Title: Tobacco; Its History, Varieties, Culture, Manufacture and Commerce

Author: E. R. Billings

Release date: January 31, 2008 [eBook #24471]

Most recently updated: January 3, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Ted Garvin, Christine P. Travers and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's note: Obvious printer's errors have been corrected, all other inconsistencies are as in the original. The author's spelling has been maintained.

Page 62-63: The part between = obviously did not belong in that place and has been removed, "From this time forward the Plantation seemed to prosper, Charles granted lands to all the planters and adventurers who would till them, upon paying the annual sum of two shillings payable to the crown for each hundred acres. =direction, appointing the governor and council himself, and= Before the death of King James, however, the cultivation of tobacco had become so extensive that every other product seemed of but little value in comparison with it, and the price realized from its sale being so much greater than that obtained for "Corne," the latter was neglected and its culture almost entirely abandoned."

Page 115: The verse "And can but end with time;" was missing and has been added.

WITH

AN ACCOUNT OF ITS VARIOUS MODES OF USE, FROM ITS FIRST DISCOVERY UNTIL NOW.

BY

With Illustrations by Popular Artists.

"My Lord, this sacred herbe which never offendit,

Is forced to crave your favor to defend it."

Barclay.

"But oh, what witchcraft of a stronger kind,

Or cause too deep for human search to find,

Makes earth-born weeds imperial man enslave,—

Not little souls, but e'en the wise and brave!"

Arbuckle.

HARTFORD, CONN.:

AMERICAN PUBLISHING COMPANY,

1875.

Entered according to act of Congress, in the year 1875, by the

AMERICAN PUBLISHING CO.,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D.C.

Is it not wondrous strange that there should be

Such different tempers twixt my friend and me?

I burn with heat when I tobacco take,

But he on th' other side with cold doth shake:

To both 'tis physick, and like physick works,

The cause o' th' various operation lurks

Not in tobacco, which is still the same,

But in the difference of our bodies frame:

What's meat to this man, poison is to that,

And what makes this man lean, makes that man fat;

What quenches one's thirst, makes another dry;

And what makes this man wel, makes that man dye.

Thomas Washbourne, D. D.

Thy quiet spirit lulls the lab'ring brain,

Lures back to thought the flights of vacant mirth,

Consoles the mourner, soothes the couch of pain,

And wreathes contentment round the humble hearth;

While savage warriors, soften'd by thy breath,

Unbind the captive, hate had doomed to death.

Rev. Walter Colton.

Whate'er I do, where'er I be,

My social box attends on me;

It warms my nose in winter's snow,

Refreshes midst midsummer's glow;

Of hunger sharp it blunts the edge,

And softens grief as some alledge.

Thus, eased of care or any stir,

I broach my freshest canister;

And freed from trouble, grief, or panic,

I pinch away in snuff balsamic.

For rich or poor, in peace or strife,

It smooths the rugged path of life.

Rev. William King.

Hail! Indian plant, to ancient times unknown—

A modern truly thou, and all our own!

Thou dear concomitant of nappy ale,

Thou sweet prolonger of an old man's tale.

Or, if thou'rt pulverized in smart rappee,

And reach Sir Fopling's brain (if brain there be),

He shines in dedications, poems, plays,

Soars in Pindarics, and asserts the bays;

Thus dost thou every taste and genius hit—

In smoke thou'rt wisdom, and in snuff thou'rt wit.

Rev. Mr. Prior.

TO

CHARLES DUDLEY WARNER,

Whose rare, good gifts have endeared him to all lovers of the English tongue, this volume, historically and practically treating of one of the greatest of plants, as well as the rarest of luxuries, is respectfully dedicated by

The Author.

Ever since the discovery of tobacco it has been the favorite theme of many writers, who have endeavored to shed new light on the origin and early history of this singular plant. Upwards of three hundred volumes have been written, embracing works in nearly all of the languages of Europe, concerning the herb and the various methods of using it. Most writers have confined themselves to the commercial history of the plant; while others have written upon its medicinal properties and the various modes of preparing it for use. For this volume the Author only claims that it is at least a more comprehensive treatise on the varieties and cultivation of the plant than any work now extant. A full account of its cultivation is given, not only in America, but also in nearly all of the great tobacco-producing countries of the world. The history of the plant has been carefully and faithfully compiled from the earliest authorities, that portion which relates to its early culture in Virginia being drawn from hitherto unpublished sources. Materials for such a work have not been found lacking. European authors abound with allusions to tobacco; more especially is it true of English writers, who have celebrated its virtues in poetry and song. All along the highways and by-paths of our literature we encounter much that pertains to this "queen of plants." Considered in what light it may, tobacco must be regarded as the most astonishing of the productions of nature, since it has, in the short period of nearly four centuries, (p. viii) dominated not one particular nation, but the whole world, both Christian and Pagan. Ushered into the Old World from the New by the great colonizers—Spain, England, and France—it attracted at once the attention of the authors of the period as a fit subject for their marvel-loving pens. It has been the aim of the writer to give as much as possible of the existing material to be had concerning the early persecution waged against it, whether by Church or State. These accounts, while they invest with additional interest its early use and introduction, serve as well to show its triumph over all its foes and its vast importance to the commerce of the world. This work has been prepared and arranged, not only for the instruction and entertainment of the users of tobacco, but for the benefit of the cultivators and manufacturers as well. As such it is now presented to the public for whatever meed of praise or censure it is found to deserve.

Hartford, Conn., 1875.

CHAPTER I.

THE TOBACCO PLANT.

Botanical Description — Ancient Plant-Bed — Description of the Leaves — Color of Leaves — Blossoms — The Capsules and Seed — Selection for Seed — Suckers — Nicotine Qualities — Medicinal Properties — Improvement in Plants. 17

CHAPTER II.

TOBACCO. ITS DISCOVERY.

Early Use — Origin of its Name — Early Snuff-Taking — Tobacco in Mexico — Comparative Qualities of Tobacco — Origin of the Plant — Early Mammoth Cigars — Sacredness of the Pipe — Early Cultivation — Proportions of the Tobacco Trade — Variety of Kinds — Tobacco and Commerce — Original Culture. 32

CHAPTER III.

TOBACCO IN AMERICA.

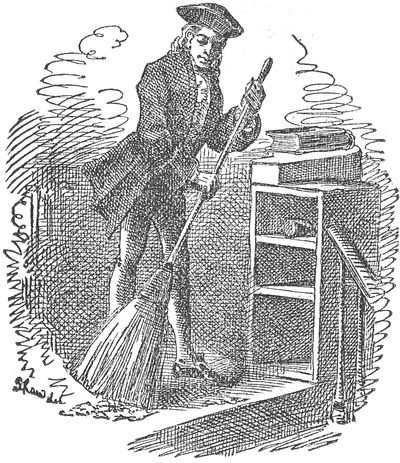

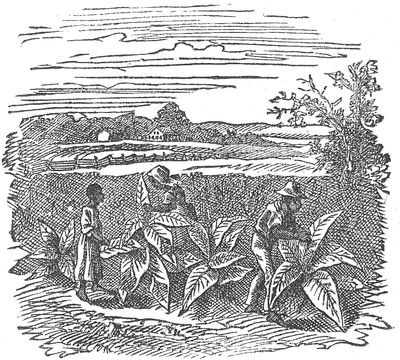

First General Planter — State of the Colony — Conditions of Raising Tobacco — Tobacco Fields, 1620 — Increase of Tobacco-Growing — Restriction of Tobacco-Growing — Tobacco used as Money — King James opposes Tobacco-Growing — Buying Wives with Tobacco — Foreign Tobacco Prohibited — King Charles on Tobacco — King Charles as a Tobacco Merchant — Tobacco Taxed — Planting in Maryland — Negro Labor — Competition — Growing Suckers — Virginia Lands — Picture of Early Planters — Large Plantations — Getting to Market — Virginia Plant-Bed — Maryland Plant-Bed — Tobacco Growing in New York and Louisiana — New England Tobacco — Commercial Value of Tobacco — Tobacco a Blessing. 47

CHAPTER IV.

TOBACCO IN EUROPE.

Introduction — The Original Importer — Wonderful Cures — How the Herb grew in Reputation — Difference of Opinion — A Smoker's Rhapsody — (p. xiv) Old Smokers — The Queen Herb — Drinking Tobacco — Tobacco on the Stage — Shakespeare on Tobacco — Smoking Taught — Ben Jonson on the Weed — Curative Qualities — Modes of Use — Held up to Ridicule — Tirades against Tobacco — Tobacco Selling — Royal Haters of Tobacco — Old Customs — A Racy Poem — A Smoking Divine. 80

CHAPTER V.

TOBACCO IN EUROPE. — Continued.

Popular use of Tobacco — Tobacco Glorified — Weight of Smoke — Anecdotes — Triumph of Tobacco — A Government Monopoly — Tobacco a Blessing. 111

CHAPTER VI.

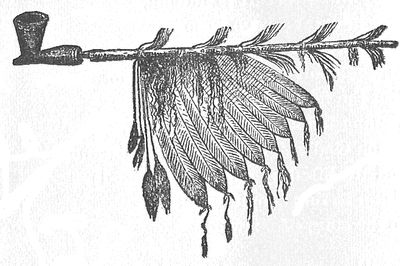

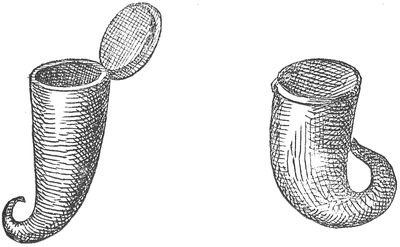

TOBACCO PIPES, SMOKING AND SMOKERS.

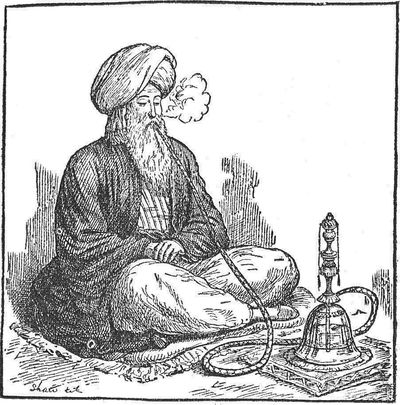

Indian Pipes — Material for Pipes — Legend of the Red Pipe — Chippewa Pipes — Making the Peace Pipes — South American Pipes — Cigarettes — Tobacco on the Amazon River — Brazilian Tobacco — Patagonians as Smokers — Form and Material — Pipe of the Bobeen Indians — The War Pipe — Pipe Sculpture — Smoking in Alaska — Smoking in Russia — Smoking in Peru — Smoking in Turkey — Moderate Smoking — Female Smoking — Early Manufacture of Pipes — French Pipes. 124

CHAPTER VII.

PIPES AND SMOKERS. — Continued.

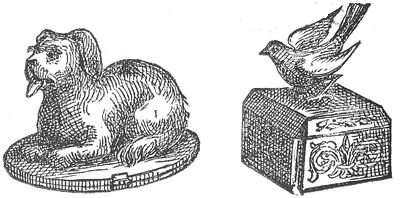

Meerschaum Pipes — Coloring Meerschaums — The City of Smokers — Hudson as a smoker — Persian Water Pipes — Turkish Pipes — Amber Mouth Pieces — Obtaining Amber — Its Value — Variety of Pipes — History of Pipes — Ancient Habit of Smoking — Buried Pipes — Jasmine Pipes — Smoking in Algiers — Smoking in Africa — Defence of Smoking — Tea and Tobacco — Chinese Pipes — Smoking in Japan — Tobacco Boxes — Tobacco Jars — Musings over a Pipe — Sad Fate of a Chewer — Triumph of the Anti's — The Smoker's Calendar — Doctor Parr as a Smoker — Smoking on the Battle-Field — Literary Smokers — Doctor Clarke on Tobacco — Noted Smokers — Pleasant Pipe — A Tobacco World — Cruelty of Smokers — Men like Pipes — Universal Use. 150

CHAPTER VIII.

SNUFF, SNUFF-BOXES AND SNUFF-TAKERS.

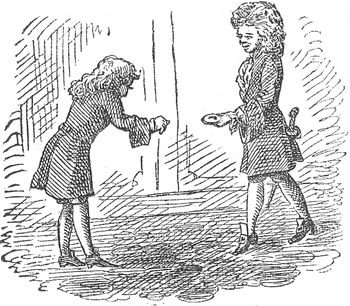

Its Introduction — Boxes and Graters — Mode of Preparation — Snuff-Boxes — A Celebrated Manufacturer — The Snuffing Period — The Monk and his Snuff-Box — A Pinch of Snuff — Pleasures of Smelling — Frederick the Great — Eminent Snuff-Takers — The Story in Verse — "Come to my Nose" — Snuff Manufacture — Preparation of Tobacco — Grinding the Leaves — Flavoring the Snuff — Profits Made — Love of Tobacco — Chewing and Dipping — Advantages of Dipping — The First Snuffers — Famous Snuff-Takers — Snuff as a Pacificator — A National Stimulant — Different Tastes — Rise and Progress of Snuff-Taking. 218

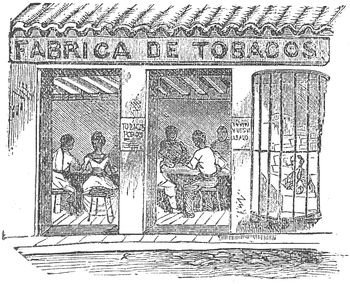

New York Cigars — Havana Cigars — Quality of Havana Cigars — Relative Value and Size — Cigar-Makers — Cuban Cigars — Cigar Manufactories — Preparation of the Tobacco — Sorting the Leaves — Sales, etc. — Large Factories — Universal Smoking — Cigar Etiquette — Reveries — Summer-Day Thoughts — American Smokers — At Home — Sentiment — Ode to a Cigar — Cigar-Lighters — Smoking an Art — Science of Lighting — Age of Fusees — "Home-Made Cigars" — Female Cigar-Makers — A Spicy Article — How to Smoke — Smoking Christians — Lamb's Poem — Tobacco Compliment — Cigarette Smoking — Thomas Hood's Cigar — Lord Byron's Opinion — Kinds of Cigars — Selecting Cigars — Yara Cigars — Manilla Cigars — Swiss Cigars — Paraguay Cigars — Brazilian Cigars — American Cigars — Connecticut Seed Leaf and Havana Cigars — The Exile's Comfort. 259

CHAPTER X.

TOBACCO PLANTERS AND PLANTATIONS.

The Connecticut Planter — Intelligence of Tobacco Growers — Best Connecticut Seed Leaf — Love for the Plant — Virginia Planters — A Virginia Plantation — The Plant-Patch — Planting, Topping and Priming — Suckering — Crop-Gathering — Curing and Sorting — Tobacco Markets — Ohio Tobacco — Mode of Cure — Kentucky Tobacco-Growing — The Kentucky Planter — Florida Tobacco — Florida Plantation — Tobacco in Louisiana — California Tobacco Lands — Mexican Tobacco — Plants around Vera Cruz — Tobacco in St Domingo — Cuba Plantations — Mode of Working — Soil and Climate — Tobacco-Growing in Germany — Method of Culture — Extent of Culture — Tobacco-Raising in Prussia — Tobacco in Holland — Dutch Planters — A Plea for Tobacco — Tobacco Culture in Australia — Arabian Plantations — Tobacco in Africa — Syrian Tobacco — Latakia Tobacco — Growing Tobacco in India — Curing Tobacco in India — Turks Cultivating Tobacco — Japanese Tobacco — Persian Tobacco — Tobacco Culture, Philippine Islands — Climate of the Islands — Fragrant Manillas — Tropical Tobacco. 311

CHAPTER XI.

VARIETIES.

Kinds used for Cigars — Dwarf Tobacco — Havana Tobacco — Yara and Virginia Tobacco — James River Tobacco — Ohio Tobacco — South American Tobacco — Celebrated Brands of Tobacco — Russian Tobacco — Columbian Tobacco — Tobacco of Brazil — The Orinoco Tobacco — Persian Tobacco — French Tobacco — Spanish Tobacco — Japanese Tobacco — Manilla Tobacco. 382

CHAPTER XII.

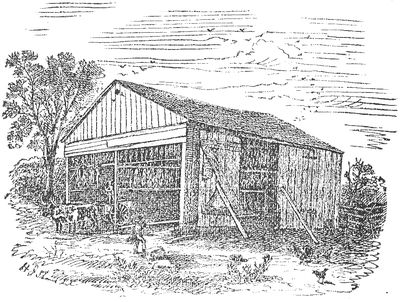

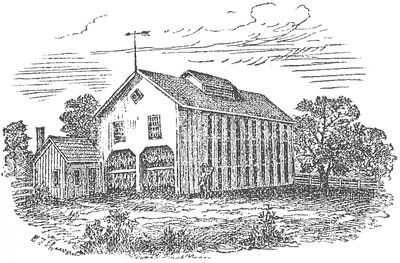

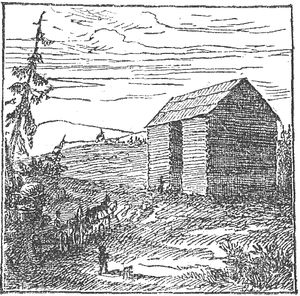

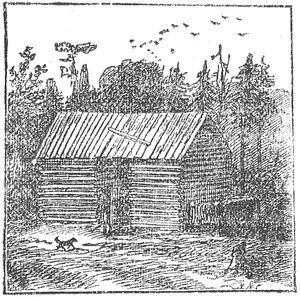

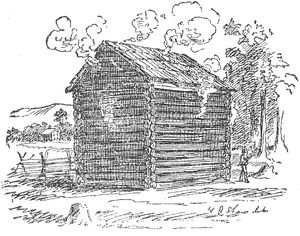

TOBACCO HOUSES.

Tobacco Sheds — Stripping Houses — Virginia Tobacco Sheds — Ordinary Sheds — Superior Sheds — Ohio Sheds — Kentucky and Tennessee Sheds — Foreign Tobacco Sheds. 405

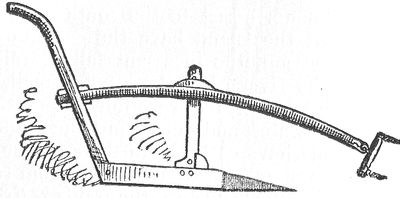

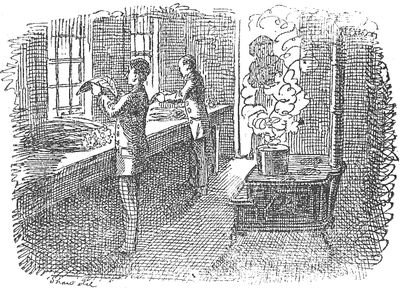

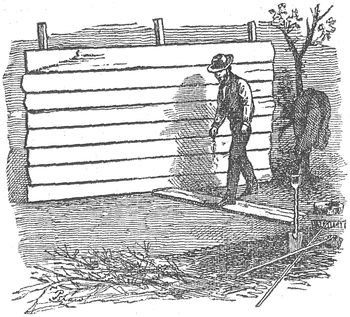

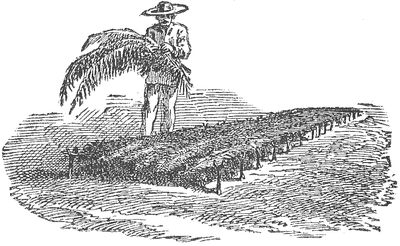

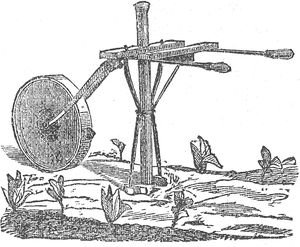

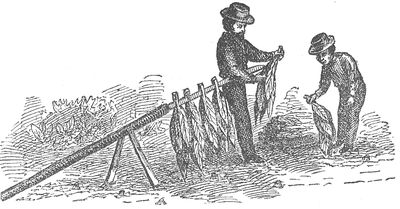

Hot Beds — Virginia Plant Patch — Tennessee Plant Bed — Cuban Plant Bed — Covering Plant Bed — Selection of Soil — The Soil Affecting Color — Preparing the Soil — Virginia Methods — Burning Brush — Implements — Transplanting Plants — Setting — Seasons in Mexico and Persia — The American Transplanter — Pests — Worming — Backward Plants — Topping — Suckers — Maturation — The Harvest — Cutting — Hanging — Cutting time in Cuba — Harvesting in Virginia — The Season in other Places — Curing — Curing by Smoke — Yellow Tobacco — Stripping — Assorting — Shading — Stemming — Packing — Casing — Old Style — Resistance to Dampness — Prizing — Marking — Baling — Certificates — Firing — White Rust — Seed Plants — Maturing of Seed — Second Growth. 415

CHAPTER XIV.

THE PRODUCTION, COMMERCE AND MANUFACTURE OF TOBACCO.

Early History of Tobacco — Cultivation by Spaniards at St. Domingo — Annual Product of Cuba — Amount of Land under Cultivation in U.S. — Cultivation in the South — Annual Product of Europe, Asia and Africa — Government Monopoly — Source of Revenue — Manufacture of Cigarettes — Increase of Tobacco Culture. 478

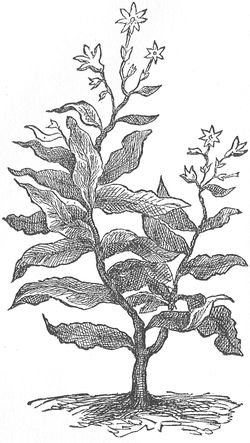

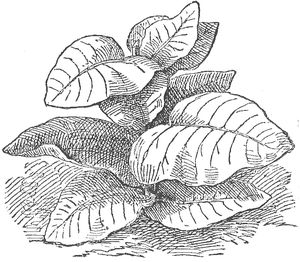

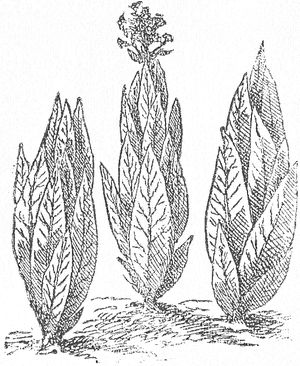

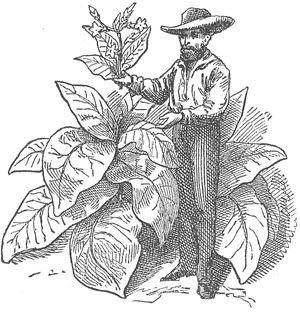

Tobacco is a hardy flowering annual[1] plant, growing freely in a moist fertile soil and requiring the most thorough culture in order to secure the finest form and quality of leaf. It is a native of the tropics and under the intense rays of a vertical sun develops its finest and most remarkable flavor which far surpasses the varieties grown in a temperate region. It however readily adapts itself to soil and climate growing through a wide range of temperature from the Equator to Moscow in Russia in latitude 56°, and through all the intervening range of climate[2].

The plant varies in height according to species and locality; the largest varieties reaching an altitude of ten or twelve feet, in others not growing more than two or three feet from the ground. Botanists have enumerated between forty and fifty varieties of the tobacco plant who class them all among the narcotic poisons. When properly cultivated the plant ripens in a few weeks growing with a rapidity hardly equaled by any product either temperate or tropical. Of the large number of varieties cultivated scarcely more than one-half are grown to any great extent while many of them are hardly known outside of the limit of cultivation. Tobacco is a strong growing plant resisting heat and drought to a far (p. 018) greater extent than most plants. It is a native of America, the discovery of the continent and the plant occurring almost simultaneously. It succeeds best in a deep rich loam in a climate ranging from forty to fifty degrees of latitude. After having been introduced and cultivated in nearly all parts of the world, America enjoys the reputation of growing the finest varieties known to commerce. European tobacco is lacking in flavor and is less powerful than the tobacco of America.

The botanical account of tobacco is as follows:—

"Nicotiana, the tobacco plant is a genus of plants of the order of Monogynia, belonging to the pentandria class, order 1, of class V. It bears a tubular 5-cleft calyx; a funnel-formed corolla, with a plaited 5-cleft border; the stamina inclined; the stigma capitate; the capsule 2-celled, and 2 to 4 valved."

A more general description of the plant is given by an American writer:—

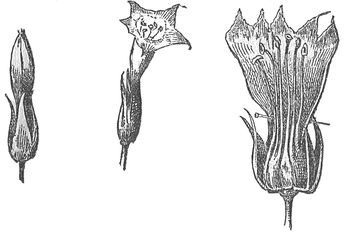

"The tobacco plant is an annual growing from eighteen inches (dwarf tobacco) to seven or eight feet in height[3]. It bears numerous leaves of a pale green color sessile, ovate lanceolate and pointed in form, which come out alternately from two to three inches apart. The flowers grow in loose panicles at the extremity of the stalks, and the calyx is bell-shaped, and divided at its summit into five pointed segments. The tube of the corolla expands at the top into an oblong cup terminating in a 5-lobed plaited rose-colored border. The pistil consists of an oval germ, a slender style longer than the stamen, and a cleft stigma. The flowers are succeeded by capsules of 2 cells opening at the summit and containing numerous kidney-shaped seeds."

Two of the finest varieties of Nicotiana Tobacum that are cultivated are the Oronoco and the Sweet Scented; they differ only in the form of the leaves, those of the latter variety being shorter and broader than the other. They are annual herbaceous plants, rising with strong erect stems to the height of from six to nine feet, with fine handsome foliage. The stalk near the root is often an inch or more in diameter, and (p. 019) surrounded by a hairy clammy substance, of a greenish yellow color. The leaves are of a light green; they grow alternately, at intervals of two or three inches on the stalk; they are oblong and spear-shaped; those lowest on the stalk are about twenty inches in length, and they decrease as they ascend.

The young leaves when about six inches, are of a deep green color and rather smooth, and as they approach maturity they become yellowish and rougher on the surface. The flowers grow in clusters from the extremities of the stalk; they are yellow externally and of a delicate red within. They are succeeded by kidney shaped capsules of a brown color.

Thompson in his "Notices relative to Tobacco" describes the tobacco plant as follows:—

"The species of Nicotiana which was first known, and which still furnishes the greatest supply of Tobacco, is the N. tobacum, an annual plant, a native of South America, but naturalized to our climate. It is a tall, not inelegant plant, rising to the height of about six feet, with a strong, round, villous, slightly viscid stem, furnished with alternate leaves, which are sessile, or clasp the stems; and are decurrent, lanceolate, entire; of a full green on the upper surface, and pale on the under.

"In a vigorous plant, the lower leaves are about twenty inches in length, and from three to five in breadth, decreasing as they ascend. The inflorescence, or flowering part of the stem, is terminal, loosely branching in that form which botanists term a panicle, with long, linear floral leaves or bractes at the origin of each division.

"The flowers, which bloom in July and August, are of a pale pink or rose color: the calyx, or flower-cup, is bell-shaped, obscurely pentangular, villous, slightly viscid, and presenting at the margin five acute, erect segments. The corolla is twice the length of the calyx, viscid, tubular below, swelling above into an oblong cup, and expanding at the lip into five somewhat plaited, pointed segments; the seed vessel is an oblong or ovate capsule, containing numerous reniform seeds, which are ripe in September and October; and if not collected, are shed by the capsule opening at the apex."

In Stevens and Liebault's Maison Rustique, or the Country Farm, (London, 1606), is found the following curious account of the tobacco plant:—

(p. 020) "This herbe resembleth in figure fashion, and qualities, the great comfrey in such sort as that a man woulde deeme it to be a kinde of great comfrey, rather than a yellow henbane, as some have thought.

"It hath an upright stalke, not bending any way, thicke, bearded or hairy, and slimy: the leaves are broad and long, greene, drawing somewhat towards a yellow, bearded or hoarrie, but smooth and slimie, having as it were talons, but not either notched or cut in the edges, a great deale bigger downward toward the root than above: while it is young it is leaved, as it were lying upon the ground, but rising to a stalke and growing further, it ceaseth to have such a number of leaves below, and putteth forth branches from half foot to half, and storeth itselfe, by that meanes with leaves, and still riseth higher from the height of four or five foote, unto three or four or five cubits according as is sown in a hot and fat ground, and carefully tilled. The boughs and branches thereof put out at joints, and divide the stalk by distance of halfe a foote: the highest of which branches are bigger than an arme.

"At the tops and ends of his branches and boughs, it putteth foorth flowers almost like those of Nigella, of a whitish and incarnate color, having the fashion of a little bell comming out of a swad or husk, being of the fashion of a small goblet, which husk becometh round, having the fashion of a little apple, or sword's pummell: as soon as the flower is gone and vanished away, it is filled with very small seedes like unto those of yellow henbane, and they are black when they be ripe, or greene, while they are not yet ripe.

"In a hot countree it beareth leaves, flowers, and seeds at the same time, in the ninth or tenth month of the year it putteth foorth young cions at the roote, and reneweth itself by this store and number of cions, and great quantity of sprouts, and yet notwithstanding the roots are little, small, fine thready strings, or if otherwise they grow a little thick, yet remaine they still very short, in respect of the height of the plant. The roots and leaves do yield a glewish and rosinith kind of juice, somewhat yellow, of a rosinlike smell, not unpleasant, and of a sharpe, eager and biting taste, which sheweth that it is by nature hot, whereupon we must gather that it is no kind of yellow henbane as some have thought. Nicotiana craveth a fat ground well stird, and well manured also in this cold countrie (England) that is to say an earth, wherein the manure is so well mingled and incorporated, as (p. 021) that it becometh earthie, that is to say, all turned into earth, and not making any shew any more of dung: which is likewise moist and shadowie, wide and roomy, for in a narrow and straight place it would not grow high, straight, great and well-branched.

"It desireth the South sun before it, and a wall behind it, which may stand in stead of a broad pair of shoulders to keep away the northern wind and to beate backe againe the heat of the sun. It groweth the better if it be oft watered, and maketh itself sport and jolly good cheer with water when the time becometh a little dry. It hateth cold, and therefore to keepe it from dying in winter, it must be either kept in cellars where it may have free benefit of air, or else in some cave made on purpose within the same garden, or else to cover it as with a cloak very well with a double mat, making a penthouse of wicker work from the wall to cover the head thereof with straw laid thereupon: and when the southern sun shineth, to open the door of the covert made for the said herb right upon the said South sun."

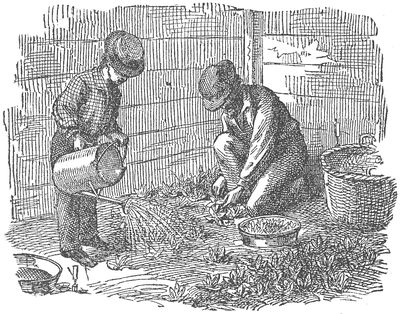

The most ludicrous part of "The discourse on Nicotian" will be found in that portion which relates to the making of the plant-bed and transplanting:—

"For to sow it, you must make a hole in the earth with your finger and that as deep as your finger is long, then you must cast into the same hole ten or twelve seeds of the said Nicotiana together, and fill up the hole again: for it is so small, as that if you should put in but four or five seeds the earth would choake it: and if the time be dry, you must water the place easily some five days after: And when the herb is grown out of the earth, inasmuch as every seed will have put up his sprout and stalk, and that the small thready roots are intangled the one within the other, you must with a great knife make a composs within the earth in the places about this plot where they grow and take up the earth and all together, and cast them into a bucket full of water, to the end that the earth may be seperated, and the small and tender impes swim about the water; and so you shall sunder them one after another without breaking of them." * *

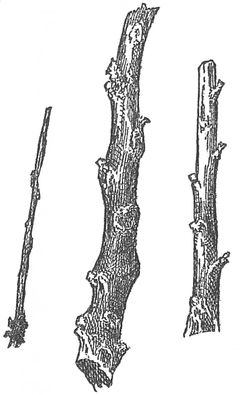

Tobacco Stalks

The Tobacco stalk varies with the varieties of the plant. All of the species cultivated in the United States have stalks of a large size—much larger than many varieties grown in (p. 022) the tropics. Those of some species of tobacco are little and easily broken, which to a certain extent is the case with most varieties of the plant when maturing very fast. The stalks of some plants are rough and uneven, while those of others are smooth. Nearly all, including most of those grown in Europe and America, have erect, round, hairy, viscid stalks, and large, fibrous roots; while that of Spanish as well as dwarf tobacco is harder and much smaller. The stalk is composed of a wood-like substance containing a glutinous pith, and is of about the same shade of color as the leaves. As the plant develops in size the stalk hardens, and when fully grown is not easily broken.

The size of the stalk corresponds with that of the leaves, and with such varieties of the plant as Connecticut seed leaf, Virginia, Kentucky, Ohio, St. Domingo, and some others; both will be found to be larger than Spanish, Latakia, and Syrian tobacco, which have a much smaller but harder stalk. It will readily be seen that the stalk must be strong and firm in order to support the large palm-like leaves which on some varieties grow to a length of nearly four feet with a corresponding breadth. The stalk does not "cure down" as fast as the leaves, which is thought now to be necessary in order to prevent sweating, as well as to hasten the curing. Most of the varieties of the plant have an erect, straight stalk, excepting Syrian tobacco, which near the top describes more of a semi-circle, but not to that extent of giving an idea of an entirely crooked plant. The stalk gradually tapers from the base to the summit, and when deprived of its leaves presents a smooth appearance not unlike that of a small tree or shrub deprived of its twigs and leaves.

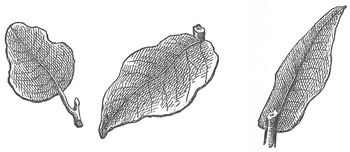

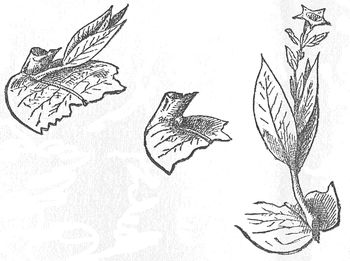

The Plant bears from eight to twenty leaves according to (p. 023) the species of the plant. They have various forms, ovate, lanceolate, and pointed. Leaves of a lanceolate form are the largest, and the shape of those found on most varieties of the American plant. The color of the leaves when growing, as well as after curing and sweating, varies, and is frequently caused by the condition of the soil. The color while growing may be either a light or dark green, which changes to a yellowish cast as the plant matures and ripens. The ground leaves are of a lighter color and ripen earlier than the rest—sometimes turning yellow, and during damp weather rotting and dropping from the stalk. Some varieties of the plant, like Latakia, bear small but thick leaves, which after cutting are very thin and fine in texture; while others, like Connecticut seed leaf and Havana, bear leaves of a medium thickness, which are also fine and silky after curing. But while the color of the plant when growing is either a light or dark green, it rapidly changes during curing, and especially after passing through the sweat, changing to a light or dark cinnamon like Connecticut seed leaf, black like Holland and Perique tobacco, bright yellow of the finest shade of Virginia and Carolina leaf, brown like Sumatra, or dark red like that known by the name of "Boshibaghli," grown in Asia Minor. The leaves are covered with glandular hairs containing a glutinous substance of an unpleasant odor, which characterizes all varieties as well as nearly all parts of the plant.

The leaves of all varieties of tobacco grow the entire length of the stem and clasp the stalk, excepting those of Syrian, which are attached by a long stem. The size of the leaves, as well as the entire plant, is now much larger than when first discovered. One of the early voyagers describes the plant as short and bearing leaves of about the size and shape of the walnut. In many varieties the leaves grow in a semi-circular form while in others they grow almost straight and still others growing erect presenting a singular appearance. The stem or mid-rib running through the leaf is large and fibrous and its numerous smaller veins proportionally larger which on curing become smaller and particularly in (p. 024) those kinds best adapted for cigar wrappers. The leaves from the base to the center of the plant are of about equal size but are smaller as they reach the summit, but after topping attain about the same size as the others. The color of the leaf after curing may be determined by the color of the leaf while growing—if dark green while maturing in the field, the color will be dark after curing and sweating and the reverse if of a lighter shade of green.

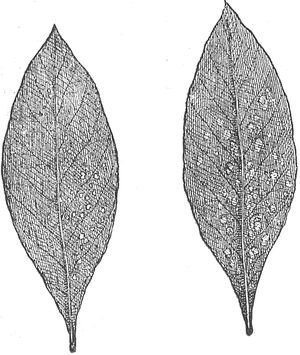

Tobacco Leaves.

If the soil be dark the color of the leaf will be darker than if grown upon a light loam. Some varieties of the plant have leaves of a smooth glossy appearance while others are rough and the surface uneven—more like a cabbage leaf, a peculiar feature of the tobacco of Syria. The kind of fertilizers applied to the soil also in a measure as well as the soil itself has much to do with the texture or body of the leaf and should be duly considered by all growers of the plant. A light moist loam should be chosen for the tobacco field if a leaf of light color and texture is desired while if a dark leaf is preferred the soil chosen should be a moist heavy loam.

The flowers of the tobacco plant grow in a bunch or cluster on the summit of the plant and are of a pink, yellow, or purple white color according to the variety of the plant. On most varieties the color of the flowers is pink excepting Syrian or Latakia which bears yellow flowers while those of (p. 025) Shiraz or Persian and Guatemala are white while those of the Japan tobacco, are purple. The segments of the corolla are pointed but on some varieties unequal, particularly that of Shiraz tobacco. The flowers impart a pleasant odor doubtless to all lovers of the weed but to all others a compound of villainous smells among which and above all the rest may be recognized an odor suggestive of the leaves of the plant.

Bud and Flowers.

When in full blossom a tobacco field forms a pleasant feature of a landscape which is greatly heightened if the plants are large and of equal size. The pink flowers are the largest while those of a yellow color are the smallest. The plant comes into blossom a few weeks before fully ripe when with a portion of the stalk they are broken off to hasten the ripening and maturing of the leaves. After the buds appear they blossom in a few days and remain in full bloom two or three weeks, when they perish like the blossoms of other plants and flowers. The flowers of Havana tobacco are of a lighter pink than those of Connecticut tobacco but are not as large—a trifle larger however than those of Latakia tobacco. Those varieties of the tobacco plant bearing pink flowers are the finest flavored and are used chiefly for the manufacture of cigars while those bearing yellow flowers are better adapted for cutting purposes and the pipe.

The American varieties of tobacco bear a larger number of (p. 026) flowers than European tobaccos or those of Africa or Asia. The color of the flowers remain the same whether cultivated in one country or another while the leaves may grow larger or smaller according to the system of cultivation adopted. Those varieties of the plant with heart-shaped leaves have paniculated flowers with unequal cups. The flower stems on the American varieties are much longer than those of European tobaccos and also larger. The season has much to do with the size of the flowers; as if very dry they are usually smaller and not as numerous as if grown under more favorable circumstances.

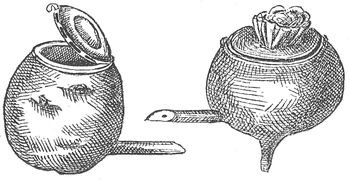

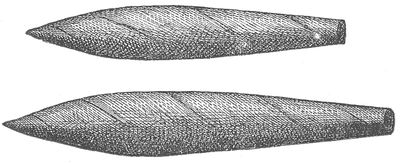

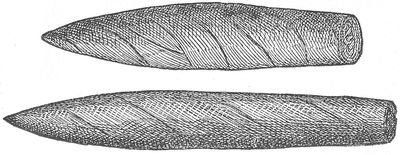

As soon as the flowers drop from the fruit bud the capsules grow very rapidly until they have attained full size—which occurs only in those plants which have been left for seed and remain untopped. When topped they are not usually full grown—as some growers top the plants when just coming into blossom, while others prefer to top the plants when in full bloom and others still when the blossoms begin to fall. The fruit is described by Wheeler

"as a capsule of a nearly oval figure. There is a line on each side of it, and it contains two cells, and opens at the top. The receptacles one of a half-oval figure, punctuated and affixed to the separating body. The seeds are numerous, kidney-shaped, and rugose."

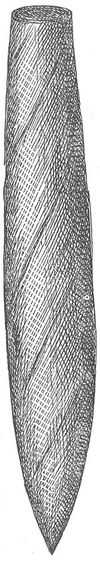

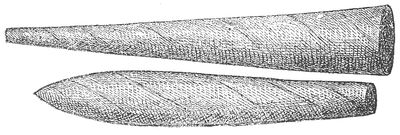

Most growers of the plant would describe the fruit bud as follows: In form resembling an acorn though more pointed at the top; in some species, of a dark brown in others of a light brown color, containing two cells filled with seeds similar in shape to the fruit bud, but not rugose as described by some botanists. Some writers state that each cell contains about one thousand seeds. The fruit buds of Connecticut, Virginia, Kentucky and Ohio Tobacco as well as of most of the varieties grown within the limits of the United States are much larger than those of Havana, Yara, Syrian, and numerous other species of the plant, while the color of these last named varieties is a lighter shade of brown. The color (p. 027) of the seed also varies according to the varieties of the plant. The seeds of some species are of a dark brown while others are of a lighter shade. The seeds, however, are so small that the variety to which they belong cannot be determined except by planting or sowing them.

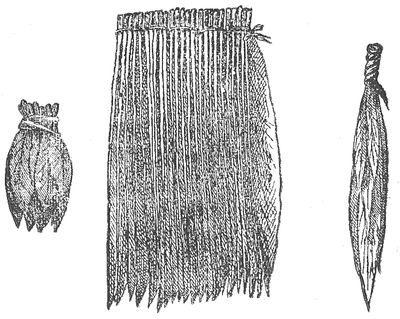

Capsules. (Fruit Bud.)

The plants selected for seed are usually left growing until late in the season, and at night should be protected from the cold and frost by a light covering of some kind—this may not be absolutely necessary, as most growers of tobacco have often noticed young plants growing around the base or roots of the seed stalk—the seeds of which germinated although remaining in the ground during the winter. Strong, healthy plants generally produce large, well filled capsules the only ones to be selected by the grower if large, fine plants are desired. Many growers of tobacco have doubtless examined the capsules of some species of the plant and frequently observed that the capsules or fruit buds are often scarcely more than half-filled while others contain but a few seeds. The largest and finest capsules on the plant mature first, while the smaller ones grow much slower and are frequently several weeks changing from green to brown. Many of the capsules do not contain any seed at all.

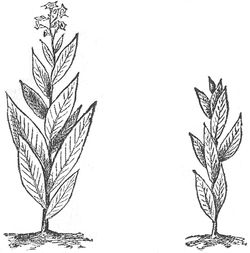

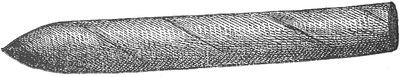

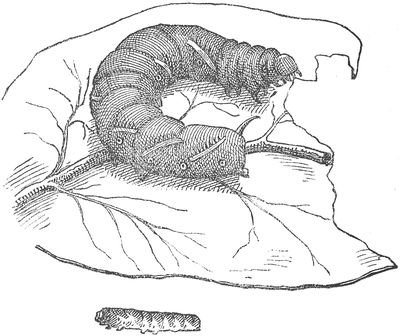

The offshoots or suckers as they are termed, make their appearance at the junction of the leaves and stalk, about the roots of the plant, the result of that vigorous growth caused by topping. The suckers can hardly be seen until after the (p. 028) plant has been topped, when they come forward rapidly and in a short time develop into strong, vigorous shoots. Tatham describing the sucker says:

"The sucker is a superfluous sprout which is wont to make its appearance and shoot forth from the stem or stalk, near to the junction of the leaves with the stems, and about the root of the plant, and if allowed to grow, injuring the marketable quality of the tobacco by compelling a division of its nutriment during the act of maturation. The planter is therefore careful to destroy these intruders with the thumb nail, as in the act of topping. This superfluity of vegetation, like that of the top, has been often the subject of legislative care; and the policy of supporting the good name of the Virginia produce has dictated the wisdom of penal laws to maintain her good faith against imposition upon strangers who trade with her."

The ripening of the suckers not only proves injurious to the quality of the leaf but retards their size and maturity and if allowed to continue, prevents them from attaining their largest possible growth.

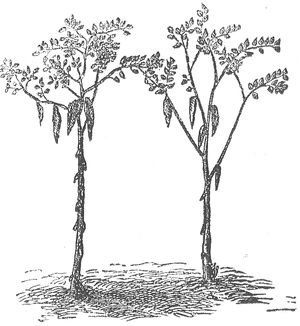

Suckers.

On large, strong, growing plants the growth of suckers is very rank after attaining a length of from six to ten inches, and when fully grown bearing flowers like the parent stalk. After growing for a length of time they become tough and attached so firmly to the stem of the leaf and stalk that they (p. 029) are broken off with difficulty, frequently detaching the leaf with them. The growth of the suckers, however, determines the quality as well as the maturity of the plants.

Weak, spindling plants rarely produce large, vigorous shoots, the leaves of such suckers are generally small and of a yellowish color. When the plants are fully ripe and ready to harvest the suckers will be found to be growing vigorously around the root of the plant. This is doubtless the best evidence of its maturity, more reliable by far than any other as it denotes the ripening of the entire plant. Suckering the plants hastens the ripening of the leaves, and gives a lighter shade of color, no matter on what soil the plants are grown. Having treated at some length of the various parts of the tobacco plant—stalk, leaves, flowers, capsules and suckers we come now to its nicotine properties. The tobacco plant, as is well known, produces a virulent poison known as Nicotine. This property, however, as well as others as violent is found in many articles of food, including the potato together with its stalk and leaves; the effects of which may be experienced by chewing a small quantity of the latter. The New Edinburgh Encyclopedia says:

"The peculiar effect produced by using tobacco bears some resemblance to intoxication and is excited by an essential oil which in its pure state is so powerful as to destroy life even in very minute quantity."

Chemistry has taught us that nicotine is only one among many principles which are contained in the plant. It is supposed by many but not substantiated by chemical research that nicotine is not the flavoring agent which gives tobacco its essential and peculiar varieties of odor. Such are most probably given by the essential oils, which vary in amount in different species of the plant.

An English writer says:

"Nicotine is disagreeable to the habitual smoker, as is proved by the increased demand for clean pipes or which by some mechanical contrivance get rid of the nicotine."

The late Dr. Blotin tested by numerous experiments the effects of nicotine on the various parts of the organization of (p. 030) man. While the physiological effects of nicotine may be interesting to the medical practitioner, they will hardly interest the general reader unless it can be shown that the effects of nicotine and tobacco should be proved to be identical.

We are loth to leave this subject, however, as it is so intimately connected with the history of the plant, without treating somewhat of its medicinal properties which to many are of more interest than its social qualities. The Indians not only used the plant socially, religiously, but medicinally. Their Medicine men prescribed its use in various ways for most diseases common among them. The use thus made of the plant attracted the attention of the Spanish and English, far more than its use either as a means of enjoyment or as a religious act. When introduced to the Old World, its claims as a remedy for most diseases gave it its popularity and served to increase its use. It was styled "Sana sancta Indorum—" "Herbe propre à tous maux," and physicians claimed that it was "the most sovereign and precious weed that ever the earth tendered to the use of man." As early as 1610, three years after the London and Plymouth Companies settled in Virginia, and some years before it began to be cultivated by them as an article of export, it had attracted the attention of English physicians, who seemed to take as much delight in writing of the sanitary uses of the herb as they did in smoking the balmy leaves of the plant.

Dr. Edmund Gardiner, "Practitioner of Physicke," issued in 1610 a volume entitled, "The Triall of Tobacco," setting forth its curative powers. Speaking of its use he says:

"Tobacco is not violent, and therefore may in my judgement bee safely put in practise. Thus then you plainly see that all medicines, and especially tobacco, being rightly and rationally used, is a noble medicine and contrariwise not in his due time with other circumstances considered, it doth no more than a nobleman's shooe doth in healing the gout in the foot."

Dr. Verner of Bath, in his Treatise concerning the taking the fume of tobacco (1637) says that when "taken moderately and at fixed times with its proper adjunct, which (as they doe (p. 031) suppose) is a cup of sack, they think it be no bad physick." Dr. William Barclay in his work on Tobacco, (1614) declares "that it worketh wonderous cures." He not only defends the herb but the "land where it groweth." At this time the tobacco plant like Indian Corn was very small, possessing but few of the qualities now required to make it merchantable. When first exported to Spain and Portugal from the West Indies and South America, and even by the English from Virginia, the leaf was dark in color and strong and rank in flavor. This, however, seems to have been the standard in regard to some varieties while others are spoken of by some of the early writers upon tobacco as "sweet."

The tobacco (uppowoc) grown by the Indians in America, at the time of its discovery, and more particularly in North America, would compare better with the suckers of the largest varieties of the plant rather than with even the smallest species of the plant now cultivated. At the present time tobacco culture is considered a science in order to secure the colors in demand, and that are fashionable, and also the right texture of leaf now so desirable in all tobaccos designed for wrappers. Could the Indians, who cultivated the plant on the banks of the James, the Amazon and other rivers of America, now look upon the plant growing in rare luxuriance upon the same fields where they first raised it, they could hardly realize them to be the same varieties that they had previously planted.[Back to Contents]

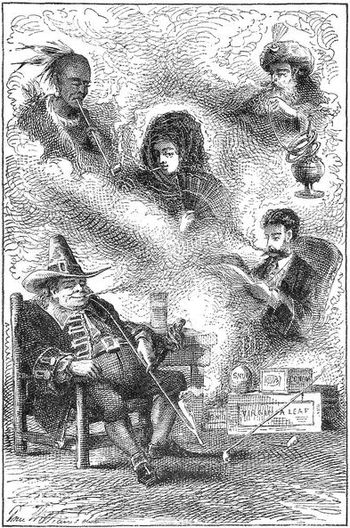

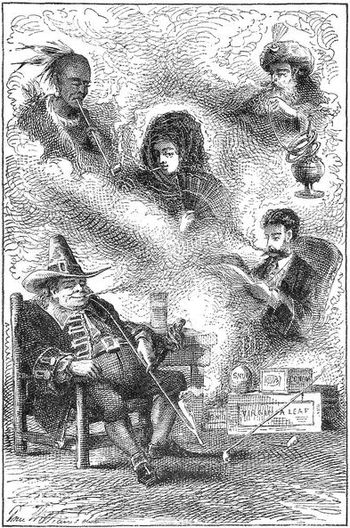

Nearly four hundred years have passed away since the tobacco plant and its use was introduced to the civilized world. It was in the month of November, 1492, that the sailors of Columbus in exploring the island of Cuba first noted the mode of using tobacco. They found the Indians carrying lighted firebrands (as they at first supposed) and puffed the smoke inhaled from their mouths and nostrils.

The Spaniards concluded that this was a method common with them of perfuming themselves; but its frequent use soon taught them that it was the dried leaves of a plant which they burned inhaling and exhaling the smoke. It attracted the attention of the Spaniards no less from its novelty than from the effect produced by the indulgence.

The use of tobacco by the Indians was entirely new to the Spanish discoverers and when in 1503 they landed in various parts of South America they found that both chewing and smoking the herb was a common custom with the natives. But while the Indians and their habits attracted the attention of the Spanish sailors Columbus was more deeply interested in the great continent and the luxuriant tropical growth to be seen on every hand. Columbus himself says of it:—

"Everything invited me to settle here. The beauty of the streams, the clearness of the water, through which I could see the sandy bottom; the multitude of palm-trees of different kinds, the tallest and finest I had ever seen; and an infinite number of other large and flourishing trees; the (p. 033) birds, and the verdure of the plains, are so amazingly beautiful, that this country excelles all others as far as the day surpasses the night in splendor."

Lowe, gives the following account of the discovery of tobacco and its uses:—

"The discovery of this plant is supposed to have been made by Fernando Cortez in Yucatan in the Gulf of Mexico, where he found it used universally, and held in a species of veneration by the simple natives. He made himself acquainted with the uses and supposed virtues of the plant and the manner of cultivating it, and sent plants to Spain, as part of the spoils and treasures of his new-found World."

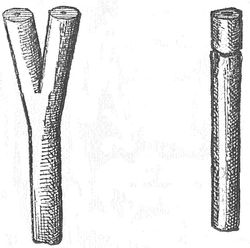

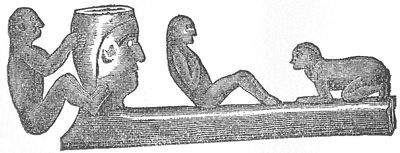

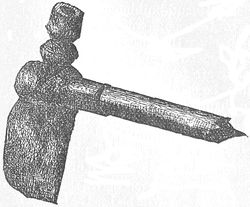

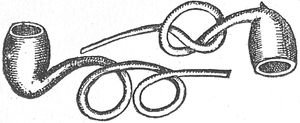

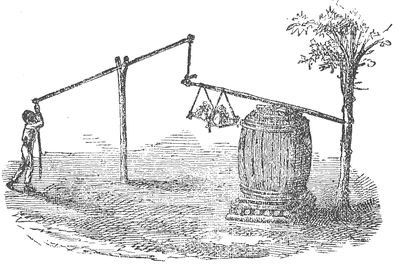

Primitive Pipe.

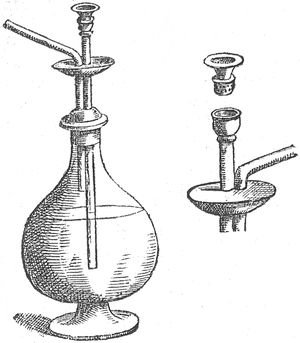

Oviedo[4] is the first author who gives a clear account of smoking among the Indians of Hispaniola[5]. He alludes to it as one of their evil customs and used by them to produce insensibility. Their mode of using it was by inhalation and expelling the smoke through the nostrils by means of a hollow forked cane or hollow reed. Oviedo describes them as

"about a span long; and when used the forked ends are inserted in the nostrils, the other end being applied to the burning leaves of the herb, using the herb in this manner stupefied them producing a kind of intoxication."

Of the early accounts of the plant and its use, Beckman a German writer says:—

"In 1496, Romanus Pane, a Spanish monk, whom Columbus, on his second departure from America, had left in that country, published the first account of tobacco with which he became acquainted in St. Domingo. He gave it the name of Cohoba Cohobba, Gioia. In 1535, the negroes had already habituated themselves to the use of tobacco, and cultivated it in the plantations of their masters. Europeans likewise already smoked it."

An early writer thus alludes to the use of tobacco among the East Indians:—

(p. 034) "The East Indians do use to make little balls of the juice of the hearbe tobaco and the ashes of cockle-shells wrought up together, and dryed in the shadow, and in their travaile they place one of the balls between their neather lip and their teeth, sucking the same continually, and letting down the moysture, and it keepeth them both from hunger and thirst for the space of three or four days."

Oviedo says of the implements used by the Indians in smoking:—

"The hollow cane used by them is called tobaco and that that name is not given to the plant or to the stupor caused by its use."

A writer alluding to the same subject says:—

"The name tobacco is supposed to be derived from the Indian tobaccos, given by the Caribs to the pipe in which they smoked the plant."

Others derive it from Tabasco, a province of Mexico; others from the island of Tobago one of the Caribbees; and others from Tobasco in the gulf of Florida.

Tomilson says:—

"The word tobacco appears to have been applied by the caribbees to the pipe in which they smoked the herb while the Spaniards distinguished the herb itself by that name. The more probable derivation of the word is from a place called Tobaco in Yucatan from which the herb was first sent to the New World."

Humboldt says concerning the name:—

"The word Tobacco like maize, savannah, cacique, maguey (agave) and manato, belong to the ancient language of Hayti, or St. Domingo. It did not properly denote the herb, but the tube through which the smoke was inhaled. It seems surprising that a vegetable production so universally spread should have different names among neighboring people. The pete-ma of the Omaguas is, no doubt, the pety of the Guaranos; but the analogy between the Cabre and Algonkin (or Lenni-Lennope) words which denote tobacco may be merely accidental. The following are the synonymes in five languages: Aztec or Mexican, yetl; Huron, oyngona; Peruvian, sayri; Brazil, piecelt; Moxo, sabare."

Roman Pane who accompanied Columbus on his second voyage alludes to another method of using the herb.

They (p. 035) make a powder of the leaves, which "they take through a cane half a cubit long; one end of this they place in the nose, and the other upon the powder, and so draw it up, which purges them very much."

This is doubtless the first account that we have of snuff-taking; Fairholt says concerning its use:—

"Its effects upon the Indians in both instances seem to have been more violent and peculiar than upon Europeans since."

This may be accounted for from the fact of the imperfect method of curing tobacco adopted by them and all of the natives up to the period of the settlement of Virginia by the English. As nearly all of the early voyagers allude to the plant and especially to its use it would seem probable that it had been cultivated from time immemorial by all the native people of the Orinoco; and at the period of the conquest the habit of smoking was found to be alike spread over both North and South America. The Tamanacs and the Maypures of Guiana wrap maize leaves round their cigars as the Mexicans did at the time of the arrival of Cortez. The Spaniards since have substituted paper for the leaves of maize, in imitation of them.

"The poor Indians of the forests of the Orinoco know as well as did the great nobles at the court of Montezuma, that the smoke of tobacco is an excellent narcotic; and they use it not only to procure their afternoon nap, but also to put themselves in that state of quiescence which they call dreaming with the eyes open or day dreaming."

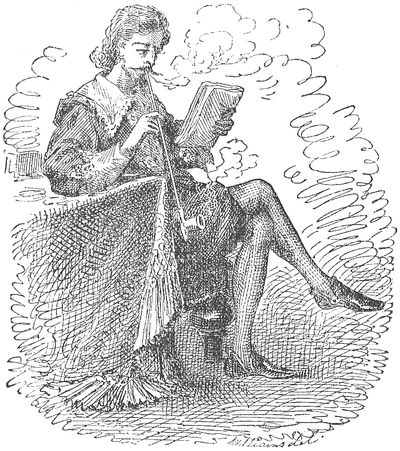

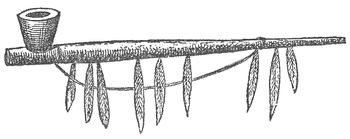

Native Smoking.

Tobacco at this period was also rolled up in the leaves of the Palm and smoked. Columbus found the natives of San Salvador smoking after this manner. Lobel in his History of Plants[6] gives an engraving (p. 036) of a native smoking one of these rolls or primitive cigars and speaks of their general use by Captains of ships trading to the West Indies.

But not only was snuff taking and the use of tobacco rolls or cigars noted by European voyagers, but the use of the pipe also in some parts of America, seemed to be a common custom especially among the chiefs. Be Bry in his History of Brazil (1590) describes its use and also some interesting particulars concerning the plant. Their method of curing the leaves was to air-dry them and then packing them until wanted for use. In smoking he says:—

"When the leaves are well dried they place in the open part of a pipe of which on burning, the smoke is inhaled into the mouth by the more narrow part of the pipe, and so strongly that it flows out of the mouth and nostrils, and by that means effectually drives out humours."

Fairholt in alluding to the various uses of the herb among the Indians says:—

"We can thus trace to South America, at the period when the New World was first discovered, every mode of using the tobacco plant which the Old World has indulged in ever since."

This statement is not entirely correct—the mode of using tobacco in Norway by plugging the nostrils with small pieces of tobacco seems to have been unknown among the Indians of America as it is now with all other nationalities, excepting the Norwegians.

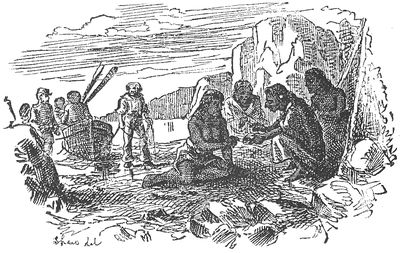

When Cortez made conquest of Mexico in 1519 smoking seemed to be a common as well as an ancient custom among the natives. Benzoni in his History of the New World[7] describing his travels in America gives a detailed account of the plant and their method of curing and using it. In both North and South America the use of tobacco seemed to be universal among all the tribes and beyond all question the custom of using the herb had its origin among them. The traditions of the Indians all confirm its ancient source; they considered the plant as a gift from the Great Spirit for their (p. 037) comfort and enjoyment and one which the Great Spirit also indulged in, consequently with them smoking partook of the character of a moral if not a religious act. The use of tobacco in sufficient quantities to produce intoxication seemed to be a favorite remedy for most diseases among them and was administered by their doctors or medicine-men in large quantities. Benzoni gives an engraving of their mode of inhaling the smoke and says of its use:—

"In La Espanola, when their doctors wanted to cure a sick man, they went to the place where they were to administer the smoke, and when he was thoroughly intoxicated by it, the cure was mostly effected. On returning to his senses he told a thousand stories of his having been at the council of the gods, and other high visions."

It can hardly be supposed that while the custom of using tobacco among the Indians in both North and South America was very general and the mode of use the same, that the plant grown was of the same quality in one part as in another. While the rude culture of the natives would hardly tend to an improvement in quality; the climate being varied would no doubt have much to do with the size and quality of the plant. This would seem the more probable for as soon as its cultivation began in Virginia by the English colonists it had successful rivals in the tobacco of the West Indies and South America. Robertson says:—

"Virginia tobacco was greatly inferior to that raised by the Spaniards in the West Indies and which sold for six times as much as Virginia tobacco."[8]

But not only has the name tobacco and the implements employed in its use caused much discussion but also the origin of the plant.

Some writers affirm that it came from Asia and that it was first grown in China having been used by the Chinese long before the narcotic properties of opium were known. Tatham in his work on Tobacco says of its origin in substantial agreement with La Bott:—

"It is generally understood that the tobacco plant of (p. 038) Virginia is a native production of the country; but whether it was found in a state of natural growth there, or a plant cultivated by the Indian natives, is a point of which we are not informed, nor which ever can be farther elucidated than by the corroboration of historical facts and conjectures. I have been thirty years ago, and the greatest part of my time during that period, intimately acquainted with the interior parts of America; and have been much in the unsettled parts of the country, among those kinds of soil which are favorable to the cultivation of tobacco; but I do not recollect one single instance where I have met with tobacco growing wild in the woods, although I have often found a few spontaneous plants about the arable and trodden grounds of deserted habitations. This circumstance, as well as that of its being now, and having been, cultivated by the natives at the period of European discoveries, inclines towards a supposition that this plant is not a native of North America, but may possibly have found its way thither with the earliest migrations from some distant land. This might, indeed, have easily been the case from South America, by way of the Isthmus of Panama; and the foundation of the Choctaw and Chickasaw nations (who we have reasons to consider as descendants from the Tloseolians, and to have migrated to the eastward of the river Mississippi, about the time of the Spanish conquest of Mexico by Cortez), seems to have afforded one fair opportunity for its dissemination."

The first knowledge which the English discoverers had of the plant was in 1565 when they found it growing in Florida, one hundred and seventy-three years after it was first discovered by Columbus on the island of Cuba. Sir John Hawkins says of its use in Florida:—

"The Floridians, when they travel, have a kind of herb dried, which with a cane and an earthen cup in the end, with fire and the dried herbs put together, do suke through the cane the smoke thereof, which smoke satisfieth their hunger, and therewith they live four or five dayes without meat or drinke, and this all the Frenchmen used for this purpose: yet do they holde opinion withall, that it causeth water and steame to void from their stomacks."

This preparation might not have been tobacco as the Indians smoke a kind of bark which they scrape from the killiconick, an aromatic shrub, in form resembling the willow; (p. 039) they use also a preparation made with this and sumach leaves, or sometimes with the latter mixed with tobacco. Lionel Wafer in his travels upon the Isthmus of Darien in 1699 saw the plant growing and cultivated by the natives. He says:—

"These Indians have tobacco amongst them. It grows as the tobacco in Virginia, but is not so strong, perhaps for want of transplanting and manuring, which the Indians do not well understand, for they only raise it from the seed in their plantations. When it is dried and cured they strip it from the stalks, and laying two or three leaves upon one another, they roll up all together sideways into a long roll, yet leaving a little hollow. Round this they roll other leaves one after another, in the same manner, but close and hard, till the roll be as big as one's wrist, and two or three feet in length. Their way of smoking when they are in company is thus: a boy lights one end of a roll and burns it to a coal, wetting the part next it to keep it from wasting too fast. The end so lighted he puts into his mouth, and blows the smoke through the whole length of the roll into the face of every one of the company or council, though there be two or three hundred of them. Then they, sitting in their usual posture upon forms, make with their hands held together a kind of funnel round their mouths and noses. Into this they receive the smoke as it is blown upon them, snuffing it up greedily and strongly as long as ever they are able to hold their breath, and seeming to bless themselves, as it were, with the refreshment it gives them."

In the year 1534 James Cartier a Frenchman was commissioned to explore the coast of North America, with a view to find a place for a colony. He observed that the natives of Canada used the leaves of an herb which they preserved in pouches made of skins and smoked in stone pipes. It being offensive to the French, they took none of it with them on their return. But writing more particularly concerning the plant he says:—

"In Hochelaga, up the river in Canada there groweth a certain kind of herb whereof in Summer they make a great provision for all the year, making great account of it, and only men use of it, and first they cause it to be dried in the Sune, then wear it about their necks wrapped in a little beast's skine made like a bagge, with a hollow piece of stone (p. 040) or wood like a pipe, then when they please they make powder of it, and then put it in one of the ends of the said Cornet or pipe, and laying a cole of fire upon it, at the other end and suck so long, that they fill their bodides full of smoke, till that it commeth out of their mouth and nostrils, even as out of the Tonnel of a chimney. They say that this doth keepe them warme and in health, they never goe without some of this about them."

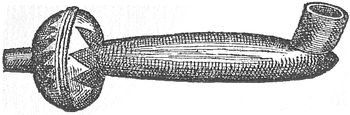

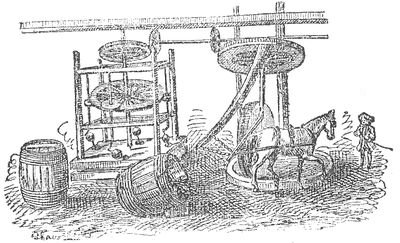

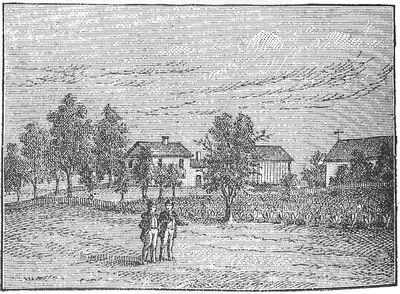

Be Bry in his History of Brazil 1590 gives an engraving of a native smoking a pipe and a female offering him a handful of tobacco leaves. The pipe has a modern look and is altogether unlike those found by the English in use among the Indians in Virginia.

Old Engraving.

An English writer says of the Tobacco using races:—

"From the evidence collected by travellers and archæologists, as to the native arts and relics connected with the use of Tobacco by the Red Indians, it would appear that not one tribe has been found which was unacquainted with the custom,[9] its use being as well known to the tribes of the North-west and the denizens of the snowy wilds of Canada, as to the races inhabiting Central America and the West India Islands."

Father Francisco Creuxio states that the Jesuit missionaries found the weed extensively used by the Indians of the Seventeenth Century. In 1629 he found the Hurons smoking the dried leaves and stalks of the Tobacco plant or petune. Many tribes of Indians consider that Tobacco is a gift bestowed by the Great Spirit as a means of enjoyment. In consequence of this belief the pipe became sacred, and smoking became a moral if not a religious act, amongst the North American Indians. The Iroquois are of opinion that by burning Tobacco they could send up their prayers to the Great Spirit with the ascending incense, thus maintaining (p. 041) communication with the spirit world; and Dr. Daniel Wilson suggests that

"the practice of smoking originated in the use of the intoxicating fumes for purposes of divination, and other superstitious rites."

When an Indian goes on an expedition, whether of peace or war, his pipe is his constant companion; it is to him what salt is among Arabs: the pledge of fidelity and the seal of treaties. In the words of a Review:

"Tobacco supplies one of the few comforts by which men who live by their hands, solace themselves under incessant hardship."

While the presence, and use of tobacco by the natives of America are among the most interesting features connected with its history, it can hardly be more so than is its early cultivation by the Spaniards, English and Dutch, and afterward by the French. The cultivation of the plant began in the West India Islands and South America early in the Sixteenth Century. In Cuba its culture commenced in 1580, and from this and the other islands large quantities were shipped to Europe. It was also cultivated near Varina in Columbia, while Amazonian tobacco had acquired an enviable reputation as well as Varinian, long before its cultivation began in Virginia by the English. At this period of its culture in America the entire product was sent to Spain and Portugal, and from thence to France and Great Britain and other countries of Europe. The plant and its use attracted at once the attention as well as aroused the cupidity of the Spaniards, who prized it as one of their greatest discoveries.

As soon as Tobacco was introduced into Europe by the Spaniards, and its use became a general custom, its sale increased as extensively as its cultivation. At this period it brought enormous prices, the finest selling at from fifteen to eighteen shillings per pound. Its cultivation by the Spaniards in various portions of the New World proved to them not only its real value as an article of commerce, but also that several varieties of the plant existed; as on removal from one island or province to another it changed in size and quality of leaf. Varinas tobacco at this time was (p. 042) one of the finest tobaccos known,[10] and large quantities were shipped to Spain and Portugal. The early voyagers little dreamed, however, of the vast proportions to be assumed by the trade in the plant which they had discovered, and which in time proved a source of the greatest profit not only to the European colonies, but to the dealers in the Old World.

Helps, treating on this same subject, says:

"It is interesting to observe the way in which a new product is introduced to the notice of the Old World—a product that was hereafter to become, not only an unfailing source of pleasure to a large section of the whole part of mankind, from the highest to the lowest, but was also to distinguish itself as one of those commodities for revenue, which are the delight of statesmen, the great financial resource of modern nations, and which afford a means of indirect taxation that has perhaps nourished many a war, and prevented many a revolution. The importance, financially and commercially speaking, of this discovery of tobacco—a discovery which in the end proved more productive to the Spanish crown than that of the gold mines of the Indies."

Spain and Portugal in all their colonies fostered and encouraged its cultivation and then at once ranked as the best producers and dealers in tobacco. The varieties grown by them in the West Indies and South America were highly esteemed and commanded much higher prices than that grown by the English and Dutch colonies. In 1620, however, the Dutch merchants were the largest wholesale tobacconists in Europe, and the people of Holland, generally, the greatest consumers of the weed.

The expedition of 1584, under the auspices of Sir Walter Raleigh, which resulted in the discovery of Virginia, also introduced the tobacco plant, among other novelties, to the attention of the English. Hariot,[11] who sailed with this expedition, says of the plant:

"There is an herb which is sowed apart by itselfe, and is (p. 043) called by the inhabitants uppowoc. In the West Indies it hath divers names, according to the severall places and countries where it groweth and is used; the Spaniards generally call it Tobacco. The leaves thereof being dried and brought into powder, they use to take the fume or smoke thereof by sucking it through pipes made of clay into their stomacke and heade, from whence it purgeth superfluous fleame and other grosse humors; openeth all the pores and passages of the body; by which means the use thereof not only preserveth the body from obstructions, but also if any be so that they have not beene of too long continuance, in short time breaketh them; whereby their bodies are notably preserved in health, and know not many grievous diseases wherewithall we in England are oftentimes affected. This uppowoc is of so precious estimation amongest them that they thinke their gods are marvellously delighted therewith; whereupon sometime they make halowed fires, and cast some of the powder therein for a sacrifise. Being in a storme uppon the waters, to pacifie their gods, they cast some up into the aire and into the water: so a weave for fish being newly set up, they cast some therein and into the aire; also after an escape of danger they cast some into the aire likewise; but all done with strange gestures, stamping, sometimes dancing, clapping of hands, holding up of hands, and staring up into the heavens, uttering there withal and chattering strange wordes, and noises.

"We ourselves during the time we were there used to suck it after their manner, as also since our returne, and have found many rare and wonderful experiments of the virtues thereof; of which the relation would require a volume of itselfe; the use of it by so manie of late, men and women, of great calling as else, and some learned phisitions also is sufficient witnes."

The natives also when Drake[12] landed in Virginia, "brought a little basket made of rushes, and filled with an herbe which they called Tobah;" they "came also the second time to us bringing with them as before had been done, feathers and bags of Tobah for presents, or rather indeed for sacrifices, upon this persuasion that we were gods."

William Strachey[13] says of tobacco and its cultivation by the Indians:

(p. 044) "Here is great store of tobacco, which the salvages call apooke: howbeit it is not of the best kynd, it is but poor and weake, and of a byting taste; it grows not fully a yard above ground, bearing a little yellow flower like to henbane; the leaves are short and thick, somewhat round at the upper end; whereas the best tobacco of Trynidado and the Oronoque, is large, sharpe, and growing two or three yardes from the ground, bearing a flower of the breadth of our bell-flower, in England; the salvages here dry the leaves of this apooke over the fier, and sometymes in the sun, and crumble yt into poudre, stalk, leaves, and all, taking the same in pipes of earth, which very ingeniously they can make."

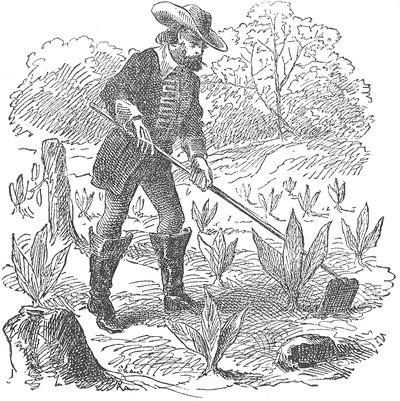

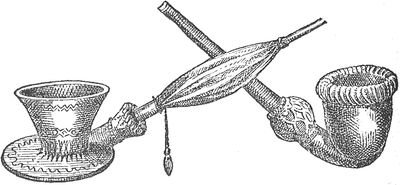

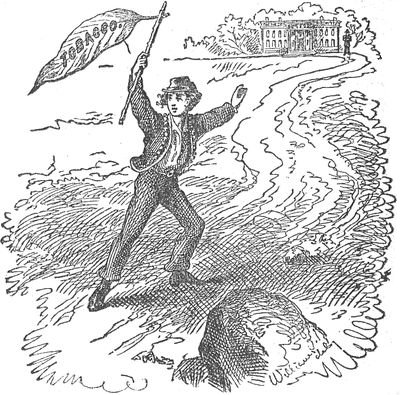

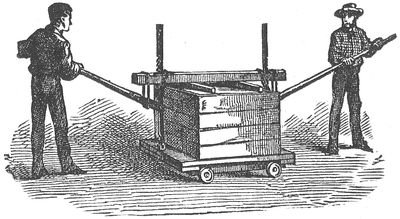

The Contrast.

It would seem then, if the account given by Strachey be correct, that the tobacco cultivated by the Indians of North America was of inferior growth and quality to that grown in many portions of South America, and more particularly in the West India islands. As there are still many varieties of the plant grown in America, so there doubtless was when cultivated by the Indians. While most probably the quality of leaf remained the same from generation to generation, still in some portions of America, owing more to the soil and climate than the mode of cultivating by them, they cured very good tobacco. We can readily see how this might have been, from numerous experiments made with both American and European varieties. Nearly all of the early Spanish, French and English voyagers who landed in America were attracted by the beauty of the country. Ponce De Leon, who sailed from Spain to the Floridas, was charmed by the plants and flowers, and doubtless the first sight of them strengthened his belief in the existence somewhere in this tropical region of the fountain of youth.

The discovery of tobacco proved of the greatest advantage (p. 045) to the nations who fostered its growth,—and increased the commerce of both England and Spain, doing much to make the latter what it once was, one of the most powerful nations of Europe and possessor of the largest and richest colonies, while it greatly helped the former, already unsurpassed in intelligence and civilization, to reach its present position at the commercial head of the nations of the world.

As Spain, however, has fallen from the high place she once held, her colonial system has also gone down. And while England, thanks to her more liberal policy, still retains a large share of the territory which she possessed at first, Spain, which once held sway over a vast portion of America, has been deprived of nearly all of her colonies, and ere long may lose control of the island on which the discoverer of America first saw the plant.[14]

It is an historical fact that wherever in the English and Spanish colonies civilization has taken the deepest root, so has also the plant which has become as famous as any of the great tropical products of the earth. The relation existing between the balmy plant and the commerce of the world is of the strongest kind. Fairholt has well said, that "the revenue brought to our present Sovereign Lady from this source alone is greater than that Queen Elizabeth received from the entire customs of the country."

The narrow view of commercial policy held by her successors, the Stuarts, induced them to hamper the colonists of America with restrictions; because they were alarmed lest the ground should be entirely devoted to tobacco. Had not this Indian plant been discovered, the whole history of some portions of America would have been far different. In the West Indies three great products—Coffee, Sugar-Cane, and Tobacco,—have proved sources of the greatest wealth—and wherever introduced, have developed to a great extent the resources of the islands. Thus it may be seen that while the Spaniards by the discovery and colonization (p. 046) of large portions of America strengthened the currency of the world, the English alike, by the cultivation of the plant, gave an impetus to commerce still felt and continued throughout all parts of the globe.

An English writer has truthfully observed that "Tobacco is like Elias' cloud, which was no bigger than a man's hand, that hath suddenly covered the face of the earth; the low countries, Germany, Poland, Arabia, Persia, Turkey, almost all countries, drive a trade of it; and there is no commodity that hath advanced so many from small fortunes to gain great estates in the world. Sailors will be supplied with it for their long voyages. Soldiers cannot (but) want it when they keep guard all night, or upon other hard duties in cold and tempestuous weather. Farmers, ploughmen, and almost all labouring men, plead for it. If we reflect upon our forefathers, and that within the time of less than one hundred years, before the use of tobacco came to be known amongst us, we cannot but wonder how they did to subsist without it; for were the planting or traffick of tobacco now hindered, millions of this nation in all probability must perish for the want of food, their whole livelihood almost depending upon it."

When first discovered in America, and particularly by the English in Virginia, the plant was cultivated only by the females of the tribes, the chiefs and warriors engaging only in the chase or following the warpath. They cultivated a few plants around their wigwams, and cured a few pounds for their own use. The smoke, as it ascended from their pipes and circled around their rude huts and out into the air, seemed typical of the race—the original cultivators and smokers of the plant. But, unlike the great herb which they cherished and gave to civilization, they have gradually grown weak in numbers and faded away, while the great plant has gone on its way, ever assuming more and more sway over the commercial and social world, until it now takes high rank among the leading elements of mercantile and agricultural greatness.[Back to Contents]

We do not find in any accounts of the English voyagers made previous to 1584, any mention of the discovery of tobacco, or its use among the Indians. This may appear a little strange, as Captains Amidas and Barlow, who sailed from England under the auspices of Sir Walter Raleigh in 1584, on returning from Virginia, had brought home with them pearls and tobacco among other curiosities. But while we have no account of those who returned from the voyage made in 1602 taking any tobacco with them, it is altogether probable that those who remained took a lively interest in the plant and the Indian mode of use; for we find that in nine years after they landed at Jamestown tobacco had become quite an article of culture and commerce.

Hamo in alluding to the early cultivation of tobacco by the colony, says, that John Rolfe was the pioneer tobacco planter. In his words:

"I may not forget the gentleman worthie of much commendations, which first took the pains to make triall thereof, his name Mr. John Rolfe, Anno Domini 1612, partly for the love he hath a long time borne unto it, and partly to raise commodities to the adventurers, in whose behalfe I intercede and vouchsafe to hold my testimony in beleefe that during the time of his aboade there, which draweth neere sixe years (p. 048) no man hath laboured to his power there, and worthy incouragement unto England, by his letters than he hath done, witness his marriage with Powhatan's daughter one of rude education, manners barbarous, and cursed generation merely for the good and honor of the plantation."

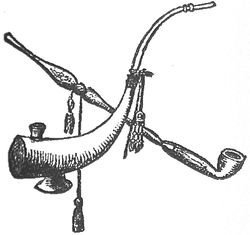

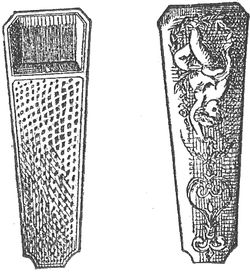

John Rolfe.

The first general planting of tobacco by the colony began according to this writer—

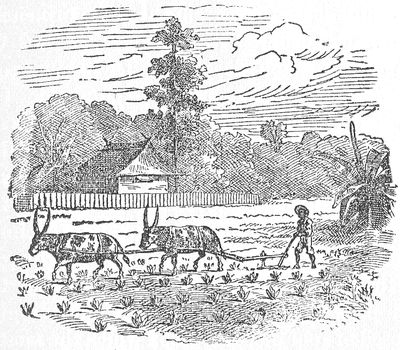

"at West and Sherley Hundred (seated on the north side of the river, lower than the Bermudas three or four myles) where are twenty-five commanded by capten Maddeson—who are imployed onely in planting and curing tobacco."

This was in 1616, when the colony numbered only three hundred and fifty-one persons. Rolfe, in his relation of the state of Virginia, written and addressed to the King, gives the following description of the condition of the colony in 1616:

(p. 049) "Now that your highness may with the more ease understand in what condition the colony standeth, I have briefly sett downe the manner of all men's several imployments, the number of them, and the several places of their aboad, which places or seates are all our owne ground, not so much by conquest, which the Indians hold a just and lawfull title, but purchased of them freely, and they verie willingly selling it. The places which are now possessed and inhabited are sixe:—Henrico and the lymitts, Bermuda Nether hundred, West and Sherley hundred, James Towne, Kequoughtan, and Dales-Gift. The generall mayne body of the planters are divided into Officers, Laborers, Farmors.

"The officers have the charge and care as well over the farmors as laborers generallie—that they watch and ward for their preservacions; and that both the one and the other's busines may be daily followed to the performance of those imployments, which from the one are required, and the other by covenant are bound unto. These officers are bound to maintayne themselves and families with food and rayment by their owne and their servant's industrie. The laborers are of two sorts. Some employed onely in the generall works, who are fedd and clothed out of the store—others, specially artificers as smiths, carpenters, shoemakers, taylors, tanners, &c., doe worke in their professions for the colony, and maintayne themselves with food and apparrell, having time lymitted them to till and manure their ground.

"The farmors live at most ease—yet by their good endeavors bring yearlie much plentie to the plantation. They are bound by covenant, both for themselves and servants, to maintaine your Ma'ties right and title in that kingdom, against all foreigne and domestique enemies. To watch and ward in the townes where they are resident. To do thirty-one dayes service for the colony, when they shalbe called thereunto—yet not at all tymes, but when their owne busines can best spare them. To maintayne themselves and families with food and rayment—and every farmor to pay yearlie into the magazine for himself and every man servant, two barrells and a halfe of English measure.

"Thus briefly have I sett downe every man's particular imployment and manner of living; albeit, lest the people—who generallie are bent to covett after gaine, especially having tasted of the sweete of their labors—should spend too much of their tyme and labor in planting tobacco, known to them to be verie vendible in England, and so neglect their tillage of corne, and fall into want thereof, it is provided for—by (p. 050) the providence and care of Sir Thomas Dale—that no farmor or other, who must maintayne themselves—shall plant any tobacco, unless he shall yearely manure, set and maintayne for himself and every man servant two acres of ground with corne, which doing they may plant as much tobacco as they will, els all their tobacco shalbe forfeite to the colony—by which meanes the magazine shall yearely be sure to receave their rent of corne; to maintayne those who are fedd thereout, being but a few, and manie others, if need be; they themselves will be well stored to keepe their families with overplus, and reape tobacco enough to buy clothes and such other necessaries as are needful for themselves and household. For an easie laborer will keepe and tend two acres of corne, and cure a good store of tobacco—being yet the principall commoditie the colony for the present yieldeth.

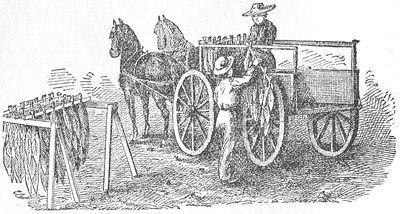

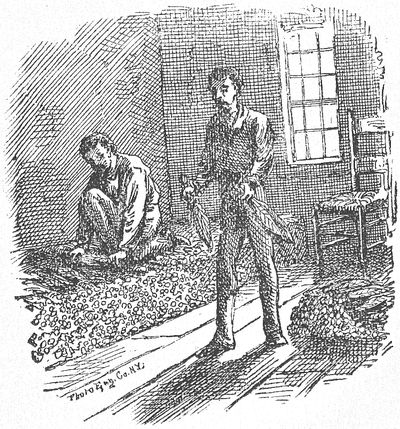

"For which as for other commodities, the councell and company for Virginia have already sent a ship thither, furnished with all manner of clothing, household stuff and such necessaries, to establish a magazine there, which the people shall buy at easie rates for their commodities—they selling them at such prices that the adventurers may be no loosers. This magazine shalbe yearelie supplied to furnish them, if they will endeavor, by their labor, to maintayne it—which wilbe much beneficiall to the planters and adventurers, by interchanging their commodities, and will add much encouragement to them and others to preserve and follow the action with a constant resolution to uphold the same."