Title: On the Tree Top

Author: Clara Doty Bates

Illustrator: Jessie Curtis

Frank T. Merrill

Release date: February 6, 2008 [eBook #24530]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Louise Hope, Marilynda Fraser-Cunliffe and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This file was made using scans of public domain works in

the International Children's Digital Library.)

This text uses utf-8 (unicode) file encoding. If the apostrophes and quotation marks in this paragraph appear as garbage, make sure that the browser’s “character set” or “file encoding” is set to Unicode (UTF-8). You may also need to change your browser’s default font.

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They have been marked in the text with mouse-hover popups.

Some illustrations have been modified to fit this e-text. Thumbnail views of all pages are shown at the end of the file. Larger page views are available as links, either from the picture itself (color plates) or in the margin (black-and-white pages). These will open in a separate window or tab.

The color plates are not listed in the Table of Contents. Each plate is a single free-standing poem. The inconsistent sequence of “Dick Whittington” and “Puss in Boots” (before or after), and the spelling of “Jack and Gill” (or Jill), are unchanged.

II.

A FISH STORY.

III.

PUSSY CAT’S DOINGS.

VII.

JOHN S. CROW.

VIII.

SILVER LOCKS AND THE BEARS.

XI.

CINDERELLA.

XII.

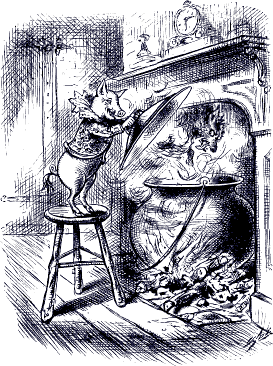

PUSS IN BOOTS.

XIII.

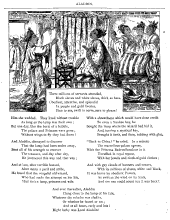

DICK WHITTINGTON AND HIS CAT.

XIV.

GOLD-LOCKS’ DREAM OF PUSSIE-WILLOW.

XV.

TONY.

XVI.

CAMPING OUT.

XVII.

DAME SPIDER.

XVIII.

HICKORY DICKORY DOCK.

XIX.

DAME FIDGET AND HER SILVER PENNY.

XXI.

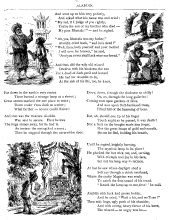

ALADDIN.

XXII.

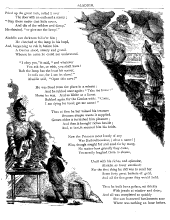

BLUE BEARD.

XXIII.

THE SLEEPING PRINCESS.

XXIV.

JACK AND GILL.

XXV.

LITTLE BO-PEEP.

XXVI.

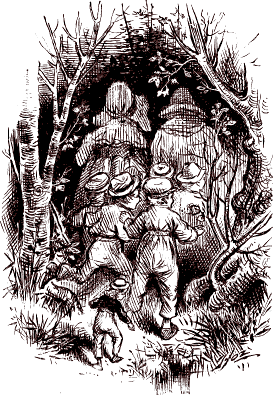

HOP O’-MY-THUMB.

XXVII.

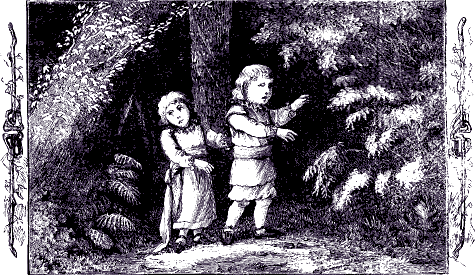

THE BABES IN THE WOOD.

XXVIII.

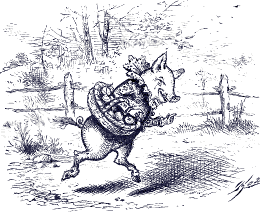

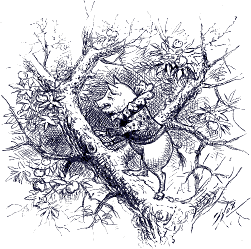

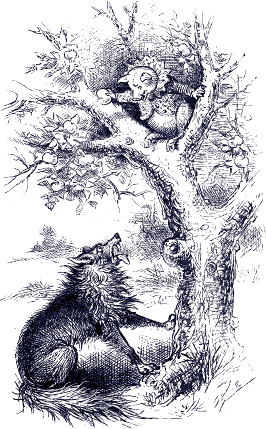

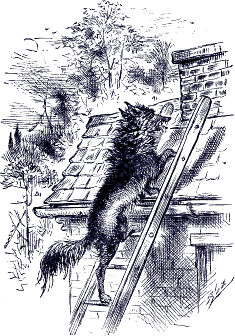

THE THREE LITTLE PIGS.

XXIX.

GOODY TWO-SHOES.

XXX.

SAARCHINKOLD.

THE GOLD-SPINNER.A miller had a daughter, And lovely, too, she was; Her step was light, her smile was bright, Her eyes were gray as glass. (So Chaucer loved to write of eyes In which that nameless azure lies So like shoal-water in its hue, Though all too crystal clear for blue.) As you would suppose, the miller Was very proud of her, And would never fail to tell some tale As to what her graces were. On the powdery air of his own mill Floated the whispers of her skill; At the village inn the loungers knew All that the pretty girl could do. |

||

|

Oft in his braggart way This foolish tale he told, That his daughter could spin from bits of straw Continuous threads of gold! So boastful had he grown, forsooth, That he cared but little for the truth: But since this was a curious thing It came to the knowledge of the king. He thought it an old wife’s fable, But senseless stuff at best; Yet, as he had greed, he cried, “Indeed! I will put her powers to test.” With a wave of his hand, he further said That to-morrow morning the clever maid Should come to the castle, and he would see What truth in the story there might be. |

|

|

Next day, with a trembling step, She reached the palace door, And was shown into a chamber, where Was straw upon the floor. They brought her a chair and a spinning-wheel, A little can of oil, and a reel; And said that unless the work was done— All of the straw into the gold-thread spun— By the time that the sun was an hour high Next morning, she would have to die. |

|

Down sat she in despair, Her tears falling like rain: She had never spun a thread in her life, Nor ever reeled a skein! Hark! the door creaked, and through a chink, With droll wise smile and funny wink, In stepped a little quaint old man, All humped, and crooked, and browned with tan. She looked in fear and amaze To see what he would do; He said, “Little maid, what will you give If I’ll spin the straw for you?” Ah, me, few gifts she had in store— A trinket or two, and nothing more! A necklace from her throat so slim She took, and timidly offered him. ’Twas enough, it seemed; for he sat At the wheel in front of her, And turned it three times round and round, Whirr, and whirr-rr, and whirr-rr-rr— One of the bobbins was full; and then, Whirr, and whirr-rr, and whirr-rr-rr again, THUMBPAGE Until all the straw that had been spread Had been deftly spun into golden thread. |

||

|

||

|

At sunrise came the king To the chamber, and, behold, Instead of the ugly heaps of straw Were bobbins full of gold! |

||

|

This made him greedier than before; And he led the maiden out at the door Into a new room, where she saw Still larger and larger heaps of straw, A chair to sit in, a spinning-wheel, A little can of oil, and a reel; And he said that straw, too, must be spun To gold before the next day’s sun Was an hour high in the morning sky, And if ’twas not done, she must die. | ||

Down sank she in despair,

Her tears falling like rain;

She could not spin a single thread,

She could not reel a skein.

But the door swung back, and through the chink,

With the same droll smile and merry wink,

The dwarf peered, saying, “What will you do

If I’ll spin the straw once more for you?”

“Ah me, I can give not a single thing,”

She cried, “except my finger-ring.”

He took the slender toy,

And slipped it over his thumb;

Then down he sat and whirled the wheel,

Hum, and hum-m, and hum-m-m;

Round and round with a droning sound,

Many a yellow spool he wound,

Many a glistening skein he reeled;

And still, like bees in a clover-field,

The wheel went hum, and hum-m and hum-m-m.

Next morning the king came,

Almost before sunrise,

To the chamber where the maiden was,

And could scarce believe his eyes

To see the straw, to the smallest shreds,

Made into shining amber threads.

And he cried, “When once more I have tried

Your skill like this, you shall be my bride;

|

For I might search through all my life Nor find elsewhere so rich a wife.” Then he led her by the hand Through still another door, To a room filled twice as full of straw As either had been before. There stood the chair and the spinning-wheel, And there the can of oil and the reel; And as he gently shut her in He whispered, “Spin, little maiden, spin.” |

|

|

Again she wept, and again Did the little dwarf appear; “What will you give this time,” he asked, “If I spin for you, my dear?” Alas—poor little maid—alas! Out of her eyes as gray as glass Faster and faster tears did fall, As she moaned, “I’ve nothing to give at all.” Ah, wicked indeed he looked; But while she sighed, he smiled! “Promise, when you are queen,” he said, “To give me your first-born child!” Little she tho’t what that might mean, Or if ever in truth she should be queen Anything, so that the work was done— Anything, so that the gold was spun! She promised all that he chose to ask; And blithely he began the task. Round went the wheel, and round, Whiz, and whiz-z, and whiz-z-z! So swift that the thread at the spindle point Flew off with buzz and hiss. |

|

She dozed—so tired her eyelids were— To the endless whirr, and whirr, and whirr; Though not even sleep could overcome The wheel’s revolving hum, hum, hum! When at last she woke the room was clean, Not a broken bit of straw was seen; But in huge high heaps were piled and rolled Great spools of gold—nothing but gold! It was just at the earliest peep of dawn, And she was alone—the dwarf was gone. |

|

It was indeed a marvellous thing For a miller’s daughter to wed a king; But never was royal lady seen More fair and sweet than this young queen. The spinning dwarf she quite forgot In the ease and pleasure of her lot; And not until her first-born child Into her face had looked and smiled Did she remember the promise made; Then her heart grew sick, her soul afraid. |

|

One day her chamber door Pushed open just a chink, And she saw the well-known crooked dwarf, His wise smile and his blink. He claimed at once the promised child; But she gave a cry so sad and wild That even his heart was touched to hear; And, after a little, drawing near, He whispered and said: “You pledged The baby, and I came; But if in three days you can learn By foul or fair my name— By foul or fair, by wile or snare, You can its syllables declare, Then is the child yours—only then— And me you shall never see again!” |

|

|

He vanished from her sight, And she called her pages in; She sent one this way, and one that; She called her kith and kin, Bade one go here, and one go there, Despatched them thither, everywhere— That from each quarter each might bring The oddest names he could to the king. |

|

|

Next morning the dwarf appeared, And the queen began to say, “Caspar,” “Balthassar,” “Melchoir”— But the dwarf cried out, “Nay, nay!” Shaking his little crooked frame, “That’s not my name, that’s not my name!” |

|

The second day ’twas the same; But the third a messenger Came in from the mountains to the queen, And told this tale to her: That, riding under the forest boughs, He came to a tiny, curious house; Before it a feeble fire burned wan, And about the fire was a little man; In and out the brands among, Dancing upon one leg, he sung: “To-day I’ll stew, and then I’ll bake, To-morrow I shall the queen’s child take; How fine that none is the secret in, That my name is Rumpelstiltskin!” |

|

|

The queen was overjoyed, And when, due time next day, The dwarf returned for the final word, She made great haste to say: “Is it Conrade?” “No,”—he shook his head. “Is it Hans? or Hal?” Still “No,” he said. “Is it Rumpelstiltskin?” then she cried. “A witch has told you,” he replied, And shrieked and stamped his foot so hard That the very marble floor was jarred; And his leg broke off above the knee, And he hopped off, howling terribly. |

|

He vanished then and there, And never more was seen! This much was in his dreadful name— It saved her child to the queen. And the little lady grew to be So very sweet, so fair to see, That none could her loveliness surpass; And her eyes—they were as gray as glass! |

|||

|

Sir Arthur, the sinner, Ate twelve fish for dinner, And you may believe it’s just as I say! For if you but knew it, ’Twas I saw him do it, And just as it happened, sir, this was the way: One day this tall fish Swallowed this small fish (He had just eaten a smaller one still); Up came this queer one And gobbled that ’ere one— Didn’t he show the most magical skill? Then came this other And chewed up his brother, Made but one gulp, and behold he was through! He was a gold fish Oh! he was a bold fish— But before he could wink he was eaten up too! Up came a flounder, He was a ten-pounder, Opened his mouth, swallowed him and was gone; Before you could blink, sir, Before he could shrink, sir, This fish came by and the flounder was gone! |

||

|

(Alas for my story, ’Tis getting quite gory! So many swallows a summer might make.) This one came smiling, And, sweetly beguiling, Gobbled the last like a piece of hot cake; A cod followed after; ’Twould move you to laughter To see in his turn how this hake came up, Swallowed that cod, sir, As if he were scrod, sir, And then went by in a kind of a huff! Last, but not least, Came this fellow, the beast— Down went the hake like a small pinch of snuff! |

|

|

|

|

||

|

Then Cap’en Jim caught him, And then mamma bought him, And then Annie cooked him, served up in a dish; And so this small sinner Who had him for dinner— ’Twas just as I say, sir—had eaten twelve fish! |

|

|

’Twas a good little lady fairy, Who saddled her wee white mouse, And rode away to the village, Long miles from her snug, wee house; She tied her steed to a flower stalk airy, And left him there—this most careless fairy! |

||

|

In Fairyland no dreadful pussies Do prowl, and do growl and slay— In Fairyland the mice have honor, And draw the queen’s carriage gay; And the little lady ne’er thought of danger Because on the fence sat a green-eyed stranger, |

||

|

|

||

|

But hurried away in a twinkling Down a dark and gloomy street, Where daily the charm of her presence Made the children’s dreams more sweet; Then Pussy Cat sprang as quick as magic! One squeal (as I’ve heard the story tragic) |

|

|

And down his throat went steed and saddle, So swiftly; and O, dear me! ’Stead of her gallant mouse, the lady Discovered, where he should be, A monster with blood on his whiskers showing, And dreadful looks in his eyes so knowing! |

|

Back to Fairyland she must walk, then;

In winter no butterfly

Is sailing that way, nor a rose-leaf,

For fairies to travel by;

She reached there at length, but with feet aching

And her little heart with fear most breaking.

And the dreadful story, spreading

Through Elfland circles, may be

The reason why never a fairy

In these later years we see,

While children in all the old, old stories

Found them as plenty as morning glories!

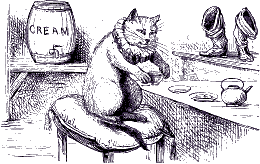

Knit, knit, knit, knit!

See old white-capped Pussy sit,

Fairly gray with worry and care,

In her little straight-backed rocking-chair?

Knit, knit, knit,

Till she is tired of it!

Why does she work so? Look and see,

There in the corner, children three!

Plump and furry and full of fun,

(A good-for-nothing is every one.)

And all those kittens

Must have mittens!

Weather is cold; and snow and sleet

Make it bad for their little feet;

And they dare not peep outside, because

Jack Frost stands ready to pinch their paws—

That’s why she sits,

And knits, and knits.

If by any chance she drops her ball,

And if one of them chases it at all,

She peeps out over her glasses’ rim

With a savage, dreadful scowl at him,

And cries out, “Scat,

You saucy cat!”

Or, if her long tail gets uncurled

And sways but the least bit in the world,

And one of them makes a roguish nip

At it, or plays at mouse with the tip,

Somebody hears,

A loud boxed ears!

With them ’tis hurry-scurry and play,

Or sleep in a round coil half the day;

While, creakety-creak, the rockers go,

And the mittens grow, and grow, and grow,

So shapely and fast—

They are done at last!

|

She summons the kittens; each one stands While the mittens are tried on his clumsy hands; Then her glasses drop to the end of her nose, And her wits go wandering off in a doze, And as never before, Does old Puss snore! |

|

|

She is off to that dream-land paradise Of cats, where cupboards are full of mice; Where white and sweet and big as the sea Are the saucers of warm new milk—ah me, There is no cream Like that in a dream! There the ways of things are very absurd; For a bobolink, or a yellow bird, Comes of its own accord, and sits On every knitting-needle that knits, And pipes and sings, As the rocker swings. |

||

Suddenly there is a noise of feet—

Rattle and clatter and patter and beat!

Old Puss makes a flying leap from her chair,

With a half-awake and startled stare,

Striving to see

What it may be.

Helter-skelter the kittens appear;

“Oh mother dear, we very much fear

That we have lost our mittens!” they cry.

“You have? Then you shall have no pie!

Lost your mittens?

You naughty kittens!”

Old mother Puss is dreadfully cross,

At the spoiled dream first, then at the loss;

And with floods of tears down either cheek

Each frightened kitten tries to speak:

“Miew, miew, miew!

Miew, miew, miew!”

|

A smart cuff over their little brains Is the only answer the mother deigns “Not another word from one of you!” It means, so without more ado, Ashamed and slow Away they go. |

|

|

Again she settles herself and sleeps; This time she dreams that she crouches and creeps, A great gray tiger along the grass, While herds of soft-eyed antelopes pass, |

||

When—patter, patter!

“Now what’s the matter?”

Again, with a scramble, the three appear;

“Oh mammy dear, see here, see here,

We have found our mittens—see!” they cry.

“You have? Then you shall have some pie!

Found your mittens?

You nice, nice kittens!”

She goes to the oven; there is a pie;

She sets it out on the floor close by;

’Tis smoking hot, and covered with juice;

And she says to them, “Eat as much as you choose.”

So up to the chin,

They all dip in.

|

Dame Puss goes out to wash her paws, And to comb her whiskers with her claws, When again the troublesome three appear; “Oh mother dear, see here—see here!” Distressed and shy They begin to cry. |

||

No wonder they cry; they did not wait

For a spoon, or knife, or fork, or plate,

But ate with their fingers! ah, how soiled!

Dame Puss declares the mittens are spoiled!

“Miew, miew, miew,

Miew, miew, miew!”

Then all run out to the rain-water tub,

Dip in their mittens, and rub, and rub;

Their little knuckles are fairly bare,

And wet, as if drowned, is every hair—

Still, over the tub,

They rub, rub, rub!

|

Once more they haste to their mother dear; “Oh mammy dear, see here, see here, We’ve washed our mittens clean!” they cry. “You darling kittens, To wash your mittens,” She says, and fondles them till they’re dry— Purr, purr, purr, Purr—pu-r-r—p-u-r-r! |

||

|

THE GROUND SQUIRREL. |

|

||

By PAUL H. HAYNE. |

|

|||

I.

|

||

|

Bless us, and save us! What’s here? Pop! At a bound, A tiny brown creature, grotesque in his grace, Is sitting before us, and washing his face With his little fat paws overlapping; Where does he hail from? Where? |

||

|

Why, there, Underground, From a nook just as cosey, And tranquil, and dozy, As e’er wooed to Sybarite napping (But none ever caught him a-napping). Don’t you see his burrow so quaint and queer? |

||

II. |

|

|

Gone! like the flash of a gun! |

|

|

This oddest of chaps, Mercurial, Disappears Head and ears! Then, sly as a fox, Swift as Jack in his box, Pops up boldly again! |

|

|

|

|

What does he mean by thus frisking about, Now up and now down, and now in and now out, And all done quicker than winking? What does it mean? Why, ’tis plain—fun! Only Fun! or, perhaps, The pert little rascal’s been drinking?— There’s a cider-press yonder all say on the run! |

|

III. |

|

|

Capture him! no, we won’t do it, Or, be sure in due time we would rue it! |

|

IV. |

||||

|

Such a piece of perpetual motion, Full of bother And pother, Would make paralytic old Bridget A Fidget. So you see (to my notion), Better leave our downy Diminutive browny |

|

|||

|

Alone, near his “diggings;” Ever free to pursue, Rush round, and renew His loved vaulting Unhalting, His whirling, And curling, And twirling, And swirling, |

|

||

|

And his ways, on the whole So unsteady! ’Pon my soul, |

||||

|

Having gazed Quite amazed, On each wonderful antic And summersault frantic, For just a bare minute, My head, it feels whizzy; My eyesight’s grown dizzy; And both legs, unstable As a ghost’s tipping table, Seem waltzing, already! |

V. |

|

Capture him! no we won’t do it, Or, in less than no time, how we’d rue it! |

|

Come, see how the ladies ride, All so pretty, all so gay, In their beauty, in their pride, Down Broadway; Prancing horses silver shod, All so pretty, all so gay; Princely feathers bend and nod, Down Broadway. |

|

||

|

|

Jiggety-jog, jiggety-jog, Over the mountain, through the bog— That’s the way the farmers go, Hear the news and see the show; Pumpkins round strapped on behind, Eggs in baskets, too, you’ll find, Soon to change for calico— That’s the way the farmers go. |

|

|

|

Bells a-jingle, fingers tingle, Ditto toes, likewise nose. The wind doth blow, And all the snow Around doth scatter; Our teeth they chatter, But that’s no matter— The song rings clear With a Happy New Year, And never a mutter, As we fly in our cutter. |

|

|

Jingle, jar, horse car, Leave you near, or take you far. Take a seat upon my lap, Cling on, swing on by the strap; Here a stop, and there a start— Let me off, I’ll take a cart! |

|

Sword and pistols by their side, And that’s the way the officers ride! Boots stretched out like a letter V, we belong to the cavalry!Over the hurdles after the hounds, tirra-la! the hunting-horn sounds— Dashaway, slashaway, reckless and fast! Crashaway, smashaway, tumbled at last! |

||

|

All alone in the field Stands John S. Crow; And a curious sight is he, With his head of tow, And a hat pulled low On a face that you never see. |

|||||

| KIN-FOLKS OF JOHN S. CROW. | |||||

|

His clothes are ragged And horrid and old, The worst that ever were worn; They’re covered with mold, And in each fold A terrible rent is torn. |

|||||

|

They once were new And spick and span, As nice as clothes could be; For though John hardly can Be called a man, They were made for men you see. |

|||||

|

That old blue coat, With a double breast And a brass button here and there, Was grandfather’s best, And matches the vest— The one Uncle Phil used to wear. |

|||||

|

The trousers are short; They belonged to Bob Before he had got his growth; But John’s no snob, And, unlike Bob, Cuts his legs to the length of his cloth. |

|||||

The boots are a mystery:

How and where

John got such a shabby lot,

Such a shocking pair,

I do declare

Though he may know, I do not.

But the hat that he wears

Is the worst of all;

I wonder that John keeps it on.

It once was tall,

But now it is small—

Like a closed accordeon.

THE FAITHFUL WATCHMAN, JOHN S. CROW.

|

But a steady old chap Is John S. Crow, And for months has stood at his post; For corn you know Takes time to grow, And ’tis long between seed and roast.

And it had to be watched And guarded with care From the time it was put in the ground, For over there, And everywhere, Sad thieves were waiting around. Sad thieves in black, A cowardly set, Who waited for John to be gone, That they might get A chance to upset The plans of the planter of corn. |

They were no kin to John,

Though they bore his name

And belonged to the family Crow;

He’d scorn to claim

Any part of the fame

That is theirs wherever you go.

|

So he has stuck to the field And watched the corn, And been watched by the crows from the hill; Till at length they’re gone, And so is the corn— They away, and it to the mill. Now the work is done, And it’s time for play, For which John is glad I know; For though made of hay, If he could he would say, “It’s stupid to be a scarecrow.” But though it is stupid, And though it is slow, To fill such an humble position; To be a good scarecrow Is better I know Than to scorn a lowly condition. |

|

NO KIN TO JOHN.

|

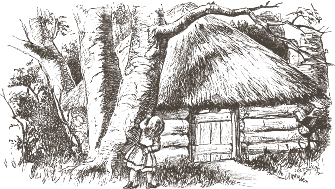

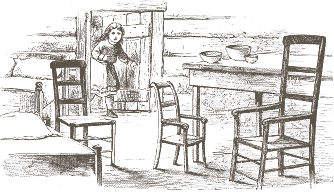

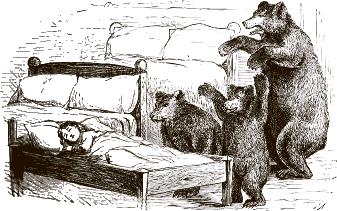

Silver Locks was a little girl, Lovely and good; She strayed out one day And got lost in the wood, And was lonely and sad, Till she came where there stood The house which belonged to the Bears. |

|

She pulled the latch string, And the door opened wide; She peeped softly first, And at last stepped inside; |

|

|

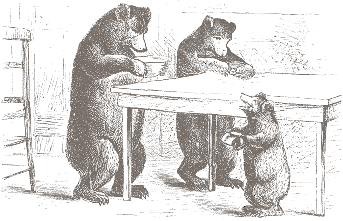

So tired her little feet Were that she cried, And so hungry she, sobbed to herself. She did not know Whether to stay or to go; But there were three chairs Standing all in a row, And there were three bowls Full of milk white as snow, And there were three beds by the wall. |

|

|

But the Father Bear’s chair Was too hard to sit in it, And the Mother Bear’s chair Was too hard to sit in it; But the Baby Bear’s chair Was so soft in a minute She had broken it all into pieces. And the Father Bear’s milk Was too sour to drink, And the Mother Bear’s milk Was too sour to drink; But the Baby Bear’s milk Was so sweet, only think, When she tasted she drank it all up. |

|

And the Father Bear’s bed Was as hard as a stone, And the Mother Bear’s bed Was as hard as a stone; |

|

|

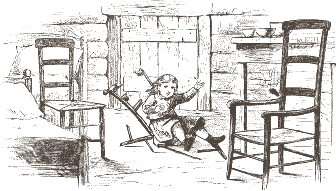

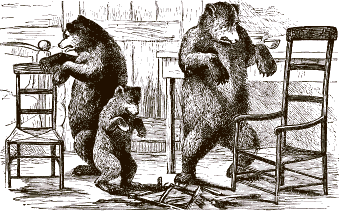

But the Baby Bear’s bed Was so soft she lay down, And before she could wink was asleep. By and by came the scratch Of old Father Bear’s claw, And the fumbling knock Of old Mother Bear’s paw, And the latch string flew up, And the Baby Bear saw That a stranger had surely been there. |

|

|

Then Father Bear cried, “Who’s been sitting in my chair?” And Mother Bear cried, “Who’s been sitting in my chair?” And Baby Bear smiled, “Who’s been sitting in my chair, And broken it all into pieces?” Then Father Bear growled, “Who’s been tasting of my milk?” And Mother Bear growled, “Who’s been tasting of my milk?” And Baby Bear wondered, “Who’s tasted of my milk, And tasting has drank it all up?” |

|

And Father Bear roared, “Who’s been lying on my bed?” And Mother Bear roared, “Who’s been lying on my bed?” |

|

|

And Baby Bear laughed, “Who’s been lying on my bed? O, here she is, fast asleep!” The savage old Father Bear cried, “Let us eat her!” The savage old Mother Bear cried, “Let us eat her!” But the Baby Bear said, “Nothing ever was sweeter. Let’s kiss her, and send her home!” |

|

|

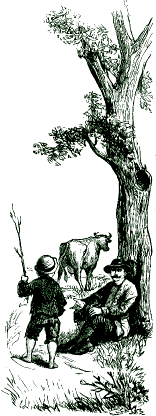

A lazy and careless boy was Jack,— He would not work, and he would not play; And so poor, that the jacket on his back Hung in a ragged fringe alway; But ’twas shilly-shally, dilly-dally, From day to day. |

|||

|

At last his mother was almost wild, And to get them food she knew not how; And she told her good-for-nothing child To drive to market the brindle cow. So he strolled along, with whistle and song, And drove the cow. |

|||

|

A man was under the wayside trees, Who carried some beans in his hand—all white. He said, “My boy, I’ll give you these For the brindle cow.” Jack said, “All right.” And, without any gold for the cow he had sold, Went home at night. Bitter tears did the mother weep; Out of the window the beans were thrown, And Jack went supperless to sleep; But, when the morning sunlight shone, High, and high, to the very sky, The beans had grown. |

|||

|

They made a ladder all green and bright, They twined and crossed and twisted so; And Jack sprang up it with all his might, And called to his mother down below: “Hitchity-hatchet, my little red jacket, And up I go!” High as a tree, then high as a steeple, Then high as a kite, and high as the moon, Far out of sight of cities and people, He toiled and tugged and climbed till noon; And began to pant: “I guess I shan’t Get down very soon!” At last he came to a path that led To a house he had never seen before; And he begged of a woman there some bread; But she heard her husband, the Giant, roar, And she gave him a shove in the old brick oven, And shut the door. |

|

|

And the Giant sniffed, and beat his breast, And grumbled low, “Fe, fi, fo, fum!” His poor wife prayed he would sit and rest,— “I smell fresh meat! I will have some!” He cried the louder, “Fe, fi, fo, fum! I will have some.” |

||

|

He ate as much as would feed ten men, And drank a barrel of beer to the dregs; Then he called for his little favorite hen, As under the table he stretched his legs,— And he roared “Ho! ho!”—like a buffalo— “Lay your gold eggs!” She laid a beautiful egg of gold; And at last the Giant began to snore; Jack waited a minute, then, growing bold, He crept from the oven along the floor, And caught the hen in his arms, and then Fled through the door. |

||

|

But the Giant heard him leave the house, And followed him out, and bellowed “Oh-oh!” But Jack was as nimble as a mouse, And sang as he rapidly slipped below: “Hitchity-hatchet, my little red jacket, And down I go!” |

||

|

And the Giant howled, and gnashed his teeth. Jack got down first, and, in a flash, Cut the ladder from underneath; And Giant and Bean-stalk, in one dash,— No shilly-shally, no dilly-dally,— Fell with a crash. This brought Jack fame, and riches, too; For the little gold-egg hen would lay An egg whenever he told her to, If he asked one fifty times a day. And he and his mother lived with each other In peace alway. |

|

|

If you listen, children, I will tell The story of little Red Riding-hood: Such wonderful, wonderful things befell Her and her grandmother, old and good (So old she was never very well), Who lived in a cottage in a wood. Little Red Riding-hood, every day, Whatever the weather, shine or storm, To see her grandmother tripped away, With a scarlet hood to keep her warm, And a little mantle, soft and gay, And a basket of goodies on her arm. |

|

|

A pat of butter, and cakes of cheese, Were stored in the napkin, nice and neat; As she danced along beneath the trees, As light as a shadow were her feet; And she hummed such tunes as the bumble-bees Hum when the clover-tops are sweet. But an ugly wolf by chance espied The child, and marked her for his prize. “What are you carrying there?” he cried; “Is it some fresh-baked cakes and pies?” And he walked along close by her side, And sniffed and rolled his hungry eyes. |

|

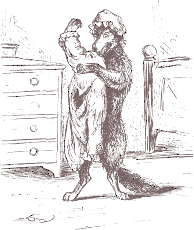

“A basket of things for granny, it is,” She answered brightly, without fear. “Oh, I know her very well, sweet miss! Two roads branch towards her cottage here; You go that way, and I’ll go this. See which will get there first, my dear!” THUMBPAGE He fled to the cottage, swift and sly; Rapped softly, with a dreadful grin. “Who’s there?” asked granny. “Only I!” Piping his voice up high and thin. “Pull the string, and the latch will fly!” Old granny said; and he went in. |

|

|

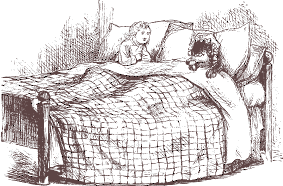

He glared her over from foot to head; In a second more the thing was done! He gobbled her up, and merely said, “She wasn’t a very tender one!” And then he jumped into the bed, And put her sack and night-cap on. And he heard soft footsteps presently, And then on the door a timid rap; He knew Red Riding-hood was shy, So he answered faintly to the tap: “Pull the string and the latch will fly!” She did: and granny, in her night-cap, Lay covered almost up to her nose. “Oh, granny dear!” she cried, “are you worse?” “I’m all of a shiver, even to my toes! Please won’t you be my little nurse, And snug up tight here under the clothes?” Red Riding-hood answered, “Yes,” of course. |

|

Her innocent head on the pillow laid, She spied great pricked-up, hairy ears, And a fierce great mouth, wide open spread, And green eyes, filled with wicked leers; |

|

|

And all of a sudden she grew afraid; Yet she softly asked, in spite of her fears: “Oh, granny! what makes your ears so big?” “To hear you with! to hear you with!” “Oh, granny! what make your eyes so big?” “To see you with! to see you with!” “Oh, granny! what makes your teeth so big?” “To eat you with! to eat you with!” |

|

|

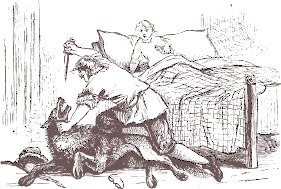

And he sprang to swallow her up alive; But it chanced a woodman from the wood, Hearing her shriek, rushed, with his knife, And drenched the wolf in his own blood. And in that way he saved the life Of pretty little Red Riding-hood. |

|

Poor, pretty little thing she was, The sweetest-faced of girls, With eyes as blue as larkspurs, And a mass of tossing curls; But her step-mother had for her Only blows and bitter words, While she thought her own two ugly crows, The whitest of all birds. |

||

|

She was the little household drudge, And wore a cotton gown, While the sisters, clad in silk and satin, Flaunted through the town. When her work was done, her only place Was the chimney-corner bench. For which one called her “Cinderella,” The other, “Cinder-wench.” |

||

But years went on, and Cinderella

Bloomed like a wild-wood rose,

In spite of all her kitchen-work,

And her common, dingy clothes;

While the two step-sisters, year by year,

Grew scrawnier and plainer;

Two peacocks, with their tails outspread,

Were never any vainer.

|

One day they got a note, a pink, Sweet-scented, crested one, Which was an invitation To a ball, from the king’s son. Oh, then poor Cinderella Had to starch, and iron, and plait, And run of errands, frill and crimp, And ruffle, early and late. And when the ball-night came at last, She helped to paint their faces, To lace their satin shoes, and deck Them up with flowers and laces; Then watched their coach roll grandly Out of sight; and, after that, She sat down by the chimney, In the cinders, with the cat, |

|

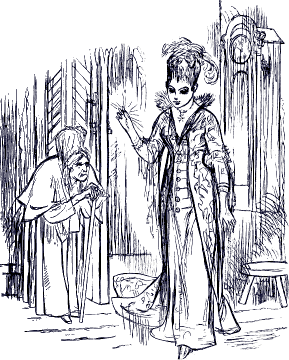

And sobbed as if her heart would break. Hot tears were on her lashes, Her little hands got black with soot, Her feet begrimed with ashes, When right before her, on the hearth, She knew not how nor why, A little odd old woman stood, And said, “Why do you cry?” |

|

|

“It is so very lonely here,” Poor Cinderella said, And sobbed again. The little odd Old woman bobbed her head, And laughed a merry kind of laugh, And whispered, “Is that all? Wouldn’t my little Cinderella Like to go to the ball? |

|

“Run to the garden, then, and fetch A pumpkin, large and nice; Go to the pantry shelf, and from The mouse-traps get the mice; Rats you will find in the rat-trap; And, from the watering-pot, Or from under the big, flat garden stone, Six lizards must be got.” Nimble as crickets in the grass She ran, till it was done, And then God-mother stretched her wand And touched them every one. The pumpkin changed into a coach, Which glittered as it rolled, And the mice became six horses, With harnesses of gold. |

|

|

One rat a herald was, to blow A trumpet in advance, And the first blast that he sounded Made the horses plunge and prance; And the lizards were made footmen, Because they were so spry; And the old rat-coachman on the box Wore jeweled livery. And then on Cinderella’s dress The magic wand was laid, And straight the dingy gown became A glistening gold brocade. The gems that shone upon her fingers Nothing could surpass; And on her dainty little feet Were slippers made of glass. THUMBPAGE “Be sure you get back here, my dear, At twelve o’clock at night,” Godmother said, and in a twinkling She was out of sight. When Cinderella reached the ball, And entered at the door, So beautiful a lady None had ever seen before. |

|

The Prince his admiration showed In every word and glance; He led her out to supper, And he chose her for the dance; But she kept in mind the warning That her Godmother had given, And left the ball, with all its charm. At just half after eleven. Next night there was another ball; She helped her sisters twain To pinch their waists, and curl their hair, And paint their cheeks again. Then came the fairy Godmother, And, with her wand, once more Arrayed her out in greater splendor Even than before. |

||

|

The coach and six, with gay outriders, Bore her through the street, And a crowd was gathered round to look, The lady was so sweet,— So light of heart, and face, and mien, As happy children are; And when her foot stepped down, Her slipper twinkled like a star. |

||

|

Again the Prince chose only her For waltz or tete-a-tete; So swift the minutes flew she did not Dream it could be late, But all at once, remembering What her Godmother had said, And hearing twelve begin to strike Upon the clock, she fled. Swift as a swallow on the wing She darted, but, alas! Dropped from one flying foot the tiny Slipper made of glass; But she got away, and well it was She did, for in a trice Her coach changed to a pumpkin, And her horses became mice; |

||

|

And back into the cinder dress Was changed the gold brocade! The prince secured the slipper, And this proclamation made: That the country should be searched, And any lady, far or wide, Who could get the slipper on her foot, Should straightway be his bride. |

||

|

So every lady tried it, With her “Mys!” and “Ahs!” and “Ohs!” And Cinderella’s sisters pared Their heels, and pared their toes,— But all in vain! Nobody’s foot Was small enough for it, Till Cinderella tried it, And it was a perfect fit. |

||

|

Then the royal heralds hardly Knew what it was best to do, When from out her tattered pocket Forth she drew the other shoe, While the eyelids on the larkspur eyes Dropped down a snowy vail, And the sisters turned from pale to red, And then from red to pale, And in hateful anger cried, and stormed, And scolded, and all that, And a courtier, without thinking, Tittered out behind his hat. For here was all the evidence The Prince had asked, complete, Two little slippers made of glass, Fitting two little feet. |

|||||

|

So the Prince, with all his retinue, Came there to claim his wife; And he promised he would love her With devotion all his life. |

|||||

|

At the marriage there was splendid Music, dancing, wedding cake; And he kept the slipper as a treasure Ever, for her sake. |

|||||

|

|

Dick, as a little lad, was told That the London streets were paved with gold. He never, in all his life, had seen A place more grand than the village green; So his thoughts by day, and his dreams by night, Pictured this city of delight, Till whatever he did, wherever he went, His mind was filled with discontent. |

|

There was bitter taste to the peasant bread, And a restless hardness to his bed; So, after a while, one summer day, Little Dick Whittington ran away. Yes—ran away to London city! Poor little lad! he needs your pity; For there, instead of a golden street, The hot, sharp stones abused his feet. So tired he was he was fit to fall,— Yet nobody cared for him at all; He wandered here, and he wandered there, With a heavy heart, for many a square. And at last, when he could walk no more, He sank down faint at a merchant’s door. And the cook—for once compassionate— Took him in at the area-gate. |

|

And she gave him bits of broken meat, And scattered crusts, and crumbs, to eat; And kept him there for her commands To pare potatoes, and scour pans, To wash the kettles and sweep the room; And she beat him dreadfully with the broom; And he staid as long as he could stay, And again, in despair, he ran away. Out towards the famous Highgate Hill He fled, in the morning gray and chill; And there he sat on a wayside stone, And the bells of Bow, with merry tone, THUMBPAGE Jangled a musical chime together, Over the miles of blooming heather: “Turn, turn, turn again, Whittington, Thrice Lord Mayor of London town!” |

|

|

And he turned—so cheered he was at that— And, meeting a boy who carried a cat, He bought the cat with his only penny,— For where he had slept the mice were many. Back to the merchant’s his way he took, To the pans and potatoes and cruel cook, And he found Miss Puss a fine device, For she kept his garret clear of mice. The merchant was sending his ship abroad, And he let each servant share her load; One sent this thing, and one sent that, And little Dick Whittington sent his cat. The ship sailed out and over the sea, Till she touched at last at a far country; And while she waited to sell her store, The captain and officers went ashore. |

|

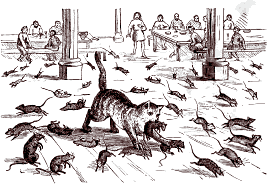

They dined with the king; the tables fine Groaned with the meat and fruit and wine; But, as soon as the guests were ranged about, Millions of rats and mice came out. They swarmed on the table, and on the floor, |

|

|

Up from the crevices, in at the door, They swept the food away in a breath, And the guests were frightened almost to death! To lose their dinners they thought a shame. The captain sent for the cat. She came! And right and left, in a wonderful way, She threw, and slew, and spread dismay. |

|

|

Then the Moorish king spoke up so bold: “I will give you eighteen bags of gold, If you will sell me the little thing.” “I will!” and the cat belonged to the king. |

|

|

When the good ship’s homeward voyage was done, The money was paid to Dick Whittington; At his master’s wish ’twas put in trade; Each dollar another dollar made. Richer he grew each month and year, Honored by all both far and near; With his master’s daughter for a wife, He lived a prosperous, noble life. And the tune the Bow-bells sang that day, When to Highgate Hill he ran away,— “Turn, turn, turn again, Whittington, Thrice Lord Mayor of London town,”— In the course of time came true and right, He was Mayor of London, and Sir Knight; And in English history he is known, By the name of Sir Richard Whittington! |

|

|

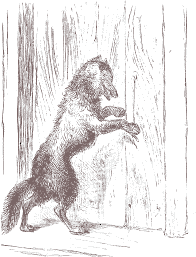

A miller had three sons, And, on his dying day, He willed that all he owned should be Shared by them in this way: The mill to this, and the donkey to that, And to the youngest only the cat. This last, poor fellow, of course Thought it a bitter fate; With a cat to feed, he should die, indeed, Of hunger, sooner or late. And he stormed, with many a bitter word, Which Puss, who lay in the cupboard, heard. |

|

She stretched, and began to purr, Then came to her master’s knee, And, looking slyly up, began: “Pray be content with me! Get me a pair of boots ere night, And a bag, and it will be all right!” |

|

The youth sighed heavy sighs, And laughed a scornful laugh: “Of all the silly things I know, You’re the silliest, by half!” Still, after a space of doubt and thought, The pair of boots and the bag were bought. And Puss, at the peep of dawn, Was out upon the street, With shreds of parsley in her bag, And the boots upon her feet. She was on her way to the woods, for game, And soon to the rabbit-warren came. |

|

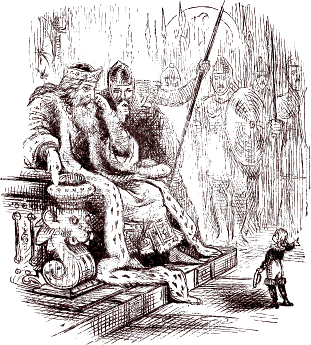

And the simple rabbits cried, “The parsley smells like spring!” And into the bag their noses slipped, And Pussy pulled the string. Only a kick, and a gasp for breath, And, one by one, they were choked to death. So Sly Boots bagged her game, And gave it an easy swing Over her shoulder; and, starting off For the palace of the king, She found him upon his throne, in state, While near him his lovely daughter sate. |

|

|

Puss made a graceful bow No courtier could surpass, And said, “I come to your Highness from The Marquis of Carabas. His loyal love he sends to you, With a tender rabbit for a stew.” |

|

And the pretty princess smiled, And the king said, “Many thanks.” And Puss strode off to her master’s home, Purring, and full of pranks. And cried, “I’ve a splendid plan for you! Say nothing, but do as I tell you to! “To-morrow, at noon, the king And his beautiful daughter ride; And you must go, as they draw near, And bathe at the river side.” The youth said “Pooh!” but still, next day, Bathed, when the king went by that way. |

|

Puss hid his dingy clothes In the marshy river-grass. And screamed, when the king came into sight, “The Marquis of Carabas— My master—is drowning close by! Help! help! good king, or he will die!” |

|

Then servants galloped fast, And dragged him from the water. “’Tis the knight who sent the rabbit stew,” The king said, to his daughter. And a suit of clothes was brought with speed, And he rode in their midst, on a royal steed. Meanwhile Puss, in advance, To the Ogre’s palace fled, Where he sat, with a great club in his hand, And a monstrous ugly head. She mewed politely as she went in, But he only grinned, with a dreadful grin. |

|

|

“I have heard it said,” she purred, “That, with the greatest ease, You change, in the twinkling of an eye, Into any shape you please!” “Of course I can!” the Ogre cried, And a roaring lion stood at her side. |

|

Puss shook like a leaf, in her boots, But said, “It is very droll! Now, please, if you can, change into a mouse!” He did. And she swallowed him whole! Then, as the king and his suite appeared, She stood on the palace porch and cheered. |

|

’Twas a grand old palace indeed, Builded of stone and brass. “Welcome, most noble ladies and lords, To the Castle of Carabas!” Puss said, with a sweeping courtesy; And they entered, and feasted royally. And the Marquis lost his heart At the beautiful princess’ smile; And the very next day the two were wed, In wonderful state and style. And Puss in Boots was their favorite page, And lived with them to a good old age. |

BY CLARA DOTY BATES.One sunny day, in the early spring, Before a bluebird dared to sing, Cloaked and furred as in winter weather,— Seal-brown hat and cardinal feather,— Forth with a piping song, Went Gold-Locks “after flowers.” “Tired of waiting so long,” Said this little girl of ours. She searched the bare brown meadow over, And found not even a leaf of clover; Nor where the sod was chill and wet Could she spy one tint of violet; But where the brooklet ran A noisy swollen billow, She picked in her little hand A branch of pussie-willow. She shouted out, in a happy way, At the catkins’ fur, so soft and gray; She smoothed them down with loving pats, And called them her little pussie-cats. She played at scratch and bite; She played at feeding cream; And when she went to bed that night, Gold-Locks dreamed a dream. Curled in a little cosy heap, Under the bed-clothes, fast asleep, She heard, although she scarce knew how, A score of voices “M-e-o-w! m-e-o-w!” And right before her bed, Upon a branching tree, Were kittens, and kittens, and kittens, As thick as they could be. Maltese, yellow, and black as ink; White, with both ears lined with pink; Striped, like a royal tiger’s skin; Yet all were hollow-eyed, and thin; And each one wailed aloud, Once, and twice, and thrice: “We are the willow-pussies; O, where are the willow-mice!” Meanwhile, outside, through branch and bough, The March wind wailed, “M-e-o-w! m-e-o-w!” ’Twas dark, and yet Gold-Locks awoke, And softly to her mother spoke: “If they were fed, mamma, It would be very nice; But I hope the willow-pussies Won’t find the willow-mice!” |

|

|

Whisk!—away in the sun His little flying feet Scamper as softly fleet As ever the rabbits run. He is gone like a flash, and then In a breath is back again. |

|

The silky flosses shine Down to his very toes: Tipped with white is his nose: And his ears are fleeces fine, Blowing a shadow-grace Breeze-like about his face. |

|

|

Quick to a whistled call Hearkens his ready ear, Scarcely waiting to hear; Silk locks, white feet, all Rush, like a furry elf Tumbling over himself. |

|

How does he sleep? He winks Twice with his mischief eyes; Dozes a bit; then lies Down with a sigh; then thinks Over some roguish play, And is up and away! |

|

|

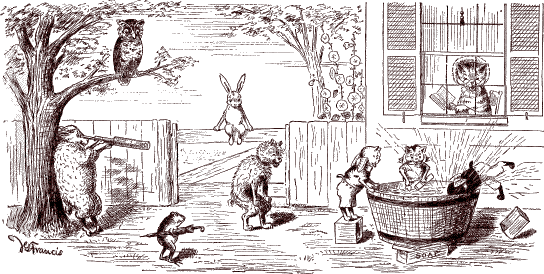

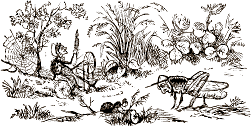

Dame Spider had spun herself lank and thin With trying to take her neighbors in; Grasshopper had traveled so far and so fast That he found he must give up at last; And the maiden Ant had bustled about The village till she was all worn out. |

|

|

Old Bumble Bee had lived on sweet Till he couldn’t help but overeat; Miss Worm had measured her puny length Till she had no longer any strength; And Mr. Beetle was shocked to find His eyes were failing and almost blind. |

|

|

|

So they all decided that they must seek Their health in the country for a week. And they made a mixed but a merry throng, For those who had children took them along. They pitched their tent and made their camp, Shelter from possible cold and damp. |

|

|

’Twas novel, and each in his own way Sought to make happy the holiday. Grasshopper took his youngest daughter Out for a stroll along the water; She shrieked with joy, “O, see the cherries!” When they found some low-bush huckleberries. |

|

|

|

THUMB PAGE

|

Dame Spider, with mischief in her eye, Thought she would angle for a fly; So, spinning a silk thread, long and fine, With wicked skill she cast the line; While Bumble Bee, in his gold-laced clothes, In the shade of a clover leaf lay for a doze. |

|

|

Miss Worm, who was full of sentiment, With the maiden Ant for a ramble went; Here was a flower, and there a flower— But suddenly rose a thunder shower. They screamed; but they got on very well, For they found what the Ant called an “umberell.” |

|

|

|

A leaf on the water lay afloat, Which the blundering Beetle thought a boat. Far down in his heart his dearest wish Was to find some hitherto unfound fish. He never came back from that fatal swim, So ’twas always thought that a fish found him. |

|

|

At night when the cheery fire was lit They heaped dry branches over it, And in the light of the crackling blaze Told funny stories of other days, And smoked, till the Ant yawned wide and said: “’Tis time we folks were all abed!” |

|

|

|

But scarce was each to his slumber laid, When the country folks came to serenade; With twang of fiddle, and toot of horn, And shriek of fife, they stayed till morn! Poor Campers! never a wink got they! So they started for home at break of day. |

|

|

Little Dame Spider had finished her spinning, Just as the warm summer day was beginning, And the white threads of her beautiful curtain Tied she and glued she to make them more certain. Dressed in her old-fashioned feathers and fringes, Then she sat down to wait; on silken hinges Swung the light fleece with a moonshiny glisten; Nothing for her but to watch and to listen. |

|

|

Presently, going off early to labor,— Bowing politely, as neighbor to neighbor, When he caught sight of this little old woman,— Sailed by a honey-bee, serge-clad and common. “Are you so scornful because I am humble? Many a time your rich relatives, Bumble, Pause in their flying to chat for an hour!” She called out after him, half gay, half sour. |

|

|

|

“O, no,” he cried. “I am off to discover What I can find fresh in the way of white clover; But since your window is cosy and shady, I will sit down half a minute, dear Lady.” Little Dame Spider arose with a rustle, Welcomed him with ceremonious bustle; Quick as a flash threw her long arms around him, Heeded no buzzing, but held him and bound him; |

|

|

Tied knots so tight that he could not undo them; Wove snares so strong that he could not break through them; Then, with a relish, stood chuckling and grinning, “This is to pay me for my early spinning!” ····· At the home-hive the bees going and coming Kept up all day their industrious humming, Nor did it one of their busy heads bother That Madame Spider had dined off their brother. |

|

|

|

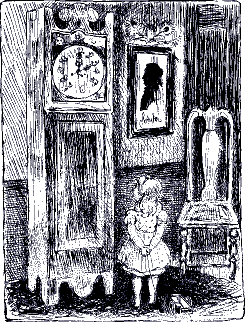

Tick-Tack! tick-tack! This way, that way, forward, back, Swings the pendulum to and fro, Always regular, always slow. Grave and solemn on the wall,— Hear it whisper! hear it call! Little Ginx knows naught of Time, But has heard the mystic rhyme,— “Hickory, dickory, dock! The mouse ran up the clock!” Tick-tack! tick-tack! White old face with figures black! So when dismal, stormy days Keep him from his out-door plays, Most that he cares for is to sit Watching, always watching it. And when the hour strikes he thinks,— (A dear, wise head has the little Ginx!) “The clock strikes one, The mice ran down!” Tick-tack! tick-tack! This way, that way, forward, back! Though so measured and precise, Ginx believes it full of mice. A mouse runs up at every tick, But when the stroke comes, scampering quick, Mice run down again; so they go, Up and down, and to and fro! Hickory, dickory, dock, Full of mice is the clock! |

|

A Wee, wee woman Was little old Dame Fidget, And she lived by herself In a wee, wee room, And early every morning, So tidy was her habit, She began to sweep it out With a wee, wee broom. |

|

|

To sweep for the cinders, Though never were there any, She whisked about, and brushed about, Humming like a bee; When, odd enough, one day She found a silver penny, Shining in a corner, As bright as bright could be. |

|

|

|

She eyed it, she took it Between her thumb and finger; She put it in the sugar bowl And quickly shut the lid; And after planning over carefully The way to spend it, She resolved to go to market And to buy herself a kid. |

|

|

And that she did next day; but, ah, The kid proved very lazy! And it moved toward home so slowly She could scarcely see it crawl; At first she coaxed and petted it, And then she stormed and scolded, Till at last, when they had reached the bridge, It would not go at all. |

|

Just then Dame Fidget saw a dog run by, And whistled to him, And cried:—“Pray dog bite kid, Kid won’t go! I see by the moonlight ’Tis almost midnight, And time kid and I were home Half an hour ago!” |

|

But no, he said he wouldn’t; So to the stick she pleaded:— “Pray stick beat dog, dog won’t bite kid, Kid won’t go! I see by the moonlight ’Tis almost midnight, And time kid and I were home Half an hour ago!” |

|

But the stick didn’t stir, So she called upon the fire:— “Pray fire burn stick, stick won’t beat dog, Dog won’t bite kid, Kid won’t go! And I see by the moonlight ’Tis almost midnight, And time kid and I were home Half an hour ago!” But the fire only smoked, So she turned and begged the water:— “Pray water quench fire, fire won’t burn stick, Stick won’t beat dog, dog won’t bite kid, Kid won’t go! |

|

|

I see by the moonlight ’Tis already midnight, And time kid and I were home An hour and a half ago!” |

|

|

“Ha, ha!” the water gurgled, So to the ox appealing:— “Pray ox drink water, water won’t quench fire, Fire won’t burn stick, stick won’t beat dog, Dog won’t bite kid, Kid won’t go! And I see by the moonlight ’Tis already midnight, And time kid and I were home An hour and a half ago!” |

|

But the ox bellowed “no!” So she shouted to the butcher:— “Pray butcher kill ox, ox won’t drink water, Water won’t quench fire, fire won’t burn stick, Stick won’t beat dog, dog won’t bite kid, Kid won’t go! I see by the moonlight ’Tis getting past midnight, And time kid and I were home An hour and a half ago!” |

|

But the butcher only laughed at her, And to the rope she hurried:— “Pray rope hang butcher, butcher won’t kill ox, Ox won’t drink water, water won’t quench fire, Fire won’t burn stick, stick won’t beat dog, Dog won’t bite kid, Kid won’t go! And I see by the moonlight ’Tis getting past midnight, And time kid and I were home An hour and a half ago.” |

|

The rope swayed round for “nay!” So to the rat she beckoned:— “Pray rat gnaw rope, rope won’t hang butcher, Butcher won’t kill ox, ox won’t drink water, Water won’t quench fire, fire won’t burn stick, Stick won’t beat dog, dog won’t bite kid, |

|

|

Kid won’t go! And I see by the moonlight ’Tis long past midnight, And time kid and I were home A couple of hours ago!” |

|

|

A scornful squeak was all he deigned, And so she called the kitten:— “Pray cat eat rat, rat won’t gnaw rope, |

|

|

Rope won’t hang butcher, butcher won’t kill ox, Ox won’t drink water, water won’t quench fire, Fire won’t burn stick, stick won’t beat dog, Dog won’t bite kid, Kid won’t go! And I see by the moonlight ’Tis long past midnight, And time kid and I were home Hours and hours ago!” |

|

|

|

|||

|

Now pussy loved a rat, So she seized him in a minute: And the cat began to eat the rat, The rat began to gnaw the rope, The rope began to hang the butcher, The butcher began to kill the ox, The ox began to drink the water, The water began to quench the fire, The fire began to burn the stick, The stick began to beat the dog, The dog began to bite the kid, And the kid began to go! And home through the moonlight, Long after midnight, The little dame and little kid Went trudging—oh, so slow! |

||||

|

|

|

|||

|

What a silly bobolink, Down in the meadow grasses! What can the noisy fellow think, When, to everyone who passes, He calls out cheerily, “Here, here is my nest! See! see!” He could hide the summer through In the thick, sweet-smelling clover, Nor could anyone from dawn to dew, His little house discover, Did he not make so free With the secret—“Here! see! see!” |

|

Little Ted has ears and eyes, And how can he keep from knowing Just where the cosy treasure lies, |

|

|

When bobolink, coming, going, Shouts, plain as plain can be, “Here, here is a nest! See! see!” |

|

|

And Teddy would like to creep Tip-toe across the meadow, And for just one minute stoop and peep Under the clover shadow. He would do no harm—not he! But would only see, see, see! And what would he find below The sheltering grass, you wonder? Why, a nest, of course, and an egg or so, A mother’s dark wings under. But bobolink—he would flee In a fright—“A boy! see! see!” So Teddy, whose heart is kind, Though he longs to venture near him, Sighs to himself, “Ah, never mind!” And listens, glad to hear him Shouting, in tireless glee, “Here, here is my nest! See! see!” |

|

I see a little group about my chair,

Lovers of stories all!

First, Saxon Edith, of the corn-silk hair,

Growing so strong and tall!

Then little brother, on whose sturdy face

Soft baby dimples fly,

As fear or pleasure give each other place

When wonders multiply;

Then Gold-locks—summers nine their goldenest

Have showered on her head,

And tinted it, of all the colors best,

Warm robin-red breast red;

Then, close at hand, on lowly haunches set,

With pricked up, tasseled ear,

Is Tony, little cleared-eyed spaniel pet,

Waiting, like them, to hear.

I say I have no story—all are told!

Not to be daunted thus,

They only crowd more confident and bold,

And laugh, incredulous.

And so, remembering how, once on a time,

I, too, loved such delights,

I choose this one and put it into rhyme,

From the “Arabian Nights.”

A poor little lad was Aladdin!

His mother was wretchedly poor;

A widow, who scarce ever had in

Her cupboard enough of a store

To frighten the wolf from the door.

No doubt he was quite a fine fellow

For the country he lived in—but, ah!

His skin was a dull, dusky yellow,

And his hair was as long as ’twould grow.

(’Tis the fashion in China, you know.)

But however he looked, or however

He fared, a strange fortune was his.

None of you, dears, though fair-faced and clever,

Can have anything like to this,

So grand and so marvelous it is!

Well, one day—for so runs the tradition—

While idling and lingering about

The low city streets, a Magician

From Africa, swarthy and stout,

With his wise, prying eyes spied him out,

|

And went up to him very politely, And asked what his name was and cried: “My lad, if I judge of you rightly, You’re the son of my brother who died— My poor Mustafa!”—and he sighed. “Ah, yes, Mustafa was my father,” Aladdin cried back, “and he’s dead!” “Well, then, both yourself and your mother I will care for forever,” he said, “And you never shall lack wine nor bread.” And thus did the wily old wizard Deceive with his kindness the two For a deed of dark peril and hazard He had for Aladdin to do, At the risk of his life, too, he knew. |

|

Far down in the earth’s very centre There burned a strange lamp at a shrine; Great stones marked the one place to enter; Down under t’was dark as a mine; What further—no one could divine! And that was the treasure Aladdin Was sent to secure. First he tore The huge stones away, for he had in An instant the strength of a score; Then he stepped through the cavern-like door. Down, down, through the darkness so chilly! On, on, through the long galleries! Coming now upon gardens of lilies, And now upon fruit-burdened trees, Filled full of the humming of bees. |

|

But, ah, should one tip of his finger

Touch aught as he passed, it was death!

Not a fruit on the boughs made him linger,

Nor the great heaps of gold underneath.

But on he fled, holding his breath,

|

Until he espied, brightly burning, The mystical lamp in its place! He plucked the hot wick out, and, turning, With triumph and joy in his face, Set out his long way to retrace. At last he saw where daylight shed a Soft ray through a chink overhead, Where the crafty Magician was ready To catch the first sound of his tread. “Reach the lamp up to me, first!” he said. |

Aladdin with luck had grown bolder,

And he cried, “Wait a bit, and we’ll see!”

Then with huge, ugly push of his shoulder,

And with strong, heavy thrust of his knee,

The wizard—so angry was he—

|

Pried up the great rock, rolled it over The door with an oath and a stamp; “Stay there under that little cover, And die of the mildew and damp,” He shouted, “or give me the lamp!”

|

|

Thus at first he but valued his treasure Because simple wants it supplied. Grown older it furnished him pleasure; And then it brought riches beside; And, at last, it secured him his bride. |

||||

|

Now the Princess most lovely of any Was Badroulboudour, (what a name!) Who, though sought for and sued for by many, No matter how grandly they came, Yet merrily laughed them to shame, |

||||

|

Until with his riches and splendor, Aladdin as lover enrolled! For the first thing he did was to send her Some forty great baskets of gold, And all the fine gems they would hold. |

||||

|

Then he built her a palace, set thickly With jewels at window and door; And all was completed so quickly She saw bannered battlements soar Where was nothing an hour before. |

||||

|

There millions of servants attended, Black slaves and white slaves, thick as bees, Obedient, attentive, and splendid In purple and gold liveries, Fine to see, swift to serve, sure to please! |

||

Him she wedded. They lived without trouble

As long as the lamp was their own;

But one day, like the burst of a bubble,

The palace and Princess were gone;

Without wings to fly they had flown!

And Aladdin, dismayed to discover

That the lamp had been stolen away,

Bent all of his strength to recover

The treasure, and day after day,

He journeyed this way and that way;

And at last, after terrible hazard,

After many a peril and strife,

He found that the vengeful old wizard,

Who had made the attempt on his life,

Had stolen lamp, princess and wife.

With a shrewdness which would have done credit

To even a Yankee boy, he

Sought the lamp where the wizard had hid it,

And, turning a mystical key,

Brought it forth, and then, rubbing with glee,

“Back to China!” he cried. In a minute

The marvellous palace uprose,

With the Princess Badroulboudour in it

Unruffled in royal repose,

With her jewels and cloth-of-gold clothes;

And with gay clouds of banners and towers,

With its millions of slaves, white and black.

It was borne by obedient Powers,

As swift as the wind on its track,

And ere one could count ten it was back!

And ever thereafter, Aladdin

Clung close to the lamp of his fate,

Whatever the robe he was clad in,

Or whether he fasted or ate;

And at all hours, early and late!

Right lucky was Lord Aladdin!

|

Once on a time there was a man so hideous and ugly That little children shrank and tried to hide when he appeared; His eyes were fierce and prominent, his long hair stiff like bristles, His stature was enormous, and he wore a long blue beard— He took his name from that through all the country round about him,— And whispered tales of dreadful deeds but helped to make him feared. |

|

||

|

|

|||

|

Yet he was rich, O! very rich; his home was in a castle, Whose turrets darkened on the sky, so grand and black and bold That like a thunder-cloud it looked upon the blue horizon. He had fertile lands and parks and towns and hunting-grounds and gold, And tapestries a queen might covet, statues, pictures, jewels, While his servants numbered hundreds, and his wines were rare and old. |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

Now near to this old Blue-beard’s castle lived a lady neighbor, Who had two daughters, beautiful as lilies on a stem; And he asked that one of them be given him in marriage— He did not care which one it was, but left the choice to them. But, oh, the terror that they felt, their efforts to evade him, With careless art, with coquetry, with wile and stratagem! |

||

|

|

|

|

He saw their high young spirits scorned him, yet he meant to conquer. He planned a visit for them,—or, ’twas rather one long fête; And to charming guests and lovely feasts, to music and to dancing, Swung wide upon its hinges grim the gloomy castle gate. And, sure enough, before a week was ended, blinded, dazzled, The youngest maiden whispered “yes,” and yielded to her fate. |

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

And so she wedded Blue-beard—like a wise and wily spider He had lured into his web the wished-for, silly little fly! And, before the honeymoon was gone, one day he stood beside her, And with oily words of sorrow, but with evil in his eye, Said his business for a month or more would call him to a distance, And he must leave her—sorry to—but then, she must not cry! |

|

|

| ||

|

He bade her have her friends, as many as she liked, about her, And handed her a jingling bunch of something, saying, “These Will open vaults and cellars and the heavy iron boxes Where all my gold and jewels are, or any door you please. Go where you like, do what you will, one single thing excepted!” And here he look a little key from out the bunch of keys. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

“This will unlock the closet at the end of the long passage, But that you must not enter! I forbid it!”—and he frowned. So she promised that she would not, and he went upon his journey. And no sooner was he gone than all her merry friends around Came to visit her, and made the dim old corridors and chambers With their silken dresses whisper, with laugh and song resound. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

Up and down the oaken stairways flitted dainty-footed ladies, Lighting up the shadowy twilight with the lustre of their bloom; Like the varied sunlight streaming through an old cathedral window Went their brightness glancing through the unaccustomed gloom, But Blue-beard’s wife was restless, and a strong desire possessed her Through it all to get a single peep at that forbidden room. |

|

|

|

|

||

|

And so one day she slipped away from all her guests, unnoted, Down through the lower passage, till she reached the fatal door, Put in the key and turned the lock, and gently pushed it open— But, oh the horrid sight that met her eyes! Upon the floor There were blood-stains dark and dreadful, and like dresses in a wardrobe, There were women hung up by their hair, and dripping in their gore! |

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Then, at once, upon her mind the unknown fate that had befallen The other wives of Blue-beard flashed—’twas now no mystery! She started back as cold as icicles, as white as ashes, And upon the clammy floor her trembling fingers dropped the key. She caught it up, she whirled the bolt to, shut the sight behind her, And like a startled deer at sound of hunter’s gun, fled she! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

She reached her room with gasping breath,—behold, another terror! Upon the key within her hand; she saw a ghastly stain; She rubbed it with her handkerchief, she washed in soap and water, She scoured it with sand and stone, but all was done in vain! For when one side, by dint of work, grew bright, upon the other (It was bewitched, you know,) came out that ugly spot again! |

||

|

|

|||

|

And then, unlooked-for, who should come next morning, bright and early, But old Blue-beard himself who hadn’t been away a week! He kissed his wife, and, after a brief pause, said, smiling blandly: “I’d like my keys, my dear.” He saw a tear upon her cheek, And guessed the truth. She gave him all but one. He scowled and grumbled: “I want the key to the small room!” Poor thing, she could not speak! |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

He saw at once the stain it bore while she turned pale and paler, “You’ve been where I forbade you! Now you shall go there to stay! Prepare yourself to die at once!” he cried. The frightened lady Could only fall before him pleading: “Give me time to pray!” Just fifteen minutes by the clock he granted. To her chamber She fled, but stopped to call her sister Anne by the way. |

|||

|

|

|

|

“O, sister Anne, go to the tower and watch!” she cried, “Our brothers Were coming here to-day, and I have got to die! Oh, fly, and if you see them, wave a signal! Hasten! hasten!” And Anne went flying like a bird up to the tower high. “Oh, Anne, sister Anne, do you see anybody coming?” Called the praying lady up the tower-stairs with piteous cry. |

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

“Oh Anne, sister Anne, do you see anybody coming?” “I see the burning sun,” she answered, “and the waving grass!” Meanwhile old Blue-beard down below was whetting up his cutlass, And shouting: “Come down quick, or I’ll come after you, my lass!” “One little minute more to pray, one minute more!” she pleaded— To hope how slow the minutes are, to dread how swift they pass! |

||

|

|

|

|

|

“Oh Anne, sister Anne, do you see anybody coming?” She answered: “Yes I see a cloud of dust that moves this way.” “Is it our brothers, Anne?” implored the lady. “No, my sister, It is a flock of sheep.” Here Blue-beard thundered out: “I say, Come down or I’ll come after you!” Again the only answer: “Oh, just one little minute more,—one minute more to pray!” |

||

|

|

|

|

“Oh, Anne, sister Anne, do you see anybody coming?” “I see two horsemen riding, but they yet are very far!” She waved them with her handkerchief; it bade them, “hasten, hasten!” Then Blue-beard stamped his foot so hard it made the whole house jar; And, rushing up to where his wife knelt, swung his glittering cutlass, As Indians do a tomahawk, and shrieked: “How slow you are!” |

||

|

|

||

|

Just then, without, was heard the beat of hoofs upon the pavement, The doors flew back, the marble floors rang to a hurried tread. Two horsemen, with their swords in hand, came storming up the stairway, And with one swoop of their good swords they cut off Blue-beard’s head! Down fell his cruel arm, the heavy cutlass falling with it, And, instead of its old, ugly blue, his beard was bloody red! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Of course, the tyrant dead, his wife had all his vast possessions; She gave her sister Anne a dower to marry where she would; The brothers were rewarded with commissions in the army; And as for Blue-beard’s wife, she did exactly as she should,— She wore no weeds, she shed no tears; but very shortly after Married a man as fair to look at as his heart was good. |

||

|

|

||

|

The ringing bells and the booming cannon Proclaimed on a summer morn That in the good king’s royal palace A Princess had been born. The towers flung out their brightest banners, The ships their streamers gay, And every one, from lord to peasant, Made joyful holiday. Great plans for feasting and merry-making Were made by the happy king; And, to bring good fortune, seven fairies Were bid to the christening. |

And for them the king had seven dishes

Made out of the best red gold,

Set thickly round on the sides and covers

With jewels of price untold.

When the day of the christening came, the bugles

Blew forth their shrillest notes;

Drums throbbed, and endless lines of soldiers

Filed past in scarlet coats.

|

And the fairies were there the king had bidden, Bearing their gifts of good— But right in the midst a strange old woman Surly and scowling stood. |

|||

|

They knew her to be the old, old fairy, All nose and eyes and ears, Who had not peeped, till now, from her dungeon For more than fifty years. Angry she was to have been forgotten Where others were guests, and to find That neither a seat nor a dish at the banquet To her had been assigned. |

|||

|

Now came the hour for the gift-bestowing; And the fairy first in place Touched with her wand the child and gave her “Beauty of form and face!” Fairy the second bade, “Be witty!” The third said, “Never fail!” The fourth, “Dance well!” and the fifth, “O Princess, Sing like the nightingale!” The sixth gave, “Joy in the heart forever!” But before the seventh could speak, The crooked, black old Dame came forward, And, tapping the baby’s cheek, “You shall prick your finger upon a spindle, And die of it!” she cried. All trembling were the lords and ladies, And the king and queen beside. But the seventh fairy interrupted, “Do not tremble nor weep! That cruel curse I can change and soften, And instead of death give sleep! |

|

|

“But the sleep, though I do my best and kindest, Must last for an hundred years!” On the king’s stern face was a dreadful pallor, In the eyes of the queen were tears. “Yet after the hundred years are vanished,”— The fairy added beside,— “A Prince of a noble line shall find her, And take her for his bride.” But the king, with a hope to change the future, Proclaimed this law to be: That, if in all the land there was kept one spindle, Sure death was the penalty. |

||

|

The Princess grew, from her very cradle Lovely and witty and good; And at last, in the course of years, had blossomed Into full sweet maidenhood. And one day, in her father’s summer palace, As blithe as the very air, She climbed to the top of the highest turret, Over an old worn stair And there in the dusky cobwebbed garret, Where dimly the daylight shone, A little, doleful, hunch-backed woman Sat spinning all alone. “O Goody,” she cried, “what are you doing?” “Why, spinning, you little dunce!” The Princess laughed: “’Tis so very funny, Pray let me try it once!” With a careless touch, from the hand of Goody She caught the half-spun thread, And the fatal spindle pricked her finger! Down fell she as if dead! |

|

And Goody shrieking, the frightened courtiers Climbed up the old worn stair Only to find, in heavy slumber, The Princess lying there. |

||||

|

They bore her down to a lofty chamber, They robed her in her best, And on a couch of gold and purple They laid her for her rest, |

||||

|

The roses upon her cheek still blooming, And the red still on her lips, While the lids of her eyes, like night-shut lilies, Were closed in white eclipse. |

||||

|

Then the fairy who strove her fate to alter From the dismal doom of death, Now that the vital hour impended, Came hurrying in a breath. And then about the slumbering palace The fairy made up-spring A wood so heavy and dense that never Could enter a living thing. |

||||

|

And there for a century the Princess Lay in a trance so deep That neither the roar of winds nor thunder Could rouse her from her sleep. Then at last one day, past the long-enchanted Old wood, rode a new king’s son, Who, catching a glimpse of a royal turret Above the forest dun Felt in his heart a strange wish for exploring The thorny and briery place, And, lo, a path through the deepest thicket Opened before his face! On, on he went, till he spied a terrace, And further a sleeping guard, And rows of soldiers upon their carbines Leaning, and snoring hard. Up the broad steps! The doors swung backward! The wide halls heard no tread! But a lofty chamber, opening, showed him A gold and purple bed. |

|

And there in her beauty, warm and glowing, The enchanted Princess lay! While only a word from his lips was needed To drive her sleep away. He spoke the word, and the spell was scattered, The enchantment broken through! The lady woke. “Dear Prince,” she murmured, “How long I have waited for you!” Then at once the whole great slumbering palace Was wakened and all astir; Yet the Prince, in joy at the Sleeping Beauty, Could only look at her. She was the bride who for years an hundred Had waited for him to come, And now that the hour was here to claim her, Should eyes or tongue be dumb? The Princess blushed at his royal wooing, Bowed “yes” with her lovely head, And the chaplain, yawning, but very lively, Came in and they were wed! But about the dress of the happy Princess, I have my woman’s fears— It must have grown somewhat old-fashioned In the course of so many years! |

||

|

Little boys, sit still— Girls, too, if you will— And let me tell you of Jack and Jill; For I think another Such sister and brother Were never the children of one mother! For an idle lad, As he was, Jack had No traits, after all, that were very bad. He, was simply Jack, With the coat on his back Patched up in all colors from gray to black. Both feet were bare; And I do declare That he never washed his face; and his hair Was the color of straw— You never saw Such a crop—as long as the moral law! |

|

When he went to school, It was the rule (Though ’twas hard to say he was really a fool) To send him at once, So thick was his sconce, To the block that was kept for the greatest dunce. |

|

|||

|

And Jill! no lass Scarce ever has Made bigger tracks on the country grass; For her only fun Was to romp and run, Bare-headed, bare-footed, in wind and sun. |

||||

|

Wherever went Jack, Close on his track, With hair unbraided and down her back, Loud-voiced and shrill, She followed, until No one said “Jack” without saying “Jill.” |

||||

|