OSCAR, II

OSCAR, IITitle: The Voyage of the Vega round Asia and Europe, Volume I and Volume II

Author: A. E. Nordenskiöld

Translator: active 1879-1882 Alexander Leslie

Release date: January 20, 2008 [eBook #24365]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Eric Hutton and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/Million Book Project)

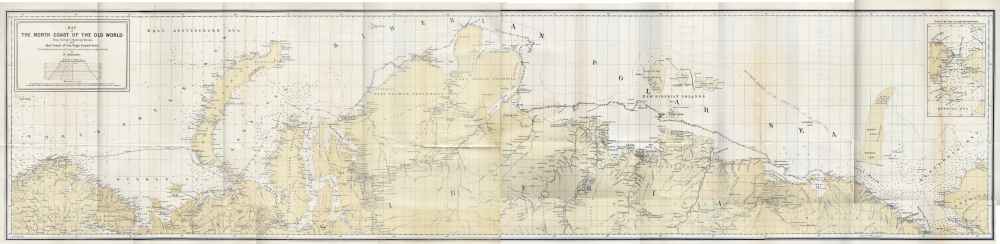

WITH A HISTORICAL REVIEW

OF PREVIOUS JOURNEYS ALONG THE NORTH COAST OF THE

OLD WORLD

TRANSLATED BY ALEXANDER LESLIE

WITH FIVE STEEL PORTRAITS, NUMEROUS MAPS, AND ILLUSTRATIONS

London

MACMILLON AND CO.

1881

IN TWO VOLUMES—VOL. I TO HIS MAJESTY

KING OSCAR II.

THE HIGH PROTECTOR OF THE VEGA EXPEDITION

THIS SKETCH OF THE VOYAGE

HE SO MAGNANIMOUSLY AND GENEROUSLY PROMOTED

IS WITH THE DEEPEST GRATITUDE

MOST HUMBLY

DEDICATED

BY

In the work now published I have, along with the sketch of the voyage of the Vega round Asia and Europe, of the natural conditions of the north coast of Siberia, of the animal and vegetable life prevailing there, and of the peoples with whom we came in contact in the course of our journey, endeavoured to give a review, as complete as space permitted, of previous exploratory voyages to the Asiatic Polar Sea. It would have been very ungrateful on my part if I had not referred at some length to our predecessors, who with indescribable struggles and difficulties—and generally with the sacrifice of health and life—paved the way along which we advanced, made possible the victory we achieved. In this way besides the work itself has gained a much-needed variety, for nearly all the narratives of the older North-East voyages contain in abundance what a sketch of our adventures has not to offer; for many readers perhaps expect to find in a book such as this accounts of dangers and misfortunes of a thousand sorts by land and sea. May the contrast which thus becomes apparent between the difficulties our predecessors had to contend with and those which the Vega met with during her voyage incite to new exploratory expeditions to the sea, which now, for the first time, has been ploughed by the keel [pg xi] of a sea-going vessel, and conduce to dissipate a prejudice which for centuries has kept the most extensive cultivable territory on the globe shut out from the great Oceans of the World.

The work is furnished with numerous maps and illustrations, and is provided with accurate references to sources of geographical information. For this I am indebted both to the liberal conception which my publisher, Herr FRANS BEIJER, formed of the way in which the work should be executed, and the assistance I have received while it was passing through the press from Herr E.W. Dahlgren, amanuensis at the Royal Library, for which it is a pleasant duty publicly to offer them my hearty thanks.

A.E. NORDENSKIÖLD.

STOCKHOLM, 8th October, 1881. [pg xii]

Having been honoured by a request from Baron Nordenskiöld that I would undertake the translation of the work in which he gives an account of the voyage by which the North-East Passage was at last achieved, and Asia and Europe circumnavigated for the first time, I have done my best to reproduce in English the sense of the Swedish original as faithfully as possible, and at the same time to preserve the style of the author as far as the varying idioms of the two languages permit.

I have to thank two ladies for the help they kindly gave me in reading proofs, and my friend Herr GUSTAF LINDSTRÖM, for valuable assistance rendered in various ways.

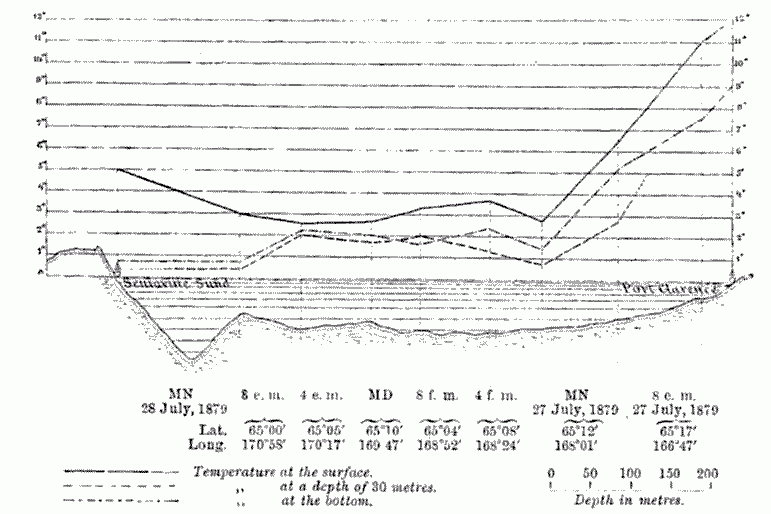

Where not otherwise indicated, temperature is stated in degrees of the Centigrade or Celsius thermometer. Longitude is invariably reckoned from the meridian of Greenwich.

Where distance is stated in miles without qualification, the miles are Swedish (one of which is equal to 6.64 English miles), except at page 372, Vol. I., where the geographical square miles are German, each equal to sixteen English geographical square miles.

ALEX. LESLIE.

CHERRYVALE, ABERDEEN, 24th November, 1881. [pg xiii]

Departure—Tromsoe—Members of the Exhibition—Stay at Maosoe—Limit of Trees—Climate—Scurvy and Antiscorbutics—The first doubling of North Cape—Othere's account of his Travels—Ideas concerning the Geography of Scandinavia current during the first half of the sixteenth century—The oldest Maps of the North—Herbertstein's account of Istoma's voyage—Gustaf Vasa and the North-East Passage—Willoughby and Chancellor's voyages

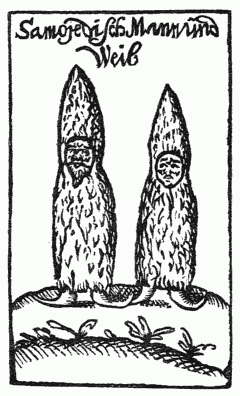

Departure from Maosoe—Gooseland—State of the Ice—The Vessels of the Expedition assemble at Chabarova—The Samoyed town there—The Church—Russians and Samoyeds—Visit to Chabarova in 1875—Purchase of Samoyed Idols—Dress and dwellings of the Samoyeds—Comparison of the Polar Races—Sacrificial Places and Samoyed Grave on Waygats Island visited—Former accounts of the Samoyeds—Their place in Ethnography.

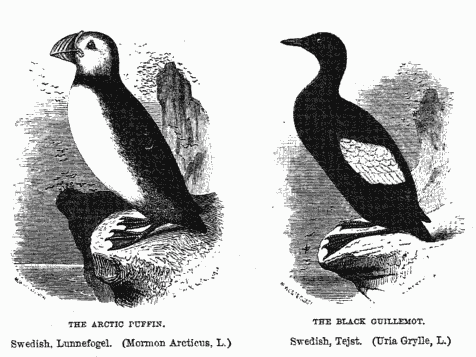

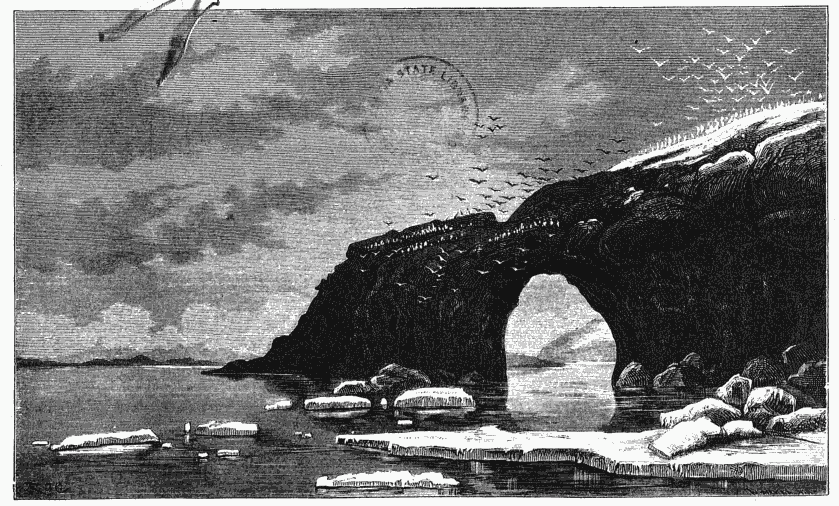

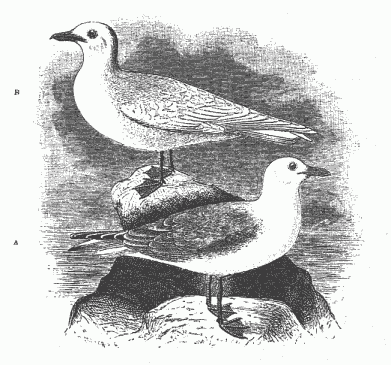

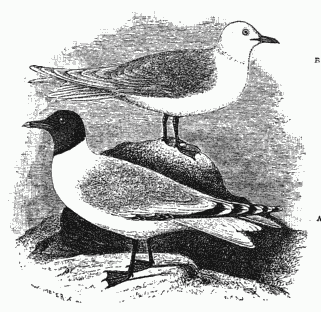

From the Animal World of Novaya Zemlya—The Fulmar Petrel—The Rotge or Little Auk—Brünnich's Guillemot—The Black Guillemot—The Arctic Puffin—The Gulls—Richardson's Skua—The Tern—Ducks and Geese—The Swan—Waders—The Snow Bunting—The Ptarmigan—The Snowy Owl—The Reindeer—The Polar Bear—The Arctic Fox—The Lemming—Insects—The Walrus—The Seal—Whales.

The Origin of the names Yugor Schar and Kara Sea—Rules for Sailing through Yugor Schar—The "Highest Mountain" on Earth—Anchorages—Entering the Kara Sea—Its Surroundings—The Inland-ice of Novaya Zemlya—True Icebergs rare in certain parts of the Polar Sea—The Natural Conditions of [pg xiv] the Kara Sea—Animals, Plants, Bog-ore—Passage across the Kara Sea—The Influence of the Ice on the Sea-bottom—Fresh-water Diatoms on Sea-ice—Arrival at Port Dickson—Animal Life there—Settlers and Settlements at the Mouth of the Yenisej—The Flora at Port Dickson—Evertebrates—Excursion to White Island—Yalmal—Previous Visits—Nummelin's Wintering on the Briochov Islands.

The history of the North-east Passage from 1556 to 1878—Burrough, 1556—Pet and Jackman, 1580—The first voyage of the Dutch, 1594—Oliver Brunel—The second voyage, 1595—The third voyage, 1596—Hudson, 1608—Gourdon, 1611—Bosman, 1625—De la Martinière, 1653—Vlamingh, 1664—Snobberger, 1675—Roule reaches a land north of Novaya Zemlya—Wood and Flawes, 1676—Discussion in England concerning the state of the ice in the Polar Sea—Views of the condition of the Polar Sea still divided—Payer and Weyprecht, 1872-74.

The North-east Voyages of the Russians and Norwegians—Rodivan Ivanov, 1690—The Great Northern Expedition 1734-37—The supposed Richness in metals of Novaya Zemlya—Iuschkov, 1757—Savva Loschkin, 1760—Rossmuislov, 1768—Lasarev, 1819—Lütke, 1821-24—Ivanov, 1822-28—Pachtussov, 1832-35—Von Baer, 1837—Zivolka and Moissejev, 1838-39—Von Krusenstern, 1860-62—The Origin and History of the Polar Sea Hunting—Carlsen, 1868—Ed. Johannesen, 1869-70—Ulve, Mack, and Quale, 1870—Mack, 1871—Discovery of the Relics of Barent's wintering—Tobiesen's wintering 1872-73—The Swedish Expeditions 1875 and 1876—Wiggins, 1876—Later voyages to and from the Yenisej.

Departure from Port Dickson—Landing on a rocky island east of the Yenisej—Self-dead animals—Discovery of crystals on the surface of the drift-ice—Cosmic dust—Stay in Actinia Bay—Johannesen's discovery of the island Ensamheten—Arrival at Cape Chelyuskin—The natural state of the land and sea there—Attempt to penetrate right eastwards to the New Siberian Islands—The effect of the mist—Abundant dredging-yield—Preobraschenie Island—Separation from the Lena at the mouth of the river Lena.

The voyage of the Fraser and the Express up the Yenisej and their return to Norway—Contract for the piloting of the Lena up the Lena river—The voyage of the Lena through the delta and up the river to Yakutsk—The natural state of Siberia in general—The river territories—The fitness of the [pg xv] land for cultivation and the necessity for improved communications—The great rivers, the future commercial highways of Siberia—Voyage up the Yenisej in 1875—Sibiriakoff's Island—The tundra—The primeval Siberian forest—The inhabitants of Western Siberia: the Russians, the Exiles, the "Asiatics"—Ways of travelling on the Yenisej, dog-boats, floating trading stores propelled by steam—New prospects for Siberia.

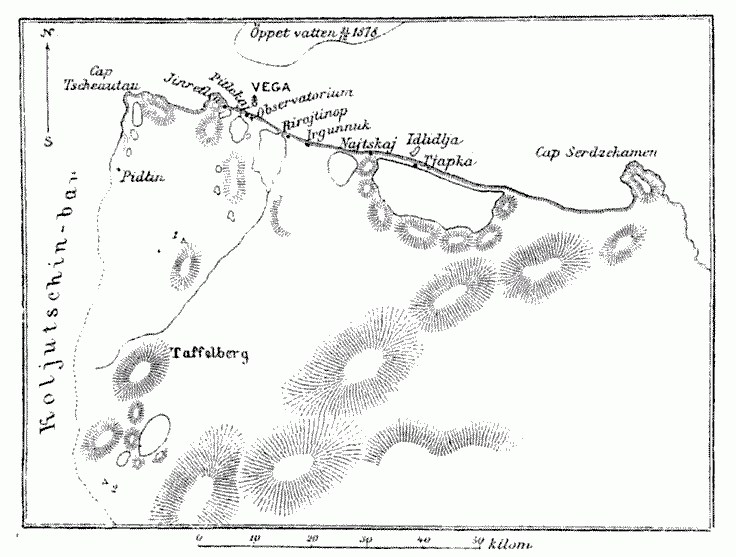

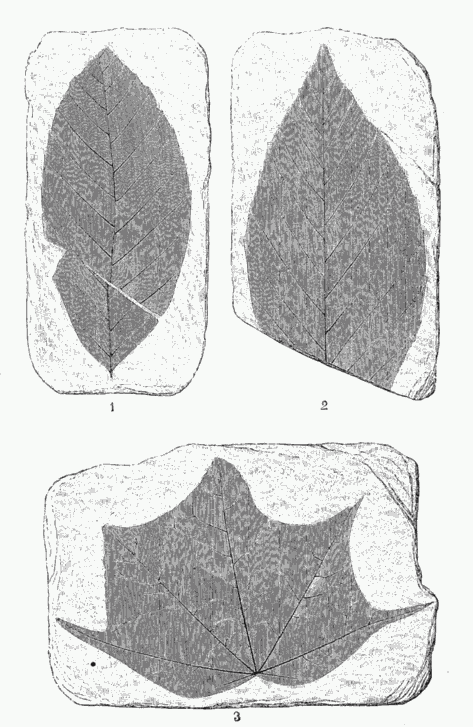

The new Siberian Islands—The Mammoth—Discovery of Mammoth and Rhinoceros mummies—Fossil Rhinoceros horns—Stolbovoj Island—Liachoff Island—First discovery of this island—Passage through the sound between this island and the mainland—Animal life there—Formation of ice in water above the freezing point—The Bear Islands—The quantity and dimensions of the ice begin to increase—Different kinds of sea-ice—Renewed attempt to leave the open channel along the coast—Lighthouse Island—Voyage along the coast to Cape Schelagskoj—Advance delayed by ice, shoals, and fog—First meeting with the Chukches—Landing and visits to Chukch villages—Discovery of abandoned encampments—Trade with the natives rendered difficult by the want of means of exchange—Stay at Irkaipij—Onkilon graves—Information regarding the Onkilon race—Renewed contact with the Chukches—Kolyutschin Bay—American statements regarding the state of the ice north of Behring's Straits—The Vega beset.

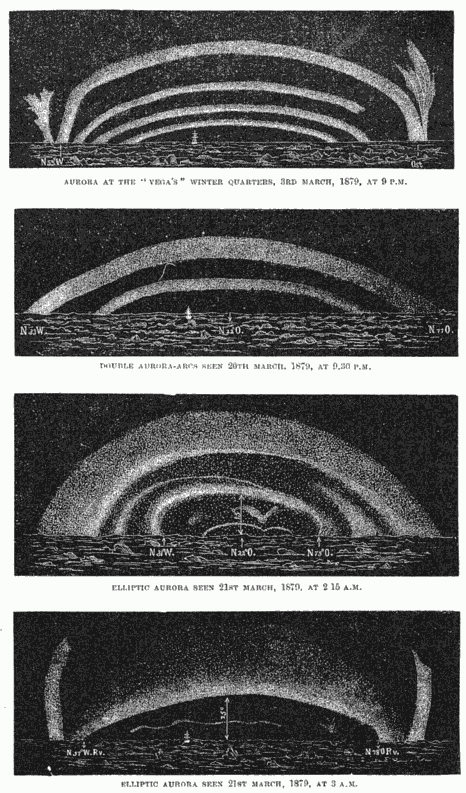

Wintering becomes necessary—The position of the Vega—The ice round the vessel—American ship in the neighbourhood of the Vega when frozen in—The nature of the neighbouring country—The Vega is prepared for wintering—Provision-depôt and observatories established on land—The winter dress—Temperature on board—Health and dietary—Cold, wind, and snow—The Chukches on board—Menka's visit—Letters sent home—Nordquist and Hovgaard's excursion to Menka's encampment—Another visit of Menka—The fate of the letters—Nordquist's journey to Pidlin—Find of a Chukch grave—Hunting—Scientific work—Life on board—Christmas Eve. [pg xvi]

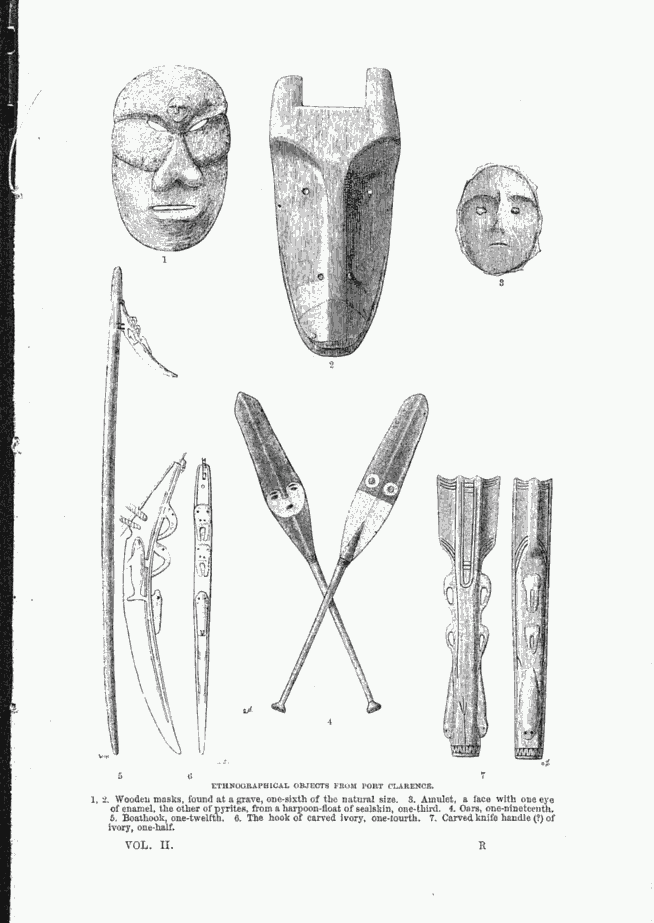

Engraved on Steel by G.J. Stodart of London.

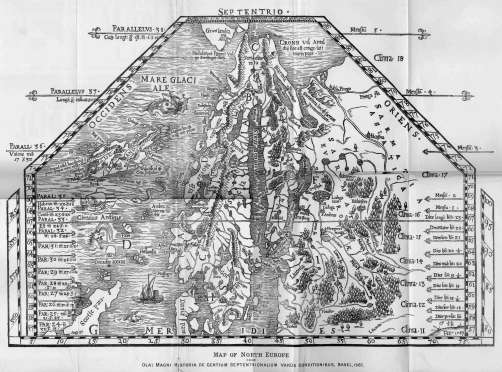

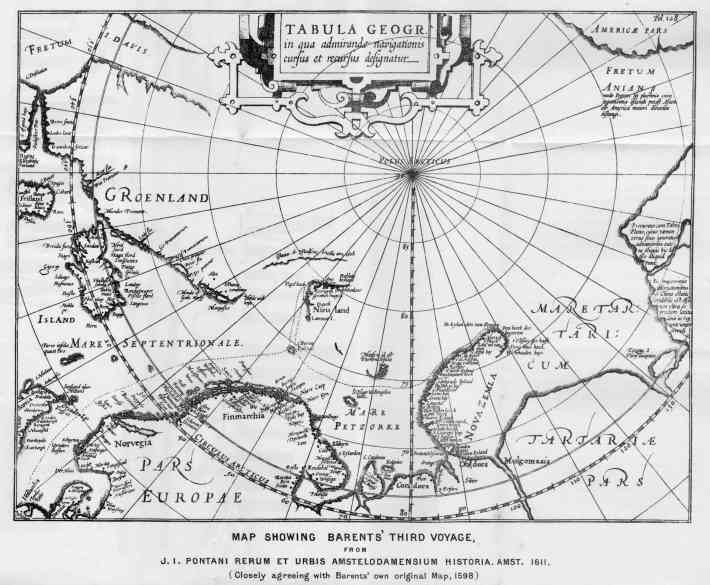

1. Map of North Europe, from Nicholas Donis's edition of Ptolemy's Cosmographia, Ulm, 1482

2. Map of the North, from Jakob Ziegler's Schondia, Strassburg, 1532

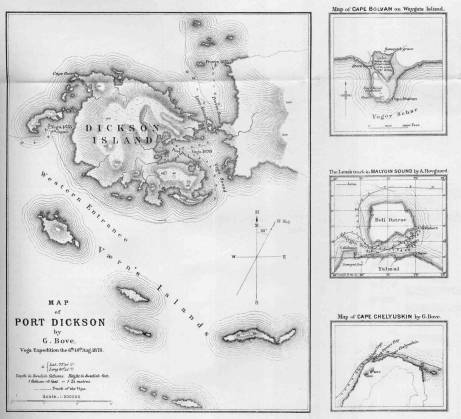

7. Sketch-Map of Taimur Sound; Map of Actinia Bay, both by G. Bove

8. Map of the River System of Siberia

The wood-cuts, when not otherwise stated below, were engraved at Herr Wilhelm Meyer's Xylographic Institute in Stockholm.

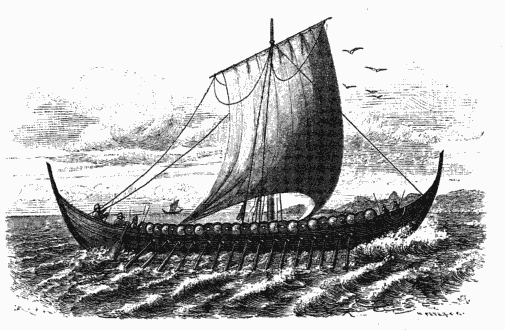

1. The Vega under sail, drawn by Captain J. Hagg

2. The Vega—Longitudinal section, drawn by Lieut. C.A.M. Hjulhammar

3. " " Plan of arrangement under deck, drawn by ditto

4. " " Plan of upper deck, drawn by ditto

5. The Lena—Longitudinal section, drawn by Marine-engineer J. Pihlgren

6. " " Plan of arrangement under deck, drawn by ditto

7. " " Plan of upper deck, drawn by ditto

8. Flag of the Swedish Yacht Club, drawn by V. Andrén

9. Tromsoe, drawn by R. Haglund

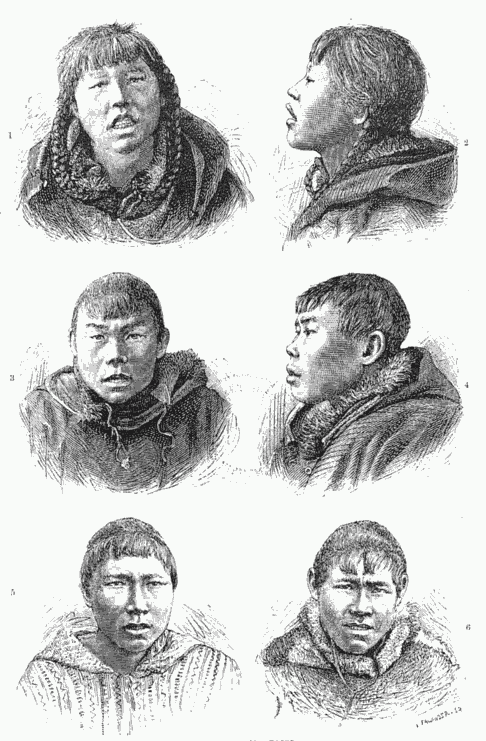

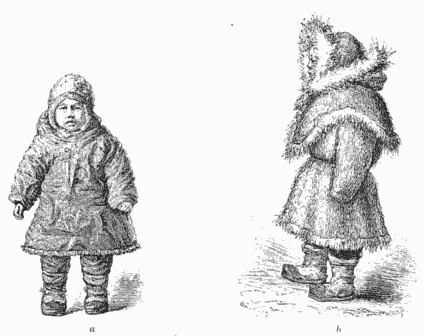

10. Old World Polar dress, drawn by O. Sörling

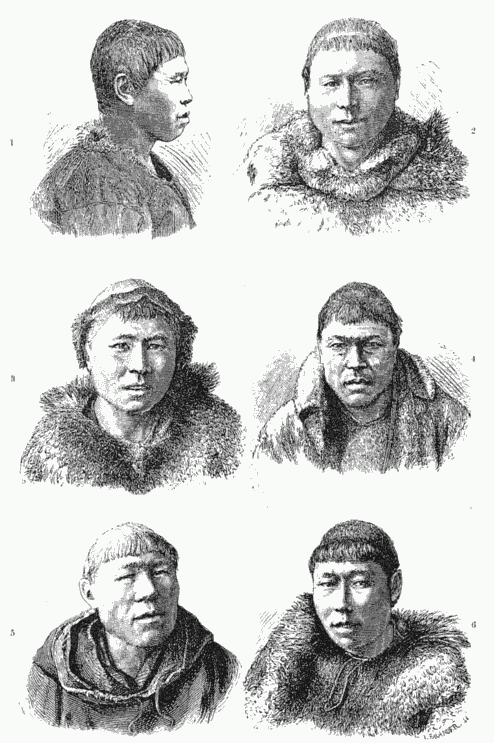

11. New World Polar Dress, drawn by Docent A. Kornrup, Copenhagen

12. Limit of Trees in Norway, drawn by R. Haglund, engraved by J. Engberg

13. Limit of Trees in Siberia, drawn by ditto

14. The Cloudberry (Rubus Chamæmorus, L.), drawn by Mrs. Professor A. Anderssen

15. Norse Ship of the Tenth Century, drawn by Harald Schöyen, Christiania

16. Sebastian Cabot, engraved by Miss Ida Falander

17. Sir Hugh Willoughby, engraved by J. D. Cooper, London

19. Vardoe in our days, drawn by R. Haglund

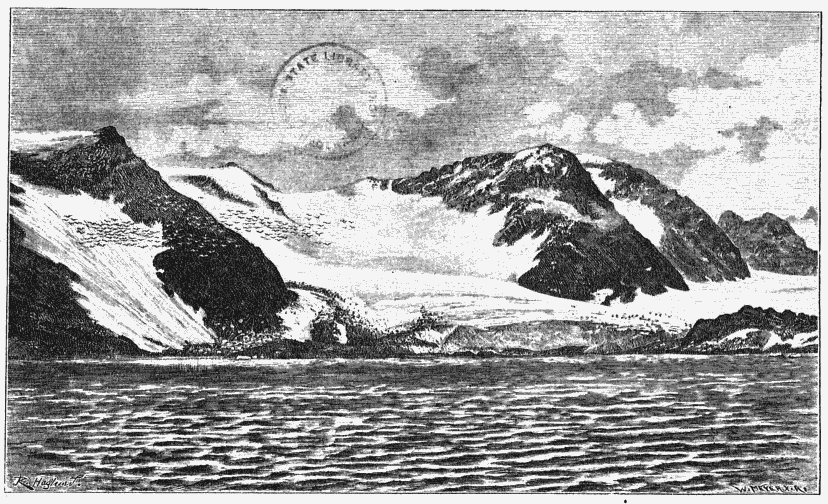

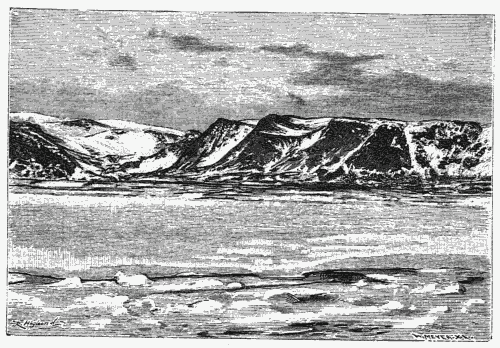

[pg xx] 20. Coast Landscape from Matotschkin Schar, drawn by R. Haglund

21. Church of Chabarova, drawn by V. Andrén

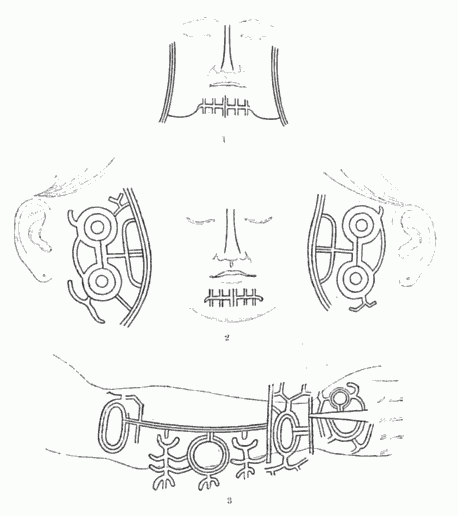

22. Samoyed Woman's Hood, drawn by O. Sörling

23. Samoyed Sleigh, drawn by R. Haglund

24. Lapp Akja, drawn by ditto; engraved by J. Engberg

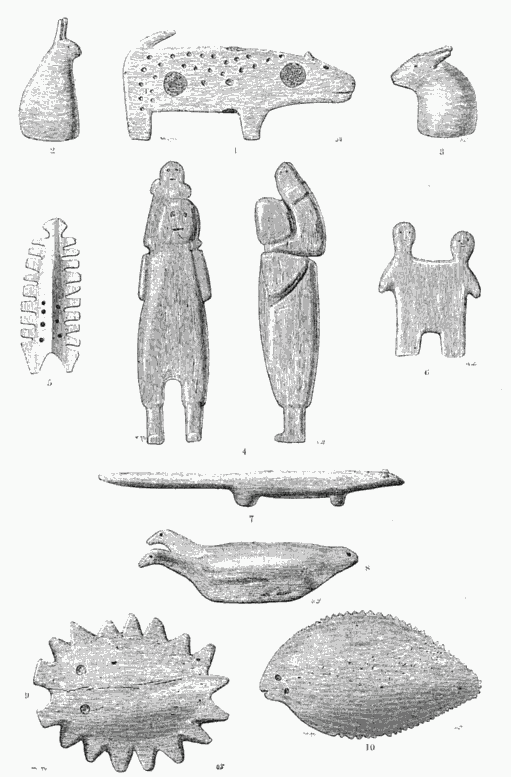

26. Samoyed Idols, drawn by O. Sörling

27. Samoyed Hair Ornaments, drawn by ditto

28. Samoyed Woman's Dress, drawn by R. Haglund

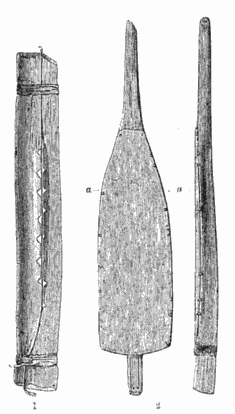

29. Samoyed Bolt with Knife, drawn by O. Sörling

30. Sacrificial Eminence on Vaygat's Island, drawn by R. Haglund; engraved by J. Engberg

31. Idols from the Sacrificial Cairn, drawn by O. Sörling

32. Sacrificial Cavity on Vaygat's Island, drawn by V. Andrén

33. Samoyed Grave on Vaygat's Island, drawn by R. Haglund; engraved by O. Dahlbäck

35. Samoyeds from Schleissing's Neu-entdektes Sieweria

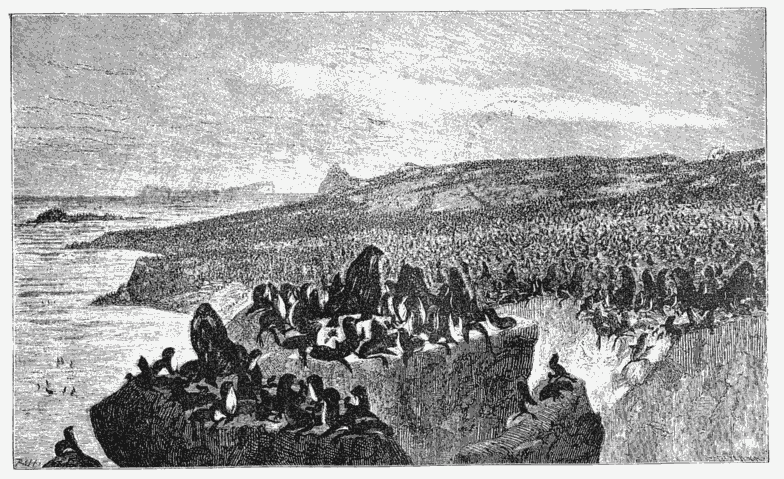

36. Breeding-place for Little Auks, drawn by H. Haglund

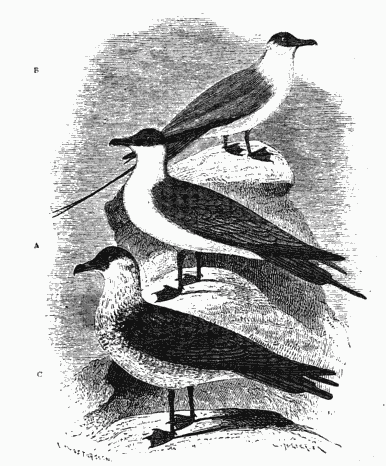

37. The Little Auk, or Rotge (Mergulus Alle, L.), drawn by M. Westergren

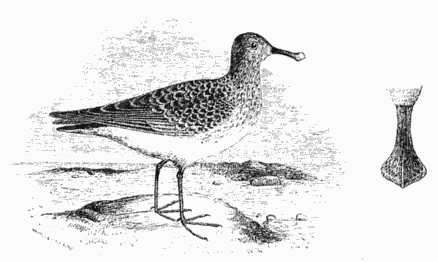

38. The Loom, or Brünnich's Guillemot (Uria Brünnichii, Sabine), drawn by ditto

39. The Arctic Puffin (Mormon Arcticus, L.), drawn by ditto

40. The Black Guillemot (Uria Grylle, L.), drawn by ditto

41. Breeding-place for Glaucous Gulls, drawn by R. Haglund

45. Heads of the Eider, King Buck, Barnacle Goose, and White-fronted Goose, drawn by ditto

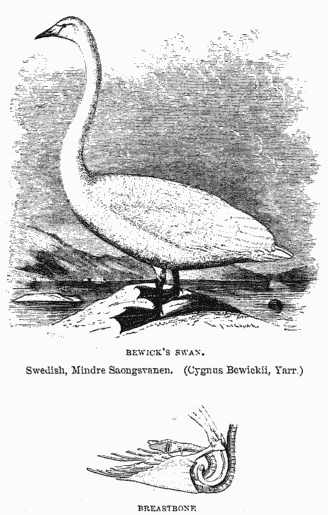

[pg xxi] 46. Bewick's Swan (Cygnus Bewickii, Yarr.), drawn by M. Westergren

47. Breastbone of Cygnus Bewickii, showing the peculiar position of the windpipe, drawn by ditto

48. Ptarmigan Fell, drawn by R. Haglund

49. The Snowy Owl (Strix nyctea, L.), drawn by M. Westergren

50. Reindeer Pasture, drawn by R. Haglund

51. Polar Bears, drawn by G. Mützel, engraved by K. Jahrmargt, both of Berlin

53. Walruses, drawn by M. Westergren

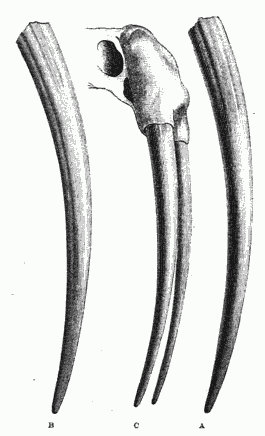

54. Walrus Tusks, drawn by ditto

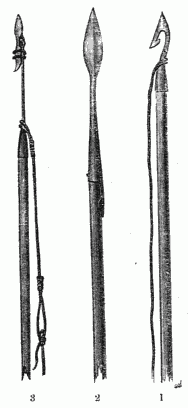

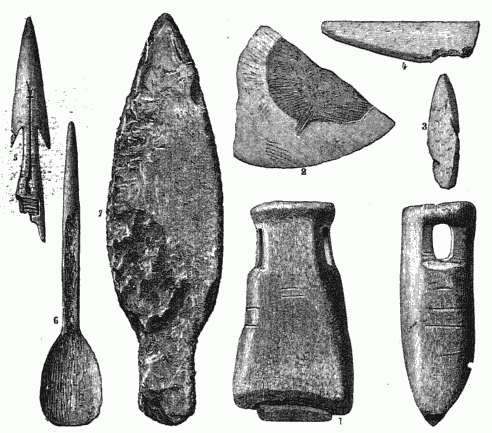

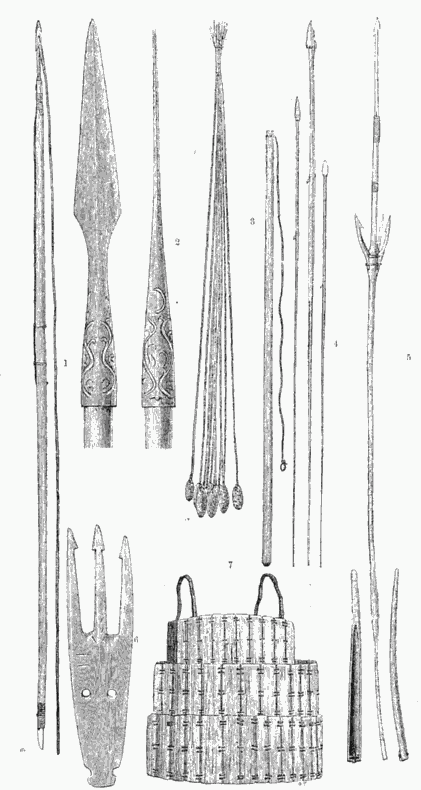

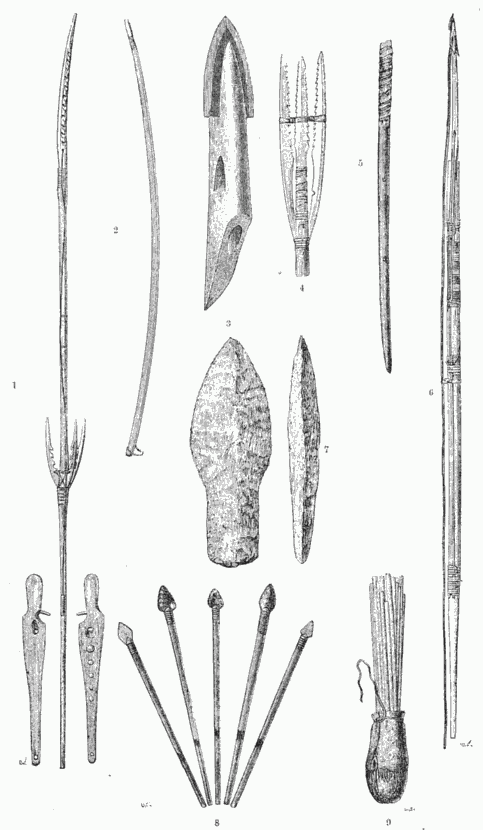

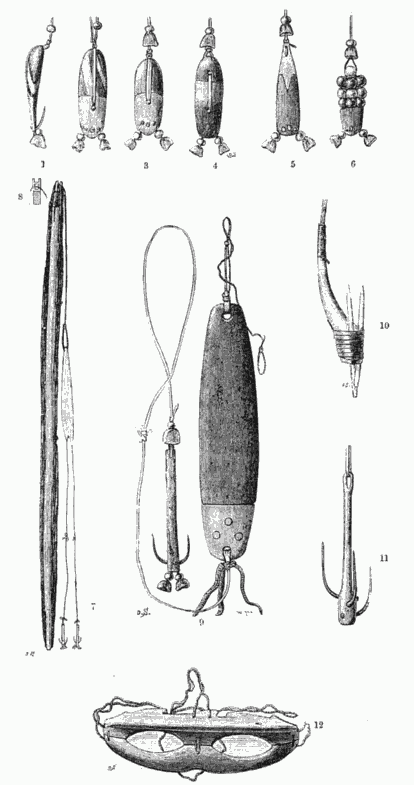

55. Hunting Implements, drawn by O. Sörling

56. Walrus Hunting, after Olaus Magnus

57. Walruses (female with young)

58. Japanese Drawing of the Walrus

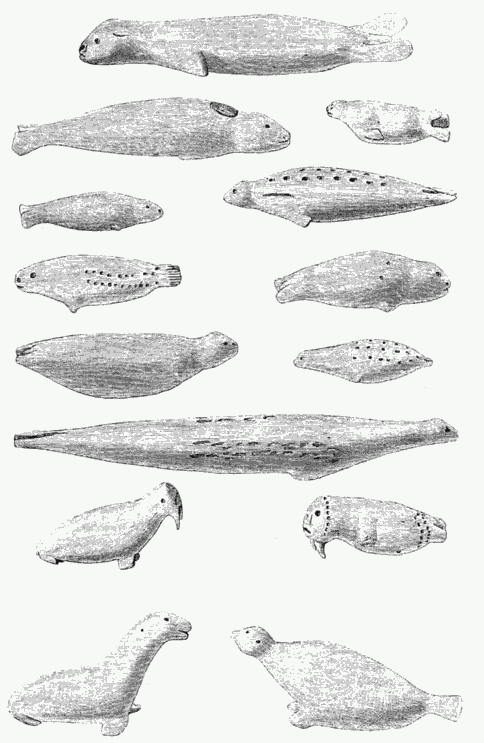

59. Young of the Greenland Seal, drawn by M. Westergren

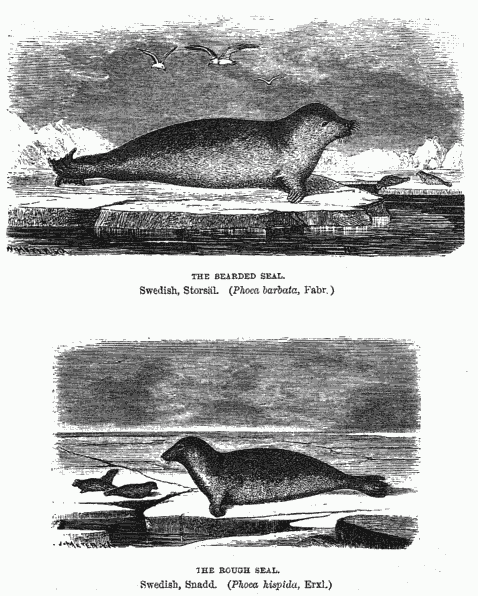

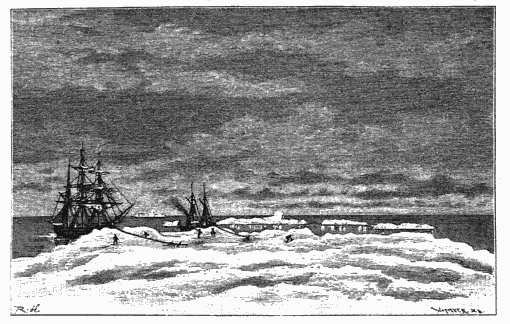

60. The Bearded Seal (Phoca barbata, Fabr.), drawn by ditto

61. The Rough Seal (Phoca hispida, Erxl.), drawn by ditto

62. The White Whale (Delphinapterus leucas, Pallas), drawn by ditto

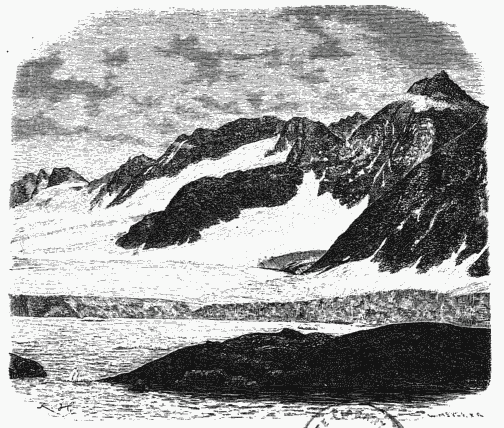

64. View from the Inland-ice of Greenland, drawn by H. Haglund

65. Greenland Ice-fjord, drawn by ditto

66. Slowly advancing Glacier, drawn by ditto

67. Glacier with Stationary Front, drawn by O. Sörling

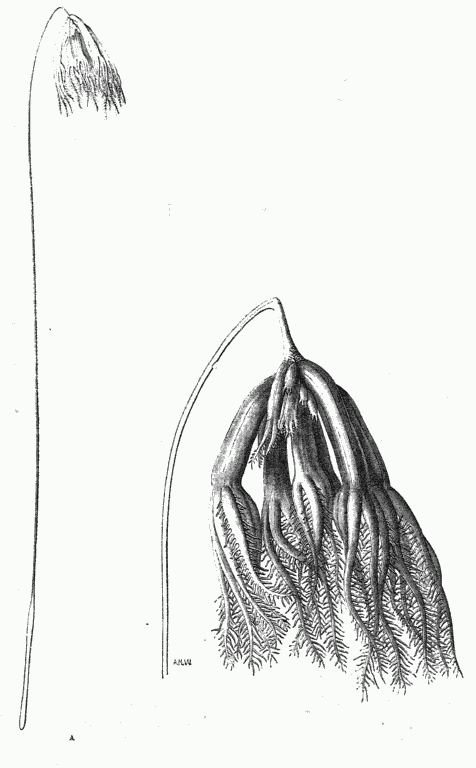

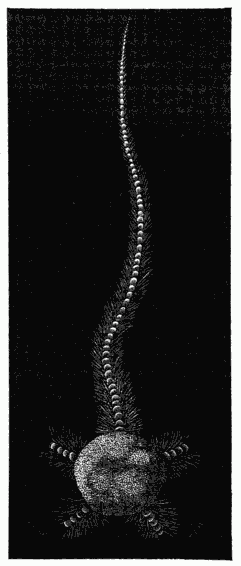

68. Umbellula from the Kara Sea, drawn by M. Westergren

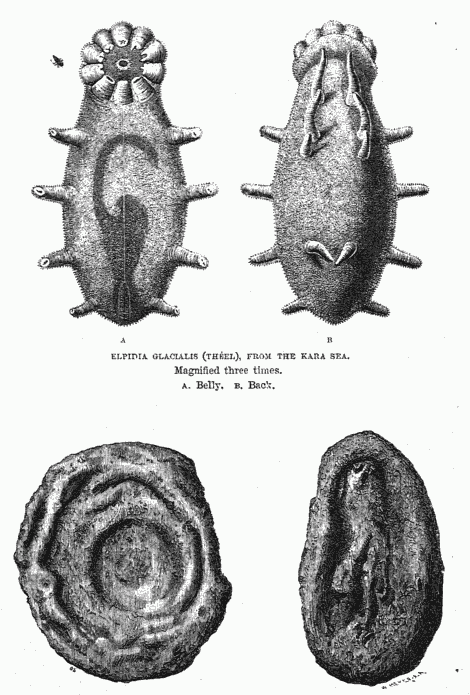

69. Elpidia Glacialis (Théel.), from the Kara Sea, drawn by ditto

70. Manganiferous Iron-ore Formations from the Kara Sea, drawn by O. Sörling

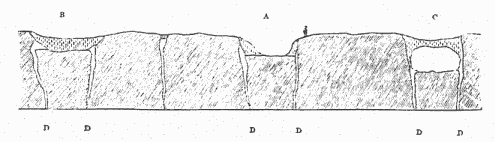

71. Section from the South Coast of Matotschkin Sound, drawn by the geologist, E. Erdman

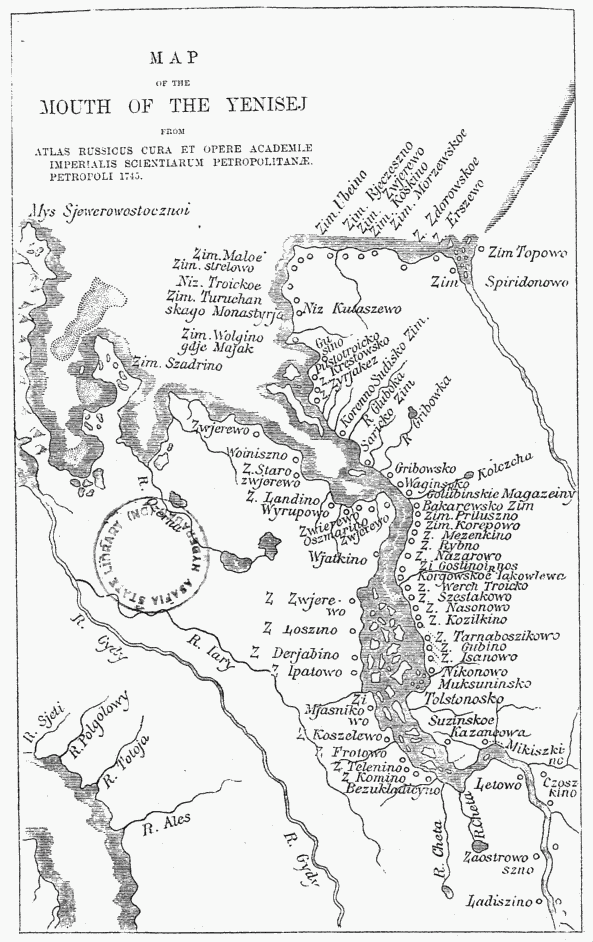

72. Map of the Mouth of the Yenisej (zincograph)

73. Ruins of a Simovie at Krestovskoj, drawn by O. Sörling

74. Sieversia Glacialis, R. Br., from Port Dickson, drawn by Mrs. Prof. Anderssen

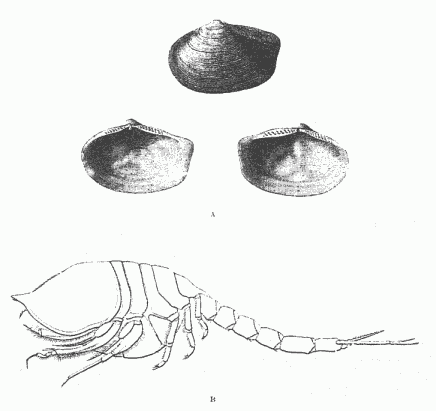

[pg xxii] 75. Evertebrates from Port Dickson, Yoldia artica, Gray, and Diastylis Rathkei, Kr., drawn by M. Westergren

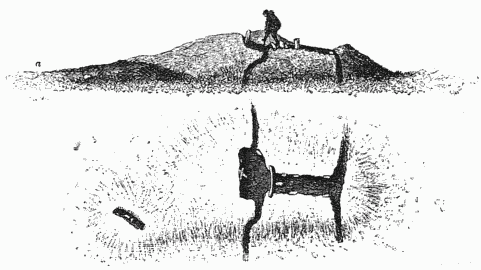

76. Place of Sacrifice on Yalmal, drawn by R. Haglund

77. "Jordgammor" on the Briochov Islands, drawn by ditto

81. Jan Huyghen van Linschoten

82. Kilduin, in Russian Lapland, in 1594

83. Map of Fietum Nassovicum or Yugor Schar

84. Unsuccessful Fight with a Polar Bear

85. Barents' and Rijp's Vessels

90. Ammonite with Gold Lustre (Ammonites alternans, v. Buch) drawn by M. Westergren

91. View from Matotschkin Schar, drawn by R. Haglund

92. Friedrich Benjamin von Lütke, drawn and engraved by Miss Ida Falander

93. August Karlovitz Zivolka, drawn and engraved by ditto

94. Paul von Krusenstern, Junior, drawn and engraved by ditto

95. Michael Konstantinovitsch Sidoroff, drawn and engraved by ditto

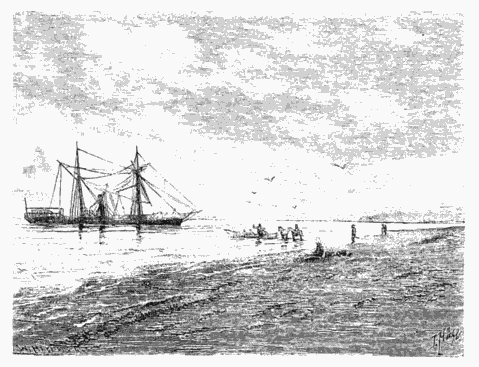

96. Norwegian Hunting Sloop, drawn by Captain J. Hagg

97. Elling Carlson, engraved by J. D. Cooper, of London

98. Edward Hohn Johannesen, engraved by ditto

99. Sivert Kristian Tobiesen, engraved by ditto

100. Tobiesen's Winter House on Bear Island, drawn by R. Haglund

101. Joseph Wiggins, drawn by R. Haglund

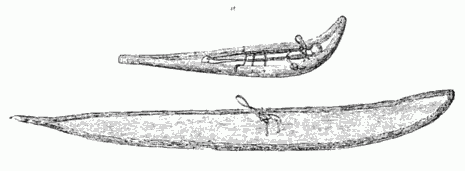

102. David Ivanovitsch Schwanenberg, drawn and engraved by Miss Ida Falander

103. Gustaf Adolf Nummelin, drawn and engraved by ditto

[pg xxiii] 104. The Sloop Utrennaja Saria, drawn by Captain J. Hagg

105. The Vega, and Lena anchored to an Ice-floe, drawn by R. Haglund

106. Hairstar from the Taimur Coast (Antedon Eschrictii, J. Müller) drawn by M. Westergren

107. Form of the Crystals found on the ice off the Taimur Coast

108. Section of the upper part of the Snow on a Drift-ice Field in 80° N.L.

109. Grass from Actinia Bay (Pleuropogon Sabini, R.Br.), drawn by Mrs. Professor Andersson

110. The Vega and Lena saluting Cape Chelyuskin, drawn by R. Haglund

111. View at Cape Chelyuskin during the stay of the Expedition, drawn by ditto

112. Draba Alpina, L., from Cape Chelyuskin, drawn by M. Westergren

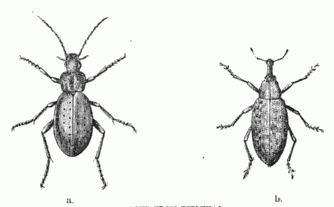

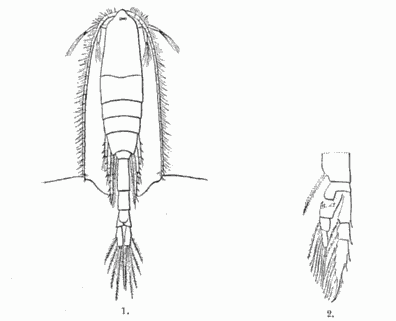

113. The Beetle living farthest to the North (Micralymma Dicksoni, Mackl.) drawn by ditto

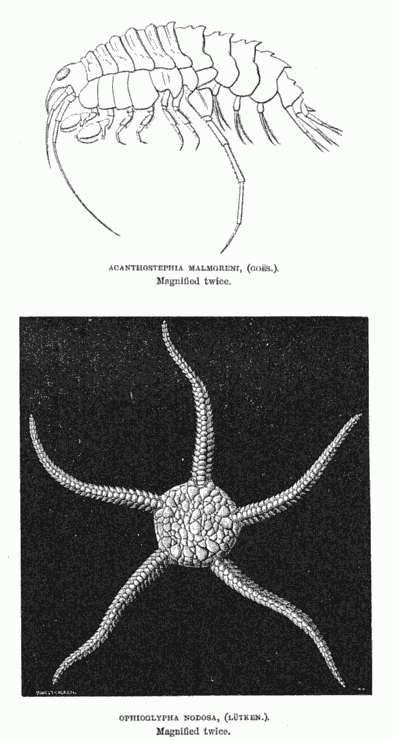

114. Ophiuroid from the Sea north of Cape Chelyuskin (Ophiacantha bidentata Retz.), drawn by ditto

115. Sea Spider (pycnogonid) from the Sea east of Cape Chelyuskin, drawn by ditto

116. Preobraschenie Island, drawn by R. Haglund

117. The steamer Fraser, drawn by ditto

118. The Steamer Lena, drawn by ditto

119. Hans Christian Johannesen, engraved by J.D. Cooper, London

120. Yakutsk in the Seventeenth Century

121. Yakutsk in our days, drawn by R. Haglund

122. River View from the Yenisej, drawn by ditto

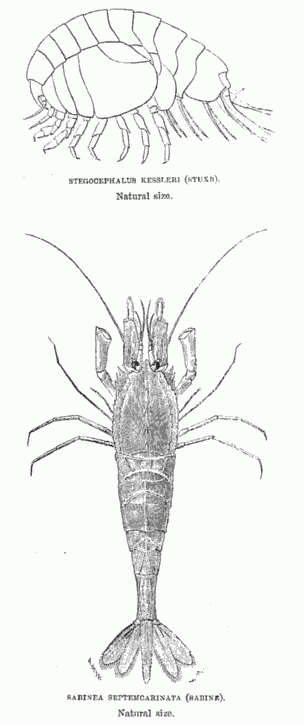

123. Sub-fossil Marine Crustacea from the tundra, drawn by M. Westergren

124. Siberian River Boat, drawn by R. Haglund

125. Ostyak Tent, drawn by ditto

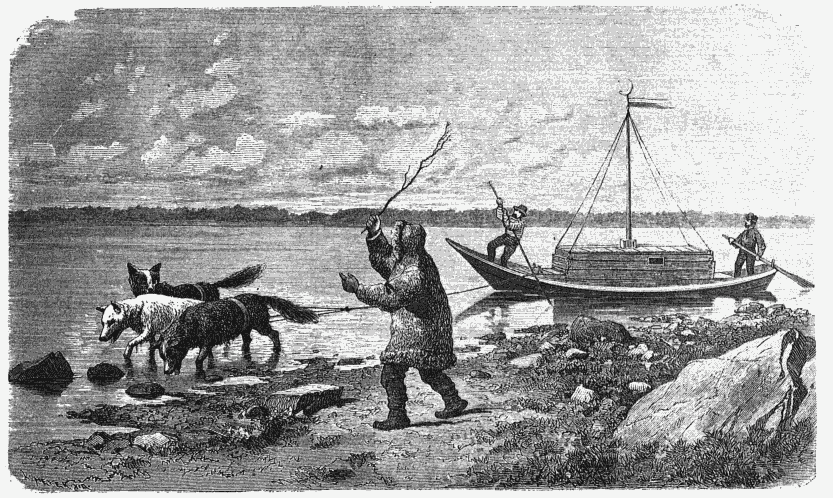

126. Towing with Dogs on the Yenisej, drawn by Professor R.D. Holm

127. Fishing-boats on the Ob, drawn R. Haglund

128. Graves in the Primeval Forest of Siberia, drawn by ditto

129. Chukch Village on a Siberian River, drawn by ditto

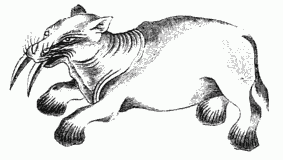

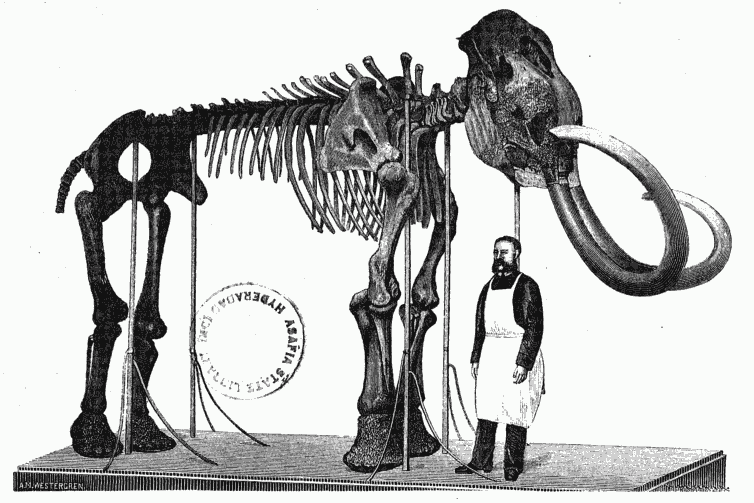

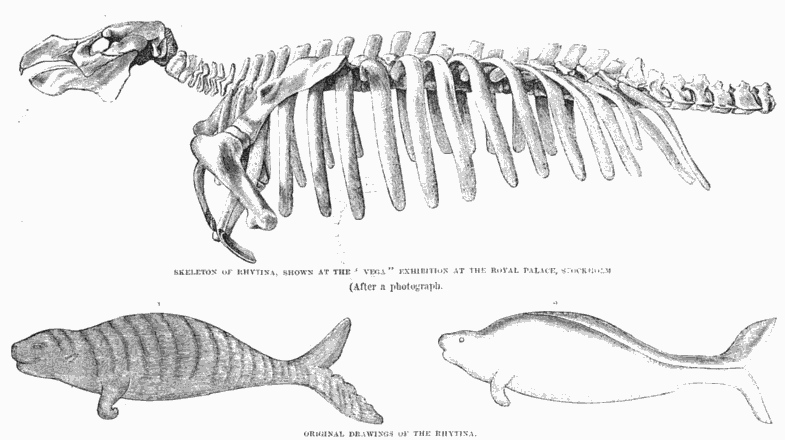

[pg xxiv] 131. Restored Form of the Mammoth

132. Siberian Rhinoceros Horn, drawn by M. Westergren and V. Andrén

133. Stolbovoj Island, drawn by R. Haglund

134. Idothea Entomon, Lin., drawn by M. Westergren

135. Idothea Sabinei, Kröyer, drawn by ditto

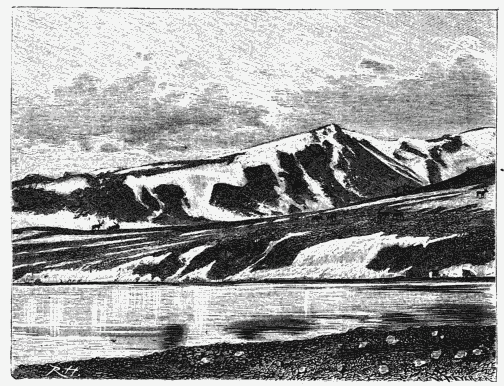

136. Ljachoff's Island, drawn by E. Haglund

137. Beaker Sponges from the Sea off the mouth of the Kolyma, drawn by M. Westergren

138. Lighthouse Island, drawn by R. Haglund

139. Chukch Boats, drawn by O. Sörling

140. A Chukch in Seal-gut Great-coat, drawn and engraved by Miss Ida Falander

141. Chukch Tent, drawn by R. Haglund

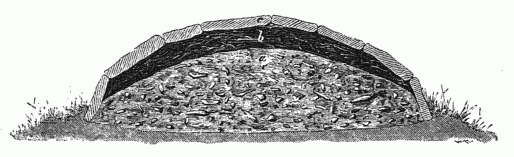

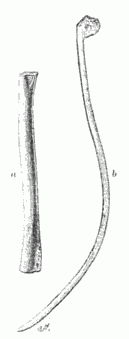

142. Section of a Chukch Grave, drawn by O. Sörling

143. Irkaipij, drawn by R. Haglund

144. Ruins of an Onkilon House, drawn by O. Sörling

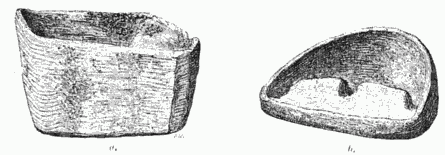

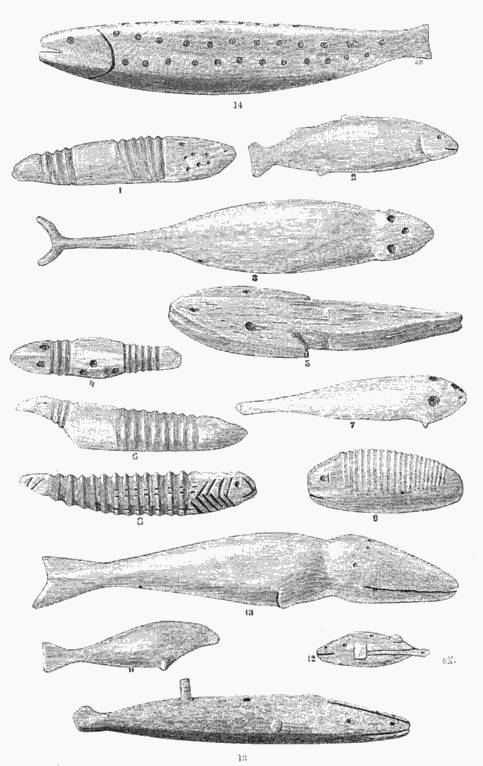

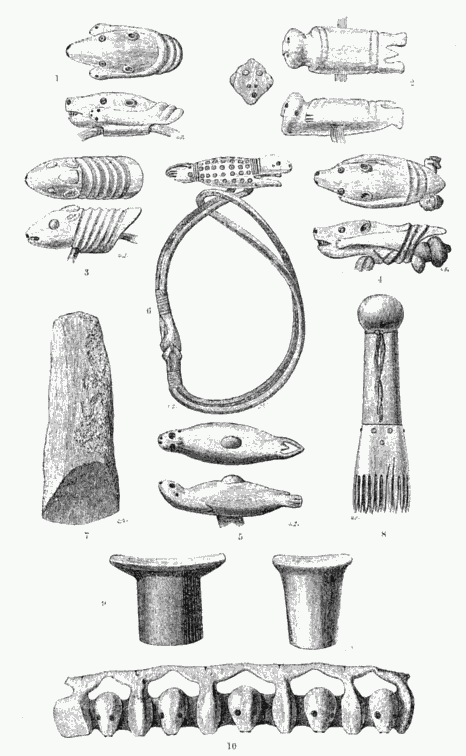

145. Implements found in the Ruins of an Onkilon House, drawn by ditto

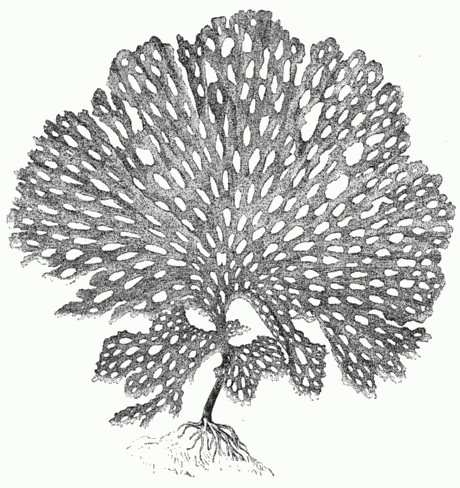

146. Alga from Irkaipij (Laminaria Solidungula, J.G. Ag.), drawn by M. Westergren

147. Cormorant from Irkaipij (Graculus bierustatus, Pallas), drawn by ditto

148. Pieces of Ice from the Coast of the Chukch Peninsula, drawn by O. Sörling

149. Toross from the neighbourhood of the Vega's Winter Quarters, drawn by R. Haglund

150. The Vega in Winter Quarters, drawn by ditto

151. The Winter Dress of the Vega men, drawn by Jungstedt

152. Cod from Pitlekaj (Gadus navaga, Kolreuter), drawn by M. Westergren

153. Kautljkau, a Chukch Girl from Irgunnuk, drawn and engraved by Miss Ida Falander

154. Chukches Angling, drawn by O. Sörling

155. Ice-Sieve, drawn by ditto

156. Smelt from the Chukch Peninsula (Osmerus eperlanus, Lin.), drawn by M. Westergren

157. Wassili Menka, drawn by O. Sörling, engraved by Miss Ida Falander

158. Chukch Dog-Sleigh, drawn by ditto

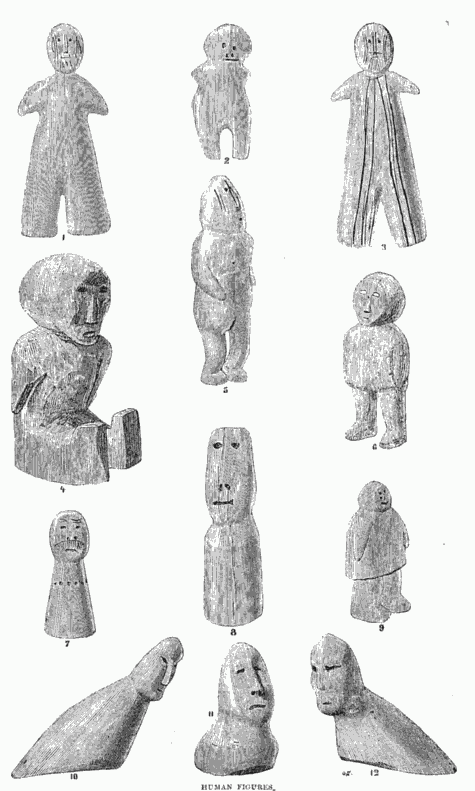

[pg xxv] 159. Chukch Bone-carvings, drawn by O. Sörling

160. Hares from Chukch Land, drawn by M. Westergren

161. The Observatory at Pitlekaj, drawn by R. Haglund

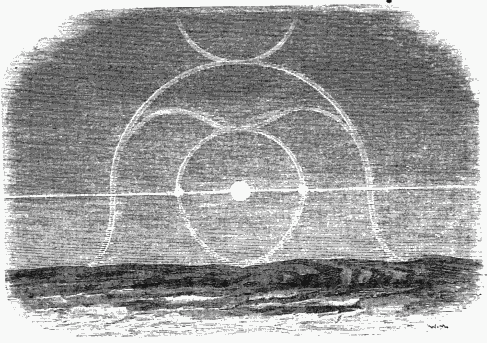

163. Refraction Halo, drawn by ditto

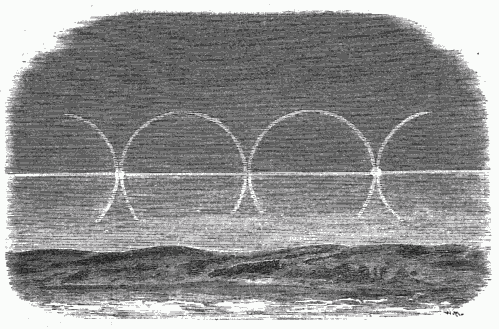

164. Reflection Halo, drawn by ditto

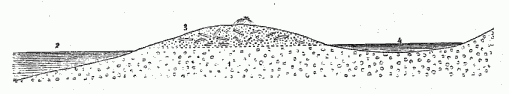

165. Section of the Beach Strata at Pitlekaj

166. Christmas Eve on the Vega, drawn by V. Andrén

ERRATA [ Transcriber's note: these have been applied to the text ]

Page 44, under Wood-cut for "chammmorus" read "chamæmorus."

Page 58, lines 21, 24, end 28 for "pearls" read "beads."

Page 140, line 13 from top, for"swallow" read "roll away."

Page 184, last line, for "one-third" read "one-and-a-half times."

Page 377, note, for "It is the general rule" read "For the northern hemisphere it is a general rule."

Page 476, line 12 from top, for "leggins" read "leggings."

Page 481, under wood-cut, for "half the natural size" read "one-third of the natural size."

Page 494, under wood-cut, for "half the natural size" read "one-third of the natural size."

The voyage, which it is my purpose to sketch in this book, owed its origin to two preceding expeditions from Sweden to the western part of the Siberian Polar Sea, in the course of which I reached the mouth of the Yenisej, the first time in 1875 in a walrus-hunting sloop, the Procven, and the second time in 1876 in a steamer, the Ymer.

After my return from the latter voyage, I came to the conclusion, that, on the ground of the experience thereby gained, and of the knowledge which, under the light of that experience, it was possible to obtain from old, especially from Russian, explorations of the north coast of Asia, I was warranted in asserting that the open navigable water, which two years in succession had carried me across the Kara Sea, formerly of so bad repute, to the mouth of the Yenisej, extended in all probability as far as Behring's Straits, and that a circumnavigation of the old world was thus within the bounds of possibility. [pg 2] It was natural that I should endeavour to take advantage of the opportunity for making new and important discoveries which thus presented itself. An opportunity had arisen for solving a geographical problem—the forcing a north-east passage to China and Japan—which for more than three hundred years had been a subject of competition between the world's foremost commercial states and most daring navigators, and which, if we view it in the light of a circumnavigation of the old world, had, for thousands of years back, been an object of desire for geographers. I determined, therefore, at first to make use, for this purpose, of the funds which Mr. A. SIBIRIAKOFF, after my return from the expedition of 1876, placed at my disposal for the continuation of researches in the Siberian Polar Sea. For a voyage of the extent now contemplated, this sum, however, was quite insufficient. On this account I turned to His Majesty the King of Sweden and Norway, with the inquiry whether any assistance in making preparations for the projected expedition might be reckoned upon from the public funds. King OSCAR, who, already as Crown Prince, had given a large contribution to the Torell expedition of 1861, immediately received my proposal with special warmth, and promised within a short time to invite the Swedish members of the Yenisej expeditions and others interested in our voyages of exploration in the north, to meet him for the purpose of consultation, asking me at the same time to be prepared against the meeting with a complete exposition of the reasons on which I grounded my views—differing so widely from the ideas commonly entertained—of the state of the ice in the sea off the north coast of Siberia.

This assembly took place at the palace in Stockholm, on the 26th January, 1877, which may be considered the birthday of the Vega Expedition, and was ushered in by a dinner, to which a large number of persons were invited, among whom were the members of the Swedish royal house that happened to be then in Stockholm; Prince JOHN OF GLÜCKSBURG; Dr. OSCAR

DICKSON, the Gothenburg merchant; Baron F.W. VON OTTER, Councillor of State and Minister of Marine, well known for his voyages in the Arctic waters in 1868 and 1871; Docent F.K. KJELLMAN, Dr. A. STUTXBERG, the former a member of the expedition which wintered at Mussel Bay in 1872-73, and of that which reached the Yenisej in 1875, the latter, of the Yenisej Expeditions of 1875 and 1876; and Docents HJALMAR THÉEL and A.N. LUNDSTRÖM, both members of the Yenisej Expedition of 1875.

After dinner the programme of the contemplated voyage was laid before the meeting, almost in the form in which it afterwards appeared in print in several languages. There then arose a lively discussion, in the course of which reasons were advanced for, and against the practicability of the plan. In particular the question concerning the state of the ice and the marine currents at Cape Chelyuskin gave occasion to an exhaustive discussion. It ended by His Majesty first of all declaring himself convinced of the practicability of the plan of the voyage, and prepared not only as king, but also as a private individual, to give substantial support to the enterprise. Dr. Oscar Dickson shared His Majesty's views, and promised to contribute to the not inconsiderable expenditure, which the new voyage of exploration would render necessary. This is the sixth expedition to the high north, the expenses of which have been defrayed to a greater or less extent by Dr. O. Dickson.[1] He became the banker of the Vega Expedition, inasmuch as to a considerable extent he advanced the necessary funds, but after our return the expenses were equally divided between His Majesty the King of Sweden and Norway, Dr. Dickson, and Mr. Sibiriakoff.

I very soon had the satisfaction of appointing, as superintendents of the botanical and zoological work of the expedition in this new Polar voyage, my old and tried friends from previous [pg 4] expeditions, Docents Dr. Kjellman and Dr. Stuxberg, observers so well known in Arctic literature. At a later period, another member of the expedition that wintered on Spitzbergen in 1872-73, Lieutenant (now Captain in the Swedish Navy) L. PALANDER, offered to accompany the new expedition as commander of the vessel—an offer which I gladly accepted, well knowing, as I did from previous voyages, Captain Palander's distinguished ability both as a seaman and an Arctic explorer. Further there joined the expedition Lieutenant GIACOMO BOVE, of the Italian Navy; Lieutenant A. HOVGAARD, of the Danish Navy; Medical candidate E. ALMQUIST, as medical officer; Lieutenant O. NORDQUIST, of the Russian Guards; Lieutenant E. BRUSEWITZ, of the Swedish Navy; together with twenty-one men—petty officers and crew, according to a list which will be found further on.

An expedition of such extent as that now projected, intended possibly to last two years, with a vessel of its own, a numerous well-paid personnel, and a considerable scientific staff, must of course be very costly. In order somewhat to diminish the expenses, I gave in, on the 25th August, 1877, a memorial to the Swedish Government with the prayer that the steamer Vega, which in the meantime had been purchased for the expedition, should be thoroughly overhauled and made completely seaworthy at the naval dockyard at Karlskrona; and that, as had been done in the case of the Arctic Expeditions of 1868 and 1872-73, certain grants of public money should be given to the officers and men of the Royal Swedish Navy, who might take part as volunteers in the projected expedition. With reference to this petition the Swedish Government was pleased, in terms of a letter of the Minister of Marine, dated the 31st December, 1877, both to grant sea-pay, &c., to the officer and eighteen men of the Royal Navy, who might take part in the expedition in question, and at the same time to resolve on making a proposal to the Diet in which additional grants were to be asked for it. [pg 5] The proposal to the Diet of 1878 was agreed to with that liberality which has always distinguished the representatives of the Swedish people when grants for scientific purposes have been asked for; which was also the case with a private motion made in the same Diet by the President, C.F. WAERN, member of the Academy of Sciences, whereby it was proposed to confer some further privileges on the undertaking.

It is impossible here to give at length the decision of the Diet, and the correspondence which was exchanged with the authorities with reference to it. But I am under an obligation of gratitude to refer to the exceedingly pleasant reception I met with everywhere, in the course of these negotiations, from officials of all ranks, and to give a brief account of the privileges which the expedition finally came to enjoy, mainly owing to the letter of the Government to the Marine Department, dated the 14th June, 1878.

Two officers and seventeen men of the Royal Swedish Navy having obtained permission to take part in the expedition as volunteers, I was authorised to receive on account of the expedition from the treasury of the Navy, at Karlskrona—with the obligation of returning that portion of the funds which might not be required, and on giving approved security—full sea pay for two years for the officers, petty officers, and men taking part in the expedition; pay for the medical officer, at the rate of 3,500 Swedish crowns a year, for the same time; and subsistence money for the men belonging to the Navy, at the rate of one and a half Swedish crowns per man per day. The sum, by which the cost of provisions exceeded the amount calculated at this rate, was defrayed by the expedition, which likewise gave a considerable addition to the pay of the sailors belonging to the Navy. I further obtained permission to receive, on account of the expedition, from the Navy stores at Karlskrona, provisions, medicines, coal, oil, and other necessary equipment, under obligation to pay for any excess of value over 10,000 Swedish crowns (about 550l.); and finally the vessel of the expedition was permitted to be equipped and made completely seaworthy at the naval dockyard at Karlskrona, on condition, however, that the excess of expenditure on repairs over 25,000 crowns (about 1,375l.) should be defrayed by the expedition.

On the other hand my request that the Vega, the steamer purchased for the voyage, might be permitted to carry the man-of-war flag, was refused by the Minister of Marine in a letter of the 2nd February 1878. The Vega was therefore inscribed in the following month of March in the Swedish Yacht Club. It was thus under its flag, the Swedish man-of-war flag with a crowned O in the middle, that the first circumnavigation of Asia and Europe was carried into effect.

The Vega, as will be seen from the description quoted farther on, is a pretty large vessel, which during the first part of the voyage was to be heavily laden with provisions and coal. It would therefore be a work of some difficulty to get it afloat, if, in sailing forward along the coast in new, unsurveyed waters, it should run upon a bank of clay or sand. I therefore gladly availed myself of Mr. Sibiriakoff's offer to provide for the greater safety of the expedition, by placing at my disposal funds for building another steamer of a smaller size, the Lena, which should have the river Lena as its main destination, but, during the first part of the expedition, should act as tender to the Vega, being sent before to examine the state of the ice and the navigable waters, when such service might be useful. I had the Lena built at Motala, of Swedish Bessemer steel, mainly after a drawing of Engineer R. Runeberg of Finland. The steamer answered the purpose for which it was intended particularly well.

An unexpected opportunity of providing the steamers with coal during the course of the voyage besides arose by my receiving a commission, while preparations were making for

the expedition of the Vega, to fit out, also on Mr. Sibiriakoff's account, two other vessels, the steamer Fraser, and the sailing vessel Express, in order to bring to Europe from the mouth of the Yenisej a cargo of grain, and to carry thither a quantity of European goods. This was so much the more advantageous, as, according to the plan of the expedition, the Vega and the Lena were first to separate from the Fraser and the Express at the mouth of the Yenisej. The first-named vessels had thus an opportunity of taking on board at that place as much coal as there was room for.

I intend further on to give an account of the voyages of the other three vessels, each of which deserves a place in the history of navigation. To avoid details I shall only mention here that, at the beginning of the voyage which is to be described here, the following four vessels were at my disposal:—

1. The Vega, commanded by Lieutenant L. Palander, of the Swedish Navy; circumnavigated Asia and Europe.

2. The Lena, commanded by the walrus-hunting captain, Christian Johannesen; the first vessel that reached the river Lena from the Atlantic.

3. The Fraser, commanded by the merchant captain, Emil Nilsson.

4. The Express, commanded by the merchant captain, Gundersen; the first which brought cargoes of grain from the Yenisej to Europe.[2]

When the Vega was bought for the expedition it was described by the sellers as follows:—

"The steamer Vega was built at Bremerhaven in 1872-73, of the best oak, for the share-company 'Ishafvet,' and under special inspection. It has twelve years' first class 3/3 I.I. Veritas, [pg 10] measures 357 register tons gross, or 299 net. It was built and used for whale-fishing in the North Polar Sea, and strengthened in every way necessary and commonly used for that purpose. Besides the usual timbering of oak, the vessel has an ice-skin of greenheart, wherever the ice may be expected to come at the vessel. The ice-skin extends from the neighbourhood of the under chain bolts to within from 1.2 to 1.5 metres of the keel The dimensions are:—

Length of keel ... ... ... 37.6 metres.

Do. over deck ... ... ... 43.4 metres.

Beam extreme ... ... ... 8.4 metres.

Depth of hold ... ... ... 4.6 metres.

"The engine, of sixty horse-power, is on Wolff's plan, with excellent surface condensers. It requires about ten cubic feet of coal per hour. The vessel is fully rigged as a barque, and has pitch pine masts, iron wire rigging, and patent reefing topsails. It sails and manoeuvres uncommonly well, and under sail alone attains a speed of nine to ten knots. During the trial trip the steamer made seven and a half knots, but six to seven knots per hour may be considered the speed under steam. Further, there are on the vessel a powerful steam-winch, a reserve rudder, and a reserve propeller. The vessel is besides provided in the whole of the under hold with iron tanks, so built that they lie close to the vessel's bottom and sides, the tanks thus being capable of offering a powerful resistance in case of ice pressure. They are also serviceable for holding provisions, water, and coal."[3]

We had no reason to take exception to this description,[4] [pg 11] but, in any case, it was necessary for an Arctic campaign, such as that now in question, to make a further inspection of the vessel, to assure ourselves that all its parts were in complete order, to make the alterations in rig, &c., which the altered requirements would render necessary, and finally to arrange the vessel, so that it might house a scientific staff, which, together with the officers, numbered nine persons. This work was done at the Karlskrona naval dockyard, under the direction of Captain Palander. At the same time attention was given to the scientific equipment, principally in Stockholm, where a large number of instruments for physical, astronomical, and geological researches was obtained from the Royal Academy of Sciences.

The dietary during the expedition was fixed upon, partly on the ground of our experience from the wintering of 1872-73, partly under the guidance of a special opinion given with reference to the subject by the distinguished physician who took part in that expedition, Dr. A. Envall. Preserved provisions,[5] butter, flour, &c., were purchased, part at Karlskrona, part in Stockholm and Copenhagen; a portion of pemmican was prepared in Stockholm by Z. Wikström; another portion was purchased in England; fresh ripe potatoes[6] were procured from the Mediterranean, a large quantity of cranberry juice from Finland; preserved cloudberries and clothes of reindeer skins, &c., from Norway, through our agent Ebeltoft, and so on —in a word, nothing was neglected to make the vessel as well equipped as possible for the attainment of the great object in view. [pg 12] What this was may be seen from the following

PLAN OF THE EXPEDITION,

PRESENTED TO HIS MAJESTY THE KING OF SWEDEN AND NORWAY, July 1877.

The exploring expeditions, which, during the recent decades, have gone out from Sweden towards the north, have long ago acquired a truly national importance, through the lively interest that has been taken in them everywhere, beyond, as well as within, the fatherland; through the considerable sums of money that have been spent on them by the State, and above all by private persons; through the practical school they have formed for more than thirty Swedish naturalists; through the important scientific and geographical results they have yielded; and through the material for scientific research, which by them has been collected for the Swedish Riks-Museum, and which has made it, in respect of Arctic natural objects, the richest in the world. To this there come to be added discoveries and investigations which already are, or promise in the future to become, of practical importance; for example, the meteorological and hydrographical work of the expeditions; their comprehensive inquiries regarding the Seal and Whale Fisheries in the Polar Seas; the pointing out of the previously unsuspected richness in fish, of the coasts of Spitzbergen; the discoveries, on Bear Island and Spitzbergen, of considerable strata of coal and phosphatic minerals which are likely to be of great economic importance to neighbouring countries; and, above all, the success of the two last expeditions in reaching the mouths of the large Siberian rivers, navigable to the confines of China—the Obi and Yenisej —whereby a problem in navigation, many centuries old, has at last been solved.

But the very results that have been obtained incite to a continuation, especially as the two last expeditions have opened a new field of inquiry, exceedingly promising in a scientific, and I venture also to say in a practical, point of view, namely, the part of the Polar Sea lying east of the mouth of the Yenisej. Still, even in our days, in the era of steam and the telegraph, there meets us here a territory to be explored, which is new to science, and hitherto untouched. Indeed, the whole of the immense expanse of ocean which stretches over 90 degrees of longitude [pg 13] from the mouth of the Yenisej past Cape Chelyuskin—the Promontorium Tabin of the old geographers—has, if we except voyages in large or small boats along the coast, never yet been ploughed by the keel of any vessel, and never seen the funnel of a steamer.

It was this state of things which led me to attempt to procure funds for an expedition, equipped as completely as possible, both in a scientific and a nautical respect, with a view to investigate the geography, hydrography, and natural history of the North Polar Sea beyond the mouth of the Yenisej, if possible as far as Behring's Straits. It may be affirmed without any danger of exaggeration, that since Cook's famous voyages in the Pacific Ocean, no more promising field of research has lain before any exploring expedition, if only the state of the ice permit a suitable steamer to force a passage in that sea. In order to form a judgment on this point, it may perhaps be necessary to cast a brief glance backwards over the attempts which have been made to penetrate in the direction which the projected expedition is intended to take.

The Swedish port from which the expedition is to start will probably be Gothenburg. The time of departure is fixed for the beginning of July, 1878. The course will be shaped at first along the west coast of Norway, past North Cape and the entrance to the White Sea, to Matotschkin Sound in Novaya Zemlya.

The opening of a communication by sea between the rest of Europe and these regions, by Sir Hugh Willoughby and Richard Chancelor in 1553, was the fruit of the first exploring expedition sent out from England by sea. Their voyage also forms the first attempt to discover a north-east passage to China. The object aimed at was not indeed accomplished; but on the other hand, there was opened by the voyage in question the sea communication between England and the White Sea; the voyage thus forming a turning-point not only in the navigation of England and Russia, but also in the commerce of the world. It also demanded its sacrifice, Sir Hugh Willoughby himself, with all the men in the vessels under his command, having perished while wintering on the Kola peninsula. In our days thousands of vessels sail safely along this route.

With the knowledge we now possess of the state of the ice in the Murman Sea—so the sea between Kola and Novaya Zemlya is called on the old maps—it is possible to sail during the latter part of summer from the White Sea to Matotschkin [pg 14] without needing to fear the least hindrance from ice. For several decades back, however, in consequence of want of knowledge of the proper season and the proper course, the case has been quite different—as is sufficiently evident from the account of the difficulties and dangers which the renowned Russian navigator, Count Lütke, met with during his repeated voyages four summers in succession (1821-1824) along the west coast of Novaya Zemlya. A skilful walrus-hunter can now, with a common walrus-hunting vessel, in a single summer, sail further in this sea than formerly could an expedition, fitted out with all the resources of a naval yard, in four times as long time.

There are four ways of passing from the Murman Sea to the Kara Sea, viz:—

a. Yugor Sound—the Fretum Nassovicum of the old Dutchmen—between Vaygats Island and the mainland.

b. The Kara Port, between Vaygats Island and Novaya Zemlya.

c. Matotschkin Sound, which between 73° and 74° N. Lat. divides Novaya Zemlya into two parts, and, finally,

d. The course north of the double island. The course past the northernmost point of Novaya Zemlya is not commonly clear of ice till the beginning of the month of September, and perhaps ought, therefore, not to be chosen for an expedition having for its object to penetrate far to the eastward in this sea. Yugor Sound and the Kara Port are early free of fast ice, but instead, are long rendered difficult to navigate by considerable masses of drift ice, which are carried backwards and forwards in the bays on both sides of the sound by the currents which here alternate with the ebb and flow of the tide. Besides, at least in Yugor Sound, there are no good harbours, in consequence of which the drifting masses of ice may greatly inconvenience the vessels, which by these routes attempt to enter the Kara Sea. Matotschkin Sound, again, forms a channel nearly 100 kilometres long, deep and clear, with the exception of a couple of shoals, the position of which is known, which indeed is not usually free from fast ice until the latter half of July, but, on the other hand, in consequence of the configuration of the coast, is less subject to be obstructed by drift ice than the southern straits. There are good harbours at the eastern mouth of the sound. In 1875 and 1876 both the sound and the sea lying off it were completely open in the end of August, but the ice was much earlier broken up also on the eastern side, so that a vessel could without danger make its way among the scattered pieces of drift ice. [pg 15] The part of Novaya Zemlya which is first visited by the walrus-hunters in spring is usually just the west coast off Matotschkin.

In case unusual weather does not prevail in the regions in question during the course of early and mid-summer, 1878— for instance, very steady southerly winds, which would early drive the drift ice away from the coast of the mainland—I consider, on the grounds which I have stated above, that it will be safest for the expedition to choose the course by Matotschkin Sound.

We cannot, however, reckon on having, so early as the beginning of August, open water direct to Port Dickson at the mouth of the Yenisej, but must be prepared to make a considerable detour towards the south in order to avoid the masses of drift ice, which are to be met with in the Kara Sea up to the beginning of September. The few days' delay which may be caused by the state of the ice here, will afford, besides, to the expedition an opportunity for valuable work in examining the natural history and hydrography of the channel, about 200 fathoms deep, which runs along the east coast of Novaya Zemlya. The Kara Sea is, in the other parts of it, not deep, but evenly shallow (ten to thirty fathoms), yet without being fouled by shoals or rocks. The most abundant animal life is found in the before-mentioned deep channel along the east coast, and it was from it that our two foregoing expeditions brought home several animal types, very peculiar and interesting in a systematic point of view. Near the coast the algæ, too, are rich and luxuriant. The coming expedition ought, therefore, to endeavour to reach Matotschkin Sound so early that at least seven days' scientific work may be done in those regions.

The voyage from the Kara Sea to Port Dickson is not attended, according to recent experience, with any difficulty. Yet we cannot reckon on arriving at Port Dickson sooner than from the 10th to the 15th August. In 1875 I reached this harbour with a sailing-vessel on the 15th August, after having been much delayed by calms in the Kara Sea. With a steamer it would have been possible to have reached the harbour, that year, in the beginning of the month. In 1876 the state of the ice was less favourable, in consequence of a cold summer and a prevalence of north-east winds, but even then I arrived at the mouth of the Yenisej on the 15th August.

It is my intention to lie to at Port Dickson, at least for some hours, in order to deposit letters on one of the neighbouring [pg 16] islands in case, as is probable, I have no opportunity of meeting there some vessel sent out from Yeniseisk, by which accounts of the expedition may be sent home.

Actual observations regarding the hydrography of the coast between the mouth of the Yenisej and Cape Chelyuskin are for the present nearly wholly wanting, seeing that, as I have already stated, no large vessel has ever sailed from this neighbourhood. Even about the boat voyages of the Russians along the coast we know exceedingly little, and from their unsuccessful attempts to force a passage here we may by no means draw any unfavourable conclusion as to the navigability of the sea during certain seasons of the year. If, with a knowledge of the resources for the equipment of naval expeditions which Siberia now possesses, we seek to form an idea of the equipment of the Russian expeditions[7] sent out with extraordinary perseverance during the years 1734-1743 by different routes to the north coast of Siberia, the correctness of this assertion ought to be easily perceived. There is good reason to expect that a well-equipped steamer will be able to penetrate far beyond the point where they were compelled to return with their small but numerously manned craft, too fragile to encounter ice, and unsuitable for the open sea, being generally held together with willows.

There are, besides these, only three sea voyages, or perhaps more correctly coast journeys, known in this part of the Kara Sea, all under the leadership of the mates Minin and Sterlegoff. The first attempt was made in 1738 in a "double sloop," 70 feet long, 17 broad, and 7-1/2 deep, built at Tobolsk and transported thence to the Yenisej by Lieutenant Owzyn. With this vessel Minin penetrated off the Yenisej to 72°53' N.L. Hence a jolly boat was sent farther towards the north, but it too was compelled, by want of provisions, to return before the point named by me, Port Dickson, was reached. The following year a new attempt was made, without a greater distance being traversed than the summer before. Finally in the year 1740 the Russians succeeded in reaching, with the double sloop already mentioned, 75° 15' N. L., after having survived great dangers from a heavy [pg 17] sea at the river mouth. On the 2nd September, just as the most advantageous season for navigation in these waters had begun, they returned, principally on account of the lateness of the season.

There are, besides, two statements founded on actual observations regarding the state of the ice on this coast. For Middendorff, the Academician, during his famous journey of exploration in North Siberia, reached from land the sea coast at Tajmur Bay (75° 40' N.L.), and found the sea on the 25th August, 1843, free of ice as far as the eye could reach from the chain of heights along the coast.[8] Middendorff, besides, states that the Yakoot Fomin, the only person who had passed a winter at Tajmur Bay, declared that the ice loosens in the sea lying off it in the first half of August, and that it is driven away from the beach by southerly winds, yet not further than that the edge of the ice can be seen from the heights along the coast.

The land between the Tajmur and Cape Chelyuskin was mapped by means of sledge journeys along the coast by mate Chelyuskin in the year 1742. It is now completely established that the northernmost promontory of Asia was discovered by him in the month of May in the year already mentioned, and at that time the sea in its neighbourhood was of course covered with ice. We have no observation as to the state of the ice during summer or autumn in the sea lying immediately to the west of Cape Chelyuskin; but, as the question relates to the possibility of navigating this sea, this is the place to draw attention to the fact that Prontschischev, on the 1st September, 1736, in an open sea, with coasting craft from the east, very nearly reached the north point of Asia, which is supposed to be situated in 77° 34' N. Lat. and 105° E. Long., and that the Norwegian walrus-hunters during late autumn have repeatedly sailed far to the eastward from the north point of Novaya Zemlya (77° N. Lat., and 68° E. Long.), without meeting with any ice.

From what has been already stated, it is evident that for the present we do not possess any complete knowledge, founded on actual observations, of the hydrography of the stretch of coast between the Yenisej and Cape Chelyuskin. I, however, consider that during September, and possibly the latter half of August, we ought to be able to reckon with complete certainty on having here ice-free water, or at least a broad, open channel along the [pg 18] coast, from the enormous masses of warm water, which the rivers Obi, Irtisch, and Yenisej, running up through the steppes of High Asia, here pour into the ocean, after having received water from a river territory, everywhere strongly heated during the month of August, and more extensive than that of all the rivers put together, which fall into the Mediterranean and the Black Seas.

Between Port Dickson and White Island, there runs therefore a strong fresh-water current, at first in a northerly direction. The influence which the rotation of the earth exercises, in these high latitudes, on streams which run approximately in the direction of the meridian, is, however, very considerable, and gives to those coming from the south an easterly bend. In consequence of this, the river water of the Ohi and Yenisej must be confined as in a proper river channel, at first along the coast of the Tajmur country, until the current is allowed beyond Cape Chelyuskin to flow unhindered towards the north-east or east. Near the mouths of the large rivers I have, during calm weather in this current, in about 74° N.L., observed the temperature rising off the Yenisej to +9.4° C. (17th August, 1875), and off the Obi to +8°C. (10th August of the same year). As is usually the case, this current coming from the south produces both a cold undercurrent, which in stormy weather readily mixes with the surface water and cools it, and on the surface a northerly cold ice-bestrewn counter-current, which, in consequence of the earth's rotation, takes a bend to the west, and which evidently runs from the opening between Cape Chelyuskin and the northern extremity of Novaya Zemlya, towards the east side of this island, and perhaps may be the cause why the large masses of drift ice are pressed during summer against the east coast of Novaya Zemlya. According to my own experience and the uniform testimony of the walrus-hunters, this ice melts away almost completely during autumn.

In order to judge of the distance at which the current coming from the Obi and the Yenisej can drive away the drift ice, we ought to remember that even a very weak current exerts an influence on the position of the ice, and that, for instance, the current from the Plata River, whose volume of water, however, is not perhaps so great as that of the Obi and Yenisej, is still clearly perceptible at a distance of 1,500 kilometres from the river mouth, that is to say, about three times as far as from Port Dickson to Cape Chelyuskin. The only bay which can be compared to the Kara Sea in respect of the area, which is [pg 19] intersected by the rivers running into it, is the Gulf of Mexico.[9] The river currents from this bay appear to contribute greatly to the Gulf Stream.

The winds which, during the autumn months, often blow in these regions from the north-east, perhaps also, in some degree, contribute to keep a broad channel, along the coast in question, nearly ice-free.

The knowledge we possess regarding the navigable water to the east of Cape Chelyuskin towards the Lena, is mainly founded on the observations of the expeditions which were sent out by the Russian Government, before the middle of last century, to survey the northern part of Asia. In order to form a correct judgment of the results obtained, we must, while fully recognising the great courage, the extraordinary perseverance, and the power of bearing sufferings and overcoming difficulties of all kinds, which have always distinguished the Russian Polar explorers, always keep in mind that the voyages were carried out with small sailing-vessels of a build, which, according to modern requirements, is quite unsuitable for vessels intended for the open sea, and altogether too weak to stand collision with ice. They wanted, besides, not only the powerful auxiliary of our time, steam, but also a proper sail rig, fitted for actual manoeuvring, and were for the most part manned with crews from the banks of the Siberian rivers, who never before had seen the water of the ocean, experienced a high sea, or tried sailing among sea ice. When the requisite attention is given to these circumstances, it appears to me that the voyages referred to below show positively that even here we ought to be able during autumn to reckon upon a navigable sea.

The expeditions along the coast, east of Cape Chelyuskin, started from the town Yakoutsk, on the bank of the Lena, in 62° N. L., upwards of 900 miles from the mouth of the river. Here also were built the vessels which were used for these voyages.

The first started in 1735, under the command of Marine-Lieutenant Prontschischev. After having sailed down the river, and passed, on the 14th August, the eastern mouth-arm of the Lena, he sailed round the large delta of the river. On the 7th September he had not got farther than to the mouth of the [pg 20] Olonek. Three weeks had thus been spent in sailing a distance which an ordinary steamer ought now to be able to traverse in one day. Ice was seen, but not encountered. On the other hand, the voyage was delayed by contrary winds, probably blowing on land, whereby Prontschischev's vessel, if it had incautiously ventured out, would probably have been cast on the beach. The late season of the year induced Prontschischev to lay up his vessel for the winter here, at some summer yourts built by fur-hunters in 72° 54' N.L. The winter passed happily, and the following year (1736) Prontschischev again broke up, as soon as the state of the ice in Olonek Bay permitted, which, however, was not until the 15th August. The course was shaped along the coast toward the north-west. Here drift ice was met with, but he nevertheless made rapid progress, so that on the 1st September he reached 77° 29' N.L., as we now know, in the neighbourhood of Cape Chelyuskin. Compact masses of ice compelled him to turn here, and the Russians sailed back to the mouth of the Olonek, which was reached on the 15th September. The distinguished commander of the vessel had died shortly before of scurvy, and, some days after, his young wife, who had accompanied him on his difficult voyage, also died. As these attacks of scurvy did not happen during winter, but immediately after the close of summer, they form very remarkable contributions to a judgment of the way in which the Arctic expeditions of that period were fitted out.

A new expedition, under Marine-Lieutenant Chariton Laptev, sailed along the same coast in 1739. The Lena was left on the 1st August, and Cape Thaddeus (76° 47' N.L.) reached on the 2nd September, the navigation having been obstructed by drift ice only off Chatanga Bay. Cape Thaddeus is situated only fifty or sixty English miles from Cape Chelyuskin. They turned here, partly on account of the masses of drift ice which barred the way, partly on account of the late season of the year, and wintered at the head of Chatanga Bay, which was reached on the 8th September. Next year Laptev attempted to return along the coast to the Lena, but his vessel was nipped by drift ice off the mouth of the Olonek. After many difficulties and dangers, all the men succeeded in reaching safely the winter quarters of the former year. Both from this point and from the Yenisej, Laptev himself and his second in command, Chelyuskin, and the surveyor, Tschekin, the following year made a number of sledge journeys, in order to survey the peninsula which projects farthest to the north-west from the mainland of Asia. [pg 21] With this ended the voyages west of the Lena. The northernmost point of Asia, which was reached from land in 1742 by Chelyuskin, one of the most energetic members of most of the expeditions which we have enumerated, could not be reached by sea, and still less had any one succeeded in forcing his way with a vessel from the Lena to the Yenisej. Prontschischev had, however, turned on the 1st September, 1736, only some few minutes, and Laptev on the 2nd September, 1739, only about 50' from the point named, after voyages in vessels, which clearly were altogether unsuitable for the purpose in view. Among the difficulties and obstacles which were met with during these voyages, not only ice, but also unfavourable and stormy winds played a prominent part. From fear of not being able to reach any winter station visited by natives, the explorers often turned at that season of the year when the Polar Sea is most open. With proper allowance for these circumstances, we may safely affirm that no serious obstacles to sailing round Cape Chelyuskin would probably have been met with in the years named, by any steamer properly fitted out for sailing among ice.

From the sea between the Lena and Behring's Straits there are much more numerous and complete observations than from that further west. The hope of obtaining tribute and commercial profit from the wild races living along the coast tempted the adventurous Russian hunters, even before the middle of the 17th century, to undertake a number of voyages along the coast. On a map which is annexed to the previously quoted work of Müller, founded mainly on researches in the Siberian archives, there is to be found a sea route pricked out with the inscription, "Route anciennement fort fréquentée. Voyage fait par mer en 1648 par trois vaisseaux russes, dont un est parvenu jusqu'à la Kamschatka."[10]

Unfortunately the details of most of these voyages have been completely forgotten; and, that we have obtained some scanty accounts of one or other of them, has nearly always depended on some remarkable catastrophe, on lawsuits or other circumstances which led to the interference of the authorities. This is even the case with the most famous of these voyages, that of the Cossack, Deschnev, of which several accounts have been preserved, only through a dispute which arose between him and [pg 22] one of his companions, concerning the right of discovery to a walrus bank on the east coast of Kamschatka. This voyage, however, was a veritable exploring expedition undertaken with the approval of the Government, partly for the discovery of some large islands in the Polar Sea, about which a number of reports were current among the hunters and natives, partly for extending the territory yielding tribute to the Russians, over the yet unknown regions in the north-east.

Deschnev started on the 1st July, 1648, from the Kolyma in command of one of the seven vessels (Kotscher),[11] manned with thirty men, of which the expedition consisted. Concerning the fate of four of these vessels we have no information. It is probable that they turned back, and were not lost, as several writers have supposed; three, under the command of the Cossacks, Deschnev and Ankudinov, and the fur-hunter, Kolmogorsov, succeeding in reaching Chutskojnos through what appears to have been open water. Here Ankudinov's vessel was shipwrecked; the men, however, were saved and divided among the other two, which were speedily separated. Deschnev continued his voyage along the east coast of Kamschatka to the Anadir, which was reached in October. Ankudinov is also supposed to have reached the mouth of the Kamschatka River, where he settled among the natives and finally died of scurvy.

The year following (1649) Staduchin sailed again, for seven days, eastward from the Kolyma to the neighbourhood of Chutskojnos, in an open sea, so far as we can gather from the defective account. Deschnev's own opinion of the possibility of navigating this sea may be seen from the fact, that, after his own vessel was lost, he had timber collected at the Anadir for the purpose of building new ones. With these he intended to send to Yakoutsk the tribute of furs which he had received from the natives. He was, however, obliged to desist from his project by an easily understood want of materials for the building of the new vessels; he remarks also in connection with this that the sea round Chutskojnos is not free of ice every year.

A number of voyages from the Siberian rivers northward, were also made after the founding of Nischni Kolymsk, by Michael Staduchin in 1644 in consequence of the reports which were current among the natives at the coast, of the existence of large inhabited islands, rich in walrus tusks and mammoth bones, [pg 23] in the Siberian Polar Sea. Often disputed, but persistently taken up by the hunting races, these reports have finally been verified by the discovery of the islands of New Siberia, of Wrangel's Land, and of the part of North America east of Behring's Straits, whose natural state gave occasion to the golden glamour of tradition with which the belief of the common people incorrectly adorned the bleak, treeless islands in the Polar Sea.

All these attempts to force a passage in the open sea from the Siberian coasts northwards, failed, for the single reason, that an open sea with a fresh breeze was as destructive to the craft which were at the disposal of the adventurous, but ill-equipped Siberian polar explorer as an ice-filled sea; indeed, more dangerous, for in the latter case the crew, if the vessel was nipped, generally saved themselves on the ice, and had only to contend with hunger, snow, cold, and other difficulties to which the most of them had been accustomed from their childhood; but in the open sea the ill-built, weak vessel, caulked with moss mixed with clay, and held together with willows, leaked already with a moderate sea, and with a heavier, was helplessly lost, if a harbour could not be reached in time of need.

The explorers soon preferred to reach the islands by sledge journeys on the ice, and thus at last discovered the whole of the large group of islands which is named New Siberia. The islands were often visited by hunters for the purpose of collecting mammoth tusks, of which great masses, together with the bones of the mammoth, rhinoceros, sheep, ox, horse, etc., are found imbedded in the beds of clay and sand here. Afterwards they were completely surveyed during Hedenström's expeditions, fitted out by Count Rumanzov, Chancellor of the Russian Empire, in the years 1809-1811, and during Lieutenant Anjou's in 1823. Hedenström's expeditions were carried out by travelling with dog-sledges on the ice, before it broke, to the islands, passing the summer there, and returning in autumn, when the sea was again covered with ice. As the question relates to the possibility of navigating this sea, these expeditions, carried out in a very praiseworthy way, might be expected to have great interest, especially through observations from land, concerning the state of the ice in autumn; but in the short account of Hedenström's expeditions which is inserted in Wrangel's Travels, pp. 99-119, the only source accessible to me in this respect, there is not a single word on this point.[12] Information on this subject, so important [pg 24] for our expedition, has, however, by Mr. Sibiriakoff's care, been received from inhabitants of North Siberia, who earn their living by collecting mammoths' tusks on the group of islands in question. By these accounts the sea between the north coast of Asia and the islands of New Siberia, is every year pretty free of ice.

A very remarkable discovery was made in 1811 by a member of Hedenström's expedition, the Yakoutsk townsman Sannikov; for he found, on the west coast of the island Katelnoj, remains of a roughly-timbered winter habitation, in the neighbourhood of the wreck of a vessel, differing completely in build from those which are common in Siberia. Partly from this, partly from a number of tools which lay scattered on the beach, Sannikov drew the conclusion, that a hunter from Spitzbergen or Novaya Zemlya had been driven thither by the wind, and had lived there for a season with his crew. Unfortunately the inscription on a monumental cross in the neighbourhood of the hut was not translated.

During the great northern expeditions,[13] several attempts were also made to force a passage eastwards from the Lena. The first was under the command of Lieutenant Lassinius in 1735. He left the most easterly mouth-arm of the Lena on the 21st of August, and sailed 120 versts eastward, and there encountered drift ice which compelled him to seek a harbour at the coast. Here the winter was passed, with the unfortunate result, that the chief himself, and most of the fifty-two men belonging to the expedition, perished of scurvy.

The following year, 1736, there was sent out, in the same direction, a new expedition under Lieutenant Dmitri Laptev. With the vessel of Lassinius he attempted, in the middle of August, to sail eastward, but he soon fell in with a great deal of drift ice. So soon as the end of the month—the time when navigation ought properly to begin—he turned towards the Lena on account of ice.

In 1739 Laptev undertook his third voyage. He penetrated to the mouth of the Indigirka, which was frozen over on the 21st September, and wintered there. The following year the voyage was continued somewhat beyond the mouth of the [pg 25] Kolyma to Cape Great Baranov, where further advance was prevented by drift ice on the 26th September. After having returned to the Kolyma, and wintered at Nischni Kolymsk, he attempted, the following year, again to make his way eastwards in some large boats built during winter, but, on account of fog, contrary winds, and ice, without success. In judging of the results these voyages yielded, we must take into consideration the utterly unsuitable vessels in which they were undertaken—at first in a double sloop, built at Yakoutsk, in 1735, afterwards in two large boats built at Nischni Kolymsk. If we may judge of the nature of these craft from those now used on the Siberian rivers, we ought rather to be surprised that any of them could venture out on a real sea, than consider the unsuccessful voyages just described as proofs that there is no probability of being able to force a passage here with a vessel of modern build, and provided with steam power.

It remains, finally, for me to give an account of the attempts that have been made to penetrate westward from Behring's Straits.

Deschnev's voyage, from the Lena, through Behring's Straits to the mouth of the Anadir, in 1648, became completely forgotten in the course of about a century, until Muller, by searches in the Siberian archives, recovered the details of these and various other voyages along the north coast of Siberia. That the memory of these remarkable voyages has been preserved to after-times, however, depends, as has been already stated, upon accidental circumstances, lawsuits, and such like, which led to correspondence with the authorities. Of other similar undertakings we have certainly no knowledge, although now and then we find it noted that the Polar Sea had in former times often been traversed. In accounts of the expeditions fitted out by the authorities, it, for instance, often happens that mention is made of meeting with hunters and traders, who were sailing along the coast in the prosecution of private enterprise. Little attention was, however, given to these voyages, and, eighty-one years after Deschnev's voyage, the existence of straits between the north-eastern extremity of Asia and the north-western extremity of America was quite unknown, or at least doubted. Finally, in 1729, Behring anew sailed through the Sound, and attached his name to it. He did not sail, however, very far (to 172° W. Long.) along the north coast of Asia, although he does not appear to have met with any obstacle from ice. Nearly fifty years afterwards Cook concluded in these waters the series of splendid discoveries with which he enriched geographical [pg 26] science. After having, in 1778, sailed a good way eastwards along the north coast of America, he turned towards the west, and reached the 180th degree of longitude on the 29th August: the fear of meeting with ice deterred him from sailing further westward, and his vessel appears to have scarcely been equipped or fitted for sailing among ice.

After Cook's time we know of only three expeditions which have sailed westwards from Behring's Straits. The first was an American expedition, under Captain Rodgers, in 1855. He reached, through what appears to have been open water, the longitude of Cape Yakan (176° E. from Greenwich). The second was that of the English steam-whaler Long, who, in 1867, in search of a new profitable whale-fishing ground, sailed further west than any before him. By the 10th August he had reached the longitude of Tschaun Bay (170° E. from Greenwich). He was engaged in whale-fishing, not in an exploring expedition, and turned here; but, in the short account he has given of his voyage, he expresses the decided conviction that a voyage from Behring's Straits to the Atlantic belongs to the region of possibilities, and adds that, even if this sea-route does not come to be of any commercial importance, that between the Lena and Behring's Straits ought to be useful for turning to account the products of Northern Siberia.[14] Finally, last year a Russian expedition was sent out to endeavour to reach Wrangel's Land from Behring's Straits. According to communications in the newspapers, it was prevented by ice from sailing thence, as well as from sailing far to the west.

Information has been obtained through Mr. Sibiriakoff, from North Siberia, regarding the state of the ice in the neighbouring sea. The hunting in these regions appears to have now fallen off so seriously, that only few persons were found who could give any answers to the questions put.

Thus in Yakoutsk there was only one man (a priest) who had been at the coast of the Polar Sea. He states that when the wind blows off the land the sea becomes free of ice, but that the ice comes back when the wind blows on to the land, and thereby exposes the vessels which cannot reach a safe harbour to great danger.

Another correspondent states, on the ground of observations made during Tschikanovski's expedition, that in 1875 the sea off the Olonek was completely free of ice, but adds at the same time that the year in this respect was an exceptional one. [pg 27] The Arctic Ocean, not only in summer, but also during winter, is occasionally free of ice, and at a distance of 200 versts from the coast, the sea is open even in winter, in what direction, however, is uncertain. The latter fact is also confirmed by Wrangel's journeys with dog-sledges on the ice in 1821-1823.

A third person says, "According to the information which I have received, the north coast, from the mouth of the Lena to that of the Indigirka, is free from ice from July to September. The north wind drives the ice towards the coast, but not in large masses. According to the observations of the men who search for mammoth tusks, the sea is open as far as the southern part of the New Siberia Islands. It is probable that these islands form a protection against the ice in the Werchnojan region. It is otherwise on the Kolyma coast; and if the Kolyma can be reached from Behring's Straits, so certainly can the Lena."

The circumstance that the ice during summer is driven from the coast by southerly winds, yet not so far but that it returns, in larger or smaller quantity, with northerly winds, is further confirmed by other correspondents, and appears to me to show that the New Siberian Islands and Wrangel's Land only form links in an extensive group of islands, running parallel with the north coast of Siberia, which, on the one hand, keeps the ice from the intermediate sea from drifting away altogether, and favours the formation of ice during winter, but, on the other hand, protects the coast from the Polar ice proper, formed to the north of the islands. The information I have received besides, refers principally to the summer months. As in the Kara Sea, which formerly had a yet worse reputation, the ice here, too, perhaps, melts away for the most part during autumn, so that at this season we may reckon on a pretty open sea.

Most of the correspondents, who have given information about the state of the ice in the Siberian Polar Sea, concern themselves further with the reports current in Siberia, that American whalers have been seen from the coast far to the westward. The correctness of these reports was always denied in the most decided way: yet they rest, at least to some extent, on a basis of fact. For I have myself met with a whaler, who for three years in a steamer carried on trade with the inhabitants of the coast from Cape Yakan to Behring's Straits. He was quite convinced that some years at least it would be possible to sail from Behring's Straits to the Atlantic. On one occasion he had returned through Behring's Straits as late as the 17th October. [pg 28] From what I have thus stated, it follows,—

That the ocean lying north of the north coast of Siberia, between the mouth of the Yenisej and Tschaun Bay, has never been ploughed by the keel of any proper sea-going vessel, still less been traversed by any steamer specially fitted out for navigation among ice:

That the small vessels with which it has been attempted to traverse this part of the ocean never ventured very far from the coast:

That an open sea, with a fresh breeze, was as destructive for them, indeed more destructive, than a sea covered with drift ice:

That they almost always sought some convenient winter harbour, just at that season of the year when the sea is freest of ice, namely, late summer or autumn:

That, notwithstanding the sea from Cape Chelyuskin to Bearing's Straits has been repeatedly traversed, no one has yet succeeded in sailing over the whole extent at once:

That the covering of ice formed during winter along the coast, but probably not in the open sea, is every summer broken up, giving origin to extensive fields of drift ice, which are driven, now by a northerly wind towards the coast, now by a south wind out to sea, yet not so far but that it comes back to the coast after some days' northerly wind; whence it appears probable that the Siberian Sea is, so to say, shut off from the Polar Sea proper, by a series of islands, of which, for the present, we know only Wrangel's Land and the islands which form New Siberia.

In this connection it seems to me probable that a well-equipped steamer would be able without meeting too many difficulties, at least obstacles from ice, to force a passage this way during autumn in a few days, and thus not only solve a geographical problem of several centuries' standing, but also, with all the means that are now at the disposal of the man of science in researches in geography, hydrography, geology, and natural history, survey a hitherto almost unknown sea of enormous extent.

The sea north of Behring's Straits is now visited by hundreds of whaling steamers, and the way thence to American and European harbours therefore forms a much-frequented route. Some few decades back, this was, however, by no means the case. The voyages of Behring, Cook, Kotzebue, Beechey, and others were then considered as adventurous, fortunate exploring expeditions of great value and importance in respect of science, [pg 29] but without any direct practical utility. For nearly a hundred and fifty years the same was the case with Spangberg's voyage from Kamschatka to Japan in the year 1739, by which the exploring expeditions of the Russians, in the northernmost part of the Pacific Ocean, were connected with those of the Dutch and the Portuguese to India, and Japan; and in case our expedition succeeds in reaching the Suez Canal, after having circumnavigated Asia, there will meet us there a splendid work, which, more than any other, reminds us, that what to-day is declared by experts to be impossible, is often carried into execution to-morrow.

I am also fully convinced that it is not only possible to sail along the north coast of Asia, provided circumstances are not too unfavourable, but that such an enterprise will be of incalculable practical importance, by no means directly, as opening a new commercial route, but indirectly, by the impression which would thereby be communicated of the practical utility of a communication by sea between the ports of North Scandinavia and the Obi and Yenisej, on the one hand, and between the Pacific Ocean and the Lena on the other.