Harriet Martineau

"The Billow and the Rock"

Chapter One.

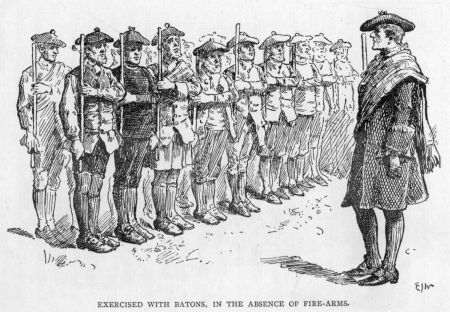

Lord and Lady Carse.

Scotland was a strange and uncomfortable country to live in a hundred years ago. Strange beyond measure its state of society appears to us when we consider, not only that it was called a Christian country, but that the people had shown that they really did care very much for their religion, and were bent upon worshipping God according to their conscience and true belief. Whilst earnest in their religion, their state of society was yet very wicked: a thing which usually happens when a whole people are passing from one way of living and being governed to another. Scotland had not long been united with England. While the wisest of the nation saw that the only hope for the country was in being governed by the same king and parliament as the English, many of the most powerful men wished not to be governed at all, but to be altogether despotic over their dependents and neighbours, and to have their own way in everything. These lords and gentlemen did such violent things as are never heard of now in civilised countries; and when their inferiors had any strong desire or passion, they followed the example of the great men, so that travelling was dangerous; citizens did not feel themselves safe in their own houses if they had reason to believe they had enemies; few had any trust in the protection of the law; and stories of fighting and murder were familiar to children living in the heart of cities.

Children, however, had less liberty then than in our time. The more self-will there was in grown people, the more strictly were the children kept in order, not only because the uppermost idea of everyone in authority was that he would be obeyed, but because it would not do to let little people see the mischief that was going on abroad. So, while boys had their hair powdered, and wore long coats and waistcoats, and little knee-breeches, and girls were laced tight in stays all stiff with whalebone, they were trained to manners more formal than are ever seen now.

One autumn afternoon a party was expected at the house of Lord Carse, in Edinburgh; a handsome house in a very odd situation, according to our modern notions. It was at the bottom of a narrow lane of houses—that sort of lane called a Wynd in Scotch cities. It had a court-yard in front. It was necessary to have a court-yard to a good house in a street too narrow for carriages. Visitors must come in sedan chairs and there must be some place, aside from the street, where the chairs and chairmen could wait for the guests. This old fashioned house had sitting-rooms on the ground floor, and on the sills of the windows were flower-pots, in which, on this occasion, some asters and other autumn flowers were growing.

Within the largest sitting-room was collected a formal group, awaiting the arrival of visitors. Lord Carse’s sister, Lady Rachel Ballino, was there, surrounded by her nephews and nieces. As they came in, one after another, dressed for company, and made their bow or curtsey at the door, their aunt gave them permission to sit down till the arrival of the first guest, after which time it would be a matter of course that they should stand. Miss Janet and her brothers sat down on their low stools, at some distance from each other; but little Miss Flora had no notion of submitting to their restraints at her early age, and she scrambled up the window-seat to look abroad as far as she could, which was through the high iron gates to the tall houses on the other side the Wynd.

Lady Rachel saw the boys and Janet looking at each other with smiles, and this turned her attention to the child in the window, who was nodding her little curly head very energetically to somebody outside.

“Come down, Flora,” said her aunt.

But Flora was too busy, nodding, to hear that she was spoken to.

“Flora, come down. Why are you nodding in that way?”

“Lady nods,” said Flora.

Lady Rachel rose deliberately from her seat, and approached the window, turning pale as she went. After a single glance in the court-yard, she sank on a chair, and desired her nephew Orme to ring the bell twice. Orme who saw that something was the matter, rang so vigorously as to bring the butler in immediately.

“John, you see?” said the pale lips of Lady Rachel, while she pointed, with a trembling finger, to the court-yard.

“Yes, my lady; the doors are fastened.”

“And Lord Carse not home yet?”

“No, my lady. I think perhaps he is somewhere near, and cannot get home.”

John looked irresolutely towards the child in the window. Once more Flora was desired to come down, and once more she only replied, “Lady nods at me.”

Janet was going towards the window to enforce her aunt’s orders, but she was desired to keep her seat, and John quickly took up Miss Flora in his arms and set her down at her aunt’s knee. The child cried and struggled, said she would see the lady, and must infallibly have been dismissed to the nursery, but her eye was caught, and her mind presently engaged by Lady Rachel’s painted fan, on which there was a burning mountain, and a blue sea, and a shepherdess and her lamb—all very gay. Flora was allowed to have the fan in her own hands—a very rare favour. But  presently she left off telling her aunt what she saw upon it, dropped it, and clapped her hands, saying, as she looked at the window, “Lady nods at me.”

presently she left off telling her aunt what she saw upon it, dropped it, and clapped her hands, saying, as she looked at the window, “Lady nods at me.”

“It is mamma!” cried the elder ones, starting to their feet, as the lady thrust her face through the flowers, and close to the window-pane.

“Go to the nursery, children,” said Lady Rachel, making an effort to rise. “I will send for you presently.” The elder ones appeared glad to escape, and they carried with them the struggling Flora.

Lady Rachel threw up the sash, crossed her arms, and said, in the most formal manner, “What do you want, Lady Carse?”

“I want my children.”

“You cannot have them, as you well know. It is too late. I pity you; but it is too late.”

“I will see my children. I will come home and live. I will make that tyrant repent setting up anyone in my place at home. I have it in my power to ruin him. I—”

“Abstain from threats,” said Lady Rachel, shutting the window, and fastening the sash.

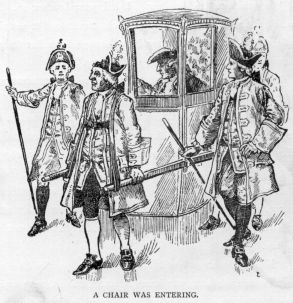

Lady Carse doubled her fist, as if about to dash in a pane; but the iron gates behind her creaked on their hinges, and she turned her head. A chair was entering, on each side of which walked a footman, whose livery Lady Carse well knew. Her handsome face, red before, was now more flushed. She put her mouth close to the window, and said, “If it had been anybody but Lovat you would not have been rid of me this evening. I would have stood among the chairmen till midnight for the chance of getting in. Be sure I shall to-morrow, or some day. But now I am off.” She darted past the chair, her face turned away, just as Lord Lovat was issuing from it.

“Ho! ho!” cried he, in a loud and mocking tone. “Ho, there! my Lady Carse! A word with you!” But she ran up the Wynd as fast as she could go.

“You should not look so white upon it,” Lord Lovat observed to Lady Rachel, as soon as the door was shut. “Why do you let her see her power over you?”

“God knows!” replied Lady Rachel. “But it is not her threats alone that make us nervous. It is the being incessantly subject—”

She cleared her throat; but she could not go on.

Lord Lovat swore that he would not submit to be tormented by a virago in this way. If Lady Carse were his wife—

“Well! what would you do?” asked Lady Rachel.

“I would get rid of her. I tell your brother so. I would get rid of her in one way, if she threatened to get rid of me in another. She may have learned from her father how to put her enemies out of the way.”

Lady Rachel grew paler than ever. Lord Lovat went on.

“Her father carried pistols in the streets of Edinburgh and so may she. Her father was hanged for it; and it is my belief that she would have no objection to that end if she could have her revenge first. Ay! you wonder why I say such things to you, frightened as you are already. I do it that you may not infuse any weakness into your brother’s purposes, if he should think fit to rid the town of her one of these days. Come, come! I did not say rid the world of her.”

“Merciful Heaven! no!”

“There are places, you know, where troublesome people have no means of doing mischief. I could point out such a place presently, if I were asked—a place where she might be as safe as under lock and key, without the trouble and risk of confining her, and having to consider the law.”

“You do not mean a prison, then?”

“No. She has not yet done anything to make it easy to put her in prison for life; and anything short of that would be more risk than comfort. If Carse gives me authority, I will dispose of her where she can be free to rove like the wild goats. If she should take a fancy to jump down a precipice, or drown herself, that is her own affair, you know.”

The door opened for the entrance of company. Lord Lovat whispered once more, “Only this. If Carse thinks of giving the case into my hands, don’t you oppose it. I will not touch her life, I swear to you.”

Lady Rachel knew, like the rest of the world, that Lord Lovat’s swearing went for no more than any of his other engagements. Though she would have given all she had in the world to be freed from the terror of Lady Carse, and to hope that the children might forget their unhappy mother, she shrank from the idea of putting any person into the hands of the hard, and mocking, and plotting Lord Lovat. As for the legality of doing anything at all to Lady Carse while she did not herself break the law, that was a consideration which no more occurred to Lady Rachel than to the violent Lord Lovat himself.

Lady Rachel was exerting herself to entertain her guests, and had sent for the children, when, to her inexplicable relief, the butler brought her the news that Lord Carse and his son Willie were home, and would appear with all speed. They had been detained two hours in a tavern, John said.

“In a tavern?”

“Yes, my lady. Could not get out. Did not wish to collect more people, to cause a mob. It is all right now, my lady.”

When Lord Carse entered, he made formal apologies to his guests first, and his sister afterwards, for his late appearance. He had been delayed by an affair of importance on his way home. His rigid countenance was somewhat paler than usual, and his manner more dictatorial. His hard and unwavering voice was heard all the evening, prosing and explaining. The only tokens of feeling were when he spoke to his eldest son Willie, who was spiritless, and, as the close observer saw, tearful; and when he took little Flora in his arms, and stroked her shining hair, and asked her if she had been walking with the nurse.

Flora did not answer. She was anxiously watching Lady Rachel’s countenance. Her papa bade her look at him and answer his question. She did so, after glancing at her aunt, and saying eagerly, in a loud whisper, “I am not going to say anything about the lady that came to the window, and nodded at me.”

It did not mend the matter that her sister and brothers all said at once, in a loud whisper, “Hush! Flora.”

Her father sat her down hastily. Lord Carse’s domestic troubles were pretty well-known throughout Edinburgh; and the company settled it in their own minds that there had been a scene this afternoon.

When they were gone, Lord Carse gave his sister his advice not to instruct any very young child in any part to be acted. He assured her that very young children have not the discretion of grown people, and gave it as his opinion that when the simplicity, which is extremely agreeable by the domestic fireside, becomes troublesome or dangerous in society, the child is better disposed of in the nursery.

Lady Rachel meekly submitted; only observing what a singular and painful case was that of these children, who had to be so early trained to avoid the very mention of their mother. She believed her brother to be the most religious man she had ever known; yet she now heard him mutter oaths so terrible that they made her blood run cold.

“Brother! my dear brother,” she expostulated.

“I’ll tell you what she has done,” he said, from behind his set teeth. “She has taken a lodging in this very Wynd, directly opposite my gates. Not a child, not a servant, not a dog or cat can leave my house without coming under her eye. She will be speaking to the children out of her window.”

“She will be nodding at Flora from the court-yard as often as you are out,” cried Lady Rachel. “And if she should shoot you from her window, brother.”

“She hints that she will; and there are many things more unlikely, considering (as she herself says) whose daughter she is.—But, no,” he continued, seeing the dreadful alarm into which his sister was thrown. “This will not be her method of revenge. There is another that pleases her better, because she suspects that I dread it more.—You know what I mean?”

“Political secrets?” Lady Rachel whispered—not in Flora’s kind of whisper, but quite into her brother’s ear.

He nodded assent, and then he gravely informed her that his acquaintance, Duncan Forbes, had sent a particular request to see him in the morning. He should go, he said. It would not do to refuse waiting on the President of the Court of Session, as he was known to be in Edinburgh. But he wished he was a hundred miles off, if he was to hear a Hanoverian lecture from a man so good natured, and so dignified by his office, that he must always have his own way.

Lady Rachel went to bed very miserable this night. She wished that Lady Carse and King George, and all the House of Brunswick had never existed; or that Prince Charlie, or some of the exiled royal family, would come over at once and take possession of the kingdom, that her brother and his friends might no longer be compelled to live in a state of suspicion and dread—every day planning to bring in a new king, and every day obliged to appear satisfied with the one they had; their secret, or some part of it, being all the while at the mercy of a violent woman who hated them all.

Chapter Two.

The Turbulent.

When Lord Carse issued from his own house the next morning to visit the President, he had his daughter Janet by his side, and John behind him. He took Janet in the hope that her presence, while it would be no impediment to any properly legal business, would secure him from any political conversation being introduced; and there was no need of any apology for her visit, as the President usually asked why he had not the pleasure of seeing her, if her father went alone. Duncan Forbes’s good nature to all young people was known to everybody; but he declared himself an admirer of Janet above all others; and Janet never felt herself of so much consequence as in the President’s house.

John went as an escort to his young lady on her return.

Janet felt her father’s arm twitch as they issued from their gates; and, looking up to see why, she saw that his face was twitching too. She did not know how near her mother was, nor that her father and John had their ears on the stretch for a hail from the voice they dreaded above all others in the world. But nothing was seen or heard of Lady Carse; and when they turned out of the Wynd Lord Carse resumed his usual air and step of formal importance; and Janet held up her head, and tried to take steps as long as his.

All was right about her going to the President’s. He kissed her forehead, and praised her father for bringing her, and picked out for her the prettiest flowers from a bouquet before he sat down to business; and then he rose again, and provided her with a portfolio of prints to amuse herself with; and even then he did not forget her, but glanced aside several times, to explain the subject of some print, or to draw her attention to some beauty in the one she was looking at.

“My dear lord,” said he, “I have taken a liberty with your time; but I want your opinion on a scheme I have drawn out at length for Government, for preventing and punishing the use of tea among the common people.”

“Very good, very good!” observed Lord Carse, greatly relieved about the reasons for his being sent for. “It is high time, if our agriculture is to be preserved, that the use of malt should be promoted to the utmost by those in power.”

“I am sure of it,” said the President. “Things have got to such a pass, that in towns the meanest people have tea at the morning’s meal, to the discontinuance of the ale which ought to be their diet; and poor women dank this drug also in the afternoons, to the exclusion of the twopenny.”

“It is very bad; very unpatriotic; very immoral,” declared Lord Carse. “Such people must be dealt with outright.”

The President put on his spectacles, and opened his papers to explain his plan—that plan, which it now appears almost incredible should have come from a man so wise, so liberal, so kind-hearted as Duncan Forbes. He showed how he would draw the line between those who ought and those who ought not to be permitted to drink tea; how each was to be described, and how, when anyone was suspected of taking tea, when he ought to be drinking beer, he was to tell on oath what his income was, that it might be judged whether he could pay the extremely high duty on tea which the plan would impose. Houses might be visited, and cupboards and cellars searched, at all hours, in cases of suspicion.

“These provisions are pretty severe,” the President himself observed. “But—”

“But not more than is necessary,” declared Lord Carse. “I should say they are too mild. If our agriculture is not supported, if the malt tax falls off, what is to become of us?”

And he sighed deeply.

“If we find this scheme work well, as far as it goes,” observed the President, cheerfully, “we can easily render it as much more stringent as occasion may require. And now, what can Miss Janet tell us on this subject? Can she give information of any tea being drunk in the nursery at home?”

“Oh! to be sure,” said Janet. “Nurse often lets me have some with her; and Katie fills Flora’s doll’s teapot out of her own, almost every afternoon.”

“Bless my soul!” cried Lord Carse, starting from his seat in consternation. “My servants drink tea in my house! Off they shall go—every one of them who does it.”

“Oh! papa. No; pray papa!” implored Janet. “They will say I sent them away. Oh! I wish nobody had asked me anything about it.”

“It was my doing,” said the President. “My dear lord, I make it my request that your servants may be forgiven.”

Lord Carse bowed his acquiescence; but he shook his head, and looked very gloomy about such a thing happening in his house. The President agreed with him that it must not happen again, on pain of instant dismissal.

The President next invited Janet to the drawing-room to see a grey parrot, brought hither since her last visit—a very entertaining companion in the evenings, the President declared. He told Lord Carse he would be back in three minutes, and so he was—with a lady on his arm, and that lady was—Lady Carse.

She was not flushed now, nor angry, nor forward. She was quiet and ladylike, while in the house of one of the most gentlemanly men of his time. If her husband had looked at her, he would have seen her so much like the woman he wooed and once dearly loved, that he might have somewhat changed his feelings towards her. But he went abruptly to the window when he discovered who she was, and nothing could make him turn his head. Perhaps he was aware how pale he was, and desired that she should not see it.

The President placed the lady in a chair, and then approached Lord Carse, and laid his hand on his shoulder, saying, “You will forgive me when you know my reasons. I want you to join me in prevailing on this good lady to give up a design which I think imprudent—I will say, wrong.”

It was surprising, but Lady Carse for once bore quietly with somebody thinking her wrong. Whatever she might feel, she said nothing. The President went on.

“Lady Carse—”

He felt, as his hand lay on his friend’s shoulder, that he winced, as if the very name stung him.

“Lady Carse,” continued the President, “cannot be deterred by any account that can be given her of the perils and hardships of a journey to London. She declares her intention of going.”

“I am no baby; I am no coward,” declared the lady. “The coach would not have been set up, and it would not continue to go once a fortnight if the journey were not practicable; and where others go I can go.”

“Of the dangers of the road, I tell this good lady,” resumed the President, “she can judge as well as you or I, my lord. But of the perils of the rest of her errand she must, I think, admit that we may be better judges.”

“How can you let your Hanoverian prejudices seduce you into countenancing such a devil as that woman, and believing a word that she says?” muttered Lord Carse, in a hoarse voice.

“Why, my good friend,” replied the President, “it does so vex my very heart every day to see how the ladies, whom I would fain honour for their discretion as much as I admire them for their other virtues, are wild on behalf of the Pretender, or eager for a desperate and treasonable war, that you must not wonder if I take pleasure in meeting with one who is loyal to her rightful sovereign. Loyal, I must suppose, at home, and in a quiet way; for she knows that I do not approve of her journey to London to see the minister.”

“The minister!” faltered out Lord Carse.

He heard, or fancied he heard his wife laughing behind him.

“Come, now, my friends,” said the President, with a good-humoured seriousness, “let me tell you that the position of either of you is no joke. It is too serious for any lightness and for any passion. I do not want to hear a word about your grievances. I see quite enough. I see a lady driven from home, deprived of her children, and tormenting herself with thoughts of revenge because she has no other object. I see a gentleman who has been cruelly put to shame in his own house and in the public street, worn with anxiety about his innocent daughters, and with natural fears—inevitable fears, of the mischief that may be done to his character and fortunes by an ill use of the confidence he once gave to the wife of his bosom.”

There was a suppressed groan from Lord Carse, and something like a titter from the lady. The President went on even more gravely.

“I know how easy it is for people to make each other wretched, and especially for you two to ruin each other. If I could but persuade you to sit down with me to a quiet discussion of a plan for living together or apart, abstaining from mutual injury—”

Lord Carse dissented audibly from their living together, and the lady from living apart.

“Why,” remonstrated the President, “things cannot be worse than they are now. You make life a hell—”

“I am sure it is to me!” sighed Lord Carse.

“It is not yet so to me,” said the lady. “I—”

“It is not!” thundered her husband, turning suddenly round upon her. “Then I will take care it shall be.”

“For God’s sake, hush!” exclaimed the President, shocked to the soul.

“Do your worst,” said the lady, rising. “We will try which has the most power. You know what ruin is.”

“Stop a moment,” said the President. “I don’t exactly like to have this quiet house of mine made a hell of. I cannot have you part on these terms.”

But the lady had curtseyed, and was gone. For a minute or two nothing was said. Then a sort of scream was heard from upstairs.

“My Janet!” cried Lord Carse.

“I will go and see,” said the President. “Janet is my especial pet, you know.”

He immediately returned, smiling, and said, “There is nothing amiss with Janet. Come and see.”

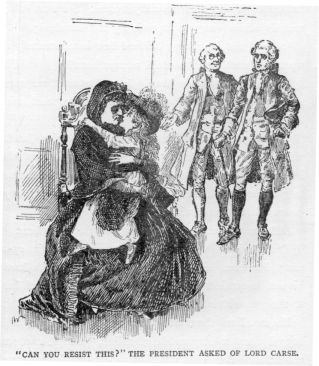

Janet was on her mother’s lap, her arms thrown round her neck, while the mother’s tears streamed over them both. “Can you resist this?” the President asked of Lord Carse. “Can you keep them apart after this?”

“I can,” he replied. “I will not permit her the devilish pleasure she wants—of making my own children my enemies.”

He was going to take Janet by force: but the President interfered, and said authoritatively to Lady Carse that she had better go: her time was not yet come. She must wait; and his advice was to wait patiently and harmlessly.

It could not have been believed how instantaneously a woman in such emotion could recover herself.

She put Janet off her knee. In an instant there were no more traces of tears, and her face was composed, and her manner hard.

“Good-bye, my dear,” she said to the weeping Janet. “Don’t cry so, my dear. Keep your tears; for you will have something more to cry for soon. I am going home to pack my trunk for London. Have my friends any commands for London?”

And she looked round steadily upon the three faces.

The President was extremely grave when their eyes met; but even his eye sank under hers. He offered his arm to conduct her downstairs, and took leave of her at the gate with a silent bow.

He met Lord Carse and Janet coming downstairs, and begged them to stay awhile, dreading, perhaps, a street encounter. But Lord Carse was bent on being gone immediately—and had not another moment to spare.

Chapter Three.

The Wrong Journey.

Lady Carse and her maid Bessie—an elderly woman who had served her from her youth up, bearing with her temper for the sake of that family attachment which exists so strongly in Scotland,—were busy packing trunks this afternoon, when they were told that a gentleman must speak with Lady Carse below stairs.

“There will be no peace till we are off,” observed the lady to her maid. In answer to which Bessie only sighed deeply.

“I want you to attend me downstairs,” observed the lady. “But this provoking nonsense of yours, this crying about going a journey, has made you not fit to be seen. If any friend of my lord’s saw your red eyes, he would go and say that my own maid was on my lord’s side. I must go down alone.”

“Pray, madam, let me attend you. The gentleman will not think of looking at me: and I will stand with my back to the light, and the room is dark.”

“No; your very voice is full of tears. Stay where you are.”

Lady Carse sailed into the room very grandly, not knowing whom she was to see. Nor was she any wiser when she did see him. He was muffled up, and wore a shawl tied over his mouth, and kept his hat on; so that little space was left between hat, periwig, and comforter. He apologised for wearing his hat, and for keeping the lady standing—his business was short:—in the first place to show her Lord Carse’s ring, which she would immediately recognise.

She glanced at the ring, and knew it at once.

“On the warrant of this ring,” continued the gentleman, “I come from your husband to require from you what you cannot refuse,—either as a wife, or consistent with your safety. You hold a document,—a letter from your husband, written to you in conjugal confidence five years ago, from London,—a letter—”

“You need not describe it further,” said the lady. “It is my chief treasure, and not likely to escape my recollection. It is a letter from Lord Carse, containing treasonable expressions relating to the royal family.”

“About the treason we might differ, madam; but my business is, not to argue that, but to require of you to deliver up that paper to me, on this warrant,” again producing the ring.

The lady laughed, and asked whether the gentleman was a fool or took her to be one, that he asked her to give up what she had just told him was the greatest treasure she had in the world,—her sure means of revenge upon her enemies.

“You will not?” asked the gentleman.

“I will not.”

“Then hear what you have to expect, madam. Hear it, and then take time to consider once more.”

“I have no time to spare,” she replied. “I start for London early in the morning; and my preparations are not complete.”

“You must hear me, however,” said the gentleman. “If you do not yield your husband will immediately and irrevocably put you to open shame.”

“He cannot,” she replied. “I have no shame. I have the advantage of him there.”

“You have, however, personal liberty at present. You have that to lose,—and life, madam. You have that to lose.”

Lady Carse caught at the table, and leaned on it to support herself. It was not from fear about her liberty or life; but because there was a cruel tone in the utterance of the last words, which told her that it was Lord Lovat who was threatening her; and she was afraid of him.

“I have shaken you now,” said he. “Come: give me the letter.”

“It is not fear that shakes me,” she replied. “It is disgust. The disgust that some feel at reptiles I feel at you, my Lord Lovat.”

She quickly turned and left the room. When he followed she had her foot on the stairs. He said aloud, “You will repent, madam. You will repent.”

“That is my own affair.”

“True, madam, most true. I charge you to remember that you have yourself said that it is your own affair if you find you have cause to repent.”

Lady Carse stood on the stairs till her visitor had closed the house door behind him, struggled up to her chamber, and fainted on the threshold.

“This journey will never do, madam,” said Bessie, as her mistress revived.

“It is the very thing for me,” protested the lady. “In twelve hours more we shall have left this town and my enemies behind us; and then I shall be happy.”

Bessie sighed. Her mistress often talked of being happy; but nobody had ever yet seen her so.

“This fainting is nothing,” said Lady Carse, rising from the bed. “It is only that my soul sickens when Lord Lovat comes near; and the visitor below was Lord Lovat.”

“Mercy on us!” exclaimed Bessie. “What next?”

“Why, that we must get this lock turned,” said her lady, kneeling on the lid of a trunk. “Now, try again. There it is! Give me the key. Get me a cup of tea, and then to bed with you! I have a letter to write. Call me at four, to a minute. Have you ordered two chairs, to save all risk?”

“Yes, madam; and the landlord will see your things to the coach office to-night.”

Lady Carse had sealed her letter, and was winding up her watch with her eyes fixed on the decaying fire, when she was startled by a knock at the house door. Everybody else was in bed. In a vague fear she hastened to her chamber, and held the door in her hand and listened while the landlord went down. There were two voices besides his; and there was a noise as of something heavy brought into the hall. When this was done, and the bolts and bars were again fastened, she went to the stair-head and saw the landlord coming up with a letter in his hand. The letter was for her. It was heavy. Her trunks had come back from the coach office. The London coach was gone.

The letter contained the money paid for the fare of Lady Carse and her maid to London, and explained that a person of importance having occasion to go to London with attendants, and it being necessary to use haste, the coach was compelled to start six hours earlier than usual; and Lady Carse would have the first choice of places next time;—that is in a fortnight.

Bessie had never seen her mistress in such a rage as now: and poor Bessie was never to see it again. At the first news, she was off her guard, and thanked Heaven that this dangerous journey was put off for a fortnight; and much might happen in that time. Her mistress turned round upon her, said it was not put off,—she would go on horseback alone,—she would go on foot,—she would crawl on her knees, sooner than give up. Bessie was silent, well knowing that none of these ways would or could be tried, and thankful that there was only this one coach to England. Enraged at her silence, her mistress declared that no one who was afraid to go to London was a proper servant for her, and turned her off upon the spot. She paid her wages to the weeping Bessie, and with the first light of morning, sent her from the house, herself closing the door behind her. She then went to bed, drawing the curtains close round it, remaining there all the next day, and refusing food.

In the evening, she wearily rose, and slowly dressed herself,—for the first time in her life without help. She was fretted and humbled at the little difficulties of her toilet, and secretly wished, many times, that Bessie would come back and offer her services, though she was resolved to appear not to accept them without a very humble apology from Bessie for her fears about London. At last, she was ready to go down to tea, dressed in a wrapping-gown and slippers. When halfway down, she heard a step behind her, and looked round. A Highlander was just two stairs above her: another appeared at the foot of the flight; and more were in the hall. She knew the livery. It was Lovat’s tartan. They dragged her downstairs, and into her parlour, where she struggled so violently that she fell against the heavy table, and knocked out two teeth. They fastened down her arms by swathing her with a plaid, tied a cloth over her mouth, threw another over her head, and carried her to the door. In the street was a sedan chair; and in the chair was a man who took her upon his knees, and held her fast. Still she struggled so desperately, that the chair rocked from side to side, and would have been thrown over; but that there were plenty of attendants running along by the side of it, who kept it upright.

This did not last very long. When they had got out of the streets, the chair stopped. The cloth was removed from her head; and she saw that they were on the Linlithgow road, that some horsemen were waiting, one of whom was on a very stout horse, which bore a pillion behind the saddle. To this person she was formally introduced, and told that he was Mr Forster of Corsebonny. She knew Mr Forster to be a gentleman of character; and that therefore her personal safety was secure in his hands. But her good opinion of him determined her to complain and appeal to him in a way which she believed no gentleman could resist. She did not think of making any outcry. The party was large; the road was unfrequented at night; and she dreaded being gagged. She therefore only spoke,—and that as calmly as she could.

“What does this mean, Mr Forster? Where are you carrying me?”

“I know little of Lord Carse’s purposes, madam; and less of the meaning of them probably than yourself.”

“My Lord Carse! Then I shall soon be among the dead. He will go through life with murder on his soul.”

“You wrong him, madam. Your life is very safe.”

“No; I will not live to be the sport of my husband’s mercy. I tell you, sir, I will not live.”

“Let me advise you to be silent, madam. Whatever we have to say will be better said at the end of our stage, where I hope you will enjoy good rest, under my word that you shall not be molested.”

But the lady would not be silent. She declared very peremptorily her determination to destroy herself on the first opportunity; and no one who knew her temper could dispute the probability of her doing that, or any other act of passion. From bewailing herself, she went on to say things of her husband and Lord Lovat, and of her purposes in regard to them, which Mr Forster felt that he and others ought not, for her own sake, to hear. He quickened his pace, but she complained of cramp in her side. He then halted, whispered to two men who watched for his orders, and had the poor lady again silenced by the cloth being tied over her mouth. She tried to drop off, but that only caused the strap which bound her to the rider to be buckled tighter. She found herself treated like a wayward child. When she could no longer make opposition, the pace of the party was quickened, and it was not more than two hours past midnight when they reached a country house, which she knew to belong to an Edinburgh lawyer, a friend of her husband’s.

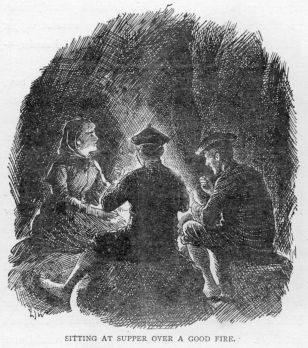

Servants were up—fires were burning—supper was on the table. The lady was shown to a comfortable bedroom.

From thence she refused to come down. Mr Forster and another gentleman of the party therefore visited her to explain as much as they thought proper of Lord Carse’s plans, and of their own method of proceeding.

They told her that Lord Carse found himself compelled, for family reasons, to sequestrate her. For her life and safety there was no fear; but she was to live where she could have that personal liberty of which no one wished to deprive her, without opportunity of intercourse with her family.

“And where can that be?” she asked. “Who will undertake to say that I shall live, in the first place, and that my children shall not hear from me, in the next?”

“Where your abode is to be, we do not know,” replied Mr Forster. “Perhaps it is not yet settled. As for your life, madam, I have engaged to transfer you alive and safe, as far as lies in human power.”

“Transfer me! To whom?”

“To another friend of your husband’s, who will take equal care of you. I am sorry for your threats of violence on yourself. They compel me to do what I should not otherwise have thought of—to forbid your being alone, even in this your own room.”

“You do not mean—”

“I mean that you are not to be left unwatched for a single instant. There is a woman in the house—the housekeeper. She and her husband will enter this room when I leave it; and I advise you to say nothing to them against this arrangement.”

“They shall have no peace with me.”

“I am sorry for it. It will be a bad preparation for your further journey. You would do better to lie down and rest,—for which ample time shall be allowed.”

The people in charge of the house were summoned, and ordered, in the lady’s hearing, to watch her rest, and on no account to leave the room till desired to do so. A table was set out in one corner, with meat and bread, wine and ale. But the unhappy lady would not attempt either to eat or sleep. She sat by the fire, faint, weary and gloomy. She listened to the sounds from below till the whole party had supped, and lain down for the night. Then she watched her guards,—the woman knitting, and the man reading his Bible. At last, she could hold up no longer. Her head sank on her breast, and she was scarcely conscious of being gently lifted, laid upon the bed, and covered up warm with cloak and plaid.

Chapter Four.

Newspapers.

Lady Carse did not awake till the afternoon of the next day; and then she saw the housekeeper sitting knitting on the same chair, and looking as if she had never stirred since she took her place there in the middle of the night. The man was not there.

The woman cheerfully invited the lady to rise and refresh herself, and come to the fire, and then go down and dine. But Lady Carse’s spirit was awake as soon as her eyes were. She said she would never rise—never eat again. The woman begged her to think better of it, or she should be obliged to call her husband to resume his watch, and to let Mr Forster know of her refusal to take food. To this the poor lady answered only by burying her face in the coverings, and remaining silent and motionless, for all the woman could say.

In a little while, up came Mr Forster, with three Highlanders. They lifted her, as if she had been a child, placed her in an easy chair by the fireside, held back her head, and poured down her throat a basin full of strong broth.

“It grieves me, madam,” said Mr Forster, “to be compelled to treat you thus—like a wayward child. But I am answerable for your life. You will be fed in this way as often as you decline necessary food.”

“I defy you still,” she cried.

“Indeed!” said he, with a perplexed look. She had been searched by the housekeeper in her sleep; and it was certain that no weapon and no drug was about her person. She presently lay back in the chair, as if wishing to sleep, throwing a shawl over her head; and all withdrew except the housekeeper and her husband.

In a little while some movement was perceived under the shawl, and there was a suppressed choking sound. The desperate woman was swallowing her hair, in order to vomit up the nourishment she had taken—as another lady in desperate circumstances once did to get rid of poison. The housekeeper was ordered to cut off her hair, and Mr Forster then rather rejoiced in this proof that she carried no means of destroying her life.

As soon as it was quite dark she was compelled to take more food, and then wrapped up warmly for a night ride. Mr Forster invited her to promise that she would not speak, that he might be spared the necessity of bandaging her mouth. But she declared her intention of speaking on every possible occasion; and she was therefore effectually prevented from opening her mouth at all.

On they rode through the night, stopping to dismount only twice; and then it was not at any house, but at mere sheepfolds, where a fire was kindled by some of the party, and where they drank whisky, and laughed and talked in the warmth and glow of the fire, as if the poor lady had not been present. Between her internal passion, her need of more food than she would take, the strangeness of the scene, with the sparkling cold stars overhead, and the heat and glow of the fire under the wall—amidst these distracting influences the lady felt confused and ill, and would have been glad now to have been free to converse quietly, and to accept the mercy Mr Forster had been ready to show her. He was as watchful as ever, sat next her as she lay on the ground, said at last that they had not much further to go, and felt her pulse. As the grey light of morning strengthened, he went slower and slower, and encouraged her to lean upon him, which her weakness compelled her to do. He sent forward the factor of the estate they were now entering upon, desiring him to see that everything was warm and comfortable.

When the building they were approaching came in view, the poor lady wondered how it could ever be made warm and comfortable. It was a little old tower, the top of which was in ruins, and the rest as dreary looking as possible. Cold and bare it stood on a waste hill-side. It would have looked like a mere grey pillar set down on the scanty pasture, but for a square patch behind, which was walled in by a hard ugly wall of stones. A thin grey smoke arose from it, showing that someone was within; and dogs began to bark as the party drew near.

One woman was here as at the last resting place. She showed the way by the narrow winding stair, up which Lady Carse was carried like a corpse, and laid on a little bed in a very small room, whose single window was boarded up, leaving only a square of glass at the top to admit the light. Mr Forster stood at the bedside, and said firmly, “Now, Lady Carse, listen to me for a moment, and then you will be left with such freedom as this room and this woman’s attendance can afford you. You are so exhausted, that we have changed our plan of travel. You will remain here, in this room, till you have so recruited yourself by food and rest as to be able to proceed to a place where all restraint will be withdrawn. When you think yourself able to proceed, and declare your willingness to do so, I, or a friend of mine, will be at your service—at your call at any hour. Till then this room is your abode; and till then I bid you farewell.”

He unfastened the bandage, and was gone before she could speak to him. What she wanted to say was, that on such terms she would never leave this room again. She desired the woman to tell him so; but the woman said she had orders to carry no messages.

Where there is no help and no hope, any force of mere temper is sure to give way, as Mr Forster well knew. Injured people who have done no wrong, and who bear no anger against their enemies, have an inward strength and liberty of mind which enable them to bear on firmly, and to be immovable in their righteous purposes; so that, as has been shown by many examples, they will be torn limb from limb sooner than yield. Lady Carse was an injured person—most deeply injured, but she was not innocent. She had a purpose; but it was a vindictive one; and her soul was all tossed with passion, instead of being settled in patience. So her intentions of starving herself—of making Mr Forster miserable by killing herself through want of sleep and food, gave way; and then she was in a rage with herself for having given way. When all was still in the tower, and the silent woman who attended her knitted on for hours together, as if she was a machine; and there was nothing to be seen from the boarded window; and the smouldering peats in the fireplace looked as if they were asleep, Lady Carse could not always keep awake, and, once asleep, she did not wake for many hours.

When, at length, she started up and looked around her, she was alone, and the room was lighted only by a flickering blaze from the fireplace. This dancing light fell on a little low round table, on which was a plate with some slices of mutton-ham, some oatcake, three or four eggs, and a pitcher. She was ravenously hungry, and she was alone. She thought she would take something—so little as to save her pride, and not to show that she had yielded. But, once yielding, this was impossible. She ate, and ate, till all was gone—even the eggs; and it would have been the same if they had been raw. The pitcher contained ale, and she emptied it. When she had done, she could have died with shame. She was just thinking of setting her dress on fire, when she heard the woman’s step on the stair. She threw herself on the bed, and pretended to be asleep. Presently she was so, and she had another long nap. When she woke the table had nothing on it but the woman’s knitting; the woman was putting peats on the fire, and she made no remark, then or afterwards, on the disappearance of the food. From that day forward food was laid out while the lady slept; and when she awoke, she found herself alone to eat it. It was served without knife or fork, with only bone spoons. It would have been intolerable shame to her if she had known that she was watched, through a little hole in the door, as a precaution against any attempt on her life.

But her intentions of this kind too gave way. She was well aware that though not free to go where she liked she could, any day, find herself in the open air with liberty to converse, except on certain subjects; and that she might presently be in some abode—she did not know what—where she could have full personal liberty, and her present confinement being her own choice made it much less dignified, and this caused her to waver about throwing off life and captivity together. The moment never came when she was disposed to try.

At the end of a week she felt great curiosity to know whether Mr Forster was at the tower all this time waiting her pleasure. She would not enquire lest she should be suspected of the truth—that she was beginning to wish to see him. She tried one or two distant questions on her attendant, but the woman knew nothing. There seemed to be no sort of question that she could answer.

In a few days more the desire for some conversation with somebody became very pressing, and Lady Carse was not in the habit of denying herself anything she wished for. Still, her pride pulled the other way. The plan she thought of was to sit apparently musing or asleep by the fire while her attendant swept the floor of her room, and suddenly to run downstairs while the door was open. This she did one day, when she was pretty sure she had heard an unusual sound of horses’ feet below. If Mr Forster should be going without her seeing him it would be dreadful. If he should have arrived after an absence this would afford a pretext for renewing intercourse with him. So she watched her moment, sprang to the door, and was down the stair before her attendant could utter a cry of warning to those below.

Lady Carse stood on the last stair, gazing into the little kitchen, which occupied the ground floor of the tower. Two or three people turned and gazed at her, as startled, perhaps, as herself; and she was startled, for one of them was Lord Lovat.

Mr Forster recovered himself, bowed, and said that perhaps she found herself able to travel; in which case, he was at her service.

“O dear, no!” she said. She had no intention whatever of travelling further. She had heard an arrival of horsemen, and had merely come down to know if there was any news from Edinburgh.

Lord Lovat bowed, said he had just arrived from town, and would be happy to wait on her upstairs with any tidings that she might enquire for.

“By no means,” she said, haughtily. She would wait for tidings rather than learn them from Lord Lovat. She turned, and went upstairs again, stung by hearing Lord Lovat’s hateful laugh behind her as she went.

As she sat by the fire, devouring her shame and wrath, her attendant came up with a handful of newspapers, and Lord Lovat’s compliments, and he had sent her the latest Edinburgh news to read, as she did not wish to hear it from him. She snatched the papers, meaning to thrust them into the fire in token of contempt for the sender; but a longing to read them came over her, and she might convey sufficient contempt by throwing them on the bed—and this she accordingly did.

She watched them, however, as a cat does a mouse. The woman seemed to have no intention of going down any more to-day. Whether the lady was watched, and her impatience detected, through the hole in the door, or whether humanity suggested that the unhappy creature should be permitted an hour of solitude on such an occasion, the woman was called down, and did not immediately return.

How impatiently, then, were the papers seized! How unsettled was the eye which ran over the columns, while the mind was too feverish to comprehend what it read! In a little while, however, the ordinary method of newspaper reading established itself, and she went on from one item to another with more amusement than anxiety. In this mood, and with the utmost suddenness, she came upon the announcement, in large letters, of “The Funeral of Lady Carse!” It was even so! In one paper was a paragraph intimating the threatening illness of Lady Carse; in the next, the announcement of her death; in the third, a full account of her funeral, as taking place from her husband’s house.

Her fate was now clear. She was lost to the world for ever! In the midst of the agony of this doom she could yet be stung by the thought that this was the cause of Lord Lovat’s complaisance in sending her the newspapers; that here was the reason of the only indulgence which had been permitted her!

As for the rest, her mind made short work of it. Her object must now be to confound her foes—to prove to the world that she was not dead and buried. From this place she could not do this. Here there was no scope and no hope. In travelling, and in her future residence, there might be a thousand opportunities. She could not stay here another hour, and so she sent word to Mr Forster. His reply was that he should be happy to escort her that night. From the stair-head she told him that she could not wait till night. He declared it impossible to make provision for her comfort along the road without a few hours’ notice by a horseman sent forward. The messenger was already saddling his horse, and by nine in the evening the rest of the party would follow.

At nine the lady was on her pillion, but now comfortably clad in a country dress—homely, but warm. It was dark, but she was informed that the party thoroughly knew their road, and that in four or five days they should have the benefit of the young moon.

So, after four or five days, they were to be still travelling! Where could they be carrying her?

Chapter Five.

Cross Roads and Short Seas.

Where they were carrying her was more than Lady Carse herself could discover. To the day of her death she never knew what country she had traversed during the dreary and fatiguing week which ensued. She saw Stirling Castle standing up on its mighty rock against the dim sky; and she knew that before dawn they had entered the Highlands.

But beyond this she was wholly ignorant. In those days there were no milestones on the road she travelled. The party went near no town, stopped at no inn, and never permitted her an opportunity of speaking to anyone out of their own number. They always halted before daylight at some solitary house—left open for them, but uninhabited—or at some cowshed, where they shook down straw for her bed, made a fire, and cooked their food; and at night they always remounted, and rode for many hours, through a wild country, where the most hopeful of captives could not dream of rescue. Sometimes they carried torches while ascending a narrow ravine, where a winter torrent dashed down the steep rocks and whirled away below, and where the lady unawares showed her desire to live by clinging faster to the horseman behind whom she rode. Sometimes she saw the whole starry hemisphere resting like a dome on a vast moorland, the stars rising from the horizon here and sinking there, as at sea.

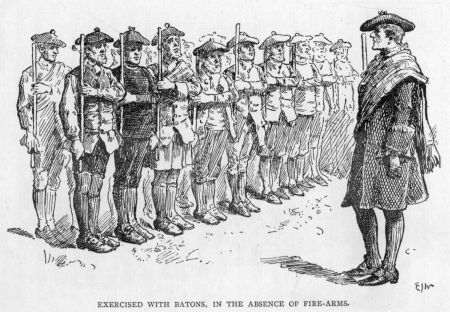

The party rarely passed any farmsteads or other dwellings; and when they did silence was commanded, and the riders turned their horses on the grass or soft earth, in order to appear as little as possible like a cavalcade to any wakeful ears. Once, on such an occasion, Lady Carse screamed aloud; but this only caused her to be carried at a gallop, which instantly silenced her, and then to be gagged for the rest of the night. She would have promised to make no such attempt again, such a horror had she now of the muffle which bandaged her mouth, but nobody asked her to promise. On the contrary, she heard one man say to another, that the lady might scream all night long now, if she liked; nobody but the eagles would answer her, now she was among the Frasers.

Among the Frasers! Then she was on Lord Lovat’s estates. Here there was no hope for her; and all her anxiety was to get on, though every step removed her further from her friends, and from the protection of law. But this was exactly the place where she was to stop for a considerable time.

Having arrived at a solitary house among moorland hills, Mr Forster told her that she would live here till the days should be longer, and the weather warm enough for a more comfortable prosecution of her further journey. He would advise her to take exercise in the garden, small as it was, and to be cheerful, and preserve her health, in expectation of the summer, when she would reach a place where all restrictions on her personal liberty would cease. He would now bid her farewell.

“You are going back to Edinburgh,” said she, rising from her seat by the fire. “You will see Lord Carse. Tell him that though he has buried his wife, he has not got rid of her. She will haunt him—she will shame him—she will ruin him yet.”

“I see now—” observed a voice behind her. She turned and perceived Lord Lovat, who addressed himself to Mr Forster, saying, “I see now that it is best to let such people live. If she were dead, we cannot say but that she might haunt him; though I myself have no great belief of it. As it is, she is safe out of his way—at any rate, till she dies first. I see now that his method is the right one.”

“Why, I don’t know, my lord,” replied Lady Carse. “You should consider how little trouble it would have cost to put me out of the way in my grave; and how much trouble I am costing you now. It is some comfort to me to think of the annoyance and risk, and fatigue and expense, I am causing you all.”

“You mistake the thing, madam. We rejoice in these things, as incurred for the sake of some people over the water. It gratifies our loyalty—our loyalty, madam, is a sentiment which exalts and endears the meanest services, even that of sequestrating a spy, an informer.”

“Come, come, Lovat, it is time we were off,” said Mr Forster, who was at once ashamed of his companion’s brutality, and alarmed at its effect upon the lady. She looked as if she would die on the spot. She had not been aware till now how her pride had been gratified by the sense of her own importance, caused by so many gentlemen of consequence entering into her husband’s plot against her liberty. She was now rudely told that it was all for their own sakes. She was controlled not as a dignified and powerful person, but as a mischievous informer. She rallied quickly—not only through pride, but from the thought that power is power, whencesoever derived, and that she might yet make Lord Lovat feel this. She curtseyed to the gentlemen, saying, “It is your turn now to jeer, gentlemen; and to board up windows, and the like. The day may come when I shall sit at a window to see your heads fall.”

“Time will show,” said Lord Lovat, with a smile, and an elegant bow. And they left her alone.

They no longer feared to leave her alone. Her temper was well-known to them; and her purposes of ultimate revenge, once clearly announced, were a guarantee that she would, if possible, live to execute them. She would make no attempts upon her life henceforward. Weeks and months passed on. The snow came, and lay long, and melted away. Beyond the garden wall she saw sprinklings of young grass among the dark heather; and  now the bleat of a lamb, and now the scudding brood of the moor-fowl, told her that spring was come. Long lines of wild geese in the upper air, winging steadily northwards, indicated the advancing season. The whins within view burst into blossom; and the morning breeze which dried the dews wafted their fragrance. Then the brooding mists drew off under the increasing warmth of the sun; and the lady discovered that there was a lake within view—a wide expanse, winding away among mountains till it was lost behind their promontories. She strained her eyes to see vessels on this lake, and now and then she did perceive a little sail hoisted, or a black speck, which must be a rowboat traversing the waters when they were sheeny in the declining sun. These things, and the lengthening and warmth of the days, quickened her impatience to be removed. She often asked the people of the house whether no news and no messengers had come; but they did not improve in their knowledge of the English tongue any more than she did in that of the Gaelic, and she could obtain no satisfaction. In the sunny mornings she lay on the little turf plat in the garden, or walked restlessly among the cabbage-beds (being allowed to go no further), or shook the locked gate desperately, till someone came out to warn her to let it alone. In the June nights she stood at her window, only one small pane of which would open, watching the mists shifting and curling in the moonlight, or the sheet lightning which now and then revealed the lake in the bosom of the mountains, or appeared to lay open the whole sky. But June passed away, and there was no change. July came and went—the sun was visibly shortening his daily journey, and leaving an hour of actual darkness in the middle of the night: and still there was no prospect of a further journey. She began to doubt Mr Forster as much as she hated Lord Lovat, and to say to herself that his promises of further personal liberty in the summer were mere coaxing words, uttered to secure a quiet retreat from her presence. If she could see him, for only five minutes, how she would tell him her mind!

now the bleat of a lamb, and now the scudding brood of the moor-fowl, told her that spring was come. Long lines of wild geese in the upper air, winging steadily northwards, indicated the advancing season. The whins within view burst into blossom; and the morning breeze which dried the dews wafted their fragrance. Then the brooding mists drew off under the increasing warmth of the sun; and the lady discovered that there was a lake within view—a wide expanse, winding away among mountains till it was lost behind their promontories. She strained her eyes to see vessels on this lake, and now and then she did perceive a little sail hoisted, or a black speck, which must be a rowboat traversing the waters when they were sheeny in the declining sun. These things, and the lengthening and warmth of the days, quickened her impatience to be removed. She often asked the people of the house whether no news and no messengers had come; but they did not improve in their knowledge of the English tongue any more than she did in that of the Gaelic, and she could obtain no satisfaction. In the sunny mornings she lay on the little turf plat in the garden, or walked restlessly among the cabbage-beds (being allowed to go no further), or shook the locked gate desperately, till someone came out to warn her to let it alone. In the June nights she stood at her window, only one small pane of which would open, watching the mists shifting and curling in the moonlight, or the sheet lightning which now and then revealed the lake in the bosom of the mountains, or appeared to lay open the whole sky. But June passed away, and there was no change. July came and went—the sun was visibly shortening his daily journey, and leaving an hour of actual darkness in the middle of the night: and still there was no prospect of a further journey. She began to doubt Mr Forster as much as she hated Lord Lovat, and to say to herself that his promises of further personal liberty in the summer were mere coaxing words, uttered to secure a quiet retreat from her presence. If she could see him, for only five minutes, how she would tell him her mind!

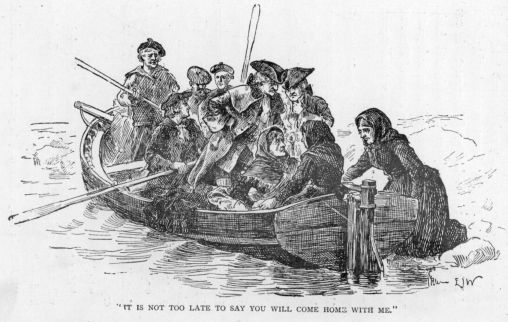

She never again saw Mr Forster: but, one night in August, while she was at the window, and just growing sleepy, she was summoned by the woman of the house to dress herself for a night ride. She prepared herself eagerly enough, and was off presently, without knowing anything of the horsemen who escorted her.

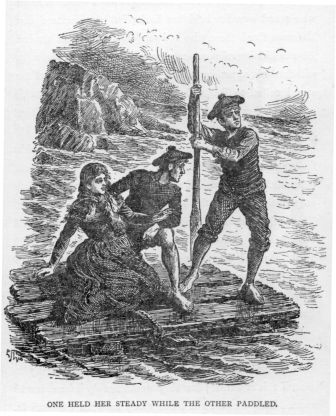

It was with a gleam of pleasure that she saw that they were approaching the lake she had so often gazed at from afar: and her heart grew lighter still when she found that she was to traverse it. She began to talk, in her new exhilaration; and she did not leave off, though nobody replied. But her exclamations about the sunrise, the clearness of the water, and the leaping of the fish, died away when she looked from face to face of those about her, and found them all strange and very stern. At last, the dip of the oars was the only sound; but it was a pleasant and soothing one. All went well this day. After landing, the party proceeded westwards—as they did nightly for nearly a week. It mattered little that they did not enter a house in all that time. The weather was so fine, that a sheepfold, or a grassy nook of the moorland, served all needful purposes of a resting place by day.

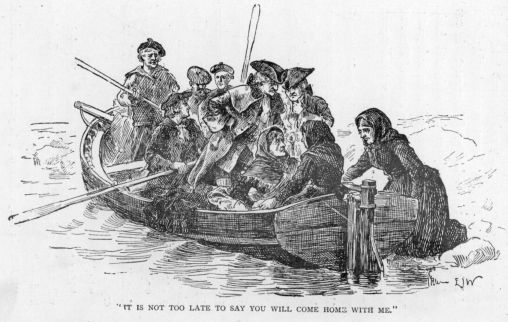

On the sixth night, a surprise, and a terrible surprise, awaited the poor lady. Her heart misgave her when the night wind brought the sound of the sea to her ears—the surging sea which tosses and roars in the rocky inlets of the western coast of Scotland. But her dismay was dreadful when she discovered that there was a vessel below, on board which she was to be carried without delay. On the instant, dreadful visions arose before her imagination, of her being carried to a foreign shore, to be delivered into the hands of the Stuarts, to be punished as a traitor and spy; and of those far off plantations and dismal colonies where people troublesome to their families were said to be sent, to be chained to servile labour with criminals and slaves. She wept bitterly: she clasped her hands—she threw herself at the feet of the conductor of the party—she appealed to them all, telling them to do what they would with her, if only they would not carry her to sea. Most of them looked at one another, and made no reply—not understanding her language. The conductor told her to fear nothing, as she was in the hands of the Macdonalds, who had orders from Sir Alexander Macdonald, of Skye, to provide for her safety. He promised that the voyage would not be a long one; and that as soon as the sloop should have left the loch she should be told where she was going. With that, he lifted her lightly, stepped into a boat, and was rowed to the sloop, where she was received by the owner, and half a dozen other Macdonalds. For some hours they waited for a wind; and sorely did the master wish it would come; for the lady lost not a glimpse of an opportunity of pleading her cause, explaining that she was stolen from Edinburgh, against the  laws. He told her she had better be quiet, as nothing could be done. Sir Alexander Macdonald was in the affair. He, for one, would never keep her or anyone against their will unless Sir Alexander Macdonald were in it: but nothing could be done. He saw, however, that some impression was made on one person, who visited the sloop on business, one William Tolney, who had connexions at Inverness, from having once been a merchant there, and who was now a tenant of the Macleods, in a neighbouring island. This man was evidently touched; and the Macdonalds held a consultation in consequence, the result of which was that William Tolney was induced to be silent on what he had seen and heard. But for many a weary year after did Lady Carse turn with hope to the image of the stranger who had listened to her on board the sloop, taken the address of her lawyer, and said that in his opinion something must be done.

laws. He told her she had better be quiet, as nothing could be done. Sir Alexander Macdonald was in the affair. He, for one, would never keep her or anyone against their will unless Sir Alexander Macdonald were in it: but nothing could be done. He saw, however, that some impression was made on one person, who visited the sloop on business, one William Tolney, who had connexions at Inverness, from having once been a merchant there, and who was now a tenant of the Macleods, in a neighbouring island. This man was evidently touched; and the Macdonalds held a consultation in consequence, the result of which was that William Tolney was induced to be silent on what he had seen and heard. But for many a weary year after did Lady Carse turn with hope to the image of the stranger who had listened to her on board the sloop, taken the address of her lawyer, and said that in his opinion something must be done.

In the evening the wind rose, and the sloop moved down the loch. With a heavy heart the lady next morning watched the vanishing of the last of Glengarry’s seats, on a green platform between the grey and bald mountains; then the last fishing hamlet on the shores; and, finally, a flock of herons come abroad to the remotest point of the shore from their roosting places in the tall trees that sheltered Glengarry’s abode. After that all was wretchedness. For many days she was on the tossing sea—the sloop now scudding before the wind, now heaving on the troubled waters, now creeping along between desolate looking islands, now apparently lost amidst the boundless ocean. At length, soon after sunrise, one bright morning, the sail was taken in, and the vessel lay before the entrance of an harbour which looked like the mouth of a small river. At noon the sun beat hot on the deck of the sloop. In the afternoon the lady impatiently asked what they were waiting for—if this really was, as she was told, their place of destination. The wind was not contrary; what where they waiting for?

“No, madam; the wind is fair. But it is a curious circumstance about this harbour that it can be entered safely only at night. It is one of the most dangerous harbours in all the isles.”

“And you dare to enter it at night? What do you mean?”

“I will show you, madam, when night comes.”

Lady Carse suspected that the delay was on her account; that she was not to land by daylight, less too much sympathy should be excited by her among the inhabitants. Her indignation at this stimulated her to observe all she could of the appearance of the island, in case of opportunity occurring to turn to the account of an escape any knowledge she might obtain. On the rocky ledges which stretched out into the sea lay basking several seals; and all about them, and on every higher ledge, were myriads of puffins. Hundreds of puffins and fulmars were in the air, and skimming the waters. The fulmars poised themselves on their long wings; the fat little puffins poffled about in the water, and made a great commotion where everything else was quiet. From these lower ridges of rock vast masses arose, black and solemn, some perpendicular, some with a slope too steep and smooth to permit a moment’s dream of climbing them. Even on this warm day of August the clouds had not risen above the highest peaks; and they threw a gloom over the interior of the small island, while the skirting rocks and sea were glittering in the sunshine. Even the scanty herbage of the slopes at the top of the rocks looked almost a bright green where the sun fell upon it; and especially where it descended so far as to come into contrast with the blackness of the yawning caverns with which the rocky wall was here and there perforated.

The lady perceived no dwellings; but Macdonald, who observed her searching gaze, pointed his glass and invited her to look through it. At first she saw nothing but a dim confusion of grey rocks and dull grass; but at length she made out a grey cottage, with a roof of turf, and a peat stack beside it.

“I see one dwelling,” said the lady.

“You see it,” observed Macdonald, satisfied, and resuming his glass. Then, observing the lady was not satisfied, he added, “There are more dwellings, but they are behind yonder ridge, out of sight. That is where my place is.”

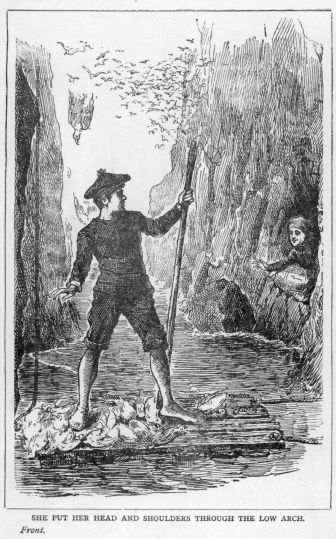

Lady Carse did not at present discern where the dangerous sympathy with her case was to come from. But there was no saying how many dwellings there might be behind that ridge. She once more insisted on landing by daylight; and was once more told that it was out of the question. She resolved to keep as wide awake as her suspicions, in order to see what was to be done with her. She was anxiously on the watch in the darkness an hour before midnight, when Macdonald said to her, “Now for it, madam! I will presently show you something curious.”

The sloop began to move under the soft breathing night wind; and in a few minutes Macdonald asked her if she saw anything before her, a little to the right. At first she did not; but was presently told that a tiny spark, too minute to be noticed by any but those who were looking for it, was a guiding light.

“Where is it?” asked the lady. “Why have not you a more effectual light?”

“We are thankful enough to have any: and it serves our turn.”

“Oh! I suppose it is a smuggler’s signal, and it would not do to make it more conspicuous.”

“No, madam. It is far from being a smuggler’s signal. There is a woman, Annie Fleming, living in the grey house I showed you, an honest and pious soul, who keeps up that light for all that want it.”

“Why? Who employs her?”

“She does it of her own liking. Some have heard tell, but I don’t know it for true, that when she and her husband were young she saw him drown, from his boat having run foul in the harbour that she overlooks, and that from that day to this she has had a light up there every night. I can say that I never miss it when I come home; and I always enter by night, trusting to it as the best landmark in this difficult harbour.”

“And do the other inhabitants trust to it, and come in by night?”

Macdonald answered that his was the only boat on the island; but he believed that all who had business on the sea between this and Skye knew that light, and made use of it, on occasion, in dangerous weather. And now he must not talk, but see to his vessel.

This is the only boat on the island! He must mean the only sloop. There must be fishing boats. There must and should be, the lady resolved; for she would get back to the mainland. She would not spend her days here, beyond the westerly Skye, where she had just learned that this island lay.

The anxious business of entering the harbour was accomplished by slow degrees, under the guidance of the spark on the hill-side. At dawn the little vessel was moored to a natural pier of rock, and the lady was asked whether she would proceed to Macdonald’s house immediately or take some hours’ rest first.

Here ended her fears of being secluded from popular sympathy. She was weary of the sea and the vessel, and made all haste to leave them.

Her choice lay between walking and being carried by Highlanders. She chose to walk; and with some fatigue, and no little internal indignation, she traversed a mile and a half of rocky and moorland ways, then arriving at a sordid and dreary looking farmhouse, standing alone in a wild place, to which Macdonald proudly introduced her as Sir Alexander’s estate on this island, of which he was the tenant.

Chapter Six.

The Steadfast.

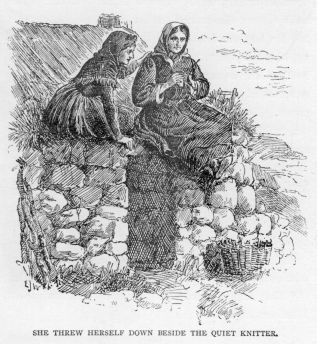

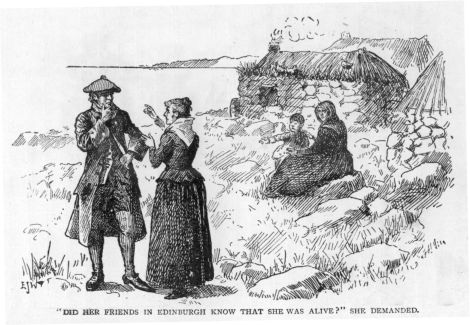

It was a serene evening when, the day after her landing, Lady Carse approached Widow Fleming’s abode. The sun was going down in a clear sky; and when, turning from the dazzling western sea, the eye wandered eastwards, the view was such as could not but transport a heart at ease. The tide was low, and long shadows from the rocks lay upon the yellow sands and darkened, near the shore, the translucent sea. At the entrance of the black caverns the spray leaped up on the advance of every wave,—not in threatening but as if at play. Far away over the lilac and green waters arose the craggy peaks of Skye, their projections and hollows in the softest light and shadow. As the sea-birds rose from their rest upon the billows, opposite the sun, diamond drops fell from their wings. Nearer at hand there was little beauty but what a brilliant sunset sheds over every scene. There were shadows from the cottage over the dull green sward, and from the two or three goats which moved about on the ledges and slopes of the upper rocks. The cottage itself was more lowly and much more odd than the lady had conceived from anything she had yet seen or heard of. Its walls were six feet thick, and roofed from the inside, leaving a sort of platform all round, which was overgrown with coarse herbage. The outer and inner surfaces of the wall were of stones, and the middle part was filled in with earth; so that grass might well grow on the top. The roof was of thatch—part straw, part sods, tied down to cross poles by ropes of twisted heather. The walls did not rise more than five feet from the ground; and nothing could be easier than for the goats to leap up, when tempted to graze there. A kid was now amusing itself on one corner. As Lady Carse walked round, she was startled at seeing a woman sitting on the opposite corner. Her back was to the sun—her gaze fixed on the sea, and her fingers were busy knitting. The lady had some doubts at first about its being the widow, as this woman wore a bright cotton handkerchief tied over her head: but a glance at the face when it was turned towards her assured her that it was Annie Fleming herself.

“No, do not come down,” said the lady. “Let me come up beside you. I see the way.”

And she stepped up by means of the projecting stones of the wall, and threw herself down beside the quiet knitter.

“What are you making? Mittens? And what of? What sort of wool is this?”

“It is goats’ hair.”

“Tiresome work!” the lady observed. “Wool is bad enough; but these short lengths of hair! I should never have patience.”

The widow replied that she had time in these summer  evenings; and she was glad to take the chance of selling a few pairs when Macdonald went to the main, once or twice a year.

evenings; and she was glad to take the chance of selling a few pairs when Macdonald went to the main, once or twice a year.

“How do they sell? What do you get for them?”

“I get oil to last me for some time.”

“And what else?”

“Now and then I may want something else; but I get chiefly oil—as what I want most.”

The widow saw that Lady Carse was not attending to what she said, and was merely making an opening for what she herself wanted to utter: so Annie said no more of her work and its payment, but waited.

“This is a dreadful place,” the lady burst out. “Nobody can live here.”

“I have heard there are kindlier places to live in,” the widow replied. “This island must appear rather bare to people who come from the south,—as I partly remember myself.”

“Where did you come from? Do you know where I come from? Do you know who I am?” cried the lady.

“I came from Dumfries. I have not heard where you lived, my lady. I was told by Macdonald that you came by Sir Alexander Macdonald’s orders, to live here henceforward.”

“I will not live here henceforward. I would sooner die.”

The widow looked surprised. In answer to that look Lady Carse said, “Ah! you do not know who I am, nor what brought me here, or you would see that I cannot live here, and why I would rather die.—Why do not you speak? Why do you not ask me what I have suffered?”

“I should not think of it, my lady. Those who have suffered are slow to speak of their heart pain, and would be ashamed before God to say how much oftener they would rather have died.”

“I must speak, however, and I will,” declared Lady Carse. “You know I must; and you are the only person in the island that I can speak to.—I want to live with you. I must. I know you are a good woman. I know you are kind. If you are kind to mere strangers that come in boats, and keep a light to save them from shipwreck, you will not be cruel to me—the most ill used creature—the most wretched—the most—”

She hid her face on her knees, and wept bitterly.

“Take courage, my lady,” said Annie. “If you have not strength enough for your troubles to-day, it only shows that there is more to come.”

“I do not want strength,” said the lady. “You do not know me. I am not wanting in strength. What I want—what I must have—is justice.”

“Well—that is what we are all most sure of when God’s day comes,” said Annie. “That we are quite sure of. And we may surely hope for patience till then, if we really wish it. So I trust you will be comforted, my lady.”

“I cannot stay here, however. There are no people here. There is nobody that I can endure at Macdonald’s, and there are none others but labourers, and they speak only Gaelic. And it is a wretched place. They have not even bread.—Mrs Fleming, I must come and live with you.”

“I have no bread, my lady. I have nothing so good as they have at Macdonald’s.”