Creatures that by a rule in Nature, teach

The art of order to a peopled kingdom.—Shakspeare.

Title: Langstroth on the Hive and the Honey-Bee: A Bee Keeper's Manual

Author: L. L. Langstroth

Release date: February 11, 2008 [eBook #24583]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Steven Giacomelli, Constanze Hofmann and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This file was produced from images produced by Core

Historical Literature in Agriculture (CHLA), Cornell

University)

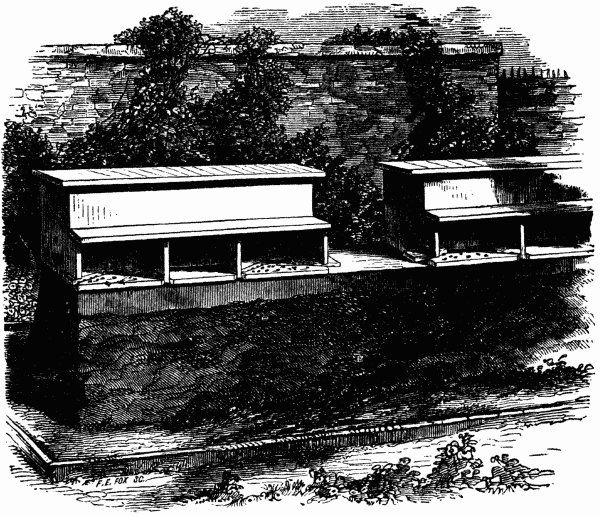

The above are a very accurate representations of the Queen, the Worker and the Drone. The group of bees in the title page, represents the attitude in which the bees surround their Queen or Mother as she rests upon the comb.

BY

REV. L. L. LANGSTROTH.

NORTHAMPTON: HOPKINS, BRIDGMAN & COMPANY. 1853.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1853, by L. L. Langstroth, In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of Massachusetts.

C. A. MIRICK, PRINTER, GREENFIELD.

This Treatise on the Hive and the Honey-Bee, is respectfully submitted by the Author, to the candid consideration of those who are interested in the culture of the most useful as well as wonderful Insect, in all the range of Animated Nature. The information which it contains will be found to be greatly in advance of anything which has yet been presented to the English Reader; and, as far as facilities for practical management are concerned, it is believed to be a very material advance over anything which has hitherto been communicated to the Apiarian Public.

Debarred, by the state of his health, from the more appropriate duties of his Office, and compelled to seek an employment which would call him, as much as possible, into the open air, the Author indulges the hope that the result of his studies and observations, in an important branch of Natural History, will be found of service to the Community as well as to himself. The satisfaction which he has taken in his researches, has been such that he has felt exceedingly desirous of interesting others, in a pursuit which, (without any reference to its pecuniary profits,) [iv] is capable of exciting the delight and enthusiasm of all intelligent observers. The Creator may be seen in all the works of his hands; but in few more directly than in the wise economy of the Honey-Bee.

The attention of Clergymen is particularly solicited to the study of this branch of Natural History. An intimate acquaintance with the wonders of the Bee-Hive, while it would benefit them in various ways, might lead them to draw their illustrations, more from natural objects and the world around them, and in this way to adapt them better to the comprehension and sympathies of their hearers. It was, we know, the constant practice of our Lord and Master, to illustrate his teachings from the birds of the air, the lilies of the field, and the common walks of life and pursuits of men. Common Sense, Experience and Religion alike dictate that we should follow his example.

L. L. LANGSTROTH.

Greenfield, Mass., May 25, 1853.

Deplorable state of bee-keeping. New era anticipated, 13. Huber's discoveries and hives. Double hives for protection against extremes of temperature, 14. Necessary to obtain complete control of the combs. Taming bees. Hives with movable bars. Their results important, 15. Bee-keeping made profitable and certain. Movable frames for comb. Bees will work in glass hives exposed to the light. Dzierzon's discoveries, 16. Wagner's letter on the merits of Dzierzon's hive and the movable comb hive, 17. Superiority of movable comb hive, 19. Superiority of Dzierzon's over the old mode, 20. Success attending it, 22. Bee-Journal to be established. Two of them in Germany. Important facts connected with bees heretofore discredited, 23. Every thing seen in observing hives, 24.

Bees capable of Domestication. Astonishment of persons at their tameness, 25. Bees intended for the comfort of man. Properties fitting them for domestication. Bees never attack when filled with honey, 26. Swarming bees fill their honey bags and are peaceable. Hiving of bees safe, 27. Bees cannot resist the temptation to fill themselves with sweets. Manageable by means of sugared water, 28. Special aversion to certain persons. Tobacco smoke to subdue bees should not be used. Motions about a hive should be slow and gentle, 29.

The Queen Bee. The Drone. The Worker, 30. Knowledge of facts relating to them, necessary to rear them with profit. Difficult to reason with some bee-keepers. Queen bee the mother of the colony—described, 31. Importance of queen to the colony. Respect shown her by the other bees. Disturbance occasioned by her loss, 32. Bee-keepers cannot fail to be interested in the habits of bees, 33. Whoever is fond of his bees is fond of his home. Fertility of queen bees under-estimated. Fecundation of eggs of the queen bees, 34-36. Huber vindicated. Francis Burnens. Huber the prince of Apiarians, 35. Dr. Leidy's curious dissections, 37. Wasps and hornets fertilized like queen bees. Huish's inconsistency, 38. Retarded fecundation productive of drones [vi] only. Fertile workers produce only drones, 39. Dzierzon's opinions on this subject, 40. Wagner's theory. Singular fact in reference to a drone-rearing colony. Drone-laying queen on dissection, unimpregnated. Dzierzon's theory sustained, 41. Dead drone for queen, mistake of bees, 43. Eggs unfecundated produce drones. Fecundated produce workers; theory therefor, 44. Aphides but once impregnated for a series of generations. Knowledge necessary for success, Queen bee, process of laying, 45. Eggs described. Hatching, 46. Larva, its food, its nursing. Caps of breeding and honey cells different, 47. Nymph or pupa, working. Time of gestation. Cells contracted by cocoons sometimes become too small. Queen bee, her mode of development, 48. Drone's development. Development of young bees slow in cool weather or weak swarms. Temperature above 70 deg. for the production of young. Thin hives, their insufficiency. Brood combs, danger of exposure to low temperature, 49. Cocoons of drones and workers perfect. Cocoons of queens imperfect, the cause, 50. Number of eggs dependent on the weather, &c. Supernumerary eggs, how disposed of, 51. Queen bee, fertility diminishes after her third year. Dies in her fourth year, 52. Drones, description of. Their proper office. Destroyed by the bees. When first appear, 53. None in weak hives. Great number of them. Rapid increase of bees in tropical climates, 54. How to prevent their over production. Expelled from the hive, 55. If not expelled, hive should be examined. Provision to avoid "in and in breeding," 56. Close breeding enfeebles colonies. Working bees, account of. Number in a hive, 58. All females with imperfect ovaries. Fertile workers not tolerated where there are queens, 59. Honey receptacle. Pollen basket. The sting. Sting of bees, 60. Often lost in using. Penalty of its loss. Sting not lost by other insects. Labors of workers, 61. Age of bees, 62. Bees useful to the last, 63. Cocoons not removed by the bees. Breeding cells becoming too small are reconstructed. Old comb should be removed. Brood comb not to be changed every year, 64. Inventors of hives too often men of "one idea." Folly of large closets for bees, 65. Reason of limited colonies. Mother wasps and hornets only survive Winter. Queen, process of rearing, 66. Royal cells, 67. Royal Jelly, 68. Its effect on the larvæ, 69. Swammerdam, 70. Queen departs when successors are provided for. Queens, artificial rearing, 71. Interesting experiment, 72. Objections against the Bible illustrated, 73. Huish against Huber, 74. His objections puerile. Objections to the Bible ditto, 75.

Comb. Wax, how made. Formed of any saccharine substance. Huber's experiments, 76. High temperature necessary to its composition, 77. Heat generated in forming. Twenty pounds of honey to form one of wax. Value of empty comb in the new hive. How to free comb from eggs of the moth, 78. Combs having bee-bread of great value. How to empty comb and replace it in the hive, 79. Artificial comb. Experiment with wax proposed, 80. Its results, if successful. Comb made chiefly in the night. 81. Honey and comb made simultaneously. Wax a non-conductor of heat. Some of the brood cells uniform in size, others vary, 82. Form of cells mathematically perfect, 83. Honey comb a demonstration of a "Great First Cause," 84.

Propolis or Bee Glue. Whence it is obtained. Huber's experiment, 85. Its use. Comb varnished with it. The moth deposits her eggs in it, 85. Propolis difficult for bees to work. Curious use of it by bees, 87. Ingenuity of bees admirable, 88.

Pollen or Bee-Bread. Whence obtained. Its use. Brood cannot be raised without it. Pollen nitrogenous. Its use discovered by Huber, 89. Its collection by bees indicates a healthy queen. Experiment showing the importance of bee-bread to a colony, 90. Not used in making comb. Bees prefer it fresh. Surplus in old hives to be used to supply its want to young hives. Pollen and honey both secured at the same time by bees. Mode of gathering pollen, 91. Packing down. Bees gather one kind of pollen at a time. They aid in the impregnation of plants. History of the bee plain proof of the wisdom of the Creator. Bees made for man, 92. Virgil's opinion of bees. Rye meal a substitute for pollen. Quantity used by each colony, 93. Wheat flour a substitute. The improved hive facilitates feeding bees with meal. The discovery of a substitute for pollen removes an obstacle to the cultivation of honey bees, 94.

Fifty-four Advantages which ought to be found in an improved hive, 95-110. Some desirable qualities the movable comb hive does not pretend to! Is the result of years of study and observation. It has been tested by experience, 111. Not claimed as a perfect hive. Old-fashioned bee-keepers found most profit, &c. Simplest form of hive, 112. Bee culture where it was fifty years ago. Best hives. New hive is submitted to the judgment of candid bee-keepers, 113.

Protection against extremes of Heat, Cold and Dampness. Many colonies destroyed by extremes of weather. Evils of thin hives. Bees not torpid in Winter. When frozen are killed, 114. Take exercise to keep warm. Perish if unable to preserve suitable degree of warmth. Are often starved in the midst of plenty. Eat an extra quantity of food in thin, cold hives, 115. Muscular exertion occasions waste of muscular fiber. Bees need less food when quiet than when excited. Experiment, wintering bees in a dry cellar, 116. Protection must generally be given in open air. None but diseased bees discharge fæces in the hive. Moisture, its injurious effects. Free air needful in cold weather, with the common hive, 117. Loss by their flying out in cold weather. Protection against extremes of weather of the very first importance. Honey, our country favorable to its production. Colonies in forests strong. Reasons for this, 118. Russian and Polish bee-keepers successful. Their mode of management, 119. Objection of want of air answered, 120. Bees need but little air in Winter if protected. Protection in reference to the construction of hives. [viii] Double hives, preferable to plank. Made warm in Winter by packing. Double hives, inside may be of glass, 121. Advantages of glass over wood, 122. Advantages of double glass. Disadvantages of double hives in Spring. Avoided by the improved hive, 123. Covered Apiaries exclude the sun in Spring. Reason for discarding them. Sun, its effect in producing early swarms in thin hives. Protected hives fall for want of sun. Enclosed Apiaries, nuisances. Thin hives ought to be given up, they are expensive in waste of honey and bees, 124. Comparative cheapness of new and old hives, 125. Protector against injurious weather. Proper location of bees. Preparations for setting hives, 126. Protector should be open in Summer and banked in Winter. Cheaper than an Apiary. Summer air of Protector like forest air. In Winter uniform and mild, 127. Bees will not be enticed out in improper weather. Secures their natural heat. Dead bees, &c., to be removed in Winter. Temperature of the Protector, 128. Importance of the Protector. Its economy in food, 129.

Ventilation. Artificial ventilation produced by bees. Purity of air in the hive, 130. Bad air fatal to bees, eggs and larvæ, 131. Bees when disturbed need much air. Dysentery, how produced. Post mortem condition of suffocated bees, 132. Great annoyance of excessive heat. Bees leave the hive to save the comb. Ventilating instinct wonderful, 133. Should shame man for his neglect of ventilation. Comparative expense of ventilation to man and bees, 134. Importance of ventilation to man. Its neglect induces disease, 135. Plants cannot thrive without free air. The union of warmth and ventilation in Winter an important question. House-builder and stove-maker combine against fresh air, 136. Run-away slave boxed up. Evil qualities of bad air aggravated by heat. Dwellings and public buildings generally deficient in ventilation. Degeneracy will ensue, 137. Women the greatest sufferers. Necessity of reform, 138. Public buildings should be required to have plenty of air. Improved hive, its adaptedness to secure ventilation, 139. Nutt's hive too complicated. Ventilation independent of the entrance, 140. Hive may be entirely closed without incommoding the bees. Ventilators should be easily removable to be cleansed. Ventilation from above injurious except when bees are to be moved, 141. Variable size of the entrance adapts it to all seasons. Ventilators should be closed in Spring. Downing on ventilation, (note,) 142.

Swarming and Hiving. Bees swarming a beautiful sight. Poetic description by Evans. Design of swarming, 143. The honey bee unlike other insects in its colonizing habits. It is chilled by a temperature below 50 deg. Would perish in Winter if not congregated in masses. Admirable adaptation, 144. Swarming necessary. Circumstances in which it takes place. June the swarming month. Preparations for swarming. Old queen accompanies the first swarm. No infallible signs of 1st swarming, 145. Fickleness of bees about swarming. Indications of swarming. Hours of swarming, 146. Proceedings within the hive before swarming. Interesting scene. Bells and frying-pans useless, 147. Neglected [ix] bees apt to fly away in swarming. Bees properly cared for seldom do it. Methods of arresting their flight when started, 148. Conduct of bees in disagreeable hives, 149. Why bees swarm before selecting a new home. They rarely cluster without the queen. Interesting experiment, 150. Scouts to search for new abodes. Scouts sent out before and after swarming, 151. Bees remain awhile after alighting. Curious incident stated by Mr. Zollickoffer. Necessity of scouts. Considerations confirmed, 152. Re-population of the hive, 153. Inability of bees to find their hive when it has been removed. After swarms, 154. Different treatment to the cells of dead and living queens. Royal larvæ sometimes protected against the queens. Anger of the queen at such interference, 155. Second swarming, its indications. Time, 156. Double swarms. Third swarm. After swarms seriously reduce the strength of the hive. Wise arrangement, 157. After-swarming avoided by the improved hive. Impregnation of queens. Dangerous for queens to mistake their own hives, 158. Precautions against this. Proper color for hives. Time of laying eggs. None but worker eggs, the first season, 159. Directions for hiving. Hives should be painted and well dried. Bees reluctant to enter thin warm hives in the sun, 160. Management with the improved hives, 161. Drone combs should never be used as guide comb. Pleasure of bees in finding comb in their new quarters. Bees never voluntarily enter empty hives. Rubbing the hive with herbs useless, 162. Small trees or bushes in front of hives. Inexperienced Apiarian should wear a bee-dress. Moderate dispatch in hiving needful, 163. Process of hiving particularly described, 164. Old method of hiving should be abandoned, 166. Importance of speedy hiving. Should be moved as soon as hived. Curious fact stated by Dr. Scudamore, (note), 167. How to secure the queen. She does not sting. Hiving before the hives are ready, 168. Another method of hiving. Natural swarming profitable. Objections to natural swarming. Common hive gives inadequate winter protection, 169. With it, the bees often swarm too much. With the improved hive this is avoided. Disadvantages of returning after-swarms. Third objection, inability to strengthen small late swarms, 170. Evils of feeble stocks. Fourth objection, loss of queen irreparable. By the new hive her loss is easily supplied, 171. Fifth, common hives inconvenient when bees do not swarm. This objection removed by the new hive. Sixth, the ravages of the moth easily prevented by the improved hive. Seventh, the old queen, when infertile, cannot be removed or replaced. Both can be done by the new hive, 172.

(Two Chapters numbered x, by error of the Press.)

Artificial Swarming. Numerous efforts to dispense with natural swarming. Difficulties of natural swarming. First, many swarms are lost, 173. Second, time and labor required. Sabbath labor, 174. Perplexities to farmers. Third, large Apiaries cannot be established, 175. Fourth, uncertainty of swarming. Disappointments from this source, 176. Efforts to devise a surer method, 178. Columellas's mode of obtaining swarms. Hyginus. Small success which attended, those efforts, Schirach's discovery, 179. Huber's directions. Not adapted to general use. Dividing hives in this country unsuitable. Bees without [x] mature queens make no preparation to rear workers, 180. Dividing hives to multiply colonies will not answer, 181. Huber's hive even, inadequate. Common dividing hives unsuccessful. Multiplying by brood comb in an empty hive, vain, 182. Multiplying by removal and substitution useless. Mortality of bees in working season, 183. Connecting apartments a failure, 184. Many prefer non-swarming hives, 185. Profitable in honey but calculated to exterminate the insect. Improved hive good non-swarmer, if desired. Disadvantages of non-swarming. Queen bee becomes infertile. Remedied by the use of the improved hive, 186. Practicable mode of artificial swarming, 187. Bees will welcome to their hives strange bees that come loaded. Will destroy such as come empty, 188. Forced swarming requires knowledge of the economy of the bee-hive. Common hives give no facility for learning the bee's habits. Equalizing a divided swarm, 190. Bees in parent hive, if removed, to be confined and watered, 191. Bees removed will return to their old place. Supplying bees with water by a straw. Water necessary to prepare food for the larvæ, 192. New forced swarms to be returned to the place of the old one, or removed to a distance. Treatment to wont them to new place in the Apiary, 193. Bees forget their new locations. Objection to forced swarming in common hives, 194. Forced swarming by the new hives removes the objection. Mode of forcing swarms by the new hives, 195. Queen to be searched for. Important that she should be in the right hive, 196. Convenience of forced swarming in supplying extra queens. Mode of supplying them. Should be done by day light and in pleasant weather, 197. Honey-water not to be used. Safety to the operator. Forced swarming may be performed at mid-day. Advantages of the shape of the new hive, 198. Huber's observation on the effect of sudden light in the hive. True solution of the phenomenon. Bees at the top of the hive, less belligerent than those at the bottom, 199. Sudden jars to be avoided. Removal of honey-board. Sprinkling with sugar-water, 200. Loosening the frames. Removing the comb. Bees will adhere to their comb, 201. Natural swarming imitated. How to catch the queen. Frames protected from cold and robbery by bees. Frames returned to the hive. Honey-cover, how managed. Motions of bee-keeper to be gentle. Bees must not be breathed on. Success in the operation certain, 202. New colonies may be thus formed in ten minutes. Natural swarming wholly prevented. If attempted by the bees cannot succeed. How to remove the wings of the queens, 203. Precaution against loss of queen by old age. Advantages of this, 204. Certainty and ease of artificial swarming with the new hive. After-swarms prevented if desired, 205. Large harvests of honey and after-swarming impracticable. Danger of too rapid increase of stocks. Importance of understanding his object, by the bee-keeper, 206. The matter made plain, 207. Apiarians dissuaded from more than tripling their stocks in a year. Tenfold increase of stocks attainable, 209. Certain increase, not rapid, most needed. Cautions concerning experiments, 210. Honey, largest yield obtained by doubling colonies. The process, 211. May be done at swarming time. Bees recognize each other by smell, 213. Importance of following these directions illustrated. Process of uniting swarms simplified by the new hive, 214. Very rapid increase of colonies precarious. Mode of effecting the most rapid increase, 215. Nucleus system, 217. Can a queen be raised from any egg? Two sorts of [xi] workers, wax workers and nurses, 218. Probable explication of a difficulty, 219. Experimenting difficult work. Swarming season best time for artificial swarming. Amusing perplexity of bees on finding their hive changed, 220. Perseverance of bees. Interesting incident illustrating it, 221. Novel and successful mode of forming nuclei, 223. Mode of managing nuclei, 225. Danger of over-feeding. Increasing stocks by doubling hives, 229. Important rule for multiplying stocks. How to direct the strength of a colony to the rearing of young bees, 230. Proper dimensions of hives. Reasons therefor, 231. Easy construction of the improved hive. Precaution of queen bees in their combats, 234. Reluctance of bees to receive a new queen. Expedient to overcome this. Queen nursery, 235. Mode of rearing numerous queens, 237. Control of the comb the soul of good bee-culture. Objection against bee-keeping answered, 233. No "royal road" to bee-keeping. A prediction, 239.

Enemies of Bees. Bee-moth, its ravages. Defiance against it, 240. Its habits. Known to Virgil. Time of appearance. Nocturnal in habits, 241. Their agility. Vigilance of the bees against the moth. Havoc of sin in the heart, 242. Disgusting effects of the moth worm in a hive. Wax the food of the moth larvæ. Making their cocoons, 243. Devices to escape the bees. Time of development, 244. Habits of the female when laying eggs. Of the worm when hatched, 245. Our climate favorable to the increase of the moth. Moth not a native of America, 246. Honey, its former plenty. Present depressure of its culture. Old mode of culture described, 247. Depredations of the moth increased by patent hives. Aim of patent hives. Sulphur or starvation, 249. Feeble swarms a nuisance, 250. Notion prevailing in relation to breaking up stocks. Improved hives valueless without improved system of treatment, 251. Pretended secrets in the management of bees. Strong stocks thrive under almost any circumstances, 252. Stocks in costly hives. Circumstances under which the moth succeeds in a hive, 253. Signs of worms in a hive, 254. When entrenched difficult to remove. Method of avoiding their ravages, 255. Combs having moth eggs to be removed and smoked, 257. Uncovered comb to be removed, 258. Loss of the queen the most fruitful occasion of ravages by the moth. Experiments on this point, 259. Attempts to defend a queenless swarm against the moth useless, 260. Strong queenless colonies destroyed when feeble ones with queens are untouched. Common hives furnish no remedy for the loss of the queen. Colonies without queens will perish, if not destroyed by the moth, 261. Strong stocks rob queenless ones. Principal reasons of protection, 262. Small stocks should have small space. Inefficiency of various contrivances, 263. Useful precautions when using common hives. Destroy the larvæ of the moth early. Decoy of a woolen rag, 264. Hollow or split sticks for traps. If the queen be lost, and worms infest the colony, break it up. Provision of the improved hives against moths, 265. Moth-traps no help to careless bee-keepers. Incorrigibly careless persons should have nothing to do with bees, 266. Worms, how removed from an improved hive. Sweet solutions useful to catch the moths. Interesting remarks of H. K. Oliver, on the bee-moth, 267. Ravages of mice. Birds. Observations on the king-bird, 269. Inhumanity and injurious effects of [xii] destroying birds, 270. Other enemies of the bee. Precautions against dysentery. Bees not to be fed on liquid honey late in the season. Foul brood of the Germans, 271. Produced by "American Honey." Peculiar kind of dysentery, 272.

Loss of the Queen. Queen often lost. Queens of strong hives seldom perish without providing for successors. Their death commonly occurs under favorable circumstances, 273. Young queen sometimes matured before the death of the old one. Superannuated queens incapable of laying worker eggs. Case of precocious superannuation, 274. Signs that there is no queen in a hive. Signs of queenless hives, 275. Exhortation to wives, 276. Difficult in common hives, to decide on the condition of the stock. Always easy with the movable comb hive, 277. Bees sometimes refuse to accept of aid in their queenless state. Parallel in human conduct. Young bees in such hives will at once provide for a queen. An appeal to the young, 278. Hives should be examined early in Spring. Destitute stocks should be united to others having queens. Reasons therefor. General treatment in early Spring, 279. Hives should be cleansed in Spring. Durability and cheapness of hives, 280. Undue regard to mere cheapness. Various causes destructive of queens, 281. Agitation of the bees on missing their queen, 282. Treatment of swarms that have lost their queens, 283. Examination of the hive needful, 284. Examination and treatment in the Fall. Persons who cannot attend to their bees themselves, may safely entrust their care to others, 285. Business of the Apiarian united with that of the gardner. Experiments with queen bees, 286.

Union of Stocks. Transferring Bees. Starting an Apiary. Queenless colonies should be broken up, Spring and Fall. Small colonies should be united. Animal heat necessary in a hive. Small swarms in Winter consume much honey, 287. Colonies to be united, should stand side by side. How to effect this. Removal of an Apiary in the working season, 288. To secure the largest quantity of honey from a given number of stocks, 289. Non-swarming plan. Moderate increase best, 290. Transferring bees from common, to the movable comb hive, 291. Successful experiment. Should not be attempted in cold weather. The process of transfer, 292. Best time. May be done at any season when the weather is warm, 294. Precaution against robbing, 295. Combs should be transferred with the bees, 296. Caution on trying new hives, 297. Thrifty old swarms. Conditions of their thrift, 298. Procuring bees to start an Apiary. New early swarms best. Signs to guide the inexperienced buyer, 299. Directions for removing old colonies. For removing new swarms, 300. To procure honey the first season. Novices should begin in a small way. Neglected Apiary, 303. Superstitions about bees. Cautions to the inexperienced, against transferring, renewed. Parallel between bees and covetous men, 304.

Robbing. Idleness a great cause of it, 305. Colonies should be examined and supplied with food in Spring. Appearance of robber bees, 306. Their suspicious actions. Are real "Jerry Sneaks," 308. Highway robbers, 309. Bee battles. Subjected bees unite with the conquerors. Cautions against robbery. Importance of guarding against robbery, 310. Efficiency of the movable blocks to this end. Comb with honey not to be exposed, 311. Curious case of robbery, 314.

Directions for Feeding Bees. Feeding greatly mismanaged. Condition of the bees should be ascertained in the Spring. They should be supplied if needy, 315. Many perish from want. Connection between feeding and breeding in the hive, 316. Caution in feeding necessary. Results of over feeding, 317. Necessary to feed largely in multiplying stocks. How to feed weak swarms in Spring, 319. Considerations governing the quantity of food, 320. Main object to produce bees. Proper condition of an Apiary at close of honey season, 321. Feeding for Winter attended to in August. Unsealed honey sours. Sour food is unwholesome to bees. Striking instance, 322. Spare honey to be apportioned among the stocks. Swarms with overstocks of honey do not breed so well. Surplus honey in Spring to be removed, 323. Full frames exchanged for empty ones. Feeble stocks in Fall, to be broken up. Profits all come from strong swarms. Composition of a good bee-feed, 324. Directions for feeding with the improved hive, 325. Feeding useless when but little comb in the hive, 326. Top feeding. Feeder described. Importance of water to bees, 328. Sugar candy a valuable substitute for honey. Summer feeding, 330. Bees with proper care need but little feeding. Quantity of honey necessary to winter a stock, 331. Feeding as a source of profit. Selling W. I. honey a cheat, 332. Honey not a secretion of the bee. Evaporation of its water the principal change it undergoes, 334. Folly of diluting the feed of bees too much. Feeders of cheap honey for market, deceivers or deceived, 335. Artificial liquid honey, 336. Improved Maple sugar, 337. Feeding bees on artificial honey not profitable, 337. Dangerous feeding bees without floats. Their infatuation for liquid sweets, 339. Like that of the inebriate for his cups, 340. Avarice in bees and men, 341.

Honey. Pasturage. Overstocking. Honey the product of flowers, 342. Honey dew. Aphides, 343. Qualities of honey, 345. Poisonous honey. Innoxious by boiling. Preserving honey, 346. Modes of taking honey from the hive. Objections to glass vessels, 347. Pasteboard boxes preferred. Honey should be handled carefully. Pattern comb to be used in the boxes. Honey safely removed, 348. Should not be taken from the bees in large quantities during honey harvest. Pasturage, 349. The Willow. Sugar Maple and other honey-yielding trees, 350. Linden tree as an ornament. White clover, 351. Recommended by Hon. Frederick Holbrook as a grass crop, 352. Sweet-scented clover, [xiv] 363. Hybrid clover front Sweden, 354. Buckwheat. Raspberry, 355. Garden flowers. Overstocking, 356. Little danger of it. Bee-keepers and Napoleon. No overstocking in this country. Letter from Mr. Wagner on the subject, 357. Flight of bees for food, 361. Advantages of a good hive in saving time and honey. Energies of bees limited. Bees injured by winds, 362. Protector saves them from harm. Estimated profits of bee-culture. Advice to the careless, 363. Value of Dzierzon's system. Adopted by the government of Norway. Want of National encouragement to agriculture, (note), 364.

Anger of Bees. Remedy for their Sting. Bee-Dress. Instincts of Bees. Gentleness of the bee, 365. Feats of Wildman. Interesting incident, 366. Discovery of a universal law. Its importance and results, 367. Cross bees diseased. Never necessary to provoke a whole colony of bees, 368. Danger from bees when provoked. A word to females, 369. Kindness of bees to one another. Contrast with some children, 370. Effects of a sting. The poison, 371. Peculiar odors offensive to bees. Precautions against animals and human robbers, 372. Sense of smell in the bee, 373. By this they distinguish their hive companions. Robbers repelled by odors, 374. Stocks united by them, 375. Warning given by bees before stinging. How to act when assaulted by bees, 376. Remedies for the sting, 377. Bee-dress, 380. Instincts of bees, 381. Distinction between instinct in animals and reason in men. Remarkable instance of sagacity in bees, 383. Facilities afforded by the Author's Improved Observing Hive. Indebtedness of the author to S. Wagner, Esq., 384.

L. L. LANGSTROTH'S MOVABLE COMB HIVE.

Patented October 5, 1862.

Each comb in this hive is attached to a separate, movable frame, and in less than five minutes they may all be taken out, without cutting or injuring them, or at all enraging the bees. Weak stocks may be quickly strengthened by helping them to honey and maturing brood from stronger ones; queenless colonies may be rescued from certain ruin by supplying them with the means of obtaining another queen; and the ravages of the moth effectually prevented, as at any time the hive may be readily examined and all the worms, &c., removed from the combs. New colonies may be formed in less time than is usually required to hive a natural swarm; or the hive may be used as a non-swarmer, or managed on the common swarming plan. The surplus honey may be taken from the interior of the hive on the frames or in upper boxes or glasses, in the most convenient, beautiful and saleable forms. Colonies may be safely transferred from any other hive to this, at any season of the year, from April to October, as the brood, combs, honey and all the contents of the hive are transferred with them, and securely fastened in the frames. That the combs can always be removed from this hive with ease and safety, and that the new system, by giving the perfect control over all the combs, effects a complete revolution in practical bee-keeping, the subscriber prefers to prove rather than assert. Practical Apiarians and all who wish to purchase rights and hives, are invited to visit his Apiary, where combs, honey and bees will be taken from the hives; colonies which may be brought to him for that purpose, transferred from any old hive; queens, and the whole process of rearing them constantly exhibited; new colonies formed, and all processes connected with the practical management of an Apiary fully illustrated and explained. [xvi]

Those who have any considerable number of bees, will find it to their interest to have at least one movable comb-hive in their Apiary, from which they may, in a few minutes, supply any colony which has lost its queen, with the means of rearing another.

The hive and right will be furnished on the following terms. For an

individual or farm right, five dollars. This will entitle the purchaser

to use and construct for his own use on his own premises, as many hives

as he chooses. The hives are manufactured by machinery, and can probably

be delivered, freight included, at any Railroad Station in New England,

or New York, cheaper than they could be made in small quantities on the

spot. On receipt of a hive, the purchaser can decide for himself,

whether he prefers to make them, or to order them of the Patentee. For

one dollar, postage paid, the book will be sent free by mail. On receipt

of ten dollars, a beautiful hive showing all the combs, (with glass on

four sides,) will be sent with right, freight paid to any railroad

station in New England or New York: a right and hive which will

accommodate two colonies, with glass on each side, for twelve dollars;

for seven dollars, a right and a well made hive that any one can

construct who can handle the simplest tools. In all cases where the

hives are sent out of New England or New York, as the freight will not

be prepaid, a dollar will be deducted from the above prices.

Address

L. L. LANGSTROTH.

Greenfield, Mass.

The present condition of practical bee-keeping in this country, is known to be deplorably low. From the great mass of agriculturists, and others favorably situated for obtaining honey, it receives not the slightest attention. Notwithstanding the large number of patent hives which have been introduced, the ravages of the bee-moth have increased, and success is becoming more and more precarious. Multitudes have abandoned the pursuit in disgust, while many of the most experienced, are fast settling down into the conviction that all the so-called "Improved Hives" are delusions, and that they must return to the simple box or hollow log, and "take up" their bees with sulphur, in the old-fashioned way.

In the present state of public opinion, it requires no little courage to venture upon the introduction of a new hive and system of management; but I feel confident that a new era in bee-keeping has arrived, and invite the attention of all interested, to the reasons for this belief. A perusal of this Manual, will, I trust, convince them that there is a better way than any with which they have yet been acquainted. They will here find many hitherto mysterious points in the physiology of the honey-bee, clearly explained, and much valuable information never before communicated to the public. [14]

It is now nearly fifteen years since I first turned my attention to the cultivation of bees. The state of my health having compelled me to live more and more in the open air, I have devoted a large portion of my time, of late years, to a careful investigation of their habits, and to a series of minute and thorough experiments in the construction of hives, and the best methods of managing them, so as to secure the largest practical results.

Very early in my Apiarian studies, I procured an imported copy of the work of the celebrated Huber, and constructed a hive on his plan, which furnished me with favorable opportunities of verifying some of his most valuable discoveries; and I soon found that the prejudices existing against him, were entirely unfounded. Believing that his discoveries laid the foundation for a more extended and profitable system of bee-keeping, I began to experiment with hives of various construction.

The result of all these investigations fell far short of my expectations. I became, however, most thoroughly convinced that no hives were fit to be used, unless they furnished uncommon protection against extremes of heat and more especially of COLD. I accordingly discarded all thin hives made of inch stuff, and constructed my hives of doubled materials, enclosing a "dead air" space all around.

These hives, although more expensive in the first cost, proved to be much cheaper in the end, than those I had previously used. The bees wintered remarkably well in them, and swarmed early and with unusual regularity. My next step in advance, was, while I secured my surplus honey in the most convenient, beautiful and salable forms, so to facilitate the entrance of the bees into the honey receptacles, as to secure the largest fruits from their labors.

Although I felt confident that my hive possessed some [15] valuable peculiarities, I still found myself unable to remedy many of the casualties to which bee-keeping is liable. I now perceived that no hive could be made to answer my expectations unless it gave me the complete control of the combs, so that I might remove any, or all of them at pleasure. The use of the Huber hive had convinced me that with proper precautions, the combs might be removed without enraging the bees, and that these insects were capable of being domesticated or tamed, to a most surprising degree. A knowledge of these facts was absolutely necessary to the further progress of my invention, for without it, I should have regarded a hive designed to allow of the removal of the combs, as too dangerous in use, to be of any practical value. At first, I used movable slats or bars placed on rabbets in the front and back of the hive. The bees were induced to build their combs upon these bars, and in carrying them down, to fasten them to the sides of the hive. By severing the attachments to the sides, I was able, at any time, to remove the combs suspended from the bars. There was nothing new in the use of movable bars; the invention being probably, at least, a hundred years old; and I had myself used such hives on Bevan's plan, very early in the commencement of my experiments. The chief peculiarity in my hives, as now constructed, was the facility with which these bars could be removed without enraging the bees, and their combination with my new mode of obtaining the surplus honey.

With hives of this construction I commenced experimenting on a larger scale than ever, and soon arrived at results which proved to be of the very first importance. I found myself able, if I wished it, to dispense entirely with natural swarming, and yet to multiply colonies with much greater rapidity and certainty than by the common methods. I [16] could, in a short time, strengthen my feeble colonies, and furnish those which had lost their Queen with the means of obtaining another. If I suspected that any thing was the matter with a hive, I could ascertain its true condition, by making a thorough examination of every part, and if the worms had gained a lodgment, I could quickly dispossess them. In short, I could perform all the operations which will be explained in this treatise, and I now believed that bee-keeping could be made highly profitable, and as much a matter of certainty, as any other branch of rural economy.

I perceived, however, that one thing was yet wanting. The cutting of the combs from their attachments to the sides of the hive, in order to remove them, was attended with much loss of time to myself and to the bees, and in order to facilitate this operation, the construction of my hive was necessarily complicated. This led me to invent a method by which the combs were attached to MOVABLE FRAMES, and suspended in the hives, so as to touch neither the top, bottom, nor sides. By this device, I was able to remove the combs at pleasure, and if desired, I could speedily transfer them, bees and all, without any cutting, to another hive. I have experimented largely with hives of this construction, and find that they answer most admirably, all the ends proposed in their invention.

While experimenting in the summer of 1851, with some observing hives of a peculiar construction, I discovered that bees could be made to work in glass hives, exposed to the full light of day. The notice, in a Philadelphia newspaper, of this discovery, procured me the pleasure of an acquaintance with Rev. Dr. Berg, pastor of a Dutch Reformed church in that city. From him, I first learned that a Prussian clergyman, of the name of Dzierzon, (pronounced Tseertsone,) had attracted the attention of crowned heads, by his important [17] discoveries in the management of bees. Before he communicated the particulars of these discoveries, I explained to Dr. Berg, my system of management, and showed him my hive. He expressed the greatest astonishment at the wonderful similarity in our methods of management, both of us having carried on our investigations without the slightest knowledge of each other's labors. Our hives, he found to differ in some very important respects. In the Dzierzon hive, the combs are not attached to movable frames, but to bars, so that they cannot, without cutting, be removed from the hive. In my hive, which is opened from the top, any comb may be taken out, without at all disturbing the others; whereas, in the Dzierzon hive, which is opened from one of the ends, it is often necessary to cut and remove many combs, in order to get access to a particular one; thus, if the tenth comb from the end is to be removed, nine combs must be first cut and taken out. All this consumes a large amount of time. The German hive does not furnish the surplus honey in a form which would be found most salable in our markets, or which would admit of safe transportation in the comb. Notwithstanding these disadvantages, it has achieved a great triumph in Germany, and given a new impulse to the cultivation of bees.

The following letter from Samuel Wagner, Esq., cashier of the bank in York, Pennsylvania, will show the results which have been obtained in Germany, by the new system of management, and his estimate of the superior value of my hive to those in use there.

York, Pa., Dec. 24, 1852.

Dear Sir,

The Dzierzon theory and the system of bee-management based thereon, were originally promulgated, hypothetically, in the "Eichstadt Bienenzeitung" or Bee-journal, [18] in 1845, and at once arrested my attention. Subsequently, when in 1848, at the instance of the Prussian government, the Rev. Mr. Dzierzon published his "Theory and Practice of Bee Culture," I imported a copy, which reached me in 1849, and which I translated prior to January 1850. Before the translation was completed, I received a visit from my friend, the Rev. Dr. Berg, of Philadelphia, and in the course of conversation on bee-keeping, mentioned to him the Dzierzon theory and system, as one which I regarded as new and very superior, though I had had no opportunity for testing it practically. In February following, when in Philadelphia, I left with him the translation in manuscript—up to which period, I doubt whether any other person in this country had any knowledge of the Dzierzon theory; except to Dr. Berg I had never mentioned it to any one, save in very general terms.

In September, 1851, Dr. Berg again visited York, and stated to me your investigations, discoveries and inventions. From the account Dr. Berg gave me, I felt assured that you had devised substantially the same system as that so successfully pursued by Mr. Dzierzon; but how far your hive resembled his I was unable to judge from description alone. I inferred, however, several points of difference. The coincidence as to system, and the principles on which it was evidently founded, struck me as exceedingly singular and interesting, because I felt confident that you had no more knowledge of Mr. Dzierzon and his labors, before Dr. Berg mentioned him and his book to you, than Mr. Dzierzon had of you. These circumstances made me very anxious to examine your hives, and induced me to visit your Apiary in the village of West Philadelphia, last August. In the absence of the keeper, as I informed you, I took the liberty to explore the premises thoroughly, opening and inspecting a [19] number of the hives, and noticing the internal arrangement of the parts. The result was, that I came away convinced that though your system was based on the same principles as Dzierzon's, yet that your hive was almost totally different from his, in construction and arrangement; that while the same objects substantially are attained by each, your hive is more simple, more convenient, and much better adapted for general introduction and use, since the mode of using it can be more easily taught. Of its ultimate and triumphant success I have no doubt. I sincerely believe that when it comes under the notice of Mr. Dzierzon, he will himself prefer it to his own. It in fact combines all the good properties which a hive ought to possess, while it is free from the complication, clumsiness, vain whims, and decidedly objectionable features, which characterize most of the inventions which profess to be at all superior to the simple box, or the common chamber hive.

You may certainly claim equal credit with Dzierzon for originality in observation and discovery in the natural history of the honey bee, and for success in deducing principles and devising a most valuable system of management from observed facts. But in invention, as far as neatness, compactness, and adaptation of means to ends are concerned, the sturdy German must yield the palm to you. You will find a case of similar coincidence detailed in the Westminster Review for October, 1852, page 267, et seq.

I send you herewith some interesting statements respecting Dzierzon, and the estimate in which his system is held in Germany.

Very truly yours,

SAMUEL WAGNER.

Rev. L. L. Langstroth.

[20]The following are the statements to which Mr. Wagner refers.—

"As the best test of the value of Mr. Dzierzon's system, is the results which have been made to flow from it, a brief account of its rise and progress maybe found interesting. In 1835 he commenced bee-keeping in the common way, with 12 colonies—and after various mishaps, which taught him the defects of the common hives and the old mode of management, his stock was so reduced that in 1838 he had virtually to begin anew. At this period he contrived his improved hive in its ruder form, which gave him the command over all the combs, and he began to experiment on the theory which observation and study had enabled him to devise. Thenceforward his progress was as rapid as his success was complete and triumphant. Though he met with frequent reverses—about 70 colonies having been stolen from him, sixty destroyed by fire, and 24 by a flood—yet in 1846 his stock had increased to 360 colonies, and he realized from them that year six thousand pounds of honey, besides several hundred weight of wax. At the same time most of the cultivators in his vicinity who pursued the common methods, had fewer hives than they had when he commenced.

In the year 1848, a fatal pestilence, known by the name of "foul brood," prevailed among his bees, and destroyed nearly all his colonies before it could be subdued—only about ten having escaped the malady, which attacked alike the old stocks and his artificial swarms. He estimates his entire loss that year at over 500 colonies. Nevertheless he succeeded so well in multiplying by artificial swarms, the few that remained healthy, that in the fall of 1851 his stock consisted of nearly 400 colonies. He must, therefore, have multiplied his stocks more than three fold each year. [21]"

The highly prosperous condition of his colonies is attested by the Report of the Secretary of the Annual Apiarian Convention which met in his vicinity last spring. This Convention, the fourth which has been held, consisted of 112 experienced and enthusiastic bee-keepers from various districts of Germany and neighboring countries, and among them were some who when they assembled were strong opposers of his system.

They visited and personally examined the Apiaries of Mr. Dzierzon. The report speaks in the very highest terms of his success, and of the manifest superiority of his system of management. He exhibited and satisfactorily explained to his visitors his practice and principles; and they remarked, with astonishment, the singular docility of his bees, and the thorough control to which they were subjected. After a full detail of the proceedings, the Secretary goes on to say:—

"Now that I have seen Dzierzon's method practically demonstrated, I must admit that it is attended with fewer difficulties than I had supposed. With his hive and system of management it would seem that bees become at once more docile than they are in other cases. I consider his system the simplest and best means of elevating bee-culture to a profitable pursuit, and of spreading it far and wide over the land—especially as it is peculiarly adapted to districts in which the bees do not readily and regularly swarm. His eminent success in re-establishing his stock after suffering so heavily from the devastating pestilence—in short the recuperative power of the system demonstrates conclusively, that it furnishes the best, perhaps the only means of reinstating bee-culture lo a profitable branch of rural economy.

Dzierzon modestly disclaimed the idea of having attained perfection in his hive. He dwelt rather upon the truth and importance of his theory and system of management." [22]

From the Leipzig Illustrated Almanac—Report on Agriculture for 1846.

"Bee culture is no longer regarded as of any importance in rural economy."

From the same for 1851, and 1853.

"Since Dzierzon's system has been made known an entire revolution in bee culture has been produced. A new era has been created for it, and bee-keepers are turning their attention to it with renewed zeal. The merits of his discoveries are appreciated by the government, and they recommend his system as worthy the attention of the teachers of common schools.

Mr. Dzierzon resides in a poor sandy district of Middle Silesia, which, according to the common notions of Apiarians, is unfavorable to bee-culture. Yet despite of this and of various mishaps, he has succeeded in realizing 900 dollars as the product of his bees in one season!

By his mode of management, his bees yield, even in the poorest years, from 10 to 15 per cent on the capital invested, and where the colonies are produced by the Apiarian's own skill and labor they cost him only about one-fourth the price at which they are usually valued. In ordinary seasons the profit amounts to from 30 to 50 per cent, and in very favorable seasons from 80 to 100 per cent."

In communicating these facts to the public, I have several objects in view. I freely acknowledge that I take an honest pride in establishing my claims as an independent observer; and as having matured by my own discoveries, the same system of bee-culture, as that which has excited so much interest in Germany; I desire also to have the testimony of the translator of Dzierzon to the superior merits of my hive. Mr. Wagner is extensively known as an able German scholar. He has taken all the numbers of the Bee Journal, a [23] monthly periodical which has been published for more than fifteen years in Germany, and is probably more familiar with the state of Apiarian culture abroad, than any man in this country.

I am anxious further to show that the great importance which I attach to my system of management, is amply justified by the success of those who while pursuing the same system with inferior hives, have attained results, which to common bee-keepers, seem almost incredible. Inventors are very prone to form exaggerated estimates of the value of their labors; and the American public has been so often deluded with patent hives, devised by persons ignorant of the most important principles in the natural history of the bee, and which have utterly failed to answer their professed objects, that they are scarcely to be blamed for rejecting every new hive as unworthy of confidence.

There is now a prospect that a Bee Journal will before long, be established in this country. Such a publication has long been needed. Properly conducted, it will have a most powerful influence in disseminating information, awakening enthusiasm, and guarding the public against the miserable impositions to which it has so long been subjected.

Two such journals are now published monthly in Germany, one of which has been in existence for more than 15 years—and their wide circulation has made thousands well acquainted with those principles, which must constitute the foundation of any enlightened and profitable system of culture.

The truth is that while many of the principal facts in the physiology of the honey bee have long been familiar to scientific observers, it has unfortunately happened that some of the most important have been widely discredited. In themselves they are so wonderful, and to those who have [24] not witnessed them, often so incredible, that it is not at all strange that they have been rejected as fanciful conceits, or bare-faced inventions.

Many persons have not the slightest idea that every thing may be seen that takes place in a bee-hive. But hives have for many years, been in use, containing only one large comb, enclosed on both sides, by glass. These hives are darkened by shutters, and when opened, the queen is exposed to observation, as well as all the other bees. Within the last two years, I have discovered that with proper precautions, colonies can be made to work in observing hives, without shutters, and exposed continually to the full light of day; so that observations may be made at all times, without in the least interrupting the ordinary operations of the bees. By the aid of such hives, some of the most intelligent citizens of Philadelphia have seen in my Apiary, the queen bee depositing her eggs in the cells, and constantly surrounded by an affectionate circle of her devoted children. They have also witnessed, with astonishment and delight, all the steps in the mysterious process of raising queens from eggs which with the ordinary development, would have produced only the common bees. For more than three months, there was not a day in which some of my colonies were not engaged in making new queens to supply the place of those taken from them, and I had the pleasure of exhibiting all the facts to bee-keepers who never before felt willing to credit them. As all my hives are so made that each comb can be taken out, and examined at pleasure, those who use them, can obtain from them all the information which they need, and, are no longer forced to take any thing upon trust.

May I be permitted to express the hope that the time is now at hand, when the number of practical observers will [25] be so multiplied, that ignorant and designing men will neither be able to impose their conceits and falsehoods upon the public, nor be sustained in their attempts to depreciate the valuable discoveries of those who have devoted years of observation and experiment to promote the advancement of Apiarian knowledge.

If the bee had not such a necessary and yet formidable weapon both of offence and defence, multitudes would be induced to enter upon its cultivation, who are now afraid to have any thing to do with it. As the new system of management which I have devised, seems to add to this inherent difficulty, by taking the greatest possible liberties with so irascible an insect, I deem it important to show clearly, in the very outset, how bees may be managed, so that all necessary operations may be performed in an Apiary, without incurring any serious risk of exciting their anger.

Many persons have been unable to control their expressions of wonder and astonishment, on seeing me open hive after hive, in my experimental Apiary, in the vicinity of Philadelphia, removing the combs covered with bees, and shaking them off in front of the hives; exhibiting the queen, transferring the bees to another hive, and, in short, dealing with them as if they were as harmless as so many flies. I have sometimes been asked if the bees with which I was [26] experimenting, had not been subjected to a long course of instruction, to prepare them for public exhibition; when in some cases, the very hives which I was opening, contained swarms which had been brought only the day before, to my establishment.

Before entering upon the natural history of the bee, I shall anticipate some principles in its management, in order to prepare my readers to receive, without the doubts which would otherwise be very natural, the statements in my book, and to convince them that almost any one favorably situated, may safely enjoy the pleasure and profit of a pursuit, which has been most appropriately styled, "the poetry of rural economy;" and that, without being made too familiar with a sharp little weapon, which can most speedily and effectually convert all the poetry into very sorry prose.

The Creator intended the bee for the comfort of man, as truly as he did the horse or the cow. In the early ages of the world, indeed until very recently, honey was almost the only natural sweet; and the promise of "a land flowing with milk and honey," had then a significance, the full force of which it is difficult for us to realize. The honey bee was, therefore, created not merely with the ability to store up its delicious nectar for its own use, but with certain properties which fitted it to be domesticated, and to labor for man, and without which, he would no more have been able to subject it to his control, than to make a useful beast of burden of a lion or a tiger.

One of the peculiarities which constitutes the very foundation, not merely of my system of management, but of the ability of man to domesticate at all so irascible an insect, has never, to my knowledge, been clearly stated as a great and controlling principle. It may be thus expressed.

A honey bee never volunteers an attack, or acts on [27] the offensive, when it is gorged or filled with honey.

The man who first attempted to lodge a swarm of bees in an artificial hive, was doubtless agreeably surprised at the ease with which he was able to accomplish it. For when the bees are intending to swarm, they fill their honey-bags to their utmost capacity. This is wisely ordered, that they may have materials for commencing operations immediately in their new habitation; that they may not starve if several stormy days should follow their emigration; and that when they leave their hives, they may be in a suitable condition to be secured by man.

They issue from their hives in the most peaceable mood that can well be imagined; and unless they are abused, allow themselves to be treated with great familiarity. The hiving of bees by those who understand their nature, could almost always be conducted without the risk of any annoyance, if it were not the case that some improvident or unfortunate ones occasionally come forth without the soothing supply; and not being stored with honey, are filled with the gall of the bitterest hate against all mankind and animal kind in general, and any one who dares to meddle with them in particular. Such radicals are always to be dreaded, for they must vent their spleen on something, even though they lose their life in the act.

Suppose the whole colony, on sallying forth, to possess such a ferocious spirit; no one would ever dare to hive them, unless clad in a coat of mail, at least bee-proof, and not even then, until all the windows of his house were closed, his domestic animals bestowed in some safe place, and sentinels posted at suitable stations, to warn all comers to look out for something almost as much to be dreaded, as [28]a fiery locomotive in full speed. In short, if the propensity to be exceedingly good-natured after a hearty meal, had not been given to the bee, it could never have been domesticated, and our honey would still be procured from the clefts of rocks, or the hollows of trees.

A second peculiarity in the nature of the bee, and one of which I continually avail myself with the greatest success, may be thus stated.

Bees cannot, under any circumstances, resist the temptation to fill themselves with liquid sweets.

It would be quite as easy for an inveterate miser to look with indifference upon a golden shower of double eagles, falling at his feet and soliciting his appropriation. If then we can contrive a way to call their attention to a treat of running sweets, when we wish to perform any operation which might provoke them, we may be sure they will accept it, and under its genial influence, allow us without molestation, to do what we please.

We must always be particularly careful not to handle them roughly, for they will never allow themselves to be pinched or hurt without thrusting out their sting to resent such an indignity. I always keep a small watering-pot or sprinkler, in my Apiary, and whenever I wish to operate upon a hive, as soon as the cover is taken off, and the bees exposed, I sprinkle them gently with water sweetened with sugar. They help themselves with the greatest eagerness, and in a few moments, are in a perfectly manageable state. The truth is, that bees managed on this plan are always glad to see visitors, and you cannot look in upon them too often, for they expect at every call, to receive a sugared treat by way of a peace-offering.

I can superintend a large number of hives, performing every operation that is necessary for pleasure or profit, and yet not run the risks of being stung, which must frequently [29] be incurred in attempting to manage, in the simplest way, the common hives. Those who are timid may, at first, use a bee-dress; though they will soon discard every thing of the kind, unless they are of the number of those to whom the bees have a special aversion. Such unfortunates are sure to be stung whenever they show themselves in the vicinity of a bee-hive, and they will do well to give the bees a very wide berth.

Apiarians have, for many years, employed the smoke of tobacco for subduing their bees. It deprives them, at once, of all disposition to sting, but it ought never to be used for such a purpose. If the construction of the hives will not permit the bees to be sprinkled with sugar water, the smoke of burning paper or rags will answer every purpose, and the bees will not be likely to resent it; whereas when they recover from the effect of the tobacco, they not unfrequently remember, and in no very gentle way, the operator who administered the nauseous dose.

Let all your motions about your hives be gentle and slow. Accustom your bees to your presence; never crush or injure them in any operation; acquaint yourself fully with the principles of management detailed in this treatise, and you will find that you have but little more reason to dread the sting of a bee, than the horns of your favorite cow, or the heels of your faithful horse.

Bees can flourish only when associated in large numbers, as a colony. In a solitary state, a single bee is almost as helpless as a new-born child; it is unable to endure even the ordinary chill of a cool summer night.

If a strong colony of bees is examined, a short time before it swarms, three different kinds of bees will be found in the hive.

1st. A bee of peculiar shape, commonly called the Queen Bee.

2d. Some hundreds, more or less, of large bees called Drones.

3d. Many thousands of a smaller kind, called Workers or common bees, and similar to those which are seen on the blossoms. A large number of the cells will be found filled with honey and bee-bread; while vast numbers contain eggs, and immature workers and drones. A few cells of unusual size, are devoted to the rearing of young queens, and are ordinarily to be found in a perfect condition, only in the swarming season.

The Queen-Bee is the only perfect female in the hive, and all the eggs are laid by her. The Drones are the males, and the Workers are females, whose ovaries or "egg-bags" [31] are so imperfectly developed that they are incapable of breeding, and which retain the instinct of females, only so far as to give the most devoted attention to feeding and rearing the brood.

These facts have all been demonstrated repeatedly, and are as well established as the most common facts in the breeding of our domestic animals. The knowledge of them in their most important bearings, is absolutely essential to all who expect to realize large profits from an improved method of rearing bees. Those who will not acquire the necessary information, if they keep bees at all, should manage them in the old-fashioned way, which requires the smallest amount either of knowledge or skill.

I am perfectly aware how difficult it is to reason with a large class of bee-keepers, some of whom have been so often imposed upon, that they have lost all faith in the truth of any statements which may be made by any one interested in a patent hive, while others stigmatize all knowledge which does not square with their own, as "book-knowledge," and unworthy the attention of practical men.

If any such read this book, let me remind them again, that all my assertions may be put to the test. So long as the interior of a hive, was to common observers, a profound mystery, ignorant and designing men might assert what they pleased, about what passed in its dark recesses; but now, when all that takes place in it, can, in a few moments, be exposed to the full light of day, and every one who keeps bees, can see and examine for himself, the man who attempts to palm upon the community, his own conceits for facts, will speedily earn for himself, the character both of a fool and an impostor.

The Queen Bee, or as she may more properly be called the mother bee, is the common mother of the whole [32] colony. She reigns therefore, most unquestionably, by a divine right, as every mother is, or ought to be, a queen in her own family. Her shape is entirely different from that of the other bees. While she is not near so bulky as a drone, her body is longer, and of a more tapering, or sugar-loaf form than that of a worker, so that she has somewhat of a wasp-like appearance. Her wings are much shorter, in proportion, than those of the drone, or worker; the under part of her body is of a golden color, and the upper part darker than that of the other bees. Her motions are usually slow and matronly, although she can, when she pleases, move with astonishing quickness.

No colony can long exist without the presence of this all-important insect. She is just as necessary to its welfare, as the soul is to the body, for a colony without a queen must as certainly perish, as a body without the spirit hasten to inevitable decay.

She is treated by the bees, as every mother ought to be, by her children, with the most unbounded respect and affection. A circle of her loving offspring constantly surround her, testifying, in various ways, their dutiful regard; offering her honey, from time to time, and always, most politely getting out of her way, to give her a clear path when she wishes to move over the combs. If she is taken from them, as soon as they have ascertained their loss, the whole colony is thrown into a state of the most intense agitation; all the labors of the hive are at once abandoned; the bees run wildly over the combs, and frequently, the whole of them rush forth from the hive, and exhibit all the appearance of anxious search for their beloved mother. Not being able anywhere to find her, they return to their desolate home, and by their mournful tones, reveal their deep sense of so deplorable a calamity. Their note, at such times, more especially [33] when they first realize her loss, is of a peculiarly mournful character; it sounds something like a succession of wails on the minor key, and can no more be mistaken by the experienced bee-keeper, for their ordinary, happy hum, than the piteous moanings of a sick child can be confounded, by an anxious mother, with its joyous crowings, when overflowing with health and happiness.

I am perfectly aware that all this will sound to many, much more like romance than sober reality; but I have determined, in writing this book, to state facts, however wonderful, just as they are; confident that they will, before long, be universally received, and hoping that the many wonders in the economy of the honey bee will not only excite a wider interest in its culture, but will lead those who observe them, to adore the wisdom of Him who gave them such admirable instincts. I cannot refrain from quoting here, the forcible remarks of an English clergyman, who appears to be a very great enthusiast in bee-culture.

"Every bee-keeper, if he have only a soul to appreciate the works of God, and an intelligence of an inquisitive order, cannot fail to become deeply interested in observing the wonderful instincts, (instincts akin to reason,) of these admirable creatures; at the same time that he will learn many lessons of practical wisdom from their example. Having acquired a knowledge of their habits, not a bee will buzz in his ear, without recalling to him some of these lessons, and helping to make him a wiser and a better man. It is certain that in all my experience, I never yet met with a keeper of bees, who was not a respectable, well-conducted member of society, and a moral, if not a religious man.[1] [34] It is evident, on reflection, that this pursuit, if well attended to, must occupy some considerable share of a man's time and thoughts. He must be often about his bees, which will help to counteract the baneful effect of the village inn. "Whoever is fond of his bees is fond of his home," is an axiom of irrefragable truth, and one which ought to kindle in every one's breast, a favorable regard for a pursuit which has the power to produce so happy an influence. The love of home is the companion of many other virtues, which, if not yet developed into actual exercise, are still only dormant, and may be roused into wakeful energy at any moment."

The fertility of the queen bee has been much under-estimated by most writers. It is truly astonishing. During the height of the breeding season, she will often, under favorable circumstances, lay from two to three thousand eggs, a day! In my observing hives, I have seen her lay, at the rate of six eggs a minute! The fecundity of the female of the white ant, is much greater than this, as she will lay as many as sixty eggs a minute! but then her eggs are simply extruded from her body, to be carried by the workers into suitable nurseries, while the queen bee herself deposits her eggs in their appropriate cells.

I come now to a subject of great practical importance, and one which, until quite recently, has been attended with apparently insuperable difficulties.

It has been noticed that the queen bee commences laying in the latter part of winter, or early in spring, and long [35]before there are any drones or males in the hive. (See remarks on Drones.) In what way are these eggs impregnated? Huber, by a long course of the most indefatigable observations, threw much light upon this subject. Before stating his discoveries, I must pay my humble tribute of gratitude and admiration, to this wonderful man. It is mortifying to every scientific naturalist, and I might add, to every honest man acquainted with the facts, to hear such a man as Huber abused by the veriest quacks and imposters; while others who have appropriated from his labors, nearly all that is of any value in their works, to use the words of Pope,

Huber, in early manhood, lost the use of his eyes. His opponents imagine that in stating this fact, they have thrown merited discredit on all his pretended discoveries. But to make their case still stronger, they delight to assert that he saw every thing through the medium of his servant Francis Burnens, an ignorant peasant. Now this ignorant peasant was a man of strong native intellect, possessing that indefatigable energy and enthusiasm which are so indispensable to make a good observer. He was a noble specimen of a self-made man, and afterwards rose to be the chief magistrate in the village where he resided. Huber has paid the most admirable tribute to his intelligence, fidelity and indomitable patience, energy and skill.

It would be difficult to find, in any language, a better specimen of the true Baconian or inductive system of reasoning, than Huber's work upon bees, and it might be studied as a model of the only true way of investigating nature, so as to arrive at reliable results.

Huber was assisted in his investigations, not only by Burnens, but by his own wife, to whom he was engaged before the [36] loss of his sight, and who nobly persisted in marrying him, notwithstanding his misfortune, and the strenuous dissuasions of her friends. They lived for more than the ordinary term of human life, in the enjoyment of uninterrupted domestic happiness, and the amiable naturalist scarcely felt, in her assiduous attentions, the loss of his sight.

Milton is believed by many, to have been a better poet, for his blindness; and it is highly probable that Huber was a better Apiarian, for the same cause. His active and yet reflective mind demanded constant employment; and he found in the study of the habits of the honey bee, full scope for all his powers. All the facts observed, and experiments tried by his faithful assistants, were daily reported to him, and many inquiries were stated and suggestions made by him, which would probably have escaped his notice, if he had possessed the use of his eyes.

Few have such a command of both time and money as to enable them to carry on, for a series of years, on a grand scale, the most costly experiments. Apiarians owe more to Huber than to any other person. I have repeatedly verified the most important of his observations, and I take the greatest delight in acknowledging my obligations to him, and in holding him up to my countrymen, as the Prince of Apiarians.

My Readers will pardon this digression. It would have been morally impossible for me to write a work on bees, without saying at least as much as this, in vindication of Huber.

I return to his discoveries on the impregnation of the Queen Bee. By a long course of experiments most carefully conducted, he ascertained that like many other insects, she is fecundated in the open air, and on the wing, and that the influence of this lasts for several years, and probably for life. He could not form any satisfactory conjecture, as [37] to the way in which the eggs which were not yet developed in her ovaries, could be fertilized. Years ago, the celebrated Dr. John Hunter, and others, supposed that there must be a permanent receptacle for the male sperm, opening into the passage for the eggs called the oviduct. Dzierzon, who must be regarded as one of the ablest contributors of modern times, to Apiarian science, maintains this opinion, and states that he has found such a receptacle filled with a fluid, resembling the semen of the drones. He nowhere, to my knowledge, states that he ever made microscopic examinations, so as to put the matter on the footing of demonstration.

In January and February of 1852, I submitted several Queen Bees to Dr. Joseph Leidy of Philadelphia, for a scientific examination. I need hardly say to any Naturalist in this country, that Dr. Leidy has obtained the very highest reputation, both at home and abroad, as a skillful naturalist and microscopic anatomist. No man in this country or Europe, was more competent to make the investigations that I desired. He found in making his dissections, a small globular sac, not larger than a grain of mustard seed, (about 1/33 of an inch in diameter,) communicating with the oviduct, and filled with a whitish fluid, which when examined under the microscope, was found to abound in spermatozoa, or the animalculæ, which are the unmistakable characteristics of the seminal fluid. Later in the season, the same substance was compared with some taken from the drones, and found to be exactly similar to it.

These examinations have settled, on the impregnable basis of demonstration, the mode in which the eggs of the Queen are vivified. In descending the oviduct to be deposited in the cells, they pass by the mouth of this seminal sac or spermatheca, and receive a portion of its fertilizing contents. Small as it is, its contents are sufficient to impregnate [38] hundreds of thousands of eggs. In precisely the same way, the mother wasps and hornets are fecundated. The females alone of these insects survive the winter, and they begin, single-handed, the construction of a nest, in which, at first, only a few eggs are deposited. How could these eggs hatch, if the females which laid them, had not been impregnated, the previous season? Dissection proves them to have a spermatheca, similar to that of the Queen Bee.