Introduction

“Nothing extenuate,

Nor set down aught in malice.”

Othello, Act V., Sc. 2.

During the three centuries and a quarter of more or less effective Spanish dominion, this Archipelago never ranked above the

most primitive of colonial possessions.

That powerful nation which in centuries gone by was built up by Iberians, Celts, Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Visigoths, Romans,

and Arabs was in its zenith of glory when the conquering spirit and dauntless energy of its people led them to gallant enterprises

of discovery which astonished the civilized world. Whatever may have been the incentive which impelled the Spanish monarchs

to encourage the conquest of these Islands, there can, at least, be no doubt as to the earnestness of the individuals entrusted

to carry out the royal will. The nerve and muscle of chivalrous Spain ploughing through a wide unknown ocean in quest of glory

and adventure, the unswerving devotion of the ecclesiastics to the cause of Catholic supremacy, each bearing intense privations,

cannot fail to excite the wonder of succeeding generations. But they were satisfied with conquering and leaving unimproved

their conquests, for whilst only a small fraction of this Archipelago was subdued, millions of dollars and hundreds of lives

were expended in futile attempts at conquest in Gamboge, Siam, Pegu, Moluccas, Borneo, Japan, etc.—and for all these toils

there came no reward, not even the sterile laurels of victory. The Manila seat of government had not been founded five years

when the Governor-General solicited royal permission to conquer China!

Extension of dominion seized them like a mania. Had they followed up their discoveries by progressive social enlightenment,

by encouragement to commerce, by the concentration of their efforts in the development of the territory and the new resources

already under their sway, half the money and energy squandered on fruitless and inglorious expeditions would have sufficed

to make high roads crossing and recrossing the Islands; tenfold wealth would have accrued; civilization would [2]have followed as a natural consequence; and they would, perhaps even to this day, have preserved the loyalty of those who

struggled for and obtained freer institutions. But they had elected to follow the principles of that religious age, and all

we can credit them with is the conversion of millions to Christianity and the consequent civility at the expense of cherished

liberty, for ever on the track of that fearless band of warriors followed the monk, ready to pass the breach opened for him

by the sword, to conclude the conquest by the persuasive influence of the Holy Cross.

The civilization of the world is but the outcome of wars, and probably as long as the world lasts the ultimate appeal in all

questions will be made to force, notwithstanding Peace Conferences. The hope of ever extinguishing warfare is as meagre as

the advantage such a state of things would be. The idea of totally suppressing martial instinct in the whole civilized community

is as hopeless as the effort to convert all the human race to one religious system. Moreover, the common good derived from

war generally exceeds the losses it inflicts on individuals; nor is war an isolated instance of the few suffering for the

good of the many. “Salus populi suprema lex.” “Nearly every step in the worldʼs progress has been reached by warfare. In modern times the peace of Europe is only maintained

by the equality of power to coerce by force. Liberty in England, gained first by an exhibition of force, would have been lost

but for bloodshed. The great American Republic owes its existence and the preservation of its unity to this inevitable means,

and neither arbitration, moral persuasion, nor sentimental argument would ever have exchanged Philippine monastic oppression

for freedom of thought and liberal institutions.

The right of conquest is admissible when it is exercised for the advancement of civilization, and the conqueror not only takes

upon himself, but carries out, the moral obligation to improve the condition of the subjected peoples and render them happier.

How far the Spaniards of each generation fulfilled that obligation may be judged from these pages, the works of Mr. W. H.

Prescott, the writings of Padre de las Casas, and other chroniclers of Spanish colonial achievements. The happiest colony

is that which yearns for nothing at the hands of the mother country; the most durable bonds are those engendered by gratitude

and contentment. Such bonds can never be created by religious teaching alone, unaccompanied by the twofold inseparable conditions

of moral and material improvement. There are colonies wherein equal justice, moral example, and constant care for the welfare

of the people have riveted European dominion without the dispensable adjunct of an enforced State religion. The reader will

judge the merits of that civilization which the Spaniards engrafted on the races they subdued; for as mankind has no philosophical

criterion of truth, it is a matter of opinion where the unpolluted fountain of the truest [3]modern civilization is to be found. It is claimed by China and by Europe, and the whole universe is schismatic on the subject.

When Japan was only known to the world as a nation of artists, Europe called her barbarous; when she had killed fifty thousand

Russians in Manchuria, she was proclaimed to be highly civilized. There are even some who regard the adoption of European

dress and the utterance of a few phrases in a foreign tongue as signs of civilization. And there is a Continental nation,

proud of its culture, whose sense of military honour, dignity, and discipline involves inhuman brutality of the lowest degree.

Juan de la Concepcion,1 who wrote in the eighteenth century, bases the Spaniardsʼ right to conquest solely on the religious theory. He affirms that

the Spanish kings inherited a divine right to these Islands, their dominion being directly prophesied in Isaiah xviii. He

assures us that this title from Heaven was confirmed by apostolic authority,2 and by “the many manifest miracles with which God, the Virgin, and the Saints, as auxiliaries of our arms, demonstrated its

unquestionable justice.” Saint Augustine, he states, considered it a sin to doubt the justice of war which God determines;

but, let it be remembered, the same savant insisted that the world was flat, and that the sun hid every night behind a mountain!

An apology for conquest cannot be rightly based upon the sole desire to spread any particular religion, more especially when

we treat of Christianity, the benign radiance of which was overshadowed by that debasing institution the Inquisition, which

sought out the brightest intellects only to destroy them. But whether conversion by coercion be justifiable or not, one is

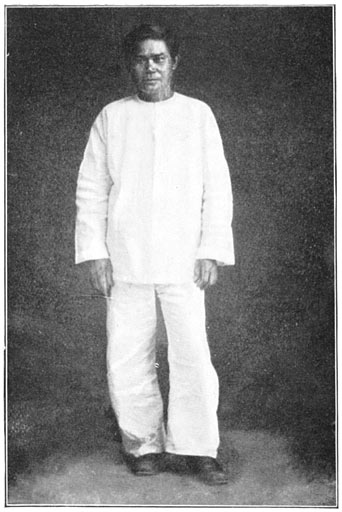

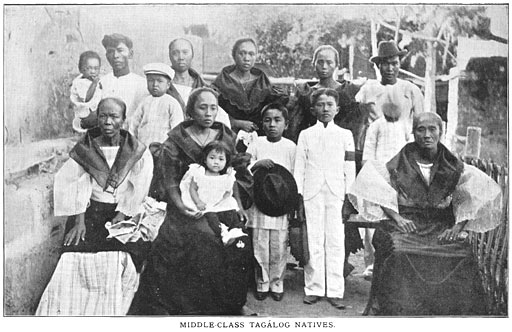

bound to acknowledge that all the urbanity of the Filipinos of to-day is due to Spanish training, which has raised millions

from obscurity to a relative condition of culture. The fatal defect in the Spanish system was the futile endeavour to stem

the tide of modern methods and influences.

The government of the Archipelago alone was no mean task.

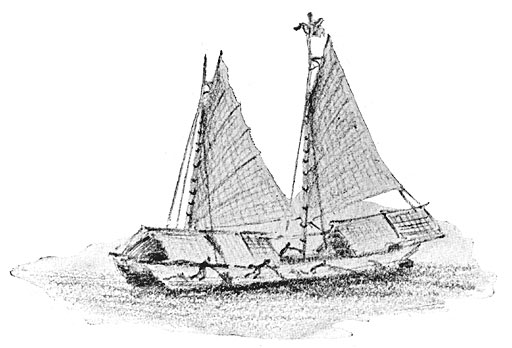

A group of islands inhabited by several heathen races—surrounded by a sea exposed to typhoons, pirates, and Christian-hating

Mussulmans—had to be ruled by a handful of Europeans with inadequate funds, bad ships, and scant war material. For nearly

two centuries the financial administration was a chaos, and military organization hardly existed. Local enterprise was disregarded

and discouraged so long as abundance of silver dollars came from across the Pacific. Such a short-sighted, unstable dependence

left the Colony resourceless when bold foreign traders stamped out monopoly and brought commerce to its natural [4]level by competition. In the meantime the astute ecclesiastics quietly took possession of rich arable lands in many places,

the most valuable being within easy reach of the Capital and the Arsenal of Cavite. Landed property was undefined. It all

nominally belonged to the State, which, however, granted no titles; “squatters” took up land where they chose without determined

limits, and the embroilment continues, in a measure, to the present day.

About the year 1885 the question was brought forward of granting Government titles to all who could establish claims to land.

Indeed, for about a year, there was a certain enthusiasm displayed both by the applicants and the officials in the matter

of “Titulos Reales.” But the large majority of landholders—among whom the monastic element conspicuously figured—could only show their title

by actual possession.3 It might have been sufficient, but the fact is that the clergy favoured neither the granting of “Titulos Reales” nor the

establishment of the projected Real Estate Registration Offices.

Agrarian disputes had been the cause of so many armed risings against themselves in particular, during the nineteenth century,

that they opposed an investigation of the land question, which would only have revived old animosities, without giving satisfaction

to either native or friar, seeing that both parties were intransigent.4

The fundamental laws, considered as a whole, were the wisest devisable to suit the peculiar circumstances of the Colony; but

whilst many of them were disregarded or treated as a dead letter, so many loopholes were invented by the dispensers of those

in operation as to render the whole system a wearisome, dilatory process. Up to the last every possible impediment was placed

in the way of trade expansion; and in former times, when worldly majesty and sanctity were a joint idea, the struggle with

the King and his councillors for the right of legitimate traffic was fierce.

So long as the Archipelago was a dependency of Mexico (up to 1819) not one Spanish colonist in a thousand brought any cash

capital to this colony with which to develop its resources. During the first two centuries and a quarter Spainʼs exclusive

policy forbade the establishment of any foreigner in the Islands; but after they did settle there they were treated with such

courteous consideration by the Spanish officials that they could often secure favours with greater ease than the Spanish colonists

themselves.

Everywhere the white race urged activity like one who sits behind a [5]horse and goads it with the whip. But good advice without example was lost to an ignorant class more apt to learn through

the eye than through the ear. The rougher class of colonist either forgot, or did not know, that, to civilize a people, every

act one performs, or intelligible word one utters, carries an influence which pervades and gives a colour to the future life

and thoughts of the native, and makes it felt upon the whole frame of the society in embryo. On the other hand, the value

of prestige was perfectly well understood by the higher officials, and the rigid maintenance of their dignity, both in private

life and in their public offices, played an important part in the moral conquest of the Filipinos. Equality of races was never

dreamed of, either by the conquerors or the conquered; and the latter, up to the last days of Spanish rule, truly believed

in the superiority of the white man. This belief was a moral force which considerably aided the Spaniards in their task of

civilization, and has left its impression on the character of polite Philippine society to this day.

Christianity was not only the basis of education, but the symbol of civilization; and that the Government should have left

education to the care of the missionaries during the proselytizing period was undoubtedly the most natural course to take.

It was desirable that conversion from paganism should precede any kind of secular tuition. But the friars, to the last, held

tenaciously to their old monopoly; hence the University, the High Schools, and the Colleges (except the Jesuit Schools) were

in their hands, and they remained as stumbling-blocks in the intellectual advancement of the Colony. Instead of the State

holding the fountains of knowledge within its direct control, it yielded them to the exclusive manipulation of those who eked

out the measure as it suited their own interests.

Successful government by that sublime ethical essence called “moral philosophy” has fallen away before a more practical régime. Liberty to think, to speak, to write, to trade, to travel, was only partially and reluctantly yielded under extraneous pressure.

The venality of the conquerorʼs administration, the judicial complicacy, want of public works, weak imperial government, and

arrogant local rule tended to dismember the once powerful Spanish Empire. The same causes have produced the same effects in

all Spainʼs distant colonies, and to-day the mother country is almost childless. Criticism, physical discovery of the age,

and contact with foreigners shook the ancient belief in the fabulous and the supernatural; the rising generation began to

inquire about more certain scientific theses. The immutability of Theology is inharmonious to Science—the School of Progress;

and long before they had finished their course in these Islands the friars quaked at the possible consequences. The dogmatical

affirmation “qui non credit anathema sit,” so indiscriminately used, had lost its power. Public opinion protested against an order of things which checked the social

and material onward [6]movement of the Colony. And, strange as it may seem, Spain was absolutely impotent, even though it cost her the whole territory

(as indeed happened) to remedy the evil. In these Islands what was known to the world as the Government of Spain was virtually

the Executive of the Religious Corporations, who constituted the real Government, the members of which never understood patriotism

as men of the world understand it. Every interest was made subservient to the welfare of the Orders. If, one day, the Colony

must be lost to them, it was a matter of perfect indifference into whose hands it passed. It was their happy hunting-ground and last refuge. But

the real Government could not exist without its Executive; and when that Executive was attacked and expelled by America, the

real Government fell as a consequence. If the Executive had been strong enough to emancipate itself from the dominion of the

friars only two decades ago, the Philippines might have remained a Spanish colony to-day. But the wealth in hard cash and

the moral religious influence of the Monastic Orders were factors too powerful for any number of executive ministers, who

would have fallen like ninepins if they had attempted to extricate themselves from the thraldom of sacerdotalism. Outside

political circles there was, and still is in Spain, a class who shrink from the abandonment of ideas of centuriesʼ duration.

Whatever the fallacy may be, not a few are beguiled into thinking that its antiquity should command respect.

The conquest of this Colony was decidedly far more a religious achievement than a military one, and to the friars of old their nationʼs gratitude is fairly due for having contributed to her glory, but that gratitude is not an inheritance.

Prosperity began to dawn upon the Philippines when restrictions on trade were gradually relaxed since the second decade of

last century. As each year came round reforms were introduced, but so clumsily that no distinction was made between those

who were educationally or intellectually prepared to receive them and those who were not; hence the small minority of natives,

who had acquired the habits and necessities of their conquerors, sought to acquire for all an equal status, for which the masses were unprepared. The abolition of tribute in 1884 obliterated caste distinction; the

university graduate and the herder were on a legal equality if they each carried a cédula personal, whilst certain Spanish legislators exercised a rare effort to persuade themselves and their partisans that the Colony was

ripe for the impossible combination of liberal administration and monastic rule.

It will be shown in these pages that the government of these Islands was practically as theocratic as it was civil. Upon the

principle of religious pre-eminence all its statutes were founded, and the reader will now understand whence the innumerable

Church and State contentions originated. Historical facts lead one to inquire: How far was Spain ever a moral potential factor in the worldʼs progress? Spanish colonization [7]seems to have been only a colonizing mission preparatory to the attainment, by her colonists, of more congenial conditions

under other régimes; for the repeated struggles for liberty, generation after generation, in all her colonies, tend to show that Spainʼs sovereignty

was maintained through the inspiration of fear rather than love and sympathy, and that she entirely failed to render her colonial

subjects happier than they were before.

One cannot help feeling pity for the Spanish nation, which has let the Pearl of the Orient slip out of its fingers through

culpable and stubborn mismanagement, after repeated warnings and similar experiences in other quarters of the globe. Yet although

Spainʼs lethargic, petrified conservatism has had to yield to the progressive spirit of the times, the loss to her is more

sentimental than real, and Spaniards of the next century will probably care as little about it as Britons do about the secession

of their transatlantic colonies.

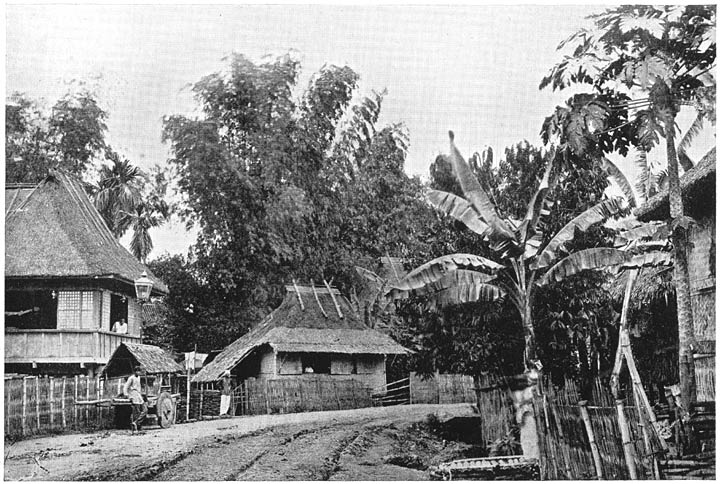

Happiness is merely comparative: with a lovely climate—a continual summer—and all the absolute requirements of life at hand,

there is not one-tenth of the misery in the Philippines that there is in Europe, and none of that forlorn wretchedness facing

the public gaze. Beggary—that constant attribute of the highest civilization—hardly exists, and suicide is extremely rare.

There are no ferocious animals, insects, or reptiles that one cannot reasonably guard against; it is essentially one of those

countries where “manʼs greatest enemy is man.” There is ample room for double the population, and yet a million acres of virgin

soil only awaiting the co-operation of husbandman and capitalist to turn it to lucrative account. A humdrum life is incompatible

here with the constant emotion kept up by typhoons, shipwrecks, earthquakes, tidal waves, volcanic eruptions, brigands, epidemics,

devastating fires, etc.

It is a beautiful country, copiously endowed by Nature, where the effulgent morning sun contributes to a happy frame of mind—where

the colonistʼs rural life passes pleasantly enough to soothe the longing for “home, sweet home.”

“And yet perhaps if countries we compare

And estimate the blessings which they share,

Though patriots flatter, yet shall wisdom find

An equal portion dealt to all mankind.”

Such is Americaʼs new possession, wherein she has assumed the moral responsibility of establishing a form of government on

principles quite opposite to those of the defunct Spanish régime: whether it will be for better or for worse cannot be determined at this tentative stage. Without venturing on the prophetic,

one may not only draw conclusions from accomplished facts, but also reasonably assume, in the light of past events, what might

have happened under other circumstances. There is scarcely a Power which has not, in the zenith of its prosperity, [8]consciously or unconsciously felt the “divine right” impulse, and claimed that Providence has singled it out to engraft upon

an unwilling people its particular conception of human progress. The venture assumes, in time, the more dignified name of

“mission”; and when the consequent torrents of blood recede from memory with the ebbing tide of forgetfulness, the conqueror

soothes his conscience with a profession of “moral duty,” which the conquered seldom appreciate in the first generation. No

unforeseen circumstances whatever caused the United States to drift unwillingly into Philippine affairs. The war in Cuba had

not the remotest connexion with these Islands. The adversaryʼs army and navy were too busy with the task of quelling the Tagálog

rebellion for any one to imagine they could be sent to the Atlantic. It was hardly possible to believe that the defective

Spanish-Philippine squadron could have accomplished the voyage to the Antilles, in time of war, with every neutral port en route closed against it. In any case, so far as the ostensible motive of the Spanish-American War was concerned, American operations

in the Philippines might have ended with the Battle of Cavite. The Tagálog rebels were neither seeking nor desiring a change

of masters, but the state of war with Spain afforded America the opportunity, internationally recognized as legitimate, to

seize any of the enemyʼs possessions; hence the acquisition of the Philippines by conquest. Up to this point there is nothing

to criticize, in face of the universal tacit recognition, from time immemorial, of the right of might.

American dominion has never been welcomed by the Filipinos. All the principal Christianized islands, practically representing

the whole Archipelago, except Moroland, resisted it by force of arms, until, after two years of warfare, they were so far

vanquished that those still remaining in the field, claiming to be warriors, were, judged by their exploits, undistinguishable

from the brigand gangs which have infested the Islands for a century and a half. The general desire was, and is, for sovereign

independence; and although a pro-American party now exists, it is only in the hope of gaining peacefully that which they despaired

of securing by armed resistance to superior force. The question as to how much nearer they are to the goal of their ambition

belongs to the future; but there is nothing to show, by a review of accomplished facts, that, without foreign intervention,

the Filipinos would have prospered in their rebellion against Spain. Even if they had expelled the Spaniards their independence

would have been of short duration, for they would have lost it again in the struggle with some colony-grabbing nation. A united

Archipelago under the Malolos Government would have been simply untenable; for, apart from the possible secessions of one

or more islands, like Negros, for instance, no Christian Philippine Government could ever have conquered Mindanao and the

Sulu Sultanate; indeed, the attempt might have brought about [9]their own ruin, by exhaustion of funds, want of unity in the hopeless contest with the Moro, and foreign intervention to terminate

the internecine war. Seeing that Emilio Aguinaldo had to suppress two rivals, even in the midst of the bloody struggle when

union was most essential for the attainment of a common end, how many more would have risen up against him in the period of

peaceful victory? The expulsion of the friars and the confiscation of their lands would have surprised no one cognizant of

Philippine history. But what would have become of religion? Would the predominant religion in the Philippines, fifty years

hence, have been Christian? Recent events lead one to conjecture that liberty of cult, under native rule, would have been

a misnomer, and Roman Catholicism a persecuted cause, with the civilizing labours of generations ceasing to bear fruit.

No generous, high-minded man, enjoying the glorious privilege of liberty, would withhold from his fellow-men the fullest measure

of independence which they were capable of maintaining. If Americaʼs intentions be as the world understands them, she is endeavouring

to break down the obstacles which the Filipinos, desiring a lasting independence, would have found insuperable. America claims

(as other colonizing nations have done) to have a “mission” to perform, which, in the present case, includes teaching the

Filipinos the art of self-government. Did one not reflect that America, from her birth as an independent state, has never

pretended to follow on the beaten tracts of the Old World, her brand-new method of colonization would surprise her older contemporaries

in a similar task. She has been the first to teach Asiatics the doctrine of equality of races—a theory which the proletariat

has interpreted by a self-assertion hitherto unknown, and a gradual relinquishment of that courteous deference towards the

white man formerly observable by every European. This democratic doctrine, suddenly launched upon the masses, is changing

their character. The polite and submissive native of yore is developing into an ill-bred, up-to-date, wrangling politician.

Hence rule by coercion, instead of sentiment, is forced upon America, for up to the present she has made no progress in winning

the hearts of the people. Outside the high-salaried circle of Filipinos one never hears a spontaneous utterance of gratitude

for the boon of individual liberty or for the suppression of monastic tyranny. The Filipinos craving for immediate independence,

regard the United States only in the light of a useful medium for its attainment, and there are indications that their future

attachment to their stepmother country will be limited to an unsentimental acceptance of her protection as a material necessity.

Measures of practical utility and of immediate need have been set aside for the pursuit of costly fantastic ideals, which

excite more the wonder than the enthusiasm of the people, who see left in abeyance the reforms they most desire. The system

of civilizing the natives on a [10]curriculum of higher mathematics, literature, and history, without concurrent material improvement to an equal extent, is

like feeding the mind at the expense of the body. No harbour improvements have been made, except at Manila; no canals have

been cut; few new provincial roads have been constructed, except for military purposes; no rivers are deepened for navigation,

and not a mile of railway opened. The enormous sums of money expended on such unnecessary works as the Benguet road and the

creation of multifarious bureaux, with a superfluity of public servants, might have been better employed in the development

of agriculture and cognate wealth-producing public works. The excessive salaries paid to high officials seem to be out of

all proportion to those of the subordinate assistants. Extravagance in public expenditure necessarily brings increasing taxation

to meet it; the luxuries introduced for the sake of American trade are gradually, and unfortunately, becoming necessities,

whereas it would be more considerate to reduce them if it were possible. It is no blessing to create a desire in the common

people for that which they can very well dispense with and feel just as happy without the knowledge of. The deliberate forcing

up of the cost of living has converted a cheap country into an expensive one, and an income which was once a modest competence

is now a miserable pittance. The infinite vexatious regulations and complicated restrictions affecting trade and traffic are

irritating to every class of business men, whilst the Colonyʼs indebtedness is increasing, the budget shows a deficit, and

agriculture—the only local source of wealth—is languishing.

Innovations, costing immense sums to introduce, are forced upon the people, not at all in harmony with their real wants, their

instincts, or their character. What is good for America is not necessarily good for the Philippines. One could more readily

conceive the feasibility of “assimilation” with the Japanese than with the Anglo-Saxon. To rule and to assimilate are two

very different propositions: the latter requires the existence of much in common between the parties. No legislation, example,

or tuition will remould a peopleʼs life in direct opposition to their natural environment. Even the descendants of whites

in the Philippines tend to merge into, rather than alter, the conditions of the surrounding race, and vice versa. It is quite impossible for a race born and living in the Tropics to adopt the characteristics and thought of a Temperate

Zone people. The Filipinos are not an industrious, thrifty people, or lovers of work, and no power on earth will make them

so. The Colonyʼs resources are, consequently, not a quarter developed, and are not likely to be by a strict application of

the theory of the “Philippines for the Filipinos.” But why worry about their lethargy, if, with it, they are on the way to

“perfect contentment”?—that summit of human happiness which no one attains. Ideal government may reach a point where its exactions

tend to make life a [11]burden; practical government stops this side of that point. White men will not be found willing to develop a policy which

offers them no hope of bettering themselves; and as to labour—other willing Asiatics are always close at hand. Uncertainty

of legislation, constantly changing laws, new regulations, the fear of a tax on capital, and general prospective insecurity

make large investors pause.

Democratic principles have been too suddenly sprung upon the masses. The autonomy granted to the provinces needs more control

than the civil government originally intended, and ends in an appeal on almost every conceivable question being made to one

man—the Gov.-General: this excessive concentration makes efficient administration too dependent on the abilities of one person.

There are many who still think, and not without reason, that ten years of military rule would have been better for the people

themselves. Even now military government might be advantageously re-established in Sámar Island, where the common people are

not anxious for the franchise, or care much about political rights. A reasonable amount of personal freedom, with justice,

would suffice for them; whilst the trading class would welcome any effective and continuous protection, rather than have to

shift for themselves with the risk of being persecuted for having given succour to the pulajanes to save their own lives and property.

Civil government, prematurely inaugurated, without sufficient preparation, has had a disastrous effect, and the present state

of many provinces is that of a wilderness overrun by brigand bands too strong for the civil authority to deal with. But one

cannot fail to recognize and appreciate the humane motives which urged the premature establishment of civil administration.

Scores of nobodies before the rebellion became somebodies during the four or five years of social turmoil. Some of them influenced

the final issue, others were mere show-figures, really not more important than the beau sabreur in comic opera. Yet one and all claimed compensation for laying aside their weapons, and in changing the play from anarchy

to civil life these actors had to be included in the new cast to keep them from further mischief.

The moral conquest of the Philippines has hardly commenced. The benevolent intentions of the Washington Government, and the

irreproachable character and purpose of its eminent members who wield the destiny of these islanders, are unknown to the untutored

masses, who judge their new masters by the individuals with whom they come into close contact. The hearts of the people cannot

be won without moral prestige, which is blighted by the presence of that undesirable class of immigrants to whom Maj.-General

Leonard Wood refers so forcibly in his “First Report of the Moro Province.” In this particular region, which is ruled semi-independently

of the Philippine Commission, the peculiar conditions require a special legislation. But, apart from this, the common policy

of its enlightened Gov.-General would serve [12]as a pattern of what it might be, with advantage, throughout the Archipelago.

So much United States money and energy have been already expended in these Islands, and so far-reaching are the pledges made

to their inhabitants, that American and Philippine interests are indissolubly associated for many a generation to come. It

does not necessarily follow that the fullest measure of national liberty will create real personal liberty. Such an idea does

not at all appeal to Asiatics, according to whose instinct every man dominates over, or is dominated by, another. If America

should succeed in establishing a permanently peaceful independent Asiatic government on democratic principles, it will be

one of the unparalleled achievements of the age.

[13]

General Description of the Archipelago

The Philippine Islands, with the Sulu Protectorate, extend a little over 16 degrees of latitude—from 4° 45′ to 21° N., and

longitude from 116° 40′ to 126° 30′ E.—and number some 600 islands, many of which are mere islets, besides several hundreds

of rocks jutting out of the sea. The 11 islands of primary geographical importance are Luzon, Mindanao, Sámar, Panay, Negros,

Palaúan (Parágua), Mindoro, Leyte, Cebú, Masbate, and Bojol. Ancient maps show the islands and provinces under a different

nomenclature. For example: (old names in parentheses) Albay (Ibalon); Batangas (Comintan); Basílan (Taguima); Bulacan (Meycauayan);

Cápis (Panay); Cavite (Cauit); Cebú (Sogbu); Leyte (Baybay); Mindoro (Mait); Negros (Buglas); Rizal (Tondo; later on Manila);

Surigao (Caraga); Sámar (Ibabao); Tayabas (Calilayan).

Luzon and Mindanao united would be larger in area than all the rest of the islands put together. Luzon is said to have over

40,000 square miles of land area. The northern half of Luzon is a mountainous region formed by ramifications of the great

cordilleras, which run N. to S. All the islands are mountainous in the interior, the principal peaks being the following,

viz.:—

| |

Feet above sea level

|

| Halcon (Mindoro)

|

8,868

|

| Apo1 (Mindanao)

|

8,804

|

| Mayon (Luzon)

|

8,283

|

| San Cristóbal (Luzon)

|

7,375

|

| Isarog (Luzon)

|

6,443

|

| Banájao (Luzon)

|

6,097

|

| Labo (Luzon)

|

5,090

|

| South Caraballo (Luzon)

|

4,720

|

| Caraballo del Baler (Luzon)

|

3,933

|

| Maquíling (Luzon)

|

3,720 |

Most of these mountains and subordinate ranges are thickly covered with forest and light undergrowth, whilst the stately trees

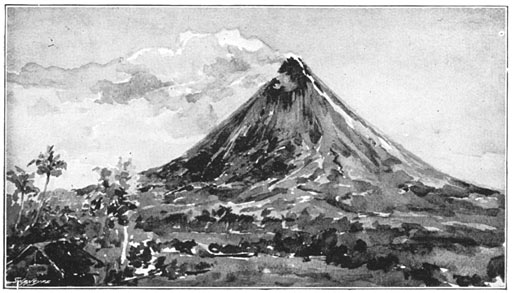

are gaily festooned with clustering creepers and flowering parasites of the most brilliant hues. The Mayon, which is an active

volcano, is comparatively bare, whilst also the Apo, although no longer in eruption, exhibits [14]abundant traces of volcanic action in acres of lava and blackened scoriae. Between the numberless forest-clad ranges are luxuriant

plains glowing in all the splendour of tropical vegetation. The valleys, generally of rich fertility, are about one-third

under cultivation.

There are numerous rivers, few of which are navigable by sea-going ships. Vessels drawing up to 13 feet can enter the Pasig

River, but this is due to the artificial means employed.

The principal Rivers are:—In Luzon Island the Rio Grande de Cagayán, which rises in the South Caraballo Mountain in the centre of the island, and runs in a tortuous

stream to the northern coast. It has two chief affluents, the Rio Chico de Cagayán and the Rio Magat, besides a number of

streams which find their way to its main course. Steamers of 11-feet draught have entered the Rio Grande, but the sand shoals

at the mouth are very shifty, and frequently the entrance is closed to navigation. The river, which yearly overflows its banks,

bathes the great Cagayan Valley,—the richest tobacco-growing district in the Colony. Immense trunks of trees are carried down

in the torrent with great rapidity, rendering it impossible for even small craft—the barangayanes—to make their way up or down the river at that period.

The Rio Grande de la Pampanga rises in the same mountain and flows in the opposite direction—southwards,—through an extensive

plain, until it empties itself by some 20 mouths into the Manila Bay. The whole of the Pampanga Valley and the course of the

river present a beautiful panorama from the summit of Arayat Mountain, which has an elevation of 2,877 feet above the sea

level.

The whole of this flat country is laid out into embanked rice fields and sugar-cane plantations. The towns and villages interspersed

are numerous. All the primeval forest, at one time dense, has disappeared; for this being one of the first districts brought

under European subjection, it supplied timber to the invaders from the earliest days of Spanish colonization.

The Rio Agno rises in a mountainous range towards the west coast about 50 miles N.N.W. of the South Caraballo—runs southwards

as far as lat. 16°, where it takes a S.W. direction down to lat. 15° 48′—thence a N.W. course up to lat. 16°, whence it empties

itself by two mouths into the Gulf of Lingayen. At the highest tides there is a maximum depth of 11 feet of water on the sand

bank at the E. mouth, on which is situated the port of Dagupan.

The Bicol River, which flows from the Bató Lake to the Bay of San Miguel, has sufficient depth of water to admit vessels of

small draught a few miles up from its mouth.

In Mindanao Island the Butuan River or Rio Agusan rises at a distance of about 25 miles from the southern coast and empties itself on the northern

coast, so that it nearly divides the island, and is navigable for a few miles from the mouth.

[15]

The Rio Grande de Mindanao rises in the centre of the island and empties itself on the west coast by two mouths, and is navigable

for some miles by light-draught steamers. It has a great number of affluents of little importance.

The only river in Negros Island of any appreciable extent is the Danao, which rises in the mountain range running down the centre of the island, and finds

its outlet on the east coast. At the mouth it is about a quarter of a mile wide, but too shallow to permit large vessels to

enter, although past the mouth it has sufficient depth for any ship. I went up this river, six hoursʼ journey in a boat, and

saw some fine timber near its banks in many places. Here and there it opens out very wide, the sides becoming mangrove swamps.

The most important Lakes are:—In Luzon Island the Bay Lake or Laguna de Bay, supplied by numberless small streams coming from the mountainous district around it. Its greatest

length from E. to W. is 25 miles, and its greatest breadth N. to S. 21 miles. In it there is a mountainous island—Talim,—of

no agricultural importance, and several islets. Its overflow forms the Pasig River, which empties itself into the Manila Bay.

Each wet season—in the middle of the year—the shores of this lake are flooded. These floods recede as the dry season approaches,

but only partially so from the south coast, which is gradually being incorporated into the lake bed.

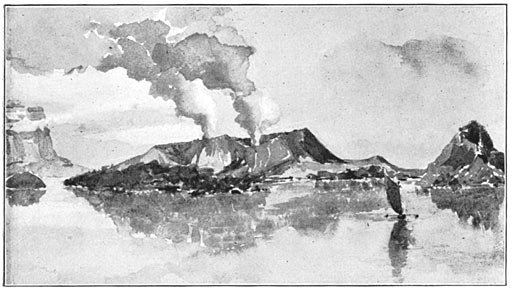

Bombon Lake, in the centre of which is a volcano in constant activity, has a width E. to W. of 11 miles, and its length from

N. to S. is 14 miles. The origin of this lake is apparently volcanic. According to tradition it was formed by the terrific

upheaval of a mountain 7,000 or 8,000 feet high, in the year 1700. It is not supplied by any streams emptying themselves into

it (further than two insignificant rivulets), and it is connected with the sea by the Pansipít River, which flows into the

Gulf of Balayan at lat. 13° 52′ N.

Cagayán Lake, in the extreme N.E. of the island, is about 7 miles long by 5 miles broad.

Lake Bató, 3 miles across each way, and Lake Buhi, 3 miles N. to S. and 2½ miles wide, situated in the eastern extremity of

Luzon Island, are very shallow.

In the centre of Luzon Island, in the large valley watered by the above-mentioned Pampanga and Agno Rivers, are three lakes,

respectively Canarem, Mangabol, and Candava; the last two being lowland meres flooded and navigable by canoes in the rainy

season only.

In Mindoro Island there is one lake called Naujan, 2½ miles from the N.E. coast. Its greatest width is 3 miles, with 4 miles in length.

In Mindanao Island there are the Lakes Maguindanao or Boayan, in the centre of the island (20 miles E. to W. by 12 N. to S.); Lanao, 18 miles

distant from the north coast; Liguasan and Buluan towards the [16]south, connected with the Rio Grande de Mindanao, and a group of four small lakes on the Agusuan River.

The Lanao Lake has great historical associations with the struggles between Christians and Moslems during the period of the

Spanish dominion, and is to this day a centre of strife with the Americans.

In some of the straits dividing the islands there are strong currents, rendering navigation of sailing vessels very difficult,

notably in the San Bernadino Straits separating the Islands of Luzon and Sámar, the roadstead of Yloilo between Panay and

Guimarrás Islands, and the passage between the south points of Cebú and Negros Islands.

Most of the islets, if not indeed the whole Archipelago, are of volcanic origin. There are many volcanoes, two of them in

frequent intermittent activity, viz. the Mayon, in the extreme east of Luzon Island, and the Taal Volcano, in the centre of

Bombon Lake, 34 miles due south of Manila. Also in Negros Island the Canlaúan Volcano—N. lat. 10° 24′—is occasionally in visible

eruption. In 1886 a portion of its crater subsided, accompanied by a tremendous noise and a slight ejection of lava. In the

picturesque Island of Camiguín a volcano mountain suddenly arose from the plain in 1872.

The Mayon Volcano is in the north of the Province of Albay; hence it is popularly known as the Albay Volcano. Around its base there are several

towns and villages, the chief being Albay, the capital of the province; Cagsaua (called Darága) and Camáling on the one side,

and Malinao, Tobaco, etc., on the side facing the east coast. The earliest eruption recorded is that of 1616, mentioned by

Spilbergen. In 1769 there was a serious eruption, which destroyed the towns of Cagsaua and Malinao, besides several villages,

and devastated property within a radius of 20 miles. Lava and ashes were thrown out incessantly during two months, and cataracts

of water were formed. In 1811 loud subterranean noises were heard proceeding from the volcano, which caused the inhabitants

around to fear an early renewal of its activity, but their misfortune was postponed. On February 1, 1814,2 it burst with terrible violence. Cagsaua, Badiao, and three other towns were totally demolished. Stones and ashes were ejected

in all directions. The inhabitants fled to caves to shelter themselves. So sudden was the occurrence, that many natives were

overtaken by the volcanic projectiles and a few by lava streams. In Cagsaua nearly all property was lost. Father Aragoneses

estimates that 2,200 persons were killed, besides many being wounded.

Another eruption, remarkable for its duration, took place in 1881–82, and again in the spring of 1887; but only a small quantity

of ashes was thrown out, and did very little or no damage to the property in the surrounding towns and villages.

[17]

The eruption of July 9, 1888, severely damaged the towns of Libog and Legaspi; plantations were destroyed in the villages

of Bigaá and Bonco; several houses were fired, others had the roofs crushed in; a great many domestic animals were killed;

fifteen natives lost their lives, and the loss of live-stock (buffaloes and oxen) was estimated at 500. The ejection of lava

and ashes and stones from the crater continued for one night, which was illuminated by a column of fire.

The last great eruption occurred in May, 1897. Showers of red-hot lava fell like rain in a radius of 20 miles from the crater.

In the immediate environs about 400 persons were killed. In the village of Bacacay houses were entirely buried beneath the

lava, ashes, and sand. The road to the port of Legaspi was covered out of sight. In the important town of Tobaco there was

total darkness and the earth opened. Hemp plantations and a large number of cattle were destroyed. In Libog over 100 inhabitants

perished in the ruins. The hamlets of San Roque, Misericordia, and Santo Niño, with over 150 inhabitants, were completely

covered with burning débris. At night-time the sight of the fire column, heaving up thousands of tons of stones, accompanied by noises like the booming

of cannon afar off, was indescribably grand, but it was the greatest public calamity which had befallen the province for some

years past.

The mountain is remarkable for the perfection of its conic form. Owing to the perpendicular walls of lava formed on the slopes

all around, it would seem impossible to reach the crater. The elevation of the peak has been computed at between 8,200 and

8,400 feet. I have been around the base on the E. and S. sides, but the grandest view is to be obtained from Cagsaua (Darága).

On a clear night, when the moon is hidden, a stream of fire is distinctly seen to flow from the crest.

Taal Volcano is in the island of the Bombon Lake referred to above. The journey by the ordinary route from the capital would be about

60 miles. This volcano has been in an active state from time immemorial, and many eruptions have taken place with more or

less effect. The first one of historical importance appears to have occurred in 1641; again in 1709 the crater vomited fire

with a deafening noise; on September 21, 1716, it threw out burning stones and lava over the whole island from which it rises,

but so far no harm had befallen the villagers in its vicinity. In 1731 from the waters of the lake three tall columns of earth

and sand arose in a few days, eventually subsiding into the form of an island about a mile in circumference. In 1749 there

was a famous outburst which dilacerated the coniform peak of the volcano, leaving the crater disclosed as it now is. Being

only 850 feet high, it is remarkable as one of the lowest volcanoes in the world.

The last and most desolating of all the eruptions of importance occurred in the year 1754, when the stones, lava, ashes, and

waves of [18]the lake, caused by volcanic action, contributed to the utter destruction of the towns of Taal, Tanaúan, Sala, and Lipa, and

seriously damaged property in Balayán, 15 miles away, whilst cinders are said to have reached Manila, 34 miles distant in

a straight line. One writer says in his MS.,3 compiled 36 years after the occurrence, that people in Manila dined with lighted candles at midday, and walked about the

streets confounded and thunderstruck, clamouring for confession during the eight days that the calamity was visible. The author

adds that the smell of the sulphur and fire lasted six months after the event, and was followed by malignant fever, to which

half the inhabitants of the province fell victims. Moreover, adds the writer, the lake waters threw up dead alligators and

fish, including sharks.

The best detailed account extant is that of the parish priest of Sala at the time of the event.4 He says that about 11 oʼclock at night on August 11, 1749, he saw a strong light on the top of the Volcano Island, but did

not take further notice. At 3 oʼclock the next morning he heard a gradually increasing noise like artillery firing, which

he supposed would proceed from the guns of the galleon expected in Manila from Mexico, saluting the Sanctuary of Our Lady

of Cagsaysay whilst passing. He only became anxious when the number of shots he heard far exceeded the royal salute, for he

had already counted a hundred times, and still it continued. So he arose, and it occurred to him that there might be a naval

engagement off the coast. He was soon undeceived, for four old natives suddenly called out, “Father, let us flee!” and on

his inquiry they informed him that the island had burst, hence the noise. Daylight came and exposed to view an immense column

of smoke gushing from the summit of the volcano, and here and there from its sides smaller streams rose like plumes. He was

joyed at the spectacle, which interested him so profoundly that he did not heed the exhortations of the natives to escape

from the grand but awful scene. It was a magnificent sight to watch mountains of sand hurled from the lake into the air in

the form of erect pyramids, and then falling again like the stream from a fountain jet. Whilst contemplating this imposing

phenomenon with tranquil delight, a strong earthquake came and upset everything in the convent. Then he reflected that it

might be time to go; pillars of sand ascended out of the water nearer to the shore of the town, and remained erect, until,

by a second earthquake, they, with the trees on the islet, were violently thrown down and submerged in the lake. The earth

opened out here and there as far as the shores of the Laguna de Bay, and the lands of [19]Sala and Tanaúan shifted. Streams found new beds and took other courses, whilst in several places trees were engulfed in the

fissures made in the soil. Houses, which one used to go up into, one now had to go down into, but the natives continued to

inhabit them without the least concern. The volcano, on this occasion, was in activity for three weeks; the first three days

ashes fell like rain. After this incident, the natives extracted sulphur from the open crater, and continued to do so until

the year 1754.

In that year (1754), the same chronicler continues, between nine and ten oʼclock at night on May 15, the volcano ejected boiling

lava, which ran down its sides in such quantities that only the waters of the lake saved the people on shore from being burnt.

Towards the north, stones reached the shore and fell in a place called Bayoyongan, in the jurisdiction of Taal. Stones and

fire incessantly came from the crater until June 2, when a volume of smoke arose which seemed to meet the skies. It was clearly

seen from Bauan, which is on a low level about four leagues (14 miles) from the lake.

Matters continued so until July 10, when there fell a heavy shower of mud as black as ink. The wind changed its direction

and a suburb of Sala, called Balili, was swamped with mud. This phenomenon was accompanied by a noise so great that the people

of Batangas and Bauan, who that day had seen the galleon from Acapulco passing on her home voyage, conjectured that she had

saluted the Shrine of Our Lady of Cagsaysay on her way. The noise ceased, but fire still continued to issue from the crater

until September 25. Stones fell all that night; and the people of Taal had to abandon their homes, for the roofs were falling

in with the weight upon them. The chronicler was at Taal at this date, and in the midst of the column of smoke a tempest of

thunder and lightning raged and continued without intermission until December 4.

The night of All Saintsʼ day (Nov. 1) was a memorable one, for the quantity of falling fire-stones, sand, and ashes increased,

gradually diminishing again towards November 15. Then, on that night, after vespers, great noises were heard. A long melancholy

sound dinned in oneʼs ears; volumes of black smoke rose; an infinite number of stones fell, and great waves proceeded from

the lake, beating the shores with appalling fury. This was followed by another great shower of stones, brought up amidst the

black smoke, which lasted until 10 oʼclock at night. For a short while the devastation was suspended prior to the last supreme

effort. All looked half dead and much exhausted after seven months of suffering in the way described.5 It was resolved to remove the image of Our Lady of Cagsaysay and put in its place the second image of the Holy Virgin.

[20]

On November 29, from seven oʼclock in the evening, the volcano threw up more fire than all put together in the preceding seven

months. The burning column seemed to mingle with the clouds; the whole of the island was one ignited mass. A wind blew. And

as the priests and the mayor (Alcalde) were just remarking that the fire might reach the town, a mass of stones was thrown up with great violence; thunderclaps

and subterranean noises were heard; everybody looked aghast, and nearly all knelt to pray. Then the waters of the lake began

to encroach upon the houses, and the inhabitants took to flight, the natives carrying away whatever chattels they could. Cries

and lamentations were heard all around; mothers were looking for their children in dismay; half-caste women of the Parian

were calling for confession, some of them beseechingly falling on their knees in the middle of the streets. The panic was

intense, and was in no way lessened by the Chinese, who took to yelling in their own jargonic syllables.

After the terrible night of November 29 they thought all was over, when again several columns of smoke appeared, and the priest

went off to the Sanctuary of Cagsaysay, where the prior was. Taal was entirely abandoned, the natives having gone in all directions

away from the lake. On November 29 and 30 there was complete darkness around the lake vicinity, and when light reappeared

a layer of cinders about five inches thick was seen over the lands and houses, and it was still increasing. Total darkness

returned, so that one could not distinguish anotherʼs face, and all were more horror-stricken than ever. In Cagsaysay the

natives climbed on to the housetops and threw down the cinders, which were over-weighting the structures. On November 30 smoke

and strange sounds came with greater fury than anything yet experienced, while lightning flashed in the dense obscurity. It

seemed as if the end of the world was arriving. When light returned, the destruction was horribly visible; the church roof

was dangerously covered with ashes and earth, and the chronicler opines that its not having fallen in might be attributed

to a miracle! Then there was a day of comparative quietude, followed by a hurricane which lasted two days. All were in a state

of melancholy, which was increased when they received the news that the whole of Taal had collapsed; amongst the ruins being

the Government House and Stores, the Prison, State warehouses and the Royal Rope Walk, besides the Church and Convent.

The Gov.-General sent food and clothing in a vessel, which was nearly wrecked by storms, whilst the crew pumped and baled

out continually to keep her afloat, until at length she broke up on the shoals at the mouth of the Pansipit River. Another

craft had her mast split by a flash of lightning, but reached port.

With all this, some daft natives lingered about the site of the town of Taal till the last, and two men were sepulchred in

the Government House ruins. A woman left her house just before the roof [21]fell in and was carried away by a flood, from which she escaped, and was then struck dead by a flash of lightning. A man who

had escaped from Mussulman pirates, by whom he had been held in captivity for years, was killed during the eruption. He had

settled in Taal, and was held to be a perfect genius, for he could mend a clock!

The road from Taal to Balayan was impassable for a while on account of the quantity of lava. Taal, once so important as a

trading centre, was now gone, and Batangas, on the coast, became the future capital of the province.

The actual duration of this last eruption was 6 months and 17 days.

In 1780 the natives again extracted sulphur, but in 1790 a writer at that date6 says that he was unable to reach the crater owing to the depth of soft lava and ashes on the slopes.

There is a tradition current amongst the natives that an Englishman some years ago attempted to cut a tunnel from the base

to the centre of the volcanic mountain, probably to extract some metallic product or sulphur. It is said that during the work

the excavation partially fell in upon the Englishman, who perished there. The cave-like entrance is pointed out to travellers

as the Cueva del Inglés.

Referring to the volcano, Fray Gaspar de San Agustin in his History7 remarks as follows:—“The volcano formerly emitted many large fire-stones which destroyed the cotton, sweet potato and other

plantations belonging to the natives of Taal on the slopes of the (volcano) mountain. Also it happened that if three persons

arrived on the volcanic island, one of them had infallibly to die there without being able to ascertain the cause of this

circumstance. This was related to Father Albuquerque,8 who after a fervent deesis entreating compassion on the natives, went to the island, exorcised the evil spirits there and

blessed the land. A religious procession was made, and Mass was celebrated with great humility. On the elevation of the Host,

horrible sounds were heard, accompanied by groaning voices and sad lamentations; two craters opened out, one with sulphur

in it and the other with green water (sic), which is constantly boiling. The crater on the Lipa side is about a quarter of

a league wide; the other is smaller, and in time smoke began to ascend from this opening so that the natives, fearful of some

new calamity, went to Father Bartholomew, who repeated the ceremonies already described. Mass was said a second time, so that

since then the volcano has not thrown out any more fire or [22]smoke.9 However, whilst Fray Thomas Abresi was parish priest of Taal (about 1611), thunder and plaintive cries were again heard,

therefore the priest had a cross, made of Anobing wood, borne to the top of the volcano by more than 400 natives, with the

result that not only the volcano ceased to do harm, but the island has regained its original fertile condition.”

The Taal Volcano is reached with facility from the N. side of the island, the ascent on foot occupying about half an hour.

Looking into the crater, which would be about 4,500 feet wide from one border to the other of the shell, one sees three distinct

lakes of boiling liquid, the colours of which change from time to time. I have been up to the crater four times; the last

time the liquids in the lakes were respectively of green, yellow, and chocolate colours. At the time of my last visit there

was also a lava chimney in the middle, from which arose a snow-white volume of smoke.

The Philippine Islands have numberless creeks and bays forming natural harbours, but navigation on the W. coasts of Cebú,

Negros and Palaúan Islands is dangerous for any but very light-draught vessels, the water being very shallow, whilst there

are dangerous reefs all along the W. coast of Palaúan (Parágua) and between the south point of this island and Balábac Island.

The S.W. monsoon brings rain to most of the islands, and the wet season lasts nominally six months,—from about the end of

April. The other half of the year is the dry season. However, on those coasts directly facing the Pacific Ocean, the seasons

are the reverse of this.

The hottest season is from March to May inclusive, except on the coasts washed by the Pacific, where the greatest heat is

felt in June, July, and August. The temperature throughout the year varies but slightly, the average heat in Luzon Island

being about 81° 50′ Fahr. In the highlands of north Luzon, on an elevation above 4,000 feet, the maximum temperature is 78°

Fahr. and the minimum 46° Fahr. Zamboanga, which is over 400 miles south of Manila, is cooler than the capital. The average

number of rainy days in Luzon during the years 1881 to 1883 was 203.

Commencing July 11, 1904, three days of incessant rain in Rizal Province produced the greatest inundation of Manila suburbs

within living memory. Human lives were lost; many cattle were washed away; barges in the river were wrenched from their moorings

and dashed against the bridge piers; pirogues were used instead of vehicles in the thoroughfares; considerable damage was

done in the shops and many persons had to wade through the flooded streets knee-deep in water.

The climate is a continual summer, which maintains a rich verdure throughout the year; and during nine months of the twelve

an alternate [23]heat and moisture stimulates the soil to the spontaneous production of every form of vegetable life. The country generally

is healthy.

The whole of the Archipelago, as far south as 10° lat., is affected by the monsoons, and periodically disturbed by terrible

hurricanes, which cause great devastation to the crops and other property. The last destructive hurricane took place in September,

1905.

Earthquakes are also very frequent, the last of great importance having occurred in 1863, 1880, 1892, 1894, and 1897. In 1897

a tremendous tidal wave affected the Island of Leyte, causing great destruction of life and property. A portion of Taclóban,

the capital of the island, was swept away, rendering it necessary to extend the town in another direction.

In the wet season the rivers swell considerably, and often overflow their banks; whilst the mountain torrents carry away bridges,

cattle, tree trunks, etc., with terrific force, rendering travelling in some parts of the interior dangerous and difficult.

In the dry season long droughts occasionally occur (about once in three years), to the great detriment of the crops and live-stock.

The southern boundary of the Archipelago is formed by a chain of some 140 islands, stretching from the large island of Mindanao

as far as Borneo, and constitutes the Sulu Archipelago, the Sultanate of which was under the protection of Spain (vide Chap. xxix.). It is now being absorbed, under American rule, in the rest of the Archipelago, under the denomination of Moro Province

(q.v.).

[24]

Discovery of the Archipelago

The discoveries of Christopher Columbus in 1492, the adventures and conquests of Hernan Cortés, Blasco Nuñez de Balboa and

others in the South Atlantic, had awakened an ardent desire amongst those of enterprizing spirit to seek beyond those regions

which had hitherto been traversed. It is true the Pacific Ocean had been seen by Balboa, who crossed the Isthmus of Panamá,

but how to arrive there with his ships was as yet a mystery.

On April 10, 1495, the Spanish Government published a general concession to all who wished to search for unknown lands. This

was a direct attack upon the privileges of Columbus at the instigation of Fonseca, Bishop of Búrgos, who had the control of

the Indian affairs of the realm. Rich merchants of Cadiz and Seville, whose imagination was inflamed by the reports of the

abundance of pearls and gold on the American coast, fitted out ships to be manned by the roughest class of gold-hunters: so

great were the abuses of this common licence that it was withdrawn by Royal Decree of June 2, 1497.

It was the age of chivalry, and the restless cavalier who had won his spurs in Europe lent a listening ear to the accounts

of romantic glory and wealth attained across the seas. That an immense ocean washed the western shores of the great American

continent was an established fact. That there was a passage connecting the great Southern sea—the Atlantic—with that vast

ocean was an accepted hypothesis. Many had sought the passage in vain; the honour of its discovery was reserved for Hernando

de Maghallanes (Portuguese, Fernão da Magalhães).

This celebrated man was a Portuguese noble who had received the most complete education in the palace of King John II. Having

studied mathematics and navigation, at an early age he joined the Portuguese fleet which left for India in 1505 under the

command of Almeida. He was present at the siege of Malacca under the famous Albuquerque, and accompanied another expedition

to the rich Moluccas, or Spice Islands, when the Islands of Banda, Tidor, and Ternate were discovered. It was here he obtained

the information which led him to contemplate the voyage which he subsequently realized.

[25]

On his return to Portugal he searched the Crown Archives to see if the Moluccas were situated within the demarcation accorded

to Spain.1 In the meantime he repaired to the wars in Africa, where he was wounded in the knee, with the result that he became permanently

lame. He consequently retired to Portugal, and his companions in arms, jealous of his prowess, took advantage of his affliction

to assail him with vile imputations. The King Emmanuel encouraged the complaints, and accused him of feigning a malady of

which he was completely cured. Wounded to the quick by such an assertion, and convinced of having lost the royal favour, Maghallanes

renounced for ever, by a formal and public instrument, his duties and rights as a Portuguese subject, and henceforth became

a naturalized Spaniard. He then presented himself at the Spanish Court, at that time in Valladolid, where he was well received

by the King Charles I., the Bishop of Búrgos, Juan Rodriguez Fonseca, Minister of Indian Affairs, and by the Kingʼs chancellor.

They listened attentively to his narration, and he had the good fortune to secure the personal protection of His Majesty,

himself a well-tried warrior, experienced in adventure.

The Portuguese Ambassador, Alvaro de Acosta, incensed at the success of his late countryman, and fearing that the project

under discussion would lead to the conquest of the Spice Islands by the rival kingdom, made every effort to influence the

Court against him. At the same time he ineffectually urged Maghallanes to return to Lisbon, alleging that his resolution to

abandon Portuguese citizenship required the sovereign sanction. Others even meditated his assassination to save the interests

of the King of Portugal. This powerful opposition only served to delay the expedition, for finally the King of Portugal was

satisfied that his Spanish rival had no intention to authorize a violation of the Convention of Demarcation.

Between King Charles and Maghallanes a contract was signed in Saragossa by virtue of which the latter pledged himself to seek

the discovery of rich spice islands within the limits of the Spanish Empire. If he should not have succeeded in the venture

after ten years from the date of sailing he would thenceforth be permitted to navigate and trade without further royal assent,

reserving one-twentieth of his net gains for the Crown. The King accorded to him the title of Cavalier and invested him with

the habit of St. James and the hereditary government [26]in male succession of all the islands he might annex. The Crown of Castile reserved to itself the supreme authority over such

government. If Maghallanes discovered so many as six islands, he was to embark merchandise in the Kingʼs own ships to the

value of one thousand ducats as royal dues. If the islands numbered only two, he would pay to the Crown one-fifteenth of the

net profits. The King, however, was to receive one-fifth part of the total cargo sent in the first return expedition. The King would defray the expense of fitting out and arming five ships of from 60 to 130 tons with a total

crew of 234 men; he would also appoint captains and officials of the Royal Treasury to represent the State interests in the

division of the spoil.

Orders to fulfil the contract were issued to the Crown officers in the port of Seville, and the expedition was slowly prepared,

consisting of the following vessels, viz.: The commodore ship La Trinidad, under the immediate command of Maghallanes; the San Antonio, Captain Juan de Cartagena; the Victoria, Captain Luis de Mendoza; the Santiago, Captain Juan Rodriguez Serrano; and the Concepcion, Captain Gaspar de Quesada.

The little fleet had not yet sailed when dissensions arose.

Maghallanes wished to carry his own ensign, whilst Doctor Sancho Matienza insisted that it should be the Royal Standard.

Another, named Talero, disputed the question of who should be the standard-bearer. The King himself had to settle these quarrels

by his own arbitrary authority. Talero was disembarked and the Royal Standard was formally presented to Maghallanes by injunction

of the King in the Church of Santa Maria de la Victoria de la Triana, in Seville, where he and his companions swore to observe

the usages and customs of Castile, and to remain faithful and loyal to His Catholic Majesty.

On August 10, 1519, the expedition left the port of San Lúcar de Barrameda in the direction of the Canary Islands.

On December 13 they arrived safely at Rio Janeiro.

Following the coast in search of the longed-for passage to the Pacific Ocean, they entered the Solis River—so called because

its discoverer, João de Solis, a Portuguese, was murdered there. Its name was afterwards changed to that of Rio de la Plata

(the Silver River).

Continuing their course, the intense cold determined Maghallanes to winter in the next large river, known then as San Julian.

Tumults arose; some wished to return home; others harboured a desire to separate from the fleet, but Maghallanes had sufficient

tact to persuade the crews to remain with him, reminding them of the shame which would befall them if they returned only to

relate their failure. He added that, so far as he was concerned, nothing but death would deter him from executing the royal

commission.

As to the rebellious captains, Juan de Cartagena was already put in [27]irons and sentenced to be cast ashore with provisions, and a disaffected French priest for a companion. The sentence was carried

out later on. Then Maghallanes sent a boat to each of three of the ships to inquire of the captains whom they served. The

reply from all was that they were for the King and themselves. Thereupon 30 men were sent to the Victoria with a letter to Mendoza, and whilst he was reading it, they rushed on board and stabbed him to death. Quesada then brought

his ship alongside of the Trinidad, and, with sword and shield in hand, called in vain upon his men to attack. Maghallanes, with great promptitude, gave orders

to board Quesadaʼs vessel. The next day Quesada was executed. After these vigorous but justifiable measures, obedience was

ensured.

Still bearing southwards within sight of the coast, on October 28, 1520, the expedition reached and entered the seaway thenceforth

known as the Magellan Straits, dividing the Island of Tierra del Fuego from the mainland of Patagonia.2

On the way one ship had become a total wreck, and now the San Antonio deserted the expedition; her captain having been wounded and made prisoner by his mutinous officers, she was sailed in the

direction of New Guinea. The three remaining vessels waited for the San Antonio several days, and then passed through the Straits. Great was the rejoicing of all when, on November 26, 1520, they found

themselves on the Pacific Ocean! It was a memorable day. All doubt was now at an end as they cheerfully navigated across that

broad expanse of sea.

On March 16, 1521, the Ladrone Islands were reached. There the ships were so crowded with natives that they were obliged to

be expelled by force. They stole one of the shipʼs boats, and ninety men were sent on shore to recover it. After a bloody

combat the boat was regained, and the fleet continued its course westward until it hove to off an islet, then called Jomonjol,

now known as Malhou, situated in the channel between Sámar and Dinagat Islands (vide map). Then coasting along the north of the Island of Mindanao, they arrived at the mouth of the Butuan River, where they

were supplied with provisions by the chief. It was Easter week, and on this shore the first Mass was celebrated in the Philippines.

The natives showed great friendliness, in return for which Maghallanes took formal possession of their territory in the name

of Charles I. The chieftain himself volunteered to pilot the ships to a fertile island, the kingdom of a relation of his,

and, passing between the Islands of Bojol and Leyte, the expedition arrived on April 7 at Cebú, where, on receiving the news,

over two thousand men appeared on the beach in battle array with lances and shields.

The Butuan chief went on shore and explained that the expedition brought people of peace who sought provisions. The King agreed

to a [28]treaty, and proposed that it should be ratified according to the native formula—drawing blood from the breast of each party,

the one drinking that of the other. This form of bond was called by the Spaniards the Pacto de sangre, or the Blood compact (q.v.).

Maghallanes accepted the conditions, and a hut was built on shore in which to say Mass. Then he disembarked with his followers,

and the King, Queen, and Prince came to satisfy their natural curiosity. They appeared to take great interest in the Christian

religious rites and received baptism, although it would be venturesome to suppose they understood their meaning, as subsequent

events proved. The princes and headmen of the district followed their example, and swore fealty and obedience to the King

of Spain.

Maghallanes espoused the cause of his new allies, who were at war with the tribes on the opposite coast, and on April 25,

1521, he passed over to Magtan Island. In the affray he was mortally wounded by an arrow, and thus ended his brief but lustrous

career, which fills one of the most brilliant pages in Spanish annals.

Maghallanes called the group of islands, so far discovered, the Saint Lazarus Archipelago. In Spain they were usually referred

to as the Islas del Poniente, and in Portugal as the Islas del Oriente.

On the left bank of the Pasig River, facing the City of Manila, stands a monument to Maghallanesʼ memory. Another has been

erected on the spot in Magtan Island, where he is supposed to have been slain on April 27, 1521. Also in the city of Cebú,

near the beach, there is an obelisk to commemorate these heroic events.

It was perhaps well for Maghallanes to have ended his days out of reach of his royal master. Had he returned to Spain he would

probably have met a fate similar to that which befell Columbus after all his glories. The San Antonio, which, as already mentioned, deserted the fleet at the Magellan Straits, continued her voyage from New Guinea to Spain,

arriving at San Lúcar de Barrameda in March, 1521. The captain, Alvaro Mesquita, was landed as a prisoner, accused of having

seconded Maghallanes in repressing insubordination. To Maghallanes were ascribed the worst cruelties and infraction of the

royal instructions. Accused and accusers were alike cast into prison, and the King, unable to lay hands on the deceased Maghallanes,

sought this heroʼs wife and children. These innocent victims of royal vengeance were at once arrested and conveyed to Búrgos,

where the Court happened to be, whilst the San Antonio was placed under embargo.

On the decease of Maghallanes, the supreme command of the expedition in Cebú Island was assumed by Duarte de Barbosa, who,

with twenty-six of his followers, was slain at a banquet to which they had been invited by Hamabar, the King of the island.

Juan Serrano had so ingratiated himself with the natives during the sojourn on shore that his life was spared for a while.

Stripped of his raiment and armour, he was [29]conducted to the beach, where the natives demanded a ransom for his person of two cannons from the shipsʼ artillery. Those

on board saw what was passing and understood the request, but they were loath to endanger the lives of all for the sake of

one—”Melius est ut pereat unus quam ut pereat communitas” (Saint Augustine)—so they raised anchors and sailed out of the port, leaving Serrano to meet his terrible fate.

Due to sickness, murder during the revolts, and the slaughter in Cebú, the exploring party, now reduced to 100 souls all told,

was deemed insufficient to conveniently manage three vessels. It was resolved therefore to burn the most dilapidated one—the

Concepcion. At a general council, Juan Caraballo was chosen Commander-in-Chief of the expedition, with Gonzalo Gomez de Espinosa as

Captain of the Victoria. The royal instructions were read, and it was decided to go to the Island of Borneo, already known to the Portuguese and

marked on their charts. On the way they provisioned the ships off the coast of Palaúan Island (Parágua), and thence navigated

to within ten miles of the capital of Borneo (probably Brunei). Here they fell in with a number of native canoes, in one of

which was the Kingʼs secretary. There was a great noise with the sound of drums and trumpets, and the ships saluted the strangers

with their guns.

The natives came on board, embraced the Spaniards as if they were old friends, and asked them who they were and what they

came for. They replied that they were vassals of the King of Spain and wished to barter goods. Presents were exchanged, and

several of the Spaniards went ashore. They were met on the way by over two thousand armed men, and safely escorted to the