Emily Sarah Holt

"Earl Hubert's Daughter"

Preface.

The thirteenth century was one of rapid and terrible incidents, tumultuous politics, and in religious matters of low and degrading superstition. Transubstantiation had just been formally adopted as a dogma of the Church, accompanied as it always is by sacramental confession, and quickly followed by the elevation of the host and the invention of the pix. Various Orders of monks were flocking into England. The Pope was doing his best, aided by the Roman clergy, and to their shame be it said, by some of the English, to fix his iron yoke on the neck of the Church of England. The doctrine of human merit was at its highest pitch; the doctrine of justification by faith was absolutely unknown.

Amid this thick darkness, a very small number of true-hearted, Heaven-taught men bore aloft the torch of truth—that is, of so much truth as they knew. One of such men as these I have sketched in Father Bruno. And if, possibly, the portrait is slightly over-charged for the date,—if he be represented as a shade more enlightened than at that time he could well be—I trust that the anachronism will be pardoned for the sake of those eternal verities which would otherwise have been left wanting.

There is one fact in ecclesiastical history which should never be forgotten, and this is, that in all ages, within the visible corporate body which men call the Church, God has had a Church of His own, true, living, and faithful. He has ever reserved to Himself that typical seven thousand in Israel, of whom all the knees have not bowed unto Baal, and every mouth hath not kissed him.

Such men as these have been termed “Protestants before the Reformation.” The only reason why they were not Protestants, was because there was as yet no Protestantism. The heavenly call to “come out of her” had not yet been heard. These men were to be found in all stations and callings; on the throne—as in Alfred the Great, Saint Louis, and Henry the Sixth; in the hierarchy—as in Anselm, Bradwardine, and Grosteste; in the cloister—as in Bernard de Morlaix; but perhaps most frequently in that rank and file of whom the world never hears, and of some of whom, however low their place in it, the world is not worthy.

These men often made terrible blunders—as Saint Louis did when he persecuted the Jews, under the delusion that he was thus doing honour to the Lord whom they had rejected: and Bernard de Morlaix, when he led a crusade against the Albigenses, of whom he had heard only slanderous reports. Do we make no blunders, that we should be in haste to judge them? How much more has been given to us than to them! How much more, then, will be required?

Chapter One.

Father and Mother.

“He was a true man, this—who lived for England,

And he knew how to die.”

“Sweet? There are many sweet things. Clover’s sweet,

And so is liquorice, though ’tis hard to chew;

And sweetbriar—till it scratches.”

“Look, Margaret! Thine aunt, Dame Marjory, is come to spend thy birthday with thee.”

“And see my new bower? (Boudoir). O Aunt Marjory, I am so glad!”

The new bower was a very pretty room—for the thirteenth century—but its girl-owner was the prettiest thing in it. Her age was thirteen that day, but she was so tall that she might easily have been supposed two or three years older. She had a very fair complexion, violet-blue eyes, and hair exactly the colour of a cedar pencil. If physiognomy may be trusted, the face indicated a loving and amiable disposition.

The two ladies who had just entered from the ante-room—the mother and aunt of Margaret were both tall, finely-developed women, with shining fair hair. They spoke French, evidently as the mother-tongue: but in 1234 that was the custom of all English nobles. These ladies had been brought up in England from early maidenhood, but they were Scottish Princesses—the eldest and youngest daughters of King William the Lion, by his Norman Queen, Ermengarde de Beaumont. Both sisters were very handsome, but the younger bore the palm of beauty in the artist’s sense, though she was not endowed with the singular charm of manner which characterised her sister. Chroniclers tell us that the younger Princess, Marjory, was a woman of marvellous beauty. Yet something more attractive than mere beauty must have distinguished the Princess Margaret, for two men of the most opposite dispositions to have borne her image on their hearts till death, and for her husband—a man capable of abject superstition, and with his hot-headed youth far behind him—to have braved all the thunders of Rome, rather than put her away.

These royal sisters had a singular history. Their father, King William, had put them for education into the hands of King John of England and his Queen, Isabelle of Angoulème, when they were little more than infants, in other words, he had committed his tender doves to the charge of almost the worst man and woman whom he could have selected. There were just two vices of which His English Majesty was not guilty, and those were cowardice and hypocrisy. He was a plain, unvarnished villain, and he never hesitated for a moment to let people see it. Queen Isabelle had been termed “the Helen of the Middle Ages,” alike from her great beauty, and from the fact that her husband abducted her when betrothed elsewhere. She can hardly be blamed for this, since she was a mere child at the time: but as she grew up, she developed a character quite worthy of the scoundrel to whom she was linked. To personal profligacy she added sordid avarice, and a positive incapacity for telling the truth. To these delightful persons the poor little Scottish maidens, Margaret and Isabel, were consigned. At what age Marjory joined them in England is doubtful: but it does not appear that she was ever, as they were, an official ward of the Crown.

The exact terms on which these royal children were sent into England were for many years the subject of sharp contention between their brother Alexander and King Henry the Third. The memorandum drawn up between the Kings William and John, does not appear to be extant: but that by which, in 1220, they were afresh consigned to the care of Henry the Third, is still in existence. Alexander strenuously maintained that John had undertaken to marry the sisters to his own two sons. The agreement with Henry the Third simply provides that “We will also marry (This meant at the time, ‘cause to be married’) Margaret and Isabel, sisters of the said Alexander, King of Scotland, during the space of one full year from the feast of Saint Denis (October 8), 1220, as shall be to our honour: and if we do not marry them within that period, we will return them to the said Alexander, King of Scotland, safe and free, in his own territories, within two years from the time specified.” (Note 1.)

This article of the convention was honestly carried out according to the later memorandum, so far as concerned Margaret, who was married to Hubert de Burgh, Earl of Kent, at York, on the twenty-fifth of June, 1221. Isabel, however, was not married (to Roger Bigod, Earl of Norfolk) until May, 1225. (Note 2.) Still, after the latter date, the convention having been carried out, it might have been supposed that the Kings would have given over quarrelling about it. The Princesses were honourably married in England, which was all that Henry the Third at least had undertaken to do.

But neither party was satisfied. Alexander never ceased to reproach Henry for not having himself married Margaret, and united Isabel to his brother. Henry, while he testily maintained to Alexander that he had done all he promised, and no further claim could be established against him, yet, as history shows, never to the last hour pardoned Hubert de Burgh for his marriage with the Scottish Princess, and most bitterly reproached him for depriving him of her whom he had intended to make his Queen.

The truth seems to be that Henry the Third, who at the time of Margaret’s marriage was only a lad of thirteen years, had cherished for her a fervent boyish passion, and that she was the only woman whom he ever really loved. Hubert, at that time Regent, probably never imagined any thing of the kind: while to Margaret, a stately maiden of some twenty years, if not more, the sentimental courtship of a schoolboy of thirteen would probably be a source of amusement rather than sympathy. But at every turn in his after life, Henry showed that he had never forgiven this slight put on his affections. It is true that his affection was of a somewhat odd type, presenting no obstacle to his aspersing the character of his lady-love, when he found it convenient to point a moral by so doing. But of all men who ever lived, surely one of the most consistently inconsistent was Henry the Third. In most instances he was “constant to one thing—his inconstancy.” Like his father, he possessed two virtues: but they were not the same. Henry was not a lover of cruelty for its own sake—which John was: and he was not personally a libertine. Of his father’s virtues, bravery and honesty, there was not a trace in him. He covered his sins with an embroidered cloak of exquisite piety. The bad qualities of both parents were inherited by him. To his mother’s covetous acquisitiveness and ingrained falsehood, he joined his father’s unscrupulous exactions and wild extravagance.

I have said that Henry was not a lover of cruelty in itself: but he could be fearfully and recklessly cruel when he had a point to gain, as we shall see too well before the story is ended. It may be true that John murdered his nephew Arthur with his own hands; but it was reserved for Henry, out of the public sight and away from his own eyes, to perpetrate a more cruel murder upon Arthur’s hapless sister, “the Pearl of Bretagne,” by one of the slowest and most dreadful deaths possible to humanity, and without any offence on her part beyond her very existence. Stow tells us that poor Alianora was slowly starved to death; and that she died by royal order the Issue Roll gives evidence, since one hundred pounds were delivered to John Fitz Geoffrey as his fee for the execution of Alianora the King’s kinswoman. (Note 3.)

It is not easy to say whether John or Henry would have made the more clever vivisector. But assuredly, while John would have kept his laboratory door open, and have sneered at anaesthetics, Henry would have softly administered curare (Note 4), and afterwards made a charming speech on the platform concerning the sacrifices of their own feelings, which physiologists are sorrowfully compelled to make for the benefit of humanity and the exigencies of science.

Thirteen years after the marriage of Margaret of Scotland, when he was a young man of six-and-twenty, Henry the Third made a second attempt to win a Scottish queen. The fair Princess Marjory had now joined her sisters in England; and in point of age she was more suitable than Margaret. The English nobles, however, were very indignant that their King should think of espousing a younger sister of the wife of so mere an upstart as Hubert de Burgh. They grumbled bitterly, and the Count of Bretagne, brother-in-law of the murdered Arthur and the disinherited Alianora, took upon himself to dissuade the King from his purpose.

This Count of Bretagne is known as Pierre Mauclerc, or Bad-Clerk: not a flattering epithet, but historians assure us that Pierre only too thoroughly deserved the adjective, whatever his writing may have done. He had, four years before, refused his own daughter to King Henry, preferring to marry her to a son of the King of France. The Count had undertaken no difficult task, for an easier could not be than to persuade or dissuade Henry the Third in respect of any mortal thing. He passed his life in acting on the advice in turn of every person who had last spoken to him. So he gave up Marjory of Scotland.

Three years more had elapsed since that time, during which Marjory, very sore at her rejection, had withdrawn to the Court of King Alexander her brother. In the spring of 1234 she returned to her eldest sister, who generally resided either in her husband’s Town-house at Whitehall,—it was probably near Scotland Yard—or at the Castle of Bury Saint Edmund’s. She was just then at the latter. Earl Hubert himself was but rarely at home in either place, being constantly occupied elsewhere by official duties, and not unfrequently, through some adverse turn of King Henry’s capricious favour, detained somewhere in prison.

“And how long hast thou nestled in this sweet new bower, my bird?” said Marjory caressingly to her niece.

“To-day, Aunt Marjory! It is a birthday present from my Lord and father. Is it not pretty? Only look at the walls, and the windows, and my beautiful velvet settle. Now, did you ever see any thing so charming?”

Marjory glanced at her sister, and they exchanged smiles.

“Well, I cannot quite say No to that question, Magot. (Note 5.) But lead me round this wonderful chamber, and show me all its beauties.”

The wonderful chamber in question was not very spacious, being about sixteen feet in length by twelve in width. It had a wide fireplace at one end—there was no fire, for the spring was just passing into summer—and two arched windows on one of its longer sides. The fireplace was filled with a grotto-like erection of fir-cones, moss, and rosemary: the windows, as Margaret triumphantly pointed out, were of that rare and precious material, glass. Three doors led into other rooms. One, opposite the fireplace, gave access to a small private oratory; two others, opposite the windows, communicated respectively with the wardrobe and the ante-chamber. These four rooms together, with the narrow spiral staircase which led to them, occupied the whole floor of one of the square towers of the Castle. The walls of the bower were painted green, relieved by golden stars; and on every wall-space between the doors and windows was a painted “history”—namely, a medallion of some Biblical, historical, or legendary subject. The subjects in this room had evidently been chosen with reference to the tastes of a girl. They were,—the Virgin and Child; the legend of Saint Margaret; the Wheel of Fortune; Saint Agnes, with her lamb; a fountain with doves perched upon the edge; and Saint Martin dividing his cloak with the beggar. The window-shutters were of fir-wood, bound with iron. Meagre indeed we should think the furniture, but it was sumptuous for the date. A tent-bed, hung with green curtains, stood between the two doors. A green velvet settle stretched across the window side of the room. By the fireplace was a leaf-table; round the walls were wooden brackets, with iron sockets for the reception of torches; and at the foot of the bed, which stood with its side to the wall, was a fine chest of carved ebony. There were only three pieces of movable furniture, two footstools, and a curule chair, also of ebony, with a green velvet cushion. As nobody could sit in the last who had not had a king and queen for his or her parents, it may be supposed that more than one was not likely to be often wanted.

The Countess of Kent, as the elder sister, took the curule chair, while her sister Marjory, when the inspection was finished, sat down on the velvet settle. Margaret drew a footstool to her aunt’s side, and took up her position there, resting her head caressingly on Marjory’s knee.

“Three whole years, Aunt Marjory, that you have not been near us! What could make you stay away so long?”

“There were reasons, Magot.”

The two Princesses exchanged smiles again, but there was some amusement in that of the Countess, while the expression of her sister was rather sad.

Margaret looked from one to the other, as if she would have liked to understand what they meant.

“Don’t trouble that little head,” said her mother, with a laugh. “Thy time will come soon enough. Thou art too short to be told state secrets.”

“I shall be as tall as you some day, Lady,” responded Margaret archly.

“And then,” said Marjory, stroking the girl’s hair, “thou wilt wish thyself back again, little Magot.”

“Nay!—under your good leave, fair Aunt, never!”

“Ah, we know better, don’t we, Madge?” asked the Countess, laughing. “Well, I will leave you two maidens together. There is the month’s wash to be seen to, and if I am not there, that Alditha is as likely to put the linen in the chests without a sprig of rosemary, as she is to look in the mirror every time she passes it. We shall meet at supper. Adieu!”

And the Countess departed, on housekeeping thoughts intent. For a few minutes the two girls—for the aunt was only about twelve years the senior—sat silent, Margaret having drawn her aunt’s hand down and rested her cheek upon it. They were very fond of one another: and being so near in age, they had been brought up so much like sisters, that except in one or two items they treated each other as such, and did not assume the respective authority and reverence usual between such relations at that time. Beyond the employment of the deferential you by Margaret, and the familiar thou by Marjory, they chatted to each other as any other girls might have done. But just then, for a few minutes, neither spoke.

“Well, Magot!” said Marjory, breaking the silence at last, “have we nought to say to each other? Thou art forgetting, I think, that I want a full account of all these three years since I came to see thee before. They have not been empty of events, I know.”

Margaret’s answer was a groan.

“Empty!” she said. “Fair Aunt, I would they had been, rather than full of such events as they were. Father Nicholas saith that the old Romans—or Greeks, I don’t know which—used to say the man was happy who had no history. I am sure we should have been happier, lately, if we had not had any.”

“‘Don’t know which!’ What a heedless Magot!”

“Why, fair Aunt, surely you don’t expect people to recollect lessons. Did you ever remember yours?”

Marjory laughed. “Sufficiently so, I hope, to know the difference between Greeks and Romans. But, however,—for the last three years. Tell me all about them.”

“Am I to begin with the Flood, like a professional chronicler?”

“Well, no. I think the Conquest would be soon enough.”

“Delicious Aunt Marjory! How many weary centuries you excuse me!”

“How many, Magot?”

“Oh, please don’t! How can I possibly tell? If you really want to know, I will send for Father Nicholas.”

Marjory laughed, and kissed the lively face turned up to her.

“Idle Magot! Well, go on.”

“I don’t think I am idle, fair Aunt. But I do detest learning dates.—Well, now,—was it in April you left us? I know it was very soon after my Lady of Cornwall was married, but I do not remember exactly what month.”

“It was in May,” said Marjory, shortly.

“May, was it? Oh, I know! It was the eve of Saint Helen’s Day. Well, things went on right enough, till my Lord of Canterbury took it into his head that my Lord and father had no business to detain Tunbridge Castle,—it all began with that. It was about July, I think.”

“I thought Tunbridge Castle belonged to my Lord of Gloucester. What had either to do with it?”

“O Aunt Marjory! Have you forgotten that my young Lord of Gloucester is in ward to my Lord and father? The Lord King gave him first to my Lord the Bishop of Winchester, when his father died; and then, about a year after, he took him away from the Bishop, and gave him to my fair father. Don’t you remember him?—such a pretty boy! I think you knew all about it at the time.”

“Very likely I did, Magot. One forgets things, sometimes.”

And Margaret, looking up into the fair face, saw, and did not understand, the hidden pain behind the smile.

“So my Lord of Canterbury complained of my fair father to the Lord King. (I wonder he could not attend to his own business.) But the Lord King said that as my Lord of Gloucester held in chief of the Crown, all vacant trusts were his, to give as it pleased him. And then—Aunt Marjory, do you like priests?”

“Magot, what a question!”

“But do you?”

“All priests are not alike, my dear child. They are like other people—some good, and some bad.”

“But surely all priests ought to be good.”

“Art thou always what thou oughtest to be, Magot?”

Margaret’s answer was a sudden spring from the stool and a fervent hug of Marjory.

“Aunt Marjory,” she said, when she had sat down again, “I just hate that Bishop of Winchester.” (Peter de Rievaulx, always one of the two chief enemies of Margaret’s father.)

“Shocking, Magot!”

“Oh yes, of course it is extremely wicked. But I do.”

“I wish he were here, to set thee a penance for such a naughty speech. However, go on with thy story.”

“Well, what do you think, fair Aunt, that my Lord’s Grace of Canterbury (Richard Grant, consecrated in 1229) did? He actually excommunicated all intruders on the lands of his jurisdiction, and all who should hold communication with them, the King only excepted; and away he went to Rome, to lay the matter before the holy Father. Of course he would tell his tale from his own point of view.”

“The Archbishop went to Rome!”

“Indeed he did, Aunt Marjory. My fair father was very indignant. ‘That the head of the English Church could not stand by himself, but must seek the approbation of a foreign Bishop!’ That was what he said, and I think my fair mother agreed with him.”

Perhaps in this nineteenth century we scarcely realise the gallant fight made by the Church of England to retain her independence of Rome. It did not begin at the Reformation, as people are apt to suppose. It was as old as the Church herself, and she was as old as the Apostles. Some of her clergy were perpetually trying to force and to rivet the chains of Rome upon her: but the body of the laity, who are really the Church, resisted this attempt almost to the death. There was a perpetual struggle, greater or smaller according to circumstances, between the King of England and the Papacy, Pope after Pope endeavoured to fill English sees and benefices with Italian priests: King after King braved his wrath by refusing to confirm his appointments. Apostle, they were ready to allow the Pope to be: sovereign or legislator, never. Doctrine they would accept at his hands; but he should not rule over their secular or ecclesiastical liberties. The quarrel between Henry the Second and Becket was entirely on this point. No wonder that Rome canonised the man who thus exalted her. The Kings who stood out most firmly for the liberties of England were Henry the Second, John, Edward the First and Second, and Richard the Second. This partly explains the reason why history (of which monks were mainly the authors) has so little good to say of any of them, Edward the First only excepted. It is not easy to say why the exception was made, unless it were because he was too firmly rooted in popular admiration, and perhaps a little too munificent to the monastic Orders, for much evil to be discreetly said of him. Coeur-de-Lion was a Gallio who cared for none of those things: Henry the Third played into the hands of the Pope to-day, and of the Anglican Church to-morrow. Edward the Third held the balance as nearly even as possible. The struggle revived faintly during the reign of Henry the Sixth, but the Wars of the Roses turned men’s minds to home affairs, and Henry the Seventh was the obedient servant of His Holiness. So the battle went on, till it culminated in the Reformation. Those who have never entered into this question, and who assume that all Englishmen were “Papists” until 1530, have no idea how gallantly the Church fought for her independent life, and how often she flung from off her the iron grasp of the oppressor. It was not probable that a Princess whose fathers had followed the rule of Columba, and lay buried in Protestant Iona, should have any Roman tendencies on this question. Marjory was as warm as any one could have wished her.

“Well, then,” Margaret went on, “that horrid Bishop of Winchester—”

“Oh, fie!” said her aunt.

”—Came back to England in August. Aunt Marjory, it is no use,—he is horrid, and I hate him! He hates my fair father. Do you expect me to love him?”

“Well done, Magot!” said another voice. “When I want a lawyer to plead my cause, I will send for thee.—Christ save you, fair Sister! I heard you were here, with this piece of enthusiasm.”

Both the girls rose to greet the Earl, Margaret courtesying low as beseemed a daughter.

It was very evident that, so far as outside appearance went, Margaret was “only the child of her mother.” Earl Hubert was scarcely so tall as his wife, and he had a bronzed, swarthy complexion, with dark hair. Though short, he was strongly-built and well-proportioned. His eyes were dark, small, but quick and exceedingly bright. He had, when needful, a ready, eloquent tongue and a very pleasant smile. Yet eloquent as undoubtedly he could be, he was not usually a man of many words; and capable as he was of very deep and lasting affection, he was not demonstrative.

The soft, caressing manners of the Princess Margaret were not in her husband’s line at all. He was given to calling a spade a spade whenever he had occasion to mention the article: and if she preferred to allude to it as “an agricultural implement for the trituration of the soil,” he was disposed to laugh good-humouredly at the epithet, though he dearly loved the silver voice which used it.

A thoroughly representative man of his time was Hubert de Burgh, Earl of Kent; and he was one of those persons who leave a deep mark upon their age. He was a purely self-made man. He had no pedigree: indeed, we do not know with absolute certainty who was his father, though modern genealogists have amused themselves by making a pedigree for him, to which there is no real evidence that he had the least claim. Yet of his wives—for he was four times married—the first was an heiress, the second a baron’s widow, the third a countess in her own right and a divorced queen, and the last a princess. His public life had begun by his conducting a negotiation to the satisfaction of Coeur-de-Lion, in the first year of his reign, 1189, when in all probability Hubert was little over twenty years of age. From that moment he rose rapidly. Merely to enumerate all the titles he bore would almost take a page. He was by turns a very rich man and a very poor one, according as his royal and capricious master made or revoked his grants.

The religious character of Hubert is not a matter of speculation, but of certainty. It was—what his contemporaries considered elevated piety—a most singular mixture of the barest and basest superstition with some very strong plain common-sense. The superstition was of the style set forth in the famous Spanish drama entitled “The Devotion of the Cross”—the true Roman type of piety, though to Protestant minds of the nineteenth century it seems almost inconceivable. The hero of this play, who is represented as tinctured with nearly every crime which humanity can commit, has a miracle performed in his favour, and goes comfortably to Heaven after it, on account of his devotion to the cross. The innocent reader must not suspect the least connection between this devotion and the atonement wrought upon the cross. It simply means, that whenever Eusebio sees the shape of a cross—in the hilt of his sword, the pattern of a woman’s dress, two sticks thrown upon one another,—he stops in the midst of whatever sin he may be committing, and in some form, by word or gesture, expresses his “devotion.”

Of this type was Hubert’s religion. His notion of spirituality was to grasp the pix with one hand, and to hold the crucifix in the other. He kept a nicely-balanced account at the Bank of Heaven, in which—this is historical—the heaviest deposit was the fact that he had many years before saved a large crucifix from the flames. The idea that this action was not most pious and meritorious would have been in Hubert’s eyes rank heresy. Yet he might have known better. The Psalter lay open to him, which, had he been acquainted with no other syllable of revelation, should alone have given him a very different conception of spiritual religion.

Athwart these singular notions of excellence, Hubert’s good common-sense was perpetually gleaming, like the lightning across a dark moor. Whatever else this man was, he was no slave of Rome. It was supported by him, and probably at his instigation, that King John had sent his lofty message to the Pope, that—

“No Italian priest

Should tithe or toll in his dominions.”

It was when the administration lay in his hands that Parliament refused to comply with the demands of the Pope till it was seen what other kingdoms would do: and no Papal aggressions were successful in England so long as Hubert was in power. To reverse the famous phrase of Lord Denbigh, Hubert was “a Catholic, if you please; but an Englishman first.”

Truer Englishman, at once loyalist and patriot, never man was than he—well described by one of the English people as “that most faithful and noble Hubert, who so often saved England from the ravages of the foreigner, and restored England to herself.” He stood by the Throne, bearing aloft the banner of England, in three especially dark and perilous days, when no man stood there but himself. To him alone, under Providence, we owe it that England did not become a vassal province of France. Most amply was his fidelity put to the test; most unspotted it emerged from the ordeal: most heavy was the debt of gratitude owed alike by England and her King.

That debt was paid, in a sense, to the uttermost farthing. In what manner of coin it was discharged, we are about to see.

Note 1. Patent Roll, 4 Henry Third; dated York, June 15 1220.

Note 2. “In the octave of Holy Trinity” (May 25—June 1), at Alnwick.—Roberts’ Extracts from Fines Rolls, 1225.

Note 3. This terrible fact has been strangely ignored by many modern historians.—Rot. Exit., Michs., 25-6 Henry Third.

Note 4. A drug which deadens the sensibilities—of the vivisector—by rendering the victim incapable of sound or motion, but not affecting the nerves of sensation in the least.

Note 5. This was in 1234, when our story begins, the English diminutive of Margaret, and was doubtless derived from the French Margot.

Note 6. Any reader who is inclined to doubt this is requested to consult Acts fifteen, 4, 22. It is unquestionably the teaching of the New Testament. The clergy form part of the Church merely as individual Christians.

Chapter Two.

“What do you lack?”

“If pestilence stalk through the land, ye say, This is God’s doing. Is it not also His doing, when an aphis creepeth on a rosebud?”

Martin F. Tupper.

Earl Hubert was far too busy a man to waste his time in lounging on velvet settles and exchanging sallies of wit with the ladies of his household. He had done little more than give a cordial welcome to Marjory, and pat Margaret on the head, when he again disappeared, to be seen no more until supper-time.

“Well, Magot,” said Marjory, sitting down in the chair, while Margaret as before accommodated herself with a footstool at her feet, “let us get on with thy story. I want to know all about that affair two years ago. Thy fair father looks wonderfully well, methinks, considering all that he has gone through.”

“Does he not? O Aunt Marjory, I scarcely know how I am to tell you about that. It was dreadful,—dreadful!”

And the tears stood in big drops on Margaret’s eyelashes.

“Well, I will try,” she said, with a deep sigh, as Marjory stroked her hair. “In the first place, the year ended all very well. My fair father had been created Justiciary of Ireland for life, and Constable of the Tower, and various favours had been granted to him. That he should be on the brink of trouble—and such trouble!—was the very last thing thought of by any one of us. And then that Bishop of Winchester came back, and before a soul knew anything about it, he was high in the Lord King’s favour, and on the twenty-ninth of July—(I am not likely to forget that date!)—the blow fell.”

“He was dismissed, then, was he not, from all his offices, without a word of warning?”

“Dismissed and degraded, without a shadow of it!—and a string of the most cruel, wicked accusations brought against him—things that he never did nor dreamed of doing—Aunt Marjory, it makes my blood boil, only to remember them! I am not going to tell you all: there was one too horrid to mention.”

“I know, my maiden.” Marjory interposed rather hastily. She had heard already of King Henry’s delicate and affectionate assault upon the fair name of Margaret’s mother, and she did not wish for a repetition of it.

“But beyond that, of what do you think he was accused?”

“I have not heard the other articles, Magot.”

“Then I will tell you. First, of preventing the Lord King’s marriage with the Duke of Austria’s daughter, by telling the Duke that the King was lame, and blind, and deaf, and a leper, and—”

“Gently, Magot, gently!” said Marjory, laughing.

“I am not making a syllable of it, fair Aunt!—And that he was a wicked, treacherous man, not worthy of the love or alliance of any noble lady. Pure foy!—but I know what I should say, if I said just what I think.”

“It is sometimes quite as well not to do that, Magot.”

“Ha! Perhaps it is, when one may get into prison by it. It is a comfort one can always think. Neither Pope nor King can stop that.”

“Magot, my dear child!”

“Oh yes, I know! You think I am horribly imprudent, Aunt Marjory. But nobody hears me except you and Eva de Braose—she is the only person in the wardrobe, and there is no one in the ante-chamber. And as I have heard her say more than I did just now, I don’t suppose there is much harm done.—Then, secondly,—they charged my fair father with stealing—only think, stealing!—a magical gem from the royal treasury which made the wearer victorious in battle, and sending it to the Prince of Wales.” (Llywelyn the Great, with whom King Henry was at war.)

“Why should they suppose he would do that?”

“Pure foy, Aunt Marjory, don’t ask me! Then, thirdly, they said it was—”

Margaret sprang from her footstool suddenly, and disappeared for a second through the door of the wardrobe. Marjory heard her say—

“Eva! I had completely forgotten, till this minute, to tell Marie that my Lady and mother desired her to finish that piece of tapestry to-night, if she can. Do go and look for her, and let her know, or she will not have time.”

A slight rustle as of some one leaving the room was audible, and then Margaret dashed back to her footstool, as if she too had not a minute to lose.

“You know, Aunt Marjory, I could not tell you the next thing with Eva listening. They said that it was by traitorous letters from my fair father that the Prince of Wales had caused Sir William de Braose to be hung.”

“Eva’s father, thou meanest?”

“Yes. Then they accused him of administering poison to my Lord of Salisbury, of sending my cousin Sir Raymond to try and force the Lady of Salisbury into marrying him while her lord was beyond seas, of poisoning my Lord of Pembroke, Sir Fulk de Breaut, and my sometime Lord of Canterbury’s Grace. He might have spent his life in poisoning every body! Then, lastly, they said he had obtained favour of the Lord King by help of the black art.”

Marjory smiled contemptuously. It was not because she was more free from superstition than other people, but simply because she knew full well that the only sorcery necessary to be used towards Henry the Third was “the sorcery of a strong mind over a weak one.” (Note 1.)

“It was rather unfortunate,” she said, “that my good Lord of Salisbury (whom God rest!) was seized with his last illness the very day after he had supped at my fair brother’s table.”

“Aunt Marjory!” cried her indignant niece. “Why, it is not a month since I was taken ill in the night, after I had supped likewise. Do you suppose he poisoned me?”

“It is quite possible that walnuts might have something to do with it, Magot. But did I say he poisoned any one?”

“Now, Aunt Marjory, you are laughing at me, because you know I like them. But don’t you think it is absurd—the way in which people insist on fancying themselves poisoned whenever they are ill? It looks as if every human being were a monster of wickedness!”

“What would Father Warner say they are, Magot?”

“Oh, he would say it was perfectly true: and he would be right—so far as my Lord of Winchester and a few more are concerned.—Well, Eva, hast thou found Marie?”

“Yes, my dear. She is with the Lady, and she is busy with the tapestry.”

“Oh, that is right! I am sorry I forgot.”

“And the Lady bade me tell thee, mignonne, that she is coming to thy bower shortly, with a pedlar who is waiting in the court, to choose stuffs for thy Whitsuntide robes.”

“A pedlar! Delightful! Aunt Marjory, I am sure you want something?”

Marjory laughed. “I want thy tale finished, Magot, before the pedlar comes.”

“Too long, my dear Aunt Marjory, unless the pedlar takes all summer to mount the stairs. But you know my Lord and father fled into sanctuary at Merton Abbey, and refused to leave it unless the Lord King would pledge his royal word for his safety. I don’t think I should have thought it made much difference. (I wonder if that pedlar has any silversmiths’ work.) The Lord King did not pledge his word, but he ordered the Lord Mayor and the citizens to fetch my fair father—only think of that, Aunt Marjory!—dead or alive. Some of the nobler citizens appealed to the Bishop, who was everything with the King just then: but instead of interceding for my fair father, as they asked, he merely confirmed the order. So twenty thousand citizens marched on the Abbey; and when my fair father knew that, he fled to the high altar, and embraced the holy cross with one hand, holding the blessed pix in the other.”

“Was our Lord in the pix?” inquired Marjory—meaning, of course, to refer to the consecrated wafer.

“I am not sure, fair Aunt. But however, things turned out better than seemed likely: for not only the Bishop of Chichester, but even my Lord of Chester—my fair father’s great enemy—interceded with the Lord King in his behalf. We heard that my Lord of Chester spoke very plainly to him, and told him not only that he would find it easier to draw a crowd together than to get rid of it again, but also that his fickleness would scandalise the world.”

“And the Lord King allowed him to say that?”

“Yes, and it had a great effect upon him. I think people who are fickle don’t like others to see it—don’t you? Do you think that pedlar will have any sendal (a silk stuff of extremely fine quality) of India?”

“Thine eyes and half thy tongue are in the pedlar’s pack, Magot. I cannot tell thee. But just let me know how it ended, and thy fair father was set free.”

“Oh, it did not end for ever so long! My Lord’s Grace of Dublin got leave for him to come home and see my fair mother and me; and after that, when he had gone into Essex, the King sent after him again, and Sir Godfrey de Craucumbe took him away to the Tower. They sent for a smith to put him in fetters, but the man would not do it when he heard who was to wear the fetters. He said he would rather die than be the man to put chains on ‘that most faithful and noble Hubert, who so often saved England from the ravages of foreigners, and restored England to herself.’ Aunt Marjory, I think he was a grand fellow! I would have kissed him if I had been there.”

As the kiss was at that time the common form of greeting between men and women, for a lady to offer a kiss to a man as a token that she approved his words or actions, was not then considered more demonstrative than it would be to shake hands now. It was, in fact, not an unusual occurrence.

“And my fair father told us,” pursued Margaret, “when he heard what the smith said, he could not help thinking of those words of our Lord, when He thanked God that His mission had been hidden from the wise, but revealed to the ignorant. ‘For,’ our Lord said, ‘to Thee, my God, do I commit my cause; for mine enemies have risen against me.’” (Note 2.)

“And they took him to the Tower of London?”

“Yes, but the Bishop of London was very angry at the violation of sanctuary, and insisted that my fair father should be sent back. He threatened the King with excommunication, and of course that frightened him. He sent him back to the church whence he was taken, but commanded the Sheriff of Essex to surround the church, so that he should neither escape nor obtain food. But my fair father’s true friend, my good old Lord of Dublin—(you were right, Aunt Marjory; all priests are not alike)—interposed, and begged the Lord King to do to him what he had thought to do to my Lord and father. The Lord King then offered the choice of three things:—my Lord and father must either abjure the kingdom for ever, or he must be perpetually imprisoned, or he must openly confess himself a traitor.”

“A fair choice, surely!”

“Horrid, wasn’t it?”

“He chose banishment, did he not?”

“He said, if the King willed it, he was content to go out of England for a time,—not for ever: but a traitor he would never confess himself, for he had never been one.”

“The words of a true man!” said Marjory.

“Splendid!—and then (Eva!—is that pedlar never coming up?) the Lord King found out that my fair father had laid up treasure in the Temple, and he actually accused him of taking it fraudulently from the royal treasury, and summoned him to resign it. My fair father replied (I shouldn’t have done!) that he and all he had were at the King’s pleasure, and sent an order to the Master of the Temple accordingly. Then—O Aunt Marjory, it is too long a tale to tell!—and I want that pedlar. But I do think it was a shame, after all that, for the Lord King to profess to compassionate my Lord and father, and to say that he had been faithful to our Lord King John of happy memory, (Note 3) and also to our Lord King Richard (whom God pardon!); therefore, notwithstanding the ill-usage of himself, and the harm he had done the kingdom, he would rather pardon my fair father than execute him. ‘For,’ he said, ‘I would rather be accounted a remiss king than a man of blood.’”

“Well, that does not sound bad, Magot.”

“Oh no! Words are very nice things, Aunt Marjory. And our Lord King Henry can string them very prettily together. I have no patience—I say, Eva! Do go and peep into the court and see what is becoming of that snail of a pedlar!”

“He is in the hall, eating and drinking, Margaret.”

“Well, I am sure he has had as much as is good for him!—So then, Aunt Marjory, my fair father was sent to Devizes: and many nobles became sureties for him,—my Lord of Cornwall, the King’s brother, among others. And while he was there, he heard of the death of his great enemy, my Lord of Chester. Then he said, ‘The Lord be merciful to him: he was my man by his own doing, and yet he never did me good where he could work me harm.’ And he set himself before the holy cross, and sang over the whole Psalter for my Lord of Chester. Well, after that,—I cannot go into all the ups and downs of the matter,—but after a while, by the help of some of the garrison, my fair father contrived to escape from Devizes, and joined the Prince of Wales. That was last November; and he stayed in Wales until the King’s journey to Gloucester. Last March the Lord King came here to the Abbey, and he granted several manors to my fair mother: and she took the opportunity to plead for my Lord and father. So when the Lord King went to Gloucester, he was met by my Lord’s Grace of Canterbury, who had been to treat with the Prince of Wales, and by his advice all those who had been outlawed, and had sought refuge in Wales, were to be pardoned and received to favour. One of them, of course, was my fair father. So they met the Lord King at Gloucester, and he took them to his mercy. My Lord and father said the Lord King looked calmly on them, and gave them the kiss of peace. But my fair father himself was so much struck by the manner in which our Lord had repaid him his good deeds, that, as his varlet Adam told us, he clasped his hands, and looked up to Heaven, and he said,—‘O Jesus, crucified Saviour, I once when sleeping saw Thee on the cross, pierced with bloody wounds, and on the following day, according to Thy warning, I spared Thy image and worshipped it: and now Thou hast, in Thy favour, repaid me for so doing, in a lucky moment.’”

It did not strike either Marjory or Margaret, as perhaps it may the reader, that this speech presented a very curious medley of devotion, thankfulness, barefaced idolatry, and belief in dreams and lucky moments. To their minds the mixture was perfectly natural. So much so, that Marjory’s response was—

“Doubtless it was so, Magot. It is always very unlucky to neglect a dream.”

At this juncture Eva de Braose presented herself. She was one of three maidens who were alike—as was then customary—wards of the Earl, and waiting-maids of the Countess. They were all young ladies of high birth and good fortune, orphan heirs or co-heirs, whose usual lot it was, throughout the Middle Ages, to be given in wardship to some nobleman, and educated with his daughters. Eva de Braose, Marie de Lusignan, and Doucebelle de Vaux, (Eva and Marie (but not Doucebelle) are historical persons,) were therefore the social equals and constant companions of Margaret. Eva was a rather pretty, fair-haired girl, about two years older than our heroine.

“The pedlar is coming now, Margaret.”

“Ha, jolife!” cried Margaret. (Note 4.) “Is my Lady and mother coming?”

“Yes, and both Hawise and Marie.”

Hawise de Lanvalay was the young wife of Margaret’s eldest brother. Earl Hubert’s family consisted, beside his daughter, of two sons of his first marriage, John and Hubert, who were respectively about eighteen and fifteen years older than their sister.

The Countess entered in a moment, bringing with her the young Lady Hawise,—a quiet-looking, dark-eyed girl of some eighteen years; and Marie, the little Countess of Eu, who was only a child of eleven. After them came Levina, one of the Countess’s dressers, and two sturdy varlets, carrying the pedlar’s heavy pack between them. The pedlar himself followed in the rear. He was a very respectable-looking old man, with strongly-marked aquiline features and long white beard; and he brought with him a lithe, olive-complexioned youth of about eighteen years of age.

The varlets set down the pack on the floor, and departed. The old man unstrapped it, and opening it out with the youth’s help, proceeded to display his goods. Very rich, costly, and beautiful they were. The finest lawn of Cambray (whence comes “cambric”), and the purest sheeting of Rennes, formed a background on which were exhibited rich diapered stuffs from Damascus, crape of all colours from Cyprus, golden baudekyns from Constantinople, fine sendal from India, with satins, velvets, silks, taffetas, linen and woollen stuffs, in bewildering profusion. Over these again were laid rich furs,—sable, ermine, miniver, black fox, squirrel, marten, and lamb; and trimmings of gold and silver, gimp and beads, delicate embroidery, and heavy tinsel.

“Here, Lady, is a lovely thing in changeable sendal,” said the old man, hunting for it among his silks: “it would be charming for the fair-haired damsel—(lift off that fox fur, Cress),—blue and gold. Or here,—a striped tartaryn, which would suit the dark young lady,—orange and green. Then—(Cress, give me the silver frieze),—this, Lady, would be well for the little maid, for somewhat cooler weather. And will my Lady see the Cyprus? (Hand the pink one, Cress.) This would make up enchantingly for the damsel that was in my Lady’s chamber.”

“Where is Doucebelle?” asked the Countess, looking round. “I thought she had come. Marie, run and fetch her.—Hast thou any broidery-work of the East Country, good man?”

“One or two small things, Lady.—Cress, give me thy sister’s scarves.”

The young man unfolded a woollen wrapper, and then a lawn one inside it, and handed to his father three silken scarves, of superlatively fine texture, and covered with most exquisite embroidery. Even the Countess, accustomed as her eyes were to beautiful things, was not able to suppress an admiring ejaculation.

“This is lovely!” she said.

“Those are samples,” remarked the pedlar, with a gleam of pleasure in his eyes. “I have more, of various patterns, if my Lady would wish to see them. She has only to speak her commands.”

“Yes. But—these are all imported, I suppose?”

“All imported, such as I have shown to my Lady.”

“I presume no broideress is to be found in England, who can do such work as this?” said the Countess in a regretful tone.

“Did my Lady wish to find one?”

“I wished to have a scarf in my possession copied, with a few variations which I would order. But I fear it cannot be done—it would be almost necessary that I should see the broideress myself, to avoid mistakes; and I would fain, if it were possible, have had the work done under my own eye.”

“That might be done, perhaps. It would be costly.”

“Oh, I should not care for the cost. I want the scarf for a gift; and it is nothing to me whether I pay ten silver pennies or a hundred.”

“Would my Lady suffer her servant to see the scarf she wishes to have imitated?”

“Fetch it, Levina,” said the Countess; “thou knowest which I mean.”

Levina brought it, and the pedlar gave it very careful inspection.

“And the alterations?” he asked.

“I would have a row of silver harebells and green ferns, touched with gold, as an outer border,” explained the Countess: “and instead of those ornaments in the inner part, I would have golden scrolls, worked with the words ‘Dieu et mon droit’ in scarlet.”

The pedlar shook his head. “The golden scrolls with the words can be done, without difficulty. But I must in all humility represent to my Lady that the flowers and leaves she desires cannot.”

“Why?” asked the Countess in a surprised tone.

“Not in this work,” answered the pedlar. “In this style of embroidery”—and he took another scarf from his pack—“it could be wrought: but not in the other.”

“But that is not to be compared with the other!”

“My Lady has well said,” returned the pedlar with a smile.

“But I do not understand where the difficulty lies?” said the Countess, evidently disappointed.

“Let my Lady pardon her servant. We have in our company—nay, there is in all England—one broideress only, who can work in this style. And I dare not make such an engagement on her behalf.”

“Still I cannot understand for what reason?”

“Lady, these flowers, leaves, heads, and such representations of created things, are the work of Christian hands. That broidery which my Lady desires is not so.”

“But why cannot Christians work this broidery?”

“Ha! They do not. My Lady’s servant cannot speak further.”

“Then what is she who alone can do this work? What eyes and fingers she must have!”

“She is my daughter,” answered the pedlar, rather proudly.

“But I am sure the woman who can broider like this, is clever enough to make a row of harebells and ferns!”

“Clever enough,—oh yes! But—she could not do it.”

“‘Clever enough,’ but ‘could not do it’—old man, I cannot understand thee.”

“Lady, she would account it sin to imitate created things.”

The Countess looked up with undisguised amazement.

“Why?”

“Because the Holy One has forbidden us to make to ourselves any likeness of that which is in heaven above, or in the earth beneath.”

“But I would pay her any sum she asked.”

“If my Lady can buy Christian consciences with gold, not so a daughter of Israel.”

The old man spoke proudly now, and his head was uplifted in a very different style from his previous subservient manner. His son’s lip was curled, and his black eyes were flashing fire.

“Well! I do not understand it,” answered the Countess, looking as much annoyed as the sweet Princess Margaret knew how to look. “I should have thought thy daughter might have put her fancies aside; for what harm can there be in broidering flowers? However, if she will not, she will not. She must work me a border of some other pattern, for I want the scarf wider.”

“That she can do, as my Lady may command.” The old Jew was once more the obsequious tradesman, laying himself out to please a profitable customer.

“What will be the cost, if the scarf be three ells in length, and—let me see—about half an ell broad?”

“It could not be done under fifteen gold pennies, my Lady.”

“That is costly! Well, never mind. If people want to make rich gifts, they must pay for them. But could I have it by Whitsuntide?—that is, a few days earlier, so as to make the gift then.”

The pedlar reflected for a moment.

“Let my Lady pardon her servant if he cannot give that answer at this moment. If my daughter have no work promised, so that she can give her time entirely to this, it can be done without fail. But it is some days since my Lady’s servant saw her, and she may have made some engagement since.”

“I am the better pleased thou art not too ready to promise,” said the Countess, smiling. “But what about the work being done under my eye? I will lodge thy daughter, and feed her, and give her a gold penny extra for it.”

The old Jew looked very grave.

“Let my Lady not be angered with the lowest of her servants! But—we are of another religion.”

“Art thou afraid of my converting her?” asked the Countess, in an amused tone.

“Under my Lady’s pardon—no!” said the old man, proudly. “I can trust my daughter. And if my noble Lady will make three promises on whatsoever she holds most holy, the girl shall come.”

“She should be worth having, when she is so hard to get at!” responded the Countess, laughing, as she took from her bosom a beautiful little silver crucifix, suspended by a chain of the same material from her neck, “Now then, old man, what am I to swear?”

“First, that my daughter shall not be required to work in any manner on the holy Sabbath,—namely, as my Lady will understand it, from sunset on Friday until the same hour on Saturday.”

“That I expected. I know Jews are very precise about their Sabbaths. Very well,—so that the scarf be finished by Wednesday before Whitsuntide, that I swear.”

“Secondly, by my Lady’s leave, that she shall not be compelled to eat any thing contrary to our law.”

“I have no desire to compel her. But what will she eat? I must know that I can give her something.”

“Any kind of vegetables, bread, milk, and eggs.”

“Lenten fare. Very well. I swear it.”

“Lastly, that my Lady will appoint her a place in her own apartments, or in those of the damsel her daughter, and that she may never stir out of that tower while she remains in the Castle.”

“Poor young prisoner! Good. If thou art so anxious to consign thy child to hard durance, I will swear to keep her in it.”

“May my Lady’s servant ask where she will be?”

The Countess laughed merrily. “This priceless treasure of thine! She might be a king’s daughter. I will put her in my daughter’s ante-chamber, just behind thee.”

The pedlar walked into the ante-chamber, and inspected it carefully, to the great amusement of the ladies.

“It is enough,” he said, returning. “Lady, my child is not a king’s daughter, but she is the dearest treasure of her old father’s heart.”

The old man had well spoken, for his words, Jew as he was—a creature, according to the views of that day, born to be despised and ill-treated—went straight to the tender heart of the Princess Margaret.

“’Tis but nature,” she said softly. “Have no fear, old man: I will take care of thy treasure. What is her name?”

“Will my Lady suffer her grateful servant to kiss her robe? I am Abraham of Norwich, and my daughter’s name is Belasez.”

Singular indeed were the Jewish names common at this time, beyond a very few Biblical ones, of which the chief were Abraham, Aaron, and Moses—the last usually corrupted to Moss or Mossy. They were, for men,—Delecresse (“Dieu le croisse”), Ursel, Leo, Hamon, Kokorell, Emendant, and Bonamy:—for women,—Belasez (“Belle assez”), Floria, Licorice (these three were the most frequent), Esterote, Cuntessa, Belia, Anegay, Rosia, Genta, and Pucella. They used no surnames beyond the name of the town in which they lived.

“And what years has she?” asked the Countess.

“Seventeen, if it please my Lady.”

“Good. I hope she will be clever and tractable.—Now, Madge, what do you want?”

The Princess Marjory wanted a silver necklace, a piece of green silk for a state robe, and some unshorn wool for an every-day dress, beside lamb’s fur and buttons for trimming. Buttons were fashionable ornaments in those days, and it was not unusual to spend six or eight dozen upon one dress.

“Now, Magot, let me see for thee,” said her mother. “Thy two woollen gowns must be shorn for winter, and thou wilt want a velvet one for gala days: but there is time for that by and bye. What thou needest now is a blue Cyprus (crape) robe for thy best summer one, two garments of coloured thread for common, a silk hood, one or two lawn wimples (Note 5), and a pair of corsets. (Note 6.) Thou mayest have a new armilaus (Note 7) if thou wilt.”

“And may I not have a new mantle?” was Margaret’s answer, in a coaxing tone.

“A new mantle? Thou unconscionable Magot! Somebody will be ruined before thy wants are supplied.”

“And a red velvet gipcière, Lady? And I did so want a veil of sendal of Inde!”

“Worse and worse! Come, old man, prithee, measure off the Cyprus, and look out the wimples quickly, or this damsel of mine will leave me never a farthing in my pocket.”

“And Eva wants a new gown,” suggested Margaret.

“Oh yes!” said the Countess, laughing. “And so does Marie, and so does Doucebelle, I suppose,—and Hawise, I have no doubt. I shall be completely ruined among you!”

“But my Lady will give me the sendal of Inde? I will try to do without the gipcière.”

A gipcière was a velvet bag dependent from the waist, which served as a purse or pocket, as occasion required.

“Magot, hast thou no conscience? Come, then, old man, let this unreasonable damsel see thy gipcières. And if she must have some sendal of Inde, well,—fate is inevitable. What was the other thing, Magot? A new mantle? Oh, shocking! I can’t afford that. What is the price of thy black cloth, old man?”

It was easy to see that Margaret would have all she chose to ask, without much pressure. Some linen dresses were also purchased for the young wards of the Earl,—a blue fillet for Eva, and a new barm-cloth (apron) for Marie; and the Countess having chosen some sendal and lawn for her own use, the purchases were at last completed.

The old Jew, helped by Delecresse, repacked his wares with such care as their delicacy and costliness required, and the Countess desired Levina to summon the varlets to bear the heavy burden down to the gate.

“Peace wait on my Lady!” said the pedlar, bowing low as he took leave. “If it please the Holy One, my Belasez shall be here at my Lady’s command before a week is over.”

Note 1. This was the answer given to her judges, four hundred years later, by Leonora Galigai, when she was asked to confess what kind of magic she had employed to obtain the favour of Queen Maria de’ Medici.

Note 2. The Earl’s quotation from Scripture was extremely free, combining Matthew eleven verse 25 with the substance, but not the exact words, of several passages in the Psalms. Nor did Friar Matthew Paris know much better, since he refers to it all as “that passage in the Gospels.”

Note 3. King Henry was given to allusions of this class, to the revered memory of his excellent father.

Note 4. “Oh, delightful!” The modern schoolboy’s “How jolly” is really a corruption of this. The companion regret was “Ha, chétife!”—(“Oh, miserable!”)

Note 5. The wimple covered the neck, and was worn chiefly out of doors. Ladies from a queen to a countess wore it coming over the chin; women of less rank, beneath.

Note 6. Tight-lacing dates from about the twelfth century.

Note 7. A short cloak, worn by both sexes, ornamented with buttons.

Chapter Three.

Belasez.

“And, born of Thee, she may not always take

Earth’s accents for the oracles of God.”

Felicia Hemans.

The last word had scarcely left the pedlar’s lips, when the door of the ante-chamber was flung open, and a boy of Margaret’s age burst into the room.

He was fair-haired and bright-faced, with a slender, elegant figure, and all his motions were very agile. Beginning with—“I say, Magot!”—he stopped suddenly both tongue and feet as he caught sight of the Countess.

“Well, Sir Richard?” suggested that lady.

“I cry you mercy, Lady. I did not know you were here.”

“And if you had done—what then?”

“Why, then,” answered Richard, laughing but colouring, “I suppose I ought to have come in more quietly.”

“Ah! Did you ever read with Father Nicholas about an old man who said that the Athenians knew what was right, but the Lacedemonians did it?”

“Your pardon, Lady! I always forget what I read with Father Nicholas.”

“I should suppose so. I am afraid there is Athenian blood in your veins, Sir Richard!”

“Lady, if it stand with your pleasure, there is none but true Christian blood in my veins!” was the proud reply.

“Pure foy! If you are so proud of your blood, I fear you will disdain to do what I was about to bid you.”

“I shall never disdain to execute the commands of a fair lady.”

“My word, Sir Richard, but you are growing a courtly knight! You see that Jew boy has left his cap behind. As there are none here but damsels, I was thinking I would ask you to call him back to fetch it.”

“He shall have it—a Jew boy! I’ll take the tongs, then!”

The next minute Delecresse, who was just turning back to fetch the forgotten cap, heard a boyish voice calling to him out of a window, and looking up, saw his cap held out in the tongs.

“Here, thou cur of a Jew! What dost thou mean, to leave thy heathen stuff in the chamber of a noble damsel?”

And the cap was dropped into the courtyard, with such good aim that it first hit Delecresse on the head, and then lodged itself in the midst of a puddle.

Delecresse, without uttering a word, yet flushing red even through his dark complexion, deliberately stooped, recovered his wet cap, and placed it on his head, pressing it firmly down as if he wished to impart the moisture to his hair. Then he turned and looked fixedly at Richard, who was watching him with an amused face.

“That wasn’t a bad shot, was it?” cried the younger lad.

“Thank you,” was the answer of Delecresse. “I shall know you again!”

The affront was a boyish freak, perpetrated rather in thoughtlessness than malice: but the tone of the answer, however simple the words, manifestly breathed revenge. Richard de Clare was not an ill-natured boy. But he had been taught from his babyhood that a Jew was the scum of the earth, and that to speak contumeliously to such was so far from being wrong, that it absolutely savoured of piety. Jews had crucified Christ. To have aided one of them, or to have been over civil to him, would in a Christian have been considered as putting a slight upon his Lord. There was, therefore, some excuse for Richard, educated as he had been in this belief.

Delecresse, on the contrary, had been as carefully brought up in the opposite conviction. To him it was the Gentile who was the refuse of humanity, and it was a perpetual humiliation to be forced to cringe to, and wait upon, such contemptible creatures. Moreover, the day was coming when their positions should be reversed; and who could say how near it was at hand? Then the proud Christian noble would be the slave of the despised Jew pedlar, and—thought Delecresse, grinding his teeth—he at least would take care that the Christian slave should indulge no mistakes on that point.

To both the youths Satan was whispering, and by both he was obeyed. And each of them was positively convinced that he was serving God.

The vengeful words of Delecresse made no impression whatever on the young Earl of Gloucester. He would have laughed with scorn at the mere idea that such an insect as that could have any power to hurt him. He danced back to Margaret’s bower, where, in a few minutes, he, she, Marie, and Eva were engaged in a merry round game.

Beside the three girls who were in the care of the Countess, Earl Hubert had also three boy-wards—Richard de Clare, heir of the earldom of Gloucester; Roger de Mowbray, heir of the barony of Mowbray, now about fifteen years old; and John de Averenches (or Avranches), the son of a knight. With these six, the Earl’s two sons, his daughter, and his daughter-in-law, there was no lack of young people in the Castle, of whom Sir John de Burgh, the eldest, was only twenty-nine.

The promise made by Abraham of Norwich was faithfully kept. A week had not quite elapsed when Levina announced to the Countess that the Jew pedlar and the maiden his daughter awaited her pleasure in the court. The Countess desired her to bring them up immediately to Margaret’s bower, whither she would go herself to meet them.

Margaret and Doucebelle had just come in from a walk upon the leads—the usual way in which ladies took airings in the thirteenth century. Indeed, the  leads were the only safe and proper place for a young girl’s out-door recreation. The courtyard was always filled by the household servants and soldiers of the garrison: and the idea of taking a walk outside the precincts of the Castle, would never have occurred to anybody, unless it were to a very ignorant child indeed. There were no safe highroads, nor quiet lanes, in those days, where a maiden might wander without fear of molestation. Old ballads are full of accounts of the perils incurred by rash and self-sufficient girls who ventured alone out of doors in their innocent ignorance or imprudent bravado. The roadless wastes gave harbour to abundance of fierce small animals and deadly vipers, and to men worse than any of them.

leads were the only safe and proper place for a young girl’s out-door recreation. The courtyard was always filled by the household servants and soldiers of the garrison: and the idea of taking a walk outside the precincts of the Castle, would never have occurred to anybody, unless it were to a very ignorant child indeed. There were no safe highroads, nor quiet lanes, in those days, where a maiden might wander without fear of molestation. Old ballads are full of accounts of the perils incurred by rash and self-sufficient girls who ventured alone out of doors in their innocent ignorance or imprudent bravado. The roadless wastes gave harbour to abundance of fierce small animals and deadly vipers, and to men worse than any of them.

Old Abraham, cap in hand, bowed low before the Princess, and presented a closely-veiled, graceful figure, as the young broideress whom he had promised.

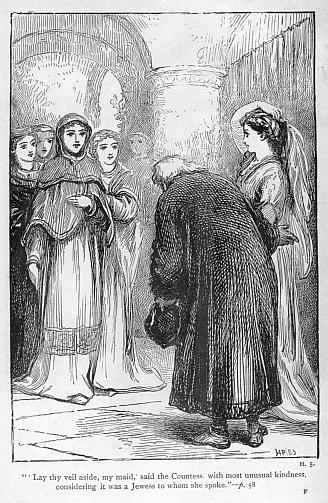

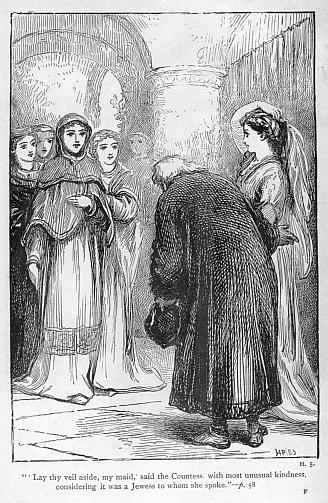

“Lay thy veil aside, my maid,” said the Countess, with most unusual kindness, considering that it was a Jewess to whom she spoke.

The maiden obeyed, and revealed to the eyes of the Princess and her damsels a face and figure of such extreme loveliness that she no longer wondered at the anxiety of her father to provide for her concealment. But the beauty of Belasez was of an entirely different type from that of the Christians around her. Her complexion was olive, her hair raven black, her eyes large and dark, now melting as if in liquid light, now brilliant and full of fire. And if Margaret looked two years beyond her real age, Belasez looked more like seven.

“Thou knowest wherefore thou art come hither?” asked the Countess, smiling complacently on the vision before her.

“To broider for my Lady,” said Belasez, in a low, clear, musical voice.

“And wilt thou obey my orders?”

“I will obey my Lady in every thing not forbidden by the holy law.”

“Well, I think we shall agree, my maid,” returned the Countess, whose private views respecting religious tolerance were something quite extraordinary for the time at which she lived. “I would not willingly coerce any person’s conscience. But as I do not know thy law, thou wilt have to tell me if I should desire thee to do some forbidden thing.”

“My Lady is very good to her handmaiden,” said Belasez.

“Margaret, take the maid into thy wardrobe for a little while, until she has dined; and after that I will show her what I require. She will be glad of rest after her journey.”

Margaret obeyed, and a motion of her mother’s hand sent Doucebelle after her. The daughter of the house sat down on the settle which stretched below the window, and Doucebelle followed her example: but Belasez remained standing.

“Come and sit here by me,” said Margaret to the young Jewess. “I want to talk to thee.”

Belasez obeyed in silence.

“Art thou very tired with thy journey?”

“Not now, damsel, I thank you. We have come but a short stage this morning.”

“Art thou fond of broidery?”

“I love everything beautiful.”

“And nothing that is not beautiful?”

“I did not say that, damsel.” Belasez’s smile showed a perfect row of snow-white teeth.

“Am I fair enough to love?” asked Margaret laughingly. She had a good deal of her mother’s easy tolerance of differences, and all her sweet affability to those beneath her.

“Ah, my damsel, true love regards the heart rather than the face, methinks. I cannot see into my damsel’s heart in one minute, but I should think it was not at all difficult to love her.”

“I want every body to love me,” said Margaret. “And I love every body.”

“If my damsel would permit me to counsel her,—love every body by all means: but do not let her want every body to love her.”

“Why not?”

“Because I fear my damsel will meet with disappointment.”

“Oh, I hate to be disappointed. Hast thou brought thine image with thee?”

To Margaret this question sounded most natural. In the first place, she could not conceive the idea of prayer without something visible to pray to: and in the second, she had been taught that all Jews and Saracens were idolaters. She was surprised to see the blood rush to Belasez’s dark cheek, and the fire flash from her eyes.

“Will my damsel allow me to ask what she means? I do not understand.”

“Wilt thou not want to say thy prayers whilst thou art here?” responded Margaret, who was at least as much puzzled as Belasez.

“Most certainly! but not to an image!”

“Oh, do you Jews sometimes pray without images?”

“Does my damsel take us for idolaters?”

“Yes, I was always told so,” said Margaret, looking astonished.

The fire died out of Belasez’s eyes. She saw that Margaret had simply made an innocent mistake from sheer ignorance of the question.

“My damsel has been misinformed. We Israelites hold all images to be wicked, and abhorrent to the holy law.”

“Then thou wilt not want to set up an idol for thyself anywhere?”

“Most assuredly not.”

“I hope I have not vexed thee,” said Margaret, ingenuously. “I did not know.”

“My damsel did not vex me, as soon as I saw that she did not know.”

“And wouldst thou not like better to be a Christian than a Jew?” demanded Margaret, who could not imagine the possibility of any feeling on Belasez’s part regarding her nationality except those of regret and humiliation.

But the answer, though it came in a single syllable, was unmistakable. Intense pride, passionate devotion to her own creed and people, the deepest scorn and loathing for all others, combined to make up the tone of Belasez’s “No!”

“How very odd!” exclaimed Margaret, looking at her, with an expression of great astonishment upon her own fair, open features.

“Is it odd to my damsel? Does she know what her question sounded like, to me?”

“Tell me.”

“‘Would she not like better to be a villein scullion-maid, than to be the daughter of my noble Lord of Kent?’”

“But Jews are not noble!” cried Margaret, gazing in bewilderment from Belasez to Doucebelle, as if she expected one of them to help her out of the puzzle.

“Not in the world’s estimate,” answered Belasez. “There is One above the world.”

Before Margaret could reply, the deep bass “Ding-dong!” of the great dinner-bell rang through the Castle, and Levina made her appearance at the door.

“My Lady has given me charge concerning thee, Belasez,” she said, rather coldly addressing the Jewess. “Thou wilt come with me.”

With a graceful reverence to Margaret, Belasez turned, and followed Levina.

At that date, no titles except those of nobility or office were usual in England. Any woman below a peer’s daughter, was addressed by her Christian name or by that of her husband. That is to say, the unmarried woman was simply “Joan;” the married one was “John’s Wife.”

Belasez was gifted by nature with a large amount of that kind of intuition which has been defined as feeling the pressure of other people’s atmosphere. It may be a gift which augurs delicacy and refinement, but it always brings discomfort to its possessor. She knew instinctively, and in a moment, that Levina was likely to be her enemy.

It was true. Levina was a prey to that green-eyed monster which sports itself with the miseries of humanity. She had been the best broideress in the Castle until that day. And now she felt herself suddenly supplanted by a young thing of barely more than half her age and experience, who was called in, forsooth, to do something which it was imagined that Levina could not do. What business had the Countess to suppose there was any thing she could not do?—or, to want something out of her power to provide? Was there the slightest likelihood, thought Levina, flaring up, that this scrap of a creature could work better than herself?—a mere chit of a child (Levina was past thirty), with a complexion like the fire-bricks (Levina’s resembled putty), and hair the colour of nasty sloes (Levina’s was nearer that of a tiger-lily), and great staring eyes like horn lanterns! The Countess was the most unreasonable, and Levina the most cruelly-outraged, of all the women that had ever held a needle since those useful instruments were originally invented.

Levina did not put her unparalleled wrongs into words. It would have been easier for Belasez to get on with her if she had done so. She held her head up, and snorted like an impatient horse, as she stalked through the door into the ante-chamber.

“This is where thou art to be,” she snapped in a staccato tone.

Any amount of personal slight and scorn was merely what Belasez had been accustomed to receive from Christians ever since she had left her cradle. The disdain of Levina, therefore, though she could hardly enjoy it, made far less impression on her than the unaccountable kindliness of the royal ladies.

“The Lady bade me ask what thou wouldst eat?” demanded Levina in the same tone as before.

“I thank thee. Any thing that has not had life.”

“What’s that for?” came in shorter snaps than ever.

“It would not be kosher.”

“Speak sense! What does the vermin mean?”

“I mean, it would not be killed according to our law.”

“Suppose it wasn’t I—what then?”

“Then I must not eat it.”

“Stupid, silly, ridiculous stuff! May I be put in a pie, if I know what the Lady was thinking about, when she brought in such road-dirt as this! And my damsel sets herself above us all, forsooth! She must have her meat served according to some law that nobody ever heard of, least of all the Lord King’s noble Council: and she must have a table set for her all by herself, as though she were a sick queen. Pray you, my noble Countess, would you eat in gold or silver?—and how many varlets shall serve to carry your dainty meat?—and is your sweet Grace served upon the knee, or no? I would fain have things done as may pleasure my right noble Lady.”

Belasez answered as she usually disposed of similar affronts,—by treating them as if they were offered in genuine courtesy, but with a faint ring of satire beneath her tone.

“I thank you. I should prefer wood, or pewter if it please you: and I should think one varlet might answer. I was never served upon the knee yet, and it will scarcely be necessary now.”

Levina gave a second and stronger snort, and disappeared down the stairs. In a few minutes she made her reappearance, carrying in one hand a plate of broiled ham, and in the other a piece of extremely dry and rather mouldy bread.

“Here is my gracious damsel’s first course! Fulk le Especer was so good as to tell me that folks of her sort are mighty fond of ham; so I took great care to bring her some. There’ll be sauce with the next.”

That there would be sauce—of one species—with every course served to her in that house, Belasez was beginning to feel no doubt. Yet however Levina chose to behave to her, the young Jewess maintained her own dignity. She quietly put aside the plate of ham, and, cutting off the mouldy pieces, ate the dry bread without complaint Belasez’s kindly and generous nature was determined that the Countess, who had been so much kinder to her than at that time Christians usually were to Jews, should hear no murmuring word from her unless it came to actual starvation.

Levina’s sauce presented itself unmistakably with the second course, which proved to be a piece of apple-pie, swimming in the strongest vinegar. Though it must have set her teeth on edge, Belasez consumed the pie in silence, avoiding the vinegar so far as she could, and entertained while she did so by Levina’s assurances that it delighted her to see how completely Belasez enjoyed it.

The third article, according to Levina, was cheese: but the first mouthful was enough to convince the persecuted Jewess that soft soap would have been a more correct epithet. She quietly let it alone.

“Ha, chétife! I am sadly in fear that my sweetest damsel does not like our Suffolk cheese?” said Levina in a most doleful tone.

“Is it manufactured in this county?” asked Belasez very coolly; for, in 1234, all soaps were of foreign importation. “I thought it tasted more like the French make.”