Title: The Nursery, June 1873, Vol. XIII.

Author: Various

Release date: January 31, 2008 [eBook #24479]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Emmy, Juliet Sutherland and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

| IN PROSE. | |

| PAGE. | |

| The Children at Grandmother's | 161 |

| The Flying Wood-Sawyer | 163 |

| Papa's Story | 167 |

| About Bees | 171 |

| Bad Luck | 174 |

| Cherry and Fair Star | 176 |

| About some Indians | 181 |

| Playing Tableaux | 183 |

| Little Mischief | 186 |

IN VERSE. | |

| PAGE. | |

| The Old Blind Man and his Granddaughter | 165 |

| Dixie | 169 |

| The Fat Little Piggies | 178 |

| A Song of Noses | 180 |

| A-Maying | 185 |

| The Seasons | 188 |

THE CHILDREN AT GRANDMOTHER'S.

THE CHILDREN AT GRANDMOTHER'S.

One fair day in June, the boys went down to the sea-beach to bathe, and the girls went out on the lawn to play. Some of them thought they would play "hunt the slipper."

But little Emma Darton, who was a cousin to the rest, said, "I promised my mother I would not sit down on the grass: so, if you play 'hunt the slipper,' I must not play with you; for in that game you have to sit."

Then her Cousin Julia replied, "Nonsense, Emma! It is a bright warm day. Don't you see the grass is quite dry? Come, you must not act and talk like an old woman of sixty. Come and join in our game."

But Emma said, "When I make a promise, I always try to keep it. If to do that is to be like an old woman of sixty, then I am glad I am like one."

"You are the oldest-talking little witch I ever knew for a five-year-old," cried Julia. "If you don't look out, you'll not live half your days."

"I think Emma is right," said Marian, another cousin. "So, if you insist on sitting on the grass, Emma and I will go and sit by ourselves on the trunk of the old fallen tree."

But Julia insisted on having her game of "hunt the slipper;" and Emma and Marian went and sat down on the fallen trunk, and looked on while the rest played.[163]

The next day five of grandmother's little visitors did not seem to be well. Some were coughing, and some were sneezing, and some were complaining of pains in their limbs.

"Why, what is the matter with you, children?" said the old lady. "If I did not know you were sensible little girls, I should say you had been sitting on the damp grass,—all of you but Emma and Marian."

The cousins looked at one another; but no one spoke aloud. Then Marian whispered to Emma, "Are you not glad you kept your promise to your mother?"

Emma looked up and smiled, but did not say a word.

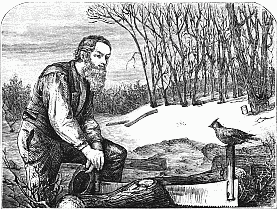

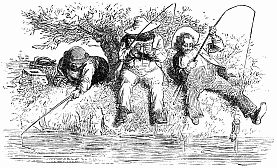

One day last winter I was cutting maple-logs in the woods with a cross-cut saw. It was about five feet long, and had a handle at each end, so as to be used by two persons together. My brother generally helped me; but, for some reason, he was not with me then, and I was at work all by myself in a rather lonesome place.

I had finished eating my dinner, set my pail under a clump of trees, and commenced my afternoon job; but, as the log was large and hard, I often had to stop and rest a minute. While I was standing still, with my hands upon one handle of the saw, all at once a bird came flying down towards me; and, after resting upon the ground behind the log a few moments, what do you suppose he did?

Whether he knew I was tired, and thought it was too hard for me to cut the wood all alone, I cannot say; but suddenly he gave a little spring, and seated himself right on the other[164] handle of my saw, as you see in the picture, grasping it with all the hands he had, and looking as though he had come on purpose to help me saw that log through.

For my part, I rather think he did help me; for, while he kept his hold upon the other end of the saw, I rested faster than I ever did before. I stood as motionless as a statue; for I feared that any movement would scare the bird away.

How soon I should have got through my sawing with his help, I cannot tell. But suddenly he seemed to think of something more important; and away he went, like a streak of sunshine, off into the woods beyond me.

I have never seen my sawyer-bird since then. I call him my "sawyer-bird" because I don't know how else to name him. He was a strange bird to me: but he seemed like a good friend; and I shall always remember him as he looked when trying to help me work that winter's day.

"Now, papa, for another army story," said little Eddie, as he climbed into papa's lap, and prepared himself to listen.

Papa closed his eyes, stroked his whiskers; and Eddie knew the story was coming. This is it,—

One day, when we were camping in Virginia, some of us got leave to go into the woods for chestnuts, which grew there in great abundance. We were busy picking up the nuts, when we heard a scrambling in the bushes. We thought it was a dog.

"Was it a dog?" asks Eddie.

"No, it was not a dog."

"Was it a cat?"

"No, it was not a cat."

"O papa! was it a bear?"[167]

"No, it was not a bear."

"Do tell me what it was!"

"Well, let me go on with my story, and you shall hear."

It was a fox. How he did run when he saw us! We ran after him, and chased him into a pile of rails, in one corner of the camp.

You see, the soldiers had torn down all the fences, and piled them up for fire-wood. The fox ran right in among the rails; and, the more he tried to get out, the more he couldn't.

"A fox, a fox!" we shouted; hearing which, all the men, like so many boys, rushed up, and made themselves into a circle around the wood-pile, so that poor foxy was completely hemmed in.[168]

Then a few of us went to work, and removed the rails one by one, until at last he was clear, and we could all see him. With a bound, he tried to get away; but the men kept their legs very close together, and he was a prisoner. We got one of the tent-ropes and tried to tie him.

Such a time as we had! One man got bitten; but after a while foxy was caught. Then what did the cunning little thing do but make believe he was dead! Foxes are very cunning: they can play dead at any time.

He lay on the ground quite still, while he was tied, and the rope was made fast to a tree. When we all stepped back, he tried again to get away. The rope held him fast; but he bit so nearly through it, that we feared we should lose him, after all.

So off rushed one of the boys, and borrowed a chain from one of the wagons at headquarters. With this Master Fox was made quite secure.

We tried to tame him; for, being away from all little children, we were glad of any thing to pet. But it was of no use; for, even when foxes are taken very young, they cannot be tamed. They do not attach themselves to men, as dogs and some other animals do. He would not play with us at all; but we enjoyed watching him, as we had not many amusements.

One day we had to go off on a march, and left our little fox tied to a tree. When we came back, he was gone. We never knew how he got away; but we were not very sorry, for he was not happy with us. It was much better for him to be in the woods with his own friends. If he was smart enough to stay there, he may be living now; but he must be a pretty old fox by this time.

Here papa stopped; and his little boy drew a long breath, as though very glad that the little fox got into the woods again.

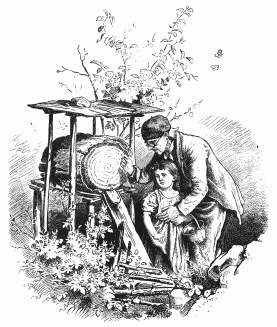

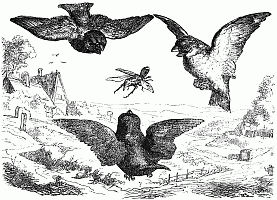

So, the first fine day, we walked to a neighboring village, and found the bee-master, as he was called, very glad to show us his little pets. He first led us to a hive made wholly of glass, so that we might watch the bees at their labors.

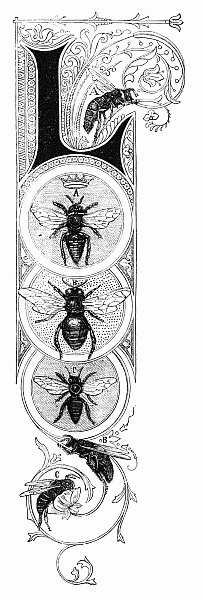

He told us there were three kinds of bees; and in the picture you may see how they look, both when flying and when at rest. Those marked A are queen-bees; B are the male bees, or drones; and C the working-bees.

The most important bee in the hive is naturally the queen. She is longer and sleeker than the others, and has a crooked sting, of which, however, she seldom makes use. Similar in form, but smaller, are the working-bees, whose sting is straight. The male bee, or drone, is thicker than the others, and stingless.

"What has the queen to do in the[172] hive?" I asked. The old gentleman replied, "She is the mother-bee, lays all the eggs, and is so diligent that she often lays twelve hundred in a day, having a separate cell for each egg. That is her only work; for she leaves the whole care of her children to the industrious working-bees, who have various labors to perform. Some of them build cells of wax; others bring in honey on the dust of flowers, called pollen; yet others feed and take care of the young; and a small number act as body-guard to the queen."

The bee-master next took us to a strange-looking old hive, and asked us what it was like. I said, "The trunk of a tree." He told me I was right, and that the wild bees still dwell in hollow trees.

He then showed us various kinds of hives, and, last of all, a glass globe, in which the bees had built a beautiful white comb in the form of a star, and filled it with honey. This he was to send as a wedding-present to a bride.

He said, "The bees can make of any egg, either a queen or a working bee, according to the food and treatment they give it. The queen requires but sixteen days in which to come to maturity; while the workers require twenty, and the drones twenty-four. When several queens appear at the same time, they fight until one gains the victory."

Honey is the nectar of flowers, which they collect with their tongues, place in their honey-bags, and deposit in cells built for the purpose, which, when filled, they cover with wax.

Bee-bread is made of the dust of flowers, with which the bee gets covered in collecting honey. This it brushes off, kneads into two little masses, which are placed in a sort of basket on the joint of the leg, where a fringe of hairs acts as a cover.

Wax is a secretion from honey, which oozes out between the rings which form the body, and is then worked with the mouth until it is fit for the construction of the comb. Bees also make a gummy substance for varnishing their cells, which they procure from the buds of trees.

When we took leave of the kind old gentleman, he gave me in a basket a nice honeycomb to take to my mother; and since that my father has bought me a hive of bees. Every summer I plant flowers in my garden for them, that they may not have far to go for their honey.

I could not have been quite six years old when I became the possessor of a canary-bird, to which I gave the name of Cherry.

There were three children of us,—myself (the oldest), Arthur, and baby. My father was at sea; and my mother had charge of us all in her little house near the ocean.

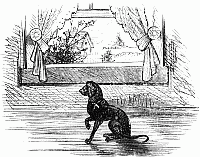

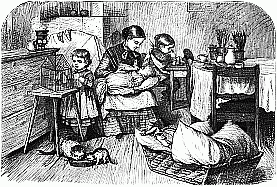

Well do I remember one cold day in winter when we were all gathered in the one little apartment that served us for nursery, dining-room, and sitting-room. Arthur, who had overslept himself, was at his breakfast; mother was feeding baby; and I was looking at my dear Cherry in his cage.

Pots of hyacinths in bloom were on the table; Mr. Punch, Arthur's Christmas present, lay as if watching the cat on baby's pillow in the basket; and Muff, the old cat, with Fair-Star her kitten, were lapping milk from a basin on the floor.

My dear mother had taught Muff to be good to Cherry; and Muff seemed to have overcome her natural propensities so far as to let Cherry even light on her head, and there sing a few notes of a song.

So, on the day I am speaking of, I let Cherry out of his cage; and he flew round, and at last lighted on the kitten's head. At this Muff seemed much pleased; and Fair-Star herself was not disturbed by the liberty the little bird took.

But all at once Muff sprang upon Cherry, and, seizing him in her mouth, jumped up on the bureau. At last it would seem as if the old cat had chosen her time to kill and eat my poor little bird.

No such thing! Our good Muff was all right. A neighbor, who had come to borrow our axe, had left the back-door open; and a hungry old stray cat had suddenly made her[177] [178] appearance. Muff saw that Cherry was in danger, and seized him so that the strange cat should not harm him.

Cherry was not only not hurt, but not frightened. Well do I remember how my mother placed baby on the pillows, drove out the strange cat, and then took up Muff, and petted and praised her till Muff's purr of pleasure was loud as the noise of a spinning-wheel.

After that adventure, Cherry and Muff and Fair-Star were all better friends than ever.

| UNCAN has a nose, Points my finger at it: Has a nose the hare, He will let you pat it. |

|

| ||||||||

| |||||||||

Last summer a party of Indians,—men, women, and children,—in nine little birch canoes, came paddling down the Mississippi River, and landed at our village in Illinois. They were of the Chickasaw tribe from Minnesota, who are half-civilized, and speak our language imperfectly.

Indians, you must know, do not live in good warm houses as we do. They live in wigwams, as they call their houses, which are merely a few poles stuck in the ground, and covered with skins or blankets.

They do not provide regular meals, but live from hand to mouth by hunting and fishing. Sometimes they have to go without food a long time. The men are too lazy to work. They like better to strut about with their faces painted all the colors of the rainbow.

The Indians who came to our village were very good[182] specimens of their race. Of course, their visit made quite a sensation, especially among our young folks. As soon as they landed, the squaws (women) threw their blankets over their shoulders, swung their pappooses (babies) on their backs, and, with their little boys and girls, came up into town.

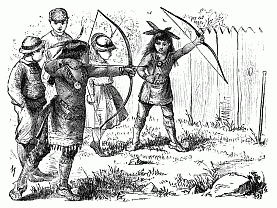

The Indian boys made some money by shooting arrows at cents stuck in a stake. They were quite skilful. The squaws offered for sale slippers, moccasons, and bags, which they had worked themselves with sinews and porcupine-quills.

Their chief, a large man, whose face was painted bright red, got the use of our town hall, and in the evening gathered his party there, and showed us some of their dances. Two of the men beat a "tum-tum" on their rude drums (which looked like nail-kegs); and the little and big Indians danced or hopped around in a circle, singing, "Ye, ye! yu, yu! hi, yi! ye, ye!"

Now and then the chief would pull out a long knife, and swing it around his head; and another Indian would draw up his bow, as if he were going to shoot. This was the war-dance.

We were all much amused; and our little boys and girls laughed heartily. We gave the Indians some money to buy their breakfast, and they said, "Yank, yank!"

When they, or a like party, come again, I will tell you more about them.

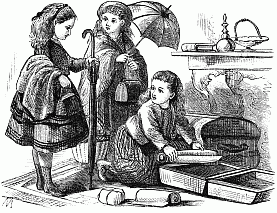

The picture of "Miss Jones" in the February "Nursery" reminded me of two other little girls who are as fond of "playing people" as Edith May.

Nearly every day in winter, when they cannot play out of doors, these little girls dress up to represent different characters. They call this "Playing Tableaux;" but their tableaux are something more than pictures, as they act their parts as well as dress them.

Sometimes, for instance, one of the little girls appears as a peddler, who is quite as hard to get rid of as a real one.

Sometimes a washerwoman comes in, and gets about tubs and clothes, and makes all the confusion of washing-day.

Sometimes papa's great shaggy black coat covers what pretends to be "your good old dog Tiger," who is very kind to his friends, but has loud, fierce "bow-wow-wows" and sharp bites for those who are not good to him.[184]

Sometimes poor little lame Jimmy, who can only walk on crutches, comes in to sell shoe-strings, "because," he says, "you know I can do nothing else to help my poor mother."

Sometimes a ring at the door-bell calls our attention to the wants of a deaf-and-dumb beggar, who makes fearful gestures till he is fed, and then forgets that he cannot speak, and says, "Thank you!" in a very familiar voice.

When these little girls have company, they often fit out travelling parties for California, or a trip to Europe; and the baggage they make out to collect would serve very well if they were "really and truly going," as they tell us they are.

Their good-bys are very affecting as they kiss us all, and beg us write by the first mail.

ALL FOR ONE, AND ONE FOR ALL.

ALL FOR ONE, AND ONE FOR ALL.

When the wild March winds were blowing, Not so very long ago, And it still kept snowing, snowing, Piling, drifting, Heaping, sifting, Snow on snow, Faithless Fanny said, "Spring never Will be here; 'twill snow forever; And I don't believe I ever Shall again a-Maying go!" April pleased her little better: Now 'twas rain as well as snow; Every day was wet and wetter, Drifting, dropping, Soaking, sopping, Raining so, That poor Fanny feared the showers Would quite drown her precious flowers; And for what, in May's bright hours, Could she then a-Maying go? Now the gay May sun is shining, Pink and sweet the Mayflowers blow; And forgetting her repining, Her complaining Of the raining And the snow, With its fitful, frosty flurries, Fanny lingers not, nor worries, But to field and greenwood hurries; For she must a-Maying go. Fenno Hayes. |

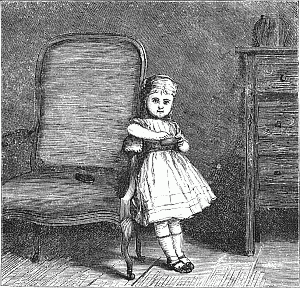

What now? Will this child never be out of hot water? What is Bessie doing now? I will tell you. She found in one of her mother's drawers a box; and, on opening it, she found some little round things something like sugar-plums.

She began putting the little round things in her mouth, and swallowing them. They were not quite so pleasant as she had expected, or she would have taken more. "I wonder what makes them taste so bitter?" thought Bessie.

She will find that out by and by, to her sorrow.[187]

"What makes me feel so?" thought Bessie as she sat in the big arm-chair in mother's best chamber, rubbing her eyes, and feeling very uncomfortable.

She had not sat there long, before she began to cry. Her mother, who had been wondering who could have been meddling with her pill-box, came in. "Have you been swallowing these pills?" she asked.

"Yes; but I didn't know they were pills," said Bessie.

"Well, you will be well punished for your fault," said her mother. "The pills will make you quite sick."

And so it happened.[188]

THE SEASONS.

|

This issue was part of an omnibus. The original text for this issue did not include a title page or table of contents. This was taken from the January issue with the "No." added. The original table of contents covered the first six months of 1873. The remaining text of the table of contents can be found in the other issues.