AN ARTISTIC JOKE.

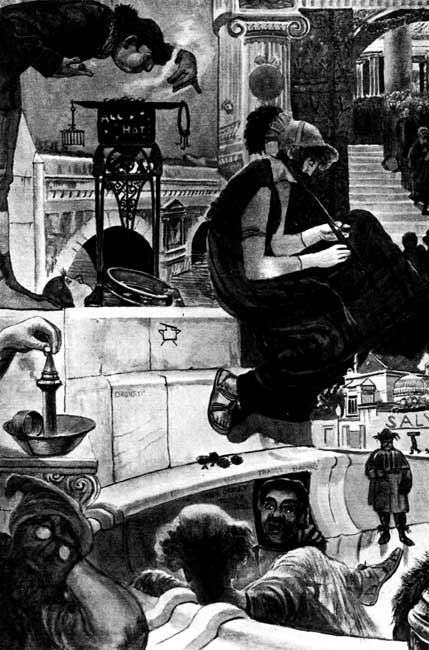

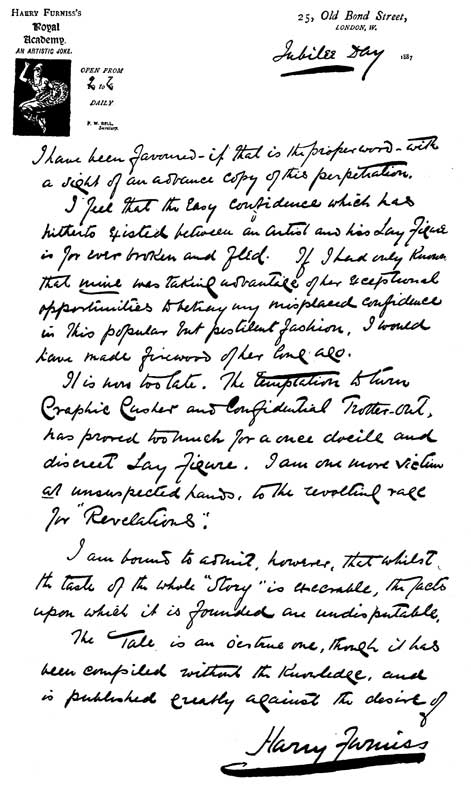

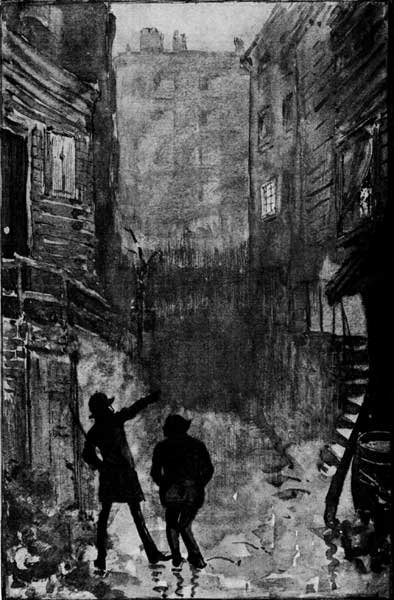

AN ARTISTIC JOKE.A London Slum. My Parody of the Venetian School.

View larger image

Title: The Confessions of a Caricaturist, Vol. 2

Author: Harry Furniss

Release date: September 20, 2007 [eBook #22689]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Janet Blenkinship and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

NEW YORK AND LONDON:

HARPER & BROTHERS, PUBLISHERS.

1902.

BRADBURY, AGNEW, & CO. LD., PRINTERS,

LONDON AND TONBRIDGE.

All rights reserved.

December, 1901.

| Page | |

| CHAPTER VIII. THE ARTISTIC JOKE. |

|

|---|---|

| The First Idea--How it was Made--"Fire!"--I am a Somnambulist--My Workshop--My Business "Partner"--Not by Gainsborough--Lord Leighton--The Private View--The Catalogue--Sold Out--How the R.A.'s Took It--How a Critic Took It--Curious Offers--Mr. Sambourne as a Company Promoter--A One-man Show--Punch's Mistake--A Joke within a Joke--My Offer to the Nation | pp. 1--25 |

| CHAPTER IX. CONFESSIONS OF A COLUMBUS. |

|

| The Cause of my Cruise--No Work--The Atlantic Greyhound--Irish Ship--Irish Doctor--Irish Visitors--Queenstown--A Surprise--Fiddles--Edward Lloyd--Lib--Chess--The Syren--The American Pilot--Real and Ideal--Red Tape--Bribery--Liberty--The Floating Flower Show--The Bouquet--A Bath and a Bishop--"Beastly Healthy"--Entertainment for Shipwrecked Sailors--Passengers--Superstition. | |

| America in a Hurry--Harry Columbus Furniss--The Inky Inquisition--First Impressions--Trilby--Tempting Offers--Kidnapped--Major Pond--Sarony--Ice--James B. Brown--Fire!--An Explanation. | |

| Washington--Mr. French of Nowhere--Sold--Interviewed--The Sporting Editor--Hot Stuff--The Capitol--Congress--House of Representatives--The Page Boys--The Agent--Filibuster--The "Reccard"--A Pandemonium--Interviewing the President. | |

| Chicago--The Windy City--Blowers--Niagara--Water and Wood--Darkness to Light--My Vis-à-Vis--Mr. Punch--My Driver--It Grows upon Me--Inspiration--Harnessing Niagara--The Three Sisters--Incline Railway--Captain Webb. | |

| Travelling--Tickets--Thirst--Sancho Panza--Proclaimed States--"The Amurrican Gurl"--A Lady Interviewer--The English Girl--A Hair Restorer--Twelfth Night Club Reception at a Ladies' Club--The Great Presidential Election--Sound Money v. Free Silver--Slumland--Detective O'Flaherty. | pp. 26--130 |

| CHAPTER X. AUSTRALIA. |

|

| Quarantined--The Receiver-General of Australia--An Australian Guide-book--A Death Trap--A Death Story--The New Chum--Commercial Confessions--Mad Melbourne--Hydrophobia--Madness--A Land Boom--A Paper Panic--Ruin. | |

| Sydney--The Confessions of a Legislator--Federation--Patrick Francis Moran. | |

| Adelaide--Wanted, a Harbour--Wanted, an Expression--Zoological--Guinea-pigs--Paradise!--Types--Hell Fire Jack--The Horse--The Wrong Room! | pp. 131--153 |

| CHAPTER XI. PLATFORM CONFESSIONS. |

|

| Lectures and Lecturers--The Boy's Idea--How to Deliver It--The Professor--The Actors--My First Platform--Smoke--Cards--On the Table--Nurses--Some Unrehearsed Effects--Dress--A Struggle with a Shirt--A Struggle with a Bluebottle--Sir William Harcourt Goes out--My Lanternists Go Out--Chairmen--The Absent Chairman--The Ideal Chairman--The Political Chairman--The Ignorant Chairman--Chestnuts--Misunderstood--Advice to Those about to Lecture--I am Overworked--"'Arry to Harry." | pp. 154-189 |

| CHAPTER XII. MY CONFESSIONS AS A "REFORMER." |

|

| Portraiture Past and Present--The National Portrait Gallery Scandal--Fashionable Portraiture--The Price of an Autograph--Marquis Tseng--"So That's My Father!"--Sala Attacks Me--My Retort--Du Maurier's Little Joke--My Speech--What I Said and What I Did Not Say--Fury of Sala--The Great Six-Toe Trial--Lockwood Serious--My Little Joke--Nottingham Again--Prince of Journalists--Royal Academy Antics--An Earnest Confession--My Object--My Lady Oil--Congratulations--Confirmations--The Tate Gallery--The Proposed Banquet--The P.R.A. and Modern Art--My Confessions in the Central Criminal Court--Cricket in the Park--Reform!--All About that Snake--The Discovery--The Capture--Safe--The Press--Mystery--Evasive--Experts--I Retaliate--The Westminster Gazette--The Schoolboy--The Scare--Sensation--Death--Matters Zoological--Modern Inconveniences--Do Women Fail in Art?--Wanted a Wife | pp. 190-234 |

| CHAPTER XIII. MY CONFESSIONS AS A "REFORMER." |

|

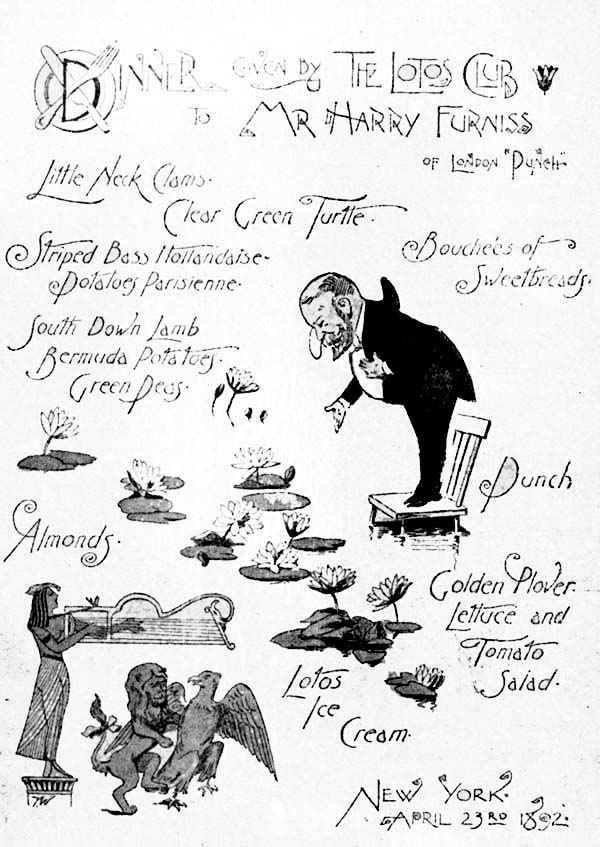

| My First City Dinner--A Minnow against the Stream--Those Table Plans--Chaos--The City Alderman, Past and Present--Whistler's Lollipops--Odd Volumes--Exchanging Names--Ye Red Lyon Clubbe--The Pointed Beard--Baltimore Oysters--The Sound Money Dinner--To Meet General Boulanger--A Lunch at Washington--No Speeches. | |

| The Thirteen Club--What it was--How it was Boomed--Gruesome Details--Squint-Eyed Waiters--Superstitious Absentees--My Reasons for being Present--'Arry of Punch--The Lost "Vocal" Chords--The Undergraduate and the Undertaker--Model Speeches--Albert Smith--An Atlantic Contradiction--The White Horse--The White Feather--Exit 13 | pp. 235-271 |

| CHAPTER XIV. THE CONFESSIONS OF AN EDITOR. |

|

| Editors--Publishers--An Offer--Why I Refused it--The Pall Mall Budget--Lika Joko--The New Budget--The Truth about my Enterprises--Au Revoir! | pp. 272-280 |

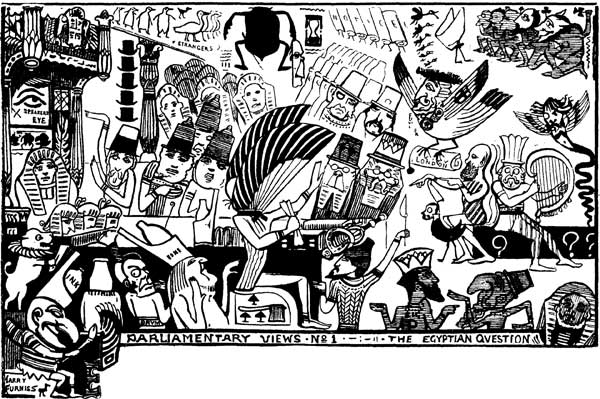

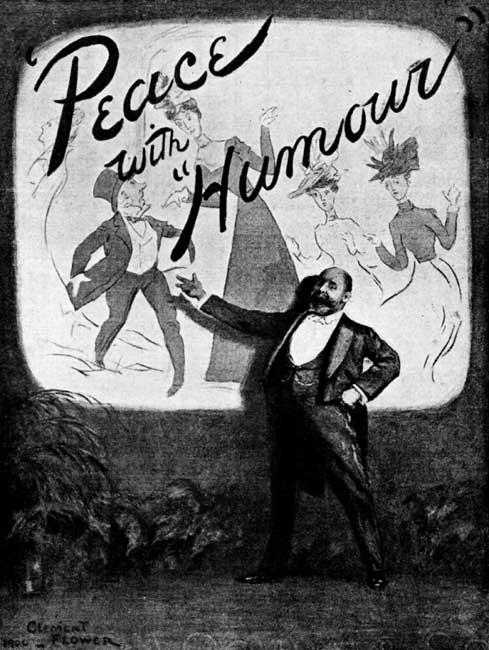

HARRY FURNISS'S (EGYPTIAN STYLE).

HARRY FURNISS'S (EGYPTIAN STYLE).| PAGE | |

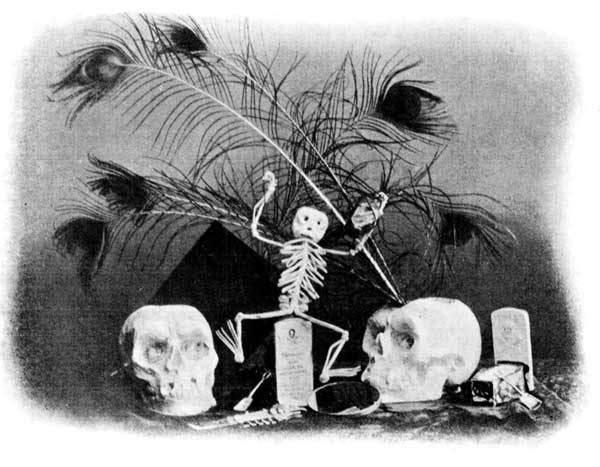

| An Artistic Joke. A London Slum. My Parody of the Venetian School. | Frontispiece. |

| My Studio during the Progress of "An Artistic Joke" | 1 |

| Harry Furniss's Royal Academy | 3 |

| Throwing myself into it | 5 |

| Fire! | 6 |

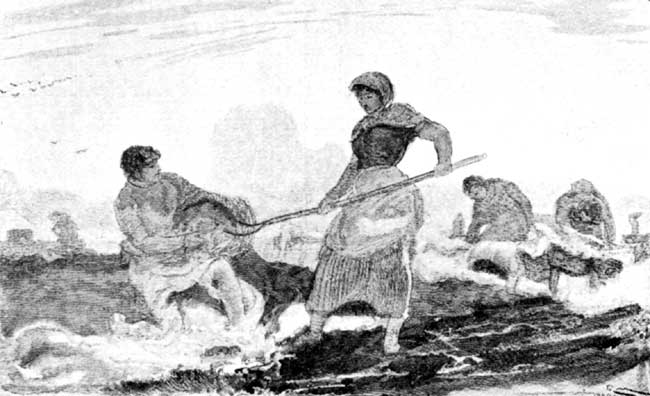

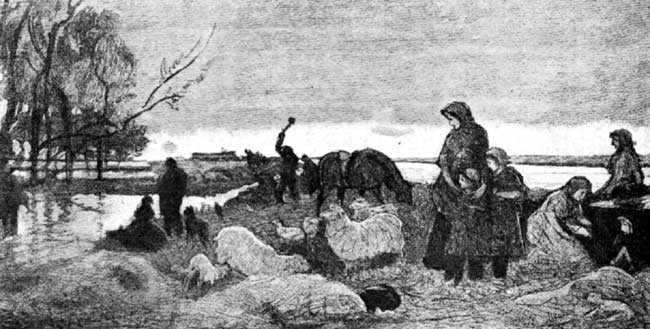

| The Pictures by R. Macbeth: | |

| Potato Gang in the Fens; | |

| Twitch-burning in the Fens; | |

| A Flood in the Fens | 8 |

| Macbeth in the Fens | 9 |

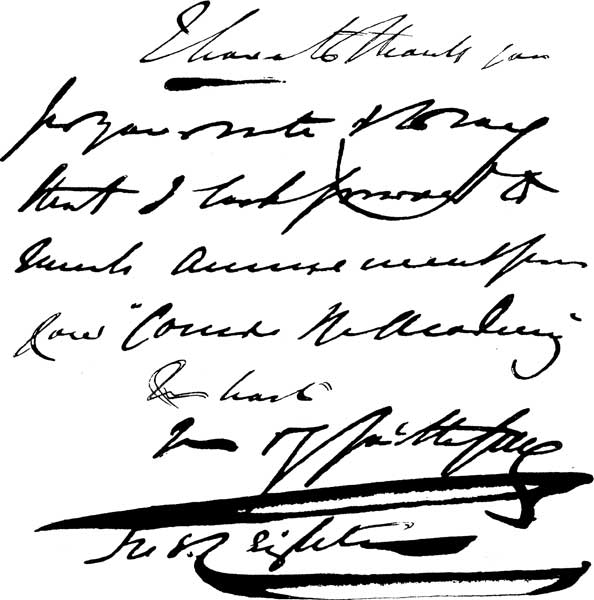

| Letter from the President of the Royal Academy | 11 |

| "An Artistic Joke" | 15 |

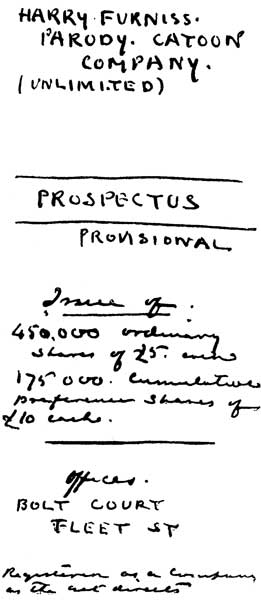

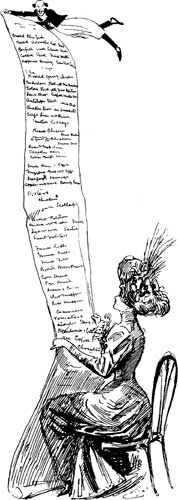

| Mr. Sambourne's Prospectus | 18 |

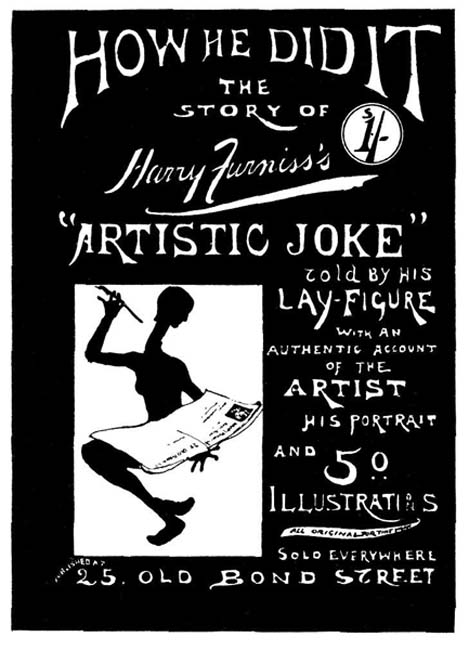

| Cover of "How he did it" | 20 |

| Initial "T" | 20 |

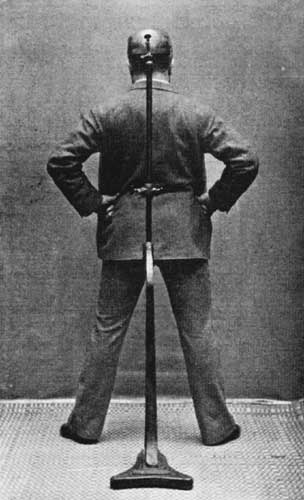

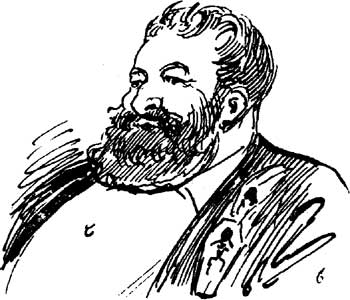

| My Portrait. Frontispiece for "How he did it" | 21 |

| Harry Furniss and his "Lay Figure" | 22 |

| Letter from the President of the Royal Academy | 25 |

| Initial "I" | 26 |

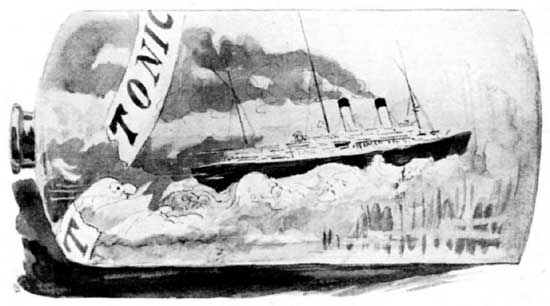

| A "T—Tonic" | 27 |

| An Atlantic "Greyhound." | 28 |

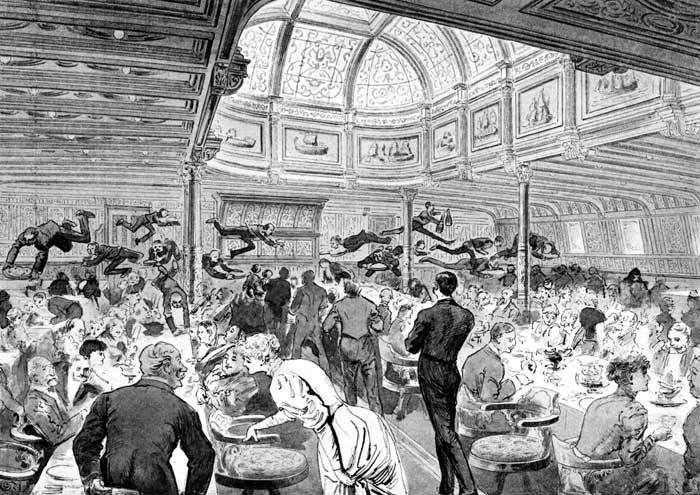

| The Saloon of the Teutonic. The First Morning at Breakfast | 30 |

| At Queenstown—A Reminiscence | 33 |

| Bog-Oak Souvenirs | 34 |

| The Captain's Table | 36 |

| Not up in a Balloon | 38 |

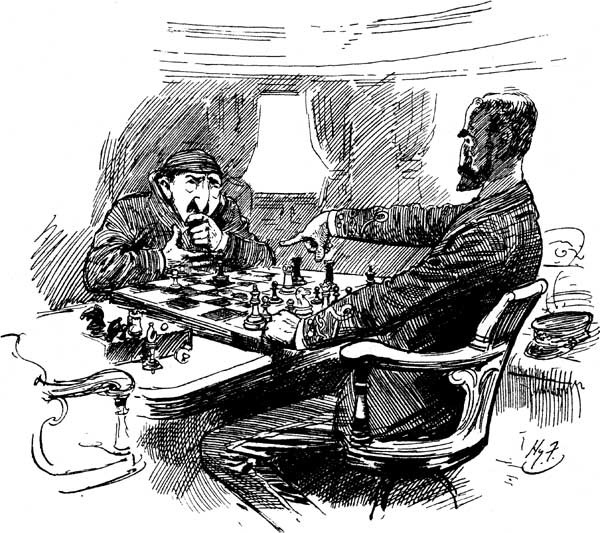

| Chess | 40 |

| Mr. Lloyd and the Lady. "If you will sing, I will!" | 42 |

| The American Pilot—Ideal | 43 |

| The American Pilot—Real | 43 |

| The Health Officer comes on Board | 45 |

| Just in Time | 46 |

| "A Floating Flower Show" | 47 |

| The Bath Steward and the Bishop. "Your Time, Sir! Your Time!" | 48 |

| Americans and English on Deck | 49 |

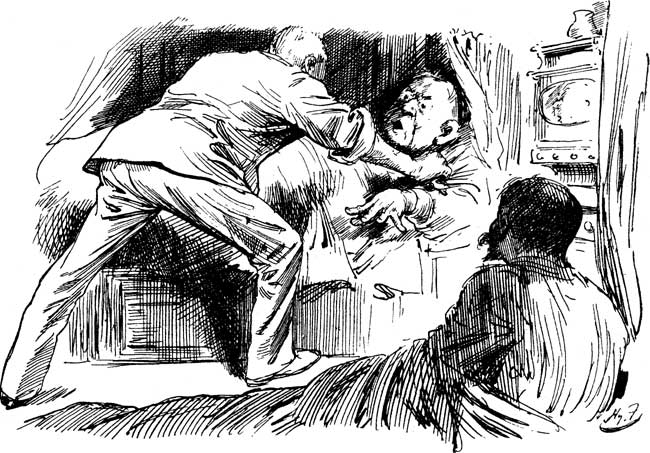

| American Interviewing—Imaginary | 52 |

| American Interviewing—Real | 53 |

| "Sandy." | 55 |

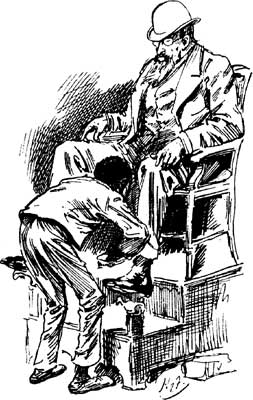

| Chiropody | 57 |

| "New Trilby." | 58 |

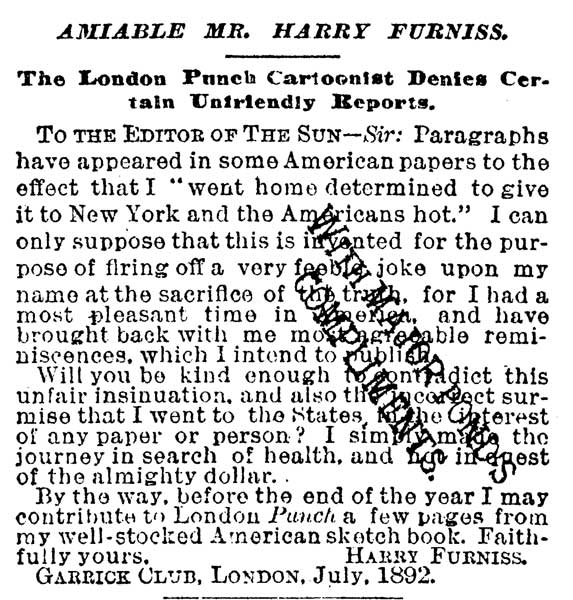

| "Amiable Mr. Harry Furniss" | 59 |

| Major Pond | 59 |

| The Great Sarony | 61 |

| James B. Brown | 63 |

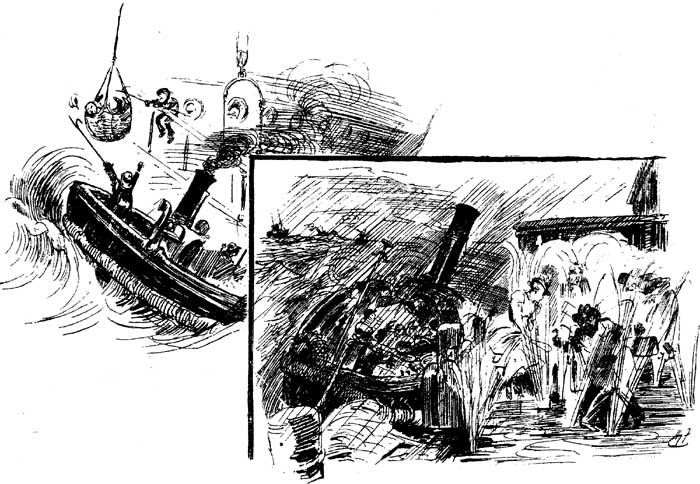

| Fire! | 65 |

| The Alarm | 67 |

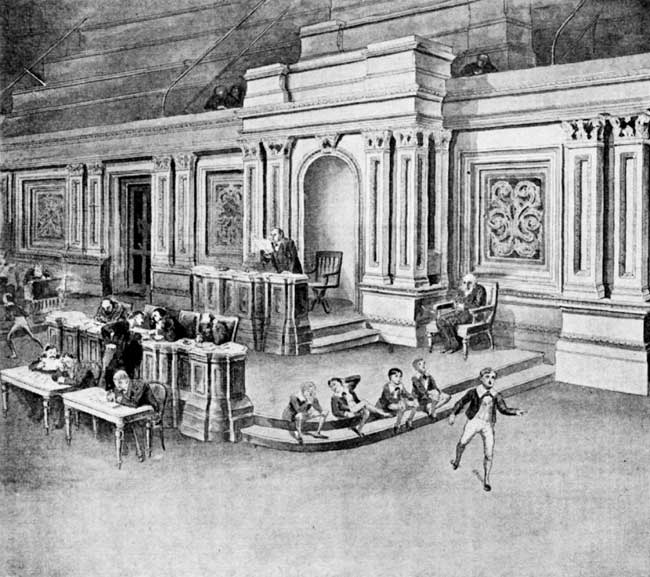

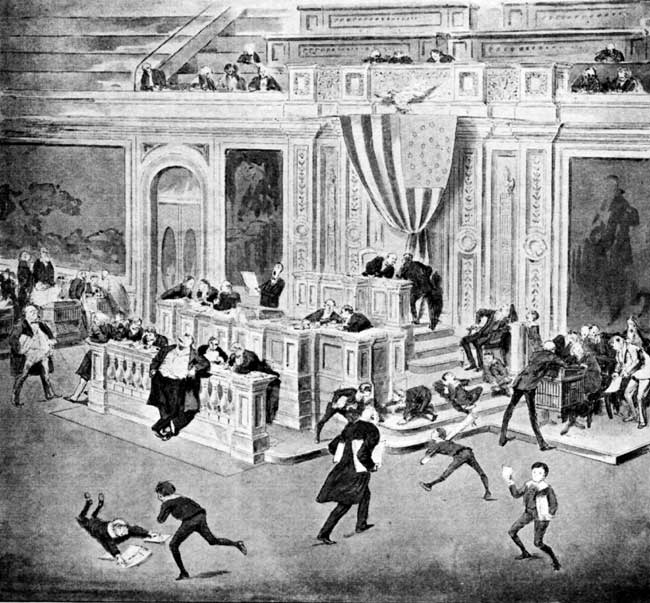

| The Throne in the Senate | 72 |

| The Throne, House of Representatives | 73 |

| Initial "T" | 74 |

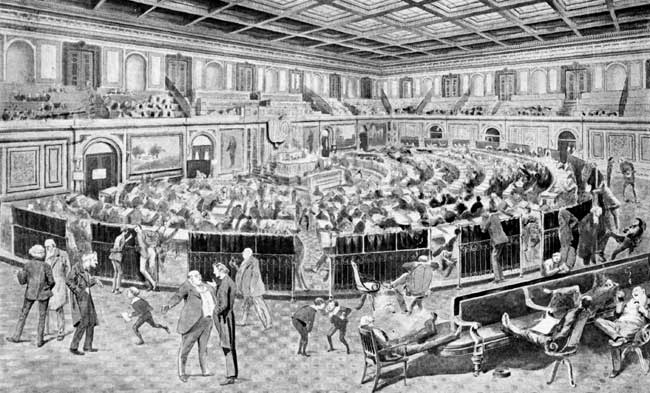

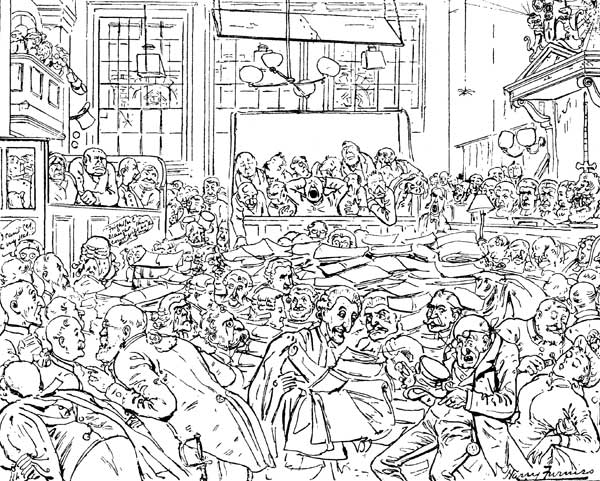

| The House of Representatives | 75 |

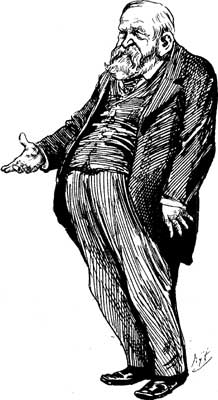

| An ex-Speaker | 77 |

| An ex-Minister | 80 |

| Anglophobia | 82 |

| The President—Ideal | 83 |

| The President—Real | 83 |

| Initial "A" | 84 |

| A Buffalo Girl | 84 |

| President Harrison's Reply | 85 |

| Mr. Punch at Niagara | 86 |

| Hebe | 86 |

| My Driver | 87 |

| Fra' Huddersfield | 87 |

| Niagara growing upon Me | 88 |

| I admire the great Horseshoe Fall | 89 |

| Jonathan harnessing Niagara | 90 |

| "The Three Sisters." | 91 |

| Inclined Railway, Niagara | 92 |

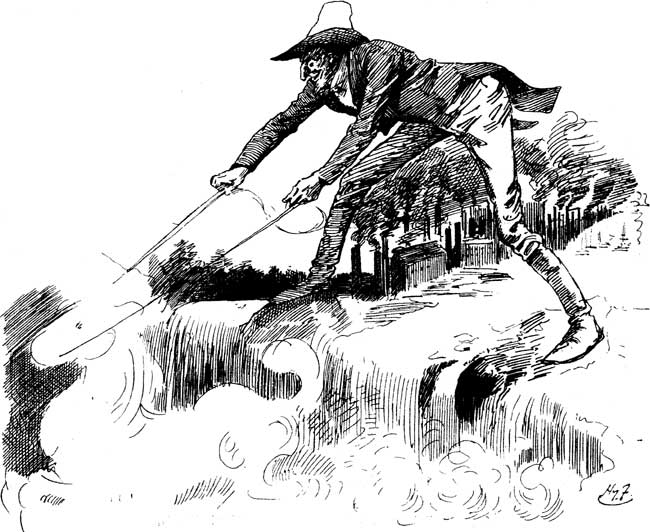

| Where Captain Webb was Killed | 93 |

| Tourists | 94 |

| American Travelling. Nothing to Eat | 96 |

| American Travelling. Nothing to Drink | 97 |

| Sleep(!) | 100 |

| A Washington Lady | 102 |

| A Lady Interviewer | 104 |

| A Sketch at "Del's" | 105 |

| Young America | 106 |

| An American Menu | 107 |

| My Portrait—in the Future | 108 |

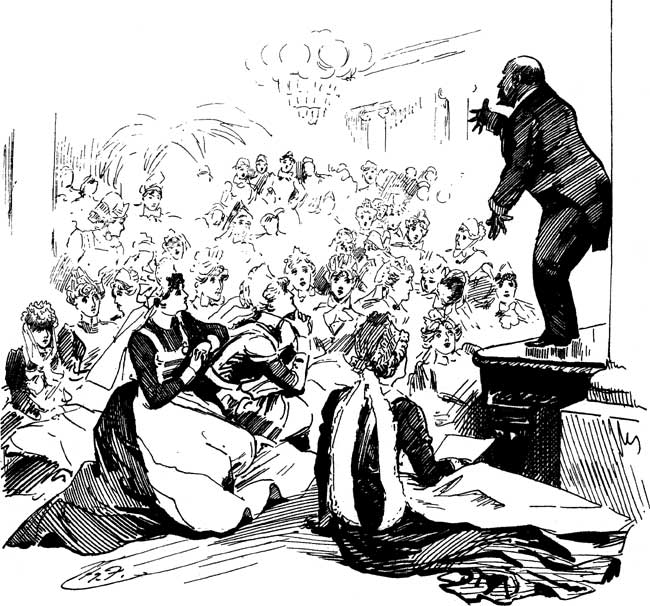

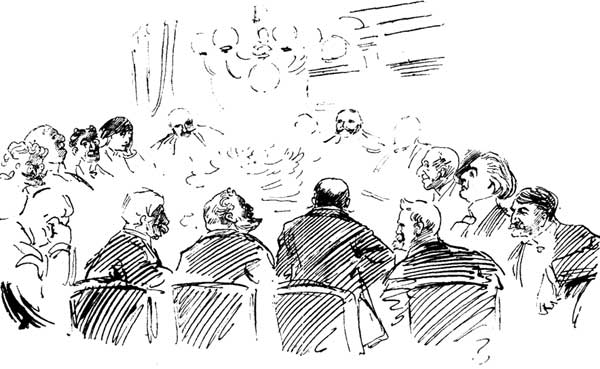

| I am Entertained at the Twelfth Night Club | 110 |

| Reception at a Ladies' Club | 112 |

| Wife and Husband | 113 |

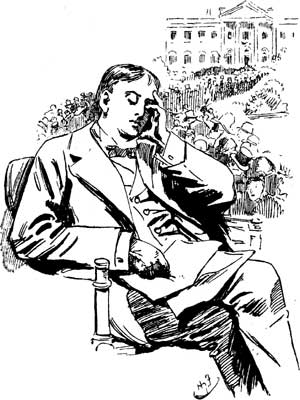

| A Dream of the White House | 114 |

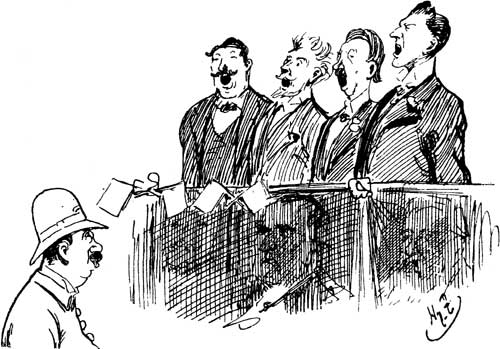

| The Political Quartette | 116 |

| After the Great Parade: "Am I to sit on an ordinary seat to-night?" | 120 |

| Italians | 123 |

| Where the Deed was done! | 125 |

| "A Youth with a Crutch" | 127 |

| In an Opium Joint | 128 |

| "In His Own Black Art" | 128 |

| "Hitting the Pipe" | 129 |

| "Good-bye" | 130 |

| Initial "W" | 131 |

| Coaling | 132 |

| Quarantine | 133 |

| Initial "T" | 134 |

| Sleepy Hollow | 135 |

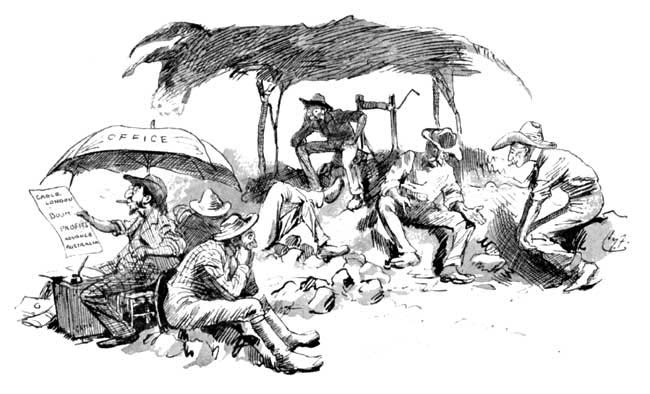

| Prospectors | 138 |

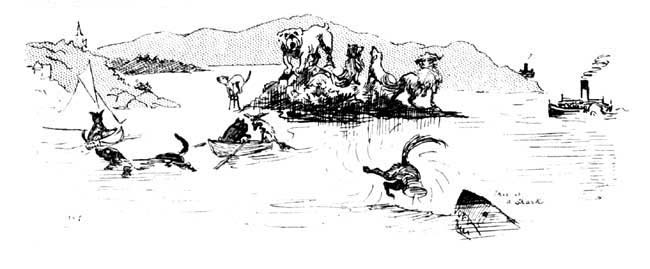

| Quarantine Island | 141 |

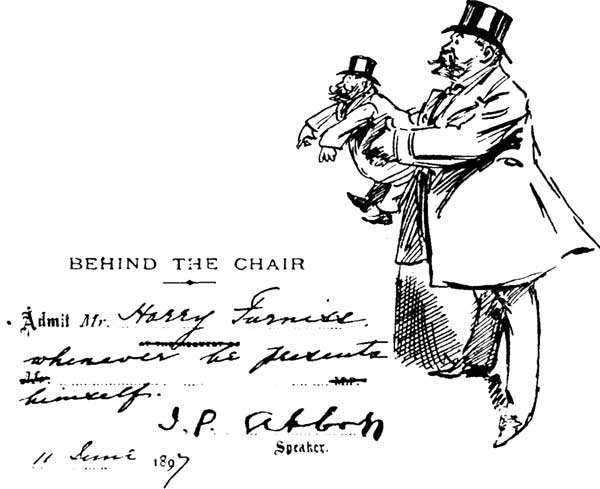

| I am invited to present myself | 143 |

| Landing at Adelaide | 148 |

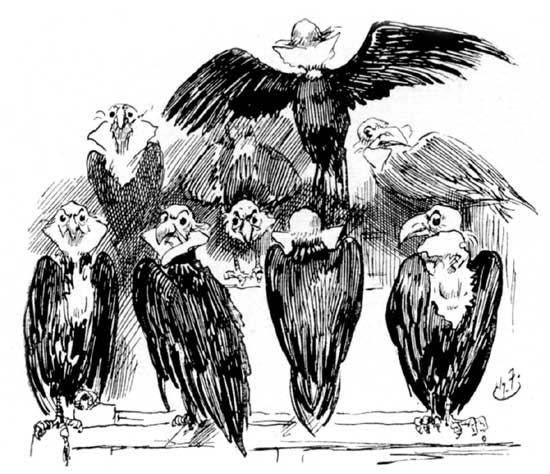

| Pondicherry Vultures | 150 |

| The Maid of the Inn | 150 |

| The Way into Paradise | 151 |

| Paradise | 151 |

| Adam and Eve | 152 |

| A Type | 153 |

| Queen's Hall, London. I was the first to speak from the Platform | 154 |

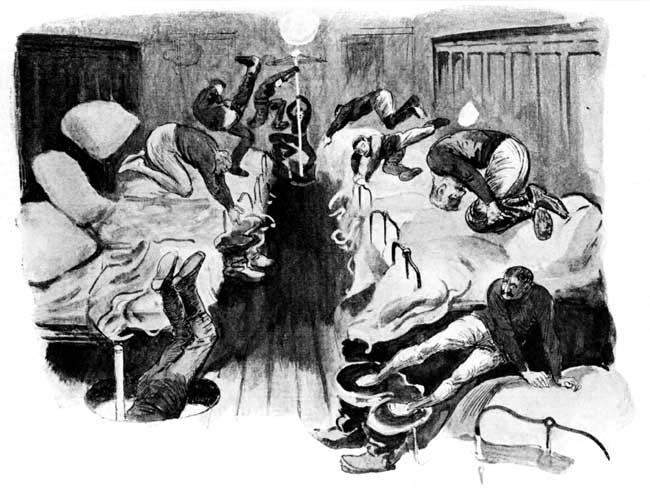

| "Parliament by Day" | 156 |

| "Parliament by Night" | 157 |

| Miss Mary Anderson | 159 |

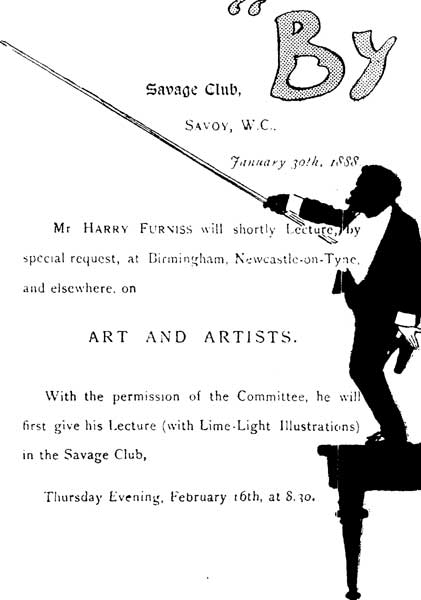

| Initial "By" | 159 |

| Giving My "Humours of Parliament" to the Nurses | 162 |

| Speaker Brand, afterwards Viscount Hampden | 164 |

| The Surprise Shirt | 166 |

| Discovered! | 168 |

| The Fly in the Camera | 169 |

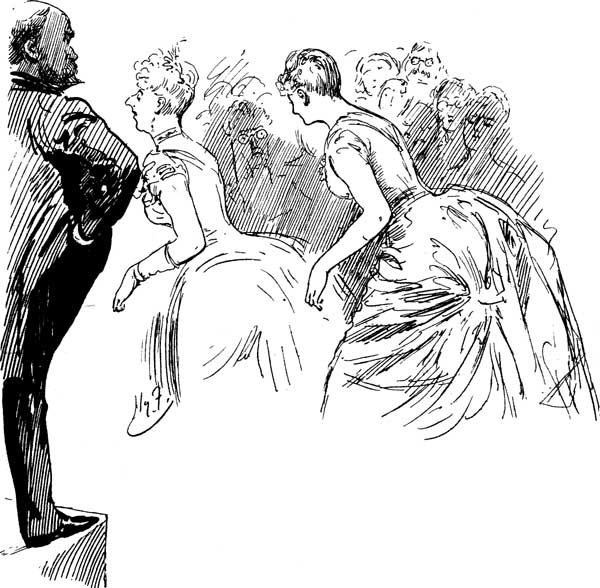

| Late Arrivals | 171 |

| Reserved Seats | 172 |

| Chairman No. 1 | 174 |

| Chairman No. 2 | 177 |

| The Pumpkin—a Chestnut | 178 |

| In "The Humours of Parliament." Ballyhooley Pathetic | 181 |

| Harry Furniss as a Pictorial Entertainer | 182 |

| "Grandolph ad Leones." Reduction of a Page Drawing for Punch made by me whilst travelling by Train | 185 |

| Down with Dryasdust | 189 |

| From a Photo by Debenham and Gould | 190 |

| G. A. Sala | 195 |

| "Art Critic of the Daily Telegraph" | 199 |

| Counsel for the Plaintiff | 200 |

| Mr. F. C. Gould's Sketch in the Westminster, which Sala maintained was mine | 200 |

| Defendant | 202 |

| My Hat | 202 |

| The Plaintiff | 203 |

| The Editor of Punch supports me | 203 |

| Sir F. Lockwood and Myself | 204 |

| "Six Toes" Signature | 205 |

| The Sequel—I Distribute the Prizes at Nottingham | 205 |

| Initial "T" | 206 |

| The See-Saw Antic | 207 |

| The first P.R.A. | 209 |

| No Water-Colour or Black-and-White need apply | 210 |

| A National Academy | 211 |

| The Central Criminal Court. From Punch | 215 |

| "Thank Y-o-o-u!" | 216 |

| Regent's Park as it was. From Punch. A Rough Sketch on Wood | 217 |

| The Late Mr Bartlett | 220 |

| Sketch by Mr. F. C. Gould | 223 |

| The Lady and Her Snakes | 226 |

| Do Women fail in Art—The Chrysalis | 228 |

| The Butterfly | 230 |

| Early Victorian Art | 232 |

| Young Lady's Portrait of her Brother | 233 |

| Waiting | 234 |

| Initial "P" | 235 |

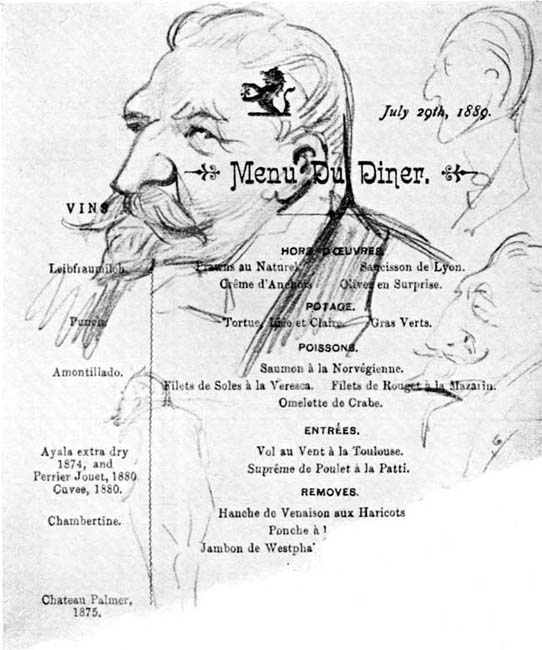

| Menu of the Dinner given to me by the Lotos Club, New York | 237 |

| Alderman—Ideal. Real | 239 |

| J. Whistler, after a City Dinner (Drawn with my Left Hand) | 241 |

| An Odd Volume | 241 |

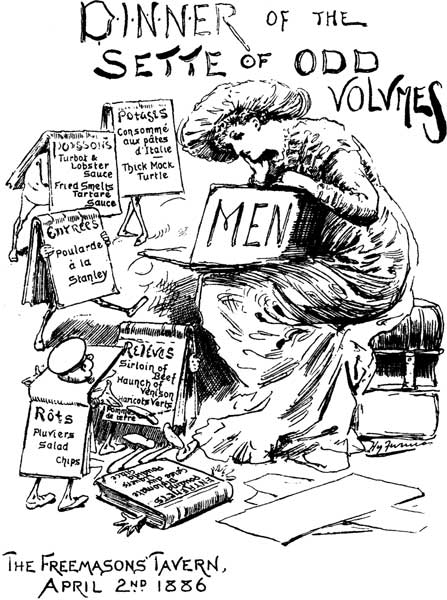

| My Design for Sette of Odd Volumes | 242 |

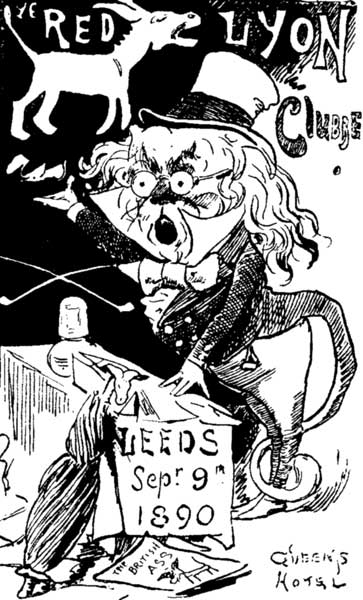

| My Design (reduced) for the Dinner of Ye Red Lyon Clubbe | 243 |

| A Distinguished "Lyon" | 243 |

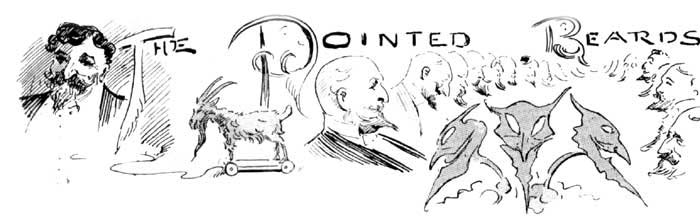

| Headpiece and Initial "S" | 245 |

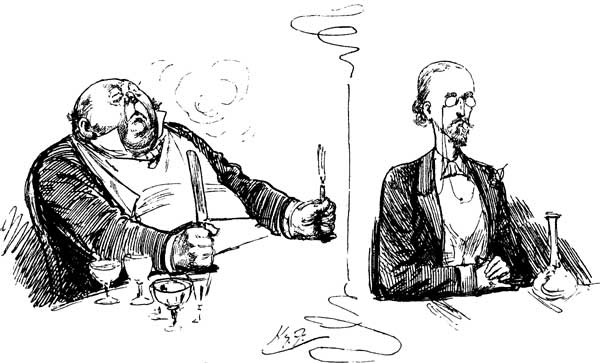

| A Sound Money Dinner | 249 |

| A Sketch of Boulanger | 251 |

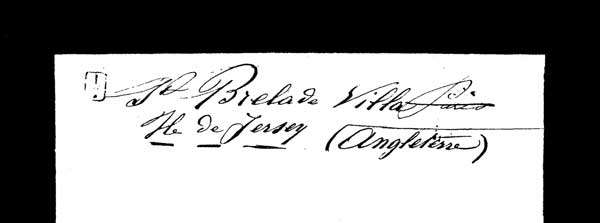

| Address of Boulanger's Retreat | 252 |

| A Note on My Menu | 253 |

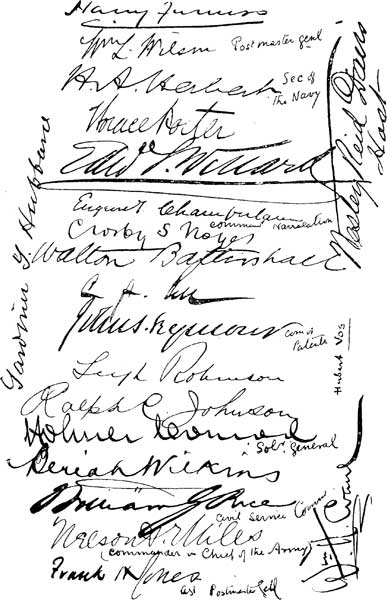

| Remarkable and much-talked-of Lunch to me at Washington. The Autographs on back of Menu | 254 |

| Mr. Punch and his Dog Toby | 256 |

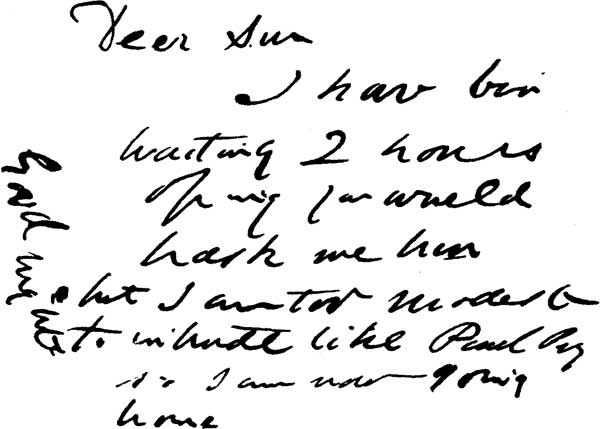

| A Memorandum in Pencil | 258 |

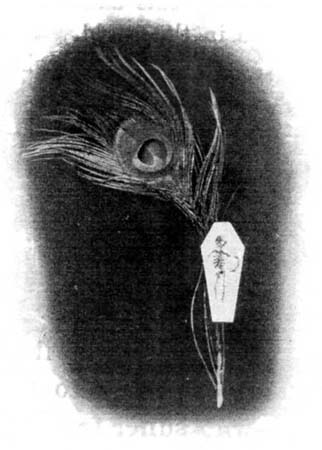

| Thirteen Club Banquet. The Table Decorations | 259 |

| Mr. W. H. Blanch | 260 |

| The Broken Looking-Glass | 261 |

| The Badge | 261 |

| Squint-Eyed Waiter | 263 |

| Coffins, Sir! | 266 |

| "The Chairman will be Pleased to Spill Salt with You." From the St. James's Budget | 267 |

| A Knife I was Presented with | 268 |

| Tailpiece | 271 |

| "Au Revoir" | 280 |

MY STUDIO DURING THE PROGRESS OF "AN ARTISTIC JOKE."

MY STUDIO DURING THE PROGRESS OF "AN ARTISTIC JOKE."

The First Idea—How it was Made—"Fire!"—I am a Somnambulist—My

Workshop—My Business "Partner"—Not by Gainsborough—Lord

Leighton—The Private View—The Catalogue—Sold Out—How the R.A.'s

Took It—How a Critic Took It—Curious Offers—Mr. Sambourne as a

Company Promoter—A One-man Show—Punch's Mistake—A Joke within

a Joke—My Offer to the Nation.

"In the year 1887 he startled the town and made a Society sensation by means of an exceedingly original enterprise which any man of less audacious[Pg 2] and prodigious power of work would have shrunk from in its very inception. For years this Titanic task was in hand. This was his celebrated 'artistic joke,' the name given by the 'Times' to a bold parody on a large scale of an average Royal Academy Exhibition. This great show was held at the Gainsborough Gallery, New Bond Street, and consisted of some eighty-seven pictures of considerable size, executed in monochrome, and presenting to a marvelling public travesties—some excruciatingly humorous and daringly satirical, others really exquisite in their rendering of physical traits and landscape features—of the styles, techniques, and peculiar choice of subjects of a number of the leading artists, R.A.'s and others, who annually exhibit at Burlington House. It was a surprise, even to his intimate friends, who, with one or two exceptions, knew nothing about it until the announcement that Mr. Furniss had his own private Royal Academy appeared in the 'Times.' He worked in secret at intervals, under a heavy strain, to get the Exhibition ready, particularly as he had to manage the whole of the business part; for the show at the Gainsborough Gallery was entirely his own speculation. Granted that the experiment was daring, yet the audacity of the artist fascinated people. Nor did the Academicians, whom some thought would have been annoyed at the fun, as a body resent it. They were not so silly, though a minority muttered. Most of them saw that Mr. Furniss was not animated by any desire to hold them up to contempt, but his parodies were perfectly good-natured, that he had served all alike, and that he had only sought the advancement of English art. During the whole season the gallery was crushed to overflowing, the coldest critics were dazzled, the public charmed, and literally all London laughed. It furnished the journalistic critics of the country with material for reams of descriptive articles and showers of personal paragraphs, and whether relished or disrelished by particular members of the artistic profession, at least proved to them, as to the world at large, the varied powers (in some phases hitherto unsuspected) and exuberant energies of the Harry Furniss whose name was now on the tongue and whose bold signature was familiar to the eyes of that not easily impressed entity, the General Public.

"In fact, London had never seen anything so original as Harry Furniss's

Royal Academy. The work of one man, and that man one of the busiest

professional men in town. Indeed it might be thought that at the age of

thirty, with all the foremost magazines and journals waiting on his

leisure, with a handsome income and an enviable social position assured,

ambition could hardly live in the bosom of an artist in black and white.

Unlike Alexander, our hero did not sit down and weep that no kingdom

remained to conquer, but set quietly to work to create a new realm all

his own. His Royal Academy, although presented by himself to the public

as an 'artistic joke,' showed that he could not only use the brush on a

large scale, but that he could compose to perfection, and after the

exuberant humour of the show, nothing delighted[Pg 3] and surprised the

public more than the artistic quality and finished technique in much of

the work, a finish far and away above the work of any caricaturist of

our time."

T

HE idea first occurred to me at a friend's house, when my host after dinner took me into the picture gallery to show me a portrait of his wife just completed by Mr. Slapdash, R.A. It stood at the end of the gallery, the massive frame draped with artistic care, while attendants stood obsequiously round, holding lights so as to display the chef d'œuvre to the utmost advantage. As I beheld the picture for the first time I was simply struck dumb by the excessively bad work which it contained. The dictates of courtesy of course required that I should say all the civil things I could about it, but I could hardly repress a smile when I heard someone else pronounce the portrait to be charming. However, as my host seemed to think that perhaps I was too near, and that the work might gain in enchantment if I gave it a little distance, we moved towards the other end of the gallery and, at his suggestion, looked into an antiquated mirror, where I got in the half light what seemed a reflection of it. The improvement was obvious, and I told my friend so. I told him that the effect was now so lifelike that the figure seemed to be moving; but when he in turn gazed into the glass he explained somewhat testily that I was not looking at his wife's portrait at all, but at the white parrot in the cage hard by. The moral of this incident is that if patrons of art in their pursuit of eccentricities will pay large sums to an artist for placing a poor portrait in a massive frame with drapery hanging round it in the most approved modern style, and be satisfied with such a result, they must not be surprised if a parrot should be mistaken for a framed type of beauty. I was, however, not satisfied until I had examined the picture in question closely and honestly in the full light of day, when I saw that Mr. Slapdash, R.A., had sold his autograph and a soiled canvas in lieu of a portrait to my rich but too easily pleased friend.[Pg 4]

As I walked back into the drawing-room, one of the musical humorists of the day was cleverly taking off the weak points of his brother musicians, and bringing out into strong light their peculiarities and faults of style. The entertainment, however, did not tend to raise my drooping spirits, for I was sad to think how low our modern art had sunk, and with a heavy heart and a sigh for the profession I pursue, I went sadly home. Of course my pent-up feelings had to find relief, so my poor wife had to listen to an extempore lecture which I then and there delivered to her on portraiture past and present—a lecture which I fear would hardly commend itself to the Association for the Advancement of British Art. Further, I asked myself why should I not take a leaf out of the musical humorist's book and like him expose the tricks and eccentricities of British art in the present day?

The following morning, being a man of action as well as of word, I started my "Artistic Joke." I was determined to keep the matter secret, so I worked with my studio doors closed, and as each picture was finished it was placed behind some heavy curtains, secure from observation, and I kept my secret for three years, until the work was complete.

I soon found that I had set myself a task of no little magnitude. Before I could really make a start I had to examine each artist's work thoroughly. I studied specimens of the work of each at various periods of his or her career. I had to discover their mannerisms, their idiosyncrasies and ideas, if they had any, their tricks of brushwork, and all the technicalities of their art. Then I designed a picture myself in imitation of each artist. In a very few instances only did I parody an actual work. This fact was generally lost sight of by those who visited the Exhibition. The public imagined that I simply took a certain picture of a particular artist and burlesqued it. I did this certainly in the case of Millais' "Cinderella" and one or two others; but in the vast majority of the works exhibited, even in Marcus Stone's "Rejected Addresses," which appeared to so many as if it must have been a direct copy of some picture of his, the idea was entirely evolved out of my own[Pg 5] imagination. In thinking out the various pictures I devoted the greatest care to accuracy of detail. I was particular as to the shape of each, and even went so far as to obtain frames in keeping with those used by the different artists. Of course it was out of the question for me to do the pictures in colour, which would have required a lifetime, and probably tempted me to break faith with my idea; not to mention the fact that I should in that case most likely have sent the collection to the Academy, of which obtuse body, if there is any justice in it, I must then naturally have been elected a full-blown member.

THROWING MYSELF INTO IT.

THROWING MYSELF INTO IT.

In order to get the Exhibition finished in time, I often had to work far into the night, and on one occasion when I was thus secretly engaged in my studio upon these large pictures until the small hours, I remember a catastrophe very nearly happened which would have put a finishing touch of a very different kind to that which I intended, not only to the picture, but to the artist himself. It happened thus. About three o'clock in the morning, long after the household had retired to rest, I became conscious of a smell of burning. I made a minute search round the studio, but could not discover the slightest indication of an incipient conflagration. Then a dreadful thought occurred to me. Beneath the studio is a vault, access to which is gained by a trap-door in the floor. Could it be that the secret of my "Artistic Joke" had become common property in the artistic world, and that some vindictive Academician, bent upon preventing the impending caricature of his chef d'œuvre, was even now, like another Guy Fawkes, concealed below, and in the dead of night was already commencing his diabolical attempt to roast me alive in the midst of my caricatures? Up went the[Pg 6] trap-door, and with candle in hand I explored the vault. The result was to calm my apprehensions upon this score, for there was no one there. Still mystified as to where the smell of fire, now distinctly perceptible, came from, I next walked round the outside of my studio, exciting evident suspicion in the mind of the policeman on his beat. No, there was not a spark to be seen; no keg of gunpowder, no black leather bag, no dynamite, no infernal machine. I returned into the house and went upstairs, roused all my family and servants, who, after a close examination, returned to their beds, assuring me that all was safe there, and half wondering whether the persistent pursuit of caricaturing does not produce an enfeebling effect upon the mind. Consoled by their assurances, I returned once more to my studio, where the burning smell grew worse and worse. However, concluding that it was due to some fire in the neighbourhood, I settled down to work once more; but hardly had I taken my brush in hand when showers of sparks and particles of smouldering wood began to descend upon my head and shoulders, and cover the work I was engaged on. I started up, and looking up at my big sunlight, saw to my horror that I had wound up my easel, which is twelve feet high, and more nearly resembles a guillotine than anything else, so far that the top of it was in immediate contact with the gas, and actually alight!

FIRE!

FIRE!

The Times took the unusual course of giving, a month in advance of its opening on April 23rd, 1887, a preliminary notice of this Exhibition.

It said: "A novel Exhibition, for which we venture to[Pg 7] prophesy no little success, is being prepared by Harry Furniss of Punch celebrity. As everyone knows, Mr. Furniss has long adorned the columns of our contemporary with pictorial parodies of the chief pictures of the Royal Academy, the Grosvenor, and other shows, and it has now occurred to him to develop this idea and to have a humorous Royal Academy of his own. He has taken the Gainsborough Gallery in Old Bond Street, which he will fill some time before the opening of Burlington House with a display of elaborate travesties of the works of all the best known artists of the day. There will be seventy pictures in black and white, many of them large size, turning into good-natured ridicule the works of every painter, good and bad, whose pictures are familiar to the public," etc., etc. This gives a very fair idea of the nature and objects of my "Royal Academy." My aim was to burlesque not so much individual works as general style, not so much specific performances as habitual manner. As an example I take the work of that clever decorative painter and etcher, Mr. R. W. Macbeth, A.R.A. By his permission I here reproduce reductions in black and white of three of his well-known pictures, and side by side I show my parody of his style and composition—not, as you will observe, a caricature of any one picture, but a boiling down of all into an original picture of my own in which I emphasise his mannerisms. Furthermore, in my catalogue I parodied the same artist's mannerism in drawing in black and white, and with one or two exceptions this applies to all the works I exhibited. I hit upon a new idea for the illustrated catalogue. The illustrations, with few exceptions, did not convey any idea of the composition of the pictures, and in many cases they were designed to further the idea and object of the Exhibition by reference to pictures not included therein. My joke was that the Exhibition could not be understood by anyone without a catalogue, and the catalogue could not be understood by anyone without seeing the Exhibition. Therefore everyone visiting the Exhibition had to buy a catalogue, and everyone seeing the catalogue had to visit the Exhibition. Q.E.D.! The idea, the catalogue, and everything connected with this "Artistic Joke" were[Pg 8] my own, with the exception of the title, which was so happily supplied by Mr. Humphry Ward as the heading to the preliminary notice he wrote for the Times. At the last moment I called in my fellow-worker on Punch, Mr. E. J. Milliken, to assist me with some of the letterpress of the catalogue and write the verses for it. I had all but a small portion of the catalogue written before he so kindly gave this assistance, but at the suggestion of a mutual friend I gave him half the profits of the catalogue, which amounted to several hundred pounds. I am obliged to make this point clear, as to my astonishment it was reported that the whole Exhibition was a joint affair, no doubt originated by Mr. Punch in a few lines: "When two of Mr. Punch's young men put their heads together to produce so excellent a literary and artistic a joke as that now on view at the Gainsborough Gallery——" This was accepted as a matter of fact by many, not knowing that this "joke," my work of years, was a secret in the Punch circle as outside it. The false impression which Mr. Punch had originated he corrected in his Happy Thought way: "The Artistic Jubilee Jocademy in Bond Street.—The fire insurances on the building will be uncommonly heavy because there is to be a show of Furniss's constantly going on inside. Why not call it 'Furniss Abbey Thoughts?'"

POTATO GANG IN THE FENS.

POTATO GANG IN THE FENS.

TWITCH-BURNING IN THE FENS.

TWITCH-BURNING IN THE FENS.

A FLOOD IN THE FENS.

A FLOOD IN THE FENS.

MACBETH IN THE FENS.

MACBETH IN THE FENS.

My parody in "An Artistic Joke" of Mr. Macbeth's composition and style of work, showing that in my "Academy" I did not parody one subject, but designed a picture embodying all the characteristics of the Artist.

The following brief correspondence passed between the President of the

Royal Academy and myself:—

"Mr. Harry Furniss presents his compliments to Sir Frederick Leighton and trusts he will forgive being bothered with the following little matter.

"Sir Frederick is no doubt aware of Mr. Furniss's intention to have a little Exhibition in Bond Street this spring,—a good-natured parody on the Royal Academy. The title settled upon—the only one that explains its object—is

"In this particular case the authorities (Mr. Furniss is informed) see no objection to the use of the word Royal pure and simple, but as a matter of etiquette he thinks it right to ask the question of Sir Frederick Leighton also.

"March 11th, 1887."

LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT OF THE ROYAL ACADEMY.

LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT OF THE ROYAL ACADEMY.

A word or two may not be out of place here on the practical difficulties which beset an artist who opens an Exhibition on his own account, and is forced by circumstances to become his own "exploiteur." Men may have worked with a more ambitious object, but certainly no man can ever have worked harder than I did at this period. Outside work was pouring in, my current Punch work seemed to be increasing, but I never allowed "Furniss's Folly" (as some good-natured friend called my Exhibition at the moment) to interfere with it. I had only arranged with a "business man" to take the actual "running" of the show off my hands, and he was to have half the profits if there should happen to be any. At the critical moment, when I[Pg 12] was working night and day at my easel, when in fact the "murther was out" and the date actually settled for the "cracking" of my joke—in short, when I fondly imagined that all the arrangements were made, I received a letter from my "business" friend backing out of the affair, "as he doubted its success." Half-an-hour after the receipt of this staggerer (I have never had time to reply to it) I was dashing into Bond Street, where I quickly made all arrangements for the hire of a gallery and the necessary printing, engaged an advertising agent and staff, and myself saw after the thousand and one things indispensable to an undertaking of this kind. And all this extraneous worry continued to hamper my studio work until the Exhibition was actually opened. Of course I had to make hurried engagements at any price, and consequently bad ones for me. Every householder is aware that should he change his abode he is surrounded in his new home by a swarm of local tradespeople and others anxious to get something out of him. Well, my experience upon entering the world of "business," hitherto strange to me, was precisely the same. All sorts of parasites try to fasten themselves on to you. Business houses regard you as an amateur, and consequently you pay dearly for your experience. You are not up to the tricks of the trade, and although you may not generally be written down an ass, you must in your new vocation pay your footing. It is therefore incumbent upon anyone entering the world of trade for the first time to keep his wits very much about him.

The local habitation for my Exhibition, which upon the spur of the moment I was fortunate enough to find in Bond Street, was called for some inexplicable reason the Gainsborough Gallery, and thereby hangs a tale. One afternoon there arrived a venerable dowager in a gorgeous canary-coloured chariot, attended by her two colossal footmen. She sailed into the gallery, which, fortunately for the old and scant of breath, was on the ground floor, and slightly raising the pince-nez on her aristocratic nose, looked about her with an air of bewilderment. Then going up to my secretary she said, "Surely! these are not by Gainsborough?"[Pg 13]

"No, madam," was the reply. "This is the Gainsborough Gallery, but the pictures are by Harry Furniss."

Almost fainting on the spot, the old lady called for her salts, her stick, and her attendants three, and was rapidly driven away from the scene of her lamentable mistake.

The public attendance at the "The Artistic Joke" was prodigious from the first. Even upon the private view day, when I introduced a novelty, and instead of inviting everybody who is somebody to pay a gratuitous visit to the show, raised the entrance fee to half-a-crown, the fashionable crowd besieged the doors from an early hour, and made a very considerable addition to my treasury. Those of my readers, however, who did not pay a visit to the Gainsborough will be better able to realise the amount of patronage we received, notwithstanding the numerous attractions of the "Jubilee" London season, if I relate an incident which occurred on the Saturday after we opened. It was the "private view" of the Grosvenor Gallery, and the crowd was immense. Indeed, many ladies and gentlemen were returning to their carriages without going through the rooms, not, like my patron the dowager, because they were disappointed at not finding the work of the old masters, but because the visitors were too numerous and the atmosphere too oppressive. As I passed through the people I heard a lady who was stepping into her carriage say to a friend, "I have just come from 'The Artistic Joke,' and the crowd is even worse there. They have had to close the doors because the supply of catalogues was exhausted." This soon caused me to quicken my pace, and hastening down the street to my own Exhibition, I found the police standing at the doors and the people being turned away. The simple explanation of this was that so great had been the public demand that the stock of catalogues furnished by the printers was exhausted early in the afternoon, and as it was quite impossible to understand the caricatures without a catalogue, there was no alternative but to close the doors until some more were forthcoming.

Finding the telephone was no use, I was soon in a hansom bound for the City, intending by hook or by crook to bring back with me the much-needed catalogues, or the body of the printer dead or alive. Upon arriving in the City, however, to my[Pg 14] chagrin I found his place of business closed, though the caretaker, with a touch of fiendish malignity, showed me through a window whole piles of my non-delivered catalogues. Not to be beaten, I hastened back to the West End and despatched a very long and explicit telegram to the printer at his private house (of course he would not be back in the City until Monday), requiring him, under pain of various severe penalties, to yield up my catalogues instanter. As I stood in the post office of Burlington House anxiously penning this message, and harassed into a state of almost feverish excitement, the sounds of martial music and the tramp of armed men in the adjacent courtyard fell upon my distracted ear. With a sickly and sardonic smile upon my face I laid down the pen and peeped through the door.

"Yes! I see it all now," I muttered. "The whole thing is a plant. The printer was bribed, and, coûte que coûte, the Academy has decided to take my body! Hence the presence of the military; and see, those cooks—what are they doing here in their white caps? My body! Ha! then nothing short of cannibalism is intended!"

This frightful thought almost precipitated me into the very ranks of the soldiery, when I discovered that the corps was none other than that of the Artist Volunteers, which contains several of my friends. Seizing one of those whom I chanced to recognise, I hurriedly whispered in his ear the thoughts of impending butchery which were passing in my terrified mind. But he only laughed. "You will disturb their digestions, my dear Furniss, some other way," he said, "than by providing them with a pièce de résistance. Make your mind easy, for we are only here to do honour to the guests. This is the banqueting night of the Royal Academy."

From what I heard, some amusing incidents occurred in the house at my "Royal Academy."

"AN ARTISTIC JOKE."

"AN ARTISTIC JOKE."

It was no uncommon sight to see the friends and relatives, even the sons and daughters, of certain well-known Academicians standing opposite the parody of a particular picture, and hugely enjoying it at the expense of the parent or friend who had painted the original. Other R.A.'s, who went about pooh-poohing the whole affair, and saying that they intended to[Pg 17] ignore it altogether, turned up nevertheless in due time at the Gainsborough, where, it is true, they did not generally remain very long. They had not come to see the Exhibition, but only their own pictures. One glance was usually enough, and then they vanished. The critics (and their friends) of course remained longer. Even Mr. Sala went in one day and seemed to be immensely tickled by what he saw. Strange to relate, however, when he had passed through about one-third of the show, he was observed to stop abruptly, turn himself round, and flee away incontinently, never to be seen there again. I was much puzzled to discover a reason for this remarkable manœuvre, the more so as at that time I had not wounded his amour propre by indulging in an "Artistic Joke" of much more diminutive proportions at his expense, or, as it subsequently turned out, at my own. Since, however, the world-famous trial of Sala v. Furniss I have looked carefully over all the pictures in my Royal Academy, with a view to throwing some light upon the critic's abrupt departure. I remain, nevertheless, in the dark, for the most rigid scrutiny has failed to reveal to me one single feature in the show, not even a Grecian nose, or a foot with six toes, which could have jarred upon the refined taste of the most sensitive of journalists. I shall return to Mr. Sala in another portion of these confessions, but am more concerned now with the parasites, the artistic failures, the common showmen, the traffickers in various wares, and other specimens of more or less impecunious humanity, who applied to me to let them participate in the profits of a success which I had toiled so hard to achieve. In imitation of Barnum, I might have had, if I had been so inclined, a series of side shows, ranging in kind from the big diamond which a well-known firm in Bond Street asked me to let them exhibit, to the "Queen's Bears" and a curious waxwork of a bald old man which by means of electricity showed the gradual alterations of tint produced by the growth of intemperance. One of these applications I was for a moment inclined to entertain. It has more than once been proposed that to enable the British public to take its annual bolus at Burlington House with less nausea, the Royal Academy should introduce a band of some sort, so that under the influence of its inspiriting[Pg 18] strains the masterpieces might be robbed of a little of their tameness, the portrait of My Lord Knoshoo might seem less out of place in a public Exhibition, and the insanities of certain demented colourists might be made less obtrusive monopolists of one's attention. Therefore, when "a musical lady and her daughters" applied to me for permission to give "Soirées Musicales" at the Gainsborough, it struck me for a moment that it would be effective to forestall the action of the Academy; but on second thoughts I reflected that as the Burlington House band would probably be of the same quality as the pictures, it would be adhering more closely to the spirit of my "Artistic Joke" if I gave my patrons a barrel organ or a hurdy-gurdy which should play the "Old Hundredth" by steam. Although one would have thought that a single visit of a few hours' duration would have sufficed to go through a humorous Exhibition of this kind, I found that several people became habitués of the place, and paid many visits; but it is of course possible to have too much of a good thing, and a joke loses its point when you have too much of it. No better illustration of this can be afforded than in the case of my own secretary at the time, who had sat in the Exhibition for many months. One day, when the plates were being prepared for an album which I published as a souvenir of the show, the engraver arrived with a proof.

MR. SAMBOURNE'S PROSPECTUS.

MR. SAMBOURNE'S PROSPECTUS.

"But there is some mistake here," said my secretary. "We have no such picture as that on the premises."

The engraver was puzzled, and as he seemed rather sceptical upon the point, he was allowed to look round, and speedily found the picture he had copied. It had actually been close at my secretary's elbow since the "Artistic Joke" was opened to[Pg 19] the public, but as the pictures were all under glass, I suppose he had only seen his own reflection when gazing at them. It was this perhaps which caused another gentleman whom I have before mentioned to beat so hasty a retreat. Both of them may have been frightened by what they saw.

The suggestion that I should be run as a public company emanated from the fertile brain of my friend Mr. Linley Sambourne. This is his rough idea of the prospectus:

This Company has been formed to acquire the sole exclusive concession of the marvellous and rapid power of production of the above-mentioned Managing Director, and to take over the same as a going concern.

These productions have been in continual flow for many years past, and are too well known to need any assurance of the possibility of a failure of supply. It is therefore with the utmost confidence that this sure and certain investment is now offered to the public with an absolute guarantee of a percentage for Fifteen Years of Forty-five per cent.

Mr. Furniss can be seen at work with the regularity of a threshing machine and the variety of a kaleidoscope any day from 8 o'c. a.m. to 8 o'c. p.m. on presentation of visiting card.

The Subscription List will close on or before Monday, April 1st, 1887.

Messrs. C. White & Greyon Grey invite subscriptions for the undermentioned Share Capital and Debentures of the

HARRY FURNISS PARODY CARTOON COMPANY

(Unlimited).

| Incorporated under the Joint Stock Companies Acts, 1862 and 1883. | ||

| Share capital | £4,000,000 | |

| Divided as follows: | ||

| 450,000 Ordinary Shares of £5 each | £2,250,000 | |

| 175,000 7 p.c. Cumulative Preference Shares of £10 each | 1,750,000 | |

Directors.

Chairman: H. V—— W——, Esq., Regent Street, photographer.

Sir John S—— V——, Kt., Pine Court, Kent.

H—— F——, Esq., Draughtsman and Designer, 45, Drury Lane.

HARRY FURNISS, Esq., R.R.A., R.R.I., &c.,

will join the Board as Managing Director on allotment.

A showman, particularly with some attraction of the passing hour, must "boom his show for all it's worth," as the Americans say; so I "boomed" my "Artistic Joke" with an advertising joke, and at the same time parodied another branch of art—the art of advertising the artists, by a special number of a magazine devoted to the work of an Academician. The special numbers, generally published at Christmas, are familiar and interesting to us all. Still, from any point of view they are fair game. They are of course merely non-critical, eulogistic accounts of the artist and his work. So

"How he Did It—The Story of my 'Artistic Joke,'" duly appeared, written by my Lay-figure.

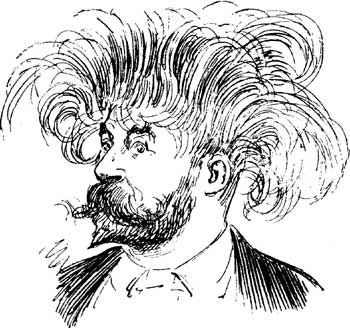

MY PORTRAIT. FRONTISPIECE FOR 'HOW HE DID IT.'

MY PORTRAIT. FRONTISPIECE FOR 'HOW HE DID IT.'

HE fact of my being only an artist's lay-figure will account for any stiffness or angularity in my literary style. Whilst conscious of my deficiencies in this respect, I am comforted by the consideration that a lay-figure attempting literature cannot by any possibility perpetrate greater absurdities than are committed by many a ready writer who indulges in those glowing and gushing descriptions of artists and their work which it is now the fashion to publish, in some such shape as the present, for the delectation (and delusion) of a gossip-loving public."

This, the origin of "The Artistic Joke," is a fair specimen[Pg 21] of the absurdity I published as an advertisement, though many bought it and read it as a "true and authentic account" of the confessions of a caricaturist's lay-figure:

"As many would be interested in knowing how this extraordinary idea of an Academy pour rire first occurred to this artist, I hasten to gratify their natural curiosity. It was before little Harry reached the age of seven, and while watching with fellow-feeling the house-painters at work in his father's house. One day, at lunchtime, when the men had left their ladders and paraphernalia near the picture-gallery (a long room containing choice works of all the great masters), he seized his opportunity: with herculean strength and Buffalo-Billish agility, our hero dragged all the ladders, paints and brushes into the gallery, and soon was at work 'touching up' the pictures, to gratify his boyish love of mischief. Truth to tell, his performance was but on a par, artistically, with that usually shown when mischievous boys get hold of brushes and paint and a picture to restore."

I have been favoured—if that is the proper word—with a sight of an advance copy of this perpetration.

I feel that the Easy confidence which has hitherto existed between an artist and his Lay Figure is for ever broken and fled. If I had only known that wine was taking advantage of her exceptional opportunities to betray my misplaced confidence in this popular but pestilent fashion, I would have made firewood of her long ago.

It is now too late. The temptation is turn Graphic Gusher and confidential Trotter-out, has proved too much for a wee docile and discreet Lay Figure. I am one more victim at unsuspected hands, to the revolting rage for "Revelations."

I am bound to admit, however, that whilst the taste of the whole "Story" is execrable, the facts upon which it is founded are undisputable.

The Tale is an o'er true one, though it has been compiled without the knowledge, and is published exactly against the desire of

"Before Harry had finished touching-up the valuable family[Pg 23] portraits, his father came in, glanced round, and fell onto a couch in roars of laughter. 'It's the best Artistic Joke I've ever seen, my boy, and here's a shilling for you!' A happy thought struck Harry at the moment. He kept it to himself for over twenty-five years; and now, standing high upon an allegorical ladder, he repeats the Joke daily, from nine to seven, admission one shilling."

This book of sixty pages sold extremely well, and, strange to say, I made more money out of this joking advertisement—the work of a few days—than I did out of my elaborate album of seventy photogravure plates which occupied two years to produce and cost me £2,000.

The following lines from Fun give the origin of my Joke's peculiar and ingenious turn:

"The fact is the Forty were sad in their mind

(Unfortunate Academicians!)

Associates also were troubled in kind,

With jeers at their works and positions,

Till one who was younger and bolder than all

Declared 'doleful dumps' to be folly,

'Come—away to the club, and for supper let's call,

And try to be decently jolly.'

"So they fed with good will on the viands prepared

(Pork chops were the principal portion),

Then retiring to bed, with their dreams they were scared,

And spent half the night in contortion;

Then rose in their sleep and came down to this room,

And, instead of a purposeless pawing,

They painted these pictures, then fled in the gloom,

And Furniss has touched up the drawing!"

Having parodied the artists' work, the R.A. catalogue, and the publishers' R.A. special numbers, I went one step further. I parodied "Art Patrons." At that time there was a great stir in art circles in consequence of the authorities of the National Gallery dallying with Mr. Tate's offer of his pictures to the nation; so to emulate him, and Mr. Alexander, and Mr. Watts, and other public benefactors in the world of art, I sent the following letter to the Directors of the National Gallery:

"Mr. Harry Furniss presents his compliments to the Trustees of the National Gallery and begs to congratulate them upon the munificent gifts[Pg 24] lately made to them, particularly Mr. Henry Tate's, which provides the nation with an excellent sample of current art. At the same time Mr. Harry Furniss feels that having it in his power to provide a more complete collection of our modern English school, he is inspired by the generous offers of others to humbly imitate this good example, and will therefore willingly give his 'Royal Academy' (parodies on modern painters), better known as 'The Artistic Joke,' which caused such a sensation in 1887, to the National Gallery if the Trustees will honour him by accepting the collection."

Yet it was not believed, at least not in Aberdeen, for the leading paper of the Granite City published the following:

"Someone has played a joke on Mr. Harry Furniss. An announcement appears this morning to the effect that 'animated by the generosity of Mr. Henry Tate and other benefactors of the National Gallery, Mr. Harry Furniss has offered to the Trustees his collection of illustrations of the work of modern artists recently on view in Bond Street,' and that he 'has received a communication to the effect that his offer is under consideration.' I believe no one was more surprised by this communication than Mr. Furniss. He never made the offer except possibly in jest to some Member of Parliament, and naturally he was much surprised to learn that his offer was 'under consideration.' The illustrations in question could scarcely be dispensed with by Mr. Furniss, as they are to him a sort of stock-in-trade."

Not only in Aberdeen but I found generally my seriousness was doubted, so I reproduce on the opposite page in facsimile the graceful reply of the authorities of our National Gallery:

The "Artistic Joke" was never intended as an attack on the Royal Academy at all, as a clear-headed critic wrote:

"It would be more just to regard it as an attempt on Mr. Furniss's part to show the Academicians the possibilities of real beauty, and wonder, and pleasure that lie hidden in their work.... On the whole, the Royal Academicians have never appeared under more favourable conditions than in this pleasant gallery. Mr. Furniss has shown that the one thing lacking in them is sense of humour, and that, if they would not take themselves so seriously, they might produce work that would be a joy, and not a weariness to the world. Whether or not they will profit by the lessons it is difficult to say, for dulness has become the basis of respectability, and seriousness the only refuge of the shallow."

The Cause of my Cruise—No Work—The Atlantic Greyhound—Irish Ship—Irish Doctor—Irish Visitors—Queenstown—A Surprise—Fiddles—Edward Lloyd—Lib—Chess—The Syren—The American Pilot—Real and Ideal—Red Tape—Bribery—Liberty—The Floating Flower Show—The Bouquet—A Bath and a Bishop—"Beastly Healthy"—Entertainment for Shipwrecked Sailors—Passengers—Superstition.

America in a Hurry—Harry Columbus Furniss—The Inky Inquisition—First Impressions—Trilby—Tempting Offers—Kidnapped—Major Pond—Sarony—Ice—James B. Brown—Fire!—An Explanation.

Washington—Mr. French of Nowhere—Sold—Interviewed—The Sporting Editor—Hot Stuff—The Capitol—Congress—House of Representatives—The Page Boys—The Agent—Filibuster—The "Reccard"—A Pandemonium—Interviewing the President.

Chicago—The Windy City—Blowers—Niagara—Water and Wood—Darkness to Light—My Vis-à-Vis—Mr. Punch—My Driver—It Grows upon Me—Inspiration—Harnessing Niagara—The Three Sisters—Incline Railway—Captain Webb.

Travelling—Tickets—Thirst—Sancho Panza—Proclaimed States—"The Amurrican Gurl"—A Lady Interviewer—The English Girl—A Hair Restorer—Twelfth Night Club Reception at a Ladies' Club—The Great Presidential Election—Sound Money v. Free Silver—Slumland—Detective O'Flaherty.

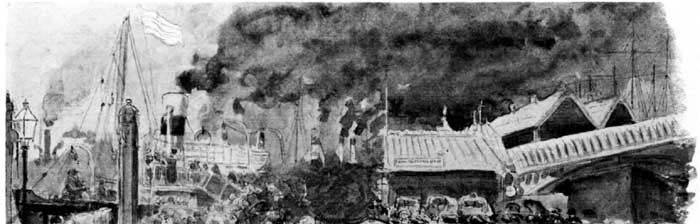

NEVER felt better in my life, but my friends all assured me that I looked ill. If I wasn't ill, I ought to be. I must be overworked and break down. I had "burnt the candle at both ends and in the middle as well," and it was a duty I owed to humanity to collapse. For years[Pg 27] I had done the work of three men with the constitution of one, so one day it came to pass that I was forced by my friends into the consulting-room of a celebrated physician, labelled "Ill. To be returned to Dead Letter Office, or to be sent by foreign mail to some distant land, or to be cremated on the spot," anything but to leave me free to return to my mad disease, the worst mania of all—the mania for work.

My good physician stripped me, pommelled me, stethoscoped me, made me say "99" when he had squeezed all the breath out of me (why "99"? Why not "98" or "4"?—he was testing internal rebellion), flashed a reflector under my eyes, seized a drumstick and hammered me under my knee-joints, sat upon me literally and figuratively, and told me to give up all food, drink, pleasure, and work for two months, which I did. My balance at the bankers' and my balance on the scales were both reduced considerably. I lost a good many pounds in weight and money.

My friends all assured me that I looked well, but I never felt so ill in all my life. If I was not ill, I ought to be. I tried to work, but broke down. I was idle in the mornings, in the evenings, and in the middle of the day as well, and it was a duty I owed to my doctor to collapse. So one day I forced myself into his consulting-room before a hundred patients waiting their turn, labelled "Well again." I pushed him into his chair, pommelled him 99 times, flashed my cane under his eyes, seized the poker and hammered him under his knee-joints, and told him I would get him six months' hard labour if he did not pronounce me sound,—he did.

"You only want a tonic now, my dear fellow—a sea-trip!"[Pg 28]

"A Teutonic," I replied Majestically. "The very thing—sails to-morrow—a new berth—I'll be born again under a White Star—au revoir!"

"Your prescription!" he called after me. "Take it, and if you value your life act up to it to the letter."

It contained two words and no hieroglyphics. Those two words were—"No Work!"

How I acted up to it the following pages will show.

AN ATLANTIC "GREYHOUND."

AN ATLANTIC "GREYHOUND."

In strong contrast to the crowd and bustle at leaving in the afternoon is the quietude late in the evening. Many promenade up and down the beautiful deck under the electrically-lighted roof, and gaze upon the lights of many craft flitting to and fro in the gentle breeze like will-o'-the-wisps, postponing retiring, as they are not yet accustomed to the vibration of the Atlantic greyhound, which trembles underneath them as if, like the real greyhound in full cry after a hare, it is literally straining every muscle to beat the record from the Old World to the New.

What a difference has taken place since those "good old days" of those good old wooden ships, with their good old slow passages and their good old uncomfortable berths! Now the state cabin is an apartment perfectly ventilated, gorgeously[Pg 29] furnished, equipped with every modern improvement, and electrically lighted; the switches close to the bed (not berth) enable one to turn the light on or off at will. The ever-watchful attendant comes in, wishes me good-night, after folding my clothes, and departs. Leaving the incandescent light burning over my head, I open the book dealing with the wonders of America which I have taken from the well-stocked library, and read of great Americans, from Washington to the man who has brought this very light to such perfection, turning over page after page of well-nigh incredible description of the country which has raised the system of "booming" to a high art, till my brain reels with an Arabian Nightish flavour of exaggeration, and turning off the electric current, I am gradually lulled to sleep by the rhythmical vibrations of the steamer, the sole reminder that I am in reality sleeping upon a ship and about to enjoy a thorough week's rest.

I awoke from the dreams in which I had pictured myself a veritable Columbus, and drawing aside the blind of my porthole, I looked out into the morning light, and was, perhaps, for a second surprised to see land. "Sandy Hook already! Can it be?" Well, hardly, just at present. Though who can tell but that in another fifty years it may be possible in the time? It is in reality the "Ould Counthry," and we are nearing Queenstown.

There is a good muster at breakfast, and everyone is smiling, having had at least one good night's rest on the voyage. The waters skirting the Irish coast sometimes outdo the fury of the broad Atlantic, and are generally just as troubled and combatant as the fiery political elements on the little island; but so far we have had a perfect passage, and the beautiful bay of Queenstown looks more charming than ever as the engines stop for a short period before their five days' incessant activity to follow.

Not only the ship, but the doctor, comes from the Emerald Isle. Who crossing the Atlantic does not know the witty Dr.——? "Ah, shure, me darlin', and isn't it himself[Pg 30] that's a broth av a bhoy?" And so he is, simply bubbling over with humour and good-nature. Presiding at one end of the long table, I have to pass him as I leave the saloon. Having sketched Irish scenery and Irish character in my youth, I am not tempted to open my forbidden sketch-book; but somehow or other I find myself making a rapid sketch of the Doctor as he rises from his seat at the end of the table to wish the "top of the mornin'" to a lady who sits on his right. My excuse is to send it to his friend, my doctor in London. Then, without thinking, I sketch in a few other passengers, and instinctively make a note of the surroundings. I confess I am already guilty of breaking my pledge! And, therefore, make my escape on deck.

The huge steamer seems to act as a sort of magnet on the small fry of the harbour, for they rush out to her from the land in all their sorts and sizes, in a desperate race for supremacy. Prominent among this fleet is a long, ungainly rowing-boat propelled by a tough Hibernian, and seated in the stern are his women folk, surrounded by baskets, who, in strong Milesian vernacular, urge the rower on in his endeavours to reach the ship first. Looked down upon them from your floating tower, they strongly resemble a swarm of centipedes. Harder and harder pull the "bhoys," and louder and louder comes the haranguing of the females as they approach us. I have my eye on the lady in the stern of the first boat. She is fair, fat, and forty, possessed of really massive proportions, most powerful lungs, and a true Irish physiognomy—a cast of countenance in which it always strikes me that Nature had originally forgotten the nasal organ, and then returning to complete the work had taken between finger and thumb a piece of flesh and pinched it, thus forming the nose rather high up on the face, while the waste of material below goes to make the upper lip.

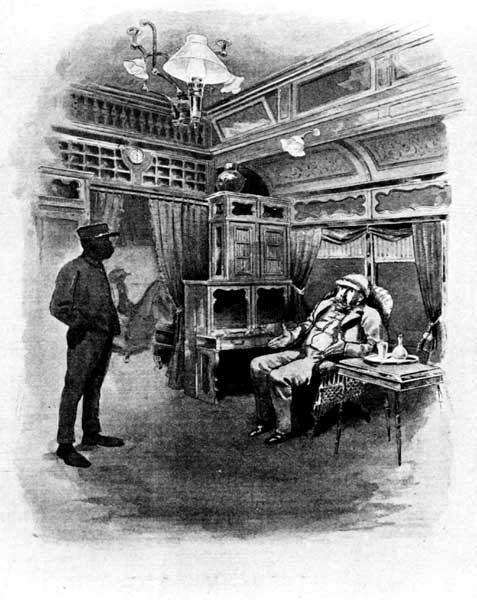

THE SALOON OF THE TEUTONIC. THE FIRST MORNING AT

BREAKFAST.

THE SALOON OF THE TEUTONIC. THE FIRST MORNING AT

BREAKFAST.

The puller of the stroke oar is probably her husband, two others are wielded evidently by her two sons, and the bow is taken by her strapping daughter. One of her arms encircles the merchandise she intends to dispose of on board our vessel,[Pg 32] while the other vigorously helps to propel the oar held by her brawny husband. All the while she is urging on her crew in her native language, with what may be commands, exhortations, or even blessings, but sounding to the unaccustomed Saxon ear very much like curses, which chase one another out of her capacious mouth with a rapidity unequalled by even an irritated monkey at the Zoo.

AT QUEENSTOWN—A REMINISCENCE.

AT QUEENSTOWN—A REMINISCENCE.

Their lumbering craft is the first to touch the side of the Teutonic. Standing up in the boat, the good old lady exerts her vocal powers on the crew on the lower deck, with the result that a rope fully fifty feet long is thrown in her direction, having a loop on the end of it, by which she is lassoed. With an agility only acquired after years of practice, she adjusts the loop rapidly round her, and calls on the crew to hoist away. The boat heels over to one side as she vigorously pushes herself away from it, and souse the old dame goes up to her waist in the water; the good-natured sailors give an extra jerk, and up she comes, with baskets tied round her waist, and her feet acting as fenders against the side of the ship. Fortunately the Teutonic is bulky enough to resist heeling over under this extra weight on the starboard side. She is shipped like a bale of[Pg 34] goods, and is immediately engaged in discharging some more of her loquacity in directing the acrobatic performances of her daughter, who is the next to ascend.

This scene caused much laughter, and I was induced to make a sketch of the lady's acrobatic performance.

The other maritime vendors are hauled up in similar unceremonious fashion, and they take possession of both decks. The pretty daughter of Erin lays out with no little artistic taste her bog-oak ornaments, and 'Arry (for the genus cad is to be encountered even on board such aristocratic ships as these) attempts to be rampantly facetious at her expense. But the damsel with the unkempt auburn locks flowing about her comely face, lit up by a pair of blue Irish eyes under their dark lashes, takes the cad's vulgarity together with his money, like the pill with the jam, giving in return the valueless pieces of carved wood, until her little stock is exhausted and a good morning's work is done.

On the lower deck trade is brisker. The emigrants (principally by this line Scandinavians, in their picturesque peasant dress, the Germans of course preferring to go by their own line, the North German Lloyd) are fitting on Tam o' Shanters of the crudest colours, scarves of hues that would cause the steamer's danger signals to turn pale, and eatables of all descriptions—I ought to say of all the worst descriptions. Unhealthy-looking cakes in which the currants are as scarce as Loyalists in the part of the country in which they are made, tinned meats and fruits that look suspiciously like condemned provisions or unsavoury salvage; in fact the only really genuine article of[Pg 35] diet was that contained in the milk-pails. I may here remark that these alien steerage passengers don't really care for wholesome food. Nothing could be better than the excellent food prepared by the ship's steward, but these emigrants prefer to bring with them provisions that beggar description.

BOG-OAK SOUVENIRS.

BOG-OAK SOUVENIRS.

All the time the Irish purveyors are emptying their baskets and filling their pockets, and rowing back to the shore enriched and delighted; their brothers and sisters are flowing up the gangway in a continual stream, with weeping eyes and breaking hearts at the thought of leaving their country perhaps for ever; and as soon as they are all on board, together with the mails, which have come overland to Queenstown, we up anchor, steam past Fastnet Rock, and soon the Old World is out of sight behind us.

But all this is a thing of the past. Ladies are not now pulled up on to the deck, nor is the promenade turned into a miniature Irish fair. When last the boat stopped as usual in Queenstown bay I sadly missed the familiar scene, and having nothing better to do I went on shore. As a number of us strolled off the tender on which the mails were to return I noticed two men in ordinary dress standing some distance off, looking on at the scene. They were both fine specimens of humanity, each of them about six feet high. "Detectives," I whispered to one of my friends. And as we approached these gentlemen, I said to one of them, "Looking for anyone this morning?"

"Not for you, Mr. Furniss."

Considering I had never been in Queenstown in my life, that I had never been in the grip of these "sleuth-hounds" of the police, I must admit that the British detective is not so stupid as we generally imagine, for no doubt these men knew by telegraph the name of everybody on board and amused themselves by placing us as I had amused myself by placing them.

The Captain generally has some voyager under his special care, and my vis-à-vis, his protégée upon this trip, was a most charming and delightful young lady on her way to rejoin her family in the Far West. The skipper's seat is vacant at breakfast time, and should the weather be rough, at the other meals also. If the elements are very boisterous, the "fiddles" are[Pg 36] screwed on to the tables, and on them a lively tune is played by the jingling glasses and rattling cutlery to the erratic beating of the Atlantic wave. The Captain's right and left hand neighbours are exempt from the use of these appliances, and the small area caused by this is the only space in the yards and yards of table unencumbered by the "fiddles." The Captain scorns the aid of such mechanical contrivances, and chatters away unconcerned, gracefully balancing his soup-plate in his hands the while. I followed his example as one to the manner born, but had I not been a bit of an amateur conjuror I am afraid that I should not have been so successful. The Captain challenged me, however, to make a sketch with the same ease as I ate my dinner—and again I was forced to break my pledge!

THE CAPTAIN'S TABLE.

THE CAPTAIN'S TABLE.

It was amusing to listen to the petty jealousies and the little grumblings of those not satisfied with their lot at table. One lady stated as an excuse for having her meals in her cabin that her neighbour, a bagman—or "drummer," as Americans would call him—made a noise with his mouth while eating; and another[Pg 37] lady elected to dine in her stateroom in solitude because in the saloon she had her back to a Bishop instead of her face!

It was my good fortune to meet on board that most genial and gifted of men, "England's greatest tenor," Mr. Edward Lloyd, who under the management of that equally genial and energetic impresario, Mr. Vert, was on his way to charm the ears of our cousins on the other side. Then we had one of the greatest favourites in the sporting world, who was popping over, as he had been continually doing from his earliest youth, to look after his estates in his native country. From the Captain down to the under stokers he had been with all a familiar figure for many years, and he had a pleasant word and a shake of the hands for everybody. He could give you the straight tip for the Derby, was a fund of information anent the latest weights for the big handicaps, and on our arrival in the States it was with general satisfaction that we learnt that one of his horses had won a race while its owner was crossing the "Herring Pond."

We had yet another celebrity on board in the person of the bright little Italian whose clever caricatures, especially those of Newmarket and Newmarket celebrities, so delight us in the pages of Vanity Fair over the nom de crayon "Lib." I think he caused us as much amusement as his sketches, caricaturing everybody on board, not even excepting himself, whom he most truthfully depicted as a common or barn owl. Or was it I who drew him as the owl? I forget. But I do know that he looked uncommonly like one as a rule, for he used to lie wrapped in his Inverness upon a deck chair, his face only visible, with pallid cheeks and distended eyes, and I did more than one caricature of him for his fair admirers. That was on the rough days, for like a great many foreigners, and English people too for the matter of that, he was a bad sailor. Fortunately for me, I am a hardened sailor, and as such cannot feel the amount of consideration I should otherwise do for those less lucky than myself.

When the weather was calm I used to notice my Italian friend seated, surrounded by the ladies, with an air of triumph and a smile upon his intelligent visage. He was having his revenge![Pg 38] When he was not sketching, he was playing chess with the Captain.

NOT UP IN A BALLOON.

NOT UP IN A BALLOON.

Now this commander was a captain from the top of his head to the soles of his feet. A stern disciplinarian, erect, handsome, uncommunicative, not a better officer ever stood on the bridge of an Atlantic or any other liner. He had a contempt for the "Herring Pond," and manipulated one of these floating hotels with as much ease as one would handle a toy boat. "When a navigator's duty's to be done," he was par excellence a modern Cæsar, but despite his sternness he had a sense of humour, and his unbending moments struck one with an emphasised surprise.

He could not bear a bore. Those fussy landlubbers who are always tapping the barometers, asking questions of every member of the crew, testing, sounding, and finding fault with the weather chart, had better steer clear of the worthy Captain, as with hands thrust deep in his pockets he strides from one end of the deck to the other during the course of his constitutional. It is on record that one of these fussy individuals, edging up to a well-known Captain as he was going on to the bridge when a mist was gathering, and the siren was about to blow as customary when entering on an Atlantic fog, remarked:

"Captain, Captain, can't you see that it is quite clear overhead?"

The Captain turned on his heel to ascend to the bridge, and scornfully rejoined:

"Yes, sir, yes, sir; but can't you see that I am not navigating a balloon?"[Pg 39]

On one occasion the Captain had been through a terribly stormy afternoon and night, and had not quitted his post on the bridge for one minute, the weather being awful. Fogs, icebergs, and the elements all combined to make it a most anxious time for the one man in charge of the valuable vessel and her cargo of 1,700 souls, and during the whole period the unflinching skipper had not tasted a mouthful of food. The Captain's boy, feeling for his master, had from time to time endeavoured with some succulent morsel to make him break his long fast; but the firm face of the Captain was set, his eyes were fixed straight ahead, and his ears were deaf to the lad's appeal. It was breakfast time when the boy once more ventured to ask the Captain if he could bring him something to eat. This time he got an answer.

"Yes," growled the Captain, "bring me two larks' livers on toast!"

These Atlantic Captains of the older school were a hardened and humorous lot of navigators, and many a story of their eccentricity survives them: one in particular of an old Captain seeing the terror of the junior officer during that nervous ordeal of treading the bridge for the first time with him. This particular old salt, after a painful silence, turned on the young man and said, "I like you. I'm very much impressed by you. I've heard a lot about you—in fact, my dear sir, I should like to have your photograph. You skip down and get it."

The nervous and delighted youth rushed off to his cabin, and informed his brother officers of the compliment the old man had just paid him. He was in luck's way, and running gaily up on to the bridge, presented his photograph, blushing modestly, to the old salt.

"'Umph! Got a pin with you?"

"Ye—es, sir."

"Ah, see! I pin you up on the canvas here. I can look at you there and admire you. You can go, sir; your photograph is just as valuable as you appear to be on the bridge. Good morning."

The Captain of the ship I was on had his chessmen pegged,[Pg 40] and holes in the board into which to place them, so that despite any oscillations of the ship they would remain in their places; but the unfortunate part of the business was that although he could provide sea-legs for his chessmen it was more than he could do for his opponent, and it was as good as a play to see Signor "Lib" hiding from the Captain when the weather was not all it might be, and he in consequence felt anything but well. One mate after another would be despatched with the strictest orders from the Captain to search for the cheerless chessite; but after a time the Captain's patience would be exhausted, his strident voice could be heard calling upon the caricaturist to come forth and show himself, and eventually he might be seen en route to his cabin with the box of chessmen under one arm and his opponent under the other.

CHESS.

CHESS.

I was cruel enough on more than one occasion to follow them and witness the sequel.

"Your move, now—your move!"

"Ah, Captain! I do veel zo ill! Ze ship it do go up and down, up and down, until I do not know vich is ze bishop and vich is ze queen!"

"Nonsense, sir, nonsense! Your move—look sharp, and I'll soon have you mated!"

The poor artist did move, and quickly too, but it was to the outside of the cabin!

The Captain was triumphant at table, telling us of his victory, but his poor opponent could only point to his untouched plate and to the waves dashing against the portholes, and with that shrug of the shoulders, so suggestive to witness but so difficult to describe, would thus in dumb show explain the cause of his defeat.

I remember well on one beautiful afternoon, the sky bright and the sea calm, just before the pilot came on board when we were nearing the States, Signor Prosperi (for that was his name) came up to me, his face the very embodiment of triumph:

"Ah, I have beaten ze Captain at last—but ze sea is smooth!"

On the outward voyage, as I said before, we had a host in Mr. Edward Lloyd, but he was under contract not to warble until a certain day which had been fixed in New York, and no doubt his presence had a deterrent effect upon the amateur talent, with the exception of one lady, who came up to Mr. Lloyd and said:

"You really must sing;—you really must!"

"I am very sorry, madam, but I really can't—I am not my own master in this matter."

"Oh, but you must," she rejoined. "I have promised that if you will sing, I will!"

An American who had "made his pile," as the Yankees say, remarked to the hard-worked vocalist:

"I think, sir, that as you are endowed with such a beautiful voice you ought by it to benefit such a deserving entertainment as this."[Pg 42]

MR. LLOYD AND THE LADY. "IF YOU WILL SING, I WILL!"

MR. LLOYD AND THE LADY. "IF YOU WILL SING, I WILL!"

"Certainly," replied the world-famed tenor. "My fee for singing is fifty guineas, and I will be pleased to oblige the company if you will pay a cheque for that amount into the sailors' fund."

And, in my opinion, a right good answer too. These middle-men and their wives and daughters are always pestering professional men to give their services to charities for nothing, but in cases like the one I have just cited they take very good care that they do not unloosen their own purse-strings to help the cause along and equalise the obligation.

However the concert took place, and I, unable to resist the flattering request to "do something," and not being prohibited from taking part—as Mr. Lloyd was—made several sketches, just to keep my hand in, and they were raffled for.

All goes well and smoothly on the voyage until one night you are awakened by a harsh, grating, shrieking sound. You start from your slumbers, and for a moment imagine that in reality you are in the interior of some fearsome ocean monster, who is bellowing either in rage or fear, for the sound is unique in its wild hideousness, half a screech and half a wail, aggressive and yet mournful. Your ears have just recovered from the first shock when they are assaulted by another, and yet another, at intervals of about a minute. It is the voice of the siren. Was ever a more inappropriate name bestowed upon the steam[Pg 43] whistle of an Atlantic liner? It conveys to me the news that we are passing through an Atlantic fog, and I defy anyone, be they in the most perfect ship, under the safest of commanders, to feel comfortable in such circumstances. The siren still wails, and like Ulysses and his companions I feel very much inclined to stuff my ears with wax. Indeed, peering out of my porthole through the mist, I almost seem to see the figures of the mythological voyager and his companions carved in ice, no doubt beguiled by the treacherous music of the siren. These are in reality our main terrors, the icebergs.

|

|

| THE AMERICAN PILOT—IDEAL. | THE AMERICAN PILOT—REAL. |

It is a relief when we have left them behind and evaded the clutches of the demon fog, and the fresh breeze and the glorious sun lend a new beauty to the sparkling water, showing us in the distance white specks skimming over the waves like gulls, the first sign that we are approaching land—the white gleaming wings of the pilot yachts.

Signals are exchanged, and one of these boats comes nearer and nearer to us, tacking to perfection. Through our glasses we already seem to see the stalwart figure of the pilot standing in the stern. On his brow he wears a storm-defying cap, the badge of the warrior of the waves; the loose shirt, the top boots, and the weather-beaten jacket all combine to make up a picturesque figure, and I sketched what seemed to me to be the figure of the man who was coming on board to guide us to the Hook of Sandy. As[Pg 44] the little vessel approaches us the intervening sail hides from my view the figure of the one man I want to see. A boat is lowered from the side of the pilot boat, into which two sailors descend. Who on earth is this who steps in after them and takes the rudder lines? He sports a top hat, kid gloves, and patent shoes. Is he a commercial traveller? He looks it. He is rowed to the side of the steamer, and then the fun begins. A rope ladder is lowered from the deck, which is immediately clutched by one of the oarsmen in the boat, and this commonplace commercial scrambles towards it. Just then a wave breaks over him, and more like a drowned excursionist than an American pilot this little man is hauled on board.

I think a great deal of the Atlantic, but I am sorely disappointed with the American pilot.