[p vii]

CONTENTS

| PAGE | |

The Rukh of Marco Polo | 3 |

The Penguins and the Seals of the Angra de Sam Bràs | 7 |

The Banda Islands and the Bandan Birds | 15 |

The Etymology of the Name ‘Emu’ | 21 |

Australian Birds in 1697 | 25 |

New Zealand Birds in 1772 | 31 |

[p ix]

LIST OF PLATES

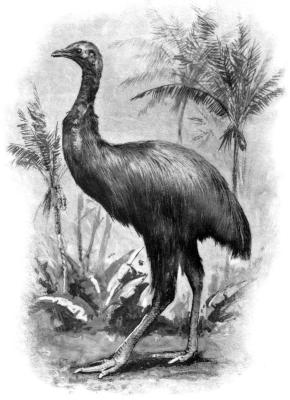

I. | Casuarius uniappendiculatus, Blyth. (juv.). From an example in the British Museum of Natural History. By permission of the Director. | Frontispiece |

This plate should be compared with that opposite p. 22, which represents a cassowary with two wattles—probably an immature Casuarius galeatus, Vieill. for that is the species which is believed to have been brought alive to Europe by the Dutch in 1597. An immature example of that species was not available for reproduction. | ||

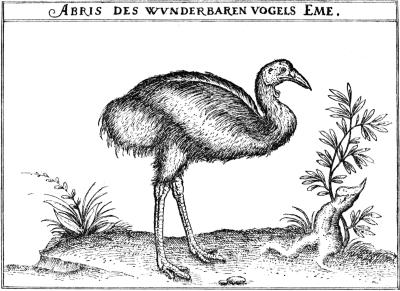

II. | Abris des wvnderbaren Vogels Eme. From the fifth edition of Erste Schiffart in die orientalische Indien so die holländische Schiff im Martio 1595 aussgefahren vnd im Augusto 1597 wiederkommen verzicht … Durch Levinvm Hvlsivm. Editio Quinta. Getruckt zu Franckfurt am Mäyn durch Hartmann Palthenium in Verlegung der Hulfischen. Anno M.DC.xxv., From a copy of the book in the British Museum. By permission of the Keeper of Printed Books. | p. 22 |

III. | The Masked or Blue-faced Gannet (Sula cyanops, S. personata). From an example in the Royal Scottish Museum. By permission of the Director. | p. 35 |

In the Manuel d’Ornithologie (1828) Lesson writes: ‘Le Fou Manche de Velours, “manga de velado” des navigateurs portugais, que l’on dit être le fou de Bassan, est de moitié plus petit. Ce serait donc une race distincte.’ tom. II. p. 375. And in the Traité d’Ornithologie the same author amplifies thus what he has written: ‘Fou Manche de Velours; Sula dactylatra, Less. Zool. de la Coq., Texte, part. 2, p. 494. Espèce confondue avec le fou de Bassan adulte; est le manga de Velado des Portugais. Plumage blanc pur; ailes et queue noires; bec corné; tarses jaunes; la base du bec cerclée d’une peau nue, qui s’étend sur la gorge en forme de demi-cercle. Femelle: Grise. L’île de l’Ascension, les mers chaudes des Tropiques.’ Texte, p. 601. |

[p1]

THE RUKH OF MARCO POLO

[p3]

Contents

Marco Polo, had he confined himself to a sober narration of his travels, would have left to posterity a valuable record of the political institutions and national customs of the peoples of his day in the Far East. He was not satisfied with doing this, but added to his narrative a number of on-dit more or less marvellous in character, which he collected from credulous or inventive persons with whom he came into contact, principally from mariners and from other travellers.

Of these addenda to his story not one is more incredible than that of the rukh, and yet that addendum may be regarded as indicating the transition from the utterly incredible to the admixture of truth with fiction in bird-lore. For, whilst the rukh possessed some characteristics which are utterly fabulous, others are credible enough. We are told, for example, that it resembled an eagle, that it was carnivorous, that it possessed remarkable powers of flight, and that it visited islands which lay to the south of Zanzibar, within the influence of an ocean current which rendered difficult or impossible a voyage from these regions to India, and which therefore must have tended in a southerly direction. In this current we have no difficulty in recognising that of Mozambique. On the other hand, that the rukh had an expanse of wing of thirty paces, and that it could lift an elephant in its talons, are of course utterly incredible assertions.

The rukh therefore holds a position in bird-lore intermediate [p4] between that of the phœnix and that of the pelican fed upon the blood of its mother whose beak is tipped with red, or that of the barnacle goose, of which the name suggests the mollusc,1 the barnacle, and which was said to proceed from the mollusc or that of the bird of paradise, the feet of which were cut off by the Malay traders who sold the skins, and which were commonly reported never to have had feet, but to float perpetually in the air.

Thus two streams united into one floated the conception of the rukh—a mythological stream taking its rise from the simourgh of the Persians and a stream of fact taking its rise in the observation of a real bird which visited certain islands off the south-east coast of Africa, and which is said to have resembled an eagle and may have been a sea-eagle. With commendable reticence lexicographers tell us that ‘rukh’ was the name of a bird of mighty wing.

1 I.e., a fabulous mollusc; the barnacle is not now regarded as a mollusc.

[p5]

THE PENGUINS AND THE SEALS

OF THE

ANGRA DE SAM BRÀS

[p7]

Contents

There exists an anonymous narrative of the first voyage of Vasco da Gama to India under the title Roteiro da Viagem de Vasco da Gama em MCCCCXCVII. Although it is called a roteiro, it is in fact a purely personal and popular account of the voyage, and does not contain either sailing directions or a systematic description of all the ports which were visited, as one might expect in a roteiro. There is no reason to believe that it was written by Vasco da Gama. An officer in such high authority would not be likely to write his narrative anonymously. The faulty and variable orthography of the roteiro also renders improbable the hypothesis that Vasco da Gama was the author.

The journal of the first voyage of Columbus contains many allusions to the birds which were seen in the course of it by the great discoverer. In this respect the roteiro of the first voyage of Vasco da Gama resembles it. The journal of Columbus is the earliest record of an important voyage of discovery which recognises natural history as an aid to navigators, the roteiro is the next.

The author of the roteiro notes that birds resembling large herons were seen in the month of August, 1497, at which time, I opine, the vessels of Da Gama were not far from the Gulf of Guinea, or were, perhaps, making their way across that gulf. [p8] On the 27th of October, as the vessels approached the south-west coast of Africa, whales and seals were encountered, and also ‘quoquas.’

‘Quoquas’ is the first example of the eccentric orthography of our author. ‘Quoquas’ is, no doubt, his manner of writing ‘conchas,’ that is to say ‘shells’; the til over the o is absent; perhaps that is a typographical error; probably the author wrote or intended to write quõquas. These shells may have been those of nautili.

On the 8th of November the vessels under the command of Vasco da Gama cast anchor in a wide bay which extended from east to west, and which was sheltered from all winds excepting that which blew from the north-west. It was subsequently estimated that this anchorage was sixty leagues distant from the Angra de Sam Bràs; and as the Angra de Sam Bràs was estimated to be sixty leagues distant from the Cape of Good Hope, the sheltered anchorage must have been in proximity to the Cape.

The voyagers named it the Angra de Santa Elena, and it may have been the bay which is now known as St. Helen’s Bay. But it is worthy of note that the G. de Sta. Ellena of the Cantino Chart is laid down in a position which corresponds rather with that of Table Bay than with that of St. Helen’s Bay.

The Portuguese came into contact with the inhabitants of the country adjacent to the anchorage. These people had tawny complexions, and carried wooden spears tipped with horn—assagais of a kind—and bows and arrows. They also used foxes’ tails attached to short wooden handles. We are not informed for what purposes the foxes’ tails were used. Were they used to brush flies away, or were they insignia of authority? The food of the natives was the flesh of whales, seals, and [p9] antelopes (gazellas), and the roots of certain plants. Crayfish or ‘Cape lobsters’ abounded near the anchorage.

The author of the roteiro affirms that the birds of the country resembled the birds in Portugal, and that amongst them were cormorants, larks, turtle-doves, and gulls. The gulls are called ‘guayvotas,’ but ‘guayvotas’ is probably another instance of the eccentric orthography of the author and equivalent to ‘gaivotas.’

In December the squadron reached the Angra de São Bràs, which was either Mossel Bay or another bay in close proximity to Mossel Bay. Here penguins and seals were in great abundance. The author of the roteiro calls the penguins ‘sotelycairos,’ which is more correctly written ‘sotilicarios’ by subsequent writers. The word is probably related to the Spanish sotil and the Latin subtilis, and may contain an allusion to the supposed cunning of the penguins, which disappear by diving when an enemy approaches.

The sotilicarios, says the chronicler, could not fly because there were no quill-feathers in their wings; in size they were as large as drakes, and their cry resembled the braying of an ass. Castanheda, Goes, and Osorio also mention the sotilicario in their accounts of the first voyage of Vasco da Gama, and compare its flipper to the wing of a bat—a not wholly inept comparison, for the under-surface of the wings of penguins is wholly devoid of feathery covering. Manuel de Mesquita Perestrello, who visited the south coast of Africa in 1575, also describes the Cape penguin. From a manuscript of his Roteiro in the Oporto Library, one learns that the flippers of the sotilicario were covered with minute feathers, as indeed they are on the upper surface and that they dived after fish, upon which they fed, and on which they fed their young, which were hatched in nests [p10] constructed of fishbones.1 There is nothing to cavil at in these statements, unless it be that which asserts that the nests were constructed of fishbones, for this is not in accordance with the observations of contemporary naturalists, who tell us that the nests of the Cape Penguin (Spheniscus demersus) are constructed of stones, shells, and débris.2 It is, therefore, probable that the fishbones which Perestrello saw were the remains of repasts of seals.

Seals, says the roteiro, were in great number at the Angra de São Bràs. On one occasion the number was counted and was found to be three thousand. Some were as large as bears and their roaring was as the roaring of lions. Others, which were very small, bleated like kids. These differences in size and in voice may be explained by differences in the age and in the sex of the seals, for seals of different species do not usually resort to the same locality. The seal which formerly frequented the south coast of Africa—for it is, I believe, no longer a denizen of that region—was that which is known to naturalists as Arctocephalus delalandii, and, as adult males sometimes attain eight and a half feet in length, it may well be described as of the size of a bear. Cubs from six to eight months of age measure about two feet and a half in length.3 The Portuguese caught anchovies in the bay, which they salted to serve as provisions on the voyage. They anchored a second time in the Angra de São Bràs in March, 1499, on their homeward voyage.

Yet one more allusion to the penguins and seals of the Angra [p11] de São Bràs is of sufficient historical interest to be mentioned. The first Dutch expedition to Bantam weighed anchor on the 2nd of April, 1595, and on the 4th of August of the same year the vessels anchored in a harbour called ‘Ague Sambras,’ in eight or nine fathoms of water, on a sandy bottom. So many of the sailors were sick with scurvy—‘thirty or thirty-three,’ says the narrator, ‘in one ship’—that it was necessary to find fresh fruit for them. ‘In this bay,’ runs the English translation of the narrative, ‘lieth a small Island wherein are many birds called Pyncuins and sea Wolves, that are taken with men’s hands.’ In the original Dutch narrative by Willem Lodewyckszoon, published in Amsterdam in 1597, the name of the birds appears as ‘Pinguijns.’

1 Roteiro da Viagem de Vasco da Gama. 2da edição. Lisboa, 1861. Pp. 14 and 105.

2 Moseley, Notes by a Naturalist on the ‘Challenger,’ p. 155.

3 Catalogue of Seals and Whales in the British Museum, by J. E. Gray. 2nd ed., p. 53.

[p13]

THE BANDA ISLANDS AND THE BANDAN BIRDS

[p15]

Contents

The islands of the Banda Sea, with the exception of Letti, Kisser, and Wetter, constitute the Ceram sub-group or the Moluccan group; the principal units are Buru, Amboyna, Great Banda, Ceram, Ceram Laut, Goram, Kur, Babar, and Dama. The Matabela Islands, the Tiandu Islands, the Ké Islands, and the Tenimber Islands also belong to the Ceram sub-group. We are only concerned with the Banda Islands, which are eight in number, and consist of four central islands in close proximity to one another, inclosing a little inland sea, and four outlying islets. The central islands are Lonthoir, or Great Banda, Banda Neira, Gounong Api, which is an active volcano, and Pisang. The remaining Banda Islands are Rozengain, which lies about ten miles distant to the south-east of Great Banda; Wai, at an equal distance to the west; Rhun, about eight miles west by south from Wai; and Suangi or Manukan, about seventeen miles north by east from Rhun.

The Banda Islands are well known as the principal centre of the cultivation of the nutmeg. When the Dutch East India Company became the possessors of the islands in the beginning of the seventeenth century, they destroyed the nutmeg trees in all the islands under their jurisdiction, with the exception of those in Amboyna and the Banda Islands. By doing so they hoped to maintain the high value of these natural products.

The Banda Islands may have been visited by Varthema, [p16] but our first reliable account of them connects the discovery of them with an expedition dispatched by order of Alfonso de Albuquerque from Malacca. Shortly after Albuquerque had defeated the Malays and taken possession of that city, he sent three vessels, under the command of Antonio de Abreu, to explore the Archipelago and to inaugurate a trade with the islanders. A junk, commanded by a native merchant captain, Ismael by name, preceded the other vessels for the purpose of announcing their approaching advent to the traders of the Archipelago, so that they might have their spices ready for shipment. With De Abreu went Francisco Serrão and Simão Affonso, in command of two of the vessels. The pilots were Luis Botim, Gonçalo de Oliveira, and Francisco Rodriguez or Roiz. Abreu left Malacca in November, 1511, at which season the westerly monsoon begins to blow. He steered a south-easterly course, passed through the Strait of Sabong, and having arrived at the coast of Java, he cast anchor at Agaçai, which Valentijn identifies with Gresik, near Sourabaya. At Agaçai, Javan pilots were engaged for the voyage thence to the Banda Islands. Banda was, however, not the first port of call. The course was first to Buru, and thence to Amboyna. Galvão relates that Abreu landed at Guli Guli, which is in Ceram. Barros, however, in his account of the voyage, makes no mention of Ceram. At Amboyna the ship commanded by Francisco Serrão, an Indian vessel which had been captured at Goa, was burnt, for, says Barros, ‘she was old,’ and the ship’s company was divided between the two other ships, which then proceeded to Lutatão, which is perhaps identical with Ortattan, a trading station on the north coast of Great Banda. Here Abreu obtained a cargo of nutmegs and mace and of cloves, which had been brought hither from the Moluccas. At Lutatão Abreu erected a pillar in token of annexation to the [p17] dominions of the King of Portugal. He had done this at Agaçai and in Amboyna also.

The return voyage to Malacca was marked by disaster. A junk, which now was bought to replace the Indian vessel, was wrecked, and the crew, who had taken refuge on a small island, was attacked by pirates. The pirates, however, were worsted and their craft was captured. Serrão, who had been in command of the junk, sailed in the pirate vessel to Amboyna, and thence eventually reached Ternate, where he remained at the invitation of Boleife, the Sultan of that island. The junk, of which Ismael was the skipper, was also wrecked near Tuban, but the cargo, consisting of cloves, was recovered in 1513 from the Javans, who had taken possession of it.

Zoologically the Banda Islands lie within Wallace’s Australian Region, and their avifauna has a great affinity with that of Australia. Wallace visited these islands in December 1857, May 1859, and April 1861, and collected eight species of birds, namely, Rhipidura squamata, a fan-tailed Flycatcher; Pachycephala phæonota, a thickhead; Myzomela boiei, a small scarlet-headed honey-eater; Zosterops chloris, a white-eye; Pitta vigorsi, one of the brightly-coloured ground thrushes of the Malayan region; Halcyon chloris, a kingfisher with a somewhat extensive range; Ptilopus xanthogaster, a fruit-eating pigeon, and the nutmeg pigeon, Carpophaga concinna. The islands were visited by the members of the Challenger expedition in September and October, 1874, but the only additional species then obtained was Monarcha cinerascens, also a Flycatcher.

These birds may be regarded as the resident birds of the Banda Islands, but there are others which are occasional visitants or migrants. Indeed, in seas so full of islands, it is inevitable that wanderers from other islands should occasionally visit the group.

[p18]

To those which I have already mentioned there may therefore

be added, as of less frequency, the accipitrine bird, Astur

polionotus, the Hoary-backed Goshawk; the Passeres Edoliisoma

dispar, a Caterpillar Shrike, the skin of a male of which from

Great Banda is in the Leyden Museum, and Motacilla melanope,

the Grey Wagtail. Of picarian birds there have been found

Cuculus intermedius, the Oriental Cuckoo; Eudynamis cyanocephala

sub-species everetti, a small form of the Koel, and Eurystomus

australis, the Australian Roller. João de Barros, in his Asia,

mentions the parrots of the Banda Islands,1 and we find accordingly

that one of the Psittaci is recorded from Banda in modern times,

namely, Eos rubra, a red, or rather a crimson lory. The ornithologist

Müller saw many of these birds in Great Banda, on the

Kanary trees. Additional pigeons are the seed-eating Chalcophaps

chrysochlora and the fruit-eating Ptilonopus wallacei, and

finally there is one gallinaceous bird which is probably resident,

but the shy and retiring habits of which have enabled it to escape

observation until recently. This is a Scrub Fowl (Megapodius

duperreyi).

1 III. v. 6. ‘Muitos papagayos & passaros diversos.’

[p19]

THE ETYMOLOGY OF THE NAME ‘EMU’

[p21]

Contents

The name ‘emu’ has an interesting history. It occurs in the forms ‘emia’ and ‘eme’ in Purchas his Pilgrimage, in 1613. ‘In Banda and other islands,’ says Purchas, ‘the bird called emia or eme is admirable.’ We should probably pronounce ‘eme’ in two syllables, as e-mé. This eme or emia was doubtless a cassowary—probably that of Ceram. The idea that it was a native of the Banda Group appears to have existed in some quarters at the beginning of the seventeenth century, but the idea was assuredly an erroneous one. So large a struthious bird as the cassowary requires more extensive feeding-grounds and greater seclusion than was to be found in any island of the Banda Group, and, as at the present day so in the past, Ceram was the true home of the Malayan cassowary, which found and which finds in the extensive forests of that island the home adapted to its requirements. It is, however, equally certain that at an early date the Ceram cassowary was imported into Amboyna and probably into Banda also, and we know of an early instance of its being introduced into Java, and from Java into Europe. When the first Dutch expedition to Java had reached that island, and when the vessels of which it was composed were lying at anchor off Sindaya, some Javans brought a cassowary on board Schellenger’s ship as a gift, saying that the bird was a rare one and that it swallowed fire. At least, so they were understood to say, but that they really did say so is somewhat doubtful. [p22] However, the sailors put the matter to the test by administering to the bird a dose of hollands; perhaps the hollands was ignited and administered in the form of liquid fire, but it is not expressly stated that this was the case. This cassowary was brought alive to Amsterdam in 1597, and was presented to the Estates of Holland at the Hague.1 A figure of it, under the name ‘eme,’ appears in the fourth and fifth German editions of the account of this voyage of the Dutch to Java, by Hulsius, published at Frankfort in 1606 and 1625. The figure is a fairly accurate representation of an immature cassowary.

Whence comes, let us ask, the name ‘eme’ and the later form, ‘emu.’ The New Historical English Dictionary suggests a derivation from a Portuguese word, ‘ema,’ signifying a crane. But no authority is quoted to prove that ema signifies, or ever signified, crane. On the other hand, various Portuguese dictionaries which have been consulted render ‘ema’ by ‘casoar,’ or state that the name ‘ema’ is applicable to several birds, of which the crane is not one. Pero de Magalhães de Gandavo, in his Historia da Provincia Sancta Cruz, published in 1576, uses the name ‘hema’ in writing of the rhea or nandu.

It is worthy of note that the Arabic name of the cassowary is ‘neâma’, and that there were many Arab traders in the Malayan Archipelago at the time when the Portuguese first navigated it. The Portuguese strangely distorted Malay and Arabic names, and it would not be surprising if they reproduced ‘neâma’ as ‘uma ema.’

1 Salvadori, referring to Hist. Gen. de Voy. VIII. p. 112, states that the Cassowary which was brought alive to Europe by the Dutch in 1597 belonged first to Count Solms van Gravenhage, then to the Elector Ernest van Keulen, and finally to the Emperor Rudolph II. Ornit. della Papuasia e delle Molucche. III. p. 481.

[p23]

AUSTRALIAN BIRDS IN 1697

[p25]

Contents

In 1696 the Honourable Directors of the Dutch Chartered Company trading to the Dutch East Indies decided to send an expedition for the purpose of searching for missing vessels, especially for the Ridderschap van Hollandt, of which no news had been received for two years. The local Board of Directors of the Amsterdam Chamber of the Company was charged to carry out this resolution, and it equipped three vessels which were placed under the command of Willem de Vlaming. The Commander was directed to search for missing vessels or for shipwrecked sailors at the Tristan da Cunha Islands, the Cape of Good Hope, and the Islands of Amsterdam and St. Paul in the Southern Ocean. Thence he was to proceed to the ‘Onbekende Zuidland,’ by which name, or by that of Eendragts Land, Australia was designated in whole or in part in the official dispatches of the Dutch East India Company in the seventeenth century.

On the 29th of December, 1696, the vessels under the command of De Vlaming lay at anchor between Rottnest Island and the mainland of Australia. The island was searched for wreckage with little result. One piece of timber was found which, it was conjectured, might have been deck timber, and a plank was found, three feet long and one span broad. The nails in the wreckage were very rusty. The search for shipwrecked sailors on the adjacent mainland was unsuccessful. On the 20th and on the 31st of December, and on the 1st of January, 1697, [p26] De Vlaming notes in his journal that odoriferous wood was found on the mainland. Portions of it were subsequently submitted to the Council of the Dutch East Indies at Batavia, and from these portions an essential oil was obtained by distillation. It may well be supposed that this experiment was the first in the manufacture of eucalyptus oil, which, however, in our day is obtained not from the wood but from the leaves of the tree. On the 13th of January De Vlaming records that a dark resinous gum resembling lac was seen exuding from trees.

In a narrative of the voyage published under the title Journaal wegens een Voyagie na het onbekende Zuid-land, we read that on the 11th of January nine or ten Black Swans were seen. In a letter from Willem van Oudhoorn, Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies, to the Managers of the East India Company at the Amsterdam Chamber, it is stated that three black swans were brought alive to Batavia, but died soon after their arrival.1

Several boat expeditions were made, and Swan River was entered and ascended. During these expeditions the author of the Journaal mentions that the song of the ‘Nachtegael’ was heard. There are no nightingales in Australia, but the bird to which the writer of the Journaal alludes may have been the Long-billed Reed Warbler, the Australian representative of the Sedge Warbler and a denizen of the reed-beds of the Swan River. Two species of geese are also mentioned by the same writer under the names of European geese. It is somewhat difficult to determine to which geese the author of the Journaal alludes under the names ‘Kropgans’ and ‘Rotgans.’

When English-speaking Dutch are asked to translate ‘kropgans,’ they do so by ‘Christmas goose’ or ‘fat goose.’ [p27] Dictionaries are silent respecting ‘kropgans,’ or render it by ‘pelican.’ I am inclined to think that this rendering arises from a confusion between ‘kropgans’ and the German word ‘kropfgans,’ and that ‘kropgans’ was formerly applied to domestic geese in general which were being fed for the market, and also, as in the present instance, to the wild goose from which they were derived, namely to the Grey Lag Goose (Anser ferus). If this be so, the Australian bird with which the kropgans is compared in the Journaal may be the Cape Barren Goose (Cereopsis novæ-hollandiæ), which is found sparingly in Western Australia. The ‘Rotgans’ is the Brent Goose (Branta bernicla) and the Australian bird which most resembles it is the Musk Duck (Biziura lobata), which also is found in the west of Australia, although more sparingly there than in the south of the island continent.

Other birds which were seen at the same part of the Australian coast were ‘Duikers,’ by which name Cormorants are probably designated, Cockatoos and Parrakeets. It is said that all the birds were shy and flew away at the approach of human beings. No aborigines were seen, although smoke was visible.

On the 15th of January De Vlaming quitted the anchorage near Rottnest Island, and followed the coast until 30° 17´ S. lat. was reached. Two boats were there sent to the shore and soundings were taken. The country near the landing-place was sandy and treeless, and neither human beings nor fresh water were to be seen. But footmarks resembling those of a dog were seen, and also a bird which the Journaal calls a ‘Kasuaris’ and which must have been one of the Emus.2

On the 30th of January, 26° 8´ S. lat. was observed, which is [p28] approximately that of False Entrance. On the 1st of February the pilot of the Geelvink left the ships in one of the Geelvink’s boats in order to ascertain the position of Dirk Hartog’s Anchorage, and the captains of two of the vessels made an excursion for a distance of six or seven miles inland. They returned to the ships on the following day, bringing with them the head of a large bird, and they imparted the information that they had seen two huge nests built of branches.3

The pilot of the Geelvink returned to the ship on the 3rd of February, and reported that he had passed through a channel—probably that which is now known as South Passage—and had followed the coast of Dirk Hartog’s Island until he reached the northern extremity of the island. There, upon an acclivity, a tin plate was found on the ground. Certain words scratched upon the metal indicated that the ship Eendragt, of Amsterdam, of which Dirk Hartog was master, had anchored off the island on the 25th of October, 1616, and had departed for Bantam on the 27th day of the same month. The pilot brought the metal plate—a flattened tin dish—with him, and also two turtles which had been caught on the island. The squadron anchored in Dirk Hartog’s Reede on the 4th of February, and remained there until the 12th day of that month.

The anonymous author of the Journaal relates that on the 6th of February many turtles were seen, and also a very large nest at the corner of a rock; the nest resembled that of a stork, but was probably that of an osprey, which places its nest on a rock—often on a rock surrounded by water.

De Vlaming quitted the Australian coast at 21° S. lat., and proceeded to Batavia, where he arrived on the 20th of March, 1697.

1 Heeres, The Part borne by the Dutch in the Discovery of Australia, p. 84.

2 No Cassowary is known to inhabit western Australia.

3 Wedge-tailed Eagles and also Ospreys build nests of sticks.

[p29]

NEW ZEALAND BIRDS IN 1772.

[p31]

Contents

Nicholas Thomas Marion Dufresne was an officer in the French navy, and was born at St. Malo in 1729. In 1771 he was commissioned at his own desire to restore to the island of his birth a Tahitian who had accompanied Bougainville to France. He was also charged to ascertain if a continent or islands existed in the Southern Ocean whence useful products might be exported to Mauritius or Reunion.

The middle of the eighteenth century is approximately the period in which the collection and classification of exotic plants and animals became one of the chief objects of exploratory voyages. This was also one of the aims of the expedition under the command of Marion and Commerson, a botanist who had accompanied De Bougainville, was to have accompanied Marion also. But he was unable to go, so that no botanist and also no zoologist made the voyage. Crozet, however, who was second in command of the Mascarin, has left not a few observations relating to the birds which he saw at sea during the voyage, or in the countries which he visited. They are embodied in his book Nouveau Voyage à la Mer du Sud.

The native of Tahiti fell sick shortly after the commencement of the voyage, and was put ashore in Madagascar, where he died. One of the objects of the voyage thus ceased to exist. The first undiscovered land which was sighted after leaving Madagascar was named Terre d’Espérance, and subsequently, by Cook, Prince [p32] Edward Island. Near it a collision with the Mascarin caused the partial disablement of the Marquis de Castries; the search for a southern continent was therefore abandoned, and it was resolved to visit the countries which had been discovered by Tasman in the seventeenth century.

Crozet’s first observation relating to sea-birds was made on the 8th of January, 1772, about twelve days after leaving the Cape of Good Hope. Terns were then in view, and thereafter, until the 13th of that month, Terns and Gulls were frequently seen. Shortly after the latter date Du Clesmeur, who was in command of the Marquis de Castries, sighted another island which was named Ile de la Prise de Possession, and which has been renamed Marion Island. Crozet landed upon it, and relates that the sea-birds which were nesting upon it continued to sit on their eggs or to feed their young regardless of his presence. There were amongst the birds penguins, Cape petrels (‘damiers’), and cormorants. Crozet also mentions divers—‘plongeons.’ It is doubtful to what birds he alludes under this name—a name which is usually applied to the Colymbidæ, a family which has no representative in the seas of the southern hemisphere.

The terns which Crozet saw were probably of the species Sterna vittata, which breeds on the islands of St. Paul and Amsterdam. It also frequents the Tristan da Cunha Group, and Gough Island and Kerguelen Island, so that it enjoys a wide distribution in the Southern Ocean. The gulls may have been Dominican Gulls (Larus dominicanus), which are to be found at a considerable distance from any continental land. The penguins which frequent the seas adjacent to the islands which Marion named Ile de la Caverne, Iles Froides, and Ile Aride are Aptenodytes patagonica, Pygoscelis papua, Catarrhactes chrysocome, and Catarrhactes chrysolophus. The eggs of the last-named penguin have [p33] been found on the Ile Aride, which is now known as Crozet Island, and the whole group as the Crozet Islands. The Cape Petrel (Daption capensis) nests on Tristan da Cunha and Kerguelen Island. A Cormorant (Phalacrocorax verrucosus) inhabits Kerguelen Island, but its occurrence on the Crozet Islands is doubtful. Finally, Crozet saw on the island on which he landed a white bird, which he mistook for a white pigeon, and argues that a country producing seeds for the nurture of pigeons must exist in the vicinity. This bird was probably the Sheath-bill (Chionarchus crozettensis) of the Crozet Islands.

The next land visited was Tasmania, where the vessels cast anchor on the east side of the island. Like their Dutch predecessors, the French mariners bestowed the names of European birds upon the birds which they saw in these new lands, and it would be an idle task to seek the equivalents of the ousels, thrushes, and turtle-doves which Crozet saw in Tasmania. There can be no doubt, however, about his pelicans, for Pelecanus conspicillatus still nests on the east coast of the island or on islets adjacent to the coast.

The duration of Crozet’s sojourn in New Zealand was about four months in the autumn and winter of 1772. The vessels anchored in the Bay of Islands. Crozet has given a long enumeration of the birds which he saw in New Zealand. We will not seek to find what his wheatears and wagtails, starlings and larks, ousels and thrushes may have been, but we may make an exception in favour of his black thrushes with white tufts (‘grives noires à huppes blanches’). These birds were evidently Tuis (Prosthemadura Novæ-Zealandiæ).

Crozet distributes the birds which he saw in New Zealand under four heads, as birds of the forest, of the lakes, of the open country, and of the sea-coast. In the forests were Wood Pigeons [p34] as large as fowls, and bright blue in colour; no doubt the one pigeon of New Zealand (Hemiphaga Novæ-Zealandiæ) is alluded to in this description. Two parrots are mentioned, one of which was very large and black or dusky in colour diversified with red and blue, and the other was a small lory, which resembled the lories in the island of Gola.1 It was no doubt a Cyanorhamphus—a genus of which there are in New Zealand more than one species. The large parrot may be the Kaka, although there is no blue in the plumage of the Kaka (Nestor meridionalis). There is blue under the wing of the Kea, but the Kea (Nestor notabilis) is not a bird of the North, but of the South Island.

In the open country were the passerine birds, which Crozet mentions by the names of European birds, and also a quail (Coturnix Novæ-Zealandiæ) which has lately become extinct.

On the lakes were ducks and teals in abundance, and a ‘poule bleue,’ similar to the ‘poules bleues’ of Madagascar, India, and China. The ‘poule bleue’ was doubtless the Swamp Hen or Purple Gallinule which, because of its rich purple plumage and red feet, is a conspicuous object in New Zealand landscapes. The species which inhabits New Zealand, Tasmania, and Eastern Australia is Porphyrio melanotus.

On the sea-coast were cormorants, curlews, and black-and-white egrets. The curlews, which pass the summer in New Zealand and the remainder of the year in islands of the Pacific Ocean, are of the species Numenius cyanopus. They leave New Zealand in autumn, with the exception of a few individuals which remain in favoured localities. The ‘aigrettes blanches et noires’ were perhaps reef herons; the black bird of the form of an oyster-catcher, and possessing a red bill and red feet, was doubtless the Sooty Oyster-catcher (Hæmatopus unicolor), which [p35] in Tasmania is known as the Redbill. Terns and gannets were amongst the birds of the coastal waters. Of New Zealand terns, Sterna frontalis and S. nereis are the species which are seen most frequently. The ‘goelette blanche’ may have been Gygis candida. The gannets may have been ‘manches de velours’—the name by which French mariners knew the Masked Gannet (Sula cyanops). The body of this gannet is white; the wings are rich chocolate brown. It is a bird of the tropical and sub-tropical seas of the world and its appearance in New Zealand waters is infrequent.

From New Zealand the two vessels, now under the command of Duclesmeur, sailed for Guam and thence to the Philippine Islands, but as Crozet’s observations on the birds which he saw after he quitted New Zealand are of little importance, we will follow him no further.

1 I am unable to identify the lories of Gola Island.

London: Printed by Strangeways & Sons, Tower Street Cambridge Circus, W.C.