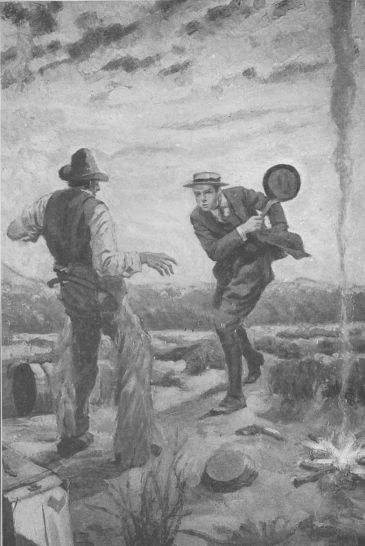

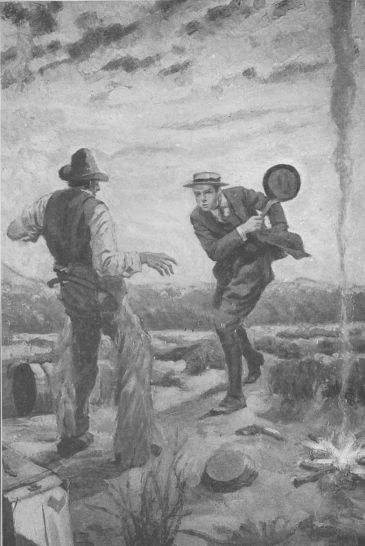

"Wallie swung the frying pan with all his strength ... knocking the six-shooter from Boise Bill's hand as he jumped across the fire at him"

Title: The Dude Wrangler

Author: Caroline Lockhart

Illustrator: Dudley Gloyne Summers

Release date: October 29, 2007 [eBook #23244]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Roger Frank and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team (https://www.pgdp.net)

E-text prepared by Roger Frank

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

|

THE DUDE WRANGLER BY CAROLINE LOCKHART  FRONTISPIECE BY DUDLEY GLYNE SUMMERS GARDEN CITY, N. Y., AND TORONTO DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY 1921 |

COPYRIGHT, 1921, BY

DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, INCLUDING THAT OF TRANSLATION

INTO FOREIGN LANGUAGES, INCLUDING THE SCANDINAVIAN

COPYRIGHT, 1921, BY STREET & SMITH CORPORATION

| CHAPTER | PAGE | ||

| I | The Girl From Wyoming | 3 | |

| II | "The Happy Family" | 10 | |

| III | Pinkey | 18 | |

| IV | The Brand of Cain | 24 | |

| V | "Gentle Annie" | 33 | |

| VI | "Burning His Bridges" | 42 | |

| VII | His "Gat" | 47 | |

| VIII | Neighbours | 62 | |

| IX | Cutting His Eyeteeth | 69 | |

| X | The Best Pulling Team in the State | 81 | |

| XI | Merry Christmas | 92 | |

| XII | The Water Witch | 112 | |

| XIII | Wiped Out | 131 | |

| XIV | Lifting a Cache | 142 | |

| XV | Collecting a Bad Debt | 156 | |

| XVI | The Exodus | 168 | |

| XVII | Counting Their Chickens | 176 | |

| XVIII | The Millionaires | 182 | |

| XIX | A Shock For Mr. Canby | 196 | |

| XX | Wallie Qualifies As a First-Class Hero | 207 | |

| XXI | "Worman! Worman!" | 221 | |

| XXII | "Knocking 'Em For a Curve" | 231 | |

| XXIII | Rifts | 247 | |

| XXIV | Hicks the Avenger | 261 | |

| XXV | "And Just Then——" | 301 |

Conscious that something had disturbed him, Wallie Macpherson raised himself on his elbow in bed to listen. For a full minute he heard nothing unusual: the Atlantic breaking against the sea-wall at the foot of the sloping lawn of The Colonial, the clock striking the hour in the tower of the Court House, and the ripping, tearing, slashing noises like those of a sash-and-blind factory, produced through the long, thin nose of old Mr. Penrose, two doors down the hotel corridor, all sounds to which he was too accustomed to be awakened by them.

While Wallie remained in this posture conjecturing, the door between the room next to him and that of Mr. Penrose was struck smartly several times, and with a vigour to denote that there was temper behind the blows which fell upon it. He had not known that the room was occupied; being considered undesirable on account of the audible slumbers of the old gentleman it was often vacant.

The raps finally awakened even Mr. Penrose, who demanded sharply:

"What are you doing?"

"Hammering with the heel of my slipper," a feminine voice answered.

"What do you want?"

"A chance to sleep."

"Who's stopping you?" crabbedly.

"You're snoring." Indignation gave an edge to the accusation.

"You're impertinent!"

"You're a nuisance!" the voice retorted. Wallie covered his mouth with his hand and hunched his shoulders.

There was a moment's silence while Mr. Penrose seemed to be thinking of a suitable answer. Then:

"It's my privilege to snore if I want to. This is my room—I pay for it!"

"Then this side of the door is mine and I can pound on it, for the same reason."

Mr. Penrose sneered in the darkness: "I suppose you're some sour old maid—you sound like it."

"And no doubt you're a Methuselah with dyspepsia!"

Wallie smote the pillow gleefully—old Mr. Penrose's collection of bottles and boxes and tablets for indigestion were a byword.

"We will see about this in the morning," said Mr. Penrose, significantly. "I have been coming to this hotel for twenty-eight years——"

"It's nothing to boast of," the voice interrupted. "I shouldn't, if I had so little originality."

Mr. Penrose, seeming to realize that the woman would have the last word if the dialogue lasted until morning, ended it with a loud snort of derision.

He was so wrought up by the controversy that he was unable to compose himself immediately, but lay awake for an hour framing a speech for Mr. Cone, the proprietor, which was in the nature of an ultimatum. Either the woman must move, or he would—but the latter he considered a remote possibility, since he realized fully that a multi-millionaire, socially well connected, is an asset which no hotel will dispense with lightly.

The frequency with which Mr. Penrose had presumed upon this knowledge had much to do with Wallie's delight as he had listened to the encounter.

Dropping back upon his pillow, the young man mildly wondered about the woman next door to him. She must have come in on the evening train while he was at the moving pictures, and retired immediately. Very likely she was, as Mr. Penrose asserted, some acrimonious spinster, but, at any rate, she had temporarily silenced the rich old tyrant of whom all the hotel stood in awe.

A second time the ripping sound of yard after yard of calico being viciously torn broke the night's stillness and, grinning, Wallie waited to hear what the woman next door was going to do about it. But only a stranger would have hoped to do anything about it, since to prevent Mr. Penrose from snoring was a task only a little less hopeless than that of stopping the roar of the ocean. Guests whom it annoyed had either to move or get used to it. Sometimes they did the one and sometimes the other, but always Mr. Penrose, who was the subject of a hundred complaints a summer, snored on victoriously. The woman next door, of course, could not know this, so no doubt she had a mistaken notion that she might either break the old gentleman of his habit or have him banished to an isolated quarter.

Wallie had not long to wait, for shortly after Mr. Penrose started again the tattoo on the door was repeated.

In response to a snarl that might have come from a menagerie, she advised him curtly:

"You're at it again!"

Another angry colloquy followed, and once more Mr. Penrose was forced to subside for the want of an adequate answer.

All the rest of the night the battle continued at intervals, and by morning not only Wallie but the entire corridor was interested in the occupant of the room adjoining his.

Wallie was in the office when the door of the elevator opened with a clang and Mr. Penrose sprang out of it like a starved lion about to hurl himself upon a Christian martyr. While his jaws did not drip saliva, the thin nostrils of his bothersome nose quivered with eagerness and anger.

"I've been coming here for twenty-eight years, haven't I?" he demanded.

"Twenty-eight this summer," Mr. Cone replied, soothingly.

"In that time I never have put in such a night as last night!"

"Dear me!" The proprietor seemed genuinely disturbed by the information.

"I could not sleep—I have not closed my eyes—for the battering on my door of the female in the room adjoining!"

"You astonish me! Let me see——" Mr. Cone whirled the register around and looked at it. He read aloud:

"Helene Spenceley—Prouty, Wyoming."

Mr. Cone lowered his voice discreetly:

"What was her explanation?"

"She accused me of snoring!" declared Mr. Penrose, furiously. "I heard the clock strike every hour until morning! Not a wink have I slept—not a wink, Mr. Cone!"

"We can arrange this satisfactorily, Mr. Penrose," Mr. Cone smiled conciliatingly. "I have no doubt that Miss—er—Spenceley will gladly change her room if I ask her. I shall place one equally good at her disposal—— Ah, I presume this is she—let me introduce you."

Although he would not admit it, Mr. Penrose was quite as astonished as Wallie at the appearance of the person who stepped from the elevator and walked to the desk briskly. She was young and good looking and wore suitable clothes that fitted her; also, while not aggressive, she had a self-reliant manner which proclaimed the fact that she was accustomed to looking after her own interests. While she was as far removed as possible from the person Mr. Penrose had expected to see, still she was the "female" who had "sassed" him as he had not been "sassed" since he could remember, and he eyed her belligerently as he curtly acknowledged the introduction.

"Mr. Penrose, one of our oldest guests in point of residence, tells me that you have had some little—er—difference——" began Mr. Cone, affably.

"I had a hellish night!" Mr. Penrose interrupted, savagely. "I hope never to put in such another."

"I join you in that," replied Miss Spenceley, calmly. "I've never heard any one snore so horribly—I'd know your snore among a thousand."

"Never mind—we can adjust this matter amicably, I will change your room to-day, Miss Spenceley," Mr. Cone interposed, hastily. "It hasn't quite the view, but the furnishings are more luxurious."

"But I don't want to change," Miss Spenceley coolly replied. "It suits me perfectly."

"I came for quiet and I can't stand that hammering," declared Mr. Penrose, glaring at her.

"So did I—my nerves—and your snoring bothers me. But perhaps," with aggravating sweetness, "I can break you of the habit."

"I wouldn't lose another night's sleep for a thousand dollars!"

"It will be cheaper to change your room, for I don't mean to change mine."

The millionaire turned to the proprietor. "Either this person goes or I do—that's my ultimatum!"

"I will not be bullied in any such fashion, and I can't very well be put out forcibly, can I?" and Miss Spenceley smiled at both of them. Mr. Cone looked from one to the other, helplessly.

"Then," Mr. Penrose retorted, "I shall leave immediately! Mr. Cone," dramatically, "the room I have occupied for twenty-eight summers is at your disposal." His voice rose in a crescendo movement so that even in the furthermost corner of the dining room they heard it: "I have a peach orchard down in Delaware, and I shall go there, where I can snore as much as I damn please; and don't you forget it!"

Mr. Cone, his mouth open and hands hanging, looked after him as he stamped away, too astonished to protest.

The guests of the Colonial Hotel arose briskly each morning to nothing. After a night of refreshing and untroubled sleep they dressed and hurried to breakfast after the manner of travellers making close connections. Then each repaired to his favourite chair placed in the same spot on the wide veranda to wait for luncheon. The more energetic sometimes took a wheel-chair for an hour and were pushed on the Boardwalk or attended an auction sale of antiques and curios, but mostly their lives were as placid and as eventful as those of the inmates of an institution.

The greater number of the male guests of The Colonial had retired from something—banking, wholesale drugs, the manufacture of woolens. The families were all perfectly familiar with one another's financial rating and histories, and although they came from diverse sections of the country they were for two months or more like one large, supremely contented family. In truth, they called themselves facetiously "The Happy Family," and in this way Mr. Cone, who took an immense pride in them and in the fact that they returned to his hospitable roof summer after summer, always referred to them.

Strictly speaking, there were two branches of the "Family": those whose first season antedated 1900, and the "newcomers," who had spent only eight, or ten, or twelve summers at The Colonial. They were all on the most friendly terms imaginable, yet each tacitly recognized the distinction. The original "Happy Family" occupied the rocking chairs on the right-hand side of the wide veranda, while the "newcomers" took the left, where the view was not quite so good and there was a trifle less breeze than on the other.

The less said of the "transients" the better. The few who stumbled in did not stay unless by chance they were favourably known to one of the "permanents." Of course there was no rudeness ever—merely the polite surprise of the regular occupants when they find a stranger in the pew on Sunday morning. Sometimes the transient stayed out his or her vacation, but usually he confided to the chambermaid, and sometimes Mr. Cone, that the guests were "doodledums" and "fossils" and found another hotel where the patrons, if less solid financially, were more interesting and sociable.

Wallace Macpherson belonged in the group of older patrons, as his aunt, Miss Mary Macpherson, had been coming since 1897, and he himself from the time he wore curls and ruffled collars, or after his aunt had taken him upon the death of his parents.

"Wallie," as he was called by everybody, as the one eligible man under sixty, was, in his way, as much of an asset to the hotel as the notoriously wealthy Mr. Penrose. Of an amiable and obliging disposition, he could always be relied upon to escort married women with mutinous husbands, and ladies who had none, mutinous or otherwise. He was twenty-four, and, in appearance, a credit to any woman he was seen with, to say nothing of the two hundred thousand it was known he would inherit from Aunt Mary, who now supported him.

Wallie's appearance upon the veranda was invariably in the nature of a triumphal entry. He was received with lively acclaim and cordiality as he flitted impartially from group to group, and that person was difficult indeed with whom he could not find something in common, for his range of subjects extended from the "rose pattern" in Irish crochet to Arctic currents.

The morning on the veranda promised to be a lively one, since, in addition to the departure of old Mr. Penrose, who had sounded as if he was wrecking the furniture while packing his boxes, the return from the war of Will Smith, the gardener's son, was anticipated, and the guests as an act of patriotism meant to give him a rousing welcome. There was bunting over the doorway and around the pillars, with red, white, and blue ice cream for luncheon, and flags on the menu, not to mention a purse of $17.23 collected among the guests that was to be presented in appreciation of the valour which, it was understood from letters to his father, Will had shown on the field of battle.

The guests were in their usual places when Wallie came from breakfast and stood for a moment in the spacious double doorway. A cheerful chorus welcomed him as soon as he was discovered, and Mrs. C. D. Budlong put out her plump hand and held his. He did not speak instantly, for his eye was roving over the veranda as if in search of somebody, and when it rested upon Miss Spenceley sitting alone at the far end he seemed satisfied and inquired solicitously of Mrs. Budlong: "Did you sleep well? You are looking splendid!"

There were some points of resemblance between Mrs. Budlong and the oleander in the green tub beside which she was sitting. Her round, fat face had the pink of the blossoms and she was nearly as motionless as if she had been potted. She often sat for hours with nothing save her black, sloe-like eyes that saw everything, to show that she was not in a state of suspended animation. Her husband called her "Honey-dumplin'," and they were a most affectionate and congenial couple, although she was as silent as he was voluble.

"My rest was broken." Mrs. Budlong turned her eyes significantly toward the far end of the veranda.

"Did you hear that terrible racket?" demanded Mr. Budlong of Wallie.

"Not so loud, 'C. D.,'" admonished Mrs. Budlong. Mrs. Budlong ran the letters together so that strangers often had the impression she was calling her husband "Seedy," though the name was as unsuitable as well could be, since Mr. Budlong in his neat blue serge suit, blue polka-dot scarf, silk stockings, and polished tan oxfords was well groomed and dapper always.

"She's driven away our oldest guest." Mr. Budlong lowered his indignant voice a little.

"He was a nuisance with his snoring," Wallie defended.

"She could have changed her room," said Mrs. Budlong, taking her hand away from him. "She need not have been so obstinate."

"He was very rude to her," Wallie maintained stoutly. "Sleeping next door, I heard it all—and this morning in the office."

"Anyway, I think Mr. Cone made a mistake in not insisting upon her changing her room, and so I shall tell him." Mr. Budlong, who had made "his" in white lead and paint and kept a chauffeur and a limousine, felt that his disapproval would mean something to the proprietor.

"Oh, Wallie!"

Wallie felt relieved when he saw Mrs. Henry Appel beckoning him. As he was on his way to Mrs. Appel Miss Mattie Gaskett clutched at his arm and detained him.

"Did you see the robins this morning, Wallie?"

"Are they here?"

"Yes, a dozen of them. They do remind me so of my dear Southland." Miss Gaskett was from Maryland.

"The summer wouldn't be the same without either of you," he replied, gallantly.

Miss Gaskett shook a coquettish finger at him.

"You flirt! You have pretty speeches for everyone."

Wallie did not seem displeased by the accusation as he passed on to Mrs. Appel.

The Appels were among the important families of The Colonial because the richest next to Mr. Penrose. They were from Mauch Chunk, Pennsylvania. Mr. Appel owned anthracite coal land and street railways, so if Mr. Appel squeezed pennies and Mrs. Appel dressed in remnants from the bargain counter their economies were regarded merely as eccentricities.

Mrs. Appel held up a sweater: "Won't you tell me how to turn this shoulder? I've forgotten. Do you purl four and knit six, or purl six and knit four, Wallie?"

Wallie laughed immoderately.

"Eight, Mrs. Appel! Purl eight and knit four—I told you yesterday. That's a lovely piece of Battenburg, Mrs. Stott. When did you start it?"

"Last month, but I've been so busy with teas and parties—so many, many things going on. Don't you think it will make a lovely dresser-scarf? What would you line it with?"

"Pink, absolutely—that delicate shade like the inside of a sea-shell."

"You are such an artist, Wallie! Your taste is perfect."

Wallie did not contradict her.

Strictly, Mrs. Stott did not belong in the group in which she was seated. She had been coming to The Colonial only eleven years, so really, she should have been on the other side of the veranda, but Mrs. Stott had such an insidious way of getting where and what she wanted that she was "one of them" almost before they knew it.

Mr. Stott was a rising young attorney of forty-eight, and it was anticipated that he would one day be a leading trial lawyer because of his aggressiveness.

Wallie's voice took on a sympathetic tone. He stopped in front of a chair where a very thin young lady was reclining languidly.

"How's the bad heart to-day, Miss Eyester?"

"About as usual, Wallie, thank you," she replied, gratefully.

"Your lips have more colour."

Miss Eyester opened a handbag and, taking out a small, round mirror which she carried for the purpose, inspected her lips critically.

"It does seem so," she admitted. "If I can just keep from getting excited."

"I can't imagine a better place than The Colonial." The reply contained a grain of irony.

"That's why I come here," Miss Eyester sighed, "though I'm pining to go somewhere livelier."

Wallie wagged his head playfully.

"Treason! Treason! Why, you've been coming here for—" Miss Eyester's alarmed expression caused him to finish lamely—"for ever so long."

"Wallie!" It was his aunt's voice calling and he went instantly to a tall, austere lady in a linen collar who was knitting wash-rags with the feverish haste of a piece-worker in a factory.

He stood before her obediently.

"Don't go in to-day."

"Why, Auntie?" In his voice there was a world of disappointment.

"It's too rough—there must have been a storm at sea."

"But, Auntie," he protested, "I missed yesterday, taking Mrs. Appel to the auction. It isn't very rough——"

"Look at the white-caps," she interrupted, curtly, "I don't want you to go, Wallie."

"Oh, very well." He turned away abruptly, wondering if she realized how keenly he was disappointed—a disappointment that was not made less by the fact that her fears were groundless, since not only was it not "rough" but he was an excellent swimmer.

"The girl from Wyoming," as he called Miss Spenceley to himself, had overheard and was looking at him with an expression in her eyes which made him redden. It was mocking; she was laughing at him for being told not to go in bathing, as if he were a child of seven.

He sauntered past her, humming, to let her know that he did not care what she thought about him. When he turned around she had vanished and a few minutes after he saw her with her suit over her arm on the way to the bath-house on the exclusive beach in front of The Colonial.

The train upon which Will Smith was expected was not due until twelve-thirty, so, since he could not go swimming and still felt rebellious over being forbidden, Wallie went upstairs to put the finishing touches on a lemonade tray of japanned tin which he had painted and intended presenting to Mr. Cone.

The design was his own, and very excellent it seemed to Wallie as he stopped at intervals and held it from him. On a moss-green background of rolling clouds a most artistic cluster of old-fashioned cabbage roses was tossed carelessly, with a brown slug on a leaf as a touch of realism.

The gods have a way of apportioning their gifts unevenly, for not only did Wallie paint but he wrote poetry—free verse mostly; free chiefly in the sense that his contributions to the smaller magazines were, perforce, gratuitous. Also he sang—if not divinely, at least so acceptably that his services were constantly asked for charity concerts.

In addition to these he had manlier accomplishments, playing good games of tennis, golf, and shuffle-board. Besides, Mr. Appel was his only dangerous opponent on the bowling alley, and he had learned to ride at the riding academy.

Now, as he worked, he speculated as to whether he had imagined it or "the girl from Wyoming" really had laughed at him. He could not dismiss her from his mind and the incident rankled. He told himself that she had not been there long enough to appreciate him; she knew nothing of his talents or of his popularity. She would learn that to be singled out by him for special attention meant something, and he did not consider himself a conceited man either.

Yet Wallie continued to tingle each time that he thought of the laughter in her eyes—actual derision he feared it was. Then he had an idea, a very clever one it seemed to him. By this time she would have returned from bathing and he would go down and exhibit the cabbage roses. They would be praised and she would hear it. It was nearly time for Will Smith to arrive, and he had to stop painting, anyhow.

Bearing the lemonade tray carefully in order not to smudge it, Wallie stepped out of the elevator and stood in the wide doorway, agreeably aware that he was a pleasing figure in his artist's smock and the flowing scarf which he always put on when he painted.

No one noticed him, however, for everyone was discussing the return of the "Smith boy," and the five dollars which Mr. Appel, the railway magnate, had unexpectedly contributed to the purse that he was going to present to him on behalf of the guests.

Miss Spenceley was on the veranda as he had surmised she would be, and Wallie debated as to whether he should wait until discovered and urged to show his roses, or frankly offer his work for criticism.

While he hesitated, the clatter of hoofs and what appeared to be a serious runaway on the side avenue brought everyone up standing. The swaying vehicle was a laundry wagon, and when it turned in at the entrance to the grounds of The Colonial, the astonished guests saw that not only had the horse a driver but a rider!

It was not a runaway. On the contrary, the person on the horse's back was using his heels and his hat at every jump to get more speed out of the amazed animal.

The wagon stopped in front of the hotel with the driver grinning uncertainly, while a soldierly figure sprang over the wheel to wring the hand of Smith, the gardener. Another on the horse's back replaced his service cap at an extraordinary angle and waited nonchalantly for the greetings to be over.

Before he went to the army "Willie" Smith had been a bashful boy who blushed when the guests spoke to him, but he faced them now with the assurance of a vaudeville entertainer as he introduced his "buddy":

"Pinkey Fripp, of Wyoming—a hero, ladies and gentlemen! The grittiest little soldier in the A.E.F., with a medal to prove it!"

Followed an account of the deed of reckless courage for which Pinkey had been decorated, and the Smith boy told it so well that everyone's eyes had tears in them. Mrs. Appel, fumbling for her handkerchief, dropped her ball of yarn over the railing, where the cat wound it among the rose bushes so effectively that to disentangle it were an endless task.

The subject of the eulogy stared back unabashed at the guests, who stared at him in admiration and curiosity. Unflattered, unmoved, he sagged to one side of the bare-backed horse with the easy grace of one accustomed to the saddle. No one just like him ever had come under the observation of the august patrons of The Colonial.

Pinkey Fripp was about five feet four and square as a bulldog. "Hard-boiled" is a word which might have been coined specially to describe him. The cropped hair on his round head was sandy, his skin a sun-blistered red, and his lips had deep cracks in them. His nose did not add to his beauty any more than the knife-scar around his neck, which looked as if someone had barely failed in an attempt to cut off his head.

The feature that saved the young fellow's face from a look of unmitigated "toughness" was his pale gray eyes, whose steady, fearless look seemed to contend with a whimsical gleam of humour.

Pinkey listened, with the disciplined patience of the army, to the recital of the exploit that had won the War Cross for him, but there was a peculiar glint in his light eyes. As Smith drew to a conclusion, Pinkey slowly lifted his leg, stiffened by a machine-gun bullet, over the horse's neck and sat sideways.

The applause was so vociferous, so spontaneous and hearty, that nothing approaching it ever had been heard at The Colonial. But it stopped as suddenly, for in the middle of it Pinkey gathered himself and sprang through the air like a flying-squirrel, to bowl the Smith boy over. "You said you wouldn't tell about that 'Craw de gare,' ner call me a hero, an' you've gone and done it!" he said, accusingly, as he sat astride of him. "I got feelin's jest like grown-up folks, and I don't like to be laughed at. Sorry, Big Boy, but you got this comin'!" Thereupon, with a grin, Pinkey banged his host's head on the gravel.

The two were surrounded when this astonishing incident was over and it was found that not only was the Smith boy not injured but seemed to be used to it and bore no malice. The guests shook hands with the boys and congratulated them; they examined the War Cross that Pinkey produced reluctantly from the bottom of the flour-sack in which he carried his clothing, and finally Mr. Appel presented the purse in a speech to which nobody listened—and the Smith boy shocked everybody by his extravagance when he gave five of it to the driver of the laundry wagon.

"I was shore pinin' to step in the middle of a horse," was Pinkey's explanation of their eccentric arrival. "It kinda rests me."

While all this was happening Wallie stood holding his lemonade tray. When he could get close, he welcomed the Smith boy and was introduced to Pinkey, and stood around long enough to learn that the latter and Helene Spenceley knew each other.

Nobody, however, was interested in seeing his roses. Even Miss Mattie Gaskett, who always clung like a burr to woollen clothing with the least encouragement, said carelessly when he showed her the lemonade tray:

"As good as your best, Wallie," and edged over to hear what Pinkey was saying.

There was nothing to do but withdraw unobtrusively, though Wallie realized with chagrin that he could have gone upstairs on his hands and knees without attracting the least attention. For the first time he regretted deeply that his eyesight had kept him out of the army, for he, too, might have been winning war crosses in the trenches instead of rolling bandages and knitting socks and sweaters.

Wallie almost hated the lemonade tray as he slammed it on the table, for in his utter disgust with everything and everybody the design seemed to look more like cabbages than roses.

There never was a nose so completely out of joint as Wallie's nor an owner more thoroughly humiliated and embittered by the fickleness and ingratitude of human nature. The sacrifices he had made in escorting dull ladies to duller movies were wasted. The unfailing courtesy with which he had retrieved their yarn and handkerchiefs, the sympathy and attention with which he had listened to their symptoms, his solicitude when they were ailing—all were forgotten now that Pinkey was in the vicinity.

The ladies swarmed around that person, quoted his sayings delightedly, and declared a million times in Wallie's hearing that "he was a character!" And the worst of it was that Helene Spenceley did not seem sufficiently aware of Wallie's existence even to laugh at him.

As the displaced cynosure sat brooding in his room the third morning after Pinkey's arrival he wished that he could think of some perfectly well-bred way to attract attention.

He believed in the psychology of clothes. Perhaps if he appeared on the veranda in something to emphasize his personality, something suggesting strength and virility, like tennis flannels, he could regain his hold on his audience.

With this thought in mind Wallie opened his capacious closet filled with wearing apparel, and the moment his eyes fell upon his riding breeches he had his inspiration. If "the girl from Wyoming" thought her friend Pinkey was the only person who could ride a horse, he would show her!

It took Wallie only so long to order a horse as it required to get the Riding Academy on the telephone.

"I want a good-looking mount—something spirited," he instructed the person who answered.

"We've just bought some new horses," the voice replied. "I'll send you the pick of them."

Wallie hung up the receiver, fairly trembling with eagerness to dress himself and get down on the veranda. He looked well in riding togs—everyone mentioned it—and if he could walk out swinging his crop nonchalantly, well, they would at least notice him! And when he would spring lightly into the saddle and gallop away—he saw it as plainly as if it were happening.

Although Wallie actually broke his record he seemed to himself an unconscionable time in dressing, but when he gave himself a final survey in the mirror, he had every reason to feel satisfied with the result. He was correct in every detail and he thought complacently that he could not but contrast favourably with the appearance of that "roughneck" from Montana—or was it Wyoming?

"What you taking such a hot day to ride for?" Mrs. Appel called when she caught sight of Wallie.

The question jarred on him and he replied coolly:

"I had not observed that it was warmer than usual, Mrs. Appel."

"It's ninety, with the humidity goodness knows how much!" she retorted.

Without seeming to look, Wallie could see that both Miss Spenceley and Pinkey were on the veranda and regarding him with interest. His pose became a little theatrical while he waited for his mount, striking his riding boot smartly with his crop as he stood in full view of them.

Everyone was interested when they saw the horse coming, and a few sauntered over to have a look at him, Miss Spenceley and Pinkey among the others.

"Is that the horse you always ride, Wallie?" inquired Miss Gaskett.

"No; it's a new one I'm going to try out for them," Wallie replied, indifferently.

"Wallie, do be careful!" his aunt admonished him. "I don't like you to ride strange horses."

Wallie laughed lightly, and as he went down to meet the groom who was now at the foot of the steps with the horses he assured her that there was not the least cause for anxiety.

"Why, that's a Western horse!" Miss Spenceley exclaimed. "Isn't that a brand on the shoulder?"

"It looks like it," Pinkey answered, ruffing the hair then smoothing it. "Shore it's a brand." He stepped off a pace to look at it.

"Pardon me, but I think you're mistaken," Wallie said, politely but positively. "The Academy buys only thoroughbreds."

"If that ain't a bronc, I'll eat it," Pinkey declared, bluntly.

"Can you make out the brand?" asked Miss Spenceley.

Pinkey ruffed the hair again and stepped back and squinted. Then his cracked lips stretched in a grin that threatened to start them bleeding: "'88' is the way I read it."

She nodded: "The brand of Cain."

Then they both laughed immoderately.

Wallie could see no occasion for merriment and it nettled him.

"Nevertheless, I maintain that you are in error," he declared, obstinately.

"I doubt if I could set one of them hen-skin saddles," observed Pinkey, changing the subject.

Wallie replied airily:

"Oh, it's very easy if you've been taught properly."

"Taught? You mean," wonderingly, "that somebody learnt you to ride horseback?"

Wallie smiled patronizingly:

"How else would I know?"

"I was jest throwed on a horse and told to stay there."

"Which accounts for the fact that you Western riders have no 'form,' if you'll excuse my frankness."

"Don't mention it," replied Pinkey, not to be outdone in politeness. "Maybe, before I go, you'll give me some p'inters?"

"I shall be most happy," Wallie responded, putting his foot in the stirrup.

He mounted creditably and settled himself in the saddle.

"Thumb him," said Miss Spenceley, "and we'll soon settle the argument."

"How—thumb him? The term is not familiar."

"Show him, Pinkey." Her eyes were sparkling, for Wallie's tone implied that the expression was slang and also rather vulgar.

"He'll unload his pack as shore as shootin'." Pinkey hesitated.

"No time like the present to learn a lesson," she replied, ambiguously.

"Certainly—if there's anything you can teach me," Wallie's smile said as plain as words that he doubted it. "Mr. Fripp—er—'thumb' him."

"You're the doctor," said Pinkey, grimly, and "thumbed" him.

The effect was instantaneous. The old horse ducked his head, arched his back, and went at it.

It was over in less time than it requires to tell and Wallie was convinced beyond the question of a doubt that the horse had not been bred in Kentucky. As he described an aërial circle Wallie had a whimsical notion that his teeth had bitten into his brain and his spine was projected through the crown of his derby hat. Darkness and oblivion came upon him for a moment, and then he found himself being lifted tenderly from a bed of petunias and dusted off by the groom from the Riding Academy.

The ladies were screaming, but a swift glance showed Wallie not only Mr. Appel but Mr. Cone and Mr. Budlong with their hands over their mouths and their teeth gleaming between their spreading fingers.

"Coward!" he cried to Pinkey. "You don't dare get on him!"

"Can you ride him 'slick,' Pinkey?" asked Miss Spenceley.

"I'll do it er bust somethin'." Pinkey's mouth had a funny quirk at the corners. "Maybe it'll take the kinks out of me from travellin'."

He looked at Mr. Cone doubtfully: "I'm liable to rip up the sod in your front yard a little."

"Go to it!" cried Mr. Cone, whose sporting blood was up. "There's nothin' here that won't grow again. Ride him!"

Everybody was trembling, and when Miss Eyester looked at her lips they were white as alabaster, but she meant to see the riding, if she had one of her sinking spells immediately it was over.

When Pinkey swung into the saddle, the horse turned its head around slowly and looked at the leg that gripped him. Pinkey leaned down, unbuckled the throat-latch, and slipped off the bridle. Then, as he touched the horse in the flank with his heels, he took off his cap and slapped him over the head with it.

The horse recognized the familiar challenge and accepted it. What he had done to Wallie was only the gambolling of a frisky colt as compared with his efforts to rid his back of Pinkey.

Even Helene Spenceley sobered as she watched the battle that followed.

The horse sprang into the air, twisted, and came down stiff-legged—squealing. Now with his head between his forelegs he shot up his hind hoofs and at an angle to require all the grip in his rider's knees to stay in the saddle. Then he brought down his heels again, violently, to bite at Pinkey—who kicked him.

He "weaved," he "sunfished"—with every trick known to an old outlaw he tried to throw his rider, rearing finally to fall backward and mash to a pulp a bed of Mr. Cone's choicest tulips. But when the horse rose Pinkey was with him, while the spectators, choking with excitement, forgetting themselves and each other, yelled like Apaches.

With nostrils blood-red and distended, his eyes the eyes of a wild animal, now writhing, now crouching, now lying back on his haunches and springing forward with a violence to snap any ordinary vertebra, the horse pitched as if there was no limit to its ingenuity and endurance.

Pinkey's breath was coming in gasps and his colour had faded with the terrible jar of it all. Even the uninitiated could see that Pinkey was weakening, and the result was doubtful, when, suddenly, the horse gave up and stampeded. He crashed through the trellis over which Mr. Cone had carefully trained his crimson ramblers, tore through a neat border of mignonette and sweet alyssum that edged the driveway, jumped through "snowballs," lilacs, syringas, and rhododendrons to come to a halt finally conquered and chastened.

The "88" brand has produced a strain famous throughout Wyoming for its buckers, and this venerable outlaw lived up to every tradition of his youth and breeding.

There never was worse bucking nor better riding in a Wild West Show or out of it, and Mr. Appel declared that he had not been so stirred since the occasion when walking in the woods at Harvey's Lake in the early '90's he had acted upon the unsound presumption that all are kittens that look like kittens and disputed the path with a black-and-white animal which proved not to be.

Mrs. C. D. Budlong was shedding tears like a crocodile, without moving a feature. Mr. Budlong put the lighted end of a cigar in his mouth and burned his tongue to a blister, while Miss Eyester dropped into a chair and had her sinking spell and recovered without any one remarking it. In an abandonment that was like the delirium of madness Mr. Cone went in and lifted Miss Gaskett's cat "Cutie" out of the plush rocker, where she was leaving hairs on the cushion, and surreptitiously kicked her.

Altogether it was an unforgettable occasion, and only Pinkey seemed unthrilled by it—he dismounted in a businesslike, matter-of-fact manner that had in it neither malice toward the horse nor elation at having ridden him. He felt admiration, if anything, for he said as he rubbed the horse's forehead:

"You shore made me ride, Old Timer! You got all the old curves and some new ones. If I had a hat I'd take it off to you. I ain't had such a churnin' sence I set 'Steamboat' fer fifteen seconds. Oh, hullo——" as Wallie advanced with his hand out.

"I congratulate you," said Wallie, feeling himself magnanimous in view of the way his neck was hurting.

"You needn't," replied Pinkey, good-naturedly. "He durned near 'got' me."

"It was a very creditable ride indeed," insisted Wallie, in his most patronizing and priggish manner. He found it very hard to be generous, with Helene Spenceley listening.

"It seemed so, after your performance, 'Gentle Annie'!" snapped Miss Spenceley.

Actually the woman seemed to spit like a cat at him! She had the tongue of a serpent and a vicious temper. He hated her! Wallie removed his hat with exaggerated politeness and decided never to have anything more to say to Miss Spenceley.

Wallie had told himself emphatically that he would never speak again to Helene Spenceley. That would be an easy matter since she had glared at him, when they had passed as she was going in for breakfast, in a way that would have made him afraid to speak even if he had intended to. To refrain from thinking of her was something different.

He sat on a rustic bench on The Colonial lawn watching the silly robins and wondering why she had called him "Gentle Annie." It was clear enough that nothing flattering was intended, but what did she mean by it? There was no reason that he could see for her to fly at him—quite the contrary. He had been very generous and gentlemanly, it seemed to him, in congratulating Pinkey when it was due to them that he, Wallie, was thrown into the petunias. His neck was still stiff from the fall and no one had remembered to inquire about it—that was another reason for the disgruntled mood in which the moment found him. The women were making perfect fools of themselves over that Pinkey—they were at it now, he could hear them cackling on the veranda.

What he could not understand was why they should act as if there was something amusing about a woman who came from west of Buffalo and then make a hero of a man from the Wild and Woolly. Yet they always did it, he had noticed. Why, that Pinkey could not speak a grammatical sentence and they hung on his every word, breathless. It was disgusting!

Wallie picked up a pebble and pelted a robin.

He wished the undertow would catch that Spenceley girl. If he should reach her when she was going down for the third time she would have to thank him for saving her and that would about kill her. He decided that he would make a point of bathing when she did, on the very remote chance that it might happen.

"Gentle Annie! Gentle Annie! Gentle Annie!" The name rankled.

Wallie pitched a pebble at another robin and accidentally hit it. Stunned for an instant, it keeled over, and Wallie glanced guiltily toward the hotel to see if by any chance Mr. Cone, who encouraged robins, was looking.

Pinkey was crossing the lawn with the obvious intention of joining him.

"Gee!" he exclaimed, sinking down beside Wallie, "I've nearly sprained my tongue answerin' questions. 'Is it true that snakes shed their skin, and do the hot pools in the Yellowstone Park freeze in winter?' I'm goin' to drift pretty pronto—I can't stand visitin'."

"Do you like the East, Mr. Fripp?" inquired Wallie, formally.

"I'm glad they's a West," Pinkey replied, cryptically.

"You and Miss Spenceley are from the same section, I take it?"

"Yep—Wyomin'."

"Er—by the way"—Wallie's tone was elaborately casual—"what did she mean yesterday when she called me 'Gentle Annie'?"

Pinkey moved uneasily.

"Could you give me the precise significance?" persisted Wallie.

"I could, but I wouldn't like to," Pinkey replied, drily

"Oh, don't spare my feelings," said Wallie, loftily, "there's nothing she could say would hurt them."

"If that's the way you feel—she meant you were 'harmless'."

"I trust so," Wallie responded with dignity.

"I'd ruther be called a—er—a Mormon," Pinkey observed.

Shocked at the language, Wallie demanded:

"It is, then, an epithet of opprobrium?"

"I can't say as to that," replied Pinkey, judicially, "but she meant you were a 'perfect lady'."

"It's more than I can say of her!" Wallie retorted, reddening.

Pinkey merely grinned and shrugged a shoulder.

He arose a moment later as if the conversation and company alike bored him.

"Well—I'm goin' to pack my war-bag and ramble. Why don't you come West and git civilized? With your figger you ought to be good fer somethin'. S'long, feller!"

Naturally, Wallie was not comforted by his conversation with Pinkey. Now he knew himself to have been insulted, and resented it, but along with his indignation was such a feeling of dissatisfaction with his life as he had never known. His brow contracted while he thought of the monotony of it. Just as this summer would be a duplicate of every other summer so the winter would be a repetition of the many winters he had spent in Florida with Aunt Mary. After a few months at home they would migrate with the robins. He would meet the same people he had seen all summer. They would complain of the Southern cooking and knit and tat while they babbled amiably of themselves and the members of their family and their doings. The men would smoke and compare business experiences when they had finished flaying the Administration. Discontent grew within him as he reviewed it. Why couldn't he and Aunt Mary do something different for the winter? By George! he would suggest it to her!

He got up with alacrity, cheerful immediately.

She was not on the veranda and Miss Eyester was of the opinion that she had gone to her room to take her tonic.

"I have turned the shoulder, Wallie." Mrs. Appel held up the sweater triumphantly.

"That's good," said Wallie, feeling uncomfortable with Miss Spenceley within hearing.

"Wallie," Mrs. Stott called to him, "will you give me the address of that milliner whose hats you said you liked particularly? Somewhere on Walnut, wasn't it?"

"Sixteenth and Walnut," Wallie replied, shortly.

"What do you think I'm doing, Wallie?"

"I can't imagine, Mrs. Budlong."

"I'm rolling!"

"Rolling?"

"To reduce. C. D. says I look like a cement-mixer in action."

Wallie was annoyed by the confidence.

Miss Gaskett beckoned him.

"Have you seen Cutie, Wallie?"

"No," curtly.

"When I called her this morning she looked at me with eyes like saucers and simply tore into the bushes. Do you suppose anybody has abused her?"

Mr. Cone, who was standing in the doorway, went back to his desk hastily.

"I'm not in her confidence," said Wallie with so much sarcasm that they all looked at him.

Miss Spenceley was talking to Mr. Appel, who was listening so attentively that Wallie wondered what she was saying. They were sitting close to the window of the reception room and it occurred to Wallie that there would be no harm in stepping inside and gratifying his curiosity. The conversation was not of a private nature and in other circumstances he would have joined them, so, on his way to the elevator to find his aunt, he paused a moment to hear what the girl was saying.

Since she was speaking emphatically and a lace curtain was the only barrier, Wallie found out without difficulty:

"I have no use for a squaw-man."

"You mean," Mr. Appel interrogated, "a white man who marries an Indian woman?"

"Not necessarily. I mean a man who permits a woman to support him without making any effort on his part to do a man's work. He may be an Adonis and gifted to the point of genius, but I have no respect for him. He——"

Wallie did not linger. He remembered the ancient adage, and while he did not consider himself an eavesdropper or believe that Miss Spenceley meant anything personal, nevertheless the shoe fit to such a nicety that he hurried to the elevator, his step accelerated by the same sense of guilt that had sent Mr. Cone scuttling to his refuge behind the counter.

"Squaw-man"—the term was as new to him as "Gentle Annie."

As Miss Eyester had opined, Miss Macpherson was taking her tonic, or about to.

"I've come to make a suggestion, Auntie," Wallie began, with a little diffidence.

"What is it?" Miss Macpherson was shaking the bottle.

"Let's not go South this winter."

"Where then?" She smiled indulgently as she measured out the medicine.

"Why not California or Arizona?" he suggested.

"I don't believe this tonic helps me a particle." She made a wry face as she swallowed it.

"That's it," he declared, eagerly. "You need a change—we both do."

"I'm too set in my ways to enjoy new experiences, and I don't like strangers. We might catch contagious diseases, and there is no place where we could be so comfortable as in Florida. No," she shook her head kindly but firmly, "we will go South as usual."

"Oh—sugar!" The vehemence with which Wallie uttered the expletive showed the extent of his disappointment.

"Wallie! I'm surprised at you!" She regarded him with annoyance.

"I'm tired of going to the same places year after year, doing the same thing, seeing the same old fossils!"

"Wallie, you are speaking of my friends and yours," she reminded him.

"They're all right, but I like to make new ones. I don't want to go, Aunt Mary."

She said significantly:

"Don't you think you are a little ungrateful—in the circumstances?"

It was the first time she had ever reminded him of his dependency.

"If you mean I am an ingrate, that is an unpleasant word, Aunt Mary."

She shrugged her shoulder.

"Place your own interpretation upon it, Wallace."

"Perhaps you think I am not capable of earning my own living?"

"I have not said so."

"But you mean it!" he cried, hotly.

Miss Macpherson was nearly as amazed as Wallie to hear herself saying:

"Possibly you had better try it."

She had taken two cups of strong coffee that morning and her nerves were over-stimulated, and perhaps with the intuition of a jealous woman she half suspected that "the girl from Wyoming" had something to do with his restlessness and desire to go West. The time she most dreaded was the day when she would have to share her nephew with another woman.

Wallie's eyes were blazing when he answered:

"I shall! I shall never be beholden to you for another penny. When I wanted to do something for myself you wouldn't let me. You're not fair, Aunt Mary!"

Pale and breathing heavily in their emotion, they looked at each other with hard, angry eyes—eyes in which there was not a trace of the affection which for years had existed between them.

"Suit yourself," she said, finally, and turned her back on him.

Wallie went to his room in a daze, too bewildered to realize immediately what had happened. That he had quarrelled with his aunt, permanently, irrevocably, seemed incredible. But he would never eat her bread of charity again—he had said it. As for her, he knew her Scotch stubbornness too well to think that she would offer it. No, he was sure the break was final.

A sense of freedom came to him gradually as it grew upon him that he was loose from the apron-strings that had led him since childhood. He need never again eat food he did not like because it was "good for him." He could sit in draughts if he wanted to and sneeze his head off. He could put on his woollen underwear when he got darned good and ready. He could swim when there were white caps in the harbour and choose his own clothing.

A fine feeling of exultation swept over Wallie as he strode up and down with an eye to the way he looked in the mirror. He was free of petticoat domination. He was no longer a "squaw-man," and he would not be one again for a million dollars! He would "show" Aunt Mary—he would "show" Helene Spenceley—he would "show" everybody!

Wallie opened his eyes one morning with the subconscious feeling that something portentous was impending though he was still too drowsy to remember it.

He yawned and stretched languidly and luxuriously on a bed which was the last word in comfort, since Mr. Cone's pride in The Colonial beds was second only to that of his pride in the hotel's reputation for exclusiveness. With especially made mattresses and monogrammed linen, silken coverlets and imported blankets, his boasts were amply justified, and the beds perhaps accounted for the frequency with which the guests tried to get into the dining room when the breakfast hours were over.

A bit of yellow paper on the chiffonier brought Wallie to his full sense as his eyes fell upon it. It was the answer to a telegram he had sent Pinkey Fripp, in Prouty, Wyoming, making inquiries as to the possibility of taking up a homestead.

It read:

They's a good piece of ground you can file on if you got the guts to hold it.

Pinkey.

Wallie grew warm every time he thought of such a message addressed to him coming over the wire. Though worse than inelegant, and partially unintelligible, it was plain enough that what he wanted was there if he went for it, and he had replied that Pinkey might look for him shortly in Prouty.

And to-day he was leaving! He was saying good-bye forever to the hotel that was like home to him and the friends that were as his own relatives! He had $2,100 in real money—a legacy—and his clothing. In his new-born spirit of independence he wished that he might even leave his clothes behind him, but he had changed his mind when he had figured the cost of buying others.

His aunt had taken no notice of Wallie's preparations for departure. The news of the rupture had spread quickly, and the sympathies of the guests were equally divided. All were agreed, however, that if Wallie went West he would soon have enough of it and be back in time to go South for the winter.

Helene Spenceley had left unexpectedly upon the receipt of a telegram, and it was one of Wallie's favourite speculations as to what she would say when she heard he was a neighbour—something disagreeable, probably.

With the solemnity which a person might feel who is planning his own funeral, Wallie arose and made a careful toilet. It would be the last in the room that he had occupied for so many summers. The hangings were handsome, the chairs luxurious, and his feet sunk deep in the nap of the velvet carpet. The equipment of the white, commodious bathroom was perfection, and no article of furniture was missing from his bedroom that could contribute to the comfort of a modish young man accustomed to every modern convenience.

As Wallie took his shower and dusted himself with scented talcum and applied the various lotions and skin-foods recommended for the complexion, he wondered what the hotel accommodations would be like in Prouty, Wyoming. Not up to much, he imagined, but he decided that he would duplicate this bathroom in his own residence as soon as he had his homestead going. Wallie's knowledge of Wyoming was gathered chiefly from an atlas he had borrowed from Mr. Cone. The atlas stated briefly that it contained 97,890 square miles, mostly arid, and a population of 92,531. It gave the impression that the editors themselves were hazy on Wyoming, which very likely was the truth, since it had been published in Mr. Cone's childhood when the state was a territory.

What the atlas omitted, however, was supplied by Wallie's imagination. When he closed his eyes he could see great herds of cattle—his—with their broad backs glistening in the sunshine, and vast tracts—his also—planted in clover, oats, barley, or whatever it was they grew in the country. For diversion, he saw himself scampering over the country on horseback on visits to the friendly neighbours, entertaining frequently himself and entertained everywhere. As for Helene Spenceley—she would soon learn the manner of man she had belittled!

This frame of mind was responsible for the fact that when he had finished dressing and gone below he spoke patronizingly to Mr. Appel, who paid an income tax on fourteen million.

It was a wrench after all—the going—and the fact that his aunt did not relent made it the harder. It was the first time he ever had packed his own boxes and decided upon the clothes in which he should travel. But she sat erect and unyielding at the far end of the veranda while he was in the midst of a sympathetic leave-taking from the guests of The Colonial. There were tears in Mrs. Budlong's eyes when she warned him not to fall into bad habits, and Wallie's were close to the surface when he promised her he would not.

"Aw—you'll be back when it gets cold weather," said Mr. Appel.

"I shall succeed or leave my bones in Wyoming!" Wallie declared, dramatically.

Mr. Appel snickered: "They'll help fertilize the soil, which I'm told needs it." His early struggles had made Mr. Appel callous.

Miss Macpherson, looking straight ahead, gave no indication that she saw her nephew coming.

"Will you say good-bye to me, Aunt Mary?"

She appeared not to see the hand he put out to her.

"I trust you will have a safe journey, Wallace." Her voice was a breath from the Arctic.

He stood before her a moment feeling suddenly friendless. "This makes me very unhappy, Aunt Mary," he said, sorrowfully.

Since she did not answer, he could only leave her, and her failure to ask him to write hurt as much as the frigidity of the leave-taking.

The motor-bus had arrived and the chauffeur was piling his luggage on top of it, so, with a final handshake, Wallie said good-bye, perhaps forever, to his friends of The Colonial.

They were all standing with their arms about each other's waists or with their hands placed affectionately upon each other's shoulders as the bus started, calling "Good-bye and good luck" with much waving of handkerchiefs. Only his aunt sat grim-visaged and motionless, refusing to concede so much as a glance in her nephew's direction.

Wallie, in turn, took off his girlish sailor and swung it through the bus window and wafted kisses at the dear, amiable folk of The Colonial until the motor had passed between the stately pillars of the entrance. Then he leaned back with a sigh and with the feeling of having "burned his bridges behind him."

"How much 'Jack' did you say you got?" Pinkey, an early caller at the Prouty House, sitting on his heel with his back against the wall, awaited with evident interest an answer to this pointed question. He explained further in response to Wallie's puzzled look: "Kale—dinero—the long green—money."

"Oh," Wallie replied, enlightened, "about $1,800." He was in his blue silk pajamas, sitting on the iron rail of his bed—it had an edge like a knife-blade.

There was no resemblance between this room and the one he had last occupied. The robin's egg-blue alabastine had scaled, exposing large patches of plaster, and the same thing had happened to the enamel of the wash-bowl and pitcher—the dents in the latter leading to the conclusion that upon some occasion it had been used as a weapon.

A former occupant who must have learned his art in the penitentiary had knotted the lace curtains in such a fashion that no one ever had attempted to untie them, while the prison-like effect of the iron bed, with its dingy pillows and counterpane and sagging middle, was such as to throw a chill over the spirits of the cheeriest traveller.

It had required all Wallie's will power, when he had arrived at midnight, to rise above the depression superinduced by these surroundings. His luggage was piled high in the corner, while the two trunks setting outside his doorway already had been the cause of threats of an alarming nature, made against the owner by sundry guests who had bruised their shins on them in the ill-lighted corridor.

Pinkey's arrival had cheered him wonderfully. Now when that person observed tentatively that $1,800 was "a good little stake," Wallie blithely offered to count it.

"You got it with you?"

Wallie nodded.

"That's chancey," Pinkey commented. "They's people in the country would stick you up if they knowed you carried it."

"I should resist if any one attempted to rob me," Wallie declared as he sat down on the rail gingerly with his bulging wallet.

"What with?" Pinkey inquired, humorously.

Wallie reached under his pillow and produced a pearl-handled revolver of 32 calibre.

"Before leaving I purchased this pistol."

Pinkey regarded him with a pained expression.

"Don't use that dude word, feller. Say 'gun,' 'gat,' 'six-shooter,' anything, but don't ever say 'pistol' above a whisper."

A little crest-fallen, Wallie laid it aside and commenced to count his money. Pinkey, he could see, was not impressed by the weapon.

"Yes, eighteen hundred exactly. I spent $250 purchasing a camping outfit."

Pinkey looked at him incredulously. He was thinking of the frying-pan, coffee-pot, and lard-kettle of which his own consisted. He made no comment, however, until Wallie mentioned his portable bath-tub, which, while expensive, he declared he considered indispensable.

"Yes," Pinkey agreed, drily, "you'll be needin' a portable bath-tub something desperate. I wisht I had one. The last good wash I took was in Crystal Lake the other side of the Bear-tooth Mountain. When I was done I stood out till the sun dried me, then brushed the mud off with a whisk-broom."

"That must have been uncomfortable," Wallie observed, politely. "I hope you will feel at liberty to use my tub whenever you wish."

"That won't be often enough to wear it out," said Pinkey, candidly. "But you'd better jump into your pants and git over to the land-office. We want to nail that 160 before some other 'Scissor-bill' beats you to it."

Under Pinkey's guidance Wallie went to the land office, which was in the rear of a secondhand store kept by Mr. Alvin Tucker, who was also the land commissioner.

The office was in the rear and there were two routes by which it was possible to get in touch with Mr. Tucker: one might gain admittance by walking over the bureaus, centre-tables, and stoves that blocked the front entrance, or he could crawl on his hands and knees through a large roll of chicken-wire wedged into the side door of the establishment.

The main-travelled road, however, was over the tables and bureaus, and this was chosen by Pinkey and Wallie, who found Mr. Tucker at his desk attending to the State's business.

Mr. Tucker had been blacking a stove and had not yet removed the traces of his previous occupation, so when Pinkey introduced him his hand was of a colour to make Wallie hesitate for the fraction of a second before taking it.

Mr. Tucker being a man of great good nature took no offense, although he could scarcely fail to notice Wallie's hesitation; on the contrary, he inquired with the utmost cordiality:

"Well, gents, what can I do for you this morning?" His tone implied that he had the universe at his disposal, and he also looked it as he tipped back his swivel chair and regarded them.

"He wants to file on the 160 on Skull Crick that Boise Bill abandoned," said Pinkey.

Tucker's gaze shifted.

"I'm not sure it's open to entry," he replied, hesitatingly.

"Yes, it is. His time was up a month ago, and he ain't even fenced it."

"You know he's quarrelsome," Tucker suggested. "Perhaps it would be better to ask his intentions."

"He ain't none," Pinkey declared, bluntly. "He only took it up to hold for Canby and he's never done a lick of work on it."

"Of course it's right in the middle of Canby's range," Tucker argued, "and you can scarcely blame him for not wanting it homesteaded. Why don't you select a place that won't conflict with his interests?"

"Why should we consider his interests? He don't think of anybody else's when he wants anything," Pinkey demanded.

"Your friend bein' a newcomer, I thought he wouldn't want to locate in the middle of trouble."

"He can take care of himself," Pinkey declared, confidently; though, as they both glanced at Wallie, there seemed nothing in his appearance to justify his friend's optimism. He looked a lamblike pacifist as he sat fingering his straw hat diffidently.

Tucker brought his feet down with the air of a man who had done his duty and washed his hands of consequences; he prepared to make out the necessary papers. As he handled the documents he left fingerprints of such perfection on the borders that they resembled identification marks for classification under the Bertillon system, and Wallie was far more interested in watching him than in his intimation that there was trouble in the offing if he made this filing.

He paid his fees and filled out his application, leaving Tucker's office with a new feeling of importance and responsibility. One hundred and sixty acres was not much of a ranch as ranches go in Wyoming, but it was a beginning.

As soon as they were out of the building, Wallie inquired casually:

"Does Miss Spenceley live in my neighbourhood?"

"Across the mounting!" Which reply conveyed nothing to Wallie. Pinkey added: "I punch cows for their outfit."

"Indeed," politely. Then, curiosity consuming him, he hazarded another question:

"What did she say when she heard I was coming?"

"She laughed to kill herself." Pinkey seldom lied when the truth would answer.

In the meantime, Tucker, in guarded language, was informing Canby of the entry by telephone. From the sounds which came through the receiver he had the impression that the land baron was pulling the telephone out by the roots in his exasperation at the negligence of his hireling whom he had supposed had done sufficient work to hold it.

"I'll attend to it," he answered.

Tucker thought there was no doubt about that, and he had a worthy feeling of having earned the yearly stipend which he received from Canby for these small services.

"We'd better sift along and git out there," Pinkey advised when they were back at the Prouty House.

"To-day?"

"You bet you! That's no dream about Boise Bill bein' ugly, and he might try to hold the 160 if he got wind of your filing."

"In that event?"

"In that event," Pinkey mimicked, "he's more'n likely to run you off, unless you got the sand to fight fer it. That's what I meant in my telegram."

"Oh," said Wallie, enlightened. "'Sand' and—er—intestines are synonymous terms in your vernacular?"

Pinkey stared at him.

"Say, feller, you'll have to learn to sling the buckskin before we can understand each other. Anyhow, as I was sayin', you got a good proposition in this 160 if you can hold it."

"If I am within my rights I shall adhere to them at all hazards," declared Wallie, firmly. "At first, however, I shall use moral suasion."

"Can't you say things plainer?" Pinkey demanded, crossly. "Why don't you talk United States? You sound like a Fifth Reader. If you mean you aim to argue with him, he'll knock you down with a neck-yoke while you're gittin' started."

"In that event, if he attempted violence, I should use my pistol—my 'gat'—and stop him."

"In that event," Pinkey relished the expression, "in that event I shall carry a shovel along to bury you."

Riding a horse from the livery stable and accompanied by Pinkey driving two pack-horses ahead of him, Wallie left the Prouty House shortly after noon, followed by comments of a jocular nature from the bystanders.

"How far is it?" inquired Wallie, who was riding his English saddle and "posting."

"Twenty for me and forty for you, if you aim to ride that way," said Pinkey. "Why don't you let out them stirrups and shove your feet in 'em?"

Wallie preferred his own style of riding, however, but observed that he hoped never to have another such fall as he had had at The Colonial.

"A feller that's never been throwed has never rid," said Pinkey, sagely, and added: "You'll git used to it."

This Wallie considered a very remote possibility, although he did not say so.

Once they left the town they turned toward the mountains and conversation ceased shortly, for not only were they obliged to ride single file through the sagebrush and cacti but the trot of the livery horse soon left Wallie with no breath nor desire to continue it.

The vast tract they were traversing belonged to Canby, so Pinkey informed him, and as mile after mile slipped by he was amazed at the extent of it. Through illegal fencing, leasing, and driving small stockmen from the country by various methods, Canby had obtained control of a range of astonishing circumference, and Wallie's homestead was nearly in the middle of it.

Although they had eaten before leaving Prouty, it was not more than two o'clock before Wallie began to wonder what they would have for supper. They were not making fast time, for his horse stumbled badly and the pack-horses, both old and stiff, travelled slowly, so at three o'clock the elusive mountains seemed as far away as when they had started.

Unable to refrain any longer, Wallie called to ask how much farther.

"Twelve miles, or some such matter." Pinkey added: "I'm so hungry I don't know where I'm goin' to sleep to-night. That restaurant is reg'lar stummick-robbers."

By four o'clock every muscle in Wallie's body was aching, but his fatigue was nothing as compared with his hunger. He tried to admire the scenery, to think of his magnificent prospects, of Helene Spenceley, but his thoughts always came back quickly to the subject of food and a wonder as to how soon he could get it.

In his regular, well-fed life he never had imagined, much less known, such a gnawing hunger. His destination represented only something to eat and it seemed to him they never would get there.

"What will we have for supper, Pinkey?" he shouted, finally.

Pinkey replied promptly:

"I was thinkin' we'd have ham and gra-vy and cowpuncher perta-toes; and maybe I'll build some biscuit, if we kin wait fer 'em."

"Let's not have biscuit—let's have crackers."

Ham and gravy and cowpuncher potatoes! Wallie rode along with his mouth watering and visualizing the menu until Pinkey came to a halt and said with a dramatic gesture:

"There's your future home, Mr. Macpherson! That's what I call a reg'lar paradise."

As Mr. Macpherson stared at the Elysium indicated, endeavouring to discover the resemblance, surprise kept him silent.

So far as he could see, it in nowise differed from the arid plain across which they had ridden. It was a pebbly tract, covered with sagebrush and cacti, which dropped abruptly to a creek-bed that had no water in it. Filled with sudden misgivings, he asked feebly:

"What's it good for?"

"Look at the view!" said Pinkey, impatiently.

"I can't eat scenery."

"It'll be a great place for dry-farmin'."

Wallie looked at a crack big enough to swallow him and observed humorously:

"I should judge so."

"You see," Pinkey explained, enthusiastically, "bein' clost to the mountings, the snow lays late in the spring and all the moisture they is you git it."

"I see." Wallie nodded comprehensively. "Why didn't you take it up yourself, Pinkey?"

"Oh, I got to make a livin'."

There was food for thought in the answer and Wallie pondered it as he got stiffly out of the saddle.

"Can I be of any assistance?" he asked, politely.

"You can git the squaw-axe and hack out a place fer a bed-ground and you can hunt up some firewood and take a bucket out of the pack and go to the crick and locate some water while I'm finding a place to picket these horses."

Because it would hasten supper, it seemed to Wallie that wood and water were of more importance than clearing a place to sleep, so he collected a small pile of twigs and dead sagebrush, then took an aluminum kettle from his camping utensils and walked along the bank of Skull Creek looking for a pool which contained enough water to fill the kettle. He finally saw one, and planting his heels in a dirt slide, shot like a toboggan some twenty feet to the bottom. Filling his kettle he walked back over the boulders looking for a more convenient place to get up than the one he had descended.

He was abreast of the camp before he knew it.

"Whur you goin'?" Pinkey, who had returned, was hanging over the edge watching him stumbling along with his kettle of water.

"I'm hunting a place to get up," said Wallie, tartly.

"How did you git down?"

"'Way back there."

"Why didn't you git up the same way?"

"Couldn't—without spilling the water."

"I'll git a rope and snake you."

"This doesn't seem like a very convenient location," said Wallie, querulously.

"You can cut out some toe-holts to-morrow," Pinkey suggested, cheerfully. "The ground has got such a good slope to drain the corrals is the reason I picked it to build on."

This explanation reconciled Wallie to the difficulty of getting water. To build a fire and make the coffee was the work of a moment, but it seemed twenty-four hours to Wallie, sitting on a saddle-blanket watching every move like a hungry bird-dog. He thought he never had smelled anything so savoury as the odour of potatoes and onions cooking, and when the aroma of boiling coffee was added to it!

Pinkey stopped slicing ham to point at the sunset.

"Ain't that a great picture?"

"Gorgeous," Wallie agreed without looking.

"If I could paint."

"Does it take long to make gravy?" Wallie demanded, impatiently.

"Not so very. I'll git things goin' and let you watch 'em while I go and take a look at them buzzard-heads. If a horse ain't used to bein' on picket he's liable to go scratchin' his ear and git caught and choke hisself."

"Couldn't we eat first?" Wallie asked, plaintively.

"No, I'll feel easier if I know they ain't tangled. Keep stirrin' the gravy so it won't burn on you," he called back. "And set the coffee off in a couple of minutes."

Wallie was on his knees absorbed in his task of keeping the gravy from scorching when a sound made him turn quickly and look behind him.

A large man on a small white pony was riding toward him. He looked unprepossessing even at a distance and he did not improve, as he came closer. His nose was long, his jaw was long, his hair needed cutting and was greasy, while his close-set blue eyes had a decidedly mean expression. There was a rifle slung under his stirrup-leather, and a six-shooter in its holster on his hip was a conspicuous feature of his costume.

He sat for a moment, looking, then dropped the bridle reins as he dismounted and sauntered up to the camp-fire.

Wallie was sure that it was "Boise Bill," from a description Pinkey had given him, and his voice was slightly tremulous as he said:

"Good evening."

The stranger paid no attention to his greeting. He was surveying Wallie in his riding breeches and puttees with an expression that was at once amused and insolent.

"Looks like you aimed to camp a spell, from your lay-out," he observed, finally.

"Yes, I am here permanently." Wallie wondered if the stranger could see that his hand was trembling as he stirred the gravy.

"Indeed! How you got that figgered?" asked the man, mockingly.

Wallie replied with dignity:

"This is my homestead; I filed on it this morning."

"Looks like you'd a-found out if it was open to entry before you went to all that trouble." Boise Bill shuffled his feet so that a cloud of the light wood-ashes rose and settled in the gravy.

Wallie frowned but picked them out patiently.

"I did," he answered, moving the pan.

"Then somebody's lied to you, fer I filed on this ground and I ain't abandoned it."

"You've never done any work on it, and Mr. Tucker has my filing fees and application so I cannot see that there is any argument about it."

Wallie was very polite and conciliatory.

"You'll find that filin' is one thing and holdin' is another in this man's country." Quite deliberately he scuffled up another cloud of cinders.

"I will appreciate it," said Wallie, sharply, "if you won't kick ashes in my gravy!"

"And I will appreciate it," Boise Bill mocked him, "if you'll git your junk together and move off my land in about twenty minutes."

"I refuse to be intimidated," said Wallie, paling. "I shall begin a contest suit if necessary."

"I allus fight first and contest afterward." Boise Bill lifted his huge foot and kicked over first the pan of ham and then the gravy. Wallie stood for a second staring at the tragedy. Then his nerves jumped and he shook in a passion which seemed to blind and choke him.

Boise Bill had drawn his six-shooter and Wallie was looking into the barrel of it. His homestead, his life, was in jeopardy, but this seemed nothing at all compared to the fact that the ruffian, with deliberate malice, had kicked over his supper!

"Have I got to try a chunk o' lead on you?" Boise Bill snarled at him.

For answer Wallie stooped swiftly and gripped the long handle of the frying-pan. He swung it with all his strength as he would have swung a tennis racket. Knocking the six-shooter from Boise Bill's hand he jumped across the fire at him. Scarcely conscious of what he was doing in the frenzy of rage that consumed him, Wallie whipped his little pearl-handled pistol from his breeches pocket and as Boise Bill opened his mouth in an exclamation of astonishment, Wallie shoved it down his throat, yelling shrilly that if he moved an eye-lash he would pull the trigger!

This was the amazing sight that stopped Pinkey in his tracks as effectively as a bullet.

Wallie heard his step and asked plaintively but without turning:

"What'll I do with him?"

"As you are, until I pull his fangs."

Pinkey threw the shells from Boise Bill's rifle and removed the cartridges from his six-shooter. Handing the latter back to him he said laconically:

"Drift! And don't you take the beef-herd gait, neither."

The malevolent look Boise Bill sent over his shoulder was wasted on Wallie who was picking out of the ashes and dusting the ham for which he had stood ready to shed his blood.

The modest herring had been the foundation of the great Canby fortune. Small and unpretentious, the herring had swum in the icy waters of the Maine coast until transformed into a French sardine by Canby, Sr. It had brought wealth and renown to the shrewd old Yankee, who was alleged to have smelled of herring even in his coffin, but the Canby family were not given to boasting of the source of their income to strangers, and by the time Canby, Jr., was graduated from Harvard they were fairly well deodorized.