MAP OF FRENCH FORTS IN AMERICA, 1750-60 From Bourinot's "Cape Breton and its Memorials of the French Régime" (Montreal, 1891). |

221 |

|

PORTRAIT OF MONTCALM From B. Sulte's "Histoire des Canadiens-Français." |

239 |

|

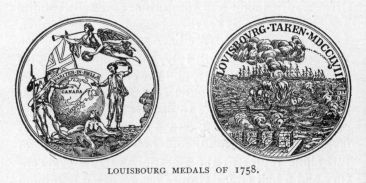

LOUISBOURG MEDALS OF 1758 From Bourinot's "Cape Breton," etc. |

244 |

|

PORTRAIT OF WOLFE From print in "A Complete History of the Late War," etc. (London and Dublin, 1774), by Wright. |

249 |

|

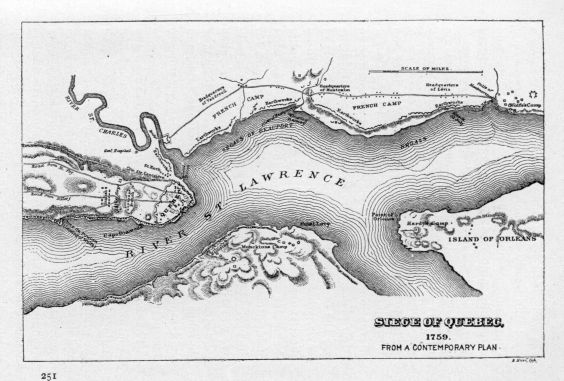

PLAN OF OPERATIONS AT SIEGE OF QUEBEC Made from a more extended plan in "The Universal Magazine" (London, Dec., 1859). |

251 |

|

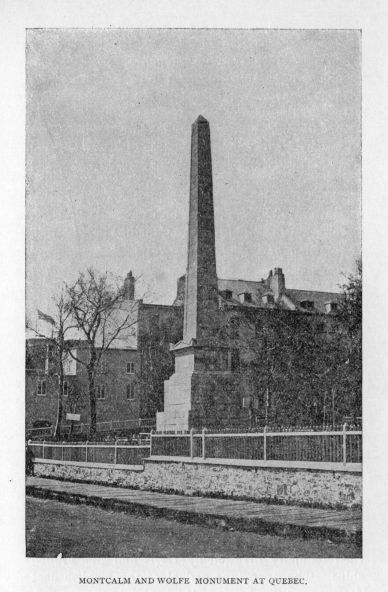

MONTCALM AND WOLFE MONUMENT AT QUEBEC From Dr. Stewart's collection of Quebec photographs. |

261 |

|

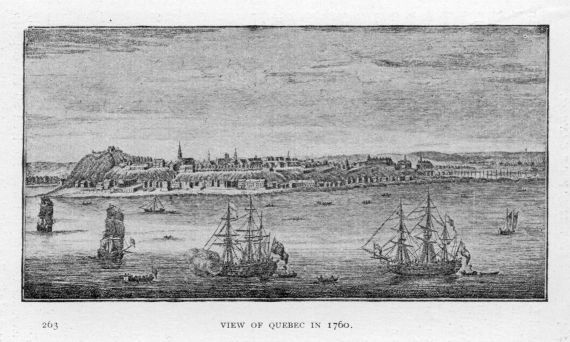

VIEW OF QUEBEC IN 1760 From "The Universal Magazine" (London, 1760). |

263 |

|

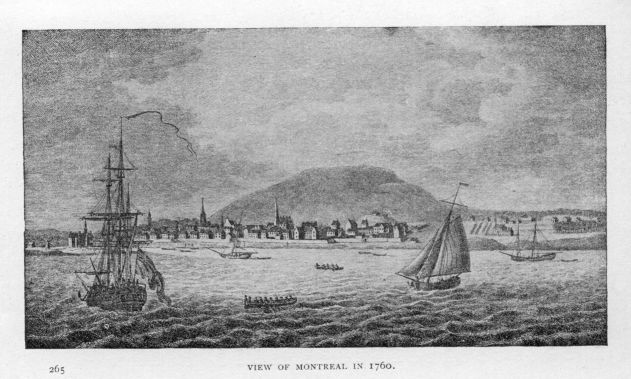

VIEW OF MONTREAL IN 1760 Ibid. |

265 |

|

PORTRAIT AND AUTOGRAPH OF JOSEPH BRANT (THAYENDANEGEA) From Stone's "Life of Joseph Brant," original ed. (New York, 1838). |

299 |

|

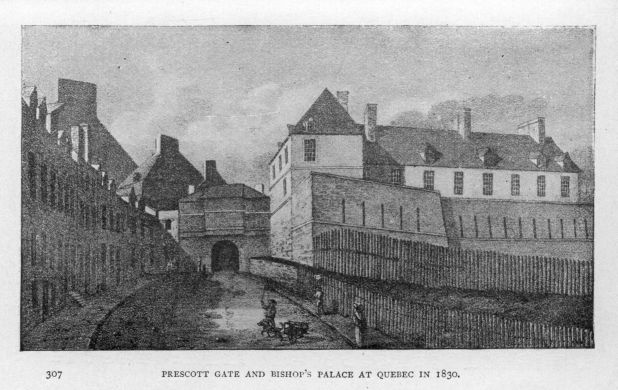

PRESCOTT GATE AND BISHOP'S PALACE IN 1800 From a sketch by A. J. Russell in Hawkins's "Pictures of Quebec." |

307 |

|

PORTRAIT OF LIEUT.-GENERAL SIMCOE From Dr. Scadding's "Toronto of Old" (Toronto, 1873). |

311 |

|

PORTRAIT OF MAJ.-GENERAL BROCK From a picture in possession of J. A. Macdonell, Esq., of Alexandria, Ontario. |

323 |

|

PORTRAIT OF COLONEL DE SALABERRY From Fennings Taylor's "Portraits of British Americans" (W. Notman, Montreal, 1865-'67). |

329 |

|

MONUMENT AT LUNDY'S LANE From a photograph through courtesy of Rev. Canon Bull, Niagara South, Ont. |

333 |

|

PORTRAIT OF LOUIS J. PAPINEAU From Fennings Taylor's "Portraits of British Americans." |

341 |

|

PORTRAIT OF BISHOP STRACHAN Ibid. |

347 |

|

PORTRAIT OF W. LYON MACKENZIE From C. Lindsey's "Life and Times of W. L. Mackenzie" (Toronto, 1863). |

349 |

|

PORTRAIT OF JUDGE HALIBURTON, AUTHOR OF "THE CLOCK-MAKER" From a portrait given to author by Mr. F. Blake Crofton of Legislative Library, Halifax, N. S. |

359 |

|

PORTRAIT OF JOSEPH HOWE From Fennings Taylor's "Portraits of British Americans." |

363 |

|

PORTRAIT OF ROBERT BALDWIN Ibid. |

365 |

|

PORTRAIT OF L. H. LAFONTAINE Ibid. |

369 |

|

PORTRAIT OF L. A. WILMOT From Lathern's "Biographical Sketch of Judge Wilmot" (Toronto, 1881). |

371 |

|

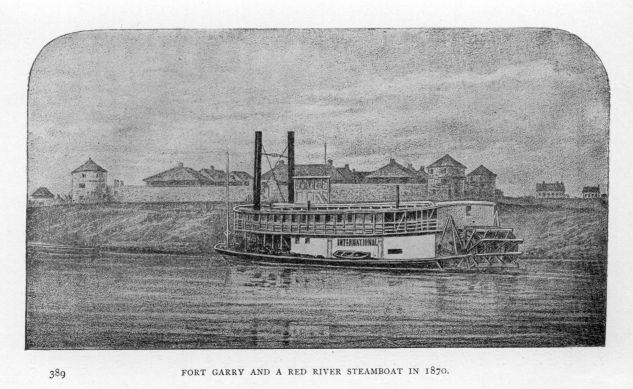

FORT GARRY AND A RED RIVER STEAMER IN 1870 From A. J. Russell's "Red River Country" (Montreal, 1870). |

389 |

|

PORTRAIT OF LIEUT.-COLONEL WILLIAMS From a photograph by Topley, Ottawa. |

399 |

|

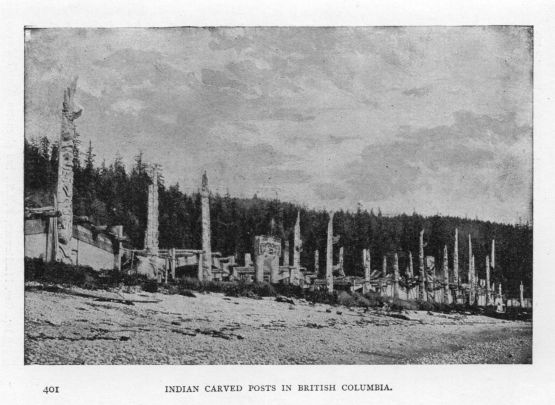

INDIAN CARVED POSTS IN BRITISH COLUMBIA From photograph by Dr. Dawson, C.M.G., Director of Geological Survey of Canada. |

401 |

|

PORTRAIT OF SIR JOHN MACDONALD From L. J. Taché's "Canadian Portrait Gallery" (Montreal, 1890-'93). |

405 |

|

PORTRAIT OF HON. GEORGE BROWN From photograph. |

409 |

|

PORTRAIT OF SIR GEORGE E. CARTIER From B. Sulte's "Histoire des Canadiens-français." |

411 |

|

SIR WILFRID LAURIER From a photograph by Ernest H. Mills. |

415 |

|

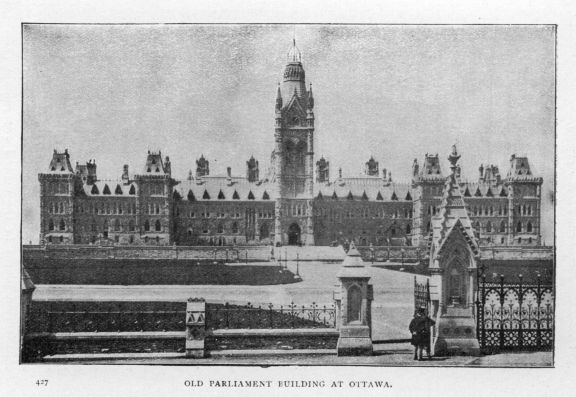

OLD PARLIAMENT BUILDING AT OTTAWA From a photograph by Topley, Ottawa. |

427 |

|

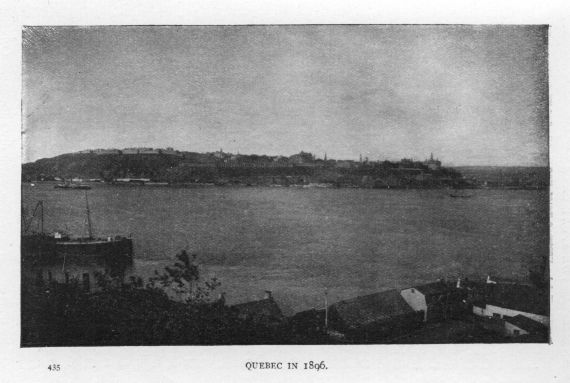

QUEBEC IN 1896 From Dr. Stewart's collection of Quebec photographs. |

435 |

|

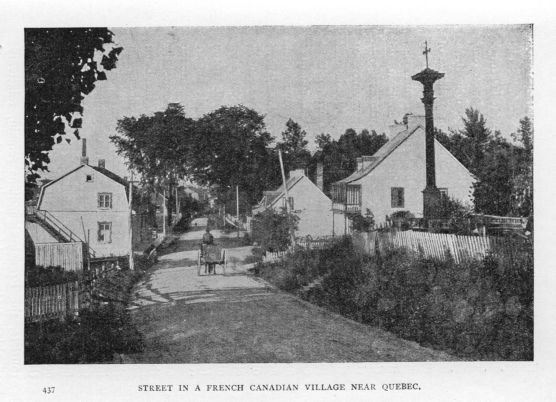

STREET SCENE IN A FRENCH CANADIAN VILLAGE NEAR QUEBEC Ibid. |

437 |

|

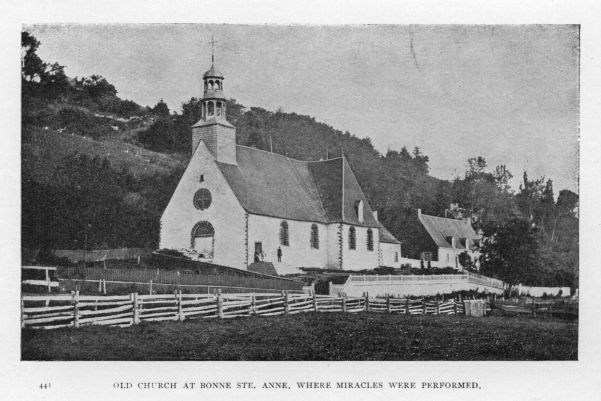

OLD CHURCH AT BONNE STE. ANNE, WHERE MIRACLES WERE PERFORMED Ibid. |

441 |

|

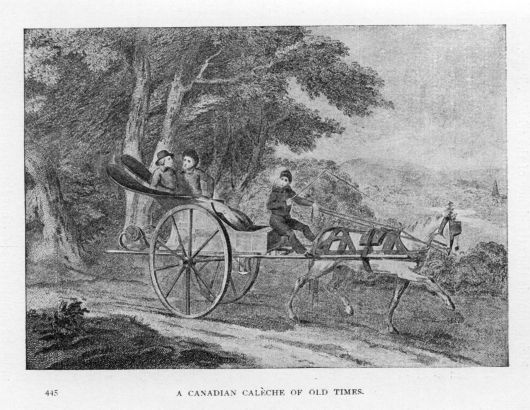

A CANADIAN CALECHE OF OLD TIMES From Weld's "Travels in North America" (London, 1799). |

445 |

|

PORTRAIT OF LOUIS FRECHETTE, THE FRENCH CANADIAN POET From L. J. Taché's "Canadian Portrait Gallery." |

449 |

|

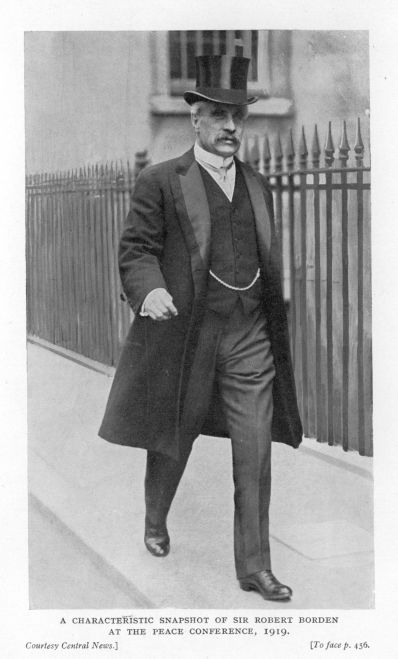

A CHARACTERISTIC SNAPSHOT OF SIR ROBERT BORDEN Courtesy "Central News." |

456 |

|

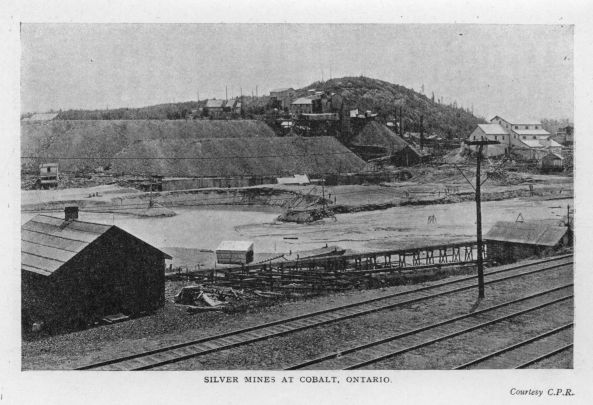

SILVER MINES AT COBALT, ONTARIO Courtesy C.P.R. |

459 |

|

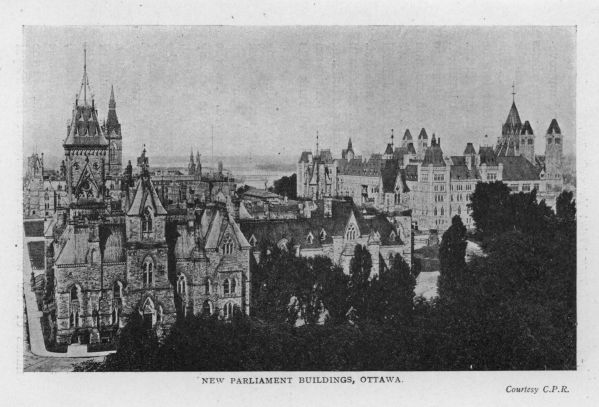

NEW PARLIAMENT BUILDINGS, OTTAWA Courtesy C.P.R. |

471 |

|

MAP OF CANADA [Transcriber's note: missing from book.] |

at end |

Jacques Cartier's Voyages, in English, by Joseph Pope (Ottawa, 1889), and H. B. Stephens (Montreal, 1891); in French, by N. E. Dionne (Quebec, 1891); Toilon de Longrais (Rennes, France), H. Michelant and E. Ramé (Paris, 1867). L'Escarbot's New France, in French, Tross's ed. (Paris, 1866), which contains an account also of Cartier's first voyage. Sagard's History of Canada, in French, Tross's ed. (Paris, 1866). Champlain's works, in French, Laverdiere's ed. (Quebec, 1870); Prince Society's English ed. (Boston, 1878-80). Lafitau's Customs of the Savages, in French (Paris, 1724). Charlevoix's History of New France, in French (Paris, 1744); Shea's English version (New York, 1866). Jesuit Relations, in French (Quebec ed., 1858). Ferland's Course of Canadian History, in French (Quebec, 1861-1865). Garneau's History of Canada, in French (Montreal, 1882). Sulte's French Canadians, in French (Montreal, 1882-84). F. Parkman's series of histories of French Régime, viz.; Pioneers of France in the New World; The Jesuits in North America; The old Régime; Frontenac; The Discovery of the Great West; A Half Century of Conflict; Montcalm and Wolfe; Conspiracy of Pontiac (Boston, 1865-1884). Justin Winsor's From Cartier to Frontenac (Boston, 1894). Hannay's Acadia (St. John, N. B., 1870). W. Kingsford's History of Canada, 8 vols. so far (Toronto and London, 1887-1896), the eighth volume on the war of 1812 being especially valuable. Bourinot's "Cape Breton and its Memorials of the French Régime," Trans. Roy. Soc. Can., vol. ix, and separate ed. (Montreal, 1891). Casgrain's Montcalm and Lévis, in French (Quebec, 1891). Haliburton's Nova Scotia (Halifax, 1829). Murdoch's Nova Scotia (Halifax, 1865-67). Campbell's Nova Scotia (Halifax, 1873). Campbell's Prince Edward Island (Charlottetown, 1875). Lord Durham's Report, 1839. Christie's History of Lower Canada (Quebec, 1848-1855). Dent's Story of the Upper Canadian Rebellion (Toronto, 1855). Lindsey's W. Lyon Mackenzie (Toronto, 1873). Dent's Canada Since the Union of 1841 (Toronto, 1880-81). Turcotte's Canada under the Union, in French (Quebec, 1871). Bourinot's Manual of Constitutional History (Montreal, 1888), "Federal Government in Canada" (Johns Hopkins University Studies, {xx} Baltimore, 1889), and How Canada is Governed (Toronto, 1895). Withrow's Popular History of Canada (Toronto, 1888). MacMullen's History of Canada (Brockville, 1892). Begg's History of the Northwest (Toronto, 1804). Canniff's History of Ontario (Toronto, 1872). Egerton Ryerson's Loyalists of America (Toronto, 1880). Mrs. Edgar's Ten Years of Upper Canada in Peace and War (Toronto, 1890). Porritt's Sixty Years of Protection in Canada (London, 1907). H. E. Egerton and W. L. Grant's Canadian Constitutional Development (London, 1907). G. R. Parkin's Sir John A. Macdonald (London, 1909). B. Home's Canada (London, 1911). W. Maxwell's Canada of To-Day (London, 1911). C. L. Thomson's Short History of Canada (London, 1911). W. L. Griffith's The Dominion of Canada (London, 1911). A. G. Bradley's Canada (London, 1912). Arthur G. Doughty's History of Canada (Year Book) (Ottawa, 1913). J. A. T. Lloyd's The Real Canadian (London, 1913). E. L. Marsh's The Story of Canada (London, 1913). J. Munro's Canada 1535 to Present Day (London, 1913). A. Shortland and A. G. Doughty's Canada and its Provinces (Toronto, 1913). W. L. Grant's High School History of Canada (Toronto, 1914). G. Bryce's Short History of the Canadian People (London, 1914). D. W. Oates's Canada To-day and Yesterday (London, 1914). F. Fairfield's Canada (London, 1914). Sir C. Tupper's Political Reminiscences (London, 1914). Morang's Makers of Canada (Toronto, 1917). Sir Thomas White's The Story of Canada's War Finance (Montreal, 1921). Prof. Skelton's Life of Sir Wilfrid Laurier (Toronto, 1922). And Review of Historical Publications Relating to Canada by the University of Toronto.

For a full bibliography of archives, maps, essays, and books relating to the periods covered by the Story of Canada, and used by the writer, see appendix to his "Cape Breton and its Memorials," in which all authorities bearing on the Norse, Cabot, and other early voyages are cited. Also, appendix to same author's "Parliamentary Government in Canada" (Trans. Roy. Soc. Can., vol. xi., and American Hist. Ass. Report, Washington, 1891). Also his "Canada's Intellectual Strength and Weakness" (Trans. Roy. Soc. Can., vol. xi, and separate volume, Montreal, 1891). Also, Winsor's Narrative and Critical History of America (Boston, 1886-89).

The view from the spacious terrace on the verge of the cliffs of Quebec, the ancient capital of Canada, cannot fail to impress the imagination of the statesman or student versed in the history of the American continent, as well as delight the eye of the lover of the picturesque. Below the heights, to whose rocks and buildings cling so many memories of the past, flows the St. Lawrence, the great river of Canada, bearing to the Atlantic the waters of the numerous lakes and streams of the valley which was first discovered and explored by France, and in which her statesmen saw the elements of empire. We see the tinned roofs, spires and crosses of quaint churches, hospitals and convents, narrow streets winding among the rocks, black-robed priests and {2} sombre nuns, habitans in homespun from the neighbouring villages, modest gambrel-roofed houses of the past crowded almost out of sight by obtrusive lofty structures of the present, the massive buildings of the famous seminary and university which bear the name of Laval, the first great bishop of that Church which has always dominated French Canada. Not far from the edge of the terrace stands a monument on which are inscribed the names of Montcalm and Wolfe, enemies in life but united in death and fame. Directly below is the market which recalls the name of Champlain, the founder of Quebec, and his first Canadian home at the margin of the river. On the same historic ground we see the high-peaked roof and antique spire of the curious old church, Notre-Dame des Victoires, which was first built to commemorate the repulse of an English fleet two centuries ago. Away beyond, to the left, we catch a glimpse of the meadows and cottages of the beautiful Isle of Orleans, and directly across the river are the rocky hills covered with the buildings of the town, which recalls the services of Lévis, whose fame as a soldier is hardly overshadowed by that of Montcalm. The Union-jack floats on the tall staff of the citadel which crowns the summit of Cape Diamond, but English voices are lost amid those of a people who still speak the language of France.

As we recall the story of these heights, we can see passing before us a picturesque procession: Sailors from the home of maritime enterprise on the Breton and Biscayan coasts, Indian warriors in their paint and savage finery, gentlemen-adventurers and pioneers, {3} rovers of the forest and river, statesmen and soldiers of high ambition, gentle and cultured women who gave up their lives to alleviate suffering and teach the young, missionaries devoted to a faith for which many have died. In the famous old castle of Saint Louis,[1] long since levelled to the ground—whose foundations are beneath a part of this very terrace—statesmen feasted and dreamt of a French Empire in North America. Then the French dominion passed away with the fall of Quebec, and the old English colonies were at last relieved from that pressure which had confined them so long to the Atlantic coast, and enabled to become free commonwealths with great possibilities of development before them. Yet, while England lost so much in America by the War of Independence, there still remained to her a vast northern territory, stretching far to the east and west from Quebec, and containing all the rudiments of national life—

"The raw materials of a State,

Its muscle and its mind."

A century later than that Treaty of Paris which was signed in the palace of Versailles, and ceded Canada finally to England, the statesmen of the provinces of this northern territory, which was still a British possession,—statesmen of French as well as English Canada—assembled in an old building of this same city, so rich in memories of old France, {4} and took the first steps towards the establishment of that Dominion, which, since then, has reached the Pacific shores.

It is the story of this Canadian Dominion, of its founders, explorers, missionaries, soldiers, and statesmen, that I shall attempt to relate briefly in the following pages, from the day the Breton sailor ascended the St. Lawrence to Hochelaga until the formation of the confederation, which united the people of two distinct nationalities and extends over so wide a region—so far beyond the Acadia and Canada which France once called her own. But that the story may be more intelligible from the beginning, it is necessary to give a bird's-eye view of the country, whose history is contemporaneous with that of the United States, and whose territorial area from Cape Breton to Vancouver—the sentinel islands of the Atlantic and Pacific approaches—is hardly inferior to that of the federal republic.

Although the population of Canada at present does not exceed nine millions of souls, the country has, within a few years, made great strides in the path of national development, and fairly takes a place of considerable importance among those nations whose stories have been already told; whose history goes back to centuries when the Laurentian Hills, those rocks of primeval times, looked down on an unbroken wilderness of forest and stretches of silent river. If we treat the subject from a strictly historical point of view, the confederation of provinces and territories comprised within the Dominion may be most conveniently grouped into {5} several distinct divisions. Geographers divide the whole country lying between the two oceans into three well-defined regions: 1. The Eastern, extending from the Atlantic to the head of Lake Superior. 2. The Central, stretching across the prairies and plains to the base of the Rocky Mountains. 3. The Western, comprising that sea of mountains which at last unites with the waters of the Pacific. For the purposes of this narrative, however, the Eastern and largest division—also the oldest historically—must be separated into two distinct divisions, known as Acadia and Canada in the early annals of America.

The first division of the Eastern region now comprises the provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island, which, formerly, with a large portion of the State of Maine, were best known as Acadie,[2] a memorial of the Indian occupation before the French régime. These provinces are indented by noble harbours and bays, and many deep rivers connect the sea-board with the interior. They form the western and southern boundaries of that great gulf or eastern portal of Canada, which maritime adventurers explored from the earliest period of which we have any record. Ridges of the Appalachian range stretch from New England to {6} the east of these Acadian provinces, giving picturesque features to a generally undulating surface, and find their boldest expression in the northern region of the island of Cape Breton. The peninsula of Nova Scotia is connected with the neighbouring province of New Brunswick by a narrow isthmus, on one side of which the great tides of the Bay of Fundy tumultuously beat, and is separated by a very romantic strait from the island of Cape Breton. Both this isthmus and island, we shall see in the course of this narrative, played important parts in the struggle between France and England for dominion in America. This Acadian division possesses large tracts of fertile lands, and valuable mines of coal and other minerals. In the richest district of the peninsula of Nova Scotia were the thatch-roofed villages of those Acadian farmers whose sad story has been told in matchless verse by a New England poet, and whose language can still be heard throughout the land they loved, and to which some of them returned after years of exile. The inexhaustible fisheries of the Gulf, whose waters wash their shores, centuries ago attracted fleets of adventurous sailors from the Atlantic coast of Europe, and led to the discovery of Canada and the St. Lawrence. It was with the view of protecting these fisheries, and guarding the great entrance to New France, that the French raised on the southeastern shores of Cape Breton the fortress of Louisbourg, the ruins of which now alone remain to tell of their ambition and enterprise.

Leaving Acadia, we come to the provinces which {7} are watered by the St. Lawrence and the Great Lakes, extending from the Gulf to the head of Lake Superior, and finding their northern limits in the waters of Hudson's Bay. The name of Canada appears to be also a memorial of the Indian nations that once occupied the region between the Ottawa and Saguenay rivers. This name, meaning a large village or town in one of the dialects of the Huron-Iroquois tongue, was applied, in the first half of the sixteenth century, to a district in the neighbourhood of the Indian town of Stadacona, which stood on the site of the present city of Quebec. In the days of French occupation the name was more generally used than New France, and sometimes extended to the country now comprised in the provinces of Ontario and Quebec, or, in other words, to the whole region from the Gulf to the head of Lake Superior. Finally, it was adopted as the most appropriate designation for the new Dominion that made a step toward national life in 1867.

The most important feature of this historic country is the remarkable natural highway which has given form and life to the growing nation by its side—a river famous in the history of exploration and war—a river which has never-failing reservoirs in those great lakes which occupy a basin larger than Great Britain—a river noted for its long stretch of navigable waters, its many rapids, and its unequalled Falls of Niagara, around all of which man's enterprise and skill have constructed a system of canals to give the west a continuous navigation from Lake Superior to the ocean for over two thousand miles. {8} The Laurentian Hills—"the nucleus of the North American continent"—reach from inhospitable, rock-bound Labrador to the north of the St. Lawrence, extend up the Ottawa valley, and pass eventually to the northwest of Lakes Huron and Superior, as far as the "Divide" between the St. Lawrence valley and Hudson's Bay, but display their boldest forms on the north shore of the river below Quebec, where the names of Capes Eternity and Trinity have been so aptly given to those noble precipices which tower above the gloomy waters of the Saguenay, and have a history which "dates back to the very dawn of geographical time, and is of hoar antiquity in comparison with that of such youthful ranges as the Andes and the Alps." [3]

From Gaspe, the southeastern promontory at the entrance of the Gulf, the younger rocks of the Appalachian range, constituting the breast-bone of the continent, and culminating at the north in the White Mountains, describe a great curve southwesterly to the valley of the Hudson; and it is between the ridge-like elevations of this range and the older Laurentian Hills that we find the valley of the St. Lawrence, in which lie the provinces of Quebec and Ontario.

The province of Quebec is famous in the song and story of Canada; indeed, for a hundred and fifty years, it was Canada itself. More than a million and a quarter of people, speaking the language and {10} professing the religion of their forefathers, continue to occupy the country which extends from the Gulf to the Ottawa, and have made themselves a power in the intellectual and political life of Canada. Everywhere do we meet names that recall the ancient régime—French kings and princes, statesmen, soldiers, sailors, explorers, and adventurers, compete in the national nomenclature with priests and saints. This country possesses large tracts of arable land, especially in the country stretching from the St. Lawrence to Lake Champlain, and watered by the Richelieu, that noted highway in Canadian history. Even yet, at the head-waters of its many rivers, it has abundance of timber to attract the lumberman.

The province of Ontario was formerly known as Upper or Western Canada, but at the time of the union it received its present name because it largely lies by the side of the lake which the Hurons and more famous Iroquois called "great." It extends from the river of the Ottawas—the first route of the French adventurers to the western lakes as far as the northwesterly limit of Lake Superior, and is the most populous and prosperous province of the Dominion on account of its wealth of agricultural land, and the energy of its population. Its history is chiefly interesting for the illustrations it affords of Englishmen's successful enterprise in a new country. The origin of the province must be sought in the history of those "United Empire Loyalists," who left the old colonies during and after the War of Independence and founded new homes by the St. Lawrence and great lakes, as well as in Nova Scotia {11} and New Brunswick, where, as in the West, their descendants have had much influence in moulding institutions and developing enterprise.

In the days when Ontario and Quebec were a wilderness, except on the borders of the St. Lawrence from Montreal to the Quebec district, the fur-trade of the forests that stretched away beyond the Laurentides, was not only a source of gain to the trading companies and merchants of Acadia and Canada, but was the sole occupation of many adventurers whose lives were full of elements which assume a picturesque aspect at this distance of time. It was the fur-trade that mainly led to the discovery of the great West and to the opening up of the Mississippi valley. But always by the side of the fur-trader and explorer we see the Recollet or Jesuit missionary pressing forward with the cross in his hands and offering his life that the savage might learn the lessons of his Faith.

As soon as the Mississippi was discovered, and found navigable to the Gulf of Mexico, French Canadian statesmen recognised the vantage-ground that the command of the St. Lawrence valley gave them in their dreams of conquest. Controlling the Richelieu, Lake Champlain, and the approaches to the Hudson River, as well as the western lakes and rivers which gave easy access to the Mississippi, France planned her bold scheme of confining the old English colonies between the Appalachian range of mountains and the Atlantic Ocean, and finally dominating the whole continent.

So far we have been passing through a country {12} where the lakes and rivers of a great natural basin or valley carry their tribute of waters to the Eastern Atlantic; but now, when we leave Lake Superior and the country known as Old Canada, we find ourselves on the northwestern height of land and overlooking another region whose great rivers—notably the Saskatchewan, Nelson, Mackenzie, Peace, Athabasca, and Yukon—drain immense areas and find their way after many circuitous wanderings to Arctic seas.

The Central region of Canada, long known as Rupert's Land and the Northwestern Territory, gradually ascends from the Winnipeg system of lakes, lying to the northwest of Lake Superior, as far as the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, and comprises those plains and prairies which have been opened up to civilisation within two decades of years, and offer large possibilities of power and wealth in the future development of the New Dominion. It is a region remarkable for its long rivers, in places shallow and rapid, and extremely erratic in their courses through the plains.

Geologists tell us that at some remote period these great central plains, now so rich in alluvial deposits, composed the bed of a sea which extended from the Arctic region and the ancient Laurentian belt as far as the Gulf of Mexico and made, in reality, of the continent, an Atlantis—that mysterious island of the Greeks. The history of the northwest is the history of Indians hunting the buffalo and fur-bearing animals in a country for many years under the control of companies holding royal charters of exclusive {14} trade and jealously guarding their game preserves from the encroachments of settlement and attendant civilisation. French Canadians were the first to travel over the wide expanse of plain and reach the foothills of the Rockies a century and a half ago, and we can still see in this country the Métis or half-breed descendants of the French Canadian hunters and trappers who went there in the days when trading companies were supreme, and married Indian women. A cordon of villages, towns, and farms now stretches from the city of Winnipeg, built on the site of the old headquarters of the Hudson's Bay Company, as far as the Rocky Mountains. Fields of golden grain brighten the prairies, where the tracks of herds of buffalo, once so numerous but now extinct, still deeply indent the surface of the rich soil, and lead to some creek or stream, on whose banks grows the aspen or willow or poplar of a relatively treeless land, until we reach the more picturesque and well-wooded and undulating country through which the North Saskatchewan flows. As we travel over the wide expanse of plain, only bounded by the deep blue of the distant horizon, we become almost bewildered by the beauty and variety of the flora, which flourish on the rich soil; crocuses, roses, bluebells, convolvuli, anemones, asters, sunflowers, and other flowers too numerous to mention, follow each other in rapid succession from May till September, and mingle with

"The billowy bays of grass ever rolling in shadow and sunshine."

Ascending the foothills that rise from the plains {16} to the Rocky Mountains we come to the Western region, known as British Columbia, comprising within a width varying from four to six hundred miles at the widest part, several ranges of great mountains which lie, roughly speaking, parallel to each other, and give sublimity and variety to the most remarkable scenery of North America. These mountains are an extension of the Cordilleran range, which forms the backbone of the Pacific coast, and in Mexico rises to great volcanic ridges, of which the loftiest are Popocatepétl and Iztaccíhuatl. Plateaus and valleys of rich, gravelly soil lie within these stately ranges.

Here we find the highest mountains of Canada, some varying from ten to fifteen thousand feet, and assuming a grandeur which we never see in the far more ancient Laurentides, which, in the course of ages, have been ground down by the forces of nature to their relatively diminutive size. Within the recesses of these stupendous ranges there are rich stores of gold and silver, while coal exists most abundantly on Vancouver [Transcriber's note: Island?].

The Fraser, Columbia, and other rivers of this region run with great swiftness among the cañons and gorges of the mountains, and find their way at last to the Pacific. In the Rockies, properly so called, we see stupendous masses of bare, rugged rock, crowned with snow and ice, and assuming all the grand and curious forms which nature loves to take in her most striking upheavals. Never can one forget the picturesque beauty and impressive grandeur of the Selkirk range, and the ride by the side of {17} the broad, rapid Fraser, over trestle-work, around curves, and through tunnels, with the forest-clad mountains ever rising as far as the eye can reach, with glimpses of precipices and cañons, of cataracts and cascades that tumble down from the glaciers or snow-clad peaks, and resemble so many drifts of snow amid the green foliage that grows on the lowest slopes. The Fraser River valley, writes an observer, "is one so singularly formed, that it would seem that some superhuman sword had at a single stroke cut through a labyrinth of mountains for three hundred miles, down deep into the bowels of the land." [4] Further along the Fraser the Cascade Mountains lift their rugged heads, and the river "flows at the bottom of a vast tangle cut by nature through the heart of the mountains." The glaciers fully equal in magnitude and grandeur those of Switzerland. On the coast and in the rich valleys stand the giant pines and cedars, compared with which the trees of the Eastern division seem mere saplings. The coast is very mountainous and broken into innumerable inlets and islands, all of them heavily timbered to the water's edge. The history of this region offers little of picturesque interest except what may be found in the adventures of daring sailors of various nationalities on the Pacific coast, or in the story of the descent of the Fraser by the Scotch fur-trader who first followed it to the sea, and gave it the name which it still justly bears.

The history of the Western and Central regions of the Dominion is given briefly towards the end of this {18} narrative, as it forms a national sequence or supplement to that of the Eastern divisions, Acadia and Canada, where France first established her dominion, and the foundations were laid for the present Canadian confederation. It is the story of the great Eastern country that I must now tell in the following pages.

[1] The first terrace, named after Lord Durham, was built on the foundations of the castle. In recent years the platform has been extended and renamed Dufferin, in honour of a popular governor-general.

[2] Akade means a place or district in the language of the Micmacs or Souriquois, the most important Indian tribe in the Eastern provinces, and is always united with another word, signifying some natural characteristic of the locality. For instance, the well-known river in Nova Scotia, Shubenacadie (Segebun-akade), the place where the ground-nut or Indian potato grows. [Transcriber's note: In the original book, "Akade" and "Segebun-akade" contain Unicode characters. In "Akade" the lower-case "a" is "a-breve", in "Segebun" the vowels are "e-breve" and "u-breve", and in "akade" the first "a" is "a-macron" and the second is "a-breve".]

[3] Sir J. W. Dawson, Salient Points in the Science of the Earth, p. 99.

[4] H. H. Bancroft, British Columbia, p. 38.

On one of the noble avenues of the modern part of the city of Boston, so famous in the political and intellectual life of America, stands a monument of bronze which some Scandinavian and historical enthusiasts have raised to the memory of Leif, son of Eric the Red, who, in the first year of the eleventh century, sailed from Greenland where his father, an Icelandic jarl or earl, had founded a settlement. This statue represents the sturdy, well-proportioned figure of a Norse sailor just discovering the new lands with which the Sagas or poetic chronicles of the North connect his name. At the foot of the pedestal the artist has placed the dragon's head which always stood on the prow of the Norsemen's ships, and pictures of which can still be seen on the famous Norman tapestry at Bayeux.

The Icelandic Sagas possess a basis of historical truth, and there is reason to believe that Leif Ericson discovered three countries. The first land he made after leaving Greenland he named Helluland on account of its slaty rocks. Then he came to a {20} flat country with white beaches of sand, which he called Markland because it was so well wooded.

After a sail of some days the Northmen arrived on a coast where they found vines laden with grapes, and very appropriately named Vinland. The exact situation of Vinland and the other countries visited by Leif Ericson and other Norsemen, who followed in later voyages and are believed to have founded settlements in the land of vines, has been always a subject of perplexity, since we have only the vague Sagas to guide us. It may be fairly assumed, however, that the rocky land was the coast of Labrador; the low-lying forest-clad shores which Ericson called Markland was possibly the southeastern part of Cape Breton or the southern coast of Nova Scotia; Vinland was very likely somewhere in New England. Be that as it may, the world gained nothing from these misty discoveries—if, indeed, we may so call the results of the voyages of ten centuries ago. No such memorials of the Icelandic pioneers have yet been found in America as they have left behind them in Greenland. The old ivy-covered round tower at Newport in Rhode Island is no longer claimed as a relic of the Norse settlers of Vinland, since it has been proved beyond doubt to be nothing more than a very substantial stone windmill of quite recent times, while the writing on the once equally famous rock, found last century at Dighton, by the side of a New England river, is now generally admitted to be nothing more than a memorial of one of the Indian tribes who have inhabited the country since the voyages of the Norsemen.

Leaving this domain of legend, we come to the last years of the fifteenth century, when Columbus landed on the islands now often known as the Antilles—a memorial of that mysterious Antillia, or Isle of the Seven Cities, which was long supposed to exist in the mid-Atlantic, and found a place in all the maps before, and even some time after, the voyages of the illustrious Genoese. A part of the veil was at last lifted from that mysterious western ocean—that Sea of Darkness, which had perplexed philosophers, geographers, and sailors, from the days of Aristotle, Plato, Strabo, and Ptolemy. As in the case of Scandinavia, several countries have endeavoured to establish a claim for the priority of discovery in America. Some sailors of that Biscayan coast, which has given so many bold pilots and mariners to the world of adventure and exploration—that Basque country to which belonged Juan de la Cosa, the pilot who accompanied Columbus in his voyages—may have found their way to the North Atlantic coast in search of cod or whales at a very early time; and it is certainly an argument for such a claim that John Cabot is said in 1497 to have heard the Indians of northeastern America speak of Baccalaos, or Basque for cod—a name afterwards applied for a century and longer to the islands and countries around the Gulf. It is certainly not improbable that the Normans, Bretons, or Basques, whose lives from times immemorial have been passed on the sea, should have been driven by the winds or by some accident to the shores of Newfoundland or Labrador or even Cape Breton, but such theories are not {22} based upon sufficiently authentic data to bring them under the consideration of the serious historian.

It is unfortunate that the records of history should be so wanting in definite and accurate details, when we come to the voyages of John Cabot, a great navigator, who was probably a Genoese by birth and a Venetian by citizenship. Five years after the first discovery by Columbus, John Cabot sailed to unknown seas and lands in the Northwest in the ship Matthew of Bristol, with full authority from the King of England, Henry the Seventh, to take possession in his name of all countries he might discover. On his return from a successful voyage, during which he certainly landed on the coast of British North America, and first discovered the continent of North America, he became the hero of the hour and received from Henry, a very economical sovereign, a largess of ten pounds as a reward to "hym that founde the new ile." In the following year both he and his son Sebastian, then a very young man, who probably also accompanied his father in the voyage of 1497, sailed again for the new lands which were believed to be somewhere on the road to Cipango and the countries of gold and spice and silk. We have no exact record of this voyage, and do not even know whether John Cabot himself returned alive; for, from the day of his sailing in 1498, he disappears from the scene and his son Sebastian not only becomes henceforth a prominent figure in the maritime history of the period, but has been given by his admirers even the place which his father alone fairly won as the leader in the two voyages on which {23} England has based her claim of priority of discovery on the Atlantic coast of North America. The weight of authority so far points to a headland of Cape Breton as the prima tierra vista, or the landfall which John Cabot probably made on a June day, the four hundredth anniversary of which arrived in 1897, though the claims of a point on the wild Labrador coast and of Bonavista, an eastern headland of Newfoundland, have also some earnest advocates. It is, however, generally admitted that the Cabots, in the second voyage, sailed past the shores of Nova Scotia and of the United States as far south as Spanish Florida. History here, at all events, has tangible, and in some respects irrefutable, evidence on which to dwell, since we have before us a celebrated map, which has come down from the first year of the sixteenth century, and is known beyond doubt to have been drawn with all the authority that is due to so famous a navigator as Juan de la Cosa, the Basque pilot. On this map we see delineated for the first time the coast apparently of a continental region extending from the peninsula of Florida as far as the present Gulf of St. Lawrence, which is described in Spanish as mar descubierta por los Ingleses (sea discovered by the English), on one headland of which there is a Cavo de Ynglaterra, or English Cape. Whether this sea is the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the headland is Cape Race, the south-eastern extremity of Newfoundland, or the equally well-known point which the Bretons named on the southeastern coast of Cape Breton, are among the questions which enter into the domain of {24} speculation and imagination. Juan de la Cosa, however, is conclusive evidence in favour of the English claim to the first discovery of Northern countries, whose greatness and prosperity have already exceeded the conceptions which the Spanish conquerors formed when they won possession of those rich Southern lands which so long acknowledged the dominion of Spain.

But Cabot's voyages led to no immediate practical results. The Bristol ships brought back no rich cargoes of gold or silver or spices, to tell England that she had won a passage to the Indies and Cathay. The idea, however, that a short passage would be discovered to those rich regions was to linger for nearly two centuries in the minds of maritime adventurers and geographers.

If we study the names of the headlands, bays, and other natural features of the islands and countries which inclose the Gulf of St. Lawrence we find many memorials of the early Portuguese and French voyagers. In the beginning of the sixteenth century Gaspar Cortereal made several voyages to the northeastern shores of Newfoundland and Labrador, and brought back with him a number of natives whose sturdy frames gave European spectators the idea that they would make good labourers; and it was this erroneous conception, it is generally thought, gave its present name to the rocky, forbidding region which the Norse voyagers had probably called Helluland five hundred years before. Both Gaspar Cortereal and his brother Miguel disappeared from history somewhere in the waters of Hudson's {26} Bay or Labrador; but they were followed by other adventurous sailors who have left mementos of their nationality on such places as Cape Raso (Race), Boa Ventura (Bonaventure), Conception, Tangier, Porto Novo, Carbonear (Carboneiro), all of which and other names appear on the earliest maps of the north-eastern waters of North America.

Some enterprising sailors of Brittany first gave a name to that Cape which lies to the northeast of the historic port of Louisbourg. These hardy sailors were certainly on the coast of the island as early as 1504, and Cape Breton is consequently the earliest French name on record in America. Some claim is made for the Basques—that primeval people, whose origin is lost in the mists of tradition—because there is a Cape Breton on the Biscayan coast of France, but the evidence in support of the Bretons' claim is by far the strongest. For very many years the name of Bretons' land was attached on maps to a continental region, which included the present Nova Scotia, and it was well into the middle of the sixteenth century, after the voyages of Jacques Cartier and Jehan Alfonce, before we find the island itself make its appearance in its proper place and form.

It was a native of the beautiful city of Florence, in the days of Francis the First, who gave to France some claim to territory in North America. Giovanni da Verrazano, a well-known corsair, in 1524, received a commission from that brilliant and dissipated king, Francis the First, who had become jealous of the enormous pretensions of Spain and Portugal in the new world, and had on one occasion sent word to {27} his great rival, Charles the Fifth, that he was not aware that "our first father Adam had made the Spanish and Portuguese kings his sole heirs to the earth." Verrazano's voyage is supposed on good authority to have embraced the whole North American coast from Cape Fear in North Carolina as far as the island of Cape Breton. About the same time Spain sent an expedition to the northeastern coasts of America under the direction of Estevan Gomez, a Portuguese pilot, and it is probable that he also coasted from Florida to Cape Breton. Much disappointment was felt that neither Verrazano nor Gomez had found a passage through the straits which were then, and for a long time afterwards, supposed to lie somewhere in the northern regions of America and to lead to China and India. Francis was not able to send Verrazano on another voyage, to take formal possession of the new lands, as he was engaged in that conflict with Charles which led to his defeat at the battle of Pavia and his being made subsequently a prisoner. Spain appears to have attached no importance to the discovery by Gomez, since it did not promise mines of gold and silver, and happily for the cause of civilisation and progress, she continued to confine herself to the countries of the South, though her fishermen annually ventured, in common with those of other nations, to the banks of Newfoundland. However, from the time of Verrazano we find on the old maps the names of Francisca and Nova Gallia as a recognition of the claim of France to important discoveries in North America. It is also from the Florentine's voyage that we may date the {28} discovery of that mysterious region called Norumbega, where the fancy of sailors and adventurers eventually placed a noble city whose houses were raised on pillars of crystal and silver, and decorated with precious stones. These travellers' tales and sailors' yarns probably originated in the current belief that somewhere in those new lands, just discovered, there would be found an El Dorado. The same brilliant illusion that led Ralegh to the South made credulous mariners believe in a Norumbega in the forests of Acadia. The name clung for many years to a country embraced within the present limits of New England, and sometimes included Nova Scotia. Its rich capital was believed to exist somewhere on the beautiful Penobscot River, in the present State of Maine. A memorial of the same name still lingers in the little harbours of Norumbec, or Lorambeque, or Loran, on the southeastern coast of Cape Breton. Enthusiastic advocates of the Norse discovery and settlement have confidently seen in Norumbega, the Indian utterance of Norbega, the ancient form of Norway to which Vinland was subject, and this belief has been even emphasised on a stone pillar which stands on some ruins unearthed close to the Charles River in Massachusetts. Si non é vero è ben trovato. All this serves to amuse, though it cannot convince, the critical student of those shadowy times. With the progress of discovery the city of Norumbega was found as baseless as the fables of the golden city on the banks of the Orinoco, and of the fountain of youth among the forests and everglades of Florida.

In the fourth decade of the sixteenth century we find ourselves in the domain of precise history. The narratives of the voyages of Jacques Cartier of St. Malo, that famous port of Brittany which has given so many sailors to the world, are on the whole sufficiently definite, even at this distance of three centuries and a half, to enable us to follow his routes, and recognise the greater number of the places in the gulf and river which he revealed to the old world. The same enterprising king who had sent Verrazano to the west in 1524, commissioned the Breton sailor to find a short passage to Cathay and give a new dominion to France.

At the time of the departure of Cartier in 1534 for the "new-found isle" of Cabot, the world had made considerable advances in geographical knowledge. South America was now ascertained to be a separate continent, and the great Portuguese Magellan had {30} passed through the straits, which ever since have borne his name, and found his way across the Pacific to the spice islands of Asia. As respects North America beyond the Gulf of Mexico and the country to the North, dense ignorance still prevailed, and though a coast line had been followed from Florida to Cape Breton by Cabot, Gomez, and Verrazano, it was believed either to belong to a part of Asia or to be a mere prolongation of Greenland. If one belief prevailed more than another it was in the existence of a great sea, called on the maps "the sea of Verrazano," in what is now the upper basin of the Mississippi and the Great Lakes of the west, and which was only separated from the Atlantic by a narrow strip of land. Now that it was clear that no short passage to India and China could be found through the Gulf of Mexico, and that South America was a continental region, the attention of hopeful geographers and of enterprising sailors and adventurers was directed to the north, especially as Spain was relatively indifferent to enterprise in that region. No doubt the French King thought that Cartier would find his way to the sea of Verrazano, beyond which were probably the lands visited by Marco Polo, that enterprising merchant of Venice, whose stories of adventure in India and China read like stories of the Arabian Nights.

Jacques Cartier made three voyages to the continent of America between 1534 and 1542, and probably another in 1543. The first voyage, which took place in 1534 and lasted from April until September, was confined to the Gulf of St. Lawrence, which he {32} explored with some thoroughness after passing through the strait of Belle Isle, then called the Gulf of Castles (Chasteaux). The coast of Labrador he described with perfect accuracy as extremely forbidding, covered with rocks and moss and "as very likely the land given by God to Cain." In one of the harbours of the Labrador coast he found a fishing vessel from La Rochelle, the famous Protestant town of France, on its way to the port of Brest, then and for some time after a place of call for the fishermen who were already thronging the Gulf, where walrus, whales, and cod were so abundant. A good deal of time has been expended by historical writers on the itinerary of this voyage, the record of which is somewhat puzzling at times when we come to fix Cartier's names of places on a modern map. Confining ourselves to those localities of which there is no doubt, we know he visited and named the isle of Brion in honour of Admiral Philip de Chabot, Seigneur de Brion, who was a friend and companion of Francis, and had received from him authority to send out Cartier's expedition. The Breton saw the great sand-dunes, and red cliffs of the Magdalens rising from the sea like so many cones. It was one of these islands he probably called Alezay, though there are writers who recognise in his description a headland of Prince Edward Island, but it is not certain that he visited or named any of the bays or lagoons of that island which lies so snugly ensconced in the Gulf. We recognise the bay of Miramichi (St. Lunaire) and the still more beautiful scenery of the much larger bay of Chaleur (Heat) which he so {33} named because he entered it on a very hot July day. There he had pleasant interviews with the natives, who danced and gave other demonstrations of joy when they received some presents in exchange for the food they brought to the strangers. These people were probably either Micmacs or Etchemins, one of the branches of the Algonquin nation who inhabited a large portion of the Northern continent. Cartier was enchanted with the natural beauties of "as fine a country as one would wish to see and live in, level and smooth, warmer than Spain, where there is abundance of wheat, which has an ear like that of rye, and again like oats, peas growing as thickly and as large as if they had been cultivated, red and white barberries, strawberries, red and white roses, and other flowers of a delightful and sweet perfume, meadows of rich grasses, and rivers full of salmon"—a perfectly true description of the beautiful country watered by the Restigouche and Metapedia rivers. Cartier also visited the picturesque bay of Gaspé, where the scenery is grand but the trees smaller and the land less fertile than in the neighbourhood of Chaleur and its rivers. On a point at the entrance of the harbour of Gaspé—an Indian name having probably reference to a split rock, which has long been a curiosity of the coast—Cartier raised a cross, thirty feet in height, on the middle of which there was a shield or escutcheon with three fleurs-de-lis, and the inscription, Vive le Roy de France. Cartier then returned to France by way of the strait of Belle Isle, without having seen the great river to whose mouth he had been so close {34} when he stood on the hills of Gaspé or passed around the shores of desolate Anticosti.

Cartier brought back with him two sons of the Indian chief of a tribe he saw at Gaspé, who seem to have belonged to the Huron-Iroquois nation he met at Stadacona, now Quebec, when he made the second voyage which I have to describe. The accounts he gave of the country on the Gulf appear to have been sufficiently encouraging to keep up the interest of the King and the Admiral of France in the scheme of discovery which they had planned. In this second voyage of 1535-36, the most memorable of all he made to American waters, he had the assistance of a little fleet of three vessels, the Grande Hermine, the Petite Hermine, and the Emérillon, of which the first had a burden of one hundred and twenty tons—quite a large ship compared with the two little vessels of sixty tons each that were given him for his first venture. This fleet, which gave Canada to France for two centuries and a quarter, reached Newfoundland during the early part of July, passed through the strait of Belle Isle, and on the 10th of August, came to a little bay or harbour on the northern shore of the present province of Quebec, but then known as Labrador, to which he gave the name of St. Laurent, in honour of the saint whose festival happened to fall on the day of his arrival. This bay is now generally believed to be the port of Sainte Geneviève, and the name which Cartier gave it was gradually transferred in the course of a century to the whole gulf as well as to the river itself which the Breton sailor was the first to place {35} definitely on the maps of those days of scanty geographical knowledge. Cartier led his vessels through the passage between the northern shores of Canada and the island of Anticosti, which he called Assomption, although it has long since resumed its old name, which has been gradually changed from the original Natiscotic to Naticousti, and finally to Anticosti. When the adventurers came near the neighbourhood of Trinity River on the north side of the Gulf, the two Gaspé Indians who were on board Cartier's vessel, the Grande Hermine, told them that they were now at the entrance of the kingdom of Saguenay where red copper was to be found, and that away beyond flowed the great river of Hochelaga and Canada. This Saguenay kingdom extended on the north side of the river as far as the neighbourhood of the present well-known Isle aux Coudres; then came the kingdom of Canada, stretching as far as the island of Montreal, where the King of Hochelaga exercised dominion over a number of tribes in the adjacent country.

Cartier passed the gloomy portals of the Saguenay, and stopped for a day or two at Isle aux Coudres (Coudrières) over fifty miles below Quebec, where mass was celebrated for the first time on the river of Canada, and which he named on account of the hazel-nuts he found "as large and better tasting than those of France, though a little harder." Cartier then followed the north shore, with its lofty, well-wooded mountains stretching away to the northward, and came at last to an anchorage not far from Stadacona, somewhere between the present Isle of {36} Orleans and the mainland. Here he had an interview with the natives, who showed every confidence in the strangers when they found that the two Gaspé Indians, Taignoagny and Domagaya, were their companions. As soon as they were satisfied of this fact—and here we have a proof that these two Indians must have belonged to the same nation—"they showed their joy, danced, and performed various antics." Subsequently the lord of Donnacona, whose Indian title was Agouahana, came with twelve canoes and "made a speech according to the fashion, contorting the body and limbs in a remarkable way—a ceremony of joy and welcome." After looking about for a safe harbour, Cartier chose the mouth of the present St. Charles River, which he named the River of the Holy Cross (Sainte Croix) in honour of the day when he arrived. The fleet was anchored not far from the Indian village of Stadacona, and soon after its arrival one of the chiefs received the Frenchmen with a speech of welcome, "while the women danced and sang without ceasing, standing in the water up to their knees."

Moored in a safe haven, the French had abundant opportunity to make themselves acquainted with the surrounding country and its people. They visited the island close by, and were delighted with "its beautiful trees, the same as in France," and with the great quantities of vines "such as we had never before seen." Cartier called this attractive spot the Island of Bacchus, but changed the name subsequently to the Isle of Orleans, in honour of one of the royal sons of France. Cartier was equally {37} charmed with the varied scenery and the fruitful soil of the country around Stadacona.

It was now the middle of September, and Cartier determined, since his men had fully recovered from the fatigues of the voyage, to proceed up the river as far as Hochelaga, of which he was constantly hearing accounts from the Indians. When they heard of this intention, Donnacona and other chiefs used their best efforts to dissuade him by inventing stories of the dangers of the navigation. The two Gaspé Indians lent themselves to the plans of the chief of Stadacona. Three Indians were dressed as devils, "with faces painted as black as coal, with horns as long as the arm, and covered with the skins of black and white dogs." These devils were declared to be emissaries of the Indian God at Hochelaga, called Cudragny, who warned the French that "there was so much snow and ice that all would die." The Gaspé Indians, who had so long an acquaintance with the religious customs and superstitions of the French, endeavoured to influence them by appeals to "Jesus" and "Jesus Maria." Cartier, however, only laughed at the tricks of the Indians, and told them that "their God Cudragny was a mere fool, and that Jesus would preserve them from all danger if they should believe in Him." The French at last started on the ascent of the river in the Emérillon and two large boats, but neither Taignoagny nor Domagaya could be induced to accompany the expedition to Hochelaga.

Cartier and his men reached the neighbourhood of Hochelaga, the Indian town on the island of {38} Montreal, in about a fortnight's time. The appearance of the country bordering on the river between Stadacona and Hochelaga pleased the French on account of the springs of excellent water, the beautiful trees, and vines heavily laden with grapes, and the quantities of wild fowl that rose from every bay or creek as the voyagers passed by. At one place called Achelay, "a strait with a stony and dangerous current, full of rocks,"—probably the Richelieu Rapids[1] above Point au Platon—a number of Indians came on board the Emérillon, warned Cartier of the perils of the river, and the chief made him a present of two children, one of whom, a little girl of seven or eight years, he accepted and promised to take every care of. Somewhere on Lake St. Peter they found the water very shallow and decided to leave the Emérillon and proceed in the boats to Hochelaga, where they arrived on the second of October, and were met by more than "a thousand savages who gathered about them, men, women, and children, and received us as well as a parent does a child, showing great joy." After a display of friendly feeling on the part of the natives and their visitors, and the exchange of presents between them, Cartier returned to his boat in the stream. "All that night," says the narrative, "the savages remained on the shore near our boats, keeping up fires, dancing, crying out 'Aguaze,' which is their word for welcome and joy." The king or chief of this Indian domain was also called Agouahana, and was a member of the Huron-Iroquois stock.

The French visitors were regarded by the Indians of Hochelaga as superior beings, endowed with supernatural powers. Cartier was called upon to touch the lame, blind, and wounded, and treat all the ailments with which the Indians were afflicted, "as if they thought that God had sent him to cure them."

Cartier's narrative describes the town as circular, inclosed by three rows of palisades arranged like a pyramid, crossed at the top, with the middle stakes standing perpendicular, and the others at an angle on each side, all being well joined and fastened after the Indian fashion. The inclosing wall was of the height of two lances, or about twenty feet, and there was only one entrance through a door generally kept barred. At several points within the inclosure there were platforms or stages reached by ladders, for the purpose of protecting the town with arrows, and rocks, piles of which were close at hand. The town contained fifty houses, each about one hundred feet in length and twenty-five or thirty in width, and constructed of wood, covered with bark and strips of board. These "long houses" were divided into several apartments, belonging to each family, but all of them assembled and ate in common. Storehouses for their grain and food were provided. They dried and smoked their fish, of which they had large quantities. They pounded the grain between flat stones and made it into dough which they cooked also on hot rocks. This tribe lived, Cartier tells us, "by ploughing and fishing alone," and were "not nomadic like the natives of Canada and the Saguenay."

Cartier and several of his companions were taken by the Indians to the mountain near the town of Hochelaga, and were the first Europeans to look on that noble panorama of river and forest which stretched then without a break over the whole continent, except where the Indian nations had made, as at Hochelaga, their villages and settlements. From that day to this the mountain, as well as the great city which it now overlooks in place of a humble Indian town, has borne the name which Cartier gave as a tribute to its unrivalled beauty. As we look from the royal mountain on the beautiful elms and maples rising in the meadows and gardens of an island, bathed by the waters of two noble rivers—the green of the St. Lawrence mingling with the blue of the Ottawa—on the many domes and towers of churches, convents, and colleges, on the stately mansions of the rich, on the tall chimneys of huge factories and blocks upon blocks of massive stores and warehouses, on the ocean steamers on their way to Europe by that very river which Cartier would not ascend with the Emérillon; as we look on this beauteous and inspiriting scene, we may well understand how it is that Canada has placed on Montreal the royal crown which Cartier first gave to the mountain he saw on a glorious October day when the foliage was wearing the golden and crimson tints of a Canadian autumn.

On Cartier's return to Stadacona he found that his officers had become suspicious of the intentions of the Indians and had raised a rude fort near the junction of the river of St. Croix and the little stream {42} called the Lairet. Here the French passed a long and dreary winter, doubtful of the friendship of the Indians, and suffering from the intense cold to which they were unaccustomed. They were attacked by that dreadful disease, the scurvy, which caused the death of several men, and did not cease its ravages until they learned from an Indian to use a drink evidently made from spruce boughs. Then the French recovered with great rapidity, and when the spring arrived they made their preparations to return to France. They abandoned the little Hermine, as the crew had been so weakened by sickness and death. They captured Donnacona and several other chiefs and determined to take them to France "to relate to the king the wonders of the world Donnacona [evidently a great story-teller] had seen in these western countries, for he had assured us that he had been in the Saguenay kingdom, where are infinite gold, rubies, and other riches, and white men dressed in woollen clothing." In the vicinity of the fort, at the meeting of the St. Croix and Lairet, Cartier raised a cross, thirty-five feet in height under the cross-bar of which there was a wooden shield, showing the arms of France and the inscription

When three centuries and a half had passed, a hundred thousand French Canadians, in the presence of an English governor-general of Canada, a French Canadian lieutenant-governor and cardinal {43} archbishop, many ecclesiastical and civil dignitaries, assisted in the unveiling of a noble monument in memory of Jacques Cartier and his hardy companions of the voyage of 1535-36, and of Jean de Brebeuf, Ennemond Massé, and Charles Lalemant, the missionaries who built the first residence of the Jesuits nearly a century later on the site of the old French fort, and one of whom afterwards sacrificed his life for the faith to which they were all so devoted.

On the return voyage Cartier sailed to the southward of the Gulf, saw the picturesque headlands of northern Cape Breton, remained a few days in some harbours of Newfoundland, and finally reached St. Malo on the sixteenth of July, with the joyful news that he had discovered a great country and a noble river for France.

[1] The obstructions which created these rapids have been removed.

The third voyage made by Cartier to the new world, in 1541, was relatively of little importance. Donnacona and the other Indians of Stadacona, whom the French carried away with them, never returned to their forest homes, but died in France. During the year Cartier remained in Canada he built a fortified post at Cap Rouge, about seven miles west of the heights of Quebec, and named it Charlesbourg in honour of one of the sons of Francis the First. He visited Hochelaga, and attempted to pass up the river beyond the village, but was stopped by the dangerous rapids now known as the St. Louis or Lachine. He returned to France in the spring of 1542, with a few specimens of worthless metal resembling gold which he found among the rocks of Cap Rouge, and some pieces of quartz crystal which he believed were diamonds, and which have given the name to the bold promontory on which stand the ancient fortifications of Quebec.

Cartier is said to have returned on a fourth voyage to Canada in 1543—though no record exists—for the purpose of bringing back Monsieur Roberval, otherwise known to the history of those times as Jean François de la Roque, who had been appointed by Francis his lieutenant in Canada, Hochelaga, Saguenay, Newfoundland, Belle Isle, Carpunt, Labrador, the Great Bay (St. Lawrence), and Baccalaos, as well as lord of the mysterious region of Norumbega—an example of the lavish use of titles and the assumption of royal dominion in an unknown wilderness. Roberval and Cartier were to have sailed in company to Canada in 1541, but the former could not complete his arrangements and the latter sailed alone, as we have just read. On his return in 1542 Cartier is said to have met Roberval at a port of the Gulf, and to have secretly stolen away in the night and left his chief to go on to the St. Lawrence alone. But these are among historic questions in dispute, and it is useless to dwell on them here. What we do know to a certainty is that Roberval spent some months on the banks of the St. Lawrence,—probably from the spring of 1542 to late in the autumn of 1543,—and built a commodious fort at Charlesbourg, which he renamed France-Roy. He passed a miserable winter, as many of the colonists he had brought with him had been picked up amongst the lowest classes of France, and he had to govern his ill-assorted company with a rigid and even cruel hand. Roberval is said to have visited the Saguenay and explored its waters and surrounding country for a considerable distance, evidently hoping {46} to verify the fables of Donnacona and other Indians that gold and precious stones were to be found somewhere in that region. His name has been given to a little village at Lake St. John, on the assumption that he actually went so far on his Saguenay expedition, while romantic tradition points to an isle in the Gulf, the Isle de la Demoiselle, where he is said to have abandoned his niece Marguérite,—who had loved not wisely but too well—her lover, and an old nurse. This rocky spot appears to have become in the story an isle of Demons who tormented the poor wretches, exposed to all the rigours of Canadian winters, and to starvation except when they could catch fish or snare wild fowl. The nurse and lover as well as the infant died, but Marguérite is said to have remained much longer on that lonely island until at last Fate brought to her rescue a passing vessel and carried her to France, where she is said to have told the story of her adventures.

After this voyage Roberval disappeared from the history of Canada. Cartier is supposed to have died about 1577 in his old manor house of Limoilou, now in ruins, in the neighbourhood of St. Malo. He was allowed by the King to bear always the name of "Captain"—an appropriate title for a hardy sailor who represented so well the heroism and enterprise of the men of St. Malo and the Breton coast. The results of the voyages of Cartier, Roberval, and the sailors and fishermen who frequented the waters of the Great Bay, as the French long called it, can be seen in the old maps that have come down to us, and show the increasing geographical knowledge. {47} To this knowledge, a famous pilot, Captain Jehan Alfonce, a native of the little village of Saintonge in the grape district of Charente, made valuable contributions. He accompanied Roberval to Canada, and afterwards made voyages to the Saguenay, and appears to have explored the Gulf and the coasts of Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, and even Maine as far as the Penobscot, where he believed was the city of Norumbega.

After the death of Francis there came dark days for France, whose people were torn asunder by civil war and religious strife. With the return of peace in France the Marquis de la Roche received a commission from Henry the Fourth, as lieutenant-general of the King, to colonise Canada, but his ill-fated expedition of 1597 never got beyond the dangerous sandbanks of Sable Island. French fur-traders had now found their way to Anticosti and even Tadousac, at the mouth of the Saguenay, where the Indians were wont to assemble in large numbers from the great fur-region to which that melancholy river and its tributary lakes and rivers give access, but these traders like the fishermen made no attempt to settle the country.

From a very early date in the sixteenth century bold sailors from the west country of Devon were fishing in the Gulf and eventually made the safe and commodious port of St. John's, in Newfoundland, their headquarters. Some adventurous Englishmen even made a search for the land of Norumbega, and probably reached the bay of Penobscot. Near the close of the century, Frobisher attempted to open up {48} the secrets of the Arctic seas and find that passage to the north which remained closed to venturesome explorers until Sir Robert McClure, in 1850, successfully passed the icebergs and ice-floes that barred his way from Bering Sea to Davis Strait. In the reign of the great Elizabeth, when Englishmen were at last showing that ability for maritime enterprise which was eventually to develop such remarkable results, Sir Humphrey Gilbert, the half-brother of Sir Walter Raleigh, the founder of Virginia, the Old Dominion, took possession of Newfoundland with much ceremony in the harbour of St. John's, and erected a pillar on which were inscribed the Queen's arms. Gilbert had none of the qualities of a coloniser, and on his voyage back to England he was lost at sea, and it was left to the men of Devon and the West coast in later times to make a permanent settlement on the great island of the Gulf.