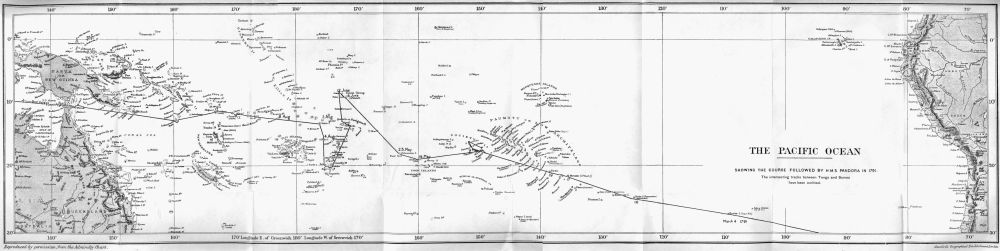

Title: Voyage of H.M.S. 'Pandora'

despatched to arrest the mutineers of the 'Bounty' in the South Seas, 1790-91

Author: Edward Edwards

surgeon George Hamilton

Commentator: Basil Thomson

Release date: October 2, 2007 [eBook #22834]

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/22834

Credits: Produced by Suzanne Lybarger and the booksmiths at

http://www.eBookForge.net

[i]

[ii]

[iii]

[iv]

[v]

[vi]

[1]

None of the minor incidents in our naval history has inspired so many writers as the Mutiny of the Bounty. Histories, biographies and romances, from Bligh's narrative in 1790 to Mr. Becke's "Mutineers" in 1898, have been founded upon it; Byron took it for the theme of the least happy of his dramatic poems; and all these, not because the mutiny left any mark upon history, but because it ranks first among the stories of the sea, instinct with the living elements of romance, of primal passion and of tragedy—all moving to a happy ending in the Arcadia of Pitcairn Island. And yet, while every incident in the moving story, even to the evidence in the famous court-martial, has been discussed over and over again, there has been lying in the Record Office for more than a century an autograph manuscript, written by one of the principal actors in the drama, which no one has thought it worth while to print.

Though the story of the mutiny is too well known to need repeating in detail, it is necessary to set forth as briefly as possible its relation to the history of maritime discovery in the Pacific. In the year 1787, ten years after the death of Captain Cook in Hawaii, a number of West India merchants in London, stirred by the glowing reports of the natural wealth of the South Sea Islands brought home by Dampier and Cook, petitioned the [2]government to acclimatize the bread-fruit in Jamaica. A ship of 215 tons was purchased into the service and fitted out under the direct superintendence of Sir Joseph Banks, who named her the Bounty, and recommended William Bligh, one of Cook's officers, for the command. It was a new departure. The object of most of the earlier government expeditions to the South Seas had been the advancement of geographical science and natural history; the voyage of the Bounty was to turn former discoveries to the profit of the empire.

Bligh was singularly ill-fitted for the command. While he had undoubted ability, his whole career shows him to have been wanting in the tact and temper without which no one can successfully lead men; and in this venture his own defects were aggravated by the inefficiency of his officers. He took in his cargo of bread-fruit trees at Tahiti, and there was no active insubordination until he reached Tonga on the homeward voyage. At sunrise on April 28th, 1789, the crew mutinied under the leadership of Fletcher Christian, the Master's Mate, whom Bligh's ungoverned temper had provoked beyond endurance. The seamen had other motives. Bligh had kept them far too long at Tahiti, and during the five months they had spent at the island, every man had formed a connection among the native women, and had enjoyed a kind of life that contrasted sharply with the lot of bluejackets a century ago. Forcing Bligh, and such of their shipmates as were loyal to him, into the launch, and casting them adrift with food and water barely sufficient for a week's subsistence, they set the ship's course eastward, crying "Huzza for Tahiti!" There followed an open boat voyage that is unexampled in maritime history. The boat was only 23 feet long; the weight of eighteen men sank her almost to the gunwale; the ocean before them was unknown, and teeming with hidden dangers; their only arms against hostile natives[3] were a few cutlasses, their only food two ounces of biscuit each a day; and yet they ran 3618 nautical miles in forty-one days, and reached Timor with the loss of only one man, and he was killed by the natives at the very outset.

The mutineers fared as mutineers have always fared. Having sailed the ship to Tahiti, they fell out among themselves, half taking the Bounty to the uninhabited island of Pitcairn, where they were discovered twenty-seven years later, and half remaining at Tahiti. Of these two were murdered, four were drowned in the wreck of the Pandora, three were hanged in England, and six were pardoned, one living to become a post-captain in the navy, another to be gunner on the Blenheim when she foundered with Sir Thomas Troubridge.

One boat voyage only is recorded as being longer than Bligh's. In 1536 Diego Botelho Pereira made the passage from Portuguese India to Lisbon in a native fusta, or lateen rigged boat, but a little larger than Bligh's. He had, however, covered her with a deck, and provisioned her for the venture, and he was able to replenish his stock at various points on the voyage.

In 1790 the publication of Bligh's account of his sufferings excited the strongest public sympathy, and the Admiralty lost no time in fitting out an expedition to search for the mutineers, and bring them home to punishment. The Pandora, frigate, of 24 guns, was commissioned for the purpose, and manned by 160 men, composed largely of landsmen, for every trained seaman in the navy had gone to man the great fleet then assembling at Portsmouth under Lord Howe. Captain Edward Edwards, the officer chosen for the command, had a high reputation as a seaman and a disciplinarian, and from the point of view of the Admiralty, who intended the cruise simply as a police mission without any scientific object,[4] no better choice could have been made. Their orders to him were to proceed to Tahiti, and, not finding the mutineers there, to visit the different groups of the Society and Friendly Islands, and the others in the neighbouring parts of the Pacific, using his best endeavours to seize and bring home in confinement the whole, or such part of the delinquents as he might be able to discover. "You are," the orders ran, "to keep the mutineers as closely confined as may preclude all possibility of their escaping, having, however, proper regard to the preservation of their lives, that they may be brought home to undergo the punishment due to their demerits." Edwards belonged to that useful class of public servant that lives upon instructions. With a roving commission in an ocean studded with undiscovered islands the possibilities of scientific discovery were immense, but he faced them like a blinkered horse that has his eyes fixed on the narrow track before him, and all the pleasant byways of the road shut out. A cold, hard man, devoid of sympathy and imagination, of every interest beyond the straitened limits of his profession, Edwards in the eye of posterity was almost the worst man that could have been chosen. For, with a different commander, the voyage would have been one of the most important in the history of South Sea discovery, and the account he has written of it compares in style and colour with a log-book.

In Edwards' place a more genial man, a Catoira, a Wallis, or a Cook, would have written a journal of discovery that might have taken a place in the front rank of the literature of travel. He would have investigated the murder of La Pérouse's boat's crew in Tutuila on the spot; he would have rescued the survivors of that ill-fated expedition whose smoke-signals he saw on Vanikoro; he would have brought home news of the great Fiji group[5] through which Bligh passed in the Bounty's launch; he might even have discovered Fletcher Christian's colony of mutineers in Pitcairn. But, on the other hand, humanity to his prisoners might have furnished them with the means of escape, and his ardour for discovery might have led him into dangers from which no one would have survived to tell the tale. Edwards had the qualities of his defects. If he treated his prisoners harshly, he prevented them from contaminating his crew, and brought the majority of them home alive through all the perils of shipwreck and famine. In all the attacks that have been made upon him there is not a word against his character as a plain, straight-forward officer, who could lick a crew of landsmen into shape, and keep them loyal to him through the stress of shipwreck and privation. If he was callous to the sufferings of his prisoners, he was at least as indifferent to his own. If he felt no sympathy with others, he asked for none with himself. If he won no love, he compelled respect.

Of his officers little need be said. Corner, the first lieutenant, was a stout seaman, who bottled up his disapproval of his captain's behaviour until the commission was out. Hayward, the second lieutenant, was a time-server. He had been a midshipman on the Bounty at the time of the mutiny, and an intimate friend of young Peter Heywood who was constrained to cast in his lot with the mutineers, yet, when Heywood gave himself up on the arrival of the Pandora at Tahiti, his old comrade, now risen in the world, received him with a haughty stare. Of Larkin, Passmore, and the rest, we know nothing.

Fortunately for us, the Pandora carried a certain rollicking, irresponsible person as surgeon. George Hamilton has been called "a coarse, vulgar, and illiterate man, more disposed to relate licentious scenes and adventures, in which he and his companions were engaged, than to give[6] any information of proceedings and occurrences connected with the main object of the voyage." From this puritanical criticism most readers will dissent. Hamilton was bred in Northumberland, and was at this time past forty. His portrait, the frontispiece to his book, represents him in the laced coat and powdered wig of the period, a man of middle age, with clever, well-cut features, and a large, humorous, and rather sensual mouth. His book, with all its faults of scandalous plain speech, is one that few naval surgeons of that day could have written. The style, though flippant, is remarkable for a cynical but always good-natured humour, and on the rare occasions when he thought it professionally incumbent on him to be serious, as in his discussion of the best dietary for long voyages, and the physical effects of privations, his remarks display observation and good sense. It must be admitted, I fear, that he relates certain of his own and his shipmates' adventures ashore with shameless gusto, but he wrote in an age that loved plain speech, and that did not care to veil its appetite for licence. Like Edwards, he tells us little of the prisoners after they were consigned to "Pandora's Box." His narrative is valuable as a commentary on Edwards' somewhat meagre report, and for the sidelights which it throws upon the manners of naval officers of those days. Even Edwards, to whom he is always loyal, does not escape his little shaft of satire when he relates how the stern captain was driven to conduct prayers in the most desperate portion of the boat voyage. His book, published at Berwick in 1793, has now become so rare that Mr. Quaritch lately advertised for it three times without success, and therefore no excuse is needed for reprinting it.

The Pandora was dogged by ill luck from the first. An epidemic fever raging in England at the time of her departure, was introduced on board, it was thought, by[7] infected clothing. The sick bay, and indeed, the officers' cabins, too, were crammed with stores intended for the return voyage of the Bounty, and there was no accommodation for the sick. Hamilton attributes their recovery to the use of tea and sugar, then carried for the first time in a ship of war. He gives some interesting information regarding the precautions taken against scurvy. They had essence of malt and hops for brewing beer, a mill for grinding wheat, the meal being eaten with brown sugar, and as much saurkraut as the crew chose to eat.

The first land sighted after rounding Cape Horn, was Ducie's island; probably the same island which, as the Encarnacion of Quiros, has dodged about the charts of the old geographers, swelling into a continent, contracting into an atoll, and finally coming to rest in the neighbourhood of the Solomon Islands before vanishing for ever. The Pandora was now in the latitude of Pitcairn, which lay down wind only three hundred miles distant. If she had but kept a westerly course, she must have sighted it, for the island's peak is visible for many leagues, but relentless ill fortune turned her northward, and during the ensuing day she passed the men she was in search of scarce thirty leagues away. One glimmer of good fortune awaited Edwards in Tahiti. The schooner built by the mutineers was ready for sea, but not provisioned for a voyage. She put to sea, and outsailed the Pandora's boat that went in chase of her, but her crew, dreading the inevitable starvation that faced them, put back during the night and took to the mountains, where they were all captured.

In the matter of "Pandora's Box," there were excuses for Edwards, who was bitterly attacked afterwards for his inhumanity. One of the chiefs had warned him that there was a plot between the natives and the mutineers to cut the cable of the Pandora in the night. Most of the[8] mutineers were connected through their women with influential chiefs, and nothing was more likely than that such a rescue should be attempted. His own crew, moreover, were human. They could see for themselves the charms of a life in Tahiti; they could hear from the prisoners the consideration in which Englishmen were held in this delightful land. What had been possible in the Bounty was possible in the Pandora. Edwards regarded his prisoners as pirates, desperate with the weight of the rope about their necks. His orders were definite—to consider nothing but the preservation of their lives—and he did his duty in his own way according to his lights. And that he was not insensible to every feeling of humanity is shown by the fact that he allowed the native wives of the mutineers daily access to their husbands while the ship lay there. The infinitely pathetic story of poor "Peggy," the beautiful Tahitian girl who had borne a child to midshipman Stewart, was vouched for six years later by the missionaries of the "Duff." She had to be separated from her husband by force, and it was at his request that she was not again admitted to the ship. Poor girl! it was all her life to her. A month before her boy-husband perished in the wreck of the Pandora, she had died of a broken heart, leaving her baby, the first half-caste born in Tahiti, to be brought up by the missionaries.

"Pandora's Box" certainly needed some excuse. A round house, eleven feet long, accessible only through a scuttle in the roof, was built upon the quarter deck as a prison for the fourteen mutineers, who were ironed and handcuffed. Hamilton says that the roundhouse was built partly out of consideration for the prisoners themselves, in order to spare them the horrors of prolonged imprisonment below in the tropics, and that although the service regulations restricted prisoners to two-thirds allowance, Edwards rationed them exactly like the ship's[9] company. Morrison, however, who seems to have belonged to that objectionable class of seamen—the sea-lawyer—having kept a journal of grievances against Bligh when on the Bounty, and preserved it even in "Pandora's Box," gives a very different account, and Peter Heywood, a far more trustworthy witness, declared in a letter to his mother, that they were kept "with both hands and both legs in irons, and were obliged to eat, drink, sleep, and obey the calls of nature, without ever being allowed to get out of this den."

Edwards now provisioned the mutineers' little schooner, and put on board of her a prize crew of two petty officers and seven men to navigate her as his tender. For the first few weeks, while the scent was keen, he maintained a very active search for the Bounty. He had three clues: first, the mention of Aitutaki in a story the mutineers had told the natives to account for their reappearance; second, a report made to him by Hillbrant, one of his prisoners, that Christian, on the night before he left Tahiti, had declared his intention of settling on Duke of York's Island; and third, the discovery on Palmerston Island of the Bounty's driver yard, much worm-eaten from long immersion. It must be confessed that hopes founded on these clues did little credit to Edwards' intelligence. Aitutaki, having been discovered by Bligh, was the last place Christian would have chosen: he might have guessed that a man of Christian's intelligence would intentionally have given a false account of his projects to the mutineers he left behind, knowing that even if all who were set adrift in the boat had perished, the story of the mutiny would be learned by the first ship that visited Tahiti; a worm-eaten spar lying on the tide-mark, at an island situated directly down-wind from the Society Islands, so far from proving that the Bounty had been there, indicated the exact contrary. But it is to be[10] remembered that at this time the islands known to exist in the Pacific could almost be counted on the fingers, and that Edwards could not have hoped, within the limits of a single cruise, to examine even the half of those that were marked in his chart. Had he suspected the existence of the vast number of islands around him, he would at once have realised the hopelessness of attempting to discover the hiding-place of an able navigator bent on concealment. Whether, as has been suggested by one writer,[10-1] Christian was piloted to Pitcairn by his Tahitian companions, of whom some were descended from the old native inhabitants, or had read of it in Carteret's voyage in 1767, or had chanced upon it by accident, he could have followed no wiser course than to steer eastward, and upwind, for any vessel despatched to arrest him would perforce go first to Tahiti for information, when it would be too late to beat to the eastward without immense loss of time.

From Aitutaki Edwards bore north-west to investigate the second clue, and in the Union Group he made his first important discovery of new land—Nukunono, inhabited by a branch of the Micronesian race, crossed with Polynesian blood. From thence he ran southward to Samoa, where he came upon traces of the massacre of La Pérouse's second in command, M. de Langle, in the shape of accoutrements cut from the uniforms of the French officers. Consistent with his usual concentration upon the object of his voyage, he does not seem to have cared to make enquiries about them.

At this stage in the voyage there occurred an accident which, from our point of view, must be regarded as the most fortunate incident of the voyage. The tender, very imperfectly victualled, parted company in a thick shower of rain. At this date Fiji, the most important group in[11] the South Pacific, was practically unknown. Tasman had sighted its north-eastern extremity: Cook had discovered Vatoa, an outlying island in the far southward, and had heard of it from the Tongans in his second voyage when he had not time to look for it; Bligh had passed through the heart of it in his boat voyage, and had even been chased by two canoes from Round Island, Yasawa; but no European had landed or held any intercourse with the natives. It is not easy to understand how islands of such magnitude as Fiji should have remained undiscovered so long after every other important group in the Pacific had found its place in the charts of the Pacific. They were known by repute; Hamilton writes of "the savage and cannibal Feegees"; they lay but two days' sail down-wind from Tonga. Three years before the Pandora's cruise the Pacific had been thrown open to the sperm whale fishery, which has had so large a part in South Sea discovery, by the cruise of the English ship Amelia, fitted out by Enderby; and yet neither ship of war nor whaler had chanced upon them. But for a meagre passage in Edwards' journal, and a traditionary poem in the Fijian language, we should not know to whom belongs the honour of first visiting them. The native tradition sets forth that with the first visit of a European ship a devastating sickness, called the Great Lila, or "Wasting Sickness," attacked the people of one of the Eastern Islands (of the Lau group), and, spreading from island to island, swept away vast numbers of the people. There are, it may be remarked, innumerable instances in history of the contact between continental and island peoples, both of them healthy at the time of contact, producing fatal epidemics among the islanders. Even among our own Hebrides the natives are said to look for an outbreak of "Strangers' Cold" after every visit of a ship. The Fijian tradition certainly dates from a few years before the beginning of the last century.

[12] The real discoverers of Fiji seem to have been Oliver, master's mate; Renouard, midshipman; James Dodds, quartermaster, and six seamen of the Pandora, who formed the crew of Edwards' tender; and surely no ship that ever ventured among those dangerous islands was so ill furnished for repelling attack. Edwards had sent provisions and ammunition on board of her when off Palmerston Island, but by this time they were exhausted, and a fresh supply was actually on the Pandora's deck when she parted company. Her provision for the long and dangerous voyage before her was a bag of salt, a bag of nails and ironware, a boarding netting, and several seven-barrelled pieces and blunderbusses. She had besides the latitude and longitude of the places the Pandora would touch at.

The following account of their cruise is drawn from the remarks of Edwards and Hamilton on finding the tender safe in Samarang, for I have searched the Record Office in vain for Oliver's log. If he kept any, it was not thought worth preserving. On the night the tender parted company, the 22nd June, 1791, the natives of the south-east end of Upolu made a determined attack upon the little vessel with their canoes. The seven-barrelled pieces made terrible havoc among them, but, never having seen fire-arms, and not understanding the connection between the fall of their comrades and the report, they kept up the attack with great fury. But for the boarding netting they would easily have taken the schooner, and indeed, one fellow succeeded in springing over it, and would have felled Oliver with his club had he not been shot dead at the moment of striking. On the 23rd they cruised about in search of the Pandora until the afternoon when, having drunk their last drop of water, they gave her up, and made sail for Namuka, the appointed rendezvous. The torture they suffered from thirst on the passage was such that poor Renouard, the midshipman, became delirious, and[13] continued so for many weeks. Their leeway and the easterly current combined to set them to the westward of Namuka, and the first land they made was Tofoa, which they mistook for Namuka, their rendezvous. The natives, the same that had attacked Bligh so treacherously two years before, sold them provisions and water, and then made an attempt to take the vessel, and would have succeeded but for the fire-arms. On the very day of the attack the Pandora dropped anchor at Namuka, within sight of Tofoa, and not finding her tender, bore down upon that island. Had Oliver been able to wait there for her, his troubles would have been at an end. But he dared not take the risk, and when Edwards sent a boat ashore to make enquiries the little schooner had sailed. The reception accorded to Edwards at Tofoa is very characteristic of the Tongans. Lieutenant Hayward, who had been present at the attack made upon Bligh, recognised several of the murderers of Norton among the people who crowded on board to do homage to the great chief, Fatafehi, who had taken passage in the frigate, but Edwards dared not punish them for fear that his tender should fall among them after he had left. Had he but known that these men had come red-handed from a treacherous attack upon the tender; that Fatafehi, who so loudly condemned their treachery to Bligh, and assured him that nothing had been seen of the little vessel, had just heard of the abortive attack they had made upon her, he would have taught them a lesson that would have lasted the Tongans many years, and might have saved the lives of the Europeans who perished in the taking of the Port-au-Prince and the Duke of Portland. For these "Norsemen of the Pacific," whom Cook, knowing nothing of the treachery they had planned against him under the guise of hospitality, misnamed the "Friendly Islanders," were, in reality, a nation of wreckers.

[14] Leaving Tofoa about July 1st, the schooner ran westward for two days "nearly in its latitude," and fell in with an island which Edwards supposed to be one of the Fiji group. The island of the Fiji group that lies most nearly in the latitude of Tofoa is Vatoa, discovered by Cook, but there are strong reasons for seeking Oliver's discoveries elsewhere. Vatoa lies only 170 miles from Tofoa, and, therefore, if Oliver took two days in reaching it, he cannot have been running at more than three knots an hour. But, early in July, the south-east trade wind is at its strongest, and with a fair wind a fast sailer, as we know the schooner to have been, cannot have been travelling at a slower rate than six knots. We are further told that Oliver waited five weeks at the island, and took in provisions and water. Now, in July, which is the middle of the dry season, no water is to be found on Vatoa except a little muddy and fetid liquid at the bottom of shallow wells which the natives, who rely upon coconuts for drinking water, only use for cooking. Provisions also are very scarce there at all times. The same objections apply to Ongea and Fulanga which lie fifty miles north of Vatoa, in the same longitude, though they certainly possess harbours in which a vessel could lie for five weeks, which Vatoa does not. If, however, the schooner ran at the rate of six knots, as may safely be assumed, all difficulties, except that of latitude, vanish together, for at the distance of 290 nautical miles from Tofoa lies Matuku, which with much justification has been described by Wilkes as the most beautiful of all the islands in the Pacific. There the natives live in perpetual plenty among perennial streams, and could victual the largest ship without feeling any diminution of their stock. In the harbour three frigates could lie in perfect safety, and the people have earned a reputation for honesty and hospitality to passing ships which belongs to the inhabi[15]tants of none of the large islands. There is another alternative—Kandavu—but to reach that island, the schooner must have run at an average of eleven knots, and the number and cupidity of the natives would have made a stay of five weeks impossible to a vessel so poorly manned and armed.

All these considerations point to the fact that Oliver lay for five weeks at Matuku, which lies but fifty miles north of the latitude of Tofoa. He was, therefore, the first European who had intercourse with the Fijians. Their traditions have never been collected, and if one be found recording the insignificant details so dear to the native poet, such as the boarding netting, or the sickness of Midshipman Renouard, or better still, the outbreak of the Great Lila Sickness, the inference may be taken as proved.

Any other navigator than Edwards would have given us details of Oliver's wonderful voyage, or, at least, would have preserved his log, but the voyage from Fiji to the Great Barrier reef is a blank. Hamilton, indeed, alludes vaguely to the crew having had to be on their guard "at other islands that were inhabited," and since their course from Fiji to Endeavour Straits would have carried them through the heart of the New Hebrides, and close to Malicolo, we may assume that they called at Api, at Ambrym or at Malicolo to replenish their stock of water. They reached the Great Barrier reef in the greatest distress, and having run "from shore to shore," i.e. from New Guinea to within sight of the coast of Queensland without finding an opening, and having to choose between the alternatives of shipwreck or of death by famine, they went boldly at it, and beat over the reef. Even then they would have starved but for their providential encounter with a small Dutch vessel cruising a little to the westward of Endeavour Straits, which supplied them with water[16] and provisions. The governor of the first Dutch settlement they touched at, having a description of the mutineers from the British Government, and observing that their schooner was built of foreign timber, refused to believe their account of themselves, especially as Oliver, being a petty officer, could produce no commission or warrant in support of his statement, and imprisoned them all, without, however, treating them with harshness. On the first opportunity he sent them to Samarang, where Edwards had them released. The plucky little schooner was sold, to begin another career of usefulness as set forth in the footnote to p. 33, and her purchase money was divided among the Pandora's crew.

Thus ended one of the most eventful voyages in the history of South Sea discovery, dismissed by Edwards in a few lines; by Hamilton in two pages. The search made among the naval archives at the Record Office leaves but little hope that any log-book or journal has been preserved.

Meanwhile, Edwards, disappointed in his search for the tender at Namuka and Tofoa, and prevented by a head wind from examining Tongatabu, set his course again for Samoa, and passed within sight of Vavau by the way. Making the easterly extremity of the group, he visited in turn Manua, Tutuila, and Upolu, but, like Bougainville, did not sight Savaii, which lay a little to the northward of his course. It is not surprising that the natives of Upolu denied all knowledge of the tender, seeing that they had made a determined attempt upon her less than a month before. From Samoa he sailed to Vavau which he named Howe's Group, in ignorance that it had been discovered by Maurelle ten years before, and subsequently visited by La Pérouse. Running southward, he made Pylstaart, at that time inhabited by Tongan castaways, and the fact that he did not stop to examine it, although he saw by the[17] smoke that it was inhabited, shows that he had begun to tire of his search for the mutineers. Having enquired at Tongatabu and Eua, he returned to Namuka for water, and at this point any systematic search either for the tender or the mutineers seems to have been abandoned.

Edwards had now been nine months at sea, and the prospect of the long homeward voyage round the Cape was still before him. With every league he had sailed westward the scent had grown fainter, and he was about to pass the spot from which the mutineers were known to have sailed in the opposite direction. His course is not easy to explain. To reason that the tender had fallen to leeward of her rendezvous, and had been compelled to seek shelter and provisions at one of the islands discovered by Bligh only two days' sail to the westward, required no high degree of foresight; and yet Edwards, who must have known the position of the Fiji islands from Bligh's narrative, deliberately set his course for Niuatobutabu, two days' sail to the north-west. But, falling to leeward of it, he made Niuafo'ou, the curious volcanic island discovered by Schouten in 1616, and never since visited. The prevailing wind making a visit to Niuatobutabu now impossible, he visited Wallis Island, and then bore away to the west.

On August 8th, 1791, he made the discovery of Rotuma, whose enterprising people now furnish the Torres Straits pearl fishery with its best divers. It is difficult to forgive him for leaving so meagre an account of this interesting little community of mixed Polynesian and Micronesian blood. Edwards was probably mistaken in thinking their intentions hostile. Kau Moala, a Tongan who visited them in 1807, and related his experiences to Mariner, describes them as always friendly to strangers. Probably they took the Pandora for a god-ship, and since the[18] Immortals of their Pantheon are generally malevolent, they left their women behind, and flourished weapons to scare the gods into good behaviour. In 1807 they had forgotten the visit, perhaps because it had brought them no calamity to inspire the native poets. Hamilton relates an incident quite in keeping with the character of this determined and sturdy little people. "One fellow was making off with some booty, but was detected; and although five of the stoutest men in the ship were hanging upon him, and had fast hold of his long flowing black hair, he overpowered them all, and jumped overboard with his prize."

The ill fortune that pursued Edwards, that had baulked him of Pitcairn when it lay within a few hours' sail, that had cheated him at once of the recovery of his tender and the discovery of Fiji, and was soon to rob him of his ship, now dealt him the unkindest cut of all. On August 13th, he sighted the island of Vanikoro, and ran along its shore, sometimes within a mile of the reef. There was no conceivable reason why he should not have made some attempt to communicate with the inhabitants whose smoke signals attracted his attention. Had he done so, he would have been the means of rescuing the survivors of La Pérouse's expedition, and of clearing away the mystery that covered their fate for so many years. For, after Dillon's discoveries, there can be little doubt that they were on the island at that very time, and it is not unlikely that the smoke was actually a signal made by them to attract his attention. The Comte de la Pérouse, who had been despatched on a voyage of discovery by Louis XVI. on the eve of the Revolution, handed his journals to Governor Phillip in Botany Bay for transmission to Europe in 1788, and neither he, nor his two frigates, nor any of their company were ever seen again. Their fate produced so painful an impression in France that the National Assembly, then in the throes of the Revolution, sent out a relief[19] expedition under "Citizen-admiral" d'Entrecasteaux, and issued a splendid edition of his journals at the public expense. We now know from the native account elicited by Dillon that during a hurricane on a very dark night both frigates struck on the reef of Vanikoro, that the Astrolabe foundered with all hands in deep water, and the crew of the Boussole got safe to land. They stayed on the island until they had built a brig of native timber, in which they sailed away to the westward to meet a second shipwreck, perhaps on the Great Barrier reef. But two of them stayed behind for many years, and of these one was certainly alive in 1825. Now, Edwards saw Vanikoro just three years after the wreck, and even if the brig had sailed, there were two castaways who could have cleared up the mystery.

After a narrow escape from shipwreck on the Indispensable Reef, he made the coast of New Guinea, supposing it to be one of the Louisiades. And here has occurred one of those curious errors in geographical nomenclature which are perpetuated by the most permanent of all histories—the Admiralty charts. Edwards gives the positions of two conspicuous headlands, which he named Cape Rodney and Cape Hood, and of a mountain lying between them which he called Mount Clarence. All these names appear in the Admiralty charts, but they are assigned to the wrong places. To a ship coming from the eastward the Cape Rodney of the charts is not conspicuous enough to have attracted Edwards' attention. The Cape Hood of the charts, on the contrary, cannot be mistaken, and it lies exactly in the position which Edwards gave for Cape Rodney. The "Cape Hood" that Edwards saw was undoubtedly Round Head, and his Mount Clarence must have been the high cone between them in the Saroa district. The Pandora must have approached on one of those misty mornings when the clouds creep down the mountain[20] sides of New Guinea, and obscure the ranges that rise, tier upon tier, right up to the towering peak of Mount Victoria, or Edwards could not have mistaken the continent for the insignificant islands of the Louisiades. On such a morning a narrow line of coast stands out clear against a background of sombre fog.

The baleful fortune of the Pandora, now folded her wings and perched upon the taffrail. By hugging the coast of New Guinea she would have won a clear passage through these wreck-strewn straits of Torres, but the navigators of those days counted on clear water to Endeavour Straits, and recked little of the dangers of the Great Barrier reef. Bligh, who chanced upon a passage in 12.34 S. Lat. so aptly that he called it "Providential Channel," cautioned future navigators in words that should have warned Edwards against the course he was steering. "These, however, are marks too small for a ship to hit, unless it can hereafter be ascertained that passages through the reef are numerous along the coast." Edwards was not looking for Bligh's passage, which lay more than two degrees southward of his course. He had lately adopted a most dangerous practice of running blindly on through the night. Until he made the coast of New Guinea, he had profited by the warning of Bougainville, the only navigator whose book he seems to have studied, and always lay to till daylight, but now, in the most dangerous sea in the world, he threw this obvious precaution to the wind. Hamilton, to whom we are indebted for this information (for it did not transpire at the court martial) says that "the great length of the voyage would not permit it." How fatuous a proceeding it was in unsurveyed and unknown waters may be judged from the fact that in coral seas that have been carefully surveyed all ships of war are now compelled to keep the lead going whenever they move in coral waters. On[21] August 25th he discovered the Murray Islands, and, after spending the day in a vain attempt to force a passage through them, he followed the reef southward for two days without finding a passage. This must have brought him very near the latitude of Bligh's passage. On the morning of August 28th Lieut. Corner was sent to examine what appeared to be a channel, and an hour before dark he signalled that he had found a passage large enough for the ship. The night fell before the boat could get back, and this induced Edwards, who had already lost one boat's crew and his tender, to lie much closer to the reef than was prudent. The current did the rest. About seven the ship struck heavily, and, bumping over the reef, tore her planking so that, despite eleven hours incessant pumping, she foundered shortly after daylight. Eighty-nine of the ship's company and ten of the mutineers were picked up by the boats and landed on a sand cay four miles distant, and thirty-one sailors, and four mutineers (who went down in manacles) were drowned.

Having read the different versions of this affair both for and against Edwards, I think it is proved that, besides treating his prisoners with inhumanity, he disregarded the orders of the Admiralty. His attitude towards the prisoners was always consistent. We learn from Corner that he allowed Coleman, Norman and Mackintosh to work at the pumps, but that when the others implored him to let them out of irons he placed two additional sentries over them, and threatened to shoot the first man who attempted to liberate himself. Every allowance must be made for the fear that in the disordered state of the ship, they might have made an attempt to escape, but during the eleven hours in which the water was gaining upon the pumps there was ample time to provide for their security. That so many were saved was due, not to him, but to a boatswain's mate, who risked his own life to[22] liberate them. Lieut. Corner, who would not have been likely to err on the side of hostility to Edwards, gives his evidence against him in this particular. But whether he is to be believed or not, the fact that four of the prisoners went down in irons is impossible to extenuate.

Edwards dismisses the boat voyage in very few words, though, in fact, it was a remarkable achievement to take four overloaded boats from the Barrier Reef to Timor without the loss of a single man. He made the coast of Queensland a little to the south of Albany Island, where the blacks first helped him to fill his water breakers, and then attacked him. He watered again at Horn Island, and then sailed through the passage which bears Flinders' name owing to the fallacy that he discovered it. After clearing the sound, he seems to have mistaken Prince of Wales' Island for Cape York, which he had left many miles behind him.

Favoured by a fair wind and a calm sea, he made the run from Flinders passage to Timor in eleven days. Like Bligh, he found that the young bore their privations better than the old, and that the first effect of thirst and famine is to make men excessively irritable. Hamilton records a characteristic incident. Edwards had neglected to conduct prayers in his boat until he was reminded of his duty by one of the mutineers, who was leading the devotions of the seamen in the bows of the boat. Scandalized at the impropriety of a "pirate" daring to appeal to the Highest Tribunal for mercy, as it were, behind the back of the earthly court before which he was shortly to be arraigned, the captain sternly reproved him, and conducted prayers himself. A sense of humour was not numbered among Edwards' endowments.

Timor was sighted on the 13th September, and on the 15th the party landed at Coupang, where the Dutch authorities received them with every hospitality. Here[23] they met the survivors of a third boat voyage, scarcely less adventurous than Bligh's and their own. A party of convicts, including a woman and two small children, had contrived to steal a ship's gig and to escape in her from Port Jackson. Sleeping on shore at nights whenever possible, subsisting on shell-fish and sea-birds, they ran the entire length of the Queensland coast, threaded Endeavour Straits, and arrived at Coupang after an exposure lasting ten weeks without the loss of a single life. Having given themselves out as the survivors from the wreck of an English ship, they were entertained with great hospitality until the arrival of Edwards two weeks later, when they betrayed their story gratuitously. The captain of a Dutch vessel, who spoke English, on first hearing the news of Edwards' landing, ran to them with the glad tidings of their captain's arrival, on which one of them started up in surprise and exclaimed, "What captain? Dam'me! we have no captain." On hearing this the governor had them arrested, and sent to the castle, one man and the woman having to be pursued into the bush before they were taken. They then confessed that they were escaped convicts.

Apart from their adventurous voyage, there is much romance about their story. William Bryant, the leader, had been transported for smuggling, and his sweetheart, Mary Broad, who was maid to a lady in Salcombe, in Devonshire for connivance in her lover's escape from Winchester Gaol. In due course they were married in Botany Bay, where Bryant was employed as fisherman to the governor, a post that enabled him to plan their successful escape. Bryant and both children died on the voyage home, together with three others, Morton, Cox and Simms, but the woman survived to obtain a full pardon, owing chiefly to the exertions of an officer of marines who went home with her in the Gorgon, and eventually married[24] her.[24-1] Butcher, who was also pardoned, returned to New South Wales and became a thriving settler. The remaining four were sent back to complete their sentences. Their story has been graphically told by Messrs. Louis Becke and Walter Jeffery in "The First Fleet Family."

During the voyage from Coupang to Batavia Edwards narrowly escaped a second shipwreck. The Rembang was dismasted on a lee shore in a cyclone, and, but for the exertions of the English seamen, would assuredly have been stranded, the Dutch sailors, who, says the facetious Hamilton, "would fight the devil should he appear to them in any other shape but that of thunder and lightning," having taken to their hammocks. At Samarang, as already related, Edwards found the tender, which he had long given up for lost, and the price she fetched enabled the crew to purchase decent clothing. Heywood afterwards asserted that no clothing was given to the prisoners but what they could earn by plaiting and selling straw hats. They were miserably housed, when on board the Rembang, and kept in rigid confinement both at Batavia, and on the Vreedemberg, in which they made the voyage to the Cape.

At Batavia Edwards divided his men among three Dutch vessels homeward bound, but at the Cape he removed his own contingent into H.M.S. Gorgon, and arrived at Spithead on June 18th, 1792. Two days later the ten mutineers were transferred to H.M.S. Hector, Captain Montague, and the convicts were sent to Newgate. The court martial, which did not assemble until September 12th, lasted five days, with the result that Norman, Coleman, Mackintosh and Byrne were acquitted,[25] and Heywood, Morrison, Ellison, Burkitt, Millward and Muspratt were condemned to death, the two first being recommended to mercy. On October 24th Heywood and Morrison received the King's pardon, and both re-entered the Navy, Heywood to retire in 1816, when nearly at the head of the list of captains; Morrison to go down in the ill-fated Blenheim in which he was serving as gunner. Muspratt also was pardoned, but the three others were hanged on board the Brunswick in Portsmouth Harbour on October 29th, 1792. Thus ended a voyage that, for adventure and discovery, deserves a high place in the history of maritime enterprise in the Pacific. Voyages take their rank from the scientific attainments and literary ability of the men who record them, and the Pandora, unlucky in her fate as in her ill-omened name, was scarcely less unfortunate in her historian.

B. T.

[10-1] Mr. Louis Becke, "The Mutineers."

[24-1] The Gorgon also carried Lieut. Clark, of the Royal Marines, whose journal of the voyage to Botany Bay and Norfolk Island in 1789 throws a very interesting light upon the early days of the colony. Unfortunately the journal says very little of the Gorgon's voyage home.

[26]

[27]

"Pandora in Sta Cruz Bay,

Teneriff,

25th November, 1790.

[R 28 Dec. and Read.]

Sir,

Be pleased to acquaint My Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty that I sailed again from Jack-in-the-Basket with His Majesty's Ship Pandora under my command on the 7th day of November, and anchored in Santa Cruz by Teneriffe on the 22nd: that nothing particular occured in my passage to this place, except that of my falling in with His Majesty's sloop Shark on the 17th November in Latitude 32° 33′ Longitude 13° 40′ W. bound to Madeira with despatches for Rear Admiral Cornish, and my learning from them that the matters in dispute with Spain were amicably settled, of which circumstance I was unacquainted when I left England. I am now compleating my water, and have taken on board full 3 months wine for my compliment, with some fruit and vegetables, and purpose and flatter myself that I shall be able to sail from hence this evening. Inclosed I send the state and condition of His Majesty's Ship Pandora for their Lordships' information, and I have the honour to be,

Sir,

Your most obedient and ever humble servant,

Edward Edwards.

Phillip Stevens, Esq."

[28]

"Pandora at Rio Janeiro,

the 6th January, 1791.

[Received 29th June and read.]

Sir,

Be pleased to acquaint My Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty that I sailed from Teneriff with His Majesty's Ship Pandora on the afternoon of the 25th November, agreeable to my intentions signified to their Lordships by letter from that island, and anchored off the city Rio Janeiro on the evening of the 31st of December with a view to compleat my water and to get refreshments for the ship's company and from my being persuaded that very long runs, particularly with new ships' companies, are prejudicial to health, and as my men are of that description, and have also suffered in their health from a fever which has prevailed amongst them in a greater or less degree ever since they left England, were other inducements for my touching at this port. I shall stay here no longer than is absolutely necessary to procure these articles, and which I expect to be able to accomplish by the seventh of this month, and I shall then proceed on my voyage as soon as wind and weather will permit.

Herewith I send the state and condition of His Majesty's Ship Pandora, and I have the honour to be, Sir,

Your most obedient and humble servant,

Edw. Edwards."

"Batavia, the 25th November, 1791.

29th May, 1792.

From Amsterdam.

Sir,

In a letter dated the 6th day of January, 1791, which I did myself the honour to address to you from Rio Janeiro I gave an account of my proceedings up to that[29] time and inclosed the state and condition of His Majesty's Ship Pandora under my command, and having compleated the water and procured such articles of provision, etc., for the use of the Ship's Company as they were in want of and I thought necessary for the voyage, I sailed from that port on the 8th January, 1791, run along the coast of America, Tierra Del Fuego, Hatin Land, round Cape Horn and proceeded directly to Otaheite, and arrived at Matavy Bay in that Island on the 23rd March without having touched in any other place in my passage thither.

It was my intention to have put into New Year's harbour, or some other port in its neighbourhood to complete our water and to refresh my people, could I have effected that business within the month of January; but as I arrived too late on that coast to fulfil my intentions within the time, it determined me to push forward without delay, by which means I flattered myself I might avoid that extreme bad weather and all the evil consequences that are usually experienced in doubling Cape Horn in a more advanced season of the year, and I had the good fortune not to be disappointed in my expectation.

After doubling the Cape, and advancing Northward into warmer weather, the fever which had prevailed on board gradually declined, and the diseases usually succeeding such fevers prevented by a liberal use of the antiscorbutics and other nourishing and useful articles with which we were so amply supplied, and the ship's company arrived at Otaheite in perfect health, except a few whose debilitated constitutions no climate, provisions or medicine could much improve.

In our run to Otaheite we discovered 3 islands: the first, which I called Ducie's Island, lies in Latitude 24° 40′ 30″ S. and Longitude 124° 36′ 30″ W. from Greenwich. It is between 2 and 3 miles long. The second I called Lord Hood's Island. It lies in Latitude[30] 21° 31′ S. and Longitude 135° 32′ 30″ W., and is about 8 miles long. The third I called Carysfort's Island. It lies in Latitude 20° 49′ S. and Longitude 138° 33′ W. and it is 5 miles long. They are all three low lagoon islands covered with wood, but we saw no inhabitants on either of them.[30-1] Before we anchored at Matavy Bay, Joseph Coleman, Armourer of the Bounty, and several of the natives came on board, from whom I learned that Christian the pirate had landed and left 16 of his men on the Island, some of whom were then at Matavy, and some had sailed from there the morning before our arrival (in a schooner they had built) for Papara, a distant part of the Island, to join other of the pirates that were settled at that place, and that Churchill, Master at Arms, had been murdered by Matthew Thompson, and that Matthew Thompson was killed by the natives and offered as a sacrifice on their altars for the murder of Churchill, whom they had made a chief.

George Stewart and Peter Heywood, midshipmen of the Bounty, came on board the Pandora soon after she came to an anchor, and I had also information that Richard Skinner was at Matavy. I desired Poen, an inferior chief (who, in the absence of Otoo, was the principal person in the district) to bring him on board. The chief went on shore for the purpose, and soon after he returned again and informed me that Skinner was coming on board. Before night he did come on board, but whether it was in consequence of the chief's instructions, or his own accord,[31] I am at a loss to say. As soon as the ship was moored the pinnace and launch were got ready and sent under the direction of Lt. Corner and Hayward in pursuit of the pirates and schooner in hopes of getting hold of them before they could get information of our arrival, and Odiddee, a native of Bolabola, and who has been with Capt. Cook, etc., went with them as a guide.

The boats were discovered by the pirates before they had arrived at the place where these people had landed, and they immediately embarked in their schooner and put to sea, and she was chased the remainder of the day by our boats, but, it blowing fresh, she outsailed them, and the boats returned to the ship. Jno. Brown, the person left at Otaheite by Mr. Cox of the Mercury,[31-1] and from whom their Lordships supposed I might get some useful information, had been under the necessity for his own safety to associate with the pirates, but he took the opportunity to leave them when they were about to embark in the schooner and put to sea. He informed me that they had very little water and provisions on board, or vessels to hold them in, and, of course, could not keep at sea long. I entered Brown on the ship's books as part of the compliment and found him very intelligent and useful in the different capacities of guide, soldier and seaman. I employed different people to look out for and to give information on their landing either on this or the neighbouring islands.

On the 26th, in the evening, sent the pinnace to Edee by desire of the old Otoo, or king, to bring him on board the Pandora. Early on the morning of the 27th, I had information that the pirates were returning with the schooner to Papara and that they were landed and retired to the mountains, to endeavour to conceal and defend themselves. Immediately sent Lt. Corner with 26 men[32] in the launch to Papara to pursue them. At night the Otoo, his two queens and suite came on board the pinnace and slept on board the Pandora, which they afterwards frequently did.

The next morning Lt. Hayward was sent with a party in the pinnace to join the party in the launch at Papara. I found the Otoo ready to furnish me with guides and to give me any other assistance in his power, but he had very little authority or influence in that part of the island where the pirates had taken refuge, and even his right to the sovereignty of the eastern part of the island had been recently disputed by Tamarie, one of the royal family. Under these circumstances I conceived the taking of the Otoo and the other chiefs attached to his interest into custody would alarm the faithful part of his subjects and operate to our disadvantage. I therefore satisfied myself with the assistance he offered and had in his power to give me, and I found means at different times to send presents to Tamarie (and invited him to come on board, which he promised to do, but never fulfilled his promise), and convinced him I had it in my power to lay his country in waste, which I imagined would be sufficient at least to make him withhold that support he hitherto, through policy, had occasionally given to the pirates in order to draw them to his interest and to strengthen his own party against the Otoo.

I probably might have had it in my power to have taken and secured the person of Tamarie, but I was apprehensive that such an attempt might irritate the natives attached to his interest, and induce them to act hostilely against our party at a time the ship was at too great a distance to afford them timely and necessary assistance in case of such an event, and I adopted the milder method for that reason, and from a persuasion that our business could be brought to a conclusion at less risk and in less time by that[33] means. The yawl was sent to Papara with spare hands to bring back the launch which was wanted to water the ship, and on the 29th the launch returned to the ship with James Morrison,[33-1] Charles Norman, and Thomas Ellison, belonging to the Bounty, and who had been made prisoners at Papara on the 7th April. The companies returned with the detachment from Papara, and brought with them the pirate schooner which they had taken there. The natives had deserted the place, and I had information that the six remaining pirates had fled to the mountains.

On the 5th I sent Lt. Hayward with 25 men in the schooner and yawl to Papara, the old Otoo and several of the youths, &c., went with him. On the 7th, in the morning, Lt. Corner was landed with 16 men at Point Venus in order to march round the back of the mountains, in which the pirates had retreated, to cooperate with the party sent to Papara. Orissia, the Otoo's brother, and a party of natives went with him as guides and to carry the provisions, &c.

On the 9th Lt. Hayward returned with the schooner and yawl and brought with him Henry Hillbrant, Thomas[34] M'Intosh, Thomas Burkitt, Jno. Millward, Jno. Sumner and William Muspratt, the six remaining pirates belonging to the Bounty. They had quitted the mountains and had got down near the seashore when they were discovered by our party on the opposite side of a river. They submitted, on being summoned to lay down their arms. Lt. Corner with his party marched across the mountains to Papara, and a boat was sent for them there, and they returned on board again on the 13th in the afternoon. I put the pirates in the round house which I built at the after part of the Quarter deck for their more effectual security, airy and healthy situation, and to separate them from, and to prevent their having any communication with, or to crowd and incommode the ship's company.

Contrary to my expectations, the water we got at the usual place at Point Venus turned out very bad, and on touching for better, most excellent water was found issuing out of a rock in a little bay to the southward of One Tree Hill. I mention this circumstance because it may be of importance to be known to other ships that may hereafter touch at that island.

The natives had in their possession a bower anchor belonging to the Bounty, which that ship had left in the bay, and I took it on board the Pandora, and made them a handsome present by way of salvage and as a reward for their ingenuity in weighing it with materials so ill calculated for the purpose. I learned from different people and from journals kept on board the Bounty, which were found in the chests of the pirates at Otaheite, that after Lt. Bligh and the people with him were turned adrift in the launch, the pirates proceeded with the ship to the Island of Toobouai in Latitude 20° 13′ S. and Longitude 149° 35′ W., where they anchored on the 25th May, 1789. Before their arrival there they threw the greatest part of the bread fruit plants overboard, and the property of the[35] officers and people that were turned out of the ship was divided amongst those who remained on board her, and the royals and some other small sails were cut up and disposed of in the same manner.

Notwithstanding they met with some opposition from the natives, they intended to settle on this island, but after some time they perceived that they were in want of several things necessary for a settlement and which was the cause of disagreements and quarrels amongst themselves. At last they came to a resolution to come to Otaheite to get such of the things wanted as could be procured there, and in consequence of that resolution they sailed from Toobouai at the latter end of the month and arrived at Otaheite on the 6th of June. The Otoo and other natives were very inquisitive and desirous to know what was become of Lt. Bligh and the other absentees and the bread fruit plants, &c. They deceived them by saying that they had fallen in with Captain Cook at an island he had lately discovered called "Why-Too-Tackee" [Aitutaki], and where he intended to settle, and that the plants were landed and planted there, and that Lt. Bligh and the other absentees were detained to assist Captain Cook in the business he had in hand, and that he had appointed Christian captain of the Bounty and ordered him to Otaheite for an additional supply of hogs, goats, fowls, bread fruit plants, &c.

These humane islanders were imposed upon by this artful story, and they were so rejoiced to hear that their old friend Captain Cook was alive and was near them that they used every means in their power to procure the things that were wanted, so that in the course of a few days the Bounty took on board 312 hogs, 38 goats, eight dozen fowls, a bull and a cow, and a quantity of bread fruit plants, &c. They also took with them a woman, eight men and seven boys. With these supplies[36] they sailed from Otaheite on the 19th June and arrived again at Toobouai on the 26th. They landed the live stock on the quays that were near the harbour, lightened the ship and warped her up the harbour into two fathoms water opposite to the place where they intended to build the fort. On this occasion their spare masts, yards and booms were got out and moored, but they afterwards broke adrift and were lost.[36-1]

On the 19th July they began to build the fort. Its dimensions were 50 yards square. These villains had frequent quarrels amongst themselves which at last were carried to such a length that no order was observed amongst them, and by the 30th August the work at the fort was discontinued. They had also almost continual disputes and skirmishes with the natives, which were generally brought on by their own violence and depredations. Christian, perceiving that he had lost his authority, and that nothing more could be done, desired them to consult together and consider what step would be the most advisable to take, and said that he would put into execution the opinion that was supported by the most votes. After long consultation it was at last determined that the scheme of staying at Toobouai should be given up, and that the ship should be taken to Otaheite, where those who chose to go on shore should be at liberty to do so, and those who remained on the ship might take her away to whatever place they should think fit.

In consequence of this final determination preparations were made for the purpose and they sailed from Toobouai on the 15th and arrived at Matavy Bay, Otaheite, on the 20th September 1789. The bull which they took from Otaheite died on its passage to Toobouai, and they killed the cow before they left that island, yet, notwithstanding this and the depredations they committed there, the[37] natives still derived considerable advantage from their visits, as several hogs, goats, fowls and other things of their introduction were left behind. These sixteen men mentioned before were landed at Otaheite, viz.:—

These fourteen were made prisoners by my people and Charles Churchill and Matthew Thompson were murdered on that island. Previous to these people being put on shore the small arms, powder, canvas and the small stores belonging to the ship were equally divided amongst the whole crew. After building the schooner six of these people actually sailed in her for the East Indies, but meeting with bad weather and suspecting the abilities of Morrison, whom they had chosen to be their captain to navigate her there, they returned again to Otaheite on the night between the 21st and 22nd of September 1789 and were seen in the morning to the N.W. of Point Venus.[37-5]

[38]Fletcher Christian, Edward Young, Matthew Quintall, William M'Koy, Alexander Smith, John Williams, Isaac Martin, William Brown and John Mills went away in the ship and they also took with them several natives of these islands, both men and women, but I could not exactly learn their numbers, only that they had on board a few more women than white men, a deficiency of whom had formerly been one of their grievances and the principal cause of their quarrels. Christian had been frequently heard to declare that he would search for an unknown or uninhabited island in which there was no harbour for shipping, would run the ship ashore and get from her such things as would be useful to him and settle there, but this information was too vague to be followed in an immense ocean strewed with an almost innumerable number of known and unknown islands; therefore after the ship was caulked, which I found was necessary to be done, the rigging overhauled and in other respects refitted her for sea, and fitted the pirates' schooner as a tender, and put on board two petty officers[38-1] and seven men to navigate her, conceiving she would be of considerable use in covering the boats in my future search for the Bounty, as well as for reconnoitring the passage through the reef leading to Endeavour Straits; I sailed from Otaheite on the 8th of May with a view to put the remainder of my orders into execution.

Oediddee was desirous to go in the Pandora to Ulietia and to Bolabola, and as I thought he would be useful as a guide for the boats I took him with me and steered for[39] Huahaine which we saw the next morning. The tender and the boats were employed the 9th and part of the 10th in examining the harbours, and Oediddee went with them as pilot. Several chiefs came on board and brought with them hogs and other articles, the produce of the island, and a servant of Omai also came on board, and said that he was not then much the better for his master's riches, however his former connections was the cause of his visit to the ship being made very profitable to him, and all the chiefs and their attendances received presents from me. Two of the chiefs of this island were desirous to go in the ship to Ulietia and I had given them leave to, but when the ship was about to make sail they suddenly changed their minds and went on shore and took Oediddee with them. Oediddee promised to follow us there the next day, but we did not see him again.

I proceeded to Ulietea Otaka and Bolabola, and the tender and boats were employed in examining the bays and harbours of these islands, but we got no intelligence of the Bounty or her people. Tahatoo, who called himself king of Bolabola, informed me that he had been a few days before at Tubai, which is a small, low island situated on the Northward of Bolabola and under its jurisdiction, and that there were no white men upon that island, nor upon Maurua, another island in sight of it and to the westward of Bolabola. He also mentioned another island which I thought he called Mojeshah, but we know no such island unless it be Howe's Island, and that seems to be situated too far to the South and to the West for the island he attempted to describe and point out to us. The chiefs and several other people came on board from these islands and brought with them the usual produce, and they were at all the isles very pressing to prevail upon us to make a longer stay with them, but as I had no object particularly in view and my people in good health, I did not think it[40] proper unnecessarily to waste my time for the sake of procuring a few articles that were in greater abundance in these islands than at Otaheite. I made presents to all those chiefs as it was my custom to do to everyone that had the least pretension to pre-eminence, and to all the people who came on board in the first boat.

After leaving Bolabola I steered for Maurua and passed it at a small distance. Howe's Island was not seen by us as it is a low island and we passed to the Southward of it. I then shaped my course to get into the latitude of and to fall in to the Eastward of Why-to-tackee [Aitutaki].

On the 14th, Henry Hillbrant, one of the pirates, gave information that Christian had declared to him the evening before he left Otaheite that he intended to go with the Bounty to an uninhabited island discovered by Mr. Byron, situated to the Westward of the Isles of Danger, which, from description of the situation, I found to be the island called by Mr. Byron "The Duke of York's Island,"[40-1] and if they could land, would settle there and run the ship upon the reef and destroy her, and if they could not land, or if on examination found it would not answer their purpose, he would look out for some other uninhabited island. However, I continued my course for Why-to-tackee, being now determined to examine the island in preference to following any intelligence, however plausible, and on the morning of the 19th saw the Island of Why-to-tackee [Aitutaki],[40-2] and sent the tender in shore to ground and look out for a harbour.

[41] At noon sent Lt. Hayward in the yawl to look into a place on the N.W. part of the island that had the appearance of a harbour and to get intelligence of the natives. In the evening he returned. The place was so far from being fit for the reception of the ship that he could scarcely find a passage through the reef for the boat; he conversed with seven or eight different sets of people, whom he met with in canoes, and they all agreed that the Bounty was not, nor had not been there since Lt. Bligh left the island, nor did any of them known anything of her. Lt. Hayward recollected one of the natives, whom he remembered to have seen on board the Bounty when he discovered the island, and he saw another savage belonging to[42] a neighbouring island who knew Captain Cook and inquired after him, Omai and Oediddee, whom he said he had seen.

These people at first approached the boat with caution, and could not be prevailed upon to come on board the ship. As I was convinced that the Bounty was not on this island, and as Hervey's, Mangea and Wattea Islands to the S.E. of Why-to-tackee were inhabited, I did not think it probable that Christian, in the weak state the ship was in, would attempt to settle upon either of them, and as there was some plausibility in the information given me by Hillbrant the prisoner, and as the Duke of York's Island seemed to answer the description of such an island as Christian had been heard by others to declare he would search for to settle on, it being by Mr. Byron's account uninhabited, and with a harbour; and as the fact that it was out of the known track of ships in these seas since our acquaintance with the Society Islands, made it still more eligible for his purpose; from these united circumstances I thought it was probable he might make choice of the Duke of York's Island for his intended settlement. I therefore determined to proceed to that island, taking Palmerston's island in my way thither, as it also answered in all respects, except situation, to the description of the other; and at night I bore away and made sail for Palmerston's Island, and made that on the 21st in the afternoon.[42-1]

On the 22nd in the morning sent the schooner tender and cutter in shore to look for the harbours or anchorage, and soon after Lt. Corner was sent in the yawl for the same purpose and to look out for the Bounty and her people. At noon, perceiving the schooner and cutter had got round the Northernmost island, I stood round the[43] S.E. island with the ship in order to join the yawl that was at a grapnel off that island, and sent the other yawl to join Lt. Corner. At 4 the two yawls returned with a quantity of cocoanuts and Lt. Corner also returned on board. Soon after, Lt. Hayward was sent on shore in the yawl to examine the S.W. island. After dark we burnt several false fires as signals to the boat, but the weather being thick and squally she did not return till the morning of the 23rd, but the tender joined us that night and informed me that she had found a yard on the island marked "Bounty's Driver Yard" and other circumstances that indicated that the Bounty was, or had been there. The tender was immediately sent on shore after the yawl.

On the 23rd provisions, ammunition, &c., was sent on board the tender,[43-1] and Lt. Corner with a party of men were sent with the yawl and tender to land on the Northernmost island. At 4 in the afternoon, perceiving that the schooner tender had anchored under that island the yawl landing the party on the reef leading to it, Lt. Corner had orders to examine that and the Easternmost island very minutely to see if any other traces besides the yard could be made out of the Bounty or her people.

On the 24th in the morning sent the cutter on board the tender for intelligence, but she did not return till nearly 2 o'clock in the afternoon, when she brought with her seven men of Lt. Corner's party. She was sent on board the tender again with orders for the remainder of the party that was returned from the search to be brought on board the Pandora in the yawl, and for the cutter to remain on board the tender to embark Lt. Corner when[44] he returned, the midshipman having represented that she answered the purpose of landing and embarking better than the larger boat from the particular circumstances of the landing place; and I stood over for the S.W. island to take on board the other yawl which had been sent to ground near the reef of that island and to procure from it some cocoanuts, &c.

At 5 the yawl came on board, and I then stood towards the schooner in order to take the other yawl on board, but the weather became squally with rain and I stood out to sea. During the night the weather was rougher than usual, with an ugly sea and I did not get close in with them again till the 28th at noon, soon after which the yawl came on board from the schooner and informed us to my great astonishment and concern that the cutter had not been on board her since she left the ship.[44-1] The tender was ordered to run down by the side of the reef and if the cutter was not seen there to run out to sea six leagues and to steer about W.N.W.-W., it being the opposite point to that on which the wind blew from the preceding night, and I waited with the ship to take on board Lt. Corner who was not then returned from the search. He soon after appeared and was taken on board.

In his search he found a double canoe curiously painted, and different in make from those we had seen on the islands we had visited. A piece of wood burnt half through was also found. The yard and these things lay upon the beach at high water mark and were all eaten by the sea worm, which is a strong presumption they were drifted there by the waves. The driver yard was probably drove from Toobouai where the Bounty lost the greater part of her spars, and as no recent traces could be found on the island of a human being or any part of the wreck of a ship I gave up all further search and hopes of finding the Bounty[45] or her people there. I then stood out to sea and the ship and the tender cruized about in search of the cutter until the 29th in the morning, when seeing nothing of her, I being at that time well in with the land, sent on shore once more to examine the reef and beach of the northernmost island, but with no better success than before, as neither the cutter or any article belonging to her could be found there.

I then steered for the Duke of York's island which we got sight of at noon on the 6th June, and in the afternoon the tender and two yawls were sent on shore to examine the coast. On the 7th in the morning Lt. Corner and Hayward were sent on shore with a party of men attended by the schooner and two yawls. We soon after saw some huts upon the island and so made a signal to the boats to warn them of danger, and for them to be upon their guard against surprise. They landed and got canoes to the within side of the lagoon in which they made a circuit of it. A few houses were found in examining the hills on the opposite side of the lagoon, and also a ship's large wooden buoy, which appeared to be of foreign make, and had evident marks of its having been long in the water.

As Mr. Byron describes the Duke of York's island to be without inhabitants, the sight of the houses and ship's buoy, before they were minutely examined wrot so strongly on the minds of the people that they saw many things in imagination that did not exist, but all tended to persuade them that the Bounty's people were really upon the island agreeable to the intelligence given by Hillbrant, but after a most minute and repeated search, no human being of any description could be found upon the island. There were a number of canoes, spare paddles, fishing gear, and a variety of other things found in the houses which seemed to prove that it was an[46] occasional residence and fishery of the natives of some neighbouring islands.[46-1]

There is so great a difference in the situation of this island as laid down in the charts of Hawkesworth's collection of voyages and also some others from that of Captain Cook that there may be some doubt about its real situation. I followed that of Captain Cook, yet the situation of this island by our account did not exactly agree with him. He lays it down in Latitude 8° 41′ S. and Longitude 173° 3′ W., and the centre of the island by our account lies Latitude 8° 34′ S. and Longitude by observation 172° 6′, and by timekeeper 172° 39′ W. By our estimation this island is not so large as it is by Mr. Byron's. In other respects, except the houses, it answers his description very well. I should have stood off to the westward to have seen if there were any other islands in that direction, but I was apprehensive by so doing that I might have much difficulty in fetching the island I had then to visit, and as the wind was favourable to stand to the Southward when I left the island, I therefore satisfied myself in passing to the westward of it and stretching to the northward so far as to know there was no island within thirty miles of it on that point of the compass, and also to pass to the windward of the island when I put about and stood to the northward.

In standing to the Northward I discovered an island on the 12th June.[46-2] We soon perceived that it was a lagoon island, formed by a great many small islands connected together by a reef of rocks, forming a circle round the lagoon in its centre. It is low, but well wooded, amongst which the cocoanut tree is conspicuous both for[47] its height and peculiar form. As we approached the land we saw several natives on the beach. Lt. Hayward was sent with the tender and yawl in shore to reconnoitre and to endeavour to converse with the natives, and if possible to bring about a friendly intercourse with them. They made signs of friendship and beckoned him to come on shore, yet, whenever he drew near with the boat, they always retired, and he could not prevail on them to come to her; and the surf was thought too great to venture to land, at least before the friendship of the natives was better confirmed.