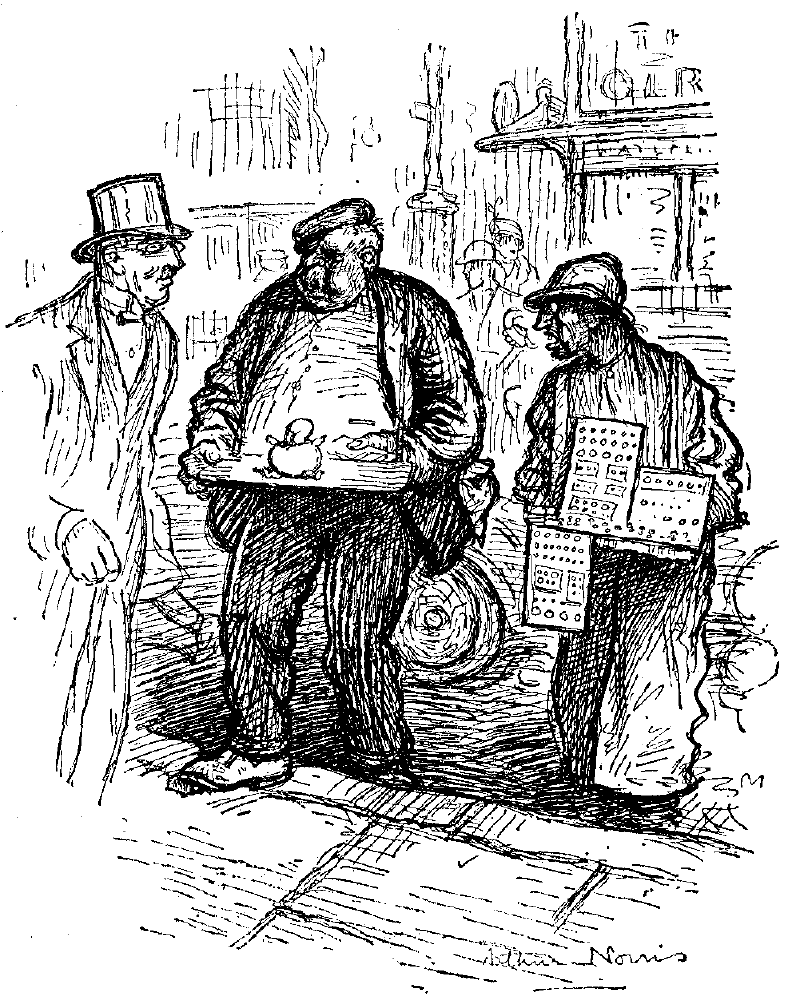

The Younger Brother (in an awestruck whisper). "Say, 'Orace, are you sure we're right for the gallery? There's a gent behind wiv spats on!"

Title: Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol. 146, April 22, 1914

Author: Various

Editor: Owen Seaman

Release date: December 11, 2007 [eBook #23815]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Matt Whittaker, Malcolm Farmer, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

E-text prepared by Matt Whittaker, Malcolm Farmer,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

Says The Times:—"It used to be a[pg 301] tradition of British Liberal statesmanship to support, without prospect of immediate advantage, the cause of nationality and freedom abroad.... It would at least be showing some interest to send a minister to Durazzo." Here, perhaps, is a post for poor Mr. Masterman.

The Kerry News states that it prefers pigs to Englishmen. This seems a queer—almost an ungracious—way of expressing its desire for a Home Rule Government.

Oil has been discovered in Somaliland, and it is rumoured that the Government is at last about to realise that its obligations to our friendlies demand a forward move against the Mullah.

Futurism is apparently spreading to the animal world. The following advertisement appeared in a recent issue of Lloyd's:—

"Dyer—Fancy Color Dyer for Ostrich required."

There is a dispute, we see, as to who invented Revues. But, even if the responsibility be fixed, the guilty party, we have no doubt, will go scot-free.

The inhabitants of Bugsworth in Derbyshire, are, The Mail tells us, dissatisfied with the name of their village. A former parish councillor has suggested that it shall be changed to Buxworth, on the ground that it was once a great hunting centre, and took its name from the buck, which used to be found in great numbers there. The present name has also a distinct suggestion of the chase about it.

Extract, from a speech by Colonel Seely on the recent Army crisis:—"The only difference is that I am £5,000 a year poorer.... I am not less Liberal but more Liberal after what has happened." To be more liberal after suffering financially does the ex-War Minister credit.

The fees charged by beauty doctors are tending to become more exorbitant than ever. To have his eyes darkened, Mr. George Mitchell, of Bolton, had to pay M. Carpentier, of Paris, no less than £100.

Old horse tramway-cars are being offered by the London County Council for sale at from £3 to £5 each. They are suitable for transformation into bungalows, tool-sheds, sanatoria and the like.

Last week, at Bristol, eleven brothers named Hunt, of Pucklechurch, played a football match against a team composed of the Miller family, of Brislington. We are always pleased to see these practical object-lessons in the advantage of having large families—a custom which is in danger of falling into desuetude.

"The Liberal Party, the Tory Party, and the House of Lords are nothing against the united intelligence of democracy," said Mr. Ramsay MacDonald at a meeting to celebrate the "coming of age" of the Independent Labour Party. We are of the opinion that Mr. Ramsay MacDonald should know better than to impose upon youth like that. Maxima debetur pueris reverentia.

According to The Evening News' critique of the exhibition of the International Society:—"Two statues by Rodin dominate the gallery. One, 'Benediction,' is in his early manner, but by Lord Howard de Walden." We suspect that there was division of labour here. Rodin sculped it (in his early manner) and Lord Howard de Walden said, "Bless you" (probably in his later manner).

New York Suffragettes have been discussing the question, "Ought women to propose?" and one of them has stated, "I am seriously thinking of proposing to a man"—and now, we suspect, she is wondering why her male acquaintances are shy about stopping to talk to her. We ought to add that her name, as reported, is Miss Bonnie Ginger.

We hear that, as a result of a contemporary drawing attention to Chicago's leniency towards women murderers, ladies whose hobby is homicide are now flocking to that city and it is becoming uncomfortably overcrowded.

"Frau Krupp von Bohlen," we are told, "is the largest payer of war tax in Germany. Her contribution amounts to £440,000." We have a sort of idea, however, that she gets some of this back.

"Sir John Collie ridiculed the present system by which 22,000 doctors depend for an income on their capacity to please their parents."—Labour Leader.

And not only doctors. The Temple is full of people in the same ridiculous position.

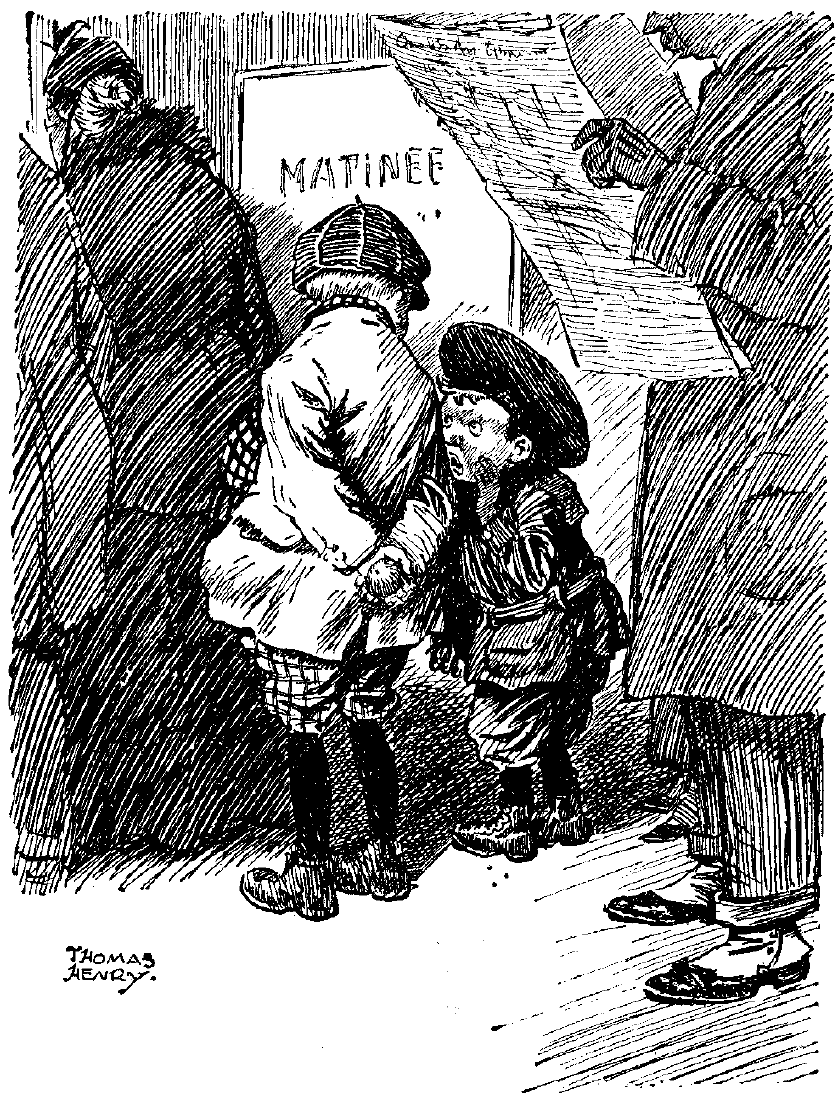

The Younger Brother (in an awestruck whisper). "Say, 'Orace, are you sure we're right for the gallery? There's a gent behind wiv spats on!"

"Mathilde explained (her name, of course, was Mathilde really but peasants in Normandy, and for that matter all over France, are curiously inaccurate with names, and often misplace letters in this manner)."

"Evening News" Feuilleton.

The printer of the above must be careful when he crosses the Channel, or he may pick up this bad habit.

"Tonight and tomorrow they will play a matched game of 1,500 points—750 each night. A local billiard enthusiast has offered $100 to either of the players who scores a 00 break or better. This to the average billiard player seems a tremendous break."

Vancouver Daily Paper.

But not to us.

I put down my morning paper as I left the train for the golf club. It contained the interesting news that the Parliamentary Golf Handicap had been postponed lest fiery politicians should run amok with their clubs. I sighed, for the spectacle of Bonar v. Bogey (The Chancellor) would have beaten the Mitchell-Carpentier fight. Then it came home to me that I, a golfer, a citizen, a voter, was taking no part in the great political struggle of the day. I had not even declined to deal with my butcher because he was a Conservative, or closed my wife's draper's account because he was a Liberal. It is a curious fact, worthy the serious attention of political philosophers, that butchers are always Conservative and drapers always Liberal.

I reached the club-house, and the first man I saw was Redford. Now Redford is a scratch player and a vice-president of a Liberal Association. He has a portrait of Lloyd George in his dining-room.

"Play you a round, old man, and give you ten," he said cheerfully.

I had to do something for my country. "Never," I replied sternly. "I do not play with homicides."

"What are you talking about?" asked Redford, who is an estate agent when he isn't golfing.

"I merely say," I replied, "that I will play with no man who deliberately connives at the slaughter of his fellow-citizens. Every Liberal vote is a vote for civil war."

"Man, this is a golf links, not Hyde Park."

"I regret the course I have to take, but my conscience is imperative. Away! your clubs are blood-stained."

Redford shrugged his shoulders and went off to get the professional to go round with him.

The next man to drop in was Pobson. He is a Grand Knight Imperial (or something similar) of the Primrose League, and makes speeches between the ventriloquist and the step-dancer at their meetings. He has signed the Covenant, and reads every column Mr. Garvin writes. In fact, I attribute it entirely to Mr. Garvin's effect on the nerves that his handicap has been increased from plus two to scratch.

"Want a round? Give you eight strokes," he began.

"No, Sir; not with a man, who tampers with the Army."

"You're either mad," said Pobson, "or else you've been reading The Daily News."

I will say this for Pobson—he seemed inclined to believe in my madness as the more credible alternative.

"Enough of this. Do you think I will be seen playing with a man who ruins our noble Army to gratify petty political spite? Every Conservative vote means an Army mutineer."

"Mad," said Pobson, still charitable, as he left me.

Then there entered a dear old stranger and my heart opened to him at once.

"I don't know whether you're waiting for a game, Sir," he began.

"Certainly," I said. "I'm an awfully rotten player. Ashamed to mention my handicap."

"Can't be worse than I am, Sir. There'll be a pair of us. What shall we play for? I like to have something on it."

"What you like," I replied. "Box of balls if you wish."

"Right."

And away we went. I beat him by eight up and seven to play and was marching triumphantly up to the club-house when Redford intercepted me.

"What's your game?" he said. "You wouldn't play with me and now you've played a round with our Candidate."

"Redford," I said, "when that dear old gentleman came along I felt that I had acted improperly in introducing political acerbity on the links. I was wrong, and as a proof of it I am willing to play level with any politician in the club for the same stakes—providing that his handicap is over twenty."

["Before the Love of Letters, overdone,

Had swamped the sacred poets with themselves."—Tennyson.]

"The poets of an older time,"

Grumbled Rossetti Jones one day,

"Have used up every blessed rhyme

And collared every thought sublime,

Leaving us nothing new to say.

"They've sung the Game of War as played

By gods and men, heroic peers;

They've sung the love of man and maid,

To Life their laughing tribute paid,

Nor grudged grim Death his toll of tears.

"What can a modern poet sing,

Describe, imagine or invent?

They've been before, they've tapped the spring,

They've laid their hands on everything,

Staked out the spacious firmament.

"Last week, a line that did me proud

Flashed on me, strolling down the Strand:—

'I wandered lonely as a cloud;'

Then conscience suddenly avowed

The simile was second-hand.

"Take birds, for instance. No remark

Of mine on birds could but be stale;

Shelley and Wordsworth own the lark

(Which Shakspeare too had bid us hark),

While Keats has bagged the nightingale.

"With rose and lily surfeited,

Burns sang the daisy. Here's a fraud

Of Tennyson's: I might have said

How daisies crimson 'neath the tread

Of more attractive girls than Maud!

"You think you've something up to date?

You'll find it's been already done;

I'd like to clean the blooming slate;

Their footprints I'd obliterate;

I want my corner in the sun."

He ceased. "Yet your revenge," I said,

Taking a classic from his shelves,

"Is ample, surely"; there I read

How moderns vex the sacred dead,

Swamping old poets with themselves.

(By a Westministering Angel.)

["Looking back at what has been achieved, we can gain fresh courage for the perplexities of the moment, in the sure and certain hope that with energy and goodwill the task of social amelioration will be safely accomplished, if never finished."

"Westminster-Gazette" leading article.]

While then we admit that President Wilson's technical violation of his policy of non-intervention is fraught with possibilities of difficulty if not of actual danger for the United States, we can at least fortify ourselves with the reassuring consolation that, where righteous intentions are backed by a strong arm, the odds are generally in favour of their prevailing, even though they may never be victorious.

The prospects of a pacific solution of the Ulster problem, though they have not visibly improved in the last week, at least cannot be said to have substantially altered for the worse. But the atmosphere, though no longer electric, is not yet unclouded. All that can be safely said is that, if only the Government continue to play the game with the same forbearance, tenacity, and transparent honesty that they have shown in the past, the gulf that yawns between the extremists on either side must one day be filled up, though never[pg 303] bridged.

As we reflect on the happenings of the last year, we cannot but be sensible of a salutary détente in the relations of [pg 304]Germany and Great Britain. That this should lead to a closer understanding, and ultimately to an alliance, [pg 305]between the two Powers must be the heartfelt prayer of every patriotic Liberal. But good wishes are seldom operative unless they are backed by action. It is the duty of every lover of his country to labour unremittingly to promote this object, and at the same time to resign himself to the conviction that he may not live to see his aim realised, though his descendants may witness its translation into actuality, even if its consummation is indefinitely postponed.

The vagaries of feminine fashion are undoubtedly a source of misgiving and disquietude to those, like ourselves, who favour the extension of civil rights to women. But, amid all the evidences of frivolity and extravagance which pain the judicious, we need never relinquish the hope that, once the pendulum swings backwards into the direction of sanity, its retrogression will probably be beneficial, even though we cannot pronounce it satisfactory.

President Huerta: "Morituri te salutamus? I don't think."

President Huerta. "AMERICAN FLEET TO VISIT ME AND EXCHANGE COMPLIMENTS? WELL, IT'S NICE TO BE 'RECOGNISED,' ANYHOW."

He got in at Peterborough; I spotted him at once by the way he talked to the porter.

He sat down heavily and looked round the carriage for victims. I was doomed. The only other passenger in it had been asleep since Grantham.

I snatched up my paper and buried my head in it and shut my eyes. Ten seconds elapsed.

"I beg your pardon, Sir——"

"Not at all," I said gruffly.

"But your paper's upside down."

"Yes. I always read papers upside down. I'm ambidextrous."

Ten seconds more silence.

"What do you think of this weather we're having?"

"Nothing," I said curtly. I gave up the paper in despair and looked hard out of the window. I knew the man was staring at me and compassing a new attack.

He leant over at last.

"Now, what are your views on Ulster?"

I couldn't say "Nothing" again; but, even so, I retained some presence of mind.

"I am a convinced Home Ruler, and I never argue," I snapped.

"I happen to have gone into the question pretty thoroughly," he began.

About ten minutes later he stopped talking and looked at me triumphantly.

"Now, what answer have you to that?" he said.

"None," I admitted.

"But you said——"

"I'm a convinced Anti-Home Ruler."

"But just now you said——"

"I know. But you've convinced me."

He snorted violently and relapsed into a moody silence until the other man awoke at Finsbury Park.

The Vicar of St. John's, Carlisle (The Carlisle Journal tells us), in moving the adoption of the past year's accounts, said:—

"About £9 was saved through not paying the choir-boys, and the result had been most satisfactory."

The note of satisfaction in the choir-boys' voices is said to be very touching.

My Uncle James, whose memoirs I am now preparing for publication, was a many-sided man; but his chief characteristic, I am inclined to think, was the indomitable resolution with which, disregarding hints, entreaties and even direct abuse, he would lie in bed of a morning. I have seen the domestic staff of his hostess day after day manœuvring restlessly in the passage outside his room, doing all those things which women do who wish to rout a man out of bed without moving Uncle James an inch. Footsteps might patter outside his door; voices might call one to the other; knuckles might rap the panels; relays of shaving-water might be dumped on his wash-stand; but devil a bit would Uncle James budge, till finally the enemy, giving in, would bring him his breakfast in bed. Then, after a leisurely cigar, he would at last rise and, having dressed himself with care, come downstairs and be the ray of sunshine about the home.

For many years I was accustomed to look on Uncle James as a mere sluggard. I pictured ants raising their antennæ scornfully at the sight of him. I was to learn that not sloth but a deep purpose dictated his movements, or his lack of movement.

"My boy," said Uncle James, "more evil is wrought by early rising than by want of thought. Happy homes are broken up by it. Why do men leave charming wives and run away with quite unattractive adventuresses? Because good women always get up early. Bad women, on the other hand, invariably rise late. To prize a man out of bed at some absurd hour like nine-thirty is to court disaster. To take my own case, when I first wake in the morning my mind is one welter of unkindly thoughts. I think of all the men who owe me money, and hate them. I review the regiment of women who have refused to marry me, and loathe them. I meditate on my faithful dog, Ponto, and wish that I had kicked him overnight. To introduce me to the human race at that moment would be to let loose a scourge upon society. But what a difference after I have lain in bed looking at the ceiling for an hour or so. The milk of human kindness comes surging back into me like a tidal wave. I love my species. Give me a bit of breakfast then, and let me enjoy a quiet meditative smoke, and I am a pleasure to all with whom I come in contact."

He settled himself more comfortably upon the pillows and listened luxuriously for a moment to the sound of rushing housemaids in the passage.

"Late rising saved my life once," he said. "Pass me my tobacco pouch."

He lit his pipe and expelled a cloud of smoke.

"It was when I was in South America. There was the usual revolution in the Republic which I had visited in my search for concessions, and, after due consideration, I threw in my lot with the revolutionary party. It is usually a sound move, for on these occasions the revolutionists have generally corrupted the standing army, and they win before the other side has time to re-corrupt it at a higher figure. In South America, thrice armed is he who has his quarrel just, but six times he who gets his bribe in fust. On the occasion of which I speak, however, a hitch was caused by the fact of another party revolting against the revolutionists while they were revolting against the revolutionary party which had just upset the existing Government. Everything is very complicated in those parts. You will remember that the Tango came from there.

"Well, the long and the short of it was that I was captured and condemned to be shot. I need not go into my emotions at the time. Suffice it to say that I was led out and placed with my back against an adobe wall. The firing-party raised their rifles.

"It was a glorious morning. The sun was high in a cloudless sky. Everywhere sounded the gay rattle of the rattle-snake and the mellow chirrup of the hydrophobia-skunk and the gila monster. It vexed me to think that I was so soon to leave so peaceful a scene.

"And then suddenly it flashed upon me that there had been a serious mistake.

"'Wait!' I called.

"'What's the matter now?' asked the leader of the firing squad.

"'Matter?' I said. 'Look at the sun. The court-martial distinctly said that I was to be shot at sunrise. Do you call this sunrise? It must be nearly lunch-time.'

"'It's not our fault,' said the firing-party. 'We came to your cell all right, but you wouldn't get up. You told us to leave it on the mat.'

"I did remember then having heard someone fussing about outside my cell door.

"'That's neither here nor there,' I said firmly. 'It was your business to shoot me at sunrise, and you haven't done it. I claim a re-trial on a technicality.'

"Well, they stormed and blustered, but I was adamant; and in the end they had to take me back to my cell to be tried again. I was condemned to be shot at sunrise next morning, and they went to the trouble of giving me an alarm clock and setting it for 3 a.m.

"But at about eleven o'clock that night there was another revolution. Some revolutionaries revolted against the revolutionaries who had revolted against the revolutionaries who had revolted against the Government, and, having re-re-corrupted the standing army, they swept all before them, and at about midnight I was set free. I recall that the new President kissed me on both cheeks and called me the saviour of his country. Poor fellow, there was another revolution next day, and, being a confirmed early riser, he got up in time to be shot at sunrise."

Uncle James sighed, possibly with regret, but more probably with happiness, for at this moment they brought in his breakfast.

Pavement Artist (who has not yet recovered the nerve which he lost on hearing of the attack upon the Velasquez Venus). "Pass along them covers, George—the Suffragettes is coming."

"It would be amusing, if it were not athletic, to read that this satirist who ridiculed sentiment made himself ridiculous by falling violently in love with a young girl of eighteen."

Winnipeg Telegram.

He who runs may read—but apparently he mustn't be amused.

"It is known the play is in three acts and nine scenes, and that there is an exceptionally long cast, but beyond that the strictest scenery is being preserved."—Birmingham Daily Mail.

Which will be good news for Mr. Gordon Craig.

(By our Special Parasitic Penman.)

How I Got There and Back is the title of a new story of adventurous exploration which Messrs. Jones, Younger announce for immediate publication. The author, Mr. J. Minch Howson, whose text has been revised by the publishers, has had some astonishing experiences as a bonzo-hunter in the Aruwhimi forest. On one occasion he was rescued by a mad elephant from the jaws of an okapi, into which he had inadvertently fallen while flying from a gorilla. During his residence among the pygmies Mr. Howson became such an adept with the long blow-pipe that they offered him the headship of the tribe; but, as this involved the adoption of anthropophagous habits, he was reluctantly obliged to decline the honour.

Mr. Bamborough, the famous violinist, who recently changed his name by deed poll from Bamberger, has compiled a further volume of reminiscences based on his experiences as a travelling virtuoso in all four hemispheres. Some of these have already been made public in the Press, but in a condensed form. He now tells us for the first time in full detail his astounding adventures in New Guinea, where he was captured and partially eaten by cannibals, and his awful ordeal in the Never-Never Land, when he was attacked simultaneously by an emu and a wallaby, and conquered them both by the strains of his violin. The volume, which will be published by the House of Pougher and Kleimer, is profusely illustrated with portraits of Mr. Bamborough at various stages of his career, before and after the execution of the deed poll; of Mrs. Bamborough and their three gifted children, Wotan, Salome and Isolde Bamborough; and of her father, Sir Pompey Boldero, F.R.G.S., formerly Attorney-General of Pitcairn Island. It is further enriched with a number of letters in fac-simile from the Begum of Bhopal, General Huerta, the Lord Chief Justice, Madame Humbert, Mr. Jerome K. Jerome, Mr. Clement Shorter, Mrs. Alec Tweedie and the late King Theebaw of Burmah.

Messrs. Vigo announce the speedy publication of a volume of reminiscences from the pen of Count Lio Rotsac, the famous Bohemian revolutionary. In it special interest attaches to the long and desperate struggle between the Count and his rival, Baron Aracsac, which ended in the supersession of the latter and his confinement in the gloomy fortress prison of Niola Stelbat.

Miss Poppy McLurkin, the composer of that delightful song Peter Popinjay, of which over a quarter of a million copies have been sold or given away, has expanded the four verses of her lyric into a full-length novel, which Messrs. Gulliver will publish under the same title. Miss McLurkin, who is still on the sunny side of thirty, is one of the few female performers on the bagpipes in the literary profession.

New novelists are always welcome if only for the titles of their books, for, after all, perusal of their contents is not compulsory. In this category may be included Telepathic Theodora, by Beryl Smuts; The Rottenest Story in the World, by Dermot Stuggy; and In the Doldrums, by Wally Gogg.

"Why, Mrs. Codlins, 'ow are you, 'ow are you? I 'aven't seen you to speak to for ages."

"No, Mrs. Whidden; no more 'aven't I you, neither."

"Amazing Realistic Drama, featuring Big Game Hunting.

1500 feet—Between Man and Beast."

This is not realistic enough for us.

Seen on an Islington baker's shop:—

"Current Bread."

A marked improvement on the stale back-numbers supplied by some bakers.

"We understand that Prince William of Wied intends to proclaim himself King of Albania as soon as certain technical difficulties have been overcome."—Times.

Unfortunately there are several thousand "technical difficulties"—all well-armed.

Celia had been calling on a newly-married friend of hers. They had been school-girls together; they had looked over the same Algebra book (or whatever it was that Celia learnt at school—I have never been quite certain); they had done their calisthenics side by side; they had compared picture-postcards of Lewis Waller. Ah me! the fairy princes they had imagined together in those days ... and here am I, and somewhere in the City (I believe he is a stockbroker) is Ermyntrude's husband, and we play our golf on Saturday afternoons, and complain of our dinners, and—— Well, anyhow, they were both married, and Celia had been calling on Ermyntrude.

"I hope you did all the right things," I said. "Asked to see the wedding-ring, and admired the charming little house, and gave a few hints on the proper way to manage a husband."

"Rather," said Celia. "But it did seem funny, because she used to be older than me at school."

"Isn't she still?"

"Oh, no! I'm ever so much older now.... Talking about wedding-rings," she went on, as she twisted her own round and round, "she's got all sorts of things written inside hers—the date and their initials and I don't know what else."

"There can't be much else—unless perhaps she has a very large finger."

"Well, I haven't got anything in mine," said Celia mournfully. She took off the offending ring and gave it to me.

On the day when I first put the ring on her finger, Celia swore an oath that nothing but death, extreme poverty or brigands should ever remove it. I swore too. Unfortunately it fell off in the course of the afternoon, which seemed to break the spell somehow. So now it goes off and on just like any other ring. I took it from her and looked inside.

"There are all sorts of things here too," I said. "Really, you don't seem to have read your wedding-ring at all. Or, anyhow, you've been skipping."

"There's nothing," said Celia in the same mournful voice. "I do think you might have put something,"'

I went and sat on the arm of her chair and held the ring up.

"You're an ungrateful wife," I said, "after all the trouble I took. Now look there," and I pointed with a pencil, "what's the first thing you see?"

"Twenty-two. That's only the——"

"That was your age when you married me. I had it put in at enormous expense. If you had been eighteen, the man said, or—or nine, it would have come much cheaper. But no, I would have your exact age. You were twenty-two, and that's what I had engraved on it. Very well. Now what do you see next to it?"

"A crown."

"Yes. And what does that mean? In the language of—er—crowns it means 'You are my queen.' I insisted on a crown. It would have been cheaper to have had a lion, which means—er—lions, but I was determined not to spare myself. For I thought," I went on pathetically, "I quite thought you would like a crown."

"Oh, I do," cried Celia quickly, "if it really means that." She took the ring in her hands and looked at it lovingly. "And what's that there? Sort of a man's head."

I gazed at her sadly.

"You don't recognize it? Has a year of marriage so greatly changed me? Celia, it is your Ronald! I sat for that, hour after hour, day after; day, for your sake, Celia. It is not a perfect likeness; in the small space allotted to him the sculptor has hardly done me justice. But it is your Ronald.... And there," I added, "is his initial 'r.' Oh, woman, the amount of thought I spent on that ring!"

She came a little closer and slipped the ring on my finger.

"Spend a little more," she pleaded. "There's plenty of room. Just have something nice written in it—something about you and me."

"Like 'Pisgah'?"

"What does that mean?"

"I don't know. Perhaps it's 'Mizpah,' or 'Ichabod,' or 'Habakkuk.' I'm sure there's a word you put on rings—I expect they'd know at the shop."

"But I don't want what they know at shops. It must be something quite private and special."

"But the shop has got to know about it when I tell them. And I don't like telling strange men in shops private and special things about ourselves. I love you, Celia, but——"

"That would be a lovely thing," she said, clasping her hands eagerly.

"What?"

"'I love you, Celia.'"

I looked at her aghast.

"Do you want me to order that in cold blood from the shopman?"

"He wouldn't mind. Besides, if he saw us together he'd probably know. You aren't afraid of a goldsmith, are you?"

"I'm not afraid of any goldsmith living—or goldfish either, if it comes to that. But I should prefer to be sentimental in some other language than plain English. I could order 'Cara sposa', or—or 'Spaghetti,' or anything like that, without a tremor."

"But of course you shall put just whatever you like. Only—only let it be original. Not Mizpahs."

"Right," I said.

For three days I wandered past gold-and-silversmiths with the ring in my pocket ... and for three days Celia went about without a wedding-ring, and, for all I know, without even her marriage-lines in her muff. And on the fourth day I walked boldly in.

"I want," I said, "a wedding-ring engraved," and I felt in my pockets. "Not initials," I said, and I felt in some more pockets, "but—but——" I tried the trousers pockets again. "Well, look here, I'll be quite frank with you. I—er—want——" I fumbled in my ticket-pocket, "I want 'I love you' on it," and I went through the waistcoat pockets a third time. "I—er—love you."

"Me?" said the shopman, surprised.

"I love you," I repeated mechanically. "I love you, I love you, I—— Well, look here, perhaps I'd better go back and get the ring."

On the next day I was there again; but there was a different man behind the counter.

"I want this ring engraved," I said.

"Certainly. What shall we put?"

I had felt the question coming. I had a sort of instinct that he would ask me that. But I couldn't get the words out again.

"Well," I hesitated, "I—er—well."

"Ladies often like the date put in. When is it to be?"

"When is what to be?"

"The wedding," he smiled.

"It has been," I said. "It's all over. You're too late for it."

I gave myself up to thought. At all costs I must be original. There must be something on Celia's wedding-ring that had never been on any other's....

There was only one thing I could think of.

The engraved ring arrived as we were at tea a few days later, and I had a sudden overwhelming fear that Celia would not be pleased. I saw that I must explain it to her. After all, there was a distinguished precedent.

"Come into the bath-room a moment," I said, and I led the way.

She followed, wondering.

"What is that?" I asked, pointing to a blue thing on the floor.

"The bath-mat," she said, surprised.

"And what is written on it?"

"Why—'bath-mat,' of course."

"Of course," I said ... and I handed her the wedding-ring.

A. A. M.

Mother (to conciliate little girl who has been whipped). "Was she a nasty cruel Mother, then?"

Modern Child. "Oh no; I deserved it."

Gwendolen, when we were wed,

In her artless manner said,

"Dear, I think I'd better

Choose a hobby, lest I find

Household duties cramp the mind."

Foolishly, I let her.

Books at first were her delight;

Gwendolen grew erudite;

Vain were my petitions,

Till in scientific terms

I dilated on the germs

Haunting first editions.

Then, for one expensive week,

China (guaranteed antique)—

Derby, Sèvres and Lustre—

Charmed her, till our Abigail

Washed them in a kitchen pail,

Dried them with a duster!

Foreign stamps her time engrossed

For a busy month at most;

I endured—and waited.

Who so proud as Gwendolen

Of each gummy specimen

Till the craze abated?

Later (if I seem severe,

Gwendolen, forgive me, dear!)

Art proved all-compelling;

Post-Impressionist indeed

Were the colour-schemes decreed

For our modest dwelling.

With her last experiment

Gwendolen appears content;

Heaven grant she may be!

For, of all the hobbies run

By my wife, there isn't one

Suits her like a baby.

Wilkinson is a sculptor. I don't mean that he lives by sculping. No. As he puts it himself: "My lower self, the self that wants bread and meat and warmth and shelter, lives on unearned increment. My higher self, the only self that counts, lives on Art."

Wilkinson and I had been sworn pals from our boyhood till the day he said: "By the way, old thing, I've never had a turn at your headpiece. You might give me a few sittings."

For the first time I found myself seated on a sitter's throne, while Wilkinson stood at his modelling stand working away at a mass of clay that faintly suggested a human head and shoulders.

"Need you yawn so often?" There was a hint of savagery in Wilkinson's tone that was new to me.

"Why, you're not doing my mouth yet," I urged.

"No, but when a mouth like yours opens wide it alters the shape of the whole skull."

I was astonished and hurt, and took refuge in dignified silence.

"Shall you send it—I mean me—to the Academy?" I asked by-and-by.

"Depends on how it pans out," grunted Wilkinson, leaving the clay, twirling the movable throne round, and taking a frowning survey of me in various aspects. "I might send it in with Popplewell's bust, as a sort of make-weight."

"As a sort of make-weight!" I echoed indignantly; and then, more calmly, "Popplewell's finished, isn't he?"

"Yes—gone to be cast; and then comes the marble."

"Oh, Popplewell's to be done in marble, is he? What shall I be done in?"

Wilkinson was taking an upward [pg 310]view of my features now, with a look of extreme distaste on his countenance.

"You? Oh, if I decide to finish you, it'll be just the clay-burnt terra-cotta, you know. Tut, tut, tut!"

"Why tut, tut, tut?" I asked.

"No offence, old chap, but you have such queer facial bones;" and as he turned back to his modelling I heard him mutter: "You never really know what people are like till they sit to you."

Again I felt a bit hurt, and this time I indulged a retort. "Wonder if you'll get Popplewell into the Academy. You've never had anything in yet, have you?"

"We sculptors are so vilely handicapped by the wretched amount of space the Academy people give us!" said Wilkinson angrily. "Still, I've great hopes this time. Not only is my work improved, but it's a popular subject—Popplewell, the novelist. There—that'll do for to-day. I've got the construction all right," looking resentfully from the clay head to mine, "though no one would believe it who hadn't your head here to compare it with."

"Why, what's the matter with my head?" I asked irritably as I got gingerly off the movable throne. "And, anyhow, I didn't ask to be modelled. You made me sit here—I didn't want to do it."

"Oh, people make practice for one, whatever they're like."

"Good-bye," I said stiffly.

At the second sitting I tried to make allowances for the artistic temperament when Wilkinson prowled round me with a look of something like horror on his face, assaulted my features with compasses, and turned away gibbering. I even kept calm when informed that one of my eyes was considerably larger and wider open than the other and that I had "no drawing" in my face. "No offence, old chap," added my former friend with a grin. "You must remember it's the artist-eye that's responsible for these cursory reflections."

"I wonder," I remarked musingly, "whether the artist-eye is a feature that occasionally gets blacked by an indignant sitter."

At the third and fourth sittings more bitter so-called truths were handed out to me, and he was down on my "construction" like a hundred of bricks.

"That's a normal one," here he indicated a skull on a shelf; "his bones are all right. But if yours were stripped of the flesh——"

"I shan't be sorry when these sittings are over," I said; then, as I caught a side view of the clay head, "I say! Am I as frightful as that?"

"As frightful as that!" snorted Wilkinson; "why, I've flattered you, if anything. People never know what they're like. There's such a lot of rotten vanity knocking about."

When the last sitting was over my wrongs found voice.

"When I first sat to you," I said in a tense tone, "I was comparatively happy; my self-esteem was in a healthy state; I felt that I was well-looking at my best, even good-looking. I go from you to-day a broken man, my confidence shaken, my manners spoiled by the consciousness that my construction is wrong, that there is 'no drawing' in my face, and that neither my eyes nor my nostrils are a pair; and, not content with this, you have darkened my remote future by implying that when it is time for me to be merely a skull I shall be an absurd one. May Heaven forgive you, Wilkinson—I never can!"

For some weeks we stood apart, "like cliffs that had been rent asunder," and then one day Wilkinson came up and thumped me on the back. "It's always the unexpected that happens, old thing," he said. "Popplewell's bust was rejected at once, but yours——"

"Am I in?" In my excitement I forgot my wrongs.

"No, not in; but you were a doubtful. Only think—first doubtful I've ever had! To have a doubtful sculpture is as good as having two or three paintings on the line. You can't be such a bad subject after all. I'll have another touch at you, and next year see if you're not in! Come and have some lunch."

"Notable things are done around a table. Corporations are formed...."

Westminster Teacher.

The beginnings of them, anyway.

(Extracted from the Diary of Toby, M.P.)

House of Commons, Tuesday, April 14.—Back to grindstone after so-called Easter recess. Divisions reveal presence of aggregate of something less than 200 Members. Watchful Whip, ever suspicious of ambush, succeeded in mustering four-fifths of the whole. Ministerial majority maintained at average of six-score.

Increased by a unit consequent on return of Premier after re-election by faithful Fife. Towards close of Questions was discovered standing at Bar awaiting Speaker's call.

"Members desiring to take their seats will please come to the Table."

As he advanced, escorted by Chief Whip and Scottish colleague, Liberals and Irish Nationalists leaped to their feet, waving hats and handkerchiefs in loyal greeting. Only the haughty Labour Member remained seated. Not for him to pay court to chiefs of other parties, howsoever friendly. He is there as representative of the Working Man; is neither to be bought nor sold, cowed nor cajoled.

A fine spectacle. Pity Strangers' Galleries almost empty.

Mr. Speaker. "Pleased to make your acquaintance, Sir. Somehow I seem to know your face."

In process of swearing-in new Member nothing taken for granted. Halsbury discovered this when, far back in the last century, he, known at the time as Hardinge Giffard, came up to take his seat for Launceston. Challenged by the Clerk for production of writ of return, made painful discovery that it was not at hand. Sure he put it in his pocket when he left home; but which pocket?

In full gaze of four hundred quizzical Members he proceeded to search. Was there ever mortal man with so many pockets stuffed with such miscellaneous contents as Disraeli's Solicitor-General littered the Table withal? In the end—and its coming seemed interminable—the desired document was found coyly hidden in his hat left on the seat he had occupied under the Gallery awaiting summons to the Table.

The Prime Minister, cool and businesslike as usual, had necessary document ready. Handing it to the Clerk, he once more signed the roll of Parliament.

Then came critical moment, awaited with keen interest by House. The roll signed, it is duty of Clerk to conduct new Member to Speaker and introduce him by name.

"Mr. Asquith!" the Clerk announced.

"Come under de ole umbrella,

Come along, piccaninnies, do;

Hark to Uncle Lulu a-callin',

Room for all ob you!"—Coon Song.

(Mr. Harcourt.)

With half start of surprise Speaker regarded newcomer; thought he recognised him as he stood at the Table. All doubt now removed. Yes, it was Asquith. With genial smile and friendly grip of the hand he welcomed the new Member. Delighted Ministerialists cheered again at this happy conclusion of the episode.

Business done.—Committee stage of Bill pledging national credit for loan to East African Protectorates entered upon. Not without opposition from Ministerial benches. Alpheus Cleophas Morton, of whom we hear little in these degenerate days, insisted that this kind of charity should begin at home—that is in the Highlands of Scotland. Wedgwood and Thorne thought Government had gone far enough in the way of lavish expenditure of tax-payers' money by providing them and others with salaries of £400 a year. From other side of House Banbury made several speeches in succession. Division called and opposition swamped.

Wednesday.—"Such larks!" as Joe Gargery used to say to Pip when they met for confidential confabulation. Of all men it was Cousin Hugh began them. At first sight difficult to associate tendency to larkiness with austerity of Member for Oxford University. But human nature is complex, and, after all, Cousin Hugh is only human.

In a former Parliament he was convicted of what was officially known as loitering in the Lobby. It was a Wednesday afternoon, and in those days debate automatically stood adjourned at half-past five. Business to the fore related to Marriage with a Deceased Wife's Sister. Every prospect of Resolution being approved if there were opportunity for division. The thing to do was to prevent one taking place. Accordingly, when House divided on Closure motion, Cousin Hugh and his confederates were such an unconscionably long time returning to their places that half-past five struck before main question could be put from Chair. Debate accordingly stood adjourned for indefinite period.

A fortnight ago another of those domestic questions which stir Cousin Hugh's soul to the depths came up. At the ballot-box a Member secured favourable position for motion relating to Divorce. Cousin Hugh [pg 314]straightway blocked it by a bogus Bill. Last Wednesday Opposition proposed on motion for adjournment for Easter to attack Government from divers points of compass. Ministerialists, taking leaf out of Cousin Hugh's book, put down notices that blocked the whole lot. To-day Premier's attention called to the matter. Admits "situation is scandalous"; undertakes forthwith to submit Resolution dealing with it.

Characteristically odd feature in case is that it was Brother Bob who brought matters to a head by tabling a Resolution making impossible in future the vagaries of Cousin Hugh.

Which shows afresh how remarkable are the resources of a family rooted in the spacious times of Queen Elizabeth.

Business done.—Criminal Justice Administration Bill read a second time.

Thursday.—As at approach of Spring the time of the singing of birds comes, and the voice of the turtle is heard in the land, so thus early in the session the voice of the objector is heard in the House of Commons. On days when Private Bills come up for consideration, there is a scene which interests while it perplexes occupants of Ladies' Gallery, in whose full view it is set. As soon as Speaker takes the Chair, before galleries are open to male strangers, there enters from hidden staircase leading to gallery over clock a procession of businesslike gentlemen. Silently, swiftly, they flood what is known as Distinguished Strangers' Gallery.

Clerk at Table reads list of Private Bills awaiting second reading: (1) Middlesbrough Corporation Bill, (2) Lurgan Gas and Electricity Bill, (3) Northwich Urban District Council Bill. From one side or other of benches below Gangway sounds a single word: "Object!" Title of next Bill on list recited. Again the cabalistic word, and so on to end of catalogue. This reached, anonymous Strangers in gallery rise and depart as swiftly, as silently, as they came, and what is still known as Question-hour (though it is limited to forty-five minutes) opens.

Whisper runs round Ladies' Gallery that mysterious Strangers are detachment of Ulster volunteers out on drill. As a matter of fact they are solicitors concerned for fate of private measures. With extreme rarity is a Private Bill debated on second reading. As a rule that stage is formally conceded, real work being done in select committees upstairs. One of the archaic absurdities of legislative practice remaining in Commons is that a single Member has autocratic power to delay progress of particular Bills approaching Committee stage by murmuring or shouting a magic dissyllable.

Last Session Tim Healy, offended at certain course taken by Board of Trade in respect of Private Bill for which he was concerned, held up for a fortnight the whole course of private legislation. At the end of that time Government with a majority still a hundred strong capitulated. It was an exceptionally weary time for solicitors filing in and filing out of the Gallery, day by day passing and their Bill "getting no forrarder."

Fortunately in these cases there are two Bills that run concurrently. One is the legislative measure to which a Member objects; the other the bill of costs in which these daily attendances at the opening of successive sittings, this mounting and descending of unsympathetic stairways, are doubtless duly noted.

Business done.—Irish Votes in Committee of Supply.

The Postmaster-General is making heroic efforts to improve the telephone service. According to the current Post Office Circular the name of the "Coed Talon" exchange has been altered to "Pontybodkin."

Aviation.

Once upon a time there was a little primrose who grew all alone on a sunny bank. All around her were primroses in clusters, but she was a solitary flower.

Having no brothers or sisters to talk to and no very near neighbours, she made a confidant of a bee, who would often sit with her for several minutes at a time. He was brusque and opinionated, but he was wise too, and, having wings, knew the world; and she never tired of hearing of his travels.

He told her of gardens where flowers of every kind and sweetness bloomed. "Not like you," he said—"not wild flowers that no one values, but choice, wonderful, aristocratic flowers that are picked out of catalogues and cost money and need attention from a gardener."

"What is a gardener?" the primrose asked.

"A gardener is a man who does nothing but look after flowers," said the bee. "He brings them water and picks off the dead leaves, and all the time he is thinking how to make them more beautiful."

"How splendid!" said the primrose.

And the bee told her of the houses in these gardens, with pleasant sunny rooms, and pictures, and flowers in vases to cheer the eyes of the rich people who lived there.

"How splendid!" said the primrose again. "I wish I could see it all. I should love to be in a vase in a beautiful room and be admired by rich people."

"You're too simple," said the bee. "You haven't a chance. You've got to stay where you are till you die."

"Why shouldn't I have wings like you?" said the primrose.

"How absurd!" replied the bee as he flew away.

But the next day the primrose looked up and saw a most wonderful thing. A primrose that really had wings! A flying primrose! A primrose that could go anywhere just like the bee. It darted hither and thither so gaily, alighting where it wished and then soaring up again right into the blue sky above the earth.

The solitary primrose called to it, but it did not hear, and was soon out of sight.

"So primroses needn't always stop where they are till they die," she said to herself. "Why did the bee deceive [pg 315]me? If I were like that I could see the garden and the gardener and the pretty gay sitting-rooms and the rich people."

She waited impatiently for the bee's return, and when he came she told him about the aviator.

"He was so splendid," she said, "so big and strong, and he flew beautifully. How can I get wings, too?"

"Pooh!" said the bee. "That wasn't a primrose. That was a brimstone butterfly; and as for flying—why, he can't compare with me. I could beat him every time: hundred yards, quarter-mile, mile, long distance—everything."

"He looked just like a wonderful big primrose," said the solitary flower wistfully.

"That's because you've got only one eye," said the bee. "He was a butterfly right enough;" and he hurried away laughing at the silliness of her mistake.

But that day the little primrose had part of her wish; for a party of children came into her corner of the wood and began to pick the flowers with cries of delight.

"Here's one all alone!" said a small girl. "I shall pick that for mother." Straightway the primrose was torn from its root and held tightly in a hand which was far too hot to be pleasant.

Down the road the children went, and the primrose looked as well as she could at the hedges and the trees.

"So this is the world," she said to herself. "It seems really interesting, but I should like it better if I didn't feel so faint."

At last they came to a garden gate and passed through it, up a long path, with strange flowers on each side, which the primrose saw mistily, for she was now really ill.

"I am sure it is all very beautiful," she murmured, "but I know I shall die if I don't have some water soon."

And then they entered a room, and the little girl hurried up to a lady and gave her the solitary primrose. "It was growing all alone," she said, "so I brought it for you."

"Put it into a vase at once," said the mother, "or it will die." And the primrose was placed in water, and at once began to revive.

Then she looked about her and saw what a nice room it was, and was happy.

The next morning in came the bee with a great fluster and bumped all over the room.

"Hullo," he said to the little primrose, "you here?"

She told him all her adventures.

"Well, what I said is right, isn't it?" the bee remarked. "It's all very jolly here, isn't it?"

"I suppose so, but I wish I didn't feel so weak. I never had an ache when I was in the wood."

"Ah, but you weren't among the nobs then," said the bee; "make the most of your time while you're here, for it won't be for long, you know."

"Come and see me to-morrow," the little primrose whimpered. "I feel so lonely here. I was happier in the wood."

"You won't be alive to-morrow," said the bee cheerily. "But never mind, you have seen the world." And out he bashed again, blowing his motor-horn to clear the way.

He. "I say, your Grannie seems rather put out to-night. What's up?"

She. "Hush! Poor dear, she's just heard my other grannie is engaged and she's so afraid she may be left on the shelf."

"Pygmalion."

The original Pygmalion took a block of dead ivory and made of it so fair a figure of a woman that he fell in love with his own creation, and Aphrodite, at his request, brought it to life. Mr. Shaw's Pygmalion takes a live flower-girl, turns her into a lifeless wax figure fit for a milliner's shop-window, and flatters himself, as an artist, on the result, but, as a man, proposes to take no interest in it, moral or physical. So you can easily see why almost any other proper name you can think of would have done better for the title.

We venture to suggest a new attitude to illustrate the ease of manner which one expects from a Master of Phonetics and Deportment.

Henry Higgins Sir Herbert Tree.

The play itself shows the same typical inconsequence, the same freedom from the pedantry of logic. Eliza Doolittle's ambition is to become fitted for the functions of a young lady in a florist's shop. Henry Higgins, professor of phonetics, undertakes for a wager to teach her the manners and diction of a duchess—a smaller achievement, of course, in Mr. Shaw's eyes, but still a step in the right direction. And he is better than his word. After six months she has acquired a mincing speech, from which she is still liable to lapse into appalling indiscretions; but after another six months the product might pass muster in any modiste's showroom. And then she turns on him and protests that he has spoilt her life. As a flower-girl, she tells him, she used to earn her living honestly; now there is nothing she is good for.

Of course, you say, her contact with refined society—"we needs must love the highest when we see it"—has unfitted her for mixing with inferior people. On the contrary. She has, it is true, passed the final test of a series of social functions; but meanwhile all this time of her apprenticeship in manners she has been living her daily life, doing half-menial duties, in the house of Higgins, who happens to have no manners at all. One trembles, indeed, to picture the figure that he himself, the master, must have cut when he took his pupil to the halls of the great.

Then perhaps, you say, she has fallen into an unrequited passion for him, and this accounts for her peevishness? Well, if she has, we have only Mr. Shaw's word for it, and she gets no sympathy from us for her deplorable taste in men. There was another man who was always about the house, a man with a habit of courtesy, but this gallant soldier left her cold. Such is the perversity of women—and Mr. Shaw. Higgins's one act of civility to his protégée, on which we had to base our hopes of a happy issue, was to throw a bunch of flowers at her from a balcony in Chelsea—not perhaps a very tactful reminder of her origin. But he was only just in time. Another two seconds of delay and the final curtain would have cut off this tardy and inadequate effort of conciliation.

(Showing middle stage in course of lessons in Polite Conversation.)

Eliza Doolittle (Mrs. Patrick Campbell) to Mrs. Eynsford-Hill (Miss Carlotta Addison). "An aunt of mine died of in-flu-en-za: but it's my be-lief they done h-her in."

However, nobody goes to a production of Mr. Shaw's with the idea of seeing a play. We go to hear him discourse on just anything that occurs to him without prejudice in the matter of his mouthpiece. This time he was represented by a dustman; and for once Mr. Shaw consented to temper his wisdom to the limitations of its repository. His Alfred Doolittle (father of the flower-girl) threw off a little cheap satire on the morality of the middle-classes, yet admitted the drawbacks of unauthorised union (as practised by himself), since a man's wife is there to be kicked, whereas a mistress is apt to be more exigent of the amenities; you must adopt a more lover-like attitude if you want to retain her. He also argued brightly in defence of his proposal to sell his own daughter to any man for a fiver; let fall a platitude or two in praise of the lot of the undeserving poor; and (having come in for a fortune) found that charity had lost its blessedness—that the touch of nature which makes the whole world kin was only admirable when you did the "touching" yourself. Not bad for a dustman, but Mr. Shaw has done better.

For the rest the attraction lay in the performance of individual actors rather than in the stuff of the play. Mrs. Patrick Campbell was delicious, both in her unregenerate state, and even more during the middle phase of the refining process. She made the Third Act a pure delight. Later, when she became tragic, she sacrificed something of her particular charm to the author's insincerity.

Sir Herbert Tree, always at his best in comedy, was an excellent Higgins in his lighter moods. As for Mr. Edmund Gurney, he was far the best dustman I have ever met. His freedom from scruples, combined with a natural gift for unctuous and persuasive rhetoric, commanded admiration. Higgins, indeed, who could read potentialities at a glance, considered that he might, under happier conditions, have gone far toward attaining Cabinet rank or filling a Welsh pulpit.

Of the others, Mr. Philip Merivale played the too subsidiary part of Colonel Pickering with admirable self-repression; and Miss Rosamond Mayne-Young, as the mother of Higgins, was a very gracious figure.

The play was curiously uneven. If one might be permitted to enter and leave at one's pleasure I would [pg 317]advise you to miss out the desultory First Act. But if you insist on seeing it then take care to read your programme before the lights go down and find out that the scene is the porch of a church. I thought all the time that it was the porch of a theatre. Make sure in the same way about the Chelsea flat, or you may mistake it for a charming country cottage. The Second and Third Acts are not to be missed on any account, but I shouldn't worry about the Fourth. In the Fifth you should go away for good the moment that the dustman makes his exit. The tedium that follows is most distressing, and can only be explained as the author's revenge for your laughter. It was a cruel thing to do.

But I forgive him. I take away many delightful memories of my evening with Pygmalion, and, best of all, the picture of Sir Herbert's frank and childlike pleasure at having discovered Mr. Bernard Shaw.

Jones (selecting a uniform for his chauffeur). "I like this one best, but it's rather expensive."

Expert Salesman. "Then I should have it. After all, the guv'nor pays!"

"Potash and Perlmutter."

If you have ever been to an American commercial drama, you will know the opening scene of this one before the curtain goes up. The business interior; the typewriter on the left; the head of the firm opening cryptic correspondence and dictating unintelligible answers; spasmodic incursions of cocksure buyers and bagmen; a prevailing air of smartness, of hustle, of get-on-or-get-out. In The Melting Pot Mr. Zangwill has been creating a diversion with an Hebraic theme, his hero being a refugee from Kieff, where his family had perished in a pogrom. This new variation has occurred—independently, no doubt—to the author of Potash and Perlmutter, who has grafted it (including the detail of the immigrant from Kieff) on the old commercial stock, and done very well indeed with his blend.

His two protagonists in the Teuton-American-Semitic firm of "cloak and suit" manufacturers that gives its title to the play are extraordinarily alive. I am but imperfectly acquainted with this racial variety, but I can easily recognise that Messrs. Augustus Yorke and Egbert Leonard, who represent the two partners, are gifted with the most amazing powers of observation and reproduction.

The pair are alike in their mercenary tastes and in that loyalty which is so fine a feature of the Jewish race, and is here found in frequent conflict with their commercial instincts. The cruel wrench that their generosity always costs them is a true measure of its excellence. They quarrel alike over details of business policy; but they always stand together where profit is obviously to be made by a common attitude, or where they find themselves in a tight corner. Yet the author has preserved a nice distinction between them. It is Potash, the elder of the two, and encumbered by fetters of domestic affection, who is the weaker vessel, and commits the indiscretions with whose issue he is impotent to cope; it is Perlmutter, with the quicker brains, contemptuous but devoted, who throws all the blame where it is due, yet stands by to share the punishment.

I found their language and accent rather hard to follow, a difficulty not shared by the strong Jewish element in an audience that was extremely quick to appreciate the humour that kept one always on the alert. It is profitless to ask how much of the fun was due to the things said and how much to the manner of saying them. The essential matter is that actors and author between them gave us an unusually good time, and I am much obliged to them.

Apart from the leading characters, the Mrs. Potash of Miss Matilda Cottrelly was a most delightful study, and the breezy methods of Mr. Charles Dickson as a buyer and Mr. Ezra Matthews as a salesman were effective of their kind.

The plot, as usual in such plays, was rather elementary. So, too, with the love interest; but the right kind of sentiment was not wanting in the very human characters of Potash and Perlmutter. For a rare moment or two there was a break in our laughter and tears were not far away.

O. S.

My nephew Rupert has been spending part of his Easter holidays with me. There is nothing like a boy of fifteen for adding an atmosphere to a house—in which term I include a garden. It is a special atmosphere, hard to define, but quite unmistakable when you have once lived in it. It is compounded of football, cricket, hockey—these are not actual, but conversational—of visits to the stables, romps with dogs in a library, tousled hair, muddy trousers, a certain contempt for time, the loan of my collar-stud, an insatiable desire to look through the back volumes of Punch, long rides on a bicycle and an irresistible tendency of ink to the fingers, presumably caused by the terrible duty of writing letters to parents. There may be other ingredients, but these are the chief. I am bound to add that he is a very amiable boy, with a strong sense of humour, and that he associates on very friendly terms with the little girls, his cousins, who form the majority of this household, it being quite understood that, for the time, they become boys while he remains what he is.

The other morning Rupert evidently had something on his mind. He made various half-hearted and thoroughly unsuccessful efforts to leave the room, twiddled his cap in his hands, tripped over the rug and finally spoke.

"Thanks awfully, Uncle Harry, for lending me your bicycle."

"That's all right," I said. "You're very welcome to it. It's a good thing for it to be used."

"Yes," he said, "but I shan't want it again."

"Tired of it?" I said. "Well, there's no compulsion."

"Oh, I know that—thanks awfully—but it isn't that. It's a ripping bicycle. I should like to ride it for ever, but——"

"Well, what is it? Out with it."

"I've got one of my own."

"One of your own!" I said. "How's that? You hadn't got one yesterday."

"No, but I've got one now. I bought it this morning at Hickleden. There's a bicycle shop there, and I heard there was a good bicycle for sale cheap, so I went over this morning and had a ride on it, and it suited me splendidly, so I bought it, and I've got it here."

"Bought it?" I said. "That's all very well; but how did you pay for it?"

"That," he said, "is where all the bother comes in."

"It generally does," I said. "Either you've got the money, and then it seems such a waste; or you haven't got it, and then it's a lifetime of misery. Debt, my boy, is an awful thing."

"Don't rag, Uncle Harry; I've got the money all right."

"Then be a man and shell out."

"Yes, but that's just what I can't do. It's this way: the price of the bicycle is five pounds seventeen and sixpence."

"And a very good price too."

"It's got three gears and a lamp and everything complete. Well, I've got three pounds ten in the Post-Office Savings Bank. I put it in in London."

"That's a good beginning, anyhow."

"Yes, and Aunt Mary gave me a pound for my birthday, and I put that in at the post-office here yesterday. It's better not to keep pounds in your pocket."

"Quite right," I said; "we have now got to four pounds ten."

"And Grandma sent me a pound this morning in a postal-order."

"We're all but up to it now," I said. "The excitement is becoming intense."

"Isn't it? And I've got the rest in shillings and sixpences and coppers."

"Away you go, then, and pay for the bicycle."

"Ah, but it isn't as easy as all that. I can't get the money out of the Post-Office."

"What," I said—"they won't let you have your own money? They calmly take the savings of a lifetime and then refuse to give them up?"

"I went round there this morning and they said I'd put the money in in London and there were various formalities to be gone through before I could draw it out here."

"The official mind," I said, "delights in technicalities. Let us see how you stand:—

To save you from the silly game of playing drakes and ducks

You banked the cash in Middlesex—but asked for it in Bucks.

Or we could put it in this way:—

In order not to spend it all in lollipops and toffees

You gave it to the P. M. G. to keep it in his office.

Or in this way:—

You bought a three-gear bicycle because you had a will for it,

And now you've gone and fetched the thing and cannot pay the bill for it.

Rupert, you're in the cart."

"By Jove, Uncle Harry," he said in an awestruck tone, "that's poetry."

"Is it?" I said. "I just threw it off."

"Oh, yes, it's poetry all right. It's got rhymes, you know."

"Rupert," I said, "let us come back to plain prose and consider your desperate financial situation. You cannot get your three pounds ten."

"No, not yet."

"And Aunt Mary's pound?"

"They said that, being holiday time, that wouldn't have got to headquarters yet."

"Gracious goodness," I said, "I never knew a savings bank had so many pitfalls. The whole thing is too complicated for my mind."

"It isn't really complicated," said Rupert. "It's quite plain; but perhaps if you put it into poetry you'll understand it better."

"Rupert," I said, "let us have no sarcasms. The thing is too serious for that. You possess your grandmother's pound in a postal-order and assorted coins to the amount of seven and sixpence, total one pound seven and six, to pay for a bicycle costing five pounds seventeen and sixpence. In short, you are a bankrupt."

"But I shall get the money."

"That is what they all say."

Eventually the matter was arranged and the bicycle man was satisfied. Rupert's correspondence with the Post Office still continues. But his faith in that institution has received a severe shock.

R. C. L.

"The Rev. C. A. Brereton has presented to the St. Pancras Guardians a donkey for the use of the children at Leavesden Poor Law Schools, and a member of the Board has presented an A B C time-table."—Daily News.

Anonymous Benefactor (when the secret of his name leaks out): "No, no, don't thank me.... It was last year's."

Headlines to adjoining columns in The Toronto Daily Star:—

| "Mayor to call meeting to discuss Scripture." | "Mayor calls 'Globe's' report a 'blasted lie.'" |

These Mayors lead a life full of variety.

Good and encouraging Samaritan (helping sportsman to remount after immersion in the brook). "Next old bruck be heaps bigger'n this un, and he do have a turrible lot o' water in he just now."

(By Mr. Punch's Staff of Learned Clerks.)

Dodo the Second (Hodder and Stoughton), by E. F. Benson. Doesn't the very title-page sound like a leaf from your dead past? I protest that for my own part I was back on hearing it in the naughty nineties, the very beginning of them indeed (the fact that I was also back in the school-room did little to impair the thrill) and agog to read the clever, audacious book that all the wonderful people who lived in those days were talking about. And behold! here they all are again—not the people who talked, but the audacious characters. Only the trouble is that we have all in the interval become so much more audacious ourselves that their efforts in this kind seem to fail to produce the old impression. This is by no means to say that I didn't enjoy Dodo the Second. I enjoyed it very much indeed; and so will you. For one thing, it was the jolliest experience to recognize so many old friends—Dodo herself (now of course the Princess Waldenech), and the wicked Prince, and the rest of them. Of Dodo at least it may be said, moreover, that she has matured credibly; this middle-aging lady is exactly what the siren of twenty years ago would have developed into, still beautiful, still alluring, and still (I must add) capable of infecting everyone else in a conversation with exactly her own trick of cheap and rather fatiguing brilliance. Added to all this there is now a new generation of characters, several of whom are quite pleasant company; for them and for one very impressive piece of descriptive work in the account of a gathering storm, this Twenty Years After may be heartily welcomed. Indeed one leaves Dodo of 1914 so vigorously alive that I am not without hope of her turning up yet again as a grandmother in 1934.

I have discovered from The Rebellion of Esther (Alston Rivers) why it is that my sympathies, usually at the disposal of insurgents, are withheld from the Suffragette. Anyone who is genuinely out to assert a principle, at the cost of quarrelling with established authority, has a certain merit of altruism which even the most law-abiding may count as a mitigating circumstance, however unworthy the end in view; but the egoism of a young lady (like Miss Margaret Legge's heroine) who in whatever cause defies all institutions with the latent motive of asserting herself will induce even the most lawless to support warmly the powers of suppression. Miss Esther Ballinger had a number of real grievances, but her point of view was typified in her attitude towards the illicit and incidental motherhood of one of her acquaintances. Without hearing the facts, she pronounced it to be "a courageous stand against conventional morality," which it just possibly might have proved to be upon enquiry, and by no means a weak surrender to immediate desires, as much more probably it was in fact. From my knowledge of Esther she had but one reason for expressing this opinion, and that was the personal pleasure of saying the unorthodox thing, an element which accounts for much of the unconventionality of that intellectual class of townsfolk figuring broadcast in the book, and largely discounts the value of its criticisms. I suspected the same flaw in her expressed convictions on religious, political and feminist matters, [pg 320]and I shouldn't be surprised to learn, though there is no hint of it, that she stopped short of complete revolt in her own big affair because she realized instinctively that even a passionate pose may lose its attractions if it has to be maintained for a lifetime. Miss Margaret Legge, though alive to the young person's faults, regards her as, on the whole, deep-thinking and right-minded; and I would not for a moment have our personal difference of opinion discourage anybody from reading a carefully studied and ably written novel.

The attitude of Militarist to Pacifist has the makings of a very pretty comedy. When the Mystics (with the Friends and the Tolstoians) were evangelical enough to preach their message of peace even to the point of non-resistance, they were broadly scouted as sentimental and idealistic idiots, and reminded of a nature red in tooth and claw rampant in this most sordid of all possible worlds. Now that the Rationalists take up the case against war from another end, they are denounced as squalid souls, with a greengrocer's outlook, morbidly anxious about the price of peas and potatoes, and urged to remember that not by bread alone doth man live. In The Foundations of International Polity (Heinemann), a series of lectures developing phases of the argument of the Great Illusion, Mr. Norman Angell incidentally deals with this greengrocery business. Nobody with knowledge of his shrewd and vigorous method will be surprised that without bluster or rhetoric he establishes a very clear verdict of acquittal. One has always the impression that the rationalist in him is deliberately repressing the mystic, lest his case be weakened by a suspicion of sentimentalism. For it must be obvious that not a cold, still less a squalid, but a generous purpose alone could inspire the fervour that flashes between the reasoned lines. When Mr. Angell pleads that policy is directed towards "self-interest," an easily misunderstandable pronouncement, it is no mean self-interest he has in view but a quality of high civilising and social value. He argues cogently that defence is not incompatible with, but rather a part of, rational pacifism, which is the protest against coercion; re-emphasises the difference between soldiering and policing; and illustrates the essential shallowness of that venerable tag, "Human nature doesn't change," by pointing to the decay of the duello, and the decline of the grill as a means of reasoning with heretics and witches. Were this learned Clerk a politician (which Heaven avert!), he would move for yet another increment to the Supplementary Navy Estimates—to wit, the price of a battleship to be expended in the distribution of this fighting pacifist's books to all journalists, attachés, clergymen, bazaar-openers, club oracles, professors, head-masters and other obvious people in both Germany and Britain.

In his new satirical study of certain modern cranks and their unpleasantness Mr. Oliver Onions has, I think, allowed his bitterness to outrun his sense of proportion. A Crooked Mile (Methuen) is a sequel to his earlier book, The Two Kisses. We meet again those two young women, Dorothy and Amory, and the natural characteristics that they once presented seem now to be tortured into caricature. Amory has indeed all my sympathy, so badgered is she by Mr. Onions, so relentlessly forced into ignominious positions; and I cannot feel, as I should do, that she would have achieved those ignominies without Mr. Onions' impelling hand behind her. I have myself considerable sympathy for cranks, and perhaps that is why I regard Mr. Onions' satire as a dry, gritty business. His humour is, of course, always a delightful thing, but here I fancy that he has not drawn the true line between comedy and farce, between satire that preserves the probabilities and indiscriminate exaggeration. Of the three Mr. Onionses who have at different times given me pleasure—the author of Widdershins, the author of In Accordance with the Evidence, and the author of Little Devil Doubt—I greatly prefer the first. In A Crooked Mile there is one chapter worthy of all three of them—that chapter where Amory discovers that her lover is going away with another woman. That is fine work. For the rest I hope that he will grow tired of his social satire and soon give us again some more of his delicate imagination and fancy.

What I felt about The Girl on the Green (Methuen) was that, however charming and capable, she was not quite likely, after but a few short months of golf, to have put up such a good fight in her great match with the crack amateur, Jim Beverley, who was giving her a half. I couldn't manage to believe it. However, that was not my business, but Mark Allerton's. According to him, Frank took her match to the last green, in spite of a number of cats, headed by the Vicar's wife, who did their best to put her off her game. Yes, you are right to presume that what began as a single developed into a flirtsome, and that the twain lived happily ever after in a nice little dormy house, and that Jim bested the Hiltons and the Ouimets, while Frank put permanently out of joint all the noses of all the Misses Leitch. Those who not only play but talk, dream, read and generally live for golf will, I can say with confidence, be grateful to Mr. Mark Allerton for this easy, hopeful narrative.

Vendor of studs and buttons (to vendor of inflating baby). "Now then, Father, not so much of it. Give an old batchiler a charnst, carn't yer?"

The Morning Post on the Army and Navy Boxing Championships:—

"These men's middles were full of good things."

Why don't they train better?