Title: The Rainy Day Railroad War

Author: Holman Day

Release date: September 18, 2007 [eBook #22666]

Most recently updated: February 24, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE—THE TRYING-OUT OF ONE RODNEY PARKER, ASSISTANT ENGINEER

CHAPTER TWO—THE WHIM THAT PROJECTED THE FAMOUS “POQUETTE CARRY RAILROAD”

CHAPTER THREE—ENGINEER PARKER GETS FINAL ORDERS FOR “THE LAND OF THE GIDEONITES.”

CHAPTER FOUR—IN WHICH THE DOUGHTY “SWAMP SWOGON” ASTONISHES SUNKHAZE SETTLEMENT

CHAPTER FIVE—HOW COLONEL GIDEON WAS BACKED DOWN FOR THE FIRST TIME IN HIS LIFE

CHAPTER SIX—IN WHICH “THE CAT-HERMIT OF MOXIE” CASTS HIS SHADOW LONG BEFORE HIM

CHAPTER SEVEN—HOW “THE FRESH-WATER CORSAIRS” CAME TO SUNKHAZE

CHAPTER EIGHT—THE LOCOMOTIVE THAT WENT SWIMMING AND THE ENGINEER WHO WAS STOLEN

CHAPTER NINE—UP THE WINDING WAY TO THE “OGRE OF THE BIG WOODS.”

CHAPTER ELEVEN—THE BEAR THAT WALKED LIKE A MAN

CHAPTER TWELVE—THE STRANGE “CAT-HERMIT OF MOXIE”

CHAPTER THIRTEEN—THE BEAR OF THE BIG WOODS “BAITED” AFTER HIS OWN FASHION

CHAPTER FOURTEEN—HOW RODNEY PARKER PAID AN HONEST DEBT

CHAPTER FIFTEEN—THE DAY WHEN POQUETTE BURST WIDE OPEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN—THE PACT THAT OPENED RODNEY PARKER'S PROFESSIONAL FUTURE

Illustrations

Then he Fell to Chuckling 049-050

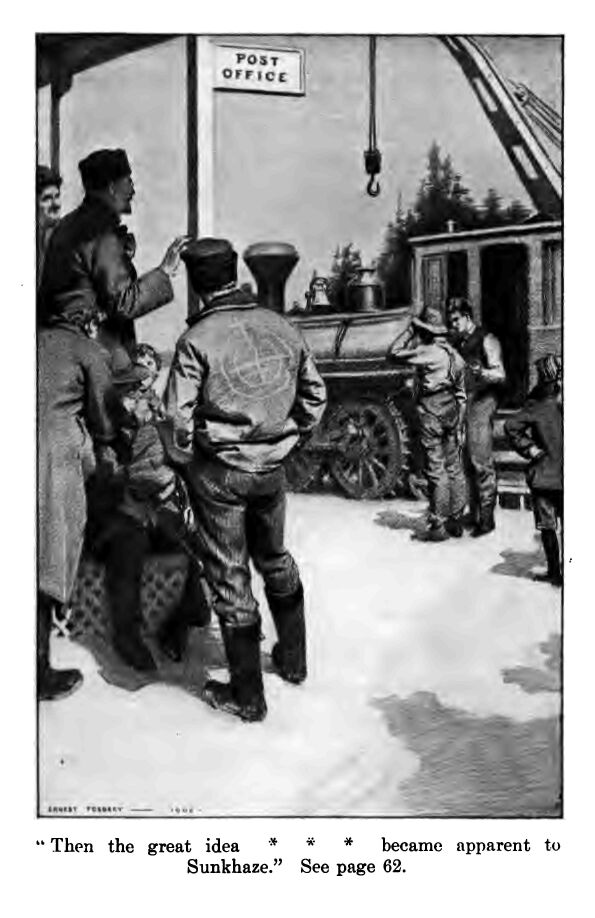

Then the Great Idea Frontispiece

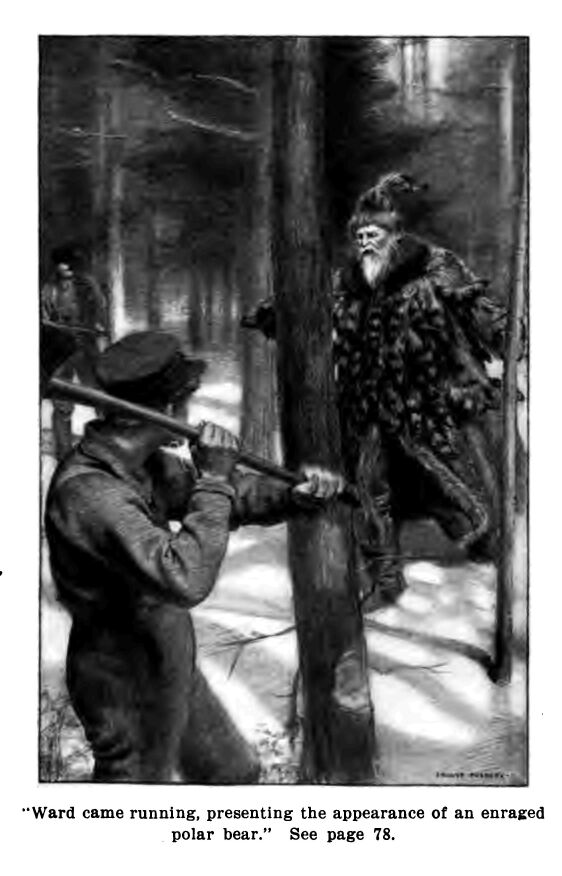

Appearance of an Enraged Polar Bear 078-100

A Dim White Hulk Seemed to Hover 117-140

Colonel Ward Stamped in 149-174

Every Inch of his Skin Was Being Tortured 197-224

All at once the stump-dotted, rocky hillside became clamorous and animated. From the little shacks sheathed with tarred paper, from the sodded huts, from burrows sunk into the hillside men suddenly came popping out with shrill cries.

Three men, shouldering surveying instruments, stopped in their tracks on the freshly-heaped soil of a new railroad embankment, and gazed up at the hillside. The railroad skirted its foot and the sudden activity on the slope was in full view. “Your lambs seem to be blatting around the fodder-rack once more, Parker,” observed the man who lugged the transit. He was a thin, elderly man and his tone was somewhat satirical.

The men were running toward a common center, uttering cries in shrill staccato and sounding like yelping dogs.

Parker drove the spurs of his tripod into the soft soil and stared up at the hillside, his tanned brow puckering with apprehension.

“I don't think there's much of the lamb to that rush,” observed the third man; “they sound to me more like hyenas after raw meat.”

“It will be Dominick they'll eat, then,” said the elderly man.

“I'm afraid you put the Old Harry into 'em last week when you took their part and straightened out Dominick's bill of fare,” he went on. “They probably think they can get quail on toast now if they yap for it.”

“I believe in letting dagoes fight it out among themselves,” announced the third man with much derision. “Helping one of 'em is like picking a hornet out of a puddle. You'll get stung while doing it.”

The men on the hillside had knotted themselves into a jostling group before the door of a long, low structure sheathed with tarred paper like the shacks. In the sunshine an occasional glint flashed above their heads.

“Yes, their stingers are out,” remarked the elderly man drily. “If they've got Dominick cornered in that eating camp I'm thinking this will be the day that he'll get his——whatever it is, they've laid up for him.”

“He promised me there should be no more weevils and no more spoiled meat,” cried the one who had been addressed as Parker, a young man whose earnest face now expressed deep trouble. “As matters were going, those Italians were half starved and doing hardly half a day's work in nine hours. Their padrone was putting the food rake-off into his own pocket.”

“I'm not backing up Dominick,” said the other. “But when you took the men's part and laid down the law to him on the grub question you gave them their cue for general rebellion. Ten chances to one the padrone has done as he agreed. I reckon you scared him enough for that. Now they're probably around with knives looking for napkins and sparkling red wine. I tell you, Parker, you're inviting trouble when you go to boosting up what you call the oppressed multitude.”

“That's a pretty hard view to take of the world and the people in it, Mr. Searles,” replied the youth. “There ought to be a bit of merit and encouragement in a man's going out of his way to right a wrong.”

“Well, Parker, I'm hired as construction engineer on the P. K. & R. railroad system and I've worked for the road a good many years and found that I get along best when I am attending strictly to my own business in my own line. I told you at the time you butted into that dago row you were laying up trouble either for yourself or for some one else—and I guess it's some one else.”

A series of pistol shots popped smartly on the hillside, the reports partly muffled by the thin walls of the shack. The cries of the men outside became shrieks. The next instant the side wall bellied outward and then burst asunder. A man came hustling through the opening, evidently self-propelled, for he struck lightly on his feet and began to run down the steep hill. A soiled canvas apron fluttered at his waist. Stones rained after him. The knot of men at the door scattered like quicksilver and howling runners pursued him.

Probably fear helped him as much as agility, for he kept well ahead of the rout, leaped a low fence at the bottom of the hill, scurried across a little valley and came floundering up the soft soil of the railroad embankment, scrambling toward the little group of engineers.

“It's Dominick,” said Searles. “There seems to be a little more work cut out for you in your side line of philanthropist.”

“I do it whatta you say,” screamed the man as his head came over the edge of the embankment. “Nice! Good! All good to eat. But they want mucha more—too mucha!”

He struck himself repeated blows on the breast with one fist and pointed with the other hand at the men who came swarming up the side of the graded road bed.

“You coma look—look to the nice br-read, meat all good, beer—plenty much to eat, dr-rink!” the padrone gasped in appeal, as he circled about Parker to put him between the rioters and himself.

The men who came after, screaming and cursing, jerking their arms above their heads, rolling back their lips from their yellow teeth, were apparently so many lunatics whose frenzy was not to be stayed. But undisciplined natures whose excesses spring from lack of self control are all the more ready to respond to the masterful control of others.

First of all the men recognized in Parker the champion who had won their first rights from the padrone.

They stopped their shrill vituperation and, crowding about him, began to bleat their explanations and appeals. But he threw out his arms, pushed them back a safe distance from the panting Dominick and roared them into silence, brandishing his fists, as he would have quelled a noisy school.

When they understood that he wished them to be quiet they were silent, all leaning forward, their eyes shining, their lips apart, their fists clinched as tho they were holding their tongues in leash by that means, their dark, brown faces alight with wistful, almost palpitating eagerness. The regard they fixed on his face was baleful in its intentness.

“Looka what they do,” yelled Dominick rushing to his side. He had stripped his sleeve back from his arm. Blood was trickling from a knife gash.

Then the tumult broke out again from the crowd. Two men leaped forward shaking their hats in their hands and screaming assertions and pointing quivering fingers at bullet holes in the crowns.

“Shut up!” barked the young man. The presence of the satiric and unsympathetic old engineer nerved him to settle the dispute, if he might. The hint from the other that he had been meddling in what was outside his business gave him an uncomfortable sense of responsibility.

“About face and back to the camp,” he shouted. “I will look at your dinner and we shall see!”

They hesitated a moment, but he went among them, pushing them down the bank.

He followed with the padrone behind the jabbering throng, and the two engineers came along at his earnest request.

“Mr. Searles,” said Parker after a little while, as they walked side by side, “being an older and wiser man than I am you are probably right in suggesting that I did wrong in interfering in this affair at the outset. But,” he half-chuckled, “I am going to lay the blame on my professor in sociology. He set me to thinking pretty hard in college and I guess I haven't been out from under his influence long enough to get hardened into the selfish views of my fellowman.”

There was earnestness under his smile.

“My boy,” said the elder, “I am not blaming you for what you have done for the poor devils. But I have been all for business in my life. Business hasn't seemed to mix well with philanthropy. I haven't dared to think of what I ought to do. I have thought only of what I had to do, to earn a living for my family.”

“Well,” said Parker, “if the P. K. & R. folks decide that I've been meddling in matters that are none of my business I have no family to suffer for my indiscretion—but I have prospects and I know that a discharged man is worse off than a man who has started.”

The elder man patted Parker's arm.

“As it stands now—and I'm speaking as a friend, young man, and not as a captious critic—you have set this Italian camp all askew by giving them countenance in the first place. They haven't any regulators in their heads, you see! When you're feeding charity to that kind of ruck you've got to be careful Parker, that they don't trample you down when they rush for the trough.”

The young man walked along up the hillside in silence. But just as they arrived in front of the long camp the scowl of puzzled hesitation disappeared from his forehead.

“As old Uncle Flanders used to say,” he muttered, “'When a man sticks his finger into a tight knot-hole he'd better pull it out mighty quick, before it swells, even if he does leave some skin on the edges.'”

The men halted and grouped themselves about the door. Their eager looks and nudgings of each other showed plainly that they expected their champion to take up their cause against the padrone once more.

Dominick prudently halted at a little distance.

“You go look for yourself, Sir Engineer,” he shouted; “on the kettle, in the table all about and you see whatta I feed to those beasts when I try to satisfy.”

The men retorted in shrill chorus leaping about and gesticulating till their joints snapped.

Parker resolutely pushed through the throng without trying to understand what they were saying to him and slammed the door in the faces of the few who attempted to crowd in with him. Those who anxiously peered through the windows saw him examine the food set out on the table for the noon meal, lift the covers from the stew pans on the rusty stove and then pass into the little building behind the main camp. The great stone ovens for the bread-baking were located there.

When at last he came out he faced them with grim visage, squared the shoulders that had borne many a football assault and called to Dominick.

“Go inside,” he said, “and coax those two helpers of yours out of those ovens. They couldn't understand my Italian. Tell them that they are safe. Let the padrone through, men! Do you hear?”

The crowd sullenly parted and Dominick trotted up the lane they left, hastening with apprehensive shruggings of his shoulders.

“Go about your work,” said Parker, clutching his arm a moment as the padrone hastened past. “I can see it isn't your fault this time.”

“Now, men,” he cried, turning to the throng, “few words and short so that you may all understand. Dominick's dinner is good. Good as any in the line boarding camps. I'm going to eat here. You come in and eat too.”

A mumbling began among them and immediately it swelled into a jabbering chorus as the few who understood translated his words to the others.

He leaped down off the muddy stoop and strode among them, cuffing this one and that of those malcontents who were noisiest.

“That young man certainly understands dago nature,” muttered Searles to the other engineer. “A club, good grit and a hard fist will drive them when a machine gun wouldn't.”

“I stood up for you when you were not used right,” shouted the young man. “He has given you what I told him to give you—what you asked for. Go in there and get it.”

He knew who the ring-leaders in the mutiny were and he drove those into the camp first. The others followed. In five minutes they were all at their places at table munching quietly. Another man, even with equal determination, might have not succeeded. But the greediest grumbler among them understood that this young man had first been as valiant to secure their rights as he was now ready to curb their rebellion.

In his own heart he was loathing this role of arbiter and mentor. His first interference had come out of his natural sense of justice. He had pitied this herd of men who had been so helplessly appealing against their wrongs.

As he stood at one end of the room now and gazed at them, he realized with a little pang of self-reproach that his latest exploit had been prompted by as much of a desire to set himself right with the company as to square the padrone's critical case.

Later, when they were trudging down the hill together Searles said with a little touch of malice,

“For a philanthropist, Parker, you seem to relish rough-house about as well as any one I ever saw, I've heard for a long time that football makes prizefighters out of college boys—so much so that they go looking for trouble. Is that so?”

“I wish you'd let the matter drop, Mr. Searles,” said the young man. “I'm thoroughly ashamed of the whole thing.”

“Well, I was going to say,” went on the elderly man, “that civil engineers in these days get just as good wages without being shoulder-hitters. You'll get along faster on the peace basis.”

That was Parker's reflection two days later when he was in the room of the chief engineer of the P. K. & R. system, at the company's general offices.

“By the way,” said the chief, after his subordinate had finished his regular report, “Mr. Jerrard wishes to see you.”

Jerrard was general traffic manager and chief executive.

The young engineer went slowly down the long corridor, apprehension gnawing at his heart. He huskily muttered his name to the clerk at the grilled door and was admitted. He fairly dragged his feet along the strip of matting that led to the general manager's private office. It was like the Bridge of Sighs to him.

“Parker, eh?” repeated the general manager, whirling in his chair and letting his eyeglasses drop against his plump “front elevation,” as Parker whimsically termed it in his thoughts, even in this moment of his distress.

Jerrard gazed at him for a little while, a rather curious expression in his eyes under their shaggy gray brows, then whirled back to his desk and scrabbled among his papers. He drew forth a sheet of memoranda, gave Parker another shrewd glance and inquired:

“Is it true, sir, that you have been interfering in the padrone system of the construction department?”

“I suppose what I did might be termed that, tho I wasn't intending to be meddlesome, Mr. Jerrard.”

“Nothing in general instructions, was there, to lead a cub assistant in the engineering corps to revise a boarding house bill of fare?”

“No, sir.”

“I find it further mentioned that you were back next day and herded about seventy-five Italians into a victualling camp as you would drive steers to a fodder rack. Don't you know that we reserve that sort of business for a squad of police?”

“Mr. Jerrard,” said the young man, recovering some of his self-possession tho his tone was apologetic, “since I have been on the road I saw what happened once when the police came with their clubs and revolvers. There was a free fight and two men were killed. I thought I saw a chance for one man to arbitrate a little difficulty—and arbitration is pretty highly recommended in these days by good authorities. When I found that arbitration didn't make things stay put I meddled once more in order to undo my first mistake—if we may call it that. It probably was a mistake, looked at officially. But you see—” his voice faltered a little, for the manager was surveying him with rather a hard look in his eyes, “I hoped that putting the padrone into line on his food question would prevent a strike; when I drove the men to table I had only the interests of the road at heart, for the strike was then fairly on.”

“Well,” said the manager, a bit of a smile at the corners of his mouth, “you certainly were not thinking very hard of your own interests when you went into that rabid gang.”

“I can see that I made a botch of it generally, Mr. Jerrard. I will save you the trouble of requesting my resignation.”

But as he bowed and turned Jerrard spoke sharply.

“Not so fast, young man,” he said. “As the executive of the P. K. & R, system it wouldn't be exactly official and proper in me to approve your judgment in that matter of the Italians; but as a man—plain man, now, you understand,—I know grit when I see it and—” he dropped his bluff stiffness got out of his chair and came along and squeezed Parker's muscular arm, “you've got a brand of it that I admire. Yes, I do. No mistake! But that is just between you and me. That is simply my own personal opinion. I don't believe the directors relish the idea of gladiators in the engineering corps. Just respect this little private hint of mine hereafter please.”

He surveyed the young man with twinkling and appreciative eyes.

“Parker,” he said, “once in a while there comes up in the railroad business a demand for a man who has brains and spunk and muscle all rolled up in one bundle. I haven't tested you out yet on the first named but the chief engineer speaks in your behalf. The last two you certainly have. There's the story of a man who was going home late at night and picked up what he thought was a kitten and found it to be a pole-cat. It was good judgment to set it down again mighty sudden. But the skin was worth something and he resolved to have the skin to pay for the damage. Now President Whittaker and myself have been up in the north woods this season—among the big game, you understand. We picked up what we thought was a kitten. It has turned out to be something else. But we are not going to drop it.”

The young engineer was looking at him with puzzled gaze.

“You don't understand a bit of it, do you?” laughed the traffic manager. “Well, I can't explain the thing just yet. I'll simply leave it this way today: Do you want to take a pole-cat and skin it for us? I don't mean by that that it's a job that any enterprising young man should be ashamed or afraid of. It's a job in your line. It's something of close personal interest to the president of this system and myself. It is going to take you away into the big woods. Do you want it—yes or no?”

The engineer hesitated only a moment.

“I'll take it,” he said simply.

“That's the boy!” cried Jerrard. His tone was so enthusiastic that Parker's instinct told him that this bluff offer was another test of his readiness in an emergency and had succeeded.

The manager put his hand against his shoulder and gently pushed him out of the office.

“Get ready for a cold winter out of doors and practice your tongue on the names To-quette Carry' and 'Colonel Gideon Ward' until you are not afraid of the sound of them.”

With a chuckle he shut the door on the astonished young man, but opened it again before Parker had moved from the mat outside.

“Don't be worried, my boy, because I cannot explain the whole situation today.” There was kindly reassurance in his tones. “You'll make out all right, I'm sure of that.” A queer little smile puckered the corners of his eyes and his voice again became teasing. “The idea is, you've taken a contract to do up the Gideonites of the Wilderness in a lone-handed job. But I think you're good for the trick.” He shut the door again.

Weeks passed before Rodney Parker got any more light on the matter in which he had blindly given his word.

He understood this silence better when the situation was set before him at last. There are some projects that captains of industry dilate upon with pride. But big men are cautious about letting the world know their whims. And whims that lead to exasperating complications that no business judgment has provided for, do not form pleasant topics for conversation or publicity.

Many railroad projects have been launched, some of them unique, but never before was enterprise conceived in just the spirit that gave the Poquette Carry Railway to the transportation world. There have been railroads that “began somewhere and ended in a sheep pasture.” The Poquette Carry Road, known to the legislature of its state as “The Rainy-Day Railroad,” is even more indifferently located, for it twists for six miles, from water to water, through as tangled and lonely a wilderness as ever owl hooted in.

Yet it has two of the country's railroad kings behind it and at its inception some very wrathful lumber kings were ahead of it, and the final and decisive battle that was fought was between the champions of the respective sides—an old man and a young one.

The old man had all the opinionated conservatism of one who despises new methods and modern progress as “hifalutin and new-fangled notions.” The young man, fresh from a school of technology and just completing an apprenticeship under the engineers of a big railroad system, had not an old-fashioned idea.

The old man came roaring from the deep woods, choleric, impatient of opposition, and flaming with the rage of a tyrant who is bearded in his own stronghold for the first time. The young man advanced from the city to meet him with the coolness of one who has been taught to restrain his emotions, and armed with determination to win the battle that would make or break him, so far as his employers were concerned.

Jerrard was the avant-courier of this novel railroad. Jerrard had been traffic-manager of the great P. K. & R. system for many years, and when he grew bilious and “blue” and very disagreeable, the doctor told him to go back into the woods so far that he would not think about tariff or rebates or competition for two months.

Jerrard chose Kennegamon Lake. A New England general passenger-agent whom he had met at a convention told him about that wilderness gem, and lauded it with a certain attractiveness of detail that made Jerrard anxious to test the veracity of New England railroad men, whose “fishin'-story” folders he had always doubted with professional scepticism.

The journey by rail was a long one, and it afforded leisure for so much cogitation that when Jerrard napped he dreamed that the ends of his nerves were nailed to his desk back in the P. K. & R. general offices, and that as he proceeded he was unreeling them as a spider spins its thread.

When he left the train at Sunkhaze station he was still worrying as to whether the assistant traffic-manager would be able to beat the O. & O. road on the grain contract. In thinking it over about a month later it occurred to him that he had dropped all outside affairs right there on that station platform.

In the first place the mosquitoes and black flies were waiting. He had never seen or felt black flies before. He would have scouted the idea that there were insects no bigger than pinheads that in five minutes would have his face streaming with blood.

“They do just love the taste of city sports,” said the guide. “We old sanups ain't much of a delicacy 'long side of such as you. Here, let me put this on.” He daubed the white face of the city man with an evil-smelling compound of tar and oil.

Jerrard's mind was rapidly freeing itself from transportation worries. Then came the long paddle across Spinnaker Lake, with only the unfamiliar insecurity of a canoe beneath him, and after that the six-mile Poquette carry.

By this time Jerrard had forgotten the P. K. & R. entirely.

The canoe and duffel went across the carry slung upon a set of wheels. Jerrard rode in the low-backed middle seat of a muddy buck-board.

The wheels ran against boulders, grated off with indignant “chuckering” of axle-boxes, hobbled over stumps and plowed through “honey-pots” of mud.

“For goodness' sake,” gasped Jerrard, holding desperately to the seat, “why don't you get into the road?”

The driver, a French-Canadian turned and displayed an appreciative grin.

“Eet ban de ro'd vat you saw de re,” he explained, pointing his whip to the thoroughfare they were pursuing.

“This a road?” demanded Jerrard, with indignation.

“Oui, eet ban a tote-road.”

“I never heard of this kind before,” ejaculated Jerrard, between bumps, “but the name 'road' ought not to be disgraced in any such fashion. How much of it is there?”

“Sax mal'.”

“Six miles! All like this?”

“Aw-w-w some pretty well, some as much bad.”

“Well, I don't know just what you mean,” muttered Jerrard, “but I fear I can imagine.” After what seemed a long interval, and when Jerrard, dizzied by the bumps and the curves, believed that the end must be near,—for six miles are but an inconsiderable item to the traffic-manager of a thousand-mile system,—he asked how far they had come. The driver looked at the trees. “Wan mal', mabbee, an' some leetle more.” The railroad man opened his mouth to make a discourteous retort reflecting on the driver's judgment of distances, but just then one of the rear wheels slipped off a rock. It came down kerchunk. Jerrard bit his cheek and his tongue. After that he sat and held to his seat with a hopeless idea that the end of the road was running away from them.

Half-way through the woods he bought two fat doughnuts and a piece of apple pie at a wayside log house. He munched his humble fare with a gusto he had not known for years. The jolting, the shaking, the tossing had started his sluggish blood and cleared his business-befogged brain. His food was spiced with the aroma of the hemlocks, and when they took to the road again he began to hum tunes.

Then he fell to chuckling. And when a smooth stretch suffered him to unclasp his cramped hold, he slapped his leg mirthfully. He was thinking what President Whittaker of the P. K. & R. would be saying in two weeks.

President Whittaker was a rotund, flabby man, whom long indulgence in rubber-tired broughams and double-springed private cars had softened until he reminded one of a fat down pillow.

“Jerrard,” he had said, at parting, “if you find good fishing I'll follow you in two weeks. I need a little outdoor relaxation myself.”

Jerrard sent an enthusiastic letter right back by the tote-road driver. He took the word of his guide about the fishing in prospect. In his new and ebullient spirits he felt that he could hardly wait two weeks for the spectacle—Whittaker in the middle seat of a buck-board, on that six-mile carry road. And when the day came, Jerrard, now bronzed, alert and agile walked out over the Poquette Carry, paddled down to Sunkhaze, and received his superior with open arms.

The unconsciousness of the corpulent Whittaker as he left the train, spick and span in tweed and polished shoes appealed to Jerrard's sense of the ludicrous so acutely that the president, following the baggage-laden guide down to the shore of the lake, stopped and looked at his friend with puzzled gaze.

“I say, Jerrard, you seem to be in a good humor.”

“Nothing like the ozone of the forest to make you sparkle,” chuckled the traffic-manager.

It is unnecessary to describe the incidents of the trip across the lake, the apprehensive flinching of the fat president whenever the canoe lurched, and his fear of breaking through the bottom of the frail shell.

But when they were well out on the carry road in the buckboard, Jerrard, gazing on the indescribable mixture of reproach, horror, pain and astonishment that the president's face presented laughed until Whittaker forgot dignity, cares and fears, and laughed, too.

Two days later, as they were eating their lunch beside the famous spring in the north cove of Kennemagon Whittaker stretched himself luxuriously on the gray moss, and said;

“Jerrard, it's an earthly paradise! I never had such fishing, never saw such scenery. I want to come here every summer. I'd like to buy a tract here. But that six-mile drive—O dear me! It makes me shiver when I think I've got to bump back over it in two weeks.”

That evening one Rowe, a timber-land exploring prospector, whose employment was locating tracts for the cutting of pulp stuff, stopped at the camp and accepted hospitality for the night. After supper the three lay in their bunks and chatted, while the guide pottered about the household tasks.

“Much travel over the Poquette Carry?” asked Whittaker.

“Good deal,” said Rowe. “It's the thoroughfare between the West Branch and Spinnaker, you know. All the men for the woods leave the train at Sunkhaze, boat it across Spinnaker, and walk the carry at Poquette. All the supplies for the camp come that way, too. They bateau goods up the river from the West Branch end of the carry.”

“Why doesn't some one fix that road?” asked the president. “Looks to me as if they had brought rocks and thrown them into the trail just to make it worse.”

“It's all wild lands hereabouts,” explained the prospector. “The county commissioners lay out the roads and the landowners are supposed to build them, but they don't. Timber-land owners don't like roads through their woods, anyway.”

“I see they don't,” replied Whittaker dryly. “What did you pay, Jerrard, for having your canoe and truck carried across?”

“Fifteen dollars for the duffel, and four dollars each for the guide, myself and you.”

“How's that for a tariff?” laughed the president. Then he took out his pencil and book and put a series of interrogations to Rowe. At the close he pondered a while, and said to Jerrard:

“According to our friend here, at least five thousand men cross that carry each year, making ten thousand through fares one way. Supplies—pressed hay, grain, foodstuffs and all that sort of freight—from ten to fifteen thousand tons. Then there's the sportsman traffic, which could be built up indefinitely if there were suitable transportation conveniences here. Say, Jerrard, do you know there's a fine place for a six-mile narrow-gage railroad right there on Poquette Carry? You and I didn't come down here looking up railroad possibilities, but really this thing strikes me favorably. Slow time and not very expensive equipment, but think what a convenience! It will also give you and me an excuse to come down here summers, eh?” he added, humorously.

“We'll establish a colony here on Kennemagon,” suggested Jerrard, half in jest, “and start a land boom.”

“Seriously,” went on Whittaker “the more I talk about that little road the more I am convinced it would pay a very good dividend. You and I can swing it. We can use some P. K. & R. rails, fix up one of those narrow-gage shifters they used on the grain spur, and have a railroad while you wait. If we only clear enough to pay our own passage twice a year we'll be doing fairly well. And I'll be willing to pass dividends for the sake of riding from Spinnaker to the West Branch on a car-seat instead of a buckboard. Say, Rowe,” he went on, jocosely, “I suppose they'll have a mass-meeting and pass votes of thanks to Jerrard and myself if we put that project through, won't they?”

Rowe squinted his eye along the sliver he was whittling. “I don't know of any one specially that's hankering for railroad-lines round here,” said he.

“You don't mean to tell me that abomination of stones and muck-holes suits the public, do you?”

“I know the folks I work for don't want to have it a mite smoother than it is. They're the public that's running this part of the world.”

“Here's a brand-new thing in transportation ideas, Jerrard!” cried the president of the P. K. &R.

“Nothing strange about our side of it,” said the prospector. “The people I work for own more than a million acres of timber land for feeding their pulp-mills, and the more city sports there are hanging round on the tracts and building fires, the more danger of a big blaze catching somewhere. And railroads bring sports. You don't hear of any lumbermen grumbling about the Poquette carry.”

“I should say, then, this section should have a little enterprise shaken into it,” said Whittaker, tartly. This promised opposition promptly fired his modern spirit of progress.

After he and his manager had returned to their duties in the city, the surprising word began to go about the district that next year there would be a railroad across Poquette carry. When the rumor was traced to Rowe, he found himself in for a good deal of rough badinage for allowing two city sportsmen to “guy” him.

The postmaster at Sunkhaze was a subscriber to a daily paper, every word of which he read. One day, among the inconspicuous notices of “New Corporations,” he found this paragraph:

“Poquette Carry Railway Company, organized for the purpose of constructing and operating a line of railroad between Spinnaker Lake and West Branch River. President, G. Howard Whittaker; vice-president and general manager, George P. Jerrard; secretary and treasurer, A. L. Bevan. Capital stock $100,000; $5,000 paid in.”

After the postmaster had read that twice, he strode out of his little pen. Men in larrigans and leggings were huddled round the stove, for the autumn crispness comes early in the mountains. The postmaster's eye singled out Seth Bowers, the guide.

“Say, Seth,” he inquired, “wa'n't your sports last summer named Whittaker and Jerrard—the men ye had in on the Kennemagon waters?”

“Yes.”

“Well, you boys listen to this,” and the postmaster read the item with unction.

“Looks 's if they were going ahead, and as if there wasn't so much wind to it, after all,” observed one of the party.

“That Poquette Carry road hasn't been touched by shovel or pick for more than three years, and I don't believe that Col. Gid Ward and his crowd ever intend to hire another day's work on it. Colonel Gid says every operator and sport from Clew to Erie goes across there, and if there's any ro'd-repairin' all hands ought to turn to an' help on the expense.”

“This new railroad idea ought to hit him all right, then,” remarked Seth, the guide.

“Well,” remarked the postmaster, “I'd just like to be round—far enough off so's the chips and splinters wouldn't hit me—when some one steps up and tells Col. Gid Ward that a concern of city men is going to put a railroad in across his land—that's all!”

“Gid Ward has always backed everybody off the trail into the bushes round here” said Seth. “But he's up against a different crowd now.”

“Do ye think, in the first place, that Colonel Gid is going to sell 'em any right o' way across Poquette?” asked the postmaster. “He owns the whole tract there.”

“Oh, there's ways of getting it,” replied Seth. “Let lawyers alone for that when they're paid. If Gid don't sell, they can condemn and take.”

In a week a portion of Seth's prediction concerning lawyers was verified.

Mr. Bevan, tall and thin and sallow, stepped off the train at Sunkhaze. He was a prominent attorney in one of the principal cities of the state, and served as clerk of this new corporation.

When he heard that Col. Gideon Ward was fifty miles up the West Branch, looking after a timber operation on Number 8, Range 23, he borrowed leggings, shoe-pacs and an overcoat and hastened on by means of a tote-team.

A week later, silent and grim and pinched with cold, he unrolled himself from buffalo-robes and took the train at Sunkhaze. The postmaster and station-agent gave him several opportunities to relate the outcome of his negotiations, but the attorney was taciturn.

The first news came down two week later by Miles McCormick, a swamper on Ward's Number 8 operation. The man had a gash on his cheek and a big purple swelling under one eye. When a man of Ward's crew came down from the woods marked in that manner, it was not necessary for him to say that he had been discharged by the choleric tyrant who ruled the forest forces from Chamberlain to Seguntiway. The only inquiry was as to method and provocation.

“He comes along to me as I was choppin',” related Miles to the Sunkhaze postmaster, “and he yowls, 'Git to goin' there, man, git to goin'!' 'An',' says I, 'sure, an' I'll not yank the ax back till it's done cuttin'.' An' then he” Miles put his finger carefully against the puffiness under his eye, “he hit me.”

“Was there a tall stranger come up on the tote-team two weeks or so ago?” asked the postmaster.

“There were,” Miles replied, listlessly, and intent on his own troubles.

“Hear anything special about his business?”

“No. The old man took the stranger into the wangun camp, where it was private, and they talked. None of us heard 'em.”

“And then the stranger went away, hey?” “Oh, well, at last we heard the old man howlin' and yowlin' in the wangun camp and then he comes a-pushing the tall stranger out with such awful language as you know he can. An' he says to the stranger, 'Talk about charters and condemning land till ye're black in the face, I say ye can't do it; and every rail ye lay I'll tie it into a bow-knot. An' I'll eat your charter, seals and all. An' I'll throw your engine into the lake. An' how do ye like the smell of those?' When he said it he cracked his old fists under the stranger's nose. An' the stranger gets into the team and goes away. So that's all of it, and none of us knowed what it meant at all.”

The postmaster darted significant glances round the circle of faces at the stove, and the loungers returned the stare with interest.

“What did I tell ye?” he demanded.

“Just as any one might ha' told that lawyer,” said a man, clicking his knife-blade.

The long autumn passed and winter set in. Snow fell on the carry and the big sleds jangled across. Men went up past Sunkhaze settlement into the great region of snow and silence, and men came down—bearded men, with hands calloused by the ax and the cross-cut saw.

But Col. Gideon Ward's well known figure was not among the passengers on the tote-road. The upgoing men were bound for his camps, and were inquiring as to his whereabouts; the downgoing men stated that he was roaring from one log-landing to another, driving men and horses to make a record-breaking season, and so busy that he would not stop long enough to eat.

Hearing the discussion of the traits and deeds of this woods ogre, the stranger might readily believe him as terrifying as the celebrated “Injun devil”—and as much a creature of fiction.

But each of the messengers that Ward sent down to the outer world bore unmistakable sign that this ruler of the wilderness was in full possession of his autocracy. This talisman was one of the most picturesque features of Ward's reign over the “Gideonites,” as his men were called all through the great north country.

He never intrusted money to woodsmen, for he deemed them irresponsible; he found that writings and orders were too easily mislaid. Therefore, whenever he sent a messenger to town or a man down the line with a tote-team for goods, he scrawled on his back with a piece of chalk the peculiar hieroglyph of crosses and circles that made up the Gideon Ward “log-mark.” This mark was good for lodging and meals at any tavern, was authority for the transfer of goods, and procured transportation for the man whose back was thus inscribed.

When Colonel Ward sent a crew of men into the woods he marked the back of each one in this fashion, as if the employees were freight parcels. The exhibition of that chalk-mark and the words “Charge to Ward” were enough. And such was the fear of all men that the chalk-mark was never abused.

Furthermore, on each grand spring settling day most of the dollars that circulated in the region came through the hands of Col. Ward. This fact naturally increased the deference paid him.

“A railroad?” sneered one man, just down from Number 4 camp. “A railroad across Poquette? Across Gid Ward's land, spouting sparks and settin' fires and hustlin' in sports? Well, you don't see any railroad-buildin' goin' on, do you?”

There was certainly but one reply to this.

“And ye won't see any, either. Gid Ward just bellowed once at that lawyer, and he ran away, ki-yi! ki-yi! You'll never hear any more railroad talk.”

He expressed the public opinion, for even Seth, the guide, regretfully came to the conclusion that the tyrant of the West Branch had “backed down” the city men by his belligerent reception of their emissary.

But soon after the first of January the postmaster's daily paper brought some further news. The state legislature had assembled in biennial session that winter. In the course of its reports the newspaper stated that the “Po-quette Carry Railway Company,” a corporation organized under the general law, had brought before the railroad commissioners a petition for their approval of the project, and that a day was appointed for a hearing.

“The city men had the sand, after all,” was his admiring comment. “They don't propose to start firing till they get all their legal ammunition ready, and that's why they've been waitin'. We're goin' to see warm times on the Spinnaker waters.”

For that matter the daily newspaper brought to snow-heaped Sunkhaze intelligence of “warm times” at the hearing. The legal counsel and lobbyists who represented the puissant timber interests of the state protested against allowing this railroad corporation to acquire any rights across the wild lands.

It was pointed out that a dangerous precedent would be established; that forest fires would be sure to originate from the locomotive's sparks, and that the Poquette woods were the center of the great West Branch timber growth.

The counsel for the incorporators said that his clients realized this danger, and anticipated that this objection, a potent one, would be made. They were willing to show their liberal intent by binding themselves to run their trains only in rainy or “lowery” weather, or when the ground was damp. In times of dangerous drought they would suspend operations.

“The Rainy-Day Railroad,” as it was nicknamed immediately, excited considerable hilarity at the state-house and in the newspapers.

The matter was fought out with much animation. The counsel for the railway made much of the fact that these timber owners had fought the very reasonable state tax that had been imposed on their vast and valuable holdings. He drew attention to the needs of the sportsman class, that was spending much money in the state each year, and declared that unless they were treated with some courtesy and generosity, they would go into New Brunswick.

But those deepest in the secrets of the very vigorous legislative fray knew that the timber-land owners feared more results than they advanced in their arguments against the charter.

For some years there had been rumors that extensive capital was ready to tap a certain big railway and afford a shorter cut to the sea. Such a cut-off would mean opening great tracts of woodland to the steam horse—and where the steam horse goes there go settlers. The timberland owners had found that settlers do not wait for clear titles, but squat and burn and plant until evicted, and eviction by course of law means expense and damage.

To be sure, the Poquette Carry line appeared on the surface to be so innocent that to allege against it the great whispered scheme seemed ridiculous. Therefore the counsel of the timber barons did not bring out in the committee-room hearings all they suspected, for fear that they would be laughed at.

So the Poquette Carry Road got what it asked for at last, the opposition daring to put forward only its slight pretexts. But the timber interests retired growling bitterly, and angrily apprehensive. They could not understand that big men are sometimes actuated by whims. Here they saw the controllers of the great P. K. & R. system behind this insignificant project in the north woods. They gave these shrewd railroad men no credit for ingenuousness. And the resolve that was thereupon made at secret conclave of the timber men to fight that first encroachment on their old-time domains and rights was a stern and a bitter resolve. The knowledge of it would have mightily astonished—might have daunted effectually a certain young engineer who was just then learning from Manager Jerrard the details of his new commission.

In the end, late in March, Whittaker and Jerrard found themselves with a charter and a location approved by the state railroad commissioners, permitting them to build a six-mile railroad across Poquette Carry; to carry passengers, baggage, express and freight, but with the limitation that when the state land-agent should think the condition of drought dangerous and should so notify the company, the road should cease to run any trains until rain wet down the woods.

The location was taken by right of eminent domain, and all the provisions of the law were complied with. No settlement for the damage caused to Colonel Ward through the loss of his land was possible, altho the railroad company made liberal offers, and he was finally left to pursue his remedy in the courts.

Up to this time Jerrard had kept his negotiations with young Parker a private matter between the two of them, even as he had kept some of the annoying legislative details away from his superior.

“What engineer can you send down there and handle the thing for us?” asked President Whittaker, when Jerrard informed him that all the legal details had been settled. “I want some one who knows enough to get the line going in season for our August trip—and above all to keep still. I don't want to hear a word about it till I get out of a canoe at Poquette Carry next summer. Here we want to build a wheelbarrow road, and I have been having hard work to convince some of our bankers that I'm not planning a coup against the Canadian Pacific. Bosh!”

“These timber-land owners started most of that foolishness,” said Jerrard. “But speaking of a man, there's Rodney Parker.”

“Never heard of him.”

“He's been with the engineers two years on the Falls cut-off's new work. I can't think of any one else who will suit us as well.”

“'Tisn't going to take any very wonderful man to build this road,” the president snapped, rather impatiently.

A smile crept into the wrinkles about Jerrard's shrewd eyes.

“Whittaker,” said he, “there's a side to our railroad enterprise that neither you nor I appreciated at first. I've been getting some points from our counsel, who had a talk with Bevan. When we were up at the lake, you remember something that Rotre said about the timber-land owners not especially hankering for a railroad at the carry. Well, Bevan says the land there is owned by a man named Ward—Col, Gideon Ward, one of the big lumber operators of that section. From Bevan's account, Ward must be something like a cross between a bull moose and a Bengal tiger, Bevan went up to see him. He thought he could make a deal for the right of way, and thus would not be obliged to bother with condemnation proceedings and stir up talk and all that. Devan declares that getting a charter is one thing but the building of that road will be another.”

“We've got the law—”

“Law gets very thin when you step over the line into an unorganized timber township. They tell me that old Ward comes pretty near making his own laws, and makes them with his fists or a club or else through his gang that they call 'The Gideonites' in that country.”

“Your Parker, is he—”

“I've got him out in my room. I've been talking with him. Better have him step in here.”

The president pushed his desk button, and the messenger hastened on his errand.

“Parker,” explained the traffic manager, “doesn't look any more savage than a house cat. But he's the man who went down into the camp of those Italians at the Fall's cut-off when they were having their bread squabble, and he backed the whole gang into the camp and made them sit down at the table. Of course, we hope we shall need only an engineer and not a warrior at Poquette, and we trust that Ward will be tractable and all that; but, Whittaker, if we're going to build that road, and are not to be backed down in such a way that we'll never dare to show our faces before the grinning natives at Sunkhaze then we need to send along a chap like—”

“Mr. Parker!” opportunely announced the boy, at the door.

Parker seemed tall and angular and rather awkward. The brown of out-of-doors was upon his skin. His eyelids dropped at the corners in rather a listless way, but the eyes beneath were gray and steady. He was young, not more than twenty-five, so Whittaker judged at his first sharp glance.

“Do you think you can build that road that Jerrard has been telling you about?” asked the president, briskly.

“I think so, sir.” Parker spoke with a drawl.

“You understand what the plan is?”

“Mr. Jerrard has explained quite fully.”

“Are you afraid of bears and owls?” The president spoke jocosely, but there was a significant tone in his voice.

“I don't think I should spend much time climbing trees,” replied Parker, smiling.

“Do you understand that the man we send must take the whole undertaking on his own shoulders? Neither Mr. Jerrard nor myself cares to think about the matter, even.” “I'll be glad to be instructed, sir.” “You'll have instructions as to limit of construction cost per mile, authority to draw on us as you need money, and the road must be in operation by the middle of July. Now Jerrard speaks well of your qualifications. What do you think?” “I am ready to accept the commission, sir.” “You'll have to get away at once, Parker,” said Jerrard. “You must get construction material and supplies across Spinnaker before the ice breaks up. You can depend on the most of April for ice.”

“I can start when you say the word.” “We shall rush material. Suppose you start to-morrow morning?” “I'll start sir.”

He left the room when he was informed that his instructions would await him that evening.

“Jerrard,” said the president, gazing after the young man, “your friend isn't an especially pretty frog but I'll bet he can jump more than once his length.”

Two days afterward Parker ate his supper at the Sunkhaze tavern and spent the evening going over the schedule of material that was following him by freight, its progress over connecting lines hastened by all the “pull” inspired by the P. K. & R.'s bills of lading.

The next morning, even while the frosty sun was red behind the spruces, he had arranged with the station agent for side-track privileges, and then questioned that functionary regarding local conditions.

“I need twenty or more four-horse teams,” said Parker. “What's the best way to advertise here?” “I reckon you can advertise and advertise,” replied the station agent, “but that's all the good it'll do you. Colonel Gid Ward has about every spare team in this county yardin' logs for him this winter.”

“What does he pay?”

“Thirty-five a month for a span o' hosses, and hosses and man kept.”

“I'll pay forty-five and feed.”

“I shouldn't want to be the man that went up on Gid Ward's operations and tried to hire his teams away!” growled the agent. “You can't hire any one round here for an errand of that kind.”

“I'd go myself if I thought I could get the horses,” said Parker.

“I'd advise you to save yourself a fifty-mile ride up the tote-road,” the agent counseled. “Even if Ward didn't catch you, you'd find that no man would da'st to leave there. Furthermore, you've only got a little, short job here, scarcely worth while.”

The logic of the reply impressed Parker.

He could not spare the time anyway, to travel far up into the woods in quest of horses. His material must be conveyed across Spinnaker Lake in some other way.

“How far is it up the lake to Poquette?” he asked the agent.

“Sixteen miles.”

An hour later Parker, after a tour of inspection, had settled his problem of transportation in his own mind. His plan was ingenious.

There were half a dozen men available in Sunkhaze, and more were arriving daily, straggling down from the woods or roaring in fresh from the city, hurrying on the way up.

The postmaster owned a hardwood tract, and Parker set his little crew at work chopping birch saplings and fashioning from them huge sleds, strongly bolted. As for himself, he entered into a contract with the local blacksmith, threw his coat off and went to work on some contrivances, round which the settlement's loungers congregated from dawn till dark the next day, watching the progress and wondering audibly “what such a blamed contraption was goin' to turn out to be.”

Parker kept his own counsel. At the end of two days, with the assistance of the blacksmith, he had remodeled four ox-cart tires. Each tire was spurred with bristling steel spikes, bolted firmly. In reply to his telegram, “Rush loco, all equipments and coal,” the little narrow-gage engine arrived, at the tail of the procession of flat cars, loaded with materials of construction.

By this time Parker's crew had been increased to a score of laborers, and he had picked up three yokes of oxen and four horses from the few pioneer farmers who lived near Sunkhaze. With tackle and derrick the locomotive was swung upon a specially constructed sled, and the spurred tires were set upon its drivers. Then the great idea locked in Parker's head became apparent to the population of Sunkhaze.

“Gorry!” said the postmaster. “If that young feller hain't got a horse there that'll beat anything that even Colonel Gid Ward himself ever sent across Spinnaker Lake!”

Amid the utmost excitement of the spectators, the “engine on runners” was “snubbed” down the steep hill and eased out upon the road leading to the lake. Two hours' work with levers and wedges had adjusted the machine until the spurred wheels had the requisite “bite” upon the ice.

At dark on the day of the “launching” Parker gazed off across the level of the lake, and said to his men:

“To-morrow, boys, the Spinnaker Lake Air-Line Railroad will run its first train to Po-quette Carry. No freight this time. I want to lay out my landing up there. So all aboard at nine o'clock. Three cars,” he said, pointing to the new sleds, “and a free ride for all of you, with my compliments.”

An honest cheer greeted his jocular announcement, and that evening all the Sunk-haze male population assembled round the stove in the post-office to discuss the matter. When the evening was yet young, a red-faced, red-whiskered man, snow-shoes on his back and fresh from the up-country trail, came and warmed himself, listening with interest to the lively discussion.

“So that's what that thing is down on the lake?” he said, at last. “'Twas dark when I came by, and I swan if it didn't scare me. Want to know if that's the engine we've been hearin' about up our way?”

His tone was significant.

“Where ye from, stranger?” asked one of the loungers.

“Number 7 cuttin'.”

“Oh, one of Gid Ward's men?”

“Yes.”

“Say, has Ward heard about the railroad preparations?” inquired the postmaster. This query had been propounded with eagerness to every new arrival from the woods for the past three days.

“Yes.”

The interest of the men quickened, and they crowded round the newcomer.

“What does he say?”

“He hain't said anything special yet, so I heard,” replied the man. “Hain't done anything but swear so far, so they tell me.”

“Has he—has he started to come down?”

“Feller from up the line telephoned across the carry that a streak of fur, bells and brimstone went past his place, and so I should judge that Colonel Gid is on the way down,” drawled the man.

“An' he'll come across that lake in the morning,” said the postmaster, jabbing his thumb over his shoulder, “scorchin' the snow and leavin' a hot hole in the air behind him.”

The door opened and Parker came in to post his letters. The crowd gazed on him with new interest and with a certain significance in their glances that caught his eyes. The postmaster noticed his mute inquiry, and remarked:

“News from the interior, Mr. Parker, is that you prob'ly won't have any ice in Spinnaker to-morrow to run your engine on.”

“Why?” demanded the young man, with some surprise. The postmaster's sober face hid his jest. Parker surveyed wonderingly the grins curling under the listeners' beards.

“Oh, Colonel Gid Ward is comin' across in the mornin' and it's reckoned he'll burn up the ice.”

A cackle of laughter came from the assemblage.

“There's plenty of room on Spinnaker for both of us, I think,” Parker replied, quietly.

“Better hitch your engine,” suggested one of the group. “She's li'ble to take to the woods and climb a tree when she hears old Gid. And you can hear him a good way off, now I can tell you.”

The postmaster knuckled his chin humorously.

“Wal, you'll hear him 'bout the same time you see him. Five years ago he was arrested down to the village for drivin' through the streets lickety-whelt without bells. Run over two or three people, first and last. Gid said he'd give 'em bells enough, if that's what they wanted. He began collecting bells all the way from a cow-bell down. At last accounts he had about two hundred on his hoss and sleigh, and was still addin'. Now he makes every hoss on the street run away. The men wish they'd let him alone in the first place. He'll prob'ly want your engine-bell when he sees it to-morrow.”

Another cackle from the crowd.

Parker left without answering, and went to his dingy little room in the tavern. He did not doubt that the timber-land owners, beaten in their earlier and formal opposition, were inciting the irascible old colonel to pit might against right. The young man went over his papers once more, carefully and methodically posted himself as to his rights and powers, and then slept with the calmness of one who knows his course and is prepared to follow it.

The next morning all the male population of Sunkhaze settlement surveyed with rapt interest the preliminaries of getting up steam under the “Swamp Swogon,” as one of the guides had humorously nicknamed the little locomotive.

Suddenly a bystander leveled his mittened hand above his eyes and gazed up the long trail across the lake. The road was “brushed out” by little bushes set along at regular intervals.

Away off on the distant perspective a dot was advancing. It resolved itself into horse and sleigh. Puffs of vapor from the steaming animal indicated the urgent precipitancy of its speed.

“I reckon that'll be Colonel Gideon Ward!” called the man who had just observed the team.

Parker, busy with his gages and oil-can, gave one look up the road and went on with his labors. In a few moments the jangling beat of many bells throbbed on the frosty air. As if answering a challenge, the locomotive's escape valve shot up its hissing volume of steam.

“We are very nearly ready, gentlemen!” called Parker. He gave an order to his volunteer fireman, and suggested that intending passengers get aboard the sleds.

“I'll sound the whistle,” said he. “There may be some still waiting up at the store.”

The whistle shrieks were many and prolonged. The horse, speeding down the lake, was only a few rods away. He stopped, crouched, and dodged sidewise in terror. An old man stood up and began to belabor the frightened animal.

He was a queer figure, that old man, in the high-backed, high-fender sleigh. On his head was a tall peaked fur cap, with a barred coon tail flopping at its apex. A big fur coat, also covered with coon tails, made the man's figure almost Brobdingnagian in circumference. It was Colonel Gideon Ward.

Above the purple knobs on his cheekbones Colonel Gideon Ward's little gray eyes snapped malevolently. He roared as he lashed at his trembling horse. The animal dodged and backed and stubbornly refused to advance on the strange thing that was pouring white clouds into the air and uttering fearful cries.

At last the horse reared, stood upright and fell upon its side, splintering the thills. Several of the men ran forward, but before the animal could scramble to its feet Ward leaped out, tied its forelegs together with the reins, and left it floundering in the snow. Then he came forward with his great whip in his hand. The crowd drew aside apprehensively, and he tramped straight up to the locomotive.

“What do ye mean,” he roared, “by having engines out here to scare hosses into conniptions? Take that thing off this lake and put it back on the railroad tracks up there where it belongs!” He shook his fists over his shoulder in the direction of the distant embankment.

“You will observe,” said Parker, blandly, “that there is some twenty inches difference between the gage of the wheels and the gage—”

“I don't care that”—and Colonel Ward snapped the great whip—“for your gages and your gouges! Take that engine off this ro'd.”

“I don't care to discuss the matter,” returned Parker, quietly. “I am busy about my own affairs—too busy to quarrel.”

“There's no use of me and you backin' and fillin'!” shouted the old man. “You know me and I know you. You think you're goin' to tote your material up over this lake and build that railroad across my carry at Poquette?”

“Yes, that's what I am going to do.”

Ward shot out his two great fists.

“Naw, ye ain't!” he howled.

Parker turned and consulted his steam-gage and water indicator. Then he rang the bell.

“All aboard!” he shouted. “First train for Poquette.”

A nervous little laugh went round at his quiet jest, and twoscore men boarded the sleds. For the first time in his roaring, reckless and quarrelsome life Colonel Gideon Ward found himself in the presence of a man who defied him scornfully and facing an obstacle that promised ridiculous defeat.

The titter of the crowd spurred his rage into fury. He took his whip between his teeth, and grasping the hand-rods, was about to lift himself into the cab. Parker put his gloved hand against the old man's breast.

“Not without an invitation, Colonel Ward,” he said. “Our party is made up.”

“Don't want to ride in your infernal engine!” bellowed Ward, “I'm goin' to hoss-whip you, you—”

“Colonel Ward, you know the legal status of the Poquette Carry Railroad, don't you?”

“I don't care—”

“If you don't know it, then consult your counsel. You are on the property of the Poquette Railroad Company. I order you off. There's nothing for you to do but to go.”

Eyes as fiery as Ward's own met the colonel. The pressure on his breast straightened to a push. He fell back upon the snow.

The next moment Parker pulled the throttle. The spike-spurred driving-wheels whirred and slashed the ice and snow until the “bite” started the train, and then it moved away up the long road, leaving Ward screaming maledictions after it.

“Well,” panted the fireman, “that'll be the first time Colonel Gid Ward was ever stood round in his whole life!”

“I'm sorry to have words with an old man,” said Parker, “but he must accept the new conditions here.”

“This is new, all right!” gasped the fireman, with an expressive sweep of his hand about the little cab.

Parker was watching his new contrivance with interest. His steering-gear was rude, being a single runner under the tender with tiller attachment, but it served the purpose. The road was so nearly a straight line that little steering was necessary.

The snow on the lake road was solid, and the spikes, with the weight of the engine settling them, drove the sleds along at a moderate rate of speed. The problem of the lake transportation was settled. When Parker quickened the pace to something like twelve miles an hour, the men cheered him hoarsely.

The trip to Poquette was exhilarating and uneventful. Parker left his fireman to look after the “train,” and accompanied by an interested retinue of citizens, tramped across the six miles of carry road on a preliminary tour of inspection.

He returned well satisfied.

The route was fairly level; a few détours would save all cuts, and the plan of trestles would do away with fills. With the eye of the practised engineer, Parker saw that neither survey nor construction involved any special problems. Therefore he selected his landing on the Spinnaker shore, and resolved to make all haste in hauling his material across the lake.

When the expedition arrived at Sunkhaze at dusk, the postmaster brought the information that Colonel Ward had stormed away on the down-train with certain hints about getting some law on his own account. He had sworn over and over in most ferocious fashion that the Poquette Carry road should not be built so long as law and dynamite could be bought.

For two days Parker peacefully transported material, twenty tons a trip and two trips a day. On the evening of the third day Colonel Ward arrived from the city, accompanied by a sharp-looking lawyer. The two immediately hastened away across the lake toward Poquette.

Parker had twenty men garrisoned in a log camp at the carry, and had little fear that his supplies would be molested. It was hardly credible, either, that a man with as extensive property interests as Colonel Ward possessed would dare to destroy wantonly the goods of a railroad company in the strong position of the Poquette road. However, Parker resolved to make a survey at once, in order to put the swampers at work chopping trees and clearing the right of way.

When he left the cab of his engine the next forenoon at Poquette, he saw the furred figure of Colonel Ward in front of his carry camp a sort of half-way station for the timber operator's itinerant crews. The lawyer was at his elbow.

Parker ignored their presence.

A half-hour later the young engineer had established his Spinnaker terminal point, and was running his lines. Still no word from the colonel, who was tramping up and down in front of the camp. Parker's whimsical fancy pictured those furs and coon tails as bristling and fluffing like the hair of an angry cat.

The young man wondered what card his antagonists were preparing to play. He found out promptly when he ordered his swampers to advance with their axes and begin chopping down the trees on the right of way. At the first “chock” ringing out on the crisp silence of the woods Ward came running down the snowy stretch of tote-road, presenting much the same appearance as would an up reared and enraged polar bear. The lawyer hurried after him, and several woodsmen followed more leisurely.

“Not another chip from those trees! Not another chip!” bawled the colonel. The men stopped chopping and looked at each other doubtfully.

“We've been told to go ahead here,” said the “boss.”

“I don't care what yeh've been told. You all know me, don't you?” Ward slapped his breast. “You know me? Well, I say stop that chopping on my—understand?—on my land.”

Parker, who was in advance of the choppers with his instruments, heard, and came plowing through the snow. He found Colonel Ward roaring oaths and abuse, brandishing his fists, and backing the crew of a dozen men fairly off the right of way. Ward's own band of “Gideonites” stood at a little distance, grinning admiringly.

Parker set himself squarely in front of the old man, elbowing aside a woodsman to whom the colonel was addressing himself. The young engineer's gaze was level and determined.

“Colonel Ward,” he said, “you are interfering with my men.”

The answer was a wordless snarl of ire and contempt.

“There's no mistaking your disposition,” continued Parker. “You have set yourself to balk this enterprise. But I haven't any time to spend in a quarrel with you.”

“Then get off my land.”

“Now, see here, Colonel Ward, you know as well as I that my principals have complied with all the provisions of law in taking this location. This road is going through. I am going to put it through.”

“Talk back to me, will you? Talk to me! ni—I'll—” Ward's rage choked his utterance.

“Certainly I'll talk to you, sir, and I am perfectly qualified to boss my men. Go ahead there, boys!” he called.

“A moment, Mr. Parker,” broke in the suave voice of the lawyer. “I see you don't understand the entire situation. Briefly, then, Mr. Ward has a telephone-line across this carry. You may see the wires from where you stand. I find that your right of way trespasses on Colonel Ward's telephone location. In this confusion of locations, you will see the advisability of suspending operations until the matter can be referred to the courts.”

“There is room for Colonel Ward's telephone and for our railroad, too,” he retorted. “If we are compelled to remove any poles, we'll replace them.”

Of course Parker did not know that the telephone-line was, in fact, only Colonel Ward's private line, and after the taking by the railroad was on the location wholly without right. But that was a matter for his superiors, and not for him.

“Another point that I fear you have not noted. Colonel Ward's telephone wires are affixed to trees, and your men are preparing to cut down these same trees in clearing your right of way. You see it can't be done, Mr. Parker.”

There was an unmistakable sneer in the lawyer's tones. Parker's anger mounted to his cheeks.

“I'm no lawyer,” he cried, “but I have been assured by our counsel that I have the right to build a railroad here, and I reckon he knows! I've been told to build this railroad and, Mr. Attorney, I'm going to build it. I've been told to have it completed by a certain time, and I haven't days and weeks to spend splitting hairs in court.”

“No, I see you're not much of a lawyer!” jeered the other. “Mr. Parker, you may as well take your plaything,” pointing to the engine, “and trundle it along home.”

“We'll see about that!” Parker snatched an ax from the nearest man. “Mr. Lawyer, you may go back to the city and fight your legal points with the man my principals hire for that purpose, and enjoy yourself as much as you can. In the meantime I'll be building a railroad. Men, those trees are to come down at once.” He began to hack at a tree with great vigor.

The choppers, encouraged by his firm attitude, promptly moved forward and began to use their axes.

“The club you must use, Colonel, is an injunction,” advised the crestfallen lawyer after he had watched operations a few moments. Ward was swearing violently. “I'll have one here in twenty-four hours.”

The irate lumberman whirled on his counsel.

“Get out of here!” he snarled. “Your injunction would prob'ly be like the law you've handed out here to-day. You said you'd stop him, but you haven't.”

“There's no law for a fool!” snapped the attorney.

“Get along with your law!” roared Ward. “I was an idiot ever to fuss with it or depend on it. 'Tain't any good up here. 'Tain't the way for real men to fight. I've got somethin' better'n law.”

He shook his fists at Parker. “Better'n law!” he repeated, in a shrill howl. “Better'n law!” he cried again. “And you'll get it, too.”

At first the engineer believed that Ward was about to rally his little band at the carry camp, but the old man turned and stumped away. His lawyer tried to interpose and address him, but the colonel angrily shoved him to one side with such force that the attorney tumbled backward into the snow.

“Get out my horse!” the colonel screamed, as he advanced toward the camp.

A helper precipitately backed the turnout from the hovel. Ward leaped into the sleigh, pulled his peaked fur cap down over his ears, and took up the reins and big whip. He brandished his great fist at the little group he had just left.

“Better'n law!” he shouted again. “That for your law!” and he struck his rangy horse with a crack as loud as a pistol-shot.

The animal leaped like a deer, fairly lifting the narrow sleigh, and with tails fluttering from his fur robes, his cap's coon tail streaming behind, away up the tote-road went Gideon Ward on his return to the deep woods, the mighty din of his myriad bells clashing down the forest aisles. At the distant turn of the road he hooted with the vigor of a screech owl, “Better'n law!” and disappeared.

“Your client doesn't seem to be in an especially amiable and lamb-like mood this morning,” said Parker.

The lawyer dusted the snow from his garments.

“Beautiful disposition, old Gid Ward has!” he snarled. “Left me here to walk sixteen miles to a railroad-station, and never offered to settle with me.”

“You forget the 'Poquette and Sunkhaze Air-Line,” Parker smiled. “You are free to ride back with us when we go.”

“No hard feelings, then?” asked the lawyer.

“I'm not small-minded, I trust,” returned Parker. The lawyer looked at the self-possessed young man with pleased interest. This generous attitude appealed to him.

“Do you realize, young man,” he inquired, “that old Gideon Ward never had a man really back him down before?”

“I don't know much about Colonel Ward personally, except that he has a very disagreeable disposition.”

“You've made him just as near a maniac as a man can be and still go about his business. There'll be a lot of trouble come from this. Hadn't you better advise your folks to call it off? They haven't the least idea, I imagine, what a proposition you are up against.”

“I shall keep on attending to my business,” Parker replied. “If any one interferes with that business, he'll do so at his own risk.”

“I am afraid you are depending too much on your legal rights and on the protection of the law. Now Gideon Ward has always made might right in this section. He is rough and ignorant, but the old scamp has a heap of money and a rich gang to back him. I tell you, there are a lot of things he can do to you, and then escape by using his money and his pull.”

“From what I have seen of the old man's temper, I am prepared to put a pretty high estimate on his capacity for mischief; but on the other hand, Mr. Attorney, suppose I should go back to my people and say I allowed an old native up here in the woods to back me off our property? I fear my chances for promotion on the P. K, and R. system would get a blacker eye than I shall give him if he ever shakes his fist under my nose again. Have all the people up here allowed that old wretch to browbeat and tyrannize over them without a word of protest?”

“Oh, he has been whaled once or twice, but it never did him any good. For instance, a favorite trick of his is to make every one flounder out of a tote-road into the deep snow. He won't turn out an inch. Most of the men he meets are working for him or selling him goods, and they don't dare to complain. However, one teamster he crowded off in that way broke two ox-goads on the old man. But that whipping only set him against other travellers more than ever.

“Another time Ward got what he deserved down at Sunkhaze. A man opened a store there and put in a plate-glass window, being anxious to show a bit of progress. There's nothing old Ward hates so much as he does what he calls 'slingin' on airs,' When he drove down from the woods and saw that new window he growled, 'Wal, it seems to me we're gettin' blamed high-toned all of a sudden!' He got out, rooted up a big rock and hove it right through the middle of that new pane of glass the only pane of plate glass Sunkhaze ever saw. Well, the storeman tore out and licked Ward till he cried. Storeman didn't know who the old man was till after it was all over. Neither did old Gid know how big that storeman was till he saw him coming out through that broken glass. Otherwise both might have thought twice.

“Ward boycotted and persecuted him till he had to sell out and leave town. He has persecuted everybody. His wife has been in the insane asylum going on ten years; his only girl ran away and got married to a cheap fellow, and his son is in state prison. The boy ran away from home, got into bad company, and shot a policeman who was trying to arrest him. If you are not crazy or dead before he gets done with you, then you'll come out luckier than I think you will.”

With this consoling remark the lawyer plodded up to the camp, to wait until it should be time to start down the lake.

As Parker toiled through the woods that day he reflected seriously on his situation. He fully appreciated the fact that Ward's malice intended some ugly retaliation. The danger viewed here in the woods and away from the usual protections of society seemed imminent and to be dreaded.

But the young man realized how skeptically Whittaker and Jerrard would view any such apprehensions as he might convey to them, reading his letter in the comfortable and matter-of-fact serenity of the city. He knew how impatient it made President Whittaker to be troubled with any subordinate's worry over details. His rule was to select the right man, say, “Let it be done,” and then, after the manner of the modern financial wizard inspect the finished result and bestow blame or praise.

Parker regretfully concluded that he must keep his own counsel until some act more overt and ominous forced him to share his responsibility.

That evening, as he sat in his room at the tavern, busy with his first figures of the survey, some one knocked and entered at his call, “Come in!”

It was the postmaster who appeared at Parker's invitation to enter. That official stroked down his beard, tipped his chair back, surveyed the young man with the solemnity of the midnight raven and observed:

“I hear you and Colonel Gid had it hot and tight up to Poquette to-day.”

“There was an argument,” returned Parker, quietly.

“I don't want to be considered as meddlin' with your affairs, Mr. Parker, but I've known Gid Ward for a good many years, and I want to advise you to look sharp that he doesn't do you some pesky mean kind of harm.”

“I have been warned already, Mr. Dodge.”