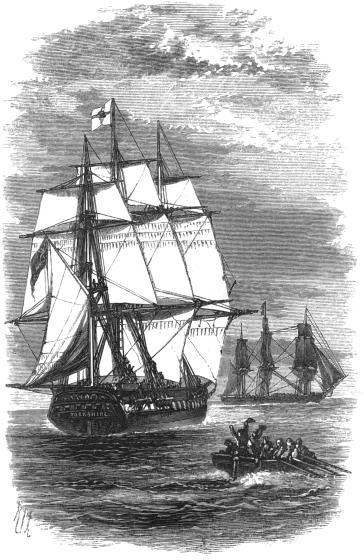

OUTWARD BOUND. See p. 27.

OUTWARD BOUND. See p. 27.

Title: A Boy's Voyage Round the World

Author: Samuel Smiles

Editor: Samuel Smiles

Release date: January 17, 2008 [eBook #24345]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Thierry Alberto, Diane Monico, and The Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

OUTWARD BOUND. See p. 27.

OUTWARD BOUND. See p. 27.

I have had pleasure in editing this little book, not only because it is the work of my youngest son, but also because it contains the results of a good deal of experience of life under novel aspects, as seen by young, fresh, and observant eyes.

How the book came to be written is as follows: The boy, whose two years' narrative forms the subject of these pages, was at the age of sixteen seized with inflammation of the lungs, from which he was recovering so slowly and unsatisfactorily, that I was advised by London physicians to take him from the business he was then learning in Yorkshire, and send him on a long sea voyage. Australia was recommended, because of the considerable time occupied in making the voyage by sailing ship, and also because of the comparatively genial and uniform temperature while at sea.

He was accordingly sent out to Melbourne by one of Money Wigram's ships in the winter of 1868-9, with directions either to return by the same ship or, if the opportunity presented itself, to remain for a time in the colony. It will be found, from his own narrative that, having obtained some suitable employment, he decided to adopt the latter course; and for a period of about eighteen months he resided at Majorca, an up-country township situated in the gold-mining district of Victoria.

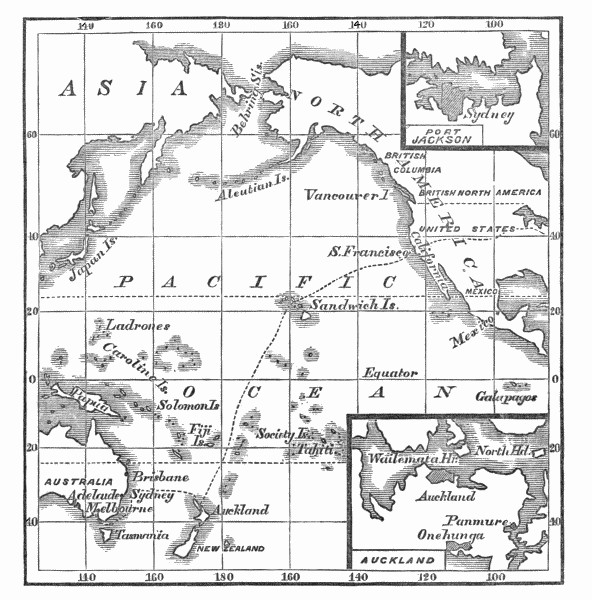

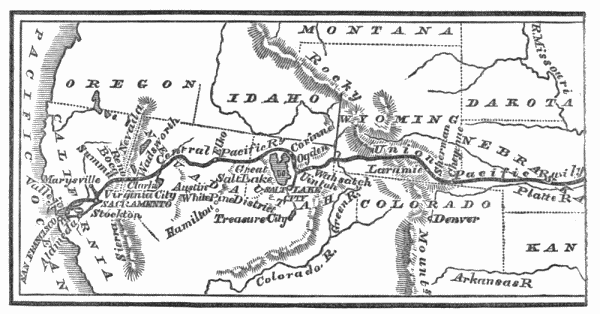

When his health had become re-established, he was directed to return home, about the beginning of the present year; and he resolved to make the return voyage by the Pacific route, viâ Honolulu and San Francisco, and to proceed from thence by railway across the Rocky Mountains to New York.

While at sea, the boy kept a full log, intended for the perusal of his relatives at home; and while on land, he corresponded with them regularly and fully, never missing a mail. He had not the remotest idea that anything which he saw and described during his absence would ever appear in a book. But since his return, it has occurred to the Editor of these pages that the information they contain will probably be found interesting to a wider circle of readers than that to which the letters were originally addressed; and in that belief, the substance of them is here reproduced, the Editor's work having consisted mainly in arranging the materials, leaving the writer to tell his own story as much as possible in his own way, and in his own words.

London, November, 1871.

At Gravesend—Taking in Stores—First Night on Board—"The Anchor's Up"—Off Brighton—Change of Wind—Gale in the Channel—The Abandoned Ship—The Eddystone—Plymouth Harbour—Departure from England

Fellow-Passengers—Life on Board Ship—Progress of the Ship—Her Handling—A Fine Run Down to the Line—Ship's Amusements—Climbing the Mizen—The Cape de Verd Islands—San Antonio

Increase of Temperature—Flying Fish—The Morning Bath on Board—Paying "Footings"—The Major's Wonderful Stories—St. Patrick's Day—Grampuses—A Ship in Sight—The 'Lord Raglan'—Rain-fall in the Tropics—Tropical Sunsets—The Yankee Whaler

April Fools' Day—A Ship in Sight—The 'Pyrmont'—The Rescued 'Blue Jacket' Passengers—Story of the Burnt Ship—Suffering of the Lady Passengers in an Open Boat—Their Rescue—Distressing Scene on Board the 'Pyrmont'

Preparing for Rough Weather—The 'George Thompson' Clipper—A Race at Sea—Scene From 'Pickwick' Acted—Fishing for Albatross—Dissection and Division of the Bird—Whales—Strong Gale—Smash in the Cabin—Shipping a Green Sea—The Sea Birds in Our Wake—The Crozet Islands

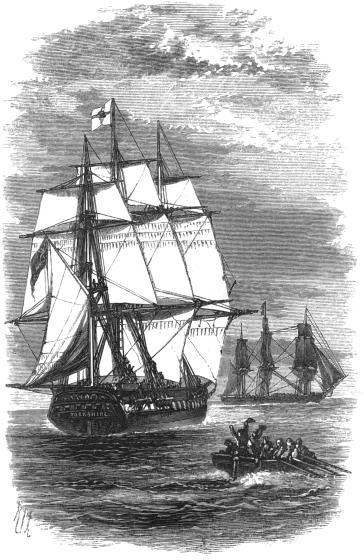

Acting on Board—The Cyclone—Cleaning the Ship for Port—Contrary Winds—Australia in Sight—Cape Otway—Port Phillip Heads—Pilot Taken on Board—Inside the Heads—Williamstown—Sandridge—The Landing

First Impressions of Melbourne—Survey of the City—The Streets—Collins Street—The Traffic—Newness and Youngness of Melbourne—Absence of Beggars—Melbourne an English City—The Chinese Quarter—The Public Library—Pentridge Prison—The Yarra River—St. Kilda—Social Experiences in Melbourne—A Marriage Ball—Melbourne Ladies—Visit to a Serious Family

Obtain a Situation in an Up-country Bank—Journey by Rail—Castlemaine—Further Journey by Coach—Maryborough—First Sight of the Bush—The Bush Tracks—Evening Prospect over the Country—Arrival at my Destination

Majorca Founded in a Rush—Description of a Rush—Diggers Camping Out—Gold-mining at Majorca—Majorca High Street—The People—The Inns—The Churches—The Bank—The Chinamen—Australia the Paradise of Working Men—"Shouting" for Drinks—Absence of Beggars—No Coppers Up Country

"Dining out"—Diggers' Sunday Dinner—The Old Workings—The Chinamen's Gardens—Chinamen's Dwellings—The Cemetery—The High Plains—The Bush—A Ride through the Bush—The Savoyard Woodcutter—Visit to a Squatter

The Victorian Climate—The Bush in Winter—The Eucalyptus or Australian Gum-tree—Ball at Clunes—Fire in the Main Street—The Buggy Saved—Down-pour of Rain—Going Home by Water—The Floods out—Clunes Submerged—Calamity at Ballarat—Damage done by the Flood—The Chinamen's Gardens Washed Away

Spring Vegetation—The Bush in Spring—Garden Flowers—An Evening Walk—Australian Moonlight—The Hot North Wind—The Plague of Flies—Bush Fires—Summer at Christmas—Australian Fruits—Ascent of Mount Greenock—Australian Wine—Harvest—A Squatter's Farm—Harvest Home Celebration—Aurora Australis—Autumn Rains

The 'Possum—A Night's Sport in the Bush—Musquitoes—Wattle Birds—The Piping-Crow—"Miners"—Paroquet-hunting—The Southern Cross—Snakes—Marsupial Animals

How the Gold is Found—Gold-washing—Quartz-crushing—Buying Gold from Chinamen—Alluvial Companies—Broken-down Men—Ups and Downs in Gold-mining—Visit to a Gold Mine—Gold-seeking—Diggers' Tales of Lucky Finds

Gold-rushing—Diggers' Camp at Havelock—Murder of Lopez—Pursuit and Capture of the Murderer—The Thieves Hunted from the Camp—Death of the Murderer—The Police—Attempted Robbery of the Collingwood Bank—Another Supposed Robbery—"Stop Thief!"—Smart Use of the Telegraph

Visit to Ballarat—The Journey by Coach—Ballarat Founded on Gold—Description of the Town—Ballarat "Corner"—The Speculative Cobbler—Fire Brigades—Return Journey—Crab-holes—The Talbot Ball—The Talbot Fête—The Avoca Races—Sunrise in the Bush

Victorian Life English—Arrival of the Home Mail—News of the Franco-German War—The German Settlers in Majorca—The Single Frenchman—Majorcan Public Teas—The Church—The Ranters—The Teetotallers—The Common School—The Roman Catholics—Common School Fête and Entertainment—The Mechanics' Institute—Funeral of the Town Clerk—Departure from Majorca—The Colony of Victoria

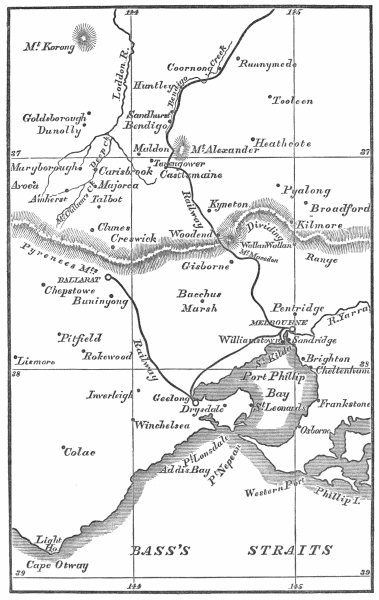

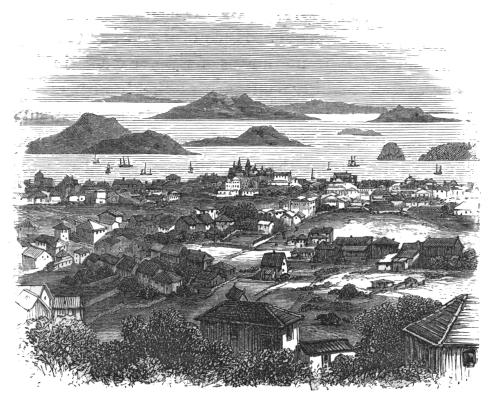

Last Christmas in Australia—Start by Steamer for Sydney—The 'Great Britain'—Cheap Trips to Queenscliffe—Rough Weather at Sea—Mr. and Mrs. C. Mathews—Botany Bay—Outer South Head—Port Jackson—Sydney Cove—Description of Sydney—Government House and Domain—Great Future Empire of the South

Leaving Sydney—Anchor within the Heads—Take in Mails and Passengers from the 'City of Adelaide'—Out to Sea Again—Sight New Zealand—Entrance to Auckland Harbour—The 'Galatea'—Description of Auckland—Founding of Auckland due to a Job—Maori Men and Women—Drive to Onehunga—Splendid View—Auckland Gala—New Zealand Delays—Leave for Honolulu

Departure for Honolulu—Monotony of a Voyage by Steam—Désagrémens—The "Gentlemen" Passengers—The One Second Class "Lady"—The Rats on Board—The Smells—Flying Fish—Cross the Line—Treatment of Newspapers on Board—Hawaii in Sight—Arrival at Honolulu

The Harbour of Honolulu—Importance of its Situation—The City—Churches and Theatres—The Post Office—The Suburbs—The King's Palace—The Nuuanu Valley—Poi—People Coming down the Valley—The Pali—Prospect from the Cliffs—The Natives (Kanakas)—Divers—The Women—Drink Prohibition—The Chinese—Theatricals—Musquitoes

Departure from Honolulu—Wreck of the 'Saginaw'—The 'Moses Taylor'—The Accommodation—The Company on Board—Behaviour of the Ship—Death of a Passenger—Feelings on Landing in a New Place—Approach the Golden Gate—Close of the Pacific Log—First Sight of America

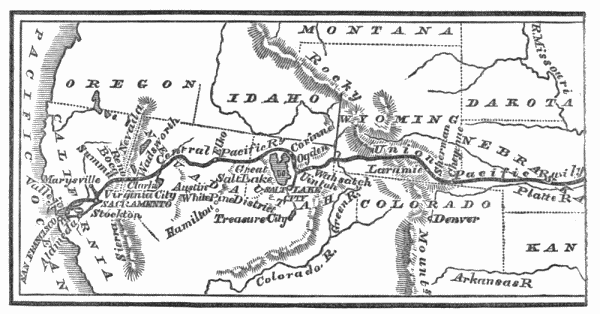

Landing at San Francisco—The Golden City—The Streets—The Business Quarter—The Chinese Quarter—The Touters—Leave San Francisco—The Ferry-boat to Oakland—The Bay of San Francisco—Landing on the Eastern Shore—American Railway Carriages—The Pullman's Cars—Sleeping Berths—Unsavoury Chinamen—The Country—City of Sacramento

Rapid Ascent—The Trestle-Bridges—Mountain Prospects—"Placers"—Sunset—Cape Horn—Alta—The Sierras by Night—Contrast of Temperatures—The Snow-Sheds—The Summit—Reno—Breakfast at Humboldt—The Sage-Brush—Battle Mount—Shoshonie Indians—Ten Mile Cañon—Elko Station—Great American Desert—Arrival at Ogden

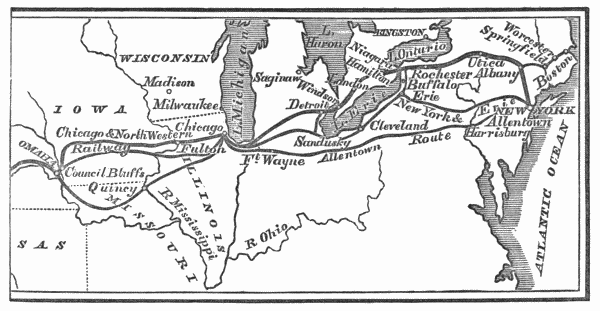

Start by Train for Omaha—My Fellow-Passengers—Passage through the Devil's Gate—Weber Cañon—Fantastic Rocks—"Thousand Mile Tree"—Echo Cañon—More Trestle-Bridges—Sunset amidst the Bluffs—A Wintry Night by Rail—Snow-Fences and Snow-Sheds—Laramie City—Red Buttes—The Summit at Sherman—Cheyenne City—The Western Prairie in Winter—Prairie Dog City—The Valley of the Platte—Grand Island—Cross the North Fork of the Platte—Arrival in Omaha

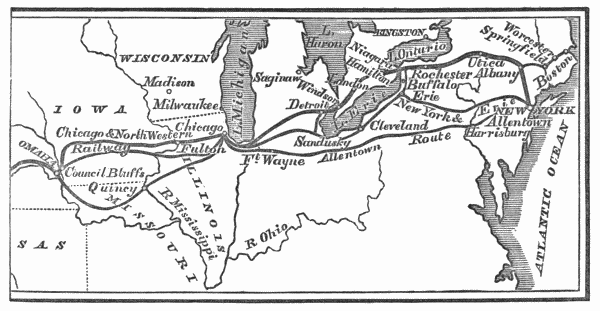

Omaha Terminus—Cross the Missouri—Council Bluffs—The Forest—Cross the Mississippi—The Cultivated Prairie—The Farmsteads and Villages—Approach to Chicago—The City of Chicago—Enterprise of its Men—The Water Tunnels under Lake Michigan—Tunnels under the River Chicago—Union of Lake Michigan with the Mississippi—Description of the Streets and Buildings of Chicago—Pigs and Corn—The Avenue—Sleighing—Theatres and Churches

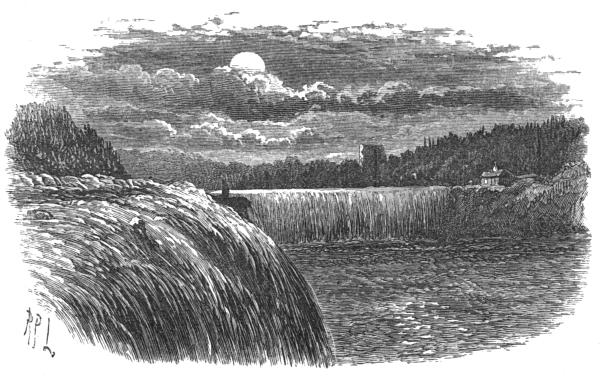

Leave Chicago—The Ice Harvest—Michigan City—The Forest—A Railway Smashed—Kalamazoo—Detroit—Crossing into Canada—American Manners—Roebling's Suspension Bridge—Niagara Falls in Winter—Goat Island—The American Fall—The Great Horse-shoe Fall—The Rapids from the Lovers' Seat—American Cousins—Rochester—New York—A Catastrophe—Return Home

At Gravesend—Taking in Stores—First Night on Board—"The Anchor's Up"—Off Brighton—Change of Wind—Gale in the Channel—The Abandoned Ship—The Eddystone—Plymouth Harbour—Departure from England.

20th February: At Gravesend.—My last farewells are over, my last adieus are waved to friends on shore, and I am alone on board the ship 'Yorkshire,' bound for Melbourne. Everything is in confusion on board. The decks are littered with stores, vegetables, hen-coops, sheep-pens, and coils of rope. There is quite a little crowd of sailors round the capstan in front of the cabin door. Two officers, with lists before them, are calling over the names of men engaged to make up our complement of hands, and appointing them to their different watches.

Though the ship is advertised to sail this evening, the stores are by no means complete. The steward is getting in lots of cases; and what a quantity of pickles! Hens are coming up to fill the hen-coops. More sheep are being brought; there are many on board already; and here comes our milk-cow over the ship's side, gently hoisted up by a rope. The animal seems amazed; but[Pg 2] she is in skilful hands. "Let go!" calls out the boatswain, as the cow swings in mid-air; away rattles the chain round the wheel of the donkey-engine, and the break is put on just in time to land Molly gently on the deck. In a minute she is snug in her stall "for'ard," just by the cook's galley.

Passengers are coming on board. Here is one mounting the ship's side, who has had a wet passage from the shore. A seaman lends him a hand, and he reaches the sloppy, slippery deck with difficulty.

It is a dismal day. The sleet and rain come driving down. Everything is raw and cold; everybody wet or damp. The passengers in wet mackintoshes, and the seamen in wet tarpaulins; Gravesend, with its dirty side to the river, and its dreary mud-bank exposed to sight; the alternate drizzle and down-pour; the muddle and confusion of the deck;—all this presented anything but an agreeable picture to look at. So I speedily leave the deck, in order to make a better acquaintance with what is to be my home for the next three months.

First, there is the saloon—long and narrow—surrounded by the cabins. It is our dining-room, drawing-room, and parlour, all in one. A long table occupies the centre, fitted all round with fixed seats and reversible backs. At one end of the table is the captain's chair, over which hangs a clock and a barometer. Near the after end of the saloon is the mizen-mast, which passes through into the hole below, and rests on the keelson.[Pg 3]

The cabins, which surround the saloon, are separated from it by open woodwork, for purposes of ventilation. The entrances to them from the saloon are by sliding doors. They are separated from each other by folding-doors, kept bolted on either side when one cabin only is occupied; but these can be opened when the neighbours on both sides are agreeable.

My own little cabin is by no means dreary or uninviting. A window, with six small panes, lets in light and air; and outside is a strong board, or "dead-light," for use in rough weather, to protect the glass. My bunk, next to the saloon, is covered with a clean white counterpane. A little wash-stand occupies the corner; a shelf of favourite books is over my bed-head; and a swing-lamp by its side. Then there is my little mirror, my swing-tray for bottles, and a series of little bags suspended from nails, containing all sorts of odds and ends. In short, my little chamber, so fitted up, looks quite cheerful and even jolly.

It grows dusk, and there is still the same bustle and turmoil on deck. All are busy; everybody is in a hurry. At about nine the noise seems to subside; and the deck seems getting into something like order. As we are not to weigh anchor until five in the morning, some of the passengers land for a stroll on shore. I decide to go to bed.

And now begins my first difficulty. I cannot find room to extend myself, or even to turn. I am literally "cribbed, cabined, and confined." Then there are the unfamiliar noises outside,—the cackling of the ducks,[Pg 4] the baa-ing of the sheep, the grunting of the pigs,—possibly discussing the novelty of their position. And, nearly all through the night, just outside my cabin, two or three of the seamen sit talking together in gruff undertones.

I don't think I slept much during my first night on board. I was lying semi-conscious, when a loud voice outside woke me up in an instant—"The anchor's up! she's away!" I jumped up, and, looking out of my little cabin window, peered out into the grey dawn. The shores seemed moving, and we were off! I dressed at once, and went on deck. But how raw and chill it felt as I went up the companion-ladder. A little steam-tug ahead of us was under weigh, with the 'Yorkshire' in tow. The deck was now pretty well cleared, but white with frost; while the river banks were covered with snow.

Other ships were passing down stream, each with its tug; but we soon distanced them all, especially when the men flung the sails to the wind, now blowing fresh. At length, in about three-quarters of an hour, the steamer took on board her tow-rope, and left us to proceed on our voyage with a fair light breeze in our favour, and all our canvas set.

When off the Nore, we hailed the 'Norfolk,' homeward bound—a fast clipper ship belonging to the same firm (Money Wigram's line),—and a truly grand sight she was under full sail. There were great cheerings and wavings of hats,—she passing up the river and we out to sea.[Pg 5]

I need not detain you with a description of my voyage down Channel. We passed in succession Margate, Ramsgate, and Deal. The wind kept favourable until we sighted Beachy Head, about half-past five in the evening, and then it nearly died away. We were off Brighton when the moon rose. The long stretch of lights along shore, the clear star-lit sky, the bright moon, the ship gently rocking in the almost calm sea, the sails idly flapping against the mast,—formed a picture of quiet during my first night at sea, which I shall not soon forget.

But all this, I was told, was but "weather-breeding;" and it was predicted that we were to have a change. The glass was falling and we were to look out for squalls. Nor were the squalls long in coming. Early next morning I was roused by the noise on deck and the rolling of things about my cabin floor. I had some difficulty in dressing, not having yet found my sea legs; but I succeeded in gaining the companion-ladder and reaching the poop.

I found the wind had gone quite round in the night, and was now blowing hard in our teeth, from the south-west. It was to be a case of tacking down Channel,—a slow and, for landsmen, a very trying process. In the midst of my first mal de mer, I was amused by the appearance on board of one of my fellow-passengers. He was a small, a very small individual, but possessed of a large stock of clothes, which he was evidently glad to have an opportunity of exhibiting. He first came up with a souwester on his head, the wrong end[Pg 6] foremost, and a pair of canvas shoes on his feet,—a sort of miniature Micawber, or first-class cockney "salt," about to breast the briny. This small person's long nose, large ears, and open mouth added to the ludicrousness of his appearance. As the decks were wet and the morning cold, he found the garb somewhat unsuitable, and dived below, to come up again in strong boots and a straw hat. But after further consideration, he retired again, and again he appeared in fresh headgear—a huge seal-skin cap with lappets coming down over his ears. This important and dressy little individual was a source of considerable amusement to us; and there was scarcely an article in his wardrobe that had not its turn during the day.

All night it blew a gale; the wind still from the same quarter. We kept tacking between the coast of England and the opposite coast of France, making but small way as regards mileage,—the wind being right in our teeth. During the night, each time that the ship was brought round on the other tack, there was usually a tremendous lurch; and sometimes an avalanche of books descended upon me from the shelf overhead. Yet I slept pretty soundly. Once I was awakened by a tremendous noise outside—something like a gun going off. I afterwards found it had been occasioned by the mainsail being blown away to sea, right out of the bolt-ropes, the fastenings of which were immediately outside my cabin window.

When I went on deck the wind was still blowing hard, and one had to hold on to ropes or cleats to[Pg 7] be able to stand. The whole sea was alive, waves chasing waves and bounding over each other, crested with foam. Now and then the ship would pitch her prow into a wave, even to the bulwarks, dash the billow aside, and buoyantly rise again, bowling along, though under moderate sail, because of the force of the gale.

The sea has some sad sights, of which one shortly presented itself. About midday the captain sighted a vessel at some distance off on our weather bow, flying a flag of distress—an ensign upside down. Our ship was put about, and as we neared the vessel we found she had been abandoned, and was settling fast in the water. Two or three of her sails were still set, torn to shreds by the storm. The bulwarks were pretty much gone, and here and there the bare stanchions, or posts, were left standing, splitting in two the waves which broke clear over her deck, lying almost even with the sea. She turned out to be the 'Rosa,' of Guernsey, a fine barque of 700 tons, and she had been caught and disabled by the storm we had ourselves encountered. As there did not seem to be a living thing on board, and we could be of no use, we sailed away; and she must have gone down shortly after we left her. Not far from the sinking ship we came across a boat bottom upwards, most probably belonging to the abandoned ship. What of the poor seamen? Have they been saved by other boats, or been taken off by some passing vessel? If not, alas for their wives and children at home! Indeed it was a sad sight.

But such things are soon forgotten at sea. We are[Pg 8] too much occupied by our own experiences to think much of others. For two more weary days we went tacking about, the wind somewhat abating. Sometimes we caught sight of the French coast through the mist; and then we tacked back again. At length Eddystone light came in view, and we knew we were not far from the entrance to Plymouth Sound. Once inside the Breakwater, we felt ourselves in smooth water again.

Going upon deck in the morning, I found our ship anchored in the harbour nearly opposite Mount Edgcumbe. Nothing could be more lovely than the sight that presented itself. The noble bay, surrounded by rocks, cliffs, cottages—Drake's Island, bristling with cannon, leaving open a glimpse into the Hamoaze studded with great hulks of old war-ships—the projecting points of Mount Edgcumbe Park, carpeted with green turf down to the water and fringed behind by noble woods, looking like masses of emerald cut into fret-work—then, in the distance, the hills of Dartmoor, variegated with many hues, and swept with alternations of light and shade—all these presented a picture, the like of which I had never before seen and feel myself quite incompetent to describe.

As we had to wait here for a fair wind, and the gale was still blowing right into the harbour's mouth, there seemed no probability of our setting sail very soon. We had, moreover, to make up our complement of passengers, and provisions. Those who had a mind accordingly went on shore, strolled through the town, and visited the Hoe, from which a magnificent view of[Pg 9] the harbour is obtained, or varied their bill of fare by dining at an hotel.

We were, however, cautioned not to sleep on shore, but to return to the ship for the night, and even during the day to keep a sharp look-out for the wind; for, immediately on a change to the nor'ard, no time would be lost in putting out to sea. We were further informed that, in the case of nearly every ship, passengers, through their own carelessness and dilly-dallying on shore, had been left behind. I determined, therefore, to stick to the ship.

After three days' weary waiting, the wind at last went round; the anchor was weighed with a willing "Yo! heave ho!" and in a few hours, favoured by a fine light breeze, we were well out to sea, and the brown cliffs of Old England gradually faded away in the distance.

Fellow-Passengers—Life on Board Ship—Progress of the Ship—Her Handling—A Fine Run Down to the Line—Ship's Amusements—Climbing the Mizen—The Cape De Verd Islands—San Antonio.

3rd March.—Like all passengers, I suppose, who come together on board ship for a long voyage, we had scarcely passed the Eddystone Lighthouse before we began to take stock of each other. Who is this? What is he? Why is he going out? Such were the questions we inwardly put to ourselves and sought to answer.

I found several, like myself, were making the voyage for their health. A long voyage by sailing ship seems to have become a favourite prescription for lung complaints; and it is doubtless an honest one, as the doctor who gives it at the same time parts with his patient and his fees. But the advice is sound; as the long rest of the voyage, the comparatively equable temperature of the sea air, and probably the improved quality of the atmosphere inhaled, are all favourable to the healthy condition of the lungs as well as of the general system.

Of those going out in search of health, some were young and others middle-aged. Amongst the latter[Pg 11] was a patient, gentle sufferer, racked by a hacking cough when he came on board. Another, a young passenger, had been afflicted by abscess in his throat and incipient lung-disease. A third had been worried by business and afflicted in his brain, and needed a long rest. A fourth had been crossed in love, and sought for change of scene and occupation.

But there were others full of life and health among the passengers, going out in search of fortune or of pleasure. Two stalwart, outspoken, manly fellows, who came on board at Plymouth, were on their way to New Zealand to farm a large tract of land. They seemed to me to be models of what colonial farmers should be. Another was on his way to take up a run in Victoria, some 250 miles north of Melbourne. He had three fine Scotch colley dogs with him, which were the subject of general admiration.

We had also a young volunteer on board, who had figured at Brighton reviews, and was now on his way to join his father in New Zealand, where he proposed to join the colonial army. We had also a Yankee gentleman, about to enter on his governorship of the Guano Island of Maldon, in the Pacific, situated almost due north of the Society Islands, said to have been purchased by an English company.

Some were going out on "spec." If they could find an opening to fortune, they would settle; if not, they would return. One gentleman was taking with him a fine portable photographic apparatus, intending to visit New Zealand and Tasmania, as well as Australia.[Pg 12]

Others were going out for indefinite purposes. The small gentleman, for instance, who came on board at Gravesend with the extensive wardrobe, was said to be going out to Australia to grow,—the atmosphere and climate of the country being reported as having a wonderful effect on growth. Another entertained me with a long account of how he was leaving England because of his wife; but, as he was of a somewhat priggish nature, I suspect the fault may have been his own as much as hers.

And then there was the Major, a military and distinguished-looking gentleman, who came on board, accompanied by a couple of shiny new trunks, at Plymouth. He himself threw out the suggestion that the raising of a colonial volunteer army was the grand object of his mission. Anyhow, he had the manners of a gentleman. And he had seen service, having lost his right arm in the Crimea and gone all through the Indian Mutiny war with his left. He was full of fun, always in spirits, and a very jolly fellow, though rather given to saying things that would have been better left unsaid.

Altogether, we have seventeen saloon passengers on board, including the captain's wife, the only lady at the poop end. There were also probably about eighty second and third-class passengers in the forward parts of the ship.

Although the wind was fair, and the weather fine, most of the passengers suffered more or less from seasickness; but at length, becoming accustomed to the[Pg 13] motion of the ship, they gradually emerged from their cabins, came on deck, and took part in the daily life on board. Let me try and give a slight idea of what this is.

At about six every morning we are roused by the sailors holystoning the decks, under the superintendence of the officer of the watch. A couple of middies pump up water from the sea, by means of a pump placed just behind the wheel. It fills the tub until it overflows, running along the scuppers of the poop, and out on to the main-deck through a pipe. Here the seamen fill their buckets, and proceed with the scouring of the main-deck. Such a scrubbing and mopping!

I need scarcely explain that holystone is a large soft stone, used with water, for scrubbing the dirt off the ship's decks. It rubs down with sand; the sand is washed off by buckets of water thrown down, all is well mopped, and the deck is then finished off with India-rubber squilgees.

The poop is always kept most bright and clean. Soon after we left port it assumed a greatly-improved appearance. The boards began to whiten with the holystoning. Not a grease-mark or spot of dirt was to be seen. All was polished off with hand-scrapers. On Sundays the ropes on the poop were all neatly coiled, man-of-war fashion—not a bight out of place. The brasswork was kept as bright as a gilt button.

By the time the passengers dressed and went on deck the cleaning process was over, and the decks were dry. After half an hour's pacing the poop the bell[Pg 14] would ring for breakfast, the appetite for which would depend very much upon the state of the weather and the lurching of the ship. Between breakfast and lunch, more promenading on the poop; the passengers sometimes, if the weather was fine, forming themselves in groups on deck, cultivating each other's acquaintance.

During our first days at sea we had some difficulty in finding our sea legs. The march of some up and down the poop was often very irregular, and occasionally ended in disaster. Yet the passengers were not the only learners; for, one day, we saw one of the cabin-boys, carrying a heavy ham down the steps from a meat-safe on board, miss his footing in a lurch of the ship, and away went our fine ham into the lee-scuppers, spoilt and lost.

We lunched at twelve. From thence, until dinner at five, we mooned about on deck as before, or visited sick passengers, or read in our respective cabins, or passed the time in conversation; and thus the day wore on. After dinner the passengers drew together in parties and became social. In the pleasantly-lit saloon some of the elder subsided into whist, while the juniors sought the middies in their cabin on the main-deck, next door to the sheep-pen; there they entertained themselves and each other with songs, accompanied by the concertina and clouds of tobacco-smoke.

The progress of the ship was a subject of constant interest. It was the first thing in the morning and[Pg 15] the last at night; and all through the day, the direction of the wind, the state of the sky and the weather, and the rate we were going at, were the uppermost topics of conversation.

When we left port the wind was blowing fresh on our larboard quarter from the north-east, and we made good progress across the Bay of Biscay; but, like many of our passengers, I was too much occupied by private affairs to attend to the nautical business going on upon deck. All I know was, that the wind was fair, and that we were going at a good rate. On the fourth day, I found we were in the latitude of Cape Finisterre, and that we had run 168 miles in the preceding 24 hours. From this time forward, having got accustomed to the motion of the ship, I felt sufficiently well to be on deck early and late, watching the handling of the ship.

It was a fine sight to look up at the cloud of canvas above, bellied out by the wind, like the wings of a gigantic bird, while the ship bounded through the water, dashing it in foam from her bows, and sometimes dipping her prow into the waves, and sending aloft a shower of spray.

There was always something new to admire in the ship, and the way in which she was handled: as, for instance, to see the topgallant sails hauled down when the wind freshened, or a staysail set as the wind went round to the east. The taking in of the mainsail on a stormy night was a thing to be remembered for life: twenty-four men on the great yard at a time, clewing[Pg 16] it in to the music of the wind whistling through the rigging. The men sing out cheerily at their work, the one who mounts the highest, or stands the foremost on the deck; usually taking the lead—

Hawl on the bowlin,

The jolly ship's a-rollin—

Hawl on the bowlin,

And we'll all drink rum.

In comes the rope with a "Yo! heave ho!" and a jerk, until the "belay" sung out by the mate signifies that the work is done. Then, there is the scrambling on the deck when the wind changes quarter, and the yards want squaring as the wind blows more aft. Such are among the interesting sights to be seen on deck when the wind is in her tantrums at sea.

On the fifth day the wind was blowing quite aft. Our run during the twenty-four hours was 172 miles. Thermometer 58°. The captain is in hopes of a most favourable run to the Cape. It is our first Sunday on board, and at 10.30 the bell rings for service, when the passengers of all classes assemble in the saloon. The alternate standing and kneeling during the service is rather uncomfortable, the fixed seats jamming the legs, and the body leaning over at an unpleasant angle when the ship rolls, which she frequently does, and rather savagely.

Going upon deck next morning, I found the wind blowing strong from the north, and the ship going through the water at a splendid pace. As much sail was on as she could carry, and she dashed along, leaving[Pg 17] a broad track of foam in her wake. The captain is in high glee at the speed at which we are going. "A fine run down to the Line!" he says, as he walks the poop, smiling and rubbing his hands; while the middies are enthusiastic in praises of the good ship, "walking the waters like a thing of life." The spirits of all on board are raised by several degrees. We have the pleasure of feeling ourselves bounding forward, on towards the sunny south. There is no resting, but a constant pressing onward, and, as we look over the bulwarks, the waves, tipped by the foam which our ship has raised, seem to fly behind us at a prodigious speed. At midday we find the ship's run during the twenty-four hours has been 280 miles—a splendid day's work, almost equal to steam!

We are now in latitude 39° 16', about due east of the Azores. The air is mild and warm; the sky is azure, and the sea intensely blue. How different from the weather in the English Channel only a short week ago! Bugs are now discarded, and winter clothing begins to feel almost oppressive. In the evenings, as we hang over the taffrail, we watch with interest the bluish-white sparks mingling with the light blue foam near the stern—the first indications of that phosphorescence which, I am told, we shall find so bright in the tropics.

An always interesting event at sea is the sighting of a distant ship. To-day we signalled the 'Maitland,' of London, a fine ship, though she was rolling a great deal, beating up against the wind that was impelling[Pg 18] us so prosperously forward. I hope she will report us on arrival, to let friends at home know we are so far all right on our voyage.

The wind still continues to blow in our wake, but not so strongly; yet we make good progress. The weather keeps very fine. The sky seems to get clearer, the sea bluer, and the weather more brilliant, and even the sails look whiter, as we fly south. About midday on the eighth day after leaving Plymouth we are in the latitude of Madeira, which we pass about forty miles distant.

As the wind subsides, and the novelty of being on shipboard wears off, the passengers begin to think of amusements. One cannot be always reading; and, as for study, though I try Spanish and French alternately, I cannot settle to them, and begin to think that life on shipboard is not very favourable for study. We play at quoits—using quoits of rope—on the poop, for a good part of the day. But this soon becomes monotonous; and we begin to consider whether it may not be possible to get up some entertainment on board to make the time pass pleasantly. We had a few extempore concerts in one of the middies' berths. The third-class passengers got up a miscellaneous entertainment, including recitals, which went off very well. One of the tragic recitations was so well received that it was encored. And thus the time was whiled away, while we still kept flying south.

On the ninth day we are well south of Madeira. The sun is so warm at midday that an awning is hung[Pg 19] over the deck, and the shade it affords is very grateful. We are now in the trade-winds, which blow pretty steadily at this part of our course in a south-westerly direction, and may generally be depended upon until we near the Equator. At midday of the tenth day I find we have run 180 miles in the last twenty-four hours, with the wind still steady on our quarter. We have passed Teneriffe, about 130 miles distant—too remote to see it—though I am told that, had we been twenty miles nearer, we should probably have seen the famous peak.

To while away the time, and by way of a little adventure, I determined at night to climb the mizen-mast with a fellow-passenger. While leaving the deck I was chalked by a middy, in token that I was in for my footing, so as to be free of the mizen-top. I succeeded in reaching it safely, though to a green hand, as I was, it looks and really feels somewhat perilous at first. I was sensible of the feeling of fear or apprehension just at the moment of getting over the cross-trees. Your body hangs over in mid-air, at a terrible incline backwards, and you have to hold on like anything for just one moment, until you get your knee up into the top. The view of the ship under press of canvas from the mizen-top is very grand; and the phosphorescence in our wake, billow upon billow of light shining foam, seemed more brilliant than ever.

The wind again freshens, and on the eleventh day we make another fine run of 230 miles. It is becoming rapidly warmer, and we shall soon be in the region of[Pg 20] bonitos, albatrosses, and flying fish—only a fortnight after leaving England!

Our second Sunday at sea was beautiful exceedingly. We had service in the saloon as usual; and, after church, I climbed the mizen, and had half an hour's nap on the top. Truly this warm weather, and monotonous sea life, seems very favourable for dreaming, and mooning, and loafing. In the evening there was some very good hymn-singing in the second-class cabin.

Early next morning, when pacing the poop, we were startled by the cry from the man on the forecastle of "Land ho!" I found, by the direction of the captain's eyes, that the land seen lay off our weather-beam. But, though I strained my eyes looking for the land, I could see nothing. It was not for hours that I could detect it; and then it looked more like a cloud than anything else. At length the veil lifted, and I saw the land stretching away to the eastward. It was the island of San Antonio, one of the Cape de Verds.

As we neared the land, and saw it more distinctly, it looked a grand object. Though we were then some fifteen miles off, yet the highest peaks, which were above the clouds, some thousands of feet high, were so clear and so beautiful that they looked as if they had been stolen out of the 'Arabian Nights,' or some fairy tale of wonder and beauty.

The island is said to be alike famous for its oranges and pretty girls. Indeed the Major, who is very good at drawing the long bow, declared that he could see a very interesting female waving her hand to him from[Pg 21] a rock! With the help of the telescope we could certainly see some of the houses on shore.

As this is the last land we are likely to see until we reach Australia, we regard it with all the greater interest; and I myself watched it in the twilight until it faded away into a blue mist on the horizon.

Increase of Temperature—Flying Fish—The Morning Bath on Board—Paying "Footings"—The Major's Wonderful Stories—St. Patrick's Day—Grampuses—A Ship in Sight—The 'Lord Raglan'—Rain-fall in the Tropics—Tropical Sunsets—The Yankee Whaler.

17th March.—We are now fairly within the tropics. The heat increases day by day. This morning, at eight, the temperature was 87° in my cabin. At midday, with the sun nearly overhead, it is really hot. The sky is of a cloudless azure, with a hazy appearance towards the horizon. The sea is blue, dark, deep blue—and calm.

Now we see plenty of flying-fish. Whole shoals of the glittering little things glide along in the air, skimming the tops of the waves. They rise to escape their pursuers, the bonitos, which rush after them, showing their noses above the water now and then. But the poor flying-fish have their enemies above the waters as well as under them; for they no sooner rise than they risk becoming the prey of the ocean birds, which are always hovering about and ready to pounce upon them. It is a case of "out of the frying-pan into the fire." They fly further than I thought they could. I[Pg 23] saw one of them to-day fly at least sixty yards, and sometimes they mount so high as to reach the poop, some fifteen feet from the surface of the water.

One of the most pleasant events of the day is the morning bath on board. You must remember the latitude we are in. We are passing along, though not in sight of, that part of the African coast where a necklace is considered full dress. We sympathise with the natives, for we find clothes becoming intolerable; hence our enjoyment of the morning bath, which consists in getting into a large tub on board and being pumped upon by the hose. Pity that one cannot have it later, as it leaves such a long interval between bath and breakfast; but it freshens one up wonderfully, and is an extremely pleasant operation. I only wish that the tub were twenty times as large, and the hose twice as strong.

The wind continues in our favour, though gradually subsiding. During the last two days we have run over 200 miles each day; but the captain says that by the time we reach the Line the wind will have completely died away. To catch a little of the breeze, I go up the rigging to the top. Two sailors came up mysteriously, one on each side of the ratlines. They are terrible fellows for making one pay "footings," and their object was to intercept my retreat downwards. When they reached me, I tried to resist; but it was of no use. I must be tied to the rigging unless I promised the customary bottle of rum; so I gave in with a good grace, and was thenceforward free to take an airing aloft.[Pg 24]

The amusements on deck do not vary much. Quoits, cards, reading, and talking, and sometimes a game of romps, such as "Walk, my lady, walk!" We have tried to form a committee, with a view to getting up some Penny Reading or theatrical entertainment, and to ascertain whether there be any latent talent aboard; but the heat occasions such a languor as to be very unfavourable for work, and the committee lay upon their oars, doing nothing.

One of our principal sources of amusement is the Major. He is unfailing. His drawings of the long bow are as good as a theatrical entertainment. If any one tells a story of something wonderful, he at once "caps it," as they say in Yorkshire, by something still more wonderful. One of the passengers, who had been at Calcutta, speaking of the heat there, said it was so great as to make the pitch run out of the ship's sides. "Bah!" said the Major, "that is nothing to what it is in Ceylon; there the heat is so great as to melt the soldiers' buttons off on parade, and then their jackets all get loose."

It seems that to-day (the 17th) is St. Patrick's Day. This the Major, who is an Irishman, discovered only late in the evening, when he declared he would have "given a fiver" if he had only known it in the morning. But, to make up for lost time, he called out forthwith, "Steward! whisky!" and he disposed of some seven or eight glasses in the saloon before the lamps were put out; after which he adjourned to one of the cabins, and there continued the celebration of St. Patrick's[Pg 25] Day until about two o'clock in the morning. On getting up rather late, he said to himself, loud enough for me to overhear in my cabin, "Well, George, my boy, you've done your duty to St. Patrick; but he's left you a horrible bad headache!" And no wonder.

At last there is a promised novelty on board. Some original Christy's Minstrels are in rehearsal, and the Theatrical Committee are looking up amateurs for a farce. Readings from Dickens are also spoken of. An occasional whale is seen blowing in the distance, and many grampuses come rolling about the ship,—most inelegant brutes, some three or four times the size of a porpoise. Each in turn comes up, throws himself round on the top of the sea, exposing nearly half his body, and then rolls off again.

To-day (the 20th March) we caught our first fish from the forecastle,—a bonito, weighing about seven pounds. Its colour was beautifully variegated: on the back dark blue, with a streak of light blue silver on either side, and the belly silvery white. These fish are usually caught from the jiboom and the martingale, as they play about the bows of the ship. The only bait is a piece of white rag, which is bobbed upon the surface of the water to imitate a flying-fish.

But what interests us more than anything else at present is the discovery of some homeward-bound ship, by which to despatch our letters to friends at home. The captain tells us that we are now almost directly in the track of vessels making for England from the south; and that if we do not sight one in the course of a day[Pg 26] or two, we may not have the chance of seeing another until we are far on our way south—if it all. We are, therefore, anxiously waiting for the signal of a ship in sight; and, in the hope that one may appear, we are all busily engaged in the saloon giving the finishing touches to our home letters.

Shortly after lunch the word was given that no less than three ships were in sight. Immense excitement on board! Everybody turned up on deck. Passengers who had never been seen since leaving Plymouth, now made their appearance to look out for the ships. One of them was a steamer, recognizable by the line of smoke on the horizon, supposed to be the West India mail-boat; another was outward-bound, like ourselves; and the third was the homeward-bound ship for which we were all on the look-out. She lay right across our bows, but was still a long way off. As we neared her, betting began among the passengers, led by the Major, as to whether she would take letters or not. The scene became quite exciting. The captain ordered all who had letters to be in readiness. I had been scribbling my very hardest ever since the ships came in sight, and now I closed my letter and sealed it up. Would the ship take our letters? Yes! She is an English ship, with an English flag at her peak; and she signals for newspapers, preserved milk, soap, and a doctor!

I petitioned for leave to accompany the doctor, and, to my great delight, was allowed to do so. The wind had nearly gone quite down, and only came in occasional slight gusts. The sea was, therefore, comparatively[Pg 27] calm, with only a long, slow swell; yet, even though calm, there is some little difficulty in getting down into a boat in mid-ocean. At one moment the boat is close under you, and at the next she is some four yards down, and many feet apart from the side of the ship; you have, therefore, to be prompt in seizing an opportunity, and springing on board just at the right moment.

As we moved away from the 'Yorkshire,' with a good bundle of newspapers and the other articles signalled for, and looked back upon our ship, she really looked a grand object on the waters. The sun shone full upon her majestic hull, her bright copper now and then showing as she slowly rose and sank on the long swell. Above all were her towers of white canvas, standing out in relief against the leaden-coloured sky. Altogether, I don't think I have ever seen a more magnificent sight. As we parted from the ship, the hundred or more people on board gave us a ringing cheer.

Our men now pulled with a will towards the still-distant ship. As we neared her, we observed that she must have encountered very heavy weather, as part of her foremast and mainmast had been carried away. Her sides looked dirty and worn, and all her ironwork was rusty, as if she had been a long time at sea. She proved to be the 'Lord Raglan,' of about 800 tons, bound from Bankok, in Siam, to Yarmouth.

The captain was delighted to see us, and gave us a most cordial welcome. He was really a very nice[Pg 28] fellow, and was kindness itself. He took us down to his cabin, and treated us to Chinese beer and cigars. The place was cheerful and comfortable-looking, and fitted up with Indian and Chinese curiosities; yet I could scarcely reconcile myself to living there. There was a dreadful fusty smell about, which, I am told, is peculiar to Indian and Chinese ships. The vessel was laden with rice, and the fusty heat which came up from below was something awful.

The 'Lord Raglan' had been nearly two years from London. She had run from London to Hong-Kong, and had since been engaged in trading between there and Siam. She was now eighty-three days from Bankok. In this voyage she had encountered some very heavy weather, in which she had sprung her foremast, which was now spliced up all round. What struck me was the lightness of her spars and the smallness of her sails, compared with ours. Although her mainmast is as tall, it is not so thick as our mizen, and her spars are very slender above the first top. Yet the 'Raglan,' in her best days, used to be one of the crack Melbourne clipper ships.

The kindly-natured captain was most loth to let us go. It was almost distressing to see the expedients he adopted to keep us with him for a few minutes longer. But it was fast growing dusk, and in the tropics it darkens almost suddenly; so we were at last obliged to tear ourselves away, and leave him with his soap, milk, and newspapers. He, on his part, sent by us a twenty-pound chest of tea, as a present for the chief[Pg 29] mate (who was with us) and the captain. As we left the ship's side we gave the master and crew of the 'Raglan' a hearty "three times three." All this while the two vessels had been lying nearly becalmed, so that we had not a very long pull before we were safely back on board our ship.

For about five days we lie nearly idle, making very little progress, almost on the Line. The trade-winds have entirely left us. The heat is tremendous—130° in the sun; and at midday, when the sun is right overhead, it is difficult to keep the deck. Towards evening the coolness is very pleasant; and when rain falls, as it can only fall in the tropics, we rush out to enjoy the bath. We assume the thinnest of bizarre costumes, and stand still under the torrent, or vary the pleasure by emptying buckets over each other.

We are now in lat. 0° 22', close upon the Equator. Though our sails are set, we are not sailing, but only floating: indeed, we seem to be drifting. On looking round the horizon, I count no fewer than sixteen ships in sight, all in the same plight as ourselves. We are drawn together by an under-current or eddy, though scarcely a breath of wind is stirring. We did not, however, speak any of the ships, most of them being comparatively distant.

We cross the Line about 8 p.m. on the twentieth day from Plymouth. We have certainly had a very fine run thus far, slow though our progress now is, for we are only going at the rate of about a mile an hour; but when we have got a little further south, we expect[Pg 30] to get out of the tropical calms and catch the southeast trade-winds.

On the day following, the 24th March, a breeze sprang up, and we made a run of 187 miles. We have now passed the greatest heat, and shortly expect cooler weather. Our spirits rise with the breeze, and we again begin to think of getting up some entertainments on board; for, though we have run some 4,800 miles from Plymouth, we have still some fifty days before us ere we expect to see Melbourne.

One thing that strikes me much is the magnificence of the tropical sunsets. The clouds assume all sorts of fantastic shapes, and appear more solid and clearly defined than I have ever seen before. Towards evening they seem to float in colour—purple, pink, red, and yellow alternately—while the sky near the setting sun seems of a beautiful green, gradually melting into the blue sky above. The great clouds on the horizon look like mountains tipped with gold and fiery red. One of these sunsets was a wonderful sight. The sun went down into the sea between two enormous clouds—the only ones to be seen—and they blazed with the brilliant colours I have described, which were constantly changing, until the clouds stood out in dark relief against the still delicately-tinted sky. I got up frequently to see the sun rise, but in the tropics it is not nearly so fine at its rising as at its setting.

A ship was announced as being in sight, with a signal flying to speak with us. We were sailing along under a favourable breeze, but our captain put the ship about[Pg 31] and waited for the stranger. It proved to be a Yankee whaler. When the captain came on board, he said "he guessed he only wanted newspapers." Our skipper was in a "roaring wax" at being stopped in his course for such a trivial matter, but he said nothing. The whaler had been out four years, and her last port was Honolulu in the Sandwich Islands. The Yankee captain, amongst other things, wanted to know if Grant was President, and if the 'Alabama' question was settled; he was interested in the latter question, as the 'Alabama' had burnt one of his ships. He did not seem very comfortable while on board, and when he had got his papers he took his leave. I could not help admiring the whale-boat in which he was rowed back to his own vessel. It was a beautiful little thing, though dirty; but, it had doubtless seen much service. It was exquisitely modelled, and the two seamen in the little craft handled it to perfection. How they contrived to stand up in it quite steady, while the boat, sometimes apparently half out of the water, kept rising and falling on the long ocean-swell, seemed to me little short of marvellous.

April Fools' Day—A Ship in Sight—The 'Pyrmont'—The Rescued 'Blue Jacket' Passengers—Story of the Burnt Ship—Suffering of the Lady Passengers in an Open Boat—Their Rescue—Distressing Scene on Board the 'Pyrmont.'

1st. April.—I was roused early this morning by the cry outside of "Get up! get up! There is a ship on fire ahead!" I got up instantly, dressed, and hastened on deck, like many more. But there was no ship on fire; and then we laughed, and remembered that it was All Fools' Day.

In the course of the forenoon we descried a sail, and shortly after we observed that she was bearing down upon us. The cry of "Letters for home!" was raised, and we hastened below to scribble a few last words, close our letters, and bring them up for the letter-bag.

By this time the strange ship had drawn considerably nearer, and we saw that she was a barque, heavily laden. She proved to be the 'Pyrmont,' a German vessel belonging to Hamburg, but now bound for Yarmouth from Iquique, with a cargo of saltpetre on board. When she came near enough to speak to us, our captain asked, "What do you want?" The answer was, "'Blue Jacket' burnt at sea; her passengers on[Pg 33] board. Have you a doctor?" Here was a sensation! Our April Fools' alarm was true after all. A vessel had been on fire, and here were the poor passengers asking for help. We knew nothing of the 'Blue Jacket,' but soon we were to know all.

A boat was at once lowered from the davits, and went off with the doctor and the first mate. It was a hazy, sultry, tropical day, with a very slight breeze stirring, and very little sea. Our main-yard was backed to prevent our further progress, and both ships lay-to within a short distance of each other. We watched our boat until we saw the doctor and officer mount the 'Pyrmont,' and then waited for further intelligence.

Shortly after we saw our boat leaving the ship's side, and as it approached we observed that it contained some strangers, as well as our doctor, who had returned for medicines, lint, and other appliances. When the strangers reached the deck we found that one of them was the first officer of the unfortunate 'Blue Jacket,' and the other one of the burnt-out passengers. The latter, poor fellow, looked a piteous sight. He had nothing on but a shirt and pair of trowsers; his hair was matted, his face haggard, his eyes sunken. He was without shoes, and his feet were so sore that he could scarcely walk without support.

And yet it turned out that this poor suffering fellow was one of the best-conditioned of those who had been saved from the burnt ship. He told us how that the whole of the fellow-passengers whom he had just left on board the 'Pyrmont' wanted clothes, shirts, and[Pg 34] shoes, and were in a wretched state, having been tossed about at sea in an open boat for about nine days, during which they had suffered the extremities of cold, thirst, and hunger.

We were horrified by the appearance, and still more by the recital, of the poor fellow. Every moment he astonished us by new details of horror. But it was of no use listening to more. We felt we must do something. All the passengers at once bestirred themselves, and went into their cabins to seek out any clothing they could spare for the relief of the sufferers. I found I could give trowsers, shirts, a pair of drawers, a blanket, and several pocket-handkerchiefs; and as the other passengers did likewise, a very fair bundle was soon made up and sent on board the 'Pyrmont.'

Of course we were all eager to know something of the details of the calamity which had befallen the 'Blue Jacket.' It was some time before we learnt them all; but as two of the passengers—who had been gold-diggers in New Zealand—were so good as to write out a statement for the doctor, the original of which now lies before me, I will endeavour, in as few words as I can, to give you some idea of the burning of the ship and the horrible sufferings of the passengers.

The 'Blue Jacket' sailed from Port Lyttleton, New Zealand, for London on the 13th February, 1869, laden with wool, cotton, flax, and 15,000 ounces of gold. There were seven first-cabin passengers and seventeen second-cabin. The ship had a fine run to Cape Horn and past the Falkland Islands. All went well until[Pg 35] the 9th March, when in latitude 50° 26' south, one of the seamen, about midday, observed smoke issuing from the fore-hatchhouse. The cargo was on fire! All haste was made to extinguish it. The fire-engines were set to work, passengers as well as crew working with a will, and at one time it seemed as if the fire would be got under. The hatch was opened and the second mate attempted to go down, with the object of getting up and throwing overboard the burning bales, but he was drawn back insensible. The hatch was again closed, and holes were cut in the deck to pass the water down; but the seat of the fire could not be reached. The cutter was lowered, together with the two lifeboats, for use in case of need. About 7.30 p.m. the fire burst through the decks, and in about half an hour the whole forecastle was enveloped in flames, which ran up the rigging, licking up the foresail and fore-top. The mainmast being of iron, the flames rushed through the tube as through a chimney, until it became of a white heat. The lady-passengers in the after part of the ship must have been kept in a state of total ignorance of the ship's danger, otherwise it is impossible to account for their having to rush on board the boats, at the last moment, with only the dresses they wore. Only a few minutes before they left the ship, one of the ladies was playing the 'Guards' Waltz on the cabin piano!

There was no hope of safety but in the boats, which were hurriedly got into. On deck, everything was in a state of confusion. Most of the passengers got[Pg 36] into the cutter, but without a seaman to take charge of it. When the water-cask was lowered, it was sent bung downwards, and nearly half the water was lost. By this time the burning ship was a grand but fearful sight, and the roar of the flames was frightful to hear. At length the cutter and the two lifeboats got away, and as they floated astern the people in them saw the masts disappear one by one and the hull of the ship a roaring mass of fire.

In the early grey of the morning the three boats mustered, and two of the passengers, who were on one of the lifeboats, were taken on board the cutter. It now contained 37 persons, including the captain, first officer, doctor, steward, purser, several able-bodied seamen, and all the passengers; while the two lifeboats had 31 of the crew. The boats drifted about all day, there being no wind, and the burning ship was still in sight. On the third day the lifeboats were not to be seen; each had a box of gold on board, by way of ballast.

A light breeze having sprung up, sail was made on the cutter, the captain intending to run for the Falkland Islands. The sufferings of the passengers increased from day to day; they soon ran short of water, until the day's allowance was reduced to about two tablespoonfuls for each person. It was pitiful to hear the little children calling for more, but it could not be given them: men, women, and children had to share alike. Provisions failed. The biscuit had been spoiled by the salt water; all that remained in the way of food,[Pg 37] was preserved meat, which was soon exhausted, after which the only allowance, besides the two tablespoonfuls of water, was a tablespoonful of preserved soup every twenty-four hours. Meanwhile the wind freshened, the sea rose, and the waves came dashing over the passengers, completely drenching them. The poor ladies, thinly clad, looked the pictures of misery.

Thus seven days passed—days of slow agony, such as words cannot describe—until at last the joyous words, "A sail! a sail," roused the sufferers to new life. A man was sent to the masthead with a red blanket to hoist by way of signal of distress. The ship saw the signal and bore down upon the cutter. She proved to be the 'Pyrmont,' the ship lying within sight of us, and between which and the 'Yorkshire' our boat kept plying for the greater part of the day.

Strange to say, the rescued people suffered more after they had got on board the 'Pyrmont' than they had done during their period of starvation and exposure. Few of them could stand or walk when taken on board, all being reduced to the last stage of weakness. Scarcely had they reached the 'Pyrmont' ere the third steward died; next day the ship's purser died insane; and two days after, one of the second-cabin passengers died. The others, who recovered, broke out in sores and boils, more particularly on their hands and feet; and when the 'Yorkshire' met them, many of the passengers as well as the crew of the burnt 'Blue Jacket' were in a most pitiable plight.

I put off with the third boat which left our ship's[Pg 38] side for the 'Pyrmont.' We were lying nearly becalmed all this time, so that passing between the ships by boat was comparatively easy. We took with us as much fresh water as we could spare, together with provisions and other stores. I carried with me a few spare books for the use of the 'Blue Jacket' passengers.

On reaching the deck of the 'Pyrmont,' the scene which presented itself was such as I think I shall never forget. The three rescued ladies were on the poop; and ladies you could see they were, in spite of their scanty and dishevelled garments. The dress of one of them consisted of a common striped man's shirt, a waterproof cloak made into a skirt, and a pair of coarse canvas slippers, while on her finger glittered a magnificent diamond ring. The other ladies were no better dressed, and none of them had any covering for the head. Their faces bore distinct traces of the sufferings they had undergone. Their eyes were sunken, their cheeks pale, and every now and then a sort of spasmodic twitch seemed to pass over their features. One of them could just stand, but could not walk; the others were comparatively helpless. A gentleman was lying close by the ladies, still suffering grievously in his hands and feet from the effects of his long exposure in the open boat, while one side of his body was completely paralysed. One poor little boy could not move, and the doctor said he must lose one or two of his toes through mortification.

One of the ladies was the wife of the passenger gentleman who had first come on board of our ship.[Pg 39] She was a young lady, newly married, who had just set out on her wedding trip. What a terrible beginning of married life! I found she had suffered more than the others through her devotion to her husband. He was, at one time, constantly employed in baling the boat, and would often have given way but for her. She insisted on his taking half her allowance of water, so that he had three tablespoonfuls daily instead of two; whereas she had only one!

While in the boat the women and children were forced to sit huddled up at one end of it, covered with a blanket, the seas constantly breaking over them and soaking through everything. They had to sit upright, and in very cramped postures, for fear of capsizing the boat; and the little sleep they got could only be snatched sitting. Yet they bore their privations with great courage and patience, and while the men were complaining and swearing, the women and children never uttered a complaint.

I had a long talk with the ladies, whom I found very resigned and most grateful for their deliverance. I presented my books, which were thankfully received, and the newly-married lady, forgetful of her miseries, talked pleasantly and intelligently about current topics, and home news. It did seem strange for me to be sitting on the deck of the 'Pyrmont,' in the middle of the Atlantic, talking with these shipwrecked ladies about the last new novel!

At last we took our leave, laden with thanks, and returned on board our ship. It was now growing dusk.[Pg 40] We had done all that we could for the help of the poor sufferers on board the 'Pyrmont,' and, a light breeze springing up, all sail was set, and we resumed our voyage south.

Two of the gold-diggers, who had been second-class passengers by the 'Blue Jacket,' came on board our ship with the object of returning with us to Melbourne, and it is from their recital that I have collated the above account of the disaster.

Preparing for Rough Weather—The 'George Thompson' Clipper—A Race at Sea—Scene from 'Pickwick' Acted—Fishing For Albatross—Dissection and Division of the Bird—Whales—Strong Gale—Smash in the Cabin—Shipping a Green Sea—The Sea Birds in our Wake—The Crozet Islands.

11th April.—We are now past the pleasantest part of our voyage, and expect to encounter much rougher seas. Everything is accordingly prepared for heavy weather. The best and newest sails are bent; the old and worn ones are sent below. We may have to encounter storms or even cyclones in the Southern Ocean, and our captain is now ready for any wind that may blow. For some days we have had a very heavy swell coming up from the south, as if there were strong winds blowing in that quarter. We have, indeed, already had a taste of dirty weather to-day—hard rain, with a stiffish breeze; but as the ship is still going with the wind and sea, we do not as yet feel much inconvenience.

A few days since, we spoke a vessel that we had been gradually coming up to for some time, and she proved to be the 'George Thompson,' a splendid Aberdeen-built clipper, one of the fastest ships out of London. No sooner[Pg 42] was this known, than it became a matter of great interest as to whether we could overhaul the clipper. Our ship, because of the height and strength of her spars, enables us to carry much more sail, and we are probably equal to the other ship in lighter breezes; but she, being clipper-built and so much sharper, has the advantage of us in heavier winds. The captain was overjoyed at having gained upon the other vessel thus far, for she left London five days before we sailed from Plymouth. As we gradually drew nearer, the breeze freshened, and there became quite an exciting contest between the ships. We gained upon our rival, caught up to her, and gradually forged ahead, and at sundown the 'George Thompson' was about six miles astern. Before we caught up to her she signalled to us, by way of chaff, "Signal us at Lloyd's!" and when we had passed her, we signalled back, "We wish you a good voyage!"

The wind having freshened during the night, the 'George Thompson' was seen gradually creeping up to us with all her sail set. The wind was on our beam, and the 'George Thompson's' dark green hull seemed to us sometimes almost buried in the sea, and we only saw her slanting deck as she heeled over from the freshening breeze. What a cloud of canvas she carried! The spray flew up and over her decks, as she plunged right through the water.

The day advanced; she continued to gain, and towards evening she passed on our weather-side. The captain, of course, was savage; but the race was not[Pg 43] lost yet. On the following day, with a lighter wind, we again overhauled our rival, and at night left her four or five miles behind. Next day she was not to be seen. We had thus far completely outstripped the noted clipper.[1]

We again begin to reconsider the question of giving a popular entertainment on board. The ordinary recreations of quoit-playing, and such like, have become unpopular, and a little variety is wanted. A reading from 'Pickwick' is suggested; but cannot we contrive to act a few of the scenes! We determine to get up three of the most attractive:—1st. The surprise of Mrs. Bardell in Pickwick's arms; 2nd. The notice of action from Dodson and Fogg; and 3rd. The Trial scene. A great deal of time is, of course, occupied in getting up the scenes, and in the rehearsals, which occasion a good deal of amusement. A London gentleman promises to make a capital Sam Weller; our clergyman a very good Buzfuz; and our worthy young doctor the great Pickwick himself.

At length all is ready, and the affair comes off in the main-hatch, where there is plenty of room. The theatre is rigged out with flags, and looks quite gay. The passengers of all classes assemble, and make a goodly company. The whole thing went off very well—indeed, much better than was expected—though I do not think the third-class passengers quite appreciated[Pg 44] the wit of the piece. Strange to say, the greatest success of the evening was the one least expected—the character of Mrs. Cluppins. One of the middies who took the part, was splendid, and evoked roars of laughter.

Our success has made us ambitious, and we think of getting up another piece—a burlesque, entitled 'Sir Dagobert and the Dragon,' from one of my Beeton's 'Annuals.' There is not much in it; but, faute de mieux, it may do very well. But to revert to less "towny" and much more interesting matters passing on board.

We were in about the latitude of the Cape of Good Hope when we saw our first albatross; but as we proceeded south, we were attended by increasing numbers of those birds as well as of Mother Carey's chickens, the storm-birds of the South Seas. The albatross is a splendid bird, white on the breast and the inside of the wings, the rest of the body being deep brown and black.

One of the most popular amusements is "fishing" for an albatross, which is done in the following manner. A long and stout line is let out, with a strong hook at the end baited with a piece of meat, buoyed up with corks. This is allowed to trail on the water at the stern of the ship. One or other of the sea-birds wheeling about, seeing the floating object in the water, comes up, eyes it askance, and perhaps at length clumsily flops down beside it. The line is at once let out, so that the bait may not drag after the ship. If this be[Pg 45] done cleverly, and there be length enough of line to let out quickly, the bird probably makes a snatch at the meat, and the hook catches hold of his curved bill. Directly he grabs at the pork, and it is felt that the albatross is hooked, the letting out of the line is at once stopped, and it is hauled in with all speed. The great thing is to pull quickly, so as to prevent the bird getting the opportunity of spreading his wings, and making a heavy struggle as he comes along on the surface of the water. It is a good heavy pull for two men to get up an albatross if the ship is going at any speed. The poor fellow, when hauled on deck, is no longer the royal bird that he seemed when circling above our heads with his great wings spread out only a few minutes ago. Here he is quite helpless, and tries to waddle about like a great goose; the first thing he often does being to void all the contents of his stomach, as if he were seasick.

The first albatross we caught was not a very large one, being only about ten feet from tip to tip of the wings; whereas the larger birds measure from twelve to thirteen feet. The bird, when caught, was held firmly down, and despatched by the doctor with the aid of prussic acid. He was then cut up, and his skin, for the sake of the feathers and plumage, divided amongst us. The head and neck fell to my share, and, after cleaning and dressing it, I hung my treasure by a string out of my cabin-window; but, when I next went to look at it, lo! the string had been cut, and my albatross's head and neck were gone.[Pg 46]

All day the saloon and various cabins smelt very fishy by reason of the operations connected with the dissecting and cleaning of the several parts of the albatross. One was making a pipe-stem out of one of the long wing-bones. Another was making a tobacco pouch out of the large feet of the bird. The doctor's cabin was like a butcher's shop in these bird-catching times. Part of his floor would be occupied by the bloody skin of the great bird, stretched out upon boards, with the doctor on his knees beside it working away with his dissecting scissors and pincers, getting the large pieces of fat off the skin. Esculapius seemed quite to relish the operation; whilst, on the other hand the clergyman, who occupied the same cabin, held his handkerchief to his nose, and regarded the débris of flesh and feathers on the floor with horror and dismay.

Other birds, of a kind we had not before seen shortly made their appearance, flying round the ship. There is, for instance, the whale-bird, perfectly black on the top of the wings and body, and white underneath. It is, in size, between a Mother Carey and a Molly-hawk, which latter is very nearly as big as an albatross. Ice-birds and Cape-pigeons also fly about us in numbers; the latter are about the size of ordinary pigeons, black, mottled with white on the back, and grey on the breast.

A still more interesting sight was that of a great grampus, which rose close to the ship, exposing his body as he leapt through a wave. Shortly after, a few[Pg 47] more were seen at a greater distance, as if playing about and gambolling for our amusement.

17th April.—The weather is growing sensibly colder. Instead of broiling under cover, in the thinnest of garments, we now revert to our winter clothing for comfort. Towards night the wind rose, and gradually increased until it blew a heavy gale, so strong that all the sails had to be taken in—all but the foresail and the main-topsail closely reefed. Luckily for us, the wind was nearly aft, so that we did not feel its effects nearly so much as if it had been on our beam. Tonight we rounded the Cape, twenty-four days from the Line and forty-five from Plymouth.

On the following day the wind was still blowing hard. When I went on deck in the morning, I found that the mainsail had been split up the middle, and carried away with a loud bang to sea. The ship was now under mizen-topsail, close-reefed main-topsail, and fore-topsail and foresail, no new mainsail having been bent. The sea was a splendid sight. Waves, like low mountains, came rolling after us, breaking along each side of the ship. I was a personal sufferer by the gale. I had scarcely got on deck when the wind whisked off my Scotch cap with the silver thistle in it, and blew it away to sea. Then, in going down to my cabin, I found my books, boxes, and furniture lurching about; and, to wind up with, during the evening I was rolled over while sitting on one of the cuddy chairs, and broke it. Truly a day full of small misfortunes for me![Pg 48]

In the night I was awakened by the noise and the violent rolling of the ship. The mizen-mast strained and creaked; chairs had broken loose in the saloon; crockery was knocking about and smashing up in the steward's pantry. In the cabin adjoining, the water-can and bath were rambling up and down; and in the midst of all the hubbub the Major could be heard shouting, "Two to one on the water-can!" "They were just taking the fences," he said. There were few but had some mishap in their cabins. One had a hunt after a box that had broken loose; another was lamenting the necessity of getting up after his washhand-basin and placing his legs in peril outside his bunk. Before breakfast I went on deck to look at the scene. It was still blowing a gale. We were under topsails and mainsail, with a close-reefed top-sail on the mizen-mast. The sight from the poop is splendid. At one moment we were high up on the top of a wave, looking into a deep valley behind us; at another we were down in the trough of the sea, with an enormous wall of water coming after us. The pure light-green waves were crested with foam, which curled over and over, and never stopped rolling. The deck lay over at a dreadful slant to a landsman's eye; indeed, notwithstanding holding on to everything I could catch, I fell four times during the morning.

With difficulty I reached the saloon, where the passengers had assembled for breakfast. Scarcely had we taken out seats when an enormous sea struck the ship, landed on the poop, dashed in the saloon skylight, and[Pg 49] flooded the table with water. This was a bad event for those who had not had their breakfast. As I was mounting the cuddy stairs, I met the captain coming down thoroughly soaked. He had been knocked down, and had to hold on by a chain to prevent himself being washed about the deck. The officer of the watch afterwards told me that he had seen his head bobbing up and down amidst the water, of which there were tons on the poop.

This was what they call "shipping a green sea,"—so called because so much water is thrown upon the deck that it ceases to have the frothy appearance of smaller seas when shipped, but looks a mass of solid green water. Our skipper afterwards told us at dinner that the captain of the 'Essex' had not long ago been thrown by such a sea on to one of the hen-coops that run round the poop, breaking through the iron bars, and that he had been so bruised that he had not yet entirely recovered from his injuries. Such is the tremendous force of water in violent motion at sea.[2]

When I went on deck again, the wind had somewhat abated, but the sea was still very heavy. While on the poop, one enormous wave came rolling on after us, seeming as if it must engulf the ship. But the stern rose gradually and gracefully as the huge wave came on, and it rolled along, bubbling over the sides of the main-deck, and leaving it about two feet deep in water.[Pg 50] As the day wore on the wind gradually went down, and it seemed as if we were to have another spell of fine weather.